FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

University of Sydney v ObjectiVision Pty Limited [2019] FCA 1625

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 21 days of these reasons the parties are to confer and provide to the Associate of Justice Burley draft short minutes of order giving effect to the conclusions that are set out in these reasons, with any points of difference between them set out in mark-up.

2. Any party wishing to make submissions as to costs, or otherwise as to the form of any final orders to be made, is to file and serve written submissions (of no more than 7 pages) and any evidence in support within 21 days of these reasons.

3. Any party wishing to respond to submissions and evidence filed in accordance with Order 2 is to do so within 14 days thereafter, such submissions also to be of no more than 7 pages in length.

4. Any reply submission (of no more than 3 pages) is to be filed and served within 7 days thereafter.

5. If any party wishes to be heard on any question arising from the question of costs or form of orders they should so indicate in their written submissions. Otherwise, any remaining questions will be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BURLEY J:

1 This case involves an unsuccessful venture to commercialise technology in the field of visual electrophysiology. The main protagonists are a university, a company incorporated to commercialise the technology, the director and majority shareholder of that company, and the people who strove without success for over a decade to achieve a commercial product.

2 The University of Sydney is a body corporate established pursuant to the University of Sydney Act 1989 (NSW). In the late 1990s two of its employees, Associate Professor Alexander Klistorner, an electrophysiologist, and Professor Stuart Graham, an ophthalmologist, developed improvements to a particular form of visual electrophysiology, using multi-focal visually evoked potential (mfVEP). This technology can be used to detect partial and complete blind spots associated with glaucoma and other diseases of the eye or the brain. In 1999, the University filed a patent application in respect of mfVEP technology, entitled “Electrophysiological Visual Field Measurement”.

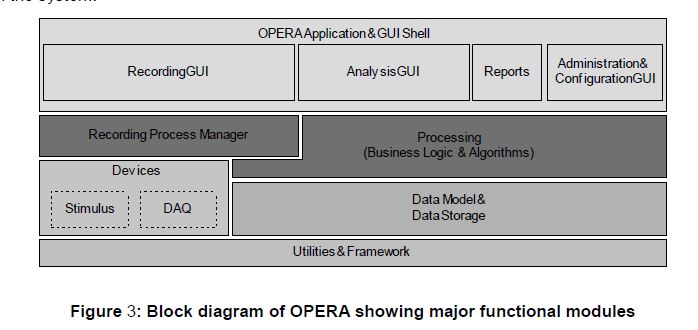

3 One of the University’s objects is to carry out research to meet the needs of the community. Another is to exercise commercial functions for the exploitation and development of its intellectual property. Pursuant to these objects, in September 2000 the University entered into an exclusive licensing agreement with ObjectiVision Pty Ltd for the commercialisation of a product, ultimately called the AccuMap, which utilised the patented technology. The AccuMap was run on computer software theatrically called OPERA (Objective Perimetry Evoked Response Analysis).

4 Things did not go well. By 2008 ObjectiVision had failed to meet the minimum performance requirements under its agreements. The University gave notice terminating the exclusivity of the licence and began to develop its own software called TERRA (Topographical Evoked Response Recording and Analysis). At the beginning of 2011 the University gave notice of termination of the licensing agreement with ObjectiVision and began to deal with Visionsearch Pty Ltd in relation to the technology. ObjectiVision did not accept the termination.

5 In 2014 the University commenced these proceedings. It alleges that ObjectiVision is infringing its patented technology and wrongly does not accept the termination of the licensing arrangements. ObjectiVision disputes these matters and advances a cross claim alleging: that the licences between it and the University were not validly terminated; that in proceeding to commercialise the technology with third parties the University acted in breach of its agreements with ObjectiVision; and that the University and Visionsearch are liable to it for substantial pecuniary remedies arising from this conduct. ObjectiVision also contends that in seeking to commercialise the technology, each of the University and Visionsearch infringed its copyright in the OPERA software and acted in breach of confidence.

6 By Orders made in May 2015, all issues, including the claims for damages, were to be heard separately and before the patent infringement case. It is those matters that this judgment is addresses.

7 The dispute concerns the conduct of the parties and various individuals from 2000 until 2011. The litigation has been hard fought and no doubt challenging for the people involved. For the reasons explained below, the litigation has been protracted. Many factual and legal issues have been raised, which have necessitated this rather long judgment.

8 The legal and factual issues between the parties are far-reaching. Before attending to the detail, it is convenient to provide a general summary, to explain the layout of the reasoning that follows. The relevant terms of the agreements and my factual findings relevant to the issues are addressed in later parts.

9 On 29 October 1999 ObjectiVision was incorporated as a vehicle through which the mfVEP technology could be commercialised. On 4 September 2000 the University and ObjectiVision entered into a Licensing Agreement for the exclusive licence of the technology. On the same day ObjectiVision, the University and several others entered into a Shareholders' Agreement. On 25 October 2001 the University and ObjectiVision entered into a Second Licensing Agreement extending the scope of the technology licensed. On 10 May 2004 the University and ObjectiVision entered into a Variation Agreement that altered the minimum performance obligations under the Licensing Agreement. The salient terms of these agreements are set out in section 5 of these reasons.

10 From 2000 ObjectiVision set out to commercialise the mfVEP technology by developing a product, initially called a Multifocal Objective Perimeter or MOP but later referred to as the AccuMap. This succeeded to a point, but in early 2005 development work stalled, and the first version of the product, called AccuMap 1, was abandoned. In 2005 Mr Arthur Cheng was brought on board as the CEO of ObjectiVision to develop a better and more viable product. Various protoype devices subsequently developed were referred to as the AccuMap 2. The OPERA software was upgraded and in its final form was OPERA v2.3. Some aspects of the case turn on the progress made by ObjectiVision in the development of AccuMap 2 from 2005 until January 2008, when it ran out of funds and ceased work. I set out a number of findings of fact in relation to these matters, in section 4.3.

11 In early 2008 the University expressed concerns that ObjectiVision had failed to commercialise its technology in accordance with the Licensing Agreements. It served notices on ObjectiVision, and expressed the view that by August 2008 it had terminated the exclusivity of ObjectiVision’s licence. In November 2008, Associate Professor Klistorner instructed Vadim Alkhimov, a software programmer who began working for ObjectiVision in 2007 and moved to work for the University in 2008, to commence development of software that would enable him to continue his research. This was later called TERRA.

12 ObjectiVision disputed that the licence had been validly rendered non-exclusive, and between 2008 and 2010 it was at issue with the University. In January 2010 they attended a mediation, at the end of which they entered into terms of agreement referred to below as the Heads of Agreement, which included a number of obligations on both parties, but most significantly provided for the reinstatement of the exclusive licence under the Licensing Agreement for a limited period, to enable ObjectiVision to find third party funding to continue the commercialisation of the technology. If it failed to do so within an agreed period of time, the Licensing Agreement could be terminated.

13 In the second half of 2010 the University considered an opportunity to provide expertise and equipment to support clinical trials that Biogen Idec planned to conduct for a drug used to treat optic neuritis. In the course of this, consideration was given to the incorporation of a new start-up company that would develop a product and enter into a contract with Biogen. Mr Ken Coles and Dr Christopher Peterson contributed funds to this end.

14 On 19 January 2011 the University wrote to ObjectiVision, indicating that in its view the Licensing Agreements were terminated as a result of the operation of the terms of the Heads of Agreement. The University’s contract claim is based on this proposition. It separately contends that the Licensing Agreement was terminated because of the failure of ObjectiVision to pay certain invoices. In response, ObjectiVision contends that the agreements were not terminated, that the University unreasonably refused to consent to terms whereby Hamisa Investments Pty Ltd would take a majority shareholding in ObjectiVision, and that the other bases upon which the University contends the Licensing Agreements to be at an end are unfounded.

15 In its cross claim based on breach of contract, ObjectiVision repeats these claims, and also contends that the University acted in breach of various terms of the Shareholders' Agreement and the Licensing Agreement in various dealings that it had with Biogen. It seeks some $25 million in damages.

16 On 28 March 2011 Visionsearch Pty Ltd was incorporated and in early May 2011 the University provided it with the TERRA software that Mr Alkhimov had been working on. Thereafter, Mr Alkhimov worked at Visionsearch with Mr Paul Peterson in the development of an mfVEP machine called Visionsearch 1 which included further development to the TERRA software.

17 In its cross claim ObjectiVision also contends that the creation and use of TERRA constitutes an infringement of its copyright. It contends that the supply of TERRA to Visionsearch, and its subsequent use in the Visionsearch 1 machine, also amounted to an infringement of ObjectiVision’s copyright and also constituted misuse of confidential information. These matters are considered in sections 9 to 13 of these reasons.

18 The University operates a number of research centres, one of which is the Save Sight Institute (SSI) which is a not-for-profit centre located at the Sydney Eye Hospital in Macquarie Street, Sydney. The SSI is part of the University Medical School and incorporates the University’s discipline of clinical ophthalmology and eye health. It is not a separate legal entity from the University.

19 One of the research groupings of the SSI is the electrophysiology and glaucoma research group, of which Associate Professor Klistorner is the leader. Associate Professor Klistorner was engaged as a full time employee of the SSI from 1997 until 2014, after which he became a part-time employee. The SSI also provides clinical services for the diagnosis, treatment and management of eye disease in the community, and educational programmes teaching ophthalmology.

20 ObjectiVision was incorporated in October 1999. Details for its shareholders are set out in some detail in section 4.4 below. Mr Cheng became the chief executive officer of ObjectiVision on 30 March 2005, was appointed as a director in April 2006, and on 29 April 2008 he became the majority shareholder.

21 Visionsearch was incorporated on 25 March 2011. Its directors were then Dr Chris Peterson, Mr Coles, and Mr Paul Peterson.

1.3 The course of the proceedings up until trial

22 The University commenced these proceedings in April 2014 alleging that the Licensing Agreements had been validly terminated and that it was entitled to claim damages of non-payment of certain costs associated with its patents. It also alleged patent infringement on the part of ObjectiVision.

23 In July 2014, ObjectiVision filed a cross-claim, alleging that the University had wrongly purported to terminate the licence agreements. In May 2014 ObjectiVision was granted orders for the provision of preliminary discovery by the University and Visionsearch of the TERRA software; ObjectiVision Pty Ltd v Visionsearch Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1087; 108 IPR 244 (Perry J) (preliminary discovery judgment). On 11 August 2014 the Court made orders by consent that all questions arising in the proceeding concerning contracts between the parties be heard and determined separately and before all questions concerning patent infringement. On 22 May 2015 ObjectiVision was granted leave to file an amended cross claim that added its claims for copyright infringement and misuse of confidential information on the part of the University and Visionsearch. On the same day, the order concerning the separation of issues was varied so that all questions relating to copyright infringement and confidential information be determined with the questions concerning contracts between the parties. It is on that basis that the present trial proceeded.

24 On 19 November 2015 ObjectiVision filed a detailed expert report prepared by Mr Robert Zeidman going to the copyright infringement case. Mr Zeidman was provided with version 2.3 of the OPERA software and asked to compare it against various files containing the TERRA software.

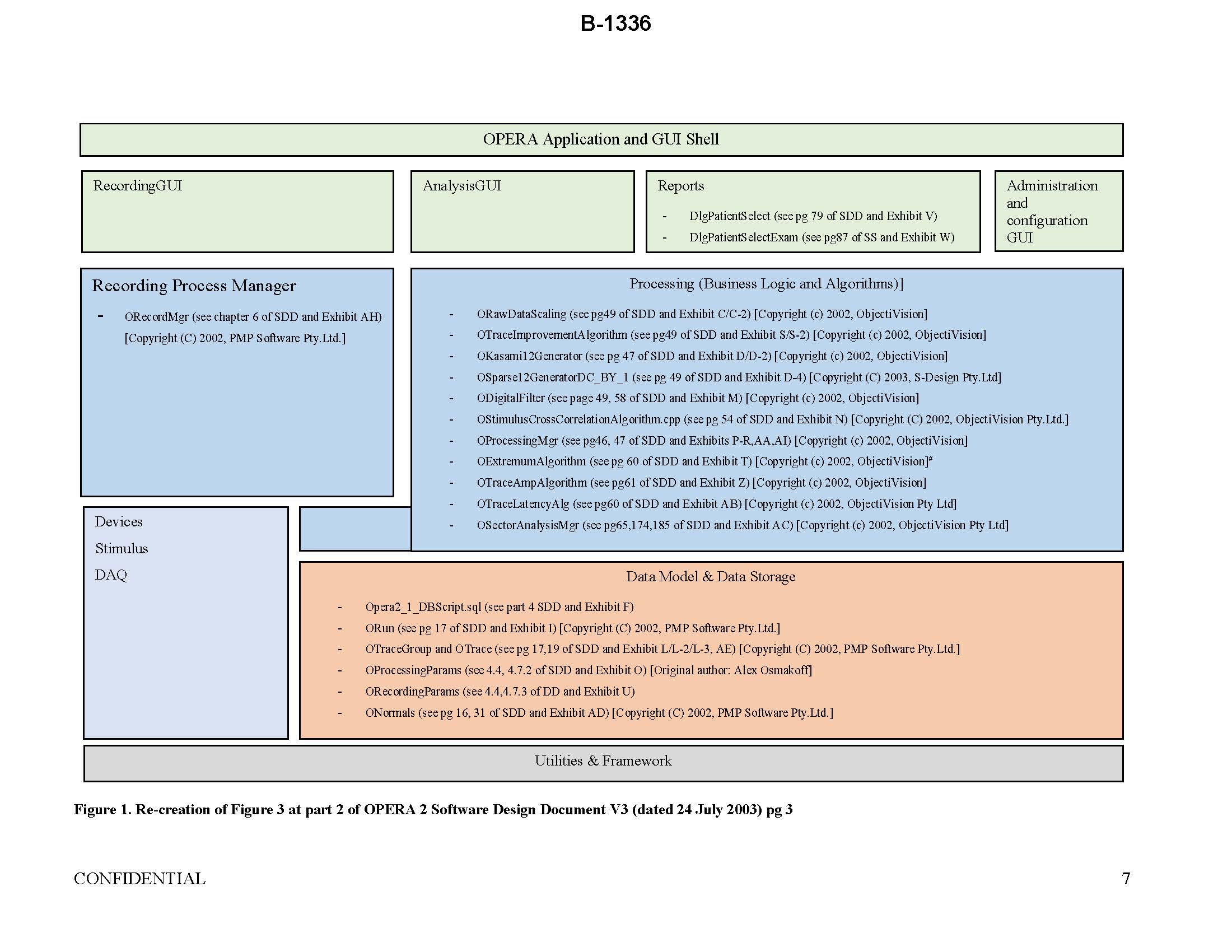

25 On 9 December 2015 Rares J ordered that ObjectiVision give security for costs in respect of its cross claim; University of Sydney v ObjectiVision Pty Limited [2015] FCA 1528 (security for costs judgment). Subsequently, the University gave discovery and proceeded to prepare its response to the Zeidman report. However, ObjectiVision ran into difficulties in funding its claim. The cross claim stalled, and was not reanimated until October 2016 when I heard an application brought by ObjectiVision for, amongst other things, leave to amend its cross claim; see University of Sydney v ObjectiVision Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 1199 (Amendment Decision) at [5] – [33]. The University expressed concerns about the proposal to amend the copyright claim because the amendments appeared to allege that earlier versions of OPERA other than OPERA v2.3 had been infringed and also because they appeared to allege that in addition to OPERA v2.3, particular algorithms identified in the amended pleadings were separate works that had been infringed. Senior counsel for ObjectiVision confirmed that neither concern was warranted (see [38], [51]) and that the separate reference to particular algorithms was to particularise the specific or most important files which ObjectiVision alleges have been copied. On this basis ObjectiVision was granted leave to re-draft its amended cross claim: Amendment Decision at [52].

26 Along the way, ObjectiVision has made numerous amendments to its cross claim. The final version is the sixth further amended statement of cross claim. That version abandons many earlier breach of contract allegations.

27 In its claim the University seeks a declaration that the Licensing Agreement and Second Licensing Agreement terminated on 19 or 20 January 2011, and judgment in the sum of $19,219.74 plus interest. It also seeks declaratory, injunctive and pecuniary relief in respect of infringement of certain patents, although as noted, this aspect of the case has been separated from the subject matter of the present proceeding.

28 In the contract aspect of its cross claim, ObjectiVision seeks a declaration that the Licensing Agreement remains in full force and effect, a declaration that the Licensing Agreement remains exclusive, and damages. In the copyright aspect of the cross claim, ObjectiVision seeks permanent injunctions restraining the use or reproduction of the TERRA software by either the University or Visionsearch, consequential orders including the delivery up of infringing copies of the software, and damages.

29 The damages claim as advanced by ObjectiVision varied considerably as the case progressed. In opening submissions it was quantified on the basis that had the University not wrongly terminated the Licensing Agreements, ObjectiVision would have had commercial opportunities to exploit the mfVEP technology valued by its expert, Mr Jeffry Aroy, at over $52.9 million. In the alternative, ObjectiVision claimed that it was entitled to $25.9 million on the basis of wasted expenditure, as a result of the University’s wrongful termination. In opening, ObjectiVision contended that it was entitled to the same measure of damages for infringement of copyright and misuse of confidential information. As the trial progressed, numerous claims of breach of several agreements as pleaded in the cross claim by ObjectiVision were abandoned. As initially pleaded, taking into account alleged implied terms and the multiple contracts alleged to have been breached, there were over 70 allegations of breach. By the end of closing submissions, the alleged breaches were reduced to four, and the claim for damages for breach of contract was advanced only on the basis of an entitlement to damages based on wasted expenditure.

30 The claim for pecuniary relief arising from copyright infringement and misuse of confidential information was abandoned save for a claim for nominal damages.

31 For the reasons set out below I find:

(1) That the Licensing Agreement and the Second Licensing Agreement terminated on 19 January 2011;

(2) That had these licensing agreements not been terminated on 19 January 2011, then they were in any event validly terminated for breach on 20 January 2011 and again on 10 October 2014;

(3) That the University is entitled to judgment in the amount of $19,219.74 plus interest for failure on the part of ObjectiVision to pay outstanding patent costs; and

(4) That ObjectiVision’s cross claim fails and must be dismissed.

32 I will make orders directing that within 21 days the parties discuss and supply draft short minutes of order giving effect to the conclusions that are set out in these reasons, with any points of difference between them set out in mark-up.

33 In the normal course I would be disposed to order that ObjectiVision pay the costs of the claim and the cross-claim. However, provision will be made in the orders for any party wishing to contend for a different order to do so.

34 Aspects of the dispute concern events that took place many years before the various witnesses supplied their written evidence, and more years before they gave their oral evidence. Memories fade and the more intricate details of events as they happened are less likely to be remembered over time. Several aspects of the dispute concern events taking place from 2005 until January 2011. In particular, a live issue at trial was how close to completion the AccuMap 2 product was by the time that the Licensing Agreements were allegedly terminated by the University, and how much time and money was likely to be needed to complete it. In this regard there was conflicting written and oral evidence between the witnesses. Taken as a whole, I consider that the lay witnesses who gave oral evidence did their best to remember events long gone. However, I consider that the distance of time has made it appropriate to pay close regard to the documentary record of events as it appears from the email traffic and board minutes prepared contemporaneously with the events as they unfolded. In this regard I was favoured with a large and well organised court book that initially included over 30 volumes of documents, and which was slimmed down somewhat after the dust of the hearing had settled. Except where I make specific comment below, I consider that the lay and expert witnesses did their best honestly to give their evidence.

2.2 The witnesses called by the University

35 Alexander (“Sasha”) Klistorner is an Associate Professor of Clinical Ophthalmology and Eye Health at the SSI. He works in the research and development of technology relating to electrophysiology and imaging of the visual pathway, in particular mfVEP. Associate Professor Klistorner is a world-leading expert in the mfVEP and electrophysiology fields and was a founding shareholder of and a consultant to ObjectiVision. In his first statement dated 20 December 2016, he gives evidence about electrophysiology and mfVEP, the patented technology and ObjectiVision, the AccuMap machine and the OPERA software, his research using the OPERA software, the development of the AccuMap 2 prototypes, his involvement with ObjectiVision from December 2007, his participation in a technical assessment of the AccuMap 2 prototype in early 2010 and his involvement in, inter alia, dealings with Biogen. In the course of this he responds to the evidence of Mr Cheng. In his second affidavit he responds to the evidence of an expert called by ObjectiVision, Mr Aroy. Associate Professor Klistorner was cross-examined.

36 ObjectiVision submits that Associate Professor Klistorner frequently sought to fashion his evidence so as to support the case advanced by the University. This was not my impression. I consider that Associate Professor Klistorner presented as a careful and honest witness, who attempted to answer the questions as best he could. In my view, ObjectiVision’s submission is not supported by the various examples that it advances. To the extent that he was unable to recall specific events, Associate Professor Klistorner frankly stated that this was so. I do not consider that the identified memory lapses, concerning events dating back more than a decade, can reasonably be characterised as “convenient”. Nor do I consider that his evidence as to the state of readiness or the worth of the AccuMap 2 prototypes was contrived. To the contrary, at various times he gave evidence of mishaps in the presentation of prototypes that credibly concern embarrassing events that he is likely to have recalled.

Stuart Graham is a professor of ophthalmology and visual science in the Faculty of Medicine and Health Science at Macquarie University, Sydney. He is also a consultant ophthalmologist with a private practice in Sydney. From 1996 until 2005 he conducted research as a PhD candidate and research fellow with Associate Professor Klistorner at the SSI. Their research concerned electrophysiology and mfVEP. Professor Graham’s PhD thesis was entitled “Development of a technique for Objective Perimetry using the multifocal visual evoked potential” and his collaboration with Associate Professor Klistorner led to them being jointly named as inventors on several patents relevant to the current proceedings. Professor Graham was one of the initial shareholders in ObjectiVision, and gives evidence about the mfVEP technique and the early history of ObjectiVision, the development of the AccuMap 2 prototypes, his involvement with ObjectiVision over time, and his dealings with other companies interested in mfVEP technology. He also provides responses to some of the expert evidence filed on behalf of ObjectiVision. He was cross-examined.

37 Anders Hallgren was employed by the University as the Director of Sydnovate from November 2010 to March 2014. Sydnovate, a group within the University, had the role of commercialising the University’s intellectual property. Dr Hallgren holds a PhD in Chemical Engineering/Industrial Process Technology from Lund Institute of Technology/Lund University, a Master of Science in Chemical Engineering and Process Technology from the same institution; and a degree in Business Administration, Management and Leadership, Business Law, and International Industrial Marketing from the Lund University School of Economics. In his position as Director of Sydnovate, Dr Hallgren was ultimately responsible for managing the University’s relationship with ObjectiVision and making decisions on behalf of the University in this regard. Dr Hallgren gives evidence about the correspondence between the University and ObjectiVision from November 2010 and, in particular, about the events leading from that date until the decision in January 2011 to terminate the Licensing Agreements. Dr Hallgren was cross-examined.

38 Vadim Alkhimov is a software engineer who graduated with an Honours Degree in Computer Science majoring in mathematics from the Moscow Power Engineering Institute in 1999. He immigrated to Australia in October 2006 and worked at ObjectiVision from January 2007 until January 2008. He then worked for the University at the SSI until May 2011. Thereafter, he worked at Visionsearch from May 2011 until November 2011, and from 30 April 2013 until 14 February 2014, whereupon he began to work for Visionsearch as a consultant for 3 days a week. Mr Alkhimov gives evidence about his work at ObjectiVision, the OPERA software, the development of the TERRA software, and gives his response to allegations that the TERRA software is a copy of the OPERA software. Mr Alkhimov was cross-examined.

39 Stephen Garton was from August 2009 to 2019 the Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Provost of the University. Immediately prior to that, he was the Dean of the Faculty of Arts at the University, a role that he had held since 2001. In his role as Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Provost, he was the Vice-Chancellor’s senior deputy and, together with the Vice-Chancellor, was responsible for the management of the University. He gives evidence about the functions and structure of the operation of the University, the delegation of authority within the University, the formation of the SSI and its operations and the University’s policies concerning academic freedom. Professor Garton was cross-examined.

40 Anna Katherine Grocholsky was from August 2004 until November 2011 engaged by the University first as a business development manager and, after 26 September 2006, as the manager of intellectual property within Sydnovate, which was later renamed the Commercial Development and Industry Partnership. She gives evidence about Sydnovate’s patent administration and payment systems, her correspondence with Mr Cheng in relation to Objectivision, and invoices rendered to ObjectiVision. Ms Grocholsky was not cross-examined.

41 Terence Potter is a forensic accountant at Axiom Forensics Pty Ltd. He obtained a Bachelor of Commerce degree from the University of Western Australia in 1987 and in 1990 became an associate member of the Institute of Chartered Accountants. In 1998 he established the forensic accounting division at Ferrier Hodgson in Sydney and in 2004 established Axiom Forensics Pty Ltd, where he now works. He gives expert evidence in answer to ObjectiVision’s claim for damages based on the calculation of wasted expenditure and in support of the University’s claim that ObjectiVision was insolvent after December 2007. He was cross-examined during the course of a concurrent evidence session (concerning insolvency) with Mr Potter.

42 Michael Khoury is a Partner at Ferrier Hodgson and the national leader of the firm’s Forensic IT practice. He specialises in computer forensics and electronic discovery. He provides evidence about the content of computer files that he examined supplied to him by the University containing the TERRA and OPERA code. Mr Khoury participated with Mr Klein in the preparation of a joint expert report. He did not give concurrent evidence and he was not cross-examined.

43 Justin Zobel is a professor and the head of the Department of Computing & Information Systems at the University of Melbourne. He is a computer scientist by training with a PhD in computer science. He has developed algorithms for text retrieval and from 1999 to 2001 led a project to identify RMIT students whose assignment submissions were plagiarised. This involved the development and enhancement of software, manual and automatic comparisons of examples of student computer programming assignments. He has published work on the detection of plagiarism for large code repositories and as the head of a large computer science school has practical and also academic experience in considering whether or not computer code has been copied. He gave evidence relevant to the copyright infringement claim.

44 Philip Dart is a senior lecturer in the Department of Computing & Information Systems at the University of Melbourne. He has a PhD in Computer Science (database systems) from the University of Melbourne and over 30 years of experience in software engineering and information technology, having worked in the industry, government and tertiary education sectors.

45 Dr Dart prepared a report under the supervision of Professor Zobel directed to the existence or absence of similarities between the source code of TERRA and final OPERA v2.3 that were identified in a report prepared by Robert Zeidman. Professor Zobel provided a report addressing the causes of extant similarities found by Dr Dart, and also the existence or absence of similarities identified by Mr Zeidman. Dr Dart and Professor Zobel participated in the preparation of a joint expert report with Mr Zeidman and were cross-examined during the course of a concurrent evidence session.

2.2.1 The witnesses called by ObjectiVision

46 Arthur Cheng has since 30 March 2005 been the chief executive officer of ObjectiVision and has been a director of ObjectiVision since 6 March 2006. He holds a Bachelor (Hons) degree and a Master’s degree in Commerce and Administration from the University of Victoria, New Zealand. Since 29 April 2008 he has directly or through his own company OV2 Pty Ltd held a majority of the shares in ObjectiVision, and since 19 August 2008 he has been the sole director of the company. He gives evidence that he, and the companies that he controls, are the largest creditors of ObjectiVision and that his wife and the companies that she controls are ObjectiVision’s next largest creditors. He has since 19 August 2008 been the company’s controlling mind.

47 The written evidence of Mr Cheng traverses many of the factual issues in the proceedings. It spans events from 1999 until after 2013 and relies on the contents of various documents, including ObjectiVision board minutes and email correspondence to recount events. One relevant aspect of his evidence concerns the progress made in the development of an AccuMap 2 product after ObjectiVision ceased selling the AccuMap 1 in 2005, and the likely cost that would be necessary to produce a final AccuMap 2 product in 2011, when the deadline expired for ObjectiVision to raise funds from a third party for that purpose. The University submits that the content of his oral evidence, and the manner in which he gave it, demonstrates that he was unable to overcome his financial and emotional commitment to the proceedings to give truthful evidence.

48 Certainly it is the case that Mr Cheng is heavily invested in the proceedings. The evidence indicates that since 2005 when he became CEO of ObjectiVision, he strove to see ObjectiVision produce a working AccuMap 2 product. As set out in detail in section 4.4 below, at the end of 2007 ObjectiVision ran out of support from its main funder and shareholder, Medical Corporation Australia Ltd (Medcorp). In early 2008 he commenced negotiations for a management buyout of the company. In April 2008 he became a majority shareholder. He has since then invested funds in the company and he and his wife have paid in excess of $2 million on the costs of these proceedings. Furthermore, he is the person responsible for giving instructions to the lawyers engaged by ObjectiVision and he had, before giving oral evidence, read the evidence adduced by the University. He had sat through the several days of opening submissions and read the University’s submissions. He was deeply versed in the factual and legal issues in the proceedings.

49 It is perhaps understandable that these factors would present a challenge to Mr Cheng in separating his role as a witness of fact from his position as a protagonist in the litigation. Regrettably, in my view he did not meet that challenge. I consider that Mr Cheng was acutely aware of the issues in the proceedings and had a tendency to tailor his evidence to suit what he perceived to be the forensic interests of his company. For instance, there was a tendency for Mr Cheng in his evidence to refuse to accept the plain meaning of his own words as they appeared in documents authored by him, in circumstances where that meaning might be disadvantageous to ObjectiVision’s case. I give several further examples during the course of my reasons. One concerns the content of a 14 April 2005 report to the Board of ObjectiVision that Mr Cheng prepared, where he stated that there were “problems” with the AccuMap 1 device. Yet in cross-examination he refused to accept that this is what he had said, or that it reflected a belief that he held at the time. At pages 449 – 551 of the transcript his answers were evasive and skewed to downplay the content of that report insofar as it identified problems. The answers that he gave in cross examination in relation to other documents yielded a similar failure to respond directly or credibly.

50 A further example of concern arises from evidence in chief given by Professor Graham. In about November 2006 Mr Cheng instructed Spruson and Ferguson patent attorneys to register two patent applications. The first was the stepped stimulus patent, which allowed ObjectiVision to overcome the issue of not being licensed to commercially use the “sparse stimulus” patented by the Australian National University (ANU). The second involved the use of disposable electrodes to work with the micro-amplifier component of the headset of AccuMap 2, and was entitled “Flexible electrode assembly and apparatus for measuring electrophysiological signals” (the flexible electrode patent). The inventors were Associate Professor Klistorner and Professor Graham. Professor Graham gives evidence in chief that in January 2008 he had a conversation with Mr Cheng during which Mr Cheng said that in order to achieve a new corporate structure for ObjectiVision, he wanted to tell MedCorp that ObjectiVision had assigned the stepped stimulus patent and the flexible electrode patent back to Professor Graham and Associate Professor Klistorner and that they had assigned them over to OV2. Professor Graham subsequently met Mr Cheng and signed the requested document to reassign the patents back from ObjectiVision to himself and, a week later, he signed a second document which assigned the patents to OV2. Professor Graham subsequently had reservations about the transfers and in an email in July 2008, asked Mr Cheng to provide copies of the documents that he had assigned.

51 In his written evidence Mr Cheng accepts that on 14 and 21 February 2007 the inventors executed the deeds of assignment mentioned, but contends that the idea to assign the patents was that of Professor Graham and Associate Professor Klistorner, and that they had expressed concerns that if ObjectiVision’s funding difficulties could not be resolved, the patents would go to the University. He further contends that the assignment to OV2 was never finalised. Neither Associate Professor Klistorner nor Professor Graham were cross-examined on these events, but Mr Cheng was. He was confronted with the email correspondence. In it, Professor Graham first asks Mr Cheng to provide him with a copy of the deeds that Mr Cheng asked him to sign. Mr Cheng responds by saying that he was too busy and would get to it as soon as he can. The next day Professor Graham pressed for the copies. Mr Cheng then responded by explaining that the purpose of the assignments was to ensure that the patents would not be ‘lost’ because of a failure on the part of ObjectiVision to pay for registration fees. He said that after the preparation of the assignment papers Medcorp agreed to allow ObjectiVision to fund the patent costs and so there was no need to assign the patents to OV2. Mr Cheng supplied no documents, and Professor Graham again pressed for them to be supplied as he wished to obtain legal advice. In response, Mr Cheng said:

ObjectiVision assigned the patents to the inventors who in turn assigned them to OV2. OV2 still exists and is the assignee of the patents. When I mentioned that there was no need to assign the patents to OV2, I meant that there was no need to formally record the assignment....

52 In cross-examination, Mr Cheng steadfastly refused to accept that in his email he accepted that the inventors had assigned the patents to OV2. For an intelligent and articulate witness, I found his answers to be obtuse and self-serving.

53 In its closing submissions the University correctly characterises Mr Cheng’s evidence in this regard as troubling in three respects. First, because Mr Cheng’s written denial of the evidence of Professor Graham was shown to be incorrect. For the avoidance of doubt, I find that it was Mr Cheng who suggested the transfer. Secondly, at the time that Mr Cheng procured the signed deed from Professor Graham, Mr Cheng was a director and CEO of ObjectiVision, owing obligations of good faith in his dealings with that company, yet he procured assignments away from it to a company he controlled, being OV2. Thirdly, in cross-examination he steadfastly refused to acknowledge the plain effect of the words that he had used in his own email, namely that the inventors had assigned the patents to OV2.

54 Overall, I find myself obliged to treat the evidence given by Mr Cheng with considerable caution.

55 Jordan Langholz is a computer programmer who worked as a software developer at PMP Software Pty Ltd from 1997 until about 2002 whereupon he became a self-employed software developer working on projects, including for PMP. He gives evidence about work that he did from mid-2002 until about July 2003 on the Orienteer Upgrade Project to assist in upgrading the OPERA software. Mr Langholz was cross-examined.

56 Martin Ford is an accountant specialising in financial analysis. In 2012 he was appointed as a director at PPB Advisory and has since been made a partner at that firm. He holds a Bachelor of Commerce (Accounting and Finance) degree from Monash University. He gives evidence in relation to the solvency of ObjectiVision. He was cross-examined during the course of giving concurrent evidence with Mr Potter.

57 Christopher Bowd is a research scientist and director of the Hamilton Glaucoma Centre of the Department of Opthalmology, School of Medicine, at the University of California, San Diego. He completed a PhD in experimental psychology/neuroscience at Washington State University in 1998 and has a current research focus on the early detection and monitoring of glaucoma, and machine learning classifier analyses of imaging and visual function measurements. In 2000 Dr Bowd’s Centre received an AccuMap 1 device, and until about 2003 it worked to participate in a clinical trial designed to assess the usefulness of the device for detecting glaucoma cross-sectionally and for monitoring glaucoma-related changes longitudinally over three years. Dr Bowd gives evidence about the usefulness of the AccuMap 1 device as a tool for the treatment of glaucoma. He was cross-examined.

58 John Michael Sinai works at Optos plc, a provider of devices to eye care professionals. He holds the position of Vice President of Clinical Development and is responsible for working with research and development to develop new optical coherence tomography. In 1988 he completed a PhD in Clinical Vision at the University of Louisville, Kentucky. From 2004 until 2007 he was the director of Clinical Applications for Heidelberg Engineering, a company that was a distributor for ObjectiVision of the Accumap 1 device. He gives evidence about actual and potential usefulness of the mfVEP technology in the AccuMap 1 device. He was cross-examined.

59 Jeffrey Aroy is employed as the Vice President in the Life Sciences Practice of Charles River Associates. He holds a Bachelor of Arts in Economics, which he obtained from Harvard University, Massachusetts, in 1988 and a Masters of Business Administration in Strategic Management from the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania. He prepared a report that was directed towards the assessment of the loss of commercial opportunity to ObjectiVision as a result of the University’s conduct. After I made a ruling as to the admissibility of certain paragraphs of his report, ObjectiVision withdrew reliance on his evidence as a whole. I give my reasons for rejecting those paragraphs in section 8.8 below.

60 Mr Nick Klein is the Managing Director of Klein & Co, a digital forensics investigation firm. He has affirmed three affidavits addressing the content of various digital files concerning the OPERA and TERRA software and responding to the evidence of Mr Khoury. He participated in the preparation of a joint expert report with Mr Khoury. He did not give concurrent evidence and was not cross-examined.

61 Mr John-Henry Eversgerd is a Partner at PPB Advisory. He completed a Bachelor of Arts in Economics and the Philosophy of Science from the University of Pennsylvania in 1994, a Master of Business Administration from the University of Michigan in 1999 and worked providing valuation services at Deloitte and Ernst & Young during the period 2000 – 2012. He gives evidence concerning the quantification of damages that ObjectiVision claims to have suffered in the nature of wasted expenditure in three affidavits. Mr Eversgerd participated in the preparation of a joint expert report with Mr Potter. He did not give concurrent evidence and was not cross-examined.

62 Robert Zeidman is an engineer and the founder and president of Zeidman Consulting, which provides engineering consulting services to high-tech companies. He has a master’s degree in Electrical Engineering from Stanford University and two bachelor’s degrees from Cornell University, one in Electrical Engineering and one in Physics. He is based in California, has been a computer software and hardware designer for about 45 years, and has designed and developed a variety of computer hardware and software products. In his first expert report he relied on software that he designed for use in detecting whether one computer program has been plagiarized from another computer program. He undertook a comparison of the final OPERA v2.3 with versions of TERRA provided in discovery. Mr Zeidman subsequently provided responses to the evidence of Professor Zobel and Dr Dart, participated with each of them in the preparation of a joint expert report, and was cross-examined during the course of a concurrent evidence session involving these three witnesses.

2.2.2 The witness called by Visionsearch

63 Paul Petersen has been a director of Visionsearch since its formation on 25 March 2011 and since then has also been contracted by Visionsearch to work as a computer programmer, systems analyst and project architect to assist in the development and commercialisation of its TERRA software. He obtained a Bachelor of Computer Science and Technology from the University of Sydney in 2000 and prior to the commencement of his work at Visionsearch, obtained experience in programming computer code, mostly in the C# language in the .NET environment. He gives evidence about his initial review of the TERRA software in September 2010, the incorporation of Visionsearch, his role in the writing of the TERRA software and his response to the allegations of copyright infringement. He was cross-examined.

64 The following is derived from a primer agreed by the parties.

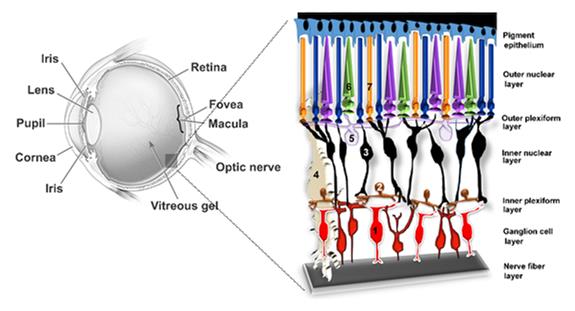

65 Electrophysiology is the study of the electrical properties of biological materials. One form of electrophysiology is visual electrophysiology, which involves the study of electrical signals produced or transmitted by the eye, optic nerve and visual cortex in response to a visual stimulus.

66 The retina is a light sensitive layer of tissue at the back of the eye. It is made up of millions of light-sensitive photoreceptor cells. The following image shows the structure of the eye and the layers of the retina. Looking at the layers of the retina (on the right hand side of the image below), the outer retina is comprised of the outer nuclear layer and the outer plexiform layer, and the inner retina is comprised of the inner nuclear layer, the inner plexiform layer and the ganglion cell layer.

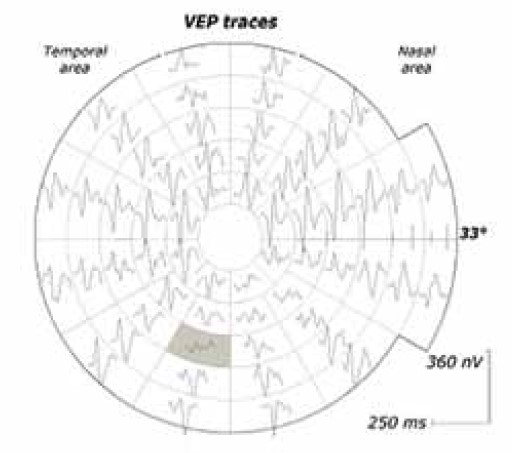

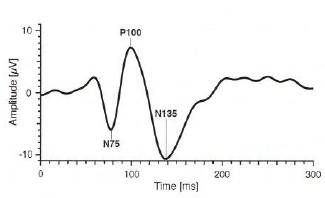

67 When light enters the eye, it stimulates the photoreceptor cells of the retina. These cells undergo chemical changes that generate electrical impulses (electrical current). The current generated is transmitted to neurons and ganglion cells, where action potentials (nerve impulses) are generated. The action potentials generally travel from the ganglion cells through the optic nerve to the lateral geniculate nucleus and then on to the primary visual cortex. The action potentials can be recorded using electrodes placed on different parts of the skull, overlying the visual cortex. These action potentials are also known as visually (or visual) evoked potentials, or VEPs. The VEP response can be displayed as a ‘trace’ that displays the amplitude and latency of the VEP response.

68 Amplitude measures the functional strength or magnitude of the VEP response of the neural structures to visual stimulation. For mfVEP, amplitude is measured in nanovolts (nV). The evidence of Associate Professor Klistorner, which I accept, is that amplitude is highly variable between persons.

69 Latency measures the time it takes a VEP response to travel from the retina, along the optic nerve, to the brain’s visual cortex. For mfVEP, latency is measured in milliseconds (ms) as the delay between the time of stimulation and the response of the neural structures. Measuring latency using VEP provides the clinician with an indication of the degree of damage or interference caused by particular neurological conditions (such as demyelination, or damage to the optic nerve, caused by optic neuritis). There are a number of ways to measure latency using different latency algorithms.

70 In addition to VEPs, ERGs (electroretinograms) can be recorded using electrodes placed on the cornea or around the eye. While VEPs measure the response of the visual cortex to visual stimuli, ERGs measure the response of the retinal cells to visual stimuli. ERGs also measure amplitude and latency.

71 A VEP records the electrical response of the primary visual cortex to either a flash or a pattern stimulus using electrodes placed on the back of the head. A VEP reflects the integrity of the entire visual pathway and the final signal in the visual cortex in response to the stimulus. Electrophysiologists have researched VEPs for about the last 50 years.

72 There are different types of VEP. The full field VEP (ffVEP) measures the aggregated response of the whole visual pathway to a stimulus. It was the first type of VEP to be developed. The ffVEP analyses the brain’s response to a single visual stimulus, which typically covers a large part of the visual field, such as a flash or pattern of light. The ffVEP cannot detect localised defects in a person’s visual field.

73 mfVEP measures the same response but from multiple locations of the visual field: the reference to “multifocal” in mfVEP refers to the ability of a multifocal stimulus to stimulate multiple areas of the visual field.

74 The image on the left below is an example of an mfVEP trace array response, and the image on the right below is an example of a standard VEP response. It can be seen that the mfVEP measures the same response but from multiple locations.

|

|

Figure 1. mfVEP trace array response (left), standard VEP response (right).

75 The purpose of mfVEP is to detect partial or complete blind spots (scotomas). These are a particular feature of glaucoma but can occur with other diseases of the visual system. mfVEP can be used to objectively assess whether the visual pathway is intact at multiple locations, not just central vision. It can be used for investigating cases of unexplained visual loss, potential malingering patients, and establishing any damage to the optic nerve – for example, in optic neuritis (a feature of multiple sclerosis in some multiple sclerosis patients).

76 mfVEP analysis involves dividing the visual field into sectors and then, by altering the stimulus for each sector using a pseudorandom sequence, measuring the response generated from each sector and extracting a VEP response for each sector of the visual field. This technique allows VEPs to be recorded simultaneously from different regions of the visual field.

77 mfVEP has the following (minimum) requirements or steps:

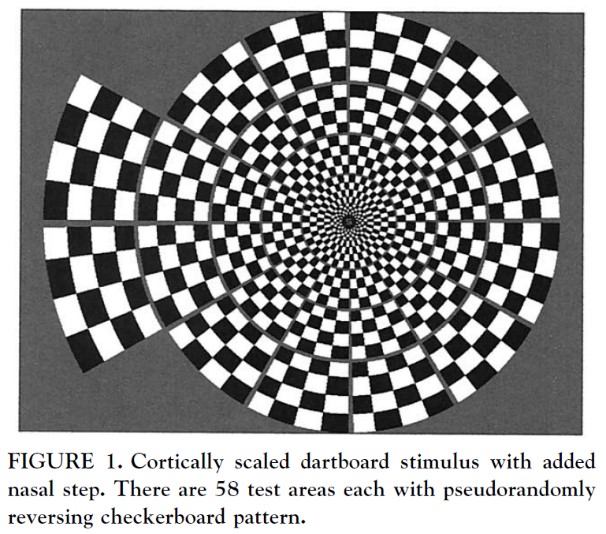

(a) Stimulating a person’s visual field using a stimulus on a computer screen (or a similar device like virtual reality goggles). An example of a typical stimulus is presented in Figure 2 below.

(b) Data acquisition: recording the person’s aggregated responses (the mfVEPs) to that stimulus in each sector of the visual field, and then digitising the signal using a digital-analogue converter.

(c) Data processing: cross-correlating the stimulus for each sector with the aggregated response in order to identify the specific response for each sector and performing other functions, such as amplifying and filtering the signals and removing noise.

(d) Data analysis: displaying the person’s results for analysis, with or without a normative database.

78 In the context of mfVEP analysis, the patient is determined to be normal or abnormal at each test point. To determine this, the patient’s test results are compared against a normative database, which is a set of values obtained from a population of normal subjects. At least 30 subjects are needed to create a normative database that has statistical power in medical research.

79 Collection of data is specific to the stimulus and the hardware (e.g., the monitor or the amplifier). Therefore, any time a change is made to the stimulus or hardware (or if one wants to test a new stimulus or new hardware), data needs to be collected from normal subjects to construct a new normative database for that stimulus or hardware.

80 The stimulus on a computer screen is most commonly a cortically scaled dartboard pattern consisting of a number of different sectors. Each sector has a 4 by 4 checkerboard pattern. The 16 squares within each sector flicker black and white according to the stimulus algorithm. The following checkerboard stimulus from the AccuMap 1 has 58 segments:

Figure 2. Cortically scaled dartboard stimulus with added nasal step.

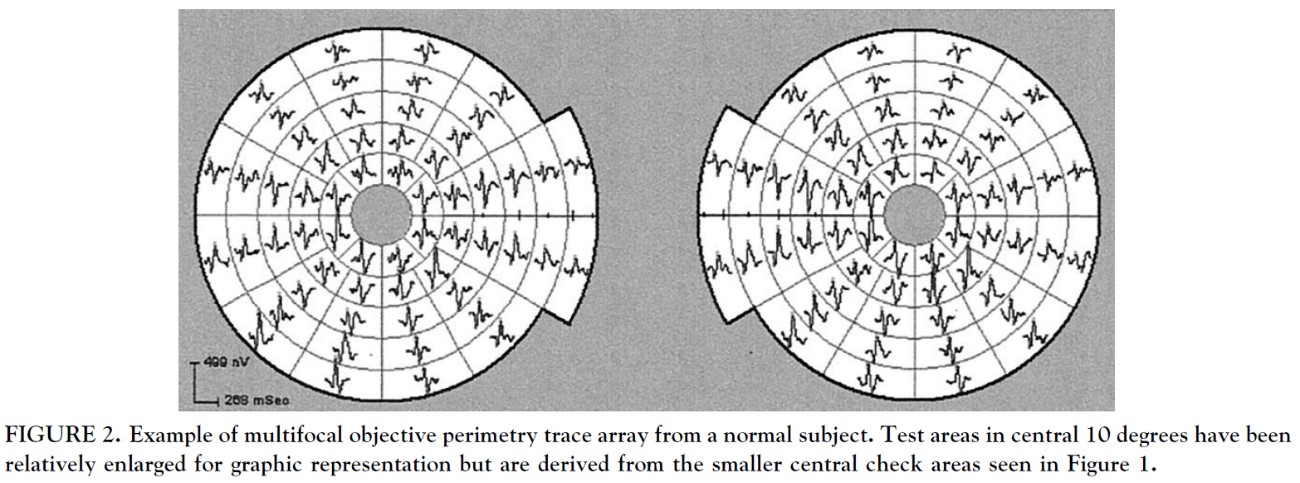

81 When conducting an mfVEP test, the mfVEP system will measure the amplitude and/or the latency of a person’s responses to the stimulus in each sector. A person’s visual response (a VEP trace or waveform) for each sector of the visual field can be displayed in the following way using what is known as a VEP trace array:

Figure 3. Example of multifocal objective perimetry trace array from a normal subject. Test areas in central 10 degrees have been relatively enlarged for graphic representation but are derived from the smaller central check areas seen in Figure 2.

82 The VEP waveform shown in the trace arrays in Figures 1 and 3 above represents the change in potential in response to visual stimulation (in nV) (amplitude, y-axis) over a defined period of time (in ms) (latency, x-axis).

83 In the early 1990s, Dr Erich Sutter, a mathematician, developed a way of stimulating multiple areas of the visual field independently using pseudorandom m-sequences. Dr Sutter patented this stimulus method and used it to build and sell a device, which he called the VERIS Multifocal system.

84 m-sequences are sequences of numbers that appear to be randomly generated, but are not (hence their classification as ‘pseudorandom’). They can be thought of as a series of 0s and 1s in which each 0 and 1 is one frame of a computer screen. Each frame has a duration of 16 ms. The 1s can be designated as a flash or other stimulus. Pseudorandom m-sequences allow researchers to record separate brain signals in response to reversals of each sequence.

85 There are a number of visual electrophysiology systems which have been on the market since the early 2000s and which can perform mfVEP analysis (in some cases, in addition to other visual electrophysiology tests). These systems capable of performing mfVEP analysis include:

(a) the VERIS Multifocal System, sold by Electro-Diagnostic Imaging, Inc., which is Dr Sutter’s company;

(b) the RETIscan, sold by Roland Consult;

(c) the Espion system sold by Diagnosys LLC;

(d) a system sold by Metrovision; and

(e) a system sold by Scottish Health Innovations Ltd.

3.4 The original AccuMap machine: an example of an mfVEP system

86 The commercially released AccuMap 1 had the following components:

(a) A headset, which fixed four electrodes in a cross-configuration over the inion of a person’s skull. The electrodes detected electric signals generated by the visual cortex.

(b) An amplifier. The amplifier amplified the signals recorded from the visual cortex by the electrodes.

(c) A patient screen. This was a cathode ray tube (CRT) computer screen that displayed the multifocal visual stimulus to the patient. The stimulus was a cortically scaled dartboard similar to the one reproduced in Figure 2 above. As described further below, this was based on the development work of Iouri Malov.

(d) An operator screen. This was a liquid crystal display (LCD) computer screen. It displayed an interface that allowed the operator to run the machine and view the patient’s results. Part of the display of patient results included a display similar to that shown in Figure 3 above.

(e) A computer central processing unit, which had the OPERA software installed for the machine.

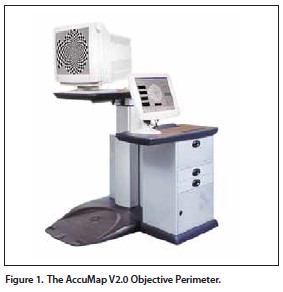

87 An image of the commercially released AccuMap appears below.

Figure 4. The AccuMap 1.

88 Glaucoma is a disease that damages the optic nerve. It usually happens when fluid builds up in the front part of the eye, increasing the pressure in the eye and damaging the optic nerve.

89 Perimetry is the investigation or assessment of the visual field. mfVEP is one form of objective perimetry. Objective perimetry means assessing the human field of vision for its sensitivity at multiple locations using an objective means. “Objective” here means that the patient does not have to physically make a response. mfVEP is one test that can be used to help diagnose glaucoma, optic neuritis, and perhaps other problems with the visual field. The development of mfVEP technology was a breakthrough as previous methods of assessing the visual field relied on the patient’s participation (subjective perimetry) and were therefore prone to errors.

90 I accept the evidence of Associate Professor Klistorner and Professor Graham that when measuring amplitude, mfVEP has problems with both inter-individual variability and reproducibility. A low level of inter-individual variability and a high level of reproducibility are important in diagnosing whether a patient’s responses are ‘normal’ compared to a given population or whether the patient’s responses indicate that the patient has glaucoma. Highly reproducible tests are also necessary in order to be able to monitor a patient’s glaucoma over time.

4. OBJECTIVISION AND THE ACCUMAP DEVICES

91 Set out below, in largely chronological order, are findings of fact relevant to several aspects of the proceedings.

4.2 The development of AccuMap 1

92 In the late 1990s Professor Graham and Associate Professor Klistorner developed technology at the SSI relating to improvements in the use of mfVEP for visual field analysis. On 7 May 1999 the University filed patent application PCT/AU99/00340 in respect of mfVEP technology developed by Professor Graham and Associate Professor Klistorner entitled “Electrophysiological Visual Field Measurement” (the EVFM patent). Patents deriving from that application are referred to as the EVFM Patent Family.

93 ObjectiVision was incorporated on 29 October 1999. There were six founding shareholders whose relevant experience, in broad outline, was as follows:

(1) Professor Graham, whose expertise as an ophthalmologist was focused on the clinical aspects of the development of the AccuMap.

(2) Associate Professor Klistorner, who had an understanding of the engineering aspects of electrophysiology and who was responsible for the design of the software for the mfVEP recording.

(3) Professor Frank Billson, who was a professor of Ophthalmology at the University.

(4) Ben Meek, a computer engineer with experience commercialising start-up technologies.

(5) Dr Alex Kozlovski, who was recruited to write the software for the machine.

(6) Dr Iouri Malov, a mathematician who was recruited to design a new algorithm to drive the stimulus for the device and to build an amplifier.

94 During 1998, Associate Professor Klistorner and Professor Graham made a decision to build a machine that could perform mfVEP. Initially, they wanted to create a system that could use off-the-shelf hardware. They could then add bespoke software that did not infringe the sequences patented by Dr Sutter. Dr Kozlovski wrote the software for the first system in return for shares in ObjectiVision. An aspect of the software involved the writing of a pseudorandom sequence that could be used as a stimulus sequence for the machine. Dr Malov had experience with pseudorandom sequences from prior work that he had done on Russian military communications systems, and he was recruited to write a multifocal stimulus that did not infringe Dr Sutter’s m-sequence stimulus. It took Associate Professor Klistorner and Dr Kozlovski about 6 months working most nights to come up with a working version of the software for the first mfVEP system that could do recordings using Dr Malov’s multifocal stimulus.

95 While Associate Professor Klistorner and Professor Graham were conducting their research and working with Dr Kozlovski, Mr Meek, who was a member of the SSI board, approached Associate Professor Klistorner with a proposal to commercialise the research. This led to the incorporation of ObjectiVision. John Newton was appointed as its first chief executive officer.

96 On 4 September 2000 the University and ObjectiVision entered into the Licensing Agreement pursuant to which the University, as the owner of the patented mfVEP technology, granted ObjectiVision an exclusive licence to use the relevant intellectual property, including the EVFM Patent Family, and bring to market a product. The purpose of this device is stated in the agreement to be to “map a patient’s visual field”.

97 Also on 4 September 2000 the Shareholders’ Agreement was entered into between: ObjectiVision, the six individuals who held the initial shares in ObjectiVision, the University, and Medcorp. The agreement records the rights and obligations of ObjectiVision shareholders and provides for the University and Medcorp to acquire shares in ObjectiVision. According to a schedule entitled Agreed Shareholding prepared for these proceedings by ObjectiVision, at this point Medcorp received an 11.76% shareholding and made an equity contribution of $400,000 to the company. By 8 February 2008 Medcorp had made an aggregated equity contribution to ObjectiVision of $11,485,847 and held 91.67% of its shares.

98 The AccuMap 1 was launched in mid to late 2001. It utilised the OPERA software written by Dr Kozlovski. The hardware components of Version 2.0 of the AccuMap 1 are depicted above in Figure 4.

99 OPERA is described in a 2001 product guide, which was written by Professor Graham, as being used for recording and analysis. It generates the multifocal stimulus on the patient’s monitor and performs signal extraction (cross correlation) and a display of the results. The results include topographical evaluation of latency and amplitude. An “asymmetry coefficient” compares right and left eyes, thereby allowing for the detection of very subtle changes. Other aspects of the software are addressed in more detail in sections 9 to 12 below, which concern the copyright aspects of the cross claim and particular aspects of the development of OPERA.

100 Professor Graham was engaged as a consultant to ObjectiVision from 17 May 2001 until February 2007. As an ophthalmologist, his involvement was particularly focused on the clinical aspects of the development of the AccuMap, such as how clinicians would use it, what sort of features they would need and the like. His role was also to assess patients’ and normal subjects’ visual function and interpret data.

101 On 25 October 2001 the University and ObjectiVision entered into the Second Licensing Agreement in which the University exclusively licensed ObjectiVision to exploit the invention in a similar patent on similar terms to the Licensing Agreement.

102 In mid-2001 Mr Newton, the CEO, decided that ObjectiVision should redevelop the system to use a custom-built amplifier rather than an off-the-shelf Grass amplifier and re-write the software that Dr Kozlovski and Dr Malov had written. ObjectiVision engaged PMP to re-write the software. Due to the change of amplifier, ObjectiVision had to collect a new normative database, because each amplifier has different technical specifications, and so the data collected using one will not be the same as the data using the other. It took PMP over a year to redesign the software, with 3 or 4 programmers working on separate modules. ObjectiVision also engaged another software engineer, Alex Osmakoff, to complete the software when PMP experienced difficulties getting the program to work. After the software had been completed and the product launched, Dr Osmakoff remained with the company.

103 The first AccuMap prototype was donated to Dr Garrick at St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney. In late 2003 the University acquired an AccuMap 1 for Associate Professor Klistorner to use for the purpose of his research work on mfVEP and also for clinical work at the SSI. A number of other devices were sold, including to ophthalmologists in Melbourne, Forster and Newcastle.

104 On 14 November 2003 United States Federal Drug Administration (FDA) approval was given for the AccuMap 1 and sales commenced with Heidelberg Engineering acting as ObjectiVision’s US distributor. In the summary provided with the FDA approval, the machine is described as using “multifocal recordings of visual evoked potentials as a diagnostic aid in the detection of glaucoma”. The next step in the development of the business for ObjectiVision was to complete clinical trials in the United States so as to convince US ophthalmologists to use the device.

105 Accounts prepared by Medcorp indicate that by June 2004, some 14 AccuMap devices had been sold (mostly in Australia, with one in the US and one in Singapore) for a total of about $526,000. Three units sold in Australia in May 2002 for $130,754.16 at an average price of $43,584.72. In June 2004 the sale value for a single unit (sold in the United States) was $19,007. The records indicate that there were additional sales of 4 units in the United States (at an average value per unit of $23,367.23), the last of which was in January 2005, and a single sale in China in October 2005 for $34,073.87 for the unit. The total value of sales recorded is $653,853.

106 On 10 May 2004 the University and ObjectiVision entered into the Variation Agreement, a term of which varied ObjectiVision’s performance obligations so that ObjectiVision was required to sell 90 units by 30 September 2006 and 80 units per annum from 1 October 2006 and ongoing (the original performance requirement was that 80 units of the product be sold by 4 September 2003).

107 On 1 April 2003 Professor Graham ceased to be a director of ObjectiVision. Prior to that time he was heavily involved in the development of the AccuMap. Afterwards, his involvement was somewhat diminished, although as an employee of the University and a researcher at the SSI he continued to do ad hoc occasional work for ObjectiVision. He gives evidence, which I accept, that in about late 2004 the clinical trial that was set up in five centres in the United States was stopped, partly due to technical problems and partly due to a lack of funding. At around that time Mr Newton stepped down as ObjectiVision’s CEO and Simon Lee, then the chairman of Medcorp, and later Ryan Lee (Simon Lee’s son) stepped in as interim CEOs. The FDA trials were formally terminated by ObjectiVision in early to mid-2005.

108 Mr Gregory Fernance was appointed as the University’s nominee director of ObjectiVision on 3 September 2004.

109 In early November 2004 Medcorp informed ObjectiVision that it required a review to be conducted of ObjectiVision before it would continue to give financial support to the company. Although there was some dispute about it at the hearing, it is tolerably clear that at about this time ObjectiVision was suffering from a number of problems. Medcorp, which had been its major funder, was reluctant to advance more funds in the face of a number of technical problems with the finalisation of the AccuMap 1. The request from Medcorp included that there be a review of the level of expenditure required to proceed any further with the commercialisation of AccuMap 1. On 12 November 2004 the Board of ObjectiVision made a resolution to cooperate with Medcorp in its review.

110 In January 2005 a Business Plan was presented by the senior management of ObjectiVision (including Associate Professor Klistorner). The authors refer to market perceptions of shortcomings in the AccuMap 1 including: doubts in the United States market that the technology worked; that the economics of the device were not sufficiently attractive to medical practices; and that there were reliability issues with the product. An extensive list of required improvements to the AccuMap 1 is set out in the document including: the need to prove the value and reliability of the technology via clinical trials in the US; the need to reduce the cost and size of the product; and the need to improve certain technical aspects of the device such as reducing the amount of noise in the signal. The “critical recording chain” of the device is said in the Business Plan to have multiple points of failure and to be “considered unreliable”. Concepts are proposed for an AccuMap 2 product. The top three priority projects are listed as first, clinical trials with an estimated budget of $260,000 in 2005 and estimated duration of 9 to 36 months, secondly, the development of “AccuMap 2” with an estimated budget of $580,000 and timing of 9 to 12 months, and thirdly the development of “Headset II” with an estimated budget of $650,000 and duration of 9 to 12 months. The Business Plan states that expenditure on the commercialisation of AccuMap 1 had by that time been $10 million.

111 In early 2005 Mr Cheng was introduced to ObjectiVision. He had previously worked in commercialising emerging technologies with a Federal Government program and as a result had contact with the University’s business liaison unit. He had indicated to the University his interest in technological investment opportunities and, in response, was informed that ObjectiVision was seeking a strategic investor.

112 On 29 March 2005 Mr Ryan Lee sent an email to Mr Fernance, Mr Mark Clements and Mr Ben Meek attaching a proposal that Mr Cheng be appointed (via Capital City Group Pty Ltd) as interim CEO of ObjectiVision with the role of decreasing expenditure, restructuring the company, including cancelling or restructuring clinical trials, and maximising the probability of raising capital from external investors. On the next day ObjectiVision’s board minutes record that Mr Lee was authorised to sign an Interim CEO Management Services Agreement with Capital City Group and that it was agreed that, subject to discussions with Mr Cheng, the US clinical trials “should be placed on hold for six months whilst an assessment is made regarding a suitable strategic partner and to decrease the company’s cash burn rate”.

113 On 14 April 2005 Mr Cheng provided the ObjectiVision board with a CEO report which included an Action Plan and a pro-forma budget for April to October 2005. In it, he recommended terminating agreements with US clinical trial sites on the basis that the original objectives of the program were no longer appropriate and that the introduction of the AccuMap 2 would invalidate the existing trial protocol. He also recommended presenting the AccuMap 2 prototype at international ophthalmology conferences in July 2005 and October 2005, and revamping the management team. The minutes record that the board resolved to approve Mr Cheng’s recommendations relating to the management team changes and the termination of clinical trial arrangements. It was also noted that any expenditure relating to product development was subject to completion of a successful capital raising by the existing shareholders of ObjectiVision.

114 An issue arises concerning the state of AccuMap 1 at the point that development of that product ceased and development of AccuMap 2 commenced. In my view the objective evidence indicates that AccuMap 1 was a product with significant shortcomings that had forced its withdrawal from the market. This was the description given by Mr Cheng to the managing director of SSI in a letter dated 6 February 2008. It is supported by more contemporaneous documents, including Mr Cheng’s assessment in his letter to ObjectiVision dated 22 February 2005 and also Mr Cheng’s Report to the board as part of his Action Plan of 14 April 2005. In the latter Mr Cheng reports that the solution to problems with AccuMap 1 required redesign and redevelopment, and identifies problems with the headset and the OPERA software that required debugging and adding an ERG module to it. The Action Plan describes a redesigned and redeveloped AccuMap as being “critical” to ObjectiVision to “restore credibility”. The budget proposal is $3,851m per annum for the new development and $1.212m per annum for clinical trials. A timeline is proposed for the completion of the AccuMap2 prototype by 30 June 2005 and to have the European launch of the product at the World Glaucoma Congress in Vienna in July 2005. An American launch at the American Academy of Ophthalmology Conference in October 2005 is also proposed.

115 In a CEO report to the board of ObjectiVision dated 16 August 2005, Mr Cheng refers to the need to convey to the market “a clean break from past failures – both financially and product wise”, the latter plainly being a reference to AccuMap 1.

116 Despite the content of these documents, in his evidence Mr Cheng sought to downplay the perceived problems with AccuMap 1 and their likely adverse effect on perceptions of ObjectiVision. An example may be seen where the 14 April 2005 report said, under the heading “Opera 2.1”:

Problems: debugging issues, no ERG capability, needs to be twice as fast during testing.

117 In cross-examination Mr Cheng denied that in so saying, he had conveyed to the board in 2005 that there was a problem at that time with the software either in relation to bugging issues, or ERG capability. For the reasons given, I prefer to rely on the content of the 2005 CEO reports.

118 In my view the objective and contemporaneous materials provide a clear picture that the AccuMap 1 product was regarded by those working for and within ObjectiVision to be an unsuccessful product because of perceptions in the market that it was not achieving clinical or commercial outcomes. Common sense dictates that a rational commercial organisation would not terminate the marketing and sale of a new product unless there was good reason to do so. At that point in time, in excess of $10,000,000 had been spent on product development. Plainly enough, the decision not to continue with FDA trials and to move to a different product was not taken lightly, and there were problems with both the product and with market perception of the product. This conclusion is supported by the documents to which I have referred above. It is also supported by the letter sent by Mr Cheng to Dr Shariv of Sydnovate on 6 February 2008, when he said that the management of ObjectiVision “inherited a product with significant shortcomings that had forced [its] withdrawal from the market”. To the extent that Mr Cheng in his evidence contends otherwise, I reject that evidence.

4.3 The development of AccuMap 2

119 There is a factual dispute between the parties as to how far the development of the AccuMap 2 device progressed. ObjectiVision contends in closing submissions that by June 2005 the first AccuMap 2 prototype was complete. The University disputes that the prototype was functional and contends that the development of the device was beset by problems and that it was never completed. This is explored below.

120 The first prototype for AccuMap 2 involved the redesign and re-development of AccuMap 1 with better componentry. Minutes of an ObjectiVision board meeting on 14 April 2005 record Mr Cheng’s recommendation, that appears to have been adopted, that the new prototype reflect a reduced footprint, a disposable headset, ERG function, and include “sparse stimulus” technology (a type of stimulus developed by the Australian National University). The budget for the development was estimated to be $3.851m per annum with an estimate for completion by 30 June 2005.

121 In early July 2005 something approximating the first prototype was put on display at the World Glaucoma Congress in Vienna. In his evidence Mr Cheng says that this was a “functioning product” that was able to be demonstrated to the public. However, this assertion is not supported by the evidence as a whole and I reject it. Mr Cheng’s CEO report of 16 August 2005 describes the prototype as “exhibited” which accords more precisely with the evidence of Professor Graham and Associate Professor Klistorner, who each attended the conference and give evidence that the device displayed was a mock-up that was not demonstrated.

122 There were problems with the software and the electrodes on the disposable headset cross. Plans to take the first prototype to the American Academy of Ophthalmology conference in Chicago in October 2005 were abandoned. In November 2005 the prototype was put on display at the World Neurology Congress in Sydney. At that point a live demonstration was attempted by Associate Professor Klistorner, but he gives evidence that it embarrassingly failed to work in front of an audience of neurologists and instead a pre-recorded demonstration version was run. Mr Cheng gives evidence that the live demonstration succeeded, however, no objective evidence supports this proposition and I consider that the recollection of Associate Professor Klistorner, who conducted the attempted trial, is more likely to be correct. It also accords with the subsequent abandonment of the first prototype.

123 After the November conference, the first prototype was abandoned. The CEO reports provided by Mr Cheng to the board of ObjectiVision in November and December 2005 record that there were “issues” with the development of the AccuMap 2. The November report notes the problem of inconsistent conductivity of new printed circuit electrode sets, which held back finalisation of the product. There was also a need to finalise drawings of components, to source materials and electronic componentry, and to document the hardware and software specifications. Without these, and a pre-manufacturing model, regulatory testing “could not begin”. Furthermore, at this time ObjectiVision was having difficulties securing sufficiently skilled staff on a full-time basis. Dr Osmakoff was assisting with IT on a part-time basis only, and engineering support was not able to be found. ObjectiVision relocated its operations to smaller premises to save money. Mr Cheng’s December 2005 report notes that the industrial designers engaged by ObjectiVision, Tiller + Tiller, were not able to finalise the headset cross and electrode placement and Mr Cheng decided to use a different designer. A plan on the part of ObjectiVision to attend an ophthalmology conference in February 2006 with the first prototype was abandoned and Mr Cheng reported to the board that he would have to “stretch our resources” beyond April 2006.

124 On 1 April 2006 Mr Cheng was appointed a director of ObjectiVision.

125 After the first prototype had been abandoned, work on the second prototype proceeded. It used generic hardware components, including an off-the-shelf laptop, articulated arm for the patient monitors and a transformer. The headset, called the “Headset2”, remained a specialised element. There were issues with the headset, and in early 2006 it was proposed that it needed to be re-designed. KWA Design was engaged on 3 March 2006 to do the design work. In his report to the board of March 2006, Mr Cheng estimated that the production of the prototype would be achieved by 7 July 2006.

126 On 1 June 2006 ObjectiVision applied for the stepped stimulus patent developed by Professor Graham and Associate Professor Klistorner. This invention allowed ObjectiVision to overcome the issue of not being licensed to commercially use the “sparse stimulus” technology patented by ANU.

127 At around this time ObjectiVision moved its servers, computers and AccuMap 2 prototypes to Associate Professor Klistorner’s offices at the SSI.

128 On 22 June 2006 Mr Cheng provided a CEO report to the ObjectiVision board which referred to an anticipated delay in the delivery of the Headset2 prototype, from April 26 to 9 June 2006. It referred to milestones in the development timeline being re-adjusted to account for the delay.

129 In the CEO report on 25 August 2006, Mr Cheng notes that KWA’s head designer, Jonathan Dyer, had been engaged to complete the prototyping and production data work on a freelance basis.

130 In late August 2006 it was planned to take the second prototype overseas for demonstrations in China and Europe. Prior to that, a synchronisation problem was discovered in the software by a software engineer engaged by ObjectiVision, Mr Alvarez. Synchronisation is important in the context of the testing done by the AccuMap. As Associate Professor Klistorner explains, in order to record a proper reading, any change to the stimulus shown on the patient monitor must be synchronised with the acquisition of the data, and this must be very precise. Even a shift of one frame of the monitor, which is 15 milliseconds, will produce an incorrect result. Associate Professor Klistorner considered that there were many problems in synchronising the video stimulus output with data acquisition from the patient.