FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Masters v Lombe (Liquidator); In the Matter of Babcock & Brown Limited (In Liq) [2019] FCA 1720

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The plaintiffs’ Application be dismissed.

2. The plaintiffs pay the defendant’s costs of and incidental to the said Application.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 947 of 2014 | ||

IN THE MATTER OF BABCOCK & BROWN LIMITED (ACN 108 614 955) (IN LIQUIDATION) | ||

BETWEEN: | BRUCE BROOME First Plaintiff MICHAEL HIRSCH Second Plaintiff STUART NORTON Third Plaintiff (and others named in the Schedule) | |

AND: | DAVID LOMBE IN HIS CAPACITY AS LIQUIDATOR OF BABCOCK & BROWN LIMITED (ACN 108 614 955) (IN LIQUIDATION) Defendant | |

JUDGE: | FOSTER j |

DATE OF ORDER: | 18 October 2019 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The plaintiffs’ Application be dismissed.

2. The plaintiffs pay the defendant’s costs of and incidental to the said Application.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 501 of 2015 | ||

IN THE MATTER OF BABCOCK & BROWN LIMITED (ACN 108 614 955) (IN LIQUIDATION) | ||

BETWEEN: | SARAH WILHELM First Plaintiff DONALD FRANCIS HAMMON Second Plaintiff MARGARET ELIZABETH HAMMON (and others named in the Schedule) Third Plaintiff | |

AND: | DAVID LOMBE IN HIS CAPACITY AS LIQUIDATOR OF BABCOCK & BROWN LIMITED (ACN 108 614 955) (IN LIQUIDATION) Defendant | |

JUDGE: | FOSTER j |

DATE OF ORDER: | 18 October 2019 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The plaintiffs’ Application be dismissed.

2. The plaintiffs pay the defendant’s costs of and incidental to the said Application.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[15] | |

[49] | |

Relevant Circumstances of BBL Between August 2008 and January 2009 | [76] |

[77] | |

[78] | |

[81] | |

[82] | |

[84] | |

[86] | |

[87] | |

[87] | |

[98] | |

[151] | |

[220] | |

[227] | |

[229] | |

The Relevant Statutory Framework and Legal Principles (Non-Disclosure) | [265] |

[291] | |

[293] | |

[316] | |

[321] | |

[326] | |

[333] | |

[335] | |

[341] | |

[342] | |

[349] | |

[352] | |

[357] | |

[362] | |

[364] | |

[372] | |

[377] | |

[382] | |

[396] |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

FOSTER J:

1 There are before the Court three sets of proceedings:

(a) Masters & Ors v Lombe (NSD 2525 of 2013);

(b) Broome & Ors v Lombe (NSD 947 of 2014); and

(c) Wilhelm & Ors v Lombe (NSD 501 of 2015).

2 When each of the above proceedings was commenced, there were:

(a) One hundred (100) plaintiffs in the Masters proceeding;

(b) Eight hundred and eighty-seven (887) plaintiffs in the Broome proceeding; and

(c) Two hundred and thirty-four (234) plaintiffs in the Wilhelm proceeding.

3 During final submissions (at Transcript 350/5–352/15), Counsel for the plaintiffs informed the Court and the legal representatives of the defendant that a number of the plaintiffs no longer pressed any of their claims for relief. The identity of those plaintiffs who no longer pressed their claims was marked on three separate lists of plaintiffs (one list for each proceeding) by ruling through the names of those plaintiffs on those lists. Those lists, marked as I have described, became Exhibits E, F and G. No plaintiff applied to the Court for leave to discontinue his, her or its claims for relief and no party applied for an order dismissing the proceedings as between those plaintiffs who no longer pressed their case and the defendant. For these reasons, those plaintiffs remained as parties to the proceedings notwithstanding that they had abandoned all of their claims for relief. When final orders are made, the claims made by those plaintiffs will need to be dismissed or otherwise disposed of. At the conclusion of the hearing before me, of the 1,221 plaintiffs who commenced these proceedings, only 347 remained active. That is, by the end of the hearing, 874 plaintiffs had formally abandoned all of their claims.

4 None of the three proceedings is a group proceeding instituted under Pt IVA of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act). Thus, each proceeding comprises a collection of individual cases with some common features. The cases all proceeded to a final hearing upon the basis that evidence in each case would be evidence in all of the others. No party sought a separate trial of any individual case and no party sought a separate trial of any one or more issues common to all cases.

5 Each of the named plaintiffs claims to have purchased ordinary shares in Babcock & Brown Limited (In Liquidation) (BBL) in the period between 12 August 2008 and 12 March 2009 (both dates inclusive) (the relevant period).

6 David Lombe, who is the liquidator of BBL, is the only defendant in each proceeding. In each proceeding, Mr Lombe is sued in his capacity as liquidator of BBL. BBL itself is not a party to any of the proceedings.

7 BBL was placed under administration on 13 March 2009. At the same time, Mr Lombe and Simon Cathro, both partners in the accounting firm then called Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu (Deloitte), were appointed as administrators of BBL.

8 On 24 August 2009, BBL was placed into liquidation by a resolution of its creditors. At the same time, Messrs Lombe and Cathro were appointed as the liquidators of BBL. On 9 August 2011, Mr Cathro resigned from the Deloitte partnership and was, for that reason, removed as one of the liquidators of BBL.

9 BBL was incorporated on 2 April 2004 and was listed on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) immediately thereafter. It was the non-trading holding company of the Babcock & Brown Group of companies (B&B Group). That group conducted a global financial services business which, according to its 2007 Annual Report, specialised in fund and asset management with longstanding capabilities in structured finance and the creation, syndication and management of asset and cash flow based investments.

10 At the end of 2007, BBL held a little over three-quarters of the issued capital of Babcock & Brown International Pty Ltd (BBIL) which, in turn, owned and controlled all of the Babcock & Brown operating and investment subsidiaries around the world. By early 2009, BBL held almost all of the issued capital of BBIL.

11 BBL’s financial year was from 1 January to 31 December.

12 On 17 April 2008, BBL lodged its 2007 Annual Report with the ASX.

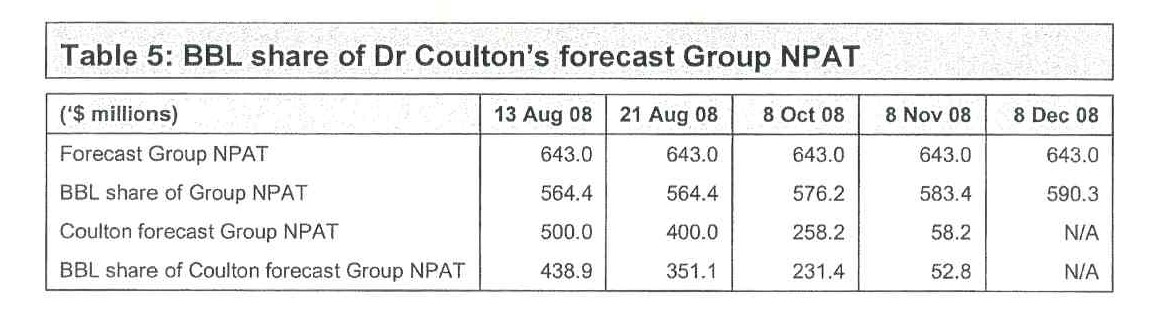

13 In that Report, BBL reported a Profit After Tax Attributable to the B&B Group for the year ended 31 December 2007 of $643,046,000. In the same Report, it reported a Profit After Tax Attributable to the members of BBL of $525,149,000.

14 By the end of 2008, BBL was in serious financial difficulty. By that time, the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) was well under way. On 15 September 2008, Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc (Lehman) collapsed and went into bankruptcy. The plaintiffs in the present proceedings contend that, throughout the second half of 2008 and during the early part of 2009, BBL concealed its true financial position from the market.

THE STRUCTURE OF THE PLAINTIFFS’ CASES

15 In each proceeding, the plaintiffs allege that BBL failed to meet its continuous disclosure obligations under s 674 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the Act) and under the ASX Listing Rules (Listing Rules) by failing to disclose to the ASX information relating to material changes in its financial position in the period after 11 August 2008. They argue, amongst other things, that, because of information which it had or of which it became aware in that period, BBL was obliged under its continuous disclosure obligations to revise downwards its earnings forecasts for 2008 and that it failed to do so. The plaintiffs contend that, as a result of these contraventions of s 674, the price of an ordinary share in BBL available for purchase on the ASX during the relevant period was inflated above the true value of such share. The plaintiffs argue that, by leaving a number of earlier earnings forecasts uncorrected, BBL continued to convey to the market an overly optimistic impression of BBL’s financial position and prospects.

16 The plaintiffs claim that they suffered loss as a result of the alleged non-disclosures. They rely upon market-based causation theory in order to establish the fact that they suffered loss and the quantum of that loss. They do not seek to establish loss by bringing forward in each individual case evidence of reliance on BBL’s compliance with the law or by seeking to establish the requisite causal connection between the alleged contraventions and the claimed loss by reference to other idiosyncratic features of each individual plaintiff’s purchase decision. Indeed, no individual plaintiff or person representing a corporate plaintiff gave evidence at the hearing before me.

17 Many (but not all) of the plaintiffs lodged a proof of debt with the liquidator seeking to claim his, her or its loss allegedly suffered as a result of BBL’s non-disclosures. Those claims were quantified as the amount by which the market price of a share in BBL was allegedly inflated at several specific points in time in the last few months of 2008 by reason of the failure of BBL to correct the earnings forecasts which it had given in early 2008. The plaintiffs allege that BBL should have downgraded those forecasts in light of its knowledge of its 2008 earnings and its financial position generally which progressively came to light during the last five months of 2008.

18 On or about 2 December 2013, all of the proofs of debt lodged with the liquidator were rejected by him.

19 In the three sets of proceedings now before the Court, each plaintiff who lodged a proof of debt appeals pursuant to s 1321 of the Act from the liquidator’s rejection of his, her or its proof of debt.

20 When the three sets of proceedings were commenced (on 13 December 2013, 19 September 2014 and 6 May 2015 respectively), s 1321 relevantly provided that a person aggrieved by any act, omission or decision of a liquidator might appeal to the Court in respect of that act, omission or decision. Under s 1321, the Court was empowered to confirm, reverse or modify that act or decision, or remedy that omission, as the case may be. The Court also had the power to make such orders and to give such directions as it thought fit.

21 The plaintiffs are clearly persons aggrieved within s 1321.

22 Section 1321 was repealed by the Insolvency Law Reform Act 2016 (Cth) (Item 253 in Sch 2, Pt 2). The repeal of s 1321 became effective on 1 September 2017. That repeal does not affect the present proceeding (s 7(2)(b), (c) and (e) of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth)). Accordingly, the plaintiffs may continue to proceed under s 1321 of the Act.

23 In the present case, the plaintiffs seek an order reversing the liquidator’s decision (or decisions) to reject their proofs of debt. They also claim declaratory relief and an order awarding compensation to them directly. Those persons and entities who are named as plaintiffs but who never lodged any proof of debt with the liquidator have no standing in the present proceedings to appeal any of the decisions which the liquidator made to reject proofs of debt in respect of BBL. For that reason, the claims made by them in these proceedings must be dismissed irrespective of the outcome in respect of those plaintiffs who lodged a proof of debt which was rejected by the liquidator.

24 Part 5.6 Div 6 of the Act deals with the proof and ranking of claims in the liquidation of a company.

25 Section 553(1) of the Act provides:

553 Debts or claims that are provable in winding up

(1) Subject to this Division and Division 8, in every winding up, all debts payable by, and all claims against, the company (present or future, certain or contingent, ascertained or sounding only in damages), being debts or claims the circumstances giving rise to which occurred before the relevant date, are admissible to proof against the company.

26 Section 553D provides that a provable debt or claim may be proved formally or informally.

27 Section 553E provides:

553E Application of Bankruptcy Act to winding up of insolvent company

Subject to this Division, in the winding up of an insolvent company the same rules are to prevail and be observed with regard to debts provable as are in force for the time being under the Bankruptcy Act 1966 in relation to the estates of bankrupt persons (except the rules in sections 82 to 94 (inclusive) and 96 of that Act), and all persons who in any such case would be entitled to prove for and receive dividends out of the property of the company may come in under the winding up and make such claims against the company as they respectively are entitled to because of this section.

28 Under s 554A of the Act, if the liquidator is minded to admit a claim or debt in the winding up, he must either make an estimate of the value of the debt or claim as at the relevant date or refer the question of the value of the debt or claim to the Court. Here, of course, the liquidator rejected the relevant plaintiffs’ claims altogether and thus was not obliged to take any action pursuant to s 554A.

29 Regulations 5.6.40–5.6.56 of the Corporations Regulations 2001 (Cth) (Corps Regs) govern the requirements with which claimants against a company in liquidation and its liquidator must comply when dealing with proofs of debt prepared and lodged for the purpose of determining the identity of the company’s creditors and the quantum of each creditor’s debt or claim.

30 Regulation 5.6.54 of the Corps Regs is in the following terms:

5.6.54 Grounds of rejection and notice to creditor

(1) Within 7 days after the liquidator has rejected all or part of a formal proof of debt or claim, the liquidator must:

(a) notify the creditor of the grounds for that rejection in accordance with Form 537; and

(b) give notice to the creditor at the same time:

(i) that the creditor may appeal to the Court against the rejection within the time specified in the notice, being not less than 14 days after service of the notice, or such further period as the Court allows; and

(ii) that unless the creditor appeals in accordance with subparagraph (i), the amount of his or her debt or claim will be assessed in accordance with the liquidator’s endorsement on the creditor’s proof.

Note: The effect of regulation 5.6.11A is that if a recipient has, in accordance with that provision, nominated electronic means to receive notices, the notifier may give or send the notice mentioned in this subregulation by the nominated electronic means.

(2) A person may appeal against the rejection of a formal proof of debt or claim within:

(a) the time specified in the notice of the grounds of rejection; or

(b) if the Court allows—any further period.

(3) The Court may extend the time for filing an appeal under subregulation (2), even if the period specified in the notice has expired.

(4) If the liquidator has admitted a formal proof of debt or claim, the notice of dividend is sufficient notice of the admission.

31 In the present cases, it is agreed that the liquidator notified the plaintiffs of the grounds for his rejection of their proofs of debt in accordance with the requirements of Form 537 which is the prescribed form for the purposes of reg 5.6.54(1).

32 Ordinarily, in an appeal pursuant to s 1321 of the Act in respect of a liquidator’s rejection of a proof of debt, the plaintiff (appellant) would tender in evidence at the hearing of the appeal his, her or its proof of debt, all material provided to the liquidator in support of the claims made by the plaintiff in that proof of debt and the documents comprising the liquidator’s decision to reject that proof of debt and the reasons given for that decision. This last category of documents would include the relevant Form 537. The plaintiff is not obliged to tender any of these materials. On the other hand, the plaintiff does not have an automatic right to tender these materials at the hearing of the appeal.

33 Here, the plaintiffs did not tender in evidence before me any of the relevant proofs of debt nor did they tender any of the other material described at [32] above except to the extent that that material was part of those volumes of the Court Book actually tendered in evidence and marked as Exhibit A. All that the Court has before it in relation to the relevant proofs of debt are allegations made in each of the Statements of Claim to the effect that the plaintiffs submitted proofs of debt to the liquidator on 18 September 2013 and on 26 September 2013 and that, on or about 2 December 2013, all of those proofs of debt were rejected by the liquidator (par 4 and par 5 of each current iteration of the Statement of Claim). These allegations are all admitted by the liquidator even though, as I noted at [17] above, not all of the plaintiffs actually lodged a proof of debt with the liquidator.

34 The prevailing view in the relevant Australian authorities is that, at least in respect of a decision of the kind made by the liquidator here, an appeal pursuant to s 1321 of the Act is a hearing de novo (Tanning Research Laboratories Inc v O’Brien (1990) 169 CLR 332 (Tanning v O’Brien) at 340–341 per Brennan and Dawson JJ; and at 354 per Toohey J who generally agreed with Brennan and Dawson JJ; In the matter of Federation Health Limited (Administrator Appointed) [2006] FCA 314 at [32]–[36]; Re North Sydney District Rugby League Football Club (admin apptd); Murray v Donnelly (2000) 34 ACSR 630 at 631 [3] per Bryson J; Brodyn Pty Ltd v Dasein Constructions Pty Ltd [2004] NSWSC 1230 at [29]–[33] per Young CJ in Eq; and Promoseven Pty Ltd v Markey, in the matter of Bluechip Development Corporation (Cairns) Pty Ltd (in liq) (Receivers and Managers Appointed) [2013] FCA 1281 at [34]). This means that, in the present cases, the plaintiffs and the liquidator are not confined to the materials which were before the liquidator when he rejected the relevant proofs of debt but may adduce such relevant and admissible evidence as they think fit in support of their respective positions.

35 In an appeal under s 1321 which concerns the rejection of a proof of debt by a liquidator, the plaintiff must identify an alleged debt or liability corresponding to that which was claimed in the proof of debt but is not strictly confined to each allegation and proposition by which he, she or it sought to advance in the relevant proof of debt (Johnston v McGrath (2008) 67 ACSR 169 at 175 [26]).

36 A decision to reject a proof of debt affects the claimant’s substantive rights against the company in liquidation. In such an appeal, the Court can consider the merits of the plaintiff’s claim against the company in liquidation and determine on a final basis whether the plaintiff has a valid claim and, if so, the quantum thereof. In this way, the Court can effectively determine the plaintiff’s rights as against the company. For example, in determining such an appeal, the Court can decide whether a contract between the plaintiff and the company in liquidation should be rectified (Re Jay-O-Bees Pty Ltd (in liq); Rosseau Pty Ltd (in liq) v Jay-O-Bees Pty Ltd (in liq) (2004) 50 ACSR 565) at 571–572 [34]) or whether the company is estopped from denying the validity of the debt or claim (Tanning v O’Brien at 338–341 per Brennan and Dawson JJ; and at 352–354 per Deane and Gaudron JJ; cf Toohey J at 354).

37 In the three sets of proceedings before me, the plaintiffs proceeded both in their pleadings and in the conduct of their cases upon the basis that the Court has the power to determine their claims for compensation against BBL caused by BBL’s alleged contraventions of s 674 of the Act and that it should do so in the present proceedings when determining their appeals under s 1321 of the Act. The liquidator appears to have accepted that this approach on the part of the plaintiffs was both correct and appropriate.

38 In particular, the plaintiffs have conducted their cases upon the basis that those cases bear a sufficiently close resemblance to the claims which they advanced in their proofs of debt as to be well within the scope of any appeal from the liquidator’s decision to reject those proofs of debt. The liquidator did not suggest otherwise.

39 Accordingly, in order to determine the plaintiffs’ appeals, I must decide whether, before BBL went into liquidation, the plaintiffs had valid claims against BBL pursuant to s 674 of the Act and pursuant to the appropriate provision in the Act which was the source of the Court’s power to award compensation at the relevant time. In the event that the plaintiffs’ claims are found to be valid, I must then determine the quantum of those claims.

40 As submitted by the liquidator, the central questions in all three proceedings are whether, during the relevant period (viz the period from 12 August 2008 to 12 March 2009 (both dates inclusive)), disclosure by BBL of the information which the plaintiffs contend should have been disclosed in that period (which information concerned BBL’s actual trading performance in the first half of 2008 and its likely Net Profit After Tax (NPAT) for the full year 2008) would have been expected by a reasonable person to have had a material effect on its share price and would, in fact, have had such an effect. If those issues are answered in favour of the plaintiffs, there will be a further question about the extent of any inflation of the price of BBL’s shares sold on-market caused by BBL’s failure to make any pertinent disclosures in the relevant period and about the quantum of any recoverable compensation.

41 The liquidator argued that the Court ought not conclude, on the balance of probabilities, that the market had any expectations of a positive 2008 B&B Group NPAT at any time during the relevant period (12 August 2008 to 12 March 2009). The liquidator also submitted that the Court should not accept the plaintiffs’ contentions concerning their market-based causation theory.

42 The allegations made by the plaintiffs in each current iteration of the Statement of Claim in each proceeding are in precisely the same terms.

43 However, the Originating Applications are not identical.

44 In the Masters proceeding and in the Wilhelm proceeding, the plaintiffs claim relief pursuant to s 1041I of the Act. The plaintiffs in those proceedings also rely upon other sections of the Act. Section 1041I provides for the recovery of compensation for losses suffered by a person or persons as a result of contraventions of one or more of ss 1041E, 1041F, 1041G or 1041H of the Act. This latter group of provisions is found in Pt 7.10, Div 2 of the Act (the Market Misconduct provisions). No case based upon any of s 1041E, 1041F, 1041G or 1041H is sought to be made in any of the three sets of proceedings with which I am dealing. For this reason, s 1041I is not the relevant statutory provision for the recovery of compensation in respect of contraventions of s 674 of the Act and is irrelevant to the matters with which I am concerned.

45 In each proceeding, the plaintiffs also rely upon s 1325 of the Act as a source of the Court’s power to award compensation to them if I am otherwise satisfied of the validity and quantum of their claims. Section 1325 provides for ancillary orders to be made which are similar to those contemplated by s 87 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth). I doubt that that provision is apt to be applied in the present cases but will proceed for the time being upon the basis that it may be a relevant source of the Court’s power to award compensation in these cases.

46 The plaintiffs in the Wilhelm proceeding also rely upon s 1317HA of the Act as the source of the Court’s power to award compensation to them had they been able to sue BBL for pecuniary relief in respect of the losses suffered by them by reason of BBL’s alleged contraventions of s 674 of the Act.

47 At all relevant times, s 1317HA was in the following terms:

1317HA Compensation orders—financial services civil penalty provisions

Compensation for damage suffered

(1) A Court may order a person (the liable person) to compensate another person (including a corporation), or a registered scheme, for damage suffered by the person or scheme if:

(a) the liable person has contravened a financial services civil penalty provision; and

(b) the damage resulted from the contravention.

The order must specify the amount of compensation.

Note: An order may be made under this subsection whether or not a declaration of contravention has been made under section 1317E.

Damage includes profits

(2) In determining the damage suffered by a person or scheme for the purposes of making a compensation order, include profits made by any person resulting from the contravention.

Damage to scheme includes diminution of value of scheme property

(3) In determining the damage suffered by a registered scheme for the purposes of making a compensation order, include any diminution in the value of the property of the scheme.

(4) If the responsible entity for a registered scheme is ordered to compensate the scheme, the responsible entity must transfer the amount of the compensation to the scheme property. If anyone else is ordered to compensate the scheme, the responsible entity may recover the compensation on behalf of the scheme.

Recovery of damage

(5) A compensation order may be enforced as if it were a judgment of the Court.

48 I think that s 1317HA was the appropriate source of the Court’s power to award compensation to the plaintiffs against BBL had they been able to bring proceedings against it directly. Subject to considering, if necessary, s 1325 of the Act, I propose to determine the plaintiffs’ s 1321 appeals upon the basis that their claims for compensation against BBL could have and should have been brought under s 1317HA.

THE PLAINTIFFS’ PLEADED CLAIMS

49 In this section of these Reasons for Judgment, I summarise the case which the plaintiffs have sought to make in support of their claims for relief. That case is founded upon the allegations made in the three current Statements of Claim.

50 In its 2007 Annual Report which was published on 17 April 2008, in addition to announcing the profit figure of $643,046,000 to which I referred at [13] above, BBL also stated the following on p 7 of that Annual Report under the heading “Outlook”:

We believe the Group is well positioned to once again deliver earnings growth in 2008 and to take advantage of the opportunities that may arise in the current market environment. Based on the prevailing market conditions and taking into account transactions already announced or completed and secured recurring revenue growth, we currently expect a 2008 Group Net Profit of at least $750 million, representing in excess of 15% growth on the 2007 result.

While we expect all Divisions to contribute to this result, the Infrastructure Division is forecast to drive the growth of the Group in 2008.

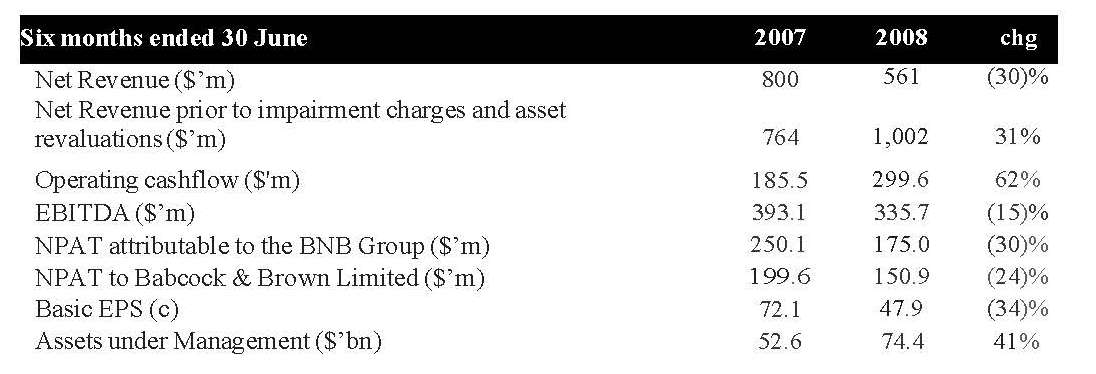

51 The statements which I have extracted at [50] above appeared in the Annual Report immediately after a relatively detailed report in respect of the various operating divisions of BBL and also followed close behind the Segment Income Statement and Statement of the Key Performance Indicators for the year ended 31 December 2007.

52 At its Annual General Meeting held on 30 May 2008, BBL reaffirmed its position that it expected a group net profit for the year ending 2008 of at least $750 million.

53 On 11 August 2008, BBL announced to the ASX that its 2008 interim group NPAT was expected to be 25%–40% below the $250 million interim result reported for the same period in 2007. In that announcement, which was headed “Interim Result and Revised Full Year Guidance”, BBL stated that the wide range in the interim group NPAT guidance was due to the fact that the final outcome of the interim result review had not been determined.

54 After recording the matters which I have summarised at [53] above, BBL said the following in its announcement made on 11 August 2008:

The decline in the interim result is primarily due to non cash impairment provisions flowing through equity accounted investments, in particular real estate and Everest Babcock & Brown and provisions taken against real estate and other Corporate & Structured Finance assets. The 2008 interim result prior to impairment provisions is expected to be above the 2007 interim result.

The impairment adjustments will flow through to our full year earnings and combined with the ongoing deterioration in global markets will mean that Babcock & Brown’s 2008 earnings are now not expected to exceed 2007 Group Net Profit of $643 million.

At the operating level the Infrastructure Division and Operating Leasing Divisions continue to benefit from strong industry dynamics despite the macro environment and have strong global positions in those sectors.

Phil Green CEO of Babcock & Brown said “The volatile global capital market conditions have made and continue to make business conditions uncertain and forecasting in the short term difficult. We look to provide more detail on the 2008 outlook with our interim result to be reported on 21 August 2008.”

55 On 18 August 2008, BBL made another announcement to the ASX. In that announcement, it confirmed that impairment charges referrable to Babcock & Brown Power, a subsidiary of BBIL, had been included in the previous guidance for BBL. It also stated in that release that all finance covenants under its corporate debt facility remained well covered and that the facility did not stipulate any requirement for asset sales. It went on to say that the majority of write downs included in the interim result were non-cash items. It stated that operating cash flow for the half year to 30 June 2008 was expected to be approximately 60% above the result for the previous corresponding period.

56 In the 18 August 2008 ASX Release, the CEO of B&B Group, Mr Green, said:

The need for a range in the guidance we gave on 11 August 2008 primarily reflected the timing of the independent audit processes of our equity accounted funds and took account of the potential impact of the announcement today by BBP [referring to Babcock & Brown Power].

The interim result has been impacted by primarily non cash write downs, reflecting the current market environment. However at the operating level, in particular in the Infrastructure Division, Babcock & Brown continues to benefit from strong industry dynamics, its leading market position and continues to take advantage of a wide range of attractive investment opportunities for its institutional investor base.

57 On 21 August 2008, BBL announced to the ASX its 2008 Interim Result and Strategic Review Update. That announcement was in the following terms:

ASX Release

21 August 2008

2008 INTERIM RESULT & STRATEGIC REVIEW UPDATE

Summary of Result

• Reported Group Profit of $175 million includes the impact of non-cash impairment charges of $386 million and realised trading losses of $55 million across the four divisions.

• Net operating cashflow increased 62% on pcp to $299.6m

• Rolling 12 month interest cover at 30 June 2008 was 5.3x

• Undrawn capacity and unrestricted cash at 20 August 2008 in excess of $800 million

• Total remuneration as a % of Net Revenue was 38% compared to 46% on pcp

• Infrastructure Division driver of growth with a 97% increase in Net Revenue1 generated primarily from the expanded funds and asset management platform and development revenue. Prior to impairment charges net revenue increased 125%

• Prior to impairment charges Real Estate Net Revenue was $1261 million. The Division recorded an overall net revenue loss of $71.71 million for the period due to non-cash impairment charges and lower overall trading profits from assets sales.

• At the operating level Aircraft Operating Leasing delivered a small increase on pcp2 a good result in the current environment. The reported result of $118.8 million was impacted by stronger $A and an impairment charge

• Higher tax rate of 24% reflects strong contribution from North America and the impact of impairment charges flowing through from the GPT Joint Venture.

1 After minority interests

2 Prior to impairment charge and impact of currency movements over pcp

International investment and specialised fund and asset management group Babcock & Brown (ASX: BNB), today announced a 2008 Interim Group Net Profit after tax of A$175 million.

Operating cashflow increased 62% over pcp to $299.6 million reflecting the non cash nature of most of the losses in the reported profit result.

New investment in the development pipeline included a 14% increase in wind energy development to $748.5 million, a further $50 million invested in solar energy development and $24.5 million in public private partnership projects. Total development investment declined to $1.2 billion due to the reclassification of completed real estate, and renewable fuel projects and the sale of the Transbay cable project.

During the six month period the three key business divisions focused on further institutional capital raising initiatives, with in excess of $2.6 billion of new capital commitments raised from co-investment partners. Uncommitted capital under discretionary management in our wholesale infrastructure funds at the current time is A$3.2 billion. Managed capital to expand aircraft under management in our Operating Leasing Division is in excess of US$584 million.

Dividend Policy

As a matter of prudence, no dividend will be paid until sufficient progress has been made on corporate debt reduction. Dividends are expected to re-commence in 2009.

Strategic Review Update

As part of the strategic review the Group is undertaking, Babcock & Brown also announced today a series of Board and Senior Executive changes. The changes include the decision by Managing Director and CEO, Phil Green, to step down from his Executive Director role with current CFO, Michael Larkin becoming Managing Director and CEO effective immediately. Mr Green will remain on the board as a Non-Executive Director.

Mr Larkin said, “Over the last few years in particular, Babcock & Brown has been very successful at achieving substantial growth based on the high levels of liquidity in the capital markets. This has led to the group being too highly leveraged and not sufficiently focussed. In view of the changed market environment, we are taking the necessary steps to reduce the leverage and refocus the Group on the areas where we can best deliver earnings growth for Babcock & Brown shareholders and investment performance for our Limited Partners and, investors in our funds other co-investors over the longer term, without taking undue risk.

“While the strategic review, which is being conducted with input from financial advisers Deutsche Bank and Goldman Sachs has some way to go, we are effecting four key areas of change that accelerate the evolution of Babcock & Brown’s business to a leading global alternative investment originator and asset manager:

1. Focus resources and capital on sectors where the company has a clear and proven competitive advantage in both origination and asset management – Infrastructure; Real Estate; and Operating Leasing.

2. Reduce the risk profile of the business through a de-leveraged and more transparent balance sheet. We will reduce the level of principal investment activity the firm undertakes and increase the emphasis on operating returns through growth in AUM. Consistent with this, we will target a lower ROE of 15-20% and operating cost savings run rate of at least 20% of annualised 2008 1H cost base to be delivered by the end of 2009.

3. Adopt a more disciplined approach to the allocation of capital focused on co investment and development activities, confined to our key business areas.

4. Enhance the alignment of interests between shareholders, fund investors, LP and other co-investor interests.

Mr Larkin said the primary purposes for which the balance sheet will be used can be broadly summarised as;

• Co-investment in our specialised fund and asset management platform.

• Greenfield and brownfield development of assets in our key business areas.

“To implement these changes, we have restructured the senior management team to improve capital allocation decisions across the Group” Mr Larkin said.

The senior management restructure includes:

• Creation of Chief Investment Officer (CIO) Role – Peter Hofbauer. In this role Peter will be responsible for the investment process across Babcock & Brown.

• Capital Markets Group to support all businesses – Headed by Richard Allsopp and Martin Rey this group will co-ordinate our interaction with long-term providers of capital across the key business and be responsible for deepening our existing relationships

• Infrastructure division organised into three regional units reporting direct to CEO – EMEA – Antonio Lo Bianco; North America – Mike Garland; Asia Pacific John Bowyer

• Real Estate and Aircraft Operating Leasing continue as global units headed by Eric Lucas Steve Zissis

• COO – David Ross to focus on achievement of reduced group operating cost base and restructuring employee compensation to achieve better shareholder / investor alignment

• New CFO – currently considering both internal and external candidates, a further announcement will be made shortly.

“The Corporate & Structured Finance Division (CSF) will gradually be wound down. Other assets and businesses not within the key areas of focus will be kept under review and divested or wound down as appropriate to maximise shareholder value,” he said.

“Existing private equity funds, BBDIF and BBGP, will continue to be managed by Babcock & Brown and have access to the Group’s co-investment pipeline. BBC, BCM, BBGI also will continue to be managed by Babcock & Brown and will pursue strategies, as previously announced, to maximise value for investors” said Mr Larkin

Rob Topfer, Head of the Corporate and Structured Finance Division will step down from that role, however he will continue to be a Director of and actively involved in BCM, BBC and BBDIF.

“The strategic review to restore value to the Australian listed funds platform also continues with fund Board initiatives underway in most funds. We remain committed to having both listed and unlisted funds, in key focus areas to ensure that value is delivered for investors,” Mr Larkin said.

Outlook

As previously advised, the Group 2008 NPAT is not expected to be above the 2007 Group NPAT of $643 million. The result is dependent on market conditions and:

• execution on the 2008 transaction pipeline

• 2008 asset sales program

• progress in relation to restructuring and cost reduction program

• impact of costs associated with the restructure

Mr Larkin said, “The volatile global capital market conditions have made and continue to make business conditions uncertain and forecasting in the short term difficult. The environment has created a number of challenges for the Group which we are actively working through at the current time to reach resolutions which endeavour to weigh the interests of all stakeholder groups.

“We believe that the changes to the business announced today will better equip Babcock & Brown to operate in the current market environment, to build on its leading position in its key markets and position itself for ongoing earnings growth in future years.

“I particularly want to acknowledge the continuous commitment and support of Babcock & Brown’s employees. The last few months have been very challenging and their support is key to the success of the Group,” Mr Larkin said.

ENDS

58 Brief pen pictures of some of the executives referred to in the 21 August announcement were attached to that announcement as an Appendix.

59 In September, November and December 2008, BBL made other announcements to the ASX but I need not refer to those announcements here.

60 On 7 January 2009, BBL made another announcement to the ASX. That announcement was in the following terms:

ASX RELEASE

7 January 2009

UPDATE ON FORECAST 2008 FINAL RESULT

Babcock & Brown (ASK: BNB) today advises that further to the announcement to the market on 19 November 2008, following progress on the asset impairment review process for its 2008 full year accounts, it now believes that asset impairment charges will be such that the Company will be in a substantial negative net asset position at 31 December 2008. This position encompasses the reclassification of ‘non-core’ assets on the balance sheet as ‘available for sale’, in line with the Company’s revised business strategy announced to the market on 19 November 2008. The impairment process is subject to finalisation and audit review which will not be completed until closer to the scheduled release of the Company’s results currently expected on 26 February 2009.

As detailed in its announcement on 4 December 2008 and reiterated in its response to the ASX on 6 January 2009, the Company is in discussions with its banking syndicate regarding a debt for equity swap or equivalent restructuring to stabilise the long term capital structure of the Group. Any debt for equity swap or similar arrangement will be designed to allow Babcock & Brown to continue operating its business and sell assets with a view to reducing its overall levels of debt. Any such capital restructure is expected to significantly dilute existing shareholders, negatively impacting the value of equity.

ENDS

61 After the ASX received the 7 January 2009 Release from BBL, BBL went into an immediate trading halt. On 10 January 2009, it was suspended from trading and did not trade again after that. As I have already mentioned, on 13 March 2009, BBL went into administration and, on 24 August 2009, BBL went into liquidation.

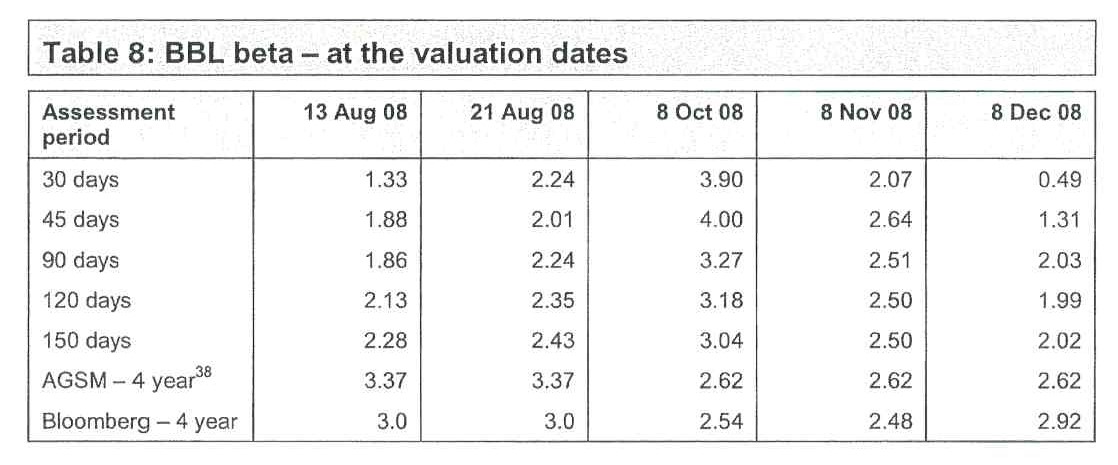

62 On 23 April 2009, BBL published its 2008 Annual Report, including the financial report of the B&B Group for the year ended 31 December 2008. That report disclosed that BBL had actually incurred a net loss of $5.6 billion for that financial year.

63 The plaintiffs allege that, between 21 August 2008 and 7 January 2009, BBL made no announcements to the ASX concerning its 2008 earnings nor did it make any announcements to the ASX revising its previous announcements concerning likely earnings for the 2008 Financial Year.

64 The plaintiffs allege that, after August 2008, BBL became aware that its business operations had made large losses in the second half of the 2008 Financial Year. The plaintiffs also allege that various internal earnings forecasts prepared by management within BBL demonstrated that, after August 2008, BBL’s expectations as to its earnings for the 2008 Financial Year were falling steeply and rapidly and that, in that period, its internal forecasts for that year were materially different from and much lower than the forecasts it had provided to the ASX earlier in 2008.

65 In their Opening Written Submissions, at pars 13–20, the plaintiffs set out the specific information of which they allege BBL was aware at certain particular times in the period from 13 August 2008 to 7 January 2009 which they contend constituted information which should have been disclosed by BBL to the ASX immediately after BBL became aware of it during the relevant period. The plaintiffs argue that, because none of the information to which reference is made in their Submissions was disclosed to the ASX during that period, or at all, BBL contravened s 674 of the Act and r 3.1 of the Listing Rules.

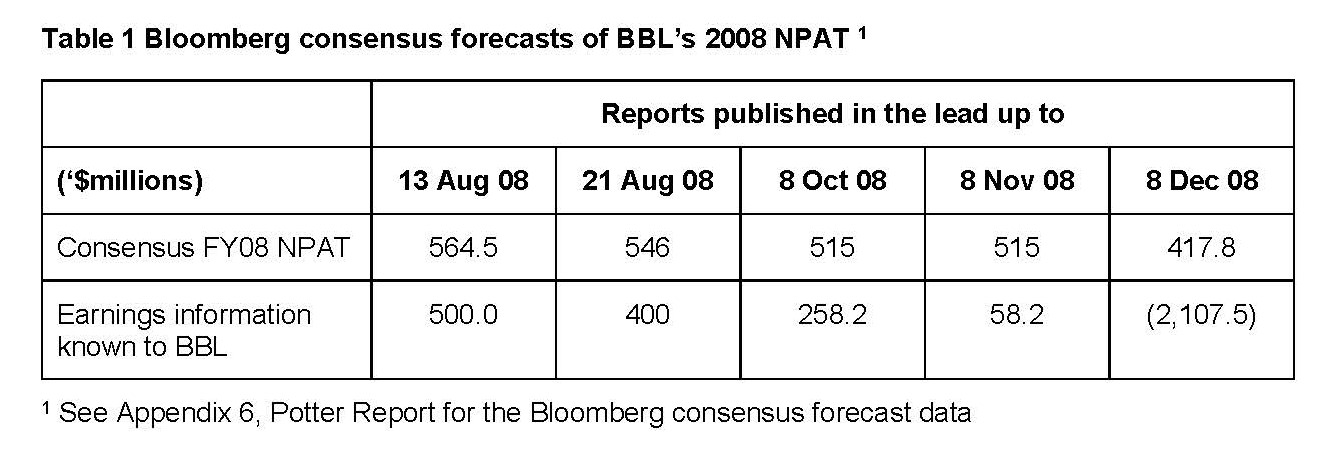

66 Paragraphs 13 to 19 of the plaintiff’s Opening Written Submissions are in the following terms:

13. In particular, by 13 August 2008, BBL was aware of the following information:

• Babcock Group’s earnings for FY 2008 were expected to be in the range between $400-$600 million, and that its earnings for FY 2008 were therefore expected to be materially different from the earnings guidance provided to the ASX on 30 May 2008 and 11 August 2008

14. By 21 August 2008, BBL was aware of the following information:

• Babcock Group’s earnings for FY 2008 were expected to be approximately $400 million, and that its earnings for FY 2008 were therefore expected to be materially different from the earnings guidance provided to the ASX on 30 May 2008, 11 August 2008 and 21 August 2008

15. By 30 September 2008, BBL was aware of the following information:

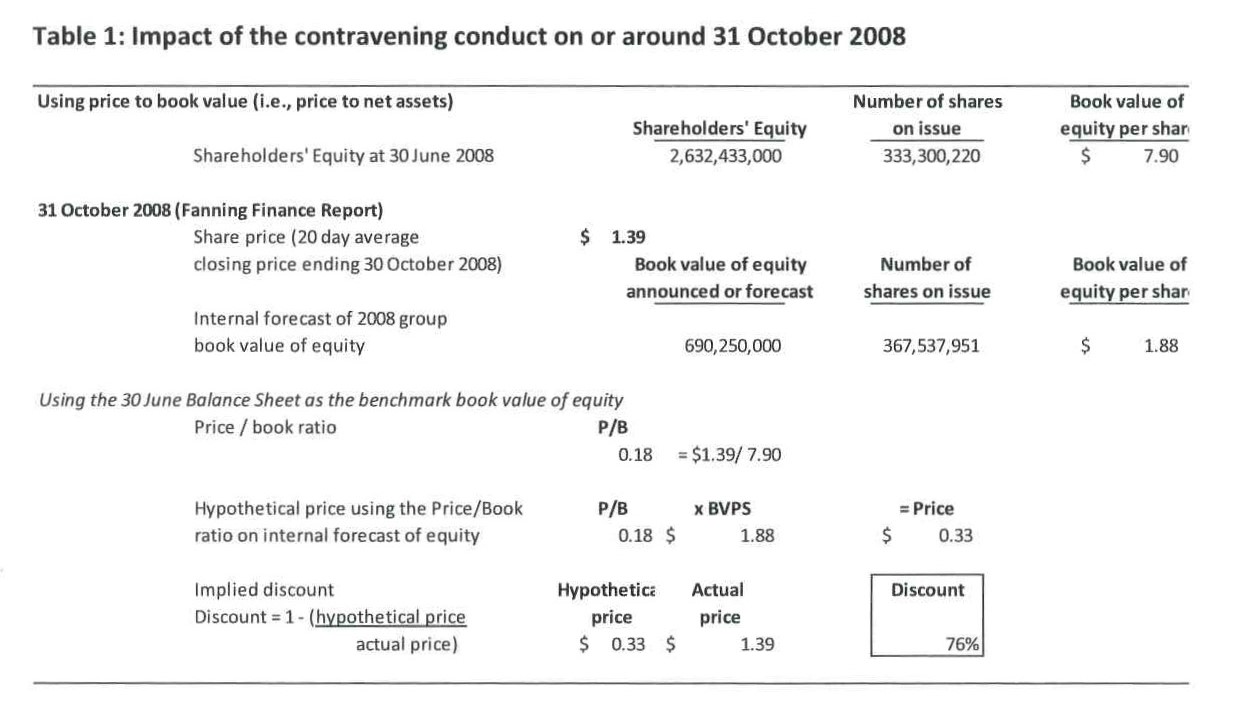

• John Fanning, BBL’s Chief Financial Officer, had written a Finance Report indicating that, for the 9 months ended September 2008, Babcock Group had lost approximately $3 million (excluding impairments), and that the Group was expected to incur further losses in the fourth quarter of 2008 of approximately $62 million [Whilst the Finance Report was prepared by the CFO, and BBL was thus aware of it on 30 September 2008, it was disclosed to the Board of BBL at its meeting on 8 October 2008] and that its earnings for FY 2008 were therefore expected to be materially different (being a loss) from the earnings guidance provided to the ASX on 30 May 2008, 11 August 2008 and 21 August 2008

16. By 8 October 2008, BBL was aware of the following information:

• The CEO of BBL reported to the BBL board at its meeting on 8 October 2008 that the Finance Report prepared by John Fanning was based on current estimates but that “reductions from this forecast are highly probable”

• The CEO Update paper presented to the BBL board at that meeting a summary table showing Babcock Group’s earnings for FY 2008 were expected to be approximately $258 million (excluding potential impairment charges) and that its earnings for FY 2008 were therefore expected to be materially different from the earnings guidance provided to the ASX on 30 May 2008, 11 August 2008 and 21 August 2008

17. By 8 November 2008, BBL was aware of the following information:

• Babcock Group’s earnings for FY 2008 were expected to be approximately $58 million (excluding potential impairment charges), and that its earnings for FY 2008 were therefore expected to be materially different from the earnings guidance provided to the ASX on 30 May 2008, 11 August 2008 and 21 August 2008

18. By 8 December 2008, BBL was aware of the following information:

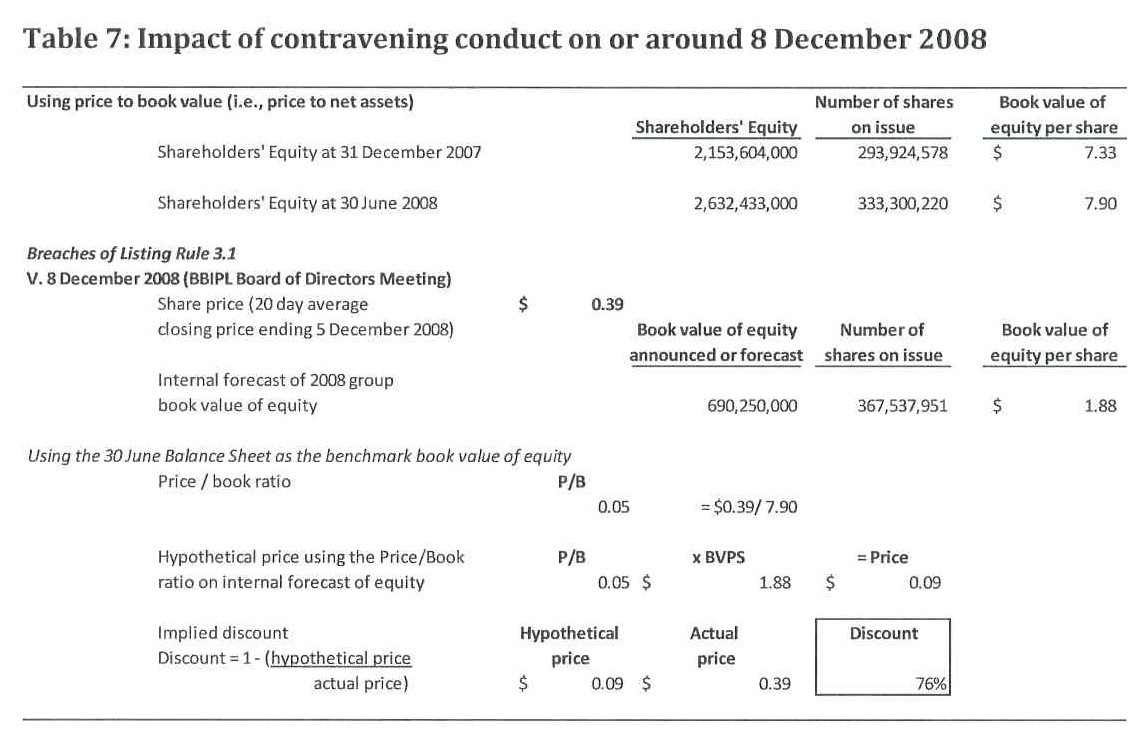

• Babcock Group forecast that it would suffer a net loss for FY 2008 of approximately $352 million (excluding impairments) and approximately $2 billion (with impairments) and that its earnings for FY 2008 were therefore expected to be materially different from the earnings guidance provided to the ASX on 30 May 2008, 11 August 2008 and 21 August 2008

19. In each instance, it is admitted that the information known to BBL was not disclosed to the ASX. The information was material and required disclosure because it was information that a reasonable person would expect, if it were generally available, to have a material effect on the price or value of securities of BBL. Information that BBL’s earnings for FY 2008 were expected to be materially lower than the forecasts announced to the ASX in May and August 2008, was significant information which would, or would be likely to, influence persons who commonly invest in securities in deciding whether to acquire or dispose of BBL shares [ASX Listing Rule 3.1 (examples); Coulton Report; ASX Guidance Note 8 (para 93)].

67 This description of the information which the plaintiffs allege should have been disclosed to the ASX but was not so disclosed, with the exception of the information referred to in par 15 of the plaintiffs’ Written Submissions, the failure to disclose which is not pleaded as a contravention of s 674 (although it is mentioned in the pleading), is a substantially accurate narrative summary of the allegations made in pars 13AAA, 14BA, 14BB, 14C, 14CA and 14CB of the current Statements of Claim. In those paragraphs, the plaintiffs describe the information which they contend should have been disclosed to the ASX.

68 In the current Statements of Claim, the plaintiffs also allege that, by November 2008, BBL had and was aware of information to the effect that BBL had incurred a loss for the period from 1 January 2008 to 31 October 2008 of $93.5 million (before impairment charges) and that the loss for the full year was expected to be $352 million (Par 13AB in each current Statement of Claim). That allegation is based upon the contents of a Draft Forecast said to have been prepared in November 2008 in circumstances where the details of BBL’s actual earnings to 31 October 2008 were available to BBL.

69 The plaintiffs also allege that, from on or about 8 November 2008, BBL had, and was aware of, information that the non-cash impairment charges incurred by the B&B Group during the 2008 Financial Year would be approximately $1.7547 billion, that the B&B Group NPAT for 2008 would be a loss of approximately $2.107 billion and that there was therefore a material risk that the actual earnings for the B&B Group for the 2008 Financial Year would differ materially from the earnings guidance forecasts for the B&B Group announced by BBL to the ASX in August 2008 (Par 19 of the current Statements of Claim).

70 The plaintiffs allege that the information which BBL had from time to time on and after 13 August 2008 which I have described at [66]–[69] above was information which it should have disclosed to the ASX and that its failure to do so in that period constituted a series of contraventions of s 674 of the Act.

71 The liquidator advanced four broad answers to the plaintiffs’ claims.

72 First, he argued that, by 11 August 2008, BBL’s share price had already fallen to $6.80 from a high of $34.63 in June 2007. From 11 August 2008 to 7 January 2009, despite no further guidance on 2008 B&B Group NPAT being given by BBL, BBL share price collapsed from $6.80 to $0.33. By 28 August 2008, BBL’s share price had fallen to $2.43 and it never exceeded $2.50 after that date. The objective circumstances between 11 August 2008 and 9 January 2009, together with the expert evidence led by the liquidator, lead to the conclusion that the market had “priced in” a decline in BBL’s 2008 NPAT after the announcements which the company made on 11 August 2008 and on 21 August 2008 and, from about the time of the collapse of Lehman in mid-September 2008, had priced in that BBL would suffer a substantial loss in 2008. The liquidator submitted that, for these reasons, at no time did the market for BBL’s shares in the period after August 2008 reflect an expectation on the part of investors and potential investors that BBL’s 2008 NPAT would exceed the NPAT figures which the plaintiffs say ought to have been announced from time to time in the period after August 2008. These conclusions were said either to mean that the plaintiffs have failed to demonstrate that the information was of a character that would have had a material effect on the share price of BBL or to mean that the plaintiffs have failed to prove any loss.

73 Second, the liquidator contended that the plaintiffs failed to prove any loss because they failed to prove price inflation over the relevant period. The liquidator submitted that the expert called on behalf of the plaintiffs provided a flawed analysis when endeavouring to demonstrate such price inflation.

74 Third, the liquidator submitted that, for each of the alleged non-disclosures, there was no contravention for the additional reasons that the information was not information of which BBL was “aware” within the meaning of s 675 and the Listing Rules and, in any event, the information was subject to the indefinite information exception in the Listing Rules.

75 Fourth, the liquidator submitted that the plaintiffs’ claims are legally flawed because they depend upon this Court’s accepting market-based causation as being an appropriate foundation for a claim for compensation for a contravention of s 674 of the Act which, as a matter of principle, the Court ought not do.

RELEVANT CIRCUMSTANCES OF BBL BETWEEN AUGUST 2008 AND JANUARY 2009

76 In this section of these Reasons, I record a number of relevant circumstances affecting BBL during the relevant period. This material is largely taken from pars 47 to 67 of the liquidator’s Written Submissions dated 13 October 2016.

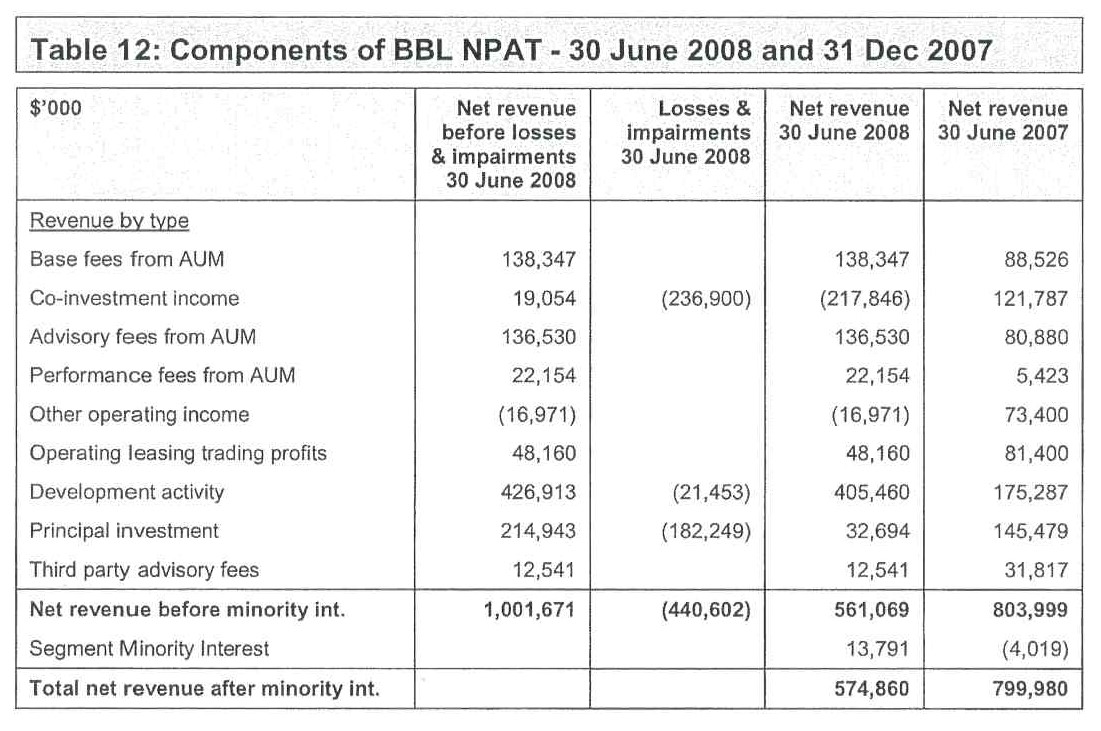

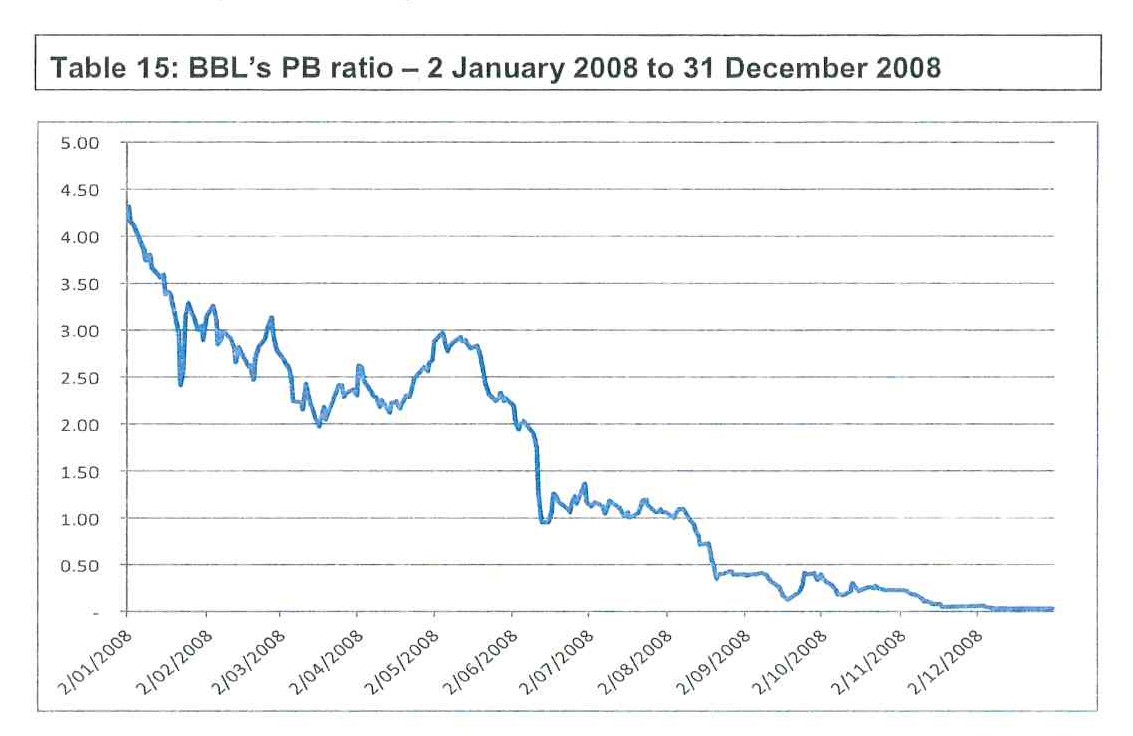

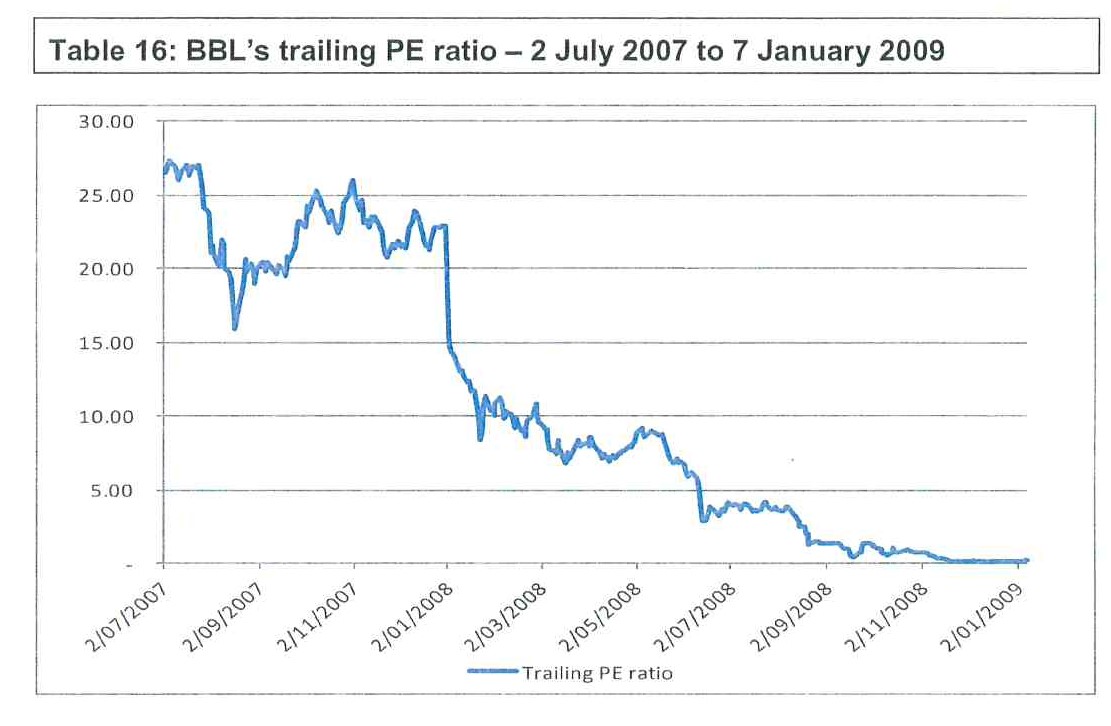

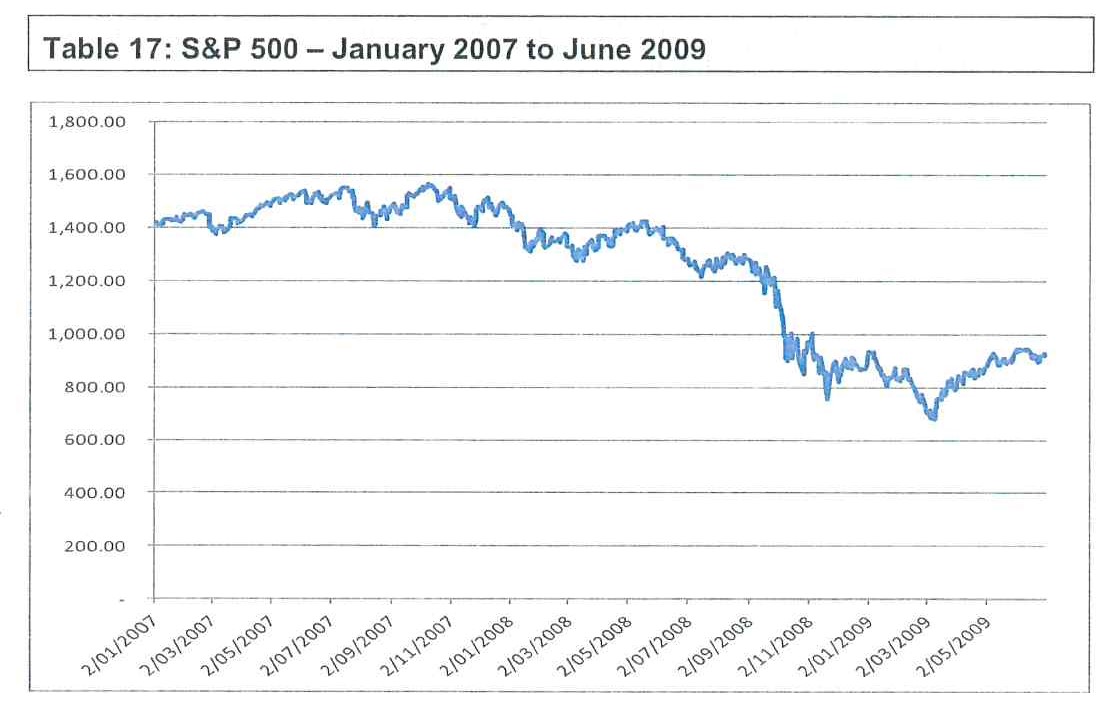

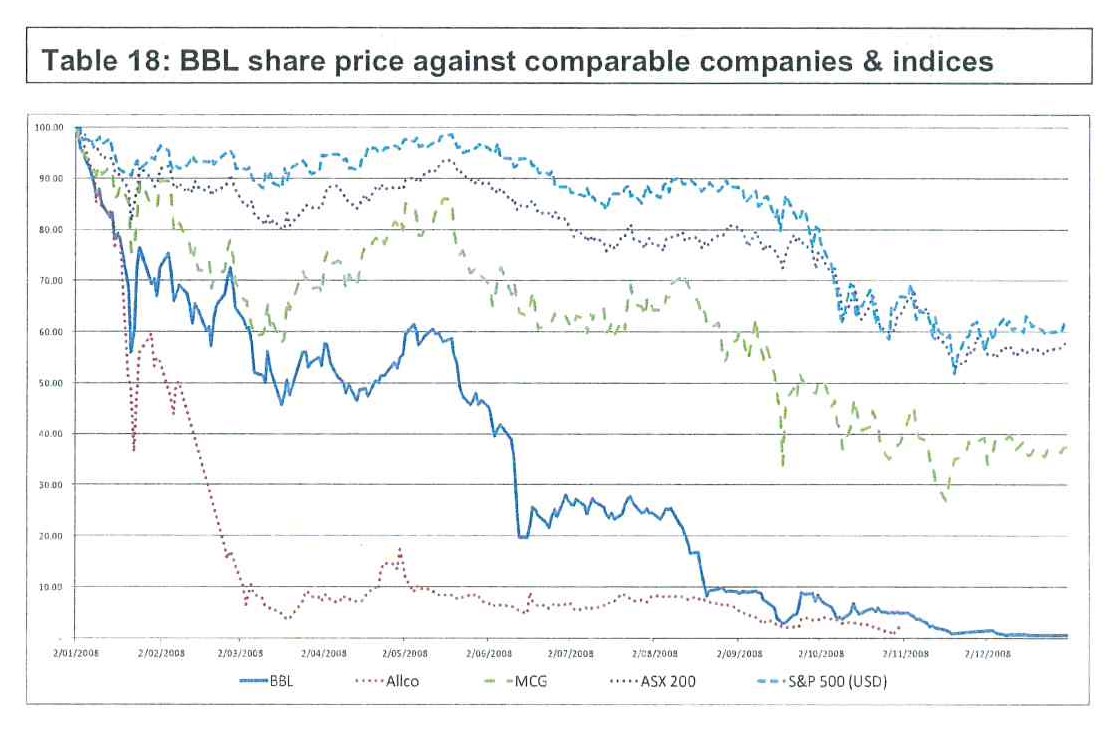

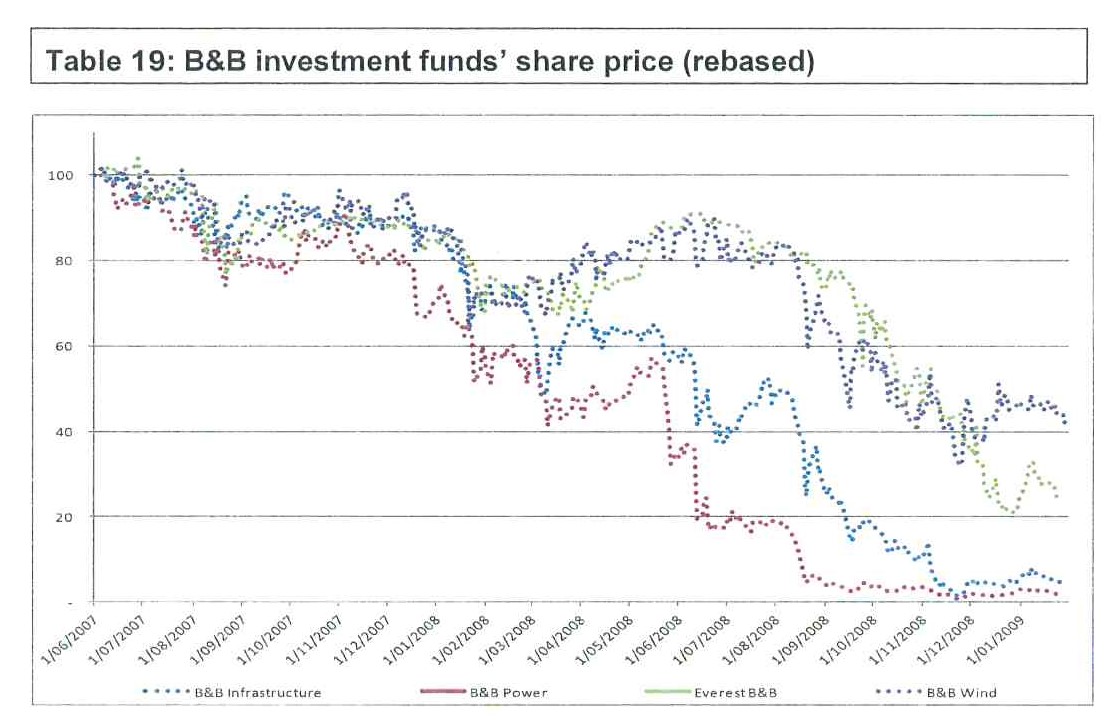

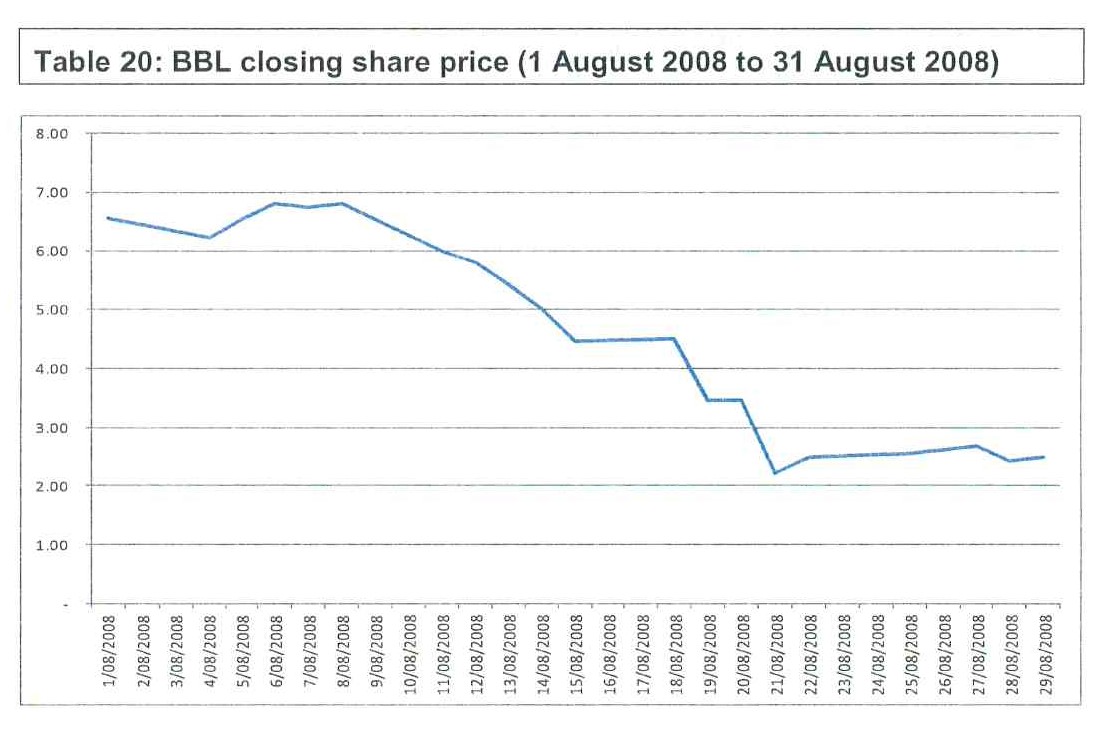

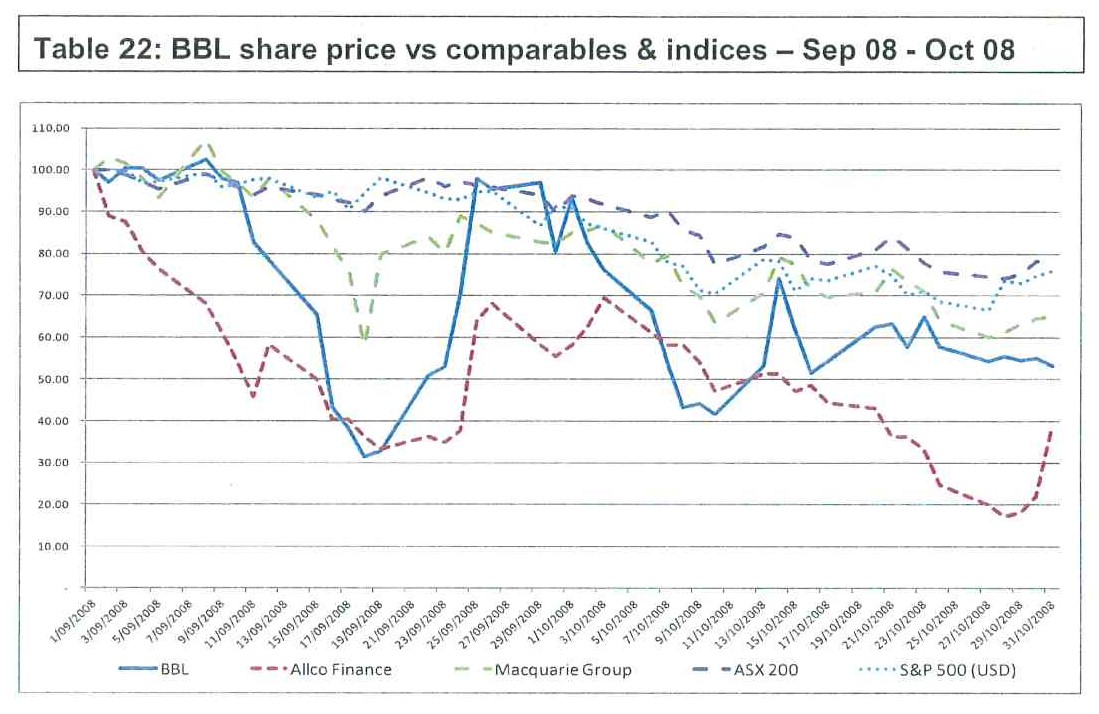

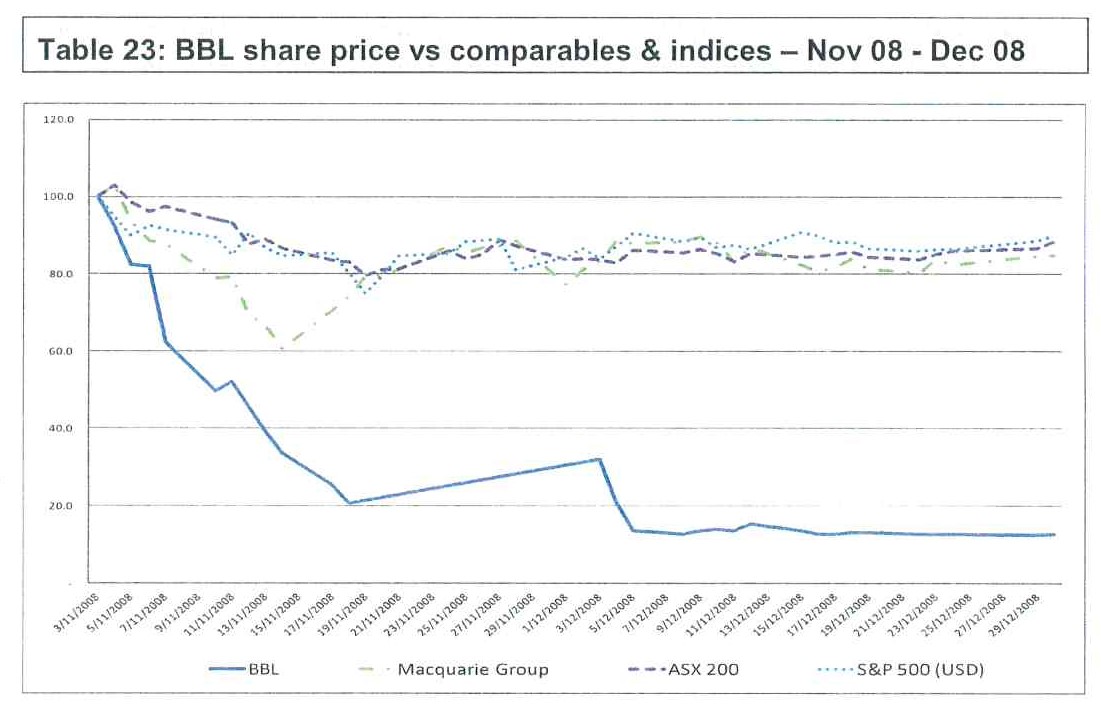

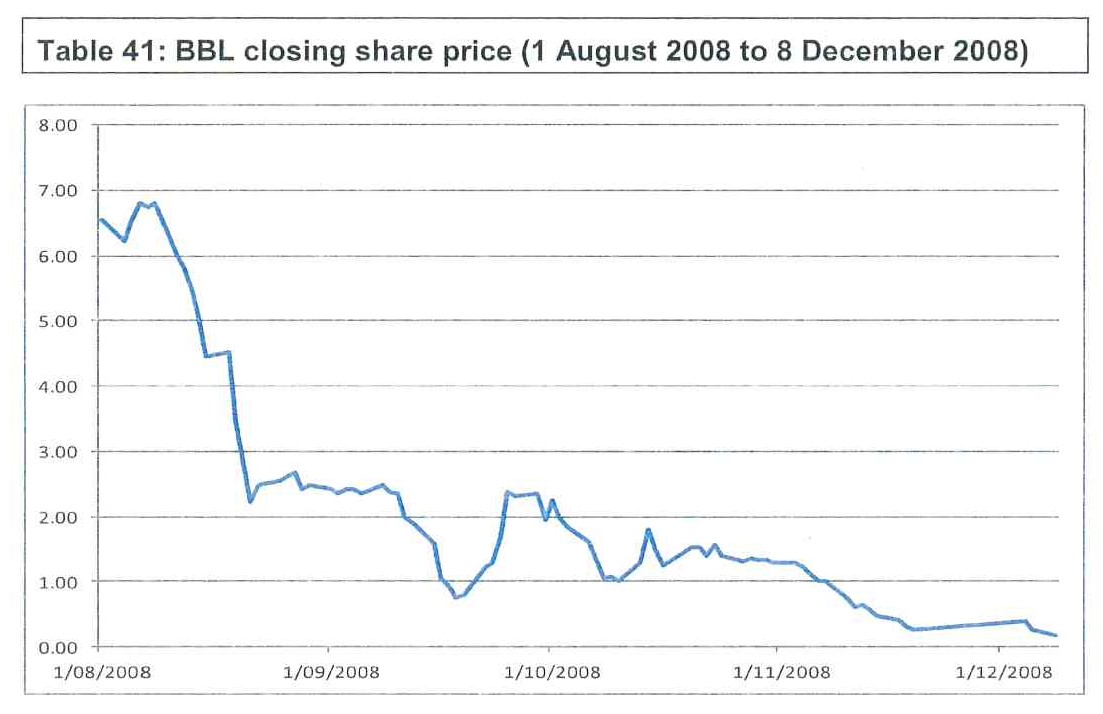

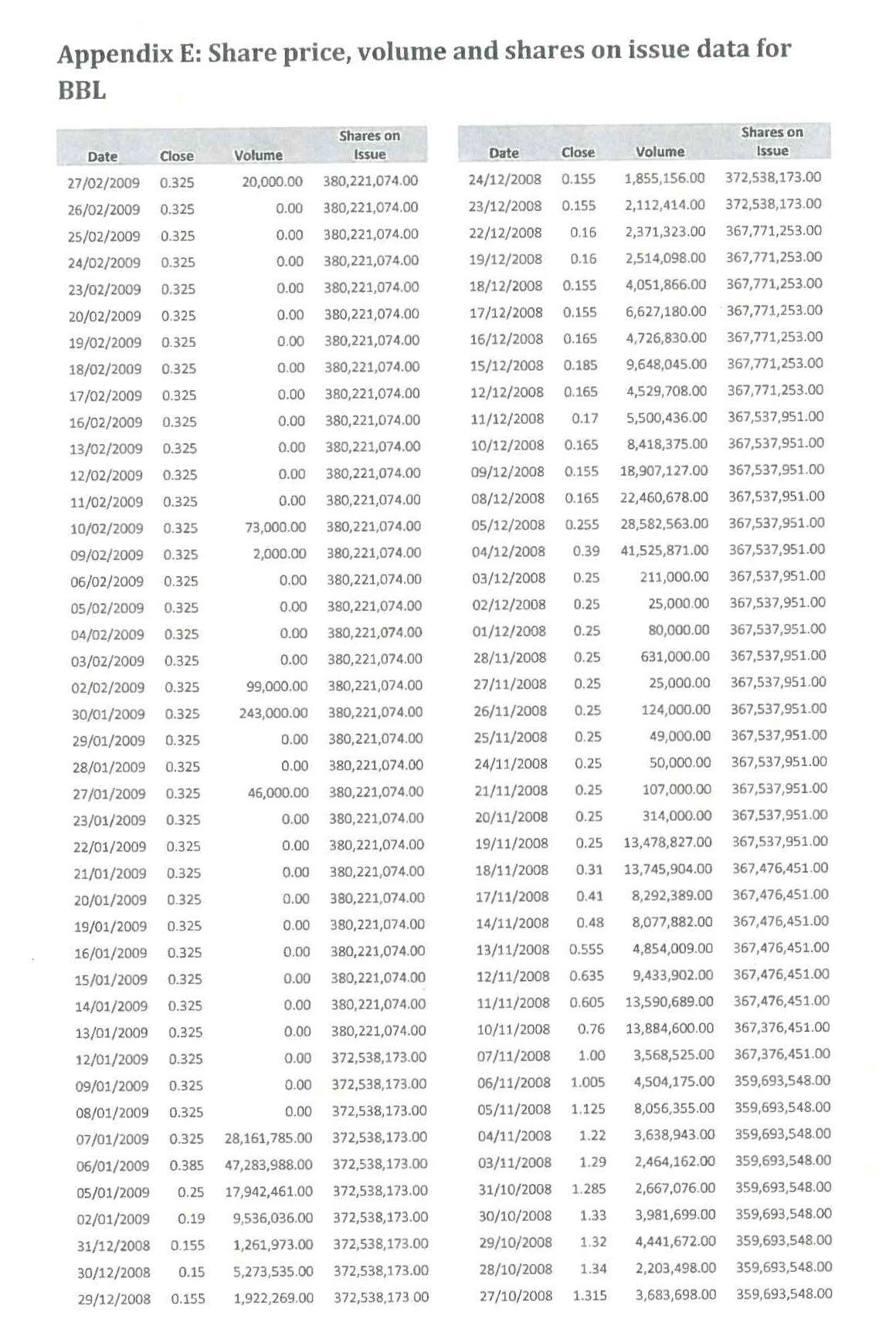

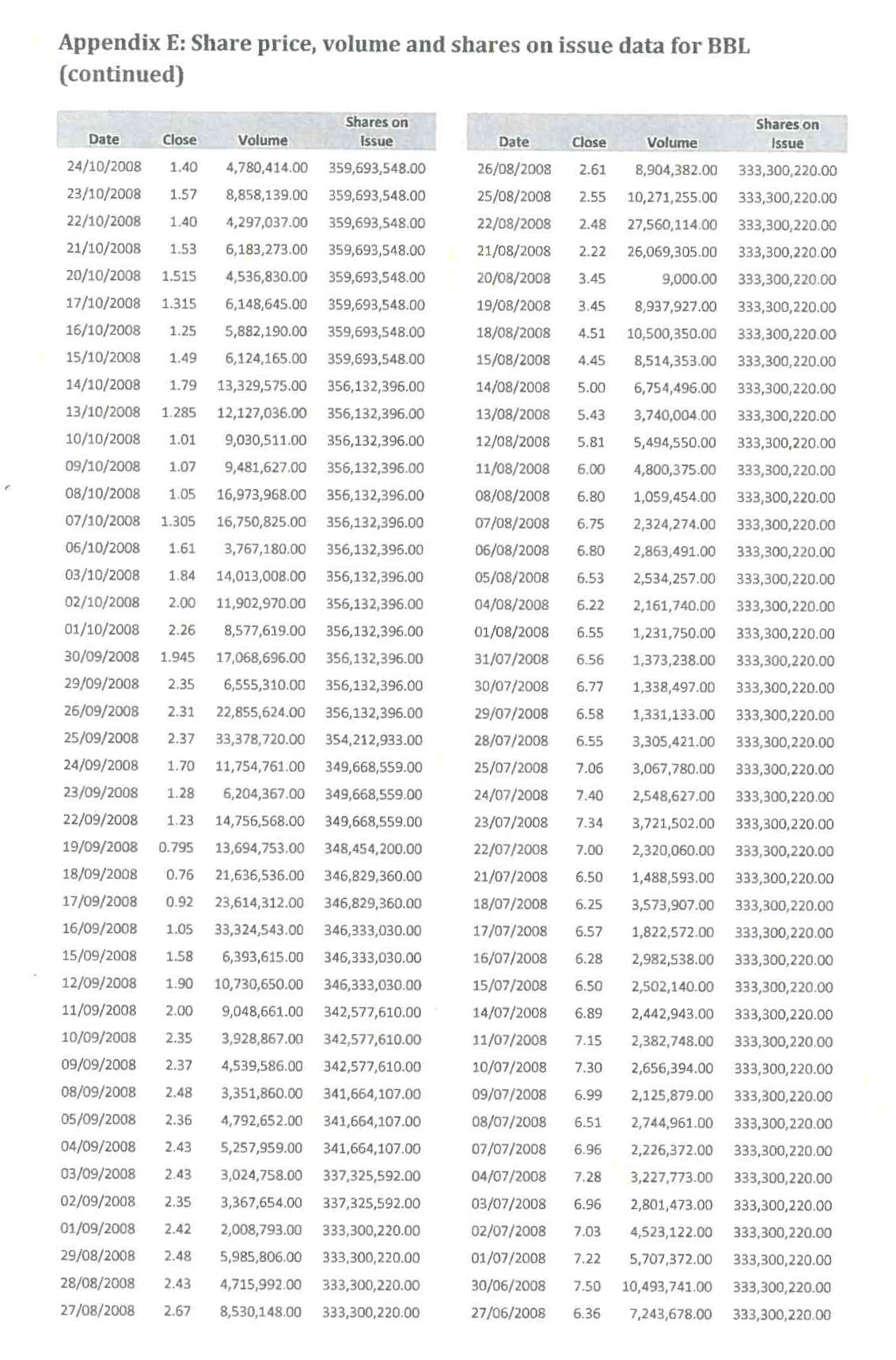

77 By 11 August 2008, BBL’s share price had fallen from a high of $34.63 in June 2007 to $6.80. During the period in question, despite the fact that no further earnings guidance on the 2008 B&B Group NPAT was given, BBL’s share price collapsed from $6.80 to $0.33. By 28 August 2008, BBL’s share price had fallen to $2.43 and never rose above $2.50 at any time after that.

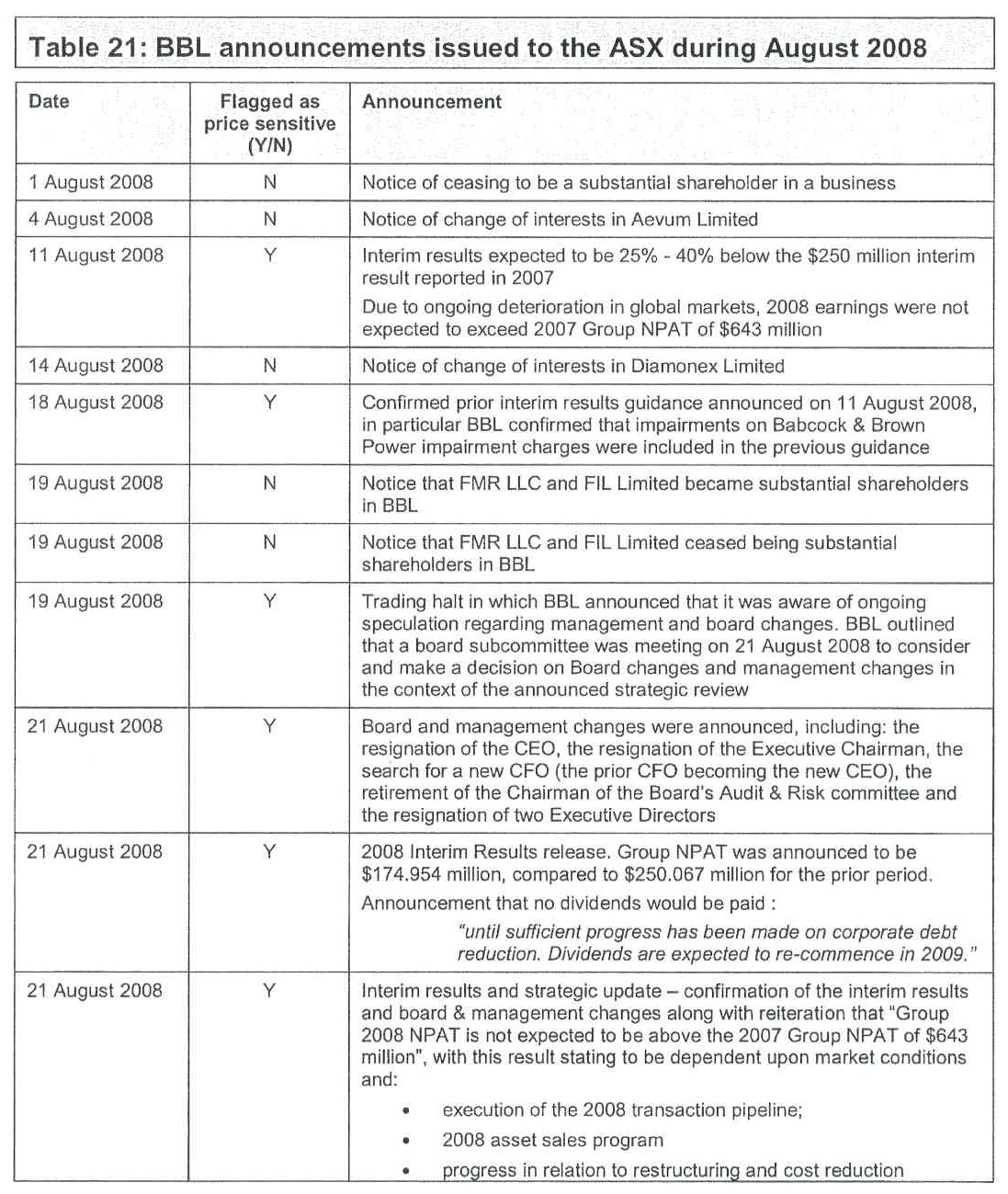

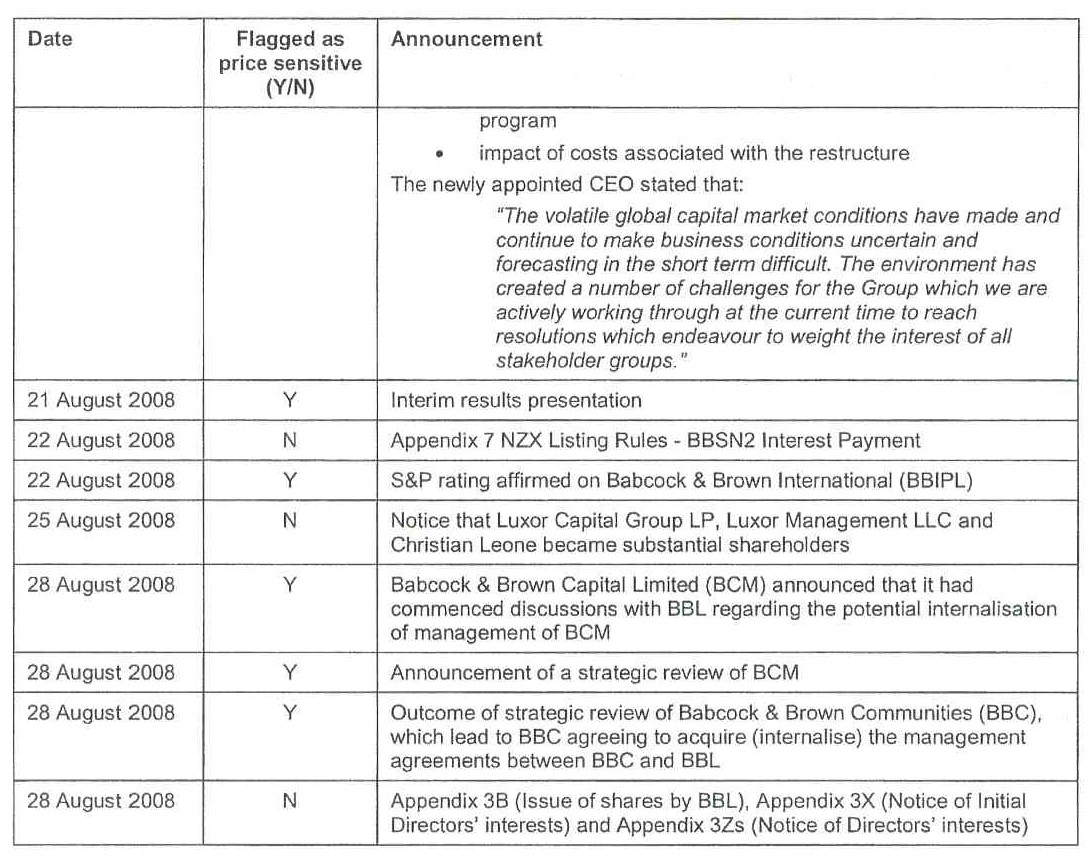

Market Announcements made by BBL

78 On 11 August 2008, BBL announced that 2008 Group NPAT was “not expected to exceed” 2007 Group NPAT of $643 million and that “… volatile global capital market conditions have made and continue to make business conditions uncertain and forecast in the short term difficult”.

79 On 21 August 2008, BBL confirmed that “the Group 2008 NPAT is not expected to be above the 2007 Group NPAT of $643 million” and stated further that “the result is dependent on market conditions” as well as “execution of the 2008 transaction pipeline”, “2008 asset sales program”, “progress in relation to restricting and cost reduction program” and “impact of costs associated with the restructure”.

80 During the relevant period, BBL and BBIL made further announcements to the ASX, namely:

(a) The CEO, the Executive Chairman, senior management and several directors were to resign (21 August 2008);

(b) BBL would restructure its business to become a specialist infrastructure business and divest all other businesses and assets when opportunities arose although there was no set timetable for asset sales (21 August 2008 and 19 November 2008);

(c) No dividend would be paid to shareholders until progress had been made on debt reduction (21 August 2008);

(d) BBL was attempting to renegotiate its credit facilities given that it would find it difficult to meet its financial covenants as a result of the “continuing and substantial deterioration in market conditions” (19 November 2008);

(e) Trading halts had been called as a result of speculation about management and board changes and the material dispute with a bank over release of a deposit (21 August 2008, 20 November 2008 and 21 November 2008). One such trading halt lasted from 20 November 2008 to 4 December 2008;

(f) BBIL’s credit rating had been downgraded to BB+, then BB-, then CCC+, then CC, the latter being the lowest issue or credit rating available in the absence of an actual payment default or bankruptcy filing (17 September 2008, 10 November 2008, 19 November 2008 and 21 November 2008); and

(g) BBIL’s credit rating had been withdrawn and there was a high risk of default in the near term (24 November 2008).

81 At pars 4.52 to 4.60 of his first report, Mr Potter explained the timeline and impact of the GFC. I adopt that explanation as fair and reasonable.

82 At pars 58 to 63 of the liquidator’s Written Submissions, the liquidator referred to significant media coverage in respect of BBL in the period from mid-August 2008 to the end of 2008. At those paragraphs, the liquidator said (footnotes omitted):

According to contemporaneous newspaper articles, BBL’s 11 August 2008 announcement was preceded by “a string of profit warnings from banks, insurers and listed property interests” in the prior weeks. In light of the “financial crisis that began to unfold in mid 2007”, the announcement was said to be further evidence of “how tough the market has become for so-called financial engineers” like BBL. The unfolding credit crisis, as well as financiers’ “increasing aversion to highly geared, complex structures”, were perceived as having “wrong-footed” the company. The financial coverage observed that BBL’s CEO had “continue[d] to make business conditions uncertain and forecasting in the short term difficult”.

According to financial press coverage, by August 2008 BBL already faced “an uphill battle to win back investor confidence”, having “dismayed investors” and having lost the “confidence and credibility” of the market, in a context where “the impact of damage to Babcock & Brown’s reputation [was] unquantifiable”. This loss of credibility was perceived as a part of a dangerous trend because of its potential to “impair [BBL’s] ability to tap into equity and debt markets.” Despite BBL shares trading at a well-publicised discount of “87 per cent from their peak”, investors perceived the outlook as “grim” and risks as being “skewed to the downside”, such that the share price was deemed “unlikely to outperform”, while “rumours swirled through the market about the future of the investment bank”.

By mid-September the financial press was reporting that the intensifying “global liquidity crisis” had “exposed several flaws in [BBL’s] business model” and the shockwaves of that crisis had “further undermined confidence” that BBL’s “business model will survive the market rout.” One market commentator queried what value there could be in a company that is “not making any money”. Any hope of salvaging the company was placed entirely in “radical plans” to restructure its business, slash its global workforce and sell off assets. At the same time there was mounting concern for “companies that are being forced to sell assets in the current market downturn”, and investors predicted that BBL would be “a victim to imploding asset prices”. By 17 September 2008, commentators considered that the company “would not be able to repay $9.6 billion of debt”, that “the equity value is virtually nil” and that the company had “effectively collapsed already”. It was in this context that BBL is recorded as having said to the market that its profit outlook was “uncertain” – a statement repeated in the financial press.

As the crisis progressed in October the newspapers reported that plans to “restore confidence in the global financial system” had “collapsed” and financial stocks “faced the wrath of investors”.

By mid-November, BBL was reported facing increasing difficulty in meeting the terms of the financing arrangements with its banks, who “watched with concern” as the company “conceded that it may face more asset write-downs”. By late November the “stricken” company was perceived by the media as being in a state of “desperation”, abandoning all but one of its remaining business lines. At this point, the media reported that the company’s shares had “lost 99% of their value over the past year”.

By late November and early December 2008 BBL was being described as subject to a “war” between its lenders which led the market to perceive it as “on the brink of being placed into administration”, with its equity “close to worthless”, and where it seemed “all over for Babcock & Brown”. Any reprieve that the company was able to gain at that point was seen as “short-term” and “temporary”, with an “emergency lifeline” granted in early December being described as “a long way from the embattled company’s original request”.

83 This is a fair and reasonable summary of the important press articles concerning BBL in the relevant period.

84 In similar vein, the liquidator provided an account of the relevant analyst’s coverage of BBL at par 64 of his Written Submissions. In that paragraph, the liquidator submitted:

The analysts who followed and published on BBL during the period that the applicants purchased shares also expressed increasingly negative views about it, although an important point is that in the period from August to November 2008 the number of analysts who followed BBL and were prepared to express expectations about 2008 Group NPAT dwindled from about 9 to only 2 (ABN AMRO and Citi) (see Joint Report, pp 12-14). A review of the analyst reports indicates that:

(a) by June 2008 analysts were already describing the stock as “speculative risk”, “highly speculative” or equivalent, by reason of BBL falling below its market capitalisation covenant, enabling its banking syndicate to call for a “review”. UBS observed in June 2008 that BBL’s share price had “collapsed”;

(b) also by June 2008, analysts were consistently referring to the high degree of uncertainty regarding BBL's earnings outlook. Credit Suisse observed on 13 and 26 June that there was “enormous uncertainty” regarding BBL “future earnings trajectory” and on 16 June Deutsche Bank observed that while it believed BBL could “survive” balance sheet de-gearing and restructuring, there could be no confidence regarding the “earnings outlook”;

(c) consistently with a move away from valuing BBL based on future earnings, a number of analysts shifted in June 2008, or had already shifted by June 2008, from a “price earnings” valuation methodology (interestingly, the methodology used by the applicants’ expert, Dr Coulton) to a “break up” or “net tangible assets” methodology, reflecting the high prospect of BBL defaulting. Deutsche Bank explained its methodology on the basis that “far less reliance can be placed on the promise of future earnings”;

(d) by late June 2008 analysts were saying that de-gearing and restructuring was inevitable irrespective of whether BBL’s banking syndicate chose to waive its right to a review, and emphasised the risks involved;

(e) the 11 August 2008 announcement and the guidance it included that BBL’s 2008 Group NPAT would be less than $643 million was greeted with scepticism by analysts, and queries were raised about the reliability of any BBL forecast given market conditions. UBS said blankly that it had “low confidence” in BBL’s earnings estimate and Credit Suisse said that it had not credited BBL with achieving its earnings guidance for some time;

(f) similar scepticism greeted the 21 August 2008 announcement, including its confirmation that 2008 Group NPAT would be less than $643 million. Aegis observed that earnings were “difficult to predict” and commented on BBL’s “near term challenges” and “lack of transparency as to its future prospects”, and confirmed that it was a “speculative investment”. Similar observations were made by Citi and ABN AMRO

(g) one thing, at least, is quite clear, which is that contrary to the applicants' initial case theory – which may now have been abandoned - the analysts did not regard the $643 million figure put forward in August 2008 as meaning that BBL was forecast to achieve earnings of $643 million. It was clearly understood as it was expressed – that is, as a ceiling. ABN AMRO observed that even approaching $643 million would be “ambitious”. Tricom observed that there was “no floor” on expected 2008 Group NPAT in BBL's announcement and opined that in the absence of asset sales the floor could be as low as $285 million (as at 21 August 2008);

(h) by September 2008 the analysts were frankly reporting that BBL was moribund. Even if positive 2008 Group NPAT estimates were maintained, the analysts' comments and discounts to valuation and target prices show that they regarded any such earnings as improbable. Citi stated that “BNB’s plight can only be described as speculative at best”;

(i) by October 2008 all remaining analysts were emphasising the likelihood of BBL breaching its debt covenants with the consequence of forced asset sales in an illiquid market, which would greatly reduce its net tangible assets;

(j) by 19 November 2008 there was plainly very little hope. Merrill Lynch moved to a “no rating”, observed that BBL’s restructuring plans were now in the hands of its banks, observed that breach of debt covenants due to asset writedowns was “likely”, and described the risk involved in the required sale of more than $7.5 billion in assets as “immense”.

85 These submissions accurately record that which they purport to record and I accept them as being accurate.

86 Upon the basis of the material to which I have referred in this section of these Reasons, the liquidator submitted that the objective circumstances set out above made it unlikely that there were any expectations in the market from the middle of 2008 to the end of December 2008 of positive earnings being achieved by BBL for the full Financial Year ending 31 December 2008 and that BBL’s actual share price throughout that period was most likely a reflection of expectations in the market of significantly depressed trading results and the impact of any restructuring. I think that this submission is correct and I accept it.

87 Each side of the record called one expert witness.

88 The plaintiffs retained Dr Jeffrey Coulton. The liquidator retained Mr Terence Michael Potter.

89 Dr Coulton has the degrees of B.Ec (Hons I), LLB and a PhD in accounting. He is also a chartered accountant.

90 At the time of the hearing before me, Dr Coulton was a full-time academic. At that time, he held the position of Senior Lecturer in Accounting at the University of New South Wales (UNSW). He had held that position since November 2005. For almost three years prior to that time, Dr Coulton had been a Lecturer in Accounting at UNSW. In the period from July 2000 to January 2003, he had been a Lecturer in Accounting at the University of Technology Sydney. In the period between July 1996 and July 2000, Dr Coulton had been an Associate Lecturer and then a Lecturer in Accounting at University of Sydney. In the period 1995 to July 1996, Dr Coulton was a solicitor employed at the law firm, Corrs Chambers Westgarth. In addition to holding the positions which I have described, in the period between August 2006 and January 2007, Dr Coulton was a Visiting Senior Lecturer in the Department of Accounting at McCombs School of Business at the University of Texas.

91 Dr Coulton has published a number of articles relating to matters of accounting and finance and has been involved in research activities concerning such matters. He also gave expert evidence in Grant-Taylor v Babcock & Brown Ltd (in liq) (2015) 322 ALR 723 (Grant-Taylor First Instance) and in Re HIH Insurance Ltd (in liq) (2016) 335 ALR 320 (Re HIH).

92 I consider Dr Coulton to be appropriately qualified to give the evidence which he gave before me. By and large, he did his best to assist the Court although, from time to time, he was a little too eager to assist the plaintiffs’ cause.

93 Mr Potter is a practising accountant. He has a Bachelor of Commerce from the University of Western Australia. He is an Associate Member of the Institute of Chartered Accountants in Australia and has been designated as a Business Valuation Specialist by that Institute. He is also an Associate Member of the Certified Practising Accountants in Australia. Mr Potter qualified as a chartered accountant in 1990 and is now the principal of Axiom Forensics Pty Ltd. In his first 13 years after qualifying, Mr Potter specialised in insolvency and reconstruction accountancy. That work included the sale, reconstruction and winding up of businesses and companies and consulting assignments. The consulting work performed by Mr Potter in this period also included reviews of the financial position of corporations for lenders and for shareholders. For approximately 18 years prior to 2016, Mr Potter conducted practice as a forensic accountant. He has conducted investigations for corporate regulators on issues including valuation, valuation disputes and competition-related disputes where accounting and/or valuation matters were at issue. He has also conducted many damages assessments for court proceedings and other consulting assignments. The Supreme Court of New South Wales has, from time to time, appointed Mr Potter as a referee.

94 I also considered Mr Potter to be qualified to express the opinions which he did in the evidence which he gave before me.

95 The only witnesses called to give oral evidence at the hearing were Dr Coulton and Mr Potter. The remaining material admitted into evidence comprised documentary material, most of which was contained in Exhibit A (the Court Book), and three particular affidavits read and relied upon by the liquidator being the affidavits of Lisa Renee Paul sworn on 23 August 2016, the affidavit of Cathy-Lee Jane Bell sworn on 23 August 2016 and the affidavit of Hiroshi Mark Oya sworn on 23 August 2016 including the annexures and exhibits annexed to those affidavits.

96 The viva voce evidence of Dr Coulton and Mr Potter was given concurrently by reference to the main matters in dispute between them. Dr Coulton and Mr Potter had prepared a Joint Report prior to the hearing and that Joint Report provided a satisfactory working basis against which consideration of those issues in dispute between the two experts was undertaken. The Joint Report is found at Vol N in Ex A.

97 The concurrent evidence proceeded as follows: Depending upon the nature of the issue, either Dr Coulton or Mr Potter gave a brief exposition of his views on the topic. Immediately after that exposition was given, the opposing expert was afforded a reasonable opportunity to outline his views on the particular matter. After the experts had given a brief outline of their views, limited cross-examination of each of them was permitted in an appropriate order. After that, re-examination took place, as necessary. Throughout the process, I had an opportunity to ask questions of the experts, as I thought fit. The concurrent evidence occupied the whole of one day and the morning of a second day.

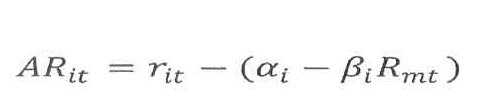

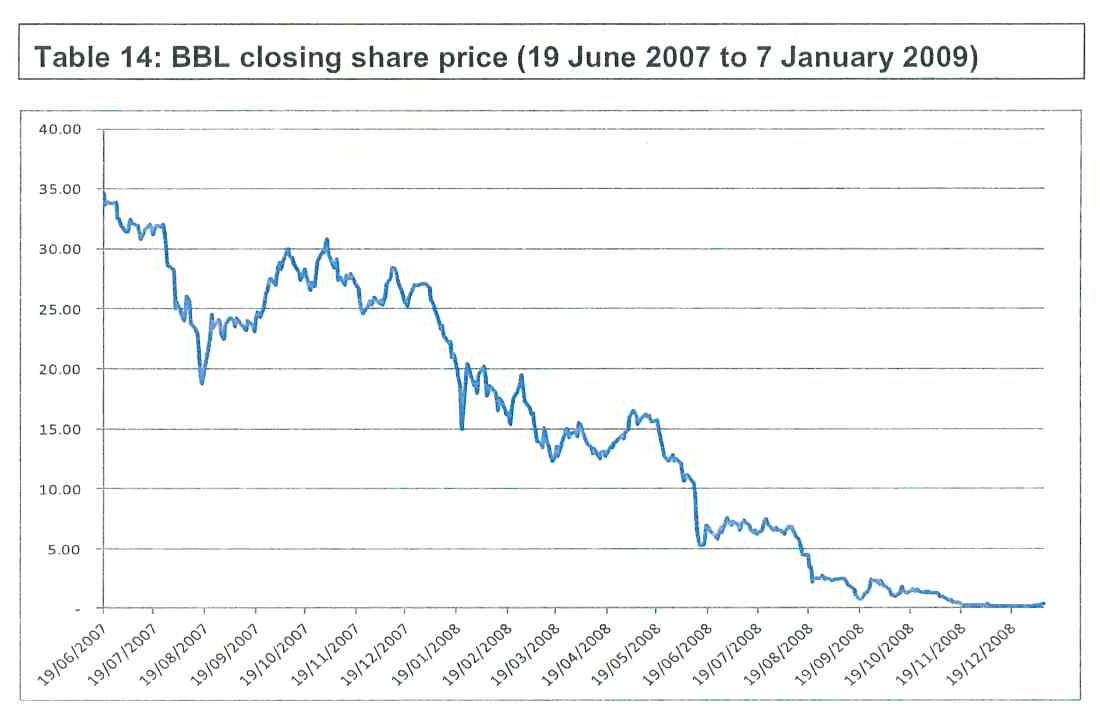

The Reports of Dr Coulton in Chief

98 Dr Coulton prepared four separate reports for the purposes of these proceedings. Those reports are dated 21 June 2016, 16 September 2016, 29 September 2016 and 5 October 2016 respectively. All four of Dr Coulton’s reports were admitted into evidence as part of Ex A. Dr Coulton’s reports are found in Vol L of Ex A. The liquidator objected to several paragraphs in Dr Coulton’s first and second reports. I ruled on those objections at Transcript 85–86. As a result, paragraphs 39, 40, 41, 42, 49, 50, 51, 58, 59, 60, 65, 66, 67, 76, 77 and 78 of Dr Coulton’s first report were allowed as submissions only. The objections taken to Dr Coulton’s second report were not upheld with the consequence that that report was admitted into evidence without restriction.

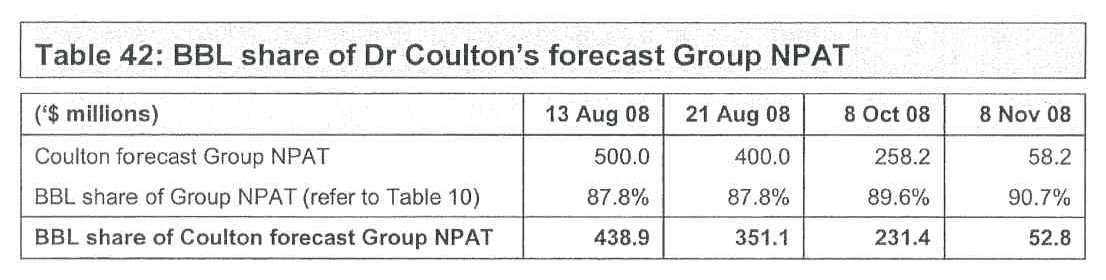

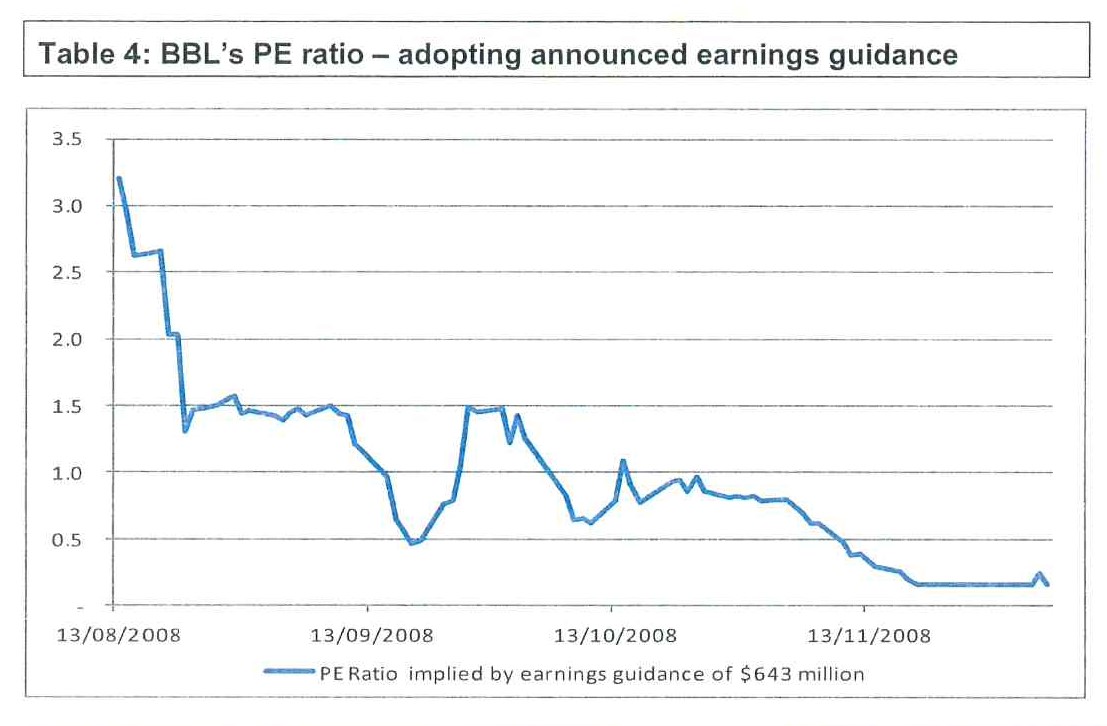

99 Those paragraphs in Dr Coulton’s first report which were admitted as submissions only contained Dr Coulton’s conclusions on the question of whether the information which he identified as information which should have been disclosed to the ASX was, in fact, “material” for the purposes of s 674(2)(c) of the Act and Listing Rule 3.1.

100 The first, third and fourth reports of Dr Coulton comprised his evidence-in-chief. Leaving aside the reworked calculations in Dr Coulton’s second report, Dr Coulton’s second report is essentially his response to Mr Potter’s Expert Report dated 26 August 2016.

101 In this section of these Reasons, I will address Dr Coulton’s first, third and fourth reports.

102 In his first report, Dr Coulton addressed three questions, as he had been instructed to do. These questions were:

a. Should Babcock & Brown Limited (BBL) have disclosed certain material information to the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) from 11 August 2008 to 9 January 2009 to comply with BBL’s obligations under s 674 of the Corporations Act 2001 and ASX Listing Rule 3.1?

b. Was the information such that a reasonable person would expect, if the material had been generally available, to have had a material effect on the price or value of shares in BBL?

c. If the information had been disclosed to the ASX in accordance with its obligations under the Listing Rules, what would have been the effect on the price or value of the shares in BBL?

103 Dr Coulton provided to the Court the letter of instructions dated 8 May 2016 which he had received from the plaintiffs’ solicitors and listed for the benefit of the Court and the liquidator the documents to which he had had regard in preparing his first report.

104 It will be immediately apparent that questions (a) and (b) asked of Dr Coulton related to important integers of liability under s 674 of the Act and that question (c) potentially concerned the issue of loss and damage.

105 In section I of his first report, Dr Coulton referred to a number of matters by way of background concerning BBL. At par 18, Dr Coulton referred to certain observations made by the liquidator in a report to creditors dated 12 August 2009 concerning the relationship between BBL and BBIL (referred to by Dr Coulton in his reports as “BBIPL”) and then said (at par 19):

I have assumed therefore, for the purposes of this report, that, for the relevant financial year ended 31 December 2008, the consolidated audited financial statements of BBIPL (excluding BBL) would be expected to be materially comparable with the BBL consolidated financial statements for the same year.

That assumption was criticised by Mr Potter as not precisely reflecting the true position.

106 In section II, Dr Coulton stated that he was proceeding upon the basis that BBL was subject to the continuous disclosure provisions in Ch 3 of the Listing Rules and the disclosure requirements in s 674 of the Act. That assumption accurately reflected BBL’s continuous disclosure obligations and was common ground among the parties.

107 In section III, Dr Coulton referred to a number of earnings announcements and profit forecasts that BBL had provided to the market in 2008.

108 This material is found at pars 21–28 of Dr Coulton’s first report.

109 The substance of the announcements referred to by Dr Coulton (as understood by him) may be summarised as follows:

(a) On 17 April 2008, BBL lodged its 2007 Annual Report with the ASX. That Report included financial statements for the Financial Year ended 31 December 2007. In that report, BBL’s consolidated profit excluding the BBIL minority interest for the Financial Year ending 31 December 2007 was stated to be $643,046,000. I note that, on p 7 of that Annual Report, BBL said that it expected that its 2008 Group Net Profit would be at least $750 million.

(b) As at 31 December 2007, BBL had on issue 293,924,578 ordinary shares.

(c) On 30 May 2008, BBL released to the ASX the Address given by its Chairman and by its CEO at its AGM. In his Address, the Chairman said that BBL remained on track to deliver NPAT of at least $750 million in 2008. The Managing Director and CEO made a statement to the same effect. The CEO described this growth in excess of 15% over the 2007 result. These statements reflected the forecast given at p 7 of the Annual Report.

(d) On 11 August 2008, BBL provided an announcement “Interim Result and Revised Full Year Guidance” to the ASX. In that announcement, BBL stated that “Babcock & Brown’s 2008 earnings are now not expected to exceed 2007 Group Net Profit of $643 million”. In that announcement, BBL also stated that “its 2008 interim Group Net Profit After Tax (NPAT) is expected to be 25% – 40% below the $250 million interim result reported in 2007”. The interim period to which those remarks were directed was the period from January to June.

(e) On 21 August 2008, BBL lodged an “Appendix 4D and Management Discussion & Analysis” with the ASX. At [57] above, I have set out a separate ASX Release dated the same day. In the Appendix 4D document, BBL’s consolidated NPAT (excluding minority interests) for the half year ended 30 June 2008 was said to be $150,920,000. (I interpolate here that this was at the very bottom of the range indicated in BBL’s announcement to the ASX made on 11 August 2008. Sixty percent of $250 million is $150 million.)

(f) On 7 January 2009, BBL announced to the ASX that “it now believes that asset impairment charges will be such that the Company will be in a substantial negative net asset position at 31 December 2008”. BBL was placed in a trading halt on 8 January 2009. BBL never lodged with the ASX its financial statements for the Financial Year ended 31 December 2008.

(g) BBL made no earnings announcement or profit forecast to the ASX between 21 August 2008 and 7 January 2009.

110 In section IV of his first report, Dr Coulton then proceeded to discuss the earnings information that he argues was known to BBL but not announced to the market or otherwise generally available in the market. He assumed, for the purposes of his first report, that none of the information to which he referred in section IV was generally available to the market.

111 First, Dr Coulton referred to information known to BBL but not generally available to the market on or around 13 August 2008. This information comprised the contents of a memorandum dated 13 August 2008 from Michael Larkin (the BBL Group Chief Financial Officer at that time who later became the Managing Director and CEO of the B&B Group) to the directors of BBL headed “FY08 Profit Guidance”. In his memorandum, Mr Larkin referred to the most recent earnings guidance provided by BBL to the ASX viz the guidance provided on 11 August 2008. Mr Larkin noted that that guidance did not provide a floor to BBL’s forecast of FY08 earnings. Mr Larkin set out in his memorandum a recommended guidance which was expressed to be subject to market conditions and outcomes from the sale of the B&B Group’s European wind assets, as well as the achievement of a number of other initiatives spelled out in his memorandum. Mr Larkin recommended that BBL retain its most recent guidance for the time being (ie that given on 11 August 2008) and that further guidance to the market be provided when the company had more clarity on some of the issues which might influence its earnings for 2008.

112 In his memorandum, Mr Larkin said that “If we adjust for the probability weighted outcome and apply +/- $100m factor, this allows earnings of between $400–$600 NPAT for the year”.