FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Community First Credit Union Limited v Bendigo and Adelaide Bank Limited [2019] FCA 1553

ORDERS

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Subject to Orders 2 and 3, on or before 4 October 2019 the parties are to endeavour to agree the appropriate form of orders to be made reflecting the conclusions expressed in these reasons, and to provide a copy of those draft orders to the Associate to Markovic J.

2. If no agreement is reached, on or before 11 October 2019 the parties are to notify the Court of the orders for which they each contend and to each provide written submissions, not exceeding three pages in length, explaining why those orders should be made.

3. If agreement cannot be reached pursuant to Order 1, the proceeding will be listed before Markovic J on 17 October 2019 at 9.30 am. The respondent is granted leave to appear by video conference facility at that time.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 1389 of 2017 | ||

BETWEEN: | COMMUNITY FIRST CREDIT UNION LIMITED Applicant | |

AND: | BENDIGO AND ADELAIDE BANK LIMITED First Respondent | |

REGISTRAR OF TRADE MARKS Second Respondent | ||

JUDGE: | markovic j |

DATE OF ORDER: | 20 september 2019 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Subject to Orders 2 and 3, on or before 4 October 2019 the parties are to endeavour to agree the appropriate form of orders to be made reflecting the conclusions expressed in these reasons, and to provide a copy of those draft orders to the Associate to Markovic J.

2. If no agreement is reached, on or before 11 October 2019 the parties are to notify the Court of the orders for which they each contend and to each provide written submissions, not exceeding three pages in length, explaining why those orders should be made.

3. If agreement cannot be reached pursuant to Order 1, the proceeding will be listed before Markovic J on 17 October 2019 at 9.30 am. The first respondent is granted leave to appear by video conference facility at that time.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

MARKOVIC J:

1 Community First Credit Union Limited (CFCU), the appellant and applicant respectively in the two proceedings before the Court described at [7] below, owns trade mark registration no. 776512 for the words COMMUNITY FIRST with a priority date of 23 October 1998 and registered in class 36 for “insurance and financial services; services of credit unions; banking services; real estate financial services” (Community First Registered Mark).

2 Bendigo and Adelaide Bank Limited (Bendigo), the respondent and first respondent respectively in the two proceedings, is the owner of trade mark registration no. 784796 for  (Bendigo Device Mark) and trade mark registration no. 887023 for the words COMMUNITY BANK (Bendigo Word Mark) (collectively Bendigo Community Marks). Both trade marks are registered in class 36 in respect of the following services, which I will refer to in these reasons as the Services:

(Bendigo Device Mark) and trade mark registration no. 887023 for the words COMMUNITY BANK (Bendigo Word Mark) (collectively Bendigo Community Marks). Both trade marks are registered in class 36 in respect of the following services, which I will refer to in these reasons as the Services:

Financial services including banking services, capital investments, financial management and valuation, financing loans, mortgage banking and saving bank services; insurance services including accident insurance, fire insurance, health insurance, life insurance and insurance underwriting; hire-purchase financing services; lease financing services; financing for leasing and hire-purchase of machines and motor vehicles; leasing and rental of farms; leasing and rental of real estate; leasing and rental of houses and apartments; leasing and rental of office buildings; leasing and rental of flats; hire purchase finance services in relation to machines and vehicles.

3 The Bendigo Device Mark has a priority date of 8 February 1999 and the Bendigo Word Mark has a priority date of 24 August 2001 (collectively the Priority Dates).

4 On 1 March 2013 CFCU lodged two trade mark applications: application no. 1541620 for COMMUNITY FIRST BANK; and application no. 1541594 for COMMUNITY FIRST MUTUAL BANK (collectively CFCU Marks). Both applications are for certain services in class 36 including “financial services” and “personal banking services”.

5 On 27 April 2015 Bendigo opposed the registration of the CFCU Marks under ss 42(b), 44, 58A, 59 and 60 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (TM Act).

6 On 21 July 2017 a delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks (Registrar) upheld Bendigo’s opposition and, with reference to the Bendigo Word Mark, applied s 44(2) of the TM Act and found that CFCU did not establish honest concurrent use under s 44(3) or continuous prior use under s 44(4) of the TM Act. The applications for registration of the CFCU Marks were thus rejected.

7 There are now two proceedings before the Court: an application by CFCU pursuant to s 88(1) of the TM Act seeking orders that the Register of Trade Marks (Register) be rectified by cancelling and removing the Bendigo Community Marks and for orders pursuant to s 97 or s 101 of the TM Act that the Bendigo Community Marks be removed from the Register (Rectification Proceeding); and an appeal brought by CFCU pursuant to s 56 of the TM Act against the Registrar’s decision (Appeal Proceeding).

8 The two proceedings were heard together. By orders made on 4 October 2017 in each of the Appeal Proceeding and the Rectification Proceeding, evidence in each proceeding is to be evidence in the other.

9 CFCU read the evidence of 10 witnesses and Bendigo read the evidence of 11 witnesses. CFCU and Bendigo also tendered a joint report prepared by their respective experts Timothy Aman and Barry Taylor. The reports of each of Mr Aman and Mr Taylor were not read but the Court was invited to have regard to them in the event that anything in the joint report required clarification. Given the significant volume of evidence, it is convenient to set out a high-level summary of the areas covered by each witness. Before doing so, I note two things.

10 First, given its volume, I do not intend to set out or address in these reasons all of the evidence relied on by the parties. A good deal of that evidence went to use of the trade marks. I will refer to that evidence in summary form where relevant. On the other hand, some of the evidence played an insignificant role in the proceedings and did not feature in the parties’ submissions or did so in a way that was of little significance to the matters in issue. To the extent that the parties relied on evidence of that nature it was of no assistance and I do not propose to refer to it.

11 Secondly, I generally found those witnesses who gave evidence before me to be reliable. Save where I note it to be the case, I found them to be thoughtful and frank in their responses to questions and to be genuine in their attempts to assist the Court.

12 Joce Tancevski is the CEO of CFCU. Mr Tancevski gives evidence about the history and business of CFCU; CFCU’s use, marketing and promotion of the “Community First” brand; CFCU’s use of “Community First” without “Credit Union”; CFCU’s applications for the CFCU Marks; and CFCU’s intention to apply to the Australian Prudential and Regulatory Authority (APRA) for use of the word “bank” or “mutual bank” in its corporate name. Mr Tancevski was cross-examined.

13 Shannon Elizabeth Platt is a partner of Sparke Helmore, the solicitors for CFCU. Ms Platt swore two affidavits:

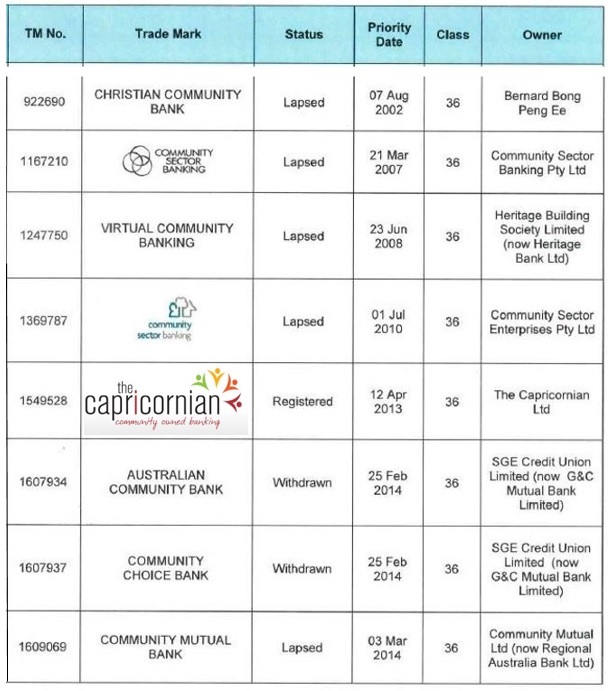

(1) in her first affidavit Ms Platt puts into evidence the results of research undertaken by members of her team at her request: Australian trade mark searches for third party trade marks containing the words “community bank” and/or “community banking”; requests to IP Australia for access to information in relation to particular trade marks; and searches of the online Hansard report of the proceedings of the Australian Parliament and other parliamentary records for instances of use of the words “community bank” and “community banking”. Ms Platt also puts into evidence documents produced by Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Ltd, the publisher of the Macquarie Dictionary, produced in answer to a subpoena; documents annexed to the affidavit of William Gerard Conlan sworn on 18 December 2018 and filed in the Rectification Proceeding (which was not read into evidence by Bendigo); a photo of and a website printout for the Cannonvale & Proserpine Community Bank Branch of Bendigo Bank; and an interview and article relating to Bendigo; and

(2) in her second affidavit Ms Platt puts into evidence documents produced in answer to a subpoena issued to G&C Mutual Bank Ltd (G&C Mutual).

Ms Platt was not cross-examined.

14 Molly Jeanne Flowers is a paralegal in the employ of CFCU’s solicitors. Ms Flowers gives evidence about her visit to the Pyrmont Community Bank Branch of Bendigo Bank in October 2017. Ms Flowers was not cross-examined.

15 Vienna Sophia Aroha Jones is a solicitor in the employ of CFCU’s solicitors. Ms Jones affirmed two affidavits in which she gives evidence about her visit in October 2017 to the Pyrmont Community Bank Branch of Bendigo Bank and her visits in August and November 2018 to the Rozelle Community Bank Branch of Bendigo Bank. Ms Jones was not cross-examined.

16 Myrna Taouil is a solicitor in the employ of CFCU’s solicitors. Ms Taouil has sworn two affidavits:

(1) in her first affidavit Ms Taouil puts into evidence the results of the following searches that she undertook in November 2018: a search of the Australian Trade Marks Register for trade marks that contain the words “community” and “bank”; and Google searches for “community bank”, “community banks Australia” and “community banking”; and

(2) in her second affidavit Ms Taouil gives evidence of a request she made of her brother-in-law in October 2018 to visit and take photos of the Bendigo Bank Community Bank Stadium at Diamond Creek and puts into evidence the photos provided to her in response to that request and a Google Maps search for 75/77 Main Hurstbridge Road Diamond Creek VIC 3089.

Ms Taouil was not cross-examined.

17 Michael John Lawrence is the chief executive officer (CEO) of the Customer Owned Banking Association Limited (COBA). Mr Lawrence, who was called as an expert, affirmed two affidavits:

(1) in his first affidavit Mr Lawrence gives evidence about his understanding of the meaning of the terms “community bank” and “community banking” in Australia, the desire of other traders to use the term “community bank” and Bendigo’s use of the term “community bank”; and

(2) in his second affidavit Mr Lawrence responds to issues raised in relation to his evidence by Associate Professor Malcolm John Abbott, an expert called by Bendigo.

Mr Lawrence was cross-examined.

18 Melina Morrison is the CEO of the Business Council of Co-operatives and Mutuals Ltd (BCCM). Ms Morrison was called as an expert. She affirmed two affidavits:

(1) in her first affidavit Ms Morrison gives evidence about what in her opinion “community bank” means and her understanding of the banking model used by Bendigo for its community bank branches; and

(2) in her second affidavit Ms Morrison responds to evidence given by Bendigo’s expert, Associate Professor Abbott.

Ms Morrison was cross-examined.

19 David Andrew Taylor is the CEO and a director of G&C Mutual. Mr Taylor was also called as an expert. Mr Taylor gives evidence about G&C Mutual’s history, its trade mark applications for “Australian Community Bank”, his understanding of the meaning of “community bank” and “community banking” and the use of “community bank” by Bendigo. Mr Taylor was cross-examined.

20 Paul Joseph Martin is an adjunct associate professor of finance at the University of Sydney. He was called as an expert. Associate Professor Martin gives evidence about the different types of banking and financial institutions in Australia; the history of banks and credit unions in Australia; and why credit unions want to become banks. Associate Professor Martin was cross-examined.

21 Marianne Robinson is a special counsel in the employ of CFCU’s solicitors with expertise in the financial services industry. Ms Robinson gives evidence of the position as at 1 March 2013 and presently in relation to:

(1) the requirements under the Banking Act 1959 (Cth) (Banking Act) for eligibility to use the term “bank”;

(2) APRA published guidelines for eligibility and the process of obtaining authorisation from APRA to use the term “bank”; and

(3) the extent, if any, to which those requirements differ for an entity wishing to use the term “mutual bank”.

Ms Robinson was not cross-examined.

22 Robert George Hunt was the managing director and CEO of Bendigo until 2009. Mr Hunt gives evidence about the creation and structure of Bendigo’s franchise distribution model; the operation of a franchise bank branch; the selection of “community bank” as the brand for the franchise business operations; the use of the Bendigo Word Mark, including by franchisees; and marketing and advertising by franchisees. Mr Hunt was cross-examined.

23 Julie Ruth Eastham is a branch manager of the Bendigo East Gosford & Districts Community Bank Branch. Ms Eastham gives evidence about her visit in June 2018 to the CFCU Lending, Investments and Insurance Centre at Erina Fair, Erina and puts into evidence photographs she took and marketing and promotional material she obtained during that visit. Ms Eastham was cross-examined.

24 Claudia Lucchiti is a branch operation manager employed by Balmain Rozelle Financial Services Ltd. She gives evidence of conversations she had with Ms Lindsay in September 2018 about the Bendigo Balmain Rozelle Community Bank Branch’s signage. Ms Lucchiti was not cross-examined.

25 Daniel John Holland is the senior stream lead new customers of Bendigo. Mr Holland affirmed two affidavits:

(1) in his first affidavit Mr Holland gives evidence about marketing and branding guidelines; processes for Bendigo’s franchisees; and marketing activities undertaken by Bendigo and offered to its franchisees; and

(2) in his second affidavit Mr Holland gives evidence about Bendigo’s marketing activities featuring the Bendigo Word Mark including putting into evidence copies of videos from Bendigo’s YouTube channel and copies of the Victorian Amateur Football League Association Magazine which include advertisements featuring the Bendigo Word Mark.

Mr Holland was not cross-examined.

26 William Gerard Conlan is Bendigo’s company secretary. Mr Conlan affirmed two affidavits:

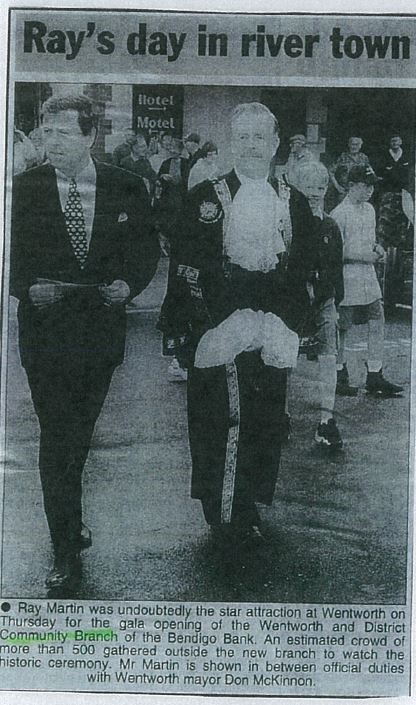

(1) in his first affidavit Mr Conlan gives evidence about Bendigo’s corporate history and its business; Bendigo’s franchise banking model and the operation of franchise bank branches from 2009 onwards; the use by franchisees of the Bendigo Word Mark and Bendigo’s intellectual property; and print media about Bendigo’s franchise banking model and sponsorship arrangements undertaken by franchisees; and

(2) in his second affidavit Mr Conlan puts into evidence lists of authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) as at 2000, 2012 and 2018; a list of the members of COBA as at October 2018; COBA’s submission to the Review of Reforms for Cooperatives, Mutuals and Member-Owned Firms; Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC) current and historical company name extracts and business name extracts for Australian member-owned banks; ASIC’s Regulatory Guide 147 Mutuality – Financial Institutions; APRA’s Guidelines: Implementation of section 66 of the Banking Act 1959 dated August 2015 (2015 Guidelines); COBA’s submission to APRA (provided under its former name ABACUS-Australian Mutuals Limited); extracts from the 2001 (Federation) edition of the Macquarie Dictionary and the 1999 and 7th editions of the Australian Oxford Dictionary; and a search of the Australian Trade Marks Register online tool for pending and registered third party marks that contain the word “bank” in class 36.

Mr Conlan was not cross-examined.

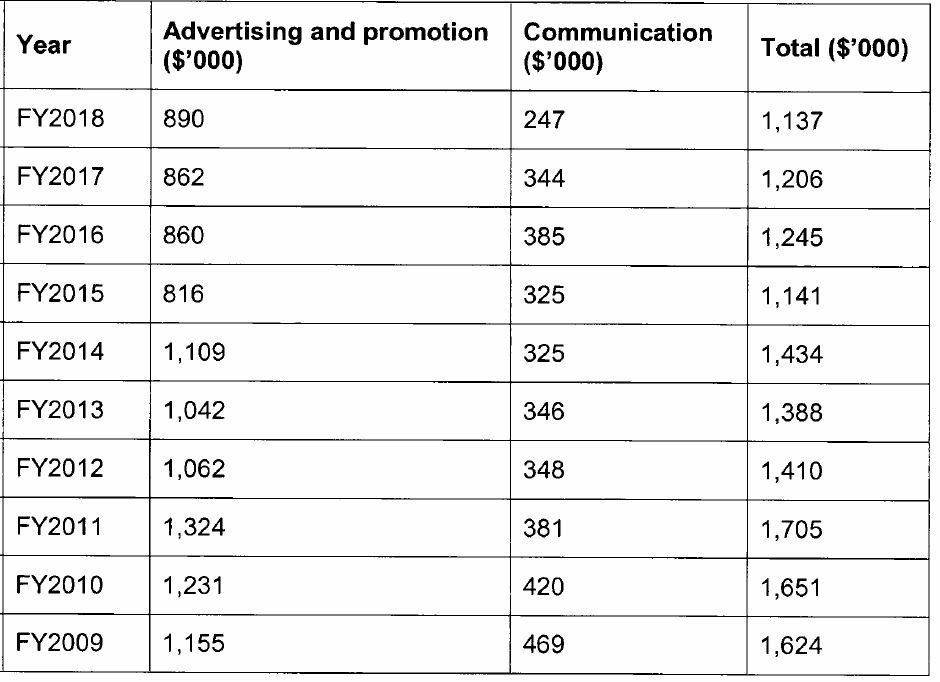

27 Allan Keith Rutter is senior manager of customer operational and performance reporting at Bendigo. Mr Rutter affirmed three affidavits:

(1) in his first affidavit Mr Rutter gives evidence of the number of Bendigo’s community bank branches and undertakes an analysis as at 30 June 2013 of whether those branches operated in areas where there were no other competitor retail bank branches, the number of customers of those branches, the number of staff employed by the branches, the amount of capital raised and total shareholders, business generated by the branches and dividends paid to shareholders of the companies operating the branches. Mr Rutter also calculates Bendigo’s total spend on marketing in the period 2005 to 2016 via its funding of the “Marketing Central” platform to which all franchisees have access;

(2) in his second affidavit Mr Rutter gives evidence about calculations that he made to calculate the proximity of Bendigo’s community bank branches to CFCU branches; and

(3) in his third affidavit Mr Rutter puts into evidence the entirety of a document referred to in one of his earlier affidavits.

Mr Rutter was not cross-examined.

28 Mark James Miller is Bendigo’s solicitor. Mr Miller has sworn two affidavits:

(1) in his first affidavit Mr Miller puts into evidence documents relating to parliamentary inquiries undertaken from the late 1990s and various submissions received by those inquiries; submissions made by BCCM including to the Senate Economics Reference Committee; various submissions made by COBA; the results of searches undertaken on his instructions for publicly available statements by credit unions, building societies and other non-bank ADIs as to why they changed to bank status or wanted to use the word “bank” as part of their trading name, and of mutual banks’, credit unions’ and building societies’ webpages with reference to their “about us” pages; and copies of extracts from annual reports and constitutions of various credit unions and mutuals; and

(2) in his second affidavit Mr Miller puts certain documents into evidence and gives evidence that, based on his review of APRA’s points of presence data, CFCU had six branches operating in parts of NSW in 2001 and 11 branches operating in parts of NSW in 2013.

Mr Miller was not cross-examined.

29 Zoe Caitlin Lindsay is a solicitor in the employ of Bendigo. Ms Lindsay swore two affidavits:

(1) in her first affidavit Ms Lindsay puts into evidence an application made by Bendigo pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (Cth) for copies of documents relating to CFCU’s applications to register the CFCU Marks and the response to that application; and

(2) in her second affidavit Ms Lindsay gives evidence about Facebook searches she undertook for various community bank branches and puts into evidence the results of those searches; the photographs she printed after visiting the Facebook pages of certain branches to locate sponsorship and community contributions referred to by particular Bendigo community bank branches; screenshots of the results of her Google Maps “street view” searches of several of Bendigo’s community bank branches including the Rozelle branch; and a video from the Bendigo Oak Flats & Shellharbour Community Bank Branch’s Facebook page.

Ms Lindsay was not cross-examined.

30 Natalie Rose Williams is a trade mark attorney and a director of Switch Legal Pty Ltd which has been engaged by Bendigo to assist with the proceedings. Ms Williams gives evidence of her visit in October 2018 to the Community Bank Stadium and the Community Bank Branch at Diamond Creek and puts into evidence the photos she took at that time. Ms Williams was cross-examined.

31 John Stephen Worthington is an adjunct professor of marketing at Swinburne University. Professor Worthington was retained as an expert and gives evidence about his understanding of “community bank” in Australia and Bendigo’s franchise operations, marketing of financial services, the use of the word “bank” in marketing to consumers and the impact of the addition of the word “bank” in the mark “Community First Bank” as opposed to “Community First Credit Union”. Professor Worthington was cross-examined.

32 Malcolm John Abbott has been an associate professor of economics at Swinburne University of Technology since 2008. He also holds the positions of Associate Colleague PROPHE Research Centre, State University of New York at Albany; Associate Researcher, Centre for Research and International Education, Auckland; and Member of the Board of Management, the Pines Learning Centre, Melbourne. Associate Professor Abbott holds a Bachelor of Economics with Honours and a Masters of Economics from La Trobe University and a PhD in Economics from the University of Melbourne. He is an economist whose main fields of work have been in the development of financial markets in the energy sector (natural gas and electricity) and the manner in which pricing and access to network infrastructure is regulated by government agencies. In the 1990s and early 2000s Associate Professor Abbott was involved in researching and writing about the structures and organisational frameworks of financial institutions in Australia.

33 Associate Professor Abbott gives evidence about his understanding of the term “community bank” in Australia and refers to papers he co-authored in the 1990s and 2001. Associate Professor Abbott was cross-examined.

2.3 Joint report of Messrs Aman and Taylor

34 Mr Aman is an audit and advisory partner of BDO East Coast Practice. Mr Aman was retained by CFCU as an expert to provide an opinion as to whether, in relation to each of the Bendigo community bank branches for which an annual report is available, that branch was operating at a profit or loss after tax; is solvent or insolvent; and is generating positive cash flow. Mr Taylor is the head of the restructuring and risk advisory division of HLB Mann Judd Sydney. Mr Taylor was retained by Bendigo as an expert to respond to Mr Aman’s report. Mr Aman prepared two reports and Mr Taylor prepared one report.

35 Messrs Aman and Taylor ultimately prepared a joint report which was tendered in evidence and in which they provided their opinions on the financial viability of 16 specified Bendigo community bank franchise companies.

2.4 Evidence of Ms Morrison and Messrs Taylor and Lawrence

36 Before proceeding further it is convenient to address an issue raised by Bendigo about the evidence of Ms Morrison and Messrs Taylor and Lawrence. As set out above, their evidence principally addresses the meaning of “community bank” and the desire of other traders to use that term.

37 CFCU called each of Ms Morrison and Messrs Taylor and Lawrence as experts. Bendigo submitted that there were significant issues with the independence of each of Ms Morrison and Messrs Taylor and Lawrence and that CFCU had failed to attend to proper compliance by each of them with the Court’s Expert Witness Code of Conduct, such that I would either reject their written evidence entirely or give it very little weight and that I would treat with caution any evidence given by them in cross-examination against Bendigo’s interests.

38 In order to address this issue it is of assistance to set out each of these witnesses’ backgrounds and some of the matters which became apparent in the course of their cross-examination.

39 Ms Morrison has been the CEO of the BCCM since July 2013. Prior to that her roles in the cooperatives and mutuals sector included:

(1) from 2001 to 2012, working as an associate for Sommerson Communications, a communications firm specialising in media, advocacy, public awareness campaigns and project management predominantly for cooperatives and cooperative research bodies. Ms Morrison’s roles included developing digital communication campaigns to promote the benefits of cooperative organisations and member-owned businesses;

(2) from about 2006 to 2012, Ms Morrison was a writer for and then the editor of the flagship publication of the International Co-operative Alliance, one of the organisations for which she provided services at Sommerson Communications. She co-wrote the global message platform for the Blueprint for a Co-operative Decade, a plan prepared for the United Nations General Assembly on the principles of cooperatives and how the goal of sustainability of cooperatives might be achieved;

(3) from about July 2009 to July 2013, Ms Morrison was a founding director of Social Business Australia which advocated for increased recognition of the added value of member-based business in the national economy. In that role, Ms Morrison was a founding member of the committee formed to drive the Australian sector’s involvement in the United Nations International Year of Co-operatives 2012 (IYC 2012); and

(4) from about March 2010 to July 2013, Ms Morrison headed the National Steering Committee and Secretariat (NSC) that oversaw the national campaign to raise awareness of the contribution of cooperative businesses to the Australian economy as part of IYC 2012. NSC was incorporated in 2011 as IYC 2012 Secretariat Limited and subsequently changed its name to BCCM.

40 The BCCM is a national body which represents businesses that ascribe to the cooperative and mutual model of enterprise in Australia. Ms Morrison explained that cooperatives and mutuals are member-owned businesses, as distinct from being owned by investor shareholders, and are referred to as cooperative and mutual enterprises (CME). The BCCM’s board comprises chief executives from its membership, including bank businesses.

41 The BCCM unites cooperative and mutual businesses across all industry sectors in which member-owned businesses operate in the Australian economy. Its membership represents a range of industries including banking and finance, superannuation, health, housing, motoring and agriculture. The objectives of the BCCM as set out in its constitution are to:

(1) demonstrate the values of cooperatives and mutuals by promoting and extending the cooperative and mutuals business model for the benefit of society and the economy, and for the broader community;

(2) recognise the unique role and contribution of cooperatives and mutuals to society, the economy and the community; and

(3) engage in activities and provide information to better inform Australians about the benefits of cooperatives and mutuals.

42 As at 21 August 2018 the BCCM had in excess of 45 full members and 20 associate members. Only enterprises that ascribe to the cooperative or mutual legal structure or have cooperative or mutual constitutions can be admitted as full members. More than 50% of the BCCM’s members, including CFCU, are member-owned firms operating in the banking and finance (including insurance) sector. CFCU was one of the BCCM’s founding members.

43 In her role as CEO of the BCCM, Ms Morrison has instigated and overseen a number of projects for the promotion and recognition of CME businesses in Australia including:

(1) in March 2018 the submissions of the BCCM to the Treasury in response to its final report of the Review into Open Banking in Australia released in December 2017;

(2) in August 2016 as a member of the advisory group for the implementation of the Senate’s $14.9 million two-year Farm Cooperatives and Collaboration Pilot Program aimed at educating Australian farmers about the benefits of cooperative and mutual businesses;

(3) in March 2015 as advocate on behalf of the BCCM for the Australian Senate to conduct an inquiry into the role, importance and overall performance of cooperative, mutual and member-owned firms in the Australian economy. The final report was published on 17 March 2016; and

(4) from 2014 to 2017 coordinating the BCCM’s annual publication, the National Economy Report, which reports on the latest research on the economic and social contribution of Australia’s cooperative, mutual and member-owned firms.

44 In cross-examination senior counsel for Bendigo explored Ms Morrison’s role as an advocate for the CME sector. Ms Morrison’s evidence was that she advocated equally across all industry sectors in which cooperatives and mutuals operate and that she acts in the interests of all members collectively. Ms Morrison described her role as an advocate on behalf of all members to create awareness in the community of the economic benefit of CMEs in the Australian economy.

45 Relevantly, Mr Tancevski, CFCU’s CEO, gave evidence in cross-examination that at some point he had discussed the meaning of “community bank” with Ms Morrison. Although not entirely clear, it seems that in the period six to nine months prior to the hearing Mr Tancevski had a short conversation with Ms Morrison at an airport. Mr Tancevski was “jumping on a plane” and said that any discussion about the meaning of “community bank” would have been “in passing”. Mr Tancevski gave the following evidence about the substance of the conversation:

Q: And what did you say to her about the meaning of “community bank”?

A: Community bank, the description we used to it, member owned, community focused.

Q: That’s what you told her, “member owned, community focused”?

A: That has been my line for many years, yes.

Q: That’s your line. Now, what did she say to you about the meaning of “community bank”?

A: I can’t recall [Ms Morrison] describing it any different terms.

Q: So she agreed with your description?

A: To my knowledge, yes.

46 Ms Morrison said that she would have discussed the meaning of “community bank” with Mr Tancevski at some stage but could not recall a specific conversation. She did recall meeting Mr Tancevski at an airport and whilst she accepted that it was possible that she discussed the meaning of “community bank” at the time, she could not recall the content of their conversation. Ms Morrison said that she had been very mindful not to discuss the proceedings with Mr Tancevski or anyone else.

47 Mr Taylor has been CEO and a director of G&C Mutual since 2010. He has over 29 years’ experience in the banking and finance industry. Prior to taking on his current role, his positions included:

(1) from 1980 to 1990, various academic and advisory positions including lecturing in Australian political economy and acting as an economic adviser;

(2) from 1990 to 2001, executive general manager of Cuscal Limited (formerly Credit Union Services Corporation (Australia) Limited) (Cuscal) and a director of a number of the subsidiaries of the Cuscal group;

(3) from 1992 to 1997, member of the Australian Payment System Council;

(4) from 1998 to about March 2001, director of the Australian Payments Clearing Association;

(5) from 2001 to 2010, managing director of Finance Industry Consulting Services Pty Ltd; and

(6) from 2008 to 2010, non-executive director of G&C Mutual.

48 In cross-examination it became clear that in 2014, when G&C Mutual was attempting to register a trade mark which included the words “community bank”, Mr Taylor was aware of and had been involved in discussions with, among others, Mr Tancevski on two to three occasions which covered, among other things, G&C Mutual’s concern about Bendigo’s asserted monopoly in the term and whether it would be useful for COBA to facilitate a process to obtain collective views from those with concerns about the issue. Mr Taylor also gave evidence about the proposal to raise a “fighting fund” from members of the “G8”, being the eight largest mutual banks or credit unions which were shareholders in Cuscal at the time. The purpose of the “fighting fund” was to obtain registration of the term “community bank” in connection with the businesses being run by the G8 and not to prevent Bendigo from using the term.

49 Mr Taylor candidly informed the Court that prior to swearing his affidavit he read the Court’s Expert Evidence Practice Note (GPN-EXPT) and that he “alerted [his] counsel” that he was not able to satisfy its terms. Mr Taylor informed the Court that he had raised the matter prior to the hearing as something that needed to be clarified and that he had made it very clear that he is not impartial.

50 Notwithstanding this evidence, Mr Taylor did not accept that his evidence that “there are no matters of significance which I regard as relevant which has been withheld” and that, other than sitting on the board of Transaction Solutions Limited with Mr Tancevski, he has had no other involvement with CFCU for at least the past 10 years, was wrong. It was Mr Taylor’s view that his affidavit covered the matters about which he was asked and that in the period, which I understand to be a reference to the past 10 years, he had not had any formal dealings with CFCU.

51 Mr Lawrence has been the CEO of COBA since 4 December 2017. He has over 30 years’ experience in the banking and finance industry including:

(1) from 1984 to 2006 with the National Australia Bank Limited where he commenced as a graduate and had various roles including as account manager corporate banking, manager state credit bureau, relationship manager business banking, area manager retail banking, regional business manager, head of personal financial services, regional manager and general manager third party business;

(2) in 2007 with Westpac Banking Corporation as head of customer solutions and integration;

(3) from 2007 to 2015 as managing director of AMP Bank Limited;

(4) from 2008 to 2015 as a non-executive director of the Australian Banking Association (ABA) during which time Mike Hirst, the former managing director of Bendigo, was also a member of the ABA board; and

(5) from 2015 to 2017 providing banking and financial consultancy services to various Australian companies.

52 COBA is the industry advocate for the customer-owned banking sector in Australia made up of credit unions, mutuals and building societies. It advocates for its members before various stakeholders and provides advisory and support services, such as fraud and financial crimes services. As CEO of COBA, Mr Lawrence’s duties include managing, overseeing and implementing COBA’s strategic goals and operations.

53 CFCU is a member of COBA. The chair of CFCU has been a member of the COBA board since 2015, a matter which only became apparent during Mr Lawrence’s cross-examination.

54 In cross-examination it also became apparent that Mr Lawrence had met with Mr Tancevski in about August 2018. His memorandum to the COBA board dated 10 August 2018 included as an item that was covered in that meeting:

Discussed at length the legal issue with Bendigo & Adelaide Bank and the use of the term “Community Bank.”

55 Mr Lawrence said that during his meeting with Mr Tancevski he discussed the meaning of the term “community bank” and spoke about the structural difference between a customer-owned bank and a listed bank. While Mr Lawrence could not recall Mr Tancevski’s response, he could not recall Mr Tancevski disagreeing with what he said. Mr Lawrence said that this meeting was disclosed in his affidavit, albeit not in terms, where he described his only involvement with CFCU being in the context of professional members’ meetings, which he said was the nature of his meeting with Mr Tancevski.

56 Mr Lawrence accepted that his role requires him to act as industry advocate on behalf of COBA’s members, including CFCU, but did not accept that because of that he could not be impartial as an expert because his role is as an advocate for the industry.

57 Ms Morrison and Mr Lawrence can be dealt with together. Their respective roles require them to act as industry advocates: in the case of Ms Morrison, to raise awareness of the CME structure and its contribution to the Australian economy across all industries; and, in the case of Mr Lawrence, to act as an advocate for the customer-owned banks that are members of COBA. Bendigo contended that this undermined their independence.

58 Bendigo suggested that, given their roles as advocates, they cannot be impartial which is contrary to the requirements of the Expert Witness Code of Conduct. I do not accept that to be so. That their roles require them to act as industry advocates does not mean that their opinions expressed in this Court are as advocates for CFCU. They each have particular expertise in their respective areas. In the case of Ms Morrison that is the CME sector generally. Her opinion is based on that expertise. In the case of Mr Lawrence it is in the area of banking. His opinion is based on that expertise. Each of Ms Morrison and Mr Lawrence were frank in their responses to questions and endeavoured to assist the Court.

59 It is also apparent that at some stage prior to giving evidence each of Ms Morrison and Mr Lawrence had discussed an aspect of the proceeding with Mr Tancevski. It was unfortunate that these matters only became apparent in cross-examination.

60 In the case of Ms Morrison she had little recollection of the content of her discussion, which might explain why it was not included in her affidavit. It is apparent that the discussion was brief and that the meeting was a chance one in an airport, and was not planned. I do not think that this one brief interaction undermines Ms Morrison’s role as an expert nor her evidence to the point that I would reject it completely or give it little weight as Bendigo contends I should.

61 In the case of Mr Lawrence the discussion about the proceeding was in the course of his role as CEO of COBA. I accept his evidence that in referring to “professional members’ meetings” he believed he was disclosing that, in that capacity, he had had interactions with CFCU. I also accept that Mr Lawrence clearly felt that the meeting was undertaken in the ordinary course of his duties. However, the content of one of those meetings, which touched upon the proceeding, was not disclosed by Mr Lawrence in his affidavit. The better course would have been for Mr Lawrence to absent himself from any meeting with Mr Tancevski during the currency of the proceeding. That did not happen.

62 I accept that what occurred was a single meeting which canvassed a number of topics, one of which was this proceeding. That said, it took place in close proximity to the date that Mr Lawrence affirmed his affidavit. Ultimately while I do not think the fact of the meeting and the failure to disclose it means that I would give no weight to Mr Lawrence’s evidence, it undermines to a significant degree the impartiality of his evidence and it follows that I would give less weight to his evidence.

63 Mr Taylor is in a different category. As noted above he candidly accepted that he is not impartial. He cannot be relied on as an independent expert. That said, his evidence covers two broad categories: first, his opinion about the meaning of “community bank”; and secondly, G&C Mutual’s own application to register a trade mark including the words “community bank”, which CFCU relies on as evidence of the desire of other traders to use the term “community bank”.

64 CFCU submitted that I would nonetheless receive Mr Taylor’s evidence (and that of Ms Morrison and Mr Lawrence in the event that I formed the view that they were not independent experts) pursuant to s 219 of the TM Act. That section provides that in any proceeding relating to a trade mark, evidence is admissible of the usage of the trade concerned and of any relevant trade mark, trade name or get-up legitimately used by other persons. In The Shell Company of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 407 in considering s 66 of the Trade Marks Act 1955 (Cth) (1955 Act), the predecessor to s 219, Windeyer J said that “all questions concerning trade marks must be considered against the background of the usages in the particular trade”, as recognised by s 66 of the 1955 Act: at 410.

65 In giving evidence about G&C Mutual’s attempts to register a trade mark with “community bank” in it, Mr Taylor gives evidence of usage of the term “community bank” in the financial services industry. In my opinion his evidence on that issue should be allowed pursuant to s 219 of the TM Act as evidence of usage of the trade. I do not think Mr Taylor’s evidence about the meaning of the term “community bank” is in the same category. It is not evidence of usage but of his opinion, offered as an expert given his experience in the sector, of the meaning of the term and I would give no weight to that evidence.

66 Before proceeding further, it is useful to set out some background matters which are common to both proceedings and which I did not understand to be in dispute.

67 CFCU was established in 1959 as a credit union for employees of the Sydney Water Board under the name “Sydney Water Board Officers Co-operative Ltd”. Since its establishment CFCU has changed its name a number of times to reflect its changing membership: in 1974 it changed its name to “S.W.B Family Credit Union Limited”; in 1983 it changed its name to “SWB Community Credit Union Ltd”; and on or about 6 September 1993 it took on its current name, “Community First Credit Union Limited”. It has traded under that name and by reference to “Community First” since that time.

68 Over time CFCU has merged with 15 other credit unions as follows:

in 1974 with Sterlac Credit Union;

in 1975 with each of Trans Australian Airline Credit Union and Glass Containers Credit Union;

in 1981 with Martin Well Credit Union;

in 1984 with AMOCO Employees Credit Union;

in 1986 with Wool Broker and Trustees Staff Credit Union;

in 1990 with Muniff Credit Union;

in 1999 with Manchester Unity Credit Union;

in 2000 with Grand United Credit Union;

in 2006 with each of Dana Employees Credit Union and Elcom Credit Union;

in 2008 with each of Croatian Community Credit Union and Hibernian Credit Union;

in 2015 with Northern Beaches Credit Union; and

in 2018 with CAPE Credit Union.

69 Since its establishment in 1959 CFCU has been a member-owned institution run for the benefit of its members and not for external shareholder profit. Each CFCU customer is a member of, and has one equal share and one vote in, CFCU; there are no external non-member shareholders; CFCU does not pay a dividend to any shareholder; and the benefit of any profits CFCU makes is returned to members, including through lower fees and competitive lending and deposit rates.

70 CFCU provides its banking and financial services:

(1) in person through its bricks and mortar branches referred to as “financial services stores”. There are currently 15 financial services stores in the Greater Sydney and Central Coast regions; and

(2) online through its website, its “Community First Mobile Banking” application and third party applications such as Apple Pay, Android/Google Pay and Samsung Pay.

71 According to CFCU’s Annual Report 2018, as at 30 June 2018 CFCU:

(1) achieved more than $1b in assets under management;

(2) managed over $814m in loans and advances to members and over $966m in deposits from members;

(3) achieved a total income of over $45m;

(4) had approximately 57,933 members with 6,331 new members joining in that financial year; and

(5) had approximately 164 staff.

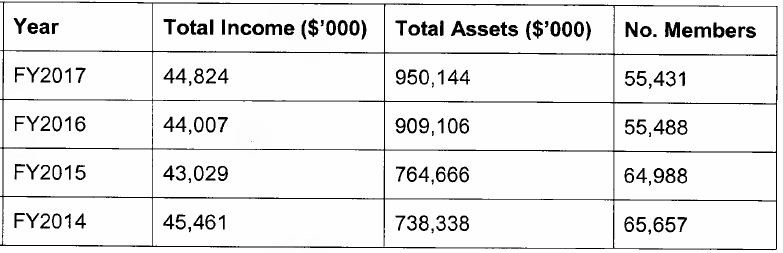

72 The Annual Report 2018 shows CFCU’s history of total income, assets and members since the 2014 financial year. Mr Tancevski has collated these figures as follows:

73 Bendigo is one of Australia’s largest banks and has been providing banking and financial services for approximately 160 years:

(1) it was established in August 1858 as Bendigo Land and Building Society;

(2) in 1865 it restructured and changed its name to Bendigo Mutual Permanent Land and Building Society;

(3) in 1876 it was incorporated in Victoria under the Building Societies Act 1874;

(4) in 1979 Bendigo Building Society was created when Bendigo Mutual Permanent Land and Building Society merged with Bendigo and Eaglehawk Star Permanent Society;

(5) in 1991 Bendigo acquired Sandhurst Trustees and changed its name to Bendigo Sandhurst Mutual Permanent Land and Building Society;

(6) in February 1993 Bendigo listed on the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX);

(7) in 1995 it converted from a building society to a bank and all of its banking business was transferred from Bendigo Sandhurst Mutual Permanent Land and Building Society to the newly incorporated Bendigo Bank Limited;

(8) in November 2007 it merged with Adelaide Bank Limited; and

(9) in January 2008 it changed its name to its current name, Bendigo and Adelaide Bank Limited.

74 Bendigo is ranked in the top 100 ASX listed companies. As at June 2018 it had 7,482 staff and around 100,000 shareholders and as at 30 June 2017 it had 1.6 million customers throughout Australia.

3.1.2.1 Bendigo’s trade mark applications using the words “community” and “bank”

75 In addition to the Bendigo Community Marks and the mark referred to at [135] (which I refer to in these reasons as the Bendigo Composite Mark), since October 1997 Bendigo has applied to register the following trade marks:

(1) on 21 October 1997:

(a) trade mark no. 746685 for COMMUNITY BANK in class 36. That application was not accepted and lapsed on 11 May 1999 (First Community Bank Trade Mark Application); and

(b) trade mark no. 746686 for COMMUNITY BANK BRANCH in class 36 (Community Bank Branch Trade Mark Application). On 11 February 1998 an adverse report was issued and the application lapsed on 17 June 1999;

(2) in December 2003 trade mark no. 981605 for “Community Banking” in class 36. Cuscal, CFCU and Heritage Building Society lodged notices of opposition to that application and on 13 February 2006 the application was withdrawn;

(3) on 19 January 2011 trade mark no. 1404733 for:

for goods and services in class 16 (bank cards) and class 36. On 25 April 2011 an adverse report was issued in relation to that application and on 16 August 2012 it lapsed;

(4) on 28 March 2011 trade mark no. 1414961 for “CommunityPos” for goods and services in class 9 (apparatus for decoding (reading) encoded cards). That application was accepted for registration;

(5) on 2 December 2013:

(a) trade mark no. 1593641 for “Community Super” in class 36. That application was accepted and the trade mark registered with a priority date of 2 December 2013; and

(b) trade mark no. 1594507 for “Bendigo Community Super” in class 36. That application was accepted and the trade mark registered with a priority date of 2 December 2013;

(6) on 22 April 2014:

(a) trade mark no. 1618421 for “Building SuperCommunities” in class 36. That application was accepted and the trade mark registered in class 36 with a priority date of 22 April 2014; and

(b) trade mark no. 1618426 for “Building Super Communities” in class 36. That application was accepted and the trade mark registered with a priority date of 22 April 2014;

(7) on 26 April 2016 trade mark no. 1766884 for COMMUNITY TELCO in class 35 (telecommunications-related billing services) and class 38 (telecommunication services). That application was accepted and the trade mark registered with a priority date of 26 April 2016; and

(8) in August 2017 trade mark no. 1869637 for COMMUNITY BANK in class 36. On 18 December 2017 an adverse report was issued. That application was, according to the evidence before me, still pending as at the date of the hearing.

76 Ms Williams was cross-examined in relation to a number of these applications. Ms Williams was not aware of Bendigo having any trade mark strategy around dominating the use of the word “community” but was of the understanding that “community bank” was in “[Bendigo’s] DNA” and that Bendigo wished to protect that mark and the other marks it had registered. When asked what she meant by the proposition that “community bank is in their DNA”, Ms Williams responded as follows:

Well, they’ve been using Community Bank since 1998 from the material and Bendigo Bank’s brand was only in existence from the 1st of – sorry, 1 July 1995, so therefore the marks are roughly only three years apart and they’ve always used Community Bank heavily, in my understanding.

3.2 Regulation of credit unions and use of the term “bank”

77 The change in the regulatory framework for credit unions and their ability to use the term “bank” is a matter which is of relevance to both the Rectification Proceeding and the Appeal Proceeding. This was explained by Associate Professor Martin and Ms Robinson, whose evidence I summarise below.

78 In Australia there are three main types of banking and financial institution including, relevantly, ADIs comprising banks, building societies and credit unions. As a result of recommendations in the Financial System Inquiry: Final Report published in March 1997 (Wallis Report), the term ADI was created to refer to all deposit taking institutions authorised to accept deposits under the new regulatory structure.

79 According to Associate Professor Martin, the Wallis Report led to major changes to the financial regulatory framework including creating a new financial regulator to supervise financial intuitions and introducing reforms allowing large credit unions and building societies to use the term “bank” in their name, to promote competition in the financial system, drive down costs and drive up service standards.

80 Since 1999 ADIs have been regulated by APRA and have been authorised under the Banking Act to accept deposits from the public. Prior to 1999 banks were regulated by the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and building societies and credit unions were regulated by the Australian Financial Institutions Commission (AFIC), a central regulator coordinating the state-based regulatory regimes.

81 On 20 September 2000, APRA issued a set of harmonised prudential standards for all ADIs which meant the regulatory framework for banks, building societies and credit unions were fully aligned.

82 With respect to the use of names, Ms Robinson explains that:

(1) ASIC is the regulator for registration of business and company names;

(2) section 24 of the Business Names Registration Act 2011 (Cth) requires ASIC to register a business name of an entity if it is satisfied that the name is available to an entity and does not include a restricted word or expression or, if the word or expression is restricted unless a condition is satisfied, the entity satisfies that condition. The Minister has power to determine if a word or expression is restricted, or restricted in relation to a specified class or business unless a condition (if one is specified in the determination) is met; and

(3) the Business Names Registration (Availability of Names) Determination 2012 (2012 Determination) sets out the words which are restricted and so require either ministerial or other authorised consent before ASIC will register a business name including any one of those words. The 2012 Determination includes the following restricted words which require the consent of APRA before ASIC will register a name including one of them:

(a) ADI;

(b) bank;

(c) banker;

(d) banking; and

(e) credit union.

83 Section 66 of the Banking Act concerns use of restricted words or expressions in connection with a financial business. While it has been amended, its effect has at all relevant times been to prohibit a person in Australia from using a restricted word or expression in relation to a financial business without APRA’s consent and to permit APRA to issue a consent to a particular person or a class of persons for the use or assumption of a restricted word or expression.

84 On 19 May 2000 APRA issued a class consent pursuant to s 66(1)(d) and s 66(2)(a) of the Banking Act titled Consent to Use Restricted Expressions – Class Consent: Building Societies and Credit Unions and Trustees of Superannuation Entities (2000 Consent). By the 2000 Consent APRA granted certain classes of entity the right to use certain restricted words. The 2000 Consent was specific to each type of institution named in it. In relation to building societies and credit unions it permitted those entities, among other things, to “use the expression banking in relation to [their] banking activities”.

85 According to Ms Robinson, the 2000 Consent meant that a credit union did not have to apply to APRA to be entitled to use the restricted terms set out therein because it was a statutory exception which allowed all ADIs listed on the APRA website under the heading “Credit Unions” to use those restricted terms.

86 In Ms Robinson’s opinion, CFCU comes within the 2000 Consent because since before 19 May 2000 (the date of the 2000 Consent) it has been an ADI operating as a credit union and as such has been listed on the APRA website under the heading “Credit Unions”.

87 In January 2006 APRA published Guidelines: Implementation of Section 66 of the Banking Act 1959 (2006 Guidelines) which included:

9. Authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) listed on the APRA web site as banks have been given an unrestricted consent to use the words ‘bank’, ‘banker’ or ‘banking’. This allows the ADI to use the word bank:

• in its company name or trading names; or

• to describe or to advertise its business.

…

18. ADIs listed on the APRA web site as credit unions or as building societies may use the word ‘banking’ in relation to their banking activities.

19. A body corporate that is related to a building society or credit union may use the word ‘banking’ in relation to the banking activities of the building society or credit union if the word is not used in a misleading or deceptive way.

This consent came into effect by the instrument dated 19 May 2000.

…

21. A body corporate that is related to a credit union may use the expressions ‘credit union’, ‘credit society’ and ‘credit co-operative’ in relation to the financial business carried on by the credit union if the expressions are not used in a misleading way.

This consent is made under the instrument dated 19 May 2000.

88 In April 2008 APRA published ADI Authorisation Guidelines (2008 Guidelines) which were expressed to apply to prospective applicants seeking an authority to carry on banking business in Australia under the Banking Act. The 2008 Guidelines included:

Use of restricted words and expressions

8. The granting of an authority to carry on banking business gives the successful applicant the right to use the expression ‘authorised deposit-taking institution’ or ‘ADI’ in relation to its business. The authority does not automatically entitle the ADI to call itself a ‘bank’. Applicants should note section 66 of the Act which restricts the use of certain words or expressions without explicit APRA consent (refer to section 66 Guidelines available on the APRA website: www.apra.gov.au).

9. An applicant wishing to use any of the restricted words or expressions on authorisation should apply concurrently to APRA for a section 66 consent.

Trading names

10. An ADI that wishes to use a trading name, other than its registered company name, may seek to use a restricted expression in that trading name. APRA will not ordinarily object to this where the ADI would otherwise be permitted to use that expression (e.g. where an ADI that is a bank wishes to use the term ‘bank’ in its trading name). If the restricted expression to be used in the trading name is not one that the ADI would ordinarily be permitted to use (e.g. where the ADI is a bank and wishes to use the term ‘credit union’ in the trading name), APRA will need to consider on a case-by-case basis whether such use could be misleading.

…

Capital

15. APRA will assess the adequacy of start-up capital for an applicant on a case-by-case basis based on the scale, nature and complexity of the operations as proposed in the business plan. Applicants proposing to operate as banks must have a minimum of $50 million in Tier 1 capital. Otherwise, no set amount of capital is required for an authority to carry on banking business. Foreign ADls are not required to maintain endowed capital in Australia.

89 In December 2010 the Commonwealth Government announced that where an ADI operating as a credit union or building society holds at least $50m in Tier 1 capital, and wishes to operate as a bank, the ADI may apply to APRA for consent to unconditionally use the restricted words “bank” and “banking” in connection with its business.

90 In 2015 APRA published further guidelines on the implementation of s 66 of the Banking Act. The 2015 Guidelines relevantly provide that where an ADI wishes to operate as a bank the ADI must hold at least $50m in Tier 1 capital and that APRA will, unless there are special circumstances, grant an ADI that wishes to operate as a bank and that holds at least $50m in Tier 1 capital an individual consent to use or assume the expressions “bank”, “banker” and “banking” on an unrestricted basis. Unrestricted consent allows the ADI to use those expressions in its company name, trading or business names and internet domain name and to describe or advertise its business.

91 In circumstances where the ADI has previously operated as a credit union, APRA will impose transitional conditions upon the grant of its consent to use the expressions “bank”, “banker” and “banking”. Relevantly, under the heading “Credit unions and building societies seeking to operate as a bank” the 2015 Guidelines provide:

40. Where an ADI operating as a credit union or building society holds at least $50 million in Tier 1 capital, and wishes to operate as a bank, the ADI may apply to APRA for consent to unconditionally use the restricted words or expressions ‘bank’, ‘banker’ and ‘banking’. APRA will consider such applications on a case-by-case basis.

41. APRA’s policy is that an ADI cannot simultaneously:

• operate as a bank with unrestricted consent to use the restricted expressions ‘bank’, ‘banker’ and ‘banking’; and

• operate as a credit union or building society entitled to the benefit of the Credit Union and Building Society Consent.

42. Accordingly, where an ADI operating as a credit union or building society wishes to operate as a bank, and use the restricted words or expressions ‘bank’, ‘banker’ and ‘banking’ under section 66 of the Banking Act on an unrestricted basis, the ADI will not be permitted to continue to use the expressions ‘credit union’, ‘credit society’, ‘credit cooperative’ or ‘building society’ (as relevant).

43. Further, an ADI that was previously a credit union or building society and that now operates as a bank will be required to take appropriate steps to ensure that members, depositors, other customers and the general public are clearly aware that it is now operating as a bank. APRA may, for instance, grant unrestricted consent to use the restricted expressions ‘bank’, ‘banker’ and ‘banking’ on the condition that the ADI use the word ‘bank’ in its corporate, trading or business name for a finite period.

92 In 2018 APRA published the Guidelines: Restricted Words under the Banking Act 1959 dated 20 August 2018 (2018 Guidelines). Chapter 3 of the 2018 Guidelines states that there is no restriction on an ADI using the terms “bank”, “banker” and “banking” except where APRA has made a determination under s 66A of the Banking Act.

3.3 CFCU’s intention to become a bank

93 CFCU is authorised by APRA to conduct banking services and is on APRA’s register of ADIs.

94 As noted above, in December 2010 the Australian Government announced that an ADI that holds at least $50 m in Tier 1 capital may apply to APRA to operate as a bank or mutual bank. According to Mr Tancevski, CFCU met this capital requirement as at December 2010 and continues to do so.

95 In 2011 CFCU surveyed its members for their opinion on whether it should change from being a credit union to become a bank or mutual bank. The Chairman’s Report included in CFCU’s Annual Report 2012 relevantly included:

Our decision around becoming a Mutual Bank

Late last year, the Board asked for your opinion on whether Community First should become a Mutual Bank. On behalf of the Board, I would like to thank all those Members who provided their feedback and who exercised their right as a Member to actively participate in the future direction of the credit union.

I am really pleased to say that Community First received an overwhelming response from our Members, which helped guide the Board and management in our deliberations. While it was clear from the research findings that Members were largely supportive of the mutual bank concept, the Board concluded that there was no significant advantage at this time in becoming a bank and accordingly, the credit union “suffix” will continue in the near term.

96 Mr Tancevski’s evidence, which I accept, is that CFCU intends to change its status from a credit union to a bank or mutual bank and that it has always been its intention to continue to use the Community First Registered Mark if and when it becomes a bank or mutual bank. CFCU has used the Community First Registered Mark for a period of 25 years and has invested in building awareness of that mark with various stakeholders (see [463]-[468] below). Thus its members, consumers and the general public associate services that CFCU provides with the Community First Registered Mark.

97 As noted at [4] above, on 1 March 2013 CFCU applied for registration of the CFCU Marks to ensure that it was prepared to become a bank or mutual bank having regard to its current branding with the Community First Registered Mark. IP Australia accepted the CFCU Marks for registration in January 2015 but, on or about 25 May 2015, it notified CFCU that it proposed to revoke acceptance of the CFCU Marks because CFCU did not have APRA’s consent to include the restricted word “bank” in the marks.

98 By letter dated 30 June 2015 CFCU sought APRA’s guidance on whether it would have any objection to it registering a trade mark that includes the word “bank”. That letter included:

As discussed on the phone, Community First is considering the option to convert from a “credit union” to a “Bank” at some future point. This transition is likely to occur in the next three years and is regularly reviewed by the Board based on current market opportunities.

However, as a defensive strategy, the Board has resolved to try and reserve a number of trademarks with IP Australia which at least prevent other parties from “squatting” our brand and trade names, APRA would be aware that other institutions have already encroached on the Community Banking model in this country and sought to trademark a variety of names, descriptors and common terms.

Therefore, Community First has approached IP Australia to reserve the names:

• Community First Bank

• Community First Mutual Bank

In this case, the word “Bank” would be used to highlight the change from one form of Approved Deposit Taking Institution, a “credit union”, to a “Bank”.

Please accept our apologies for creating any unnecessary confusion in not approaching APRA earlier but our simplistic view was that there would be no point in approaching APRA to become a Bank without a name or firm commitment to proceed at this time?

IP Australia originally approved the trademark(s) but has since rescinded its decision, subject to an upcoming hearing, based on the Section 66 rules in the Banking Act (1959) referring to “restricted words”, specifically the use of the word “Bank” after the name “Community First”?

At the upcoming hearing, Community First Credit Union proposes to highlight to IP Australia that Community First meets the requirements of the Banking Act to become a “Bank”, subject to APRA approval, and already meets the preliminary requirements of the Act to lodge an application.

Accordingly, Community First seeks APRA’s guidance on whether the regulator (APRA) would have any objection to Community First registering a trademark with IP Australia that included the name “Bank”?

This guidance will be used to counter IP Australia’s view that APRA would object to the use of a “restricted word” Bank in the proposed trade-marks?

Your earliest guidance is appreciated and please contact me if you require any further information. …

(emphasis in original.)

99 By letter dated 24 July 2015 APRA confirmed that it had no objection to CFCU registering the CFCU Marks and noted that its position was “taken on the understanding that none of the [CFCU Marks] should be used for any commercial purpose until APRA has consented to their use under section 66 of the [Banking Act]”.

100 On 29 October 2015 a delegate of the Registrar refused to revoke acceptance of the applications to register the CFCU Marks.

101 According to Mr Tancevski at all times since 1 March 2013 CFCU has met the criteria prescribed by APRA for use of the word “bank” or “mutual bank” in its corporate name or trade marks. But, in order for CFCU to become a bank or mutual bank it will need to apply to APRA for approval of its intended change in its corporate name to “bank” or “mutual bank”, and at the same time it will need to inform APRA of its proposed new corporate name, either “Community First Bank” or “Community First Mutual Bank”.

102 In Mr Tancevski’s experience APRA usually takes about 6 to 12 months to approve a corporate name change because the process requires an applicant to prove to APRA that it will continue to meet all prudential standards following the name change.

103 Mr Tancevski is of the view that it is only after these proceedings are resolved that CFCU could apply to APRA for approval of its proposed name change. He recognises that, while it would be possible for CFCU to apply to APRA for approval of the alternative corporate names “Community First Bank” and “Community First Mutual Bank”, it is unlikely that APRA would consider the applications until these proceedings, which would be disclosed to APRA as part of CFCU’s application, are resolved. Mr Tancevski also points out that, as the words “credit union” are restricted words under the Banking Act, he anticipates that CFCU will not be able to describe itself as a credit union after APRA approves it to be a bank or mutual bank.

104 I turn then to first consider the Rectification Proceeding followed by the Appeal Proceeding.

4. the rectification proceeding

105 CFCU seeks rectification of the Register by cancellation or removal of each of the Bendigo Community Marks pursuant to s 88(1) of the TM Act and orders pursuant to s 97 or s 101 of the TM Act requiring the Registrar to remove the Bendigo Community Marks from the Register.

106 Section 88(1) of the TM Act provides that the Court may, on the application of an aggrieved person, order that the Register be rectified by, among other things, cancelling the registration of a trade mark or removing an entry wrongly made or remaining on the Register. The exercise of the power in s 88(1) is subject to s 88(2) and s 89.

107 Section 88(2) provides that an application can only be made on the grounds set out therein. CFCU relies on the grounds in subs 88(2)(a) and (c) which respectively provide that an application can be made on any of the grounds on which registration of the trade mark could have been opposed under the TM Act; or, because of the circumstances applying at the time when the application for rectification is filed, the use of the trade mark is likely to deceive or cause confusion. As to the latter, the application for rectification was filed with the Court on 14 August 2017 (see [375] below).

108 For the purposes of s 88(2)(a), the grounds on which CFCU says it could have relied to oppose the registration of the Bendigo Community Marks are those in ss 41, 42(b), 43, 44 and 59 of the TM Act. In the context of an application under s 88(1), the question of whether any of those grounds would have been available to CFCU to oppose the Bendigo Community Marks is to be determined as at the date of registration of each of the Bendigo Community Marks, namely 8 February 1999 and 24 August 2001 (which are also the Priority Dates): see Unilever Australia Ltd v Karounos (2001) 113 FCR 322 at [13].

109 Section 89 relevantly provides:

(1) The court may decide not to grant an application for rectification made:

…

(b) on the ground that the trade mark is liable to deceive or confuse (a ground on which its registration could have been opposed, see paragraph 88(2)(a)); or

(c) on the ground referred to in paragraph 88(2)(c);

if the registered owner of the trade mark satisfies the court that the ground relied on by the applicant has not arisen through any act or fault of the registered owner.

(2) In making a decision under subsection (1), the court:

(a) must also take into account any matter that is prescribed; and

(b) may take into account any other matter that the court considers relevant.

110 It was common ground that CFCU is an “aggrieved person” for the purposes of s 88(1) of the TM Act. It was also common ground that CFCU bears the onus of establishing each of the grounds it relies on under s 88 of the TM Act: see Yarra Valley Dairy Pty Ltd v Lemnos Foods Pty Ltd (2010) 191 FCR 297 at [39]-[41].

111 CFCU also relies on s 92(4) of the TM Act as a basis on which it says the Bendigo Community Marks should be removed for non-use. That subsection provides:

(4) An application under subsection (1) or (3) (non‑use application) may be made on either or both of the following grounds, and on no other grounds:

(a) that, on the day on which the application for the registration of the trade mark was filed, the applicant for registration had no intention in good faith:

(i) to use the trade mark in Australia; or

(ii) to authorise the use of the trade mark in Australia; or

(iii) to assign the trade mark to a body corporate for use by the body corporate in Australia;

in relation to the goods and/or services to which the non‑use application relates and that the registered owner:

(iv) has not used the trade mark in Australia; or

(v) has not used the trade mark in good faith in Australia;

in relation to those goods and/or services at any time before the period of one month ending on the day on which the non‑use application is filed;

(b) that the trade mark has remained registered for a continuous period of 3 years ending one month before the day on which the non‑use application is filed, and, at no time during that period, the person who was then the registered owner:

(i) used the trade mark in Australia; or

(ii) used the trade mark in good faith in Australia;

in relation to the goods and/or services to which the application relates.

(notes omitted.)

112 I will consider each of the grounds upon which CFCU relies in support of its application for rectification of the Register in turn.

4.1 Sections 88(2)(a) and 41 of the TM Act – lack of distinctiveness

113 CFCU’s principal focus, of the grounds raised by it under s 88(2)(a), was s 41 of the TM Act. CFCU contends that it was a ground of opposition it could have relied on to oppose the registration of the Bendigo Community Marks.

114 In summary, CFCU contends that as at the Priority Dates neither the Bendigo Device Mark nor the Bendigo Word Mark were to any extent inherently adapted to distinguish the Services from the goods and services of other persons.

115 In the alternative, CFCU contends that if as at 8 February 1999 and 24 August 2001 respectively the Bendigo Device Mark and Bendigo Word Mark were to some extent inherently adapted to distinguish the Services from the goods and services of other persons, those trade marks did not and would not distinguish the Services as being those of Bendigo having regard to, among other things, the combined effect of the extent to which those marks were each inherently adapted to distinguish the Services and the lack of use by Bendigo of the Bendigo Device Mark and the Bendigo Word Mark.

116 It was common ground that s 41 of the TM Act as it existed prior to the enactment of the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth) (IPL Amendment Act), which repealed s 41 and inserted a substitute, applies in this case. At the time of the Priority Dates, s 41 provided:

41 Trade mark not distinguishing applicant’s goods or services

(1) For the purposes of this section, the use of a trade mark by a predecessor in title of an applicant for the registration of the trade mark is taken to be a use of the trade mark by the applicant.

(2) An application for the registration of a trade mark must be rejected if the trade mark is not capable of distinguishing the applicant’s goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is sought to be registered (designated goods or services) from the goods or services of other persons.

(3) In deciding the question whether or not a trade mark is capable of distinguishing the designated goods or services from the goods or services of other persons, the Registrar must first take into account the extent to which the trade mark is inherently adapted to distinguish the designated goods or services from the goods or services of other persons.

(4) Then, if the Registrar is still unable to decide the question, the following provisions apply.

(5) If the Registrar finds that the trade mark is to some extent inherently adapted to distinguish the designated goods or services from the goods or services of other persons but is unable to decide, on that basis alone, that the trade mark is capable of so distinguishing the designated goods or services:

(a) the Registrar is to consider whether, because of the combined effect of the following:

(i) the extent to which the trade mark is inherently adapted to distinguish the designated goods or services;

(ii) the use, or intended use, of the trade mark by the applicant;

(iii) any other circumstances;

the trade mark does or will distinguish the designated goods or services as being those of the applicant; and

(b) if the Registrar is then satisfied that the trade mark does or will so distinguish the designated goods or services—the trade mark is taken to be capable of distinguishing the applicant’s goods or services from the goods or services of other persons; and

(c) if the Registrar is not satisfied that the trade mark does or will so distinguish the designated goods or services—the trade mark is taken not to be capable of distinguishing the applicant’s goods or services from the goods or services of other persons.

(6) If the Registrar finds that the trade mark is not inherently adapted to distinguish the designated goods or services from the goods or services of other persons, the following provisions apply:

(a) if the applicant establishes that, because of the extent to which the applicant has used the trade mark before the filing date in respect of the application, it does distinguish the designated goods or services as being those of the applicant—the trade mark is taken to be capable of distinguishing the designated goods or services from the goods or services of other persons;

(b) in any other case—the trade mark is taken not to be capable of distinguishing the designated goods or services from the goods or services of other persons.

(notes omitted.)

117 The accepted approach to s 41 of the TM Act prior to its amendment by the IPL Amendment Act is as set out in Blount Inc v Registrar of Trade Marks (1998) 83 FCR 50 at 56. There Branson J observed that subss 41(3) to (6) are “designed to control the process by which the Registrar is to reach a conclusion as to whether the trade mark for which registration is sought is capable of distinguishing the applicant’s goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is sought to be registered”. If it is not so capable, the trade mark must be rejected pursuant to s 41(2) of the TM Act. Her Honour continued:

… Subsection (3) requires the Registrar first to “take into account the extent to which the trade mark is inherently adapted to distinguish the designated goods or services from the goods or services of other persons”. Having taken such matter into account, it is theoretically open to the Registrar to conclude:

(a) that the trade mark is inherently adapted to distinguish the designated goods or services from the goods or services of other persons and capable, on that basis alone, of so distinguishing the designated goods or services; or

(b) that the trade mark is not to any extent inherently adapted to distinguish the designated goods or services from the goods or services of other persons; or

(c) that the trade mark is to some extent inherently adapted to distinguish the designated goods or services from the goods or services of other persons, but there is uncertainty, on that basis alone, that the trade mark is actually capable of so distinguishing the designated goods or services.

118 As Her Honour went on to explain, if conclusion (a) is reached, the application for registration of the trade mark will be accepted; if conclusion (b) is reached, then s 41(6) comes into play and if the applicant can establish that, because of the extent to which it has used the trade mark before the filing date of the application, the trade mark does distinguish the designated goods or services as being those of the applicant, the Registrar will accept the application, but if the applicant fails to establish that to be the case, the Registrar must reject the application pursuant to s 41(2); and if conclusion (c) is reached, s 41(5) operates such that if the Registrar is satisfied of the matters listed in subs 41(5)(a)(i), (ii) and (iii), the application will be accepted but if the Registrar is not so satisfied the application must be rejected.

4.1.1 Section 41(3) - inherently adapted to distinguish