FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Repipe Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2019] FCA 1956

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer to bring in a minute reflecting these reasons within 14 days.

2. Any dispute on the content of the minute be addressed by written submissions not exceeding five pages to be dealt with by the Court on the papers unless otherwise ordered.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

INTRODUCTION

1 Repipe Pty Ltd was the registered proprietor of two Australian Innovation Patents. They are described as number 2017100560, entitled ‘Methods and Systems for Providing and Receiving Information For Risk Management in the Field’ (the 560 Patent) and number 2017100943, entitled ‘Methods and Systems for Providing and Receiving Information For Risk Management in the Field’ (the 943 Patent) (together, the Patents). A delegate of the Commissioner of Patents revoked each of the Patents on the basis that the inventions claimed in them were not ‘a manner of manufacture’ within the meaning of s 18(1A)(a) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the Decision). Repipe appealed. The appeal is a hearing de novo in the Court’s original jurisdiction.

2 Repipe challenges the Decision, asserting that the inventions claimed in the Patents are a manner of manufacture, contrary to the Commissioner’s view. Repipe appeals against the revocation orders made by the Commissioner’s delegate, seeking that the delegate’s decision be set aside and that certificates of examination under s 101E of the Patents Act be issued and registered. Repipe also seeks its costs of its appeal.

3 In January and February 2018, Repipe proposed amendments to the claims in the 560 Patent and the 943 Patent respectively. The Commissioner held that the Patents did not disclose a manner of manufacture, consequently no purpose was identified in allowing the proposed amendments. No specific objection to the proposed amendments themselves was raised. The parties have proceeded on the basis that the claims in issue in this proceeding (the appeal) are the claims as amended. The parties have made submissions concerning the claims of the Patents in their amended form. I have been asked to refrain from making any orders pending publication of the reasons so the parties have an opportunity to consider the consequences of the reasons.

THE PATENTS – CLAIMS AND BACKGROUND

4 The earliest priority date of the Patents is 12 March 2015.

5 Claim 1 of the 560 Patent claims:

A method of providing information for risk management to a user of a portable personal computing device performing a job in the field, said method comprising:

selecting a document to be completed by the user related to a job to be performed by the user;

downloading information to the portable personal computing device;

displaying the downloaded information for selection of items in the information so as to complete the selected document; wherein the downloaded information comprises information provided by one or more other users having an administrative role and information provided by one or more other users having a field worker role;

receiving input to the portable personal computing device, wherein the input comprises selection of one or more of the items in the information, and/or the input comprises providing new information;

uploading the input, whereby a record of the input is stored in relation to the selected document, and the new information is added to the information to be downloaded by other users.

6 The document selected by the user can be a task type template, where the template preselects the labels of the fields of information that the user is to fill in (dependent claim 2). That template can be allocated by a user with a field supervisor or manager role to a user with a field-worker role (dependent claim 3). In that case, the template can comprise fields for inputting method steps, tasks, risks and controls to be assessed by the user prior to commencement of the job, which the user does using the downloaded information (dependent claim 4). The method can further comprise tracking whether the user has completed the form and indicating that to the field supervisor or manager (dependent claim 5).

7 Claim 1 of the 943 Patent claims:

A method of providing information for risk management to a user of a portable personal computing device performing a job in the field, where the job is one of a number of possible jobs the user may be assigned to perform in the field and where the assignment of the user to one of the jobs is recorded on a server, and where the user has one or more possible roles to perform in relation to the job and is assigned a current role from one of the possible roles in relation to the job, where the user has a maximum authority in relation to the respective role for the respective job, and where the user is assigned a current authority in relation to the respective role for the respective job, said method comprising:

identifying the user using the portable personal computing device;

receiving, by the portable personal computing device, a list of the possible jobs associated with the identified user from the server;

selecting a job to be performed by the identified user from the received list;

downloading from the server information related to the selected job to the portable personal computing device, wherein the downloaded information comprises information determined according to the user’s role in relation to the selected job, and the current authority that user has in relation to the selected job;

displaying the downloaded information for selection of one or more indicia in the information so as to complete a risk related dynamic document created from the received information, wherein completion of the dynamic document is required for the user to be able to commence or to complete the work required of the identified user’s role in relation to the selected job;

receiving user input to the portable personal computing device, wherein the user input comprises a selection of at least one of the indicia;

uploading the user input to the server, whereby a record of the input is able to be used in relation to the selected job.

8 The 943 Patent may further comprise determining what the user is permitted to do in relation to the selected job (according to the role the user has in relation to the job, the received user input, and the user’s current permitted authority in relation to the role for the selected job) and displaying what the user is permitted to do on the portable device (dependent claim 2). The downloaded information can comprise a form template determined by the user’s role for the selected job. The user completes the form by using the portable device to allocate roles to other people allocated to the job, by selecting indicia displayed on the portable device. The downloaded information tells the user the maximum authorities that can be allocated to each other person. The portable device displays what the user has been permitted to do, including whether they are currently permitted to perform the job (dependent claim 3). The current authority for a user in a particular role for a particular job can be allocated by a supervisor from a hierarchy of authorities, up to the user’s maximum authority (dependent claim 4). Independent claim 5 claims a risk management system comprising a server, multiple portable personal computing devices, and a communication channel between the server and each portable device.

9 The difference between the 560 Patent and the 943 Patent is that in the latter, the field worker has a level of authority in relation to the job as determined by a human supervisor. The downloaded information comprises information determined in relation to the selected job and the current authority that the user has in relation to the selected job and the documents required to be filled out before the worker can begin or complete the job. Thus, in claim 1 of the 943 Patent, the document is also described as a ‘dynamic document’. This means that the document is updated automatically in response to the field worker’s input.

10 The background to the invention of both Patents is that compliance with field risk management requirements is difficult for companies whose employees are ‘in the field’, such as in the construction and mining industries and for companies whose employees work across multiple sites or sites that change daily.

11 In short, the Patents contemplate that an aspect of the invention is implemented in the field, on a portable device, and another aspect is implemented at a remote location accessible from a more general computing device. The claimed inventions prompt employees in the field to consider lists of method steps, tasks, risks and controls. Field workers can also add other items to these lists, and any such additions are reported to the employees who manage those lists. The Patents also contemplate providing a ‘score’ for each upload and keeping record of those scores that may be linked to performance reviews and compensation.

12 The inventions can improve the timeliness and accuracy of risk information by:

(a) applying GPS tracking to the time and location of each access or upload;

(b) preventing frontline employees from commencing a task before controls are in place; and

(c) cross-referencing GPS and time-stamp data with other records such as incident investigations, compliance audits, and invoices.

The GPS tracking can also be used to process whether permits relating to jobs at the location of the computer have expired, with a consequent notification.

13 The Patents contemplate that the data will be used to create a database of real-time health and safety data, which could be used to complete statistical and other analytics on the data to identify patterns and ‘lead indicators’ of risk incidents.

14 When field employees log into the system, they may be allocated to a job. If they are working on multiple jobs, they can select the job they are presently working on. Once the job is selected, the information accessible to the employees will be specifically tailored to the jobs. The Patents contemplate that the inventions will enable the portable device to perform checks in order to indicate to the user whether they are permitted to perform the job (which would include, for example, whether all of the necessary safety checks have been checked off). For high-risk tasks, if a pre-start checklist indicates a problem, the system can automatically alert other personnel on the same site.

15 The Patents contemplate that the mobile device will be configured with searchable and expandable lists of information. The system can be configured to log data entered (for example, location records or time stamps) and then match completion of forms with commencement of, and completion of, tasks. Assignment to a job can trigger creation of a geofence (a virtual geographic perimeter) which the user should not exit or should not enter. The mobile device checks the user’s location against the geofence and creates an alert when the geofence is crossed.

16 An issue for field personnel is the renewal or re-issue of permits and plans to ensure the timely, continuous and safe completion of works. In the inventions claimed in the Patents, information about permits may be recorded in the system, such as the assignment of roles to a permit, the responsibilities conveyed by the permit and time/date limits. The specifications describe in detail how this information is to be conveyed to the user.

17 The Patents also encompass risk assessments. A list of risks is displayed for the user to select. The user is then asked to select a risk rating. In some circumstances, a pop-up risk matrix opens. Further, the Patents provide for other types of risk management checks, such as ‘Equipment Pre-Start Visual Prompts’ and ‘Equipment Heavy Usage Checks’.

18 The Patents contemplate that alerts can be provided to GPS-tracked field personnel when particular on-site events occur.

CHRONOLOGY AND AGREED FACTS AND ISSUES

19 Both the Patents claim divisional status from international patent application PCT/AU2016/050179 (published as WO 2016/141442).

20 As noted, the earliest priority date of both Patents is 12 March 2015.

21 As to the subsequent chronology, a Request for Examination of the 560 Patent was filed on 17 May 2017. The 560 Patent was granted on 1 June 2017. Adverse examination reports were issued on 3 August 2017, 22 November 2017 and 29 January 2018. Repipe proposed amendments to the claims in the 560 Patent on 17 January 2018. Repipe requested to be heard on 2 February 2018.

22 A Request for Examination of the 943 Patent was filed on 10 July 2017. The 943 Patent was granted on 20 July 2017. Adverse examination reports were issued on 7 September 2017, 22 November 2017 and 5 March 2018. Repipe proposed amendments to the claims in the 943 Patent on 27 February 2018. Repipe requested to be heard on 7 March 2018. The hearing in relation to the Patents took place in Melbourne on 10 April 2018. By way of examination, the Commissioner, by a delegate, delivered the Decision on 28 June 2018, which determined that the Patents should be revoked: Repipe Pty Ltd [2018] APO 42.

23 The delegate revoked the Patents because the inventions, so far as claimed, were not a manner of manufacture within the meaning of s 18(1A)(a) of the Patents Act. The delegate further held that there was no patentable subject matter in the applications: the Decision (at [69]).

24 Repipe lodged the appeal to this Court on 17 July 2018. Repipe appeals, under s 101F(4) of the Patents Act, from the whole of the Decision.

25 It is common ground between the parties that:

(1) There is often a disconnect between policy and procedure on the one hand, and what happens in the workplace on the other.

(2) Risk management often entails the implementation of complex and overlapping procedures, particularly in high risk environments.

(3) The tasks performed by a computer or smartphone may involve routine computer functions. A computer or smartphone does not perform ingenious functions simply because it has been loaded with specific software.

(4) The technology that existed for database management is generally as described by Assoc Prof Hussain in his affidavit dated 20 March 2019 (at [18]-[26]) to the following effect:

(a) In March 2015, databases and associated database programming were commonly used to store, combine, compare, provide access to, and display information. These databases and the associated database programming could provide information to users of portable electronic devices over a communications network, such as the internet. Applications of this database technology included programs installed on mobile phones to allow users to access data held by banks and insurance companies. These programs relied on a single database or multiple databases managed by the bank or insurance company, and a server which communicated with the user’s device. These programs were capable of displaying a customised document to the user, which the user could then interact with. For example, a user could input data into a form. Such programs were commonly used in March 2015.

(b) In March 2015, there were two broad approaches to storing the information that would be required for a tool such as the one described in Patent 560. The two broad approaches were ‘SQL databases’ and ‘NoSQL databases’.

(c) SQL databases can be regarded as a storage mechanism wherein information is stored in ‘tables’ and relations between the tables. A table is a structure in which information is stored in ‘records’. Each record has a number of ‘fields’. For example, a table might be created to store information about vehicles owned by a company. The table would include a record for each vehicle. Each vehicle record would include a series of fields, which might include the numberplate, brand, model and colour of each vehicle in the table. Information can be stored in one or more of the fields that are associated with each record. Tables can be related to each other. SQL databases are not flexible when it comes to changing the fields of a table or the relations between tables.

(d) NoSQL databases on the other hand do not impose a pre-defined scheme or structure. Instead, they lend themselves to storing information (such as documents) in a way that allows the database to develop to suit unexpected types of information. NoSQL databases increased in popularity between about 1998 and about 2010. Generally speaking, NoSQL databases lend themselves easily to customisations. By March 2015, a number of commercially-available NoSQL database implementations or solutions were available.

(e) Cloud-based services were used to deliver many applications involving databases in March 2015. Applications that use cloud-based services, such as cloud-based databases, can be more convenient for small organisations as they reduce the complexity of the task of procuring, hosting, managing and backing up the databases.

(f) In March 2015, information in databases was commonly compared, combined, analysed and displayed to users using algorithms. Information about geographic location or time could be combined with information in the database to produce alerts or warnings that were sent or displayed to a user based on their location, the location of another user or an object, the time of day and the passage of a period of time.

(g) In March 2015, it was possible for databases to be designed and implemented in a way that assigned different roles to different users. A user’s role could be used to control their access to information in the database, to control their ability to change information in the database, and to define whether they were alerted to changes to the information in the database.

(5) Implementing the invention claimed in the Patents requires the combination of known hardware components, which would need to be programmed to perform the invention.

(6) The PCT application from which the Patents were divided had an International Search Report with four documents cited. One of the cited documents was US2004/0078098, titled ‘Computer System for Assessing Hazards’ (Jeffries Patent).

(7) There is a difference between the user roles described in the 560 Patent and the authorised persons mentioned in the Jeffries Patent.

(8) The Jeffries Patent does not involve updating information and providing it to other people in the field.

(9) There are differences between the nature of the report in the Jeffries Patent and the dynamic document claimed in the 943 Patent.

26 It is agreed between the parties that the only issue in the appeal is whether each of the inventions claimed in the Patents is a manner of manufacture under s 18(1A)(a) of the Act.

RELEVANT PRINCIPLES

27 It is necessary to identify the proper approach to answering the key question. Section 18(1A)(a) of the Patents Act provides as follows:

18 Patentable inventions

...

Patentable inventions for the purpose of an innovation patent

(1A) Subject to subsections (2) and (3), an invention is a patentable invention for the purposes of an innovation patent if the invention, so far as claimed in any claim:

(a) is a manner of manufacture within the meaning of section 6 of the Statute of Monopolies; and

…

28 Determining whether there is a manner of manufacture is a different inquiry from that involved in determining questions of novelty or assessing whether the claimed invention involves an innovative step when compared to prior art. Innovation patents, as these Patents are, do not require an inventive step.

29 In National Research Development Corporation v Commissioner of Patents (1959) 102 CLR 252, Dixon CJ, Kitto and Windeyer JJ relevantly held:

(1) First, the relevant inquiry is whether the invention in issue is a proper subject of letters patent according to the principles which have been developed for the application of s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies 1623, 21 Jac 1 c 3 (at 269).

(2) Secondly, to be a manner of manufacture, a process must offer some material advantage of economic value. It must belong to a useful art as distinct from a fine art (at 275).

(3) Thirdly, the mode or manner by which an invention provides some new and useful effect, and thereby an improved result, may involve patentable subject-matter (at 276). The new and useful result must be observable in ‘something’; however, that ‘something’ need not be an article; it may be ‘any physical phenomenon in which the effect, be it creation or merely alteration, may be observed’ (at 276).

30 In addressing the process the subject of the dispute before it, the Court in National Research answered the question it posed in the first query by reference to the two conclusions it reached, identified in the second and third queries. The Court observed the method the subject of the relevant claims had as its end result an artificial effect falling squarely within the true concept of what must be produced by a process if it is to be held patentable; the significance of the product was economic (at 277).

31 The Court in National Research also cautioned that any attempt to state the ambit of s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies by precisely defining ‘manufacture’ is likely to fail and, further, ‘to attempt to place upon the idea the fetters of an exact verbal formula…would be unsound to the point of folly’ (at 277).

32 Fifty-five years later, in D’Arcy v Myriad Genetics Inc (2015) 258 CLR 334, Gageler and Nettle JJ emphasised that the way in which a claim is drafted cannot transcend the reality of what is in suit. Monopolies are granted for inventions, not for the inventiveness of the drafting with which patent applicants choose to describe them. The matter must be looked at as a question of substance. Effect must be given to the true nature of the claim: Myriad per Gageler and Nettle JJ (at [144]); see also French CJ, Kiefel, Bell and Keane JJ (at [6], [87]-[88] and [94]) and Gordon J (at [255], in passing). An invention is to be understood as a matter of substance and not merely as a matter of form.

33 A mere scheme or plan is not patentable. However, an improvement in computer technology, including one that implements a method used in the conduct of business, is patentable. The business criterion for patentable subject matter is an artificially created state of affairs that has economic significance or utility, although this may not be sufficient in all circumstances. No special rules or exclusions apply to claims for functions performed by software. Claims to computer programs having ‘the effect of controlling computers to operate in a particular way’ may be patentable subject matter: Data Access Corporation v Powerflex Services Pty Ltd (1999) 202 CLR 1 per Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow and Hayne JJ (at [20]). So the application of selected mathematical methods to computers to produce an improved curve image was held to be patentable in International Business Machines Corporation v Commissioner of Patents (1991) 33 FCR 218. A claim to software enabling the word processing of Chinese characters was held to be patentable in CCOM Pty Ltd v Jiejing Pty Ltd (1994) 51 FCR 260. A method for keeping track of rewards on loyalty cards was held to be patentable in Welcome Real-Time SA v Catuity Inc (2001) 113 FCR 110.

34 There is a difference between an unpatentable abstract idea, method or scheme for carrying on a business and a claim for a method and a device for use in businesses. For a business method to be patentable, it must produce a ‘physical effect in the sense of a concrete effect or phenomenon or manifestation or transformation’: Grant v Commissioner of Patents (2006) 154 FCR 62 per Heerey, Kiefel and Bennett JJ (at [26] and [32]). The physical effect can be embodied by electronic processes in a computer system, such that it may not necessarily need to be a piece of hardware.

35 Consideration of whether there is an improvement in this context, or of matters of invention or ingenuity, directs attention to the subject-matter of the invention as a matter of substance. It does not import into the manner of manufacture ground, considerations of novelty or of the inventive or innovative step: Research Affiliates LLC v Commissioner of Patents (2014) 227 FCR 378 per Kenny, Bennett and Nicholas JJ (at [111], citing CCOM (at 291)). Repipe also stresses that a patent’s specification need not identify the inventive or innovative step. It is sufficient that the specification describes in a claim or a series of claims what is or are claimed to be the patentable subject matter: Winner v Ammar Holdings Pty Ltd (1993) 41 FCR 205 (at 217). The approach is not to compare the claim against the common general knowledge in the field of computer technology or against prior art in that field.

36 In Rokt Pte Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2018] FCA 1988 (presently under appeal), Robertson J said (at [201]):

For example, both sides agreed that the matter had to be addressed as a matter of substance. I agree. I also accept that there is no formula to be mechanically applied, and that it is necessary to understand where the inventiveness or ingenuity is said to lie. A mere business innovation is insufficient and a business method or scheme is not, per se, a proper subject for letters patent. Nor are abstract ideas. The issue is whether there is a technological innovation. Where, as here, the claimed invention is to a computerised business method, the invention must lie in the computerisation and it is not enough simply to put a business method into a computer. The search is for an improvement in computer technology ...

37 Two key cases established that a method defined as a ‘computer-implemented’ method, but not otherwise specifically directed to computer technology, is not patentable: Commissioner of Patents v RPL Central Pty Limited (2015) 238 FCR 27 per Kenny, Bennett and Nicholas JJ (at [96] and [107]); Research Affiliates (at [115] and [118]-[119]). (Special leave to appeal the decision in RPL was refused on the basis that ‘the Full Court was plainly correct’.) It has been held that mere implementation in a computer of any abstract idea or scheme is insufficient to give rise to an ‘artificial effect’ and therefore insufficient to constitute patentable subject matter: Research Affiliates (at [113]-[118]). Attention must be paid to the substance of the invention, such as where the method claimed is a scheme which is merely implemented in a computer. In that instance, there is no ‘improvement in what might broadly be called “computer technology”’: Research Affiliates (at [19]).

38 An invention will be patentable where ‘part of the invention is the application and operation of the method in a physical device’: RPL (at [101], citing Research Affiliates (at [104])). It will also be patentable where the invention involves the creation of an artificial state of affairs where the computer is integral to the invention or where the invention involves the use of a computer in a way that is itself claimed to be inventive, so that the invention lies in the computerisation or where there is some ingenuity in the way in which computer is utilised: RPL (at [104]).

39 The Commissioner contends, and I accept, that the following propositions emerge from RPL, Research Affiliates and the earlier authorities:

(1) The Court must decide, as matter of substance not form, whether the claimed invention is proper subject-matter for a patent: RPL (at [98]); Research Affiliates (at [107]). This requires consideration of both the claims and the body of the specification.

(2) The assessment is not done mechanically pursuant to precise guidelines: Research Affiliates (at [117]). It is a question of understanding what has been the work of, the output of, and the result of, human ingenuity and then applying the developed principles recognising that the claims are to a method and system comprising a combination of integers. It is necessary to understand where the inventiveness or ingenuity is said to lie: RPL (at [112]).

(3) A distinction exists between a technological innovation and a business innovation. The former is patentable, the latter is not. A business method or scheme is not, per se, a proper subject for letters patent, nor are abstract ideas, mere intellectual information or mere directions to implement a method using a computer: RPL (at [100]); Research Affiliates (at [101]).

(4) A computerised business method or scheme can, in some cases, be patentable. However, where the claimed invention is to a computerised business method, the invention must lie in that computerisation: RPL (at [96]). This requires some ingenuity in the way the computer is used: RPL (at [104]). It is not a patentable invention to simply put a business method into a computer to implement the business method using the computer for its well-known and understood functions: RPL (at [96]). For the Commissioner it is observed that there is an affinity between this approach and the proposition illustrated by Commissioner of Patents v Microcell Ltd (1959) 102 CLR 232, referred to in National Research (at 262) and in Myriad per Gageler and Nettle JJ (at [131]). The use of a known device for a new but analogous purpose, for which its known properties make it suitable, is not a proper subject of letters patent.

(5) An invention must be examined to ascertain whether it is, in substance, a scheme or whether it can broadly be described as an improvement in computer technology: RPL (at [96]). In conducting this analysis, it may be useful to consider:

whether the contribution is technical in nature: RPL (at [99]); Research Affiliates (at [114]);

whether the invention solves a technical problem within or outside the computer: RPL (at [99]); Research Affiliates (at [114]);

whether the invention results in an improvement in the functioning of the computer, regardless of the data being processed: RPL (at [99]); Research Affiliates (at [118]);

whether the invention requires generic computer implementation, as distinct from steps ‘foreign’ to the normal use of computers: RPL (at [99] and [102]); Research Affiliates (at [101]); and

whether the computer is merely an intermediary, configured to carry out the method using program code for performing the method, but adding nothing to the substance of the idea: RPL (at [99]).

(6) Where a business method or scheme cannot be implemented without using a computer that does not, of itself, provide patentability. The speed and power of computers make them a fast and efficient tool for businesses and few business processes today are performed without the use of a computer. Where a business method or scheme is implemented by using a computer to perform its ordinary functions, the claimed invention is still to the business method itself and, therefore, unpatentable. Similarly, the physical effects that computers generate by ordinary computational processes, such as displaying an object on a screen are not, of themselves, sufficient to render a computerised method or scheme patentable.

(7) It is insufficient when assessing a computer-implemented invention merely to ask whether the claimed invention satisfies the two limbs identified in National Research of:

(a) an artificially created state of affairs; and

(b) utility in the field of economic endeavour.

Encompass

40 The parties requested to be heard following delivery of judgment in Encompass Corporation Pty Ltd v InfoTrack Pty Ltd (2019) 145 IPR 1. The parties filed supplementary written submissions following delivery of Encompass.

41 In Encompass, the Full Court (Allsop CJ, Kenny, Besanko, Nicholas and Yates JJ), dismissed an appeal from a decision of Perram J in Encompass Corporation Pty Ltd v InfoTrack Pty Ltd (2018) 130 IPR 387, who had held that the patents in suit did not claim an invention that was a manner of manufacture within the meaning of s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies. The Full Court also held there was no basis for revisiting the correctness of Research Affiliates and RPL.

42 The invention concerned a method and apparatus for displaying information relating to entities (exemplified as ‘individuals, corporations, businesses, trusts, or any other party involved in a business or other commercial environment’) so as to ‘provide business intelligence’. The complete specification disclosed that there were many electronic date collections containing information about entities, including ‘information regarding land ownership, association with corporate entities, police records, or the like’ and that the information is provided across multiple different repositories, such that identifying and accessing relevant information was difficult and may consequently be overlooked when performing searches. The specification described a variety of processes for better representing such information but, as the Full Court noted (at [22]), the description was ‘largely agnostic as to how the method should be implemented’. The specification made clear that the processing system for implementing the method could be formed from any suitable processing system such as ‘a suitably programmed computer system, PC, web server, network server, or the like’.

43 There were six steps involved in the method claims, which were summarised in the Full Court’s decision (at [28]):

(a) generating a network representation by querying remote data sources;

(b) causing the network representation to be displayed to a user;

(c) in response to user input commands, determining at least one user-selected node corresponding to a user-selected entity;

(d) determining at least one search to be performed in respect of the corresponding entity associated with the (at least one) selected node;

(e) performing at least one search to determine additional information regarding the entity from at least one of a number of remote data sources by generating a search query; and

(f) causing any additional information to be presented to the user.

44 The Full Court referred with apparent approval to Research Affiliates and National Research, noting that a vendible product, as discussed in National Research, was not enough to afford patentability. There was a distinction to be drawn between mere implementation of an abstract idea in a computer and implementation of an idea in a computer that creates an improvement in the computer. The Full Court in Encompass (at [40]) referred to the question asked in RPL, namely, ‘does the claimed method merely require generic computer implementation?’.

45 It was argued in Encompass that the Full Court’s reference in Research Affiliates to an ‘improvement’ in ‘computer technology’ should not be understood as an improvement confined to hardware and that the Full Court should be understood as distinguishing what would be patentable subject matter (an improvement in computer technology) from what was not patentable subject matter (a mere scheme, such as assembling a share portfolio). The appellants in Encompass argued that the correct question was whether the claims defined the content of information (indicative of a mere scheme) or the functionality of a computer which would provide, the appellants said, patentable subject matter.

46 In Encompass, the Full Court noted that in considering whether mere implementation by a computer of an abstract idea or scheme is enough to transform unpatentable subject matter into patentable subject matter, the Full Court in Research Affiliates (at [115]) had resorted to the language of ‘artificial’ or ‘physical’ effect, ‘technical contribution’ and such like expressions as used by the High Court in National Research. But by resorting to this language, the Full Court was doing no more than explaining that the claimed method in Research Affiliates did not transcend, as a matter of substance, what remained an abstract idea or mere information of the kind that has never been considered to be patentable subject matter under Australian law. In Encompass, the Full Court accepted, as the primary judge had, that the contention that the method claims in suit were in truth no more than an instruction to apply an abstract idea, the steps of a method using generic computer technology. None of the steps taken individually or collectively amounted to anything more than a method in which an uncharacterised electronic processing device, for example, a computer, would be employed as an intermediary to carry out the method steps where the method itself was claimed in terms which amounted to no more than an abstract idea or scheme: see Encompass (at [99]).

47 The Full Court in Encompass explained (at [91]):

In each case, the Full Court was seeking to describe the conceptual distinction between a manner of manufacture and an unpatentable abstraction. In each case, the Full Court was explaining that a claimed method that is unpatentable does not change its legal character merely because the method is implemented by the instrumentality of a computer.

EVIDENCE

48 Repipe relied on two affidavits made by Dr Aitken: first, an affidavit deposed to on 10 December 2018 (Aitken 1); and, secondly, an affidavit deposed to on 22 May 2019 (Aitken 2). He is an expert in computer systems. He gave evidence as to his understanding of the operation and programming of computers and the difference between general-purpose and specific purpose computers and computer implementation as at the priority date. He also gave evidence about the person to whom the Patents are directed, the nature of the inventions in the Patents, what is needed to implement the inventions in the Patents and whether programming a computer to implement the inventions is technical in nature.

49 The Commissioner’s expert was Assoc Prof Hussain. He is a tenured academic with expertise in developing and implementing databases.

50 Evidence was also foreshadowed by the Commissioner’s Workplace Health and Safety/Risk Management (WHS) expert, Ms Shaw. Repipe also foreshadowed reliance on two affidavits of Mr McDonald, who is a risk management consultant. Ultimately, that evidence was not adduced.

DO THE PATENTS DISCLOSE A ‘MANNER OF MANUFACTURE’?

51 Repipe argues that both Patents are not merely business methods or schemes implemented using a computer. The computer is not merely an intermediary or a tool. Rather, the Patents claim technological inventions where the computer technology is integral to, and is the most significant feature of, the claims.

52 For the Commissioner it is contended that the substance of the invention claimed in each of the Patents is an unpatentable business, method or scheme. On the Commissioner’s reading, what Repipe claims is a scheme for sharing and completing workplace health and safety documents. It is implemented by using computers to perform their ordinary functions, there being no invention in the way that the computers carry out the scheme or method.

53 The Commissioner particularly emphasises that the claimed inventions use ordinary computing functions to share and enable completion of the necessary forms, as is apparent from the words used in the claims themselves: for example, ‘selecting a document’, ‘downloading information’, ‘displaying the downloaded information’, ‘receiving input’ and ‘uploading the input’. In short, it is argued that the claims do not define, and the specifications do not disclose, any technical means by which these ordinary computing functions are performed. No such means is described, because the inventions are not a technical advance or contribution to computing. The inventions are a mere scheme that utilise the well-understood ability of computers to enable documents to be shared and completed in a faster and more convenient way.

54 The submissions of the parties quite appropriately often dealt with the 560 Patent and the 943 Patent collectively. However, it is appropriate to consider each in turn, while noting much submitted in relation to the 560 Patent is relevant to the 943 Patent.

The 560 Patent

Repipe’s contentions

55 Repipe argues that there are three components of the method claimed in the 560 Patent:

(a) a source and destination of date, namely, a server;

(b) a portable computing device, such as a smartphone; and

(c) a communications network - because to download or upload data a network connecting the portable computing device to the source destination is necessary.

56 To implement the method, Dr Aitken explained that each of these elements must be configured to operate in a manner to enable the method to be performed. This requires programming with specific application software. The evidence from Dr Aitken was that the invention requires specific functionality from each component of the method.

57 On that basis, Dr Aitken concluded that the substance of the invention claimed in the 560 Patent was the combination of the server, communications network and a portable computing device, such as smartphone, configured and controlled in the specified way by a specific software application so the user can use and create an expanding collection of items (i.e. a list) to select from as each field worker completes his or her own risk management document

58 Dr Aitken’s evidence was that the invention identified in the 560 Patent provides a technical solution to the problem of not being able to share new information that arises in the field between field workers in real time. The technical solution is described as being brought about by the use of a specifically programmed server and to allow field workers to create a risk assessment document with ‘expanding lists’ and to share it with other field workers in a timely manner independent of distance. A non-technical solution, such as a paper-based solution, could not achieve this. Further, a generic server or smartphone would not be capable of performing the steps of the method without the addition to each of a specific program to configure and control these devices to perform the method. Without the appropriate programming, the devices are, according to Dr Aitken, ‘like a malleable lump of clay without being formed into a bowl shape and fired to form the rigid bowl’.

59 Dr Aitken’s evidence was that the programming of the server and portable device itself is a technical task, requiring knowledge of the steps of the method to be performed and the capabilities that the software must create in the devices. The programming will configure the devices to perform the necessary functions and will also control the operation of these configured capabilities as the devices are operated so that they can move from state to state as required. Dr Aitken’s evidence considered the technical nature of programming work.

60 Once configured as required to perform the steps of the claims, the server and smartphones are not generic. Rather, they are ‘machines altered by way of technical endeavour from their generic state’. Dr Aitken’s evidence was that the things they must be configured to do are not things which they are normally configured to do or that they are known to be configured to do. The inventions involve more than simply implementing known paper-based risk management methods on a computer. Repipe refers to Assoc Prof Hussain’s evidence that ‘the use of computer technology is integral to the claimed inventions’.

61 Repipe characterises Assoc Prof Hussain’s evidence as having proceeded by comparing the programming required to implement the invention claimed in the 560 Patent against that commonly used in the field of computer technology at the priority date. He concluded the invention disclosed in the 560 Patent did not make any technical contribution, involving no ‘computing ingenuity, nor containing any technical information to indicate that the invention involves any advance in the computer processing function …’. As to that, Repipe submits that the basis for those conclusions was that the individual components of the invention, and the way they are combined, and the programming and databases required to implement the invention on those components, go to a consideration of what was commonly-used or well-known before the priority date. This, Repipe stresses, is the wrong test.

62 Repipe argues that Assoc Prof Hussain attempted to compare the Patents to specific pieces of prior art information, as would be necessary for a novelty or innovative step analysis. Assoc Prof Hussain said the invention in the 560 Patent does not make any technical contribution to computing technology, which Repipe says that is wrong as a matter of fact. There is no suggestion on the face of the specification that the method can be implemented using existing software. It is also said that the assertion is unfounded because if the computer could not do what is claimed before the invention, but it can do something new after and with the inventions, then logically it must be improved. As to the dependent claims, Repipe contends the same erroneous test was applied by Assoc Prof Hussain. His essential evidence was that the computer technology as described in the claims is not new over the existing art. The comparison between the claims and the prior art or the common general knowledge is the enquiry in novelty or obviousness, not in manner of manufacture.

63 Repipe submits to survive a manner-of-manufacture objection, the patentee need not prove that the invention is novel or inventive over known computer systems. It need only prove that the inventiveness or ingenuity is said to lie in the computerisation, not in the scheme itself. Repipe says it is not required to show that the claims are in fact ingenious: only that the field in which ingenuity is claimed to exist is the field of computer technology. It contends it has satisfied that requirement.

64 Repipe contends that the essential aspect of the claims, that which permits all of the functionality contemplated by the inventions, is the computer technology described in the claims. Central to Repipe’s case is the contention that this functionality could not only not be achieved in a paper system, but that it also could not be achieved using generic computing equipment or with existing software.

The Commissioner’s contentions

65 In relation to the 560 Patent, the Commissioner emphasises the content in claim 1 (set out at [5]). The Commissioner argues that it is apparent on the face of claim 1 itself that the substance of the invention defined is a mere scheme for sharing and completing workplace health and safety documents. Put another way, it is a mere direction to implement a method for carrying out the identified steps using computers. This is apparent because:

(1) The claim does not define any hardware features of the computing devices used apart from requiring the user’s device to be a ‘portable computing device’. Any existing portable computing device could meet such a description.

(2) The claim defines the identified steps of the method by reciting ordinary computer processing functions.

(3) The claim does not define any technical means by which these ordinary computer processing functions are performed. It simply assumes they will be used to carry out the identified steps.

(4) No software application or programming code for carrying out the steps is defined.

(5) There is no suggestion (nor could there be) that any of the identified steps, alone or in combination, would involve or require any ingenuity in their implementation. The selection of hardware and creation of software to implement the steps is left entirely to the skilled person reading the claim.

(6) There is no suggestion (nor could there be) that any of the steps require any artificial intelligence on the part of the computer.

66 The description is in broad and general terms, describing the performance of various methods of sharing and completing documents using computers. Nowhere is there any disclosure of the technical means that the computers must use to perform the ordinary identified processes of document or information storage, selecting documents, downloading information, displaying the downloaded information, receiving input and uploading the input.

67 The Commissioner further notes that the specification does not disclose that any specific hardware or computer programming code or software application must be used. Instead, the teaching is that the claimed method is implemented by programming the existing hardware with any suitable software that causes the existing hardware to select documents, download information, display documents, receive user input and upload the user input as claimed. For example, the specifications state (at [0064] and [0066]):

[0064] In an embodiment the tools of the present invention are provided via an application operating on a mobile computing device, such as a smart phone. It is known that a smart phone is a mobile computing device which has a processor, memory, a display screen which is also an input device in the form of a touch screen and a network communication device(s). Typically the smart phone is loaded with a computer program stored in the memory, which when executed by the processor forms the application. Put another way the computer program comprises instructions for controlling the processor to configure the mobile device as a system according to an aspect of the invention. When the computer programs instructed are executed, the mobile station performs a method according to another aspect of the invention.

…

[0066] In an embodiment an aspect of the tools are provided on a more general computing device, such as, but not limited to a laptop or desktop personal computer. The term personal computer is not intended to be limiting as it could be implemented on a portable computing device, although when used in an office environment, size, weight and portability more generally are less constraining. Some of the aspects of the present invention need not be implemented in the field, as will be explained in more detail below. Such implementation can be provided by software installed on the personal computer, or they can be implemented by software at a remote location which is assessable from the personal computer, such as via a browser installed on the personal computer. Such implementation is commonly referred to as a software as a service model or software in the “cloud”.

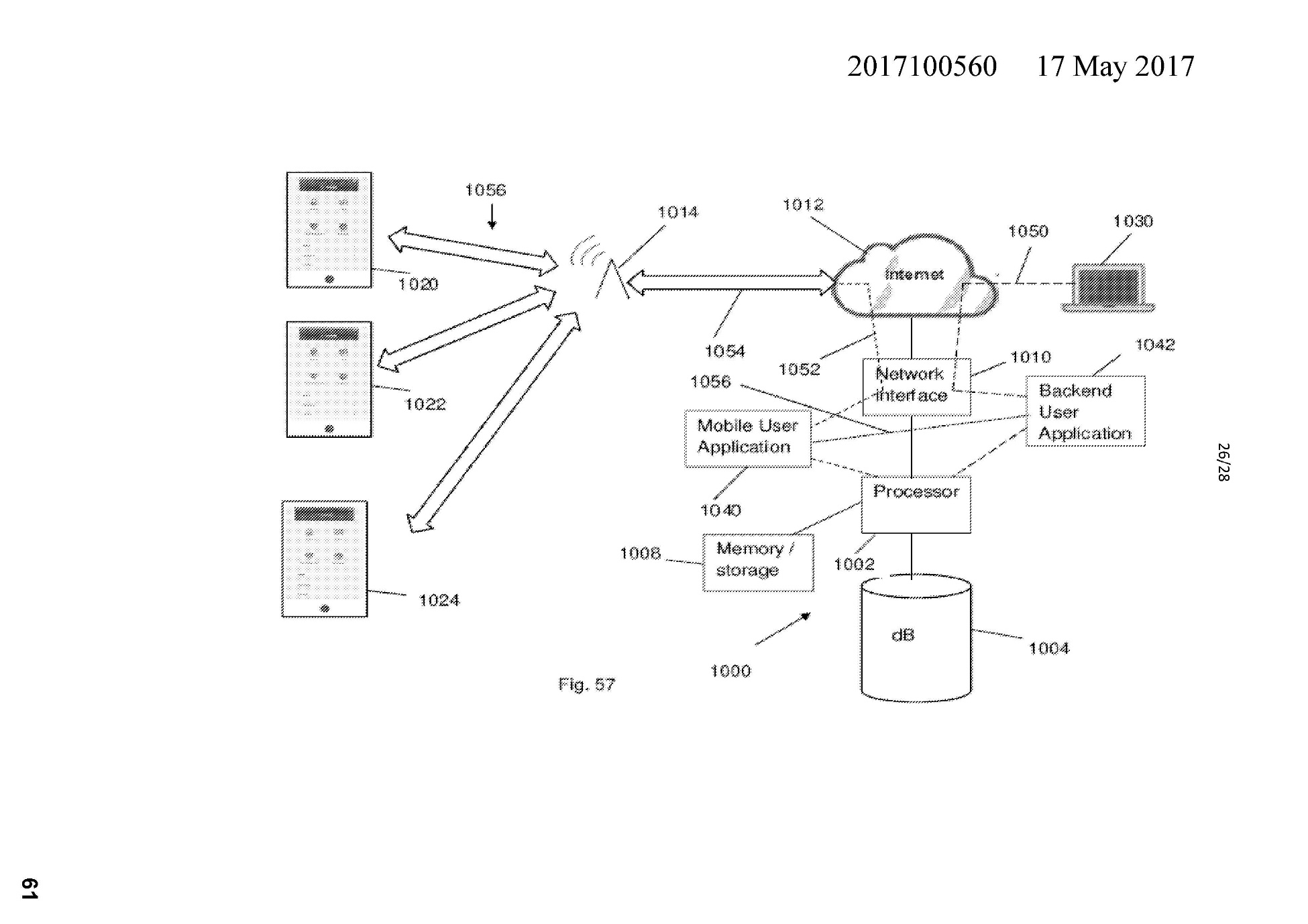

68 The Commissioner argues that the nearest that the body of the specification comes to addressing ‘technical’ subject-matter is fig 57 and fig 58 (Annexure A) and the accompanying description (at [0067]-[0071]):

[0067] Referring to Figure 57 there is shown a system 1000 according to an embodiment of the present invention, the system 1000 comprising a processor 1002, a database 1004, memory/storage 1008, a network interface 1010 connected to a computer network 1012 (such as the Internet). The network 1012 comprises a mobile telephone network 1014, (or other wireless network) which connects to a plurality of portable computing devices 1020, 1022 and 1024. The network 1012 also connects to a personal computer 1030.

[0068] Executing on the processor 1002 are a mobile user application interface 1040 and a backend user application 1042. The mobile user application interface 1040 interfaces with the portable devices 1020, 1022 and 1024 by communication channel 1052 via the network interface 1010, the network 1012 and 1014. The communication channel includes a communication 1054 into the mobile telephone network 1014 and wirelessly by communication 1056 between a base station and the mobile devices 1020, 1022 and 1024. The backend user application 1042 has a communication channel 1050 to the personal computer 1030 via the network 1012.

[0069] The personal computer 1030 gives offsite personnel access to the present invention. Whereas the mobile user application interface 1040 gives onsite users of the personal devices 1020, 1022 and 1024 access to the present invention. The mobile user application 1040 is able to interact with and exchange information with the backend user application 1042 by communication channel 1056.

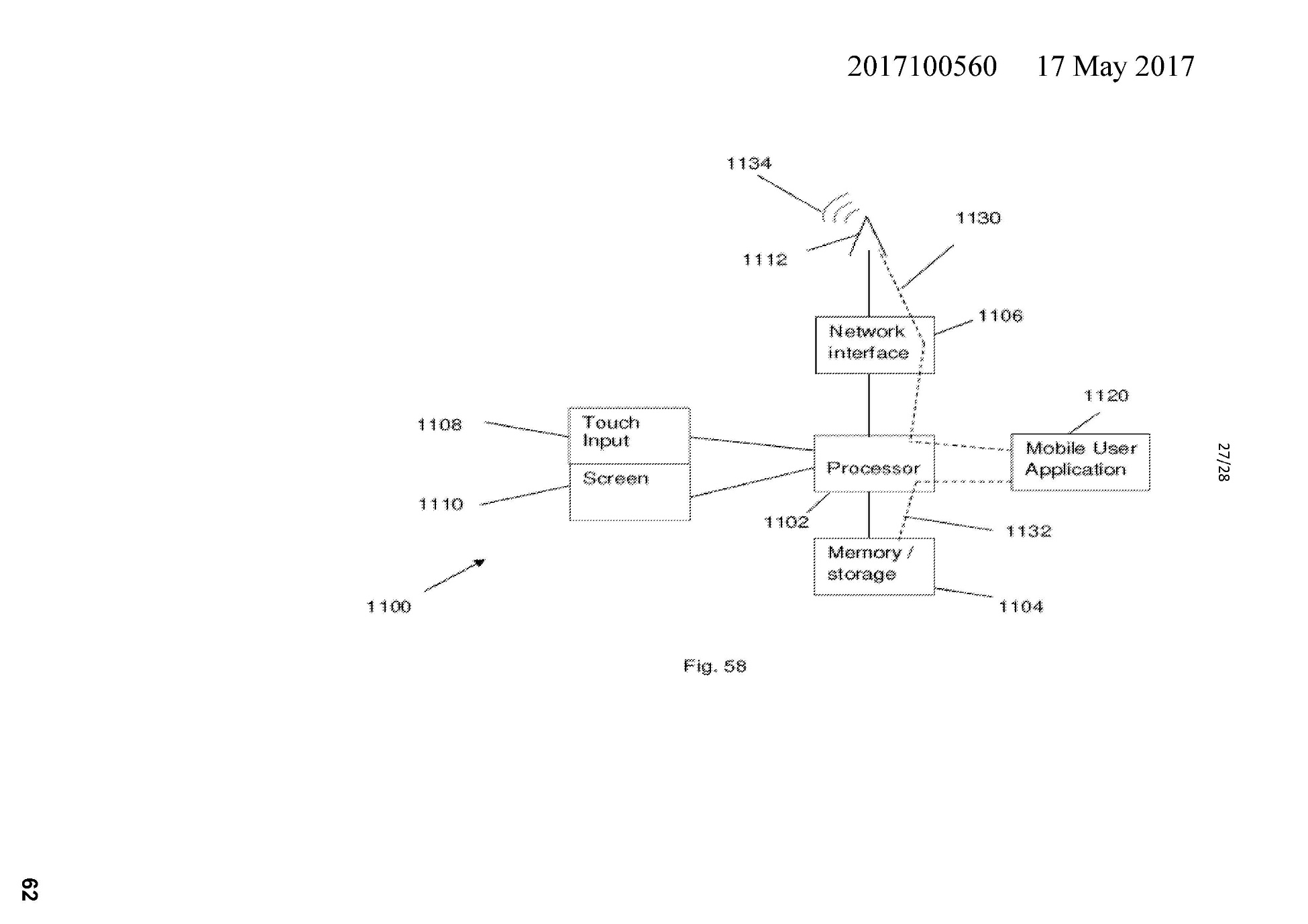

[0070] Referring to Figure 58, each personal computing device 1020, 1022 and 1024 comprises components 1100. These components 1100 comprise a processor 1102, memory/storage 1104, network interface 1106, a screen 1110 and touch input 1108 which is typically a touchscreen combining elements 1108 and 1110.

[0071] Executing on the processor 1102 is a mobile user application 1120 which communicates by network interface 1106 and antenna 1112 with the mobile telephone network by wireless communication 1134. As an alternative to the mobile telephone network, a Wi-Fi network or other wireless network may be used instead. The mobile user application interface 1040 is able to communicate with the mobile user application 1120 by a communication channel 1130. The mobile user application 1120 is able to store data via communication channel 1132.

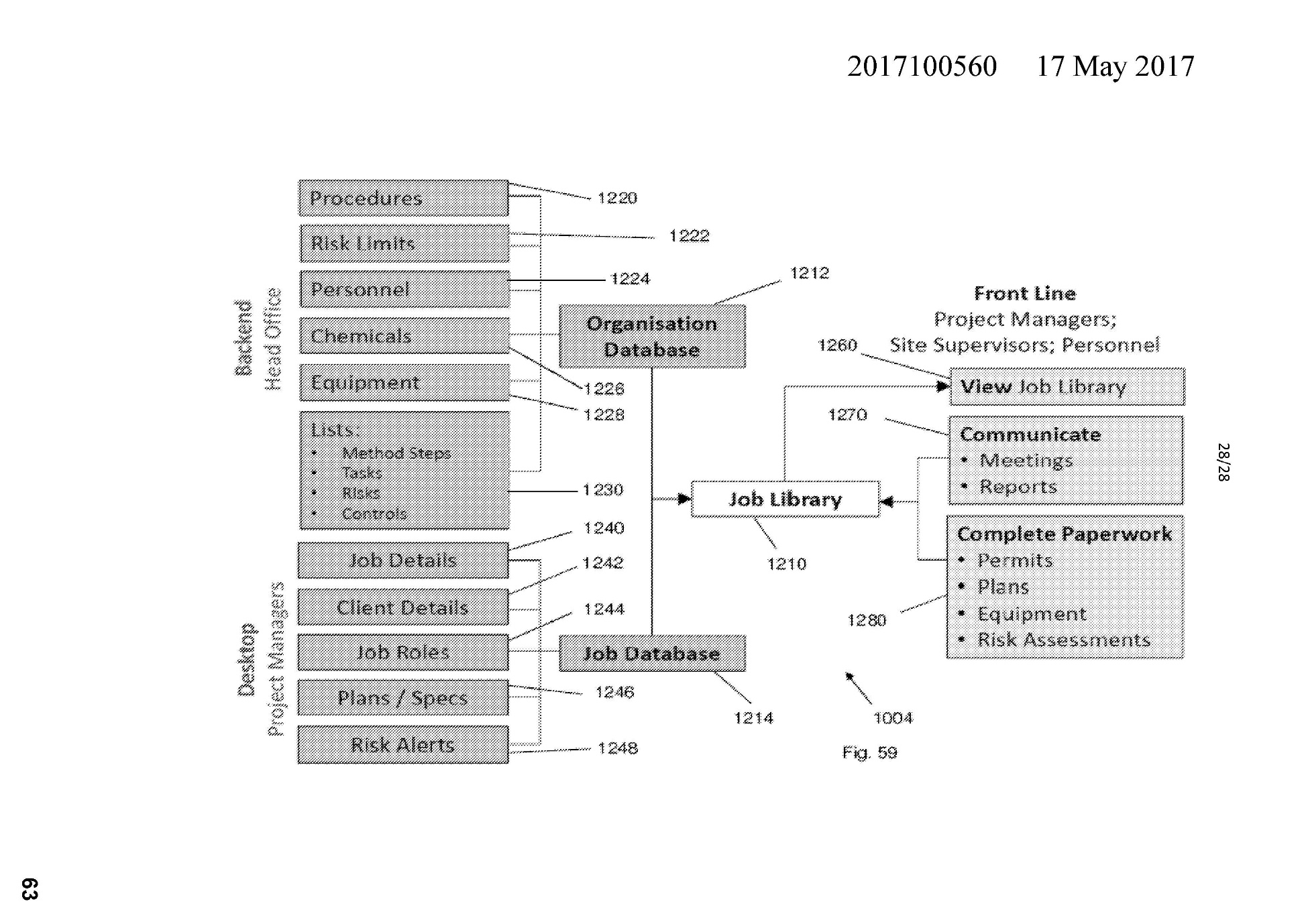

69 Even this, the Commissioner says does not reveal any ‘technical’ content. Figure 57 and fig 58 comprise basic block diagrams. The diagrams illustrate the hardware and software components that computers implementing the claimed methods may use. However, the figures reveal no more than a standard hardware and software configuration for performing ordinary computing functions of the kind that are recited in claim 1. The same may be said of fig 59 (Annexure A), which provides a basic example of a standard database structure that can be used to implement the invention. Further, and in any event, these details are not claimed.

70 Therefore, the Commissioner argues claim 1 is not limited by any requirement that the computer hardware, software or database components used be configured in the arrangements shown in figs 57 to 59. Thus, these basic arrangements do not form part of the invention claimed. Consistently with this, the specification does not assert the arrangements shown in figs 57 to 59 form part of the invention claimed. On the contrary, the specification explains (at [0056]):

The instant disclosure is provided to explain in an enabling fashion the best modes of making and using various embodiments in accordance with the present invention. The disclosure is further offered to enhance an understanding and appreciation for the invention principles and advantages thereof, rather than to limit in any manner the invention. While the preferred embodiments of the invention are illustrated and described here, it is clear that the invention is not so limited. Numerous modifications, changes, variations, substitutions, and equivalents will occur to those skilled in the art having the benefit of this disclosure without departing from the spirit and scope of the present invention as defined by the following claims.

(Emphasis added.)

71 The Commissioner contends the lack of any patentable matter is reinforced by the following considerations that are compared with conclusions in RPL and Research Affiliates:

(1) There is no ‘technical problem’ inside or outside a computer that the invention of claim 1 solves: RPL (at [99]), see also Research Affiliates (at [103]). Rather, the ‘problem’ that claim 1 addresses is the inconvenience of having to share and complete a large volume of paper-based workplace health and safety documents, particularly given the natural aversion of ‘front line employees’ to paperwork: see the ‘Background’ to the 560 Patent (at [0002] to [0005]). The ‘solution’ proposed is to share and complete the documents electronically by using the well-understood functions of a computer.

(2) None of the computer functions recited in the claims is ‘foreign’ to the normal use of computers: RPL (at [102]); Research Affiliates (at [111]). Rather, they are ordinary and well-understood computing functions.

(3) The claimed invention does not result in any improvement in the functioning of a computer: RPL (at [99]); Research Affiliates (at [104]). In this regard, as both RPL and Research Affiliates demonstrate, the mere fact that a computer is used to carry out a method that may not have been carried out using a computer before does not equate to an improvement in the functioning of the computer, or an improvement in computer technology.

(4) The computers used to implement claim 1 are properly characterised as merely an intermediary: RPL (at [99]). The computers do not decide themselves what document is required for any given job or user, or what information about hazards, for example, the user should record in the document. Rather, the computers follow program logic that will implement a management decision about which jobs require which forms to be completed. Further, human actors, not computers, decide what information to populate into the necessary documents. The computer merely serves an intermediary function. The Commissioner emphasises the title of the Patents: ‘Methods and Systems for Providing and Receiving Information For Risk Management in the Field’.

(5) In substance the claimed invention is not technical in nature. It provides no technical contribution to the art of computing: RPL (at [99]); Research Affiliates (at [114]).

72 As a consequence, the Commissioner contends claim 1 of the 560 Patent is plainly, as a matter of substance, a scheme for sharing and completing workplace health and safety documents. There is no patentable subject-matter.

The 943 Patent

73 The arguments in relation to the 943 Patent were similar to those in the 560 Patent. It is unnecessary to repeat them in the same detail.

Repipe’s contentions

74 Repipe says that the 943 Patent addresses the problem of not being able to dynamically create a document in the field where there are multiple types of documents needed, for a multitude of actors, all of whom interact with the system in different ways and whose jobs, roles and authorities change in the field frequently and in real time. The solution it proposes is a technical one: namely, a method or system with a specific-purpose server and specific-purpose smartphones, together with a communication network. From Dr Aitken’s evidence, the invention claimed in the 943 Patent has the same three essential components as the 560 Patent.

75 Repipe places reliance on the evidence of Dr Aitken, who explained that the invention requires specific functionality from each component of the method. For example, the smartphone must be able to communicate with the communication network in the field, identify the user of the smartphone, request from the server a list of possible jobs that the user is associated with, receive the list from the server, display the list to the user, monitor for and receive a selection of a job by the user, request information about the selected job from the server, listen for and receive that information from the server, display the information so that the user can select indicia, receive that input from the user and send that input to the server. The other components must undertake a similarly specific and technical set of tasks. Dr Aitken’s evidence was that because the requirements of the claims are so specific, the server and the smartphones must be specifically programmed in order for the invention to be performed. Generic or un-configured servers and smartphones would not be able to perform their parts of this invention without being specifically programmed to do the necessary steps. Once configured, as required to perform the steps of the claims, the server and smartphones are not generic.

76 Repipe says the substance of the invention in the independent claims, per the evidence of Dr Aitken, is the combination of infrastructure items referred to above, configured and controlled by a specific computer program installed on the server and the smartphones to operate them to undertake the steps of the claims. The programmed server and smartphone are machines altered by technical skill from their generic state. Dr Aitken said the programming is technical work. The programming steps require logic and sequence of operation of the server and the sequence of operation of the smartphone to perform the necessary steps. This includes, not only what each of these devices must do, but also what and how they communicate with each other and with the users. That logic and sequence of operation would then be implemented in a series of instructions, being the specific computer software.

77 As with the 560 Patent, the evidence from Assoc Prof Hussain focussed, Repipe says, on whether the invention was new as at the priority date. This involves the same errors of approach, Repipe contends, which were committed in relation to the 560 Patent.

The Commissioner’s contentions

78 The Commissioner argues, as he did with the 560 Patent, that no part of the 943 Patent requires or involves artificial intelligence. Rather, the claimed steps will be performed by the computer using programmed logic that dictates which information is appropriate for the selected job and the user’s current authority and, therefore, which information should therefore be downloaded.

79 The substance of the 943 Patent invention is the same as claim 1 of the 560 Patent. It is simply a scheme for sharing and completing WHS documents. The Commissioner says this conclusion, again, follows from the lack of any meaningful technical detail in the claim words or the accompanying description in the body of the specification. The claim adopts the same practice of reciting ordinary computer functions without prescribing the technical means by which any such functions must be performed. The body of the specification contains, in substance, the same disclosures as the 560 Patent, including the same figures. For the same reasons identified in respect of the 560 Patent, the Commissioner contends there is no manner of manufacture.

The dependent claims of the Patents

80 The Commissioner asserts that none of the features added by the dependent claims of either Patent adds patentable subject matter. Rather, the claims merely define the scheme in greater detail. Claim 2 of the 560 Patent, for example, requires the selected document to be a task type template with preselected labels.

81 Repipe contends claim 5 is an independent claim comprising the same three components previously identified. The Commissioner argues claim 5 of the 943 Patent is a ‘system’ claim, adopting the same general form as claim 5 in RPL. In other words, claim 5 is a system claim that merely specifies the ordinary computing components that may be used to implement the scheme of claim 1 of the 943 Patent, namely, a server, a plurality of portable personal computing devices, a communications channel and a ‘rules engine’. The ‘rules engine’ is simply the programming logic that will determine what the user is permitted to do according to the role and authority the user has. The program logic itself is not disclosed in the specification of the 943 Patent and the specification proceeds on the basis that the existing portable computing devices, servers and communication channels can be programmed in the manner described in claim 5. Compared with claim 1, claim 5 also contains the additional feature of transmitting a response to the information that was uploaded by the worker. This is mere detail about the scheme.

CONSIDERATION

82 It is accepted by Repipe that the need to complete routine WHS documents, such as Equipment Pre-Starts, Job Safety Assessments, ‘Take 5’ Assessments and Job Permits identified in the Patents, ‘formed part of the common general knowledge and the regulatory milieu for workplace health and safety before the priority date’. The Patents do not say otherwise. That is, the Patents do not say that the inventiveness or ingenuity of the inventions is in the field of WHS. This, Repipe says, reinforces the centrality of the computer aspects to the claimed inventions. This must be so.

83 Repipe submits, and I accept, that the fact that the Patents do not claim to have invented new hardware does not mean they are not patentable. Nor does the fact that they do not claim to rely on artificial intelligence. Artificial intelligence is not a pre-requisite for patentability of a computer-implemented business method.

84 The solution disclosed in the Patents is put into effect by executing specific software applications on the server and the smartphones. The inventions could not be carried out using a generic or unconfigured server or smartphone, because the tasks those devices must perform are so specific. A generic server or smartphone would not be capable of performing the steps of the method without the addition to each of a specific program to configure and control these devices to do so. Without the appropriate programming, the devices are, as Dr Aitken put it, ‘like a malleable lump of clay without being formed into a bowl shape and fired to form the rigid bowl’. Once configured as required to perform the steps of the claims, the server and smartphones are not generic. The things they must be configured to do are not things they are normally configured to do.

85 It is common ground that the claims assume that software will be written to configure the hardware to carry out the steps of the claim. However, Repipe notes that software is not at large – it must conform to the technical architecture and functional requirements mandated by the claims. By the specifications, the programmer is given the ‘architecture’ of the system and the steps of the method to be performed, including the sequence of operation and functionality of the server and the smartphone. Then the programmer would write code to carry out that logic and sequence of operation and to provide that functionality. The programming will configure the device to perform the necessary functions and will also control the configured capabilities as the devices are operated so that they can move from step to step as required.

86 No computer code is disclosed and that the code is not the inventions. Repipe says that the inventions are broader than that. They are the whole system or method, including the architecture of the computer system required to carry out the steps in the claims and the functionality required of every component in the system. It is this functionality which is to be produced by the software. As Assoc Prof Hussain acknowledged in cross-examination, claim 1 of the Patents is concerned with achieving the functionality they respectively describe rather than the particular form of the software that achieves that functionality.

87 Repipe relies on the fact that Assoc Prof Hussain agreed that a software development team could not sit down to write the software to implement the method without first having a statement of the functional specification that the software needed to comply with. It is said to be nonsensical to speak of the development of software without a list of functional requirements. The functional specification will set out the hardware elements of the system – which the Patents do in fig 57. It will also set out the particular steps that the method needs to perform – the functionality – which the Patents do in the claims. That, Repipe contends, is the substance of the inventions in the Patents: the architecture and functionality of a computer system that can solve the problems identified in the Patents.

88 Repipe points out that if the claims had included code, an infringer could avoid infringement by producing the same functionality, but with slightly different code. This is not a technicality. Assoc Prof Hussain acknowledged that it would be very unlikely that two different coding teams given the functional requirements set out in the claims would produce the same code.

89 Looked at as a whole, and as a matter of substance, Repipe says the inventions have technical subject matter. It is the architecture and functionality of a computer system. The Patents expressly provide, ‘[m]uch of the inventive functionality and many of the inventive principles are best implemented with or in software programs or instructions’. As these are innovation patents, an inventive step is not required; but the specifications expressly describe the functionality (which is technical subject-matter) as the subject-matter of the inventions they describe.

90 Although code required to implement the inventions is not part of the technical contribution of the Patents, Repipe contends that the fact that computer code is required to put the inventions into practice further demonstrates that the subject-matter of the inventions is technical. Further, Repipe says the inventions claimed in the patents are not mere abstract ideas; they are concrete descriptions of a computer system. Assoc Prof Hussain accepted that the substance of the inventions are ‘a tool that performs certain defined steps’ that they are ‘more than simply an abstract idea’ and rather are ‘a technologically driven solution so as to implement that idea’.

91 Repipe seeks to distinguish RPL. There was no suggestion in RPL that the invention was ‘other than a standard operation of generic computers with generic software to implement a business method’ (at [110]). That is not the case here. Repipe says that here, the inventions are not, and could not be, carried out on generic computers with generic software. The Patents prescribe specific functional requirements and computer code must be written to meet those requirements. This is the essential element to Repipe’s argument.

92 Research Affiliates is also distinguishable, Repipe contends. Claim 1 in Research Affiliates was said to be ‘a computer-implemented method’, but the claim did not otherwise refer to computer technology (at [63]). Repipe contends that claim focused on the non-technological aspects of the invention. The Full Court held that the work of was done by an analyst, not a computer (at [108]):

It is apparent from the description in the specification that the computer is simply the means whereby the analyst accesses data to generate an index. The work in generating the index and weighting is described in terms of the work of the analyst rather than as some technical generation by the computer. Indeed, while the specification states that the invention may be used for investment management or investment portfolio benchmarking, the exemplary embodiment makes it clear that it may be, but is not necessarily, implemented on a computer.

93 I am not persuaded the Patents in this case are readily distinguishable. No specific application software has been claimed or even identified in any claim of the Patents. No computing programming logic or code is disclosed anywhere in the Patents. The substance of both inventions is a mere scheme that can be implemented using some unidentified software application to cause a server computer and smartphone to perform the steps identified in the claim. To implement the scheme, a reader must use his/her own skill and knowledge to write an appropriate software application. No such application is disclosed in the Patents.

94 It is not sufficient to rely on the form of the claims rather than their substance. This is clear from the authorities. It is not appropriate for Repipe to simply rely upon the field on which ingenuity is claimed to exist, being the field of computer technology. The language used by patent attorneys when drafting and amending claims cannot convert what is, in substance, an unpatentable business method or scheme into a patentable invention by merely asserting that the invention is in the field of computer technology or by using words in the claim or specification that refer to computer technology: Myriad (at [144]). The issue must be addressed as a matter of substance. As a matter of substance, there is no meaningful technical content in the description in the body of the claims or specification. There is only a scheme. The fact that the scheme may be quicker using a computer than using a paper system is a function of computers not the Patents: see, for example, RPL (at [85] and [104]).

95 In my view, the question is whether or not the method merely requires generic computer implementation of a scheme or abstract idea. In Encompass, the claimed method was no more than an idea for a computer program to be implemented in an electronic processing device (with the manner of implementation not characterised).

96 As noted in Encompass (at [108]), if on proper analysis, and as a matter of substance, a claimed method merely requires generic computer implementation then the method cannot be a manner of manufacture. Although in Encompass it was argued that the claim integers required specific computer functionality that could not be implemented using generic software, the contention was rejected on the basis that the claimed invention as a matter of substance was merely an instruction to apply an abstract idea: namely, the steps of the method using generic computer technology. Those conclusions were reached because the claim was nothing more than a method in which an uncharacterised electronic processing device was employed as an intermediary to carry out the method steps, where the method itself was no more than an abstract idea or scheme: see Encompass (at [99]). Further, even if the claimed invention could not be implemented using ‘generic software’, the claims did not secure as an essential feature of the invention any particular software or programming that would carry out the method. Rather, it was left to those wishing to use the method to devise and then implement a suitable computer program for that purpose: see Encompass (at [100]). Finally, the method was ‘an idea for a computer program, it being left … to the user to carry out that idea in a electronic processing device’: see Encompass (at [101]).

97 Repipe stresses that the claimed methods in this instance are far from abstract ideas or mere information, rather they prescribe detailed technological architecture and functional requirements for the technology and claimed technology driven solutions. However, in my view and following the Full Court’s analysis in Encompass, it must be concluded that the substance of the invention claimed in each Patent is an unpatentable business method or scheme in that:

(a) A scheme or method is claimed for sharing and completing WHS documents.

(b) The scheme or method is implemented by using computers which perform their ordinary functions.

(c) There is no invention as to the way that the computers carry out the scheme or method.

98 The problem that each Patent solves is a business problem in the field of WHS. More specifically:

(1) The problem the Patents identify is the ‘volume’ of WHS paperwork and its inefficiency. The 560 Patent, for example, records (at [0004]) that the ‘great majority of these checklists and risk assessments are paper-based – and the volume of paperwork generated is very large’. The 560 Patent also states (at [0005]):

Of course, front line employees have a natural aversion to paperwork, especially when they have done the same task or job hundreds of times. The key faults of the paperwork are:

It’s a lot like telling field employees to ‘write lines’ every day.

Field employees don’t respect the paperwork - so they arbitrage it.

It’s extremely inefficient. …

(2) The Patents do not refer to any technical problem in the field of computing.

(3) The parties’ experts identified the ‘problem’ as the inability of field workers using paper-based forms to:

(a) share new information (such as information about a newly arising hazard) with other field workers ‘in real time’, in the case of the 560 Patent; and

(b) create documents dynamically in the field, where multiple types of documents may be needed for different workers whose jobs, roles and authorities might change in the field ‘in real time’, in the case of the 943 Patent.

(4) The business problems are not problems in the field of computing.

99 The claimed inventions do not rise above a scheme simply because, as Assoc Prof Hussain described, they are ‘a technology driven solution to be able to – for any organisation to be able to comply with work health and safety procedures’. The sense in which the inventions are ‘technology driven’ is that the schemes use computers to implement a solution to a business problem. The claims use the ‘standard’ computing functions to provide a non-standard solution. The ‘architecture’ shown in the figures is nothing more than a standard (generic) server, network and a smartphone or similar, for example, a tablet.

100 It may well be that specific software needs to be designed to achieve the ‘invention’, but even so, that is not the substance of the claimed inventions. As to the ‘specific application software’:

(a) No software application or program code for carrying out the identified steps in the computer is defined by the claims or made the subject of the claims.

(b) No software application or program code for carrying out the identified steps in the computer is disclosed anywhere in the complete specifications.

(c) The specifications admit that the claimed inventions may be implemented using any software application, that uses any technical means, that causes a generic server and smartphone to perform the claimed steps.

(d) The ‘specific application software’ referred to by Dr Aitken is something that must be developed and written by a programmer in order to implement the claimed inventions.

CONCLUSION

101 The claimed inventions are as to a business method. Even if construction of the specifications alone were to produce a different characterisation, that would be to elevate form over substance. The Patents may well contain a good idea, but they are not a manner of manufacture and are not patentable subject matters.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and one (101) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice McKerracher. |

ANNEXURE A