FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Worimi Local Aboriginal Land Council v Attorney General of New South Wales [2019] FCA 1270

ORDERS

WORIMI LOCAL ABORIGINAL LAND COUNCIL Applicant | ||

AND: | ATTORNEY GENERAL OF NEW SOUTH WALES Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DETERMINES THAT:

1. Native title does not exist in relation to the area of land and waters in the State of New South Wales comprised in and known as Lot 227 in DP 1097995 at Stockton in the Parish of Stowell, County of Gloucester.

2. No order as to costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

JAGOT J:

Background

1 This is a non-claimant application made pursuant to s 61(1) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the NTA) in which the applicant seeks a determination that native title does not exist within the application area.

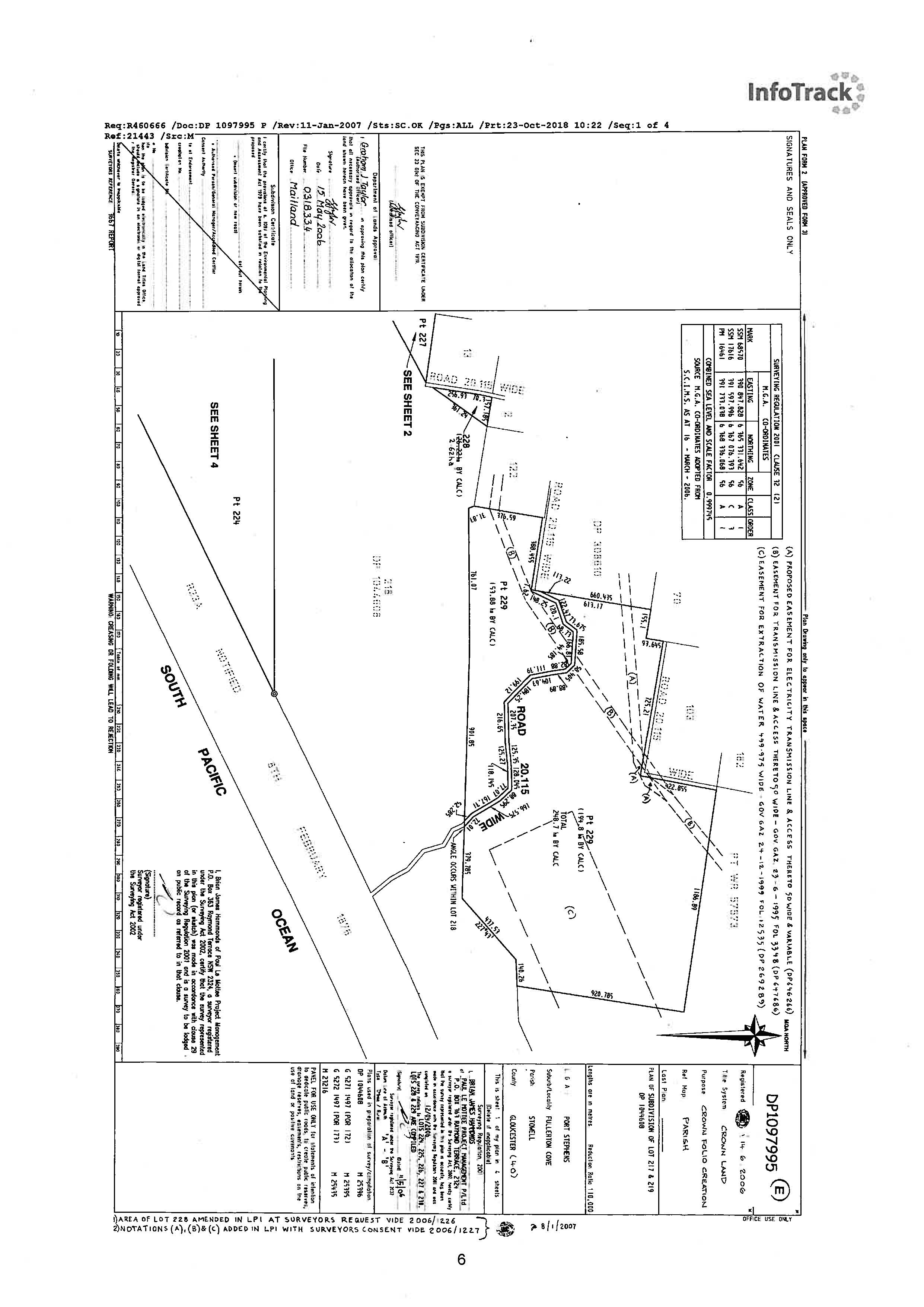

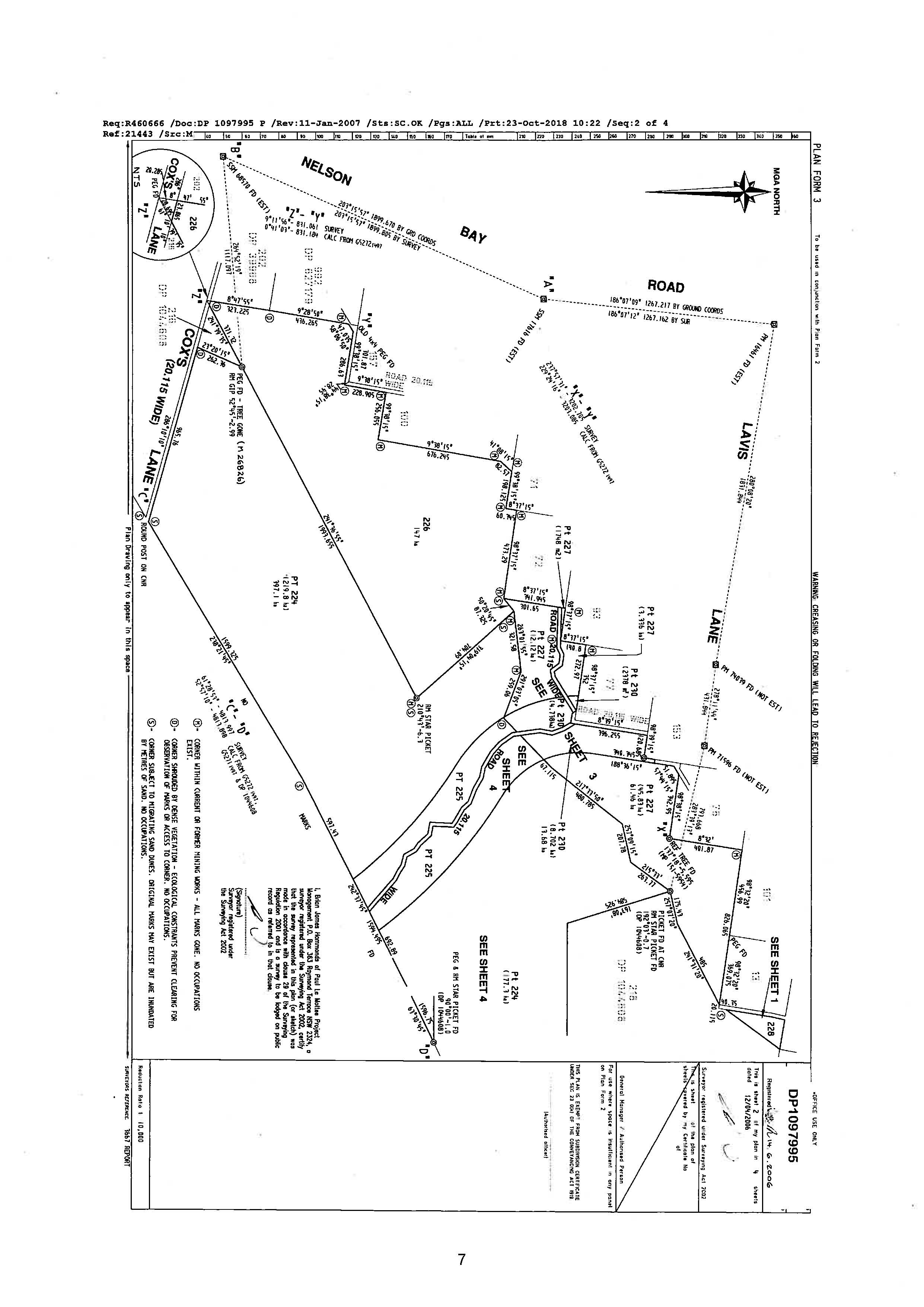

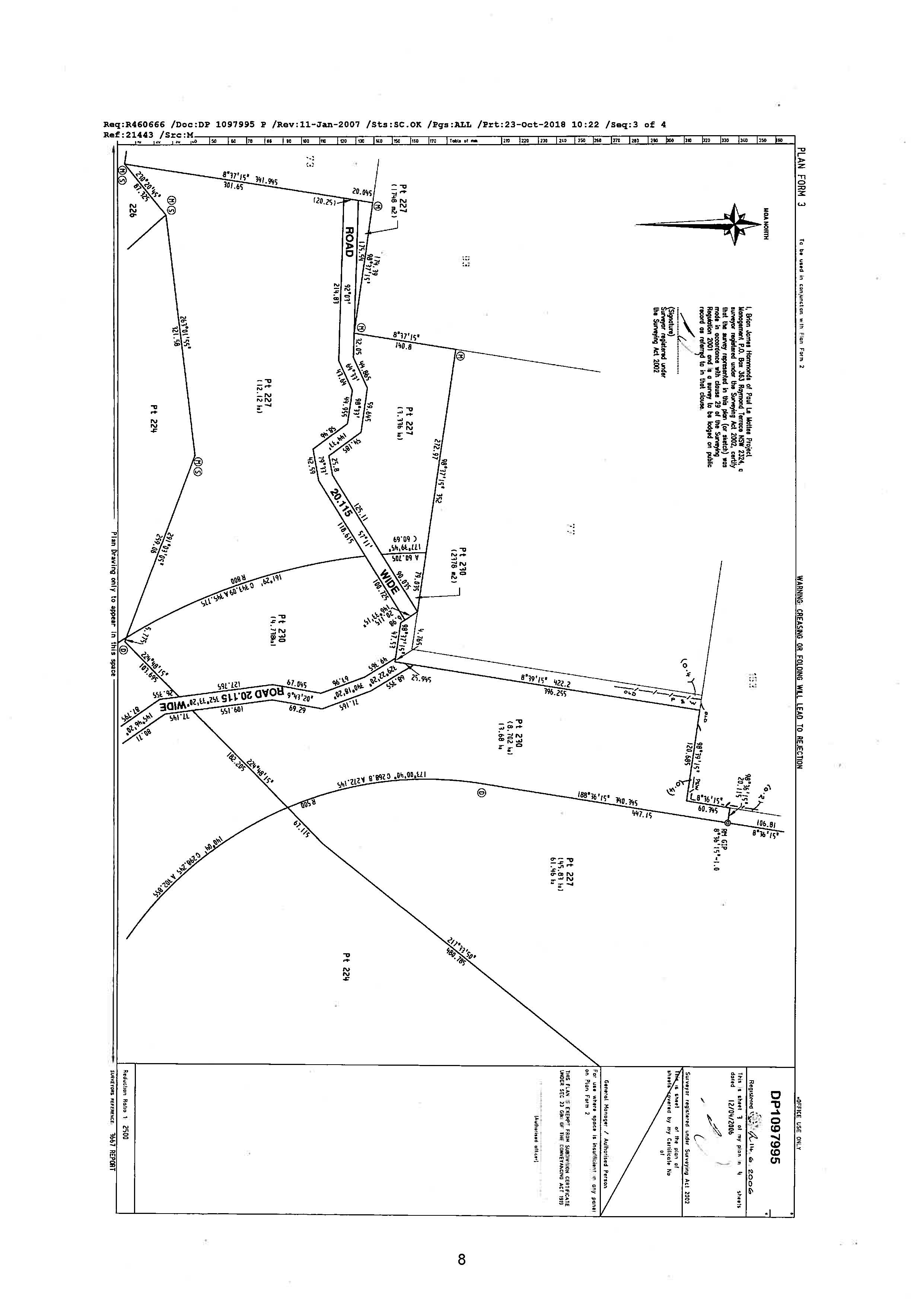

2 The application area is a single lot of land known as Lot 227 in DP 1097995 at Stockton in the Parish of Stowell, County of Gloucester (the Land). The Land is approximately 0.6 square kilometres in size. A map of the Land is provided at annexure A to these reasons.

3 The applicant, Worimi Local Aboriginal Land Council, as the registered proprietor of the Land, seeks a negative determination due to the restrictions on dealing with the land as a result of ss 36(9) and 42 of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW) (the ALRA).

4 The land was transferred to the applicant pursuant to s 36(9) of the ALRA following a successful claim under the ALRA, on or about 1 August 2006.

5 Section 42 of the ALRA operates to prevent the applicant from dealing with the land which is vested in it “subject to native title rights and interests under s 36(9),” unless the land is subject to “an approved determination of native title (within the meaning of the Commonwealth Native Title Act)”. This therefore requires the grantee to first gain a negative determination of native title so that it may deal with the land in accordance with, and for the purposes of the ALRA. Sections 36(9) and 42 relevantly provide:

36 Claims to Crown lands

…

(9) Except as provided by subsection (9A), any transfer of lands to an Aboriginal Land Council under this section shall be for an estate in fee simple but shall be subject to any native title rights and interests existing in relation to the lands immediately before the transfer.

…

42 Restrictions on dealing with land subject to native title

(1) An Aboriginal Land Council must not deal with land vested in it subject to native title rights and interests under section 36 (9) or (9A) unless the land is the subject of an approved determination of native title (within the meaning of the Commonwealth Native Title Act).

(2) This section does not apply to or in respect of:

(a) the lease of land by the New South Wales Aboriginal Land Council or one or more Local Aboriginal Land Councils to the Minister administering the NPW Act under Part 4A of that Act in accordance with a condition imposed under section 36A (2), or

(b) a transfer of land to another Aboriginal Land Council, or

(c) a lease of land referred to in section 37 (3) (b).

6 The application was filed in the Federal Court on 25 October 2018.

7 On 25 October 2019, a copy of the application was provided to the Native Title Registrar at the National Native Title Tribunal (the NNTT) in accordance with s 65 of the NTA, the receipt of which was confirmed by the NNTT to the Court in correspondence dated 26 October 2018.

8 The application underwent the requisite three month notification period from 26 December 2018 to 25 March 2019, as required by s 66(3) of the NTA.

9 During that notification period, no ‘Form 5: Notice of intention to become a party to an application’ was filed. Neither has any ‘Form 105: Interlocutory application to join parties to main application after relevant period’ been filed pursuant to r 34.105 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) since the conclusion of the notification period. Therefore the parties to the application are the applicant, and the respondent, the Attorney General of New South Wales. NTSCORP, the native title representative body in New South Wales, did not seek to join the proceeding.

10 The matter was first before a Registrar of the Court for case management, as is standard practice for non-claimant applications that are filed in New South Wales. At the first case management hearing on 26 April 2019, Registrar Stride made the following orders:

1. There be no mediation.

2. The applicant file any submissions and evidence on which it seeks to rely by 30 April 2019.

3. By 21 May 2019, the respondent file:

(a) any notice pursuant to section 86G of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth); and

(b) any submissions and evidence on which it seeks to rely.

4. The matter be substantively allocated to a Docket Judge for hearing.

5. The matter be listed on a date to be fixed.

6. Liberty to restore on three (3) days’ notice.

11 By consent orders made on 21 May 2019 by Registrar Stride, the applicant was given an opportunity to put on further submissions by 31 May 2019, and the date in order 3 of the 26 April 2019 orders was amended to fall due on 28 June 2019.

12 The applicant has filed and relies on the following documents which have been filed in the proceeding pursuant to both sets of orders made by Registrar Stride:

(1) Submissions filed 20 April 2019 (applicant’s primary submissions);

(2) Affidavit of James Konrad Walkley affirmed 4 April 2019 and filed 30 April 2019 (First Walkley affidavit);

(3) Affidavit of James Konrad Walkley affirmed 24 April 2019 and filed 30 April 2019 (Second Walkley affidavit);

(4) Submissions field 30 May 2019 (applicant’s further submissions);

(5) Affidavit of James Konrad Walkley affirmed 30 May 2019 and filed 30 May 2019 (Third Walkley affidavit); and

(6) Affidavit of James Konrad Walkley affirmed 19 June April 2019 and filed 20 June 2019 (Fourth Walkley affidavit).

13 The respondent likewise relies on the following documents:

(1) Submissions filed 28 June 2019; and

(2) Section 86G notice filed 28 June 2019.

14 For the following reasons, I am content that the orders the applicant sought should be made.

Consideration

15 Pursuant to s 86G of the NTA, power is conferred on the Court to determine the matter on the papers if both limbs of s 86G(1) are satisfied.

16 Section 86G of the NTA relevantly provides:

86G Unopposed applications

Federal Court may make order

(1) If, at any stage of a proceeding in relation to an application under section 61, but after the end of the period specified in the notice given under section 66:

(a) the application is unopposed; and

(b) the Federal Court is satisfied that an order in, or consistent with, the terms sought by the applicant is within the power of the Court;

the Court may, if it appears appropriate to do so, make such an order without holding a hearing or, if a hearing has started, without completing the hearing.

Note: If the application involves making a determination of native title, the Court’s order would need to comply with section 94A (which deals with the requirements of native title determination orders).

Meaning of unopposed

For the purpose of s 86G, an application is unopposed if the only party is the applicant or if each other party notifies the Federal Court in writing that he or she does not oppose an order in, or consistent with, the terms sought by the applicant.

17 Each limb will be examined in turn as follows.

Application is unopposed

18 As already mentioned, no other party has been joined to the proceeding during either the notification period nor subsequent to that via interlocutory application.

19 Given that the respondent indicated to the Court in its submissions and notice pursuant to s 86G of the NTA that it does not oppose the Court making an order in, or consisted with, the terms sought by the applicant, there is no party that objects to orders being made consistent with what is sought by the applicant, and s 86G(1)(a) is satisfied.

20 As no other party has been joined or has sought to be joined to the proceeding as a party, and the sole respondent to the application has filed a notice consistent with s 86G, I consider this application to be unopposed. It will now be considered whether the order sought by the applicant is appropriate, and whether the Court has power to make that order.

Appropriateness of the order sought by the applicant

21 As outlined in Deerubbin Aboriginal Land Council v Attorney-General of New South Wales [2017] FCA 1067, Griffiths J provides two bases upon which the Court may be satisfied, on the balance of probabilities, that native title does not exist in an area of land and waters as outlined at [48]:

(a) native title does not presently exist because it is not claimed by or cannot be proved by a native title claimant; [or]

(b) native title has been extinguished by prior acts of the Crown.

22 It is (a) that is relied upon by the applicant. The applicant does however provide evidence in relation to (b) of previous extinguishment of native title over the Land, which will be discussed later.

23 Consistent with the guiding principles in Worimi v Worimi Local Aboriginal Land Council [2010] FCAFC 3, Deerubbin provides the relevant principles which would satisfy (a) as above as at [52] and [53]:

52. Where an unopposed non-claimant application in which orders are sought by consent of the parties and:

(a) notice has been given to the relevant representative body under s 66 of the NT Act;

(b) public notice has been given under s 66 of the NT Act and no response received following that notice; and

(c) National Native Title Tribunal (NNTI) searches establish that there is:

(i) no previous approved determination of native title in the land the subject of the application; and

(ii) no current application in relation to the land the subject of the application,

the Court is normally “entitled to be satisfied that no other claim group or groups assert a claim to hold native title to the land” and that finding “supports an inference of an absence of native title” (Worimi No 2 at [46] citing Commonwealth v Clifton [2007] FCAFC 190; 164 FCR 355 at [59]).

53. In accordance with the guiding principles identified in Worimi No 2, many non-claimant applications have been granted on the basis of proof of the formal requirements of the NT Act only, in the absence of any detailed evidence about the existence or otherwise of native title (see, for example, Application for the Determination of Native Title made by the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council [1998] FCA 402; Deniliquin Local Aboriginal Land Council [2001] FCA 609 and Kennedy v Queensland [2002] FCA 747; 190 ALR 707). That is not to say, however, that every case must be approached by reference to such cases. Primacy has to be given to the statutory language. The cases simply provide general guidance on how those powers should be exercised and applied by reference to the particular facts and circumstances of each individual case. There is a danger in viewing statements in individual cases too literally and as though they provide the answer in all cases. A more sophisticated approach is required, one which ultimately focuses upon the relevant statutory provision as applied in the particular facts and circumstances of an individual case

24 In summary, and as is the accepted practice for the determination of non-claimant applications of this kind, the Court may be satisfied that native title does not presently exist if the notification requirements of s 66 of the NTA are satisfied and it has been confirmed that there is no previously approved determination, or current application, over the application area.

25 The second Walkley affidavit outlines the measures taken to notify the application pursuant to s 66 of the NTA. This is helpfully summarised in the applicant’s primary submissions from [12]-[17] as follows:

12. The National Native Title Tribunal (“NNTT”) provided a copy of the application to NTSCORP Ltd and to the Crown Solicitor's Office on or about 26 October 2018.

13. Pursuant to section 66 of the NTA, the notification period for the application was 26 December 2018 to 25 March 2019.

14. The NNTT, on behalf of the Native Title Registrar, advised the Applicant that the application would be notified in accordance with section 66(3) of the NTA by public notice to be published in the Koori Mail on 12 December 2018 and the News of the Area on I3 December August 2018.

15. Public notices were then published in accordance with the NNTT’s advice.

16. The terms of the NNTT's public notice as set out in Annexures JKW17-19 to the second Walkley affidavit relevantly included that:

(d) the Applicant is “seeking a determination that native title does not exist in the area described” in the notice.

(e) “Under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the Act) there can only be one determination of native title for a particular area.”

(f) with original bold text for emphasis: “A person who claims to hold native title rights and interests in this area may wish to me a native title claimant application prior to 25 March 2019. Unless there is a relevant native title claim (as defined in section 24FE of the AGO over this area on or before 25 March 2019, the area may be subject to protection under section 24FA and acts may be done which extinguish or otherwise affect native title. The Tribunal may be able to assist people wishing to make a relevant native title claim.”

(g) “A person who claims native title rights and interests may also seek to become a party to the non-claimant application in order for those rights and interests to be taken into account in the Federal Court’s determination. Other than filing a native title claim in response to the non-claimant application, this may represent the only opportunity to have those rights and interests in relation to the area considered.”

17. Notwithstanding the terms of the public notice, during the notification period no person filed a native title claimant application over the Land. No native title claimant application has since been filed over the Land. No Form 5 was filed during the notification period, and nor has any interlocutory application subsequently been made by a person seeking to be joined to the proceeding.

26 The fourth Walkley affidavit outlines to whom and in what manner notification was given, confirming to the Court that all of the statutory preconditions have been satisfied so that the proceeding may be determined on the papers. This affidavit provides (at annexure JKW30) the email correspondence that took place on Monday 17 June 2019 between a solicitor employed at the office of Mr Walkley and Ms Sylvia Jagtman of the NNTT. In summary, the annexed correspondence relevantly confirms that:

(1) The NNTT notified the non-claimant application in accordance with s 66(3)(a) of the NTA to the persons and bodies that are provided in an attached table; and

(2) In accordance with s 66(3)(d), notice of the application and the relevant notification period was also published in both the Koori Mail, and News of the Area in mid-December 2018.

27 Given the above evidence provided in the second and fourth Walkley affidavits, and related submissions, I am satisfied that notification was duly carried out by the NNTT and that therefore the requirements of s 66 of the NTA have been satisfied.

Court’s power to make the determination

28 The applicant’s primary submissions outline the following reasons why the Court has power to make the determination sought. At [20] the applicant submitted:

(a) this application is a native title determination application made under section 61 of the NTA. The Applicant is the registered proprietor of the Land and is a person who holds a non-native title interest in relation to “the whole of those lands” for the purposes of section 61(I) of the NTA;

(b) there is no overlap between the application area and any previous approved determination of native title for the purposes of sections 13(1) and 68 of the NTA.

(c) the Court has jurisdiction to hear and determine the application under section 81 of the NTA;

(d) the relevant State Minister and representative body have received notice of the application;

(e) public notice was given under section 66 of the NTA;

(f) notification period specified under section 66 of the NTA expired on 25 March 2019 and the Court may make a determination of native title pursuant to section 86G of the NTA after the notification period has expired; and

(g) the proposed order set out in Attachment A to these submissions includes all of the details required under section 225 of the NTA.

29 The applicant’s further submissions were filed following the respondent bringing to the applicant’s attention a now discontinued native title claim, Maaiangal Clan v NSW Minister for Land & Water Conservation (NSD6009/2000) (the Maaiangal claim), which fell within the external boundary of the Land. Such historical undetermined native title claims, or historical overlaps, have recently become of concern following the Pate v State of Queensland [2019] FCA 25 decision. Evidence of the existence of the Maaiangal claim is provided in the third Walkley affidavit.

30 As explained by the respondent in his submissions at [33], Pate has:

…given rise to some uncertainty as to whether establishing that the formal requirements of s 66 have been met is a sufficient basis for the Court to exercise what is ultimately, a discretionary power to make an order that no native title exists: see Pate at [19]

31 In Pate, Reeves J declined to exercise his discretion under s 86G of the NTA to make a negative determination in an unopposed non-claimant application because the applicant had not produced “such evidence as the facts and circumstances of the individual case dictate is sufficient to discharge his or her onus to provide that no native title exists in the area concerned”: at [46]. This was despite the applicant complying with the formal elements as required by s 66 of the NTA.

32 As with Pate, there is a historical overlap that falls within the external boundaries of the current application that was previously accepted for registration pursuant to s 190A of the NTA. However, as the applicant and the respondent have submitted in the current proceeding, in the overlapping Maaiangal claim, the rights and interests were not claimed in relation to land which had been subject to a previous exclusive possession act, as covered by s 23B of the NTA. One of the historical overlaps in Pate did claim exclusive possession, which is markedly different from the current matter.

33 In the applicant’s primary submissions at [25]-[42], an explanation of how the application area was subject to a previous exclusive possession act, namely the granting of a scheduled interest prior to 23 December 1996 (the date of the Wik Peoples v The State of Queensland & Ors (1996) 187 CLR 1 decision) is explained.

34 The evidence of the scheduled interest over the land is provided for in the first Walkley affidavit. At annexure JKW3 of that affidavit, the registered land surveyor engaged by the solicitor for the applicant provides that the application area, previously identified as Portion 173, Parish of Stowell, County of Gloucester, was wholly within Special Lease 1923-4, which was for “Wells, Tanks, Water Conservation and Pole Lines”.

35 The first part of s 249C of the NTA provides a scheduled interest as:

(a) anything set out in Schedule 1, other than a mining lease or anything whose grant or vesting is covered by subsection 23B(9), (9A), (9B), (9C), or (10) (which provide that certain acts are not previous exclusive possession acts)

36 The individually listed purposes in Schedule 1, Part 1, Item 3(8) are as follows:

(a) “construction of drainage canal”,

(b) “construction of irrigation canal”,

(c) “dam”,

(d) “dam, weir or tank”,

(e) “storage purposes”,

(f) “tank”,

(g) “water race”,

(h) “water storage”, and

(i) “well”.

37 As the applicant submitted in its primary submissions, I accept that although there is no composite purpose exactly in Schedule 1 as has been granted in Special Lease 1923-4, the individually listed purposes as set out in Schedule 1, Part 1, Item 3(8) of the NTA allow an analogy to be drawn between the purposes for which the particular lease was granted, and those appearing in the list. The ability of this analogy to be drawn was specifically discussed by Griffiths J in Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council v Attorney-General of New South Wales [2018] FCA 1136 at [36(e)]. I therefore accept that the application area in this instance was subject to a previous exclusive possession act, as covered by s 23B of the NTA. As this is the case, the historical overlap with the Maaiangal claim is not relevant in this proceeding given that that claim did not claim any exclusive native title.

38 Further, and of greater significance, is the fact that the applicant in this matter is a Local Aboriginal Land Council (LALC), which is subjected to state-based legislation (the ALRA) and which has been forced to make this application for a negative determination so that it may deal with the land. This key fact was directly addressed by Reeves J in Pate, where his Honour mentions the main differences between the facts in Pate and the novel situation faced by LALCs in New South Wales, which is discussed at [54] and [55] as follows:

54 The difficulties created by this section of the ALRA constitute the peculiar circumstance I have mentioned above. It is a circumstance which may explain why, when confronted with the “irony” to which Perram J referred in Lightning Ridge, some judges may have been willing to apply a less stringent approach to the evidence necessary to discharge the onus a non-claimant applicant bears when that applicant is a Local Aboriginal Land Council in New South Wales and it is being forced by s 42 of the ALRA to apply for a negative determination of native title.

55 Whether or not that is so, that peculiar circumstance is certainly not present in this matter. Ms Pate is not an Aboriginal Land Council. Nor, so far as I am aware, is she an Aboriginal person. More importantly, there is no Queensland State legislation forcing her to make this application for a negative determination.

39 The Pate decision has been considered in New South Wales in one other proceeding where an LALC has been the applicant. In Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council v Attorney General of New South Wales [2019] FCA 76, Griffiths J did not consider that Pate established a different approach to that which was adopted in Deerubbin, but rather Pate was a reflection of the particular facts and circumstances of that case: at [38]. I agree.

40 Given the above, I am satisfied that in light of the specific facts and circumstances of this case, the Court should make an order consistent with what is sought by the applicant.

41 As such, I am satisfied that the Court has the power to, and should, make the determination.

Conclusion

42 As the application is unopposed and has been duly notified without another individual or group coming forward to claim native title over the land, as already accepted, it is clear that there is no other interest, in terms of native title, which impedes the granting of the application in the form of orders consistent with what the applicant seeks.

I certify that the preceding forty-two (42) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Jagot. |

Annexure A