FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Gill v Ethicon Sàrl (No 5) [2019] FCA 1905

ORDERS

NSD 1590 of 2012 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | KATHRYN GILL First Applicant DIANE DAWSON Second Applicant ANN SANDERS Third Applicant | |

AND: | ETHICON SÀRL First Respondent ETHICON INC. Second Respondent JOHNSON & JOHNSON MEDICAL PTY LTD (ACN 000 160 403) Third Respondent | |

JUDGE: | KATZMANN J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 21 november 2019 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. By 20 December 2019, each applicant is to notify the respondents and the Court of her election as to whether she will accept an award of damages under the relevant provisions of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) or at common law, as modified by the statutory scheme, if any, that operates in the State in which she lives.

2. By 14 February 2020, the parties bring in short minutes giving effect to these reasons.

3. In the event that the parties are unable to agree on the form of orders or all of the orders, including the form of the common questions and the answers to them for the purposes of s 33ZB of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), a timetable for the filing and exchange of submissions be forwarded to chambers by 17 January 2020, with a view to a hearing in the week commencing 10 February 2020.

4. Liberty to apply be granted on two (2) days’ notice.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

Table of contents

KATZMANN J:

1 This is a representative action concerning nine medical devices, all made using knitted polypropylene, a thermoplastic polymer. The devices were designed to be surgically implanted in women to alleviate either stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse. The action calls into question the safety of those devices. Its outcome will affect thousands of women who were implanted with any of the devices in Australia and who suffered any complications caused by those devices at any time before 4 July 2017. A number of the final orders that will be made in the proceedings will bind all such women except for those who have exercised their rights to opt out of the action.

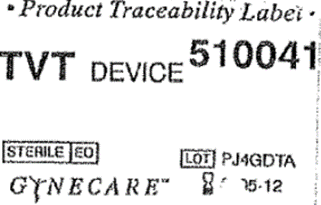

2 The medical devices used for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence which are the subject of this action are known by the trade names Gynecare Tension-free Vaginal Tape System (TVT), Gynecare TVT Obturator System (TVT-O), Gynecare TVT Secur System (TVT Secur), Gynecare TVT Exact Continence System (TVT Exact) and Gynecare TVT Abbrevo Continence System (TVT Abbrevo). When I refer to them collectively in this judgment, I use the shorthand expression “the SUI devices”.

3 The medical devices used for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse which are the subject of this action are known by the trade names Gynecare Gynemesh Prolene Soft (Gynemesh PS), Gynecare Prolift Pelvic Floor Repair System (Prolift), Gynecare Prolift+M Pelvic Floor Repair System (Prolift+M) and Gynecare Prosima Pelvic Floor Repair System (Prosima). I refer to them collectively as “the POP devices”.

4 When I refer to the SUI devices as well as the POP devices, I call them “the Ethicon devices”.

5 In a nutshell, the applicants’ case is that all the Ethicon devices cause a number of potentially serious complications but the respondents were so driven by commercial interests that they neglected to undertake the investigations reasonably necessary to inform themselves and the community of the extent, if not also the nature, of the risks posed by the devices and to take appropriate or sufficient remedial action. To the extent that they were aware, they failed to make adequate disclosure. As the applicants put it in their opening submissions:

[A]t all times from the development of the first TVT products, to the commencement of proceedings, the Respondents were motivated by a sales-driven culture, with an emphasis on the perceived urgent need to get products to doctors before competitors. There was a focus on profit and maintaining market share, without adequate focus on safety, efficacy and potential complications. In the race to sell as many products as possible, the Respondents failed to undertake proper or adequate evaluations or [disclose] known complications and risks. 1

6 Since the commencement of this proceeding, all the POP devices have been removed from the market but, with the exception of TVT Secur, all the SUI devices are still available for sale.2

7 The devices in question were made by two foreign companies: the first respondent, Ethicon Sàrl (Société Anonyme à Responsabilité Limitée or Limited Liability Company) and; the second respondent, Ethicon Inc., both members of the Johnson & Johnson group of companies.

8 Ethicon Sàrl is a Swiss corporation and the manufacturer of a variety of polypropylene implantable medical devices, including all but one of the devices the subject of this litigation. Ethicon Inc. is an American corporation and the manufacturer of the remaining one, Gynemesh PS.3 It was also involved in the marketing of all the relevant devices through its Gynecare division. Ethicon Inc. is a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson, an American public company, listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Ethicon Sàrl is a subsidiary of another Swiss company but the ultimate parent company is Johnson & Johnson. In these circumstances, unless it is necessary for a particular reason to distinguish between them, I will generally refer to both Ethicon companies simply as “Ethicon”.

9 Ethicon Sàrl and Ethicon Inc. supplied the Ethicon devices to the third respondent, a related Australian company, Johnson & Johnson Medical Pty Limited (JJM). JJM promoted and supplied the Ethicon devices to Australian hospitals and doctors.

10 The respondents were represented by the same lawyers and, through their senior counsel, made it clear that no point would be taken that the knowledge of one of the companies in the group was not shared by another.4

11 According to statements made on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG), the purpose of each of the SUI devices is to, by way of a sling, treat stress urinary incontinence and female urinary incontinence resulting from urethral hypermobility and/or intrinsic sphincter deficiency.5 The purpose of the POP devices was to provide “tissue reinforcement and long-lasting stabilisation of fascial structures of the pelvic floor in vaginal wall prolapses”.6

12 The devices were promoted as effective in restoring normal anatomy and sexual function, as not subject to degradation or weakening by tissue enzymes, and as having high patient satisfaction. Instructions for use (IFU) supplied with the devices warned of some possible adverse reactions and contraindications. Yet, a number of potential complications, known to the respondents from the time the devices were first supplied, were not disclosed and those that were disclosed were often minimised. Some of the potential complications could occur with any form of pelvic surgery. Others were unique to implantable synthetic mesh devices.

PART II: OVERVIEW OF THE PROCEEDING

13 This action is brought under Pt IVA of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act) by three applicants, both on their own behalf and on behalf of other women who claim to have suffered complications from the implantation of one or other of the Ethicon devices during the relevant period. I was informed at the beginning of the trial that there are some 700 registered group members but as the class is an open one, and more than 90,000 Ethicon devices have been supplied in Australia,7 it is highly likely that there are many more.

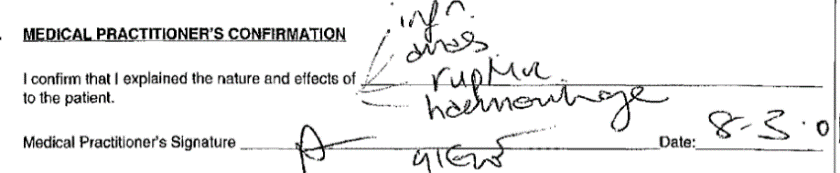

14 The three applicants are Kathryn Gill, Diane Dawson, and Ann Sanders. Mrs Gill had pelvic organ prolapse and was implanted with a Prolift device on 12 January 2007. Mrs Dawson also had pelvic organ prolapse and was implanted with Gynemesh PS on 8 May 2009. Mrs Sanders suffered from stress urinary incontinence and was implanted with TVT on 12 March 2001.8

15 The applicants allege that the respondents contravened various provisions of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (TPA) and the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA). The statutory claims are based on:

s 74B of the Trade Practices Act, because it is alleged that the Ethicon devices were not reasonably fit for the particular purpose for which they were acquired by the group members and not fit for the disclosed purpose under s 55 of Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act — the Australian Consumer Law (ACL);

s 74D of the Trade Practices Act, because it is alleged that the Ethicon devices were not of merchantable quality and did not comply with the guarantee given by s 54 of the ACL in that they were not of acceptable quality;

s 75AD of the Trade Practices Act in that the Ethicon devices were allegedly supplied with a “defect” and s 138 of the ACL because they were allegedly supplied with “a safety defect”; and

s 52 of the Trade Practices Act and s 18 of the ACL in that the information the respondents released in connection with the Ethicon devices, including the IFUs accompanying the products, and the way in which they were marketed and promoted was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive consumers.

16 The applicants also allege that the respondents are liable to the applicants in negligence for:

failing to undertake any, or any adequate, clinical or other evaluation of the Ethicon devices before releasing them in Australia;

failing to conduct any, or any adequate, evaluation of safety and effectiveness of the Ethicon devices after their release in Australia; and

failing to inform them, their treating doctors, and/or the hospitals in which the treatments were administered, of the inadequate evaluations about, and the risks of, or susceptibilities to, complications of the kinds from which they suffered.

17 The respondents deny liability and, in the cases of Mrs Gill and Mrs Sanders, they contend that, in any event, their actions are statute-barred.

18 An Originating Application and Statement of Claim were filed on 15 October 2012 naming a single applicant, Mrs Julie Davis. On 6 April 2016, by orders of the Court, Mrs Gill, Mrs Dawson, and Mrs Sanders were substituted for Mrs Davis, and two sub-groups were created, one referred to in the pleading as the “Mesh Sub-Group”, mesh being a reference to the POP devices, the other as the “Tape Sub-Group”, tape being a reference to the SUI devices.

19 The trial commenced at the beginning of July 2017 and did not conclude until the end of February 2018. Evidence was adduced from 48 witnesses, 35 of whom gave oral evidence. Of the 48 witnesses, 37 were experts hailing from nine different disciplines. Each witness gave evidence individually, as my proposal that experts in the same discipline prepare joint reports and give concurrent evidence was opposed by both parties. Extensive written and oral submissions were made.

20 More than 5,500 documents were tendered, running to over 164,000 pages. Mercifully, the trial was conducted electronically, which, to some extent, eased the burden on the Court.

21 Each of the applicants gave evidence on affidavit and was cross-examined. Affidavits were also read from their husbands, only one of whom, Steven Gill, was required for cross-examination.

22 The applicants adduced evidence from four urogynaecologists. They were Andrew Korda, Wael Agur, Jerry Blaivas, and Michael Thomas Margolis. Professor Korda is an Australian. Dr Agur practises in Scotland and was described by one of the respondents’ experts as an opinion leader in Great Britain.9 Professor Blaivas and Assistant Professor Margolis hail from the United States. Urogynaecology, I should explain, is a surgical subspecialty of urology and gynaecology, which involves the diagnosis and treatment of female pelvic floor disorders.10

23 After the respondents had indicated they would not be calling him, the applicants tendered a report prepared for the respondents by Malcolm Frazer, another urogynaecologist.

24 The applicants also tendered reports and read affidavits from a number of other expert witnesses in a range of disciplines. They included the following people who, unless otherwise indicated, are based in Australia: Bilal Chughtai, a urologist, from the United States; Uwe Klinge, a general surgeon and biomaterials researcher who lives in Belgium; Bernd Klosterhalfen from Germany and Vladimir Iakovlev from Canada, both pathologists; two biomechanical engineers, Russell Dunn and Scott Guelcher from the United States; four regulatory experts, Derrick Beech, Bryan Allman from the United Kingdom, Peggy Pence and Anne Holland from the United States; three epidemiologists, Howard Hu from Canada, Cara Krulewitch from the United States, and Mark Woodward; Ian Gordon, a biostatistician; two colorectal surgeons, Alan Meagher and Anthony Eyers; Patricia Jungfer, a psychiatrist; Joseph Slesenger, a specialist in occupational medicine; and Lindy Williams and Timothy Walsh, both occupational therapists.

25 Of these witnesses, only Dr Beech, Professor Woodward, Ms Williams, and Mr Walsh were not required for cross-examination.

26 Affidavits were also read from Robyn Leake, an obstetrician and gynaecologist who treated Mrs Gill for a number of years, James Swan, an obstetrician and gynaecologist who treated Mrs Dawson, and Sandra McNeill, an obstetrician and gynaecologist who assisted in the operation in which Mrs Sanders was implanted with TVT.

27 The respondents adduced evidence from six urogynaecologists: Piet Hinoul from the United States, Pierre Collinet from France, Jan Deprest from Belgium, Alan Lam, Jan-Paul Roovers from the Netherlands, and Anna Rosamilia; an engineer, Steven McLean from the United States; Paul Santerre, a professor of biomaterials from Canada; Thomas Wright, a pathologist from the United States; three psychiatrists, Lisa Brown, Anthony Samuels, and Rosalie Wilcox; and an occupational therapist, Susan Borthwick. All of these witnesses, except Dr Wilcox, were required for cross-examination.

28 Dr Hinoul was the only witness from any of the three respondents to give evidence. Dr Hinoul is a urogynaecologist born in Belgium and educated in the United States, Belgium, and the Netherlands. He holds a PhD in bio-medical sciences from the University of Amsterdam. Since June 2014 he has held the position of Vice President–Medical Affairs at Ethicon Inc., based in Somerville, New Jersey, USA.11 He gave evidence about the Ethicon devices and their development and Ethicon’s conduct. Some of that evidence was based on company records. Not all of it concerned matters of fact.

29 Dr Hinoul joined Ethicon in 2008, when he was appointed Director of Medical Affairs – Europe, Middle East and Africa (Women’s Health and Urology), based in Paris, France.12 According to Dr Hinoul, the Director of Medical Affairs is responsible for “generating evidence for new medical devices”, “for ensuring that there is sufficient evidence to enable products to be released onto the market” and for products that are already on the market, and for “monitoring the literature and the various studies involving the products”.13 The Director of Medical Affairs is also responsible for assessing their risks and benefits. As Director of Medical Affairs, Dr Hinoul said that he was responsible for Ethicon’s pelvic floor repair and incontinence repair products. His duties included undertaking risk/benefit analyses of devices, drafting clinical evaluation reports, assessing clinical literature, presenting at panel meetings, and reviewing adverse events. He also contributed to various Ethicon documents which required “medical input”. They included IFUs supplied with the devices, patient brochures, marketing, design verification, and professional education materials.14

30 In December 2010 Dr Hinoul became the Worldwide Director of Medical Affairs (Women’s Health and Urology) for Ethicon Inc., based in Somerville, New Jersey. In June 2012 his responsibilities increased to cover other aspects of the Ethicon business and from April 2013, until his promotion to Vice-President–Medical Affairs, he held the position of Worldwide Director of Medical Affairs (Ethicon Endo-Surgery (Energy Franchise)).15

31 Dr Hinoul presented as a company spokesman. His affidavit was lengthy (363 pages) but not full and frank. It cast Ethicon’s conduct in the most favourable light. In cross-examination, Dr Hinoul was inclined not to give responsive answers to potentially uncomfortable questions and tended to be evasive where direct answers would not suit the respondents’ interests. At times he steadfastly defended the indefensible.

32 Of the Medical Affairs Directors who preceded him, only his immediate predecessor, Dr Axel Arnaud,16 remains with Ethicon.17 Dr Arnaud was a key figure in the development and post-market surveillance of a number, if not all, of the Ethicon devices. In particular, he investigated the TVT procedure in 1996 and TVT-O in 2002 and was a moving force in the development of the POP devices. No explanation was provided to the Court for his absence nor for the absence of the other Medical Affairs Directors. Presumably the respondents were content to rely solely on their reports, despite the criticisms made of them by the applicants’ experts and others.

33 The rest of the evidence consisted of documents. One legacy of the parties’ approach to tendering documents is that documents referenced by multiple witnesses or submissions were tendered multiple times. Sometimes the same document was tendered by both parties. Sometimes the same document was tendered multiple times by the same party. The result was that one document might have two or more document identification (ID) numbers. Rather than refer to multiple document ID numbers for the same documents, I have elected to use one only, and where a document is mentioned more than once in these reasons, I have endeavoured to refer to the document by the same ID number throughout. No significance should be attached to the choice of ID tender number. Moreover, a source cited in a footnote should not be regarded as the only source upon which I relied to form the view expressed in the relevant sentence or paragraph. The ID numbers have been included in the footnotes to assist the parties to identify source material. They are otherwise of no consequence.

34 In a case of this magnitude, it is impossible to refer to all the evidence and it is unnecessary to do so. My failure to refer to any particular item of evidence, however, ought not to be taken as an indication that I have not considered it. Having regard to the length of the judgment and the connection between the subject-matter of its various parts, a degree of repetition is unavoidable. Indeed, it is often necessary. I have tried to keep repetition to a minimum, although some readers may consider that I did not try hard enough.

35 At this point I also wish to make some remarks about the conduct of the trial. An extraordinary amount of work goes into a trial of this size and nature and the stakes are high. No doubt these pressures take their toll on lawyers and their clients. Despite these pressures, and notwithstanding the zealous prosecution of their clients’ interests, counsel conducted the trial with a good deal of equanimity and courtesy. This made the herculean task that confronted me far less daunting and much more tolerable than it might otherwise have been. For that, I am truly grateful.

36 On the other hand, the case could certainly have been conducted with greater efficiency.

37 It is questionable, for example, whether it was necessary for the applicants to plead so many causes of action. The applicants’ pleadings were convoluted and, owing to cumbersome cross-referencing, often difficult to follow. The parties quarrelled about points upon which they should have been able to reach agreement. Insufficient judgment was exercised about the number of experts that should be retained in each discipline, the way in which the evidence should be elicited, and the documents that should be tendered. Sources for some submissions were not always provided, which meant that I had to trawl through the evidence to find them for myself. I appreciate that the litigation was a substantial logistical exercise and that it is easy to be wise after the event. I do hope, however, that when the dust settles, both sides reflect on what could have been done better, as I have done.

PART III: THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE ETHICON DEVICES

38 Despite some sharp and often irreconcilable differences of opinion, there was a good deal of common ground. Unless otherwise indicated, my account of the facts is based on agreed facts, and evidence which was not contradicted or challenged.

The use of synthetic mesh and polypropylene in surgery

39 Prolene is a polypropylene resin first made by Ethicon in the 1960s.18 Subject to certain conditions, it was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States in April 1969 for use in non-absorbable surgical sutures.19 Ethicon Inc. had sought approval for its product as a new “drug”. Strict conditions had to be satisfied before approval could be given. Ethicon was required to submit detailed reports of preclinical investigations, including studies on laboratory animals. In order for an animal study to be considered appropriate, proper attention had to be given to the conditions of use recommended in the proposed labelling, including whether the “drug” was intended for short or long-term administration.20 Ethicon conducted studies of tissue reactions to the sutures in rats, rabbits, and dogs. It conducted studies of the tensile strength of the sutures when implanted in rats. Ethicon was also required to submit reports of all clinical testing and all information relating to the evaluation of the safety and effectiveness of the sutures.21 After approval had been granted, Ethicon continued to test its sutures and submitted quarterly reports to the FDA.22

40 Prolene sutures continue to be widely used, including in pelvic reconstructive surgery. Dr Hinoul described them as “functional, safe and effective”.23 The applicants did not suggest otherwise.

41 Synthetic mesh was first used in the repair of hernias in the abdominal wall. Francis Usher was the pioneer. In 1958 he published on the use of synthetic mesh in six dogs to reinforce the abdominal wall and close the abdominal wall and thoracic tissue defects. Dr Usher initially used a woven material made of polyester but rapidly changed to a knitted fabric made of a high-density polyethylene known as Marlex.24 Marlex became increasingly stiff after implantation and at times caused considerable local wound complications, seroma formation, infection, and “stiff belly”.25 At some later point in time, another polymer, polypropylene, was used in the manufacture of Marlex.

42 In the early 1970s, Ethicon developed Prolene sutures into a knitted flat mesh26 and, in 1997, into a three-dimensional form known as the “Prolene Hernia System”.27 Ethicon conducted a good deal of research on Prolene sutures, both before and after it had obtained regulatory approval for their use. But the Prolene Hernia System was cleared for sale on the back of the approval for Prolene sutures, based on their supposed “substantial equivalence”. The first of the Ethicon devices was cleared for sale on the back of the regulatory approval of Prolene sutures and, in part, because of its supposed “substantial equivalence” to the Prolene Hernia System, despite the differences in design, use, anatomy, and site-specific considerations.

Stress urinary incontinence and its treatments

43 Stress urinary incontinence is the involuntary leakage of urine during activities such as coughing, sneezing, lifting, laughing or exercising.28 It is to be contrasted with urge urinary incontinence which is involuntary leakage of urine accompanied by a compelling urge or need to urinate.29 For completeness, overactive bladder is a symptom complex characterised by urgency (the compelling need to urinate), usually with urinary frequency and nocturia (rising at night to urinate) and, sometimes, with urge incontinence.30 Mixed urinary incontinence is a combination of stress urinary incontinence and urge urinary incontinence.31

44 The only symptom of stress urinary incontinence is leakage of urine during activities accompanied by increased abdominal pressure like coughing, sneezing, lifting, running, and various other forms of physical exercise. It does not affect any aspect of the anatomy. It affects the quality of the sufferer’s life. It is undoubtedly distressing. But it is never life-threatening.

45 The urethra (the duct or tube extending from the bladder down to the wall of the upper vagina through which urine is carried out of the body) and the bladder are supported by pelvic floor muscles, which contract during coughing, sneezing and exercise to prevent leakage of urine.

46 Whereas urge incontinence is a “bladder problem”, caused by involuntary contraction of the detrusor muscle), stress urinary incontinence is a “sphincter problem”.32 The urinary sphincter is an arrangement of muscles situated closest to the bladder. Ordinarily, voluntary urination causes the sphincter to relax and the detrusor muscle (the smooth muscle in the wall of the bladder) to squeeze or contract, resulting in the expulsion of urine from the bladder down the urethra and out of the body. Weakness in the muscles or damage to the bladder neck support can result in leakage.

47 There are two types of stress urinary incontinence: urethral hypermobility and intrinsic sphincter deficiency. Urethral hypermobility describes the situation in which the urethra has moved outside the pelvis and activities such as coughing or sneezing (known as Valsalva activities) put added pressure on the bladder, causing leakage. Intrinsic sphincter deficiency simply refers to weak urethral sphincter muscles or poor urethral closure function.33

48 Risk factors include pregnancy and vaginal birth and other conditions which cause an increase in abdominal pressure, such as obesity, chronic cough, chronic heavy lifting and constipation.

49 Treatment is always elective.

Traditional treatments for stress urinary incontinence

50 There are surgical and non-surgical options.

51 Non-surgical (or conservative) treatments include general lifestyle changes, pelvic floor exercises, and the use of continence devices such as a pessary. Conservative treatments are not always successful. Some women experience alleviation of their symptoms; some do not and elect to have surgery.

52 Traditional surgical treatment options include:

(1) Burch colposuspension, named after Dr John Burch who first described it in 1961,34 which is used to correct urodynamic stress incontinence.

(2) needle suspension procedures;

(3) sling procedures using either the patient’s own connective tissue (fascia) (known as autologous slings) or foreign graft material; and

(4) use of urethral bulking agents, involving injection of a variety of different substances around the bladder neck and into the urethral sphincter, to thicken the urethral wall so as to provide greater urethral resistance during increases in abdominal pressure.35

53 In Australia, at least until the late 1990s, the Burch colposuspension was described as “the gold standard” surgical treatment for stress urinary incontinence. Associate Professor Rosamilia said that it had an 85% cure rate at five years, although she did not cite a source.36

54 The Burch colposuspension is performed either through abdominal incision (open abdominal surgery) or laparoscopically (keyhole surgery) in which the retropubic space (the space between the pubic bone and the bladder) is dissected and the neck of the bladder is elevated (or suspended) by sutures passed through the Cooper’s ligament, which borders the femoral ring, and attached to the pubic bone.37 The effect on the anatomy is to prevent or minimise descent of the proximal urethra during increases in abdominal pressure and to create a sling of tissue against which the urethra is compressed;38

55 The object of autologous slings is to cause the urethra to hit against something during a Valsalva activity so that the urethra momentarily shuts off. A Valsalva manoeuvre, named after an Italian anatomist, Antonio Valsalva, is the action of attempting to exhale with a closed mouth and nostrils. It increases pressure in the middle ear and chest and is used as a means of equalising pressure in the ears.39 The slings are placed under the neck of the bladder and are commonly referred to as “pubovaginal slings”.

56 The autologous fascial sling procedure was first described in 1907.40 Although it was a mode of treatment favoured by Professor Blaivas, it never achieved widespread popularity, because of its high complication rates, particularly in inexperienced hands.41 The complications with which it was associated included increased rates of urinary tract infection, urge incontinence, voiding dysfunction, erosion, and, occasionally, the need for surgical revision to improve voiding.42 It is not in dispute that the complications include continued incontinence, voiding dysfunction, urinary retention, pain, and dyspareunia (pain with sexual intercourse).43 Historically, the procedure was reserved for cases of intrinsic sphincter deficiency or prior surgical failure but there was evidence that it was an effective treatment for all types of stress incontinence with acceptable “long-term” efficacy.44 In 1998, Chaikin et al published the results of a prospective and retrospective study of 251 women with all types of stress incontinence who underwent pubovaginal fascial sling surgery by a single surgeon, and were followed up after a median period of three years (with a range of one to 15 years). Chaikin et al (1998) claimed that they had “demonstrated that the procedure [could] be performed in a reproducible fashion with minimal morbidity”.45 They said that postoperative urinary retention should be minimal if the sling is not tied with excessive tension. They acknowledged, however, that persistent and de novo urge incontinence remained “a vexing problem”. In cross-examination, Professor Blaivas, who was a co-author of the Chaikin article, suggested that in 1998 a five year follow-up would have been considered “long term”, although he would not consider it to be long term now.46

57 The SUI devices are midurethral slings. Midurethral slings may be surgically implanted in a number of ways. They may pass under the midurethra, run behind the pubic bone through the retropubic space (the cavity between the urethra and the muscles above it, the rectus muscles and the peritoneum) and exit above the pubic bone. This type of sling is known as a retropubic sling. Then there are those which are also placed under the midurethra but, unlike the retropubic slings, they pass through the obturator space and exit in the groin. They are called transobturator slings.

58 There are also single-incision slings, sometimes called “mini-slings”, which also pass under the midurethra, but are typically shorter in length than the multi-incision midurethral slings, and can be placed via either the retropubic or the transobturator route.

59 Despite the variety of approaches and materials used, it is widely accepted that all these slings should be placed under “minimal tension” to prevent the development of additional voiding dysfunction, such as obstruction with incomplete voiding.47

60 Every one of these surgical treatment options is attended by risks, although the nature and extent of the risks vary from procedure to procedure. The complications associated with the Burch colposuspension, for example, include urinary tract infection, urinary retention, urethral obstruction, de novo overactive bladder, haematuria, neurologic symptoms, pelvic pain, dyspareunia, and death. The most common complications associated with the other traditional forms of surgery are voiding dysfunction and urethral and urinary retention. They are managed conservatively with either intermittent self-catheterisation or an indwelling catheter. Refractory pain, that is pain that is resistant to treatment, is exceedingly rare after any of these procedures.48 The complications of treatment with the SUI devices are discussed below.

61 Regardless of the nature of the surgery, clinical outcomes appear to be worse for patients who have had previous surgery for stress urinary incontinence.49

62 It is common ground that, before deciding on the most appropriate course or method of treatment, a treating surgeon would consult with the patient, obtain her medical and surgical history, and assess her clinical needs.

The development of midurethral synthetic slings

63 As I have noted, the SUI devices are midurethral slings. The object of midurethral and pubovaginal slings is similar, but, unlike pubovaginal slings, midurethral slings are placed under the midurethra. Presumably for this reason, they are sometimes referred to as “suburethral slings”. The SUI devices are designed to be inserted without tension.

64 Tension-free vaginal tape was the brainchild of an Australian pelvic floor surgeon, Peter Petros. Its story begins in 1986 with two unrelated observations, which I gather were made by Dr Petros. The first was that a haemostat (an instrument for preventing blood flow by compression of a blood vessel) applied immediately behind the pubic symphysis (the immovable joint between the pubic bones in the centre of the pelvis), at the level of the midurethra, controlled urine loss on coughing. The second was that, on implantation, polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE, such as Teflon) tape created a collagenous tissue reaction around it. These observations generated two hypotheses: that a loose pubourethral ligament causes stress urinary incontinence and that a tape implanted in the exact position of the damaged pubourethral ligament would create a collagenous “neoligament” to reinforce it, restoring function and continence.50

65 Dr Petros began animal studies at the Royal Perth Hospital in 1987 using a tape made from Mersilene, a polyester material produced by Ethicon.51 The tape was inserted in the vaginal cavities of 13 dogs for periods from six to 12 weeks. Apart from a sticky yellow vaginal discharge, there were apparently no “ill effects”.

66 Human studies began over the following two years and continued into the 1990s. Between 1998 and 1999, 30 women underwent a “combined intravaginal sling and tuck” procedure, which involved creating an artificial pubourethral ligament and tightening the suburethral vagina. At the end of six weeks, all patients remained continent.52 Within two weeks of the tape being removed, however, 50% of the patients reported recurrent incontinence.53

67 In the early 1990s, doctors from the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at the University Hospital in Uppsala, Sweden, developed a technique for treating female urinary incontinence under local anaesthetic. Their objective was to restore the pubourethral ligament and the suburethral vaginal hammock. The technique was described in a paper by Professor Ulmsten and Dr Petros entitled “Intravaginal Slingplasty (IVS): an ambulatory surgical procedure for treatment of female urinary incontinence” published in 1995. 54 It involved placing under the urethra a tape-like strip of mesh in a U-shape sling formation using a specially designed instrument referred to as a “tunneller” introduced through paraurethrally dissected canals. The technique was used on 50 patients and drew on previous experimental and clinical studies. Thirty-eight of the 50 patients suffered from genuine stress incontinence, objectively verified, and 12 had symptoms and signs of both urge and stress incontinence. The mesh used was Mersilene (in 37 patients), Goretex (in five), Teflon (in six), and Lyodura (in two). Patients were evaluated post-operatively at intervals of one month, six months, and one to two years.55

68 The work of Ulmsten and Petros appears to have been driven by the prevalence of urinary leakage in post-menopausal women and the fact that the surgical treatment was generally extensive and required general anaesthesia. Ulmsten and Petros considered that there was “a strong need for more precise and simple ambulatory surgical methods to treat female urinary incontinence”. They specified the following criteria for these procedures:

(1) the type of defect causing the patient’s leakage must be defined and described in the work-up, as should the manner in which surgery can restore the dysfunction;

(2) the procedure should allow the patient to return to work shortly after the operation;

(3) the operation should be carried out under local anaesthesia, enabling the patient’s cooperation during the procedure and reducing costs and the number of services otherwise required; and

(4) both subjective and objective evaluation of the patient should be carried out, “recognizing her symptoms and the quality of life situation both before and after the operation”.56

69 Early results appeared promising. The authors wrote that 39 patients (78%) were completely cured of their stress incontinence and another six (12%) reported a considerable improvement of their urinary incontinence, leaking only occasionally. They also wrote that there were no intra or post-operative complications. They acknowledged, however, that, since the technique was new, no long-term results were available, although they speculated that the long-term results of their prosthetic sling would be similar to those involving “conventional” sling procedures. Ulmsten and Petros concluded that if their results were to be reproduced in ongoing follow-up studies including more patients (how many more they did not say) their method “should be considered as a promising new ambulatory procedure for treatment of female urinary incontinence”.57

70 It transpired, however, that, upon surgical insertion, the Goretex and Mersilene tapes were rejected in eight to 10 percent of patients. Further work followed, and in 1996 the results of another study by Ulmsten and others were published.58 This time the tapes were fashioned from Prolene and the technique was said to have been improved. I return to this study later in these reasons. It is sufficient at this point to note that the work of Professor Ulmsten and his team culminated in the production of the Ethicon midurethral sling known as TVT.

71 As noted above, the SUI devices the subject of the current litigation are TVT, TVT-O, TVT Secur, TVT Exact and TVT Abbrevo.

72 Each of the SUI devices consists of a sterile, single use device comprising polypropylene mesh in the form of a tape and a set of instruments to facilitate mesh implant placement. Each was designed for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence resulting from urethral hypermobility or intrinsic sphincter deficiency. TVT and TVT Exact were designed for use as pubourethral slings. TVT-O, TVT Secur and TVT Abbrevo were designed for use as suburethral slings.

The mesh used in the SUI devices

73 The mesh used in the SUI devices is made from Prolene, which, as I mentioned earlier, was developed by Ethicon in the 1960s as a suture material. Prolene consists of a non-absorbable polypropylene base resin and a number of additives. Polypropylene is a polymer made from the monomer propylene, a component of natural gas made from carbon and hydrogen.59 A polymer, I interpolate, is a material composed of long chains of chemical building blocks, called monomers, bonded together. Propylene is polymerised into polypropylene in a chemical reaction in which propylene molecules (monomers) are combined together in a step-wise fashion to ultimately form linear, chain-like macromolecules60 which turn into flakes, chips or pellets.61 In the manufacturing process, efforts are made to control the lengths of the individual chains (referred to as polymer molecular weight) and the variation in lengths between the different chains (referred to as polydispersity).62 The mechanical properties of polypropylene are directly influenced by its molecular weight and/or molecular weight distribution, which is the name given to the range of polymer chain lengths.63

74 Prolene fibres are manufactured by melting polypropylene flakes or pellets in a heated extruder which exit through a spinneret (a metal end cap on the extruder with holes of various shapes) forming strands or filaments.64 During this process, various additives are added to the polypropylene, including:

(1) two antioxidants: dilauryl thiodipropionate (or DLTDP), to improve long-term storage of the resin and fibre and to reduce the potential oxidative reaction with UV light, and Santonox R, to promote stability during compounding and extrusion;

(2) two lubricants: calcium stearate and Procol LA-10 (previously Luberol), to help reduce tissue drag and promote tissue passage; and

(3) a colourant: copper phthalocyanate (or CPC), to enhance visibility when it is desired to have a blue dyed monofilament fibre rather than a clear monofilament fibre.65

75 The additive package in use in 2003 was the same as that used in the original 1991 formulation save that the Santonox levels were reduced slightly (by 0.05%).66 There has been no change since. Neither side contended that the reduction in Santonox was of significance.

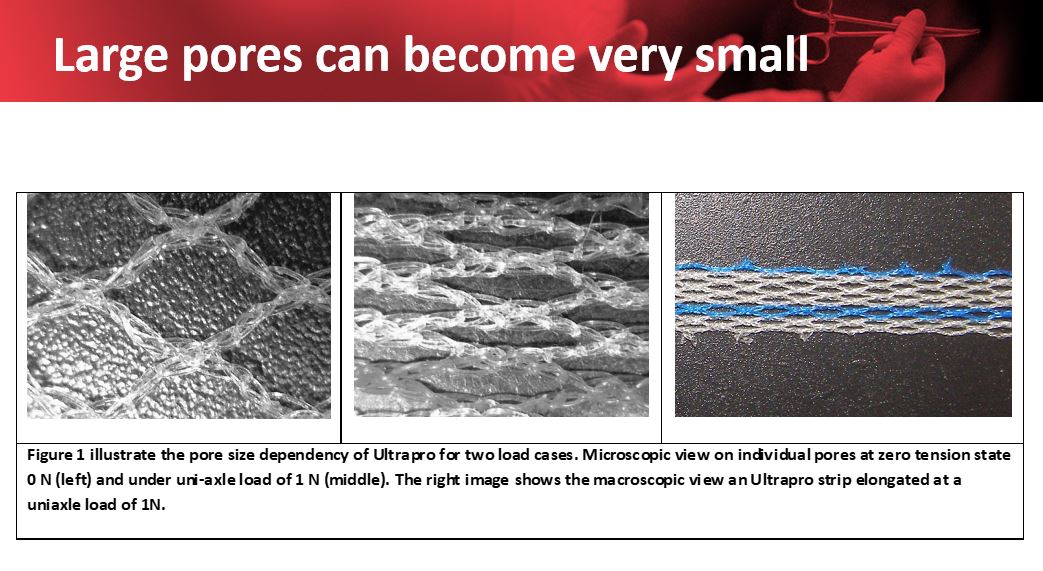

76 The single strands of Prolene (referred to as monofilaments) were then knitted into a specific pattern to form the mesh and the mesh was then scoured and annealed.67

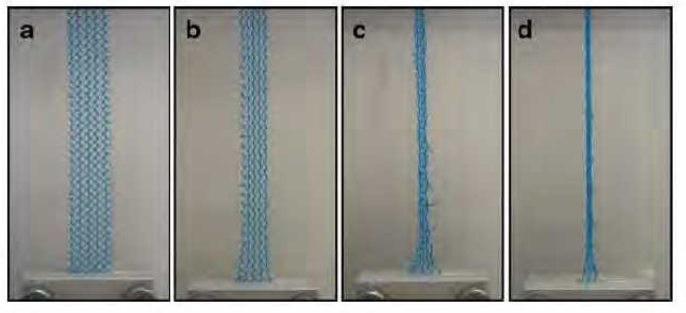

77 Finally, the mesh was cut into various sizes. The mesh was originally mechanically cut and sealed using a hot knife.68 From June 2006, laser cutting was introduced after Ethicon was inundated with complaints from surgeons about particle loss. 69 In a PowerPoint presentation from August 2006,70 no doubt designed to showcase the benefit of laser-cut over mechanically cut mesh, samples of mesh that had been laser-cut were compared with samples that had been mechanically cut after both sets had been pulled to 50% elongation and then relaxed.71 The mechanically cut (MCM) samples were described as follows:

The MCM samples show the degradation of the structure of the mesh in certain areas where, because of particle loss, the knit has opened and a portion of the construction has been lost. The area may also be stretched and narrowed resulting in roping due to this occurrence.

78 Accompanying photographs illustrated the description and also showed fraying of the mesh, a phenomenon described by Carol Holloway, Product Complaint Analyst, Worldwide Customer Quality, for Gynecare, in a letter dated 12 October 2005 as “inherent in the product based on the mesh construction”.72

79 In contrast, the laser-cut samples showed no degradation of the structure of the mesh, because no, or nearly no, particles were lost. The knit construction stayed intact and there was no roping. Although the mesh could be stretched and narrowed it was “generally less than the [mechanical cut mesh]”.73

80 The TVT system (sometimes referred to as “TVT Classic” or “TVT Retropubic”) is a sterile, single patient use device made up of one piece of undyed or blue Prolene, in the form of a tape, covered by a plastic (polyethylene) sheath (cut and overlapping in the middle) and held between two curved stainless steel needles (trocars) that are bonded to the mesh and sheath with plastic collars. The trocars (also called introducers) have two parts: a handle and an inserted threaded metal shaft designed to facilitate the passage of the tape from the vagina to the skin of the abdomen.74

81 The tape is 1.1cm wide and 45cm long.75 According to the description in the TVT technical file, maintained by Ethicon, it is about 0.7mm thick.76 It is inserted at the midurethral region, to create a sling on which the urethra can rest when there is a sudden increase in abdominal pressure.77

82 When the device was first supplied, however, it appears that the tape was shorter. It was 40cm, not 45cm, in length.78

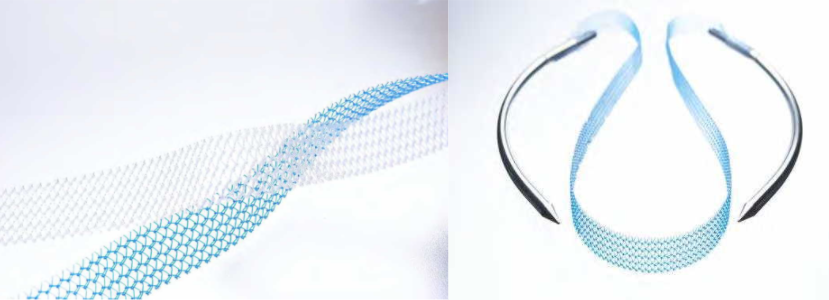

83 The images below show the tape (left) and the tape together with the trocars (right):

84 TVT requires the surgeon to use a retropubic (bottom to top) transvaginal surgical approach. The sling is inserted by means of the trocar through a small vaginal incision under the midurethra, passes vertically behind the pubic bone through the retropubic space, and exits through the skin in the lower abdomen. This is known as a “U” shaped sling orientation. The surgeon is unable to see where the trocar goes. It is not in dispute that the blind passage of the trocar creates a risk of perforation of the bladder and urethra and of damage to blood vessels and nerves in the retropubic space.79 Serious complications due to perforation of the large vessels and intestinal viscera have also been reported.80

85 TVT gained regulatory approval in Europe in 199781 and was cleared by the FDA on 28 January 1998.82 On 21 July 1998 it was approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) as a class IIB device for supply in Australia. It was first sold here in October 1999.83

86 Dr Hinoul deposed that TVT was cleared by the FDA on the basis that it was substantially equivalent to the ProteGen sling manufactured by Boston Scientific, one of Ethicon’s competitors, which was already on the market.84 Both TVT and ProteGen were intended for use as pubourethral slings for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence but, as Dr Bryan Allman, a regulatory expert who worked for Boston Scientific at the time, observed, the two devices were very different.85 For a start, they were made of different materials. TVT was made of knitted filaments of extended polypropylene (Prolene). ProteGen was made of woven polyester impregnated with bovine collagen. TVT was entirely non-absorbable. ProteGen had an absorbable collagen coating. The tools were also different. TVT was supplied with a reusable introducer and rigid catheter guide. ProteGen was supplied with disposable single use instruments: a bone locator, a suture anchor system, a suture passer, and a suture spacer. Both were intended for anterior fixation, but TVT was to be fixed to abdominal skin by friction at first and later by tissue ingrowth, whereas ProteGen was fixed by a suture anchored to bone.86

87 Certain modifications were made over time. I have already mentioned the change in the cutting technique. In addition, in 1999 the diameter of the needles used with the device was reduced from 6mm to 5mm.87 A blue version of the TVT tape was developed in October 2001, by incorporating a pigmented blue fibre into the knitted mesh. The stated purpose of this development was to enhance visibility in the surgical field.88

88 Fundamentally, however, the tape did not change. It has always been made from Prolene and the composition of Prolene has not altered in any material respect.

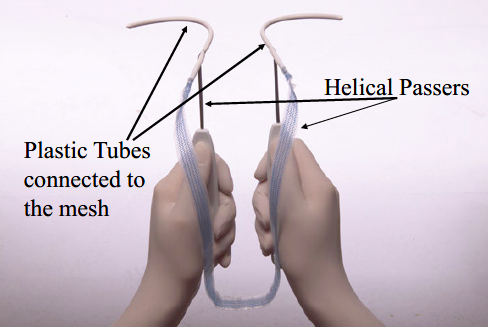

89 TVT-O is also a sterile, single patient use device, which consists of a piece of undyed or blue Prolene mesh tape covered by a plastic sheath overlapping in the middle. Plastic tube receptacles are attached at each end. TVT-O is made from the same Prolene mesh used in TVT and its dimensions are identical. It differs from TVT in only two respects: the tools or instruments supplied with the device and the method of attachment. The tools or instruments consist of two helical passers, shown in the photograph below taken from Dr Hinoul’s affidavit, and a winged guide, which facilitates the passage of the helical passers through the obturator membrane.

90 The helical passers are inserted through the vagina but then pass through the obturator foramen, a large opening between the ischium (the curved bone forming the base of each half of the pelvis and one of the three bones that fuse to form the hip) and the pubic bones, rather than the retropubic space as with TVT and, unlike TVT, exit through the upper legs, rather than the abdomen.89

91 Like TVT, TVT-O was developed by a surgeon. As we shall see, Ethicon’s interest in such a device was largely, if not entirely, motivated by its concern about increasing competition in the marketplace that followed the early success of TVT.

92 TVT-O received regulatory approval in Europe and the United States in December 2003.90 It was first supplied in Australia in March 2004.91

93 TVT Secur was indicated for use in women as a suburethral sling for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence resulting from urethral hypermobility and/or intrinsic sphincter deficiency.92 But it was significantly different from its predecessors in composition, size, and method of fixation.

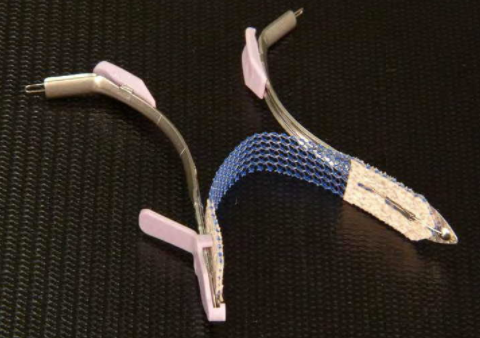

94 The “Gynecare TVT Secur System” consisted of the implantable device together with a set of instruments to facilitate the placement of the device in the pelvis.

95 The device was a piece of blue Prolene mesh in the form of a tape (8cm long and 1.1cm wide) sandwiched between layers of absorbable fleece (2cm long) made from Vicryl (polyglactin 910) and PDS (poly-p-dioxanone) undyed yarn. The instruments were two metal inserters, a finger pad, a protective cover, and a release wire.93

96 This is what it looked like, with the instruments:

97 The tape was inserted via a single, small vaginal incision. It could be implanted in either a “U” position (which is comparable to a retropubic position) or a “hammock” position (which is comparable to the transobturator sling).94 In the former case, the mesh is implanted towards the retropubic space but not through it. In the latter case, the tape is implanted towards the obturator opening but does not exit the opening or the externus muscle. In neither case is there an exit site.95 Unlike TVT and TVT-O, the mesh in TVT Secur was not covered with a plastic sheath96 and the mesh used to make the tape was always laser-cut rather than mechanically cut.97

98 TVT Secur was the only one of the SUI devices that required a single incision.

99 A single-incision sling is defined as a sling that does not involve either a retropubic or transobturator passage of the tape or trocar and involves only a single vaginal incision so there are no exit wounds in the groin or lower abdomen.98 The background to the development of single-incision slings was described by Nambiar et al (2014):

Historically many types of surgery have been performed to treat women with stress urinary incontinence. Over the past 10 years, the accepted standard technique has been the mid-urethral sling operation, whereby an artificial tape or mesh is placed directly beneath the urethra and is anchored to the tissues in adjacent parts of the groin or just above the pubic bone. Examples of such slings that are commonly used are tension-free vaginal tape (TVT™) and transobturator tape (TOT). These operations are usually quite successful, with success rates approaching 80%or 90%. However, they have been shown to result in significant side effects, which can be bothersome and sometimes even dangerous, such as damage to the bladder caused by tape insertion, erosion of the tape into the urethra during the healing period or chronic thigh/groin pain.

In an effort to maintain efficacy while eliminating some of the side effects, a new generation of slings has been developed, called ’single incision slings’ or ’mini-slings’ (sic); these slings are the subject of this review. They are designed to be shorter (in length) than standard mid-urethral slings and do not penetrate the tissues as deeply as standard slings. It was therefore thought that they would cause fewer side effects while being no less effective…99

100 TVT Secur was cleared for sale in the United States on 28 November 2005 and in Europe on 4 May 2006.100 It was launched in Australia in April 2007,101 but sold for less than a year. Sales were halted in March 2008 and its registration was cancelled by the TGA in June 2012.102

101 According to a Clinical Expert Report signed by two of Ethicon’s medical directors on 28 February 2006,103 TVT Secur was intended to address the complication of bladder perforation (with the retropubic approach) and thigh pain (with the obturator approach) using a less invasive procedure.

102 TVT Exact is a retropubic sling made of Prolene mesh, just like TVT, and, despite the respondents’ submission to the contrary,104 at 1.1 x 45cm, the dimensions of its sling are identical to the TVT sling.105 Unlike TVT, however, all the instruments supplied with the device are fully disposable. The mesh is covered by a clear plastic implant sheath and held between two white trocars which are bonded to the implant and the implant sheath. The trocar is slightly thinner (at 4.2mm) than the TVT trocar (at 5.0mm).106

103 TVT Exact was released to the Australian market in July 2010.107

104 TVT Abbrevo gained regulatory clearance in the United States on 1 July 2010, and in Europe in September 2010. It was first supplied in Australia in October 2010.108

105 It is a transobturator sling like TVT-O.109 It is made up of a single piece of laser-cut blue Prolene mesh tape covered by clear polyethylene sheaths and was supplied with a set of instruments to facilitate placement of the device: a placement loop, a pair of helical passers, and a winged guide.110 The mesh used in the system, however, is considerably shorter than TVT and TVT-O (12cm as against 45cm111) and has sometimes been called a mini TVT-O. Unlike TVT-O, the mesh does not need to be trimmed on either end once it has been implanted.112

106 According to a clinical evaluation report dated 17 August 2010 and signed by Dr Hinoul, TVT Abbrevo was designed to reduce the amount of mesh left behind in the body, to reduce pain possibly caused by the presence of the tape in the adductor muscles, and to improve the ergonomics of the TVT-O procedure. Dr Hinoul claimed that this modified TVT-O device “leads to reduction of tissue trauma, and reduction in the total length of mesh left behind in the body to a total of 12cm”.113

Pelvic organ prolapse and its treatments

107 Pelvic organ prolapse is the downward displacement of a pelvic organ, which, in the case of a woman means the uterus, the different vaginal compartments or neighbouring organs such as the bladder, rectum or bowel.114 As Professor Deprest stressed, it is an anatomical finding, that is, a change from the normal anatomy, and it may not be associated with any symptoms.115

108 Prolapse occurs when the muscles, ligaments and fascia (the network of supporting tissues that hold the organs in their correct positions) fall or slip out of place.

109 Pelvic organ prolapse is defined as an anatomical change in which there is downward displacement of a pelvic organ.116 There are three different types of pelvic organ prolapse: uterine prolapse in which the uterus descends, cervical prolapse involving the descent of the cervix (the neck of the uterus) and vaginal prolapse involving the descent of one or more of the compartments of the vagina.117 In a prolapse of the anterior compartment of the vagina, either the bladder or uterus (or, in the absence of a uterus the vaginal vault) bulges into the front wall of the vagina.118 This is also referred to as a cystocoele (from the Greek kustis meaning bladder and kele meaning “tumour”) or urethrocoele. In an apical compartment prolapse (sometimes called a vault, uterine, or middle compartment prolapse), the uterus descends or herniates into or outside the vagina or, if the uterus has been removed, the vaginal vault descends.119 In a posterior compartment prolapse, the rectum (the lower part of the large bowel) or part of the small intestine bulges into the upper part of the back wall of the vagina. The former is known as a rectocoele and the latter as an enterocoele.120

110 Diagnosis is based on a combination of information provided by a patient to her doctor about her medical history and symptoms, and a medical examination. The major cause is vaginal childbirth, which requires the levator ani muscle to substantially distend.121 A levator muscle is a muscle whose contraction causes a part of the body to be lifted. The levator ani muscle supports the pelvic organs and helps to prevent urinary incontinence. Professor Korda explained that, when a woman gives birth vaginally, the levator ani muscle in the average woman stretches by 150%. It is known that if that muscle is stretched in a laboratory setting beyond 150% it will never be able to return to normal tensile strength or length. This overstretching causes the natural “hammock” support of the pelvic floor to disappear and the downward descent of the pelvic organs to occur.122

111 Prolapse is described in stages, indicating the extent of the descent. Different staging or grading systems have been devised, including the Baden-Walker classification and the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) classification.

112 Risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse include pregnancy and childbirth; ageing and menopause; and conditions that cause excessive pressure on the pelvic floor, such as obesity, chronic cough, and chronic constipation.

113 Other factors which have been implicated in pelvic organ prolapse are asthma, genetic predisposition, and metabolic disorders. Age is universally cited as an established risk factor and uterine prolapse appears to be age-related. But Professor Korda’s evidence was that the general proposition was not supported by unexpectedly high rates of mild or moderate prolapse in young or asymptomatic women and increased tissue stiffness after menopause. He said that anterior and central compartment prolapse appear to deteriorate up until the age of 55 but thereafter improvement occurs.123

114 Symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse in women can include a heavy dragging feeling in the vagina or lower back; the feeling of a lump or bulge in or outside the vagina; urinary symptoms such as slow urinary stream, a feeling of incomplete bladder emptying, urinary frequency (needing to pass urine eight or more times a day), 124 or urgent desire to pass urine; 125 bowel symptoms such as difficulty moving the bowel or a feeling of incomplete bowel evacuation, or needing to press on the vaginal wall to empty the bowel; and pain, including lower back pain.126

115 Lower urinary tract symptoms, such as incontinence, are sometimes associated with prolapse but are not caused by it. Recurrent urinary tract infections can be caused by prolapse due to incomplete bladder emptying.

116 Prolapse can affect sexual function and cause dyspareunia, inability to penetrate the vagina due to obstruction, vaginal laxity, and loss of libido.

117 Depending on its severity or extent, while pelvic organ prolapse is not a life-threatening illness, as Associate Professor Rosamilia observed it can have a drastic effect on a woman’s quality of life.127

Traditional treatments for pelvic organ prolapse

118 As with stress urinary incontinence, there are both non-surgical and surgical treatment options.

119 Non-surgical treatments include lifestyle interventions, pessaries and pelvic physiotherapy. Symptoms may be improved with the use of vaginal oestrogen to improve the epithelium in post-menopausal women, avoidance of constipation and chronic cough, and training the pelvic floor muscles.128

120 Surgical treatment options include reconstructive surgery and vaginal closure or removal surgery (also known as obliterative procedures). The objective of all these treatments is to correct the prolapse while maintaining or improving vaginal sexual function and remedy lower urinary tract symptoms and disorders. Although it is not always feasible, their broad purpose is to restore the so-called normal pelvic anatomy.129

121 Reconstructive surgery may be accomplished using vaginal or abdominal approaches.

122 One of the forms of vaginal closure is colporrhaphy (literally, suturing the vagina in place). This is a procedure used to repair an anterior or posterior vaginal wall prolapse. It involves an incision into the relevant compartment of the vagina and plication (folding) of the pubocervical fascia (connective tissue forming layers between the vagina and bladder) with sutures. The objective is to repair the midline fascial defects by using and tightening up the stretched-out fascia.130

123 Apical prolapse can be repaired vaginally using sacrospinous ligament fixation (also called colpopexy), which involves suspension of the apex of the vagina to the sacrospinous ligament by means of (usually absorbable) sutures or uterosacral ligament suspension, which involves suturing the vagina to the uterosacral ligaments.131

124 A culdoplasty is performed to correct an apical prolapse after hysterectomy. Sutures are used to suspend the vaginal vault at the origin of the uterosacral ligaments, which support the vagina, and to close off the pouch of Douglas (a small area between the uterus and the rectum).132

125 The abdominal procedures include sacrocolpopexy (also called “sacral colpopexy”), which can be performed laparoscopically, robotically or by open surgery via an abdominal approach in the lower abdomen. This procedure is used to correct apical prolapse. The apex of the vagina is stitched or fixed to the sacrum by means of sutures and a small amount of surgical mesh.133 The procedure is also used to correct a combination of apical, anterior and posterior prolapse. It is only available for women who have undergone a hysterectomy. Often the two procedures are performed in the same operation. Another option is an abdominal hysteropexy, which is also used to correct apical prolapse but in which the uterus is preserved. As with a sacrocolpopexy, the apex of the vagina is stitched or fixated to the sacrum by means of a small quantity of surgical mesh, and the surgery can be performed either laparoscopically or by open surgery via an abdominal approach in the lower abdomen.134

126 Obliterative procedures include vaginal closure surgery (colpocleisis), which involves stitching the vaginal walls together to create a barrier in order to prevent the prolapse re-occurring,135 or total colpectomy, which involves the total excision of the vagina in a woman with no uterus and vaginal eversion (that is, where the vagina is turned outwards or inside out).

127 Surgery which uses the patient’s own tissue is commonly referred to as “native tissue repair”.

128 Prosthetic material used during surgery may be made from absorbable material such as animal tissue, non-absorbable synthetic material, or a combination of absorbable and non-absorbable material.

129 There is no single best approach for all patients. Treatment is individualised according to each patient’s symptoms.

130 All surgical treatment options are associated with risks, although the evidence indicates that complications from native tissue repair are generally short-lived and treatable.136 Professor Korda listed them as failure; injury to adjacent and contiguous organs, such as the bladder, urethra, ureters, bowel, major blood vessels, and nerves; the development of lower urinary tract symptoms such as urinary incontinence, narrowing of the vagina, and dyspareunia.137

131 The medical devices used for the treatment of prolapse which are the subject of the current litigation are Gynemesh PS, Prolift, Prolift+M and Prosima.

132 Prolift, Prolift+M, and Prosima were intended for tissue reinforcement and long-lasting stabilisation of fascial structures of the pelvic floor in vaginal wall prolapse where surgical treatment was intended, either as mechanical support or bridging material for the fascial defect. Gynemesh PS had the same indication until March 2013, when its indication for use was changed, as discussed below at [139].

133 Before any of these devices was available, however, it appears that surgeons concerned about the failure rate with native tissue repairs experimented with synthetic hernia mesh to treat pelvic organ prolapse. Dr Hinoul was one of these surgeons. He said he began to use a polypropylene hernia mesh to treat pelvic organ prolapse in the late 1990s or early 2000s. He used a transvaginal approach, inserting the mesh through the obturator foramen using needle drivers and anchoring it in the muscles of the groin using a technique similar to that later used to implant the Prolift device.138

The meshes used in the POP devices

134 The meshes used in all these devices were made from non-absorbable polypropylene (Ethicon’s Prolene Soft, except for Prolift+M, which is made from Gynemesh M.

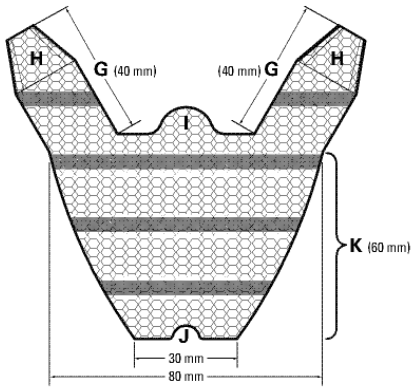

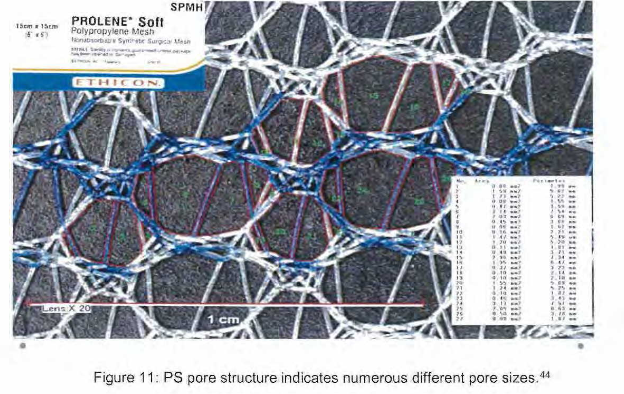

135 Prolene Soft mesh was developed by Ethicon in the late 1990s for use in hernia repair and approved by the FDA for that purpose. Like Prolene it was and is made from knitted filaments of polypropylene.139 Prolene Soft was described in a memorandum from Dr Ning Wang of Corporate Product Characterization at Ethicon Inc. as “a revised construction [Prolene] mesh, fabricated of knitted filaments of natural color and blue pigmented polypropylene identical in composition to that used in [Prolene]”.140 It differs from Prolene, however, in two respects. It has a smaller filament diameter (at 3.5mm as against 6mm), which is said to give it a softer feel,141and it has a different knit design.142

136 Gynemesh M is a partially absorbable mesh consisting of approximately equal parts of Prolene Soft and Monocryl, an absorbable poliglecaprone-25 monofilament fibre.143

137 Gynemesh PS received regulatory clearance in the United States on 8 January 2002, in Europe on 20 March 2003, and in Australia on 26 May 2003. It was first supplied to the Australian market in July 2003.144

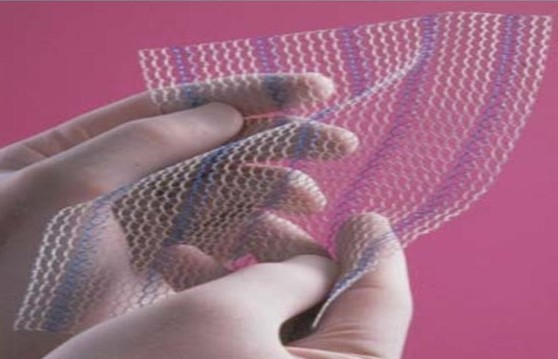

138 Gynemesh PS is made from Prolene Soft mesh.145 The “PS” in its name is an acronym for Prolene Soft. It consists of rectangular sheets of mesh that may be cut as desired by the surgeon. This is what it looks like.

139 According to Dr Hinoul, the only difference between Prolene Soft and Gynemesh PS was that Gynemesh PS was cleared for the specific indication for use in “tissue reinforcement and long-lasting stablization of the pelvic floor in vaginal prolapse”, whereas Prolene Soft was cleared for the general indication for use in “repair of hernia or other fascial defects that require the addition of a reinforcing or bridging material”.146 Ethicon treated the change of indication as a matter of no consequence. Its position was that the change was not a new intended use, which might have led to additional regulatory obligations, but a subset of the previous one, which enabled Ethicon to rely on earlier regulatory approval or clearance. In her 2005 Clinical Expert Report on Prolift, Dr Charlotte Owens, then Medical Director for Gynecare, claimed that this approach arose from the “[r]ealization that pelvic floor disorders are physiologic and functional fascial hernias”.147

140 Between March 2003 and March 2013, Gynemesh PS was indicated for tissue reinforcement and long-lasting stabilisation of fascial structures of the pelvic floor in vaginal wall prolapse where surgical treatment was intended, either as mechanical support or bridging material for the fascial defect. On 16 March 2013, however, the indication for use of Gynemesh PS was narrowed to “a bridging material for apical vaginal and uterine prolapse where surgical treatment (laparotomy or laparoscopic approach) is warranted”.148 In other words, it was no longer indicated for transvaginal use but only for prolapse repair using an abdominal approach. The reasons for the change of indication are discussed later in these reasons.

141 On 17 August 2017, JJM notified the TGA that it would be discontinuing Gynemesh effective immediately and on 22 August 2017 the TGA cancelled its entry on the ARTG.149

142 Prolift was cleared for sale in Europe on 2 March 2005, around the same time in the United States, and in Australia on 30 March 2005. It was supplied in this country in and from June 2005 until 15 August 2012.150 Registration was cancelled on 21 April 2015.151

143 The Prolift pelvic floor repair system consisted of a pre-cut Gynemesh PS mesh implant (featuring a central mesh body and mesh arms) and included surgical tools used to facilitate insertion of the mesh fabric through the vaginal area (the Prolift Guide, the Prolift cannula and the Prolift retrieval device).

144 There were three different Prolift systems: anterior, posterior and apical, and total vaginal repairs (the “Anterior”, “Posterior” and “Total” pelvic floor repair systems respectively). Each system was sold separately and included the same guides, cannulas, and retrieval devices but the numbers of accessories varied. The mesh fabric was pre-cut into different shapes to accomplish the different types of repair, but a surgeon could choose to trim the mesh to suit the patient’s anatomy.

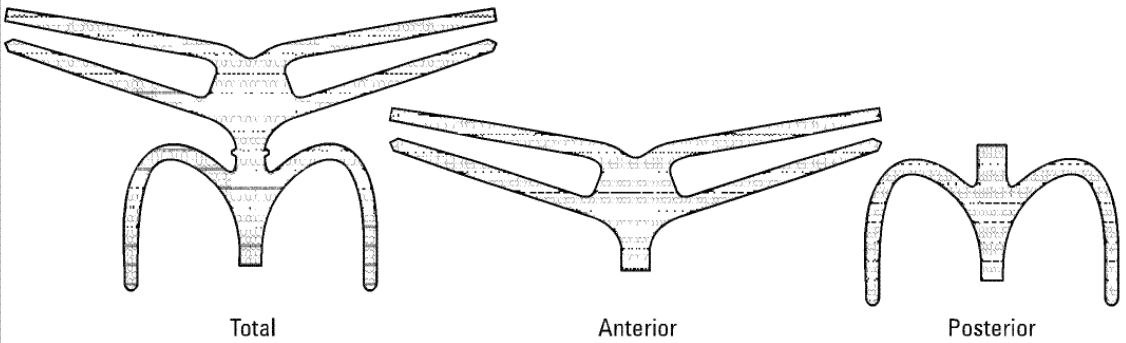

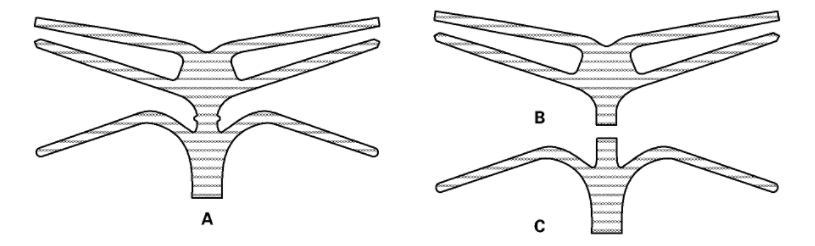

145 “Prolift Anterior” consisted of a piece of Prolene Soft with four arms secured through a transobturator approach.152 Self-evidently, it was designed for the repair of anterior vaginal defects. “Prolift Posterior” consisted of a piece of Prolene Soft with two arms secured using a transgluteal approach.153 It was designed to repair posterior and/or apical vaginal vault defects. “Prolift Total” was a combination of a Prolift Anterior and a Prolift Posterior.154 It was designed for a total vaginal repair. This is how the mesh implants were depicted in the IFU:

146 All three devices were developed for the surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse via a vaginal, as opposed to an abdominal, approach.

147 Dr Arnaud explained the background to the development of Prolift in a memorandum he prepared in January 2007:

In the mid 2000, at a time Gynecare [a division of Ethicon Inc.] was enjoying a great monopolistic position on the market for slings, I thought that the next opportunity for the company could be the development of meshes for pelvic organ prolapse repair. Unfortunately, no one such as Ulmsten had come to me with a great solution and I had to be proactive.155

It was quite obvious that no advance could be made in this area as long as a standardized procedure would not be described.

Thus, I took the initiative of setting up a group of experts in order to work on the development of a standardized procedure which would make sense and would be reproducible by the average gynecologist.

148 Dr Arnaud said that he visited Professor Bernard Jacquetin, whom he described “an indisputable [key opinion leader] in the area of prolapse repair” and invited him to become “the ‘Ulmsten’ of POP repair”. Professor Jacquetin took up the invitation and the two of them chose a number of other French experts to work on the project. Their objectives, according to Dr Arnaud, were twofold: to work on developing a standardised technique for the surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse with mesh via a vaginal approach and to try to better understand the mechanism of vaginal erosion which was associated with the use of synthetic materials in order to reduce its occurrence. The group of experts, which became known as the “TVM Group”, met for the first time in June 2000. Gynecare France was placed in charge of its logistic and material coordination.156

149 Before going any further, I should explain what is meant by “erosion” in this context. Like a good deal of the nomenclature in this area, different terms are sometimes used to mean the same thing and there is a lack of precision in the terminology. Some of the professional associations have tried to do something about it, but the evidence in the present case suggests that their efforts have not had any significant effect.

150 The medical definition of an erosion is the “state of being worn away, as by friction or pressure”.157 In 2011 the Working Group on Complications Terminology, established by the International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) and the International Continence Society (ICS), considered that this definition was not necessarily apt to describe the clinical process and recommended that the term be abandoned and replaced with two new terms:

Exposure: A condition of displaying, revealing, exhibiting or making accessible … (e.g. vaginal mesh visualized through separated vaginal epithelium …)

Extrusion: Passage gradually out of a body structure or tissue … (e.g. a loop of tape protruding into the vaginal cavity …)158

151 Sometimes, the evidence indicates, the term “erosion” is used to refer to the migration of mesh into an organ, like the bladder or the urethra, which is an extension of the process of extrusion described in the IUGA/ICS lexicon and “exposure” to refer to anything short of that. Often, “erosion” is used in the literature, and also by some of the expert witnesses in this case, as a synonym for exposure and/or extrusion. Other commentators used the term “protrusion” in lieu of extrusion.159 Generally speaking, in this judgment I use the terms used by the witnesses when I refer to their evidence and the terms used in the scientific literature when I refer to that evidence. Otherwise, I may use the term “erosion” to capture any or all of these events.

152 I now return to the narrative.

153 Once he was convinced of the viability of the TVM project, Dr Arnaud set out to persuade others within Ethicon. In his memorandum on the development of Prolift to which I referred above, Dr Arnaud confessed to having had a hard time persuading some of “the marketing people” of the wisdom of the project. He said that they “wanted to kill [the] project as they found the procedure was too difficult and could only be a procedure for some happy few”. By early 2005, however, Dr Arnaud had prevailed160and, once Ethicon agreed to proceed, the evidence indicates that the marketing people enthusiastically embraced the project. It was only a matter of a few months before regulatory approval was obtained and the Prolift device was released to the market.

154 I hasten to add that the fact that this initiative was taken to exploit a marketing opportunity does not mean that advances in surgical treatment for pelvic organ prolapse were not desirable. There was a common perception that the rate of recurrent prolapse after native tissue repair was too high. The TVM Group put it at 20 to 30%. Surgeons had experimented with mesh as a means of reducing the rate, but the Group noted that “[a]lthough meshes … have been used to repair type 3 or 4 prolapse recurrence, authors still do not recommend their use for primary repair because of reported complications”.161 The desire to improve the status quo through innovation and to commercialise the resulting technology was not in itself problematic. It is, however, part of the context in which to consider the more critical question, which is whether the clinical data available to Ethicon were sufficient to support the conclusions expressed in its pre-market clinical evaluation report for Prolift and the decision to take the device to market, a question to which I will come in due course.

155 It will be recalled that one of Dr Arnaud’s two objectives in developing meshes for the repair of pelvic organ prolapse was to come up with a standardised procedure which the average gynaecologist would understand and could reproduce. Ethicon described the objective of the Prolift procedure as the achievement of “a complete anatomic repair of pelvic floor defects in a standardized way”.162

156 The technique for inserting the Prolift prostheses is described in a 30-page illustrated guide entitled “Gynecare Prolift – Total Pelvic Floor Repair, Anterior Pelvic Floor Repair, Posterior Pelvic Floor Repair – Surgical Technique” (the Guide).163 The metadata in the electronic court book indicates that this document was completed in early January 2005. There is no evidence as to its distribution but Dr Hinoul deposed that the Prolift IFU advised surgeons to review the Guide because it instructed them to refer to “the recommended surgical technique” for “further information” on the Prolift procedures.164 There was no relevant mention of a guide or guidebook in the Prolift IFU. It was mentioned in the Prolift+M IFU, which instructs surgeons to contact their “company sales representative” to obtain the Guide.165

157 A summary of the surgical technique, explained in greater length in the Guide, appears in the first publication on the technique. That was an article by Fatton et al (2007) entitled “Transvaginal repair of genital prolapse: preliminary results of a new tension-free vaginal mesh (Prolift™ technique) – a case series multicentric study”.166 The authors explained that the technique had been refined over a five-year period through more than 600 surgical interventions by nine French skilled vaginal surgeons. They described the technique in this way:

The synthetic material is a pre-cut non-absorbable monofilament soft prolene mesh. The mesh has three distinct parts … The anterior part is inserted between the bladder and the vagina and secured bilaterally by two arms through each obturator foramen. The posterior part is placed between the rectum and the vagina and is secured bilaterally by one arm passing through each ischiorectal fossa and sacrospinous ligament. The intermediate section corresponding to the vaginal apex separates the anterior and posterior parts and can be cut if needed. Instruments were designed to facilitate proper implant placement … Cannula-equipped guides were used to optimize the passage through the tissues, preventing muscle trauma and disruption of the arcus tendinous fascia pelvis (ATFP) and to allow the placement of the retrieval device. Retrieval devices were provided to easily catch and smoothly pass each prosthesis strap through the pelvis …

This procedure may be performed under spinal or general anesthesia. All patients were placed in the lithotomy position with thighs flexed at approximately 90°. After cleaning the entire surgical area with antiseptic, a urine culture is performed and an in-dwelling catheter is placed. All patients had an intravenous perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis.

158 More detail is provided in the article. It is unnecessary to repeat it here. It is sufficient to make the following observations.

159 First, is common ground that the technique is difficult and that it involved complex pelvic surgery.167

160 Associate Professor Rosamilia described Prolift surgery as “technically challenging”. She believed it required “considerable skill with sacrospinous colpopexy and deeper dissection”.168 She said that surgery with anchored mesh kits (like Prolift or Prolift+M) is “more complex” than native tissue repair.169