FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Ashwin on behalf of the Wutha People v State of Western Australia (No 4) [2019] FCA 308

|

WAD 6064 of 1998 | ||

|

| ||

|

BETWEEN: |

RAYMOND WILLIAM ASHWIN & ORS ON BEHALF OF THE WUTHA PEOPLE Applicant | |

|

AND: |

STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA & ORS Respondents | |

|

[5] | |

|

[5] | |

|

[14] | |

|

[22] | |

|

[25] | |

|

[30] | |

|

[34] | |

|

[38] | |

|

[41] | |

|

[44] | |

|

[48] | |

|

[51] | |

|

[57] | |

|

[61] | |

|

[65] | |

|

[69] | |

|

[73] | |

|

[77] | |

|

[80] | |

|

[108] | |

|

[115] | |

|

[116] | |

|

[120] | |

|

[136] | |

|

[168] | |

|

Has the application been authorised by all parties in the “native title claim group”? |

[177] |

|

Did the decision-making process adopted invalidate authorisation? |

[225] |

|

[254] | |

|

ASSUMING IT TO BE AUTHORISED, SHOULD THE WUTHA APPLICATION SUCCEED? |

[262] |

|

[263] | |

|

[278] | |

|

Traditional laws concerning rights to land and waters (Question 1) |

[301] |

|

[320] | |

|

[419] | |

|

Do the descendants of Julia Sandstone hold rights in the Body? |

[424] |

|

[432] | |

|

Whether traditional laws and customs provide a connection with the Trial Area (Question 4) |

[451] |

|

[452] | |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

BROMBERG J:

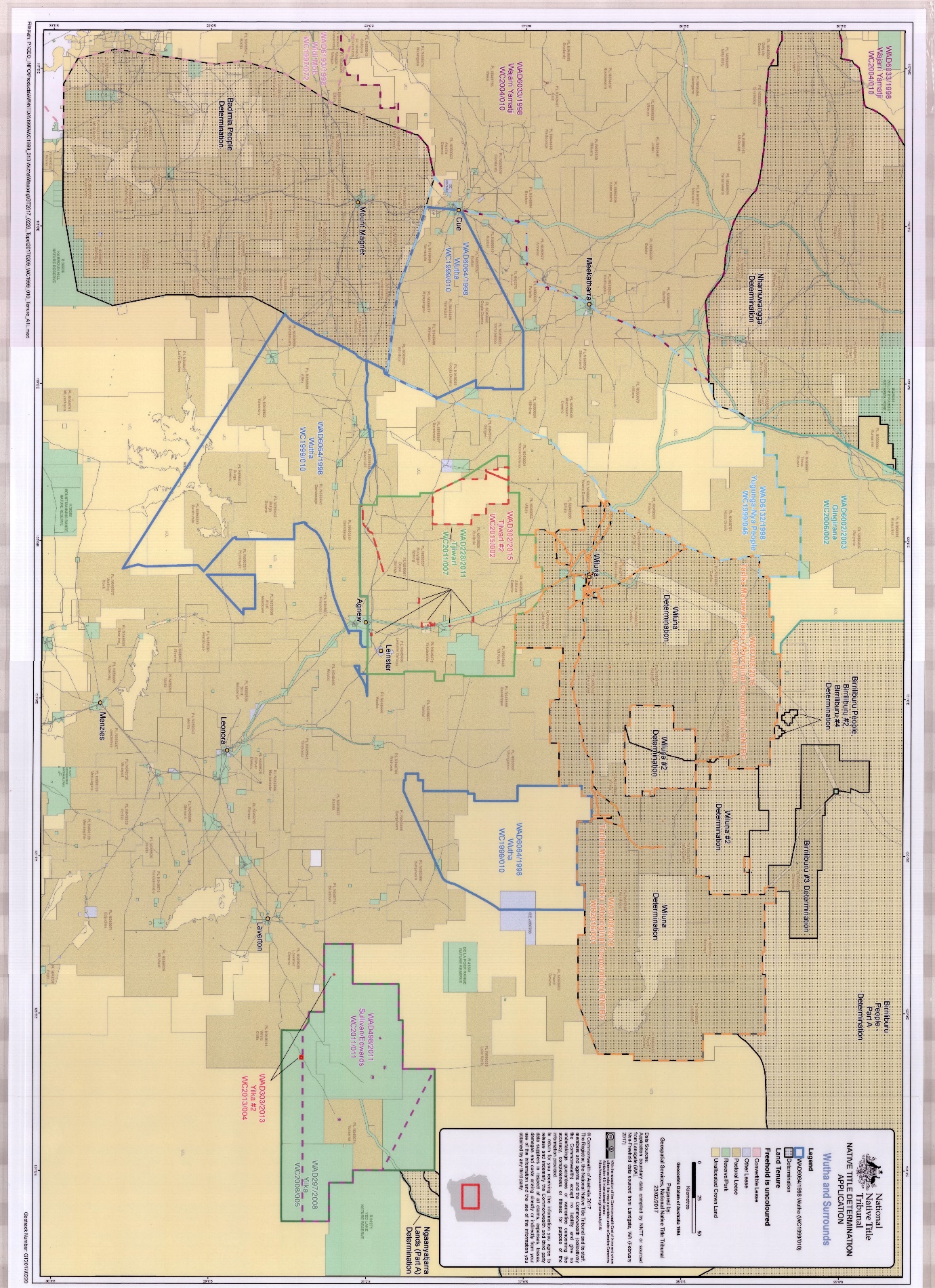

1 The applicant in proceeding WAD 6064 of 1998 (the “Wutha proceedings”) has applied under s 61 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (“NTA”) for a determination of native title in relation to an area of some 32,630 square kilometres in the Western Australian ‘Goldfields Region’. The applicant applies on behalf of persons which the application (“the Wutha application”) calls “the Wutha people” and makes a claim for native title on behalf of a group of persons which includes the three surviving individuals who constitute the applicant (“Wutha claim group”).

2 As I will further explain, the claim made is made by a group of persons who are each said to be descendants of six named apical ancestors. The claim is a group claim in which the applicant asserts that each member of the group holds, in common with other members of the group, native title rights and interests over the entire area of the claim. The group has taken the name “Wutha” for the purposes of this application. The word “wutha” means bush potato. It is not a traditional name which, outside of this proceeding, is or has been associated with the Wutha claim group or their predecessors. The name has been chosen for the purpose of this proceeding as a label for identifying the claimants and their forebears (“the Wutha group”).

3 On 9 March 2016 Barker J ordered that certain questions (“Separate Questions”) be decided separately from any other questions in the Wutha proceedings as follows:

The following questions are to be set down for hearing in respect of a separate proceeding solely on the issue of connection in respect of all areas claimed, save for the area of the overlap with the Yugunga-Nya native title determination application (WAD 6132/1998):

(a) does native title exist in relation to land and waters in the area?;

(b) if the answer to (a) above is yes:

(i) who are the persons or each group of persons holding the individual, common or group rights comprising the native title?; and

(ii) what are the native title rights and interests held by the native title holders identified in (i) above?

4 These reasons for judgment concern the trial of the Separate Questions as well as a further separate question as to whether the applicant is authorised to bring the Wutha proceeding.

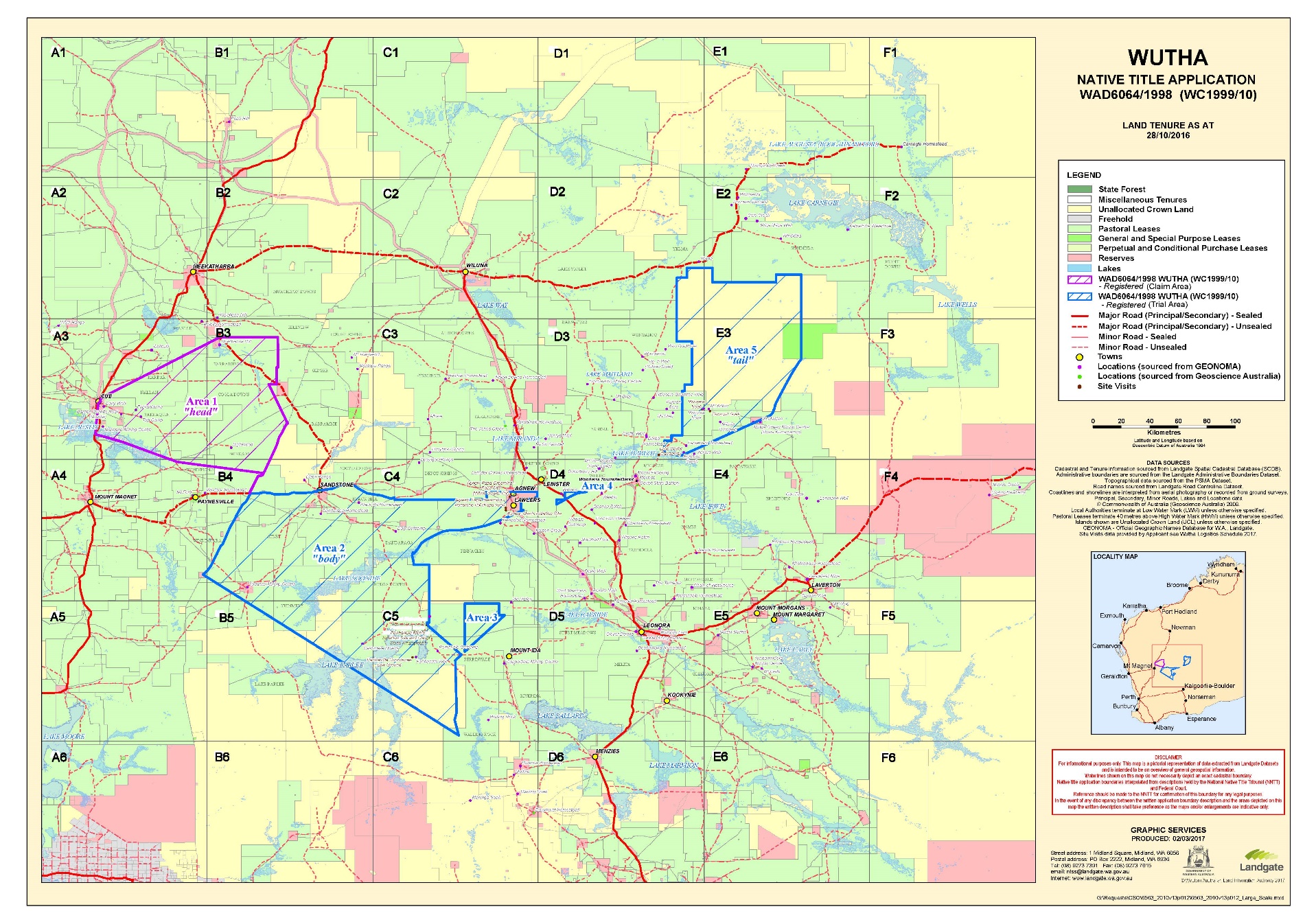

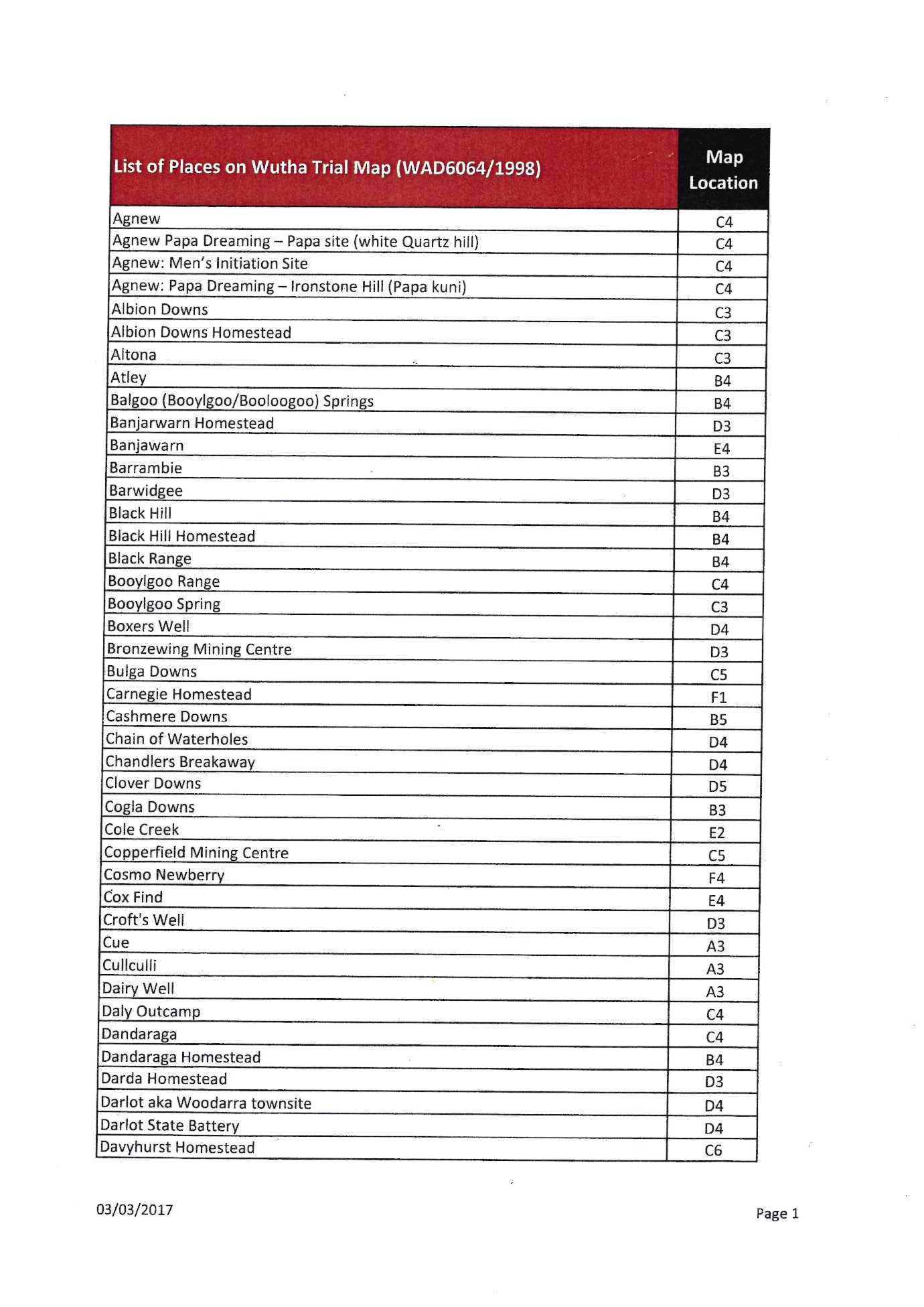

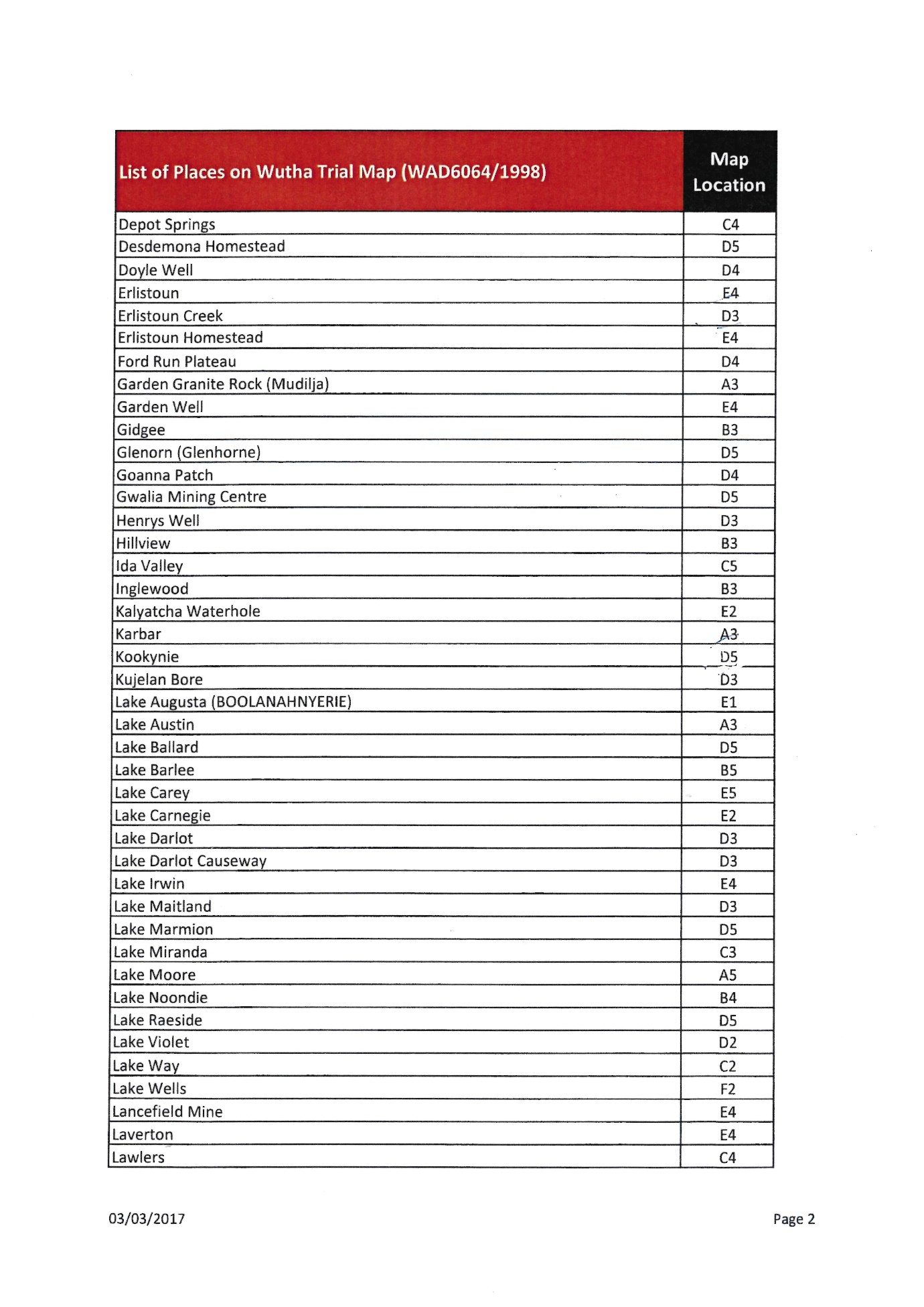

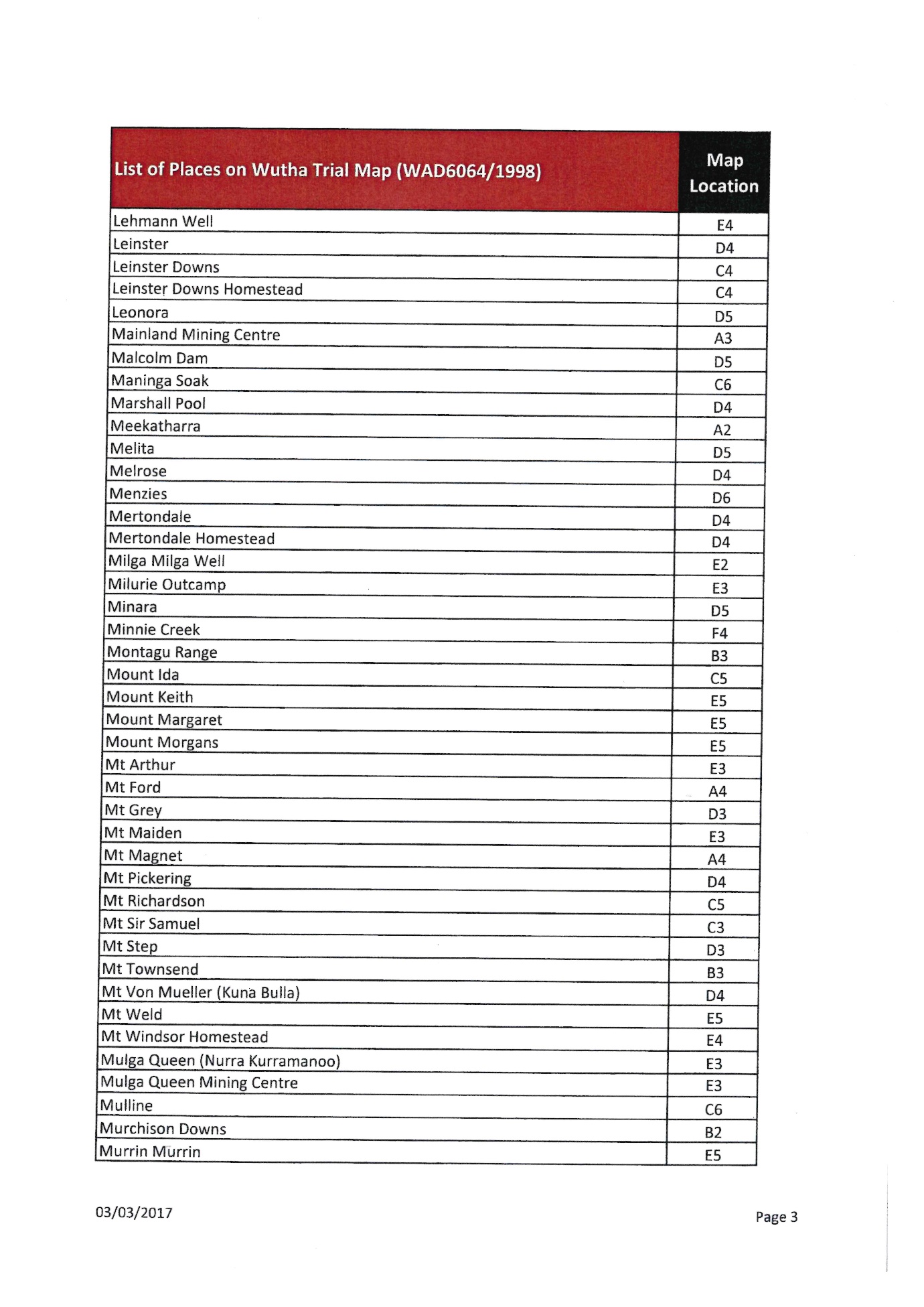

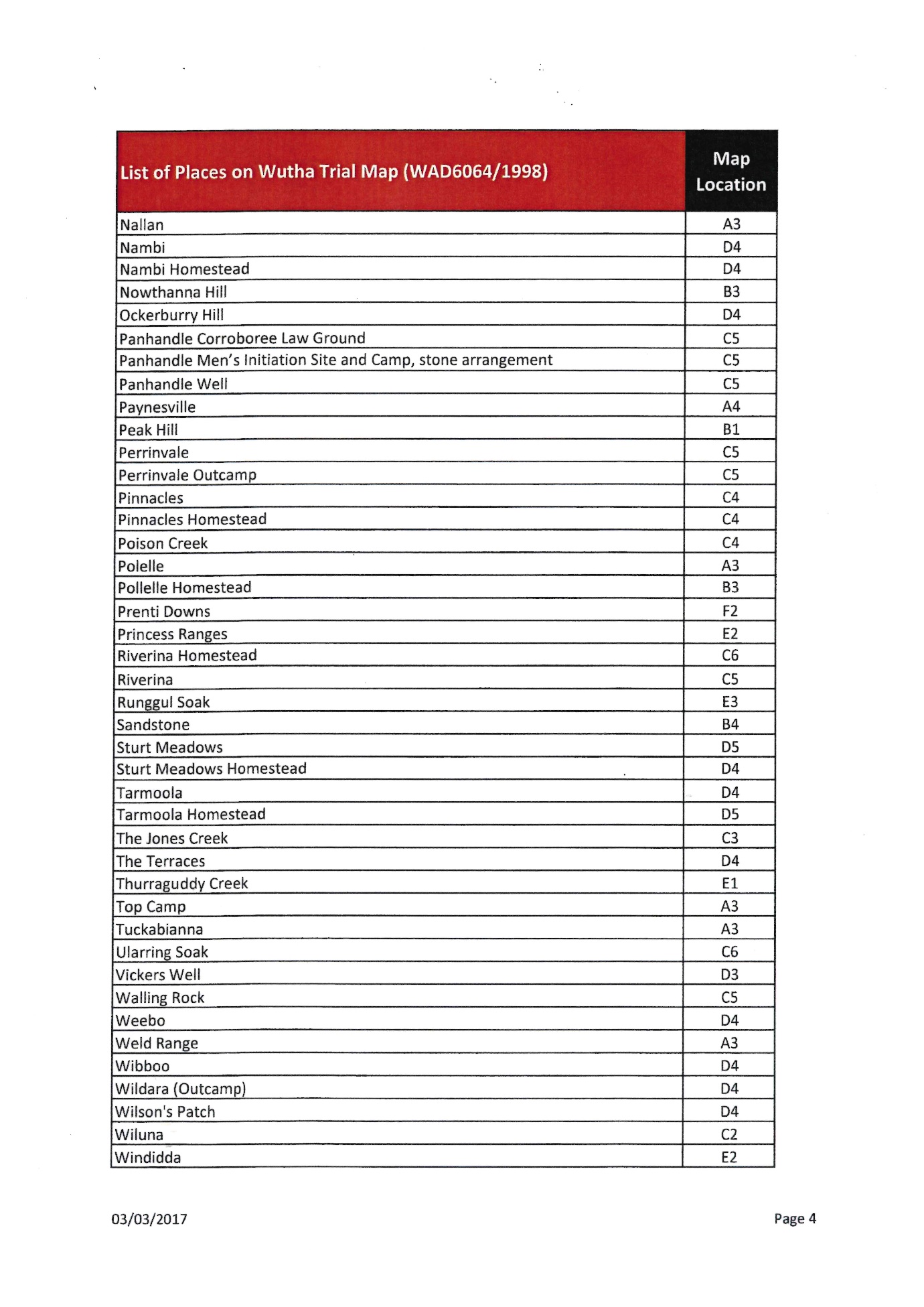

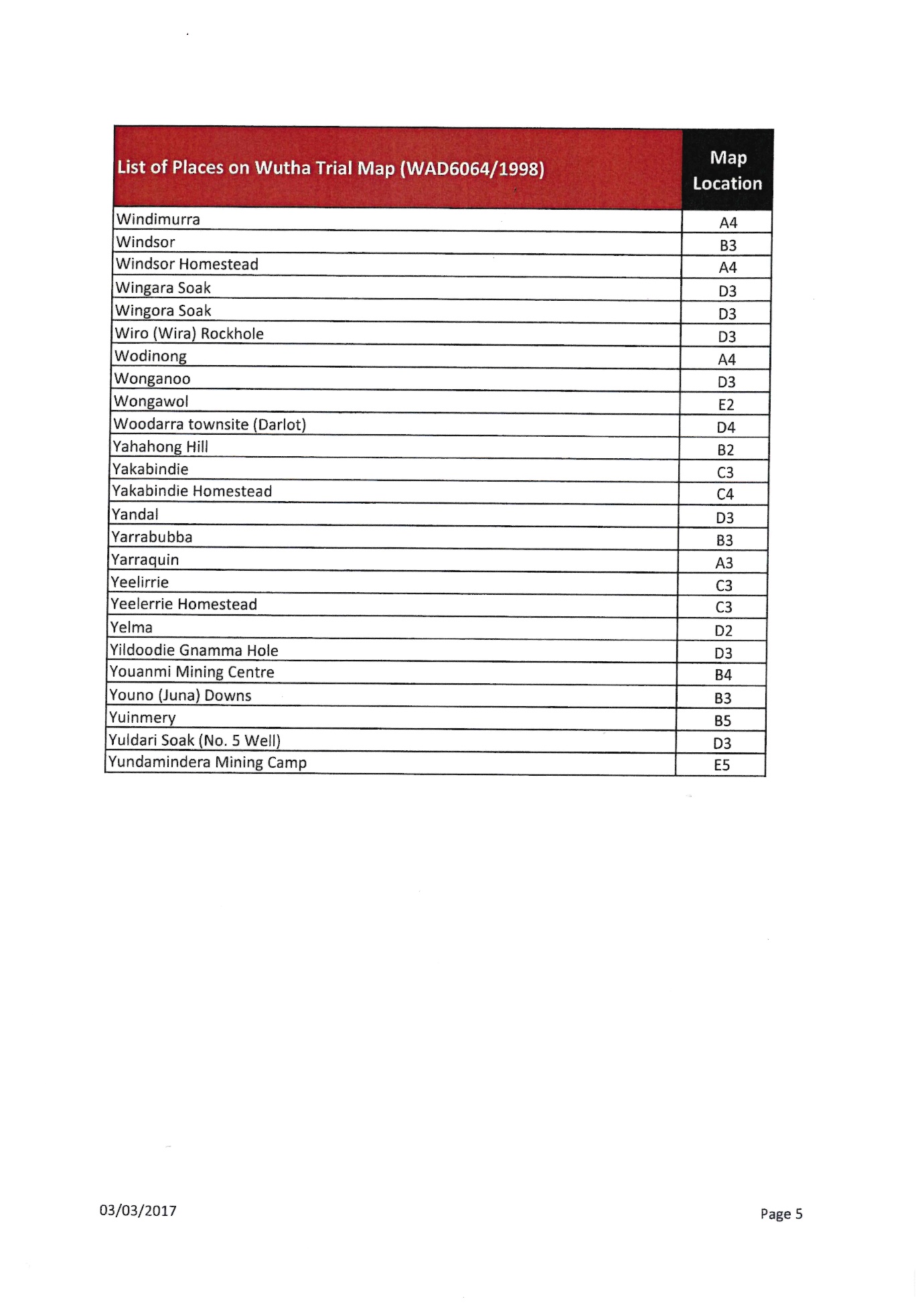

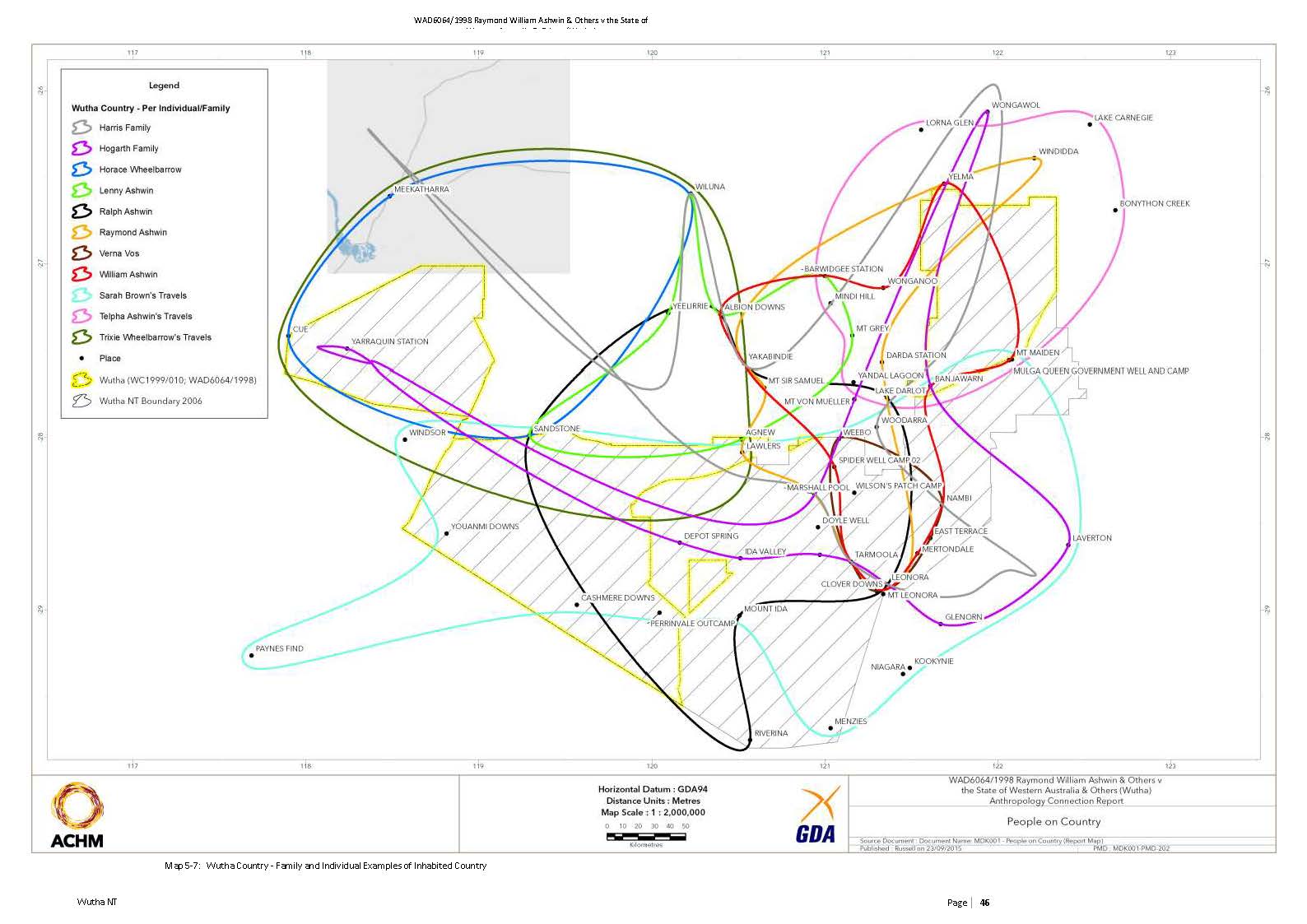

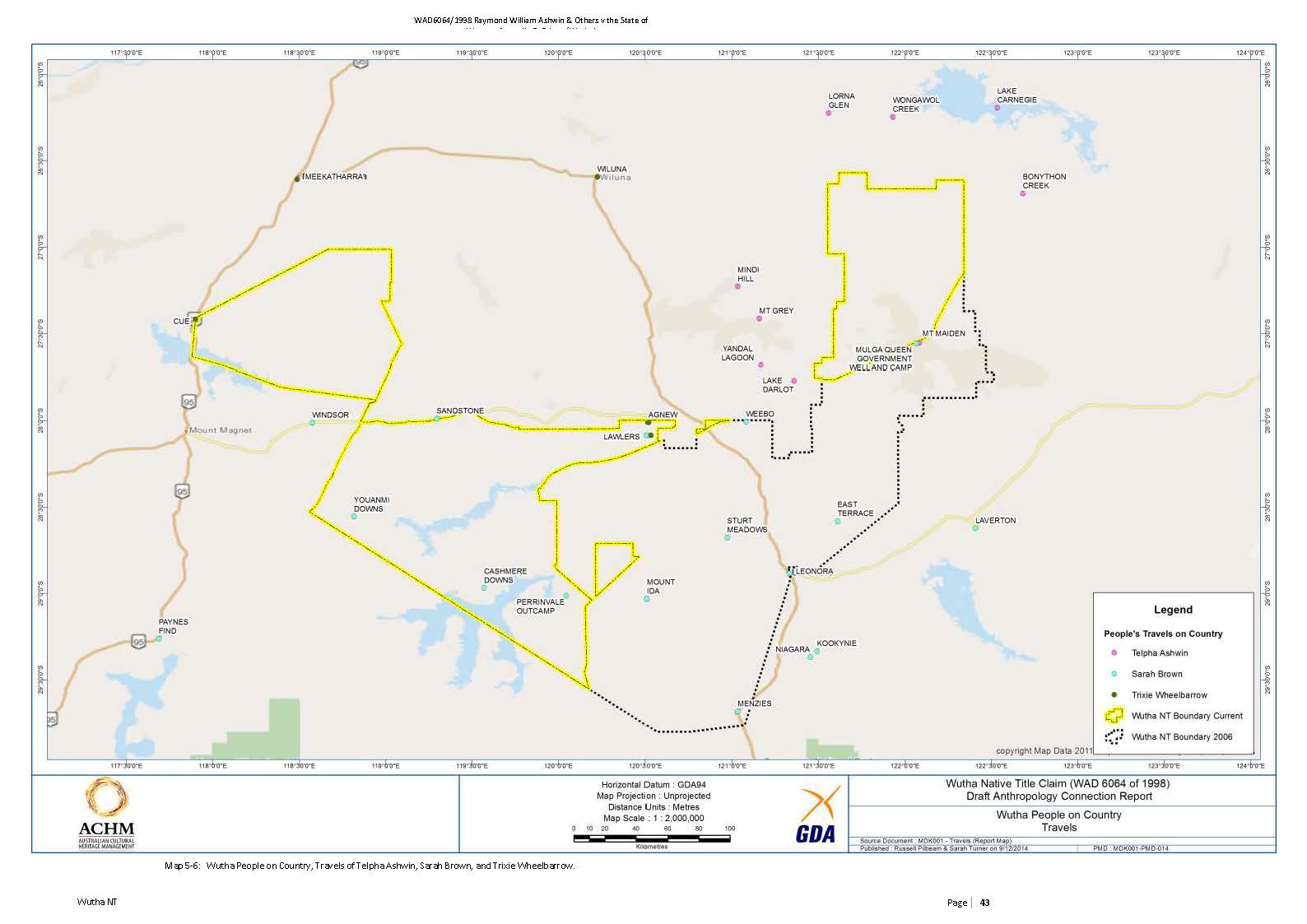

5 The location and boundaries of the area claimed by the Wutha claim group (“Wutha claim area”) are shown in the map attached to these reasons as Annexure 1. As I will be extensively referring to various locations or places on that map, a list of places found on Annexure 1 and their location on that map is given in Annexure 2.

6 As can be seen from Annexure 1, the claim area comprises 5 discrete areas identified as Areas 1 to 5. As is also apparent from Annexure 1, Area 1 has been designated as the “Head”, Area 2 the “Body” and Area 5 the “Tail”. Those designations reflect the idea that, with some imagination, the Wutha claim area broadly reflects the shape of a dog. I will hereafter refer to Area 1 as the “Head”, Area 2 as the “Body” and Area 5 as the “Tail”.

7 Areas 3 and 4 may be referred to separately however unless expressly stated to the contrary, a reference to the Body is intended to also include a reference to Areas 3 and 4.

8 The area of the Head is the subject of an overlapping claim with the Yugunga-Nya native title determination application (WAD 6132 of 1998). In accordance with the orders of Barker J made on 9 March 2016, the trial of the Separate Questions did not address the existence of native title in relation to the land and waters in the area of the Head. The area the subject of the Separate Questions will be referred to as the “Trial Area” and comprises only the Body and the Tail. The Trial Area is hatched in blue on Annexure 1.

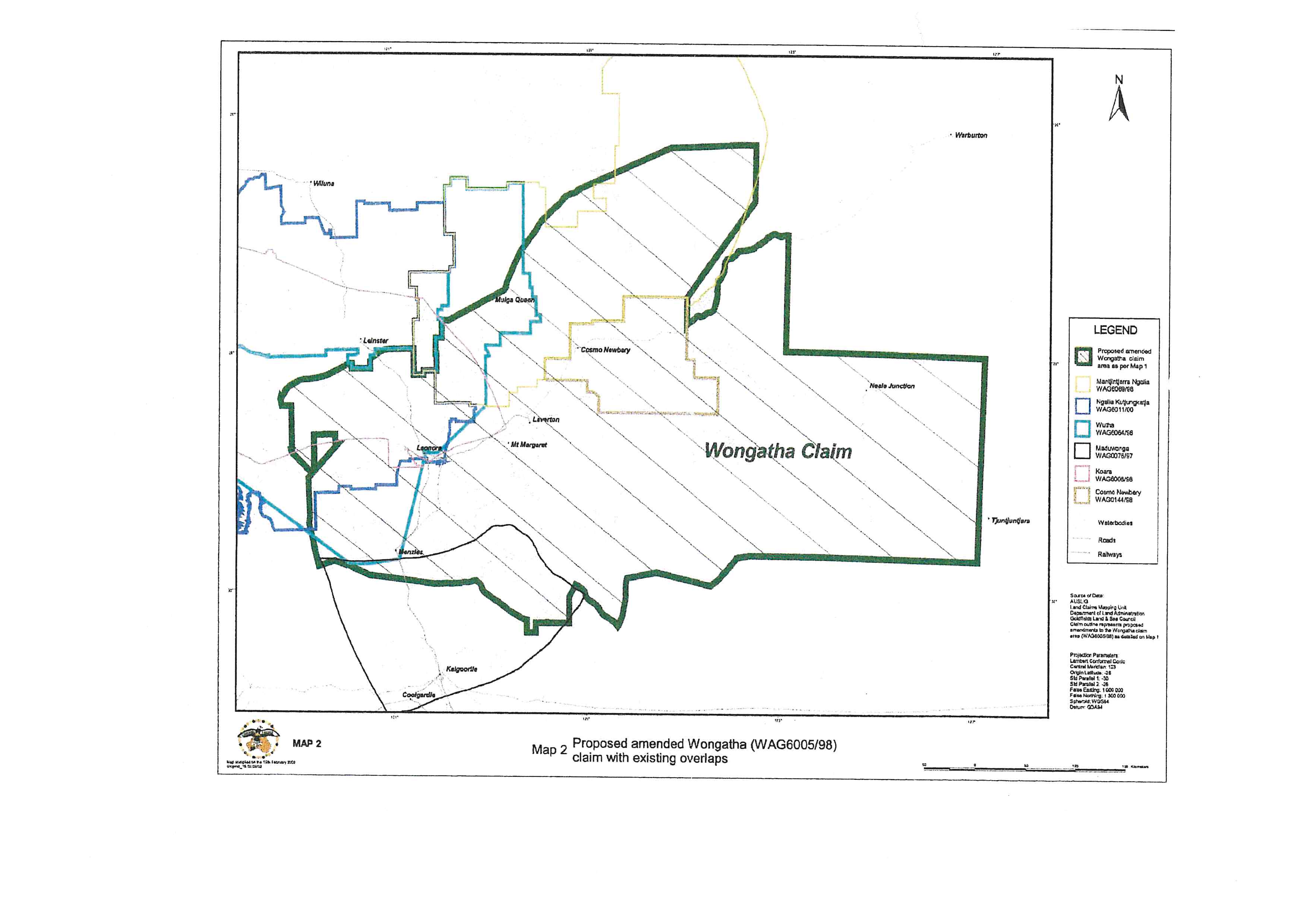

9 In its original form, the Wutha application made a claim for a single and continuous area of land and waters far greater in size than the present claim area. Various parts of the area formerly claimed overlapped with claims made in other native title proceedings concerning the Goldfields Region of Western Australia. That overlap was the subject of a determination in Harrington-Smith v State of Western Australia (No.9) (2007) 238 ALR 1 (“Wongatha”). A map of the area claimed in Wongatha is shown in Annexure 4. By orders made in Wongatha, the Wutha claim was dismissed in so far as the area claimed was the subject of an overlap with other claims dealt with by that judgment. It is for that reason that what remains of the Wutha claim area are the five disjointed areas shown on Annexure 1.

10 Whilst by this judgment, the Court can only determine whether native title exists in the Trial Area, the determination of that question necessarily involves a consideration of places (and circumstances associated with those places) located outside of the Trial Area. In particular many of those places of significance are located to the south of the Tail and to the east of the Body and include Darlot and Weebo and the area down to Leonora, where many of the witnesses called now reside.

11 The Body is an area comprising approximately 16,920 square kilometres. The Body includes the area around the town of Sandstone on its northern boundary, and the area around Lake Barlee at its southern boundary, where the applicant contended that significant ceremonial sites exist including the Panhandle Law Grounds and the Panhandle Corroboree Law Ground. Lawlers and Agnew sit in the north-eastern corner of the Body where further significant sites including the Agnew Men’s Initiation Site, Papa Kanu (Ironstone Knoll) and Papa Quartz Hill were the subject of evidence.

12 The Body is immediately south of the area the subject of the native title determination in Narrier v State of Western Australia [2016] FCA 1519 (Mortimer J) (“Tjiwarl”). The location and boundaries of the Tjiwarl native title claim, and other native title claims in close proximity to the area of the Wutha claim, are shown in the map in Annexure 3.

13 The Tail is an area comprising approximately 7,750 square kilometres. Locations of significance to the issues I need to consider include Lake Darlot, Darlot (also known as Woodarra Township), Mulga Queen, Wingara Soak and Runggul Soak, all of which are located at the southern end of the Tail. Wongawol is to the north of the Tail, and Lake Carnegie is to the north-west. Those places are also of significance.

14 The trial took place in three phases: an on-country hearing between 13 and 22 March 2017 where lay evidence was taken, a hearing in Perth between 29 May and 1 June 2017 where the lay evidence was completed and where expert anthropologists gave evidence, and final submissions in Perth on 19 to 20 September 2017.

15 The on-country hearing was held over eight days at Leonora and a number of locations throughout the Trial Area. The Court convened at the Leonora Recreation Centre exclusively on the first and fifth to eighth days. The on-country portion of the trial included site views in a number of remote locations in the Trial Area, as well as male and female gender-restricted evidence sessions. The Court was welcomed to country by members of the Wutha claim group, Geoffrey Ashwin and Gay Harris.

16 The site views included the following locations in the southern area of the Tail: Lake Darlot Causeway, Wingara Soak and Runggul Soak. Each of these sites is marked in the map in Annexure 1 to these reasons.

17 The Lake Darlot Causeway is said to be a traditional crossing point through Lake Darlot. This place is associated with the Kuna Bulla tjukurrpa which passes the edge of Lake Darlot at Mount Von Muller. Tjukurrpa or thukur are Aboriginal words which translate as dreaming stories or dreamtime stories. This area is also associated with the Goombawan tjukurrpa. Geoffrey Ashwin, Gay Harris, Lorraine Barnard and June Harrington-Smith (nee Ashwin) (“June Ashwin”), Luxie Hogarth and Geraldine Hogarth gave some of their evidence at Lake Darlot Causeway.

18 Located at the southern end of the Tail, Wingara Soak is on dry open ground with a soak of about half an acre featuring some green pasture and water holes. It is suggested to be close to a camp site where ancestors of the Wutha group lived. Evidence was given that the camp site features soft ground, fire places and stones for grinding. It was also suggested that this was a good place for bush food (including wantirri (seeds), kampurarra (wild tomato), berries and grub) and bush medicine (including sandalwood). Wingara Soak is said to be the birth place of Telpha Ashwin, an ancestor of substantial significance to the Wutha claim. Wingara Soak is associated with the Goomboowan tjukurrpa and some of the evidence given at this site was female gender-restricted evidence. June Ashwin, Gay Harris and Geraldine Hogarth gave some of their evidence at Wingara Soak.

19 Runggul Soak is approximately 10 kilometres to the east of Wingara Soak. The site is open ground surrounded by a range of small hills. There is a soak with water holes and some large distinctive granite boulders. The site is suggested to be close to a camp utilised by ancestors of the Wutha claimants including those of the Hogarth family. Luxie Hogarth gave evidence that Runggul Soak was in her mother’s (Daisy Cordella) country and that at various times her grandmother (Mary) and apical ancestor Billy had their main camp here, and together with extended family roamed near here because of the soak. Geraldine Hogarth and Luxie Hogarth gave some of their evidence at Runggul Soak.

20 The Court also conducted site views and heard male gender-restricted evidence at various locations in the Body. In the southern area of the Body, near the north-eastern end of Lake Barlee, the Court heard evidence at the various Panhandle sites. Each of these sites is marked in the map in Annexure 1 to these reasons. Geoffrey Ashwin, Gary Ashwin and Ron Harrington-Smith gave some of their evidence at the Panhandle sites.

21 In the northern area of the Body, near the area of Agnew and Lawlers, the Court heard evidence at the Agnew Men’s Initiation Site, Papa Kanu (Ironstone Knoll) and Papa Quartz Hill. Each of these sites is marked in the map in Annexure 1 to these reasons. Geoffrey Ashwin, Gary Ashwin and Ron Harrington-Smith gave some of their evidence at these sites.

Lay witnesses and apical ancestors

22 Beginning with the three siblings who constitute the applicant and John Ashwin (the “Ashwin siblings”), the Wutha claim group includes the following persons who each gave evidence in support of the application: Geoffrey Ashwin, Ralph Ashwin, June Ashwin, John Ashwin, Bradley Ashwin, Calvin Ashwin, Gary Ashwin, Sheldon Harrington-Smith, Joshua Harrington-Smith, Gay Harris, Lorraine Barnard, Luxie Hogarth, and Geraldine Hogarth.

23 Those witnesses are members of one or more of the four ancestral families of the apical ancestors by whom the Wutha claim group is defined. Those ancestral families are: Darugadi, Murni and Matjika (“Darugadi ancestral family”), whose decedents include families of the Ashwin siblings through Telpha Ashwin and the non-Aboriginal pastoralist Arthur Ashwin, and the Harris family through Jumbo Harris (Telpha’s brother); Billy (“Billy ancestral family”), whose decedents include the Hogarth family; Inyarndi (“Inyarndi ancestral family”), whose decedents include the Barnard family; and Julia Sandstone (“Julia Sandstone ancestral family”), whose decedents also include the families of the Ashwin siblings because Julia Sandstone’s daughter Sarah Brown married William Ashwin.

24 In this section I further identify each claimant witness, the witness’ connection to one or other of the ancestral families and give a brief outline of the witness’ evidence.

25 Geoffrey Ashwin is one of the persons who constitute the applicant. He has a connection to both the Darugadi and the Julia Sandstone ancestral families. He is one of the children of Sarah Brown and William Ashwin. William Ashwin’s parents were the non-Aboriginal owner of Dada station Arthur Ashwin and the Aboriginal woman Telpha Ashwin who was part of the Darugadi ancestral family. Sarah Brown was the daughter of Julia Sandstone and an unknown non-Aboriginal.

26 Geoffrey was 76 years old at the time of giving evidence. He is the eldest living descendent of Telpha Ashwin after his older brother, Raymond Ashwin, who is now deceased. He is not an initiated man.

27 Geoffrey has played, at least on the face of the documentations filed with the court, a leading part in the pursuit of the claim. He is the deponent of a number of affidavits filed by the applicant including to support amendments made to the Wutha application.

28 Geoffrey provided a witness statement. A video recording of an interview of Geoffrey was also tendered. He gave oral evidence on site at Lake Darlot Causeway and gender-restricted evidence at the Panhandle sites. He gave evidence and was cross-examined at Leonora.

29 Geoffrey was, not surprisingly, uncomfortable in giving evidence. Although I hold reservations about the reliability of some of the evidence given, I do not doubt his honesty. He gave evidence on matters including his:

(1) understanding of tjukurrpa and other traditional laws and customs, such as his knowledge of the Kuna Bulla dreaming story, the pathways whereby under traditional laws and customs persons can gain rights and interests in land, traditional decision-making processes and authority to speak for country;

(2) family history, including about his grandmother Telpha Ashwin, his mother Sarah Brown, and what he understood about their country; and

(3) connection to country through hunting and cooking in the bush with his predecessors.

30 Ralph Ashwin is the younger brother of Geoffrey Ashwin. He is also one of the persons who constitute the applicant. He has the same ancestry as Geoffrey and is a descendent of both the Darugadi and the Julia Sandstone ancestral families.

31 Ralph Ashwin gave gender-restricted evidence at the Agnew Men’s Initiation Site. He gave evidence and was cross-examined at Leonora.

32 Ralph came across as a knowledgeable, straightforward and honest witness who was doing his best to assist the Court. He gave evidence on matters including his:

(1) understanding of tjukurrpa and other traditional laws and customs, including traditional skin systems, the pathways whereby under traditional laws and customs persons can gain rights and interests in land, traditional decision-making processes and authority to speak for country;

(2) connection to country; and

(3) family history, including how his father William Ashwin had described his country and about his mother Sarah Brown.

33 Ralph had previously given evidence in the Wongatha proceeding. He was taken to the summary of his evidence prepared by Lindgren J (at Annexure F of that judgment) and generally confirmed the accuracy of that summary.

34 John Ashwin is a sibling of Geoffrey and Ralph Ashwin and his ancestry is the same as theirs. He has a connection by descent to both the Darugadi and the Julia Sandstone ancestral families.

35 John was too ill to attend the hearing at Leonora. He made a witness statement and it was tendered. A video recording of an interview with John was also tendered. He was not cross-examined.

36 John was 66 years old at the time of making his witness statement and gave evidence that he was not an initiated man. He grew up around Leonora but moved to Cue when he was 17 years old.

37 By his witness statement John gave evidence on matters including his:

(1) understanding of tjukurrpa and other traditional laws and customs;

(2) family history, including his knowledge of Julia Sandstone and her country and his family’s connection to country; and

(3) his connection to the claim area, including being taught to hunt and live on country by his elders (including his uncle Jumbo Harris and his parents).

38 Bradley Ashwin is the son of John Ashwin. He is the grandson of William Ashwin and Sarah Brown and thereby a descendant of the Darugadi and Julia Sandstone ancestral families. He was 48 years old at the time of giving evidence.

39 Bradley Ashwin made a statement. He gave evidence and was briefly cross-examined at Leonora.

40 Bradley gave evidence on matters including his:

(1) understanding of tjukurrpa and other traditional laws and customs, including his knowledge of Western Desert language, his knowledge and engagement with various sites in the Head (not in the Trial Area) and his knowledge of the Water Snake dreaming story; and

(2) connection to country through camping and hunting with his family.

41 Calvin Ashwin is also a son of John Ashwin and has the same ancestry as his brother Bradley. He is a descendant of both the Darugadi and Julia Sandstone ancestral families.

42 Calvin made a statement. He gave evidence and was cross-examined at Leonora.

43 Calvin gave evidence on matters including his:

(1) understanding of tjukurrpa and other traditional laws and customs, including his knowledge of Western Desert language, his knowledge and engagement with various sites in the Head (not in the Trial Area) and his knowledge of the Water Snake and Ancestral Snake dreaming stories; and

(2) connection to country through camping and hunting with his family.

44 Gary Ashwin is the son of Gary James Ashwin and Cynthia Beasley. He is the grandson of Raymond Ashwin and a great-grandson of William Ashwin and Sarah Brown. He has a descent connection with the Darugadi and Julia Sandstone ancestral families.

45 Gary gave male gender-restricted evidence at the Panhandle site. He made a witness statement. He gave evidence and was cross-examined at Leonora.

46 Gary is a young man who was 31 years of age at the time of giving evidence. He is a wati and an initiated man. He lives in Wiluna, and was initiated there largely at his own initiative.

47 Gary gave evidence on matters including his:

(1) understanding of tjukurrpa and other traditional laws and customs, including going through the law, the traditional pathways whereby persons can gain rights and interests in land, traditional decision-making processes and authority to speak for country; and

(2) connection to country, including through his knowledge and experience of camping, hunting and bush medicine.

48 June Ashwin is the sister of Geoffrey, Ralph and John Ashwin and has the same relevant ancestry. She is also one of the persons who constitute the applicant. June has a descent connection to both the Darugadi and Julia Sandstone ancestral families. She was 69 years old at the time of giving evidence.

49 June gave evidence at the Lake Darlot causeway and at Wingara Soak. She made a witness statement. She gave evidence and was cross-examined at Leonora.

50 June gave evidence on matters including her:

(1) understanding of tjukurrpa and other traditional laws and customs, including the traditional pathways whereby persons can gain rights and interests in land, traditional decision-making processes and authority to speak for country;

(2) family history, including regarding her parents Sarah Brown and William Ashwin and her paternal grandmother Telpha Ashwin, and her understanding of their country and language; and

(3) connection to country through camping and hunting with her family.

51 Ron Harrington-Smith is the husband of June Ashwin. He is not a descendant of any of the apical ancestors upon which the applicant relies. He was 71 years old at the time of giving evidence.

52 Ron refers to himself as the “spokesman” for the claim group and represented the Wutha claim group in this proceeding prior to legal representation being formally obtained.

53 Ron gave male gender-restricted evidence at the Panhandle sites. He gave a witness statement. He gave evidence and was cross-examined at Leonora.

54 Ron gave evidence that he had been told the history of the “Wutha families” and their traditional association with the country for which they are seeking a native title determination by Sarah Brown, Lenny Ashwin, Raymond Ashwin, and Danny Harris, each of whom are now deceased.

55 Ron had previously given evidence in the Wongatha proceeding. He was taken to and generally confirmed the accuracy of the summary of his evidence in that proceeding.

56 I hold some concerns about the reliability of the evidence given by Ron who, at times, gave his evidence in the guise of an advocate rather than a witness. In particular, the evidence he gave about his understanding of Sarah Brown’s claimed association with the Panhandle sites was evasive and non-responsive to the questions asked of him.

57 Sheldon Harrington-Smith is the son of June and Ron Harrington-Smith. Through his mother, June, and his grandparents, William Ashwin and Sarah Brown, he has a descent connection to the Darugadi and Julia Sandstone ancestral families. He was 31 years old at the time of giving evidence.

58 Sheldon made a witness statement. He gave evidence and was cross-examined at Leonora. A video recording of an interview with Sheldon was also tendered.

59 Sheldon lives in Perth where he has lived for 10 years having prior to that lived and grown up in Kalgoorlie where he was born. He is not an initiated man.

60 Sheldon gave evidence of his connection to country and his understanding of tjukurrpa and other traditional laws and customs. His evidence was that he had been taught by his parents and elders the importance of hunting and cooking and eating food in the “right” traditional way and the importance of looking after the country you travel over and respecting traditional places and dreaming stories.

61 Joshua Harrington-Smith is also the son of June and Ron Harrington-Smith, and has the same ancestry as his brother Sheldon. He has descent connection to both the Darugadi and the Julia Sandstone ancestral families. He was 29 years old at the time of giving evidence.

62 Joshua made a witness statement and was cross-examined at Leonora. A video recording of an interview with Joshua Harrington-smith was also tendered.

63 Joshua lives in the Rockingham areas south of Perth where he has lived for 8 years having prior to that lived and grown up in Kalgoorlie where he was born. He is not an initiated man.

64 Joshua gave evidence of his connection to country and his understanding of tjukurrpa and other traditional laws and customs. His evidence was that he had been taught by his parents and elders the importance of hunting and cooking and eating food in the “right” traditional way and the importance of looking after the country you travel over and respecting traditional places and dreaming stories.

65 Gay Harris is the daughter of Jumbo Harris and Elyon Bella Harris. She has seven siblings. Her father, Jumbo Harris, was the brother of Telpha Ashwin and the son of Darugadi. Through Jumbo, Gay Harris is a descendent of the Darugadi ancestral family. She was 70 years old at the time of giving evidence.

66 Gay gave evidence at Lake Darlot causeway and Wingara Soak, including female gender-restricted evidence. Gay made a witness statement. She gave evidence and was extensively cross-examined at Leonora. A video recording of an interview with Gay Harris was tendered. The summary of Gay’s evidence given in Wongatha prepared by Lindgren J (at Annexure F of that judgment) was also tendered.

67 Gay was an impressive witness. She was evidently intent on providing the Court with her honest account of events. Gay had an understanding of who her people were and the land that she considered they were entitled to exercise native title rights over. Her evidence demonstrated good knowledge of the families involved in the Wutha application and their connection with other families, with apical ancestors and with the places at which they lived or were otherwise associated with.

68 Gay gave evidence on matters including her:

(1) understanding of tjukurrpa and other traditional laws and customs, including about thukur or dreaming stories and significant places on country associated with them, the traditional pathways whereby persons can gain rights and interests in land, traditional decision-making processes and authority to speak for country; and

(2) family history and the apical ancestors, including their connection with other families in the Wutha claim group and their traditional connection with country.

69 Lorraine Barnard is the daughter of Trixie Wheelbarrow and Alec Barnard. Her grandfather was Jimmy Wheelbarrow and through him her apical ancestor is her great-great grandmother Inyarndi. She has a descent connection with the Inyarndi ancestral family.

70 Lorraine gave some evidence at Lake Darlot causeway. She provided a witness statement. She gave evidence and was cross-examined at Leonora. A video recording of an interview with Lorraine was also tendered.

71 Lorraine has lived most of her life around Cue which she described as her country. She moved to Leonora about 12 years ago. She was around 69 years old at the time of giving evidence.

72 Lorraine was quite knowledgeable about her genealogy and the history of her own family. She gave evidence including about her:

(1) understanding of tjukurrpa and traditional laws and customs, including dreaming stories;

(2) personal and family history; and

(3) connection to country through living on country and learning bush skills and bush medicine.

73 Luxie Hogarth is the daughter of Daisy Cordella and the granddaughter of apical ancestor Billy. She has a descent connection to the Billy ancestral family.

74 Luxie gave evidence at Lake Darlot Causeway and at Runggul Soak, including female gender-restricted evidence. She made a witness statement. She gave evidence and was cross-examined in Leonora. A video recording of an interview with Luxie Hogarth was also tendered. Luxie previously gave evidence in the Wongatha proceeding. The witness statement that Luxie gave in that proceeding, together with the summary of her evidence prepared by Lindgren J (at Annexure F of that judgment) were tendered.

75 Luxie was 76 years old at the time of giving evidence and is an elder. At various times she found it difficult to communicate and needed the assistance of her daughter Geraldine Hogarth, and because of this, in a practical sense, much of their evidence was given together.

76 Luxie gave evidence on matters including her:

(1) understanding of tjukurrpa and other traditional laws and customs;

(2) personal and family history, including her family’s connection with other families in the Wutha claim group and her family’s traditional connection with country; and

(3) her connection to country, including by living on and looking after her country.

77 Geraldine is the daughter of Luxie Hogarth, great-granddaughter of apical ancestor Billy and a descendant of the Billy ancestral family. She was 57 years old at the time of giving evidence.

78 Geraldine gave evidence at Lake Darlot Causeway, Wingara Soak and Runggul Soak, including female gender-restricted evidence. She made a witness statement and was extensively cross-examined at Leonora. A video recording of an interview with Geraldine Hogarth was also tendered. Geraldine previously gave evidence in the Wongatha proceeding. The witness statement that Geraldine gave in that proceeding, together with the summary of her evidence prepared by Lindgren J (at Annexure F of that judgment) were tendered.

79 Geraldine is an impressive woman who is obviously deeply committed to her people. She gave evidence including about her:

(1) understanding of tjukurrpa and other traditional laws and customs, including various dreaming stories and significant places on country associated with them, and traditional skin groups, burial practices and languages;

(2) personal and family history, including her family’s connection with other families in the Wutha claim group and her family’s traditional connection with country; and

(3) connection to country, including by looking after her country, camping and hunting.

80 The applicant and the participating respondents - the State of Western Australia (“the State”) and the Central Desert Native Title Services Ltd (“Central Desert”) - called expert anthropologists who prepared reports, participated in a joint experts’ conference and gave oral evidence. Those experts were:

(1) Associate Professor Neale Draper (“Dr Draper”), called by the applicant;

(2) Dr Ron Brunton (“Dr Brunton”), called by the State; and

(3) Dr Heather Lynes (“Dr Lynes”), called by Central Desert.

81 Dr Draper prepared three reports which were tendered in the proceeding:

(1) Anthropology Connection Report, revised October 2016, comprising volume 1 (the main body of the report), volume 2 (genealogies) and a restricted section (chapter 15 of volume 1) (“Dr Draper's first report”);

(2) Supplementary Expert Anthropology Report for the Applicant, dated 13 January 2017 (“Dr Draper's second report”); and

(3) Second Supplementary Report for the Applicant, dated 5 May 2017 (“Dr Draper's third report”).

82 Dr Draper is a qualified anthropologist and archaeologist, holding a PhD in anthropology from the University of Queensland. He has over 30 years of experience in research, tertiary teaching and professional practice in anthropology and archaeology, mostly related to Australian Aboriginal culture. He is an Associate Professor (Academic Level D) in the School of Humanities (Department of Archaeology), Faculty of Education, Humanities and Law at the Flinders University of South Australia. He has previous experience in the research and preparation of anthropology connection reports for native title cases in Western Australia and South Australia, including as a consultant anthropologist to the Goldfields Land and Sea Council.

83 The issues that Dr Draper addressed in his first report included, amongst other matters, his opinion on whether the Wutha claim area falls inside the area of land that is known by anthropologists as the Western Desert, whether there are acknowledged traditional laws and customs under which rights and interests in the Wutha claim area are possessed, the identity of the people and or groups of people who held rights and interests in the Wutha claim area at sovereignty (as I later explain sovereignty refers to the year 1829), whether the pre-sovereignty community maintained its identity and has continued to acknowledge and observe traditional laws and customs without significant interruption from sovereignty to present, and whether any persons have rights and interests in the Wutha claim area.

84 Dr Draper’s first report addressed those issues in respect of the area of the Head, the Body and the Tail. Dr Draper’s subsequent reports were confined to addressing the Body and the Tail (the Trial Area).

85 Dr Draper’s second report addressed Dr Draper’s response to the expert reports filed by Dr Brunton and Dr Lynes. His third report addressed the evidence given during the trial by the lay witnesses and additional evidence in reply to the expert reports of Dr Brunton and Dr Lynes.

86 Dr Brunton has been involved in the discipline of anthropology for fifty years. Dr Brunton obtained his PhD in anthropology from La Trobe University and has lectured at Macquarie University, La Trobe University and the University of Papua New Guinea. Over the last 25 years, Dr Brunton has focused on a number of issues related to Australian Aboriginal people including native title, cultural heritage, social welfare and reconciliation. Dr Brunton has been retained by the State to provide anthropological reports for a number of native title claims in Western Australia and has also provided anthropological reports for respondent parties to native title claims in South Australian and Queensland.

87 Dr Brunton prepared two reports which were tendered in the proceeding:

(1) First Respondent's Anthropological Report, dated 4 November 2016, which included a statement of Errata (“Dr Brunton's first report”); and

(2) First Respondent's Supplementary Anthropological Report dated 5 May 2017 (“Dr Brunton's second report”). The State filed versions of this report with and without references to gender-restricted evidence.

88 Dr Brunton’s reports address the area of the Trial Area. Dr Brunton’s first report responds to a number of questions posed by the State on the nature and content of the traditional laws and customs in respect of the Trial Area and the nature and extent of the rights and interests to which they gave rise, the identity of the people and or groups of people who held rights and interests in the Trial area at sovereignty, whether the pre-sovereignty community maintained its identity and has continued to acknowledge and observe traditional laws and customs without significant interruption from sovereignty to present and whether any persons have rights and interests in the Wutha claim area. Dr Brunton’s first report also provided detailed comments on Dr Draper’s first report.

89 Dr Brunton’s second report addressed the evidence given during the trial by the lay witnesses and additional evidence in reply to the expert reports of Dr Draper and Dr Lynes.

90 Dr Lynes obtained her PhD in Social Anthropology from the University of Edinburgh. From January 2011 until January 2016, she was employed by Central Desert to undertake anthropological research for native title claims in the desert region of Western Australia. During that time and since, Dr Lynes has been retained to do research and provide anthropological repots for a number of native title claims in Western Australia, including for the Kimberley Land Council.

91 Dr Lynes prepared two reports which were tendered:

(1) Anthropological Report of Dr Heather Lynes, dated 25 November 2016 (“Dr Lynes' first report”); and

(2) Supplementary Anthropological Report of Dr Heather Lynes, dated 5 May 2017 (“Dr Lynes' second report”).

92 Dr Lynes’ first report deals only with the “research area”, being that part of the Tail in respect of which Central Desert performs its functions as a native title representative body under the NTA. Dr Lynes’ second report extends to the whole of the area of the Tail.

93 In her first report, Dr Lynes responds to a number of questions posed by Central Desert on the area of land that is known by anthropologists as the Western Desert, the extent to which the “research area” formed and continues to form part of the Western Desert, the extent to which the research area formed part of the Wutha society at sovereignty and continues to form part of Wutha society, and the extent to which the Wutha claim group hold rights and interests in the research area under Western Desert traditional laws and customs. Dr Lynes’ first report also provided detailed comments on Dr Draper’s first report.

94 Dr Lynes’ second report addressed the evidence given during the trial by the lay witnesses and additional evidence in reply to expert reports of Dr Draper and Dr Brunton.

95 In accordance with Court orders, all three of the experts participated in a conference of experts on 5 and 6 April 2017 in Perth. The experts responded to 19 propositions which had been agreed by the parties prior to the conference. The results of the conference are contained in the Report of Conference of Experts held on 5 and 6 April 2017 in Perth, dated 6 April 2017 (“Experts’ Report”).

96 The three experts also participated in a concurrent evidence session on 29 and 30 May 2017, followed by individual evidence and cross-examination on 31 May and 1 June 2017 in Perth.

97 Each of the experts relied on ethno-historical materials prepared by anthropologists who conducted research regarding the Aboriginal people in the general area of the Trial Area in the early to mid-20th Century. Key anthropologists whose work has been referred to and relied upon to some extent by each of the experts include Daisy Bates (“Bates”), Norman Tindale (“Tindale”), Ronald Berndt (“Berndt”), Fred Myers (“Myers”), John Stanton (“Stanton”) and William Stanner (“Stanner”). A brief introduction to these anthropologists is set out below.

98 Bates was an amateur anthropologist who visited the general vicinity of the Trial Area in around the period 1908 to 1911. While she was not a trained anthropologist, she produced a substantial corpus of material regarding Aboriginal people in various regions of Western Australia. Bates is heavily relied upon by Dr Brunton.

99 The works of Bates cited by the experts include:

(1) Bates, Daisy, 1911, ‘My camp in the Murchison Bush’, Western Mail, June 13: 44;

(2) Bates, Daisy, 1985, The Native Tribes of Western Australia, edited by Isobel White, Canberra: National Library of Australia; and

(3) Bates, Daisy, 1908, ‘Summary of Journeys, Southern’, SROWA Cons 1023 AN 24.

100 Tindale is a key anthropologist whose work has been referred to and relied upon by each of the experts. In 1939, Tindale visited the Goldfields Region of Western Australia. It is of particular relevance to this proceeding that Tindale interviewed and recorded a genealogy for Telpha Ashwin at Mount Margaret in 1939.

101 The works of Tindale referred to and relied upon by the experts include:

(1) Tindale Norman, 1939, Genealogical Data on the Aborigines of Australia Gathered During the Harvard and Adelaide Universities Anthropological Expedition 1938-9, vol VII, Unpublished ,South Australia Museum;

(2) Tindale Norman, 1939, Harvard and Adelaide Universities Anthropological Expedition Journal, vol 2, pp 759 to end, 1938-39, Unpublished, South Australia Museum;

(3) Tindale, Norman, 1939c, Data Card 2105, Daisy Cordella; and

(4) Tindale, Norman, 1939c, Data Card 2131, Maxie Warrigal.

102 In 1957 and 1959, Berndt visited the region of the Trial Area, making stops at Leonora, Laverton, Mount Margaret and Mulga Queen. By his work Berndt sought to analyse and map the western edge of the “Western Desert Cultural Bloc” which I have referred to as the Western Desert. As I explain later, Western Desert is an anthropological construct for the society of Western Desert peoples identified as having shared cultural and linguistic traditions and customs.

103 The works of Berndt relied upon by the experts include:

(1) Berndt, R. M, 1959, ‘The Concept of the “Tribe” in the Western Desert of Australia’, Oceania 30: 81-107; and

(2) Berndt, R. M, 1980, ‘Traditional Aboriginal life in Western Australia: as it was and is’, Pp 3-27 in R. M. Berndt and C. H. Berndt, (eds) Aborigines of the West: Their Past and Present, Perth: UWA Press.

104 Myers, Stanton and Stanner are more contemporary archaeologists who are referred to by Dr Brunton and Dr Lynes as authorities on Western Desert societies.

105 Myers is considered an authority on the operation of rights and interests in the Western Desert. The relevant works of Myers referred to in the evidence include:

(1) Myers, Fred, 1982, ‘Always ask: resource use and land ownership among Pintupi Aborigines of the Australian Western Desert’, in N. M. Williams and E. S. Hunn (eds), Resource Managers: North American and Australian Hunter-Gatherers, Boulder: Westview Press;

(2) Myers, Fred, 1986, Pintupi Country, Pintupi Self, Berkley: University of California Press; and

(3) Myers, Fred, 2016, ‘Burning the truck and holding the country: Pintupi forms of property and identity’, Hau: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 6: 553–575.

106 Amongst other matters, Stanner’s work is of importance because of his analysis of the nature of an “estate group” in the Western Desert. The works of Stanner cited in the evidence include:

(1) Stanner, W. E. H. 1965a, ‘Religion, Totemism and Symbolism’, in R. M. Berndt & C. H. Berndt (eds), Aboriginal Man in Australia: Essays in Honour of Emeritus Professor A.P. Elkin, Sydney: Angus and Robertson; and

(2) Stanner, W. E. H. 1965b, ‘Aboriginal Territorial Organization: Estate, Range, Domain and Regime’, Oceania 36: 1-26.

107 Finally, Stanton’s work in relation to the Western Desert is of particular relevance because his research was carried out in the vicinity of the Wutha claim area at Mount Margaret. The works of Stanton cited in the evidence include:

(1) Stanton, John, 1983, ‘Old business, new owners: succession and “the Law” on the fringe of the Western Desert’, in Nicholas Peterson & Marcia Langton (eds), Aborigines, Land and Land Rights, Canberra, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies

(2) Stanton, John, 1984, Conflict, Change and Stability At Mt Margaret: An Aboriginal Community in Transition, Unpublished PhD Thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Western Australia; and

(3) Stanton, John, 1988, ‘Mt. Margaret: Missionaries and the aftermath’, in T. Swain and D.B. Rose (eds), Aboriginal Australians and Christian Missions, Australian Association for the Study of Religions

Use of lay and expert evidence and objections to evidence

108 In determining the ultimate issues in dispute in native title proceedings, the lay evidence of Aboriginal witnesses about their traditional laws and customs and their rights, interests and responsibility with respect to land and waters, is of the highest importance. The importance of this evidence has been affirmed on numerous occasions. I respectfully agree with the observations of the Full Court (North and Mansfield JJ) in Sampi on behalf of the Bardi and Jawi People v State of Western Australia (2010) 266 ALR 537 (at [57]), that “Aboriginal testimony is of the highest importance in a determination of the evidence of native title”.

109 In this observation, the Full Court were approving the remarks made by French J at first instance in Sampi v State of Western Australia [2005] FCA 777 (at [48]) where his Honour said:

Their testimony about their traditional laws and customs and their rights and responsibilities with respect to land and waters, deriving from them, is of the highest importance. All else is second order evidence. It is necessary therefore to review the evidence of the Aboriginal witnesses in some detail.

110 See also Alyawarr, Kaytetye, Warumungu, Wakay Native Title Claim Group v Northern Territory (2004) 207 ALR 539 at 562 (Mansfield J) and De Rose v State of South Australia [2002] FCA 1342 at [351] (O’Loughlin J).

111 Accordingly, as a general proposition, evidence from Aboriginal witnesses will normally provide the most reliable account of traditional laws and customs of the relevant people: Jango v Northern Territory of Australia [2006] FCA 318 at [291] (Sackville J).

112 Expert anthropological evidence is also of some importance. As Mansfield J observed in Alyawarr (at [89]); cited with approval in Bidjara People v State of Queensland (No 2) [2013] FCA 1229 at [478] (Jagot J):

Not only may anthropological evidence observe and record matters relevant to informing the court as to the social organisation of an applicant claim group, and as to the nature and content of their traditional laws and traditional customs, but by reference to other material including historical literature and anthropological material, the anthropologists may compare that social organisation with the nature and content of the traditional laws and traditional customs of their ancestors and to interpret the similarities or differences. And there may also be circumstances in which an anthropological expert may give evidence about the meaning and significance of what Aboriginal witnesses say and do, so as to explain or render coherent matters which, on their face, may be incomplete or unclear.

113 Anthropological evidence will not generally establish that the content of the relevant traditional laws and customs acknowledged and observed by contemporary members of a native title claim group is contrary to that which the members of that claim group themselves say it is: Jango at [291] (Sackville J).

114 Various evidentiary objections were raised by each of the parties in relation to the lay and/or expert evidence relied upon by other parties. Most of the objections raised were not ultimately pressed. Insofar as objections were pressed I have given consideration to them. Later in these reasons I refer to evidence that was the subject of objections. Unless expressly addressed, inherent in the use of that evidence is my ruling that the objection has not been sustained.

115 There are a number of non-controversial background matters that it is of assistance to briefly outline in order to better understand the particular issues in dispute in this proceeding. In this section I address those matters.

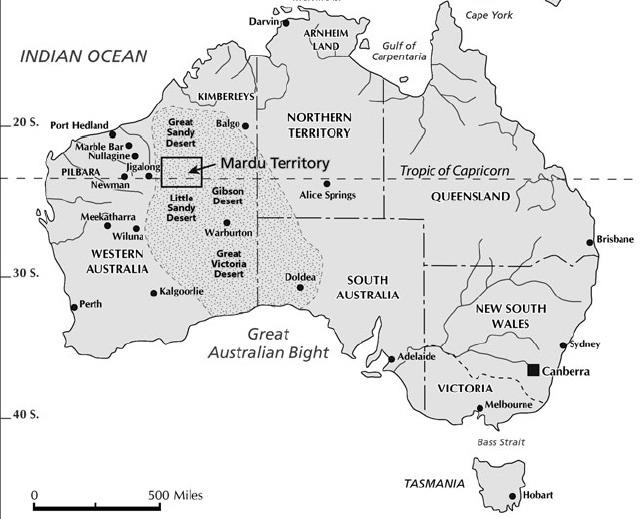

116 Each of Drs Lynes, Brunton and Draper gave evidence about the Western Desert. Despite its topographical nomenclature, the Western Desert is not a topographical region with defined boundaries locatable on a map of Australia. The Western Desert is an anthropological construct used by anthropologists to identify an area of some 650,000 square kilometres (Tjiwarl at [373] (Mortimer J)) in Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory, in which the culture, language, customs and laws of the people in various land-holding groups within that region bear sufficient commonality and sufficient distinctiveness from their neighbours, to permit their classification as a single cultural block. Hence the alternative name “Western Desert Cultural Bloc” coined by Berndt in 1959.

117 The following map, cited in Dr Brunton’s first report, gives an indication of the approximate boundaries of the Western Desert. The map was prepared by Professor Robert Tonkinson (see Tonkinson, R. 1991, The Mardu Aborigines: Living the Dream in Australia's Desert, 2nd ed. Fort Worth, Texas: Holt, Rinehart and Winston; Tonkinson, R. 2011, ‘Landscape, Transformations, and Immutability in an Aboriginal Australian Culture’ in P. Meusburger, M. Heffernan, & E. Wunder (eds), Cultural Memories: The Geographical Point of View, Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer).

118 The origins and development of the Western Desert as an anthropological construct, including Berndt’s analysis, were summarised and discussed by Lindgren J in Wongatha at [495]-[498]. His Honour there said (emphasis in original):

[495] The expression ‘Western Desert Bloc’ derives from a seminal article by Professor RM Berndt, the eminent anthropologist and foundation Professor of Anthropology at the University of Western Australia. The article is ‘The Concept of “the Tribe” in the Western Desert of Australia’, Oceania, vol 30, no 2, 1959 (‘Berndt 1959’).

[496] Berndt was not, however, the first anthropologist to discuss the cultural, social and linguistic similarities of the people of the Western Desert. Professor AP Elkin, Professor of Anthropology at the University of Sydney, had used the term ‘Western Group of South Australian tribes’ in his article ‘The Social Organisation of the South Australian Tribes’, Oceania, vol 2, no 1, 1931 (‘Elkin 1931’) p 60 ff. In that article, he identified two groups of “tribes” found in the vast dry area of the Northern Territory, Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia: an eastern or ‘Lakes’ group, and a western group. He said that the western group included ‘tribes in the south-western corner of Central Australia and in the south-east of Western Australia’. He called that group ‘the western group of South Australian tribes’ (ibid pp 50, 60–61). He said that the group was ‘characterised by a remarkable unity of language, mythology and social organisation’ (ibid p 60). As noted above, Professor Berndt was later to designate the same people the [Western Desert Cultural Block].

[497] Professor Elkin stated that ‘dialects of the hordes now working towards Laverton from the desert country on the east and south-east of that town [Laverton] differ little from those heard in the Ooldea district ...’ (ibid pp 61-2); and see his book, The Australian Aborigines: How to Understand Them (2nd ed, Angus and Robertson, Sydney/London, 1943) (‘Elkin’s book’) p 64 ff. Elkin does not seem to describe the western group as the ‘Aluridja’ in his 1931 article, but he applied that term to the entire region in his later article, ‘Kinship in South Australia’, Oceania, vol 10, no 2, 1939 (‘Elkin 1939’) p 204.

[498] In 1974, Professor Robert Tonkinson also commented on the [Western Desert Cultural Block], describing it in the following terms, in The Jigalong Mob: Aboriginal Victors of the Desert Crusade (Cummings Publishing, Menlo Park, 1974) (‘Tonkinson, The Jigalong Mob’) p 16:

Correlated with the physiographic and climatic commonalities of the Western Desert are its uniformities as a cultural bloc (…). Its Aboriginal inhabitants speak a common language with dialectical variations and share a similar basic social organization, relationship to the natural environment, religion, mythology, and artistic expression. The relatively homogeneous nature of Western Desert culture is evident from the available literature, and recent ethnoarchaeological findings suggest that, technologically at least, cultural continuities have existed in this area from several thousand years ago to the present (…).

Any traveller who is familiar with Western Desert culture and who speaks one of its dialects will notice obvious similarities among widely separated groups of Aborigines within the cultural bloc. I travelled extensively in the area and could make myself understood everywhere using the dialect I had learned. I encountered many identical kinship terms in use, and although they did not always connote the same classes of relatives in different areas, they formed part of the same type of social organization. Also many of the rituals and associated ancestral beings were substantially the same in areas hundreds of miles apart. The regular contact between contiguous Aboriginal groups in the Western Desert that has always been a feature of the area ensures a steady flow of information and objects. This cultural transmission reinforces the Aborigines’ awareness of their common interests and helps give the Western Desert its markedly homogenous countenance. (my emphasis)

119 There was an apparent controversy between the parties in this proceedings as to the western extent of the Western Desert and whether the Body, in its entirety or otherwise, falls within the Western Desert. A great deal of evidence was given by Drs Brunton and Draper on this issue. However, for reasons which will become apparent, I come to the conclusion that the resolution of this proceeding does not require a definitive assessment of whether the Wutha claim area (and in particular the Body) is or is not part of the Western Desert. For that reason I do not consider it necessary that I engage in an exercise of mapping or defining the boundary (or even the western boundary) of the Western Desert. I note that that exercise would be particularly difficult because the Western Desert is an anthropological construct in relation to which reasonable anthropologists differ as to whether those boundaries are definable and if and where those boundaries may lay.

120 As will be seen later in these reasons, tjukurrpa is relevant to this proceeding as the principal source of rights and interests in land and waters recognised by traditional laws and customs, and a principal manifestation of the connection between land and waters and the persons who rightfully may claim them

121 Translating the meaning and significance of tjukurrpa into written non-Aboriginal language has its challenges. Tjukurrpa is a belief system which forms the basis of peoples’ spiritual connection to country and to each other, as well as providing the basis for and source of traditional laws and customs. It is a central part of the world view of the Aboriginal persons who have knowledge of and observe traditional laws and customs.

122 Tjukurrpa comes from mythical beings that shape and mould the landscape. Those beings are often personified as possessing human, plant, animal or natural object characteristics. However, the nature and function of tjukurrpa is not limited to being a spiritual, religious or mythical account of the creation of the landscape and natural world in which Aboriginal people live. The concept of tjukurrpa was discussed by Mortimer J in Tjiwarl, and described by her Honour as follows at [538]:

[C]ombining many concepts in one word, the Tjukurrpa is past and present, myth and reality, belief and law. It connotes beings who have always existed and still occupy the landscape, and that continued presence is part of the reason that there is a body of rules of behaviour which exists around sites and knowledge related to the Tjukurrpa. Transgressions have a real and immediate effect. The Tjukurrpa is not consigned to history, but rather is a living guide for the lives of Aboriginal people.

123 The evidence demonstrates that tjukurrpa is associated with and evidenced by particular features in the landscape. The country through which the tjukurrpa travelled is referred to as “dreaming tracks”, and the tracks and locations through which the tjukurrpa travelled are often associated with the use and acquisition of the land and waters in question.

124 A number of tjukurrpa were outlined in the lay and expert evidence. Those dreaming stories related to significant sites and dreaming tracks in the Wutha claim area, but also continue outside of the Wutha claim area, linking the claim area to land and waters in the broader Wester Desert region.

125 Some of the tjukurrpa in evidence was gender-restricted, or partly restricted. Since the applicant’s written submissions and expert reports refer to these tjukurrpa by name, and with brief identifying details, I will also do so, but will not traverse in these reasons the details of any evidence given in restricted sessions, or in the written sections of expert reports or the submissions of the parties.

126 There are four relevant tjukurrpa of particular importance to this claim which I will briefly outline here, being the Goomboowan dreaming, Kuna Bulla dreaming, Papa Dingo dreaming and Mithilpithii dreaming. The Goomboowan and Papa Dingo dreaming are gender-restricted stories but the broad detail of those stories was addressed in unrestricted evidence and to that extent is included in these reasons. There were references to other tjukurrpa in the evidence, but for reasons that will become apparent these are the key tjukurrpa with associations to the area in the Body and the Tail.

127 The Goomboowan story is an important source of knowledge about the line of water sources in a wide swathe of country from Wongawol and Lake Carnegie down the west side of the Tail to Lake Darlot and beyond. Evidence was given about the Goomboowan tjukurrpa by Gay Harris, Luxie Hogarth and Geraldine Hogarth.

128 Broadly, the Goomboowan tjukurrpa is about an ancestral woman who had a very full bladder and when she urinated her gooboon (urine) water filled up lakes, rock-holes and streams and spread out across the country in a general southerly direction. Geraldine Hogarth explained that the Goomboowan tjukurrpa comes from the north, but that “our people are responsible… the Pini, Dalgandarda Koara people responsible here”.

129 Gay Harris gave evidence that when the ancestral woman urinated:

[H]er Gooboon filled up Lake Matland and overflowed south to from Woganoo and Goonboowan Creek filing soaks and waterholes like Yuldari and Mt Step, then spread out across the flat Melrose country, going underground heading south through the spinifex country where there are no creeks. Then it comes out through a blowhole at Melrose country – darnu, it bursts, when the bladder got too full. It goes into Lake Darlot then Lake Irwin and on to the Lake Raeside, then south east to Coonana where it becomes a little creek. But it continues all the way to the Head of the Blight – the goombooh nutrients feed the whales that come there.

130 Luxie Hogarth told Dr Draper that there is a lengthy song for this story, although it does not seem that she herself sang it for him. Gay Harris said that the story is connected with women’s birthing sites and places where women can conceive.

131 The Kuna Bulla tjukurrpa is also referred to as the “Two Snake” dreaming story. It is an open tjukurrpa (that is, not knowledge restricted by gender or some other attribute). During the on-country hearing, the Court viewed some of the principal sites related to this tjukurrpa, including at Lake Darlot Causeway. The primary witness who spoke about it in oral evidence was Gay Harris.

132 Gay Harris gave evidence that this tjukurrpa is a story about two snakes that travel from somewhere in South Australia, past Darlot along the flat towards Lake Darlot where they rested. The snakes then travel across west into the Tjiwarl determination area where they go up the hill and are killed by the dragonfly. Gay Harris gave evidence that when you go to Albion Downs, you can see a big quartz hill and at times you will see a “smoky haze” associated with this tjukurrpa.

133 Gay Harris deposed that there are other people who tell this story, not just Wutha (Gay made reference to a “Bandu Wati” from Wiluna telling this story but giving the snakes a different name). Gay Harris gave evidence that it is a sacred dreaming story of the Koara, Dalgandarda and Pini tribes. This is consistent with the evidence in Tjiwarl, in which the story of the Tjila Kutjara (two carpet snakes being chased by a dragonfly) was a significant tjukurrpa (see Tjiwarl at [546]-[555] (Mortimer J)).

134 The Papa Dingo dreaming is a dreaming story about a dingo bitch and has topographical associations with the landscape running through the north-eastern corner of the Body down to Leonora and beyond. It is a male gender-restricted story and is associated with significant sites including the Agnew Men’s Initiation Site visited by the Court during the on-country hearing. The key witnesses that gave evidence of this tjukurrpa were Ralph Ashwin, Geoffrey Ashwin and Ron Harrington-Smith.

135 Mithilpithii tjukurrpa is associated with the area around Weebo near Darlot. It is a story that relates to the giving of life. The Court was not taken to the site. However, the significance of this tjukurrpa emerged in evidence given by Geraldine Hogarth and Gay Harris.

THE PROCEDURAL HISTORY OF THE WUTHA APPLICATION

136 It is necessary that I set out the procedural history of the Wutha application in detail because of its importance to the question of whether the Wutha application was properly authorised in accordance with the requirements of the NTA.

137 The original Wutha application was lodged with the National Native Title Tribunal (“NNTT”) on 19 January 1996. The applicant was Raymond Ashwin and the application was simply described as having been made on behalf of “Wutha”. That matter, together with other aspects of the early procedural history of the Wutha claim, is recorded in Wongatha. In Wongatha, Lindgren J dealt with a claim brought on behalf of “the Wongatha people” over an area of some 160,000 square kilometres located in the Western Australian Goldfields and each of seven applications which overlapped that claim (that claim is shown on the map in Annexure 4). One of those overlapping claims was the Wutha claim. To the extent that the Wutha claim overlapped with the Wongatha claim, it was heard and determined by Lindgren J in Wongatha.

138 As Lindgren J recorded at [178] in Wongatha, the original Wutha application was amended in February and April of 1996. That was followed by a second Wutha application lodged in the NNTT on 13 March 1996 in which the applicant was again Raymond Ashwin. The second Wutha application was subsumed by the first on 22 January 1999. That occurred following the filing of a further amended Form 1 filed in the first application on 19 January 1999. The further amended Form 1 described the native title claim group as follows:

The name of the claim group is Wutha and the Wutha people are those persons who identify themselves as Wutha and are the biological descendants of:

(a) Wunal (also known as Tommy) Ashwin (m) and Telpha Ashwin (f); and

(b) those persons adopted by the biological descendants or with marital relations to those persons.

139 As Lindgren J recorded at [179] and [180], a further amendment was made to the Wutha claim on 4 March 1999 in which the Wutha claim group was defined as consisting of the biological descendants of “Wunal (aka Tommy) (m) Ashwin and Telpha Ashwin (f)” and the adoptees of those biological descendants. By this time the Ashwin siblings were named as applicant. As is further recorded at [181], the claim group description was further amended on 29 April 1999 so as to exclude from the biological descendants of Wunal and Telpha Ashwin, twenty named individuals and their offspring. The Wutha claim group description was in that form at the time of the Wongatha proceeding.

140 The Wutha claim as pursued before Lindgren J in Wongatha was made on the basis that the native title rights and interests asserted were held at sovereignty pursuant to the laws and customs of the Western Desert (Wongatha at [1743]). Evidence led in the Wongatha proceedings on behalf of the Wutha claim group included evidence of Lenny Ashwin, Ralph Ashwin, Raymond Ashwin, Katherine Adams and Verna Voss. A summary of the evidence given by those persons is found in Annexure F to the Wongatha judgment.

141 Lindgren J outlined the reasons why the Wutha claim failed at [2725] as follows:

1. The Wutha applicants were not authorised to make the Wutha application as required by s 61(1) of the NTA.

2. The evidence does not establish that the Wutha Claim group is a group recognised by [Western Desert Culture Block] traditional laws and customs as a group capable of possessing group rights and interests in land or waters.

3. The evidence does not establish that group rights and interests exist in the Wongatha/Wutha overlap under [Western Desert Culture Block] traditional laws and customs.

4. The evidence does not establish that at sovereignty, [Western Desert Culture Block] laws and customs provided for an ancestral group of the Wutha Claim group to possess group rights and interests in the Wongatha/Wutha overlap, or for individuals to be able to form themselves into a group possessing such rights and interests.

5. The Wutha Claim, in so far as it relates to the Wongatha/Wutha overlap, is an aggregation of claims of individual rights and interests, and the Wongatha/Wutha overlap is based on an aggregation of individual ‘my country’ areas the subject of those claimed individual rights and interests, and the NTA does not provide for the making of a determination of native title consisting of group rights and interests in these circumstances.

6. The Wongatha/Wutha overlap is not an area, or part of an area that is ultimately, whether directly or indirectly, defined by reference to Tjukurr (Dreaming) sites or tracks.

7. Approximately the Western one half to two thirds of the Wongatha/Wutha overlap lies outside the area of the [Western Desert Culture Block] ‘society’ on which the Wutha Claim is based.

8. Telpha Ashwin, a post-sovereignty apical ancestor of the Wutha claimants, claimed as her country the former Dada Station, Darlot and Melrose Station, all being just north of the Wongatha Claim area, and it is not established that the ancestors of the Wutha claimants or their descendants, including the Wutha claimants, subsequently acquired rights and interests in the Wongatha/Wutha overlap under pre-sovereignty [Western Desert Culture Block] laws and customs.

9. The evidence does not establish that the claimants constituting the Wutha Claim group have a connection with the Wongatha/Wutha overlap by Western Desert traditional laws and customs as required by s 223(1)(b) of the NTA.

142 Lindgren J dismissed the Wutha claim insofar as it related to the overlap with the Wongatha claim (at [4010]).

143 That part of the Wutha claim not the subject of the Wongatha proceedings remained on foot but has been the subject of several interlocutory challenges and various further amendments to which I will now turn.

144 As earlier outlined, the area covered by the Wutha claim includes the Head. An area of the Head overlaps with an area claimed in an application for native title made on behalf of the Yugunga-Nya People in proceeding WAD 6132 of 1998. In 2009, the Yugunga-Nya People brought an application which sought orders under s 84D(1) of the NTA requiring the applicant in the Wutha claim produce evidence of the authorisation of that claim. That application was determined by Siopis J in Ashwin on behalf of the Wutha People v State of Western Australian [2010] FCA 206. His Honour referred to the findings made by Lindgren J in Wongatha as to the lack of authorisation and concluded that those findings “were of general application and have the propensity to invalidate the Wutha claim as a whole” (at [36]). Orders were made that the applicant in the Wutha claim file and serve further evidence to satisfy the statutory requirements that the persons comprising the applicant were authorised to bring the Wutha application.

145 On 23 December 2010 in Ashwin on behalf of the Wutha People v State of Western Australia (No 2) [2010] FCA 1472, Siopis J dismissed an application brought by the State pursuant to s 84C of the NTA by which orders were sought striking out or dismissing the Wutha claim on the basis that the claim was not authorised and bound to fail. It was contended that, by reason of an issue of estoppel, the applicant in the Wutha claim was bound by the finding made in Wongatha that the Wutha claim was not authorised. His Honour determined, with particular regard to s 84D of the NTA and the discretion there given for the Court to hear and determine an application despite a defect in authorisation, that the findings made by Lindgren J in Wongatha did not pose “such an insurmountable obstacle to the prospects of success of the Wutha claim … as to warrant the claim being summarily dismissed or struck out” (at [15]).

146 In furtherance of the orders made by Siopis J in Ashwin, affidavits were filed and served dealing with the authorisation of the Wutha claim. Following a number of programming orders that issue was listed for hearing and came before Jagot J on 4 July 2013. Her Honour determined that the issue of authorisation ought not to be dealt with separately as a threshold issue but ought instead be dealt with as part of the trial of all issues. Her Honour ordered, inter alia, that:

1. The application in proceeding WAD 6064 of 1998 proceed to a hearing on all issues, excluding the issue of extinguishment and such other issues as may be subject to any future order for separate determination in accordance with Pt 30 r 1 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (not including the issue of authorisation which is to be heard at the same time as all issues arising under s 223 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth)).

2. To the extent necessary to enable Order 1 to be achieved, the discretion in s 84D(4)(a) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) to hear the application in proceeding WAD 6064 of 1998 is exercised.

147 On 30 June 2015, an interlocutory application was made by the applicant which sought leave to amend the Wutha application by amending Schedule A of Form 1. The effect of the proposed amendment was to substantially alter the description of the native title claim group. The proposed amendment removed reference to the twenty persons and their offspring which were part of the exclusion earlier referred to and identified additional apical ancestors to those previously included in the claim group description.

148 On 29 July 2015, Barker J ordered that the applicant file further affidavit evidence in support of its interlocutory application. Geoffrey Ashwin filed an affidavit made on 21 August 2015. He deposed to being the eldest surviving male descendent of Telpha Ashwin and Wunal Ashwin and that for that reason, by the traditional law and custom of the Wutha people, decision-making authority in relation to the native title rights and interests of the Wutha people was held by him. Furthermore, he explained the basis for the proposed amendment to the description of the native title claim group. He referred to Dr Draper having been engaged to prepare a connection report and to various meetings attended by him and/or June Ashwin and Dr Draper with representatives of the Harris, Hogarth and Barnard/Wheelbarrow families. He stated that he agreed that each of those families should be included in the Wutha claim group and that Dr Draper had prepared an amended Form 1 to include an amended description of the native title claim group in order to include members of those families. He deposed that in exercising his traditional decision-making authority for the Wutha claim group he authorised the filing on 30 June 2015 of the amended Form 1 prepared by Dr Draper.

149 The proposed amended claim group description read:

The Wutha people, being those persons (including the applicants) who are:

1. The biological descendants of:

(a) Darugadi (aka Thurraguddy), his affine Murni and her mother Matjika, whose descendants include the Ashwin and Harris families.

(b) Julia Sandstone, whose descendants include some of the Ashwin Family.

(c) Billy, Mary-Ann and Mary-May’s sister, whose descendants include the Hogarth and Brennan and Tulloch Families.

(d) Maude Yarlyen and Jimmy Wheelbarra (aka Wheelbarrow), whose descendants include the Barnard Family.

and

2. Those persons adopted by those biological descendants in accordance with Wuthu tradition and custom. (Adoption refers to the situation where a child is ‘grown up’ by a relative or someone without a biological relationship, either because they have been gifted them, or left in their care, as the biological parents are not in a position to care for them. This applies regardless of whether or not the child has been formally adopted under the non-Aboriginal legal system).

150 Another affidavit filed in support of the order seeking leave to amend the Wutha application was made by June Ashwin on 29 October 2015. June deposed to an authorisation meeting held in Leonora on 17 October 2015. At that meeting a resolution was carried to amend the Wutha native title application by amending the native title claim group description to the form set out above. June’s affidavit included the notice of the meeting published in the Kalgoorlie Miner newspaper. That notice extended an invitation to attend the 17 October 2015 meeting to “an Aboriginal person whom is a biological descendant, or is adopted by those biological descendants in accordance with Wutha tradition and custom, of one or more of the following ancestors”, and thereafter described those ancestors referred to above (at [149]) in the proposed amended claim group description.

151 June Ashwin deposed to the authorisation occurring pursuant to “Wutha traditional decision-making”. It appears from an attendance sheet annexed to June’s affidavit that some 21 persons attended the 17 October 2015 meeting.

152 On 30 October 2015, the interlocutory application seeking leave to amend the Wutha application was adjourned to 21 December 2015.

153 At the hearing held before Barker J on 21 December 2015, an affidavit of June Ashwin made on 11 December 2015 was filed. June Ashwin deposed to a meeting held on 5 December 2015 in Leonora in which a resolution authorising the amendment of the Wutha application was carried. The resolution relevantly stated:

Authorisation of Amendments to the Wutha Native Title Claim

Resolution 1: Amended Native Title Application

That the applicant group of the Wutha People in relation to the native title determination application WAD 6064/98 being Geoffrey Alfred Ashwin, June Rose Harrington Smith and Ralph Edward Ashwin are authorised by traditional decision making by Geoffrey Alfred Ashwin to amend the description of the Wutha Peoples native title claim group pursuant to section 64 of the Native Title Act 1994 (Cth) and otherwise amend the Federal Court Form 1 Application for Native Title Determination, commenced by the Wutha People to comply with the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

154 The resolution proposed the following claim group description:

The Wutha people being those persons (including the applicants) who identify themselves as Wutha and are:

(1) The biological descendants of:

(a) Darugadi (aka Thurraguddy), his affine Murni and her mother Matjika

(b) Julia Sandstone (“Old Julia”)

(c) Billy

(d) Inyarndi

and

(2) Those persons adopted by those biological descendants in accordance with Wutha tradition and custom. (Adoption refers to the situation where a child is ‘grown up’ by a relative or someone without a biological relationship, either because they have been gifted to them, or left in their care, as the biological parents are not in a position to care for them. This applies regardless of whether or not the child has been formally adopted under the non-Aboriginal legal system).

155 The description of the native title claim group in the resolution carried in the meeting of 5 December 2015 differs from that of the meeting of 17 October 2015 in two respects. First, “Inyarndi” replaced the apical ancestors “Maude Yarlyen and Jimmy Wheelbarra” and secondly, where reference had previously been made to the connection between particular apical ancestors and particular families, that reference was removed.

156 June Ashwin also deposed as to the notice given of the 5 December 2015 meeting. A public notice of the meeting had been published in the Kalgoorlie Miner newspaper, a copy of which was attached to June’s affidavit. The invitation to attend given by that notice was in the same form as that earlier discussed in relation to the 17 October 2015 meeting, save that the references made to apical ancestors was updated in accordance with the proposed claim group description. June deposed that she was satisfied “that pursuant to Wutha traditional decision-making and following the results of the abovementioned authorisation meeting that the Wutha people fully support the amendment to the Wutha native title claim”.

157 The attendance sheet for the 5 December 2015 meeting annexed to June Ashwin’s affidavit disclosed that some fifteen persons had attended.

158 On 21 December 2015, Barker J made orders including an order granting leave to amend the Form 1 of the Wutha application in terms of the native title claim group description the subject of the resolution carried at the 5 December 2015 meeting.

159 On 7 March 2016 an amended Form 1 was filed in accordance with the leave granted by Barker J on 21 December 2015. The claim group description in the amended Form 1 is that described at [154] above.

160 On 30 July 2016 a further application to amend the Form 1 of the Wutha claim was made. No amendment was sought to the claim group description. The amendment sought by that application may be regarded as technical and is of no particular import to the matters I need to consider. Nevertheless, that application was the last occasion on which the Wutha application was amended and is therefore of particular relevance to the question of whether the Wutha application is authorised. That application was supported by affidavits of Geoffrey Ashwin, June Ashwin and Ralph Ashwin each sworn on 30 July 2016.

161 Each of those affidavits refer to an authorisation meeting held on 30 July 2016 at Leonora. June Ashwin deposed as to the resolutions passed by the meeting authorising the making of the amended application. The two resolutions carried at the meeting were in the following terms:

Resolution 1: Authorisation of Amended Native Title Application

That the applicant group of the Wutha People in relation to the native title determination application WAD 6064/98 being Geoffrey Alfred Ashwin, June Rose Ashwin (also known as Harrington Smith) and Ralph Edward Ashwin are authorised by the traditional decision making by Geoffrey Alfred Ashwin to amend the Wutha People native title determination application (Form 1) and presented at this meeting and to make and deal with matters arising in relation to it.

Resolution 2: Amended Native Title Application