FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application filed on 13 August 2018 be dismissed.

2. The applicant pay the respondent’s costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MARKOVIC J:

1 On 13 August 2018 the applicant, LFDB, commenced this proceeding. At that time LFDB sought orders on an ex parte basis, including orders extending the time for compliance with bankruptcy notice BN225015 issued on 18 July 2018 and received by him on 24 July 2018 (Bankruptcy Notice) and abridging the time for service of the application on the respondent, MS S M. Ex parte orders to that effect were made. Relevantly, the time for compliance with the Bankruptcy Notice was extended up to and including 15 August 2018 and the application was adjourned for hearing to 15 August 2018, at which time it was listed before me as the commercial and corporations duty judge.

2 LFDB seeks an order that the Bankruptcy Notice be set aside. LFDB contends that the Bankruptcy Notice is a nullity by reason of defects that deprive it of essential criteria of a bankruptcy notice in that it fails to name any addressee; fails to name any creditor; the description of the purported creditor is ambiguous; and it is incapable of supporting a creditor’s petition or of fulfilling the public interest objectives of bankruptcy. Those defects are alleged to arise because of the use of pseudonyms in the Bankruptcy Notice to name the debtor and creditor.

background

3 LFDB and SM are pseudonyms which have been used to describe the applicant and respondent respectively in a number of proceedings before the courts in New Zealand, in the Federal Circuit Court of Australia (Federal Circuit Court) and in this Court. Details of the orders made in the Federal Circuit Court and this Court requiring the use of those pseudonyms are set out at [7] below.

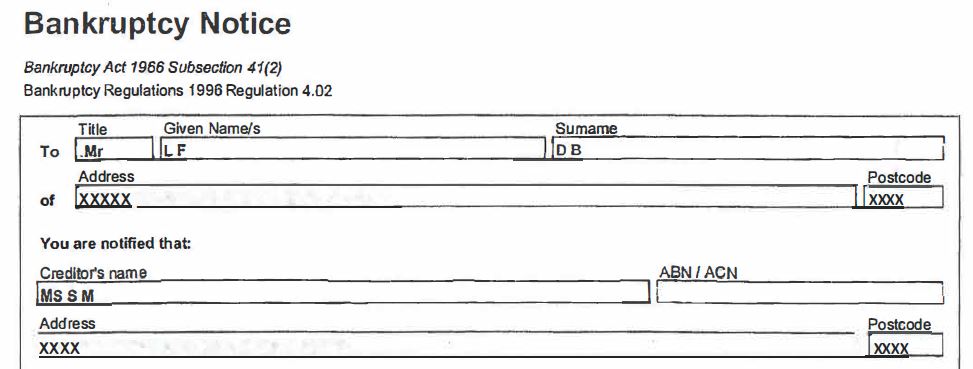

4 The Bankruptcy Notice, insofar as it names the addressee/debtor and the creditor, is relevantly in the following form:

5 The Bankruptcy Notice claims a total debt of $6,558,934.61 made up of the “attached final judgement/s or final order/s” plus “interest accrued since date of judgment/s or order/s” less “payments made and/or credit allowed since judgment/s or order/s”. A “Schedule of Post-Judgment Interest Calculation” (Schedule) is annexed to the Bankruptcy Notice. The Schedule sets out the seven proceedings in which orders were made requiring payment by LFDB and the interest calculated on each amount the subject of those orders. The Bankruptcy Notice annexed copies of the orders which made up the amount claimed in the Bankruptcy Notice and which are also included in the Schedule.

6 It is evident that the orders made, which are the subject of the amount claimed in the Bankruptcy Notice, are the result of a long history of litigation between LFDB and SM in the courts in New Zealand, in the Federal Circuit Court and this Court. Some of that history is set out by a Full Court of this Court (Besanko, Jagot and Lee JJ) in LFDB v SM [2017] FCAFC 178, which concerned an appeal against orders dismissing an application made by the appellants, LFDB and companies associated with LFDB, under s 72(1) of the Trans-Tasman Proceedings Act 2010 (Cth) (Trans-Tasman Act) seeking to set aside the registration of two judgments of the High Court of New Zealand obtained by SM against LFDB and companies associated with LFDB. Under the heading “Relevant Background” at [10]-[17] and [20]-[21] the Full Court said:

10 LFDB and SM lived together in a domestic relationship in Australia and New Zealand for some time until they separated in early 2009. As noted at [2(a)] above, the second to fifth appellants are companies associated with LFDB.

11 In March 2009, SM commenced an action against LFDB in the Family Court of New Zealand seeking division of property under the NZ Act. In October 2011, the proceeding was transferred to the High Court of New Zealand. By this time, remarkably, the parties “had indulged in 23 interlocutory applications, 53 affidavits, 7 court judgments (all directions), 5 judicial conferences and a hearing, one appeal to the High Court, a High Court application and hearing, and further High Court proceedings involving a mortgagee sale”: see SM v LFDB [2012] NZHC 1152 at [7] per Priestley J.

12 This litigious saga had costs consequences for LFDB and after a failure to pay adverse costs orders dating back to January 2010, described by Priestley J as “longstanding and conspicuous”, an order was made in September 2012 providing that unless the costs ordered were paid by LFDB, then he was “to be barred from taking any further part in the proceedings currently before this Court”. Apparently, at the heel of the hunt, on the last day before this self-executing order took effect, the relevant costs were paid: see SM v LFDB [2014] NZCA 326; [2014] 3 NZLR 494 at 497 [10] (Court of Appeal of New Zealand).

13 In July 2013, after another unsuccessful stage of the litigation, LFDB was ordered to pay a further fixed sum for adverse costs plus interest within seven working days. The judge making the order (Ellis J) gave SM leave “to seek unless orders in the event that [LFDB] fails to pay any part of those amounts as directed”.

14 Payment was not made and in August 2013, Ellis J ordered:

If LFDB does not pay to SM’s solicitors by 5:00pm on Monday, 9 September 2013 (New Zealand time) the sum of $24,435.08 plus interest accrued due at 5% per annum from 10 May 2013 to date of payment:

LFDB shall be debarred from taking any further part in the proceedings presently before this Court...

15 Ellis J, in her reasons for making this second self-executing order (Unless Order), explained that the order:

…in question was made principally because of my view that SM’s preparation for the trial in February was being unduly and unfairly prejudiced by her comparative lack of access to funds (a considerable proportion of which is said by her to constitute relationship property)… The effect of LFDB’s failure to meet the costs awards, in circumstances where I had formed the view that he had the means to do so, was therefore particularly acute.

16 An appeal was lodged in relation to the Unless Order and a number of interlocutory skirmishes followed, however, in October 2013, LFDB paid the amount specified in the Unless Order and the following month, Ellis J was persuaded to discharge the Unless Order: SM v LFDB [2013] NZHC 3105. This discharge was also the subject of an appeal and in July 2014, the Court of Appeal of New Zealand allowed the appeal and made an order reinstating the Unless Order, with the consequence of debarring LFDB from taking any further part in the proceeding: SM v LFDB [2014] NZCA 326; [2014] 3 NZLR 494.

17 In doing so, the Court of Appeal held that LFDB had “deliberately flouted” the Unless Order, and characterised the breach as contumacious and agreed that Ellis J was right to observe “that [LFDB] continued to play “some protracted game of ‘chicken’ with the Court”” (at 502 [33]).

…

20 Not daunted, LFDB sought leave to appeal the decision of the Court of Appeal. At first the application for leave was successful but in December 2014, leave was revoked (LFDB v SM [2014] NZSC 197; (2014) 22 PRNZ 262) when the Supreme Court of New Zealand became aware of yet another costs order. In revoking leave, the Court noted:

[25] When the Court granted leave to appeal it was appreciated that [LFDB] had demonstrated a defiant attitude to past orders and that the trial Judge was concerned at the prospect of this conduct causing continuing prejudice to the respondent. But the Court also understood that he had paid what was due on outstanding costs orders, and saw the case as suitable for addressing the issues we have mentioned.

[26] The further information we received at the hearing made clear that [LFDB’s] ongoing conduct of the litigation was such that it would inevitably create more continuing problems for the respondent and the courts than we had appreciated at the time leave was granted. In light of that information, the Court has formed the view that the manner in which [LFDB] has continued to conduct the proceeding is oppressive. It is clear the court system is being abused.

[27] [LFDB’s] offer to make payment of the ordered costs in response to the indication at the hearing that the Court would consider withdrawing leave does not persuade us otherwise. It came too late. Plainly he has always had the means to comply with the unless orders in issue. [LFDB] is gaming the court system. It is intolerable for [SM] to be faced with this and inappropriate for the Court to countenance such abuse of its process.

21 Accordingly, the Unless Order remained extant and LFDB was debarred from taking any further part in the substantive proceeding.

7 The history of the suppression orders made in the Federal Circuit Court and this Court, which resulted in the use of the pseudonyms LFDB and SM for the applicant and respondent in the various proceedings to date, is as follows:

(1) on 17 April 2012 in proceeding SYG1575/2011 between LFDB as applicant and SM as respondent, concerning an application by LFDB to set aside a bankruptcy notice issued by SM and following the making of suppression orders in related proceedings in New Zealand, the Federal Magistrates Court (as it then was) ordered, among other things, that the publication of information identifying the respondent be suppressed; the reasons for judgment as originally published be suppressed and that those reasons be published in a modified form deleting or modifying references to the applicant; and that references to the name, address and occupation of the applicant in documents filed with the court be suppressed and their publication prohibited;

(2) in proceeding NSD354/2015 between LFDB as applicant and SM as respondent, in relation to an application to set aside New Zealand freezing orders registered by SM in Australia, Gleeson J made orders:

(a) on 4 May 2015 prohibiting the publication of any information that identifies or could identify the first applicant, the respondent and the respondent’s name, occupation, employment history and/or health and that the first applicant be referred to as “LFDB” and the respondent be referred to as “SM”;

(b) on 14 September 2015 suppressing the names and places identified in a confidential exhibit and requiring that they be referred to by their respective pseudonyms identified in the confidential exhibit in the reasons for judgment and in any other court documents or judgments published in connection with the proceeding, including any appeal or related proceedings. That order remained in force for one year from the date of that order;

(3) in proceeding NSD1665/2015 between LFDB and others as applicants and SM as respondent, in relation to an application to set aside the registration of two New Zealand judgments, on 14 March 2016 Griffiths J made orders, among others, that:

1. Pursuant to s 37AF of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), on the ground that the orders are necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, and in accordance with paragraph 183 of the decision of Ellis J of the High Court of New Zealand, registered in proceedings NSD1665 of 2015 at orders 35, 36, 37 to 40, the Court orders as follows:

(a) the permanent suppression of the parties’ names and any other information that could identify SM, including her occupation, employment, history and health, howsoever (to be described as the identifying information), whether in the proceedings or in any related proceedings or otherwise;

(b) the prohibition of any publication past, present, future, of any identifying information so defined;

…

On 8 February 2017 Griffiths J dismissed the application to set aside registration and ordered LFDB to pay SM’s costs: see LFDB v SM (No 3) [2017] FCA 80 (NSD1665/2015 Orders); and

(4) in proceeding NSD301/2017 between LFDB and others as appellants and SM as respondent, which was an appeal from the NSD1665/2015 Orders, on 31 July 2017 the following orders were made:

…

(a) the permanent suppression of the parties’ names and any other information that could identify SM, including her occupation, employment, history and health, howsoever (to be described as the identifying information), whether in the proceedings or in any related proceedings or otherwise; and

(b) the prohibition of any publication past, present, future, of any identifying information so defined.

…

legislative framework

8 Section 40(1) of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) (Act) relevantly provides that a debtor commits an act of bankruptcy:

…

(g) if a creditor who has obtained against the debtor a final judgment or final order, being a judgment or order the execution of which has not been stayed, has served on the debtor in Australia or, by leave of the Court, elsewhere, a bankruptcy notice under this Act and the debtor does not:

(i) where the notice was served in Australia—within the time specified in the notice; or

…

9 Section 41(1) of the Act provides that an Official Receiver may issue a bankruptcy notice on the application of a creditor who, relevantly, has obtained against a debtor two or more final judgments or orders that are of the kind described in s 40(1)(g) and which, taken together, are for an amount of at least $5,000. Section 41(2) requires that the notice must be in accordance with the form prescribed by the regulations.

10 LFDB referred the Court to ss 43, 44 and 49 of the Act which relate to creditor’s petitions and which respectively concern the jurisdiction to make a sequestration order, the conditions on which a creditor may petition and the court’s power to permit the substitution of another creditor. As to the latter the court may permit another creditor to be substituted as petitioner where a creditor’s petition is not prosecuted with due diligence or, for another reason, the court considers it proper to do so and the debtor is indebted in the amount required by the Act to the substituted creditor.

11 Section 306(1) of the Act provides that proceedings under the Act are not invalidated by a formal defect or irregularity unless the court before which the objection on that ground is made is of the opinion that substantial injustice has been caused by the defect or irregularity which cannot be remedied by an order of that court.

12 Regulation 4.02 of the Bankruptcy Regulations 1996 (Cth) (Regulations) provides:

(1) For the purposes of subsection 41(2) of the Act, the form of bankruptcy notice set out in Form 1 is prescribed.

(2) A bankruptcy notice must follow Form 1 in respect of its format (for example, bold or italic typeface, underlining and notes).

(3) Subregulation (2) is not to be taken as expressing an intention contrary to section 25C of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901.

…

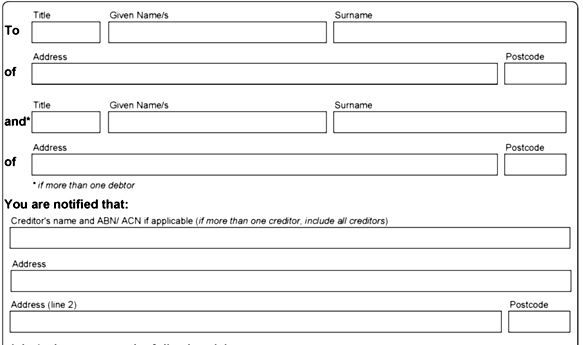

13 Form 1 is included in Sch 1 to the Regulations. In relation to nomination of the addressee/debtor and creditor the form is as follows:

14 Regulation 4.03(1) provides that, subject to subreg (2), the only persons who may inspect a bankruptcy notice lodged with the Official Receiver are: a person specified in the notice; a party to a proceeding to which the notice relates; and a solicitor acting for one of those persons. Regulation 4.03(2) provides that if a creditor’s petition is presented that is founded on an act of bankruptcy consisting of a failure to comply with a bankruptcy notice, that notice, as lodged with the Official Receiver, is open to public inspection.

15 The National Personal Insolvency Index (NPI Index) is an electronic index, the responsibility for operation of which lies with the Inspector General: see reg 13.02(1) and (2) of the Regulations. Regulation 13.03(1) provides for the information that is to be entered on the NPI Index and relevantly includes for each creditor’s petition information of the kind specified in Sch 8, to the extent applicable, and information concerning a creditor’s petition, including details of any orders made in relation to the petition or withdrawal of the petition. In turn, Sch 8 provides that, for the purposes of s 43 and s 47 of the Act, the information to be included on the NPI Index is:

date of petition;

particulars of debtor;

name of petitioning creditor;

name and telephone number of petitioning creditor's solicitors; and

date of court hearing for sequestration order.

16 Rule 4.04(1) of the Federal Court (Bankruptcy) Rules 2016 (Cth) (Bankruptcy Rules) requires that a creditor’s petition founded on an act of bankruptcy specified in s 40(1)(g) of the Act must also be accompanied by:

…

(a) an affidavit stating:

(i) that the records of the Court and the records of the Federal Circuit Court have been searched and no application in relation to the bankruptcy notice has been made; or

(ii) that an application was made in the Court or in the Federal Circuit Court (as the case may be) for an order setting aside the relevant bankruptcy notice and the application has been finally decided; or

(iii) that an application was made in the Court or in the Federal Circuit Court (as the case may be) for an order extending the time for compliance with the bankruptcy notice and the application has been finally decided; and

…

17 Rule 4.06(3) of the Bankruptcy Rules requires that the applicant creditor file an affidavit of a person who has, no earlier than the day before the hearing date for the petition, searched or caused a search to be undertaken of the NPI Index that:

(a) sets out the details of any references in the [NPI] Index to the debtor; and

(b) states that there were no details of a debt agreement, about the debt on which the applicant creditor relies, in the [NPI] Index:

(i) on the day when the petition was presented; and

(ii) on the day when the search was made; and

(c) has attached to it a copy of the relevant extract of the [NPI] Index.

relevant principles

18 In McWilliam v Jackson (2000) 96 FCR 561 (McWilliam) the applicant, Mr McWilliam, applied to set aside a bankruptcy notice which was founded on a judgment entered in the District Court of New South Wales (District Court) for the value of a certificate of assessment of costs in a Supreme Court of New South Wales (Supreme Court) proceeding plus costs. That judgment identified “Anthony Jackson & Ors” as plaintiff and Bruce Scott McWilliam as defendant.

19 Mr McWilliam contended that the bankruptcy notice was a nullity for two reasons of which, relevantly, the first was because it failed to identify the creditor to whom the addressee of the notice was to pay the money claimed in the notice or alternatively with whom the addressee was to make an arrangement for settlement of the debt. In relation to that ground, Wilcox J noted at [17] that the prescribed form at the time required the insertion of the name and address of the addressee of the notice at the commencement of a bankruptcy notice and that paragraph one provided for the name and address of a person called “‘the creditor’ who, the notice says, ‘claims you owe the creditor a debt of $[amount] as shown in the Schedule’”. That is, as his Honour observed, “the claim is that the debt is owed to the person whose name and address is stated and who is called ‘the creditor’”.

20 After setting out the requirements of paragraphs two and three of the prescribed form of bankruptcy notice, his Honour said at [19] “that identification of the relevant creditor is of central importance to a proper understanding of a bankruptcy notice and the obligations of the addressee in respect of the notice”. At [20]-[22] his Honour continued:

20 In the present case the creditor was identified as “Anthony Jackson & Ors”. Presumably, “Anthony Jackson” is identical to “Anthony Charles Badham Jackson”, the second defendant in the Supreme Court proceeding. But who are the others? The bankruptcy notice does not say.

21 Ms J Oakley of counsel appeared to resist Mr McWilliam’s application. She did so on the instructions of Sally Nash & Co. I gather from Ms Oakley that this firm currently acts for Mr Jackson and those members of Norton Smith & Co who were named as third defendants in the Supreme Court action. Ms Oakley asserted Mr McWilliam would have realised these were the people referred to in the bankruptcy notice as “others”. But there is no evidence of this; Mr McWilliam was not cross-examined. In any event, the test is not whether the addressee of the bankruptcy notice was in fact misled, but whether he or she could have been misled: see James v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) (1955) 93 CLR 631 at 644.

22 In Re Hansen; Ex parte Hansen (1985) 4 FCR 590 Beaumont J dealt with a case where a bankruptcy notice was issued in the name of “Mortgage Guaranty Insurance Corporation of Australia Limited”, although that company had by then changed its name to “MGICA Limited”. Following the issue of the bankruptcy notice, the debtor’s solicitor had sought out the judgment creditor. However, he failed to make contact because only the name “MGICA Limited” was displayed at the address stated in the bankruptcy notice; the solicitor did not connect the two names. Beaumont J said:

In my opinion, it is essential to the validity of a bankruptcy notice that the judgment debtor be in no reasonable doubt as to the identity of the judgment creditor. In the present case, the judgment creditor was identified by a name which it had abandoned some considerable time previously. That name was quite different from the name of the judgment creditor at the time of issue of the bankruptcy notice and the judgment debtor could hardly be expected to connect the two corporate names. The judgment debtor could thus have been misled as to the identity of the party with whom he had to deal in order to comply with the requirements of the bankruptcy notice. The notice was accordingly defective.

21 At [24] Wilcox J noted that in the case before him the problem was compounded by the fact that, apart from the creditors named in the bankruptcy notice, there were four other defendants to the Supreme Court proceeding on which the costs assessment was based, all of whom were beneficiaries of the costs order made against Mr McWilliam and his fellow plaintiffs. His Honour was of the view that Mr McWilliam might have been misled into thinking these other persons were amongst the “others” referred to in the bankruptcy notice and that “[p]utting the matter at its lowest, the identification of the persons who constituted the creditor was left a matter of doubt”.

22 At [25] his Honour concluded:

Ms Oakley defended the identification of the creditor on the bankruptcy notice by pointing out it followed the identification of the plaintiff in the District Court judgment. So it did. … But that cannot be a justification for the form of the bankruptcy notice; any more than it could be a justification for the judgment that Mr Lancken had also used the short form in his costs certificate. The certificate could and should have been amended in such a way as precisely to identify the parties. Whatever the form of earlier documents, it was essential the bankruptcy notice properly identify the person or persons who constituted “the creditor”. This notice did not do that. For that reason, alone, it is a nullity.

23 Matheson v Scottish Pacific Business Finance Pty Ltd [2005] FCA 670 concerned an appeal from the making of a sequestration order. Mr Matheson raised five grounds of appeal including as ground five that “[a] bankruptcy notice is void if full legal name of person is not complete”. Kiefel J (as her Honour then was) noted that, in both the District Court of Queensland and in the proceeding before this Court, Mr Matheson was referred to as “Frederick Matheson” and not by his full name “Frederick James Matheson”. At [10] her Honour said:

Mr Matheson has referred me to the definition of ‘legal name’ in Black’s Law Dictionary, 8th edn, ed BA Garner, West Pub Co, USA (2004) pg 1048 as ‘a person’s full name as recognised in law’. That does not however mean that a court document such as a bankruptcy notice or petition is void if the full legal name of the person is not provided. There is no doubt that Mr Matheson is the person named in the District Court proceedings and in these proceedings and that he has understood that to be the case. He has represented himself and appeared. There was no ambiguity created by the bankruptcy notice or petition. In any event if there was an irregularity in the mode of description, it is of a formal nature and one that can be validated by s 306(1) of the Bankruptcy Act: Re Draper; Ex parte Australian Society of Accountants (1989) 154 FCR 41. A ‘formal defect or an irregularity’ within the meaning of that section is one that could not reasonably mislead the debtor: Re Wimbourne; Ex parte The Debtor (1979) 24 ALR 494. In my opinion, the petition notice does not cause any injustice as it was not likely to mislead the debtor.

24 MS SM referred to Viavattene v Birch [2015] FCCA 2676, a decision of the Federal Circuit Court, in which Judge Jarrett said at [14]-[15]:

14. It is necessary for the bankruptcy notice to follow the judgment upon which it relies. That includes the description of the parties to the judgment: Swart v Carr (No.2) [2008] FMCA 1204 at [14]. Here there are two judgments, only one of which has the correct spelling of the applicant’s surname. The name on the bankruptcy notice is also incorrect.

15. However, whilst the proper identification of the creditor to a bankruptcy notice might be said to be an essential requirement of a bankruptcy notice (see for example, Re Hansen; Ex parte Hansen (1985) 4 FCR 590), formal errors in a bankruptcy notice do not result in its invalidity unless they cause “substantial injustice”: Kyriackou v Shield Mercantile Pty Ltd (2004) 138 FCR 324 at 336. “The touchstone of invalidity is thus whether any error is “capable of misleading” a debtor in a manner that results in “substantial injustice” ”: Yang v Mead [2009] FCA 1202 at [15].

consideration

25 In support of his contention that the Bankruptcy Notice is a nullity LFDB essentially raised two issues for determination by the Court. First, whether the way in which the addressee and creditor are named in the Bankruptcy Notice render it a nullity because of the public interest policy which underpins bankruptcy; and secondly, whether the addressee, LFDB, was likely to be misled as to the identity of the creditor named in the Bankruptcy Notice. I consider each of these issues in turn below.

The first issue

26 In relation to this issue, LFDB relies largely on the public interest policy which underpins bankruptcy. He submitted that:

(1) the Act and subordinate instruments make it an essential requirement of a bankruptcy notice that both the addressee and the creditor be named and that such requirements put the alleged debtor on unequivocal notice of the circumstances and consequences faced by that debtor, as asserted by the named creditor, and inform creditors and the general public of the circumstances of the alleged debtor;

(2) the consequences of issuing a bankruptcy notice to a debtor in an anonymous form is that any search of the relevant court’s records will not return a result. Thus, if a proceeding was commenced by the anonymous creditor in respect of an anonymous debtor, other creditors would not become aware of that proceeding so as to be able to participate as supporting creditors or to seek to be substituted as petitioning creditor. Accordingly, the purpose of s 49 of the Act, in seeking to prevent a multiplicity of proceedings, would not be achieved should any other creditor seek to have the same debtor bankrupted;

(3) any proceeding under a creditor’s petition would also have to be anonymous as the bankruptcy notice would necessarily become a public document upon filing of the petition and the verifying affidavit which must attach it;

(4) whilst suppression orders might suit the creditor’s purposes, they would subvert the fundamental public interest principle upon which the process of bankruptcy is founded. It is of central importance that the creditor be named in a bankruptcy notice so as to ensure that the addressee does not misunderstand the notice and its ramifications;

(5) it must be of equal importance that the debtor be named in a bankruptcy notice so as not to subvert the fundamental public interest objective of bankruptcy law. To allow any act of bankruptcy to occur by reason of an anonymous bankruptcy notice would cause substantial injustice to the addressee and to any other creditor who would necessarily remain unaware of the act of bankruptcy and unaware of any proceedings commenced in respect of it. It is thus an essential requirement of a bankruptcy notice that it name both the debtor and the creditor; and

(6) in this case not only is the public interest foundation of bankruptcy subverted by the anonymisation of the addressee and creditor but the addressee is left uncertain about the identity of the creditor.

27 Central to LFDB’s argument is the requirement that, at the point of the presentation of a creditor’s petition, certain information becomes public because:

of its inclusion on the NPI Index: reg 13.03(1) of the Regulations;

the creditor must file an affidavit accompanying the petition which deposes to the fact that a search was undertaken of the records of the Federal Circuit Court and this Court and that there is no application in relation to the bankruptcy or, if an application was made, that it has been finally determined: r 4.04(1)(a) of the Bankruptcy Rules; and

the creditor must file an affidavit of service of the bankruptcy notice on which the act of bankruptcy is based which annexes that bankruptcy notice: r 4.04(1)(b) of the Bankruptcy Rules.

28 That is, LFDB relies on the public nature of the information and that, in his submission, there is a need for other creditors to be aware of the identity of an alleged debtor before taking any step or pursuing any application under the Act.

29 As LFDB correctly points out bankruptcy is not mere inter partes litigation but involves a change in status and has quasi-penal consequences: see Ahern v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation (Qld) (1987) 76 ALR 137 at 148. That effect of bankruptcy and its public interest was recently reinforced in Culleton v Balwyn Nominees Pty Ltd (2017) 343 ALR 632; [2017] FCAFC 8 where a Full Court of this Court (Allsop CJ, Dowsett and Besanko JJ) relevantly said at [40]:

In considering the question of an adjournment of the hearing of a creditor’s petition, it is fundamental to keep firmly in mind, at all times, the nature of the jurisdiction. Bankruptcy is not just a variety of inter partes litigation; it does not deal only with the private rights and obligations of the debtor and creditor; it is not a form of judgment execution. It is directed to the estate of a person who is insolvent. In that sense it has a public interest, through the general body of creditors and potential creditors of the debtor and prospective bankrupt, and through what is referred to as the change of status of the person who becomes a bankrupt. That status is changed because of the provisions of the Act which inhibit conduct and affect rights and obligations of the bankrupt, including making the bankrupt susceptible to criminal punishment for what would otherwise be innocent conduct. …

30 Notwithstanding that, in my opinion, the issues raised by LFDB and their impact on the bankruptcy process and its potential effect do not arise at the stage of service of a bankruptcy notice. True it is, as LFDB pointed out, that service of a bankruptcy notice can have either one of two functions: to compel payment of the amount claimed therein or, in the absence of payment or an order setting the bankruptcy notice aside, to ground the presentation of a creditor’s petition. However, at the point of its issue, a bankruptcy notice operates only as between the addressee and the creditor. The Official Receiver may issue a bankruptcy notice on the application of a creditor who has obtained a judgment or judgments which meet the requirement of s 41(1) of the Act. The creditor makes the application and the bankruptcy notice is issued to it. The creditor will then serve it on the debtor. At that stage it is not a public document and no other creditor of the same debtor can rely on that bankruptcy notice. That the issue and existence of a bankruptcy notice is a matter limited to the parties to it, being the creditor and the debtor, is reinforced by reg 4.03(1) of the Regulations which at that stage limits the persons who can inspect a bankruptcy notice lodged with the Official Receiver.

31 The failure to comply with a bankruptcy notice or otherwise satisfy the requirements of s 40(1)(g) of the Act will entitle the creditor to present a creditor’s petition against a debtor. Where a creditor’s petition is founded on an act of bankruptcy based on a failure to comply with s 40(1)(g) of the Act, the relevant bankruptcy notice must be annexed to an affidavit of service which accompanies the petition. At that stage the bankruptcy notice forms a part of the evidence upon which a creditor will rely for the making of a sequestration order. In addition the creditor must provide an affidavit, based on a search of court records, deposing to the matters referred to at [16] above; the bankruptcy notice lodged with the Official Receiver is open to public inspection; details of the creditor’s petition must be entered on the NPI Index; and prior, to the date fixed for hearing of the creditor’s petition, a search of the NPI Index must be undertaken and the results of that search then forms part of the evidence before the Court at the hearing. That being so, the need to be able to identify the parties and, in particular, the debtor is brought into sharp focus upon the filing of a creditor’s petition. Although not in issue on this application, at that stage the issues raised by LFDB take on a different complexion and would lead one to conclude that the use of acronyms or pseudonyms in a creditor’s petition would not be appropriate given the policy behind, and scheme of, the Act. Senior Counsel for MS S M seemed to accept as much.

32 LFDB submitted that a bankruptcy notice and creditor’s petition are “linked”. Clearly, where the act of bankruptcy relied on by a creditor is a failure to comply with s 40(1)(g) of the Act the bankruptcy notice and creditor’s petition are connected; the latter cannot issue absent the former. But it does not follow that the use of pseudonyms is precluded in a bankruptcy notice. Ultimately, in my opinion, it would be necessary for the creditor to establish that the person named as the debtor/respondent in the creditor’s petition was served with a bankruptcy notice issued at the request of the creditor to that person or, put more simply, that the persons named as addressee/debtor and creditor in the bankruptcy notice are the same as the persons named as debtor/respondent and creditor in the creditor’s petition.

33 LFDB also submitted that a search of court records as required by r 4.04 of the Bankruptcy Rules would ordinarily return a proceeding such as this one seeking to set aside a bankruptcy notice but, where acronyms or pseudonyms are used for the bankruptcy notice and in any proceeding to set it aside, a creditor searching the court records would not become aware of the proceeding. That would be so. But it does not advance the argument contended for by LFDB. Where those circumstances arise the relevant creditor, who for ease I shall refer to as Creditor A, would be armed with its own bankruptcy notice issued to a debtor which had not been satisfied. The search to be undertaken pursuant to r 4.04 of the Bankruptcy Rules concerns the bankruptcy notice issued by and relied upon by Creditor A. That is, Creditor A would search for a proceeding that concerned the bankruptcy notice issued at its request and not a bankruptcy notice issued by another creditor to the same debtor which may be subject to an application to set it aside or orders extending the time for compliance with it. Any extant application to set aside orders made affecting a bankruptcy notice issued to the same debtor by a different creditor would not affect Creditor A’s ability to file and proceed with its creditor’s petition.

34 In my opinion, in the circumstances of this case, the way in which the addressee and creditor are named in the Bankruptcy Notice does not render it a nullity.

The second issue

35 I turn then to consider the second issue: whether LFDB was likely to be misled as to the identity of the creditor named in the Bankruptcy Notice.

36 LFDB submitted that the various judgments relied upon by the alleged creditor refer to the parties as “LFDB” and “SM” but the Bankruptcy Notice, which provides no field for a creditor’s title to be included, names the creditor as “MS S M”. LFDB further submitted that any suggestion that “MS” may indicate the marital status neutral title “Ms” only raises more ambiguity in light of the addressee’s title being recorded as “Mr” rather than “MR”. LFDB contended that this was especially so in circumstances where the proceedings relied upon were proceedings from which he was debarred and in which he could not participate.

37 LFDB submitted that the naming of the addressee and creditor go to an essential requirement of a bankruptcy notice and that, relying on McWilliam, a failure to properly name a party is not a formal defect. Thus LFDB submitted that the bankruptcy notice is a nullity. LFBD further submitted that even if anonymisation was a mere formal defect, it would cause substantial injustice that could not be remedied by order of the Court. He said that that injustice would not only affect the addressee but any other creditor interested in an act of bankruptcy by LFDB.

38 In the circumstances of this case, the submission that LFDB could be misled about the identity of the creditor described as “MS S M” is rejected. First, the parties to this proceeding have been engaged in litigation both in Australia and New Zealand for many years. It is clear from the evidence before me that in many of those proceedings the pseudonyms “LFDB” and “SM” were used. In those circumstances it is difficult to accept that LFDB would have been misled by the description of the creditor as “MS S M” in the Bankruptcy Notice. Further, the Bankruptcy Notice annexes copies of the orders made in proceedings between LFDB and SM and, where relevant, certificates of registration of judgments under the Trans-Tasman Act, which make up the amount claimed in it. In each case those orders were made in proceedings which include SM and LFDB as parties. That fact further detracts from the possibility of confusion as to the identity of the creditor.

39 I do not accept that the use of “MS” before “S M” could cause or “raise more” ambiguity. Contrary to LFDB’s submission, the only possible interpretation is that “MS” is intended to indicate the marital status neutral title “Ms”. That “Mr” was used in the description of the debtor rather than “MR” would not be a reason why one would draw any other conclusion nor would it add to any confusion.

40 I similarly do not accept the submission that LFDB being debarred from participating in proceedings before the courts in New Zealand is a matter that would cause me to conclude that he could be misled as to the identity of the creditor in the Bankruptcy Notice. LFDB was clearly aware of the proceedings, participated in them until orders were made debarring him from continuing to do so and has subsequently participated in proceedings before this Court. The submission that LFDB could not understand how a person described as MS S M could refer to the same person who was described as SM in the many proceedings in this Court and in New Zealand is rejected. To adopt the words of Beaumont J in Re Hansen; Ex parte Hansen (1985) 4 FCR 590 at 594, in my opinion, in the circumstances of this case LFDB could “be in no reasonable doubt as to the identity of the judgment creditor”. He could not have been misled about the identity of the party with whom he must deal to comply with the requirements of the Bankruptcy Notice.

41 Both parties relied on the proposition that a bankruptcy notice must follow the judgment on which it is founded. LFDB submitted that the description of the creditor as “MS S M” did not follow the judgments because of the inclusion of “MS”. The insertion of “MS” before “S M” in the Bankruptcy Notice does not lead to the conclusion that the Bankruptcy Notice does not follow the judgment. The contrary is the case. “MS” can only be read as the title “Ms”. But, in any event, as is clear from the authorities, the touchstone of invalidity is whether the error is capable of misleading a debtor. I have already expressed the view that LFDB could not be misled by either the use of SM or, as appears in the Bankruptcy Notice, the description “MS S M”.

42 If I am wrong in that conclusion then, in my opinion, the irregularity in description of the creditor is a formal defect which could be validated by s 306 of the Act. It is an error which could not cause any substantial injustice because it was not likely to mislead LFDB. Nor, contrary to LFDB’s submission, would it be likely to mislead any other creditor who, at the stage of service of a bankruptcy notice, would not be aware of its existence.

43 It follows that, in my opinion, LFDB has not succeeded in relation to the second issue. LFDB could not have been misled as to the identity of the creditor named in the Bankruptcy Notice.

conclusion

44 LFDB has not succeeded in establishing that the Bankruptcy Notice is a nullity. Accordingly, the application to set aside the Bankruptcy Notice should be dismissed. Costs should follow the event. I will make orders accordingly.

I certify that the preceding forty-four (44) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Markovic. |