FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Dometic Australia Pty Ltd v Houghton Leisure Products Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 1573

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The matter be adjourned to a date to be fixed for submissions with respect to the orders which are appropriate to give effect to these reasons.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

WHITE J:

[1] | |

[10] | |

[21] | |

[30] | |

[36] | |

[36] | |

[36] | |

[36] | |

[36] | |

[36] | |

[37] | |

[59] | |

[60] | |

[65] | |

[67] | |

[71] | |

[80] | |

[102] | |

[107] | |

[117] | |

[139] | |

Integer 1.11: an exiting airflow in a substantially horizontal plane | [140] |

[142] | |

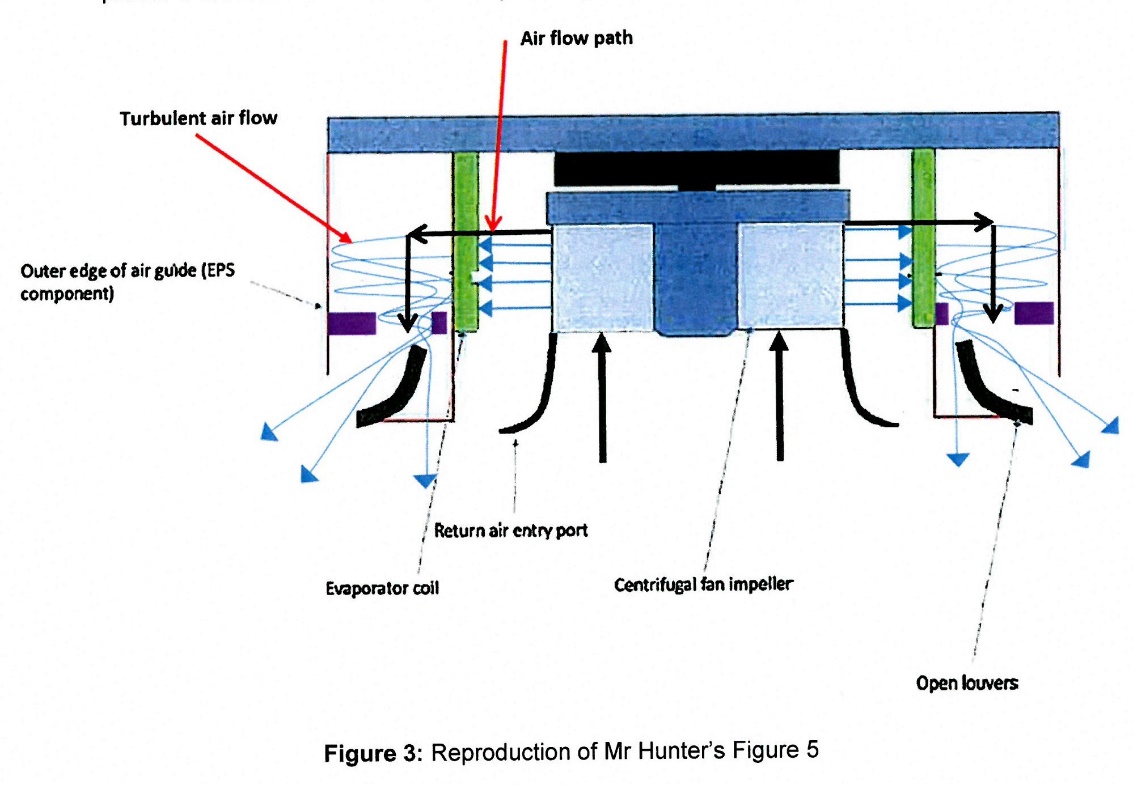

Does the air exit the Belaire Unit in a substantially horizontal plane? | [149] |

[160] | |

[161] | |

[172] | |

[181] | |

[184] | |

[186] | |

[195] | |

[196] | |

[200] | |

The admissibility of Mr Henshall's evidence concerning the best method | [209] |

[217] | |

[220] | |

[235] | |

[237] | |

[262] | |

[264] | |

[265] | |

[270] | |

[281] | |

[285] | |

[287] | |

[297] | |

[299] | |

[304] | |

[306] | |

[310] | |

[311] | |

[320] | |

[321] |

1 Since about July or August 2016, the Second Respondent (Finch) has imported into Australia and sold reverse cycle air conditioning units for recreational vehicles such as caravans, branded as the Houghton Belaire 3200 (the Belaire Unit).

2 The Applicants (collectively Dometic) contend that, by that conduct, Finch has infringed certified Australian Innovation Patent No 2016101949, entitled "Improved Air Conditioning System" filed on 7 November 2016 (the Patent). They allege that the First Respondent (Houghton) is also liable for the infringement because it authorised the relevant conduct or because it is a joint tortfeasor with Finch.

3 The Second Applicant (Dometic Sweden) is the registered proprietor of the Patent. On 16 February 2017, Dometic Sweden granted an exclusive licence to the First Applicant (Dometic Australia) to exploit the Patent. The commencement date for the licence was stated to be 6 March 2015.

4 An air conditioning unit, known as the IBIS 3, is a commercial embodiment of the Patent. Aircommand Australia Pty Ltd (referred to by the parties as New Aircommand) imports the IBIS 3 into Australia. Since October 2014, New Aircommand has been a wholly owned subsidiary of Dometic Sweden.

5 Finch and Houghton (collectively the Respondents) deny the allegation of infringement. They contend that the Belaire Unit does not embody at least four of the essential integers of the claim stated in the Patent.

6 The Respondents then allege that, if the Belaire Unit does constitute an infringement of the Patent, the Patent is invalid. By cross-claim, Houghton (but not Finch) seeks an order pursuant to s 138 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the Act) for the revocation of each of the five claims in the Patent. Its Amended Particulars of Invalidity contain the following grounds:

(a) Priority Date – To the extent that Dometic relies on a construction of the term "centrifugal fan" as including an axial fan, it is is not entitled to a Priority Date before 7 November 2016 and, in particular, is not entitled to the claimed Priority Date of 6 March 2014;

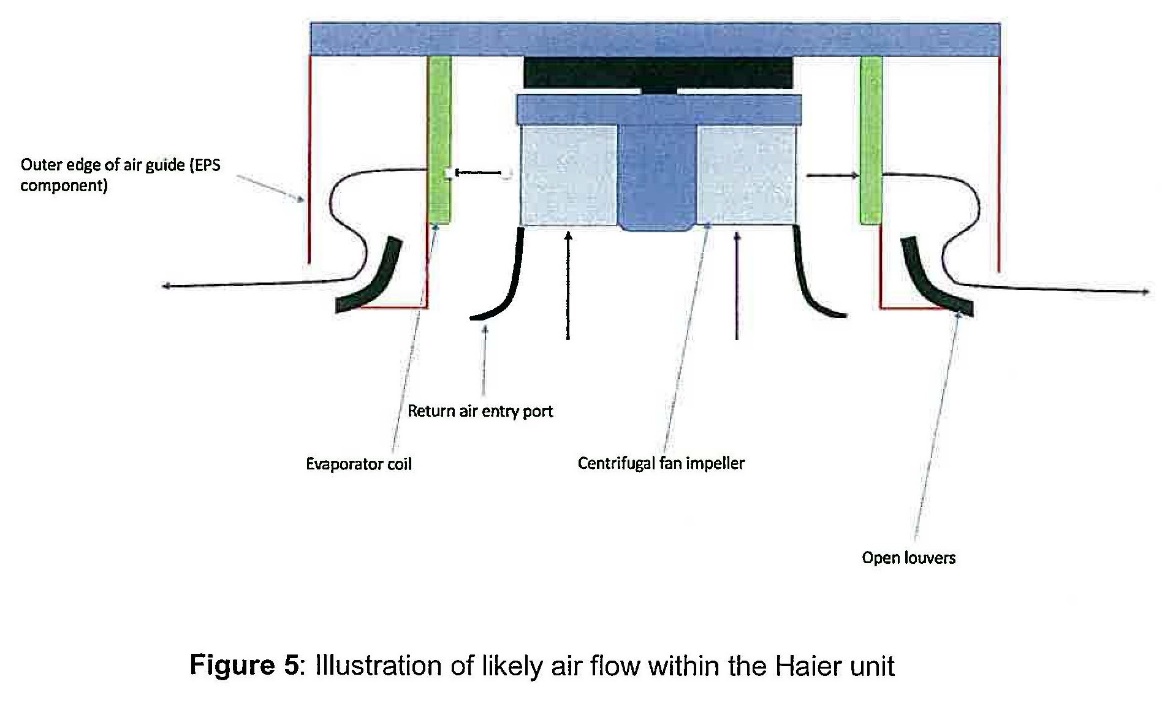

(b) Lack of Novelty – Houghton contends that the Patent was not patentable within the meaning of s 18(1)(b)(i) of the Act because it was not novel. Houghton relies on this ground on a disclosure of information said to have occurred by the exploitation by a bus manufacturer in China since November 2013 of an air conditioning system made by Haier;

(c) Lack of enablement – Houghton contends that the Patent does not comply with s 40(2)(a) of the Act in that it does not disclose the invention in a manner which is clear and complete enough for the invention to be performed by a person skilled in the relevant art;

(d) Lack of clarity – Houghton contends that the specification for the Patent does not comply with s 40(3) of the Act in that it does not describe the claimed invention clearly and succinctly;

(e) Lack of support – Houghton alleges that the specification for the Patent does not comply with s 40(3) of the Act in that the invention claimed is not supported by matters disclosed in the specification;

(f) Lack of best method – Finally, Houghton claims that the specification in the Patent does not disclose the best method known to the "patent applicant" of performing the invention and therefore was not compliant with s 40(2)(aa) of the Act.

7 On the application of Dometic, a Judge of this Court ordered an expedited trial of the proceedings. The Judge also ordered that the issues of quantum were to be determined separately from, and following, the determination of all other issues in the proceedings.

8 During the course of the final submissions, Houghton abandoned a further pleaded ground of invalidity, namely, lack of innovative step. The principal grounds of invalidity which it pursued were grounds (b) (lack of novelty) and (f) (lack of best method).

9 For the reasons which follow, I consider that both Dometic's claim of infringement and the Respondents' claim of invalidity fail.

10 The matters which I record under this heading were uncontroversial and may be regarded as findings of fact.

11 From at least 2003-2004, a company then known as Aircommand Australia Pty Ltd (to which the parties referred to as "Old Aircommand") sold air conditioning units suitable for use in recreational vehicles, caravans, crane cabs and the like. One such unit was known as the "IBIS". Old Aircommand is owned, or at least substantially owned, by members of the Henshall family, including Mr David Henshall but not his son, Bruce Henshall, to whom I will refer shortly.

12 In or around 2009, Old Aircommand commenced selling an upgraded air conditioning unit referred as the "IBIS 2". An upgraded model, the IBIS 3, was released to the market in Australia in about March 2014, although its manufacture had commenced in China in November 2013.

13 On 15 July 2013, Old Aircommand sold its business to Atwood Investment Holdings LLC by means of an asset sale to a new company, also known as Aircommand Australia Pty Ltd. This was New Aircommand, which is a subsidiary of Atwood Australia Holdings Pty Ltd (Atwood). As part of that sale, Old Aircommand agreed to change its name so as to remove altogether the name "Aircommand". It did so with effect from 18 July 2013.

14 On 17 October 2014, Dometic Sweden acquired all of the shares in Atwood. As a result, New Aircommand became an indirect subsidiary of Dometic Sweden. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) granted approval for the acquisition on 10 April 2015.

15 On 1 January 2016, New Aircommand sold its business to Dometic Australia as a going concern, this being the distribution of air conditioners and hot water services for the mobile accommodation market, together with the assets owned by New Aircommand relating to, or necessary for, the conduct of that business. These included New Aircommand's rights under the Provisional Patent and the PCT Application which are the subject of this litigation.

16 Houghton is a wholly owned subsidiary of Ningbo Hongdu Electrical Appliance Co Ltd (DayRelax). DayRelax was previously known as Ningbo DayRelax Electrical Appliance Co Ltd and was established in China in 2000 by Mr Shihong Bei. Mr Bei is President of the DayRelax Group of Companies and the sole director and secretary of Houghton.

17 DayRelax had traded with Old Aircommand from 2004. From about 2007, DayRelax had supplied air conditioners and air conditioning parts to Old Aircommand pursuant to a Supply Agreement. In addition, DayRelax distributed in China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Thailand and Korea products which it had manufactured on Old Aircommand's behalf.

18 It was an agreed fact that, following the acquisition of New Aircommand by Dometic, DayRelax had become concerned that Dometic and the companies under its control, including New Aircommand, would over time cease to acquire goods from it. It considered developing, manufacturing and supplying its own air conditioning products under a name of its own directly to original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) and after market (AM) channels in Australia. DayRelax commenced developing its own range of branded products in 2014. It discussed these plans with representatives of Dometic and, in February 2016, invited Dometic to become a distributor of the products. Dometic declined that invitation.

19 In about 2015, DayRelax determined to brand its product range "Houghton". It incorporated Houghton in November 2015 with a view to it being the importer and distributor to OEMs and AMs in Australia of Houghton-branded products. In December 2015, Houghton filed Australian Trademark Applications 1742574 and 1740765 for "HOUGHTON + DEVICE" and "BELAIRE".

20 However, Houghton did not become the importer and distributor. Instead, DayRelax entered into an agreement with Finch, pursuant to which Finch purchases Houghton-branded products from DayRelax in China, imports them into Australia, and promotes and sells them to OEMs and AMs and to another distributor of products for recreational vehicles.

21 On 6 March 2014, New Aircommand had filed Provisional Patent Application No 2014900754 (the Provisional Patent Application). Then, on the last day of the period prescribed pursuant to s 38 of the Act, ie, 6 March 2015, New Aircommand filed International Application PCT/AU2015/000126 (the PCT Application) with the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO). In the PCT Application, New Aircommand claimed priority from 6 March 2014, being the date on which it had filed the Provisional Patent Application.

22 The PCT Application was published as a national phase application on 11 September 2015.

23 On 18 March 2016, Dometic Sweden assigned the PCT Application to Dometic Australia. A Confirmation of Assignment document was lodged with WIPO on 22 March 2016.

24 The Patent identifies Dometic Sweden as the applicant. It was filed on 7 November 2016 and certified on 8 February 2017. It also records that it is a divisional patent of the PCT patent. The inventors are shown as David Henshall, Andrew Karas and Bruce Henshall.

25 The statement of the field of the invention is:

The present invention relates generally to air conditioning systems and in particular to air conditioning systems that are located in a compact slim line housing that is suitable for use in a confined area.

26 The Patent then records some difficulties commonly experienced in providing air conditioning to recreational vehicles such as caravans, motor homes and the like. The first difficulty arises from the desirability of keeping the weight and overall size of the air conditioning unit as low as possible. This has the consequence that the power of the air conditioning system is limited. The second difficulty arises from the short path between the cooling chamber and conventional outlets. The difficulty is in distributing the conditioned air (and thereby enhancing the cooling effect) and avoiding the air being drawn almost immediately back into the air conditioning unit to be conditioned further. In buildings, ducts can be used to distribute the conditioned air away from the inlet port but there are a number of problems in using ducting in recreational vehicles.

27 The background statement then continues:

[0013] It is an object of the present invention to overcome, or at least substantially ameliorate, the disadvantages and shortcomings of the prior art.

[0014] It is an object of the present invention, in at least one preferred form, to provide an air conditioning system for use in a recreational vehicle that provides a greater distribution of air without the need for ducting.

28 This feature of the Patent is elaborated in the detailed description statement in the Patent:

[0044] The present invention also provides the unexpected benefit of better managing the flow of air back into the return air inlet port 32. One of the known problems with traditional vehicle air conditioning units is that conditioned air is often ejected relatively closely to the return air inlet port without having travelled far enough to cool the air space generally or the occupants. Whilst air conditioning systems that use ducts to take the conditioned air away from the return air inlet port partially address this problem, they introduce the complexity of having ducting work in the roof space of the vehicles cabin area as well as reducing the capacity of the air conditioner due to the decrease in air flow and thermal losses through the ducts.

[0045] The system of the present invention, which includes a substantially flat layer of airflow adjacent to and along the interior roof surface, allows the conditioned air to travel further away from the return air inlet port 32 and so the air being drawn into the return air inlet port 32 is less likely to be recently conditioned air, which greatly enhances the effect of the conditioned air within the vehicle's cabin by ensuring that the conditioned air is being used effectively to take heat out of the vehicle.

29 In summary, the patented invention consists of a combination of integers affecting the movement and distribution of air flow, both within and outside the air conditioning unit. The system causes the conditioned air to travel a substantial distance from the outlet, thereby increasing the areas which will be cooled and reducing the amount of recently conditioned air which is drawn into the unit's inlet. This increases the cooling effect of the unit.

30 The claims defining the Patent pursuant to s 40(2)(c) of the Act are stated as follows:

(1) An air conditioning system for a vehicle having a roof, the air conditioning system having at least one air conditioning unit, including:

at least one centrifugal fan;

at least one return air entry port;

at least one outlet port;

at least one evaporator coil operatively connected to a compression refrigeration system;

a chamber formed by the at least one evaporator coil substantially surrounding the at least one centrifugal fan, the at least one centrifugal fan being operable to draw in indoor air via the return air entry port and eject the indoor air in a substantially horizontal plane such that it is forced into the at least one evaporator coil; and

a conditioned air flow path adapted to direct conditioned air from the chamber in a downward direction and towards the at least one return air entry port and then redirecting the air flow path outwards and away from the at least one return air entry port to exist the at least one outlet port in a substantially horizontal plane adjacent to the roof.

(2) The air conditioning system of claim 1, wherein the airflow path is "S" – shaped.

(3) The air conditioning system of claim 1 or claim 2, wherein in the at least one outlet port is configured to direct the air flow path in a substantially horizontal plane adjacent to the roof and away from the return air entry port by at least one louver.

(4) The air conditioning system of claim 3, wherein the at least one louver is pivotable between an open position and a closed position.

(5) The air conditioning system of any one of the preceding claims, wherein the fan is located directly above the return air entry port.

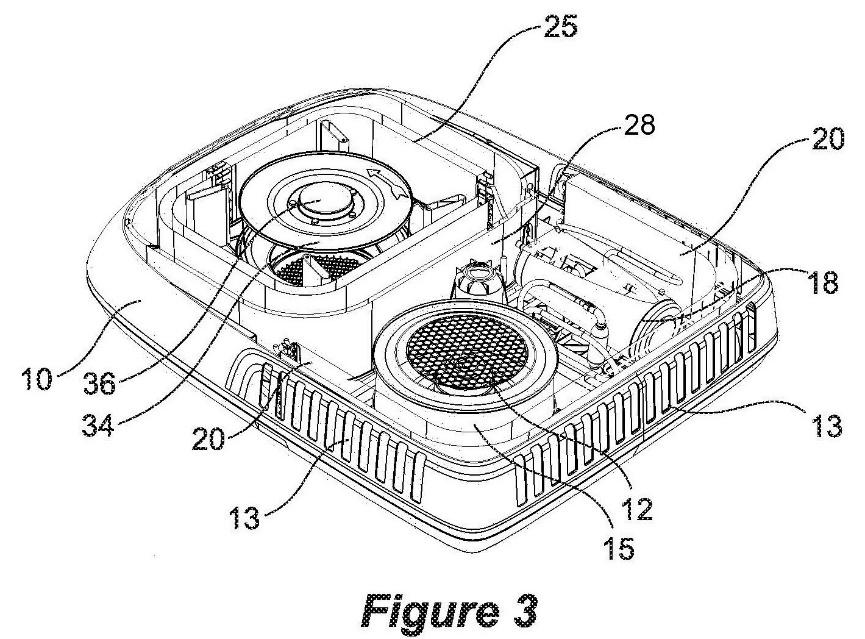

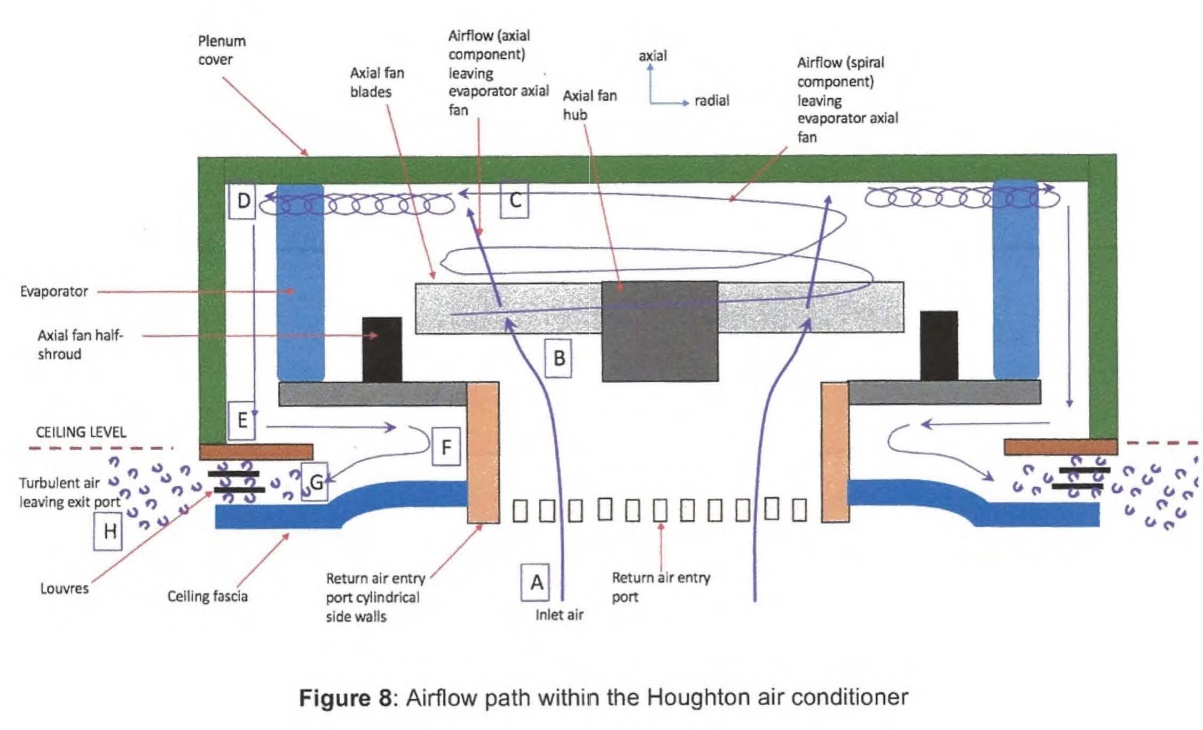

31 The Patent also includes schematic drawings of an air conditioner constructed in accordance with the invention. Figures 3, 4 and 9 are helpful in understanding the issues which arise for determination.

32 Figure 3 shows the air conditioner with its outer cover removed. The compressor 18 is connected to a condenser 20, which substantially surrounds the fan 15. Air drawn in from the outside by the fan 15 (referred to by the parties as "the condenser fan") is forced through the condenser 20 to cool the refrigerant within it. That air is then forced out through openings 13. The cooled refrigerant passes through an expansion valve into the evaporator 25 to absorb heat from the indoor heat which passes over it. The refrigerant then returns back to the condenser to be cooled once again.

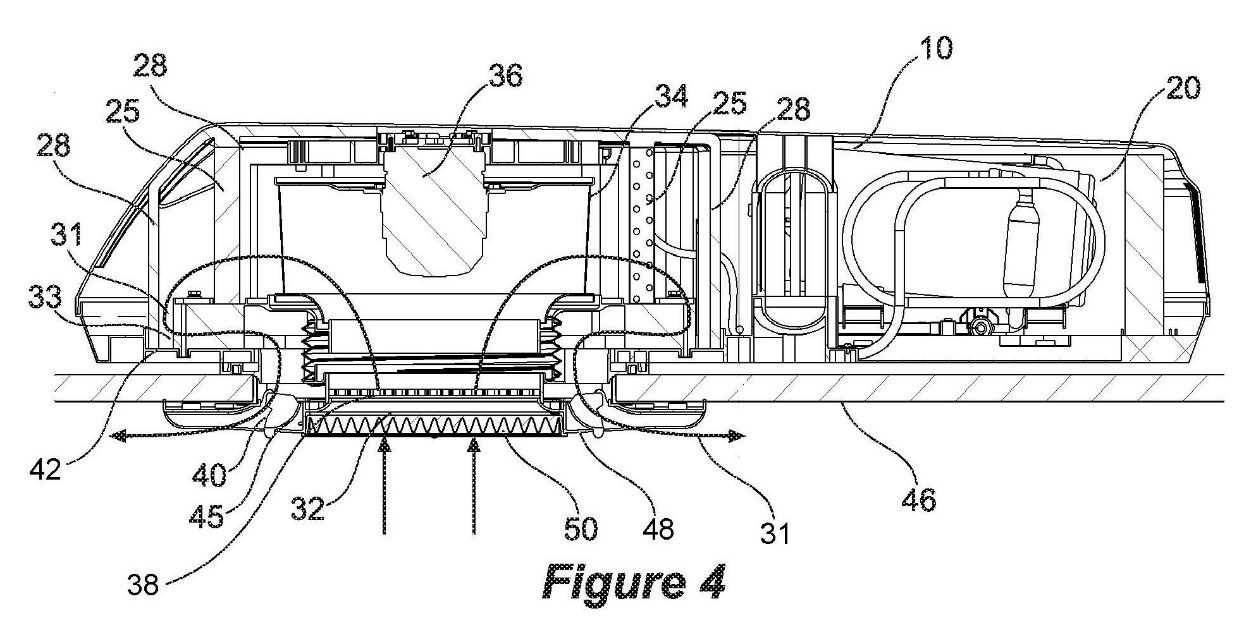

33 Figure 4 shows that air is drawn into the air conditioning unit by the centrifugal fan 34 and into the enclosure formed by the evaporator cover 28 and the base 42. The centrifugal fan (sometimes referred to as "the evaporator fan") then forces the air in substantially horizontal directions into and around the evaporator 25. It is thereby cooled. The air is then forced into adjacent chambers, along the path 31, through the opening 33, down and away from the air inlet port 32, and is ultimately ejected through the outlets 40. The louvres 45 on these outlets are shaped to direct the outgoing air stream substantially horizontally, adjacent to the interior roof surface of the area being cooled.

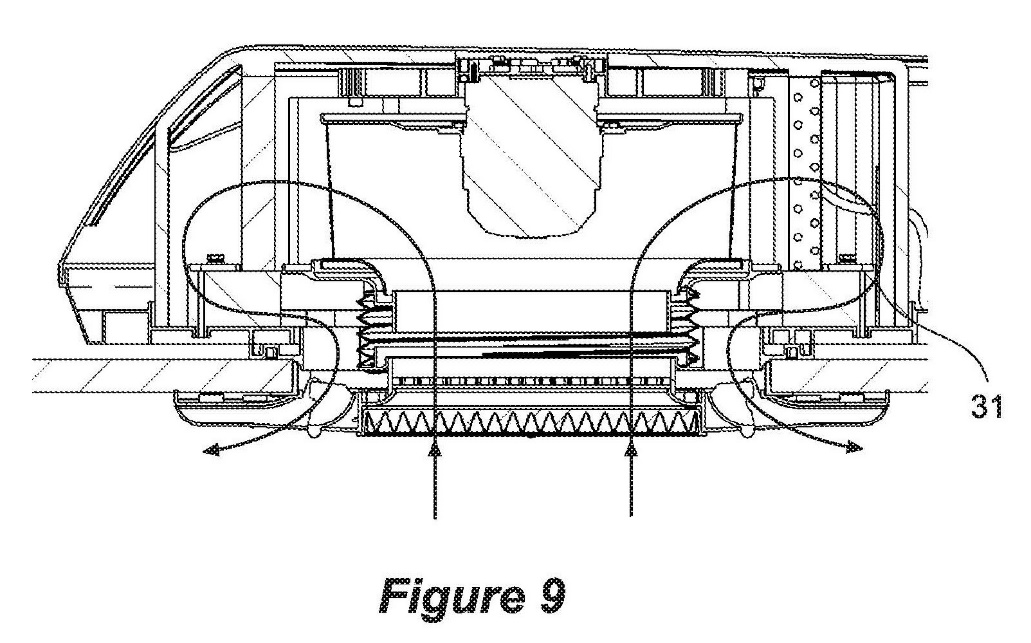

34 Figure 9 is a cross section view of the invention showing the air paths through its interior.

35 As is apparent, the Patent is a combination patent of the kind described by Aickin J in Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Co Ltd v Beiersdorf (Australia) Ltd [1980] HCA 9; (1980) 144 CLR 253 at 266:

The patent thus claimed is a combination patent in the proper sense of that term, i.e. it combines a number of elements which interact with each other to produce a new result or product. Such a combination may be one constituted by integers each of which is old, or my integers some of which are new, the interaction being the essential requirement.

See also Aktiebolaget Hässle v Alphapharm Pty Ltd [2002] HCA 59; (2002) 212 CLR 411 in which Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ said:

[6] The tablet or pellet thus claimed is a combination in the proper sense of that term, combining three elements which interact with each other to produce the new product; it is the interaction which is the essential requirement of invention and such a combination may be constituted by integers each of which is old or some of which are new. Thus, for example, in the present case, it is not to the point that of the three integers it may be said that omeprazole was known as an acid labile compound and that it was known that enteric coatings were resistant to acids. The question for decision concerns the ingenuity of the combination, not of the employment of any one or more integers taken individually.

36 It was common ground that the integers arising from the five claims are as follows:

1.1 an air conditioning system for a vehicle having a roof;

1.2 the air conditioning system having at least one air conditioning unit, including;

1.3 at least one centrifugal fan;

1.4 at least one return air entry port;

1.5 at least one outlet port;

1.6 at least one evaporator coil operatively connected to a compression refrigeration system;

1.7 a chamber formed by the at least one evaporator coil substantially surrounding the at least one centrifugal fan;

1.8 the at least one centrifugal fan being operable to draw in indoor air via the return entry port and eject the air in a substantially horizontal plane such that it is forced into the at least one evaporator coil;

1.9 a conditioned airflow path adapted to direct conditioned air from the chamber in a downward direction and towards the at least one return air entry port;

1.10 and then redirecting the air flow path outward and away from the at least one return air entry port;

1.11 to exit the at least one outlet port in a substantially horizontal plane adjacent to the roof.

2.1 the air conditioning system of claim 1;

2.2 wherein the airflow path is S-shaped.

3.1 the air conditioning system of claim 1 or claim 2;

3.2 wherein in the at least one outlet port is configured to direct the airflow path in a substantially horizontal plane adjacent to the roof and away from the return air entry port by at least one louver.

4.1 the air conditioning system of claim 3;

4.2 wherein the at least one louver is pivotable between an open and closed position.

5.1 the air conditioning system of any one of the preceding claims;

5.2 wherein the fan is located directly above the return air entry port.

37 The Court heard expert evidence from three independent experts: from Mr Robert Tiller who was called by Dometic, and from Mr William Hunter and Dr Allan Wallace who were called by Houghton.

38 Dr Wallace is a well-qualified and well-experienced professional engineer. His academic qualifications comprise a Bachelor of Technology (Mechanical Engineering) from the University of Adelaide in 1971, a Bachelor of Engineering (Honours) from the University of Adelaide in 1975, and a Doctor of Philosophy in the field of Fluid Mechanics from the University of Adelaide in 1981. He has worked as a Mechanical Engineer for more than 45 years, including working on several occasions in the fields of air conditioning and fluid dynamics. I am satisfied that Dr Wallace has extensive working knowledge of the use, design and operation of fans, in particular of axial and centrifugal fans, including in air conditioning applications. I consider that Dr Wallace is able to speak authoritatively about these matters.

39 Mr Hunter is also well-qualified and well-experienced, although not to the same extent as Dr Wallace. He obtained a Degree in Mechanical Engineering Science at the University of Melbourne in 1982. A core subject in his degree was fluid mechanics, which he studied for three years. It was common ground that the subject of fluid dynamics (which is a subset of fluid mechanics) includes the movement and behaviour of air in air conditioning systems of the kind in question in the present case. In the course of his work as an Engineer, Mr Hunter has obtained considerable experience with both centrifugal and axial fans. Dometic did not challenge his expertise in relation to the matters in issue in this litigation.

40 Mr Tiller describes himself as an "Industrial Design and Engineering Consultant". He is the Chief Executive Officer of two companies, Tiller Design Pty Ltd and Tiller Manufacturing Pty Ltd, both of which specialise in providing consultant services in relation to the development, design and engineering of a broad range of consumer, industrial and medical products. Mr Tiller's academic qualification is a Bachelor of Industrial Design which he obtained from the University of South Australia in 1988. Between 1988 and 1997, Mr Tiller was employed as an Industrial Designer. Since then, he has been engaged in his own consultancies. Mr Tiller acknowledged that he has had no formal training in fluid dynamics or in mechanical engineering. He did not claim to have had formal training in relation to the operation of air conditioning units. He has, however, acquired some knowledge of these matters by reason of his experience in working on projects with other professionals which did involve air conditioning and/or refrigeration systems. Mr Tiller said, and I accept, that fluid dynamics has played an important role in a number of the projects on which he has worked. I accept that Mr Tiller has thereby acquired some expert knowledge of these matters. I note however that on more than one occasion in his consultancy, Mr Tiller has engaged specialists in the analysis of fluid dynamics, rather than attempting to provide that service himself. This seemed to reflect a recognition by him of limitations on his expertise in fluid dynamics. In fact, Mr Tiller claimed only that his collaboration with other professionals had given him "a good basic solid understanding of how fluids move through systems". This level of understanding contrasts with Mr Hunter's evidence (which I accept) that "[f]luid dynamics is a highly-complex subject" for which he had studied "the foundational theory exclusively for 3 years during [his] 4 year undergraduate mechanical engineering degree".

41 The Respondents challenged the ability of Mr Tiller to provide expert opinion evidence. I overruled that objection, accepting that Dometic had established that Mr Tiller had some expertise in relation to air conditioning units and fluid dynamics sufficient to entitle them to lead opinion evidence from him. I am satisfied, however, that Mr Tiller's qualifications and experience are less than those of Dr Wallace and Mr Hunter and that this limits the weight which can be attached to his opinions. Although I accept that Mr Tiller gave his evidence honestly and in an attempt to assist the Court, I have, in general, attached greater weight to the evidence of Dr Wallace and Mr Hunter when Mr Tiller's evidence has been in conflict with theirs.

42 In addition, Houghton led some evidence of an expert opinion kind from Mr Bruce Henshall. From 2004 until July 2013, Mr Henshall was employed by Old Aircommand as Project Co-ordinator. Initially, Mr Henshall was engaged to oversee the manufacture and assembly of mobile air conditioners but, over time, his role evolved. From about 2007-2008, he was more involved in the design and development of Old Aircommand's products and his oversight of the manufacturing and assembling of products became a minor part of his role.

43 Mr Henshall's formal qualification is an Advanced Certificate in Chemical Technology from the University of South Australia, obtained in 1994.

44 After New Aircommand took over the conduct of the business of Old Aircommand in July 2013, Mr Henshall continued in the same role as he had previously. In fact, his role did not change before he resigned from New Aircommand with effect from 6 December 2015.

45 By 2012, it was apparent to Mr Henshall and to his father (David Henshall) that updating of the IBIS 2 model was required. Together with Mr Karas, they established a design team in Old Aircommand for that purpose. They continued in that role after New Aircommand took over the business in July 2013. Mr Henshall made, or was instrumental in, a number of the design decisions concerning the IBIS 3 model and which culminated in the invention which is the subject of the Patent. These included the decision to use a centrifugal fan, the decision concerning the airflow path, and the decision concerning the shape and form of the outlets so as to achieve the Coandă effect, to which I will return later.

46 I accept that Mr Henshall has, by reason of his experience, acquired expertise in the design of mobile air conditioning units. To an extent, the expressions of opinion by Mr Henshall based on his expertise were intrinsically involved in his evidence regarding more factual matters about which he was entitled to give evidence. Having regard to that consideration and to Mr Henshall's expertise, I considered that the Respondents were entitled to lead evidence of expert opinion from Mr Henshall.

47 However, when evaluating Mr Henshall's evidence, I have kept firmly in mind that he is not an independent expert witness. It is apparent that, at least from late 2016, Mr Henshall has actively supported Houghton and its owner Mr Bei. I mention in this respect that, when Mr Henshall resigned from New Aircommand with effect from 6 December 2015, he regarded himself as subject to a restraint of trade obligation which precluded him acting in competition with New Aircommand for a period of 12 months. During that 12 months, Mr Henshall established his own business, QDOT Pty Ltd (QDOT). Since the end of 2016, QDOT has consulted to Houghton, so much so that it derives approximately 80-90% of its revenue from Houghton. Mr Henshall acknowledged that it is in his interests for Houghton to succeed in Australia. There were times when I considered that Mr Henshall's alignment with Houghton and Mr Bei did affect the completeness and accuracy of his evidence.

48 At the end of the opening submissions, I heard Dometic's interlocutory application seeking leave to adduce evidence from Dr Carlos Gonzalez Toro in the form of a 97 page affidavit (inclusive of annexures but excluding spreadsheets) made on 22 June 2017. Exhibit CGT-6 to the affidavit was a USB stick containing data. I refused that leave and said that I would provide reasons for doing so in this judgment.

49 Dr Gonzalez is a Mechanical Engineer with a Doctorate of Philosophy in "Thermo Dynamic and Fluid Dynamic Processes in Diesel Engines". Between 18 and 20 April 2017, he undertook, at the request of Dometic's solicitors, an "experimental study" of the Belaire Unit to analyse "the volume of flow exiting the Evaporator Fan in the axial and radial directions". Earlier, on 11 April 2017, Dometic's solicitors had met Dr Gonzalez to discuss the testing which Dometic sought. Dr Gonzalez did not prepare a written report of his analysis until 22 June 2017. That report was annexed to his affidavit of 22 June 2017 which was the subject of Dometic's application.

50 On 27 March 2017, a Judge of this Court made case management orders which fixed the trial to commence in the week beginning 10 July 2017 and required Dometic to file and serve its lay and expert evidence by 1 May 2017. Dometic complied with that order by filing and serving the affidavit of Mr Tiller made on 1 May 2017.

51 Dometic's solicitors deposed that Dometic had not included a report from Dr Gonzalez on the results of his testing in the evidence filed on 1 May 2017 for two reasons:

(a) the solicitors considered that the results of Dr Gonzalez's testing were consistent with the opinions of Mr Tiller; and

(b) Dometic did not have sufficient time to comply with r 34.50(1) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (FCR) before filing the evidence in support of its claim of infringement on 1 May 2017.

52 Rule 34.50 provides:

34.50 Experimental proof as evidence

(1) If a party (the proponent) proposes to tender, as evidence in a proceeding, experimental proof of a fact, the proponent must apply for orders in relation to the experimental proof, including orders about any of the following:

(a) the service on other parties of particulars of the experiment and of each fact that the proponent asserts is, will or may be proved by the experiment;

(b) any persons who must be permitted to attend the conduct of the experiment;

(c) the time when, and the place where, the experiment must be conducted;

(d) the means by which the conduct and results of the experiment must be recorded;

(e) the time by which any other party (the opponent) must notify the proponent of any grounds on which the opponent will contend that the experiment does not prove a fact that the proponent asserts is, will or may be proved by the experiment.

(2) Evidence of the conduct and results of the experiment is admissible in the proceeding, only:

(a) if the proponent has complied with subrule (1) and any orders given under that subrule; or

(b) with the leave of the Court.

(3) If an order mentioned in paragraph (1) (e) has been made, and the opponent has not complied with the order in relation to a ground, the opponent may rely on the ground only with the leave of the Court.

53 Rule 34.50 concerns the proof of experimental evidence. Its evident purpose is to ensure that other parties have an adequate opportunity to challenge the validity of the experiment or test and to avoid wasteful duplication by that party of an experiment which can be seen to be valid: Lucent Technologies Inc v Krone Aktiengesellschaft (No 2) [1999] FCA 1462; (1999) 94 FCR 124 at [8].

54 Following its receipt of Mr Hunter's affidavit made on 13 June 2017 and the draft of Dr Wallace's report, Dometic changed its mind about adducing evidence from Dr Gonzalez. The solicitors took the view that the reports of Mr Hunter and Dr Wallace contained evidence of an experimental kind to which they wished to respond with evidence from Dr Gonzalez. The solicitors then requested Dr Gonzalez to prepare a written report on his analysis, and Dr Gonzalez did so on 22 June 2017.

55 At a case management hearing on 27 June 2017, Dometic made an oral application for leave to rely on Dr Gonzalez's affidavit. However, it provided a copy of Dr Gonzalez's report to the Court only part-way during the hearing with the consequence that the Court could not deal with the application at that time. Counsel for Dometic accepted that that was so.

56 Later on 27 June 2017, Dometic's solicitors filed Dr Gonzalez's affidavit and, on 4 July 2017, filed the interlocutory application seeking leave to be able to rely on his evidence.

57 My reasons for declining the grant of leave included:

(a) although Dometic had the carriage of the case on infringement, it had made a strategic decision before 1 May 2017 not to request Dr Gonzalez to prepare a report, so that it would be able to file and serve the report in accordance with the Court's orders of 27 March 2017. Dometic was content to proceed with Mr Tiller being the only expert witness from whom it would adduce evidence in chief. The belief of Dometic's solicitors that, in the event that the Respondents sought to adduce experimental proof, Dometic would then be able to adduce experimental proof in response involved an unreasonable assumption on their part;

(b) the explanation that Dometic had had insufficient time after 21 April 2017 in which to make an application pursuant to r 34.50 was inadequate. That application could have been made at any time after Dometic commenced the proceedings on 17 February 2017 and, in particular, after it decided to proceed with the request to Dr Gonzalez to undertake his analyses. It was Dometic's own decision not to make that application. It was apparent that Dometic chose to find out the results of the proposed experimentation before engaging in the process contemplated by r 34.50;

(c) the fact that Mr Hunter and Dr Wallace's evidence involved some reports of experimentation was not a sufficient justification for Dometic being entitled, despite its earlier strategic decision, to lead the substantial evidence from Dr Gonzalez. The experimentation of Mr Hunter and Dr Wallace was of a relatively simple, and even unsophisticated, kind. It was of a kind which Mr Tiller could (and later did) replicate. Dr Gonzalez's experimentation and analysis was much more detailed; and

(d) the grant of leave to Dometic would have caused prejudice to the Respondents and to the conduct of the trial. Both Mr Hunter and Dr Wallace had indicated that they may, having regard to their other work commitments, need a period of three to four weeks in which to consider Dr Gonzalez's report, the data attached to it, Dr Gonzalez's assumptions and methodologies, and to attempt to replicate what Dr Gonzalez had done. Even if these were over estimates, it was plain that the grant of leave to Dometic to adduce evidence from Dr Gonzalez would derail the trial.

58 These are my reasons for the refusal of Dometic's interlocutory application of 4 July 2017.

59 Infringement occurs when a person exercises any of the exclusive rights of the patentee without the patentee's authorisation: Eli Lilly & Co v Pfizer Overseas Pharmaceuticals [2005] FCA 67; (2005) 218 ALR 408 at [222]-[223]. If the alleged infringement differs materially from an essential feature of the applicant's claim, there is no infringement: Commonwealth Industrial Gases Ltd v M.W.A. Holdings Pty Ltd [1970] HCA 38; (1970) 180 CLR 160 (CIG v MWA) at 168.

Does the Belaire Unit have a centrifugal fan?

60 A principal basis on which the Respondents dispute that the Belaire Unit infringes the Patent concerns Integers 1.3 and 1.8, namely, that the air conditioning system have an air conditioning unit including at least one centrifugal fan which is "operable to draw in indoor air via the return air entry port and eject the indoor air in a substantially horizontal plane such that it is forced into the at least one evaporator coil". The Respondents contend that the evaporator fan in the Belaire Unit is an axial fan and that this, by itself, indicates that the Belaire Unit does not infringe the Patent.

61 Mr Henshall said, and I accept, that, when designing the IBIS 3, he had thought that a centrifugal fan had three advantages over an axial fan. First, generally the noise produced by a centrifugal fan is less than that of an axial fan moving an equivalent volume of air. This is because of the higher speed required of an axial fan to move an equivalent volume of air. Secondly, a centrifugal fan has the advantage of ejecting the air horizontally directly to the surrounding evaporator coil. Thirdly, he had thought that the shape of a centrifugal fan would require little or no clearance above the fan to allow for the ejection of the air to the evaporator coil. This meant that the air conditioning unit would have a lower overall profile.

62 The dispute between the parties arises from Dometic's contention that the term "centrifugal fan" in the meaning of the Patent would be understood by a skilled addressee as "an apparatus that has the effect of taking in air axially and ejecting it radially". Its submission was that any "apparatus" which has that effect would be understood to be a centrifugal fan. For this reason, Dometic contended that the identification of a fan as centrifugal or otherwise can only be made by observation of the fan in operation.

63 Much of the evidence and submissions in the trial was directed to the construction of the term "centrifugal fan" in the Patent, and as to whether the evaporator fan in the Belaire Unit is such a fan.

64 It is appropriate to address first the proper construction of the term "centrifugal fan" in the meaning of the Patent.

65 The parties were in agreement as to the principles to be applied in resolving the issues of construction in the case. Those principles are, in any event, well-settled. The authorities in which they have been stated include Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel [1961] HCA 91, (1961) 106 CLR 588 at 610; Minnesota Mining at 286; Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd [2001] HCA 8, (2001) 207 CLR 1; H Lundbeck A/S v Alphapharm Pty Ltd [2009] FCAFC 70, (2009) 177 FCR 151 at [118]; Inverness Medical Switzerland GmbH v MDS Diagnostics Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 108, (2010) 85 IPR 525 at [12]-[15]; Streetworx Pty Ltd v Artcraft Urban Group Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1366, (2014) 110 IPR 82 at [57]-[69]. The principles which are particularly pertinent in the circumstances of this case include the following.

66 The proper construction of a patent is a question of law but may nevertheless be assisted by evidence. The question is what a hypothetical non-inventive person skilled in the relevant art (the skilled addressee) would have understood the language used by the patentee to mean, having regard to the whole of the patent, the specification and the claims and taking account of the matters of common knowledge at the priority date and the context in which the words appear: Kimberly-Clark at [24]. The claims in the patent are to be construed in the context of the specification as a whole. The meaning of terms in a claim may be clarified by reference to the specification but not so as to restrict, expand or qualify the terms of the claims which are clear. The Court adopts a purposive construction and avoids an overly technical or narrow construction of claims: Populin v HB Nominees Pty Ltd (1982) 59 FLR 37 at 43. A specification is to be read in a practical and common sense way: Tramanco Pty Ltd v BPW Transpec Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 23; (2014) 105 IPR 18 at [175].

67 In Streetworx at [67], Beach J identified the following principles as being applicable to the Court's consideration of the understanding of the skilled addressee:

• First, to identify the characteristics of the skilled addressee, the field to which the invention relates must be identified.

• Second, the skilled addressee is taken to be a person of ordinary skill (as opposed to a leading expert) in that field and equipped with the relevant common general knowledge including the art before the priority date (Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing Co v Beiersdorf (Aust) Ltd (1980) 144 CLR 253 (Minnesota Mining) at 293; Kimberley-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd (2001) 207 CLR 1 at [24]; Jupiters at [67]).

• Third, the qualifications and experience of the skilled addressee will depend on the particular case, having regard to the nature of the invention and the relevant industry. Formal qualifications are not essential. Practical skill and experience in the field may suffice (Britax Childcare at [239] per Middleton J). A patent specification is addressed to those having a practical interest in the subject matter of the invention; such persons are those with practical knowledge and experience of the kind of work in which the invention is intended to be used.

• Fourth, the hypothetical person skilled in the art may possess an amalgam of attributes drawn from a team of persons whose combined skills, even if disparate, would normally be employed in interpreting and carrying into effect instructions such as those contained in the specification (The General Tire & Rubber Co v The Firestone Tyre & Rubber Co Ltd [1972] RPC 457 (The General Tire) at 485).

• Fifth, as the skilled addressee comes to a reading of the specification with the common general knowledge of persons skilled in the relevant art, they read it knowing that its purpose is to describe and demarcate an invention. But the person skilled in the art is not particularly imaginative or inventive (or innovative) (NSI Dental Pty Ltd v University of Melbourne (2006) 69 IPR 542 at 570).

68 In the present case, I consider the skilled addressee to be a person with an understanding, whether gained by education or experience or both, of fluid dynamics and of the issues that arise in the movement of air in air conditioning systems. Such a person does not require the formal qualifications of the kind possessed by Dr Wallace and Mr Hunter. I consider that Mr Henshall can be regarded as fitting the description of the hypothetical skilled addressee to be considered in construing the Patent.

69 Dometic was inclined to disparage reliance on Dr Wallace's evidence for the purpose of informing the understanding of the skilled addressee. It referred to Carter Holt Harvey v Weyerhaeuser Co HC Wellington [2010] NZHC 573 at [56] wherein it was said:

[I]t makes sense to look at the reasons given for an opinion as they should reveal whether the expert has drawn on highly refined sophisticated concepts known only to those with his or her high level qualifications, or on more basic knowledge.

The submission was that Dr Wallace's opinion was based on his high level knowledge of sophisticated concepts and did not reflect the knowledge and understanding of a skilled addressee.

70 I do not accept that submission. It is very apparent that, in addition to his academic qualifications and knowledge, Dr Wallace has considerable practical experience. His opinions were informed both by his academic training and that experience. I also note that Dometic itself sought to rely in numerous instances on the opinions expressed by Dr Wallace.

The meaning of the term "centrifugal fan" in Claim 1

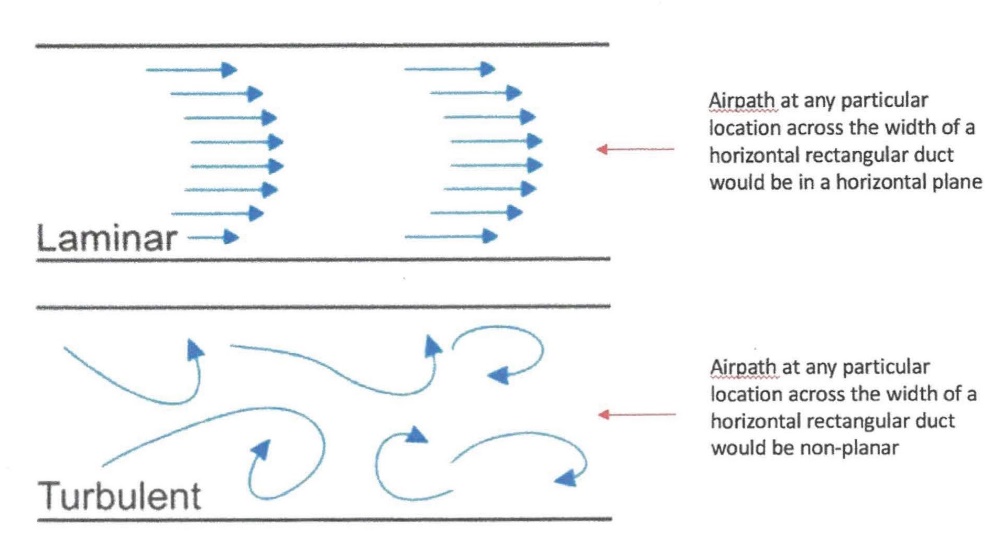

71 The evidence indicated that there are various types of fans, of which centrifugal and axial fans are two principal kinds.

72 At a level of generality, the experts were in agreement as to the effect of centrifugal fans and axial fans. A centrifugal fan takes in air axially (parallel to the rotational axis of the impeller) and ejects it radially (90o to the axial direction) or at least tangentially, whereas an axial fan takes in air axially and ejects it in the same direction. There is a qualification to those propositions because a small amount of radial movement of air is a necessary incident of the operation of an axial fan and a small amount of axial movement is a necessary incident of the operation of a centrifugal fan. However, those small incidental movements can be ignored for the purposes of the issues in these proceedings.

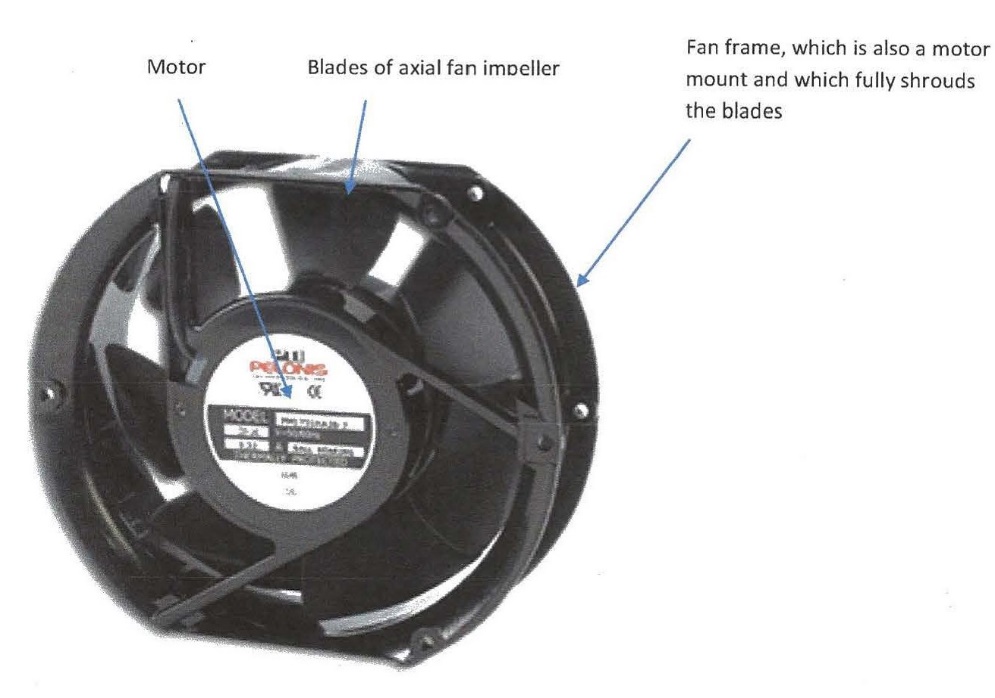

73 A common feature of axial fans is that the blades are attached to, and radiate from, the rotating hub. Mr Hunter provided the following depiction of a typical axial fan:

The domestic pedestal fan is a common example of an axial fan.

74 Mr Hunter also provided a depiction of a centrifugal fan which he described as "typical".

75 In his affidavit of 1 May 2017, Mr Tiller gave the following description of the difference between the two types of fans:

[31] … I understand a centrifugal fan to be a type of fan that draws air into the fan in an axial direction (that is, parallel to the axis on which the blades (or impellers) of the fan rotate) and pushes the air out in a perpendicular direction (that is, at 90 degrees to the axis of the fan). Centrifugal fans are also referred to as 'radial' fans because they direct air in an outward direction from the centre of the fan. By contrast, axial fans such as domestic fans and those used in computer hard-drives do not change the direction of the air – that is, air enters in the axial direction of the fan and exits linearly in that same axial direction. Therefore, the distinction between an axial fan and a centrifugal fan is based on the direction at which the air exits the fan, when contrasted with the direction at which the air enters the fan.

76 Mr Hunter and Dr Wallace gave evidence of a broadly similar kind (although they disagreed with the proposition in the last sentence) and their accounts were more technically detailed. Mr Hunter said that the term "centrifugal fan" is a common term which has been used by mechanical engineers over a long period of time. It refers to a fan with an impeller which draws in air axially and ejects it radially. The fan is described as centrifugal because the centrifugal forces generated by the rotating impeller throw air outwardly in a radial direction.

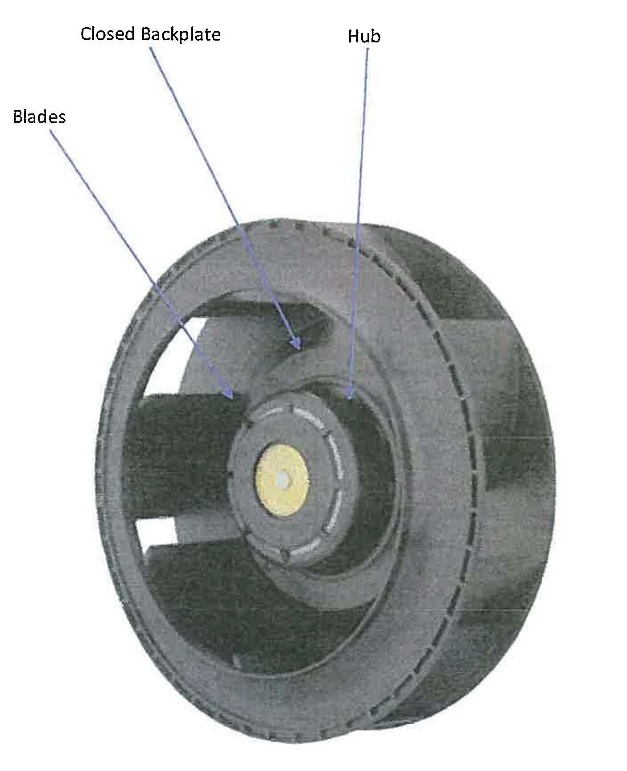

77 Mr Hunter said that the impellers of centrifugal fans typically have three features:

(a) the roots of the fan blades are not attached to the hub;

(b) the blade's two dimensional profile is constant in the axial direction; and

(c) the impeller has a solid back plate so that the air flow cannot leave the impeller in the axial direction, but must be ejected radially.

78 In the course of the joint expert conference, Mr Tiller presented Mr Hunter with some examples of centrifugal fans which did not have back plates. In the light of those examples, Mr Hunter modified his position a little and said that the presence of a back plate was not essential in order that a fan be characterised as centrifugal. He said that he had referred to centrifugal fans with a back plate because, without such a plate, the air would not be distributed uniformly so as to achieve its purpose. Mr Hunter also said that the back plate prevents leakage of air and thereby adds to the efficiency of the centrifugal fan.

79 Dr Wallace said that:

For a fan to be a centrifugal fan, the blades are required to be disposed nominally parallel to each other and to the axis of rotation of the impeller. The blades are configured to spin the air, promoting centrifugal forces in a radial direction. For a fan to be an axial fan, the blade axes are disposed radially from the axis of rotation. The blades are configured to lift the air in an axial direction.

80 There was disagreement between the experts as to what constitutes a fan and how one determines whether a fan is axial or centrifugal.

81 All agreed that a fan comprises, at the least, a motor and an impeller. The motor drives the impeller. Mr Tiller considered that the terms "impeller" and "blades" are interchangeable, whereas Mr Hunter and Dr Wallace considered that the blades form part of the impeller. They both agreed that the term "impeller" describes the whole of the rotating part of the fan which moves the air, and does not comprise only the fan blades. On my understanding, not a lot turns for present purposes on the resolution of this difference.

82 Mr Tiller was of the view that, in addition to the motor and impeller, a fan comprises the enclosure or mounting used by a manufacturer in conjunction with the fan. That enclosure or mounting may affect the direction in which the ejected air moves and is, accordingly, to be taken into account in the characterisation of a fan as either axial or centrifugal. Each of Dr Wallace and Mr Hunter disagreed with that view, although they accepted that a fan may include the mounting to which the motor is attached. As will be seen, I prefer the views of Dr Wallace and Mr Hunter on this topic and do not think that the skilled addressee would understand a fan as including the apparatus associated with the fan, even if that apparatus may influence the flow of air produced by the fan. This difference of views is significant in the present case because the Belaire Unit includes an evaporator fan deck, to which I will return shortly.

83 Mr Tiller accepted that the structural design and features of a fan may provide "an indication" as to the likely effect of the fan in moving air but maintained that the character of a fan can be determined only by observation of the fan in operation (and specifically, how air enters and exits the fan). Mr Henshall provided some support for this view:

XXN: Do you say that you're able to recognise something [as] an axial or [a] centrifugal fan immediately by looking at it?

A: It certainly gives you a very good lead as to the family, yes.

XXN: But the only way to satisfy yourself as to whether it's an axial fan or a centrifugal fan is to put it into operation, is that right?

A: It would be a combination of both inspection and looking at the performance characteristics of the fan.

84 The evidence of Mr Hunter and Dr Wallace was to different effect. Mr Hunter said that the impeller is the key differentiator between the two types of fans.

85 Dr Wallace gave similar evidence, saying that, in his experience, it is the physical form of the impellers which differentiates axial and centrifugal fans. He said that "[u]niversally, the distinction between axial and centrifugal fan types is made on the physical form of the impeller". That is because the blades of centrifugal fans are configured to produce centrifugal forces. In axial fans, the blades are configured differently so as to force the air in an axial direction, that is, parallel to the direction of the rotational axis. The particular configuration of the blades in a fan is a matter of choice and design.

86 Dr Wallace likened a centrifugal fan to a squirrel cage wheel, and an axial fan to an aeroplane propeller. This means that the assessment of whether a fan is axial or centrifugal may be made by observation, before the fan is operated. Dr Wallace attached less significance to observations of the actual airflow produced because that airflow may be influenced by extraneous factors, including the equipment in which the fan is mounted.

87 The opinions of Mr Hunter and Dr Wallace are supported by other evidence.

88 The Respondents adduced evidence from Mr Hu Guojun principally, as I understood it, for the purposes of establishing that the manufacturer's description of the evaporator fan used in the Belaire Unit as a centrifugal fan was incorrect. I will refer to that evidence later. Mr Hu is a well-qualified and experienced engineer. He graduated in 2005 from the University of Shanghai for Science and Technology with a Bachelor of Engineering degree, having majored in Refrigeration and Cryogenic Engineering. In 2008, he received a Master's Degree, also from the University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, having studied Fluid Machine Engineering.

89 Since October 2015, Mr Hu has worked with Hangzhou Dunli Electric Appliances Co (Dunli) as the Vice-Manager of its Technical Department. Dunli is a major manufacturer of fans and blowers used in the ventilation, air conditioning and refrigeration industries. Mr Hu described Dunli as being one of the top manufacturers of fans in China with substantial export markets. Dunli manufactures the evaporator fan used in the Belaire Unit.

90 The Respondents arranged for Mr Hu to give evidence only shortly before the trial commenced, when the witness they had intended to call became unavailable. He gave his evidence through an interpreter. I considered that he was a careful, honest and reliable witness. I have confidence in accepting his evidence.

91 Mr Hu deposed that, by reason of his studies and experience, he knows that there are recognised categories of fans, of which centrifugal and axial fans are two principal kinds. Each of these types of fans has distinctive features and each is featured separately in the Dunli catalogue of its fans. Mr Hu annexed a copy of the catalogue to his affidavit. Each of the 26 principal models of axial fans manufactured by Dunli and shown in its catalogue comprise fan blades radiating from a hub. I have described these as the principal models because it is apparent that there are variations or sub-models of each of the principal models. The fan blades in those sub-models also radiate from the hub. None of the 49 principal forms of centrifugal fans shown in the Dunli catalogue have this configuration.

92 Pertinently, for present purposes, the Dunli catalogue depicts many fans without an indication that mountings or enclosures (other than safety guards) comprise part of the fan. Instead, in most instances, fans are presented as free standing units. The extracts of catalogues or promotional material provided by two companies in the United States, Buffalo Fan and Cincinnati Fan, which Dometic tendered, are to the same effect.

93 Dometic referred to evidence which Mr Hu gave to the effect that some customers acquire Dunli motors and impellers without any housing because they wish to use their own housing. To my mind, that evidence tended to support the proposition that the housing is not an intrinsic part of a fan but, instead, something which can vary according to a particular customer's needs or desires.

94 Dometic sought to diminish the significance of the evidence from manufacturers' catalogues, promotional materials and the like by submitting that these showed only the "rotor" and not the fan. That submission cannot be accepted. The apparatus depicted in the promotional material produced by Buffalo Fan are described as fans, and not as rotors. Likewise, all of the apparatus shown in the Dunli catalogue are described as fans (whether axial or centrifugal) and not simply as rotors.

95 It is significant that, while there is documentary evidence in the form of catalogues and other literature which supports the views of Dr Wallace and Mr Hunter, Dometic did not adduce any evidence in the literature which supports the view that the character of a fan is to be determined having regard to the apparatus surrounding the impeller, let alone that that character may vary according to the effect which that apparatus has on the airflow produced by the impeller. Nor did Mr Tiller point to any such evidence.

96 I also note that Mr Tiller acknowledged that, without turning the evaporator fan on, he would have assumed that it was axial and that he would take at face value a manufacturer's description of a fan as axial or centrifugal. This acknowledgement was unsurprising as one would not ordinarily expect that a fan made and sold by a manufacturer as either axial or centrifugal, as the case may be, had to be operated before its type could be determined.

97 I mentioned earlier the example of a centrifugal fan without a backing plate which Mr Tiller produced in the joint expert conference. In addition to that fan not having a backing plate, its blades radiated from the hub so that it was similar in appearance to an axial fan. However, as Dr Wallace pointed out, the blades on the example fan have a particular form and profile. He considered that the blades were placed so as to be still nominally parallel to the axis of rotation of the fan. In addition, Mr Hunter thought that a centrifugal fan of this kind would only be used with a scroll casing. Dometic produced another example of a centrifugal fan which was quite distinctive in appearance. However, this was a compressor fan designed to develop high pressure and its configuration is attributable to that purpose. Both of the examples appear to be special purpose fans. In my view, even if skilled addressees were aware of these examples it would not affect their understanding of the term "centrifugal fan" in the meaning of the Patent.

98 Dometic referred to evidence from the experts that the structure, housing or casings surrounding a fan may affect the direction of the airflow produced by the fan. Plainly, such structures may have some effect. It does not follow however, that such structures are to be regarded as part of the fan, so that the character of the fan can be identified only by observation of the fan in operation. The structures of the kind to which Dometic referred affect the airflow only after the impeller, which produces the forces moving the air (whether axially or radially), has completed its work. They do not form part of the impeller itself. The skilled addressee would, in my opinion, understand that some structures serve particular functions (such as providing safety) or adding to the efficiency of the fan (such as the inclusion of a back plate on a centrifugal fan) but unless forming part of the impeller are not part of the fan itself.

99 Both Mr Hunter and Dr Wallace were firmly of the view that the apparatus surrounding a fan does not form part of the fan. Mr Hunter said:

[T]here's no magic wand here. We can't turn an axial fan into a centrifugal fan. It's not – that's not possible.

100 Dr Wallace said:

During a long participation in the fan industry I have never come across the suggestion that fan type changes according to the perceived airflow directions which are frequently distorted by installation in a compact air conditioning unit. Universally, the distinction between axial and centrifugal fan types is made on the physical form of the impeller. Evidence for this view can be found when surveying the images presented in many manufacturers' catalogues, in engineering text books, in engineering standards (such as ISO 5801) and on the internet.

101 I accept that evidence. In particular, I am satisfied that it also reflects the understanding of the hypothetical skilled addressee on the relevant date. Such a person would understand that it is possible for the apparatus surrounding a fan to be so shaped as to alter the direction of the airflow produced by the fan. I am satisfied, however, that a skilled addressee would not regard the potential for modification of the airflow to mean that the characterisation of a fan of one type may be changed to that of a different type, or that the character of a fan may be determined only by observation of the fan in operation.

Dometic's reliance on the evidence of Dr Wallace

102 Dometic sought to rely on evidence from Dr Wallace to support the submission that the direction of the airflow produced by a fan can be determined only by observation of the fan in operation. However, in my opinion, Dometic sought to read more into Dr Wallace's evidence than is appropriate, as the following passages, including those on which Dometic relied, indicate:

XXN: But generally speaking it's called a "centrifugal fan" by people because of the way that the airflow comes in and goes out.

A: I would say it's called a centrifugal fan because it looks like a centrifugal fan …

XXN: Sure. And you can make a prediction.

A: Yes.

XXN: But to actually work out whether something is a centrifugal fan – it's where the airflow is going. You would agree with that, wouldn't you?

A: Yes, but we – the blades are configured to – to create that, but doesn't necessarily say that – because it has got radial flow, that it has to be a centrifugal fan.

XXN: Sure. Thank you. But just in terms of terminology, the fact that you call something a "centrifugal fan" is a reference to – rough, perhaps, of the way the air is flowing.

A: I would say of a centrifugal fan, it has got an arrangement of blading which promotes that – that mode of operation. (Transcript at 237)

…

XXN: What I was simply putting to you is that based on the text books that you have annexed, whether something is "centrifugal" or "axial" in general terms, is governed by the airflow characteristics of the fan.

A: Only partially. Certainly when – when I look at fans as an engineer and I design these fans, I have to apply certain design principles and rules. And – and there are, in fact, some fundamental equations which are used by fan-designers. And these can be formulated in two ways, one – one way for axial fans and one way for centrifugal fans. And you can't really mix the two up. So when – when I – I see a rotor, I can tell that it's axial, centrifugal, on the basis of which set – which formulation of these questions will I use. (Transcript at 238)

(Emphasis added)

…

XXN: Going to your paragraph 12, where you explained how it's to be defined, you – the sentence is:

The axis of the blade can be considered to be a line on one of the blade's surfaces which is nominally perpendicular to the airflow over that surface.

And it's right, isn't it, that inherent in your definition is an observation as to how the air is flowing over the blades?

A: That's correct, yes. Yes. (Transcript at 241)

…

XXN: But I think what this fan shows is that the structural definitions that you've put forward are general and non-exhaustive, which is your evidence in your affidavit?

A: That's correct. Yes.

XXN: Yes. Thank you. And I would suggest to you that this emphasises the point that whether a fan is properly classified as centrifugal depends upon the airflow characteristics of that fan.

A: No. I – I disagree with that. (Transcript at 245)

(Emphasis added)

…

XXN: And I think the effect of your evidence is that the airflow characteristics of a fan are affected by the structural characteristics of the impeller and also the presence of any obstruction within the airflow field immediately adjacent to that impeller. That's the effect of your …

A: Yes. That's what I'm saying. Yes.

XXN: Thank you. And so what I'm – what I suggest to you is that those two matters, being the structural characteristics of the impeller as well as the presence of any obstruction – those two matters enable a prediction to be made, with varying levels of confidence, as to the resulting airflow.

A: Yes. I think what you're saying is that the – the direction of – the flow-field shape is affected by both the rotor and whatever equipment you have it installed in.

XXN: Yes. And I have a further point, which is that you can look at the shape of the rotor and you can look at the obstructions in the airflow field near that rotor, and you can make the prediction, with varying degrees of confidence, as to how the airflow is going to be affected?

A: Yes. With the right tools and the right equations, one can, yes, make predictions about what the flow-field would look like and roughly how much flow has been – has been … and so on.

XXN: Thank you. And – but it's actually necessary to confirm what the airflow characteristics are by observing the apparatus in operation.

A: No. No. You can simulate it, for instance. (Transcript at 247)

(Emphasis added)

…

XXN: Based upon the two matters, being the structural characteristics of an impeller and also the presence of any obstructions within the airflow field immediately adjacent to that impeller – those two matters enable you to make a prediction about the directionality of the resulting airflow?

A: Yes. That's standard engineering technique to predict what happens in … including when it includes rotors and boundaries and so on.

XXN: Yes. Thank you. And – but whether – to actually confirm the directionality of the airflow created, it's necessary to either observe the apparatus and operation or alternatively, if you're skilled enough, to simulate that in a computer?

A: Yes. If you – yes, want to. (Transcript at 248)

103 In the first of these passages, I consider that Dr Wallace was confirming that it is the arrangement of the blades which determines the character of the fan and that the mere fact that a fan placed in a particular situation may produce a radial flow of air does not mean, of itself, that it is a centrifugal fan.

104 In the second of these passages, Dr Wallace confirmed that the character of a fan as centrifugal or axial is indicated by its design. To my mind, that is persuasive because it is to be expected that a manufacturer setting out to produce either an axial or centrifugal fan will use a design adapted for that purpose.

105 The third of the passages upon which Dometic relied does not do the work for which it contended because, on my understanding, Dr Wallace was there identifying the manner in which one determines the axis of a fan blade, rather than the character of the fan itself.

106 As can be seen from the passage extracted from the Transcript at 245, Dr Wallace disagreed expressly with the proposition that the classification of a fan as centrifugal depends upon its airflow characteristics. In the passages extracted from the Transcript at 247 and 248, Dr Wallace again confirmed that observation of the airflow is not necessary in order to identify the airflow characteristics of a fan but, if one wished to confirm it, one could do so by simulation or by observation.

Conclusion on the issue of construction

107 I consider that the skilled addressee reading the Patent would know that there are various kinds of fans and that axial fans and centrifugal fans are the two principal types. The skilled addressee would know the effect on air movement produced by each type of fan. In particular, such a person would know that a centrifugal fan has the effect of taking in air axially and ejecting it radially. The skilled addressee would understand that the invention involved the requirement for the air drawn in vertically through the return inlet to be forced horizontally through the evaporator. That being so, the skilled addressee would understand the requirement for the fan to be centrifugal.

108 The skilled addressee would also be able to identify a centrifugal fan by its appearance. Such a person would not need to see the fan operating in order to assess its effect on the air.

109 In these circumstances, the skilled addressee would understand the adjective "centrifugal" (appearing three times in the first claim) to have been used deliberately so as to identify the kind of fan required for the invention. That is to say, the skilled addressee would understand that the Patent is not contemplating the use of any fan at all, providing that the ultimate effect of the fan in conjunction with other apparatus is that air is forced horizontally into the evaporator coil.

110 Dometic submitted that the term "centrifugal fan" would be understood by the skilled addressee as indicating the effect which the fan is to produce, that is, "to draw in indoor air via the return air entry port and eject the air in a substantially horizontal plane such that it is forced into the at least one evaporator coil". That is to say, Dometic submitted that the term "centrifugal" would be understood as referring to effect rather than structure. I do not accept that submission. In my view, the skilled addressee would know that the effect of the centrifugal fan is to draw in air through the return air entry port and to eject it horizontally. Such a person would not need the words on which Dometic relies to understand that that is the intended purpose of the fan. Instead, I consider that the skilled addressee would understand those words to indicate that the particular centrifugal fan selected must be capable (that is, of sufficient capacity) to draw in and eject the air so that it is forced into and through the evaporator coil.

111 Acceptance of Dometic's submission would deprive the adjective "centrifugal" of meaning. The claim in the Patent is not to be read as though that term is not present.

112 I have not been able to discern any indication in the Patent, read as a whole, which supports the construction for which Dometic contends. On the contrary, as Mr Hunter observed, the type of fan shown in the description of the invention in Figure 3 appears to be a centrifugal fan with a closed backplate impeller. Mr Hunter also said that "[e]ven without having read the detailed description of the invention contained in the specification, I would have automatically inferred that the type of fan being referred to was the commonly known centrifugal fan described by me in the paragraphs 17-21 above". That fan, and the depiction provided by Mr Hunter, have been set out earlier. I consider that the hypothetical skilled addressee would understand the term "centrifugal fan" in the terms of the Patent in the same way.

113 It follows that I reject Dometic's submission that the Patent is "agnostic" as to which of the many different ways by which the air can be forced to travel horizontally through the evaporator coil. To the contrary of being agnostic, the Patent states specifically that the invention involves the use of a centrifugal fan.

114 In my view, the present case is analogous with Baygol Pty Ltd v Foamex Polystyrene Pty Ltd [2005] FCA 624; (2005) 66 IPR 1. The claim in the patent under consideration in that case referred to the placement of "concrete" spacers in a method of forming a building foundation. The question was whether the respondents' use of the method but with plastic spacers infringed the patent. Tamberlin J answered that question in the negative:

[52] The word "concrete" is not one which has been shown to be ambiguous or to raise questions of fact and degree within a spectrum as to its interpretation, as was the case in Catnic in relation to the word "vertical". No reasonable connotation of the word "concrete" could include "plastic". The word "concrete" is one of ordinary English usage. … The applicant's submission is that the word "concrete" should be ignored and the express requirement of "concrete" spacers should be replaced with a requirement which simply provides for the spacers to be made of plastic or of any material which could make the invention work. There is no contextual justification for doing such violence to the language of the claim or ignoring the language chosen to express the claim.

115 The immediately following paragraph in Baygol is also apposite in the present case:

[53] As a matter of first impression, one would expect a person directed to implement the method set out in the claim to follow the wording and use concrete spacers. If the patentee had intended to refer to spacers made of other materials, then, given the simplicity of the requirement, it would have been easy to simply omit the reference to "concrete" or to designate a range of other suitable materials. This step was not taken by the patentee. The evidence does not disclose any reasons for the patentee not taking such an obvious course if he regarded the word "concrete" as too restrictive. It must be borne in mind that patent claims are not drafted by inexperienced or unqualified authors. They are usually the result of considered and deliberate choice, using the English language, with all its subtleties and precision, to delimit the boundaries of the claimed monopoly. The drafting of patent claims is an arcane and sophisticated art. As Lord Hoffman pointed out in Kirin-Amgen at [34], it will be an infrequent case in which it can be said that a patentee departed from the conventional use of language by including an element which was not meant to be essential.

(Emphasis added)

116 In the present case, had the patentee wished the claim to refer to any fan, including a fan which, in conjunction with other apparatus, produced the effect of a centrifugal fan, it would have been easy to say so. The fact that it did not do so appears to reflect a deliberate choice.

The evaporator fan in the Belaire Unit

117 Mr Tiller considered that the evaporator fan in the Belaire Unit is a centrifugal fan. He did so for three reasons.

118 First, he considered that the evaporator fan had the effect of drawing air into the unit vertically via the return air entry port and then ejecting that air horizontally (as distinct from forcing the air vertically along the axis of the fan). Mr Tiller said that he had observed that this was so after the external cover of the air conditioning unit and the polystyrene cover over the evaporator coil had been removed. He had placed his hand at the sides (that is, between the fan and the evaporator coils) and had felt the horizontal movement of the air. Secondly, he had held 20 mm wide stripes of A4, 80 GSM paper above and in the centre of the fan and had not noted that they had been forced in an upward direction. Mr Tiller said that he had noted a minimal degree of uplift but he attributed this to turbulence. When Mr Tiller placed the piece of paper at the circumference of the fan, he observed a stable horizontal airflow supporting the piece of paper. Mr Tiller observed some air moving vertically around the inside perimeter of the evaporator coil but considered that this was a consequence of the air ejected from the fan in a horizontal direction being diverted upwards when it met the evaporator coil.

119 Mr Tiller's second reason rested on his comparison of the evaporator and condenser fans. He noted that the latter was an axial fan because it ejected air in the axial direction. The former, although having blades which were of similar shape, pitch, depth and orientation, had the effect of causing the air to move in a horizontal direction. Mr Tiller attributed this to the different plastic shrouds around each fan. In both cases the shrouds form part of the plastic structure supporting the fan hub. The shroud around the condenser fan is closed, leading Mr Tiller to conclude that that fan had been designed to permit the ejection of air only in the axial direction. The shroud around the evaporator fan is open (or at least substantially open). This enabled the evaporator fan (which Mr Tiller described as a centrifugal fan) to eject the air in a horizontal direction.

120 Mr Tiller's third reason was that the marking by the manufacturer (Dunli) on the underside of the evaporator fan described it as a "Single-Phase Centrifugal Fan" (emphasis added).

121 Mr Hunter described the evaporator fan in the Houghton unit as being "clearly of an axial fan type, and not of a centrifugal fan type". This was because it comprised a rotating axial fan impeller drawing air inwardly from the axial direction and directing it outwardly in the axial direction. Dr Wallace expressed the same view, saying that both the condenser fan and the evaporator fan have the characteristics of an axial fan.

122 In my opinion, there are a number of reasons why the opinions of Mr Hunter and Dr Wallace should be preferred and that of Mr Tiller on this point rejected.

123 First, I indicated earlier my general preference for the evidence of Dr Wallace and Mr Hunter over that of Mr Tiller.

124 Secondly, I have already indicated earlier my satisfaction that the surrounding encasing of the fan should be ignored in the determination of its character. The effect of such surrounds can be seen in the comparison which Mr Tiller himself made between the evaporator fan and the condenser fan. The blades on both fans are identical in shape, pitch, depth and orientation. The hubs to which the blades were attached in each case are also identical. It is accordingly natural to regard both fans as being of the same character, that is, axial fans. It is not reasonable to suppose that the character of fans which are identical may vary according to the nature of the plastic shroud with which a particular manufacturer chooses to surround them.

125 In order to assess the effect on the airflow produced by the apparatus surrounding the evaporator fan, the Respondents caused Mr Henshall to assemble two test units. Mr Henshall removed the lower part of the evaporator assembly from a Belaire Unit. This comprised the evaporator fan, its mounting and the evaporator fan deck to which the mounting is attached. The evaporator fan deck is a piece of flat plastic which is essentially rectangular in shape (425 mm x 315 mm). It is bolted to the floor of the air conditioning unit. The evaporator coils are mounted at its perimeter and form a continuous enclosure within which the evaporator fan is located. There is a circular aperture in the evaporator fan deck with a diameter of about 200 mm. The mounting containing the evaporator fan and the surrounding shroud is bolted onto the evaporator fan deck so that the centre of the aperture aligns with the centre of the hub of the fan. As the diameter of the blades (including the hub) is approximately 300 mm, the evaporator fan deck overlaps approximately the outer 40% of each blade. That overlap partially obstructs the intake of air into the evaporator fan.

126 In establishing this assembly (Assembly No 1), Mr Henshall removed the evaporator coils. He bolted the evaporator fan deck to a bench into which a circular aperture below the aperture in the evaporator fan deck had also been cut.

127 Mr Henshall then prepared a second assembly (Assembly No 2). This comprised the same elements as Assembly No 1, but without the evaporator fan deck. In this assembly, the mounting containing the fan was attached directly to a bench top into which a circular aperture with a diameter of approximately 300 mm had been cut.

128 The effect was that, in Assembly No 2, the movement of the air produced by the fan could be assessed without it being influenced by the evaporator fan deck. In the case of Assembly No 1, the movement of the air could be assessed without being influenced by the surrounding evaporator coil (and for that matter, the evaporator cover).

129 The Belaire Unit and the two assemblies prepared by Mr Henshall were in Court and the experts gave evidence by reference to them, including with the fans in operation.