FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Workers’ Union v Registered Organisations Commissioner (No 9) [2019] FCA 1671

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | REGISTERED ORGANISATIONS COMMISSIONER First Respondent COMMISSIONER OF THE AUSTRALIAN FEDERAL POLICE Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The proceeding be listed for further hearing on a date to be fixed and on an estimate of half a day.

2. On or before 14 days prior to the further hearing, the applicant file and serve any further submissions addressing the matters raised by [385]-[391] of the Court’s reasons published on 11 October 2019, as well as a Minute setting out the orders that should be made to give effect to those reasons.

3. On or before 7 days prior to the further hearing, the respondents file and serve any further submissions addressing the matters raised by [385]-[391] of the Court’s reasons, as well as a Minute setting out the orders that should be made to give effect to those reasons.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ground 1 – Can the Commissioner investigate “historical conduct” ocurring prior to 1 May 2017? | [15] |

The Competing Contentions and Relevant Legislative Provisions | [15] |

[39] | |

[76] | |

[77] | |

[84] | |

[87] | |

[96] | |

[173] | |

The Nature of the Relationship between the Commissioner and the Minister under the RO Act | [174] |

[179] | |

[182] | |

[189] | |

[195] | |

[205] | |

[209] | |

[214] | |

[221] | |

[229] | |

Ground 3 – Was the Investigation Commenced for an Improper Political Purpose? | [261] |

[261] | |

[262] | |

[264] | |

Mr Enright’s Knowledge or Understanding of the Minister’s Political Purpose | [269] |

[282] | |

Was Mr Enright Transparent about his Communications with the Minister’s Office? | [295] |

[310] | |

[315] | |

[325] | |

[326] | |

[338] | |

[342] | |

[344] | |

Ground 4 – Was an Irrelevant Consideration Taken into Account? | [347] |

Ground 5 – Was the Investigation Commenced at the Direction of the Minister? | [351] |

[353] | |

[356] | |

[357] | |

[378] | |

[392] | |

BROMBERG J:

1 The Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Act 2009 (Cth) (“RO Act”) provides for the formation of associations of employees and associations of employers and for the registration of those associations as registered organisations. In setting out Parliament’s intention in enacting the RO Act, s 5 of that Act records that registered organisations are required to meet standards set out in the Act including standards which “encourage the efficient management of organisations and high standards of accountability of organisations to their members” (s 5(3)(c)). Regulatory processes are provided for by the RO Act and facilitated by the establishment of the office of the first respondent, the Registered Organisations Commissioner (“Commissioner”) (s 329AA). The functions of the Commissioner are specified by s 329AB and include to promote “efficient management of organisations and high standards of accountability of organisations and their office holders to their members”; and also to promote “compliance with financial reporting and accountability requirements” of the RO Act (s 329AB(a)).

2 The RO Act also establishes the Registered Organisations Commission (“Commission”) (s 329DA). As s 329DB specifies, the Commission consists of the Commissioner and any staff assisting the Commissioner as mentioned in s 329CA(1). The function of the Commission is to “assist the Commissioner in the performance of the Commissioner’s functions” (s 329DC).

3 At all relevant times the Minister with oversight responsibility for the Commission was Senator the Honourable Michaelia Cash, the Minister for Employment (“Minister Cash” or “Minister”).

4 The applicant (“AWU”) is an association of employees registered as an organisation under the RO Act.

5 Section 331 of the RO Act empowers the Commissioner to conduct investigations. Relevantly, s 331(2) provides:

(2) If the Commissioner is satisfied that there are reasonable grounds for doing so, the Commissioner may conduct an investigation as to whether a civil penalty provision (see section 305) has been contravened.

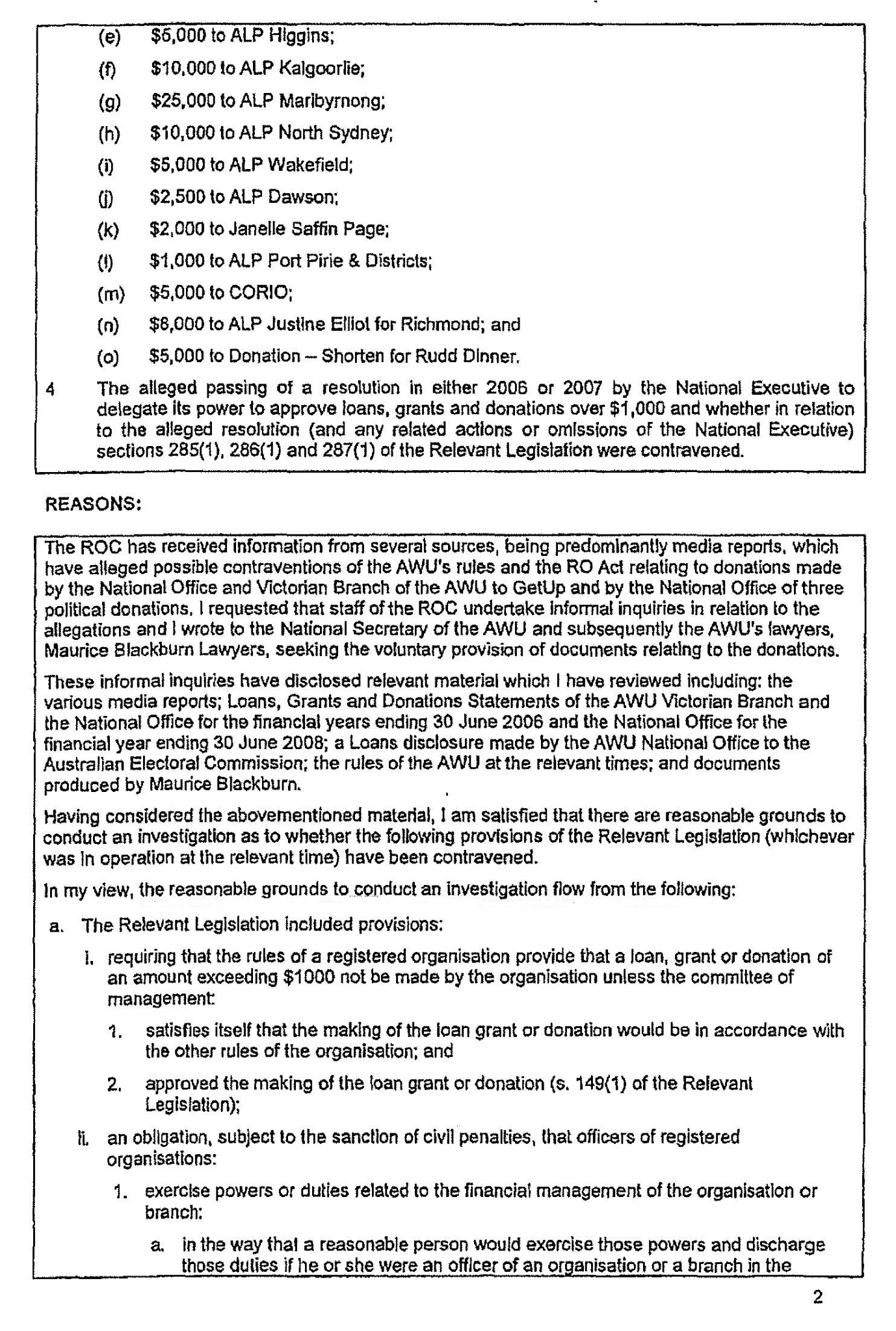

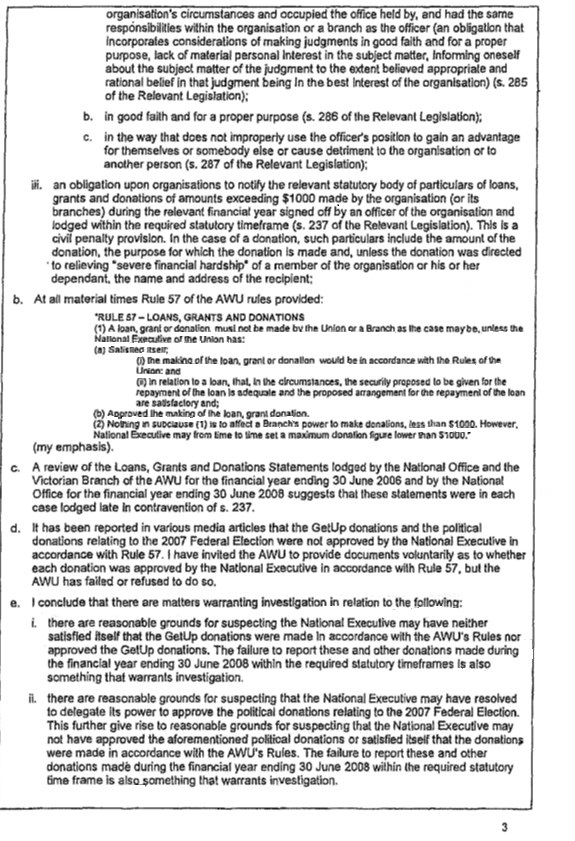

6 On 20 October 2017, Mr Chris Enright, the Executive Director of the Commission and a delegate of the Commissioner decided (“Decision”) to conduct an investigation (“Investigation”) described by the decision record made by him (“Decision Record”) as “an investigation under section 331(2) of the [RO Act] in relation to the National Office and Victorian Branch of [the AWU] as to whether various civil penalty provisions within the meaning of section 305 have been contravened”. Mr Enright’s Decision Record identified the matters that the Investigation related to. Those matters included a donation of $50,000 from the National Office of the AWU to GetUp Limited (“GetUp”) during the financial year ending 30 June 2006; a donation of $50,000 from the Victorian Branch of the AWU to GetUp during the financial year ending 30 June 2006; and fifteen other donations made by the AWU in the financial year ending 30 June 2008 to persons or entities associated with the Australian Labour Party (“ALP”) (collectively “Donations”). The Decision Record identifies that the making of the Donations involved possible contraventions of ss 237(1), 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) of what was Schedule 1B of the Workplace Relations Act 1996 (Cth) (“WR Act”) and which later became Schedule 1 of the WR Act. Section 237 deals with a financial reporting requirement, namely an obligation imposed on registered organisations to file within a specified time a statement of particulars of any loans, grants or donations made in a particular financial year. Sections 285 to 287 deal with financial probity obligations and impose care, diligence and good faith obligations upon the officers of organisations and protect against the misuse by an officer of his or her office.

7 Those provisions were in the following terms:

237 Organisations to notify particulars of loans, grants and donations

(1) An organisation must, within 90 days after the end of each financial year (or such longer period as the Registrar allows), lodge in the Industrial Registry a statement showing the relevant particulars in relation to each loan, grant or donation of an amount exceeding $1,000 made by the organisation during the financial year.

Note: This subsection is a civil penalty provision (see section 305).

…

285 Care and diligence—civil obligation only

(1) An officer of an organisation or a branch must exercise his or her powers and discharge his or her duties with the degree of care and diligence that a reasonable person would exercise if he or she:

(a) were an officer of an organisation or a branch in the organisation’s circumstances; and

(b) occupied the office held by, and had the same responsibilities within the organisation or a branch as, the officer.

Note: This subsection is a civil penalty provision (see section 305).

...

286 Good faith—civil obligations

(1) An officer of an organisation or a branch must exercise his or her powers and discharge his or her duties:

(a) in good faith in what he or she believes to be the best interests of the organisation; and

(b) for a proper purpose.

Note: This subsection is a civil penalty provision (see section 305).

...

287 Use of position—civil obligations

(1) An officer or employee of an organisation or a branch must not improperly use his or her position to:

(a) gain an advantage for himself or herself or someone else; or

(b) cause detriment to the organisation or to another person.

Note: This subsection is a civil penalty provision (see section 305).

8 On 24 October 2017, upon the application of the Commissioner under s 335K of the RO Act, a magistrate issued a warrant authorising officers of the second respondent (“AFP”) to search the premises of the National Office of the AWU in Sydney, and a warrant authorising officers of the AFP to search the premises of the Victorian Branch of the AWU in Melbourne (collectively “search warrants”). Later that day, officers of the AFP accompanied by representatives of the Commissioner executed the search warrants at each of the National and Victorian Branch offices of the AWU. In the execution of the search warrants, the AFP took possession of various documents.

9 On 25 October 2017, the AWU filed an originating application in this Court seeking relief in relation to the acts and decisions of the Commissioner and the AFP referred to above. In summary, the AWU seeks, among other things:

(i) a declaration that the Decision of the Commissioner (by his delegate) to conduct the Investigation is invalid, and orders in the nature of certiorari and prohibition quashing that Decision and prohibiting the Commissioner from giving further effect to it;

(ii) a declaration that the search warrants are invalid, and an order in the nature of prohibition or an injunction preventing the AFP from giving further effect to either of the warrants; and

(iii) an injunction requiring the AFP to return to the AWU the documents seized in the execution of the search warrants.

10 The AWU challenged the Investigation on the basis of five grounds which are set out in the AWU’s Grounds of Review dated 13 February 2019, the substance of which are as follows:

Ground 1 - That the Commissioner’s decision to conduct the Investigation under s 331(2) of the RO Act was affected by jurisdictional error, because he purported to investigate conduct occurring before 1 May 2017 whereas the provision (s 331(2)) is limited to investigating whether a civil penalty provision has been contravened after 1 May 2017.

Ground 2 - That the Commissioner’s decision to conduct the Investigation under s 331(2) of the RO Act was affected by jurisdictional error, because:

(i) it was not open to the Commissioner to be satisfied that there were “reasonable grounds” to conduct an investigation for breach of the AWU’s rules, due to the operation of s 320 of the RO Act;

(ii) further or alternatively, in not adverting to s 320 of the RO Act, the Commissioner misunderstood the law he was to apply.

Ground 3 - That the Commissioner’s decision to conduct the Investigation under s 331(2) of the RO Act was affected by jurisdictional error, because a decision was made for an improper political purpose (“improper purpose”) of aiding in, assisting or promoting the political purpose of Minister Cash and or members of her office (“Minister Cash’s political purpose”) who wanted the AWU to be investigated by the Commissioner in order to discredit, embarrass or politically harm the Honourable Bill Shorten MP (“Mr Shorten”).

Ground 4 - That the Commissioner’s decision to conduct the Investigation under s 331(2) of the RO Act was affected by jurisdictional error, because the Decision was made taking into account a mandatory irrelevant (political) consideration, namely Minister Cash’s political purpose.

Ground 5 - That the Commissioner’s decision to conduct the Investigation under s 331(2) of the RO Act was affected by jurisdictional error, because the Commissioner impermissibly acted upon the advice or direction of Minister Cash.

11 The AWU also challenged the validity of the search warrants on the basis of three grounds, only two of which were pressed:

Ground 6 - That the warrants are invalid because there was no valid investigation and thus no power to obtain a warrant under s 335K of the RO Act;

Ground 7 - That the warrants are invalid because there was no power for the Commissioner to apply for them in connection with the conduct under investigation (which allegedly occurred before 1 May 2017)

12 The AFP did not participate in the trial having requested and obtained leave to be excused. The AWU called a number of witnesses who gave evidence in response to subpoenas. Those witnesses included Mr Enright as well as Mr Mark Lee and Mr Greg Russo each of whom were involved in assisting the Commission. Additionally, the AWU called Minister Cash and members or former members of her staff – Mr Ben Davies and Mr David De Garis. The Commissioner did not call any witnesses. A large number of documents were tendered.

13 In the main, the evidentiary case which the AWU sought to establish was relevant to grounds 3, 4 and 5. The other grounds for review challenging the Investigation (grounds 1 and 2) largely turn on questions of statutory construction and the proper characterisation of the Decision Record. The grounds which challenge the search warrants (grounds 6-7) are largely contingent on whether the AWU succeeds on its challenge to the validity of the Investigation. It is convenient that I deal with each of the grounds of review in turn and address most of the relevant facts when I deal with grounds 3-5, the resolution of which is largely fact dependent.

14 There is no issue that the Court has jurisdiction to hear and determine this application or that it has the power to make the orders and declarations sought. Section 338 of the RO Act confers on the Court jurisdiction in relation to any matter arising under that Act. It is not in contest that each of the challenges made to the validity of the Investigation and the validity of the search warrants raise a matter arising under the RO Act, including because the Commissioner’s power to investigate and the power to issue a warrant are conferred by and owe their existence to the RO Act: R v Commonwealth Court of Conciliation Arbitration; Ex parte Barrett (1945) 70 CLR 141 at 154 (Latham CJ); Re McJannet; Ex parte Australian Workers’ Union of Employees, Queensland [No 2] (1997) 189 CLR 654 at 656 (Brennan CJ, McHugh and Gummow JJ).

ground 1 – Can the Commissioner investigate “historical conduct” ocurring prior to 1 May 2017?

The Competing Contentions and Relevant Legislative Provisions

15 It is not in contest that if it occurred, the conduct the subject of the Investigation occurred during the 2006 and 2008 financial years and therefore prior to 1 May 2017.

16 The AWU contended that the Commissioner’s power to conduct investigations is qualified by a temporal limitation such that, the Commissioner’s power to conduct investigations under s 331(2) of the RO Act is only enlivened where the Commissioner (or the Commissioner’s delegate) is satisfied that there are reasonable grounds to investigate whether a civil penalty provision has been contravened by conduct occurring after 1 May 2017. In this respect, the AWU contended that the Commissioner’s investigative function was prospective in the sense that it is confined to conduct which post-dated the conferral of that function upon the Commissioner and did not extend to historical conduct, that is, conduct which pre-dated the conferral of the function (“Historical Conduct”).

17 The first of May 2017 is the date on which Sch 1 of the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Amendment Act 2016 (Cth) (“RO Amendment Act”) commenced and the date upon which the investigative function in s 331 was conferred upon the Commissioner. Schedule 2 of that Act commenced on 2 May 2017.

18 Prior to addressing the relevant operation of that Act and in order to provide an understanding of the AWU’s contention, it is necessary to outline in broad terms the legislative history of the provisions in the RO Act of relevance to the proper construction of s 331(2). Unless otherwise stated, a reference to the current terms of a legislative provision is an intended reference to the terms of that provision as at the date of the Decision.

19 The principal Commonwealth Act dealing with workplace relations is the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (“FW Act”). That Act received Royal Assent on 7 April 2009 and commenced substantially on 1 July 2009. Its legislative predecessor was the WR Act. Unlike the current arrangement, where provisions relating to registered organisations are dealt with by an Act (RO Act) separate from the principal Act (FW Act), the WR Act itself contained the legislative provisions relating to registered organisations. From 12 May 2003 and until 27 March 2006 provisions relating to registered organisations were dealt with in Sch 1B of the WR Act. On and from 27 March 2006, Sch 1B of that Act was renumbered as Sch 1. Unlike the bulk of the WR Act, Sch 1 was not repealed upon the commencement of the FW Act, but was renamed and became the RO Act (Item 3, Pt 1, Sch 22 of the Fair Work Act (Transitional Provisions and Consequential Amendments) Act 2009 (Cth) (“FW (TPCA) Act”).

20 Neither the Commissioner nor the Commission were referred to in Sch 1 of the WR Act. Section 133 of the WR Act provided for the appointment of an “Industrial Registrar” to exercise powers and functions including those conferred by Sch 1 of the WR Act. Section 141 of the WR Act made the same provision for “Deputy Industrial Registrars”. Section 331 of Sch 1 of the WR Act was in the same terms as the current terms of s 331 of the RO Act, save that the provision empowered “a Registrar” (defined as the Industrial Registrar or a Deputy Industrial Registrar) rather than the “Commissioner” to conduct investigations.

21 However, s 305 of Sch 1 of the WR Act was in different terms to its current form in the RO Act. Its current form is as follows:

305 Civil penalty provisions

(1) Subject to this Part, an application may be made to the Federal Court for orders under sections 306, 307 and 308 in respect of conduct in contravention of a civil penalty provision.

(2) A civil penalty provision is a subsection, or a section that is not divided into subsections, that has set out at its foot a pecuniary penalty, or penalties, indicated by the words “Civil penalty”.

(3) For the purposes of this Part, any contravention of a civil penalty provision by a branch or reporting unit is taken to be a contravention by the organisation of which the branch or reporting unit is part.

(4) The Federal Court must apply the rules of evidence and procedure for civil matters when hearing and determining an application for an order under this Part.

22 The terms of s 305 and relevantly s 305(2) in Sch 1 of the WR Act differed because, at that time, a different technique was utilised for identifying which provisions were “civil penalty provisions”. Rather than the current approach in the RO Act of a provision self-identifying itself as a civil penalty provision, in Sch 1 of the WR Act, s 305(2) listed each of the 43 provisions designated to be “civil penalty provisions” and each of those provisions had a note stating “This [section/subsection] is a civil penalty provision (see section 305)”. Accordingly, each of the provisions there listed did not set out at its foot (as is the current approach) the words “Civil penalty”.

23 When Sch 1 of the WR Act was re-named the RO Act and commenced on 1 July 2009, many of the regulatory functions which had been held by the Industrial Registrar or Deputy Industrial Registrar (including the function under s 331 to conduct investigations) became the functions of an office created by s 656 of the FW Act and titled “General Manager of Fair Work Australia” (from 1 January 2013 “General Manager of the Fair Work Commission”) (“General Manager”). Those amendments were made by the FW (TPCA) Act, and in particular, by Pt 7 of that Act including by Items 540-546 which had the effect of omitting “Registrar” and substituting “the General Manager” wherever appearing in s 331. No transitional provisions addressed the issue of whether the investigation function then conferred upon the General Manager was subject to any temporal limitations, and in particular, limited to prospective conduct rather than conduct which had occurred prior to the conferral of the investigative function.

24 The FW (TPCA) Act made no amendments to s 237(1), other than substituting “the General Manager” for “the Registrar” and “with FWA” for “in the Industrial Registry” (Item 488 and 489 of Pt 7). No amendments were made to ss 285(1), 286(1) or 287(1).

25 The office of the General Manager remains an office established under the FW Act. However, the functions and powers of that office were altered in 2016 by the RO Amendment Act.

26 The office of the Commissioner and the Commission were established by the insertion of Pt 3A into the RO Act. Additionally, amongst other similar amendments, the RO Amendment Act amended s 331 of the RO Act, dealing with the conduct of investigations, by omitting “General Manager” wherever occurring and substituting “Commissioner” (Item 92, Pt 3A, Sch 1).

27 Also of relevance to the AWU’s contention, to which I will shortly return, Sch 2 of the RO Amendment Act repealed s 305(2) which had contained the list of civil penalty provisions and inserted the current form of s 305(2) set out above. Each of the provisions that had been listed in the former s 305(2) was amended by Sch 2 of the RO Amendment Act to add the words “Civil penalty” as well as a specification of the maximum penalty units applicable to a contravention of that provision.

28 Further, it is relevant to note that the RO Amendment Act conferred on the Commissioner a range of powers in relation to the conduct of an investigation that were not previously available to the General Manager. Those powers, include:

(i) the power to require a person to take an oath or make an affirmation (s 335D(1));

(ii) the power to require a person to answer a question on pain of a criminal penalty (s 335D(3) and s 337(1)(d)(i)); and

(iii) the power to apply for a warrant which, on issue, would authorise a member of the AFP to obtain documents by executing the warrant upon specified premises with authority to use such force as is necessary and reasonable to enter on or into those premises, search the premises, break open and search anything and take possession of documents (ss 335K and 335L).

29 Division 6 of Pt 4 of Ch 11 of the RO Act imposes criminal sanctions upon a person who fails to comply with, or obstructs, the exercise of these powers.

30 Lastly, Pt 2 of Sch 1 of the RO Amendment Act sets out transitional provisions. Those transitional provisions include some provisions which identify the intended interaction between the functions and powers of the General Manager and those of the Commissioner. In particular, Item 130 of Sch 1 (“Item 130”) deals with “a process” begun under the RO Act by the General Manager or the Fair Work Commission (“FWC”). It is not in contention that an investigation of the kind contemplated by s 331(2) of the RO Act is a “process” within the meaning of Item 130. Item 130 is in the following terms:

130 Commissioner to complete certain processes

(1) This item applies if:

(a) a process begun under the Act is incomplete at the commencement time; and

(b) because of the amendments made by this Schedule, a function or power that the General Manager or the FWC was required, or able, to perform or exercise in relation to the process has become a function or power of the Commissioner.

(2) For the purposes of completing the process:

(a) the Commissioner must or may, as the case requires, perform the function or exercise the power; and

(b) things done by or in relation to the General Manager or the FWC before the commencement time have effect as if they were done by or in relation to the Commissioner.

31 The AWU contended that its proposition that the investigative function conferred upon the Commissioner by s 331(2) does not extend to Historical Conduct, is supported by the following considerations. First, that on 1 May 2017, the Commissioner was established “as a new entity with a new suite of coercive powers”. Second, that specific and limited provision was made for the Commissioner to perform a function or exercise a power that the General Manager or the FWC was required, or able, to perform or exercise before 1 May 2017. In particular, the AWU relied upon Item 130 providing for the Commissioner to assume only the functions and powers of the General Manager in relation to a process already commenced under the RO Act as at 1 May 2017. Third, that there is no provision in either the RO Act or the RO Amendment Act which provides for the Commissioner to generally assume the functions and powers of the General Manager or the FWC under the RO Act as in force before 1 May 2017.

32 Accordingly, the AWU submitted that by making specific and limited provision for the Commissioner to perform a function or exercise a power that the General Manager or the FWC was required, or able, to perform or exercise before 1 May 2017, and not providing for the Commissioner generally to assume the functions and powers of the General Manager or the FWC under the RO Act as in force before 1 May 2017, Parliament must be taken to have intended to limit the power of the Commissioner in relation to conduct that occurred before 1 May 2017.

33 Four further considerations were relied upon by the AWU in support of the Parliamentary intent contended for. The fourth and fifth considerations were each based on the suite of new powers available in the conduct of an investigation to the Commissioner. The AWU contended that, to read into the RO Act a general power for the Commissioner to conduct an investigation as to whether a civil penalty provision was contravened before 1 May 2017, would undermine the express limitations on the Commissioner’s powers provided for in Item 130 which confined the Commissioner to exercise only the functions and powers of the General Manager. Additionally, the AWU contended that as the exercise of the new powers would involve a substantial intrusion into fundamental common law rights, in the absence of clear language to the contrary, the principle of legality requires that s 331(2) of the RO Act be read as only authorising an investigation as to whether a civil penalty provision has been contravened after 1 May 2017.

34 Sixth, the AWU contended that concern about retrospectivity was another factor tending against any expansive or generous interpretation of the Commissioner’s powers and, applying well settled principles of the common law, it ought to be presumed that s 331(2) is not intended to have retrospective effect.

35 Seventh, the AWU relied upon the amendments made by the RO Amendment Act to s 305(2) to contend that the Commissioner is only empowered to conduct an investigation as to whether there has been a contravention of a provision that has at its foot the words “Civil penalty” and, that it must follow from the amendments made, that the power is confined to an investigation of a contravention suspected to have occurred after 2 May 2017. The AWU submitted that this is apparent from the ordinary meaning of the statutory text employed.

36 The Commissioner’s response to the construction of s 331(2) contended for by the AWU included the submission that it would result in irrational or absurd outcomes. The Commissioner contended that on that construction, other than for investigations already commenced by the General Manager prior to 1 May 2017, there would be no capacity to investigate suspected contraventions.

37 The AWU had two answers to that submission. First, that the function of investigating a contravention by Historical Conduct under s 331(2) remained with the General Manager. For that proposition the AWU relied upon s 7(2)(e) of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth). Section 7(2) relevantly provided:

(2) If an Act, or an instrument under an Act, repeals or amends an Act (the affected Act) or a part of an Act, then the repeal or amendment does not:

(a) revive anything not in force or existing at the time at which the repeal or amendment takes effect; or

(b) affect the previous operation of the affected Act or part (including any amendment made by the affected Act or part), or anything duly done or suffered under the affected Act or part; or

(c) affect any right, privilege, obligation or liability acquired, accrued or incurred under the affected Act or part; or

(d) affect any penalty, forfeiture or punishment incurred in respect of any offence committed against the affected Act or part; or

(e) affect any investigation, legal proceeding or remedy in respect of any such right, privilege, obligation, liability, penalty, forfeiture or punishment.

Any such investigation, legal proceeding or remedy may be instituted, continued or enforced, and any such penalty, forfeiture or punishment may be imposed, as if the affected Act or part had not been repealed or amended.

Note: The Act that makes the repeal or amendment, or provides for the instrument to make the repeal or amendment, may be different from, or the same as, the affected Act or the Act containing the part repealed or amended.

38 Second and in the alternative, the AWU contended that if there was a lacuna in the capacity for investigations to be conducted, that was to be rectified by an appropriate statutory amendment rather than by the Court impermissibly filling gaps by straining for a construction thought to be consistent with an assumed legislative purpose. The AWU submitted that the Commissioner’s interpretation departs from the statutory text and that it is unclear how the Commissioner’s interpretation can be reconciled with s 305(2) of the RO Act.

39 The AWU’s construction of s 331(2) of the RO Act requires that the general words of s 331(2) be read down to impose a temporal limitation not expressly made. For the reasons that follow, none of the considerations relied upon by the AWU justify the construction of s 331(2) contended for.

40 Turning to each of the considerations relied upon by the AWU, the AWU’s contention that as at 1 May 2017 the Commissioner was a “new entity” is of itself, a neutral factor. I will return to the AWU’s reliance upon the Commissioner having “a new suite of coercive powers”. However, the fact that an entity, different to the General Manager in whom the investigative function provided for by s 331 had been reposed was newly established and given that function, does not of itself support the existence of an intended temporal limitation on the exercise of that function.

41 The AWU’s second point was that, by Item 130, specific and limited provision was made for the Commissioner to assume the functions and powers of the General Manager. However, on its own, that consideration is also neutral. It is only supportive of the AWU’s construction if the AWU’s third point is correct: that there is no provision in either the RO Act or the RO Amendment Act which provides for the Commissioner generally to assume the functions and powers of the General Manager.

42 The fundamental difficulty for the AWU is that s 331(2) of the RO Act is such a provision. It is helpful that the terms of that provision be set out again:

(2) If the Commissioner is satisfied that there are reasonable grounds for doing so, the Commissioner may conduct an investigation as to whether a civil penalty provision (see section 305) has been contravened.

43 The provision provides for the Commissioner to conduct an investigation as to whether a civil penalty provision has been contravened. The capacity there given to conduct an investigation is qualified by the need for the Commissioner to be satisfied that there are reasonable grounds for doing so, but in terms it is not otherwise qualified and, in particular, there is no temporal qualification or limitation expressed.

44 Prior to the amendment made to s 331(2) by the RO Amendment Act on 1 May 2017, the function conferred by that provision operated upon past events – namely, whether a civil penalty provision “has been” contravened. The operative scope of that function could have been limited to suspected contraventions that post-dated the amendment, but it was not. That aspect of the operation of s 331(2) was left textually unchanged. Whilst the language utilised may be characterised as general and thus susceptible to being read down if that course was justified, in the absence of such a justification the words are capable of bearing a sufficiently clear meaning to the effect that the function conferred is temporally unconfined in respect of conduct that may have contravened a civil penalty provision.

45 Item 130 provides no justification for reading down the text of s 331(2). Item 130 only serves to demonstrate the existence of the need for the transitional provisions to address the special case there dealt with. In so far as Item 130 concerns the function conferred upon the Commissioner by s 331(2), it is there to effectuate the performance of that function in particular or special circumstances. In the ordinary case, an investigation under s 331(2) will be conducted by a single entity. Given the change of entities effected by the amendments made to s 331(2) by the RO Amendment Act, a possibility arose that a single investigation may be conducted in part by the outgoing entity (the General Manager) and in part by the incoming entity (the Commissioner). Item 130 addresses such a special case, not only in relation to s 331(2), but in relation to any process begun by the General Manager or by the FWC which was incomplete as at 1 May 2017. That was obviously done to ensure that any process commenced by the General Manager or the FWC was able to be validly completed by the Commissioner.

46 The fourth point made by the AWU also relied upon the terms of Item 130. That contention is premised upon a construction of Item 130 that, in exercising powers when completing an investigation commenced by the General Manager, the Commissioner is confined to only exercising the powers formerly held by the General Manager and not any additional powers conferred upon the Commissioner by the RO Amendment Act. For that reason, the AWU contended that the express limitations on the Commissioner’s powers provided for in Item 130 would be undermined if it were intended that the Commissioner, using his new suite of powers, could conduct an investigation as to whether a civil penalty provision was contravened before 1 May 2017.

47 There are a number of difficulties with that proposition. First, it is not at all clear that Item 130 confines the Commissioner to the exercise of only those powers formerly held by the General Manager. Item 130(2)(a) provides that in completing the process begun by the General Manager, the Commissioner may exercise a power held by the General Manager. That provision is explicable including because a power exercised by the General Manager may have only been partly exercised as at 1 May 2017. It seems to me that it is that circumstance that Item 130(2)(a) is principally seeking to address, and in doing so, the provision operates to confirm that the Commissioner is reposed with the former powers of the General Manager. It is not necessarily the case that in providing for the Commissioner to complete a process commenced by the General Manager, the provision intends to exclude the exercise of a power held by the Commissioner but not formerly held by the General Manager. On its face, Item 130(2)(a) contains no words of limitation. It is not clear that an implied limitation was intended, although that may well be the better view.

48 However, even if I were to presume that the AWU’s construction is correct, the fact that the Commissioner’s powers are restricted to those that were available to the General Manager, in circumstances where an investigation had already been commenced by the General Manager, does not serve to undermine the proposition that the Commissioner has available to him his full suite of powers in dealing with an investigation commenced by him in relation to Historical Conduct. There is a basis for saying that, in relation to a process already underway, the goal posts ought not to be shifted. The existence of an intention consistent with that objective does not, however, support the idea that in relation to a process not yet commenced a limitation was intended upon the exercise of the powers conferred on the Commissioner.

49 In my view, Item 130 has nothing to say about how s 331(2) was intended to operate in the ordinary case where an investigation is commenced by the Commissioner in the expectation that it will be completed by the Commissioner.

50 The essence of the AWU’s fifth point about the principle of legality and the AWU’s sixth point about a concern for retrospectivity, is that clear words are required in order for s 331(2) to be read as authorising the Commissioner to conduct an investigation as to whether a civil penalty provision has been contravened by Historical Conduct. I would accept that if the principle of legality or the presumption against retrospectivity were attracted, the words of s 331(2) may need to be read down in the manner contended for by the AWU.

51 It may be accepted in favour of the AWU that the Commissioner has powers, the exercise of which may involve a substantial intrusion into fundamental common law rights sufficient to engage the principle of legality. One such power referred to by the AWU is a power potentially intrusive of the privilege against self-incrimination, to require a person to answer a question on pain of criminal penalty (ss 335D(3); 337(1)(d)(i); 337AD). It may also be accepted that, by reason of the principle of legality, a statutory provision will not be read as authorising an intrusion into fundamental common law rights or freedoms unless it does so in clear language: North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency Ltd v Northern Territory (2015) 256 CLR 569 at [11] (French CJ, Kiefel and Bell JJ).

52 However, the AWU did not contend that any particular provision conferring on the Commissioner a power, the exercise of which may intrude upon fundamental common law rights, suffered from an absence of clear language. For instance, the AWU was not contending that s 335D(3) did not, by clear words, empower the Commissioner to compel a person to answer a question despite the possible intrusion into the privilege against self-incrimination. To construe the RO Act as permitting the Commissioner to compel an answer in the context of a s 331(2) investigation into conduct occurring after 1 May 2017 was not said by the AWU to offend the principle of legality. However as I understood it, the AWU was contending that to construe the RO Act as permitting the Commissioner to compel such an answer in the context of a s 331(2) investigation into Historical Conduct would offend the principle.

53 That reveals that the vice that the AWU really had in mind was not an intrusion into common law rights per se but an intrusion involving retrospectivity. The AWU’s reliance upon the principle of legality is, in substance, no different to its reliance upon the common law presumption against retrospectivity. Indeed as French CJ, Crennan and Kiefel JJ observed in Australian Education Union v Fair Work Australia (2012) 246 CLR 117, the underlying rationale or assumption upon which the presumption against retrospectivity is based may be viewed as an aspect of the principle of legality. Relevantly, and at [30] their Honours said:

The preceding observations should not be taken as minimising the importance of the rationale underlying the common law principles of construction. In a representative democracy governed by the rule of law, it can be assumed that clear language will be used by the Parliament in enacting a statute which falsifies, retroactively, existing legal rules upon which people have ordered their affairs, exercised their rights and incurred liabilities and obligations. That assumption can be viewed as an aspect of the principle of legality, which also applies the constructional assumption that Parliament will use clear language if it intends to overthrow fundamental principles, infringe rights, or depart from the general system of law. The existence of those assumptions is, in the words of Gleeson CJ in Electrolux Home Products Pty Ltd v Australian Workers’ Union,

‘a working hypothesis, the existence of which is known both to Parliament and the courts, upon which statutory language will be interpreted. The hypothesis is an aspect of the rule of law.’

54 I proceed on the basis that both the fifth and sixth points raised by the AWU turn on whether a presumption against retrospectivity is attracted to support the contention that, absent clear words, the RO Act does not authorise the Commissioner to conduct an investigation into whether a civil penalty provision was contravened before 1 May 2017 (except for the extent provided for in Item 130), or to exercise powers that were not available to the General Manager in the course of such an investigation.

55 In my view, a presumption against retrospectivity is not attracted.

56 There have been many formulations of the common law principle here being addressed. Some of the formulations were relied upon by French CJ, Crennan and Kiefel JJ (at [26]) in Australian Education Union:

The common law principles of interpretation require careful consideration of the adjective “retrospective” in its application to statutes. Interference with existing rights does not make a statute retrospective. Many if not most statutes affect existing rights. As Fullagar J said in Maxwell v Murphy:

‘I think that the word ‘retrospective’ has acquired an extended meaning in this connection. It is not synonymous with ‘ex post facto’, but is used to describe the operation of any statute which affects the legal character, or the legal consequences, of events which happened before it became law.’

In Chang Jeeng v Nuffield (Australia) Pty Ltd Dixon CJ referred to ‘the rules of interpretation affecting what is so misleadingly called the retrospective operation of statutes’. Repeating a passage from his judgment in Maxwell v Murphy, the Chief Justice said:

‘The general rule of the common law is that a statute changing the law ought not, unless the intention appears with reasonable certainty, to be understood as applying to facts or events that have already occurred in such a way as to confer or impose or otherwise affect rights or liabilities which the law had defined by reference to the past events.’

57 Furthermore, as Winneke CJ, Gowans and Starke JJ said in Robertson v City of Nunawading [1973] VR 819 at 824, the presumption against retrospectivity:

is not concerned with the case where the enactment under consideration merely takes account of antecedent facts and circumstances as a basis for what it prescribes for the future, and it does no more than that…The principle is concerned with the case where the enactment would apply to these antecedent facts and circumstances in such a way ‘as to impair an existing right or obligation’ or ‘as to confer or impose or otherwise affect rights or liabilities which the law had defined by reference to the past events’.

58 The AWU did not identify as part of its submission on retrospectivity, existing rights, liabilities or obligations said to be affected by the amendments made by the RO Amendment Act to the functions and powers of the Commissioner in relation to the conduct of an investigation under s 331(2). The submission was undeveloped. In any event, no effect of the requisite kind is apparent.

59 A person whose conduct is the subject of a s 331(2) investigation has no right not to be subjected to such an investigation, let alone a right existing prior to 1 May 2017 to be subjected only to an investigation in which the powers available to the General Manager prior to that time may be utilised. Further, it may be accepted that the exercise of the Commissioner’s powers in relation to an investigation can affect the rights of persons, whether the subject of the investigation or not. For example, the right to silence or rights to property. However, the rights affected are not rights which are changed with effect prior to the commencement of the RO Amendment Act. The effect upon those rights cannot therefore be said to operate retrospectively.

60 As the Commissioner contended, the relevant facts here are not materially different to that considered by Marks J (with whom Murphy and McGarvie JJ agreed) in Commissioner for Corporate Affairs v X and Y [1987] VR 460.

61 The respondents in that case were acting as receivers and managers of a particular company between 1978 and 1980. On 1 July 1982, a new power was conferred upon the Commissioner for Corporate Affairs by s 541 of the Companies (Victoria) Code (“Code”). That provision empowered the Commissioner for Corporate Affairs to apply to a court for an order compelling persons who had taken part or had been concerned in the affairs of a corporation and who had been or may have been guilty of fraud, negligence, default, breach of trust, breach of duty or other misconduct in relation to that corporation, to be compulsorily examined in relation to the affairs of the corporation concerned. Non-compliance with that requirement gave rise to a criminal sanction. On 12 July 1985, the Commissioner for Corporate Affairs applied to the Supreme Court of Victoria for an order compelling the respondent receivers and managers to be examined in relation to their conduct in 1978-1980.

62 On those facts, the Full Court of the Supreme Court of Victoria rejected the proposition that the presumption against retrospectivity was attracted, holding that s 541 of the Code operated prospectively, stating at 464 “legislation is not properly called retrospective merely because events are by virtue of it the subject of prospective action such as examination under court order”.

63 The seventh consideration relied upon by the AWU turned on the amendments made by the RO Amendment Act to s 305(2). Relying on the terms of s 331(2) and in particular that “the Commissioner may conduct an investigation as to whether a civil penalty provision (see section 305) has been contravened”, the AWU contended that reading the definition of “civil penalty provision” provided by s 305(2) into s 331(2), has the consequence that the Commissioner only has the power to conduct an investigation as to whether there has been a contravention of a provision that has, set out at its foot, a pecuniary penalty indicated by the words “Civil penalty”. The AWU contended, by reference to the legislative history of s 305(2) to which I have referred, that it was only after 2 May 2017 that civil penalty provisions in the RO Act had, set out at their foot, a pecuniary penalty indicated by the words “Civil penalty”. It follows, so the AWU contended, that the Commissioner only has the power to conduct an investigation as to whether a provision of the RO Act was contravened after 2 May 2017. Any contravention that occurred before 2 May 2017 would necessarily involve a provision that did not have, set out at its foot, a pecuniary penalty indicated by the words “Civil penalty” and, so the AWU contended, the Commissioner has no power to investigate such a contravention under s 331(2) of the RO as in force at the time the Investigation commenced.

64 The RO Amendment Act introduced new provisions into the RO Act and designated some as civil penalty provisions. That, however, is not material. What is material, is that prior to the commencement of the RO Amendment Act some 43 provisions of the RO Act were designated to be civil penalty provisions and, by reason of s 331(2), a suspected breach of those provisions could have been the subject of a s 331(2) investigation. After the commencement of the RO Amendment Act those provisions continued as civil penalty provisions of the RO Act. The only relevant alteration made by the RO Amendment Act was to the means by which those provisions were identified as civil penalty provisions. Prior to the amendments being made, the provisions were listed in s 305(2) and designated as “civil penalty provisions”. After the amendments were made, those provisions self-identified as civil penalty provisions by containing the words “Civil penalty” in the manner provided for by the current terms of s 305(2).

65 The change made cannot be understood as anything more than the result of the adoption of a different drafting technique. The change was stylistic. There is nothing to support the idea that a change of any substance was intended by the amendment made to s 305(2) of the RO Act by the RO Amendment Act.

66 The AWU’s contention must be that despite the RO Amendment Act continuing the status of those provisions as civil penalty provisions, the RO Amendment Act stripped those provisions of that status in relation to their operation prior to the commencement date of that Act. In other words, the AWU’s contention is that the operation of those provisions was retrospectively altered so that they no longer operated as civil penalty provisions in the period prior to 2 May 2017.

67 The AWU offers no policy rationale to support any discernible Parliamentary intention to effectuate that retrospective alteration, the unameliorated consequence of which would be that persons who had contravened those provisions but who had not been dealt with by 2 May 2017, would effectively be immune, not only from a s 331(2) investigation, but also from proceedings for contraventions of civil penalty provisions in this Court.

68 The AWU’s contention must be rejected, including its reliance, in the alternative, on the inexplicable consequences of its construction being unintended but nevertheless unrectifiable in the absence of legislative amendment.

69 A complete answer to the AWU’s unattractive construction is provided by s 7(2)(b) of the Acts Interpretation Act. That provision relevantly provides that an amendment to an Act does not “affect the previous operation of the affected Act or part”.

70 As Gleeson CJ said in Attorney-General (Q) v Australian Industrial Relations Commission (2002) 213 CLR 485 at [8]:

Acts of Parliament are drafted, and are intended to be read and understood, in the light of the Acts Interpretation Act. A particular Act, and the Acts Interpretation Act, do not compete for attention, or rank in any order of priority. They work together. The meaning of the particular Act is to be understood in the light of the interpretation legislation.

71 Prior to the amendments made by the RO Amendment Act, the relevant provisions operated as civil penalty provisions. By reason of s 7(2)(b) of the Acts Interpretation Act the operation of those provisions as civil penalty provisions was unaffected by the amendments made by the RO Amendment Act, and in particular, the amendments made to s 305(2). It ought to be presumed that those amendments were drafted on the basis that they would be read in light of the Acts Interpretation Act. A similar argument was made by the Commissioner by reference to s 7(2)(c) of the Acts Interpretation Act. I need not determine whether that provision would provide for the same result. I am satisfied that s 7(2)(b) is sufficient of itself. There can be no doubt that the application of that provision is not subject to any contrary intention (see s 2(2) of the Acts Interpretation Act).

72 Accordingly, the provisions in question bore the description used in s 331(2) of the RO Act “a civil penalty provision” and continued to bear that description in relation to their operation after 2 May 2017 without being affected by the amendments made to s 305(2) by the RO Amendment Act. The AWU’s seventh point must therefore be rejected.

73 Lastly, in so far as the AWU relied on the operation of s 7(2)(e) of the Acts Interpretation Act to contend that the General Manager still holds the function of conducting a s 331(2) investigation into Historical Conduct, I would conclude that that provision has no application because a contrary intention is demonstrated by the terms of s 331(2) as amended by the RO Amendment Act. That provision, as I have construed it, is clearly inconsistent with the survival of the General Manager’s investigative function: Attorney-General (Q) at [52] (Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow and Hayne JJ).

74 A number of contentions were raised by the Commissioner which, in the circumstances, it is unnecessary for me to address. Each of the parties referred to explanatory memoranda and the AWU also referred to amendments made to the commencement date of Sch 1 and 2 of the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Amendment Bill 2014. Whilst I have considered that material, I have found it of little or no assistance in the interpretive task here addressed.

75 For all those reasons, I conclude that s 331(2) empowers the Commissioner, where satisfied that there are reasonable grounds to do so, to conduct an investigation as to whether a civil penalty provision has been contravened. There is no justification for reading into the text of that provision the temporal restriction contended for by the AWU. The Commissioner’s decision to conduct the Investigation under s 331(2) into conduct occurring before 1 May 2017 did not involve any misconstruction of the statutory task conferred upon him by that provision and was not affected by jurisdictional error as contended for by the AWU. Ground 1 of the AWU’s grounds of review must be rejected.

ground 2 – Was the Commissioner validly satisfied that there were reasonable grounds for conducting the Investigation?

76 Under this ground the AWU challenged the Investigation contending that the condition on the Commissioner’s exercise of power to conduct an investigation under s 331(2), that “the Commissioner is satisfied that there are reasonable grounds for doing so”, was not validly met. There are two limbs to ground 2 but they are best addressed together. Before doing so it is necessary to set out the relevant legislative provisions.

Relevant Legislative Provisions

77 Section 140(1) of the RO Act provides that a registered organisation “must have rules that make provision as required by this Act”. That is the current requirement but was also the requirement under s 140(1) of Sch 1 of the WR Act which was applicable at the time that each of the Donations were made.

78 Section 149(1) of the RO Act specifies that the rules of a registered organisation must provide conditions in relation to loans, grants and donations made by the organisation. Relevantly, s 149(1) provides:

Rules to provide conditions for loans, grants and donations by organisations

(1) The rules of an organisation must provide that a loan, grant or donation of an amount exceeding $1,000 must not be made by the organisation unless the committee of management:

(a) has satisfied itself:

(i) that the making of the loan, grant or donation would be in accordance with the other rules of the organisation; and

(ii) in the case of a loan – that, in the circumstances, the security proposed to be given for the repayment of the loan is adequate and the proposed arrangements for the repayment of the loan are satisfactory; and

(b) has approved the making of the loan, grant or donation.

79 At the time of the making of the Donations, a legislative predecessor to s 149(1) (s 149(1) of Sch 1 of the WR Act) specified the same requirements.

80 It is not in contest that at the time the Donations were made, the rules of the AWU (“Rules”) relevantly included r 57 which was in the following terms:

(1) A loan, grant or donation, must not be made by the Union or any Branch as the case may be, unless the National Executive of the Union has:

(a) Satisfied itself:

(i) that the making of the loan, grant or donation, would be in accordance with the Rules of the Union; and

(ii) in relation to a loan, that, in the circumstances, the security proposed to be given for the repayment of the loan is adequate and the proposed arrangements for the repayment of the loan are satisfactory; and

(b) Approved the making of the loan, grant or donation.

(2) Nothing in sub-clause (1) is to affect a Branch’s power to make donations, less than $1,000. However, National Executive may from time to time set a maximum donation figure lower than $1,000.

81 The Decision Record refers to r 57 and, as I will detail shortly, relies upon the possibility that the Donations were not made in accordance with r 57 as a basis for Mr Enright’s satisfaction that “there are reasonable grounds to conduct an investigation”.

82 Section 320(1) of the RO Act is a deeming provision which applies to certain acts done, by a collective body or office-holder of a registered organisation (or by person/s purporting to act as such), after the end of four years from the doing of those acts. Relevantly s 320(1) provides:

Validation of certain acts after 4 years

(1) Subject to this section and section 321, after the end of 4 years from:

(a) the doing of an act:

(i) by, or by persons purporting to act as, a collective body of an organisation or branch of an organisation and purporting to exercise power conferred by or under the rules of the organisation or branch; or

(ii) by a person holding or purporting to hold an office or position in an organisation or branch and purporting to exercise power conferred by or under the rules of the organisation or branch; or

the act, election or purported election, appointment or purported appointment, or the making or purported making or alteration or purported alteration of the rule, is taken to have been done in compliance with the rules of the organisation or branch.

83 At the time that the Donations were made, the legislative predecessor of s 320(1) the RO Act (s 89 of Sch 1 of the WR Act) was in similar terms.

84 Under the first limb of ground 2, the AWU contended that the Decision was affected by jurisdictional error because it was not open for Mr Enright to be satisfied that there were reasonable grounds to conduct the Investigation. The second and related basis for ground 2 was that, in not adverting to s 320 of the RO Act or, alternatively by proceeding on an erroneous view of that provision, Mr Enright misunderstood the law he was to apply.

85 The AWU contended that the ground (and only ground) relied upon by Mr Enright in being satisfied that there were reasonable grounds to conduct the Investigation as to whether ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) had been contravened, was that the making of the Donations involved suspected non-compliance with the Rules and in particular r 57. The AWU contended that the basis for Mr Enright’s satisfaction was misconceived. Relying on the operation of s 320 of the RO Act, the AWU submitted that the making of the Donations was “taken to have been done in compliance with the Rules” at the end of the 4 year period after each of the Donations were made and that therefore, at the time of the Decision, there was no possibility of non-compliance with the Rules in relation to the making of the Donations. Accordingly, so the AWU contended, it was not open for Mr Enright to have reached the state of satisfaction required by s 331(2) and the Decision was therefore affected by jurisdictional error and invalid.

86 The submission is inapplicable to the Decision so far as it concerned the conduct of an investigation into whether s 237(1) was contravened because that aspect of the Investigation had nothing to do with suspected contraventions of the Rules. Nevertheless, the AWU contended that the Decision, as a whole, was invalid. It may be that the AWU intended to say, as its submission did say in a similar context, that the Decision to conduct the Investigation is an integrated whole which cannot be severed without “radically recast[ing] its nature and effect” (Plaintiff S4/2014 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2014) 253 CLR 219 at [55]).

Deliberation – The Relevant Principles

87 It was not in contest that the state of satisfaction required by s 331(2) is a condition upon the exercise of the function or power there conferred. Nor was it in contest that whether the state of satisfaction required by s 331(2) exists, is a question amenable to judicial review. The applicable principle for assessing whether the formation of a statutory state of satisfaction is affected by jurisdictional error was recently stated by Kiefel CJ, Gageler and Keane JJ in Hossain v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2018] HCA 34. At [34] their Honours said that the “[f]ormation of the [decision-maker’s] state of satisfaction or of non-satisfaction is in each case conditioned by a requirement that the [decision-maker] … must proceed reasonably and on a correct understanding and application of the applicable law”. For that proposition their Honours referred to a number of authorities including the survey of authorities provided by Gummow J in Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs v Eshetu (1999) 197 CLR 611, in which (at [133]) his Honour relied upon the following seminal observations of Latham CJ in R v Connell; Ex parte Hetton Bellbird Collieries Ltd (1944) 69 CLR 407 (at 430 and 432):

[W]here the existence of a particular opinion is made a condition of the exercise of power, legislation conferring the power is treated as referring to an opinion which is such that it can be formed by a reasonable man who correctly understands the meaning of the law under which he acts. If it is shown that the opinion actually formed is not an opinion of this character, then the necessary opinion does not exist.

…

It should be emphasized that the application of the principle now under discussion does not mean that the court substitutes its opinion for the opinion of the person or authority in question. What the court does do is to inquire whether the opinion required by the relevant legislative provision has really been formed. If the opinion which was in fact formed was reached by taking into account irrelevant considerations or by otherwise misconstruing the terms of the relevant legislation, then it must be held that the opinion required has not been formed. In that event the basis for the exercise of power is absent, just as if it were shown that the opinion was arbitrary, capricious, irrational, or not bona fide.

88 In Graham v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2017) 263 CLR 1 at [57], Kiefel CJ, Bell, Gageler, Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ, in support of their observation that the satisfaction required of the decision-maker by the legislative provision there under consideration had to be “formed … reasonably and on a correct understanding of the law”, said (quoting from R v Anderson; Ex parte Ipec-Air Pty Ltd (1965) 113 CLR 177 at 189) that such a statutory condition had to be exercised by the decision-maker “according to the rules of reason and justice, not according to private opinion; according to law, and not humour, and within those limits within which an honest man, competent to discharge the duties of his office, ought to confine himself”.

89 Reasonableness as a condition of an opinion or state of satisfaction bears a relationship to reasonableness as a condition upon the exercise of a discretionary power, as formulated in Minister for Immigration and Citizenship v Li (2013) 249 CLR 332. That relationship was explained by Gageler J in Li at [90]:

Implication of reasonableness as a condition of the exercise of a discretionary power conferred by statute is no different from implication of reasonableness as a condition of an opinion or state of satisfaction required by statute as a prerequisite to an exercise of a statutory power or performance of a statutory duty. Each is a manifestation of the general and deeply rooted common law principle of construction that such decision-making authority as is conferred by statute must be exercised according to law and to reason within limits set by the subject-matter, scope and purposes of the statute.

90 However, as Gageler J observed in Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v SZVFW [2018] HCA 30 at [53], reasonable grounds as a condition of an opinion or state of satisfaction imposes a condition on the exercise of power on the repository of a “higher standard” than that imposed by the requirement that a statutory power be exercised within the bounds of reasonableness as an implied condition of the statutory conferral of the power.

91 His Honour relevantly referred to Prior v Mole (2017) 261 CLR 265 where the applicable principles on reasonableness as a condition of an opinion or state of satisfaction were helpfully summarised by Gordon J at [98]-[100] in the context of the formation of a predictive opinion:

[98] When a statute prescribes that there must be “reasonable grounds” for a state of mind, it requires the existence of facts sufficient to induce that state of mind in a reasonable person. It is an objective test. The question is not whether the relevant person thinks they have reasonable grounds.

[99] In explaining the connection between the “reasonable grounds” and the requisite “belief”, this Court in George v Rockett stated:

‘The objective circumstances sufficient to show a reason to believe something need to point more clearly to the subject matter of the belief, but that is not to say that the objective circumstances must establish on the balance of probabilities that the subject matter in fact occurred or exists: the assent of belief is given on more slender evidence than proof.’

[100] Belief is not certainty. ‘Belief is an inclination of the mind towards assenting to, rather than rejecting, a proposition and the grounds which can reasonably induce that inclination of the mind may, depending on the circumstances, leave something to surmise or conjecture’.

92 Prior concerned s 128(1) of the Police Administration Act (NT). Under that section, a police officer was given the power to apprehend a person without a warrant where the police officer had reasonable grounds for believing, inter alia, that the person was intoxicated; was in a public place; and because of the person’s intoxication, the person may intimidate, alarm or cause substantial annoyance to people or is likely to commit an offence.

93 In that context, Gordon J continued at [101]:

Those considerations are important in this appeal. The matters set out in s 128(1)(c)(iii) and (iv) are the “subject matter” of the belief. That subject matter necessarily involves an element of opinion and judgment – a predictive opinion and judgment about what the person (here, Mr Prior) may or is likely to do in the future. That opinion and judgment is related to, but separate from, the objective facts and circumstances. Together, they constitute all of the relevant circumstances for assessing the reasonableness of the grounds. Accordingly, when considering whether there were reasonable grounds for the relevant belief for the purposes of s 128(1)(c)(iii) and (iv), matters of both fact and opinion must be considered.

94 Further, as Gageler J stated in Prior at [27] “[t]he Court must arrive at its own independent answer through its own independent assessment of the objective circumstances which the [decision-maker] took into account”; see further George v Rockett (1990) 170 CLR 104 at 114-117 (Mason CJ, Brennan, Deane, Dawson, Toohey, Gaudron and McHugh JJ). The circumstances that were taken into account by the decision-maker may or may not be set out in the reasons for decision provided by the decision-maker. If reasons are given by the decision-maker which explain the basis for the decision-maker reaching the requisite state of satisfaction or opinion, it is to those reasons that a supervising court should look to understand how the state of satisfaction or opinion was reached. That is the approach taken by a supervising court in the related field of legal unreasonableness. I can see no reason why the same approach is not apposite.

95 As was stated by Allsop CJ, Robertson and Mortimer JJ in Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v Singh (2014) 231 FCR 437 at [47]:

where there are reasons for the exercise of a power, it is those reasons to which a supervising court should look in order to understand why the power was exercised as it was. The “intelligible justification” must lie within the reasons the decision-maker gave for the exercise of the power — at least, when a discretionary power is involved. That is because it is the decision-maker in whom Parliament has reposed the choice, and it is the explanation given by the decision-maker for why the choice was made as it was which should inform review by a supervising court

See further Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v Haq [2019] FCAFC 7 at [35] (Griffiths J with whom Gleeson J agreed) and at [91]-[97] (Colvin J).

Deliberation – Application of the Principles to the Facts

96 Applying that approach and looking to the reasons given by Mr Enright for the Decision, for the reasons I will expand upon, I have come to the view that the only circumstance or ground relied upon by Mr Enright to form the opinion that there were reasonable grounds to conduct the Investigation as to whether ss 237(1), 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) of the RO Act had been contravened was that there was a basis for suspecting that each of those provisions had been contravened and, further that Mr Enright’s only basis for the suspicion that ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) had been contravened was that the Donations were not made in accordance with the Rules.

97 In relation to the suspected contraventions of s 237(1) it was not contested and, objectively considered by reference to the Decision Record, it is clear that Mr Enright had a reasonable basis for suspecting that, by the failure of the AWU to lodge a statement of particulars of donations made in the 2006 and 2008 financial years within 90 days of the end of each of those years, s 237(1) was contravened. It follows that it was open to Mr Enright to be satisfied that there were reasonable grounds to conduct an investigation as to whether s 237(1) “has been contravened” and the conduct of the Investigation for that purpose was not invalid because the requisite state of satisfaction did not exist.

98 However, in relation to the conduct of the Investigation for the purpose of investigating whether ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) had been contravened, I have arrived at the opposite conclusion. In summary, that is because I have concluded that Mr Enright’s suspicion that various acts had occurred in contravention of ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) was predicated upon the view that those acts, if done, were done in breach of the Rules and that, in each case, the breach of the Rules was the basis for the suspected contravention. It was for that reason that Mr Enright formed the opinion that there were reasonable grounds to conduct an investigation as to whether those provisions had been contravened.

99 Taking into account matters of both fact and opinion and objectively considered, the basis relied upon by Mr Enright to ground his suspicion could not sustain the opinion that there were reasonable grounds to conduct an investigation as to whether those provisions had been contravened. There was no basis for Mr Enright’s opinion that the suspected contraventions would be grounded in acts done in contravention of the Rules. That is because, by the operation of s 320 of the RO Act (which Mr Enright regarded as inapplicable), the suspected acts in question, if done, must be “taken to have been done in compliance with the [Rules]”. The circumstances relied upon by Mr Enright to form his opinion, were insufficient to induce a reasonable person to form the opinion that there were reasonable grounds to conduct an investigation as to whether ss 285(1), 286(1) or 287(1) had been contravened.

100 Consequently, the condition upon the exercise of the power given by s 331(2) for conducting an investigation as to whether ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) had been contravened, was not satisfied. The statutory power to do so was not engaged and the Commissioner’s investigation in relation to those provisions exceeded the statutory power conferred by s 331(2) upon the Commissioner. To that extent, the AWU has established jurisdictional error under ground 2.

101 I turn then to provide the detail for the conclusion just expressed.

102 As Allsop CJ said in Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v Stretton (2016) 237 FCR 1 (at [11]), in the related context of legal unreasonableness, the boundaries of power may be difficult to define and an evaluation of whether a decision has been made within those boundaries “is conducted by reference to the relevant statute, its terms, scope and purpose”. It is best therefore to commence with observations about the RO Act, the investigative task conferred upon the Commissioner by s 331 and any evident purpose for the imposition of the condition on the exercise of that power expressed by s 331(2).

103 The functions of the Commissioner specified in s 329AB as well as the terms of s 317, which provides a simplified outline of Chap 11 (including for Pt 4 where s 331(2) is found), make it clear that an important part of the Commissioner’s function is regulatory and concerned with compliance. The Commissioner’s statutory functions are concerned with contraventions or possible contraventions of specified provisions of the RO Act. The Commissioner is empowered to apply to this Court for orders, including for the imposition of civil penalties (s 310(1)). It is evident that, to facilitate that compliance function, the Commissioner has been given the power to make inquiries and the further power to conduct investigations.

104 Section 330 addresses the Commissioner’s discretionary power to make inquiries. Section 330(1) empowers the Commissioner to make inquiries as to whether Pt 3 of Chap 8 of the RO Act (dealing with records and accounts) is being complied with, including the reporting guidelines and regulations made under and for the purpose of that Part and rules of a “reporting unit” of a registered organisation relating to its finances or financial administration. Section 330(2) provides that the Commissioner “may make inquiries as to whether a civil penalty provision (see section 305) has been contravened”.

105 Subsections 331(1) and (2) are, save for one aspect of significance, in almost identical terms to ss 330(1) and (2). The difference is that the Commissioner need not be “satisfied that there are reasonable grounds for doing so” when exercising his discretion to conduct an inquiry but must be so satisfied when exercising his discretion to conduct an investigation. The reason for that disparity in treatment is, I think, revealed by the nature of the powers made available to the Commissioner for the purposes of making inquiries as compared to the powers available to the Commissioner to conduct an investigation. The difference in approach is most apparent from the terms of s 330(3) which, in relation to inquiries, provide (emphasis added):

(3) The person making the inquiries may take such action as he or she considers necessary for the purposes of making the inquiries. However, he or she cannot compel a person to assist with the inquiries under this section.

106 In contrast to the restriction imposed by that provision, in the conduct of an investigation under s 331 the Commissioner has available a wide array of coercive powers with potential consequences for the rights of others, including upon fundamental common law rights as discussed at [51]. As Gleeson CJ and Kirby J observed in McKinnon v Secretary, Department of Treasury (2006) 228 CLR 423 at [9], the conferral of statutory powers of search and seizure and arrest are often conditioned by the requirement of reasonable grounds for a state of mind such as a suspicion or belief.

107 The comparison with s 330 reveals a relation between the coercive powers conferred on the Commissioner and the limitation imposed on the investigative function for which those powers have been conferred. That relation suggests that the purpose of imposing upon the Commissioner the limitation upon his discretion to commence an investigation is not merely concerned with the utility of the investigation. It may well be that utility, economy, efficiency and even propriety of purpose are not considerations that the limitation has in mind at all. Considerations of that kind are obviously relevant to whether a statutory discretion involving time, effort and resources ought to be exercised and need not be spelt out. The requirement that the power conferred be exercised within the bounds of reasonableness is an implied condition of the conferral of the power.

108 The capacity given to the Commissioner to access coercive power through an investigation, and the fact that s 331 expressly imposes a limitation on the discretion and does so on the standard that the power is only to be exercised on “reasonable grounds”, are indicative of a protective purpose for the limitation on power in s 331(2). That limitation is to be understood as harbouring a concern for the rights ordinarily enjoyed by others and the capacity for those rights to be adversely affected by the conduct of an investigation.

109 Further, coercive powers are not usually conferred on fishing expeditions and the language of s 331(2) is specific. The Commissioner is not at large. The purpose of the investigation is to determine “whether a civil penalty provision has been contravened”. The subject of the power conferred is particular conduct which may have resulted in a particular contravention of a civil penalty provision.

110 All of those considerations should be kept in mind in the assessment of whether a particular investigation has been commenced within the boundaries of the power conferred by s 331(2).

111 The nature of the state of satisfaction required by s 331(2) was in contest. The AWU contended that there will be reasonable grounds to conduct an investigation to which s 331(2) refers if there are sufficient facts to satisfy a reasonable person that:

there are reasonable grounds to believe that a civil penalty provision may have been contravened; and

there are reasonable grounds to believe that the investigation will assist the Commissioner to establish that a civil penalty provision has been contravened.