FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

R & B Directional Drilling Pty Ltd (in liq) v CGU Insurance Limited (No 2) [2019] FCA 458

ORDERS

R & B DIRECTIONAL DRILLING PTY LTD (IN LIQ) ACN 163 164 234 First Applicant RL INDUSTRIES PTY LTD ABN 95 602 202 317 Second Applicant | ||

AND: | CGU INSURANCE LIMITED ABN 27 004 478 371 Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 5 APRIL 2019 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed with costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ALLSOP CJ:

1 The first applicant is a company in liquidation (R & B). Prior to being placed in liquidation on 28 February 2017, R & B carried on business providing specialist drilling services to the construction industry, including at remote sites in Western Australia.

2 The second applicant, which trades as Longfield Services (Longfield) is a construction company with which R & B entered into a sub-contract to do work near Port Hedland.

3 The applicants assert that R & B’s legal liability to Longfield that arose out of the performance of the relevant sub-contract entitled R & B to payment under the liability section of a business insurance policy issued by the respondent CGU Insurance Limited (CGU) to R & B, the benefit of which claim Longfield seeks to derive in the liquidation. For the reasons that follow, the application should be dismissed with costs.

Background facts

4 The facts are largely uncontroversial and are in large part taken from the Agreed Statement of Facts (ASoF).

5 On 7 August 2015, Regional Power Corporation trading as Horizon Power (Horizon) engaged Broadspectrum (Australia) Pty Limited (Broadspectrum) to design, procure and construct certain works called the Port Hedland Substation and Power Transmission Works.

6 On 13 May 2016, Broadspectrum sub-contracted a portion of the work to Longfield. Longfield’s responsibility was set out in clause 3.1 of its sub-contract with Broadspectrum:

The Subcontractor acknowledges that it is primarily contractually responsible for the planning and performance of the Services in accordance with this Agreement, and that any part of the Services that the Subcontractor may subcontract out to any person in no way relieves the Subcontractor of any of its obligations or warranties under this Agreement.

7 The Scope of Works in the Broadspectrum / Longfield sub-contract included the following:

The civil works for the underground 132kV transmission line shall consist of the following, to be installed in accordance with the drawings listed in Section 12 Reference Documents:

• Cable Trenching – excavation and backfilling of approx. 1160m of cable trench, using open trench methods.

• Pipe Jacking – installation of approx. 80m of pipe-jacking for the cable crossing at the BHPB rail corridor.

• Directional Boring – installation of approx. 20m of UPVC conduits by directional bore for the cable crossing at Utah Rd. and approx. 15m of UPVC conduits by directional bore for the cable crossing of the FMG site access Rd adjacent to the SWC Substation.

• Joint Bay – Installation of arrangement for one (1) underground cable concrete joint bay.

Installation of Cables as per the details below:

• Installation of underground cables (3 off single core, 1600 mm2 HV cables, 240 mm2 earthing cable and 24 / 48 core Fibre Optic cable) and associated accessories (link boxes etc.) in accordance with all statutory requirements, relevant Australian International Standards (including Australian codes and regulations)

• Testing of the HV cables (prior to and after installation)

• Submission of a cable pulling report (confirming that the pulling tension was well within the allowed limits (as specified by the cable manufacturer))

[Emphasis added]

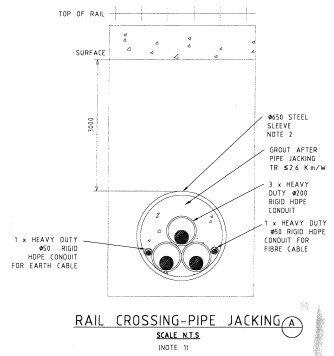

8 The part of the Scope of Works in the Broadspectrum / Longfield sub-contract that is emphasised above was later expanded to nearly 120m of pipe-jacking for cables to pass underneath and across the BHP Fortescue rail line to and from Port Hedland. The work was to provide conduit pipes that would carry high voltage and other types of cables to the Port Hedland Substation and Power Transmission Works.

9 The drawings listed in Section 12 Reference Documents referred to above included that described as follows:

BROADSPECTRUM / ICD Asia Pacific: HV Cable Trench Details HDT – SWC 132kV Transmission Line | Rev 0 | SWC-TL-E-20001-01 |

10 The evidence discloses that this document was substantially in the form of that contained at page 77D of the Court Book which showed the “RAIL CROSSING – PIPE JACKING” in accordance with the following drawing:

11 This drawing shows, by cross section, the railway line at the top, below which there is three metres of ground, under which there is a steel sleeve which has, by the method described below, been put through the ground underneath and across the rail line. Into this steel sleeve, once the earth is removed, are placed three heavy duty rigid HDPE conduits 200 mm in diameter and two smaller heavy duty rigid HDPE conduits, one for an earthing cable and one for a fibre cable. These smaller heavy duty rigid HDPE conduits are labelled above as 50 mm in diameter; in fact they were 63 mm in diameter.

12 None of Horizon, Broadspectrum or Longfield owned the site of the work.

13 On 20 June 2016, Longfield sub-contracted part of its sub-contract to R & B. Longfield’s responsibility included the installation of underground cables as detailed in the scope of works in its sub-contract with Broadspectrum. This was not part of the work for R & B.

14 R & B’s work under its sub-contract with Longfield was described in the R & B quote dated 15 June 2016 and the purchase order of Longfield dated 3 August 2016, substantially identically, as follows:

Pipe Jacking CHP Rail Corridor | |

Preliminaries/mobilisation/demobilisation of micro tunnelling equipment | $116,863.75 |

Supply and install 120m x 650mm in OTR | $186,066.72 |

Supply and install 120 x 3 – 200mm rigid UPVC carrier pip/proving of spacers and grouting | $37,411.20 |

Supply and install 120m x 2 – 63mm comms conduit | $9,540 |

Launch shaft/receival shaft/set ups x 1 | $54,058.30 |

15 Thus Longfield sub-contracted to R&B the work in the second dot point in the Broadspectrum / Longfield Scope of Works at [7] above. There was a debate in the proceeding about the meaning and extent of “pipe-jacking”. Mr Riches, an officer of Longfield, said it meant a method of installing the steel sleeve into the earth by hydraulic rams as earth was removed from the ground by flushing. This would be only that work referred to in the third box above: “Supply and install 120m x 650mm in OTR”. (OTR is other than rock.) In the debate about “pipe-jacking” and its meaning, Mr Riches sought to give it this narrow meaning. The drawing for the Broadspectrum / Longfield sub-contract (referred to at [10] above), plainly described as pipe-jacking the totality of the work of installation of the metal sleeve, creation of the tunnel, insertion of the conduits, and grouting. The relevant quote and purchase order do the same.

16 By reference to the drawings and documents in evidence, the work for which R & B was responsible can be described as follows: (after preliminaries and mobilisation) the installation into the ground under the railway line of a 650 mm steel sleeve, with a void within it, after the removal of soil in it by flushing. The soil was removed by forcing the sleeve forward by hydraulic rams and water being used at the head of the process to wash and flush out the soil through the sleeve as it was rammed forward. Within the steel sleeve were to be installed five conduit pipes, through which the relevant cables would be threaded and would reside. R & B was not to be responsible for the placement of the cable in the conduit pipes, rather only the placement and fixing of the conduit pipes in the steel sleeve. Once the conduit pipes were placed into the steel sleeve or tunnel, concrete grouting was to be pumped in to fill the void. On setting, the concrete grouting would make the conduit pipes stable in the now filled and solid cylindrical structure in the earth. The work required the digging of pits on either side of the rail line, known as the launching pit (from where the pipe-jacking commenced) and the receival pit (on the other side of the rail line).

17 Unfortunately, in the exercise of pumping the concrete into the tunnel void, concrete entered a hole or break in one of the conduits. It is unclear how that hole or break occurred. Attempts to flush the concrete out of the conduit in question were unsuccessful. The concrete in the conduit hardened making that conduit useless to carry a cable.

18 The work, at least up to the pumping of the concrete grouting into the void on 29 September 2016, is described in a little more detail at paragraphs 18–28 of the ASoF from which the following is taken.

19 On 24 August 2016, R & B issued a Tax Invoice to Longfield for Preliminaries and Mobilisation Costs, and for Project Materials and Freight Costs. This invoice had not been paid as at 29 September 2016.

20 On 29 August 2016, R & B’s personnel were mobilised to Port Hedland to commence work on the project.

21 On 30 August 2016, R & B began excavating and preparing an entry pit on one side of BHP’s railway line to enable it to undertake the works.

22 On 1 September 2016, R & B began excavating and preparing an exit pit on the other side of BHP’s railway line to enable it to undertake the works.

23 On or after 1 September 2016, R & B commenced simultaneously drilling out soil and inserting a steel sleeve underneath BHP’s railway line. This work was carried out without incident. By 22 September 2016 the steel sleeve extended from the entry pit to the exit pit and was empty inside.

24 On 23 September 2016, R & B commenced the insertion of the conduits into the steel sleeve. Each conduit comprised multiple lengths of pipe joined together by joints to form one length. When joined together the conduit should be impervious to grout.

25 On 24 September 2016, R & B issued an invoice to Longfield for certain costs including:

a. Supply and install 120m x 650mm in OTR (Other Than Rock) for “$108,029.19 including GST;

b. 90% complete – Supply and install 120m x3 200mm Rigid UPVC carrier pipe / proving of spacers and grouting for $37,037.08 including GST;

c. Supply and install 120m x2 63mm Comms Conduit for $10,494 including GST;

d. Launch Shaft / Receival Shaft / Set Ups x 1 / x1 Strips for $59,464.13 including GST.

26 This invoice had not been paid as at 29 September 2016.

27 On 29 September 2016, R & B commenced pumping grout around the conduit pipes to hold them in place. After pumping commenced, grout was found to have leaked into one of the conduit pipes.

28 During the works described above, the entry and exit pits were fenced off.

29 Each of the tasks (preliminaries/mobilisation/demobilisation; supply and installation of the steel sleeve; supply and installation of the three 200 mm wide conduit pipes; and supply and installation of the two 63 mm wide conduit pipes) had separate lines and prices in the quote and purchase order. Grouting was dealt with in the line item for supplying and installing the three 200 mm wide conduits. It was, however, a process that took place after the installation of all five of the conduit pipes.

30 As described above by reference to invoices, by 24 August 2016, R & B invoiced Longfield for preliminaries and mobilisation and for part of the supply and installation of the steel sleeve. The balance of the invoicing by R & B to Longfield for the supply and installation of the steel sleeve took place on 24 September 2016. Under the sub-contract invoices were payable after 30 days. Thus the steel sleeve was finished by 24 September 2016. The conduits were installed and concrete was placed in the void which all seems to have been completed by 4 October. On 4 October, a Mr Caruana, signing off as Operations Manager of Longfield, sent an email to a Mr Phillips. This email recognised that one pipe had leaked grouting, although all other pipes have remained perfect. Grouting was to be completed on 6 October.

31 By 14 October 2016, Longfield was dissatisfied with the situation. On that day Longfield served a notice on R & B in the following terms set out at paragraph 29 of the ASoF:

In relation to the current Pipe Jacking situation, the current status of the pipe jacking is unacceptable. Under clause 4.1 of the Longfield Services Subcontract/New Supplier Agreement, we are directing you to fix the Defective work & Materials or perform the Services again, and to make good all damage caused as a result, at R&B Directional Drillings [sic] cost.

As an estimate to perform the services again I would assume the cost would be approx. $438,889.97 + GST, as per you [sic] quote + accommodation that Longfield Services provides (based on 15 days).

Please note that completion date for this project is 31st of October, R&B Directional Drilling will be liable to pay daily Liquidated Damages of $5,431.75 + GST everyday [sic] after this date.

Please confirm receipt of this letter by responding to this email.

32 Clause 4.1 of the terms and conditions of the sub-contract between Longfield and R & B was as follows:

At any time we direct you to let Us or the Principal inspect and test Your work or the Materials. This may involve you uncovering or removing some of the work or Materials. If the work or Materials do not comply with the Specifications or Purchase order or are otherwise deficient or defective (a “Defect”), We may direct You to fix the Defective work or Materials or perform the Services again, and to make good all damage caused as a result. You will promptly comply with any direction under this clause.

33 Clause 11.1 of the same Terms and Conditions of the Sub-contract between R & B and Longfield provided for an indemnity as follows:

You indemnify Us and our officers, employees, contractors and agents against all damage, expense (including reasonable lawyers’ fees and expenses), loss or liability of any nature suffered or incurred by Us or our officers, employees, contractors or agents arising out of the performance or non-performance of the Services including:

(a) loss or damage to Our property;

(b) damage, expense, loss or liability in respect of loss or damage to any other property (including the Principal’s such property);

(c) financial loss or expense;

(d) damage the Environment; and

(e) economic loss.

34 Plainly, the 14 October notice was one given by Longfield to R & B to remedy defective work.

35 On 17 October, R & B told Longfield that it intended to make an insurance claim in respect of the job. This was done on 20 October by claim on CGU. I will come to the insurance policy shortly.

36 After R & B had been unsuccessful in removing the concrete that had leaked into the broken conduit, between 19 November 2016 and 6 December 2016, Longfield caused the grout and conduit pipes to be removed from the steel sleeve by high pressure, industrial strength water blasting. This work was undertaken by Cleanaway Industrial Solutions Pty Ltd (Cleanaway). It was undertaken to enable the work to be repeated: further conduit pipes capable of carrying cables to be inserted into the steel sleeve. Conduit pipes capable of carrying cables were subsequently inserted into the steel sleeve with grouting then being pumped into the steel sleeve to hold the conduit pipes in place.

37 At this point it is helpful to conceptualise what had happened. After the launching and receiving pits had been excavated, the steel sleeve, being physical property, was inserted underground 120 metres across and three metres beneath the railway line. It contained a void once the soil and earth had been displaced from inside it by flushing. Thus before the conduit pipes and grouting were placed into the void, there was a physical structure of a steel sleeve or steel pipe with a void, constituting a tunnel. The commercial and physical utility of this tunnel was that it was to have placed in it five differently sized conduit pipes for three types of cables. The pumping of concrete grouting into the void created a solid structure surrounded by the steel sleeve within the ground. Part of that solid structure was the five conduit pipes into which cables would be placed. The placement of the defective or damaged conduit pipe into the sleeve or the damaging of the conduit as it was placed in the sleeve or as the concrete grouting was being poured, which allowed liquid concrete grouting into its internal chamber, made the now solid structure that had been created useless for its intended purpose. The void, filled as it was with concrete and five conduit pipes, only four of which were fit to carry cables, was not capable of fulfilling the purpose intended for the structure, that is to carry cables in five conduits. The work, as Longfield complained, was plainly defective. After the vain attempts to clear the defective conduit of concrete, the only solution was to remove the hardened grouting which filled the void, and the five conduits which were encased in the grouting. Once this was done by Cleanaway, the void within the steel sleeve was restored, without being damaged in any way, ready for the process to be repeated, this time with five sound conduit pipes and concrete grouting which once again was to fill the steel sleeve or pipe or tunnel. Great care was taken to remove the concrete without damaging the integrity of the sleeve.

38 Longfield subsequently made a claim upon R & B. The claim was for the cost of removing the conduits and grouting, for wasted expenditure, liabilities Longfield said it had to Broadspectrum and others, and for late delivery of the job. All these can be seen as the kinds of damages that would flow naturally from the provision of defective work that then requires removal and redoing, setting the project behind time. The form of the claim, however, was not as a contractual claim under the sub-contract for failure properly to perform the work required under the sub-contract; rather it was expressed in a manner that sought to have it conform to CGU’s responsibilities to R & B under the insurance policy.

39 Thus one comes to the insurance policy, the nature of Longfield’s claim, and the legal issues raised by the relationship between the two.

The insurance policy

40 It was a condition of the sub-contract between Longfield and R & B that R & B hold public and products liability insurance. R & B held an Austbrokers Business Insurance Policy with the respondent CGU for the period 28 March 2016 to 28 March 2017 which had been arranged through its broker, Austral Risk Services. On 22 August 2016, CGU issued an Endorsement Schedule in respect of the Policy for a premium of $1,719.77.

41 I will come to terms of the Policy presently but it is to be noted that the Endorsement on 22 August included situation number 4: “Anywhere in Australia (operations based in WA) occupied as: site preparation services / earthmoving / excavation / land clearing & levelling / trench” with a similar description for “the business”.

42 The Policy comprised the Endorsement Schedule dated 22 August 2016 and the Policy wording contained in a booklet. The Policy was styled a “Business Insurance Policy” and had various sections. R & B did not take out cover for all sections. Relevantly, liability insurance in Section 5 was taken out for the relevant work. There was a limited indemnity of $20,000,000.

43 Section 5 for liability insurance was divided into two parts in the Endorsement Schedule: public liability and product liability. That distinction was reflected in the wording of Section 5 in the definition of “General Liability” as meaning “your legal liability covered by this policy but not arising out of your products”. Cover under Section 5 was set out in a clause so entitled, as follows:

Subject to the limits of indemnity stated in the schedule and the terms and conditions of this cover section, we will pay all sums that the insured person shall become legally liable to pay for compensation in respect of:

• personal injury;

• property damage;

• advertising liability;

happening during the period of insurance within the territorial limits as a result of an occurrence in connection with your business or products.

[Emphasis in original.]

44 The claim by R & B was made under Section 5 for legal liability to pay compensation in respect of property damage. The definition of “Property Damage” was as follows:

Property damage means:

(a) physical injury to or loss of or destruction of tangible property including loss of use of that property at any time resulting therefrom

(b) loss of the use of tangible property which has not been physically injured or destroyed provided such loss of use is caused by physical damage or destruction of other tangible property.

45 Put shortly, R & B claims that the damage was to the tunnel, being the steel sleeve and internal void. The tunnel is said to be tangible property to which there has been injury or harm that impaired its value or usefulness until rectified. It was damaged by being rendered imperfect or inoperative or useless, even if not permanently. Paragraphs 13 and 14 of the written outline of submissions of the applicants express the matter thus:

13. In summary, once the cement grout hardened to fill the Tunnel with unusable conduit pipes, the Tunnel was damaged because it became useless to Longfield for the purpose of carrying the requisite high voltage cables under the BHP railway line.

14. The measure and extent of the direct damage was the cost to restore the Tunnel to its prior condition. This involved the use of high pressure water blasting by Cleanaway to remove the concrete … This loss and damage is the foundation of R & B’s claim under the policy.

46 For various reasons, CGU disputes that the coverage clause is engaged. If it be wrong in that proposition, it also relies upon a number of exclusions: exclusion 3 on “Property in physical or legal control”; exclusion 4 on “Faulty workmanship”; and exclusion 13 on “Contractual liability”. These exclusions were in the following terms:

Exclusions

We will not pay anything in respect of:

…

3. Property in physical or legal control

Property damage to property owned by or in the physical or legal control of an insured person.

Exclusion 3 does not apply to property damage to:

a) premises leased or rented to you, but no cover is provided by this policy if you have assumed the responsibility to insure such premises

b) personal effects of your directors, employees and visitors

c) premises (and their contents) where the premises are temporarily occupied by an insured person to carry out work

d) any vehicle (including its contents, spare parts and accessories while they are in or on such vehicle) in a car park unless:

I. the vehicle is used by or on behalf of the insured person; or

II. The car park is occupied or operated by an insured person for reward.

e) other property, not owned by you, but in your physical or legal control subject to a maximum of $250,000 for any one occurrence and in the aggregate during any one period of insurance.

4. Faulty workmanship

The cost of performing, correcting or improving any work undertaken by an insured person.

…

13. Contractual liability

Any liability or obligation assumed by an insured person under any agreement or contact except to the extent that:

a) The liability or obligation would otherwise have been implied by law

b) The liability or obligation arises from incidental contracts

c) The liability or obligation is assumed by an insured person under any warranty under the requirement of Federal or State legislation in respect to product safety

d) The liability or obligations is assumed under those agreements specified in the schedule.

47 The word “premises” used in proviso (c) in exclusion 3 was defined in the general definition section of the Policy as meaning:

… the premises at the situation shown in the schedule.

48 The schedule is the endorsement which described the situation as I have set out above:

Anywhere in Australia (operations based in WA) occupied as: site preparation services / earthmoving / excavation / land clearing & levelling / trench.

The claim of Longfield

49 Longfield lodged a proof of debt in R & B’s liquidation in the sum of $774,726.07 plus GST for a total of $852,198.68. This claim (slightly reduced) is made against CGU in full. It is said to comprise three types of costs: direct, delay, and indirect (wasted) costs, totalling $773,947.44 (excluding GST). The detail of that claim is found in the Applicant’s Statement of Quantum which is annexed to these reasons.

50 The direct costs of restoration are all the costs to remove the concrete and conduits placed into the sleeve by R & B and to restore the tunnel to a state it was in prior to the placement of the conduits and the grouting.

51 The claim is not constructed as one for breach of contract, rather it is for liability consequent on damage to property under the public liability Policy.

Further terms of the sub-contract between R & B and Longfield

52 I have already referred to clauses 4.1 and 11.1 of the sub-contract. The balance of the clauses that are relevant are as follows:

Recitals

1. Longfield Services (LFS) being The Principal, has entered into a contract with its client for the provision of Civil & Construction Services. Depending on the specific contract at the time, this may be for a singular site or on various sites owned or operated by the client throughout Australia.

2. The Principal elects to have part of the contracted works performed by The Subcontractor, as specifically defined and issued in an individual LFS Scope of Work document and on a per job basis.

Clauses 1.1 and 1.2:

These Terms and the Purchase order contain all the terms and conditions on which you agree to provide the services described in our Purchase order (“Services”) and any ancillary materials (“Materials”)…

You will provide the services and materials in accordance with these terms and the purchase order, and any written directions we give You.

Clauses 2.1 and 2.3:

We will take reasonable steps to give you access to the site, so you can perform the services. When providing the services and on Site, you must co-operate with us and with the person we are acquiring your services for (the “Principal”), and the owner of the site. You will perform the services efficiently, in accordance with the Specifications and the Plan. You will comply with our (and the Principal’s) reasonable instructions, guidelines and procedures. You will provide your own equipment and only use materials that comply with the Specifications in performing the Services.

When you finish the services at the site, You must remove all rubbish, debris and waste resulting from Your performance of the Services, and leave the Site in at least as good a state of repair as it were when You began the Services.

The evidence of Mr Riches

53 Matthew Riches, a director of the second applicant (Longfield), gave evidence. Whilst I do not consider that Mr Riches was at any time intending to be dishonest, he gave evidence with a keen eye to what he saw as the issues. As a director of Longfield, he, through Longfield, was directly interested in the outcome of the proceedings. He gave evidence by way of an affidavit, upon which he was cross-examined. He also gave some supplementary evidence-in-chief.

54 In the affidavit Mr Riches first discussed the expression “pipe-jacking”. He said that the term was used in the construction industry to describe a process of creating a small bore tunnel by removing soil and simultaneously replacing it with a circular steel sleeve that provided a tunnel through a portion of earth, rock or soil. The task of “pipe-jacking” is complete once the tunnel is installed with the steel sleeve in place, with open ends and an empty void within the tunnel.

55 The evidence was given in an attempt to distinguish between pipe-jacking on the one hand and a later and separate task of installing conduits and placing grouting in the tunnel. The relevance of this will become clearer in due course, but was given in support of the proposition relevant to exclusion 3 that after completing the insertion of the sleeve and the creation of the tunnel the property in, control of, and access to the tunnel had passed to Longfield.

56 The difficulty with this evidence is that the documents in the relevant sub-contracts refer to the pipe-jacking work as including the placement of the conduits and the grouting. It can be accepted that these were separately quoted upon and invoiced, nevertheless the term pipe-jacking when used in the documentation clearly encompasses the totality of R & B’s work. Mr Riches also gave evidence of the payment of the company’s invoices and of the rectification and restoration of the tunnel.

57 Mr Riches gave some evidence-in-chief which was not critical for present purposes but which explained the structure of the site and the work in question.

58 The inclusion of the insertion of the conduits and the grouting in pipe-jacking work under the sub-contracts was made clear by another contemporaneous document. This was a document to which Mr Riches was taken. It was a work methodology for micro-tunnelling of Longfield. It was prepared in connection with the Broadspectrum contract and it represents the methodology of the pipe-jacking task. The document was created by Mr Caruana in conjunction with specialists and engineers. The numerous bullet points explaining pipe-jacking include “supply of three by DN200 HDPE and two by DN50 HDPE” and “grouting the cavity”.

59 To the extent that it matters, I find that pipe-jacking as a phrase in the relevant sub-contract documents meant the work of insertion of the sleeve, creation of the tunnel, insertion of the conduits and insertion of grouting to fill the tunnel and fix the conduits in place.

The meaning and application of the insurance policy

The coverage clause

Introductory comments and the parties’ submissions

60 Reading the coverage clause with Section (a) of the definition of “Property Damage”, for the Policy to respond there must be a sum that R & B is legally liable to pay for compensation (to someone, here, Longfield) in respect of physical injury to tangible property including loss of use of that (tangible property) at any time resulting from the physical injury to the tangible property.

61 Before turning to R & B’s arguments it is helpful to be clear about the property involved. The work involved creating a tunnel 650 mm wide, three metres below ground level from one pit (the launching pit) to another pit (the receiving pit) on either side of the railway line over 120 metres apart. The metal sleeve forced into the earth over 120 metres becomes part of the land; it maintains the integrity of the ground above it, the earth that previously occupied the area inside it having been removed by the process of watering at the head and washing it back out. The soil, having been removed for 120 metres in a circular space 650 mm wide plus the width of the sleeve, has been replaced by the steel sleeve with a void inside, creating a tunnel. The steel sleeve and the tunnel structure can be seen to be a fixture to or within the land, annexed to the land by the weight of the three metres of ground above and around it and forming an integral part of the support of the land. If a fixture, it comes to be owned by the owner of the realty. The full statutory and proprietary context to the title of the steel sleeve and tunnel was not investigated in argument, beyond its place in the sub-contractual relationships.

62 The applicants emphasised that the tunnel is the relevant tangible property, not the sleeve alone and not the conduit pipes. The tangibility is satisfied by the nature of the steel. The tunnel being a steel sleeve with a void can be seen to be a tangible structure within the ground. It is a structure and it had a specific utility or usefulness, having been constructed for one purpose: to hold five conduit pipes (of two sizes) fixed in concrete grouting to carry high voltage and related cables for power transmission. From this conception of property put forward it can be seen that the tangible property is also not the tunnel filled with concrete and the conduit pipes. It was said to be the steel sleeve and the void being the structure for the reception of that other material.

63 The meaning of the word “property” depends, of course, on its context. Its context here is as tangible property, and so property that can be touched or felt, physically: property as a thing. So physical injury to or destruction of tangible property (paragraph (a) in the definition) is a reference to physical injury to or destruction of a thing. The sleeve is a thing, but a tunnel is also said to be a thing: the sleeve and the void as a structure. In other contexts, such as the Fauna Conservation Act 1974 (Qld) discussed by Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Kirby and Hayne JJ in Yanner v Eaton [1999] HCA 53; 201 CLR 351 at 365–367 [17]–[19], “property” is not a thing, but a description of the legal relationship with a thing. The elusiveness of this conception is discussed by the High Court in Yanner. Citing Professor Gray, their Honours referred to an extensive frame of reference of “control and access”. Though tangible property here is physical, these notions are not irrelevant to the applicants’ arguments. The tangible property is said to be the tunnel, formed by the steel sleeve in the ground; but its proprietary characteristics are framed by what it is and what relationships parties have with it. The tunnel’s purpose, its nature and character, the relationships of persons to it in respect of control and access, and how it can be physically injured or impaired are informed by various contractual engagements concerned with the work. With respect, there is significant force in that submission. The meaning of property damage or physical injury to tangible property is affected by the legal and factual context.

64 The applicants emphasised that the tunnel is the tangible property – not the sleeve, not the conduit pipes and not the grouting. They relied on what the plurality said in Yanner 201 CLR at 365-367 [17]–[21]:

17. The word “property”" is often used to refer to something that belongs to another. But in the Fauna Act, as elsewhere in the law, “property” does not refer to a thing; it is a description of a legal relationship with a thing. It refers to a degree of power that is recognised in law as power permissibly exercised over the thing. The concept of “property” may be elusive. Usually it is treated as a “bundle of rights”. But even this may have its limits as an analytical tool or accurate description, and it may be, as Professor Gray has said, that “the ultimate fact about property is that it does not really exist: it is mere illusion”. Considering whether, or to what extent, there can be property in knowledge or information or property in human tissue may illustrate some of the difficulties in deciding what is meant by “property” in a subject matter. So too, identifying the apparent circularity of reasoning from the availability of specific performance in protection of property rights in a chattel to the conclusion that the rights protected are proprietary may illustrate some of the limits to the use of “property” as an analytical tool. No doubt the examples could be multiplied.

18. Nevertheless, as Professor Gray also says, “An extensive frame of reference is created by the notion that “property” consists primarily in control over access. Much of our false thinking about property stems from the residual perception that “property” is itself a thing or resource rather than a legally endorsed concentration of power over things and resources.”

19. “Property” is a term that can be, and is, applied to many different kinds of relationship with a subject matter. It is not “a monolithic notion of standard content and invariable intensity”. That is why, in the context of a testator’s will, “property” has been said to be “the most comprehensive of all the terms which can be used, inasmuch as it is indicative and descriptive of every possible interest which the party can have”.

20. Because “property” is a comprehensive term it can be used to describe all or any of very many different kinds of relationship between a person and a subject matter. To say that person A has property in item B invites the question what is the interest that A has in B? The statement that A has property in B will usually provoke further questions of classification. Is the interest real or personal? Is the item tangible or intangible? Is the interest legal or equitable? For present purposes, however, the important question is what interest in fauna was vested in the Crown when the Fauna Act provided that some fauna was “the property of the Crown and under the control of the Fauna Authority”?

21. The respondent’s submission (which the Commonwealth supported) was that s 7(1) of the Fauna Act gave full beneficial, or absolute, ownership of the fauna to the Crown. In part this submission was founded on the dictum noted earlier, that “property” is “the most comprehensive of all the terms which can be used”. But the very fact that the word is so comprehensive presents the problem, not the answer to it. “Property” comprehends a wide variety of different forms of interests; its use in the Act does not, without more, signify what form of interest is created.

[Citations/footnotes omitted.]

65 They did not rely on this for the proposition that here the word “property” meant something broad and intangible. They could not. The words “tangible property” can only mean a physical thing in this kind of policy. But the applicants emphasised that the character of the property includes notions of “control over access”. The tunnel, as the sleeve and the void, was said to be the property over which access is to be controlled and by that control of access utility is made of it by its constructed purpose.

66 A tunnel was said to represent “tangible property” because it can be touched (the sleeve) and perceived as materially existing: cf D K Derrington and R S Ashton, The Law of Liability Insurance (Lexis Nexis, 3rd ed, 2013) vol 1 at 1356–1357 [8-454].

67 The applicants submitted that damage includes injury or harm that impairs value or utility or usefulness which does not have to be permanent, citing Derrington and Ashton op cit at 1351 [8-451]. The injury here was said by the applicants to be the rendering of the tunnel functionally useless. It was not submitted that there had been any deleterious change to the fabric or composition of the sleeve.

68 CGU disputes all elements of the application of the coverage clause. CGU emphasised by way of preliminary comment that although the application of the Policy was governed by the words used, certain matters are to be recalled about the nature of public liability cover. It was submitted that as a general proposition public liability insurance is not directed to covering an insured against a failure to properly perform work: see Tesco Stores Ltd v Constable [2008] EWCA Civ 362 at [24]. Likewise in F & H Construction v ITT Hartford Insurance Company of the Midwest 12 Cal Rptr 3d 896 (2004), the Third Appellate District Court of Appeal of California quoted with approval statements made in Maryland and Casualty Co v Reeder 270 Cal Rptr 719 (1990) at 722 that liability policies:

…are not designed to provide contractors and developers with coverage against claims their work is inferior or defective. The risk of replacing and repairing defective materials or poor workmanship has generally been considered a commercial risk which is not passed on to the liability insurer. Rather liability coverage comes into play when the insured’s defective materials or work cause injury to property other than the insured’s own work or products…

69 CGU accepts that the steel sleeve is tangible property, but the tunnel is not. CGU submitted that the steel sleeve was in no way physically damaged by injury to its physical condition. The applicants accepted this. Rather, they submitted the damage was the making of the tunnel useless for its intended purpose by the grout hardening to fill the tunnel with five conduit pipes, only four of which were usable. This was said to be physical injury to the tunnel, being tangible property.

Consideration

70 The meaning to be given to the coverage clause in Section 5 is, of course, by giving a business-like interpretation to the words of a commercial contract. There was no debate about the proper approach to the construction of the Policy. See McCann v Switzerland Insurance Australia Ltd [2000] HCA 65; 203 CLR 579 at [22] (Gleeson CJ) and [73]-[74] (Kirby J); and Wilkie v Gordian Runoff Ltd [2005] HCA 17; 221 CLR 522 at [15]-[16] (Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow and Kirby JJ).

71 The structure of the coverage clause and the definition of property damage are, however, in well-known form. There was no particular contextual matter peculiar to these parties that would go to affect the objectively intended meaning of the clause. Authorities from the United States, Canada, England and Australia are relevant to consider in order, to the extent possible, to help provide a consistent and stable meaning to a clause in a standard business insurance policy: cf the comments of Lord Diplock in The ‘Maratha Envoy’ [1978] AC 1 at 8 D-H. This does not require other than rendering the meaning of the words of the Policy in accordance with the proper approach under Australian law. However, the views expressed in considered decisions of appellate courts of other countries in respect of clauses in like policies, in similar or identical terms, are invaluable to the process of consideration.

72 It is helpful to begin with the words of the Policy unvarnished by any consideration of the case law.

73 Section 5 of the Policy covered R & B for all sums that it becomes legally liable to pay for compensation in respect of physical injury to or loss of or destruction of tangible property, including loss of use of that (tangible) property at any time resulting from the physical injury or loss or destruction of it, happening during the period of insurance as a result of an occurrence in connection with its business. (Coverage clause in Section 5 read with paragraph (a) of the definition of property damage.)

74 The understanding of the content of the above is illuminated by the extension in paragraph (b) of the definition of “property damage”. Under that paragraph there is cover for loss of use of tangible property which has not been physically injured or destroyed if the loss of use is caused by physical damage to or destruction of other tangible property. This would seem to indicate that loss of use of tangible property, itself, is not damage, but such loss of use is property damage when it has been caused by that tangible property itself being physically injured or destroyed (paragraph (a)) or when the loss of use of tangible property has been caused not by that tangible property being physically injured or destroyed, but by other tangible property being injured or destroyed (paragraph (b)). Loss of use is a concept distinct from injury. This may not be a determinative insight, but it seems to make more difficult the applicants’ submission that physical injury is the lack of functional utility of the tunnel by the physical filling of the void with only four working conduits and surrounding concrete.

The relevant authorities

75 Primary reliance was placed by the applicants on two Canadian cases that may be seen to have been referred to with approval by the Queensland Court of Appeal.

76 In Canadian Equipment Sales & Service Co Ltd v Continental Insurance Co (1975) 59 DLR (3d) 333, the Ontario Court of Appeal was concerned with a liability policy under which the insurer agreed to pay all sums which the insured was legally liable to pay “because of injury to or destruction of property, including loss of use”. A subcontractor of the insured allowed material to fall into a pipe. Money was expended to clear the pipe lest it became blocked and cause damage. The Court of Appeal overturned the trial judge who had distinguished between expenses to protect the pipe and damage to the pipe. The Court said at 336:

…the dropping of the coupon into the pipe … was an injury to the pipeline, and Dow Chemical, from that moment, had an imperfect or impaired pipeline. The attempt to locate the coupon was a direct and natural consequence of the injury to the pipeline. …

77 “Injury” to tangible property included the impairment of its use. That conception of injury is not limited to the physical constitution of the pipe being in some way deleteriously changed. Rather, the injury or harm was to the functionality of the thing. Importantly, however, the word “injury” was not qualified by the word “physical”.

78 The second Canadian case upon which significant reliance was placed, Carwald Concrete and Gravel Co Ltd v General Security Insurance Company of Canada and Anor (1985) 24 DLR (4th) 58, did concern a liability policy using the phrase “physical injury”, indeed the policy terms were very similar to those here. The facts were that the insured poured a concrete pad that was to have a certain strength to support heavy compressors and other associated equipment at a gas processing plant. The concrete was inadequate. It had to be taken up and repoured. The removal of the concrete affected associated reinforcing steel bars, ducting, grounding wire, plumbing and anchor bolts. The policy was relevantly for liability to pay compensatory damages for property damage defined as:

(1) physical injury to or destruction of tangible property…including the loss of use thereof at any time resulting therefrom; or

(2) loss of use of tangible property which has not been physically injured or destroyed provided such loss of use is caused by an occurrence during the policy period.

79 The first part of this definition is almost identical to paragraph (a) of the definition of property damage here. The second part is similar to paragraph (b), with, however, an important difference in causal qualification: (2) above refers to the loss of use being caused by an occurrence; paragraph (b) of the definition in this Policy refers to it being “caused by physical damage to or destruction of other tangible property”.

80 In Carwald, the Court first looked to the Supreme Court decision of Attorney General of Ontario v Fatehi [1984] 2 SCR 536 dealing with the recovery of economic loss (not an insurance case). Due to the respondent’s negligence there was a highway accident which caused debris and gasoline to be strewn across the road, making it impassable. The cost of cleaning up the highway was said by the respondent to be pure economic loss and so unrecoverable. The Supreme Court disagreed. The road had ceased to be a road in the sense of a traffic carrying facility. This was, the Supreme Court said, damage to the property of the owner of the road. The Court then referred to two other Canadian cases: one where there was, and another where there was not, found to be property damage. In Poole-Pritchard Canadian Ltd v Underwriting Members of Lloyds (1969) 71 WWR 684, there was damage to pipe and vessel insulation material which failed because of the application of defective asphalt emulsion. In Rivtow Marine Ltd v Washington Iron Works [1974] SCR 1189, the cost of repairing latent defects was purely economic and not property damage.

81 At [20], the Court in Carwald said:

…where, as here, the pouring of defective concrete made the rebars, reinforcing steel, ducting, wiring, plumbing and anchor bolts useless for the purpose for which they were installed as the pad could not be used and this constituted physical injury to tangible property.

82 The applicants here draw a direct parallel with the facts in the present case. They submit that the defective conduit and grouting filling the tunnel made the tunnel useless for the purpose for which it had been installed. Indeed, even if the tangible property was the steel sleeve, it, likewise, had been made useless for the purpose for which it had been installed. This was said to be physical injury; just as the Alberta Court of Appeal said that the making of the rebars, reinforcing steel and other equipment useless for the purpose for which they were installed was physical injury to tangible property.

83 The Court in Carwald referred to three American cases. Importantly in the American jurisprudence, two of which concerned the form of liability insurance which rested on property damage being defined as “injury” to property, not “physical injury”; the third dealing with “physical injury”. The first was Bundy Tubing Company v Royal Indemnity Company 298 F 2d 151 (6th Cir, 1962), a decision of the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals. There the insured manufacturer’s defective heating system was installed in concrete floors. Hot water was carried through tubing which was defective. There was damage to household furnishings from leakage for which the insurer accepted liability. The contest was over the cost of the removal of the defective system which required digging up the concrete. The concrete, said the insurer, had not been injured or damaged by the leakage or the defective system. The clause provided indemnity for “all sums which the insured shall become legally obligated to pay as damages because of injury to or destruction of property, including loss of use thereof, caused by accident.” The Court of Appeals said that the home with a heating system which did not function would not be “suitable for living quarters in the winter time.” The market for its sale would be affected. This is an example of “injury to property” represented by the affectation of the value of property into which a defective component had been installed. I will return to a body of United States cases to that effect, under this form of definition. Bundy Tubing can perhaps be put more persuasively than a case merely about affectation of value. The home could be seen to be physically injured by being made unsuitable for winter habitation.

84 The other two cases to which the Alberta Appeal Court referred were St Paul Fire and Marine Insurance Co v Coss 145 Cal Rptr 836 (1978), a decision of the Second District Court of Appeal of California, and Hamilton Die Cast Inc v United States Fidelity and Guaranty Co 508 F 2d 417 (7th Cir, 1975). It will be necessary to see where these cases fit with other authoritative American appellate decisions. For the present, they are to be examined to illuminate the conclusion (and its limits) of the Alberta Court of Appeal.

85 The earlier case, Hamilton Die Cast, concerned an insured who had supplied tennis rackets with defective frames. The incorporation of a defective part, the frame, was said to be property damage, being “injury to … tangible property” (the definition present in this Policy without the word “physical” before “injury”). The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals rejected the claim:

We do not think that the mere inclusion of a defective component, where no physical harm to the other parts results therefrom, constitutes “property damage” within the meaning of the policy.

86 Hamilton Die Cast was cited by the Californian Second District Court of Appeal in St Paul Fire and Marine v Coss, which concerned a general liability policy in the form introduced in the early 1970s where “property damage” was defined as meaning: “(1) physical injury to or destruction of tangible property which occurs during the policy period, including loss of use thereof at any time resulting therefrom; or (2) loss of use of tangible property which has not been physically injured or destroyed or provided such loss of use is caused by an occurrence during the policy period.” (These were the same policy terms as were being dealt with by the Alberta Court of Appeal in Carwald with the same similarity to the Policy here that I have already mentioned.)

87 Coss was contracted to build a home. Disputes arose about workmanship at a point when completion was near. He left the site, and was sued by the owner for damages for the remedying of defective work and for the supply of defective materials. Whilst the defective workmanship and materials produced an inferior home (as the defectively designed racket frame produced an imperfect tennis racket in Hamilton Die Cast), this was said not to be property damage.

88 The Alberta Court of Appeal distinguished these two cases (Hamilton Die Cast and St Paul Fire and Marine v Coss) on the basis that in the case before it, the pouring of the defective concrete did damage other property: that is physically injured other property by making the other property, being the rebars, reinforcing steel and other equipment, useless for their purpose.

89 From the above the following can be stated: first, on the authority of the Ontario Court of Appeal in Canadian Equipment, impairment of functional use of physical property (there dropping a coupon into a pipe) is injury to that property; secondly, on the authority of the Alberta Court of Appeal in Carwald, the making (by covering with defective concrete) of equipment being tangible property useless for the purpose for which it or they were installed (if it or they had been covered by non-defective concrete) constitutes physical damage to that equipment; thirdly, on the authority of the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals in Bundy Tubing, the making of a home unsuitable for occupation for a significant part of the year by the installation of a defective heating system was injury to the home; and fourthly, such injury to property is to be distinguished from the consequences of the mere inclusion of a defective component into a whole where there is no physical harm to the other parts.

90 The applicants relied on the Queensland Court of Appeal in Austral Plywoods Pty Ltd v FAI General Insurance Company Ltd [1992] QCA 4; 7 ANZ Insurance Cases 61-110. There the insured had supplied plywood to a boat builder who had affixed it to the hull of a boat by fixing it with screws and glue. The plywood was defective and had to be removed from the hull, the glue chiselled or scraped off the hull, and the screw holes on the hull filled. The policy liability for “property damage” was defined as, relevantly, “physical injury to … tangible property”. The Court of Appeal said:

… But, of course, if the plywood is not defective there is no physical injury which would give rise to a legal liability in the supplier to pay compensation for it.

Upon the permanent affixation of the defective plywood to the hull, the hull was not only physically injured by the screw holes and glue but was rendered unsuitable, or less suitable, for the purpose for which it was constructed. Compare Carwald Concrete & Gravel Co. Ltd. v. General Security Insurance Co. of Canada 24 D.L.R. (4th) 58 at 63; Canadian Equipment Sales & Service Co. Ltd. v. Continental Insurance Co. 59 D.L.R. (3d) 333 at 336.

To remedy that injury the plywood had to be removed and the hull restored to a state in which new plywood could be affixed.

91 The proper reading of this is that the physical injury to the hull was the fixing of the defective plywood by physical means of screws and glue making the hull unsuitable or less suitable for its purposes and requiring the restoration of the physical state of the hull upon removal of the plywood.

92 Whilst Austral Plywoods does not take the matter any further than Carwald, and while there was actual interference with the integrity of the hull (the screw holes and glue), the case in its reference to Carwald and Canadian Equipment can be seen as support for the proposition that making, by defective work, tangible property useless or unsuitable for its purpose is physical injury to that tangible property.

93 Austral Plywoods and Canadian Equipment were the subject of some remarks by Pincus JA in Re Mining Technologies Australia Pty Ltd [1999] 1 Qd R 60. The case concerned recovery of expenses incurred in retrieving equipment that had become buried. It could be seen as expenditure to avoid an imminent and insured loss or event. The argument was that there was an implied suing and labouring clause or that what was done was a form of “repair”, which was expressly covered. In dissent, Pincus JA said the following at 64–65:

… In Austral Plywoods…the question was whether there was “property damage” defined as “physical injury to…tangible property” caused by the affixation of defective plywood to a hull. It was held that the hull was damaged by this affixation, because it was not only physically injured by the screw holes and glue, but was rendered unsuitable or less suitable for the purpose for which it was constructed. To say that an object can be said to be “damaged” by having affixed to it material which is intended permanently to alter it is one thing; it is another to say that an object is “damaged” if it is covered by or buried in a substance such as earth or water which is not affixed to it and on removal of which the object is left in its original condition. And of course the question directly in issue here is not whether to bury an object is to damage it, but rather whether to extract a buried object is to repair it. In Canadian Equipment Sales…it was held that expenses incurred in removing from a pipe a piece of material which had fallen into it were within an insurer’s agreement to pay sums which the insurer was liable to pay if there was injury to property. It was held that there was an injury to the pipeline because the material in the pipeline made it an “imperfect or impaired pipeline”. I can see the force of that, but on the other hand it would make sense to say, in answer to an inquiry whether a pipeline obstructed by some loose material was damaged: “No, there is no actual damage, but until this material is removed the pipeline will not function properly.” I would not accept that machinery is, in the ordinary sense, damaged by every circumstance which makes it, for the time being, unusable; an object dropped into deep water is an example, and an object hidden away is another.

[Citations omitted.]

94 These comments perhaps do not take the matter much further except to say that it can be seen to be a matter of degree in the process of characterisation and ascription of meaning as to whether something is physically injured by being rendered unsuitable for its purpose, depending on whether it has things affixed to it which so render it, or whether it is simply covered by a substance that can be removed. Here, it is more than being covered by dirt – the tunnel was filled with concrete that fixed itself to the steel pipe upon setting; but it is less than the interference with the surface of the hull. The internal surface of the steel sleeve was not impugned, but the job of removal of all the concrete required the force of high pressure water blasting.

95 The decision of the New South Wales Court of Appeal in Transfield Construction Pty Ltd v GIO Australia Holdings Pty Ltd (1997) 9 ANZ Insurance Cases 61-336 stands as contrary to the cases that see impairment of functionality as physical injury. The insured contracted to construct grain silos. The policy insured the works against physical loss or damage. A defect in construction caused the fumigation pipes in each silo to become blocked by grain. The insured removed the grain and carried out repairs. Meagher JA (with whom Clarke and Sheller JJA agreed) said the following at 76-616:

The risks again for which the appellant was insured were physical loss or damage, which includes destruction. The question for Mr Justice Rolfe, therefore, was whether the blockage from the fumigation pipes by grain, so that the fumigants could not escape from the pipes into the silos, constituted physical loss or damage.

The question really is one of first impression on the construction of the words I have quoted. I think His Honour was correct. No pipes were lost, no pipes were destroyed, no pipes were damaged. It is not contested that to remove the pipes and re-install them would have caused a financial loss to the plaintiff/appellant. That again is beside the point. Mr Maconachie, learned senior counsel for the appellant said “The fact that the pipes were rendered useless constituted physical damage within the meaning of the policy.” I do not think so. Loss of usefulness might in some context amount to damage, though even that is not beyond dispute, but in my view it cannot amount to physical damage. Functional in utility is different from physical damage. For these reasons which were substantially the reasons given by His Honour below, I think the appeal should be dismissed with costs.

96 The decision was based on first impression in an ex tempore judgment. Nevertheless, it stands as authority that functional utility was not physical damage, at least in the circumstances before the Court.

97 Transfield is, however, supported by a decision of the New Zealand Court of Appeal, and the approach taken under English law. In Kraal v Earthquake Commission [2015] NZCA 13; 2 NZLR 589, the Court of Appeal dealt with the claim that there had been “physical loss or damage” to a property otherwise relevantly undamaged by the 2010 and 2011 Christchurch earthquakes, but made uninhabitable by order of the Council because of its proximity to the danger of rock and boulders falling nearby. The words construed were not “physical injury”, but a cognate phrase. The Court referred to Moore v Evans [1917] 1 KB 458 where the Court of Appeal had rejected a claim under a policy for “loss of or damage or misfortune to” property in circumstances where goods were in Brussels and irretrievable because of the outbreak of war and the occupation of Brussels. There was no evidence that the goods had been interfered with or taken. There was required to be actual loss of or damage to the property. The Court also relied on Pilkington United Kingdom Ltd v CGU Insurance Plc [2004] EWCA Civ 23; [2005] 1 All ER (Comm) 283, Promet Engineering (Singapore) Pte Ltd v Sturge (The “Nukila”) [1997] EWCA Civ 1358; 2 Lloyd’s Rep 146; Allstate Exploration NL v QBE Insurance (Australia) Ltd [2008] VSCA 148; 15 ANZ Insurance Cases 61-773 (to which cases I will presently come); and Transfield, for the construction of physical damage as involving a necessary change of physical state.

98 Allstate concerned a composite physical damage and business interruption policy taken out by the owner of the Beaconsfield mine. A seismic disturbance caused a rock fall which did not physically damage the mine, but there was a closure by order of a governmental authority. In construing a clause dealing with consequences of actions of civil authorities, the Victorian Court of Appeal construed the phrase “risk of loss, destruction or damage” as limited to physical loss or damage, and not extending to other loss by deprivation of use.

99 The English cases referred to in Kraal reflect the clear view that a phrase such as “physical damage to physical property” requires a changed physical state to the property affected; and, depending on the terms of the clause, were confined to the physical consequences, not financial consequences. In Pilkington, heat-soaked toughened glass panels manufactured by the insured, Pilkington, were installed in the roof and vertical panelling at the Eurostar Terminal at Waterloo. A small number proved defective (13 out of 3,000). Remedial measures not involving removal of any panels were undertaken. The cause of any defect was said to be the presence of nickel sulphide in the glass, not removed by the heat-soaking. There was no physical damage. The claims of the insured was under a CGU liability policy which had a products liability section covering loss of or physical damage to physical property. The insured relied on certain American authorities and in particular Eljer Manufacturing Inc v Liberty Mutual Insurance Co 972 F 2d 805 (7th Cir, 1992) (Eljer 1992). The majority opinion of Circuit Judge Posner was rejected in favour of the dissent of Circuit Judge Cudahy. The insured also relied on Sturges Manufacturing Co v Utica Mutual Insurance Co 37 NY 2d 69; 332 NE 2d 319 (1975) and Maryland Casualty Company v WR Grace & Company 23 F 3d 617 (2nd Cir, 1993). Sturges was distinguished as based on a policy that referred to “injury” not “physical injury”. Maryland Casualty was explained by reference to its treatment by the Illinois Supreme Court in Traveler’s Insurance Co v Eljer Manufacturing Inc 197 Ill 2d 278; 757 NE 2d 481 (2001) as an asbestos case in which there was contamination and physical damage to the relevant property into which asbestos was incorporated.

100 It will be necessary to come to the American jurisprudence shortly but it is helpful to note two things. First, in Pilkington and many of the American cases the claims relate to assertions of defective work or products, incorporated into other property which is working and which is not (at least as yet) physically affected by the defect, though there may be a diminution in value. At least in degree, this can be distinguished from the product or work having a physical effect on the state of the property into which it is physically incorporated such that the property is useless for its purpose, at least to a significant degree. An example of the latter is Bundy Tubing ([83] above, an “injury” not “physical injury” case) where the house with a defective heating system was rendered unliveable in winter; another is perhaps Austral Plywoods ([90] above).

101 Secondly, the distinctions that are capable of being drawn in each case do not easily translate into a simple coherent definition or universally applicable rules capable of being applied to varied factual circumstances to reach deduced logical results. To say that there must be physical interference with property is to require facts or circumstances that can be so characterised. In Bundy Tubing it could be said, as a matter of meaning and characterisation, that a house that had installed in concrete flooring a defective and inoperable heating system had been injured by being physically affected because it could no longer function as a house in winter. Likewise in Austral Plywoods, the affixing of the defective plywood physically affected the hull, not just because of screw holes, but also because with such physical change it was unsuitable to use as a hull. The physical integrity of the property (the house and the hull) has been so compromised as not to be functional. In some circumstances, functionality and physical affectation may be seen as interwoven. This can be seen as different in degree from the circumstances in Eljer 1992 (to which I will come) where there were claims against the insurer for defective water systems that had not failed but were said to have damaged the value of the property into which they were installed. As the dissentient Circuit Judge Cudahy said (972 F 2d at 814):

There is immediately something counterintuitive about saying that physical injury has been done to a house in which a functioning plumbing system has been installed.

102 Perhaps illustration of the potential for the inter-relationship between physical effect and functionality can be seen in the asbestos cases to which I will come. There, the release of asbestos fibres and the integration of exposed asbestos so intermingled itself with the host property that that property can be seen to be contaminated and so affected physically as to now be harmful. Physical affectation, danger and functionality are all interwoven to permit the characterisation of physical injury to tangible property.

103 The fineness of the distinctions in this process of meaning and characterisation is perhaps well illustrated by what Pincus JA said in Re Mining Technologies about Canadian Equipment. For myself, I would agree with Pincus JA’s implicit view that the pipeline was not damaged, but it would not function property until removal of the material. Likewise, I respectfully agree with Meagher JA’s characterisation of the facts in Transfield. This was not physical damage or injury to the silos. There was a defect that prevented operation until remedied.

104 I turn to the American cases. Some were relied upon by each party. Unfortunately, it is not possible to dip into them and deal with only a few cases. There is not one common law in America: Erie Railroad Co v Tompkins 304 US 64 (1938) reversing Swift v Tyson 41 US 1 (1842). Thus, it is necessary to examine individual State law. I will restrict myself to appellate decisions of the three influential commercial centres: Illinois, California and New York. Some of the insight from these cases is as to the history of the wordings of commercial liability policies. I do not use this as if it were evidence; but it is helpful to understand and contextualise the decisions.

105 The debate has been concerned with the width and nature of the notion of “physical injury” and, in particular, whether it is satisfied by functional impairment to a larger physical entity by the defective work or product incorporated somehow into that larger physical entity.

Illinois

106 It is helpful to commence with the clear and powerfully expressed decision of the Illinois Supreme Court in 2001 in Traveler’s Insurance v Eljer 757 NE 2d 481 that was also dealt with in Pilkington. It is an important decision because it rejects as wrong the views and the constructional approach taken by the majority opinion of the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals written by Circuit Judge Posner in Eljer 1992.

107 Traveler’s Insurance v Eljer concerned the many suits that had been brought against United States Brass Corporation in respect of a plumbing system sold to plumbing contractors who installed the system in construction sites, usually behind walls or between floors and ceilings. There were defects in the system causing it to leak. The insurance claims included liability for removing systems from their locations in constructed buildings and for diminution of value of the buildings from the presence of allegedly defective plumbing (even if not yet leaking).

108 The policies in the cases were of different forms, from different eras. One group of policies (referred to as pre-1982 policies) were excess comprehensive general liability policies indemnifying for “damages because of property damage caused by [an] occurrence”, “property damage” being defined as “injury to or destruction of tangible property” (that is, not “physical injury” but “injury”).

109 The policies in this group were governed by New York law. The insurers said that there was no injury to tangible property until a leak occurs. The insured said that injury to tangible property may include diminishment in value of the property into which the system had been incorporated greater than the value of the system. The Court, applying New York law, upheld the insured’s argument, relying on the New York Court of Appeals’ decision in Sturges Manufacturing. That case involved defective straps on ski bindings. The New York Court of Appeals stated 37 NY 2d at 72–73 and 332 NE 2d at 322:

When one product is integrated into a larger entity, and the component product proves defective, the harm is considered harm to the entity to the extent that the market value of the entity is reduced in excess of the value of the defective component…

110 Thus, under New York law applicable to a policy defining property damage as “injury to tangible property”, diminution of value is injury.

111 The Illinois Supreme Court then addressed policies of different wording referred to as post-1981 policies. These were governed by Illinois law. The wording defined “property damage” as “physical injury to tangible property”.

112 The insureds submitted that the change in wording made no difference and the same conclusion as in Sturges should be drawn. The requirement of physicality was supplied by the physical incorporation and connection to the structures and their diminution in value. Reliance was put on the majority decision in Eljer 1992. The insureds also relied on a group of asbestos liability cases.

113 The Illinois Supreme Court rejected this submission, principally by reference to what it saw as plain language: the injury just be physical in nature. The Court also analysed and rejected the majority decision in the Seventh Circuit in Eljer 1992.

114 Eljer 1992 concerned one of the insureds as were before the Illinois Supreme Court, and its primary layer insurer. It was a diversity case governed by Illinois law, concerned with the definition of property damage as “physical injury to tangible property”. The majority held that the property damage occurred at the time of the installation of the system, and before it failed. The principal complaint of the Illinois Supreme Court in Traveler’s Insurance v Eljer with the approach of the majority in Eljer 1992 was the putting to one side of the clear and unambiguous words of the clause in favour of extrinsic considerations. Crucial to the difference between the courts was the importance given to the changes to the language of the covering clauses. The majority in Eljer 1992 looked at the significance of this drafting history from articles and commentary to discern whether the words in their context were wider than a literal ordinary sense. They noted that from 1966 the usual clause defining “property damage” was “injury to or destruction of tangible property”. Most courts, in what was referred to as apparent harmony with the drafters’ intentions set out in secondary material, had given the word “injury” a broad meaning referring to the Illinois Appellate Court in Elco Industries v Liberty Mutual Insurance Co 90 Ill App 3d 1106; 414 NE 2d 41 (1980) where the court said (414 NE 2d at 45), referring to Pittway Corp v American Motorists Insurance Co 56 Ill App 3d 338; 370 NE 2d 1271 (1977) and Hauenstein v St Paul Mercury Indemnity Co 242 Minn 354; 65 NW 2d 122 (1954):

…A majority position holds that “property damage” includes tangible property which has been diminished in value or made useless irrespective of any actual physical injury to the tangible property. …

115 The majority in Eljer 1992 identified the change to the wording as directed to the problem of loss of use caused not by injury or damage to the tangible property, but by injury to other property. An example of a crane falling in front of (but not injuring or damaging) a restaurant was given. The blocking of access may not have been covered without a loss of use extension (as appears in paragraph (b) of the definition in this case). Circuit Judge Posner described the changes as follows at 972 F 2d at 810:

… To allay doubts on this score by sharpening the aim of the 1966 definition, the insurance industry’s committee charged with updating the Comprehensive General Liability Insurance policy form redid the definition in 1973, producing the two-part definition that we quoted earlier from Liberty’s policies. The second part, which is new, explicitly covers the injury inflicted by our hypothetical crane manufacturer – a “loss of use of tangible property which has not been physically injured or destroyed.” The first part of the new definition is the old definition with “physical” prefixed to “injury” to distinguish the two parts. Both cover injury, but the second part covers injury which is not “physical” because there is no physical touching of the tort victim’s property. Society of Chartered Property and Casualty Underwriters, 1973 CGL Changes 9 (1971); Fred L. Bardenwerper & Donald J. Hirsch, General Liability Insurance – 1973 Revisions 11, 32 (Defense Research Institute, Inc. 1974); Guide to Liability Insurance 4 (Rough Notes Co. 1973). There was no intent to curtail liability in a case of physical touching, as where a defective water system is installed in a house.

116 Thus, in relation to both the 1966 changes and the changes in the early 1970s, the majority had regard to secondary sources to understand the meaning of injury and physical injury. Circuit Judge Posner continued at 972 F 2d at 810:

We can now see more clearly that two senses of “physical injury” are competing for our support. One, which the insurers want us to adopt, is an injury that causes a harmful physical alteration in the thing injured. The other, which is what the draftsmen of the Comprehensive General Liability policy apparently intended and what rational parties to such a policy would intend in order to make the policy’s coverage real and not illusory, is a loss that results from physical contact, physical linkage, as when a potentially dangerous product is incorporated into another and, because it is incorporated and not merely contained (as a piece of furniture is contained in house but can be removed without damage to the house), must be removed, at some cost, in order to prevent the danger from materializing.

[Emphasis added.]

117 After discussing the possible influence of the development of the law in relation to the recovery of economic loss on the definitional changes, Circuit Judge Posner said at 972 F 2d at 812: