FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Australia Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 676

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | GLAXOSMITHKLINE CONSUMER HEALTHCARE AUSTRALIA PTY LTD First Respondent NOVARTIS CONSUMER HEALTH AUSTRALASIA PTY LTD Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties furnish agreed or competing procedural orders for the penalty hearing of the contraventions admitted by the respondents at least 48 hours prior to the next case management hearing.

2. The proceeding be listed for case management at 9.00 am on Friday 31 May 2019, or such later date as may be fixed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BROMWICH J:

Introduction

1 The two respondents, GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Australia Pty Ltd (GSK) and Novartis Consumer Healthcare Australasia Pty Ltd, now known as VOG AU Pty Ltd, were involved in marketing and selling a single formulation of an over-the-counter pharmaceutical product used to treat pain and inflammation, being a skin gel in a tube, as two different products. Both products were sold under the primary brand name of Voltaren, one with the sub-brand name of Emulgel and the other with the sub-brand name Osteo Gel.

2 Osteo Gel was, and Emulgel still is, marketed to be used for the temporary relief of local pain and inflammation, but focused on osteoarthritis in the case of Osteo Gel. Both have as their active ingredient diclofenac diethylammonium, at an identical dose level of 11.6 milligrams per gram. Neither has any ingredient that the other does not. The contents of the tubes of Emulgel and Osteo Gel are therefore the same, but with some differences in the range of available tube sizes. Osteo Gel has a higher recommended retail price per gram, in the same or similar sized tubes. The cap on the Osteo Gel is different, in that it is designed to be easier for a person with osteoarthritis in the hands to open. The use instructions on the Emulgel packaging are directed to general use for up to two weeks at a time, while the use instructions on the Osteo Gel packaging are directed to the treatment of osteoarthritis for up to three weeks at a time. At an earlier time, Emulgel packaging contained both sets of instructions.

3 The respondents made different claims about Emulgel and Osteo Gel on packaging and via two different websites, reflective of the different types of condition which the same gel could be used to treat. The applicant, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), alleges that this conveyed to consumers the impression that there were material differences between Emulgel and Osteo Gel, and their use, when in fact they were the same. The ACCC contends that at all times when Osteo Gel was sold, this was contrary to ss 18, 29(1)(g) or 33 of the Australian Consumer Law, which is to be found in Sch 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth).

4 The substance of the ACCC’s complaint is that it was not made sufficiently clear that there was no difference at all between the gel in the two products. This position is not disputed in the period up to March 2017, but is disputed for the period from March 2017, when changes were made to the packaging of Osteo Gel, until the sale of Osteo Gel was discontinued in May 2018.

The pleaded contraventions

5 While the ACCC pleads its case in respect of both Emulgel and Osteo Gel, at the hearing it was made clear that the focus is on the express and implied representations made about Osteo Gel in the context of Emulgel, rather than suggesting that Emulgel marketing itself constituted any contravention. The pleaded provisions had the effect that respondents would be in breach if they, in trade or commerce (which was not an issue):

(1) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive in relation to Osteo Gel in the context of Emulgel packaging: s 18;

(2) made false or misleading representations about the performance characteristics, uses or benefits of Osteo Gel in the context of Emulgel packaging: s 29(1)(g); and/or

(3) engaged in conduct that was liable to mislead the public as to the characteristics of Osteo Gel or its suitability for the claimed purpose in the context of the characteristics and suitability of Emulgel packaging: s 33.

6 The three pleaded provisions have aspects in common, and to that extent overlap, but also some important areas of difference. There is no material difference in the factual inquiry as between s 18 and s 29(1)(g) in this case because:

(1) there is no meaningful distinction between “misleading or deceptive” and “false or misleading”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dukemaster Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 682 at [14]-[15]; and

(2) the conduct, both admitted and denied, is by way of the same express or implied representations in relation to both provisions, even though s 18 is general in its scope and does not attract any civil penalty consequences, while s 29(1)(g) is specific in its focus and does have civil penalty consequences.

7 Section 33 is in a somewhat different category, because the requirement to establish that the impugned conduct was “liable to mislead the public” as to characteristics or suitability is both narrower than “likely to mislead or deceive” in s 18, and requires proof of an actual probability that the public would be misled: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Limited [2014] FCA 634; 317 ALR 73 (ACCC v Coles) at [44] and the cases there cited.

8 In the greater part, the principles in relation to ss 18, 29(1)(g) and 33, and in relation to the various forms of relief sought, are not in dispute.

9 The respondents admit a number of pleaded contraventions by way of earlier packaging and website representations occurring in the period from January 2012 to March 2017, and by way of further website representations in the period from 10 July 2017 to 24 November 2017. It is only necessary to detail those contraventions in these reasons to the extent that they are relevant to later alleged contraventions. Those later alleged contraventions are denied due to a change in Osteo Gel packaging in March 2017. The respondents contend those packaging changes fully address the issues raised by the contraventions that are admitted.

10 The ACCC seeks relief by way of declarations of contravention, injunctions, publication orders and compliance orders. GSK was solely responsible for the representations and conduct in the period from March 2017 until the sale of Osteo Gel ceased in May 2018. For the contraventions that are admitted, and any that are otherwise made out, the ACCC also seeks pecuniary penalties. As noted above, a breach of s 18 does not carry any civil penalty sanction. The respondents contend that the further contraventions have not been made out and accordingly relief should be confined to declarations as to the admitted contraventions. It is common ground that the question of pecuniary penalties for the admitted contraventions, and for any further contraventions that are found, will need to be addressed at a further hearing.

Background

11 Emulgel was first registered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) in 1994. The sponsor responsible for that registration, and thus for Emulgel from that time, was neither of the respondents. Novartis subsequently became the sponsor of Emulgel, and GSK later assumed that role.

12 The ARTG is administered by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Both the TGA and the ARTG were established and administered under the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth) and associated regulations. It is unlawful to sell a product making therapeutic claims if it is not registered (or for less substantial products, such as vitamins, listed), with registration requiring a number of conditions to be met. The TGA’s role is as a therapeutic claims regulator, leaving general consumer protection regulation to the ACCC and its State and Territory counterparts.

13 Novartis first sold Emulgel in about 2000. In about 2010, Novartis also began selling Osteo Gel, which was also registered on the ARTG. TGA records as at October 2014 provide for both Emulgel and Osteo Gel:

(1) the following summary of the “pharmacodynamics”:

Pharmacotherapeutic group: Topical products for joint and muscular pain, anti-inflammatory preparations, non-steroids for topical use (ATC code M02A A15).

Diclofenac is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) with pronounced analgesic, anti-inflammatory and antipyretic properties. Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis is the primary mechanism of action of diclofenac.

Voltaren Emulgel / Voltaren Osteo Gel is an anti-inflammatory and analgesic preparation designed for external application.

In inflammation and pain of traumatic or rheumatic origin, Voltaren Emulgel and Voltarne Osteo Gel has been shown to relieve pain, reduce oedema, and shorten the time to return of normal function.

Due to an aqueous-alcoholic base, the gel also exerts a soothing and cooling effect.

(2) the following indications:

For the short term (up tp [sic] 2 weeks) local symptomatic treatment of the following musculoskeletal inflammatory conditions:

acute soft-tissue injuries, including sprains, strainsand [sic] sports injuries

localised forms of soft tissue rheumatism such as tendinitis (eg tennis elbow) and bursitis.

For the short term (up to 3 weeks) relief of pain in non-serious arthritis (i.e. mild and localised forms of osteoarthritis) of the knees or fingers. Relief of osteoarthritic pain builds up gradually over the first few days of treatment; a significant effect can be expected after one week of application.

14 Neither ARTG registration, nor the ARTG pharmacodynamics or specific indications, provide much, if anything, to assist in the determination of the issues before this Court, beyond:

(1) putting it beyond doubt that the gel in an Emulgel tube was interchangeable in its use with the gel in an Osteo Gel tube; and

(2) making it clear that the gel was suitable for use up to two weeks for general conditions, and for up to three weeks for osteoarthritis.

15 Between October 2010 and March 2016, Novartis marketed and sold both Emulgel and Osteo Gel. The consumer divisions of GSK and Novartis were combined via a joint venture under a new GSK umbrella which was finalised on 2 March 2015. Between February or March 2016 and May 2016, GSK marketed and sold Emulgel and Osteo Gel on Novartis’ behalf as a transitional measure.

16 From mid-November 2014, the packaging for Emulgel changed as it ceased to be promoted for the treatment of osteoarthritis, instead focusing on general use.

17 From June 2016, GSK alone marketed and sold Emulgel and Osteo Gel. The packaging changed for Osteo Gel in March 2017. The sale of Osteo Gel was discontinued by GSK in May 2018. The ACCC’s pleaded case reflects those changes.

18 The respondents admit to the pleaded packaging and website contraventions up until March 2016 in the case of Novartis, and until March 2017 in the case of GSK. GSK also admits to the pleaded website contraventions from July 2017 to November 2017. GSK contends that the changes it made to packaging in March 2017 meant that the packaging did not constitute any contravention from then until the sale of Osteo Gel was discontinued in May 2018. A version of Osteo Gel with a different quantity of the active ingredient – Osteo Gel 12 Hourly – continues to be sold by GSK, but no complaint is made by the ACCC about that. Osteo Gel was not recalled as GSK maintains that it had no reason or obligation to do so.

19 The acceptance by the respondents of contraventions taking place followed the outcome in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd (No 7) [2016] FCA 242 on 29 April 2016 (Nurofen penalty judgment), subject only to a different penalty result on appeal on 16 December 2016 in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; 340 ALR 25 (Nurofen appeal judgment), together, the Nurofen case. GSK contends that from March 2017 until Osteo Gel ceased to be sold in May 2018, the conduct engaged in was a legitimate means to target different consumers with different ailments, responsive to the same active ingredient, but used in different ways, and that the difference in the caps and duration of use for the different ailments was also material.

20 The ACCC’s case is that the changes introduced in March 2017 did not go far enough and the representations and thereby conduct of GSK also contravened ss 18, 29(1)(g) and 33 of the Australian Consumer Law. These reasons are confined to an adjudication of the conduct which took place in the disputed period from March 2017 to May 2018. There is a live dispute as to the use that may be made of the prior, admitted, contravening conduct, addressed below.

21 There is no dispute as to what was literally conveyed to consumers during the two periods. It is convenient to reproduce this first of all visually, and then by closer consideration of the representations and conduct over which the ACCC maintains its complaint, and which GSK, as the sole respondent by then responsible, denies.

Packaging

22 The form of Novartis’ Emulgel packaging from October 2010 to November 2014 was as follows (the yellow highlighting was in the digital copy provided to the Court, but was not part of the original packaging), making specific reference to osteoarthritis in the more detailed product use information:

23 The form of Novartis’ Osteo Gel packaging between October 2010 and March 2016 was as follows, making no reference to Emulgel:

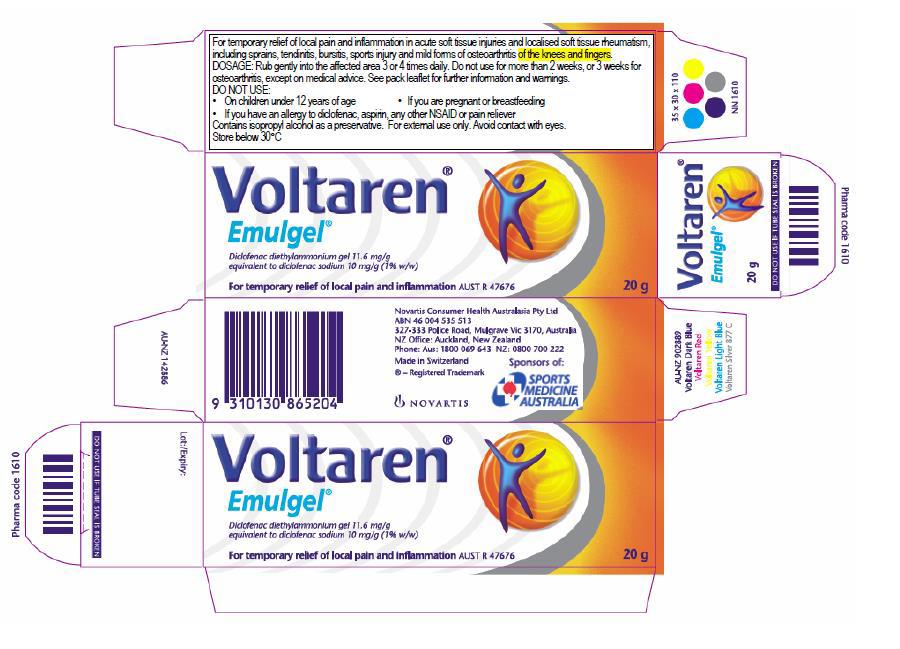

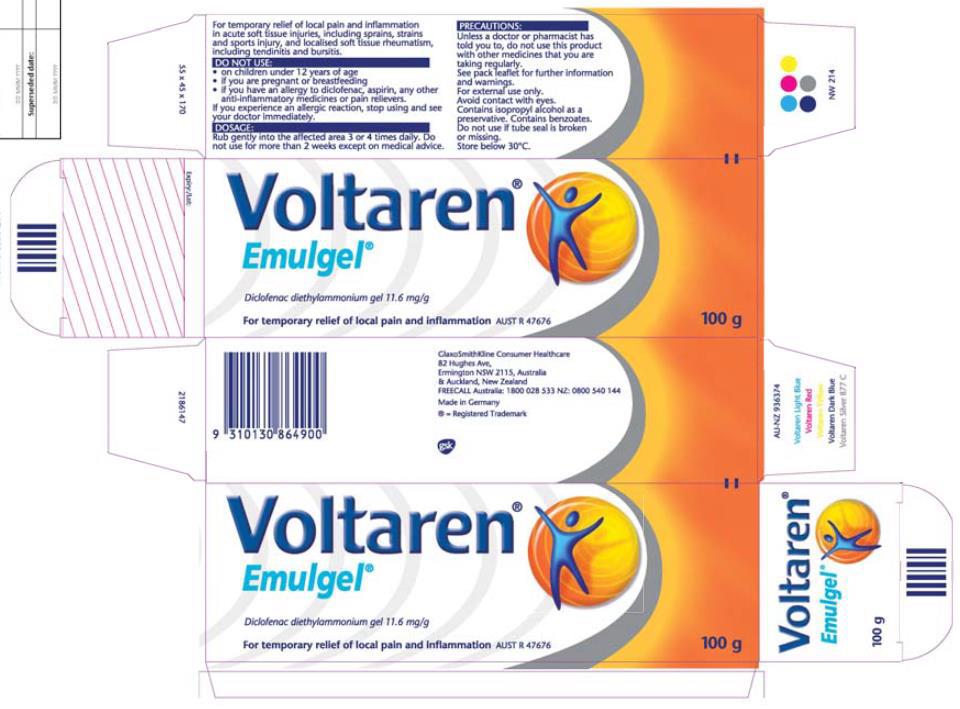

24 The form of Novartis’ Emulgel packaging from mid-November 2014 until March 2016 was as follows (no longer making reference to osteoarthritis and usage periods for that condition in the more detailed product use information):

25 The form of GSK’s Emulgel packaging from March 2016 until December 2017 (when this proceeding commenced) was as follows, with GSK as the sponsor in place of Novartis, but with no other changes, and therefore still making no reference to osteoarthritis and usage periods for that condition in the more detailed product use information:

26 The form of GSK’s Osteo Gel packaging between March 2016 and March 2017 was as follows, with GSK as the sponsor in place of Novartis, and with only minor changes to the packaging at [23] above, and therefore still making no reference to Emulgel:

The respondents admit that this packaging constituted contraventions in the context of Emulgel. The nature and extent of the contraventions is in dispute, but that is not the direct subject of these reasons.

27 From March 2017 to May 2018, the form of Osteo Gel packaging was as follows, making specific reference to Emulgel:

The ACCC contends that this packaging also contravenes ss 18, 29(1)(g) and 33 of the Australian Consumer Law. GSK denies that has been established. This is the central issue addressed by these reasons.

Legal principles

28 There is no material dispute as to when, as a matter of legal principle, representations or conduct are liable to be found to be misleading, deceptive, false, or liable to mislead the public contrary to ss 18, 29(1)(g) and/or 33 of the Australian Consumer Law, informed by many decisions on the corresponding antecedent provisions under the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth). Those principles were thoroughly but succinctly summarised by Allsop CJ in ACCC v Coles at [35]-[47] and do not need to be repeated in these reasons.

29 What matters is whether the Osteo Gel packaging sold between March 2017 and May 2018, in the context of the Emulgel packaging during that period, and perhaps also influenced by any lasting effect demonstrated to have arisen from the prior packaging (admitted to be contravening):

(1) was likely to have been misleading or deceptive and thus be conduct of that character (s 18); or

(2) conveyed false or misleading representations about the performance characteristics, uses or benefits of Osteo Gel (s 29(1)(g)); or

(3) gave rise to an actual probability that the public would be misled (s 33).

30 This is an assessment to be made by the Court based on the totality of what was conveyed in its proper context, having regard to the dominant message being conveyed, and the effect that message is likely to have on ordinary, reasonable members of the class of persons to whom it was directed. It is not enough that the packaging may have caused confusion or given rise to questions as to what was meant, as that falls short of having the proscribed misleading, deceptive, or false character that leads, or at least is likely to lead, to an erroneous impression of the correct position.

31 The proven objectives of the marketing strategy deployed and any other evidence may therefore be useful to the extent that they shed light on how such a message is likely to be perceived, but do not replace the proper assessment by reference to what consumers would see and have conveyed to them.

The competing cases

32 An important aspect of the competing cases on the disputed question of contraventions having taken place in relation to Osteo Gel in the period from March 2017 to May 2018 turns on the use that may be made of the prior representations and conduct that is admitted to be contravening by the respondents. The dispute is as stark as this in substance, if not entirely in the form in which the arguments were presented:

(1) The ACCC contends that the starting point is to look at the Osteo Gel packaging prior to the changes made in March 2017, which is admitted by the respondents to be contravening as pleaded, and consider whether those changes went far enough to address and correct the character of being misleading, deceptive, false or liable to mislead the public.

(2) GSK contends that the ACCC’s approach is an inversion of the correct inquiry, and that the question raised by the contested aspect of the ACCC’s pleadings is whether the Osteo Gel packaging for the period from March 2017 to May 2018, in the context of the Emulgel packaging and in all the circumstances, had the character of being misleading, deceptive, false or liable to mislead the public, with the prior packaging being part of the context, but not the starting point for the inquiry.

33 The ACCC approach has the effect, although disavowed in terms, of treating the March 2017 packaging changes, and in particular the addition of the words “Same effective formula as Voltaren Emulgel”, as being in the nature of a disclaimer (or other qualifying statement) to what would otherwise be contravening conduct. The ACCC contends that the admitted contraventions created a lasting or otherwise ongoing misleading impression, which needed to be dispelled. On the ACCC’s case, this is so both in relation to prior contraventions of Osteo-Gel, but also in relation to potential new consumers insofar as the same dominant message retains its contravening character and is not sufficiently corrected. If that is the correct characterisation of the inquiry, then the established authority as to disclaimers may be seen to be engaged, at least to some degree. The effect of that authority may be summarised as follows:

(1) There may be occasions upon which the effect of otherwise misleading or deceptive conduct may be neutralised by an appropriate disclaimer: Abundant Earth Pty Ltd v R & C Products Pty Ltd (1985) 7 FCR 233 at 239.

(2) A person engaging in misleading or deceptive conduct cannot readily or easily use the device of a disclaimer to evade responsibility, unless that disclaimer erases the proscribed effect: Benlist Pty Ltd v Olivetti Australia Pty Ltd (1990) ATPR 41-043; (1990) ASC 55-997.

(3) A disclaimer having the effect of dispelling otherwise misleading or deceptive effects of conduct may be a rare occurrence given the onus that is ordinarily on the person making the otherwise contravening representation to establish that the disclaimer it relies upon creates an overall effect that is benign: Hutchence v South Seas Bubble Co Pty Ltd (1986) 64 ALR 330 at 338.

(4) Disclaimers or qualifications must be taken into account in evaluating the conduct as a whole: Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd [2009] HCA 25; 238 CLR 304 at [25].

(5) Carelessness on the part of consumers in how they treat or view a representation, including any disclaimers or additional information, may be relevant: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; 250 CLR 640 at [49].

(6) It may be relevant to consider whether or not an advertisement or other representation or conduct has the capacity to lead a consumer into error because it selects some words for emphasis and relegates the balance, including any disclaimer or other information, to relative obscurity: TPG Internet at [51].

(7) A disclaimer must be very clear when there is a substantial disparity between the primary representation and the true position: National Exchange Pty Ltd v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2004] FCAFC 90; 49 ACSR 369 at [55]. In National Exchange, shareholders had been offered $2 per share when the current share price was $1.93. But they were only told in a different and less prominent location that payment would be made by 15 annual instalments making the offer worth less in current value than $2 and also less in current value than $1.93. Without the qualifying context the primary representation was false because the shareholder was not being offered $2 in value per share at the time the offer was made, and was in fact being offered less than the current share price.

(8) A disclaimer that is static may bear more weight than one that is evanescent. In a printed format, even an asterisk that indicates the presence of additional information, if it is sufficiently prominent and the qualifying text is sufficiently proximate, may be effective to draw attention to an explanation of, or qualification upon, a statement made in advertising: George Weston Foods Ltd v Goodman Fielder Ltd [2000] FCA 1632; 49 IPR 553 at [46].

34 Thus, on the ACCC’s case, the issue is whether the corrective actions of GSK in changing the Osteo Gel packaging have gone far enough to dispel both the admitted contravening effect of the pre-change packaging and contravening effect of the new packaging in that context. On this approach, as a practical matter, and perhaps even as a matter of onus, it would arguably be for GSK to demonstrate that the changes went far enough to create a benign overall effect, rather than for the ACCC to prove the contraventions alleged, as the starting point would be one of contravention.

35 GSK, while referring to the case law on disclaimers and qualifying information, contends that the Court’s task is not to treat the prior contraventions as the “embarkation point” and then enquire as to whether the prior contravening character has been negated or neutralised, but rather to assess whether the new packaging conveys the pleaded proscribed effect. To that end, GSK refers to the earlier packaging to emphasise the nature of the changes made, not to discharge any onus that the revised packaging had been effective in negating otherwise contravening conduct.

36 It is appropriate to chart a course that is somewhere midway between the approach urged by the ACCC and the approach urged by GSK. This is because, contrary to the substance if not the form of the ACCC’s argument, there is no starting point of contravention required to be negated by GSK, because the packaging was sufficiently changed, including with the lesser changes beyond the additional words, as to require a fresh assessment. Any possible lasting impression from the prior contraventions does not give this the character of being a disclaimer case per se. The ACCC therefore bears the onus of establishing that what was conveyed by the revised Osteo Gel packaging sold between March 2017 and May 2018 was prohibited. However, the prior contravening packaging provides a useful and valid evaluative tool by which to appreciate what was ultimately conveyed and whether it too met the pleaded contravening description.

37 Most of the evidence relied upon by the parties beyond the packaging itself provided only limited assistance in conducting the required objective assessment, especially as the Court is required to view the material from the perspective of:

(1) a person suffering from osteoarthritis; or

(2) a person seeking treatment for such a person, such as a spouse, other relative or friend,

rather than someone in that position who is more fully informed as to background and collateral matters that would not be apparent at the point of sale.

38 The ACCC did not have to call any evidence of anyone who was actually misled, or otherwise seek to adduce evidence of any lasting effect, but in the absence of any such evidence the task is even more starkly objective. Speculation is not the same as inference, and weak inferences may not suffice.

39 The respondents’ concession that the omission of any reference to Emulgel in the preceding two sets of substantially identical Osteo Gel packaging preceding the March 2017 changes meant that the contraventions were able to be established was sensible in light of the Nurofen case. That is because the overall impression given to consumers, seeing the two products side by side, was of different products for different conditions, not merely differential use of the same product for different conditions. The former is proscribed; the latter is not. The reference in the pre-March 2017 Osteo Gel packaging to the same active ingredient was too muted to allay the overall proscribed impression. It is important, however, to be clear that the contraventions admitted to are those conveyed by implication, not by any express false statement, a point of some importance when the changed packaging is considered.

40 GSK submits that, in principle, and subject to prohibitions on not misleading consumers, there is nothing wrong with marketing a therapeutic good which has dual and even overlapping uses to different target markets; and no legal principle that requires that a therapeutic good be marketed simultaneously by reference to the full range of approved indications and thus possible uses (arguing that this may in itself be misleading, or at least confusing). The ACCC does not say that GSK was not entitled to market Emulgel and Osteo Gel separately for the different conditions, but maintains that if this is done, it is necessary to be very clear about the lack of any real difference between the two products, at least in terms of having the same active ingredient. The ACCC ended up relying heavily on the use of the product name “Osteo Gel” as of itself conveying the misleading impression of a product specifically formulated for osteoarthritis. Such clarity can be a curate’s egg, according to the perspective of the viewer: that is, good in parts and bad in parts. The ACCC and GSK urge the Court to place emphasis on different things, and to see the same things differently.

41 Support for the above general proposition that there may be differential marketing of the same product for different conditions may be sought to be drawn by implication from the Nurofen case, which did not entail any finding that there was anything inherently wrong with Reckitt Benckiser marketing a particular identical formulation as four different products for four different uses, provided it did not do so in a way that misled consumers. It may even be beneficial for consumers to be able to find more easily a medication that treats a particular condition, which also treats other particular conditions, rather than having to work it out for themselves, even by reference to a shopping list of conditions. However, this is subject to the proviso that there is no element of being misled, such as by way of an effective representation that the product is specifically formulated for any such condition, or that another product identical in substance cannot be used or is less effective. Reliance on the Nurofen case beyond that general proposition is limited, because the contravening conduct there was so clear and extreme.

42 The real vice in the Nurofen case was that consumers were overtly told that the identical product, packaged in four different ways, was part of a range of pain relief of products, each of which was “targeted” for four different types of pain. In fact the active ingredient, ibuprofen, in identical doses, addressed the four different types of pain in exactly the same way, and there was no other difference, such as duration of use. The active ingredient and dose, which would assist a consumer in recognising that the four different packages contained the same contents, was only disclosed in small print, and without reference to the other products.

43 The ACCC relied upon the packaging changes that had occurred in the Nurofen case as set out in the Nurofen appeal judgment at [101] and commented upon at [102] to [105]. The text of [101] does not need to be reproduced, but sets out the contravening packaging claims, a proposed variation rejected by the ACCC and an interim corrective sticker to facilitate the sale of otherwise contravening stock, which the ACCC approved. The ACCC in this case sought to equate the Osteo Gel packaging change to the rejected change in the Nurofen case. However, that submission does not survive close scrutiny.

44 The contravening claim in the Nurofen case was that four Nurofen “specific pain” products were said to provide “fast targeted relief from pain” for each of back pain, period pain, tension headache and migraine, when they were not targeted at all and operated in precisely the same way as ordinary Nurofen and each other. The rejected variation maintained the same claim, adding the words “also suitable for general pain relief”, but leaving intact the false claim that each was “fast targeted relief from pain”. The interim sticker solution added words referring to the other three types of pain, taking as an example the back pain product, which was claimed to be “equally effective for tension headache, migraine, period pain and general pain”, although not referring to the other three products. The false claim “fast targeted relief from pain” was retained. Importantly, that approved interim change said nothing about Nurofen Back Pain, Nurofen Tension Headache, Nurofen Migraine or Nurofen Period Pain products having the same formula as ordinary Nurofen, or as each other.

45 The ACCC in the Nurofen case did not contend that with the interim sticker, the claims remained contravening (nor, apparently, that it was not contravening). The Full Court therefore found that the primary judge could not be said to have erred in proceeding upon the assumed, but not proven, basis that the interim package did not contravene. The Full Court expressly declined to determine the question of whether the interim packaging in fact contravened in those circumstances. The Full Court’s position falls well short of any actual finding that the interim packaging did not in fact contravene. The issue simply did not arise for determination.

46 The change in the packaging in this case not only exceeds the rejected change in the Nurofen case, but also exceeds the approved interim change in that case. No overtly false claim is maintained (none having been made in the first place) and overt reference is made not just to being able to treat the same condition as Emulgel, but also to Osteo Gel having the “same effective formula as Voltaren Emulgel”, thus directly cross-referencing the alternative product with the same gel.

47 This case was also not as clear cut as the Nurofen case because there was a material difference in the maximum duration of use of the gel to treat osteoarthritis and the same quantity of the active ingredient was not hidden away. The representation that Osteo Gel could be used for three weeks (which is up to 50% longer than the Emulgel maximum of two weeks) was appropriate given its intended use by osteoarthritis sufferers, as opposed to the treatment of more general conditions of pain or inflammation. There was also a material difference in the cap which was easier to open, especially for someone with osteoarthritis in the hands.

48 GSK does not shy away from the different dosage instructions on the packaging for Osteo Gel and Emulgel, but rather embraces that as part of a legitimate form of differential marketing, meeting a need for consumers with osteoarthritis.

49 The dispute thus turns on meaning. That is, what should be made of the representations concerning Osteo Gel, in the context of the parallel representations made about Emulgel, especially given that the two were generally, like the four “specific pain range” products in the Nurofen case, sold side by side. This largely took place in accordance with planograms furnished by the respondents, and relevantly by GSK, being diagrams that showed how and where Osteo Gel and Emulgel were recommended to be placed on retail shelves or displays, for the purpose of encouraging consumers to purchase those products. While there was a deal of documentary evidence on this topic, the substance of that evidence is sufficiently addressed by an agreed fact. The agreed fact is to the effect that the while the respondents, and thus GSK in the relevant period, had no actual control of product placement, if the recommendation in the planograms they provided was followed, Osteo Gel and Emulgel would typically be placed either next to one another, or in close proximity, along with other products in the Voltaren range and products from other suppliers relevant to inflammatory pain. That proximity was a problem if it led to a comparison that contributed to a misleading impression, but not if it contributed to allaying such an impression.

50 The evidence of photographs taken at retail outlets establishes that the planogram recommendation was, as might be expected, generally followed. The evidence is therefore clear that all representations made about Osteo Gel are to be read and understood in the context of representations made about Emulgel. The necessary evaluation is to be carried out by considering the Osteo Gel packaging next to the Emulgel packaging in the period in contention, physical copies of each being in evidence as the first two exhibits. The conclusions reached in these reasons largely turn on the physical appearance and information conveyed by the Emulgel box and tube and the Osteo Gel box and tube on sale in the disputed period, viewed side by side as they would be by a consumer.

51 The ACCC contends that the respondents illegitimately continued to represent that Osteo Gel, by reason of its name and by reference to the treatment of “local pain and inflammation associated with mild forms of osteoarthritis of the knees and fingers”:

(1) was “specifically formulated”;

(2) “solely or specifically” treats that condition; and

(3) is “more effective” than Emulgel (collectively referred to as the Osteo Gel Representations),

when none of those claims were true; and that the effect of the cross-reference to Emulgel in the revised packaging was inadequate or otherwise ineffective in ameliorating those representations. The ACCC’s case is that none of this was accidental: rather, it was the product of GSK’s deliberate marketing strategy, going back to the introduction of Osteo Gel as a “new” product in 2010, advanced further by changes in the Emulgel packaging in 2014 by which the references to osteoarthritis were removed. GSK’s case is that Osteo Gel was introduced as a new product bundle, comprising not just the gel contents, but also the easy to open cap and the directions for use for a longer period than Emulgel, reflecting two separate and distinct markets for the treatment of quite different conditions, albeit with the same gel.

52 The ACCC characterises the first two representations as being akin to those in the Nurofen case, but the third representation as being unique to this case in also suggesting greater effectiveness than the differently packaged identical gel. The ACCC takes issue with the Osteo Gel cap amounting to any substantial difference; and contends that the reference to Emulgel did not go far enough. The ACCC characterises the different usage recommendations as contributing to an illusory distinction between the identical gels, pointing out that the duration for general use (up to 2 weeks), and the longer duration for osteoarthritis use (up to 3 weeks), appeared on Emulgel packaging before it ceased being marketed for osteoarthritis. The substance of this stance seems to be not just that the different duration of use was not a real point of distinction, but perhaps went so far as to be part of the misleading conduct or representations.

53 The ACCC also place some weight on the fact that Osteo Gel was sold at a price premium over Emulgel for comparable tube sizes. The ACCC submit that the recommended retail price (RRP) that GSK relies upon is not what the consumer sees unless that is the price that is in fact charged, but even the RRP indicated a significant and systematic price differential. GSK did not question that there was a price premium for Osteo Gel, but sought to demonstrate that the difference was not significant when regard is had both to the different pricing across different package sizes and also to the fact that the two major retailers, Coles and Woolworths, sold the products at a price somewhat above recommended retail, over which GSK had no control. For present purposes, I am not convinced that the RRP is so disparate from the price actually faced by consumers as to render it other than a reasonable proxy for what consumers did in fact have conveyed to them.

54 GSK relies upon a table tendered and admitted into evidence which depicts the RRP set in the period from 2016 to 2018 for Emulgel and Osteo Gel, and that price calculated by reference to price per 100 g and price per gram, together with an average RRP over those three years. For present purposes, it suffices to use the 2018 figures:

Brand | Size (g) | 2018 RRP | 2018 $ per 100g | 2018 $ per g |

Voltaren Emulgel | 180 | 27.29 | 14.68 | 0.147 |

Voltaren Emulgel | 150 | 25.99 | 17.33 | 0.173 |

Voltaren Osteo Gel 1% | 150 | 28.99 | 19.33 | 0.193 |

Voltaren Emulgel | 120 | 24.85 | 20.71 | 0.208 |

Voltaren Emulgel | 100 | 22.95 | 22.95 | 0.230 |

Voltaren Osteo Gel 1% | 75 | 19.95 | 26.60 | 0.266 |

Voltaren Emulgel | 50 | 13.95 | 27.90 | 0.279 |

Voltaren Emulgel | 20 | 6.95 | 34.75 | 0.348 |

It should be noted that Voltaren Emugel 120 g was not sold in 2018, so that the figures above were those from 2016 and 2017.

55 The point made by GSK was that the price premium difference between Emulgel and Osteo Gel when it is in the same or similar size packaging is not as great as the greater price charged for Emulgel for smaller packaging. As GSK puts it, by far the most expensive of these products in price per 100 g or price per gram is the Emulgel 20 g, which is sold in quite substantial numbers, and the next most expensive is Emulgel 50 g. Thus economies of scale accounted for a much bigger difference in the purchase price per 100 g or price per gram than the differential pricing between Emulgel and Osteo Gel. GSK submit that there was nothing misleading about charging a higher price for a product that has the innovative feature of a cap that no one else apparently had. That submission should be accepted. While there is no doubt that the targeted marketing of Osteo Gel enabled GSK to charge a premium, that has not, as the ACCC submits, been shown of itself to have had any significant effect in reinforcing any message of substantial difference going beyond the packaging claims, let alone to do so in a way that contributed in any real way to any misleading or deceptive effect. If there was already any misleading or deceptive effect, the price difference might, to a limited extent, reinforce that effect.

56 In relation to the revised packaging, GSK not only admits, but relies upon the fact:

(1) that Emulgel was promoted for use in treating local pain and inflammation in acute soft tissue injuries and localised soft tissue rheumatism; and

(2) that Osteo Gel was promoted for use in treating local pain and inflammation associated with mild forms of osteoarthritis of the knees and fingers, reflecting the indications for use of the products approved by the TGA.

57 GSK contends that the above approach to marketing was to ensure “clear communication of the approved duration of use for each condition and to target osteoarthritis sufferers who were not purchasing Emulgel without alienating Emulgel customers”. The substance of the GSK’s case is that the different ailments targeted by the two products, including different maximum duration of use, justified the differential claims made, supported by the different cap for the Osteo Gel tube. GSK defends the use of the word “effective” in the cross-reference to Emulgel as emphasising that the gel in each had the same effect, or at worst as being of no moment; and maintain that this, along with other lesser packaging changes, rendered the overall effect as not contravening.

58 Plainly enough, from late 2014 Emulgel was being marketed in a way that no longer encouraged its use for those with osteoarthritis, confining its use advice to a shorter duration of a maximum of two weeks. Osteo Gel was being marketed in a way that was clearly directed for use with osteoarthritis, with a longer duration of use advice of a maximum three weeks, and with the additional feature of a cap that was easier to open and therefore particularly better for those individuals who had that condition in their hands. Osteo Gel was, from a consumer’s perspective, a product for the treatment of osteoarthritis, while Emulgel was not on its face or in the claims made about it, directed to such a specific condition involving local pain and inflammation, although that particular use was not excluded. Was there anything wrong with the way in which this was done once the Osteo Gel packaging was changed in March 2017 to state “Same effective formula as Volatren Emulgel”, along with other changes?

59 As already noted, the ACCC emphasises the fact that the changed packaging for Osteo Gel was introduced in March 2017 in the context of its prior, and now admitted, misleading character, relying also on correspondence between the parties leading up to that change, and beyond. The ACCC’s core case is that the dominant, misleading, message was still present and that it was not sufficiently abated by those changes. Understanding why the original packaging was misleading is an important consideration in helping to decide whether the changed packaging contravened.

60 The ACCC asserts that it is likely that there are consumers who have purchased Osteo Gel in both the original and revised packaging, with the later purchases informed by the prior understanding of its suitability, and thereby that of Emulgen, based on the understanding gleaned from the original packaging. That may well be correct for some consumers, but that will only be the response of a reasonable, ordinary consumer of Osteo Gel (including those who buy it on behalf of those afflicted by osteoarthritis) if the new packaging is not clear enough in its own terms. If it is clear enough, then it becomes an assumption that a consumer will not pay heed to adequate packaging information. I therefore consider that this argument does not assist the ACCC in the absence of any evidence to demonstrate, beyond speculation and perhaps weak inference, how and why a consumer who was misled by the prior packaging was more likely to be misled by the new packaging if it was satisfactory in its own terms, than someone who had never bought Osteo Gel before.

61 The detail of the balance of the ACCC’s argument may be summarised as follows:

(1) The original Osteo Gel name and packaging, in the context of the Emulgel packaging, combined to convey the Osteo Gel Representations (that is, to use the summary in the ACCC’s submissions, “Osteo Gel was specifically formulated to treat, and solely or specifically treats, local pain and inflammation associated with mild forms of osteoarthritis of the knees and fingers, and is more effective than Emulgel at treating those conditions”), when none of those matters were true, by reason of the following features:

(a) the product names for both were in large, bold and prominent lettering, on the front and back panels, and gave a clear indication to the prospective purchaser that the products were different, with Osteo Gel clearly intended to be associated with a serious medical condition, osteoarthritis;

(b) the benefit statements were prominently set out on the front and back panels, reinforcing that purported difference:

(i) Emulgel packaging bearing the benefit statement “For temporary relief of local pain and inflammation” underneath the description of the active ingredient, making no reference to mild forms of osteoarthritis despite the ARTG approved specific indications extending to that pain condition; and

(ii) Osteo Gel packaging bearing the benefit statement, in white letters superimposed on a blue stripe, “For the temporary relief of local pain and inflammation associated with mild forms of osteoarthritis of the knees and fingers” immediately beneath the name Osteo Gel and above the description of the active ingredient on the front and back panels; and

(iii) Osteo Gel’s benefit statement also appeared at the very top of the side panel above the “Do Not Use” and “Dosage” instructions, in contrast to the side panel of the Emulgel packaging which contained the statement “For temporary relief of local pain and inflammation in acute and soft tissue injuries, including sprains, strains and sports injury, and localised soft tissue rheumatism, including tendinitis and bursitis”, noting that prior to 2014, the Emulgel benefit statement on its packaging had the additional words “and mild forms of osteoarthritis of the knees and fingers” (see the image at [22] above);

(c) Osteo Gel packaging had an x-ray style image of a knee joint next to the benefit statement, with redness signalling inflammation shown between the femur and tibia reinforcing the impact of the benefit statement as to osteoarthritis of the knee;

(d) Osteo Gel packaging had a triangular blue cap instead of the white round cap of the Emulgel product, with an image of the cap displayed on the front and back panels underneath the words “easy-to-open cap”, with reliance on internal media briefings for Novartis on this topic as to how this was relied upon to differentiate between Osteo Gel and Emulgel;

(e) the “Dosage” instruction for Osteo Gel instructed “Do not use for more than 3 weeks for osteoarthritis except on medical advice”, and for Emulgel instructed “Do not use for more than 2 weeks except on medical advice”, in the context of both instructions appearing on the Emulgel packaging prior to late 2014, but deliberately excluded in the revised Emulgel packaging.

(2) The effect of the above representations was reinforced by the proximate display of Osteo Gel and Emulgel, encouraging comparison and the enhancement of perceived, but not real, difference, with Osteo Gel being typically more expensive than Emulgel, supporting the perception of Osteo Gel being a “specialised product” that was superior to Emulgel in treating osteoarthritis pain because it was specifically formulated to do so, with the differential pricing being deliberate.

(3) As a result of the five aspects of the original packaging described at (1)(a)-(e) above, and still forming the main part of the revised packaging, in the context of (2) above, the dominant message was that Emulgel and Osteo Gel were different, and that Osteo Gel was specifically formulated to treat, specifically treated, and was more effective than Emulgel in treating, mild forms of osteoarthritis of the knees and fingers. Thus the Osteo Gel Representations continued to be made.

(4) Further, each product’s original packaging, prior to the change for Osteo Gel in March 2017, included the active ingredient statement “Diclofenac diethylammonium gel 11.6 mg/g” in smaller italicised font on the front and back panels (some versions of the Emulgel and Osteo Gel packaging included the additional words “equivalent to diclofenac sodium 10 mg/g (1% w/w)”):

(a) for Emulgel, set out underneath the product name and above the benefit statement;

(b) for the Osteo Gel packaging, set out underneath both the product name and the purported benefit statement;

enabling a careful and astute customer to read and compare the two and conclude the gels were the same, causing the dominant messages to be questioned, but this was insufficient to negate or neutralise the dominant impression and in particular failed to draw consumers’ attention to “the true position in the clearest possible way”, citing National Exchange at [55].

62 The ACCC also relied upon evidence in the form of media briefings and internal communications proposals to demonstrate that Novartis had launched Osteo Gel as an additional product that was distinct from Emulgel to increase market share without cannibalising sales of Emulgel. To that end, Novartis had deliberately targeted osteoarthritis pain sufferers as potential purchasers, intending them:

(1) to think that Osteo Gel was a new treatment for osteoarthritis pain and had unique benefits; and

(2) to think that Osteo Gel was not a “homogenous topical rub” because it specifically treated osteoarthritis pain.

The ACCC submits that all of this was consistent with making the admitted Osteo Gel Representations, and that, given Novartis’ expertise in this field of marketing, an inference may readily be drawn that the objective so derived was achieved, including by the use of differential packaging of Emulgel and Osteo Gel.

63 Each of the propositions in the preceding paragraph may be accepted for present purposes as forming part of the contravening conduct to which the respondents have admitted, even if not in letter and verse and in respect of every nuance. The respondents may revisit the issue of how far their admissions as to the contraventions of the original packaging go on the question of penalty for that conduct. However, assuming for present purposes that each proposition is established without qualification, that does not, of itself, answer the question of whether or not that impression remains. The changes in the packaging at the very least would have tended to operate against the marketing objectives of encouraging those with osteoarthritis to buy Osteo Gel instead of Emulgel. That is because the additional words “Same effective formula as Volatren Emulgel” at least pointed to the active ingredients in the two products being the same, reinforced by the statement of those same active ingredients on the Emulgel packaging.

64 The ACCC contends that despite the changes to the Osteo Gel packaging in March 2017, in particular the introduction of the additional words, the representations and thereby conduct was still misleading, deceptive, false and liable to mislead, such that the Osteo Gel Representations also took place from March 2017 to May 2018. The ACCC’s argument as to why that is so may be summarised as follows. It is convenient at this point to comment on each argument.

(1) The five aspects of the packaging referred to at [61(1)] above, were likely to have left the ordinary and reasonable consumer with the “overwhelming initial impression” that Osteo Gel was a distinct product that specifically treated osteoarthritis.

Comment: While the prior packaging did give the proscribed impression, and this was the dominant impression, it is overstating it to say that this impression was overwhelming, in the sense of eliminating any other reasonable impression. It was nothing as extreme as the Nurofen case. The statement of the active ingredients was on the front of both the original Osteo Gel and Emulgel packaging, rather than hidden away. While the dominant message was still initially misleading – and that was enough to amount to contravening conduct – it was not overwhelmingly misleading. A consumer who was more careful, thorough or astute than they should have to be would not easily have been misled, especially once the presence of identical active ingredients was appreciated.

(2) Correction of that false impression required direct and prominently displayed statements to the contrary, because consumers who have been misled so overwhelmingly are less likely to be receptive to disclaimers pointing to the opposite being true.

Comment: This proposition relies upon acceptance of the first proposition, and therefore overstates the position for the same reason.

(3) The additional information failed to draw attention to the true position in the clearest possible way by stating that the formulation of each product was identical, again citing National Exchange at [55].

Comment: This is a very different case to National Exchange, with the degree of disparity between what was represented and the correct position being real, but not anywhere near as extreme. At trial, the original packaging would have been found to be misleading, but not in the most egregious category. Some ordinary consumers, perhaps many, would have been misled, but others would not.

(4) The use of the word “effective” was superfluous to the formulation and therefore confusing – it could mean a number of different things:

(a) that the formula is effective in the way it works, although for what is not stated; or

(b) that the formulas of Osteo Gel and Emulgel are effectively (but not entirely) the same.

Comment: While the GSK contrary argument outlined below goes too far, in that the word “effective” did not have the positive effect contended for, the ACCC makes too much of the use of an apparently superfluous word. In the context of this case, the dominant message, when read with the actual formula on both packages, is that consumers were being told that the gel in each tube is the same. That said, clearer language would have been preferable. GSK were taking a risk in choosing indirect language to convey the fact that the gel in Osteo Gel was the same as the gel in Emulgel.

(5) While the active ingredient was listed, neither packaging sets out the other ingredients so as to permit comparison.

Comment: This is not entirely correct. While there is no exhaustive list of everything that is in the gel, both sets of packaging advise that the contents include isopropyl alcohol as a preservative and also benzoates. In any event, it is unclear why this makes any difference given that there was expressly no difference in the active ingredient by reason of the same formula being set out. Any message of similarity will be diluted rather than enhanced by two longer lists of identical inactive ingredients requiring comparison.

(6) Even if consumers did end up appreciating that Osteo Gel and Emulgel were identically formulated, the clear impression that Osteo Gel was a specific treatment product may still have persisted because the overwhelming tendency of the packaging was to lead consumers to think exactly that, as intended. The vice of the packaging was that it required “consumers to find their way through to the truth past advertising stratagems which have the effect of misleading or being likely to mislead them”: TPG Internet at [54].

Comment: This submission is too speculative in nature as the overall effect either was, or was not, of a proscribed character. The submission again relies upon an exaggerated characterisation of the prior misleading impression being overwhelming, as opposed to dominant.

(7) It could not be safely assumed that reasonable consumers would recognise and navigate the logical disconnect between Osteo Gel being a specialised product and containing the same formula as Emulgel.

Comment: Again, either the overall effect carried a proscribed dominant effect, or it did not, with there being no useful role for any assumption of this kind being made or not being made. The asserted “logical disconnect” does not add anything useful to the analytical task required to be carried out, nor to the pleaded Osteo Gel Representations.

(8) In any event there was no corresponding disclaimer on the Emulgel packaging, which failed to make it clear the product was suitable or equally effective for the treatment of osteoarthritis.

Comment: There is no case brought that the Emulgel packaging was itself contravening. It is going too far to require that Emulgel packaging detail more specifically the uses to which it could be put, including osteoarthritis.

(9) It is not clear that the additional statement was sufficiently prominent to capture consumers’ attention and divert them from the dominant message of the packaging.

Comment: The additional statement, if sufficient in content, was also sufficient in prominence. It was both larger and clearer than any other claim other than the claim that the cap was “easy-to-open” (which was not suggested to be misleading), and immediately above the substantially larger statement of the formula than had appeared on the packaging admitted to be contravening.

(10) The mistaken belief that Osteo Gel is a specific treatment product still created by the post-March 2017 packaging for Osteo Gel was not limited to influencing purchasing decisions, but also deprived consumers of the opportunity of engaging with alternative products on a rational basis. This is because, on the ACCC’s argument, the consumer has been enticed into Voltaren’s “marketing web” by the initial impression that Osteo Gel was a specifically formulated product, citing TPG Internet at [50].

Comment: GSK was not entitled to divert customers of competitors to its products by misleading or deceptive conduct. But either that proscription was breached, or it was not. If the ACCC cannot first establish that GSK has misrepresented Osteo Gel as a specific treatment product, then this argument as to a further consequence of doing that does not assist.

(11) It is likely that existing users of Osteo Gel did not notice the packaging change, because, having previously purchased it, they may not have reviewed the packaging with the scrutiny that they otherwise might have when making a subsequent purchase, citing TPG Internet at [50].

Comment: This is an inapt application of the principle stated in TPG Internet, which was directed to assessing conduct at the time it took place, not at the later time that a contract is entered into when the incorrect impression may have been corrected.

65 GSK’s counter arguments turn on a number of key propositions, supported by references to the evidence which I accept establishes the essentially uncontroversial factual foundation for what is asserted to explain and justify what took place. GSK submits that the packaging changes gave a final impression that was not proscribed for the following key reasons, again with comments:

(1) GSK characterises the ACCC’s case on context as incomplete, because it fails to give sufficient acknowledgement to the difference in the conditions for which the same gel is used, including in particular the different maximum duration of use, being specifically acknowledged and approved by the TGA.

Comment: The different duration of use is important. Users treating different conditions with the same medication require different information. There is nothing inherently wrong with having this packaged and sold differently, so that the user only obtains the information they need, and does not obtain information they do not need. Combining such information may itself lead to confusion and error. In the case of persons with more general conditions, there is a risk of using the product for too long, presumably outweighing the benefits for such a condition. Separate packaging, with separate maximum duration of use instructions, is inherently less likely to lead to user error in that regard.

(2) GSK contends that the difference in the two classes of conditions is not artificial, but is reflected in the existing market, with two quite different “pain states” being involved. Each pain state may be treated by the same gel up to the common maximum period of two weeks. But the consumer responses to each pain state will necessarily be different. GSK evocatively and diplomatically refers to the two markets, involving two separate classes of consumers required to be identified, citing Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Limited [2000] HCA 12; 202 CLR 45 at [103], as:

(a) the young (or young-at-heart) “weekend warriors” with sports injuries or strains want[ing] pain relief; and

(a) those with more years behind them but still “forever young” who suffer from pain associated with osteoarthritis,

with those in either not necessarily appreciating being grouped with the other.

Comment: This reinforces the notion in the preceding comment that users treating different conditions have different needs. Weekend warriors should ordinarily not use Emulgel for more than two weeks; while osteoarthritis suffers may get less relief than is ideal if they cease use at the two week mark.

(3) GSK suggests that the ACCC does not advance any different position on the proposition that the different “triangular winged cap” on Osteo Gel provided a practical benefit to people with osteoarthritic conditions of the hand who may encounter difficulties in gripping, opening and closing things and for who such a modification will materially assist, including by minimising pain. GSK points out that osteoarthritis is a commonly occurring disease with prevalence increasing with age, skewed towards women.

Comment: The different cap is a genuine point of difference, although doubtless also a useful marketing angle. There is no doubt that the Osteo Gel cap is easier to open, and not just for those suffering from osteoarthritis.

(4) GSK therefore characterises its conduct as entailing, via the new packaging, the legitimate marketing of an existing anti-inflammatory gel as a separate retail product with the different cap, specific use instructions, and advertising for consumers with osteoarthritis, and to do so without alienating users of Emulgel.

(5) GSK accepts that it (and Novartis earlier) went about this in the wrong way to start with by reason of not sufficiently qualifying the claims made about Osteo Gel to make it clear enough that the gel component of the two products was the same, and so falling short of what was required. GSK submits that this failing was no longer present following the change in packaging in March 2017, adding the additional information, and reducing the size of the Osteo Gel font, adding the additional information and relocating the active ingredient information, in a larger font, immediately below that additional information.

(6) As noted previously, GSK characterises the ACCC’s approach of asking whether the changes went far enough to counter the prior contravening conduct as “an inversion of the analytical task”, with the proper approach being to assess whether or not the new packaging does or does not, by implication in the absence of express representations, convey the pleaded Osteo Gel Representations. Rather, GSK contends, what is required is an overall assessment of the impression conveyed by the packaging with appropriate weight being given to the various features, including in particular the prominence given to the additional words, which does not involve any maze to uncover the true meaning. GSK contends that the additional words, as a matter of plain English, tell a consumer that the gel in Osteo Gel is the same as that in Emulgel, and is just as effective, with there being no logical disconnect as alleged by the ACCC.

(7) GSK places some collateral reliance on the ACCC declining at one point to meet with it and suggests that this might have been productive of an earlier interim arrangement as happened in the Nurofen case.

Comment: The ACCC is correct to point out that this Court was not called upon to adjudicate upon the interim packaging in the Nurofen case. This is not a path for redemption if the representations are found to continue to contravene from March 2017.

66 The ACCC in closing oral submissions relies on numerous arguments to meet GSK’s case. Three in particular have not been mentioned above and warrant specific reference.

67 First, the ACCC takes issue with the proposition that it is permissible to market the same gel to distinct markets, describing it as an acceptance by GSK that it is marketing an illusion, being that Osteo Gel is specifically formulated. The ACCC characterises this “commercial advantage” as being no more than taking advantage of osteoarthritis suffers who are overwhelmed, reliant purchasers. Such purchasers want a product to address their specific needs, but GSK want to avoid losing customers who are young and do not want to be associated with osteoarthritis sufferers. The ACCC submits that this entails going beyond the permissible step of marketing the same gel for use in one part of the market and the same gel for a different use in a different segment of the market. The objection comes down to the specific formulation in the use of the words “Osteo Gel”. The ACCC’s greatest concern is with the use of those words, in effect proposing to deny the right in most circumstances to use a product name that suggests that it can be used for a specific condition when it has not been formulated for such a condition. The ACCC’s case, in substance, is that the use of the name “Osteo Gel” had the same effect as the use of the word “targeted” in the Nurofen case. That is, the use of that name conveyed the meaning “targeted for osteoarthritis”.

68 It may be accepted that GSK took a real risk with such a name and therefore such an impression being conveyed. GSK accepts that this was so with the earlier packaging, but maintains that it is adequately corrected with the March 2017 packaging.

69 Secondly, the ACCC’s case is that the easy-to-open cap was part of what made the March 2017 packaging misleading, adding to the deceptive nature, and not being any genuine point of difference. Had it been a real point of difference, it would have featured in the advertising, yet it did not in the sample advertisement played at the hearing. Thus, on the ACCC’s case, the product bundle was an aspect of the misleading or deceptive illusion created by GSK.

70 Thirdly, the ACCC’s case is that repurchasing frequency is not as clear and supportive of GSK’s case and that it may be more frequent than annually. In the result, I can only safely conclude that Osteo Gel is not a frequent purchase, with that being logically determined by how advanced a sufferer’s osteoarthritis condition is, and how much the gel is applied. It may be an annual purchase, or it could be a number of times in a year.

71 Finally, the ACCC relies upon TPG Internet at [55] to draw from the marketing evidence an intent to create a favourable impression, which was realised in the sense of an intent to achieve a result, rather than any necessary intent to mislead. It may be accepted that GSK fully intended to encourage the purchase of Osteo Gel for use by osteoarthritis sufferers. The live question is whether it has been proven that this objective was sought to be achieved by proscribed means.

Consideration

72 It is convenient to start by reference to several overarching conclusions I have reached, including in light of the comments recorded above, as that informs the approach to be taken to the competing arguments and the view formed as to what has taken place.

73 It was legitimate for GSK to market a general product and a specialist product, each containing the same gel. Generally older consumers, suffering from a condition that is at least uncomfortable, and may also be distressing and even debilitating, are not compelled by the consumer protection provisions that the ACCC relies upon to have presented to them a shopping list of conditions that are mostly irrelevant to them in order to find out if a given product will address their specific need.

74 Nor do those consumer protection provisions prevent such a consumer from being provided with use duration information that is specific to their kind of condition, and not have to work out for themselves that a shorter maximum duration of use did not apply to them, with a corresponding chance at least of not treating a condition for as long as would more fully alleviate symptoms.

75 Nor is the provision of ease of use innovations, such as the different cap, to be discouraged, even if they enable more to be charged for a product.

76 However, each of the above observations is subject to a critical qualification: such consumers must not be thereby misled into reasonably believing that another product by the same supplier with the same, or substantially the same, active ingredients is not suitable, or is otherwise somehow inherently inferior for treating their condition. Subject to that, differential marketing of this kind is unobjectionable. To be clear, the Nurofen case did not involve any genuine attempt at differential marketing, as opposed to flagrant deception. This case, even for the admitted contraventions, is in a different category.

77 The competing arguments on whether or not GSK, in selling Osteo Gel in revised packaging in the period from March 2017 to May 2018, contravened the Australian Consumer Law as alleged are impossible to reconcile. A choice has to be made. In the end, it comes down to a question of onus as to the conclusion required to be reached. That is, has the ACCC, on the balance of probabilities, and having regard to the seriousness of the allegations, by sufficiently compelling evidence and arguments, satisfied me that the name “Osteo Gel” and the packaging in use for Osteo Gel between March 2017 and May 2018, with the additional words and the other lesser (but still important) packaging changes, have the character proscribed by any of ss 18, 29(1)(g) or 33 of the Australian Consumer Law, as was admitted to in relation to the earlier packaging? After anxious and prolonged consideration, I have reached the conclusion that it has not. For the following reasons I have concluded that GSK, perhaps by a whisker, went far enough by the additional words and other changes, in the context of the different cap and the different usage duration, not to bear the asserted proscribed character.

78 A difficult balance may need to be struck between marketing to the effect that a product is, correctly, suitable for use in treating a specific condition, which is not of itself proscribed, and giving the misleading impression that a product has been specifically formulated for such a condition, which is proscribed if that is not true. The use of an evocative product name that is clearly associated with a particular ailment or condition carries the inherent risk of conveying the wrong impression.

79 Osteo Gel is plainly being encouraged for use with osteoarthritis. That encouragement is enhanced by also having a cap that is easy to open. If the prospective buyer wants to go further in the comparison exercise, the back of each package discloses a differential maximum duration of use. But the use of the name “Osteo Gel”, so clearly connected with such a well-known condition as osteoarthritis, carried with it the risk that it would convey not just the permitted impression, but also a proscribed impression. The respondents took that risk with the initial marketing of Osteo Gel, and crossed the line. That crossing of the line has been admitted.

80 The admitted contraventions may be seen to have turned on the interplay of a number of factors. Non-exhaustively, they include the uninterrupted flow from the name to the contiguous claim in white text on a blue background as to the use for treating osteoarthritis. That name and that claim were mutually reinforcing, further reinforced by appearing side by side with Emulgel packaging which had a more general use claim. While both products listed the same active ingredient, this was subordinate to the main effect. The dominant message and thus overall effect was of a product that was, to repeat the ACCC’s summary description, specifically formulated to treat, and solely or specifically treats, local pain and inflammation associated with mild forms of osteoarthritis of the knees and fingers, and is more effective than Emulgel at treating those conditions. It is not necessary to go further and refer to other features that reinforced this proscribed impression, although it may be seen that the increase in price for the same or similar sized tubes would reinforce, rather than create, that effect.

81 The task now is to examine the revised packaging to understand which side of the line it falls, and more particularly, whether the ACCC has established that it falls on the wrong side. However, there is no longer any mutually reinforcing effect arising between the name Osteo Gel, in slightly smaller text than before, and a contiguous claim in white text on a blue background as to its use for treating osteoarthritis. Instead, the contiguous text below the name are the additional words “Same effective formula as Voltaren Emulgel”, followed by that formula in larger text than before. Those words, with the product name, and followed by the benefit statement in white text on a blue background, indicate that Osteo Gel is suitable for use in treating osteoarthritis, but may be seen to fall short of giving the misleading impression it has been specifically formulated for treating that condition.

82 Previously, the proximity of packages of Osteo-Gel to packages of Emulgel had the effect of inviting a comparison that contributed to the misleading impression, suggesting a difference that did not really exist. With the revised packaging, the comparison is encouraged to a greater degree, but this time drawing attention to the two products having the “same effective formula”. The language used is more opaque than it needed to be, which would make comparison less likely than if clearer words had been used. But if the comparison takes place, instead of adding to the misleading effect, it would tend to add to the correct impression.

83 It is true that in some circumstances a person may not engage in a process of careful comparison. The ACCC places some reliance on Novartis marketing material produced in 2013 to the effect that Osteo Gel was sold into “a market of habitual purchase” where the consumer was “overwhelmed with options and default to habit” and “when in pain habitual purchase is also a way to ‘guarantee’ effect”. However, I am unable to convert that marketing information into any reliable evidence that such an approach would be more likely than not to survive the change in the Osteo Gel packaging and labelling.

84 In the abstract, and without any specific evidence, it is impossible to safely conclude that the presence of pain, age and perhaps other infirmities among the relevant consumer class are such that the March 2017 change in the packaging and labelling did not go far enough. But there is no such evidence. That is not to criticise the ACCC, such admissible evidence being perhaps hard to come by, but to point to the difficulty of the exercise being conducted in the abstract.

85 The risk or possibility of a misleading impression being conveyed by reason of any special susceptibility in the relevant consumer class needs to be balanced against the assistance given to such a consumer, be that an osteoarthritis sufferer, or someone seeking a treatment product for such a sufferer, in readily finding a product that will treat that condition, without having to look to small print, and potentially a list of other irrelevant conditions. That is, the marketing of a product for use in treating a specific condition, even if it is the same underlying product used to treat other conditions, can be beneficial in some circumstances.

86 An average, sensible consumer with osteoarthritis, or considering buying a treatment product for such a person, might have stopped and wondered. They might have questioned what the difference was between Emulgel and Osteo Gel. Upon reading the additional words on the Osteo Gel packaging, which were, only just, sufficiently clear and prominent, they most likely would have realised that the gel in each was the same, or at least that there was no material difference between the formula for Emulgel and the formula for Osteo Gel. They would have had clear information that Osteo Gel did treat osteoarthritis, a claim that was not made for Emulgel. They would have had the treatment duration information for osteoarthritis, with a longer maximum period of use; and they would have been aware that the cap would be easier to open (especially, but not only, for those with osteoarthritis in their hands).

87 On a reasonably finely balanced basis, I am unable to conclude that the overall impression created by the revised packaging is that of a product that has been specifically formulated for treating osteoarthritis, or that solely or specifically treats osteoarthritis, or that is more effective than Emulgel in treating osteoarthritis, as opposed to a product that is suitable for use in treating osteoarthritis. By the narrowest of margins, the disputed contraventions have not been established.

88 It follows that I find for GSK in relation to the packaging of Osteo Gel for the period from March 2017 to May 2018, straddling this proceeding commencement date of 5 December 2017, did not breach ss 18, 29(1)(g) or 33 of the Australian Consumer Law. As a result of there being no finding of contravening conduct as alleged and disputed, I am not satisfied that the ACCC is entitled to the collateral relief that it seeks of injunctions, publication orders or compliance orders arising from the contraventions that are admitted. That is principally because I am satisfied that GSK’s recognition of its earlier contravening conduct, albeit that it took the commencement of proceedings and the context of the Nurofen case, and the fact the Osteo Gel is no longer sold, deprives the ACCC of the circumstances necessary for that relief to be granted.