FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Kimberley Land Council Aboriginal Corporation (ICN 21) v Williams [2018] FCA 1955

ORDERS

WAD 179 of 2018 | ||

KIMBERLEY LAND COUNCIL ABORIGINAL CORPORATION (ICN 21) AND OTHERS First Applicants STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA AND ANOTHER Second Applicants | ||

AND: | Respondents | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applications in each proceeding be dismissed.

2. By 12 December 2018, the parties to make written submissions on costs, to be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BARKER J:

1 On 27 January 2017, an indigenous land use agreement, known as the Balanggarra #3 ILUA (the ILUA) was lodged with the Native Title Registrar for registration pursuant to the terms of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA).

2 The ILUA is between the State of Western Australia, the Minister for Lands, the persons who jointly comprise the registered native title claimant in WAD6004/2000, the Kimberley Land Council (KLC), and the Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation.

3 The ILUA deals with six parcels of land, comprising, in total, approximately 0.09 sq km.

4 These six parcels of land were referred to in the earlier determination of native title in Cheinmora v State of Western Australia (No 3) [2013] FCA 769, otherwise known as the Balanggarra #3 determination, which determined that native title over some 4,303 sq km in the north-east of Western Australia surrounding the town of Wyndham, is held in common by members of the Balanggarra community, as described in the determination.

5 The Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation was nominated under the NTA as the registered native title body corporate to hold the determined native title in trust for the native title holders.

6 Subsequent to the Balanggarra #3 determination, the ILUA was negotiated in respect of the remaining six parcels of land which are in and near Wyndham and wholly within the determination area of the Balanggarra #3 determination.

7 On 16 March 2018, a delegate of the Registrar decided to not register the ILUA under the NTA, following an objection to registration lodged on behalf of the Williams/French family (objectors), who are also members of the Balanggarra community that has been determined to be the native title holders under the Balanggarra #3 determination.

8 There are now before the Court two judicial review applications in respect of the delegate’s decision to not register the ILUA: one on behalf of the KLC and the claimant, in WAD178/2018; and the other by the State and the Minister, in WAD179/2018.

9 It is submitted in each proceeding that the making of the decision by the delegate involved an error of law, one of the grounds specified in s 5(1) of the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) for review of the exercise of a statutory power. The KLC and the claimant also allege the making of the decision involved an improper exercise of power, another ground of review specified in s 5(1).

10 The questions falling for consideration are whether the delegate’s decision not to register the ILUA constituted either an error of law or an improper exercise of power.

The Delegate’s decision

11 In order to understand how it is contended that the making of the decision involved either an error of law or an improper exercise of power, or both, it is first necessary to identify the delegate’s reasons for refusing to register the ILUA.

12 Because the ILUA was an area agreement, s 24CK of the NTA applied to the registration of the ILUA. Section 24CK provides:

24CK Registration of area agreements certified by representative bodies

Registration only if conditions satisfied

(1) If the application for registration of the agreement was certified by representative Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander bodies for the area (see paragraph 24CG(3)(a)) and the conditions in this section are satisfied, the Registrar must register the agreement. If the conditions are not satisfied, the Registrar must not register the agreement.

First condition

(2) The first condition is that:

(a) no objection under section 24CI against registration of the agreement was made within the notice period; or

(b) one or more objections under section 24CI against registration of the agreement were made within the notice period, but they have all been withdrawn; or

(c) one or more objections under section 24CI against registration of the agreement were made within the notice period, all of them have not been withdrawn, but none of the persons making them has satisfied the Registrar that the requirements of paragraphs 203BE(5)(a) and (b) were not satisfied in relation to the certification of the application by any of the representative Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander bodies concerned.

Second condition

(3) The second condition is that if, when the Registrar proposes to register the agreement, there is a registered native title body corporate in relation to any land or waters in the area covered by the agreement, that body corporate is a party to the agreement.

Matters to be taken into account

(4) In deciding whether he or she is satisfied as mentioned in paragraph (2)(c), the Registrar must take into account any information given to the Registrar in relation to the matter by:

(a) the persons making the objections mentioned in that paragraph; and

(b) the representative Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander bodies that certified the application;

and may, but need not, take into account any other matter or thing.

13 In her registration decision, the delegate noted that the State made the application to the Registrar for registration of the ILUA, as an area agreement, on 27 January 2017.

14 The delegate also noted that an objection to the registration had been made under the NTA on behalf of the objectors.

15 The delegate first considered whether the ILUA met the requirements of ss 24CB to 24CE of the NTA, such that it met the definition of an ILUA within the meaning of s 24CA. She was satisfied that those requirements were met.

16 Next, the delegate determined that the objectors had lodged a valid objection. That objection was on the ground that the registration application was not properly certified by the native title representative body, the KLC, in accordance with s 203BE(5)(a) and (b) of the NTA.

17 The delegate said that registration of the ILUA would not be possible unless, ultimately, the requirement in para (c) of s 24CK(2) of the NTA was met, which was that:

(c) one or more objections under section 24CI against registration of the agreement were made within the notice period, all of them have not been withdrawn, but none of the persons making them has satisfied the Registrar that the requirements of paragraphs 203BE(5)(a) and (b) were not satisfied in relation to the certification of the application by any of the representative Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander bodies concerned.

18 The delegate said that the condition in para (c) would be met unless the objectors satisfied the Registrar that the requirements of s 203BE(5)(a) and (b) were not satisfied in relation to the certification.

19 The delegate then noted the terms of s 203BE(5):

(5) A representative body must not certify under paragraph (1)(b) an application for registration of an indigenous land use agreement unless it is of the opinion that:

(a) all reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that all persons who hold or may hold native title in relation to land or waters in the area covered by the agreement have been identified; and

(b) all the persons so identified have authorised the making of the agreement.

Note: Section 251A deals with authority to make the agreement.

20 No issue is taken by the KLC or the claimant or the State or Minister, or any other party to these proceedings, with the findings or observations of the delegate to this point.

21 The delegate then added that while s 203BE(5) refers to the “opinion” of the representative body, it is s 24CK(2)(c) that directs the test to be applied, as a result of which the specific requirements set out in paras (a) and (b) of subs (5) are the focus of the condition.

22 The delegate observed that the onus was upon the objectors to satisfy her that the requirements set out in paras (a) and (b) were not satisfied. That is to say, the objectors had to satisfy her: first, that all reasonable efforts were not made to ensure that all persons who hold or may hold native title in the ILUA area had been identified; and, secondly, that all the persons so identified had not authorised the making of the ILUA. The delegate correctly noted that I had expressed this understanding of the test in Corunna v South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council and Another (2015) 235 FCR 40 at [61]; [2015] FCA 491.

23 Again, no dissent to these statements of principle made by the delegate is advanced by any of the parties to these proceedings.

24 Thus, the delegate said, where the objectors are able to satisfy her that either one of the two requirements in paras (a) and (b) were not satisfied, the condition for registration of the ILUA would not be met.

25 Before the delegate there was no issue concerning the satisfaction of para (a). Nor is there in these proceedings. The delegate was satisfied on the materials before her (excusing the double negative) that the objectors had not satisfied her that the requirements of para (a) were not satisfied by the KLC.

26 The key issue before the delegate, and in these proceedings, is whether the persons so identified for the purposes of para (a), had authorised the making of the ILUA for the purposes of para (b).

27 As to the satisfaction of para (b), after further reference to Corunna, the delegate stated that the onus was on the objectors to satisfy her that the persons identified by the KLC as the persons who hold or may hold native title in the ILUA area, had not authorised the making of the ILUA.

28 The delegate then drew attention to the “note” referring to s 251A that follows s 203BE(5)(b) of the NTA, which “deals with authority to make the agreement” (emphasis in original). She explained that, as a result of this note, s 251A became the focus of her consideration of the authorisation requirement.

29 Section 251A of the NTA, as it stood at material times, provided:

For the purposes of this Act, persons holding native title in relation to land or waters in the area covered by an indigenous land use agreement authorise the making of the agreement if:

(a) where there is a process of decision‑making that, under the traditional laws and customs of the persons who hold or may hold the common or group rights comprising the native title, must be complied with in relation to authorising things of that kind—the persons authorise the making of the agreement in accordance with that process; or

(b) where there is no such process—the persons authorise the making of the agreement in accordance with a process of decision‑making agreed to and adopted, by the persons who hold or may hold the common or group rights comprising the native title, in relation to authorising the making of the agreement or of things of that kind.

30 The delegate ultimately concluded, at [83] of her reasons, by reference to a range of material before her – provided by members of the objectors and by other members of the native title party, the Balanggarra claim group – that “there is a traditional decision-making process for authorising things of this kind”.

31 The delegate went on to say, at [83], that the information she had received was from senior persons and persons of authority within the group who had explained their detailed knowledge of the laws and customs of the Balanggarra community, including those surrounding decision-making processes. The delegate added:

Each claimant describes how this information has been passed down to them by their parents and grandparents, and other elders. The process asserted by these persons, as I understand it, is one where particular family groups have the authority to speak for and make decisions about, particular parts of the Balanggarra #3 claim area. This authority stems from the ancestral connections those persons have to that place. Where there are decisions that need to be made that will affect a particular part of Balanggarra country, it is the family with the traditional connection to that area that has pre-eminence in what the decision should be. This view is shared with the rest of the group, who, as required by their traditional laws and customs, ‘come behind’ and support that view, expressed by the persons who speak for the area.

(Emphasis added.)

32 At [84]-[87], the delegate stated:

[84] I do not consider that the statements provided in response to the objection by other members of the claim group refute the existence of such a process. As submitted by the objector, Vernon Gerrard’s statements appear to support the decision-making process outlined by the objectors.

[85] The objectors do not argue that the decision should only have been made by the members of the French/Williams family, as the persons within the group with the ancestral connection to the agreement area. They do not assert that the decision-making process they propose prohibits the involvement of all members of the group in making a decision. It’s my understanding, as above, that rather, they describe a process where those with the authority to speak for an area have pre-eminence in the decision-making process, but the final decision is one of the Balanggarra group as a whole.

[86] The submissions from the KLC explain that it was the representative body’s view that while the group have traditional decision-making processes, or decision-making processes with elements of traditional laws and customs, those processes are not mandatory. In light of the material submitted by the objectors supporting a mandatory process, and in the particular circumstances of this decision (a decision by the group to authorise the making of an agreement for the surrender of native title rights), my view is that this was not a reasonable conclusion. As above, I consider there is strong and detailed information before me addressing the way in which the Balanggarra are bound, by their traditional laws and customs, to support the decision-making authority of the persons or families with the requisite ancestral connection to the affected country.

[87] Having legally represented the group over a period of almost 20 years, the objectors and other members of the group assert that the KLC has an understanding of the laws and customs of the group involving pre-eminence in decision-making by persons with particular connections to particular areas. Noting the way in which decision-making is structured under the rules of the Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation (the PBC), it would suggest that the KLC has taken actions in certain circumstances to ensure decision-making processes comply with those laws and customs. While Mr Tunstall of the KLC states that during his seven years working with the Balanggarra claim group he has never observed decisions being made by a mandatory traditional process, he does refer to decisions being made by consensus, which, as Shirley Williams explains, best mirrors the required traditional process. In addition, Mr Tunstall does not address whether those previous decisions involved the surrender of native title rights by members of the group. It is my understanding that they did not.

(Footnotes omitted. Emphasis added.)

33 The delegate, however, at [88], said that, in her view, the way the KLC and its staff directed persons at the meeting did not provide an opportunity for them “to understand the operation of s 251A”; in particular, that it did not provide an opportunity for them to appreciate that, where their traditional laws and customs dictate a process for making decisions about surrendering native title, they must use it. Importantly, the delegate said that, at the meeting, it appeared that the KLC’s instructions to the group implied that they had “free range” to adopt whatever decision-making process they wished. The delegate added that Shirley Williams, who was in attendance at the meeting, explained (after the fact) that she now understood what the NTA says about decision-making to authorise such an ILUA, but that was not explained by the KLC at the authorisation meeting.

34 At [89] of her reasons, the delegate found that at the authorisation meeting the KLC was required to address the existence of a mandatory decision-making process in relation to the proposed surrender of native title rights.

35 At [90], the delegate found that para (b) was not met as the material before her suggested that the persons present did not understand what was required by s 251A.

36 The delegate added:

Had they properly understood the definition of authorise set out in that provision, I consider that there was a strong possibility the meeting would have taken a different course.

37 At [92], the delegate concluded:

As the group proceeded to authorise the making of the agreement using an agreed to and adopted process, my view is that all of the persons identified by the KLC through its efforts pursuant to s 203BE(5)(a) did not authorise the making of the agreement as required by s 203BE(5)(b).

38 Thus, the delegate decided the ILUA should not be registered.

The KLC and claimant’s grounds of judicial review

39 The KLC and the claimant advance three grounds of judicial review, two alleging the improper exercise of power and one alleging an error of law, in the following terms:

Grounds of application

1. The making of the decision was an improper exercise of the power conferred by the NTA as the decision maker failed to take into account a relevant consideration when making the decision, namely whether the laws and customs said to be the basis of the putative traditional decision-making process described in the objection of First to Fifth Respondents ‘must be complied with’ in the requisite sense under s.251A(a) of the NTA.

PARTICULARS

A In the reasons of the delegate of the Third Respondent, the decision maker did not advert to the requirement in s.251A(a) of the NTA that the decision-making process in question ‘must be complied with’.

B. By reasons of the matter in paragraph A, it is to be inferred that the delegate of the Third Respondent failed to consider whether the decision-making process alleged to exist was mandatory.

C. Whether or not an alleged decision-making process was, under the traditional law and custom of the native title claim group for the Balanggarra #3 claim (WAD6004/2000), one which ‘must be complied with’ was a relevant consideration for the delegate of the Third Respondent when making the decision under review.

2. The making of the decision was an improper exercise of the power conferred by the NTA as the decision maker failed to take into account a relevant consideration when making the decision, namely whether the laws and customs said to be the basis of the putative traditional decision making process described in the objection of First Respondent was ‘traditional’ in the requisite sense under s.251A(a) of the NTA.

PARTICULARS

A. In the reasons of the delegate of the Third Respondent, the decision maker did not advert to the requirement in s.251A(a) of the NTA that the alleged decision-making process arising from law and custom is ‘traditional’ in the sense of being:

(a) grounded in the past;

(b) something passed from one generation to the next since the time of effective sovereignty; or

(c) based in a normative system that has had continuous existence and vitality since the time of effective sovereignty.

B. By reasons of the matter in paragraph A, it is to be inferred that the delegate of the Third Respondent failed to consider whether the alleged decision-making process was ‘traditional’ in the requisite sense.

C. Whether or not an alleged decision-making process was ‘traditional’ in the sense described in paragraph A was a relevant consideration for the delegate of the Third Respondent when making the decision under review.

3. The making of the decision involved an error of law, namely that the decision maker erred in his or her construction of the phrase ‘where there is a process of decision-making that, under the traditional laws and customs of the persons who hold or may hold the common or group rights comprising the native title, must be complied with in relation to authorising things of that kind’ that appeared in s.251A(a) of the NTA at the time of the decision.

PARTICULARS

A. The decision maker erred by construing the phrase ‘must be complied with’ in s.251A(a) of the NTA as encompassing:

(a) ‘authority to speak for and make decisions about’ particular areas (at [83] of the Reasons);

(b) that a particular family has ‘pre-eminence in what the decision should be’ (at [83] of the Reasons);

(c) a decision-making process in which the decision is that of the entire Balanggarra #3 native title claim group, but where group members with authority to speak for an affected area have ‘pre-eminence in the decision-making process’ (at [85] of the Reasons).

B. The decision maker erred by characterising (at [85] of the Reasons) the differential authority between families comprising the native title claim group for the Balanggarra #3 claim (WAD6004/2000) as a ‘decision-making process’ in s.251A(a) of the NTA.

C. The decision maker erred by concluding that law and custom that had been ‘passed down to [persons] by their parents and grandparents, and other elders’ was ‘traditional’, within s.251A(a) of the NTA, when the proper construction of the phrase ‘traditional law and custom’ in s.251A(a) of the NTA requires that law and custom be:

(a) grounded in the past;

(b) something passed from one generation to the next since the time of effective sovereignty; or

(c) based in a normative system that has had continuous existence and vitality since the time of effective sovereignty.

D. The Delegate erred by not considering whether the objectors discharged the onus of satisfying the Delegate that the process of decision making, under traditional laws and customs, advocated by them related to authorising ‘things of that kind’ being the Balanggarra #3 ILUA as required by s. 251A(a) NTA.

40 These three grounds overlap.

41 In summary, having regard to the way these applicants, by counsel, presented their arguments at the hearing, they contend that, at the authorisation meeting, the claim group in fact properly met and determined that they did not have a traditional decision-making process for authorising the ILUA and thereby proceeded, amongst themselves, to determine by what method the question of authorisation should be determined.

42 As to what happened at the claim group meeting, counsel for the KLC and claimant contended:

And what happened on the particular day was that a vast majority after discussions chose a different method of authorising this particular ILUA. After knowing what the ILUA was to do, the bulk of the group said, ‘We will do it by majority vote,’ and that was put to the group and five didn’t vote for the majority, but the majority, 37, said, ‘Yes, we want to go by a majority vote.’ So what the essential part of the argument is, if it was a traditional decision-making process, they have a normative quality, then the people themselves would know.

43 The argument put by these applicants is that the broader Balanggarra community who hold the traditional native title rights and interests in the Balanggarra #3 determination area – including the objectors identified by the delegate as holding the pre-eminent rights in the ILUA area in which the surrender of native title is to occur under the ILUA – met to decide whether the authorisation of an ILUA of the kind in question was governed by a traditional decision-making process or otherwise. In the result, by a majority – with five dissentients from the objectors – it was decided there was no relevant traditional decision-making process for a decision of the kind involving the authorisation of the ILUA; and that the process should, amongst the options they then considered, be by a majority vote of all present.

44 Counsel for the KLC and claimant submitted that it was entirely for the claim group members holding all of the native title rights and interests in Balanggarra country to determine that question for themselves – and not for anybody else to determine that question; that the question having been determined by the appropriate people, it was not proper for the delegate to upset the decision taken; and the delegate in purporting to do so, committed an error of law.

45 The delegate’s concern, as noted above, was that the larger group of native title claimants present at the authorisation meeting were not asked to focus on the question whether there was a traditional decision-making process for the purpose of authorising an ILUA involving the surrender of native title rights over an area where it was generally understood by the group as a whole that a particular family had pre-eminent decision-making rights.

46 These applicants, in effect, join issue on the correctness of that finding.

47 The KLC and claimant submit that the delegate had evidence before her that there was a KLC led discussion which provided information to the native title claim group about the ILUA and that the group, when they met to discuss the appropriate decision-making process, were not “voting blind”: they knew the ILUA involved the extinguishment of native title; they knew the elements of the ILUA. They then proceeded to discuss amongst themselves how they wanted to make the decision. A decision-making process was not imposed upon them. Four methods were identified for consideration by the group. One of those methods was that there be a “land group vote”. The minutes recorded that nobody supported that option. Rather, the decision was that the majority vote option should be adopted. Counsel for these applicants submitted that “consensus” does not mean that a minority can veto the decision. The group had a discussion about the different ways of making the decision and decided for themselves that there should be a majority vote.

The State and Minister’s grounds of judicial review

48 The State and the Minister advance three grounds of judicial review, each alleging an error of law, in the following terms:

Grounds of application

1. Having found that there was a traditionally mandated process for deciding about the surrender of native title (the Surrender Decision Making Process) (First Respondent's reasons for decision at [75], [76], [77], [86], [87], [88], [89], [91]), the First Respondent erred in law in:

a. determining that, pursuant to s 251A(1)(a) of the Native Title Act, the Surrender Decision Making Process was a decision making process that under the traditional laws and customs of the Balanggarra people or community must be complied with in authorising the making of the Balanggarra #3 ILUA; and

b. failing to determine that, pursuant to s 251A(1)(a) of the Native Title Act, the Surrender Decision Making Process was not a decision making process that under the traditional laws and customs of the Balanggarra people or community must be complied with in authorising the making of the Balanggarra #3 ILUA.

2. As a result of the errors identified in [1] above, the First Respondent erred in law in:

a. concluding, pursuant to s 24CK(2)(c) of the Native Title Act, that she had been satisfied that the requirements of s 203BE(5)(b) of the Native Title Act had not been satisfied in relation to the Kimberley Land Council's certification of the State's application for registration of the Balanggarra #3 ILUA; and

b. failing to conclude that, pursuant to s 24CK(2)(c) of the Native Title Act, she had not been satisfied that requirements of s 203BE(5)(b) of the Native Title Act had not been satisfied in relation to the Kimberley Land Council's certification of the State's application for registration of the Balanggarra #3 ILUA.

3. As a result of the errors identified at [2] above, the First Respondent erred in law in failing to comply with the requirements of s 24CK(1) of the Native Title Act and register the Balanggarra #3 ILUA.

49 The State and the Minister refer to s 251A(a) and the term “things of that kind”. They submit that the “thing” referred to is the ILUA and not a particular subject matter with which an agreement is concerned. The State and Minister submit this is supported by the plain terms of the provision and the relevant Explanatory Memorandum.

50 The State and Minister submit, in this light, that s 251A(a) of the NTA does not require an enquiry into the subject matters with which an agreement may be concerned and then consideration of whether any part of that agreement involves a subject matter for which a mandatory decision-making process applies. They say this is not to submit that a particular subject matter may not inform what decision-making process may be used in authorising a particular agreement, which, they submit, is the very purpose of s 251A(b).

51 They contend that the ILUA is concerned with a number of subject matters or issues, of which only one is the surrender of any extant native title rights and interests in the ILUA area. The resolution of any compensation, for example, is not limited to the act of surrendering native title rights and interests, nor is the transfer of certain land and payment of monies as consideration.

52 They also submit it is significant that the ILUA provides for the resolution of the relevant claim by a consent determination, because the delegate’s decision proceeded on the basis that, as a matter of fact, there was a distinction between decisions made concerning surrender of native title and decisions made concerning the progress and finalisation of the native title claim. The State and Minister say the delegate’s findings, especially at [75] and [76], are either to be understood as: (1) determining positively that the alleged decision-making process did not apply to decisions concerning the Balanggarra #3 claim; or (2) stating that the alleged decision-making process applied to the making of decisions concerning the surrender of native title rights and interests (and not anything else).

53 Whichever is the case, they submit, having found that the alleged decision-making process concerned decisions relating to the surrender of native title, the delegate could not, as a matter of law, be satisfied by the objectors that the requirement of s 203BE(5)(b) of the NTA was not satisfied. This is because s 251A(a) provides that only where the relevant decision-making process applies to the making of an agreement such as an ILUA, rather than a decision which “involves” a subject matter, must that process be used. In the absence of such a mandatory process it becomes a matter for the native title holders/claimant to decide what decision-making process they wish to use.

54 The State and Minister submit that, had the delegate construed and applied s 251A(a) of the NTA according to its terms, the only conclusion which was available on the facts was that the objectors had not satisfied her that the requirements of s 203BE(5)(b) were not made out, and the only lawful conclusion open was to register the ILUA pursuant to s 24CK(2)(c) of the NTA.

Did the delegate improperly exercise power or make an error of law?

55 In my view, having regard to the submissions made on behalf of the KLC and claimant, and the State and Minister, and the submissions made on behalf of the objectors, who, by counsel at the hearing, strongly supported the approach and reasoning of the delegate, it is necessary to carefully regard what exactly is required by the NTA in relation to the authorisation of an area agreement, having regard to s 251A, and exactly what, factually, occurred at the authorisation meeting.

56 While important general and specific principles may be involved in this analysis, questions of fact are also important to the ultimate resolution of the proceedings before me.

57 The starting point is, as the delegate observed, the requirements of s 251A, as they govern the process by which the persons who hold native title in relation to land or waters in the area covered by an ILUA authorise the making of an agreement.

58 In this case, the persons who attended the authorisation meeting in respect of the ILUA were members of the Balanggarra community who held or claimed the native title to an area of land or waters greater than, but including, the very small area the subject of the ILUA.

59 The evidence before the delegate was capable of supporting the view that under Balanggarra law and custom, to use the language of the delegate in her reasons, some claimants may be members of a “pre-eminent” group with familial traditional connections to a particular area holding a right to “speak for country”; whereas other claimants may “come behind” and have other rights or interests.

60 This does not necessarily mean, though, that the ILUA had to be approved by such a process of decision-making.

61 Section 251A, so far as authorisation is concerned, focuses attention on whether there is:

(a) … a process of decision-making that, under the traditional laws and customs of the persons who hold or may hold the common or group rights comprising the native title, must be complied with in relation to authorising things of that kind …; or

(b) where there is no such process–the persons authorise the making of the agreement in accordance with a process of decision-making agreed to and adopted, by the persons who hold or may hold the common or group rights comprising the native title, in relation to authorising the making of the agreement or of things of that kind.

62 Certain expressions used in paras (a) and (b) of s 251A should here be noted:

The first is the expression, “persons who hold … the common or group rights comprising the native title”. In present circumstances, these comprise the broader Balanggarra community who hold/claim native title rights, including those who the delegate found to be “coming behind”, as well as those with the “pre-eminent” right to speak for country in respect of particular areas of Balanggarra territory.

The second is the expression, “things of that kind”, used in both para (a) and para (b). Paragraph (a) focuses on the question whether there is a traditional process of decision-making that must be complied with in relation to authorising “things of that kind”. On the proper construction of para (a), this may be taken to refer to the authorising of an agreement either like an ILUA generally (as the applicants contend), or an ILUA specifically dealing with the surrender of native title (as the delegate found and the respondent objectors agree with). The delegate effectively adopted the latter meaning in the circumstances of the ILUA in issue here. I consider she was correct to do so. The content of any agreement assists in its proper characterisation. Substance must come before form on this question. Depending on what an ILUA deals with, there may or may not be a relevant traditional decision-making process to cover it. Paragraph (a) is not limited just to “the making of the agreement”.

By comparison, para (b), which operates where there is no such traditional decision-making process, focuses on the adoption of a decision-making process in relation to authorising “the making of the agreement or of things of that kind”. The particular scenario – “the making of the agreement” – appears in para (b). The additional words in para (b) may be taken to accommodate the making of a decision where the process has earlier been adopted by the group for agreement making.

63 In substance, the delegate here decided that the group of native title claimants who attended the authorisation meeting, in effect were never asked whether there was a traditional decision-making process, for the purposes of para (a), that “must be complied with in relation to authorising things of that kind” – being the authorisation of an agreement that involved the surrendering of native title in the agreement area.

64 Rather, the delegate found that the claim group never addressed that question but were asked and simply decided whether one of four nominated options of decision-making, including by “the land group” or “by majority” should be adopted. By simply voting upon which one of four decision-making processes of authorisation should be followed, the delegate concluded that the group never addressed the question whether there was a traditional process that had to be complied with in relation to the authorisation of an ILUA of that kind.

65 If that correct question had been focused on, the delegate found, the outcome of the authorisation vote may have been different, because members of the family with the “pre-eminent” rights of decision-making would, on her view, have been identified as relevant to the decision-making and might have influenced a different decision.

66 One of the features of the present case is that the ILUA proposed the surrender of native title rights in the agreement area; not merely the carrying out of development in that area. Native title, as originally characterised in Mabo and Others v The State of Queensland (No 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1; [1992] HCA 23, and as explicated, under the NTA, by a number of leading authorities, including The State of Western Australia v Ward and Others (2002) 213 CLR 1; [2002] HCA 28 – is inalienable. The idea that it might be “surrendered” under traditional law and custom, is not easily reconciled with the common law or NTA understanding of the nature of native title. It may be surrendered only because the NTA provides a mechanism for it to be surrendered.

67 On that basis the idea that there might be a traditional law providing the process for authorising an agreement whereby native title is surrendered, presents a challenge.

68 However, on the other hand, if the purpose of a surrender of native title is to enable some physical development or use of the area to be surrendered, then perhaps the concept of a pre-eminent native title right holding family having an influential say as to the authorisation of an agreement concerning surrender of native title, may be seen to have a traditional component to it, or a component that might be seen to attract a traditional decision-making process that must be complied with.

69 The existence of people with “pre-eminent” rights in relation to an area does not, however, carry with it the necessary understanding that other native title holders in a local area not holding such pre-eminent rights, do not also have rights and interests in a relevant area.

70 Here, the evidence before the delegate shows that the group of native title claimants who met to discuss the authorisation of the ILUA did not explicitly address this question, but appear to have proceeded on the basis there was no relevant traditional decision-making process for authorising the ILUA.

71 As to whether or not there is a traditional decision-making process as described in para (a) in relation to authorisation of the ILUA is a question, having regard to the terms of s 251A, falling to the group of native title claimants themselves to decide. It is not a question, in my view, for the Registrar, upon registration of the determination or registration application, or for this Court on judicial review, to decide.

72 To the extent that the delegate purported to state whether there was a traditional decision-making process in relation to the ILUA, therefore, I consider she erred. The substance of her decision, however, as I have explained above, is that the claim group was not asked the right question about whether there was a traditional decision-making process for the authorisation of the ILUA by which the claimants agreed to surrender native title.

73 The subtleties and intricacies of a traditional decision-making process, including in those cases where there is an acknowledged “pre-eminent” or “estate” or local group aspect to decision-making in relation to certain things, must be appreciated. It is difficult, in the extreme, for a person external to the broader group of native title claimants, to say with any confidence or precision exactly how a traditional system of land use decision-making operates. It may be relatively easy to say that certain families have “pre-eminent” decision-making rights about what happens in relation to certain things. It is not so easy, though, to say exactly what things are the subject of traditional decision-making; and where there is a thing in relation to which traditional decision-making applies, just how it applies.

74 In my view, properly understood, the evidence before the delegate did not enable the delegate to determine exactly what the extent of the rights of the “pre-eminent” rights holders were, or how the traditional system of decision-making in such circumstances operates, but only that there may exist a traditional decision-making process for the purposes of para (a) in relation to authorisation of the ILUA, and that the group of native title claimants who ultimately resolved to adopt the majority vote option did not turn their minds to the question whether there was, in fact, a traditional decision-making system that existed and had to be complied with under para (a) in respect of the authorisation of the ILUA that dealt with the surrender of native title and payment of compensation.

75 So, it is now necessary to turn to the facts to ascertain what happened at the authorisation meeting in order to test this latter finding.

76 In his affidavit made 31 July 2017, and given to the delegate by the KLC, Mr Kevin John Murphy, principal legal officer of the KLC, gave evidence of decision-making by members of the Balanggarra community by way of agreed and adopted decision-making processes on this and prior occasions.

77 He provided by way of examples:

A decision to authorise a consent determination over the majority of the Balanggarra #3 claim on 1 and 2 May 2013.

A decision to authorise the applicant for the Balanggarra #3 claim to enter into an ILUA over the remainder of the Balanggarra #3 claim with the State on 25 August 2016.

A decision to authorise an application to replace the registered applicant of the Balanggarra #3 claim, pursuant to s 66B of the NTA on 8 November 2016.

A decision to authorise the Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC (which is the prescribed body corporate (PBC) for three Balanggarra native title determinations) to enter into an ILUA with the State on 29 November 2016.

78 In relation to the meeting to authorise the consent determinations of 2013, Mr Murphy explained how on 1 and 2 May 2013, a meeting of the Balanggarra #3 claim group and the Balanggarra combined WAD6027/1998 claim group held a meeting to consider authorising a consent determination over the majority of the Balanggarra #3 claim area and to consider authorising a consent determination over the Balanggarra combined claim area.

79 He said that at the 2013 authorisation meeting there was a discussion about how the members of the Balanggarra community had made such decisions in the past and how they would make decisions at that meeting, and a resolution was passed that resulted in the meeting agreeing to and adopting the following decision-making process for the making of decisions about native title claims that day, namely:

(1) all four “land groups” must be represented at the meeting;

(2) there will be a chance to discuss each matter before a decision is made;

(3) any proposed decision will be written up as a resolution and displayed and read out at the meeting;

(4) there is no formal vote – the decision will be by consensus. Consensus means that when the matter is raised people indicate they support the resolution and no-one says they do not support the resolution; and

(5) once a resolution is passed in this way it binds all the members of the Balanggarra claim group.

80 So far as the authorisation of the ILUA on 25 August 2016 is concerned, Mr Murphy explained that a meeting of the claim group was held at Home Valley to consider whether to authorise the ILUA. He said that at the meeting:

… there was discussion about how the Balanggarra #3 Claim group should make decisions and a vote was taken on the decision making options discussed. Based on the vote it was agreed that decisions at the meeting would be decided by majority vote.

81 He said the members thereby agreed to and adopted a decision-making process under s 251A of the NTA.

82 He says that a similar process was adopted on 8 November 2016 in relation to the replacement, under s 66B of the NTA, of the members of the applicant.

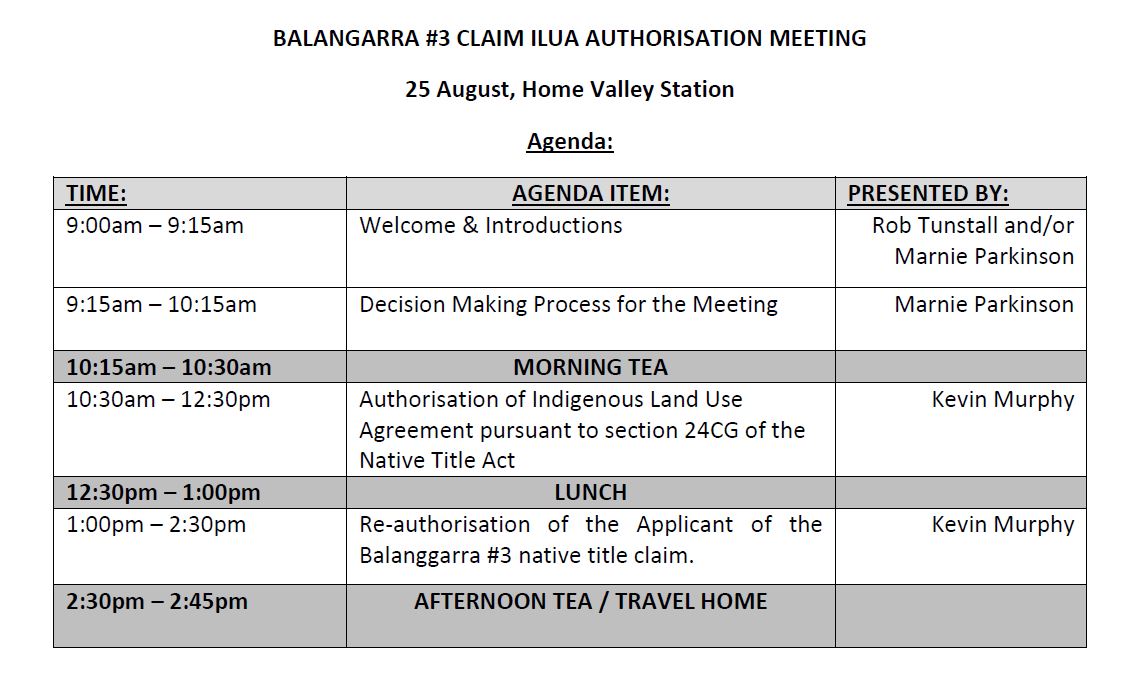

83 The agenda for the ILUA authorisation meeting of 25 August 2016, was produced to the delegate. It set out the following agenda:

84 The minutes of this meeting were also provided to the delegate. They included the following statement:

The meeting discussed who was involved in drafting the ILUA. Kevin Murphy explained that the KLC (as Balanggarra’s legal representative) and the State have negotiated this draft, and the purpose of this meeting is to put it to the Balanggarra claim group for input. The next step of the meeting is to go through the ILUA to get input from Balanggarra.

The meeting discusses who is part of the claim group for the purposes of the ILUA. Everyone who is part of the claim group (everyone present, and anyone else part of the claim group) are part of the group required to decide about the ILUA. All of Balanggarra. It is not just one family or one land group. The ILUA is dealing with the last part of the Balanggarra #3 claim, it requires the whole claim group to agree to the ILUA. How that agreement is reached is for the claim group as a whole to decide.

85 The minutes disclose that the meeting then discussed what land was covered by the ILUA as it does not apply to all Balanggarra country, only to those six parcels of land affected by the ILUA in and around Wyndham.

86 The minutes further show that Mr Murphy read out and explained the main clauses of the ILUA which included obligations by which the Balanggarra agree to validate the tenure over the six parcels; to native title being surrendered over the six parcels; that on registration of the ILUA, to a consent determination with the State that native title does not exist over the six parcels; and related provisions.

87 The minutes also note what those attending were told about what the State was agreeing to, including an ILUA package for monetary compensation and land.

88 The minutes further show that Mr Murphy reminded people that it was Balanggarra’s decision “whether or not to accept the ILUA”.

89 The minutes additionally indicate there was discussion about the role of the PBC versus the claim group and that the PBC does not make native title decisions and that was why the decision was coming before the whole group and not before the PBC.

90 The minutes then state that:

Shirley Williams raises concerns about the voice of NT holders. Discussion about the native title decision making process and what process was adopted for Balanggarra #4 in 2013 – being a consensus approach to decision making.

Ivan Morgan talks about the layers of governance/decision making – that the Government needs ILUA passed by all of the claim group. Explains there is a separate question/decision that is internal about what happens once the ILUA is passed.

The group discusses who the applicants are. Shirley Williams raises concerns regarding who was the original application versus those added in 2013. Shirley Williams asks who should get compensated under the ILUA and who is affected by the impact of the ILUA?

91 The minutes go on to identify a discussion about the quantum of compensation that would flow.

92 The minutes show that there was a break for morning tea with the resumption of the meeting at 11.10am.

93 The minutes disclose that Mr Murphy “calls the meeting back” and then show that Mr Murphy read out three proposed resolutions and explained the effect and intent of them. A discussion about whether to pass them individually or jointly was had.

94 The minutes then state that:

Shirley Williams raises the question of a decision making process and what the decision making process will be.

95 The minutes record that:

The group identifies four different decision making processes, and Kevin Murphy and Patricia Birch facilitate a discussion on what each of these involve:

1. Majority vote – show of hands and majority carries the day.

2. Consensus vote – If a resolution is put up and some don’t support it, the resolution doesn’t pass.

3. Delegated vote – delegate to someone to make decisions.

4. Land group vote – break into land groups and make a decision then report back

Colin Morgan explains that we are going to make a decision on how to make decisions.

96 The minutes record that:

Kevin Murphy facilitates a vote on the preferred decision making process by show of hands.

97 The results are then shown as follows:

Option 1 Majority vote:

In favour: 37

Those against 5: Les French, Saged French, Shirley Williams, Christine Williams, Peggy Truss

Option 2 Consensus:

In favour: 5

Those against: 37

Option 3 Land Group

None in favour.

Based on this, it is agreed that the resolutions will be decided on by majority vote.

98 The reference to voting by “land group vote” is apt to be a little misleading if read in isolation. If one goes back to the earlier references, by Mr Murphy, to voting by land groups in the 2013 authorisation process, the proposal seems to indicate that, within the Balanggarra community as a whole, there are various land groups. The suggestion would appear to be that, if the claimants break into land groups, each land group considers the relevant issue and reports back (or votes) on it. Plainly, that option did not receive any support in this case, including from the objectors. The objectors appear to have supported the “consensus” method.

99 While the KLC and claimant contend otherwise, it is difficult to see at what point the native title claimants at the authorisation meeting specifically addressed the question whether there was a traditional decision-making process in relation to the authorising of decisions of the kind that they were then being presented with, namely, the authorisation of this ILUA involving the surrender of native title.

100 I do not consider that question was expressly, or impliedly, put and dealt with by the native title claim group at the authorisation meeting.

101 The most that can be said is that, having regard to the past practices of the members of the Balanggarra community in dealing with approval of things such as the making of the consent determination and the other decisions referred to at [77] above, they had been obliged to consider the question of whether there were traditional decision-making processes governing their decision-making more generally. In this case, it might be contended that, by implication, the group rejected any suggestion that there was a traditional decision-making process for authorising the ILUA.

102 Upon closer examination, however, it is difficult to see how the para (a) question as to whether there was a traditional decision-making process in relation to the authorising of the ILUA of this kind was ever raised for consideration by the claimants present at the meeting. Section 251A of the NTA was not mentioned either in terms or in substance. Rather, assumptions were made and four decision-making options were considered. The question was not addressed whether there was a traditional process in relation to the authorisation of the ILUA of this kind.

103 In the result, I consider the delegate did not improperly exercise her power or make any error of law in deciding not to register the ILUA. The delegate, in substance, correctly decided that the question whether or not there was a traditional decision-making process that had to be complied with pursuant to para (a) in relation to the authorisation of the ILUA dealing with surrender of native title, was not addressed by the claimants at the authorisation meeting.

Conclusion

104 The result is that the delegate is not shown ultimately to have erred or improperly exercised her power in not registering the ILUA.

105 As a result, regrettably the authorisation of the ILUA will have to be reconsidered by the claimants. It will be for them to decide, by reference to s 251A(a) of the NTA, if there is a relevant traditional decision-making process that “must be complied with” in relation to the ILUA surrendering native title over the six parcels of land. If there is, the ILUA must be authorised “in accordance with that process”. If there is not, then a process agreed and adopted by the claimants may be followed, as provided by s 251A(b). It is for them to decide those questions as a group, as a whole.

Orders

106 For these reasons the applications for judicial review should be dismissed.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and six (106) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Barker. |