Mylan Health Pty Ltd (formerly BGP Products Pty Ltd) v Sun Pharma ANZ Pty Ltd (formerly Ranbaxy Australia Pty Ltd) [2019] FCA 28

ORDERS

(FORMERLY BGP PRODUCTS PTY LTD) First Applicant BGP PRODUCTS OPERATIONS GMBH Second Applicant | ||

AND: | (FORMERLY RANBAXY AUSTRALIA PTY LTD) First Respondent ALKERMES PHARMA IRELAND LIMITED Second Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | (FORMERLY RANBAXY AUSTRALIA PTY LTD) Cross-Claimant | |

AND: | (FORMERLY BGP PRODUCTS PTY LTD) First Cross-Respondent BGP PRODUCTS OPERATIONS GMBH Second Cross-Respondent ALKERMES PHARMA IRELAND LIMITED Third Cross-Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Claims 1, 5, 6, 7, 10, 11 and 12 of Australian Patent No. 2006313711 be revoked.

2. Claims 12 and 13 of Australian Patent No. 731964 be revoked.

3. Claims 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 11, 12, 18, 19, 20, 21, 23, 24, ,26, 27, 31, 32, 36, 37, 38, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 47, 49, 50, 56, 57, 58, 59, 61, 62, 64, 65, 69, 70, 74, 75, 76, 78, 79, 80 of Australian Patent No. 2003301807 be revoked.

4. The second further amended originating application be dismissed.

5. The Confidential Schedule to the attached reasons for judgment not be published or disclosed to any person apart from the solicitors and counsel for the parties without the agreement of the first respondent or the leave of the Court.

6. Within 14 days, the parties file and serve (by way of exchange) brief written submissions (limited to 3 pages in length) on questions of costs.

7. Within 21 days, the parties file and serve (by way of exchange) brief written submissions in reply (limited to 2 pages in length) on questions of costs.

8. Order 5 made on 4 May 2016 be discharged.

9. Upon the applicants, by their counsel, undertaking to the Court during the period of the stay:

A. to prosecute any appeal expeditiously; and

B. forthwith to serve on the Commissioner of Patents copies of these orders pursuant to s 140 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) with a request that particulars of Orders 1, 2 and 3 (“the Revocation Orders”) be registered in accordance with s 187 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth),

the Revocation Orders be stayed:

(a) initially for a period of 21 days from today; and

(b) if an appeal from any of the Revocation Orders is lodged within that period, until the final determination of that appeal or further order.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

NICHOLAS J:

Introduction

1 In this proceeding, the applicants seek injunctive relief restraining the first respondent from infringing certain claims of three patents. The three patents (“the Patents”) are:

Australian Patent No. 2006313711, a method of treatment patent titled “Use of fenofibrate or a derivative thereof for preventing diabetic retinopathy” (“the 711 Patent”). The asserted priority date for the 711 Patent is 10 November 2005. The second applicant owns, and the first applicant is the exclusive licensee of, the 711 Patent.

Australian Patent No. 731964, a formulation patent titled “Pharmaceutical composition of fenofibrate with high biological availability and method for preparing same” (“the 964 Patent”). The asserted priority date for the 964 Patent is 17 January 1997. The second applicant owns, and the first applicant is the exclusive licensee of, the 964 Patent.

Australian Patent No. 2003301807, a formulation patent titled “Nanoparticulate fibrate formulations” (“the 807 Patent”). The asserted priority date for the 807 Patent is 24 May 2002. The second applicant and the second respondent co-own the 807 Patent.

2 The first respondent proposes to market in Australia a number of fenofibrate products that were entered in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (“ARTG”) on about 29 February 2016, specifically 45 mg and 145 mg fenofibrate film coated tablets presented in a bottle or in a blister pack under the brand names FENOFIBRATE RBX, FENOFIBRATE SUN and FENOFIBRATE RAN. These products are collectively called “the Ranbaxy Products” in the pleadings and evidence and I will adopt that nomenclature in these reasons. The second respondent is a co-owner of the 807 Patent but has not taken any active role in the proceeding. For ease of reference, I will refer to the first respondent as the respondent.

3 The respondent denies that it will infringe any of the claims upon which it is sued (the relevant claims) by importing into Australia or supplying in Australia, any of the Ranbaxy Products. It also challenges the validity of the relevant claims and seeks orders for their revocation on various grounds. It does not dispute any of the asserted priority dates.

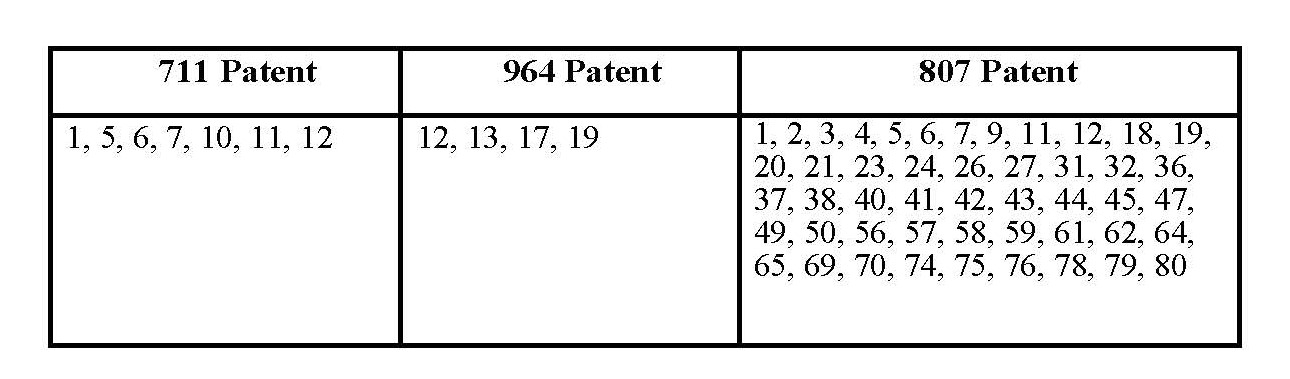

4 The relevant claims are:

5 An order was previously made that the question of infringement of the 807 Patent insofar as it requires certain experimental evidence to be adduced be deferred until after the determination of all other issues of liability in the proceeding. That experimental evidence relates to the following integers:

(a) whether the composition exhibits bioequivalence upon administration to a human subject in a fed state as compared to a fasted state, by reference to AUC and Cmax, which is a requirement of claims 1, 2, 3, 40, 41 and 42 (and their dependent claims);

(b) whether the difference in AUC of the composition administered in a fed versus fasted state is less than about 35% or lower, which is a requirement of claim 7 (and its dependent claims); and

(c) whether the composition redisperses in a biorelevant media, which is a requirement of claims 1, 2, 3, 40, 41 and 42 (and their dependent claims).

6 The respondent has made a number of admissions relevant to the applicants’ infringement case concerning the manufacturing process and specifications relevant to the production of the Ranbaxy Products. These admissions form the basis of the brief description of the respondent’s manufacturing process that is set out in the Confidential Schedule that forms part of these reasons.

The witnesses

7 There was a considerable body of evidence adduced by both parties. Most of the oral evidence was given in concurrent sessions. The only exceptions to this were Professor Elam and Mr Butler who were cross-examined separately.

8 The witnesses called by the applicants were:

Professor Michael Stephen Roberts

9 Professor Roberts is a NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellow, a Professor of Therapeutics and Pharmaceutical Science at the University of South Australia and a Professor of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics at the University of Queensland. He is also the Director of the Therapeutics Research Centre at the Princess Alexandra Hospital in Brisbane. Professor Roberts has been a Professor since 1989 and a NHMRC Research Fellow since 1994.

10 After obtaining a Bachelor of Pharmacy in 1970, Professor Roberts practiced as a pharmacist and completed a Master of Science and Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Sydney. He then worked as a lecturer and academic at the University of Tasmania and the University of Otago.

11 Between 1978 and 1984, he worked on a project at the University of Tasmania to develop a slow release oral dosage form of aspirin which could be used in the prevention of stroke and heart attacks. From 1986 to 1989, as Head of the Department of Pharmacy at the University of Otago, Professor Roberts conducted various research projects for pharmaceutical companies, including overseeing research studies relating to the examination of bioavailability and bioequivalence of oral dosage in human volunteers. He has also been involved in the creation, development and testing of fast release oral dosage forms.

12 Professor Roberts is a named co-inventor of several patents. He has written many peer-reviewed articles, including in relation to oral delivery, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, toxicology, and drug formulation.

Professor Clive Allan Prestidge

13 Professor Prestidge is a Professor of Pharmaceutical Science at the University of South Australia. He has degrees in Chemistry and Pharmaceutical Science and has worked in a variety of academic and research roles since completing his PhD in 1990. Since 1994, Professor Prestidge has led a research group at the University of South Australia whose primary focus is nano-structured drug delivery systems and interfacial science applied to pharmaceutical formulation and delivery.

14 Professor Prestidge’s research projects before May 2002 involved using nanomaterials, either as a drug or excipient. This included research on particle-based suspensions and colloidal (nano-particle-based) drug delivery, and use of laser diffraction and laser light scattering measurement techniques.

15 Professor Prestidge has published widely in relation to nanostructured pharmaceutical delivery systems, pharmaceutical characterisation, biointerfacial processes and lipid particle based drug delivery. He is a named inventor of several patents.

Professor Richard Charles O’Brien

16 Professor O’Brien is an endocrinologist and the clinical Dean of Medicine of the Austin Clinical School at the University of Melbourne. He has a special interest in lipid disorders and diabetes, and describes himself as a clinical lipidologist. He is Director of the Lipid Services at Austin Health. His degrees include a Doctor of Philosophy from the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Melbourne awarded in 1992 for a thesis entitled “Diabetic nephropathy: early pathophysiology and therapeutic intervention.” He has held numerous clinical positions since 1982 and various academic positions at Monash University and the University of Melbourne before becoming clinical Dean of Medicine in 2007.

17 Professor O’Brien was the Head, and later the Director, of the Diabetes Section of Monash Medical Centre (1992 to 2004), the Director of Lipid Services and Deputy-Director of Diabetes at Southern Health (2005 to 2007), the Chair of the Lipid Management in Diabetes Guidelines Committee of the NHMRC (2010 to 2012) and the Chair of the Expert Committee on Hyperlipidaemia for the Australian Diabetes Society (since 2010). He has authored or co-authored articles and texts concerning the management of dyslipidaemia and treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes.

18 In addition to his academic and clinical duties, Professor O’Brien has been a member of advisory boards associated with a number of pharmaceutical companies, including, since 2007, the first applicant (then known as BGP Products Pty Ltd) in relation to the interpretation of trial data and educational material relating to fenofibrate.

Feras Karem

19 Mr Feras Karem is the Managing Director of Pharmacy 4 Less Pty Ltd which operates 45 pharmacy stores around Australia. Mr Karem holds a Bachelor of Pharmacy and a Master of Business Administration. Mr Karem gave evidence in respect of the practice of filling prescriptions and dispensing medicine to patients. Mr Karem was not cross-examined.

Professor Ronald Paul Mitchell

20 Professor Mitchell is the Professor of Clinical Ophthalmology & Eye Health at the University of Sydney and an ophthalmologist at the Westmead Hospital where he is the director of its Ophthalmology Department. His clinical practice involves management of age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy and other vascular retinopathies. Professor Mitchell has practiced as an ophthalmologist for over 25 years.

21 Professor Mitchell obtained a Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (with Honours) from the University of New South Wales in 1975 and a Doctor of Medicine from the University of New South Wales in 1981. His post-doctoral program involved investigation into diabetic retinopathy and was conducted in conjunction with another ophthalmologist, Dr Paul Beaumont.

22 Since 1978, Professor Mitchell has held a number of academic and leadership positions in the field of ophthalmology, including membership of the Retinopathy Sub-Committee of the Australian Diabetes Society (1985 to 2004), a board member and, later chairman, of the Ophthalmic Research Institute of Australia (1993 to 2001) and chairman of the Information and Data Sub-Committee of the Visual Impairment Prevention Program for NSW Health (1999 to 2002). He has authored or co-authored over 1,000 publications, including in respect of the pathology, management and treatment of diabetic retinopathy.

23 Professor Mitchell was the principal author of the Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Diabetic Retinopathy published by the National Health and Medical Research Council in June 1997 (the 1997 NHMRC Guidelines) and the subsequent version of those guidelines published in 2008. Professor Mitchell also assisted in the development of the protocol for the “Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes Study (“the Field Study”) and in the conduct of that study as an investigator. He later co-authored an article reporting on this study entitled “Effect of fenofibrate on the need for laser treatment for diabetic retinopathy (Field Study): a randomised controlled trial” that was published in The Lancet in November 2007.

24 The witnesses called by the respondent were:

Dr Paul Ernest Beaumont AM

25 Dr Beaumont is a consultant ophthalmologist at the Retinal & Vitreous Centre in Sydney. He obtained a Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery from the University of New South Wales in 1967.

26 During the period from approximately 1970 to 1974, Dr Beaumont worked as an Honorary Ophthalmology Registrar, and subsequently, an Ophthalmology Registrar and a Senior Ophthalmology Registrar, at the Prince of Wales Hospital in Randwick. While at the Prince of Wales Hospital, he trained under the late Professor Frederick (Fred) Hollows AC and carried out research into the causes and treatment of diabetic retinopathy. Before moving to private practice in 1976, Dr Beaumont worked under Professor Hollows as an Honorary Neuro-Ophthalmologist at the Prince Henry Hospital and Prince of Wales Hospital.

27 Since 1976, he has been engaged in private practice as an ophthalmologist specialising in medical retinal disease and, in particular, the treatment of diabetic retinopathy, retinal venous occlusion and macular degeneration. Dr Beaumont estimates that, as at November 2005, approximately 40% of the patients he treated had diabetic retinopathy.

28 Dr Beaumont later served as chairman of the NSW branch of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologist (2001 to 2003), chairman and director of the Macular Degeneration Foundation (2001 to 2013), vice-president of the Diabetic Association of New South Wales (1974 to 1975) and chairman and director of the Eye and Vision Research Institute (1978 to 2011). Dr Beaumont has authored or co-authored several publications in peer-reviewed academic journals.

29 In 2013, Dr Beaumont received the award of Member of the Order of Australia “for significant service to medicine, particularly in the field of ophthalmology”.

Christopher Butler

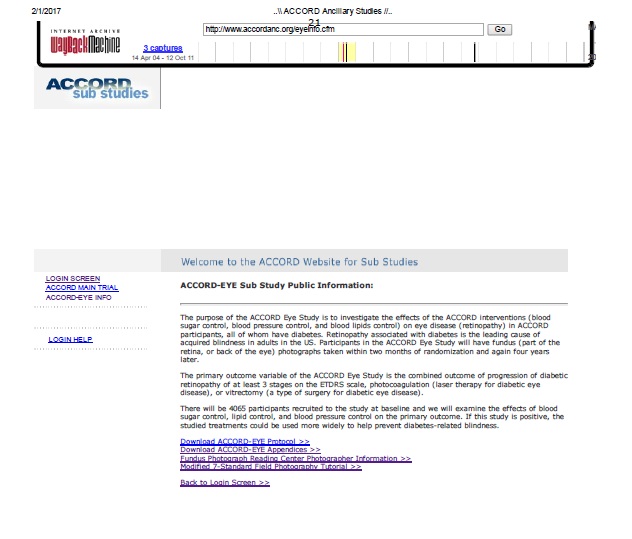

30 Mr Christopher Butler is the Office Manager of Internet Archive in San Francisco, California. Mr Butler was called by the respondent and gave evidence in relation to the working of the Internet Archive Wayback Machine (“the Wayback Machine”).

Leilani Epifanio Au

31 Ms Au is a Deputy Managing Editor at MIMS Australia Pty Limited (MIMS Australia) and has been in this role since around October 2016. Ms Au holds a Bachelor of Science (Pharmacy) degree and became a registered pharmacist in the Philippines in 1997. Ms Au gave evidence about works published by MIMS Australia or its predecessors. Ms Au was not cross-examined.

Ngaire Pettit-Young

32 Ms Pettit-Young is the Managing Director of Information First Pty Ltd. Ms Pettit-Young holds a Bachelor of Arts and a Graduate Diploma of Information Management and has worked as a research and reference librarian for over 20 years. Ms Pettit-Young was not cross-examined.

Ben Teeger

33 Mr Teeger is a solicitor employed by Ashurst Australia and gave evidence in relation to searches he conducted using the Wayback Machine for historical versions of the Accord Website. Mr Teeger was not cross-examined.

Professor John Norman Carter AO

34 Professor Carter is a consultant endocrinologist with particular expertise in the diagnosis and management of diabetes. He is a Clinical Professor of Medicine at Sydney Medical School, University of Sydney and Consultant Emeritus (Endocrinology) for the New South Wales Ministry of Health’s Northern Sydney Local Health District Network.

35 Professor Carter was awarded his first degree in medicine (BSc (Med)) from the University of Sydney in 1967 followed by degrees (MB, BS) from the University of Sydney in 1969. Between 1973 and 1975 he was a Clinical Fellow in Endocrinology and a National Health and Medical Research Council (“NHMRC”) Research Fellow at the Garvan Institute at St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney.

36 After completing a postgraduate fellowship in Canada, Professor Carter returned to Australia in 1977 and was appointed inaugural Director of the Endocrine Unit at the Repatriation General Hospital based in Concord where he worked until 1983. Between 1983 and 2013 he was a Senior Visiting Medical Officer (“VMO”) (Endocrinology) at Hornsby Ku-ring-gai Hospital and the Sydney Adventist Hospital.

37 Professor Carter has been a member of the Australian Diabetes Society since 1974, an Honorary Life Member since 2009, and has also served as a Councillor and President of that organisation. Since 1993 he has also been a member of the Endocrine Society of Australia which is a non-profit association of scientists and clinicians who conduct research or practice in the field of endocrinology.

38 Between 1992 and 1994 Professor Carter was a member of the NHMRC’s Expert Panel in Diabetes. Between 1992 and 1993 he was also Chairman of the National Action Plan Management Group responsible for finalising the National Action Plan for the prevention and control for non-insulin dependent diabetes in Australia (“NAP”). From 1993 to 1997, he was Chairman of the Diabetes National Action Plan Implementation Committee (DNAPIC), which was responsible for implementing recommendations contained in the NAP.

39 In 1996, the Commonwealth Government established the Ministerial Advisory Committee on Diabetes (MACOD), which reported to the then Commonwealth Minister for Health and Family Services, the Honourable Dr Michael Wooldridge MP. Professor Carter was appointed as the Chairman of the MACOD by the Minister, a position he held from 1996 to 2000.

40 In the course of his duties as Chairman of the MACOD, Professor Carter commissioned the “National Diabetes Strategy and Implementation Plan” (NDSIP). The purpose of the NDSIP was to guide the allocation of government funding relating to improvements in diabetes care and prevention, as well as to suggest structural and functional reorganisation to ensure equitable access to effective, efficient and economically viable diabetes services for all Australians. In 1998, the Commonwealth Government established the National Diabetes Taskforce (NDT) to oversee the implementation of the NDSIP. Professor Carter was a member of the NDT from 1998 to 2002 and its successor, National Diabetes Strategy Group (NDSG). From 2002 to 2006, he was a member of the NDSG.

41 In 2000, Professor Carter received the award of Officer of the Order of Australia “for service to medicine, particularly through research and policy development on diabetes, and through endocrinology”.

Dr Louisa King

42 Dr King is the Principal of and a Patent and Design Searcher at King Search Pty Limited. Dr King holds a Bachelor of Science (organic chemistry) degree and was awarded a Doctor of Philopshy on 1992. Dr King’s doctoral research was in the field of organic chemistry. Dr King was not cross-examined.

Associate Professor David Alexander Vodden Morton

43 Mr Morton is an Associate Professor of Pharmaceutical Science at Monash University. He obtained a Bachelor of Science (Chemistry) in 1986 from the University of Bristol and a PhD in Chemistry from the same university in 1990. Mr Morton immigrated to Australia in 2007.

44 Before May 2002, Mr Morton worked at the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority, the Centre for Drug Formulation Studies (CDFS) at the University of Bath and Ventura Ltd. As part of his responsibilities at CDFS and Ventura Ltd, Mr Morton worked on projects involving formulations and the application of particle size to drug delivery systems for pharmaceutical companies.

Dr Desmond Berry Williams

45 Dr Williams is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Pharmacy and Medical Sciences at the University of South Australia. He graduated with a Bachelor of Pharmacy from the South Australian Institute of Technology in 1975 and was awarded a Master of Science in 1981 and Doctor of Philosophy in 1983 from the University of Kansas.

46 In 1983, Dr Williams joined the Research and Development Division of F H Faulding & Co Ltd (“Faulding”) as a Development Pharmacist based in Adelaide. He was promoted to the position of Clinical Research Manager of the Research and Development division of Faulding in 1985. At Faulding, Dr Williams worked on improving bioavailability of new and existing pharmacological compounds and controlled release dosage formulations. In 1996, Dr Williams took up a position as Group Manager of Research and Development at Sigma Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd where he worked on new formulations of existing drug products in various dosage forms, including oral (tablets and capsules), parenteral products, lotions and creams.

47 Dr Williams joined the University of South Australia as a Senior Lecturer in 1999. During his tenure at the University of South Australia, a focus of Dr Williams’ research was on biopharmaceutics and pharmacokinetics, drug product formulation design and product assessment.

Professor Marshall Elam III

48 Professor Elam III is the Chief of the Division of Clinical Pharmacology in the Departments of Pharmacology, Preventative Medicine and Medicine (Cardiovascular Diseases) at the University of Tennessee Health Science Centre in Memphis, Tennessee.

49 Professor Elam has a Bachelor of Science (Biology) cum laude, a Doctor of Philosophy (Pharmacology) and a Doctor of Medicine. Professor Elam has been licensed to practice medicine in the State of Tennessee since 1979 and in 1985 was licensed to practice as a specialist in the field of cardiology.

Andrew Rankine

50 Dr Rankine is a partner at Ashurst Australia. Dr Rankine was not cross-examined.

The 711 Patent

The common general knowledge

51 The matters referred to in this section of my reasons form part of the common general knowledge in the field of the invention described in the 711 Patent as at 10 November 2005.

Diabetes mellitus

52 Diabetes mellitus (“diabetes”) is an endocrine (or hormonal) disorder characterised by an absolute or relative deficiency of insulin. Insulin is a hormone produced in the endocrine part of the pancreas, which is responsible for regulating glucose metabolism in the body.

53 Diabetes is a common disorder in Australia, with more than 7% of the population over 25 years of age suffering from it. The incidence of diabetes increases with age and, in Australia, over 20% of people aged over 75 suffer from it. The condition remains undiagnosed in a large proportion of people who suffer from diabetes in Australia.

54 Patients with diabetes are at risk of developing a wide variety of acute and long-term complications including macrovascular complications, such as coronary artery disease (leading to heart attack), cerebrovascular disease (leading to strokes), peripheral vascular disease (leading to infection or gangrene), microvascular complications, including diabetic retinopathy (eye disease), diabetic nephropathy (kidney disease) and diabetic neuropathy (nerve damage).

Type 1 Diabetes

55 Type 1 diabetes is the less common of the two forms of diabetes, accounting for around 10% to 15% of cases in Western countries such as Australia. Type 1 diabetes is most often diagnosed in children and young adults (although it can present at any stage of life). In patients affected by type 1 diabetes, there is a progressive destruction of the cells (known as “islet cells”) in the pancreas that are responsible for insulin synthesis and release. Generally speaking, by the time that insulin deficiency becomes clinically apparent, the islet cells in patients affected by type 1 diabetes have typically lost at least 90% of their insulin-producing capacity. Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune condition.

56 People affected by type 1 diabetes may present with a range of symptoms and signs, including fatigue, increased thirst (polydipsia), increased urine production (polyuria), weight loss, increased appetite and dehydration. In some cases, people affected by type 1 diabetes may develop life-threatening acute complications, such as the metabolic disturbance known as diabetic ketoacidosis.

Type 2 Diabetes

57 Type 2 diabetes is the more common form of diabetes in Western countries, including Australia, and accounts for around 85% of cases in Western countries. Patients affected by type 2 diabetes suffer from insulin resistance, whereby insulin is less efficient in transporting glucose from the blood stream into cells.

58 In order to exert its normal biological actions, insulin must initially attach to specific insulin receptors on surface membranes of cells. In people affected by insulin resistance (including people with type 2 diabetes), there is typically a reduction in the number of insulin receptors and, in addition, a reduction in the attraction (or affinity) between the insulin and its receptors.

59 In the initial stages of type 2 diabetes, the body responds to insulin resistance by increasing the production of insulin from the islet cells in the pancreas, leading to an increase in the levels of insulin circulating in the blood (hyperinsulinaemia). In this early stage of type 2 diabetes, blood glucose levels typically remain within the normal range, but as the disease progresses, due to both insulin resistance becoming more severe and the islet cells becoming less able to maintain increased levels of insulin production, blood glucose levels rise. Over the longer term, insulin production typically declines to such an extent that insulin deficiency develops and insulin therapy is required to normalise blood glucose levels.

Dyslipidaemia

60 Dyslipidaemia is a condition caused by abnormal levels of the following lipids (fats) in the body:

(a) cholesterol, which is insoluble in blood and exists as one of the following complexes in the body:

(i) very low density lipoprotein cholesterol (“VLDL-C”);

(ii) low density lipoprotein cholesterol (“LDL-C”);

(iii) high density lipoprotein cholesterol (“HDL-C”); and

(b) triglycerides.

61 VLDL-C is the form in which cholesterol is secreted from the liver, where most cholesterol is made. As VLDL-C enters the bloodstream it is converted into LDL-C, which transports the cholesterol around the body. HDL-C is often referred to as the “good” cholesterol, because it transports cholesterol present in the body back to the liver, to remove it from circulation. A patient's total cholesterol levels refer to the sum of their LDL-C, VLDL-C and HDL-C levels (ie. the sum of all lipoproteins that are complexed with cholesterol). Triglycerides are another type of lipoprotein principally used for energy. A large proportion of dietary fat is transported around the body in the form of triglycerides.

62 A patient is described as having dyslipidaemia (abnormal lipid levels) or hyperlipidaemia (elevated lipid levels) if they have:

(a) elevated LDL-C levels;

(b) elevated triglyceride levels; and/or

(c) low HDL-C levels.

63 Since around the mid-1990s a class of drugs called statins have been the primary drug treatment for patients with elevated total cholesterol and LDL-C levels. For patients with elevated triglyceride levels, and/or low HDL-C levels, another class of drugs called fibrates were a primary drug treatment. Professor Carter estimated that as many as 25% of his patients were being treated with fenofibrates for lipid control as at November 2015 which I am satisfied would be fairly typical for that time. One of these, fenofibrate, became available in Australia in late 2004. Lipidil, in which fenofibrate is the active ingredient, was first described in the 29th Edition of the MIMS Annual dated June 2005 (“MIMS”). According to MIMS at p 2-181:

During clinical trials with fenofibrate, total cholesterol was reduced by 20 to 25%, triglycerides by 40 to 50%; and HDL cholesterol was increased by 10 to 30%.

Diabetic retinopathy

64 Retinopathy is “disease of the retina” whether or not it is associated with diabetes. Diabetic retinopathy is a long-term complication associated with diabetes that affects a patient's eyes. It is a complication related to increasing changes to the blood vessels in the retina.

65 The first stage of the development of retinopathy in a patient is called non-proliferative retinopathy. This is characterised by lesions in the form of microaneurysms (macular swelling across the course of a retinal capillary), and then haemorrhages (which may indicate blood vessel leakage), in the retina. Both of these types of lesions occur in the capillary bed of the retina. Other lesions characteristic of retinopathy include:

(a) hard exudates (lipid material deposited in the retina from the blood stream);

(b) cotton wool spots (small areas of infarcted retina, which is retina that has lost its blood supply); and

(c) vessel calibre changes (particularly involving the veins, which become dilated).

These early signs of retinopathy generally do not affect vision unless the macula is affected, especially where the non-proliferative retinopathy involves only a few of the lesions characteristic of retinopathy.

66 Non-proliferative retinopathy can progress to proliferative retinopathy, which is vision threatening. In this stage of retinopathy, new blood vessels develop from the retinal veins or from vessels at the optic disc. These have a propensity to bleed (haemorrhage) into the vitreous of the eye. Following haemorrhage, fibrous tissue can develop at the site of the new vessels, which can then lead to traction on the retina and retinal detachment. The vitreous haemorrhage can itself black out vision and lead to severe vision loss.

67 Another condition called macular oedema can occur at any stage of non-proliferative or proliferative retinopathy. This is caused when capillaries (small blood vessels) in the retina close to the macula become occluded (closed or non-perfused), such that there is reduced flow through these capillaries. In response, adjacent capillaries start to leak fluid (oedema) into the retina. The macula is structured so that all of the supporting cells are aligned to give a maximum light signal to the cones at the base of the macula, which means that it can accumulate fluid easily, leading to swelling and damage to the macula.

68 Because of its importance in providing sharp vision, the macula is critical to vision function. Macular oedema is the most frequent cause of vision loss in people with diabetic retinopathy. However, oedema can also occur at other parts of the retina, away from the macula. This generally does not need to be treated unless it threatens the macula.

69 In addition to the damage caused by swelling as a result of oedema or macular oedema, the leakage of fluid from the bloodstream into the retina can result in the formation of small deposits of lipid and other materials in the retina. These small deposits are called ‘hard exudates’. Hard exudates can form at any stage of diabetic retinopathy, as a result of fluid leakage from the retinal capillary bed. Hard exudates tend to occur in the outer part of the retina and, in most patients, close to or involving the macula. Hard exudate deposition is damaging when it occurs at the macula because it can cause irreversible structural changes to the macula within a period of months. If present for a long period, it will result in permanent vision loss.

Risk factors for diabetic retinopathy

70 The longer a patient has had diabetes, the more likely it is that diabetic retinopathy will develop, particularly if the patient’s blood glucose levels have been persistently elevated. Persistently elevated (poorly controlled) blood glucose levels, also known as hyperglycaemia, is the primary risk factor for diabetic retinopathy.

Detection and treatment of diabetic retinopathy

71 The person conducting the diabetic retinopathy screening will be looking for signs of the early stages of retinopathy, typically microaneurysms or haemorrhages, which look like red dots in the retina. It is the pattern and symmetry of these signs in both eyes that indicates the presence of diabetic retinopathy, because such signs in isolation in one eye could result from, for example, elevated blood pressure or other conditions.

72 In general, screening for diabetic retinopathy should be conducted for all people with diabetes at least every two years. Once retinopathy is detected in a patient, the patient needs to be reviewed, generally by an ophthalmologist, on a regular basis to assess the progress of the condition, including whether there are any signs of the development of vision threatening retinopathy, usually proliferative retinopathy or macular oedema, which would require treatment. Where the diabetic retinopathy in a patient has progressed to proliferative retinopathy or macular oedema, treatment is required. As at November 2005, the main treatment options for preventing the progression of vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy, once it was detected in a patient, were the following:

(a) Laser treatment: Laser treatment kills off areas of ischemia (loss of capillary bed, which is a network of capillaries) in the retina, and areas where the blood supply has been compromised. The laser treatment causes the new blood vessels to regress and stop bleeding, which is the main complication of proliferative retinopathy.

(b) Pan-retinal photocoagulation: This is widespread laser treatment of the peripheral retina, used for proliferative retinopathy. In this condition, the peripheral retina becomes ischemic (loss of capillary bed). Pan-retinal photocoagulation to these ischemic areas leads to regression of the new blood vessels, reducing the risk of bleeding.

(c) Steroid injection: Injection of steroids into the eye can reduce the swelling associated with macular oedema. However, this treatment option has a number of side effects and, in 2005, was used much less frequently than laser treatment.

(d) Vitrectomy: Proliferative diabetic retinopathy can cause traction on the retina or the macula, which may lead to retinal detachment and blindness. Vitrectomy is a surgical operation whereby the vitreous of the eye is removed from the patient's eye, and any tractional bands are cut and/or removed.

73 These four treatment options are intended to reduce the rate of progression of diabetic retinopathy or macular oedema, and to reduce progressive visual loss, in patients with proliferative retinopathy or macular oedema. As a result of the findings from the “Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study” (“the ETDRS”), it was recommended that laser treatment around the macula be used to clear hard exudates threatening or beginning to involve the macula. Laser treatment does not have a direct effect on hard exudates. Rather, the laser treatment reduces fluid leakage as a result of oedema or macular oedema and thus stops the further deposition of hard exudates. The body can then naturally clear the existing hard exudates from the macula.

The specification

74 The specification is said to relate to the use of fenofibrate as a derivative thereof for the treatment of retinopathy.

75 The specification states at page 1 line 7 to page 2 line 5:

Diabetes is a disorder in which the body is unable to metabolize carbohydrates (e.g., food starches, sugars, cellulose) properly. The disease is characterized by excessive amounts of sugar in the blood (hyperglycemia) and urine, inadequate production and/or utilization of insulin, and by thirst, hunger, and loss of weight. Diabetes affects about 2% of the population. Of these 10-15% are insulin dependant (type 1) diabetics and the remainder are non-insulin dependant (type 2) diabetics.

Diabetic retinopathy represents one of the most debilitating microvascular complications of diabetes. Diabetic retinopathy is a specific microvascular complication of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. After 20 years of diabetes nearly all patients with type 1 diabetes and over 60% of patients with type 2 diabetes have some degree of retinopathy. Additionally, retinopathy develops earlier and is more severe in diabetics with elevated systolic blood pressure levels. On average, a careful eye examination reveals mild retinal abnormalities about seven years after the onset of diabetes, but the damage that threatens vision usually does not occur until much later. It can lead to blindness in its final stage. It is the second leading cause of acquired blindness in developed countries, after macular degeneration of the aged. The risk of a diabetic patient becoming blind is estimated to be 25 times greater than that of the general population. At present there is no preventive or curative pharmacological treatment for this complication. The only treatment is laser retinal photocoagulation or vitrectomy in the most severe cases.

Diabetic retinopathy is a progressive diabetic complication. It advances from a stage referred to as “simple” or initial (background retinopathy) to a final stage referred to as “proliferative retinopathy” in which there is formation of fragile retinal neovessels, leading to severe hemorrhages, sometimes with detachment of the retina, and to loss of vision. The microvascular lesions in simple retinopathy are characterized by microaneurysms, small petechial hemorrhages, exudates and venous dilations. This simple retinopathy form can remain clinically silent for a long period of time. At this simple retinopathy stage cellular and structural deterioration of the retinal capillary can be observed in the postmortem examinations of retinas from diabetic patients, compared to the retinas from normal subjects of comparable age. If proliferative retinopathy is left untreated, about half of those who have it will become blind within five years, compared to just 5% of those who receive treatment.

76 There follows a discussion in relation to the treatment of diabetic retinopathy including laser treatment of pre-proliferative retinopathy, severe pre-proliferative or proliferative retinopathy.

77 The specification states at page 2 lines 25-33:

Preventing the development or progression of diabetic retinopathy has the potential to save vision at a relatively low cost compared to the costs associated with a loss of vision. Thus, it is an object of the present invention to provide further means which contribute to the prevention of the development or progression of diabetic retinopathy.

The present invention is based on the discovery that patients taking fenofibrate or a derivative thereof need fewer treatment [sic] by retinal laser therapy than placebo-allocated patients. The results obtained from a large clinical trial demonstrate the favourable effect of fenofibrate in the prevention of retinopathy.

78 Then follows a consistory statement that mirrors the language of claim 1. A number of terms are then defined. “Prevention” is defined as “preventing the development or progression of diabetic retinopathy.” The specification then states at page 3 lines 3-5:

According to the present invention, “diabetic retinopathy” is defined as severe non proliferative grade of diabetic retinopathy, proliferative grades of diabetic retinopathy, macular edema and hard exsudates [sic].

79 The expert evidence established that “non-proliferative” and “proliferative” stages of diabetic retinopathy are mutually exclusive in the sense that a patient cannot have both non-proliferative and proliferative retinopathy at the same time. In the circumstances, I consider that the skilled addressee would understand the definition of diabetic retinopathy to encompass any one or more of the various conditions referred to in the definition in a patient suffering from diabetes. This is how I interpret the definition of diabetic retinopathy as used in the claims.

80 The specification then refers to the association between type 2 diabetes and high cardiovascular risk and the fact that very few trials of lipid-lowering therapy have focused on type 2 diabetes. There is then a discussion of two previous studies trialling the use of fibrate therapy. The specification states at page 8 lines 8-11:

Both studies were limited to people with prior myocardial infarction (MI) and have reported reductions in major cardiovascular events among participants with low HDL and high triglyceride (TG) at baseline, which were greater than those seen with use of the same fibrate among those without dyslipidaemia.

81 There is then a reference to a third study which showed reduced progression of coronary artery disease in type 2 diabetes compared with placebo.

82 The specification then refers to what is known as the Field Study. The specification states at page 8 lines 21-29:

As fibrates are known to correct the typical dyslipidaemia of diabetes, their role in cardiovascular risk reduction in diabetes may be especially important. A study called Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes (FIELD) has been carried out which study is a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trail evaluating the effects on coronary morbidity and mortality of longterm treatment with fenofibrate to elevate high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels and lower triglyceride (TG) levels in patients with type 2 diabetes and total blood cholesterol between 3 and 6.5 mmol/L (115 and 250 mg/dL) at study entry.

83 The specification then proceeds to discuss the significance of elevated low-density lipoprotein (“LDL”) cholesterol and triglycerides (“TG”) levels in patients with type 2 diabetes. The specification states at page 9 lines 3-35:

Blood total cholesterol levels are not substantially different between patients with type 2 diabetes and those of nondiabetic populations of similar age and sex. However, evaluation of other lipoprotein fractions shows that those with diabetes more often have a below-average HDL cholesterol level and elevation of TG levels in the blood which together confer an independent additionnal [sic] risk of CHD. Furthermore, although low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels are not substantially raised, the HDL particle is often smaller and denser than in similar nondiabetic populations, which is considered to be a more atherogenic state. An increased number of LDL particles, as seen in diabetes, is reflected in an elevated level of plasma apolipoprotein B, a more powerful predictor of risk for cardiovascular events than either total cholesterol or LDL cholesterol.

The strength of cholesterol-CHD relationship is very similar for those with type 2 diabetes as for nondiabetics, although at a higher background rate of CHD. Evidence from Helsinki Heart Study, which tested long-term fibrate (gemfibrozil) use in hypercholesterolaemic men and women without prior coronary disease, showed a significant reduction in coronary events, with the reduction among the small numbers of people with diabetes not being separately significant but appearing somewhat greater. The reductions in events observed were greater than would have been expected on the basis of lowering of LDL cholesterol alone. So, whether substantially increasing low HDL cholesterol levels and reducing elevated triglyceride levels independently reduces cardiovascular events and mortality and should be a specific target for therapy remains less well agreed.

For patients with type 2 diabetes and its typical dyslipidaemia, many physicians believe that fibrates are the logical first choice of drug treatment. The fibrates have been in clinical use for a long time, being well tolerated and with few short-term side -effects. Fenofibrate has been widely used and marketed for more than 20 years and is an effective agent for reducing plasma triglyceride and raising HDL cholesterol. Although the effects on lipid fractions may vary with the population under study, a fall of 15 % or more in total cholesterol, mediated through a reduction in LDL cholesterol, is often seen with long-term use. In parallel, HDL cholesterol elevation of 10-15 % is common, together with large reductions in plasma triglycerides of 30-40 %. In addition, a reduction in plasma fibrinogen of about 15 % has been observed.

84 This is followed by a detailed discussion of the Field Study which is said to have been designed to provide the first properly randomized evidence as to whether fenofibrate confers a benefit on clinical cardiovascular events in persons with type 2 diabetes. The principal study outcome was said to be the combined incidence of first nonfatal MI or CHD death among all randomized patients. Various secondary outcomes are then described including the effect of fenofibrate on major cardiovascular events and mortality. There follows a brief discussion of what are referred to as tertiary outcomes which are said to include at page 11 lines 12-15:

… the effects of treatment on development of vascular and neuropathic amputations, nonfatal cancers, the progression of renal disease, laser treatment for diabetic retinopathy, hospitalization for angina pectoris, and numbers and duration of all hospital admissions.

85 The specification includes a table (Table 1) describing the baseline characteristics of the 6051 subjects who participated in the study.

86 The specification then refers to the results for what is described as the tertiary outcome related to the laser treatment for diabetic retinopathy. These are said to show that more placebo-allocated patients (253 or 5.2%) than fenofibrate-allocated patients (178 or 3.6%) required one or more laser treatments for retinopathy. The specification states at page 14 lines 23-27:

These results provide the first evidence of the favourable effect of fenofibrate on the need for retinal laser therapy. As the patients taking fenofibrate had fewer treatment by retinal laser therapy than the placebo-allocated patients, the prevention and treatment of retinopathy by fenofibrate has been clearly demonstrated.

The claims

87 The relevant claims of the 711 Patent are for:

1. Use of fenofibrate or a derivative thereof for the manufacture of a medicament for the prevention and/or treatment of retinopathy, in particular diabetic retinopathy.

…

5. Use according to any of claims 1 to 4, wherein said medicament contains 200 mg, 160 mg, 145 mg or 130 mg of fenofibrate or a derivative thereof.

6. Use according to any of claims 1 to 5, wherein said medicament is an oral formulation of fenofibrate or a derivative thereof.

7. A method for the prevention and/or treatment of retinopathy, the method comprising administration of fenofibrate or a derivative thereof to a patient in need thereof.

…

10. The method according to any one of claims 7 to 9 wherein said method further comprises administration of a statin.

11. The method according to any one of claims 7 to 10 wherein 200 mg, 160 mg, 145 mg or 130 mg of fenofibrate or a derivative thereof is administered.

12. The method according to any one of claims 7 to 11 wherein the fenofibrate or derivative thereof is administered in an oral formulation.

88 Claims 1, 5 and 6 are a Swiss-style claim.

89 Claims 5 and 6 of the 711 Patent are dependent on claim 1. It is not disputed by the respondent that if claim 1 is infringed, claims 5 and 6 will also be infringed.

90 Claims 7 and 10-12 are method of treatment claims. It is not disputed by the respondent that if claim 7 is infringed, each of claims 10-12 will also be infringed.

Infringement

91 The applicants contend that the respondent threatens to directly infringe claims 1, 5 and 6 of the 711 Patent (the Swiss-style claims), and to indirectly infringe claims 7 and 10-12 of the 711 Patent (the method of treatment claims) pursuant to s 117(1) when read with s 117(2)(b) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (“the Act”). The applicants do not rely on s 117(2)(c) of the Act for the 711 Patent.

Swiss-style claims

92 Swiss-style claims were considered by Yates J in Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co Ltd v Generic Health Pty Ltd (No 4) (2015) 113 IPR 191 (“Otsuka”) at [100]-[121]. As his Honour explained, such claims are appropriately characterised as claims to a method or process for the manufacture of a known medicament where the novelty of the claim arises from the therapeutic use to which the medicament is applied.

93 It is useful to first consider the respondent’s submission that a Swiss-style claim cannot be infringed by importation and supply in the patent area of a medicament that is manufactured outside the patent area. The submission is based on a legal argument as to the proper interpretation of the word exploit as defined for the purposes of the Act. I do not accept the submission for the reasons stated in the judgment in Apotex Pty Ltd v Warner-Lambert Company LLC (No 2) (2016) 122 IPR 17 (“Apotex No 2”) at [296] – [298] and, on appeal, Warner-Lambert Company LLC v Apotex Pty Limited (No 2) (2018) 129 IPR 205 at [167] – [168] (“Warner-Lambert No 2”).

94 However, it does not follow that the applicants have established that the Swiss-style claims will be infringed. In order to decide whether such a finding is justified, it is necessary to say a little more about the requirements of a Swiss-style claim.

95 In Warner Lambert Company LLC v Generics (UK) Ltd [2018] UKSC 56, the United Kingdom Supreme Court accepted that a Swiss-style claim for a second medical use of a drug (pregablin) was “purpose limited” in the sense that the monopoly claimed is a monopoly for the preparation or manufacture of a medicament for the designated purpose, namely, the treatment of a particular medical condition.

96 One of the principal issues that was considered by the Supreme Court (even though it was strictly not necessary to decide the point for the purpose of disposing of the appeal) was the proper construction of Swiss-style claims, especially those involving second medical uses. At the hearing of the appeal before the Supreme Court, the parties conceded that, as a matter of construction, a Swiss-style claim required a “mental element” in the sense that the manufacturer must have manufactured the relevant medicament with the intention that it would be used to treat the medical condition designated in the claim. The judgments given make clear that all members of the Supreme Court considered that this concession was rightly made. The crux of the debate before their Lordships was whether the mental element involved an objective or a subjective intention. The majority held that, properly construed, a Swiss-style claim requires that the manufacturer who makes the relevant medicament do so with the objective intention that it be used to treat the medical condition designated in the claim.

97 Lord Sumption referred to the distinction between subjective intention and objective intention which he described as “legally fundamental”. His Lordship said at [72]:

…Subjective intention is a state of mind, ascertained as a matter of fact. A person may subjectively intend X if, for whatever reason, he deliberately does an act which is liable to bring X about, desiring it to happen. The degree of probability of X occurring may be relevant to the question whether it should be inferred as a fact that such a desire existed, but that is a question of proof and not of principle. Objective intention by comparison is not so much a matter of fact as an artificial construct for attributing legal responsibility. A person is taken to intend the ordinary and natural consequences of his acts. He objectively intends those consequences if they were foreseeable to a reasonable person, whether or not they were actually foreseen by him. Policy considerations may determine the degree of probability with which the consequence must be foreseeable if legal responsibility is to be attributed on that basis.

98 For reasons which will become apparent, it is not necessary to decide in the present case whether the Swiss-style claims are concerned with the objective or the subjective intention of the manufacturer. However, it seems to me that the reasons given by those of their Lordships who favoured the “objective intention” are particularly persuasive, especially in so far as they highlight the difficulties that may be involved in ascertaining the subjective intention of a manufacturer, an intention that may or may not be carried into effect, and about which distributors, pharmacists, medical practitioners and patients often will have little or no knowledge.

99 The applicants submitted that a Swiss-style claim will be infringed if the manufacturer has prepared the relevant medicament knowing that it is suitable for use in the treatment of the condition designated in the claim. On their analysis, the manufacturer’s intention is irrelevant to the question of infringement. In support of their submission the applicants referred to the following passage in the judgment of Yates J in Otsuka at [172]:

For the purpose of determining infringement of a Swiss type claim, does it matter that the alleged infringer does not actually advertise or promote the medicament specifically for the therapeutic use defined in the claim? I do not think it necessarily does. The question is whether, objectively ascertained, the medicament that results from the claimed method or process is one that has the therapeutic use defined in the claim. The question is not really about how the alleged infringer markets its product, although, plainly, its conduct in that regard may well assist in determining, objectively, whether the accused product has the claimed therapeutic use.

100 The principal point that was considered by Yates J in Otsuka concerned the question of whether a Swiss-style claim should be characterised as a process or method claim (a matter of importance given the statutory definition of exploit) rather than the true scope of the purpose limiting requirement of a Swiss-style claim. In fact, it does not appear from my reading of his Honour’s judgment that any party addressed the latter issue. The particular observation relied upon by the applicants (in the last sentence of the quoted paragraph) while directed to the question of suitability for a particular therapeutic use, does not indicate that a Swiss-style claim imposes no requirement as to the purpose or intention of the manufacturer. In my view that aspect of Swiss-style claims was not a matter that was addressed by his Honour.

101 Suitability for use cannot be determinative of the question of infringement of a Swiss-style claim. If it were, it would render a person liable for infringement who manufactured a medicament for the purpose of using it to treat an indication which it had been used to treat before the priority date of the Swiss-style claim merely because the medicament might also be used for the purpose of treating a second indication that provided the novelty-conferring subject matter of the claim. If the applicants’ submission is correct, there would be an infringement even if the manufacturer took steps to ensure that the product was not used to treat the designated condition, and had no reason to believe that it would be so used. I do not think there is any doubt that this would be an absurd result, and contrary to the policy behind modern patent legislation.

102 The crucial question is whether the manufacturer has made (or will make) the relevant medicament with the intention that it be used in the treatment of the designated condition. In my view, the answer to that question is to be ascertained objectively in light of all the relevant facts and circumstances including, in particular, the approved product information (“PI”) for the product, any product labelling, and the nature, size and other pertinent characteristics of the market into which the product is to be sold.

103 Of course, it is for the applicants to establish that the manufacturer has made (or will make) the relevant medicament with the objective intention that it be used to treat the condition designated in the Swiss-style claims. The fact that it may be reasonably foreseeable or even likely that a substantial portion of the product manufactured will be used to treat that condition is certainly not determinative at least not where the product is also used extensively in the treatment of other non-designated conditions.

104 The Ranbaxy Products were originally approved for the same indications as the applicants’ fenofibrate product marketed under the name Lipidil. In particular, the Ranbaxy Products were indicated “for the reduction in the progression of diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes and existing diabetic retinopathy”. This was recorded in the PI for the Ranbaxy Products, as was supporting clinical trial information for that indication. However, the PI for the Ranbaxy Products has since been amended to remove any reference to diabetic retinopathy. According to the amended PI, fenofibrate is indicated as an adjunct to diet in the treatment of hypercholesterolaemia, various types of dyslipidaemia, and dyslipidaemia associated with type 2 diabetes.

105 The applicants referred to the following three matters in support of their infringement case:

(a) the amended PI for the Ranbaxy Products asserts that the Ranbaxy Products are bioequivalent to Lipidil;

(b) the PI for Lipidil expressly states that Lipidl is indicated for the reduction in the progression of diabetic retinopathy and includes details of the FIELD and ACCORD trials relevant to that indication; and

(c) the PI for the Ranbaxy Products does not assert that the Ranbaxy Products are not indicated for diabetic retinopathy or that it is somehow not relevantly bioequivalent for that purpose.

106 The applicants submitted that these matters demonstrated that there is a sound medical basis for considering that the Ranbaxy Products are suitable to be administered for the therapeutic use designated in each of the Swiss-style claims. Although I accept this submission, for the reasons I have stated it is not to the point, and does not provide a sufficient basis for finding that any of the Swiss-style claims have been, or will be, infringed by the respondent. Further, the three matters to which the applicants referred do not indicate that the Ranbaxy Products have been, or will be, made for the purpose of being used for the prevention or treatment of diabetic retinopathy. In my view the evidence does not support a finding that the Ranbaxy products will be manufactured with the intention that they be used for the prevention or treatment of diabetic retinopathy. The infringement case based on the Swiss-style claims must fail.

Method of treatment claims

107 Section 117 of the Act provides:

117 Infringement by supply of products

(1) If the use of a product by a person would infringe a patent, the supply of that product by one person to another is an infringement of the patent by the supplier unless the supplier is the patentee or licensee of the patent.

(2) A reference in subsection (1) to the use of a product by a person is a reference to:

(a) if the product is capable of only one reasonable use, having regard to its nature or design—that use; or

(b) if the product is not a staple commercial product—any use of the product, if the supplier had reason to believe that the person would put it to that use; or

(c) in any case—the use of the product in accordance with any instructions for the use of the product, or any inducement to use the product, given to the person by the supplier or contained in an advertisement published by or with the authority of the supplier.

108 It is not necessary for a patentee to succeed under s 117 that he or she identify any particular person or persons who the supplier has reason to believe will use the product in question in an infringing manner: AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd (2014) 226 FCR 324 (“AstraZeneca FC”) at [433].

109 Section 117(2)(b) proceeds on the basis that a product (not being a staple commercial product), may be capable of various uses, some of which would infringe the claims of the patent in suit, and others that would not. The respondent did not contend that fenofibrate is a staple commercial product for the purposes of s 117(2)(b).

110 In Apotex Pty Ltd v Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty Ltd (2013) 253 CLR 284 Crennan and Kiefel JJ construed the method of treatment claim in the patent in suit in that case as limited to use of the relevant method for a specific purpose. Their Honours said at [289] that “[c]laim 1 is recognisably a claim limited to the specific purpose of preventing and treating psoriasis.” Hayne J adopted an analysis similar to that of the Full Court in Apotex Pty Ltd v Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) (2012) 204 FCR 494, where Keane CJ said at [37]:

The claim is for a method of treatment of a human ailment. That method necessarily presupposes a deliberate exercise of diagnosis and prescription by a medical practitioner. The treatment or prevention of psoriasis by the use of the claimed method presupposes a diagnosis of psoriasis and the consequent prescription of the application of leflunomide. That this is so is hardly controversial: as is apparent from all the potential constructions of the patent advanced by the parties, the claim in the patent involves the application of leflunomide by a medical practitioner.

111 The applicants accept that claim 7 and its dependent claims are properly construed as claims that require the deliberate exercise of diagnosis and prescription by a medical practitioner (based on sound medical evidence) of fenofibrate (or a derivative thereof) for the purpose of preventing or treating diabetic retinopathy.

112 The applicants submitted that if the respondent had reason to believe that a medical practitioner would, based on sound medical evidence, diagnose and prescribe the Ranbaxy Products for the purpose of preventing or treating diabetic retinopathy then any supply of the Ranbaxy Products by the respondent is an infringement of the relevant method of treatment claims.

113 In support of its contention that the respondent has the necessary reason to believe, the applicants relied upon the same three matters to which I previously referred in the context of the Swiss-style claims.

114 The evidence does not permit me to draw any precise conclusions as to the extent to which fenofibrate is currently prescribed by medical practitioners in order to treat diabetic retinopathy. The applicants submitted that about 50% of the time that fenofibrate is currently prescribed, it is prescribed solely for the purpose of treating diabetic retinopathy. The evidence relied upon by the applicants in support of that submission is mostly anecdotal and not very persuasive. In any event, the submission indicates that, on the applicants’ own case, in about 50% of the cases in which fenofibrate is prescribed, it is prescribed either to manage the patient’s lipid levels or to manage lipid levels and to prevent or treat diabetic retinopathy.

115 I think it likely that fenofibrate is mostly prescribed for the purpose of managing a patient’s lipid levels in circumstances where the medical practitioner either wishes merely to manage lipid levels or both manage lipid levels and reduce the development or the progression of diabetic retinopathy. On any view, a large proportion of the fenofibrate that is currently prescribed is for what should be considered non-infringing use. This includes cases in which fenofibrate is used specifically for the purpose of reducing levels of triglycerides, increasing levels of HDL-C or, more generally, to control lipid levels in patients who will not tolerate a statin.

116 Medical practitioners do not generally identify on a prescription for fenofibrate the indication for which the drug has been prescribed. Practitioners instead keep patient notes recording their diagnosis and (at least implicitly) their reasons for making the prescription. Most medical practitioners generally do not tick the "brand substitution not permitted" box on the prescription. If ticked, in most cases, that would prevent the pharmacist from offering a patient the Ranbaxy Products if the prescription had been written for fenofibrate. If the “brand substitution not permitted” box has not been ticked, regardless of whether the brand name is used on the prescription, the pharmacist will typically offer the patient a generic product if it is available, which most patients will accept, particularly if it results in cost savings.

117 The applicants submitted that if the Ranbaxy Products were launched, medical practitioners could be expected to permit the supply of (by not ticking the “brand substitution not permitted” box) the Ranbaxy Products for the prevention or treatment of diabetic retinopathy, regardless of whether “fenofibrate” or “Lipidil” is specified on the prescription. As to the content of the PI for the Ranbaxy Products and the absence of any reference to diabetic retinopathy, the applicants submitted:

Medical practitioners do not typically read the PI for a generic product, but assume that the indications for the generic will be identical to the original drug unless any difference is specifically drawn to their attention.

In any event, if they read the PI for the Ranbaxy Products, it sets out the information relevant to the utility of the drug for diabetic retinopathy, in that it says it is bioequivalent to Lipidil, which is commonly known to be indicated for diabetic retinopathy and does not state any reason why the Ranbaxy Products cannot be used to prevent or treat that condition.

Independent third-party materials directed to medical practitioners, such as the RACGP Diabetes Guidelines, refer to the TGA having approved the use of fenofibrate (not specifically Lipidil) for the treatment of diabetic retinopathy.

118 I accept this submission which is in my view supported by unchallenged evidence. Further, the matters referred to by the applicants in their submissions are matters that are likely to be known to the respondents at the time of supply of the fenofibrate to wholesalers or pharmacists. In those circumstances, I am satisfied that the respondent has reason to believe that a significant portion of the Ranbaxy Products that it proposes to supply will be used in a manner which would infringe claims 7, 10, 11 and 12 of the 711 Patent.

119 Accordingly, I am satisfied that the respondent threatens to indirectly infringe claims 7 and 10-12 (the method of treatment claims) by supplying the Ranbaxy Products in the patent area in the circumstances referred to in s 117(1) when read with s 117(2)(b) of the Act.

Validity

120 The validity issues that arise in relation to the 711 Patent are as follows:

(a) Whether the relevant claims lack novelty having regard to each of the following documents:

(i) The ACCORD Eye Study Protocol: Version January 2004 (“the Accord Protocol”); and

(ii) European Patent Application EP D 482 498 A (“the Squibb Patent”) when read with the Physicians’ Desk Reference, 59th Edition 2005 at pages 523-525 and 1325-1328 (“the Desk Reference”).

(b) Whether the relevant claims lack novelty having regard to the following acts:

(i) The prescribing by medical practitioners, dispensing and administering to patients with type 2 diabetes and dyslipidaemia oral formulations containing fenofibrate (including Lipidil 67 mg capsules and 160 mg tablets) to prevent or treat the symptoms and complications of diabetes including diabetic retinopathy;

(ii) The prescribing by medical practitioners, dispensing and administering to patients with type 2 diabetes of an oral formulation containing 160mg of fenofibrate to prevent or treat the symptoms and complications of diabetes including diabetic retinopathy in the course of the Accord Study;

(iii) The prescribing by medical practitioners, dispensing and administering to patients with type 2 diabetes of an oral formulation containing 200mg of fenofibrate to prevent or treat the symptoms and complications of diabetes including diabetic retinopathy in the course of the Field Study.

(c) Whether the invention, as claimed, lacks any inventive step:

(i) in light of the common general knowledge;

(ii) in light of the common general knowledge together with the information made publicly available in the documents referred to in (a) above?

(iii) in light of the common general knowledge together with any of the information made publicly available through any one of the acts referred to in (b) above.

121 The respondent carries the legal burden of establishing that the relevant information was made “publicly available” before the 10 November 2005 priority date. As Crennan J explained in JMVB Enterprises Pty Ltd v Camoflag Pty Ltd (2005) 67 IPR 68 (“JMVB”) at [53]-[54]:

[53] Prior art will only be relevant to the consideration of novelty or inventive step if it was “made publicly available” before the priority date of the claim in question. The respondent bears the onus of proof with respect to establishing that the prior art information was “publicly available” at the relevant priority date: s 7(1) Patents Act.

[54] The requisite degree of publication will be met if the prior publication or act communicates the information to any one member of the public in a manner which left that person free, in law and in equity, to make use of the information: Humpherson v Syer [1887] 4 RPC 407; Stanway Oyster Cylinders Pty Ltd v Marks (1996) 66 FCR 577 at 581; 144 ALR 627 at 630–1; 35 IPR 71 at 74–5 …

See also Insta Image Pty Ltd v KD Kanopy Australasia Pty Ltd (2008) 78 IPR 20 at [124].

Novelty

122 The respondent contended that the relevant claims were not novel in light of one or more publications or prior acts that made information publicly available before the priority date: see s 18(1)(b)(i) and s 7(1) of the Act.

Documentary Disclosures

123 When considering whether a documentary disclosure constitutes an anticipation it is necessary to consider the document as at the date of its publication and in light of the common general knowledge as it stood at that time. This proposition is in my view supported by a preponderance of authority including the decisions in General Tire & Rubber Co v Firestone Tyre & Rubber Co Ltd [1972] RPC 457 at 485, JMVB at [55] and Bradken Resources Pty Ltd v Lynx Engineering Consultants Pty Ltd (2012) 210 FCR 21 at [219].

124 Other relevant principles were discussed by the Full Court in AstraZeneca FC. With regard to sufficiency of disclosure, the plurality said at [299]-[302]:

[299] … In Meyers Taylor Pty Ltd v Vicarr Industries Ltd (1977) 137 CLR 228 Aickin J (at 235) said:

The basic test for anticipation or want of novelty is the same as that for infringement and generally one can properly ask oneself whether the alleged anticipation would, if the patent were valid, constitute an infringement.

[300] But it is important to note that the reverse infringement test is not applied by simply asking whether something within the prior art document would, if carried out after the grant of the patent, infringe the invention as claimed. In Flour Oxidizing Company Ltd v Carr & Company Ltd (1908) 25 RPC 428, Parker J (at 457) observed:

… where the question is solely a question of prior publication, it is not, in my opinion, enough to prove that an apparatus described in an earlier Specification could have been used to produce this or that result. It must also be shown that the Specification contains clear and unmistakable directions so to use it.

[301] These observations are the wellspring of a long line of cases that recognise that, in order for a prior art document to be anticipatory, there must be (to adopt the language in General Tire) a clear description of, or clear instructions to do or make, something that would infringe the patentee’s claim if carried out after the grant of the patentee’s patent. In Bristol-Myers Squibb Company v FH Faulding & Company Ltd (2000) 97 FCR 524 (Bristol-Myers), Black CJ and Lehane J reviewed the relevant authorities and concluded (at [67]):

What all of those authorities contemplate, in our view, is that a prior publication, if it is to destroy novelty, must give a direction or make a recommendation or suggestion which will result, if the skilled reader follows it, in the claimed invention. A direction, recommendation or suggestion may often, of course, be implicit in what is described and commonly the only question may be whether the publication describes with sufficient clarity the claimed invention or, in the case of a combination, each integer of it. But in this case medical practitioners hardly needed to be told that it was possible to infuse a particular dose of taxol over three hours, or how to do it. Nor, equally obviously, is that the point of the claims. The claims of the earlier of the petty patents are for a method for administration of taxol to a patient suffering from cancer; the claims of the later one are for a method of treating cancer. In each case the method involves a particular regimen for the infusion of taxol. The context was that great difficulties had been encountered in using taxol, despite its known anti-carcinogenic properties, in the treatment of cancer, because of the drug’s side effects. Each of the trials reported in the articles referred to was an investigation directed towards finding a solution of the difficulties: directed, particularly, to ascertaining safe dosage levels. But, though methods falling within the claims of the patents were used in each trial, none of the reports can be said to teach (a word which in this context encompasses direct, recommend and suggest) that which the petty patents claim.

[302] Sufficiency of disclosure is a cardinal anterior requirement in the analysis of whether a prior art document anticipates a claimed invention. It is only after the stage of assessing the sufficiency of disclosure — which involves a determination about whether a prior document has “planted the flag” as opposed to having provided merely “a signpost, however clear, upon the road” or, perhaps, something less — that the notion of reverse infringement comes into play as the final and resolving step of the required analysis. It is not the first step of the required analysis; nor is it the only step.

125 I should also refer to the Full Court’s decision of Merck & Co Inc v Arrow Pharmaceuticals Ltd (2006) 154 FCR 31 (“Merck”) in the patentee’s appeal against the decision of the primary judge (Gyles J) (see Arrow Pharmaceuticals Ltd v Merck & Co Inc (2004) 63 IPR 85). Claim 3 of the patent in suit in that case claimed a method of treatment involving the oral administration of a drug “according to a continuous schedule having a dosage interval which is once weekly.” Gyles J found that this claim was anticipated by the publication of an article in Lunar News (relevant parts of which appear at [25] of his Honour’s reasons) which included the following statement:

An intermittent treatment program (for example, once per week, or one week every three months), with higher oral dosing, needs to be tested.

126 Gyles J found (at [104]-[105]) that the Lunar News article was an anticipation of claim 3 because the article disclosed a continuous schedule of oral administration having a dosage interval which was once weekly. His Honour said at [107]:

It is submitted for Merck that the decision of the Full Court in Faulding establishes that to suggest that something needs to be tested is not to anticipate that which is suggested. Black CJ and Lehane J said (at FCR 548–9 [67]; ALR 461; IPR 576):

What all those authorities contemplate, in our view, is that a prior publication, if it is to destroy novelty, must give a direction or make a recommendation or suggestion which will result, if the skilled reader follows it, in the claimed invention.

That statement of principle was based upon a review of certain of the authorities. Those authorities stand for the proposition that the claimed invention must be disclosed as such and not simply as a possibility. If the Lunar News article had said “in view of these problems a continuous dosing schedule with various intervals greater than one day should be tested” it would not anticipate claim 3, even though a weekly dosage interval would be both technically and practically contemplated by that suggestion. On the contrary, here, the disclosure is quite precise and accords with the gist of the claimed invention. I do not accept the submission on behalf of Merck that the passage in question from Faulding adds an additional requirement for anticipation, namely that the publication should recommend the use of the invention as disclosed. That is not what the passage from Faulding says and it does not follow from the authorities analysed in that judgment. The essential difference in the treatment of the prior publications in Faulding lay in the view that one publication pointed clearly to one solution which was the invention rather than other publications which did not so point. That was a factual rather than a legal judgment and cannot be translated to the present circumstances.

127 On appeal, the Full Court rejected the patentee’s challenge to Gyles J’s findings on novelty. The Full Court referred to [107]-[108] of Gyles J’s reasons with apparent approval, clearly endorsing (at [112]) his Honour’s reasoning in relation to the Lunar News article. As to the need for further testing or clinical trials, the Full Court in Merck referred at [104]-[107] to a number of authorities which distinguished between steps leading to the discovery of the invention and subsequent checking and testing and remarked at [109]-[110]: