FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Education Union v Yooralla [2019] FCA 1511

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 14 days the parties are to file orders by agreement giving effect to the reasons for judgment or, if no agreement is reached, submissions of no more than four pages in length as to the form of final relief to be ordered.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

STEWARD J:

1 This is an appeal from a decision of the Federal Circuit Court dismissing the Australian Education Union’s (the “AEU”) application for declaratory and ancillary relief. The AEU claims that one of its members, a Ms Legg, has been underpaid in contravention of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) by reason of the application of the wrong industry awards. Ms Legg had been an employee of Yooralla, a provider of disability services. She had worked at the “Naroo Day Service” at Naroo Street, Balwyn (the “Naroo Centre”). What she did there is not disputed but is nonetheless important for the disposition of this appeal. That is because the parties are in disagreement about the correct characterisation of her services at the Naroo Centre in the context of various industry awards which applied during Ms Legg’s period of employment.

2 The AEU contended below: (i) that Ms Legg was an “instructor” under the Disability Services Award (Victoria) 1999 (the “Disability Award”) for the purposes of an application of Ms Legg’s Transitional Minimum Wage; and (ii) that she was a “Level 3” employee for the purposes of the applicable modern award, namely, the Social, Community, Home Care and Disability Services Industry Award 2010 (the “Modern Award”), which applied from 1 January 2010.

3 Yooralla disagreed. In her contract of employment, Ms Legg had agreed to serve as a “Disability Support Worker” and to be paid as an “attendant carer”, Grade 2, under the Attendant Care – Victoria Award 2004 (the “Carer Award”). This was the award Yooralla said was applicable in determining Ms Legg’s Transitional Minimum Wage. Thereafter, it was submitted, she was a “Level 2” employee under the Modern Award.

4 The learned primary judge dismissed the AEU’s application. His Honour found that Ms Legg had not been underpaid. For the reasons given below, and with the greatest of respect, I have found that the learned primary judge erred in considering Ms Legg’s Transitional Minimal Wage, and in his Honour’s consideration of the Modern Award. However, I nonetheless agree for other reasons that Ms Legg should be categorised as a “Level 2” employee for the purposes of that Modern Award.

Facts

5 The learned primary judge summarised the primary facts as follows at [19] and [23]-[30]:

19. On or about 28 October 2013 Ms Legg applied to Yooralla for employment in the role of “disability support worker 2” and on 3 December 2013 she was employed in that role. Her contract of employment provided that she was a disability support worker classified as an attendant carer award grade 2 year one. As mentioned above, it was common cause between the parties that Yooralla provided disability services including the provision of personal care and lifestyle support to persons with a disability in a community or residential setting including respite care and day services. One of those services was Naroo Day Service (“Naroo”). Persons who attended Naroo were called “clients” in this proceeding. They had varying degrees of disability and varying degrees of ability. The day service now known as Naroo was previously owned by Eastern Disability Access and Resource (“EDAR”) and operated by Yooralla.

….

23. On and from July 2014 Ms Legg reported to her supervisor, Sonia Marie Faulkner, Yooralla’s programme manager.

24. Ms Legg gave evidence that at any given time she had responsibility for between four and six of Yooralla’s clients. She said her duties that she was required to and in fact performed included ‒

a) training people with an intellectual, physical or sensory disability;

b) developing and maintaining and supporting individual training programs, in a variety of settings;

c) preparing and maintaining client and service documentation;

d) conducting client lifestyle programmes; and

e) administrative duties.

25. Ms Legg gave evidence that she did not usually assist people with a disability to perform day-to-day activities that a person without a disability would do for himself or herself, including eating, bathing, picking up items and so on.

26. Ms Legg said that person centred planning, as it was called at Naroo, involved the development of programmes, tailored to the specific needs and disabilities of Yooralla’s clients on an individual basis. It focused on the specific goals each client sought to achieve. Ms Legg gave evidence that person centred planning was a key aspect of her role. She said she prepared various documents, individual versions of which were kept in folders for each client and on a regular basis Ms Legg and Ms Faulkner reviewed the content page to ensure each client was supported in the planned manner. The documents that Ms Legg prepared were identified by her as ‒

a) “client specific dictionaries”;

b) “my lifestyle plan”;

c) “lifestyle plan action plan”; and

d) “client support plan”.

27. Ms Legg said she prepared individual weekly plans for each of the clients in consultation with Ms Faulkner. Ms Legg said she prepared progress notes and graph documents for each client. She also prepared programme outlines with specific client information concerning each client. The programmes Yooralla offered to its clients at Naroo included bowling, pamphlet collation, pamphlet delivery, cooking, swimming, disco, scrapbooking, iPad operation and café outings.

28. Ms Legg gave evidence that she took two programmes each day. She said that typically she ‒

a) informed clients where they were to keep food and medication;

b) assisted clients having lunch;

c) where another colleague was available, Ms Legg took half hour breaks;

d) kept records of clients who took medication at lunch;

e) assisted clients to use toilets prior to commencing the programme held after lunch; and

f) completed progress notes and assessments during the break.

29. On a monthly basis Ms Legg communicated with Ms Faulkner on feedback given about the services provided at Naroo. Ms Legg also prepared interim progress reports in respect of clients after evaluating each client’s progress during each of the four terms during which Naroo was in operation.

30. According to Ms Faulkner, Ms Legg performed her duties to a high standard.

6 These findings of fact were not disputed before me. It is necessary, however, to consider the evidence in a little more detail. Ms Legg’s description of her activities at the Naroo Centre was not challenged, although she was cross-examined about her employment by Mr Rinaldi of Counsel for Yooralla.

7 Ms Legg, who holds bachelor degrees in Applied Science (Physical Education) and in Occupational Therapy, usually started her day at the Naroo Centre at around 8 am. She was subject to the supervision of a “Service Manager”. She worked with six employees who provided services to around 17 clients affected by a range of intellectual (and sometimes physical) disabilities. The clients arrived around 8.45 am. It would take an hour for them to settle in. They would be told to put their food away in the fridge (or, if an outing was planned for that day, to put it in their bags), to lock their medication away, and to go to the toilet (if needed). The day’s planned activities would be discussed. These may sound like banal matters; but they may not be for a person affected by an intellectual disability. The clients would then participate in two programs: one in the morning (from about 9.45 am to noon), and one in the afternoon (from about 1 pm to 2.30 pm). Each program would be carried out by a Yooralla employee such as Ms Legg. I shall return to describe these. Lunch typically took place at around noon. Ms Legg would assist the clients to have lunch. She might heat up a meal, cut up food where this was needed, or assist those clients experiencing difficulty with using their hands. She also helped those who needed assistance to go to the toilet. She would record the medication taken. Save for the participation in the programs, the AEU did not dispute that these types of activities should be characterised as personal care and not as instructing. But they were, it was submitted, incidental to the essential role performed by Ms Legg, which was carrying out the programs. After completion of the second program, from about 2.30 pm to 3.30 pm, taxis would start to arrive to collect the clients. No client lived at Naroo Street. Ms Legg prepared and kept records concerning her clients’ participation in the programs. She worked on these at lunchtime (for 30 minutes) and after the clients had left for the day.

8 Ms Legg prepared written plans for each of her clients for use in the programs. In that respect, one of the documents she would consider was called “My Lifestyle Plan”. An example of one was in evidence. Amongst other things, it described what was important to the client, including key people in the client’s life, and what the client did and did not like. Based on this document, and following consultation with the client and her or his advocate, Ms Legg would then prepare a “Lifestyle Plan Action Plan” (“Action Plan”). An example of one of these was before me. The first page of it described the client and then set out what she considered to be her best attributes, the matters important to her, and how she communicated. It recorded the following:

I use simple verbal language to communicate, however sometimes what I say does not always indicate what I would like to express. Alternatively I will communicate using pointing, gestures, facial expressions and sometimes using objects. I will understand and respond to simple sentences when being spoken to.

9 On the next page a desired goal was identified. This was then broken down into columns which addressed the “goal broken into chunks”, what needed to happen to achieve the goal, the person responsible for achieving it, a timeline, and “outcome measurements”. On this occasion, the goal identified was “[t]o further my practice and skills with my wallet and money handling”. In the second column, the following was recorded:

Advise [client] firstly on the task she needs to undertake and then give her space to perform it before advising or putting prompts in place.

10 Another goal appeared on another page. It was “[t]o further increase and maintain my strength, flexibility and fitness for better health management”. This was to be achieved by walking three laps in a pool with a water noodle. The plan recorded how Ms Legg was to achieve that outcome. At the end of the Action Plan, there was a space for Ms Legg to record the client’s progress and to record suggestions for further support. For example, the following was recorded:

[The client] has performed well in the delivery program over the past 6 months. On occasions she has been able to complete it independently, but mostly she has required a gesture to ensure 100% completion.

11 In order to provide services to her clients, Ms Legg would also consult a “Client Support Plan” prepared for each client and updated from time to time. This set out, amongst other things, certain medical and behavioural details about the client.

12 At the end of the fourth term in each year, employees at the Naroo Centre, including Ms Legg, would plan the types of programs to be offered in the coming year. Before me was a document describing the programs to be offered in “Term 1 2017”. The programs covered the delivery of activities in fields such as sport, work, recreation and health.

13 Ms Legg would meet with her supervisor, Ms Faulkner, to discuss the programs that she proposed should be allocated to her clients. Timetables would be prepared together with the Action Plans. Outlines for each program would also be prepared setting out the activities to be done and logistical information that needed to be taken into account.

14 During term, Ms Legg would also prepare progress notes for each client and program. She would handwrite notes of what occurred for each client on each day. An example of these was before me which I have reviewed. It recorded, in brief terms, the activities undertaken. It included comments such as “has had a good week this week reaching some goals set out”.

15 Prior to term commencing, Ms Legg also prepared for each client an “Interim Progress Report”. One of these was before me and it recorded the following goals (reproduced verbatim):

Goals that [the client] participates in are as follows, please refer to accompanying documentation for further information.

When arriving or leaving the disco venue, I will look for cars when crossing the road or entering the car park by looking both left and right before attempting to cross with 100% accuracy over 3 consecutive weeks.

When provided with an iPad I will use my finger in the screen in order to unlock or draw on the iPad with 80% accuracy over 3 consecutive weeks.

When ingredients are set up for me in the kitchen I will independently put my ingredients on the pizza base with 100% accuracy over 3 consecutive weeks.

When given the ipad and it is set up ready to take photo’s I will learn how to push the shutter button on the ipad to take a photo with 100% accuracy over 3 consecutive weeks.

During the art program I will make myself a hot drink with help only with the hot water with 100% accuracy over 3 consecutive weeks.

When provided with my own brush I will independently pick up my own brush and brush my hair with 100% accuracy over 3 consecutive weeks.

16 This report contained a long table of “progress notes” handwritten by Ms Legg for the period 28 September 2015 to 21 December 2015 in relation to the task of learning how to take photographs using an iPad. The first entry reads as follows:

[The client] understood that she needed to tap the ipad to take the photo, however had trouble finding the button so required finger guiding.

17 There are then 12 further entries recording the client’s progress. As an indication of the importance of the challenge faced by this client, the task of taking photos was not achieved notwithstanding months of training. Ms Legg recorded:

[The client] had a few times throughout the term where she was able to take a photo with a verbal cue of “press the white button.” However it seemed as though [the client] would get a little disorientated with her surroundings and required more of a physical finger guiding assistance to ensure that she was taking a photo.

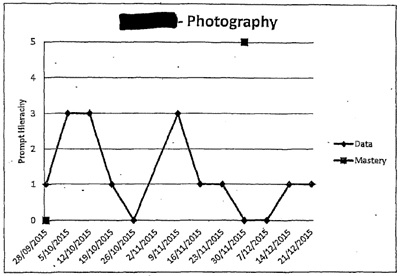

18 Each attempt at taking photos was graded by Ms Legg from 0 to 5 and then recorded in the following graph:

19 The observations made by Ms Legg in her various reports were detailed and nuanced. They well demonstrate the high seriousness and commitment required to assist a person with an intellectual disability to perform everyday tasks with accuracy and dignity. They also reveal a clear and professional dedication to the task of teaching essential daily tasks to clients of the Naroo Centre. Like any teacher, Ms Legg graded each client’s performance. The grades were recorded and analysed. Progress was often slow. Clients relapsed from time to time.

20 I would characterise Ms Legg’s participation in the programs as teaching or instructing. That characterisation is in no way diminished by the fact that the tasks that were set would be easy for some of us to achieve. The fact remains they were not easy for many of Ms Legg’s clients.

21 There was some debate before me concerning the task of teaching a client to use a seatbelt. Ms Legg was cross-examined about this. It was put to her that this was not “teaching”. This was denied. Ms Legg explained that it might take years for a client to learn this task but that with “time and patience” this task could be learned. Yooralla submitted that if the clients learned a skill “along the way” during their participation in an Action Plan, it would not follow that the plans were training programs. To make good that proposition, the following questions were asked:

These are activities, would you agree, for the enjoyment of the people who come to the centre, for them to get something out of life, but they’re not training programs, are they?---They’re activities, but it doesn’t mean that they aren’t learning within these activities.

And I understand what you mean, they might learn simple things such as putting on a seatbelt. They might learn to do freestyle, maybe, if they didn’t already, but that learning is part of the activity. It’s not part of a training program. You’d accept that?---I disagree.

Well, you just agreed with me a moment ago that there wasn’t a swimming training program, so all I’m saying to you, if they learn a skill along the way, then that’s implementing client skills and activities programs. That’s not, itself, a training program, is it?---No.

The learned primary judge addressed this task in a key section of his reasons for rejecting the proposition that Ms Legg’s activities should be characterised as teaching or training. At [36]-[39], his Honour said:

36. In ordinary parlance, the verb “to train” is commonly understood to involve the task of teaching a particular skill or type of behaviour through sustained practice and instruction. As an adjective, the word means “develop and improve (mental or physical faculty) through instructional practice.”

37. Ms Legg gave evidence she did not train clients to take their medication. Next, she was asked about the activity she undertook involving a client and the affixing of his or her seatbelt. She said showing a person how [to put on] their seatbelt could potentially be regarded as part of their learning and it would be part of the training programme because for her the client has learnt a new thing and that person was achieving goals as an adjunct to daily living.

38. On that analysis, any activity undertaken by Ms Legg leading in some way to the client learning a new thing or achieving goals of daily living was “training”. That is to give the word “to train” an extremely wide meeting and it ignored the aspect of the sustained practise and instruction that the verb ordinarily connotes. Further, for the purpose of the decided cases, especially City of Wanneroo v Holmes and Joyce v Christoffersen, the principal aspect of the work, not an incidental adjunct to it, is an important feature. Training was not the principal aspect of the work. She asserted that 40% of her time was allocated to client training and support and that an additional 20% of her time was allocated to preparing client focused documentation, thereby rendering 60% of the time devoted to some aspect or other related training.

39. I disagree.

(Footnote omitted.)

22 I make two observations at this point:

(1) first, the characterisation of Ms Legg’s activities does not depend on the answers she gave in the witness box about whether she considered she was teaching or instructing at the Naroo Centre. In that respect, some of the affidavit material filed below contained conclusionary language about this issue. I have given no weight to such “evidence”; and

(2) secondly, I respectfully consider that the learned primary judge, in the passages set out above, may have failed to appreciate that this was not a case of providing activities per se from which a skill might be obtained “along the way”. The evidence I have examined shows that the purpose of each program was to identify a skill or skills to be learned, to record the method of learning that skill within a defined framework, to record a client’s progress in using that method and finally to assess that progress and determine whether or not the skill had been acquired at the end of the program. In my view, all of the programs in aggregate constituted a sustained course of training of multiple skills. And each program of itself comprised a sustained set of training activities with respect to a particular skill. The nature of the skills that were taught focused upon achieving an ability to pursue everyday life independently and successfully.

The Competing Awards

23 Ms Legg’s rate of pay consisted of two parts: (i) the Transitional Minimum Wage; and (ii) the Equal Remuneration Payment. I will address these parts seriatim.

Transitional Minimum Wage

24 It was not in dispute that Ms Legg’s Transitional Minimum Wage depended upon whether she was an “instructor” under the Disability Award or an “attendant carer” under the Carer Award (the parties referred to each of these as a “pre-modern award”).

The Disability Award

25 The Disability Award binds members of the AEU. It was also accepted that it bound Yooralla. It applied to the following “industry”:

the industry means the occupations of Instructors, Program Directors, Assistant Program Directors, Supervisors, Assistant Supervisors, Teachers, Teacher’s Assistants and Employment Officers, howsoever called, who are engaged in the performance of all work in or in connection with or incidental to the industries and/or industrial pursuits of disability services education.

26 The AEU relied upon cl 6.7.1 of the Disability Award:

An Instructor means an Instructor as outlined in 21.1 of this award. In this regard, qualifications as outlined in 21.2 and experience as outlined in 21.3 shall be the determining factors.

It was accepted that cl 21.1 did not define the word “instructor” in any way. This was an oversight. I was nonetheless invited by the AEU to give meaning and effect to that word by a consideration of cll 21.2 and 21.3. These contained the “determining factors” in deciding whether Ms Legg was an “instructor” for the purposes of the Disability Award. Yooralla did not submit that the failure to expressly define the term “instructor” in cl 21.1 was necessarily fatal to the AEU’s case. It appeared to accept that I should endeavour to give some meaning to that word for the purposes of this appeal.

27 Clauses 21.2 and 21.3 were relevantly in the following terms:

21.2 Qualifications

…

An Instructor in an Adult Unit shall receive the rate of pay according to the range for which the Instructor is entitled after taking into consideration both qualifications and experience. Recognised qualifications are those set out in the schedules below.

…

21.2.1(f) Tertiary qualification – Degree level

B Applied Science (DT)

B Occ. Therapy (overseas)

…

21.3 Experience

21.3.1 An Instructor with no recognised qualification shall be allocated to the salary subdivision range 1-10, commencing at subdivision 1. Upon the production of documentary evidence indicating attainment of knowledge and skill components relevant to the position and specific to the job specification or centre’s program needs, an Instructor shall be awarded a higher commencement subdivision, eg.:

• an Instructor with one year experience is to commence on subdivision 2;

• an Instructor with two years’ experience is to commence on subdivision 3, etc.

21.3.2 For the purposes of this award applicable experience is defined as experience relevant to the education and/or training of persons with an intellectual disability.

…

28 The AEU contended that I should read the letters “DT” after “B Applied Science” to refer to Diploma of Teaching. I was also invited to effectively ignore the word “overseas” after “B Occ. Therapy”. By so doing I should conclude, it was said, that Ms Legg held degrees of a kind that the Disability Award contemplated might be held by an “instructor”. The AEU also relied upon cl 23 and its reference to time “spent in preparation and evaluation” in addition to “client attendance”. It was said this reflected what Ms Legg did.

29 Clause 21.1 lists a series of salaries for different “instructors subdivisions”. The subdivisions were identified by a number which did not appear to be defined separately. Presumably, participants in the industry know what these subdivisions are. No party raised as an issue before me which “instructors subdivision” in cl 21.1 Ms Legg might fall within, assuming her to be an “instructor”.

The Carer Award

30 The Carer Award also bound Ms Legg (assuming her to be an “attendant carer”) and Yooralla. It applied to all persons employed in the “attendant care industry”. That term would appear not to have been defined. However, the term “Attendant carer” was defined in cl 4.2 as follows:

4.2 Attendant carer means a person who provides assistance, in a non-institutional setting (including a home or workplace), to a person with a disability as a means to enable that person to achieve maximum personal independence within the community.

4.2.1 Attendant carers provide assistance to a person with a disability with every day tasks that a person without a disability would be doing for themselves and may include the following personal activities:

• lifting;

• showering;

• toileting;

• grooming;

• meal assistance;

• meal preparation;

• exercise;

• domestic responsibilities;

• recreation;

• personal development;

• communication;

• mobility;

• personal administration;

• shopping; and

• other independent living skills.

4.2.2 The employer will require an attendant carer to take direction from the consumer or the consumer’s representative.

4.3 Attendant carer grade 1 means a person who is not required to have previous experience or training.

4.4 Attendant carer grade 2 means a person working as an attendant carer with a minimum of one year’s experience who provides assistance to persons with complex support needs where a more advanced level of skill is required beyond that required by an Attendant carer grade 1.

4.5 Attendant carer grade 3 means a person working as an attendant carer who is appointed as such and who is proficient in all aspects of Attendant care work and is required to supervise the work of other attendant carers.

The Equal Remuneration Payment

31 The second part of Ms Legg’s pay was the “Equal Remuneration Payment”. This is an amount equal to a percentage of Ms Legg’s rate of pay under the Modern Award. The dispute between the parties is whether she should be characterised as a “Social and community services employee level 2” or a “Social and community services employee level 3”. I note parenthetically that the application of the Modern Award to Ms Legg was initially in dispute but this point was not ultimately pressed by Yooralla.

32 It is regrettably necessary to set out the applicable clauses in the Modern Award in full. Schedule B.2 addresses the position of a Level 2 employee as follows:

Social and community services employee level 2

B.2.1 Characteristics of the level

(a) A person employed as a Social and community services employee level 2 will work under general guidance within clearly defined guidelines and undertake a range of activities requiring the application of acquired skills and knowledge.

(b) General features at this level consist of performing functions which are defined by established routines, methods, standards and procedures with limited scope to exercise initiative in applying work practices and procedures. Assistance will be readily available. Employees may be responsible for a minor function and/or may contribute specific knowledge and/or specific skills to the work of the organisation. In addition, employees may be required to assist senior workers with specific projects.

(c) Employees will be expected to have an understanding of work procedures relevant to their work area and may provide assistance to lower classified employees or volunteers concerning established procedures to meet the objectives of a minor function.

(d) Employees will be responsible for managing time, planning and organising their own work and may be required to oversee and/or guide the work of a limited number of lower classified employees or volunteers. Employees at this level could be required to resolve minor work procedural issues in the relevant work area within established constraints.

(e) Employees who have completed an appropriate certificate and are required to undertake work related to that certificate will be appointed to this level. Where the appropriate certificate is a level 4 certificate the minimum rate of pay will be pay point 2.

(f) Employees who have completed an appropriate diploma and are required to undertake work related to the diploma will commence at the second pay point of this level and will advance after 12 full-time equivalent months’ satisfactory service.

B.2.2 Responsibilities

A position at this level may include some of the following:

(a) undertake a range of activities requiring the application of established work procedures and may exercise limited initiative and/or judgment within clearly established procedures and/or guidelines;

(b) achieve outcomes which are clearly defined;

(c) respond to enquiries;

(d) assist senior employees with special projects;

(e) prepare cash payment summaries, banking reports and bank statements, post journals to ledger etc. and apply purchasing and inventory control requirements;

(f) perform elementary tasks within a community service program requiring knowledge of established work practices and procedures relevant to the work area;

(g) provide secretarial support requiring the exercise of sound judgment, initiative, confidentiality and sensitivity in the performance of work;

(h) perform tasks of a sensitive nature including the provision of more than routine information, the receiving and accounting for moneys and assistance to clients;

(i) assist in calculating and maintaining wage and salary records;

(j) assist with administrative functions;

(k) implementing client skills and activities programmes under limited supervision either individually or as part of a team as part of the delivery of disability services;

(l) supervising or providing a wide range of personal care services to residents under limited supervision either individually or as part of a team as part of the delivery of disability services;

(m) assisting in the development or implementation of resident care plans or the planning, cooking or preparation of the full range of meals under limited supervision either individually or as part of a team as part of the delivery of disability services;

(n) possessing an appropriate qualification (as identified by the employer) at the level of certificate 4 or above and supervising the work of others (including work allocation, rostering and providing guidance) as part of the delivery of disability services as described above or in subclause B.1.2.

B.2.3 Requirements of the position

Some or all of the following are needed to perform work at this level:

(a) Skills, knowledge, experience, qualification and/or training

(i) basic skills in oral and written communication with clients and other members of the public;

(ii) knowledge of established work practices and procedures relevant to the workplace;

(iii) knowledge of policies relating to the workplace;

(iv) application of techniques relevant to the workplace;

(v) developing knowledge of statutory requirements relevant to the workplace;

(vi) understanding of basic computing concepts.

(b) Prerequisites

(i) an appropriate certificate relevant to the work required to be performed;

(ii) will have attained previous experience in a relevant industry, service or an equivalent level of expertise and experience to undertake the range of activities required;

(iii) appropriate on-the-job training and relevant experience; or

(iv) entry point for a diploma without experience.

(c) Organisational relationships

(i) work under regular supervision except where this level of supervision is not required by the nature of responsibilities under B.2.2 being undertaken;

(ii) provide limited guidance to a limited number of lower classified employees.

(d) Extent of authority

(i) work outcomes are monitored;

(ii) have freedom to act within established guidelines;

(iii) solutions to problems may require the exercise of limited judgment, with guidance to be found in procedures, precedents and guidelines. Assistance will be available when problems occur.

33 Schedule B.3 addresses the position of a Level 3 employee in these terms:

Social and community services employee level 3

B.3.1 Characteristics of this level

(a) A person employed as a Social and community services employee level 3 will work under general direction in the application of procedures, methods and guidelines which are well established.

(b) General features of this level involve solving problems of limited difficulty using knowledge, judgment and work organisational skills acquired through qualifications and/or previous work experience. Assistance is available from senior employees. Employees may receive instruction on the broader aspects of the work. In addition, employees may provide assistance to lower classified employees.

(c) Positions at this level allow employees the scope for exercising initiative in the application of established work procedures and may require the employee to establish goals/objectives and outcomes for their own particular work program or project.

(d) At this level, employees may be required to supervise lower classified staff or volunteers in their day-to-day work. Employees with supervisory responsibilities may undertake some complex operational work and may undertake planning and co-ordination of activities within a clearly defined area of the organisation including managing the day-to-day operations of a group of residential facility for persons with a disability.

(e) Employees will be responsible for managing and planning their own work and that of subordinate staff or volunteers and may be required to deal with formal disciplinary issues within the work area.

(f) Those with supervisory responsibilities should have a basic knowledge of the principles of human resource management and be able to assist subordinate staff or volunteers with on-the-job training. They may be required to supervise more than one component of the work program of the organisation.

(g) Graduates with a three year degree that undertake work related to the responsibilities under this level will commence at no lower than pay point 3. Graduates with a four year degree that undertake work related to the responsibilities under this level will commence at no lower than pay point 4.

B.3.2 Responsibilities

To contribute to the operational objectives of the work area, a position at this level may include some of the following:

(a) undertake responsibility for various activities in a specialised area;

(b) exercise responsibility for a function within the organisation;

(c) allow the scope for exercising initiative in the application of established work procedures;

(d) assist in a range of functions and/or contribute to interpretation of matters for which there are no clearly established practices and procedures although such activity would not be the sole responsibility of such an employee within the workplace;

(e) provide secretarial and/or administrative support requiring a high degree of judgment, initiative, confidentiality and sensitivity in the performance of work;

(f) assist with or provide a range of records management services, however the responsibility for the records management service would not rest with the employee;

(g) proficient in the operation of the computer to enable modification and/or correction of computer software systems or packages and/or identification problems. This level could include systems administrators in small to medium-sized organisations whose responsibility includes the security/integrity of the system;

(h) apply computing programming knowledge and skills in systems development, maintenance and implementation under direction of a senior employee;

(i) supervise a limited number of lower classified employees or volunteers;

(j) allow the scope for exercising initiative in the application of established work procedures;

(k) deliver single stream training programs;

(l) co-ordinate elementary service programs;

(m) provide assistance to senior employees;

(n) where prime responsibility lies in a specialised field, employees at this level would undertake at least some of the following:

(i) undertake some minor phase of a broad or more complex assignment;

(ii) perform duties of a specialised nature;

(iii) provide a range of information services;

(iv) plan and co-ordinate elementary community-based projects or programs;

(v) perform moderately complex functions including social planning, demographic analysis, survey design and analysis.

(o) in the delivery of disability services as described in subclauses B.1.2 or B.2.2, taking overall responsibility for the personal care of residents; training, co-ordinating and supervising other employees and scheduling work programmes; and assisting in liaison and co-ordination with other services and programmes.

B.3.3 Requirements of the job

Some or all of the following are needed to perform work at this level:

(a) Skills, knowledge, experience, qualifications and/or training

(i) thorough knowledge of work activities performed within the workplace;

(ii) sound knowledge of procedural/operational methods of the workplace;

(iii) may utilise limited professional or specialised knowledge;

(iv) working knowledge of statutory requirements relevant to the workplace;

(v) ability to apply computing concepts.

(b) Prerequisites

(i) entry level for graduates with a relevant three year degree that undertake work related to the responsibilities under this level-pay point 3;

(ii) entry level for graduates with a relevant four year degree that undertake work related to the responsibilities under this level-pay point 4;

(iii) associate diploma with relevant experience; or

(iv) relevant certificate with relevant experience, or experience attained through previous appointments, services and/or study of an equivalent level of expertise and/or experience to undertake the range of activities required.

(c) Organisational relationships

(i) graduates work under direct supervision;

(ii) works under general supervision except where this level of supervision is not required by the nature of the responsibilities under B.3.2 being undertaken;

(iii) operate as member of a team;

(iv) supervision of other employees.

(d) Extent of authority

(i) graduates receive instructions on the broader aspects of the work;

(ii) freedom to act within defined established practices;

(iii) problems can usually be solved by reference to procedures, documented methods and instructions. Assistance is available when problems occur.

Principles of Construction

34 There was no dispute about the applicable principles of construction. They were helpfully summarised at para 4 of the AEU’s written submissions which state as follows:

Disputes about the issues in this appeal commonly concern two matters: which award applies and which classification within an award applies? So it is here. The law governing those issues is settled. The text, context and purpose of the provisions of an industrial instrument determine its legal meaning. A narrow and strict construction is inapt: a broad and beneficial construction is appropriate. A comparison and evaluation between the different awards and the different classifications is required. The primary judge was required to ascertain the ‘major and substantial employment’ of Ms Legg. This test is determined both qualitatively and quantitatively. The quality, nature or particular character of the person’s work are relevant considerations, as is the amount of time she spent on different tasks. In determining these issues, the language of the relevant industrial instrument is always central.

(Footnotes omitted.)

Citing Maribyrnong City Council v Australian Municipal, Administrative, Clerical and Services Union [2019] FCA 773 at [39]-[42] per Wheelahan J; Shop Distributive and Allied Employees’ Association v Woolworths SA Pty Ltd [2011] FCAFC 67 at [16]; Amcor Ltd v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (2005) 222 CLR 241 at 246-247 [2] per Gleeson CJ and McHugh J; 270-271 [96] per Kirby J; Choppair Helicopters Pty Ltd v Bobridge [2018] FCA 325 at [64]-[71] per Bromberg J.

35 Senior Counsel for the AEU also relied upon the decision of the Full Court of this Court in Transport Workers’ Union of Australia v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 148; (2014) 245 IR 449. He did so because the terms of the Disability Award and the Carer Award appear potentially to overlap. A similar potential overlap exists in the language used to describe Level 2 and Level 3 positions in the Modern Award. In that respect, and on one view, Ms Legg appeared to undertake activities which, at least in part, fell within both the pre-modern awards, and within the descriptions of both the Level 2 and 3 positions in the Modern Award. This may be the inevitable outcome of adopting generalised language to the particular circumstances of a given person’s employment. In Coles Supermarkets Australia there were also two competing awards. The Full Court said at [34]:

When the primary judge turned to examine the question of whether Transport Worker Grade 2 or Retail Employee Level 1 was the more appropriate award classification his Honour was influenced by the fact that the latter classification appeared to be a more comprehensive match with the work of [Customer Service Agents] than the former.

Thus, it was said, one determined which award applied by seeing which is the “more comprehensive match with the work” that was carried out. That requires one to ascertain the “major and substantial employment” of the employee.

36 The AEU also relied upon the decision of Logan J in Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Anglo Coal (Callide Management) Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 696, which I have found to be of assistance. At [38]-[39] his Honour said:

More recently, in Logan v Otis Elevator Company Pty Ltd [1997] IRCA 200 at 68-73 (Logan v Otis Elevator) Moore J collected and discussed many of the plethora of cases in which courts or the industrial commission have had to confront the phenomenon of an employee whose position required the undertaking of multiple duties only some of which were mentioned in a particular classification in an industrial instrument or, as the case may be, were disparately stated in different industrial instruments. Like Moore J in that case, I consider that a [judgment] given by Sheldon J in Ware v O’Donnell Griffin (Television Services) Pty Ltd [1971] AR (NSW) 18 offers assistance. Also like Moore J, I do not consider that the observations made by Sheldon J are to be confined just to a case where it is necessary to choose as between which of two industrial instruments applies to particular employment. That circumstance merely provided the context in which observations of pervasive relevance came to be made by Sheldon J. What Sheldon J observed was this (as set out in Logan v Otis Elevator at 68):

The finding of the Chief Industrial Magistrate raises two questions: Firstly, whether this is a case to be determined on the principle of major and substantial employment; and, secondly, if it is, whether the evidence justified his finding as to what the major and substantial employment of the complainant was.

It seems to me that this is clearly a case to which this principle is applicable. This principle is almost as old as industrial arbitration and it makes a practical approach to determining the application of awards where duties are of a mixed character and contain elements which have taken alone would be covered by more than one award. This is not an appropriate occasion on which to discuss the method by which this test should be applied except to say that it is not merely a matter of quantifying the time spent on the various elements of work performed by a complainant; the quality of the different types of work done is also a relevant consideration.

A pithy way of putting the same proposition is that both quality and quantity are relevant when it comes to employee classification, subject always to the language employed in the particular industrial instrument.

The Decision Below

37 I have already set out the key part of the reasons of the learned primary judge. In essence, his Honour decided that Ms Legg performed the work of an “attendant carer” in respect of which some training was involved but that this training was not “the mainstay or even a substantial part of her work” (at [41]). The fact that she held an academic degree was said to be not “determinative nor even useful” in ascertaining the “principal purpose of her work” (at [34]).

38 His Honour also observed that the “[t]he activities identified in paragraph 48 of Ms Legg’s submissions dated 4 December 2017 did little to illuminate the precise nature of the activity involved and so it was not possible to say whether or not any of those activities involved “training” or “instructing” even though phrases such as “delivery of training”, “client training” and “maintaining individual training” were used” (at [35]). I do not know what was said at para 48 of the AEU’s submissions below. Before me, however, there was sufficient evidence to enable me to determine whether the “major and substantial employment” was that of being an “instructor” or an “attendant carer”.

39 His Honour also appeared to conflate the application of the pre-modern awards and the Modern Award. It was said that the issue concerning the characterisation of Ms Legg’s activities as that of “attendant carer” or “instructor” governed not only the application of the pre-modern awards but also his Honour’s application of the Modern Award. That is evident in the reasoning below at [32]. That conflation may have arisen because of the way the case was presented to the learned primary judge. Certainly before me, Counsel did their best to distil the issues between them in the simplest form possible. However, an examination of the language used in the Modern Award makes it abundantly plain that the resolution as to whether Ms Legg was a Level 2 or Level 3 employee could not solely turn upon characterising her as an “attendant carer” or “instructor”.

Grounds of Appeal

40 The AEU’s notice of appeal disclosed the following grounds of appeal:

1. The learned primary judge misunderstood and/or misapplied the test to be applied in determining the appropriate award classifications under which Ms Legg fell.

2. The learned primary judge erred in finding that for the purposes of clause 5.3(b) of the Equal Remuneration Order, the transitional minimum wage instrument was the pay and classification scale derived from the Attendant Care – Victoria Award 1995 (Attendant Care Award) instead of from the Disability Services Award (Vic) 1999 (Disability Services Award).

3. The learned primary judge erred in finding that the training and associated work carried out by Ms Legg was not a major or substantial or principal aspect of Ms Legg’s employment.

4. The learned primary judge erred in his construction of the Common Rule Declaration – Victoria in the Disability Services Award by finding that Ms Legg was not an employee in the industry, as defined in clause 1.4 of the Declaration, who performed work of a kind that would have been covered by the Disability Services Award as set out at clause 1.2 of the Declaration.

5. The learned primary judge erred in finding that for the purposes of the Equal Remuneration Order, the relevant classification for Ms Legg in the Social, Community, Home Care and Disability Services Industry Award 2010 (Modern Award) was Level 2 rather than Level 3.

6. The learned primary judge erred in finding that Ms Legg did not conduct training within the meaning of the Level 3 classification.

7. The learned primary judge erred in applying an incorrect construction of Schedule B of the Modern Award to the facts:

a. by not undertaking a comparative analysis between a Schedule B.2 social and community services employee Level 2 and a Schedule B.3 social and community services employee Level 3; and/or

b. by failing to take into account Ms Legg’s responsibilities in allowing the scope for exercising initiative in the application of established work procedures, assisting with or providing range of records management services and/or providing assistance to senior and/or providing assistance to senior employees as set out in Schedule B.3.2 of the Modern Award

8. The learned primary judge erred in finding that Ms Legg was properly classified under Level 2 rather than level 3 of the Modern Award.

9. The learned primary judge erred in finding that Ms Legg’s four year degree was irrelevant to her level of classification or pay point in the Modern Award.

10. The learned primary judge erred by failing to find that the Respondent contravened section 305 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (FW Act) by failing to pay Ms Legg the minimum hourly rates for ordinary hours worked in contravention of clause 5.5 of the Equal Remuneration Order.

11. The learned primary judge erred by failing to find that the Respondent contravened section 305 of the FW Act by failing to pay Ms Legg the minimum hourly rates for public holiday hours in contravention of clause 5.5 of the Equal Remuneration Order.

12. The learned primary judge erred by failing to find that the Respondent contravened section 44 of the FW Act by failing to pay Ms Legg the minimum hourly rates for annual leave taken in contravention of section 90(1) of the FW Act.

13. The learned primary judge erred by failing to find that the Respondent contravened section 45 of the FW Act by failing to pay Ms Legg the minimum hourly rates for annual leave loading in contravention of clause 31.3(a) of the Modern Award.

14. The learned primary judge erred by failing to find that the Respondent contravened section 44 of the FW Act by failing to pay Ms Legg the minimum hourly rates for personal leave taken in contravention of section 99 of the FW Act.

15. The learned primary judge erred by failing to find that the Respondent contravened section 45 of the FW Act by failing to advise Ms Legg of her classification under the Modern Award on commencement of her employment in contravention of clause 13.2 of the Modern Award.

Grounds 11 and 15 were abandoned by the AEU.

41 As I understood it, and owing to the guidance of Counsel before me, this impressive list of appeal grounds was to be resolved by determining which pre-modern award applied to Ms Legg, and by determining whether she should be a Level 3 instead of a Level 2 employee for the purposes of the Modern Award.

Disposition

(a) The Pre-Modern Awards

42 The nub of the AEU’s submission, as presented by Mr Irving, Q.C. and his learned junior Ms Knowles, is that the difference between instructing and caring boils down to the proposition that instructing involves learning whereas the essential attribute of a carer is to provide help. In that respect, it was submitted that teaching involves setting a goal or a learning outcome, and then a process of improvement. It is a transformative process. I respectfully agree with that submission.

43 Mr Irving supported his submission with reliance upon cll 21.2 and 21.3 of the Disability Award. I have not been much influenced by the reliance upon cl 21.2, which sets out a long list of eligible qualifications. It was not clear to me that the two degrees identified by the AEU in that list (set out above) were the same as those held by Ms Legg, although I am prepared to assume that they were (Yooralla did not press the point). However, the other qualifications listed in that clause were so numerous (over 100 are identified) and so varied as to be of little assistance in ascertaining the meaning of the word “instructor”. They included various bachelor degrees in a range of disciplines such as Arts, Science and Home Economics; trade qualifications such as that of a plumber, a cabinet maker, a chef, a panel beater etc.; and the achievement of diplomas in fields as various as Horticulture Science and in Art and Fashion. The sheer number and variety of eligible qualifications do render it probable that the degrees held by Ms Legg were appropriate qualifications for the purposes of cl 21.2. However, not much can otherwise be inferred from the list of qualifications in that clause that might inform the meaning of the word “instructor” as it appears in the Disability Award. In that respect, Yooralla emphasised that, in relation to Ms Legg’s experience, cl 21.3.2 required that it be relevant to the training or education of persons with an intellectual disability. It was not clear that Ms Legg’s degrees were of this nature. But in my view that is of no moment because her qualifications, in any event, probably fell within those recognised by cl 21.2.

44 Mr Rinaldi of Counsel said that the question before the Court was finely balanced. But he emphasised the language of the Carer Award. It categorised as an “attendant carer” a person who assists in a non-institutional setting a “person with a disability as a means to enable that person to achieve maximum personal independence within the community” (cl 4.2). That, Mr Rinaldi submitted, is precisely what Ms Legg was doing with her programs and Action Plans. Each Action Plan was directed at securing “maximum independence within the community” for each client. I accept that characterisation. He then also emphasised the language of cl 4.2.1 and its reference to a carer providing “assistance to a person with a disability with [everyday] tasks that a person without a disability would be doing for themselves”. The personal activities thereafter listed included activities that were of a kind that were similar to the “goals” sought to be achieved in the Action Plan, such as “exercise”, “shopping” and “domestic responsibilities”.

45 I agree with Mr Rinaldi that the matter is finely balanced. It also appears to me that there is potential for overlap between the Carer Award and the Disability Award. Both awards, at least in part, are directed at individuals providing services to people with a disability. How the two awards are to be read together remained unclear. The context in which each was made also remained uncertain.

46 As I have already mentioned, the Disability Award does not define the term “instructor”. In order to give meaning to that word, I have considered the context in which it appears, including those clauses relied upon by the AEU. I have not found this context to be helpful other than to note that an “instructor” is juxtaposed in the Disability Award against “Assistant Supervisors”, “Supervisors”, a “teacher”, a “teacher’s assistant” and an “untrained teacher”. The first three terms are not defined in the award but a “determining factor” for each is said to be specified “qualifications”. The difference between an “instructor” and a “teacher” appears in the award to turn upon the qualifications held by the employee. The qualifications specified for a “teacher” are much narrower than those listed for an “instructor”. As already mentioned, the list of qualifications in cl 21.2 was of little or no assistance. I am nonetheless prepared to accept that an “instructor” is relevantly a person who is engaged in the training or teaching of a person with a disability, in the sense submitted by the AEU.

47 In that respect, I do not think that the learned primary judge erred when, at [36], he described the meaning of the verb “to train”. His Honour said that this verb “is commonly understood to involve the task of teaching a particular skill or type of behaviour through sustained practice and instruction”. In my view, that is also an apt description of what an “instructor” does, and what is meant by that word in the Disability Award.

48 However, I respectfully do agree with the AEU that the learned primary judge misapplied the term “instructor” to the evidence and, in particular, in deciding that instruction or training was not the major or principal aspect of Ms Legg’s employment. His Honour thus erred in deciding that the Carer Award applied to Ms Legg. On balance, and again with great respect, I do not think that the Carer Award applies to Ms Legg. The key phrase in the definition of “Attendant carer” is “provides assistance”. The essential quality of the work of a carer is to assist. They assist with the performance of those “everyday tasks” which are ordinarily encountered by a person with a disability. This includes showering, lifting, grooming, recreation and other “personal activities”. Ms Legg did not do this. She did not assist her clients to perform these tasks, save in an incidental way. Rather, Ms Legg was teaching her clients how to undertake these tasks, without assistance, and independently. To use the example of taking photos with an iPad, I am amply satisfied that Ms Legg was not assisting her client to take actual photos with such a device; rather, she was teaching her client how to take such photos in a self-sufficient and effective way. I am also satisfied that the teaching of these skills was the essential reason why clients attended the Naroo Centre. The personal care also provided by Ms Legg to her clients, such as meal preparation, was, in my view, incidental to the core task of teaching undertaken by Ms Legg and her colleagues. Clients did not attend the Naroo Centre to secure those services; they attended for the programs offered. It is true that the language of the Carer Award suggests that the supply of assistance might enhance a person’s ability to achieve “maximum personal independence”. But that is as a consequence of the assistance so provided. In contrast, the essential purpose and function of the programs was not assistance but teaching. Learned skills were not a by-product of what occurred, but the central concern.

49 For these reasons, in my view, and with respect to Mr Rinaldi, Ms Legg’s salary was governed by the Disability Award and not by the Carer Award. It was common ground that if I so found, the fact that her contract specified that her remuneration would be determined by reference to the Carer Award was of no moment.

(b) The Modern Award

50 The AEU submitted that the learned primary judge was mistakenly of the view that to be a “Level 3” employee, Ms Legg had to be a trainer or instructor. The language used in Sch B.3 did not support that approach. I respectfully agree with that submission. The AEU submitted that subcl B.3.2 identified 15 responsibilities and it was sufficient if Ms Legg’s employment satisfied one or more of these. It contended that her employment answered the description of five named responsibilities. The AEU’s written submissions thus state:

(a) Ms Legg’s work allowed scope for exercising initiative in the application of established work procedures. Her role involved the development of and contribution to one of those procedures called ‘person centred planning’.

(b) Ms Legg assisted with or provided a range of records management services. She prepared a variety of documents in accordance with the ‘person centred planning’ approach.

(c) Ms Legg provided assistance to senior employees. She reported to Sonia [Faulkner], Yooralla’s programme manager. Ms Legg prepared individual weekly plans in consultation with Ms Faulkner: they reviewed relevant documents to ensure each client was supported in the planned manner. According to Ms Faulkner, Ms Legg performed her duties to a high standard.

(d) In the delivery of disability services as described in Level 2 (relevantly, the extent to which Ms Legg implemented client skills and activities programmes), Ms Legg assisted in liaison and coordination with other services and programmes.

(e) Ms Legg delivered single stream training programmes, that is, programmes for individual people, in this case a client. These individual programmes were tailored and delivered by her. They involved Ms Legg teaching clients to complete activities and goals and assessing the extent to which clients had achieved their goals throughout the day.

(Footnotes omitted.)

51 I was assured that the foregoing submission was made to the learned primary judge but his Honour made no findings about it. Once again, the reasons below may well reflect the way the case was presented, and in particular, what was emphasised by Counsel in a somewhat complex case. Nonetheless, I must now consider the submission as put by the AEU. It submitted that Ms Legg’s employment satisfied the following subparas of subcl B.3.2:

(a) Subpara (c) which refers to “exercising initiative”;

(b) Subpara (f) which refers to providing assistance with “records management services”;

(c) Subpara (k) which refers to the delivery of “single stream training programs”;

(d) Subpara (m) which refers to providing assistance “to senior employees”; and

(e) Subpara (o) which refers to the “delivery of disability services”.

52 Mr Irving submitted that I should not read subcl B.3.2 as requiring a search for which responsibility was the “best fit” with Ms Legg’s employment. He contended that a person’s “major and substantial employment” may meet a number of descriptors within subcl B.3.2.

53 There are great difficulties in determining whether a person’s employment should fall within the highly generalised language of Sch B.2 or Sch B.3. One can see that, in general terms, Sch B.3 deploys language directed at activities which involve more responsibility and seniority than those mentioned in Sch B.2. The Modern Award appears to be capable, in that sense, of working in the abstract. But applying the generalised language to a person’s actual employment is another matter. For example subcl B.2.2(d) refers to a person who assists “senior employees with special projects”. Such a person is to be categorised as “Level 2”. However, a “Level 3” job will also be one with responsibility, to use the language of subcl B.3.2(m), for providing “assistance to senior employees”.

54 I respectfully disagree with the submissions of the AEU. That is because an examination of the descriptors of Levels 1, 2 and 3 responsibilities reveals that the provision of disability services is expressly addressed at each level. For convenience, the more specific language is as follows:

(1) For Level 1 it is: “resident contact and interaction including attending to their personal care or undertaking generic domestic duties under direct or routine supervision and either individually or as part of a team as part of the delivery of disability services” (subcl B.1.2(g)). It is also: “preparation of the full range of domestic duties including cleaning and food service, assistance to residents in carrying out personal care tasks under general supervision either individually or as part of a team as part of the delivery of disability services” (subcl B.1.2(h));

(2) For Level 2 it is: “implementing client skills and activities programmes under limited supervision either individually or as part of a team as part of the delivery of disability services” (subcl B.2.2(k)). It is also: “supervising or providing a wide range of personal care services to residents under limited supervision either individually or as part of a team as part of the delivery of disability services” (subcl B.2.2(l)); “assisting in the development or implementation of resident care plans or the planning, cooking or preparation of the full range of meals under limited supervision either individually or as part of a team as part of the delivery of disability services” (subcl B.2.2(m)); “possessing an appropriate qualification (as identified by the employer) at the level of certificate 4 or above and supervising the work of others (including work allocation, rostering and providing guidance) as part of the delivery of disability services as described above or in subclause B.1.2” (subcl B.2.2(n)).

(3) For Level 3 it is: “in the delivery of disability services as described in subclauses B.1.2 or B.2.2, taking overall responsibility for the personal care of residents; training, co-ordinating and supervising other employees and scheduling work programmes; and assisting in liaison and co-ordination with other services and programmes” (subcl B.3.2(o)).

55 The specific way in which the provision of different types of disability services across Levels 1, 2 and 3 is expressed suggests that I should apply that language to determine Ms Legg’s categorisation as a person supplying such services, rather than by reference to the more general language invoked by the AEU (for example, their reliance upon the category for providing assistance to senior employees). In my view, the Modern Award should not be read to permit generalised descriptors to govern a person’s categorisation in the disability services industry in the face of specific paragraphs dealing with that industry.

56 The history of the Modern Award supports that conclusion. When originally made in 2010, the Modern Award contained a separate definition of the “disability services sector” and addressed the position of employees in that sector distinctively from those in the “social and community services sector”. Persons supplying disability services did not fall within Sch B of the Modern Award (as they do now) but in a different Sch E (now repealed) from that which now appears. That schedule categorised employees in the disability services sector into five levels. Level 3 included the duty of “implementing client skills and activities programs” (language which may now be found in Sch B.2). Level 5 included the duty of “taking overall responsibility for the provision of personal care to residents” (language which may now be found in Sch B.3).

57 On 26 March 2010, the Full Bench of Fair Work Australia made orders (following its decision in [2010] FWAFB 2024) for the Modern Award to be amended. It had received submissions that argued that distinguishing between the disability services sector and the social and community services sector did not reflect the reality that many employers provide a combination of services. Fair Work Australia agreed with this. It was decided to delete Sch E, to amend the definition of “social and community services sector” in the Modern Award to include the provision of disability services, and to transfer the five disability services sector levels into Levels 1, 2 and 3 of Sch B. The highest former Level 5 effectively became a part of Level 3 of Sch B. There is nothing in the reasons of Fair Work Australia which suggests that disability service workers were not in principle to remain categorised in accordance with those specific categories relating to the supply of disability services, as now expressed in Levels 1, 2 and 3 of Sch B, rather than by reference to the more general descriptors found in those levels.

58 In my view, read in context, Ms Legg’s “major and substantial employment” falls within the descriptor for the provision of disability services in Level 2. Her activities did not meet the description of “taking overall responsibility” in the delivery of disability services as described in subcll B.1.2 and B.2.2. It was not suggested that Ms Legg ran the Naroo Centre or supervised the other employees. Rather, she reported to Ms Faulkner. In contrast, I have little doubt that Ms Legg’s “major and substantial employment” comprised the implementation of “skills and activities programmes under limited supervision … as part of the delivery of disability services”, to use the language of cl B.2.2(k) (the other disability services paragraphs in Level 2 are inapplicable). This is what she did with her development and implementation of specific Action Plans for individual clients. It follows that Ms Legg’s employment should be categorised as “Level 2” for the purposes of the Modern Award.

59 That conclusion is supported by the fact that a Level 3 categorisation appears to be limited to those working in the disability services sector who previously merited the highest Level 5 categorisation (in the former Sch E). In my view, Ms Legg’s employment did not fall within former Level 5 or current Level 3.

60 Both the AEU and Yooralla have had some measure of success before me. In those circumstances, I will give the parties 14 days within which either to file final orders by agreement or submissions of no greater than four pages in length concerning the form of final relief.

I certify that the preceding sixty (60) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Steward. |