FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Cantor v Audi Australia Pty Limited (No 4) [2019] FCA 1633

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | AUDI AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED (ACN 077 092 776) Respondent | |

JUDGE: | FOSTER J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 23 SEPTEMBER 2019 |

BY CONSENT, THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Respondent’s Non-Publication Application

1. Pursuant to s 37AF and s 37AG(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (Federal Court Act), on the ground that it is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, the information in the attached Schedule 1 and Schedule 2 (Non-Publication Material) not be disclosed (by publication or otherwise) to any person other than:

(a) The Court;

(b) The applicant;

(c) The legal representatives of the applicant for the purpose of this proceeding only;

(d) Employees of any third party engaged to provide document management or litigation support services in relation to this proceeding; and

(e) For the information contained in Schedule 2 only, any expert witness retained by a party for the purpose of this proceeding who has signed an Expert Undertaking in the form previously agreed by the parties.

2. Pursuant to s 37AJ of the Federal Court Act, Order 1 above shall operate until the earlier of midnight on 18 December 2020 or further order of the Court.

3. Order 1 above does not affect the existing confidentiality regime including Orders 7 and 8 of the Orders made by Foster J on 12 July 2016 in this proceeding in respect of any document discovered, produced, prepared or filed in this proceeding and which is not admitted into evidence.

BY CONSENT, THE COURT NOTES THAT:

4. The parties will be notified and provided with an opportunity to be heard in the event that a person who is not a party to this proceeding makes a request to inspect any document on the Court’s file which has been highlighted in accordance with the confidentiality orders referred to in Order 3 above.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 1308 of 2015 | ||

BETWEEN: | JOSEFINA TOLENTINO Applicant | |

AND: | VOLKSWAGEN GROUP AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED (ACN 093 117 876) Respondent | |

JUDGE: | FOSTER J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 23 SEPTEMBER 2019 |

BY CONSENT, THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Respondent’s Non-Publication Application

1. Pursuant to s 37AF and s 37AG(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (Federal Court Act), on the ground that it is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, the information in the attached Schedule 1 and Schedule 2 (Non-Publication Material) not be disclosed (by publication or otherwise) to any person other than:

(a) The Court;

(b) The applicant;

(c) The legal representatives of the applicant for the purpose of this proceeding only;

(d) Employees of any third party engaged to provide document management or litigation support services in relation to this proceeding; and

(e) For the information contained in Schedule 2 only, any expert witness retained by a party for the purpose of this proceeding who has signed an Expert Undertaking in the form previously agreed by the parties.

2. Pursuant to s 37AJ of the Federal Court Act, Order 1 above shall operate until the earlier of midnight on 18 December 2020 or further order of the Court.

3. Order 1 above does not affect the existing confidentiality regime including Orders 7 and 8 of the Orders made by Foster J on 12 July 2016 in this proceeding in respect of any document discovered, produced, prepared or filed in this proceeding and which is not admitted into evidence.

BY CONSENT, THE COURT NOTES THAT:

4. The parties will be notified and provided with an opportunity to be heard in the event that a person who is not a party to this proceeding makes a request to inspect any document on the Court’s file which has been highlighted in accordance with the confidentiality orders referred to in Order 3 above.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 1459 of 2015 | ||

BETWEEN: | ALISTER DALTON First Applicant JOANNA DALTON Second Applicant | |

AND: | VOLKSWAGEN AG First Respondent VOLKSWAGEN GROUP AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED (ACN 093 117 876) Second Respondent | |

JUDGE: | FOSTER J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 23 SEPTEMBER 2019 |

BY CONSENT, THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Respondents’ Non-Publication Application

1. Pursuant to s 37AF and s 37AG(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (Federal Court Act), on the ground that it is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, the information in the attached Schedule 1 and Schedule 2 (Non-Publication Material) not be disclosed (by publication or otherwise) to any person other than:

(a) The Court;

(b) The applicants;

(c) The legal representatives of the applicants for the purpose of this proceeding only;

(d) Employees of any third party engaged to provide document management or litigation support services in relation to this proceeding; and

(e) For the information contained in Schedule 2 only, any expert witness retained by a party for the purpose of this proceeding who has signed an Expert Undertaking in the form previously agreed by the parties.

2. Pursuant to s 37AJ of the Federal Court Act, Order 1 above shall operate until the earlier of midnight on 18 December 2020 or further order of the Court.

3. Order 1 above does not affect the existing confidentiality regime including Orders 7 and 8 of the Orders made by Foster J on 12 July 2016 in this proceeding in respect of any document discovered, produced, prepared or filed in this proceeding and which is not admitted into evidence.

BY CONSENT, THE COURT NOTES THAT:

4. The parties will be notified and provided with an opportunity to be heard in the event that a person who is not a party to this proceeding makes a request to inspect any document on the Court’s file which has been highlighted in accordance with the confidentiality orders referred to in Order 3 above.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 1472 of 2015 | ||

BETWEEN: | ROBYN TANYA RICHARDSON Applicant | |

AND: | AUDI AG First Respondent AUDI AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED (ACN 077 092 776) Second Respondent VOLKSWAGEN AG Third Respondent | |

JUDGE: | foster j |

DATE OF ORDER: | 23 SEPTEMBER 2019 |

BY CONSENT, THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Respondents’ Non-Publication Application

1. Pursuant to s 37AF and s 37AG(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (Federal Court Act), on the ground that it is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, the information in the attached Schedule 1 and Schedule 2 (Non-Publication Material) not be disclosed (by publication or otherwise) to any person other than:

(a) The Court;

(b) The applicant;

(c) The legal representatives of the applicant for the purpose of this proceeding only;

(d) Employees of any third party engaged to provide document management or litigation support services in relation to this proceeding; and

(e) For the information contained in Schedule 2 only, any expert witness retained by a party for the purpose of this proceeding who has signed an Expert Undertaking in the form previously agreed by the parties.

2. Pursuant to s 37AJ of the Federal Court Act, Order 1 above shall operate until the earlier of midnight on 18 December 2020 or further order of the Court.

3. Order 1 above does not affect the existing confidentiality regime including Orders 7 and 8 of the Orders made by Foster J on 12 July 2016 in this proceeding in respect of any document discovered, produced, prepared or filed in this proceeding and which is not admitted into evidence.

BY CONSENT, THE COURT NOTES THAT:

4. The parties will be notified and provided with an opportunity to be heard in the event that a person who is not a party to this proceeding makes a request to inspect any document on the Court’s file which has been highlighted in accordance with the confidentiality orders referred to in Order 3 above.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 1473 of 2015 | |

BETWEEN: | STEVEN ROE Applicant |

AND: | SKODA AUTO A.S. First Respondent VOLKSWAGEN GROUP AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED (ACN 093 117 876) Second Respondent VOLKSWAGEN AG Third Respondent |

JUDGE: | foster j |

DATE OF ORDER: | 23 SEPTEMBER 2019 |

BY CONSENT, THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Respondents’ Non-Publication Application

1. Pursuant to s 37AF and s 37AG(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (Federal Court Act), on the ground that it is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, the information in the attached Schedule 1 and Schedule 2 (Non-Publication Material) not be disclosed (by publication or otherwise) to any person other than:

(a) The Court;

(b) The applicant;

(c) The legal representatives of the applicant for the purpose of this proceeding only;

(d) Employees of any third party engaged to provide document management or litigation support services in relation to this proceeding; and

(e) For the information contained in Schedule 2 only, any expert witness retained by a party for the purpose of this proceeding who has signed an Expert Undertaking in the form previously agreed by the parties.

2. Pursuant to s 37AJ of the Federal Court Act, Order 1 above shall operate until the earlier of midnight on 18 December 2020 or further order of the Court.

3. Order 1 above does not affect the existing confidentiality regime including Orders 7 and 8 of the Orders made by Foster J on 12 July 2016 in this proceeding in respect of any document discovered, produced, prepared or filed in this proceeding and which is not admitted into evidence.

BY CONSENT, THE COURT NOTES THAT:

4. The parties will be notified and provided with an opportunity to be heard in the event that a person who is not a party to this proceeding makes a request to inspect any document on the Court’s file which has been highlighted in accordance with the confidentiality orders referred to in Order 3 above.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 1462 of 2016 | |

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant |

AND: | VOLKSWAGEN AKTIENGESELLSCHAFT First Respondent VOLKSWAGEN GROUP AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED (ACN 093 117 876) Second Respondent |

JUDGE: | foster j |

DATE OF ORDER: | 23 SEPTEMBER 2019 |

BY CONSENT, THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Respondents’ Non-Publication Application

1. Pursuant to s 37AF and s 37AG(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (Federal Court Act), on the ground that it is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, the information in the attached Schedule 1 and Schedule 2 (Non-Publication Material) not be disclosed (by publication or otherwise) to any person other than:

(a) The Court;

(b) The applicant;

(c) The legal representatives of the applicant for the purpose of this proceeding only;

(d) Employees of any third party engaged to provide document management or litigation support services in relation to this proceeding; and

(e) For the information contained in Schedule 2 only, any expert witness retained by a party for the purpose of this proceeding who has signed an Expert Undertaking in the form previously agreed by the parties.

2. Pursuant to s 37AJ of the Federal Court Act, Order 1 above shall operate until the earlier of midnight on 18 December 2020 or further order of the Court.

3. Order 1 above does not affect the existing confidentiality regime including Orders 1 and 2 of the Orders made by Foster J on 26 October 2016 in this proceeding in respect of any document discovered, produced, prepared or filed in this proceeding and which is not admitted into evidence.

Future Listing

4. The proceeding be listed for further hearing at 10.15 am on 3 October 2019 before Foster J.

5. All parties have liberty to apply on 24 hours’ notice.

BY CONSENT, THE COURT NOTES THAT:

6. The parties will be notified and provided with an opportunity to be heard in the event that a person who is not a party to this proceeding makes a request to inspect any document on the Court’s file which has been highlighted in accordance with the confidentiality orders referred to in Order 3 above.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 322 of 2017 | |

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant |

AND: | AUDI AKTIENGESELLSCHAFT First Respondent AUDI AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED (ACN 077 092 776) Second Respondent VOLKSWAGEN AKTIENGESELLSCHAFT Third Respondent |

JUDGE: | FOSTER J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 23 SEPTEMBER 2019 |

BY CONSENT, THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Respondents’ Non-Publication Application

1. Pursuant to s 37AF and s 37AG(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (Federal Court Act), on the ground that it is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, the information in the attached Schedule 1 and Schedule 2 (Non-Publication Material) not be disclosed (by publication or otherwise) to any person other than:

(a) The Court;

(b) The applicant;

(c) The legal representatives of the applicant for the purpose of this proceeding only;

(d) Employees of any third party engaged to provide document management or litigation support services in relation to this proceeding; and

(e) For the information contained in Schedule 2 only, any expert witness retained by a party for the purpose of this proceeding who has signed an Expert Undertaking in the form previously agreed by the parties.

2. Pursuant to s 37AJ of the Federal Court Act, Order 1 above shall operate until the earlier of midnight on 18 December 2020 or further order of the Court.

3. Order 1 above does not affect the existing confidentiality regime including Orders 17 and 18 of the Orders made by Foster J on 13 April 2017 in this proceeding in respect of any document discovered, produced, prepared or filed in this proceeding and which is not admitted into evidence.

Future Listing

4. The proceeding be listed for further hearing at 10.15 am on 3 October 2019 before Foster J.

5. All parties have liberty to apply on 24 hours’ notice.

BY CONSENT, THE COURT NOTES THAT:

6. The parties will be notified and provided with an opportunity to be heard in the event that a person who is not a party to this proceeding makes a request to inspect any document on the Court’s file which has been highlighted in accordance with the confidentiality orders referred to in Order 3 above.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

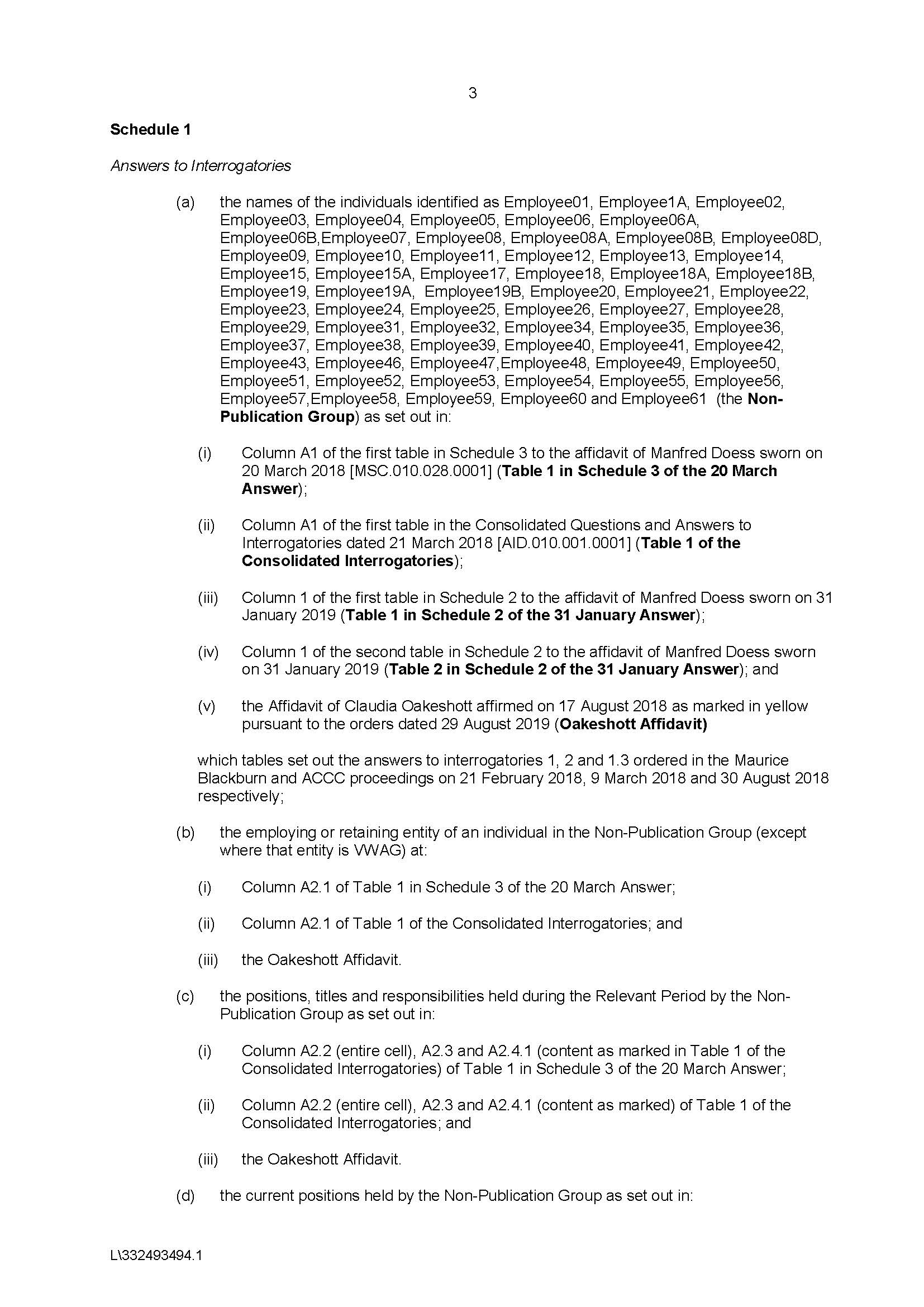

SCHEDULE 1

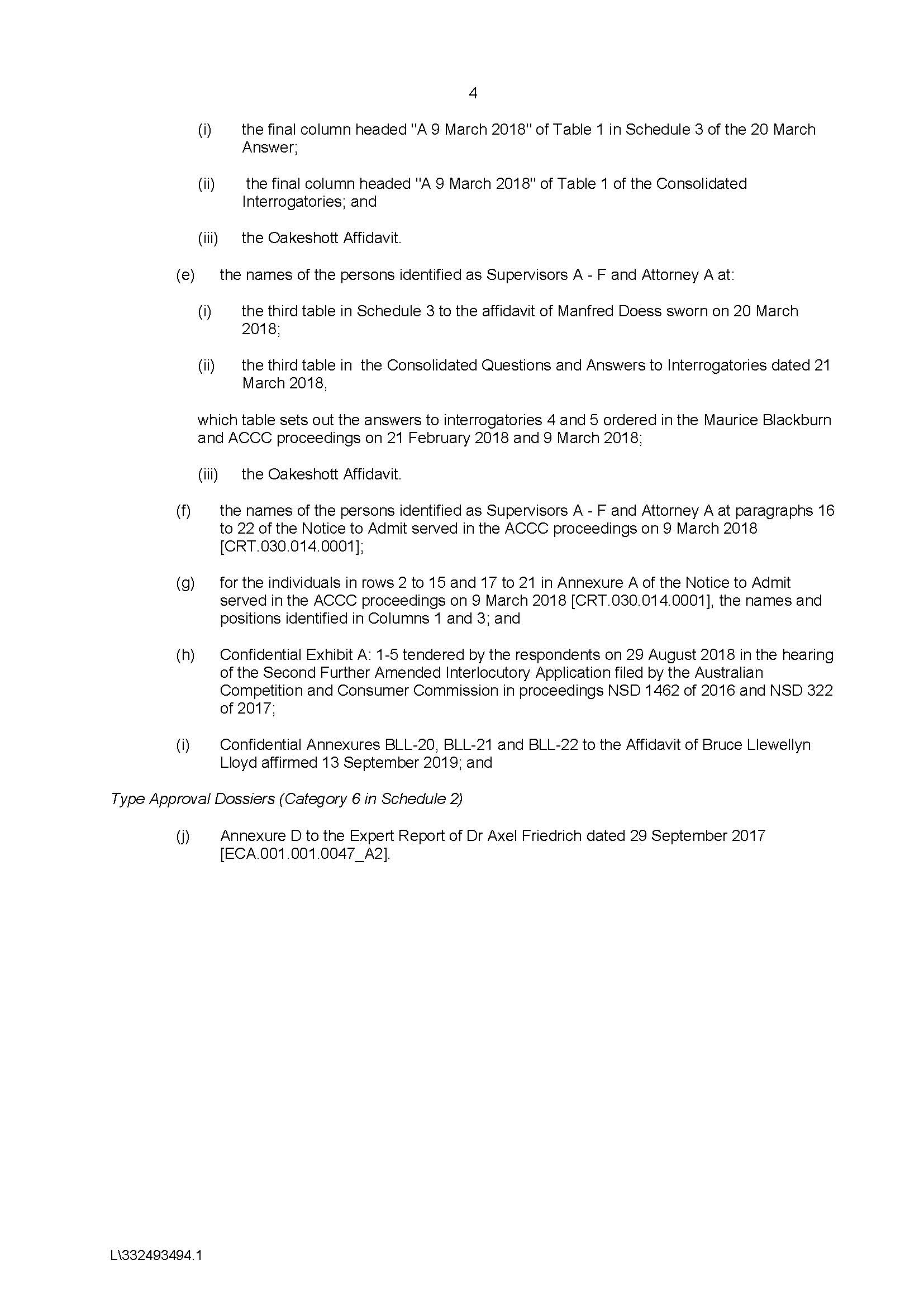

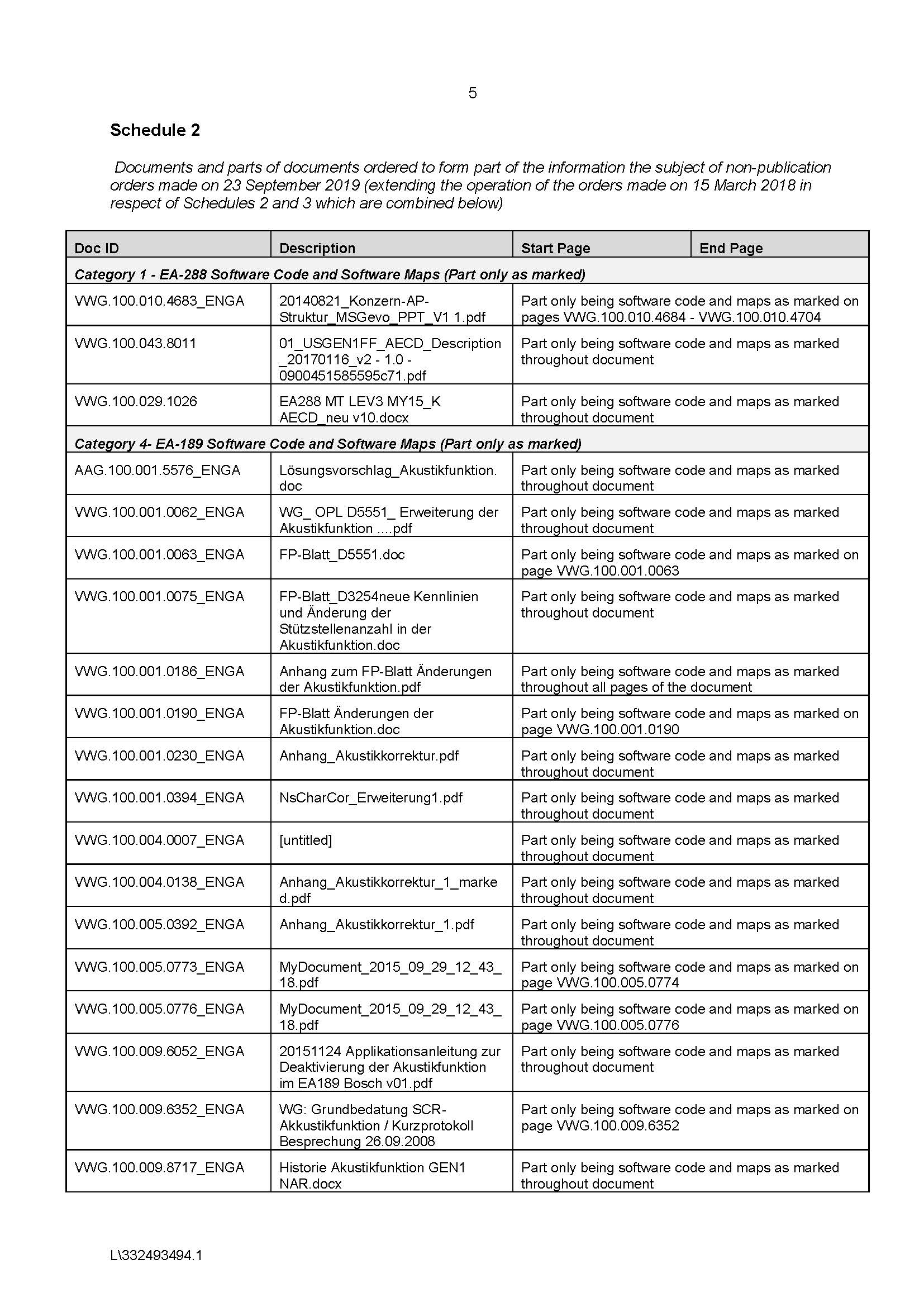

SCHEDULE 2

FOSTER J:

1 By Interlocutory Application filed on 27 July 2019 in proceeding NSD 1459 of 2015 (Dalton v Volkswagen AG) but taken to be filed in the seven sets of proceedings presently before the Court (the respondents’ IA), the respondents in those proceedings (Volkswagen AG (VWAG) and its related corporations) applied to the Court pursuant to s 37AF of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (the Act) for an order prohibiting the disclosure of certain information more particularly described in Schedules 1 and 2 to the respondents’ IA (the confidential information) to persons other than those persons specified in the claimed order upon the basis the claimed order was necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice. Although the respondents’ claim was refined somewhat as the matter progressed, the essence of that claim remained as originally formulated in the respondents’ IA.

2 On 23 September 2019, I made suppression orders substantially in the form sought by the respondents (the 23 September Orders). These are my reasons for making those orders.

3 The seven sets of proceedings referred to at [1] above all concern the global corporate scandal involving VWAG, its related corporations and its affiliates colloquially known as “dieselgate”. In Cantor v Audi Australia Pty Limited (No 2) [2017] FCA 1042, at [1]–[14], I explained the nature of those seven proceedings and the substance of the issues raised therein. It is not necessary to repeat the content of those paragraphs here although they comprise a useful description of the background to the respondents’ IA.

4 In support of the relief claimed by them in their IA, the respondents read and relied upon the following affidavits filed herein:

(a) The affidavit of Dr Eike Hendrik Duckwitz affirmed on 3 March 2018;

(b) The affidavit of Gregory John Williams sworn on 13 March 2018;

(c) The affidavit of Dr Manfred Doess sworn on 8 March 2018;

(d) The affidavit of Gregory John Williams sworn on 23 March 2018;

(e) The affidavit of Professor Michael Kubiciel sworn on 25 April 2018;

(f) The affidavit of Bruce Llewellyn Lloyd sworn on 27 April 2018;

(g) The affidavit of Bruce Llewellyn Lloyd sworn on 26 July 2019; and

(h) The affidavit of Bruce Llewellyn Lloyd sworn on 13 September 2019.

The respondents also relied upon a Written Submission dated 26 July 2019 and a Written Submission in Reply dated 13 September 2019. The 26 July 2019 Written Submission incorporated to some extent the substance of an earlier relevant Written Submission dated 27 April 2018.

5 I read and took into account all of the above materials in determining the claim for relief made by the respondents in their IA.

6 By that IA, the respondents sought protection in respect of five broad categories of information.

7 First, they claimed a suppression order in respect of the names of certain current and former employees of one or more of the respondent corporations (the Non-Publication Group) found in:

(a) Answers to interrogatories provided by the respondents to interrogatories administered by the applicants from time to time;

(b) A Notice to Admit Facts answered by the respondents;

(c) Several affidavits filed in one or more of the relevant proceedings; and

(d) A Confidential Exhibit (Ex A) tendered in applications heard in all of the proceedings on 29 August 2018.

8 The Non-Publication Group comprises persons who are or were associated with one or more of the respondents, all of which, of course, are parties to proceedings before the Court. In addition, the first category of confidential information “otherwise concerns” those parties. Accordingly, the names of such persons (Category 1) is information which is of a kind which may be suppressed (as to which, see s 37AF(1)(a) of the Act).

9 Next, the respondents also sought an order preventing disclosure of the identity of the employing or retaining entity of each individual identified in the Non-Publication Group except where that entity is VWAG and also of the positions, titles and responsibilities held during the relevant period by the individuals comprising the Non-Publication Group (Category 2). The respondents sought to have this information suppressed on the ground that, if it were to become generally available, it may reveal the identity of one or more of the persons who comprise the Non-Publication Group.

10 In respect of the first two categories of information described above, the respondents contended that the information should be the subject of a suppression order because, if disclosed, it had the potential to detrimentally and unfairly affect or contaminate criminal prosecutions of a number of individuals in the Non-Publication Group already under way or foreshadowed in Germany and in the United States of America which are or might be based upon the same substrate of facts about which this Court would be called upon to make findings in the proceedings in this Court concerning dieselgate.

11 The applicants have already been provided with unexpurgated versions of the answers to interrogatories and other documents referred to in Schedules 1 and 2 to the respondents’ IA on a confidential basis agreed among the parties.

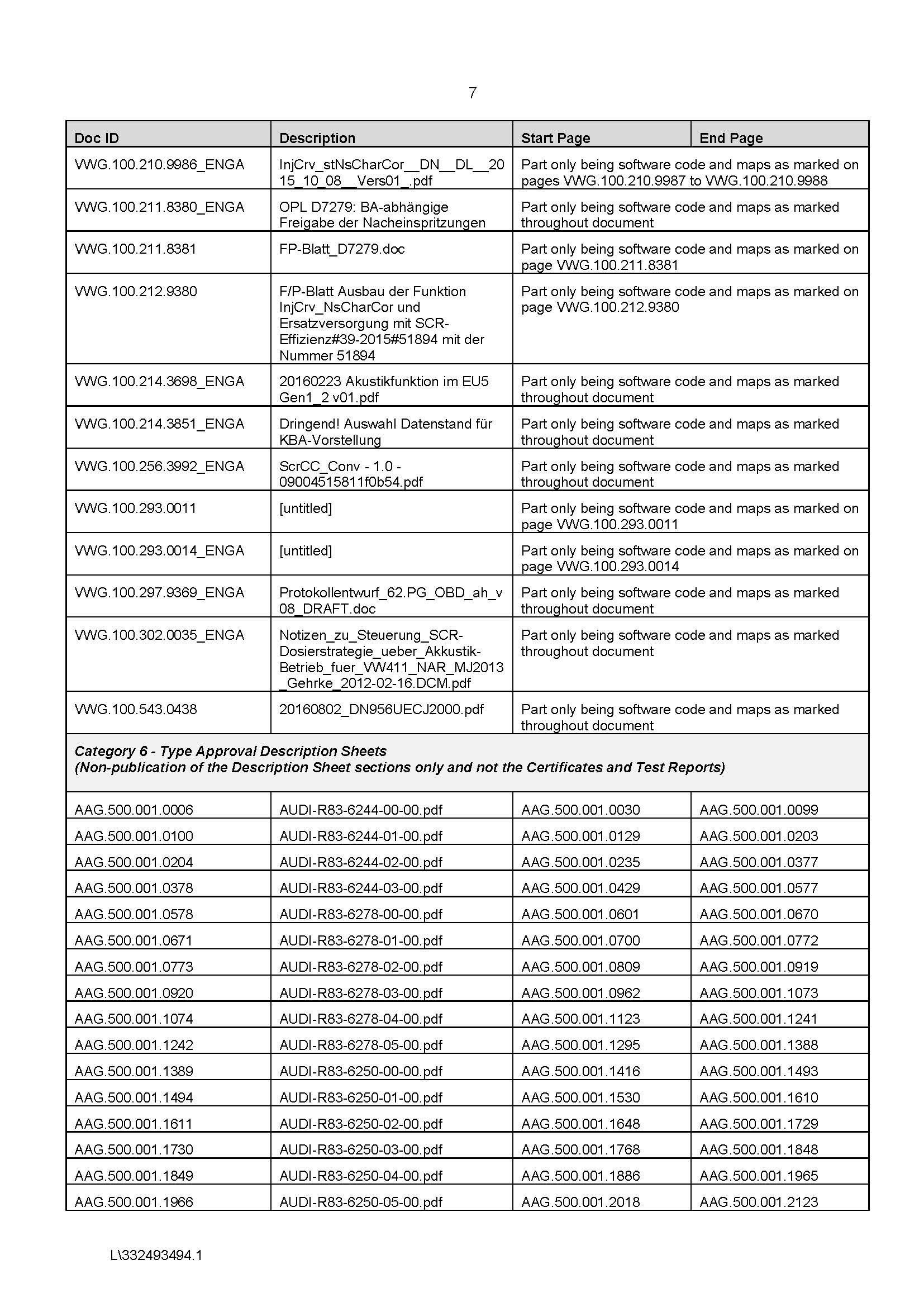

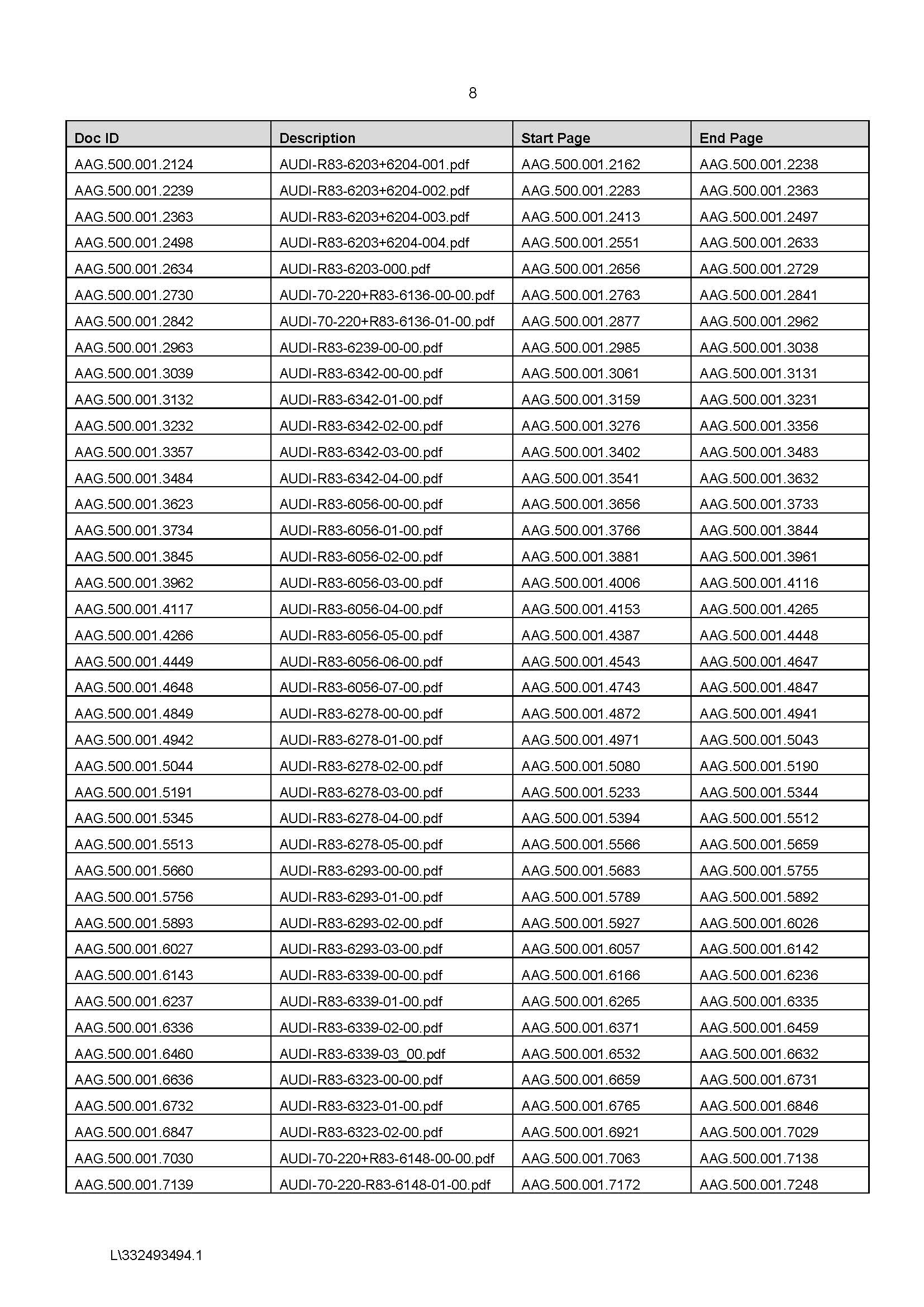

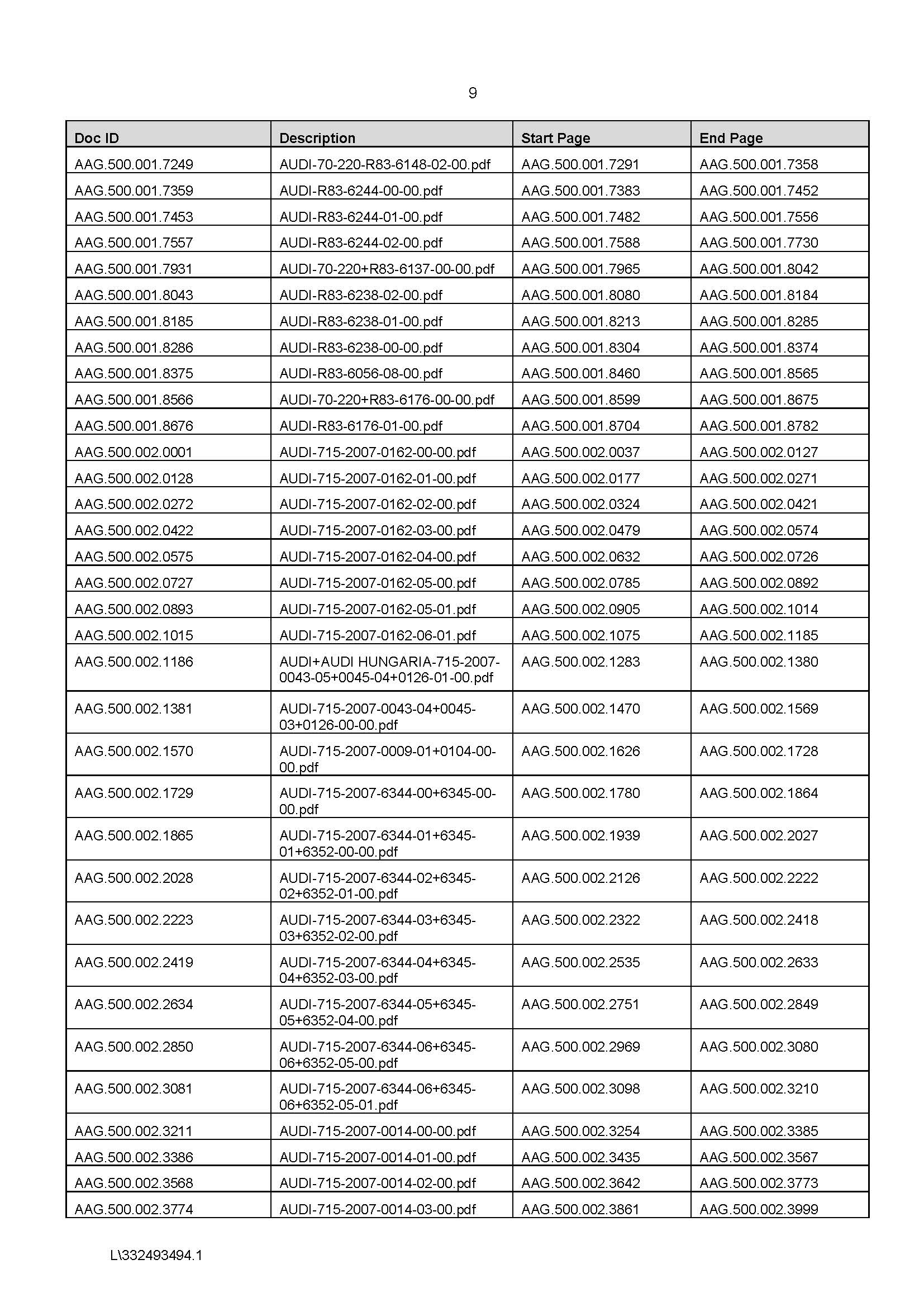

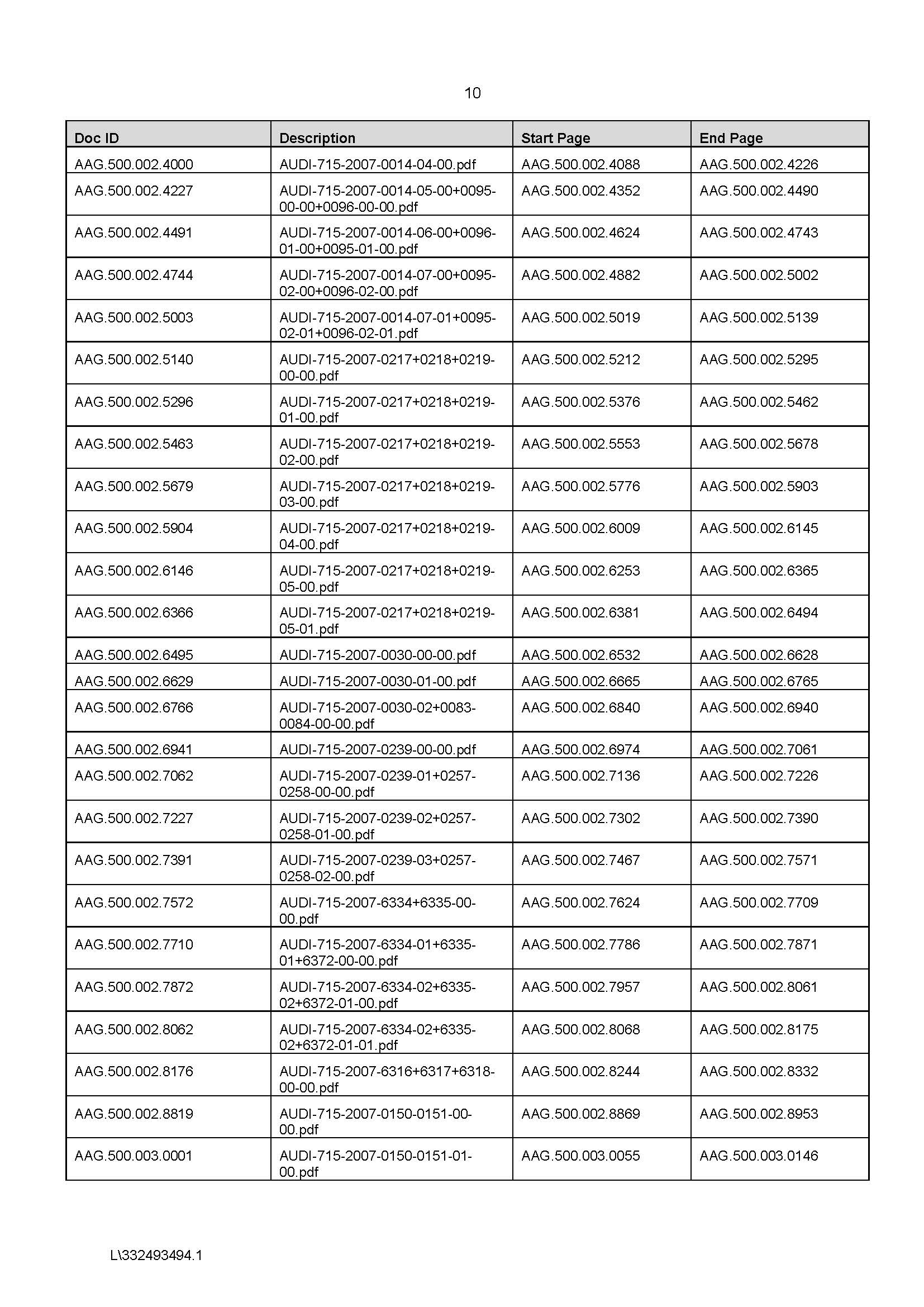

12 The remaining three categories of information in respect of which the suppression order is sought are found in three particular groups of documents listed in Schedule 2 to the respondents’ IA being:

(a) Documents containing detailed explanations of the structure, operation and strategy of the engine management software in Volkswagen’s EA288 (current three and four cylinder diesel engine) and Volkswagen’s EA288 evo diesel engine (the future four cylinder diesel engine) (Category 3). According to the evidence tendered before me in support of the respondents’ IA, neither the EA288 engine nor the EA288 evo engine is installed in any of the vehicles the subject of any of the seven proceedings with which I am concerned;

(b) Documents containing reference to or information concerning the EA189 software code and engine maps (Category 4); and

(c) Documents comprising Type A Approval Dossiers (Category 5).

13 The three categories of information referred to at [12] above are said to constitute information which is commercially sensitive and which should, for that reason, be protected from disclosure. This information is found in documents which have been produced by the respondents to the applicants on discovery pursuant to discovery orders made by the Court and which, for the most part, have not yet been tendered in evidence although many of them may ultimately have been the subject of evidentiary tender had the Stage 2 Trial proceeded. These documents contain information that is of a kind covered by s 37AF(1)(b)(i), (ii) and (iv). The documents which contain the relevant information have been redacted in order to excise from them the information the subject of the suppression order claim. The order is only sought in respect of the redacted material.

14 The applicants in all of the proceedings have been provided with unredacted copies of these documents in accordance with an agreed inter partes confidentiality protocol. The applicants have also been provided with the redacted versions.

15 When the respondents’ IA was filed (26 July 2019), the Stage 2 Trial of certain issues in all seven proceedings was fixed to commence on 23 September 2019. Shortly before that date, the Court was informed that the five class actions comprising proceedings NSD 1307 of 2015, NSD 1308 of 2015, NSD 1459 of 2015, NSD 1472 of 2015 and NSD 1473 of 2015 had been settled in principle and that the two regulatory actions comprising proceedings NSD 1462 of 2016 and NSD 322 of 2017 were likely to be settled quite soon. Subsequently, on 20 September 2019, I was told that the two regulatory actions had also been settled in principle. Therefore, when I made the 23 September Orders, all seven sets of proceedings had been settled in principle but neither of the settlements had, by then, been consummated.

16 Prior to the class action proceedings being settled, there had been some opposition to the relief claimed by the respondents in the respondents’ IA. In particular, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) had opposed most of the claims for relief made in that IA. By 23 September 2019, that opposition had evaporated. The applicants did, however, reserve the right to revisit the question in the event that the settlements did not come to fruition.

17 Notwithstanding that there was no opposition from the parties, the Court was nonetheless required to be satisfied that it was appropriate to grant the relief sought.

THE RELEVANT PRINCIPLES

18 Sections 37AE, 37AF and 37AG are found in Pt VAA—Suppression and non-publication orders of the Act. Those sections provide:

37AE Safeguarding public interest in open justice

In deciding whether to make a suppression order or non-publication order, the Court must take into account that a primary objective of the administration of justice is to safeguard the public interest in open justice.

37AF Power to make orders

(1) The Court may, by making a suppression order or non-publication order on grounds permitted by this Part, prohibit or restrict the publication or other disclosure of:

(a) information tending to reveal the identity of or otherwise concerning any party to or witness in a proceeding before the Court or any person who is related to or otherwise associated with any party to or witness in a proceeding before the Court; or

(b) information that relates to a proceeding before the Court and is:

(i) information that comprises evidence or information about evidence; or

(ii) information obtained by the process of discovery; or

(iii) information produced under a subpoena; or

(iv) information lodged with or filed in the Court.

(2) The Court may make such orders as it thinks appropriate to give effect to an order under subsection (1).

37AG Grounds for making an order

(1) The Court may make a suppression order or non-publication order on one or more of the following grounds:

(a) the order is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice;

(b) the order is necessary to prevent prejudice to the interests of the Commonwealth or a State or Territory in relation to national or international security;

(c) the order is necessary to protect the safety of any person;

(d) the order is necessary to avoid causing undue distress or embarrassment to a party to or witness in a criminal proceeding involving an offence of a sexual nature (including an act of indecency).

(2) A suppression order or non-publication order must specify the ground or grounds on which the order is made.

19 In s 37AG, the legislature has specified the grounds upon which a suppression order or non-publication order might be made. In s 37AG(1)(a)–(d), four such grounds are set out. Here, the respondents rely upon the ground specified in s 37AG(1)(a), namely, that the suppression order is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice.

20 In the event that the Court makes a suppression order or non-publication order, it is required to specify the ground or grounds upon which the order is made (see s 37AG(2)).

21 The concept of “open justice” in the present context was recently considered by O’Bryan J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v BlueScope Steel Limited [2019] FCA 1532 at [26]–[30] where his Honour said:

… It is immediately apparent that the FCA Act proceeds on the basis that the administration of justice is ordinarily promoted by safeguarding the public interest in open justice, but as recently observed by Allsop CJ in Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v Egan [2018] FCA 1320 at [4]:

Open justice is not an absolute concept, unbending in its form. It must on occasion be balanced with other considerations, including but not limited to considerations such as the avoidance of prejudice in the administration of justice…

The public interest in open justice was explained by Gibbs J in Russell v Russell (1976) 134 CLR 495 in the following terms (at 520):

It is the ordinary rule of the Supreme Court, as of the other courts of the nation, that their proceedings shall be conducted “publicly and in open view” (Scott v Scott [1913] AC 417 at 441). This rule has the virtue that the proceedings of every court are fully exposed to public and professional scrutiny and criticism, without which abuses may flourish undetected. Further, the public administration of justice tends to maintain confidence in the integrity and independence of the courts. The fact that courts of law are held openly and not in secret is an essential aspect of their character. It distinguishes their activities from those of administrative officials, for “publicity is the authentic hallmark of judicial as distinct from administrative procedure” (McPherson v McPherson [1936] AC 177 at 200).

The primary safeguard of open justice is the requirement, contained in s 17 of the FCA Act, that the jurisdiction of the Federal Court of Australia be exercised in open court. In Hogan v Hinch (2011) 243 CLR 506, French CJ said of that requirement (at [20]):

An essential characteristic of courts is that they sit in public. That principle is a means to an end, and not an end in itself. Its rationale is the benefit that flows from subjecting court proceedings to public and professional scrutiny. It is also critical to the maintenance of public confidence in the courts. Under the Constitution courts capable of exercising the judicial power of the Commonwealth must at all times be and appear to be independent and impartial tribunals. The open-court principle serves to maintain that standard. However, it is not absolute.

His Honour also observed that reporting of court proceedings is a common law corollary of the open-court principle (at [22]):

It is a common law corollary of the open-court principle that, absent any restriction ordered by the court, anybody may publish a fair and accurate report of the proceedings, including the names of the parties and witnesses, and the evidence, testimonial, documentary or physical, that is being given in the proceedings.

A secondary safeguard of open justice is the entitlement, in r 2.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), of a person who is not a party to a court proceeding to inspect and copy certain categories of documents filed in the Federal Court Registry including an originating application, a pleading or similar document, a statement of agreed facts and an interlocutory application. …

22 The relevant principles guiding the exercise of the Court’s power to make a suppression order are well-known and are not controversial. In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cascade Coal Pty Ltd (No 4) [2018] FCA 1243 at [34]–[36], I explained those principles in the following terms:

In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cascade Coal Pty Ltd (No 1) (2015) 331 ALR 68 at 73–74 [28]–[30], I said:

In Hogan v Australian Crime Commission (2010) 240 CLR 651; 267 ALR 12; [2010] HCA 21 at [30], the High Court said, in respect of the use of the word “necessary” in s 50 of the FCA Act, the predecessor to Pt VAA that it is “a strong word”. The Court observed that the collocation of necessity to prevent prejudice to the administration of justice and the necessity to prevent prejudice to the security of the Commonwealth suggests that the Parliament is not dealing with trivialities. The Court went on to hold that:

“the administration of justice” spoken of in s 50 is that involved in the exercise by the Federal Court of the judicial power of the Commonwealth; this is a more specific discipline than broader notions of the public interest.

The Court continued at [31]–[33] as follows:

It is insufficient that the making or continuation of an order under s 50 appears to the Federal Court to be convenient, reasonable or sensible, or to serve some notion of the public interest, still less that, as the result of some “balancing exercise”, the order appears to have one or more of those characteristics (A statement by Fullerton J to like effect, with respect to the powers of the Supreme Court of New South Wales, was approved by Hodgson JA (Hislop and Latham JJ concurring) in Attorney-General (NSW) v Nationwide News Pty Ltd (2007) 73 NSWLR 635; [2007] NSWCCA 307 at [31]).

If it appears to the Federal Court, on the one hand, to be necessary to make a particular order forbidding or restricting the publication of particular evidence or the name of a party or witness, in order to prevent either species of prejudice identified in s 50, or, on the other hand, that that necessity no longer supports the continuation of such an order, then the power of the Federal Court under s 50 is enlivened. The appearance of the requisite necessity (or supervening cessation of it) having been demonstrated, the Court is to implement its conclusion by making or vacating the order. The expression in s 50 “may … make such order” is to be understood in this sense.

It may tend to distract attention from the particular terms of s 50 to describe the Federal Court as embarking upon the exercise of a “discretion” when entertaining an application under s 50 (Dwyer v Calco Timbers Pty Ltd (2008) 234 CLR 124; 244 ALR 257; [2008] HCA 13 at [40]). Once the Court has reached the requisite stage of satisfaction, it would be a misreading of s 50 to treat it as empowering the Court nevertheless to refuse to make the order, or to leave in operation the now impugned order. It would, for example, be an odd construction of s 50 which supported the refusal of an order under s 50 notwithstanding that it appeared to the Court to be necessary to make an order to prevent prejudice to the security of the Commonwealth.

The threshold which a suppression order applicant must satisfy is high. Mere embarrassment, inconvenience, annoyance or unreasonable or groundless fears will not suffice.

In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Valve Corporation (No 5) [2016] FCA 741, Edelman J, when sitting as a Judge of this Court and in determining an application pursuant to s 37AF of the FCA Act that certain answers to interrogatories be suppressed, said the following at [8]–[9]:

The onus of persuading the Court to make an order which restricts publication of evidence has been described as “a very heavy one” (see Computer Interchange Pty Ltd v Microsoft Corp [1999] FCA 198; (1999) 88 FCR 438, 442 [16] (Madgwick J)). The order must be necessary to prevent prejudice to the administration of justice, not merely that it is desirable to address a potential prejudice to the administration of justice. In Hogan v Australian Crime Commission (664 [30]) the joint judgment of the High Court emphasised that “‘necessary’ is a strong word”. Justice Perram has explained that “[m]ere embarrassment or annoyance will not suffice”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Air New Zealand Ltd (No 12) [2013] FCA 533 [7].

Valve asserts that there is prejudice to the proper administration of justice due to its claimed confidentiality in relation to the information in each of the categories outlined above. It is important to draw a distinction between information which is not public and information which is truly confidential. The mere fact that information relevant to a proceeding is not in the public domain will rarely be a sufficient basis to suppress its publication. The interest in confidential information can be different if the disclosure of that information could “become a vehicle for advantaging or prejudicing trade rivals”: Australian Competition & Consumer Commission v Origin Energy Electricity Ltd [2015] FCA 278 [148] (Katzmann J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cement Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2010] FCA 1082 [23] (Greenwood J); see also Yara Australia Pty Ltd v Burrup Holdings Limited (No 2) [2010] FCA 1304 [25] (Barker J).

His Honour dismissed the application before him, primarily upon the ground that it had been made prematurely. In support of that conclusion, at [21]–[22], his Honour said:

Even apart from these doubts there is another fundamental obstacle for Valve. Any assessment of any prejudice to the administration of justice will require consideration of the interest in transparency and open justice. Section 37AE of the Federal Court of Australia Act provides that in deciding whether to make a suppression order or non-publication order, the Court must take into account that a primary objective of the administration of justice is to safeguard the public interest in open justice. Each of the matters over which Valve seeks confidentiality orders may be matters which are relevant to the assessment of remedies including pecuniary penalties.

Further, s 37AJ(2) of the Federal Court of Australia Act also requires that the order should operate for no longer than is reasonably necessary to achieve the purpose for which it is made. It might be open to doubt, for instance, whether it is necessary to maintain a suppression of the publication of Valve’s financial information, including in any reasons for decision which are given, even for the year 2015 beyond, say, 2017 or 2018. The extent and importance of each of these matters can only be properly assessed in light of the evidence and written submissions at the remedies hearing.

23 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Air New Zealand Limited (No 3) [2012] FCA 1430 at [25], Perram J held that Pt VAA of the Act did not effect any substantive alteration in the way that the relevant principles as to the making of suppression orders in this Court are to be applied. I agree.

24 The prevention of prejudice to the proper administration of justice may, in an appropriate case, extend beyond the proceedings before the Court in which the relevant application for a suppression order is made. As Bowen CJ said in Australian Broadcasting Commission v Parish (1980) 43 FLR 129 (Parish) at 132–133 in relation to s 50 of the Act:

… The possible cases where an order may be necessary to prevent prejudice to the administration of justice range fairly widely. The categories of this public interest are not closed and must alter from time to time whether by restriction or extension as social conditions and legislation develop (see D. v. National Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Children per Lord Hailsham [[1978] A.C. 171, at p. 230]; Science Research Council v. Nassé per Lord Fraser [[1979] 3 W.L.R. 762, at p. 784]—cases concerning discovery).

The importance of the principle of open justice is not in doubt (see Scott v. Scott [[1913] A.C. 417]; Russell v. Russell per Gibbs J. [(1976) 134 C.L.R. 495, at p. 520]) nor is the need to depart from it in the interests of justice on occasion (see Attorney-General v. Leveller Magazine Ltd. per Lord Diplock [[1979] 2 W.L.R. 247, at p. 252]; cf. Halcon International Inc. v. Shell Transport and Trading Co. [[1979] R.P.C. 97]). Cases which deal with the course a court should follow where there are no sections corresponding with ss 17 and 50, although illuminating and helpful, are not decisive for a court constituted by an Act containing those sections. Such a court has the slightly different task of interpreting and applying the statute which governs it.

Open justice is the underlying assumption of s 50, not the criterion it prescribes. The section refers to preventing “prejudice to the administration of justice”. This is not a reference to the need to preserve open justice. It is, as I have already suggested, a reference to another public interest, that is, the public interest that the court should endeavour to achieve effectively the object for which it was appointed: to do justice between the parties.

It is not possible to define in advance the degree of prejudice to the administration of justice, which will justify the making of an order under s 50. The collocation of the alternative phrase “security of the Commonwealth” suggests Parliament was not dealing with trivialities. The case where failure to make an order under s 50 would lead to the destruction of the very subject matter of the suit would seem to be the kind of case which might ordinarily attract the exercise of the discretion. The refusal to make an order in such a case might well defeat the purpose of achieving justice between the parties and disappoint the public interest in having the court deal responsibly with the confidential affairs of citizens.

25 Although in Parish the Chief Justice was addressing s 50 of the Act, his remarks hold good in respect of Pt VAA. It is true that s 37AE explicitly gives primacy to the notion of open justice. However, the new provisions nonetheless contemplate that the concept of “the proper administration of justice” encompasses more than the notion of open justice. The High Court said as much in Hogan v Australian Crime Commission (2010) 240 CLR 651 (Hogan) at 667 [42]. In Parish, the Chief Justice spoke of the need to do justice between the parties but did not confine the Court’s commitment to justice in this context to the interests of the parties to the proceedings then before the Court.

26 In my view, in an appropriate case, the proper administration of justice permits the taking into account of relevant considerations which extend beyond the particular proceedings in which the suppression order is sought and which also extend beyond considering only the interests of the parties to that proceeding.

27 In Australian Broadcasting Corporation v L (2005) 16 NTLR 186 at 188 [3], Martin (BR) CJ said the power to make a suppression order under a similar provision in the Evidence Act 1939 (NT) (s 57) is not limited by considerations of the interests of the administration of justice only in respect of the proceedings before the Court. In that case, the Chief Justice held that the power extends to securing the interests of the administration of justice in connection with proceedings other than those before the Court.

28 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Prysmian Cavi E Sistemi Energia SRL (2011) 283 ALR 137 (Prysmian), the ACCC initiated proceedings claiming that the respondents had engaged in price fixing, market sharing and other anti-competitive conduct contrary to s 45 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth). Under the ACCC’s immunity policy in respect of cartel conduct in force at the relevant time, an entity (JPS) was granted conditional immunity under that policy as in force at the relevant time. Mr A, who was not an Australian resident but was an employee of JPS, was granted derivative conditional immunity in accordance with the ACCC’s immunity policy. Within the principal proceeding, ACCC made an interlocutory application seeking that the contents of certain annexures to an affidavit filed in that proceeding and the identity of Mr A be kept confidential. Mr A had provided the ACCC with information about the respondents’ alleged cartel conduct and was concerned that he might also be subject to investigation and prosecution if his identity were revealed. His particular concern related to the potential for prosecution overseas.

29 In support of its claims for confidentiality, the ACCC invoked the doctrine of public interest immunity and also relied upon s 50 of the Act.

30 At 163–170 [180]–[226], Lander J dealt with the ACCC’s claim based upon public interest immunity. At 170–172 [227]–[243], his Honour addressed s 50.

31 In the course of dealing with the ACCC’s public interest immunity claim, at 165 [188]–[191], his Honour said:

Before turning to consider this question it is important to appreciate that Mr A is in a somewhat different position to that of a police informer. The harm that non-disclosure seeks to prevent to a police informer is harm from the accused person who has been informed on. If the identity of the informer is disclosed, the accused person may take retaliatory action against the informer. This might have the effect of intimidating potential future informers. Accordingly, there is a public interest in protecting the informer to prevent this harm.

However, the harm Mr A says he will suffer as a result of the disclosure of the documents is that the documents might come to the attention of prosecuting authorities in other jurisdictions, and that he might then be subject to investigation and civil or criminal proceedings in those jurisdictions. Put another way, the harm Mr A complains of is that he may be prosecuted in other jurisdictions for his conduct.

It is not the role of this court, or indeed the informer rule in the context of public interest immunity, to protect Mr A from lawful prosecution in other jurisdictions. The adverse consequences that he might suffer in other jurisdictions for conduct that may be unlawful in those jurisdictions are not matters of public interest in this jurisdiction.

Accordingly, I do not think that the risk of prosecution in other jurisdictions is a matter to which I should have regard in determining whether Mr A’s identity should be released without conditions, or whether the documents should be given to the respondents without conditions. ...

32 In the passages at 165 [188]–[191] which I have extracted at [31] above, Lander J had under consideration the balancing exercise which he was required to undertake in determining the ACCC’s claim for confidentiality based upon notions of public interest immunity. At the point in his Honour’s reasons where his Honour made those observations, his Honour was not addressing s 50 of the Act at all. Notwithstanding this fact, his Honour did observe that it is not the role of this Court to protect persons in the position of Mr A from lawful prosecution in other jurisdictions. His Honour said that the adverse consequences that Mr A might suffer in other jurisdictions for conduct that may be unlawful in those jurisdictions are not matters of public interest in this jurisdiction. It must be remembered, of course, that the task which his Honour was required to undertake in respect of the ACCC’s claim for public interest immunity was a balancing exercise between two or more identifiable public interests. The task of the Court when considering an application for a suppression order under s 37AF is quite different. I do not consider that the observations made by Lander J at 165 [188]–[191] were intended by his Honour to address s 50 of the Act or the principles which should guide its application. For that reason, I do not consider those remarks to be of assistance in the present case.

33 After determining that the ACCC’s claim for relief based upon public interest immunity should be rejected, his Honour then turned to the ACCC’s claim for relief pursuant to s 50 of the Act.

34 At 171–172 [236], his Honour cited [30]–[31] from Hogan. At 172 [237]–[238], his Honour then said:

The “administration of justice” that is referred to in s 50 is the exercise of the judicial power of the Commonwealth by the Federal Court itself. It has nothing to do with the ACCC’s responsibilities in detecting or preventing cartel conduct, or prosecuting a party who is engaged in such conduct.

Accordingly, a party who applies for an order under s 50 must satisfy the court that the order is necessary, in the sense described in Hogan, for the administration of justice by the Federal Court itself. If the court is satisfied that such an order is necessary, it implements its conclusion by making the order.

35 His Honour then proceeded to reject the ACCC’s claim made pursuant to s 50.

36 I do not think that, at 172 [237]–[238] in Prysmian, Lander J intended to say anything different from that which the High Court had said in Hogan. In Hogan, at 664 [30], the High Court said that “the administration of justice” spoken of in s 50 is that “involved in” the exercise by the Federal Court of the judicial power of the Commonwealth. That choice of language may describe a wider set of circumstances than a strict reading of the exposition of the Court’s role in this context given by Lander J in the first sentence of [238] in Prysmian might suggest. The High Court contrasted the notion of “the (proper) administration of justice” with broader notions of the public interest. In my view, by using the expression “involved in” in relation to the exercise by this Court of the judicial power of the Commonwealth, the High Court had in mind the possibility that this Court might legitimately consider as part of the concept of “the (proper) administration of justice” circumstances arising outside proceedings commenced in this Court but affected or impacted by the conduct of (including the making of orders in) proceedings in this Court. As the High Court also said in Hogan (at 667 [42]):

… The administration of justice by the Federal Court, which is the focus of s 50, certainly includes not only the generally recognised interest in open justice openly arrived at [See K-Generation Pty Ltd v Liquor Licensing Court (2009) 237 CLR 501 at 520-521 [49]] which is reinforced by the terms of s 17(1), but also restraints upon disclosure where this would prejudice the proper exercise of its adjudicative function. Bowen CJ pointed this out in Australian Broadcasting Commission v Parish [(1980) 43 FLR 129 at 133; 29 ALR 228 at 233]. His Honour went on to describe the litigation in Parish as analogous to a case where confidential information “is the subject matter of the proceedings”; he concluded that it was in the interests of justice that the processes for determination of those very proceedings not destroy or seriously depreciate the value of that subject matter [(1980) 43 FLR 129 at 135; 29 ALR 228 at 235].

37 The exercise by this Court of the judicial power of the Commonwealth in connection with applications of the kind presently before the Court may require this Court to consider the impact of the deployment of its compulsory processes (such as the power to compel a party to give discovery of documents or to answer interrogatories or to respond to a Notice to Admit Facts) upon individuals who may or may not be parties to the particular proceeding in this Court in the traditional sense, who ordinarily reside in places other than Australia and who may well be subject to the criminal law of countries other than Australia. Such individuals will necessarily have some connection with the proceeding in this Court but the connection may be quite tenuous. For example, in an appropriate case, this Court may suppress information which concerns any person named in evidence in a proceeding (see the extended definition of “party” in s 37AA of the Act and s 37AF(1)).

CONSIDERATION

Categories 1 and 2—Suppression of Names

38 The first category of information sought to be protected by the order sought in the respondents’ IA is information that reveals or tends to reveal the identity of persons who are related to or otherwise associated with VWAG (former or current employees of VWAG, its related corporations and affiliates) which, of course, is a party in five of the seven proceedings presently before the Court and which is the parent company of other parties to those proceedings, or otherwise concerns VWAG and/or its subsidiaries. As I noted at [8] above, such information is within the type of information described in s 37AF(1)(a) of the Act. In the circumstances of the present case, that information may also fall within the type of information specified in s 37AF(1)(b)(iv) of the Act.

39 The answers to interrogatories provided by the respondents contain the names of 67 current or former employees of VWAG, its related corporations or affiliates, who VWAG believes were involved in some way in the development, installation, modification or approval of the switching or 2 mode software installed in motor vehicles fitted with the EA189 diesel engine (affected vehicles). In its answers to interrogatories, VWAG stated that it believed that the purpose of some of those persons in engaging in that conduct was to enable the affected vehicles to pass emissions tests required to be conducted in Europe and in the US even though they would not have passed such tests if they had been tested in road mode. In other words, the answers to interrogatories provided by the respondents, if made available publicly without restriction, might well serve not only to identify those responsible for conceiving the scheme and putting it into effect but might also serve to incriminate those persons in a manner which could visit a serious injustice upon them. The respondents’ response to the relevant Notice to Admit Facts also contains the names of individuals whom the respondents consider were implicated in dieselgate.

40 None of the individuals named in the respondents’ answers to interrogatories or in their response to the relevant Notice to Admit Facts has appeared before me in relation to the respondents’ IA. None of them is a party to any of the proceedings before the Court. The identity of each of the persons comprising the Non-Publication Group has been disclosed to the applicants and to the Court by the respondents under compulsion and not by the individuals themselves. All of those individuals have been made aware of the fact that certain interrogatories were required to be answered by the respondents in the Australian proceedings and have also been made aware generally of the substance of the answers that VWAG intended to give in response to those interrogatories. Many of those persons advised VWAG’s lawyers that they had concerns that any form of disclosure in the present proceedings might prejudice their criminal trial and that they supported the respondents’ claims for relief in their IA.

41 As at mid-September 2019, the evidence before me proved that:

(a) Potentially more than 40 current and former VWAG employees, many of whom are referred to in the respondents’ answers to interrogatories, are the subject of criminal investigations in Germany in connection with dieselgate. In addition, the Public Prosecutor in Braunschweig in Germany has submitted to the Court there, for its consideration, indictments of five individuals all of whom are mentioned in the answers to interrogatories. Further indictments in Germany of approximately 27 other persons named in the answers to interrogatories are likely to be filed. A number of other individuals are formal suspects in ongoing investigations. Some of these will be persons who are mentioned in the materials specified in Schedule 1 to the 23 September Orders;

(b) The hearings of the criminal prosecutions in Braunschweig are likely to commence later this year and may continue for a period of up to a year thereafter. These proceedings will likely be tried before two professional judges and two lay judges. German law contains a number of provisions designed to protect lay judges from being influenced by prejudicial material and to maintain their impartiality;

(c) The offences alleged against those persons who have been indicted in Germany and the offences the subject of investigations by authorities in Germany are very serious. They all carry penalties by way of imprisonment, in some cases for a maximum term of ten years; and

(d) Several persons have been charged, convicted and imprisoned in the US for their role in dieselgate. Others are under indictment and yet others are being investigated. Investigations by the US Department of Justice are continuing. Other criminal proceedings have been instituted in the US including a proceeding recently brought by the US Securities and Exchange Commission. At the moment, it is not possible to be certain as to the identity of further individuals who may be the subject of prosecutions in the US. All of the criminal matters in the US would be tried before a judge and a jury. All of those matters involve very serious offences.

42 The evidence before me established that, despite the fact that there has been some publicity overseas in relation to criminal investigations in Germany and in the US, with the exception of those individuals in relation to whom an indictment has been made public in the US or who have been convicted of a crime in the US, no employee identified in the answers to interrogatories or the relevant Notice to Admit Facts has yet been identified in any publicly available documents as being involved in the conduct the subject of the Australian proceedings in the manner and with the specificity described in the answers to interrogatories and the Notice to Admit Facts.

43 The respondents submitted that, absent an order under s 37AF of the Act, the involvement in dieselgate of the individuals named in the answers to the interrogatories and in the other materials specified in Schedule 1 to the 23 September Orders will become public in connection with dieselgate for the first time in the present proceedings. Once made public, that information could easily be disseminated in Germany and in the US. It is very likely that it would be so disseminated. After all, there has been considerable public interest and public reporting of the dieselgate scandal both in Australia and elsewhere and it is reasonable to assume that the media and the relevant authorities will continue to maintain a keen interest in developments around the world including in Australia. The internet would, of course, facilitate the speedy dissemination of such information.

44 In the circumstances which I have outlined, there is a real risk that the judges in the German criminal proceedings as well as the judges and juries in the US criminal proceedings would not only learn of the detail of the answers to interrogatories and the response to the relevant Notice to Admit Facts provided by the respondents in the present proceedings but would find it difficult to put that detail out of their minds.

45 This gives rise to a real risk of compromise to the fairness of the criminal trials of those persons in the Non-Publication Group who are already the subject of charges in Germany and in the US and who may, in the future, be subject to such charges. If, for example, a lay judge in one of the German trials or a jury member in one of the US trials becomes aware of the fact that the respondents have given verified answers to interrogatories in connection with the Australian proceedings that, to the best of their knowledge, information and belief, the particular accused was involved in the development of the impugned software and that his or her purpose in being so involved was to defeat the European or US vehicle emissions tests, that lay judge or jury member, even acting conscientiously, would find it difficult to place that fact out of his or her mind. As far as the evidence before me went, the essence of many of the criminal charges of which the respondents are aware relates to the development of the impugned software or the concealment of its existence in motor vehicles sold in Europe and the US.

46 In my judgment, there is a substantial risk that the revelation in the Australian proceedings of the identity of those whom the respondents consider to be responsible for the development of the impugned software and the installation of that software in vehicles around the world will unfairly prejudice the trial of many members of the Non-Publication Group in Germany and in the US and is prejudicial to the administration of justice by this Court and, more than likely, by courts in Germany and in the US.

47 For the above reasons, I consider that the making of a suppression order which protects from public disclosure the identity of the members of the Non-Publication Group is well-warranted.

48 In addition, I am satisfied that the Stage 2 Trial of the five class actions and the two regulatory proceedings with which I am concerned would not have been rendered unworkable by the making of a suppression order in respect of the first and second categories of information referred to above had that trial proceeded. It must be remembered that all of the applicant parties and the Court have access to the respondents’ answers to interrogatories and the other materials described in Schedule 1 to the 23 September Orders and the applicant parties would have been free to tender so much of that material as they may have been advised. The material would have been important had the Stage 2 Trial proceeded because the applicant parties bore the onus of proving that the relevant conduct was engaged in by persons whose conduct can be attributed to the respondents for liability purposes. However, discharging that onus did not require that the identity of the relevant persons be made public. Furthermore, none of the individuals named in the answers to interrogatories was likely to give evidence at the Stage 2 Trial. In any event, this Court has at its disposal a number of ways of managing the need for confidentiality during the course of a trial and would have been well equipped to manage that need in the present case as required during the run of the trial.

Categories 3–5

49 These categories concern the information specified in Schedule 2 to the 23 September Orders. That material comprises proprietary information of the respondents in the form of software code and software maps of the EA189 engine and other technical information which, if disclosed publicly or made available to third parties, would provide trade rivals of the respondents with information of significant value and a competitive advantage that would not otherwise have been able to be obtained. This information is properly characterised as VWAG’s trade secrets. In addition, the particular information would be of significant value to the respondents’ trade rivals in developing engines which might compete with the respondents’ EA288 engine and the respondents’ EA288 Evo engine, the first of which is their current diesel engine and the second of which is the next generation of diesel engine being developed by VWAG. The evidence supported the proposition that knowledge of the EA189 engine software code and maps would provide an effective blueprint to understanding the way in which the later engines are configured. The evidence also established that this information would not otherwise be discoverable by a trade rival even if such a rival purchased a vehicle with an EA189 or EA288 engine fitted and sought to reverse engineer the engine in order to unlock the software code and engine architecture. Such an endeavour, even if it could provide a competitor with some information about the software and the engine’s structure, could not have achieved the level of precision and understanding of the software described in the redacted parts of the documents in Schedule 2 to the respondents’ IA. The disclosure of this information to trade rivals of the respondents would lead to the respondents suffering significant commercial prejudice.

50 The documents in Category 5 above (the Type Approval dossiers) are confidential documents under three separate German statutes and also under EU legislation. They contain detailed technical information, which is not publicly available, about Volkswagen, Audi and Skoda vehicles equipped with an EA189 diesel engine. This information comprises diagrams, schematics and specifications about vehicle components, engine design and engine operation which is confidential and proprietary to VWAG, Audi AG and Skoda Auto a.s. These documents also contain information describing the design and functioning of all major parts of the vehicles. These technical data and specifications concerning the hardware and software components of the engines in particular are trade secrets which belong to VWAG and its related corporations.

51 In the circumstances, I was prepared to protect the commercially sensitive proprietary information of the respondents from unfair exploitation by their trade rivals.

Conclusion

52 For all of the above reasons, I made the orders which I made on 23 September 2019.

I certify that the preceding fifty-two (52) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Foster. |

Associate: