FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

TPT Patrol Pty Ltd as trustee for Amies Superannuation Fund v Myer Holdings Limited [2019] FCA 1747

ORDERS

TPT PATROL PTY LTD AS TRUSTEE FOR AMIES SUPERANNUATION FUND Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 14 days of the date of these orders, the applicant file and serve minutes of orders and submissions (limited to 5 pages) to give effect to these reasons including a protocol for stipulating declarations on s 33C common issues, further proceedings on loss and damage and on costs.

2. Within 14 days of the receipt of the applicant’s minutes of orders and submissions, the respondent file and serve responding minutes of orders and submissions (limited to 5 pages) on the said topics.

3. Liberty to apply.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BEACH J:

1 The applicant, TPT Patrol Pty Ltd, has brought the present representative proceeding for itself and on behalf of all persons who acquired ordinary fully paid shares (MYR ED securities) in the respondent, Myer Holdings Limited (Myer), on or after 11 September 2014 and who were at the commencement of trading on 19 March 2015 holders of any of those MYR ED securities and who have claims for loss and damage caused by Myer’s alleged breaches of ss 674 and 1041H of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the Act) concerning non-disclosure to the ASX of price sensitive information about MYR ED securities and misleading or deceptive conduct.

2 Let me introduce my reasons with the following factual summary.

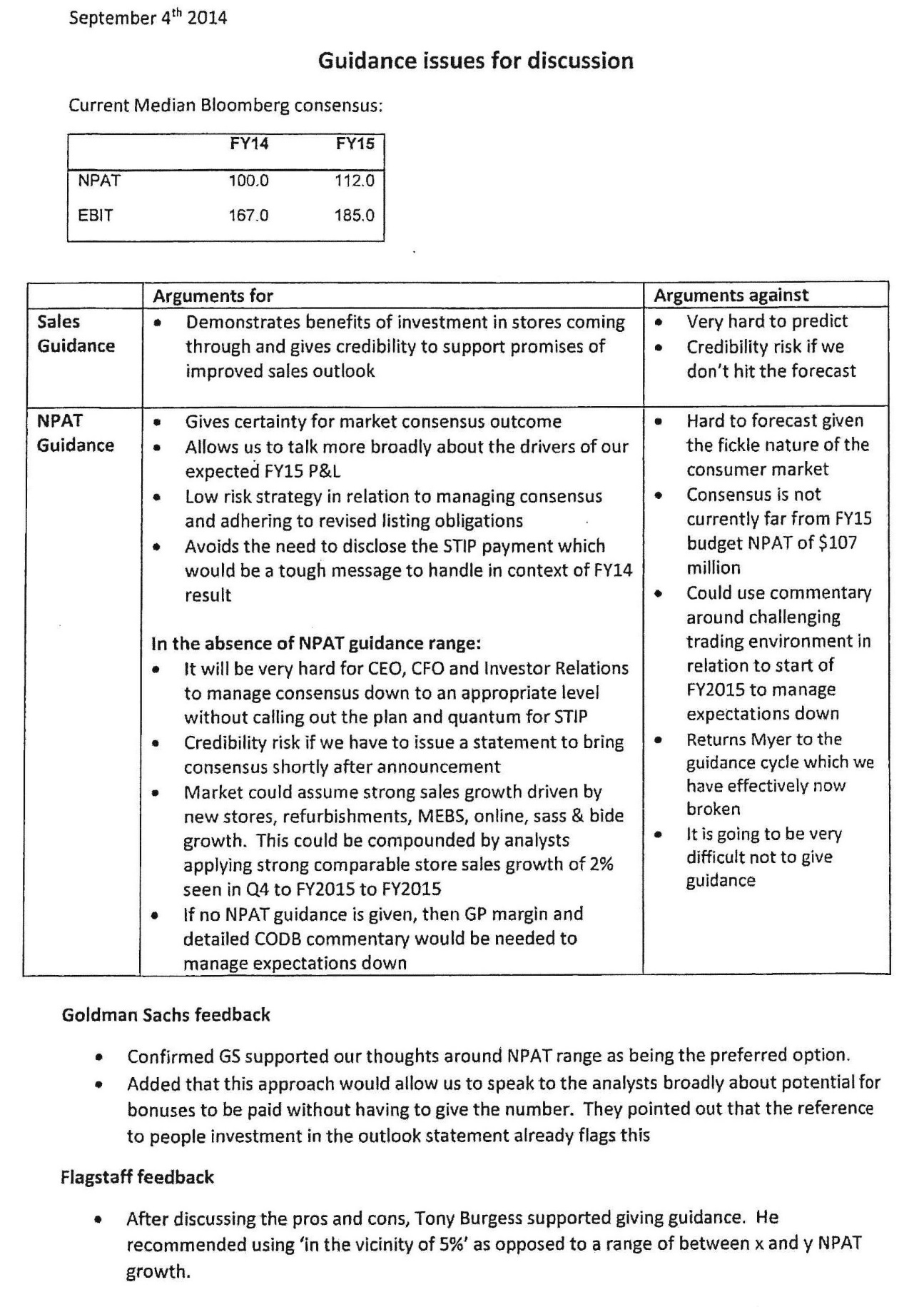

3 On 11 September 2014, in presentations and in question and answer sessions with equity analysts and financial journalists, Myer’s chief executive officer, Mr Bernie Brookes, represented that in his opinion in the financial year ending 26 July 2015 (FY15) Myer would likely have a net profit after tax (NPAT) in excess of Myer’s NPAT in the previous financial year which ended on 26 July 2014 (FY14) (the 11 September 2014 representation), with the implication being that it would be materially above although nothing turns on that implication save an aspect of the counterfactual disclosure that I will discuss later concerning 21 November 2014. Myer’s FY14 NPAT had on 11 September 2014 been announced as $98.5m. Mr Brookes’ opinion which was also in the nature of a forecast was clearly to be attributed to Myer in terms of both the statement made and the opinion held.

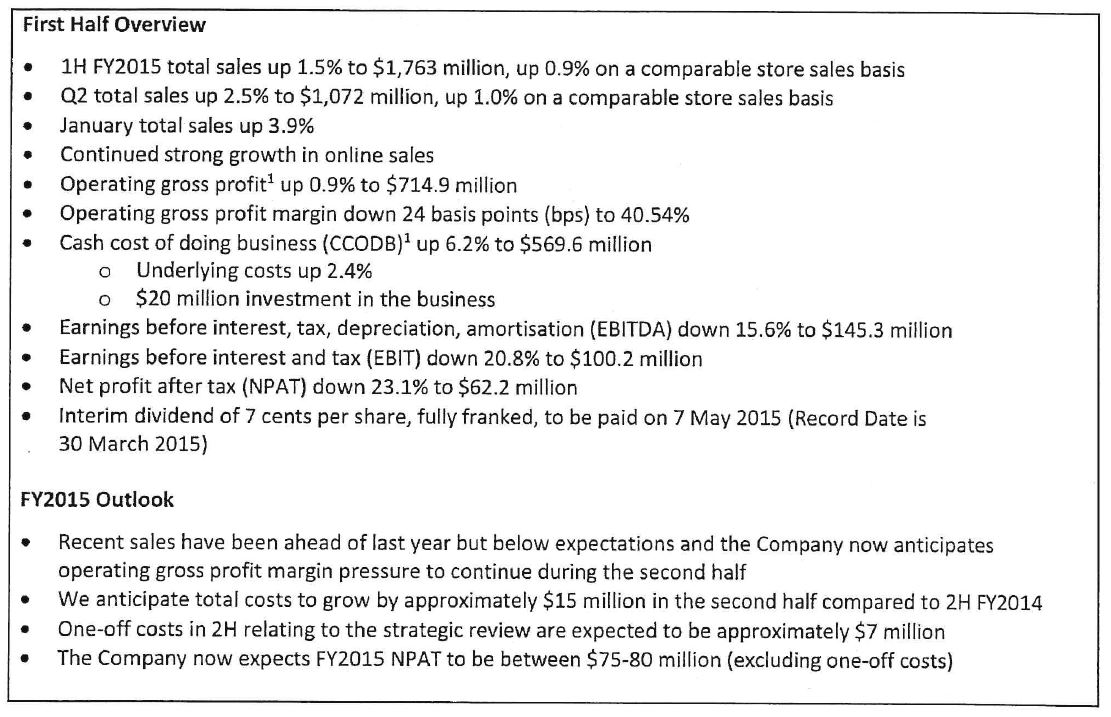

4 On 19 March 2015, Myer announced to the ASX that Myer then expected its FY15 NPAT to be between $75 to 80 million excluding one-off costs. In its 19 March 2015 announcement, Myer told the market that:

(a) its sales were up only 1.5% in the FY15 first half (H1);

(b) its operating gross profit (OGP) margin had declined year-on-year by 24 basis points to 40.54%;

(c) its cash cost of doing business (CCODB) had increased from $536.2m in FY14 H1 to $569.6m in FY15 H1 and now represented 32.3% of sales up from 30.87% of sales in FY14 H1;

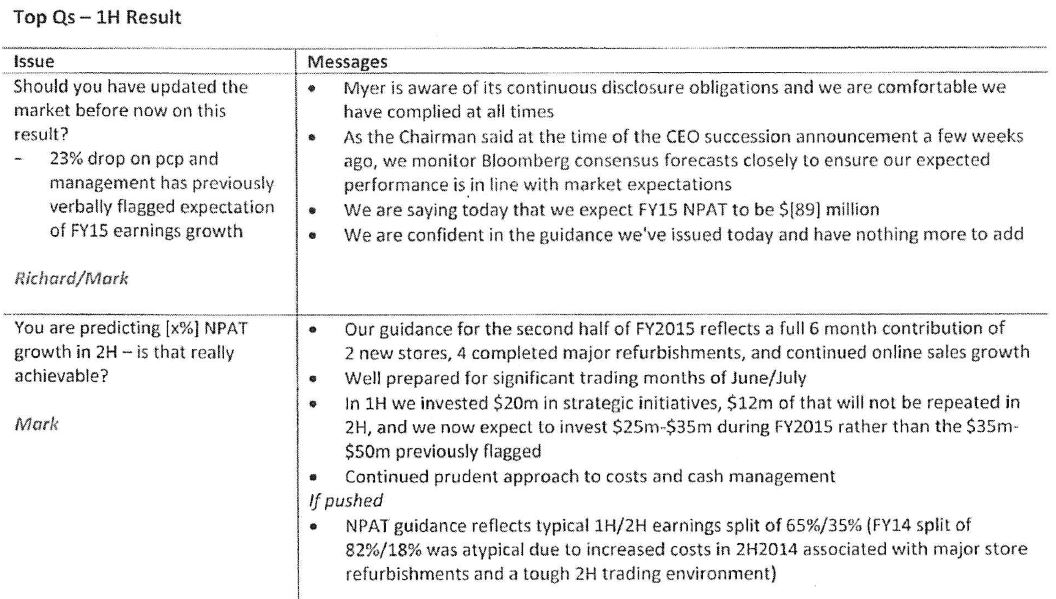

(d) its NPAT for FY15 H1 had fallen to $62.2m, 23.1% below FY14 H1, when NPAT of $80.8m had been achieved; and

(e) NPAT for FY15 was expected to be in a range from $75m to $80m before one-off costs, which was down from NPAT of $98.5m achieved in FY14.

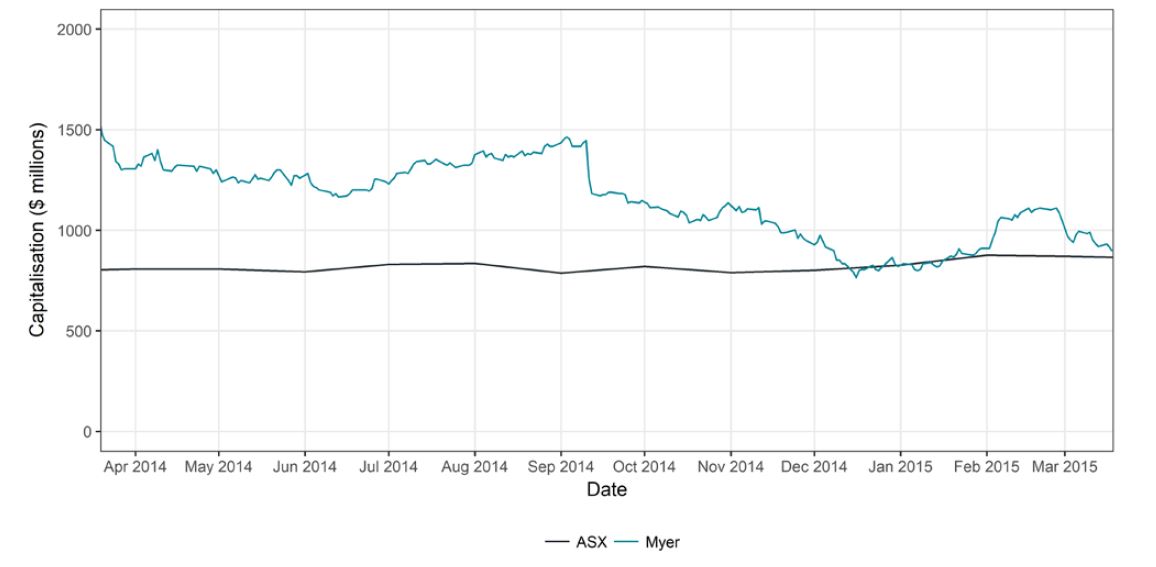

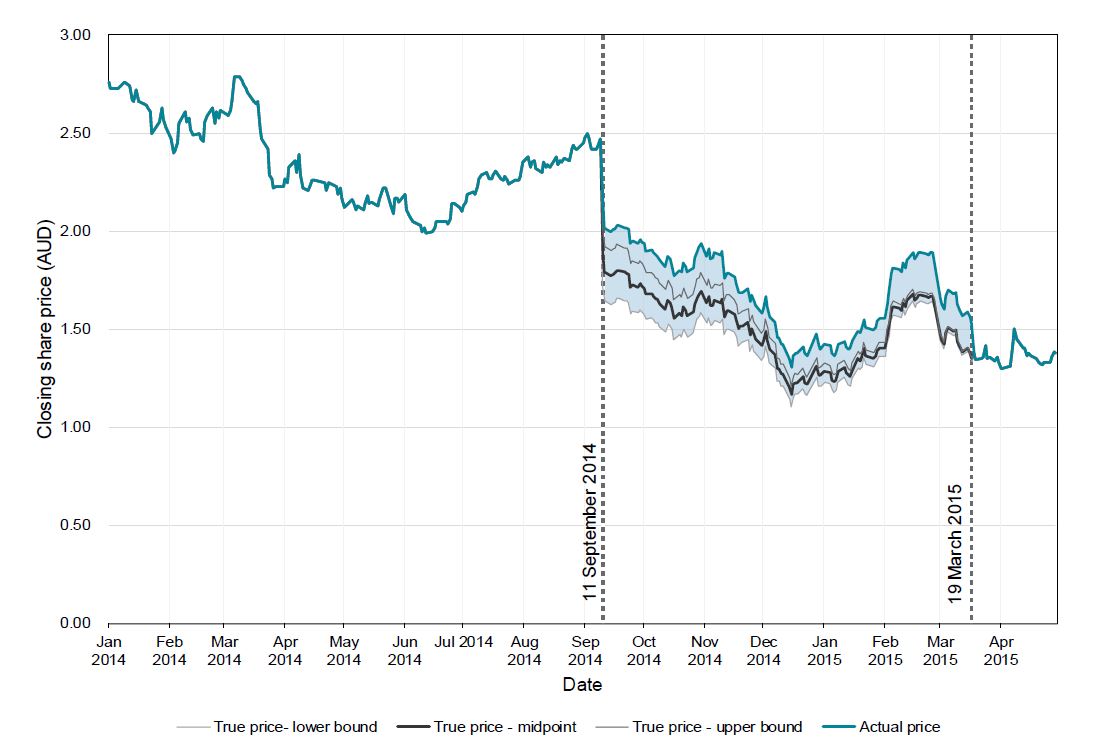

5 Immediately after Myer announced this adverse information concerning its year-to-date and expected final FY15 performance, its share price declined materially; correspondingly its market capitalisation declined by $90.8m or by more than 10%.

6 At its core, the applicant’s claim is for losses caused to itself and group members by Myer, inter-alia:

(a) making the 11 September 2014 representation to the market that its NPAT in FY15 would be higher than its FY14 NPAT, when Myer did not have reasonable grounds for making that representation; and

(b) failing to disclose at any time after 11 September 2014 and prior to 19 March 2015 that Myer did not have reasonable grounds for making the 11 September 2014 representation or that the 11 September 2014 representation of increased FY15 NPAT was wrong.

7 Now throughout 11 September 2014 to 19 March 2015 inclusive (the relevant period), Myer was subject to continuous disclosure obligations pursuant to s 674 of the Act and listing rule 3.1 of the ASX listing rules. Subject to exceptions arising under listing rule 3.1A, which are relied upon in Myer’s defence and which I will discuss later, listing rule 3.1 required Myer to immediately notify the ASX, once Myer was or became aware of any information concerning it that a reasonable person would expect to have a material effect on the price or value of MYR ED securities, of that information.

8 For the purposes of listing rule 3.1, the word “aware” was explained in listing rule 19.12 at the relevant time as follows:

an entity becomes aware of information if, and as soon as, an officer of the entity … has, or ought reasonably to have, come into possession of the information in the course of the performance of their duties as an officer of that entity.

9 Moreover, for the purposes of listing rule 3.1, “information” was defined in listing rule 19.12 to include:

(a) matters of supposition and other matters that are insufficiently definite to warrant disclosure to the market; and

(b) matters relating to the intentions, or likely intentions, of a person.

10 As I say, the starting point for the applicant’s case is the statement made by Mr Brookes on 11 September 2014 that Myer anticipated NPAT growth in FY15, which I have defined in terms of the 11 September 2014 representation. In the context of Myer’s NPAT for FY14 being $98.5 million, it is alleged that the 11 September 2014 representation disclosed to the market that Myer expected to achieve NPAT in FY15 in excess of $98.5 million.

11 The applicant claims that Mr Brookes and therefore Myer, under the usual rules of attribution, did not have reasonable grounds for the 11 September 2014 representation and accordingly engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of s 1041H of the Act.

12 The applicant’s allegation that Mr Brookes did not have reasonable grounds for the 11 September 2014 representation is also a building block for the applicant’s continuous disclosure claim. The applicant’s continuous disclosure claim has in substance two parts to it. The first part is an allegation that Myer was aware as at 11 September 2014 that it “had no reasonable grounds for representing that it would achieve NPAT in the 2015 financial year in excess of $98.5 million” (no reasonable grounds information). The second part is an allegation that Myer was aware by no later than 11 November 2014 that Myer’s NPAT in FY15 “would be materially lower than in the 2014 financial year [viz. $98.5 million]” (NPAT information). It is alleged that in failing to disclose that specific information of which it is alleged to have been aware, Myer breached its continuous disclosure obligations under listing rule 3.1 and therefore under s 674 of the Act.

13 A yet further claim pleaded by the applicant is that particular publications of Myer on certain dates, being 21 October, 11 November and 21 November 2014, and 2 and 3 March 2015, constituted misleading conduct because those publications did not disclose the specific information which I have identified as underpinning the continuous disclosure claim.

14 Finally, I should note at this point that on 10 October 2018, after the applicant had completed its closing submissions, I granted leave to the applicant to amend its statement of claim to introduce a new claim by which it alleged that Mr Brookes’ statement on 11 September 2014 was a continuing representation. The applicant’s further amended statement of claim was subsequently filed on 15 October 2018. Relevantly, the applicant amended its pleading to advance an extended claim relying on s 769C of the Act. Further, it also amended to allege that Myer’s failure to disclose the information about the earnings forecast matter, which I will define later, and which in essence amounted to a failure to correct case, was misleading or deceptive conduct.

15 The present trial has dealt with all aspects of the applicant’s individual claims and the common issues. For the reasons that I will now elaborate on, the applicant has succeeded on part of its case concerning establishing contraventions of ss 674 and 1041H.

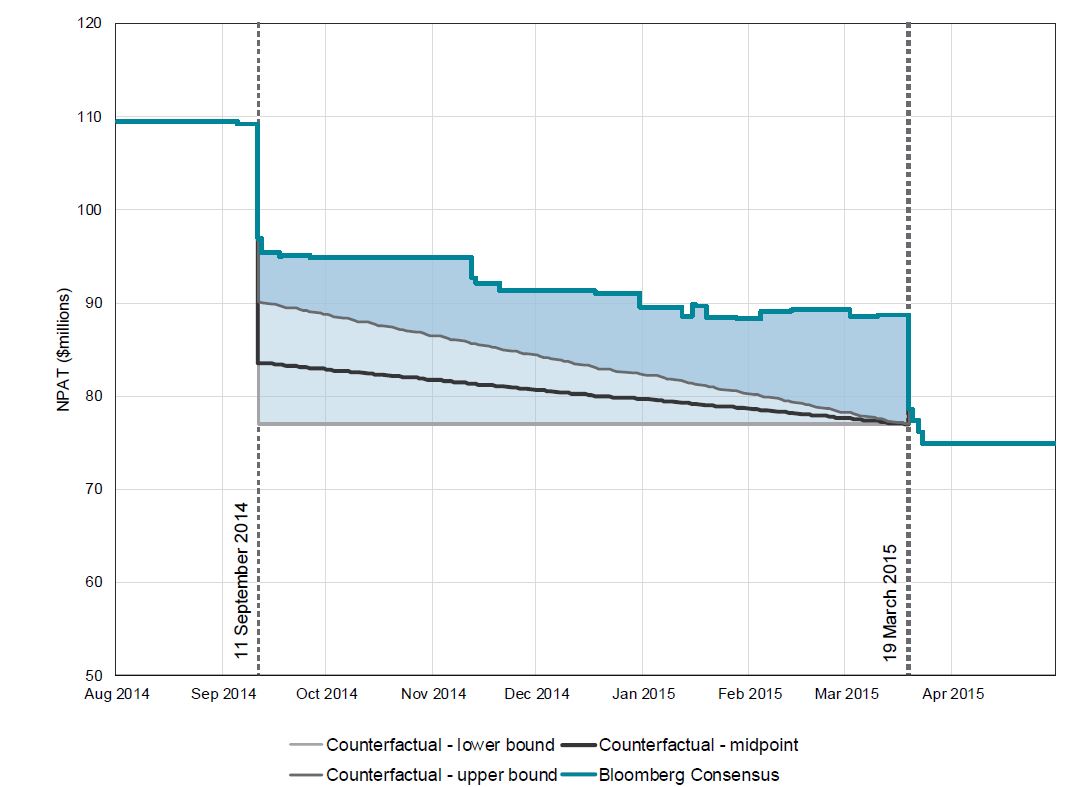

16 In the context of and given the fact that the 11 September 2014 representation had been made, Myer should have disclosed to the market:

(a) by no later than 21 November 2014 that its likely NPAT for FY15 would not be materially above the FY14 NPAT;

(b) by no later than 9 December 2014 that its likely NPAT for FY15 was around $92 million;

(c) by no later than 22 December 2014 that its likely NPAT for FY15 was in the range of $89 to $90 million;

(d) by no later than 5 January 2015 that its likely NPAT for FY15 was around $90 million;

(e) by no later than 21 January 2015 that its likely NPAT for FY15 was in the vicinity of $90 million;

(f) by no later than 9 February 2015 that its likely NPAT for FY15 was in the vicinity of $90 million; and

(g) by no later than 27 February 2015 that its likely NPAT for FY15 was in the range of $87 to $91 million, depending upon the costs of the strategic review.

17 Now in a sense these are cascading possibilities because making any one disclosure may have removed the need for any later disclosure in the sequence that I have just outlined.

18 In my view on the evidence, Myer can be taken to have held such an opinion as to the likely FY15 NPAT on each of the above dates and accordingly there should have been disclosure of such an opinion under listing rule 3.1 and s 674. But in any event in the context of the 11 September 2014 representation, such a disclosure should have been made at these various points in time to correct the 11 September 2014 representation. By not having so corrected at each of these points in time, Myer engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of s 1041H.

19 But notwithstanding these contraventions, I am not convinced that the applicant and group members have suffered any loss flowing from such contraventions.

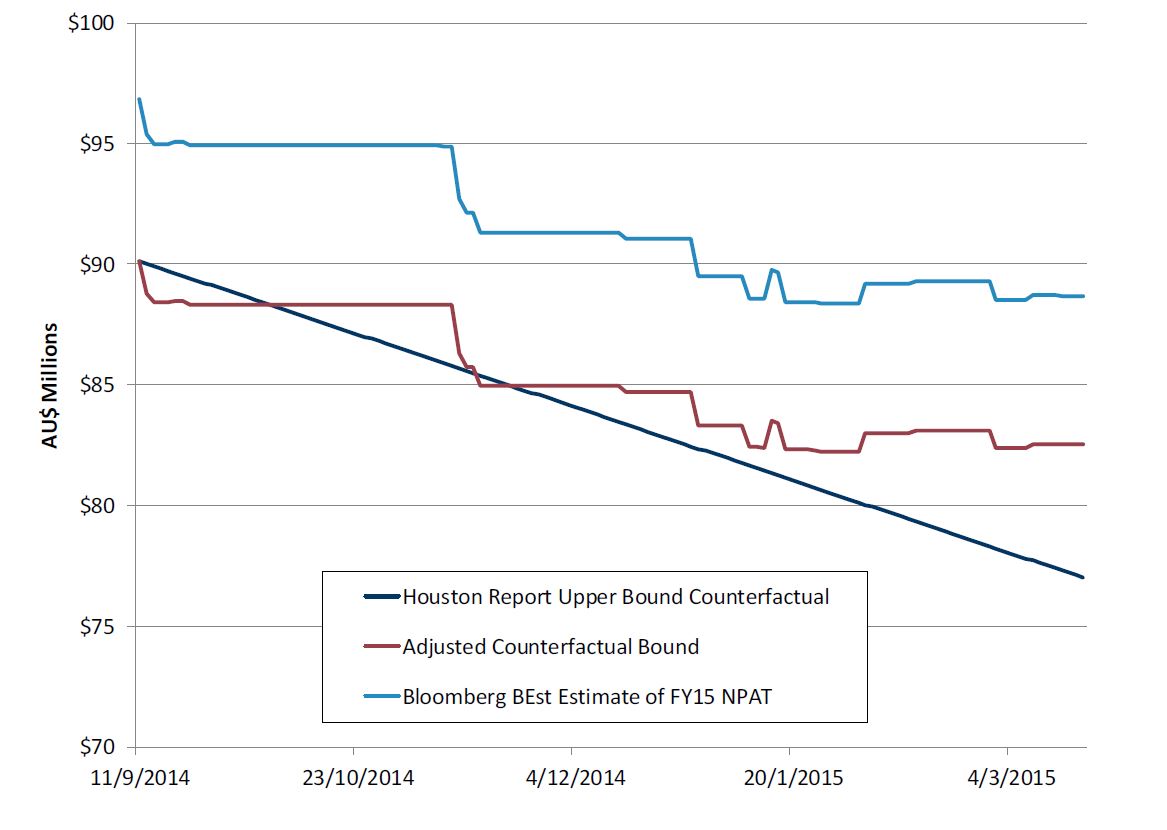

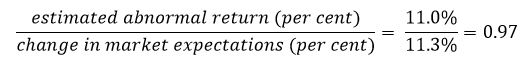

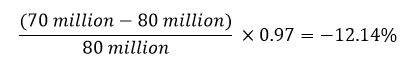

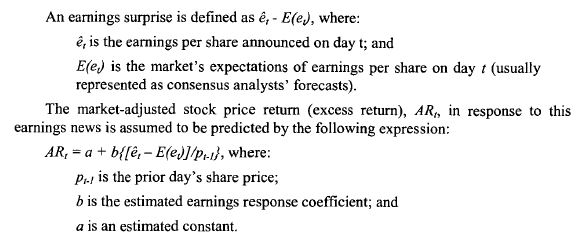

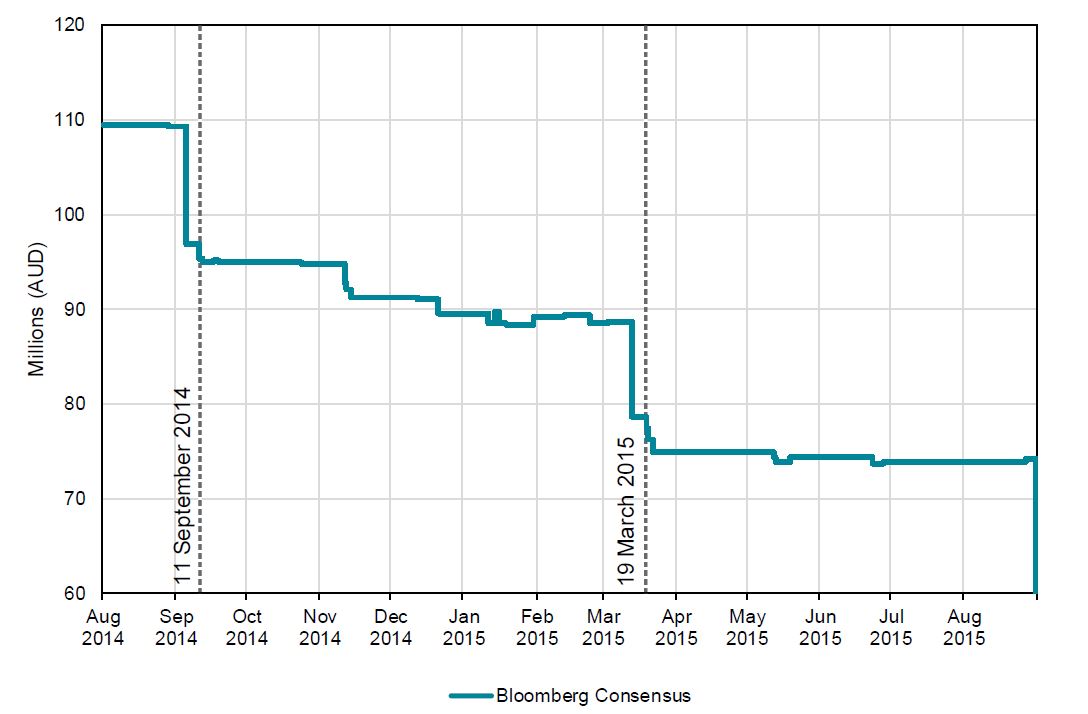

20 As will become apparent later, I have accepted the market-based causation theory. I have also accepted and found to be valuable event study analysis in terms of assessing materiality and share price inflation. Nevertheless, the applicant and group members may not have suffered any loss flowing from the contraventions that I have identified. This is because the market price for MYR ED securities at the time the contraventions occurred already factored in an NPAT well south of Mr Brookes’ rosy picture painted on 11 September 2014. In other words, the hard-edged scepticism of market analysts and market makers at the time of the contraventions had already deflated Mr Brookes’ inflated views. So, any required corrective statement that should have been made at the time of the contraventions, if it had been made, is likely to have had no or no material effect on the market price of MYR ED securities. QED: As the applicant only advanced a market-based causation theory and an inflation-based measure for its loss analysis for itself and on behalf of group members, all claims for damages would appear to fail.

21 It is convenient to divide my discussion into the following topics:

(a) The pleaded case – [23] to [49];

(b) The applicant – [50] to [75];

(c) Key lay witnesses – [76] to [94];

(d) The structure of Myer’s business – [95] to [113];

(e) The development and approval of the FY15 budget – [114] to [296];

(f) 11 to 30 September 2014 events – [297] to [378];

(g) October – November 2014 events – [379] to [491];

(h) December 2014 – March 2015 events – [492] to [639];

(i) Event study framework – [640] to [774];

(j) Application of event study framework – [775] to [923];

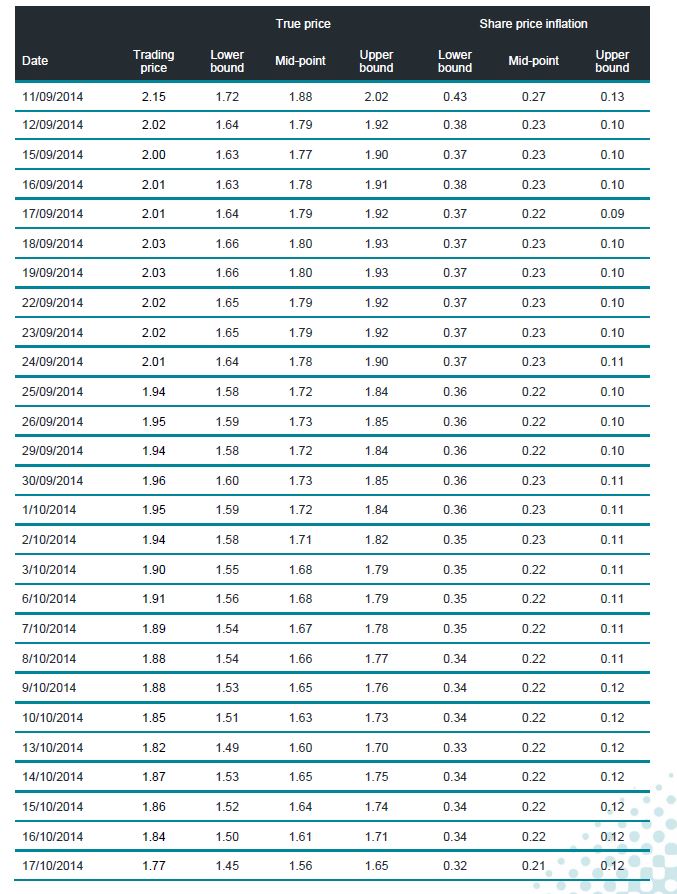

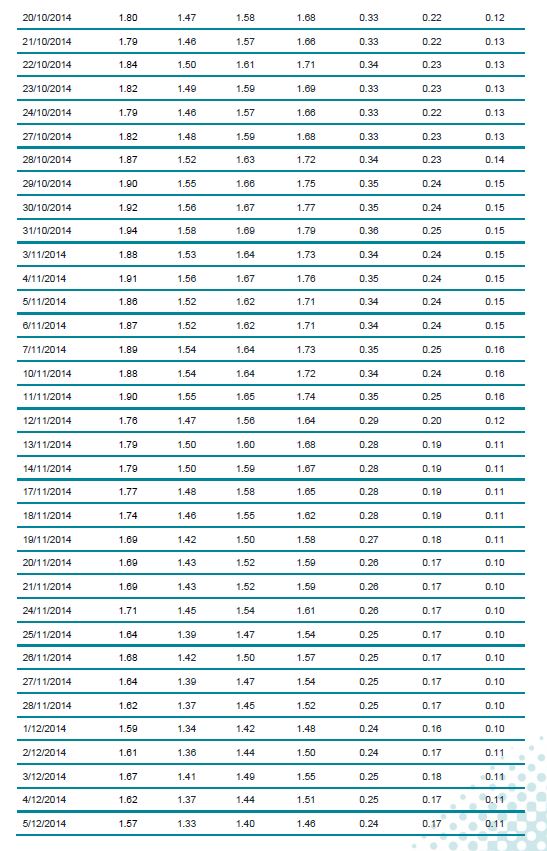

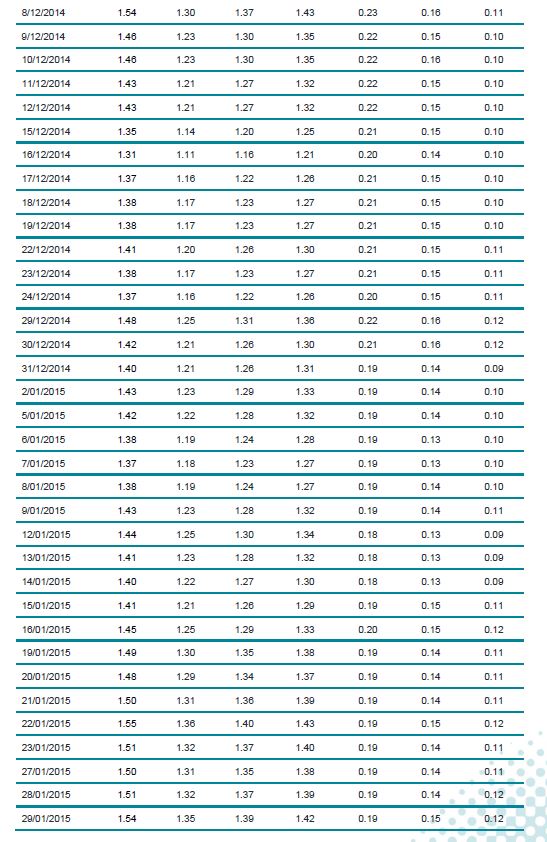

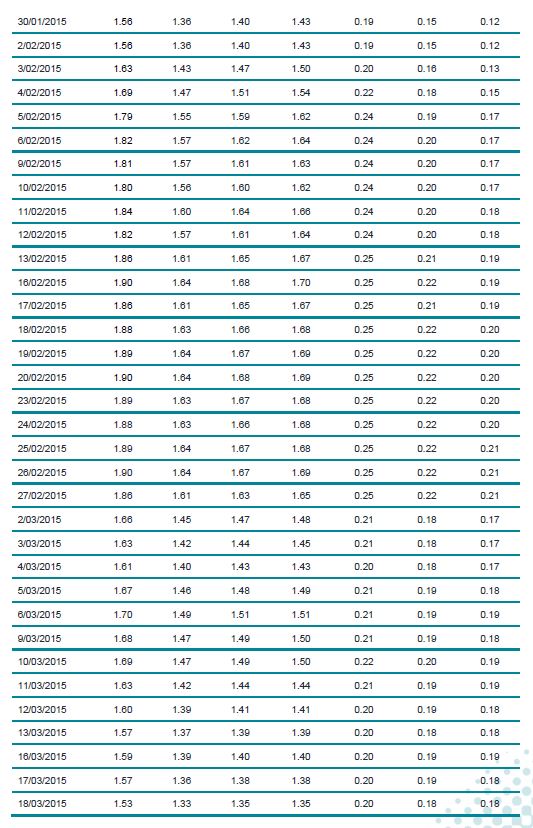

(k) Share price inflation – [924] to [1120];

(l) Continuous disclosure claim – [1121] to [1315];

(m) The “no reasonable grounds” claim and other claims – [1316] to [1499];

(n) Causation and loss analysis – [1500] to [1718];

(o) Conclusion – [1719] to [1721].

22 But before proceeding further, let me say that I was much assisted by the comprehensive legal and forensic presentations made by Mr Norman O’Bryan SC for the applicant and Mr Ian Waller QC for Myer including plummeting the depths of statistical theory, although I was not completely convinced about the former’s knowledge of heteroskedasticity.

THE PLEADED CASE

23 It is appropriate at this point to set out in some detail the applicant’s final version of its pleaded case. I gave the applicant leave late in the piece during closing addresses to amend its case. I will explain why I did so and its consequences later in this section.

24 The applicant alleges that on 11 September 2014, Myer announced an NPAT for FY14 of $98.5 million. This was stated in Myer’s ASX & Media Release concerning “Myer Full Year Results ending 26 July 2014” and “Preliminary Financial Report” each published on 11 September 2014.

25 The applicant says that on 11 September 2014 Myer disclosed to the market that it forecast profit growth in FY15. In a statement made by Myer’s then CEO, Mr Brookes on 11 September 2014 as part of Myer’s “Preliminary 2014 Myer Holdings Ltd Earnings Call”, Myer disclosed to the market that its outlook in 2015 was that “[w]e will therefore not only have anticipated sales growth, but anticipated profit growth this year”.

26 It is said that on 11 September 2014 by Myer announcing its FY14 NPAT and its expectation of profit growth, Myer represented to the market that its forecast NPAT for FY15 would be in excess of $98.5 million.

27 The applicant says that Myer’s representation of anticipated profit growth in FY15 made on 11 September 2014 was a representation with respect to a future matter, namely that Myer expected to achieve NPAT in excess of $98.5 million in FY15, which representation was continuing until 19 March 2015.

28 Further, it says that Myer had no reasonable grounds for making the representation alleged and accordingly the representation was taken to be misleading or deceptive pursuant to s 769C(1) of the Act.

29 Accordingly, the applicant says that Myer’s publication of the statements made by Mr Brookes on 11 September 2014 as part of Myer’s “Preliminary 2014 Myer Holdings Ltd Earnings Call” was conduct by Myer in relation to a financial product (namely MYR ED securities) that was misleading or deceptive or was likely to mislead or deceive in breach of s 1041H of the Act, with the publication taken to be misleading or deceptive by operation of s 769C(1).

30 The applicant says that on 19 March 2015 Myer issued a release to the ASX which disclosed that it expected that Myer’s NPAT for FY15 would be in the range of $75 to $80 million excluding one-off costs. Myer disclosed its revised forecast for FY15 in an ASX & Media Release of 19 March 2015 entitled “Myer First Half 2015 Results and Full Year 2015 Guidance”.

31 According to the applicant, Myer’s disclosure to the ASX on 19 March 2015 advised the market for the first time that Myer would not achieve NPAT in FY15 in excess of $98.5 million (the earnings forecast matter).

32 The applicant says that the information concerning the earnings forecast matter that a reasonable person would have expected to have a material effect on the price or value of MYR ED securities, if that information was made generally available, was that:

(a) Myer had no reasonable grounds for representing that it would achieve NPAT in FY15 in excess of $98.5 million;

(b) Myer’s sales would not increase in FY15 as previously forecast;

(c) Myer’s OGP margin would not improve in FY15 as previously forecast;

(d) Myer’s CCODB in FY15 would increase more than previously forecast; and

(e) Myer’s NPAT in FY15 would be materially lower than in FY14.

(together, the information about the earnings forecast matter).

33 As to (a) immediately above, the applicant says that on 11 September 2014, Myer was aware that it had no reasonable grounds for representing that it would achieve NPAT in FY15 in excess of $98.5 million.

34 Further, the applicant says that by no later than 11 November 2014, Myer was aware of the information about the earnings forecast matter alleged in (b) to (e) immediately above.

35 Further, the applicant says that despite Myer’s awareness of the above matters, the information about the earnings forecast matter was not generally available until Myer made it generally available by releasing the information about the earnings forecast matter to the ASX on 19 March 2015.

36 Accordingly the applicant says that Myer’s failure to disclose the information about the earnings forecast matter to the market immediately upon becoming aware of the earnings forecast matter constituted a breach of s 674(2) of the Act.

37 Further, the applicant says that Myer’s failure to disclose between 11 September 2014 and 19 March 2015 any information about the earnings forecast matter, including when it published each of the:

(a) Myer Holdings Limited 2014 Annual Report on 21 October 2014;

(b) “Q1 2015 Myer Holdings Ltd Corporate Sales Call” on 11 November 2014;

(c) Myer Holdings Limited Annual General Meeting Chairman’s Address on 21 November 2014;

(d) “Myer Holdings Ltd Strategic Review Conference Call” on 2 March 2015;

(e) ASX & Media Release of 2 March 2015 entitled “Myer announces CEO succession and update on strategic review to transform business for future growth”; and

(f) Letter to shareholders on 3 March 2015;

was conduct by Myer that was misleading or deceptive or was likely to mislead or deceive, in breach of s 1041H of the Act including by reason of the operation of s 769C.

38 Now various particulars were given of this allegation. As concerns the allegation that Myer had no reasonable grounds for continuing to represent that it would achieve NPAT in FY15 in excess of $98.5 million (the first element of “the information about the earnings forecast matter” alleged as (a) above), the applicant referred to matters in existence on 11 September 2014 and from time to time thereafter during the period 11 September 2014 to 19 March 2015 from which it could be inferred that Myer, by continuing to represent by its silence that it would achieve NPAT in FY15 in excess of $98.5 million, engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct.

39 Further, the applicant says that the matters referred to in para (a) of the particulars to paragraph 21 filed on 14 July 2017 (the [21] particulars) and the documents referred to therein were also relevant to a consideration of the matters in existence immediately following the making of the 11 September 2014 representation. For present purposes it is not necessary to detail those matters.

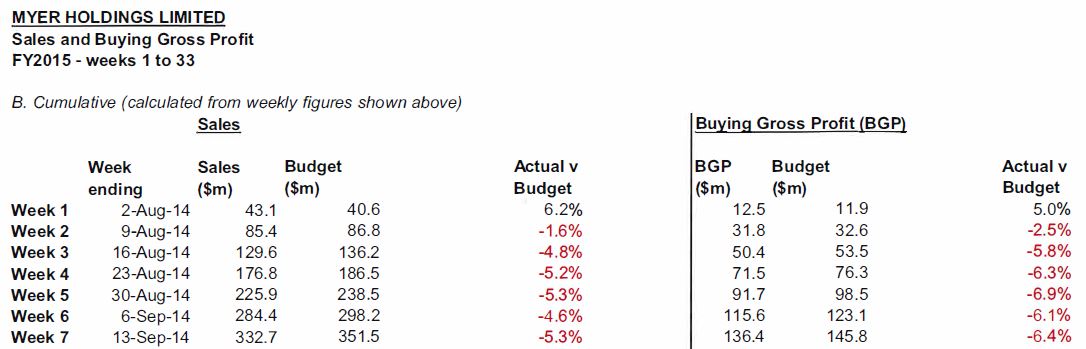

40 Further, the applicant also relies upon the following matters which occurred on various dates that I will shortly identify between 11 September 2014 and 19 March 2015 and which it is said were cumulative upon one another:

(a) 14 September 2014:

(i) the identification by Myer’s CEO in an email to Myer’s directors that “[t]he pleasing news is that the median NPAT consensus has fallen 14% to $92m and this reflects in the share price”;

(ii) Myer’s General Manager of Merchandise Planning identifying that Myer’s sales were already $18m behind budget with at least a $22m “sales risk moving forward”;

(b) 15 September 2014: the matters referred to in (b) of the [21] particulars and the documents referred to therein;

(c) 25 September 2014: the matters referred to in (c) of the [21] particulars and the documents referred to therein;

(d) 2 October 2014: the matters referred to in (d) of the [21] particulars and the documents referred to therein;

(e) 5 October 2014: by that date the sales and buying gross profit for week 10 were available, which showed that sales for the year to date were $27.86m behind budget and $4.90m behind forecast and buying gross profit was $14.34m behind budget and $2.28m behind forecast;

(f) 8 October 2014: the matters referred to in (e) of the [21] particulars and the document referred to therein;

(g) 12 October 2014: by that date the sales and buying gross profit for week 11 were available, which showed that sales for the year to date were $33.07m behind budget and $9.45m behind forecast and buying gross profit was $17.35m behind budget and $4.46m behind forecast;

(h) 15 October 2014:

(i) the matters referred to in (f) of the [21] particulars and the document referred to therein;

(ii) the matters referred to in the September FY15 Financial Board Report, including the note that Myer had reversed the year-to-date provision for the Myer Annual Incentive and that the NPAT loss of $5.8m was nonetheless $1.6m below budget;

(i) 16 October 2014: the matters referred to in (g) of the [21] particulars and the documents referred to therein;

(j) 26 October 2014: the matters referred to in (h) of the [21] particulars and the documents referred to therein;

(k) 30 October 2014: by that date the “November Forecast for FY15” had been prepared, including “the actualisation of August to October”, which disclosed that “the NPAT forecast (on a consolidated basis) for the year is $95m, which is $11m below budget ($107m) and $3m down on last year ($98.5m)”. The document also noted that removing “unidentified savings” and “vacancy provisions” from the forecast “would reduce the npat forecast to $90m” and that there was a $6m risk to NPAT from “the Online operation”. If both risks were included, a FY15 NPAT forecast of $84m would have been calculated;

(l) 31 October 2014: the matters referred to in (i) of the [21] particulars and the documents referred to therein;

(m) 2 November 2014: by this time:

(i) sales and buying gross profit results for week 14 were known, which disclosed for the year-to-date that sales were $15.09m below forecast and buying gross profit was $10.37m below forecast;

(ii) “The Good, The Bad and the Ugly” email had been sent to the Myer’s directors; and

(iii) Myer’s Chairman had replied to “The Good, The Bad and the Ugly” email and said: “I get the complex message!”;

(n) 9 November 2014: by this time sales and buying gross profit results for week 15 were known which disclosed for the year-to-date that sales were $23.40m below forecast and buying gross profit was $13.56m below forecast;

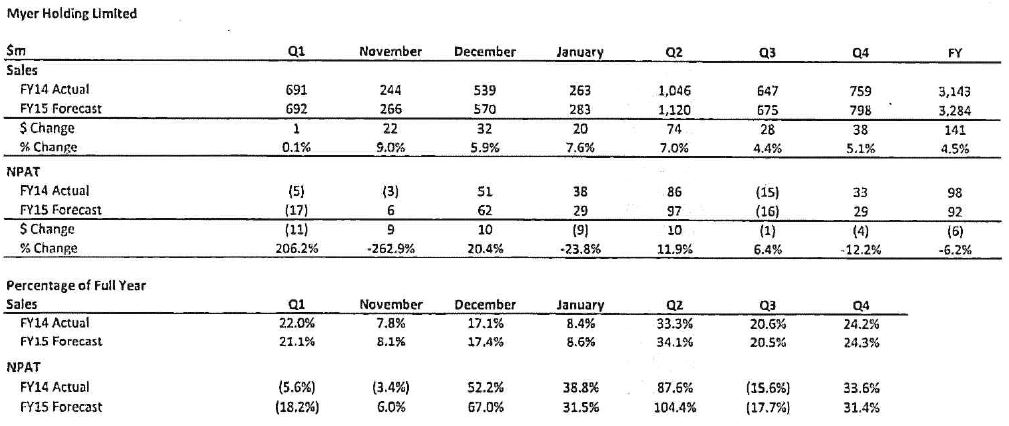

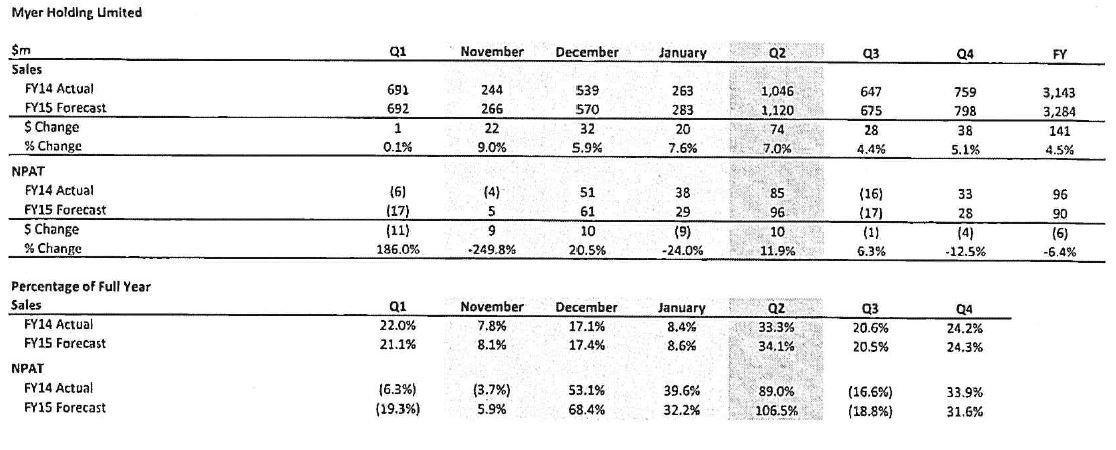

(o) 13 November 2014: by this date Myer had prepared a draft FY15 budget disclosing an NPAT forecast for FY15 of $92m, with that forecast reliant upon the second quarter achieving NPAT of $97m (or 104.4% of the forecast NPAT for the full year) in circumstances where Myer had made a net loss of $17m in the first quarter, and had forecast that it would achieve NPAT of only $13m in the second half of FY15;

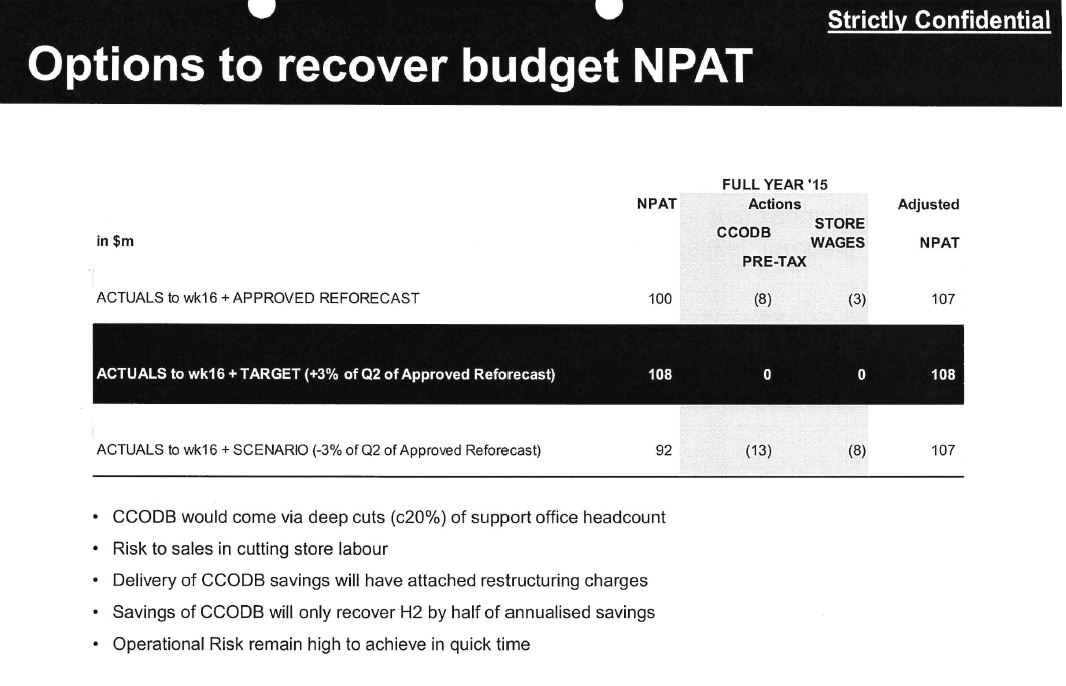

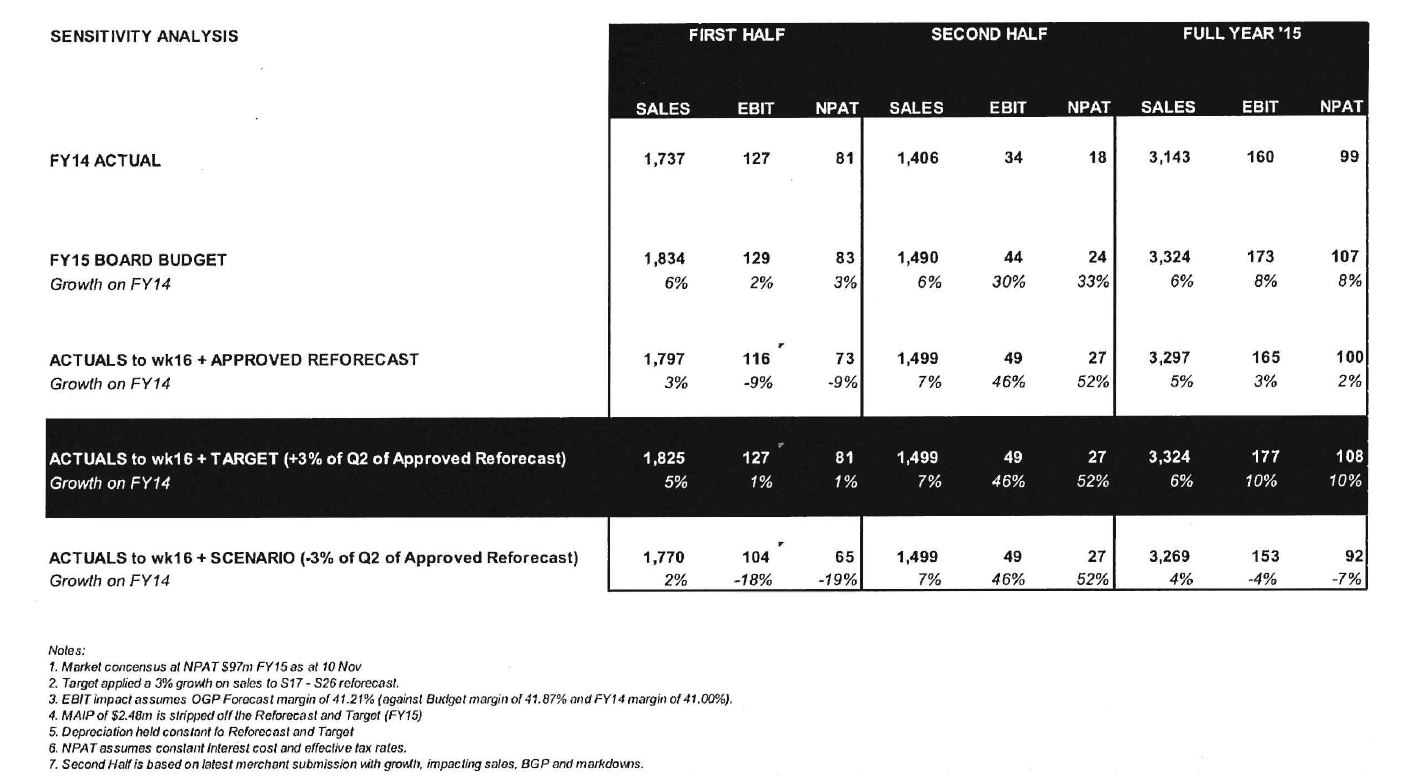

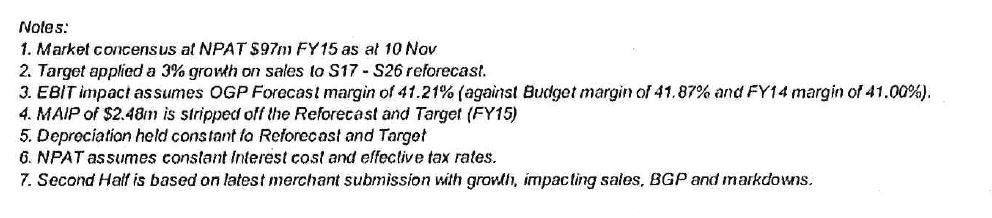

(p) 14 November 2014: by this date Myer had prepared a draft presentation entitled “Revised Forecast FY15 Quarter 2 Focus” disclosing a then-current forecast or “FY Actualised S15 to FY 15 Forecast” NPAT of $91m for the full year, and outlining options to recover NPAT to the budgeted level. The options included cutting the CCODB including by “deep cuts (20%) of support office headcount”;

(q) 16 November 2014: by this date the sales and buying gross profit results for week 16 were known which disclosed that for the year-to-date that sales were $22.52m below forecast and buying gross profit was $13.95m below forecast;

(r) 17 November 2014: by this date the “FY15 Target: A Quarter 2 Focus” document had been finalised, which disclosed an “Actuals to wk16 + approved reforecast” NPAT of $100m, which was reliant on first half NPAT of $73m and second half NPAT of $27m, but which provided no explanation as to how the “approved reforecast” figures had been significantly increased above those calculated on inter-alia 13 and 14 November 2014;

(s) 20 November 2014: by this date Myer had prepared an FY15 budget (not marked as “draft”) in the same format as that dated 13 November 2014 disclosing an NPAT forecast for FY15 of $90m, with that forecast reliant upon achieving NPAT of $96m (or 106.5% of the forecast NPAT for the full year) in the second quarter in circumstances where Myer had made a net loss of $17m in the first quarter, and had forecast that it would achieve an NPAT of only $11m in the second half;

(t) 24 November 2014: by this date the sales and buying gross profit results for week 17 were known which disclosed that for the year-to-date sales were $23.07m below forecast and buying gross profit was $17.17m below forecast;

(u) 30 November 2014: by this date the sales and buying gross profit results for week 18 were known which disclosed that for the year-to-date sales were $29.18m below forecast and buying gross profit was $19.86m below forecast;

(v) 7 December 2014: by this date the sales and buying gross profit results for week 19 were known which disclosed that for the year-to-date sales were $32.51 m below forecast and buying gross profit was $22.45m below forecast;

(w) 8 December 2014: on this date Myer’s CFO gave to Myer’s CEO a draft “Full Year Forecast- FY15” presentation which disclosed an “FY15 Forecast” lower than “FY 14 Actual” and which disclosed that with sales growth of 4% on FY14 an NPAT of $92m could be achieved, with sales growth of 3% on FY14 an NPAT of $83m could be achieved, and with sales growth of 2% on FY14 an NPAT of $74m could be achieved without “Actions/Levers” being employed to recover NPAT to a $94m level;

(x) 9 December 2014: on this date:

(i) a revised version of the “Full Year Forecast - FY15” presentation (see para (w) above) was tabled at Myer’s board meeting which disclosed an FY15 Forecast of $92m, approximately $7m less than the FY14 Actual NPAT of $98.5m. With lower sales growth rates of 4%, 3% and 2% on FY14 sales, NPAT forecasts of $89m, $80m and $74m respectively were shown, although “Actions/Levers” said to be capable of recovering NPAT to a $91m or $92m level were also shown;

(ii) Myer’s board discussed the forecast and noted that “the full year revised forecast is slightly above consensus”;

(y) 14 December 2014: on this date the sales and buying gross profit results for week 20 were known which disclosed that for the year-to-date sales were $8.44m below forecast and buying gross profit was $3.25m below forecast;

(z) 18 December 2014: on this date Myer’s CEO sent an email setting out his concerns in relation to achieving “forecast” over the Christmas trading period;

(aa) 21 December 2014: on this date the sales and buying gross profit results for week 21 were known which disclosed that for the year-to-date sales were $22.59m below forecast and buying gross profit was $12.26m below forecast;

(ab) 22 December 2014: on this date:

(i) Myer’s board conducted a “board discussion” by telephone, the minutes of which disclose that the current forecast NPAT could potentially be materially less than consensus but that with planned actions the forecast for FY15 NPAT would be $89m; and

(ii) Myer’s board was given a presentation entitled “Full Year Forecast- FY15 December 22 Board update” which disclosed that the “FY15 Current Forecast (CF)” was for FY15 NPAT of $68m and that only with a $21m boost to NPAT in the second half could an FY15 NPAT of $89m be achieved;

(ac) 23 December 2014: on this date Myer’s General Manager Corporate Affairs and Media gave a statement drafted to notify the market on or around 5 January 2015 that Myer no longer expected to achieve earnings growth on last year to Myer’s CEO, CFO and Company Secretary for their consideration;

(ad) 28 December 2014: on this date the sales and buying gross profit results for week 22 were known which disclosed that for the year-to-date sales were $21.14m below forecast and buying gross profit was $11.08m below forecast;

(ae) 4 January 2015: on this date the sales and buying gross profit results for week 23 were known which disclosed that for the year-to-date sales were $20.96m below forecast and buying gross profit was $12.80m below forecast. For week 23, Myer’s sales were $93m, up $0.17m on a forecast of $92.8m;

(af) 5 January 2015: on this date:

(i) Myer’s board conducted a “board discussion” by telephone, the minutes of which disclose that “the full year forecast NPAT is $90m, with cost actions, although the full year forecast is still being finalised” and that the board determined that no update to the market was necessary because “the current forecast NPAT result [was] in line with the Bloomberg consensus”;

(ii) Myer’s board was given a presentation entitled “Full Year Forecast - FY15 January 5 Board update” which disclosed at slide 4 an “FY15 Current Forecast (CF)” of FY15 NPAT of $74m, and an NPAT “with actions” of $90m;

(ag) 11 January 2015: on this date the sales and buying gross profit results for week 24 were known which disclosed that for the year-to-date sales were $21.77m below forecast and buying gross profit was $12.27m below forecast. For week 24, Myer’s sales were $69.5m, down $0.81m on a forecast of $70.3m;

(ah) 18 January 2015: on this date the sales and buying gross profit results for week 25 were known which disclosed that for the year-to-date sales were $24.43m below forecast and buying gross profit was $11.11 m below forecast. For week 25, Myer’s sales were $54.8m, down $2.65m on a forecast of $57.5m;

(ai) 21 January 2015: on this date:

(i) Myer updated its “FY15 Current Forecast (CF)” and “FY15 CF + Actions” showing figures of $76m and $90m respectively;

(ii) Myer’s CEO sent an email to each of the directors of Myer as well as Myer’s CFO and Company Secretary in which it was stated that “[o]ur belief is that we have no need to disclose any updates to the market out of our normal cycle” on inter-alia the following grounds:

1. Myer’s forecast showed $90m with less cost reduction than previously presented to the board;

2. “January trade is up 5% on last year and 3% ahead of forecast with good momentum”, although according to the applicant the statement concerning January trade being 3% ahead of forecast was inconsistent with the matters referred to in paragraphs (ee), (gg) and (hh) above;

3. “split of 68% average in first half profit is in line with this year but 2014 was a one-off”, although according to the applicant the status of FY14 as a “one-off” is not supported by the figures shown in Exhibit A1 tendered before me;

(iii) Myer’s board conducted a “board discussion” by telephone, the minutes of which disclose that “[t]he Board discussed the NPAT split between H1 and H2, and compared it to the historic split. Whilst last year the NPAT split between H1 and H2 was 82%:12% [sic], in the previous four years the split has been around two thirds:one third. The current forecast for the split for 2015 will be approximately two thirds:one third. Further, it was noted that the Bloomburg [sic] consensus NPAT figure is currently $90m, which is in line with the FY2015 NPAT forecast with cost actions, although the full year NPAT forecast is being finalised”;

(aj) 9 February 2015: on this date:

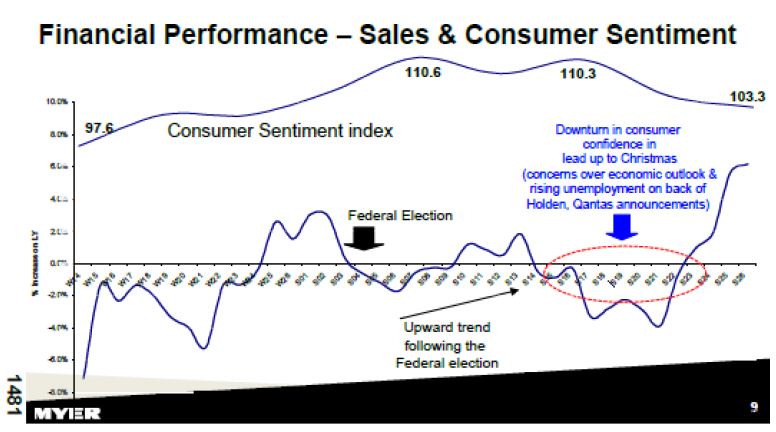

(i) Myer’s “FY15 Forecast February 2015 Board update” disclosing an “FY15 Current Forecast (CF)” of $76m and “FY15 CF + Actions” of $90m, was presented at Myer’s board meeting. Both the “CF” and “CF + Actions” forecasts were said to be dependent on 4% growth in sales over FY14 in H2, where only 2% growth had been achieved in H1 of FY15; and

(ii) Myer’s January FY15 financial performance was known and advised to Myer’s board which showed that January performance was below the “forecast” level and that Myer had been unable to constrain its costs as forecast;

(ak) 27 February 2015: on this date a revised forecast was presented at Myer’s board meeting and Myer’s board noted inter-alia that “the forecast NPAT for the year, before the strategic review costs, is $91m, and including the strategic review costs is $87m. The Bloomberg consensus NPAT is $89m” and that there were “potential downside risks” to sales and operating gross profit;

(al) early-March 2015: Myer’s performance in February 2015 was weaker than Myer’s forecast and Myer had been unable to constrain its costs as forecast with a CCODB of $102.2m achieved as against a forecast of $100.1m, and an NPAT of ($18.7m) as against a forecast of ($14.8m). The figures are recorded in the “Financial Summary February 2015” completed on 11 March 2015 and set out in the “February FY2015 Financial Board Report” at page 2; and

(am) for each week in FY15 up to and including week 33 ending on 14 March 2015, the sales and buying gross profit figures recorded in Exhibit A7 as tendered before me.

41 Let me state now that I have considered each and every one of the above documents and matters although the more detailed chronology that I have set out later places varying emphasis on these matters.

42 Further, as noted above, at the heel of the hunt I gave the applicant leave to amend to plead a continuing representation case and a failure to correct case, bounded only by the 19 March 2015 date. Myer opposed the application. But its disappointment in my granting leave and any prejudice were ameliorated by my giving Myer leave to re-open its case and to call further evidence to address the amendments. It took that opportunity. It was also protected by any costs consequences.

43 Let me turn to another part of the applicant’s pleaded case. The applicant’s loss and damage case is the following.

44 The applicant and group members held their interests in MYR ED securities in a market:

(a) regulated by, inter-alia, the ASX listing rules and the Act; and

(b) where the price or value of MYR ED securities would reasonably be expected to be informed and affected by information disclosed in accordance with the ASX listing rules and the Act.

45 The applicant expected that Myer had complied with its obligations under the ASX listing rules and the Act and had no knowledge of the information about the earnings forecast matter when it purchased 40,000 MYR ED securities on 17 November 2014.

46 It is said that the applicant and the group members acquired their MYR ED securities in a market:

(a) in which Myer had failed to disclose information about the earnings forecast matter that a reasonable person would expect to have a material effect on the price or value of MYR ED securities;

(b) in which Myer had engaged in the misleading or deceptive conduct alleged above, where each instance of misleading or deceptive conduct affected the applicant and those sub-groups of group members who acquired their MYR ED securities after the occurrence of each respective instance of misleading or deceptive conduct alleged; and

(c) in which the significant falls in the price of MYR ED securities on and after 19 March 2015 were caused by and were a result of the disclosure of information about the earnings forecast matter.

47 The applicant says that the failure to disclose the information about the earnings forecast matter caused the market price for MYR ED securities prior to 19 March 2015 to be substantially greater than:

(a) their true value;

(b) further or alternatively, the market price for MYR ED securities that would have prevailed but for Myer’s failure to disclose the information about the earnings forecast matter at any time prior to 19 March 2015.

48 The applicant says that the applicant and group members have each suffered loss and damage because of and resulting from the failure to disclose the information about the earnings forecast matter to the market, the applicant and those sub-groups of group members who acquired their MYR ED securities after the occurrence of each respective instance of misleading or deceptive conduct by Myer alleged have also suffered loss by that misleading or deceptive conduct, and all group members are entitled to compensation pursuant to ss 1041I, 1317HA and 1325 of the Act. It is said that Myer’s failure to disclose the information about the earnings forecast matter caused the applicant and the group members to suffer loss and damage because the failure to disclose caused the market price for MYR ED securities prior to 19 March 2015 to be substantially greater than their true value or further or alternatively, the market price for MYR ED securities that would have prevailed but for Myer’s failure to disclose the information about the earnings forecast matter. Accordingly the applicant and the group members overpaid for their MYR ED securities. The losses are said to be comprised of the difference between the prices at which the MYR ED securities were acquired by the applicant and the group members and the prices that would have prevailed at the times of those acquisitions had the information about the earnings forecast matter been disclosed at that time and, as relevant to the applicant and those sub-groups of group members who acquired their MYR ED securities after the occurrence of each respective instance of misleading or deceptive conduct alleged, had Myer not engaged in the alleged misleading or deceptive conduct.

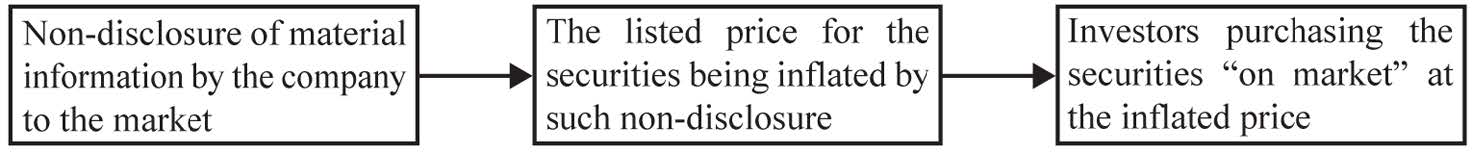

49 It will be apparent that the applicant and group members are not putting a causation and loss case based upon specific reliance, but rather are putting a case solely on the basis of an indirect or market-based causation thesis, which causation thesis in my view is available as a matter of law.

THE APPLICANT

50 Before proceeding further, let me say something about the applicant.

51 The applicant is the trustee of a self-managed superannuation fund known as the “Amies Superannuation Fund” for Mr Christopher Amies (the SMSF). Prior to the appointment of the applicant as trustee of the SMSF in 2015, Mr Amies and his sister, Ms Jacinta Amies, were the trustees of the SMSF.

52 Mr Amies had spent most of his career working in finance and investment banking roles. He had also been active in small business, including as a franchisee of several cafes and most recently as the owner of Sunshine Coast Organic Meats, the largest organic butcher in South East Queensland. The finance and investment banking roles he had held included being an investment manager for an investment company over a thirteen year period, investment banking roles with Prout Partners and First Class Capital, chief financial officer of Bright Eyes, a subsidiary of Oakley, Inc and various roles with North Ltd and its subsidiary Energy Resources of Australia Ltd.

53 He held a Bachelor of Commerce from the University of Queensland, a Graduate Diploma in Applied Finance and Investment from the Securities Institute of Australia, and a Masters of Applied Finance from Macquarie University.

54 Mr Amies gave evidence of the following matters on behalf of the applicant. He was not cross-examined.

55 Mr Amies had been investing in listed companies since 1985 when he was at high school. He had invested continuously since then. Over the last ten years he had managed an investment portfolio with a value ranging from $1m to $10m.

56 He established the SMSF in March 2004. The purpose of establishing the SMSF was to take ownership of investment decisions for his, and his sister’s, superannuation purposes. From the establishment of the SMSF, both he and his sister had accounts with the SMSF and both acted as trustees.

57 His investment strategy for the SMSF was to be a long-term investor in shares in listed companies. But his investment strategy for his share investments other than those in the SMSF had been focused on achieving trading gains over the short to medium-term.

58 When he made investment decisions, including for the SMSF, he tried to take relevant financial information into account. The information he habitually took into account included earnings outlooks, market consensus expectations, company outlook statements, commentary by public commentators, economic conditions generally or in the specific sector, as well as his own thoughts and analysis.

59 He also took into account the views of various stockbrokers to whom he talked from time to time. He had used several different stockbrokers over the years and from time to time he discussed with them general market conditions and specific stocks.

60 When he made investment decisions, he took into account a company’s share price, its most recent results, statements which had been made by the company, and whether he considered the market as a whole to be relatively cheap or expensive.

61 He was aware that listed public companies had a continuous disclosure obligation which obliged them to make announcements to the market as soon as they became aware of materially price-sensitive information.

62 He always assumed that market prices for shares reflected all available information which was known to the market. As I say, he held a Masters of Applied Finance degree from Macquarie University and had studied the operation of the stock market.

63 Mr Amies made the decision for the SMSF to purchase Myer shares in November 2014.

64 He discussed the potential purchase with a stockbroker friend of his, Mr Shayne Gilbert, who worked as a broker for Ord Minnett at the time.

65 Mr Gilbert and he had a particular and long-running interest in Myer. They attended together one of the town-hall investor meetings held in late 2009 at the time of the initial public offering of Myer shares. I note that in evidence was a photograph of Mr Amies with Myer ambassador, Ms Jennifer Hawkins, taken at that meeting.

66 Mr Amies did not do any particular research into Myer at the time of the initial public offering of Myer shares. Generally, he read the Australian Financial Review and the business section of The Australian every day, along with reports from several stockbrokers each day. He also kept a good working knowledge of the activities and performance of many listed companies, including Myer. And when brokers released research reports on particular companies, he tended to read those reports.

67 In 2014 he was aware that Myer’s share price had declined since listing but, despite this, Myer’s management commentary remained positive. As a consequence, he thought that Myer shares looked cheap in 2014.

68 When he spoke to Mr Gilbert, they discussed the fact that Myer shares appeared to be cheap, offered a good dividend, and that Myer’s outlook was positive based on Myer’s own guidance to the market.

69 Mr Amies did not execute the purchase of Myer shares on 17 November 2014 with Mr Gilbert because the SMSF did not have a trading account with Ord Minnett. Instead he gave instructions to Morgan’s to buy the shares on an “execution only” basis.

70 The trustees of the SMSF, Mr Amies and his sister, purchased 40,000 MYR ED securities on 17 November 2014, with settlement on 20 November 2014.

71 As trustees they paid $1.7575 for each MYR ED security which were acquired on-market on 17 November 2014.

72 They held those 40,000 MYR ED securities at the opening of the market on 19 March 2015.

73 When the SMSF purchased the shares on 17 November 2014, Mr Amies did not have any inside information about Myer and, in particular, he did not know any of the information which was disclosed by Myer to the market for the first time on 19 March 2015.

74 The applicant was appointed trustee of the SMSF on 31 July 2015 and so the trust property of the SMSF vested in the applicant from that time.

75 The applicant, as trustee of the SMSF, continued to hold the MYR ED securities following its appointment as trustee until their sale on 1 November 2016 at a price of $1.1650 for each MYR ED security.

KEY LAY WITNESSES

76 Myer principally relied on evidence from Mr Brookes and its chief financial officer, Mr Mark Ashby at the relevant time. Mr Brookes and Mr Ashby were involved in the preparation of the budget for FY15 and the decision to present that budget to the board for approval, and they also gave evidence in relation to these matters.

77 Myer also relied on evidence from the heads of its stores and merchandise teams, being Mr Anthony Sutton, the Executive General Manager of the Stores team and Mr Adam Stapleton, the Executive General Manager of Merchandise.

78 Further, Myer also relied on evidence from each of its directors at the relevant time, which in addition to Mr Brookes included Mr Eric Paul McClintock, Mr Robert Edward Thorn, Mr Rupert Horden Myer, Mr Ian Grainger Cornell, Ms Christine Joanna Froggatt, and Ms Anne Bernadette Brennan.

79 Mr Brookes, Mr Ashby, Mr Sutton and Mr Stapleton had between them considerable retail experience.

80 Mr Brookes was the CEO and MD of Myer from 12 July 2006 to 24 February 2015, and had therefore had ultimate management responsibility for the Myer business, subject to oversight by the board, for a period of about eight years at the time the FY15 budget was prepared. Prior to his time at Myer, Mr Brookes worked for 25 years at Woolworths in Australia, including as the General Manager of Woolworths in Queensland. Mr Brookes had very significant corporate experience in the retail sector in Australia (over 30 years), and following his time at Myer he became the CEO of the largest clothing, footwear and general merchandise retailer in South Africa (which has over 1,400 stores).

81 Mr Ashby also had significant relevant experience and qualifications. He was a certified practising accountant with around 30 years of corporate and finance experience, the majority of which has been in senior finance roles with retail companies. Further, he had substantial experience at Myer, having been, at the relevant time, the CFO at Myer for over six years since 14 January 2008. Further, he had substantial corporate experience, having been the CFO of Mitre10 Australia Limited between 2004 and 2008, and having been involved as both a senior executive and in less senior roles in forecasting, budgeting and preparing business plans for various retail businesses.

82 In my view both Mr Brookes and Mr Ashby were honest witnesses, but some aspects of their evidence were problematic particularly once one proceeded into and past October 2014 concerning their states of mind as to the likely NPAT for FY15. I was also left surprised about their professed ignorance concerning some of the draft forecasts and the like that were prepared at and after that time. Further, in relation to Mr Brookes’ evidence concerning his understanding as to the board’s position at the board meeting on 10 September 2014, his understanding was in tension with the understanding of other directors. I do not need to linger on this aspect at this point.

83 Mr Stapleton, the head of the Merchandise team, was also an experienced and senior retailer, who has gone on to hold senior management roles at Coles, and then to become the CEO of Grill’d Burgers, since he left Myer. At the relevant time, his experience included working with Myer for more than 12 years, including more than 10 years in senior merchandise and marketing roles, including as head of Merchandise from December 2012 to July 2014.

84 Mr Tony Sutton, the head of the Stores team, had worked at Myer for over 25 years in roles related to the operations of Myer’s department stores. In these roles he had extensive experience in relation to store operations, and in relation to the process of preparing budget submissions by the Stores team.

85 Each of these members of the senior management team also gave evidence as to their role in the preparation of the FY15 budget.

86 Each of the directors also had significant relevant experience. Let me give a brief summary.

87 Mr McClintock, the Chair of the board, had been a director of Myer since August 2012. Mr McClintock had very significant corporate experience, including serving on the boards of dozens of companies and entities, a number of which were listed on the ASX.

88 Mr Thorn had over a decade of experience as a director of numerous retail companies.

89 Mr Myer, the Deputy Chair of the board at the relevant time, had been a director of Myer since 2006, as well as having served as a director of a number of other companies including ASX listed companies.

90 Ms Brennan had been a director of Myer since 2009, was the director of a number of other ASX listed companies, had been the CFO of an ASX listed company (CSR Limited) and had worked for almost 20 years at Ernst & Young, Arthur Anderson and KPMG.

91 Ms Froggatt had also been a director of Myer since 2010, and was the director of various other companies, including an ASX listed company.

92 Mr Cornell had worked in senior roles in the retail industry for over 15 years.

93 These directors gave evidence in relation to their practice in approving budgets at Myer, and in relation to their knowledge, particularly whether they knew that Myer’s NPAT in FY15 would be materially lower than in FY14.

94 On the whole their evidence was credible and compelling, particularly the evidence given by Mr McClintock who was smart, competent and direct.

THE STRUCTURE OF MYER’S BUSINESS

95 It is necessary at this point to say something about the structure of Myer’s business. What I am about to describe is not controversial and is largely taken from Myer’s accurate summary of the evidence.

Teams and key personnel at Myer

96 The key “teams” at Myer were the following.

97 First, the National Store Operations team (Stores team or NSO). This was the team that was directly responsible for running the department stores. The head of the Stores team at all relevant times was Mr Sutton. He reported directly to Mr Brookes. Reporting to Mr Sutton were a series of Regional Managers who were responsible for the stores in a particular State (or part of a State, for example, NSW had two Regional Store Managers) as well as various administrative positions.

98 Second, the Merchandise and Marketing team (Merchandise team). This was the team that was directly responsible for running the merchandise and marketing aspects of the Myer business, including product selection, range allocations, development of new product ranges and negotiations with suppliers. The head of the Merchandise team at the time of the preparation of the FY15 budget was Mr Stapleton. The head of Merchandise Planning (who was then Mr Darrel Maillet) reported to Mr Stapleton.

99 Third, the Property team, which worked on all issues associated with new stores and refurbishments, lease negotiation, space allocation, store maintenance and property design. Mr Tim Clark was the head of the Property team and reported directly to Mr Brookes. In relation to new stores, this team worked on the evaluation of new sites and consideration of matters such as local demographics, the size of a centre in which a new store would be located, potential population growth in the area, and the likely capital costs of the new store.

100 Fourth, the Online team, which worked closely with the IT and supply chain teams. When preparing the yearly budget, this team provided an analysis of the sales and forecast for the online component of the business. At the relevant time Mr Richard Umbers was the Chief Information and Supply Chain Officer and the head of this team.

101 Fifth, the Finance team, which was responsible for all of the traditional financial elements of the business, including accounting, treasury and tax, as well as investor relations, audit, risk, compliance and assurance. Mr Ashby was the head of the Finance team.

102 The heads of each of these teams formed part of the Executive General Management (EGM), and reported directly to Mr Brookes.

The department store business and other parts of the business

103 At the relevant time, the Myer business consisted of:

(a) its physical department stores;

(b) the online business, by which it sold merchandise to customers online;

(c) the Sass & Bide business, being a separate brand owned by Myer which was sold out of separate Sass & Bide stores; and

(d) free-standing stores, being three speciality stores that were being trialled in Epping and which only sold Myer Exclusive Brand (MEB) products.

104 Various internal Myer documents that forecast or discuss sales and other financial metrics only refer to or incorporate figures for the “Department Store” business, which was typically used in internal documents to mean both the physical department stores and the online business, but which did not include the Sass & Bide or “free-standing” stores.

Key financial metrics

105 The key drivers of Myer’s NPAT which are evident from the documents are:

(a) Sales, being the total amount received by Myer for inventory sold;

(b) OGP margin, which is the operating gross profit as a percentage of sales. Operating gross profit consisted of total sales minus the cost of goods sold with other adjustments made for the cost of markdowns, discounts on gift cards and other matters; and

(c) CCODB, which as I have said is Myer’s cash cost of doing business. The CCODB was all costs incurred in running the business excluding depreciation and amortisation.

MEBs, National Brands and Concessions

106 Myer’s merchandise offering fell into three general categories which were referred to as MEBs, National Brands and Concessions. The mix of sales as between these categories was important and influenced the OGP margin. In particular, MEBs had the highest OGP margin, and therefore increasing sales of MEBs, relative to National Brands and Concessions, would improve the OGP margin.

Key trading periods relative to annual results

107 Myer’s financial year ended on the last Saturday in July, beginning on the Sunday following.

108 Historically, a very significant proportion of Myer’s sales and full year NPAT was achieved during the second quarter (Q2), which comprised the months of November, December and January, particularly in December and January which include the Christmas, Boxing Day and New Year sales. As an example, in FY14 Q2 generated 87.6% of NPAT, Q4 generated 33.6% of NPAT, and Q1 and Q3 generated losses.

109 According to Myer’s case, the actual results for Q1 are not, given their relative insignificance when compared to Q2 and Q4, a sure guide for the likely full year result and it is difficult to determine, at least until the results for Q2 are available which does not occur until early February, where NPAT is likely to end up for the full year based on actual results.

MAIP and CEO One Time Costs

110 The FY15 budget included two relatively significant cost items in the figures that were factored into the forecast NPAT of $107 million.

111 The first was “CEO One Time Costs”. These were essentially discretionary one-off or non-recurring costs that the CEO could determine whether to incur. Mr Brookes’ evidence was that he would typically only incur these costs if the business was going well. Mr Ashby’s evidence was that if sales performance was lower than expected it was relatively easy to cut these costs back. The FY15 budget included $17 million for such costs, being an increase of $6 million from FY14.

112 The second was MAIP. MAIP was the Myer Annual Incentive Plan, which was a bonus scheme (also known as “STIP”, short term incentive plan) which provided for potential additional remuneration to be payable to Myer senior management including the CEO and CFO. The criteria for payment of MAIP focused on financial and non-financial targets, including, in particular, earnings before interest and tax (EBIT) and sales growth. Accordingly, if EBIT and sales growth were below budget, then at least 80% of the MAIP provided for in the budget would not be paid.

113 The FY15 budget made a provision of $12 million for MAIP being 85% of the total MAIP payment that might become due. This was in circumstances where no MAIP had been paid in FY14.

THE DEVELOPMENT AND APPROVAL OF THE FY15 BUDGET

114 The evidence is that the FY15 budget was prepared as the result of a comprehensive and thorough process. Indeed, I should say now that at the time the budget was approved and also as at 11 September 2014, all of Myer’s directors and relevant senior executives considered the forecast figures in the budget to be achievable.

The budgeting process

115 The process for preparing a budget including the FY15 budget was a lengthy and detailed one, which involved input from a substantial number of experienced people within the Myer business.

116 The first important step was for the key teams within Myer to prepare and submit to the Finance team their initial submission setting out what they expected Myer’s financial metrics would be for the coming year.

117 This aspect of the budget was a “bottom up” process, which involved the build-up of financial information for the business from the work of staff in particular in the Merchandise and Stores teams, albeit that this process would involve broad guidance from senior management.

118 This process commenced around January or February each year. Early in the process a series of key parameters were provided to the teams involved in the preparation of the budget (including the Merchandise team and the Stores team) and there would be a strategy session which focused on development of the following year’s budget.

119 The Merchandise team, and the Stores team, would each undertake substantial work in order to prepare a submission to the Finance team in relation to estimated sales for the coming year.

120 Relevantly, the Merchandise team consisted of:

(a) the head of Merchandise Planning who reported to Mr Stapleton;

(b) heads of each of 12 trading product categories (TPCs), being a “general manager” and a “head planner” (Merchandise Planning Manager or MPM) for each TPC;

(c) “buyers” within each TPC; for each TPC there were a number of “buyers”, who would be responsible for purchasing one or more specific products within that TPC; and

(d) “planners”, being staff who analysed the performance of TPCs (or specific products within TPCs), and worked with the buyers in each TPC.

121 The evidence was that there were various reasons that militated against buyers estimating an unrealistically high sales figure for their products for the coming year.

122 The Merchandise team would prepare its own forecast of sales. This would commence by preparing:

(a) a sales forecast for each category of product within a TPC; this “sales plan” was prepared by the buyer and planner for each product category to create a sales estimate for that category; and

(b) a sales forecast for each TPC as a whole, which involved combining the sales plans for each product category within the TPC.

123 The sales plan (forecast) for each category within a TPC was then reviewed by the general manager and MPM for that TPC. The job of the general manager and MPM in conducting this review was to ensure that each category was setting itself a realistic budget.

124 The MPM for each TPC would then present the sales plan for that TPC to the head of Merchandise Planning (Mr Maillet), who would review it.

125 The sales plan for each TPC would then be reviewed by Mr Stapleton.

126 The forecasts for each TPC would then be combined into a submission by the Merchandise team to the Finance team setting out estimated sales (and the First Margin and Buying Gross Profit (BGP)) for the coming year. In the submission, as estimating the sales for each TPC, the Merchandise team would also break down the estimated sales for each TPC within National Brands, MEBs and Concessions.

127 In preparing the sales figures for each TPC, the Merchandise team would consider factors such as sales in that TPC for the previous year, whether new brands would be introduced for that TPC in the coming year, store openings and closures, and the entry or exit of a competitor.

128 I would note that relevantly to the FY15 budget, the sales figure included by the Merchandise team in its original submission was $3,266m excluding Sass & Bide and free-standing stores. The final sales figure adopted in the FY15 budget was $3,267m excluding Sass & Bide and free-standing stores.

129 As I said above, the Stores team consisted of a series of Regional Managers, each of whom would be responsible for a particular State (or part of a State). It also consisted of Store Managers, each of whom would be responsible for a particular store.

130 The Stores team would prepare a separate submission of what sales it anticipated for the store network for the coming year. These sales figures would be prepared by each Regional Manager, with input from each Store Manager, and would be prepared by considering factors such as:

(a) how each store performed in the previous year;

(b) refurbishments, and whether sales would increase due to a completed refurbishment or sales would decrease due to the commencement of a refurbishment;

(c) whether any store may be subject to disruptions such as renovations to the mall it was situated in or roadworks around the mall;

(d) whether the mall could attract more customers due to developments to the mall being completed;

(e) economic factors and demographic factors of the area the store was located in;

(f) competitors entering or exiting the area the store was located in; and

(g) new initiatives for individual stores.

131 The Stores team would have regard to each of these factors to ensure that a balanced view was reached as to the estimated sales which a store was expected to achieve in the coming year.

132 The Stores team would also consider the opening of new stores and the closure of existing stores. The estimate of sales for a new store that was to be opened involved consideration of the business case for opening the new store, including cannibalisation of sales from existing stores (i.e. loss of sales by an existing store that was located close by to the new store).

133 The impact of the closure of an existing store considered the extent to which customers who shopped at the existing store might shop at another Myer store in a nearby area.

134 The sales for each store would then be combined into a submission from the Stores team to the Finance team. Relevantly to the FY15 budget, the submission of the Stores team was for sales of $3,286m excluding Sass & Bide and free-standing stores. This figure built from the “bottom-up” was ultimately higher than the sales figure that Myer included in the FY15 budget being $3,267m excluding Sass & Bide and free-standing stores.

135 The submissions of the Merchandise team and the Stores team were two different perspectives on the one matter, being sales, with each submission being a useful check against the other.

136 After the initial submissions of the Merchandise team and the Stores team were prepared:

(a) Mr Ashby would analyse the budget with his direct reports and seek to identify further opportunities to increase sales and decrease costs; and

(b) senior management (the EGMs) would meet to consider the first cut of the draft budget.

137 From this point a detailed process would be undertaken by which the proposed budget would be considered, discussed and refined, so as to ultimately result in a final budget that would be presented to and approved by the board.

The purpose and uses of a budget at Myer

138 The finalised budget, and the figures and details underlying it, served several purposes. First, it was used to determine where resources were to be allocated within Myer’s business, that is, in relation to matters such as staffing. Second, it was used to run the business, such as determining what stock to purchase. Third, bonuses under the MAIP were significantly dependent on achieving metrics in the budget, and in particular earnings and sales. Overall, the intention underlying the budget was to prepare figures that were realistic and achievable or which were considered to be realistically achievable although not easy to achieve.

139 The evidence was that an unrealistic budget was likely to have several negative effects on the business. First, if an unachievable sales figure was set this would likely lead to a surplus of inventory, which would in turn harm margins due to the need to sell stock at a “markdown”. Second, an unrealistic sales figure would lead to excess store costs, that is, by way of overstaffing. Third, an unrealistic budget may disincentivise staff, who would not be paid bonuses, or would be paid smaller bonuses, because bonuses were dependent on figures in the budget. Fourth, an unrealistic budget may lead to a loss of credibility by senior management among staff.

140 According to Myer’s submissions, the process undertaken by Myer, along with the evident issues that would arise if an unrealistic budget was set, meant that the process by which the budget was arrived at was predisposed not to be unduly optimistic, whilst setting a budget that presented a challenge to the business, and that there is in turn a strong inference that management would be unlikely to present for approval a budget which they did not consider to be realistic. To put the matter another way, there is no proper basis to suggest any reason why management would knowingly inflate the figures in a budget.

The FY15 budget – Applicant’s submissions

141 Let me at this point summarise the applicant’s contentions.

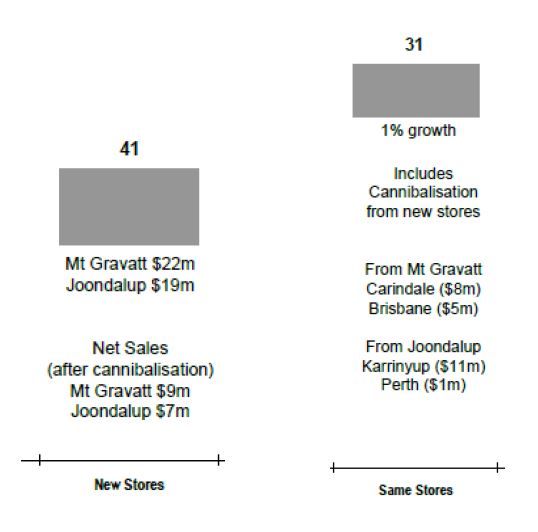

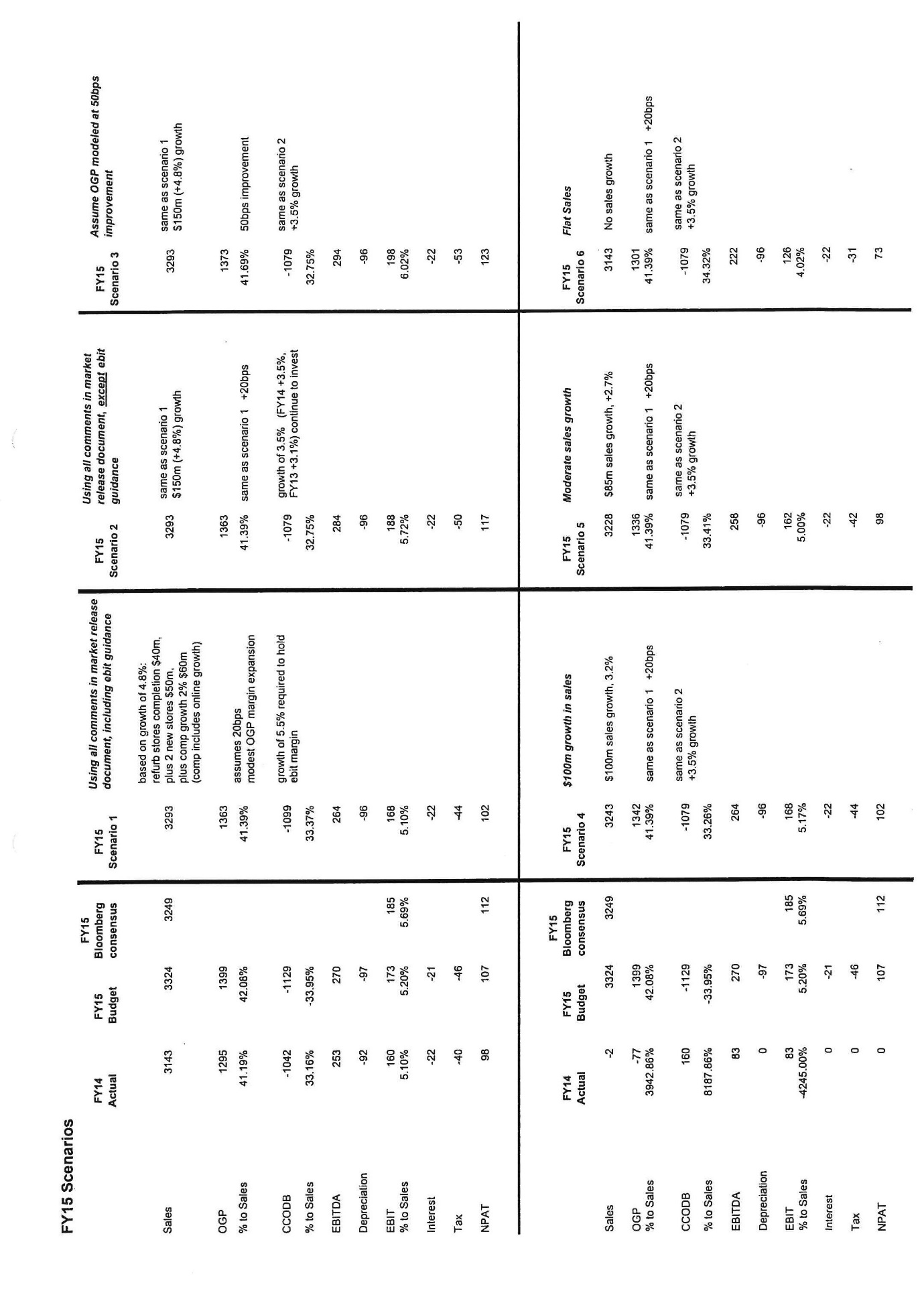

142 The applicant contends that the senior management of Myer, particularly Mr Brookes and Mr Ashby were determined to produce a FY15 budget showing substantial growth in sales and profits and which reversed the declines in sales and profitability which Myer had experienced in the preceding four financial years, since its maiden profit result in FY10. It is said that this can be seen in the FY15 budget preparation and planning documents, for example Mr Ashby’s email of 26 March 2014 to Mr Sutton, Ms Kerry Davenport and Mr Chris Lauder in which he described the budget submission which he had received in respect of the new store sales cannibalisation. He said “clearly it is a net unacceptable level for mt gravatt and joondalup” and demanded to see “realistic sales numbers ASAP”. According to the applicant, the figures which Mr Ashby had received are consistent with the figures which appeared in the original draft of the budget but which were later amended.

143 Further, the applicant submitted that Mr Ashby’s longer email of the following day, at 2.02 am on 27 March 2014, to Mr Stapleton, Mr Sutton, Mr John Joyce, Mr Timothy Clark, Ms Louise Tebutt, Mr Anthony Coelho, Ms Marion Rodwell and Ms Megan Foster with Mr Brookes, Mr Richard Harrison, Mr Len Kocovic, Mr Lauder, Ms Vicki Reid and Mr Greg Travers copied in, and titled “FY15 budget build up” more clearly illustrates his ambitions for the FY15 budget, in which he described the need to align Myer’s budget targets to its business strategy and complained that “[i]n the first cut budget, whilst I am sure elements of this are calculated, there is not the outcome we require. There does appear to be a need for more confidence to back our strategy”. He later stated “when I look at the numbers on a store basis, the new stores appear to be a profit drag – because of significantly lower than business case sales and higher cannibalisation…[a]gain we seem to be heading too conservative – we are investing heavily in service initiatives, but not backing with sales targets”. Further, in relation to investment in the Myer one program “the numbers we see in the budget really don’t back our plans” and “[t]here is a disconnect between what we are strategising and promoting to our shareholders and our confidence to back the outcome”. He noted that “[f]ollowing on from the last EGM, where it was proposed to issue targets, something we are generally reluctant to do, we now need to move down this path”.

144 Mr Ashby then announced the targets in respect of sales (“current department stores forecast for fy14 is $3118m, budget submission was $3266m, the new target is $3290m”), the MEB mix (“MEB mix forecast for fy14 is 20.7%, the proposed was 21.7%, new target is 22.0%”), MEB first margin (“MEB first margin forecast for FY14 is 72.68%, FY 15 submission is 71.98% - the new target is at FY 14 levels of 72.70%”) and stated that Mt Gravatt and Joondalup needed to generate a certain level of sales from the opening year and that cannibalisation should be no more than a particular level from the two stores. Significantly, so it was said, Mr Ashby stated:

We need 2 years of “clean air” to deliver eps growth. Our Capex and associated opex will have to be moderated to support the future. In each EGM discipline we need to develop financial thought processes that have the shareholder in mind, rather than what is right for that function in isolation.

You will see this in the budget process as we set the business for the next few years.

145 Further, in an email sent at 2.49 pm on 27 March 2014 in response to Mr Ashby, Mr Stapleton said:

What is your expectation regarding the pre-read information for the FY15 budget meeting on 8th April? The planning team sent through to your team last night the monthly splits detail (see attached), but those monthly splits are on the sales number we went through in the February budget meeting, not the below target. It took the planning teams over 2 weeks to build this level of detail so we don’t have the time or bandwidth to go back and do it again. From what I have been able to think of, the options are:

• present the monthly splits as per what has been built and then talk to where we have identified the difference to the $3,290m ($+24m to current budget proposal)

• identify exactly where the extra $24m sales growth is coming from and then take a relatively unscientific approach to allocating out the extra $24m across TPC’s and weeks so that when we talk about the detail in the budget meeting at least it adds to the number the company is targeting

In regards to the targets themselves, I have communicated the below note to my GM’s and Darrel and I have spent some time today working on it. If it was easy we would have already put it into the budget but I fully understand why we need to find a way to get these targets.

146 Mr Ashby replied at 9.43 pm on 27 March 2014 stating “thanks Adam appreciate the note. I am comfortable with the first option, talking to where the $24m has been identified”.

147 The applicant pointed out that Mr Ashby’s evidence was that he did not recall following up with Mr Stapleton after this email exchange to discuss with him whether or not the targets that he had set were or were not in fact achievable.

148 Now the applicant said that neither Mr Ashby nor Myer’s senior management team could be criticised for having or expressing their high ambitions for Myer’s FY15 sales, but it said that the ambitious FY15 budget must be considered in its actual business context. Its actual business context included aspirations and desires on the part of the Myer senior management to turn the business around in FY15 which can with the benefit of hindsight be seen to have been overly optimistic and which were ultimately not able to be achieved. Mr Brookes’ short email response “[g]reat note well done!” at 1.31 pm on 27 March 2014 indicates his support for Mr Ashby’s agenda of improvement in FY15 sales and profits, which coincided with his own.

149 According to the applicant, Mr Ashby’s directions given to the senior executives of Myer to produce a FY15 budget showing higher sales and profit numbers had their desired effect.

150 According to the applicant it is also apparent from the draft budget documents that Mr Ashby was explicitly targeting 2015 NPAT growth, which would achieve the earnings per share (EPS) hurdles which applied under the Myer Long Term Incentive Plan (LTIP). It is said that this is made clear by the reference to that consideration in the 14 May 2014 budget document, which refers to targeted NPAT growth of 9%, which is said to be “consistent with past EPS hurdles for LTI (2%-7%) as communicated to shareholders” and also consistent with the sales and NPAT figures, where sales of $3,365m produce NPAT of $113m, being an increase of 9.3% above the then anticipated FY14 NPAT forecast of $103m. It is also consistent with the draft budget document appearing, where 10% earnings per share growth is the target set in the budget, requiring an NPAT target $116m or, in order “to outperform Consensus”, an NPAT target of $120m. Setting a growth target for NPAT was an explicit objective of the FY15 budget.

151 The applicant says that despite the optimism which was expressed in the draft sales and profit targets in the versions of the budget which were prepared in May 2014, Myer’s actual trading performance at that time was not giving any indication that there was likely to be a significant improvement in sales or profits in the near future. In Mr Brookes’ board update for the board meeting in May 2014, he noted that both sales and profits for April 2014 were below the reforecast figures which had previously been given to the Myer board (and therefore necessarily below the original FY14 budget, which had presumably been superseded some time earlier, when the reforecast was prepared). Mr Brookes referred to “a disappointing performance in MEB’s, with sales down $2.8m and the continued sales growth of [the lower margin] concessions up $2.3m”. Mr Brookes also referred to “difficulties in first margin reflecting the changes in the Australian dollar and the change in MEB mix” which was compensated for with lower mark downs. This report was presented to the board at its meeting in New York in May 2014.

152 The applicant says that in relation to the draft of the FY15 budget which was presented to the Myer board in New York in May 2014 Mr Ashby noted in a presentation dated 14 May 2014 that the FY15 budget in its then current draft “highlights market expectations” and “details major initiatives supporting the 5 point plan”. The market expectations include a number of positive and negative sentiments which had been expressed by the various stock market analysts whose reports are there summarised, which were said to be “impacting [the Myer] share price”. Included amongst them, under the heading “Earnings” are the comments: “[e]xpect underlying cost growth to rise ahead of sales growth in FY17 and beyond” (attributed to UBS), “[d]eclining historical EBIT margin trend, concern about outlook for EBIT margin” (unattributed). Later, the draft noted various “Strategies / actions to address Analyst concerns” and noted under the heading “earnings”: “[a]nticipate earnings growth in FY2015”, consistent with the representations which had been made for the past few years by Myer and Mr Brookes in particular.

153 There was an examination of various external market factors which were identified as representing “the challenge” to Myer. The first of these were the consumer sentiment index figures at the time. The Westpac Consumer Sentiment Index, an index followed closely by Myer’s board and senior management, was said to have risen to 99.7 in April, from 99.5 in March. It was also said to have fallen 9.6% since November 2013, when job cuts were announced across several sectors of the Australian economy. The slide notes that an index of 100 indicates that there is an equal number of optimists and pessimists in the marketplace. Various other macro and microeconomic challenges were identified. The budget as presented maintained an NPAT forecast of $113 million, up 9.3% on the then anticipated $103 million NPAT for FY14, and the sales were assumed to be $3,365m, up $198m or 6.2% above the $3,167m of sales then expected to be achieved in FY14.

154 The applicant says that also in this draft budget pack was a summary of the “current consensus” for sales, EBIT and NPAT, showing a Bloomberg consensus for FY15 NPAT of $120m, whereas the Bloomberg average was said to be $112m and the median the same amount. It is unclear from what source those Bloomberg figures derived or what they were understood to mean by Myer’s directors or its senior management.

155 At its meeting in New York on 14 May 2014 the board noted a concern that, after the passage of the Federal Budget on the previous day in Australia, Myer’s sales had declined 2%. This was the low period of consumer sentiment following the first budget of the Liberal Government elected in September 2013. The consumer sentiment index plunged to 92.94 in May 2014 and did not again recover to equilibrium until briefly in February 2015. The index remained subdued throughout the 2015 financial year.

156 In respect of the May 2014 draft budget presented to the board in New York, the applicant says that the minutes record that the proposed sales growth of $198m was “aggressive” and the board acknowledged “that the strategy was currently being developed, and that the budget was being drafted prior to the strategy being completed”. Mr Ashby was asked to “reconsider the draft budget, on the business being conducted in the manner in which it is currently being conducted (without strategy overlay)”.

157 According to the applicant it is not clear how this instruction was carried out by Mr Ashby. The reference to the “aggressive” sales growth of $198m assumed in the budget appears to come from the slides which Mr Ashby presented to the board at its meeting in New York.

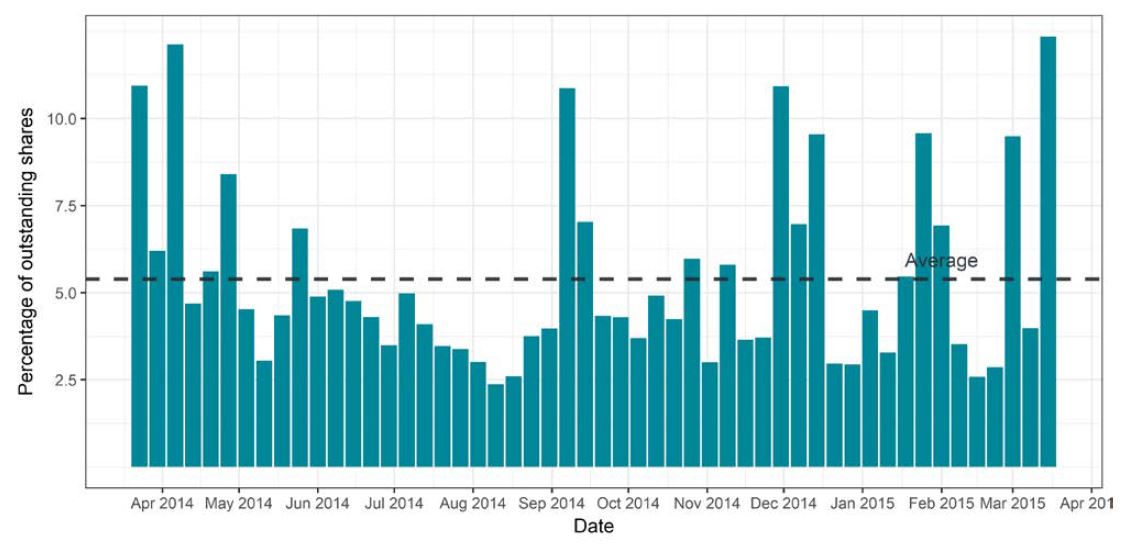

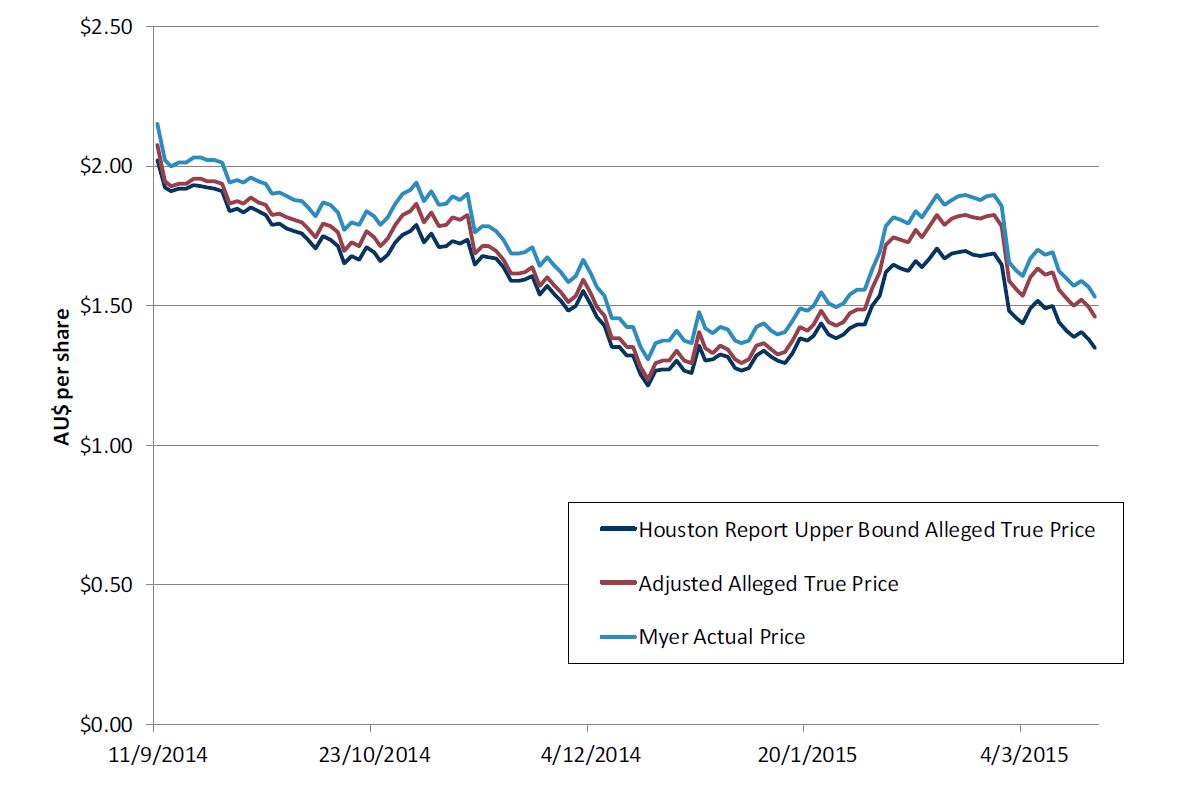

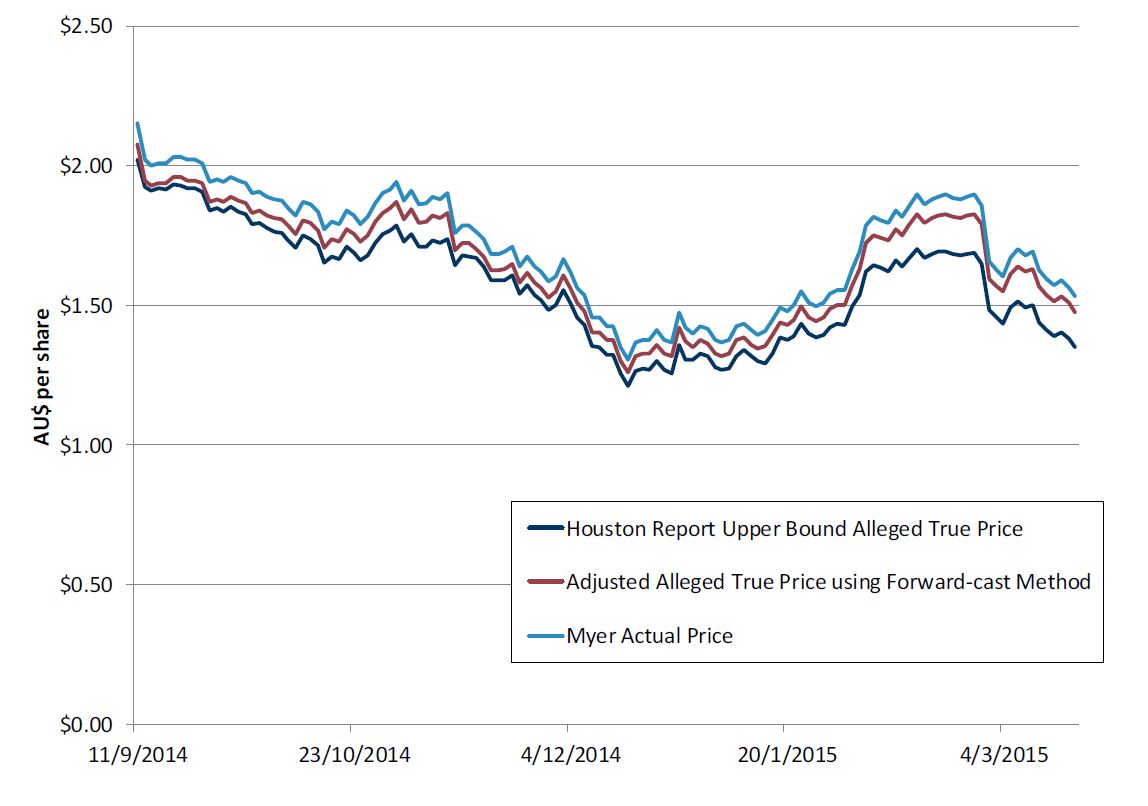

158 The FY15 budget remained a work-in-progress at this time.