FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

CWS16 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2019] FCA 1414

ORDERS

First Appellant | ||

CWT16 Second Appellant | ||

CWU16 Third Appellant | ||

AND: | MINISTER FOR IMMIGRATION AND BORDER PROTECTION First Respondent IMMIGRATION ASSESSMENT AUTHORITY Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 30 August 2019 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. The appellant pay the first respondent’s costs of this appeal and the appeal in VID 390 of 2019, to be fixed by way of a single lump sum.

3. By 4 pm on 13 September 2019, the parties file any agreed proposed minute of orders fixing a single lump sum in relation to the costs of both this proceeding and VID 390 of 2019.

4. In the absence of agreement, the matter of an appropriate single lump sum figure for the first respondent’s costs be referred to a Registrar for determination.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

VID 390 of 2019 | |

| |

BETWEEN: | CWX16 Appellant |

AND: | MINISTER FOR IMMIGRATION AND BORDER PROTECTION First Respondent IMMIGRATION ASSESSMENT AUTHORITY Second Respondent |

JUDGE: | MORTIMER J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 30 August 2019 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Leave be refused to raise the new ground of appeal identified in the amended notice of appeal attached the appellant’s submissions dated 30 July 2019.

2. The appeal be dismissed.

3. The appellant pay the first respondent’s costs of this appeal and the appeal in VID 389 of 2019, to be fixed by way of a single lump sum.

4. By 4 pm on 13 September 2019, the parties file any agreed proposed minute of orders fixing a single lump sum in relation to the costs of both this proceeding and VID 389 of 2019.

5. In the absence of agreement, the matter of an appropriate single lump sum figure for the first respondent’s costs be referred to a Registrar for determination.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MORTIMER J:

1 Before the Court are two appeals from orders made by the Federal Circuit Court on 1 April 2019, dismissing the appellants’ application for judicial review of a decision of the Immigration Assessment Authority and ordering the appellants to pay the first respondent’s costs in an agreed or otherwise assessed amount: see CWS16 & Ors v Minister for Immigration & Anor and CWX16 v Minister for Immigration & Anor [2019] FCCA 816.

2 Separate orders dismissing each appeal will be made. These reasons explain why, in each proceeding, the appeal has been dismissed.

Relevant background

3 The appellants in these matters are husband and wife, and have two dependent children. The appeal by CWS16 includes the father and two children CWT16 and CWU16, and the appeal by CWX16 is by the wife, who is also the mother of CWT16 and CWU16. Their applications and court proceedings have always been dealt with together. I shall refer to CWS16 and CWX16 as “the appellants”, unless it is necessary to refer to them separately, in which case I will refer to CWS16 as the “appellant husband” and CWX16 as the “appellant wife”.

4 The appellants are citizens of Sri Lanka and are of Tamil ethnicity. They arrived in Australia by boat on 13 October 2012 and initially made a visa application, which was invalid by operation of s 46A of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth). In May 2015 the Minister lifted the “bar” under s 46A and the appellants were each permitted to apply for a temporary protection (subclass 785) visa. They each did so on 19 August 2015. On 7 December 2015 the appellants attended an interview with the delegate.

5 The appellants’ visa applications were rejected in two separate decisions made on 21 July 2016. The decisions were referred to the IAA on 26 July 2016 under Pt 7AA of the Migration Act. On 31 August 2016, the appellants’ migration agents made a joint submission to the IAA on behalf of the appellants. On 13 September 2016 the IAA affirmed the decision of the delegate of the Minister not to grant the temporary protection visa to each of the appellants.

6 On 5 October 2016 the appellants applied to the Federal Circuit Court for judicial review of the IAA’s decision and on 1 April 2019 the application was dismissed. The appellants filed a notice of appeal on 18 April 2019.

The appeal

7 The appellants were represented before the Federal Circuit Court, but no notice of a legal representative acting on their behalf was filed with this Court until three weeks before the hearing of the appeal. The hearing was adjourned once to accommodate the dates their counsel was available.

8 The appellants filed written submissions on their own behalf. It appears they had some assistance in drafting those submissions. Attached to the submissions was an amended notice of appeal. It contained two grounds of appeal: one which was before the Federal Circuit Court and one which is new on this appeal:

1. Ground 1 of the appeal to the Federal Circuit Court is: “The IAA acted unreasonably in the exercise of its discretion or alternatively constructively failed to exercise its jurisdiction, in failing to exercise or filing to consider whether to exercise its discretion under 473DC to get new information from the Department of Immigration and Border Protection, the UNHCR or the Malaysian Authorities that formed an integral part of the applicant’s claim, namely information regarding the assessment conducted by the UNHCR in Malaysia which determined the applicant and her family to be refugees within the meaning of the Refugees Convention.”

2. The Federal Circuit erred when it dismissed Ground 1 of the Appeal to the FCC (para 37), by failing to find the IAA acted as pleaded in para 1 above, such error amounting to jurisdictional error.

9 In the prayer for relief appeared the following:

Leave to the Appellants to rely upon a New Ground not argued in the lower Court: The IAA failed to consider the explicit or implied claim that CWT16 would be unable to receive adequate medical treatment for her diabetes if returned to Sri Lanka, thereby committing jurisdictional error.

10 At the hearing, counsel for the appellants indicated that the appellants pressed both what was called “Ground 1” in the amended notice of appeal, and what he described as the “new ground”, which I have set out at [9] above. The Minister opposed leave being granted to the appellants to raise the new ground, on the basis that there was no explanation as to why it was not raised before the Federal Circuit Court, and the ground had no merit. The Minister was content for the leave application to be dealt with as part of the final disposition of the appeal, and the Court accordingly heard arguments on both grounds.

11 Where necessary, I refer to the parties’ arguments, the Federal Circuit Court decision and the IAA reasons in my consideration of each of the grounds. For the reasons I set out below, leave should not be granted to raise the ‘new ground’, and the appeal on ground 1 in both appeals should be dismissed.

Resolution

12 Ground 1 is a ground raised on behalf of both of the appellants; the new ground applies only to the decision of the IAA in relation to the appellant wife.

13 In terms of general background, and subject to the appellants’ arguments on the new ground, the Minister’s submissions accurately summarise the background to the appellants’ visa applications, and their claims for protection:

a. The Appellant husband claimed he was forced by the LTTE to transport officers and goods in 1994 and was forced to do manual labour for the LTTE when the family resided in an LTTE camp from 1995 to 1998.

b. Around 1995 or 1996, the brother of the Appellant wife was taken and detained by the Army for one and a half years. Around 2002, another brother went missing while he was fishing after the Navy shot at his boat.

c. In mid-2006, the Appellant husband was taken by the Army or other Sri Lankan authorities for his previous connection to the LTTE to an Army camp, where he was repeatedly assaulted and interrogated until his wife’s family paid to have him released. He has a scar on his leg as a result of being assaulted by the Army.

d. The Appellant wife had developed PTSD as a result of her experiences

e. The Appellants left for Malaysia in mid-2007, where they were assessed as refugees by UNHCR but were not granted visas in Malaysia.

f. The Appellant wife and Appellant daughter also claimed harm as Tamil women who might be sexually abused if they returned to Sri Lanka.

g. The Appellants feared harm as returned failed asylum seekers and due to an Australian Government data breach.

Ground 1

14 There was no dispute between the parties about a number of factual matters relevant to ground 1 of the appeal in each proceeding.

15 Around mid-2007, with the help of the appellant wife’s father, and an agent who arranged passports (without requiring them to visit the passport office), the appellants left Sri Lanka for Malaysia with their daughter. Their son was born in Malaysia: see IAA reasons at [10].

16 The UNHCR in Malaysia assessed them to be refugees but they did not receive Malaysian visas. They stayed five years and then came to Australia. They do not have a right to re-enter Malaysia: see IAA reasons at [11].

17 The appellants produced, as part of their identity documents for their visa applications, cards issued to them by the UNHCR, each with a photograph on it. The cards used the Malay language and there did not appear to be any English translation of them before the delegate or the IAA. Nevertheless, there was no doubt they were issued to the appellants and their children because the UNHCR had assessed all of them to be refugees within the terms of the Refugees Convention.

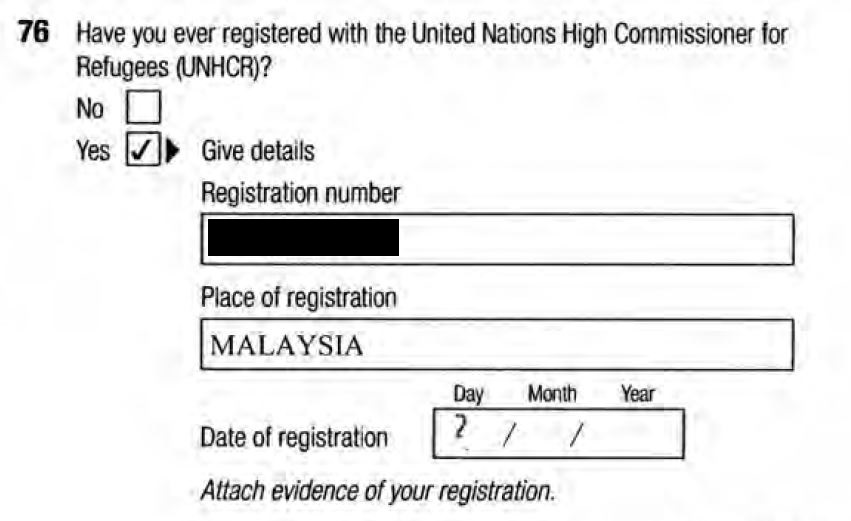

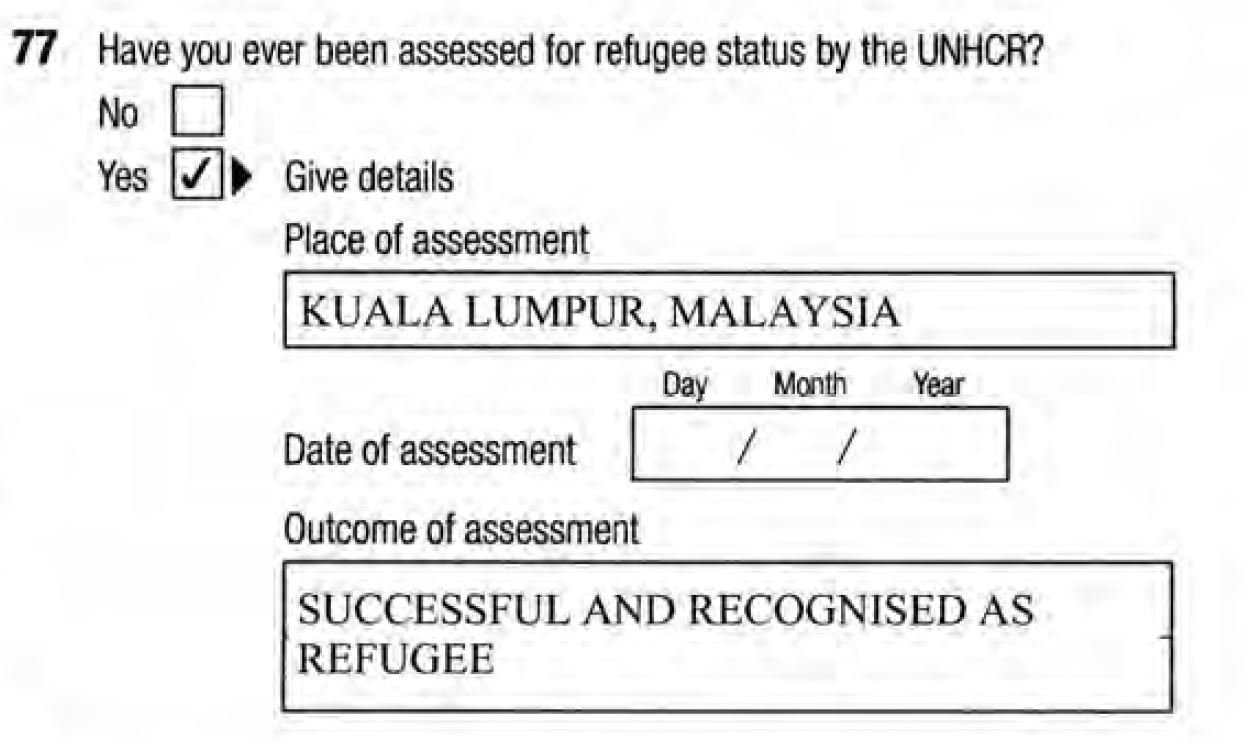

18 In their protection visa applications, the appellants each answered a question about whether they had ever been granted protection before. The question and their answers were as follows:

19 The appellants had each signed documents called “Consent to Share and Release Information” form and a Departmental “Authority to Seek Personal Information in Relation to Effective (Prior) Protection”. These were UNHCR documents, and copies were in evidence before the Federal Circuit Court and on this appeal. The consent given in these two forms allowed the UNHCR to release information provided to it by the appellants, and allowed the Australian Government to make inquiries of the UNHCR regarding that information.

20 However, the evidence before the Federal Circuit Court and also this Court on appeal was that these consent forms had been attached to the invalid visa applications made by the appellants, and were located on those files. That meant, as the legal representative of the Minister deposed, that those files were not forwarded to the IAA pursuant to s 473CB(1) of the Migration Act. In other words, the two consent forms were not before the IAA. The Federal Circuit Court made a finding of fact to this effect, which it was asked to do: see [25] of the Federal Circuit Court reasons.

21 Nevertheless, it is apparent from the IAA’s reasons that it was aware the consent forms existed, because it referred to a submissions from the appellants’ agent about them. A key passage in the IAA reasons is [30], which states:

It was submitted to the IAA that the UNHCR’s assessment conducted in Malaysia which found the applicants to be refugees should stand, and that only an application of a cessation clause under the Refugees Convention and Protocol should change their protection status. It was also submitted that although the applicants provided their consent, the delegate did not obtain or verify the applicants’ information with the UNHCR. However, on the evidence, no further information has been provided by the applicants or their representatives about this UNHCR process or the information given therein. Given this, and that the current assessment is being conducted under the Migration Act, I am not satisfied that the previous UNHCR determination is determinative of this review.

22 Against that background, the appellants submitted it was legally unreasonable for the IAA not to have exercised, or considered exercising, its power under s 473DC(1) of the Migration Act to “get” new and further information about the UNHCR’s assessment of the appellants’ as refugees.

23 The Federal Circuit Court rejected this argument, finding as follows:

35. In this case, it is clear that the applicant was aware from the decision of the delegate that the UNHCR material had not been obtained by the Minister or the delegate. The applicant had, at that point, an opportunity to seek that information him or herself and place it before the IAA, by way of seeking the IAA’s exercise of the discretion to admit that additional material. No material was placed before the IAA.

36. The UNHCR material, on the facts, and circumstances and claims presented to the Minister and the delegate, was not likely to be determinative but, at best, evidence of a different administrative decision-maker’s views of the facts and circumstances of the case, and the possibility that some other evidence which the applicant was unaware of may be before the UNHCR. The latter point is speculative, at best, and akin to fishing for evidence that one does not know exists. More significantly, the UNHCR decision in this case was eight years ago, and prior to the end of the civil war in Sri Lanka – there have been the most significant changes in circumstances in Sri Lanka in the relevant period.

37. Given the nature of the possible material that could come from the UNHCR, it does not appear to me to have been of sufficient significance to call for the IAA to specifically address exercising its powers to seek out that information in the context of this case. In these circumstances, I therefore am not persuaded that this ground is made out and I therefore dismiss ground 1.

24 In my opinion, there was no error in the conclusion reached by the Federal Circuit Court. Before explaining why that is so, it is necessary to set out my approach to the question of legal unreasonableness and the terms of s 473DC of the Migration Act.

25 In DPI17 v Minister for Home Affairs [2019] FCAFC 43 at [78]-[90], I explained why I had some reservations about judicial observations that the discretion in s 473DC(1) should not be viewed through a “natural justice lens”. In substance, my view was that the whole context of the question of whether the exercise of powers and procedures in Pt 7AA have been approached in a way which falls within the bounds of legal reasonableness, is a context of procedural fairness, or “natural justice”, to use the language of Div 3 of Pt 7AA: see DPI17 at [88] and [91]-[95]. At [92] I stated:

92 While the plurality in Plaintiff M174 recognised at [22] that the primary requirement for the IAA’s review, as provided in s 473DB, is to carry out that review “by considering the review material provided to the Authority under s 473CB without accepting or requesting new information and without interviewing the referred applicant”, the plurality also recognised that the primary rule “admits of exceptions”, including the facultative provisions in s 473DC

26 I adhere to the views I expressed there. In terms of the correct approach to legal unreasonableness, I also adhere to and adopt what I said in DPI17 at [110]-[111]:

110 For my own part, and with great respect to those who have a different view, until the law about legal unreasonableness in Australia becomes more developed in its application and in its nuances, I prefer to restrict my articulation of principle to asking whether the exercise of power or performance of a function is such that no decision-maker, acting reasonably, could have approached the exercise of power or performance of the function in that way, in the statutory context and factual circumstances as they were at the relevant time. To my mind, adhering to that kind of approach emphasises, as Gageler J said in Li at [113], the stringency of the test, and the fact that judicial determinations of legal unreasonableness have, in practice, been “rare”. Of course, the descriptor “rare”, in the migration jurisdiction of the Federal Circuit Court, this Court and the High Court, must be applied taking into account the thousands of cases determined each year. In that context, the number of times a legal unreasonableness ground is upheld remains, in my view, “rare”.

111 Justice Gageler repeated observations to this effect in SZVFW at [52], in terms with which I respectfully agree:

Expression of the standard of legal reasonableness in terms of the minimum to be expected of any “reasonable repository of the power” in the circumstances of the impugned decision or action has the benefit of emphasising both the “extremely confined” scope and context-specific operation of the limitation it imposes. That is not to say that the standard might not be appropriately expressed in another form of words.

(Footnotes omitted.)

27 I also stated, at [106] that:

However, as the law currently stands, I do not understand that the ratio of the decisions in Hossain and SZMTA require that where an exercise of power has been found to be legally unreasonable (a ground not addressed in either of those decisions), the supervising court must conduct a separate assessment of “materiality”, before being able to characterise the error as jurisdictional in character.

28 I adhere to that view also, although materiality was not an argument expressly put on behalf of the Minister on this appeal.

29 In the context of the IAA’s two decisions in relation to the appellants, I reject the proposition that no decision-maker, acting reasonably, could have approached the exercise, or the consideration of the exercise, of the discretionary power in s 473DC(1) in the way the IAA did. Its approach was within the range of lawful choices open to, in the factual circumstances as they were at the relevant time.

30 The Minister submits the IAA did, in fact, consider whether to exercise its power in s 473DC(1) to “get” information about the UNHCR process, and the Court should infer it decided not to do so. He submits this is the point at which legal unreasonableness should be considered. It would seem that the appellants also put their argument principally at the stage of whether the IAA considered whether to exercise the power. In [12] of their written submission, they contend:

The IAA referred to the UNHCR assessment at paragraph 30 [AB221], which clearly averted to documents not having been obtained by the delegate but yet the IAA did not consider whether the IAA ought to exercise its discretion to obtain same.

(Emphasis added.)

31 If the question of legal unreasonableness is put at this point, in my opinion, it is clear as a matter of fact (and I find) that the IAA did not consider whether to exercise its discretion to “get” further information from the UNHCR. I accept it did consider to exercise its discretion under s 473DC(1) in relation to other information, and in fact did exercise its discretion, finding there were exceptional circumstances to do so, within the terms of s 473DD(1).

32 If it had also considered whether to exercise its discretion to “get” the UNHCR information, in my opinion it would have said so, and would have explained why it decided not to do so. The IAA was otherwise quite focussed on the terms of s 473DC(1) and their application to the appellants’ review. However, in my opinion, for two reasons, it placed the UNHCR information in quite a different category and did not turn its mind to whether it should “get” further information from the UNHCR.

33 The IAA generally accepted the appellants as credible: see [12] of its reasons. Yet, even accepting their accounts of what had occurred in Sri Lanka, it found (at [35]) that:

I am satisfied that subsequent to his release in 2006, the applicant was not perceived as being an LTTE member and although they asked after his whereabouts in the subsequent months, I am satisfied that their interest in the applicant’s previous residence in [redacted] and his support for the LTTE decreased, such that by the time he obtained a passport and departed in 2007, he was no longer of interest to them.

34 In other words, the IAA had reached a factual conclusion which appears to be inconsistent with the view of the UNHCR, if one assumes (as it appears the delegate and the IAA had done) that the appellants’ answers to the two questions on the protection visa application are correct and their refugee status was accepted by the UNHCR in 2008.

35 In my opinion, the IAA was determined to reach its own conclusions, and was not in that sense inclined to see any explanation for the UNHCR’s assessment as relevant to its task. That is precisely what it said at [30] of its reasons, which I have extracted above. In my opinion, where the IAA says “determinative”, it actually means “relevant”. The IAA did not see the 2008 UNHCR assessment as even relevant to its task in September 2016.

36 That is why, together with the absence of any express reasons despite consideration of s 473DC(1) in relation to other information, in my opinion, it should not be inferred that the IAA did consider whether to “get” the UNHCR information. It did not, but it was not legally unreasonable for it to fail to consider whether to do so.

37 Although that might sound like a surprising proposition, given the status of the UNHCR and the conclusion the UNHCR had reached about the appellants being refugees, in the context of the IAA’s task, this was not a legally unreasonable approach.

38 The IAA’s task was to consider, de novo, whether it was satisfied – relevantly – that the appellants had a well-founded fear of persecution if returned to Sri Lanka, as the conditions in Sri Lanka existed in September 2016 at the time of its review, and into the reasonably foreseeable future. However, how the UNHCR had approached its assessment in 2008 was unlikely to have any material bearing on the IAA’s assessment eight years later. Especially where, as the IAA found (at [34] of its reasons), the UNHCR had in 2012 revised its own guidelines for protection of Tamils claiming to fear persecution in Sri Lanka.

39 The IAA was also entitled to take into account as it did at [30], that the appellants themselves had not provided any further information about the UNHCR process or decision. If, hypothetically, the appellants had tried and failed to secure any information from the UNHCR because the UNHCR would only give such information to a government body (such as the Department, the Administrative Appeals Tribunal or the IAA), and the IAA was made aware of this, then closer consideration may have been needed to the question whether a refusal to consider: “getting” the UNHCR information in those circumstances was legally unreasonable. Even then, the difference in the time and circumstances of the refugee assessment would have remained an obstacle to this ground succeeding in the present circumstances. The IAA was plainly influenced, as it said at [32], by the fact that:

It is relevant, however, that these events occurred in 2006/07, the final years of the war marred by intense fighting. Since the end of the war (particularly in the almost four years that the applicant has been in Australia) the situation for Tamils in Sri Lanka has changed considerably.

40 Ground 1 must be rejected.

The new ground

41 In my opinion, leave should not be granted to the appellants, or more particularly, the appellant wife, to raise the new ground. While if the ground had merit, I would not have been troubled by the absence of any explanation for it not having been raised in the Federal Circuit Court, in my opinion, the new ground has no arguable prospects of success and leave should be refused on that basis.

42 The parties accepted that the correct approach to the question whether a claim was raised, or arose on the material, is set out by Allsop J (as his Honour then was) in NAVK v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs [2004] FCA 1695 at [15]:

… From NABE I take it that the Tribunal is not required to consider a claim that is not expressly made or does not arise clearly on the materials before it: NABE at [61]. As the Full Court said at [63] much depends on the circumstances. Whatever adverb or adverbial phrase is used to describe the apparentness of the unarticulated claim, it must, it seems to me, either in fact be appreciated by the Tribunal or, if it is not, arise sufficiently from the material as to require a reasonably competent Tribunal in the circumstances to appreciate its existence. A practical and common sense approach to everyday decision-making requires the unarticulated claim to arise tolerably clearly from the material itself, since the statutory task of the Tribunal is to assess the claims by reference to all the material, not to undertake an independent analytical exercise of the material for the discovery of potential claims which might be made, but which have not been, and then subjecting them to further analysis to assess their legitimacy.

43 After some discussion during oral argument, both parties also accepted that the principles as set out in NAVK were equally applicable to the judicial review of the approach of a decision-maker, such as the IAA, to whether a person met the criteria for the grant of complementary protection. I proceed on the basis that is the case.

44 I accept the Minister’s submission that all that was before the IAA was the following:

(a) In her statutory declaration, the appellant wife stated she had diabetes and took medication every day. She described the effects of having diabetes, such as that she became dehydrated easily and that one of her shoulders was displaced. She also described that life was difficult in Malaysia due to her diabetes.

(b) In the context of being asked if there were any factors that needed to be considered if she was called for an interview, the appellant wife had stated in her protection visa application that she had diabetes. This reference was obviously for quite a distinct purpose, and not related to the nature of her claims but to how she should fairly be interviewed.

45 It is true that the appellant husband had also referred to his wife’s diabetes in his statutory declaration. He had stated that part of why life in Malaysia was difficult was because his wife needed treatment for diabetes, and they came to Australia so their children could go to school and his wife could get better treatment for her diabetes.

46 No information was ever provided – to the delegate or to the IAA – about how the appellant wife’s diabetes should give the delegate or the IAA “substantial grounds for believing” that, as a necessary and foreseeable consequence of the appellant wife being removed from Australia to Sri Lanka, there was a real risk that she will suffer significant harm – that being the criterion set out in s 36(2)(aa) in relation to complementary protection. There was no link provided between the appellant’s wife diabetes and a risk of significant harm in Sri Lanka.

47 The appellants’ counsel fairly conceded that the delegate had not identified any such claim in his decision, where he listed the claims made by the appellant wife. He also fairly conceded there was nothing in the appellants’ agent’s submissions to the IAA about this issue.

48 Counsel submitted that having described her suffering with diabetes, and given the whole point of the IAA review was about whether she should be compelled to return to Sri Lanka, it was implicit that the appellant wife was raising a claim of complementary protection based on her being a diabetic. I do not accept this submission: it goes well beyond the applicable principles in NAVK. It cannot be said that the appellants’ references to the appellant wife having diabetes suggest a claim to protection on that basis arises “tolerably clearly from the material itself”, to use Allsop J’s words in NAVK. What was tolerably clear, if anything, was that the appellants referred to the appellant wife’s diabetes to explain why they came from Malaysia to Australia, rather than staying in Malaysia, and why the appellant wife might have needed extra consideration during any visa interviews.

49 Leave to raise the proposed new ground is refused.

Conclusion

50 The appeal in each proceeding must be dismissed. There is no basis to refuse to make an order for costs in the Minister’s favour. However, the lump sum which is to be agreed, or fixed, for the two appeals should take into account that the matters have been dealt with together all along: in other words, the costs agreed or fixed should be substantially less than would be the case in two appeals run independently of one another, and closer to the costs of a single appeal. A single lump sum should be fixed.

I certify that the preceding fifty (50) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Mortimer. |

Associate:

Dated: 30 August 2019