FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Meat & Livestock Australia Limited v Cargill, Inc (No 2) [2019] FCA 33

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The respondents within 14 days of the date hereof file and serve proposed minutes of orders and short submissions (limited to 3 pages) to give effect to these reasons including the making of final orders concerning the disposition of the appellants’ appeal and the respondents’ amendment application and on any question of costs.

2. The appellants within 14 days of the service of the respondents’ proposed orders and submissions file and serve proposed minutes of orders and short submissions (limited to 3 pages) on such topics.

3. Liberty to apply.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BEACH J:

1 On 9 February 2018, I delivered my principal reasons on the appeal brought by Meat & Livestock Australia Limited and another (collectively, MLA); see Meat & Livestock Australia Limited v Cargill, Inc (2018) 354 ALR 95; 129 IPR 278; [2018] FCA 51. I also ordered that the parties file minutes of orders and submissions to give effect to those reasons, including concerning any steps necessary to deal with any application by Branhaven LLC (Branhaven) and Cargill, Inc (Cargill) to amend the claims of the 253 Application which I anticipated that they would make.

2 To recap, the principal claims of the 253 Application involve method claims for identifying a trait of a bovine subject from a nucleic acid sample of that subject. The field of the invention relates to gene association analyses, specifically to single nucleotide polymorphisms and correlated traits of bovine subjects. The scientific disciplines that are relevant are molecular genetics and quantitative genetics. The 253 Application was filed on 1 June 2010 as a divisional application of the parent Australian patent application filed on 31 December 2003, which has now been withdrawn. The parent application claimed a priority date of 31 December 2002 based upon US application number 60/437,482. Accordingly, the co-applicants of the 253 Application, Branhaven and Cargill assert, unsurprisingly, that the earlier priority date applies. In the present context I do not need to add to what I said in my principal reasons concerning the priority date.

3 In my principal reasons I explained why I rejected MLA’s grounds of appeal concerning non-satisfaction of the “manner of manufacture” requirement, lack of novelty, lack of inventive step, lack of sufficiency, lack of fair basis and most of the dimensions of MLA’s lack of utility challenge. But I upheld some of MLA’s grounds concerning lack of clarity and lack of definition, and a residual aspect dealing with lack of utility. I indicated that several integers of the relevant claim(s) would need to be amended to deal with linkage disequilibrium between relevant single nucleotide polymorphisms and also to address questions of statistical significance. I also indicated that if appropriate amendments were made, then my concerns relating to lack of clarity, lack of definition and the residual aspect of lack of utility would fall away.

4 In the circumstances, I refrained from making final orders on MLA’s appeal in order to enable Branhaven and Cargill to consider their position and, if thought appropriate, to apply to amend the relevant claim(s) to address my concerns.

5 On 15 May 2018, Branhaven applied under s 105(1A) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the Act) to amend various claims of the 253 Application (the amendment application). It purported to do so to address the issues that I had raised in my principal reasons. Cargill was not a co-applicant to the amendment application. I have set out as a schedule to my present reasons the form of these proposed amendments.

6 The amendment application has been supported by evidence adduced by Branhaven from Dr Karen Bentley, a principal of FPA Patent Attorneys and the patent attorney responsible for the prosecution of the 253 Application, Mr Daniel Smith, the intellectual property manager for Branhaven who has been managing its intellectual property portfolio since April 2011, and Professor Jeremy Taylor, a quantitative geneticist who gave expert evidence before me on MLA’s appeal. MLA has relied upon expert evidence from Professor Peter Visscher, a quantitative geneticist, in opposition to the amendment application; he previously gave evidence on the appeal. My principal reasons elaborate on the backgrounds of Professor Taylor and Professor Visscher.

7 Predictably, MLA has opposed the amendment application. Some of the highlights of MLA’s grounds of opposition to the amendment application concern questions of power and are to the following effect:

(a) First, it says that its appeal is no longer on foot in the relevant sense because a final decision has been made by me dealing with all matters in issue. Accordingly, s 105(1A) cannot confer power and jurisdiction where it does not exist. It says that my power and jurisdiction were exhausted when I decided that the claims of the unamended 253 Application would be invalid if granted. And that it makes no difference that final orders have not yet been made.

(b) Second and relatedly, it says that my observations in my principal reasons regarding appropriate amendments do not answer the question of whether I have the jurisdiction to deal with the amendment application.

(c) Third, it says that the Commissioner of Patents’ practice does not answer the question of whether the Court, exercising federal judicial power rather than administrative power, has jurisdiction to entertain an application to amend in the same circumstances or to exercise analogous power.

(d) Fourth, it says that the proposed amendments are not allowable pursuant to s 102(1) of the Act because the amended claims of the 253 Application would claim matter not in substance disclosed in the specification as filed.

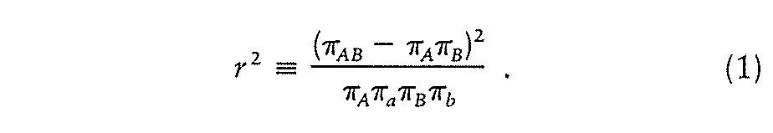

(e) Fifth, it says that the proposed amendments are not allowable pursuant to s 102(2)(b) on the ground of lack of fair basis because, as a result of the proposed amendments, the specification of the 253 Application would not comply with s 40(3). In particular, the proposed amendments would add an r2 value for linkage disequilibrium of ≥ 0.7 or ≥ 0.8 in each of the claims and thereby would result in each of those claims not being fairly based on the matter described in the specification because the specification does not describe that linkage disequilibrium should be determined or measured in any particular way. In particular it is said that there is no disclosure in the specification of any method for determining or measuring linkage disequilibrium per se, an r2 value per se, an r2 value as a method for determining or measuring linkage disequilibrium, an r2 value of greater than or equal to 0.7 as a measure of linkage disequilibrium or an r2 value of greater than or equal to 0.8 as a measure of linkage disequilibrium. Further, MLA points out that the specification describes that the degree of linkage disequilibrium varies considerably throughout the genome and is a function of time, recombination events, mutation rate and population structure. Further, MLA highlights that the specification uses distance as a proxy for linkage disequilibrium (see Example 3). Further, it says that the specification uses 500 kilo base pairs (kb) (described as 500,000 nucleotides) either side of a specified SNP as a proxy for linkage disequilibrium.

(f) Sixth, it says that the proposed amendments are not allowable pursuant to s 102(2)(b) on the ground of lack of clarity because, as a result of the proposed amendments, the specification of the 253 Application would not comply with s 40(3). In particular, the proposed amendments would add the word “significantly” before “associated” in each of claims 1, 6, 7, 8, 12 and former claim 14 (now proposed claim 13) and new claims 15, 20, 21, 22, 26 and 27 which include the same phrase “significantly associated”, and thereby would result in each of those claims and claims dependent on them lacking clarity. It is said that it is not clear how the word “significantly” interacts with the added requirement of a particular degree of statistical significance of association identified in each of those claims. Further, it is said that the proposed amendments would add a value of statistical significance of p ≤ 0.05 or of p ≤ 0.01 to each of the claims and thereby would result in each of those claims lacking clarity. It is said that such p-values do not provide a workable standard by which the skilled addressee could determine the boundaries of the claims. In particular, because the p-value will vary depending upon a number of factors including the nature of the population of cattle tested, the skilled addressee would not know whether applying the claimed method to a particular population would infringe the patent. Further, it is said that the proposed amendments would add an r2 value for linkage disequilibrium of ≥ 0.7 or of ≥ 0.8 to each of the relevant claims and thereby would result in each of those claims lacking clarity because such r2 values do not provide a workable standard by which the skilled addressee could determine the boundaries of the claims. In particular, it is said that because the r2 value will vary depending upon a number of factors including the population of cattle tested, the skilled addressee would not know whether applying the claimed method to a particular population would infringe the patent.

(g) Seventh, it says that the proposed amendments are not allowable pursuant to s 102(2)(b) on the ground of lack of definition because, as a result of the proposed amendments, the specification of the 253 Application would not comply with s 40(2)(b) of the Act because the claims would not clearly define the invention for the same reasons I have just described relating to the lack of clarity objection.

8 Now as I have said, each of the above grounds of opposition can best be characterised as a power question. And broadly speaking they can be subdivided into two sub-categories. The first sub-category, which consists of the first three arguments, relates to the question of whether I lack jurisdiction or power to either entertain the amendment application or exercise any power under s 105(1A) because I have already finally determined MLA’s appeal, which determination is said to be embodied in my principal reasons. The second sub-category, which consists of the fourth to seventh arguments, relates to more traditional grounds of objection, namely, whether the proposed amendments are not allowable under ss 102(1) or (2). I will deal with each of these sub-categories of power arguments separately.

9 Now before proceeding further, I would note that there is one other power type argument that is not now pressed in any meaningful sense. Section 105(1A) required the amendment application to be made by the patent applicant(s). In the present case, Cargill and Branhaven were co-applicants of the 253 Application, but the amendment application as instituted had only been made by Branhaven. But on 12 July 2018, Cargill assigned all of its right, title and interest in the 253 Application to SelecTraits Genomics LLC (SelecTraits), a Delaware limited liability company. Further, on 31 July 2018 a copy of the relevant confirmatory assignment deed together with a request to amend ownership details was lodged with IP Australia. Moreover, on 31 July 2018 SelecTraits executed a power of attorney in favour of Branhaven constituting the latter as its attorney to prosecute the amendment application before me on its behalf. On 1 August 2018 I ordered that SelecTraits be added as a party to the proceeding and gave leave to file and serve an amended amendment application reflecting the fact that both Branhaven and SelecTraits were applying to amend the 253 Application. Accordingly, any perceived deficiency on the applicant identity question has now been resolved. For convenience, I will refer to Branhaven in these reasons as also encompassing SelecTraits and its assignor Cargill, unless I indicate otherwise.

10 In addition to the two sub-categories of power questions, MLA has raised various discretionary grounds against granting the amendment application. On the assumption that I have jurisdiction and power, MLA says that I ought not to exercise my discretion pursuant to s 105(1A) in favour of directing the amendment of the 253 Application according to the proposed amendments for the following reasons. First, it says that Branhaven has sought to obtain and has obtained an unfair advantage from the breadth of the claims of the 253 Application in its current form, and it would be unfair for it to now be permitted to amend the 253 Application to narrow those claims. In particular, Branhaven has negotiated to license persons to exploit in Australia the invention the subject of the claims of the 253 Application in their unamended form. Second, it says that Branhaven has unreasonably delayed in seeking to make the proposed amendments. Third, it says that Branhaven was aware or ought to have been aware that the breadth and lack of clarity of the claims of the 253 Application in their unamended form were of great concern to the public including Australian cattle farmers, but persisted in maintaining those claims for as long as it was possible to do so, thereby making unwarranted assertions to the public regarding the potential scope of its monopoly regarding the selection of cattle for breeding. Again to be clear, references to Branhaven include Branhaven and Cargill, with SelecTraits being subject to any burden or impediment to which its assignor was subject and attributed with its assignor’s knowledge.

11 I would also note at this point that MLA’s discretionary arguments proceed on an assumption that Branhaven has challenged. Branhaven contends that absent any s 102 impediment provided by operation of s 105(4), and providing that the power in s 105(1A) has been enlivened, the power in s 105(1A) is not discretionary. In other words I must allow the amendments. Accordingly, it contends that MLA’s discretionary arguments are misconceived. I will dispose of this point later.

12 Further, MLA has asserted that Branhaven elected to persist with the 253 Application in its current form until after I had made my final decision on the appeal and is now bound by its election. Relatedly it says that Branhaven is estopped from bringing the amendment application in accordance with the principles of Anshun estoppel. It says that the issue of the amendment of the 253 Application was so connected with the subject matter of the appeal relating to the unamended 253 Application that it was unreasonable for Branhaven not to have applied to amend the 253 Application during the previous hearing, before I determined all of the issues in the appeal regarding the 253 Application in its current form.

13 In summary, MLA submits that I should refuse the amendment application and that the only appropriate orders I should make given the delivery of my principal reasons on the appeal are that:

(a) MLA’s appeal be allowed;

(b) the decision of the delegate be set aside; and

(c) the 253 Application not proceed to grant.

14 Now given the novelty of some of the legal issues concerning the first sub-category of power questions (non-s 102) and whether the power under s 105(1A) is discretionary, I invited the Commissioner of Patents to make submissions to me on these questions, which the Commissioner did through counsel, Dr Warwick Rothnie, who was of considerable assistance.

15 I would also note one other preliminary matter. The amendment application has been appropriately advertised. On 18 May 2018 I made the following orders:

1. On or before 21 May 2018, the Second Respondent provide to the Commissioner of Patents an advertisement stating the matters identified in r 34.41(1)(a) to (d) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) with respect to the amendments to the patent request now sought by the Second Respondent in its interlocutory application filed 15 May 2018 (the amendment application).

2. The Commissioner of Patents publish the advertisement referred to in order 1 in the 31 May 2018 edition of the Official Journal.

3. Any person intending to oppose the amendment application who is not a party to the proceeding and who has notified the parties and the Commissioner of Patents of that intention by 28 June 2018 in accordance with Rule 34.41(1)(d) (third parties), must, by 5 July 2018, file and serve its particulars of grounds of objection to the amendment application.

16 Those orders were complied with. No opposition to the amendment application from any quarter has been forthcoming other than from MLA.

17 In summary, I have decided to reject all of MLA’s principal arguments save the s 105(1A) discretionary power point, and would grant the amendments sought of the 253 Application.

18 For convenience, I have divided my reasons into the following sections:

(a) The progress of the 253 Application ([20] to [37]);

(b) First sub-category of power questions ([38] to [121]);

(c) Some evidence on p-values and r2 ([122] to [193]);

(d) Second sub-category of power questions (s 102) ([194] to [333]);

(e) Discretion ([334] to [466]); and

(f) Conclusion ([467] to [470]).

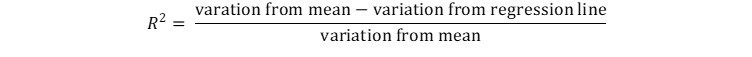

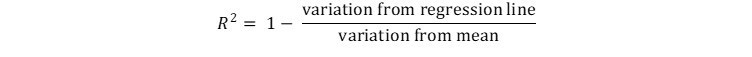

19 The present reasons are to be read with my principal reasons with defined terms used in my principal reasons equally applying here unless I indicate otherwise. I will also assume a familiarity with the molecular genetics and statistical concepts discussed in my principal reasons and will only elaborate further where necessary. After all, p-values used to reject the null hypothesis and squared coefficients of correlation such as r2 values should be well understood and require only modest elaboration. Generally speaking, the idea, indeed the ideal, is that p-values should be as small as possible to avoid a type 1 error, that is, incorrectly rejecting the null hypothesis or, in other words, to minimise the risk of false positives. The squared coefficient of correlation (r2) should be as high as possible. Let me also be clear at this point that I am not here referring to another capitalised metric R2, which is well known as the coefficient of determination and is used in multiple linear regression analysis. In using the lower case r2 I am here referring to the square of a correlation coefficient “r”; the correlation coefficient “r” can be the Pearson correlation coefficient modified by the Fisher transformation.

THE PROGRESS OF THE 253 APPLICATION

20 It is convenient to begin with a short chronology of the progress of the 253 Application.

21 The 253 Application was filed at the Australian Patent Office on 1 June 2010 as a divisional application of AU2003303599. Examination of the application was requested on 7 December 2010. The first examination report issued on 18 January 2012. No objection to the clarity of the claims, the failure to define the invention or inutility was raised. A second examination report issued on 21 March 2012. No objection to the clarity of the claims, the failure to define the invention or inutility was raised. A third examination report issued on 16 October 2013. No objection to the clarity of the claims, the failure to define the invention or inutility was raised. A notice of acceptance issued on 22 October 2013.

22 A notice of opposition was filed by IP Organisers on 31 January 2014 opposing the grant of the 253 Application. By way of an amendment of notice of opposition dated 17 April 2014, the right on which IP Organisers relied to file the notice of opposition was transferred to MLA.

23 On 30 April 2014, MLA filed a statement of grounds and particulars (the SOGAP). The SOGAP particularised MLA’s allegation of a lack of clarity. An amended SOGAP was filed on 19 December 2015, although no changes were made to the particulars of the allegation of a lack of clarity.

24 Following a hearing held on 1 July 2015, the delegate of the Commissioner of Patents handed down her decision on 6 May 2016 (see Meat & Livestock Australia Ltd and Anor v Cargill, Inc & Anor [2016] APO 26). The delegate concluded that the opposition was only successful concerning a minor issue of clarity relating to claim 13 which Branhaven could overcome by amendment putting to one side the manner of manufacture question concerning claim 13.

25 On 27 May 2016, MLA filed a notice of appeal in this Court from her decision. An amended notice of appeal was filed on 9 September 2016. A further amended notice of appeal was filed on 25 January 2017. A third amended notice of appeal was filed on 15 May 2017. The original notice included a ground of lack of clarity. The amended notice particularised terms alleged to be unclear:

12(b) The following terms in the claims are unclear:

(i) “a method for identifying a trait of a bovine subject”;

(ii) “the at least three SNPs are associated with the trait”;

(iii) “wherein the at least three SNPs occur in more than one gene”;

(iv) “the SNP is about 500,000 or less nucleotides from position 300 of any one of SEQ ID nos 19473 to 21982”.

(Original emphasis.)

26 No amendments to the ground of lack of clarity were made thereafter. There were of course other grounds including lack of definition and also lack of sufficiency which encompassed concerns relating to limb (b) SNPs.

27 On 9 February 2018, I delivered my principal reasons in the appeal from the delegate’s decision. At [944] and [945] of my reasons, I said:

In terms of lack of clarity and for the reasons that I have already expressed in the construction section, claim 1 (and analogous claims) will require amendment to:

(a) define “associated” in terms of statistical significance at the p value of equal to or less than 0.01 (or such other measure as I decide after hearing from counsel further);

(b) require each of the 3 SNPs to satisfy that level of statistical significance (to be discussed further with counsel); and

(c) require the limb (b) SNP to be in LD with the relevant limb (a) SNP and to the requisite degree (to be discussed further with counsel).

As presently formulated, claim 1 and analogous claims fail for lack of clarity and proper definition, and also give rise to aspects of inutility. But if such amendments are made, these matters may be rectified.

28 Branhaven’s amendment application seeks orders for the amendment of the claims of the 253 Application to address my concerns. As I say, I have set out in a schedule to the present reasons the claims with the proposed amendments. In summary, the proposed amendments purport to address the matters referred to in my principal reasons as well as the deletion of claim 13.

29 More particularly, the claims as proposed to be amended may be put into three groups, being claims 1 to 14, claims 15 to 28, and claims 29 to 34. The amendments reflected in these claim groups are as follows.

Claims 1 to 14

30 Claims 1 to 14 are an amended version of existing claims 1 to 15 in the 253 Application.

31 In claim 1 as proposed to be amended:

(a) the words “significantly” and “with the degree of statistical significance being p≤0.05” are inserted so as to define “associated” in terms of statistical significance at that p-value;

(b) the words “each of” are inserted so as to require each of the 3 SNPs to satisfy that level of statistical significance;

(c) the words “and is in linkage disequilibrium with the SNP at position 300 with an r2 value of ≥0.7” are inserted so as to require the limb (b) SNP to be in linkage disequilibrium with the relevant limb (a) SNP to an appropriate degree; and

(d) for ease of reference, the letters “(a)” and “(b)” have been inserted so as to identify those parts of the claim that were referred to at the trial before me and in my principal reasons as “limb (a)” and “limb (b)”.

32 Claim 1 as sought to be amended is in the following marked up form:

1. A method for identifying a trait of a bovine subject from a nucleic acid sample of the bovine subject, comprising identifying in the nucleic acid sample an occurrence of at least three single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) wherein each of the at least three SNPs are significantly associated with the trait, with the degree of statistical significance being p≤0.05, and wherein the at least three SNPs occur in more than one gene; and wherein

and wherein(a) at least one of the SNPs corresponds to position 300 of any one of SEQ ID NOS: 19473 to 21982, or

(b) the SNP is about 500,000 or less nucleotides from position 300 of any one of SEQ ID NOS: 19473 to 21982 and is in linkage disequilibrium with the SNP at position 300 with an r2 value of ≥0.7.

33 Corresponding amendments are made to the similar language in claims 6, 7, 8, 12 and 13 (formerly 14). No amendment has been made to the wording of dependent claims 2 to 5, 9 to 11 and 14 (formerly 15).

34 Further, what was formerly claim 13 is deleted entirely.

Claims 15 to 28

35 Claims 15 to 28 are a new set of claims. They are identical to claims 1 to 14 as proposed to be amended, save that the p-value specified for the degree of statistical significance of the association is 0.01, rather than 0.05. The p-value of 0.01 was, of course, my personal preference as discussed in my principal reasons.

36 It is convenient to set out Claim 15 as sought to be added:

15. A method for identifying a trait of a bovine subject from a nucleic acid sample of the bovine subject, comprising identifying in the nucleic acid sample an occurrence of at least three single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) wherein each of the at least three SNPs are significantly associated with the trait, with the degree of statistical significance being p≤0.01, and wherein the at least three SNPs occur in more than one gene; and wherein

(a) at least one of the SNPs corresponds to position 300 of any one of SEQ ID NOS: 19473 to 21982, or

(b) the SNP is about 500,000 or less nucleotides from position 300 of any one of SEQ ID NOS: 19473 to 21982 and is in linkage disequilibrium with the SNP at position 300 with an r2 value of ≥0.7.

Claims 29 to 34

37 Claims 29 to 34 are a new set of dependent claims. They specify a higher r2 value of ≥0.8 for the degree of linkage disequilibrium between the limb (b) SNP and the relevant limb (a) SNP.

FIRST SUB-CATEGORY OF POWER QUESTIONS

38 It is convenient to now address MLA’s contentions that I do not have jurisdiction to entertain the amendment application or power to grant the amendment sought. I am at this point only dealing with the non-s 102 questions.

(a) MLA’s arguments

39 MLA contends that I do not have the jurisdiction to determine the amendment application or power to grant it.

40 It points out that s 154(1) of the Act confers jurisdiction on the Federal Court with respect to “matters arising under this Act”; see s 39B(1A)(c) of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) and s 76(ii) of the Constitution. Section 154(2) specifically gives the Court jurisdiction to hear and determine appeals against decisions or directions of the Commissioner of Patents.

41 MLA says that the “matter” or justiciable controversy in dispute before me on the appeal was whether the unamended 253 Application could proceed to grant in its current form. This was the subject matter of MLA’s appeal under s 60 of the Act.

42 Now in my principal reasons I upheld MLA’s appeal on the grounds of lack of clarity, failure to define the invention and some aspects of lack of utility. I therefore decided that these grounds of opposition were made out to the requisite high standard required in an appeal from an opposition and that the claims in their unamended form could not proceed to grant. MLA says that my decision that the 253 Application could not proceed to grant with the claims in their original unamended form was a final decision, which dealt with all of the issues arising in its appeal from the opposition so far as they were capable of final determination.

43 MLA made reference to R v Smith; Ex parte Mole Engineering Pty Ltd (1981) 147 CLR 340 at 348 and 349. MLA submitted that in Mole Engineering it was decided that a “decision” of the Commissioner that the claims could not proceed to grant in their current form but could be cured by amendment was a “final decision” for the purposes of an appeal. Similarly here, so MLA contends, my decision concerning the unamended claims is a final decision because the Court, exercising judicial power rather than administrative power, in essence stands in the shoes of the Commissioner in an appeal to the Court from a decision of the Commissioner.

44 Now MLA accepts that final orders disposing of its appeal have neither been pronounced nor entered. Nevertheless, it says that no issues that were in dispute in the appeal remain to be determined. It says that these have been decided for the reasons that I published. In this sense, so MLA submits, I have become functus officio except to the extent necessary to permit the performance of my judicial function to ensure that orders are made and entered to reflect my reasons.

45 Now MLA says that its submission does not detract from the proposition that until the decision is “formally completed”, the Court may amend or reverse the decision. In Smith v New South Wales Bar Association (1992) 176 CLR 256 at 265, Brennan, Dawson, Toohey and Gaudron JJ said:

It has long been the common law that a court may review, correct or alter its judgment at any time until its order has been perfected. … The power is discretionary and, although it exists up until the entry of judgment, it is one that is exercised having regard to the public interest in maintaining the finality of litigation. Thus, if reasons for judgment have been given, the power is only exercised if there is some matter calling for review. And there may be more or less reluctance to exercise the power depending on whether there is an avenue of appeal.

(Citations omitted.)

46 But MLA says that it is well-established that the jurisdiction of the Court to reopen a judgment and to grant a rehearing is to be exercised in “extremely rare” circumstances and with “great caution”, having regard to the importance of the public interest in the finality of litigation; see Wentworth v Woollahra Municipal Council (1982) 149 CLR 672 at 684 cited with approval in Autodesk Inc v Dyason (No 2) (1993) 176 CLR 300 at 302.

47 In the present case, MLA says that there is no application by Branhaven to reopen any part of the decision on the appeal. Put another way, Branhaven necessarily accepts that on the basis of my principal reasons, the unamended 253 Application that was before me on the appeal cannot proceed to grant.

48 MLA says that the issues on the appeal having been determined, and there being no matter calling for review with respect to those issues, I have exhausted my functions with respect to the subject matter of the appeal, save that it remains for orders giving effect to my decision to be made in the exercise of my judicial function.

49 Further, MLA says that, importantly, Branhaven did not file any application to amend the claims of the 253 Application under s 105(1A) before final reasons were delivered. Accordingly, no matter arising under the Act with regard to an amendment was before me in these proceedings.

50 MLA stresses that I do not have jurisdiction or power after making a final decision on the issues in dispute to invite Branhaven to amend the claims of the 253 Application nor to decide such an application. It is said that it was not a matter in dispute before me.

51 Now MLA had to accept that in my principal reasons I said that I would not “make any final orders until Branhaven has been given the opportunity to consider whether to apply to amend any of the claims to address the concerns” (at [948]). But MLA says that once it is recognised that the decision on the issues in dispute (at [945] and [947]) was final and conclusive, the fact that orders have not yet been made does not change the position. Only orders consistent with that decision can be made, namely, that the 253 Application not proceed to grant and that costs be awarded against Branhaven.

52 Let me now turn to another dimension of MLA’s argument on this aspect.

53 Now I accept that s 105(1A) is the only potential source of jurisdiction for me to hear and determine an amendment application in the context of an appeal from a decision of the Commissioner concerning opposition proceedings. But MLA contends that properly construed, s 105(1A) does not provide me with such a jurisdiction. To the contrary, MLA says that the text of s 105(1A) itself, and the background to its introduction, support the conclusion that it is not a source of jurisdiction for the Court to hear and determine an amendment application after the Court has determined all of the issues in an appeal from opposition proceedings, and found that the claims of the patent application cannot proceed to grant because they would not be valid.

54 Section 105(1A) provides as follows:

Order for amendment during an appeal

(1A) If an appeal is made to the Federal Court against a decision or direction of the Commissioner in relation to a patent application, the Federal Court may, on the application of the applicant for the patent, by order direct the amendment of the patent request or the complete specification in the manner specified in the order.

55 MLA says that s 105(1A) gives the Court jurisdiction and accordingly power to hear and determine an amendment application during an appeal from an opposition. But it says that the grant of the power to direct amendment of a patent application is conditioned on the current existence of an appeal that has been made to the Court i.e. on an appeal remaining pending. It is said that this also flows from the introductory words “If an appeal is made …”.

56 MLA says that s 105(1A) assumes that the amendment application was made before or during the hearing of the appeal (i.e. within the period when the appeal is made but not decided), with the amendment application heard and determined before or with the appeal itself. Accordingly, so it is said, the Court could refuse to permit the patent application to proceed to grant in any form that would be invalid. Alternatively, so it is said, the Court could permit the unamended application to proceed to grant (if no ground of opposition were upheld to any extent) or otherwise may direct the amendment of the patent application to overcome any ground of opposition and permit the amended application to proceed to grant. MLA says that such an approach would ensure that “all matters in controversy between the parties may be completely and finally determined and all multiplicity of proceedings concerning any of those matters avoided”, consistently with s 22 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth).

57 But MLA says that s 105(1A) does not give the Court power expressly or impliedly to hear and determine an application to amend a patent application, which amendment application is made after the Court has heard and determined all of the issues in the appeal from opposition proceedings. More particularly, s 105(1A) does not contemplate a separate hearing and determination of an amendment application made only after the determination of the appeal. Put another way, MLA says that s 105(1A) only gives jurisdiction to the Court in relation to an amendment application made during (within) the appeal. This may be contrasted with s 154(2), which specifically gives the Court jurisdiction to “hear and determine appeals against decisions or directions of the Commissioner”. MLA says that s 105(1A) is a more narrow and specific grant of power dependent upon the currency of an appeal. Section 105(1A) does not give the Court the power to hear and determine an amendment application independently of the appeal against the decision of the Commissioner under s 60(4) of the Act. Accordingly, MLA says that as I have already heard and decided the appeal, and there being no application to reopen the appeal, s 105(1A) has no work to do. On its argument I simply do not have the jurisdiction to hear and determine Branhaven’s amendment application.

58 Furthermore, MLA says that its construction is consistent with the background to the section. Section 105(1A) was introduced into the Act in 2013 by the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth) (the 2012 Amending Act) specifically to address the situation where amendments were made or proposed to be made to overcome deficiencies identified by the Commissioner after hearing an opposition.

59 MLA says that it is clear from the extrinsic material, which I will discuss later, that s 105(1A) was introduced to deal with the previous situation where the Commissioner found that the claims of a patent application had deficiencies that could be cured by amendment and an application to amend the claims had been made to the Commissioner. In such a case the Court could only deal with an appeal on the unamended specification and did not have the jurisdiction to deal with the amended specification or a proposed amendment to the specification except in a separate appeal against a decision of the Commissioner on the amended claims.

60 Now MLA had to accept that the power conferred by s 105(1A) is not confined to overcoming the deficiencies identified by the Commissioner in the opposition. In particular, it had to accept that s 105(1A) includes the power to amend a patent application to overcome deficiencies identified by the opponent or indeed the Court itself of its own motion during the appeal. This is consistent with one mischief at least which s 105(1A) was intended to fix. But MLA says that s 105(1A) does not provide or encompass a power to amend the 253 Application to overcome my principal decision that the claims would not be valid if granted. MLA says that there is no suggestion in the extrinsic material that s 105(1A) gives the Court the power to consider and decide upon an amendment application made with the purpose of overcoming the Court’s decision that the claims would not be valid if granted. To the contrary, s 105(1A) refers to an amendment application made in the context of an appeal to the Court against a decision or direction of the Commissioner. It does not refer to an amendment application made with the purpose of overcoming an adverse decision of the Court. It says that s 105(1A) can be contrasted with the use of the broader words “in any relevant proceedings in relation to a patent” in s 105(1).

61 Further, MLA says that under the virtue of the construction of s 105(1A) that it extols, s 105(1A) achieves its purpose. When the amendment application is heard and determined with the appeal, the complexity of the appeal process is reduced. Contrastingly, so MLA submits, reading the provision in a way that permits an amendment application to be heard and determined separately from and after the determination of the appeal has the opposite effect. It increases the complexity of the appeal process. It has an effect that is contrary to the statutory purpose.

62 Further, MLA ambitiously asserted that the construction for which Branhaven contends would have the vice of discouraging patent applicants from making an amendment application before or during an appeal, but would rather encourage them to adopt a “wait and see” strategy.

63 Moreover, MLA pushed the envelope even further by saying that if I permit a patent applicant to propose amendments after a final decision, this could lead to the situation where a patent applicant could make applications to amend in perpetuity. It says that, in principle, each time reasons were delivered rejecting a particular set of amendments, a further set of amendments could be proposed. A patent applicant could therefore keep proposing amendments until they were accepted. MLA says that this could not have been the legislative intention in enacting s 105(1A).

64 Further, MLA says that the construction of s 105(1A) for which it contends may be tested in the following way. MLA prays in aid Lord Hoffman’s speech to the House that the “specification is a unilateral document in words of the patentee’s own choosing” and that the “words will usually have been chosen upon skilled advice” (Kirin-Amgen Inc v Hoeschst Marion Roussel Ltd [2005] 1 All ER 667; [2005] RPC 169; (2004) 64 IPR 444; [2004] UKHL 46 at [34]). MLA says that it is up to the applicant to choose the form of the patent application which it propounds, both before the Commissioner and then in any appeal before the Court. MLA says that where issues of potential invalidity by reference to the grounds of opposition have been identified, the patent applicant may seek only to support the unamended specification. Alternatively, the patent applicant may seek to put forward amendments and support those alone, or only if objections are made out. But MLA says that all of this is the patent applicant’s forensic choice which it makes and is required to make before the appeal is decided.

65 MLA says that if issues of invalidity have been identified in the Commissioner’s decision, then the patent applicant is on notice of them. It then must decide what is to be done about them. Alternatively, if the issues of invalidity have been identified for the first time on appeal, whether by the opponent’s grounds of opposition in the Court, or by the Court during the hearing of the appeal, then again the patent applicant is on notice of them. It must then decide what is to be done about them. MLA says that where a patent applicant is on notice of the issues of invalidity, but then stands by and elects to maintain the application in its unamended form instead of seeking amendments either instead of the unamended claims or as a fall back position if objections are made out during the appeal, it cannot later be heard to complain if the decision goes against it.

66 MLA refers to Raleigh Cycle Co Ltd v Miller H & Co Ltd [1951] AC 278 at 291 to 292 where Lord Morton of Henryton said:

in the absence of exceptional circumstances a patentee should not be allowed to amend invalid claims after he has sought to maintain their validity up to this House…

67 Now I would note at this point that this part of Lord Morton’s speech was directed to the question of discretion rather than absence of jurisdiction. And in any event his context is not a relevant analogue. He was dealing with a granted patent and where validity of the original claims had been persisted with right “up to this House”. I am not dealing with either comparable scenario. Moreover, even if I was in an analogous position, no Australian case supports any “exceptional circumstances” threshold, whether under s 105(1) or s 105(1A).

68 More generally, MLA says that the law confines a party to an election that it has made, requires that a party be bound by the conduct of its case and precludes parties in subsequent proceedings from raising causes of action or issues which they could and should have raised in earlier proceedings. MLA says that there is nothing to suggest that the introduction of s 105(1A) was intended to modify this position at general law. In particular, there is nothing to suggest that s 105(1A) was intended to permit a patent applicant to wait until after the determination of an appeal and then apply to amend the patent application in order to overcome the Court’s decision. MLA says that to the contrary, that would involve a radical departure from the position that usually applies to litigants in judicial proceedings.

69 Further, subject to particular exceptions such as statutory provisions permitting the giving of directions to liquidators or receivers or the giving of advice to trustees, MLA says that I ought not give advice to parties in adversarial litigation, but rather I should quell the dispute between them. It says that there is nothing to suggest that s 105(1A) was intended to modify this position. It says that this conclusion is reinforced by s 60(3B), which was also introduced by the 2012 Amending Act. Section 60(3B) provides that “[t]he Commissioner must not refuse an application under this section unless the Commissioner has, where appropriate, given the applicant a reasonable opportunity to amend the relevant specification for the purpose of removing any ground of opposition and the applicant has failed to do so”. But there is no commensurate provision in s 105(1A). But MLA says that this is because it is not needed. It says that patent applicants are subject to the same principles and obligations that apply to all litigants, and a patent applicant should be presumed to act and have acted in the conduct of an appeal to protect its own interests.

70 Now MLA was prepared to entertain the possibility that there may be cases where an issue as to invalidity emerges only during the course of the Court’s consideration of the appeal after hearing but before the delivery of the decision. But it says that this situation is likely to be rare and is not the present case. But in such a case, it says that it may be expected that the Court would bring that issue to the parties’ attention before the determination of the appeal and invite further argument. And if the issue so identified was capable of being overcome by amendment, the patent applicant could then take the opportunity before the appeal was determined to apply for amendment. But MLA says that such a scenario is consistent with its construction of s 105(1A). Moreover, MLA says that if the Court did not bring the issue to the parties’ attention before the delivery of the decision on the appeal such that, on MLA’s construction, the Court would not have the power to entertain an amendment application, then a patent applicant could apply to reopen the appeal. But in such a case the purpose of reopening the appeal (if permitted) would be to permit argument on the issue of invalidity that had not previously been identified and to permit the patent applicant to apply to amend the patent application in accordance with s 105(1A), that is, while the appeal being then reopened on this hypothesis was still on foot. But that is not the present case.

71 Further, for good measure, MLA also threw in the proposition that on the authorities, amendments of granted patents after judgment on validity has been delivered have not been permitted as a matter of procedural fairness.

(b) Analysis

72 Let me first deal with the contention that I am in essence functus officio, to use MLA’s description, because I have made a final decision or determination on MLA’s appeal.

73 First, it should be obvious that I have not yet disposed of MLA’s appeal. No final orders have been made. My principal reasons and the publication thereof are not a judicial act to be characterised as a final decision or determination. Indeed as my principal reasons make clear (see at [15], [944], [946] and [948]), I have refrained from making final orders until any amendment question has been dealt with one way or the other in order to avoid the very consequence for which MLA now contends. No attractive advocacy on Ms Katrina Howard SC’s part can transform my principal reasons into a judicial final order or determination. The reality of the distinction between a court’s reasons for decision on the one hand and the court’s judgment on the other hand is not in doubt. The distinction explains of course why a disappointed litigant can only appeal a judgment (including an order or decree), but not the court’s reasons per se.

74 Second, my jurisdiction to entertain MLA’s appeal was invoked by MLA’s invocation under s 60(4). But at this stage that jurisdiction is still open as I have not formally and finally disposed of MLA’s appeal.

75 Third, in the context of such an appeal and as I have already set out, s 105(1A) provides:

Order for amendment during an appeal

If an appeal is made to the Federal Court against a decision or direction of the Commissioner in relation to a patent application, the Federal Court may, on the application of the applicant for the patent, by order direct the amendment of the patent request or the complete specification in the manner specified in the order.

76 Given that, strictly speaking, MLA’s appeal is still on foot, Branhaven is entitled to make the amendment application and my jurisdiction to entertain that application has been properly invoked. Further, if the heading to s 105(1A) is to be given any weight, the temporal frame of “during an appeal” has not yet terminated.

77 Before dealing with s 105(1A) in detail, let me say something further concerning s 60(4).

78 The nature and scope of the Court’s powers falls to be determined by construing the statutory grant of power in its context and in its historical and constitutional setting. That context now includes ss 105(1A) and 112A, following the passage of the 2012 Amending Act, Sch 3 “Reducing delays in resolution of patent and trade mark applications”, items 6, 7 and 10.

79 In exercising its powers under s 60(4), the Court albeit in the exercise of judicial power is carrying out the same task as the Commissioner and dealing with the same subject matter. The Court stands in the shoes of the Commissioner and exercises the powers and function of the Commissioner to decide the opposition in the context of the appeal before it.

80 In such a context, it is well accepted that in upholding objections to the grant of a patent, the Commissioner in deciding an opposition under s 60(1) should refrain from refusing the application where the objections may be cured by amendment. This is because a decision on an opposition is a final decision only on the issues in the opposition so far as they are capable of final determination at that stage. In Mole Engineering both Mason J (at 349 and 350) and Wilson J (at 355 and 356) referred with approval to passages from:

(a) Richard Fullagar J’s decision in Broken Hill Proprietary Co. Ltd v American CanCo. [1980] VR 143 at 147 that:

the case which the Commissioner is bound by statute ultimately to decide is the opposition proceeding, but I see no reason why the opposition proceeding should not be decided by several decisions provided that each of them can be said in a real sense to decide ‘the case’ as presently constituted so far as that case is at the time susceptible of present decision.

(b) Lloyd-Jacob J’s observations in L Oertling Ltd’s Application for a Patent [1959] RPC 148 at 148 that:

An interim decision, no less than a final decision, conclusively determines the position of the Comptroller-General in relation to such matters as the decision may specify. It is the means whereby the Comptroller notifies the parties of his decision in relation to so much of the dispute as is susceptible of present determination and his decision also as to the manner in which the remaining matters in dispute may be dealt with.

81 Accordingly, although the Commissioner’s decision on an opposition finally determined the issues between the parties on the matters raised in the opposition to that stage subject to any appeal, it did not finally determine the whole opposition if it was appropriate to afford the patent applicant an opportunity to amend. If the patent applicant did not seek to amend, refusal of the application could follow.

82 Now prior to the 2012 Amending Act, the powers of the Court on an appeal from an opposition were arguably more limited than the powers of the Commissioner. One perceived consequence of New England Biolabs Inc v F Hoffman-La Roche AG (2004) 141 FCR 1 at [22] to [50] was that the Court was limited to considering the specification in the form before the Commissioner when deciding the opposition. Unsatisfactorily, this meant that any application to amend the patent application to address objections upheld in the opposition on appeal had to be remitted to the Commissioner to be dealt with.

83 Unsurprisingly, the legislature considered that such a consequence led to inefficiency and unnecessary duplication. Accordingly, s 105(1A) was introduced into the Act by the 2012 Amending Act.

84 The amendment of the Act to include ss 105(1A) and 112A expanded the powers of the Court to deal with the controversy fully and finally. The explanatory memorandum explained (see explanatory memorandum, Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Bill 2011 (Cth), p 76) in relation to the proposed schedule 3 amendments:

Item 6: Patent opposition – amendments directed by the court

[s 105]

This item amends the Patents Act to provide that a court may consider and decide on amendments to a patent application during an appeal from a decision of the Commissioner.

Currently, during an appeal from a decision of the Commissioner the Court must confine itself to the same subject matter as considered by the Commissioner [New England Biolabs Inc v F Hoffman-La Roche AG (2004) 141 FCR 1]. This means that where an applicant has amended their specification subsequent to the Commissioner’s decision, the Court cannot consider the amended specification, even where the amendments may overcome the grounds on which the decision is being appealed.

This adds complexity to the appeals process and to resolution of opposed patent applications.

The item addresses this problem by giving a court power to consider and decide upon any amendments proposed by the applicant while an appeal is on foot. These amendments would be considered under the existing provisions under which courts may direct amendments [Section 105].

The provision applies only to amendment of patent applications, not to amendment of granted patents.

Existing section 105 applies to amendment of patents. It is expected that in exercising their discretion under new subsection 105(1A), the courts will give account to the different factors that are relevant to applications, in contrast to those applying to patents.

(Emphasis added.)

85 This amendment followed from a consultation process undertaken during 2009. It is worth elaborating on that process as the Commissioner’s counsel helpfully did before me as it elucidates in part the genesis of the proposed changes.

86 In June 2009, IP Australia published a consultation paper (Resolving patent opposition proceedings faster: Towards a stronger and more efficient IP rights system, consultation paper, June 2009). In section 3.12 at [92] to [97] the following was stated:

3.12 Amendments directed by the courts

Decisions of the Commissioner in relation to a patent opposition are appellable to the Federal Court of Australia, as are some other decisions of the Commissioner. The Federal Court is able to affirm, reverse or vary the Commissioner’s decision.

After a successful or partly successful opposition, the Commissioner sometimes gives a patent applicant an opportunity to amend the application. For example, even if the application does not validly claim a patentable invention, it might be possible to craft valid claims on the basis of what has been disclosed in the application.

There are two problems relating to appeals of decisions of the Commissioner, principally related to how amendments are dealt with under such appeals, which are of concern to IP Australia.

The first problem is as follows. When an applicant proposes such amendments, there has been some doubt whether the Federal Court is able to consider the appeal on the basis of the amended specification, or whether it has to consider the form of the specification that was considered by the Commissioner, prior to the amendments. Recent case law indicates that the Court is restricted to the latter. This gives rise to inefficiencies in determining appeals of decisions of the Commissioner, and can protract a final resolution of the matter. It would be more practical and efficient if the Court was able to consider an amended specification – the fact that an applicant has proposed amendments indicates a lack of interest on the applicant’s part in pursuing the specification in its form prior to amendment.

The second problem is as follows. There has been conflicting case law in relation to whether the Court is able to direct that a patent application be amended during an appeal. Giving the Court such a power would streamline the appeals process, and would effectively mean that the court could consider the entire appeal, without referring the matter back to IP Australia to consider amendments. This would be similar to the court’s existing power to direct amendment of a patent, and would permit appeals to be dealt with in a less costly and more expeditious manner.

To address this, IP Australia proposes the following changes:

3.12 Proposed change

• The Federal Court would be given the power to direct amendment of an application for a patent, at the request of the patent applicant, during an appeal of a decision of the Commissioner.

• On an appeal of the Commissioner’s decision, the Federal Court would be able to consider any amendments that may have been proposed or made to a specification or patent request since the Commissioner’s decision.

• The Commissioner would not be able to deal with a request for amendment to an application for a patent while an appeal of the Commissioner’s decision in relation to the application is pending before the Federal Court. Any such amendments would have to proceed before the court under its proposed new power.

87 IP Australia received submissions responding to such suggested changes.

88 In November 2009, IP Australia published a further consultation paper (Towards a Stronger and More Efficient IP Rights System, consultation paper, November 2009). In section 3.12 at [112] to [116], referring back to its June proposal, it said the following:

Proposal 3.12 proposed changes to the way the Federal Court deals with amendments to an application which is the subject of an appeal against a decision of the Commissioner. The proposed changes were that:

• the Court would be given the power to direct amendment

• the Court would be able to consider amendments made to the application following the Commissioner’s decision; and

• the Commissioner would not be able to deal with amendments to an application while an appeal of the Commissioner is under appeal.

These changes were intended to clarify and streamline processes in relation to amendments made during an appeal of a decision of the Commissioner.

Submissions generally agreed with the proposals. However one submission disagreed with the proposal that applicants would be unable to prosecute amendments before the Commissioner while the decision of the Commissioner is on appeal.

IP Australia acknowledges that the inability to prosecute amendments before the Commissioner may cause additional costs for parties. However, amendments prosecuted before the Commissioner may be opposed, leading to concurrent proceedings and unnecessary delays. Accordingly, IP Australia considers it better that amendments to applications on appeal from a decision of the Commissioner be dealt with through the Courts. This is analogous to the existing provisions for amendments to granted patents that are subject to court proceedings. IP Australia considers that this could be achieved by amendment of s 105 to include amendments to applications.

It is intended that all amendments to applications on appeal from a decision of the Commissioner be processed through the Court. To this end, a further change is proposed that sets out that a complete specification relating to an application must not be amended, except under s 105, while relevant proceedings in relation to the application are pending. A similar provision presently exists under s 112 for granted patents.

89 As is apparent, the provision which became s 112A was proposed to reinforce and ensure the objective sought to be achieved by the proposed amendment inserting s 105(1A) into the Act.

90 To that end, the explanatory memorandum explained in relation to s 112A:

Item 10: Patent opposition – decisions on appeal

[s 112A]

This item inserts a new provision, section 112A.

This item is consequential upon item 6 above, which gives a court the discretion to consider and decide on amendments to a patent application during an appeal from a decision of the Commissioner.

The item specifies that only the Court can deal with amendments to an application during an appeal to the Court against a decision of the Commissioner relating to that application. This is similar to an existing prohibition, where there are court proceedings in respect of a granted patent [s 112]. The intention is to avoid having the same issues dealt with by different decision makers.

91 In the present case the Court is exercising judicial power for the first time in the controversy between the parties, rather than executive or administrative power. But there is nothing which causes the nature of the task to change.

92 The fact that the Court has decided the issues in the opposition in the context of the appeal as presently constituted before it does not mean that the Court is functus officio. Consistently with the introduction into the Act of ss 105(1A) and 112A, the Court, standing in the shoes of the Commissioner and undertaking the Commissioner’s task of deciding the opposition, has power to consider an application to amend in an appropriate case.

93 The decision from which the appeal to this Court was brought was, as reflected in Meat & Livestock Australia Limited and Anor v Cargill, Inc. and Anor [2016] APO 26 at 2 that:

The opposition succeeds to the extent that claim 13 lacks clarity.

I allow the applicant two months from the date of this decision to propose amendments.

I award costs according to Schedule 8 against the opponent, Meat & Livestock Australia Limited and Dairy Australia Limited.

94 Accordingly, the decision under appeal did not finally resolve all issues between the parties. Subject to any appeal, it decided the opposition only as far as then constituted and afforded the patent applicant an opportunity to amend.

95 Correspondingly and subject to any further appeal, my principal reasons decided the issues in dispute between the parties in the appeal as then constituted. However, my principal reasons contemplated that Branhaven would be given an opportunity to seek to amend, subject to further ruling on the allowability of any proposed amendments.

96 It is a long-established practice in Australian patent law that if the Commissioner or the Court upholds objections to the grant of a patent, the decision-maker will refrain from refusing the application in circumstances where it appears that the objections may be cured by amendment.

97 Mason J acknowledged this practice in Mole Engineering in the context of analogous provisions of the Patents Act 1952 (Cth) as follows (at 348 and 349):

It is a natural consequence of the procedures under Pt V and Pt VIII that an officer who upholds objections to the grant of an application under Pt V will refrain from refusing the application where it appears that the objections may be cured by amendment. Then it is a practical and sensible course to allow the applicant time within which to lodge a request to amend the specification, as Mr Kildea did in this instance. But his decision was nonetheless a final decision on the original unamended application – there was nothing provisional or tentative about the finding on the grounds of objection. It dealt with all the issues arising on the notice of opposition so far as they were capable of final determination.

(Emphasis added.)

98 Contrary to MLA’s contention, the principle to be distilled from this passage and Mole Engineering generally is not that a final decision on an original unamended patent application closes off any opportunity for the patent applicant to amend. Rather the point is that such a decision finally decides all questions of validity arising on the grounds of opposition so far as they are capable of final determination by reference to the form of the patent application as it then stands. It follows that it is not open to the parties and relevantly the opponent to seek to reargue such questions of validity at a later stage by reference to any amended form of the patent application. But such a decision leaves open the prospect that the deficiencies found to exist in the patent application might be addressed by amendment.

99 Indeed, Moshinsky J said in Merial Inc v Intervet International BV (No 4) (2017) 124 IPR 1 at [10] to [25], particularly at [25(d)]:

Where the Commissioner or the Court upholds objections to the grant of a patent, the decision-maker will “refrain from refusing the application where it appears that the objections may be cured by amendment”, such as by the narrowing of the claims set out in the specification: Mole Engineering.

(Emphasis added.)

100 Now the case before me is not like that which was before Moshinsky J, where his Honour declined to grant the applicant an opportunity to amend for the reasons outlined by him at [35] to [36]. His Honour held inter-alia that the applicant was not entitled to the patent by reason of the fact that it did not derive title from the inventor. This was an issue that went to the heart of the patent application and was not capable of being overcome by an appropriate amendment. His Honour considered that the issue of the applicant’s title to the invention had been dealt with generally and finally at the hearing.

101 But the case before me is rather a case of the kind described by Moshinsky J “where grounds of opposition have succeeded in establishing that the specification as it stands is deficient, but the decision-maker (whether it be the Commissioner of Patents or the Court on appeal) decides that the deficiency can be cured by amendments to the specification” (at [34]). I will return to the nature of the power later, whether discretionary or not, and whether the power should be exercised in the case before me.

102 Let me deal with a number of other points.

103 First, s 105(1A) contains no limitation as to the point in time during an appeal at which an amendment application can be made or determined or the relevant amendment power exercised, providing of course that the appeal remains on foot and has not yet been finally disposed of. In such a context, the question of the timing only has relevance to the exercise of the amendment power, not its existence. For completeness and as I have said, the word “during” in the heading to s 105(1A) encompasses any time prior to final disposition of the appeal.

104 Second, any amendment power under s 105(1A) is clearly not confined to addressing adverse findings made by the Commissioner. On its face, s 105(1A) can extend to permitting amendments to address adverse findings by me. And indeed, if I am in essence standing in the shoes of the Commissioner, there would be little reason in logic to distinguish between the two scenarios. Moreover, it is a non-sequitur to argue that because s 105(1A) refers to “an appeal…against a decision or direction of the Commissioner…” that the amendment power is confined to addressing adverse findings of the Commissioner. These words refer to the nature of the appeal itself rather than to confine the scope of the amendment power.

105 Third, if the second point is good, namely that amendments can be made under s 105(1A) to address adverse findings of the Court, where would one find such adverse findings? Why, of course, the Court’s reasons, as in the present case. This demonstrates in another way how flimsy MLA’s arguments are concerning what it describes as functus officio, estoppel etc.

106 Fourth, MLA’s contentions lead to a bizarre result. MLA says that I have no power to make any amendment. Moreover, it says that I have no power to remit the amendment application to the Commissioner; I will discuss this in a moment. Yet if the amendment application had been made in opposition proceedings before the Commissioner, she would have had power to deal with it. But on appeal I am supposed to be standing in the shoes of the Commissioner. So, on the logic of MLA’s argument, I am standing in the shoes of the Commissioner but cannot do the very thing that she could do if the matter were still before her. And even more bizarrely, not even she can now do it. I cannot remit. And if I make final orders at MLA’s insistence that the 253 Application not proceed to grant, there would be no patent application left on foot to amend. MLA’s contentions all lead to a perverse outcome and a significant lacuna in the legislative scheme. This is also a further reason to reject its contention that I have no power to now deal with the amendment application.

107 Fifth, MLA’s approach arguably puts patent applicants in a difficult position. Where an opponent adopts a “kitchen sink” approach and raises numerous grounds of opposition and amends its notice of appeal several times in the course of doing so, a patent applicant would be forced to take the irreversible step of amending its claims prior to the evidence on which those grounds were based being tested at the hearing and prior to the grounds being considered by the Court on the merits. The alternative course would be to abandon any opportunity to amend. This could, in effect, give the opponent a victory on grounds that might ultimately have had little merit, without them being actually determined by the Court. Such a consequence would discourage patent applicants from relying on legitimate and reasonably arguable defences to grounds of opposition, for fear of being found to be wrong and losing the patent application entirely. Moreover, an amendment is generally speaking irreversible, in that once the claims have been narrowed it is not possible to broaden them again. But perhaps the answer to this is that the patent applicant could make a contingent amendment application during the running of the appeal and as a fall back position.

108 Sixth, and contrary to MLA’s submission, I do not consider that CRI026 v Republic of Nauru (2018) 355 ALR 216 at [60] and [63] assists its position. A question in CRI026 concerned the effect of a “corrigendum” to correct a textual error in a tribunal’s reasons. Their Honours said (albeit obiter) at [60]:

where a discretionary power reposed by statute in a decision maker is, upon proper construction, of such a character that it is not exercisable from time to time but rather is spent upon publishing a decision, the decision maker is prevented from later resiling from the decision because the power to do so is spent and the proposed second decision would be ultra vires. … as a general rule, once an administrative tribunal have reached a final decision in respect of a matter before them in accordance with their enabling statute, the decision cannot be revisited because the tribunal have made an error within jurisdiction. ... in such a case, the principle of functus officio applies on policy grounds favouring the finality of proceedings as opposed to the rules of procedure which apply to formal judgments of courts whose decisions are subject to a full appeal. But it is apparent that those observations were directed to the possibility of a statutory tribunal making substantive changes to a decision as the result of a change of mind, substantive error within jurisdiction or subsequent change of circumstances.

(Citations omitted.)

109 But these principles do not deprive me of power to hear the amendment application. Putting to one side that this is a proceeding in the Court, rather than before the Commissioner as an administrative decision maker, I am not being asked to make substantive changes to the conclusions I have already reached in relation to the construction and clarity of the unamended claims. Rather, I am being asked to consider the allowability of amendments consequent upon my earlier findings. In doing so, I am engaging in a separate exercise of power under s 105(1A), rather than re-exercising any spent power.

110 Moreover, as I have already indicated, Mole Engineering does not deny my power to deal with the amendment application. The point in that case was that the matters decided in the hearing of the opposition as then constituted were finally decided and could not be revisited. But the amendment application in the present case does not seek to reopen matters already decided, but to address them on the foundation that they are correct.

111 Seventh, MLA’s federal matter argument may be rejected. The “matter” is the controversy enlivened by the appeal which has not been finally disposed of, the controversy as to whether amendments are allowable, or both.

112 Eighth, MLA’s construction argument that s 105(1A) ought not to be construed so as to allow a radical departure from “common law principles” such as election or estoppel go nowhere. Such questions are adequately dealt with on the question of the exercise of the power, whether discretionary or not, rather than on the question of the existence of the power.

113 Ninth, MLA says that the words “in any relevant proceedings” in s 105(1) give the Court broad powers to amend a patent, including after a decision by the Court that the patent is not valid. By contrast, the opening words of s 105(1A) restrict the power to hearing and determining an amendment application in an appeal from the Commissioner, not after the appeal has been finally decided. If that were intended to be the case, the Act would also have used the words “in any relevant proceedings” in s 105(1A). Now accepting all this to be so, so what? The appeal has not been finally disposed of.

114 Tenth, MLA’s suggestion that one could contingently apply to amend during the hearing of the appeal or before its commencement as a fall back position also has difficulties. It seems to assume that there are only two realistic possibilities for the form of the claim sets: the unamended claim set or an amended claim set that Branhaven might reasonably anticipate was appropriate as a fall back position. But this is unduly narrow. There may be numerous realistic possibilities that could be chosen for the amended claim set as a fall back position. How is Branhaven to know which to choose in advance? And is it seriously suggested that it should put forward multiple contingent amended claim sets as numerous alternative fall back positions to cover itself, such that I would have to deal with all multiple possible alternatives in the one judgment on the appeal and on the amendment application? After all, the hypothesis here is based on MLA’s foundation that I can only deal with the amendment application and appeal together, or that at least I cannot deal with the amendment application after I have ruled in substance on the original claim set. It seems to me that MLA’s position has an air of unreality to it. The Commissioner is empowered to deal with amendments after giving a ruling on the substance of opposition proceedings. I do not see why s 105(1A) should be construed so as to deny me a similar power particularly as in substance I am standing in the shoes of the Commissioner, providing that I have made no final orders on the appeal. Symmetry of context supports symmetry of power, providing that the text of s 105(1A) in context so permits. Of course I accept that the Commissioner can entertain an amendment application at any time, whereas I am circumscribed by s 105(1A). But as I say, the timeframe under s 105(1A) has not yet been exhausted.

115 In my view, whether a patent applicant ought to bring forward amendments during or prior to the hearing of an appeal, as opposed to bringing forward amendments to address objections upheld by a judge after he has addressed them in his reasons, does not go to the existence of power under s 105(1A) but rather whether it should be exercised.

116 Let me deal with one final topic. I have considered whether I could and should remit the amendment application to the Commissioner. But I have decided that I have no power to do so. And even if I did, I do not consider this to be appropriate. Let me explain my reasons.

117 First, the Commissioner has power to deal with the amendment of a patent application pursuant to s 104. But this is subject to s 112A, which precludes the Commissioner from doing so where a relevant appeal to the Court remains on foot. As I have explained, s 112A was introduced into the Act at the same time as s 105(1A), which gave the Court the power to deal with amendments in the course of such an appeal. The statutory scheme as it presently exists thus encourages and requires that amendments in this context will be dealt with by the Court.

118 Second, as Branhaven points out, there have been cases where the Court has suspended its consideration of an appeal such as the present in order to allow the patent applicant the opportunity to amend by way of an application to the Commissioner under s 104. But such cases were prior to the introduction of ss 105(1A) and 112A. Given the latter provision, that practice is no longer possible while such an appeal remains on foot. And in the present case, strictly the appeal before me remains on foot.

119 Third, I raised the question as to whether the Court could finally determine an appeal, and in doing so remit the matter to the Commissioner in order to allow the patent applicant the opportunity to amend. Now the Court’s powers in an appeal, aside from the express power to amend under s 105(1A), are set out in s 160. These include the power to “(d) affirm, reverse or vary the Commissioner’s decision or direction” and “(e) give any judgment, or make any order, that, in all the circumstances, it thinks fit”. But there is no express power to remit the matter to the Commissioner, although it may be that this is encompassed by the broadly stated power to make any order in s 160(e). But in any event, the statutory scheme in its current form, including ss 105(1A) and 112A, evinces an intention that amendments in this context will be dealt with by me.