FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Stambe v Minister for Health [2019] FCA 43

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent YL HEALTH GROUP PTY LTD (ACN 602 917 742) Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties are to confer and attempt to agree appropriate final orders reflecting the Court’s decision, including as to costs.

2. Any agreed proposed orders are to be filed and served on or before 4 pm on 5 February 2019.

3. In the absence of any agreed proposed orders:

(a) the applicant is to file and serve submissions on appropriate final orders and any further affidavit evidence relevant to the orders sought, together with a proposed form of final order on or before 4 pm on 12 February 2019; and

(b) the second respondent is to file and serve submissions on appropriate final orders and any further affidavit evidence relevant to the orders sought, together with a proposed form of final order on or before 4 pm on 19 February 2019.

4. Subject to any further order, the question of appropriate final orders will be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MORTIMER J:

1 The applicant is the operator of two pharmacies, both of which are approved premises under s 90 of the National Health Act 1953 (Cth). Both those pharmacies are located in Mount Waverley in the State of Victoria: one is called in the materials the “Centreway Pharmacy” and the other is called the “Priceline Mount Waverley Pharmacy”. The second respondent, which I will call YL Health Group, now operates a 24 hour pharmacy attached to a large medical centre, called Waverley Family Health Care. Approval was given to YL Health Group to operate this pharmacy pursuant to a personal power conferred on the first respondent (the Minister) by s 90A(2) of the National Health Act. Waverley Family Health Care is a medical centre which operates over extended hours, at the time of the decision between 7 am and 10 pm seven days a week, although the materials before the Minister indicated the Centre intended to provide 24 hour seven days a week medical services when it became fully operational. The evidence did not go so far as to indicate whether it was in fact offering 24 hour service now it is operational.

2 It is the Minister’s decision under s 90A(2) which is the subject of the judicial review application in the proceeding. That decision was made on 1 November 2017. YL Health Group’s pharmacy was, at the time of the final hearing of this proceeding, operating under that approval.

3 For the reasons set out below, I have upheld the applicant’s first ground of judicial review, and not upheld his two other grounds. The parties will be given an opportunity to agree upon appropriate relief, or failing agreement, make submissions on that matter.

Background

4 The dispute about YL Health Group’s pharmacy is of long standing, and has already been the subject of proceedings in this Court in 2016, which resulted in the setting aside of an earlier decision of the Australian Consumer Pharmacy Authority to recommend YL Health Group be approved to supply pharmaceuticals from its Mount Waverley premises. The approval application was remitted to the Authority for reconsideration.

5 On reconsideration, the Authority recommended the rejection of YL Health Group’s application, on the basis that the proposed pharmacy did not meet the requirements in the applicable pharmacy rules because it was less than 500 metres from the nearest approved pharmacy premises, being the applicant’s two pharmacies, and those premises were not in a shopping centre that met the definition of a “large shopping centre”. The distance requirement that there be at least 500 metres between approved pharmacies, and the “large shopping centre” requirement, were imposed under the applicable rules at the relevant time: the National Health (Australian Community Pharmacy Authority Rules) Determination 2011 (Cth), which I will call “the Rules”. The Rules were made under s 99L of the National Health Act.

6 There is no dispute between the parties in the present proceeding that the pharmacy now operated by YL Health Group would in fact be, and in fact is, considerably less than 500 metres from the applicant’s pharmacies.

7 The decision to reject YL Health Group’s application was made by a delegate of the Secretary on 9 May 2017. On 7 June 2017, YL Health Group made a request under s 90B(1) of the National Health Act for the Minister to exercise the power reposed in him under s 90A(2) of the Act.

8 Section 90A relevantly provides:

90A Minister may substitute decision approving pharmacist

(1) This section applies in relation to a decision of the Secretary under section 90 rejecting an application by a pharmacist for approval to supply pharmaceutical benefits at particular premises, if:

(a) the application was made on or after 1 July 2006; and

(b) the decision was made on the basis that the application did not comply with the requirements of the relevant rules determined by the Minister under section 99L.

(2) The Minister may substitute for the Secretary’s decision a decision approving the pharmacist for the purpose of supplying pharmaceutical benefits at the particular premises if the Minister is satisfied that:

(a) the Secretary’s decision will result in a community being left without reasonable access to pharmaceutical benefits supplied by an approved pharmacist; and

(b) it is in the public interest to approve the pharmacist.

(3) For the purposes of subsection (2):

community means a group of people that, in the opinion of the Minister, constitutes a community.

reasonable access, in relation to pharmaceutical benefits supplied by an approved pharmacist, means access that, in the opinion of the Minister, is reasonable.

(4) The power under subsection (2) may only be exercised:

(a) on request by the pharmacist made under section 90B; and

(b) by the Minister personally.

(5) Subject to subsection 90B(5), the Minister does not have a duty to consider whether to exercise the power under subsection (2) in respect of the Secretary’s decision.

9 Thus, the Minister has a personal power under this provision to substitute a decision made by the Secretary with a different decision. It can be seen that the Minister’s power to substitute a different decision is conditioned on the Minister being satisfied of the two matters set out in s 90A(2)(a) and (b).

10 On 8 August 2017, the Minister decided to consider the request by YL Health Group for approval under s 90A.

11 As part of the Minister’s consideration of the request by YL Health Group for a substituted decision, the Minister invited the applicant as the owner of two existing approved pharmacies close to the proposed pharmacy to provide comments, information or documents relating to YL Health Group’s request for approval. The applicant submitted material in response to this request on 30 August 2017. He submitted:

(1) A 19 page written submission;

(2) Some “feedback forms” from each of his two pharmacies; and

(3) An email about an existing 24 hour pharmacy which he contended was accessible by the Mount Waverley community.

12 I will return to the applicant’s submission to the Minister in considering his grounds of judicial review.

13 The Minister decided to exercise his discretion to approve the request of YL Health Group on 1 November 2017. A “Notice of approval” was provided to YL Health Group on 3 November 2017.

14 The Minister subsequently gave reasons for his decision, pursuant to s 13 of the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth), after a request by the applicant. The reasons were drafted by others but were endorsed by the Minister on 21 November 2017. They were provided by email to the applicant’s legal representative on 28 November 2017.

15 This proceeding was commenced on 15 December 2017. It seeks judicial review of the Minister’s decision on three grounds under s 5 of the AD(JR) Act.

The Minister’s reasons for decision

16 The evidence shows that a set of proposed reasons for decision was prepared for the Minister by officers within the Department of Health, after consultation with the legal services branch of the Department. The Minister was provided with a briefing note on 21 November 2017. He signed the briefing note endorsing the statement of reasons attached to it, on 21 November 2017.

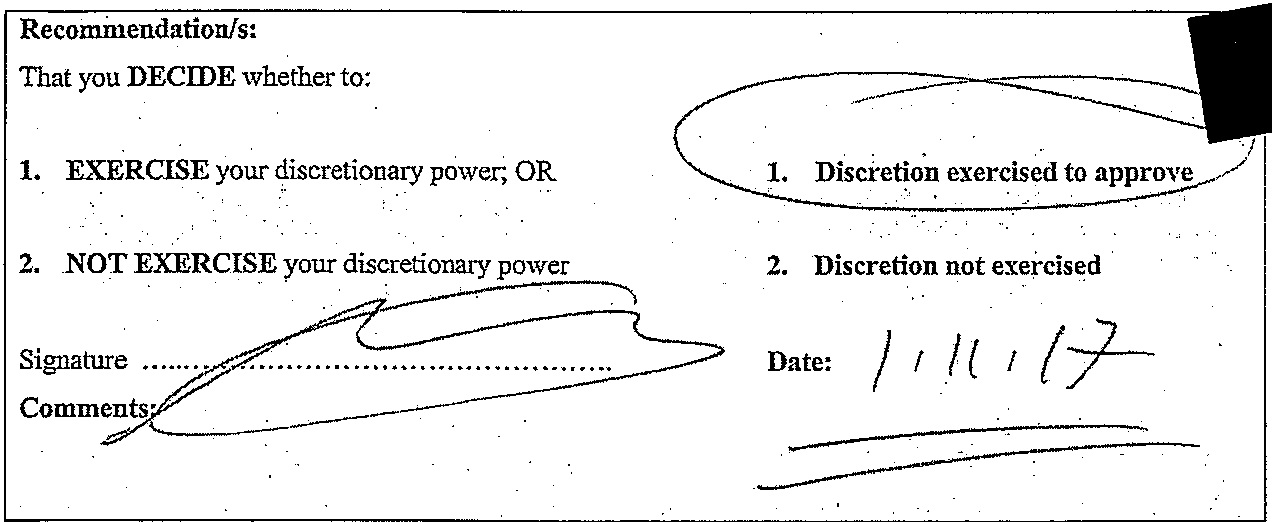

17 The relevant part of the document, with the Minister’s endorsement is in the following form:

18 I shall call this document, with the Minister’s endorsement, the “reasons briefing note”.

19 One of the attachments to the reasons briefing note was an earlier briefing note to the Minister dated 23 October 2017, which was the briefing note to the Minister on which he made his decision to exercise his power under s 90A(2) of the Act. I shall call this the “decision briefing note”.

20 The decision briefing note refers to yet another earlier briefing note, and decision, of the Minister made on 8 August 2017, to consider whether to exercise the approval power in s 90A(2). In considering statutory provisions which were materially the same, the High Court has held that the taking of this step (to decide to consider whether to exercise a power) renders the repository of the power amenable to judicial review for non-compliance with Australian law and (where applicable) with the law of procedural fairness: see Plaintiff M61/2010E v Commonwealth [2010] HCA 41; 243 CLR 319 at [9], [70], [77]-[78].

21 The decision briefing note had summarised the applicant’s submissions in opposition to the proposed approval application, together with other material either supporting or opposing the request for approval, including material provided by one Dr Alan Cunneen, the director of a corporation which operated Waverley Family Health Care. The decision briefing note also contained a summary of the facts the Departmental officers appeared to consider relevant to the Minister’s decision, but the decision briefing note does not make any substantive recommendation to the Minister about how his power should be exercised.

22 The Minister did not alter or annotate the draft proposed reasons given to him: he simply adopted them. The structure of the reasons is as follows. There is an introductory part which recites the request for reasons and the decision the Minister made, with a definition section of terms used in the reasons. The reasons then turn to the background to the Minister’s exercise of power on 1 November 2017. The reasons set out a chronology leading up to that exercise of power which is not in dispute between the parties. The statement of reasons then sets out the evidence considered by the Minister, the material parts of which I reproduce below in my consideration of the grounds of review.

23 The Minister then sets out 33 paragraphs constituting his findings of fact, and a further paragraph setting out his decision. Most if not all of those findings of fact are not controversial in this judicial review application. The relevance of some of those findings to the exercise of power is challenged by the applicant, but as I understand it there are no grounds of review to challenge the Minister’s fact finding itself.

24 The parts of the Minister’s reasons to which I have referred to this point occupy 57 paragraphs. The Minister’s actual explanation for his decision, based on the findings made, occupies only three paragraphs. Those paragraphs are:

58. On the basis of my findings regarding the distance that residents of Mount Waverley who attended Waverley Family Health Centre needed to travel to access pharmaceutical benefits outside the opening hours of the two nearest approved pharmacies, I was satisfied that the decision of the Secretary’s delegate would leave that community without reasonable access to pharmaceutical benefits.

59. On the basis of my findings regarding the opening hours of Waverley Family Health Care, the number of general practitioners practising at Waverley Family Health Care the planned delivery of 24 hour, 7 day medical services by Waverley Family Health Care, and the distance residents of Mount Waverley who attended Waverley Family Health Centre needed to travel to access pharmaceutical benefits after hours, I was satisfied that it was in the public interest to approve the Applicant.

60. Accordingly, I was satisfied that the section 90B request had met the criteria for me to exercise my discretionary power to approve the Applicant under subsection 90A(2). I understand that, in making my decision to approve the Applicant I could only do so if I was satisfied that both the ‘reasonable access’ and ‘public interest’ criteria outlined in subsection 90A(2) of the Act were satisfied.

The applicant’s grounds of judicial review

25 The applicant puts forward three grounds of review. The first, in reliance on s 5(1)(b) of the AD(JR) Act is that the procedures that were required by law to be observed in connection with the making of the Minister’s decision were not observed. The applicant contends that:

…contrary to s 90D(3)(a) of the National Health Act, the Minister failed to consider, or alternatively failed to give proper genuine and realistic consideration to, the comments, information and documents dated 30 August 2017 provided by the applicant to the Minister…

26 The second ground of review invokes the considerations grounds set out in ss 5(1)(e), 5(2)(a) and 5(2)(b) of the AD(JR) Act. The applicant makes two contentions:

(a) That the Minister took an irrelevant consideration into account, namely that “the Victorian Government had committed $28.7 million to deliver 20 x 24/7 pharmacies by 2018 under the Super Pharmacies Initiative”.

(b) That the Minister failed to take five matters into account which the applicant contends were relevant considerations in the exercise of his power. Those five considerations are described by the applicant in the following way:

(i) the applicant’s comments, information and documents dated 30 August 2017;

(ii) the fact that in Mount Waverley the pharmacy to population ratio was 1:3734.55 whereas the Victorian pharmacy to population ratio was 1:4741;

(iii) the history, intent and purpose of the Rules;

(iv) the fact that the Waverley Family Health Care medical centre is not currently operating on a 24 hour basis and will not operate on a 24 hour basis unless a pharmacy is approved at the premises; and

(v) the Ministerial Discretion Guidelines (August 2017), in particular paragraph 1.3 wherein it is stated that “[t]he intention of the discretionary power is to enable the Minister to respond on an individual and timely basis in unique circumstances where the application of the Pharmacy Location Rules has resulted in an unforeseen and anomalous situation and a community is left without reasonable access to the supply of Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) medicines.”

27 The third ground of review put forward by the applicant, relying on s 5(1)(f) of the AD(JR) Act, is that the Minister’s decision involved an error of law. The error of law is contended by the applicant to be that the Minister confined his consideration of “a community” for the purposes of s 90A(2)(a) to the residents of Mount Waverley and in particular those who attend Waverley Family Health Care.

28 I note that on 25 July 2018 the Minister filed a submitting notice in the proceeding, save as to costs. Accordingly the active contradictor in the proceeding is the second respondent, YL Health Group. Unless I make it clear otherwise, where I refer to the parties, this means the active parties: namely, the applicant and YL Health Group.

resolution of the application

29 I refer to the relevant provisions of the National Health Act and the Rules and to the parties’ competing submissions, where necessary to do so in my consideration of each ground of review.

30 I have discussed the scheme of approval of pharmacies under the National Health Act in more detail in my reasons for judgment in Walkerden v Wodonga Pharmacy Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 273; 230 FCR 243 at [9]-[22] and [50]-[66]. I adopt what I said in those paragraphs for the purposes of these reasons.

31 Further, relevant aspects of the legislative history of s 90A, and its role in the scheme, are set out by Jacobson J in Kong v Minister for Health [2014] FCAFC 149; 227 FCR 215 at [14]-[24], and I respectfully agree with his Honour’s description in those passages.

32 However, there are several aspects of the text of s 90A, and the meanings to be given to aspects of it, which require further exploration.

33 Section 90A cannot be engaged if the Secretary exercises the residual discretion in s 90 for a reason other than non-compliance with the Rules: see the terms of s 90A(1)(b). This indicates the personal discretion in s 90A is not intended to operate as a substitute in all situations for a decision by the Secretary, but has a more confined operation.

34 There are at least two concepts in s 90A which are undefined, but whose meaning is important. The first is the concept of “community”, being the group which is the focus of the first of the two criteria in s 90A(2). The National Health Act purports to give the concept some kind of definition, although the “definition” is one which reposes in the Minister the identification of which “community” needs to be considered for the purposes of the exercise of the power.

35 In the absence of any statutory intention to the contrary (assuming such a provision could be valid), the Minister’s identification of the relevant “community” must be one which is rational, and legally reasonable, and which bears a discernible connection to the purpose and context of the power which is being exercised: see Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v SZVFW [2018] HCA 30; 357 ALR 408 at [4], [10]-[12], (Kiefel CJ), [53], [59]-[60] (Gageler J), [79]-[80], [89] (Nettle and Gordon JJ), [131], (Edelman J); Probuild Constructions (Aust) Pty Ltd v Shade Systems Pty Ltd [2018] HCA 4; 351 ALR 225 at [75]-[76] (Gageler J); Minister for Immigration and Citizenship v SZMDS [2010] HCA 16; 240 CLR 611 at [130] (Crennan and Bell JJ).

36 The use of the noun “community” suggests that the “group” to which the definition directs the Minister’s attention is a group which has some shared characteristic or attribute (such as language or ethnicity), or shares some other feature (such as geographic location). In other words, there is something which connects the people within the group to each other, and gives the group commonality.

37 The use of the noun “group”, given the nature of the decision (provision of pharmacy services to the Australian public, usually with location restrictions) must have some numerical element, but the fact the group must fit within the concept of “community” means – as I have noted – that the “group” must have some other characteristics.

38 In its application for an exercise of the s 90A power, YL Health Group did not explicitly invite the Minister to identify the “community” in the way the Minister ultimately did: although its application refers variously to “the community of Mount Waverley”, to a “growing aged community”, “residents of the local community” and to “retirees and elderly”. The applicant submits YL Health Group invited the Minister to define the “community” as the residents of Mount Waverley.

39 A number of the applicant’s arguments relied on the asserted purposes of the Rules. For example, the applicant described a purpose of the Rules as to provide a sustainable and viable network of pharmacies.

40 That is a phrase apparently sourced from my reasons in Walkerden, and which has been cited with apparent approval by Griffiths J in Murray v Australian Community Pharmacy Authority [2017] FCA 705 and by Kerr J in Hope v Australian Community Pharmacy Authority [2016] FCA 1597.

41 It is true as the applicant submits that the Rules are given statutory force by s 99L, and are intended to limit the exercise of power by the Authority in making its recommendations to the Secretary, and to limit the Secretary’s power to approve, or refuse approval, to a pharmacy. It is also true that some of the Rules (such as the 500 metre location rule) might appear to be directed at the commercial viability of pharmacies, but that has not been identified as the purpose of such restrictions. In Assarapin v Australian Community Pharmacy Authority [2016] FCAFC 9; 239 FCR 161 at [41], and by reference to earlier authorities, the Full Court said:

In the fourth place, the focus in the requirements prescribed by the Rules upon the proximity of a proposed approved pharmacy to other approved pharmacies further supports the primary judge’s construction of Item 124. The origin of the proximity requirements lies in amendments made to the Act by the Community Services and Health Legislation Amendment Act 1990 (Cth) (the 1990 Amendments). Those amendments were directed to reducing the number of existing pharmacies and regulating the approval of new pharmacies so as to reduce the cost of dispensing prescriptions by increasing the average output per pharmacy with consequential savings for the Commonwealth: Pharmacy Restructuring Authority v Chatfield (1993) 43 FCR 418 (Chatfield) at 420 (Davies and Lee JJ); see also at 433-434 (French J). As the Full Court held in Pharmacy Restructuring Authority v Martin (1994) 53 FCR 589 (Martin) at 597:

The relevant provisions are not concerned with minimising competition in the pharmaceutical industry but with reducing the Commonwealth’s financial burden in providing pharmaceutical benefits while maintaining an acceptable level of community service.

42 A similar approach was taken in Kong at [96]-[97], where Jacobson J said, in the context of determining a contention that an objecting pharmacist was owed procedural fairness in relation to an s 90A application):

Second, the interest which Mr Williams seeks to glean from the statutory scheme is merely an economic or commercial interest. So much is plain from the attempt to characterise it as an interest in the nature of a statutory monopoly or a statutory pole position.

The background to the 1990 Amendments as explained in Chatfield and Smoker, and the observations of the Full Court in Martin at 597, set out at [70] above, make it plain that the 1990 Amendments were not concerned with the protection of commercial interests of existing pharmacies but, rather, with balancing the Commonwealth’s financial burden against the need for an acceptable level of community service.

43 And see Pagone J at [183]:

The protection of their [the objecting pharmacists’] commercial interests is not within the scope and purpose of the Act or of the scheme established by Pt VII of the Act. The Full Court in Martin observed that the relevant provisions were not concerned with minimising competition in the pharmaceutical industry but with reducing the Commonwealth’s financial burden in providing pharmaceutical benefits while maintaining an acceptable level of community service. The introduction of s 90A has not altered the correctness of that view, nor is s 90A itself directed to promoting, limiting or in any way concerned with, the competitive supply of pharmaceutical benefits as between competitors.

44 Thus, the Rules do not disclose any single purpose or objective concerning the commercial viability of existing pharmacies. Irrespective of the nuances of this issue, I fail to see how any purpose or objective of the Rules (which condition the powers of the Authority and the Secretary) assists in the proper construction and operation of the Minister’s personal power in s 90A. After all, as s 90A(1)(b) makes clear, that an application has been rejected as non-compliant with the Rules is a precondition to the exercise of the s 90A power. The Minister is, it seems to me, entitled to look at matters in a context which is quite different from the prescriptions in the Rules: that is one of the purposes of the conferral of this power. That is confirmed by the second criterion – the public interest.

45 By reference to a number of earlier authorities, in Pilbara Infrastructure Pty Ltd v Australian Competition Tribunal [2012] HCA 36; 246 CLR 379 at [42] the plurality said that, subject to the subject matter, scope and purpose of the enactment concerned, the concept of “public interest” imported:

…a discretionary value judgment to be made by reference to undefined factual matters.

46 In Pilbara Infrastructure, the breadth of the approach available to the repository was heightened by the fact that the relevant criterion in the (then) Part IIIA of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) was whether a matter would not be contrary to the public interest. In contrast, in s 90A(2), the Minister must be positively satisfied that giving an approval is in the public interest. In context, this may involve the Minister considering any number of factors, well beyond the specific consideration in s 90A(2)(a) that a community will be left without reasonable access to pharmaceutical benefits.

47 As YL Health Group submitted, the Full Court confirmed the breadth of this consideration in Kong at [132] (Jacobson J), [138] (Logan J – dissenting on the outcome but not on this point), [190] (Pagone J).

48 Nor, contrary to the applicant’s submissions, is any assistance to be derived from the “Ministerial Discretion Guidelines”, issued by the Department of Health in 2017, a copy of which was in evidence. This administrative document is expressly described as a general guide:

…for pharmacists making a request for approval by the Minister for Health under section 90A of the National Health Act 1953 (the Act).

49 At best then, the Guidelines might be seen as executive policy promulgated to inform affected pharmacists of how the Minister will usually go about deciding whether to consider exercising the s 90A personal power, and setting out a framework for affected persons to bring matters to the Minister’s attention. Just as a failure by a pharmacist to follow these Guidelines may not insulate the Minister from a successful judicial review application (cf the processes prescribed in s 90B for such applications), so too the contents of the Guidelines cannot be used to circumscribe the power in s 90A(2).

50 The applicant sought to derive support for some of his contentions from the following statements in particular in these Guidelines:

The intention of the discretionary power is to enable the Minister to respond on an individual and timely basis in unique circumstances where the application of the Pharmacy Location Rules has resulted in an unforeseen and anomalous situation and a community is left without reasonable access to the supply of Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) medicines.

The commercial interests of the pharmacist making the request, or of any other party, are not generally considered to be relevant considerations.

51 It is axiomatic that statements in an administrative document such as this have no effect on the proper construction and operation of a statutory provision. They are not even at the margins of extrinsic material, emanating as they do from the Executive, prepared after the enactment of the legislative scheme by Parliament. Further, although irrelevant, the statements are also incorrect: the Minister’s power is not confined in the way these statements suggest.

52 The notice provisions in s 90D are also relevant to the applicant’s contentions. Section 90D provides:

90D Provision of further information

(1) For the purpose of deciding whether to consider a request made by a pharmacist under subsection 90B(1) or whether to exercise the power under subsection 90A(2) in relation to such a request:

(a) the Minister may, by notice in writing given to the pharmacist, require the pharmacist to provide such further information, or produce such further documents, to the Minister as the Minister specifies, within the period specified in the notice; and

(b) the Minister may give a notice in writing to any other person:

(i) advising the person of the request; and

(ii) inviting the person to provide comments on, or information or documents relevant to, the request within the period specified in the notice.

(2) If:

(a) the Minister gives a notice to a pharmacist under paragraph (1)(a); and

(b) the pharmacist does not provide the information specified in the notice or produce the documents specified in the notice within the period specified in the notice;

the Minister may treat the request as having been withdrawn.

(3) If the Minister gives a notice to a person under paragraph (1)(b), the Minister:

(a) is only required to consider comments, information or documents provided by the person during the period specified in the notice; and

(b) if the person does not provide any comments, information or documents within that period—is not required to take any further action to obtain such comments, information or documents.

53 As its terms suggest, s 90D confers a power on the Minister to do one of two things: to give the applying pharmacist a notice to provide further information, and to give “any other persons” a notice informing that person of the s 90A application and inviting comments. Jacobson and Pagone JJ in Kong appear to accept that there is no entitlement in a third party pharmacist who is a competitor of the applying pharmacist to receive a notice under s 90D: see [104]-[105], read with [53] (Jacobson J); and [186] read with [178] (Pagone J).

54 Further, whether or not s 90D(3) is exhaustive of the Minister’s legal obligations also need not be determined (cf the debate in Kong about the effects of the decisions of Jessup J in Yu v Minister for Health [2013] FCA 261; 216 FCR 168 and Jagot J in Hanna v Minister for Health [2013] FCA 303). However, the applicant’s first ground of review squarely raises the question of what the verb “consider” means in s 90D(3)(a). I return to this below.

Ground one: procedures required by law but not observed

55 This ground challenges the Minister’s consideration of the applicant’s submissions. It does so primarily by reference to what is in the Minister’s statement of reasons, but more importantly for the applicant’s argument, what is not. In the amended originating application the ground is framed thus:

The procedures that were required by law to be observed in connection with the making of the Minister’s decision were not observed (Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) (ADJR Act), s5(1)(b)), in particular, contrary to s90D(3)(a) of the National Health Act, the Minister failed to consider, or alternatively failed to give proper genuine and realistic consideration to, the comments, information and documents dated 30 August 2017 provided by the applicant to the Minister subsequent to an invitation to do so having been given to the applicant under s90D(1)(b) of the National Health Act.

56 The uncontroverted evidence is that all of the material submitted by or on behalf of the applicant was attached to the briefing note to the Minister when he made his decision on 1 November 2017. This material was provided by the applicant in response to notices issued to him under s 90D, as the notices given to the applicant explain. There was a summary of the applicant’s arguments in the decision briefing note itself, which the applicant contends is materially incomplete, and I return to this below.

57 The applicant contends that the only references to his submission in the Minister’s reasons for decision relate to the opening hours of other nearby pharmacies (at [34]-[38] of the reasons). There, the Minister refers to information provided by Ms Stephanie McGrath of Robert James Lawyers, the legal representatives of the applicant, and makes findings on the location of the Centreway Pharmacy and the Priceline Mount Waverley Pharmacy, and about their opening hours. The Minister finds that the Centreway Pharmacy is approximately one minute walk from Waverley Family Health Care, and the Priceline Mount Waverley Pharmacy is approximately a three minute walk from Waverley Family Health Care. The Minister also finds that, respectively:

(1) The Centreway Pharmacy was open from 9 am to 5.30 pm weekdays and from 9 am to 12.30 pm on Saturdays, a total of 46 hours per week.

(2) The Priceline Mount Waverley Pharmacy was open from 9 am to 8 pm weekdays and from 9 am to 6 pm on weekends, a total of 73 hours per week.

58 These findings of fact were important for the Minister’s factual conclusion, at [39] of his reasons that:

I found that, based on the opening hours of Waverley Family Health Care and the opening hours of the two nearest approved pharmacies, there was a gap of 32 hours a week when Waverley Family Health Care was open and the two nearest approved pharmacies were closed.

59 The applicant contends that there were at least three matters of significance in his submissions which were not addressed at all by the Minister in his reasons. These were:

(1) How the relevant “community” should be identified. The applicant had contended the “community” should be identified as “Mount Waverley postcode 3149” and in his submissions to the Minister he set out what he contended to be demographic details of that community. In contrast to the way the applicant submitted to the Minister the “community” should be understood, the applicant contends the Minister adopted a narrower approach looking only at those residents of Mount Waverley who attended Waverley Family Health Care.

(2) The applicant contends the Minister’s reasons do not deal with his submission about a “saturation” of pharmacies, meaning that Mount Waverley was also significantly below the Victorian average pharmacy to population ratio. The applicant contended this was relevant to whether the Minister could be satisfied the (Mount Waverley) community had reasonable access to pharmaceutical benefits.

(3) The applicant had submitted to the Minister that it was important to understand that Waverley Family Health Care was not intending to shift to a 24 hour service unless a 24 hour pharmacy was approved on the premises, and the Minister should thus not consider the application on the basis that the health centre was already providing 24 hour health care.

60 YL Health Group contends the Minister discharged his statutory obligation in s 90D(3) of the Act. It submits the decision briefing note demonstrates clearly that the applicant’s submissions were drawn to the Minister’s attention, and were attached. Further, a summary was given in the decision briefing note itself. YL Health Group submits the Court should infer the Minister read the decision briefing note. It further submits that the following statements in the reasons are probative of the factual proposition that the Minister “considered” the applicant’s submissions. At [22] of his reasons, the Minister states:

Evidence

22. I considered the second Ministerial Submission from Mr Simon Cotterell, First Assistant Secretary, Provider Benefits Integrity Division of my Department, including the following:

• The first Ministerial Submission.

• Department’s letter dated 10 August 2017 advising the Applicant of my decision to consider the request and the Applicant’s response.

• Department’s letters, dated 10 August 2017, to the owner of the two existing pharmacies in Mount Waverley and the response from Ms McGrath.

• Summary of the Ministerial discretionary process and the Location Rules.

• Map of the proposed pharmacy, nearest approved pharmacies and medical centres.

• Correspondence sent to me and my Department relating to the request to exercise my personal power.

61 At [54], the Minister states:

I found that, based on a letter to me dated 10 August 2017, from Mt Stambe, owner of the two closest approved pharmacies, Mr Stambe opposed the approval of the proposed pharmacy.

62 YL Health Group goes further, and submits the Court should infer that when the Minister endorsed the first page of the reasons briefing note, thus adopting the entirety of the reasons as his own, he had read the submissions from Ms McGrath on behalf of the applicant, and had also considered the submissions from Ms McGrath as summarised in the decision briefing note. YL Health Group goes even further, and submits that where the Minister states in his findings of fact that he finds a fact “on the basis of research” by his Department, that he read the research before making the finding. I understand the reference to “research” to be to material attached to the reasons briefing note, and attached to or contained in the decision briefing note.

63 YL Health Group further submits, on the basis of the Full Court’s decision in Carrascalao v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2017] FCAFC 107; 252 FCR 352, that the Minister was not legally obliged to read any source material submitted to him before exercising the power under s 90A(2). I deal with Carrascalao below: it concerned a personal Ministerial discretionary power in s 501(3) of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth).

64 The particular “procedure” the applicant contends the Minister was required to follow, but did not, was what the applicant contends is the mandatory obligation in s 90D(3) that the Minister “consider” the comments, information or documents provided in response to a notice issued under s 90D(1).

Factual findings

65 I am prepared to infer that the Minister read the decision briefing note provided to him before he decided to exercise the power in s 90A(2) favourably to YL Health Group. I am prepared to find that the Minister therefore “considered” what was in the briefing note, in the sense I find that term should be understood in s 90D(3): see [103]-[112] below. I am not prepared to draw an inference beyond that, nor to draw either of the second or the third inferences for which YL Health Group contends.

66 The evidence is scant about how the Minister approached his decision-making task. The Minister gave no evidence. An officer of the Department swore two “institutional” affidavits, to which I refer below and which were taken as read in the proceeding. No-one who might have been present when the Minister made his decision gave any evidence about what the Minister said, or did, or how he approached his task. There was no evidence about how long the Minister took to make his decision (apart from that in the “institutional” affidavits referred to below at [140]). The evidence is that the Minister signed the briefing note and dated it “1 November 2017”. I infer the date was entered by the Minister as it appears to be in the same handwriting as the signature. In the rest of the material this date is nominated as the date the power was exercised.

67 In Nezovic v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs (No 2) [2003] FCA 1263; 133 FCR 190, French J (as his Honour then was) considered and ruled on the admissibility of a set of reasons produced to the Court through the affidavit of a solicitor, and to which objection was taken on the basis that only the Minister could depose to his reasons. At [31]-[45], French J considered the authorities about whether a ministerial briefing note endorsed by a Minister as an exercise of power constitutes a statement of reasons, noting that will be a question of fact and deciding in the case before his Honour the endorsed briefing note was not a statement of reasons. However, French J also considered the admissibility of the set of reasons produced some time later and which was sought to be adduced before the Court through the Minister’s solicitor. His Honour ruled the reasons inadmissible, and said at [56]-[59]:

In that connection, I refer to what I said in Taveli about the duty of a decision-maker providing reasons under s 13 of the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act:

It is not enough that an administrator confronted with a request for reasons should draft a set of reasons and findings which he or she think will stand up in court. The duty under s 13 is clear. It is to set out “the findings on material questions of fact” and “the reasons for the decision”. That does not require the degree of precision or detail which may be appropriate to a judicial decision. But it demands a statement of the real findings and the real reasons. It is an incident of the obligation that the statement should not omit findings or reasons for the decision which may, in the light of a pending review application, appear to be irrelevant or reflective of some false assumption or prejudgment. If an official or his or her advisors discover error when asked to provide a s 13 statement, the appropriate course may be to concede that the decision requires reconsideration. It is not appropriate to draft a statement from which the error is censored. The Court is sufficiently aware of the pressures associated with administrative responsibility for high volume and urgent decision-making to accept that mistakes will occur which can and should be redressed without any personal reflection upon the competence or integrity of the officials whose decisions are under challenge. But the statute requires that a statement provided under s 13 will reflect the true reasons for the decision in question. Anything less would approach, if not amount to, a fraud upon the public and the Court.

The thrust of that passage is that the reasons for decision given must be the true reasons. A statement of reasons produced long after the decision to which they refer, may fall short of that standard for a variety of reasons including the fallibility of human memory.

It is not necessary for present purposes to canvass generally the circumstances in which a decision-maker subject to judicial review should be available for cross-examination on the reasons for the decision. Where, however, reasons for decision have been produced after the grounds for review have been identified and where it is arguable, as in this case, that they have been structured to avoid criticisms, contained in the applicant’s grounds of review, of the sequence of reasoning suggested by the departmental issues paper, then there are legitimate questions which counsel for the applicant would be entitled to put to the decision-maker in cross-examination.

In the circumstances, the reasons for decision exhibited to Mr Blades’ affidavit will not be received in evidence. Should the Minister swear an affidavit exhibiting the reasons then, in my opinion, he should make himself available for cross-examination as a condition of the tender of his affidavit or oral evidence verifying the reasons. No question of issuing a subpoena arises. His availability is a condition of the admissibility of the reasons. I should add that the person who must verify the reasons is the person who actually made the decision as Minister and not his successor in that office. It is also that person who must be available for cross-examination if the reasons are to be received in evidence.

68 There have been more recent statements to similar effect. In CRI026 v Republic of Nauru [2018] HCA 19; 355 ALR 216 the High Court said at [61]:

That said, as Hill J observed in Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs v Taveli, in relation to the admissibility of a statement of reasons provided by an administrative decision maker under s 13 of the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth), where a statement of reasons is made after the event it will as a matter of general principle not be received as evidence in favour of the person making the statement, because it is both self-serving and a narrative of the past event which purports to be the equivalent of or a substitute for direct testimony of the event it narrates. In terms of general principle, parity of reasoning suggests that the same is true of an ex post facto amendment to reasons for decision. If so, except where it is admitted into evidence by consent, it should not be received.

(citations omitted)

69 Nezovic was cited favourably in a footnote to this passage.

70 In a similar way, I consider the Court should be cautious about the inferences it draws about what a Minister did or did not do, read or did not read, considered or did not consider, in exercising a statutory power, in the absence of any direct evidence about these matters. The inferences proposed by YL Health Group are self-serving, and a substitute for direct testimony, even though the submission is made on its behalf rather than by the Minister.

71 I accept that sometimes an inference may be available from a Minister’s reasons, but whether such an inference should be drawn might depend on how the reasons were drafted and prepared. If the author is the repository of the power, the inference may be more safely drawn. Just as the reasons for decision are to be the “true” reasons, as French J pointed out, so too the reliability of what the repository of the power examined before exercising the power, and adopting the reasons, should be the subject of evidence if there is any controversy about it.

72 Where, as here, reasons are drafted and settled by departmental officers and lawyers for a repository of the power well after the exercise of power, and the repository simply adopts them, I consider it is more difficult for inferences to be drawn about what the repository of the power “considered” or read, or did, at the time the power was exercised, unless that is plain from other evidence, or plain from the reasons themselves. Without other evidence, the level of independent thought and consideration applied by a repository of the power at the time the power was exercised will remain unknown to the Court.

73 In some cases (examples appear below), draft reasons are prepared and provided to a Minister at the time of the exercise of power. The Minister then adopts them at that time. In such cases, the content of those reasons may inform more reliably what the Minister “considered”, or read, prior to deciding how to exercise a power.

74 As a general principle, I consider it reliable and appropriate to infer, consistently with the purpose and practice of ministerial briefing notes, that a Minister reads a briefing note with which she or he is provided, where that briefing note is intended to provide the Minister with sufficient information to make a decision about whether or how to exercise a statutory power. Sometimes there may be evidence which assists the drawing of such an inference, such as handwriting, or marks such as circles or underlining, by the Minister on the contents of a briefing note itself. Such evidence is not necessary for the inference to be available and drawn, but it may be persuasive.

75 Of course, the drawing of such an inference may be actively contested by admissible evidence. If it is not, then it would tend to undermine the practice of executive decision-making at ministerial level if supervising Courts were to require direct evidence that the contents of each briefing note were read by a Minister. Whether an inference should be drawn in an individual case will remain a matter for each judge in the circumstances, but for my own part I consider this an appropriate general approach.

76 The other inferences for which YL Health Group contends are in a different category. There is simply no evidence to support them. They are in the realm of sheer speculation, and the Court does not engage in speculation: see Seltsam Pty Ltd v McGuiness [2000] NSWCA 29; 49 NSWLR 262 at [84]-[87] (Spigelman CJ). His Honour quotes the following passage from Caswell v Powell Duffryn Associated Collieries Ltd [1940] AC 152; [1939] 3 All ER 722 at 169-170:

Inference must be carefully distinguished from conjecture or speculation. There can be no inference unless there are objective facts from which to infer the other facts which it is sought to establish. In some case the other facts can be inferred with as much practical certainty as if they had been actually observed. In other cases the inference does not go beyond reasonable probability. But if there are no positive proved facts from which the inference can be made, the method of inference fails and what is left is mere speculation or conjecture.

77 That is all the more so when the reasons are on the evidence drafted by departmental officers and lawyers well after the exercise of power and in anticipation of legal proceedings, and the connection with the Minister’s actual reasoning process is an ex post facto adoption of a document as drafted. In making that finding, I do not suggest there is anything improper with the method chosen by the Minister, but there may well be forensic consequences for the use of that method. The Court is left in a position of being unable to determine, by reliance on any probative material, what the Minister read or what he did not, or what the Minister’s reasoning processes were at the time he exercised the power, as opposed to at some later stage when he was called upon, with the assistance of his departmental officers and lawyers, to explain why he had exercised the power as he had.

Other authorities

78 At the hearing, the parties were directed to file a joint note dealing with any other authorities, aside from Carrascalao concerning the exercise of personal statutory powers and express or implied obligations to consider submissions or material, and any authorities concerning the available inferences where a Minister adopts or signs reasons prepared by her or his staff.

79 On the first issue, the parties referred the Court to Tickner v Chapman [1995] FCA 987; 57 FCR 451, and also to Chetcuti v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2018] FCA 477 and NBMT v Minister for Immigration and Citizenship [2012] FCA 508; 128 ALD 119. Those authorities illustrate an applicant bears an onus of proving a decision-maker did not “consider” material as the law obliges a decision-maker to do and that clear evidence is required to support such a finding. Carrascalao also makes this point at [48]. Both Chetcuti and NBMT are cases where the Court found that onus had not been discharged. Each turned on its own facts. In NBMT, Bennett J noted that the applicant’s submissions invited the Court to find the statement in the Minister’s reasons about what the Minister “took into account” or “considered” were false.

80 That is not the case in the present proceeding. The Minister’s reasons simply state that he “considered” the decision briefing note, and I have explained above what I find this statement means, read fairly and in context.

81 On the second issue, the parties referred the Court to Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs v W157/00A [2002] FCAFC 281; 125 FCR 433; Navarrete v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs [2004] FCA 1723; Maxwell v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2016] FCA 47; 249 FCR 275 and Folau v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2017] FCAFC 214; 256 FCR 455. Folau involved a substantial review of previous authorities.

82 In W157, the Court was concerned with arguments about whether an issues paper placed before the Minister at the time of exercising a power to cancel a visa could constitute the Minister’s reasons if the Minister had endorsed that part of the issues paper which sought the Minister’s indication of whether or not he had decided to exercise the power. The terms of the issues paper are set out at [23] of the reasons of Branson J:

Part E of the issues document is headed “Minister’s Decision”. It reads:

“I have considered all relevant matters including an assessment of the character test within the meaning of s 501 Migration Act 1958 and the non citizen’s comments and have decided that:

[the respondent] passes the character test and

the visa should not be cancelled AGREED/NOT AGREED

[the respondent] does not pass the character test and does not satisfy me that he does pass the character test AGREED/NOT AGREED

I exercise my discretion to not cancel the visa AGREED/NOT AGREED

[the respondent’s] visa should be cancelled AGREED/NOT AGREED.”

It is signed by the Minister and dated 3 July 2000. It appears that it was the Minister who effected the crossing out illustrated above.

83 At [38]-[40], Branson J (with whom Goldberg J and Allsop J – as his Honour then was – agreed) said:

In Suresh v Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) 2002 SCC 1 File No 27790 at [126] the Supreme Court of Canada, in reviewing under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms a Ministerial decision to declare that an asylum seeker was a danger to the security of Canada, said:

“The Minister must provide written reasons for her decision ... The reasons must ... articulate why, subject to privilege or valid legal reasons for not disclosing detailed information, the Minister believes the individual to be a danger to the security of Canada as required by the Act. In addition the reasons must also emanate from the person making the decision, in this case the Minister, rather than take the form of advice or suggestion, such as the memorandum of Mr Gautier. Mr Gautier’s report, explaining to the Minister the position of Citizenship and Immigration Canada, is more like a prosecutor’s brief than a statement of reason for a decision.”

I doubt that s 501G(1) is intended to require that the notice therein referred to should emanate from the Minister in the sense that it must be drafted by the Minister. In my view, it would be sufficient for the Minister to adopt as his or her own written reasons prepared by a departmental officer provided, of course, that such reasons actually reflected the reasons why the Minister had reached his or her decision. However, I respectfully agree with the Supreme Court of Canada that a document that does not purport to explain why a decision has been reached is not transmogrified into reasons for that decision by ministerial adoption.

I conclude that the issues document, as completed and signed by the Minister, may only be regarded as a notice that sets out the reasons for the Minister’s decision to cancel the respondent’s visa if it in fact tells the respondent why his visa was cancelled in the sense of explaining to him how the Minister arrived at the conclusion that cancellation of his visa was the appropriate outcome of the exercise of his discretion to cancel or not to cancel the visa. It is thus necessary to give careful consideration to the form and content of the issues document.

84 Her Honour concluded (and the other members of the Full Court agreed) at [55], that the Minister “did not give to the respondent a written notice that sets out the reasons for the decision to cancel the respondent’s visa as required by s 501G(1)(e) of the Act”.

85 The decision in W157 is thus authority for what can constitute reasons under a particular reasons provision of the Migration Act. It certainly endorses the (non-contentious) proposition that others can draft and prepare a statement of reasons for a Minister, but a Minister must always consciously elect to adopt those reasons as her or his own. The decision is more concerned with when a document will satisfy the description of reasons under the particular terms of s 501G(1)(e) of the Migration Act.

86 In Navarrete, the factual situation was that at the time of the exercise of power (a visa cancellation power), the Minister had before him not only a departmental submission but a set of draft reasons for the proposed exercise of power (negatively to the applicant). Of this, Allsop J (as his Honour then was) said at [31]:

It is important, however, to appreciate what the “reasons” were before they were adopted. They were part of the submission. They were no doubt read and intended to be read as part of the process of decision-making by the Minister. On one view they can be seen as a Departmental recommendation, not so much the personal view of the author, but an expression of view purportedly conformable with Government policy which would justify a decision to cancel the applicant’s visa. As such they are part of the submission to be taken into account and considered before the decision. The submission, including the draft reasons viewed as I have indicated, is an integral part of the decision-making process. Unless it falls to be judged otherwise, it is not required to be viewed as adverse information obtained from a third party about the applicant: Bushell v The Secretary of State for the Environment [1981] AC 75, 95-6; Alphaone; and Re Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs; Ex parte Palme (2003) 77 ALJR 1829; 201 ALR 327.

87 This passage indicates, as do the following passages in the judgment, that the preparation and submission of draft reasons to the Minister gave rise to a procedural fairness argument by the applicant in that proceeding. That aspect of Navarrete is not relevant to the present proceeding. However, it is worth noting that Allsop J was not dealing with reasons prepared (and adopted) well after the exercise of power. That is, I consider, a not insignificant factor in the present proceeding, in terms of the inferences that might be drawn about what material the Minister considered (and read) at the time the power was exercised.

88 What is relevant from Navarrete is what his Honour said about the use of draft reasons, and their adoption by a Minister at [39]-[41]. In substance, his Honour accepted the process of a draft set of reasons being prepared and adopted by a Minister did not, of itself, affect the legality of the exercise of power. However, his Honour also said (at [40]):

If the Minister gave no consideration to the terms of the draft, for instance because the author was known to be reliable and she was prepared to sign a memorandum from that person without giving it consideration, it might be said that there was jurisdictional error for the failure by the Minister to make the decision personally. However, there was no evidence here upon which I could conclude otherwise than that the draft reasons were adopted by the Minister as her own reasons after due consideration and that she made the decision for herself and adopted the draft reasons therefor.

89 It is not suggested, nor have I found, that this is what occurred in relation to the exercise of the s 90A power. However, it is an important reminder that there are legal limits to the adoption of reasons prepared by others.

90 In Maxwell at [31]-[32], by reference to the Full Court’s decision in Javillonar v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs [2001] FCA 854; 114 FCR 311, Perry J found there was no basis to conclude that the Minister failed to exercise a personal statutory power personally as required, and to do so “independently”. Her Honour found it was lawful for the Minister to adopt a draft set of reasons. Again, that proposition is not challenged in this proceeding. What is in issue here is what inferences can be drawn from the evidence about what the Minister read, and what he “considered” (which may not be the same conduct).

91 Perry J also refers to the Full Court decision of Ayoub v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2015] FCAFC 83; 231 FCR 513 at [49] (Flick, Griffiths and Perry JJ), for the proposition that “it can be inferred that the Minister considered all of the material before her”. With respect to Perry J, I cannot see that [49] stands for this proposition. Even if it did, respectfully, such a proposition cannot be applied to different cases, in different statutory circumstances and upon different evidence, in any broad way.

92 Folau was an appeal where the appellant had directly sought to attack the quality of the “consideration” given by the Minister to the cancellation of his visa, through a notice to admit. The contents of the notice are set out at [71] of the reasons of Murphy and Burley JJ. Like Navarrete and Maxwell, Folau was a case where a draft set of reasons were provided to the Minister at the time of the exercise of power. Those facts which, for reasons that need not be set out, were ultimately not contested by the Minister on appeal (and were thus taken as having been admitted) were:

1. The Minister was given an “Issues” paper (see p. 2 of the Court Book) and a draft “Statement of Reasons” (see p. 25 of the Court Book) under cover of a “Submission” (see p. 1 of the Court Book).

2. The Minister signed the “Statement of Reasons” without making or requesting any amendments to it.

3. From the date he became the Minister until 17 March 2016, the current Minister for Immigration and Border Protection has made other cancellation and refusal decisions under s 501 of the Act (the other decisions).

4. All of the Statements of Reasons in respect of the other decisions (the other statements) were prepared by somebody else and signed by the Minister.

5. The Minister made or requested no changes to any of the other statements before signing them.

93 From these admissions, the appellant in Folau sought to contend that, in justifying the exercise of a personal power, the Minister was not lawfully entitled to adopt a set of reasons prepared by others unless those reasons “actually reflected” the Minister’s own reasoning process. The appellant’s argument was described at [81]:

Putting to one side bad faith, which was not alleged, Mr Folau contended that there were only two possible explanations for the Minister adopting the draft reasons in his case, without making any change:

(a) first, the Minister might have personally decided to cancel Mr Folau’s visa and found, upon examining the draft reasons, that those reasons coincidentally “accurately reflected” his actual process of reasoning in every respect. However, having regard to the admitted facts, Mr Folau submitted that whatever the likelihood in a given case of the draft reasons accurately reflecting the Minister’s own reasoning process, the possibility of that happening in every visa cancellation and refusal decision the Minister made over a 15 month period could safely be discounted. Mr Folau submitted that was quite improbable; or

(b) second, the Minister might not have engaged in a genuine personal exercise of discretion. He may have read the draft reasons and considered those reasons to be reasonable or defensible and decided to exercise his discretion to cancel Mr Folau’s visa. He might have done so because he misunderstood what a personal exercise of the discretion entailed.

Mr Folau contended therefore that the Minister did not give proper, genuine and realistic consideration to the merits of his case.

94 That is not the argument made by the applicant in this proceeding but nevertheless, some of the observations of Murphy and Burley JJ should be noted, especially those from [85] onwards, where their Honours point out that the admitted facts in Folau placed the evidence in a different category from previous cases such as Navarrete, and Maxwell. At [88]-[90] their Honours said:

In Lek v Minister for Immigration, Local Government and Ethnic Affairs (1993) 43 FCR 100 at 122 Wilcox J said, and we agree, that:

… the use by decision makers of reasons devised by others is a matter that should excite concern about the possibility that individual decisions were taken in accordance with an overriding rule or policy or at the direction or behest of others.

Such concerns are likely to be deepened by the Minister’s apparent practice of adopting draft reasons prepared by others in every visa cancellation and refusal decision he makes, without amendment.

One might reasonably ask why Parliament would provide the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection with a personal power to cancel a visa (as an alternative to having the decision made by a delegate), and oblige the Minister to give reasons for doing so, if Parliament understood or intended that in every case the Minister would adopt, without change, the draft reasons prepared by departmental officers. Such a practice has a tendency to undercut Parliament’s intention to provide a right to merits review where a visa cancellation decision is made by a delegate rather than by the Minister personally.

95 Nevertheless, on the evidence before them, noting (at [91]) the issue of lawful consideration was one of fact, their Honours concluded (at [92]) the appellant had not discharged his onus of proving absence of active intellectual engagement by the Minister with the material before him:

In the present case the materials show that the Minister:

(a) was provided all the relevant materials to make a personal decision in relation to Mr Folau’s case;

(b) selected the option in the Submission which stated that he wished to consider Mr Folau’s case personally, and signed and dated it;

(c) selected the “cancellation outcome” in the pro forma decision which included statements that the Minister had decided to exercise his discretion to cancel Mr Folau’s visa and that “[m]y reasons for this decision are set out in the attached Statement of Reasons”, and signed and dated it; and

(d) signed and dated the draft reasons.

That provides a strong basis to conclude that the Minister gave proper consideration to the merits of Mr Folau’s case and after doing so adopted the draft reasons as his own reasons. While the admitted facts point to a contrary inference, they are insufficient to outweigh what are, in effect, express statements by the Minister that he personally made the decision for the reasons he signed and dated.

96 Since Folau, at least two Full Courts have referred to that decision: see Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v Maioha [2018] FCAFC 216 and Hooton v Minister for Home Affairs [2018] FCAFC 142.

97 Those decisions do not take the issues in this proceeding any further, although I note in Maioha at [69] Flick J said:

…For the Minister or Assistant Minister to simply acknowledge that the submission had been made, without more, may expose the decision-making process to judicial scrutiny by reason of failing to engage with a submission identified by the Minister or Assistant Minister as assuming relevance.

98 All of these cases are (from W157 onwards), in my opinion, circumstantially similar. They all concern “consideration” of the kind in issue in Carrascalao, but which the Full Court distinguished from “consideration” of a specific mandatory consideration, like Tickner: see Carrascalao at [46]. It is that alternative circumstance which, like Tickner, arises in this proceeding.

99 The consequence of that difference is significant. The consequence concerns how the Court goes about its fact finding about what the Minister did, or did not, do. In the present case, the nature of the statutory obligation on the Minister is different. So too, is the current factual situation, and the evidence. Much turns on what was before the Minister at the time he made his decision, the absence of any evidence about how long he took to make it or what he read, combined with what was actually in the decision briefing note and whether it contained material inaccuracies, the fact the reasons were drafted by others (including lawyers) well after the exercise of power and in anticipation of legal proceedings, the absence or existence in the reasons of any references to the content of the applicant’s response, the Minister’s adoption of the briefing note without annotation or comment and the absence of any direct evidence from the Minister or his advisers about how the Minister came to adopt the s 13 reasons. I am not persuaded statements in any of these authorities should cause me to modify the findings of fact I have made above.

The outer limits of what needs to be considered

100 I do not accept YL Health Group’s broad submission that the obligation to give any consideration at all to the applicant’s submissions arose solely by virtue of s 90D(3). I find there is such an obligation present in subsection (3), but whether outside the terms of subsection (3), a Minister might be obliged to consider material or argument placed before her or him by a third party prior to exercising the power in s 90A(2) is not necessary, as a blanket proposition, to decide.

101 YL Health Group relied on the reasons of White J in Angelos v Minister for Health [2014] FCA 706; 226 FCR 275 at [88]-[91] to submit that the Minister is charged in s 90A(2) with making a decision in the public interest, and therefore “any submissions advanced by a person invited to make them do not necessarily assume any particular importance in the public interest calculus”. In Angelos, White J found there had been a denial of procedural fairness to a pharmacist applicant in the course of making a determination under s 90A, in circumstances where third party material provided to the Minister was relevant to the Minister’s assessment of where the public interest lay, and the material was adverse to the applicant and capable of having a prejudicial effect on the decision. However, White J rejected another ground advanced by the applicant in Angelos, dealing with an argument that the Minister had failed to consider contentions put to her. While his Honour appeared to accept that the “essential integer” analysis which had been applied in the migration practice area to the assessment (and review) of claims made by those seeking protection visas (see: eg Htun v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs [2001] FCA 1802; 233 FCR 136 at [42]) could be applied to s 90A(2) as far as the two preconditions in subsection (2) were concerned, his Honour rejected the matters put forward by the applicant in Angelos as falling within such a characterisation.

102 I do not consider his Honour’s reasons support the somewhat wider submission made by YL Health Group. They relate to the specific situation decided by his Honour. While it might be uncommon, I see nothing in the terms of s 90A (nor s 90D) to preclude an argument that a matter put by a third party to a Minister (who has decided to consider whether to exercise the s 90A power) is so material to the question whether or not to approve a new pharmacy that the Minister would not be performing the task assigned to her or him if that matter were ignored. In reality, the basis for the “integer analysis” in migration decisions such as Htun lies with an assessment of the task to be performed by the decision-maker. So it might be with s 90A: it is not necessary to decide the outer limits of any such arguments in this proceeding.

What does “consider” mean in s 90D(3)?

103 Although as I have noted, the outer limits of how the Minister discharges her or his task under s 90A(2) do not need to be set in this proceeding, it is necessary to determine the scope of the obligation imposed by s 90D(3) to “consider comments, information or documents”, as this is what the applicant relied on for ground one.

104 If the Minister does issue a notice to “any other person”, then s 90D(3) governs what the Minister must do with any information or comments received. The purpose of s 90D is to give the Minister a discretion whether to notify certain people of an s 90A application, and to invite comments from them. The provision is intended to provide a form of procedural fairness, albeit at the discretion of the Minister. That intention could be defeated if the Minister were not required to consider the information she or he had invited people to provide: an opportunity to be heard is little more than theoretical unless the repository of the power is required to consider what has been said or submitted. Doing so is indeed part of procedural fairness. The context of s 90D is one where the power which the Minister is considering whether to exercise is a power which can have a commercial effect on other pharmacists, a financial effect on Commonwealth funds and an effect in terms of the access to pharmaceutical services of parts of the Australian community. Context suggests s 90D(3) is obligatory in nature where the Minister has invited comments or submissions about such matters, amongst others. Third, the text supports such a construction. Section 90D(3)(a) uses the word “required”, which suggests obligation. Even if there is an exclusionary aspect to the provision (and there may well be), what is excluded is an obligation to consider comments, information or documents provided outside a particular time frame. Finally, the text of the provision indicates the notice power is intended to elicit information to feed into the Minister’s decision-making process. By s 90D(2) if an applying pharmacist does not comply with a notice, the Minister has a discretion to treat the application under s 90A as withdrawn: that is a drastic consequence indicative of the importance of compliance with a notice. Similarly, having conferred a discretion on the Minister whether or not to notify others, and so to control what further information is available for the decision-making process, it is unlikely Parliament intended the Minister then to be able to disregard any responses to her or his invitation.

105 Thus, properly construed, s 90D(3) imposes an obligation on the Minister to consider any comments, information or documents received in response to an invitation from the Minister, but only insofar as they are provided during the period specified in the notice.

106 What then is the content of the obligation to “consider” any such comments, information or documents? To some extent, the applicant’s submissions on this question of construction appear to be intertwined with his submissions about the need for the Minister to give “proper, genuine and realistic consideration” to such material.

107 In Bat Advocacy NSW Inc v Minister for Environment Protection, Heritage and the Arts [2011] FCAFC 59 at [44]-[47] the Full Court explained, in terms of general principle, what is required of a decision-maker in taking into account a mandatory consideration. That is, as I have found, in effect what comments, information or documents responsive to an invitation under s 90D become: they become a relevant consideration which the Minister is bound to take into account in reaching her or his decision on whether or not to grant an approval under s 90A. The Court said:

The obligation of a decision-maker to consider mandatory relevant matters requires a decision-maker to engage in an active intellectual process, in which each relevant matter receives his or her genuine consideration (see Tickner v Chapman (1995) 57 FCR 451 at 462 and Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs v Jia (2001) 205 CLR 507 at [105]). However, in the absence of any statutory or contextual indication of the weight to be given to factors to which a decision-maker must have regard, it is generally for the decision maker to determine the appropriate weight to be given to them. The failure to give any weight to a factor to which a decision-maker is bound to have regard, in circumstances where that factor is of great importance in the particular case, may support an inference that the decision-maker did not have regard to that factor at all. Similarly, if a decision-maker simply dismisses, as irrelevant, a consideration that must be taken into account, that is not to take the matter into account. On the other hand, it does not follow that a decision-maker who genuinely considers a factor but then dismisses it as having no application or significance in the circumstances of the particular case, will have committed an error. The Court should not necessarily infer from the failure of a decision-maker to refer expressly to such a matter, in the reasons for decision, that the matter has been overlooked. But if it is apparent that the particular matter has been given cursory consideration only so that it may simply be cast aside, despite its apparent relevance, then it may be inferred that the matter has not in fact been taken into account in arriving at the relevant decision. Whether that inference should be drawn will depend on the circumstances of the particular case (see Minister for Immigration and Citizenship v Khadgi (2010) 274 ALR 438 at [58]–[59]).

Once a matter has been identified as a mandatory relevant consideration, it is the salient facts that give shape and substance to the matter that must be brought to mind. These are the facts which are of such importance that, if they are not considered, it could not be said that the matter has been properly considered (see Minister for Aboriginal Affairs v Peko-Wallsend Ltd (1986) 162 CLR 24 at 61).

A statement of reasons given by a decision maker can constitute evidence of the material put before the decision maker, the way in which that material has been dealt with and the reasons for which the decision was made. A failure to include reference to a matter in a statement of reasons may justify the inference that, as a matter of fact, the matter was not taken into account. Thus, a statement of reasons may be accepted as evidence of the truth of what it says, namely, that the findings made and the evidence referred to and the reasons set out are as stated in the statement of reasons. It can be accepted as evidence that no finding, evidence or reason that was of any significance to the decision has been omitted (see Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs v Taveli (1990) 23 FCR 162 at 179 and 182).

A statement of reasons under s 13 of the Review Act does not require a decision-maker to pass comment on all of the material to which his attention has been drawn and to which he has had regard. What the provision requires is that the decision-maker set out his or her findings on “material questions of fact”. While a failure to include a matter in a statement of reasons may justify a court inferring, as a matter of fact, that the matter was not taken into account, such an omission is not necessarily conclusive (see Our Town FM Pty Ltd v Australian Broadcasting Tribunal (1987) 16 FCR 465 at 485). Whether that inference will be drawn in a particular case will depend on all the circumstances (see ARM Constructions Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (1986) 10 FCR 197 at 205).