FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Unilever Australia Ltd v Beiersdorf Australia Ltd [2018] FCA 2076

|

Table of Corrections |

|

|

27 February 2019 |

Paragraph 227 has been changed from ‘…between a product with an absolute efficacy of 20% and a product with an absolute efficacy of 10%’ to ‘…between a product with an absolute efficacy of 20% and a product with an absolute efficacy of 30%’. |

|

|

Paragraph 330 has been changed from ‘test #3 may nonetheless have been relatively significant’ to ‘test #3 may nonetheless have been relatively insignificant’. |

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicant’s amended originating application filed 9 June 2016 be dismissed.

2. The applicant pay the respondent’s costs.

3. Pursuant to r 1.39 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), the time within which the applicant must file and serve any notice of appeal pursuant to rr 36.02 and 36.03 of the Rules is to commence to run from 4 February 2019.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

WIGNEY J:

1 The applicant, Unilever Australia Ltd, is a consumer goods company which, amongst other things, markets, distributes and sells antiperspirant deodorants in Australia under the well-known brands, Rexona and Dove. In July 2009, Unilever began to market, distribute and sell a “Clinical Protection” range of Rexona and Dove antiperspirant deodorants. The key features of the products in that range were that they were “soft-solid” creams contained in canisters from which they were applied; were offered for sale in boxes which contained an instructional leaflet; and prominently featured the words “Clinical Protection” on both the canister and box. The Clinical Protection range was marketed as being particularly suitable for persons who sweated heavily and was generally sold at significantly higher prices than other antiperspirant deodorants.

2 By December 2013, another major distributor of antiperspirant deodorants, Revlon Australia Pty Ltd, began selling a range of antiperspirant deodorants named “Mitchum Clinical”. Products in that range were also soft-solid creams contained in a canister; were sold in a box containing an instructional leaflet; prominently featured the word “clinical” on the canister and box; were marketed as being particularly suitable for persons who sweated heavily; and were generally sold at a higher price than other antiperspirant deodorants, other than products within the Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection range.

3 Like Unilever and Revlon, the respondent, Beiersdorf Australia Ltd, also markets, distributes and sells antiperspirant deodorants in Australia. It does so under the well-known brand, Nivea. In about July 2014, Beiersdorf began to market, distribute and sell a “Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength” range of antiperspirant deodorants. The key features of the products within that range were that they were deodorant “sticks” located in a canister from which the stick could be applied; were sold in a box which contained an instructional leaflet; prominently featured the words “Clinical Strength”, albeit along with the equally prominent words “Stress Protect”; and were generally sold at a higher price than other antiperspirant deodorants, other than the Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection range and the Mitchum Clinical range.

4 In this proceeding, Unilever alleged that, in marketing, distributing and selling the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength range of antiperspirant deodorants in the way it did, Beiersdorf engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct, or made false or misleading representations, contrary to, respectively, ss 18 and 29(1)(a) and (g) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), which is Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth). Unilever contended, in short, that Beiersdorf’s conduct was misleading or deceptive because, in marketing, distributing and selling the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength range in the way it did, Beiersdorf made a number of representations to consumers concerning the antiperspirant efficacy of that range. Those alleged representations included representations about the efficacy of the range as compared to the antiperspirant efficacy of the Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection range and the Mitchum Clinical range, and the antiperspirant efficacy of the range as compared to all other so-called “non-clinical” antiperspirant deodorants. Some of the representations said to have been made by Beiersdorf related to future matters. Unilever alleged that the representations made by Beiersdorf were false or misleading.

5 Beiersdorf disputed Unilever’s claims and defended the proceedings. There was, of course, no dispute that, at all relevant times, Beiersdorf marketed, distributed and sold antiperspirant deodorants as part of the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength range. Beiersdorf disputed, however, that its conduct in so doing was in any sense misleading or deceptive. In particular, it disputed that its conduct gave rise to any of the representations alleged by Unilever, other than two that related to the efficacy of its product for consumers who suffer from stress sweat. Beiersdorf characterised Unilever’s claim as an allegation of “comparative advertising by stealth”. It contended, amongst other things, that its marketing and distribution of the product, including use of the words “clinical strength”, the packaging in a box, the inclusion of a leaflet and the higher price, said nothing to consumers about the antiperspirant efficacy of the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength range as compared to either the Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection range, or any other antiperspirant deodorants. Beiersdorf also contended that, even if the Court found that any of the alleged representations had been conveyed to consumers, Unilever had not discharged its burden of proving that they were false or misleading as alleged by Unilever. As for the representations that related to future matters, Beiersdorf’s case was that, if they were made, it had reasonable grounds to make them.

6 The principal questions thrown up by the rival claims and contentions are, at least on one level, relatively easy to frame: did Beiersdorf, by its marketing, distribution and sale of the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength range, make representations to consumers about the antiperspirant efficacy of that range as compared to the Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection range and all other “non-clinical” antiperspirant deodorants; if so, were any of those representations false or misleading; and, in respect of the representations as to future matters, did Beiersdorf have reasonable grounds to make those representations?

7 While the principal questions may be easy to frame, they are by no means easy to answer.

8 The question whether Beiersdorf made any of the alleged representations hinges, to a large extent, on whether there was a “clinical” subcategory or segment in the market for antiperspirant deodorants in Australia at the relevant time and, if so, what ordinary consumers perceived, or were likely to perceive, about the characteristics or qualities of products within that subcategory or segment. If, by its conduct in marketing, distributing and selling the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength range, Beiersdorf effectively represented to ordinary reasonable consumers of antiperspirant deodorants in Australia that those products properly belonged in any existing “clinical” subcategory or segment, did it follow that it thereby represented that those products had similar antiperspirant efficacy and characteristics to the existing products in that subcategory or segment, the Rexona, Dove and Mitchum “clinical” products? And did it also follow that Beiersdorf thereby represented that its products had greater antiperspirant efficacy than all other “non-clinical” antiperspirant deodorants in the Australian market for antiperspirant deodorants?

9 The question whether the representations, if found to have been made by Beiersdorf, were false or misleading, turns to a large extent on the nature and reliability of various laboratory tests which measured the relative effectiveness of the products in reducing the amount of perspiration excreted in various conditions or circumstances. Unilever relied on the results of a number of so-called “head-to-head” tests which tended to show that its products generally reduced perspiration by some percentage more than Beiersdorf’s products. It also relied on comparisons between various “absolute” tests which recorded the overall sweat reduction qualities of various products. There was, however, considerable dispute and debate about the tests, and the test results and their interpretation, including about the reliability or ability of the test results to gauge the relative significance of the differences between the tested products.

10 Before turning to address the facts and evidence in more detail, it is necessary to say something about the relevant provisions of the ACL and the legal principles that apply to them in cases like this.

Relevant Statutory Provisions and Applicable Principles

11 Section 18 of the ACL provides as follows:

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

(2) nothing in Part 3-1 (which is about unfair practices) limits by implication subsection (1).

12 Section 29(1)(a) and (g) of the ACL are in the following terms:

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

(a) make a false or misleading representation that goods are of a particular standard, quality, value, grade, composition, style or model or have had a particular history or particular previous use; or

…

(g) make a false or misleading representation that goods or services have sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses or benefits;

…

13 Section 4 of the ACL, which relates to misleading representations with respect to future matters, provides as follows:

(1) If:

(a) a person makes a representation with respect to any future matter (including the doing of, or the refusing to do, any act); and

(b) the person does not have reasonable grounds for making the representation;

the representation is taken, for the purposes of this Schedule, to be misleading.

(2) For the purposes of applying subsection (1) in relation to a proceeding concerning a representation made with respect to a future matter by:

(a) a party to the proceeding; or

(b) any other person;

the party or other person is taken not to have had reasonable grounds for making the representation, unless evidence is adduced to the contrary.

(3) To avoid doubt, subsection (2) does not:

(a) have the effect that, merely because such evidence to the contrary is adduced, the person who made the representation is taken to have had reasonable grounds for making the representation; or

(b) have the effect of placing on any person an onus of proving that the person who made the representation had reasonable grounds for making the representation.

(4) Subsection (1) does not limit by implication the meaning of a reference in this Schedule to:

(a) a misleading representation; or

(b) a representation that is misleading in a material particular; or

(c) conduct that is misleading or is likely or liable to mislead

and, in particular, does not imply that a representation that a person makes with respect to any future matter is not misleading merely because the person has reasonable grounds for making the representation.

14 The applicable principles in relation to actions for misleading or deceptive conduct under s 18 of the ACL and false or misleading representations under s 29 of the ACL are relatively well settled. There was ultimately no significant or material dispute about those principles. The real issue in this matter is the application of those principles to the facts and circumstances of this case. It is accordingly unnecessary to discuss the relevant principles in any great detail. It should also be noted that many of the principles concerning misleading or deceptive conduct that are discussed in the authorities are really just common sense or logical guides to the approach that should be taken in deciding what is, at the end of the day, a question of fact.

15 Section 18 of the ACL is not limited to misleading or deceptive representations. The question is whether the respondent’s conduct, which may include acts, omissions, statements or silence, is misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640 at 655 [49] (per French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ).

16 For the enquiry under s 18, it is necessary to identify the impugned conduct and then to consider whether that conduct, considered as a whole and in context, is misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive: Google Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2013) 249 CLR 435 at [89], [102] and [118]. The same applies to the enquiry as to false or misleading representations under s 29 of the ACL: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd (2014) 317 ALR 73; FCA 634 at [38].

17 There is no meaningful difference between the words and phrases “misleading or deceptive” and “mislead or deceive” in s 18 and “false or misleading” in s 29(1): Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dukemaster Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 682 at [14]; Coles Supermarkets at [40].

18 Conduct is misleading or deceptive if it has a tendency to lead a person into error, or lead them to believe what is, in fact, false. There must be a sufficient causal link between the conduct and the error on the part of persons exposed to it: TPG Internet at 651 [39].

19 Conduct is likely to mislead or deceive if there is a real or not remote chance or possibility that it will have that effect: Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Pty Ltd (1984) 2 FCR 82 at 87. It is insufficient for the impugned conduct to only cause confusion or wonderment: Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Ltd (2000) 202 CLR 45 at 87 [106] citing the judgment of a majority of the Full Court in Taco Company of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd (1982) 42 ALR 177 at 201; 2 TPR 48 (per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ).

20 The question whether conduct is misleading or deceptive, or is likely to mislead or deceive, is an objective question of fact that is to be determined on the basis of the conduct of the respondent as a whole viewed in the context of all relevant surrounding facts and circumstances. Viewing isolated parts of the conduct of a party “invites error”: Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty Pty Ltd (2004) 218 CLR 592 at 625 [109] (per McHugh J); Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd (2009) 238 CLR 304 at 341-342 [102] (per Gummow, Hayne, Heydon and Kiefel JJ).

21 Where the conduct or representation is in the form of words, it would be wrong to fix on some words and ignore others which may provide relevant context and give meaning to the impugned words. It is necessary to have regard to the whole context: Butcher at 638-639 [152] (per McHugh J).

22 The relevant context may include consideration of the type of market in which the goods are sold, the manner in which such goods are sold and the habits and characteristics of purchasers in such a market: see, generally, TPG Internet at 656 [52]; Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191 at 199; Reckitt & Colman Products Ltd v Borden Inc (1990) 17 IPR 1 at 16-17; 1 WLR 491 at 509; Coles Supermarkets at [41].

23 The question involves the characterisation of the relevant conduct. Evidence that persons have in fact been misled or deceived by the conduct is not an essential element, however, it can in some cases be relevant and material: Parkdale at 198-199 (per Gibbs CJ): Coles Supermarkets at [45].

24 The tendency of the conduct or representation to mislead or deceive is to be considered or tested against the ordinary or reasonable members of the class to whom the representation was made or the conduct directed. In Campomar, the High Court said (at 87 [105]):

The initial question which must be determined is whether the misconceptions, or deceptions, alleged to arise or to be likely to arise are properly to be attributed to the ordinary or reasonable members of the classes of prospective purchasers.

25 The question is whether a substantial, or at least a reasonably significant, number of that class is likely to be misled or deceived: see Optical 88 Ltd v Optical 88 Pty Ltd (No 2) (2010) 275 ALR 526; FCA 1380 at [336]-[342]. The focus on ordinary or reasonable members of the relevant class of consumers means, in effect, that possible extreme, unreasonable or illogical reactions can be put to one side.

26 It is not necessary to prove that the respondent intended to mislead or deceive, however, evidence of such an intention may constitute evidence that the conduct was likely to succeed in misleading or deceiving, and may make a finding of contravention more likely: Yorke v Lucas (1985) 158 CLR 661 at 666 (per Mason ACJ, Wilson, Deane and Dawson JJ); Verrocchi v Direct Chemist Outlet Pty Ltd (2016) 247 FCR 570 at [103]; Australian Woollen Mills Ltd v FS Walton & Co Ltd (1937) 58 CLR 641 at 657 (per Dixon and McTiernan JJ).

27 Where the conduct or representation is in the form of an advertisement, the “dominant message” or “general thrust” of the advertisement is important: TPG Internet at [47]. It is nevertheless important to have regard to the whole advertisement because context is or may be important. It may also be relevant to have regard to the external context in which a consumer is likely to view an advertisement: TPG Internet at 653-655 [45]-[52] (per French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ).

28 Where an advertisement is capable of more than one meaning, the question of whether the advertisement is misleading or deceptive must be tested against each meaning that is reasonably open: Tobacco Institute of Australia Ltd v Australian Federation of Consumer Organisations Inc (1992) 38 FCR 1 at 50. If one or more of the reasonably available different meanings is misleading, the conduct may well be misleading or deceptive, or false or misleading: Coles Supermarkets at [47].

29 The question whether Beiersdorf made any of the alleged representations turns on a close consideration of the facts and evidence relating to the market for antiperspirant deodorants in Australia, including Unilever’s Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection range of antiperspirant deodorants, and Beiersdorf’s marketing, distribution and sale of the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength range. The facts and evidence concerning the testing of the antiperspirant efficacy and effectiveness of the rival products will be considered separately in the context of the question whether the representations, if found to have been conveyed, were false or misleading.

30 The market for deodorants in Australia accounts for over $300 million by retail sales value. The market includes deodorants, which impact odour by imparting a perfume, and antiperspirant deodorants which, in addition to imparting a perfume, also operate by reducing the amount of perspiration released by the apocrine and eccrine sweat glands under the arms.

31 In very general terms, an antiperspirant deodorant reduces perspiration by “plugging” the eccrine glands. The active ingredients which are responsible for that action are aluminium salts or actives. Different types of aluminium actives are better able to operate to plug the eccrine glands than others. It appears to be generally accepted that Activated Aluminium Zirconium Tetrachlorohydrex Glycine (AZAG) is the most effective aluminium active at plugging the eccrine glands. The amount and type of aluminium active in an antiperspirant deodorant is an important characteristic in any assessment of antiperspirant efficacy, though there is no precise or linear relationship between efficacy and the amount or type of aluminium active. Other things that may impact on the efficacy of an antiperspirant deodorant include the nature of the delivery mechanism and the nature or type of formulation of the antiperspirant deodorant.

32 Various different types and formulations of antiperspirant deodorants are sold in Australia. They include: stick antiperspirant deodorants, which are a solid or waxy formulation dispensed by a winder mechanism; pump antiperspirant deodorants, which are liquid, pumped out of a container by a pump mechanism; aerosol antiperspirant deodorants, which operate by expelling a gas from a container under pressure; roll-on antiperspirant deodorants, which operate by dispensing a liquid from a container using a rolling ball at the top of the container; and soft-solid antiperspirant deodorants, which are a soft-solid or cream formulation which is applied from a container with a winder mechanism which pushes the formulation through a grate at the top of the container.

33 It is possible to generalise or theorise about the comparative efficacy of the various different formulations, though ultimately the antiperspirant efficacy of any particular antiperspirant deodorant can only be definitively determined by laboratory testing. In very general terms, however, aerosols are usually less efficacious than roll-ons, sticks and soft-solids. That is because the higher efficacy aluminium actives cannot be used in aerosols, the amount of active in aerosols is generally limited and the delivery mechanism is not as efficient. Roll-ons are generally more efficacious than aerosols because they can contain the higher efficacy aluminium salts. They cannot, however, contain AZAG. Both sticks and soft-solids can contain AZAG and are therefore generally more efficacious than other formulations. Though theories and opinions may be expressed concerning the comparative efficacy of sticks and soft-solids, ultimately, the antiperspirant efficacy of any particular stick or soft-solid would be likely to depend on a number of considerations, not just the amount and type of the aluminium actives, including AZAG, in the particular product.

Unilever’s Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection range

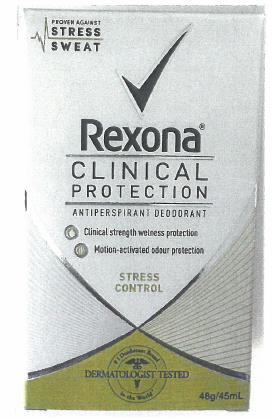

34 In July 2009, Unilever commenced marketing, distributing and selling what it referred to as its “Clinical Protection” antiperspirant deodorant range. That range included the following products: “Rexona Clinical Protection”, “Rexona Men Clinical Protection” and “Dove Clinical Protection”. Those products all had the following characteristics.

35 First, they were offered for sale in a box which was approximately 11cm high, 7cm long and 4.5cm wide.

36 Second, the product itself was an antiperspirant deodorant soft-solid cream within a canister from which the soft-solid cream could be applied.

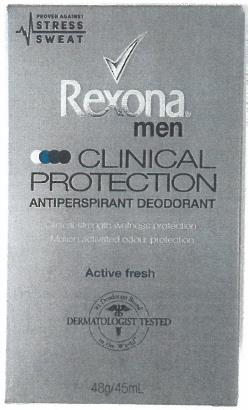

37 Third, also located in the box was an instructional leaflet. The Rexona Clinical Protection leaflet relevantly included the following statements or claims: “Rexona Clinical Protection provides our most advanced, long-lasting protection against wetness and odour”; “clinical strength wetness protection”; and “motion activated odour control technology”. The Dove Clinical Protection leaflet relevantly included the following statements or claims: “[p]rovides clinical strength protection against wetness”; “[d]elivers all-day freshness through odour-fighting technology”; and “[f]eatures a signature fragrance”. Both the Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection leaflets also provided directions for use and answers to questions such as “[w]hat is the difference between deodorants and anti-perspirant deodorants?” and “[a]re anti-perspirants safe?”. The leaflets do not contain any specific quantified or quantifiable claims concerning perspiration reduction.

38 Fourth, both the box and the canister in which the product was located prominently featured, along with the brand name “Rexona” or “Dove”, as the case may be, the words “clinical protection” above the words “antiperspirant deodorant”. While there were some variations between different boxes and canisters, they almost invariably included the words “[c]linical strength wetness” protection. Some of the boxes and canisters also included, after those words, the words “& odour protection” or “for heavy sweating”. Some included the words “Dermatologist Tested” or, in one case, “Doctor Recommended”. From about 2014, some included the words “[m]otion activated odour protection”.

39 Fifth, the products within the Clinical Protection range were sold in supermarkets at prices substantially higher than other antiperspirant deodorants; often as much as two to three times higher. That was the case until, as will be seen, Revlon introduced into the market its Mitchum Clinical range and Beiersdorf later introduced its Stress Protect Clinical Strength range.

40 The products within the Clinical Protection range were sold with different types of fragrances and other apparently distinguishing features. For example, some of the boxes and canisters included labels or descriptions such as “sport”, “adventure”, “stress control” and “summer strength”.

41 Appendix 1 contains images of various boxes used in the range.

42 From 2009, Unilever marketed its “Clinical Protection” range in Australia as being particularly suitable for persons who sweat heavily, or who were concerned about heavy sweating.

43 Unilever’s Clinical Protection range was the subject of fairly extensive advertising and publicity from the time of its launch. The focus of that advertising and publicity was that the Clinical Protection range was designed, tested and proven to be effective for people who were heavy sweaters. In a segment on a current affairs program broadcast on television in August 2012, for example, it was said, amongst other things, that “[a]fter ongoing testing and development for five years, it [Rexona Clinical Protection] claims to be the only antiperspirant deodorant that works for heavy sweaters who don’t have a medical problem”. A television advertisement that was broadcast from about 2011 to early 2014 said that people who sweat more than normal should try Rexona Clinical Protection deodorant because “it’s the most effective antiperspirant deodorant in Australia that protects you twice as much”. An advertisement relating to Dove Clinical Protection stated that it was “clinically proven to give twice the protection of a basic antiperspirant”. A Rexona Clinical Protection advertisement broadcast throughout 2014 and into the first quarter of 2015 emphasised that “[n]othing is stronger”.

Other “clinical” products before July 2014

44 In about December 2013, Revlon commenced marketing, distributing and selling a range of antiperspirant deodorants using the name “Mitchum” or “Mitchum Clinical”. Those products included the following features.

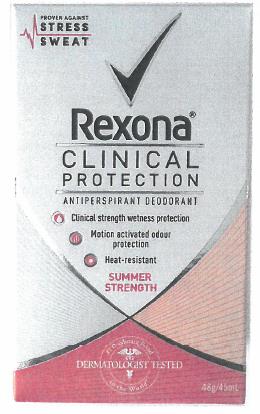

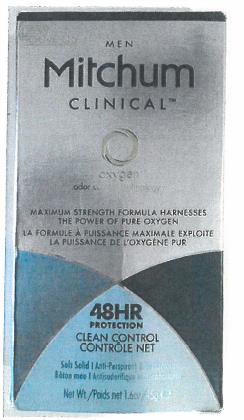

45 First, they were offered for sale in a box which was approximately 12.5cm high, 7cm long and 3cm wide.

46 Second, the product itself was an antiperspirant deodorant soft-solid cream within a canister from which the soft-solid cream could be applied.

47 Third, also located in the box was an instructional leaflet. There was no evidence concerning the contents of the Mitchum Clinical leaflet.

48 Fourth, both the box and the canister in which the product was located prominently featured the word “clinical”, either as part of, or along with, the brand name “Mitchum”. While there were some variations between different boxes and canisters, they generally also included the words “Oxygen odour control technology”, “maximum strength formula harnesses the power of pure oxygen” and “48 hr protection”.

49 Fifth, the product was sold in supermarkets at prices substantially higher than other antiperspirant deodorants, other than Unilever’s Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection range and, subsequently, Beiersdorf’s Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength range.

50 The products within the Mitchum Clinical range were sold with different types of fragrances and other apparently distinguishing features. For example, some of the boxes and canisters included labels such as “sport”, “clean control” and “powder fresh”.

51 Appendix 2 contains images of various boxes used in the “Mitchum Clinical” range.

52 In 2011 and early 2012, antiperspirant deodorants using the brand name “Brut V8 Clinical Protection” and “Norsca Clinical Protection” were sold in Australia. Between 2011 and early 2013, an antiperspirant deodorant called “Lady Speed Stick Clinical Proof” was also sold in Australia. There was very little evidence concerning those products, though it was common ground that, like Unilever’s Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection range and Revlon’s Mitchum Clinical range, they were sold in a rectangular box, prominently featured the word “clinical” as part of their name or otherwise, and were generally sold at prices substantially higher than all other antiperspirant deodorants. It was also common ground that, in the period 2011 to 2013, those products had a combined market share of antiperspirant deodorants which used “clinical” as part of their name by units sold of less than 6%.

The Australian antiperspirant deodorant market as at July 2014

53 As at July 2014, the deodorant and antiperspirant deodorant market in Australia, measured by units sold from August 2013, was divided as follows: 53.6% aerosol antiperspirant deodorants; 21.16% roll-on antiperspirant deodorants; 19.81% body spray deodorants; 2.58% stick antiperspirant deodorants; 1.95% soft-solid antiperspirant deodorants, being essentially the Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection range and the Mitchum Clinical; and 0.90% pump, creams and other deodorants. The Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection range accounted for 90.8% of the sales of soft-solid antiperspirant deodorants, and the Mitchum Clinical range accounted for 9.2%.

54 The Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection range and the Mitchum Clinical range were the only antiperspirant deodorants sold in Australian supermarkets as at July 2014 which: were packaged in a rectangular box; were supplied with an instructional leaflet inside the box; prominently featured the word “clinical” as part of the product name or otherwise; and were sold at a price which was substantially higher than all other antiperspirant deodorants.

Beiersdorf’s launch of the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength range

55 In July 2014, Beiersdorf commenced marketing, distributing and selling in Australia a new Nivea range of antiperspirant deodorants called Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength. Before considering the particular features of that range, and the marketing and advertising that accompanied its launch, it is relevant to have regard to the circumstances in which that range came to be launched in Australia.

56 In June 2012, Beiersdorf decided to introduce a new range of antiperspirant deodorants in Australia called the “Stress Protect” range developed by its parent company, Beiersdorf AG, which was based in Hamburg, Germany. That range included a roll-on, an aerosol spray and an antiperspirant stick. Beiersdorf initially decided to only launch the Stress Protect roll-on and aerosol in Australia. That was in part due to the fact that antiperspirant sticks were only a small segment of the Australian market. In September 2012, however, Beiersdorf decided to investigate the possibility of also introducing the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength stick into Australia. The intention was to market that product as having a high efficacy against stress sweat in particular.

57 Ms Julia Braun was the General Manager of Marketing at Beiersdorf. Her evidence was that a number of considerations were taken into account in deciding to launch the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength stick in Australia as a high-efficacy product. Those considerations included that, unlike its competitors at that time, Beiersdorf did not have any products which were specifically marketed as having high efficacy. In addition, Beiersdorf AG had advised that, as compared to the roll-on and aerosol formats of the Stress Protect range, the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength stick had the highest concentration and the most scientifically advanced form of antiperspirant active. It was the most efficacious of the three products.

58 According to Ms Braun, Beiersdorf AG had also advised Beiersdorf that each of the roll-on, aerosol and stick formats of the Nivea Stress Protect range had been proven, in scientific testing conducted by Beiersdorf AG, to have a high level of efficacy against stress sweat. Nevertheless, Beiersdorf did not wish to launch the roll-on or aerosol formats as high-efficacy products against stress sweat at the time because the “high efficacy segment” represented only a small segment of the Australian market, whereas the general roll-on and aerosol segments were much larger. Beiersdorf did not wish to limit the marketing of the roll-on and aerosol formats to the high efficacy segment at the expense of capturing market share in the general roll-on and aerosol segments. Since the stick segment of the market in Australia was small, it was considered that marketing the stick format as high efficacy would not limit, but, rather, would assist with the sale of the product.

59 In cross-examination, Ms Braun agreed that she believed or was aware that there was a “clinical protection” or “highly efficacious clinical protection” segment of the antiperspirant deodorant market in Australia. She also agreed that that segment was established by Rexona and Dove in 2009. Ms Braun also knew, in September 2012, that Rexona, Dove and Lady Speed Stick had products which were specifically marketed as having high efficacy. Those products were marketed as being “clinical” or “clinical protection” products, which she understood as meaning high efficacy.

60 In September 2012, Ms Braun and Mr Paul Croci, who was the Marketing Services Manager at Beiersdorf, decided to engage a consumer research agency, Lonergan Research, to conduct a blind home user test to assess whether the female variant of the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength stick would perform as well, or better than, Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection and the Lady Speed Stick antiperspirant deodorants, each of which was marketed as having high efficacy. The results of that testing were to be used by Beiersdorf to assess whether it would be desirable to introduce the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength stick into Australia as a high-efficacy product against stress sweat.

61 The research brief prepared by Mr Croci and another Senior Brand Manager noted:

1.1 What is the situation, and why are we doing this research?

The ANZ Deodorant Category is traditionally an Aerosol and Roll On format market, and consumers are highly format loyal (dislike other formats). Three years ago, our key competitor Rexona introduced a new product called ‘Clinical Protect’ x 2 to the mass market in a creamy stick format. Since then Rexona have launched 4 further Clinical Protect variants, now contributing 11% of their sales; this range is by far the largest contributor to the overall growth of the deodorant category, which otherwise is commoditized and competes highly on price. More recently, Dove have also launched 2 Clinical Protection variants.

The NIVEA Deodorant brand has enjoyed significant growth over the past two years with true market innovations in form of added benefit or formulation innovations like NIVEA & NIVEA MEN INVISIBLE FOR BLACK & WHITE, NIVEA MEN SILVER PROTECT, which are driving the brand forward. At the same time, it is the brands challenge to overcome its poor efficacy perception in the mind of the consumer; efficacy is the No 1 Purchase Driver in the ANZ market.

2013 will see the brand launch another true market innovation with the launch of NIVEA & NIVEA Men Stress Protect in the traditional Aerosol & Roll on Format. Following the establishment of this new range & benefits, we are considering extending this line into Clinical Strength Stress Protect Sticks x 2 (launch in June).

62 The report also stated, under the subheading “What do we already know?”:

The Clinical Protection Range is marketed & formulated for people that perceive themselves to be ‘heavy sweaters’ or sweat excessively (highly efficacious against underarm wetness & odour). These consumers are prepared to pay a premium for a product that finally helps with their underarm sweat problems, which emotionally provides them with a huge amount of confidence.

63 Under the subheading “Crux”, the following was recorded:

Our stick format would be intended to compete against the Dove and Rexona Cream Sticks; however, we still face the perception of lower efficacy in the minds of consumers. Our stick format would be branded as Clinical Strength Stress Protect, but to be successful it would have to work at least as well as the competitors. This research is intended to determine whether our Stress Protect stick does perform as well as (or better than) our key competitors – because if it doesn’t, we won’t launch it.

64 When taken to this passage in cross-examination, Ms Braun gave the following evidence:

Yes?---Because, you know, for us at Nivea it was of utmost importance, you know, that when we launch in a segment which is high efficacy that then we also fulfil the needs of the consumers, in this case heavy sweaters, that it is highly efficacious. And as this high efficacy segment was formed by Rexona and Dove you know, then it is to have one – yes, you know, you want to be – to offer to the consumer something which is similar, you know, to their offering in terms of satisfying them against heavy sweat and, in our specific case, stress sweat.

(Emphasis added.)

65 As will be seen, Unilever relied heavily on Ms Braun’s use of the word “similar” when giving that evidence. It would appear from Ms Braun’s evidence as a whole, however, that her concern in launching the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength stick in Australia was not so much with the comparative efficacy of the Nivea product in a purely quantitative sense. Nor was she referring to what Beiersdorf’s proposed marketing of the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength stick in the “high efficacy” segment would convey, or would be likely to convey, to Australian consumers of antiperspirant deodorants. Rather, her concern was that, before deciding to launch the product, Beiersdorf wanted to be satisfied that its product would be able to effectively compete with the Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection range as a high-efficacy product. That was likely to depend on consumer perceptions concerning the overall efficacy of the product as compared to the existing high-efficacy products. It did not necessarily depend on specific quantitative measures or levels of efficacy. Ms Braun did not believe that consumers thought in terms of “levels” of efficacy.

66 Ms Braun gave the following evidence in that regard:

Yes. I want to suggest to you that you, as marketing general manager of Beiersdorf Australia, reading this document had in your mind that users of Dove and Rexona cream sticks had formed a certain expectation of a level of efficacy?---I think consumers, they don’t think in level of efficacy. It has to – it’s very simple. It has to work for them or not and especially heavy sweaters. You know, they go trial and error. When something works [for] them, then it’s an efficacious product and they stick with them.

Do you accept that the notion of determining whether the Stress Protect stick “performs as well as or better than” starts with an assumption of a level of efficacy which the new product wants to either equal or exceed?---That was to be competitive in the market, you know. I mean, and for – in order to be so, you know, to be competitive you have to perform compared to the market leader at least on a similar level.

Yes. And on a similar level means with a similar level of efficacy or a better level than efficacy?---As perceived by the consumer.

Thank you. And it doesn’t – that includes, does it not, the idea that the consumer being the Dove or Rexona consumer has a present level of perception of the level of efficacy?---When they have used the products and they are happy with and they say it works for them, then it works for them. They don’t think in levels.

67 The results of the blind testing survey conducted by Beiersdorf are considered in some detail later in the context of the issue concerning whether the representations, if found to have been made, were false or misleading. Suffice it to say at this stage that Ms Braun’s evidence concerning the results was that the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength stick generally performed on par with or close to the Rexona, Dove and Lady Speed Stick products in terms of perceived antiperspirant efficacy and deodorant efficacy. Nevertheless, Beiersdorf decided not to proceed with the launch at that time on the basis that the results could be further improved. In February 2013, Beiersdorf decided to ask Beiersdorf AG to reformulate the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength stick “to further improve the product’s perceived deodorant efficacy”. Beiersdorf AG subsequently substantially increased the amount of fragrance in the formulation.

68 Beiersdorf commissioned further blind home user tests in 2013. The results of those tests are also considered later. Suffice it to say at this stage that, so far as Ms Braun was concerned, the results showed that the reformulated Nivea products generally performed on par with or close to the Rexona products, in terms of both perceived antiperspirant and deodorant efficacy.

69 In November 2013, Beiersdorf decided to launch “a Nivea high efficacy product for stress sweat” in Australia. Ms Braun’s evidence was that Beiersdorf decided to adopt the name “Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength” for its “high efficacy product for stress sweat” in Australia for essentially five reasons.

70 The first reason was that Beiersdorf wanted to capitalise on the success of the “‘Stress Protect’ sub-brand”. Ms Braun’s evidence in cross-examination was that “Stress Protect was first and foremost, you know, because we were building the sub-segment and this launch could further enhance and positive[ly] build the sub-segment”.

71 The second reason was that “[e]ach of the Rexona, Mitchum, Dove and Lady Speed Stick products sold in the Australian market which were marketed as having high efficacy … were described as ‘clinical’”.

72 The third reason was that there was no legal or regulatory definition of “clinical” or “clinical strength” in respect of antiperspirant deodorants in Australia. In those circumstances, Beiersdorf “considered ‘clinical’ to be a descriptor which different suppliers were using to identify a product which falls within the high efficacy subcategory”.

73 The fourth reason was that Beiersdorf was satisfied that the Nivea product was a high-efficacy product with respect to stress sweat.

74 The fifth reason, which Ms Braun referred to during cross-examination, was that “clinical strength is the subcategory in the market” which included products with “extra efficacy”.

75 A campaign brief prepared by Ms Kate Hensley, a Senior Brand Manager at Beiersdorf, in January 2014 provided some further insight into Beiersdorf’s perceptions concerning the launch and marketing of the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength stick at the time. It stated, amongst other things, that Nivea “will launch into the highly efficacious ‘clinical protection’ antiperspirant segment” which was “established by Rexona & Dove in 2009”. It also noted that the “Clinical Protection segment” had been used by Unilever to “imply superior product efficacy of their products in treating excessive sweating”.

76 The campaign brief included the following questions and answers:

What makes a product Clinical Strength?

1. No legal or regulatory definition for ‘Clinical Strength’

2. Efficacy vs. standard anti-perspirant deodorants (ingredients & concentration)

3. Clinically proven

…

What makes NIVEA Stress Protect Clinical Strength?

1. TSST study conduc[t]ed by BDF research Efficient sweat reduction of three different antiperspirant application forms during stress-induced sweating. International Journal of Cosmetic Science 35, 622-631, 2013

2. Concentration & type of Anti-perspirant ingredients

3. Results from local BHUT (superior to market leader for female and on par with market leader for male).

77 The reference in this document to “TSST study” was reference to a “Trier Social Stress Test” study which was discussed in a paper co-authored by a biochemist employed by Beiersdorf AG, Dr Thomas Schmidt-Rose. That paper was published in the December 2013 edition of the International Journal of Cosmetic Science. That study will be referred to in detail later in the context of the relevant test results and the alleged falsity of the representations. It is sufficient to note at this stage that Ms Braun’s evidence was that, at the time of the launch of the Nivea Stress Protect range, she understood that scientific testing conducted by or on behalf of Beiersdorf AG had established that the products within that range, including the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength stick, had a high level of antiperspirant efficacy against stress sweat.

Marketing, distribution and sale of Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength

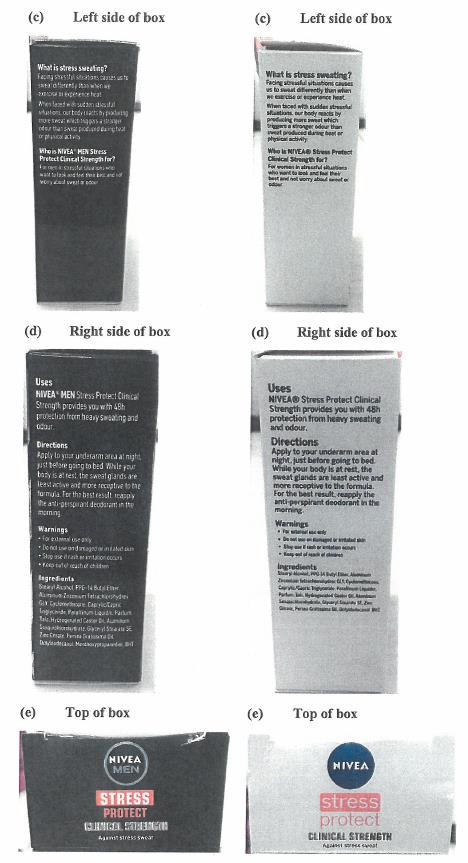

78 From July 2014, Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength antiperspirant deodorants were offered for sale in two variants. Both variants had the following key features.

79 First, the product was sold in a box which was approximately 13cm high, 7cm long and 4cm wide.

80 Second, the product itself was an antiperspirant deodorant stick, as opposed to a soft-solid cream, located in a canister from which the stick could be applied.

81 Third, the product was sold with an instructional leaflet inside the box. The leaflet posed and answered three questions, each directed in one way or another at “stress sweating”. The first question was: What is stress sweating? The answer provided was that there are two types of sweating: thermal sweating, produced by the eccrine glands as the body’s reaction to temperature and physical exertion; and stress sweating, which is produced by activation of the apocrine gland as the body’s reaction when facing a heightened emotionally stressful situation. The second question was: Do I need protection from stress sweating? The answer provided was, in essence, “yes”. The third question was: How does Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength work? The answer referred to the “latest generation anti-perspirant actives”, a “Zinc complex which prevents the production of odour-causing bacteria” and a “fresh and subtle scent”.

82 Fourth, the box and canister prominently featured the words “Stress Protect” and “Clinical Strength”. The words “Stress Protect” were in a different and perhaps even more prominent typeface than the words “Clinical Strength”. The words “against stress sweat” appear below the words “Clinical Strength” in smaller typeface.

83 Appendix 3 contains an image of the box.

84 The price recommended by Beiersdorf as a retail price for the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength antiperspirant deodorants was a price which was similar to the Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection antiperspirant deodorants and was substantially higher than all other antiperspirant deodorants.

85 Ms Braun’s evidence was that Beiersdorf decided to sell the product in a box with a leaflet “to align with the [cues] of the segment and to say clearly, ‘[h]ere is a special stress sweat solution for heavy sweaters which is highly efficient’”. She regarded the box “as an important part of the clinical category” and as “[r]einforcing that these are specific products for heavy sweaters … which are highly efficient”. Ms Braun was aware that Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection, Mitchum Clinical and Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength were the only antiperspirant deodorants in supermarkets that were sold in a box.

86 Ms Braun’s evidence was that the addition of the words “Clinical Strength” to the stick product differentiated it from the Stress Protect roll-on and aerosol and was intended to signal to the market that the product was “above those two [the roll-on and aerosol] in efficacy”, was “especially for heavy sweaters” and “was a product with a specially high efficacy”. Nevertheless, the “get-up” of the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength stick was designed to indicate that it was still part of the same range as the Stress Protect roll-on and aerosol, which was why it carried the words “Stress Protect” so prominently on the pack.

87 Ms Braun’s evidence in relation to pricing was similar. The price recommended by Beiersdorf as the retail price for the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength stick was similar to Unilever’s recommended price for the Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection range. As has already been noted, that price was substantially higher than most other antiperspirant deodorants. Ms Braun’s evidence was that the recommended pricing of the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength stick was “a [cue] of the sub-category” and that she expected that it would be a strong cue that the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength stick would be more effective than its Stress Protect “siblings”. Beiersdorf’s intention in relation to the pricing was to “adapt to” or to be “aligned with” the segment because the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength stick was Beiersdorf’s strongest antiperspirant deodorant.

Advertising of Beiersdorf’s product

88 During the period 14 August 2014 to 2 April 2015, two Beiersdorf television commercials were broadcast throughout Australia. The common theme of those advertisements was fighting stress sweat and associated body odour. The advertisements included the following visual or audio cues or messages: “Nivea’s strongest protection against heavy stress sweat”; “[p]ut an end to extra heavy stress sweating or your money back”; “Nivea’s strongest stress sweat solution”; and “with the highest concentration and most advanced stress sweat fighting anti-perspirant ingredients”.

89 As can be seen, the claims concerning the properties of the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength product that were made in the advertisements related almost exclusively to protection against stress sweat. Little or nothing was made of any property or properties relating to the word “clinical”. Perhaps more significantly, to the extent that the advertisements contained any comparative claims, the comparisons related to other Nivea products. There was certainly no express comparisons with, or even mention of, the Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection products or Mitchum Clinical.

90 The Nielsen Company is a company which, amongst other things, provides market data including sales, distribution, market share and market pricing covering major Australian retailers including Woolworths, Coles and IGA. Nielsen’s data concerning antiperspirant deodorants included information about the type or category of each product. That information was provided by the suppliers, including Unilever and Beiersdorf. The vast majority of the products in Nielsen’s database were simply described as being “anti-perspirants”. The exception was that each of the products in Unilever’s Clinical Protection range, the Mitchum Clinical range and Beiersdorf’s Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength range were described in the Nielsen data as being “clinical” products. The effect of Ms Braun’s evidence was that Beiersdorf supplied information to Nielsen concerning the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength range on the basis that the products within the range were in the “clinical category” because Beiersdorf was “launching [the range] into the clinical category”.

Nivea Stress Protect range in the United Kingdom

91 Beiersdorf also marketed, distributed and sold a Nivea Stress Protect range in the United Kingdom. That range included a Nivea Stress Protect stick. That product was essentially the same as the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength stick sold in Australia, save for the fact that the Australian product had a different and stronger fragrance. As noted earlier, Beiersdorf arranged for the formulation of the Stress Protect stick which was to be launched in Australia to have a stronger fragrance following the 2012 blind home user tests.

92 The Nivea Stress Protect stick which was sold in the United Kingdom was not called “Clinical Strength”, was not sold in a box and was not sold at a significantly higher price than the Nivea Stress Protect roll-on or aerosol. It should be noted, however, that there was no “clinical” subcategory or segment of antiperspirant deodorants in the United Kingdom. Ms Braun’s evidence was that the “clinical” segment was specific to Australia.

Expert marketing evidence concerning antiperspirant deodorants

93 Unilever adduced expert evidence from Professor Jill Klein, Professor of Marketing at the Melbourne Business School, University of Melbourne. There was no issue concerning Prof. Klein’s experience, qualifications or expertise. Nor was there any dispute that the opinions she expressed were based wholly or substantially on specialised knowledge derived from her training, study or experience.

94 In preparing her expert report, Prof. Klein was asked to assume a number of facts, including facts relating to the market for antiperspirant deodorants in Australia as at July 2014. It is unnecessary to set out the facts that Prof. Klein was asked to assume. It should, however, be observed that Prof. Klein was in effect asked to assume that there was a “clinical” segment of the Australian market which was occupied by the Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection products and Mitchum Clinical. She was also asked to assume that those “clinical” products provided a greater level of protection against excessive sweating. As will be seen, some of Prof. Klein’s key opinions did not travel much beyond those assumptions.

95 Prof. Klein was asked to report on how consumers, or different types of consumers, form opinions about the strength of an antiperspirant deodorant in combatting perspiration amongst products ordinarily available in supermarkets in Australia. She was asked to answer that question in relation to both products ordinarily available in supermarkets in Australia and the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength products. Prof. Klein was asked to address those questions by reference to any relevant statements of accepted marketing principle, research or characteristics of consumer behaviour.

96 Prof. Klein’s evidence was that the answer to the key question asked of her “very much related to the issue of how consumers learn about and categorise products and the cues consumers use to assign a particular product to a category or subcategory”. According to Prof. Klein, as consumers are exposed to information about different products, they develop “schemas”, organised around taxonomic categories or divisions that classify similar objects into the same category. She gave, as an example, the schema for soft drinks, which would include Coke, Pepsi, Diet Pepsi, Sprite, Coke Zero, Fanta Orange and, no doubt, a number of other carbonated drinks. Prof. Klein’s evidence was that schemas can contain category and object associations, and are hierarchical and organised into subcategories. The soft drink schema, for example, could be organised into subcategories, such as diet and non-diet soft drinks. Advertising, pricing, packaging and shelving placement can all contribute to consumers developing subcategories.

97 Prof. Klein’s opinion, based on the facts she was asked to assume and her knowledge of consumer behaviour, was that there was a “clinical subcategory” of antiperspirant deodorants in the minds of consumers in Australia. That view was supported by the following factors: the advertising of “clinical products” that emphasised the word “clinical” and that the products were for heavy sweaters or people who needed a very strong deodorant; the pricing of products in the subcategory, which was two to three times higher than regular antiperspirants; the packaging of the “clinical” products, which was distinct in the use of a box and the prominent display of the word “clinical”; and the fact that supermarkets typically shelved the clinical products together, often in the top or second from the top shelf.

98 In cross-examination, Prof. Klein explained the development of the subcategory for clinical deodorants in the following terms:

Did you study that …..?---So it’s hierarchical. So people – people in Australia would probably have an antiperspirant schema. And it may have subcategories or – you know, there’s the general category – and above that is toiletries and healthcare products and all kinds of things. So it’s – it’s a very broad category. Within that we have antiperspirants, deodorants. And growing up, learning about these things, seeing our parents use them, seeing advertisements, seeing the products, we would then get a more complicated schema. And it wouldn’t just be the one mum uses but we would start to get more and more information populated. And we might – you know, perhaps someone would have the roll-on subcategory or the not-roll-on subcategory. There might be different kinds of – the very smelly, perfume-y ones. The not so perfume-y one. Women’s ones. Men’s ones. You know, depending on how much someone has paid attention, they might have more or less complex schemas. So what I’m suggesting in – in my statement is that over time as these clinical products started to become known, people saw them on the shelves, people talked about them, people started using them, people saw advertisings for them – they would start creating a subcategory of clinical antiperspirant deodorants. And then there would be associations they would make with those: that they’re very strong or that they solve a special person’s problem or something like that.

99 Importantly, in Prof. Klein’s opinion, consumers were very likely to classify the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength stick as a “clinical product” due to: the similarities between the advertising of that Nivea product and the advertising for the other “clinical protection products” (principally the Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection range); the price, which was roughly two to three times higher than normal antiperspirant deodorants; the packaging, which was in a box with the prominent display of the word “clinical”; the shelving of the products in supermarkets, which was typically together with other so-called clinical products; the fact that the “point [was] clearly made that these products [were for] people who sweat a great deal and/or need a very strong deodorant”; and the fact that the “clinical product advertised is different from regular antiperspirants”.

100 As will be discussed in more detail shortly, however, Prof. Klein’s opinions did not directly address what were perhaps the most critical questions. Those questions relate to what the ordinary reasonable consumer perceived, or was likely to perceive, that “membership” of the clinical subcategory entailed. What did a particular product’s membership, or claimed membership, of the clinical subcategory represent to consumers? What did consumers perceive to be the common qualities or characteristics of the products within the clinical subcategory?

101 Consumers presumably did not buy, or consider buying, products in the clinical subcategory simply because they were sold in a box, or included a leaflet, or were described by reference to the word “clinical”, or (almost self-evidently) because they were more expensive. They presumably bought them because they associated those features with certain characteristics or qualities of the products in the subcategory. Prof. Klein did not indicate, from a marketing or consumer behaviour perspective, exactly what those characteristics or qualities were. To the extent that her evidence did touch on that issue, it tended to suggest that consumers simply perceived that the products in the clinical subcategory were high-strength or high-efficacy products for use, or intended use, by heavy sweaters.

Supermarket shelves and planograms

102 The major supermarkets determine how particular products, including antiperspirant deodorants, are to be placed on their shelves. They prepare “planograms” which depict how the various brands and product ranges are to be shelved.

103 Planograms prepared by Woolworths and Coles during the relevant period tended to reveal that the supermarkets generally grouped the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength range together with the Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection range and the Mitchum Clinical range. Those products tended to be grouped together towards the middle of either the top or second top shelf of the shelving that housed antiperspirant deodorants. Photographs taken at various supermarkets also showed that the planograms were generally implemented.

104 Unilever tendered summaries of various consumer complaints received and recorded by Beiersdorf in relation to the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength stick. The nature of some of those complaints is dealt with in more detail later in the context of the question whether the alleged representations, if made, were false or misleading. Some of the complaints, however, are also potentially relevant in considering whether the alleged representations were made.

105 The content of some of the consumer complaints tended to suggest that consumers did associate the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength stick with the Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection range and the Mitchum Clinical range. One consumer, for example, said “I have previously used the same style deodorant Rexona and Mitchum”. Others reported that they had used Rexona Clinical Protection but thought they would “give Nivea a go” or “try the Nivea version”. One consumer reported that he or she had “changed from a similar deodorant from Rexona”.

106 Beiersdorf ceased supplying the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength products in Australia on and from 31 December 2016.

107 The representations allegedly made by Beiersdorf, as pleaded in Unilever’s Further Amended Statement of Claim (FASOC), were as follows:

1. Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength is a product with similar antiperspirant efficacy and characteristics to the Clinical Products [FASOC 28(a)].

2. Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength is a product which will, if used, provide similar antiperspirant protection to the Clinical Products [FASOC 28(b)].

3. Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength is a product with greater antiperspirant efficacy than all other non-clinical antiperspirant deodorants ordinarily available from supermarkets in Australia [FASOC 28(c)].

4. Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength is a product which will, if used, provide a greater level of antiperspirant protection than all other non-clinical antiperspirants ordinarily available from supermarkets in Australia [FASOC 28(d)].

5. Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength is a product which has a similar efficacy in preventing stress sweat to the Clinical Products [FASOC 28(e)].

6. Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength is a product which will, if used, provide similar antiperspirant protection to the Clinical Products against stress sweat [FASOC 28(f)].

7. Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength is a product with greater antiperspirant efficacy in protecting against stress sweat than all other non-clinical antiperspirant deodorants ordinarily available from supermarkets in Australia [FASOC 28(g)].

8. Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength is a product which will, if used, provide a higher level of protection from stress sweat than all other non-clinical antiperspirant deodorants ordinarily available from supermarkets in Australia [FASOC 28(h)].

9. Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength has a particularly strong efficacy for consumers who suffer from stress sweat [FASOC 35(a)].

10. Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength will provide particularly strong protection against stress sweat [FASOC 35(b)].

11. Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength will, if used, provide a higher level of protection from stress sweat than all other non-clinical antiperspirant deodorants ordinarily available from supermarkets in Australia [FASOC 35(c)].

108 The term “Clinical Products” is defined in the pleading as comprising, essentially, the Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection range and the Mitchum Clinical range. While not specifically defined in the pleading, the expression “non-clinical [a]ntiperspirant [d]eodorants” would appear to include all antiperspirant deodorants other than the “Clinical Products”. The term “[a]ntiperspirant [d]eodorants” is defined as products which combine antiperspirant and deodorant characteristics.

109 Beiersdorf admitted that it made representations 9 and 10. It denied making any of the other representations.

110 It was common ground that representations 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 11 were representations as to future matters within the meaning of s 4 of the ACL.

111 It should perhaps be noted that representations 8 and 11 are in almost identical terms. Unilever did not explain why that was the case or whether anything turned on the different context in which those particular representations were pleaded.

112 While there are various differences between the representations, some of them fairly minor, it is possible and useful to group the representations into three groups: first, those that involve a representation that Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength was a product which had, or would if used have, similar antiperspirant efficacy and characteristics to the Clinical Products, or similar efficacy in preventing stress sweat to the Clinical Products (representations 1, 2, 5 and 6); second, those that involve a representation that Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength was a product which had, or would if used have, greater antiperspirant efficacy, or greater antiperspirant efficacy in protecting against stress sweat, than all other non-clinical antiperspirant deodorants ordinarily available from supermarkets in Australia (representations 3, 4, 7, 8 and 11); and third, those that involve a representation that Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength was a product which had a particularly strong efficacy or would provide particularly strong protection in relation to stress sweat (representations 9 and 10).

113 The first group will be referred to generally as the Similarity Representations; the second group will be referred to as the Superiority Representations; and the third group will be referred to as the Stress Sweat Representations. As has already been noted, Beiersdorf admitted that it made the Stress Sweat Representations.

114 It can be seen that each of the pleaded representations refer, in one way or another, to either “antiperspirant efficacy” or “antiperspirant protection”. At Beiersdorf’s request, Unilever provided further particulars of those expressions in the context in which they were used in the representations. Unilever’s further particulars stated, perhaps unhelpfully, that the expressions “similar antiperspirant efficacy” and “similar antiperspirant protection” were to be given their “ordinary English meaning”. More significantly, Unilever’s case as further particularised was said to be that the “criterion for efficacy and protection is a comparison of perspiration reduction, following use of antiperspirants by a consumer”. Similarly, it was said that the “criterion for efficacy in preventing stress sweat, acting against stress sweat and protecting against stress sweat is a comparison of stress sweat reduction following use of antiperspirants by a consumer”.

115 The pleaded representations must be read and construed having regard to the further particulars provided by Unilever. The criterion for the efficacy and protection of antiperspirant deodorants, on Unilever’s case, was strictly quantitative and limited to the amount by which the respective products reduced the amount of sweat that would otherwise have been excreted. The efficacy that the relevant products might have had in terms of preventing or masking odour associated with perspiration – the efficacy of the products as deodorants – was, on Unilever’s case, essentially irrelevant. As will be seen, there was a significant issue concerning whether the ordinary reasonable consumer of antiperspirant deodorants in Australia would have seen or perceived efficacy, or representations or claims about efficacy, in such narrow terms.

116 There are four principal issues.

117 The first issue is whether, in marketing, distributing and selling the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength product in the way it did, Beiersdorf made any of the Similarity or Superiority Representations.

118 The second issue is whether the Similarity and Superiority Representations which did not involve representations as to future matters (representations 1, 3, 5 and 7), if found to have been made by Beiersdorf, were false. It should be noted in this context that, while Unilever pleaded that the Similarity and Superiority Representations were false, misleading or deceptive, it ultimately put its case solely in terms of the representations being false.

119 The third issue is whether the Stress Sweat Representation which did not involve a representation as to future matters (representation 9) was false.

120 The fourth issue is whether Beiersdorf had reasonable grounds to make such of the Similarity, Superiority and Stress Sweat Representations which involved representations as to future matters (representation 10, which Beiersdorf admitted to making, and representations 2, 4, 6, 8 and 11, if it is found to have made them).

Issue 1: Did Beiersdorf make the Similarity and Superiority Representations?

121 The first issue is whether, in marketing, distributing and selling the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength product in the way it did, Beiersdorf made any of the Similarity or Superiority Representations.

122 The first point that should be made in respect of this issue is a rather obvious one. The point is that this is not a passing-off case, or at least not the usual type of passing-off case, where a trader who has established a reputation in a particular or distinctive name, “get-up”, or other trade indicia, alleges that a competitor had effectively appropriated that name or get-up and was thereby misleading consumers by representing that there was some association between the two rival traders or their products. Unilever did not allege that, by using the name “clinical”, or by selling its products in a box with a leaflet, or by selling its products at a price which was higher than other “non-clinical” antiperspirant deodorants, Beiersdorf misled, or was likely to have misled, consumers into believing that the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength products were somehow associated or affiliated with Unilever or its Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection range. There was also no allegation that consumers were, or were likely to be, misled as to the source or origin of the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength range. There could be little doubt that consumers were aware, or were likely to be aware, that Unilever’s Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection products and Beiersdorf’s Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength products were rival products that were marketed, distributed and sold by rival traders.

123 As Beiersdorf pointed out, it was not in any way prevented from using the word “clinical” in its product name or in its marketing, unless in doing so it misled or deceived consumers in some way. Nor was it prevented from selling its product in a box with a leaflet, again unless in some way it misled or deceived consumers. Beiersdorf argued that that was unlikely to be the case, at least in the conventional passing-off sense, in circumstances where it had clearly marked its product to distinguish it from Unilever’s products. In that regard, the following observations of Gibbs CJ in Parkdale were apposite (at 199-200):

Speaking generally, the sale by one manufacturer of goods which closely resemble those of another manufacturer is not a breach of s. 52 if the goods are properly labelled. There are hundreds of ordinary articles of consumption which, although made by different manufacturers and of different quality, closely resemble one another. In some cases this is because the design of a particular article has traditionally, or over a considerable period of time, been accepted as the most suitable for the purpose which the article serves. In some cases indeed no other design would be practicable. In other cases, although the article in question is the product of the invention of a person who is currently trading, the suitability of the design or appearance of the article is such that a market has become established which other manufacturers endeavour to satisfy, as they are entitled to do if no property exists in the design or appearance of the article. In all of these cases, the normal and reasonable way to distinguish one product from another is by marks, brands or labels. If an article is properly labelled so as to show the name of the manufacturer or the source of the article its close resemblance to another article will not mislead an ordinary reasonable member of the public.

124 The second point is perhaps equally obvious. With the possible exception of the Stress Sweat Representations, which were in any event admitted, Beiersdorf did not expressly make any of the representations. Neither the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength advertisements, nor the get-up or other trade or marketing indicia or material, expressly stated that the Nivea product was or would be similarly efficacious, or would provide similar antiperspirant protection, to the products in the Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection range and the Mitchum Clinical range. No such statement was made on the relevant Nivea canisters, or the box in which they were sold, or in the leaflet that was included in the box. The marketing material did not contain or include any express comparison of any sort between the antiperspirant efficacy of the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength products and the Rexona or Dove Clinical Protection and Mitchum Clinical products.

125 The Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength advertisements and other marketing material also did not expressly state that the products had greater antiperspirant efficacy than all other “non-clinical” antiperspirant deodorants. Nor was such a representation expressly made on the relevant Nivea canisters, or the box in which they were sold, or in the leaflet included in the box.

126 In those circumstances, Unilever’s case was, in substance, that the Similarity and Superiority Representations were to be implied or inferred from Beiersdorf’s conduct in marketing, distributing and selling the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength range; that Beiersdorf’s conduct in that regard impliedly or implicitly conveyed the representations. Unilever contended, in short, that Beiersdorf had not employed the “primitive club of direct misrepresentation”, but had instead employed the “more sophisticated rapier of suggestion”: cf. Pacific Dunlop Ltd v Hogan (1989) 23 FCR 553 at 586.

127 It should be emphasised, in this context, that the question whether the representations were conveyed as alleged must be approached from the perspective of the relevant class of people who were, or were likely to be, misled or deceived by the representations if they were false as alleged. The relevant class of persons, having regard to the way Unilever pleaded its case, was the class of ordinary or reasonable consumers of antiperspirant deodorants in Australia. Unilever alleged that the relevant market was the Australian market for antiperspirant deodorants. While Unilever contended that there was a clinical subcategory or segment within the Australian market for antiperspirant deodorants, it did not go so far as to allege or contend that there was a separate market for so-called clinical antiperspirant deodorants.

128 Unilever’s case, in simple terms, was that the Similarity Representations and the Superiority Representations were implicitly or impliedly conveyed to ordinary reasonable consumers of antiperspirant deodorants by Beiersdorf’s marketing, distribution and selling of the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength range having regard to particular features of the market for antiperspirant deodorants in Australia at the relevant time. In that regard, Unilever pointed, in particular, to evidence that suggested that there was a clearly established “clinical” subcategory or segment of the antiperspirant deodorant market in Australia. Prior to the launch of the Nivea product, the Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection range and the Mitchum Clinical range were essentially the only products in the clinical subcategory. Those products had particular and unique features: use of the word “clinical”; packaging in a box; the inclusion of a leaflet in the box; and a significantly higher price than products that were not within the clinical subcategory or segment.

129 Unilever’s case was that, when Beiersdorf launched its Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength range in Australia in July 2014, it consciously and deliberately launched it in the clinical subcategory or segment. It prominently used the word “clinical” on the canisters and packaging; it sold the product in a box; it provided a leaflet in the box; and it recommended that the product be priced at a price similar to the Rexona, Dove and Mitchum products in the clinical segment, being a price significantly higher than most, if not all, other antiperspirant products. Unilever contended that, in those circumstances, Beiersdorf impliedly conveyed to ordinary reasonable consumers of antiperspirant deodorants that, in general terms, the Nivea Stress Protect Clinical Strength product would have similar antiperspirant efficacy, or provide similar antiperspirant protection, as the antiperspirants that were already established in the clinical subcategory: the Rexona and Dove Clinical Protection antiperspirant deodorants and the Mitchum Clinical range.