FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Pinnacle Runway Pty Ltd v Triangl Limited [2019] FCA 1662

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent TRIANGL GROUP LIMITED Second Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | Cross-Claimant | |

AND: | Cross-Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

2. The cross-claim be dismissed.

3. The parties file and serve submissions on the question of costs within 21 days, and file and serve any submissions in reply within seven days thereafter.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MURPHY J:

Introduction

1 These are ill–advised proceedings in respect of alleged trade mark infringement and cancellation of a trade mark, and there is no clear winner. The applicant and cross-respondent, Pinnacle Runway Pty Ltd (Pinnacle), designs, manufactures, supplies and sells women’s clothing in Australia and overseas under the registered trade mark, DELPHINE (the DELPHINE Trade Mark). It alleged but failed to establish that Triangl infringed its registered mark. The second respondent and cross-claimant, Triangl Group Limited (Triangl) designs, manufactures, supplies and sells women’s swimwear in Australia and around the world under the registered trade mark, TRIANGL (the TRIANGL Trade Mark). It alleged but failed to establish that Pinnacle’s registration of the DELPHINE Trade Mark should be cancelled on the basis that Pinnacle was not the first to use it.

2 Even if Pinnacle had been successful in its claim, its damages entitlements were not worth the powder and shot. The period of alleged trade mark infringement was six weeks from 24 April 2016 to 2 June 2016 (the relevant period), the alleged infringing use ceased within three weeks of Pinnacle’s letter of demand, and Triangl agreed to desist from the allegedly infringing use before the proceeding was filed. The total revenue Triangl made through the alleged infringing conduct was less than $40,000, and Pinnacle was unable to establish that it had lost any sales. Pinnacle was also a young brand at the time, having been operating for less than a year. Its reputation at that stage was only budding and any entitlement it had to damages for diminution of reputation were de mimimis. Pinnacle spent many times more in legal costs in bringing the claim than it could ever have reasonably hoped to recover by way of damages. Triangl spent many times more defending the claim and bringing the cross-claim than it could have possibly been required to pay in damages. This unfortunate litigation involved substantial expenditure of the parties’ and Court resources and, for reasons which are unclear, the parties were unable to reach a commercial settlement.

3 Triangl admitted that, over a period of six weeks, it marketed and sold in Australia a bikini style in three different floral designs under the TRIANGL Trade Mark using the name DELPHINE, but denied using DELPHINE “as a trade mark”. It argued that it employed the TRIANGL Trade Mark to distinguish its products from those of other traders and it only used DELPHINE as a “style name” so as to assist consumers to differentiate that one of its many bikini styles from its other styles. It put on evidence to show that there is a widespread practice in the women’s fashion industry in Australia of using style names in relation to women’s fashion garments, including swimwear, and that women’s names are commonly so used. Triangl contended that consumers were used to this practice and that its use of the name DELPHINE was unlikely to be perceived by consumers as distinguishing Triangl’s goods from the goods of other traders.

4 For the reasons I explain Pinnacle did not establish that Triangl’s use of DELPHINE amounted to use as a trade mark under s 120 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (the Act). It is appropriate to dismiss Pinnacle's claim.

5 Triangl alleged in the cross-claim that Pinnacle was not the first trader to use DELPHINE in the course of trade in Australia in relation to the goods for which the mark is registered. On that basis it sought orders to cancel the registration of the DELPHINE Trade Mark under s 88 of the Act. Triangl did not however adduce admissible and probative evidence in support of its claim of use in Australia by other traders of a mark having substantial identity with the DELPHINE Trade Mark before the priority date of that mark. It is appropriate to dismiss Triangl’s cross-claim.

Pinnacle’s claim

The Facts

6 Many of the facts in relation to Pinnacle’s claim are uncontroversial. Where they are contentious, I set out my view of the evidence in the course of recounting the facts.

7 Pinnacle relied upon affidavits by:

(a) Mr Fabian Daniel Bucoy, general manager of Pinnacle, affirmed 13 April 2018;

(b) Mr Andrew Selim Petale, at the relevant time a solicitor with Actuate IP, the solicitors for Pinnacle, affirmed 26 March 2018;

(c) Ms Kerri Lambrianidis, at the relevant time a solicitor with Actuate IP, affirmed 27 March 2018; and

(d) Dr Stephen Downes, a branding and marketing expert, affirmed 27 March 2018 and 18 September 2018 (respectively the first and second Downes reports).

Mr Bucoy and Dr Downes were cross-examined.

8 Triangl relied upon affidavits by:

(a) Mr Craig Ellis, a director, shareholder and founder of Triangl Limited and Triangl Group Limited, affirmed 6 August 2018;

(b) Mr Gary Saunders, a marketing and public relations expert, affirmed 15 August 2018;

(c) Mr Fabien Lalande, a trade mark practitioner with Corrs Chambers Westgarth (Corrs), the solicitors for Triangl, affirmed 15 August 2018;

(d) Mr Christopher Butler, office manager of the Internet Archive, affirmed 11 June 2018, which was relied upon in a voir dire regarding the admissibility of Mr Lalande’s evidence.

Mr Ellis, Mr Saunders and Mr Butler were cross-examined.

Pinnacle and the DELPHINE brand

9 Mr Bucoy is Pinnacle’s General Manager. Much of his evidence is uncontentious but I found his evidence on some issues of significance in the case to be unreliable in certain respects. The assistance his evidence provided in relation to some important aspects of Pinnacle's claim was to a significant extent undercut in cross-examination.

10 Mr Bucoy has approximately 10 years of experience working in finance for Coles Myer in the retail sector and he subsequently spent a further 10 years working for his own women’s fashion companies. In approximately 2009 he co-founded Luvalot Clothing Pty Ltd, an Australian fashion company operating as an independent designer, manufacturer and wholesaler of women’s fashion and he continues to be a co-owner of that company. In February 2014 he incorporated Pinnacle which, at that time, operated as a wholesaler and retailer of women’s fashion under its own name. He co-owned Pinnacle until 2017 when he transferred his shares to his wife.

11 In approximately early 2015 Mr Bucoy decided to develop the Pinnacle business into an independent women’s fashion label that would manufacture and design its own products. Around that time Pinnacle began undertaking work to prepare for the launch of this new fashion label, which included the selection of an appropriate name. After considering a range of names with the staff at Pinnacle, Mr Bucoy chose the name DELPHINE as he considered it to be “a distinctive and pleasant sounding brand which fit[ted] the feminine image [he] wanted for the label.”

12 On 6 July 2015 Pinnacle lodged a trade mark application for the word DELPHINE in class 25, which, relevantly, covers most types of clothing, headwear and swimwear. On 3 February 2016 Pinnacle was registered as the owner of that mark in Australia and it has owned the DELPHINE Trade Mark in relation to goods and services in class 25 at all material times since then. An image of the mark appears below:

As is apparent, DELPHINE is in uppercase, it is not stylised and there is nothing distinctive in the font style, size or colour.

13 On 6 August 2015 Pinnacle registered DELPHINE THE LABEL as a business name in Australia. Subsequently Pinnacle also registered DELPHINE as a trade mark in the USA, the UK and New Zealand. The USA trade mark states that the mark comprises “consistent standard characters, without claim to any particular font style, size or colour”.

Pinnacle’s promotion of the DELPHINE brand

14 In preparation for the launch of the DELPHINE brand, Pinnacle:

(a) constructed a website located at <www.delphinethelabel.com> (the DELPHINE website) in or around July 2015 which included an online shop offering products for sale directly to customers;

(b) set up a Facebook page located at <www.facebook.com/delphinethelabel> (the DELPHINE Facebook page) in or around August 2015; and

(c) set up an Instagram account @delphinethelabel (the DELPHINE Instagram account) in or around early August 2015.

15 In or around August 2015, Pinnacle officially launched the DELPHINE label and celebrated the occasion with a launch party held on 18 September 2015.

16 Pinnacle operated the DELPHINE business from its Melbourne head office and it promoted its products around Australia and overseas. During the relevant period it had a sales and marketing presence in each State, the Northern Territory and in several locations overseas.

17 Mr Bucoy stated that, since the launch of the DELPHINE brand in August 2015, the brand “encompassed all manner of women’s fashions including but not limited to swimsuits and bodysuits/leotards, dresses, outerwear, tops, jumpsuits, and bottoms namely skirts, pants and shorts” (the DELPHINE Products). He adduced screenshots of pages on the DELPHINE website from the period September 2015 to April 2017 showing the promotion of DELPHINE Products (obtained through searches using the internet ‘Wayback Machine’) which I infer were taken around the time that Mr Bucoy made his affidavit. Triangl raised no objection to Mr Bucoy adducing these screenshots into evidence and I have treated them as admissible.

18 He said that, following its launch, Pinnacle used social media extensively to help promote DELPHINE Products, including via its Facebook page and its Instagram account. There is some direct evidence of Pinnacle’s promotion of DELPHINE Products via its Facebook page from August 2015 but, because its Instagram account was hacked in August 2017 and the contents of the account lost, there is no evidence about the number of followers it had or the extent of Instagram posts promoting DELPHINE Products prior to and during the relevant period. Mr Bucoy said that the DELPHINE Instagram account had approximately 20,000 followers prior to August 2017 and that it gained 3,256 followers between August 2017 and April 2018, but he did not estimate how many there were up to and including the relevant period. Up to and including the relevant period DELPHINE was just starting up and I infer that the DELPHINE Instagram account had many less followers than that during the relevant period, but the number is unknown.

19 Pinnacle employed fashion agencies to promote the DELPHINE label and DELPHINE Products domestically and internationally. The evidence shows that up to and including the relevant period Pinnacle engaged the Halation Agency to represent the DELPHINE label in New South Wales, Queensland and the Northern Territory, and the 4Threads Fashion Agency to represent the DELPHINE label in Victoria and Tasmania. Pinnacle also employed public relations agencies to promote the DELPHINE label in various media, forums and events both in Australia and internationally. I accept Mr Bucoy’s unchallenged evidence that these agencies assisted in raising brand awareness of the DELPHINE label by arranging promotion and feature articles of DELPHINE Products in blogs, online and print magazines and newspapers and through their contacts with stylists and influencers on social media.

20 Mr Bucoy stated that DELPHINE Products were marketed and sold by a number of large and popular online and off-line fashion retailers, including THE ICONIC, an online retailer located at <www.theiconic.com.au> (THE ICONIC website). THE ICONIC is a large and popular online fashion retailer in Australia and in the relevant period it was the principal stockist of DELPHINE Products.

21 Mr Bucoy adduced screenshots of webpages from the DELPHINE website in March 2016 (obtained through internet searches using the Wayback Machine) which listed the online and in-store stockists of DELPHINE Products at that time. Triangl again raised no objection to this evidence and I have treated it as admissible. I infer these screenshots were taken at around the time Mr Bucoy made his affidavit and they indicate that, shortly before the relevant period, eight online retailers and 23 in-store retailers marketed and sold DELPHINE Products in Australia. Mr Bucoy also provided Pinnacle’s current list of online and in-store retailers, which shows that as at the date of his affidavit seven online retailers and 24 in-store retailers marketed and sold DELPHINE Products in Australia. Mr Bucoy also adduced various screenshots of THE ICONIC website which I infer were taken at the same time and which show the promotion of various DELPHINE Products on that website.

The limited extent of Pinnacle’s marketing and sale of women’s swimwear

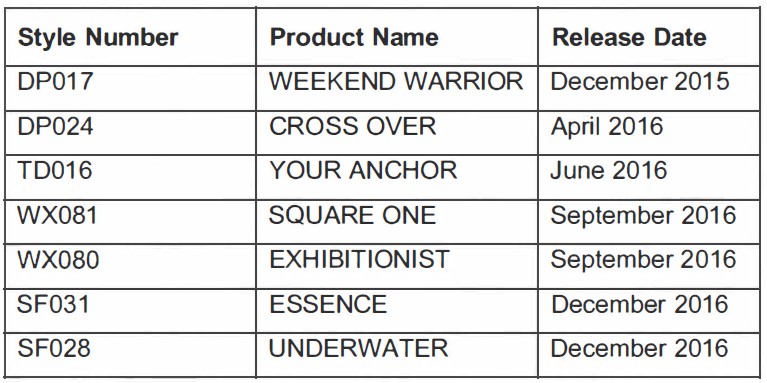

22 Mr Bucoy said that during the period December 2015 to December 2016 Pinnacle released the following collection of seven Delphine Products which he described collectively as the “DELPHINE Swimwear Products”:

23 That description was misleading. Except for one item named ‘Underwater Swim’ the collection cards Pinnacle used to promote this collection show all the products to be bodysuits or leotards rather than swimwear. Those cards record the full names of the products as follows:

(a) style number DP017 - Weekend Warrior Leotard;

(b) style number DP024 - Cross Over Leotard;

(c) style number TD016 - Your Anchor - Bodysuit;

(d) style number WX081 - Square One - Bodysuit;

(e) style number WX080 - Exhibitionist - Bodysuit;

(f) style number SF031 - Essence Bodysuit; and

(g) style number SF028 - Underwater Two Piece.

24 In cross-examination Mr Bucoy was taken to various screenshots from the DELPHINE and THE ICONIC websites showing what he described as DELPHINE “swimsuits and bodysuits”. Mr Bucoy was hard to pin down when he was questioned about whether the DELPHINE bodysuits and leotards were marketed for or used for swimming, and he equivocated when it was put to him that when Pinnacle wished to market and sell a DELPHINE Product as swimwear it expressly said so.

25 Mr Bucoy took that position notwithstanding that the websites described the bodysuits and leotards in the following terms:

(a) the Awakening Bodysuit is “an absolute must have for your versatile wardrobe staple pieces” and the “long lines of the cut will flatter your figure no matter what you layer it with”. In cross-examination Mr Bucoy accepted that ‘layering’ meant adding clothes on top and that the description made no mention of swimming or swimwear;

(b) the False Love Bodysuit can be “pair[ed] with denim for a cute afternoon look and match[ed] with beige, pinks and white for an evening ensemble that’s as sweet as it is powerful.” In cross-examination Mr Bucoy accepted that the garment was marketed as something that you would add other garments to. The description made no mention of swimming or swimwear;

(c) the Essence Bodysuit has “back scoops to the waist for simple elegance. You can build your perfect summer outfit around this ultimate wardrobe staple.” The description made no mention of swimming or swimwear and the garment appeared on the section of THE ICONIC website relating to ‘tops’ rather than the section relating to ‘swimwear’. Mr Bucoy accepted in cross-examination that it was not marketed as swimwear; and

(d) the images promoting the Cross Over Leotard showed items of clothing being worn over it. Mr Bucoy accepted in cross-examination that the description of that item made no mention of swimming or swimwear and that there was nothing to suggest that the leotard was intended for swimming.

26 It is plain on the evidence that when Pinnacle marketed swimwear it made that intended usage clear to customers. For example, the advertising of the Underwater Two Piece swimwear on THE ICONIC website said “[o]ur model is wearing a size 8 swimsuit” and that it was made of “high-stretch swim jersey” (emphasis added). The advertising of the Compass Swimsuit on the DELPHINE website said that it is “[p]erfect for cocktails by the pool on a stunning summer afternoon, these designer bathers will flatter your figure and help you stand out from the crowd” (emphasis added).

27 The gist of Mr Bucoy’s evidence was that the DELPHINE bodysuits and leotards were also suitable for swimming or that women might choose to use them for swimming. While it is impossible to know whether some consumers purchased and used such bodysuits or leotards for swimming, it is clear that Pinnacle did not promote them for that purpose. I doubt that its customers purchased them for that purpose.

28 Importantly, Mr Bucoy’s evidence shows that during the relevant period Pinnacle did not market or sell any women’s swimwear under the DELPHINE mark. In that period the sole swimwear item that Pinnacle listed as a DELPHINE Swimwear Product (the Underwater Swim) was not marketed or offered for sale. During the relevant period Pinnacle only sold two styles of one-piece leotard, the Weekend Warrior and the Cross Over. I consider Mr Bucoy sought to obscure the fact that, during the relevant period, Pinnacle did not market or sell any women’s swimwear under the DELPHINE mark.

29 It is likely that he tried to maintain that DELPHINE bodysuits and leotards were marketed to and used by consumers as swimwear in an effort to show that its products were substitutable for TRIANGL bikinis, in an effort to bolster its claim for damages for lost sales. Although his evidence shifted around Mr Bucoy ultimately accepted in cross-examination that a floral bikini is not substitutable for a leotard. I consider it to be quite unlikely that consumers would have seen the relevant TRIANGL bikinis as substitutable for the DELPHINE bodysuits and leotards and I found Mr Bucoy’s evidence in regard to Pinnacle's marketing of women's swimwear unreliable.

30 Mr Bucoy’s evidence also shows that up to and including the relevant period Pinnacle sold very few items of the (misleadingly described) DELPHINE Swimwear Products. For the six month period from 1 December 2015 to 1 June 2016 Pinnacle’s total sales of DELPHINE Swimwear Products was only $366, and during the relevant period Pinnacle’s total sales of such products was only $186.

Triangl and the TRIANGL brand

31 Mr Ellis is a co-founder, director and shareholder of the two respondents, Triangl Group Limited and Triangl Limited. His evidence aligned with Mr Bucoy’s evidence on several issues of significance in the case. I found him to be a credible witness and I broadly accept his evidence.

32 Mr Ellis has many years of experience in the fashion industry. He was the owner of a men’s fashion t-shirt business named St Lenny from about 2002 to about 2009 and a designer of women’s and men’s fashion with a large fashion retailer and wholesaler named Factory X from about 2009 to 2012.

33 Mr Ellis said that, in November 2011, he discussed with Ms Erin Deering her frustration with the lack of good quality bikinis that cost less than $100. In early 2012 they decided to move to Hong Kong to start their own business selling swimwear, particularly women’s bikinis, trading as Triangl. Ms Deering and Mr Ellis became co-directors, shareholders and founders of the Triangl business. Mr Ellis said and I accept that the Triangl Group Limited is the relevant entity for the proceeding as it was the trading entity for the Triangl group of companies during the relevant period.

34 He said that in early 2013 Triangl switched from a wholesale model, selling Triangl products to Australian retailers, to selling Triangl products direct to customers via its website and social media pages. Triangl’s business started to expand quickly and Triangl bikinis are now sold around the world in over 100 countries, solely online via Triangl’s website.

35 Triangl has registered the following Australian trade marks:

(a) Trade Mark No 1581504 for the word TRIANGL in class 25 for clothing, headwear and swimwear;

(b) Trade Mark No 1619504 for the word TRIANGL in class 35 for retail services, wholesale services, mail-order services and online retailing in respect of various kinds of clothing and other apparel;

(c) Trade Mark No 1747701 for the following device in class 25:

; and

; and

(d) Trade mark No 1766 7234 for SUMMER NEVER ENDS in classes 25 and 35.

36 Since moving to a solely online business in 2013 Triangl products have only ever been advertised to Australian consumers via a small number of media, including:

(a) the Triangl website located at <www.triangl.com> (the TRIANGL website). At the relevant time the website required an Australian person wishing to make a purchase to select their region, which then directed the customer to the pages of the website targeted at Australia;

(b) the Triangl social media outlets, being:

(i) the TRIANGL Instagram page – <www.instagram.com/triangl>; and

(ii) the TRIANGL Facebook page – <www.facebook.com/trianglofficial>;

(c) Electronic Direct Mail (EDM) communications with customers and prospective customers who set up an account through the TRIANGL website; and

(d) in some limited magazines and traditional forms of media.

37 Social media is the main channel through which Triangl markets its products. As at 21 June 2016, Triangl had over 2 million social media followers, but the evidence does not show how many of those followers live in Australia.

The use of ‘style names’ in women’s fashion in Australia

38 Mr Ellis gave unchallenged evidence that over his years working in the fashion industry he had seen that style names are commonly used, both globally and in Australia, to assist customers to distinguish between different products sold by a trader. He also said that he was aware that many other brands in the women’s swimwear industry adopted style names. I accept that evidence.

39 He also said that the rapid turnover of stock and repeated use of the same colours meant that it was much easier for a customer to refer to a name or other word for a garment than it was for the customer to refer to the garment by reference to a style number. He said that the use of style names made the business of retailing products easier as when dealing with customer queries and complaints both parties more readily knew what product was being talked about. He also said that the benefit of style names applied to internal discussions within a clothing business as a style name more readily brought to mind the product in question, in much the same way as a person’s name brings to mind that person’s face. He said that a style number or code does not so easily serve that purpose and that it was not difficult to accidentally transpose an incorrect number when dealing with a style number rather than a style name. I accept that evidence.

40 Mr Bucoy essentially confirmed the gist of Mr Ellis’ evidence in this regard. He accepted that traders in the women’s fashion industry assign style or product names to their products because it is a more convenient way of identifying the product, more convenient than requiring either the business or the customer to have to describe all the characteristics of the garment they are talking about, and easier and more convenient than using a model or style number. I accept his evidence in this regard.

41 The evidence shows that Pinnacle itself repeatedly used style names, including women’s names, in relation to DELPHINE Products. Mr Bucoy accepted in cross-examination that Pinnacle marketed and sold a DELPHINE Product under the style name ‘Clementine’, which is a women’s name (although Mr Bucoy argued that it was also a man’s name). He accepted that DELPHINE Products were marketed and sold on the DELPHINE and THE ICONIC websites using style names including: Sovereign, Anarchy, On the Run, Revolution, Riot, Compass, Libertine, Damsel, Gallows, Essence, Temptress and Larva. Mr Bucoy accepted that the benefit of using a style name was that it allowed identification of a particular garment within an apparel range. It is also worth noting that many of the style names which Pinnacle used in relation to DELPHINE Products had been previously registered as Australian trade marks by other traders in respect of class 25 goods, including clothing. The evidence shows the following registered Australian trade marks and the date of its registration which correspond with a style name which Pinnacle used:

(a) SOVEREIGN - December 1946;

(b) REVOLUTION - January 1989;

(c) Anarchy (in stylised form) - November 1997;

(d) ON THE RUN - October 2005;

(e) TEMPTRESS - July 2004;

(f) Libertine - June 2006;

(g) Damsel - February 2009;

(h) GALLOWS - expired in March 2018;

(i) LARVA - October 2011;

(j) RIOT - November 2011;

(k) COMPASS - December 2014; and

(l) ESSENCE - January 2014.

Mr Bucoy agreed that it would be “disastrous” if every time Pinnacle’s designers came up with a style name for a DELPHINE Product it was required to check the register of trade marks.

42 Mr Saunders also gave evidence confirming the widespread use of women’s names as product names in the women’s fashion industry. He said that in his experience style or product names are easier for people to remember than other kinds of words and are more convenient. In his view using a women’s name can add “a poetic, feminine quality” to a garment. He said that during his time in the women’s fashion industry he had seen many hundreds of products named by reference to women’s names, and that in his experience the use of women’s names as style names or product names was “extremely common”. I accept that evidence.

43 There was also some evidence that DELPHINE, which I consider to be a woman’s name, was used by other traders in relation to women’s apparel. In cross-examination Mr Bucoy was taken to pages from the websites of a variety of traders marketing and selling women’s apparel in Australia under the name DELPHINE (Exhibit R4). The evidence shows that:

(a) THE ICONIC website, which was the principal online stockist of DELPHINE Products, marketed women’s apparel in Australia under various different women’s fashion brands, using DELPHINE as a style or product name. On this website such marketing sometimes appeared directly alongside advertisements for DELPHINE Products. The relevant apparel marketed on THE ICONIC website included:

(i) the Delphine Support Sports Bra and Delphine Oversized Sweat, under the Lorna Jane brand, which is a well-known women’s athletic wear company;

(ii) the Delphine Long Sleeve Mini, under the Rebecca Vallance brand;

(iii) the Delphine Midi Dress, under the Tussah brand;

(iv) the Delphine Denim Shorts, under the Camilla and Marc brand;

(v) the Delphine Dress, Delphine Top and Delphine Skirt, under the Princess Highway brand; and

(vi) the Delphine Long Sleeve Dress, under the Rusty brand.

(b) the Myer website which advertised a dress with the name Delphine, under the Leona Edmiston brand, a well-known Australian designer;

(c) the Fame and Partners website which advertised a dress named The Delphine under the Fame and Partners brand;

(d) the Ozsale website which marketed a dress named the Delphine Shift Dress, under the French Connection brand;

(e) the Mytheresa website which marketed an embroidered linen shirt named Delphine, under the Isabel Marant brand; and

(f) the Surfstitch website which marketed a dress named Delphine Long Sleeve Dress.

44 In cross-examination Mr Bucoy accepted that when consumers looked at THE ICONIC website and saw DELPHINE Products advertised next to garments by Lorna Jane and other traders also using the name DELPHINE, they would be used to seeing that kind of marketing and use of style names. He accepted that consumers would understand that the brand was, for example Princess Highway, and DELPHINE was just the name of that garment. He accepted that there was available for consumers to see, from a range of trading sources, multiple uses of the name DELPHINE by different brands to identify their particular garments. Importantly Mr Bucoy accepted that this kind of usage of DELPHINE by other traders in Australia also happened in 2016.

45 I am satisfied that up to and including the relevant period it was commonplace for traders marketing and selling women’s fashion in Australia, including women’s swimwear, to use style names including women’s names in relation to their products. I infer that during the relevant period consumers in Australia were accustomed to seeing style names, including women’s names, used in relation to women’s fashion, including women’s swimwear.

Triangl’s use of style names

46 Mr Ellis stated that at the time Triangl was starting up he carried out Google searches of women’s swimwear brands to see how those brands operated. He said that, his having seen that many brands in the women’s swimwear industry adopted style names for their products, Triangl decided to use the same practice when it commenced operations.

47 He said and I accept that since commencement of the Triangl business it has consistently used style names to identify and differentiate between TRIANGL bikini styles in its range, including women’s names. He adduced a list of approximately 100 style names used by Triangl and the date when their use started and finished. Many of the style names Triangl used are women’s names, but it also used other non-descriptive style names (for example, “Confetti Garden”, “Poker Face”, “Charms” and “Famous”) and the great majority of the names Triangl used are non-descriptive.

48 Mr Ellis said and I accept that the process within Triangl by which style names were chosen for its bikinis was quite informal. He said that commonly he, Ms Deering or another member of Triangl’s public relations or marketing team suggested a loose theme for a product range (e.g. “Bond Girls” or “European Summer”) and then Triangl staff members contributed names along the lines of the selected theme. The names were then assigned to a bikini style on a “first-come, first-served basis”; that is, no particular name was singled out for a particular bikini. Mr Ellis said that Triangl did not consider that it had exclusive rights to any of the style names that it employed, and saw them as just a convenient way of delineating between its different products.

49 In cross-examination senior counsel for Pinnacle put to Mr Ellis that the bulk of the women’s names Triangl used are not commonplace and they were chosen because they are unusual or distinctive. Mr Ellis denied that this was Triangl’s intention, but he accepted that some staff members who chose style names as part of the informal process he outlined might have been looking for names which were distinctive. He said that if that occurred it was not at Triangl’s direction.

50 Mr Ellis also said that style names did not matter to Triangl, that it did not “care that much” about style names, and that in the context of the international market in which Triangl operated the names it used as style names were not unusual, although it might be said they were so in an Australian context. In his view there was no value, benefit or reputation to be attributed to Triangl in the style names that it applied to its bikini styles. I accept Mr Ellis’ evidence in this regard but the question as to whether Triangl’s use of DELPHINE constituted use as a trade mark does not turn on Triangl’s intent and it is a matter for the Court to decide.

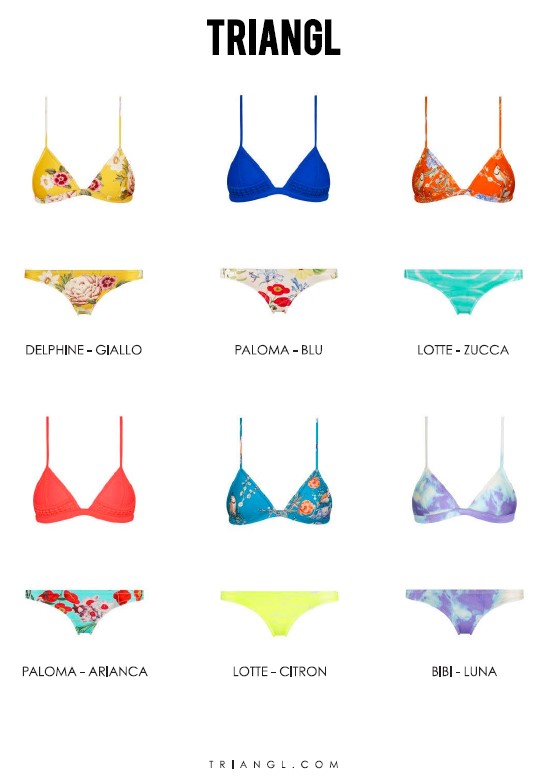

Triangl’s decision to use DELPHINE

51 Mr Ellis deposed that he was unable to recall specifically who chose the name DELPHINE for one of the four new bikini styles Triangl was planning to launch as part of its Spring/Summer 2016 campaign. Then, in cross-examination, he said that a designer Triangl employed at the time came up with the names PALOMA, LOTTE, BIBI and DELPHINE for the four styles in the new collection. He said that the designer had an Italian background and she was trying to give the collection a more Mediterranean slant “just to vary it up - to step away from what we had done previously”. He said that Triangl chose the name DELPHINE along with PALOMA, LOTTE and BIBI as the new style names in line with the informal naming practice outlined above, and the four style names chosen were then arbitrarily assigned to the four new bikini styles. I accept his evidence in this regard.

52 I also accept Mr Ellis' evidence that he was unaware of the existence of Pinnacle and of the DELPHINE Trade Mark at the time Triangl decided to use the name DELPHINE.

Triangl’s use of DELPHINE

53 It is uncontentious that during the relevant period (24 April 2016 to 2 June 2016) Triangl marketed and sold in Australia a bikini style in three colours and floral designs under the name DELPHINE, naming the three different designs as DELPHINE – FIORE, DELPHINE – FIORE ROSA and DELPHINE – FIORE NERO (the Triangl DELPHINE bikinis).

54 It is also uncontentious that Triangl only used the name DELPHINE in Australia in that short period and that its use was restricted to:

(a) the TRIANGL website;

(b) three electronic direct mail (EDM) communications with customers and prospective customers who had set up an account through the TRIANGL website; and

(c) 12 posts on the TRIANGL Instagram page, 7 posts on the TRIANGL Facebook page, and in a press pack sent to Elise Garland Public Relations in June 2016 (the press pack).

Pinnacle relied upon Triangl’s use of DELPHINE on the TRIANGL website and in the EDMs for the claim of trade mark infringement. It only relied on Triangl’s use of DELPHINE on the TRIANGL Instagram and Facebook pages as part of the context in which a consumer would perceive the use of DELPHINE on the TRIANGL website and in the EDMs. It did not rely on the use of DELPHINE in the press pack. I proceed upon that basis.

The use of DELPHINE on the TRIANGL website

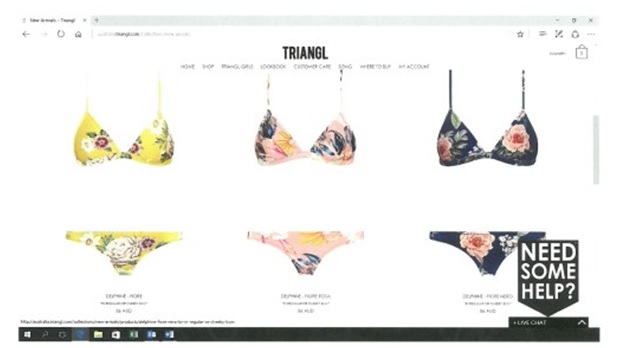

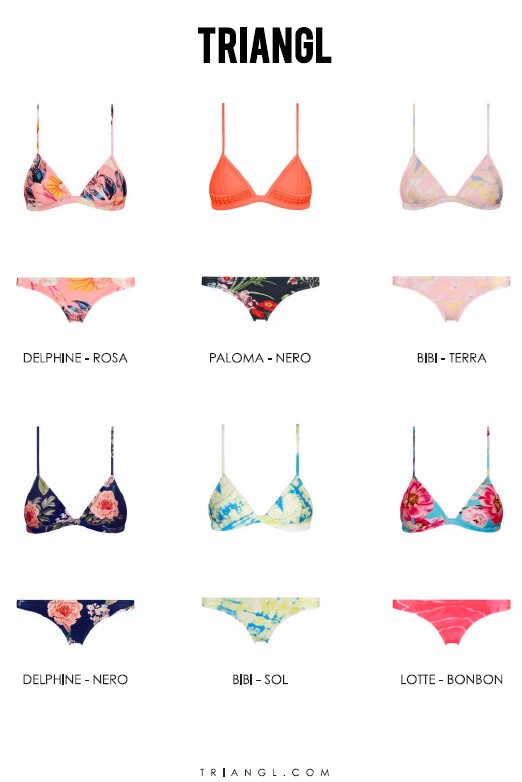

55 Ms Lambrianidis adduced screenshots of webpages on the TRIANGL website which she took on or around 10 May 2016. An image of the first screenshot she adduced is reproduced below. As is apparent, the TRIANGL Trade Mark is central and prominent at the top of the page and the name DELPHINE accompanied by either FIORE, FIORE ROSA or FIORE NERO appears under each colour or pattern variant of the bikinis.

56 It is impossible to read from the image reproduced above but the domain address <http://australia.triangl.com/collections/new-arrivals/products/delphine-fiore-nero-br-in-regular-or-cheeky-bum> appears in small font at the base of the page. This indicates that the page was reached by the user clicking on the “New Arrivals” button. Pinnacle did not however adduce screenshots of the page showing the three other new TRIANGL bikini styles in the Spring/Summer 2016 campaign which I infer were shown when the “New Arrivals” button was clicked.

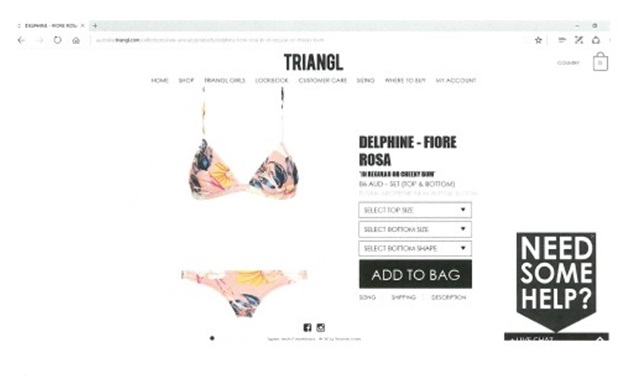

57 An image of the second screenshot Ms Lambrianidis adduced is reproduced below. I infer that a user of the website would arrive at this page by clicking on the image of the DELPHINE- FIORE ROSA bikini on the page displayed in the first screenshot.

58 Pinnacle did not put into evidence any other screenshots from the TRIANGL website during the relevant period. For example, it did not put into evidence: (i) the home page; (ii) the page which appeared if the user clicked the “View All” button; or (iii) the page which appeared if the user clicked the “New Arrivals” button. In my view it did not provide the full context in which a person viewing the TRIANGL website in the relevant period would have seen and understood the pages on which Pinnacle’s case relied.

59 Mr Ellis said, and I accept, that in the relevant period potential Australian customers were required to take the following steps if they wished to make a purchase on the TRIANGL website:

(a) visit the home page of the website which prominently bears the TRIANGL Trade Mark and name;

(b) select their region as Australia, which then directed the customer to the page of the TRIANGL website targeted at Australia;

(c) select an option labelled “Shop” from the range of options listed;

(d) select an option from a drop-down menu of buttons which then appeared, namely one of “New Arrivals”, “TRIANGL”, “Balconnet”, “Cheeky”, “Strapless” and “View All” which in each case led to a page showing images of various TRIANGL bikinis together with the style name of that bikini and its price;

(e) click on a particular product to arrive at a page dedicated to that product, at which a number of different viewing angles of the bikini were available;

(f) select the size and bottom shape for the bikini and “add” the TRIANGL product to their “cart”;

(g) click on a “check-out” button where they would be presented with an image of the product to the customer had selected together with the name of that product style, the size, bottom shape and price of that product;

(h) click on a box labelled “continue to next step”, and then enter the shipping address and contact details;

(i) select a shipping method, which was limited to a single method of Flat Rate Shipping of AUD$10 for Australian customers; and

(j) confirm all of their previously entered details and provide payment details.

60 Mr Ellis said and I accept that during the relevant period the name DELPHINE appeared on the Australian version of the TRIANGL website if the user selected either the “New Arrivals” or “View All” buttons. Having regard to his evidence and the structure of the TRIANGL website, I infer that there were further relevant pages on the TRIANGL website to those Pinnacle adduced.

61 Mr Ellis adduced screenshots of webpages on the TRIANGL website, which I infer were taken when he made his affidavit in or about August 2018 and he said that the website had only been altered slightly in the period between April-June 2016 and August 2018. The only change he identified was that, during the relevant period, style names of each bikini style appeared under the relevant image, whereas by August 2018 the website had been changed so that the style names were only displayed if the computer mouse was hovered over the relevant image. I accept his evidence in this regard; having regard to which some limited inferences can be drawn about the appearance of the home page, the “New Arrivals” and the “View All” pages of the TRIANGL website during the relevant period.

62 One of the screenshots Mr Ellis adduced is a copy of the TRIANGL home page as at August 2018. It carries a prominent TRIANGL brand at the top, below which appear the following buttons: “Home”, “Shop”, “Triangl Girls”, “Lookbook”, “Customer Care”, “Sizing”, “Where to Buy”, and “My Account”; superimposed over a full-page image of a model wearing a Triangl branded bikini. The same buttons appear in the screenshots obtained by Ms Lambrianidis in May 2016. I infer that during the relevant period the home page had a similar structure with the same or similar menu items.

63 Mr Ellis also adduced a screenshot of the TRIANGL website as at August 2018 which shows the drop-down menu which appears when the “Shop” button is clicked. The menu has the following buttons: “New Arrivals”, “Cheeky Bum”, “High Waist”, “Triangl” “Crop Top”, “Strapless”, “Balconett”, “One Piece”, “Accessories”, and “View All”. Having regard to Mr Ellis’ evidence, it is likely that during the relevant period the “Shop” page of the TRIANGL website had a similar structure with the same or similar menu items.

64 As Mr Ellis’ evidence tends to show, upon clicking one of those buttons, the user would be taken to a page dedicated to that type of product, for example: “New Arrivals” which showed the latest collection, or “High Waist” which showed bikinis in a high waisted style or “Strapless” which showed strapless bikinis. I infer that if during the relevant period an Australian consumer clicked on:

(a) the “View All” button, he or she would have arrived at a page with images of all of Triangl’s bikini styles, including the Triangl DELPHINE bikinis; or

(b) the “New Arrivals” button, he or she would be arrive at a page with images of each the four new bikini styles Triangl was marketing as part of its Spring/Summer 2016 campaign, including the Triangl DELPHINE bikinis.

What is likely to have been shown to a consumer using the View All button

65 To understand what a consumer is likely to have seen upon clicking the “View All” button on the TRIANGL website during the relevant period, it is necessary to understand that Triangl marketed and sold many different bikini styles. Mr Ellis said and I accept that in 2016 Triangl had approximately 35 bikini styles. It is appropriate to infer that clicking on the “View All” button would take the user to images of 35 bikini styles which would appear above the style names of those bikinis. The number of bikini styles meant that the user would be required to scroll through a number of different views to see all of the bikinis, included in which was the Triangl DELPHINE bikinis.

What is likely to have been shown to a consumer using the New Arrivals button

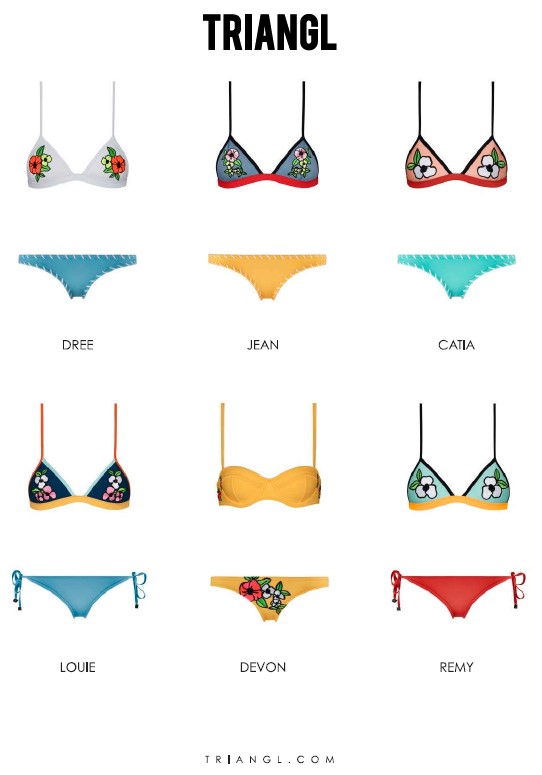

66 For similar reasons, I infer that a user that clicked on the “New Arrivals” button during the relevant period would arrive at a page with images of the four new bikini styles Triangl had launched as part of its Spring/Summer 2016 campaign under their respective style names PALOMA, LOTTE, BIBI and DELPHINE. Like the three colour or pattern variants of the Triangl DELPHINE bikinis, the new PALOMA, LOTTE and BIBI bikini styles also had colour or pattern variants. Some of these variants can be seen from Triangl’s press pack, images from which are reproduced below.

67 It is appropriate to infer that a consumer that clicked on the “New Arrivals” button on the TRIANGL website during the relevant period would be taken to images of four new TRIANGL bikini styles under their respective style names including the different variants of the new styles. The number of bikini styles meant that the user would be required to scroll through several views in order to see all the variants of the new collections, including the Triangl DELPHINE bikinis.

68 Thus, whether during the relevant period a user clicked on the “View All” or “New Arrivals” button on the TRIANGL website he or she would arrive at pages carrying images of a variety of TRIANGL bikini styles under different style names, including the Triangl DELPHINE bikinis. Then, if the consumer clicked on an image of those bikinis he or she would be taken to the images to which Ms Lambrianidis referred.

The use of DELPHINE on the EDMs

69 It is uncontroversial that in the relevant period Triangl sent three EDMs to persons who had signed up on its website to receive such marketing. Copies of the EDMs were annexed to the affidavits of Ms Lambrianidis, Mr Petale, Mr Bucoy and Mr Ellis, images from which I reproduce below. It is though necessary to keep in mind that the EDMs would have been viewed by consumers as an attachment to an email.

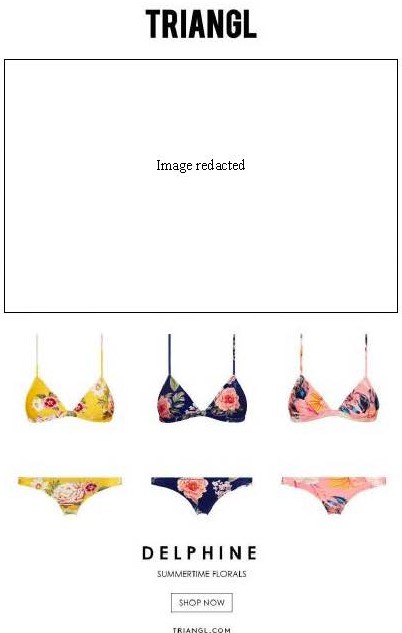

70 Reproduced below is an image of the first EDM. It carries a prominent TRIANGL brand, centred at the top of the page, above an image of a model wearing a Triangl DELPHINE bikini, above images of the three Triangl DELPHINE bikini styles, followed by the name DELPHINE in a smaller and less prominent font than TRIANGL, above the words SUMMERTIME FLORALS in again smaller font, and above a SHOP NOW button over the name of the website TRIANGL.COM in again smaller font. It is unnecessary to show the image of the model and I have redacted it.

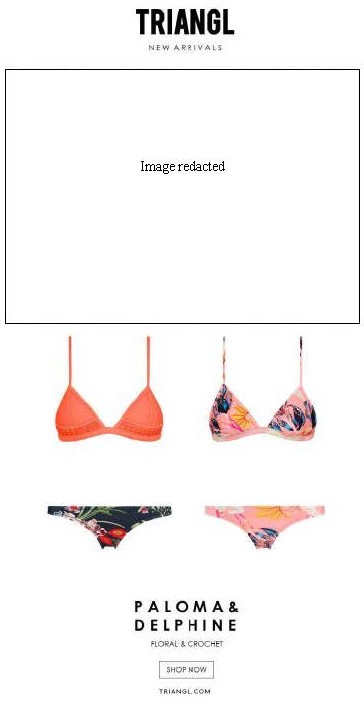

71 Reproduced below is an image of the second EDM. It carries a prominent TRIANGL brand, centred at the top of the page, above an image of two models wearing two different Triangl DELPHINE bikini styles, above images of two Triangl bikini styles, followed by the names PALOMA & DELPHINE in smaller and less prominent font than TRIANGL, above a SHOP NOW button over the name of the website TRIANGL.COM in again smaller font. I have again redacted the image of the models.

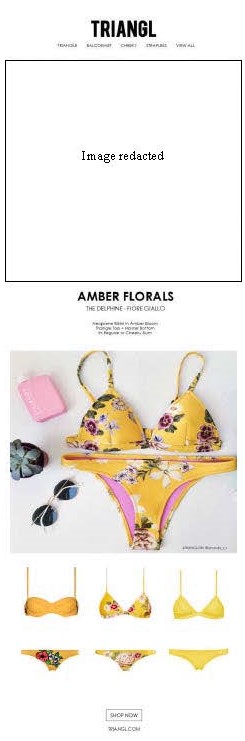

72 Reproduced below is an image of the third EDM. It also carries a prominent TRIANGL brand, centred at the top of the page, above an image of a model wearing a Triangl DELPHINE bikini, above the words AMBER FLORALS in the next largest font, followed by the name THE DELPHINE - FIORE GALLO in smaller font, above an image of the bikini that the model is wearing. Below that appears an image of three pattern variants of the same bikini, above a SHOP NOW button over the name of the website TRIANGL.COM in again smaller font. Again, I have redacted the image of the model.

Pinnacle’s letter of demand and the filing of the proceeding

73 On 16 May 2016 Pinnacle’s solicitors, Actuate IP, sent a letter of demand to Triangl asserting that it was selling a range of swimwear online by reference to the name DELPHINE. The letter stated that Pinnacle owned the registered DELPHINE Trade Mark, which covered swimwear, and it enclosed copies of pages from the TRIANGL website, the EDMs, and the TRIANGL Facebook and Instagram accounts which showed Triangl’s use of DELPHINE in relation to its bikinis. Pinnacle alleged that Triangl’s marketing constituted trade mark infringement, misleading or deceptive conduct and passing off.

74 Pinnacle’s solicitors demanded that Triangl immediately cease any manufacture, importation, advertisement, promotion or sale of any products under or by reference to the DELPHINE Trade Mark, that Triangl execute an enclosed deed of undertaking, and that upon provision of financial and other information required under the deed, to pay compensation to Pinnacle. The deed of undertaking required that Triangl:

(a) immediately cease and permanently refrain from infringing Pinnacle’s intellectual property rights;

(b) not use or authorise the use of the name DELPHINE or any trade mark that is substantially identical or deceptively similar to the DELPHINE Trade Mark;

(c) immediately cease and permanently refrain from manufacturing, importing, advertising, promoting, selling or otherwise dealing with any goods identical to or similar to the registered goods of the DELPHINE Trade Mark or which bear the name DELPHINE or any trade mark that is substantially identical or deceptively similar to the DELPHINE Trade Mark;

(d) within seven days provide copies of all tax invoices, import/purchase orders, receipts and other documentation in its possession or control that relate to the manufacture, importation, sale, promotion or any other dealings with the alleged infringing products including but not limited to the number of units manufactured and/or imported into Australia, the number of units sold in Australia, the per-unit sale price in Australia, and the gross profit made on the sales;

(e) within 14 days surrender to Pinnacle for disposal as it sees fit all infringing products as well as any advertising and promotional material relating to those products; and

(f) refrain from representing that it has any connection, affiliation, sponsorship or association with Pinnacle or its products.

75 On 26 May 2016 Mr Ellis telephoned Ms Lambrianidis in response to the letter of demand. Ms Lambrianidis made a contemporaneous file note of the discussion that ensued. She was not cross-examined and I accept her file note as a reasonably accurate account of that conversation. The file note records the following:

- Craig said his company was not aware of our client’s DELPHINE brand up until they received our LOD.

- He appreciates the TM position given our client’s registered rights but he is not convinced that our client would be able to establish the ACL and passing off claims given DELPHINE is only 6 or so months old. He said he doesn’t think that they have an “amazing” reputation given this short use and certainly consumers would not be confused by their respective brands, particularly given DELPHINE is used in conjunction with the TRIANGL brand.

- He said that the adoption of the DELPHINE name was not in an attempt to be deceptive and was adopted without the knowledge of our client’s brand. His company has spent over US$1M being on the other side of the coin trying to protect its IP over the past three years so he is familiar with the process.

- Craig mentioned that they are an international business with no physical offices in AU and raised the difficulties of trying to serve court docs on foreign companies if Pinnacle want to pursue the matter further.

- He said he is not going to pay a lawyer to handle the matter and respond to us. Instead he wants to open up a discussion about the matter. He said that if Triangl dig their heels in our client will spend $20-$30K to sue them which in his opinion is not a commercially viable decision for a 6 month old brand. He considers that it is likely that our client has seen the success of Triangl and is now being opportunistic in trying to get some money out of them. He said hand on heart that if he thought they were deliberately ripping off our client’s brand and damaging it they would pay but that is not the case here.

- Craig said we would obviously advise our client not to waste its resources in pursuing such frivolous claims that is not worth it for them.

- I asked Craig whether he would be responding to the allegations in writing at all. He said no. I told him we will go back to the client with the matters discussed and ultimately how our client decides to proceed is entirely up to them. Irrespective of whether their adoption of the DELPHINE brand was intentional or not, our client’s trade mark rights have been infringed and they are entitled to enforce them. I also said that we are well versed with dealing with foreign companies and just because it could potentially be difficult to serve court documents on them, if it ultimately gets to that, doesn’t prevent our client from doing so.

- Craig’s email address is [email address redacted] and he is the owner of the company.

76 It appears that Mr Ellis was not at that point prepared to cease using DELPHINE as a style name. Instead he wanted to “open up a discussion about the matter”.

77 On 1 June 2016 Mr Petale and Ms Lambrianidis sent another letter to Triangl. The letter referred to Mr Ellis’ discussion with Ms Lambrianidis and noted that Triangl’s refusal to comply with Pinnacle’s demands:

…appears to be based upon the misguided assumption that our client lacks the resolve to enforce its legal rights against your company and that the fact that your company is based in Hong Kong would cause difficulties for our client in terms of effecting service and the overall conduct of those proceedings. Our client’s owners have been involved in the fashion industry for many years and in many other fashion ventures and labels apart from Delphine, and are well-versed in conducting these kinds of proceedings, including as against international entities.

It said that Pinnacle had instructed Actuate IP to prepare to initiate proceedings against Triangl.

78 On 2 June 2016 Mr Ellis telephoned Mr Petale in response to the 1 June letter. Mr Petale gave the following account of the discussion that ensued. He was not cross-examined and I accept that his account, set out below, is reasonably accurate:

(a) Mr Ellis said that Triangl had spent three years and close to US$1,000,000 defending its own intellectual property rights against infringers;

(b) Mr Ellis said that the name DELPHINE was chosen by Triangl as it was a girl’s name and Triangl used girls’ names for all its product lines;

(c) Mr Ellis said the name DELPHINE was being used descriptively;

(d) I said to Mr Ellis that using a girl’s name is not descriptive, and that it could still be use [sic] as a trade mark even when used as a secondary trade mark in conjunction with the primary trade mark TRIANGL;

(e) Mr Ellis said that the conduct of Triangl cannot have amounted to passing off, being it was unintentional;

(f) I said to Mr Ellis that passing off was only one of the claims made by Pinnacle, and that, at the very least in relation to the trade mark infringement claim, it is irrelevant whether or not use of the trade mark was intentional;

(g) I said to Mr Ellis that Pinnacle’s primary concern was for Triangl to cease using the DELPHINE name, but that Pinnacle still also required the financial information sought in the First Letter and Second Letter in order to determine what, if any, monetary compensation it ought to seek from Triangl;

(h) Mr Ellis said that Triangl would be willing to cease using the DELPHINE name, and issue an apology, but only if Pinnacle agreed to forego any claim for monetary compensation;

(i) Mr Ellis said that Pinnacle should not need any financial information from Triangl in order to determine what damages it had suffered;

(j) I said to Mr Ellis that in legal proceedings Pinnacle would have the option of seeking either damages or an account of profits and therefore the requested financial information was relevant to Pinnacle’s assessment;

(k) Mr Ellis asked how much money Pinnacle intended to spend on legal proceedings in relation to this matter and whether it expected to profit from those proceeding in light of the potential monetary compensation involved;

(l) I said to Mr Ellis that it was ultimately Pinnacle’s decision whether or not to commence legal proceedings to protect its intellectual property rights, and that in any case Pinnacle was not in a position to answer Mr Ellis’ question given that it did not have the requested financial information from Triangl;

(m) I then asked Mr Ellis to confirm what Triangl’s position was in relation to the demands made in the First Letter and Second Letter, so that I could relay that position to Pinnacle;

(n) Mr Ellis said that Triangl would be willing to cease using the DELPHINE name, and issue an apology, but only if Pinnacle agreed to forego any claim for monetary compensation;

(o) I said that I would relay Mr Ellis’ statements to Pinnacle and then the call was ended.

79 It appears that by this point Mr Ellis’ position had shifted and he was prepared to agree to Triangl ceasing to use the name DELPHINE and to provide an apology, but only if Pinnacle agreed not to pursue a claim for damages.

80 By the following day Mr Ellis’ position had shifted one step further. On 3 June 2016 he sent an email to Mr Petale and Ms Lambrianidis in which he strongly contested the assertion that Triangl was infringing the DELPHINE Trade Mark but said that Triangl had “in good faith” removed the name DELPHINE from all of its global websites and changed the name of the relevant bikini style to DELILAH. On the presumption that this step would be sufficient to quell the dispute, Mr Ellis requested that Pinnacle provide Triangl with a letter stating that no further action would be taken by it.

81 Pinnacle did not agree to take no further action. On 7 June 2016 Mr Petale wrote to Mr Ellis and rejected the contention that Triangl’s use of DELPHINE did not infringe Pinnacle’s registered mark. Mr Petale seemed to accept that Triangl was no longer advertising bikinis for sale under the name DELPHINE and had changed the name of the particular style to DELILAH, but he required Triangl to provide the undertakings and the sales and financial information earlier demanded, together with delivery up of any infringing products bearing the DELPHINE mark as well as any advertising material relating to those products. He gave Triangl until close of business on 10 June 2016 to meet those demands.

82 On 10 June 2016 Mr Stephen Stern, a partner of Corrs, sent an email to Mr Petale advising that he had been instructed to act for Triangl and seeking further time within which to provide a response to the 7 June letter. It is unnecessary to repeat the arguments Mr Stern advanced except to note that they are essentially the same as the submissions Triangl ultimately advanced in defending this proceeding. Mr Stern said that Triangl had:

… as a gesture of good faith (and without any admission of liability), ceased and hereby agrees to forever desist from using the name Delphine in relation to its swimwear products. Indeed, our client was invited to do so by your firm as a way of resolving the entire issue and now considers this matter closed.

83 Pinnacle did not accept that Triangl’s agreement to cease using DELPHINE resolved the issue. On 6 July 2016 Mr Petale requested Mr Stern’s advice as to whether he had instructions to accept service on Triangl’s behalf. On 11 July 2016, Mr Stern said that he did not have such instructions. Later that day Mr Ellis telephoned Mr Petale and asked why proceedings had been commenced when Triangl had ceased to use the name DELPHINE. Mr Petale said that Pinnacle required Triangl to comply with its other demands including by providing the requested financial information.

84 On 13 July 2016 Pinnacle filed the proceeding.

85 In cross-examination Mr Ellis agreed that he sought to dissuade Pinnacle from taking any proceedings against Triangl for trade mark infringement. He said that he did so because he considered litigation to be counter-productive in terms of the costs and resources involved and he wanted to emphasise to Pinnacle and its lawyers that it would be difficult and expensive for it to pursue Triangl in regard to the alleged infringement. I accept that evidence. I also accept Pinnacle’s contention that Mr Ellis likely declined to instruct Mr Stern to accept service of the proceeding and that he did not inform Pinnacle’s solicitors that it (initially) brought the proceeding against the wrong Triangl entity.

86 Ultimately, Pinnacle experienced significant difficulties in serving the proceeding on Triangl in Hong Kong and service was achieved through an order for substituted service. In cross-examination Mr Ellis denied that he did not alert Pinnacle to the fact that it had commenced the proceeding against the wrong Triangl entity because he wanted to make the case as difficult and expensive as possible for Pinnacle. Mr Ellis said that the last thing he was thinking about was whether Pinnacle was suing the right entity, and in any event the name of the proper respondent and its address appeared on the EDMs. Essentially he said that he did not inform Pinnacle of its mistake because he had a lot to do and he had to prioritise his work. I accept the thrust of this evidence but I also infer that he did not think that it was his obligation to inform Pinnacle of its mistake.

The screenshots obtained through the Wayback Machine

87 Triangl sought to rely on the affidavit of Mr Lalande, a trade mark practitioner with Corrs. He deposed that he undertook online searches in July and August 2018 to search for historic versions of the websites of a range of women swimwear brands and fashion brands over the period from 2012 until June 2016. To carry out those searches he used the digital library of the Internet Archive, a not-for-profit organisation, which created and operates the website at <http://web.archive.org> (known as the ‘Wayback Machine’). The Wayback Machine purports to archive pages of the internet such that they can later be accessed through a search functionality.

88 Mr Lalande said that:

(a) on 20 July and 25 July 2018 he used the Wayback Machine to carry out searches of the websites of a range of women swimwear brands which sell swimwear in Australia for uses of women’s names as style names in relation to women’s swimwear over the period January 2016 to June 2016. He took screenshots of pages from those websites and attached them to his affidavit. If those screenshots are accepted as admissible they show that on various dates over the relevant period women’s swimwear brands named Baku Swimwear, Gypsea Swimwear, Myra Swim, Palm Swimwear, Rip Curl, Tigerlily, and Solid & Striped used women’s names in relation to their swimwear styles. The screenshots show approximately 45 examples of the use of women’s names as style names; and

(b) on 15 August 2018 he used the Wayback Machine to carry out searches of the websites of the fashion brands referred to by Mr Saunders in his report, over the period when Mr Saunders deposed that those fashion brands were his clients, again for use of women’s names as style names. He took screenshots of pages from those websites and attached them to his affidavit. If those pages are accepted as admissible they show that on various dates in 2012, 2013, 2015 and 2016, fashion and footwear brands such as Aje, Crocs, Lee Matthews, Moss & Spy, Triumph and Zambelli used women’s names in relation to women’s clothing and footwear.

Some of the pages appear to have been aimed at Australian consumers because they carry prices in Australian dollars, and others do not. I have not had regard to the screenshots that are not obviously directed at Australian consumers.

89 From his searches Mr Lalande tabulated the relevant fashion brand, product type (e.g. bikini top and bottom, silk top, maxi dress or shirt), the women’s name used, and the date of the page he sought to rely on. The tables are only for clarity and they do not add anything to the information contained in the screenshots.

90 Triangl sought to adduce his evidence for the limited purpose of showing that, up to and including the relevant period, consumers in Australia were used to seeing women’s names used as style names in relation to women’s fashion, including women’s swimwear.

91 Pinnacle objected to the admissibility of the screenshots and tables on the basis that this evidence was inadmissible hearsay under s 59 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (the Evidence Act). Pinnacle argued, in the alternative, that they should be excluded under the general discretion pursuant to s 135 or their use limited under s 136 to use which does not include establishing that prior to the relevant period traders in Australia actually used the names listed in the course of trade.

92 Triangl contended that the screenshots were not hearsay as it did not seek to adduce them to prove the truth of their contents. I do not accept that. Triangl relied upon the screenshots to make out its assertion that, up to and including the relevant period, consumers in Australia were used to seeing women’s names used as style names in relation to women’s fashion, including women’s swimwear. Each screenshot only assists to establish that asserted fact if its content is accepted as showing that the website of the relevant fashion brand or online retailer marketed items of women’s fashion or swimwear in Australia and used women’s names as a style names in relation to those goods. In my view Triangl sought to use the screenshots to prove the truth of their contents. They are evidence of a previous out of court representation by the relevant fashion house or online retailer to prove the fact asserted by the representation, which is inadmissible unless it falls within one of the exceptions to the hearsay rule.

93 There are authorities which provide that such documents do not fall within the business records exception in s 69 of the Evidence Act but, for the reasons I explain, I consider that they do.

94 In Roach v Page (No 27) [2003] NSWSC 1046 (Roach v Page (No 27)), Sperling J held that extracts from websites operated by Irish and Dutch peat exporters, which described the quality control procedures undertaken by those businesses, constituted inadmissible hearsay. His Honour referred to his earlier ruling in Roach v Page (No 15) [2003] NSWSC 939 in which he had observed that not every publication by a business is a “record of the business” within the meaning of s 69. In the earlier ruling (at [5] and [6]), Sperling J said:

The records of a business are the documents (or other means of holding information) by which activities of the business are recorded. Business activities so recorded will typically include business operations so recorded, internal communications, and communications between the business and third parties.

On the other hand, where it is a function of a business to publish books, newspapers, magazines, journals (including specialised professional, trade or industry journals), such publications are not records of the business. They are the product of the business, not a record of its business activities. Similarly, publications kept by a business such as journals or manuals (say, for reference purposes) are not records of the business.

95 In Roach v Page (No 27) Sperling J said (at [9]-[12]):

So far as is presently relevant, it is the recording of business activities in the course of carrying on the business which is critical. The publication of a book by a business providing a history of the business may record details of the business carried on but it is not a “record of business” within the meaning of s 69. Similarly, a flyer or a media advertisement or a website publication, extolling the virtues of the business in the way such publications do, is not a record of a business merely because it purportedly records activities of the business.

It is necessary to place such a restrictive construction on s 69 because it cannot have been intended that publications of this kind would qualify, any more than it would have been intended that – in the ordinary course – books, magazines or newspapers published by the business would be covered by that section.

The thinking behind the section is clear enough. Things recorded or communicated in the course of the business and constituting or concerning business activities are likely to be correct. There is good reason for the courts to afford to such records the same kind of reliability as those engaged in business operations customarily do. The same is not true of publications made for wider dissemination, for entertainment, for advertising or for public relations purposes. Such publications are justifiably received with healthy scepticism.

The publications now tendered are not business records within the meaning of s 69.

(Emphasis added.)

96 Sperling J’s reasoning has been cited with approval on many occasions, including in: Hansen Beverage Company v Bickfords (Australia) Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 406; (2008) 75 IPR 505 at [133] (Hansen Beverage) (Middleton J); National Telecoms Group Ltd v John Fairfax Publications Pty Ltd (No 1) [2011] NSWSC 455 at [70]-[71] (Davies J); McMahon v John Fairfax Publications Pty Ltd (No 4) [2012] NSWSC 216 at [22]-[26] (McCallum J); and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Air New Zealand Limited (No 5) [2012] FCA 1479; (2012) 301 ALR 352 at [11]-[15] (Perram J). Pinnacle relied on this line of authorities to argue that the screenshots are not “business records” within the ambit of s 69.

97 Sperling J’s remarks in relation to the reliability of representations made on business websites are well made, and there are sound policy reasons for treating some parts of business websites as not having the reliability of business records. Having said this, to decide whether a document is a business record requires consideration of the type of document in issue and its contents. I respectfully agree with O’Bryan J’s observations in Rodney Jane Racing Pty Ltd v Monster Energy Company [2019] FCA 923; (2019) 42 IPR 275 (Rodney Jane Racing) (at [175]-[177]) where his Honour said:

Sperling J’s rulings were, of course, directed to the specific types of documents in issue before him. In Southern Cross Airports v Chief Cmr of State Revenue [2011] NSWSC 349, Gzell J cautioned against applying Sperling J’s reasoning as a rule of law in place of the statutory test, stating (at [41]-[44]):

I do not understand Sperling J to have spoken categorically about what constituted a business record. In addition to the documents by which activities of a business are recorded I would include as business records documents relevant to the conduct of the business.

The introductory words of s 69(1)(a)(i) of the Evidence Act that the provision applies to a document that is, or forms part of, the records belonging to or kept in the course of, or for the purposes of a business, encompasses more than documents recording the activities of a business.

For example, a valuation of the assets of a business for insurance purposes or for the purpose of determining appropriate depreciation rates does not record the activities of a business but it is kept in the course of, or for the purposes of, the business.

It is preferable, in my view, not to seek to define a business record but to be guided to a decision whether or not a document is a business record by the terms of the statutory provision itself.

Similarly, in Charan v Nationwide News Pty Ltd [2018] VSC 3, Forrest J observed (at [463]):

…the distinction between “product” and “records” is problematic. It does not appear in the text of s 69(1). The language used in the provision is broad and appears to encompass any documents kept by a person, body or organisation “in the course of, or for the purposes of” a business. To exclude documents that are part of the records of an organisation, however generated and for whatever purpose under this provision (as opposed to a subsequent discretionary exclusion under s 135) involves, I think, an artificial distinction not covered by the wording of the section.

As recognised by Perram J in both ACCC v Air New Zealand Ltd (No 5) and Voxson Pty Ltd v Telstra Corporation Ltd (No 10) (2018) 134 IPR 99 at [37] (Voxson), there is no invariable rule that pages of a website are not business records within the meaning of s 69. Ultimately, whether the results of an internet search can be shown to be a business record within the meaning of s 69 depends upon the content of the webpage and what is able to be established (whether directly or by inference) about the content of the page. Business records include invoices (as per Asden Developments Pty Ltd (in liq) v Dinoris (No 2) (2015) 235 FCR 382 at [11]-[16] per Reeves J) and contractual terms and conditions and customer communications (as per Dowling v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [2008] FCA 59 at [13], [15] per Reeves J).

98 O’Bryan J concluded (at [178]):

In my view, documents by which a business offers a product for sale, which typically includes a description of the product and the price and possibly other terms and conditions of the offer, would constitute business records within the meaning of s 69. That would be so whether the documents are made available to potential customers via the company’s website or in the company’s retail store. However, documents which are merely promotional or descriptive of the activities of a company, such as might be found on an “About Us” link on a website, are unlikely to constitute business records, consistently with the conclusions reached in Roach v Page (No 27) and ACCC v Air New Zealand (No 5).

(Emphasis added.)

99 Selling goods or services online is now one of the most common methods by which retail commerce is undertaken, and the terms of the transaction are those set out on the website of the business. The part of a business website which offers a particular product for sale under a product name, with a product description and at a specified price is more than “a flyer or a media advertisement or a website publication extolling the virtues of the business”, to use Sperling J’s expression. It sets out the essential terms of the proposed transaction, which will be completed if the consumer clicks on another button on the website and provides his or her credit card details. If there is any dispute between the trader and a consumer in relation to the product sold through the website or its price, that part of the website will be central in the determination of that dispute. In my view it is appropriate to treat the content of a webpage that sets out the product name, description and price as a business record. Except perhaps in circumstances of fraud or misleading or deceptive conduct, of which there is no suggestion in the present case, it is hard to see why a business website would offer a product for sale under a product description and name and at a specified price unless that was actually the position. Such material is likely to be reliable.

100 In my view the type of screenshots in issue in the present application fall within the “business records” exception to the hearsay rule in s 69. They either are or form part of the records belonging to or kept by the relevant fashion house or online retailer in the course of or for the purposes of its business, or at any time was or formed part of such a record. They contain a previous representation as to the product name, description and price made or recorded on the webpage in the course of or for the purposes of that business, and it is appropriate to infer that information was put on the website by a person who had or might reasonably be supposed to have had personal knowledge of the asserted fact, or was made on the basis of information directly or indirectly supplied by such a person.

101 The question is, however, complicated by the fact that the screenshots (taken in 2018) purport to be screenshots of pages from websites as they appeared between 2012 and 2016, obtained by using the Wayback Machine. Each screenshot purports to be a digital copy of a page said by the Internet Archive to have been present on the website of the relevant fashion house or online retailer on the date specified. Each image therefore involves a representation by the Internet Archive that it copied the page into its archive and recorded the date on which it did so and that the page which appears in its archive is the page which existed on that date. Triangl sought to adduce the screenshots as evidence that those website pages were in fact in that form, on those dates.

102 In Voxson Pty Ltd v Telstra Corporation Limited (No 10) [2018] FCA 376; (2018) 134 IPR 99 (Voxson) at [35]-[37] Perram J considered the admissibility of archived webpages produced by the Wayback Machine, through which Voxson sought to prove the truth of their contents. His Honour said that this “involves second-hand hearsay: a representation by the operator of the Wayback Machine that the webpages had a particular content on a particular date and a representation by the Respondents by means of the pages in question as to the matters which Voxson seeks to prove.”

103 Copies of historical versions of webpages obtained by use of the Wayback Machine have been held to constitute inadmissible hearsay in a number of cases, including E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 934; (2008) 77 IPR 69 (Gallo Winery) at [126]-[127] (Flick J); Shape Shopfitters Pty Ltd v Shape Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2017] FCA 474 (Shape Shopfitters) at [21]-[23] (Mortimer J); Voxson at [35]-[37] (Perram J) and Rodney Jane Racing at [169], [179].

104 I note however that, in each of those cases, there was no admissible evidence before the Court as to the operation of the Wayback Machine.

(a) In Gallo Winery Flick J said (at [124]) the only material before the Court as to the operation of the Wayback Machine was a page from the Internet Archive website which said:

The Internet Archive Wayback Machine is a service that allows people to visit archived versions of Web sites. Visitors to the Wayback Machine can type in a URL, select a date range, and then begin surfing on an archived version of the Web.

His Honour said (at [127]) that:

Nothing is known as to the “business” of the “Internet Archive Wayback Machine” other than the hearsay statement itself that it “allows people to visit archived versions of Web sites.” And nothing is known as to the knowledge of the persons who recorded the information.

(b) In Shape Shopfitters (at [23]) Mortimer J said the reasoning adopted by Flick J in Gallo Winery was applicable in this case because “no evidence has been adduced to this Court in relation to the provenance of the Internet Archive WayBack Machine.”

(c) In Voxson the only information before the Court as to the operation of the Wayback Machine was again a page from the Internet Archive website. Perram J said (at [37]):

An attempt was made to prove some facts about the Wayback Machine from its public information page at archive.org/about. However, that involves relying on that page for the truth of its contents which is a hearsay use of the material (to which objection was taken).

and

(d) In Rodney Jane Racing O’Bryan J said (at [181]) that no evidence had been adduced concerning the business of the Wayback Machine.

This stands in contrast to the present case where the Court has the evidence of Mr Butler, an employee of the Internet Archive, as to the operation of the Wayback Machine. In my view the earlier decisions can be distinguished on that basis.

105 I consider that the representation by the Internet Archive – that the Wayback Machine copied the relevant webpage into its archive and recorded the date on which it did so, and that the page retrieved from its archive is the same page which existed on that date – is only hearsay under s 59 if the archiving and retrieval process involved human input. That is, that a person or persons was involved in copying and uploading the page to the Internet Archive database or later retrieving it for production. Section 59 of the Evidence Act is concerned with representations “made by a person”. In Odgers S, Uniform Evidence Law, (14th ed, Lawbook Co, 2019) at 382 the learned author states “[i]t is clear that this provision does not apply to machine generated information in respect of which there is no relevant human input.” In Cross on Evidence (10th Aust ed, Lexis Nexis Butterworths, 2015) 1,358 [35560], Heydon J.D. similarly states that “the narrow definition of hearsay in s 59 as ‘evidence of a previous representation made by a person’ does not render machine-generated material hearsay” (emphasis in original). In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Meriton Property Services Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1305; (2017) 350 ALR 494 at [43] Moshinsky J cited these references with apparent approval.