FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Wing v The Australian Broadcasting Corporation [2018] FCA 1340

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | THE AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION First Respondent FAIRFAX MEDIA PUBLICATIONS PTY LIMITED ACN 003 357 720 Second Respondent NICK MCKENZIE Third Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 31 August 2018 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Paragraphs 13.1 and 13.2 and the particulars of truth in paragraphs A1-54 of the defence filed on 6 October 2017 be struck out.

2. The respondents’ oral application made on 27 June 2018 to file an amended defence be dismissed.

3. The respondents pay the applicant’s costs of his interlocutory application filed on 21 March 2018 and of their oral application to amend made on 27 June 2018.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

RARES J:

1 Dr Chau Chak Wing commenced this proceeding on 3 July 2017 seeking damages for defamation in respect of the broadcast and rebroadcast by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), of its Four Corners television program, first published on 5 June 2017. He also sued Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd (Fairfax) and its employed reporter, Nick McKenzie, who was the presenter of the program. Dr Wing alleged that both the ABC and Fairfax republished the program by making it available on their websites for downloading and viewing. A transcript of the program is in Annexure A to these reasons.

2 The program lasted about 45 minutes. Dr Wing alleged in his amended statement of claim that it conveyed the following imputations of and concerning him (that I found were capable of being conveyed in the course of oral argument on 18 August 2017), namely:

(a) The Applicant betrayed his country, Australia, in order to serve the interests of a foreign power, China, and the Chinese Communist Party by engaging in espionage on their behalf.

(d) The Applicant is a member of the Chinese Communist Party and of an advisory group to that party the People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPCCC) and, as such, carries out the work of a secret lobbying arm of the Chinese Communist Party, the United Front Work Department.

(e) The Applicant donated enormous sums of money to Australian political parties as bribes intended to influence politicians to make decisions to advance the interests of the Republic of China, the Chinese government and the Chinese Communist Party.

(f) The Applicant paid Sheri Yan, whom he knew to be a corrupt espionage agent of the Chinese government, in order to assist him in infiltrating the Australian government on behalf of the Chinese Communist Party.

(g) The Applicant paid a $200,000 bribe to the President of the General Assembly of the United Nations, John Ashe.

(h) The Applicant was knowingly involved in a corrupt scheme to bribe the President of the General Assembly of the United Nations.

3 In addition, Dr Wing relied on the extrinsic fact that, on becoming an Australian citizen, he made the pledge of loyalty that all persons must make when becoming a citizen, to allege that the matter complained of conveyed a further imputation or true innuendo (the extrinsic imputation), namely:

The Applicant broke the pledge of loyalty he took to Australia on becoming an Australian citizen by secretly advancing the interests of a foreign power at the expense of the interests of Australia.

4 He pleaded the extrinsic fact as follows:

[T]he pledge of loyalty is… in the following terms:

From this time forward I pledge my loyalty to Australia and its people, whose democratic beliefs I share, whose rights and liberties I respect. and whose laws I will uphold and obey.

5 On 6 October 2017, the first and second respondents filed their defence that, relevantly, pleaded justification on the basis that each of Dr Wing’s pleaded imputations including the extrinsic imputation (Dr Wing’s imputations) was substantially true. The respondents also pleaded variants of each of those imputations that commenced with the words “there are reasonable grounds to believe” before repeating each of Dr Wing’s imputations (the variant imputations). They pleaded that and that each variant imputation was both, not substantially different from, and not more injurious than, the unqualified form of the same imputation as Dr Wing pleaded and that because each variant imputation was substantially true, the respondents had a defence of justification at common law. Thus, for example variant imputation (a) read:

There are reasonable grounds to believe that the Applicant betrayed his country, Australia in order to serve the interests of a foreign power, China, and the Chinese Communist Party by engaging in espionage on their behalf. (emphasis added)

6 The respondents also relied on a defence of qualified privilege under s 30 of the Act, to which Dr Wing responded in his reply.

7 On 21 March 2018, Dr Wing filed the present interlocutory application seeking to strike out the defences of justification of Dr Wing’s imputations and the variant imputations, together with the particulars pleaded in support of them, on the basis that they disclosed no reasonable defence and or were likely to cause prejudice, embarrassment and delay.

8 The parties have served outlines of evidence and expert reports under timetables that I had ordered, with some extensions of time. On 19 February 2018, I had extended the time for the respondents to file and serve expert material on which they intended to rely to 5 March 2018. The respondents did not comply with that order and on 16 May 2018, I extended the time for compliance to 15 June 2018. I also set the interlocutory application down for argument on 27 June 2018 and gave directions for the parties to file and serve submissions.

9 On 29 May 2018, Dr Wing served his written submissions in support of his interlocutory application, and on 22 June 2018, the respondents served their written submissions together with a proposed amended defence. That amended defence substantially altered the particulars of justification, while maintaining the existing pleading of truth in respect of both Dr Wing’s and the variant imputations. The respondents orally applied for leave to file the amended defence. The respondents explained that the proposed amended particulars of justification reflected material that, by 21 June 2018, they had served (and or filed).

10 Dr Wing opposed the grant of leave for the respondents to file the amended defence. It was common ground that if I refused to grant that leave, the respondents’ pleading of justification and the particulars in support of them in the filed defence should be struck out under r 16.21(1)(d) and or (e) of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

The issues

11 There are two principal issues, namely, whether, first, the variant imputations fail to disclose a reasonable defence of justification, and secondly, the amended particulars of justification are so imprecise or embarrassing that they do not provide a fair indication of the case Dr Wing has to meet or, in any event, are not capable of establishing the truth of Dr Wing’s imputations.

The legislative context

12 The Defamation Act 2005 (NSW) provides in s 8 that a person has a single cause of action for defamation in relation to the publication of defamatory matter about the person, even if it carries more than one imputation about him or her. By dint of s 24(1), a defence available under Div 2 is additional to any other defence available to the defendant apart from the Act. Relevantly, Div 2 contains s 25 which provides:

It is a defence to the publication of defamatory matter if the defendant proves that the defamatory imputations carried by the matter of which the plaintiff complains are substantially true. (emphasis added)

13 Thus, the scheme of the Act is to create a cause of action, as does the common law, based on the publication of a matter complained of that conveys one or more imputations that are defamatory of the plaintiff. The imputations are meanings that the plaintiff identifies in the statement of claim that he (in Dr Wing’s case) alleges an ordinary reasonable viewer of the program (being the matter complained of) would understand it to convey about him and which are calculated to lower his reputation in the eyes of persons who know him and watched the program. Section 25 provides that the defendant (or respondents here) will have no liability for defamation if they can prove that the pleaded imputations, or meanings not substantially different from them, are substantially true.

The particulars

14 The amended defence pleaded 80 main paragraphs of particulars of truth, many of which also had numerous subparagraphs that appeared under several headings that I will summarise below. In par 81, the respondents asserted that they reserved “the right to provide further particulars following discovery and interrogatories”.

The Chinese Communist Party and the ‘united front’

15 The particulars asserted (in pars 1-6) that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) had absolute political power in China, as a party-State, and had a very important role in China’s foreign policy. They asserted that the CCP conducts foreign affairs that included conduct supplementing and or overriding the work of Chinese State sector organisations. Next pars 3-4 alleged that there is a ‘united front’ that is central to China’s foreign policy in which the CCP, its members and non-members work together to achieve the CCP’s objectives or strategy including to “get foreign political and economic elites to accept [China’s] foreign policy goals”, promote China’s agenda, gather strategic information and break up or neutralise opposition and alliances that are contrary to China’s interests. The united front strategy allegedly includes that CCP officials and their agents seek to develop relationships and promote the CCP’s goals with senior and or influential foreign and overseas Chinese persons to influence, subvert or bypass the policies of their own nations’ governments.

The United Front Work Department

16 The particulars asserted (in pars 7-17) that the United Front Work Department (UFWD) was highly secretive in relation to its overseas work and reported directly to the Central Committee of the CCP. Paragraph 9 alleged: “The CCP and/or the UFWD recruit and use a range of individuals, including foreigners and Chinese expatriates living outside China (Agents) to promote and further the political ends of the CCP and the United Front Strategy”. Paragraph 10 asserted that Agents included persons who may act voluntarily or under coercion. Paragraph 12 alleged that wealthy individuals with significant Chinese business interests, particularly in real estate and property development in China, are susceptible to being coerced or persuaded into cooperating as Agents for the CCP because of their vulnerability to allegations, such as personal corruption, to explain how they became so wealthy, that could result in loss of status or wealth. The CCP used Agents to gather information, cultivate or influence foreign politicians, governments, universities and engage in “espionage” that par 14 defined as follows:

(14) Espionage (Espionage) includes, in relation to [China], attempting to advance the United Front Strategy and the interests of the CCP and [China] globally by, inter alia:

(a) obtaining confidential information or documents of another country so as to provide them to [China]; or

(b) conduct which achieves or is intended to achieve, or is intended to make possible, influencing and/or subverting and/or otherwise interfering with, covertly and/or deceptively (in the sense that the Agent’s role as such Agent is not disclosed), the policies of foreign governments and/or the political and democratic processes of foreign countries.

17 Then pars 15-17 asserted ways in which Agents seek to influence policies of foreign governments in support of the united front strategy. For example, Agents may make or promise significant donations to political parties, offer or provide current or former politicians or influential persons with free trips to China, gifts, access to Chinese political and business leaders or board or university positions, in order to encourage policies or attendances favourable to China’s or the CCP’s interests.

The Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference

18 The particulars asserted (in pars 18-22) that the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) is a consultative body of the Chinese party-State and a core agency of the CCP that collaborates with the UFWD. Paragraph 18 asserted that the CPPCC provides funds to overseas bodies associated with the UFWD, including ones promoting the reunification of China, to facilitate making donations to foreign political parties. The UFWD must allegedly approve persons as members of the CPPCC (who need not be CCP members), which is seen as a reward for UFWD work, confers status and prestige on Agents and provides them with business opportunities. The particulars asserted in par 20 that becoming a member of the CPPCC “reduces the risk for Agents of business and reputational damage” (emphasis added) and in par 22, that the CPPCC sets up institutions in other countries with which the CPPCC cooperates.

The CPPCC and UFWD in Australia

19 The particulars asserted (in pars 23-28) that one objective of the united front strategy was “to get foreign political and economic elites to accept [China’s] foreign policy goals. Australia has been and remains a significant target of CCP United Front work” (par 23). The UFWD’s overseas operations were managed in its “third bureau” (par 24). The UFWD oversees a number of other “platforms” to promote the CCP internationally sometimes with the CPPCC, including the Chinese Council for Promotion of Peaceful Reunification of China (CCPPRC). The CCPPRC in collaboration with the CPPCC, promoted and maintained the Australian Council for Promotion of Peaceful Reunification of China (ACPPRC). And par 28 asserted:

(28) The objectives of the CCP’s united front activities in Australia include the following:

(a) weakening the alliance between Australia and the United States of America;

(b) the recognition of China’s disputed territorial claims over the South China Sea;

(c) promoting and advancing Chinese economic and strategic initiatives such as the One Belt, One Road (Belt and Road) initiative;

(d) the practice of Falungong; [sic]

(e) the re-unification of China and Taiwan;

(f) promoting and advancing China-Australia relations (including trade and investment) to the advantage of China;

(g) reducing Australian official criticism of and resistance to Chinese foreign policy in the Indo-Pacific region;

(h) silencing dissent against the CCP inside the Chinese diaspora community within Australia.

(the CCP Australian Objectives)

The Applicant

20 The particulars asserted (in pars 29-31) that Dr Wing:

was also known by another Chinese name;

had been born in eastern Guangdong Province about 70 years ago;

had moved to Australia in the 1980s;

was a businessman, real estate developer and philanthropist;

owned through the Kingold Group a newspaper in Guangzhou, a Chinese language newspaper published in Australia, namely the Australian New Express Daily (the subject of further particulars in par 43), the Imperial Springs Resort, in Guangzhou, and “a business conglomerate based in Guangzhou” which he also operated;

had a net worth, in 2014, of over USD1 billion; and

resided for most of each year in China.

The particulars then asserted:

(30) On becoming an Australian citizen, the Applicant made a pledge of loyalty to Australia by taking the Australian Citizenship Pledge (Citizenship Pledge).

(31) By reason of the Applicant’s background, business acumen and general knowledge, he knew, and/or it is to be inferred that he knew, the facts, matters and circumstances set out in particulars (1) to (28) (emphasis added).

21 Next the particulars used headings to relate allegations to the various imputations. The particulars (in pars 32-59) alleged matters to support the truth of Dr Wing’s imputations (a), (d) and (e), the extrinsic imputation and the corresponding variant imputations. These particulars asserted that, in about 2004, Dr Wing had become a standing committee member of a Guangdong district CPPCC, in about 2006, he became the first president or chairman of the Guangdong Provincial Overseas Chinese Enterprises Association that was “backed by the CCP” and that he attended its first meeting with, among others, the director-general of the UFWD. They also asserted that by no later than 2010, Dr Wing had become a national committee member of the CPPCC. On that basis, the respondents alleged in par 35 that, coupled with their particulars about the CPPCC, it was “to be inferred that, at all material times since at least 2004, [Dr Wing] has carried out the work of the UFWD and the CCP, including seeking to implement the United Front Strategy in Australia” (emphasis added).

22 Next, the particulars asserted (in pars 36-40) that Dr Wing had served as honorary chairman of the ACPPRC in its third and fourth terms, organised or taken an active part in high profile conferences and events that nurtured the interests of the CCP, CPPCC and UFWD, including the 2011 China Australia Economic and Trade Friendship and Exchange Conference, the July 2014 China Australia Economic Forum, the October 2015 International Forum, and the May 2016 International Forum on Cities and Development, most of which were held at his Imperial Springs Resort, and the 2012 Australia-China Desert Adventurer (Australia stage) Kick-off Ceremony held in Guangzhou. Dr Wing allegedly had also established and became head of one named organisation in 2005 and became executive director of another named organisation in 2008 each of which had “close” or “deep” links with the CCP and UFWD. The particulars asserted (in par 40) that these facts justified the inference that at all material times Dr Wing “was engaged in CCP united front activities including seeking to implement the United Front Strategy in Australia”.

23 The particulars then asserted (in pars 41-43) that in 2014, the United Front of Shantou, a body that undertook united front activities, promoted Dr Wing as having met with prominent members of the CCP, including the former president, Hu Jintao and former Premier, Wen Jaibo. Then par 42 alleged that Dr Wing acquired the New Express newspaper in Guangzhou in a joint venture with a newspaper of the provincial government, in circumstances where the CCP controlled, and its propaganda department had to approve, media ownership in China and the CCP retained editorial control over such publications. This allegedly occurred while Dr Wing was, and continued to be, an Australian citizen. The particulars asserted that the Chinese Government’s published official policy document on foreign investment restrictions in China stated that foreigners were not permitted to publish newspapers in China. Dr Wing, while an Australian citizen, also launched, according to par 43, the Australian New Express Daily in about 2004, with the assistance of the CPPCC and Mr Jia Qinglin, “who is China’s fourth highest ranking leader and Chairman of the National Committee of the CPPCC”. The particulars asserted in both pars 42 and 43, that the inference should be drawn that the CCP permitted Dr Wing to own and operate the New Express and had assisted him in starting the Australian New Express Daily newspaper “because of his connections to and or membership of the CCP, the CPPCC and the UFWD”. There was no elaboration of the basis of the allegation in these paragraphs that Dr Wing was a member of the CCP.

24 Next pars 44-49 asserted:

(44) In about February 2016, the Applicant met with senior members of the UFWD at the Applicant’s business, Kingold Group in Guangzhou, China for the purpose of, amongst other things, discussing Chinese interests in Australia and, specifically, the role that overseas Chinese leaders such as the Applicant play and can play in promoting exchanges and cooperation in countries such as Australia.

(45) Sometime prior to 27 June 2017, the Applicant participated in an interview with journalist Simon Benson, the substance of which was published in The Australian newspaper on 27 June 2017.

(46) In the course of the interview, the Applicant falsely denied that he had ever been a member of the CPPCC, and falsely denied any knowledge of the UFWD.

(47) In or about late 2017, the Applicant was received in Beijing (along with others) by the Chinese President and CCP General Secretary, Xi Jinping. It is to be inferred that this honour was bestowed upon him because of the Applicant’s deep connections to the CCP and/or the CPPCC and/or the UFWD as set out above.

(48) Since at least 2007, the Applicant has had a close association with Ms Sheri Yan, including in the circumstances outlined in particulars (60) – (80) below.

(49) It is to be inferred from particulars (32) to (48) that the Applicant deliberately attempted to conceal his connections to the CCP, the CPPCC and the UFWD, so as to secretly advance their interests by engaging in the activities set out below. (emphasis added)

Dr Wing’s activities in Australia

25 In pars 50-59, the particulars then dealt with Dr Wing’s activities in Australia. Those asserted (in pars 51-52) that he had made donations, from 2007 to 2016, totalling over AUD5.16 million to various Australian political parties at federal and State level and from 2010 to 2016, totalling over $45 million to Australian universities. The particulars alleged (in par 52) that by about 2016, the Director-General of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) had briefed at least three Australian federal political parties and the universities, to each of which Dr Wing had donated, about the national security risks posed by foreign-linked donations. The particulars then alleged:

(53) In the ASIO Briefings, the Applicant was named as a donor that ASIO was concerned about because it suspected that he engages in espionage on behalf of the CCP. Among other things, ASIO was concerned:

(a) that the Applicant was closely connected to the CCP;

(b) that the Applicant’s donations may be connected to the CCP and its objectives, including influencing Australian trade policy to the advantage of the CCP;

(c) that the Applicant had otherwise engaged in intelligence-related activities on behalf of the CCP.

26 The particulars next asserted (in pars 54-57) that those ASIO briefings were “a most unusual if not unprecedented step for ASIO to take”, and that after them, at least one of the political parties ceased to accept donations from Dr Wing. The particulars alleged that Dr Wing, prior to about 2015, had “enjoyed privileged access to, and met with, many of Australia’s most prominent politicians”, including 11 who were identified as four former Prime Ministers, other former ministers, a former Leader of the Opposition, as well as a serving Minister for Foreign Affairs and a serving Leader of the House of Representatives. The particulars baldly asserted, in par 57, that an inference should be drawn that in those meetings Dr Wing, first, did not disclose his connections to the CCP, CPPCC and UFWD, secondly, discussed and learned about the policies of the Australian Government and Opposition and, thirdly, attempted to influence the politicians that he met in relation to trade policy and/or in relation to the CCP’s objectives in respect of Australia so as to advance the interests of China, the UFWD and CCP in priority to the interests of Australia.

27 I should interpolate here that, despite naming nine former ministers and asserting that a highly adverse inference should be drawn against Dr Wing, the particulars did not suggest that any one of those former ministers, all of whom are alive and well known public figures, had provided the respondents with any information at all to support this suggested inference.

28 Next, the particulars asserted that in 2017 and 2018, the Australian Government and the Parliament had been considering proposed amendments to national security legislation, including a 2017 Bill, “by reason of, amongst other things, the Applicant’s activities in Australia and ASIO’s concerns about them, as outlined above” (emphasis added) (par 58) and that:

(59 ) It is to be inferred that the Applicant:

(a) made the Applicant’s Political Donations and the Applicant’s University Donations in order to establish for himself a reputation in Australia as a person able to make substantial donations to political and other causes;

(b) intended that, by making those donations and/or establishing such a reputation, he would be able to gain privileged access to politicians and businesspeople and university leaders; and

(c) made the Applicant’s Political Donations intending that the recipient political party would thereby be induced into favouring the policies and/or position of [China] and/or the CCP;

(d) intended to use that privileged access to attempt to gather information about the policies of the Australian government and opposition, and/or to influence Australian politicians and businesspeople and university leaders, so as to advance the interests of [China], UFWD and the CCP;

(e) is an Agent of the CCP:

(f) has engaged in UFWD work within Australia by making the Applicant’s Political and University Donations;

(g) has engaged in Espionage on behalf of the CCP and/or the UFWD by, at least, attempting to influence the Australian political parties named in Schedule A in relation to Australian trade policy and/or in relation to the CCP Australian Objectives so as to advance the interests of [China], the UFWD and the CCP; and

(h) is loyal to, and serves the interests of, the CCP in priority to the interests of Australia. (emphasis added)

(The Schedule A, referred to in par 59(g), identified the donations that Dr Wing or one or more of his companies made to political parties).

Particulars as to Dr Wing’s and the variant imputations (f), (g) and (h)

29 Finally the particulars (in pars 60-80) sought to support the truth of Dr Wing’s and the variant imputations (f), (g) and (h). These particulars focused on Ms Yan and her alleged connection to Dr Wing. They alleged that Ms Yan, who was named in the matter complained of, was an Australian-Chinese businesswoman, “closely connected to the CCP as is apparent from, amongst other things, the fact that her father was an officer in the People’s Liberation Army” and closely connected to Chinese intelligence officials. She was married to an Australian career diplomat who had been an assistant secretary in the Australian Office of National Assessments and resided with him, when in Australia, although she was a citizen of the United States of America and, until her arrest and subsequent imprisonment for bribery in that nation, had resided principally in China, dividing her time between China, Australia and the United States. The particulars asserted that (in pars 61-63) Ms Yan and Dr Wing “were good friends” and she worked closely with him between 2007 and 2015 in arranging several conferences at his Imperial Springs Resort and as a business consultant, whom he engaged for remuneration to introduce him to her network of contacts in Australia.

30 The particulars next made assertions (in pars 64-68) about Ms Yan’s alleged activities in Australia. They alleged that she was one of two directors and shareholders of a Hong Kong company with Heidi Park (also known as Heidi Hong Piao) that operated from Australia. Between 2007 and 2015, Ms Yan allegedly had privileged access to international politicians and businesspeople in Australia and the United States and, pursuant to Dr Wing’s engagement of her services, she allegedly introduced him “to persons of influence in Australian and United States political and business circles” (none of whom, I interpolate, is named in the particulars).

31 The particulars then referred to a raid in October 2015 by ASIO and the Australian Federal Police on the Canberra apartment of Ms Yan and her husband that allegedly occurred “because it was believed … that Ms Yan was engaging in espionage on behalf of the CCP”. The particulars asserted that the raid resulted in the discovery and retrieval of highly classified Australian intelligence documents. Then par 69 alleged Ms Yan should be inferred to be an Agent of the CCP and or UFWD and to have engaged in espionage (as defined in par 14).

32 The particulars then recited a criminal complaint against Ms Yan, Ms Piao and others filed in October 2015 in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York that alleged that both women had committed offences relating to the bribery, in contravention of the United States Code, of John Ashe, who was the Antiguan permanent representative to the United Nations and the President of the General Assembly from about August 2013. The particulars continued:

(72) The Complaint relevantly alleged that:

(a) Yan and Piao, together with other co-conspirators, corruptly conspired as part of a scheme to pay, and to facilitate payment of, bribes to a United Nations Official namely, Ashe;

(b) Yan and Piao arranged for a US$200,000 wire transfer to a US bank account belonging to Ashe in exchange for him attending, in his official capacity, a conference in Guangdong, Guangzhou, China on 17 November 2013 (Guangzhou Conference); and

(c) The wire transfer to Ashe’s bank account was made by a co-conspirator of Yan and Piao;

(d) The Guangzhou Conference was organised by an “old friend” of Yan’s who was an extremely wealthy Chinese real estate developer only identified in the Complaint as co-conspirator “CC-3”;

(e) Ashe received the US$200,000 by way of wire transfer from one of CC-3’s companies; and

(f) Ashe subsequently attended the Guangzhou Conference and delivered a speech

(the Bribery Allegations). (emphasis added)

33 The particulars then asserted (in pars 73-79) that the Kingold Group organised, or co-organised, the Guangzhou conference held at the Imperial Springs Resort in 2013, Dr Wing hosted that conference and Mr Ashe, as President of the General Assembly, attended and delivered a speech there. Ms Yan pleaded guilty to the bribery allegations on about 20 January 2016 and:

(76) At that hearing, Yan orally admitted in open court that:

(a) she, along with other people, i.e. co-conspirators, agreed to pay money to Ashe;

(b) numerous such payments (one of them being the $200,000) were made so that, in exchange, Ashe would:

(i) persuade officials in Antigua to enter into business contracts with foreign companies; and

(ii) use his position as the President of the General Assembly to assist Yan and “others”, i.e. co-conspirators, to promote business ventures from which they would profit. (emphasis added)

34 I again interpolate that nowhere in the particulars is there any allegation that Dr Wing had any connection to, or participation in, any activity in Antigua, whether for business or otherwise, or the actual name of the “one of CC-3’s companies” referred to in par 72(e).

35 Next the particulars asserted (in pars 77-78) that Ms Yan was corrupt and that on 29 July 2016 she was sentenced to 20 month’s imprisonment, fined USD12,500 and ordered to forfeit USD300,000.

36 Then, in breach of s 16(3)(a) of the Parliamentary Privileges Act 1987 (Cth), the particulars of truth asserted:

(79) On 22 May 2018, Andrew Hastie MP, Chair of the Parliamentary [Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security], revealed in a speech in the Federal Parliament that:

(a) he had travelled to the US with other members of the [Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security] with whom he had attended a meeting with a US intelligence agency controlled by the Department of Justice.

(b) In that meeting, "CC-3" was identified by the US intelligence personnel as the Applicant.

37 Relevantly, s 16(3)(a) provides:

(3) In proceedings in any court or tribunal, it is not lawful for evidence to be tendered or received, questions asked or statements, submissions or comments made, concerning proceedings in Parliament, by way of, or for the purpose of:

(a) questioning or relying on the truth, motive, intention or good faith of anything forming part of those proceedings in Parliament… (emphasis added)

38 Whatever Mr Hastie MP may have been told (leaving aside that, even if he had said this outside the House, it would have been hearsay and incapable of being evidence of the truth of the assertion), s 16(3)(a) prohibited the respondents from relying on it as a submission or particular of truth that Dr Wing was the person named as CC-3 in the bribery allegation. For that reason, par 79 must be struck out and I can have no regard to what it asserted. Except as asserted in par 80(a) (set out below), there is no other matter particularised to connect the identity of CC-3 with his being Dr Wing.

39 Finally, the particulars concluded:

Conclusion in relation to Yan and the Bribery Allegations

(80) It is to be inferred from particulars (70) to (79):

(a) that “CC-3” is the Applicant and a co-conspirator of Yan and others in the corrupt scheme to bribe Ashe;

(b) that the Applicant must have known that Yan was corrupt;

(c) that the Applicant knowingly participated in the payment of the $200,000 bribe to a US bank account in the name of Ashe;

(d) that the Applicant did so in order to profit from Ashe’s activities on behalf of the co-conspirators in return for the bribe.

(81) The Respondents reserve the right to provide further particulars following discovery and interrogatories. (emphasis added)

The respondents’ submissions as to the variant imputations

40 The respondents argued that the variant imputations, that there were reasonable grounds to believe the facts asserted in each of Dr Wing’s imputations, constituted a good Hore-Lacy defence (based on David Syme & Co Ltd v Hore-Lacy (2000) 1 VR 667) to Dr Wing’s imputations. They contended that the variant imputations were not imputations of mere suspicion, but were of reasonable grounds to believe. Rather they submitted, the variant imputations meant that both parties’ sets of imputations did not differ in substance from one another. The respondents argued that this position was supported by the following authorities that had held that imputations to the effect of the variant imputations were available as meanings at common law to support a defence of justification in accordance with Polly Peck (Holdings) Ltd v Trelford [1986] QB 1000, namely what Steytler P (with whom McLure JA agreed) had held in West Australian Newspapers Ltd v Elliot (2008) 37 WAR 387 at 405 [49], 410 [70], in apparent reliance on what Cooke P had said in Hyams v Peterson [1991] 3 NZLR 648 at 655. That was because, the respondents submitted, other authorities, including Lewis v Daily Telegraph Ltd [1964] AC 234 and Mirror Newspapers Ltd v Harrison (1982) 149 CLR 293, recognised that, as Steytler P had said in Elliot 37 WAR at 410 [70]:

for practical purposes there can be an imputation of suspicion so strong as to be indistinguishable from guilt and that it must always be a question of fact how far the defamatory meaning goes.

41 The respondents contended that in those circumstances, their defence of justification, based on the variant imputations, could not be characterised as so obviously untenable that it cannot possibly succeed, or as manifestly groundless, relying on General Steel Industries Inc v Commissioner for Railways (NSW) (1964) 112 CLR 125; and Trkulja v Google LLC (2018) 356 ALR 178.

The variant imputations - consideration

42 In Farah Constructions Pty Ltd v Say-Dee Pty Ltd (2007) 230 CLR 89 at 151-152 [135], Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Callinan, Heydon and Crennan JJ said that intermediate appellate courts and trial judges in Australia should not depart from decisions of intermediate appellate courts in another jurisdiction on the interpretation of Commonwealth legislation or uniform national legislation or non-statutory law unless they are convinced that the interpretation is “plainly wrong”: see too Australian Securities Commission v Marlborough Gold Mines Ltd (1993) 177 CLR 485 at 492 per Mason CJ, Brennan, Dawson, Toohey and Gaudron JJ.

43 I am of opinion that Elliot 37 WAR 387 is plainly wrong and inconsistent with Harrison 149 CLR 293, as well as George v Rockett (1990) 170 CLR 104 and long established principle. In Harrison 149 CLR at 300-303, Mason J with whom Wilson J and, with a limited reservation, each of Gibbs CJ and Brennan J (at 295 and 303) agreed, held that a report that does no more than state that a person has been arrested and charged with an offence cannot convey to an ordinary reasonable reader, listener or viewer that the person is guilty of the offence. That was because the ordinary reasonable reader (of a newspaper) is mindful of the principle that a person charged with a crime is presumed innocent until it is proved that he (or she) is guilty (see at 300). Mason J explained the principle as follows (149 CLR at 300-301):

Although he knows that many persons charged with a criminal offence are ultimately convicted, he is also aware that guilt or innocence is a question to be determined by a court, generally by a jury, and that not infrequently the person charged is acquitted.

In this situation the reader will view the plaintiff with suspicion, concluding that he is a person suspected by the police of having committed the offence and that they have ground for laying a charge against him. But this does not warrant the conclusion that by reporting the fact of arrest and charge a newspaper is imputing that the person concerned is guilty. A distinction needs to be drawn between the reader’s understanding of what the newspaper is saying and judgments or conclusions which he may reach as a result of his own beliefs and prejudices. It is one thing to say that a statement is capable of bearing an imputation defamatory of the plaintiff because the ordinary reasonable reader would understand it in that sense, drawing on his own knowledge and experience of human affairs in order to reach that result. It is quite another thing to say that a statement is capable of bearing such an imputation merely because it excites in some readers a belief or prejudice from which they proceed to arrive at a conclusion unfavourable to the plaintiff. The defamatory quality of the published material is to be determined by the first, not by the second, proposition. Its importance for present purposes is that it focuses attention on what is conveyed by the published material in the mind of the ordinary reasonable reader. (emphasis added)

44 Critically, Mason J said (149 CLR at 303):

… any publication which goes on to say or suggest that the charge was well founded, i.e., that the plaintiff was guilty, carries the further imputation of guilt. (emphasis added)

45 Mason J held (but Gibbs CJ and Brennan J reserved their opinion on this point) that the publication of a report of the arrest and charge would be understood by the ordinary reasonable reader to convey that the person laying the charge suspected, with reasonable cause, that the accused had committed the offence alleged (149 CLR at 302). Brennan J quoted the well-known passage from Lord Devlin’s speech in Lewis [1964] AC 234 at 285 that Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow and Heydon JJ applied in Favell v Queensland Newspapers Pty Ltd (2005) 221 ALR 186 at 190 [10]-[11] (and see also my reasons in Adeang v The Australian Broadcasting Corporation [2016] FCA 1200 at [14]-[58]). In Favell 221 ALR at 190 [10]-[11] Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow and Heydon JJ said:

[10] In determining what reasonable persons could understand the words complained of to mean, the court must keep in mind the statement of Lord Reid in Lewis v Daily Telegraph Ltd ([1964] AC 234 at 258):

The ordinary man does not live in an ivory tower and he is not inhibited by a knowledge of the rules of construction. So he can and does read between the lines in the light of his general knowledge and experience of worldly affairs.

[11] Lord Devlin pointed out, in Lewis v Daily Telegraph Ltd ([1964] AC 234 at 277), that whereas, for a lawyer, an implication in a text must be necessary as well as reasonable, ordinary readers draw implications much more freely, especially when they are derogatory. That is an important reminder for judges. In words apposite to the present case, his Lordship said ([1964] AC 234 at 285):

It is not … correct to say as a matter of law that a statement of suspicion imputes guilt. It can be said as a matter of practice that it very often does so, because although suspicion of guilt is something different from proof of guilt, it is the broad impression conveyed by the libel that has to be considered and not the meaning of each word under analysis. A man who wants to talk at large about smoke may have to pick his words very carefully if he wants to exclude the suggestion that there is also a fire; but it can be done. One always gets back to the fundamental question: what is the meaning that the words convey to the ordinary man: you cannot make a rule about that. They can convey a meaning of suspicion short of guilt; but loose talk about suspicion can very easily convey the impression that it is a suspicion that is well founded. (emphasis added)

46 In that passage, Lord Devlin was not saying that because suspicion could impute guilt, and in practice very often did so, an imputation of suspicion was, or could convey, the same defamatory meaning as guilt. Indeed, his Lordship said in terms (Lewis [1964] AC at 284 and see too per Lord Reid at 260):

Equally, in my opinion, it is wrong to say that, if in truth the person spoken of never gave any cause for suspicion at all, he has no remedy because he was expressly exonerated of fraud. A man’s reputation can suffer if it can truly be said of him that although innocent he behaved in a suspicious way; but it will suffer much more if it is said that he is not innocent. (emphasis added)

47 As a matter of ordinary experience, there is a substantive distinction between a suspicion, however well founded, and a fact, as Lord Devlin held in Lewis [1964] AC at 284-285 and as Harrison 149 CLR 293 decided as its ratio decidendi. An imputation of suspicion necessarily falls short of an imputation of guilt. That is because each of suspicion and belief is a state of mind, while guilt is a state of fact: George 170 CLR at 112 per Mason CJ, Brennan, Deane, Dawson, Toohey, Gaudron and McHugh JJ. And, they held that the facts that can reasonably ground a suspicion, may be quite insufficient to ground a belief (170 CLR at 115). Their Honours approved Lord Devlin’s advice in Hussien v Chong Fook Kam [1970] AC 942 at 948 that suspicion “in its ordinary meaning is a state of conjecture or surmise where proof is lacking: “I suspect but I cannot prove’”. The High Court said (170 CLR at 116):

The objective circumstances sufficient to show a reason to believe something need to point more clearly to the subject matter of the belief, but that is not to say that the objective circumstances must establish on the balance of probabilities that the subject matter in fact occurred or exists: the assent of belief is given on more slender evidence than proof. Belief is an inclination of the mind towards assenting to, rather than rejecting, a proposition and the grounds which can reasonably induce that inclination of the mind may, depending on the circumstances, leave something to surmise or conjecture. (emphasis added)

48 In my opinion, what Cooke P said when giving the reasons of himself, Richardson and Hardie Boys JJ in Hyams [1991] 3 NZLR at 655, does not support what Steytler P drew from it. To the contrary, Cooke P was applying the settled law that a publisher has to choose his, her or its words carefully if the publisher wants to avoid elevating an allegation of suspicion into a statement of guilt. And he held that the question of whether the matter complained conveys one or other imputation depended on what meaning it conveys to the ordinary reasonable reader (listener or viewer). Cooke P said there:

It is also plain that to say there are grounds for suspecting a person of fraud or other discreditable conducts is, although defamatory, often different from and less serious than an assertion of his guilt: Lewis v Daily Telegraph Ltd [1964] AC 234; Truth (NZ) Ltd v Bowles [1966] NZLR 303; Broadcasting Corporation of New Zealand v Crush [1988] 2 NZLR 234, 239-240; Mirror Newspapers Ltd v Harrison (1982) 42 ALR 487. These judgments also recognise that for practical purposes there can be an imputation of suspicion so strong as to be indistinguishable from guilt; it must always be a question of fact how far the defamatory meaning goes. (emphasis added)

49 In relying on Lewis [1964] AC 234 and Harrison 149 CLR 293, Cooke P was not saying that an imputation of suspicion can ever be indistinguishable from guilt; rather he was saying, albeit perhaps a little loosely, that the question of what the matter complained of actually conveys, can require the Court to decide if a suspicion is so strongly expressed that the publication is really saying that the plaintiff is guilty. The second sentence of what Cooke P said, quoted above, has to be read with his first sentence. His sentence first dealt with the capacity of the matter complained of to convey an imputation of a particular strength or degree – namely, suspicion or guilt. Cooke P’s second sentence discussed “how far the defamatory meaning goes” – that is, whether the imputation actually conveyed is suspicion (however strongly based or held) or guilt.

50 If (contrary to my understanding) Cooke P was saying what Steytler P held in Elliot 37 WAR at 410 [70], with respect, both judgments are plainly wrong. They are in the teeth of both Lewis [1964] AC 234 and Harrison 149 CLR 293, the ratio decidendi of both of which is that an imputation of suspicion is never equivalent to the more serious imputation of guilt. Both the House of Lords and the High Court dealt with the capacity of a matter complained of to convey an imputation of guilt by embellishing a report of police laying a criminal charge in a court against an individual following his arrest. They explained that a publisher can easily cross the line between the two levels of meaning by what the matter complained of, as published, conveys to the ordinary reasonable reader, listener or viewer.

51 But there is nothing in Lewis [1964] AC 234 or Harrison 149 CLR 293 that supports the approach taken in Elliot 37 WAR 387 that conflated the preliminary issue as to the capacity of a publication to convey an imputation of either suspicion or guilt, with the ultimate issue of what meaning in fact it conveys. The second issue, namely what the publication actually conveys to the ordinary reasonable reader, listener or viewer, the House of Lords and High Court both held depended on the judge or jury (as the tribunal of fact) assessing whether the way in which the publication is expressed actually does impute either guilt or suspicion. But, if it is found to impute guilt, that is because the tribunal of fact has decided that the natural and ordinary meaning of the matter complained of does not stop at suspicion (however strongly it is held or expressed) but crosses a substantive line of meaning to assert guilt as a fact.

52 Once a court finds on the preliminary issue that a matter complained of is capable of conveying an imputation of guilt, then the publisher can defend that imputation by, first, arguing that, in fact, it conveyed or meant no more than an imputation of suspicion (or in this case, reasonable belief) and not guilt (in other words the plaintiff failed to prove that the ordinary reasonable reader actually did not read it as conveying guilt), or secondly, arguing that the imputation of guilt is true. But, if the plaintiff succeeds in persuading the tribunal of fact that the matter complained did actually convey the imputation of guilt, the defendant cannot defend it as true by proving only that the plaintiff was only suspected or believed (however reasonably or strongly) of being guilty: Lewis [1964] AC at 286. Indeed, s 25 of the Defamation Act makes clear that the statutory defence of justification is directed to establishing the truth of the imputations that the plaintiff alleges.

53 One only has to consider the prefatory words of the variant imputations, namely “there are reasonable grounds to believe that” to perceive that the meaning that those words convey is of belief, or state of mind, not the existence of a fact. As Mason J said in Harrison 149 CLR at 300-301, a person who faces trial on a criminal charge (of whom it can be said that there are reasonable grounds to believe or suspect that the person is guilty) can still be (and not infrequently will be) acquitted. Likewise, proof of guilt is different from proof of there being reasonable grounds to believe (or suspect) guilt. Lord Reid said in Lewis [1964] AC at 260:

Before leaving this part of the case I must notice an argument to the effect that you can only justify a libel that the plaintiffs have so conducted their affairs as to give rise to suspicion of fraud, or as to give rise to an inquiry whether there has been fraud, by proving that they have acted fraudulently. Then it is said that if that is so there can be no difference between an allegation of suspicious conduct and an allegation of guilt. To my mind, there is a great difference between saying that a man has behaved in a suspicious manner and saying that he is guilty of an offence, and I am not convinced that you can only justify the former statement by proving guilt. (emphasis added)

54 The decisions in Polly Peck [1986] QB 1000 and Hore-Lacy 1 VR 667 do not lead to any different conclusion. In Polly Peck [1986] QB at 1023G and 1032B-D, O’Connor LJ, with whom Robert Goff and Nourse LJJ agreed, said that where a plaintiff selected part of a larger publication and alleged that this part conveyed a defamatory imputation, the defendant could rely on the whole of its publication and defend the action by pleading that a different meaning was conveyed by the whole and that that meaning was true. Thus, he said ([1986] QB at 1032B-D):

In cases where the plaintiff selects words from a publication, pleads that in their natural and ordinary meaning the words are defamatory of him, and pleads the meanings which he asserts they bear by way of false innuendo, the defendant is entitled to look at the whole publication in order to aver that in their context the words bear a meaning different from that alleged by the plaintiff. The defendant is entitled to plead that in that meaning the words are true and to give particulars of the facts and matters upon which he relies in support of his plea…

Where a publication contains two or more separate and distinct defamatory statements, the plaintiff is entitled to select one for complaint, and the defendant is not entitled to assert the truth of the others by way of justification. (emphasis added)

55 O’Connor LJ said that where the matter complained of made several defamatory allegations that had a common sting, the defendant could plead that it conveyed that sting and justify it as an answer to all the allegations with that common sting ([1986] QB at 1032D-E).

56 Thus, if the sting is guilt, an attempt to justify suspicion or belief of guilt is outside the common sting. To see the fallacy of the reasoning in Elliot 37 WAR 387 one only has to reverse the position of the parties, by assuming that the publication alleged, and the defendant proved, that the matter complained of conveyed an imputation of guilt. In such a case, the plaintiff could not recover because the publication also alleged that he or she was suspected or believed to be guilty. That is because, as Lewis [1964] AC 234, Harrison 149 CLR 293 and George 170 CLR 104 all establish, each state of mind, namely suspicion and belief on reasonable grounds is substantively different from one another and also, crucially, distinct from the existence of the actual facts suspected or believed.

57 At common law and under s 8 of the Defamation Act, a person has a single cause of action for defamation in relation to the publication of defamatory matter of and concerning him or her, regardless of how many meanings or imputations that matter carries or conveys.

58 Where a party pleads that the matter complained of conveys in its natural and ordinary meaning an imputation defamatory of the plaintiff, such an imputation is confusingly described as a “false innuendo”. Each of Dr Wing’s imputations is a “false innuendo”. A false innuendo has the purposes of specifying the natural and ordinary meaning for which the pleader contends and of narrowing the issues for trial, namely: what meanings the party or parties contend that the matter complained of conveys: cf Chakravarti v Advertiser Newspapers Ltd (1998) 193 CLR 519 at 532 [18]–[19] per Brennan CJ and McHugh J, 579 [139(2)] per Kirby J.

59 In Hore-Lacy 1 VR at 689 [63], Charles JA, with whom Ormiston JA agreed at 675 [22], 676 [24], expressly departed from Polly Peck [1986] QB 1000, by requiring the defendant to plead the specific imputation that it alleged the matter complained of conveyed (and, if it wished, to justify it) so that “at trial neither the plaintiff nor the defendants should be permitted to raise (nor should the defendants be permitted to justify) a meaning substantially different from, or more injurious than, the meanings alleged by the plaintiff” (emphasis added).

60 In other words, Ormiston and Charles JJA held that a defendant could assert a differently nuanced meaning or imputation from that asserted by the plaintiff, but not one that differs in substance (whether more or less injurious or serious in its defamatory character). That outcome, respected the common law position in which, the jury (or judge) could find for a plaintiff on the basis of a natural and ordinary meaning which was not one pleaded or alleged by the plaintiff, provided that this departure from pleadings did not create unfairness for the defendant (1 VR at 688 [58]). This is because the alternate meaning as found amounts, in substance, to another way of phrasing or encapsulating in words the same defamatory sting. However, it cannot be a substantively different sting from the plaintiff’s pleaded imputation: see too Gutnick v Dow Jones & Co Inc (No 4) (2004) 9 VR 369 at 372-374 [8]-[13] per Bongiorno J, whom Beach J followed in Cunliffe v Woods [2012] VSC 254 at [10]-[12] and cf Hore-Lacy v Cleary (2007) 18 VR 562 at 574-575 [50]-[54] where Ashley JA, with whom Neave and Redlich JJA agreed, at 584 [103] and [104], referred with apparent approval to Gutnick (No 4) 9 VR at 373 [11]-[12] on the substantive difference or gulf between an imputation of guilt and one of suspicion, belief or other state of mind. Indeed, as Lord Hughes JSC, with whom Baroness Hale of Richmond PSC, Lord Burnett of Maldon CJ, Lord Hodge JSC and Lord Mance agreed, said in R v Lane [2018] 1 WLR 3647 at 3655 [22]:

it is plain beyond argument that the expression “has reasonable grounds for suspicion” cannot mean “actually suspects”.”

61 In Mickelberg v Hay [2006] WASC 285 at [51]-[54], Hasluck J discussed the way in which the Full Court of the Supreme Court of Western Australia in Nationwide News Pty Ltd v Moodie (2003) 28 WAR 314 had dealt with Polly Peck [1986] QB 1000 and Hore-Lacy 1 VR 667. Anderson J, Stetlyer J and McLure J each found that a defendant could plead and justify meanings that were “less injurious and not substantively different from” (emphasis added) those pleaded in the statement of claim: Moodie 28 WAR at 320 [19]-[20] per Anderson J, 328 [58] per Stetlyer J at 335-336 [94] and per McLure J at [59].

62 Although, the Full Court in Moodie 28 WAR 314 seemed to think it was following Hore-Lacy 1 VR 667, in my opinion it adopted a different and, with respect, wrong test by allowing the defendant to plead the truth of an imputation of a lesser degree of seriousness, as a complete defence to the plaintiff’s claim. It is one thing to plead a defence of partial justification, as Levine J explained in Whelan v John Fairfax Publications Pty Ltd (2002) 56 NSWLR 89, and another to plead Polly Peck defence. However, Levine J also allowed the defendant there to plead a Polly Peck imputation of a lesser degree of seriousness (56 NSWLR at 97 [39], 100 [51]-[52]) because of the uncertain state of the law, but his Honour did not analyse what Hore-Lacy 1 VR 667 had held. Levine J noted that the Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court of Queensland had held in Robinson v Laws [2003] 1 Qd R 81 that a Polly Peck defence was not available under the then Queensland law (56 NSWLR at 99[44]).

63 In any event, if an imputation is less injurious than the one that the plaintiff alleges, it must be substantially different from the one it is less serious than. They just are not the same. The above review of the uncertain scope of a Polly Peck defence in Australia reflects what Kirby J lamented in Chakravarti 193 CLR at 583 [144], namely, it “shows what a muddle an over-nice attention to the pleadings of imputations has produced for defamation laws and practice in Australia. It is extremely convoluted and unacceptably confusing”.

64 Yet in the 20 years since the High Court, in Chakravarti 193 CLR 519, discussed Polly Peck [1986] QB 1000, without settling its scope (since the question did not arise on the facts in that appeal), Australian courts and litigants have struggled to know what the test is for determining what a defendant can plead as a defence of justification to imputations that the plaintiff particularises. Brennan CJ and McHugh J held that Polly Peck [1986] QB 1000 was wrong in principle (193 CLR at 529 [11]-[13]). Gaudron and Gummow JJ considered that a defendant could plead an alternative imputation or meaning (193 CLR at 544-545 [56]-[57]) and that such a meaning should be viewed like those that the plaintiff pleaded as “no more than a statement of the case to be made at trial”. They said (193 CLR at 546 [60]):

As a general rule, there will be no disadvantage in allowing a plaintiff to rely on meanings which are comprehended in, or are less injurious than the meaning pleaded in his or her statement of claim. So, too, there will generally be no disadvantage in permitting reliance on a meaning which is simply a variant of the meaning pleaded. On the other hand, there may be disadvantage if a plaintiff is allowed to rely on a substantially different meaning or, even, a meaning which focuses on some different factual basis. Particularly is that so if the defendant has pleaded justification or, as in this case, justification of an alternative meaning. However, the question whether disadvantage will or may result is one to be answered having regard to all the circumstances of the case, including the material which is said to be defamatory and the issues in the trial, and not simply by reference to the pleadings. (emphasis added)

65 Gaudron and Gummow JJ there encapsulated a similar test to that which Brennan CJ and McHugh J discussed for deciding whether the plaintiff could be allowed at trial to rely on a different nuance of meaning, including a less serious meaning than that pleaded (see 193 CLR at 533 [22], 534 [24]). They said that the test is to ask “whether it is prejudicial, embarrassing or unfair to the defendant” to allow the plaintiff to amend to plead a, or rely at trial on an unpleaded, new meaning different from that which the plaintiff had previously pleaded (and see per Kirby J at 580-581 [139(4)]).

66 Thus, all five justices expressed their views about the way in which a plaintiff may or may not be allowed to rely on a different or lesser meaning at trial than what he or she had earlier pleaded. However, each of the joint reasons accepted that, where a party had pleaded or asserted that the matter complained of conveyed a specified meaning (or imputation) “ordinarily… [the party will] be held to the particulars or those parts of the pleadings which specify the case to be made if departure would occasion delay or disadvantage to the other side” (193 CLR at 545 [58], see too at 533-534 [22]-[24] and 580-581 [139(4)] per Kirby J). Gaudron and Gummow JJ noted that it may well create a disadvantage for a defendant who had pleaded justification, if the plaintiff were subsequently allowed to rely on a less serious and substantively different meaning.

67 I am of opinion that the variant imputations are substantively less serious than Dr Wing’s imputations (including the extrinsic imputation). The respondents will be entitled to argue at trial not only that the matter complained of did not convey to the ordinary reasonable viewer Dr Wing’s imputations, but also that it conveyed only, or no more than, the variant imputations. Dr Wing will lose the proceeding if he fails to prove that any of his pleaded imputations was conveyed to the ordinary reasonable viewer, and so, there will be no remaining issue about whether the variant imputations were true. However, it would occasion delay and disadvantage to Dr Wing to allow the respondents to seek to prove that the variant imputations were true if he proved that any of his pleaded imputations was in fact conveyed by the program: Chakravati 193 CLR at 533 [22], 534 [24], 544-545 [56]-[57], 580-581 [139(4)].

68 Adherents of a religious faith believe in its deity just as much as atheists believe that there is no such deity. Both beliefs are ordinarily reasonable, can be strongly held and can exist together. But, if one were able to know the facts, either the theists or the atheists would be wrong. Belief is not the same, or substantially the same as fact, nor is suspicion: George 170 CLR at 116.

Conclusion

69 For the reasons I have given, the variant imputations differ in substance from Dr Wing’s imputations because an imputation of belief, however reasonably based, is not capable of conveying the same or substantially the same as, one of fact.

70 An application to strike out all or part of a pleading under r 16.21(1)(d) or (e) of the Federal Court Rules on the ground that it is likely to cause prejudice, embarrassment or delay in the proceeding or it fails to disclose, relevantly, a reasonable defence, can only be granted in the clearest of cases: Agar v Hyde (2000) 201 CLR 552 at 575-576 [56]-[60]; Trkulja v Google LLC (2018) 356 ALR 178 at 183 [21] per Kiefel CJ, Bell, Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ.

71 I have approached my consideration of the present issue on this basis. Because I am the docket judge and thus, the trial judge, I am of opinion that it is both desirable and necessary to determine, in advance, the purely legal question of whether proof of the truth of the variant imputations at trial provides a reasonable defence to Dr Wing’s imputations. For the reasons I have given, there is no reasonable basis to hold that proof the truth of the variant imputations at trial would be a defence to any of Dr Wing’s imputations and that that defence is likely to cause prejudice to Dr Wing, embarrassment and delay if not struck out.

72 Accordingly, the variant imputations must be struck out.

The sufficiency of the particulars – the respondents’ submissions

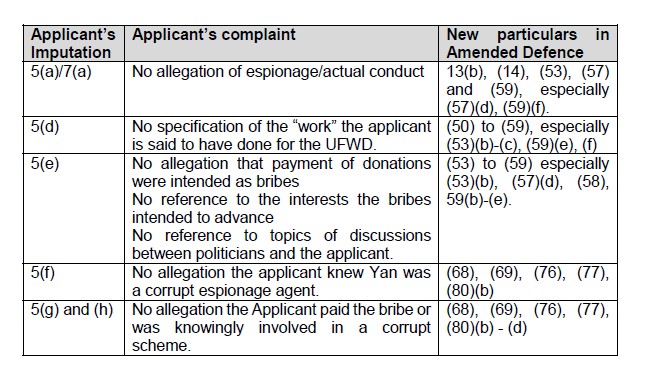

73 The respondents argued that, even if the variant imputations were struck out, the particulars in the amended defence identified the basis on which they will seek to prove the truth of Dr Wing’s imputations. They contended that Dr Wing also had now received the outlines of evidence of their only three lay witnesses, being Mr McKenzie, Chris Uhlmann and Sashka Koloff and reports of four (being “most of the”) expert witnesses whom the respondents intend to call. (I note there is no order, at present, that allows the respondents to file any further expert or other lay evidence). They submitted that the particulars now linked or supported the plea of truth for each of Dr Wing’s imputations in the manner identified in the table below that they included in their written submissions:

74 The respondents argued that the purpose of particulars was to indicate, not the outer limits of what may be proved, but rather, the topics on which evidence may be led. And, they contended, Dr Wing could understand the case against him based on the particulars in light of the outlines and expert reports that the respondents had served. They submitted, however, that there may be more material revealed once Dr Wing gave, what they termed “proper discovery”, and they alleged (without tendering any evidence of this) that he had not complied with his obligations and had “provided only cursory if not derisory discovery”.

75 They argued that the matter complained of itself explained that the nature of the activities that Dr Wing’s imputations distilled were notoriously opaque. They submitted that those activities could be proved by inferences to be drawn at trial from what will be mostly indirect evidence of Dr Wing’s involvement. However, they contended that the evidentiary material that they had served and the particulars would enable Dr Wing to know how the respondents would seek to prove their justification defence.

The sufficiency of the particulars – Consideration

76 Relevantly, rr 16.41 and 16.43 provide a supplement to the requirement of r 16.02(1)(d) that a pleading must “state the material facts on which a party relies that are necessary to give the opposing party fair notice of the case to be made against that party at trial, but not evidence by which the material facts are to be proved”. Thus rr 16.41 and 16.43 provide:

Division 16.4 - Particulars

16.41 General

(1) A party must state in a pleading, or in a document filed and served with the pleading, the necessary particulars of each claim, defence or other matter pleaded by the party.

Note: See rule 16.45.

(2) Nothing in rules 16.42 to 16.45 is intended to limit subrule (1).

Note 1: The object of particulars is to limit the generality of the pleadings by:

(a) informing an opposing party of the nature of the case the party has to meet; and

(b) preventing an opposing party being taken by surprise at the trial; and

(c) enabling the opposing party to collect whatever evidence is necessary and available.

Note 2: The function of particulars is not to fill a gap in a pleading by providing the material facts that the pleading must contain.

Note 3: A party does not plead to the opposite party’s particulars.

Note 4: Particulars should, if they are necessary, be contained in the pleading but they may be separately stated if sought by the opposite party or ordered by the Court.

16.43 Conditions of mind

(1) A party who pleads a condition of mind must state in the pleading particulars of the facts on which the party relies.

(2) If a party pleads that another party ought to have known something, the party must give particulars of the facts and circumstances from which the other party ought to have acquired the knowledge.

(3) In this rule:

condition of mind, for a party, means:

(a) knowledge; and

(b) any disorder or disability of the party’s mind; and

(c) any fraudulent intention of the party.

77 In Dare v Pulham (1982) 148 CLR 658 at 664, Murphy, Wilson, Brennan, Deane and Dawson JJ held that pleadings and particulars had, among others, the following functions, namely:

to furnish a statement of each parties’ case that should be sufficiently clear to allow the other party a fair opportunity to meet it (citing Gould and Birbeck and Bacon v Mount Oxide Mines Ltd (In liq) (1916) 22 CLR 490 at 517 per Isaacs and Rich JJ); and

to define the issues for decision and thereby enable determination at the trial of the relevance and admissibility of evidence.

78 A defendant must specify the particulars of truth to support a plea of justification with the same precision as in an indictment. In Wootton v Sievier [1913] 3 KB 499 at 503, Kennedy LJ, giving his and Cozens-Hardy MR’s reasons, said (and see also Crosby v Kelly [2013] FCA 1343 at [35]-[36]):

In every case in which the defence raises an imputation of misconduct against him, a plaintiff ought to be enabled to go to trial with knowledge not merely of the general case he has to meet, but also of the acts which it is alleged that he has committed and upon which the defendant intends to rely as justifying the imputation. (emphasis added)

79 The reason for this principle is that a person who publishes a serious allegation that he or she seeks to defend as true, must know, at the time of publication, the facts that justify the charge that the publisher makes about the plaintiff in it. In Johnson v Miller (1937) 59 CLR 467 at 489-490 (see too: John L. Pty Ltd v Attorney-General (NSW) (1987) 163 CLR 508 at 519-520 per Mason CJ, Deane and Dawson JJ and cf: Hamra v The Queen (2017) 260 CLR 479 at 488-489 [18]-[20], per Kiefel CJ, Bell, Keane, Nettle and Edelman JJ), Dixon J stated the principle for ascertaining whether a criminal charge is properly particularised, saying:

a defendant is entitled to be apprised not only of the legal nature of the offence with which he is charged but also of the particular act, matter or thing alleged as the foundation of the charge. The court hearing a complaint or information for an offence must have before it a means of identifying with the matter or transaction alleged in the document the matter or transaction appearing in evidence. (emphasis added)

80 It is an abuse of process to plead justification in order to use discovery to elicit such facts from the plaintiff: Zierenberg v Labouchere [1893] 2 QB 183 at 186 per Lord Esher MR with whom Bowen LJ agreed, 190 per Kay LJ. Lord Esher MR explained that mere assertions of the truth of a charge or imputation in general terms will not amount to sufficient particulars of justification. He said ([1893] 2 QB at 187):

The libel is in effect that the plaintiffs are “charity swindlers and impostors and the home is a monstrous swindle.” That is a general statement, and he is asked for particulars, that is, for the instances on which he relies to justify that statement, and he says: “The instances are that they appropriated for their own purposes monies received for, or earned by, the home, and they caused statements to appear in the annual balance-sheets of the home of cash supplies by the female plaintiff, and loans made by the male plaintiff, which were not, in fact, supplied or lent out of their own monies, but in reality out of the monies of the home.” Is that answer sufficient? No doubt it states the way in which the defendant means to justify; but it is almost as general as the statement in the alleged libel. It does not give the instances, nor does it state the times or occasions on which the swindles are alleged to have been done, nor does it give the names of the persons whose money is alleged to have been misappropriated. In old days a plea that did not give such particulars of justification would have been bad, and at the present time particulars that fail in this respect are insufficient. (emphasis added)

81 As I noted in Crosby [2013] FCA 1343 at [36], this principle is also reflected in the general principle that the pleadings and particulars must identify with sufficient clarity the case the parties have to meet and that conduct, such as fraud, must be pleaded specifically and with particularity: cf Banque Commerciale SA (En liq) v Akhil Holdings Ltd (1990) 169 CLR 279 at 285-286 per Mason CJ and Gaudron J, 290 per Brennan J. I agree with what Wigney J said in further explaining the application of this principle in Rush v Nationwide News Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 357 at [52]-[54] and [172]-[174].

82 These principles are applicable to assessing the sufficiency of the respondents’ particulars of justification in the proposed amended defence that they seek leave to file. They argued that the amended defence is supported by proposed evidence in the outlines of their three lay witnesses and their expert reports. Of course, the expert reports were not available when the matters complained of were first published. This context, however, reveals that the particulars in pars 1-80 are based on all the evidence that the respondents are now able to marshal in support of their pleas of justification.

83 As appears in [16] above, the respondents gave their own, bespoke definition of the word “espionage” in par 14 of their particulars for the purposes of the allegations that they made. However, Dr Wing’s imputation (a) used the word “espionage” in its natural and ordinary meaning, namely:

the practice of spying (or of employing spies) (Oxford English Dictionary Online)

the practice of spying on others (Macquarie Dictionary: sense 1)

84 The dictionaries define spying as “is to act as a spy or to make secret or stealthy observations”. And a spy is someone who spies upon, or watches, someone secretly or who is employed by a government to obtain information or intelligence relating to the military or naval or governmental affairs of one or more other countries, or to collect intelligence of any other kind.

85 It may have been that par 14(a) would be unobjectionable were it not accompanied by the alternative in (b), which is not a natural or ordinary meaning of “espionage”. That is because par 14(b) used a concept of “conduct which achieves or is intended to achieve, or … make possible, influencing and/or subverting and/or otherwise interfering with, covertly and/or deceptively (in the sense that the Agent’s role as such Agent is not disclosed), the policies of foreign governments and/or the political and democratic processes of foreign countries”. That concept is equally capable of applying to a dual citizen or foreigner who exercises his or her right publicly to criticise, or lobby to change, government policy. Indeed, apart from the adjective “foreign” and the words “covertly and/or deceptively (in the sense that the Agent’s role as such Agent is not disclosed)” the concept in par 14(b) is descriptive of the activities of the Opposition, other minority parties and independents in our parliamentary system, as well as those of the media and any member of the population who seeks to influence or change a government’s policy. The bespoke definition of espionage included a meaning that went well beyond its ordinary meaning of intelligence gathering.

86 Particular 14 is embarrassing. It does not describe espionage as pleaded in Dr Wing’s imputation (a). Rather it seeks to expand that well known everyday word to encompass vague and imprecise concepts so that the activity can also be what the respondents call “espionage” because the person has not disclosed his or her connection to China. Such alleged conduct may be characterised as objectionable, but it is not within the natural and ordinary meaning of espionage. Nor are the activities alleged in pars 15 to 17 of the particulars, such as the making of donations, offers, provision of trips or access to persons of influence in China. Rather that conduct is typical of a lobbyist. And, the fact that the conduct is alleged to encourage the donee or beneficiary of the largesse to favour China’s interests, reinforces a conclusion that the supposed “Agent” is acting overtly as a lobbyist for China as opposed to acting covertly as a spy, gathering intelligence.

87 The respondents argued that the ordinary reasonable viewer would have understood “espionage” in the sense defined in par 14 because of the way in which the respondents expressed the matter complained of. However, although I do not consider that the respondents can justify an imputation of “espionage”, used in its natural and ordinary meaning, by redefining that word in their particulars and then use that bespoke sense to justify the imputation as redefined, particularly in par 14(b), it is not necessary to decide this question. The particulars have more fundamental flaws.

88 The allegations conveyed in Dr Wing’s imputations and the extrinsic imputation are very serious. Thus, imputation (a) asserts that Dr Wing is, in effect, a traitor to Australia because he spied on it for China and the CCP.

89 Yet, the particulars did not identify one occasion on which Dr Wing is alleged to have engaged in a specific act of espionage or what he did on any specific occasion to amount to espionage (in its natural and ordinary meaning as conveyed in the imputations). The high point of the espionage particulars appears in pars 53 to 57. Despite asserting there that Dr Wing had met with 11 present and past prominent Australian politicians, the respondents have pleaded not one word of what was said, done or gleaned in those meetings. Instead, their particulars suggest that, because Dr Wing made large donations to political parties and ASIO had suspicions about him, one can draw an inference that, somehow, he must have spied on, or betrayed, Australia and advanced some interest of the Chinese State at each of those meetings.

90 There is no basis to draw such an inference. That is because the particulars reveal that the respondents have no information about what happened in any of those meetings. They have simply asserted that, somehow, just because the meetings occurred (and ASIO had suspicions), an inference should be drawn against him that he concealed his connections to the CCP (and other entities), and, attempted to influence each politician “so as to advance the interests of China … in priority to the interests of Australia”. Perhaps one could infer that the participants in the meetings exchanged pleasantries but, beyond that lies only speculation, since the respondents have not served any outline of evidence of any witness present at, or particularised anything that occurred in, any of those meetings. Those particulars are embarrassing because they are conclusory and have no content or substance.