FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Woolworths Limited [2019] FCA 1039

Table of Corrections | |

In the last sentence of paragraph 147, the word “had” has been replaced with “did not have”. |

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 5 july 2019 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

2. The applicant pay the respondent’s costs of and incidental to the proceeding, including any reserved costs, to be fixed by way of a lump sum.

3. On or before 4 pm on 26 July 2019, the parties are to submit proposed agreed orders as to lump sum costs, or alternatively inform the Court the parties have not reached agreement on the question of costs.

4. In the absence of any agreement as to the appropriate lump sum to be fixed for the respondent’s costs, the matter be referred to a Registrar for determination.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MORTIMER J:

1 This proceeding concerns labelling on certain disposable dishes and cutlery supplied and sold by the respondent (Woolworths) in its stores between November 2014 and November 2017. The products were sold in packaging branded with the word “Eco”, and featured a green colour scheme, with graphics of grass and butterflies around the label. The packaging also contained the statement “Made from a renewable resource”. I have reproduced some photos of the products at [17] below. I refer to them as the “Products” in these reasons.

2 Critically for the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s allegations in the proceeding, the packaging carried the label “Biodegradable and Compostable”. The ACCC alleges that by offering for sale and selling the Products in this packaging, Woolworths represented to consumers that the Products would:

… biodegrade and compost within a reasonable period of time when disposed of

(i) using domestic composting; or

(ii) in circumstances ordinarily used for the disposal of such products,

including conventional Australian landfill.

3 The ACCC contends these were representations as to future matters, and Woolworths did not have reasonable grounds for making the representations. Alternatively, the ACCC contends if they were not representations as to future matters, then the representations were in any event false or misleading or deceptive, or likely or liable to mislead or deceive, because the Products did not biodegrade and compost within a reasonable period of time when disposed of either using domestic composting or by ordinary disposal methods such as conventional Australian landfill.

4 Woolworths denies the Products carried the representations alleged, and denies the representations (however formulated) are properly characterised as representations as to future matters. Alternatively, Woolworths contends that if the representations are considered to be as to future matters, it had reasonable grounds for making those representations. Woolworths further contends the Products simply conveyed the representations that the Products are biodegradable and compostable, and this is accurate.

5 For the reasons set out below, I consider the ACCC has not proven the allegations it has made, and the application should be dismissed.

6 In these reasons, I have taken the approach of, in the alternative, determining the case as alleged by the ACCC, both in terms of its allegation that the representations related to future matters, and also on the basis of the representations it alleged were made. I consider that as a trial judge it is appropriate for me to take that approach, and to make all necessary findings of fact, including on an alternative basis in case I am wrong in my primary conclusions. This has, however, made the reasons somewhat complex.

7 The proceeding was commenced by way of an Originating Application and Concise Statement in March 2018. Initially the ACCC put its case only on the basis that the representations were as to future matters. After the first case management hearing, the ACCC amended its case to include, in the alternative, an allegation that even if the representations were as to present fact, they contravened the Australian Consumer Law (Cth) (which is Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)) because they were false and misleading.

8 The parties cooperated in having the matter come to trial promptly, and a statement of agreed facts, together with agreed documents, was tendered pursuant to s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). During the course of the trial a number of rulings were made on objections to evidence, in particular regarding the ACCC’s objection to the evidence of Mr Lothar Brosig, who conducted a composting trial of the Products. For reasons I gave at the time, Mr Brosig’s evidence was admissible.

9 Despite the parties’ best endeavours, a number of objections to evidence remained outstanding. Some objections were resolved by agreement between the parties and the evidence to which the objections related was not admitted, either in whole or in part, according to the agreement reached. Other evidence was admitted by agreement subject to use restrictions such as those in s 136 of the Evidence Act. After trial the parties agreed on further rulings thus resolving some outstanding evidentiary objections. Proposed consent orders were filed and those orders were made prior to the delivery of judgment. The parties’ submissions, both oral and in writing, were of great assistance to the Court.

10 The ACCC relied on evidence from the following witnesses:

an affidavit affirmed by Laughlin Joseph Nicholls, Senior Investigator at the ACCC, which described the ACCC’s purchase of some of the Products and annexed photographs of those Products, in addition to relevant information and screenshots obtained by the ACCC from the Greengood Eco-Tech Co. Ltd website, the Woolworths website, and the Municipal Association of Victoria’s website;

an affidavit sworn by Deirdre Ellen Griepsma, Manager of Sustainable Environment at the Bass Coast Shire Council, which described the program introduced by the Council for management of “food organics and garden organics” (FOGO) waste, and the materials the Council permits residents to place in FOGO bins;

an expert report of John Gerard Nolan in which Mr Nolan provided his opinion on the meaning of the words “biodegradable and compostable” as applied to a disposal consumer product, circumstances in which food and green waste composts, and the biodegradability and compostability of the Products; and

a reply expert report of John Gerard Nolan, in response to expert reports filed by Woolworths.

11 Woolworths relied on evidence from the following witnesses:

an affidavit affirmed by Susan Maree Gregory, Secretariat Manager of Woolworths Group Limited, which described the relationship between Woolworths and its subsidiary Woolworths (H.K.) Procurement Limited and briefly outlined the employment history of Ms Usagi Ho, a former employee of that subsidiary;

an expert report of Lothar Brosig in which Mr Brosig reported on a composting trial he had conducted on samples of the Products;

an expert report of Simon Leake in which Mr Leake provided his opinion on the meaning of the terms “biodegradable” and “compostable”, what materials are biodegradable and compostable and how this is determined, composting processes available in Australia and whether the Products are compostable; and

an expert report of Professor William Clarke in which Professor Clarke provided his opinion on the meaning of the terms “biodegradable” and “compostable”, factors which affect the rate at which material degrades or decomposes, the biodegradability and compostability of the Products, the waste management industry in Australia, and standards relating to compostability and degradability of plastics.

the products, their supply and sale

12 In this part of my reasons, I make findings of fact based on matters in the agreed facts, or matters which were not the subject of any contested evidence.

13 The Products can be divided into two categories: disposable cutlery and disposable dishes, the latter consisting of both plates and bowls of various sizes. The cutlery came in packages of 20 pieces and the dishes came in packages of 10, 20 or 100 pieces.

14 The cutlery is made of Crystallised Polylactic Acid, or CPLA. CPLA comprises approximately 90% polylactic resin (made from fermented corn starch) and approximately 10% talc.

15 The dishes are made of bagasse, which is a fibrous product left over after sugarcane or sorghum stalks are crushed to extract their juice. Bagasse comprises approximately 98.8% of bagasse pulp, in addition to about 1% of a water resistant chemical and less than or equal to 0.2% of an oil resistant chemical. In other words, as Woolworths submitted, bagasse is a reconstituted natural fibre, not dissimilar in that sense to paper.

16 Both CPLA and bagasse are non-toxic and it is an agreed fact that upon decomposition in an “appropriately managed environment”, both may be used as a soil additive.

17 The following photos provide examples of some of the Products.

How Woolworths came to purchase and offer the Products for sale

18 There are agreed facts that:

(a) the cutlery was supplied to Woolworths by Huhtamaki Josco Limited (Huhtamaki), and was manufactured by its majority-owned subsidiary Shandong Greengood Eco-Tech Co. Ltd (GreenGood); and

(b) the dishes were supplied to Woolworths by Huhtamaki, and manufactured during the period of the alleged contraventions by two different entities. Between 2014 and 2016, the dishes were manufactured by Huhtamaki’s subsidiary GreenGood, and between 2016 and November 2017, by Huhtamaki’s partner factory, Shandong Teanhe Green Pak Science and Technology Co Ltd (STG).

19 The narrative about how Woolworths came to decide to supply and sell the Products is somewhat opaque. Woolworths took the course in this proceeding of adducing limited documentary evidence which could be said to relate to its decision-making process, and did not call the then employee of its subsidiary (Ms Usagi Ho) who had engaged in some correspondence with Huhtamaki about the Products. Nor did it call any other employee. A narrative of sorts can be cobbled together from these documents and the agreed facts. Each of the parties sought to put these documents to forensic use to advance their own arguments and where necessary later in these reasons I refer to how the parties deployed these documents. The ACCC seeks to make something of the absence of evidence from Woolworths on these matters and I return to this later in these reasons.

20 In January 2014, Woolworths received a report about bioplastics it appears to have commissioned, entitled “The future role of bioplastics in Australian consumer goods packaging”. I refer to this as the “bioplastics report” in these reasons. In an apparent coincidence, the reviewer of the report was Mr Nolan, an expert witness for the ACCC in this proceeding. The term “bioplastics”, and the specific term “biobased bioplastics”, were described in the executive summary in the following way:

The term ‘bioplastic’ is used in this report to describe a large and diverse grouping of polymer types, which are generally defined as being biobased (renewably based), biodegradable (at end-of-life), or both.

The primary focus of this study is biobased bioplastics. The definition of a ‘biobased’ plastic, as applied in this report, is a polymer in which 100% of the carbon in the plastic is derived from renewable agricultural and forestry resources such as plant starch from sugarcane or corn, cellulose or plant/animal proteins.

21 The executive summary described the purpose of the review in the following terms:

To help Woolworths, its suppliers and other stakeholders make more informed decisions when considering the use of bioplastics for consumer packaging, Woolworths and Landcare commissioned this study to look at three key questions:

• Do bioplastics compete with food supply and affordability?

• Are bioplastics a better environmental choice than conventional alternatives?

• Are bioplastics compatible with the recovery and reprocessing systems currently prevalent in Australia?

22 In its terms therefore, the focus of the report was packaging, rather than products. However, the report did contain a section on “Consumer views” about biodegradable and compostable plastics. Neither party took the Court to this specific section, but I consider it is worthwhile extracting (with some typographical errors, as they appear in the original report):

4 CONSUMER VIEWS

A comprehensive market research study and report ‘Consumer attitude to biopolymers’ was commissioned by WRAP UK. The report discussed the extent of consumer confusion around biopolymers, and made the following summary points (WRAP, 2007, p. 29):

1. Consumers are not generally aware that they may already be buying biodegradable and compostable plastics.

2. Consumers do not generally look for information on how to dispose of packaging on the packaging itself.

3. Even when told that they are using biodegradable or compostable plastics, most consumers will dispose of it as they would a similar product made from conventional plastic.

The WRAP report went on to state that:

If consumers continue to behave as they have in the past, this will mean the quantities of biopolymers entering the recycling stream become large enough to cause serious problems for the plastics recycling industry.

The report’s conclusion was that clear policy was urgently required on how consumers should deal with the new plastics and this should be succinctly communicated, as it was important that conventional plastics recycling and recycling generally should not be jeopardised.

In the Australian context, the approach has not been to form such centralised policy or Directives as in Europe, but to encourage designers and specifiers to consider and make decisions on packaging on the basis of priority.

One of the clearest explanations is provided in the Australian Packaging Covenant Design Smart Material Guide on compostable plastic packaging (APC, 2013b). This guide systematically sets out the options and implications of design decisions ranging from: fitness for purpose, maximising product weight to packaging ratios and end of life management.

The APC Guide points out that bioplastics can fulfil the same function and performance as conventional polymers, and require the same considerations, compliance with standards, and product/packaging information for consumers. It also discusses end‐of‐life pathways, and the probability that most bioplastics will be disposed to landfill where they may decompose anaerobically over time.

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) has produced two documents to clarify requirements: one on green marketing (ACCC, 2011) and another on end of life disposal claims on plastics bags, including claims on biodegradability, degradability and recyclability (ACCC, 2010). In the earlier document with respect to end of life, the ACCC states that:

being able to substantiate claims is particularly important if those claims predict future outcomes, such as whether plastics will biodegrade or degrade within a certain time frame and under certain conditions.

To date in Australia there has beens comparatively low level of general communications to households or commercial businesses encouraging separation of organics from recyclables and general waste. There has been even less communication on the matter of end‐of‐life impacts and composting of biodegradable plastics.

23 This report was admitted pursuant to a ruling under s 136 of the Evidence Act that its use was limited to the issue of whether Woolworths had reasonable grounds for the representations, if s 4 of the ACL applied and the representations were characterised as future representations. It was not therefore admitted as to the truth of its contents. Nevertheless, it may be relevant to note the following matters from this extract:

(a) the terms “biodegradable” and “compostable” are used in the report as descriptions of kinds of biopolymers;

(b) there had been some market research done about consumer attitudes to these kinds of products and it had been drawn to Woolworths’ attention; and

(c) the ACCC had produced two documents (in 2010 and 2011) about claims made in relation to such packaging. Neither of these documents were in evidence.

24 The bioplastics report contained definitions of the terms “compostable” and “biodegradable”. These assumed some relevance in the ACCC’s arguments about s 4 of the ACL and whether Woolworths had reasonable grounds for the alleged representations. Aside from those arguments, in this proceeding, it is a matter for the Court to determine how the reasonable consumer would understand those terms as they appeared on the packaging of the Products, and what if any representations were conveyed by the use of those terms.

25 Turning now to the chronology of how the Products came to be on Woolworths’ shelves, it is an agreed fact that Huhtamaki had been supplying products to Woolworths since approximately 2003. There is limited evidence about how these particular Products came to be developed for or supplied to Woolworths. The next relevant piece of evidence in the chronology concerns inquiries made in February 2014 about what “claims” were available to put on packaging for bagasse products. I find that inquiry was made by Ms Usagi Ho on behalf of Woolworths. Ms Ho was, at the time, an employee of Woolworths (H.K.) Procurement Limited, which the parties agree is and was a wholly-owned subsidiary of Woolworths. Woolworths (H.K.) Procurement Limited appears to have operated as a procurement business for Woolworths’ group operating companies in Australia and New Zealand, particularly for the purpose of procuring products from suppliers based in China and elsewhere in Asia. I shall call that corporation “Woolworths Hong Kong” in these reasons.

26 There is no context provided in the evidence for her inquiry, but the terms of Ms Ho’s email were as follows:

Hi Sheila,

We are working on the bagasse products packaging now.

Can you pls forward your current bagasse range claims on the packaging? We want to tell our customer how eco friendly of this material and put it on the packaging.

Can you pls forward your example for our reference today?

Thanks and regards,

Usagi Ho

Sourcing Manager

Everyday Needs

Woolworths (H.K.) Procurement Limited

27 An employee of Huhtamaki responded, as requested, on the same day, attaching a number of documents including “certificates” and reports for their bagasse products. I will return to the content of those documents in my findings about the parties’ respective “reasonable grounds” arguments for the purposes of s 4 of the ACL. I note at this point, however, as Woolworths contends, that in the material supplied by Huhtamaki in response to Ms Ho’s request there were also some limited references to CPLA products.

28 The ACCC contends that Woolworths adduced no evidence about:

… what, if anything, was done with the email or its annexures, whether it was read by or relied on by the recipient at Woolworths HK, let alone by any relevant decision maker at Woolworths. Indeed, Woolworths has adduced no evidence about who the relevant decision maker/s were, or what regard was had to the communication by the recipient or other staff at Woolworths. Woolworths led no evidence from anyone involved in the communication at all, and took the view that it was not required to provide any explanation itself as to its conduct or the decision process it pursued.

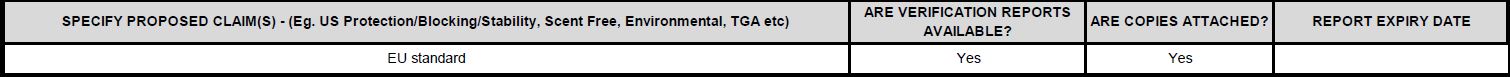

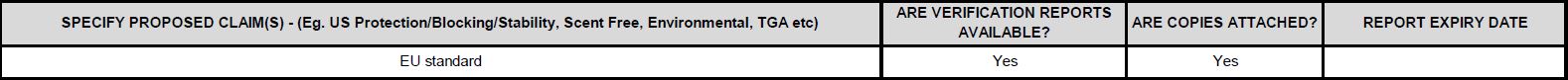

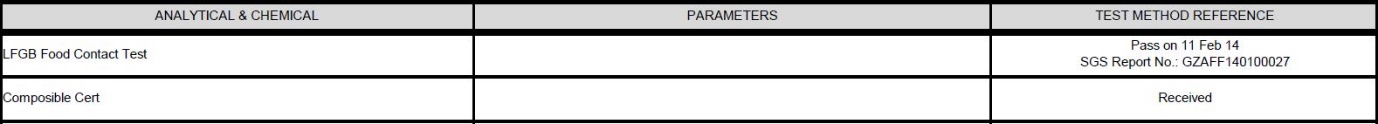

29 Woolworths challenged this submission, and referred to a series of forms which had been tendered, called “Sample Submission Specification” forms or “SSS” forms (later re-named “Product Specification” forms or “PS” forms). There was no witness evidence about the role played by these forms: Woolworths invited the Court to draw inferences from the documents themselves. For present purposes one example will suffice. One SSS form related to a 20 pack “Select Eco Side Plate”, one of the dishes in the range covered by the ACCC’s allegations in this proceeding. The form contained details of who, on behalf of Woolworths, was identified as the “buyer” of the sample, and then all the details of the supplier/vendor, which in this case was Huhtamaki. There were descriptions of the packaging and dimensions of the product, and then under the heading “Labelling & Packaging Details”, the following information appeared:

(a) The country of manufacture and packaging is specified as China;

(b) Under the heading “Retail Pack Product Claims” there are the following entries:

30 Under the heading “Document Completed By”, the name of an employee of Huhtamaki was entered. The date the SSS form was prepared is stated to be 14 May 2014. The purpose of these forms, and whether, as their headings indicated, they related to the provision of “samples”, and for what purposes, is not the subject of any additional evidence.

31 If, as I find based on the date entered on most of the SSS forms in evidence, that these forms were completed in May 2014, by that stage, on the agreed chronology, Woolworths had already awarded Huhtamaki the supply of the Products. This appears to have occurred around 24 March 2014. It is an agreed fact that on that date an employee of Woolworths Hong Kong sent an email to Huhtamaki confirming it had been awarded the supply for those Products.

32 Between this date, and around mid-July 2014, on the agreed chronology, Woolworths undertook a process of commissioning, reviewing and approving the artwork for the packaging of the Products. At the end of July 2014, it is an agreed fact that there were further communications between Woolworths Hong Kong and Huhtamaki about the provision of “certificates” for some of the bagasse products. Whether or not these certificates have any relevance or probative force in the question of Woolworths’ “reasonable grounds” is a live issue between the parties, and I return to it below.

33 It is an agreed fact that from around 11 August 2014, Woolworths began receiving the Products, and in November 2014 it is an agreed fact that it commenced retail sales of the Products. There was further correspondence during 2016 between Woolworths Hong Kong and Huhtamaki about reports and certificates for the bagasse products and again, where necessary, I refer to this correspondence in the section of these reasons dealing with my findings on whether Woolworths had reasonable grounds for the representations it made, for the purpose of s 4 of the ACL.

34 Woolworths was notified of the ACCC’s investigation into the Products in early February 2017. It is agreed there were further communications between Woolworths Hong Kong and Huhtamaki during 2017 about certifications, some of which were expressly directed at the Products, but the underlying correspondence was not ultimately admitted into evidence, by agreement.

35 The final aspect of the narrative to which reference should be made is an email exchange that occurred in March 2014 between two Woolworths employees: Mr Kane Hardingham and Mr Adam Carrig.

36 Again, Woolworths adduced no contextual evidence about this email exchange, and no evidence about or from these two employees. Accordingly, I make findings on the basis of what is on the face of the emails themselves. Mr Carrig identified himself as holding a B.Sc. Biological Sciences, and as occupying the position of “Lead Quality Specialist - HardGoods / GM” at Woolworths. Mr Hardingham identified himself as occupying the position of “Environmental Manager” for Woolworths.

37 On 13 March 2014, Mr Carrig emailed Mr Hardingham in the following terms (with any typographical errors in the original):

Hi Kane,

As per our conversation earlier today regarding the select eco range of plates, bowls, cups etc...

After talking to the business team about only having the biodegradable claim on BOP, the feeling is that this claim is the major selling point and if we are not going to shout about it (ie; not on the front of pack), then why have it at all?

I can see the logic behind that thinking but are we restricted in anyway to not do this?

Any feedback or guidance would be greatly appreciated mate.

Cheers

38 Mr Hardingham replied later that day in the following terms:

Hi Adam,

Advice on the biodegradable claim has been given with the ACCC’s focus on green claims and the limited availability of council services which will take this material, all in mind.

Technically the products are biodegradable but as there is only 6-8% of councils offering this service the consumer has a limited opportunity to dispose of this material correctly.

With this all in mind, there are two options for these products.

1) A claim of biodegradable on back of pack.

2) No claim of biodegradable on pack at all, as is the case at the moment.

This advice is made based on the original product that was developed, if the specification and/or supplier changes then we would need to reassess the certifications for the product.

We have also arranged independent research on bioplastics, looking at three key questions:

Do bioplastics compete with food supply and affordability? In the short-term, no.

Are bioplastics a better environmental choice than conventional materials? There are still a lot of unknowns in life cycle assessments and the science in this area.

Are bioplastics compatible with the recovery and reprocessing systems currently available in Australia? Significant barriers exist.

This research supports a cautious approach when it comes to this material.

Hope this helps. I am happy to meet with the team if further discussion is required.

39 Each of the parties sought to put these communications to different forensic uses in advancing their case, and where necessary I refer to them later in these reasons.

40 For present purposes, it is sufficient to find, as I do, that these communications were occurring within Woolworths itself, and at a reasonably senior level of management, given Mr Hardingham’s position title. In his email to Mr Carrig, Mr Hardingham was, I infer, referring to the bioplastics report, which I have referred to and set out excerpts of above. These communications occurred before Woolworths, on the timeline contained in the parties’ agreed chronology, settled on a version of the packaging artwork for the Products, and well before the Products went on sale in its stores.

Where and how the Products were displayed

41 It is an agreed fact that the Products were available for sale both online and in Woolworths’ stores.

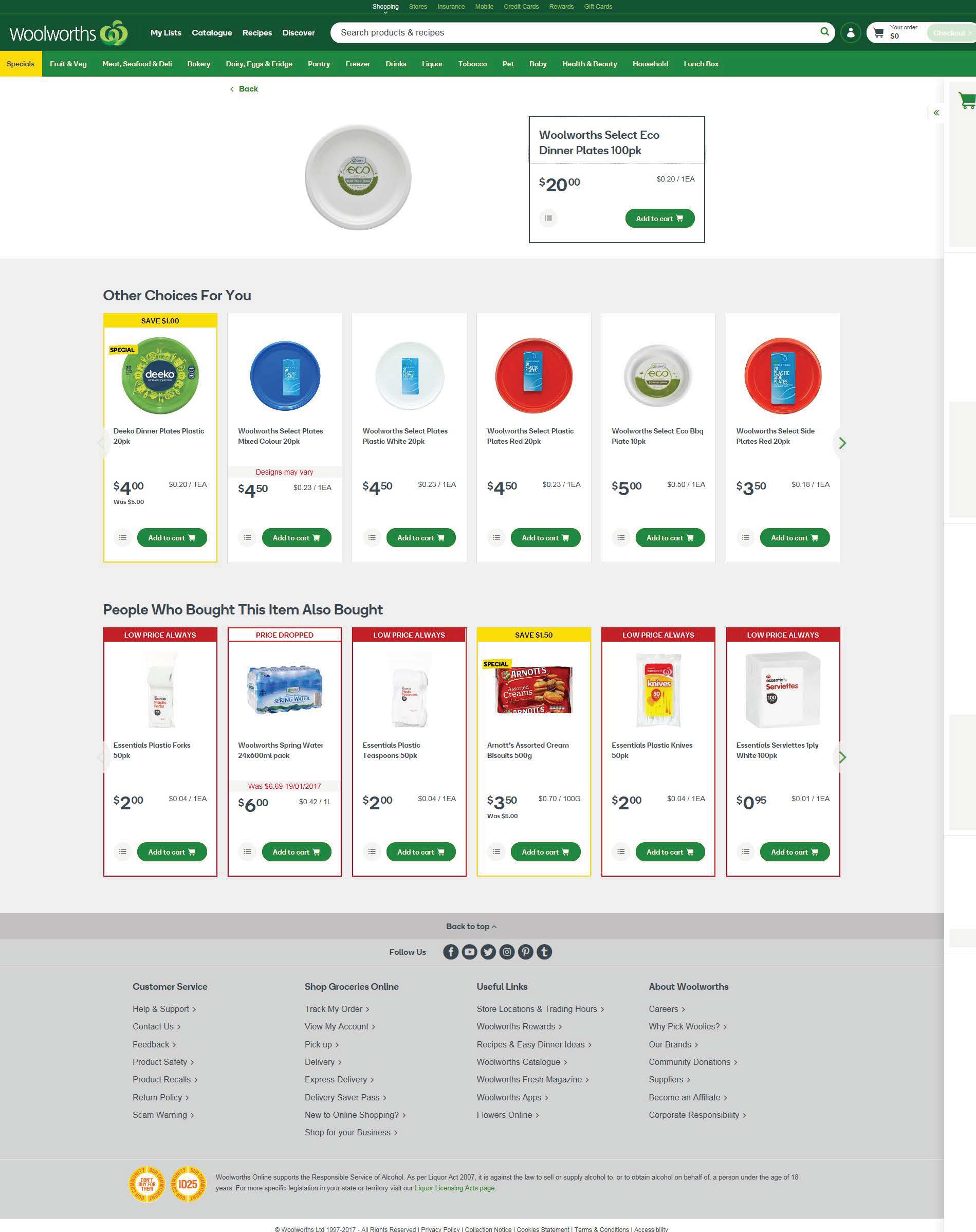

42 Mr Nicholls gave evidence about having accessed the Woolworths online store, and having found the Products available to purchase online. He exhibited to his affidavit a number of webpage captures from the Woolworths website, all of which provide similar displays of the Products. One example will suffice:

43 Mr Nicholls also exhibited to his affidavit a number of photographs taken by him and his colleague, Ms Kate James, of the Products displayed on shelves in Woolworths’ stores. Woolworths did not dispute the representativeness of these photos, in terms of how the Products were displayed for sale in its stores. I accept these photos are representative of how the Products were displayed in Woolworths’ stores. They were located in an aisle and on shelves amongst other disposable crockery and cutlery products, serviettes and other products intended for use in eating and drinking. They were displayed close to Woolworths’ “Essentials” range of similar products, including paper crockery and plastic cutlery, and also appear, from the photographs, to be located amongst a number of other brands of mostly plastic products.

44 It was an agreed fact that the Products were offered for sale in packs of 10, 20 and 100 items. From the photographs, it appears various sizes of packs were on display. The following photographs depict an example of the way the Products were displayed in Woolworths’ stores (located on the bottom shelf in these examples):

45 The webpage captures from Woolworths’ online store which were annexed to Mr Nicholls’ affidavit establish, and Woolworths did not dispute, that the pricing of the Products was higher than comparable plastic or paper products. As the ACCC submits, the webpage captures demonstrate, and I find, that:

(a) Woolworths offered for sale a 20 pack of plastic plates at $4.50, whereas a 10 pack of the Products was advertised for sale at $5.00; and

(b) Woolworths offered for sale an 80 pack of paper plates at $5.00, whereas a 100 pack of the Products was advertised for sale at $20.00.

46 It is also the case, and Woolworths did not dispute, that the packaging did not provide any instructions on how to dispose of the Products, or indicate whether consumers needed to do anything to the Products before disposing of them (such as cut the dishes up).

47 The ACCC places some emphasis in its submissions on the overall appearance of the packaging of the Products, in particular (and aside from the words at the centre of the proceeding):

the prominence of the word “Eco”;

the use of the colour green; and

the use of images such as grass and butterflies.

48 The ACCC submits that:

The purpose of the message conveyed by the packaging was to provide assurance to consumers about an environmental benefit that would occur following the use and disposal of the product. This assurance was a matter of substance and importance given the marketing appeal of positive environmental messaging to the public generally, and the importance of ensuring that such messaging is properly considered, and used with accuracy and care — attributes missing with respect to the impugned conduct of Woolworths.

(Footnote omitted.)

49 Woolworths addresses these contextual submissions only briefly, as I understood it, really to contend that the context does not make the representations conveyed by the phrase “biodegradable and compostable” any less accurate or true, and that the additional components on the packaging were merely consistent with that primary phrase.

50 I deal with the substance of this submission later in these reasons, in resolving the question whether the alleged representations were made by Woolworths, and if so, whether they contravened the ACL. For present purposes, in terms of findings about how the Products were displayed and sold, I accept the ACCC’s submission that the context in which the Products were displayed and sold included the whole appearance of the packaging, with the components identified in [47] above being prominent.

Legal principles and issues in dispute

51 I propose to outline the issues in dispute, as they arise from the parties’ respective statements and submissions. It is these issues which determine the applicable legal principles. For ease of reference I shall refer to the words on the packaging of the Products as “the labelling”, and where I do so, I take into account all of the features and characteristics of the Products which I have set out at [1], and [13]-[17] above.

52 As I have noted, the ACCC’s case was initially put only as a case about future representations, pursuant to s 4 of the ACL. It was then amended to allege an alternative case of false, misleading or deceptive conduct if, contrary to the ACCC’s primary position, the representations made by Woolworths were not as to future matters.

Were these representations as to “future matters”?

53 The ACCC submits that the labelling, seen in the context of the packaging as a whole, contained an “element of prediction”: namely, it contained a representation about the “likely performance” of the Products; or the ability of the Products “to do something in the future”. It submits:

Biodegrading and composting could only occur at some time in the future: following purchase, and after use, which was conceivably some time thereafter. The message conveyed by the product packaging was likely to cause consumers to anticipate things that would happen when disposing of these goods, in a predictive sense.

54 Woolworths, on the other hand, submits the labelling did not convey any prediction, forecast, promise or opinion about future events. To be a future matter, Woolworths contends, the factual matter represented must not be capable of being true or false at the time the representation is made. Woolworths further contends the labelling of these Products described the inherent properties of the Products, in the same way as a statement that a product is “flammable”, or “poisonous”, or “non-toxic”. Woolworths relies on the example of the word (or label) “recyclable”, submitting (by reference to s 51A of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth), the predecessor to s 4 of the ACL):

The word “recyclable” provides a close analogy to “compostable”. It would be difficult to contend that a statement that a conventional cardboard box, or an ordinary glass bottle, was “recyclable” was a representation “with respect to a future matter”. The statement is true at the time it is made. One does not need to wait and see what transpires. It does not fall within the mischief of that which s 51A was seeking to address.

55 The ACCC contests Woolworths’ contention that the labelling concerned an “immediately demonstrable fact”, such as the words “flammable” or “watchable” might convey. It contends the labelling involved predictions about how the Products would behave in “potential future circumstances”, depending on how they were treated and disposed of. As to the comparison with the word “recyclable”, the ACCC is not prepared to accept that word contains a representation as to a present matter, and appears to suggest it might also contain a representation as to a future matter for the purposes of s 4 of the ACL.

56 Woolworths submits, as I understood it, that the ACCC’s approach is too broad. It would encompass words or labelling on a product whenever there were future events attaching to the use or disposal of the product. For example, Woolworths submits:

If this was the proper way in which to approach consumer goods then nearly every representation on a product – that describes what the product will do when the product is being used – would be a representation with respect to a future matter. The possibilities are endless: “stain remover”, “air freshener”, “floor cleaner”, “disinfectant wipes”. Rather than being statements as to “future matters”, they all tell us what happens when the existing properties of the product in each case are utilised or engaged: common stains will be removed, the air will be freshened, the floor will be cleaned, a surface will be disinfected. Properly understood, they are statements of about the present nature or qualities of the product in question.

57 The second aspect of prediction said by the ACCC to attach to the labelling is that there was an implied representation that the Products would biodegrade and compost within a reasonable period of time. This might be seen as something of a self-fulfilling prophecy for the ACCC’s case: if the ACCC is correct that the labelling contained such an implied representation, then it is likely the labelling as a whole is properly characterised as being about a “future matter”, in the sense of a prediction (which is how Woolworths sought to describe the effect of s 4 of the ACL).

58 However, Woolworths contends that even if the ACCC is correct about the implied representation concerning “reasonable time”, then the representation was still one as to the inherent qualities of the Products. That is, if the representation was the Products “would biodegrade and compost within a reasonable period of time when disposed of using domestic composting or in circumstances ordinarily used for the disposal of such products, including conventional Australian landfill” (being the contention taken from the ACCC’s amended Concise Statement) then such a statement was either correct or incorrect at the time it was made, because those characteristics are “knowable and testable”.

If future matters, did Woolworths have reasonable grounds for making the representations?

59 The ACCC contends the effect of s 4(2) is to impose on Woolworths an evidentiary onus to prove it had “reasonable grounds” for making the representations, failing which the “deeming operation of the section is engaged”. The ACCC describes this onus in its written submissions as one requiring Woolworths to “adduce evidence”. I note this emphasis, because it runs through the ACCC’s submissions and its criticisms of the nature and extent of the evidence adduced in this proceeding by Woolworths.

60 Relying on the judgment of Heerey J in Sykes v Reserve Bank of Australia [1998] FCA 1405; 88 FCR 511 at 513, the ACCC contends Woolworths must prove, by evidence, the facts and circumstances existing at the time of the representations and on which it in fact relied. Those facts and circumstances must be objectively reasonable and support the representations made. The ACCC emphasises the need for proof of actual reliance and, where a corporation is the representor (as here), for the corporation to identify and adduce evidence of its state of mind. The ACCC submits this cannot be done in this proceeding through reliance on information held by an employee of a subsidiary (being Ms Ho of Woolworths Hong Kong).

61 The ACCC points to some of the documentary evidence to contend that Woolworths had a specific policy for the making of environmental claims (the Environmental Claims Policy), but also refers to the absence of evidence about whether that policy was followed in Woolworths’ decision-making concerning the acquisition and sale of the Products. There was, the ACCC contended, no evidence from Woolworths about communication of the procurement documents to any person or persons within Woolworths who made the decisions about the supply and sale of the Products, or evidence of reliance on those documents as grounds for making the alleged representations.

62 If the Court accepts (contrary to the ACCC’s contentions) that Woolworths has adduced evidence of actual reliance, the ACCC contends the available material did not provide Woolworths with objectively reasonable grounds on which to make the representations. On this limb of its case, the ACCC again emphasises Woolworths’ non-compliance with its own Environmental Claims Policy, the timing and content of some of the correspondence from Huhtamaki (including that some of the correspondence took place after the operative decision to sell the Products), concerns raised in the correspondence between Mr Hardingham and Mr Carrig (which I refer to above) which “demonstrates that Woolworths was aware that the claims [on the Products’ labelling] were problematic”, the absence of any testing or trials of the Products before they were made available for purchase, as well as the information provided from the manufacturer of the products (GreenGood) on its own website. The ACCC also contends:

The certificates provided to the Woolworths HK procurement employee, in light of the guidance available to Woolworths at the relevant time, provided no assurance to Woolworths that these specific Products would, following disposal using available waste disposal methods in Australia at the time, undergo biodegradation and composting into a useful, non-toxic soil additive within a reasonable period of time.

63 Nor, the ACCC submits, can Woolworths prove it had reasonable grounds because it relied on Huhtamaki’s status as a “reputable supplier”.

64 Even if the Court finds actual reliance does not need to be proved by Woolworths, in the alternative, the ACCC contends Woolworths did not have reasonable grounds, based on the information presented at trial, and relies in this regard on the evidence relevant to its alternative s 18 case.

65 Woolworths accepts the question whether the maker of a representation has reasonable grounds is an “objective question”, by which I take it to accept the question is to be answered objectively. Woolworths disputes the need for the existence of reasonable grounds to be established by evidence from the representor, and also disputes that there is a need to prove – in all cases – that the representor in fact relied on materials which were sufficient to provide reasonable grounds. Woolworths contends that criterion, drawn from Sykes, should not be seen as required in every case under s 4.

66 In any event, Woolworths contends that the test in Sykes is satisfied on the evidence. It contends it requested and received information – including certifications and test results – from Huhtamaki, and that Huhtamaki was a “reputable supplier” of the kind discussed in the relevant authorities. Woolworths further contends that Huhtamaki provided information to Woolworths at the time the representations were made and that Woolworths in fact relied upon the information received from Huhtamaki by its employees (or employees of its subsidiary), as demonstrated by the information contained in the SSS and PS forms. Woolworths also contends it was objectively reasonable for it to rely on the materials received from Huhtamaki, and that those materials supported the truth of the representations made in the labelling on the Products. Woolworths contends that the matters on which the ACCC relies to prove lack of reasonable grounds are insufficient. In its closing submissions, Woolworths contends:

The respondent has discharged its burden pursuant to s.4 of the ACL of adducing “evidence to the contrary”. In those circumstances, the deeming effect of s 4(2) no longer applies and the ACCC has to establish a lack of reasonable grounds for the making of the representation. The ACCC has failed to do so.

Do the representations have a temporal aspect?

67 This issue is one of characterising the representations made by the labelling “biodegradable and compostable” on the product packaging. The ACCC contends the Court must determine what was the “dominant message” given by the labelling on the Products, considered in their packaging and context as a whole, and then contends that there is a “necessary temporal aspect” to the labelling. The focus in this aspect of the ACCC’s case appeared to be on the “compostable” aspect of the label. It submits that, as to the use of the word “compostable”:

Consumers understood that there would be a finished product, and that the finished product would look and feel a certain way, and be able to be used in certain ways — in other words a completed process within a reasonable time.

68 Woolworths submits there was no such temporal aspect: it contends the ACCC has not adduced any evidence to suggest that consumers believed there were time limits, or time periods, around composting processes. It contends that the evidence before the Court, in large part consisting of expert evidence, suggests composting periods vary substantially, depending on factors including the composting regime and the attentiveness to ideal composting requirements. Woolworths further contends that the process would have to be “very slow indeed” to be able to say a product that is slow to compost was not “compostable”. The time taken would need to be out of line with that taken for “other conventional compostable material” (such as grass clippings and leaves) to compost. On the evidence, Woolworths contends such material might take from a number of weeks to up to two years to break down into usable compost. The ACCC has not, Woolworths submits, proven the Products were so slow to compost as to be out of step with other, comparable, compostable materials. It also submits that the evidence available suggests the Products would break down into usable and useful compost within a reasonable period of time, and probably at the outer limits in less well-managed composting systems at around ten weeks.

69 While these submissions overlapped with submissions about whether the representations were false or misleading, as I understood the argument, another point made by Woolworths’ submissions was that it would be incorrect for the Court to imply into the label “biodegradable and compostable” any representation about a period of time over which those processes would occur, because in fact those time periods are so variable.

Were the representations false or misleading?

70 The resolution of this issue, obviously one of the principal contested issues at trial, has a number of components. That is because there were competing contentions, and reliance on competing evidence, which were said variously to tend to prove each party’s case in relation to Woolworths’ alleged contraventions of the ACL. I shall refer to this as the “ACCC’s alternative s 18 case” in these reasons.

The identification of the class of consumers and the attributes of members of that class

71 The ACCC emphasises that the class of consumers should not be identified as having a sophisticated knowledge of biodegradation and composting, or of the differences between disposal in landfill and disposal in a compost. The ACCC contends that consumers with home composts or “some degree of knowledge about home composting but who do not practise it” would expect, absent qualification or disclosure, that the Products would compost at the same or a similar rate as other organic waste products. The ACCC refers to the “environmental messaging” on the packaging and submits that:

In the absence of any direction or qualification on the product packaging, such a consumer would reasonably think that the product would biodegrade and compost if disposed of in the ordinary course after typical use, such as in a council bin after use at a picnic or at home in ordinary waste.

(Footnote omitted.)

72 Woolworths submits that the class of consumers can be assumed to have a degree of common sense, and in this case it was relevant the Products were sold next to “conventional disposable cutlery and plate products”, because that would be the comparison consumers were making. In other words, a comparison with products which are not biodegradable and cannot be composted. Woolworths submits consumers would have a variety of states of knowledge about composting – from none at all, to a sophisticated knowledge and practice of home composting – but ordinary consumers would understand that products are composted to avoid them going into landfill, that people compost to reduce waste and produce a material that may be useful for their garden, and that the composting process involves material breaking down organically. It submits the label “biodegradable” would speak to a larger range of consumers than “compostable”, depending on a consumer’s own waste disposal practice.

The time taken, and the circumstances needed, for the Products to biodegrade and to turn into useful compost

73 This was the issue which occupied most of the expert evidence and a substantial portion of the parties’ submissions. Again, the focus was predominantly on the composting process, rather than biodegradation. The ACCC also seemed to focus on the fact the label stated “biodegradable and compostable” and not “biodegradable or compostable”. This also appeared to explain why the focus was on whether the Products were “compostable”, because the ACCC contended that the labelling “g[ave] work to both words” and was thereby false or misleading to the extent it suggested that the Products could be disposed of in both landfill and compost, in circumstances where the Products would not compost in landfill. I do not consider this point has any merit, but in any event I make findings about how consumers would understand each part of the phrase, and the whole of the phrase.

74 The ACCC submits – relying more on “misleading” than on “false” or “deceptive” – that no matter what kind of common disposal method was used (disposal in a council bin that goes to landfill or in a home compost), the Products would not biodegrade and compost within a reasonable period of time. It also submits that, no matter what composting system was used, the Products would compost more slowly into a usable form than other organic products suitable for composting, such as food scraps. It contends the volume of the Products disposed of in one site would significantly affect the rate of composting, and slow it down even further. Further, the ACCC contends the Products would take longer to transform into an “acceptable” looking product to be used in compost because they would not be suitable as a finished compost product any time prior to complete disintegration.

75 In answering these submissions, Woolworths places great emphasis on the absence of any tests or trials conducted by the ACCC to make out its case regarding the compostability of the Products. The only trial conducted was done on behalf of Woolworths, by Mr Brosig on the instructions of Mr Leake. Woolworths submits Mr Brosig’s test demonstrated the Products were “readily compostable” in an industrial composting system, and were indicative of the time the Products would take to compost in a well-managed home compost system. Woolworths further submits the trial also indicated that even in a home compost that was not well-managed, the Products would turn into usable compost in a longer period of time, but contends that other compostable products would also take longer to compost in those conditions.

76 In dealing with these competing submissions, the Court will need to determine the weight to be given to Mr Brosig’s trial, and to the opinions of Professor Clarke, Mr Leake and Mr Nolan respectively. Included in this determination will be the weight to be given to the evidence about the voluntary Australian Standard AS 5810-2010 entitled “Biodegradable plastics – Biodegradable plastics suitable for home composting” from Mr Nolan, Mr Leake and Professor Clarke. Consideration will also need to be given to the evidence about the range of conditions likely to exist in home composting systems, and to the differences between thermophilic and non-thermophilic conditions for composting. The ACCC’s submissions about the numbers of the Products which might be disposed of by a consumer at any one time (given their character as disposable cutlery and dishes) will also need to be considered. Woolworths contends this point is without merit.

77 The evidence before the Court suggested that some councils in the States of Victoria and New South Wales offered consumers the option of having their organic waste disposed of in an industrial composting system. There was evidence from Ms Griepsma, of the Bass Coast Shire Council, that the absence of an appropriate marker or symbol on the Products would mean the Products would be rejected for such processing and directed to landfill. Therefore, the parties’ arguments focussed on the options generally available to most consumers for disposal of the Products, being placing the Products in ordinary waste bins to be disposed of in landfill, or disposal in home composting systems. Although neither party addressed this, it seems to be assumed by both parties that it is irrelevant if consumers (wrongly) think they can dispose of these Products in recycling bins.

78 Since the ACCC maintained the “future matters” allegations as the principal way in which it put its case against Woolworths, I deal first with the applicable principles concerning the scope and operation of s 4 of the ACL.

79 Although some are well-known, it is still useful to set out the text of the relevant provisions. Especially in relation to s 4, the text is important in resolving some of the contentions between the parties about its operation.

80 Section 4 provides:

4 Misleading representations with respect to future matters

(1) If:

(a) a person makes a representation with respect to any future matter (including the doing of, or the refusing to do, any act); and

(b) the person does not have reasonable grounds for making the representation;

the representation is taken, for the purposes of this Schedule, to be misleading.

(2) For the purposes of applying subsection (1) in relation to a proceeding concerning a representation made with respect to a future matter by:

(a) a party to the proceeding; or

(b) any other person;

the party or other person is taken not to have had reasonable grounds for making the representation, unless evidence is adduced to the contrary.

(3) To avoid doubt, subsection (2) does not:

(a) have the effect that, merely because such evidence to the contrary is adduced, the person who made the representation is taken to have had reasonable grounds for making the representation; or

(b) have the effect of placing on any person an onus of proving that the person who made the representation had reasonable grounds for making the representation.

(4) Subsection (1) does not limit by implication the meaning of a reference in this Schedule to:

(a) a misleading representation; or

(b) a representation that is misleading in a material particular; or

(c) conduct that is misleading or is likely or liable to mislead;

and, in particular, does not imply that a representation that a person makes with respect to any future matter is not misleading merely because the person has reasonable grounds for making the representation.

81 Section 18 provides:

18 Misleading or deceptive conduct

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

(2) Nothing in Part 3-1 (which is about unfair practices) limits by implication subsection (1).

Note: For rules relating to representations as to the country of origin of goods, see Part 5-3.

82 Relevantly to the provisions on which the ACCC relies, s 29 provides:

29 False or misleading representations about goods or services

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

(a) make a false or misleading representation that goods are of a particular standard, quality, value, grade, composition, style or model or have had a particular history or particular previous use; or

…

(g) make a false or misleading representation that goods or services have sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses or benefits; or

…

Note 1: A pecuniary penalty may be imposed for a contravention of this subsection.

Note 2: For rules relating to representations as to the country of origin of goods, see Part 5-3.

83 Section 33 provides:

33 Misleading conduct as to the nature etc. of goods

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is liable to mislead the public as to the nature, the manufacturing process, the characteristics, the suitability for their purpose or the quantity of any goods.

Note: A pecuniary penalty may be imposed for a contravention of this section.

84 At a general level, it should be recalled that consideration of alleged contraventions of provisions such as s 18 or s 29 involves a two-stage process: first, determination of whether the alleged representation is made (or what, if any, representation is made) by the statement or conduct impugned; and second, whether the representation is misleading, or deceptive or false, or likely to have those effects: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Telstra Corporation Ltd [2007] FCA 1904; 244 ALR 470 at [14]-[15] (Gordon J).

Authorities on “future matters”

85 There are three aspects of the applicable principles to be considered:

(a) what is meant by a “representation with respect to any future matter” in s 4;

(b) what is the onus borne by the representor for the purposes of s 4; and

(c) if that onus is discharged, what the applicant must prove, in relation to reasonable grounds.

The meaning of “representation with respect to any future matter”

86 The parties’ submissions diverge about the width of this phrase in s 4. The approach I have taken, which accepts the contentions put by Woolworths, is also consistent with the approach recently taken by Gleeson J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 992, particularly at [276]-[286], especially at [285].

87 Woolworths submits the phrase is concerned with:

… representations, such as predictions, promises, forecasts and opinions as to future events where the factual matter represented is not capable of being true or false at the time the representation is made (because it lies in the future).

(Original emphasis.)

88 The ACCC submits that language is too narrow, and does not accommodate authorities which have applied s 4 to situations where there is “a representation of likely performance”. It also relies on descriptions such as whether the representation has “an aspect of futurity about it”, referring to the observations of Foster J in GlaxoSmithKline Australia Pty Ltd v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd (No 2) [2018] FCA 1; 133 IPR 190.

89 Woolworths’ submissions should be accepted. They reflect the text of s 4, when seen in its context, and having regard to its purpose. Those are the governing principles for construing the phrase: see my summary of the relevant authorities in Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum Inc v VicForests [2018] FCA 178; 228 LGERA 255 at [44]-[46].

90 However, some preliminary observations should be made. The purpose of s 4 is facultative: it does not itself impose any separate or different liability. The prohibitions remain in the operative provisions in Ch 2 of the ACL. In circumstances to which it applies, s 4 imposes an evidentiary onus on a representor, but maintains the legal onus on the party alleging a contravention of Ch 2 of the ACL: see in particular confirmation of this in s 4(3)(b). Conversely, s 4(3)(a) makes it clear that compliance with the evidentiary onus does not necessarily result in rejection of the alleged contravention: rather, it simply places the party making the allegation of contravention in the usual position of being required to prove the allegation on the balance of probabilities. As Foster J said in GlaxoSmithKline at [137]:

It is an evidentiary provision only and does not reverse the legal or persuasive burden which the applicant bears of establishing that reasonable grounds for making the representations did not exist (see also Crowley v WorleyParsons Ltd [2017] FCA 3 at [71]).

91 Where the deeming effect of s 4(2) is displaced by the adducing of “evidence to the contrary”, then the ultimate onus of proving the absence of reasonable grounds will remain with the party alleging contravention: here, the ACCC.

92 It is accepted that s 4 bears a relationship to s 51A of the TPA, although it does not operate in quite the same way. It is worth setting out the terms of s 51A:

(1) For the purposes of this Division, where a corporation makes a representation with respect to any future matter (including the doing of, or the refusing to do, any act) and the corporation does not have reasonable grounds for making the representation, the representation shall be taken to be misleading.

(2) For the purposes of the application of subsection (1) in relation to a proceeding concerning a representation made by a corporation with respect to any future matter, the corporation shall, unless it adduces evidence to the contrary, be deemed not to have had reasonable grounds for making the representation.

(3) Subsection (1) shall be deemed not to limit by implication the meaning of a reference in this Division to a misleading representation, a representation that is misleading in a material particular or conduct that is misleading or is likely or liable to mislead.

93 The history of the introduction of s 51A into the TPA in 1986 was traced by Allsop J (as his Honour then was) in McGrath and Another v Australian Naturalcare Products Pty Ltd [2008] FCAFC 2; 165 FCR 230 at [166]-[176]. As his Honour recognised at [165], by reference to the authorities there cited, legislative history can assist a court in determining the context of a statutory provision. In tracing the history of the provision, his Honour noted the reference in the Explanatory Memorandum to the Trade Practices Amendment Bill 1985 (Cth) to the observations of Franki J in Thompson v Mastertouch TV Services Pty Limited (1977) 15 ALR 487 at 495, where Franki J had identified the gap that the introduction of s 51A was designed to fill. Justice Franki had stated:

… a prediction or statement as to the future is not false within the words of [s 59] if it proves to be incorrect unless it is a false statement as to an existing or past fact which may include the state of mind of the person making the statement or of a person whose state of mind may be imputed to the person making the statement.

94 Reference should also be made to the observations of the Full Court in Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Pty Ltd [1984] FCA 180; 2 FCR 82, a defamation action which also alleged contraventions of s 52 of the TPA in relation to published statements about the second applicant, a professional cricketer. The Full Court said at 88:

If a corporation is alleged to have contravened s. 52(1) by making a statement of past or present fact, the corporation’s state of mind is immaterial unless the statement involved the state of the corporation’s mind. Whether or not s. 52(1) is contravened does not depend upon the corporation’s intention or its belief concerning the accuracy of such statement, but upon whether the statement in fact contains or conveys a meaning which is false; that is to say whether the statement contains or conveys a misrepresentation. Most commonly, such a statement will contain or convey a false meaning if what is stated concerning the past or present fact is not accurate; but a statement which is literally true may contain or convey a meaning which is false.

Many statements, for example, promises, predictions and opinions, do involve the state of mind of the maker of the statement at the time when the statement is made. Precisely the same principles control the operation of s. 52(1) with respect to the making of such statements. A statement which involves the state of mind of the maker ordinarily conveys the meaning (expressly or by implication) that the maker of the statement had a particular state of mind when the statement was made and, commonly at least, that there was basis for that state of mind. If the meaning contained in or conveyed by the statement is false in that or in any other respect, the making of the statement will have contravened s. 52(1) of the Act. Compare Lyons v. Kern Konstructions (Townsville) Pty Ltd (1983) 47 A.L.R. 114.

The non-fulfilment of a promise when the time for performance arrives does not of itself establish that the promisor did not intend to perform it when it was made or that the promisor’s intention lacked any, or any adequate, foundation. Similarly, that a prediction proves inaccurate does not of itself establish that the maker of the prediction did not believe that it would eventuate or that the belief lacked any, or any adequate, foundation. Likewise, the incorrectness of an opinion (assuming that can be established) does not of itself establish that the opinion was not held by the person who expressed it or that it lacked any, or any adequate, foundation.

95 In McGrath at [177]-[191], Allsop J also traced the judicial interpretation of s 51A, and the debate about whether it imposed a legal onus of proof or an evidentiary burden to remove the effect of the deeming provision. Having determined it was the latter, Allsop J (at [192]) described the effect of s 51A(2):

If evidence is adduced by the representor that is said to be evidence to the contrary, it will be for the Court to determine whether it is to the contrary in the sense just discussed. If it is, the deeming provision will cease to operate. That was the view of Emmett J, as understood by Keane JA. That is my view. That was not, however, an expression of the view that the legal or persuasive onus has been changed by s 51A(2), as some of the judgments in the “trend of established authority” referred to by Keane JA have stated. For instance, if evidence “to the contrary” is adduced by the representor, and if the representee itself adduces evidence tending to the lack of reasonable grounds, the matter might be equally poised. In such a case, there has been evidence “to the contrary” adduced by the representee, thereby eliminating the operation of the deeming provision, and, on the totality of the evidence, the proof of the reasonableness (or lack thereof) of the grounds is evenly balanced. Section 51A(2) does not, in my view, mean that in those circumstances the representor has not met an onus. The section does not cast the legal or persuasive onus, in such a case, on the representor. Its terms do not say so. The enactment history makes clear that the terms were deliberately chosen not to say so.

96 The difference between s 51A and s 4 is that s 4(3) implements the approach set out by Allsop J in McGrath. See also: Lockhart C, The Law of Misleading or Deceptive Conduct (5th ed, LexisNexis Butterworths, 2019) at [4.38].

97 I consider this was the kind of construction of the term “future matter” that was adopted by Nicholas J in Samsung Electronics Australia Pty Ltd v LG Electronics Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 227; 113 IPR 11. The facts in Samsung concerned television commercials and related internet, cinema and point of sale advertising undertaken by LG to advertise and promote a range of 3D televisions that employed a particular form of 3D technology. Samsung alleged the advertising contravened s 18 and s 29(1)(a) of the ACL. Some of the representations conveyed by the advertising were said to be about “future matters”. For example, as Nicholas J explained at [82], one advertisement was alleged to convey a representation that “conventional 3D TVs can only be viewed in the dark” and also to convey a representation that “a person watching conventional 3D TV will have to do so in the dark”, which Samsung alleged to be false or misleading.

98 The parties referred the Court to [85] of his Honour’s reasons, but what his Honour said at [83] is also important:

Most of the representations which Samsung alleges were conveyed by the TVCs consist of representations about the performance characteristics of conventional 3D TVs and LG Cinema 3D TVs. Each of these representations is pleaded as, and in substance is, a statement of fact. Whether or not the TVCs also convey representations with respect to future matters depends upon the proper characterisation of the representations actually conveyed.

99 At [84], Nicholas J then set out his understanding of the operation of s 4:

The expression “future matter” is not defined by the ACL. The same expression as used in s 51A of the TPA, was also not defined. However, when read in context, the expression is not hard to understand. A “representation with respect to any future matter” for the purposes of s 4 of the ACL and, before it, s 51A of the TPA, is a representation which expressly or by implication makes a prediction, forecast or projection, or otherwise conveys something about what may (or may not) happen in the future.

100 At [85], Nicholas J distinguished between a statement about the “character” of a representation and conclusions that might be drawn from that character:

It is important to distinguish between the representation actually conveyed by a product advertisement and what conclusions might be drawn from it. A person may reasonably infer from the statement “this is a 3D TV” that he or she will be able to view the TV in 3D at some time in the future. However, this does not change the fundamental character of the representation which is one made with respect to an existing state of affairs. In this case I am satisfied that none of the representations conveyed by the TVCs can be characterised as having been made with respect to a future matter.

101 Then at [86], Nicholas J distinguished the authorities about health and therapeutic products (referring specifically to Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Giraffe World Australia Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 1161; 95 FCR 302 which concerned an electrified mat, represented to have particular health effects once a person slept on it). His Honour relevantly said:

The representations made, as found by his Honour, were broadly to the effect that as a result of its emission of negative ions, the mat benefits the health of persons who sleep on it. That decision, and others concerned with the efficacy of therapeutic products that are said to offer health benefits when administered or used as directed, are distinguishable from the present case. In such cases the representation is made with respect to a future matter in that the consumer is told that if he or she uses the product a particular health benefit will be obtained at some time in the future. I do not think it is possible to tease any such representation out of any of the TVCs in issue in this proceeding.

102 That conclusion is consistent with his Honour’s interpretation of the term “future matter” as involving a prediction, forecast or projection.

103 I accept Woolworths’ submissions that this construction of “future matter” as involving a prediction, forecast or projection is also consistent with the concept of “reasonable grounds”, present in both s 4 and in s 51A. Representations about the future inherently involve an opinion or prediction of some sorts, and thus involve the disclosure of a (present) state of mind by the representor. The purpose of the “reasonable grounds” criterion is to require an appropriate basis for the state of mind (being the opinion or prediction) disclosed by the representation. Whether or not there were reasonable grounds for the representation about what might happen in the future would be relevant to establishing the character of the representation as misleading, or false, or deceptive. This point is, with respect, well made by Rares J in Ackers v Austcorp International Ltd [2009] FCA 432 at [359] and [363]:

When, as here, the representation is an assurance of an income stream over a period, it has the character of a prediction or forecast. It is about a future state of affairs which can only be verified by future experiences over the term of 10 years. Such a representation has a character distinct from that of a statement about rent which is currently due and payable. The latter is a statement with respect to an existing or present state of fact. The maker of a representation with respect to a future matter cannot know, however sure he or she is, that it will come true…

…

Section 51A recognises that representations with respect to a future matter can be objectively misleading or deceptive if the prediction turns out in due course to be wrong. If s 52 operated in that unqualified way, because of the consequence of future error it would create liability for every representation about future matters, however responsibly the representation may have been made at the time. So, s 51A ordinarily affords a representor an important protection in making such a wrong prediction if, when making it, the representor had reasonable grounds for doing so.

104 Despite the submissions made by the ACCC, I do not consider this construction is in substance any different to a construction which uses the language of “likely performance” of a product. A “prediction” may be a form of representation about “likely performance”. So might a “forecast”. Altering the language used in this way does little to elucidate the meaning of the phrase in s 4.

105 The ACCC gives a large number of examples in its written closing submissions (at [71]-[80]) to support the proposition that the term “future matters” extends to the “likely performance” of a product. As I understand it, that proposition is said to be applicable to the present case because the labelling “biodegradable and compostable” is said by the ACCC to involve a representation as to the “likely performance” of the cutlery and the dishes following their disposal. Aside from the authorities to which I refer below, I do not consider any of the authorities on which the ACCC relies suggest a meaning of the phrase “future matter” which is different from the meaning of a prediction, forecast or projection, and that they do not suggest anything other than that where a “future matter” is involved, there is an opinion being expressed by the representor about what will happen at some future time.

106 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Purple Harmony Plates Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1062 concerned advertising in a brochure and on the internet for a range of products which, as Goldberg J noted at [3], “were stated to have various benefits”. For example, as Goldberg J explained at [9], wearing the “Purple Harmony Disk” was said to:

(a) help strengthen the immune system (if worn over the thymus gland);

(b) enable the human body to cope better with the electrified and toxic environment;

(c) increase a person’s general health; and

(d) cause aches, pains, niggly coughs and colds to be less severe.

107 These are all aptly described as predictions. They concern the effects that a consumer might experience, in the future, from wearing the disk. That is why, in the passage relied on by the ACCC in this proceeding, Goldberg J said (at [18]) that these representations were:

… not merely representing matters of present or past fact; rather they were couched in terms that represented that the products presently possessed characteristics and benefits, the characteristics and benefits had been demonstrated to exist in the past and would be maintained and enjoyed in the future.

108 In Gwam Investments Pty Ltd v Outback Health Screenings Pty Ltd [2010] SASC 37; 106 SASR 167, the appellant had contracted to supply a mobile drug testing unit to the respondent, which would be attached to an Isuzu truck. The truck had to weigh less than six tonnes to be lawfully driven on public roads. Once the drug testing unit was attached, this weight was exceeded. The ACCC refers in its submissions to the reasons of White J, who was in dissent on the question of whether there were contraventions of the TPA. But in any event, on the facts the representations were said to be by silence as to the final combined weight of the truck with the unit attached. Justice White’s finding (on which the ACCC relies) at [150] was that:

… the defendants’ conduct in combination had conveyed a representation that an Isuzu NPS 300 truck with the unit designed by Christian Albertini mounted on it would be able to be driven lawfully on the roads. This was a representation as to a future matter.

109 Again, it is not difficult to describe this representation as a forecast or a prediction, and it is clearly the expression of an opinion about a state of affairs in the future (that is, the weight of the truck once the drug testing unit was attached and it was ready to drive on public roads).

110 Finally, in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Danoz Direct Pty Ltd [2003] FCA 881; 60 IPR 296, the subject-matter of the proceeding concerned television, website and catalogue advertising about a product called “AbTronic”, which was a pad with electrodes attached, and which consumers were instructed to place on their bodies to provide electronic stimulation to muscles, causing the muscles to contract. There were a large number of alleged misrepresentations (some of which were admitted) but Dowsett J described them generally at [5] of his reasons:

Broadly speaking, it is alleged that the first respondent represented that use of the AbTronic would cause weight loss, reduce body fat and improve the “tone” of musculature.

111 As Dowsett J recorded at [125] of his reasons, the respondents admitted that certain representations made were as to future matters. It is in that context that Dowsett J said at [126], in a passage on which the ACCC relies:

Representations as to the capacity or qualities of any device almost invariably carry predictions as to the way in which it will perform in the future. Thus a statement as to such capacity may be misleading pursuant to s 52, both because the device does not have the relevant capacity, and because there were no reasonable grounds for the statement, contrary to s 51A. It will not necessarily always be appropriate to pursue both routes to a finding of contravention of s 52. In most cases, an applicant should decide whether the statement in question was misleading because of demonstrable factual incorrectness or because it was made without reasonable grounds. Pursuing both courses may lead to a waste of resources, as appears from the present case.

112 Ironically, in the present case the ACCC appears to have pursued the very course Dowsett J counselled against. It has relied on misrepresentations as to existing future matters, in the alternative to existing fact. Be that as it may, the point of this paragraph of his Honour’s reasons, and the two more specific ones on which the ACCC also relies, is to illustrate that the respondent’s statements were predictions about how the AbTronic might perform in the future, and what effects it might have, in the future, on the body of the person using it. There could be no debate that those statements would fall within the scope of s 4(1).