FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

InterPharma Pty Ltd v Hospira, Inc (No 5) [2019] FCA 960

ORDERS

INTERPHARMA PTY LTD (ACN 099 877 899) Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | First Cross-Claimant | |

PFIZER AUSTRALIA PTY LTD Second Cross-Claimant | ||

AND: | INTERPHARMA PTY LTD (ACN 099 877 899) Cross-Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to s 136 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) the use of the following documents be limited to the use stated below:

(a) The document entitled “Abbott-85499 Dexmedetomidine Clinical Study Report: A Phase III, Multicenter, Double-Blind, Randomized, Comparative Study Evaluating The Effect of Two Doses of Dexmedetomidine Versus Placebo In Adult Patients Undergoing Elective Coronary Artery Bypass Graft(s) Surgery”, be admitted and used solely as evidence of the previous representations that the study identified as DEX-95-004:

(i) was a Phase III, Multicenter, Double-Blind, Randomized, Comparative Study Evaluating The Effect of Two Doses of Dexmedetomidine Versus Placebo In Adult Patients Undergoing Elective Coronary Artery Bypass Graft(s) Surgery;

(ii) (ii) was initiated on 2 January 1996 and completed on 7 December 1997; and

(iii) was conducted in compliance with Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines.

(b) The document entitled “Abbott-85499 Dexmedetomidine Clinical Study Report: A Phase II, Single-Center, Two-Part Study Evaluating the Safety, Efficacy, and Dose Titratability of Dexmedetomidine in ICU Sedation” be admitted and used solely as evidence of the previous representations that the study identified as W97-249:

(i) was a Phase II, Single-Center, Two-Part Study Evaluating the Safety, Efficacy, and Dose Titratability of Dexmedetomidine in ICU Sedation;

(ii) was initiated on 14 January 1998 and completed on 12 March 1998; and

(iii) was conducted in compliance with GCP guidelines.

(a) The document entitled “Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB)” and an attached document entitled “Duke University Medical Center – Informed Consent for a Research Project: A Phase III, Multicenter, Double-Blind, Randomized, Comparative Study Evaluating The Effect of Two Doses of Dexmedetomidine Versus Placebo In Adult Patients Undergoing Elective Coronary Artery Bypass Graft(s) Surgery: DEX-95-004, Version 2” (Duke Form) be admitted and used solely as evidence of the previous representations that:

(i) the patient informed consent form that was approved by the IRB for use in the DEX-95-004 study at the Duke Medical Center was the Duke Form;

(ii) the DEX-95-004 study was a Phase III, Multicenter, Double-Blind, Randomized, Comparative Study Evaluating the Effect of Two Doses of Dexmedetomidine Versus Placebo In Adult Patients Undergoing Elective Coronary Artery Bypass Graft(s) Surgery; and

(iii) the approval was given for a period of one year terminating on 11 October 1996.

(b) The document entitled “Information for Patients: A phase II, single-center, two part study evaluating the safety, efficacy and dose titratability of Dexmedetomidine in ICU sedation”, having the protocol “W97-249”, version 5 (part 1) dated 14 January 1998 (249 Form) and correspondence dated 19 January 1998 on behalf of the Board of Directors of the Academic Hospital Utrecht be admitted and used solely as evidence of the previous representations that:

(i) the patient informed consent form that was approved for use in part 1 of the W97-249 study was the 249 Form; and

(ii) the W97-249 study was a Phase II, Single-Center, Two-Part Study Evaluating the Safety, Efficacy and Dose Titratability of Dexmedetomidine in ICU Sedation.

2. Leave be granted to amend the Third Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity in accordance with these reasons (delivered on 20 June 2019) (these reasons).

3. The Proposed Fourth Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity stand as the Fourth Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity to the extent leave is granted in Order 2 above.

4. By 4:00 pm on 4 July 2019, each party file and serve proposed minutes of orders reflecting the conclusions in these reasons and short submissions (limited to 3 pages) addressing:

(a) the form of the proposed orders; and

(b) costs (other than with respect to the interlocutory application filed on 12 January 2018).

5. By 2:00 pm on 21 June 2019, each party inform the other parties and the associate to Justice Kenny whether it has any confidentiality issue with these reasons.

6. Until 2:00 pm on 21 June 2019 or further order, these reasons not be made available to or published to any person other than the parties and their legal advisors.

7. The question of costs be determined on the papers unless a party wishes to be heard on that question orally.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

KENNY J:

Introduction

1 This proceeding involves the construction, validity and, if valid, alleged infringement of a patent entitled “Use of dexmedetomidine for ICU sedation” (Patent). Hospira, Inc and Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd (together referred to as Pfizer) are respectively the registered proprietor and exclusive licensee of the Patent. The Patent is Australian Patent No 754484. Pfizer sells pharmaceutical products under the name “Precedex®”, the sole active ingredient of which is dexmedetomidine hydrochloride (a pharmaceutically acceptable salt of dexmedetomidine). These products are registered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG), with Pfizer as sponsor.

2 InterPharma Pty Ltd (InterPharma), which carries on the business of importing and distributing pharmaceutical products for sale in Australia, is the sponsor of a listing on the ARTG for a family of products, which contain dexmedetomidine hydrochloride as their sole active ingredient (Generic Products). The Generic Products are listed on the ARTG under the brand name “Dexmedetomidine Ever Pharma” and are registered “for sedation of initially intubated patients during treatment in an intensive care setting” (ICU sedation indication) and “for sedation of non-intubated patients prior to and/or during surgical and other procedures” (procedural sedation indication). These indications are the same as for Precedex®.

3 InterPharma, which initially commenced the proceeding to revoke the claims of the Patent, relied on a number of grounds of invalidity. The grounds relied on were that the invention as claimed: (a) was not a “manner of new manufacture”; (b) was not novel; (c) lacked an inventive step; (d) was not fairly based on the matter described in the specification; and (e) did not comply with s 40 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (Patents Act) in that the claims were not clear and succinct.

4 In a cross-claim, Pfizer contended that InterPharma threatened to infringe each claim of the Patent by, amongst other things, offering to supply and supplying the Generic Products. InterPharma admitted that, subject to the question of validity, its proposed conduct threatened to directly infringe claim 1 and indirectly infringe claims 13, 15 and 26 of the Patent. InterPharma also admitted threatened infringement of claims 2, 14 and 27 of the Patent on the basis of a particular construction of those claims (which, for the reasons given below, I accept).

5 There was a substantive hearing of the claim and cross-claim on 3, 4, 7, 21 and 22 May 2018. On 6 August 2018, InterPharma filed an application to re-open the hearing. The hearing was resumed, by consent, on 15 November 2018, when further expert evidence was adduced.

6 InterPharma was, until the Patent expired on 31 March 2019, subject to interlocutory orders restraining it from apprehended infringement of the Patent. The focus at this stage of the proceeding was on Pfizer’s entitlement to final relief. For the reasons stated below, I have found that InterPharma threatened to infringe the Patent during its term and that InterPharma’s challenge to the validity of the Patent should be rejected.

Abbreviated references

7 In these reasons, the following abbreviations are used:

Belleville means the article by Belleville J, Ward D, Bloor B, and Maze M, “Effects of intravenous dexmedetomidine in humans: I. Sedation, ventilation, and metabolic rate”, Anesthesiology 1992, 77: 1125-1133.

Bloor means the article by Bloor B, Ward D, Belleville J, and Maze M, “Effects of intravenous dexmedetomidine in humans: II. Hemodynamic changes”, Anesthesiology 1992, 77: 1134-1142.

Belleville/Bloor means Belleville and Bloor together.

Böhrer 1990 means the article by Böhrer H, Bach A, Layer M and Werning P, “Clonidine as a sedative adjunct in intensive care”, Intensive Care Medicine 1990, 16: 265-266.

GCP Guidelines means the Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6(R1), Current Step 4 version dated 10 June 1996, developed by the appropriate Expert Working Group of the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use.

Hall 2010 means the article by Hall J, “Creating the animated intensive care unit”, Critical Care Medicine 2010, 38(10): S668-S675.

Jalonen 1997 means the article by Jalonen J, Hynynen M, Kuitunen A, Heikkila H, Perttila J, Salmenpera M, Valtonen M, Aantaa R, and Kallio A, “Dexmedetomidine as an anaesthetic adjunct in coronary artery bypass grafting”, Anesthesiology 1997, 86: 331-345.

Kress 1996 means the article by Kress J, O’Connor M, Pohlman A, Olson D, Lavoie A, Toledano A, and Hall J, “Sedation of critically ill patients during mechanical ventilation”, American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 1996, 153: 1012-1018.

Kress 2000 means the article by Kress J, Pohlman A, O’Connor M, and Hall J, “Daily interruption of sedative infusions in critically ill patients undergoing mechanical ventilation”, New England Journal of Medicine 2000, 342(20): 1471-1477.

Petty editorial means the editorial by Petty T, “Suspended life or extending death?”, Chest 1998, 114(2): 360-361.

Pohlman 1994 means the article by Pohlman A, Simpson K, and Hall J, “Continuous intravenous infusions of lorazepam versus midazolam for sedation during mechanical ventilator support: a prospective, randomized study”, Critical Care Medicine 1994, 22(8): 1241-1247.

Talke means the article by Talke P, Li J, Jain U, Leung J, Drasner K, Hollenberg M, and Mangano D, “Effects of perioperative dexmedetomidine infusion in patients undergoing vascular surgery”, Anesthesiology 1995, 82: 620-633.

Tuxen 1998 means the article by Tuxen D, “Sedation and paralysis in mechanical ventilation”, Clinical Pulmonary Medicine 1998, 5(5): 314-328.

1997 Review Article means the article by French C and Bellomo R, “The role of [alpha]-receptor manipulation in the prevention of renal dysfunction”, Current Opinion in Critical Care 1997, 3: 408-413.

Overview of the patent

8 The Patent claimed an earliest priority date of 1 April 1998 (priority date). The priority date is uncontested. The Patent expired on 31 March 2019 (Patent expiry date).

9 The application for the Patent was made on 31 March 1999. Issues of infringement and validity are therefore to be determined under the Patents Act, in the form in which it existed prior to, among other Acts, the Patents Amendment (Innovation Patents) Act 2000 (Cth), the Patents Amendment Act 2001 (Cth), and the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth).

The background to the invention

10 The invention the subject of the Patent relates to the use of dexmedetomidine or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof (referred to in these reasons as dexmedetomidine unless specified otherwise) in intensive care unit (ICU) sedation; a method of sedating a patient in the ICU by administering dexmedetomidine; and the use of that compound in the manufacture of a medicament for ICU sedation.

11 The specification explains:

In addition to the actual sedation of a patient in the ICU, the word sedation in the ICU context also includes the treatment of conditions that affect patient comfort, such as pain and anxiety. Also, the word intensive care unit includes any setting that provides intensive care.

…

The aim of ICU sedation is to ensure that the patient is comfortable, relaxed, and tolerates uncomfortable procedures such as placement of iv-lines or other catheters, but is still arousable.

12 According to the specification:

Particularly, the present invention relates to a method of sedating a patient while in the ICU by administering dexmedetomidine … wherein dexmedetomidine is essentially the sole active agent or the sole active agent administered for this purpose.

13 The specification explains that ICU patients often receive a variety of drugs concurrently. It states:

The agents used most commonly are given to achieve patient comfort. Various drugs are administered to produce anxiolysis (benzodiazepines), amnesia (benzodiazepines), analgesia (opioids), antidepression (antidepressants/benzodiazepines), muscle relaxation, sleep (barbiturates, benzodiazepines, propofol) and anaesthesia (propofol, barbiturates, volatile anaesthetics) for unpleasant procedures. These agents are cumulatively called sedatives in the context of ICU sedation, though sedation also includes the treatment of conditions that affect patient comfort, such as pain and anxiety, and many of the drugs mentioned above are not considered sedatives outside the context of ICU sedation.

14 The specification describes the side effects associated with ICU sedatives as follows:

The presently available sedative agents are associated with such adverse effects as prolonged sedation or oversedation (propofol and especially poor metabolizers of midazolam), prolonged weaning (midazolam), respiratory depression (benzodiazepines, propofol, and opioids), hypotension (propofol bolus dosing), bradycardia, ileus or decreased gastrointestinal motility (opioids), immunosuppression (volatile anaesthetics and nitrous oxide), renal function impairment, hepatotoxicity (barbiturates), tolerance (midazolam, propofol), hyperlipidemia (propofol), increased infections (propofol), lack of orientation and cooperation (midazolam, opioids, and propofol), and potential abuse (midazolam, opioids, and propofol).

15 The specification further states that the combination of ICU sedatives (referred to as polypharmacy) “may cause adverse effects”:

For example, the agents may act synergistically, which is not predictable; the toxicity of the agents may be additive; and the pharmacokinetics of each agent may be altered in an unpredictable fashion.

16 According to the specification, “[t]he preferred level of sedation for critically ill patients has changed considerably in recent years”. It explains:

Today, most intensive care doctors in the ICU prefer their patients to be asleep but easily arousable, and the level of sedation is now tailored towards the patient’s individual requirements.

17 The specification identifies the known problems with α2-adrenoceptor agonists, particularly clonidine. It states that:

According to Tryba et al., clonidine has its limitations in sedating critically ill patients mainly because of its unpredictable hemodynamic effects, i.e., bradycardia and hypotension, so that it must be titrated for each individual patient. Long term treatment of critically ill patients with clonidine has been reported to be associated with such rebound effects as tachycardia and hypertension.

18 The specification states that “α2-agonists are not presently used by themselves in ICU sedation”. It continues as follows:

Further, α2-agonists are not generally used in ICU sedation even in conjunction with other sedative agents. Only clonidine has been evaluated for use in ICU sedation, and then only in conjunction with opioids, benzodiazepines, ketamine, and neuroleptics. Further, administration of clonidine as essentially the sole active agent or the sole active agent to a patient in the ICU to achieve sedation has not been disclosed to the best of the applicants’ knowledge.

19 Some of the characteristics of an “ideal sedative agent for a critically ill patient” are identified. According to the specification:

An ideal sedative agent for a critically ill patient should provide sedation at easily determined doses with ready arousability together with hemodynamic stabilizing effects. Further, it should be an anxiolytic and an analgesic, and should prevent nausea, vomiting, and shivering. It should not cause respiratory depression. Preferably, an ideal sedative agent should be used by itself in ICU sedation to avoid the dangers of polypharmacy.

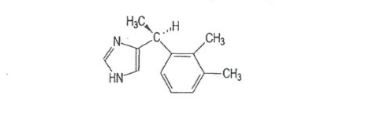

20 The specification depicts the chemical structure of dexmedetomidine as follows:

21 The specification states that dexmedetomidine has been described in US Patent 4910214 (US 214) as “an α2-receptor agonist for general sedation/analgesia and the treatment of hypertension or anxiety”.

The invention as described in the specification

22 Under the heading, “Summary of the invention”, the specification states that it had been “unexpectedly found that dexmedetomidine … is an ideal sedative agent to be administered to a patient in the ICU to achieve patient comfort”. Regarding the invention as a method of sedating a patient in the ICU by administering dexmedetomidine, wherein that compound is essentially the sole active agent or the sole active agent, the specification states:

The method is premised on the discovery that essentially only dexmedetomidine … need[s] to be administered to a patient in the ICU to achieve sedation and patient comfort. No additional sedative agents are required.

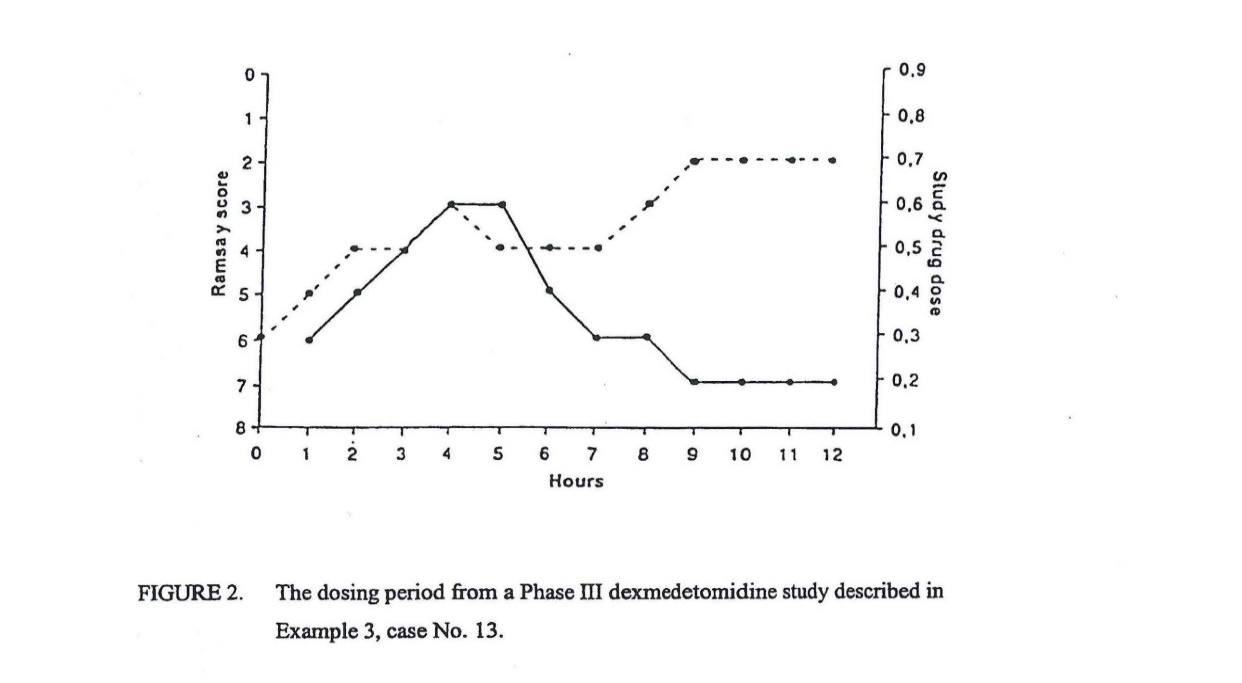

23 The Ramsay Scale (an assessment of the level of sedation in experimental subjects) is described under the heading, “Brief description of the drawings”. The specification states that, in the Ramsay Scale, the level of wakefulness is scored on a scale of 1 to 6 (Ramsay Sedation Score) based on progressive loss of responsiveness to stimuli ranging from auditory to deep painful stimuli. Figure 2 (set out below) shows the Ramsay Sedation Score of a patient in the dexmedetomidine study described in example 3.

24 The dotted line signifies fluctuations in the Ramsay Sedation Score in response to dose adjustments.

25 Under the heading, “Detailed description of the invention”, the specification further explains the particular method of sedating a patient in the ICU by administering dexmedetomidine as essentially the sole active agent or the sole active agent for this purpose. It states:

Particularly, it has been found that dexmedetomidine … can be essentially the sole active agent or the sole active agent administered to a patient in the ICU in order to sedate the patient.

26 The specification goes on to describe the unique quality of the sedation in the ICU achieved by administering dexmedetomidine. It states, in particular:

Patients sedated by dexmedetomidine … are arousable and oriented, which makes the treatment of the patient easier. The patients can be awakened and they are able to respond to questions. They are aware, but not anxious, and tolerate an endotracheal tube well. Should a deeper level of sedation or more sedation be required or desired, an increase in dexmedetomidine dose smoothly transits the patient into a deeper level of sedation.

27 It is further said that:

Dexmedetomidine does not have adverse effects associated with other sedative agents, such as, respiratory depression, nausea, prolonged sedation, ileus or decreased gastrointestinal motility, or immunosuppression.

28 The specification explains that the precise amount of dexmedetomidine to be administered to achieve the desired outcome depends on a number of factors. It further states that:

The dose range of dexmedetomidine can be described as target plasma concentrations. The plasma concentration range anticipated to provide sedation in the patient population in the ICU varies between 0.1-2 ng/ml depending on the desired level of sedation and the general condition of the patient. These plasma concentrations can be achieved by intravenous administration by using a bolus dose and continuing it by a steady maintenance infusion. For example, the dose range for the bolus to achieve the forementioned plasma concentration range in a human is about 0.2-2 µg/kg, preferably about 0.5-2 µg/kg, more preferably 1.0 µg/kg, to be administered in about 10 minutes or slower, followed by a maintenance dose of about 0.1-2.0 µg/kg/h, preferably about 0.2-0.7 µg/kg/h, more preferably about 0.4-0.7 µg/kg/h.

29 The specification provides 3 examples, which exemplify the invention.

The claims

30 The independent claims of the Patent are:

Claim 1: “Use of dexmedetomidine … in the manufacture of a medicament for use in intensive care unit sedation”.

Claim 13: “A method of sedating a patient in an intensive care unit, wherein said method comprises administering dexmedetomidine … to a patient in need thereof”.

Claim 15: “A method of sedating an intensive care unit patient, comprising administering a pharmaceutical composition to the patient, wherein the pharmaceutical composition comprises an active agent and an inactive agent, wherein the active agent consists of dexmedetomidine”.

Claim 26: “Use of dexmedetomidine … in the intensive care unit sedation”.

Claim 1, dependent claims 2 to 12 and omnibus claim 38

31 The use according to claim 1 is the use of dexmedetomidine in the manufacture of a medicament for use in ICU sedation. Claim 1 is therefore a “Swiss-style” or “Swiss-type” claim in the form of “the use of [known] compound X in the manufacture of a medicament for a specified (and new) therapeutic use”: see Apotex Pty Ltd v Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 50; 253 CLR 284 (Apotex v Sanofi-Aventis HCA) at [248].

32 In Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co Ltd v Generic Health Pty Ltd (No 4) [2015] FCA 634; 113 IPR 191 (Otsuka Pharmaceutical v Generic Health (No 4)) at [120], Yates J explained that a claim of this kind should be characterised as a method (or process) claim. Although the Swiss-style claim in that case (as here) was to a method of manufacture of a medicament, it was accepted that the novelty of the claim might arise from the new therapeutic use to which the medicament was applied: Otsuka Pharmaceutical v Generic Health (No 4) at [116]; see also Actavis UK Ltd v Merck & Co Inc [2008] EWCA Civ 444; [2009] 1 All ER 196 (Actavis UK v Merck) at [31], [49].

33 As will be seen, claims 2 to 12 are dependent Swiss-style claims, dependent on claim 1. Each of claims 2 to 12 further qualifies what is said to be the hitherto undiscovered therapeutic use of the medicament by reference to its particular administration (see [189]-[199] below). Claim 38, which is to a “use according to claim 1 substantially as hereinbefore described”, is an omnibus claim to claim 1. As stated below, I reject InterPharma’s submission that the use claimed in claims 2 to 12 and 38 can be understood as “directed to the clinician administering the product that results from the manufacture of the medicament”.

34 It is convenient to note at this point that claim 3 relates to the use of dexmedetomidine in the manufacture of a medicament for use in ICU sedation (as described in claim 1 or 2), “wherein the dexmedetomidine … is administered in an amount to achieve a plasma concentration of 0.1-2 ng/ml”; and that InterPharma made submissions about the plasma concentration integer, which are considered below.

Claims 13, 15 and 26, dependent claims 14, 16 to 25, 27 to 37 and omnibus claim 39

35 Claims 13, 15 and 26 are method (of treatment) claims. Claim 13 is for a method of sedating a patient in an ICU, wherein the method comprises administering dexmedetomidine to a patient in need of that drug. Claim 14 is a dependent claim, dependent on claim 13.

36 Claim 15 is for a method of sedating an ICU patient, comprising administering a pharmaceutical composition to the patient, amongst other things, “wherein the active agent consists of dexmedetomidine”.

37 Claim 16 is a dependent claim, dependent on claims 13, 14 or 15, wherein dexmedetomidine is administered “in an amount to achieve a plasma concentration of 0.1-2 ng/ml”. Again, I note that the significance of this latter integer is considered below.

38 Claims 17 to 25 are all dependent claims (dependent on claims 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 23 or 24). Relevant aspects of these claims are discussed below.

39 Claim 26 is an independent claim for the “[u]se of dexmedetomidine … in the intensive care unit sedation”.

40 Claim 27 is a dependent claim (dependent on claim 26), wherein dexmedetomidine is “essentially the sole active agent or the sole active agent”. Claims 28 to 37 are also dependent claims (dependent on claims 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 35 or 36), relevant aspects of which are further discussed below.

41 Claim 39 is a second omnibus claim, for a method according to claim 13 or 15 “substantially as hereinbefore described”.

Overview of witness evidence

Intensive care specialists

42 Three specialists in intensive care medicine gave evidence at trial. They were: Professor Russell Booth Hall; Professor Rinaldo Bellomo; and Associate Professor (Assoc Professor) Craig John French.

43 Professors Hall and Bellomo and Assoc Professor French met together on 2 May 2018, and created their Joint Expert Report (Joint Report). The Joint Report was in evidence.

44 InterPharma called Professor Hall. Since 1981, Professor Hall has been an Attending Physician, Critical Care Services, at the University Of Chicago Pritzker School Of Medicine. Amongst other things, he holds a certification in Critical Care Medicine from the American Board of Internal Medicine and is a Member of the Society for Critical Care Medicine. He is an author or co-author of very many articles published in leading medical journals.

45 Professor Hall had a specific interest in ICU sedation as at the priority date (April 1998). It may be accepted that his interest and knowledge about ICU sedation would have been significantly greater than that of the average ICU specialist at that time.

46 Professor Hall’s research interest is particularly relevant to the invention of the Patent. He was a co-author of Kress 2000, a highly influential paper leading intensive care specialists to question the previously accepted practice of deep sedation (see [537], [549] below). He was also a co-author of Kress 1996 and Pohlman 1994 (see [550] below).

47 Professor Hall is an experienced witness, who, on his own account, gives evidence in 15 to 20 cases a year, and has given evidence in United States (US) courts in two cases concerning the US equivalent of the Patent in suit.

48 Pfizer called Professor Bellomo, who has been delivering intensive care medicine to patients in Australia for well over 25 years. Professor Bellomo is the Director of Intensive Care Research at the Austin Hospital and has worked and continues to work as an intensive care specialist at that hospital and other hospitals, including the Royal Melbourne Hospital (RMH) ICU. Since 2002 he has been a Professor in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Melbourne and since 2016 he has been a Board Member of the Australian and New Zealand College of Intensive Care Medicine.

49 Professor Bellomo came to intensive care medicine from a general physician’s background. Throughout his career, he has been engaged in clinical research in intensive care medicine, with a particular interest in the kidneys. He has an extensive list of publications, and has held editorial and reviewer positions for leading international medical journals, including US journals.

50 Pfizer also called Assoc Professor French, who has been practising in both anaesthesia and intensive care medicine in Australia since 1995. Assoc Professor French was undergoing training in both anaesthesia and intensive care medicine between 1992 and 1997. He was working as an anaesthetics registrar during 1995 and, from midway through that year, as an intensive care registrar. In 1998, he was admitted to the Fellowship of the Faculty of Intensive Care of the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists.

51 From January 1998 to 2001, Assoc Professor French worked as a consultant intensive care specialist and anaesthetist at the Western Hospital in Melbourne. In 2002, he was appointed Director of Intensive Care at the Sunshine Hospital, also in Melbourne. Since 2003, he has been the Director of Intensive Care at Western Health, a health services body that manages multiple hospitals in Melbourne. Among other things, he has been a Clinical Associate Professor at the University of Melbourne since 2011.

52 At the priority date, in April 1998, Assoc Professor French was a recently qualified specialist intensivist and anaesthetist. He considered his breadth of knowledge in intensive care and anaesthesia as at that date to be at its greatest level in his career. In subsequent years he maintained his overall general knowledge of intensive care and anaesthesia, although he gravitated towards his particular interests. Also as at the priority date, he had been involved in clinical trials for the development of new drugs within the ICU. Since 2015, he has been the chair of the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group.

53 Assoc Professor French has a particular interest in transfusion medicine in the ICU and the role of erythropoietin in clinical illness, although he had an early interest in mechanical ventilation and volatile anaesthetics. He published two papers prior to April 1998, and subsequently a large number of papers, many of them in the intensive care field. He co-authored numerous papers with Professor Bellomo. He has held editorial and reviewer roles for international, including US, medical journals.

54 As noted, Professors Hall and Bellomo and Assoc Professor French were each involved in research, including clinical trials, in intensive care medicine before April 1998. Both Professor Bellomo and Assoc Professor French specifically attested to their familiarity with the GCP Guidelines, the principles required to be followed in clinical trials, and with the investigator brochure supplied by drug companies to those designing and carrying out clinical trials. They both gave evidence about the training that was required to become an intensive care specialist in Australia. For example, Assoc Professor French had obtained an undergraduate medical degree in 1988, completed his residency in 1991, was an anaesthetic registrar from 1992 to 1995, and qualified as an intensive care specialist in 1998. Their evidence was, and it may be accepted, that the training to become an intensive care specialist called for extensive knowledge and the standard for the examinations was high. Those practising in intensive care medicine in Australia at the priority date also had another specialist qualification in medicine. Assoc Professor French and Professor Bellomo both affirmed that all intensive care specialists, regardless of their background or their additional practice, were equally skilled and equipped to administer intensive care medicine.

55 In addition to giving evidence at the trial, Professors Hall and Bellomo and Assoc Professor French each subsequently gave further evidence at the resumed hearing in November 2018.

Other witnesses

56 There were five other witnesses whose affidavits were tendered without objection and without cross-examination.

57 InterPharma adduced the affidavit evidence of Ms Carolyn Stewart. Ms Stewart is the Business and Operations Manager of the Melbourne Children’s Trials Centre at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute. She has a Masters of Medical Science (Drug Development) from the University of New South Wales and, since the late 1980s, she has acquired extensive experience in respect of the conduct of local and international clinical trials.

58 While working for Amgen Australia Pty Ltd and its US parent company (Amgen) between 1992 and 2004, Ms Stewart was involved in drug research and development, and in clinical trials in Australia and overseas. Her responsibilities during those years included clinical trial management and conduct, writing protocols, designing and preparing participant information sheets and consent forms, and preparing study reports and publications.

59 Since working for Amgen, Ms Stewart has provided consultancy services to third parties regarding clinical trial site management and third party vendor management of clinical trials. She has also worked for the Nucleus Network Centre for Clinical Studies, where she was engaged in similar work. Ms Stewart gave evidence about the applicable legal and ethical requirements for the management and conduct of clinical drug trials and about good clinical practice.

60 InterPharma also adduced the affidavit evidence of Mr Bob van Der Kamp. Mr van Der Kamp is an Attorney at Law in the Netherlands. His evidence was confined to confirming: (1) the implementation into Dutch law of European Union (EU) Directive 91/507/EEC concerning good clinical practice for clinical trials, by a Decree on Manufacturing and Delivery of Pharmaceutical Products (Decree); and (2) that the Decree was part of Dutch law in 1998. His evidence was that the Decree became effective on 1 August 1994 and was in force until 1 July 2007. As will be seen, his evidence was relevant because one of the clinical trials on which InterPharma’s lack of novelty case relied was carried out in the Netherlands at the relevant time (see [400] below).

61 Pfizer relied on the affidavit evidence of Mr Rodney Ian Lindsay Cruise. Mr Cruise is a Patent Attorney with more than 28 years’ experience in conducting intellectual property research in the areas of patents, trademarks and designs. He was familiar with the conduct of searches on different databases of medical scientific literature and gave evidence about conducting searches of the medical literature as at the priority date. The evidence of Mr Cruise was that the most common medical scientific literature search database used as at 1 April 1998 was Medline, and that the two platforms most commonly used at that time for searching that database were PubMed and STN. His evidence was relevant to Pfizer’s response to InterPharma’s case on lack of inventive step (see [593] below).

62 At the start of the trial, Pfizer also relied on the affidavit evidence of Ms Melissa Jane Ankravs. Ms Ankravs is the Senior ICU Pharmacist and Team Leader at the RMH and is based in the ICU at the RMH. Ms Ankravs gave evidence about the role of the RMH Pharmacy and the means by which medicines were made available by the RMH Pharmacy for administration to patients in the RMH. She stated that she was involved in maintaining the stock levels in the ICU imprest at the RMH. She gave evidence about the numbers of vials of dexmedetomidine 200microg/50mL distributed to the ICU imprest and to the operating theatre imprests (located at other hospital locations outside the ICU). Her evidence was relevant to an issue that arose concerning the use of dexmedetomidine for procedural sedation, an aspect of the way InterPharma initially put its case. As this aspect of InterPharma’s case was subsequently abandoned, her evidence was not relied on in the parties’ final submissions.

63 Lastly, Pfizer relied on the affidavit evidence of Mr Michael Joseph Ryan. Mr Ryan had been the Director of Pharmacy at a number of hospitals in Melbourne between 1977 and 1994. He subsequently held the following positions: Manager of Health Information and Technology Services at the Victorian Healthcare Association (1997 to 1999); National Pharmacy Services Manager for Hospital Supplies of Australia (HSA) (1999 to 2001); and National Business Manager – Pharmacy at HSA (2001 to 2004). By 2018, he was an independent hospital and medicines management consultant, who ran his own business, PharmConsult Pty Ltd. He was also a Fellow of the Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia, having completed his Fellowship between 1979 and 1983.

64 It may be accepted that Mr Ryan had substantial knowledge and experience in the provision of pharmacy services within public and private hospitals, the procurement and supply of pharmaceutical products in the public health system, and in prescribing practices in hospitals. He gave evidence about the way in which medicines were dispensed to public and private hospital patients. He described tendering processes and outcomes. He gave evidence about the anticipated effect of the Generic Products entering the market, in terms of lessening restrictions related to cost-minimisation on the formulary in public hospitals. Pfizer relied on his evidence in support of an aspect of its case on infringement concerning the “essentially the sole active agent or the sole active agent” integer in claims 2, 14 and 27. It was unnecessary to refer to this aspect of Mr Ryan’s evidence in these reasons in light of InterPharma’s admission of infringement of these claims on the basis of a construction which, as will be seen, I accept. His evidence was also referred to in opening submissions in the context of the procedural sedation issue that was not ultimately pursued by InterPharma (see [62] above).

Principles of patent construction

65 In Jupiters Ltd v Neurizon Pty Ltd [2005] FCAFC 90; 65 IPR 86; 222 ALR 155 (Jupiters) at [67], a Full Court of this Court summarised the principles for the construction of patents as follows:

(i) the proper construction of a specification is a matter of law: Décor Corporation Pty Ltd v Dart Industries Inc (1988) 13 IPR 385 at 400;

(ii) a patent specification should be given a purposive, not a purely literal, construction: Flexible Steel Lacing Co v Beltreco Ltd (2000) 49 IPR 331; [2000] FCA 890 at [81] … ; and it is not to be read in the abstract but is to be construed in the light of the common general knowledge and the art before the priority date: Kimberley-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd (2001) 207 CLR 1; 177 ALR 460; 50 IPR 513; [2001] HCA 8 at [24];

(iii) the words used in a specification are to be given the meaning which the normal person skilled in the art would attach to them, having regard to his or her own general knowledge and to what is disclosed in the body of the specification: Décor Corporation Pty Ltd at 391;

(iv) while the claims are to be construed in the context of the specification as a whole, it is not legitimate to narrow or expand the boundaries of monopoly as fixed by the words of a claim by adding to those words glosses drawn from other parts of the specification, although terms in the claim which are unclear may be defined by reference to the body of the specification: Kimberley-Clark v Arico at [15]; Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel (1961) 106 CLR 588 at 610; Interlego AG v Toltoys Pty Ltd (1973) 130 CLR 461 at 478; the body of a specification cannot be used to change a clear claim for one subject matter into a claim for another and different subject matter: Electric & Musical Industries Ltd v Lissen Ltd [1938] 4 All ER 221 at 224–5; (1938) 56 RPC 23 at 39;

(v) experts can give evidence on the meaning which those skilled in the art would give to technical or scientific terms and phrases and on unusual or special meanings to be given by skilled addressees to words which might otherwise bear their ordinary meaning: Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd v Koukourou & Partners Pty Ltd (1994) 30 IPR 479 at 485–6 … ; the court is to place itself in the position of some person acquainted with the surrounding circumstances as to the state of the art and manufacture at the time (Kimberley-Clark v Arico at [24]); and

(vi) it is for the court, not for any witness however expert, to construe the specification; Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd, at 485–6.

66 The need to read a patent specification as a whole and in light of the common general knowledge in the art before the priority date continues to be emphasised. So too is the need to read a patent specification in a practical way and to give it a purposive construction.

This approach to construction requires the court to read the specification through the eyes of the skilled addressee with practical knowledge and experience in the field of work in which the invention was intended to be used and a proper understanding of the purpose of the invention.

See GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Investments (Ireland) (No 2) Ltd v Generic Partners Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 71; 131 IPR 384 (Generic Partners) at [106].

67 As Lord Hoffmann explained in Kirin-Amgen Inc v Hoechst Marion Roussel Ltd [2004] UKHL 46; 64 IPR 444; [2005] 1 All ER 667 at [34]:

“Purposive construction” does not mean that one is extending or going beyond the definition of the technical matter for which the patentee seeks protection in the claims. The question is always what the person skilled in the art would have understood the patentee to be using the language of the claim to mean. And for this purpose, the language he has chosen is usually of critical importance. … There will be occasions upon which it will be obvious to the skilled man that the patentee must in some respect have departed from conventional use of language or included in his description of the invention some element which he did not mean to be essential. But one would not expect that to happen very often.

68 With respect to this passage, the Full Court in Generic Partners at [109]-[110] added:

It is important to note that Lord Hoffman[n] was referring here to the meaning conveyed to the skilled addressee by the language used and was not directing himself to a situation in which the skilled addressee deduced that the language of the claim, although conveying to him or her a particular meaning, could never have been intended to mean what it conveyed.

… These are situations in which the court endeavours to give effect to the skilled addressee’s understanding of the claim language in preference to a purely literal or grammatical construction, not because the skilled addressee understands that the claim contains a mistake that requires correction, but because, when read in the context of the document as a whole and the common general knowledge, the words used would convey that meaning to the skilled addressee.

Regarding the claims

69 With respect to the claims in a patent specification, as Lord Russel explained in Electric and Musical Industries, Ltd v Lissen, Ltd [1938] 4 All ER 221 at 224; (1939) 56 RPC 23 at 39:

The function of the claims is to define clearly and with precision the monopoly claimed, so that others may know the exact boundaries of the area within which they will be trespassers. Their primary object is to limit, and not to extend, the monopoly. What is not claimed is disclaimed. The claims must undoubtedly be read as part of the entire document, and not as a separate document. Nevertheless, the forbidden field must be found in the language of the claims, and not elsewhere.

See also Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co Ltd v Generic Health Pty Ltd (No 2) [2016] FCAFC 111; 120 IPR 431 (Otsuka FCAFC) at [94] (Besanko and Nicholas JJ).

70 Section 40(3) of the Patents Act requires that the claims of a patent be clear and succinct. It is an objection to the validity of a patent that “the scope of any claim of the complete specification is not sufficiently and clearly defined”: see Blanco White, Patents for inventions and the protection of industrial design (5th ed, 1983) (Blanco White) at 4-701, p 143. The need for clarity arises because, as Dixon CJ said in Martin v Scribal Pty Ltd (1954) 92 CLR 17 (Martin v Scribal) at 59, “the principles governing the definition of a monopoly operating over the public at large require a description which is not reasonably capable of misunderstanding”.

71 A court may refer to the body of the specification to identify the background of the claims and the meaning of technical terms, and also to resolve ambiguities in, or other doubts about, the claims’ construction: Austal Ships Sales Pty Ltd v Stena Rederi Aktiebolag [2008] FCAFC 121; 77 IPR 229 (Austal Ships) at [13], citing Flexible Steel Lacing Co v Beltreco Ltd [2000] FCA 890; 49 IPR 331 (Flexible Steel) at [71]-[78]; Nesbit Evans Group Australia Pty Ltd v Impro Ltd [1997] FCA 1092; 39 IPR 56 (Nesbit Evans) at 94-95. A claim is not invalid merely because it might have been better drafted nor because it is difficult to construe, “provided it can be properly and fairly construed”: Britax Childcare Pty Ltd v Infa-Secure Pty Ltd (No 4) [2015] FCA 651; 113 IPR 280 at [583] (emphasis in original); see also Flexible Steel at [80]-[81], quoting Blanco White at 4-701, and cited with approval by the Full Court in Austal Ships at [14].

72 In Martin v Scribal at 97, Taylor J observed:

The claims also must be construed without an eye on the alleged infringer’s acts. … On the other hand, it is right to construe a claim with an eye benevolent to the inventor and with a view to making the invention work — this is an application of the old doctrine ut res magis valeat quam pereat … ; and, where the language of a claim is obscure or doubtful, the doubt may sometimes be resolved by referring to words in the body of the document to explain it. This is known as the dictionary principle. …

This remains a correct approach: see Otsuka FCAFC at [95] (Besanko and Nicholas JJ).

73 In Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Co v Beiersdorf (Australia) Ltd (1980) 144 CLR 253 (Minnesota Mining) at 274, Aickin J said that the principle with respect to clarity is that “[l]ack of precise definition in claims is not fatal to their validity so long as they provide a workable standard suitable to the intended use”. Stephen J had applied this principle in Monsanto Co v Commissioner of Patents (1974) 48 ALJR 59 (Monsanto), in holding at 61 that the use of the word “substantial” was clear in the phrase “in an amount to have any substantial effect as a cooling medium” in a claim in the patent in suit. Stephen J said, at 60, that:

The lack of clarity which is complained of results, it is said, solely from the use of the adjective “substantial” in the phrase “any substantial effect as a cooling medium”. It is said that its use makes it impossible to determine the limits of the claim to monopoly, that the specification contains no criteria of substantiality of effect and that its meaning cannot be determined by simple experiment.

… Of course what is substantial is a question of degree and is, in that sense, imprecise but in its present context it does not, I think, give rise to any ambiguity.

…

It will in each case be a question of fact and degree whether or not an injected admixture has a substantial effect as a cooling medium and this is the very sort of question which not only do courts have to answer daily, but which I believe that those skilled in the art would have little difficulty in resolving. When only small quantities of admixed fluids are involved, as will be the case when modifiers or solvents are in question, the evidence discloses that they will have no “substantial” effect as cooling media. …

There will, I think, in the present case be no difficulty in a third party ascertaining whether or not what he proposes to do falls within the ambit of the claim … .

74 The principle stated by Aickin J in Minnesota Mining has since been regularly applied in Australian courts: see, for example, Freeman v TJ and FL Pohlner Pty Ltd (1994) 30 IPR 377 at 381-382; Nesbit Evans at 94-95; Austal Ships at [14], quoting Flexible Steel at [81]. In Nesbit Evans at 95, Lindgren J, with whom Hill J agreed, said that:

… it is not unusual for a claim to define an invention partly by the use of a relative expression which necessitates exercise of judgment … and so long as the claims provide a workable standard suitable to the intended use, they will be valid … . The expressions in question must be understood in a practical, common sense manner.

75 In Flexible Steel at [81], Hely J said that:

It is permissible for an invention to be described in a way which involves matters of degree. Lack of precise definition in claims is not fatal to their validity, so long as they provide a workable standard suitable to the intended use. The consideration is whether, on any reasonable view, the claim has meaning. In determining this, the expressions in question must be understood in a practical, commonsense manner. Absurd constructions should be avoided and mere technicalities should not defeat the grant of protection.

(Citations omitted)

76 Whether or not a degree of imprecision is fatal to the validity of a claim depends on whether the claim provides a workable standard for those skilled in the art in the circumstances of the intended use. Where there is no workable standard, imprecision in a claim spells invalidity for lack of clarity, as Albany Molecular Research Inc v Alphapharm Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 120; 90 IPR 457 (Albany Molecular) illustrates. In that case, Jessup J held at [174]-[175] that the expression “substantially pure” when used in the claims in the patent in suit failed to satisfy s 40(3) of the Patents Act, because it left “the definition of the boundaries of the invention uncertain or variable”. (The lack of clarity in that case was cured by a subsequent amendment to the specification, which indicated that the claim to substantial purity was limited to compounds of at least 98% purity: Albany Molecular at [182], [186].)

Regarding the skilled addressee

77 The construction of a patent specification is the responsibility of the Court, since it is a matter of law. To construe a specification, however, the Court must place itself in the positon of the skilled addressee in Australia to whom the specification is addressed: see W R Grace & Co v Asahi Kasei Kogyo Kabushiki Kaisha (1993) 25 IPR 481 (Grace v Asahi) at 496. The words of the specification are to be given the meaning that that skilled addressee would give them in light of the common general knowledge immediately prior to the priority date and what is disclosed in the specification itself.

[S]ince documents of this nature are almost certain to contain technical material, the court must, by evidence, be put in the position of a person of the kind to whom the document is addressed, that is to say, a person skilled in the relevant art at the relevant date. If the art is one having a highly developed technology, the notional skilled reader to whom the document is addressed may not be a single person but a team, whose combined skill would normally be employed in that art in interpreting and carrying into effect instructions such as those which are contained in the document to be construed.

General Tire & Rubber Co v Firestone Tyre & Rubber Co Ltd [1972] RPC 457 (General Tire) at 485.

78 The “skilled addressee” is essentially a hypothetical construct equivalent to a person “acquainted with the surrounding circumstances as to the state of [the] art and manufacture at the time”: Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd [2001] HCA 8; 207 CLR 1 at [24], citing with approval British Dynamite Co v Krebs (1879) 13 RPC 190 at 192. Such a person is “likely to have a practical interest in the subject matter of the invention”: Catnic Components Ltd v Hill & Smith Ltd [1982] RPC 183 at 242. The skilled addressee is taken to be a person of ordinary skill in the field to which the invention relates, rather than a leading expert in the field: see Streetworx Pty Ltd v Artcraft Urban Group Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1366; 110 IPR 82 at [67] (Beach J). As the Full Court in Jupiters at [67] said, “the words used in a specification are to be given the meaning which the normal person skilled in the art would attach to them, having regard to his or her own general knowledge and to what is disclosed in the body of the specification”.

79 The Patent relates to the field of intensive care medicine and concerns the sedation of patients in intensive care using dexmedetomidine. The skilled addressee to whom the Patent is addressed is an intensive care specialist engaged in clinical practice and in some research in the field of intensive care medicine in Australia immediately prior to the priority date. Such a person would have the requisite knowledge of the state of the “art and manufacture” at the relevant time and a practical interest in the subject matter of the invention.

80 Intensive care specialists (or intensivists) in Australia at the priority date were the specialist doctors who were responsible for the clinical care of patients in an intensive care setting in a hospital. Such specialists were typically physicians or anaesthetists with specialist intensive care training. The clinical practice of intensive care specialists in Australia at the priority date would have included sedating intensive care patients in the ICU.

81 Professor Bellomo’s evidence was (and I accept) that immediately before the priority date, intensivists in Australia generally focussed their research on “issues related to major organs of the body rather than on areas such as sedation”. Assoc Professor French gave evidence to the same effect. Assoc Professor French explained (and again I accept) that, at the priority date, sedation was thought to be “a fairly benign procedure” in that “the practice of ICU sedation was not thought to generally impact patient outcomes adversely”.

82 Although the Patent concerns the sedation of patients in the ICU using dexmedetomidine, I do not accept, as InterPharma contended, that the relevant skilled addressee was an intensive care specialist with a particular interest in research in the field of intensive care sedation. To qualify the skilled addressee in this way is to select a sub-set of intensivists, with a particular level of interest, knowledge and skill in an aspect of intensive care medicine. This is not to identify the person of ordinary skill who works in the field of the invention (intensive care medicine) in Australia, and therefore not to identify the skilled addressee. Whilst highly skilled individuals, the ordinary intensive care specialist in Australia at the priority date did not have a specific interest, let alone research interest, in the sedation of patients in intensive care.

83 It may be accepted that the skilled addressee is not a manifestation of or “avatar” for the expert witness whose testimony is accepted by the court: AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd [2015] HCA 30; 257 CLR 356 (AstraZeneca HCA) at [23]. The skilled addressee is a tool of analysis that is given form and content by the testimony of those witnesses. In this context, I accept that Professor Bellomo in particular was able to, and did, give relevant evidence as to how the skilled addressee would have understood the teaching, terms and expressions in the Patent and the relevant prior art. His evidence also assisted in ascertaining the knowledge that the skilled addressee would have had immediately before the priority date, including what the skilled addressee would have done as a matter of routine when faced with the problem that the invention of the Patent was intended to address.

84 The evidence of Assoc Professor French was able to, and did, assist from time to time with respect to particular matters, often in explaining or augmenting Professor Bellomo’s evidence. It is necessary to bear in mind, however, that although he had been working in the field of intensive care medicine as a registrar for some years before April 1998, Assoc Professor French did not complete his qualification as an intensive care specialist until early 1998. It will be recalled that he said, and I accept, that he had a greater breadth of knowledge of matters relevant to intensive care medicine at the time he completed his examinations for Fellowship of the Faculty of Intensive Care in 1998 than thereafter. It may be inferred from this that, as at and immediately before the priority date, his knowledge of some matters relevant to intensive care medicine would have been greater than that of the ordinary intensivist at that time. It may also be relevant to bear in mind that although Assoc Professor French had been engaged in clinical trials for the development of new drugs and had published two papers, as at April 1998, his research interest was to develop much more in the ensuing years.

85 Care also needs to be taken as regards Professor Hall’s evidence, bearing in mind that his medical training and clinical experience are in the US, including his training and experience in critical care medicine (as intensive care medicine is called in the US). For this reason, the testimony of Professor Bellomo and, subject to the qualifications already mentioned, the testimony of Assoc Professor French are likely to be of more assistance in enabling the Court to place itself in the positon of the skilled addressee in Australia than the evidence of Professor Hall. This does not mean that Professor Hall’s testimony can or should be entirely disregarded, since the evidence showed that the relevant “art and manufacture” had some important international dimensions. Rather, the fact that Professor Hall gave testimony based on knowledge and experience gained outside Australia has to be borne in mind in considering issues of evidentiary relevance, cogency and weight. It has also to be borne in mind that, in contrast to the ordinary intensive care specialist in Australia at the priority date, Professor Hall had at that date a particular research interest in sedation in critical care medicine and, in consequence, his knowledge of sedation in this field would have been more extensive than that of the ordinary intensive care specialist. It is also the case that his field of research was relevant to the invention of the Patent.

Are the claims in the Patent clear?

86 It is convenient to address the parties’ submissions on clarity at this point, since they also involve issues concerning the construction of the claims of the Patent in suit.

87 Before doing so, however, it is necessary to address InterPharma’s application for leave to amend its particulars of invalidity as regards its clarity ground in accordance with its Proposed Fourth Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity.

Leave to amend particulars of invalidity — clarity

88 When the hearing began on 3 May 2018, InterPharma was relying on its “Further Further [sic] Amended Particulars of Invalidity” filed on 12 April 2018. InterPharma subsequently prepared another document entitled “Third Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity”, which it filed on 11 May 2018. This document was created following a discussion in court on 7 May 2018, in the course of which senior counsel for Pfizer noted that InterPharma’s case on invalidity appeared to have “slimmed down somewhat” and requested that InterPharma file amended particulars of invalidity and an amended defence to cross-claim (the effect of which need not be addressed here) to reflect the case that it sought to make. The Court granted leave to InterPharma that day to amend its pleadings and particulars to this end.

89 In its closing submissions filed on 18 May 2018, however, Pfizer took issue with the form of the particulars filed by InterPharma on 11 May 2018. The matter was taken up at the commencement of the hearing of closing submissions on 21 May 2018. In response to the discussion that day, InterPharma filed another document on 24 May 2018, also entitled “Third Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity”. A Proposed Fourth Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity was filed on 25 May 2018 (incorporating the amendments made by the Third Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity filed on 24 May 2018). This document also indicated the proposed amendments for which leave was still required. Pfizer opposed a substantial part of these amendments, including InterPharma’s proposed amendments with respect to its clarity objection.

90 As indicated, when the trial began, InterPharma was relying on its Further Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity, according to which it alleged (in para 7A) that all the claims were invalid on the basis that they did not comply with s 40(3) of the Patents Act, because the limitation “for use in intensive care unit sedation” in claims 1 to 12 and 38, the limitation “a patient in an intensive care unit” in claims 13 to 25 and 39, and the limitation “in the intensive care unit sedation” in claims 26 to 37 were not clear to the skilled reader. This was said to be because it was not clear to the skilled reader:

... whether “intensive care unit sedation” referred to in claims 1 to 12, and claims 26 to 38, inclusive comprises sedation of all patients who are in an intensive care unit or only comprises sedation of a sub-set of critically ill patients who are in an intensive care unit and if so how that sub-set is defined[; and]

… whether a “patient in an intensive care unit” referred to in claims 13 to 25 inclusive includes any patient who is in an intensive care unit or only includes a sub-set of critically ill patients who are in an intensive care unit and if so how that sub-set is defined.

InterPharma retained these particulars in its Proposed Fourth Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity.

91 In opening written submissions filed before trial, InterPharma submitted as to lack of clarity that:

20. While the Patent states that an ICU encompasses “any setting that provides intensive care”, it does not further describe or elucidate the features of such a setting.

21. The Patent also states that in the ICU context, sedation includes the actual sedation of a patient and “the treatment of conditions that affect patient comfort, such as pain and anxiety”. Thus, analgesic agents such as opioids are “called sedatives in the context of ICU sedation …”.

…

23. InterPharma will contend that the claims of the Patent lack clarity because the concept of an ICU, which is a limiting feature of all of the claims of the Patent, lacked a sufficiently clear meaning before April 1998 to define a precise boundary of Pfizer’s patent monopoly. …

24. [T]he claims of the Patent are not directed to the particular qualities of the patients to whom dexmedetomidine is administered but rather the setting of that administration. The Patent covers any use of dexmedetomidine in an intensive care setting suitable to achieve sedation of a patient (or, as that term is defined in the Patent, to treat their pain or anxiety).

…

26. While intensivists agree that there are areas within hospitals that are designated as ICUs, and that these areas have certain features such as constant monitoring and availability of life support, there is no delineation between the level of care relevantly given to patients in other hospitals settings such as the operating theatre, a high care post-operative unit, high dependency unit or recovery room. …

27. The lack of clarity of what is an ICU cannot be resolved by defining a certain class of ICU patients. … Pfizer’s attempt to do so depends on excluding certain ICU patients (e.g. those not intubated) from the class for the reason that sedatives are less important for those ICU patients.

(Citations omitted)

92 In her oral opening, senior counsel for InterPharma also submitted, in relation to these limitations, that “the boundaries are not clear and it includes, on our case, the … relatively healthy compared to the critically ill who are being monitored in the ICU”.

93 Pfizer contended that InterPharma did not pursue the sub-set argument foreshadowed in its Further Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity. I reject this submission. It seems to me that InterPharma retained this argument throughout, although it also mounted other arguments (foreshadowed above) to support its fundamental contention that the limitations “for use in intensive care unit sedation”, “a patient in an intensive care unit”, and “in the intensive care unit sedation” are so unclear as to invalidate the claims in which they appear, essentially because the concept of an ICU is itself unclear.

94 InterPharma’s case in closing was not substantially different from its case in opening. In closing written submissions, InterPharma submitted:

86. The concept of an ICU lacked a sufficiently clear meaning before April 1998 to define a precise boundary of Pfizer’s patent monopoly.

87. While the Patent states that an ICU encompasses “any setting that provides intensive care”, it does not further describe or elucidate the features of such a setting.

88. As appears from the discussion earlier, the experts agreed that there were units designated as ICUs and that these were intensive care settings that shared certain features. However, intensive care could also be given outside a unit designated as an ICU. The independent claims lack clarity as there is no clear boundary to be drawn between, for example, the level of monitoring and care provided to patients in an ICU who are not on life support, and that which they received in other post-operative care units. A sensible boundary cannot be drawn by reference to the person overseeing the care: it was clear that not every intensive care setting was overseen by an ICM specialist.

89. The concept of an ICU patient cannot clarify or confine the meaning of an ICU. While the specification refers for example to “critically ill patients” and those who are “mechanically ventilated”, and provides examples of post-surgical patients who were sedated in an ICU (such as those who underwent coronary artery bypass surgery, or aortic valve replacement), there is no definition of an ICU patient in the Patent. An ICU patient is any patient who is in an intensive care setting, and the experts agree that such patients are a heterogeneous group. Further, whether a given patient is in an ICU … depends on clinical judgment, the availability of ICU beds and other care options.

90. In any event, the claims are not drawn by reference to the patients who are treated with dexmedetomidine but rather the setting of its administration. It would be impermissible to put a gloss on the claims by limiting their scope to a specific population of ICU patients described in the Patent.

91. Nor can the concept of ICU sedation itself clarify or confine the meaning of ICU. It is clear that ICU sedation could be given to any patient who is in an intensive care setting and is to be broadly construed, including the “actual sedation of a patient” and “the treatment of conditions that affect patient comfort, such as pain and anxiety”. ...

95 The sub-set argument is included at [89] of InterPharma’s closing submissions, although these submissions evidently include other arguments, foreshadowed in opening, in support of the proposition that the relevant limitations are so unclear as to invalidate the claims.

96 At a general level, this is the position that is sought to be reflected in InterPharma’s Proposed Fourth Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity. By this document, InterPharma indicates that it seeks leave to incorporate paras (f) and (g) into the particulars to para 7A. These proposed particulars allege that it is not clear to the skilled reader:

(f) … whether a patient outside a unit designated as an intensive care unit does or does not constitute a “patient in an intensive care unit”/“intensive care unit patient” referred to in claims 13 to 25 and 39 of the Patent and if so in what circumstances[; and]

(g) … whether sedation of patients outside a unit designated as an intensive care unit does or does not constitute “intensive care unit sedation” referred to in claims 1 to 12, and claims 26 to 38, and if so in what circumstances.

97 In submissions filed, with leave, on 29 May 2018, Pfizer opposed the grant of leave to permit the incorporation of paras (f) and (g), on the basis that they alleged a new basis for invalidity and that the evidence at trial had been completed. Pfizer submitted that, had these amendments been made at trial, it might have questioned witnesses and cross-examined Professor Hall on relevant matters and that it had now lost the opportunity to do so. Pfizer also submitted that the proposed amendments were unclear and ambiguous.

98 Pfizer argued that the proposed paras (f) and (g) to the particulars to para 7A would give rise to new factual issues not in issue at trial, including as to whether a patient outside a unit designated as an “ICU” did or did not constitute an “ICU patient” and whether sedation outside a unit designated as an “ICU” did or did not constitute “intensive care unit sedation”.

99 Noting that amendments to the same or similar effect had been proposed in the earlier Third Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity filed on 11 May 2018, Pfizer also emphasised that InterPharma had added, without explanation, a reference to claim 39 in para (f) of the particulars to para 7A.

100 In any event, so Pfizer contended, it was apparent from the expert evidence that the skilled addressee would have no difficulty reading and understanding each of the claims in the context of the Patent and that invalidity did not arise by virtue of failure to comply with s 40(3) of the Patents Act on the basis that the expressions “patient in an intensive care unit”, “intensive care unit patient”, “intensive care unit sedation”, and “intensive care unit” lacked clarity.

101 Save for two matters, I am not persuaded that, if leave were granted, Pfizer would have missed a relevant opportunity to meet the case delineated by paras (f) and (g) to the particulars to para 7A of InterPharma’s Proposed Fourth Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity. It should be inferred from InterPharma’s written and oral submissions in opening that, in substance, InterPharma’s clarity case at the commencement of the trial was that the use in the claims of the relevant limitations deprived the claims of the requisite clarity because the concept of an ICU was not sufficiently clear before the priority date, and intensive care could be given both within and outside a designated ICU, the concept of ICU sedation was very broad, and the lack of clarity could not be resolved by reference to a defined class of ICU patients. InterPharma’s written opening submissions made it clear that its attack on clarity included the proposition that there was no clear boundary between the level of care in an ICU and the level of care in other hospital settings, and that, in this context, it was unclear whether “intensive care unit sedation” included the sedation of patients who were not in a designated ICU. These arguments were filled out at [88] and [91] of InterPharma’s closing written submissions, but they remained the same arguments. Doubtless, the addition of paras (f) and (g) to the particulars to para 7A of the Fourth Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity will elaborate on what was earlier set out in para 7A of the Further Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity. Save in two respects, this elaboration will merely express the case that InterPharma opened and ran at trial. Pfizer was put on notice of InterPharma’s case before the commencement of the trial, when InterPharma filed its opening written submissions. It is not the case that these proposed new particulars raise factual issues that were not raised at the commencement of, or during, the trial. This is, so it seems to me, confirmed by certain of the questions addressed to the medical experts, the answers to which were included in the Joint Report, by the course of some of the concurrent evidence, and by other evidence adduced by Pfizer in chief and in cross-examination.

102 It does not seem to me, however, that leave should be given to include the words “and if so in what circumstances” in either para (f) or (g) of the particulars to para 7A. The inclusion of these words would, in my view (and substantially for the reason identified by Pfizer in connection with the proposed amendment to the particulars to para 7B), enlarge the case beyond that made at the trial, after the close of evidence and to Pfizer’s prejudice since it has lost the opportunity to adduce evidence or cross-examine Professor Hall on relevant matters. In any event, the intended significance of these words is unclear.

103 Secondly, in the absence of any explanation by InterPharma as to the late incorporation of claim 39 into para (f) of the particulars to para 7A, leave to include a reference to claim 39 should be granted only on the basis that, as it is an omnibus claim, then if InterPharma were successful in this aspect of its invalidity case, any such success should flow through to claim 39 on the same basis and no other basis.

104 Accordingly, subject to these qualifications, leave is granted to InterPharma to amend its particulars to include paras (f) and (g) to the particulars to para 7A in its Proposed Fourth Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity (hereafter referred to as the Fourth Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity).

105 There was a second basis for the alleged invalidity of the Patent’s claims on the basis of lack of clarity, as set out in para 7B of InterPharma’s Further Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity. This referred to the limitation introduced by the expression “essentially the sole active agent or the sole active agent” in claims 2 to 12, 14 to 25, 27 to 37 and 39 (although claim 15 did not include this specific limitation but an analogous limitation “an active and an inactive agent”). The particulars to para 7B of InterPharma’s Further Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity relevantly alleged that it is not clear to the skilled reader:

(c) … whether the administration of dexmedetomidine … with an anaesthetic, analgesic, anti-psychotic or a non-sedative agent in an intensive care unit constitutes its use as “essentially the sole active agent” for sedation and/or for sedating a patient.

106 By its Fourth Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity, InterPharma sought to add the words “or in what circumstances”, so that proposed para (c) of the particulars to para 7B alleged that:

(c) It is not clear to the skilled reader whether or in what circumstances the administration of dexmedetomidine … with an anaesthetic, analgesic, anti-psychotic or non-sedative agent in an intensive care unit constitutes its use as “essentially the sole active agent” for sedation and/or for sedating a patient.

(Emphasis added)

107 InterPharma also sought to delete para (b) of the particulars to para 7B of its Further Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity.

108 In its 29 May 2018 submissions Pfizer opposed the grant of leave to add the words “or in what circumstances” to para (c) of the particulars to para 7B. As Pfizer noted, InterPharma has not provided any explanation as to why it seeks to add the words “in what circumstances”. It may be that the proposed amendment is intended to align the particulars to this paragraph more closely to InterPharma’s opening written submissions, which stated:

The word “essentially” indicates that dexmedetomidine may be co-administered with another agent. If the other agent is a drug with analgesic or anxiolytic qualities then, given that the Patent defines ICU sedation to include actual sedation and the treatment of pain or anxiety, it is not clear in what circumstances involving the administration of a second agent with analgesic or anxiolytic qualities, such as an opioid or benzodiazepine, the use of dexmedetomidine would fall within these claims.

(Emphasis added)

109 Viewed in this way, it may be that the proposed amendment to para (c) of the particulars to para 7B is not intended to expand InterPharma’s case beyond its submissions in opening. The precise import of the proposed amendment is, however, uncertain. On another reading, the amendment would, as Pfizer contended, substantially expand InterPharma’s case in relation to the clarity of the “essentially the sole active agent” limitation, by advancing an alternative case to that which InterPharma ran at trial. That is, the proposed addition of “or in what circumstances” might be thought to raise the possibility that:

if contrary to InterPharma’s pleaded case, it is clear to the skilled addressee that the administration of dexmedetomidine with an anaesthetic, analgesic, anti-psychotic or a non-sedative agent in an intensive care setting does or does not constitute use of dexmedetomidine as “essentially the sole active agent” for ICU sedation, … [then] it is not clear “in what circumstances” the administration of dexmedetomidine with such an agent constitutes use of dexmedetomidine as “essentially the sole active agent” for ICU sedation.

110 This question was not put in issue in the Further Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity or in any subsequent version of InterPharma’s Particulars of Invalidity. It was not raised at trial. The proposed amendment to para (c) would in this case prejudice Pfizer since it has lost the opportunity to adduce evidence or cross-examine Professor Hall about this issue. In any event, as before, the intended significance of the proposed additional words is unclear.

111 In these circumstances, I would not grant leave to amend para (c) of the particulars to para 7B. In any event, it does not seem to me that the amendment is necessary. InterPharma will not be prevented from advancing the case it has already run with respect to this limitation at trial.

112 Pfizer did not oppose the proposed deletion of para (b) of the particulars to para 7B of InterPharma’s Further Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity. Leave will be granted to make this amendment.

113 There was a third basis for the alleged invalidity of the claims for reason of lack of clarity set out in para 8 of InterPharma’s Further Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity. Paragraph 8 asserted that claims 3 to 12 and 38 do not comply with s 40(3) because “[i]t is unclear which ‘use’ in claim 1 is the intended ‘use’ in claims 3 to 12 and 38”. Further, it was asserted that to the extent that the “use” is:

… use of dexmedetomidine to make a medicament of claim 1 it is not clear to the skilled reader how this could be construed to include a method of administering the medicament of claim 1 to a patient as part of the process for making the medicament [; and]

… the “for use” defining the purpose of the medicament in claim 1 it is not clear to the skilled reader how the method or process of manufacturing the medicament of claim 1 could be construed to include a method of administering the medicament.