FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Hanson-Young v Leyonhjelm (No 4) [2019] FCA 1981

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The matter is adjourned to Monday 2 December 2019 at 2:15pm (ACDT) in Adelaide for submissions with respect to interest, the application for injunctive relief and costs.

2. There be liberty to the parties to appear at that hearing by videolink.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

WHITE J:

[1] | |

[17] | |

[20] | |

[30] | |

[34] | |

[35] | |

[36] | |

[38] | |

[48] | |

[49] | |

[52] | |

[66] | |

[69] | |

[81] | |

[100] | |

[104] | |

[106] | |

The reliability of the accounts of the witnesses of the applicant’s interjection | [113] |

[122] | |

[135] | |

[141] | |

[143] | |

[144] | |

[145] | |

[148] | |

[151] | |

Some residual matters regarding the defence of justification | [177] |

[180] | |

[181] | |

[184] | |

[191] | |

[211] | |

[213] | |

[215] | |

[221] | |

[224] | |

Common law, qualified privilege and the Lange extended privilege | [236] |

[237] | |

[239] | |

[249] | |

[251] | |

[252] | |

[253] | |

[255] | |

[257] | |

[269] | |

[286] | |

[293] | |

[296] | |

[321] | |

[327] | |

[347] | |

[354] | |

[364] | |

[372] | |

[378] | |

[386] | |

[390] | |

[394] | |

[403] | |

[406] | |

[407] | |

[408] |

1 In 2018, both the applicant and the respondent were members of the Senate in the Australian Parliament. The applicant was then, and is now, a member of The Australian Greens political party elected as a Senator for the State of South Australia. The respondent was a member of the Liberal Democrats political party, and until 1 March 2019, an elected Senator for the State of New South Wales.

2 The applicant alleges that she was defamed by statements made or published by the respondent on four occasions:

(a) in a media statement published by the respondent on a blogging platform, Medium.com, on 28 June 2018 and republished on 29 June 2018 on the respondent’s personal Facebook Page and on the Facebook Page of the Liberal Democrats;

(b) in the Sky News Australia program “Outsiders” broadcast on 1 July 2018 which was republished on 1 July 2018 on the Sky News Australia website, on 10 July 2018 on YouTube and on 11 July 2018 by the respondent himself;

(c) in the “Sunday Morning” program of Radio 3AW broadcast on 1 July 2018; and

(d) in the ABC program “7.30 with Leigh Sales” broadcast on 2 July 2018, which was republished later that same day on the ABC website, the ABC News Facebook Page and the ABC News Twitter page.

3 The applicant alleges that each of the second, third and fourth publications of the respondent conveyed the following defamatory meanings:

(i) the applicant is a hypocrite in that she claimed that all men are rapists but nevertheless had sexual relations with them;

(ii) the applicant had, during the course of a Parliamentary debate, made the absurd claim that all men are rapists; and

(iii) the applicant is a misandrist, in that she publicly claimed that all men are rapists.

4 In relation to the first publication published on 28 and 29 June 2018, the applicant alleges that it conveyed the first and second of these meanings only.

5 The applicant claims damages, including aggravated damages, in respect of the defamatory publications alleged as well as injunctive relief.

6 The defence of the respondent to the applicant’s claim underwent some development and refinement as the proceedings progressed.

7 The filed defence of the respondent did not admit that he had “published” any of the four publications of which the applicant complains. Instead, the respondent admitted that he had “disseminated” the media statement on or about 28 June 2018 by “posting it” on the Medium.com website and that he “spoke and thereby disseminated” the words identified as spoken by him in each of the second, third and fourth publications of which the applicant complains. However, in the trial, the respondent did not dispute that he had published each of the impugned matters. In any event, that was established by the evidence. The respondent admitted, for example, that his interviews on the Sky News and Radio 3AW programs were “live” and that he had known at the time of each that the interview would be broadcast live on the Sky News Channel and on Radio 3AW respectively. He can be taken in these circumstances to have known of the further publication of his words as that was the natural and probable consequence of his conduct.

8 In his filed defence, the respondent denied that any of his publications had conveyed the meanings alleged by the applicant. However, in the opening submissions at the trial, senior counsel for the respondent accepted that the imputations conveyed were as “averred” by the applicant. He said, however, that his statements had not defamed the applicant.

9 The filed defence of the respondent raised the following substantive defences:

(a) justification under s 25 of the Defamation Act 2005 (NSW) (the Defamation Act) and its State and Territory counterparts;

(b) qualified privilege under both s 30 of the Defamation Act and its State and Territory counterparts and under the common law;

(c) extended qualified privilege (the so-called Lange defence) to which the respondent referred as “constitutionally protected free speech”;

(d) honest opinion under s 31 of the Defamation Act and its State and Territory counterparts; and

(e) fair comment on a matter of public interest;

10 However, in his opening submissions at trial, the respondent withdrew the defences of honest opinion and fair comment on a matter of public interest. Moreover, in closing submissions, senior counsel conceded that, if the respondent’s defence of statutory qualified privilege did not succeed, he could not advance any basis on which the defences of common law qualified privilege and the Lange defence could succeed. Senior counsel then accepted that it was not necessary for the Court to deal with those two defences if the defence of statutory qualified privilege failed.

11 The respondent contended that, if defamatory meaning was established and his substantive defences failed, the applicant should be awarded only “nominal or derisory damages”. His filed defence contained pleadings said to support this conclusion.

12 In addition to his substantive defences and the position just mentioned concerning damages, the respondent pleaded that, by reason of the publications impugned by the applicant being either a repetition of, or responsive to, statements made by the applicant and him in the Senate Chamber, they could not be adjudicated upon in this Court without infringing s 16 of the Parliamentary Privileges Act (1987) (Cth) (the PP Act). That being so, he contended that the Court should, in the exercise of a discretion, stay the proceedings permanently. For reasons which will become apparent, the application of s 16 of the PP Act and the respondent’s application for a permanent stay were argued in the trial itself.

13 Accordingly, the issues in the trial were:

(a) does s 16(3) of the PP Act mean that the Court cannot hear all the evidence and submissions otherwise appropriate in the proceedings and, if not, should the Court grant a stay of the proceedings?

(b) are the admitted imputations defamatory of the applicant?

(c) if so, has the respondent established the defence of justification?

(d) alternatively, has the respondent established the defence of statutory qualified privilege?

(e) if these issues are resolved in favour of the applicant, what are the damages to which she is entitled?

14 Because the provisions in the Defamation Act are the model law provisions which are replicated in the Defamation Acts or provisions concerning defamation in the other States and Territories, I will hereafter refer only to the Defamation Act.

15 I indicate now my satisfaction that the conduct of the proceedings did not involve an infringement of s 16(3) of the PP Act and that a permanent stay of the proceedings on that basis is not appropriate. It is convenient, however, to address the other issues in the trial before expressing my reasons for that conclusion.

16 For the reasons which follow, I am satisfied that:

(a) the imputations admitted by the respondent to have been conveyed by the impugned matters were defamatory of the applicant;

(b) the respondent has not established the substantive defences of justification or statutory qualified privilege; and

(c) the applicant is entitled to an award of damages in the aggregate sum of $120,000.

17 The Court directed that the evidence in chief of each witness, including of the parties, be provided by way of affidavit. The respondent’s affidavit was made on 11 December 2018. The applicant objected to numerous paragraphs within that affidavit and the Court directed senior counsel to confer with a view to seeing whether agreement for the resolution of the objections could be achieved. Following that conferral, the parties informed the Court that they were agreed that the objections with respect to [18]-[46] of the respondent’s affidavit should, with one or two exceptions which are not presently material, be addressed in final submissions. The respondent’s affidavit was then received into evidence on that basis.

18 However, in the final submissions, neither counsel sought a ruling on the objections. Counsel for the applicant submitted only that the Court could take the view that it did not need to decide the objections because, having regard to the content of the impugned paragraphs, it could decide to give them no weight. Counsel for the respondent did not contend that all of the paragraphs to which objection was taken should be received. The position is unsatisfactory. The Court should have been told those paragraphs on which the respondent sought to rely and, in the event that the applicant persisted with an objection to them, a ruling sought.

19 I resolve this unsatisfactory state of affairs in this way. The only paragraphs of the respondent’s affidavit on which counsel for the respondent relied in closing submissions were [12], [21]-[22], [27]-[29], [49]-[51] and [54]-[56]. I uphold the applicant’s objection to [49]-[51] (save for a passage in [49] which was admitted as evidence only of the respondent’s belief) and overrule the applicant’s objection with respect to the remaining paragraphs to which objection was taken and on which the respondent relied in the closing submissions. I indicate now that I have attached relatively little weight to those paragraphs, preferring instead to rely on the oral and documentary evidence received in the trial. I have not received the remaining paragraphs in the respondent’s affidavit to which the applicant took objection. Even had I admitted them, I would have attached little, if any, weight to them.

20 Thursday, 28 June 2018 was the last sitting day of the Senate before it adjourned for the winter recess. The Senate commenced sitting at 9.30 am.

21 At about midday, the Senate moved to consideration of motions put forward by individual Senators. One such motion was from Senator Anning. It is reported in Hansard under the heading “Prevention of Violence Against Women”. The motion proposed that the Senate note certain matters and accept that “access to a means of self-protection by women in particular would provide greatly increased security and confidence that they will not become just another assault, rape or murder statistic”.

22 The motion then proposed that the Senate call on the Australian Government:

(i) to allow the importation of pepper spray, mace and tasers for individual self-defence, and

(ii) to encourage state governments to legalise and actively promote carrying of pepper spray, mace and tasers by women for political protection.

23 Part of the context in which Senator Anning moved his motion was the rape and murder of Ms Eurydice Dixon in the early hours of 13 June 2018, which had been the subject of considerable public, media and political attention.

24 Three Senators were granted leave to speak for one minute on Senator Anning’s motion. These were Senator McGrath (an Assistant Minister to the Prime Minister), Senator Rice (Australian Greens) and Senator Chisholm (Australian Labor Party), who spoke in that order. All three Senators spoke against the motion. The Senate divided on the vote on the motion, with five supporting it and 46 opposed. The respondent was one of the five in the minority.

25 The respondent pleads that, at or shortly before the conclusion of the speech of Senator Rice, the applicant, by an interjection, made a claim “which was tantamount to a claim that all men are responsible for sexual assault or that or all men are rapists”. The applicant denies that she made a claim to that effect. She accepts that she made an interjection but says that the words she used were “putting tasers on the street isn’t going to make women safer from men”.

26 The question of whether the applicant did make a claim to the effect alleged by the respondent is at the heart of the issues in the case. The Court heard evidence from a number of witnesses concerning the words spoken by the applicant and it is sufficient at this stage to say that there was little unanimity amongst them. It is also pertinent to note that the applicant accepted that, if the respondent proved that she had made the claim that “all men are rapists”, then his defence of justification would be made out and that her claim in defamation must fail.

27 It was common ground that, shortly after the disputed interjection of the applicant, the respondent had interjected by saying “you should stop shagging men, Sarah”. At the conclusion of the vote on Senator Anning’s motion, the applicant approached the respondent and asked him to confirm what he had said. The respondent confirmed that he had made the interjection just referred to. The applicant then called the respondent “a creep” and he told her to “fuck off”.

28 The applicant reported the respondent’s statements to the Leader of the Australian Greens, Senator Di Natale. He in turn reported the matter to the President of the Senate. The President spoke to the respondent but he declined to withdraw his statement concerning the applicant “shagging men”.

29 Later that day, the applicant was granted leave to make a short statement to the Senate. In that statement, she referred to the respondent’s comment to her and the events which followed it. She expressed her disappointment that the respondent had refused to apologise to her and called on him to do so.

The respondent’s media statement of 28 June 2018

30 Later on 28 June 2018, the respondent posted a media statement onto the blogging website “Medium.com”. It commenced with the Australian Coat of Arms and underneath had the heading:

SENATOR DAVID LEYONHJELM

Leader of the Liberal Democrats

31 The balance of the media statement was as follows (with the line referencing added for ease of later reference):

5 | In the Senate this afternoon my colleague Senator Fraser Anning moved that the Australian Government lift the ban on the importation of non-lethal methods of self-defence such as pepper sprays, mace and tasers and for state governments to be encouraged to actively promote such devices to women for their personal protection. |

10 | The defeat of the motion 46 votes to 5 was disappointing. The recent spate of horrific crimes against women has shocked us all. |

Greens Senator Janet Rice spoke against this motion. During her speech fellow Greens Senator Sarah Hanson-Young interjected, saying something along the lines of all men being rapists. | |

15 | I responded by suggesting that if this was the case she should stop shagging men. |

I did not yell at her. | |

Following the division, Senator Hanson-Young approached me and called me a creep. | |

20 | I told her to fuck off. |

Leader of the Greens Senator Richard Di Natale subsequently approached me and said he planned to report my comments to the president. | |

The president subsequently advised me to withdraw my comments and apologise. | |

25 | I informed the president I would not be doing this. |

I do not agree with Senator Hanson-Young’s sentiments about all men being rapists and I believe I have the right to voice my opinion accordingly. That Senator Hanson-Young took offence from my comments is an issue for her, not me. | |

However, I am prepared to rephrase my comments. | |

30 | I strongly urge Senator Hanson-Young to continue shagging men as she pleases. |

Meanwhile, the rest of the Senate will return to the business of voting down all common-sense proposals that might make society a safer place for women to exercise their right of freedom of movement. | |

Media: Kelly Burke [phone number provided] | |

(Emphasis in the original) |

32 On or about 29 June 2018, the respondent republished the media statement on his personal Facebook Page by posting a link to the statement on the Medium.com website.

33 On the same day, the respondent republished, or caused to be republished, the same media statement on the Facebook Page of the Liberal Democrats by similarly posting a link to the statement on the Medium.com website.

The Sky News Australia program “Outsiders”

34 On the morning of Sunday 1 July 2018, the respondent participated in an interview on a program on Sky News entitled “Outsiders”. The hosts of the program were a Mr Dean and a Mr Cameron. The transcript of the relevant portion of the Outsiders program is as follows (with the line numbering added for ease of later reference):

5 10 | MR DEAN: | “And welcome back to Outsiders you’re with Ross Cameron and Rowen Dean. And we’re very excited to have on Outsiders the great Senator David Leyonhjelm who is of course of the Liberal Democrats. Senator David you have caused, you know you’re in the headlines again you are, you’re worse than Ross. You grab these headlines, you outrage everybody, this time you made some comments last week about Sarah Hanson-Young that got her very upset and you suggested that she stop shagging men.” |

15 | “Now when I heard this Senator, I immediately thought you were enforcing Malcolm Turnbull’s anti-bonking ban! And this is of course we know nowadays in Canberra the Prime Minister has said there will be no no way in which attractive female staffers are allowed to bonk their Ministers even if they think that they are going to do well out of it. They’re not allowed to do that anymore.” | |

MR CAMERON: | “… and unattractive as well …” | |

20 | MR DEAN: | “Yes un-attractive as well. It’s all banned, bonking is all banned in Canberra that’s the safest thing. So when Senator David Leyonhjelm said in Parliament in the Senate the other day, Sarah Hanson-Young stop shagging men, I thought well of course! What else would you tell her to do? What other advice, but tell us the real story what happened David?” |

25 30 35 40 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “It was in a Motion to consider self-defence. There was a Motion calling on the Government to make it possible for women to protect themselves, thinking in terms of the Eurydice Dixon case or even the Jill Meagher case, and there was the Green’s Senator Janet Rice was making a one minute statement which suggested that it was all men and that men need to change their behaviour and so forth. Sarah called out, I don’t know the exact words because there was a lot of chatter going on, but it was to the effect of, ‘men should stop raping women’, the implication being all men are rapists. Now Sarah’s, this is not a criticism, but Sarah is known for liking men. The rumours about her in Parliament House are well known, so I just said ‘well stop shagging men then Sarah’. I mean it just doesn’t make any sense if you think they’re all rapists why would you shag them? So she took great offence at that which is her problem not my problem. In retrospect I, you know, um she um, she has a right to shag as many men as she likes I don’t care you know … but she took great offence, she came and called me a creep, I told her to … am I allowed to say the F word on TV?” |

45 | MR DEAN: | “We’d prefer not, Sunday morning, I mean we’ve got a religious audience as Ross was explaining earlier.” |

SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “Well you don’t have to be religious to avoid …” | |

MR DEAN: | “Mind you Ross liberally sprinkles the F word around, but look we’ll pass on the F word but we get it, we get the gist of what you are implying.” | |

50 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “Well I told her to make love in another place …” |

MR DEAN: | “Ok …” | |

SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “and so she lodged a complaint.” | |

55 60 | MR DEAN: | “OK so the bigger issue here ok, so jokes aside, and personalities and all that aside it’s always very easy for, we had Malcolm Turnbull came out, and obviously we had the Dixon murder is horrific but we had straight after it we had Malcom Turnbull coming out and saying words to the effect of ‘men must change what’s in their hearts’, men, not that man – the accused man/murderer or not some men but MEN. We had Daniel Andrews made a similar statement ‘men must change their behaviour’ and Adam Bandt also said ‘men must change their behaviour’.” |

65 70 | “So there’s this broad collective idea David that somehow all men are guilty of these crimes unless men as a collective, as a group, change what it is about us these crimes will continue and this is the Prime Minister, the Victoria leader and the Green’s idiot all saying the same thing and so Sarah Hanson-Young was picking up on the idea that all, or allegedly, that all men are rapists was the sort of thing she was saying. You objected to that. Talk us though it”. | |

75 80 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “That’s right. I mean if I had said, or somebody had said all women are sluts the outrage would have been monumental. It would have been called misogyny and it would have been criticised and called out, and rightly so. You know you shouldn’t really say that sort of thing. The male version of that is misandry. I don’t think it’s any less forgivable. If you say all men are rapists or all men do anything, that’s misandry. It’s equally as objectionable as misogyny and yet we have these leading politicians sort of more or less rolling over and saying yes I am a male therefore I am guilty. You know it is the equivalent of this male privilege, white privilege even straight gender privilege issue that because you are something which you have no control over therefore you have inherited guilt.” |

85 | MR DEAN: | “Well, lets just have a quick look at where the whole misogyny caper began. We will take a quick little look at our former Prime Minister putting misogyny not only onto the national but the global table if you like.” |

… | ||

95 | MR DEAN: | “So Julia Gillard went on to make an entire career and a multi-million dollar salary package out of this misogyny thing and we are still hearing about it from Hilary Clinton and others. You are saying misandry is the one that you are putting on the table now?” |

100 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “Yes it is.” |

MR DEAN: | “Will we get the David L.... ‘We will not be lectured on misandry by this woman Senator Hanson Young’.” | |

105 110 115 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “Well yes I mean I think it’s time for at least us alpha males to stand up and say that this is not legitimate, it is not more legitimate than misogyny. If you want to go apologising for your gender, apologising for your colour, apologising for something you have no control over, then you’re not my kind of a guy and I think the rest of us should stand up for ourselves. And in any case we are talking about collectivism v individualism. I am an individualist, libertarians are individualists, we don’t judge people based on the group they belong to. We are all individuals we don’t see colour we don’t even see gender particularly other than that men are from Mars and women are from Venus argument and we take people as individuals and this idea that because you belong to a certain social grouping or an ethnic grouping or racial grouping that you can be defined by that and that you have inherited guilt as a consequence of that is obnoxious. Those of us who think for ourselves anyway.” |

… |

The 3AW “Sunday Morning” program of 1 July 2018

35 A transcript of the interview between the respondent and Mr Nick McCallum (NM) and Ms Rita Panahi (RP) on the Sunday Morning program on Radio 3AW is as follows (again with the lines added for ease of later reference):

NM: | “Fairly heated discussion during the week, wasn’t it?” | |

5 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “Good morning, oh yes, yes, it got a little bit heated, yes. The, um, offence industry was, er, in full swing. So, er, feelings, feelings run high.” |

10 15 | NM: | “But, Senator my argument was, that we’re talking Parliament here, so if, if you come back and I am not a huge fan of Senator Hanson-Young and I know she is an offender in many things but in this particular case when you are actually having a serious discussion and you were discussing you know violence against women and you were trying to give women the opportunity to have pepper spray and lasers, so it’s a serious topic so when you use language like stop shagging men to the Senator that downgrades Parliament but also downgrades a very serious topic. That was my point.” |

20 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “You, you do know what I was responding to don’t you?” |

25 | NM: | “Yes I do and you claim that she said something like, all men are rapists, but her spokesperson actually says that she said, “putting tasers on the streets is not going to protect women from men”. So there is a very big difference in what she says she said and what you claim she said.” |

30 35 40 | SENATOR DAVID LEYONHJELM: | Yeah, I was there and, er, there was, er, very much a, or well along the lines of what Daniel Andrews and several others have commented said commented (sic)subsequent to the rape and murder of Eurydice Dixon, that it is a, a men’s responsibility, men have to change their behaviour. Um, I don’t remember the precise words but I, it was near enough to men having to stop raping women, um, implication being all men are rapists or, you know, that was the definite meaning. Now, um er, that’s misandry. Um, it’s the male version, or the equivalent of misogyny, it’s, um, not forgivable under any circumstances in my view, now Sarah is a normal healthy woman and, um er, straight as well, um, and um yet I can’t see, I-I-I, the double standards involved in saying on the one hand, all men are rapists, or inferring all men are rapists” |

NM: | “But she didn’t say that Senator, you know she didn’t say that” | |

45 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “You, you weren’t there Nick,” |

NM: | “I know I wasn’t but” | |

SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “I was there” | |

50 | NM: | “But you know, and you’re not even saying that she said ‘all men are rapists’ say, you are saying something like that,” |

SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “So, so because I don’t quote the precise words therefore you believe her, is that what you are saying?” | |

55 | NM: | “Well, no, well you can’t tell us, her spokesperson said. She said ‘putting tasers on the streets isn’t going to protect’” |

RP: | “Her spokesperson also put out a” | |

NM: | “Women from men” | |

60 | RP: | “You did clarify the statement Senator, you came out and, er, I thought you were going to apologise but” |

[SENATOR LEYONHJELM LAUGHS] | ||

RP: | “But um it wasn’t really an apology was it?” | |

65 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “Absolutely not, no, no actually what I said, the only thing I said, was that she could shag as many men as she likes” |

RP: | “as she pleases” | |

70 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “if she pleases, yes, so um, I mean, my, my point and I think you are missing that next was that …” |

75 80 | RP: | “but you weren’t slut shaming her? I want to get to that because that’s not on, you can’t be, er, suggesting that someone is a loose women or that she, her personal life is somehow, um, being called, called into question, so I just want to get that, er, clarified because a lot of people when they read that statement and weren’t, er you know, aware of the exchange, whatever it was to the lead up, immediately looked at that and thought this is a Senator slut shaming a woman and that’s just not on” |

SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “Well that would be misogyny” | |

RP: | “that would be misogyny,” | |

85 90 95 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “Um, how-, what I was referring to was the double standards on the one hand saying all men are responsible for the violence that occurred to Eurydice Dixon, on the other hand having relationships with men as she does and it is well known for, not that I am critical of that, um so that is the double standards that, er, I was concerned about, I am also concerned about the misandry. I don’t think it is legitimate, er, any more legitimate to be a misandrist than it is to be a misogynist and, er, I was calling that out as well. I, I also take exception to this idea that there is some kind of collective responsibility for men, or women for that matter, um it’s er for bad things that happen” |

… | ||

135 140 | RP: | “and society looks at those crimes and, ah er, is appalled by them, we do not have a culture that either turns a blind eye or tolerates violence against women, so let’s get that straight. but I want to go back, I spoke, I asked you before about slut shaming, and whether, the statement you said could be interpreted that way and that not being on and you agreed slut shaming is misogyny but then you did have a bit of a dig there when you said, you know, Sarah Hanson-Young is known for having lots of relationships with men” |

SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “No” | |

145 | RP: | “having relationships with lots of men, again, I mean that to me could be seen as” |

SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “I think you are putting words in my mouth Rita” | |

RP: | “she is known for having relationships with lots of men” | |

150 155 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “She is known for lots of relationships with men, she had a quite famous one with a, with a Liberal member of parliament a few years ago, Barry Haase, now there’s, I am not criticising her for that, she is perfectly entitled to do that, but the double standard” |

RP: | “but when you mention are you, are you, are you kind of” | |

160 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “The double standards are what I am concerned about. You can’t, you can’t on the one hand say or infer all men are rapists and on the other hand have relationships with men, so my comment was to the stop shagging men then otherwise you are being, er, you are being hypocritical. That was the point of my comment, that it wasn’t slut shaming, and um …” |

165 170 | NICK MCCALLUM: | “Do you regret, do you regret senator that whatever the, the circumstances, this debate has actually detracted from an important debate that you were debating at the time and that is whether women should be allowed to have pepper spray or tasers.” |

SENATOR DAVID LEYONHJELM: | “No I don’t think, I don’t agree …” | |

175 | NICK MCCALLUM: | “And its totally, totally distracted because that was an important debate and your, you know, stop shagging men and, and and wherever she said, she claims one thing you say another, that it’s the whole important debate has now been hijacked and this is what we’re talking about” |

180 | SENATOR DAVID LEYONHJELM: | “No, I don’t agree. If it hadn’t been for this um, the fact that she, er um um, she went to the President and er made an issue out of this, um unfortunately, regrettably, the issue of self-defence for women, and indeed for all people, would have er dropped off, off the agenda” |

… | ||

245 250 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “Sarah is, Sarah is known for, er well outrageous speech in fact some of her stuff goes onto Hansard. One day, in chamber there was a, um, issue about immigration Michaelia Cash, … this was a year or so ago, Michaelia Cash was the um member, ah – the Minister representing the Minister for Immigration and always, and Sarah was representing the Greens on immigration on an issue and Sarah called out to um Michaelia Cash ‘why don’t you just build some gas chambers for them …” |

RP: | sigh | |

255 260 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “referring to the immigrants on Manus Island and er, um, er um Nauru. I mean, you know, Sarah is known for absolutely outrageous stuff and to not believe that she would say words to the effect that all men are rapists is naïve in the extreme ….. she did, I was there and I heard her and now she is entitled to say that but I am entitled to react as well and I am entitled to call out misandry and I am entitled to point out double standards and that’s what I was doing. |

… | ||

285 290 295 | SENATOR DAVID LEYONHJELM: | “I replied, I-I-I rejected the double standard, I rejected, I reject the misandry, just as I reject misogyny and there is an issue which um as, er, a consequence of this dispute, is being kept alive and that is our government prevents women and indeed everybody, from carrying any means to protect themselves, any self-defence um device, pepper spray, tasers, pocket knives, anything at all, lethal, non-lethal, or prohibited, you can be arrested for carrying it, so Eurydice Dixon if she had been carrying anything, a pepper spray, um a taser, mace, um a pocket knife anything like that, er specifically for self-defence, she would have been committing a very serious offence, they are er, they are regarded as prohibited weapons. Er I think that is outrageous,” |

NM: | “Now we have to move on, Senator David Leyonhjelm thanks for joining us, er enjoy the rest of your Sunday at 12 to 12.” | |

The ABC “7.30 with Leigh Sales” program – 2 July 2018

36 A transcript of the respondent’s interview with Ms Virginia Trioli on the ABC 7.30 program on Monday 2 July 2018 is (relevantly) as follows:

5 10 15 | MS TRIOLI: | “Now politics is often a grubby business of name-calling, back-stabbing and buffoonery but even by those standards, Parliament hit a new low last week. You might remember during a Senate debate Senator David Leyonhjelm called out across the chamber to Senator Sarah Hanson-Young for her to quote “stop shagging men”. That was during a debate about protecting women in the form of pepper spray and tasers. Senator Hanson-Young later went up to Senator Leyonhjelm and asked him if he said what she thought he had. He confirmed that he had told her to stop shagging men and he also told her to ‘F-off’. Senator Leyonhjelm doesn’t dispute her version of events. But in media interviews afterwards, he didn’t apologise and he went further airing more rumours about the Senator. He’s been roundly condemned for that but he’s not backing down, I spoke to him a short time ago …” |

MS TRIOLI: | “Senator David Leyonhjelm, welcome to 7:30.” | |

SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “Thank You.” | |

20 | MS TRIOLI: | “Ahhh, Senator Hanson-Young has engaged lawyers ahead of a potential defamation action for you and others, we understand. Would you like to take this opportunity to withdraw those comments you made and apologise for them?” |

25 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “No, no … Bring it on” |

MS TRIOLI: | “Why not? Why won’t you withdraw them?” | |

30 35 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “Because the point I was trying to make is, is valid, I’m on very solid ground, very legitimate. Um I am opposed to misandry just as I am opposed to misogyny and I am also entitled to call out double standards. So, arguing on the one hand that, um er, all men, um are evil, the enemy, um rapists, er sexual er sexual predators and then on the other hand having a normal relationships with men obviously is contradictory and I can call it out.” |

MS TRIOLI: | “So, um, give me the quote from Senator Hanson-Young where she said any of those things that you just mentioned there “all men are rapists” and the like. Where’s the quote?” | |

SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “I, I was there…It wasn’t caught on Hansard. I was in the Chamber, it was in the context of a great deal of, of backchat going on …” | |

5 | MS TRIOLI: | “I understand Senator that you actually can’t really recall exactly what it was that she said.” |

10 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “I can recall the, the context, it was in the context of a self-defence motion, it was in the context of a one-minute statement by Senate Janet Rice to the effect that men are collectively are responsible for the violence and it was, er, Senator Hanson-Young called out words very similar, or if not identical, to “If only men would stop raping women” or “all men are rapists” or words to that effect …” |

15 | MS TRIOLI: | “No they’re, they’re not the same thing but as we’ve established and I think you’ve admitted that you don’t exactly remember and she certainly denies saying those things” |

SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “She …” | |

20 | MS TRIOLI: | *interrupts* “but in any case, in any case … Do you, do you you see, as it would seem virtually everyone in Australia sees right now, how offensive, how inappropriate and hurtful those remarks are? Or do you, do you simply not see that?” |

25 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “Um offence is taken personally, misandry is offensive and I take offence at that …” |

MS TRIOLI: | “We’ll leave misandry to one side, do you see …” | |

30 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | *interrupts* “No, no let’s not take it, take it to to one side …” |

MS TRIOLI: | “No because we’re dealing, we’re dealing with something that actually happened in the, in the Senate. Do you, do you …” | |

35 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | *interrupts* “Yes I was there and it was offensive.” |

40 | MS TRIOLI: | *interrupts* “Do you, do you accept that those comments that you made were inappropriate to be made to a woman and in, in the Senate chamber?” |

SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “No.” | |

5 | MS TRIOLI: | “So, how is it that you can sit here and say that but I imagine if that comment was made to any women in your family, I should imagine that you’d take a very different view, wouldn’t you?” |

SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “No, no woman in my family would accuse all men of being sexual predators.” | |

10 | MS TRIOLI: | “And neither did Sar-, Senator Sarah Hanson-Young. You certainly can’t produce that quote and she certainly denies it.” |

SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “So you believe her and you’re calling me a liar? Thank you very much.” | |

15 | MS TRIOLI: | “No I’m saying that you actually can’t remember, you’ve, you’ve said that you can’t exactly remember what she said.” |

SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “and, and do I have to …” | |

20 | MS TRIOLI: | *interrupts* “and, and you give me words to the effect that range across a number of different scenarios …” |

SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “Do I have to remember every word precisely for it to be true?” | |

MS TRIOLI: | “In order to justify a pretty strong comment, yeah I reckon you do …” | |

25 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “No, I don’t reckon I don’t …” |

30 | MS TRIOLI: | “Um, I’ve ever wondered if you’ve ever paused to reflect on why you sometimes have such a reflex to get so personal, and frankly bitchy, when women take you on. Have you ever stopped and wondered about that?” |

SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “I don’t accept the premise of your question.” | |

35 | MS TRIOLI: | “Let me say, tell you what its based on … its based on comments that you made to Senator Sarah Hanson-Young, its made on comments you made to an elderly woman once who criticised you and you told her to quote “Go away and stop proving you’re a bimbo”. I’d say those two examples constitute a reflex to get pretty bitchy with women, why do you think that is?” |

SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “Well, er, let me, er, let me put it this way. When I am abused, accused of something such as being a sexual predator, along with all the other, all the other men in Australia …” | |

5 | MS TRIOLI: | “I’m going to jump in there, I don’t think anyone accused you of that but go on …” |

10 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “Yes, no, well you weren’t there, I was … um and, er, when, when people irrespective of their age, irrespective of their gender, write obnoxious e-mails to me and the woman who wrote that did, um I feel that I am perfectly entitled to respond …” |

MS TRIOLI: | *interrupts* “I guess Australia will …” | |

15 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “I don’t, I don’t …” |

MS TRIOLI: | *interrupts* “I guess Australia will form its own view on that, time is tight so we’ll have to leave it there. Senator, thank you.” | |

20 | SENATOR LEYONHJELM: | “Thank you.” |

37 There was no dispute at trial about the accuracy of the three transcripts.

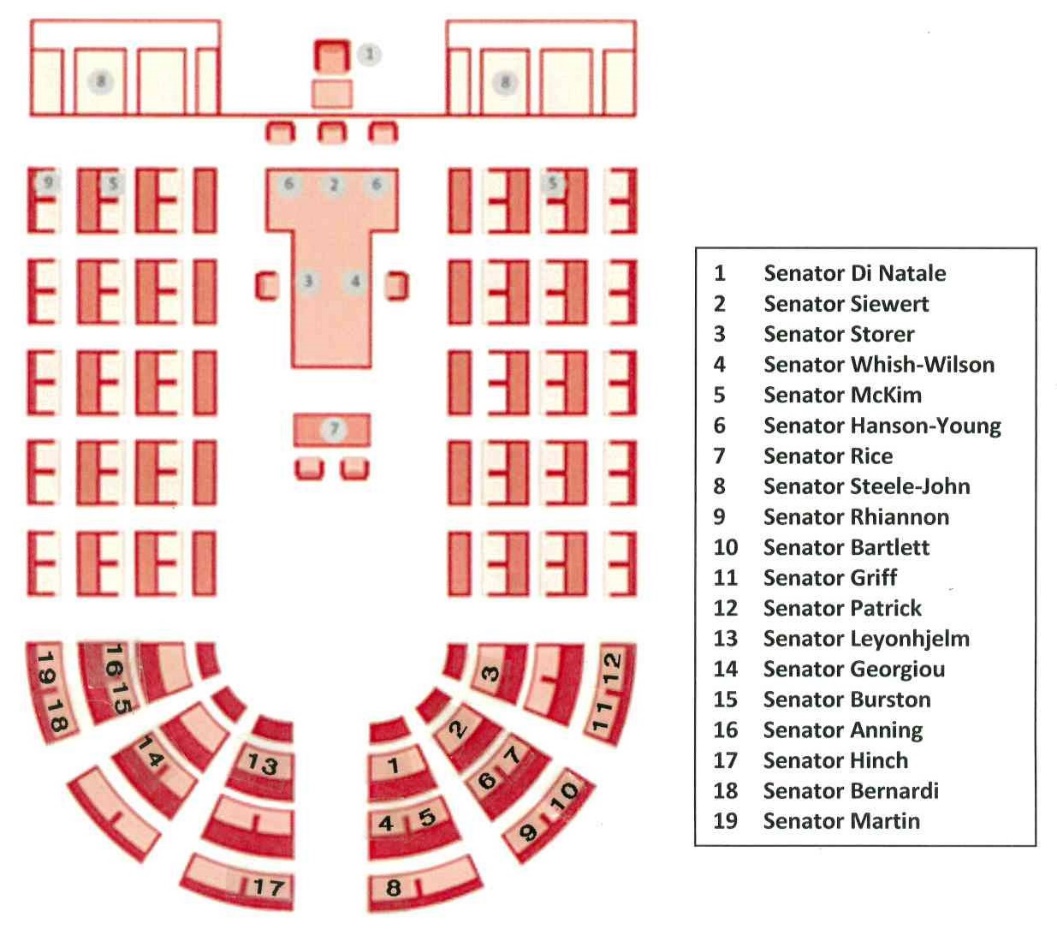

38 Apart from the applicant and the respondent, the Court heard evidence from eight Senators. Of these, five (Senators Siewert, Whish-Wilson, Rice, McKim and Steele-John) are members of the Australian Greens party. The remaining three Senators were Senator Keneally (Australian Labor Party), Senator Griff (Centre Alliance) and Senator Hinch (Independent). The latter two Senators were called to give evidence by the respondent. The remainder were called by the applicant.

39 With the exception of the applicant, the respondent and Senator Keneally, the evidence of the other Senators concerned principally the words spoken by the applicant in her interjection on 28 June 2018, although some also gave evidence of subsequent events.

40 In addition to leading evidence concerning that issue, the applicant led reputation evidence from her Chief of Staff (Ms Marion Gerlaud), Mr Bill Kelty and Dr Katriona Wylie.

41 The respondent submitted that the Court should have reservations about the credibility of the evidence of the applicant, Senators Keneally, Siewert, Rice and Steele-John and of Ms Gerlaud.

42 The applicant submitted that the Court should have doubts about the credibility of much of the respondent’s evidence and that Senator Griff’s evidence seemed to reflect his reconstruction of what must have been said, rather than an account of what he had actually heard.

43 I consider that all of the witnesses were endeavouring to assist the Court by giving their evidence honestly. However, I regarded the evidence of some of the witnesses who gave evidence about the applicant’s interjection in the debate on 28 June 2018 as being more reliable than that of others.

44 Senator Keneally was a member of the Legislative Assembly in New South Wales from 2003 to 2012 and the Premier of that State from 2009 to 2011. Between 2014 and 2018, she worked as a journalist and presenter at Sky News Australia. The Senator’s evidence in chief concerned matters relating to the applicant’s reputation, but her cross-examination extended to matters more broadly. I assessed her evidence as being both honest and reliable and, despite the criticisms made by the respondent, accept it.

45 Mr Kelty is a former Secretary of the Council of Australian Trade Unions and has held several senior directorships. He too was an impressive witness and, save for one matter, I accept his evidence generally,

46 I regarded the evidence of Ms Gerlaud and Dr Wylie as generally reliable.

47 I indicate now that, despite the submissions of the respondent, I regarded the evidence of Senators Siewert, Rice, McKim and Whish-Wilson as reliable and I accept it. For reasons which will become apparent, there is an aspect of Senator Steele-John’s evidence which I do not accept. Senator Siewert’s evidence concerning the events in the Senate on 28 June 2018 was particularly impressive and I have relied on it in making my findings as to the words spoken by the applicant.

48 The respondent accepted that each of his publications conveyed the imputations alleged by the applicant. However, he denied that they were defamatory of the applicant.

49 There was little difference between the parties as to the principles to be applied in the determination of the issues of defamatory meaning. The principles concerning the question of whether a publication did convey the meanings alleged have been stated and summarised in numerous authorities. Given the respondent’s acknowledgement that his publications did convey the imputations pleaded by the applicant, it is not necessary to refer to them in detail. It is sufficient to refer to Radio 2UE Sydney Pty Ltd v Chesterton [2009] HCA 16, (2009) 238 CLR 460 at [5]-[6]; John Fairfax Publications Pty Ltd v Rivkin [2003] HCA 50, (2003) 201 ALR 77 at [26]; Reader’s Digest Services Pty Ltd v Lamb [1982] HCA 4, (1982) 150 CLR 500 at 505-6; Amalgamated Television Services Pty Ltd v Marsden [1998] NSWSC 4, (1998) 43 NSWLR 158 at 164-5, and Rush v Nationwide News Pty Ltd (No 7) [2019] FCA 496 at [70]-[85].

50 In determining whether imputations conveyed are defamatory of an applicant, the Court considers whether the publication had a tendency to lead ordinary reasonable people to think less of the applicant: Radio 2UE Sydney Pty Ltd v Chesterton at [5]. Ordinary reasonable people for this purpose are those “of ordinary intelligence, experience, and education”, “not avid for scandal” and “fair-minded”: ibid at [6]. They are expected to bring to the matter in question their general knowledge and experience of worldly affairs: ibid. In times past, they have been referred to as “right thinking members of society”: Slatyer v Daily Telegraph Newspaper Co Ltd [1908] HCA 22, (1908) 6 CLR 1 at 7 (Griffith CJ); Sim v Stretch [1936] 2 All ER 1237 at 1240.

51 In Trkulja v Google LLC [2018] HCA 25; (2018) 263 CLR 149, the High Court said in respect of the capacity of a published matter to defame:

[31] The test for whether a published matter is capable of being defamatory is what ordinary reasonable people would understand by the matter complained of. In making that assessment, it is necessary to bear in mind that ordinary men and women have different temperaments and outlooks, degrees of education and life experience. As Lord Reid observed in Lewis v Daily Telegraph Ltd, "[s]ome are unusually suspicious and some are unusually naive". So also are some unusually well educated and sophisticated while others are deprived of the benefits of those advantages. The exercise is, therefore, one of attempting to envisage a mean or midpoint of temperaments and abilities and on that basis to decide the most damaging meaning that ordinary reasonable people at the midpoint could put on the impugned words or images considering the publication as a whole.

[32] As the Court of Appeal of England and Wales observed in Berezovsky v Forbes Inc, that exercise is one in generosity not parsimony. The question is not what the allegedly defamatory words or images in fact say or depict but what a jury could reasonably think they convey to the ordinary reasonable person; and it is often a matter of first impression. The ordinary reasonable person is not a lawyer who examines the impugned publication over-zealously but someone who views the publication casually and is prone to a degree of loose thinking. He or she may be taken to "read between the lines in the light of his [or her] general knowledge and experience of worldly affairs", but such a person also draws implications much more freely than a lawyer, especially derogatory implications, and takes into account emphasis given by conspicuous headlines or captions. Hence, as Kirby J observed in Chakravarti v Advertiser Newspapers Ltd, "[w]here words have been used which are imprecise, ambiguous or loose, a very wide latitude will be ascribed to the ordinary person to draw imputations adverse to the subject".

(Citations omitted)

52 Counsel for the respondent emphasised the importance of context in assessing the presence or absence of defamatory meaning. He submitted that what is defamatory of one person may not be defamatory of another and that what may be defamatory coming from the mouth of one person, may not be defamatory when coming from the mouth of another.

53 These propositions are undoubtedly correct. Words which may diminish the standing of one person in the minds of ordinary reasonable people may not diminish the way those people view another: Berkoff v Burchill [1996] 4 All ER 1008. To adopt the example given by counsel for the applicant, to say of most people that they play the violin badly is not likely to be defamatory, but to say it of a concert violinist may be a serious slur. This is why the tort of defamation focuses on the effect on the reputation of the particular applicant.

54 Counsel then submitted that, just as a form of words may be defamatory of a particular applicant but not defamatory of persons generally, so also may a form of words which would be defamatory of “a typical plaintiff” not “tend to lower a particular – and relevantly atypical – plaintiff in the public’s esteem”. In the present case this meant, he said, that account had to be taken of the “political brand” which the applicant has established, with the consequence that ordinary reasonable people would not have regarded the admitted imputations as defamatory of her, even if they would, had the same imputations been conveyed in respect of others. The respondent also contended that, in addition to considering the applicant and her “political brand”, account had also to be taken of his status as a rival politician.

55 In support of the respondent’s submission that the identity of the person making the impugned statement bears on the determination of whether a defamatory meaning is conveyed, counsel contended that ordinary reasonable people may view differently a statement made of a politician by a rival politician than they would the same statement made by, say, a member of the media. He submitted that ordinary reasonable persons may see media commentators as “relatively impartial “umpires” of politics”, such that adverse statements made by them about a politician may more readily be regarded as tending to diminish the politician’s standing in the public mind. However, a like statement by a rival politician may be regarded by ordinary reasonable persons as “just part of the theatre of politics”. Right thinking ordinary members of the community, he submitted, are not only “capable of discounting what one politician says about another”, they are “apt to do so”.

56 Counsel submitted that, in the present case, ordinary reasonable people who saw or heard the impugned matters would know that the applicant and the respondent were both politicians; that they generally held different policy positions; that when they did happen to hold the same policy positions, they did so for very different reasons; that their bases of support did not overlap; and that the respondent’s impugned statements were made in a political environment in which politics has become more aggressive than in the past.

57 A related submission of the respondent was that the applicant had, before 28 June 2018, made public statements about men which he contended were absurd, consistent with an attitude of misandry and (when measured against her own actions) hypocritical. Counsel referred in this respect to two public statements of the applicant. The first was a Twitter post of the applicant on 11 December 2016, in the context of a debate about whether women who are victims of domestic violence should be granted leave from their employment:

Note to Minister: It would be even cheaper on the economy if men just stopped hitting women, but sadly they won’t!

58 The second was the applicant’s appearance on the “Sunrise” program on 18 June 2018 in which she referred to men as “pigs” and “morons” and said that “men cannot control themselves and deal with their own issues”.

59 Counsel then submitted that by reason of these statements the applicant had, as at 28 June 2018, established a political identity as a person who made “sweeping, collectivist statements about men”, and “in which she imputed to men truly horrible traits and actions against women”. In this circumstance, the respondent submitted that his publications were not capable of “shifting” the applicant’s image, because they were consistent with it. The consequence, he contended, was that the imputations conveyed by the impugned matters had not been defamatory of the applicant.

60 The respondent made other submissions. One was that each of the impugned statements had conveyed a “promiscuity imputation” which the applicant had not sued on. The respondent’s submissions did not specify the content of the “promiscuity imputation”. It seemed to be the imputation that the applicant is sexually promiscuous conveyed by the respondent’s statements in the impugned matters concerning the applicant “shagging” men, that the applicant had a reputation for “liking” men, and that the applicant is known for having “lots of relationships” with men. The respondent submitted in relation to the first and fourth impugned matters that the material conveying the pleaded imputations had been “drowned out” by material going to the “promiscuity imputation”. He also submitted that, if the “promiscuity imputation” was put to one side, each of the impugned matters was “relatively anodyne”. A related submission was that each publication, taken as a whole, was “a relatively weak expression of the (pleaded) imputations”.

61 In relation to the first impugned matter, apart from his “drowning out” submission, the respondent submitted that the words spoken by the applicant were not the focus of the article but were expressed as a contextual matter explaining why the respondent made his own interjection. That may be so, but it does not detract from the force of the sting in the two imputations which the respondent admits were conveyed.

62 In relation to his statements on the Sky News Outsiders program, the respondent submitted that he had in the course of the interview:

(a) explained the context in which the interjection by the applicant was said to have occurred;

(b) moved quite swiftly away from discussion of the applicant’s words to discussing the broader issues said to arise from them;

(c) focussed primarily on the topic of equality, and repeatedly returned the conversation to that topic such that the focus on the imputations against the applicant was minimised. A related submission was that in that interview, he had been the “adult in the room” and had largely resisted the overtures of his hosts to dwell predominantly on the imputations;

(d) eventually moved to discussing the substance of the motion that was before the Parliament when the relevant exchange occurred, with the effect that the focus on the pleaded imputations was minimised further;

(e) criticised the “46 other senators” who voted against Senator Anning’s motion, such that the focus on the applicant was diminished; and

(f) did not resort to extravagant language which highlighted the imputations.

63 In relation to the statements on the 3AW Sunday Morning program, the respondent said that he had:

(a) focussed in large part upon the issue of equality and had put the imputation of misandry in that broader context;

(b) discussed the surrounding debate about the issue of self-defence and had stressed its importance relative to the imputations; and

(c) stated that Australians speak in colourful terms, thereby diminishing the significance which might otherwise be given to the words imputed to the applicant.

64 In relation to his statements on the ABC’s 7.30 with Leigh Sales program, the respondent submitted that he had:

(a) focussed largely upon “the promiscuity imputation”, such that the pleaded imputations were largely “drowned out”; and

(b) put forward the relevant comments in a hostile and sceptical environment and under intense interrogation by his interviewer, such that viewers were encouraged to be sceptical of the imputations.

65 Finally, the respondent submitted that the “relative mildness” of the publications was assisted by the fact that he had not, in any of the publications, attributed precise words to the applicant and had in fact conceded at all times that he was not in a position to do so. The respondent then submitted that, as his attribution to the applicant of certain words was at the heart of each imputation, this approach had carried “less sting” than a precise quote would have.

66 The assessment of whether the admitted imputations had the defamatory effect on the applicant should take account of a number of matters. These include the words used and the context in which they were spoken.

67 Two matters may be noted at the outset. First, it can be said that each of the imputations admitted by the respondent to have been conveyed was, of its nature, of a kind which could lead ordinary reasonable people to think less of the applicant. The first conveyed that the applicant was engaging in a particular form of hypocrisy; the second that the applicant had made a claim which was plainly absurd; and the third that the applicant was engaging in a serious form of sexism, namely, misandry, which the respondent characterised as “offensive” and “not forgivable”.

68 Secondly, although the respondent described each of the impugned matters as “anodyne” and as a “relatively weak expression of the (pleaded) imputations”, he did not contend that the imputations had to satisfy a threshold of seriousness of the kind discussed in Jameel (Yousef) v Dow Jones & Co Inc [2005] EWCA Civ 75, [2005] QB 946 and in Thornton v Telegraph Media Group Ltd [2010] EWHC 1414 (QB), [2011] 1 WLR 1985. See also Lachaux v Independent Print Ltd [2019] UKSC 27 and Armstrong v McIntosh (No 2) [2019] WASC 379, both of which were delivered after judgment in this matter had been reserved. Nor did the respondent raise a defence of triviality under s 33 of the Defamation Act. In these circumstances, I consider that the weakness, if any, for which the respondent contended is to be considered in assessing whether the imputations were defamatory at all. Otherwise, “relative weakness” is not an issue which arises on the issue of defamatory meaning. The relative seriousness of the imputations may, however, be relevant to the other issues in the trial, including the question of the relief which may be appropriate.

Defamatory meaning and politicians

69 The respondent gave evidence in support of his contention concerning the public perception of the political differences between the applicant and him. The evidence of Senator Keneally supported that evidence in some respects and I consider that, at least at a general level, the respondent’s submission on this topic may be accepted. I do not consider it necessary to make detailed findings concerning the political and philosophical differences between the Liberal Democrats and the Australian Greens, or between the respondent and the applicant. It is sufficient to say that I accept that many ordinary reasonable people who read, saw or heard the impugned matters are likely to have been aware that there were differences. Counsel submitted that in these circumstances, ordinary reasonable persons who saw or heard the impugned matters were unlikely, on the basis of the respondent’s statements, to have formed an unfavourable view of the applicant.

70 The authorities support the view that, given the public perception of the robustness of political activities, a derogatory remark about a politician may not have the same effect in the mind of the ordinary and reasonable listener as it may if made about someone else. For example, in Gorton v Australian Broadcasting Commission (1973) 22 FLR 181, Fox J said at 189:

The finding of a derogatory imputation is not an end of the matter; it must have been such as to affect adversely the reputation of the plaintiff. A person in public office expects to be, and is, frequently the subject of comment and criticism, and not a little of that comment or criticism is of a personal nature. Sometimes a slur is cast on his honesty, or integrity. The television viewer recognises these things. The result is that criticism and comments made of public figures are apt to have less impact than similar remarks made of others.

71 In Australian Consolidated Press Ltd v Uren [1966] HCA 37; (1966) 117 CLR 185 at 210, Windeyer J noted that “a man who chooses to enter the arena of politics must expect to suffer hard words at times” and Menzies J at 195 noted that “[p]olitical differences not infrequently find public expression in unrefined figures of speech and language”.

72 The applicant herself referred to the robust nature of politics in the booklet “En Garde” which she published on 1 October 2018. At page three of that booklet, the applicant said:

Politics is, by its nature, a tough gig and therefore not for the faint-hearted. The increasingly rigorous debate about ‘values’ means things in and around parliament often become intensely passionate and personal. I’ve always given as good as I get – debating issues and pushing for the ideas I believe in. I’ve never been too shy to say I agree or disagree with something. So, I’m used to the rough and tumble, but that doesn’t mean I like it or that it’s easy. While I’m talking about what we can do to make this country better, I’m constantly preparing for the insults to start flying.

73 The evidence indicates that the applicant is an active participant in the “rough and tumble” of politics. She has at times referred to fellow politicians as a “racist bigot”, as “corrupt” and as “supporting white supremacists”.

74 I accept that account is to be taken of the circumstance that, whether desirable or not, it is commonplace in political discourse for denigratory remarks to be made by one politician about another. The political give and take can be less than civil. Ordinary reasonable people may be taken to be aware that that is so and, at least to an extent, are likely to attach less significance to castigations by politicians of political opponents. Perhaps for this reason, the instances of one politician suing another for defamation tend to be infrequent. But there are examples, of which Rann v Olsen [2000] SASC 83; (2000) 76 SASR 450 (to which the respondent referred in relation to s 16(3) of the PP Act) is one.

75 It is not the case, however, that a politician’s reputation in the minds of ordinary reasonable people is not capable of being diminished by the harsh or derogatory words of another politician. Quite plainly it can and there are numerous instances of that having been achieved effectively (often without becoming the subject of defamation proceedings). The law recognises that politicians may be as entitled to protection from damage to their reputations as any other member of society. As was noted in Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (1997) 189 CLR 520 at 568:

The protection of the reputations of those who take part in the government and political life of this country from false and defamatory statements is conducive to the public good. The constitutionally prescribed system of government does not require – to the contrary, it would be adversely affected by – an unqualified freedom to publish defamatory matter damaging the reputations of individuals involved in government or politics.

(Citations omitted)

76 In Australian Consolidated Press v Uren at 195, Menzies J said:

[A] politician is no doubt entitled to compensation for any loss of reputation brought about by an earthy political libel.

77 As the respondent acknowledged, there are numerous instances of politicians succeeding in defamation proceedings against media entities: Uren v John Fairfax & Sons Pty Ltd (1966) 117 CLR 118; Gorton v ABC; Costello v Random House Australia Pty Ltd (1999) 137 ACTR 1; Conlon v Advertiser-News Weekend Publishing Co Pty Ltd [2008] SADC 91; Hockey v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 652, (2015) 237 FCR 33; and Mirabella v Price [2018] VCC 650. In each of these cases, the politician plaintiffs had established that their reputations in the eyes of reasonable ordinary people had been damaged by the impugned statements.

78 In my view, the ordinary reasonable reader, viewer or listener of the impugned matters would have appreciated that the applicant and the respondent were politicians and that their personal and political views were commonly opposed. They would take into account that political discourse can be robust and that personal denigration in the cut and thrust of politics is not uncommon. Many ordinary reasonable people have their own political views and convictions and may not be influenced, whether positively or negatively, by statements concerning a politician about whom they have already formed a view. I accept the submission of the respondent to that extent.

79 However, common experience indicates that the ordinary reasonable person does make assessments of the character of a politician, irrespective of the political party to which the politician belongs. Those assessments are often made progressively, as the person learns more about the politician. In doing so, the ordinary reasonable person does take into account the nature and content of the castigations of opposing politicians.

80 It is also commonplace for ordinary reasonable persons to have respect for the character and integrity of politicians whose political views they do not share. Mr Kelty gave examples from his own participation in political and governmental life of this being so. A reputation for integrity is part of a politician’s stock-in-trade which, even taking account of the robustness to which Fox J referred in Gorton v ABC, can be damaged by defamation. Some of the respondent’s submissions and evidence overlooked this fact as they seemed to have as an implicit premise that an imputation concerning a politician will be defamatory only if it causes a listener to change his or her support for that politician. Such a premise is unsound. It is overly simplistic to think that a politician’s reputation may not be lowered in the eyes of ordinary reasonable people simply because they do not share that politician’s political views. There are, in any event, many ordinary reasonable people with no fixed political views, sometimes referred to as “swinging voters”. In addition, those with no existing view about a politician are likely to be influenced by what they see and hear and, in particular, by the criticisms made of a politician. Moreover, those within the same political party as the subject of the imputations may form a lesser view of the politician by reason of defamatory imputations. The respondent’s binary position that ordinary reasonable people, seeing, hearing or viewing his statements would not be influenced in the views of the applicant because they would have existing firm views about her, whether favourable or unfavourable, is unsound.

Assessment of defamatory meaning – general

81 There is little doubt that the impugned matters did convey the “promiscuity imputation” for which the respondent contended. It is not necessary to attempt to identify more precisely the content of that imputation. Amongst other things, it seemed to be reflected in the reference in the third impugned matter to the respondent having “slut-shamed” the applicant.

82 The respondent’s submission did not explain why the “promiscuity imputation” had the “drowning out” effect for which he contended. The ordinary reasonable person is likely to have been struck by the apparent uncouthness in the respondent’s comments that the applicant should “stop shagging men”, had a “liking” for men, and has had “lots of relationships” with men but such a reader is likely at the same time to have understood the sting in his attribution to the applicant of double standards, sexism and absurdity. Moreover, the “promiscuity imputation” and the imputation that the applicant is a hypocrite were very much interlinked as the latter depended on the former, and the ordinary reasonable person would have understood that to be so. It was, as the respondent would have it, that the applicant is sexually promiscuous with men, and that she was thereby guilty of double standards, ie, hypocrisy. Instead of drowning out the other imputations, the “promiscuity imputation” is likely to have drawn the attention of readers, listeners and viewers to the admitted imputations. This was a point which Ms Panahi seemed to make to the respondent in the Radio 3AW Sunday Morning program.

83 In my opinion, the respondent’s attempt to give a relatively benign view of the impugned matters is belied by their content.

84 In relation to the first imputation, the respondent put his claim concerning the applicant’s hypocrisy at the centre of his statements. In the Radio 3AW Sunday Morning program, he referred on no less than eight occasions to the “double standards” or “hypocrisy” in the applicant’s statements and conduct. In his very first contribution on the Sky News Outsiders program, the respondent drew attention to the inconsistency he perceived in the applicant’s “liking” of men and the statement which he attributed to her. In addition, he asked the rhetorical question “if you think they’re all rapists why would you shag them?” The respondent referred again to the applicant’s double standards in the ABC 7.30 with Leigh Sales program and emphasised the contradiction he saw in the applicant having said that all men are rapists or sexual predators, on the one hand, and the applicant’s engagement in normal sexual relationships with men, on the other. In his media statement on 28 June 2018, the respondent sought to justify his statement that the applicant should stop “shagging men” if she considered that all men are rapists. As counsel for the applicant submitted, the ordinary reasonable reader of that statement would have understood the respondent to be asserting that the applicant’s position was inconsistent and hypocritical: why does she sleep with men if she believes that all men are rapists?

85 In relation to the misandrist imputation, it was the respondent who introduced the word “misandry” into the impugned matters. He did so by contrasting misandry with misogyny. Commencing at line 73 of the Sky News Outsiders program, the respondent described a statement that “all women are sluts” as misogyny which would have been “rightly” criticised. He then identified “misandry” as the male version of misogyny and described it as “equally as objectionable”. The respondent thereby made it plain that he was attributing to the applicant an objectionable form of sexism. The ordinary reasonable viewer would have understood the respondent to be conveying that the applicant engaged in a form of sexism of an offensive kind and, further, that she did so hypocritically. Although the respondent did not mention the word “misandry” thereafter in the Outsiders program, he did by its use provide one of the significant themes for his interview as the term was then adopted by his hosts. In the Radio 3AW interview, the respondent characterised the statement which he attributed to the applicant (“all men are rapists”) as “misandry” and used that expression or a cognate on no less than five occasions. He again described misandry as “the male version, or the equivalent of misogyny” and said that it was “not forgivable under any circumstances”. The respondent insisted that he was entitled to call it out. In the interview of the ABC 7.30 with Leigh Sales program, the respondent twice referred to misandry, describing it as “offensive” and rejected Ms Trioli’s suggestion that it be put to one side in the interview.

86 Moreover, the respondent defended the credibility of his claims. When challenged in the Radio 3AW program and on the ABC 7.30 program as to whether the applicant had actually said the words which he regarded as offensive, the respondent insisted that he was correct because he had been there to hear the words, and his interviewer had not. The implicit assertion was that he should be believed on his account.

87 In my opinion, the very persistence with which the respondent conveyed the imputations of hypocrisy and misandry and his insistence when challenged that the applicant had spoken the words which he attributed to her belies his characterisation of the imputations as “anodyne”. The respondent acknowledged in his cross-examination that accusing an Australian Senator of sexism and hypocrisy were serious allegations, although he said that both were regular events, and that he regarded an accusation of sexism as more serious than an accusation of hypocrisy.

88 The submission that the imputations conveyed by the media statement on 28 June 2018 are anodyne and weak fails to have regard to its context. The respondent published the media statement as a serious document in that he published it under the Australian Coat of Arms, announced himself as a Senator, described himself as the leader of the Liberal Democrats, and identified the applicant as the subject matter of the statement. The fact that the respondent chose to use this “official” means of making the statement would have suggested to the ordinary reasonable reader that the respondent was intending a serious statement concerning the applicant.

89 The respondent is correct in submitting that the focus of the Sky News Outsiders program moved from the applicant’s statement to the issue characterised by him as “collectivism v individualism”. But that shift in focus did not negate the defamatory effect of the words used by the respondent which had preceded it. The respondent not only made the imputations of which the applicant complains, he sought to justify them. His reference to the “collectivism v individualism” debate was part of that justification. In that context, the latter part of the interview served to reinforce the making of the imputations.

90 The respondent’s submission that he had been the “adult in the room” on the Sky News program seemed to imply that there had been a certain juvenile quality about the interview. Counsel elaborated this submission by saying that, whereas the two “professional journalists” had chosen “to focus on sensational aspects of the matter”, the respondent had sought to “steer” the interview to “considerations of principle”. It is not necessary for the Court to express any view about the respondent’s assessment of the character of the interview. One thing which is plain is that, as already noted, it was the respondent who introduced the notions of hypocrisy and misandry and then sought to justify them. This would have reinforced his imputations in the minds of the ordinary reasonable viewers.

91 The respondent’s characterisation of the tone of Ms Trioli’s interview with him on the ABC 7.30 with Leigh Sales program as “hostile and sceptical” has some force. I accept that viewers may thereby have been encouraged to be sceptical of the imputations. However, despite the challenges which Ms Trioli made, the respondent chose to persist with them and, as just noted, sought to add credibility to them by his insistence that he had been present to hear the applicant’s comment. The imputations would thereby have been reinforced.

92 I am unable to regard the respondent’s acknowledgement that he could not state the precise words used by the respondent as reducing the defamatory sting of his imputations. If anything, that is a circumstance which may have added to them.

93 It is the fact that, in each of the impugned matters, the respondent had addressed issues other than his imputations concerning the applicant. These included the issues concerning violence against women, the availability to women of means of self-defence and “collectivism v individualism”. The admitted imputations were not the sole subject matter of any of the impugned publications. However, they do not lose their defamatory effect on that account. It is not uncommon for a defamatory imputation to be part of a larger non-defamatory publication. An incidental comment may cause ordinary reasonable people to think less of a person in the same way as a publication dedicated to the same subject matter. In my view, that is the case presently.

94 I do not accept that ordinary reasonable people at 28 June 2018 would have viewed the applicant as a person who made “sweeping, collectivist statements about men” or as a person prone to input to men “truly horrible traits and actions against women”. The first matter on which the respondent relied for that submission, namely, the applicant’s Twitter post of 11 December 2016, made in the context of a discussion about whether women who are victims of domestic violence should have access to paid leave, cannot reasonably be regarded as causing ordinary reasonable persons to have that view of the applicant as at 28 June 2018. First, a considerable period of time had elapsed between the two events. Secondly and in any event, ordinary reasonable persons would have understood the applicant to be referring only to those men responsible for domestic violence, and not to men generally.

95 It is true that in the Sunrise program on 18 June 2018, the applicant did refer to men as “pigs” and “morons” and said that “men cannot control themselves and deal with their own issues”. However, those remarks are to be understood in context. The applicant was then being interviewed about the defacement of the memorial for Ms Eurydice Dixon. The Court was not provided with full details concerning the defacement, but it appears to have been of an offensive kind. It is apparent that the fire service in Melbourne took prompt action to eradicate a principal component of the defacement. Having referred to the conduct of the person or persons responsible, and in fact describing them as “morons”, the applicant then moved to the entitlement of women to feel safe as they engage in ordinary every day activities, whether it be day or night.