FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Birubi Art Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 1595

File number: | NSD 425 of 2018 |

Judge: | PERRY J |

Date of judgment: | 23 October 2018 |

Catchwords: | CONSUMER LAW – whether respondent wholesaler engaged in conduct likely or liable to mislead or deceive potential purchasers by implying that five product lines were hand painted, or made, by an Aboriginal person and/or were made in Australia – where the place of origin of the products, Indonesia, was not disclosed– where all but one product line comprised objects of cultural significance to Aboriginal peoples – where no dispute as to the literal truth of express representations – scope of the surrounding circumstances to be taken into account in determining whether false or misleading representations were made –whether surrounding circumstances includes the way the products were presented in retail outlets by third parties, the characteristics of other products for sale in those outlets, and the products’ price placement vis a vis other products - where implied false or misleading representations upheld – finding that all the products breached s 18 and subs 29(1)(a) and (k), Australian Consumer Law – finding that boxed boomerangs, didgeridoos and message stones breached s 33 of the Australian Consumer Law CONSUMER LAW – discussion of the principles applicable to ss 19, 29 and 33 of the Australian Consumer Law – discussion of the principles applicable to implied representations CONSUMER LAW – identification of class of persons to whom the implied representations were made – where class included international tourists, interstate tourists, and those seeking to purchase a gift – where international tourists may have a low degree of familiarity with the Aboriginal art and cultural practices but would recognise the association between such objects and their artwork, symbols and designs, on the one hand, and Aboriginal art and culture, on the other hand EVIDENCE – whether contextual evidence of the retail environment in which the products sold admissible – where ACCC submitted context was confined to the products themselves, together with the images and representations made on the products and their packaging – where respondent had no control over manner in which products presented by retailers – whether evidence sufficient to establish the price differential and other aspects of the retail environment relied upon by the respondent |

Legislation: | Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) |

Cases cited: | Astway Pty Ltd v Council of the City of the Gold Coast [2008] QCA 73 .au Domain Administration Ltd v Domain Names Australia Pty Ltd [2004] FCA 424 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 634; (2014) 317 ALR 73 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2008] FCA 678 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dell Computers Pty Ltd [2002] FCA 847 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Homeopathy Plus [2014] FCA 1412; (2014) 146 ALD 278 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Nonchalant Pty Ltd (in liq) [2013] FCA 605 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Telstra Corporation Ltd [2004] FCA 987; (2004) 208 ALR 459 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Telstra Corporation Ltd [2007] FCA 1904; (2007) 244 ALR 470 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; (2013) 250 CLR 640 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Turi Foods Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 665 Bennett v Elysium Noosa Pty Ltd (in liq) [2012] FCA 211; (2012) 202 FCR 72 Campbell v Backoffıce Investments Pty Ltd [2009] HCA 25; (2009) 238 CLR 304 Campomar Sociedad Limitada v Nike International Ltd [2000] HCA 12; (2000) 202 CLR 45 Commercial Union Assurance Company of Australia Ltd v Ferrcom Pty Ltd (1991) 22 NSWLR 389 Downey v Carlson Hotels Asia Pacific Pty Ltd [2005] QCA 199 Dynamic Lifter Pty Ltd v Incitec Ltd (1994) 30 IPR 198 Given v Pryor (1979) 39 FLR 437 Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Pty Ltd (1984) 2 FCR 82 Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd (1978) 140 CLR 216 Netcomm (Australia) Pty Ltd v Dataplex Pty Ltd (1988) 81 ALR 101 Noone (Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria) v Operation Smile (Aust) Inc [2012] VSCA 91; (2012) 38 VR 569 Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191 Puxu Pty Ltd v Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd (1980) 31 ALR 73 Taco Company of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd (1982) 42 ALR 177 Trade Practices Commission v J & R Enterprises Pty Ltd (1991) 99 ALR 325 Westpac Banking Corporation v Northern Metals Pty Ltd (1989) 14 IPR 499 |

Registry: | New South Wales |

Division: | General Division |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Regulator and Consumer Protection |

Category: | Catchwords |

Number of paragraphs: | |

Counsel for the Applicant: | Ms K Stern SC with Ms V Brigden |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | Australian Government Solicitor |

Counsel for the Respondent: | Mr N H Ferrett |

Solicitor for the Respondent: | Archibald & Brown |

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | BIRUBI ART PTY LTD ACN 118 654 336 Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application for declaratory relief is allowed in part.

2. In the absence of agreement as to the terms of the declaratory relief to be granted in order to give effect to these reasons, on or before 4 pm on Tuesday, 30 October 2018 the parties are to file and serve an outline of written submissions not exceeding 5 pages in length in support of the terms of the declaratory relief proposed and indicating whether or not a further hearing is requested or they are content for the terms of the declaratory relief to be determined on the papers.

3. The matter is listed for case management for the second stage of the trial at 9.30 am on Wednesday, 7 November 2018.

4. There by liberty to apply on 48 hours’ notice.

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

5. The parties are to endeavour in the first instance to agree the terms of declaratory relief which otherwise give effect to these reasons.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

PERRY J:

1.1 The originating application

1 By an originating application filed on 22 March 2018, the applicant, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (the ACCC), seeks declarations under the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (the FCA Act), together with an injunction, civil penalties, a disclosure order, and a compliance program order under the Australian Consumer Law (the ACL), being Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the CCA).

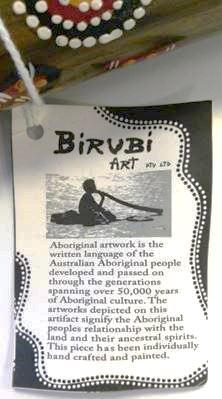

2 The respondent, Birubi Art Pty Ltd (Birubi), operates as a wholesaler of approximately 1300 product lines of wide variety to approximately 152 retail outlets across Australia.

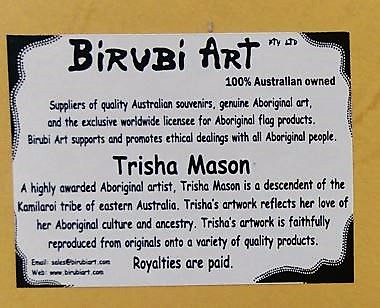

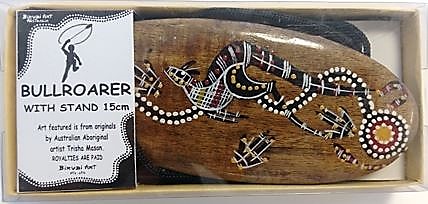

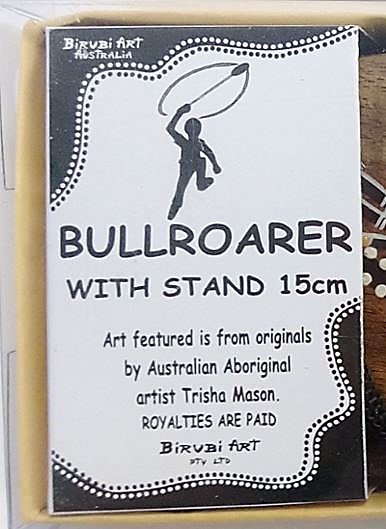

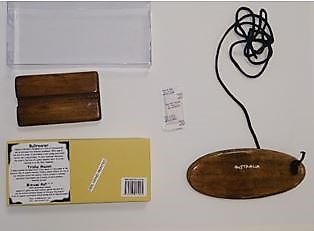

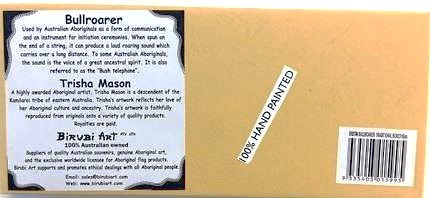

3 The ACCC seeks relief in respect of alleged implied representations made by Birubi over the period 1 July 2015 and 14 November 2017 (the relevant period) about the provenance and characteristics of five product lines containing visual images, symbols and styles of Australian Aboriginal art. The focus of the ACCC’s case is upon the impact of the alleged representations upon purchasers and prospective purchasers, as opposed to the retailers who purchased the products from Birubi for sale to the public. The five product lines in question are loose boomerangs (the loose boomerangs), boomerangs presented in boxes (the boxed boomerangs), bullroarers, bamboo didgeridoos, and message stones (cumulatively, the Products). Three of these products, namely the loose boomerangs, boxed boomerangs and bullroarers, reproduce artwork designed by an artist, Trisha Mason, who identifies, and is recognised, as an Aboriginal Australian (the Trisha Mason Products) pursuant to a royalty agreement concluded between Birubi and Ms Mason on or about 1 October 2014 (the royalty agreement). It is not in dispute that all of the Products are produced by artisans in Indonesia.

4 The ACCC seeks declarations in two categories, namely:

(1) during the relevant period, by representing to consumers that each of the Products were hand painted by Australian Aboriginal persons (the Hand Painted by an Aboriginal person representation) or made by an Australian Aboriginal person (the Made by an Aboriginal person representation), in trade and commerce, Birubi:

(a) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s 18 of the ACL;

(b) in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods, or the promotion of the supply of goods, made false or misleading representations that the Products were of a particular style or have had a particular history in contravention of subs 29(1)(a) of the ACL; and

(c) engaged in conduct that was liable to mislead the public as to the nature, manufacturing process, or characteristics of the Products in contravention of s 33 of the ACL.

(2) during the relevant period, by representing to consumers that the Products were made in Australia (the Made in Australia representation), Birubi, in trade or commerce:

(a) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18 of the ACL; and

(b) in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods, or the promotion of the supply of goods, made false or misleading representations concerning the place of origin of goods, in contravention of subs 29(1)(k) of the ACL.

5 This judgment addresses only the question of whether the alleged contraventions have been established thereby founding a basis for declaratory relief. In the event that I find all or some of contraventions to have been established, Birubi has conceded that declarations are appropriate but has asked to be heard on the precise terms of that relief. In that event, it will also be necessary to afford the parties the opportunity to be heard on the other relief sought by the ACCC, including to lead further evidence on penalty.

6 There was considerable common ground between the parties relevant to the question of liability.

7 First, it was not in issue that each of the Products (aside from the message stones) were objects of cultural significance to Aboriginal peoples, and that the art, symbols and designs depicted on the Products were art, symbols and designs of a character culturally associated with Aboriginal peoples.

8 Secondly, there is no dispute that Biribi’s conduct in wholesaling the Products was conduct in trade or commerce within the meaning of the ACL.

9 Thirdly, it is not in issue that none of the alleged representations were expressly made by Birubi; nor is any issue taken with the literal truth of those express representations made on the Products themselves or their packaging or labels. The contravening conduct alleged is by implied representations only.

10 Fourthly, it is not in dispute that, in the event that the Court should find that the implied representations alleged were made, those representations were false. Thus, with respect to the Made in Australia representation it was common ground that during the relevant period, the Products:

(1) were manufactured in Indonesia and not in Australia;

(2) were supplied by Birubi in Australia; and

(3) were not labelled so as to disclose the fact that they were made in Indonesia.

11 With respect to the Hand Painted by an Aboriginal person and Made by an Aboriginal person representations, it was accepted by Birubi that there was no evidence that anyone in Indonesia who was involved in the manufacture of the Products identified as an Australian Aboriginal person (notwithstanding the longstanding and historically significant Makassar trade route).

12 The issues between the parties at this stage of the proceeding therefore largely reduce to the question of whether the implied representations were made. In this regard, the parties were divided as to the circumstances relevant to resolving this question. The ACCC’s case that the implied (false and misleading) representations were made turns upon the characteristics of the Products themselves and their labelling and packaging, as well as the imputed attributes of a reasonable ordinary member of the class of purchasers or potential purchasers of the Products. Birubi denies that the ordinary member of the class acting reasonably would or may draw the alleged inferences. In particular, Birubi alleges that the surrounding circumstances for these purposes must include the way in which the Products were presented in the various retail outlets to which they were supplied and offered for sale to the public (the Outlets), and the characteristics of other products also likely to be sold in those outlets, as well as their price placement vis a vis other products. When considered in that broader context, Birubi contends that a reasonable ordinary member of the class would not draw the implied representations alleged by the ACCC. However, even if the Court should find that the broader context is relevant as alleged by Birubi, the ACCC submits that the same representations would be implied by an ordinary and reasonable member of the class of purchasers.

13 My conclusions are expressed in more detail in the conclusion. In short, however, for the reasons set out below, I consider that the breaches of s 18 and subs 29(1)(a) and (k) of the ACL alleged with respect to all of the Products have been established. I also find that Birubi has breached s 33 of the ACL with respect to the boxed boomerangs, didgeridoos and message stones, but not with respect to the loose boomerangs and the bullroarers.

14 It is important also to emphasise that in making these findings, I have not found that Birubi had any intention to mislead potential purchasers of the Products. As I later explain, the question of whether the sections in issue were contravened is an objective one. Nor was there any challenge to the literal truth of express representations made on the Products such as the representation made on some products that royalties were paid to the Aboriginal artist whose work had been reproduced on those products.

15 In support of its application, the ACCC sought to rely upon:

(1) the affidavit of Robert Michael Albertson Kill, investigator employed by the ACCC, affirmed on 16 May 2018; and

(2) the affidavit of Jane Roisin Black, senior investigator employed by the ACCC, affirmed on 16 May 2018.

16 Both witnesses were cross-examined.

17 The affidavit of Mr Kill was read without objection. In the case of Ms Black’s affidavit, objection was initially taken to paragraphs [3]-[7] and the annexures thereto on the ground of relevance. The objections related to correspondence between the ACCC and Mr Benjamin David Wooster, the sole director of Birubi, pursuant to which Mr Wooster: (a) voluntarily disclosed information about certain of Birubi’s products; and (b) subsequently provided information by (relevantly) letters dated 21 December 2017 and 14 January 2018 in response to a notice under subs 155(1)(a) and (b) of the CCA dated 14 November 2017 to Birubi (and variations altering the due date for the reply).

18 It was, however, ultimately not in issue that the answers given, and material produced, in response to the s 155 notice was admissible in these proceedings being civil in nature: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2008] FCA 678 at 49 at [131] (Finn J); see also ss 81, 83 and 87, of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (the Evidence Act) as to the admissibility of the admissions against interest made in the answers.

19 More specifically, at the hearing Birubi did not press objections to those pages of annexure JRB-2 to Ms Black’s affidavit at pp. 76-79, 83-90, and 92-100 of the Court Book comprising sales ledgers (the sales ledgers). Otherwise, the affidavit and annexures were read with the qualification that [3]-[7] and their accompanying annexures were read subject to relevance and on the basis that the ACCC would take the Court to anything relevant in chief so as to enable Birubi the opportunity to object if so advised after hearing submissions as to why it was said that particular portions were relevant. These passages were helpfully identified in the ACCC’s list of relevant extracts from the annexures to Ms Black’s affidavit, which was handed up at the hearing.

20 The sales ledgers listed sales by Birubi to identified retail outlets in Australia for the period 1 January 2016 to 13 April 2017 and tallied the total amount received during the two separate financial years this period encompassed, of the following products:

(1) “C701 Coaster set 6 Tribal Gathering” and “NTC05 Table cloth Col. Bush Berries” for the purposes of demonstrating the nature of the outlets to which Birubi supplied products (which I note were not products to which this proceeding related but the ledgers were said to identify some of the types of the retail outlets to which Birubi supplied products); and

(2) “BOAN08 Boomerang Cont. T. Mason 20cm” and “DITB40 Didgeridoo bamboo Trad. 40cm”, being one of each of the product lines of the loose boomerangs and didgeridoos respectively which are the subject of this proceeding.

2.2 Witnesses for the respondent

21 In support of its defence, Birubi sought to rely upon:

(1) the affidavits of Leslie Edward Moore, solicitor, sworn on 30 May 2018 and 17 July 2018 (Mr Moore’s first and second affidavits respectively);

(2) the affidavit of Mr Wooster, the sole director of Birubi, sworn on 30 May 2018 (Mr Wooster’s first affidavit) which was read save for paragraph 27; and

(3) the affidavit of Mr Wooster sworn on 29 August 2018 as corrected in an unsworn, marked up version of his affidavit which he adopted in cross-examination and which was marked as Exhibit R-1 (Mr Wooster’s second affidavit).

22 Both witnesses were cross-examined.

2.3 Ruling on the admissibility of Mr Moore’s contextual evidence in his first affidavit

23 In his first affidavit, Mr Moore gave evidence that he attended two businesses on 30 May 2018 which Mr Wooster had told him currently stocked Birubi products, namely, Mak3 Gifts on Surfers Paradise Boulevard, Surfers Paradise, in Queensland, (Mak3 Gifts) and the Spirit of Australia Gallery on the Gold Coast Highway, Surfers Paradise, Queensland (the Spirit of Australia Gallery). Mr Moore took an extensive number of photographs of the stock located at both premises, including Birubi stock. Mr Wooster’s second affidavit was sworn for the purpose of providing further detail of the content of the photographs exhibited in Mr Moore’s first and second affidavit. Birubi submitted that the purpose of the evidence was to show what the outlets selling Birubi stock are like generally. That evidence was admitted subject to relevance for the reasons explained below.

24 The ACCC submitted that the evidence was irrelevant on two grounds, namely: the photographs were not of outlets to which any of the Products in question had been supplied during the relevant period; and the photographs were taken outside the relevant period. It is true there was no evidence that Mak3 Gifts or the Spirit of Australia Gallery stocked any of the Products in question in the relevant period. That notwithstanding, there was no challenge to Mr Moore’s evidence that the outlets stocked Birubi products as at 30 May 2018. In my view, while of limited use, the evidence is nonetheless indicative of some of the types of Outlets to which the Products in issue here were supplied and the types of products which they displayed for sale, and can be admitted for those purposes.

2.4 Ruling on the admissibility of Mr Moore’s contextual evidence in his second affidavit

25 In his second affidavit, Mr Moore gave evidence that on a visit to Darwin on or about 22 to 23 June 2018, he and Mr Wooster also visited the Mason Galleries, NT Souvenirs and Darwin Souvenirs. Mr Moore took photographs of the products for sale, prices and the store setup at each of those retailers’ premises. These photographs were annexed to his second affidavit, together with a table explaining what the photographs depicted. In order to meet certain objections filed by the ACCC in advance of the hearing, Mr Wooster sought and was granted leave to file and serve his affidavit sworn on 29 August 2018 to identify those photographs annexed to Mr Moore’s affidavits which depicted examples of the Products the subject of these proceedings. However, the ACCC maintained its objection to Mr Moore’s second affidavit on other grounds.

26 It was not in issue that during the relevant period, Birubi sold the bamboo didgeridoos to Darwin Souvenirs, bullroarers to the Mason Gallery, and boxed boomerangs and message stones to NT Souvenirs. However, in the ACCC’s submission, the photographs were still irrelevant because they depicted the store premises outside the relevant period and there was no evidence linking those photographs to the store setup and stock during the relevant period. In this regard, the ACCC placed emphasis upon the fact that it would have been open to Birubi to call evidence to address this gap from the shopkeepers themselves or, more importantly, from Mr Wooster given his evidence that he regularly visited the stores stocking his product lines and would observe how the stores presented his product lines during those visits.

27 Against this, Birubi submitted that evidence of each of the store premises and set up was admissible, despite the photographs having been taken after the relevant period. In support of that submission, counsel for Birubi relied by analogy upon the decision of the Queensland Court of Appeal in Astway Pty Ltd v Council of the City of the Gold Coast [2008] QCA 73. In that case, the appellant sought a declaration that the respondent Council no longer required land within seven years of its compulsory acquisition for the purpose for which it was acquired thereby enlivening a statutory obligation to offer the land for sale to the former owner. In support of that claim, the appellant objected to what it characterised as “retrospectant” evidence, being documentary evidence relating to the Council’s actions and decisions after the expiry of the relevant seven-year period. Justice Atkinson (with whose reasons Holmes JA agreed at [1]) held that the retrospectant evidence was admissible, being “a type of circumstantial evidence in which the subsequent occurrence of an act, state of mind or state of affairs justifies an inference that the act was done, or that the state of mind or affairs previously existed.” (at [43]). However Atkinson J also observed that “such evidence may need to be treated with some circumspection in terms of the weight attached to it: see Melchior v Cattanach [2001] QCA 246 at [136]; R v N [2006] VSCA 111 at [37].”

28 Birubi also submitted that the question of whether the implied false representations were made must be considered having regard to the surrounding circumstances (see further below at [77]-[101]), and not merely by reference to the Products and their packaging. In its submission, the evidence was relevant to this aspect of its defence, because it provided a basis on which the Court could draw inferences about the way in which the Outlets displayed the Products to potential purchasers, their placement with other objects for sale which were expressly “trumpeted” as “Australian Made” and/or made or hand painted by Aboriginal artists, and as to the differential pricing of these rival goods with the Products. That evidence in turn was said to be relevant to the conclusions which customers might reach about the origins and production of the Products as opposed to those other objects for sale. While Birubi did not lead evidence as to why shop owners had not been called to give evidence which might address the gap in the evidence linking the photographs to the presentation of the Products as at the relevant time, Birubi submitted that no adverse inference could be drawn, but accepted that this may affect the appropriate weight given to the evidence. No adverse inference should be drawn because, in its submission, it could be inferred that this decision was driven by practical concerns, namely, to avoid involving clients in litigation unless necessary and subsequently, and more fundamentally, in the interests of ensuring that the trial ran no longer than necessary.

29 In my view, the photographs of the Mason Galleries, NT Souvenirs and Darwin Souvenirs are potentially relevant to the general context in which the Products were presented for sale by these and similar retail outlets at the relevant time, and more generally as being indicative of some of the kinds of outlets where the Products were sold. On this basis, I would admit the evidence albeit with caution as to the weight to be afforded to the evidence with respect to contentious issues.

30 Finally, while it was suggested to Mr Moore in cross-examination that he may have been selective in taking certain of the photographs so as to focus upon photographing certain objects from other suppliers with higher price-tags than the Birubi products, Mr Moore gave clear and straight-forward evidence that he did not act in this manner. I accept his evidence and note that ultimately no suggestion was made in closing in reliance upon this line of cross-examination.

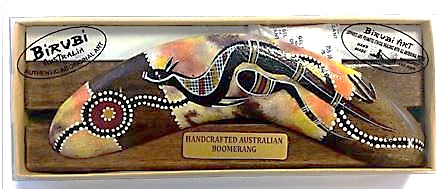

31 Schedule 1 to the applicant’s amended Concise Statement contains photographs of one example of each of the five product lines in issue in the proceeding, including their packaging (where applicable) and their labelling (the sample Products). Birubi admitted that these photographs accurately depict the Products. Larger, higher resolution copies of these photographs were contained in the bundle of applicant’s photos (Exhibit A-1), together with photographs reproduced from Mr Kill’s affidavit of the Mason Gallery taken on 10 November 2017 when a sample product was purchased by the ACCC, printouts of the Mason Gallery Website reproduced from Ms Black’s affidavit, and photographs provided by the ACCC in response to Birubi’s request for particulars. The sample Products themselves were also received in evidence.

32 The five sample Products were purchased in the following manner.

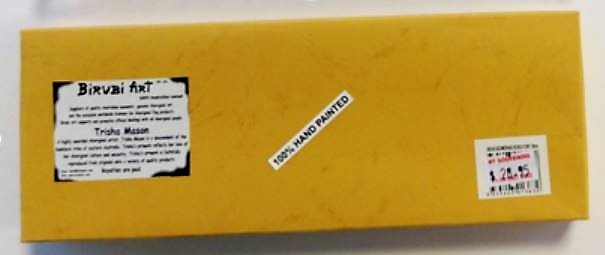

(1) Mr Kill, then a graduate with the ACCC, visited the Mason Gallery on Cavanagh Street in Darwin, Northern Territory, on 10 November 2017 at the instruction of Ms Black and purchased a boxed bullroarer for $35.00.

(2) On 7 November 2017, Mr Kill purchased the boxed boomerang and message stone from NT Souvenirs on Smith Street, Darwin, in the Northern Territory for $28.95 and $9.95 respectively.

(3) On 21 October 2016, Ms Black purchased the loose boomerang for $20.99 from Oz Australia on High Street, Fremantle, Western Australia.

(4) On 3 November 2016, Mark Holden purchased the bamboo didgeridoo for $9.99 from Australia the Gift on George Street, Sydney, New South Wales.

33 There are a number of different product codes for each of the Products. In the case of the loose boomerangs, boxed boomerangs, didgeridoos and bullroarers, the different codes define different lines of the product defined by their size. In the case of the message stones, the different product codes relate to different designs on the stones. While the sample products each comprise only one example from each product line, importantly it was accepted by Birubi that they were illustrative of the Products, as packaged and labelled, for the period of their supply over the relevant period. In this regard, it was not in issue that not all of the Products were supplied over the whole of the relevant period. Specifically, it appears from Birubi’s response to the s 155 notice and evidence given by Mr Wooster (albeit that there is some uncertainty) that the dates on which various product lines were first supplied in Australia were as follows:

Product Code (Product) | Date on which product line was first supplied in Australia by Birubi |

BBC (Boxed Boomerangs) | December 2014 |

BRBT (Bullroarers) | December 2016 (I note that the parties agreed that the s 155 response mistakenly referred to December 2017 and accepted that the date should have been December 2016) |

MEST (Message Stones) | March 2016 |

DITB40 (the sample bamboo didgeridoo tendered in the proceeding) | March 2016 |

DIBP03, DIPB04, DIBP05, DIBB40 (Didgeridoos in the form in Annexure A to the s 155 notice) | January 2007 |

DIBB (Didgeridoos) | June 2016 |

34 The evidence did not, however, reveal the date on which the loose boomerangs were first supplied in Australia (sample product code BOAN08). Birubi also advised that DIBP and DIBB ceased supply in the form referred to in Annexure A to the s 155 notice in August 2017.

35 Furthermore, while evidence was not led (at least at this stage of the proceedings) of the total number of the Products allegedly supplied by Birubi over the relevant period, it is clear that the number of Products supplied was substantial. Thus in its revised response to the s 155 notice, Birubi identified sales of the Products totalling at least 12,974 for the financial year ending 30 June 2017. Birubi also identified that 1,429 boomerangs in product line BOAN08 were supplied between 1 January 2016 and 13 April 2017, and in the same time period 4,034 didgeridoos were supplied in the product line DITB40. In total the ACCC identified, and Birubi conceded at the hearing, that over 18,000 of the Products were supplied to retailers in Australia during the relevant period. As such, it was not in issue that the total number of the Products supplied to retail outlets by Birubi over the whole of the relevant period would have exceeded that figure.

3.2 Production of the Trisha Mason Products

36 Mr Wooster gave unchallenged evidence regarding the Trisha Mason products (i.e., the loose boomerangs, boxed boomerangs and bullroarers). As earlier mentioned, these products reproduce artwork produced by an Aboriginal artist, Trisha Mason, pursuant to the royalty agreement with Birubi. The ACCC accepted that Ms Mason identifies as a person of Aboriginal ethnicity and that she is accepted by her local Aboriginal community as a person of Aboriginal ethnicity.

37 Mr Wooster explained that Ms Mason is the most popular artist with the retail outlets supplied by Birubi, with some retailers wanting to stock only the Trisha Mason Products because of their quality and consistency. However he explained that the production of a commercially viable quantity of such products is an issue, and, as Ms Mason could not physically paint the commercial quantities required to meet demand, it was necessary to produce commercial quantities of stock by digital manufacturing, screen, offset printing or hand-painting by artisans.

38 Birubi has one supplier of commercial stock based in Indonesia named Enigma (Eniquema) (the Indonesian Supplier). While the Indonesian Supplier supplies a number of Birubi’s competitors, Birubi has used the Indonesian Supplier since about 2006. Since then, the Indonesian Supplier has been used by Birubi primarily to reproduce designs by Ms Mason. The Indonesian Supplier provides any packaging, prints, swing tags and the labelling for the products. However, the final decision as to the text on those labels is made by Mr Wooster.

39 The Trisha Mason Products were produced by a process described by Mr Wooster as follows:

(a) Trisha Mason produces a number of prototype blanks (i.e. an artefact such as a boomerang in a raw unfinished state) or canvas glued to cardboard. Several styles are produced of varying artwork and colours for commercial production (Prototypes).

(b) The Prototypes are mounted and/or photographed for production to specific instructions to persons who copy those artworks for commercial production (the Instruction Sets).

(c) A copy of the Instruction Sets are produced for each supplier to Birubi who are contracted to produce commercial quantities of either hand painted or digitally manufactured stock based on the original designs/artworks.

(d) Some product lines are produced by digital manufacturing or by screen or offset printing (e.g. coasters and placemats, magnets, stickers etc).

(e) Hand painted product lines are produced by artisans. Birubi has a sole supplier from Indonesia who employs the artisans who hand paint the stock from the Prototypes and Instruction Sets on a commercial quantity.

3.3 Production of the bamboo didgeridoos and message stones

40 Mr Wooster’s evidence as to the means by which the bamboo didgeridoos and message stones were produced was also not challenged.

41 Bamboo didgeridoos of the kind the subject of this proceeding were produced by the Indonesian supplier for Birubi from about March 2016 until they were discontinued in or about December 2017. At that time, Mr Wooster decided that the quality was inferior to the Trisha Mason Products and he migrated the product line to a “‘Trisha Mason’ style of product”.

42 Mr Wooster explained that the product code for the bamboo didgeridoos subject to this proceeding was DITB40 and that this identified it as a “40cm traditional painted product”. These didgeridoos were described by Mr Wooster as “a very low-cost item which commonly retail for about $12.95 per piece. It was the bottom of the souvenir range.” He intended the bamboo didgeridoos to be a cheap product which would compete with similar products being imported by other souvenir wholesalers. I note that Mr Wooster’s evidence on this point does not specifically address the other bamboo digeridoo product lines subject to this proceeding.

43 As to production of the sample bamboo didgeridoo, Mr Wooster explained that:

28. The specification when ordering the didgeridoos was very simple. I specify the length, blank material, that Aboriginal style be used and that each product had to have two Australian animals on it, one of them being a kangaroo. Based on the knowledge the Indonesian Supplier had acquired, they simply produced samples which I approved then made the didgeridoos in the quantity ordered.

44 The message stones were also acquired from the Indonesian Supplier and Mr Wooster explained that they were hand painted. However, in the case of the message stones, Mr Wooster specified and briefed the Indonesian Supplier with the Aboriginal symbols to be used and his understanding of the meaning of the symbols. He further explained that:

30. …. I obtained the aboriginal symbols graphic from internet research (mainly Google) and simply printed them off when I saw a symbol which I thought would make a good product. To my understanding from the research I completed, the symbols were common symbols (similar to a hieroglyphic) which Aboriginal [persons] used to communicate in written form. They are not produced in the same way that the Trisha Mason products are produced but are based on the symbols I provided to the Indonesian Supplier obtained from the Internet.

31. Message stones were similarly [a] very cheap part of the souvenir range. They were only ever intended to be a cheap keepsake by a frugal purchaser. Some of the Symbols can be seen in artworks by Trisha Mason and are recognised as Aboriginal Symbols used in Aboriginal Art.

45 Mr Wooster explained that the message stones were not a popular item and he discontinued the line in March 2018.

3.4 The retail outlets to which the Products were supplied

46 The parties also accepted that the retail outlets to which the Products were supplied (the Outlets) were illustrated by the sales ledgers to which I have earlier referred, even though those ledgers were confined to the sale of the bamboo didgeridoos and loose boomerangs. The sales ledgers relating to the loose boomerangs identified by the code “BOAN08” for the period 1 January 2016 to 13 April 2017 identified retail outlets at which the products were for sale as including Australia the Gift at locations around Australia, Cairns Didgeridoos, City Convenience Store in Sydney, Heinemann Australia (which Mr Wooster explained was located at Sydney Airport), Kiama Visitor Centre, Kings Canyon Resort, Melbourne Souvenirs (OzLand), the Mount Lofty Summit Gift Shop, South Australian Museum Shop, and Souvenirs Plus at Bondi Beach. The sales ledgers identify a range of similar retail outlets for the sale of the bamboo didgeridoos over the period 1 January 2016 to 13 April 2017 including Australia the Gift on George Street, Sydney (where the sample bamboo didgeridoo received in evidence was purchased), Everything Australian and Everything Tropical at Port Douglas in Queensland, Free Choice Tobacconist at Lismore, Heinemann Australia at Sydney Airport, Kakadu Snacks and Souvenirs, Melbourne Souvenirs (OzLand), and Opal Paradise in Cairns.

47 In addition, as earlier mentioned, the boxed bullroarer was purchased from the Mason Gallery in Darwin which had been a retail customer of Birubi since about August 2015, albeit that it was not a large customer and made orders about once a year through the Birubi website. The bullroarer purchased by Mr Kill from the Mason Gallery on 10 November 2017 had been displayed at the front of the Mason Gallery near the window with what appears to be approximately 15 boxed bullroarers, as well as a smaller number of unboxed bullroarers, variously labelled “Birubi Art Australia” and “Birubi Art Pty Ltd”. Mr Kill also saw a range of “dot paintings” displayed for sale at the Mason Gallery, as well as other objects such as boomerangs, rugs and woven baskets, as was apparent in the photographs which he took at the time. A screenshot taken by Mr Wooster from a promotional video available on the website of the Mason Gallery on an unknown date, and photographs taken of the Mason Gallery by Mr Moore on 22 and 23 June 2018, similarly depict Birubi products on shelves with other apparently similar souvenirs, together with large pieces of Aboriginal art.

48 It was not in issue that Birubi has no control or say in how its stock is displayed for sale by retailers, its retail price, its location within a particular outlet, or the other goods with which Birubi stock is placed. That notwithstanding, Mr Wooster often visits various Birubi retailers’ stores on sales trips in order to “review how Birubi’s products are going in the market, which product is left on the shelves (i.e. not sold)”, and what similar products from other suppliers are being sold with Birubi’s products. Mr Wooster was aware that retailers often removed Birubi products from their packaging for display. He also often saw Birubi products “mingled with other suppliers’ products on display stands, both Birubi stands and non-Birubi stands.” Birubi supplied these display stands at the request of retailers.

49 Finally, I accept Mr Wooster’s evidence that Birubi seldom offers to provide stands to new suppliers as they cost Birubi money. I also accept his evidence about a sticker affixed to a stand supplied by Birubi on which Birubi loose boomerangs were stacked which was depicted in a photograph put to him in cross-examination. The sticker headed Birubi Art described how Birubi worked with a pool of talented Aboriginal artists. Mr Wooster explained that he had been surprised to see the photograph when a copy was provided to his solicitors by the ACCC and considered that it must have been affixed to the stand by a storeman in error. It was, in his words, “an anomaly” and typically Birubi would paint only the words “Birubi Art” on any stands which it supplied. As such, in making findings about the implied representations, I have disregarded the sticker photographed on the stand.

4.1 The relevant statutory causes of action

50 Section 18 of the ACL provides that:

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

51 It was not in issue that Birubi is a person for the purposes of the ACL and that the conduct complained of was engaged in trade or commerce.

52 Nor was it in dispute that representations, including those which are implied, may constitute “conduct” for the purposes of ss 18 and 33 of the ACL: see e.g. Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 634; (2014) 317 ALR 73 (Coles Supermarkets) at [38] (Allsop CJ) (with respect to conduct comprised of representations that par-baked bread was freshly baked in-store) and subs 4(2) of the CCA. Furthermore, as the parties accepted, conduct is “likely” to mislead or deceive for the purposes of (now) s 18 if there is “a real or not remote chance or possibility regardless of whether it is less or more than fifty per cent’”: Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Pty Ltd (1984) 2 FCR 82 (Global Sportsman) at 87 (the Court) (citations omitted); see also Noone (Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria) v Operation Smile (Aust) Inc [2012] VSCA 91; (2012) 38 VR 569 at [60] (Nettle JA) (Warren CJ and Cavanough AJA agreeing relevantly at [33]). There is however no requirement to establish that significant members of the public have been misled: .au Domain Administration Ltd v Domain Names Australia Pty Ltd [2004] FCA 424 (.au Domain) at [25] (Finkelstein J).

53 I later consider what is meant by misleading and deceptive, and the circumstances in which the making of a representation may be implied, as is alleged by the ACCC here: see below at [62]-[70].

54 Section 29 of the ACL relevantly provides that:

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

(a) make a false or misleading representation that goods are of a particular standard, quality, value, grade, composition, style or model or have had a particular history or particular previous use; or

…

(k) make a false or misleading representation concerning the place of origin of goods;…

(emphasis added)

55 As such, s 29 applies only to a “representation” rather than the broader concept of “conduct” used in s 18, and proscribes only false or misleading representations about specific matters. Nonetheless, its reach encompasses representations made orally or in writing, and may include pictorial material, as well as other conduct in an appropriate case (at least to the extent that is embraced within the ordinary meaning of the word): Given v Pryor (1979) 39 FLR 437 at 440-441 (Franki J).

56 The principles relevant to subs 29(1)(a) of the ACL were not in issue and I adopt as an accurate description of relevant principle, the ACCC’s summary, with which Birubi agreed, as follows:

21. “Particular” does not mean “precise”, just an indicated or certain standard, quality, grade etc: Gardam v George Wills & Co Ltd (1988) 82 ALR 415 per French J [at 423].

22. The application of the term “style” has been described as “obvious”. The Honourable Dyson Heydon, writing extra-judicially, has said that “[t]o call furniture ‘Danish’ or ‘Danish Modern’ is probably false if it was not produced entirely in Denmark, and to call it ‘Danish designed’ is false if it was not entirely designed or styled in Denmark.”

23. A representation can be about the history of a thing even though it does not comprehend the whole of the period during which the thing has been in existence. The processes and place of manufacture of a chattel are part of its history: Korczynski v Wes Lofts (Australia) Pty Ltd (1985) 10 FCR 348 [at 353 (Jenkinson J)]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Lovelock Luke Pty Ltd (1997) 79 FCR 63.

24. As is the case with s 18 of the ACL, intent is irrelevant to a determination of whether a breach of s 29 of the ACL has occurred: Darwin Bakery Pty Ltd v Sully (1981)[36 ALR 371 at 376 (the Court)].

25. Statements made in labels affixed on goods can be treated as representations made by the person who affixed them: Barton v Croner Trading Pty Ltd (1984) 3 FCR 95 at 106 (the Court).

57 Further, with respect to subs 29(1)(k) of the ACL, it was not in issue that to describe goods as made in Australia is to make a statement concerning their “place of origin” for the purposes of subs 29(1)(k) of the ACL. As Gummow J held in Netcomm (Australia) Pty Ltd v Dataplex Pty Ltd (1988) 81 ALR 101 (Netcomm) at 106, “‘Origin’ directs attention … to the beginnings of existence of the goods with reference to a source or cause of that existence; the concept is that of beginning regarded in connection with its cause.” As his Honour then held at 107, “[t]o say of goods that they were made in Australia plainly is to make a statement concerning their place of origin. The making of goods involves the steps and procedures which preceded and resulted in the formation or composition of the goods”.

58 Accordingly, the issue for resolution with respect to s 29 is whether, as the ACCC alleges, Birubi made a false or misleading (implied) representation that the Products were of a particular style and had a particular history, and/or made false representation that the goods were made in Australia, in breach of subs 29(1)(a) and (k) respectively of the ACL.

59 Finally, s 33 of the ACL provides that:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is liable to mislead the public as to the nature, the manufacturing process, the characteristics, the suitability for their purpose or quantity of any goods.

(emphasis added)

60 Again the principles relevant to s 33 were not in issue. In contrast to s 18 of the ACL, s 33 applies only if the relevant conduct “is liable” to mislead. It has been held that this means that s 33 applies to a narrower range of conduct than s 18 and requires proof that it is more probable than not that the public would be misled: Coles Supermarkets at [44] (Allsop CJ); see also Westpac Banking Corporation v Northern Metals Pty Ltd (1989) 14 IPR 499 at 502 (Northrop J); Trade Practices Commission v J & R Enterprises Pty Ltd (1991) 99 ALR 325 at 338-339 (O’Loughlin J); and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Turi Foods Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 665 (Turi) at [79] (Tracey J).

61 The issue raised with respect to s 33 is whether, as alleged by the ACCC, Birubi engaged in conduct liable to mislead the public into thinking that the Products were hand painted by an Australian Aboriginal person or made by an Australian Aboriginal person. No issue was taken by Birubi with the proposition that representations about these matters may constitute conduct liable to mislead as to “the nature, the manufacturing process, [or] the characteristics” of the Products.

4.2 What is meant by “misleading or deceptive”, “false or misleading” and “mislead”?

62 It has been held that there is no meaningful difference between the words “misleading or deceptive” and “mislead or deceive” in s 18 of the ACL, “false or misleading” in subs 29(1)(a), and “mislead” in s 33. Furthermore, s 18 and subss 29(1)(a) and (k) of the ACL are in effectively the same terms as their predecessor provisions, s 52 and subs 53(a) and (eb) of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (the TPA), save that the phrase “[a] person must not” is used in the ACL rather than the phrase “[a] corporation shall not” in the TPA. That difference is not of any relevant consequence here, as was also the case in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; (2013) 250 CLR 640 (TPG Internet) at [11] (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ). As such, the consideration by authorities of whether conduct was “misleading or deceptive” or “false or misleading” conduct for the purposes of ss 52 and 53 of the TPA remains relevant to ss 18, 29 and 33 of the ACL.

63 Bearing these matters in mind, the principles to be applied in determining whether conduct is false, misleading or deceptive can conveniently be summarised as follows. In so summarising the relevant principles, I emphasise that they are interrelated.

64 First, the question of whether representations are misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive is a question of fact: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Telstra Corporation Ltd [2004] FCA 987; (2004) 208 ALR 459 at [49] (Gyles J). That said, the test is an objective one. Thus, while evidence that an erroneous conclusion has been formed by reference to the impugned conduct is admissible and may be persuasive, it is not essential. The Court must determine the question for itself: Global Sportsman at 87 (the Court). It also follows that an intention to mislead or deceive is not an element of s 18 (or ss 29 or 33) of the ACL, even though the respondent’s intention in making the representation (for example, to create a favorable impression in relation to an offer) may be relevant to the question of whether it may be inferred that a representation is misleading or deceptive or likely to be so: TPG Internet at [55]-[56] (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Nonchalant Pty Ltd (in liq) [2013] FCA 605 at [10] (Gordon J). Equally, save where the representation is about the maker’s state of mind, the maker’s belief in the accuracy of the meaning conveyed by the statement is irrelevant to the question of whether the meaning conveyed by the statement is false: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Homeopathy Plus [2014] FCA 1412; (2014) 146 ALD 278 (Homeopathy Plus) at [124] (Perry J).

65 Secondly, the question of whether conduct is misleading or deceptive (or likely to be so) “… is concerned with the effect or likely effect of conduct upon the minds of those by reference to whom the question of whether the conduct is or is likely to be misleading or deceptive falls to be tested”: Global Sportsman at 87 (the Court) (emphasis added). Similarly as French CJ explained in Campbell v Backoffıce Investments Pty Ltd [2009] HCA 25; (2009) 238 CLR 304 (Backoffice Investments) at [25], and as was subsequently endorsed in TPG Internet at [49], the characterisation of conduct as misleading or deceptive or as likely to mislead or deceive “generally requires consideration of whether the impugned conduct viewed as a whole has a tendency to lead a person into error” (emphasis added). “That is to say…”, as their Honours explained in their joint reasons in TPG Internet at [39], “there must be a sufficient causal link between the conduct and error on the part of persons exposed to it.” In practical terms, Allsop CJ in Coles Supermarkets explained that this means that:

41. It is necessary to view the conduct as a whole and in its proper context. This will or may include consideration of the type of market, the manner in which such goods are sold, and the habits and characteristics of purchasers in such a market… The context will also include relevant disclaimers or explanations: Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty Pty Ltd (2004) 218 CLR 592; … [2004] HCA 60 at [49] (where the disclaimer, in small print, but in a short document, was “there to be read”).

42. In assessing advertising material, the “dominant message” of the material will be of crucial importance: TPG at [45].

66 Thirdly, in line with these principles, the question of whether or not any loss was suffered is logically irrelevant to a consideration of liability under these provisions, although in practice characterizing conduct may require assessing its effects upon the notional consumer: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dell Computers Pty Ltd [2002] FCA 847 at [32] (Jacobson J); Backoffıce Investments at [24] (French CJ).

67 Finally, the question of whether the representation or conduct had a tendency to lead a consumer into error can meaningfully be addressed only once the class of persons likely to be affected and their relevant attributes have been identified. As Gibbs CJ held in Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191 (Parkdale) at 199:

…consideration must be given to the class of consumers likely to be affected by the conduct. Although it is true, as has often been said, that ordinarily a class of consumers may include the inexperienced as well as the experienced, and the gullible as well as the astute, the section must in my opinion by [sic] regarded as contemplating the effect of the conduct on reasonable members of the class. The heavy burdens which the section creates cannot have been intended to be imposed for the benefit of persons who fail to take reasonable care of their own interests. What is reasonable will [of] course depend on all the circumstances.

See also CPA Australia Ltd v Dunn [2007] FCA 1966 at [27] (Weinberg J); Turi at [75] (Tracey J); .au Domain at [12] - [25] (Finkelstein J).

68 The High Court further explained the approach to be adopted in Campomar Sociedad Limitada v Nike International Ltd [2000] HCA 12; (2000) 202 CLR 45 at [103] (Campomar) in the following passage:

103. … it is necessary to isolate by some criterion a representative member of that class. The enquiry thus is to be made with respect to this hypothetical individual why the misconception complained has arisen or is likely to arise if no injunctive relief be granted. In formulating this enquiry, the courts have had regard to what appears to be the outer limits of the purpose and scope of the statutory norm of conduct fixed by s 52. Thus, in [Parkdale], Gibbs CJ observed that conduct not intended to mislead or deceive and which was engaged in “honestly and reasonably” might nevertheless contravene s 52. Having regard to these “heavy burdens” which the statute created, his Honour concluded that, where the effect of conduct on a class of persons, such as consumers, was in issue, the section must be “regarded as contemplating the effect of the conduct on reasonable members of the class”.

69 Thus at [105] the High Court held that, in assessing the reactions or likely reactions of the ordinary or reasonable members of the class of prospective purchasers of a mass-marketed product for general use, the court may well disregard those assumptions by persons whose reactions are “extreme or fanciful”.

70 As I explained in Homeopathy Plus, it is useful to illustrate how the task of assessing what can reasonably be expected of the relevant class is undertaken, by contrasting the circumstances in TPG Internet and Parkdale respectively:

123. …. greater attention might be imputed to what might colloquially be called “small print” where the target audience consists of potential purchasers in the calm of a showroom who are visiting with a substantial purchase in mind (as was the case in [Parkdale]) as opposed to that which might reasonably be expected of the target audience regarding representations and qualifications in advertisements that were an unbidden intrusion on the consciousness of the target audience intended to arrest its attention (as in TPG Internet). In the latter case, “…the attention given to the advertisement by an ordinary and reasonable person may well be ‘perfunctory’, without being equated with a failure on the part of the members of the target audience to take reasonable care of their own interests”: TPG Internet at [47]. In such a case, many members of the general public may absorb only the general thrust: as above. Thus, the majority held in TPG Internet that “questions of carelessness by consumers in viewing advertisements may be relevant to that question of characterisation.”: at [49]. Relevantly also in TPG Internet, the tendency to lead potential customers into error arose because the advertisements themselves selected certain words for emphasis and relegated the balance to relative obscurity. Thus, in all of the circumstances, the majority held that carelessness in absorbing all of the detail was not an unreasonable response.

5. HAS THE ACCC ESTABLISHED THAT THE IMPLIED REPRESENTATIONS WERE MADE?

5.1 Identification of the class to whom the representations were made

71 The first question, therefore, in assessing whether the representations were likely or liable to be misleading and deceptive is to identify the class of persons to whom the representations were made and the attributes of an ordinary member of that class acting reasonably in all the circumstances (the reasonable member). Equally where it is said that the representations are implied, the issue is determined by considering whether an ordinary member of the class, acting reasonably, would draw the implied false and misleading representation in all of the circumstances: Dynamic Lifter Pty Ltd v Incitec Ltd (1994) 30 IPR 198 (Dynamic Lifter) at 203 (Whitlam J).

72 As the ACCC submitted, the class of persons to whom the representations were relevantly made is comprised of those who, it can be inferred, frequented the Outlets (as described at [46] above). The Outlets comprised souvenir shops, gift shops, museum gift shops, shops described as galleries, and convenience stores; each of which sell souvenirs, keepsakes and gifts. The Outlets, not surprisingly, tended to be located at places frequented by tourists including Sydney Airport and popular tourist destinations such as Bondi Beach, Kings Canyon, Mount Lofty, and Cairns. Furthermore, at least in the case of the Mason Gallery, the Products were also sold alongside what the Birubi described as “more expensive, authentic artworks”, as well as a variety of other souvenirs, gifts and mementos. As such, it was not in issue that the relevant class of purchasers and potential purchasers of the Products includes international tourists, interstate tourists, and those seeking to purchase a gift. Moreover, it is clear that the Products were not directed toward sophisticated consumers of Aboriginal art. As such, I agree with the ACCC that the potential class of consumers is a broad one and should be presumed to include “the astute and the gullible, the intelligent and the not so intelligent, the well educated as well as the poorly educated, and men and women of various ages pursuing a variety of vocations”: Puxu Pty Ltd v Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd (1980) 31 ALR 73 at 93 (Lockhart J) (cited with approval by Deane and Fitzgerald JJ in Taco Company of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd (1982) 42 ALR 177 (Taco Bell) at 202; see also Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Telstra Corporation Ltd [2007] FCA 1904; (2007) 244 ALR 470 (ACCC v Telstra) at [17] (Gordon J).

73 Added to this, the ACCC also submitted that international tourists “may be accepted to have a relatively low degree of familiarity with Aboriginal art and cultural practices and to rely to a greater degree upon matters disclosed to them by the sellers of such goods than would otherwise be the case”. As such, the ACCC submitted that the hypothetical purchaser would not be astute to the intricacies of the Aboriginal art world, nor astute to identifying anything about the likely mode of production or origin by reference to price. However, the ACCC submitted that the hypothetical purchaser would recognize the symbols, designs, artwork and cultural objects on, and represented by, the Products as characteristic of that which would be made by Indigenous Australians.

74 Against this, Birbui submitted that, to the extent that tourists are one of the defining features of the class, they have the “know-how” and resources to travel, and it can be assumed therefore that they are reasonably educated and unlikely to be unusually vulnerable or gullible. This, in Birubi’s submission, is consistent with that part of the ACCC’s case outlined above that ordinary members of the class would be familiar with Aboriginal symbols, designs and cultural objects. Ultimately, in Birubi’s submission, apart from references to notions of common sense and a general understanding of the sorts of people who visit the Outlets and the nature of the Outlets themselves, there is very little evidence about the members of the class in question led by the ACCC. As such, Birubi submitted that, in the absence of such evidence, “one must approach the issue as to what the advertising material conveyed to them on the footing that they are taken to be ordinary and reasonable readers of the material”, quoting Keane JA (with whose reasons Williams and Atkinson JJA agreed) in Downey v Carlson Hotels Asia Pacific Pty Ltd [2005] QCA 199 (Downey) at [70].

75 Birubi submitted that I ought not to go beyond Keane JA’s statement of principle in Downey in characterising the class, and not make assumptions about the kind of people who patronise the Outlets and may purchase the Products. I do not accept that submission. First, Keane JA’s comment seems directed, not to the question of who appropriately comprised the class of consumers who may purchase the Products, but to the question of the standard against which the effect of the conduct is to be tested, that is, the ordinary reader who is a member of the class acting reasonably). Nonetheless, it may be accepted, as Birubi submits, that international tourists may have the know-how to travel and a degree of education. Further, it can reasonably be inferred that it is highly likely that a prospective purchaser would consider purchasing items such as the Products because they recognise the association between such objects and their designs, on the one hand, and traditional Aboriginal art and cultural objects, on the other hand. This association is also chosen for emphasis on the labelling on the Products, as is explained below, as a feature rendering the Products more attractive to prospective purchasers. In this regard, Mr Wooster explained that Birubi “create[s] the packaging to highlight the product within the package.” However, it is also reasonable to infer that, at least in the case of overseas visitors, their familiarity with Aboriginal art and cultural practices is likely to be limited.

76 Finally, with respect to the assessment of what the ordinary member may reasonably infer from the Products, this is not a case such as Parkdale where the target audience is potential customers visiting a showroom with a substantial purchase in mind. Nor, at the other end of the spectrum, does the present case equate to the purchase of a staple product, such as bread, among many other items in a supermarket (as in Coles Supermarkets) or involve an advertisement constituting an unbidden and arresting intrusion on the consciousness of the targeted audience (as in TPG Internet). Nonetheless, in my view, the nature of the purchase, the pricing of the Products, the nature of the outlets in which they are presented for sale, and the composition of the target audience, render it likely that the reasonable hypothetical purchaser would typically absorb the dominant message conveyed by the Products and their presentation, rather than engaging in a close intellectual analysis of what was and was not stated and depicted on the products and their labelling. As such, I accept the ACCC’s submission that the choices made by potential customers will likely be affected by an “intuitive sense” of attraction and association based upon the impression conveyed by the Products and their labelling, “rather than by any process of analytical or logical choice” (adapting the passage from Coles Supermarkets at [43]).

5.2 The issue as to the width of the surrounding circumstances relevant to determining whether the false and misleading representations were impliedly conveyed

77 As earlier explained, the primary issue between the parties turns upon whether each or any of the implied representations pleaded by the ACCC was conveyed in the circumstances: ACCC v Telstra at [14] (Gordon J).

78 It will be recalled that the ACCC accepts that the representations are not expressly made but that it is incumbent on it to demonstrate that they are implied. In other words, while the various statements made on the Products were literally true, the combined effect of the design, symbols, labelling and cultural associations of the objects, together with what was not said on the products or their labels, is said to result in them conveying the alleged false representations. As Stephen J explained in Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd (1978) 140 CLR 216 at 227-228 in relation to then s 52 of the TPA, “To announce an opera as one in which a named and famous prima donna will appear and then to produce an unknown young lady bearing by chance that name will clearly be to mislead and deceive. The announcement would be literally true but none the less deceptive, and this because it conveyed to others something more than the literal meaning which the words spelled out…. a statement which is literally true and accurate may nevertheless carry with it a false representation” (emphasis added). Equally, half-truths may be misleading where the insufficiency of information permits a reasonably open, but wrong, conclusion to be drawn: Coles Supermarkets at [46] (Allsop CJ).

79 It was not in issue that determining whether or not something more than literal meaning has been conveyed is a question of fact and involves a consideration of the surrounding circumstances: e.g. Taco Bell at 202 (Deane and Fitzgerald JJ) and Campomar at [100] (the Court). As Reeves J explained in Bennett v Elysium Noosa Pty Ltd (in liq) [2012] FCA 211; (2012) 202 FCR 72 at [40]:

… it is important to note that the determination of the question of fact whether a statement was made that constitutes a representation… is of a different kind to the determination whether an implied representation was made. With both, the ultimate issue is whether the applicant was led into error by the representation; see Parkdale at 198. However, the exercise involved with the latter is to determine whether what was actually said or done, in all the relevant circumstances, conveyed something more, such that it led the applicant into error… Similarly, in Henjo Investments Pty Ltd v Collins Marrickville Pty Ltd (No 1) (1988) 39 FCR 546 … where it may have been literally true to say that the restaurant concerned had seating arrangements for 128 persons. Nonetheless, Lockhart J held at 555 – 556 that the provision of a card on which the words “Seats 128” appeared immediately above the word “Licensed”, combined with a sign on the front of the restaurant which said “Fully Licensed”, conveyed the impression that the restaurant was licensed to seat 128 persons when in fact it was only licensed to seat 84. I should add that while Lockhart J came to this conclusion at 556, his Honour also proceeded to deal with the case as one involving a representation by silence (see at 556 – 557). Burchett J agreed with Lockhart J at 568 and Foster J dissented on a different aspect at 568 – 571.

80 While the ACCC submits that context is relevant, as earlier indicated its approach to the relevant context was narrower than that urged by Birubi. In the ACCC’s submission, consideration of the Products themselves, together with the images and representations made on the Products and their packaging, are central to appreciating how the reasonable member would understand these Products and what they might reasonably infer about them. As I later explain, in support of the implied representations, the ACCC relies on the words, images and labels included on, or attached to, the Products or as part of their packaging, and the following matters:

(1) all of the Products, aside from the message stones, are objects known as traditional Aboriginal cultural objects;

(2) the artwork, symbols and/or designs reproduced on the Products are characteristic of Aboriginal artwork, symbols and designs; and

(3) there is no reference on the Products or their labels or packaging to the Products having been made in Indonesia.

81 When these characteristics and the express representations are considered together, the ACCC submits that the Products stand in a different category from, for example, a keyring depicting the Sydney Harbour Bridge or a road sign depicting a kangaroo or emu. The key characteristic is that they are presented either as Australian Aboriginal cultural objects with corresponding Australian Aboriginal art, designs and/or symbols, or in the case of the message stones are decorated with designs that would be associated with Aboriginal culture and art. This impression, in the ACCC’s submission, is reinforced by the labelling, and (where applicable) the packaging, of all the Products. This characteristic is said to be key because the class of persons to whom the Products were addressed would recognise these as typical of objects, symbols, designs and art made by Aboriginal people, without being knowledgeable about the Aboriginal art market and price placement.

82 Birubi, on the other hand, submitted that there was no real risk that a reasonable member would be misled into thinking that that the Products were hand painted, or handmade, by an Aboriginal person, or made in Australia. It relied in particular upon the truth of what was stated on the labels, on inferences that purchasers could reasonably be expected to draw based upon statements that the Trisha Mason products were reproductions for which royalties were paid, and the retail setting in which the Products were displayed for sale in the Outlets. It is convenient to start with the last of these matters, as it pertains to all of the Products.

5.3 Relevance of the retail environment in which the Products were displayed for sale

83 Birubi’s submission that no false or misleading representations are conveyed when the Products are considered in their retail context is premised among other things upon the Court finding that competing products which were made in Australia, and/or made or hand painted by an Aboriginal person expressly and prominently displayed those claims, in contrast with the Products, and were more highly priced than the Products.

84 In support of its submission that these broader surrounding circumstances must be taken into account, Birubi relied upon the statement by Gibbs CJ in Parkdale at 199 that:

The conduct of a defendant must be viewed as a whole. It would be wrong to select some words or act, which, alone, would be likely to mislead if those words or acts, when viewed in their context, were not capable of misleading.

85 Birubi also placed relied upon the decision of Allsop CJ in Coles Supermarkets, with particular weight upon his Honour’s explanation of the applicable approach as follows:

41. It is necessary to view the conduct as a whole and in its proper context. This will or may include consideration of the type of market, the manner in which such goods are sold, and the habits and characteristics of purchasers in such a market…

(emphasis added)

86 Thus in Coles Supermarkets, Allsop CJ took into account contextual matters not simply pertaining to the product (par-baked bread) itself, but store signage, the “availability of bread on show”, and the in-store bakery, as combining “to communicate to the ordinary purchaser of bread that baking takes place on the premises and is freshly done” (Coles Supermarkets at [49]). By analogy, Birubi submitted that the “manner in which” the Products were sold in this case requires consideration of the kinds of retail outlets which stocked the Products, their layout, other products displayed for sale with the Products, and so forth.

87 A potential difficulty with the reliance which Birubi seeks to place upon these decisions, however, is that Gibbs CJ refers to the need to view the conduct of the defendant as a whole. Consistently with this, in Coles Supermarkets, the contextual matters which Alsop CJ took into account, such as store signage and store layout, was conduct undertaken by Coles and was taken into account by his Honour as part of the means by which Coles communicated the impugned representation about the baking of fresh bread to customers. By contrast, in the present case Birubi seeks to rely upon conduct by third parties (retailers and the producers of competing products) as part of the surrounding circumstances which the reasonable member may or would take into account in drawing inferences about the provenance and means of production of the Products. Furthermore, that conduct, namely the pricing, stocking and display of products in retail outlets, is conduct which Mr Wooster accepted was not within Birubi’s control.

88 It may be that the fact that broader contextual matters are within the control of a third party or outside the control of the person allegedly engaging in the misleading or deceptive conduct does not necessarily mean that those matters are irrelevant to a consideration of whether or not particular conduct or representations are likely or liable to mislead or deceive. Certainly matters such as the prevailing market conditions in which goods are represented may bear upon whether or not the representations are misleading (as Allsop CJ explained in Coles Supermarkets). In any event, this issue was not the subject of developed argument in the absence of which it would be undesirable to decide the point of principle.

89 Rather, the ACCC submitted that the evidence, even if admitted, falls well short of establishing the contextual matters on which Birubi seeks to rely. Further and in any event, the ACCC submitted that neither the range of locations at which the Products were sold, nor their price, would alter the impression which an the reasonable member would gain from the Products and their packaging, namely, that the Products were hand painted or handmade by an Australian Aboriginal person in Australia. For reasons I later explain, I accept those submissions in relation to context.

90 First, Birubi submitted that the evidence established that, within the five retail outlets photographed (and by inference, other outlets where the Products were sold), there were goods claiming expressly to be Australian made, including products displaying the “Australian made” logo. It further submitted that the reason why these stickers and the logo were used was to distinguish between those products which were Australian made and those which were not, and that, in so doing, products making those express representations gained a competitive advantage. Equally, Birubi submitted that there were also products expressly representing that they were made or painted by Aboriginal people which would also thereby have a competitive advantage. As a result, Birubi submitted that a prospective purchaser at an Outlet would be exposed to products that expressly make such claims and products, such as those in question here, which do not. In that context, Birubi submitted that it is highly unlikely that the reasonable member would consider that the Products, which do not make any express claim that they were made in Australia, or that they were made or hand painted by an Australian Aboriginal person, were nonetheless made in Australia and/or were made or painted by an Australian Aboriginal person. Further, Birubi submitted that, if a consumer is not led by the product, labelling and context to conclude that the Product is made in Australia, then that consumer would be unlikely to draw any conclusion as to the ethnicity of the person who made the product.

91 I accept that if the ordinary member of the class could not reasonably conclude that the product was made in Australia, it is unlikely that the reasonable member could nonetheless infer that the product was made or hand painted by an Australian Aboriginal person; indeed that possibility is in my view remote. However, I agree with the ACCC that the presence or absence of express claims on other products displayed in the same outlets to have been made in Australia is not inconsistent with the representation that the Products were made in Australia being implied, especially given the prominence afforded to the word “Australia” on the Products or in the case of the message stones, on the packaging (as I later explain). I also accept that the presence or absence of express claims on other products displayed in the same outlets to have been hand painted, or made, by an Australian Aboriginal person would not negate an inference which the ordinary member of the class may reasonably draw that the Products were hand painted by an Australian Aboriginal person.

92 Secondly, Birubi submitted that a reasonable member of the class would be unlikely to conclude that the Products were painted by anyone in particular, or manufactured in any particular way, in circumstances where the Products are sold in a retail environment where multiple instances of the one product are on display. Birubi submitted that this feature of the Products’ display would suggest that they were mass-produced. This conclusion was said to be all the more likely given the express representation that “royalties are paid” in the case of the Trisha Mason Products, making it clear that they are reproductions and not “one off” originals. Specifically, Birubi submitted that:

35. … Because the Boomerangs, again like the other Birubi products, are relatively inexpensive and are sold alongside much more expensive items, they are unlikely to be regarded as authentic in the sense that each one is individually painted by an Aboriginal person. The Outlets commonly carry both inexpensive keepsakes and more expensive, authentic artworks. The Reasonable Member, seeing the range of things available, is unlikely without express representations, to conclude that comparatively inexpensive items, obviously mass-produced, have aspects of authenticity such as being hand painted by a person of a particular ethnicity.

36. If matters of authenticity were important, the obvious disparity in price would likely lead the Reasonable Member to inquire as to the reasons for that disparity. That enquiry would likely reveal that the more expensive product was a one-off product actually made by an Aboriginal person, that being the basis upon which the higher price is demanded.

93 I note that there was no evidence that the Outlets were aware that the Products were manufactured in Indonesia.