FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Mitchell [2019] FCA 1484

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Plaintiff | ||

AND: | First Defendant STEPHEN JAMES HEALY Second Defendant | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The first defendant’s application challenging ASIC’s claims to legal professional privilege in relation to communications between ASIC and potential witnesses be dismissed.

2. Within 7 days of the date of this order ASIC file and serve an affidavit verifying that document 119 in its amended list of witness communications dated 4 September 2019 does not fall within the terms of the second defendant’s notice to produce dated 28 August 2019.

3. The first defendant pay two thirds of ASIC’s costs of and incidental to his application, and otherwise all other costs be the parties’ costs in the cause.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BEACH J:

1 The trial in this matter is to begin before me on 4 November 2019 for a period of three weeks. Consequently the present privilege dispute requires prompt dispatch. The defendants, particularly the first defendant Mr Harold Mitchell, have challenged ASIC’s claims to legal professional privilege concerning numerous communications with potential witnesses. To establish the requisite dominant purpose, ASIC has relied upon the limb of reasonably anticipated legal proceedings, namely, the prospect of commencing Federal Court proceedings against the defendants for pecuniary penalties and disqualification orders.

2 The communications over which ASIC claims privilege are communications which it had from 5 July 2017 with whom it has characterised as potential witnesses and their lawyers. These may be divided into three categories.

3 The first category constitutes confidential communications by ASIC made after 5 July 2017 to potential witnesses or their lawyers for the purpose of eliciting evidence or other information for use in such anticipated proceedings.

4 The second category constitutes confidential communications made by potential witnesses or their lawyers to ASIC. It is said that each of those communications were solicited by ASIC after 5 July 2017 for the purpose of eliciting evidence or other information for use in such anticipated proceedings.

5 The third category consists of documents which record confidential communications held after 5 July 2017 between ASIC and potential witnesses or their lawyers. It is said that in each of those communications when a representative of ASIC was speaking they were doing so for the purpose of eliciting evidence or other information for use in such anticipated proceedings, and when the witness or lawyer was answering, they were responding to that solicitation.

6 On 30 August 2019 the present challenge came on for hearing before me. But during the running it became clear that ASIC needed to supplement its evidence. I permitted it to do so and the hearing was adjourned to and concluded last Friday.

7 Counsel for Mr Mitchell principally put the arguments in support of the defendants’ challenge. For the reasons that follow I would reject these submissions. But in summary I would note at the outset three matters.

8 First, the submission that ASIC’s disclosure in its affidavit material “lacked candour” had no substance.

9 Second, the submission that ASIC had merely taken a formulaic approach to verifying its claims was itself superficial when one appreciates the specificity of ASIC’s affidavit material, beyond which it would have risked waiving the very privilege it sought to maintain.

10 Third, the belated submission concerning waiver only has to be stated to be rejected. I had encouraged ASIC to disclose, prematurely on one view, its indemnity or other arrangements with one of its witnesses; I say prematurely as I was two months away from dealing with any exception to the credibility rule under s 103 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). I did so out of fairness to the defendants, and at their urging and over the initial opposition of ASIC. I had also been influenced by the opening left by Weinberg J in Visy Industries Holdings Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2007) 161 FCR 122 at [35] and my desire not to disturb the flow of the trial by any late but likely production during cross-examination. It was put to me last Friday by counsel for Mr Mitchell that there was now an associated waiver of other material. But this was flawed for at least the reason that no relevant inconsistency had been established. What had been disclosed reluctantly by ASIC at my behest was not what it wanted to use or deploy; indeed that was the ambition of the defendants. In any event the subject relatedness had not been established save as to doubt concerning document 119 which I will give ASIC an opportunity to clarify. I propose to say nothing more about this opportunistic submission, which in any event lacked bounce. This is a characterisation, not a criticism.

11 Let me turn to some facts and detail what ASIC’s affidavit evidence discloses as to the purpose of these communications. There was no cross-examination, although I invited counsel for Mr Mitchell to do so given the nature of some of his attacks.

The facts disclosed by the evidence

12 On 19 August 2016 ASIC commenced an investigation into the matters which now form the basis of its allegations in this proceeding. The ASIC officer with ultimate responsibility for the investigation and subsequently for this proceeding is Mr Brendan Caridi.

13 Mr Caridi is a legal practitioner and holds the position of Senior Manager within the Corporations and Corporate Governance Enforcement team of ASIC. He has been employed in this position since 2010 and by ASIC since 2001. He has overseen the present matter since ASIC commenced its investigation.

14 By mid March 2017, ASIC had interviewed in relation to its investigation:

(a) Mr Mitchell, former Vice-President of Tennis Australia, and now the first defendant;

(b) Mr Stephen Healy, former President and Chairman of Tennis Australia, and now the second defendant;

(c) Mr Christopher Freeman, former Vice-President of Tennis Australia;

(d) Mr Scott Tanner, former director of Tennis Australia;

(e) Ms Janet Young, former director of Tennis Australia;

(f) Ms Kerryn Pratt, former director of Tennis Australia;

(g) Mr Steve Wood, former Chief Executive Officer of Tennis Australia;

(h) Mr Craig Tiley, subsequent Chief Executive Officer of Tennis Australia to Mr Wood;

(i) Mr David Roberts, former Chief Financial Officer, Chief Operating Officer, and company secretary of Tennis Australia;

(j) Mr Stephen Ayles, former Commercial Director of Tennis Australia;

(k) Mr Hamish McLennan, former Chief Executive Officer of Network Ten; and

(l) Mr Jonathan Marquard, former Chief Operating Officer of Network Ten.

15 On 24 March 2017, Mr Caridi made a request to Mr Conrad Gray, Special Counsel, Civil Litigation for ASIC, that Litigation Counsel be appointed to this matter. That request was referred to Mr Kim Turner, who was then acting Special Counsel, Civil Litigation.

16 Litigation Counsel are employed within ASIC’s Chief Legal Office. They provide advice and guidance to enforcement teams in the preparation and conduct of civil litigation.

17 When civil litigation is commenced by ASIC, Litigation Counsel often act as solicitor on the record in those proceedings and are independent of enforcement teams, such as the Corporations and Corporate Governance Enforcement team.

18 Now although as indicated in ASIC’s Best Practice Guidelines in relation to aspects of ASIC Investigations and Civil Litigation, Litigation Counsel may be assigned to an ASIC investigation when it is commenced, that is not usually the case. In the present case, Mr Caridi requested that Litigation Counsel be appointed only when and because he was giving serious consideration to recommending that ASIC institute proceedings arising out of the investigation.

19 On or around 5 June 2017 Mr Timothy Honey was allocated to act as Litigation Counsel in this matter. Mr Honey is a legal practitioner and holds the position of Litigation Counsel within the Chief Legal Office team of ASIC. He has been employed in this position since June 2017. He is responsible for the care and conduct of the present proceeding on behalf of ASIC, subject to the supervision and direction of his superiors within the Chief Legal Office. He was the solicitor on the record for ASIC in this proceeding from its commencement until 18 June 2019.

20 Mr Honey said that he had been informed by Mr Caridi and believed the following matters.

21 First, on the basis of Mr Caridi’s review of the information which had been gathered by ASIC pursuant to the notices that had by then been issued under ss 19, 30 and 33 of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act) and in voluntary interviews with potential witnesses (relevant material), on 24 March 2017 he made a formal request for the assignment of Litigation Counsel to the matter.

22 Second, the purpose for which Mr Caridi sought the assignment of Litigation Counsel to the matter was for that person to brief external counsel to advise whether ASIC had reasonable grounds arising out of the relevant material to commence a proceeding against the defendants.

23 Third, by March 2017, subject to the receipt of positive advice from external counsel, it was Mr Caridi’s intention to seek the approval of the relevant commissioners of ASIC for the commencement of such a proceeding.

24 As I say, Mr Honey was assigned as Litigation Counsel to this matter in June 2017.

25 On 5 July 2017, Mr Honey caused briefs to be delivered to senior and junior counsel to advise whether ASIC had reasonable grounds arising out of the relevant material to commence a proceeding against either or both of the defendants. As at that time, he was of the view that it was likely that ASIC would commence this proceeding if counsels’ view was that it had reasonable grounds to do so and subject to approval by the relevant commissioners of ASIC. Of course to express such a likelihood (in terms of more probable than not) so conditioned is a higher threshold than a real prospect, which is the relevant test. In other words, his view is not inconsistent with a view, objectively ascertained, that as at 5 July 2017 there was a reasonable anticipation of litigation in terms of a real prospect, even though at that time counsels’ advice had not been received and the relevant commissioners had made no decision.

26 On 5 December 2017, advice from senior and junior counsel was received. I should say that counsel for Mr Mitchell asserted that the authorities demonstrate that a reasonable anticipation of litigation could only occur when counsel gave their advice. In my view they say no such thing.

27 On 4 January 2018, a report was provided in relation to this matter to Commissioner John Price concerning that advice and further investigative steps that the project team were proposing to take before instituting proceedings.

28 On 31 January 2018, at Mr Caridi’s direction a report was submitted to the Enforcement Committee relating to the advice received from counsel and indicating that the team proposed to take further information gathering steps before instituting proceedings.

29 I note that generally speaking, ASIC’s Enforcement Committee provides direction and oversight in relation to ASIC’s enforcement activities. It makes decisions about the conduct of major enforcement matters, including the final decision on initiation of proceedings in those matters. Those decisions are generally based upon recommendations from the relevant project team, which the Enforcement Committee will consider and then either make a decision or seek further information.

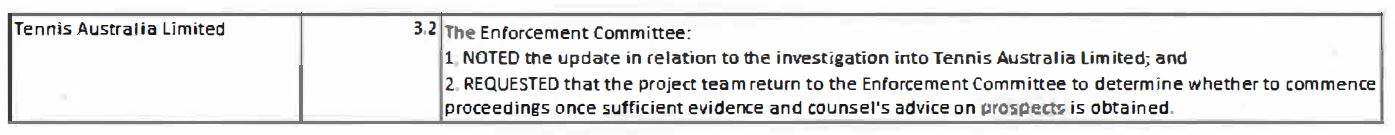

30 On 5 February 2018, ASIC’s Enforcement Committee considered the report provided to it by the project team. The outcome of that meeting was as follows:

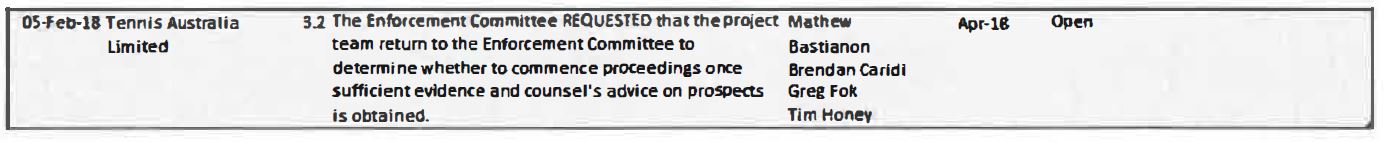

31 The action from that meeting was as follows:

32 On 17 May 2018, Mr Caridi submitted a further report to the Enforcement Committee on the progress made in ASIC’s investigation.

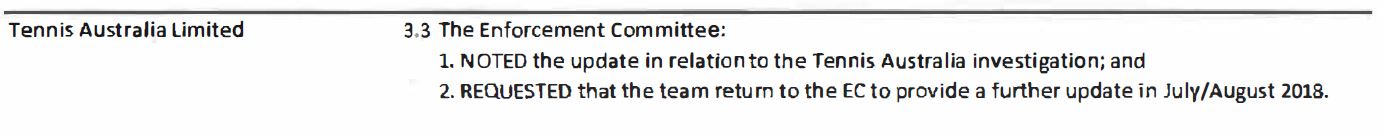

33 On 21 May 2018, ASIC’s Enforcement Committee considered the report provided to it by the project team. The outcome of that meeting was as follows:

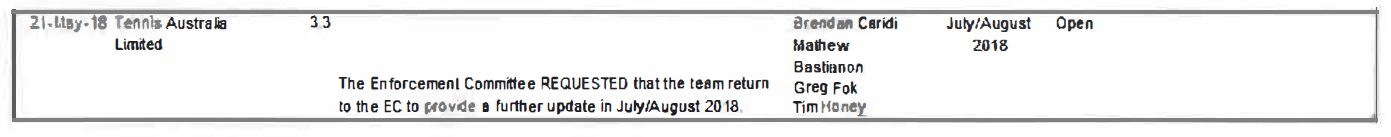

34 The action from that meeting was as follows:

35 On 15 and 27 June 2018, counsel were briefed with further information obtained as a result of further investigative steps taken by the project team.

36 On 15 August 2018, counsel provided supplementary advice.

37 On 17 August 2018, Mr Caridi submitted a further paper to the Enforcement Committee recommending the commencement of proceedings in this matter.

38 On 20 August 2018, the Enforcement Committee considered that paper. The outcome of its meeting so far as is relevant to this matter was as follows:

The Enforcement Committee AGREED that the team should commence proceedings against:

(a) Harold Mitchell, current non-executive director and vice-president of Tennis Australia Ltd (TA), for breaches of ss 180(1) (duty to act with care and diligence), 182(1) (misuse of position) and s 183(1) (misuse of information) of the Corporations Act 2001 (the Act);

(b) Stephen Healy, former TA Chair and President, for breaches of s 180(1) of the Act,

with Deputy Chair Crennan and Commissioner Price to make the final decision as to which TA officers ASIC should commence proceedings against.

39 On 13 November 2018, instructions to file proceedings in the Federal Court against Mr Mitchell and Mr Healy were sought from Deputy Chairman Daniel Crennan QC and Commissioner Price.

40 On 16 November 2018, Deputy Chairman Crennan and Commissioner Price gave instructions to file such proceedings against Mr Mitchell and Mr Healy.

41 Mr Honey has deposed that each of the documents in the first category identified at the outset of my reasons numbered 86-89; 91-100; 102A-105; 108-139; 142-157, 159-173; 175-180; 186-187, 189-226 and 230 in ASIC’s revised communications list were created after those briefs were delivered. Of those documents, documents numbered 88, 91A, 95-97A, 100, 103, 111, 113, 115, 117, 118, 120-123, 125, 127-128, 130-132, 135, 137, 139, 144, 144A, 146-148, 151, 153-157, 159-160, 162, 165, 167-170, 172-173, 176, 179, 187, 190, 191A, 191B, 193, 195, 197, 199, 200, 202, 204-207, 209, 211, 213, 215, 216, 218, 219, 222, 224 and 225 record confidential communications made by ASIC after 5 July 2017 to potential witnesses or their lawyers in this proceeding for the purpose of eliciting evidence for use in the proceeding.

42 Further, he deposed that documents in the second category identified at the outset of my reasons numbered 87, 89, 91, 92, 102A, 110, 112, 114, 116, 119, 129, 133, 134, 136, 138, 142, 143, 145, 149, 150, 152, 161, 163, 164, 166, 171, 175, 177, 178, 180, 186, 189, 192, 194, 196, 198, 201, 203, 208, 210, 214, 217, 220, 221, 223, 230 in the revised communications list record confidential communications made by potential witnesses or their lawyers in the proceeding to ASIC. He said that each of these communications was solicited by ASIC after 5 July 2017 for the purpose of eliciting from a potential witness evidence or other information for use in the proceeding.

43 Further, he deposed that documents in the third category identified at the outset of my reasons numbered 86, 93, 94, 98, 99, 104-105, 108-109, 124, 126, 191, 212 and 226 in the revised communications list record confidential conversations between representatives of ASIC and potential witnesses in the proceeding. In those conversations, which were held after 5 July 2017, when the representatives of ASIC were speaking they were doing so for the purpose of eliciting from a potential witness evidence or other information for use in the proceeding; when the potential witnesses were speaking, they were responding to those solicitations. I note that Mr Caridi has also provided further detail in relation to this category verifying the privilege claims.

44 Generally the detailed evidence from ASIC is to the effect that each identified document above in the revised communications list records a communication made by or to ASIC for the purpose of, or in connection with, gathering the evidence of potential witnesses for the proceeding or otherwise to assist ASIC in its preparation of evidence from witnesses in the proceeding.

45 Now I have set out the evidence dealing with the states of mind of Mr Caridi and Mr Honey. It was not disputed that either or both of their states of mind were the relevant minds to attribute to ASIC in terms of the relevant subjective purpose of ASIC for the creation or making of the communications. No other mind was suggested. But it may be accepted that as the relevant dominant purpose is to be objectively ascertained, evidence of subjective purpose is not definitive in ascertaining what the dominant purpose was, and is only one matter to consider.

Mr Mitchell’s complaints

46 Mr Mitchell has disputed ASIC’s claims for privilege over the relevant documents on the basis that:

(a) ASIC’s evidence has failed to establish a reasonable anticipation of legal proceedings as at 5 July 2017; and

(b) ASIC’s evidence, which uses formulaic language, has failed to demonstrate that the relevant documents were created or made for the dominant purpose of use in any anticipated litigation.

47 Counsel for Mr Mitchell has criticised the evidence given by ASIC. He asserted that the evidence fails to establish a real prospect that ASIC would commence legal proceedings on the relevant date as claimed. He said that the evidence rises no higher than establishing that litigation was a mere possibility as at 5 July 2017.

48 Counsel for Mr Mitchell submitted that the evidence adduced by ASIC is to the effect that as at 5 July 2017, ASIC had formed no view of its own, one way or the other, about whether it even had an arguable claim against the defendants. It had, instead, determined to brief counsel to advise it as to whether there was a reasonable basis for bringing a claim. He said that the prospect of ASIC commencing a proceeding was speculative as at 5 July 2017. It was entirely dependent on the receipt of positive advice from counsel. He submitted that there could be no real prospect of ASIC commencing a proceeding until, at the very least, that advice was received and considered.

49 Counsel for Mr Mitchell submitted that in order for there to be a real prospect of litigation, especially at the instance of a regulator, someone with the requisite authority within the moving party must at the very least have formed the view that there were reasonable grounds for bringing that litigation. Short of evidence of such a belief, the prospect of litigation could not be described as more than speculative or a mere possibility.

50 Further, he submitted that even if I were to conclude that someone within ASIC thought there was a real prospect of litigation as at the relevant date, it does not follow that litigation was reasonably apprehended at that time.

51 Counsel for Mr Mitchell said that ASIC’s evidence is insufficient to establish that the relevant documents were made or created for the dominant purpose of use in any anticipated litigation. It is said that the evidence rises no higher than formulaic or conclusionary assertions of privilege.

52 Further, counsel for Mr Mitchell said that on the face of their descriptions, a number of the documents over which ASIC claims privilege appear to be for the “purpose of compliance with [ASIC’s] compulsory powers”. By way of illustration, documents numbered 87 to 90 are titled “Examination of Craig Tiley on 29 March 2017”, being the date of his examination under s 19 of the ASIC Act. Further, documents 91 and 92 are titled “Scott Tanner - ASIC notices and examination”.

53 Counsel for Mr Mitchell said that if, as appears from the face of their descriptions, these communications occurred for the dominant purpose of the execution of ASIC’s compulsory powers, they are not privileged. It is said that ASIC’s evidence fails to grapple with this issue. He said that having regard to the descriptions of the documents and the formulaic assertions in the affidavit material, I should conclude that ASIC has not discharged its onus to prove the facts on which the privilege is founded on sworn direct evidence.

Analysis

54 Let me begin by restating some of the principles that I set out in Asahi Holdings (Australia) Pty Ltd v Pacific Equity Partners Pty Ltd (No 4) [2014] FCA 796 at [28] to [34] with some modification to the present context.

55 First, the claims for privilege are to be assessed under common law principles rather than under s 119 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth); the present case is not a context where there is an evidentiary dispute as to whether privileged communications should be adduced in evidence. The relevant issue is whether the communications were created or made for the dominant purpose of actual or reasonably anticipated legal proceedings.

56 Second, ASIC bears the onus of establishing the claims, including each factual element necessary to establish the requisite dominant purpose. In that respect, focused and specific evidence is required in respect of each communication, rather than mere generalised assertion let alone opaque and repetitious verbal formulae. There should be sufficient evidence which proves directly or by inference the requisite dominant purpose for the communication. The communication also has to be confidential. I note that the fact of each communication being relevantly confidential is not in dispute in this case.

57 Third, the relevant time for ascertaining purpose is when the communication was made. If the communication was a written communication, the relevant time is when the document came into existence. If the communication was constituted by the forwarding of a copy document, the purpose for the creation of the copy document at the time that the copy was created is what is relevant, not the purpose for the creation of the original document that may not be privileged.

58 Fourth, the relevant purpose may be either that of the author or initiator of the communication, or the person at whose request or under whose authority the communication was created or made. The circumstances will dictate the focus.

59 Fifth, the purpose is to be objectively ascertained and requires consideration of all the facts and circumstances. Now evidence of the subjective intention of the author or person requesting the creation of the communication (document) is significant but not conclusive. Further, purpose can also be determined from the content of the document understood in its full context. Indeed, the latter analysis may carry greater weight, particularly over generalised hearsay or even compounded hearsay evidence from a person other than the author or person requesting the creation of the communication (document).

60 Sixth, it is not sufficient to show a substantial purpose or that the privileged purpose is only one of two or more purposes of equal weighting. The requisite purpose must predominate. It must be the paramount or most influential purpose. One practical test is to ask whether the communication would have been made (whether the document would have been brought into existence) irrespective of the litigation purpose. If so, the communication (document) may not satisfy the dominant purpose test. Such a test will entail addressing the question of the intended use(s) of the document which accounted for it being brought into existence.

61 Seventh, it may be that that the entirety of a document may be privileged. Alternatively, it may be that only part of a document meets the dominant purpose test. A particular document may contain or consist of many communications, such as an email chain, only some of which were made for the requisite dominant purpose.

62 Eighth and relatedly, a document may be privileged to the extent to which it records a privileged communication, even if the document itself would not satisfy the dominant purpose test.

63 Ninth, I have power to examine the documents for myself, but the power should not always be exercised. As Jenkins LJ explained in Westminster Airways Ld v Kuwait Oil Co Ld [1951] 1 KB 134 at 146:

if, looking at the affidavit, the court finds that the claim to privilege is formally correct, and that the documents in respect of which it is made are sufficiently identified and are such that, prima facie, the claim to privilege would appear to be properly made in respect of them, then … the court should, generally speaking, accept the affidavit as sufficiently justifying the claim without going further and inspecting the documents.

64 Looking at the affidavit of Mr Honey together with Mr Caridi’s affidavit, I am of the view that this three-part test is satisfied for the following reasons.

65 First, Mr Honey (at [25] to [28]) satisfies the requirement “that the claim to privilege is formally correct”.

66 Second, Mr Honey by reference to his affidavit (at [25] to [28]) and in his annexure TGH-1, including the modified form thereof annexed to Mr Caridi’s affidavit, satisfies the requirement “that the documents in respect of which it is made are sufficiently identified”. Each document is identified by reference to:

(a) the maker of the communication it records;

(b) if the maker was ASIC, why ASIC made the communication;

(c) if the maker was not ASIC, who had solicited the communication and why;

(d) the subject matter of the communication; and

(e) the person to whom the communication was made.

67 Moreover, Mr Caridi has given an even fuller description of the documents in the third category which were referred to in Mr Honey’s affidavit at [27].

68 Third, Mr Honey has given evidence (at [19] to [24]) that the communications “are such that, prima facie, the claim to privilege would appear to be properly made in respect of them”, by putting forward evidence that when the communications were made the proceeding for which they were made was reasonably anticipated.

69 On the basis of this evidence I am satisfied that there is sufficient to proceed to deal with the claim without going further and inspecting the documents. Indeed, no party suggested that I should inspect the documents for myself. And if they had done so I would have referred the matter to another judge.

70 Now as I have already indicated, for present purposes the relevant test is that a communication including a document recording the communication is privileged if it was created for the dominant purpose of use in existing or reasonably anticipated legal proceedings.

71 In my view the test has been satisfied in the present case in respect of all of the documents in question. The evidence establishes that litigation was a real prospect from 5 July 2017, and that all the documents were created after that date for the dominant purpose of, or in connection with, the preparation of evidence in that litigation. As the Full Court clarified in Ensham Resources Pty ltd v AIOI Insurance Company Ltd (2012) 209 FCR 1 at [55] and [57] per Lander and Jagot JJ, a proceeding is “reasonably anticipated” not only if it is more likely than not, but even if it is only at the level of a real prospect as distinct from a mere possibility. And to determine such a question is fact sensitive.

72 I am satisfied that the numbered documents in each of the three categories that I have identified earlier in the amended list of communications records or constitutes a confidential communication made after 5 July 2017, made between ASIC and a person, or the lawyer for a person, who will or might be a witness in this proceeding, and made for the dominant purpose of eliciting evidence from witnesses or other information for use in this proceeding.

73 That assessment had been made by the time, that is, 5 July 2017, ASIC briefed counsel to advise on the strength of its case. By that time as ASIC correctly points out, the following had occurred:

(a) ASIC’s investigation into Tennis Australia’s broadcast rights agreement made in 2013 with Seven Group Holdings Ltd had been on foot for approximately 11 months.

(b) ASIC had interviewed 12 potential witnesses in the case.

(c) By March 2017, Mr Caridi had reviewed the information that had been gathered pursuant to the statutory coercive notices issued by then and the interviews held by then.

(d) On 24 March 2017, a request was made by Mr Caridi for the appointment of a Litigation Counsel in respect of the investigation, the purpose of which was for that person to brief external counsel to advise whether ASIC had reasonable grounds, based on the material available to date, for the commencement of such a proceeding.

(e) By March 2017, subject to the receipt of positive advice from external counsel, it was Mr Caridi’s intention to seek the approval of the relevant commissioners of ASIC for the commencement of proceedings.

(f) Mr Honey was assigned as Litigation Counsel in respect of this matter in June 2017. Counsel were then briefed by ASIC on 5 July 2017 to advise on the prospects of a proceeding alleging contraventions of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) arising out of Tennis Australia’s 2013 broadcast rights agreement with Seven Group Holdings Ltd. When counsel were briefed, Mr Honey was of the view that it was likely that ASIC would commence this proceeding if counsel considered that it had reasonable grounds to do so and the relevant commissioners approved.

74 I agree with ASIC that by 5 July 2017 it could be said that legal proceedings were reasonably anticipated in terms of there being a real prospect as distinct from more likely than not.

75 Now it is true that the subjective beliefs of the relevant ASIC officers that litigation was a real prospect are not determinative. But those beliefs are relevant, although the question of whether litigation is a real prospect is an objective one based on all the facts and circumstances. In the present case, and as ASIC points out, those facts and circumstances are as follows:

(a) An assessment had been made by 5 July 2017 by relevant officers of ASIC with legal qualifications that, subject to:

(i) counsels’ advice that ASIC had reasonable grounds; and

(ii) the approval of the relevant commissioners,

proceedings would be issued for contraventions of the Corporations Act.

(b) Thereafter ASIC’s gathering of information into these contraventions continued including communicating with persons who might give evidence in the proceeding.

(c) Those communications involved meetings, telephone conversations and correspondence with the potential witnesses and, in some cases, with their lawyers, with the objective purpose of these communications being to assist ASIC in the preparation of its potential case.

76 Let me deal with some other arguments put by counsel for Mr Mitchell.

77 It was submitted that because external counsel were being briefed on 5 July 2017 to advise on whether there were reasonable grounds, that this entails that as at 5 July 2017 ASIC could not have reasonably anticipated litigation. But there are a number of flaws with that suggestion.

78 The two concepts albeit related are different. The fact there may have been no reasonable grounds held as at 5 July 2017, assuming that to be the case for the sake of argument, does not necessarily entail that at that time litigation could not have reasonably been anticipated. Of course if there were such grounds held, then that would assist in showing such anticipation.

79 Further, what was being sought was external counsels’ view as to whether there were such reasonable grounds. That did not deny that reasonable grounds could be held internally within ASIC at the time of briefing or that such was the objective fact, whether so internally expressed or not.

80 Indeed, Mr Caridi deposed at [9]:

Although, as indicated in the document, Best Practice Guidelines in relation to aspects of ASIC investigations and civil litigation (a copy of which is annexure JMW-51 to the affidavit of Janet Mary Vivienne Whiting sworn on 29 August 2019), Litigation Counsel may be assigned to an ASIC investigation when it is commenced, in my experience this is not usually the case. In this particular case, I requested that Litigation Counsel be appointed only when and because I was giving serious consideration to recommending that ASIC institute proceedings arising out of the investigation.

81 There was no cross-examination as to this paragraph. Counsel for Mr Mitchell flimsily sought to undermine its significance by reference back to [5] of Mr Caridi’s affidavit and the consequent cross-referencing to Mr Honey’s affidavit at [21], but none of this argument worked to diminish the force of what Mr Caridi said. Moreover it is to be remembered that both Mr Caridi and Mr Honey are experienced corporate lawyers.

82 Further, to accept that “subject to the receipt of positive advice from external counsel” it was Mr Caridi’s intention to seek the approval of the relevant commissioners of ASIC for the commencement of proceedings does not entail that litigation was not reasonably anticipated at the time counsel were briefed (as distinct from when the advice was received), in terms of a real prospect of proceedings. All that this indicates is that external counsels’ positive advice was a necessary condition for recommendation and formal approval, but again does not deny a reasonable anticipation at the time of briefing (as distinct from when the advice was received).

83 Further, it was put by counsel for Mr Mitchell that there had been no explanation for the gap of five months between when counsels’ advice was sought and when counsels’ written advice was received. All true. Perhaps there was interactive dialogue over that period necessitating the procuring of further information. Perhaps counsel were engaged on other matters. Perhaps senior counsel was taking an extended cycling tour of the Bordeaux region in the late European summer. Perhaps all of the above, and more. Who knows? But none of this matters. If the relevant dominant purpose was formed at the time of briefing counsel, the consequent delays by counsel and the lack of explanation thereof hardly matters to the question I have to consider.

84 Further, counsel for Mr Mitchell at one stage sought to draw a bright line between an investigative purpose and a litigation purpose. There is no such bright line. The reality is that one such purpose may shade into another, such that ASIC may have had at a particular time or in relation to a particular communication both purposes. The real question therefore becomes as to which was the dominant purpose for each communication in order to assess the validity of the privilege claim. I am satisfied that on the evidence from Mr Caridi and Mr Honey, on and after 5 July 2017 in relation to the purpose for each of the relevant communications the litigation purpose pre-dominated, even if there was also an investigative purpose.

85 Counsel made reference to documents 87 to 92 and sought to finesse from the disclosure of document 90 and the attachment a non-litigation purpose for documents 87 to 89, 91, 91A and 92. None of this works. Document 90 and the attachment were volunteered. Further, even if the dominant purpose for document 90 and the attachment was an investigative purpose, that did not entail the same for the other communications. There had been a s 19 examination of Mr Tiley in March 2017, but on the evidence it would seem that in October 2017 the follow ups and the communications in that context were for the dominant litigation purpose. I debated with counsel that that was the likely conclusion to draw, notwithstanding the email headings. Similar points can be made concerning the communications relating to Mr Tanner in December 2017 (documents 91, 91A and 92).

86 Further, counsel’s submissions concerning documents 96, 97 and 110 to 114 concerning Mr Wood also lacked substance. Even if they were partly for an investigative purpose, on the evidence the dominant purpose was clearly the litigation purpose. Indeed, these were all shortly before the issue of proceedings.

87 Further, much reference has been made by counsel for Mr Mitchell to the absence of any decision by the Enforcement Committee at an earlier time, that is, as at 5 July 2017, or indeed their lack of involvement at that time. Now factually, so much may be accepted. So too may be accepted the fact that from the decisions register of the Enforcement Committee, the entries for 5 February and 21 May 2018 suggest that evidence gathering was a work in progress. But all of this is quite consistent with the notion that ASIC, particularly the relevant persons responsible for creating or causing to bring about the relevant communications, at the earlier point in time, that is, from 5 July 2017 considered that there was a real prospect of litigation. After all, the earlier entries referred to obtaining sufficient evidence. Moreover, one does not need a decision of the Enforcement Committee to commence proceedings to demonstrate a real prospect. To show a decision to proceed is to show that proceedings will occur or at the least are more likely than not. But I am dealing with the lower threshold at the earlier time, that is, 5 July 2017, of a real prospect of proceedings beyond the mere possibility.

88 Further, counsel for Mr Mitchell contended that neither Australian Competition & Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd (1998) 81 FCR 526 nor Visy Industries supports the position taken by ASIC. Having had a more than passing familiarity with these cases, the more accurate assessment is that these cases do not support a result in favour of the defendants before me.

89 Counsel pointed out that in Safeway, litigation privilege was claimed in respect of draft witness statements and other documents. Evidence was given from an officer of the ACCC (Mr Eva). Evidence was adduced about, inter alia, Mr Eva’s purpose in creating the draft witness statements for use in anticipated litigation, reports prepared by Mr Eva for the ACCC and the receipt of advice from counsel that the draft witness statements disclosed likely contraventions. It was said by counsel for Mr Mitchell that Goldberg J found that legal proceedings were reasonably anticipated “from the earliest when counsel’s advice was received”. A proper understanding of the case reveals that his Honour in fact identified the earlier date when counsel were briefed. As Goldberg J said at 561:

By 13 December 1995 I do not consider that it can be said that proceedings were reasonably anticipated against Safeway as Mr Eva, and through him the Commission, was still very much in an investigative mode so far as Safeway was concerned. Although Mr Eva was anticipating on 20 February 1996 that proceedings would be instituted against Safeway, it does not appear that at that time the evidence available to the Commission justified the conclusion that proceedings were reasonably anticipated against Safeway. That position was not reached until 6 March 1996 at the earliest but in any event by 3 April 1996. On 3 April 1996 Mr Henderson sent a memorandum to Mr Asher in which he referred to his request for a brief to be forwarded to counsel and to the fact that Safeway was anxious to talk. On 4 April 1996 a “brief of evidence” had been forwarded to counsel. It is not to the point that the Commission had not yet decided to institute proceedings. Certainly by this date proceedings were reasonably anticipated against Safeway.

(Emphasis added.)

90 And contrary to counsel’s submissions, the timeline revealed in Visy Industries at [61] to [64] per Lander J hardly assists the defendants before me.

91 Further, I note that in Visy Industries, Heerey J held at first instance that after the date that the ACCC had determined that there was a real prospect of litigation arising from its investigation, in respect of documents created after that date there was “an irresistible inference that the production of the documents was for the dominant purpose of contemplated judicial proceedings” (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Visy Industries Holdings Pty Ltd (No 2) (2007) 239 ALR 762 at [99]). This was because the description of the nature of the documents showed that they were “virtually all concerned with the laborious process of preparing witness statements, the very stuff of litigation preparation” (at [100]). Indeed I agree with ASIC that the same conclusion should be reached in the present case. The descriptions of the nature of the documents show that they are concerned with the preparation of evidence by prospective witnesses, being “the very stuff of litigation preparation”.

92 In summary, the defendants’ challenge to ASIC’s claims is not made good.

Other matters

93 Let me dispose of one other matter. I note that on 5 September 2019 Mr Mitchell gave a notice to produce to ASIC to produce the reports and papers of 4 January, 31 January, 17 May and 17 August 2018 referred to in Mr Caridi’s affidavit. ASIC objected to production based upon legal professional privilege as detailed in the letter of Norton Rose Fulbright to Gilbert and Tobin dated 5 September 2019. I was prepared to assume that this was a valid claim to privilege for the reasons set out in that letter, subject to the statements contained therein being verified by affidavit. ASIC undertook to do this. There was also no waiver. The chronology of the Enforcement Committee’s consideration and the summary given by Mr Caridi was not in issue; as I say, there was no cross-examination. The relevant question was what could be gathered from this summary as to when proceedings were reasonably anticipated. There is no inconsistency of ASIC in maintaining its claim to privilege in these documents, notwithstanding Mr Caridi’s summary. ASIC also claimed protection from production under public interest immunity, but I do not see the need to rule on this. Further, even if legal professional privilege does not apply, I would in the exercise of my discretion have not required production in any event. For the purposes of the application I was considering, there was no suggestion that these documents had not been adequately described by Mr Caridi or that their content would add anything meaningful and direct to my assessment of whether there was a real prospect of future proceedings when looked at on and from 5 July 2017.

Conclusion

94 In summary, I uphold ASIC’s privilege claims.

95 On the question of costs, ASIC has had considerable success and should be entitled to its costs. However, some costs were wasted by the adjournment on 30 August 2019 to allow ASIC to supplement its evidence. In the circumstances and also as Mr Mitchell was the principal protagonist, I will order him to pay two thirds of ASIC’s costs on the legal professional privilege challenge; all other costs will be the parties’ costs in the cause.

I certify that the preceding ninety-five (95) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Beach. |

Associate: