FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pacific National Pty Limited (No 2) [2019] FCA 669

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 14 days of the date hereof, each party file proposed minutes of orders and short submissions (limited to 3 pages each) addressing:

(a) the necessary undertaking to be given by the Pacific National parties;

(b) orders disposing of this proceeding;

(c) costs; and

(d) any confidentiality issues or restrictions.

2. Until further order, these reasons not be made available to or published to any person save for the parties’ legal advisors, Qube Holdings Limited’s legal advisors and senior staff members and commissioners of the ACCC.

3. Liberty to apply.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[Redacted version]

BEACH J:

1 This case concerns competition questions involving the ownership and operation of a Queensland rail terminal known as the Acacia Ridge Terminal (ART). It concerns the competition consequences of a vertical merger rather than a horizontal merger and so has engaged economic theory on vertical integrations. The ART is a significant facility in terms of rail linehaul services provided in relevant interstate and Queensland markets. Specifically, the case concerns arrangements between the first respondent, Pacific National Pty Limited (PN P/L), and its related bodies corporate (collectively PN), and the fifth respondent, Aurizon Holdings Limited (AHL), and its related bodies corporate (collectively Aurizon), affecting the supply of intermodal freight and bulk steel rail linehaul services to various end-users for whom transportation by road or sea was not an economically effective substitute. The arrangements that were entered into in July 2017 involved:

(a) the sale of the ART owned by Aurizon to PN;

(b) the granting, so the ACCC says, to PN of operational control of the standard gauge terminal at the ART regardless of whether the ART sale completed; and

(c) exclusive negotiations between PN and Aurizon in relation to the sale of Aurizon’s Queensland intermodal business (QIB), with a subsequent agreement for sale, although that transaction has not proceeded with PN and the QIB has now been sold to Linfox Australia Pty Ltd (Linfox).

2 According to the ACCC, the effect of these arrangements was that Aurizon would cease to provide rail linehaul services and PN would gain control of the ART that new entrants need to use to compete to supply rail linehaul services in Queensland and on relevant interstate routes. According to the ACCC, the effect of the arrangements was that PN would be the only provider of rail linehaul services in Queensland, and one of only two providers of rail linehaul services on relevant interstate routes. In essence, the ACCC alleges that these arrangements were likely to have or would be likely to have the effect of substantially lessening competition in the relevant market(s) in contravention of ss 45(2)(a) and 50 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA).

3 It is said that the harm to competition was both immediate and likely to be enduring. It is said that the closure of Aurizon’s interstate intermodal business (IIB) resulted as a direct consequence of these arrangements. Further, and as a consequence, there are now or are likely to be increased barriers to entry through PN’s control of the ART, which are likely to foreclose the real prospect of new entry in the foreseeable future.

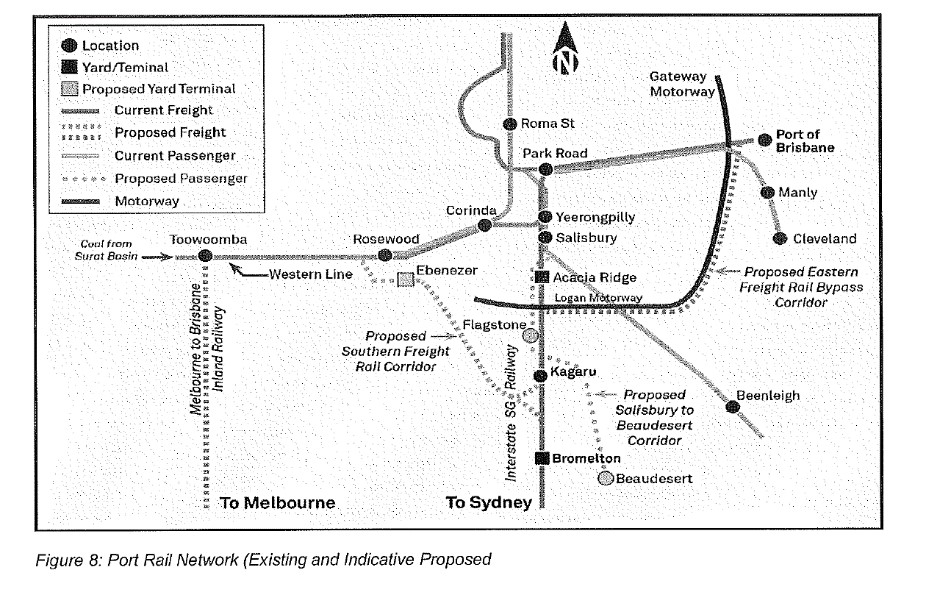

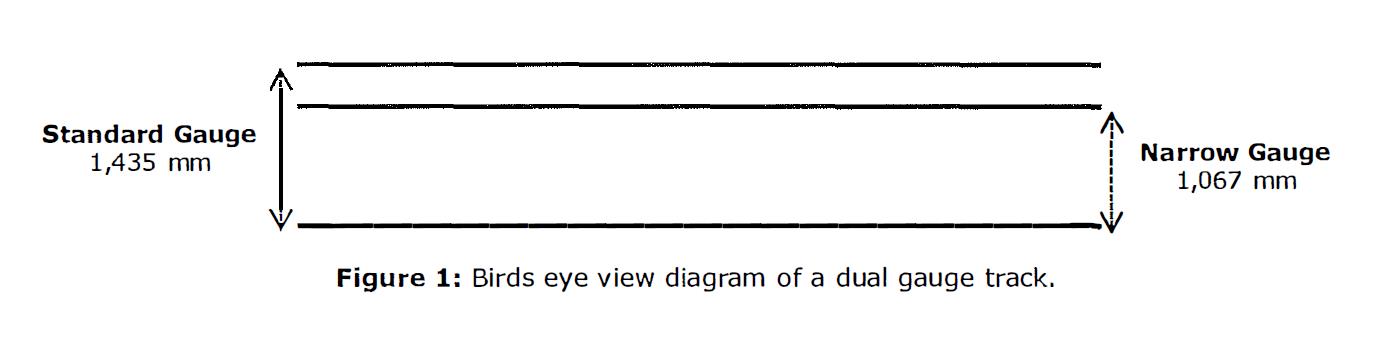

4 Now the ART and its significance is central to these proceedings. Currently, it is owned by Aurizon. It contains two terminals: the Brisbane Multi User Terminal (BMUT), which is connected to the standard gauge network and the Queensland Terminal, which is connected to the narrow gauge network. The ART is not an open access terminal.

5 The ACCC’s case is that the ART is an important strategic asset for a new operator wishing to provide interstate rail linehaul services and within Queensland. On its case, there are no sufficiently viable alternative terminals available that would support new entry on the relevant routes. It is said that this was recognised by both PN and Aurizon in litigation between them about the control of the ART between 2003 and 2006 (Pacific National (ACT) Limited v Queensland Rail [2006] FCA 91). I might say that reference to that authority has not been useful to me in the present case, which needs to be decided on the present evidence concerning a comparison of the likely competition futures with and without either the acquisition of the ART or the alleged infringing provisions of a terminal services subcontract that I will identify in a moment.

6 PN and Aurizon have both used the BMUT as a terminal for their interstate rail linehaul services. But since the closure of Aurizon’s IIB, only PN operates from the BMUT. Aurizon has used the Queensland Terminal for its intrastate rail linehaul operations, and it is intended that the purchaser of the QIB, Linfox, will continue to do so with Aurizon’s assistance.

7 The ACCC says that PN and Aurizon (and now Linfox with Aurizon’s assistance) are the only providers in the market for the supply of rail linehaul services over long distances in Queensland. Further, prior to December 2017 when Aurizon closed its IIB, PN and Aurizon were two of only three providers of rail linehaul services in the market or markets for the supply of such services over long distances between interstate locations, with the other provider being SCT Logistics (SCT). The only providers in relation to such services now are PN and SCT.

8 The background to this present structural position is briefly the following.

9 From April 2017, Aurizon conducted a sale process for the ART, the IIB and the QIB. In May 2017, Aurizon received six non-binding offers for parts or all of that business. It invited PN, Qube Holdings Ltd and three other bidders to make binding bids by 4 August 2017.

10 On 20 July 2017, PN made a pre-emptive binding bid for the ART. Following subsequent negotiations, on 27 July 2017 the boards of PN P/L and AHL each resolved to authorise the entry into of a package of agreements which were then executed on 28 July 2017 including:

(a) a Business Sale Agreement (ART BSA), pursuant to which the sixth respondent (Aurizon Operations) and the seventh respondent (Aurizon Terminal) agreed to sell, and the second respondent (HV Rail) agreed to buy, the ART (ART acquisition);

(b) a Terminal Services Subcontract (TSS) between PN P/L and Aurizon Operations pursuant to which PN P/L was appointed as operator of the BMUT in place of Qube Logistics (Qld) Pty Ltd from 1 December 2018; Qube Logistics (Qld) Pty Ltd at the time had its own terminal services subcontract with Aurizon (Qube TSS); Qube Logistics (Qld) Pty Ltd is a subsidiary of Qube Holdings Ltd; for convenience I will refer to the holding company and/or its subsidiaries as “Qube”;

(c) a Commitment Deed pursuant to which PN P/L was to pay Aurizon Operations a bid bond of $10 million in consideration for Aurizon Operations granting PN P/L exclusive preferred bidder status in relation to the possible sale of the QIB; and

(d) an Agreement for Ongoing Commercial Arrangements (AOCA) between PN P/L and Aurizon Operations under which PN agreed to pay the sum of $30 million.

11 On 11 August 2017, Aurizon Operations and the eighth respondent Aurizon Property Pty Ltd (Aurizon Property), PN P/L and the third and fourth respondents Queensland LH Co Pty Ltd (Queensland LH) and Queensland PUD Co Pty Ltd (Queensland PUD) (being two PN entities) executed a Business Sale Agreement under which the PN entities agreed to acquire the QIB (QIB acquisition) for a payment of $20 million, against which the Commitment Deed payment would be offset.

12 On the same day, Aurizon resolved to close the IIB, and this closure was announced on 14 August 2017. In December 2017, Aurizon closed the IIB.

13 On 12 February 2018 and 15 March 2018, Aurizon announced that it would close the QIB if it was not able to gain ACCC approval for the QIB acquisition. Following the granting of an interlocutory injunction by me on 13 August 2018 requiring Aurizon to continue to operate the QIB (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pacific National Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 1221), Aurizon entered into an agreement to sell the QIB to Linfox.

14 Now the ACCC’s case at the start of the trial had the following elements.

15 First, it was said that PN P/L and AHL had made a contract or arrangement or arrived at an understanding with each other on or about 28 July 2017 (the principal understanding) containing the following provisions:

(a) From at least 1 December 2018, PN would have operational control of the ART including the standard gauge BMUT, by a PN entity acquiring the ART or, if the acquisition did not proceed, by a PN entity being appointed to operate the BMUT, so that a PN entity would have substantive responsibility for and control of the BMUT including responsibility for loading and unloading trains, storing containers, and overseeing and co-ordinating the provision of locomotives to rail operators, and input into future decision making regarding allocation of capacity at the BMUT to other rail operators (the control provision). As consideration, PN would pay to Aurizon $200 million, of which $30 million was a non-refundable upfront payment, and $170 million was payable if PN acquired the ART.

(b) Aurizon would negotiate exclusively with PN in relation to the sale of Aurizon’s QIB for a defined exclusivity period, in return for PN paying a substantial fee, refundable only in limited circumstances (the exclusivity provision).

(c) If the QIB was not acquired by PN, Aurizon would cease to provide rail linehaul services in the market for the supply of the relevant services over long distances in Queensland and would close the QIB (the QIB provision).

16 It was said that each of these provisions had the purpose, or would be likely to have the effect, of substantially lessening competition in one or more markets for the supply of rail linehaul services between relevant interstate locations to end users for whom road services or sea services were not adequate substitutes (Interstate markets) or within Queensland (Queensland market) and that each of PN and Aurizon had thereby contravened s 45(2)(a)(ii) (as then in force).

17 Second, it was said that each of the respondents had contravened s 45(2)(b)(ii) (as then in force) and s 45(1)(b) (as currently in force) by giving effect to one or more of the said provisions of the principal understanding.

18 Third, it was said that by entering into the TSS relating to the BMUT on 28 July 2017, PN P/L and Aurizon Operations had made a contract containing provisions that had the purpose, or would be likely to have the effect, of substantially lessening competition in each of the Queensland market and Interstate markets in contravention of s 45(2)(a)(ii) (as then in force). Further, it was said that AHL was knowingly concerned in Aurizon Operations’ contravention of s 45(2)(a)(ii) (as then in force).

19 Fourth, it was said that the acquisition by HV Rail of the ART whether pursuant to the ART BSA or otherwise, would contravene s 50 because it would be likely to have the effect of substantially lessening competition in each of the Queensland market and Interstate markets.

20 But towards the end of the trial, the ACCC abandoned its case concerning the making of and the giving effect to the principal understanding. Further, in relation to its case concerning the TSS, it abandoned the purposive element of its s 45(2)(a)(ii) case and now only relies upon the effect or likely effect aspect. Further, it has abandoned its case concerning the giving effect to the TSS. Accordingly, all that needs to be considered for present purposes is the s 45(2)(a)(ii) case concerning the making of the TSS relating to its effect or likely effect including the accessorial case, and the s 50 case concerning the ART acquisition.

21 Let me now summarise the case that the ACCC closed with.

22 The ACCC says that PN as the proposed owner of the ART and operator of the BMUT will be or is likely to be the dominant supplier of rail linehaul services on the North-South and East-West interstate routes and one of two suppliers on the North Coast Line (NCL). I will elaborate later on what I precisely mean by the interstate routes and the NCL.

23 In the future in which PN acquires the ART, PN will own the only terminal that a new entrant rail operator needs to use to economically supply rail linehaul services to, from or within Queensland. It is said that PN’s control of the ART would allow PN to limit or deny access to the ART by competing rail operators.

24 In the alternative, where there is no ART acquisition but the TSS is in force, PN will have substantial operational control of the BMUT, being the only terminal which a new entrant rail operator could economically use to supply rail linehaul services on interstate routes that begin or end in Queensland. It is said that this control would allow PN to provide services to a potential new entrant in a way that would place that entrant at further substantial competitive disadvantage to PN.

25 Further, in both scenarios it is said that PN will have, and be reasonably perceived by new entrants to have, the ability and incentive to discriminate against a potential new entrant. The ACCC says that in acquiring the ART, or operating the BMUT under the TSS, PN will gain the ability and have the commercial incentive to deter others from entering and commencing the supply of rail linehaul services, thereby materially raising barriers to entry. Accordingly in the future with the ART acquisition or the TSS, the ACCC says that it is highly unlikely that a potential new entrant would commence operating rail linehaul services on any interstate route.

26 But contrastingly, the ACCC says that in the future without the ART acquisition and the TSS, neither the ART nor the BMUT will be controlled by PN, barriers to entry will not be increased, and there is a real chance that Qube or another potential new entrant will commence supplying rail linehaul services on interstate routes in competition with PN.

27 Let me elaborate further on the ACCC’s case concerning the ART acquisition and its s 50 case.

28 The ACCC says that the ART acquisition would or is likely to substantially lessen competition in contravention of s 50.

29 The ACCC says that PN’s ownership of the ART and the control that it will confer will materially increase barriers to entry. Potential new entrants who might otherwise consider commencing supply of rail linehaul services will either know that PN will have the ability and commercial incentive to use its control of the ART to deter others from entering the relevant market(s) or reasonably perceive that to be the case. Potential new entrants will know that the ART is very different to other terminals in Australia. The ACCC says that unlike the position in Melbourne and Sydney, the ART does not face competition from other interstate intermodal terminals in Queensland. Potential new entrants will know that without access to the ART they cannot sustainably commence operating rail linehaul services on any interstate route in the foreseeable future. Further, the ACCC also says that potential new entrants’ reasonable perceptions of PN’s ability and incentive will have the effect of deterring those potential new entrants from making the substantial investment required to commence supplying rail linehaul services.

30 Further, not only does the ACCC say that the consequence of PN’s ownership of the ART is that it is highly unlikely that any new entrant will commence supplying rail linehaul services on any interstate route beginning or ending in Queensland, but it says that the best evidence of that is that Qube says it will not enter if PN owns the ART. Accordingly it says that if a well-resourced, experienced operator like Qube will not enter in these circumstances, it is highly unlikely that other potential new entrants will consider doing so. I will discuss in detail later the probative value and reliability of Qube’s evidence on this aspect.

31 Further, the ACCC says that there are some beneficial freight owners (BFOs) or freight forwarders acting on their behalf who acquire rail linehaul services over long distances, and for whom road services provided for intermodal freight and bulk steel linehaul (road services) or sea services provided for intermodal freight and bulk steel linehaul (sea services) do not provide an effective substitute (relevant users). For the purposes of my reasons, the term “relevant users” includes freight forwarders because freight forwarders stand in the market effectively on behalf of BFOs who are relevant users. And if a freight forwarder has no effective substitute for the use of rail linehaul services, this may reflect the fact that the BFO for whom they are arranging transport has no such substitute. So, and to be clear, references to freight forwarders as relevant users are references to those freight forwarders in their capacity as an intermediary acting on behalf of a BFO, and such relevant users that are not BFOs but are freight forwarders in this respect include Austrans, K&S and McColl’s.

32 In respect of the relevant users, the ACCC says that a new entrant seeking to commence supplying rail linehaul services on an interstate route would be one of only two competitors to PN (the other being SCT) for the supply of such services on interstate routes. It says that increasing the barriers to entry would preclude such new entry and therefore leave those relevant users with only two potential suppliers of rail linehaul services on interstate routes being PN and SCT, with PN the dominant supplier.

33 Now the respondents in summary have raised four matters in response to the ACCC’s s 50 case, including rebutting the suggestion that potential entrants might be deterred from entering if the ART acquisition proceeds.

34 First, the respondents say that the ACCC’s market definitions confining the markets to relevant users are not justifiable economically or supported by the evidence. Further, on the respondents’ market definition there is no material competition or likely competition differences in the future with the ART acquisition as compared with the future without the ART acquisition. Therefore, so the respondents say, the ACCC case fails at that point. I would note that the respondents contend that for a market to be defined not only by the usual dimensions of product, functional level and geography but also by a subset of end users, economic theory requires the two Hausman pre-conditions to be satisfied, that is, the likely potential for feasible price discrimination between end users and no profitable arbitrage opportunity available between end users; what this all means will become apparent later.

35 Second, the respondents say that PN would have no ability to discriminate given the form of undertaking that it now offers to the Court. But the ACCC says that that view is not shared by Qube or supported by Dr Kuypers, the ACCC’s expert witness, and would not be shared by potential new entrants.

36 Third, the respondents say that PN would not discriminate or be likely to do so. On their case, if PN did so it would breach s 46. But the ACCC says that that contention is commercially unrealistic, is not supported by any evidence, and is not supported by any available construction of s 46. Further, the ACCC says that the evidence establishes that in the highly complex operations of an intermodal terminal, a terminal operator routinely makes a number of individual decisions that could have a discriminatory effect on another rail operator. And in many cases, decisions of that nature would be almost impossible to detect or prove in terms of a s 46 breach or otherwise.

37 Further, the ACCC says that the respondents’ position on these matters fails to take into account that the co-ordinational complexities of a multi-user terminal offer ample opportunities for differential treatment of users by a terminal owner or operator. Those complexities require the terminal owner to make decisions on a day to day basis about the operation of the terminal. At the same time this creates material difficulty for any user of the terminal in detecting or establishing the causes of, or the terminal operator’s reasons for, decisions leading to such differential treatment. The ACCC says that these matters would be understood or reasonably perceived by a potential new entrant as creating an insurmountable risk to investing its capital and reputation in a new intermodal business.

38 Fourth, the respondents say that PN is unlikely to have an incentive to discriminate because a new entrant would not gain [Redacted] or more of its business in competition with PN. But the ACCC says that in circumstances where PN is the dominant supplier of rail linehaul services on interstate routes, it is highly unlikely, and PN could have no certainty, that less than that percentage of a new entrant’s business would be won in competition with PN. Therefore, so the ACCC says, it is commercially implausible to suggest that PN would refrain from discriminating on this basis, or that a potential new entrant might perceive that it would so refrain.

39 Generally, the ACCC says that if PN did not acquire the ART, the heightened barriers to entry brought about by PN’s ownership and control of the ART would not exist. Potential new entrants seeking to supply rail linehaul services in the Interstate markets using the ART would not confront PN’s ownership and control of that essential asset. They would have the opportunity to enter such markets if it were profitable for them to do so, and using the ART under the ownership of Aurizon, Qube or a third party owner which was not the dominant supplier of rail linehaul services as PN is.

40 Let me now turn to the other part of the ACCC’s case concerning its assertion that the entry into of the TSS contravened s 45. The TSS contains provisions under which PN has been appointed to carry out certain services relating to the BMUT and granted associated rights.

41 There are two aspects to the ACCC’s case.

42 The first aspect of the ACCC’s case is that it says that the entry into of the TSS creates barriers to new entry, and gives rise to the same types of issues that I have just referred to in relation to the ART acquisition. The ACCC says that the appointment of PN to provide services under the TSS puts PN, the dominant supplier of rail linehaul services on the interstate routes, in substantial control of operations at the BMUT, in circumstances where PN stands to lose business to any new entrant which might commence supplying those rail linehaul services in competition with it. According to the ACCC, PN will have, and will be reasonably perceived by a new entrant to have, the ability and incentive to use its position under the TSS to deter new entry. Moreover, potential entrants’ perception of that fact will deter them from entering. The ACCC says that the best evidence of this is Qube’s evidence that it will not enter if PN controls the ART under the TSS. And the ACCC says that if Qube will not enter, it is highly likely that no other potential entrants will do so either.

43 Now I would note at this point that I have received considerable evidence regarding the proper interpretation of the TSS. This includes assertions from witnesses who claim to be closely familiar with the BMUT as to how they say that the TSS will operate. But the interpretation of the TSS is a matter for me. But in approaching that task, I am entitled to have and have had regard to the commercial and operational context in which the TSS is to be applied. That context has informed me on matters such as the extent to which the TSS addresses, or fails to address, the types of opportunities for discrimination that are said by the ACCC to arise as a result of the complex workings of an intermodal terminal. But of course that context cannot be used to contradict the words chosen by the parties to express the terms of the TSS, nor to narrow the scope of the TSS to become something less than that expressed in the document executed by the parties. Now I also accept that a proper commercial interpretation of the particular terms of the TSS only determines the question whether the TSS does objectively confer on PN the ability to discriminate against new entrants. It does not necessarily determine the question as to whether new entrants will perceive that PN will, by means of its appointment under the TSS, have the ability and incentive to discriminate against them. And in this respect the ACCC relies on the evidence of the Qube witnesses, with Qube being a potential new entrant. It is said that Qube is in an atypical position in that it has had the opportunity to review the terms of the TSS which would normally remain confidential as between PN and Aurizon. But having done so, Qube has determined that it would not commence providing rail linehaul services whilst the TSS is in place. Now another new entrant would not have the opportunity to scrutinise the TSS. They would have to make their decisions based on the knowledge that Qube had been replaced by PN as the operator of the BMUT. So, they would not know the particular terms of the TSS. And they would not know PN’s views as to how the TSS would operate in practice. But the ACCC says that such a new entrant could be expected to reach at least the same conclusion as Qube, which is that PN as operator of the BMUT would have the ability and incentive to discriminate against them.

44 Accordingly, so the ACCC says, the consequence of PN’s operation of the BMUT under the TSS is that a potential new entrant would be highly unlikely to commence supplying rail linehaul services on the relevant routes.

45 The second aspect of the ACCC’s case concerning the TSS is that the entry into of the TSS on 28 July 2017 brought Aurizon’s sale process to an end, and on the ACCC’s case gave operational control of the ART to PN. It is said that this result then precluded potential purchasers of Aurizon’s QIB and IIB from acquiring those businesses. Consequently, as at 28 July 2017, the QIB was likely to be shut down if it was not sold to PN. And it says that this would have occurred had I not restrained Aurizon from giving effect to its plan to close the QIB. The ACCC also says that as at 28 July 2017 the IIB was likely to be shut down because there was no bidder who was likely to acquire it on a standalone basis.

46 Accordingly, so the ACCC says, without entry into of the TSS the sale process would have likely continued, and there would have been a real chance that a participant in the sale process other than PN would have acquired the ART, the IIB and/or the QIB, and commenced supplying rail linehaul services on interstate routes and in Queensland. Further, it says that even if the acquirer did not commence supplying these services, barriers to entry in the relevant markets would have been reduced by reason of the new ART owner having a strong incentive to earn revenue from providing open access to the ART, unlike PN.

47 For the reasons that follow, the ACCC has not established its s 45 case. As to its s 50 case, it would have established its case in the absence of an undertaking. But a suitable undertaking has now been offered to the Court.

48 As to the ACCC’s case concerning the TSS and the alleged contravention of s 45(2)(a) (as then in force), it has not made out its case and the relevant claims will be dismissed. The first aspect of its case concerning the TSS is not made good on my analysis of the relevant provisions of the TSS, and particularly with Aurizon (or a non-PN entity) owning the ART, that is, on the scenario of the future without the ART acquisition. Moreover, in my view the ACCC has not on the evidence been able to succeed based upon the perceptions of Qube or any other new entrant. The second aspect of its case concerning the TSS fails because of an impermissible causation analysis that is not justified by the proper approach to s 45(2)(a) (as then in force). But even if such a causation analysis was permissible, it fails in any event.

49 As to the ACCC’s case concerning the ART acquisition and the alleged contravention of s 50, but for PN’s new undertaking given to the Court unconditionally on the last day of the trial, which is now to be considered as part of the future with the ART acquisition scenario, the ACCC would have made good its case. But with the undertaking now given unconditionally, no contravention of s 50 is established with the undertaking, which I accept.

50 For convenience, I have divided my reasons into the following sections:

(a) The relevant transactions ([51] to [80]);

(b) Some relevant concepts ([81] to [143]);

(c) Market definition – Primary facts ([144] to [368]);

(d) Market definition – Secondary analysis ([369] to [537]);

(e) The ART ([538] to [753]);

(f) Lay witnesses – reliability ([754] to [774]);

(g) Discrimination – Ability and incentive ([775] to [937]);

(h) The prospect of new entry ([938] to [1005]);

(i) The TSS – Section 45(2)(a) ([1006] to [1252]);

(j) ART acquisition – Section 50 ([1253] to [1426]);

(k) Proposed undertaking ([1427] to [1609]);

(l) Conclusion ([1610] to [1613]).

THE RELEVANT TRANSACTIONS

51 At this point let me recount some of the background relevant to the transactions under consideration.

52 In February 2017, Aurizon initiated Project Eyre, being an assessment of market interest in the sale or shutdown of, or joint venture to own and operate, its intermodal business including the ART, the QIB and the IIB.

53 On or about 20 March 2017, Aurizon prepared a plan for the sale of its intermodal business and assets titled “Project Eyre – Soft Market Testing – Logistics Plan”. The document identified key target bidders, and stated that the target bidders had been identified by Aurizon and UBS taking into account previous expressions of interest, likely and credible interest in a whole of business acquisition or joint venture, and competitive and ACCC considerations. PN was not identified as a target bidder, but was identified as one of a number of parties whose inclusion was to be discussed “post first phase of soft market testing”, including a face to face meeting proposed for early April.

54 Aurizon’s preference was for a “clean” exit from the whole of its intermodal business. In an internal strategy submission dated 4 April 2017 for provision to the Aurizon Executive Committee on 11 April 2017, Aurizon referred to PN as one of the bidders who had not been prioritised due to Aurizon’s preference for a “whole of business solution”. The report included the following statements concerning PN:

(a) “very interested in participating in [the] process”;

(b) “strong interest in parts of business, included stating preparedness to pay an amount “approaching total Intermodal book value [$177m] for Acacia Ridge””; and

(c) “proposed to receive an [information memorandum] allowing them to put forward bid on terminals and QLD business”.

55 In April 2017, Aurizon provided an information memorandum to PN and other parties in respect of the whole or parts of its intermodal business, a version of which is in evidence and was received inter-alia by Qube on or about 13 April 2017.

56 Throughout April 2017, there was continued engagement between Aurizon and PN. In an email from Mr George Lippiatt, head of strategy and corporate development at AHL, to Mr Andrew Harding, managing director and chief executive officer of AHL, on 5 April 2017, Mr Lippiatt provided Mr Harding with “talking points” for upcoming meetings with PN. The email recorded that:

(a) Global Infrastructure Partners (GIP) (a PN shareholder) had made several approaches to Aurizon and UBS over the previous two months “driven by interest in Acacia Ridge and concern about sale of Aurizon Intermodal maintaining the current 3 player market”;

(b) GIP “believe they could likely acquire majority of business if Aurizon made decision to shut down (i.e. PN/GIP want to incentivise us to exit market rather than sell”;

(c) Aurizon’s focus was on a “whole of business transaction”;

(d) Aurizon intended to “bring [PN] into the process in April so they can bid on Acacia Ridge/Forrestfield and QLD”, but “remains focused on whole of business transaction – our preference remains to consider a whole of business sale, and for that reason we won’t contemplate a decision to shut down/break-up until we’ve finalised our strategic process and sale process”; and

(e) “based on our work we believe PN could value component parts of the business at a value that exceeds that of the whole”.

57 On 28 April 2017, UBS, on behalf of Aurizon Operations, wrote to PN inviting it to put forward an indicative proposal for Aurizon’s intermodal business. The invitation recorded Aurizon’s preference for a “clean whole of business exit through the Sale Process” and that any proposal received from PN would be considered against criteria that (inter alia) it “provides a clean exit and whole of business solution for Aurizon Intermodal, either by itself or when combined with other actions or proposals”.

58 On or about 2 May 2017, representatives of PN expressed interest to representatives of Aurizon in acquiring the ART and the QIB and confirmed that PN would not seek to acquire the IIB.

59 On 9 May 2017, Mr Robert Stewart (a director of PN and managing partner of GIP) recorded in an internal email to GIP that:

(a) GIP and PN had been “interacting with Aurizon [about the Aurizon business and the fact that it is losing money] since they announced their review”;

(b) Aurizon was “focused on two preferred options for the business”:

(i) “sale of business as a whole (complicated because it loses money)”;

(ii) “[d]ivestment of pieces and shut-down of the balance of the business”;

(c) PN was seeking to “assist Aurizon in a “sale of pieces and shut-down” scenario”.

60 On 12 May 2017, Qube lodged a non-binding indicative proposal to acquire the entirety of the intermodal business for $240 million excluding certain land at Aurizon’s Forrestfield site in Western Australia.

61 On 16 May 2017, PN submitted an indicative proposal to acquire the ART and the QIB for $175 million and to provide Aurizon with haulage services for its interstate customers in the event the IIB was shut down.

62 By mid-May 2017, Aurizon had received six nonbinding indicative bids in respect of the intermodal business:

(a) two indicative offers from Qube and Oaktree for the whole of the intermodal business, including the ART, the QIB and the IIB;

(b) two indicative offers from Genesee & Wyoming and PN for the QIB and ART only; and

(c) two indicative offers from the Australian Rail Track Corporation (ARTC) and Charter Hall for the ART.

63 On 25 May 2017, Mr Lippiatt presented a board paper to the AHL board of directors dated 22 May 2017 titled “Submission No: S17 – 529 for Decision, Title: Freight Review Outcomes: Intermodal” which recommended that the AHL board of directors resolve to move forward with four participants in the sale process (Qube, PN, Genesee & Wyoming and the ARTC), with binding bids to be received by August 2017.

64 On 19 June 2017, UBS sent letters on behalf of Aurizon Operations to PN, Qube and the ARTC inviting them to make binding bids in respect of the intermodal business by 4 August 2017.

65 On 17 July 2017, in a meeting between representatives of Qube, Aurizon and UBS, Mr John Digney of Qube stated that although Qube remained an interested bidder and was intending to submit a binding bid, the intermodal business may only be worth around $165 million.

66 On 20 July 2017, PN made Aurizon a binding offer to acquire the ART. The offer did not include a bid for the QIB, but stated that PN was “confident that it will be in a position to provide an offer for [the QIB] by Friday 4 August 2017”.

67 From 21 July 2017, Aurizon and PN engaged in negotiations in relation to the possible sale of the ART by Aurizon to PN. In negotiating the terms of that sale, the parties negotiated the terms of a package of draft documents which comprised draft versions of each of the transaction documents, which I have referred to earlier and also below.

68 In the period from or about 25 July 2017, the board of each of AHL and PN P/L considered the arrangements contemplated by those draft documents.

69 In a board paper dated 25 July 2017 titled “Submission No: S17-576 for Decision, Title: Project Eyre – Progress Update”, the management of AHL recommended that the board of AHL should resolve:

(a) to accept the PN P/L offer for the ART and to delegate authority to the managing director and the chief executive officer to finalise and execute binding transaction documents on the terms proposed by PN P/L; and

(b) that if AHL did not receive binding offers for the IIB and the QIB by 4 August 2017, the IIB and the QIB should be shut down.

70 On 27 July 2017, AHL’s board held a meeting, at which the board noted management’s recommendation in a board paper dated 27 July 2017 titled “Submission No: S17-616 for Decision, Title: Project Eyre – PN Acacia Ridge Binding Offer”. The recommendation was to shut down the QIB and the IIB unless Aurizon received an acceptable offer for the intermodal business. AHL’s board resolved to consider all options including shutdown of the IIB on 11 August 2017 in light of any binding offer from PN for the QIB. AHL’s board also resolved:

(a) to accept the PN P/L binding offer (as subsequently negotiated) for the ART; and

(b) to approve the delegation of authority to certain Aurizon executives to execute the transaction documents described below.

71 On 27 July 2017, PN P/L’s board resolved:

(a) to delegate to a sub-committee the approval of the bid price related to the ART and a “commitment deed” in relation to the QIB, and any subsequent changes to that bid price, which price was to be up to a maximum of $230 million in proceeds to the vendor, excluding stamp duty and transaction costs; and

(b) to authorise any member of the sub-committee to execute agreements related to the ART and the said Commitment Deed in accordance with the bid price approved by the sub-committee.

72 On 28 July 2017, Aurizon and PN entered into the following agreements:

(a) the ART BSA;

(b) an AOCA that I have referred to earlier;

(c) the Commitment Deed; and

(d) the TSS.

73 As I have said, the ART BSA was a written agreement entered into between Aurizon Operations, Aurizon Terminal, HV Rail and PN P/L, which took effect on 28 July 2017. Under the ART BSA, Aurizon Operations and Aurizon Terminal agreed to sell, and HV Rail agreed to buy, on the terms set out therein, the business comprising the operation of the ART and the leasing of the freehold premises on which the ART was located, and assets associated with that business, for a purchase price of $170 million, as adjusted in accordance with the terms of the ART BSA. The ART BSA has not been terminated, and remains in effect. The completion of PN’s acquisition of the ART in accordance with the ART BSA, that I have referred to as the ART acquisition, is subject to the satisfaction or waiver of certain conditions, including a condition that PN P/L have received competition clearance for the ART acquisition by a particular date, which can be waived by all parties and by any one of several means identified in the ART BSA, including competition clearance from me. Clause 5.1(a)(i) provides as follows:

5.1 Conditions Precedent

(a) Regulatory approvals

Subject to clause 5.4(a), the obligations of the parties with respect to Completion are conditional on the satisfaction or waiver in accordance with clause 5.2 of the following regulatory conditions:

(i) (Competition law) the occurrence of one of the following events:

(A) the Buyer has received, by the End Date, competition clearance for the acquisition of the Business and the Assets whether by way of:

(aa) written notification from the Australian Consumer and Competition Commission (ACCC) to the effect that either:

(a) based on the information provided by the Buyer to the ACCC, the ACCC does not propose to intervene in the acquisition by the Buyer of the Business and the Assets pursuant to section 50 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (whether or not the notification also states that the ACCC reserves its position if other material information emerges); or

(b) based on the information provided by the Buyer to the ACCC and the acceptance by the ACCC of written undertakings provided or agreed to be provided to the ACCC, the ACCC does not propose to intervene in the acquisition by the Buyer of the Business and the Assets pursuant to section 50 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (whether or not the notification also states that the ACCC reserves its position if other material information emerges);

(bb) authorisation of the acquisition of the Business and the Assets is granted by the Australian Competition Tribunal under Part VII of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) and no application has been for judicial review of the decision of the Tribunal within the prescribed period; or

(cc) the Federal Court of Australia declared or makes orders to the effect that the acquisition of the Business and the Assets by the Buyer will not contravene section 50 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth);

(a Competition Clearance); or

(B) either party has received, within 10 Business Days prior to the End Date, written notice from the other party that that party considers that the acquisition by the Buyer of the Business and the Assets will not contravene section 50 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth).

74 Let me say something further concerning the AOCA and the other agreements. The AOCA was a written agreement between Aurizon Operations and PN P/L, which took effect on 28 July 2017. Pursuant to cl 3 of the AOCA, PN P/L was to pay Aurizon Operations $30 million within 7 days of 28 July 2017 subject relevantly to PN P/L and Aurizon Operations entering into a TSS in the form contained in schedule 2 to the AOCA within 7 days of 28 July 2017. According to the ACCC, the payment of $30 million was intended and understood by Aurizon and PN to operate as a non-refundable “break fee” regarding PN’s acquisition of the ART.

75 The Commitment Deed was a written agreement between Aurizon Operations and PN P/L which took effect on 28 July 2017. Pursuant to cl 4.1 of the Commitment Deed, PN P/L was to pay Aurizon Operations a bid bond of $10 million within 7 days of the commencement of the Commitment Deed, in consideration of Aurizon Operations negotiating with PN P/L in relation to the possible sale of the QIB on an exclusive basis for a period of up to 14 days in accordance with the term of that Deed. Pursuant to cl 4 of the Commitment Deed, the bid bond of $10 million was not refundable, except in limited circumstances.

76 The TSS was a written contract or arrangement between PN P/L and Aurizon Operations, which took effect on 28 July 2017. The terms of the TSS were substantially the same as the terms set out in schedule 2 to the AOCA, and PN P/L and Aurizon Operations entered into the TSS pursuant to cl 3 of the AOCA.

77 On or about 28 July 2017:

(a) PN P/L paid $30 million to Aurizon Operations pursuant to clause 3 of the AOCA, and Aurizon Operations accepted that payment; and

(b) PN P/L paid $10 million to Aurizon Operations pursuant to cl 4.1 of the Commitment Deed, and Aurizon Operations accepted that payment.

78 Between 28 July 2017 and 11 August 2017, pursuant to cl 4.1 of the Commitment Deed, PN and Aurizon exclusively negotiated the terms on which PN would acquire the QIB from Aurizon. On 11 August 2017, Aurizon Operations, Aurizon Property, Queensland LH, Queensland PUD and PN P/L entered into a written agreement titled “Business Sale Agreement” (the QIB BSA), which took effect on 11 August 2017. Pursuant to cl 2.1 of the QIB BSA, Aurizon Operations and Aurizon Property agreed to sell the QIB to Queensland LH and Queensland PUD in accordance with the terms of the QIB BSA.

79 Following the entry into of the above arrangements:

(a) on 11 August 2017, a sub-committee of the board of AHL, comprising Mr Timothy Poole, Chairman of AHL, and Mr Harding, resolved to shut down the IIB;

(b) on 14 August 2017, AHL announced to the ASX that it would close the IIB; and

(c) in December 2017, Aurizon closed the IIB.

80 On 12 February 2018 and 15 March 2018, Aurizon announced that it would close the QIB if it was not able to gain ACCC approval for the QIB acquisition by PN. Such approval was not forthcoming and accordingly the QIB acquisition by PN did not proceed. Given that Aurizon threatened to close the QIB in such circumstances, on 18 July 2018 the ACCC applied for an interlocutory injunction seeking to prevent the closure of the QIB, which injunction I granted on 13 August 2018 as I have already said. The QIB has since been sold to Linfox.

SOME RELEVANT CONCEPTS

81 Let me at this point say something concerning market definition, competition and barriers to entry by way of introduction only before I get into the evidence relevant to the application of these concepts. An appreciation of the detailed evidence that I will later lay out will be facilitated by setting out this conceptual framework at the outset. I will discuss more focused legal issues relating to ss 45 and 50 later in my reasons.

(a) Market definition

82 The following general propositions do not appear to be in doubt. Let me begin by distinguishing the use of “market” as a concept from its use as something more tangible such as the sphere of actual or potential rivalry between traders.

83 First, at a conceptual level a market is an economic tool used to analyse asserted anti-competitive conduct. It is a conceptual framework to analyse competitive processes and market power. But it is to be used and applied having regard to the text and context of the statutory provision which gives rise to the relevant inquiry in the first place. If the question is whether conduct is caught by a particular statutory provision, the concept of a market must be informed by the context in which the question is posed (Air New Zealand Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2017) 262 CLR 207 (Air New Zealand) at [57], [58] and [62] per Gordon J).

84 Second, so to accept context and the reason why one is posing the question in the first place is not to deny that a detailed examination of the facts are all important when dealing with questions of market definition. As Nettle J said in Air New Zealand Ltd at [39], market definition involves a fact intensive exercise centred on the commercial realities of the market and competition citing EI de Pont de Nemours and Co v Kolon Industries Inc 637 F 3d 435 at 442 (4th Cir, 2011).

85 Third, as McHugh J said in Boral Besser Masonry Ltd v Australian Competition & Consumer Commission (2003) 215 CLR 374 (Boral Besser) at [247]:

Section 4E does not define what a market is for the purposes of the Act. But it makes clear that the parameters of the market are governed by the concepts of substitution and competition. The inclusion of the terms “substitutable” and “competitive with” in s 4E also means that market definition must be determined in accordance with economic principles. The terms of the Act have economic content and their application to the facts of a case combines legal and economic analysis. Their effect can only be understood if economic theory and writings are considered.

(Citations omitted.)

86 Fourth, there is no one correct answer to market definition. As was pointed out by McHugh ACJ, Gummow, Callinan and Heydon JJ in NT Power Generation Pty Ltd v Power and Water Authority (2004) 219 CLR 90 at [68]:

The Act is seeking to advance the broad goal of promoting competition. Certain provisions of the Act, particularly in Pt IV, necessarily turn to a significant degree on expressions which are not precise or formally exact. One example is “market”: there can be overlapping markets with blurred limits and disagreements between bona fide and reasonable experts about their definition, as in this case. Other examples are “substantial”, “competition”, “arrangement”, “understanding”, “purpose” and “reason” (which need only be a “substantial” purpose or reason: s 4F). It is not appropriate to subject the application of this type of legislation to a process of anatomising, filleting and dissecting in the fashion advocated by PAWA.

(Citation omitted.)

87 Fifth, to be competitors, parties must be rivals or constrain each other in respect of the relevant acquisition or supply of goods or services. Parties constrain each other if they supply substitutable goods or services to the same class of customers or if they would do so given a sufficient price incentive (Re Queensland Co-operative Milling Association Ltd (1976) 8 ALR 481 (QCMA) at 517). The sphere of that actual or potential rivalry or what has been described as competition is sometimes referred to as the market; see generally Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Flight Centre Travel Group Pty Ltd (2016) 261 CLR 203 (Flight Centre Travel) at [66] to [70] per Kiefel and Gageler JJ. Indeed, to have relevant rivalry in relation to relevant goods or services, including their ready substitutes on the demand side and on the supply side, whether in terms of their type or supply source and depending upon the cross-elasticity of demand and the cross-elasticity of supply, presupposes the context in which such rivalry occurs. The rivalry is not in the ether. The space where it occurs is usually given the label of “market”. Its dimensions are also geographic (the geographic area of supply and acquisition), functional (the level of the distribution chain at which the supply and acquisition occurs) and temporal but with one qualification. If one is talking about the temporal aspect, one is usually referring to the long run anyway in assessing substitution possibilities on either the demand side or the supply side, with any shorter timeframe moving into the realm of a conceptual discussion of sub-markets as QCMA explains.

88 Sixth, let me at this point say something more on the question of substitutability.

89 The product and geographic boundaries of a market are partly defined by considering the products and geographic sources of supply that are substitutable for the relevant good or service in question (s 4E).

90 Substitution may occur on the demand side or on the supply side. And substitutability itself is a question of degree. Demand side substitution occurs where buyers will switch their patronage from one firm’s product to another, or from one geographic source of supply to another, if given a sufficient price incentive. Supply side substitution occurs where sellers adjust their production plans in response to a sufficient price incentive, substituting one product for another in their output mix, or substituting one geographic source of supply for another. And the greater the degree of substitutability on the demand side or the supply side the greater the degree of competition between the suppliers of the relevant goods or services.

91 The “hypothetical monopolist” test or what is sometimes known as the “SSNIP” test can be used to assess substitution possibilities on the demand side. The question posed is whether a hypothetical monopolist supplier could profitably impose a small but significant non-transitory increase in price (so the SSNIP acronym) say between 5-10%, for the supply of the relevant product or service, but holding constant the terms of sale of all other products and services. The SSNIP being considered is relative to the prices that would prevail but for the merger. The thought experiment, whether built upon detailed data of the relevant variables or assessed more qualitatively, starts with the hypothetical monopolist supplier and the product or service in issue to define the product and geographic market; the test does not assist concerning defining the functional dimension. The question is then posed as to whether a SSNIP could be profitably imposed. If not, the next best substitute on the demand side is added to the market definition. The new market is then tested with the SSNIP test. If a SSNIP could be profitably imposed, then you have your market definition. If not, you again add the next best substitute to your market definition and test again, and so on. The idea is to find the smallest area (product and geographic) over which the hypothetical monopoly supplier can impose the SSNIP which then provides the boundaries of the market as Yates J discusses in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Metcash Trading Ltd (2011) 198 FCR 297 at [247] to [251].

92 But it should go without saying that the hypothetical monopolist test or SSNIP test is only a conceptual aid to assist in market definition, nothing more. And as I say, it is a test looking at demand side (product or geographic) substitutability rather than supply-side substitutability.

93 Further, the functional dimensions of a supply chain are generally considered to be economic complements rather than substitutes. Where a firm that is not vertically integrated engages in significant transactions at a particular level of the supply chain (e.g. manufacture, wholesale or retail), that level will ordinarily constitute a separate functional level of the market.

94 Finally on this aspect, it is not in doubt that although s 4E refers to substitutability, it is not necessarily the defining feature for identifying a market, as Kiefel CJ, Bell and Keane JJ said in Air New Zealand, in analysing QCMA, at [25] and [26]:

The Tribunal did not say that substitutability will be the defining feature of a market in every case…

This is not to suggest that substitutability may not be an important, or even a decisive, factor in market definition in some cases, just as barriers to entry may be. It is rather that concepts such as market and cross-elasticity of supply and demand provide no complete solution to the definition of a market, as Dawson J observed in Queensland Wire Industries. Much will depend upon the context in which the question arises. The exercise of market definition needs to take into account the conduct in question and its effects, and the statutory terms governing the question.

(Original emphasis; citations omitted.)

95 Seventh, the definition of a market does not require satisfaction of any size, value or other de minimis threshold. There may be both a wider and a narrower area of rivalry. But if the narrower area itself constitutes a market, then it is power and conduct in that area that is to be examined. So, provided that the identified area of rivalry is not trivial, a market can be identified.

96 Eighth, as McHugh J pointed out, the “views and practices of those within the industry are often most instructive on the question of achieving a realistic definition of the market” (Boral Besser at [257]). And in this regard, as he said, the “internal documents and papers of firms within the industry and who they perceive to be their competitors and whose conduct they seek to counter is always relevant to the question of market definition”. So, what market actors do or do not do can inform market definition. Further, what market actors perceive others to be doing or not doing or what they could do, which perceptions may inform their own actions, can also inform the question of market definition.

97 Ninth, not only is there no one correct answer to market definition as I have said, but as Deane J in Queensland Wire Industries Pty Ltd v Broken Hill Proprietary Co Ltd (1989) 167 CLR 177 (Queensland Wire) at 196 explained:

…The economy is not divided into an identifiable number of discrete markets into one or other of which all trading activities can be neatly fitted. One overall market may overlap other markets and contain more narrowly defined markets which may, in their turn, overlap, the one with one or more others. The outer limits (including geographic confines) of a particular market are likely to be blurred: their definition will commonly involve assessment of the relative weight to be given to competing considerations in relation to questions such as the extent of product substitutability and the significance of competition between traders at different stages of distribution…

98 Moreover, there may be sub-markets. Accepting, as one must, that within a market there may be demand-side substitutability and supply side-substitutability, there may be even more narrowly defined markets (sub-markets) within the broader market where, as QCMA explained it, there may be “discontinuity in substitution possibilities” (at 514) particularly in the short term so that only a closer and more immediate set of substitutes are relevant. So, sub-markets may be a useful conceptual tool “in registering the short-run effects of change”.

99 To conclude at this point and drawing together some of the themes that I have just discussed, I would note the observations of Kiefel and Gageler JJ in Flight Centre Travel at [69] and [70] that:

…(b)ecause the economy is not divided into an identifiable number of discrete markets into one or other of which all trading activities can be neatly fitted”, the identification and definition of a market for particular services will often involve “value judgments about which there is some room for legitimate differences of opinion”. Identifying a market and defining its dimensions is “a focusing process”, requiring selection of “what emerges as the clearest picture of the relevant competitive process in the light of commercial reality and the purposes of the law”. The process is “to be undertaken with a view to assessing whether the substantive criteria for the particular contravention in issue are satisfied, in the commercial context the subject of analysis”. “The elaborateness of the exercise should be tailored to the conduct at issue and the statutory terms governing breach”. Market definition is in that sense purposive or instrumental or functional.

The functional approach to market definition is taken beyond its justification, however, when analysis of competitive processes is used to construct, or deconstruct and reconstruct, the supply of a service in a manner divorced from the commercial context of the putative contravention which precipitates the analysis…

(Citations omitted.)

(b) The relevance of price discrimination to market definition

100 One concept that was much debated before me concerned the potential for price discrimination to justify defining markets by reference to a subset of end users. The issue arose because of the way in which the ACCC has defined the relevant market(s) by reference to end users for whom road or sea was not a ready substitute for rail. In other words the market(s) were defined not just by product and location but by the identity or characteristics of targeted buyers. Now this is not an impermissible approach, but there are complications. The question of the possibility or reality of price discrimination comes into play and the necessary conditions for that to occur. Now the ACCC sought to side-step such matters and to inject as much flexibility as it could into the functional and focusing approach discussed in Air New Zealand at [57], [58] and [62] by Gordon J. Now the ACCC’s approach is all very well, but one cannot completely step away from the theory that has been developed concerning this question. Let me discuss the theory first, and I will discuss the facts later and the ACCC’s attempt to finesse itself out of the theoretical difficulties, which attempt I must say has been successful.

101 Professor Jerry Hausman et al explained the relevant theory in the following terms (Hausman J, Leonard G and Vellturo C, “Market Definition Under Price Discrimination” (1996) 64 Antitrust Law Journal 367 at 369).

102 Price discrimination affects market definition when the hypothetical monopolist would have the ability to distinguish infra-marginal customers from marginal customers. If the hypothetical monopolist has the ability to identify the infra-marginal customers, it will have the incentive to charge customers different prices depending on their willingness to pay for the product. In particular, the hypothetical monopolist could charge each customer a price above the competitive price, just below the customer’s maximum willingness to pay for the product, that is, a price just below where the customer would no longer buy the product. Thus, even though the hypothetical monopolist may not find it profitable to raise price 5% above the competitive level uniformly across all its customers, it may find it profitable to raise price 5% to some of its customers. So, if the hypothetical monopolist could profitably raise price to a subset of its customers, these customers constitute a separate relevant market. If, on the other hand, profitable price discrimination against the subset of customers is not feasible, the subset does not define a separate relevant market. Accordingly the question is whether a hypothetical monopolist could profitably price discriminate.

103 Now in terms of terminology I should note here what is meant by a marginal customer and an infra-marginal customer. Take the SSNIP test or the hypothetical monopolist test that I have just been discussing. If say in response to a 5% increase in price a customer would switch to another product or would purchase less of the product, then they would be described as a marginal customer. If, however, the customer did not switch and would not have purchased less despite the price increase, then they would be described as an infra-marginal customer.

104 Now for feasible price discrimination to occur, such that the relevant subset of the hypothetical monopolist’s customers or potential customers can be treated as a separate relevant market, two conditions must be satisfied (Hausman at 370 and see also Baker JB, “Market Definition: An Analytical Overview” (2007) 74 Antitrust Law Journal 129 at 151).

105 The first condition is that the hypothetical monopolist is able to identify the customers to whom price can be increased.

106 As Hausman explains, the necessity for this first condition is obvious. If you cannot identify customers who are willing to pay a price above the competitive level, you cannot sensibly price discriminate let alone profitably.

107 I should say now that PN’s and Aurizon’s central attack on the ACCC’s case concerning market definition sought to show that this first condition had not been satisfied or proven.

108 The second condition is that the product or service in question could not be profitably arbitraged by customers of the hypothetical monopolist.

109 And again, as Hausman explains, the necessity for this second condition is also self-evident. Assume for the moment the converse position that arbitrage was possible. The customer receiving the product or service from the hypothetical monopolist at the “low” price could have the incentive to resell the product or service to a customer who receives the “high” price from the monopolist. So, the resellers would be competing with the monopolist. Consequence? That competition would just drive prices back to the competitive level, and would make the price discrimination self-defeating. Hence the necessity for the second condition: no opportunity for profitable arbitrage.

110 Now given the nature of the services in the present case, PN and Aurizon were not able to show that the condition of no opportunity for profitable arbitrage was not satisfied.

111 Further, various regulatory guidelines in Australia and overseas confirm that market definition may be appropriately undertaken by reference to the identity or characteristics of targeted buyers if the two conditions that I have discussed above are satisfied; see the ACCC’s Merger Guidelines (November 2008, but updated to include the Harper reforms) at [4.36], the Merger Assessment Guidelines (UK) jointly published by the Competition Commission and the Office of Fair Trading (September 2010) at [5.2.28] to [5.2.30], and the Horizontal Merger Guidelines (US) jointly published by the US Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission (August 2010) at sections 3 and 4.1.4.

112 Now generally speaking the question before me so far as PN and Aurizon were concerned at least did not so much involve a challenge to the above theories, but rather their application. And putting to one side the ACCC’s attempts to side-step the theory, the ACCC also had to engage with its application. The application gave rise to the following questions.

113 Has PN individually negotiated prices or could it? Does this enable it to be demonstrated that the first condition applies? In other words, can it or does it identify the infra-marginal customers so that it can profitably price-discriminate? Has it price discriminated in the past? Is there evidence of PN charging a different price to cost ratio for the same service? But I do accept, and so did Dr Williams, what Hausman said (at 372) that “even if price discrimination is not being practiced currently in the proposed market, it may be feasible once the proposed market is under the control of the hypothetical monopolist. Thus, the feasibility of price discrimination by the hypothetical monopolist must often be determined by verifying the necessary conditions for price discrimination”.

114 But what about the situation where customers cannot be identified with certainty in order to price discriminate? Hausman discussed this question in the following terms.

115 If customers do not differ in their end uses, the hypothetical monopolist will generally not be able to perfectly identify the inframarginal customers who have high willingness to pay. Often it is suggested that, in the course of serving customers, producers learn about their customers’ preferences over various alternative products and, therefore, are able to infer which customers have high willingness to pay for a given product. Thus, the argument goes, the hypothetical monopolist could make educated guesses about which customers would accept a price increase. However, customers have the incentive to disguise their preferences precisely because they want to avoid becoming targets for higher prices. Thus, any assessment by a producer of a customer’s willingness to pay will involve substantial uncertainty. Like any guess, this guess can be wrong. A sufficient number of wrong guesses can make the attempt to price discriminate unprofitable. In many cases only a small percentage of wrong guesses is required before an attempt at price discrimination becomes unprofitable.

116 In the case where the monopolist cannot perfectly identify the customers to target, the targeting must be correct in a large percentage of cases or the price discrimination attempt will fail to be profitable. This burden increases for products that exhibit high fixed costs and low marginal costs. Thus, it is insufficient to argue that some inframarginal customers exist (or even that inframarginal customers constitute a majority of purchasers) and that the hypothetical monopolist could raise price to them. This argument is based on the assumption that the hypothetical monopolist can perfectly identify the inframarginal customers. Without such an assumption one cannot decisively conclude that such a group of inframarginal customers indeed corresponds to a relevant market for antitrust analysis.

(c) Competition

117 I have discussed market definition. But the matter can be approached from another way, which is to focus on and identify where the competition is or is likely to be. Competition may be viewed in the following way, as QCMA explains (511 to 512).

118 First, it is a process and not a situation. Indeed it is a dynamic process, with its dynamics affected, inter-alia “by market pressure from alternative sources of supply and the desire to keep ahead”, including devising new products, new technology, new cost efficiencies and the like.

119 Second, it “expresses itself as rivalrous behaviour”. And that rivalrous process and the relevant conduct in question must be analysed in the commercial setting in which it occurs.

120 Third, whether and the extent to which firms compete is dependent upon market structure. As explained in QCMA at 512:

…Nevertheless, whether firms compete is very much a matter of the structure of the markets in which they operate. The elements of market structure which we would stress as needing to be scanned in any case are these:—

(1) the number and size distribution of independent sellers, especially the degree of market concentration;

(2) the height of barriers to entry, that is the ease with which new firms may enter and secure a viable market;

(3) the extent to which the products of the industry are characterized by extreme product differentiation and sales promotion;

(4) the character of “vertical relationships” with customers and with suppliers and the extent of vertical integration; and

(5) the nature of any formal, stable and fundamental arrangements between firms which restrict their ability to function as independent entities.

Of all these elements of market structure, no doubt the most important is (2), the condition of entry. For it is the ease with which firms may enter which establishes the possibilities of market concentration over time; and it is the threat of the entry of a new firm or a new plant into a market which operates as the ultimate regulator of competitive conduct.

121 Fourth, effective competition is characterised by the situation that no one seller or group of sellers acting in concert has the power to choose its level of profits by giving less and charging more. So, effective competition requires both “that prices should be flexible, reflecting the forces of demand and supply, and that there should be independent rivalry in all dimensions of the price-product-service packages offered to consumers and customers”. Further, a situation of effective competition may exist where inter-alia rival sellers, whether existing or new entrants, keep in check such power of the seller(s) to give less and charge more.

122 Fifth, let me say something about the concept of “workable competition” as distinct from effective competition.

123 The concept of “workable competition” was developed in the recognition that perfect competition was “not a reliable basis for normative appraisal of actual markets”, with the concept of workable competition being “an attempt to indicate what practically attainable state of affairs are socially desirable in individual capitalistic markets” (Sosnick SH “A Critique of Concepts of Workable Competition” (1958) 72 Quarterly Journal of Economics 380). Sosnick discussed various individual performance, conduct and structural attributes designed to assist in applying the concept. But ultimately its questionable utility and vagueness was reflected in his statements (for example at 382 and 411) discussing degrees of workability and the qualitative and quantitative imprecision in the formulation, measurement and weighing of the various criteria and the relevant standard for the assessment.

124 Professor Maureen Brunt also discussed the concept in her article “‘Market Definition’ Issues in Australian and New Zealand Trade Practices Litigation” (1990) 18 Australian Business Law Review 86 at 100 in the following terms:

The phrase “workable competition” is not susceptible to precise, universally accepted definition but usually carries two connotations: first, that the concept of competition must be of a process that is practically achievable in commercial reality; and secondly, that it must be a reliable mechanism for achieving good economic performance– in short, efficiency and progressiveness constrained by market forces…

125 The Australian Competition Tribunal in Re Application by Chime Communications Pty Ltd (No 2) (2009) 257 ALR 765 stated at [36] and [37] (Finkelstein J presiding):

Much of the literature on workable competition was analysed by S H Sosnick in his paper “A Critique of Concepts of Workable Competition” (1958) 72 Quarterly Journal of Economics 380. Sosnick suggests a large number of characteristics that will determine whether a market is workably competitive. Scherer and Ross (at 53–4) have divided them into structural, conduct and performance categories as follows:

Structural criteria:

• The number of traders should be at least as large as scale economies permit.

• There should be no artificial inhibitions on mobility and entry.

• There should be moderate and price-sensitive quality differentials in the products offered.

Conduct criteria:

• Some uncertainty should exist in the minds of rivals as to whether price initiatives will be followed.

• Firms should strive to attain their goals independently, without collusion.

• There should be no unfair, exclusionary, predatory, or coercive tactics.

• Inefficient suppliers and customers should not be shielded permanently.

• Sales promotion should be informative, or at least not be misleading.

• There should be no persistent, harmful price discrimination.

Performance criteria:

• Firms’ production and distribution operations should be efficient and not wasteful of resources.

• Output levels and product quality (that is, variety, durability, safety, reliability, and so forth) should be responsive to consumer demands.

• Profits should be at levels just sufficient to reward investment, efficiency, and innovation.

• Prices should encourage rational choice, guide markets toward equilibrium, and not intensify cyclical instability.

• Opportunities for introducing technically superior new products and processes should be exploited.

• Promotional expenses should not be excessive.

• Success should accrue to sellers who best serve consumer wants.

The point we draw from Sosnick’s work, as is made evident by Scherer and Ross, is that determining whether competition is “workable” involves an analysis of empirical data regarding the structure and dynamics of a market and its participants.

Perhaps the best shorthand description of workable competition is to envisage a market with a sufficient number of firms (at least four or more), where there is no significant concentration, where all firms are constrained by their rivals from exercising any market power, where pricing is flexible, where barriers to entry and expansion are low, where there is no collusion, and where profit rates reflect risk and efficiency.

126 But Scherer and Ross have explained (Scherer FM and Ross D, Industrial Market Structure and Economic Performance (3rd ed, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990)) that there are problems with the concept and use of the said criteria. As they said (at 54):

Critics of the workable competition concept have questioned whether the approach is as operational as its proponents intended. On many of the individual variables, difficult quantitative judgments are required. How price sensitive must quality differentials be? When are promotional expenses excessive, and when are they not? How long must price discrimination persist before it is persistent? And so on. Furthermore, fulfilment of many criteria is difficult to measure. For instance, to determine whether firms’ production operations have been efficient, one needs a yardstick calibrated against what is possible. Finally and most important, how should the workability of competition be evaluated when some, but not all, of the criteria are satisfied? If, for example, performance but not structure conforms to the norms, should we conclude that competition is workable, since it is performance that really counts in the end? Perhaps not, because with an unworkable structure there is always a risk that future performance will deteriorate. If stress is placed on performance, what conclusion can be drawn when performance is good on some dimensions but not on others? Here a decision cannot be reached without introducing subjective value judgments about the importance of various dimensions. And as George Stigler warned with characteristic irony, embarrassing disagreements may result:

To determine whether any industry is workably competitive, therefore, simply have a good graduate write his dissertation on the industry and render a verdict. It is crucial to this test, of course, that no second graduate student be allowed to study the industry.

127 Chime went on to discuss the notion of “effective competition” in the following terms (at [38]):

There are some economists who speak of “effective competition”. For example, Shepherd ((1997) at 18) describes effective competition as requiring internal and external conditions. The internal conditions are: (a) a reasonable degree of parity among the competitors; and (b) a high enough number of competitors to prevent effective collusion among them to rig the market. The external condition is easy entry. Effective competition denotes the idea that firms should be subject to a reasonable degree of competitive constraint from actual and potential competitors as well as from customers.

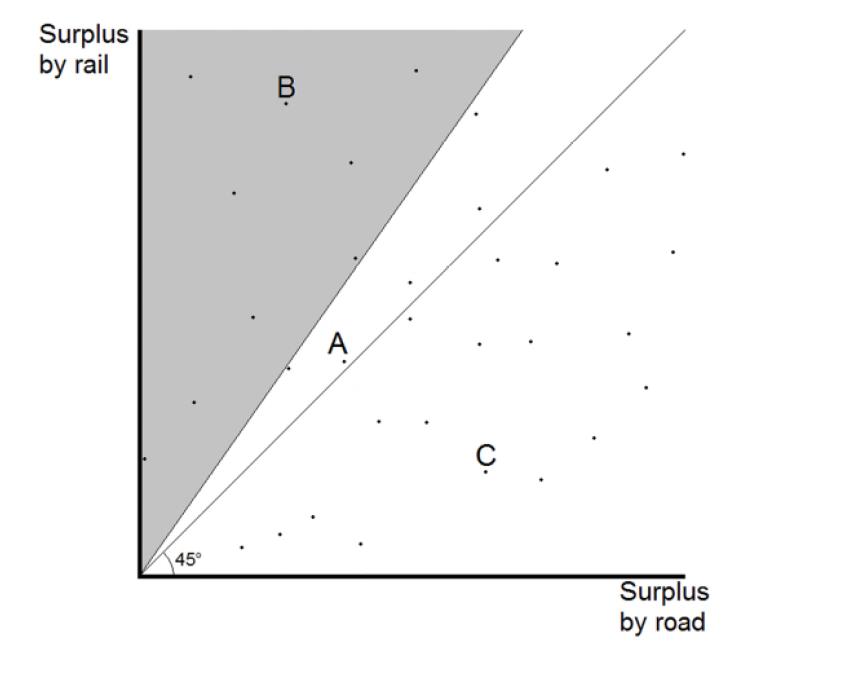

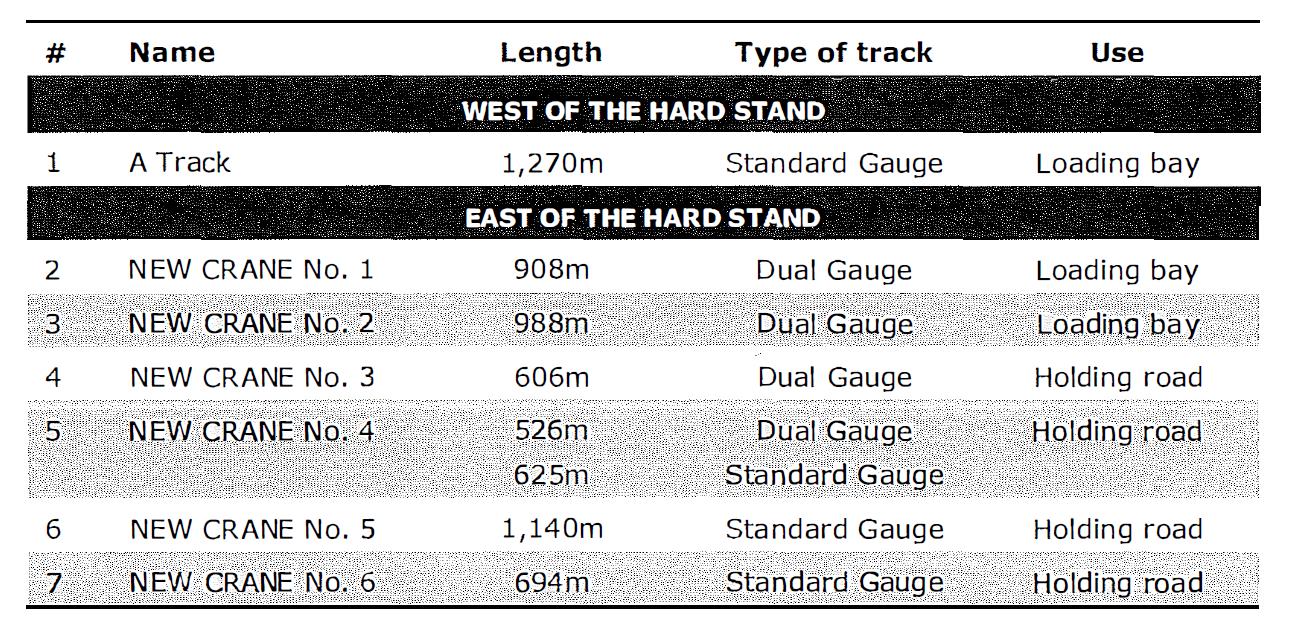

128 The ACCC also advanced in Chime an “effective competition” model which I find attractive. Effective competition is more than the mere threat of competition and requires that competitors be active in the market, holding a reasonably sustainable market position. Further, it requires that over the long run prices are determined by underlying costs rather than the existence of market power although a party may hold a degree of market power from time to time. Further, it requires that barriers to entry are sufficiently low and that the use of market power will be competed away in the long run, so that any degree of market power is only transitory. Further, it requires that there be independent rivalry in all dimensions of the price/product/service package. Finally, it does not preclude one party holding a degree of market power from time to time, but that power should pose no significant risk to present and future competition.