FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Prudential Regulation Authority v Kelaher [2019] FCA 1521

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN PRUDENTIAL REGULATION AUTHORITY Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent GEORGE VENARDOS Second Respondent DAVID COULTER (and others named in the Schedule) Third Respondent | |

JAGOT j | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The amended originating application be dismissed.

2. The applicant pay the respondents’ costs as agreed or taxed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

JAGOT J:

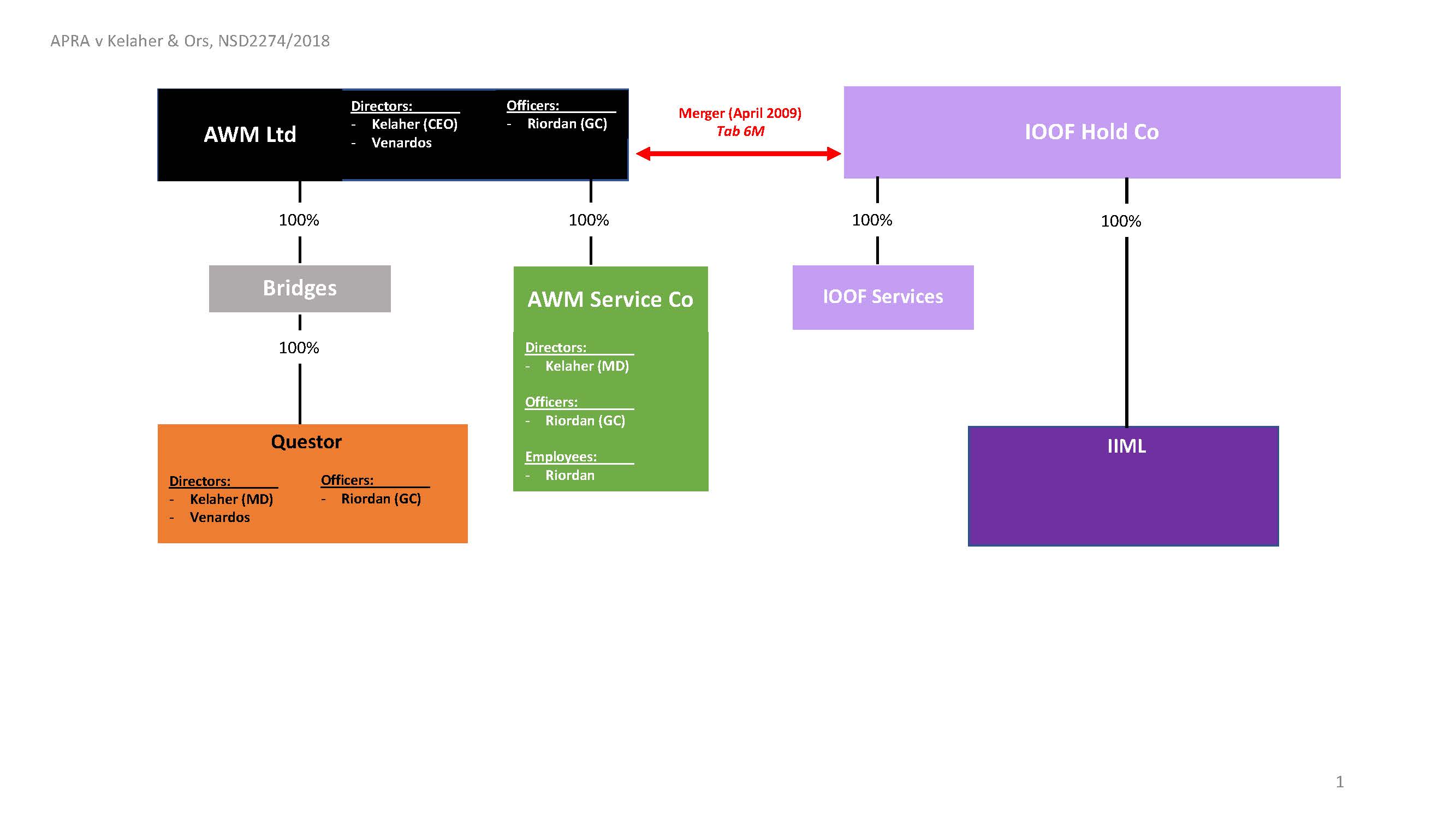

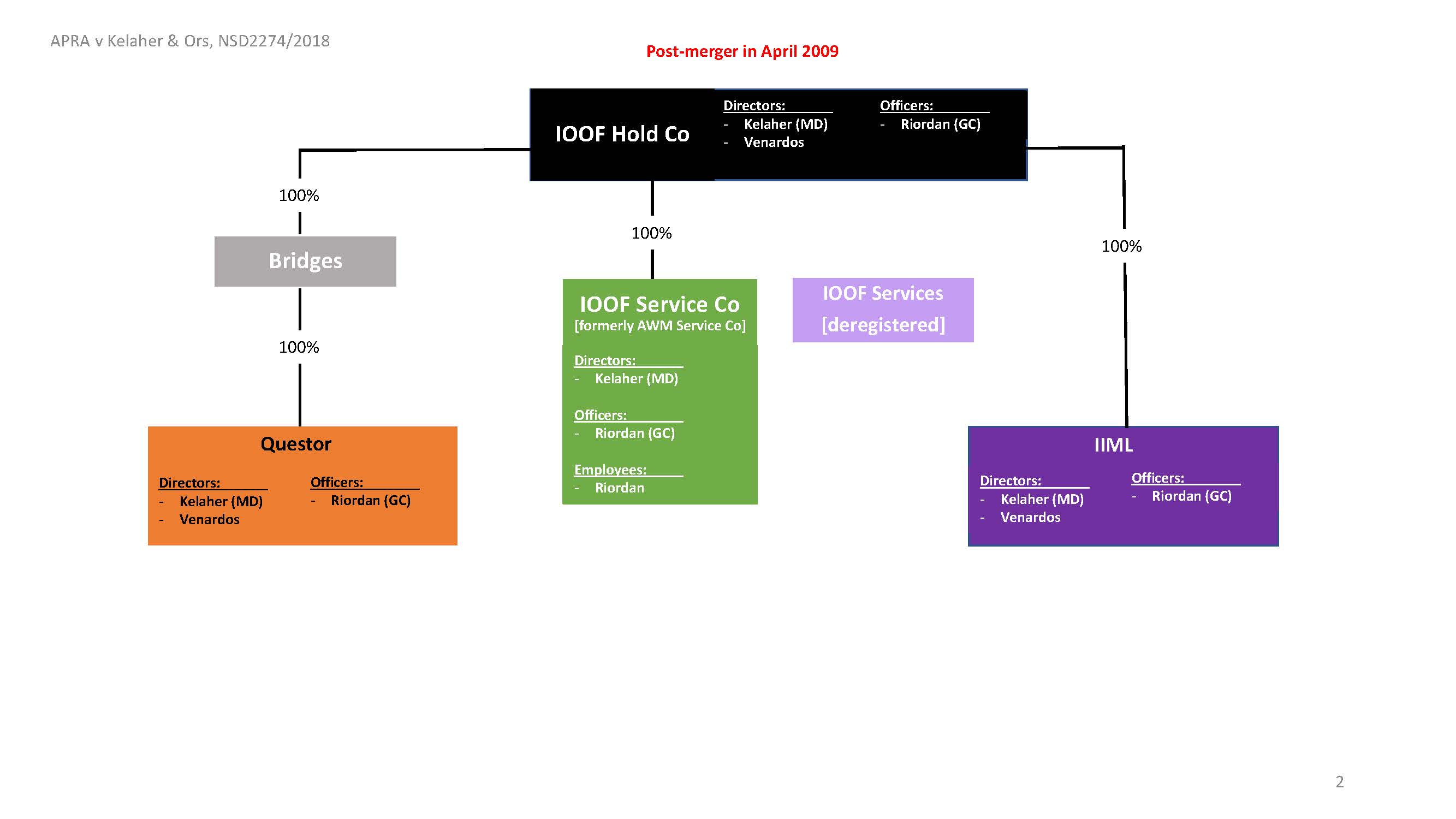

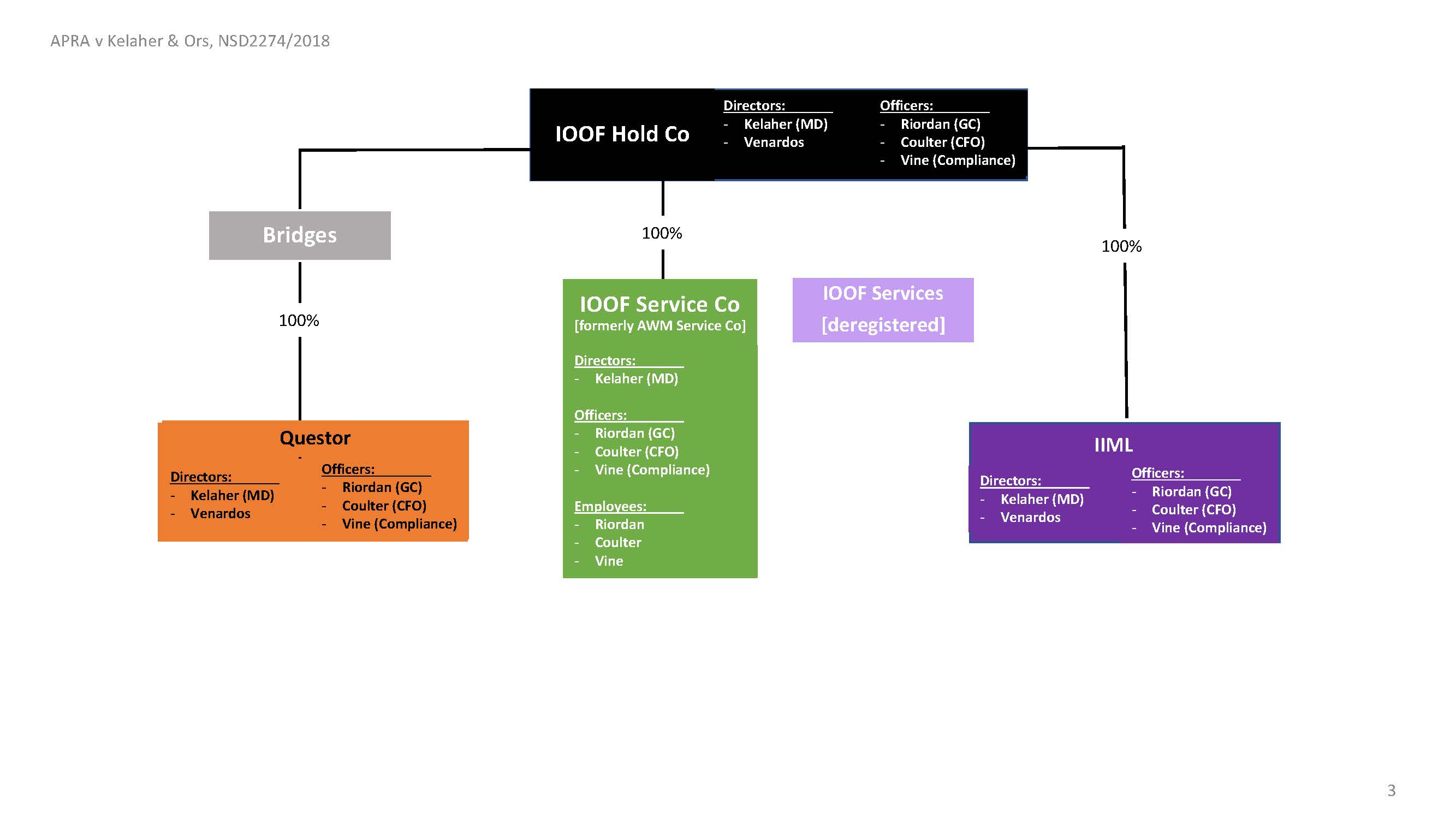

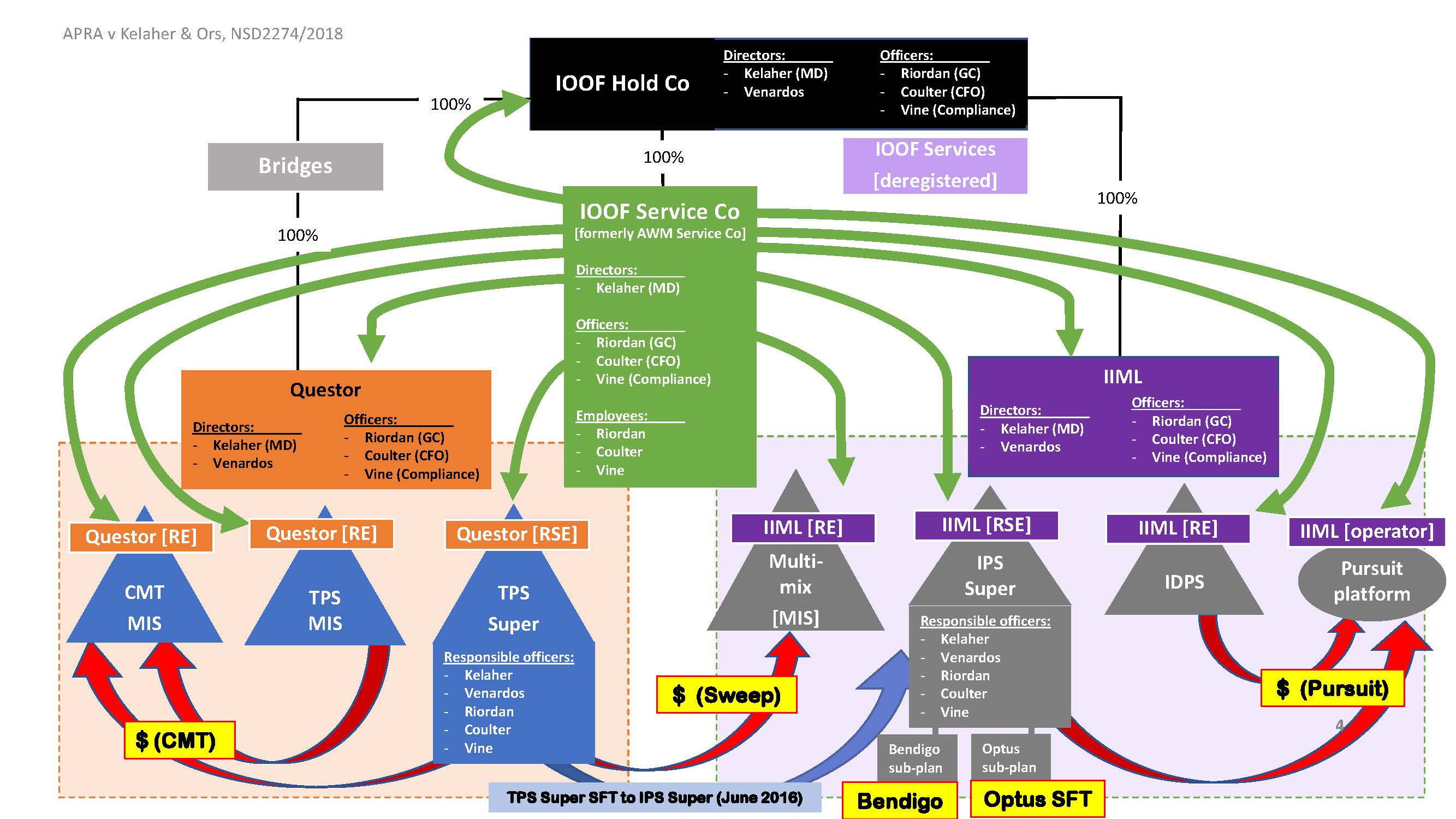

1 The applicant, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, (APRA), alleged that two entities within the IOOF Group of companies, referred to as IIML (the sixth respondent) and Questor (the seventh respondent), and two of their directors, Mr Kelaher (the first respondent) and Mr Venardos (the second respondent), contravened ss 52 and 52A of the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (Cth) (the SIS Act). APRA sought disqualification orders against the directors and three responsible officers of the entities, Mr Coulter (the third respondent), Mr Vine (the fourth respondent) and Mr Riordan (the fifth respondent). The issue of potential disqualifications was deferred for hearing and determination at a later time. These reasons for judgment concern only the alleged contraventions.

2 IIML was the trustee and licensee of the IOOF Portfolio Superannuation Fund (IPS Super). Questor was the trustee and licensee of The Portfolio Service Retirement Fund (TPS Super) until June 2016 when the beneficiaries and assets of TPS Super were transferred by a successor fund transfer to IPS Super. IPS Super and TPS Super were “registrable superannuation entities” for the purpose of the SIS Act: APRA’s amended statement of claim or ASOC [5]-[6], as admitted in Defences [5]-[6].

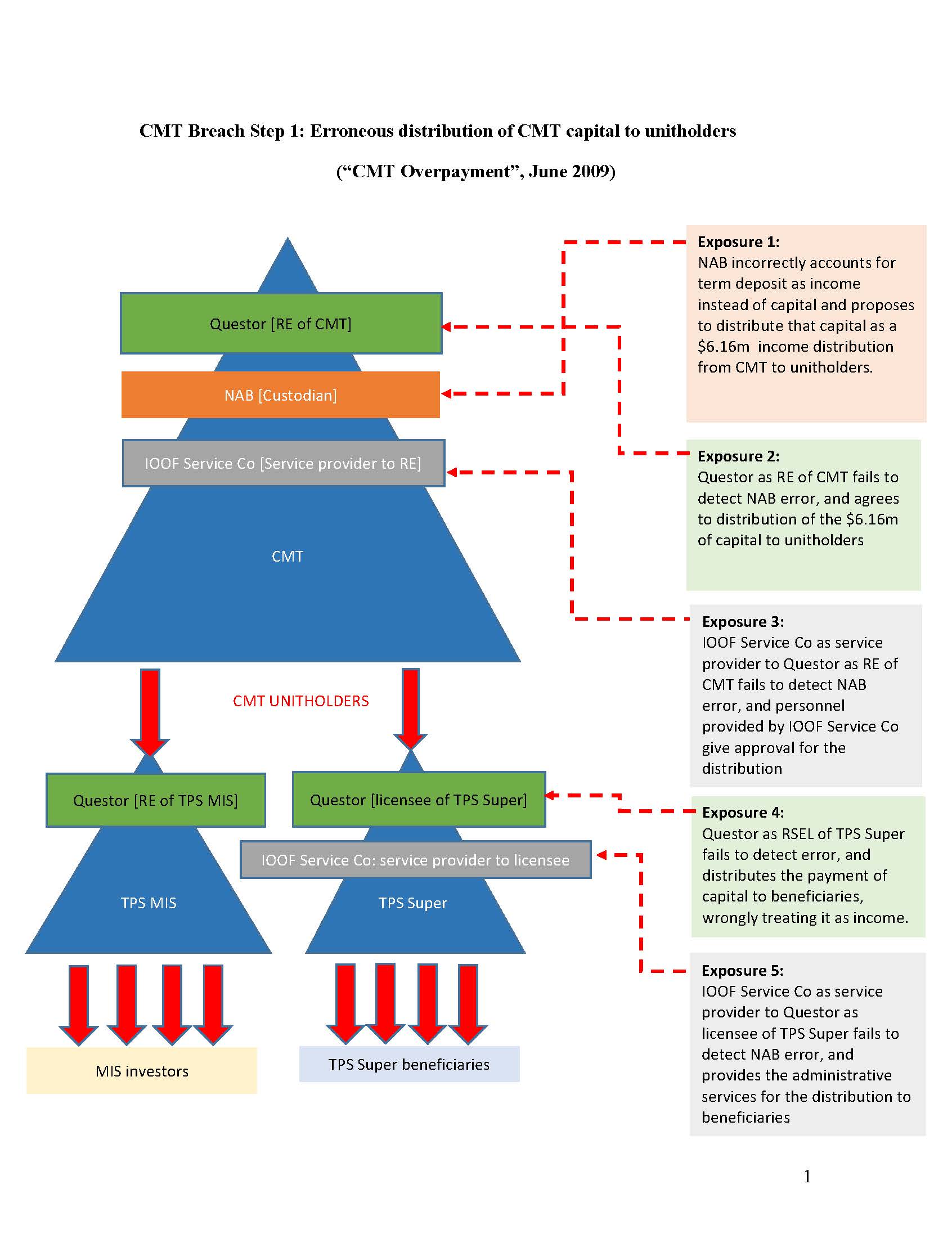

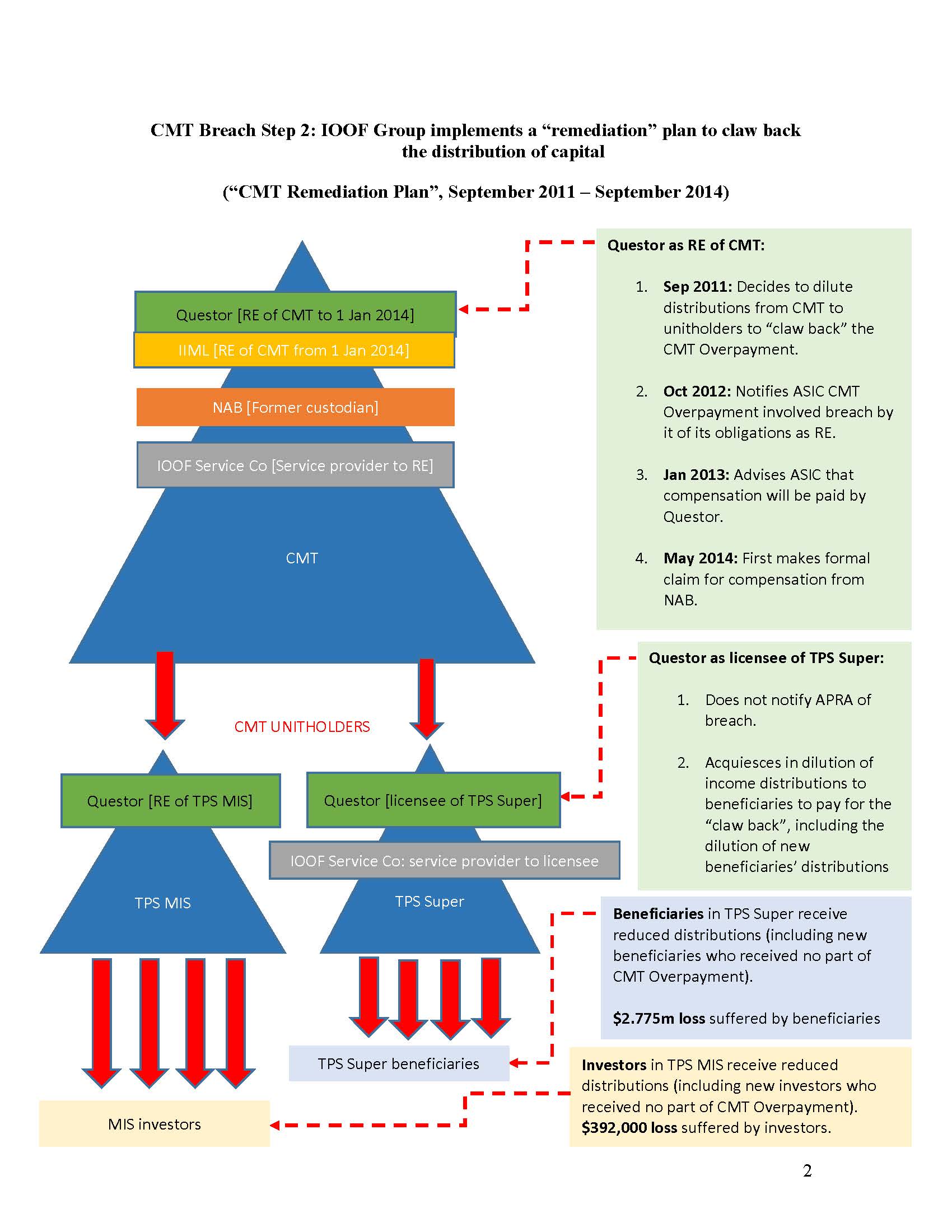

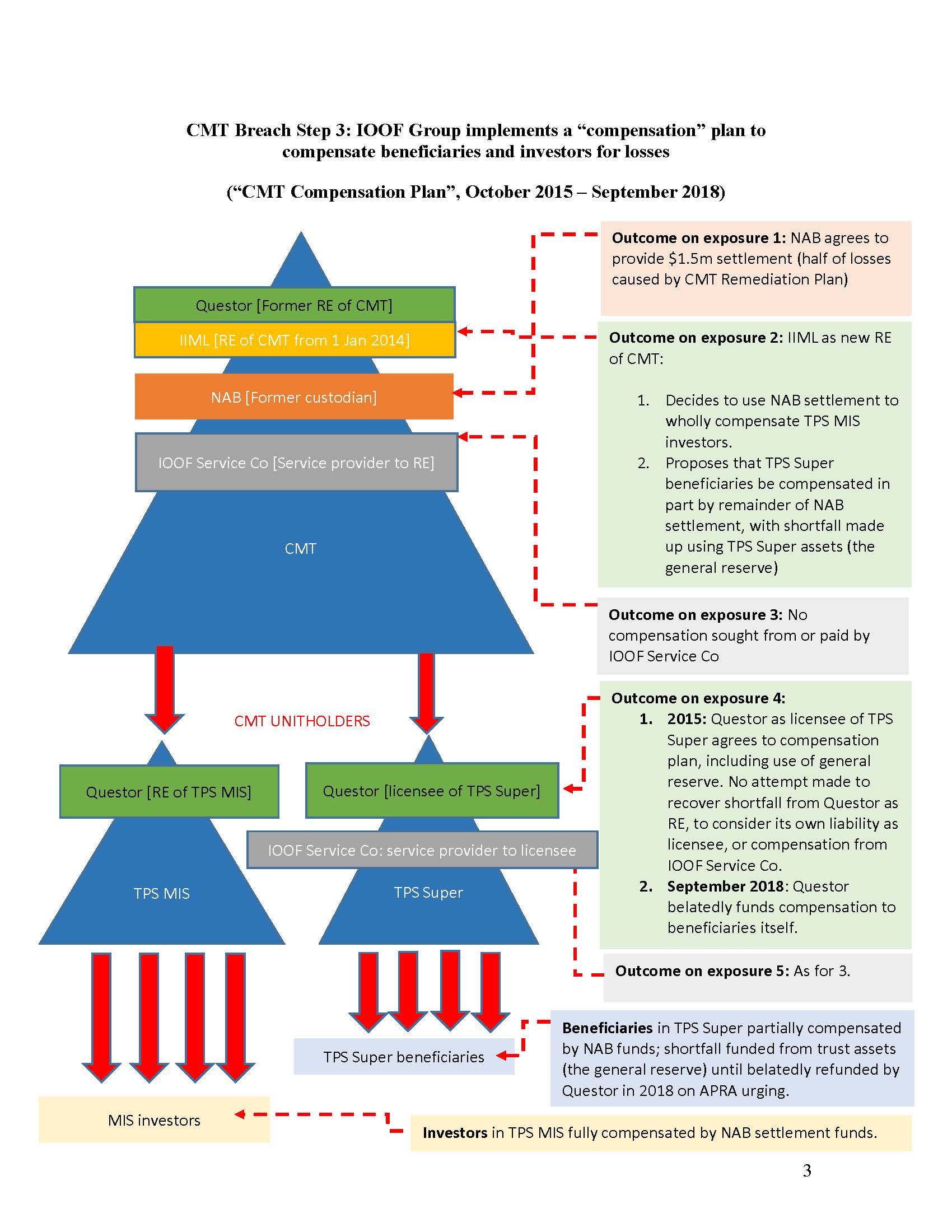

3 APRA contended that the respondents (excluding the third, fourth and fifth respondents who were not subject to these obligations) contravened various covenants imposed on them by the SIS Act, in effect, to exercise the requisite degree of care, skill and diligence, to act in the best interests of the beneficiaries of the super funds, and to give priority to the interests of the beneficiaries in the event of a conflict of interest. These contraventions were said to have occurred in the course of five incidents affecting the super funds known as CMT, Pursuit, Sweep, Bendigo and Optus.

4 APRA sought to prove its case relying solely on documents brought into existence by the respondents in connection with the incidents. As a result, there was no dispute about the primary facts. Both parties recorded the salient aspects of the facts on which they sought to rely in their written submissions. I have relied on the factual summaries of the parties as indicated in the reasons below. As will become apparent APRA relied on the IOOF documents as containing admissions against interest by the respondents including, as I would understand it, admissions of contravention of the statutory covenants. For a number of reasons I have found APRA’s approach unpersuasive. The documents were all produced with the benefit of hindsight. Apart from the opinions or conclusions expressed as to breach of the statutory covenants, the documents are expressed at a high level of generality, assuming knowledge on the part of the reader as to IOOF’s systems, policies and procedures (which remained unproved by other evidence). I also do not accept that there can be an effective admission of a legal conclusion, which is a matter for the Court based on the whole of the evidence. Even if such a statement could constitute an admission I would not be persuaded as to its reliability. It was for APRA to prove its case of contraventions by such evidence as it saw fit. The fact that it has chosen to run a purely documentary case means that it must take the documents as it finds them – as documents brought into existence for specific purposes, mostly by authors whose qualifications and experience are unknown, using the benefit of hindsight, often expressed at a high level of generality, and assuming otherwise unproven knowledge of IOOF’s systems, policies and procedures.

5 Another related, systemic weakness in APRA’s case is that it has asserted contravention of the covenants and, in so doing, has alleged defaults and inadequacies in IOOF’s systems, policies and procedures, without descending into the detail of proving the actual systems, policies and procedures in play in respect of the incidents in question. Instead it has relied on IOOF’s documents as described above which do not themselves identify those systems, policies and procedures. As one of the respondents put it, a critical plank in APRA’s case is that alleged defaults gave rise to causes of action or reasonably arguable causes of action for recovery against IOOF entities, the claims being in the nature of claims for contractual negligence, but APRA has given no attention to the kind of factors which would necessarily inform the foundation of any such claims such as the details of the actual system in existence, the nature of the default or flaw in the system, the reasonable foreseeability of that default or flaw, the reasonable availability of any alternative that might have avoided the default or flaw, and the materiality of the potential consequences of the default or flaw. Without expressly saying so APRA’s approach involved reliance on the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur when the one thing that is clear is that the facts of the incidents in question in this case by no means speak for themselves.

6 As will also become apparent, in treating the facts as if they automatically bespeak liability, APRA has effectively cast the trustees in the role of insurer to the beneficiaries, which is contrary to principle. APRA has also sought to extend legal principle by applying the kind of requirements to which a trustee is subject in deciding whether or not a beneficiary is entitled to a payment out of the trust, a circumstance in which the trustee is bound to give proper consideration to the relevant information and if necessary obtain relevant information to fulfil its trust duty, to the day-to-day decisions which a trustee of a large fund must make in the administration of the trust. APRA has not explained why this extension of legal principle is warranted and, as explained below, I am unpersuaded that it is warranted.

7 For these reasons, and as explained in more detail below, I have decided that none of APRA’s claims of contraventions of the SIS Act against the respondents are sustainable with the consequence that there is no foundation for the making of any disqualification orders and the further amended originating application should be dismissed.

2. SECTIONS 52, 55, 56 AND 57 OF THE SIS ACT

8 There is a preliminary dispute between APRA and the respondents which is fundamental to their competing cases. In short, APRA contended that despite their governing rules IIML and Questor could not be exempted from liability for contraventions of the s 52 covenants and could not indemnify themselves from the assets of the trusts in respect of liability for such contraventions. The respondents contended that the governing rules of the trusts, in conformity with the SIS Act, excluded liability for the alleged contraventions of the s 52 covenants and enabled IIML and Questor to indemnify themselves from the assets of the trusts in respect of any such liability.

9 The relevant provisions of the SIS Act include s 3, which provides that the main object of the Act is to make provision for the prudent management of, relevantly, superannuation funds.

10 Section 7 provides that:

This Act applies to a superannuation entity despite any provision in the governing rules of the entity, including any provision that purports to substitute, or has the effect of substituting, the provisions of the law of a State or Territory or of a foreign country for all or any of the provisions of this Act.

11 The “governing rules” are defined in s 10(1) to mean in relation to a fund, scheme or trust,:

(a) any rules contained in a trust instrument, other document or legislation, or combination of them; or

(b) any unwritten rules;

governing the establishment or operation of the fund, scheme or trust.

12 Part 6 contains ss 51 to 60A of the SIS Act. Section 51 provides that the object of the Part is to set out rules about the content of the governing rules of superannuation entities. Section 51A confirms that the covenants taken to be contained in the governing rules of a superannuation entity are cumulative. Section 52 contains the covenants by the trustee taken to be contained in the governing rules of a superannuation entity. Section 52A contains the covenants by the directors of a corporate trustee taken to be contained in the governing rules of a superannuation entity. Section 55 concerned the consequences of the contravention of covenants. In this regard, it should be noted that s 55(1) was repealed by the Treasury Laws Amendment (Improving Accountability and Member Outcomes in Superannuation Measures No. 1) Act 2019 (Cth) and replaced by ss 54B(1) and (2) to the same material effect. As the relevant conduct pre-dates this amendment it is the form of the Act before this amendment which is relevant.

13 Section 55 included the following provisions:

(1) A person must not contravene a covenant contained, or taken to be contained, in the governing rules of a superannuation entity.

(2) A contravention of subsection (1) is not an offence and a contravention of that subsection does no result in the invalidity of a transaction.

(3) Subject to subsection (4A), a person who suffers loss or damage as a result of conduct of another person that was engaged in in contravention of subsection (1) may recover the amount of the loss or damage by action against the other person or against any person involved in the contravention.

(4) Unless an action under subsection (3) is of a kind dealt with in subsections (4A) to (4D), it may be begun at any time within 6 years after the day on which the cause of action arose.

(4A) If:

(a) the person who is alleged to have contravened subsection (1) is or was a director of a corporate trustee of a registrable superannuation entity; and

(b) it is alleged that the contravention is of a covenant that is contained, or taken to be contained, in the governing rules of the entity, and is:

(i) a covenant of the kind mentioned in subsection 52A(2); or

(ii) a covenant prescribed under section 54A that relates to the conduct of the director of a corporate trustee of a registrable superannuation entity;

an action under subsection (3) may be brought only with the leave of the court.

(4B) A person may, within 6 years after the day on which the cause of action arose, seek the leave of the court to bring such an action.

(4C) In deciding whether to grant an application for leave to bring such an action, the court must take into account whether:

(a) the applicant is acting in good faith; and

(b) there is a serious question to be tried.

(4D) The court may, in granting leave to bring such an action, specify a period within which the action may be brought.

(5) It is a defence to an action for loss or damage suffered by a person as a result of the making of an investment by or on behalf of a trustee of a superannuation entity if the defendant establishes that the defendant has complied with all of the covenants referred to in sections 52 to 53 and prescribed under section 54A, and all of the obligations referred to in sections 29VN and 29VO, that apply to the defendant in relation to each act, or failure to act, that resulted in the loss or damage.

(6) It is a defence to an action for loss or damage suffered by a person as a result of the management of any reserves by a trustee of a superannuation entity if the defendant establishes that the defendant has complied with all of the covenants referred to in sections 52 to 53 and prescribed under section 54A, and all of the obligations referred to in sections 29VN and 29VO, that apply to the defendant in relation to each act, or failure to act, that resulted in the loss or damage.

(7) Subsections (5) and (6) apply to an action for loss or damage, whether brought under subsection (3), section 29VP or otherwise.

14 Section 56 is relevantly in these terms:

(1) Subject to subsections (2) and (2A), a provision in the governing rules of a superannuation entity is void if:

(a) it purports to preclude a trustee of the entity from being indemnified out of the assets of the entity in respect of any liability incurred while acting as trustee of the entity; or

(b) it limits the amount of such an indemnity.

(2) A provision in the governing rules of a superannuation entity is void in so far as it would have the effect of exempting a trustee of the entity from, or indemnifying a trustee of the entity against:

(a) liability for breach of trust if the trustee:

(i) fails to act honestly in a matter concerning the entity; or

(ii) intentionally or recklessly fails to exercise, in relation to a matter affecting the entity, the degree of care and diligence that the trustee was required to exercise; or

(b) liability for a monetary penalty under a civil penalty order; or

(c) the payment of any amount payable under an infringement notice; or

(d) liability for the costs of undertaking a course of education in compliance with an education direction; or

(e) liability for an administrative penalty imposed by section 166.

15 Section 57 is relevantly in these terms:

(1) Subject to subsection (2), the governing rules of a superannuation entity may provide for a director of the trustee to be indemnified out of the assets of the entity in respect of a liability incurred while acting as a director of the trustee.

(2) A provision of the governing rules of a superannuation entity is void in so far as it would have the effect of indemnifying a director of the trustee against:

(a) a liability that arises because the director:

(i) fails to act honestly in a matter concerning the entity; or

(ii) intentionally or recklessly fails to exercise, in relation to a matter affecting the entity, the degree of care and diligence that the director is required to exercise; or

(b) liability for a monetary penalty under a civil penalty order; or

(c) the payment of any amount payable under an infringement notice; or

(d) liability for the costs of undertaking a course of education in compliance with an education direction; or

(e) liability for an administrative penalty imposed by section 166.

(3) A director of the trustee of a superannuation entity may be indemnified out of the assets of the entity in accordance with provisions of the entity's governing rules that comply with this section.

16 The governing rules of the TPS trust included these provisions:

Cl 15.4: The Trustee is only liable for its acts or omissions which are dishonest or constitute an intentional or reckless failure to exercise the degree of care and diligence required of it.

Cl 15.5: the Trustee may recover from the Fund any loss or expense incurred in relation to the Fund unless:

(a) it results from the Trustee’s dishonesty or intentional or reckless failure to exercise the degree of care and diligence required of it; or

(b) the law prevents it.

17 The governing rules of the IPS trust included these provisions:

Cl 11.5: No Trustee or director of the Trustee shall be liable under any personal liability in respect of any loss or breach of trust in respect of the Fund or the benefits of a Member unless the same shall have been due to:

11.5.1 its own failure to act honestly in a matter concerning the Fund;

11.5.2 intentional or reckless failure to exercise, in relation to a matter affecting the Fund, the degree of care and diligence that the Trustee or director was required to exercise.”

…

Cl 11.7: The Trustee and the directors of the Trustee shall be indemnified out of the assets of the Fund against all liabilities and expenses incurred by them in the execution of their duties hereunder and shall have a lien on the Fund for such indemnity.

18 In support of its contentions, APRA submitted that:

(1) s 55 does not provide that it is a defence to liability to rely on an exemption or indemnity in a trust instrument;

(2) s 55 cannot be modified or excluded by a trust instrument. If it were otherwise, s 55 would not apply according to its terms as provided for in s 7;

(3) the object in s 3 reinforces this approach to the construction of s 55;

(4) s 56 preserves a trustee’s general right of indemnity out of the trust assets for liabilities incurred in the proper performance of its duties or exercise of its powers;

(5) ss 56(2) and 57(2) do not specify the universe of limitations on the provisions of a trust instrument; and

(6) the terms of the provisions, in the overall context of the SIS Act, mean that no provision of a trust instrument can purport to exclude or modify liability under s 55(3).

19 The respondents submitted that:

(1) s 56(1)(a) refers to “any liability” which is of the broadest scope and would include s 55(3) liability;

(2) s 56(1) leaves open to a trustee to agree governing rules that provide for the trustee to be indemnified for any liability, subject only to ss 56(2) and (2A);

(3) s 55(3) liability is not identified in ss 56(2) or 57(2) as a liability which cannot be excluded by a trust instrument;

(4) s 56(2) includes liability for breach of trust and thus liability to beneficiaries;

(5) the exclusion in s 56(2)(a)(1) overlaps entirely with the covenant in s 52(a) and the exclusion in s 56(2)(a)(ii) overlaps in part with the covenant in s 52(b) which demonstrates the permitted scope of an exemption from liability arising under s 55(3);

(6) if it were right that no s 55(3) liabilities could be excluded or the subject of an indemnity it would follow from s 55(1) that contravention of any covenant, not just the s 52 covenants, would be protected thereby prohibiting the ordinary right of a trustee and beneficiaries to agree to exclude a trustee’s liability for breaches of covenants contained in the trust deed; and

(7) it is wrong to say that the respondents’ construction leaves trustees free to contravene the s 52 covenants. Remedies such as an injunction may be granted to prevent or retrain a breach of a covenant.

20 I do not find resolution of this aspect of the dispute straightforward. There are what appears to be anomalies on both approaches to construction. On balance, however, I consider that APRA’s approach better reflects the provisions construed in the context of the SIS Act as a whole. This is because I consider s 7 of the SIS Act to be of fundamental importance to the resolution of this aspect of the dispute. By s 7 the SIS Act applies despite any provisions in the governing rules. Section 55(3) provided for a statutory cause of action, with its own limitation period and its own defences, which included compliance with all of the covenants in ss 52 to 53 (amongst others). If, by governing rules, a trustee may exclude liability under s 55(3) then it cannot be said that the SIS Act is being applied despite anything in the governing rules. Similarly, if, by governing rules, a trustee may indemnify itself out of the trust assets then it cannot be said that the SIS Act, specifically the statutory cause of action and limited defences, are being applied.

21 It may be accepted that s 56(1) uses the words “any liability”, but the section is to be read in harmony with ss 7 and 55. Section 56(1) is also about provisions in the governing rules which are void because they purport to preclude or limit the trustee’s right of indemnity in respect of any liability from the assets of the entity. The liability with which s 55 is concerned is that provided for in s 55(3). Section 56(1) is not purporting to operate on s 55(3). As such, it is not trespassing on the code which s 55 has created. Section 56(2), in contrast, is not a code of any kind. It is identifying some kinds of provisions of governing rules which will be void. The fact that liability under s 55(3) does not appear in the list of void provisions is immaterial. Section 55 operates according to its terms and, by s 7, despite any provision in the governing rules of a trust.

22 For these reasons, to the extent that the respondents’ defences depended on the proposition that IIML and Questor could never have been liable under s 55(3) and would have had a right of indemnity under the trust instruments for any such liability, I do not accept those defences. If my conclusion is incorrect then, as the respondents submitted, APRA’s case must fail. There is no allegation of dishonesty or an intentional or reckless failure to exercise the required degree of care, skill and diligence.

23 The conduct in issue spans the period from 2007 to 2018. Accordingly, the covenants in their form before and after 1 July 2013, when the Superannuation Legislation Amendment (Trustee Obligations and Prudential Standards) Act 2012 (Cth) came into force, are relevant.

24 APRA conveniently summarised the pre and post 1 July 2013 covenants by the trustee of a registrable superannuation entity (or RSE) as follows:

During the relevant period, the s 52 covenants [which are covenants by each trustee of a registrable superannuation entity] relevantly included covenants:

(a) s 52(2)(b) (due care, skill and diligence covenant) ASOC [25(a)], [26], [38], [39]:

[Pre-1 July 2013]: “to exercise, in relation to all matters affecting the entity, the same degree of care, skill and diligence as an ordinary prudent person would exercise in dealing with property of another for whom the person felt morally bound to provide”;

[Post 1 July 2013]: “to exercise, in relation to all matters affecting the entity, the same degree of care, skill and diligence as a prudent superannuation trustee would exercise in relation to an entity of which it is trustee and on behalf of the beneficiaries of which it makes investments”.

(b) s 52(2)(c) (best interests covenant) ASOC, [27], [39];

[Pre- 1 July 2013]: “to ensure that the trustee’s duties and powers are performed and exercised in the best interests of the beneficiaries”

[Post 1 July 2013]: “to perform the trustee’s duties and exercise the trustee’s powers in the best interests of the beneficiaries”.

(c) s 52(2)(d) (conflicts covenant) [post 1 July 2013 only] ASOC [27], [39]:1

“where there is a conflict between the duties of the trustee to the beneficiaries, or the interests of the beneficiaries, and the duties of the trustee to any other person or the interests of the trustee or an associate of the trustee:

(i) to give priority to the duties to and interests of the beneficiaries over the duties to and interests of other persons; and

(ii) to ensure that the duties to the beneficiaries are met despite the conflict; and

(iii) to ensure that the interests of the beneficiaries are not adversely affected by the conflict; and

(iv) to comply with the prudential standards in relation to conflicts”.

25 Before 1 July 2013, there was only one covenant by a director of a trustee of a registrable superannuation entity in s 52(8) requiring the director to exercise a reasonable degree of care and diligence for the purposes of ensuring that the trustee carried out its s 52 covenants.

26 After 1 July 2013, s 52A was inserted into the SIS Act which provided for covenants from each director of a corporate trustee of the entity including:

s 52A(2)(b): to exercise, in relation to all matters affecting the entity, the same degree of care, skill and diligence as a prudent superannuation entity director would exercise in relation to an entity where he or she is a director of the trustee of the entity and that trustee makes investments on behalf of the entity's beneficiaries;

s 52A(2)(c): to perform the director's duties and exercise the director's powers as director of the corporate trustee in the best interests of the beneficiaries;

s 52A(2)(d): where there is a conflict between the duties of the director to the beneficiaries, or the interests of the beneficiaries, and the duties of the director to any other person or the interests of the director, the corporate trustee or an associate of the director or corporate trustee:

(i) to give priority to the duties to and interests of the beneficiaries over the duties to and interests of other persons; and

(ii) to ensure that the duties to the beneficiaries are met despite the conflict; and

(iii) to ensure that the interests of the beneficiaries are not adversely affected by the conflict; and

(iv) to comply with the prudential standards in relation to conflicts;

s 52A(2)(f): to exercise a reasonable degree of care and diligence for the purposes of ensuring that the corporate trustee carries out the covenants referred to in section 52.

3.2 Care, skill and diligence covenant, s 52(2)(b) and s 52A(2)(b)

27 APRA submitted that IIML and Questor were professional trustees and held themselves out as such with the consequence that they should be held to a higher standard of care than that of an ordinary prudent person (that is, before 1 July 2013). APRA referred to Australian Securities Commission v AS Nominees (1995) 62 FCR 504 in which Finn J said at 516 – 517 that:

It is old and accepted law that in managing a trust business the trustee should exercise the same care as an ordinary, prudent business person would exercise in conducting that business as if it were his or her own: Speight v Gaunt (1883) 9 App Cas 1; Learoyd v Whiteley (1887) 12 App Cas 727; Knox v Mackinnon (1888) 13 App Cas 753. There is an equally well-accepted gloss on (or adjunct to) this in relation to trustee investments which is aptly described in Scott on Trusts, par 227.3 as the "requirement of caution".

…

Where the trustee is itself a company the requirements of care and caution are in no way diminished. And here, unlike with companies in general, these requirements have a flow-on effect into the duties and liabilities of the directors of such a company. It was established early - largely it would seem from case law on charitable and municipal corporations - that at least when, and to the extent that, directors of a trustee company are themselves "concerned in" the breaches of trust of their company, they are liable to the company according to the same standard of care and caution as is expected of the company itself: Charitable Corporation v Sutton (1742) 2 Atk 400; 26 ER 642; Attorney General v Wilson (1840) 10 LJ Ch 53; Joint Stock Discount Co v Brown (1869) LR 8 Eq 381; Fouche v Superannuation Fund Board (1952) 88 CLR 609.

To affirm such a limited coalescence in the standard of care of directors and trustees in the case of directors of trust companies is not to reignite the arid debate on whether directors are trustees: cf Re International Vending Machines Pty Ltd at 473; L S Sealy, "The Director as Trustee" [1967] Camb LJ 83. It is merely to say that in this context the duties of trusteeship of the company can give form and direction to the common law and statutory duties of care and diligence imposed on directors, where the directors themselves have caused their company's breach of trust: on the duty of care of directors generally, see Daniels v Anderson; Permanent Building Society v Wheeler (1994) 11 WAR 187; see also Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (Cth), s 52(8), (9).

28 At 517-518 Finn J concluded that if it were necessary to do so he would hold the trustee in that case to a higher standard of care than the ordinary prudent businessperson on the basis that the trustee was a professional trustee company holding itself out as having special or particular knowledge, skill and experience which invited “reliance upon themselves by members of the public in virtue of the knowledge, etc, they appear so to have”.

29 Further, APRA noted that in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Drake (No 2) [2016] FCA 1552; (2016) 340 ALR 75 at [273] Edelman J agreed with Finn J’s observations in AS Nominees at 517-518. His Honour said at [276] that:

…any holding out by a trustee of a special or particular knowledge, skill and experience reflects an assumption of that special degree of responsibility. Again, the question is an objective one which is based upon the circumstances of the trust deed or declaration of trust and the acceptance of the obligation by the trustee.

30 APRA also referred to Finch v Telstra Super Pty Ltd [2010] HCA 36; (2010) 242 CLR 254 in which the principles in Karger v Paul [1984] VR 161 were considered. At [28] French CJ, Gummow, Heydon, Crennan and Bell JJ identified Karger v Paul as a case involving a trustee’s discretion under a will. At [29] they contrasted that kind of power with the case at hand in which the trustee was bound to consider whether to reach opinions which determined eligibility for a benefit to be paid from the trust. While the consideration involved factors “difficult to weigh, impressions to be formed, and judgments to be made” the trustee was not exercising a discretion. Accordingly, forming the required opinion “was not a matter of discretionary power to think one thing or the other; it was an ingredient in the performance of a trust duty”: at [30]. At [66] their Honours said:

There is no doubt that under Karger v Paul principles, particularly as they have been applied to superannuation funds, the decision of a trustee may be reviewable for want of “properly informed consideration”[Kerr v British Leyland (Staff) Trustees Ltd [2001] WTLR 1071 at 1079; Stannard v Fisons Pension Trust Ltd [1992] IRLR 27 at 31.]. If the consideration is not properly informed, it is not genuine. The duty of trustees properly to inform themselves is more intense in superannuation trusts in the form of the Deed than in trusts of the Karger v Paul type. It is extremely important to the beneficiaries of superannuation trusts that where they are entitled to benefits, those benefits be paid. Here, for example, the applicant was claiming a Total and Permanent Invalidity benefit to support himself for the rest of his life. His claim depended on the formation of an opinion by the Trustee about the likelihood that he would ever engage in “gainful Work”: that was not a mere discretionary decision. In the Deed there was a power to take into account “information, evidence and advice the Trustee may consider relevant”, and that power was coupled with a duty to do so. It would be bizarre if knowingly to exclude relevant information from consideration were not a breach of duty. And failure to seek relevant information in order to resolve conflicting bodies of material, as here, is also a breach of duty. The Scheme is a strict trust. A beneficiary is entitled as of right to a benefit provided the beneficiary satisfies any necessary condition of the benefit

31 As noted above, a consistent theme of APRA’s case is its attempts to draw an analogy between the kind of decision with which Finch v Telstra was concerned and the kinds of decisions which the trustees were making in the present case. As will become apparent, I am not persuaded that the analogy is sustainable.

32 APRA also noted Apostolovski v Total Risk Management [2010] NSWSC 1451; (2010) 79 NSWLR 432 in which Gzell J said:

21 A trustee’s duties under a superannuation deed were limited by McLelland J to those applicable to the exercise by a trustee of discretionary powers in Rapa v Patience, NSWSC, unreported, 4 April 1985. His Honour adopted what had been said by McGarvie J in Karger v Paul [1984] VR 161 about the challenge to a trustee’s exercise of discretionary power.

22 In Karger a testatrix left her entire estate to her husband during his lifetime with power in her trustees in their absolute and unfettered discretion, upon the request of the husband, to pay or transfer the whole or part of the capital of the estate to the husband for his own use absolutely. Upon the death of the husband the trustees were to pay the residue to the plaintiff for her own use absolutely. The husband and the testatrix’s solicitor were the trustees. The husband made a written request to pay the entire capital of the estate to him and he and his co-trustee acceded to the request.

23 At 164 McGarvie J said that the issues examinable by the court were limited to whether there had been a failure to exercise the discretion in good faith, upon real and genuine consideration and in accordance with the purposes for which the discretion was conferred. In short, the court examines whether the discretion was exercised but does not examine how it was exercised.

24 In Rapa, McLelland J adopted this approach with respect to a claim by an employee for breach of duty by the trustee of a superannuation fund for failing to allow his claim for total and permanent disablement. His Honour said:

“The grounds on which the performance by trustees of functions such as these may be successfully challenged are those applicable generally to the exercise by trustees of discretionary powers, helpfully discussed by McGarvie J in Karger v Paul (1984) VR 161. As encapsulated by his Honour in that case there are three such grounds and in some circumstances a fourth. They are, first, that the discretion was not exercised by the trustees in good faith, second, that the discretion was not exercised upon real and genuine consideration (which includes consideration of the wrong question - see Scott on Trusts 3rd ed. Vol. 3, para. 187.3), third, that the discretion was not exercised in accordance with the purposes for which it was conferred and, fourth, where the trustees have disclosed (otherwise than in the course of the proceedings in which the discretion is challenged) the reasons for the exercise of their discretion that those reasons are not sound.”

25 As Ormiston JA remarked in Telstra Super Pty Ltd v Flegeltaub [2000] VSCA 180; (2000) 2 VR 276 at 278 [6] it seems to have been assumed since the decision in Rapa that similar restrictions to those discussed in Karger apply to the formation of opinions as to the qualification of a beneficiary for benefit under a superannuation trust deed.

26 Judicial dissatisfaction with such limitations has been expressed from time to time (Vidovic v Email Superannuation Pty Ltd, NSWSC, unreported, 3 March 1995; Flegeltaub at 277 [4], 283 [25] and 284-285 [33]; Jeffrey Guy Baker v Local Government Superannuation Scheme Pty Ltd [2007] NSWSC 1173 at [8]; John Gilberg v Stevedoring Employees Retirement Fund Pty Ltd [2008] NSWSC 1318 at [18]; Kowalski v MMAL Staff Superannuation Fund Pty Ltd (No 3) [2009] FCA 53 at [25]; Tuftevski v Total Risk Management Pty Ltd [2009] NSWSC 315 at [128]).

27 In Finch v Telstra Super Pty Ltd [2010] HCA 36; (2010) 84 ALJR 726 the High Court recently held that a decision that a person was entitled to payment out of a superannuation fund for total and permanent invalidity was not a discretionary decision in the sense used in Karger. A decision whether a member of such a fund was unlikely ever to engage in gainful work was an ingredient in the performance of a trust duty.

…

28 Here the fault was not to fail to take relevant information into account: it was to fail to act with reasonable dispatch. But, in my view, that also is a breach of fiduciary duty by Total Risk as trustee of the Fund.

29 In Finch there was no discussion of an award of damages against the trustee. But a trustee must bring to his or her office the same degree of care, skill and diligence as an ordinary prudent person would exercise in performing the duties of a trustee and to fail or exercise that degree of care, skill and diligence constitutes a breach of fiduciary duty.

30 In Government Employees Superannuation Board v Martin (1997) 19 WAR 224 at 273 Ipp J said as much:

“It was the duty of the Board to preserve the trust property (the fund) and observe the terms of the trust. In managing the fund, the Board was required to exercise the same diligence and prudence as an ordinary prudent man of business would exercise in conducting that business if it were his own: see Austin v Austin (1906) 3 CLR 516; Fouche v Superannuation Fund Board (1952) 88 CLR 609 at 641. The duty so imposed is an equitable one: see Permanent Building Society v Wheeler (1994) 11 WAR 187 at 237.”

31 In Austin the High Court held that it was the duty of a trustee, in managing the trust affairs, to take those precautions which an ordinary man of business would take in managing similar affairs of his own. In Fouche at 641 the Court said that the duty of a trustee of a superannuation fund was a duty of reasonable care – care which an ordinary prudent man of business would take.

32 In my view, by at least 7 September 2007 Total Risk as trustee, through its servants or agents managing the Fund, had failed to exercise that degree of care, skill and diligence that an ordinary prudent person would exercise in the circumstances.

33 APRA said that the equivalent duty of directors to exercise due care, skill and diligence is analogous to that of directors of corporations to “take reasonable steps to place themselves in a position to guide and monitor the management of the company”. A director cannot necessarily avoid liability merely by relying on conduct of officers of the corporation: Daniels v Anderson (1995) 37 NSWLR 438 at 501-503. Further, as Finn J explained in AS Nominees at [517], the duties of trusteeship can give form and direction to the common law and statutory duties of care and diligence imposed on directors. APRA said that this duty may be heightened where there is a conflict of interest, referring to the statement of Santow J in HIH Insurance Limited (in prov liq) v Adler [2002] NSWSC 171; (2002) 41 ASCR 72 at [372(14)] that:

Where there is a transaction involving the potential for conflict between interest and duty, as here arose, the duty of care and diligence falls to be exercised in a context requiring special vigilance, calling for scrupulous concern on the part of those officers who become aware of that transaction to ensure that any necessary corporate approvals are obtained and safeguards put in place. While the primary responsibility will fall on the director or officer proposing to enter into the transaction, this does not excuse other directors or officers who become aware of the transaction.

34 APRA referred also to Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Healey [2011] FCA 717; (2011) 196 FCR 291 where Middleton J said:

18 A board should be established which enjoys the varied wisdom, experience and expertise of persons drawn from different commercial backgrounds. Even so, a director, whatever his or her background, has a duty greater than that of simply representing a particular field of experience or expertise. A director is not relieved of the duty to pay attention to the company’s affairs which might reasonably be expected to attract inquiry, even outside the area of the director’s expertise.

19 The words of Pollock J in the case of Francis v United Jersey Bank (1981) 432 A 2d 814 (1981), quoted with approval by Clarke and Sheller JJA in Daniels v Anderson (1995) 37 NSWLR 438, make it clear that more than a mere ‘going through the paces’ is required for directors. As Pollock J noted, a director is not an ornament, but an essential component of corporate governance.

…

170 …In Vines v Australian Securities and Investments Commission (2007) 62 ACSR 1, Santow JA (who dissented on the facts but not on principle) clarified the position as follows (at [731]):

The degree of an officer’s permissible reliance on others will turn on similar considerations as those that determine the overall standard of care for an individual director. They focus particularly on the characteristics of the company, the skills and experience of the officer concerned and the delegate, and the reasonably anticipated risks entailed in so doing. What is expected here is a level of scrutiny as befits supervision, not the detailed direct involvement that is associated with operational responsibility. Where there is no cause for suspicion nor circumstances demanding critical and detailed attention, it is reasonable for an officer to rely on advice, without independently verifying the information or scrutinising the data or circumstances upon which that advice is based: see Re HIH Insurance Ltd (in prov liq); ASIC v Adler (2002) 168 FLR 253; 41 ACSR 72; [2002] NSWSC 171 at [372].

171 The position of non-executive directors (as distinct from directors in general) has also been the subject of judicial consideration. In ASIC v Macdonald, Gzell J noted at [255] that:

While Clarke and Sheller JJA in Daniels rejected the test propounded by Rogers CJ Comm Div for the limit of a director’s entitlement to rely on management, they did recognise that the role of a non-executive director was to guide and monitor the management of the company rather than to be involved at an operational level.

172 It is clear that an objective standard of care is applicable to both executive and non-executive directors.

173 This approach to the standard of care has been adopted by the case law. An example of such is found in Gamble v Hoffman (1997) 24 ACSR 369. The court refused to subjectify the standard of care to (namely, in that case) the standard of a person who “left school at the age of 14 years, has no tertiary qualifications and has spent his life…essentially as a fruit and vegetable market gardener”. The court, at [373], rejected the assertion that:

[S]ubjective considerations of that nature and extent should affect the minimum content of the duty or standard of care required of the respondents in this matter…

…

[T]he ambit of the duty and the standard of care depend on particular circumstances. However, the test is essentially objective that is did the officer exercise the degree of care and diligence that a reasonable person in a like position in a corporation would exercise in the corporation’s circumstances? I doubt whether the factors which Mr Bates advanced would justify a lower standard of care.

174 In this proceeding, the directors’ responsibilities and duties were outside the realm of operational responsibility. ASIC does not contend that the directors needed to be involved at “an operational level”. This is not a case concerning the need to verify information or scrutinise data of a type outside each director’s own knowledge. The salient feature here is that each director armed with the information available to him was expected to focus on matters brought before him and to seriously consider such matters and take appropriate action. This task demands critical and detailed attention, and not just ‘going through the motions’ or sole reliance on others, no matter how competent or trustworthy they may appear to be.

175 Directors cannot substitute reliance upon the advice of management for their own attention and examination of an important matter that falls specifically within the Board’s responsibilities as with the reporting obligations. The Act places upon the Board and each director the specific task of approving the financial statements. Consequently, each member of the board was charged with the responsibility of attending to and focusing on these accounts and, under these circumstances, could not delegate or ‘abdicate’ that responsibility to others.

35 APRA submitted that:

(1) “Under s 52A, as with s 180(1) of the Corporations Act [2001 (Cth)], directors cannot substitute reliance upon the advice of management for their own attention and examination of an important matter that falls specifically within the directors' responsibilities, such as a compensation plan for beneficiaries: cf ASIC v Healey at [170], [171] and [175]”.

(2) “…the Court would not accept that blind reliance on management could discharge [a director’s] duties under s 52(8) (prior to 1 July 2013) and s 52A in circumstances where, to [the director’s] knowledge, those very executives and lawyers had a conflict of interest or duty and the decision in question concerned one of the core functions of the trustee, namely, protecting the trust estate from being dissipated”.

(3) “…the issue of the appropriate approach to rectification of breaches and the use of beneficiaries’ reserves were matters that should have ‘attract[ed] inquiry’ of Kelaher and Venardos”.

(4) “It is relevant to observe that neither Kelaher nor Venardos has chosen to give evidence in these proceedings. To make out a defence based on reasonable reliance on management the Court would need to make factual findings as to the state of mind of those directors. The Court should be cautious in making such findings in the absence of evidence and in circumstances where the one person who could give that evidence had deliberately chosen not to do so.”

36 The respondents submitted that the higher standard of care of a prudent superannuation trustee was introduced only by the 1 July 2013 amendments to the SIS Act. Before those amendments the statutory standard of care was the ordinary prudent person. Accordingly, care must be taken to ensure that the higher standard of care is not imposed on conduct occurring before 1 July 2013. They referred to Manglicmot v Commonwealth Bank Officers Superannuation Corporation Pty Ltd [2011] NSWCA 204; (2011) 282 ALR 167 at [120] in which the New South Wales Court of Appeal held that the pre-1 July 2013 statutory formula did not “materially add to… [the] general law duty to exercise reasonable care”.

37 I agree that in the face of the clear words of the SIS Act before and after 1 July 2013 it would be wrong to impose any standard on conduct which occurred before 1 July 2013 other than the ordinary prudent person standard. The higher standard of the prudent superannuation trustee applies only to conduct after 1 July 2013.

38 The respondents submitted that the circumstances of each alleged breach are critical. The question will always be whether what was done satisfied the relevant standard of care, skill and diligence in the particular circumstances. This question is to be answered prospectively and without the benefit of hindsight: Elder’s Trustee and Executor Co Ltd v Higgins (1963) 113 CLR 426 at 448. I agree also with this submission. It is the particular circumstances of the conduct which will be determinative. For example, it is not possible to characterise the issue of a “compensation plan” as a non-operational matter divorced from the particular circumstances as they existed at the relevant time.

39 The respondents referred to the fact, which I accept, that a trustee’s duty does not amount to a duty to avoid all loss and that an ordinary prudent person (and for that matter prudent superannuation trustee) can commit errors of judgement without being liable: In re Chapman [1896] 2 Ch 763 at 765; Jacobs’ Law of Trusts in Australia (8th ed, 2016), at [17]-18].

40 The respondents said, and I accept, that the post-1 July 2013 higher standard of care does not convert a superannuation trustee into a surety of no loss and does not involve strict liability.

41 I accept also that APRA’s submission that “[i]t is no longer the law that directors can rely upon officers without verification” goes too far. As the first respondent submitted there are many circumstances in which a director is entitled to rely on management provided that there are not circumstances from which the director knew or ought reasonably to have known that such reliance was misplaced: Healey at [37], [170] and [174]. As the second respondent submitted:

In Re HIH Insurance; ASIC v Adler (2002) 41 ACSR 72, Santow J observed at 167 that “at general law, a director is entitled to rely without verification on the judgment, information and advice of management and other officers appropriately so entrusted” unless “the directors know, or by the exercise of ordinary care should have known, any facts that would deny reliance on others.” Similarly, in ASIC v Healey (2011) 196 FCR 291, Middleton J noted that “[w]hile directors are required to take reasonable steps to place themselves in a position to guide and monitor the management of the company, they are entitled to rely upon others, at least except where they know, or by the exercise of ordinary care should know, facts that would deny reliance” (at [167]).

Further, in Morley v ASIC (2010) 81 ACSR 285, the NSW Court of Appeal recognised at [807] that a “non-executive director may be reliant on management and other officers to a greater extent than an executive director.”

42 I do not accept APRA’s attempt to label “compensation plans” as matters uniquely within the sphere of responsibility of the directors. As the second respondent submitted:

This is a mischaracterisation of Healey, which was concerned with the particular responsibility directors have for a company’s financial reports. The relevant extract of the judgment on which APRA seeks to rely states that directors could not substitute reliance upon others:

“…for their own attention and examination of an important matter that falls specifically within the Board’s responsibilities as with the reporting obligations. The Act places upon the Board and each director the specific task of approving the financial statements. Consequently, each member of the Board was charged with the responsibility of attending to and focusing on these accounts and, under these circumstances, could not delegate or ‘abdicate’ responsibility to others.”

That this obligation is a matter that falls specifically within the Board’s responsibilities is expressly provided for in s 295(4) of the Corporations Act.

The compensation plans in these proceedings are not “matters that fall specifically within the Board’s responsibilities as with the reporting obligations.” There is no provision in the SIS Act, analogous to s 295(4) of the Corporations Act, which provides that the compensation plans are specifically the responsibility of the board.

43 It may be accepted that, as APRA said, “IOOF’s Delegated Authority Policy (CB F6/84A, p. 1703_0011) provided that officers only had delegated authority to approve a compensation plan of up to $500,000 without recourse to the Board. Other than the [so-called] Bendigo Failure, all of the compensation plans in issue in these proceedings were for amounts greater than $500,000”. But this does not mean that the directors were disentitled from relying on the information that the management provided to them in respect of the compensation plans. As was submitted for Mr Venardos:

APRA has neither alleged, nor proved, that IOOF’s management was dishonest or incompetent. Nor has APRA alleged or proved that the legal advice given by Mr Riordan and Mr Vine as to the ability of the companies to access the reserves or pursue other sources of compensation was wrong or given in bad faith. Furthermore, as officers and employees of IOOF Service Co, each of Mr Riordan and Mr Vine assisted the trustee companies to give primacy to the interests of beneficiaries. There was nothing to suggest they were not familiar with that responsibility or to suggest to the board that they were acting in dereliction of their duties.

There is also no evidence that Mr Venardos knew facts or ought to have known facts which would deny reliance on management. To the contrary, the evidence is that each of Mr Coulter, Mr Riordan and Mr Vine were skilled and experienced in their respective fields, as were the members of the Rectifications Committee:

(a) Mr Coulter was appointed the Chief Financial Officer of IOOF in 2009. He has over 25 years’ experience having worked at JP Morgan, ANZ, Colonial and PwC.

(b) Mr Riordan is the Group General Counsel. In that role, he is responsible for, among other things, the provision of internal and external legal, risk and compliance services across the IOOF Group. This includes the provision of internal and external legal advice, ensuring that IOOF’s business practices are both legally enforceable and defensible, and ensuring the Board is informed of “significant regulatory contact”. Mr Riordan has more than 25 years’ experience in financial services, trustee services and governance. Prior to joining IOOF in 2009, he was a partner at the law firms Holding Redlich and Cornwall Stodart.

(c) Mr Vine is the Group General Manager of Legal, Risk and Compliance and reports to Mr Riordan. Among other duties, Mr Vine is responsible for the provision of legal advice and for ensuring IOOF and its subsidiaries comply with its obligations. Mr Vine has more than 20 years’ experience and prior to joining the IOOF Group in August 2014, he held in-house legal and governance roles at AXA, Bell Potter and Telstra.

(d) The Rectifications Committee was a management committee formed in the first half of 2015. It comprised key management stakeholders and management experts from the Compliance, Fund Accounting, Operations and Tax teams, with the stated purpose of facilitating the payment of compensation to affected members and investors.

44 The first respondent submitted that “the assessment of what was required of the trustee and the directors to discharge their obligation to act with due care, skill and diligence necessarily must also take account of the scale of the superannuation trusts and the relevantly immaterial amounts at issue, and the other tasks to which IIML, Questor and their directors had to attend in managing the superannuation trusts”. I accept that all relevant circumstances must be taken into account and that the materiality of the amounts involved is one such consideration. As the first respondent submitted:

In the present case, the assessment of what was required of the trustee and the directors to discharge their obligation to act with due care, skill and diligence necessarily must also take account of the scale of the superannuation trusts and the relevantly immaterial amounts at issue, and the other tasks to which IIML, Questor and their directors had to attend in managing the superannuation trusts. APRA does not do this; instead, it invites the Court to review the decisions in a vacuum. That is a legally wrong approach.

For example, as at 30 June 2015, the size of the IPS Super fund was approximately $5.15 billion, and its ORFR reserve was approximately $10.17 million. It was in these circumstances that, on 27 May 2015, the Board of IIML considered the recommendation of management to pay compensation to superannuation members in connection with the Pursuit incident in an amount of $696,436.06, representing 0.00014% of the total fund and less than 7% of the ORFR. While superannuation trustees are doubtless required to exercise due care, skill and diligence in relation to all trust monies, it is uncommercial, unreasonable and unrealistic to suggest that a prudent superannuation trustee or its directors would engage in lengthy and detailed investigation, deliberation and cogitation where the amounts at issue were relevantly immaterial to the proper and sound functioning of the superannuation trust as a whole.

45 This is not to say that the content of the duty of due care, skill and diligence is to be assessed by merely comparing the amounts in issue with the amounts in the fund as a whole. Nevertheless, the size of the fund and the size of the losses, which APRA alleges beneficiaries had to be compensated for, is a critical part of the relevant context. Given that APRA’s case depends on the existence of reasonably arguable causes of action for liability on the part of the trustees and IOOF Service Co, by analogy, the full range of considerations which would inform a case in negligence would be relevant to any evaluation of the existence of the putative causes of action. APRA’s case, however, eschews any such detail, instead relying on the fact of an event and loss, along with the purported admissions, to make good its proof. As will become apparent, this approach is insufficient.

46 For these reasons while I do not accept the first respondent’s submission that I should be slow to conclude that any respondent fell below the relevant standard of care merely because APRA did not call expert evidence to this effect, expert evidence not being essential, there does need to be proof of facts from which a rational conclusion may be drawn that there has been a failure to measure up to the standard of care required. APRA’s case, as will be explained, fails at the hurdle of proof.

3.3 Bests interests of beneficiaries, s 52(2)(c) and s 52A(2)(c)

47 APRA referred to Manglicmot at [121] where Giles JA (with whom Young JA and Whealy JA agreed) said:

Nor in my opinion does s 52(2)(c) materially add to breach by the respondent of its general law duty to act in the best interests of members of the Fund. The respondent's general law obligation could be expressed, in the language of s 52(2)(c), as an obligation to perform and exercise its duties and powers in the best interests of the beneficiaries. The words "to ensure" add nothing; an obligation is an obligation. Again, the respondent was exercising a discretionary power, and "to ensure" does not turn the question of exercise of a discretionary power into one of strict liability. There is liability if the discretionary power is exercised improperly, but otherwise there is not.

48 APRA observed that while Finch v Telstra did not concern the best interests covenant the High Court “was emphatic that the superannuation context is relevant to the construction of a trustee’s duties and obligations”, saying:

33 Another aspect of the factual context is that the Deed is dealing with the superannuation of employees. For some people, superannuation is their greatest asset apart from their houses; for others it is even more valuable. Different criteria might be thought to apply to the operation of a superannuation fund from those which apply to discretionary decisions made by a trustee holding a power of appointment under a non-superannuation trust. Employer superannuation is part of the remuneration of employees. Membership of the employee superannuation fund may be compulsory. Superannuation, unsurprisingly, is a matter of trade union interest. The question of superannuation entitlements may form the subject of an industrial dispute within the meaning of s 51(xxxv) of the Constitution. Superannuation is not a matter of mere bounty, or potential enjoyment of another's benefaction. It is something for which, in large measure, employees have exchanged value – their work and their contributions. It is "deferred pay". These are propositions which are not falsified by arguments advanced by the Trustee to the effect that the Death and Total and Permanent Invalidity benefits under the Deed involve in part an element of bounty. Superannuation is a method of attracting labour. The legitimate expectations which beneficiaries of superannuation funds have that decisions about benefit will be soundly taken are thus high. So is the general public importance of them being sound.

34 A further factor is the public significance of superannuation. The federal government has attempted to reduce outflows by reducing the dependence of retired persons on the old-age pension funded out of general revenue. The taxation concessions now provided pursuant to Pt 3-30 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) are designed to encourage citizens to make provision for their retirement by investing in superannuation and to encourage their employers to create superannuation funds in their favour. The Parliament also has required employers to contribute a certain percentage of the employee's salary for these purposes. Partly as a result, large amounts of assets are administered by the trustees of superannuation funds.

49 I accept APRA’s submission that this context informs the application of the best interest covenant. APRA said:

…the application of the requirement that the trustee “do the best they can for the benefit of their beneficiaries and not merely avoid harming them”: Cowan v Scargill [1985] Ch 270 at 295, referred to with approval by Byrne J in Invensys Australia Superannuation Fund Pty Ltd v Austrac Investments Ltd [2006] VSC 112; 198 FLR 302 at [107]. The “best interests” are those of present and future beneficiaries, and the trustee is required to hold “the scales impartially between different classes of beneficiaries”: Cowan v Scargill at 286-287. As Megarry V-C observed, “When the purpose of the trust is to provide financial benefits for the beneficiaries, as is usually the case, the best interests of the beneficiaries are normally their best financial interests”: at 287. Consequently, applied to a power of investment (which was the subject matter of Cowan v Scargill), the power was required to be “exercised so as to yield the best return for the beneficiaries, judged in relation to the risks of the investments in question; and the prospects of the yield of income and capital appreciation both have to be considered in judging the return from the investment”.

By parity of reasoning, the trustee’s best interests obligation when applied to the duty to get in the trust property and to protect and vindicate the rights attaching to it (CGU Insurance Limited v One.Tel Ltd (in liq) (2010) 242 CLR 174 at [36]; Fischer v Nemeske Pty Ltd (2016) 257 CLR 615 at [11]) requires, in the superannuation context, that the trustee seek to achieve the best outcome for the capital of the fund, judged in relation to the risks of particular action and the prospects that it might provide a partial or complete recovery of funds for the trust.

50 APRA submitted that the trustee’s duty to inform itself properly is also relevant, citing Commonwealth Bank Officers Superannuation Corporation Pty Ltd v Beck & Anor [2016] NSWCA 218 at [137] - [140]. At [137] Bathurst CJ said:

137. In Finch, the Court left open the application of Karger v Paul principles to superannuation funds: at [64]. However, it emphasised that so far as they may apply, the decision may be reviewable for want of properly informed consideration: at [66]. The importance of this matter in the context of superannuation funds was explained by Nettle JA in Alcoa of Australia Retirement Plan Pty Ltd v Frost [2012] VSCA 238; 36 VR 618 at [59] in the following terms (Redlich JA and Davies AJA agreeing):

“With respect, I entirely agree with his Honour. As the decision in Finch has enabled us better to understand, trustees of superannuation funds are no longer to be conceived of in the same way as custodians of charitable or family settlements through the exercise of whose absolute discretion settlors have chosen to channel their beneficence. The economic, industrial and ultimately social imperatives which inform the advent of the superannuation industry, not to mention that beneficiaries of the kind with which we are concerned in one way or the other invariably purchase their entitlements, are productive of legitimate expectations which the law will enforce. Superannuation fund trustees are bound to give properly informed consideration to applications for entitlements and, if that necessitates further inquiries, then they must make them.”

51 On this basis APRA submitted that:

In Finch v Telstra the High Court stated that that duty “is more intense in superannuation trusts” than in trusts of the type discussed in Karger v Paul [1984] VR 161: at [66]. If the consideration is not “properly informed, it is not genuine”: at [66]. Knowingly to exclude relevant information from consideration is a breach; so too is a failure to seek relevant information in order to resolve conflicting bodies of material: at [66]. By parity of reasoning to Cowan v Scargill, the trustee’s best interests obligation when applied to the duty of trustees properly to inform themselves requires the trustee properly to inform itself of all relevant information affecting the financial interests of members in the preservation and maximisation of the capital of the trust, and where it is not available, to seek it.

52 In other words, APRA sought to extend the principle applying to decisions about entitlements to any and all matters potentially affecting the capital of the trust. There must be a myriad of decisions taken every day by trustees of large superannuation funds which potentially affect the fund both materially and immaterially. The extension of the principle which APRA proposes appears onerous in the extreme and highly impractical.

53 APRA said this principle answered a submission that there will be no breach of the best interests covenant if the “act or omission can be objectively supported, no matter that the subjective decision-making process of the trustee was defective”. I disagree. A decision which is taken to ensure and is objectively in the best interests of beneficiaries at the time it is made does not lose that character because, at that time, more information could have been obtained.

54 APRA said that it “may be that the contravention of the best interests covenant, and hence s 55(1) of the Act, does not also sound in loss sufficient to accrue a statutory cause of action for members and a liability of the trustee to compensate such persons for loss or damage, but that is a different thing from whether it founds a contravention by a superannuation trustee of its statutory obligation in s 55(1) of the Act”. As APRA put it:

There will be a breach of the obligation if the exercise of the power in issue or performance of a duty, or the failure to exercise a power or perform the duty, could not reasonably be regarded as in the best interests of beneficiaries. This is not to suggest that there is, in every case, only one possible course of action that is in members’ “best interests”. APRA agrees with the submission made by the 4-7th R OS [25], there will often be more than one course of action that could be regarded as being in the “best interests of members”, and in some cases, a decision “either way” might be capable of being regarded as “objectively right” (citing Nestle v National Westminster Bank [1993] 1 WLR 1260 at 1270. That is why the focus of the inquiry, and how APRA has framed its case, is always on whether the decisions actually made by the trustees, their directors and their responsible officers “could not reasonably be regarded as in the best interests of members”…

55 This much may be accepted. It will frequently be the case that there is more than one course of action which may be regarded as being in the best interests of the beneficiaries. The test is objective and is to be applied prospectively, that is, from the position of the trustee at the time of the decision, without impermissible hindsight.

56 APRA also cited the first instance decision of Rein J in Manglicmont v Commonwealth Bank Officers Superannuation Corporation Pty Ltd [2010] NSWSC 363; (2010) 239 FLR 159 at [51] that:

I do not accept that the trustee is made liable for any outcome which turns out to be unbeneficial to members, even if the original decision which led to that outcome was taken with the best interests of all members in mind. Another way of describing this approach is to say that s 52(2) is concerned with process, not outcome.

57 APRA noted the observations of the New South Wales Court of Appeal in Manglicmont at [104]-[105] and Mercer Superannuation (Australia) Limited v Billinghurst [2017] FCAFC 201; (2017) 255 FCR 144 at [38] in support of its submission that the distinction between “process” and “outcome” is apt to distract from the core question. As APRA put it:

A course of conduct that later turns out to have been unbeneficial to members’ interests is not a breach of s 52(2)(c) because of how events in fact play out. The converse is also true: a course of conduct that, assessed by reference to the time it was made, involved conduct that was not in the best interests of beneficiaries is not rendered otherwise because of how events in fact play out. Section 52(2)(c) is agnostic in both cases to hindsight developments; it focuses on whether the conduct or course of conduct was or was not capable of being described, at the time it was done or engaged in, as “in the best interests of beneficiaries”.

58 Again, so much may be accepted, but this does not mean that the mere fact further information could have been obtained at the time of the impugned decision necessarily means that the trustee has breached the best interests covenant.

59 APRA also relied on Mercer per Flick and Kerr JJ at [62] to support the submission that “this Court has recognised that s 52(2)(c) requires trustees to make enquiries and, even in cases where liability is not clear-cut, to seek to obtain through negotiation an outcome in the best interests of beneficiaries having regard to the possibility that a third party has an exposure to contribute monies to the assets of the fund”. I am unable to draw the same principle from Mercer. As far as I am aware, there is no authority that supports this proposition as some form of rigid principle which is to be applied irrespective of the circumstances of the particular case.

60 The fourth to seventh respondents described APRA’s submissions about the best interests covenant as “incoherent” noting that in some respects the submissions were orthodox and in others sought to expand the scope of the covenant, particularly in relation to the concept of the alleged duty of the trustee to properly inform itself. This submissions accords with the views I have expressed above, in particular relating to APRA’s approach to the principles in Finch v Telstra.

61 The fourth to seventh respondents also disputed APRA’s approach to the decision-making of a trustee citing Cowan v Scargill [1985] 1 Ch 270 at 294 that:

If trustees make a decision upon wholly wrong grounds, and yet it appears, from matters which they did not express or refer to, that there are in fact good and sufficient reasons for supporting their decision, then I do not think that they would incur any liability for having decided the matter upon erroneous grounds; for the decision itself was right.

62 As the fourth to seventh respondents put it (my emphasis):

Once it is appreciated that the power or duty in relation to which the “best interests” obligation arises is the obligation to vindicate the rights attaching to trust property, it is clear that the relevant question can only be whether the trustees’ decisions to pursue alternative sources of compensation are objectively capable of being supported. APRA’s attempts to convert the inquiry mandated by the “best interests” obligation into one concerned with “process”, rather than “action”, should be rejected.

The observations in the cases to which APRA refers in its submissions at [51]-[52] reinforce, rather than undermine this point. Indeed, the point being made in Mercer Superannuation (Australia) Ltd v Billinghurst (2007) 255 FCR 144 at [38] was that flaws in the decision-making process were only relevant to the extent that they produced a flawed decision.

63 Subject to one matter I find the respondents’ submissions in this regard persuasive. I would not, however, exclude from breach of the best interests covenant a case in which it is proved that the trustee’s subjective purpose or object in acting was contrary to the best interests of the beneficiaries.

64 It will also be apparent that the reference in Cowan v Scargill is to the existence of circumstances at the time of the decision to which the decision-maker had no apparent regard. The reference does not suggest that a decision which was in breach of the duty by reference to existing circumstances can be transformed into a decision not in breach of the duty by subsequent events. The “good and sufficient reasons” in support of the decision must exist at the time the decision is made. One aspect of APRA’s submission, consistent with the reasoning in Cowan v Scargill, is that the best interests of beneficiaries is to be assessed by reference to the circumstances as they exist when the decision is made and not by reference to subsequent unforeseen events. Another aspect of its submission put orally, however, is inconsistent with Cowan v Scargill. APRA proposed that the only relevant matter was the respondent’s state of mind at the time of the decision. I disagree. In my view, a decision which is not reasonably justifiable as in the best interests of the beneficiaries, assessed objectively by reference to the circumstances as they in fact existed at the time, will be in breach of the covenant. Equally, subject to the exception I have noted, a decision which is reasonably justifiable as in the best interests of the beneficiaries, assessed objectively by reference to the circumstances as they in fact existed at the time, will not be in breach of the covenant.

65 I also accept the further submissions of the fourth to seventh respondents, citing G Thomas, “[t]he duty to trustees to act in the ‘best interests of their beneficiaries’” (2008) 2 Journal of Equity 177, that (1) a standard of perfection is not imposed on trustees; (2) in cases where the purpose of the trust is to provide financial benefits for the beneficiaries, “the best interests of the beneficiaries are normally their best financial interests”: Cowan v Scargill [1985] 1 Ch 270 at 287, 289: (3) acting in the best interest of the beneficiaries is in effect synonymous with a trustee’s obligation to promote and act consistently with the purpose for which the trust was established; (4) in relation to discretionary powers, there will be “liability” pursuant to s 52(2)(c) “if the discretionary power is exercised improperly, but otherwise there is not”: Manglicmot at [121]; (5) the duty applies when the power is exercised; (6) there may be cases where an issue is so finely balanced that “a decision either way can be regarded as objectively right”: Nestle v National Westminster Bank [1993] 1 WLR 1260 at 1270; and (7) the relevant question is whether the course of action that was taken was one of the courses of action that may be described as being in the best interests of the beneficiaries.

3.4 No conflicts, s 52(2)(d) and 52A(2)(d)

66 Sections 52(2)(d) and 52A(2)(d) came into force on 1 July 2013, by amendments introduced by the Superannuation Legislation Amendment (Trustee Obligations and Prudential Standards) Act 2012 (Cth).

67 According to APRA, the terms of the statutory text are clear and unambiguous so that the suffering of loss by beneficiaries is not a necessary ingredient for contravention, and in many cases will be irrelevant. APRA said its case was one in which the respondents did not acknowledge the conflicts that existed and did not give priority to the interest of the beneficiaries over other interests but that APRA did not need to go further and prove that the respondents were actually motivated by a competing interest in their decision-making. APRA also emphasised that the covenants bind each director individually, including the obligation to “comply with prudential standards in relation to conflicts”, relevantly, Superannuation (prudential standard) determination No. 7 of 2012 (Prudential Standard SPS 521) (SPS 521) which came into force on 1 July 2013.

68 SPS 521, as APRA submitted, provides that:

(a) a trustee must have a conflicts management framework, approved by the Board, to ensure that the trustee identifies all potential and actual conflicts in its business operations and takes all reasonably practicable actions to ensure that they are avoided or prudently managed (para 8);

(b) the Board is ultimately responsible for the development and maintenance of the conflicts management framework (para 10);

(c) the Board must take all reasonable steps to ensure that all responsible persons and other employees of the trustee clearly understand the need to identify conflicts, the content and purpose of the conflict management framework, and their obligations as a responsible person of a superannuation trustee (para 11);

(d) the trustee must have a conflicts management policy approved by the Board that includes certain minimum requirements including, most relevantly, recording in the minutes of the Board, board committee and other relevant meetings details of each conflict identified and the action taken to avoid or manage the conflict (para 10).

69 APRA acknowledged that at all relevant times Questor and IIML had a Conflicts of Interest Policy in place which required:

(a) all matters affecting the beneficiaries of the relevant trusts to be addressed at subsidiary company board level;

(b) disclosure of conflicts of interest as a standing item on the agenda for meetings of the boards of each company;

(c) the Board to affirm at the conclusion of each RSE Licensee (superannuation trustee) meeting that all directors of the meeting have acted in the capacity as trustee, that all matters have been considered in that capacity, and that priority has been given to the duties to and interests of, beneficiaries in all situations where there is a conflict of interest, as required under sections 52(2)(d) and 52A(2)(d) of the SIS Act;

(d) The priority given to beneficiaries’ interests as part of the decision making must be demonstrated in the minutes in respect of trustee decisions that present a potential conflict.

70 APRA contended that the requirements of this policy had not been met, noting that at the relevant meetings the boards did not make the declaration referred to in paragraph (c) and there is nothing in the minutes to demonstrate the decision-making process referred to in paragraph (d). As to (c), there is no requirement that the affirmation appear in the minutes of the meeting. Accordingly, it would not be inferred from the minutes alone (as APRA assumed) that the affirmation in (c) did not occur. Further, (d) applies only if in the objective circumstances there was in fact a potential conflict. In any event, compliance or otherwise with the policy does not of itself establish any contravention of the no conflicts covenant.