FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

The Environmental Group Ltd v Bowd [2019] FCA 951

ORDERS

THE ENVIRONMENTAL GROUP LTD (ACN 000 013 427) First Applicant BALTEC IES PTY LTD (ACN 124 484 108) Second Applicant TOTAL AIR POLLUTION CONTROL PTY LTD (ACN 097 531 416) Third Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

AND

VID 580 of 2017 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | PETER BOWD Applicant | |

AND: | THE ENVIRONMENTAL GROUP LTD (ACN 000 013 427) First Respondent ELLIS RICHARDSON Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties are to file within 14 days hereof consent orders giving effect to the reasons of this judgment, or if the parties cannot so agree, submissions limited to four pages setting out what each party contends should be the form of final relief.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

STEWARD J:

1 Before me are two proceedings. In one, Mr Peter Bowd sues his former employer, The Environmental Group Ltd (“EG”), and its then managing director, Mr Ellis Richardson, contending that there were contraventions of ss 340 and 352 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (the “FW Act”) and Pt 9.4AAA of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the “CA”). He seeks damages and the imposition of the maximum penalty. In the other proceeding, EG and two of its subsidiaries, namely Baltec IES Pty Ltd (“Baltec”) and Total Air Pollution Control Pty Ltd (“TAPC”), sue Mr Bowd for breach of contract, detinue and breach of copyright in relation to confidential information and property retained by Mr Bowd following his dismissal by EG. Both proceedings are the product of a breakdown in the relationship between the board and Mr Bowd who had been the Chief Executive Officer (“CEO”) of EG. That breakdown was severe. It left both the board of EG and Mr Bowd damaged. Reflecting this state of affairs, the parties in both proceedings filed statements of facts in dispute; there were 32 disputed facts.

2 By agreement of the parties the issue of liability was tried separately from the assessment of damages and penalty (if any) in both proceedings. What follows is my judgment in relation to the issue of liability.

Applicable Legislation

3 Section 340 of the FW Act provides:

(1) A person must not take adverse action against another person:

(a) because the other person:

(i) has a workplace right; or

(ii) has, or has not, exercised a workplace right; or

(iii) proposes or proposes not to, or has at any time proposed or proposed not to, exercise a workplace right; or

(b) to prevent the exercise of a workplace right by the other person.

(2) A person must not take adverse action against another person (the second person) because a third person has exercised, or proposes or has at any time proposed to exercise, a workplace right for the second person’s benefit, or for the benefit of a class of persons to which the second person belongs.

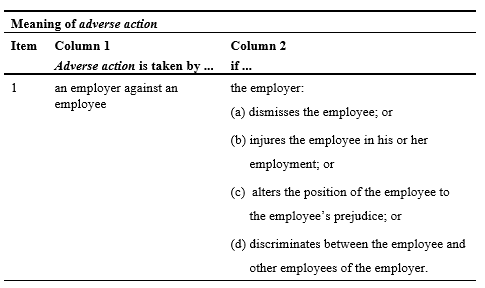

4 Section 342 of the FW Act relevantly defines the term “adverse action” as follows:

(1) The following table sets out circumstances in which a person takes adverse action against another person.

…

5 Section 341(1) of the FW Act defines the term “workplace right” as follows:

A person has a workplace right if the person:

(a) is entitled to the benefit of, or has a role or responsibility under, a workplace law, workplace instrument or order made by an industrial body; or

(b) is able to initiate, or participate in, a process or proceedings under a workplace law or workplace instrument; or

(c) is able to make a complaint or inquiry:

(i) to a person or body having the capacity under a workplace law to seek compliance with that law or a workplace instrument; or

(ii) if the person is an employee—in relation to his or her employment.

6 Section 341(2) of the FW Act defines the term “process or proceedings under a workplace law or workplace instrument” as follows:

Each of the following is a process or proceedings under a workplace law or workplace instrument:

(a) a conference conducted or hearing held by the [Fair Work Commission];

(b) court proceedings under a workplace law or workplace instrument;

(c) protected industrial action;

(d) a protected action ballot;

(e) making, varying or terminating an enterprise agreement;

(f) appointing, or terminating the appointment of, a bargaining representative;

(g) making or terminating an individual flexibility arrangement under a modern award or enterprise agreement;

(h) agreeing to cash out paid annual leave or paid personal/carer’s leave;

(i) making a request under Division 4 of Part 2-2 (which deals with requests for flexible working arrangements);

(j) dispute settlement for which provision is made by, or under, a workplace law or workplace instrument;

(k) any other process or proceedings under a workplace law or workplace instrument.

7 Section 12 of the FW Act, the Dictionary, defines the term “workplace law” as follows:

workplace law means:

(a) this Act; or

(b) the Registered Organisations Act; or

(c) the Independent Contractors Act 2006; or

(d) any other law of the Commonwealth, a State or a Territory that regulates the relationships between employers and employees (including by dealing with occupational health and safety matters).

8 Section 352 of the FW Act is in these terms:

An employer must not dismiss an employee because the employee is temporarily absent from work because of illness or injury of a kind prescribed by the regulations.

9 Relevant to the alleged breaches of ss 340 and 352 is s 361(1), which prescribes a presumption that relevantly adjusts the onus of proof. It is in these terms:

(1) If:

(a) in an application in relation to a contravention of this Part, it is alleged that a person took, or is taking, action for a particular reason or with a particular intent; and

(b) taking that action for that reason or with that intent would constitute a contravention of this Part;

it is presumed that the action was, or is being, taken for that reason or with that intent, unless the person proves otherwise.

10 Mr Bowd also contended that there had been breaches of what are sometimes called the “whistleblower” provisions as contained in Pt 9.4AAA of the CA. The relevant provisions are ss 1317AA, 1317AB, 1317AC, and 1317AD, which provide as follows:

1317AA Disclosures qualifying for protection under this Part

(1) A disclosure of information by a person (the discloser) qualifies for protection under this Part if:

(a) the discloser is:

(i) an officer of a company; or

(ii) an employee of a company; or

(iii) a person who has a contract for the supply of services or goods to a company; or

(iv) an employee of a person who has a contract for the supply of services or goods to a company; and

(b) the disclosure is made to:

(i) ASIC; or

(ii) the company’s auditor or a member of an audit team conducting an audit of the company; or

(iii) a director, secretary or senior manager of the company; or

(iv) a person authorised by the company to receive disclosures of that kind; and

(c) the discloser informs the person to whom the disclosure is made of the discloser’s name before making the disclosure; and

(d) the discloser has reasonable grounds to suspect that the information indicates that:

(i) the company has, or may have, contravened a provision of the Corporations legislation; or

(ii) an officer or employee of the company has, or may have, contravened a provision of the Corporations legislation; and

(e) the discloser makes the disclosure in good faith.

(2) A reference in subsection (1) to a person contravening a provision of the Corporations legislation includes a reference to a person committing an offence against, or based on, a provision of this Act.

1317AB Disclosure that qualifies for protection not actionable etc.

(1) If a person makes a disclosure that qualifies for protection under this Part:

(a) the person is not subject to any civil or criminal liability for making the disclosure; and

(b) no contractual or other remedy may be enforced, and no contractual or other right may be exercised, against the person on the basis of the disclosure.

(2) Without limiting subsection (1):

(a) the person has qualified privilege in respect of the disclosure; and

(b) a contract to which the person is a party may not be terminated on the basis that the disclosure constitutes a breach of the contract.

(3) Without limiting paragraphs (1)(b) and (2)(b), if a court is satisfied that:

(a) a person (the employee) is employed in a particular position under a contract of employment with another person (the employer); and

(b) the employee makes a disclosure that qualifies for protection under this Part; and

(c) the employer purports to terminate the contract of employment on the basis of the disclosure;

the court may order that the employee be reinstated in that position or a position at a comparable level.

1317AC Victimisation prohibited

Actually causing detriment to another person

(1) A person (the first person) contravenes this subsection if:

(a) the first person engages in conduct; and

(b) the first person’s conduct causes any detriment to another person (the second person); and

(c) the first person intends that his or her conduct cause detriment to the second person; and

(d) the first person engages in his or her conduct because the second person or a third person made a disclosure that qualifies for protection under this Part.

Threatening to cause detriment to another person

(2) A person (the first person) contravenes this subsection if:

(a) the first person makes to another person (the second person) a threat to cause any detriment to the second person or to a third person; and

(b) the first person:

(i) intends the second person to fear that the threat will be carried out; or

(ii) is reckless as to causing the second person to fear that the threat will be carried out; and

(c) the first person makes the threat because a person:

(i) makes a disclosure that qualifies for protection under this Part; or

(ii) may make a disclosure that would qualify for protection under this Part.

Officers and employees involved in contravention

(3) If a company contravenes subsection (1) or (2), any officer or employee of the company who is involved in that contravention contravenes this subsection.

Threats

(4) For the purposes of subsection (2), a threat may be:

(a) express or implied; or

(b) conditional or unconditional.

(5) In a prosecution for an offence against subsection (2), it is not necessary to prove that the person threatened actually feared that the threat would be carried out.

1317AD Right to compensation

If:

(a) a person (the person in contravention) contravenes subsection 1317AC(1), (2) or (3); and

(b) a person (the victim) suffers damage because of the contravention;

the person in contravention is liable to compensate the victim for the damage.

Relevantly, and in general terms, once validly engaged the “whistleblower” provisions prevent a company from dismissing an employee who has made a complaint, for example, to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (“ASIC”).

Facts

11 EG is a publicly listed company which relevantly owns two subsidiaries, namely Baltec and TAPC. Baltec designs and manufactures products for companies within the power industry. It was formerly owned by the Richardson family. From time to time, it had dealings with an Indonesian subsidiary, known as PT Baltec Indonesia (“PT Baltec”). Baltec owned 80% of the shares in that company; the other 20% were owned by an Indonesian national. It was said that the most valuable “asset” of Baltec was its staff. This included Mr Sinan Boratav, Mr Dexter Hartono, Mr Olivier Latorre and Mr Quang Ly.

12 TAPC is in the business of industrial air pollution control, particularly in the field of particulate capture using electrostatic precipitation and fabric filters.

13 At all material times the board of EG comprised its chairman, Mr David Cartney, its managing director, Mr Ellis Richardson, and its non-executive director, Ms Lynn Richardson. The chief financial officer (“CFO”) was Mr Allan Fink. Each member of the board gave evidence before me as did Messrs Latorre and Hartono.

14 Mr Bowd’s contract of employment comprised a letter of offer sent to him by EG on 12 September 2016. This was signed by each of Mr Bowd and Mr Richardson. The contract provided for the appointment of Mr Bowd to be the CEO of EG. The letter described that position in the following way:

Position

Chief Executive Officer (CEO) – reporting to the board, initially through the Managing Director Ellis Richardson. In this capacity you will be responsible for the development, profitability, and culture of EGL. The effective use of cash flow will be a critical aspect of your role. The full roles and responsibilities of this role will be described separately in a position description.

Direct Reports

Sinan Boratav, Rob Henderson and Stirling Schunemann who are senior members of the management team, will report directly to you. You will be responsible for assisting and directing each manager to achieve the outcomes agreed by the board.

The Chief Financial Officer (CFO), Allan Fink, will continue to report to the board through the Managing Director for the remainder of the 2016/2017 financial year.

Both Mr Bowd and EG were entitled to terminate this contract on three months’ notice. The letter recorded:

Termination

Either party may terminate the employment relationship on 3 months’ written notice.

The company may terminate your employment at any time without notice if:

• you are guilty of serious misconduct or

• you are in material breach of a provision of this contract, including confidentiality undertakings.

Following the termination of your employment you will be required to return all company property.

The letter also contained terms requiring Mr Bowd to comply with company policies and to keep confidential company information.

15 Mr Bowd’s initial focus was on TAPC’s business. It would appear that he had considerable success in improving that business, for which he was praised. However, when in late 2016 he subsequently focused his efforts on Baltec’s business, difficulties were encountered. It is useful to give a brief summary of those difficulties about which the parties were in dispute.

16 According to Mr Bowd, he performed well at Baltec. He uncovered irregularities in that company’s dealings with PT Baltec. He commenced an investigation into those irregularities, dismissed an employee for misconduct (Mr Ly), ultimately reported some of the irregularities to the board, and then reported more serious allegations to ASIC, to the Victorian police and to the Australian Federal Police (the “AFP”). According to Mr Bowd, he was first told that there were issues about his performance at Baltec in January 2017. He was suspended and then dismissed on 2 March 2017. The letter of termination gave no reason for this decision.

17 According to the board of EG, they had serious concerns about Mr Bowd’s performance at Baltec, which they had first raised with him in November and December 2016. At that time Mr Richardson said he had counselled Mr Bowd that he should learn how things were done at Baltec, before criticising staff and making changes. Mr Bowd’s behaviour led to the resignation of a key employee, namely Mr Boratav, on 23 November 2016. Baltec staff complained about Mr Bowd. They were unhappy. The board was also concerned with the hiring by Mr Bowd of three new employees, namely Mr Gordon Blakemore, Mr Brian Hooker and Ms Sally Stahmer. Each of these employees was perceived to be primarily loyal to Mr Bowd. Only one of them gave evidence before me, namely Mr Blakemore. When the board confronted Mr Bowd with these concerns at a meeting in January 2017, Mr Bowd left the meeting, on one view, abruptly. He sought legal advice and engaged new third-party auditors to investigate the Baltec irregularities, without the consent and knowledge of the full board. He then made his complaints to ASIC and to the police before the commencement of that audit, again without the knowledge or consent of the board. What followed was an understandable and complete breakdown in the board’s relationship with its CEO. EG exercised its contractual right to terminate its contract with Mr Bowd.

18 For the reasons which follow I have generally accepted EG’s account of what happened. The complaint to ASIC did not just contain allegations about possible irregularities at Baltec; it included allegations which were far more serious. I have found that Mr Bowd made his complaints because he feared that he would be dismissed as a result of his performance at Baltec, and he wished to secure the protection from dismissal afforded by the whistleblower provisions of the CA, which he knew about at that time. To secure that protection he needed to make his complaint to ASIC. As it happens, his complaint was misconceived. No severe irregularities have been uncovered. Neither ASIC nor the police have taken any action against EG or Mr Richardson.

19 It is not uncommon for a new CEO to want to stamp his or her own objectives and aspirations on a business he or she has been asked to lead; this can lead to changes in work practices and culture; it can lead to the insertion of new employees over the top of existing employees; and it can lead to resignations and terminations. Sometimes, changes of this kind can lead to success; sometimes they do not. Sometimes they result in personality clashes, paranoia and plotting. In essence, that is what happened here when Mr Bowd commenced to lead the Baltec business. It led to the irretrievable breakdown in the relationship between him and the board.

Concerns regarding Mr Bowd’s performance as CEO

20 I turn to consider the chronology of events in more detail. It was Mr Bowd’s case that until 19 January 2017 he had received no prior notification from any director or officer of EG concerning his performance as CEO of the Baltec business. I reject that contention. Difficulties commenced with the resignation of Mr Boratav on 23 November 2016; he was a key man who had worked at Baltec for approximately 20 years. Mr Boratav did not give evidence before me, but I accept that he resigned because he had a personality clash with Mr Bowd. His resignation greatly concerned the board. On 23 November 2016, Ms Richardson attended a Baltec marketing meeting. She was appalled by Mr Bowd’s dismissive attitude to the Baltec staff. The next day, EG held its annual general meeting. After that, the members of the board met with Mr Bowd and raised with him what they considered were his poor communications with the staff at Baltec and what they thought was his mishandling of the employment of Mr Boratav.

21 Contemporaneous emails are consistent with the board’s version of what happened at this meeting. On 24 November 2016, Ms Richardson sent the following email to Mr Bowd:

Hi Pete

Did not get a chance to say goodbye before you left today but I wanted to wish you well with your procedures tomorrow and also let you know that I will be thinking of you and Rona (? sorry not sure of the spelling).

I am sorry we did not get a chance to speak a little more constructively before the meeting today. I feel like we probably had a smash and grab version of what should have been a longer and more supportive conversation and although we reached a more productive place by the end of the board meeting I am still feeling a bit flat about the situation and honestly hate to think that this has caused you distress. I hope you are feeling a little more settled now than earlier in the day. I very much appreciate all that you have done over the past 3 months and the pace and effort you have put into the business.

22 On 29 November 2016, Mr Bowd replied to Ms Richardson’s email and relevantly wrote as follows:

There is a lot of risk mitigation to implement, I am still trying to ascertain the best way to communicate this without offending people, given the feedback from last Thursday, however we must also remove the risk to our board and executive. A more rounded view of how to achieve this will be discussed between the Ex-com team at our next meeting.

23 In a further email sent on the same day to Ms Richardson, Mr Bowd said, amongst other things:

We remain inspired and keep focused on the positives, Thursday was a good reminder that we are all human and make mistakes on occasions…it keeps me grounded

24 On 16 December 2016, Mr Bowd sent the following email to Mr Richardson which, in relation to a decision to remove him from all communications concerning a certain issue, relevantly stated as follows:

I believe the board and I must meet at a matter of urgency as soon as I am home to discuss this immediate issue and the Increasing lack of trust in my judgement and ability to [fulfil] my role as CEO. There is an ongoing pressure and view that I caused [Mr Boratav] to resign. However, I believe the decisions regarding provision of parts from China to IHI and the lack of governance around the project in Egypt are more specific to the decisions.

Should the board wish to discuss my current choices as CEO and my decisions re staffing and changes, I am happy to remain awake tonight to take a group call.

It is most unusual that the executive managing me would openly discuss their unhappiness in my management and choices unless there was other intent in the background. Which I am happy to discuss immediately.

(Errors in the original.)

Whilst this email referred to an “increasing lack of trust”, some of the language used in other emails sent at this time, which I have not reproduced, was also polite and encouraging. The board having only recently hired Mr Bowd were keen for him to succeed. Nonetheless they continued to have concerns. On 20 December 2016, Mr Richardson sent the following email to his fellow board members, reproduced in part as follows (the reference to “Pete” is to Mr Bowd):

Hi David and Lynn, I am sending a few emails re communications from Pete which I would like to share with you. please do not distribute and keep confidential. I am returning to Melbourne tomorrow morning and am free to meet say 9:30 Thursday or earlier if required.

I am concerned at the emails from Peter,

…

It appears anyone on Pete’s team can do no wrong and anyone on the other side can be bullied to submission. If this attitude is reflected towards other staff then no wonder people are uncomfortable.

(Errors in the original.)

25 I infer that the reference to “Pete’s team” is a reference to the staff hired by Mr Bowd. There was another board meeting held on 22 December 2016, which Mr Bowd attended. The board raised with him again his poor communications with the board and Baltec staff members, and his appointment of new employees who reported directly to him. In cross-examination, Mr Bowd admitted that his performance had been raised at this board meeting. He conceded that the board said to him that if he continued to be critical of Baltec staff they would not feel welcome. It is unnecessary for me to decide further whether Mr Bowd also told Baltec staff that they had made “crap” decisions.

26 Contemporaneous emails also support the board’s version of what took place at this meeting and the growing concern with Mr Bowd’s performance. In one email, dated 5 January 2017, sent to Mr Richardson, Mr Bowd wrote that he had had to take an “almost bullish approach” to get to the bottom line on issues. Mr Richardson responded on the same day as follows:

Hi Pete, I too feel saddened as Baltec has been profitable for over 20 years yet over the past 3 months’ new senior people at every level of management has been engaged to fix the Baltec problems. As you mentioned this bullish approach was necessary however this high-risk strategy was not fully explained to the board and will bring with it significant risks to customer and technical reputation.

In hindsight if all of these people needed to be replaced then one would expect that their replacements would be researched, considered and be far more competent than their predecessors. You and the Board need to review the performance of the new team to be comfortable that they are the best in the market place and will achieve outcomes in excess of the team they replaced. I have already raised my concerns with you but will await other board member’s comments which we should discuss ahead of our strategic meeting.

Thanks

Ellis

(Errors in the original.)

27 A more extensive email was then sent in reply by Mr Bowd to Mr Richardson later that day which relevantly stated:

I am sorry that my choices have left the board feeling disconnected, more importantly that my work has left you personally feeling that I am putting down what is a great business. I am not, the brand is a great brand that I am personally engaged with. I am unsure how best to reconcile this issue, because at no stage have I placed the Baltec/EGL/TAPC brands at risk, promoting it with some very senior people in Solar turbines, the US government, Arizona state government. We have a growing profile with Origin energy, that with on-going discussions will hopefully lead to a scope of work on their Qld asset base.

I appreciate that the board are unhappy in regards to the decisions [Mr Boratav] has made, I am sure I could have done a better job of engaging, however the challenges of time with TAPC, the need to have a positive shift with regards to cashflow has in many ways been the driving factor. I am a part of the board team and am trying to do my best to navigate the nuances of the business whilst rectifying the small but significant challenges that face our company.

Ellis, I am here to help you as our MD achieve the success you want for your/our company, I have been committed from the very first day, working long hours, placing work before personal matters and genuinely taking on the responsibility of your company so that you can find balance with your own. family, if I have not achieve this I am truly sorry, because I like working for you.

I hope that my words can bring us closer as a team and friends, I am at no stage trying to damage what you have spent many years building.

Have a good week off next week and know I am deeply committed to the ongoing success of your/our company.

(Errors in the original.)

Discovery of potential expense irregularities at Baltec

28 One of the issues Mr Bowd was confronting at this time at Baltec was potential inaccuracies in reporting expenditure, especially in relation to expenses incurred by Baltec employees whilst working overseas. Some of these appeared to Mr Bowd to have no supporting evidence or data. His evidence was that during December he continued to conduct a “detailed internal audit” of Baltec’s expenses. That audit was not mentioned in his report to the board for their meeting held on 22 December 2016. However, the minutes of the December meeting do record that Mr Bowd had undertaken an “analysis into expense claims”. It was during this same period that Mr Bowd hired Mr Blakemore, Mr Hooker and Ms Stahmer. Mr Bowd exhibited to his affidavit some of the expense claims which he considered were not corroborated by “supporting data”. They included relatively small payments for drivers, for lunches and for dinners.

29 Other Baltec staff uncovered potential expense irregularities. For example, in December 2016, Mr Hartono raised directly with Mr Richardson certain marketing expense irregularities he had found. Significantly, Mr Richardson told him to follow the formal reporting lines and speak to Mr Bowd about the issue. Mr Latorre also found some potential cost irregularities. He raised these with Mr Richardson in early January 2017. Mr Richardson told him to raise the issue with Mr Blakemore. In these proceedings, Mr Bowd has made a series of allegations against Mr Richardson which, if true, would be inconsistent with Mr Richardson directing staff to raise irregularities with Mr Bowd or Mr Bowd’s staff.

30 On 10 January 2017, a Baltec employee, Mr Ly, was dismissed by Mr Bowd. This was done with the knowledge and support of Mr Richardson. He was dismissed, according to Mr Bowd, for “serious misconduct” although the Court was not told what this was. Mr Latorre gave evidence that the dismissal was “abrupt” and that Mr Ly was not given the opportunity to say goodbye to his fellow staff members or given the chance to collect his belongings. The dismissal of Mr Ly, and Mr Bowd’s handling of it thereafter, was a turning point for Mr Latorre. Whilst he was initially impressed with Mr Bowd, Mr Latorre’s relationship with him had deteriorated over time. Following the dismissal of Mr Ly, Mr Latorre ceased to trust Mr Bowd. He deposed:

… I lost all trust in the man as a leader and a CEO, and only saw a person willing to carry out a personal agenda with little to no regard for the consequences it may have on the [EG] staff. From that moment on, I was convinced that the only way for [EG] to survive as a company was for Peter Bowd to leave the company.

Needless to say, Mr Bowd’s evidence was that he needed, as CEO, to dismiss Mr Ly. Whether his actions were justified or not is a matter I express no views about.

31 On the same day, Mr Bowd claims he established a whistleblower policy for EG. However, no contemporaneous documents were adduced into evidence to support that assertion. In fact, the policy was adopted later in January. Mr Bowd’s knowledge of the whistleblower provisions was striking for someone who is not legally qualified. As we shall see, this included him at one point emailing Mr Cartney the provisions contained in Pt 9.4AAA of the CA.

32 On 11 January 2017, a meeting took place at Baltec. What happened at this meeting is disputed. According to Mr Bowd, Messrs Hartono and Latorre raised with him concerns that payments had been made to PT Baltec in relation to two projects “without formal processes being followed” and that payments were still being made in relation to certain other projects which had closed. The accumulated amount of irregularities was said to be in the order of $17,500. This meeting prompted further investigative work by Mr Bowd who said he then discovered additional “discrepancies” in excess of $95,000. The exact nature of the irregularities and discrepancies was never clearly identified by Mr Bowd.

33 In an email exchange earlier on 11 January 2017, Mr Bowd had written to Mr Hooker to say that there needed to be carried out a “subtle review on PT Baltec and its invoicing strategy”. Mr Hooker replied: “Ok, [Mr Hartono] has called a meeting this morning titled PT Baltec so not sure what that is about”. Mr Bowd asked for the time of the meeting. When told when it was to be held he responded: “Ok, that’s bloody good news ... I will attend to [sic]”.

34 In cross-examination, Mr Bowd said that the “news” which was “bloody good” was a reference to Mr Hooker coming back from Egypt. It was put to him that in fact the “news” was the prospect of finding irregularities in Baltec. I reject Mr Bowd’s evidence that the news concerned the return of Mr Hooker to Australia. In the context of the email exchange, I find that the “news” was the meeting to discuss PT Baltec.

35 Mr Hartono gave evidence about this meeting. He said that towards the end of it one of either Mr Bowd, Mr Hooker or Mr Blakemore made reference to the “Whistleblowers Act” and that they seemed “excited” by the concerns raised by Messrs Hartono and Latorre about the financial irregularities.

Mr Bowd’s suspicions of breaches of the CA

36 It was Mr Bowd’s evidence that between 11 and 13 January 2017 he conducted further investigations. Within a matter of days, he commenced to form firm conclusions. As a result of finding “discrepancies” Mr Bowd deposed that he had formed the view that there “could have been” breaches of the CA. He based this conclusion on “the fact” that PT Baltec had not been audited for two years contrary to the requirements of the CA and “secondly because expense claims appeared to me to be outside of Australian Tax Legislation”. As to the first reason given, in cross-examination Mr Bowd admitted that this was a mistake. PT Baltec’s accounts had in fact been audited for the year ended 31 December 2015; in relation to the 2016 year, the time for completing and publishing those accounts had yet, by January 2017, to pass. I also find that any failure to prepare audited accounts for PT Baltec could not have amounted to breaches of the CA; PT Baltec is an Indonesian company. It is not subject to the requirements of the CA. As for the second reason given – it simply makes no sense. At no stage did Mr Bowd submit any evidence concerning breaches of what he called “Australian Tax Legislation”. At this stage, Mr Bowd’s highly generalised conclusions appeared to me to lack a proper basis.

37 Then Mr Bowd did something which I find odd. He stated in his main affidavit that on 13 January 2017 “while searching the [Australian Securities Exchange (“ASX”)] for details on who owned” PT Baltec he came across two forms titled “Notice of change of interest of substantial holder”. Both notices were exhibited to Mr Bowd’s affidavit. Neither concerned PT Baltec. Each concerned EG and the Richardsons. Attached to one document was a copy of an “Option Deed” entered into between Messrs Boratav and Richardson whereby Mr Boratav granted an option to Mr Richardson to purchase his shares in EG. Why the CEO of EG was doing searches on the ASX about the ownership of PT Baltec was not explained. It is not conduct I would expect a CEO to undertake without proper cause.

38 In his affidavit, Mr Bowd then made the following statement:

I carried out a detailed review of these documents and came to the conclusion that these actions were in breach of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). It was my honest belief that Mr Richardson may have procured the 14 September 2016 Options Agreement whilst he possessed information not generally known to the market. In particular, I believed there may have been a breach of section 182 and section 611 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). I also believed that both Mr Richardson and Ms Richardson had failed to disclose a change in director’s interests. No Appendix 3Y form had been lodged in accordance with Rule 3.19A.2 of the ASX Listing Rules.

39 How these conclusions were reached was not explained. Suffice to say the documents obtained from the ASX do not appear to support the conclusions reached by Mr Bowd and no other evidence was adduced by him to support them. I have found this aspect of Mr Bowd’s evidence to be troubling. Within a day or so of meeting Messrs Hartono and Latorre, Mr Bowd’s highly generalised suspicions about possible breaches of the CA and concerns about the accuracy of the accounts and expense irregularities had transformed into firm conclusions about misuse of market information, as well as breaches of ss 182 and 611 of the CA and of directors’ duties by Mr Richardson. It would appear that a routine investigation into irregularities in the accounts had been turned into a much wider search into the probity of Mr Richardson, with Mr Bowd, as CEO, taking it upon himself to undertake searches and investigations on the ASX. In cross-examination, Mr Bowd denied that he undertook a witch-hunt of Mr Richardson. “Witch-hunt” may be too strong a word to describe what had occurred. But certainly I find that at this time Mr Bowd appeared to be going out of his way to find breaches of the CA concerning Mr Richardson.

40 On 12 January 2017, Mr Bowd engaged the accounting firm BDO Australia (“BDO”) in a telephone meeting with Mr Hooker to perform the following services:

examination of employee expenses to ensure compliance with EG policy and procedure;

examination of the payment of invoices across multiple projects, as determined by EG, to ensure compliance with EG policy and procedure;

to undertake any further work as directed by EG; and

preparation of a report detailing the results of the examination.

41 Mr Bowd did not disclose this retainer to the full board at this time. Nor did he engage EG’s usual external auditors. Strangely, he used BDO’s Perth office instead of its Melbourne office. No part of the retainer would appear to address, at least expressly, the conclusions Mr Bowd had formed about Mr Richardson at this time.

42 During the period 11 to 17 January 2017, Mr Richardson states that Mr Boratav made frequent phone calls to him advising him that a succession of Baltec employees had complained about Mr Bowd. Mr Boratav did not give evidence before me but what he said was corroborated, in general terms, by Messrs Hartono and Latorre.

Mr Bowd’s CEO Report

43 On 16 January 2017, Mr Bowd submitted his CEO’s report for the January board meeting. The report described the audit into Baltec’s expenses in measured tones. It did not disclose the BDO retainer but did refer to the “urgent need” to implement a “whistle blower policy”. It recorded relevantly:

Baltec:

A difficult month, with substantial unrest due to the implementation of an audit into the governance and application of expenses. The audit continues with a more refined and delicate application across projects and fabrication suppliers. We are applying ourselves in regards to team based communication and how we re-engage the team, it has become evident that there are still substantial external influences at hand with [Mr Ly] meeting team members outside of work and expressing his views and influence where possible.

Ex-Com have reviewed a number of group needs, including IT and systems management, action plans for the rectification and development of group based systems is well under way.

The Audits of TAPC/Baltec expenses and cost management has led to the urgent need to implement a formal “Whistle Blower” policy in line with Australian and ASIC standards. This policy is specifically designed to protect our staff, executive and Board members from inappropriate retaliation should they feel the need to come forward with an occurrence of inappropriate behaviour across the group. This is an operational policy that is normal corporate governance with ASX listed companies and will be in place ASAP so that the [sic] we are protecting all employees from Board down and across the business.

44 The report also highlighted the need for a “more detailed review” of the expenses issue. It recorded the following:

There have been a number of significant breaches of process in regards to expense claims by staff members, with an audit underway and a more detailed investigation into expense submission protocol and lodgement of expenses against projects and cost codes. It has been noted that there are substantial variances across a number of projects where expenses and additional costs have been recognised without supporting documents, invoices or quotes from suppliers.

…

As with November and December there are on-going challenges in regards to the implementation of project related decision making. The audit into payments has highlighted a number of areas in regards to PT Baltec projects and payments of invoices for local supervision that has been charged to the project and then invoiced again and paid for on separate invoices. There are substantial variances in the initial projects costing Vs the final costs and invoices from PT Baltec, this includes costs without any supporting data and payment for work scope that has then been carried out by Baltec, which in effect is double or triple dipping. This requires a more detailed review which is underway, the scope of which will also look into the substantial increase of costs by sub-contractors and how we manage the contracts/agreements for PT Baltec.

45 The report also stated that “a more formal report will be provided to the board once the factual details have been correlated and governance applied”. The views Mr Bowd had formed at this time about Mr Richardson were not disclosed.

Lead up to the strategic meeting

46 On 17 January 2017, Mr Bowd met with the board at the offices of a recruitment agency. EG was looking to hire a new CFO. Prior to that meeting the board had met at a café to discuss Mr Bowd’s performance. Ms Richardson’s evidence was that the board was concerned that experienced Baltec staff had not been invited to an upcoming “strategic meeting” scheduled for 18 January 2017 and was also concerned about Mr Hooker’s recent appointment as Group Operations Manager of Baltec. When the board met with Mr Bowd later that day, it was his evidence that his performance was not discussed. Ms Richardson disagreed with that evidence. So did Mr Cartney. His evidence was that the board discussed with Mr Bowd his poor communications with board members and with Baltec staff, and the fact that the board had not received details from Mr Bowd about any of the new senior staff he had hired. Given the board’s existing concerns about Mr Bowd, I prefer the evidence of Ms Richardson and Mr Cartney. That conclusion is also supported, inferentially, by the email Mr Bowd sent to the board early the next day, which included details of the new employees and which stated:

I appreciate that there is a perception that I am not doing a very good job, this needs to be openly discussed as we attempt to realign over the coming 48 hours.

47 The day before this meeting Mr Bowd was sent what is called the “Board Pack”. The pack contained highly confidential information about EG. At 3:19pm on 17 January 2017, Mr Bowd emailed the Board Pack to Mr Blakemore. This email had been relied upon as part of a claim that Mr Bowd had breached his obligation of confidence to EG. That claim has not been pursued. Mr Bowd said that he had made a mistake in emailing the Board Pack to Mr Blakemore.

The strategic meeting

48 On 18 and 19 January 2017, the “strategic meeting” was held. In attendance was the board, Messrs Bowd, Hooker, Blakemore, Mr Ian Buick and Ms Stahmer. The board was not happy about the non-attendance of Baltec staff. Mr Bowd’s evidence was that on 18 January his performance was not discussed. Both Mr Richardson and Ms Richardson have given evidence that contradicts that assertion. Again, I prefer the evidence given by the board members. It is improbable that Mr Bowd’s performance was not discussed. Mr Richardson also gave evidence that he said that with the loss of Mr Boratav, the lowest cost option might have been to close PT Baltec. Mr Bowd’s recollection was that Mr Richardson said that he had decided to close PT Baltec. I prefer Mr Richardson’s evidence. There is no contemporaneous evidence which supports the making of a decision to close PT Baltec in January 2017.

49 That evening, Mr Richardson’s evidence was that he had an “off-site” meeting with a long-standing Baltec employee, Mr Phil Dart, at a well-known fast food chain “restaurant”. Mr Dart made broad complaints against Mr Bowd. He said that the new management style was “threatening” and that there would be a “mass exodus” if things were not addressed quickly. This employee was not called to give evidence before me. However, the complaints made are generally consistent with the evidence of Messrs Hartono and Latorre.

50 On the second day of the strategic meeting (19 January 2017), there occurred a breakdown between the board and Mr Bowd. It will be recalled that Mr Bowd’s evidence was that it was only on this day that he received for the first time from the board a complaint or concern about his behaviour. There was a dispute about what was said at this meeting. However, I accept that Mr Richardson drew, on a whiteboard, two diagrams of chimneys with foundations. One chimney was said to have strong foundations and was identified by Mr Richardson as being the business of TAPC. The other chimney was said by Mr Richardson to represent the business of Baltec. He said that it had weak foundations. The foundations were said to represent the staff of each business. Mr Richardson told Mr Bowd that Baltec staff had complained about him. He said that morale was low and that staff were nervous that they could lose their jobs. Mr Richardson said there was a risk that EG could lose $4 million of value from the Baltec business unless things improved. Mr Richardson otherwise denied blaming Mr Bowd for all these problems. He denied that he said to Mr Bowd that he would be the subject of an internal investigation. He said that his expectation was that the issues would be worked out with Mr Bowd over time. He said that Mr Bowd appeared to take all of this as a personal criticism and that he packed his papers and left the meeting.

51 Ms Richardson’s evidence was that during the course of the meeting Mr Bowd became “increasingly belligerent” and at a break in the meeting, she said Mr Bowd took his belongings and left without explanation. Mr Cartney gave evidence that Mr Bowd “stormed out”.

52 In contrast, Mr Bowd said that Mr Richardson stated that there was to be an internal investigation into his behaviour. Mr Blakemore also gave evidence that the issue of investigation was raised at the meeting. He said that the meeting was not pleasant.

53 I accept that the meeting was tense. Whether Mr Bowd was told that he was to be investigated or not, I certainly find Mr Bowd thought, rightly or wrongly, that he was being accused of something in relation to Baltec. As it happens, the board ended up ordering an investigation into his behaviour on 21 January 2017. Mr Blakemore’s evidence was that Mr Bowd was “shattered” by what he had been told at the meeting, and that when he left he said “I have got to excuse myself” and “I just can’t do this at the moment”. I find that Mr Bowd left the meeting abruptly.

54 From time to time Messrs Bowd and Cartney sent each other text messages. When Mr Bowd left the meeting, Mr Cartney sent the following text to Mr Bowd: “Pete call me”. Mr Bowd texted back:

I need a moment please David I have to re group because I am seeing an accusation that I’ve lost the company $4M in value but the share value has increased... I am seeking legal advice re my position...Thanks

55 The evidence is that Mr Bowd then rang a former colleague from Gadens lawyers seeking advice about how he should handle the situation. Mr Bowd returned later that day to attend a board meeting. At that meeting, Ms Richardson stated that earlier that day she had observed Mr Blakemore reading what she thought was the January Board Pack. Mr Blakemore said he could not recall reading the Board Pack on that day, but could not be sure.

56 Mr Blakemore also gave evidence that after Mr Bowd left the meeting he met with Mr Cartney who was disparaging of Mr Richardson. He said that Mr Cartney told him that he should make a complaint to ASIC. Mr Blakemore was cross-examined about this meeting and swore that the conversation took place. On balance, I am persuaded that a conversation probably did take place along these lines. However, I am not persuaded that it took place on 19 January 2017. That is because I accept, for the reasons set out below, that Mr Cartney was only told about Mr Bowd’s plan to complain to ASIC the following day. Before that time, Mr Cartney was unaware of the seriousness of the allegations Mr Bowd would make. After 20 January 2017, Mr Cartney, in his capacity as chairman, may have suggested to Mr Blakemore that he should lodge a complaint with ASIC because this was what he knew Mr Bowd was doing. In my view, the evidence suggests that Mr Cartney tried to behave as a chairman would in the light of the very serious allegations Mr Bowd had commenced to make. Quite properly, given the nature of what was alleged, and not knowing anything more, he may have encouraged both Messrs Bowd and Blakemore to go to ASIC. At the very least, he probably acquiesced in, and did not resist, the plan to make a complaint to ASIC. He was concerned to do the right thing. None of this is inconsistent with the view he had formed that Mr Bowd was not performing well as CEO.

Key events of Friday 20 January 2017

57 The next day, 20 January 2017, which was a Friday, four events took place:

(1) First, Mr Bowd decided to make his complaint to ASIC. He told Mr Cartney about this in a text sent at 7:24am. The text, sent in response to an invitation for coffee, was as follows:

Ok. 10.30. I am currently drafting an initial report for ASIC and will be instructing the Audit company today. I am unsure that my attendance at the CFO interviews is or will be a positive given the past 48 hours and the discussion I have had with my family. Happy to discuss further today.. Best … Pete.

Mr Cartney did not tell his fellow board members about this until 27 January 2017. Mr Cartney also gave Mr Bowd the phone number of a contact in Victoria Police at a meeting held later that day in a café. In cross-examination, Mr Bowd said that Mr Cartney had suggested he lodge the complaint with ASIC and that it was his idea. This allegation did not appear in Mr Bowd’s numerous affidavits. He also said that Mr Cartney had told him to instruct Gadens. He denied that he had reached his decision to lodge the ASIC complaint in order to protect his position as CEO by triggering the protections contained in the whistleblower provisions. I shall return to this issue. For the moment, I record my finding that on 20 January 2017 Mr Bowd assumed he was going to be removed as CEO. He said as much in the witness box. Later that day he sent in the evening the following text to Mr Cartney:

Please let me know if you’ve spoken to Ian ... I’m wondering how copler will be completed when I am removed? Because Brian, Sally and Gordon will follow! That’s huge risk David!

“Copler” was a project Mr Bowd had been working on. The references to “Brian, Sally and Gordon” are to Mr Hooker, to Ms Stahmer, and to Mr Blakemore respectively.

At another meeting held at the same café on 24 January 2017, Mr Cartney said he had raised with Mr Bowd why it had been necessary to lodge the ASIC complaint before commencement of the external audit. Mr Cartney’s evidence is that Mr Bowd told him he went to ASIC because he thought his job was on the line and that he would be going. I accept that evidence as accurate.

Mr Cartney otherwise denied that he had suggested to Mr Bowd that he should go to ASIC; it was not his idea. He also denied that he had first been given notice of a proposed ASIC complaint either on 17 or 19 January 2017. His evidence was that the first time he had heard about a possible complaint to ASIC was when he read Mr Bowd’s text. I accept that evidence. In my view, if Mr Cartney had really been the person who had proposed the making of a complaint to ASIC, this would have appeared in one of Mr Bowd’s affidavits. It did not. It only emerged for the first time in cross-examination. There is no contemporaneous evidence to support the contention that the ASIC complaint originated with Mr Cartney. Perhaps Mr Bowd had confused the chronology of events. In any event, I find that the ASIC complaint was Mr Bowd’s idea. I otherwise accept that it is possible that Mr Bowd had discussed the need for an audit of the Baltec expenses with Mr Cartney earlier on 17 January 2017. I also accept that around this time Mr Bowd possibly raised the effect of the whistleblower provisions with Mr Cartney.

(2) Secondly, at 4:55pm, Ms Stahmer sent an email to all EG employees stating that Mr Bowd had approved a whistleblower policy for EG. The policy was attached to the email. Whilst Mr Bowd had asserted that he had established this policy on 10 January 2017, there were no supporting documents or additional evidence which corroborated that claim. Reading the email sent by Ms Stahmer, I find that the policy was not implemented and announced until 20 January. Mr Bowd denied in cross-examination that he had deliberately implemented the policy on that day to protect his position as CEO. I find otherwise.

(3) Thirdly, at 6:17pm, Mr Bowd himself emailed all of EG’s employees about the whistleblower policy (calling them “team”) stating, amongst other things:

Please rest assured, these procedures are here to keep you safe, keep you out of harm’s way and to support your position in the company and group that you are an integral part of. I know we have had lots of change, and this change is difficult to understand and in many ways accept.

However, our need to keep our company well governed so that you have jobs that are safe and free of inappropriateness is the intention and the commitment from me as your CEO.

Just before sending this email, Mr Bowd sent an email to the board concerning a meeting he had had with a Mr James Shaw, who worked for a recruitment agency, about hiring the new CFO earlier that day. Mr Bowd complained in the email that Mr Shaw seemed to know about his issues at Baltec. He said that this was unacceptable. He made allegations that he had been bullied and witnessed yelling at meetings, and demanded that this behaviour needed to stop. He said that there needed to be an “immediate resolution” by the board. He said that he was seeking “external advice”. The email should be set out in full as follows:

Board,

I have just taken a call from James Shaw in regards to the CFO interviews.

However, the conversation moved very quickly to my current role, how things are and issues with regards to feedback he is getting about my performance.

I am letting you know that [Mr Boratav] has met with James and has discussed the following in person with him, my performance and the issues, the impact I am having on the business and how I have taken a good business and broken it. I have a number of issues with this, and need to inform the board that in all of my years of executive management I have never experienced such behaviour. I am seeking immediate resolution from the board.

The discussion with James made it very clear that the ongoing improvement and engagement with TAPC was in fact a problem in regards to how I was leading Baltec, and his language reflected exactly the language used in the meeting with [Mr Richardson] yesterday. That I was engaged with TAPC and not engaged with Baltec and the gravitas of the situation. The team I have engaged and their fit with Baltec, the perception that I am not engaged with Baltec people, and that I have disregarded the team. I have a number of questions I require answers to please:

1. How does James Shaw know that I have problems in the company and with [Mr Boratav]?

2. How did James Shaw become aware that there is conflict in regards to the views of TAPC and Baltec an my leadership

3. How is it James used almost the same language used yesterday in regards to Baltec and the view that I was not taking Baltec forward and was not respecting the people within it.

James Shaw is a 3rd party, and an external recruiter, he is an influential leader in his industry and has influence in the market, I am appalled that I am now in a position where someone outside of this organisation has become involved in what can only be considered inappropriate, what is more disappointing is the reality that the discussion creates a potential for deformation of character.

There comes a time when we all have to look at the ongoing behaviour of staff and people within the work place because of the following, you might consider this with regards to the above and the yelling that has taken place in recent meetings by [Mr Boratav].

BULLYING

Bullying is defined as any on-going anti-social or unreasonable behaviour that offends, degrades, intimidates or humiliates a person, and has the potential to create a risk to health, safety, and wellbeing. Bullying refers to activities that create an environment of harm through repeated, unreasonable and unwelcomed acts such as:

• Cruelty, belittlement, or degradation

• Public reprimand or behaviour intended to punish, such as isolation and exclusion from workplace activities

• Ridicule, insult(s) or sarcasm

• Trivialisation of views and opinions, or unsubstantiated allegations of misconduct

• Physical violence such as pushing, shoving, or throwing of objects

• Playing jokes or spreading rumours

This behaviour cannot go on any further, and as previously mentioned in this email, I am seeking immediate resolution from the board, the above information is not fabricated and as such in am seeking external advice on the impact this can potentially have on my personal and professional circumstances and my career. I am disappointed and feel that the past 48 hours and [Mr Boratav’s] actions with Six Degrees Personnel has impacted on the current relationship between the board and myself as CEO.

Peter Bowd

Chief Executive Officer

(Errors in the original.)

(4) Fourthly, at about 6:00pm, Mr Bowd saw a portable Z drive sitting at the reception of EG. It was a Friday night. The drive contained EG’s confidential information, including: fabrication drawings and designs of equipment; engineering data; a supplier database; a customer database; historical and current information concerning contracts, tenders and pricing; information about Baltec’s business and about employee resumes, leave entitlements and emergency contact details. Mr Bowd picked it up and put it in his bag. Mr Bowd denied in cross-examination that he took this drive to give to ASIC and the police. He said he took the drive to keep it safe as it was late in the day. I reject that explanation as improbable. He gave the drive to BDO which at some point gave it back to him. Mr Bowd eventually returned it to EG on 24 May 2017.

58 The contents of Mr Bowd’s email to the board corroborates my earlier finding that he thought that his job was under threat. That is why he was seeking external advice. In circumstances where he expected to be terminated, I also find that Mr Bowd planned on 20 January 2017 to invoke the whistleblower provisions of the CA by making his complaint to ASIC in order to protect his job as CEO. That was his defence. That defence also explains the timing of the issue of the whistleblower policy on that day and, inferentially, the taking of the Z drive.

59 Timing in this case is important. Mr Bowd had reported to the board days earlier that he had commenced an audit into expense irregularities at Baltec. His CEO report expressly stated that the inquiry was incomplete and that more work was needed. Mr Bowd, for that purpose, had engaged external auditors. They had yet to commence their work. There was thus no need yet to make any complaint to ASIC. That Mr Bowd decided to make that complaint on 20 January 2017 was, I find, the product of his fear of dismissal. I find that Mr Bowd was in a heightened state of emotion on that day as a result of that fear. That is reflected in the contents of the email he sent to the board and the complaints he made about bullying. He had never before raised the issue of bullying. In the witness box, Mr Bowd presented as a man who had plainly been scarred by the events leading up to his dismissal. He struggled at times to contain himself. That is not intended as a criticism of him. Rather, it is entirely understandable that he found the process of his dismissal and this court case to be very stressful. The events which took place after 20 January 2017 support these findings.

Contemporaneous text messages of significance to the narrative

60 One of the difficulties about this case has been the lack of contemporaneous evidence as to what had been said at the various meetings which had taken place. That includes the strategic meeting of 19 January 2017 where the parties had strikingly different recollections of what was said. The principal sources of contemporaneous evidence have been the emails sent by the parties and the text messages sent between Messrs Bowd and Cartney. Where possible, I have placed greatest probative value on these types of evidence. The text messages, some of which I have already referred to, are deserving of particular mention. In that respect I note the following texts:

(a) Mr Bowd sent the following text to Mr Cartney on 21 January 2017 at 8:05am:

Hi David, I just wanted to share a thought... This decision by board members and share holders to call the employees into a closed meeting where they can “gang up” without fair and due process will prevent any further ability for any management in the company to apply good governance and the FWA process. Because every time management do something to pull the individual into line this will happen.... And the Richardson family will oust the manager who’s responsible without following due process

I have 3 management team members all on edge an in fear of losing their jobs. Because of this, which is now going to cause a knock on effect with regards to morale in TAPC also.

Just want you to have a think about that before your meeting,

If [Mr Richardson’s] wife is present then we have a more serious problem.

Best Regards

Peter

(Errors in the original.)

It is not clear to me what was meant when Mr Bowd referenced “FWA process”.

(b) On 24 January 2017, Mr Bowd texted Mr Cartney to say that it was “[a]ll good with ASIC, once it’s lodged I will receive immediate response with a case number confirmation that I’ve lodged a whistleblowing case”. Mr Cartney then texted Mr Bowd to say that Mr Richardson was about to withdraw Mr Bowd’s email access. This followed the board’s decision the day before to remove Mr Bowd, at least temporarily. That decision is discussed below. Later that day, Mr Bowd texted Mr Cartney telling him that he had “lodged with ASIC”. The complaint itself was not attached to the text and Mr Cartney did not at that stage tell the other board members about this development.

(c) On 26 January 2017, in a text sent by Mr Bowd to Mr Cartney, Mr Bowd said that he needed to inform Mr Cartney that his internal investigation had highlighted that payments had been made “outside of our due process… AbsoluteLY [sic] fraud… Skimming monies out of the company… I have almost completed my own police statement. I am planning on seeking legal advice on behalf of the company [shareholders]… Whilst still being CEO. Do you wish to be in this meeting? Thanks. Peter”.

(d) Later that day, another text was sent by Mr Bowd. It told Mr Cartney that Mr Bowd and two others had submitted statements to Victoria Police and suggested the need for “an immediate injunction” in relation to his “removal”. It was in these terms:

David, this text message informs you that 3 of the company executives, [myself] included have submitted statements to the Victorian Police. These statements explain the expense fraud and other substantial anomalies that specifically show and confirm payments being made to PT Baltec.

With this in mind I strongly suggest we seek legal advice for the company and its “public shareholders” as per my last message, you are welcome to attend this meeting that will be held tomorrow. If you have a specific preference in regards to whom we meet with, please advise.

I appreciate this has been a tough journey but we now have substantial data. Expressly highlighting [Mr Boratav] as a main contributor.

More will come to light as we carry on with this process... We must also apply for an immediate injunction on the board in regards to my removal. I am working on this today and tomorrow AM.

Best

Peter

The evidence does not support Mr Bowd’s belief that he in fact was about to be removed and no such injunction was sought. Mr Cartney responded to Mr Bowd’s text with concern about whether he had a duty to tell his fellow directors about “the fraud”.

(e) On the same day Mr Bowd texted Mr Cartney, following a phone conversation with police, that “interestingly the locks have been changed at the Baltec offices”. I shall return to consider the issue of the change of locks. Mr Cartney replied later that day to explain that he was trying to set up a meeting with Ms Richardson to consider the issue of the expenses.

(f) The next day, 27 January 2017, commenced with a text from Mr Bowd to Mr Cartney stating “I believe [Mr Richardson] has intentions of removing me next week. Locks changed! I have informed the police and the [officer’s] comment was interesting! “Why lock me out unless there is something to hide” … What does that tell you?”. He then observed that the auditors had enough with which to start. There was then an exchange of texts about the whistleblowing provisions and about getting legal advice. For example, at one stage Mr Bowd sent Mr Cartney a text saying he had just sent him “the Act”, which I infer is a reference to the CA.

(g) There are also texts in which Mr Bowd explains that he had engaged with Gadens, had been attending their offices, and that, he needed copies of EG’s constitution and shareholders agreement.

61 In my view, these text messages show that Mr Bowd was taking very active steps to protect his job, including the consideration of “injunctive relief”, engaging with his lawyer and lodging complaints with ASIC and the police.

Lead up to the suspension of Mr Bowd

62 Returning to the events of 20 January 2017, Mr Latorre had earlier contacted Mr Richardson seeking to have a meeting at a cake shop. They met at about 4:00pm. Mr Latorre complained about Mr Bowd. He said that the Baltec business would “fold” in three to six months unless something was done. He said that key employees were actively considering leaving Baltec. He told Mr Richardson that Mr Bowd should be relieved of his position as CEO.

63 Mr Richardson decided that he should now share Mr Latorre’s concerns with his fellow board members and for that purpose organised a meeting with Ms Richardson and Mr Cartney for the following day. In Mr Richardson’s own language, Mr Bowd’s “position was now irretrievable”. The meeting took place on 21 January 2017 with Mr Latorre explaining his concerns separately to each of Ms Richardson and Mr Cartney. The board then met to consider what to do. It was suggested that the concerns should be raised with Mr Bowd who was to be encouraged to take a month off. Mr Bowd had previously disclosed that he had a pressing health issue concerning his kidney, and had been prescribed pain medication. The board was worried about his health (Mr Cartney’s evidence was that he was only told about this health issue the next day). The board also decided to engage Lewis Holdway Lawyers to conduct an independent workplace investigation into Mr Bowd’s conduct.

64 On 23 January 2017, members of the board and Mr Bowd conducted more interviews of potential CFOs. At the end of the day Mr Richardson met with Mr Hartono, and other Baltec team members. This meeting was important for Mr Bowd’s case. These employees made similar complaints about Mr Bowd. They said a major client was at risk.

65 Mr Hartono gave evidence that he then met Mr Richardson in private and said to him that he believed that Mr Bowd was “going after him”. In cross-examination, Mr Hartono said that when told of this warning Mr Richardson seemed surprised, leaned back in his chair and said something like “really”. Mr Richardson was cross-examined about this conversation. He had no recollection of it. He said that he had simply said goodbye to Mr Hartono and the others at the lift well area. His evidence was that Mr Hartono was agitated because he had been told by Mr Bowd that he was not to speak to Mr Richardson.

66 I accept Mr Hartono’s recollection that he told Mr Richardson that Mr Bowd was going after him. I have no reason to doubt that evidence. I also accept that Mr Richardson did not remember being told this.

67 In closing address, counsel for Mr Bowd placed great emphasis on this meeting. He said that it was the likely “trigger point” that led to Mr Bowd’s suspension and then dismissal. He contended that if it were true that Mr Bowd had been dismissed for poor performance, and nothing else, one might have expected to see a gradual build-up of repeated warnings and reports concerning his performance. Instead, Mr Bowd was suspended seven days later. The inference I was asked to draw from this chronology was that Mr Richardson suspended (and ultimately dismissed) Mr Bowd because he had been told that Mr Bowd was “going after him”. I shall return to the reasons for the dismissal of Mr Bowd, but note that the board was already considering a suspension of Mr Bowd (or time off) before this “trigger” had occurred.

68 After the meeting with the Baltec employees, the board met again separately and decided that Mr Bowd had to be removed, at least temporarily. Mr Richardson’s evidence was that when he got home he started to draft an email to staff, which he then sent in draft to Mr Cartney and Ms Richardson the following day. A copy of that email, including Ms Richardson’s comments concerning its contents, was in evidence. The draft relevantly said as follows (with Mr Cartney’s comments at the start and Ms Richardson’s comments bolded and underlined):

Ellis,

I agree with [Ms Richardson’s] suggestions and Questions.

Paragraph 3 about [Mr Bowd’s] health is more problematic.

Perhaps say: To bed down the rapid changes and to re-establish the core Baltec way of doing business we are going to step [Mr Bowd] back to focus on TAPC for the next few months and give the Baltec team time to settle down and adapt to the recent changes. We will reassess the health of the business during this period and any lessons to be learned or changes needed to make improvements.

Sent from my iPhone David Cartney

On 24 Jan 2017, at 11:48 am, Lynn Richardson (EGL)

[redacted] wrote:

My thoughts - See below

Draft

Draft

Dear xxxx,

I would like to thank you for your support and valuable contribution to the success of [EG], it is very much appreciated by myself and the [EG] Board.

Over the past 3 months there have been many and rapid changes in the structure and culture within the company and it is time to pause and take stock of where we are and refine our current position to build on the successful integration of our 2 brands. Many of the changes made have been to improve our company safety and governance and the board supports those changes and insists that they continue.

The health of our CEO is a major concern to the board and I am sure all staff. I am pleased to advise that [Mr Bowd] has agreed to take extended leave (not sure about this wording – [Mr Bowd] and his team [may] object to the open ended nature of extended leave) to undergo his major surgery and then to fully recover his health. I will step back into a fulltime position during this period and be in my “old “office as [Mr Bowd] has expressed a wish to be located in the general office area so that you can get to know him better.

I am pleased to advise that [Mr Boratav] has decided to remain with us in Business development and this is a great relief to me and for our market. – Is this true? As an employee or agent? MUST sort out the behaviour issue including an apology to [Ms Stahmer] and [Mr Buick].

To enhance the integration of our businesses we will refine the organisation structure as follows.

1. [Mr Hooker] and [Mr Boratav] will work together to head business development where [Mr Boratav] will defer to [Mr Hooker]decision regarding TAPC issues and [Mr Hooker] will defer to [Mr Boratav] regarding Baltec issues. This way both managers can learn from one another and build on their combined experience to the benefit of the group.

2. Similarly, [Mr Blakemore] and [Mr Hartono] will work together. Announce [Mr Hartono] as Ops Manager? Or do we have a PME TAPC and PME Baltec? - What is the term of [Mr Blakemore’s] contract?

3. The same arrangements will be implemented for Ryan and Michael. What about Andrew? -Who is Michael? Peter has advised of significant issues with the Vietnamese manufacturing operations - in light of the concerns raised by the team I am unsure what is real and what has been ‘exaggerated’. Any real issue fixes and therefore improvements need to be maintained.

4. [Messrs Hooker, Boratav, Blakemore, Hartono and Bowd] will be located in the newly created office which will also have a desk for [Mr Buick] during his visits. [Ms Stahmer] will take over [Mr Hartono’s] desk.

5. The ex com will be chaired by [Mr Buick] and comprise of [Messrs Hooker, Boratav, Blakemore, Hartono] plus the CFO. [Mr Bowd] and myself will attend these meetings as appropriate. The CEO/MD is integral to excom. My understanding is that the chair and note taker rotates through the members and this is not a bad model. [Ms Stahmer] needs to remain on this if she is the IT/HR/Systems person

Please refer to the attached organisation chart for further details. - This needs to be clear and with some supporting detail - Potentially may reduce [Mr Buick’s] scope and this needs to be managed carefully so that he does not see this as a negative.

Thanks again for your support of our great company.

Ellis

69 In my view, this is contemporaneous evidence of EG’s general objectives and intentions in relation to Mr Bowd as at 24 January 2017. Contrary to Mr Bowd’s subjective beliefs about dismissal, the board at this stage had no intention of dismissing Mr Bowd, but did intend to reconsider his role within EG. The board was concerned both about his performance and his health. At this time, neither Mr Richardson nor Ms Richardson knew that Mr Bowd was about to launch his complaint to ASIC and the Victorian police and was considering seeking an injunction against EG. Mr Cartney knew about these matters, but he informed neither Mr Richardson nor Ms Richardson about them at this stage. It is true that by this time Mr Hartono had told Mr Richardson that Mr Bowd was “going after him”, but I do not find that this was the reason for the suspension decision. There was no evidence before me in support of the proposition that both Ms Richardson and Mr Cartney knew about Mr Hartono’s warning to Mr Richardson. The board’s concern was the future of the Baltec business, and about fixing the specific problems that had been reported to the board by Baltec employees. In contrast, and in my view, Mr Hartono’s warning was far too general to be of any real consequence.

70 On 24 January 2017, Mr Cartney sent the following email to Mr Bowd:

Pete,

Following the various comments you have made yesterday re your health (and Kidneys in particular) the Board are concerned and must now be satisfied on your health prior to your imminent air travel.

We appreciate this is short notice however please provide either appropriate medical advice or we can arrange a medical as soon as possible.

I would also like you to attend a meeting with the board members this Thursday (Australia Day) at 9 am at Baltec to discuss possible solutions to the current organisational problems.

The board wanted to discuss, I infer, his proposed suspension. Mr Bowd immediately responded and agreed to have his specialist send a letter about his health, but he otherwise declined to meet with the board because he had committed to spending Australia Day, which was a public holiday, with his family. That evening Mr Bowd emailed Mr Cartney. The email stated:

… I have formally lodged my report with ASIC. I now invoke the Whistleblower policy by ASIC as CEO of [EG].

71 Mr Bowd explained the reasons for lodging his complaint to ASIC as follows:

I provided the report to ASIC as it was my honest opinion that there had been breaches of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). I was fulfilling my duties as Chief Executive Officer of the First Respondent.

As already mentioned, I do not accept that explanation. On the same day he made what he called a report of “inappropriate governance” to Victoria police.

Mr Bowd’s complaint to ASIC

72 The complaint to ASIC is short and thin on detail. This is what it relevantly said:

My name is Peter Bowd, I am the CEO of The Environmental Group Limited. (An ASX Listed company) I am writing to inform ASIC of a serious fraud within EGL. At 2PM on the 11/1/17 I received an invite to a meeting by two of my engineering team. In this meeting the two employees enacted our company (whistleblower policy) they explained to my self, and two of my management team that monies had been paid to one of our sister companies in Indonesia. Monies that did not have supporting invoices or documentation that substantiates the costs occurring in Indonesia (PT Baltec). Upon further investigation I have found that multiple transactions have taken place and substantial funds have been transferred from the ASX listed business unit (EGL)(Baltec) to the Indonesian company PT Baltec without any supporting documents or evidence of costs or third party invoices. The PT Baltec business has not been audited for over two years and substantial monies have been transferred on multiple occasions without the application of financial governance or appropriate evidence relating to these cost. these monies are in excess of $400,000 for the past 12 months. there are loans to the PT Baltec company that have not been repaid over the past 3 years. the Managing Director (Ellis Richardson) told EGL executives that he intends to close PT Baltec. The closure will lead to substantial loan defaults. In turn this will lead to share holders of the company loosing substantial capital and operating profit. At this stage documents and reports highlight substantial discrepancies. As CEO I believe there is substantial fraud and laundering of funds from the Australian business into the Indonesian company by the MD & Sales Director. I have implemented a forensic Audit by a 3rd party. And I have informed our non executive board member (Chairman) in regards to these findings. and given the seriousness of this breach of duties by the Managing Director I am informing ASIC as per the whistleblowing process. Regards Peter Bowd

(Errors in the original.)

73 I make the following observations about this complaint: