FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Nature’s Care Manufacture Pty Ltd v Australian Made Campaign Limited [2018] FCA 1936

Table of Corrections | |

5 December 2018 | Paragraphs 8, 15, 18, 21, 32, 34 and 40 have been amended to correct minor typographical errors. |

ORDERS

NATURE'S CARE MANUFACTURE PTY LTD ACN 059 975 834 Applicant | ||

AND: | AUSTRALIAN MADE CAMPAIGN LIMITED ACN 086 641 527 Respondent | |

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Intervener | ||

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The amended originating application filed 22 October 2018 be dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

PERRAM J:

1. Introduction

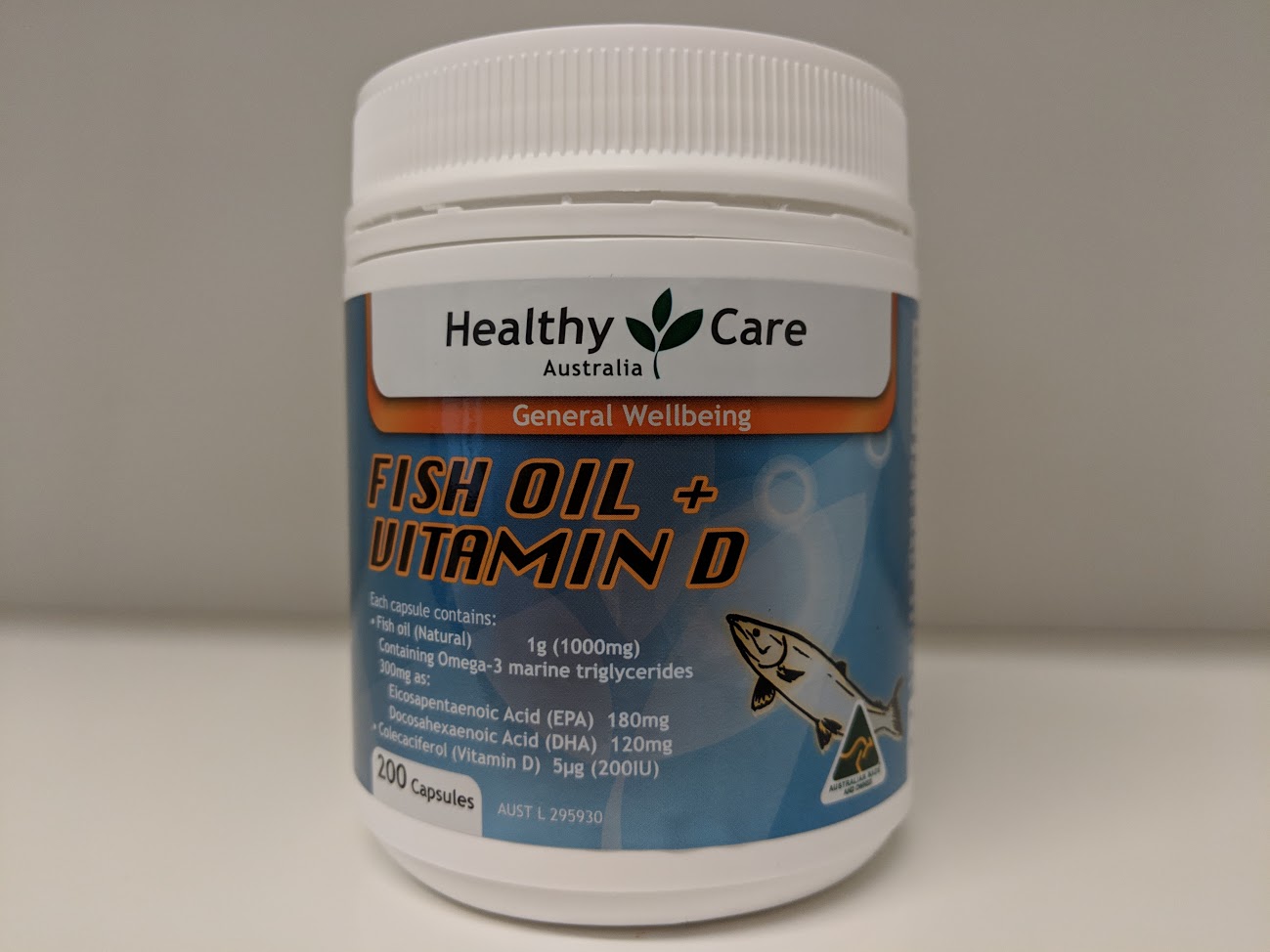

1 When is it permissible to claim that goods manufactured in Australia from ingredients sourced from overseas are ‘Made in Australia’? That is the question in this case. The Applicant is a manufacturer of complementary medicines. One of its product lines is a soft-gel capsule marketed as ‘Fish Oil + Vitamin D’ which is marketed to the public by the Applicant under its ‘Healthy Care Australia’ brand. Exhibit 1 was a jar of 200 of these capsules. The jar with its label appears as follows:

2 For present purposes three aspects of the label should be noted. First, it bears the well-known ‘Australian made and owned’ kangaroo logo (‘Logo’) on the bottom right. Secondly, it indicates that each capsule contains 1g of fish oil and 5µg of vitamin D. Thirdly, it is consistent with a label which suggests that what is inside the jar is fish oil and vitamin D.

3 The issues in this case concern the Applicant’s claim by its use of the Logo that the capsules are made in Australia. The Logo is a registered certification trade mark owned by the Respondent who is responsible for regulating its use including by the issue of 12-month renewable licences which allow businesses to use the Logo. The Applicant has been licensed to use the mark in relation to a number of its products since 2012 including in respect of its Healthy Care Fish Oil and Vitamin D capsules. For reasons to which I will briefly return at the end of these reasons, the Respondent does not accept that the Applicant’s Fish Oil and Vitamin D capsules are manufactured in Australia and has indicated that it does not propose to licence the Applicant to use the Logo on the relevant products after 31 December 2018.

4 The Applicant does not agree with the Respondent’s position and now seeks declaratory relief which would vindicate its view that its capsules are made in Australia. The Respondent’s position is, to a large extent, driven by views published by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (‘ACCC’) about when a claim that a product is manufactured in Australia may be made. As a result, the ACCC intervened to make substantive submissions and the Respondent filed a submitting notice.

2. Basic facts

5 The central issue in this case is, therefore, whether it is accurate to say that the capsules are made in Australia. It arises this way. The fish oil is imported into Australia by the Applicant from Chile in 200kg drums. Fish oil is a pale yellow oil with a vague but distasteful odour of fish. The vitamin D (more precisely, vitamin D3 or ‘Coleralciferol’) is imported from China in 25kg or 1kg drums. It is a white crystalline powder with no odour according to the parties’ witnesses. Having smelt Exhibit MX-4 (Vitamin D3 Sample) I am not sure I agree but this is of no moment.

6 The soft-gel capsules (into which the fish oil and vitamin D would be eventually inserted) were made from gelatine sheets which were themselves manufactured from gelatine powder, purified water and glycerol. The glycerol is imported from Indonesia in 220kg drums but the water and the gelatine powder were sourced in Australia.

7 It will be seen that the Applicant’s product is quite cosmopolitan in terms of the sources of its constituent elements. However, those elements are put together in Australia by the Applicant. Dr Chuan-Liang Xie is the Applicant’s Regulatory Affairs Manager and has a distinguished background in post-doctoral work as a Research Fellow at the Australian National University Research School of Chemistry and the University of Sydney School of Chemistry. He gave detailed evidence about the precise industrial means by which the capsules are manufactured.

8 At the risk of over-simplifying Dr Xie’s account, there are five basic stages for a production run which resulted in 500,000 capsules. First, the gelatine powder, glycerol and purified water are processed in such a way as to produce a clear gelatine sheet. This process involves heating a mixture of the purified water and glycerol to 85° Celsius then introducing the gelatine granules. Over time, the globular structure of the gelatine changes to a chain structure which allows hydrogen bonding with the molecules of water and glycerol. The outcome of this process is the production of the gelatine sheet. The implication of Dr Xie’s evidence is that the sheet contains glycerol, water and gelatine although he was not entirely explicit about this. My acceptance of that implication is buttressed by the fact that neither party suggested that the glycerol disappears through this process.

9 Secondly, 500kg of fish oil and 2.8g of vitamin D3 are sourced and dispensed in preparation for combination. Because it will be relevant later to a submission about the inability of consumers to dispense very small quantities of vitamin D3, the - indeed very small - quantity of vitamin D3 involved at this stage should be particularly noted (recalling, especially, that each capsule contains just 5µg of vitamin D3).

10 Thirdly, the fish oil and the vitamin D3 are then mixed to produce the material which is placed in the capsules. Dr Xie said that this material is a uniform solution. The expert evidence proffered by the ACCC supported this conclusion. Professor Colin Barrow is an Alfred Deakin Professor and the Chair in Biotechnology in the Faculty of Science, Engineering and Built Environment at Deakin University and gave evidence on behalf of the ACCC. He agreed with Dr Xie that the combination of the fish oil and the vitamin D3 results in a uniform solution. He explained that a uniform solution is essentially a solution where the vitamin D3 was distributed evenly in the fish oil. The use of a uniform solution is necessary where, as here, a process of soft-gel encapsulation is being undertaken to ensure that the same amount of vitamin D3 is in each capsule.

11 Fourthly, the continuous sheet of the gelatine produced at the first stage is then fed into a machine known as an encapsulation machine which compresses it and forms an open pocket into which the uniform solution produced at the third stage is then injected in a precise quantity. The pocket is then closed under pressure which results in the final form of the capsule.

12 Finally, the capsules are dried and checked for quality before being packaged and warehoused.

3. Relevant laws

13 The Australian Consumer Law (‘ACL’) is contained in Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth). The ACL includes a number of prohibitions on engaging in misleading and deceptive conduct. Amongst these is the central prohibition in s 18 (‘A person shall not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct which is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive’). There are other prohibitions of a more specific nature but these may be disregarded for present purposes.

14 The ACL contains a number of rules about specific conduct which is taken not to be a breach of s 18 (and the other related prohibitions). One of these rules insulates claims that particular goods were manufactured in a particular country. Provided its requirements are satisfied such a claim is taken not have been a breach of s 18 et al. Because of its operation in rescuing conduct from being subject to s 18 et al, provisions of this kind are frequently referred to as safe harbour provisions. The relevant safe harbour provision is s 255. So far as it is relevant it provides:

‘255 Country of origin representations do not contravene certain provisions

(1) A person does not contravene section 18, 29(1)(a) or (k) or 151(1)(a) or (k) only by making a representation of a kind referred to in an item in the first column of this table, if the requirements of the corresponding item in the second column are met.

Country of origin representations | ||

Item | Representation | Requirements to be met |

1 | A representation that goods were grown in a particular country | (a) each significant ingredient or significant component of the goods was grown in that country; and (b) all, or virtually all, processes involved in the production or manufacture of the goods happened in that country. |

2 | A representation that goods are the produce of a particular country | (a) the country was the country of origin of each significant ingredient or significant component of the goods; and (b) all, or virtually all, processes involved in the production or manufacture of the goods happened in that country. |

3 | A representation that goods were made or manufactured in, or otherwise originate in, a particular country | (a) the goods were last substantially transformed in that country; and (b) the representation is not a representation to which item 1 or 2 of this table applies. |

4 | A representation in the form of a mark specified in an information standard relating to country of origin labelling of goods | the requirements under the information standard relating to the use of that mark. |

(2) Goods were substantially transformed in a country if:

(a) the goods met, in relation to that country, the requirements of item 1 or 2 in the second column of the table in subsection (1); or

(b) as a result of one or more processes undertaken in that country, the goods are fundamentally different in identity, nature or essential character from all of their ingredients or components that were imported into that country.

(3) Without limiting subsection (2), the regulations:

(a) may prescribe (in relation to particular classes of goods or otherwise) processes or combinations of processes that, for the purposes of that subsection, do not have the result described in subsection (2)(b); and

(b) may include examples (in relation to particular classes of goods or otherwise) of processes or combinations of processes that, for the purposes of that subsection, have the result described in subsection (2)(b).

(5) Item 2 of the table in subsection (1) applies to a representation that goods are the produce of a particular country whether the representation uses the words “product of”, “produce of” or any other grammatical variation of the word “produce”.’

15 The relevant item in the table in s 255(1) is item 3 but I have included items 1 and 2 as well as they featured in some of the Applicant’s arguments as to how item 3 is to be interpreted. So far as this case is concerned, what item 3 says is that one can only represent that one’s goods are made in Australia if the goods ‘were last substantially transformed’ in Australia and the effect of s 255(2)(b) is that goods will only be ‘substantially transformed’ in Australia if it can be said – and these are the critical words in the case – that:

‘…as a result of one or more processes undertaken in [Australia], the goods are fundamentally different in identity, nature or essential character from all of their ingredients or components that were imported into [Australia].’

16 This requires a comparison between the ‘ingredients’ which were imported and the goods which were produced as a result of the ‘processes undertaken’. The comparison requires one to ask whether the manufactured goods differ ‘fundamentally’ from the imported ingredients ‘in identity, nature or essential character’.

4. The relationship between the manufactured goods and the imported ingredients: further findings

17 In this case the imported ingredients are fish oil, vitamin D3 and glycerol whose physical attributes I have described above. The goods produced as a result of the ‘processes undertaken’ are capsules marketed as ‘Fish Oil and Vitamin D’ containing vitamin D3 from China dissolved in fish oil from Chile contained in a soft-gel capsule made from, inter alia, glycerol from Indonesia.

18 I do not accept that there is any change in any of the qualities of the fish oil as a result of its mixing with the vitamin D3. It is still, when all is said and done, fish oil and there is no chemical change to its molecular structure or fundamental change to its chemical qualities. I also do not accept that there is any change to the vitamin D3. There was a hint at the start of the case that an argument might have been pursued that the solution of vitamin D3 into the fish oil improved the bioavailability of the vitamin D3. However, Professor Barrow gave evidence to the contrary and the point was not thereafter pursued. I therefore accept that the vitamin D3 which is imported into Australia is the same as the vitamin D3 which is found in the fish oil within the capsules.

19 I accept that it would be practically impossible for consumers to extract the vitamin D3 from its solution in the fish oil. There are sophisticated ways this could be done such as distillation, bleaching or chromatography but these are not practical for most people (assuming for the sake of argument that there are people who might desire to extract vitamin D3 from products such as the Applicant’s).

20 On the other hand, I do accept that the 5µg dose of vitamin D3 contained in each capsule is so small that it would not be feasible for a consumer to dispense such a dose from one of the 25kg barrels of vitamin D3 powder imported from China. I also accept that the glycerol is transformed from a liquid into part of the soft-gel coating of the capsules although its molecular structure remains intact. However, its form certainly changes from a liquid to a chemically separate component in a soft-gel coating. It may fairly be said that this change reflects a fundamental difference in the nature of the glycerol as it is in the capsules from as it is as imported.

21 I find that the fish oil imported from Chile smells unpleasant. I was provided with a sample of this fish oil as Exhibit MX-3 and have smelt it. It smells like a cross between stale fish and vinyl. My associate thinks it smells like semi-fermented grass cuttings revealing his more sophisticated nose. I have not tasted it but I am prepared to infer that it would be very unpleasant to consume even in small doses. I also accept that placing the fish oil in the soft-gel capsules has the effect of making palatable and flavourless a product which is essentially very unpleasant. It has another benefit too. By sealing the fish oil in the capsules the speed of oxidation is reduced and, along with that, the rate of deterioration in the fish oil caused by exposure to light. This is not the case with the liquid fish oil imported from Chile.

22 I also find that the fish oil can be extracted from the capsules. Indeed, the labelling suggests that in the case of children it may be appropriate to pierce the capsule and squeeze its contents into milk, juice or cereal. It is inevitable when this is done that the malodour of the fish oil will re-emerge. It is to be noted, therefore, that whilst encapsulation of the fish oil removes the odour problem for most users the Applicant contemplates some uses of its fish oil with vitamin D capsules where that odour problem will re-emerge.

23 There is a related issue. Professor Barrow properly drew my attention to the phenomenon of ‘burp-back’. ‘Burp-back’ occurs when a soft-gel capsule containing something malodorous such as fish oil is consumed. Once the capsule descends into the digestive depths of the stomach the soft-gel dissolves releasing its noxious payload the odour of which, thus liberated, rises up the gullet to the mouth where, unsought and unwelcome, it presents itself as a salutary warning against the perils of belching. Professor Barrow succinctly described it as ‘unpleasant fishy burping’. Just because the soft-gel fails in the inhospitable regions of the upper reaches of the alimentary canal does not mean that for many people the capsule is not effective to protect them from the smell of the fish oil. It does mean, however, that it cannot be entirely correct to say that encapsulation has changed the nature of the fish oil so that its odour is no longer present. It can be present when the fish oil is extracted from the capsules and it may emerge if a consumer should burp.

24 On the other hand, I do accept that the capsules are a means by which a precisely measured dose of fish oil and vitamin D3 may be delivered. I do not think that there would be any particular difficulties in administering an equivalent dose of the fish oil to that contained in a capsule if all one had was the 200kg barrel of fish oil imported from Chile. A teaspoon would suffice for that enterprise. That said, I do accept the Applicant’s submission that the vitamin D3 in the capsules differs from the imported vitamin D3 ingredients because the dose within each capsule is minute and a consumer would not be able to administer a dose of 5µg without special equipment.

5. What s 255(2)(b) means: preliminary contentions

25 So the question is whether in light of those findings one can say that the capsules ‘are fundamentally different in identity, nature or essential character’ from the fish oil, vitamin D3 and glycerol which were imported in Australia. This is a question of statutory interpretation. I take the position to be that one starts, as a beginning point, with the ordinary meaning of the words on the page and asks whether some other meaning is required by the statutory context where that concept includes, if they throw any light on the issue, the text and architecture of the surrounding statute, the legislative history and other extrinsic materials such as second reading speeches and explanatory memoranda: SZTAL v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2017] HCA 34; 91 ALJR 936 at 940-941 [14], citing CIC Insurance Limited v Bankstown Football Club Limited [1997] HCA 2; 187 CLR 384 at 408.

26 The Applicant’s first contention was that the references to identity, nature or essential character were disjunctive alternatives. A related submission was that ‘essential’ only qualified ‘character’ and not ‘identity’ or ‘nature’. The consequence was that the fundamental difference which s 255(2)(b) called for could be established by reference to any one or more of ‘identity’, ‘nature’ or ‘essential character’ and in that exercise it did not need to be shown that the difference was related to ‘essential identity’ or ‘essential nature’.

27 The Applicant’s second contention did not seize upon any particular word in s 255(2)(b) but pointed out that the wording of the provision had been amended in 2017. It appeared to be uncontroversial that the Applicant’s capsules had been able to take advantage of the former wording. The Applicant now pointed to statements made during the legislative process which suggested that it had not been intended that manufacturers of non-food products who could avail themselves of the former wording would be unable to avail themselves of the new wording.

28 The Applicant’s third contention, which was related to the second, was that the same legislative process showed the 2017 amendments had been designed only to make clear that minor processes such as dicing or canning would not be sufficient (with the implicit submission that what the Applicant had done was not to be seen as a minor process equivalent to canning or dicing).

29 The Applicant’s fourth contention, which built on the first, was that in considering nature, identity or essential character, s 255(2)(b) should not be understood as turning its face against considerations of form or appearance. In a sense, this was a pre-emptive submission to protect against any suggestion by the ACCC that all that the Applicant had done was to change the form or appearance of the fish oil, vitamin D3 and glycerol. It denied as a matter of fact that was all it had done but, even if that were true, it was not to be seen as fatal to its case.

30 Finally, the Applicant submitted that its construction was supported by the hierarchical nature of the table in s 255(1). It was said that item 3 should be read liberally to avoid rendering items 1 and 2 unnecessary.

31 It is necessary to deal with each of these contentions.

Section 255(2)(b) contains disjunctive alternatives and ‘essential’ only qualifies ‘character’

32 I accept the Applicant’s submission that the provision requires only a fundamental change in at least one of identity, nature or essential character. The provision uses three words with different meanings and I do not think it would be appropriate to blur them together as if it only said something akin to ‘essential character’. No doubt these three words have a very considerable overlap but they are not identical.

33 I accept, of course, that sometimes expressions of this kind can have a composite meaning and are better viewed as a single expression. Mr Lenehan, who appeared for the ACCC, instanced the expression ‘possession, custody or control’ in s 35A(1) of the Customs Act 1901 (Cth) which the High Court recently held to have a composite meaning: Comptroller General of Customs v Zappia [2018] HCA 54 at [32], [43].

34 A non-composite construction of the expression in s 255(2)(b) – which accords with my own view of what the words on the page actually mean – is, however, supported by the legislative process which led to the current wording of the provision. That wording was brought about by the passage of the Competition and Consumer Amendment (Country of Origin) Act 2017 (Cth). On the introduction of the bill into the House of Representatives an explanatory memorandum was distributed by the responsible Minister which, at 87, discussed the wording of the proposed amendment in terms antithetical to a composite construction:

‘It is important to note that the concepts of identity, nature or essential character are not mutually exclusive. In many instances one or more of these criteria may be achieved, thus allowing the goods to be considered substantially transformed.’

35 I therefore accept the submission of Mr Free SC who, with Mr Bhasin of junior counsel, appeared for the Applicant, argued that each word has a separate meaning and that it is enough if the fundamental difference relates only to at least one of them. I also accept his submission that the word ‘essential’ only qualifies ‘character’ and not ‘identity’ or ‘nature’.

Coverage by former text of s 255(2)(b) does not entail coverage by the new form of s 255(2)(b)

36 I do not, however, accept Mr Free’s second contention. It is true that the same explanatory memorandum contains a statement (at 47) that businesses that could currently make a claim that goods manufactured in a particular country (including obviously enough Australia) were ‘expected’ to be able to able to continue to make such claims. However, that expectation cannot be matched up with any part of the wording of s 255(2)(b). Put another way, there is no plausible method of construing s 255(2)(b) which can accommodate that expectation (making the assumption that a legislative expectation can be assimilated with a legislative intention).

Amendments were not limited to exclude only minor processes such as canning and dicing

37 I accept Mr Free’s submission that there appears to have been a legislative intention that ‘minor processes’ such as ‘canning’ or ‘dicing’ would not be sufficient to engage s 255(2)(b). It was said as part of an outline for the memorandum that (at 1):

‘The proposed changes are aimed at providing businesses with increased certainty about what activities constitute, or do not constitute, substantial transformation. It will make clear that importing ingredients and undertaking minor processes that merely change the form or appearance of imported goods, such as dicing or canning, are not sufficient to justify a ‘made in’ claim.’

38 A similar statement appears in the Minister’s second reading speech. However, I do not think that either advances the construction issues which arise. Granted that this was the intention, it is reasonably plain that the Parliament decided to give effect to that intention with the language it used in s 255(2)(b) and, in particular, with the requirement that the manufactured goods should be fundamentally different in identity, nature or essential character from all of the imported ingredients. I do not think that the explanatory memorandum throws any light on how that expression should itself be construed save that it indicates that ‘fundamentally different’ should not be interpreted to permit minor processes to suffice. However, the words ‘fundamentally different’ do that all by themselves and do not need the explanatory memorandum to help them along. In the same basket may be placed the Applicant’s similar argument based on Art 6 of the International Convention on the Simplification and Harmonization of Customs Procedure, Appendix K and the General Standard for the Labelling of Prepackaged Foods (CODEX STAN 1-1985). At their highest these would show that processes which have only a minor impact are not intended to be included. But the wording of s 255(2)(b) does that anyway.

Section 255(2) does not exclude considerations of form or appearance

39 The passage set out above at [37] from the explanatory memorandum suggests that minor processes such as dicing and canning were not intended to be within the safe harbour but in the course of doing so it describes those processes as ones which merely change the form or appearance of goods. I accept Mr Free’s submission that this does not entail that changes to form or appearance are irrelevant to the inquiry set up by s 255(2)(b) because there is no textual hook upon which such a limitation might be hung. There may be some manufactured goods and ingredients whose identity, nature or essential character turns upon their form or appearance. For example, the painting of blank canvasses with mass produced art might well raise a real issue under s 255(2)(b). I accept therefore that it is permissible to consider the role of form and appearance in asking what a fundamental difference between the manufactured goods and the imported ingredients might be. In practice, however, they are unlikely to offer much assistance in answering the questions which will usually arise in an ordinary case.

A liberal reading of item 3 is not required to avoid items 1 and 2 being otiose

40 Item 1 creates another safe harbour for claims that products are grown in a particular country. Such a claim can safely be made if, first, the significant ingredients, or a significant component of the goods, were grown in that country; and, secondly, that ‘all, or virtually all, processes involved in the production or manufacture of the goods happened in that country’. The Applicant submitted that this showed that a ‘made in’ claim under item 3 was a weaker claim in relation to origin than a ‘grown in’ claim under item 1. A similar point was made about produce claims under item 2.

41 In amplification of that point the Applicant submitted that under the tests for items 1 and 2 it was necessary to consider all of the manufacturing or production steps regardless of where they happened and then to ask whether all, or virtually all, of those steps took place in the suggested country of origin. This was to be contrasted with item 3 which required only consideration of the steps taken in the country of manufacture and the effect they had upon the imported ingredients. The upshot of these contentions was that if item 3 were to be given a strict construction it would elide the difference between the test in item 3 and the tests in items 1 and 2.

42 I do not accept this argument. Regardless of whether s 255(2)(b) (i.e. the test in item 3) is read strictly, liberally or with wild abandon, the suggested elision does not occur. Items 1 and 2 are concerned with the proportion of manufacturing activities which occur in the origin country. Item 3 is concerned with the relationship between the nature, identity or essential character of the manufactured goods and all the imported ingredients. This case makes the point. Regardless of the controversy as to whether the Applicant is entitled to say its goods are made in Australia under item 3, one can see at once that it can certainly not claim that they are the produce of Australia. And, one can arrive at that conclusion irrespective of how broadly or narrowly s 255(2)(b) is read. In short, items 1, 2 and 3 deal with entirely different subject matters. They do not form a hierarchy and items 1 and 2 provide no basis for construing s 255(2)(b) one way or the other.

6. What s 255(2)(b) means: construction

43 These five contentions did not, in themselves, result in a particular submission by the Applicant as to what is was that s 255(2)(b) meant. However, it is clear that the Applicant put them forward in support of its submission that s 255(2)(b) should be interpreted in a broad fashion and, in particular, in such a way that a significant change in the qualities that distinguished the manufactured goods from the imported ingredients should be sufficient.

44 The overall form of the Applicant’s argument was that such a reading of s 255(2)(b) was open on some of the dictionary definitions. If this resulted in a somewhat loose interpretation of s 255(2)(b) then the five matters of statutory interpretation with which I have just dealt provided sound reasons to approach the interpretation that way.

45 I reject this argument for two reasons. First, the dictionary definitions relied upon by the Applicant do not in fact support it. The ordinary meaning of the words ‘identity, nature or essential character’ is much more basal than merely a set of qualities by which one good can be distinguished from another.

46 The Applicant relied upon the Macquarie Dictionary (Online edition as at 22 November 2018) definition of ‘identity’ in these terms:

‘4. condition, character, or distinguishing features of persons or things…

…

7. exact likeness in nature or qualities.’

47 The Applicant relied upon these definitions of the word ‘nature’ from the same dictionary:

‘1. the particular combination of qualities belonging to a person or thing by birth or constitution; native or inherent character…

…

3. character, kind, or sort.’

48 And these definitions of the word ‘character’:

‘1. the aggregate of qualities that distinguishes one person or thing from others.

…

6. an account of the qualities or peculiarities of a person or thing.’

49 The Applicant submitted that a common thread to these definitions was the notion of a quality or combination of qualities that belong to a thing and that can distinguish one thing from another. Further, the Applicant submitted that ‘fundamentally’ and ‘essential’ were merely words of emphasis embodying the legislative intention that minor differences such as canning or dicing would not suffice.

50 In my view, this involves a significant understatement of meaning of these words. They are concepts which may be used to distinguish one good from another. But they are much more than that. They are concepts going to the essence of a thing, to its true nature, to its pith. The statutory construction points I have discussed above do not require a different outcome. This is, in part, because I rejected three of them. The two I accepted provide no warrant for watering down the meaning of ‘identity, nature or essential quality’. Nor does the ordinary meaning of ‘substantially transformed’ in item 3 assist.

51 Thus whilst it is true that each of those words does have a separate meaning that does not help the Applicant because none of those meanings is as loose as merely being constituted by distinguishing features. Likewise, being able to consider questions of form or appearance in the analysis does not, in this case, lead to any different outcome. This is not a case where the form or appearance of the ingredients or goods goes to their essential nature. Fish oil is fish oil.

7. The application of s 255(2)(b) to the facts

52 What s 255(2)(b) requires is a fundamental change in the essential characteristics of the imported ingredients collectively when compared to the manufactured goods. In a sense this makes no strict sense because it is impossible to compare the essential characteristics of a combined good with the essential characteristics of each of its constituent elements in the same way that it is idle to ask whether a car is a tyre. In this case, for example, it is nonsensical to ask whether the capsules differed in their essential characteristics from the glycerol. Plainly a capsule containing fish oil and vitamin D is fundamentally different to a barrel of glycerol. However, what is required by s 255(2)(b) is an overall assessment: the manufactured goods must be compared to the imported ingredients collectively and an overall opinion formed as to whether they are fundamentally different in nature, identity or essential character.

53 In this case, the answer to that question is clear. The fish oil and vitamin D3 in the capsules is identical to the fish oil imported from Chile and the vitamin D3 imported from China. The only differences between the capsules and the fish oil and vitamin D3 are:

(a) the fish oil and vitamin D3 are mixed together with no chemical change to either;

(b) the capsules generally conceal the bad flavour of the fish oil (although not invariably as in some circumstances the capsule is deliberately pierced and there remains the ever-present threat of burp-back);

(c) the capsules provide an easy means of delivering a 5µg dose of vitamin D3 which could not practically be achieved using the substance in its raw crystalline form;

(d) the capsule retards the oxidation and degradation of the fish oil; and

(e) the capsule is made from gelatine sheets.

54 However, those matters do not establish that the capsules are fundamentally different to the fish oil or vitamin D3 which were imported in their nature, identity or essential character. Far from it. What was imported from Chile and China was fish oil and vitamin D3. What is being sold is as is what is being marketed, that is capsules containing ‘Fish Oil and Vitamin D’.

55 That leaves the question of the glycerol. I accept that the glycerol is fundamentally different in nature in the capsules to the form it was in when imported from Indonesia as a liquid in a drum. It is now part of a gel. However, when viewed overall I do not regard the role of the glycerol as being significant. Granted that the glycerol has been substantially altered, I do not accept that, overall, the capsules are fundamentally different in their nature identity or essential character from the fish oil, vitamin D3 and glycerol imported into Australia.

8. Result

56 The safe harbour is therefore not available and the claims made by the Applicant are not protected by s 255 of the ACL. That conclusion is sufficient to dispose of the proceeding which should be dismissed.

57 Had I been satisfied that s 255 did protect the Applicant’s claim to be made in Australia I would have been satisfied of its entitlement to declaratory relief. Very briefly the reasons for this are that the Respondent has indicated it will not continue to licence the Applicant to use the Logo if to do so would be contrary to the views of the ACCC. The ACCC publicly indicated in March 2018 that it does not accept that the encapsulation of imported substances fell within the safe harbour provisions even with the addition of bulking oils. It gave the particular example of a capsule of imported krill oil as a good which would not satisfy the test and also rejected the view that it would make any difference if the gelatine casing were itself made from imported gelatine. The consequence of that stance was that the Respondent will not licence the Applicant beyond 31 December 2018 to use the Logo unless the Applicant is able to reverse the ACCC’s position. For that reason, I would have granted the relief sought had I reached the opposite view about the operation of s 255(2)(b).

58 At the hearing the ACCC wished to be heard further on costs, a time for which can be determined in consultation with my associate, Mr Wilkinson. The only order I make now is that the amended originating application dated 22 October 2018 be dismissed.

I certify that the preceding fifty-eight (58) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Perram. |