FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Rokt Pte Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2018] FCA 1988

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The notice of contention is dismissed.

3. The decisions of the Commissioner given on 11 October 2016 and 11 July 2017 are set aside.

4. Australian patent application No. 2013201494, in the form which includes the claims dated 11 November 2016, proceed to grant.

5. The respondent pay the applicant’s costs, as agreed or taxed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ROBERTSON J:

Introduction

1 On 13 March 2013, the applicant (Rokt) applied for the grant of a patent entitled “A Digital Advertising System and Method” and requested examination. The application number was 2013201494 and its claimed priority date was 12 December 2012.

2 The patent was the subject of a number of amendments and re-examinations in the period 2013-2017. Relevantly, the Commissioner, by her delegate, considering the patent in a re-examination initiated pursuant to s 97(1) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth), decided on 11 July 2017 that the patent application should not proceed to grant: Rokt Pte Ltd [2017] APO 34.

3 The applicant appeals, under s 100A(3) of the Patents Act, from the whole of that decision.

4 To the extent necessary, the applicant also appeals from the decision of the Commissioner, by her delegate, given on 11 October 2016 providing the applicant one month to file amendments and supporting submissions, absent which the delegate would proceed to refuse the application: Rokt Pte Ltd [2016] APO 66.

5 That step having been taken by the applicant, it is not necessary to consider whether the applicant needed to challenge both the Commissioner’s 11 October 2016 decision as well as her 11 July 2017 decision.

The patent

6 Claim 1 of the patent, as amended, was as follows, the applicant accepting that claim 15, the other independent claim, was somewhat similar:

1. A computer implemented method for linking a computer user to an advertising message by way of an intermediate engagement offer which is operable to drive a higher level of engagement with the advertising message than if the advertising message was presented without the offer, the method comprising:

providing computer program code to be delivered with publisher content to a computing device operated by the computer user and which computing device comprises an interface arranged to display the publisher content, the computer program code operable to be implemented by a processor of the computing device to perform the additional steps of:

gathering engagement data associated with the user, the engagement data derived from interactions made by the user with the interface and related to at least one of the following:

an attribute of the publisher content;

an interaction with the publisher content by the computer user; and

an attribute of the user;

communicating the engagement data as it is gathered to a remote advertising system implementing an engagement engine, the engagement engine operable to:

continuously evaluate the engagement data to determine whether a predefined engagement trigger has occurred, the predefined engagement trigger being representative of a user response or action that is contextually relevant for presentation of the engagement offer;

responsive to determining that the predefined engagement trigger has occurred, selecting an engagement offer from a pool of different engagement offers stored by the remote advertising system that is relevant to the evaluated engagement data and wherein, where multiple engagement offers are deemed to be relevant, the engagement engine implements a ranking algorithm operable to dynamically rank the relevant engagement offers based on at least one of:

(a) an engagement score determined from one or [more] performance metrics recorded from past user interactions with the corresponding engagement offers;

(b) a revenue score determined from one or more revenue metrics recorded from past user interactions with the corresponding engagement offers, and

wherein the engagement engine selects which engagement offer to present based [on] the rankings;

causing the interface to insert the selected engagement offer into the publisher content for displaying to the computer user;

implementing the computer program code to determine an acceptance of the engagement offer by the computer user based on a user interaction with the engagement offer; and

following the determined acceptance, presenting an advertising message comprising one or more advertisements selected from a pool of different advertisements on the interface and wherein user interactions with each of the presented advertisements are gathered by the widget script and communicated to the remote advertising system for use in selecting subsequent advertisements, and whereby the selection of [sic] engagement offer is additionally made such that there is no direct advertising benefit to the subsequent advertisers of the selected advertisements through presentation of the selected engagement offer to the computer user other than encouraging positive engagement by the user with the advertising system prior to presentation of the advertising message.

The primary difference between claim 1 and claim 15 was that claim 1 was a computer-implemented method and claim 15 was a system for linking a user to an advertising message by way of an intermediate offer. One element of difference which counsel drew to attention was that a remote advertising system implementing a database storing engagement offers and advertisements was claimed in claim 15, and that was not explicitly found in claim 1.

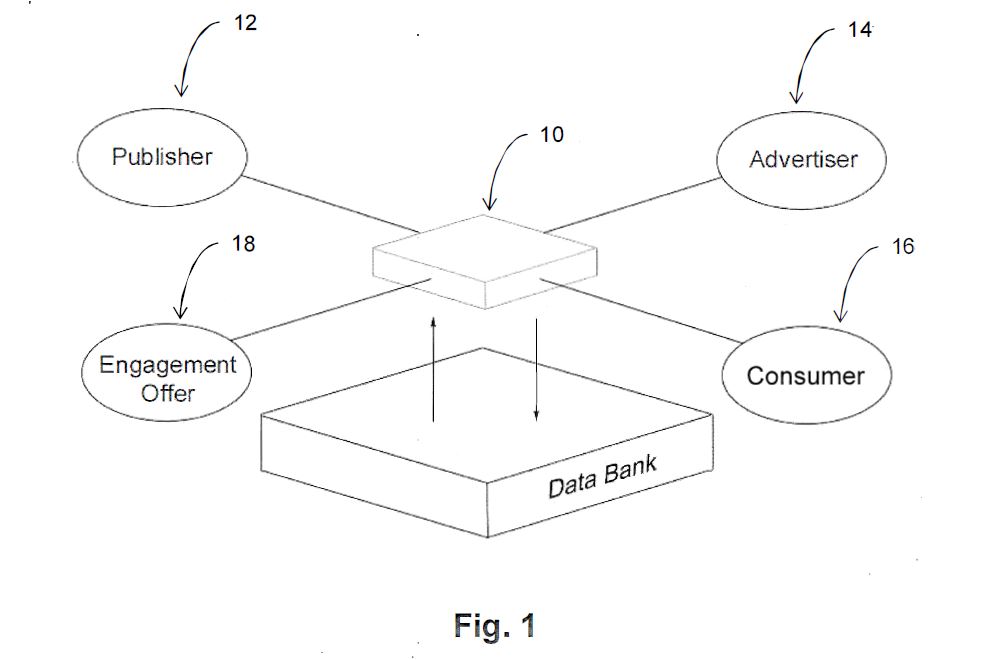

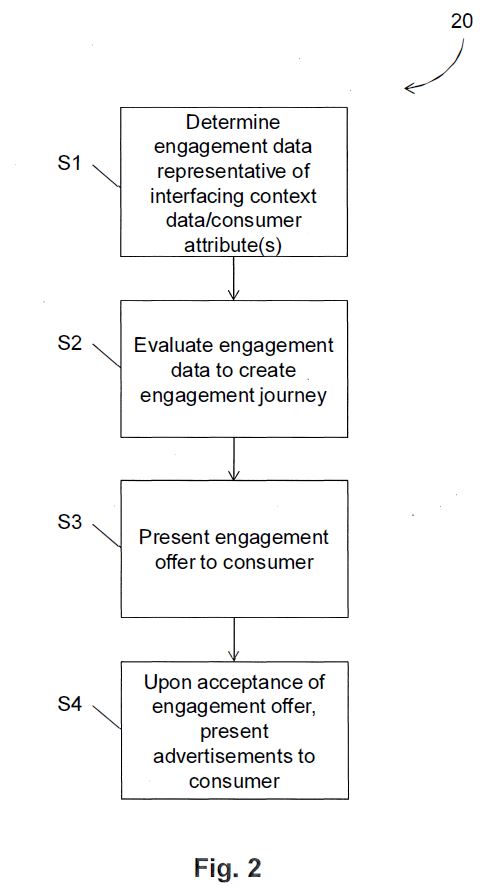

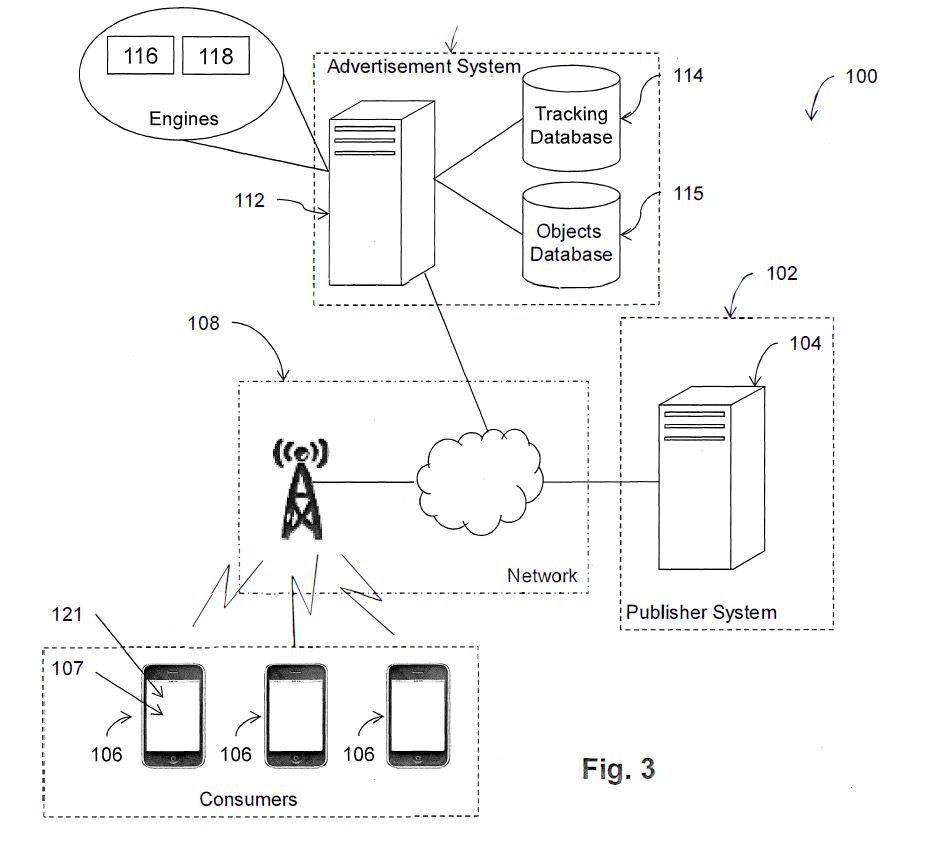

7 Figures 1, 2 and 3 were as follows:

The pleadings

8 In its amended notice of appeal filed on 20 July 2018, the applicant relied on the following grounds:

1. The delegate erred in

a) holding that claim 1 of the application did not disclose a manner of manufacture within the meaning of section 18(1)(a) of the Patents Act 1990;

b) holding that the remaining claims of the application did not add any patentable subject matter to the substance of the invention; and

c) refusing to grant the patent.

2. The delegate ought to have concluded that claim 1 of the application (as amended) discloses a manner of manufacture within the meaning of section 18(1)(a) of the Patents Act 1990, that it and each of the remaining claims of the application contains patentable subject matter, and that the application should proceed to grant.

9 The Commissioner filed an amended notice of contention on 16 April 2018, as follows:

The Respondent contends that if the Court finds that the invention claimed in Australian Standard Patent Application No. 2013201494 (Application) involves a manner of manufacture within the meaning of s 18(1)(a) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (Act), then:

(a) the decision of the Commissioner should be affirmed on the separate ground for refusing the grant of the Application that is stated below;

(b) alternatively to sub-paragraph (a), the issue of whether the grant of a patent on the Application should be refused on the ground stated below should be remitted to the Commissioner to be dealt with in re-examination pursuant to s 97(1) of the Act.

GROUND RELIED ON:

1. The complete specification does not describe the invention fully, including the best method known to the applicant of performing the invention, as required by s 40(2)(a) of the Act.

Particulars

(a) The complete specification does not contain sufficient information concerning the following alleged aspects of the invention to enable a person skilled in the art to produce something within each claim without new inventions, or additions, or prolonged study of matters presenting initial difficulty:

(i) the “ranking engine” that is referred to in paragraph 58 of the affidavit of Professor Karin Verspoor filed on 28 November 2017 (the Verspoor affidavit);

(ii) the “algorithm” that is referred to in paragraph 60 of the Verspoor affidavit;

(iii) the combination of techniques and integration of components that is referred to in paragraphs 68 to 69 of the Verspoor Affidavit; or

(iv) the system that is used to determine what publisher content exists on the Internet that contains content that is contextually relevant to the pool of available engagement offers.

(b) Further or alternatively, the complete specification does not describe any method of performing the invention that addresses the alleged aspects of the invention referred to in sub-paragraphs (a)(i)-(iv) above.

(c) If the invention is, or includes, a superior system for assessing website contextual relevance and/or a superior engine or algorithm for ranking advertising objects compared with the systems, engines and algorithms that were conventionally used in display-based advertising before December 2012, then the Patent Application does not:

(i) contain sufficient information to enable a person skilled in the art to determine without new inventions, or additions, or prolonged study of matters presenting initial difficulty (1) why the Applicant’s system, engine or algorithm is superior or (2) what technical features enable that superiority to be achieved; or

(ii) further or alternatively, describe any method of performing the invention that enables that superiority to be achieved.

(d) The Respondent reserves her right to provide further particulars following the completion of evidence and other interlocutory steps.

The statutory provisions

10 Sections 98 and 100A of the Patents Act were amended with effect from 15 April 2013: see items 17 and 18 of the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth), Sch 1. However, although the amendment to s 98 took effect in relation to ROKT’s application (expanding the grounds that can be considered), the amendment to s 100A (which changed the standard of proof) does not apply because ROKT had requested examination on 13 March 2013, which was before the date of commencement of the amendment: see the transitional provisions in items 55(4) and 55(5) of Sch 1 to the Raising the Bar Act respectively.

11 The central provision, s 18, was in the following form:

Patentable inventions for the purposes of a standard patent

(1) Subject to subsection (2), an invention is a patentable invention for the purposes of a standard patent if the invention, so far as claimed in any claim:

(a) is a manner of manufacture within the meaning of section 6 of the Statute of Monopolies; and

(b) when compared with the prior art base as it existed before the priority date of that claim:

(i) is novel; and

(ii) involves an inventive step; and

(c) is useful; and

(d) was not secretly used in the patent area before the priority date of that claim by, or on behalf of, or with the authority of, the patentee or nominated person or the patentee’s or nominated person’s predecessor in title to the invention.

By Schedule 1, unless the contrary intention appears:

invention means any manner of new manufacture the subject of letters patent and grant of privilege within section 6 of the Statute of Monopolies, and includes an alleged invention.

The evidence

12 Rokt relied on two affidavits of Professor Karin Verspoor. Professor Verspoor is a Professor in the School of Computing and Information Systems at the University of Melbourne. Her academic focus is on computational, algorithmic and programmatic methods for analysis of natural language text and other digitally-represented data. The entirety of her first affidavit, affirmed 28 November 2017, was read. Some parts of her second affidavit, affirmed 4 May 2018, were not read as they were responsive to parts of the affidavit relied on by the Commissioner which were not read, as next explained.

13 The Commissioner relied on parts of an affidavit of Mr Scott Ries affirmed 16 March 2018. Until recently, Mr Ries was the Director of Technical Services at DG/Sizmek, a large, independent digital advertising business. Mr Ries was unavailable to give oral evidence at the hearing of the matter. Only parts of that affidavit were read. The parts that were read were [1]-[28], all but the first sentence of [31], [42]-[45], [49], [53], the first sentence of [54], [60]-[61], the first sentence of [62], [69]-[71], [75], [76] but omitting the words “the same” in the first line, [79], [83] but omitting the last sentence, [84]-[85], the fourth sentence of [86], [88] and [90]-[92].

14 In her first affidavit, Professor Verspoor was asked to give her opinion on the following questions as she would have understood the answer as at December 2012, the claimed priority date:

(1) What is the “substance” of the invention? In other words, what specifically lies at the heart of the invention?

(2) Does the invention solve a technical problem?

(3) Is the use of a computer (or computers) integral to carrying out the invention, or could the invention be carried out in the absence of a computer (or computers)?

(4) Does the invention involves steps that are foreign to the normal use of computers (as at December 2012)?

15 Before addressing question 1, Professor Verspoor first set out her interpretation of each major feature of claim 1 as she would have understood that feature as at December 2012. What follows, at [16]-[38] below, is Professor Verspoor’s understanding.

16 The words “A computer implemented method for linking a computer user to an advertising message” meant a method that selected and presented an advertisement to a consumer through a computer-based device.

17 “Intermediate engagement offer” referred to a computer-based interaction opportunity that was presented to a consumer, for example one of the forms of engagement offers listed on page 9 of the patent, and described pictorially in figures 6 and 7. This opportunity was not an advertising message, but rather was designed to gain the consumer’s attention and interest and was therefore “intermediate”. As an “intermediate” offer, an advertising message would follow only if the consumer’s interest had been signalled through a positive response to the opportunity.

18 “Which is operable to drive a higher level of engagement with the advertising message than if the advertising message was present without the offer” meant that the objective of introducing the intermediate step of the engagement offer was to increase interest in the following advertising message. The patent indicated elsewhere (line 10, page 10) that testing had shown that this two-part strategy was indeed more effective at achieving engagement with the final advertising offers.

19 “Providing computer program code to be delivered with publisher content to a computing device operated by the computer user” introduced a piece of “computer program code”, also described in the patent as a “widget”, which was delivered to a consumer along with publisher content on the user’s device. For instance, this computer program code could be implemented as a piece of Javascript code which was delivered along with the publisher content on a webpage written in HTML (HyperText Markup Language) as described on line 25 of page 12 of the patent.

20 “Which computing device comprises an interface arranged to display the publisher content” meant a user’s device that was capable of accessing and displaying content available on the internet. For example, a laptop or mobile phone with an internet browser, or via an “app” (application) on such a device that directly accessed and displayed internet content. This was described on page 11, line 2 of the patent.

21 “The computer program code operable to be implemented by a processor of the computing device” referred to the execution of the program code, i.e. the “widget”, on the device that the user was using to access the publisher content. This meant that the “widget” effectively changed the local display of the content for the specific user only, by inserting a piece of code that ran on their specific device.

22 “Gathering engagement data associated with the user” meant that the widget that was running on the user’s device was collecting the data.

23 “The engagement data derived from interactions made by the user with the interface” meant that the data that the widget collected from the user’s device was related to at least one of:

(a) Data about the publisher’s content that the user was viewing: “an attribute of the publisher content” referred to characteristics of the content itself, such as the words on a webpage, the URL of the page, a product ID of a product that a user may be viewing, etc.

(b) Data about how the user was interacting with the publisher’s content that they were viewing: “an interaction with the publisher content by the computer user” referred to actions that the user took on a publisher webpage, including purchasing of a specific product or service, clicking on links for more information, etc.

(c) Data about the user: “an attribute of the user” referred to any data that could be collected from the user’s device, including the user’s current physical location (GPS coordinates), or demographic information such as age or gender that might be accessible.

24 “Communicating the engagement data as it is gathered to a remote advertising system implementing an engagement engine in real time” referred to the widget sending the engagement data from the user’s computer device to the advertising system through the computer network. The advertising system was hosted on a separate computer or computers, and would receive the data sent from the user’s device “in real time”, e.g. as soon as it could be transmitted through the network.

25 “The engagement engine operable to continuously evaluate the engagement data to determine whether a predefined engagement trigger has occurred” referred to the use of the data by the engagement engine that was part of the advertising system to decide when to present an engagement offer to the consumer. In other words, there was, as part of the engagement engine, a computer program running on a server that accepted the engagement data transmitted by the widget and continuously evaluated it against pre-defined rules, to determine when to instruct the widget to display an engagement offer. This engagement engine appeared in figure 3 as object 116, and was described, for example, on page 15 line 20 of the patent, as well as on page 17 lines 25-26.

26 “The predefined engagement trigger being representative of a user response or action that is contextually relevant for presentation of the engagement offer” indicated the rules defined by the engagement engine for deciding when to present an engagement offer to a consumer on the user device, specifically whether or not the user characteristics or interactions with the publisher content satisfied criteria for displaying an engagement offer. In other words, the rules were set such that the engagement offer was displayed at an appropriate time based on what the user was doing. For example, as described on page 21, lines 27-34 of the patent, an appropriate time for displaying an engagement offer to a user who was purchasing band tickets may be immediately after the purchase had been completed. The completion of the ticket purchase would be part of the engagement data transmitted by the widget to the engagement engine.

27 “Responsive to determining that the predefined engagement trigger has occurred, selecting an engagement offer from a pool of different engagement offers stored by the remote advertising system” meant that once the rules defined by the engagement engine for presenting an engagement offer were satisfied, then the engagement engine would select which engagement offer to present to the consumer from those stored in the advertising system in the objects database (item 115 in figure 3) based on the engagement data. The data had been defined in the claims as “the evaluated engagement data” which meant the specific user data that had been sent to the engagement engine from the user’s device, as described in [23] above, i.e., based on the consumer’s data previously gathered by the widget. In other words, to use the example just given, where the user was purchasing band tickets, relevant engagement offers were likely to include offers related to the band or the performance, such as the “VIP backstage pass” promotion mentioned on page 21 line 34 of the patent.

28 “Wherein, where multiple engagement offers are deemed to be relevant, the engagement engine implements a ranking algorithm operable to dynamically rank the relevant engagement offers” referred to an algorithm implemented in the engagement engine that used the consumer’s data and other historical user-specific data stored in the tracking database to select engagement offers and order them by preference (rank). An algorithm in this sense meant a specification of a series of computational steps acting on data involving calculation, evaluation, and modification of the data. Algorithms were usually defined in order to achieve a particular result or to solve a problem. In the case of a relevancy ranking algorithm, the result to be achieved was to order a series of “objects” (e.g., engagement offers) from most to least relevant.

29 One set of data used by this algorithm was “an engagement score determined from one or [sic] performance metrics recorded from past user interactions with the corresponding engagement offers;”, that is, data for each engagement offer, including whether or not the target user or other consumers responded to it, as well as what actions they took in responding to it. For example, as described on page 18, from line 22, any given consumer’s behaviour could be quantified with positive and negative points depending on how that user responded to an engagement offer.

30 Another set of data used by this algorithm was “a revenue score determined from one or more revenue metrics recorded from past user interactions with the corresponding engagement offers,” that is, data for each engagement offer about whether or not the target user or other consumers responded to the advertising message that followed after the engagement offer. For example, as set out on page 19, lines 3-11, this may include calculation of the amount of revenue earned by an advertiser resulting from a positive response to the advertising message.

31 “Wherein the engagement engine selects which engagement offer to present based on the rankings” referred to the use of the preference ordering (ranking) based on the data described in [29]-[30] above to pick the engagement offer to present to the user. In other words, after applying the ranking algorithm, the engagement engine might select the highest-ranked engagement offer (the engagement offer at the “top” of the ordered list) and send it to the widget on the user’s device for display to that user.

32 “Causing the interface to insert the selected engagement offer into the publisher content for displaying to the computer user” referred to the action that was taken by the computer program code (widget) on the user’s device after the engagement engine had selected which offers to present to the user. This meant that the computer program code (i.e., the widget) changed what the user saw on their device, i.e., that there were new images, text, or pop-up windows that were displayed to the user on their device when they were accessing the publisher’s content, such as through a web page. This was described pictorially in figures 4 and 6-7. The result was that after an engagement offer had been selected by the engagement engine, it would be transmitted over the internet to the widget and presented on the user device by the widget.

33 “Implementing the computer program code to determine an acceptance of the engagement offer by the computer user based on a user interaction with the engagement offer” referred to the widget recording how the user responded to the presentation of the engagement offer. If the consumer clicked on a relevant link or pressed a button on their display to indicate their interest, or pressed a “skip” button (recorded for example on page 22, line 30 of the patent) to express lack of interest, then the widget would record that action.

34 “Following the determined acceptance, presenting an advertising message ... on the interface” referred to the action that the advertising system took when the widget recorded a positive interaction from a user, specifically to display one or more advertisements on the user’s computer device, again through the widget program code modifying the content of what the user saw on their device.

35 “Comprising one or more advertisements selected from a pool of different advertisements” referred to the fact that there may be multiple advertising messages that could follow on from a given accepted engagement offer, and the advertising system would select one or more of these possible messages.

36 “Wherein user interactions with each of the presented advertisements are gathered by the widget script” meant that the widget monitored and recorded the actions that the user took when each advertising message was displayed, i.e., whether or not they responded positively to the advertising message (e.g., a positive response through purchasing the advertised product or service, or a negative response through skipping or declining the advertisement as mentioned for example on page 14 line 3 and page 15 line 2 of the patent). In other words, the widget introduced a user-monitoring aspect which was not part of the standard publisher content displayed in the browser.

37 “Communicated to the remote advertising system for use in selecting subsequent advertisements” referred to the transmission of data captured by the widget about the user’s response to the advertisement via the computer network for storage in the tracking database for subsequent use in selecting advertisements. The tracking database was a computer database shown as item 114 in figure 3. For instance, as described in claim 12 of the patent (page 31), this data could be used subsequently to select engagement offers to show to other users who shared one or more attributes with this user.

38 “Whereby the selection of engagement offer is additionally made such that there is no direct advertising benefit to the subsequent advertisers of the selected advertisements through presentation of the selected engagement offer to the computer user other than encouraging positive engagement by the user with the advertising system prior to presentation of the advertising message” referred to the non-advertising nature of the engagement offer. The tracking database recorded the user’s response to each engagement offer and each advertisement that was presented, and that data may be used to select an engagement offer. As was made clear, however, the engagement offer itself was something that was not an advertisement promoting a specific advertiser, and it did not provide any direct benefit to an advertiser whose advertisement may be subsequently displayed. In other words, it would not directly benefit any individual advertiser but was used only to attract engagement with the subsequent advertising messages.

39 In Professor Verspoor’s view, having regard to both the claims and the body of the specification, the substance of this invention was to introduce a dynamic, context-based advertising system. The invention introduced a distinction between an engagement offer, designed to capture a user’s attention but without a direct advertising benefit, and an advertisement, designed to directly lead to the sale of the product. She referred to the specification at page 10. She referred to the contrast, in the preamble, with the traditional type of advertising where the actual consumer engagement levels were still very low.

40 She deposed that there were four key stakeholders in the invention: the users (consumers), the publishers, the advertisers, and the operator of the advertising system itself. The role and participation of each of these stakeholders in the patent were set out in detail on pages 8-26. These stakeholders were shown in figure 1 and again, in a slightly different configuration, in figure 3 (although she noted that the role of the “advertiser” did not explicitly appear in figure 3, she understood that it was implicit in the reference to the “advertising system”). In particular, she noted that what the patent called the “basic process flow” was set out in figure 2 and the implementation of that basic process flow occurred within the overall architecture shown in figure 3. These figures are reproduced at [7] above.

41 Professor Verspoor deposed that by providing a common platform to relate consumers visiting content on publisher websites to advertising derived from advertisers, the invention was able to make use of wide-ranging data to rank engagement offers. This data derived from both the target consumer as well as from other consumers interacting with the system, and resulted in the calculation of an engagement score and a revenue score used for ranking.

42 In Professor Verspoor’s opinion, the process which she had described and which she observed to be the substance of the patent could be described as an improvement in computer technology. The invention introduced a novel architecture for the advertising system, through the new layer of engagement offers. Through direct collaboration with the publishers, the invention involved insertion of a widget into the publisher content to serve the engagement offer.

43 Further, the use of a data-based scoring algorithm to decide what engagement offers to serve presented an important improvement to existing computer-based advertising.

44 The invention also introduced a novel architecture for an advertising system, through the recording and transmitting of user interactions with advertisements and using that data to select subsequent advertisements.

45 She deposed that, having significant experience from both an academic and industry perspective in digital advertising methods, she was not aware of any similar methods of computer-based advertising models as at December 2012.

46 Turning to question 2, whether the invention solved a technical problem, Professor Verspoor deposed that the key technical problem that was addressed by the invention was that of providing a single platform in which user engagement data could be coupled with transactional data (for instance, as described on page 17 line 13 of the patent) and user context data (including real-time information based on time, location, and mode of access to publisher content as well as historical data for both the user and similar users), in order to provide a personalised ranking of engagement offers to the user.

47 In Professor Verspoor’s experience, an ever-present challenge in the context of data analytics (which was most definitely involved in this patent, particularly within the ranking engine feature) was being able to access relevant data to effectively tailor decisions or outputs, meaning having the right data utilised in the right context to personalise the experience of the system for a user. This naturally presented technical difficulties when multiple stakeholders were involved and when a system must manage each of their requirements.

48 Having regard to the patent, in Professor Verspoor’s view this technical problem was solved by introducing two databases - the tracking database and the objects database - and designing two engines - the ranking engine and the engagement engine - which accessed and manipulated the data in these databases to rank and select engagement offers.

49 In Professor Verspoor’s opinion, the ranking engine was important. Claim 1 of the patent included a feature of a ranking engine which included the running of an algorithm. This was further described commencing on page 18 of the patent, as follows:

At step S6a, the ranking engine 118 filters the retrieved behavioural metrics such that only those metrics relevant to the retrieved objects are kept for evaluation.

At step S7a, the ranking engine 118 implements a ranking algorithm which ranks the retrieved objects by a combination of an engagement score and revenue score (where applicable)...

50 In this way, Professor Verspoor deposed, the ranking engine optimised the personalised output for the consumer.

51 Professor Verspoor deposed, in effect, that the role of the relevant algorithm here was important because the quality of the result to the user depended on the quality of the algorithm.

52 Based on the statements in the patent, the implementation of the claimed advertising method may also have the effect of increasing user engagement with subsequent advertising offers. If this improvement had the effect of solving (or at least improving) the problem associated with traditionally low consumer follow-up, then the invention appeared to Professor Verspoor to also solve that problem.

53 To this end, in the context of the stakeholders, she noted that the patent stated the following on page 25:

Further, the ability to inter-connect stakeholders in this manner allows the advertising system 10 to provide a rich and deep pool of advertising content that can be drawn on to better match individual consumers with individual advertisers, in turn increasing the likelihood of a positive engagement.

54 Further, this solution to the technical problem was not, in Professor Verspoor’s view, limited to any specific content. This was a technical problem faced by all software that delivered online digital advertising. That is, the claimed advertising method was not dependent on the nature of the engagement or advertising content itself; the content could comprise any information from any advertiser. Similarly, the “consumer” (as described on page 12 and in figure 3 of the patent) could be any consumer, in any context.

55 Turning to question 3, whether the use of a computer was integral to the invention, Professor Verspoor’s opinion was that the use of computers was integral to carrying out the invention. In the first instance, the data bank (figure 1) that was the source of both engagement objects (item 115) and historical/tracking data (item 114) were critical components of the invention. In her experience, it was not feasible for a non-digital implementation (i.e. one which did not involve the use of computers) to: (a) store and manage large amounts of tracking data collected from real-time interactions with digital devices; and (b) manipulate large quantities of data for context-sensitive decision making.

56 Storage and manipulation of data, including real-time, context-specific data (with which the patent was concerned), at the magnitude and speed that was required to implement this method, could only be done on a computer. In Professor Verspoor’s view, it was infeasible to perform the type of data analysis claimed in the patent without a computer (indeed, without several computers). This was particularly so having regard to the gathering, manipulation and subsequent use of the data by the engagement engine.

57 Since the user interactions took place on a computer (i.e., the user’s device), it was also integral to the invention that data be collected, and engagement offers be presented, through that computer. The method could not be implemented without the user’s device. The transmission and receipt of data over the internet to and from the advertising system could also only be done using computers.

58 Turning to question 4, whether the invention involved steps foreign to the normal use of computers, Professor Verspoor’s opinion was that this invention introduced new uses of computer technology. If the phrase “foreign to the normal use of computers” was intended to mean “the use of computers in a way that they have not been used before”, she was of the view that the patent introduced a method which was foreign to the normal use of computers. This followed from her preceding observations about:

(a) the novel architecture adopted in the invention; and

(b) the existence of the technical problem that was said to be solved by the invention.

59 In Professor Verspoor’s opinion, the invention the subject of the patent drew together different streams of information, put them together and worked with them in a way that was new and had not been done before. The combination of these techniques was therefore new. Certain elements of the invention were also new and were not known as at December 2012. The concept and implementation of an engagement offer, the use of a widget to continuously monitor the user’s interaction with the website to determine when to display the engagement offer, the use of a widget to monitor the user’s interaction with the engagement offer, the offering of a choice to engage with or skip the engagement offer, and the monitoring of the user’s interaction with an advertisement to determine which subsequent advertisement to show, were all new and innovative uses of computers as at December 2012.

60 Additionally, although some other components of the advertising system claimed in the patent, such as a database, a client-server architecture, the running of a Javascript program on a publisher’s website, the creation of a ranking engine to rank abstract data to achieve an ordered list, were, when taken in isolation, known as at December 2012, these components had been integrated into a single system in an innovative and previously unknown way. In other words, the invention that was the subject of claim 1 brought together some new elements and some known elements to form a working combination that had not previously been achieved and involved the use of computers in a way that was foreign to their normal use (as at December 2012).

61 In Professor Verspoor’s view, the architecture distinguishing between engagement offers and general advertising, coupled with the algorithms making use of background data for personalisation and ranking, represented a new combination of new and previously existing components and hence new use of computer technology. It therefore represented a contribution to the state of the art for the provision of digital advertising via a computer.

62 The paragraphs of the affidavit of Mr Scott Ries tendered by the respondent Commissioner were to the following effect.

63 Mr Ries wrote that he had specialised knowledge and experience of internet advertising techniques and strategies, advertising formats, systems, databases, hardware and software. He had developed this knowledge and experience through his work for companies engaged in internet advertising since 2006. As a result of that work, Mr Ries considered that he had developed a thorough understanding of the internet advertising market, techniques and strategies, including the roles played by advertising firms, creative agencies, publishers, ad server providers, demand side platform providers and data management platform providers, together with clients. He said he was also proficient in a number of computer programming languages, including HTML5, Javascript, ASP and SQL. He had used his computer programming skills to write the source code for digital advertisements and for a variety of other purposes related to internet advertising.

64 Mr Ries was asked by the solicitors for the Commissioner to briefly explain:

1. In December 2012, how did Internet advertising platforms select advertisements to display to users on third party websites?

2. In December 2012, how were databases and engines used to combine all of the following:

2.1. data about Internet user engagement;

2.2. data about transactions conducted by Internet users, and

2.3. data about Internet users’ location, time of access to a website, mode of access to a website, and Internet browsing history,

in order to select Internet advertisements to display to users?

3. In December 2012, how were web scripts and widget scripts used to collect data about Internet users and select advertisements to display to users on third party websites?

65 Mr Ries addressed these questions by first explaining, having regard only to what he knew and regarded to be well-known and generally accepted in internet advertising in December 2012, what digital display-based advertising was, and how it was implemented by ad servers, demand side platforms and data management platforms, including the hardware and software involved.

66 He wrote that digital display-based advertising involved the display of advertisements on websites or mobile applications. Digital display-based advertising could be targeted or nontargeted. In non-targeted advertising, advertisements were displayed without any analysis of whether the advertising content was relevant to the particular viewer’s habit, interest or activity. In targeted advertising, the advertisement was selected for display based on some level of analysis of viewer engagement data. Engagement data was a record of viewer habit, activity or interest based upon data points such as the viewer’s past or current online searches, websites visited, specific webpages visited, online purchases, videos viewed and advertising engagement (e.g. clicks, views, expansions etc). Other data points could also be used.

67 He wrote that a data management platform was a centralised computing system for collecting, integrating and managing large sets of engagement data. Data management platforms obtained engagement data from site interaction in large part collected using cookies. A cookie was a small text file that contained a record of the user’s browsing activity. Cookies were stored on the user’s device while the user was browsing. Data management platforms had their own computer program code that they embedded in publisher/advertiser websites to write cookies and transmit those cookies back to the data management platform. The kinds of records that cookies captured included all of the engagement data recorded in [66] above. Other sources of engagement data that data management platforms utilised included online or offline purchase information, historical data, rewards cards etc.

68 Mr Ries said that a data management platform recorded engagement data about individual internet users, and identified those users’ habits, interests and/or activities based on that data. Generally, this process of using engagement data to identify habits, interests and/or activities was referred to as segmentation. To carry out the process of segmentation, the data management platform would maintain a central database. A data management platform database could be visualised as a very complex spreadsheet, where each user corresponded to a row in the spreadsheet. Each user was allocated a unique identifier, such as a customer identification number, an Internet Protocol (IP) address associated with their internet connection, a device identification number, and/or an email address.

69 Mr Ries wrote that users could be segmented based on a range of attributes. To extend the spreadsheet analogy, each attribute would correspond to a column in the spreadsheet. A data management platform could record a large number of attributes for each user, including the user’s gender, age, interests (e.g. recreational pastimes, hobbies, entertainment preferences, employment) and past purchases. These attributes were used to compare users. Where users shared attributes, a data management platform would assume that they were also likely to share habits or interests, or undertake similar activities. In this way, users were grouped into segments who may be interested in purchasing different goods or services.

70 Mr Ries wrote that a data management platform relied on hardware, including a server and distributed computer architecture. Distributed computer architecture was a model in which hardware components (e.g. processors) located on networked computers communicated and coordinated their actions by passing messages. The components interacted with each other in order to achieve a common goal. A data management platform also relied on at least one database (as earlier described) and software that collected data about users from cookies, and which caused the processor to analyse that raw data to identify user attributes and segments. The term “engine” may be used to describe these kinds of software components.

71 He wrote that a demand side platform was used to locate (track) individual users and present relevant targeted advertisements to those users. Demand side platforms gathered real time data about how and where individual users were interacting with the internet. Typically, they did this by providing website publishers with program code that would communicate to the demand side platform what a user visiting the website was viewing and/or doing. For example, demand side platforms were able to gather data that a user was visiting a particular webpage (e.g., an e-commerce site) and engaging in a particular transaction (e.g., a product purchase) while located in a particular geographic location (e.g., the Sydney CBD), at a particular time (e.g., around lunchtime on a weekday). A demand side platform relied on similar hardware to a data management platform, being a server and distributed computer architecture. Like a data management platform, a demand side platform also relied on at least one database and software that collected data about user activity online, and which analysed that raw data about users.

72 Mr Ries wrote that demand side platforms also contained a pool of potential advertisements. Demand side platforms used algorithms to select which advertisement(s) to display to individual users. These algorithms evaluated engagement data concerning the attributes of the user (obtained from a data management platform) together with the demand side platform’s own data concerning how and where the user was interacting with the internet. Other attributes may also be evaluated by demand side platform algorithms, such as the demand side platform provider’s profit margin that would be obtained from the particular advertising media (demand side platform providers received more advertising revenue from impressions or click-throughs of certain media, compared with other media). The demand side platform algorithms selected the most relevant (targeted) advertisement to present to that user.

73 He wrote that demand side platform algorithms typically involved multiple algorithm layers and sophisticated processes for attributing preferential weight to different algorithm parameters. It was industry practice for demand side platform providers to keep their algorithms confidential from one another.

74 Sometimes, Mr Ries wrote, demand side platforms were configured so that an advertisement was displayed at a particular point in time or activity in the user’s interaction with the website, for example, after completing a purchase transaction. This was achieved by the demand side platform gathering and analysing data gathered in real time about the user’s online activity. User inactivity (for example, failure to click-through advertisements) could also be monitored by demand side platforms and/or data management platforms and used as a basis for making advertising decisions (for example, a demand side platform may decide to no longer display particular types of advertising content to a user, where that user had never taken up that advertising content). In a similar way, demand side platforms and/or data management platforms could keep a record of which advertisements individual users had clicked on in the past. The demand side platform algorithm could use this data to determine that the same kind of advertising media should be displayed when selecting an advertisement for the user.

75 Mr Ries wrote that a demand side platform drew the content of advertisements from an ad server. An ad server contained the text, graphics and code that made up an advertisement. When a demand side platform identified a user to present advertising to, it communicated with the ad server to obtain the text, graphics and code and present them to the user in the form of the advertisement. The code that was used to present the advertisement format to the user could be referred to as a widget or web script. The terms “widget” and “web script” had different meanings in different contexts, and could also be used to refer to the code that collected information about a user’s online activity. By advertising format, Mr Ries meant the particular configuration of text, styling data and images which were displayed to the user.

76 Mr Ries wrote that a data management platform, a demand side platform and an ad server communicated with each other through an application programming interface (API). An API was a software application that was able to match data in a data management platform, demand side platform and/or ad server so that the data in each database could be compared to the data in the other. This matching process enabled a data management platform, demand side platform and/or ad server to work together. Segments identified by the data management platform were used by the demand side platform to identify users who might respond positively to an advertisement.

77 He wrote that before December 2012, data management platforms and demand side platforms were commonly operated by separate companies which co-operated with one another. However, Mr Ries wrote he was also aware, and regarded it as well-known and generally accepted before December 2012, that a dual data management platform/demand side platform distributed computer architecture could be operated by a single company. For example, as part of his work at MediaMind/DG/Sizmek before December 2012, Mr Ries worked directly with the businesses Lotame and Radium One to present online advertising. MediaMind/DG/Sizmek performed the role of the ad server provider and Lotame and Radium One each performed the dual role of a data management platform/demand side platform provider. The reason why other companies focussed on performing a single demand side platform provider role or data management platform provider role was that this enabled them to provide highly sophisticated data management platform or demand side platform functionality (e.g., the processing in real time of many billions of items of user data).

78 Mr Ries wrote that it was very common for websites to invite users to “opt in” to an emailing list by ticking a box while making a purchase through the website, or entering their email address into a field on the website. If the user opted in to the emailing list, the company that operated the website and/or the emailing list would send emails to the user containing advertisements. In other words, advertisements were only displayed to the user after taking up an online offer to see those advertisements. Best practice dictated that each such email should allow the user the opportunity to leave the emailing list. This was known in the industry as “opting out”.

79 Mr Ries wrote that the advertising format of claim 1 was implemented by way of computers (i.e. a “computer implemented method”) and, more particularly, an online advertising system. All of the hardware components that were used to implement the system (servers, processors and network components) were well known and widely used in the digital advertising industry before December 2012. Mr Ries did not understand the invention to be any new or improved hardware technology. To the contrary, he understood the specification to teach the reader that the existing computer hardware could be used to implement the advertising system. He directed attention, in particular, to the patent application on page 25, lines 5-16, which stated:

The server computer 112 on which the advertisement system 10 is implemented can be any form of suitable server computer that is capable of communicating with the consumer devices 106. The server 112 may include typical web server hardware including a processor, motherboard, memory, hard disk and a power supply. The server also includes an operating system which co-operates with the hardware to provide an environment in which software applications can be executed. In this regard, the hard disk of the server is loaded with a processing module which, under the control of the processor, is operable to implement the various afore-described engagement and ranking engines 116, 118 for determining engagement offers and advertisements.

80 Mr Ries noted that, while the above passage referred to a (single) “server computer”, implementing the invention of claim 1 on a commercial scale would require a large number of computers that were organised in a distributed architecture, because a very large volume of engagement data would need to be processed at any given time.

81 Mr Ries wrote that figure 3 illustrated the databases, software and consumer device components that could be used to implement the online advertising system of claim 1. The components shown included:

1. a tracking database 114, which was used for storing the user engagement data and behavioural metrics (patent application, page 15, lines 11-14);

2. an engagement object database 115, which was used for storing the engagement offers and advertisements (patent application, page 15, lines 14-16);

3. an engagement engine 116, which was used to retrieve user engagement data and behavioural metrics from the tracking database and pass that data to the ranking engine (patent application, page 18, lines 4-7);

4. a ranking engine 118, which retrieved objects (engagement offers and/or advertisements) from the object database. The ranking engine also applied the ranking algorithm, for the purposes of selecting the object to be displayed (patent application, page 18, lines 8-20);

5. a publisher system 104, which housed the content on the website that the user was browsing (patent application, page 12, lines 9-13);

6. the consumer devices 106 that were used for web-browsing and connected to the publisher system 104 and the advertisement system 112 over the network (e.g. internet) 108 (patent application, page 12, lines 15-21); and

7. the widget script 121, which was the program code that gathered engagement data and behavioural metrics and presented the engagement offer and (if accepted) subsequent advertisements to the user (patent application, page 14, line 19 to page 15, line 4; page 16, lines 4-9).

82 Mr Ries recognised each of the databases and the software components depicted in figure 3 to be standard components that were routinely used in demand side platform and data management platform display-based advertising systems before December 2012. For example:

1. user engagement data and behavioural metrics data was kept in a data management platform database that was conceptually the same as the “tracking database” of the patent application;

2. the advertisements themselves were kept in a database maintained by a demand side platform and/or ad server that was conceptually the same as the “object database” of the patent application; and

3. program code, such as widgets, was routinely used to gather the user engagement data (including behavioural metrics about past user interaction with advertising content) and present advertising content to the user.

83 Mr Ries wrote that, as with conventional demand side platform and data management platform implemented digital advertising, the invention of claim 1 could be implemented as a third party advertisement system (that is, a system that was operated by a third party who was independent of the website publisher and advertiser). The patent application referred, on page 25 line 27 to page 26 line 10, to various advantages of third party advertising systems. In Mr Ries’ opinion, the advantages of using third party systems were already well-known and generally accepted in the internet advertising industry before December 2012. For example, a well-known advantage of demand side platform and data management platform advertising over customer relationship management database advertising was that even if a user had not previously accessed a publisher’s website, data management platform and demand side platform based systems were able to provide targeted advertising the first time the user visited that website, based on engagement data gathered from the user having visited other websites: cf the patent application, page 26, lines 1-7.

84 Mr Ries wrote that for the advertising system to make a determination that a user’s interaction with website (publisher) content was “contextually relevant for presentation of the engagement offer”: claim 1, page 28, line 34 and for the system to determine that the engagement offer was “relevant to the evaluated engagement data”, the advertising system must first gather the relevant engagement data. Claim 1 stated that computer program code (a widget script) was delivered with the publisher content to gather the engagement data: claim 1, lines 14-21. Consistently with claim 1, the following passage on page 16, line 30ff of the patent application stated:

At step S2a, the widget script 121 determines engagement data representative of the interfacing context. In a particular embodiment, the engagement data determined by the widget script 121 comprises at least one of the following: a URL for the website; a referring URL; screen content obtained through capturing the HTML of a current page for particular keywords and content (also known in the industry as “scraping”); through API (application programming interface) parameters passed directly to the widget script 121 by the publisher 102; a current location of the consumer; a time at the current location; a type of network over which the consumer is making the connection (e.g. wi-fi hotspot, cellular network, etc.); and/or any other data that can be determined in order to glean an understanding of how the consumer is interfacing with the digital content.

85 Mr Ries wrote that this passage described techniques for gathering engagement data that he knew and regarded as well-known and widely used in internet advertising before December 2012.

86 Mr Ries wrote that the discussion in the patent application of the ranking algorithm appeared on page 18, line 17 to page 20, line 18. This discussion provided an example (in table 1) of how user behavioural metrics for each engagement offer could be scored. The patent application also stated that the revenue score was determined by “evaluating how much revenue resulted through presentation of the engagement objects to consumers”: page 19, lines 3-5. The patent application then continued, on page 19 line 16ff:

It will be understood that any combination of engagement score and revenue score may be evaluated by the ranking engine and need not simply be the sum of the two scores. For example, the ranking algorithm implemented by the ranking engine 118 may apply a greater weighting to the determined engagement score than for the revenue score, so as to enable selection of engagement objects that are more likely to keep a consumer engaged during an engagement journey, in turn resulting in greater sustainability of the model. In this regard, the ranking engine 118 may be configured to dynamically adjust the weightings responsive to determining that levels of consumer engagement have fallen below a predefined threshold. This may be applied on an individual basis (i.e. by an evaluation of the metrics for a particular consumer) or across the consumer base as a whole (i.e. by an evaluation of the aggregated metrics).

87 Mr Ries wrote that, before December 2012, algorithms that ranked parameters such as engagement data (including behavioural metrics) and revenue metrics were in widespread use in internet advertising. However, it was common practice for industry participants to keep the algorithms they used strictly confidential. For example, every demand side platform provider that he was aware of before December 2012 did so. In Mr Ries’ opinion, industry participants kept their ranking algorithms confidential, because devising their algorithms involved complex, time consuming and costly work.

88 The passages of the patent application set out above indicated, Mr Ries wrote, that the ranking algorithm had the same functionality of ranking content based on behavioural and revenue metrics that was routinely used to rank advertisements before December 2012.

89 Mr Ries wrote that Professor Verspoor stated that “the key technical problem” that was addressed by the invention was “providing a single platform in which user engagement data can be coupled with transactional data ... and user context data ... in order to provide a personalised ranking of engagement offers to the user”: at [55] (underlining added by Mr Ries). Professor Verspoor stated that this problem was “solved by introducing two databases - the tracking database and the objects database - and designing two engines - the ranking engine and the engagement engine - which access and manipulate the data in these databases to rank and select engagement offers”: at [57]. Mr Ries wrote, however, that the ranking and selection of advertisements based upon user engagement data (including “transactional” or “context” data about the user) was routinely performed before December 2012 by demand side platform and data management platform systems. Moreover, he wrote that this function was performed by using tracking databases (in which engagement data was stored) and objects databases (in which advertisements were stored).

90 Mr Ries agreed with Professor Verspoor (at [65]) that it was infeasible to perform the type of data analysis claimed in the patent application without several computers. Therefore, he wrote, at least several computers (on a large commercial scale, hundreds of processors) would underlie any “single platform”. These computers would be programmed to communicate with one another, including by extracting, communicating and evaluating the data and content that was stored in the tracking database and the objects database. Mr Ries wrote that the process of extracting, communicating and evaluating engagement data and objects data was routinely performed by data management platform and demand side platform systems before December 2012. The data management platform and demand side platform systems were programmed to communicate with one another using an API. Once an appropriate API was coded, Mr Ries wrote, it made no difference to how the computing technology functioned whether human instructions were received through one interface, or multiple interfaces, from a single provider or two companies. Source code that performed an API equivalent role was needed even if the advertising system was instructed using a “single platform” operated by one provider (the multiple computers must always be programmed in a way than enabled them to communicate with one another).

91 Mr Ries wrote that in her affidavit (at [47]), Professor Verspoor stated that “the substance of the invention is to introduce a dynamic, context-based advertising system”. However, contextbased advertising, Mr Ries wrote, was very common, and was very common in December 2012. The technology that he had earlier described was used in dynamic, context-based systems that determined what advertisements to display based upon parameters that could include website content, user attributes, historical behaviour, their interaction with the publisher’s website and other websites, the user’s location, the time of day, and other contextual data.

92 Mr Ries wrote that, for many years before December 2012, advertisements were inserted into published content by program code (sometimes referred to as a widget) that was provided by the advertising system to the website publisher. He wrote that, at [52], Professor Verspoor stated that “the use of a data-based scoring algorithm to decide what engagement offers to serve represents an important improvement to existing computer-based advertising”. However, Mr Ries wrote, in December 2012, it was widely known and generally accepted that demand side platforms used algorithms to process engagement data and rank which advertisements should be displayed to users. He wrote that in the invention of claim 1, the same kind of software tool (a ranking engine that applied a ranking algorithm) was applied to different content i.e. an engagement offer.

93 Mr Ries wrote that, at [53], Professor Verspoor stated “the invention also introduces a novel architecture for an advertising system, through the recording and transmitting user interactions with advertisements and using that data to select subsequent advertisements.” However, Mr Ries wrote, in December 2012, it was very common for data management platforms and demand side platforms to record data about a user’s interaction (or lack of interaction) with advertisements and use that data to decide whether or not to display an advertisement to that user, or a user with similar attributes.

94 Mr Ries wrote that the ability to provide contextual ranking of the website and user behaviour to select the most appropriate advertisement was routinely done by demand side platforms and data management platforms before December 2012.

95 At [64] to [66] of her affidavit, Professor Verspoor explained why it was necessary to use a computer to implement the invention. In light of the large volume of data involved, and the need to quickly retrieve and manipulate that data, Mr Ries agreed that it was necessary to use (at least several) computers to implement the invention.

96 In her second affidavit, Professor Verspoor responded to the material tendered from Mr Ries’ affidavit. As I have said, parts of Professor Verspoor’s second affidavit were not read as they were responsive to paragraphs of Mr Ries’ affidavit which were not tendered.

97 In summary, Professor Verspoor deposed, none of the computer programming languages referred to by Mr Ries would be used on their own by software engineers to build standalone applications, such as a robust advertising system or a ranking engine. She deposed that on the basis of Mr Ries’ statements he had no direct technical experience with implementation of large-scale software systems but was, rather, a user of the systems. In her opinion, in order to be able to comment in an informed way on the technical characteristics of a software system of the kind described in the patent application (including any technical problem it solved and how it solved that problem), it was necessary to have sufficient technical programming and system design expertise to be able to build such a system oneself. For example, in order to understand the detailed flow of logic to be implemented by the system, one would need to have the experience of implementing similar logic flows in computer code. Professor Verspoor deposed that she did have that expertise: she was fluent in several advanced programming languages. In addition, she had experience developing a front-end application (that ran in a web browser) in Javascript in the context of a web-based visualisation tool she designed in the last two years. She had the experience of building large software systems including the implementation of algorithms for retrieving data from databases and manipulating that data. Her experience included writing the code to implement ranking engines of the kind described in the patent application.

98 Professor Verspoor deposed that she was one of four co-authors, along with the Principal Investigator of the IBM Watson project, David Ferrucci, of the “Unstructured Information Management Architecture” technical standard. That standard was promulgated by OASIS, which was an international “not-for-profit consortium that brings people together to agree on intelligent ways to exchange information over the internet and within their organizations” (per the OASIS website at https://www.oasis-open.org/) whose foundation members included IBM and Microsoft. The standard defined a protocol for building large modular systems that manipulated and analysed unstructured data such as text, by defining an interface for the integration and interoperability of analytic modules developed by various technical teams.

99 Professor Verspoor disagreed with Mr Ries’ definition of “engagement data”. She said his use of the word “engagement” should not be confused with the use of the word in the patent application in the context of the phrase “engagement offer”, where the engagement represented the objective of displaying an offer. To paraphrase, “engagement offer” in the patent application meant “an offer intended to engage”.

100 Professor Verspoor disagreed with Mr Ries’ statement as to whether a data management platform relied on a “distributed computer architecture”, defined as networked computers. She did not agree that a data management platform must necessarily be implemented via a distributed architecture. She deposed that the basic definition of a data management platform as a central hardware server with at least one software database was in no way dependent on having multiple computers in a network to instantiate the data management platform.

101 Professor Verspoor disagreed with Mr Ries’ explanation of demand side platforms. Her understanding of demand side platforms as they stood in December 2012 was that a demand side platform was a real-time bidding system that connected media buyers with data exchanges through a single interface. A demand side platform supported valuation of advertising opportunities by providing access to and utilisation of data of how and where individual users were interacting with the internet. This data could be collected via placing computer program code into a website.

102 As to Mr Ries’ explanation that demand side platforms used algorithms to select advertisements, using attributes including user attributes but also attributes related to the demand side platform provider’s profit margin and revenue, Professor Verspoor deposed that Mr Ries did not carefully explain the competitive aspect that determined the pricing of the advertising selected by demand side platforms. He appeared to overlook the bidding aspect of the demand side platforms. He focused on the revenue to the demand side platform provider but did not describe the role of the advertisers in the system; these advertisers and their preferences and limits were not captured in Mr Ries’ description. The “profit margin” that was associated with an advertisement was ultimately determined by what the advertiser was willing to pay for that advertisement to be displayed; this was not captured in Mr Ries’ explanation.

103 Professor Verspoor deposed that at a technical level the software that might cause advertisements to be displayed was very different from email technology.

104 As to whether the specification in the patent application identified only a business problem but not a technical problem, Professor Verspoor deposed that the final paragraph of the first page of the specification did indeed identify a business problem. It was provided as motivation for the technical solution proposed in the patent application, clearly indicated as such by its presentation in the background of the invention. The specification then translated this business problem into the technical problem of how to utilise computer technology to address the business problem. That is, the technical challenge was how to design and implement computer programs that could work together in real time over the internet to display advertisements in such a way that a user was much more likely to engage with them voluntarily while the user was using a website for a different purpose (i.e., while visiting a publisher’s website).

105 As Professor Verspoor had said in her first affidavit when addressing the question of whether the invention solved a technical problem, this involved creating a single platform that comprised the two databases and two engines described in [48] above. The specification introduced a novel system architecture with a novel method that addressed the technical problem of how to use computer technology to more effectively engage consumers with digital advertising. She said the invention in the patent application was not the first attempt to solve this technical problem; engaging users with advertisements was a long-standing challenge in online advertising. However, in her opinion, the method set out in the patent application was a new and improved way to overcome that problem. A “computer system” comprising hardware and software that implemented the method in the patent application was a new, more improved “computer system” for delivering online digital advertising.

106 In Professor Verspoor’s opinion, it was not only the structure and content of the “engagement offer” (as presented to the user) that differed from a traditional advertisement. The patent application described a sequence of technical steps that were executed to select an “engagement offer”, display it, track the user’s interaction with it, and eventually select and present an advertisement to a user. These technical steps were also different as compared to the standard process of displaying advertisements to a user in demand side platform plus data management platformbased systems as at December 2012. This difference in both content and the sequence of technical steps described a technical solution using the novel concept of an “engagement offer” plus additional data sources that were then used by algorithms described in the patent application.

107 As captured in figures 1 and 2 of the specification (as reproduced at [7] above), Professor Verspoor deposed, there was an additional component of the overall architecture, the “engagement offer” itself (element 18 of figure 1), as well as a distinct “engagement journey” (captured in figure 2). Mr Ries had acknowledged that “whether or not an engagement trigger event has occurred is determined by continuously evaluating the user’s engagement data”. In Professor Verspoor’s opinion, this continuous evaluation of user engagement data required the use of a computer program to collect and analyse the data. It also introduced the new intermediate step of selecting and displaying an “engagement offer” into the process of displaying advertising in response to user behaviour.

108 The purpose of the “engagement offer”, Professor Verspoor deposed, was to provide a user something that they would engage with, i.e. click on or otherwise continue to interact with, such that they were more likely ultimately, after the “engagement journey”, to engage with (click on) subsequently displayed advertising (if any). This problem of attracting the attention of a user, and having the user choose to interact with the advertiser was a problem that advertisers had long been trying to solve.

109 The invention in the patent application aimed to solve this problem through the introduction of the “engagement offer”, and identified what steps the software needed to execute in order to dynamically modify the website that the user was browsing, while they were browsing it, to (a) implement in the web browser or device the concept of the “engagement offer”, (b) implement in the “computer system” the necessary software for selecting “engagement offers” and advertisements for the given user based on their previous interactions with the system, and the interactions of other similar users, and (c) to have that system interact with the widget in the web browser in real time.

110 Professor Verspoor’s interpretation of the description in the specification was that the “engagement offer” would not include a direct request related to a user’s interest in advertising from a specific source. In the patent application, page 9 line 21ff, the list did not include anything of that nature. An offer for a coupon or discount was perhaps the closest in the list, but it was qualitatively different because the user was offered an immediate opportunity within their current session interacting with the browser, rather than an offer to be put on a list to obtain unspecific benefits at some point in the future.

111 Professor Verspoor’s opinion was that the “engagement offer” did not have the immediate purpose of asking for permission to serve advertising, but rather had the purpose of maintaining an interaction with the user. This was stated directly in the patent application, page 9 lines 11-15. Furthermore, the “engagement offer” was described as having “no direct advertising benefit to the advertisers of the selected advertisements through presentation of the selected engagement offer” in claim 1, page 28, lines 13-16; an opt-in process or pop-up would have direct advertising benefit for the advertiser.

112 She deposed that the timing in which subsequent advertising would be delivered to the user was substantially different as described in the patent application, as compared to an “opt-in” for email or future advertisements. As captured in figure 2, and described in the patent application page 12 lines 1-3, the advertisements were presented to the consumer in a sequence of “modules” during the engagement journey, which proceeded within the immediate session, that is, while the user was on the website. In contrast, Mr Ries’ idea was that the user was choosing to receive advertising that would be delivered hours or days later. In Professor Verspoor’s opinion, Mr Ries fundamentally did not understand the process of the engagement journey described in the invention.

113 Professor Verspoor deposed further that the mechanism by which subsequent advertising would be delivered to the user was also substantially different as described in the patent application, as compared to an “opt-in” for email or future advertisements. The patent application described in claims 1 (page 28, lines 13-16) and 14 (page 30, lines 21ff) the presentation of digital advertisements responsive to acceptance of the “engagement offer” via the presentation interface (page 28, lines 7-10 and page 30, line 14). This was a technically distinct process as compared with future display or provision of advertising. Additionally, the patent application involved a step of continuously evaluating engagement data (i.e., the data derived from the user’s interaction with the interface) which was not present in email advertising (or indeed in a company using its customer relationship management database to choose users to receive targeted advertising).