FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Eckford v Six Mile Creek Pty Ltd (No 2) [2019] FCA 1307

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | SIX MILE CREEK PTY LTD ACN 059 767 994 First Respondent DANIEL MCLAUGHLIN Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 20 August 2019 |

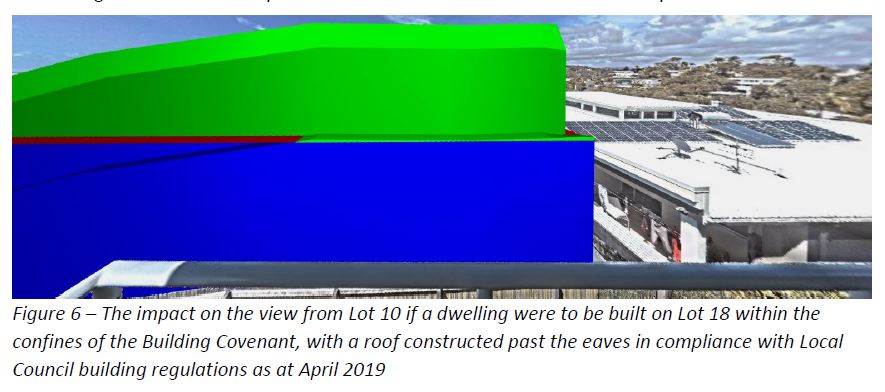

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The matter be listed for case management hearing at 9.30am on 22 August 2019 for the purpose of making orders in accordance with the reasons given on 20 August 2019.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

FINAL ORDERS

NSD 279 of 2017 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | DEREK DIXON ECKFORD Applicant | |

AND: | SIX MILE CREEK PTY LTD ACN 059 767 994 First Respondent DANIEL MCLAUGHLIN Second Respondent | |

JUDGE: | RARES J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 22 August 2019 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Judgment Amount

1. There be judgment for the applicant against the first and second respondents in the sum of $2,573,542.46, made up of the following amounts:

(a) $936,304.26 on account of the Purchase Claim;

(b) $1,153,396.55 on account of the Loan Claim;

(c) $915,936.65 on account of the Construction Cost Claim;

(d) $592,905 on account of pre-judgment interest in accordance with s 51A of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth); and

(e) less the sum of $1,025,000 being the current value of lot 10.

Costs

2. The first and second respondents pay the applicant’s costs.

3. The question of whether the applicant’s costs payable by the first and second respondents be on the ordinary basis or otherwise be reserved.

4. The applicant file and serve written submissions of no more than 3 pages on the question of costs by 30 August 2019.

5. The respondents file and serve written submissions in reply of no more than 3 pages on the question of costs by 6 September 2019.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

RARES J:

[1] | |

[15] | |

[17] | |

[19] | |

[25] | |

[46] | |

[50] | |

[53] | |

[54] | |

[59] | |

(c) The circumstances in which Six Mile Creek came to sell lot 10 to Mr and Mrs Eckford | [109] |

Mc McLaughlin’s state of mind at the time of the making of the representation | [119] |

[123] | |

[147] | |

[154] | |

The circumstances in which Mr Eckford claims there was fraudulent concealment | [161] |

Mr Eckford and Jason Eckford discover the sale of lots 17, 18 and 19 without the height restrictions | [184] |

[198] | |

[198] | |

[207] | |

[217] | |

Did Six Mile Creek or Mr McLaughlin make the price list representation? | [222] |

[222] | |

[225] | |

[248] | |

[254] | |

(a) Did the respondents make the price list representation fraudulently? | [273] |

[283] | |

(a) Fraudulent concealment under the Limitation of Actions Act 1974 (Qld) | [283] |

[283] | |

[288] | |

[305] | |

[305] | |

[306] | |

[313] | |

[313] | |

[333] | |

[339] | |

[341] | |

[350] | |

[358] | |

[359] | |

[364] | |

[369] | |

[371] | |

[374] |

1 In about late September, the applicant, Derek Eckford, and his late wife, Gale, were on a family holiday on the Gold Coast in Queensland. At that time, they resided in Dubbo, New South Wales. They both had lived there for about 40 years and had raised their family of three sons, one of whom subsequently died. One of their sons, Jason Eckford, and his wife, was on the holiday, together with his parents.

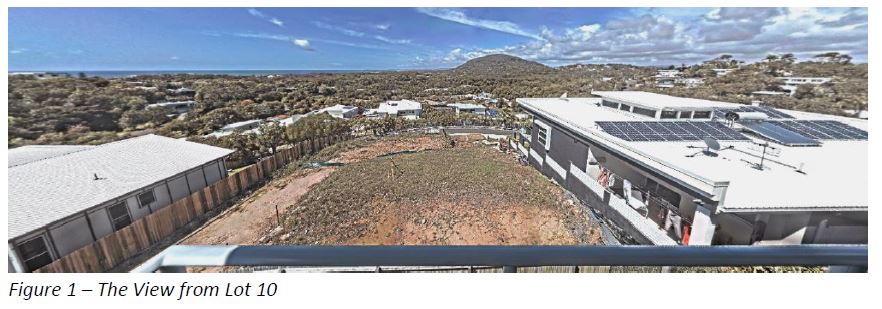

2 One day in late September or early October 2007, Mr and Mrs Eckford drove from the Gold Coast to the Sunshine Coast. There, they noticed a sign advertising undeveloped lots of land for sale in an estate then called “Avalon @ Coolum”. They drove around the estate, which consisted of about 60 parcels of undeveloped, subdivided lots. The estate was located on hilly terrain. They drove up to the sales office for the estate where Ken Guy Real Estate, the selling agent, had a site office. It was located on the highest point and had views to the Pacific Ocean and Coolum Beach on the eastern side, and to Mount Coolum on the south.

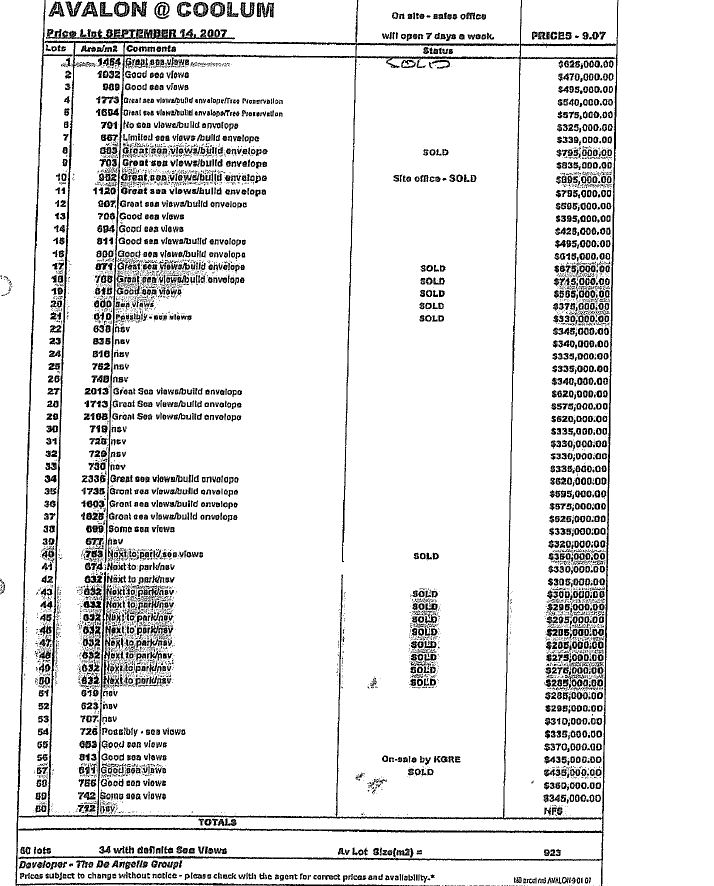

3 Six Mile Creek Pty Ltd owned the estate and it, together with its principal and controlling mind, Daniel (Danny) McLaughlin, are the respondents. The site office was on lot 10. Lot 10 had a “sold” sign placed next to the site office. The real estate agent at Ken Guy responsible for conducting sales of Avalon @ Coolum lots was Mark Boulter. His daughter, Angela, was on duty in the site office at the time Mr and Mrs Eckford called in to enquire about whether any lots were for sale. She arranged for her father, Mr Boulter, to attend and he gave Mr and Mrs Eckford a sales brochure, a price list dated 14 September 2007 and a copy of the plan of subdivision for the estate. The latter two documents had highlighting that showed that certain lots had been “sold” and their prices were recorded on the price list.

4 It is common ground that Mr Boulter made four representations to Mr and Mrs Eckford on both this and a subsequent visit on a Saturday, probably 29 September 2007. The representations in substance were that three lots (lots 17, 18 and 19), located on the southern boundary of lot 10, had building covenants on them that contained height restrictions limiting the height of any buildings, trees and vegetation that could be on those lots, so as to ensure, as the brochure promised, that lot 10 would keep its ocean views “FOREVER”, and, also, that lots 8 (which was directly north of lot 10, but below and separated from it by lot 9, and had a similar aspect), 17, 18 and 19 had been “sold” at the prices specified in the price list.

5 Subsequently, Mr and Mrs Eckford agreed with Jason Eckford that he would lend them the money to buy lot 10 for its list price of $895,000 plus stamp duty. On 20 November 2007, they entered into a contract to purchase lot 10 from Six Mile Creek that contained the building covenants including the height restrictions that supposedly would bind the owners of lots 17, 18 and 19 “FOREVER”. Mr and Mrs Eckford then sold their Dubbo home and built a house using their funds on lot 10, all the while believing that lots 17, 18 and 19 were burdened with the height restrictions.

6 In February 2016, Mr Eckford and Jason Eckford learnt that, at some time after Mr Boulter had shown them the price list, Six Mile Creek had sold lots 17, 18 and 19 to third parties on contracts which contained none of the height restrictions to bind the new purchasers of those lots.

7 Mr Eckford, as the surviving joint tenant of lot 10, contends that Six Mile Creek and Mr McLaughlin engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct and made false or misleading representations in contravention of each of ss 52(1) and 53A(1)(b) of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (TPA) in making representations concerning the effect and operation of the height restrictions and the nature of existing “sales” of lots in the estate as stated in the price list.

8 Mr Eckford also contends that Six Mile Creek and Mr McLaughlin made a fraudulent representation that lots 17, 18 and 19, together with lot 8, had been “sold”. That was because, previously, Six Mile Creek, through Mr McLaughlin, had agreed to terminate the contract for lot 19, so that the purchaser of that lot could buy lot 9 (and in fact had terminated the contract for lot 19 on 1 October 2007), and lots 8, 17 and 18 were the subject of contracts under which the purchasers had either paid no deposit at all, or a partial deposit of $1,000, were persistently in default and were never likely complete those contracts. Mr Eckford contends that the statement that those lots had been “sold”, unqualified as it was, conveyed the representation that the lots were, in the belief of the vendor, the subject of contracts that either had been completed already or would be completed so as to ensure that the height restrictions in the building covenants would be enforceable to protect Mr and Mrs Eckford’s views from lot 10 to the south. Mr Eckford claims damages for the tort of deceit against both respondents in respect of this representation.

9 Mr Eckford alleges that Six Mile Creek made two representations about the height restrictions with respect to future matters and that it did not have reasonable grounds for making them by reason of which they were taken to be misleading, pursuant to s 51A(1) of the TPA. In addition, Mr Eckford also alleges that Six Mile Creek and Mr McLaughlin had fraudulently concealed from him, until 2016, the falsity of the height representations.

10 Mr Eckford says that, had he realised that the representations were not correct in stating that the views of lot 10 were protected by the height restrictions by reason of the “sales” of lots 17, 18 and 19, he and his wife would never have bought lot 10. Mr Eckford claims injunctions under s 80 of the TPA restraining Six Mile Creek from approving any development on lots 17, 18 and 19 exceeding the height restrictions on each of those lots in the building covenants forming part of the contract of purchase for lot 10, declarations that Six Mile Creek and Mr McLaughlin, as an accessory, engaged in conduct in contravention of ss 52 and 53A(1)(b) of the TPA, and damages under ss 82 and 87(1) of the TPA on the basis of a no transaction case.

11 Mr Eckford claims damages under the following five heads:

Item | Description | Amount |

1. | Cost of lot 10, stamp duty and associated expenses (the purchase claim) | $936,304.26 |

2. | Costs of construction of a dwelling on lot 10, relocation from Dubbo to lot 10 and associated expenses (the construction cost claim) | $915,936.65 |

3. | Interest at prejudgment rates under s 51A of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) on items 1 and 2 or only on item 2 calculated from dates when money was expended (the interest claim) | About $1,300,000.00 or $539,188.37 |

4. | Interest due to Jason Eckford on his loan (the loan claim) | $1,029,474.08 |

5. | Loss of a capital gain on the Dubbo property | $71,000.00 |

12 The respondents deny all liability. They assert that Mr and Mrs Eckford did not rely on any representation. Mr McLaughlin also denies that he has any personal liability for any of the representations.

13 In essence, Six Mile Creek and Mr McLaughlin accept that the representations about the height restrictions were made, but say that, first, they were true at the time they were made because of the contemporaneous existence of exchanged contracts for the sale of lots 8, 17, 18 and 19 when Mr and Mrs Eckford first visited the site office, and, secondly, even if those representations and the representation in the price list that those lots had been “sold” were misleading or deceptive or false or misleading, the conduct occurred more than six years before Mr and Mrs Eckford entered into the contract of purchase on 20 November 2007 and completed it on 11 January 2008, and ss 82(2) and 87(1CA) of the TPA made the claims unmaintainable. In addition, Six Mile Creek and Mr McLaughlin deny that they were in any way fraudulent in representing that lots 8, 17, 18 and 19 had been sold or that Mr and Mrs Eckford had relied on that representation in going into the contract to purchase lot 10. They also contend that Mr Eckford cannot succeed on his claim that they had made a fraudulent representation because he had, or with reasonable diligence could have, discovered the alleged fraud more than 6 years before he commenced this proceeding on 24 February 2017.

14 The respondents say that any damages, on a no transaction case, should be limited to $627,248.16, being the difference in the total of the purchase and construction cost claims, and what they asserted, based on the valuation evidence that they adduced, as the current value of lot 10 of $1,225,000.

The pleaded representations and issues

15 Mr Eckford pleaded that Six Mile Creek engaged in conduct that conveyed the following representations to Mr and Mrs Eckford, namely that:

(1) Six Mile Creek had sold, at least, each of lots 17, 18 and 19 on conditions that included a covenant that restricted the maximum height of any buildings on each lot, and that would be passed on to future owners of those lots;

(2) Six Mile Creek would not approve or permit the construction of any building on any of lots 17, 18 or 19 that exceeded the respective height restriction in the building covenants in respect of that lot;

(3) Six Mile Creek would remove or prune, or cause to be removed or pruned, any trees or shrubs located on at least each of lots 17, 18 and 19 that interfered with the sea view sight lines of lot 10 (I will refer to representations (1), (2) and (3) collectively as the height representations); and

(4) Six Mile Creek had sold already:

(a) lot 8 for a price of $795,000;

(b) lot 17 for a price of $675,000;

(c) lot 18 for a price of $715,000;

(d) lot 19 for a price of $565,000.

(the price list representation)

16 The following issues arise in the proceeding:

(1) did Six Mile Creek and or Mr McLaughlin engage in conduct that conveyed any of the representations on which Mr and Mrs Eckford had relied and was any such representation misleading or deceptive, or false or misleading, or, in respect of representations (2) and (3), made without reasonable grounds (the liability issue);

(2) did Six Mile Creek and or Mr McLaughlin make the price list representation knowing that it was untrue or recklessly indifferent as to whether it was true or false (the fraud issue);

(3) are Mr Eckford’s claims statute barred and did Six Mile Creek and or Mr McLaughlin fraudulently conceal from Mr Eckford the fact that Six Mile Creek had sold each of lots 17, 18 and 19 without any height restrictions (the limitation issue); and

(4) did Mr Eckford suffer any, and if so what, loss or damage or become entitled to any, and if so what, relief (the relief issue).

17 The TPA provided, as at September to November 2007, relevantly:

4K Loss or damage to include injury

In this Act:

(a) a reference to loss or damage, other than a reference to the amount of any loss or damage, includes a reference to injury; and

(b) a reference to the amount of any loss or damage includes a reference to damages in respect of an injury.

51A Interpretation

(1) For the purposes of this Division, where a corporation makes a representation with respect to any future matter (including the doing of, or the refusing to do, any act) and the corporation does not have reasonable grounds for making the representation, the representation shall be taken to be misleading.

(2) For the purposes of the application of subsection (1) in relation to a proceeding concerning a representation made by a corporation with respect to any future matter, the corporation shall, unless it adduces evidence to the contrary, be deemed not to have had reasonable grounds for making the representation.

52 Misleading or deceptive conduct

(1) A corporation shall not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

53A False representations and other misleading or offensive conduct in relation to land

(1) A corporation shall not, in trade or commerce, in connexion with the sale or grant, or the possible sale or grant, of an interest in land or in connexion with the promotion by any means of the sale or grant of an interest in land:

[…]

(b) make a false or misleading representation concerning the nature of the interest in the land, the price payable for the land, the location of the land, the characteristics of the land, the use to which the land is capable of being put or may lawfully be put or the existence or availability of facilities associated with the land;

[…]

(1) …where, on the application of the Commission or any other person, the Court is satisfied that a person has engaged, or is proposing to engage, in conduct that constitutes or would constitute:

(a) a contravention of any of the following provisions:

(i) a provision of Part IV, IVA, IVB, V or VC;

[…]

(b) attempting to contravene such a provision;

(c) aiding, abetting, counselling or procuring a person to contravene such a provision;

(d) inducing, or attempting to induce, whether by threats, promises or otherwise, a person to contravene such a provision;

(e) being in any way, directly or indirectly, knowingly concerned in, or party to, the contravention by a person of such a provision; or

(f) conspiring with others to contravene such a provision;

the Court may grant an injunction in such terms as the Court determines to be appropriate.

[…]

(5) The power of the Court to grant an injunction requiring a person to do an act or thing may be exercised:

(a) whether or not it appears to the Court that the person intends to refuse or fail again, or to continue to refuse or fail, to do that act or thing;

(b) whether or not the person has previously refused or failed to do that act or thing; and

(c) whether or not there is an imminent danger of substantial damage to any person if the first-mentioned person refuses or fails to do that act or thing.

(1) Subject to subsection (1AAA), a person who suffers loss or damage by conduct of another person that was done in contravention of a provision of Part IV, IVA, IVB or V or section 51AC may recover the amount of the loss or damage by action against that other person or against any person involved in the contravention.

[…]

(2) An action under subsection (1) may be commenced at any time within 6 years after the day on which the cause of action that relates to the conduct accrued.

(1) Subject to subsection (1AA) but without limiting the generality of section 80, where, in a proceeding instituted under this Part, ….the Court finds that a person who is a party to the proceeding has suffered, or is likely to suffer, loss or damage by conduct of another person that was engaged in (whether before or after the commencement of this subsection) in contravention of a provision of Part…V…, the Court may, whether or not it grants an injunction under section 80 or makes an order under section 82…make such order or orders as it thinks appropriate against the person who engaged in the conduct or a person who was involved in the contravention (including all or any of the orders mentioned in subsection (2) of this section) if the Court considers that the order or orders concerned will compensate the first-mentioned person in whole or in part for the loss or damage or will prevent or reduce the loss or damage.

[…]

(2) The orders referred to in subsection (1) and (1A) are:

[…]

(c) an order directing the person who engaged in the conduct or a person who was involved in the contravention constituted by the conduct to refund money or return property to the person who suffered the loss or damage;

(d) an order directing the person who engaged in the conduct or a person who was involved in the contravention constituted by the conduct to pay to the person who suffered the loss or damage the amount of the loss or damage;

[…]

(g) an order, in relation to an instrument creating or transferring an interest in land, directing the person who engaged in the conduct or a person who was involved in the contravention constituted by the conduct to execute an instrument that:

(i) varies, or has the effect of varying, the first-mentioned instrument; or

(ii) terminates or otherwise affects, or has the effect of terminating or otherwise affecting, the operation or effect of the first-mentioned instrument.

(emphasis added)

18 The Limitation of Actions Act 1974 (Qld) (the Limitation Act) provided:

38 Postponement in cases of fraud or mistake

(1) Where in an action for which a period of limitation is prescribed by this Act—

(a) the action is based upon the fraud of the defendant or the defendant’s agent or of a person through whom he or she claims or his or her agent; or

(b) the right of action is concealed by the fraud of a person referred to in paragraph (a); or

(c) the action is for relief from the consequences of mistake;

the period of limitation shall not begin to run until the plaintiff has discovered the fraud or, as the case may be, mistake or could with reasonable diligence have discovered it.

(emphasis added)

The assessment of the evidence

19 In this case, as will appear, there is little doubt that Six Mile Creek made the representations substantively in the contemporaneous documents which Mr and Mrs Eckford received and that the real estate agent whom they met at the estate, Mr Boulter, also made them, orally, to reinforce the selling message. There are issues whether, so far as Mr Eckford’s evidence is concerned, he and his wife relied on what they read and heard and how, relevantly, Mr Eckford understood those representations and, so far as the respondents’ evidence is concerned, what they intended to convey to Mr and Mrs Eckford.

20 As the principal events in dispute occurred over 12 years before the non-expert witnesses gave evidence at the trial, it is particularly apposite to apply the principles identified by Dowsett, Rares and Logan JJ in Julstar Pty Ltd v Hart Trading Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 151 at [73]-[74]:

The assessment of the evidence of witnesses in such a case, ordinarily, will be approached in the manner discussed by McLelland CJ in Eq in Watson v Foxman (1995) 49 NSWLR 315 at 318-319 as follows:

“Where, in civil proceedings, a party alleges that the conduct of another was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive (which I will compendiously described [sic] as “misleading”) within the meaning of s 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (or s 42 of the Fair Trading Act), it is ordinarily necessary for that party to prove to the reasonable satisfaction of the court: (1) what the alleged conduct was; and (2) circumstances which rendered the conduct misleading. Where the conduct is the speaking of words in the course of a conversation, it is necessary that the words spoken be proved with a degree of precision sufficient to enable the court to be reasonably satisfied that they were in fact misleading in the proved circumstances. In many cases (but not all) the question whether spoken words were misleading may depend upon what, if examined at the time, may have been seen to be relatively subtle nuances flowing from the use of one word, phrase or grammatical construction rather than another, or the presence or absence of some qualifying word or phrase, or condition. Furthermore, human memory of what was said in a conversation is fallible for a variety of reasons, and ordinarily the degree of fallibility increases with the passage of time, particularly where disputes or litigation intervene, and the processes of memory are overlaid, often subconsciously, by perceptions or self-interest as well as conscious consideration of what should have been said or could have been said. All too often what is actually remembered is little more than an impression from which plausible details are then, again often subconsciously, constructed. All this is a matter of ordinary human experience.

Each element of the cause of action must be proved to the reasonable satisfaction of the court, which means that the court “must feel an actual persuasion of its occurrence or existence”. Such satisfaction is “not … attained or established independently of the nature and consequence of the fact or facts to be proved” including the “seriousness of an allegation made, the inherent unlikelihood of an occurrence of a given description, or the gravity of the consequences flowing from a particular finding”: Helton v Allen (1940) 63 CLR 691 at 712.

Considerations of the above kinds can pose serious difficulties of proof for a party relying upon spoken words as the foundation of a causes of action based on s 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) … in the absence of some reliable contemporaneous record or other satisfactory corroboration.” (non-italic bold emphasis added)

That caution is also reflected in s 140 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) and in what Dixon J said in Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 at 361-363 about the standard of proof. Dixon J emphasised that, when the law requires proof of any fact, the Court must feel an actual persuasion of its occurrence or existence before it can be found. He said that a mere mechanical comparison of probabilities, independent of any belief in its reality, cannot justify a finding of fact: see too Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2007) 162 FCR 466 at 479-482 [29]-[38] per Weinberg, Bennett and Rares JJ. As Dixon J said (60 CLR at 362): “In such matters ‘reasonable satisfaction’ should not be produced by inexact proofs, indefinite testimony, or indirect inferences”. But, the nature of the fact to be proved necessarily affects the sufficiency of the evidence by which it can be established.

(bold emphasis in original; underline emphasis added)

21 In addition, in evaluating whether a person has contravened the statutory norm in s 52 of the TPA and its analogues, the tools of analysis drawn from the laws of deceit, namely misrepresentation and reliance, can sometimes be helpful in identifying such conduct and deciding whether loss or damage has been suffered by the contravention. However, Gummow, Hayne, Heydon and Kiefel JJ noted in Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd (2009) 238 CLR 304 at 341-342 [102]:

But as McHugh J correctly pointed out in Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty Pty Ltd [(2004) 218 CLR 592 at 623 [103]], the “conduct” with which s 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) deals is not confined to “‘representations’, whether they be representations as to matters of present or future fact or law” [McHugh J dissented in the result of the particular case but not as to these questions of principle]. This proposition applies with equal force to s 42 of the Fair Trading Act. References to misrepresentation or reliance must not be permitted to obscure the need to identify contravening conduct (here, misleading or deceptive conduct) and a causal connection (denoted by the word “by”) between that conduct and the loss and damage allegedly suffered. As McHugh J also pointed out in Butcher [(2004) 218 CLR 592 at 625 [109]. See also the judgment of the Court in Campomar Sociedad Limitada v Nike International Ltd (2000) 202 CLR 45 at 84 [200]], with particular reference to s 52 of the Trade Practices Act, but with equal application to s 42 of the Fair Trading Act:

“The question whether conduct is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive is a question of fact. In determining whether a contravention of s 52 has occurred, the task of the court is to examine the relevant course of conduct as a whole. It is determined by reference to the alleged conduct in the light of the relevant surrounding facts and circumstances. It is an objective question that the court must determine for itself [See Equity Access Pty Ltd v Westpac Banking Corporation [1990] ATPR ¶50,943 (40-994) at 50,950 per Hill J; see also Taco Co of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd (1982) 42 ALR 177 at 202-203 per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ]. It invites error to look at isolated parts of the corporation’s conduct. The effect of any relevant statements or actions or any silence or inaction occurring in the context of a single course of conduct must be deduced from the whole course of conduct [See, eg, Trade Practices Commission v Lamova Publishing Corporation Pty Ltd (1979) 42 FLR 60 at 65-66; 28 ALR 416 at 421-422 per Lockhart J]. Thus, where the alleged contravention of s 52 relates primarily to a document, the effect of the document must be examined in the context of the evidence as a whole [See, eg, Lezam Pty Ltd v Seabridge Australia Pty Ltd (1992) 35 FCR 535 at 541 per Sheppard J, Hill J agreeing]. The court is not confined to examining the document in isolation. It must have regard to all the conduct of the corporation in relation to the document including the preparation and distribution of the document and any statement, action, silence or inaction in connection with the document.”

(italic emphasis in original)

22 Mr Eckford is in his early 80s, and Mr McLaughlin is 86 years old. Both men gave evidence over what for them was a relatively long period in the witness box. I attempted to give each of them breaks on a regular basis, particularly when it appeared either was looking or, appearing by his answers, to be exhausted or needing a rest. That said, each generally gave evidence in a way which satisfied me that he fully understood what he was asked and was alert and responsive to the question. To the extent that, on isolated occasions, particularly Mr McLaughlin, appeared tired when he gave particular answers, I have given those answers no probative weight.

23 In Mr McLaughlin’s case, I have also taken into account, in assessing his overall evidence, the fact that the events that he had been asked to recall and the state of mind that he formed at the relevant times, all occurred over 12 years ago, and that the passage of time and the advancing of his age have appeared to play a greater role, than with Mr Eckford, in some aspects of his recollection. Nonetheless, contemporaneous documents and Mr McLaughlin’s obvious astuteness, as an experienced property developer as at 2007 and in his oral evidence, have enabled me to form what, I am comfortably satisfied, is a reliable view of his overall credibility.

24 Of course, here, Mr Eckford claims on the basis of contraventions of ss 52 and 53A and fraud against each of Six Mile Creek and Mr McLaughlin. In evaluating the fraud allegations, I also have had regard to s 140 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) and Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australian v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2007) 162 FCR 466 at 480 [30] per Weinberg, Bennett and Rares JJ.

Mr and Mrs Eckford decide to buy lot 10

25 When Mr and Mrs Eckford first drove around the estate in late September 2007 and reached its highest point, they found the site office. It was located on lot 10. Mr and Mrs Eckford went into the office and spoke to Ms Boulter. They told her that they were rather interested in the estate. She asked whether they would like to see a sales representative. As a result, Mr Boulter arrived at the site office shortly afterwards and introduced himself.

26 Mr and Mrs Eckford told Mr Boulter that they had an interest in lot 10. He said that it was the “premier lot”. They went out onto the verandah, which had an elevated view, while Mr Boulter paced out the block (lot 10), by reference to the boundary pegs from the survey, to give them an indication of its size. They all then went inside the site office. Mr Boulter handed Mr and Mrs Eckford the brochure, the plan, that had highlighted on it the lots that had been sold, and the price list dated 14 September 2007, similarly highlighted.

27 Mr Boulter pointed out the various features of the subdivision and made frequent reference to the sea views. He discussed lot 10 and, when Mr Eckford pointed out that it had been marked as “sold”, Mr Boulter told him that the purchaser had not settled and had been delaying settlement. Mr Boulter then said lot 10’s views of the ocean were protected. He explained that was because the lots to the south between it and its sea view (lots 17, 18 and 19), which abutted onto, and fell away from, lot 10, had already been sold with the building covenants and height restrictions.

28 Lots 17, 18 and 19 were located on land that was running downhill from the summit on which lot 10 was located. Thus, lot 10 overlooked the hillside to its south on which lots 17, 18 and 19 were located on land falling away from the southern boundary of lot 10. As Mr Eckford went through the brochure, what caught his eye was its emphasis on there being ocean views “FOREVER”. Mr Boulter showed Mr and Mrs Eckford a copy of the building covenants. He told them that the purpose of the building covenants was to protect their investment in the land they would be buying because it restricted the heights of any buildings that could be constructed in front of lot 10 (i.e. to the south). Mr Boulter told Mr and Mrs Eckford that the building covenants applied to all lots on the estate including the existing purchaser of lot 10. He pointed out cl 4.5, which contained the height restrictions that applied to lots 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 and two other blocks. He emphasised that lots 17, 18 and 19, as immediately below lot 10, had already been sold with the building covenants (including the height restrictions on them) in force, saying “so that protects your view from hereon in”. Mr Boulter also said that the building covenants would apply to, and benefit, Mr and Mrs Eckford if they bought lot 10. He said that the building covenants had to be transferred by persons when selling the land.

29 Mr Eckford also noticed in the brochure that all plans for building work had to be approved by both the developer and the owner before they went to the local Council (for approval) and that there also were covenants restricting landscaping. Mr Boulter told them again that because the height restrictions were in place, and lots 17, 18 and 19 had been sold with them, this would protect views from lot 10 for all time. He added that the landscaping restraints also ensured that lot 10’s sea views could never be interfered with by another lot. Mr Boulter said that he wanted to reinforce the fact that the building covenants offered Mr and Mrs Eckford protection, were they to buy lot 10, and “was your insurance for your investment”. Mr Boulter said to them:

We [i.e. Six Mile Creek or Ken Guy] had already ascertained what the safe maximum height limits were on specific lots so that we could keep in perpetuity those view lines and give people quiet enjoyment of what they bought [so] that they had certainty and surety of that.

30 When Mr and Mrs Eckford looked through the building covenants with Mr Boulter at the site office, they raised a concern with him that cll 1.1 and 11 permitted the owner to waive, vary or relax the building covenants. Mr Boulter told them that that was not a concern because lots 17, 18 and 19, where building work could affect their views, had been sold with the building covenants attached so that “you have no problem with this”. Mr Boulter also explained that the height restrictions relating to trees and other plants, limited the height of vegetation on the burdened lots (17, 18 and 19) to three metres, and when the growth exceeded that height, the owner (i.e. the existing vendor) had the right to go onto the relevant lot to prune or remove the excess trees or plants. Mr Eckford said that he and Mrs Eckford discussed with Mr Boulter the fact that future purchasers would also be bound by the building covenants, both for lot 10 and the burdened lots. Mr Boulter did not have a copy of the building covenants for Mr and Mrs Eckford to take away with them, but they took the brochure, price list and plan with the lots sold highlighted on it.

31 Mr Boulter said that if they were interested, he would speak to the owner (i.e. the vendor) to see whether it would be prepared to “forego” the existing contract for lot 10 and give Mr and Mrs Eckford the opportunity to purchase lot 10. Mr and Mrs Eckford responded that, of course, they were interested, and that they wanted to have their son have a look at the property because he would have to help them with the finance.

32 I have reproduced below the price list that Mr and Mrs Eckford received when they first visited the estate in late September 2007, which had the shading or highlighting that indicated lots that had been sold, as it appeared in the reproduction. (The abbreviation “nsv” signified “no sea view”.)

33 The brochure showed, on page 2, a road plan of the estate with the site office and indicated that an ocean and a beach walk were to the east of the estate. The heading on page 2 included “Ocean View Land Estate” and a box on its right side had the heading “A new exclusive subdivision, many with OCEAN VIEWS FOREVER”. A contour plan of the estate was on page 3, and the next four pages contained extracts from the plan that showed the location of the various lots and their areas in square metres. Page 8 was headed “Summary of Building Covenants” and stated:

1. Benefit | To all owners – ensures a quality estate. |

2. Approvals | Must be approved by [the developer] The De Angelis Group and Six Mile Creek Pty Ltd [the owner]. |

3. Comply with Law | All buildings must also be approved by Maroochy Council. |

4. Dwellings | Governs size, approved materials, building heights – minimum house size [internal – including garage] is 240m2. Patios and Balconies are not included. |

5. Other structures | Garages, sheds, driveways, pools, display homes – what they need in order to comply. |

6. Fencing, walls & screening | What is required in order for them to comply. |

7. Construction & Maintenance obligations | The basic do’s and don’ts [sic] for building in this estate. |

8. Environmental Requirements | Landscaping and restrictive covenant to ensure that sea views are never interfered with by another lot. |

9. External Structures | Just what is allowed and where. |

10. Miscellaneous | Where to park, restriction to structures, legal right, signage, a future buyer to also be governed by these Covenants. |

11. Building Covenants | The approval process prior to any work commencing. |

(emphasis added)

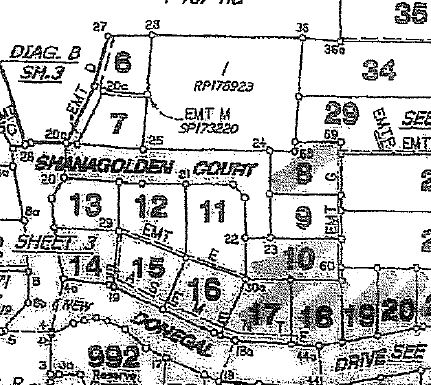

34 Below is an extract from the plan that Mr Boulter gave Mr and Mrs Eckford, with shading to indicate the lots already sold. (North is at the top.)

35 Mr Eckford said that he observed that his wife was involved in all the conversations and was perusing the documents with him. Sensibly, senior counsel for the respondents said that I could infer, if I accepted Mr Eckford’s evidence, that Mrs Eckford would have understood and relied on the same matters as her husband. I have drawn that commonsense inference.

36 When Mr and Mrs Eckford returned to their holiday accommodation, they had a discussion with Jason Eckford and showed him the documentation they had brought back, being the brochure, price list and plan. They told him that they were both quite interested but could not afford to both buy the land and build a house on it and asked whether he would be prepared to assist them. Jason Eckford said that he would have to see the lot they were interested in first, and they then arranged to meet Mr Boulter at lot 10 again.

37 They all returned on the following Saturday (probably 29 September 2007) and met Mr Boulter. He said that he had spoken to “Danny”, the owner, and that he (Danny) would be prepared to “forego” the existing contract for lot 10 if Mr and Mrs Eckford were prepared to put down a deposit of $1,000 on that day, because the other purchaser had been delaying settlement. Mr Boulter said that the purchase price would have to remain at $895,000. He said that when the contract was signed later, Mr and Mrs Eckford would have to pay the balance of the 10% deposit and that settlement would have to occur within 30 days.

38 Jason Eckford spoke with Mr Boulter, and asked him about the building covenants and height restrictions, and in particular, how they affected lots 17, 18 and 19. Mr Boulter told Jason Eckford, in his parents’ presence, that lots 17, 18 and 19 had already been sold with the building covenants attached and that those covenants would also apply to unsold lots.

39 Jason Eckford said that he would be prepared to finance his parents if they could afford the construction of a home on the new property. Mrs Eckford said that she was very thrilled that they could acquire the block and looked forward to building a home on it where their children and grandchildren could visit the couple on the holidays. After discussing matters with Jason Eckford, Mr and Mrs Eckford agreed and they paid $1,000 to Mr Boulter to secure the purchase.

40 Importantly, prior to paying the $1,000 holding deposit and signing a document that Mr Boulter wrote out about the proposed sale, Mr Eckford considered the asking price of $895,000 for lot 10 and decided that it was “an acceptable figure in view of what else was sold of the properties” that he noted as recorded on the price list. However, Six Mile Creek only terminated the existing contract for lot 10 on 1 October 2007 (see [123] below).

41 The prices that Mr Eckford saw in the price list had “a big influence” on his decision to purchase. He explained that, for example, the price list recorded a sold price (of $795,000) for lot 8. He said that lot 8 was one lot removed from, and behind, lot 10 (i.e. to its north) and its views (to the south) would be restricted by the building that he and his wife intended to construct because lot 10 had no height restrictions. He said that he considered the information about other lots that were smaller in area than lot 10 (which was 952m2), like lots 17 and 18 (which, he said, were around 700m2) and had sold for, he thought, $735,000. He gave those estimates of size and price in his evidence in chief without referring to the price list. I am satisfied that, at the time of his actual consideration of those matters in 2007, he took the actual sizes and prices set out in the price list into account in his thought process.

42 In fact, the price list stated that each of lots 8, 17, 18 and 19 was “sold”, and that lot 8 was 803m2 and had sold for a price of $795,000, lot 17 was 871m2 and had sold for a price of $675,000, lot 18 was 768m2 and had sold for a price of $715,000, and lot 19 was 615m2 and had sold for a price of $565,000. The price list had a comment “Great sea views/build envelope” next to each of lots 8, 17 and 18 and the comment “Good sea views” for lot 19. Lot 10 had the same comment as lots 8, 17 and 18 but it was 952m2 and had sold for $895,000. At the foot of the price list, there appeared a concluding section stating that there were, in total, 60 lots, 34 of which had “definite Sea Views” and the average size of the lots was 923m2.

43 Mr Eckford said that if lots 17, 18 and 19 did not have the height restrictions controlling the height of buildings on them, he would not have purchased lot 10. For him, the importance of the height restrictions was strictly to preserve the views from lot 10 and it was essential that lots 17, 18 and 19 be restricted to the heights that were set out in the building covenants that he saw at the site office (and which were later included in the contract for purchase of lot 10).

44 On Friday, 5 October 2007, Ken Guy sent Mr and Mrs Eckford a proposed contract for lot 10 together with a note of instructions on how it and its annexures should be completed and a request that deposits be made out to Brennans Solicitors’ trust account. I infer that on or shortly after 1 October 2007, Mr Boulter told Mr and Mrs Eckford that the “owner” had terminated the existing contract for lot 10 and would sell it to them. One of the annexures to the note was a selling agent’s disclosure to buyer form under the Property Agents and Motor Dealers Act 2000 (Qld) (form 27c). That form stated that its purpose was to make the purchaser aware of the relationships that the selling agent had with persons to whom the agent referred the purchaser and of the benefits that the agent and other people received from the sale.

45 The selling agent’s disclosure in the form 27c stated that the agent had referred Mr and Mrs Eckford to a company called Pangus Pty Ltd, and that its relationship with the selling agent was as “the Developer”. The disclosure in that form 27c was somewhat obscure. It stated that the selling agent would receive a total of $59,070 including GST, as marketing fees from the sale. Under the column headed “Benefit to person/entity to whom buyer referred (if any) $ Amount” was the following: “Avalon @ Coolum Sales/The Project Marketing Group acting for The De Angelis Group trading as Pangus Pty Ltd”. The selling agent’s disclosure declaration on the form 27c stated that the selling agent was Sydney Fish Pty Ltd and Cross Match Holdings Pty Ltd [t/as Avalon @ Coolum Sales] which signed and dated it 5 October 2007. (That document was later signed by Mr and Mrs Eckford.)

The contract for the sale of lot 10 to Mr and Mrs Eckford

46 On 20 November 2007, Mr and Mrs Eckford exchanged contracts with Six Mile Creek for the purchase of lot 10 for the price of $895,000. The contract contained a number of standard and special conditions, and included the whole of the building covenants. Special condition 7.1 provided that the purchaser acknowledged that the building covenants, special conditions and annexures to the contract formed part of it and that:

The Buyer acknowledges that:

[…]

(c) it shall be at the discretion of the Seller as to whether or not the Seller seeks to enforce covenants which are obtained from any other Buyer of Land within Avalon@Coolum Development.

(d) the Buyer has no claim or action against the Seller if the Seller adopts an altered form of Building Covenants in contracts of sale for other land within the Avalon@Coolum Development.

(emphasis added)

47 Clearly enough, special condition 7.1(d) applied to future sales, not (what Mr and Mrs Eckford had been told were) completed sales of other lots which included all of the building covenants, especially the height restrictions.

48 The building covenants (as Mr and Mrs Eckford saw at the site office and included in their contract for purchase of lot 10), relevantly provided:

1 BENEFIT OF COVENANT

1.1 Avalon @ Coolum is a prestige residential estate. In order to encourage the ‘At One with Nature Theme’ and the Green Smart HIA initiative, these Covenants have been developed to continue to encourage this quality environment and are intended to establish standards of construction for all residences constructed in the estate, with a consistently high standard of house design encouraged with due recognition given to interest, variety and compatibility within the streetscape and be for the benefit of the Buyer and any party to whom the Buyer assigns the benefits of these covenants and to SIX MILE CREEK PTY LIMITED ACN 059 767 994 the Seller and its assigns. However, notwithstanding the Covenants contained herein the Seller reserves the right at the request of a Buyer or at its own discretion to vary, add to or exclude any of the obligations under the Covenants in respect of any Lot provided that such action will only be taken by it in keeping with the aims to establish a modern well designed residential estate. The Seller will not be liable to the Buyer or any other owner for any variation, addition or exclusion of these Covenants.

1.2 The Building Covenants and Design Guidelines are intended to act as investment protection so all proposed homes must satisfy the requirements, hence owners can be confident that future houses, garages and gardens will be constructed in a manner complimentary [sic] to the streetscape and the character of this environment.

2 APPROVALS

2.1.1 No construction of any improvements or structures on the site (including any dwelling, outbuildings or other structures such as a pergola, carport, fences and pools) is to take place unless all plans and specifications are approved in writing by the Seller.

[…]

4.5 Building Heights – Restrictive covenant.

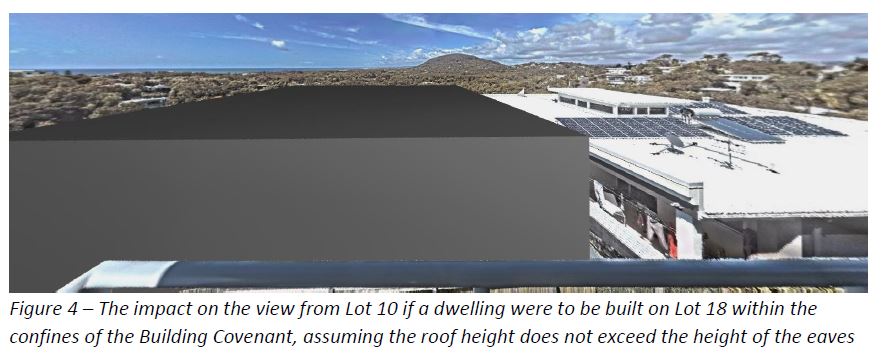

With the object and intent of preserving the views of other lots the maximum permitted height to the top of the eaves of the upper storey of the following lots above and relative to the maximum natural ground level at the rear of these lots individually shall be as follows:--

Lot 15 – 5 metres

Lot 16 – 4 metres

Lot 17 – 3 metres

Lot 18 – 4 metres

Lot 19 – 4 metres

Lot 57 – 4 metres

Lot 58 – 4 metres

[…]

8.3 Restrictive covenant

8.3.1 With the object and intent of preserving the sea views envisaged by the estate layout trees and shrubs on Lots 2, 3, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 21–26, 30, 33, 51–59 inclusive shall be of a type that will not interfere with the sea view lines from Lots 1–40.

8.3.2 Should trees or shrubs planted initially or subsequently interfere with the sea view lines of any of the Lots 1–40, then the trees shall be (at the option of the Seller) removed or pruned at the cost of the Buyer and where the Buyer falls [sic] to act promptly after a request to either remove or prune the trees then the Buyer shall allow access to the lot by the seller or its agents to do so at the cost of the Buyer.

[…]

11.1 Seller may vary or relax Building Covenants and Design Guidelines

The Buyer agrees that the Seller has the right to waive, vary or relax the Building Covenants and Design Guidelines, particularly in relation to any other sale of any part or stage of the Estate, and in that event, the Buyer agrees that it will have no claim whatsoever against the Seller.

The Buyer may not bring any action or make any claim against the Seller in respect of:--

(a) any change to the Building Covenants and Design Guidelines from time to time; and

(b) any non-compliance with the provisions of Building Covenants and Design Guidelines by any third party or by the Seller.

11.2 Enter and Remedy

The Seller or its agents may come onto the Land after reasonable notice and remedy any breach of these Building Covenants and Design Guidelines by the Buyer or any future owner (or the Buyer’s or the future owner’s tenants or agents) and the Seller’s costs (including legal costs) of notifying and (if necessary) remedying that breach may be recovered from the Buyer as a liquidated debt.

[…]

(underline emphasis added; bold emphasis in original)

49 Clauses 4.5 and 8.3 contained the height restrictions.

The loan deed with Jason Eckford

50 On 27 December 2007, Mr and Mrs Eckford entered into a deed of arrangement and debt with their son, Jason Eckford (the loan deed). The loan deed contained a preamble reciting that:

Jason Eckford had lent his parents $930,000 to purchase lot 10 and pay stamp duty; and

it was an essential term that interest on the balance of the loan would be calculated annually and that the repayment of the loan, plus accrued interest, had to be made within six months of any of the parties electing to bring it to an end.

51 The interest rate under the loan deed was to be the Reserve Bank of Australia cash rate, plus 4% per annum, with accrued interest to be added at the end of each year. The loan deed provided that:

in the event that each of the borrowers died, the last surviving borrower would direct his or her executor to repay the balance of the loan plus accrued interest before any distribution to other beneficiaries of the balance of the estate under a will; and

the surviving parent agreed that the balance of the loan plus interest and obligations accrued by the deceased parent would be assumed by the survivor.

52 On 11 January 2008, Mr and Mrs Eckford completed the purchase of lot 10 from Six Mile Creek using about $936,000 that Jason Eckford had lent them to do so and to pay the stamp duty on the contract and their associated expenses.

Six Mile Creek begins marketing the estate

53 I accept Mr Boulter’s evidence generally as reliable. He said that, in about early 2007, he and Mr McLaughlin discussed the proposed plan of subdivision for the estate, local government requirements, the encumbrances that would be placed on specific lots and the proposed building covenants, including those relating to the maximum height of buildings and vegetation growth allowable on particular lots so as to protect the views from lots situated above those (to be burdened) lots. Mr Boulter explained that this occurred in the context that Six Mile Creek had engaged Ken Guy to sell the estate as a whole. That activity culminated in the entry, on 29 May 2007, into a put and call option deed between Six Mile Creek, Pangus and Agostino (Gus) De Angelis as guarantor of Pangus’ obligations.

54 Mr McLaughlin received advice from his accountant, James Whitelaw, about the commercial terms that came to form part of the put and call option, including the values given for the lots in each of the list price and minimum resale price in schedule 1 of the put and call option. Mr Whitelaw recommended to Mr McLaughlin that Paul Baynes of Nicholsons solicitors act for Six Mile Creek in drafting the put and call option and in respect of matters arising under it. Mr McLaughlin accepted that advice.

55 Mr Whitelaw composed the prices for the list price in schedule 1 by averaging the values for each lot that Six Mile Creek had obtained from each of Mr De Angelis, Watpac (another entity which had also negotiated to buy or arrange sales of lots in the estate) and PRD Nationwide’s Andy Lake. Mr Whitelaw suggested (and Mr McLaughlin accepted) that the list price effectively would represent the net minimum proceeds Six Mile Creek had to receive after all selling costs had been paid while the minimum resale price would ensure that, after any sale, Pangus had achieved a sufficient margin to meet those selling costs, as well as enabling each of Six Mile Creek and Pangus to receive 50% of any excess, which would build up Pangus’ equity in meeting the total of the project fee.

56 The put and call option relevantly provided that:

Six Mile Creek granted Pangus a call option, being the right to require Six Mile Creek to enter into a contract for the sale of a lot in the estate with a third party purchaser on specific terms, including that:

the purchaser had to pay, at least, the minimum resale price for that lot set out in schedule 1;

the purchaser had to pay a deposit equal to 10% of the purchase price;

settlement had to occur 30 days after the date of the contract;

the purchaser had to “abide by and be bound by the building covenants for Avalon@Coolum (as notified by [Six Mile Creek])”; and

where a company was the purchaser, the purchaser had to include its directors as guarantors (cl 2.1(b)).

When Pangus exercised a call option, it had to deliver to Six Mile Creek’s conveyancing solicitors (who were Bakers Lawyers of Buderim, Queensland) a notice doing so, two copies of the contract executed by the purchaser (and any guarantor) and the amount of the deposit then payable in accordance with the contract (cll 2.4 and 2.5). Unless Six Mile Creek had agreed in writing, a call option would not be exercised validly if the purchase price shown in the contract were less than the minimum resale price (for the lot set out in schedule 1), the provisions of cl 2.4 were not complied with, completion was specified to occur more than 30 days from the contract date, or Pangus was in default of its obligations under the put and call option (cll 2.6 and 2.7).

Pangus had to pay Six Mile Creek:

(a) $500,000 as an advance on the project fee of $16.112 million on the next business day after execution of the put and call option; and

(b) $6.925 million, as a second advance on the project fee, by 28 June 2007 (cl 4.1).

When a sale of a lot completed, Six Mile Creek had to pay its bank, as mortgagee, what the bank required, any balance up to the list price in schedule 1 (being a price for each lot (and which was less than the minimum resale price), the total for which equalled the project fee of $16.112 million), any other sum then due to Six Mile Creek, the selling agent’s commission, and half of any residue paying the balance, if any, to Pangus (cl 5.1).

Bakers had to advise Pangus of any requests by purchasers for extensions of the finance date in any contract, alterations to the standard form of the contract, settlement figures and the occurrence of completion of a contract (cl 5.2).

Pangus would engage the selling agent (which, in the event, was Ken Guy) and agreed to indemnify Six Mile Creek against all claims for commission and marketing fees (cl 5.3) while Six Mile Creek agreed to give the agent access to the estate to market it (cl 9).

The put and call deed also provided:

9.2 The Grantee [Pangus] must use its best endeavour to market, advertise and otherwise promote the sale of the Lots as soon as possible after the date of this Deed but otherwise generally in the manner necessary to achieve the payment of the Project Fee to the Grantor [Six Mile Creek] in the time and in the manner detailed in this Deed.

[…]

9.4 The Grantee is responsible for and must ensure that in respect of each Third Party Contract any agent engaged by the Grantee to sell the Lot has compiled with the provisions of PAMDA [the Property Agents and Motor Dealers Act 2000 (Qld)] with respect to the provision of statements and warnings to the third party purchaser prior to the Contract being signed by the buyer.

57 In particular, cl 14.2 prohibited Pangus, without Six Mile Creek’s prior consent, from exercising a call option if it was in default under the put and call option, and cl 18.1 made time of the essence of the put and call option. Clause 24.1 provided:

The parties are to act in good faith towards the other parties in respect of this Agreement including being just and faithful in all activities and dealings with the other party.

58 The two sets of prices in schedule 1 to the put and call option referred to four lots (20, 21, 56 and 60) that a previous agent, Kevin Ball, had already sold and did not comprise part of the total of the project fee. The list price for lot 10 was $537,933 and its minimum resale price was $600,968.

(b) The “sale” of lots in the estate

59 Mr Boulter said that he and Mr McLaughlin formulated together the brochure and the terms of the building covenants (including the height restrictions) and that Mr McLaughlin specifically approved the final form of each of those documents.

60 On 9 June 2007, Mr McLaughlin left Australia and travelled to Ireland. He remained overseas until 12 September 2007. Mr Whitelaw appears to have had day-to-day carriage of the commercial decision-making for Six Mile Creek in Mr McLaughlin’s absence, while Mr McLaughlin’s daughter, Elizabeth Sutton, acted as the office manager and executed contracts under a power of attorney on its behalf. Mr Whitelaw spoke with Mr McLaughlin while the latter was overseas in 2007, about once per fortnight.

61 Initially, Mr McLaughlin had agreed to pay Mr Boulter’s firm, Ken Guy, project marketing fees or commission (as Mr Boulter indicated in his email of 14 June 2007 to Mr De Angelis), but subsequently Pangus took over that obligation under the put and call option.

62 On 20 June 2007, Mr McLaughlin had a telephone conversation with the proposed purchaser of lot 20 (which was not part of the put and call option) concerning the issue of whether he would extend the 30 day settlement date for that purchase. Ultimately, Mr McLaughlin, through Mrs Sutton, advised Chris Baker of Bakers (Six Mile Creek’s solicitors for conveyancing of lots on the estate) that the 30 day settlement period for lot 20 would remain.

63 On 28 June 2007, Pangus defaulted in paying the sum of $6.925 million under the put and call option. Soon after, Mr McLaughlin became aware that Pangus had defaulted, while he was on his holiday in Ireland. Mr De Angelis had made efforts to obtain finance for Pangus to make the outstanding payment during June 2007, before the default occurred and had sought help, through Mr Boulter, from Six Mile Creek and Mr Whitelaw.

64 On 25 July 2007, Rob Buckland of McDonald, Balanda & Associates (MBA), acting on behalf of Trent Caruana, sent a letter to Paul Brennan of Brennans (who acted for Pangus and Mr De Angelis). MBA wrote that they enclosed contracts for lots 10, 43, 44, 45, 50 and 57 signed by their client (the Caruana contracts). They requested that the vendor sign the contracts and return one copy of each to the intending purchaser. The letter stated:

The signing of the Contracts by our client, and submission of same to you for signing by the Seller is subject to and conditional upon the separate Agreement between our client, ACN 097 611 535 Pty Ltd [the ACN company], [Pangus] and [Mr De Angelis] being signed [the Caruana agreement].

65 On 30 July 2007, when Mr Baker received the letter together with the contracts, he sent an email to Mr Whitelaw (he misaddressed the copy of this email that he intended also to send to Six Mile Creek by leaving a letter off its email address). He headed his email, “Deed of Release – Trent and Gus”, referring to Mr Caruana and Mr De Angelis. The heading suggested that the existing commercial relationship between Mr Caruana and Mr De Angelis was already known to Six Mile Creek and Mr McLaughlin. He observed in the email to Mr Whitelaw and its intended recipient, Mrs Sutton, that:

It seems they have done a deal on these 6 lots with someone who has lent finance to Pangus. 2 of the contracts are on terms (180) days that I would imagine will not be acceptable. You will see there are rebates in the agreement which reduce the price and with 1 contract conditions that need to be attended to before it goes unconditional. On the whole I imagine that the terms will not be acceptable to you, but of course I will await your instructions.

66 Mr Whitelaw thought that the Caruana contracts “looked a bit skinny”. Coincidentally, on 27 July 2007, Mr McLaughlin had sent a fax in his handwriting (which was not easily legible) to Mr Whitelaw’s firm without indicating that it was for his attention. Ultimately, Mr Whitelaw received the fax on 31 July 2007 and asked Mrs Sutton to translate it. She wrote back that Mr McLaughlin had written:

Re: Coolum & Gus

Hows [sic] the non payment going. How are sales & settlements? Can u fax me an update

67 Later on 31 July 2007, Mr Whitelaw emailed Mr Baynes of Nicholsons saying that he had spoken to Mr De Angelis that day and they had made arrangements for Mr De Angelis to make an appointment for them to meet later that week. Mr Whitelaw noted that Pangus was in breach of the put and call option and had not paid the $6.925 million. He said that Mr De Angelis had sold approximately nine lots “but 6 are at a relatively low value, but above the release value” (i.e. within the list prices making up the projected $16.112 million). Mr Whitelaw wrote that he had told Mr McLaughlin on the phone on the previous night (30 July 2007):

that we need to start talking to Gus’s agents with a view to cutting Gus loose. We cannot miss the peak selling period which is fast approaching.

(emphasis added)

68 The references to “Gus’s agents” appear to be a reference to Mr Boulter and his firm, and the “peak selling period” to the forthcoming spring and summer.

69 On 6 August 2007, MBA sent to Brennans a signed version of the Caruana agreement. In it, the ACN company had the same address as Pangus and Mr De Angelis and, I infer, it was a related company. The Caruana agreement recited that:

Mr Caruana and the ACN company were parties to an investment agreement dated 5 October 2006 to develop land at Peregian Beach in Queensland under which Mr Caruana had lent the ACN company $580,000 and Mr De Angelis had guaranteed the obligations of the ACN company to Mr Caruana; and

the put and call option and the fact that Mr Caruana was desirous of purchasing lots 10, 43, 44, 45, 50 and 57.

70 The Caruana agreement provided that purchases of the six lots in the Caruana contracts would occur relevantly at discounts, including for lot 10, of $290,000, from its price of $895,000 in the price list. The structure of the Caruana agreement was that, notwithstanding the nominal purchase prices in the Caruana contracts, Six Mile Creek as vendor would enter with Mr Caruana as purchaser, as between the De Angelis entities and Mr Caruana, he would only have to pay the discounted price (in the case of lot 10 of $605,000) and the De Angelis entities would be responsible for paying the total difference of $290,000 to Six Mile Creek.

71 The details of this arrangement were not known to those on Six Mile Creek’s part, save for Mr Baker’s deduction in his email of 30 July 2007 that Mr Caruana had “done a deal on those 6 lots with someone who has lent finance to Pangus”. Obviously enough, Mr Caruana’s ability to complete the Caruana contracts depended on Mr De Angelis’ ability to supplement Six Mile Creek’s 50% share of the amount by which the purchase price exceeded the minimum resale price under the put and call option (being, in lot 10’s case, $600,968) and the amounts Mr Caruana would pay under the Caruana agreement. The total difference between the contract prices for the six lots and the prices Mr Caruana had agreed to pay the De Angelis entities was $580,000. The settlement times for lots 50 and 57 were to be 180 days, and for the other four lots, 30 days.

72 Thus, by about 31 July 2007, Six Mile Creek had received the Caruana contracts signed by Mr Caruana and needed to decide whether it would execute them. And, Mr De Angelis was in the position where, to use Mr Whitelaw’s words, if he did not perform, he would be “getting the boot”.

73 On 10 August 2007, Mr Brennan emailed Mr Buckland of MBA and Mr Baker, informing them that, among other matters, the settlement time for lot 10 was to be amended to 37 days from the date of the contract, and all of the Caruana contracts were to be amended by deleting the special conditions that made them subject to the Caruana agreement. Mr Brennan wrote to Mr Baker later that day attaching a copy of Mr Buckland’s email in which he had noted that the Caruana contracts had been delivered to Mr Baker’s office but “stand in “limbo” due to special conditions which your client is not prepared to accept”. Mr Brennan said that Mr Caruana now wished to proceed on the basis that the special conditions be deleted, but that he would require finance and asked whether that was acceptable to Six Mile Creek.

74 Next, on 15 August 2007, Brennans delivered to Bakers contracts for the sale of lots 17 and 18. The purchaser of lot 17 was Leighton Dial, whose address was a post office box in Kent Town, South Australia, at a price of $725,000. A deposit of $1,000 was payable after execution of the contract and 5% of the purchase price was payable later at an unspecified date. The purchaser of lot 18 was Nick Dean Properties Pty Ltd which had exactly the same post office box address in Kent Town as Mr Dial. The price was $715,000, with a deposit of $1,000 payable after execution, together with 5% of the purchase price at an unspecified time. Each of the contracts for lots 17 and 18 incorporated the building covenants with the height restrictions. Nick Dean Properties and Mr Dial signed their contracts on 9 and 10 August 2007 respectively.

75 On 15 August 2007, Mr Brennan emailed Mr Baker the then current position in respect of 15 contracts that Pangus had negotiated thus far. The email noted that lots 47 and 49 had a settlement date fixed and the Caruana contracts had been signed by Mr Caruana and submitted to Bakers. Mr Brennan noted that Mr Caruana’s solicitor had confirmed that the Caruana contracts could be amended by deleting the special conditions that Mr Caruana had sought previously to include in relation to the Caruana agreement. Mr Brennan said that Mr Baker had told him earlier that day that he was awaiting instructions from Mr Whitelaw about a contract for lot 46 that had already been delivered to Bakers and contracts for lots 8, 17, 18, 19, 40 and 48 that Mr Brennan had caused to be delivered to Bakers that day. He added:

It is clearly apparent from the number of contracts in existence that our client has worked very hard and redoubled his efforts since meeting with Mr Whitelaw to discuss the delay. I am instructed to advise that our client visited the Sunshine Coast today in order to negotiate 4 further contracts which shall be available within 48 hours. Further, three more contracts are being negotiated and are likely to be available next Monday.

(emphasis added)

76 The contracts for lots 43 and 44 provided for settlement to take place 30 days from the contract date, but the contracts were subject to Mr Caruana obtaining sufficient finance to complete the contract, to be notified within 14 days of the contract date. The price for lot 43 was $300,000 and for lot 44 was $295,000 and each contract had a deposit of $1,000 payable when the buyer signed the contract, and a further deposit of $4,000 payable 14 days from the contract date.

77 The purchaser in the contracts for lots 8 and 19 was Bolivar Road Pty Ltd, which had an address in Kensington Gardens, South Australia. The price for lot 19 was $725,000, with deposits of $1,000 due on the buyer’s signature and $10,000 payable within 14 days of the contract date. The price for lot 8 was $995,000, with deposits of $1,000 due on the buyer’s signature and $14,000 within 14 days of the contract date. Mr De Angelis had an interest in Bolivar Road, as did his business associate in Pangus, Walid Najjar, although there is no evidence that, at this time, Mr McLaughlin knew of Mr Najjar’s involvement in Bolivar Road. Both contracts incorporated the building covenants and height restrictions and provided for settlement to occur 45 days after exchange (without any conditions such as the contract being subject to finance). Curiously, the price list (as at 14 September 2007) stated that lot 8 had been sold for $795,000. There was no evidence (including of some other extant contract) to explain how that sum, rather than the sum of $995,000 in the contract for lot 8, came to be used in the price list.

78 On 20 August 2007, Mr Whitelaw emailed Mr Baynes to bring him up to date with the current position under the put and call option, noting that “We have told Gus he has to perform or he gets the boot”. That referred to an earlier conversation between Mr Whitelaw and Mr De Angelis to which Mr Brennan’s email to Mr Baker of 15 August 2007 above, in turn, referred (see [75] above). Mr Whitelaw wrote that he had sent Mr De Angelis an email in the previous week informing Mr De Angelis that his finance broker was not performing and “would be the end of him”. The email continued:

We are just giving him enough time to convert his leads to contracts and then a decision will be made, probably this week.

(emphasis added)

79 Mr McLaughlin gave evidence about the above ultimatum that Mr Whitelaw had given Mr De Angelis while he was in Ireland. He had agreed with Mr Whitelaw that Pangus or Mr De Angelis be allowed to convert whatever leads that they had at that particular point in time into contracts because he, Mr McLaughlin, was thinking of terminating the put and call option. He was concerned that Pangus could not actually perform. Mr McLaughlin said that if the leads had been converted into contracts, then Six Mile Creek would be in a lot better position to influence prospective purchasers to take interest in other lots because it could say that those lots had been “sold”. He gave this evidence:

But but good for Six Mile Creek because you were wanting these lots to be sold, particularly as this was the peak period? --- Yes. That’s correct. Yes, yes.

And if lots were sold, it would then enable the agent to inform other purchasers that this particular lot has sold for X or Y dollars and that might influence a prospective purchaser to buy another lot? --- Yes. That yes, that’s the way that real estate works, I think. Yes. Yes.

(emphasis added)

80 On 21 August 2007, Mr Baker emailed Mr Whitelaw and Mrs Sutton copies of the Caruana contracts, together with contracts for lots 17, 18, 40, 46 and 48. He said that there were two more contracts, namely for lots 8 and 19, but that they had not been completed properly and he needed to amend them before sending them. Mr Whitelaw emailed Mr Baker on 22 August 2007 saying that he was preparing a schedule to send over to Mr McLaughlin that night. Mr Whitelaw enquired about what the prices for lots 8 and 19 were and Mr Baker responded with the prices.

81 Importantly, on 22 August 2007, Mr Baker settled a letter with Mr Whitelaw that Bakers sent on 23 August 2007 to Brennans in relation to the put and call option. The letter referred to Pangus’ breach in failing to pay the $6.925 million and previous discussions between Mr De Angelis and Mr Whitelaw on this topic. It stated that Six Mile Creek was not prepared to allow the breach to continue any further and required Pangus to pay default interest of 15% per annum, to apply from 28 June 2007, in respect of the unpaid amount that would continue to accrue until it had been paid in full. Next, the letter required that any funds received from completed contracts be applied, first, in payment of the interest due on the outstanding $6.925 million, secondly, in reduction of the balance of the remaining principal due of $8.687 million and, thirdly, in reduction of the unpaid $6.925 million. The letter stated that nothing would be paid to Pangus until the breach was rectified or the put and call option had been completed.

82 Mr McLaughlin learnt of the contract for lot 8, probably either from Mr Whitelaw’s summary sent on about 22 August 2007 or from earlier reports given to him by his daughter, while he was in Ireland. He gave this evidence about what he appreciated about the contract for lot 8 at that time, which I accept:

And the fact that only $1000 was nominated on this contract was another reason to cause you to think that there was something wrong with this contract? --- Yes. Well, yes, I thought it was, probably, they would never find the money to you know, to pay for it. Yes.

And you see that below the $1000 is $14,000? --- Yes. Yes.

And adding those two sums together obviously gives $15,000, and that is nowhere near a 10 per cent deposit, is it? --- That’s right.

And you know that the option deed with Pangus required third-party contracts, such as this, to provide 10 per cent, didn’t you? --- Correct.

In other words, a deposit of $95,000? --- That’s right.

And you knew that there was something wrong with this contract, didn’t you? --- Yes, well, I thought they would never they had to borrow that sort of money against it, yes.

And you knew also that they wouldn’t be able to actually purchase they wouldn’t be able to complete this contract? --- Yes, and I thought that in my own mind, yes.

(emphasis added)

83 Moreover, Mr McLaughlin knew that lot 8 was a difficult block on which to build a house and “wasn’t one of the better blocks”. He considered that the price of $995,000 was an overpayment. I am satisfied, having seen Mr McLaughlin give evidence about the contract for lot 8, that he knew at the time that he learnt about it, in the second half of August 2007, that it was a commercially unrealistic contract that involved a very substantial overpayment for the lot and was never likely to be completed.

84 Mr McLaughlin said that he did not remember too much about the contracts for lots 8 and 19. Senior counsel for Mr McLaughlin had objected to Mr McLaughlin being asked questions based on documents, such as the contracts for lots 8 and 19, that were open in front of him in the witness box. Senior counsel asserted that it was obvious that Mr McLaughlin was responding to questions about them on the basis that he was reconstructing his evidence from the documents. However, I did not form that impression.

85 I sought to clarify with Mr McLaughlin what his actual evidence was in circumstances where he said it was his practice to look at contracts either when they were made or when he returned to Australia. Mr McLaughlin said, “well I don’t remember too much about them, but I do remember that the deposits [for lots 8 and 19] were very weak and I always thought to myself, these contracts will fall over anyhow, you know. That was my opinion” (emphasis added). Mr McLaughlin said the fact that he knew that Brennans were acting for both Pangus and Bolivar Road caused him to think at this time in late August 2007 that there could be an association between those two companies. Mr McLaughlin learned of the details of the contract for lot 19 at the same time as that for lot 8 and that Bolivar Road was the purchaser for each. He noticed the small amounts of the deposits of $1,000 and $10,000 for lot 19, and considered at the time that “it wasn’t a solid contract”, meaning (in his mind) that it could have fallen over or not proceeded the next day. He gave this evidence:

And you realised that this was not a bona fide contract that would go to completion and result in Bolivar Road Proprietary Limited purchasing Lot 19 for $725,000? ---Yes, well, again, again, I did think it could be a bodgy contract, yes.

(bold emphasis added)

86 Mr McLaughlin said that he was sure that he learned of the details of the contract for lot 17 (and, I infer, all the other contracts for the lots marked as “sold” in the price list to the extent he did not already know of them in Ireland) when he returned on 12 September 2007 or shortly thereafter. When he learned the details of the contract for lot 17, he noticed the deposit was only $1,000 and realised there was something unusual about that contract. He thought, like the other contracts, it was “bodgy”. He gave this evidence concerning not just lot 17 but also each of the contracts for lots 8, 18 and 19:

Yes. And you as at the time you became familiar with the terms of this contract, were of the opinion that because the deposits were very weak, you always asked yourself whether this contract would fall over anyway. Correct? --- Correct. Yes.

And as a result of that state of mind, you didn’t intend that Six Mile Creek would complete this contract, did you? --- No. Well, I wasn’t 100 per cent sure. No.

You agree with me that Six Mile Creek your state of mind was that Six Mile Creek would not be completing this contract, correct? --- Well, I wasn’t, I wasn’t fully sure. No.

[…]

[W]hen you saw the terms of this contract you understood that the contract would not settle, in other words, it wouldn’t go through with Nick Dean Properties Proprietary Limited becoming the owner of Lot 17? --- Well, it looked dodgy. Yes. I said it looked dodgy.

It looked dodgy? --- Yes