FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

DHQ17 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2019] FCA 1975

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | MINISTER FOR IMMIGRATION AND BORDER PROTECTION First Respondent IMMIGRATION ASSESSMENT AUTHORITY Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 25 november 2019 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The appellant is to pay the first respondent’s costs as agreed or taxed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MARKOVIC J:

1 This is an appeal from orders made by the Federal Circuit Court of Australia (Federal Circuit Court) on 7 December 2018 dismissing an application for judicial review of a decision of the second respondent (Authority). The Authority had affirmed a decision of a delegate of the first respondent (Minister) to refuse the grant of a Safe Haven Enterprise (subclass 790) visa (SHEV) to the appellant.

Background

2 The appellant is a citizen of Sri Lanka of Tamil ethnicity and Hindu religion. He travelled from Sri Lanka by boat and arrived in Australia on 18 November 2012 as an unauthorised maritime arrival.

3 On or about 8 April 2016 the appellant applied for the SHEV. The appellant’s reasons for claiming protection, set out in his application, are in summary as follows:

(1) from about the summer of 1997 the appellant was in the village of Palugamam, located near Batticaloa in Eastern Sri Lanka. Sri Lankan government defence forces would surround and enter the village and round up its inhabitants for interrogation in order to extract information about members of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and its activities;

(2) on one occasion approximately 200 people, including the appellant, were taken to a school, divided into groups, their upper bodies were stripped of clothing and they were kept in the sun. The appellant was interrogated by two officers at a time. One officer held his arms behind his back and the other hit him and asked questions about persons thought to be active LTTE members;

(3) in 2000 the appellant travelled to Colombo to stay with his brother and work in his brother’s small jewellery business. He remained in Colombo until 2002, when he moved to the United Arab Emirates (UAE);

(4) the appellant returned to Sri Lanka in 2011 and became active in the Tamil National Alliance (TNA) as a relative was standing as a candidate for the TNA in the 2012 election. His older brothers had been politically active in Tamil freedom movements and the appellant wanted to do something for his country;

(5) the appellant’s activities with the TNA drew the attention of the Karuna Group, pro-Sinhalese agents, groups and paramilitary agencies; and

(6) the appellant considered that he may be in danger or be harmed and he decided to leave Sri Lanka.

4 The appellant claims to fear harm and mistreatment if he were to return to Sri Lanka because, as a single male person of Tamil ethnicity, he would likely face scrutiny from the Sri Lankan government; he was involved with the TNA and political processes in the lead-up to an election; he was associated with a certain person who stood for office in the TNA; his family members have been associated with Tamil independence politics; he was recognised by opposition political groups as having been so associated; and he is fearful of persecution by political entities in Colombo and pro-Sinhalese agents, groups and paramilitary forces in Eastern Sri Lanka given remaining uncertainties there and because opposition political groups recognise his association with the TNA. The appellant claims that he does not consider that he can rely on the Sri Lankan government or its agencies to protect him and fears mistreatment in the form of violence, extortion, abduction and unlawful imprisonment.

5 On 17 November 2016 a delegate of the Minister refused to grant the SHEV.

6 The refusal decision was automatically referred to the Authority for review. On 8 and 16 December 2016 the appellant’s representative provided submissions and additional country information to the Authority (Submissions).

7 On 30 June 2017 the Authority affirmed the delegate’s decision.

Authority’s decision

8 The Authority first addressed the information that was before it. It noted that it had had regard to the material referred to it by the Secretary under s 473CB of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (Act). The Authority also noted that three documents had been withdrawn by the appellant prior to the delegate’s decision, that it accepted that withdrawal and had not given those documents weight or drawn any adverse inference from their removal.

9 The Authority referred to the Submissions and additional country information which accompanied them. As the reports contained in the country information had also been provided to the delegate in a post-interview submission, the Authority did not consider the contents of the Submission to be new information for the purposes of s 473DC(1) of the Act.

10 The Authority also referred to an updated country information report from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade that provided information about the position of Tamils, people linked with the LTTE, persons who departed Sri Lanka illegally and returning asylum seekers. The Authority considered that the report may be relevant to its assessment of the application, that it was new information because it was not before the delegate (who had relied upon an earlier report), and that exceptional circumstances justified its consideration.

11 The Authority then turned to consider the appellant’s claims for protection, summarising them at [8] of its decision record. It accepted that:

(1) the appellant is a single male Hindu Tamil from the Batticaloa district in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka and is a national of Sri Lanka;

(2) two of the appellant’s brothers were LTTE cadres active in the early years of the war, were imprisoned for three years and continued to be monitored by the authorities after their release;

(3) the appellant’s brother was imprisoned for more than 12 months and visited by delegates of the International Committee of the Red Cross during this time;

(4) aside from his brothers’ involvement with the LTTE, no other members of the appellant’s family were engaged in supporting the LTTE or political activity in support of pro-Tamil causes;

(5) the appellant was included as part of a round-up in about 1997 with 200 others who were stripped of their shirts, made to stand in the sun and beaten whilst being interrogated about suspected active LTTE members;

(6) the appellant relocated from Batticaloa to Colombo in 2000, intensified fighting in the East may have formed part of the reason for the move, and he resided there without incident until his departure for the UAE in 2002;

(7) the appellant had a relative who was elected to stand for the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) in the 2012 Eastern Provincial Council election. The appellant’s involvement in supporting his relative’s campaign consisted of organising meetings, pasting posters and canvassing voters for him;

(8) during the course of and arising out of his campaigning for the TULF and TNA candidate, the appellant was the subject of threats and intimidation from people who may have included people aligned with paramilitary groups such as the Karuna Group;

(9) people may have been looking for the appellant in the immediate aftermath of the election until the end of September 2012; and

(10) the appellant departed Sri Lanka illegally and would return as a returned asylum seeker and likely be identified as such. Should he plead guilty he would likely be fined and then be free to go. Such a fine would not amount to serious harm and there was no evidence that detention arrangements are applied in a discriminatory manner.

12 The Authority was not satisfied that:

(1) the appellant’s brothers held any significant rank or senior profile with the LTTE;

(2) people came searching for the appellant at his house after he had left Sri Lanka;

(3) the same people who had intimidated and threatened him in 2012 would resume their adverse interest in him on his return to his village, given that nearly five years had passed since the elections, the political environment had changed and the appellant’s family had not been visited by people searching for the appellant since he left Sri Lanka;

(4) upon returning to Sri Lanka the appellant would be prevented from obtaining employment that would permit him to subsist;

(5) the appellant has a profile with the Sri Lankan authorities for actual or imputed support of the LTTE, or is considered to be a person of interest to members of pro-government parties or paramilitary groups such as the Karuna Group due to his political opinion or his involvement in his relative’s election campaign;

(6) the appellant would be targeted by the Sri Lankan authorities or members of pro-government or paramilitary groups upon his return given the appellant’s profile, country information about changes in Sri Lanka’s political and security landscape, and the reduced influence of paramilitary groups including the Karuna Group;

(7) the appellant would face the intimidation he experienced in 2012 if he returned to Sri Lanka, given the passage of time and that the appellant’s family continues to reside in his village without reports of harassment or further visits from persons looking for him; and

(8) the appellant would be targeted or subjected to processes different to the usual processes upon re-entry to Sri Lanka, given that he does not have a profile for LTTE involvement and would not attract the interest of authorities for his involvement in the 2012 election.

13 At [28] and [32] of its decision record it said:

28 The delegate suggested to the applicant during the visa interview that a number of significant political changes in Sri Lanka have occurred since the applicant’s departure from Sri Lanka that would reduce the risk he would face harm as a result of actual or imputed political opinion and his support for his relative’s campaign in 2012. In particular, he raised that country information indicated that paramilitary groups such as the Karuna Group had lost power and influence and were no longer politically active and that since 2012, Sri Lanka has engaged in relatively peaceful elections, with the TNA now formally leading the Opposition. The delegate indicated that reports about the circumstances in Sri Lanka did not indicate TULF/TNA supporters had been targeted based on their political opinion. The applicant responded by stating that while this may be the status at the moment, there was a chance that the government could change in one to two years, with the previous President coming back into power and the paramilitary groups rising again. I consider the applicant’s concern, while genuine, is speculative at best and I do not consider this concern to undermine or detract from the force of the country information.

…

32 For reasons already stated, I do not consider the applicant has a profile with the Sri Lankan authorities for actual or imputed support of the LTTE, or is considered to be a person of interest to members of pro-government parties or paramilitary groups, such as the Karuna Group, for his political opinion and arising from his involvement in his relative’s election campaign for the 2012 Eastern Provincial Council. Given the applicant’s profile, the country information about the change in Sri Lanka’s political and security landscape and the reduced influence of paramilitary groups, including the Karuna Group, I am not satisfied that the applicant would be targeted by the Sri Lankan authorities or members of pro-government parties or paramilitary groups on return to Sri Lanka. In respect of the individuals who were responsible for intimidating and threatening the applicant during the course of the election campaign and in its immediate aftermath in 2012, given the passage of time and that his family continue to reside in the village and have not reported any harassment or further visits by people searching for the applicant since his departure, I am not satisfied that the intimidation faced by the applicant in 2012 would resume on his return to Sri Lanka.

14 The Authority was not satisfied that the appellant would face a real chance of serious harm due to his being a returned asylum seeker and/or for his illegal departure. Nor was it satisfied, given the appellant’s history and profile, along with country information about Sri Lanka’s political and security situation, that the appellant faces a real chance of serious harm now or in the reasonably foreseeable future.

15 Accordingly, the Authority concluded that the appellant did not meet the requirements of the definition of refugee in s 5H(1) of the Act and did not meet s 36(2)(a).

16 The Authority also considered whether complementary protection obligations were owed to the appellant. At [46] it said:

For the reasons already stated, I have found that there is not a real chance the applicant will face serious harm from the Sri Lankan authorities or from members of pro-government political parties which may include members of paramilitary groups such as Karuna, on return to Sri Lanka due to his Tamil ethnicity and/or because he originates from the Eastern Province, for imputed LTTE involvement due to his familial connections, for his political opinion arising from his support of a TULF/TNA candidate in the 2012 Eastern Province Council elections, or as a returned asylum seeker. As ‘real chance’ and ‘real risk’ involve the same standard, it follows that based on the same information, and for the reasons stated above, I am also satisfied there is no real risk of significant harm on these bases if returned to Sri Lanka.

(footnotes omitted.)

17 The Authority concluded that there was no real risk of significant harm to the appellant if he were returned to Sri Lanka and thus that he did not meet the requirements of s 36(2)(aa) of the Act.

federal circuit court proceeding

18 In his amended application filed on 5 March 2018 the appellant raised three grounds of review before the Federal Circuit Court:

1. In 2012 the applicant assisted a candidate in the Eastern Provincial Council election. The applicant was subjected to intimidation and threats from people during the course of and arising out of his campaigning activities: at [25]. The applicant stated in his SHEV application that his “activities with the Tamil National Alliance ... put [him] at real risk”. The applicant told the Department that he supported the Tamil people in achieving freedom through political means. In the circumstances, an issue for the Immigration Assessment Authority (“the IAA’’) to determine was:

a) whether the applicant would continue to engage in political activities if required to return to Sri Lanka and, if so, whether he faced a real risk of persecution or significant harm as a result; or

b) whether the applicant would be dissuaded from re-engaging in political activities if required to return to Sri Lanka because of his fear of persecution or significant harm.

The IAA failed to deal with this aspect of the applicant’s claims, which is a jurisdictional error.

2. The IAA accepted nearly all of the applicant’s claims, other than his claim that, after arriving in Australia, “people continued to come to his home searching for him for another year but stopped when they knew he had come to Australia”: at [27]. On a fair reading of the IAA’s decision, the IAA had a real doubt as to whether its finding on this material question of fact was correct. The IAA ought to have considered, but failed to consider, the possibility that this claim by the applicant was true. This was a jurisdictional error by the IAA.

3. The IAA failed to consider the applicant’s claims cumulatively. This is a jurisdictional error.

19 The primary judge first addressed grounds 2 and 3.

20 His Honour noted that ground 2 concerned a statement at [27] of the Authority’s reasons that it had considerable doubt that opposing party members would continue to seek out or target the appellant in retaliation for the election result more than a year after the election had passed. His Honour rejected the contention that that statement evinces some doubt in the Authority’s finding of fact and that, in light of the principle in Minister for Immigration & Multicultural Affairs v Rajalingam (1999) 93 FCR 220, the Authority ought to have considered the possibility that the appellant’s claim was true. The primary judge observed that it is not the case that the expression of any doubt whatsoever gives rise to the obligation to consider the correctness or otherwise of other findings of fact or claims made by an applicant. He found that the doubt expressed by the Authority at [27] of its decision record was another way of expressing disbelief and did not evince the possibility that the Authority might have been wrong in its conclusion about the continued interest in the appellant after the end of the election; it was doubt about the appellant’s claim not the Authority’s conclusion.

21 The primary judge also rejected ground 3 noting that it appeared to be based on the fact that the Authority did not say, in terms, that it had cumulatively assessed the appellant’s claims. The primary judge accepted the Minister’s submission that there was no obligation on the Authority to give a further assessment beyond that already undertaken because of its conclusion that nothing that the appellant had put forward would give rise to ongoing problems on his return to Sri Lanka.

22 The primary judge then turned to consider ground 1, which raised the issue of whether the Authority had made a jurisdictional error because it failed to consider whether the appellant might resume political activity or refrain from such activity out of fear of persecution. The appellant contended that this claim arose on the material.

23 After referring extensively to the authorities, the primary judge considered the material before the Authority, including the application for the SHEV, the interview with the delegate and the Submissions. At [21] the primary judge found that the Authority considered the claim as expressly made, namely that the appellant held a particular political opinion and that he feared harm as a result of that opinion and his involvement in the 2012 election campaign. His Honour then noted that the issue raised was whether the Authority ought to have gone further and assessed the possibility that in the future the appellant would again be involved in election campaigns.

24 The primary judge considered that the matter was finely balanced, noting that, on one hand, the established facts were that the appellant had a political opinion and as an expression of that had engaged in certain political activities. At [23] his Honour said:

There is no question on the Authority’s findings that the applicant maintained his political opinion, and there was no real question that there would in the future be election campaigns. So the question arises from those established facts whether there would be a bridge between the [appellant’s] continued political opinion and those election campaigns. Standing against the argument that the Authority considered the existence of that bridge, is the fact that although the [appellant] was represented by migration agents, that particular claim was never expressly made and quite clearly, the claim was based upon past involvement in such activities.

25 The primary judge concluded that, although finely balanced, the application of the principles explained in AYY17 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2018) 261 FCR 503 (AYY17) dictated the outcome of the case. In light of those principles, the primary judge gave greater weight to the fact that the appellant was represented and, in spite of the articulation of his claim by the delegate, there was no attempt to explain that the claim in fact went further than as expressly made in the application for the SHEV, as reflected in the delegate’s decision. Accordingly the primary judge concluded that the appellant’s possible future involvement in election campaigns was not a claim that was sufficiently raised such that the Authority was required to consider it and thus was not satisfied that the Authority fell into jurisdictional error by reason of failing to consider that possibility.

a single ground of appeal

26 Although the notice of appeal filed on 19 December 2018 raises four grounds of appeal, the appellant only pressed ground 1. That ground is in materially the same terms as ground 1 before the primary judge and provides:

1. In 2012 the applicant assisted a candidate in the Eastern Provincial Council election. The applicant was subjected to intimidation and threats from people during the course of and arising out of his campaigning activities: at [25]. The applicant stated in his SHEV application that his “activities with the Tamil National Alliance ... put [him] at real risk”. The applicant told the Department that he supported the Tamil people in achieving freedom through political means. In the circumstances, an issue for the Immigration Assessment Authority (“the IAA”) to determine was:

a) whether the applicant would continue to engage in political activities if required to return to Sri Lanka and, if so, whether he faced a real risk of persecution or significant harm as a result; or

b) whether the applicant would be dissuaded from re-engaging in political activities if required to return to Sri Lanka because of his fear of persecution or significant harm.

c) The IAA failed to deal with this aspect of the applicant’s claims, which is a jurisdictional error.

The appellant’s submissions

27 The appellant submitted that there were four strands to the primary judge’s ruling: first, the appellant had not expressly articulated that he would be involved in future election campaigns in Sri Lanka; secondly, the delegate had proceeded as if the appellant had nonetheless made such a claim; thirdly, the Authority did not consider such a claim; fourthly, and in accordance with AYY17 at [18] and authority approved therein, the Authority had not been obliged to consider such a claim. The appellant only takes issue with the fourth of those propositions.

28 The appellant relies on the dissenting judgment of Logan J in Hong v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2019] FCAFC 55 (Hong), who the appellant noted preferred not to apply AYY17 in favour of final appellate authority and formally submitted that the decision of the majority in AYY17 is wrong and that Logan J’s dissent is to be preferred. The appellant submitted that the approach of Logan J in Hong would favour his case but, aside from the formal submission, noted that the point need not detain this Court.

29 Subject to the formal submission set out above, the appellant accepts that the primary judge was bound to apply AYY17, as is this Court. However, the appellant submitted that the proper application of AYY17 yields the conclusion that the Authority was obliged to consider matters related to the appellant’s future involvement in election campaigns. The appellant submitted that the majority in Hong identified a dichotomy in AYY17 between claims raised by argument or which clearly emerge from the materials. The appellant contended that his case concerns the second of those limbs and that the primary judge was right to consider that AYY17 requires clear emergence to be based on established facts.

30 The appellant noted that the primary judge referred to the established facts in this case as being the appellant’s past and presently maintained political opinion and past involvement in an election as well as the fact that future elections would occur and submitted that his Honour was right to identify that the established facts for the purpose of AYY17 rose no higher and did not include the indication of a desire on the part of the appellant to participate in future election campaigns or to refrain from doing so.

31 The appellant submitted that as AYY17 recognises, there is no “precise standard to determining whether an unarticulated claim” clearly emerges from the materials, which is why the courts will apply AYY17 in a more forgiving fashion in a case where a party has not been represented when applying for a visa. The appellant contended that it follows that there is no absolute standard of established facts needed for a claim to clearly emerge from the materials, that evidently some established facts are needed but there is not a perfect constitution of established facts required. The appellant said that such a constitution would result in a claim clearly emerging from the materials but, on the other hand, a claim may still so emerge without that being so.

32 The appellant contended that in this case the established facts considered necessary by this Court must be determined in light of the claim which is alleged to fall for assessment and would not be limited to the Authority assessing whether there was a real chance of relevant harm in the event that the appellant would participate in future election campaigns. The appellant submitted that rather, in accordance with settled jurisprudence, it would also be necessary for the Authority to assess whether the appellant would refrain from participating in future election campaigns and would engage in that modification of his behaviour to avoid relevant harm, relying on Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v BBS16 (2017) 257 FCR 111 at [82]-[83], referring to Appellant S395/2002 v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs (2003) 216 CLR 473 (S395) at [43] and [82]. The appellant identified the “perfect constitution of established facts” from which such a claim would clearly emerge as follows:

(1) he had previously held a political opinion and participated in past election campaigns;

(2) he had in the past suffered harm due to his political opinion and activity;

(3) he maintained his political opinion; and

(4) he wished to participate in future election campaigns and feared a real chance of further relevant harm or he would refrain from participating in future election campaigns because he feared a real chance of further relevant harm.

33 The appellant submitted that the established facts required by AYY17 ought to be less than such a perfect constitution and that what might broadly be called an “S395 category of claim” is unusually important. The appellant contended that it is not enough for the Authority, in order to properly consider such a claim, to conclude that the appellant would not participate in future election campaigns but it is also necessary to consider why the appellant would not do so. The appellant submitted that if he were to refrain from doing so because of fear of relevant harm, he would at least ex facie be entitled to the SHEV. The appellant said that an “S395 category of claim”, which is that material to him, is multifaceted and not decided by the bare conclusion that he will refrain from particular conduct in the future.

34 Accordingly the appellant submitted that there were sufficient established facts to have required the Authority to consider an “S395 category of claim” in relation to him. This was because, on the Authority’s own conclusions, he maintained his political opinion in an environment where elections would recur and the complexity and sensitivity of S395 demands that these facts suffice for AYY17 with the result that the Authority failed to consider a claim arising from his case.

consideration

35 The appellant contends that the claim that emerged from the materials before the Authority was not confined to whether he would participate in future election campaigns but also whether he would refrain from participating in future election campaigns because of fear of a relevant harm. In order to consider whether the primary judge fell into error and the claim articulated by the appellant clearly emerged from the established facts it is first necessary to consider the material that was before the Authority.

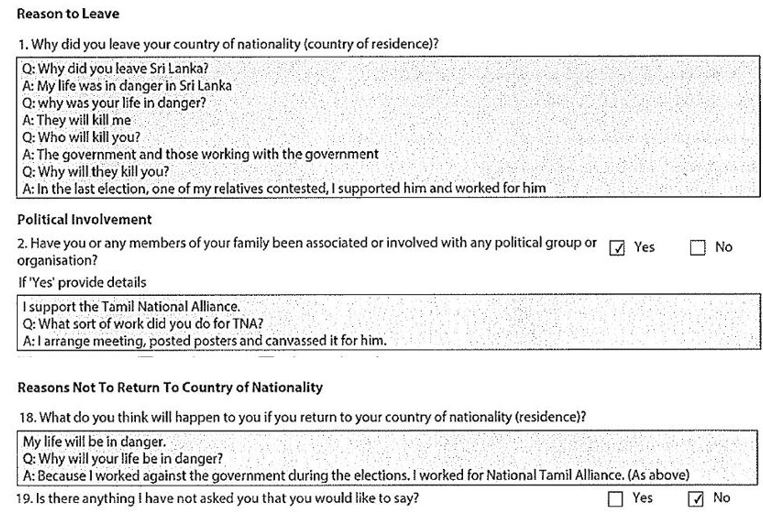

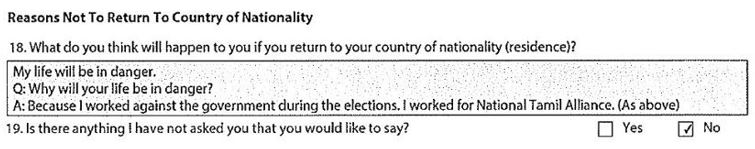

36 The starting point is the appellant’s irregular maritime arrival entry interview form (IMA Interview). On that occasion, the appellant relevantly answered a series of questions as follows:

And:

37 Next is the appellant’s application for the SHEV. At question 89 the appellant was asked why he left Sri Lanka. His response included:

After working in the United Arab Emirates for many years I returned to Sri Lanka in 2011 and became active in the Tamil National Alliance, as a result of a relative standing for this political group. Some of my older brothers had been politically active in Tamil freedom movements, I wanted to do something for my country. My activities with the Tamil National Alliance drew the attention of the Karuna Group, I chose to depart Sri Lanka in order to protect myself as I considered I may be in danger and harmed.

38 At question 90 the appellant was asked what he thought would happen if he returned to Sri Lanka. He responded as follows:

Given the history I have provided in part 89 and given the remaining uncertainties in Eastern Sri Lanka and given that I am a single male person of Tamil ethnicity, and thus would likely face scrutiny and be fearful of persecution in Colombo and Sinhalese. I am fearful of persecution by political entities and I do not consider I can rely on the protection of the government of Sri Lanka or its associated agencies.

My immediate family has experienced significant trauma through the civil war in Sri Lanka and I am well aware of fragilities in security and of guarding personal safety. Political realities are complicated and retribution may be perpetuated for real or even perceived slights. I departed Sri Lanka for nearly a decade to work in the United Arab Emirates and to avoid hostility, fear of persecution, and extortion.

I fear that if I return to Sri Lanka even given the passage of time since the demise of the active LTTE my activities with the Tamil National Alliance and residual splinter groups and paramilitary forces in Eastern Sri Lanka, my home, put me at real risk.

39 At question 94 the appellant was asked if he thought he would be harmed or mistreated if he returned to Sri Lanka. In response, the appellant said:

Yes I consider I will be harmed or mistreated should I return to Sri Lanka. Because I was involved with the Tamil National Alliance and the political processes leading up to the election I am associated with that entity, oppositional political groups recognise my association, and being of Tamil ethnicity I still fall under scrutiny of the Sri Lankan government. Mistreatment in Sri Lanka may come in many forms examples that may happen to me should I return include, voilence [sic] against my person, extortion, abduction and unlawful imprisonment. I am a single Tamil male whose family members have been associated with Tamil independence politics and I am associated with [xx] who stood for office in the Tamil nation alliance.

40 In these responses, both at the IMA interview and in the SHEV application, the appellant did not indicate any intention on his part to participate in future election campaigns or other political activity, or that he wished to do so but would refrain from participating because of a fear of harm.

41 The primary judge also considered the appellant’s SHEV application and, in particular, the answers to questions 89 and 94 set out at [37] and [39] above as the starting point in his analysis of whether the claim as framed by the appellant before him was made.

42 The primary judge then turned to consider the matters raised by the appellant before the delegate. As his Honour observed, when asked by the delegate about his involvement with the TNA, the appellant gave evidence about his previous support for the TNA in the 2012 election. As recorded in the delegate’s decision, as cited by the primary judge, the appellant said that “during a 2012 election campaign that was occurring in Batticaloa District, he provided propaganda, canvassed and arranged meetings for the TNA”. The appellant did not raise future involvement in any election campaigns or in the TNA nor did he say that, while he wished to so participate, he would refrain from doing so for fear of harm.

43 In AYY17 a Full Court of this Court (Collier, McKerracher and Banks-Smith JJ) considered the duty of the Authority to consider claims and/or issues that arise from its own findings. In that case it was common ground that the issue which it was said the Authority should have considered was not expressly raised by the appellant in his claims or otherwise. That is also the case here. At [18] the Full Court set out the relevant principles as follows:

18 It is common ground that nothing in the statutory constraints to be found within Pt 7AA of the Migration Act (as discussed, for example, in BMB16 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2017) 253 FCR 448 per Dowsett, Besanko and Charlesworth JJ) affects the relevant existing case law on this topic, namely, the duty to consider claims and issues arising from material before it as that law applies to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal under Pt 5 of the Migration Act. In that regard, we note that:

• The Tribunal review function requires it to consider all claims made by an applicant and its essential components or integers: Htun v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs (2001) 233 FCR 136 (Htun) per Allsop J (as the Chief Justice then was) (at [42]), with whom Spender J agreed.

• The Tribunal is only required to consider such claims where they are either:

(a) the subject of substantial clearly articulated argument, relying on established facts; or

(b) clearly emerge from the materials: NABE v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs (No 2) (2004) 144 FCR 1 (NABE) per Black CJ, French and Selway JJ (at [55] and [68]) and AWT15 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2017] FCA 512 (AWT15) per Barker J (at [67]).

• These principles apply to the IAA regime: Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v BBS16 (2017) 257 FCR 111 per Kenny, Tracey and Griffiths JJ (at [79]) where their Honours said:

... A body such as the IAA, which is conducting an inquisitorial review process in which there is a claim for protection under s 36(2)(a) of the [Migration] Act must not only consider and determine the case as articulated by the protection visa applicant, but also do so in relation to an unarticulated claim which is nevertheless raised clearly or squarely on the material before that review body (see NABE at [58]-[61] per Black CJ, French and Selway JJ).

(Emphasis added.)

• As to whether a claim clearly emerges, the following principles were collected in AWT15 by Barker J (at [67]-[68]):

(a) such a finding is not to be made lightly (NABE at [68]);

(b) the fact that a claim might be said to arise from materials is not enough (NABE at [68]);

(c) to clearly emerge from the materials, the claim must be based on “established facts” (SZUTM v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2016) 241 FCR 214 (SZUTM) per Markovic J (at [37]-[38])). In SZUTM, Markovic J said:

37 While the tribunal is not required to deal with claims which are not clearly set out and which do not clearly arise from the material before it, the tribunal is not limited to dealing with claims expressly articulated by an applicant. A claim not expressly advanced by an applicant will attract the review obligation of the tribunal when it is plain on the face of the material before it.

38 Both the appellant and the Minister have made submissions on whether there is a requirement that there be a claim based on “established facts”. At [35], the primary judge found, relying on NABE and Dranichnikov that, as the threshold point the claim must “emerge clearly from the materials before the Tribunal and should arise from established facts”. I agree with the primary judge’s approach: the decision in NABE must be read in light of the principle set out in Dranichnikov.

(d) while there is no precise standard to determining whether an unarticulated claim has been “squarely raised” or “clearly emerges” from the materials “a court will be more willing to draw the line in favour of an unrepresented party”: Kasupene v Minister for Immigration and Citizenship (2008) 49 AAR 77 per Flick J (at [21]); and

(e) understanding whether a claim has clearly emerged from materials cannot be assessed in a vacuum. Consideration must be given to the way an applicant’s claims are presented over time.

44 The Authority is only required to consider claims that are the subject of clearly articulated argument, relying on established facts; or that clearly emerge from the materials. As Barker J recognised in AWT15 v Minister for Immigrations and Border Protection [2017] FCA 512 (AWT15), a finding as to whether a claim clearly emerges from the materials is not to be made lightly: AWT15 at [67].

45 As the above analysis demonstrates, the facts underlying the claim which the appellant contends for were not before the delegate or the Authority. The primary judge reached the same conclusion. The Authority addressed the claim as made.

46 The established facts do not support a claim that the appellant would participate in future elections or other political activity or that, despite a desire to do so, he would refrain from doing so because of a fear of harm. There was simply no evidence that upon return to Sri Lanka the appellant would engage in, or refrain from engaging in, future elections or political activity or about what he proposed to do in that regard.

47 The appellant, in effect, asked the court below to infer that he had intended to make the claim which he says arose from the materials. That is not enough: AWT15 at [67] referring to NABE v Minister for Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs (No 2) (2004) 144 FCR 1 (NABE) at [68]. While, as the appellant suggests, the authorities do not require a “perfect constitution of facts”, it is well established that any claim must be apparent from the material. The Authority is not required to engage in creative activity to expose a claim: NABE at [58].

48 The appellant’s contention that in the case of an “S395 category of claim”, some lesser constitution of facts is required should be rejected. A claim is made on the material or facts presented. It either arises because it is either clearly articulated or it clearly emerges from the materials. There is no basis to conclude that the Authority should be required to apply a lower threshold for particular types of claims.

49 There was no error in the approach of the primary judge. Although his Honour described the matter as finely balanced, he applied the applicable principles in an orthodox fashion and as required by the authorities to reach his ultimate conclusion and finding that the claim contended for by the appellant did not arise such that the Authority was required to consider it.

50 For those reasons the appellant has not made out his ground of appeal.

conclusion

51 The appeal should be dismissed with costs. I will make orders accordingly.

I certify that the preceding fifty-one (51) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Markovic. |

Associate: