FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 1677

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The proceeding be dismissed.

2. The applicant pay the respondent’s costs of the proceeding.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

O’CALLAGHAN J:

The agreed facts

1 The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) brings this proceeding under the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), sch 2 (‘Australian Consumer Law’) (the ACL) against TPG Internet Pty Ltd (TPG), alleging that a term contained in plans offered on its website for various mobile, internet and home telephone services is misleading or deceptive, and is unfair.

2 The parties tendered an agreed statement of facts dated 15 April 2019 (ASOF). The agreed facts may be summarised as follows.

3 TPG is a retailer of mobile, internet and home telephone services. It supplies services to consumers on a prepaid basis, meaning that customers are required to pay TPG in advance for the TPG services selected by them.

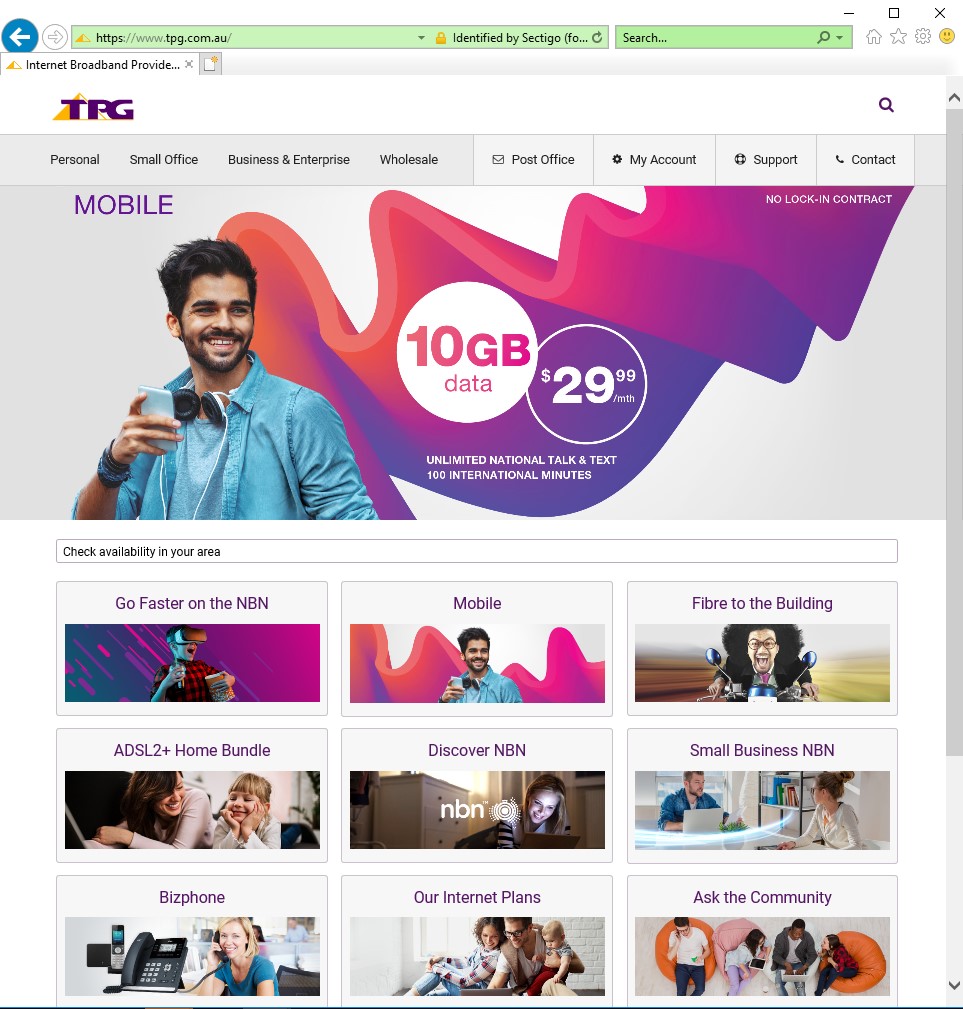

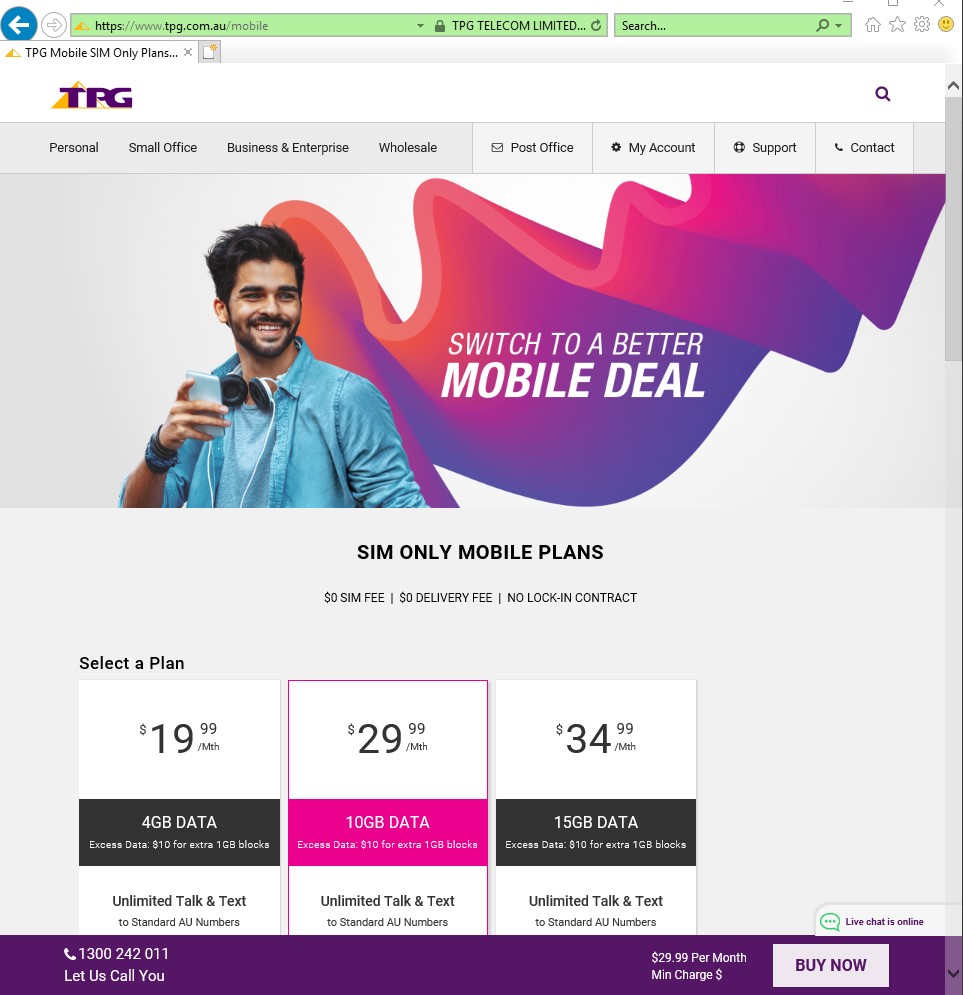

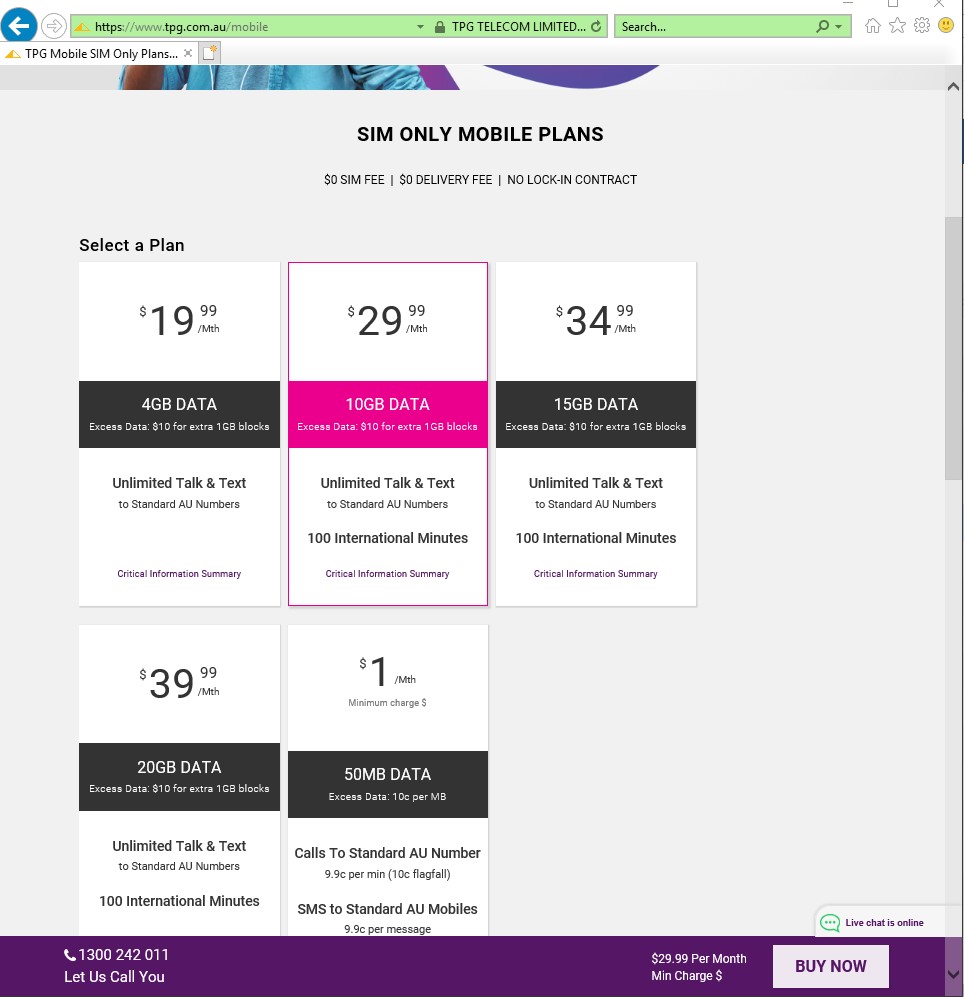

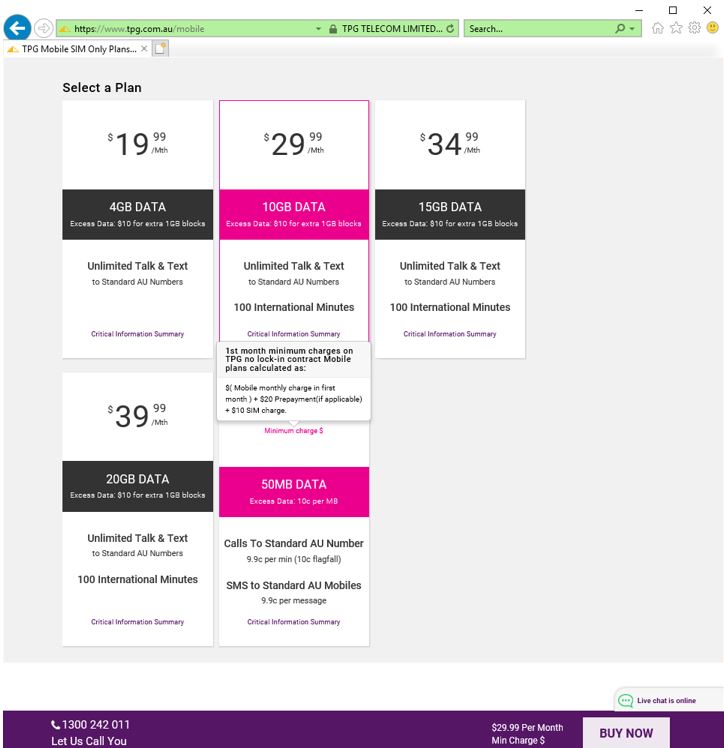

4 Since 14 March 2013, TPG has marketed on its website, http://tpg.com.au, (TPG Website) a variety of personal mobile, internet and home telephone plans.

5 Each such plan requires a fixed monthly amount to be paid by the customer in advance for the particular services (mobile, home telephone, internet) that are included in the plan acquired by the customer.

6 In order to enter into a plan, customers must make what is described by TPG as a “prepayment” of $20 (or more if nominated by the customer) for usage that is not within the included value of the plan acquired.

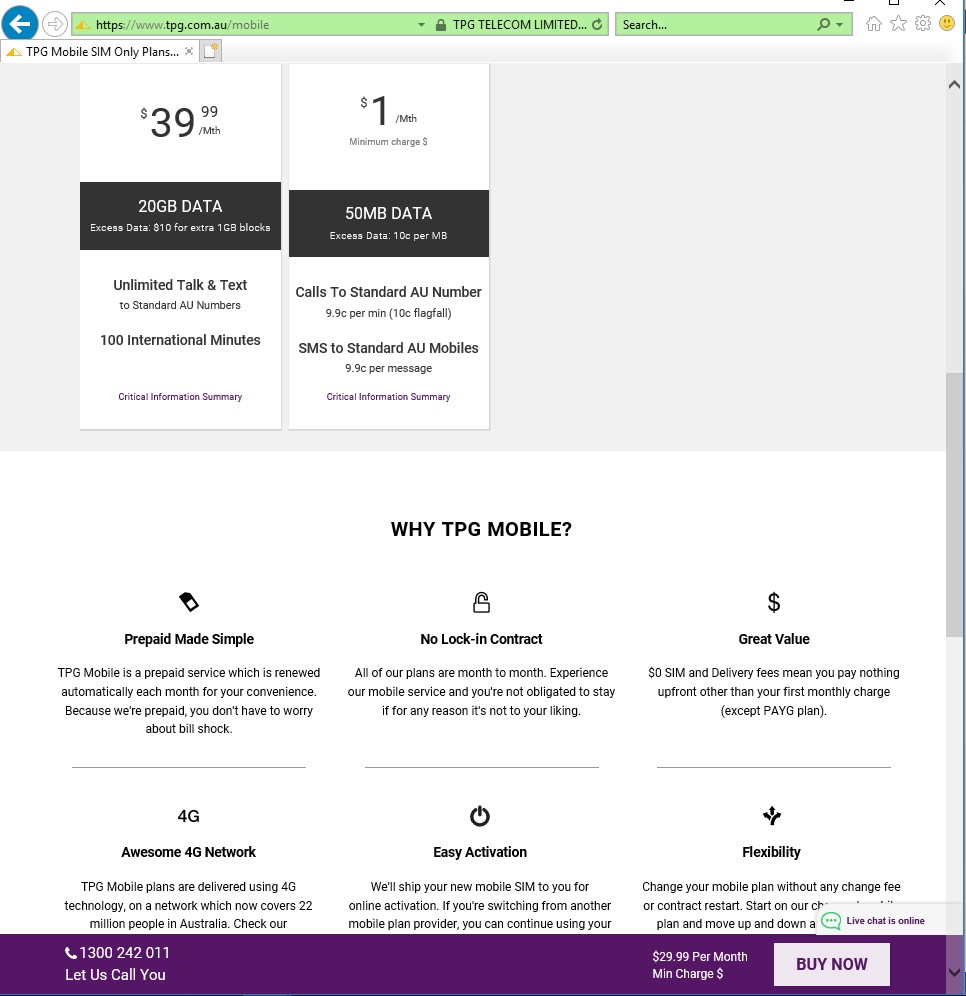

7 The prepayment is debited from the customer’s nominated bank account or credit card.

8 Usage charges incurred by the customer for services not within the included value of the plan acquired are deducted by TPG from the prepayment amount or balance.

9 Since 14 March 2013, there have been terms in the plans which provide that when:

(a) the balance of the prepayment falls to below $10, TPG will debit a sufficient amount from the customer’s bank account or credit card (if available) to restore the prepayment amount (Automatic Top-Up Term); and

(b) the customer cancels their plan, the unused balance of the prepayment is forfeited to TPG (Forfeiture Term).

10 In respect of the “Mobile Plans”, during the period from March 2013 to November 2016 the relevant webpages of the TPG Website included the following term under the heading “Mobile Prepayment Outside Included Value”:

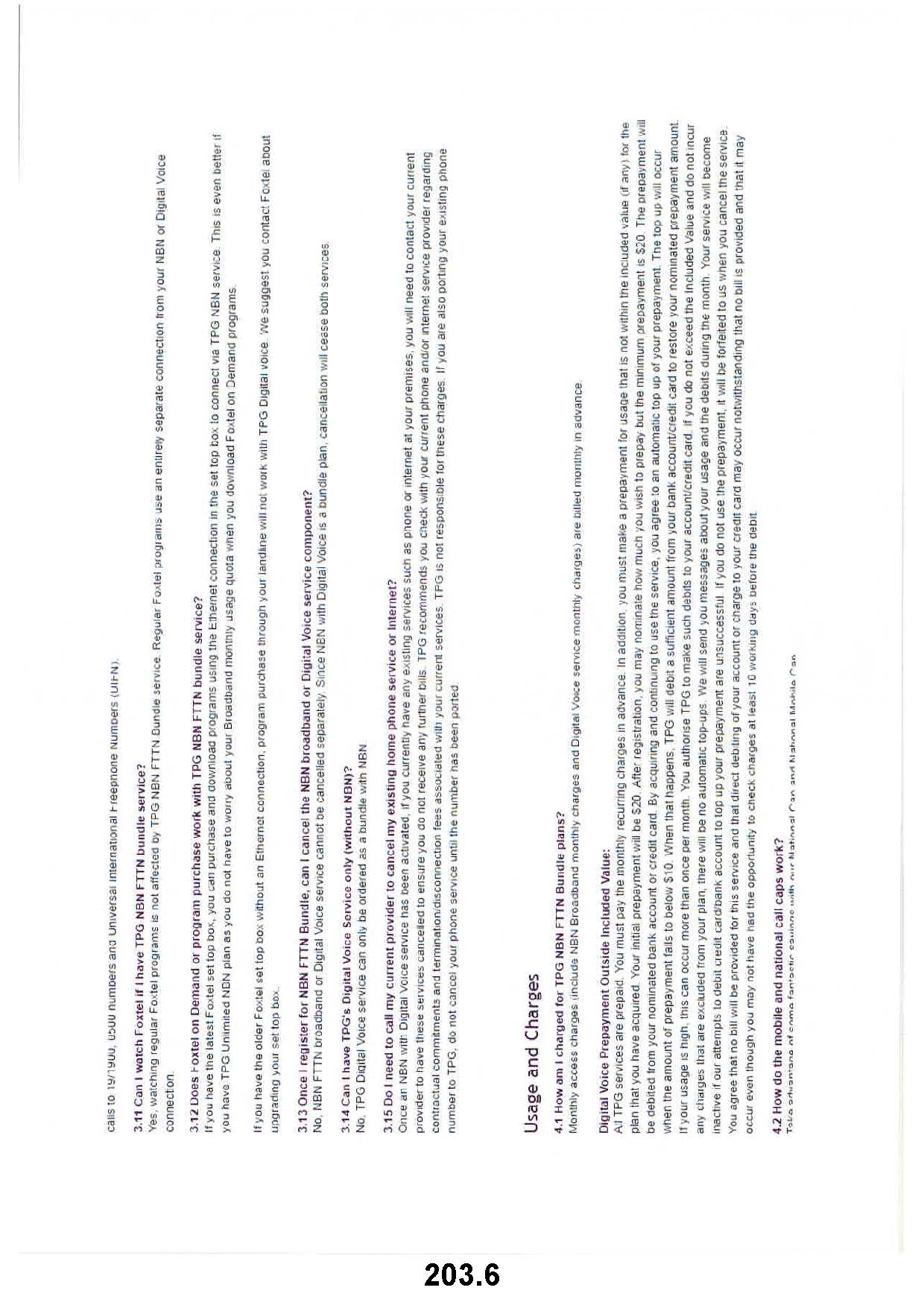

All TPG services are prepaid. You must pay the monthly recurring charges in advance. In addition, you must make a prepayment for usage that is not within the included value (if any) for the plan that you have acquired. Your initial prepayment will be $20. After registration, you may nominate how much you wish to prepay but the minimum amount is $20. The prepayment will be debited from your nominated bank account or credit card. By acquiring and continuing to use the service, you agree to an automatic top up of your prepayment. The top up will occur when the amount of prepayment falls to below $10. When that happens, TPG will debit a sufficient amount from your bank account/credit card to restore your nominated prepayment amount. If your usage is higher, this can occur more than once per month. You authorise TPG to make such debits to your account/credit card. If you do not exceed the Included Value and do not incur any charges that are excluded from your plan, there will be no automatic top-ups. We will send you messages about your usage and the debits during the month. Your service will become inactive if our attempts to debit credit card/bank account to top up your prepayment are unsuccessful. If you do not use the prepayment, it will be forfeited to us when you cancel the service. You agree that no bill will be provided for the service and that direct debiting of your account or charge to your credit card may occur notwithstanding that no bill is provided and that it may occur even though you may not have had the opportunity to check charges at least 10 working days before the debit.

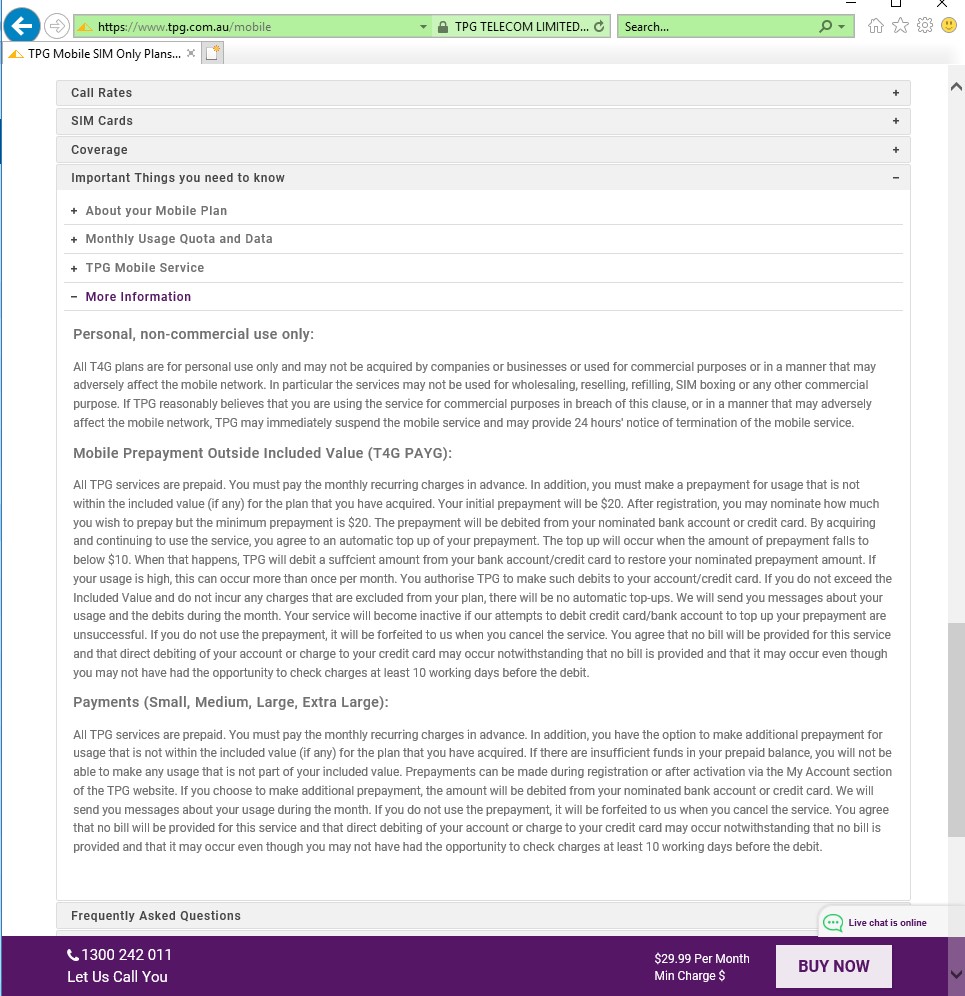

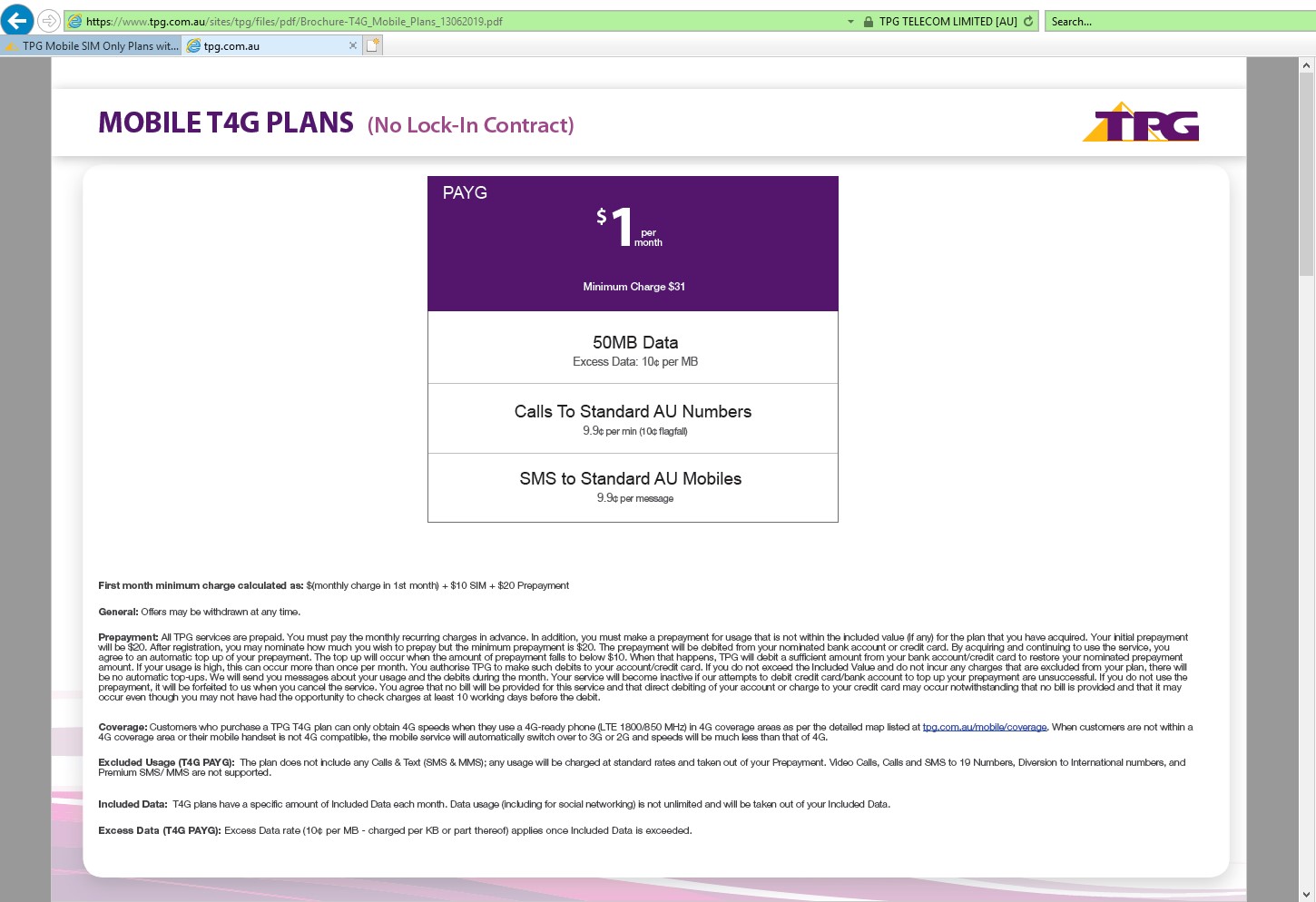

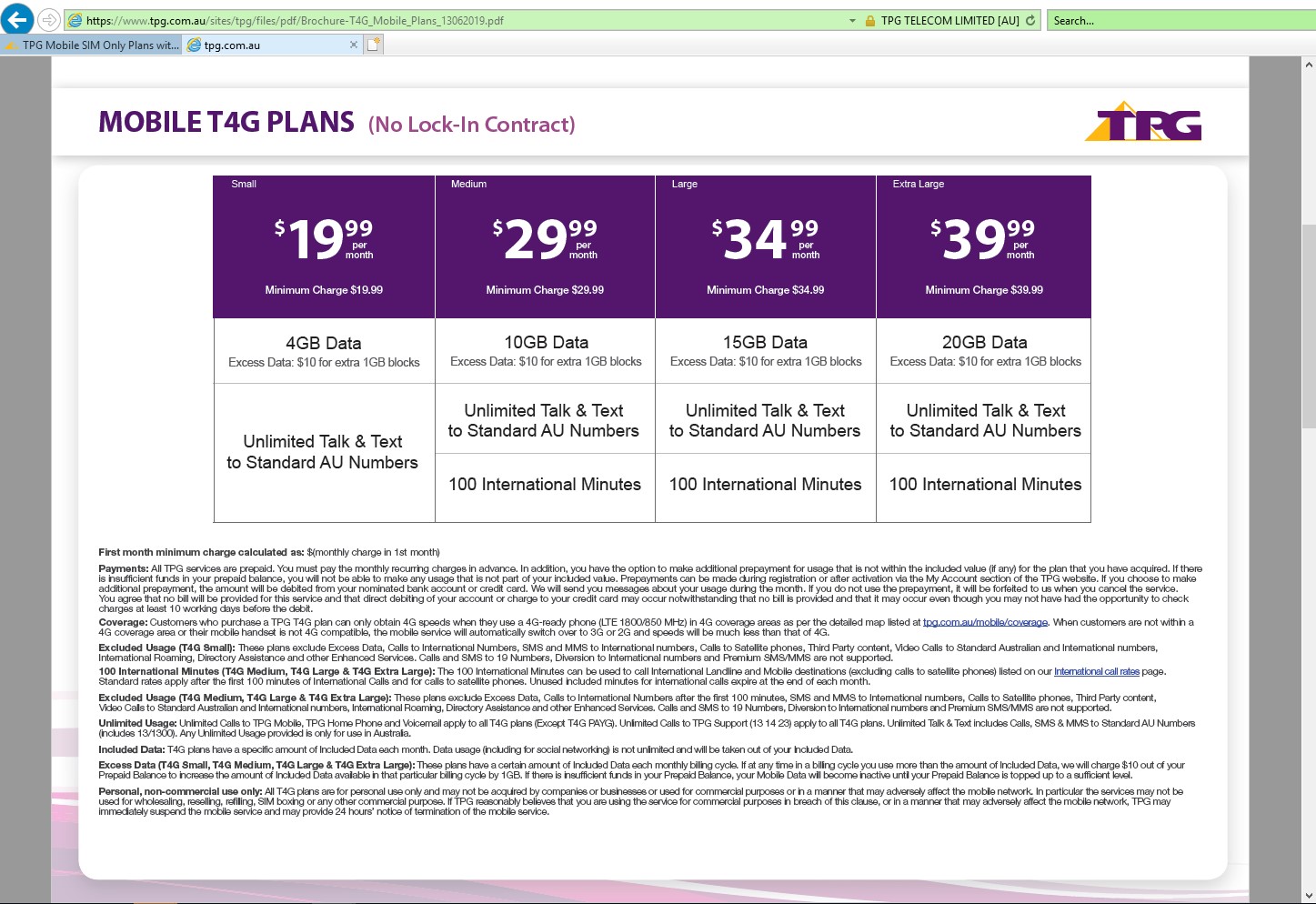

11 In respect of the Mobile Plans during the period from around November 2016 to the present, the relevant webpages of the TPG Website included the following term under the heading “Mobile Prepayment Outside Included Value (T4G PAYG)”:

All TPG services are prepaid. You must pay the monthly recurring charges in advance. In addition, you must make a prepayment for usage that is not within the included value (if any) for the plan that you have acquired. Your initial prepayment will be $20. After registration, you may nominate how much you wish to prepay but the minimum prepayment is $20. The prepayment will be debited from your nominated bank account or credit card. By acquiring and continuing to use the service, you agree to an automatic top up of your prepayment. The top up will occur when the amount of prepayment falls to below $10. When that happens, TPG will debit a sufficient amount from your bank account/credit card to restore your nominated prepayment amount. If your usage is higher, this can occur more than once per month. You authorise TPG to make such debits to your account/credit card. If you do not exceed the Included Value and do not incur any charges that are excluded from your plan, there will be no automatic top-ups. We will send you messages about your usage and to the debits during the month. Your service will become inactive if our attempts to debit credit card/bank account to top up your prepayment are unsuccessful. If you do not use the prepayment, it will be forfeited to us when you cancel the service. You agree that no bill will be provided for this service and that direct debiting of your account or charge to your credit card may occur notwithstanding that no bill is provided and that it may occur even though you may not have had the opportunity to check charges at least 10 working days before the debit.

12 The parties agreed that there is no relevant difference between those two provisions for the purposes of this proceeding.

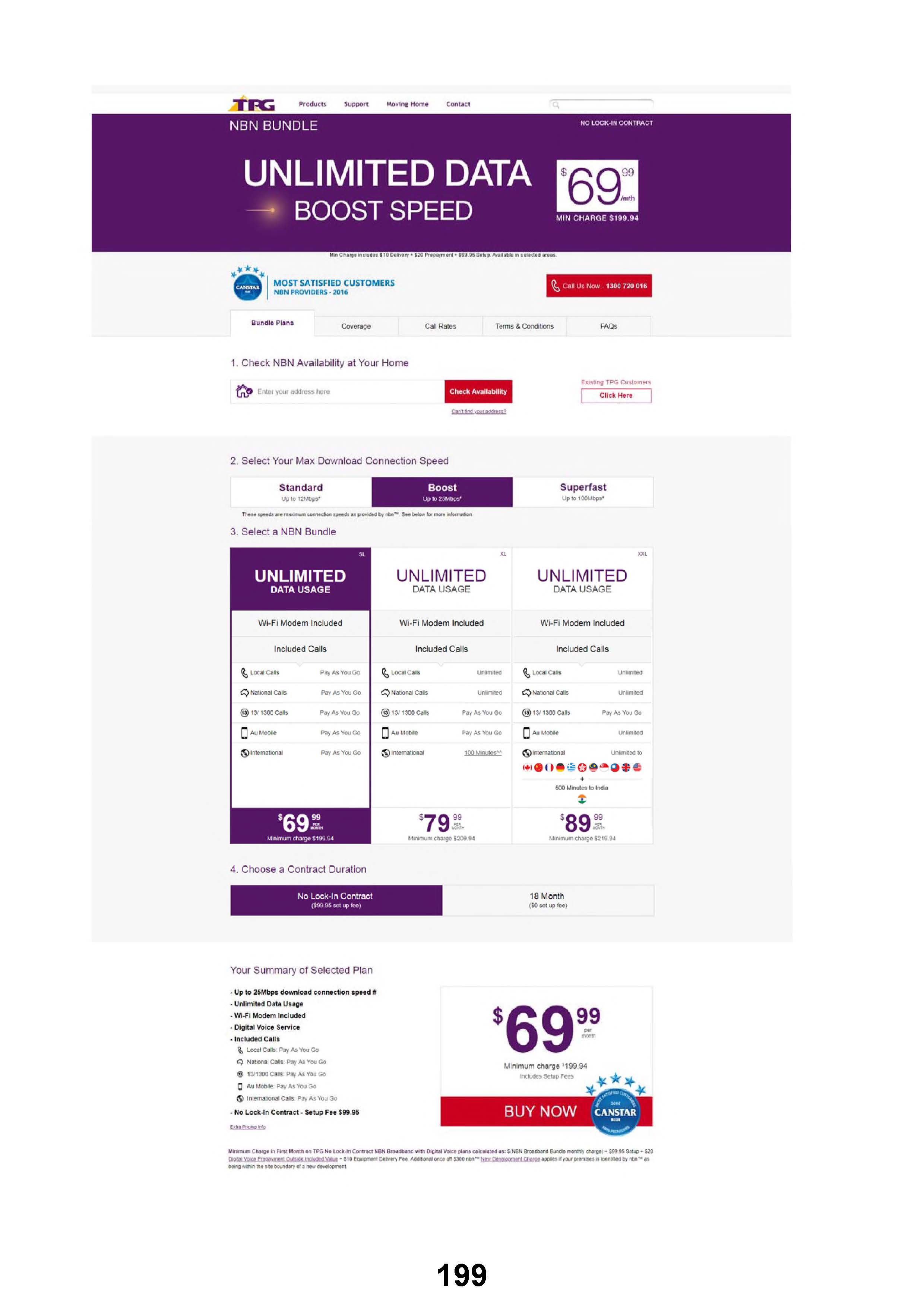

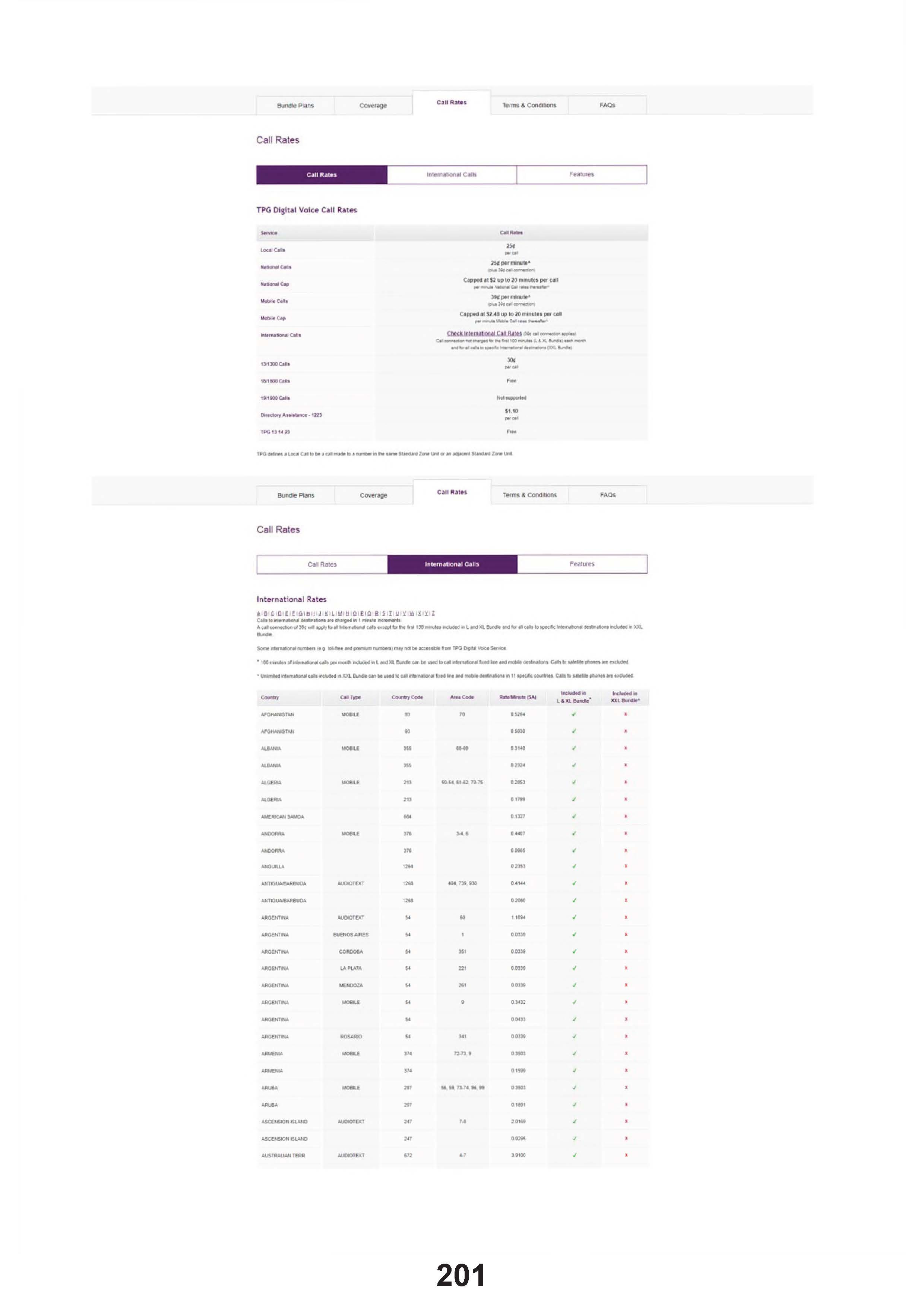

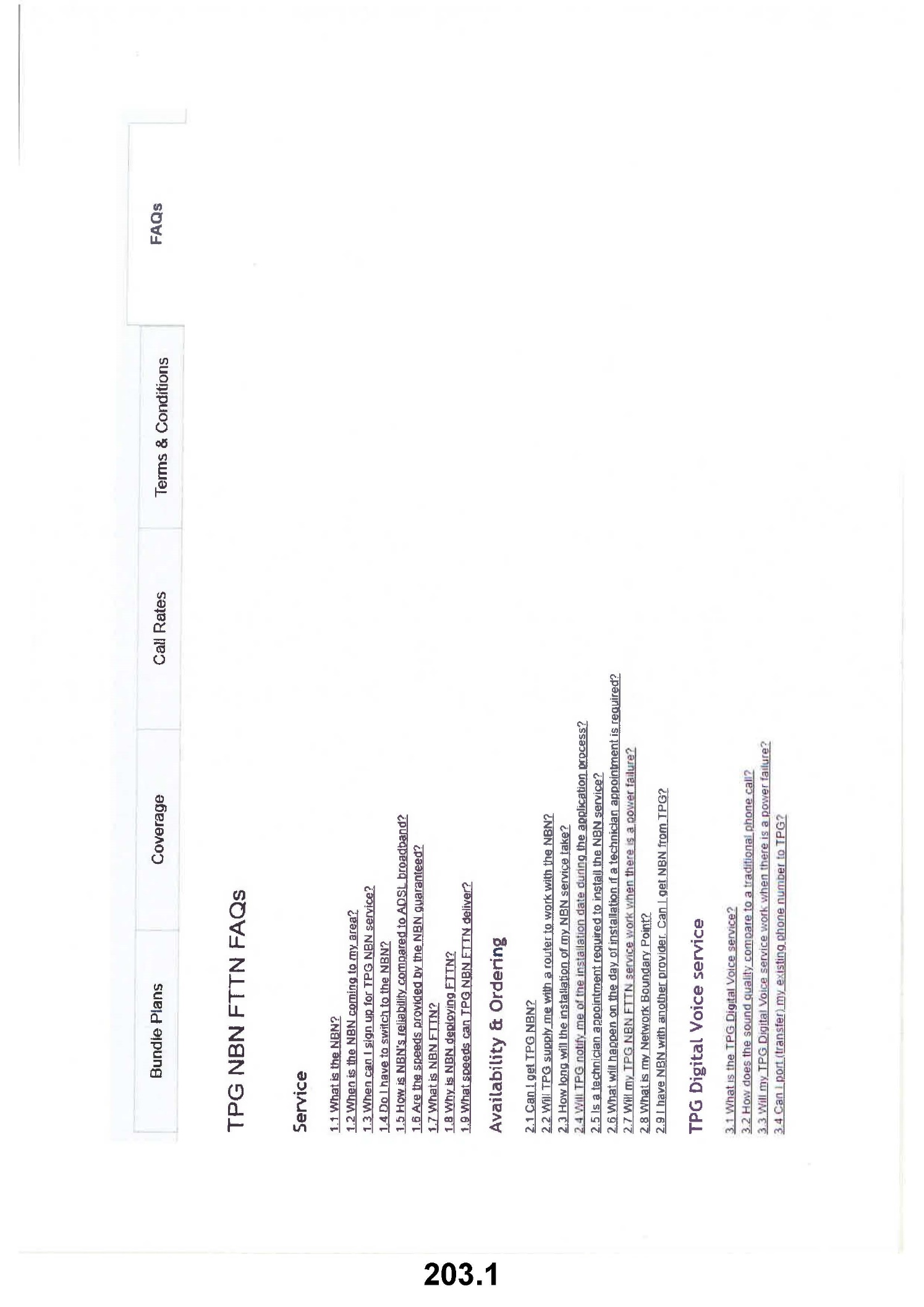

13 The parties also agree that the webpages for other plans (called the ADSL2+ with Home Phone Bundle Plans, the FTTB Bundle Plans and the NBN Bundle Plans (the other plans)) contain, and have at all material times contained, relevantly identical terms.

14 A customer intending to acquire a plan from TPG via the TPG Website must navigate through an online “purchase pathway”, including banner advertising and pop-up information.

15 For the purposes of this proceeding, it was agreed that, between March 2013 and November 2016, the webpages that a person contemplating, or intending to purchase, one of the Mobile Plans via the TPG Website could or needed to access:

(a) did not vary substantively from the example “purchase pathway” displayed in annexures A – I inclusive to the ASOF; and

(b) did not substantively change during this period.

16 The webpages for Mobile Plans since November 2016 are in relevantly identical terms.

17 The TPG Website “purchase pathways” for the other plans are, and have been at all material times, relevantly identical.

18 During the course of the hearing, I was shown by junior counsel for the ACCC a “live” demonstration of the online pathway for purchasing and accessing information about TPG’s Mobile plans on the TPG Website. Paginated screenshots that mimic that demonstration are attached to these reasons as Annexure A. Although hyperlinks within a webpage can, of course, be accessed in various sequences, the screenshots that comprise Annexure A appear in the following order, which is the order adopted by counsel during the demonstration:

- Screenshot 1: Homepage;

o Scroll down to screenshot 2A;

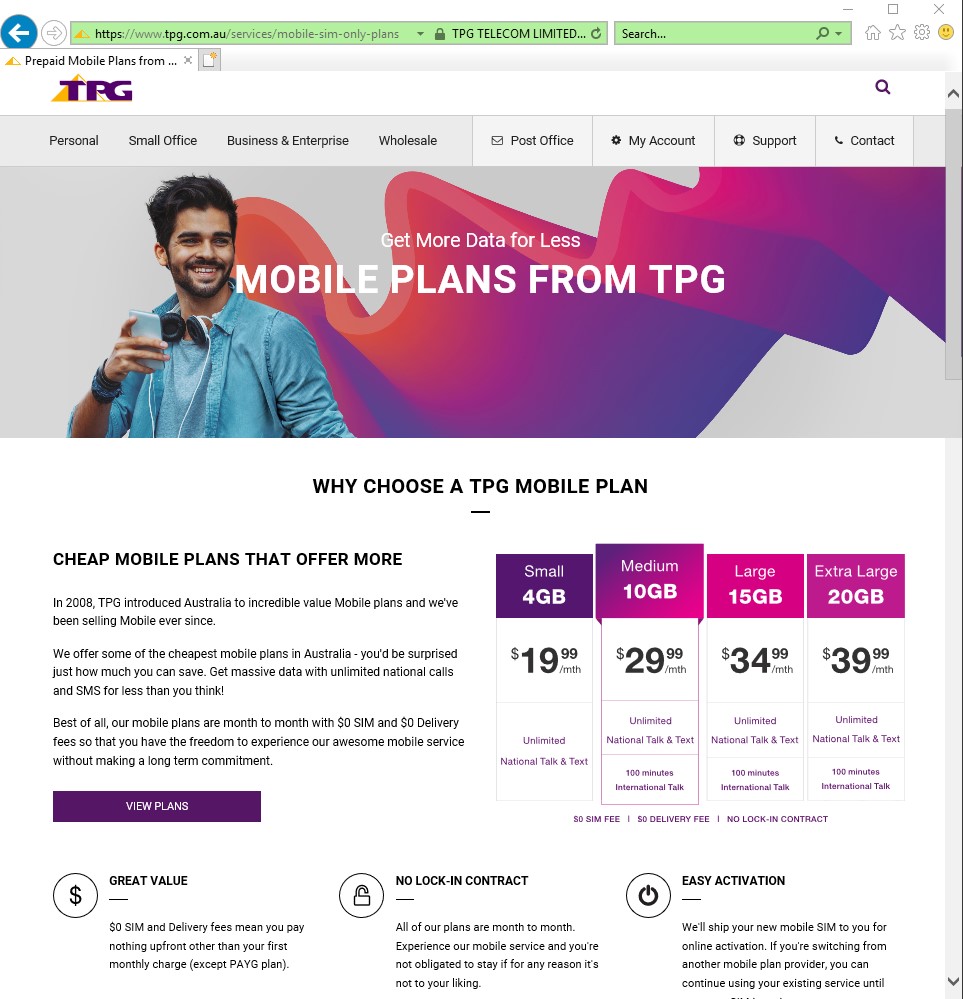

- Screenshot 2A: “Why Choose a TPG Mobile Plan”;

o Note link to “view plans” (click through to reach screenshot 3A);

o For screenshot 2B and 2C, scroll down;

- Screenshot 2B-2C: “Check Out Our Prepaid Mobile Plans”

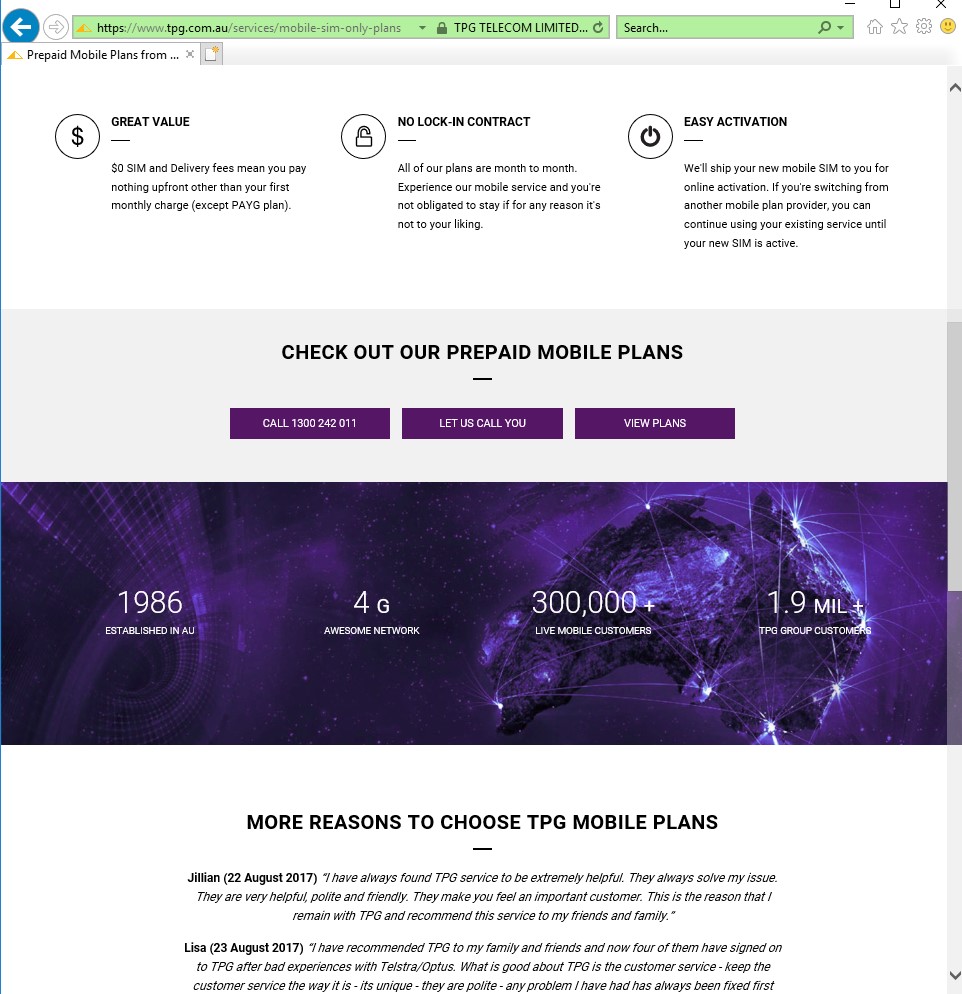

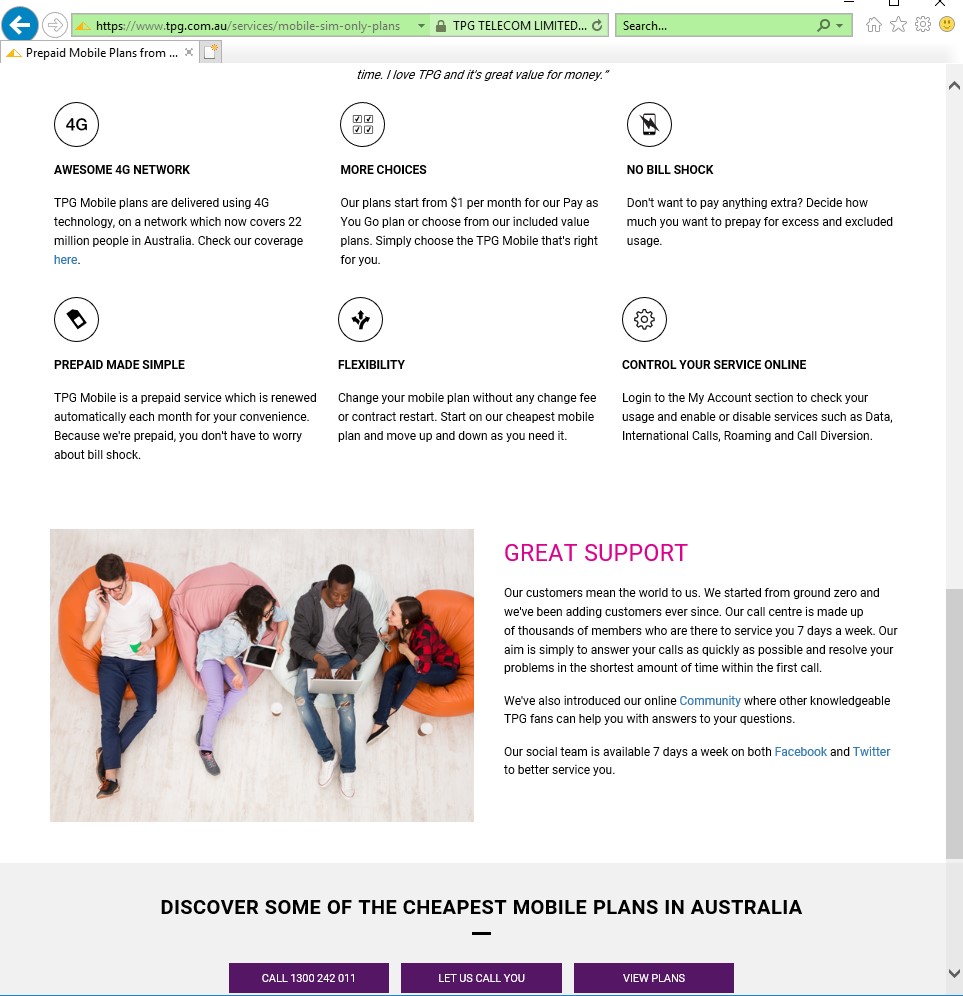

- Screenshot 2C: More details/features

- Screenshot 3A-3B: Various plans, listed according to their per month price;

o “Hover” over “minimum charge” (on the “$1/Mth” option);

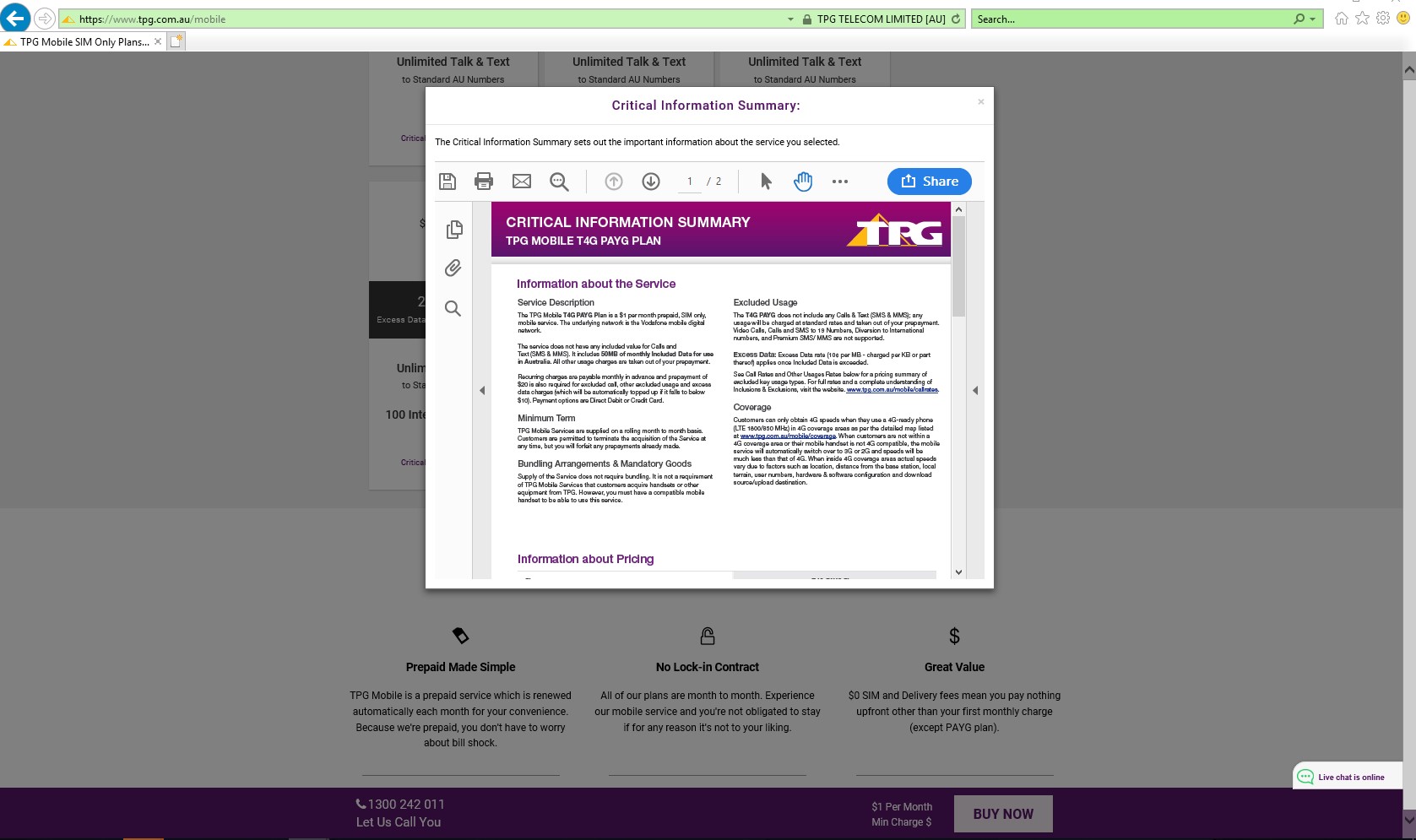

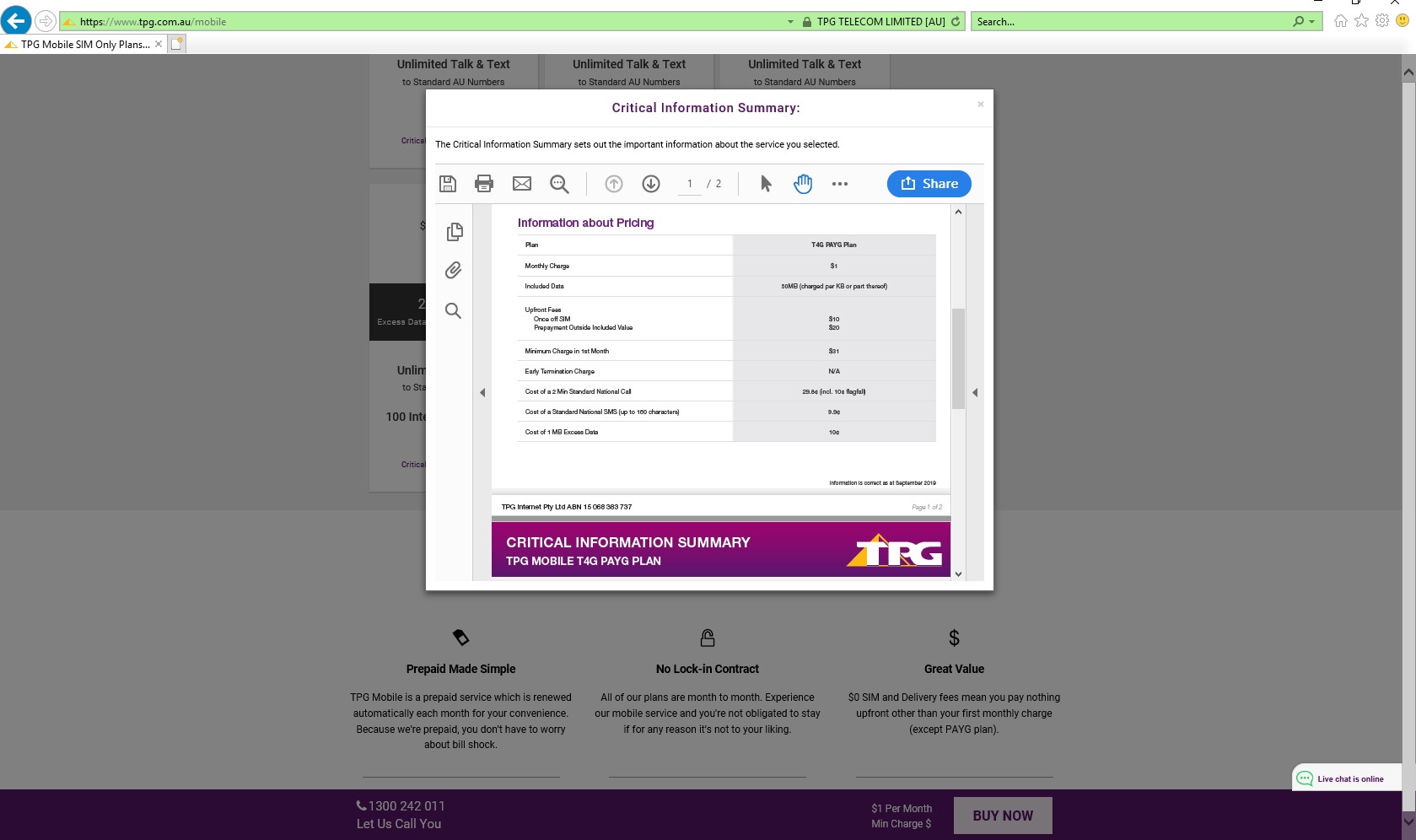

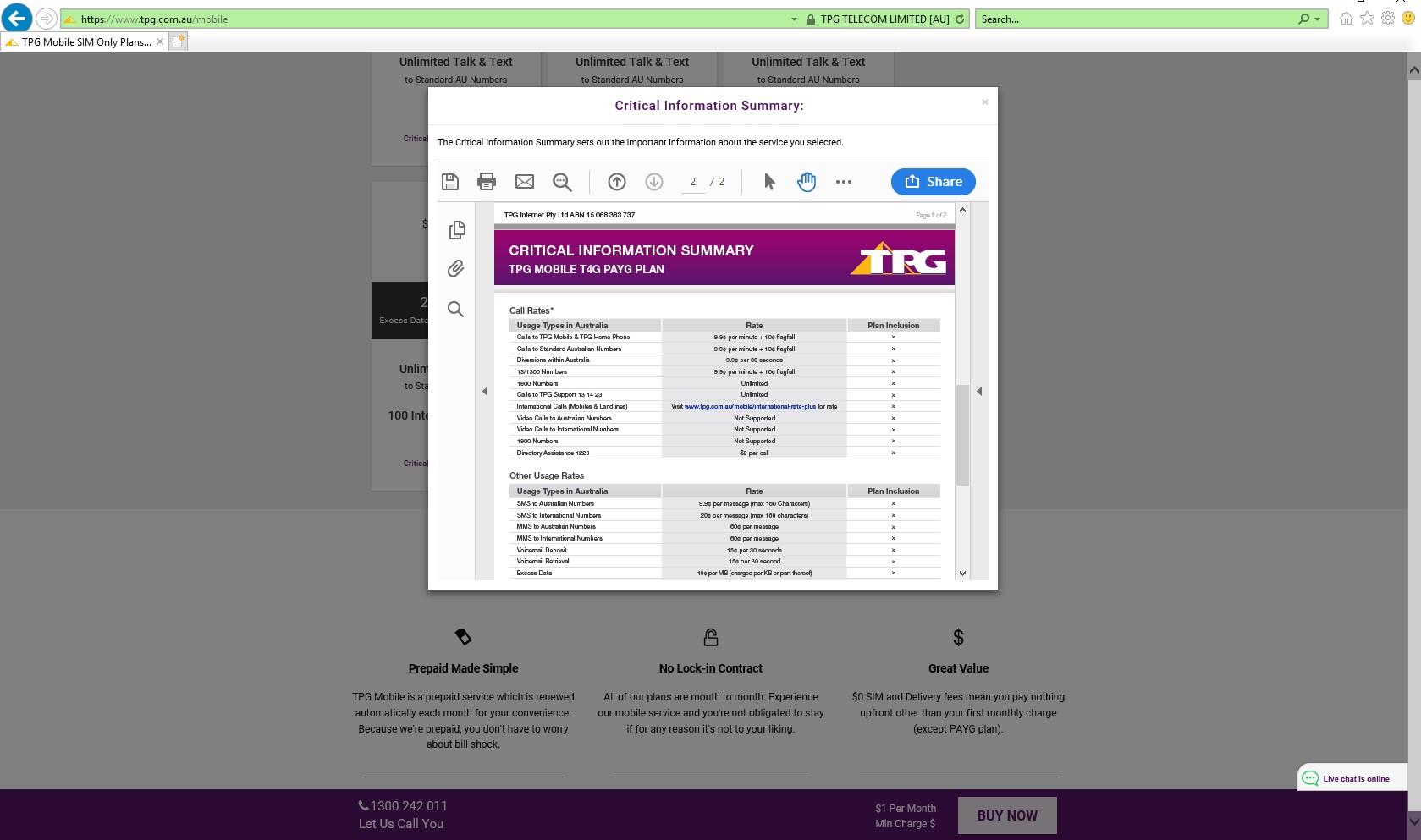

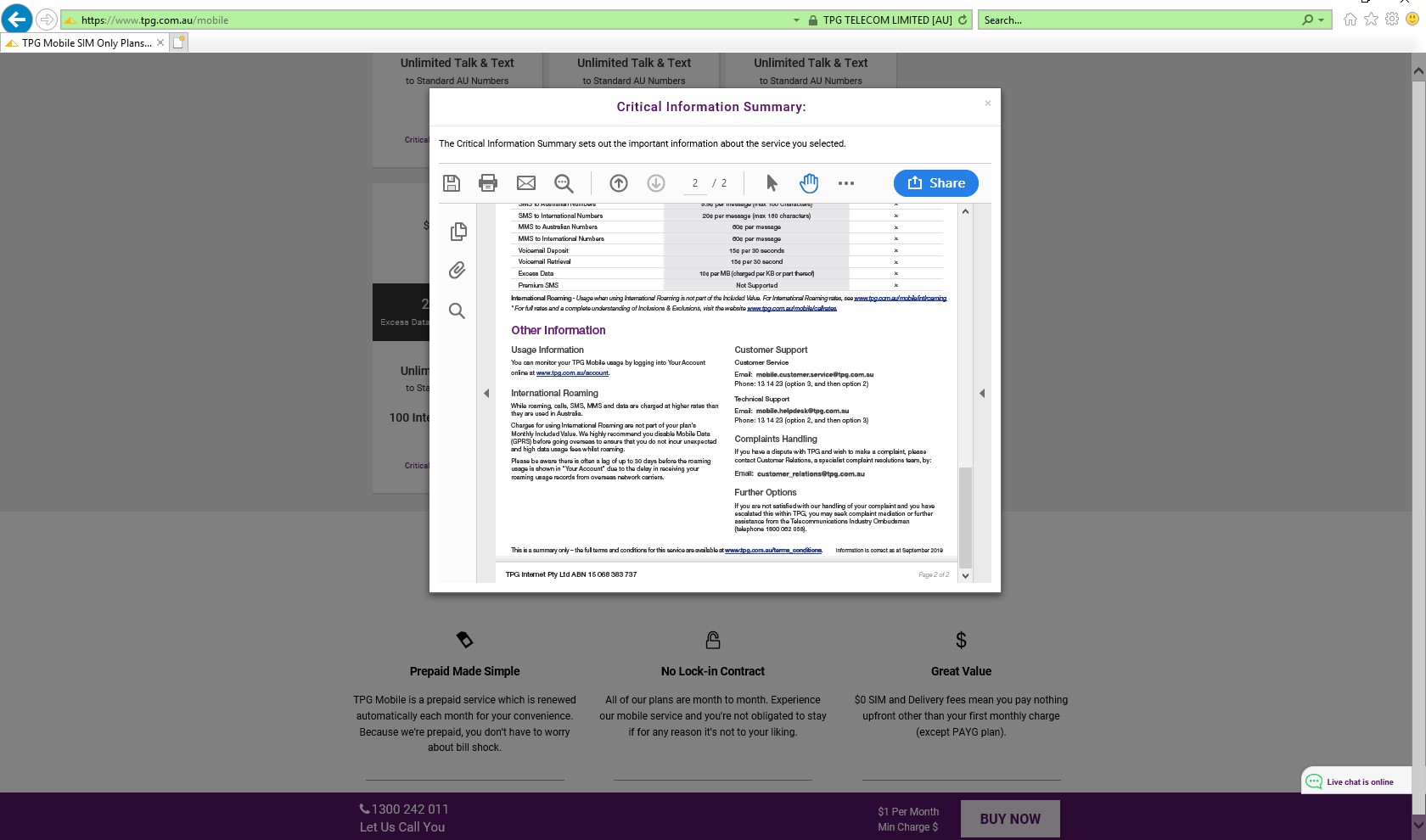

o (Click on “Critical Information Summary” to download pdf – included in Annexure A as Critical Information Summary 1 – 4);

- Screenshot 4: Information regarding minimum charge;

o Scroll down, through Screenshot 5 until Screenshot 6;

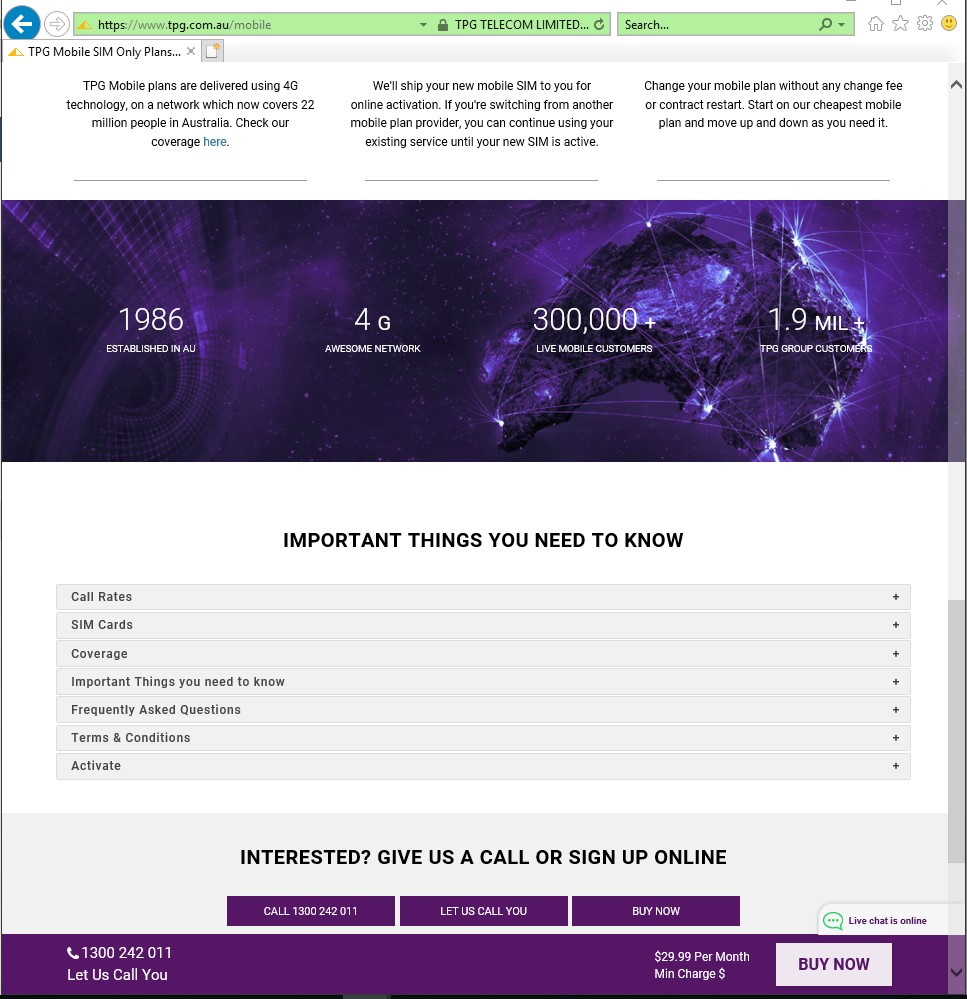

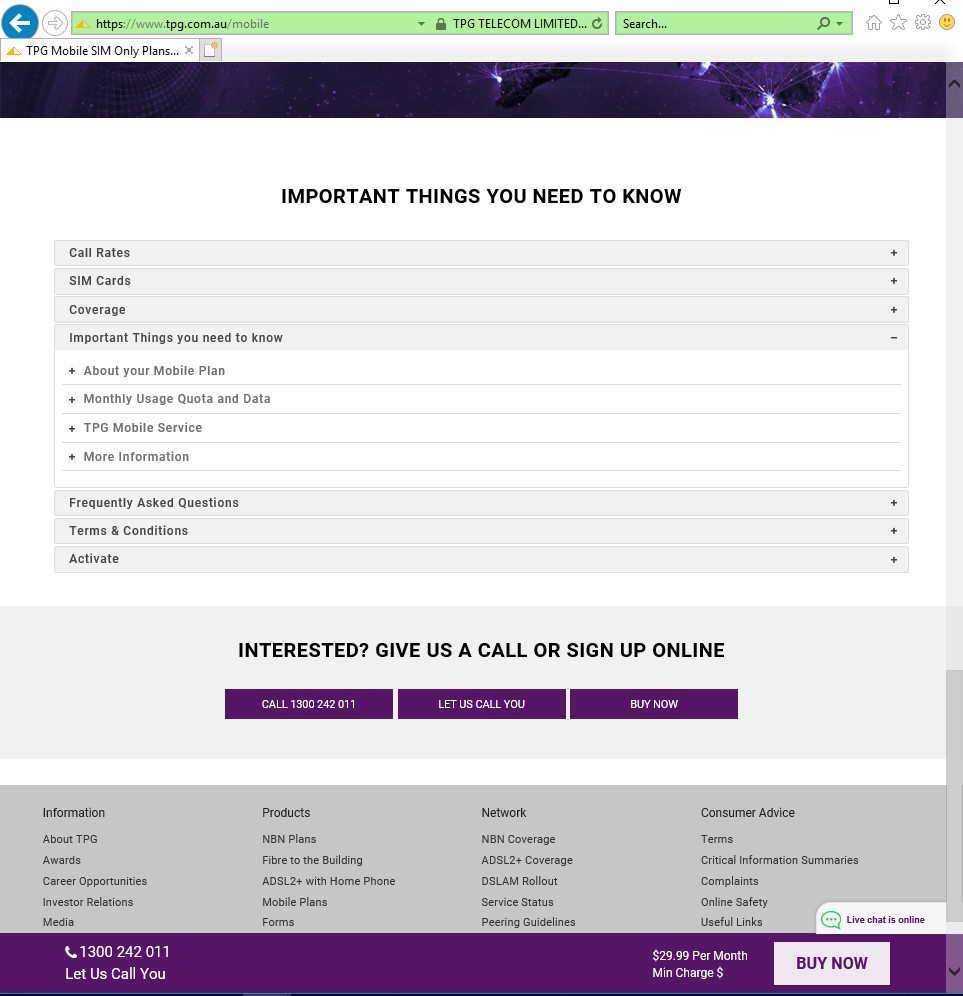

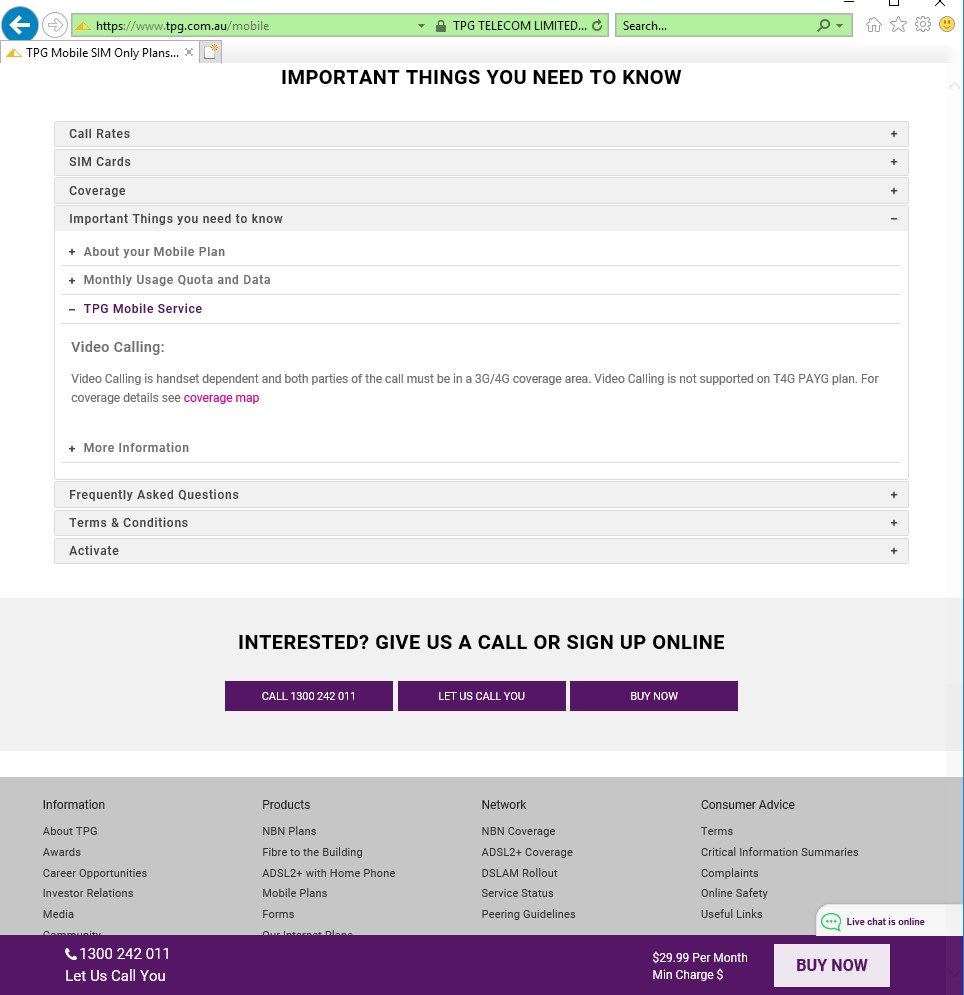

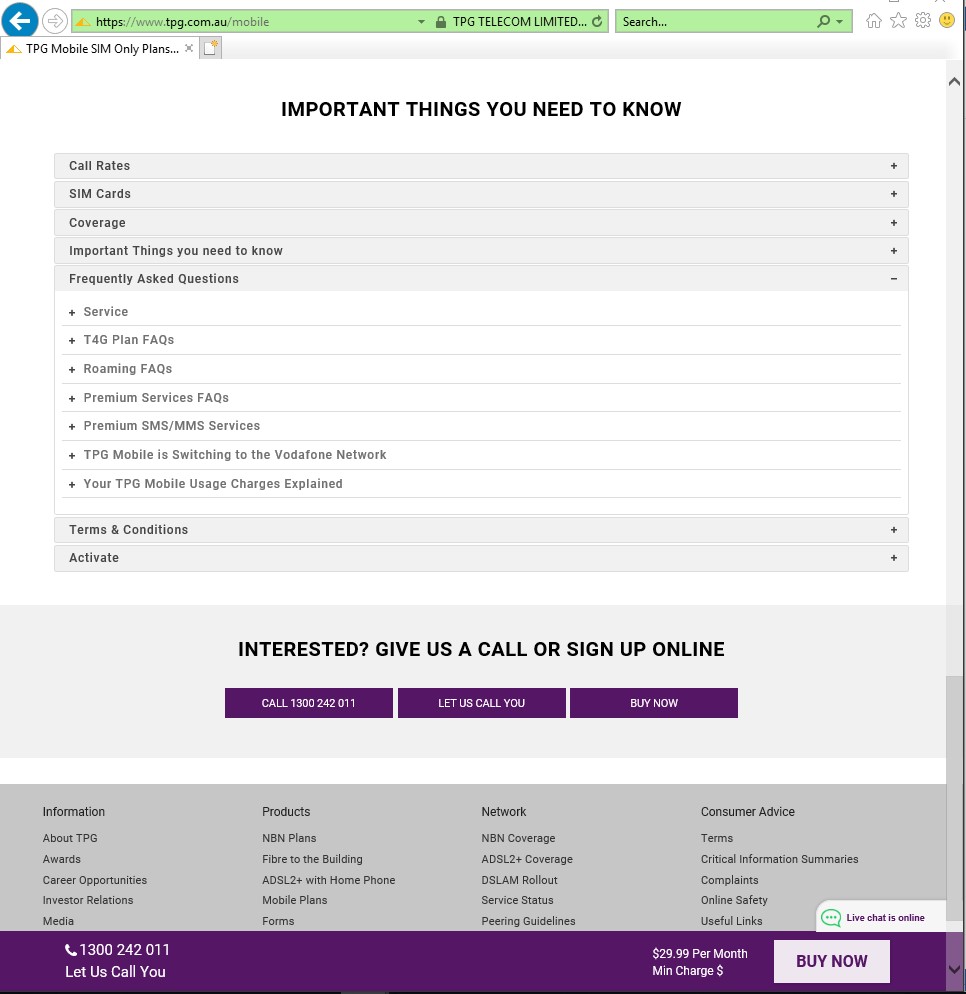

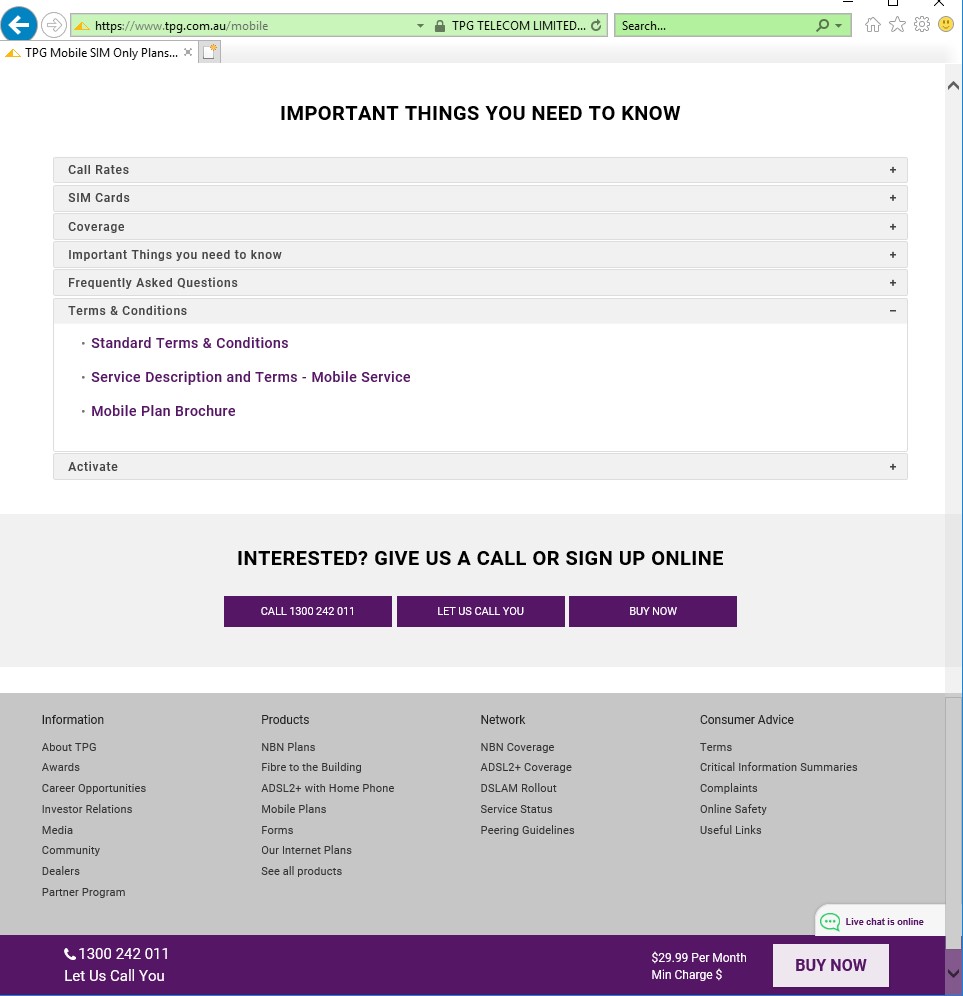

- Screenshot 6: “Important Things You Need To Know”

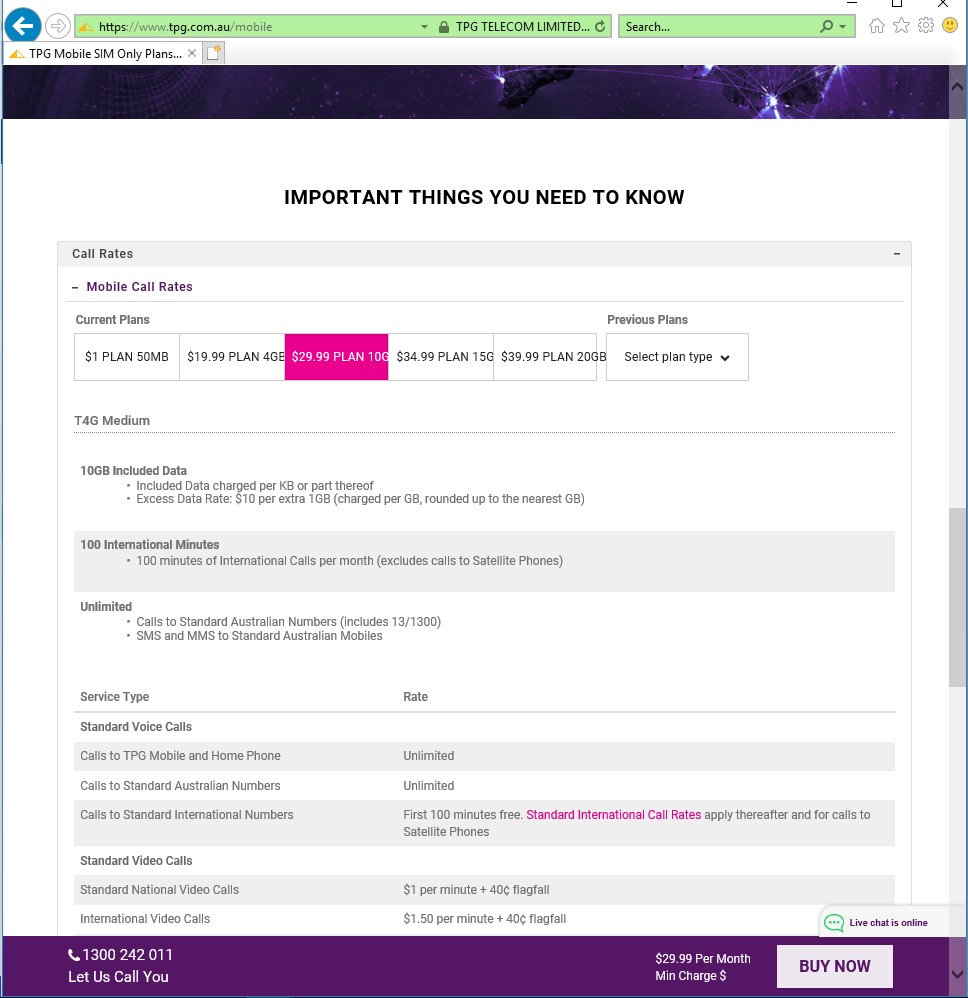

o Click on “Call Rates”;

o Click on “Mobile Call Rates”;

- Screenshot 7: “Important Things You Need To Know” – “Mobile Call Rates”

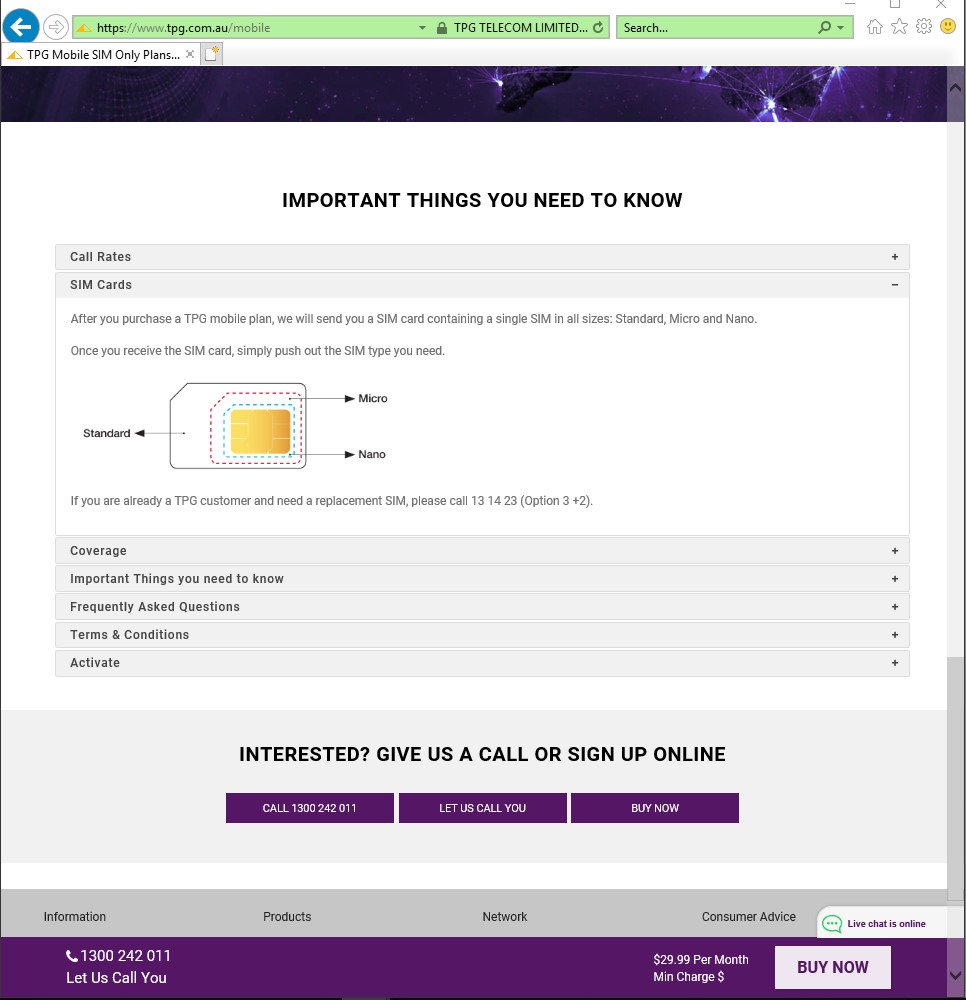

o Scroll down to and click on “SIM Cards”;

- Screenshot 8: “Important Things You Need To Know” – “Sim Cards”

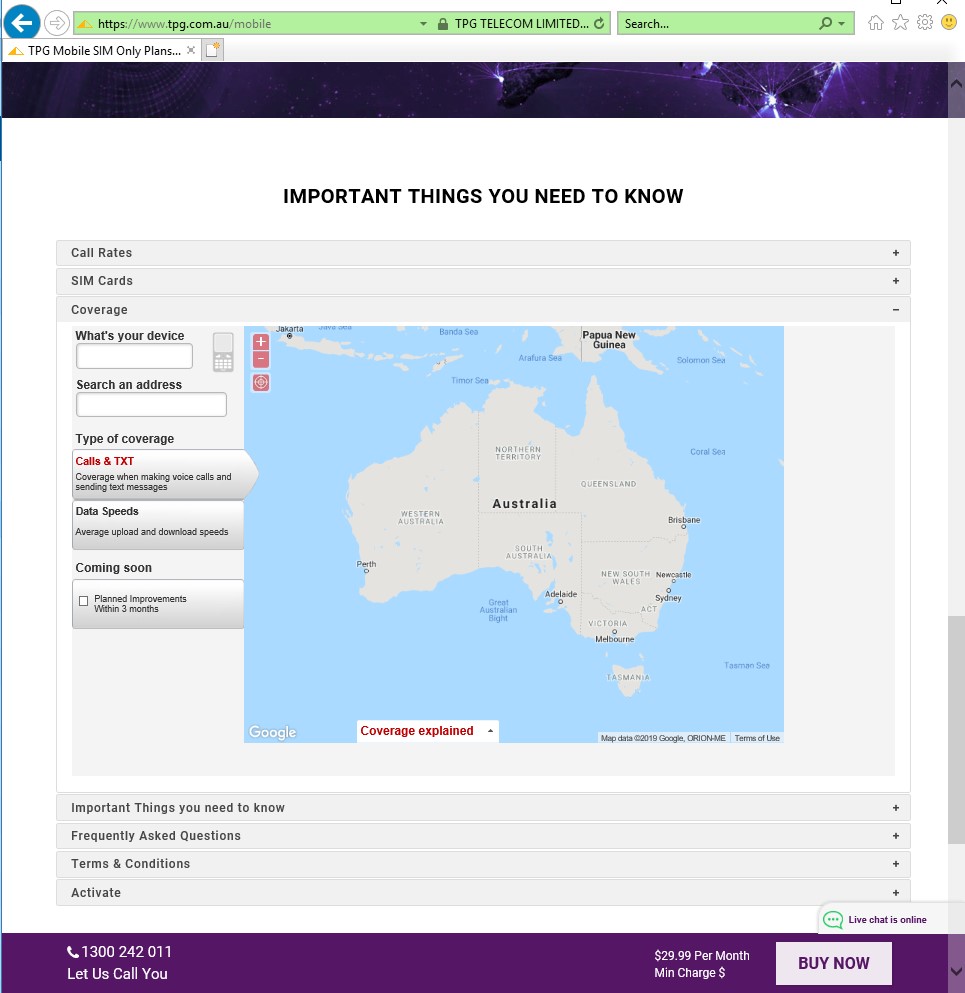

o Scroll down to and click on “Coverage”;

- Screenshot 9: “Important Things You Need To Know” – “Coverage”

o Scroll down to and click on “Important Things you need to know” (also a heading included within the “Important Things You Need To Know” section) (Screenshot 10);

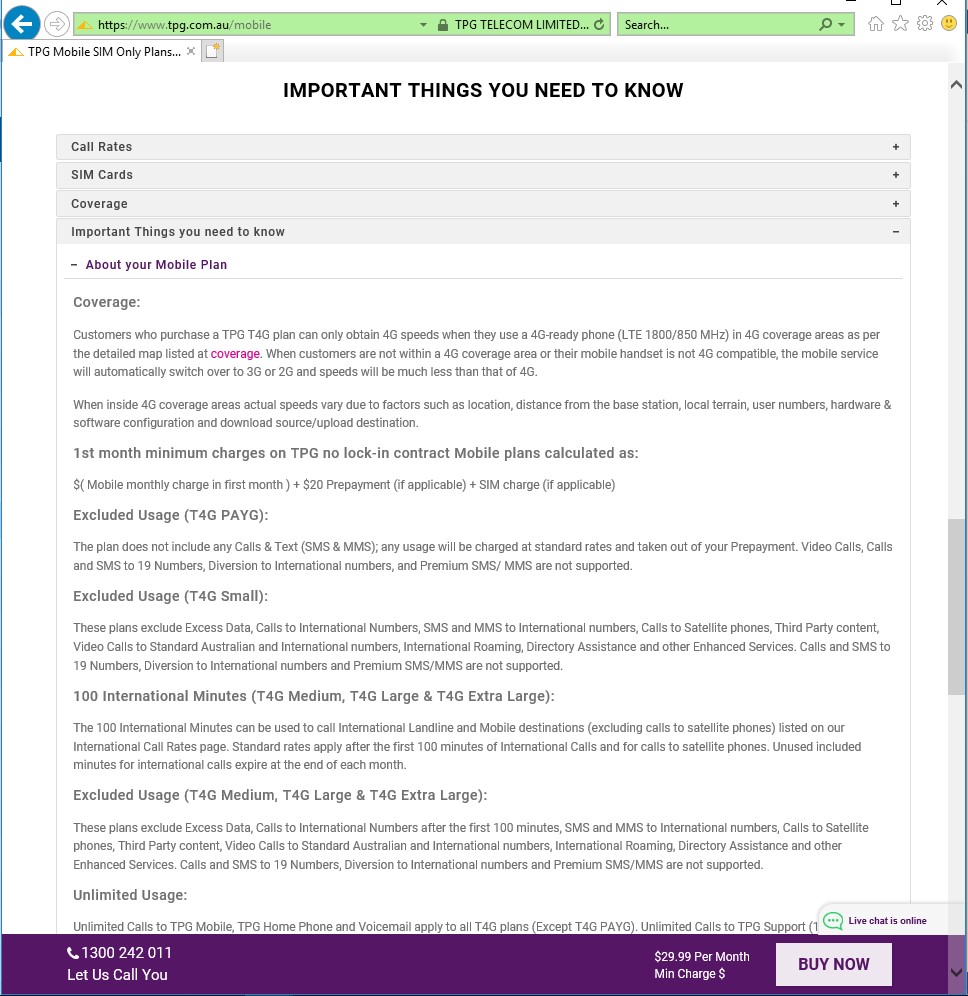

o Click “About your Mobile Plan”;

- Screenshot 11A-11B: “Important Things You Need To Know” – “Important Things you need to know” – “About your Mobile Plan”

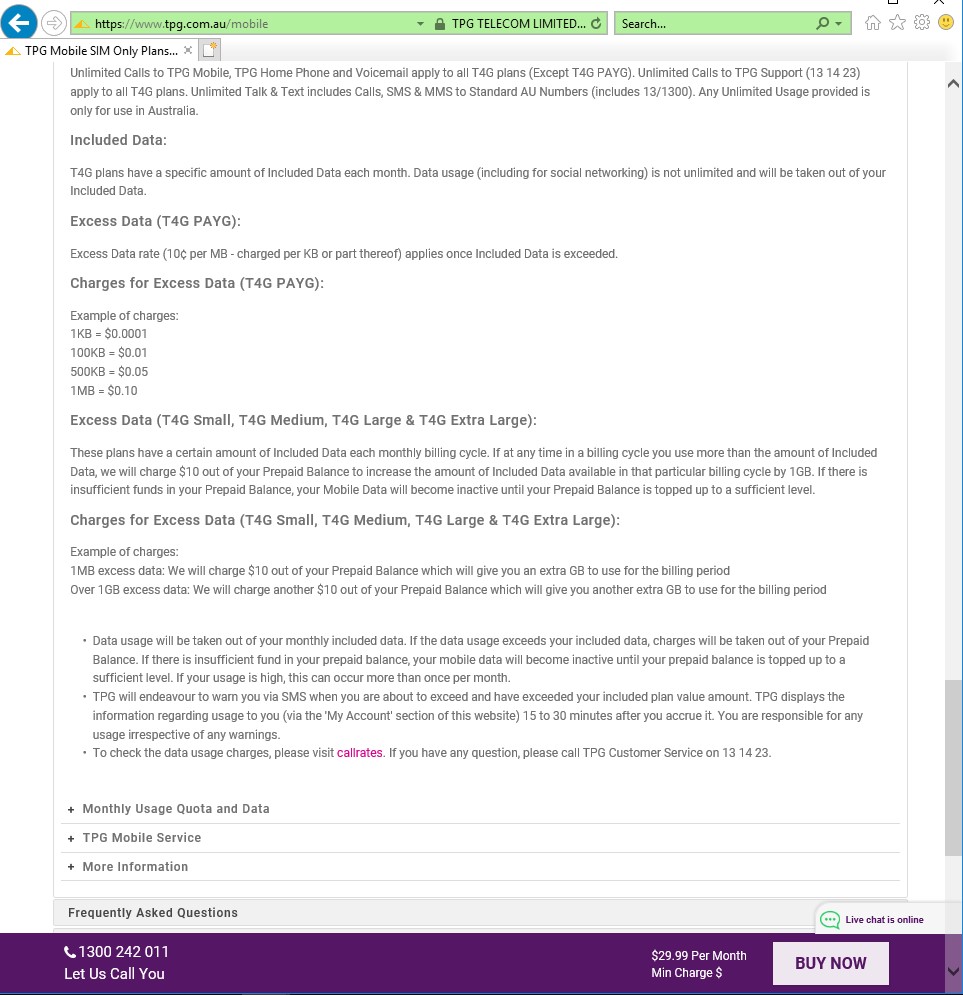

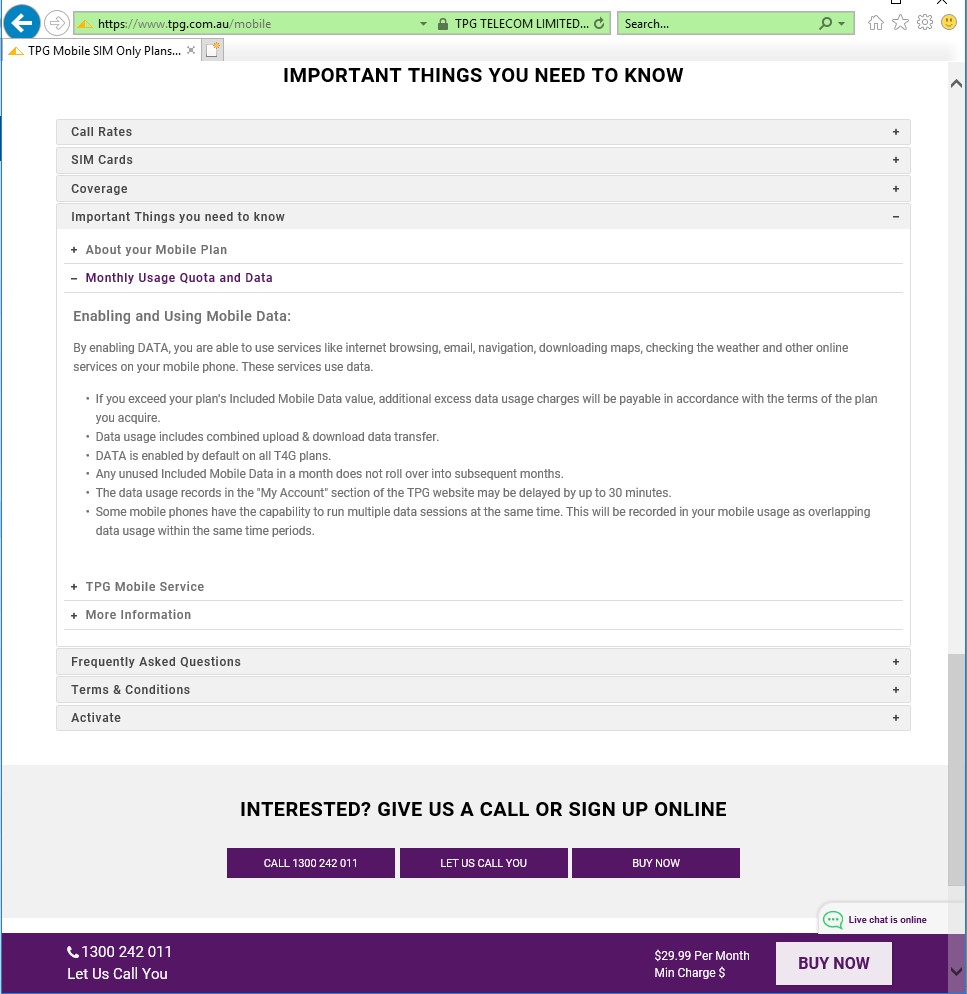

o Scroll down to and click “Monthly Usage Quota and Data”;

- Screenshot 12A: “Important Things You Need To Know” – “Important Things you need to know” – “Monthly Usage Quota and Data”

o Scroll down to and click “TPG Mobile Service”;

- Screenshot 12B: “Important Things You Need To Know” – “Important Things you need to know” – “TPG Mobile Service”;

o Scroll down to and click “More Information”;

- Screenshot 13: “Important Things You Need To Know” – “Important Things you need to know” – “More Information”;

o Click on the “Terms and Conditions”, and then “Mobile Plan Brochure” within that;

o Scroll down and click on “Terms and Conditions” (Screenshot 14), then “Mobile Plan Brochure” (Screenshot 15);

- Plan Brochure Page 1-4: Mobile Plan Brochure for $1 per month plan.

19 The Automatic Top-Up Term and the Forfeiture Term are found in Annexure A, at pages 45 and 51.

20 Under the Telecommunications Consumer Protection Code, telecommunications service providers must provide such a summary of their offers. The Critical Information Summary extracted in Annexure A (see pages 52-55) is provided in compliance with that Code, and relevantly states:

The service does not have any included value for Calls and Text (SMS & MMS). It includes 50 MB of monthly Included Data for use in Australia. All other usage charges are taken out of your prepayment.

Recurring charges are payable monthly in advance and prepayment of $20 is also required for excluded call, other excluded usage and access data charges (which will be automatically topped up if it falls to below $10). Payment options are Direct Debit or Credit Card.

Minimum Term

TPG Mobile Services are supplied on a rolling month to month basis. Customers are permitted to terminate the acquisition of the Service at any time, but you will forfeit any prepayments already made.

21 The parties also agreed that the contractual provisions are not open for negotiation by customers and that the Forfeiture Term, in the context of the Automatic Top-Up Term, is a term of a consumer contract within the meaning of the ACL.

22 The ACCC did not adduce evidence, other than to tender certain of the attachments to the ASOF. It is not necessary to go to those documents in any detail in these reasons, because the hearing was conducted on the basis that the screenshots in Annexure A are sufficiently representative of each of the plans the subject of this proceeding since 2013.

Additional evidence relied on by TPG

23 TPG read the following affidavits:

(a) an affidavit of Caroline Zhi Hong He, Corporate Counsel of TPG, sworn 21 May 2019, exhibiting a bundle of documents comprising the terms and conditions of various other products or plans offered by other telecommunications providers and other companies;

(b) an affidavit of Gregory David Churchill-Bateman, Manager, Research and Development, of TPG, affirmed 22 May 2019, giving evidence in relation to the management and administration of prepayments by TPG through the Internet Administration System; and

(c) a second affidavit of Mr Churchill-Bateman, affirmed 12 July 2019.

24 It also sought to rely on parts of an expert report of Jason Ockerby, Economist with the Competition Economist Group, dated July 2019.

25 Ms He’s affidavit exhibited a series of documents containing the terms and conditions upon which similar mobile, internet and home telephone services are offered by TPG’s competitors, together with a summary of their terms relating to “top up” and “forfeiture”. The point of doing so was in aid of a written submission, not referred to in the course of TPG’s oral submissions, that it is reasonable to infer that a reasonable member of the relevant class of consumers of telecommunications services may have some general familiarity with, and awareness of, contracts offering services of a particular value on the basis that if the value is not used by the expiry date, the value is forfeited. In the absence of any relevant evidence from consumers about it, I am not inclined to draw such an inference.

26 Mr Churchill-Bateman’s affidavit evidence included evidence to the effect that a customer, in certain limited circumstances, is able to use all of the prepayment for telecommunications services while their plan remains on foot, including where the automatic top-up payment is not received by TPG (either by virtue of some error, or because the customer takes steps to withdraw their authority for that payment) or where customers use all of the value of the prepayment prior to cancellation, but before the automatic top-up occurs. But those numbers are small. 5,936 out of approximately 593,000 fixed line customers, and 1,755 out of approximately 214,000 mobile customers who cancelled their plans during the relevant period forfeited no amount of their prepayment. Although something was sought to be made of this point in TPG’s written submissions, the fact that in some limited circumstances a customer may be able to cancel without forfeiting any amount of prepayment was not accorded any significance in closing oral submissions. Indeed senior counsel for TPG, Mr BW Walker SC, who appeared with Ms V Brigden, described those circumstances as “accidental”.

27 Mr Churchill-Bateman also gave evidence that in certain circumstances customers are able to use services to a greater value than that of their prepayment, and that in those circumstances, where the individual amounts are, taken in isolation, minor, TPG does not seek to recover them. He swore that “[t]he commercial effect of the Plan is that [TPG] absorbs and bears any amount in excess of the Prepayment balance … by adjusting the charge applicable to a call that would, in the ordinary course take the Prepayment balance to below $0, to an amount that is $0.” He did so by reference to specific examples, including where the customer had incurred $144.43 for call charges that were not recovered by Top-Up Payments. In his second affidavit, Mr Churchill-Bateman swore that the total of the customer unrecovered usage charges for May 2013 to May 2019, for both mobile and fixed line services, was $9.544m.

28 TPG also relied on correspondence between it and the ACCC, dating back to 16 January 2015, about the commercial rationale and effect of the plans offered by TPG. In a letter bearing that date, the General Counsel of TPG told the ACCC that there had been a change in TPG’s mobile plan arrangements commencing in around February 2013. The letter said that the change, meaning the introduction of the form of plan a subject of this proceeding, had been made to ensure compliance with the then recently introduced Telecommunications Consumer Protection Code. The letter continued that the “business model” of the then new arrangements “was designed to minimise the serious effects that bad debt has on the telecommunications industry and the cost of telecommunications services” and that “[b]ad debt on mobile services has historically been very high, the effect of which was that good payers were paying for the telecommunications services of bad payers”.

29 The letter also explained that before the introduction of the Code, that is prior to April 2013, the TPG business model “was that a $20 payment would be made from which TPG would deduct charges incurred for usage outside included value. This payment was referred to predominantly as a deposit. As charges were incurred, an automatic top up of the $20 would be made. The $20 was refunded when the customer terminated the service.”

30 The letter then said that “[t]he TCP code had the effect of removing our ability to offer our services on those terms unless the service was a prepaid service, that is a service for which payment must be made before usage could occur”. (Emphasis in original).

31 In another letter from TPG’s General Counsel to the ACCC, dated 1 August 2017, TPG explained:

TPG’s general view is that a good competitive market requires innovative business models and services to be made available to consumers so that they have a choice. The reason TPG has brought its particular model is predominantly so that it can offer a low-cost plan to telecommunications consumers. In order to keep the product cheap, business must run at its most efficient. Bad debts and collections have been a significant overhead cost that telecommunications consumers have been required to bear. The TPG arrangements improve that efficiency for the benefit of all consumers.

32 TPG also submitted, and the ACCC did not dispute, that an inference may be drawn that in the ordinary case the amount forfeited when a customer cancels their plan is somewhere between $10 and $20.

33 I should also say something about Mr Ockerby’s report. The parties agreed that large parts of it should be excluded, and further agreed that I should make a direction under r 5(3), Item 19, of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (the Rules) that the balance of it “be read as amounting to a submission”. I made such a direction, but it was not explained to me what use I could or should make of the material, especially matters of alleged fact, when the material is advanced by way of submission. Most of what remained of the report concerns the results of a survey that Mr Ockerby conducted of products offered by competitors in the market, and sought to advance what I would have thought is the obvious enough proposition that if TPG were effectively not permitted to sell its products with the existing “Prepayment Plan”, it would need to change the structure of its product offerings in order to maintain profit levels. He also “submitted” that TPG’s repayment arrangements, including the Forfeiture Term, is part of its “legitimate business strategy”. In any event, as I say, it was not explained what use I should or could make of an untested expert report about such matters of fact and opinion “converted” into a submission, so I will put it to one side.

The issues

34 Two questions arise:

(a) is the use of the word “Prepayment” misleading or deceptive?; and

(b) is the Forfeiture Term unfair?

Is use of the word “Prepayment” misleading or deceptive?

Applicable legal principles not disputed

35 Section 18(1) of the ACL provides:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

36 Section 29(1) of the ACL provides (relevantly):

A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of … services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply of ... services:

…

(b) make a false or misleading representation that services are of a particular ... value … ; or

…

(i) make a false or misleading representation with respect to the price of services.

37 Section 34 of the ACL provides:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is liable to mislead the public as to the nature, the characteristics, the suitability for their purpose or the quantity of any services.

38 TPG agreed with the following statements of principle contained in the ACCC’s written submissions, subject to some additional points.

39 Conduct, including the making of representations, is misleading or deceptive if it has a tendency to lead into error, provided that there is a sufficient causal link between the conduct and the error on the part of the person exposed to the conduct. See Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640 at 651, [39] (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ).

40 The question of whether conduct, including conduct by way of the making of representations, is misleading or deceptive or false is a question of fact, to be determined by an objective consideration in light of all the relevant surrounding circumstances.

41 The words used in advertising or promotional material are in many cases capable of conveying different meanings. The question is whether the meaning said to be false or misleading is reasonably open and may be drawn by a significant number of persons to whom the presentation was addressed. See Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v HJ Heinz Company Australia Ltd [2018] FCA 360; (2018) 363 ALR 136 at 145, [43] (White J).

42 As Weinberg J said in CPA Australia Ltd v Dunn [2007] FCA 1966; (2007) 74 IPR 495 at 501, [28]:

Statements that are capable of more than one meaning may be misleading or deceptive provided that the meaning for which the applicant contends is one that would be reasonably open, and might be drawn by a significant number of those to whom the representation is made. In the same way, a statement may contain a representation that is implied, rather than express. That is why a statement that is literally true can be misleading or deceptive.

43 When the impugned conduct involves representations or conduct towards the public at large or to a section of the public, such as prospective retail purchasers of goods or services, regard must be had to the effect of the representation on “ordinary” or “reasonable” members of the class of prospective purchasers. The range of persons in such a class may be quite broad, and may include the intelligent as well as the less intelligent, and those who are well educated as well as those who are less literate. See HJ Heinz at 145, [42]. Generally speaking, the class will not include those who fail to take reasonable care for their own interests.

44 In that class of case where the “actual or threatened conduct involving representations to the public at large or to a section thereof, such as prospective retail purchasers of a product the respondent markets … the issue with respect to the sufficiency of the nexus between the conduct or the apprehended conduct and the misleading or deception or likely misleading or deception of prospective purchasers is to be approached at a level of abstraction not present where the case is one involving an express untrue representation allegedly made only to identified individuals”. See Campomar Sociedad Limitada v Nike International Ltd (2000) 202 CLR 45 at 84-85, [101] (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby, Hayne and Callinan JJ).

45 It is in these cases that enter the “ordinary” or “reasonable” members of the class of prospective purchasers. As the Court explained in Campomar at [102]:

Although a class of consumers may be expected to include a wide range of persons, in isolating the “ordinary” or “reasonable” members of that class, there is an objective attribution of certain characteristics. Thus, in Puxu, Gibbs CJ determined that the legislation did not impose burdens which operated for the benefit of persons “who fail[ed] to take reasonable care of their own interests”. In the same case, Mason J concluded that, whilst it was unlikely that an ordinary purchaser would notice the very slight differences in the appearance of the two items of furniture in question, nevertheless such a prospective purchaser reasonably could be expected to attempt to ascertain the brand name of the particular type of furniture on offer.

46 Where the persons in question are not identified individuals to whom a particular misrepresentation has been made, but are members of a class to which the misrepresentation was directed in a general sense, “it is necessary to isolate by some criterion a representative member of that class. The inquiry thus is to be made with respect to this hypothetical individual why the misconception complained has arisen or is likely to arise if no injunctive relief be granted”. See Campomar at [103].

47 In that regard, the relevant class of consumers includes prospective purchasers of prepaid retail telecommunications services, being mobile, internet and home telephone services. TPG agrees with the ACCC’s submission that the class comprises the majority of the Australian adult population, but submits that the class is limited to people with some knowledge of, and familiarity with, the internet and navigation of web pages.

48 TPG submitted that the following propositions, which the ACCC did not dispute, were also relevant.

49 The effect of the relevant conduct must not be judged by reference to those who fail to take reasonable care of their own interests. See Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu (1982) 149 CLR 191 at 199 (Gibbs CJ).

50 The context in which the alleged representations were made is material to a consideration of whether they conveyed the matters alleged. The statements were not made in the context of advertisements that might be described as “an unbidden intrusion on the consciousness of the target audience intended to arrest its attention”. See Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Homeopathy Plus! Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1412; (2014) 146 ALD 278 at 305, [123] (Perry J). As in Homeopathy Plus! (at 305, [123]), the only members of the class who would see the alleged representations would be those who chose to access and navigate the TPG Website, presumably potential purchasers, in the context of the calm of a (virtual) showroom. For this reason, it could be expected that a reasonable consumer in the particular class would take the time to ascertain contractual terms of importance to them before entering into a transaction.

51 In that regard, the nature of the TPG Website and of the intended purchase is such that consumers are able to take the time to study particular webpages, and to go back and forward between the pages should they so desire, and may click on all or some, or none, of the available hyperlinks. The information displayed on the TPG Website is not fleeting or momentary, but may be viewed and digested at whatever pace the individual consumer chooses. These features were considered relevant to the overall context of the website statements in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Jetstar Airways [2015] FCA 1263 at [174] (Foster J).

The ACCC’s case

52 The ACCC submits that by the website statements, examples of which are in Annexure A to these reasons, TPG represented to its prospective customers that the prepayment was an advance payment for services that the customer could use, and that the full amount of the prepayment could be used for telecommunications services before the customer cancelled their plan. In the ACCC’s pleading, that was called the “Prepayment Use Representation”.

53 The ACCC submits that prospective TPG customers were told that the prepayment was for “usage that (was) not part of the included value” of their plan, and that it is necessarily implied from the use of the words “prepayment” and “usage” that the customer is making a payment in advance for services and that the customer can in fact use the payment for services.

54 The ACCC submits that by making the Prepayment Use Representation, TPG engaged in conduct which was misleading and deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18(1) of the ACL, and made false and misleading representations with respect to the value and price of telecommunications services in contravention of ss 29(1)(b) and (i) of the ACL because, by the combined operation of the Automatic Top-Up Term and the Forfeiture Term, at least $10 of the prepayment cannot be used for services. That is so, it is alleged, because once the balance of the prepayment falls below $10, TPG automatically tops up the balance by taking payment from the customer’s credit card or bank account, and any prepayment balance is forfeited if and when the customer cancels their plan.

55 During the course of his oral submissions, senior counsel for the ACCC, Mr CM Scerri QC, who appeared with Ms E Bennett, put the ACCC’s submission in this way:

MR SCERRI: So say that the customer … uses $9, there is no top-up on that occasion, but the customer has still made a prepayment of $11. He …or she cannot use [more than a dollar of] that $11 … without triggering the top-up. And then we’re back in the same situation. It’s … the top-up provision that causes the problem. If there were no automatic top-up provision, we couldn’t be making our [principal] allegation, which is that the prepayment is [a mis-]description of the payment because it relates to services in relation to the $10 or the $11 or whatever it is that cannot be used. So you really have to look at it with the [question] – is that proposition valid? That is, if [you] can’t use the service, is it misleading to describe the amount as a prepayment? … [I]t’s no more than an access fee, a non-refundable access fee. Access to the entitlement or the opportunity to use the excluded services.

HIS HONOUR: If they called it an access fee, would you have a complaint?

MR SCERRI: We wouldn’t be complaining if they called it an access fee. That would be correct.

56 It follows that the ACCC attributes particular significance to TPG’s use of the word “prepayment”, as Mr Scerri later explained in his oral submissions:

MR SCERRI:… we do put a lot of weight on what prepayment means, and we say prepayment means you’re paying in advance for something you can use. So that’s why it’s so different to the case where I buy a $20 phone plan and I’m told if you don’t use it all this month, it’s forfeited or it’s cancelled. That’s a genuine prepayment. And I’ve got no complaint about that; that’s what it says. But here it’s calling it prepayment, and interacting with the way the … automatic top-up works, and which can happen … several times, and then you combine it with the forfeiture of the amount – not the usage, but the amount. That’s the vice. That’s what we say is misleading or deceptive, in a nutshell.

57 Mr Scerri made an additional point in his oral submissions about the importance of the context in which the Prepayment Use Representation is made, which has to do with the order in which the relevant provisions appear to the consumer:

MR SCERRI: Well, it’s really the obvious point that it’s about context. And that you can have – conduct can be misleading even though, before the customer signs, the true position is disclosed. So here what happens is you go to the web page. You see it’s a – the one we took you to was a $1 plan. It tells you in your first month it’s actually $31, $20 of which is the so-called prepayment. And we say that’s misleading. And if you read on you will find out that you lose that upon cancellation if you haven’t used it. We say that, in that context, it is still misleading to call it a prepayment, because the fact that it’s forfeited and the fact that the forfeiture is disclosed, doesn’t dispel the misleading representation that it’s a prepayment for services you can actually use in the real world.

And the reason for that is because the automatic top-up operates, and upon cancellation, if you haven’t used it, you haven’t used it. It’s as basic as that proposition.

58 Before turning to TPG’s submissions, I should briefly mention another point that the ACCC made in its written submissions, but which was not embraced with any enthusiasm by counsel during oral submissions. The written submission relates to the second pleaded representation and is as follows:

40 The ACCC submits that by characterising the amount as a “prepayment” for usage outside the included value, TPG also represented to customers that the purpose of holding these funds was to apply them to the payment of telecommunications services and that if the Prepayment was not required for that purpose, it would be returned to the customer (Prepayment Refund Representation).

41 Customers must navigate through multiple drop-down buttons on TPG’s website to locate the Forfeiture Term. It is in very fine print in a detailed clause in the terms and conditions. If the customer finds the clause, they would then need to carefully read the clause in order to be informed that the Prepayment is forfeited on cancellation. This disclosure to customers was inadequate.

59 But as Mr Scerri volunteered at the hearing, “it’s not our strongest point, I readily concede”. I do not propose to deal with the point in any detail, save to say that I do not accept it, among other reasons, because each of the relevant terms, including the Forfeiture Term and the Automatic Top-Up Term, is in the same sized print; there is no evidence or other basis to assume (as the submission does) that a consumer would read some clauses and not others, merely because of the order in which they appear; and a forfeiture clause, in the natural sequence of things, would be expected to appear at the end of the relevant sequence of provisions.

TPG’s case

60 Mr Walker submitted that the payment of $20 (or more if the customer asked) is properly to be characterised as a prepayment, and that there is nothing misleading or deceptive about so describing it. His main submissions in support of that proposition are these.

61 First, TPG accepts the ACCC’s contention that the $20 fee is indeed “a cost that TPG’s customers must pay to enter into the plan”. As Mr Walker said, “[a]nd so it is, and none the worse for that” because “prepayment and compulsory cost … are not mutually exclusive”. His submission in that regard continued:

They’re describing different aspects of the matter: “If you want to make an agreement with me, you must make this payment”. It is a prepayment in the sense that I’ve described. It’s also something you must do in order to obtain the services. These are not mutually exclusive categories and nothing is misleading, in different aspects of the stipulated terms, focusing on those different aspects of the same required payment.

62 Secondly, TPG submitted that, on the logic of the ACCC’s case, it could have no complaint if the word “prepayment” instead read “payment”. As Mr Walker put it, “if you took off ‘pre’ apparently it would be okay because it’s true that a payment of [$20] is required for usage not within the included value”.

63 Thirdly, TPG submitted that once it is understood that it is in the nature of things that the sum of $20 will commonly be fully expended in return for services used, and then “iteratively refreshed”, then it is a prepayment, as a matter of ordinary English. As Mr Walker put it:

It’s a payment in advance of services, and you can expend the whole of the $20, and the succeeding $20, and the succeeding $20 as long as you’re in the plan, except for a rump of the last $20 as you exit. That doesn’t mean it’s not a prepayment – far from it. It means it’s a prepayment on terms.

64 Fourthly, and relatedly, TPG submitted that there are no misrepresentations of the types alleged because the plans make clear the true position, namely that the $20 is money that a consumer can use for relevant “excluded services”, and in the usual case, where there will be at least $10, but no more than $20, left to the consumer’s credit upon cancellation, that amount will be forfeited. As Mr Walker put it:

And that is said up front, and it’s said that you won’t get that back. It’s a cost you pay as part of the overall service. It makes no difference whether you use the word “access” or “fee” or anything like that. It is genuinely a prepayment, in that over and over and over again it may be fully expended to pay. But if you have not fully expended it, then you will lose it. So it is a form of use-it-or-lose-it. And nobody has ever said that there is anything wrong, representationally, about use-it-or-lose-it provisions. No one would dream of saying that a use-it-or-lose-it tariff – which is, after all, represented to be a tariff for usage – is one that has become misleading because it may be lost.

Consideration of the pleaded misrepresentations

65 It seems to me, for reasons which I will explain, that there are two fundamental difficulties with the ACCC’s case about TPG’s use of the word “prepayment”. First, it assumes that a reasonable and ordinary consumer will not read, from its beginning to its end, the clause in which the Forfeiture Term is found, which appears as part of a number of “Important Things You Need To Know”. Secondly, it relies on a myopic approach to the definition of the word “prepayment”.

66 The ACCC agrees that it would have no issue with TPG if it used, instead of the word “prepayment”, the words “access fee”. And it did not cavil with Mr Walker’s submission that if the word “payment” had been substituted for “prepayment” then, likewise, it would take no issue with TPG. Further, the ACCC did not rely on evidence about any particular understanding of the term in the market place. Nor, for that matter, did it cite a dictionary definition of the word.

67 In my view, it is artificial to give the single word “prepayment” as much work to do as the ACCC case requires, and the meaning for which it contends is not reasonably open (cf CPA Australia Ltd v Dunn [2007] FCA 1966; (2007) 74 IPR 495 at 501, [28] (Weinberg J)).

68 In my view, a reasonable or ordinary prospective purchaser of retail mobile, internet and home telephone services would take the time to ascertain the contractual terms of importance to them, including reading the whole of the clause that contains the Forfeiture Term under the heading “Important Things You Need To Know”, before entering into a transaction to buy a relevant plan.

69 When the clause containing the Forfeiture Term is read from beginning to end, a reasonable or ordinary consumer would understand that the clause includes terms, one of which is that upon cancellation, whatever prepaid amount remains unspent (usually between $10 and $20) will be forfeited to TPG.

70 By the express terms of the clause in which the Forfeiture Term is found, a consumer is told, and a reasonable or ordinary consumer would understand, that:

(1) all TPG services are prepaid;

(2) monthly recurring charges are payable in advance;

(3) in addition, a prepayment for usage that is not within the included value (if any) for the plan acquired must be made;

(4) the initial prepayment will be $20;

(5) an automatic top up will occur when the amount of prepayment falls to below $10;

(6) if the included value is not exceeded, and no charges are incurred that are excluded from the plan, there will be no automatic top-ups; and

(7) if the prepayment is not used, it will be forfeited when the service is cancelled.

71 In my view, a reasonable or ordinary prospective purchaser of retail mobile, internet and home telephone services would read, and readily understand, each of those things. In particular, such a consumer would understand that the amount of the prepayment, which is only ever $20 in the ordinary case, over the whole term of the plan, is to be available for Excluded Services; that he or she must replenish the amount of the prepaid amount if it dips below $10; and that the benefits of that arrangement are available on condition that, if and when the customer cancels the plan, whatever amount of the prepayment that is not used (almost always between $10 and $20) is forfeited to TPG.

72 Otherwise, the prepayment is wholly referrable to excluded services, because aside from whatever amount is forfeited upon cancellation, the whole of the amount that otherwise sits in a consumer’s prepaid account from time to time during the term of the plan can only ever be used for such (prepaid) services. But a reasonable or ordinary consumer will know that there will always be an amount held by TPG in advance of providing any excluded service. As Mr Walker put it, and I agree, “the notion that there is some violent or radical contradiction between the word ‘prepayment’ and the real likelihood of some or all of the $20 being forfeited eventually is not real, and barely apparent…prepayments and compulsory cost [are] … not mutually exclusive… ‘If you want to make an agreement with me, you must make this payment’. It is a pre-payment in [that] sense … It’s also something you must do in order to obtain the services. These are not mutually exclusive categories and nothing is misleading, in different aspects of the stipulated terms, focusing on those different aspects of the same required payment”.

73 Mr Walker also put the point this way in his oral submissions:

Once one contemplates that it is in the nature of things that the $20 will commonly – not remotely or fancifully, but commonly – be fully expended in return for services used, then, with respect, the footing for both representations in the first part of the case is cut away. It is a prepayment, as a matter of English.

It’s a payment in advance of services, and you can expend the whole of the $20, and the succeeding $20, and the succeeding $20 as long as you’re in the plan, except for a rump of the last $20 as you exit. That doesn’t mean it’s not a prepayment – far from it. It means it’s a prepayment on terms.

74 It follows that the pleaded Prepayment Use Representation and the Prepayment Refund Representation are not made out.

Is the Forfeiture Term unfair?

75 Section 23 of the ACL provides that a term of a consumer contract is void if the term in unfair.

76 Section 24 of the ACL defines the meaning of unfair for the purposes of s 23, as follows:

Meaning of unfair

(1) A term of a consumer contract or small business contract is unfair if:

(a) it would cause a significant imbalance in the parties’ rights and obligations arising under the contract; and

(b) it is not reasonably necessary in order to protect the legitimate interests of the party who would be advantaged by the term; and

(c) it would cause detriment (whether financial or otherwise) to a party if it were to be applied or relied on.

(2) In determining whether a term of a contract is unfair under subsection (1), a court may take into account such matters as it thinks relevant, but must take into account the following:

(a) the extent to which the term is transparent;

(b) the contract as a whole.

(3) A term is transparent if the term is:

(a) expressed in reasonably plain language; and

(b) legible; and

(c) presented clearly; and

(d) readily available to any party affected by the term.

(4) For the purposes of subsection (1)(b), a term of a contract is presumed not to be reasonably necessary in order to protect the legitimate interests of the party who would be advantaged by the term, unless that party proves otherwise.

77 Section 24(1) of the ACL requires the three elements in (a) to (c) to be satisfied. The term must:

(1) cause a significant imbalance in the parties’ rights and obligations arising under the contract;

(2) not be reasonably necessary in order to protect the legitimate interests of the party who would be advantaged by the term; and

(3) cause detriment (whether financial or otherwise) to a party if it were to be applied or relied on.

78 The characterisation of unfairness is “of course, evaluative and a task to be carried out with a close attendance to the statutory provisions”. See Paciocco v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd (2015) 236 FCR 199 at 287, [364] (Allsop CJ, Besanko and Middleton JJ agreeing).

79 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v CLA Trading Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 377; (2016) ATPR 42-517 at [54], Gilmour J summarised the applicable principles as follows:

(a) The underlying policy of unfair contract terms legislation respects true freedom of contract and seeks to prevent the abuse of standard form consumer contracts which, by definition, will not have been individually negotiated: Jetstar Airways Pty Ltd v Free [2008] VSC 539 at [112];

(b) The requirement of a “significant imbalance” directs attention to the substantive unfairness of the contract: Director General of Fair Trading v First National Bank plc [2002] 1 AC 481; [2001] UKHL 52 at [37];

(c) It is useful to assess the impact of an impugned term on the parties’ rights and obligations by comparing the effect of the contract with the term and the effect it would have without it: Director General of Fair Trading v First National Bank plc at [54];

(d) The “significant imbalance” requirement is met if a term is so weighted in favour of the supplier as to tilt the parties’ rights and obligations under the contract significantly in its favour – this may be by the granting to the supplier of a beneficial option or discretion or power, or by the imposing on the consumer of a disadvantageous burden or risk or duty: Director General of Fair Trading v First National Bank plc at [17] per Lord Bingham, applied in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v ACN 117 372 915 Pty Limited (in liq) (formerly Advanced Medical Institute Pty Limited) [2015] FCA 368 at [950];

(e) Significant in this context means “significant in magnitude”, or “sufficiently large to be important”, “being a meaning not too distant from ‘substantial’”: Jetstar Airways Pty Ltd v Free at [104]-[105] per Cavanough J; cf Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria v AAPT Limited [2006] VCAT 1493 at [32]-[33];

(f) The legislation proceeds on the assumption that some terms in consumer contracts, especially in standard form consumer contracts, may be inherently unfair, regardless of how comprehensively they might be drawn to the consumer’s attention: Jetstar Airways Pty Ltd v Free at [115]; and

(g) In considering “the contract as a whole”, not each and every term of the contract is equally relevant, or necessarily relevant at all. The main requirement is to consider terms that might reasonably be seen as tending to counterbalance the term in question: Jetstar Airways Pty Ltd v Free at [128].

80 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Chrisco Hampers Australia Ltd (2015) 239 FCR 33 at 41-42, [43], Edelman J accepted each of the following matters concerning the construction of s 24 put to him by senior counsel for the respondent in that case:

(1) for a term to be unfair it must satisfy the requirements of all of s 24(1)(a) to (c);

(2) the onus is upon the applicant to prove the matters in s 24(1)(a) and (c) but it is upon the respondent in relation to s 24(1)(b);

(3) s 24(2)(a) only requires the Court to consider transparency in relation to the particular term that is said to be unfair and only in relation to the matters concerning that term in s 24(1)(a) to (c);

(4) similarly, the assessment of the contract as a whole in s 24(1)(c) only requires the Court to consider the contract as a whole in relation to the particular term that is said to be unfair and only in relation to the matters concerning that term in s 24(1)(a) to (c);

(5) as the Explanatory Memorandum to the Trade Practices Amendment (Australian Consumer Law) Bill (No 2) provided at [5.39], “if a term is not transparent it does not mean that it is unfair and if a term is transparent it does not mean that it is not unfair”; and

(6) guidance can be had to s 25 which provides examples of unfair terms.

81 Section 25 of the ACL provides examples of unfair terms. Relevantly, s 25(1) provides that “[w]ithout limiting section 24, the following are examples of the kinds of terms of a consumer contract that may be unfair … (c) a term that penalises, or has the effect of penalising, one party (but not another party) for a breach or termination of the contract”.

The competing submissions on the unfair contract point

Significant imbalance

82 The ACCC submits that the Forfeiture Term, “in the context of the Automatic Top-Up Term”, is an unfair contract term and thereby void by operation of s 23(3) of the ACL. It submits that the unfairness of the Forfeiture Term arises in each of the TPG contracts which includes the Automatic Top-Up Term, because “the effect of the operation of the two terms is that $10 of a customer’s Prepayment cannot be used for services”; and “[t]his is not disclosed to customers”, and that there is a significant imbalance in rights between and obligations as between TPG and its customers because TPG’s customers are required to make a payment for which they receive nothing.

83 The ACCC also says that there is an imbalance in rights and obligations because it is unlikely that a customer, seeking to cancel a contract years down the track, would remember the Automatic Top-up and Forfeiture Term.

84 It was also submitted that TPG “us[ed] its position as the architect of the contractual scheme to arrange financial matters in a way that benefits it and exposes customers to an undisclosed detriment” and that TPG is “effectively leveraging each customer to offset the risk of default by other customers” which results in TPG presently “holding” $16.9m in forfeited sums in respect of fixed line plans and $600,000 in respect of mobile plans.

85 TPG submits that there is no significant imbalance in rights and obligations for the following main reasons.

86 First, it says that there is nothing unfair about the Forfeiture Term, and that what the ACCC seeks “is not simply the avoiding of an unfair term but the re-striking of a commercial bargain which obviously involves pricing at its heart”. TPG submits that the Forfeiture Term is part of the business model that produces highly competitive pricing and “the notion that you can simply take out a forfeiture term and not produce an effect on pricing is fundamentally wrong because you have an effect on one of the aspects of cost and it follows that [you are] likely to have an effect on … margin”.

87 Secondly, TPG submits that the fact that TPG holds in excess of $16m in respect of “forfeited” amounts is irrelevant.

88 Thirdly, it says that TPG’s customers make a payment for which they receive the benefit of the right to access and use services outside the included value of the services available for their plan (that is, Excluded Services).

89 Fourthly, TPG says that, in the scheme of things, the forfeiture of $10 at the end of a contract does not give rise to a significant imbalance in the sense of “significant in magnitude”, “sufficiently large to be important”, or close to substantial, and that any “imbalance” is marginal, especially for customers who reduce their prepayment, and top-up it up time and time again. In those cases, their prepayments, it was submitted, “are being wholly, 100 percent, applied to services enjoyed by them”, until such time as they choose to cancel their plan. It was submitted that in assessing the significance of the so-called imbalance, it is relevant to take into account that whatever amount remains in the prepayment account at the time of the cancellation of a plan between $10 and $20 should effectively be amortised over the term of the plan.

90 Fifthly, it points to the benefits of the plans to customers, including the flexibility to use services outside the included value of their plans as it suits them, rather than needing to pay a higher fixed monthly charge for the availability of services which they otherwise may not use, and the fact that TPG customers are protected from so-called “bill shock”, because they pay in advance for services they use.

Is the term reasonably necessary?

91 The ACCC submits that TPG has not discharged its onus to identify a sufficient “legitimate business interest” it is seeking to protect by including the Forfeiture Term in its contractual arrangements for the plans. It says that Mr Churchill-Bateman’s evidence to the effect that prepayment balances for all customers on cancellation are forfeited to cover the costs that TPG absorbs when some customers exceed their prepayment is beside the point, because customers are unaware of that (because they are never told), and because it is a matter of TPG’s unilateral choice, not reflected in the contract, not to seek to recover such costs.

92 Further, the ACCC submits that TPG “is in effect spreading the risk of some customers exceeding their Prepayment over its entire customer base”. It points, by way of example, to the evidence about TPG’s 1.5m fixed line customers, only 97,392 of whom incurred overrun charges in the relevant period (May 2013 to May 2019). Further, it submits:

62 TPG has spread the risk in this way with no consideration about whether or not the customer may be a bad debt risk. The Forfeiture Term applies to all customers, including customers who never go over their Prepayment during the life of their Plan, and indeed includes customers who have never used any value of their Prepayment.

63 TPG has profited from this risk allocation: it has enjoyed a windfall gain of approximately $5 million in Prepayments which have not been required to offset customer ‘overrun charges’. Further, it has not and will not incur any additional costs in attempting to recover any ‘overrun charges’.

93 TPG submits that the Forfeiture Term is reasonably necessary to protect its interest in offsetting losses it incurs for usage by consumers outside their included value, to the extent that those costs exceed the balance of the prepayment, and that it is reasonably necessary to protect TPG’s legitimate interests in that TPG would suffer a commercial disadvantage if the term were removed, as many other operators also use a similar term. And TPG relies on its own statistics to justify the term, as follows:

42 In the period May 2013 to May 2019, TPG incurred customer usage charges for mobile and fixed line services greater than the total of customers’ Prepayment balances in the total amount of $9,544,593.84. These amounts are not recovered by TPG. The operation of the Forfeiture Term provides TPG with protection against these charges, in circumstances where the Automatic Top-Up Term will not be applied in time to restore a customer’s Prepayment balance. The TPG Plans operate entirely on a prepaid model, and by removing the need to recover bad debts, TPG considers that it is able to offer a cheaper service. Individual customers are able to utilise their Prepayment balances so that no amount is forfeited by them.

94 As to the ACCC’s point that it is TPG’s choice not to seek to recover charges for excluded services that exceed the prepaid amount, not a contractual term, TPG says that it is commercially unrealistic in the extreme to expect it to sue customers at its own loss, and it is, on the other hand, entirely acceptable to spread the risk of those commercially unrecoverable costs across the relevant constituency of customers.

Detriment

95 As to detriment, the ACCC says that the Forfeiture Term causes financial detriment to TPG’s customers when applied in circumstances where the customer is not able to use $10 of the prepayment for services and that “[t]he customer pays a fee and receives nothing in return”. They further point to TPG having profited by a “windfall gain of approximately $5 million”.

96 TPG accepts that, viewed in isolation, the practical effect of the Forfeiture Term in conjunction with the Automatic Top-Up Term is that customers will forfeit the remaining prepayment balance. But it submits that when “[v]iewed in conjunction with the other terms of the TPG contracts, the Forfeiture Term in the context of the Automatic Top-Up Term does not cause detriment because it results in a lower-priced contract for consumers, provides customers with certainty as to their payments, and provides customers with the flexibility to nominate payment amounts that suit their needs”. As Mr Walker put it in his oral submissions, “ [a] standard consumer contract … [is] likely to produce the economies which provide the benefit of this technology at startlingly low prices by reason of scale, that is, volume of customers and custom. It’s entirely appropriate that costs be spread” and that in considering the question of “unfairness” the court should take into account the “keenness” of pricing that is the product of TPG’s business model.

97 TPG also takes issue with the ACCC’s contention that because years might pass until a customer decides to cancel their plan they may by then have forgotten the existence of the Forfeiture Term. It was submitted that there is no “substance in the proposition that a term which if remembered, would not be unfair becomes unfair if forgotten, particularly if forgotten because [the customer has] been happy with the service for so long that [he or she has] not wanted to terminate the plan”.

Transparency

98 The ACCC also submits that “[t]he Forfeiture Term is a small part of a long clause, and must be read in combination with both the Forfeiture term and the Automatic Top-Up Term for its impact to be properly understood. TPG provides customers with no assistance in understanding these impacts”. The ACCC also says that such a lack of “transparency” is relevant to the question of significant imbalance and detriment, because the Forfeiture Term only appears at the end of the process by which a putative customer may – not must – navigate the website (see Annexure A).

99 TPG says that there is no lacking of transparency and that all the relevant terms and conditions are readily accessible via the pathways on the TPG website. TPG says that the ACCC’s claim that the Forfeiture Term lacks “transparency” should not be accepted because it wrongly assumes that a reasonable consumer would read the beginning of the paragraph (that a prepayment must be made), but not the Forfeiture Term at the end of the paragraph. It submits that, absent any consumer evidence that consumers would do such a thing, the ACCC’s contention must be rejected.

Consideration – is the Forfeiture Term unfair?

100 The questions of significant imbalance and detriment may be considered together.

101 The ACCC’s case on unfairness is premised on the over-arching contention that the Forfeiture Term is unfair because the effect of the operation of it, and the Automatic Top-Up Term, is that (up to) $10 of a customer’s prepayment cannot be used for services, and that this is not disclosed to customers. It submits that there is a significant imbalance in rights between and obligations as between TPG and its customers, because TPG’s customers are required to make a payment for which they receive nothing, and in such circumstances the customers suffer detriment.

102 I do not accept the ACCC’s premise of non-disclosure. In my view, for reasons that I have explained, the Forfeiture Term, and the effect of it, would be sufficiently apparent to the reasonable or ordinary consumer, on the face of the clause containing it. As I have said earlier in these reasons (at [70]), the reasonable or ordinary consumer knows that a prepayment, in the usual case $20, must be made for usage that is not within the included value (if any) for the plan acquired, and that among other things:

an automatic top up will occur when the amount of prepayment falls to below $10; and

if the prepayment is not used, it will be forfeited when the service is cancelled.

103 By a simple enough process of deduction, it would therefore be sufficiently apparent to a reasonable or ordinary consumer of telecommunication services that he or she will forfeit between $10 and $20 upon cancellation of their plans.

104 I also do not accept that a customer receives nothing for making the prepayment. As I have explained above, it is necessary to consider the contract as a whole, and to consider terms or matters that might reasonably be seen as tending to counterbalance any perceived unfairness. Here, the Forfeiture Term is a term which enables the customer to select, on the example relied on by ACCC in oral argument, a very cheap plan (a $1 per month monthly charge, with 50MB of data, and a 2 minute Standard National Call charged at 29.8 cents). Calls and texts (SMS and MMS) form part of the Excluded Usage and are taken out of the prepayment amount, if they are used. Whether a customer chooses that plan, rather than say, an Unlimited Data Plan at $79.99 per month (see annexure G to the ASOF, attached to these reasons as Annexure B), for example, depends on the individual and subjective preferences, including the anticipated usage needs, of each customer. The “fairness” of one plan versus another must surely therefore depend on matters of individual preference, the permutations and combinations of which were not the subject of any consumer evidence, but which are in any event self-evidently many and varied.

105 It seems to me therefore that there is much to be said for TPG’s submission that the Forfeiture Term permits TPG to offer plans with low monthly charges, and that there is nothing unfair in conducting a business model, including by offsetting losses it incurs for usage by consumers outside their included value, in such a manner that it has the capacity to charge low prices. And as Mr Walker put it, in such circumstances, “[t]he make up of a low price is … not something that is really amenable to an atomised detection of fairness or unfairness for any element of it”.

106 It follows that there is no significant imbalance between the parties, and the detriment, if it be one, is not unfair because, as TPG submitted, the Forfeiture Term is but one term of the relevant contract, which offers low prices, and provides customers with certainty as to their payments, and the flexibility to nominate payment amounts that suit their individual needs or expectations.

107 I also do not accept the ACCC’s submissions that it is relevant to any issue of significant imbalance or unfairness generally that TPG holds in excess of $16 million in respect of forfeited amounts. As Mr Walker put it, it “has got nothing to do with anything. That is driven by arithmetic which, in turn, is driven by volume. It says nothing whatever about unfairness…”

108 I also do not accept that the fact that TPG chooses not to seek to recover charges for excluded services that exceed the prepaid amount is unfair.

109 If I am wrong about the absence of “significant imbalance” and “detriment” as those terms are used in the ACL, the question of whether TPG has demonstrated that the Forfeiture Term is reasonably necessary to protect its legitimate interests would arise.

110 In my view, TPG has shown that the Forfeiture Term is reasonably necessary to protect its legitimate interests. Those legitimate interests were identified by TPG’s General Counsel in his letter to the ACCC in January 2015, when TPG explained why it changed the terms of its plans to comply with the Telecommunications Consumer Protection Code in 2013. Those interests were identified as including the minimising the serious effects that bad debts had on the telecommunications industry and the cost of telecommunication services. See [28] above. Those interests were also described by General Counsel in his August 2017 letter to the ACCC (see [31] above) as:

engaging in a competitive market;

adopting innovative business models and services, so that telecommunications consumers have a choice;

offering low-cost plans to those consumers; and

improving the inefficiencies caused by bad debts and collections the benefit of all consumers.

111 The extent of the impact of effectively irrecoverable bad debts is considerable. As Mr Churchill-Bateman said, the total of TPG’s customer unrecovered usage charges for May 2013 to May 2019, for both mobile and fixed line services, greater than the total of the customers’ prepayment balance, was $9.544m.

112 The ACCC submitted that the fact that TPG’s bad debts were not recovered was a product of its own choice, but that is, with respect, an unrealistic response, because even assuming that a judgment debt of (say) $150, which was one example in the evidence, could be recovered in one jurisdiction or another, the associated legal and other costs would make the exercise counter-productive.

113 The last matter is “transparency”. In my view, the Forfeiture Term does not suffer from any lack of transparency, for the reasons advanced by TPG (see [99] above).

114 For those reasons, the Forfeiture Term is not unfair.

Disposition

115 For the foregoing reasons, the proceeding will be dismissed with costs.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and fifteen (115) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice O'Callaghan. |

Associate:

Transcript ref | Content | Screenshot # |

T27:23-28 | This, your Honour, is the TPG homepage… If I as a consumer who wanted to, for example, purchase a prepaid mobile plan, the first thing I would do would be… to look for mobile… | Screenshot 1 |

T27:29-30 | … if I would like to view any plans, I need to click on this link here that says ‘view plans’. | Screenshot 2A – 2C |

T27:35-37 | And it shows you the different plants available. They’re quite low-cost, good value: 19.99, 29.99… | Screenshot 3A – 3B |

T27:37-39 | … so I would focus in on the dollar per month and I would see the headline of the data that I get and I would – I could hover here and that will show, for example, a prepayment… | Screenshot 4 |

T28:2-16 | [Incorrect document brought up on screen] | - |

T28:18 | Then we go here to see why TPG… | Screenshot 5 |

T28:19 | … We go down here to “important things you need to know”… | Screenshot 6 |

T28:21 | … click into the call rates… | Screenshot 7 |

T28.23-24 | … Then you go into SIM cards is the next tab down… | Screenshot 8 |

T28:24-25 | … The next tab is coverage… | Screenshot 9 |

T28:26-27 | … Then we have ‘important things you need to know’… | Screenshot 10 |

T28:29 | There’s About Your Mobile Plan… | Screenshot 11A – 11B |

T28:31-33 | … and then the next heading down is Monthly Usage Quotas and Data, and then, again, TPG Mobile Service, Video-Calling and then this More Information tab… | Screenshot 12A – 12B |

T28:34-45 | … and this is where we get to Mobile Prepayment Outside Included Value… | Screenshot 13 |

T29:13-15 | … Frequently asked questions, the curious person might click on that… | Screenshot 14 |

T29:15-16 | … now, the terms and conditions appear here and this is where the plan brochure is… | Screenshot 15 |

T29:19-20 | … And so here we have the plan brochure… | Plan Brochure Pages 1 – 4 |

T29:33-36 | … The standard terms and conditions, the service description and the plan brochure… | Screenshot 15 |

T29:43-45 | … then the critical information summary… | Critical Information Summary 1 – 4 |

Screenshot 1:

Screenshot 2A:

Screenshot 2B:

Screenshot 2C:

Screenshot 3A:

Screenshot 3B:

Screenshot 4:

Screenshot 5:

Screenshot 6:

Screenshot 7:

Screenshot 8:

Screenshot 9:

Screenshot 10:

Screenshot 11A:

Screenshot 11B:

Screenshot 12A:

Screenshot 12B:

Screenshot 13:

Screenshot 14:

Screenshot 15:

Plan Brochure Page 1:

Plan Brochure Page 2:

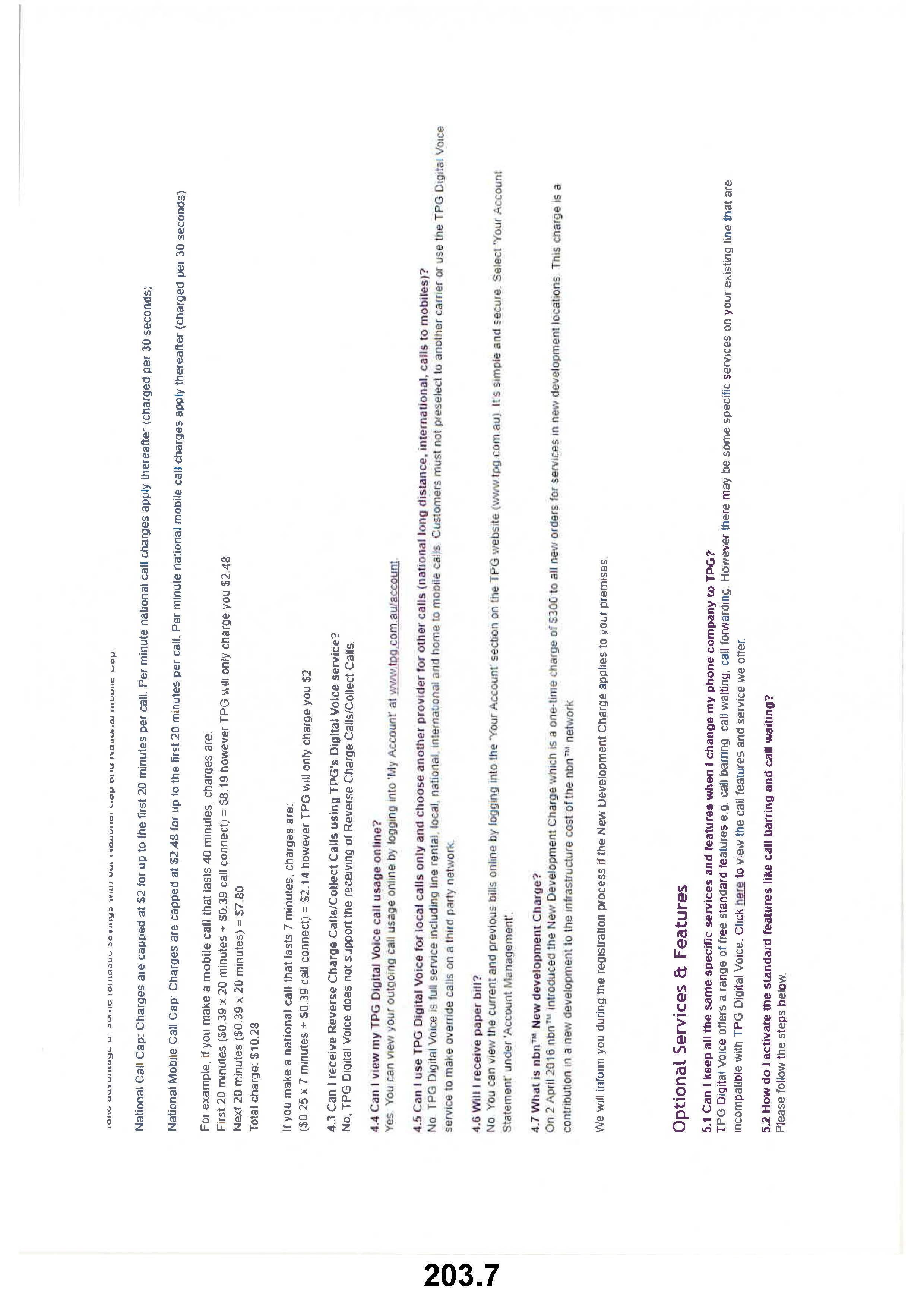

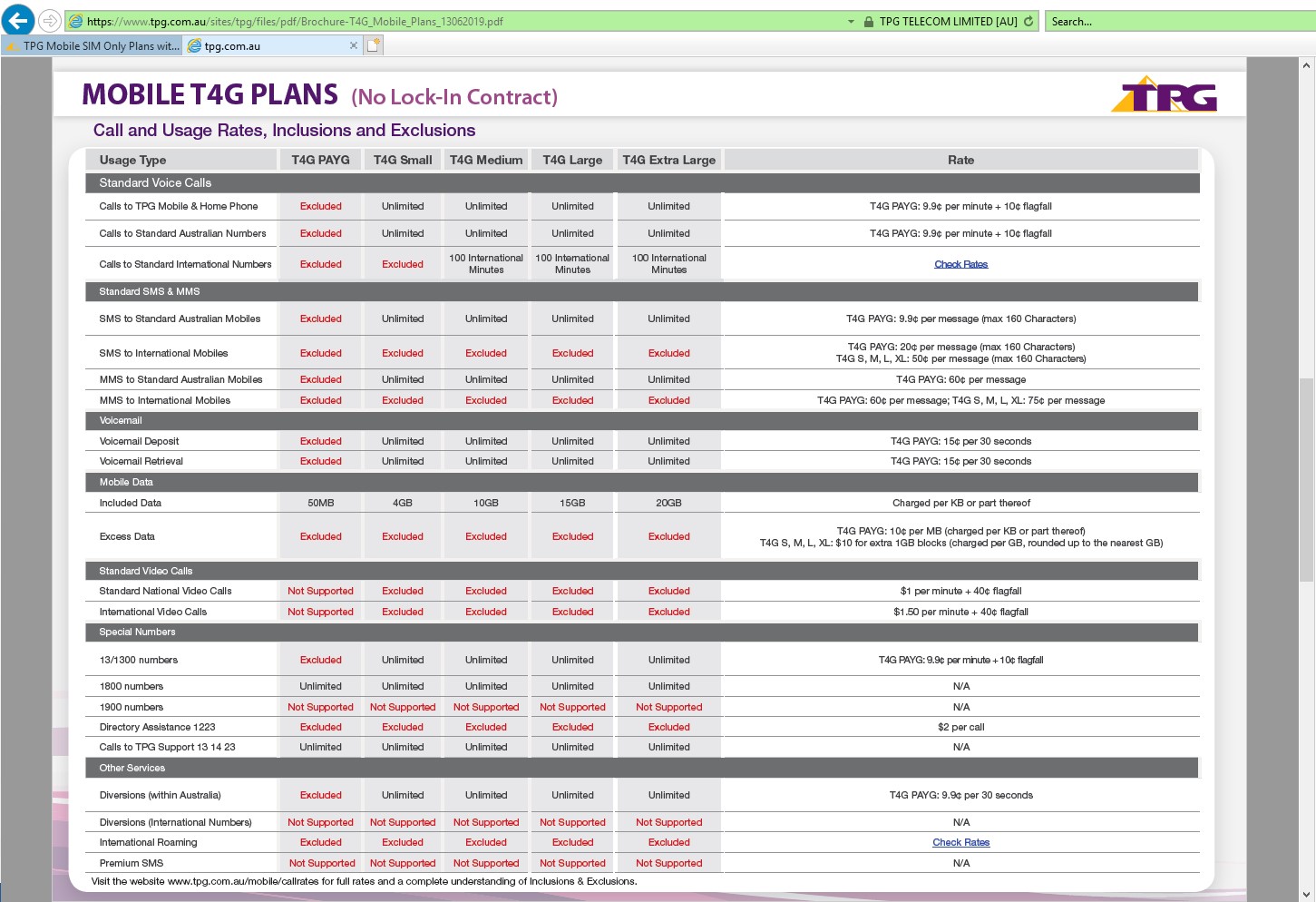

Plan Brochure Page 3:

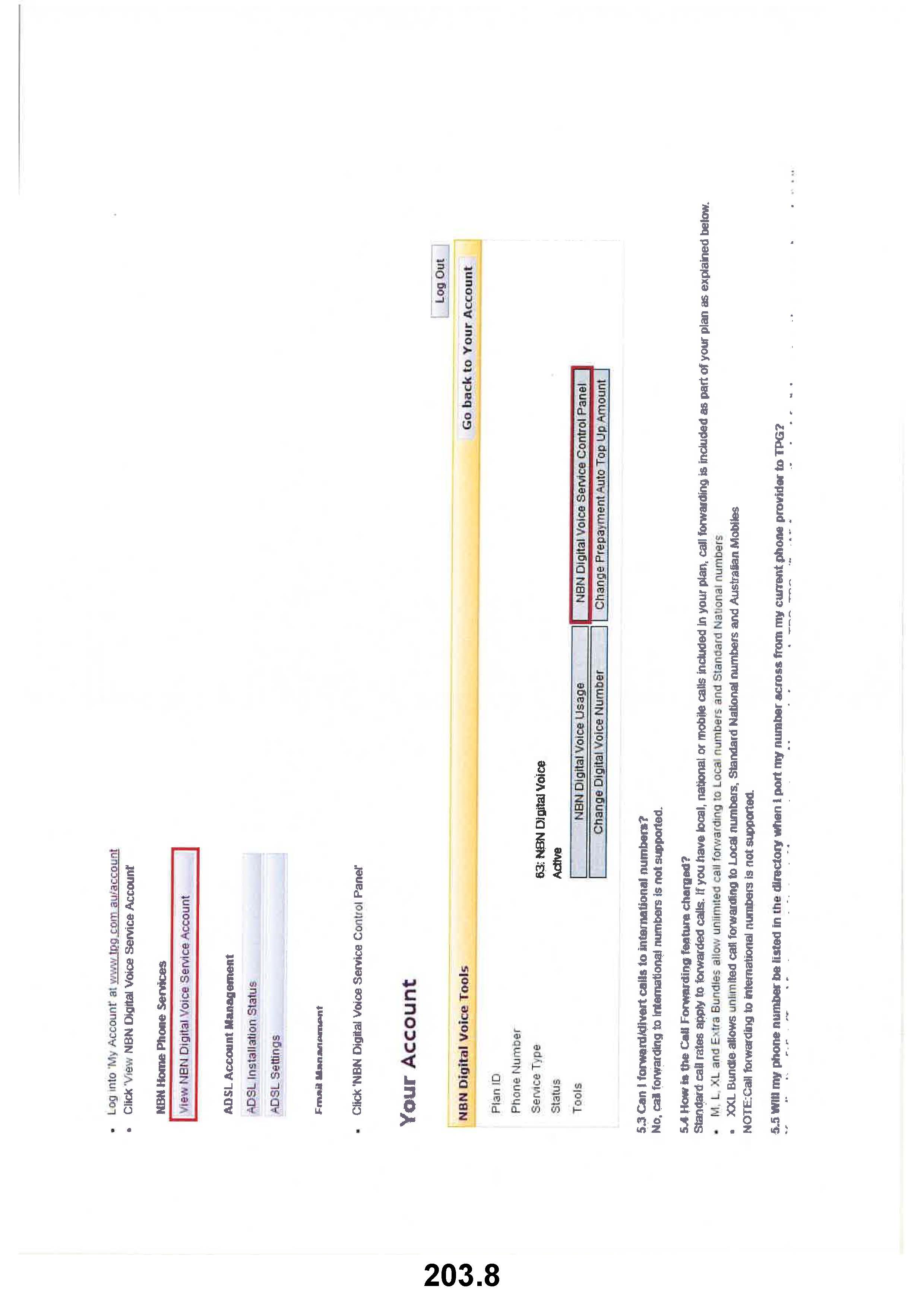

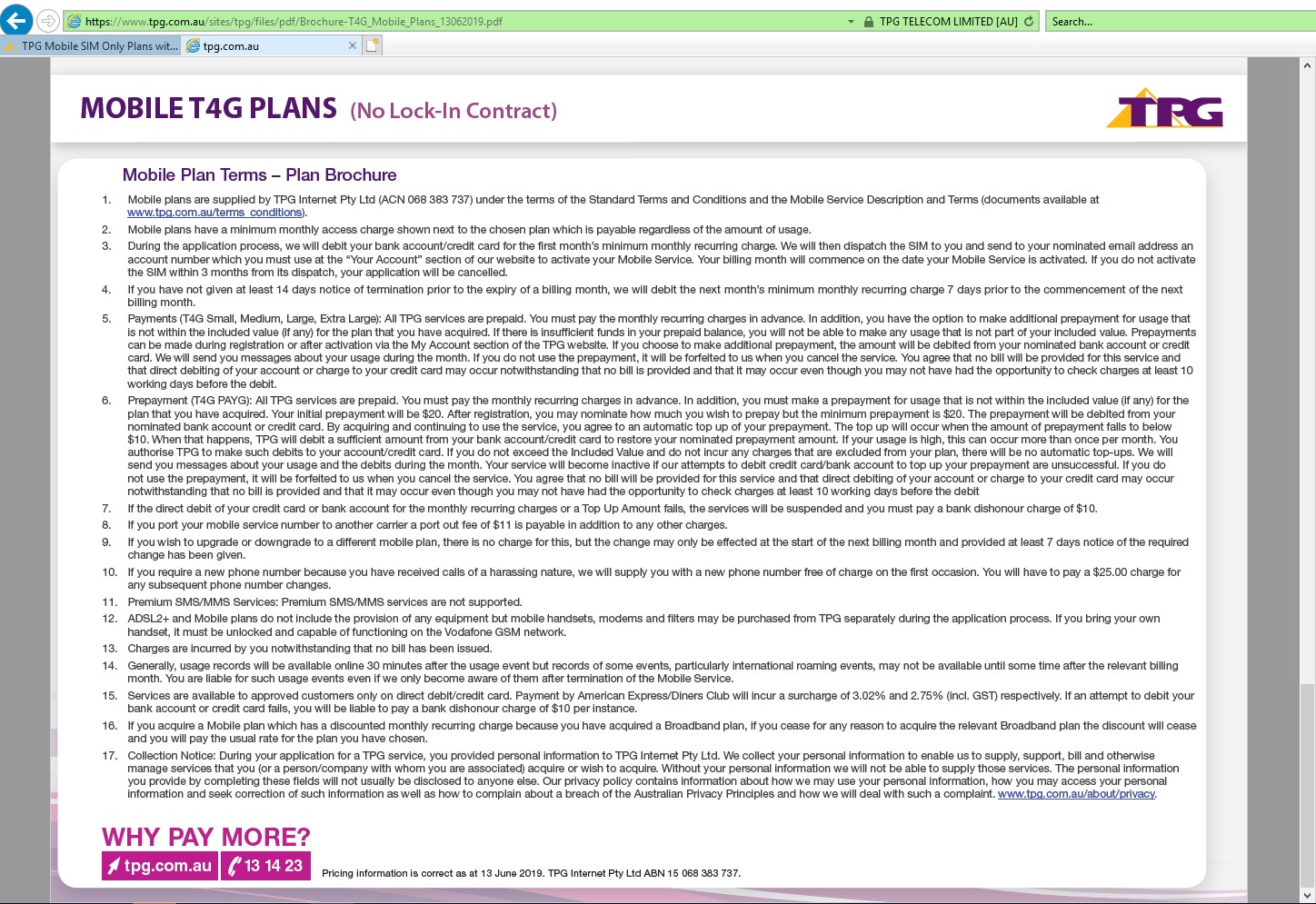

Plan Brochure Page 4:

Critical Information Summary 1:

Critical Information Summary 2:

Critical Information Summary 3:

Critical Information Summary 4:

ANNEXURE B