FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Mount Isa Mines Ltd v The Ship “Thor Commander” [2018] FCA 1326

ORDERS

Plaintiff | ||

AND: | Defendant | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties agree on orders to give effect to the reasons for judgment published today, on or before 31 August 2018.

2. The proceeding be stood over to 4.15pm on 31 August 2018 for the making of final orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 104 of 2015 | ||

BETWEEN: | MOUNT ISA MINES LTD Plaintiff | |

AND: | THE SHIP "THOR COMMANDER" Defendant | |

JUDGE: | JUSTICE RARES |

DATE OF ORDER: | 31 AUGUST 2018 |

1. The Plaintiff is not liable to make any contribution in the General Average declared on 13 January 2015 in respect of the main engine breakdown of the ship “Thor Commander” on her voyage from Puerto Angamos, Chile to Townsville Australia.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. There be judgment for the Plaintiff against the Defendant and MarShip GmbH & Co. KG MS “Sinus Aestuum” in the sums of:

(a) USD1,010,262.60 (being damages of USD909,000 together with interest thereon of USD101,262.60 pursuant to section 51A(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth)).

(b) £47,492.46 (being damages of £42,660.47 plus £431.99 together with interest thereon of £4,400 pursuant to section 51A(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth)).

(c) AUD175,956.27 (being damages of AUD147,956.27 together with interest thereon of AUD28,000 pursuant to section 51A(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth)).

3. The Cross Claim be dismissed.

4. The Defendant and MarShip GmbH & Co. KG MS “Sinus Aestuum” pay the Plaintiff’s costs of the proceedings (including its costs of and occasioned by the Cross Claim).

5. The Plaintiff’s application for an order for costs on an indemnity basis from 18 June 2017 be stood over for hearing to 26 October 2018 at 2.15pm.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

RARES J:

[13] | |

[23] | |

[39] | |

[46] | |

[47] | |

[52] | |

[57] | |

[68] | |

[72] | |

[104] | |

[118] | |

[118] | |

[132] | |

[140] | |

5.4 Rolls-Royce reduces the running hours before fuel injection nozzle should be replaced | [185] |

[193] | |

[198] | |

5.7 MarShip breaches the Court order to retain parts of cylinder 5 | [205] |

[217] | |

[266] | |

[268] | |

[268] | |

[278] | |

[309] | |

[321] | |

[330] | |

[339] | |

7.1 The salvage quantum issue – the legal principles as to a reward | [339] |

7.2 The relevant criteria in Art 13(1) of the 1989 Convention | [355] |

7.3 The salvage quantum issue – the negotiations and settlement of Xinfa Hai’s claim against Mount Isa | [364] |

[403] | |

[407] | |

[411] | |

[431] | |

[457] | |

[457] | |

[470] | |

[485] | |

[485] | |

[488] | |

[505] |

1 The mythological Norse god, Thor, wielded a hammer and (like his Greek and Roman counterparts, Zeus and Jupiter) was associated with, among other phenomena, thunder, lightning and storms. Fortunately, it is not necessary to decide whether Thor was at work at about 15:20 local time (LT) on 11 January 2015 when the main engine of Thor Commander suffered a major breakdown in close proximity to the Great Barrier Reef. There were other causes operating that resulted in the main engine’s No 5 cylinder (cylinder 5) seizing, that have a more prosaic explanation.

2 The engine failure occurred while Thor Commander was en route from Puerto Angamos, in Chile, to Townsville on the north eastern coast of Australia. She was a general cargo vessel of 6,351 gross registered tonnes, with a value for limitation and general average purposes of USD7,344,289.83. The ship was carrying a cargo of 3,044 bundles of altonorte copper anodes, weighing 8,508.768 metric tonnes, worth USD63,178,742.45, owned by the plaintiff, Mount Isa Mines Ltd.

3 Mount Isa was a member of the Glencore International AG group, as was Copper Refineries Pty Ltd, that operated the Townsville Copper Refinery.

4 On 27 November 2014, Mount Isa and a company in the Danish fleet operator group controlled by Thorco Shipping A/S (Thorco Denmark) agreed the terms of the recap for a voyage charter of Thorco Challenger to carry the cargo from Angamos to Townsville. The recap did not name the disponent or actual owner of Thorco Challenger, but, in the past, Mount Isa had regularly chartered vessels in Thorco Denmark’s fleet.

5 The recap allowed “owners” to substitute another vessel seven days before the laycan commenced, subject to charterer’s approval. The recap provided that any bill of lading be claused “freight payable as per CP”. Thor Commander came to be substituted as the carrying vessel. There is a dispute as to whether her German owner, MarShip GmbH & Co KG MS “Sinus Aestuum”, carried the cargo on terms governed by a bill of lading or the charterparty reflected in the recap. If the bill of lading was the contract of carriage, then it was governed by the amended Hague Rules in Sch 1A to the Carriage of Goods by Sea Act 1991 (Cth) (COGSA) as provided in cl 2(b) of the bill.

6 The copper anodes had a purity of 99.7% of copper that would be ameliorated at the refinery to 99.995% purity to enable the copper to be sold into the world market for copper cathode production. The refinery comprised 37 sections each of which required a constant supply of anodes for refining. An electrolytic process operated in a cycle of 18 days. If a section of the refinery could not be reloaded, it had to be shut down until the next 18 day production cycle began. And, because of the constancy of the worldwide demand for purified copper cathode anodes, any loss from a section of the refinery being withdrawn from a production cycle could not be made up by later cycles, as the refinery ran continuously at full capacity.

7 After the main engine breakdown, Thor Commander drifted in the Coral Sea, off Mackay towards the Reef. As I will explain in more detail below, her owners organised for a tug, Smit Leopard, to leave Townsville to tow the vessel to Gladstone. However, the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) and the Ukrainian master of Thor Commander, Captain Glib Chaplin, were uncertain whether Smit Leopard would arrive in time before the prevailing weather conditions might cause the ship to ground on the Reef.

8 At about 07:45 LT on 12 January 2015, AMSA issued a pan-pan signal (that is an international alert of an urgent situation) seeking assistance to provide a tow for the distressed ship. Later that morning, Captain Li Fazhong, the master of Xinfa Hai, a 289 metre l.o.a. capesize of 174,766 metric tonnes, made contact with both AMSA and Capt Chaplin to offer assistance. Xinfa Hai was in ballast heading south to Newcastle to load a cargo. As events unfolded, Xinfa Hai came to tow Thor Commander away from the Reef to where she was met, on 13 January 2015, by Smit Leopard which then towed her to Gladstone.

9 On 13 January 2015, Thor Commander declared general average. Those events resulted in three issues in this proceeding, first, whether Xinfa Hai was entitled to a salvage reward, secondly, whether the USD1 million that Mount Isa, through its marine cargo insurers, paid for salvage was a reasonable sum, and if not, what was, and thirdly, whether Mount Isa acted reasonably in incurring about AUD147,956.27 in costs to tranship some of the cargo from Gladstone to the refinery to maintain it in full production while Thor Commander underwent repairs at Gladstone.

10 MarShip argued that it is not liable for the transhipment costs because of, for among other reasons, the terms of a letter of indemnity dated 19 January 2015 between it and Mount Isa pursuant to which the ship partially discharged about 1,030 metric tonnes of the cargo at Gladstone.

11 On 31 October 2016, Groninger, Welke, Janssen reported their preliminary adjustment of general average. That ascertained that the cargo interest (Mount Isa) was liable to pay the owners of Thor Commander (i.e. MarShip) was USD1,163,681.77. Mount Isa denies that it is liable to contribute to general average because of MarShip’s actionable fault within the meaning of rule D of the York-Antwerp Rules 1994 (as amended) at London in respect of the maintenance of the ship’s main engine.

12 In substance, there are six major issues to resolve, namely:

(1) What was the contract of carriage (the contract issue)?

(2) What was the cause of the breakdown of the main engine on 11 January 2015 and was MarShip at fault or negligent in the circumstances in which the breakdown occurred (the causation issue)?

(3) Was Thor Commander in need of salvage by Xinfa Hai (the salvage issue)?

(4) Was the USD1 million settlement of the cargo owner’s liability for salvage reasonable and, if not, what sum was reasonable (the salvage quantum issue)?

(5) Is Mount Isa able to recover its transhipment costs (the transhipment issue)?

(6) Is Mount Isa entitled to a declaration that it is not liable to contribute to general average and is entitled to reimbursement of its costs in providing its general average bond (the general average issue)?

1. The Thorco Denmark group structures

13 Before I deal with each of the above issues, it is necessary to explain the structures of the Thorco Denmark and MarShip groups. That will assist in ascertaining the identity of the parties to the contract of carriage and the charterparty.

14 Thomas Mikkelsen was the chief executive officer of Thorco Denmark. He said that Thorco Denmark was “a controlling shareholder” of each of the Brazilian company, Thorco Shipping Brazil-Empress de Navagacao Ltda (Thorco Brazil), the Chilean company, Thorco Shipping SpA (Thorco Chile) and the German company, Thorco Shipping Germany GmbH (Thorco Germany), in which it held 60%, or 150, of the 250 issued shares.

15 On 17 February 2014, MarShip entered into a pool agreement together with other ship owners and disponent owners (including Thorco Denmark, as disponent owners) as pool partners on the one part and, on the other part, with Thorco Germany as pool manager. The pool partners agreed to form “an undisclosed civil law partnership” for the purposes of creating a revenue pool to evenly distribute the risks of fluctuating returns in the chartering trade. The revenue earned by each pool partner’s ship or ships (including, as cl 6(6) provided, charter hire and freight) would be pooled together in a bank account conducted in Thorco Germany’s name.

16 Thorco Germany would manage each pool vessel (cl 1(3)). Although the pool agreement was executed on 17 February 2014, cl 2(1) provided that it had commenced on 31 May 2013. Importantly, cl 5 provided that the pool manager conducted the commercial employment of the pool vessels and it could enter into all contracts of affreightment, charterparties “and all other services in connection with the commercial management as agent for and on behalf of the owners”, subject to obtaining a respective owner’s written consent for contracts with a term greater than three months. In addition, cl 6(6) provided that, as Mr Mikkelsen explained:

It is understood that the Pool Manager [Thorco Germany] is entitled to subcontract administration tasks to the mother company in Copenhagen [Thorco Denmark] at their own cost and risk.

17 In June 2013, MarShip entered into a BIMCO SHIPMAN 2009 form standard ship management agreement (the Shipman agreement) with Thorco Germany in relation to the commercial management of Thor Commander. The Shipman agreement excluded technical and crew management from its scope of management services (boxes 6 and 7 and cl 1.5) but included chartering services (box 8).

18 Thorco Germany would carry out the management services in respect of the vessel as agents for and on behalf of her owners, MarShip (cl 3), including seeking and negotiating her employment, and the conclusion and execution of charterparties (subject to first seeking MarShip’s written consent if the term exceeded six months (cl 6(a) box 9)). Because Thorco Germany was not providing technical services under the Shipman agreement, cl 9(c) required MarShip to procure satisfaction of the requirements of Thor Commander’s flag State and to notify the name and contact details of the organisation that MarShip had engaged for that purpose. And, cl 11 provided that all moneys would be collected and dealt with under the pool agreement that (or an earlier version) was an annexure.

19 On 1 November 2013, each of Thorco Brazil, Thorco Chile and Thorco Germany entered into a separate, but relevantly identical, commercial agreement with Thorco Denmark that recited that Thorco Denmark “partly owned and controlled” the other respective party. Each commercial agreement was in materially identical terms. Each recited that the respective partly owned company provided vessel chartering and management services to Thorco Denmark acting on its behalf in commercial matters.

20 Thorco Germany’s version of the commercial agreement provided it would act as agents on behalf of Thorco Denmark and be responsible for the commercial chartering, booking and fixing of vessels defined as Thorco Vessels, in an annexed list of vessels that Thorco Denmark owned, chartered or commercially managed (cll 1.1, 1.3). Thorco Germany had to cooperate with Thorco Denmark “and other Thorco offices in fixing Thorco Vessels” (cl 1.2). Importantly, cl 1.4 provided:

All fixtures relating to Thorco Vessels concluded by Thorco Germany are to be made on behalf of, in the name of, and at the risk of Thorco Denmark.

21 Moreover, in providing the services, Thorco Germany “acts under the instructions of Thorco Denmark” (cl 1.5). Thorco Germany was responsible for providing the services under cl 1.1 in the area of Germany and elsewhere as agreed (cl 2). Thorco Germany received stipulated rates of commission for fixtures depending on whether Thorco Denmark owned, time chartered or commercially managed the vessel and whether the fixture was within or outside the agreed area under cl 2 (cl 3). The Thorco Vessels in Thorco Denmark’s commercial management, relevantly, included Thor Glory, Thorco Challenger and Thor Commander (albeit that she was named in the list of Thorco Vessels as “Thorco Commander”).

22 Michael Dragsbæk was the managing director of Thorco Chile in 2014 and responsible within the Thorco group for fixing the charter of Thor Commander with Mount Isa. Prior to holding that position, he had been chartering manager for Thorco Brazil. He was aware of the terms of the commercial agreements that each of his employers had with Thorco Denmark that provided that each acted as agent of Thorco Denmark in fixing of ships that it owned, chartered or commercially managed. He had acted for Thorco Brazil in fixing shipbrokers for charters with Mount Isa in respect of an unnamed vessel on 11 June 2013, and Thor Glory on 17 July 2013, similarly for Thorco Chile, in fixing Thor Asia on 8 July 2014, Thorco Clairvaux on 27 August 2014, Thorco Atlantic on 29 October 2014 (that was subsequently cancelled), Thor Asia on 30 October 2014 and, importantly, Thorco Challenger on 27 November 2014.

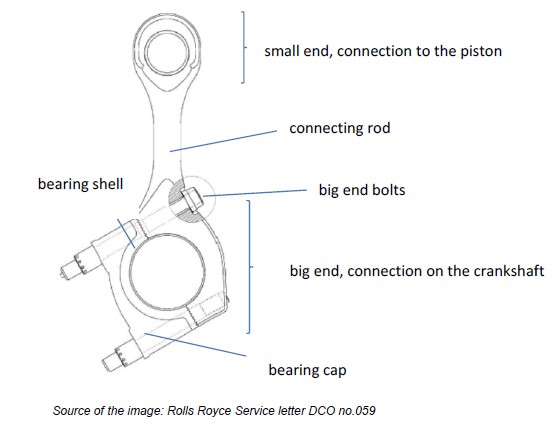

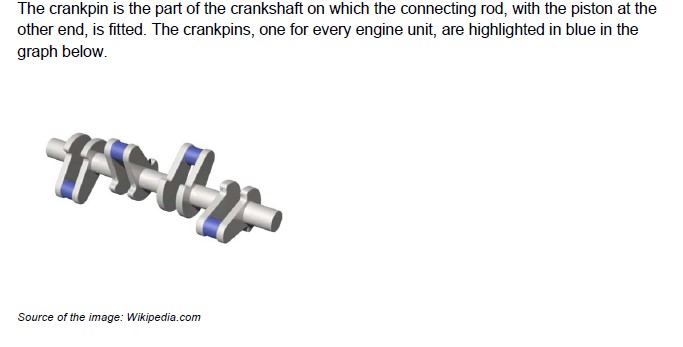

23 Thor Commander was a single screw, general cargo ship, with a Rolls-Royce main engine. She displaced 9,739 deadweight tonnes and was 132.2 metres l.o.a. She was launched in November 2010. Jan Held was the managing director of MarShip GmbH and the fleet manager of the MarShip group. MarShip GmbH was the sole partner authorised under German law to act on behalf of MarShip. Another company in the MarShip group was MarShip Bereederungs GmbH & Co KG (MarShip Management).

24 On 3 January 2011, MarShip entered into a ship management agreement in respect of Thor Commander with MarShip Management, as ship operator. MarShip Management agreed to carry out all measures necessary to operate, use, maintain and charter the ship exercising due care, including conducting technical inspections and taking all measures necessary to maintain her class and certificates necessary for her to operate (cl 2(1)). Its primary tasks included adequately maintaining the ship, including providing services such as qualified masters, officers, engineers and crews required for that purpose and maintaining her and all her machinery and equipment in operational condition (cl 2(3)(b), (e), (f)). MarShip Management also had to provide MarShip with a report on Thor Commander’s technical condition after each docking, quarterly operating reports on her ongoing operations and immediate reports about any unusual events. It also had to allow MarShip to inspect business documents relating to the ship’s operation (cl 6). MarShip Management had authority under cl 7(2) “to create seamen’s work contracts in its own name on behalf of” MarShip.

25 Mr Held graduated in 1998 as a master mariner and was at sea in that role from then until 2001. After holding two positions in shipping companies he became managing director of Held Bereederung from 2003 to 2013 when, as he said in his affidavit, “after a change in corporate structure” he became managing director of MarShip GmbH and was fleet manager responsible for overseeing the management of about 40 ships, including Thor Commander. He described MarShip Management as the technical manager of Thor Commander.

26 Mr Held said that he assigned a technical superintendent to each vessel, and that in about June 2012, he assigned Vladimir Smirnov to that role in respect of Thor Commander and seven other vessels. Mr Held said that he employed Mr Smirnov after receiving details of his qualifications and experience, and interviewing him. Mr Held routinely met weekly with Mr Smirnov and the group’s other technical superintendents to discuss issues or concerns in relation to any vessel in the fleet. Mr Held had begun this practice in 2003. He said that as at 2014, he did not have a practice of minuting these weekly meetings. He said that Mr Smirnov also routinely provided him with quarterly reports relating to Thor Commander that he read.

27 Mr Held said that his practice was he would “take any appropriate action required”. He said that, “I delegate to Mr Smirnov the day to day technical management of” Thor Commander. Mr Smirnov had authority to purchase, in any one order, technical supplies up to a value of €10,000, while Mr Held had full authority, on behalf of MarShip GmbH and MarShip, to approve operating and capital expenditure for any amount in excess of that sum.

28 Mr Held said that he was also available to Mr Smirnov as and when required, in addition to their weekly meetings, in respect of any matter relating to the technical management of Thor Commander. Mr Held had conducted a spot inspection of the ship, her records and her equipment in Emden in October 2013. He said that MarShip Management was the ISM Code Document of Compliance holder for Thor Commander and that it had to conduct regular internal audits to keep her in class.

29 Mr Held said that MarShip had appointed Thorco Germany as commercial manager of Thor Commander. He said that Thorco Germany was responsible for negotiating the ship’s employment “as agent for” MarShip. He said that MarShip had never made any agreement or charterparty with any Thorco company to allow the latter to charter out the ship as owner or disponent owner.

30 Mr Smirnov gave oral evidence as a result of which I formed the view that what he said and did could not be taken at face value. As I will explain, I am satisfied that he was party to the fabrication of maintenance records for Thor Commander’s oil filters. Although English was not his first language, Mr Smirnov willingly and fluently gave most of his evidence in English (by video link to Germany) without using or requiring assistance, except on a few occasions, from the Russian interpreter who was present in court throughout Mr Smirnov’s evidence.

31 Mr Smirnov graduated as a mechanical engineer in 1981 and was at sea from then until 2006. He served as an engineer rising to the rank of chief engineer in 1992. In April 2006, he began employment as a technical superintendent. His role as technical superintendent of Thor Commander included:

involvement with the crew manager in selecting and evaluating the performance of masters and chief engineers of the ship and oversighting their choice of lower ranks as crew members;

routinely, usually twice a year, attending on board the ship to meet the master and chief engineer in order to discuss any issues in reports that the vessel had sent that he had identified in advance and others that they might raise. He also said that he examined the deck log, engine log and the oil record book for the period since his preceding visit. He conducted spot checks and other activities that he thought necessary. After the attendance, he prepared an inspection report for MarShip, as owners;

routinely reporting to Mr Held, at least quarterly, on budgets for any identified maintenance needs. In addition, Mr Smirnov had weekly meetings with Mr Held to discuss any issues with the eight vessels in his section of the fleet; and

reviewing all monthly technical reports from the ship that he received by email, such as monthly measurement reports and engine run[ning] time reports, as well as other reports or emails that the vessel might send to him.

32 Mr Smirnov said that when he attended on board the ship, he examined the deck log, the engine log, the oil record book and the air pollution prevention file for the period since his previous examination. He would discuss any reports that the vessel had sent him if necessary. He would also perform spot checks and other tasks that he considered necessary. Following these attendances, Mr Smirnov prepared a report for the owners.

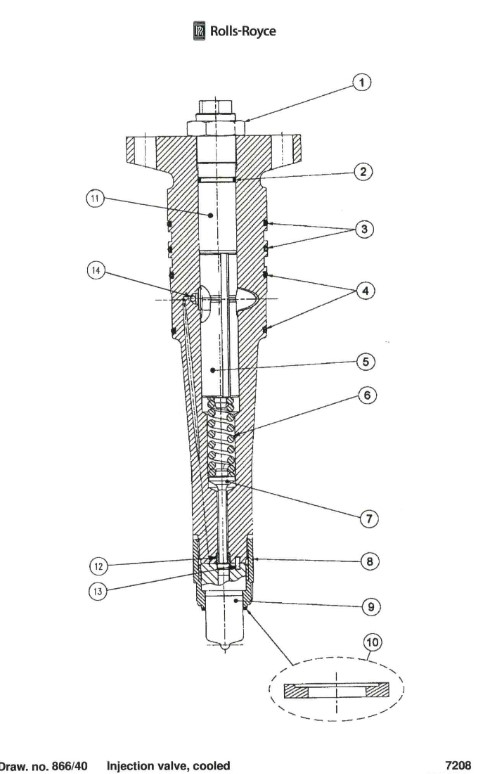

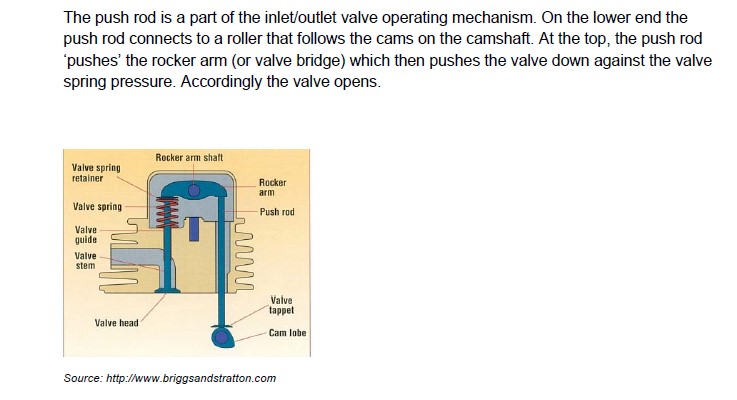

33 Mr Smirnov also said in his affidavit that the run[ning] time reports and measurement reports would provide information from which it can be seen that one or other component of the ship’s machinery requires servicing, renewal or replacement. He said that he was responsible for, took control of, and organised, “the big items (e.g. cylinder heads, turbochargers)” and that he relied on the chief engineer who had responsibility for, and would organise, work in respect of lesser items, such as fuel injector valves and fuel injector nozzles (and somewhat inconsistently, replacing turbochargers). And, Mr Smirnov said that he would raise any queries that he had about matters in the reports that he received with the appropriate person on board, such as the chief engineer. He said that he used his qualifications, training and experience as a former chief engineer, together with relevant manuals, to oversee the maintenance and service requirements for Thor Commander generally, including her main engine. He also received requests for, reviewed, approved (as he thought appropriate) and then arranged for delivery of, spare and replacement parts for the ship.

34 He said that he routinely took control of any substantial maintenance or replacement matters (such as replacing cylinder heads) and relied on the chief engineer to manage smaller, day-to-day matters such as replacing fuel injector nozzles (which, as will appear below, were key items associated with the failure of Thor Commander’s main engine on her voyage in January 2015).

35 Mr Smirnov said that he had attended on board and inspected Thor Commander twice in 2012, once in November 2013, again in May and July 2014 and that, when he was on vacation, another colleague had done so in January 2014. He said that he followed the practice described above on each inspection. He said that in his July 2014 inspection, in Burgas, Bulgaria, he had not identified any issue that he found of concern in relation to cylinder 5 of the main engine.

36 Thus, Mr Smirnov exercised considerable control over the performance of the maintenance of Thor Commander. In particular, he controlled what spare and replacement parts could be obtained for the ship and the port at which those parts would be delivered.

37 He had arranged for an inspection of the ship by another colleague to occur when she was scheduled to dock in Townsville in January 2015. Mr Smirnov said that the ship had received “technical supply” on 5 November 2014 and 1 December 2014 in Port Calliao, Peru, and a further such supply was scheduled for Townsville in January 2015.

38 I will describe what the crew and Mr Smirnov did in relation to the circumstances in which the main engine failed in discussing the causation issue below.

39 The Sea-Carriage Documents Act 1996 (Qld) contained the following relevant definitions in s 3:

bill of lading means a bill of lading (including a received for shipment bill of lading) capable of transfer—

(a) by endorsement; or

(b) as a bearer bill, by delivery without endorsement.

contract of carriage, in relation to a sea-carriage document, means—

(a) for a bill of lading or a sea waybill—the contract of carriage contained in, or evidenced by, the document; or

(b) for a ship’s delivery order—the contract of carriage in association with which the order is given.

…

goods, in relation to a sea-carriage document, means the goods to which the document relates.

…

sea-carriage document means a bill of lading, a sea waybill or a ship’s delivery order.

sea waybill means a document, other than a bill of lading, that—

(a) is issued by the carrier of the goods; and

(b) is a receipt for the goods; and

(c) contains or evidences a contract for the carriage of the goods by sea; and

(d) identifies the person to whom delivery of the goods is to be made by the carrier in accordance with the contract.

ship’s delivery order means a document, other than a bill of lading or a sea waybill, that—

(a) is given in association with a contract for the carriage of goods by sea, including goods to which the document relates; and

(b) contains an undertaking by the carrier to deliver the goods to which the document relates to a person identified in the document. (bold, non-italic emphasis added)

40 Section 6 provided:

6 Transfer of rights

(1) All rights under the contract of carriage in relation to which a sea-carriage document is given are transferred to—

(a) for a bill of lading—each successive lawful holder of the bill; or

(b) for a sea waybill—the person (other than an original party to the contract) to whom delivery of the goods is to be made by the carrier in accordance with the contract; or

(c) for a ship’s delivery order—the person to whom delivery of the goods is to be made in accordance with the order.

(2) Rights in a contract of carriage transferred to a person under subsection (1) vest in that person as if the person had been an original party to the contract.

(3) Rights in a contract of carriage in relation to which a ship’s delivery order is given are transferred under subsection (1)—

(a) subject to the terms of the order; and

(b) only in relation to the goods to which the order relates.

41 The amended Hague Rules in Sch 1A of COGSA relevantly provided definitions in Art 1, including that “carrier” included the owner or charterer who entered into a contract of carriage with the shipper (Art 1(1)(a)) and:

(b) “Contract of carriage” means a contract of carriage covered by a sea carriage document (to the extent that the document relates to the carriage of goods by sea), and includes a negotiable sea carriage document issued under a charterparty from the moment at which that document regulates the relations between its holder and the carrier concerned.

…

(g) “Sea carriage document” means:

(i) a bill of lading; or

(ii) a negotiable document of title that is similar to a bill of lading and that contains or evidences a contract of carriage of goods by sea; or

(iii) a bill of lading that, by law, is not negotiable; or

(iv) a non negotiable document (including a consignment note and a document of the kind known as a sea waybill or the kind known as a ship’s delivery order) that either contains or evidences a contract of carriage of goods by sea.

[NOTE: These Rules do not apply to all sea carriage documents—see Article 10.] (emphasis added)

42 Article 3(1)(a) and (b) provided the carrier was bound before and at the beginning of the voyage to exercise due diligence to, first, make the ship seaworthy and, secondly, properly man, equip and supply her. Article 3(3) required the carrier or its agent or the master, on demand of the shipper, to issue a sea carriage document showing identifying details of the goods, their quantity and weight as furnished by the shipper and their apparent order and condition.

43 Importantly, Art 3(8) provided:

8. Any clause, covenant, or agreement in a contract of carriage relieving the carrier or the ship from liability for loss or damage to, or in connexion with, goods arising from negligence, fault, or failure in the duties and obligations provided in this article or lessening such liability otherwise than as provided in these Rules, shall be null and void and of no effect. A benefit of insurance in favour of the carrier or similar clause shall be deemed to be a clause relieving the carrier from liability.

44 Next, Art 4(1) provided:

ARTICLE 4

1. Neither the carrier nor the ship shall be liable for loss or damage arising or resulting from unseaworthiness unless caused by want of due diligence on the part of the carrier to make the ship seaworthy, and to secure that the ship is properly manned, equipped and supplied, … in accordance with the provisions of paragraph 1 of Article 3. Whenever loss or damage has resulted from unseaworthiness the burden of proving the exercise of due diligence shall be on the carrier or other person claiming exemption under this article. (emphasis added)

45 By force of Art 10(2), the amended Hague Rules applied to the carriage of goods by sea from ports outside Australia to ports in Australia, whereas it is common ground in this proceeding, no international convention for carriage of goods by sea applied to the carriage. And, Art 10(6) and (7) provided:

6. These Rules do not apply to the carriage of goods by sea under a charterparty unless a sea carriage document is issued for the carriage.

7. These Rules apply to a sea carriage document issued under a charterparty only if the sea carriage document is a negotiable sea carriage document, and only while the document regulates the relationship between the holder of it and the carrier of the relevant goods. (emphasis added)

46 The fixture of Thorco Challenger in the recap of 27 November 2014 did not proceed and Thor Commander carried the cargo instead. How this occurred, who were the parties to the charterparty, what were its terms and whether Mount Isa can sue MarShip only as the charterer under the recap or as holder of the bill of lading are the questions that arise on the contract issue.

4.1 The contract issue – background

47 On 20 March 2008, Mount Isa as buyer entered into a copper anodes/blister purchase and sale agreement with Xstrata Commodities Middle East DMCC (another Glencore subsidiary) as sellers for a term that, originally, was to end on 31 December 2010, but would continue thereafter on a year to year basis until one party gave six months’ notice (cl 2). The agreement was for Mount Isa to purchase between 20,000 to 70,000 MT of copper anodes per annum for delivery to the Townsville refinery. Payment of the provisional invoice value was due no later than 30 days after the bill of lading date (cl 9). Risk passed to the buyer upon delivery of the material over the ship’s rail at the load port (cl 12), and under an amendment agreed on 9 April 2013, delivery would be FOB ST (free on board stowed and trimmed) Antofagasta, Chile.

48 Mount Isa’s shipbroker was OCT Ocean Chartering + Transport Mühle + Sachs (GmbH & Co) in Hamburg. OCT, usually through Jan Uleman, had negotiated several earlier charterparties on behalf of Mount Isa Mines and its parent, Glencore, for the ships to which Mr Dragsbæk referred.

49 The charterparty for the fixture of Thor Glory on 17 July 2013 that I describe below is relevant because it formed the basis of the terms of the recap under which Thor Commander came to be fixed as a substitute vessel to carry the cargo from Angamos to Townsville.

50 On 17 July 2013, OCT, on behalf of Mount Isa, agreed the terms of a recap with Thorco Brazil for Thor Glory to carry a cargo of 9,000 MT of copper anodes from Antofagasta to Townsville. The recap email provided that Mount Isa had the right to assign the charterparty to Glencore “at any moment”. The recap required the owners to perform several specific obligations. The ship was due at Antofagasta on 18 July 2013 and this recap made no reference to any right to substitute another vessel. The recap stated that the owners had to clause bills of lading, in case of any cargo damage, but otherwise would issue clean bills if the charterer provided a letter of indemnity. The recap concluded “[o]therwise as per attached Gencon 94 incl. rider terms”. It attached copies of Thor Glory’s classification certificate, which identified her owners as Eastern Comet Maritime S.A., and the classification society’s register of her lifting appliances. It also attached a copy of the ship’s technical specifications that named Thorco Denmark as her commercial managers.

51 The version of the GENCON 1994 form attached to the 17 July 2013 recap related to a 2011 charter by Glencore. Relevantly, it included cll 2 and 10 in Pt II of the GENCON 1994 form which, it is common ground, were also terms of the charterparty for Thor Commander. Clauses 2 and 10 provided (as amended in the GENCON 1994 form attached to the 17 July 2013 recap):

2. Owners’ Responsibility Clause

The Owners are to be responsible for loss of or damage to the goods or for delay in delivery of the goods only in case the loss, damage or delay has been caused by personal want of due diligence on the part of the Owners or their Manager to make the Vessel in all respects seaworthy and to secure that she is properly manned, equipped and supplied, or by the personal act or default of the Owners or their Manager.

And the Owners are not responsible for loss, damage or delay arising from any other cause whatsoever, even from the neglect or default of the Master or crew or some other person employed by the Owners on board or ashore for whose acts they would, but for this Clause, be responsible, or from unseaworthiness of the Vessel on loading or commencement of the voyage or at any time whatsoever.

…

10. Bills of Lading

Bills of Lading shall be presented and signed by the Master as per the “Congenbill” Bill of Lading form, Edition 1994, without prejudice to this Charter Party, or by the Owners’ agents provided written authority has been given by Owners to the agents, a copy of which is to be furnished to the Charterers. The Charterers shall indemnify the owners against all consequences or liabilities that may arise from the signing of bills of lading as presented to the extent that the terms or contents of such bills of lading impose or result in the imposition of more onerous liabilities upon the Owners than those assumed by the Owners under this Charter Party. (emphasis added)

4.2 How Thor Commander came to perform the voyage

52 On 29 October 2014, Mr Uleman of OCT agreed the terms of a recap with Mr Dragsbæk on behalf of Thorco Chile for the fixture of Thorco Atlantic to carry a cargo of 7,500 MT of copper anodes from Antofagasta to Townsville with a laycan between 13 to 17 December 2014. Although this fixture was later cancelled, it again provided, after setting out the specific terms relevant to the intended voyage, that the terms were “otherwise as Thor Glory/Glencore 17 July 2013”. Relevantly, this recap nominated Thorco Atlantic and attached a copy of her technical specifications stating:

MV THORCO ATLANTIC – DESCR ATTACHED

OR OWS SUITABLE SUB (emphasis added)

53 I infer the last wording meant “or otherwise suitable substitute”. The recap went on to state “OWNERS TO PROVIDE UPON NOMINATION”, followed by a list of certificates. The recap then set out, the following clause:

In case owners nominate a substitute performing vessel then same to be nominated 7 working days prior laycan commencement – and to comply with vessel specification as set out at condition four (4) above. Substitute nomination to be subject to charters approval. (emphasis added)

There was no condition numbered 4 in this recap.

54 On 27 November 2014, Mr Uleman of OCT, on behalf of Glencore, agreed with Mr Dragsbæk of Thorco Chile, first, the cancellation of the fixture of Thorco Atlantic and, secondly, the terms of a new recap. The new recap was for a voyage (which ultimately became the subject of this proceeding) from Angamos to Townsville. It commenced:

MV THORCO CHALLENGER – DESCR ATTACHED

OR OWS SUITABLE SUB

– Owners/ Disponent Owner/ commercial manager Thorco confirm vessel is fully suitable for Australia trading.

55 The recap then set out four more matters that “Owners/ Disponent Owner/ commercial manager Thorco” had to confirm or do relating to the vessel’s compliance with local and flag State legal requirements and past cargoes she had carried. The recap set out verbatim the same substitution clause as in the 29 October 2014 recap for Thorco Atlantic (although, again there was no condition numbered 4). It provided that the charter was for Mount Isa’s account. The cargo was to be 8,500 MT of copper anodes with a laycan between 5 and 8 December 2014. The recap provided that bills of lading be claused “Freight payable as per CP”. It provided that 95% of the freight had to be paid “within 3 banking days from signing releasing OBL’s [on board bills of lading]”. It concluded, again “– otherwise as Thor Glory / Glencore 17 July 2013”. The recap provided that the freight was “LUMPSUM 618,750 - USD”.

56 There was no direct evidence of how Thor Commander came to be the ship that loaded the cargo at Angamos instead of the ship nominated in the 27 November 2014 email, namely, Thorco Challenger. Neither of the parties had been able to locate the emails or other documents by which that change of vessel occurred.

4.3 The documentation relevant to the voyage

57 On 8 December 2014, Capt Chaplin, in a letter written in Angamos, authorised Ultramar Agencia Maritima of Antofagasta to sign on board bills of lading for cargo loaded on Thor Commander on three conditions, one of which was that they be claused:

All terms, conditions, liberties, exceptions and arbitration clause of relevant Charter Party/Booking Note, and any addenda thereto, are herewith incorporated.

58 The master began the letter by noting that the bills would not be presented to him for his signature before the vessel’s departure. He instructed Ultramar to contact “my ship’s despondent [sic] managers via Thorco Shipping, Denmark” if it encountered any difficulty.

59 On 10 December 2014, Bianca, an employee of OCT, emailed Mr Dragsbæk a PDF of a filled in working copy of the GENCON 1994 form under the heading “M/V Thorco Commander or sub”. That named Thorco Brazil as owners and the vessel, in box 5, as “M/V Thorco Commander or sub. see Clause 21”. Clause 21 dealt with the vessel’s description, again naming her as “MV Thorco Commander or Owners’ suitable sub”.

60 Mr Dragsbæk replied to that email on 11 December 2014, “Thanks below, well received”. He said in his affidavit that he had no specific recollection “but I probably did not read the document closely or perhaps at all before I responded back to Bianca”.

61 On 13 December 2014, Ultramar signed and issued a set of three original clean on board bills of lading “as agents only for and on behalf of the carrier” in respect of the cargo of 8,508,768 kgs of copper anodes that had been loaded on board Thor Commander at Angamos on 13 December 2014 for carriage to Townsville. The shipper was Compelejo Metalurgico Altonorte Panam Norte KM of Antofagasta (CMA) and Mount Isa was named as both consignee and notify party. The bills stated that freight was “payable as per CHARTER-PARTY dated 27-11-2014”. The bills of lading were in the CONGENBILL Edition 1994 form. The reverse side of the bills of lading contained five conditions of carriage, including, relevantly, conditions that:

(1) All terms and conditions, liberties and exceptions of the Charter Party dated as overleaf, including the Law and Arbitration Clause, are herewith incorporated.

(2) General Paramount Clause

(a) The Hague Rules contained in the International Convention for the Unification of certain rules relating to Bills of Lading, dated Brussels the 25th August 1924 as enacted in the country of shipment, shall apply to this Bill of Lading. When no such enactment is in force in the country of shipment, the corresponding legislation of the country of destination shall apply, but in respect of shipments to which no such enactments are compulsorily applicable, the terms of the said Convention shall apply.

(b) Trades where Hague-Visby Rules apply

In trades where the International Brussels Convention 1924 as amended by the Protocol signed at Brussels on February 23rd 1968 – the Hague-Visby Rules – apply compulsorily, the provisions of the respective legislation shall apply to this Bill of Lading.

(c) The Carrier shall in no case be responsible for loss of or damage to the cargo, howsoever arising prior to loading into and after discharge from the Vessel or while the cargo is in the charge of another Carrier, nor in respect of deck cargo or live animals.

(3) General Average

General Average shall be adjusted, stated and settled according to York-Antwerp Rules 1994, or any subsequent modification thereof, in London unless another place is agreed in the Charter Party.

Cargo’s contribution to General Average shall be paid to the Carrier even when such average is the result of a fault, neglect or error of the Master, Pilot or Crew. The Charterers, Shippers and Consignees expressly renounce the Belgian Commercial Code, Part II, Art. 148. (emphasis added)

62 It is common ground that if the bill of lading evidences the contract of carriage between Mount Isa and MarShip, then the amended Hague Rules apply as part of that contract pursuant to COGSA. MarShip, however, contends that the charterparty was the contract of carriage.

63 Also on 13 December, Glencore issued a provisional invoice to Mount Isa for the cargo under which USD62,559,992.45 was payable on 12 January 2015.

64 On about 29 December 2014, Glencore emailed Mount Isa attaching a copy of the set of bills of lading and the originals arrived at the refinery on 2 January 2015. Keryn Thomson, an employee of Mount Isa, had responsibility for administration of, among others, metal sales and purchases. She arranged to send the original bills of lading to Townsville Shipping Agencies in order that it could present them and take delivery of the cargo when Thor Commander arrived, as was then expected, in Townsville.

65 After the failure of Thor Commander’s main engine, she was towed to Gladstone. Ms Thomson retrieved one of the original bills of lading in the set of three from Townsville Shipping Agencies and provided it to John Cordingley, Mount Isa Mines’ Townsville superintendent of port operations.

66 I will describe the circumstances more fully in discussing the transhipment issue below, but for present purposes, it suffices to say that, in order to obtain partial delivery of about 1,030 MT of the cargo at Gladstone while Thor Commander was being repaired, Mount Isa had to agree to provide her master with the letter of indemnity. On 19 January 2015, Richard Harvey, Mount Isa’s chief operating officer (and chief processing officer of the refinery), signed the letter of indemnity. It was addressed to Thorco Denmark as agents of the owners of Thor Commander (i.e. MarShip). The letter asked MarShip to deliver 1,030 MT of the cargo to Mount Isa at Gladstone in consideration of which it agreed:

1. To indemnify you, your servants and agents and to hold all of you harmless in respect of any liability, loss, damage or expense of whatsoever nature which you may sustain by reason of the ship proceeding and giving delivery of the cargo against production of at least one original bill of lading in accordance with our request.

…

3. If, in connection with the delivery of the cargo as aforesaid, the ship, or any other ship or property in the same or associated ownership, management or control, should be arrested or detained or should the arrest or detention thereof be threatened, or should there be any interference in the use or trading of the vessel (whether by virtue of a caveat being entered on the ship’s registry or otherwise howsoever), to provide on demand such bail or other security as may be required to prevent such arrest or detention or to secure the release of such ship or property or to remove such interference and to indemnify you in respect of any liability, loss, damage or expense caused by such arrest or detention or threatened arrest or detention or such interference, whether or not such arrest or detention or threatened arrest or detention or such interference may be justified. (emphasis added)

67 On about 22 January 2015, after the master received the letter of indemnity, Thor Commander discharged over several days a total of 1,033.6 MT of the cargo that Mount Isa then transhipped to Townsville.

4.4 The contract – the parties’ submissions

68 MarShip argued that the contract of carriage was the charterparty, not the bill of lading. It contended that when Thor Commander was substituted as the chartered vessel under the 27 November 2014 recap, MarShip was also substituted as, or became, the disponent owner with which Mount Isa contracted for the charter of that ship. It submitted that because the recap permitted the substitution of a vessel for Thorco Challenger, when that substitution occurred the recap contemplated, and operated to effect, its contemporaneous assignment to, or novation with, the owner (or disponent owner) of Thorco Challenger. It relied on authorities including Leveraged Equities Ltd v Goodridge (2011) 191 FCR 71 to advance its contention that the parties to the recap could (and did) consent in advance to its novation with the owner (or disponent owner) of any substituted ship, if and when any substitution occurred.

69 MarShip also contended that it and Mount Isa subsequently had entered into a further contract in terms of the letter of undertaking. MarShip claimed, in its amended cross-claim, that Mount Isa had agreed, by the letter of indemnity, to indemnify it for any claim arising in respect of the transhipment costs. (I will deal with this claim when I consider the transhipment issue.)

70 Finally, MarShip argued that Mount Isa could not sue on the bills of lading because they were straight bills and the named shipper, CMA, had not transferred its rights to the consignee, Mount Isa, pursuant to s 6 of the Sea-Carriage Documents Act or its analogues.

71 For its part, Mount Isa relevantly contended that the use of the expression “Owners/ Disponent Owner/ commercial manager Thorco” in the recap dated 27 November 2014 and the version of the charterparty that OCT sent to Mr Dragsbæk on 10 December 2014 naming Thorco Brazil as owners of the chartered ship, indicated that Thorco Denmark was intended to be a party to the recap, and hence, the charterparty, and that Thorco Denmark continued as a contractual party whatever the outcome of MarShip’s novation argument.

4.5 The contract issue – consideration

72 I reject MarShip’s argument that it became the owner or other party to the recap dated 27 November 2014 or charterparty it evidenced. The substitution clause permitted the owners of the chartered vessel, namely Thorco Challenger, to substitute another vessel that was suitable to perform the voyage. How those owners arranged for the substitute to perform the voyage was a matter for them. They might source her within their own fleet, as an owned or chartered vessel, or enter a subcharter to ensure that they complied with their obligation under the recap to have Thorco Challenger or a suitable substitute ready at Angamos and there in time to perform the voyage.

73 In ALH Group Property Holdings Pty Ltd v Chief Commissioner of State Revenue of the State of New South Wales (2012) 245 CLR 338 at 346 [12], French CJ, Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ said:

A novation, in its simplest sense, refers to a circumstance where a new contract takes the place of the old [Olsson v Dyson (1969) 120 CLR 365 at 389]. It is not correct to describe novation as involving the succession of a third party to the rights of the purchaser under the original contract. Under the common law such a description comes closer to the effect of a transfer of rights by way of assignment. Nor is it correct to describe a third party undertaking the obligations of the purchaser under the original contract as a novation. The effect of a novation is upon the obligations of both parties to the original, executory, contract. The inquiry in determining whether there has been a novation is whether it has been agreed that a new contract is to be substituted for the old and the obligations of the parties under the old agreement are to be discharged. (emphasis added)

74 Their Honours held that a novation of a contract necessarily involves the rescission of the existing contract (for which the new one is a novation) and a release of any person to the existing one who is not a party to the new one (245 CLR at 349-350 [26]-[28]). They explained that, as Dixon J had held in Vickery v Woods (1952) 85 CLR 336 at 345, rescission and novation ultimately depend on intention, and that such an intention can be express or inferred, including from conduct (245 CLR at 350-351 [31]-[32]).

75 MarShip’s argument, if accepted, did not answer why the original owner under the recap would escape all liability if the vessel that the owners sought to substitute turned out not to be suitable, in accordance with the requirements of the recap (e.g. because it was not fully suitable for Australian trading). MarShip did not offer a reason why the substitution clause in the recap would operate to excuse the original owners from their obligations in that respect when they had chosen to substitute a different vessel from that initially agreed, or how any novation of the contract in the recap came into being between Mount Isa and the owners of the substituted vessel.

76 The purpose of the substitution clause was to enable the owners who were the original party to the recap to discharge their obligation to provide Thorco Challenger by substituting another vessel that they had arranged to perform the voyage. I agree with what Mance J held in E.G. Cornelius & Co v Christos Maritime Co Ltd (The “Christos”) [1995] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 106 at 110, namely:

Any contract by which a substitute vessel or a transhipment vessel is chartered in is a matter between owners and the owner of that other vessel.

77 Of course, for the purpose of the further performance of the charterparty (as evidenced in the recap) by the owners of Thorco Challenger, many references to that or any performing vessel will be read as referring to the substitute: Bennett H (ed), Carver on Charterparties (Sweet & Maxwell, 2017) at [3-047]-[33-050]; Cooke J, Young T, Ashcroft M, Taylor A, Kimball J, Martowski D, Lambert L, Sturley M, Voyage Charters (4th ed, Informa, 2014) at [3.7], [3.12].

78 Because Thorco Denmark was the commercial manager of a pool of vessels in different ownership, it could arrange the substitution of Thor Commander without needing to subcharter another vessel. However, that happenstance cannot determine the construction of the terms of the substitution clause. The construction of a written contract depends on how a reasonable person in the position of the parties would have understood the clause, read in the context of the contract as a whole and having regard to the surrounding circumstances known to the parties and the purpose and object of the transaction: Toll (FGCT) Pty Ltd v Alphapharm Pty Ltd (2004) 219 CLR 165 at 179 [40] per Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne, Callinan and Heydon JJ. French CJ, Hayne, Crennan and Kiefel JJ further explained the principles of construction of such a contract in Electricity Generation Corporation v Woodside Energy Ltd (2014) 251 CLR 640 at 656-657 [35] as follows:

The meaning of the terms of a commercial contract is to be determined by what a reasonable businessperson would have understood those terms to mean [McCann v Switzerland Insurance Australia Ltd (2000) 203 CLR 579 at 589 [22] per Gleeson CJ; Pacific Carriers Ltd v BNP Paribas (2004) 218 CLR 451 at 462 [22] per Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne, Callinan and Heydon JJ; International Air Transport Association v Ansett Australia Holdings Ltd (2008) 234 CLR 151 at 160 [8] per Gleeson CJ; see further Maggbury Pty Ltd v Hafele Australia Pty Ltd (2001) 210 CLR 181 at 188 [11] per Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ, citing Investors Compensation Scheme Ltd v West Bromwich Building Society [No 1] [1998] 1 WLR 896 at 912; [1998] 1 All ER 98 at 114. See also Homburg Houtimport BV v Agrosin Private Ltd (The Starsin) [2004] 1 AC 715 at 737 [10] per Lord Bingham of Cornhill]. That approach is not unfamiliar [See, eg, Hydarnes Steamship Co v Indemnity Mutual Marine Assurance Co [1895] 1 QB 500 at 504 per Lord Esher MR; Bergl (Australia) Ltd v Moxon Lighterage Co Ltd (1920) 28 CLR 194 at 199 per Knox CJ, Isaacs and Gavan Duffy JJ; see generally Lord Bingham of Cornhill, “A New Thing Under the Sun? The Interpretation of Contract and the ICS Decision”, Edinburgh Law Review, vol 12 (2008) 374]. As reaffirmed, it will require consideration of the language used by the parties, the surrounding circumstances known to them and the commercial purpose or objects to be secured by the contract [Pacific Carriers Ltd v BNP Paribas (2004) 218 CLR 451 at 461-462 [22] per Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne, Callinan and Heydon JJ; Toll (FGCT) Pty Ltd v Alphapharm Pty Ltd (2004) 219 CLR 165 at 179 [40] per Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne, Callinan and Heydon JJ; International Air Transport Association v Ansett Australia Holdings Ltd (2008) 234 CLR 151 at 160 [8] per Gleeson CJ; at 174 [53] per Gummow, Hayne, Heydon, Crennan and Kiefel JJ; Byrnes v Kendle (2011) 243 CLR 253 at 284 [98] per Heydon and Crennan JJ. See also Charter Reinsurance Co Ltd v Fagan [1997] AC 313 at 326, 350; Rainy Sky SA v Kookmin Bank [2011] 1 WLR 2900 at 2906-2907 [14]; [2012] 1 All ER 1137 at 1144]. Appreciation of the commercial purpose or objects is facilitated by an understanding “of the genesis of the transaction, the background, the context [and] the market in which the parties are operating” [Codelfa Construction Pty Ltd v State Rail Authority (NSW) (1982) 149 CLR 337 at 350 per Mason J, citing Reardon Smith Line v Hansen-Tangen [1976] 1 WLR 989 at 995-996; [1976] 3 All ER 570 at 574. See also Zhu v Treasurer (NSW) (2004) 218 CLR 530 at 559 [82] per Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Kirby, Callinan and Heydon JJ; International Air Transport Association v Ansett Australia Holdings Ltd (2008) 234 CLR 151 at 160 [8] per Gleeson CJ]. As Arden LJ observed in Re Golden Key Ltd [[2009] EWCA Civ 636 at [28]], unless a contrary intention is indicated, a court is entitled to approach the task of giving a commercial contract a businesslike interpretation on the assumption “that the parties … intended to produce a commercial result”. A commercial contract is to be construed so as to avoid it “making commercial nonsense or working commercial inconvenience” [Zhu v Treasurer (NSW) (2004) 218 CLR 530 at 559 [82] per Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Kirby, Callinan and Heydon JJ. See also Gollin & Co Ltd v Karenlee Nominees Pty Ltd (1983) 153 CLR 455 at 464]. (emphasis added)

79 If MarShip’s argument (namely, that the owners of Thorco Challenger ceased to be a party to the charterparty, by novation), were correct, once Mount Isa agreed to its substitution, then the charterer would have no contractual recourse against those owners if, for example, the substituted vessel turned out not to be suitable or never arrived at the load port. The charterparty evidenced in the recap works well enough by treating the substituted vessel as that of, or under the contractual control of, the owners of Thorco Challenger (whether she is in their ownership or they subchartered her or made other arrangements, such as those Thorco Denmark could make on their behalf by resort to the pool of vessels it managed).

80 The next question that arises is if the substitute vessel is not owned by the original owners under the voyage charterparty, does a bill of lading, that her master signs, become or evidence the contract of carriage for the cargo rather than the charterparty itself?

81 In the ordinary course, a charterparty between owners (or a disponent owner) and a charterer under which the charterer loads goods to be carried on the chartered ship to a destination, will provide the terms of the contract of carriage of those goods and any bill of lading issued by her master will operate as a mere receipt in the hands of the charterer. That is because such a charterparty is treated as containing the terms on which the charterer, as shipper, and the owners, as carrier, have agreed are to govern their relationship both for the voyage itself and the carriage of the shipper’s goods: Rodocanachi v Milburn (1886) 18 QB 67. There, Lord Esher MR (at 75), Lindley LJ (at 78) and Lopes LJ (at 79) held that a bill of lading issued to the shipper did not alter the pre-existing contract in the charterparty between him and the owners. Rather, in such a case, the bill of lading served only as an acknowledgment of receipt of the goods, as between the charterer or shipper and owners although, if the bill were later endorsed to a third party, it would then contain the terms of the contract of carriage between the third party and owners; see too: Turner v Haji Goolam Mahomed Azam [1904] AC 826 at 836 per Lord Lindley, giving the advice of himself, Lord Macnaghten and Sir Arthur Wilson.

82 Ordinarily, a charterparty will operate as the only contract of carriage where the charterer has contracted to buy goods from a vendor who, under the contract for sale, will be the shipper of the goods on the chartered ship. This principle was first explained by Lord Sumner, with whom Lords Parker of Waddington and Wrenbury agreed in Love and Stewart Ltd v Rowtor Steamship Co Ltd [1916] 2 AC 527 at 540. There, the vendor sold goods f.o.b. and obtained a bill of lading from the master of the ship that the purchaser had chartered for the voyage. Lord Sumner said:

… in presenting the hill [sic] of lading the [purchaser] merely did what they must needs do in order to get delivery of their cargo. They received it from [the vendor] under the contract of sale as the symbol of the delivery of goods while afloat. Nothing had occurred by which any contract for the carriage of the goods arose between them and the shipowners other than the charter itself. No new bargain had been made, under which the [shipowners] carried for the [purchaser] under a bill of lading instead of a charter. The freight earned was chartered freight and the bill of lading in the [purchaser’s] hands was only the ship’s receipt for the goods. This is the ordinary effect of documents such as these under such circumstances, and the cases cited do not bear upon them. (emphasis added)

83 As Lord Denning MR explained in President of India v Metcalfe Shipping Co Ltd (The “Dunelmia”) [1970] 1 QB 289 at 305B-C, before applying what Lord Sumner had said, as a matter of principle:

whenever an issue arises between the charterer and the shipowner, prima facie their relations are governed by the charterparty. The charterparty is not merely a contract for the hire of the use of a ship. It is a contract by which the shipowners agree to carry the goods and to deliver them.

He held that the master could not vary the contract, being the charterparty, by signing and issuing bills of lading, where the charterparty provided that in doing so he would act “without prejudice to the terms of the charterparty”, as Lord Esher MR earlier had explained in Hansen v Harrold Brothers [1894] 1 QB 612 at 619 (see too per Edmund Davies LJ [1970] 1 QB at 309, and Fenton Atkinson LJ at 310).

84 Here, cl 10 of the GENCON 1994 form, that was a term of the charterparty created by the recap dated 27 November 2014, reflected this position. But that raises the question here as to whether the bill of lading, that the master authorised to be issued, was given by him as agent of the owners of Thorco Challenger under the charterparty in the recap, or as agent of MarShip, as owners of Thor Commander. The answer to that question depends on whether there is privity of contract between Mount Isa and MarShip in the charterparty; in other words, whether the effect of the substitution of Thor Commander for Thorco Challenger was to assign or novate the charterparty to MarShip so that it can be said to have agreed with Mount Isa, as opposed to the owners of Thorco Challenger, to perform the voyage and carry the cargo under that contract.

85 As Ryan, Tamberlin and Conti JJ held in The Ship “Socofl Stream” v CMC (Australia) Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 961 at [60], The Dunelmia [1970] 1 QB 289 does not cover the circumstances where there is no privity of contract. They referred to Hi-Fert Pty Limited v Kuikiang Maritime Carriers Inc (The Kuikiang Career) (2000) 173 ALR 263 at 268 [26]-[28] with apparent approval. There Tamberlin J had held that the bill of lading was the contract of carriage between the owners of Kuikiang Career and the voyage charterer. That was because the vessel’s owners had time chartered her to the disponent owner which, in turn, had entered into both a voyage charter to, and a contract of affreightment with, the owner of the cargo shipped on board under a bill of lading. The voyage charter and bill of lading, as here, were both on GENCON forms.

86 Tamberlin J held that, in The Dunelmia [1970] 1 QB 289, “the parties to the charterparty and the bills were effectively identical”, whereas in the case before him there were two contracts, the charterparty was between the owners and charterer/disponent owner, while the bill of lading was between the owner and cargo owner, so that the latter document was the contract of carriage. That was because the parties to the bill were not the same as to the charterparty (Kuikiang Career 173 ALR at 268 [26]). Ryan, Tamberlin and Conti JJ said (Socofl Stream [2001] FCA 961 at [63]):

The Court, of course, will not find, wherever there are different parties to a bill of lading and a charterparty, that the bill of lading must be considered as a contract of carriage. Much will depend on the surrounding circumstances. Nevertheless, the distinction between the two sets of parties is an important consideration.

87 Here, the bill of lading issued for the copper anodes will only be capable of operating as a mere receipt for the cargo if MarShip was already in a contractual relationship with Mount Isa under which Thor Commander would carry the cargo.

88 In my opinion, MarShip was not in such a contractual relationship. The substitution clause in the recap operated to authorise the owners of Thorco Challenger to substitute, with Mount Isa’s approval, another vessel to perform the voyage. If that vessel were also owned by Thorco Challenger’s owners, then her master would be acting as their agent in signing (or authorising the signing) of any bill of lading for the cargo. In consequence, the bill of lading would be only a mere receipt and the recap charterparty would continue to operate as the contract of carriage. However, if a vessel not owned by Thorco Challenger’s owners were substituted for her, then the master of the substituted ship would take the cargo into his possession as agent of his owners (here MarShip) and when he signed (or authorised the signing of) the bill of lading, it would be the contract of carriage; see too: Girvin S, Carriage of Goods by Sea (2nd ed, Oxford University Press, 2011) at [12.06]; Eder B, Bennett H, Berry S, Foxton D, Smith C, Scrutton on Charterparties and Bills of Lading (22nd ed, Sweet & Maxwell, Thomson Reuters, 2011) at [4-019]; Davies M, Dickey A, Shipping Law (4th ed, Lawbook Co, 2016) at [12.10], [12.69]-[12.70].

89 I reject MarShip’s argument that the substitution clause operated as an actual or prospective authority to the owners (or disponent owner) of Thorco Challenger, as a party to the recap, to novate the recap so as to create a new voyage charter between Mount Isa and MarShip. The substitution clause is a permission to the owners, as a party to the charter, to perform the voyage using a different ship, subject to the charterer’s approval. The clause expressly dealt with the identity of any vessel that is to perform the voyage, as opposed to a clause dealing with assigning or novating the recap itself. In Leveraged Equities 191 FCR at 85 [74], the assignment and novation clause expressly provided that the bank there could both assign or novate the benefit of the contract with its borrower.

90 The essence of the substitution clause is that it permits the contracting owner (or disponent owner with the charterer’s consent) to substitute a vessel in lieu of the original ship as that owner’s performance of his contractual duty to provide a ship to undertake the voyage. The clause supplies an agreed method by which the contracting owner can perform the charterparty. There is no commercial necessity to add unexpressed contractual terms or concepts, such as assignment, or to interpolate both a rescission of the original contract in the recap and to infer a novation, to make the charterparty work according to its terms: ALH Group 245 CLR at 346 [12], 349-351 [26]-[28], [31]-[32]. And, because it must have been in the reasonable contemplation of the parties when they entered into the recap on 27 November 2014, that if a substitution occurred, the owners of the substituted vessel would be bound by any bill of lading issued by her master, they could have made, but did not, provision for the contract of carriage to be under an assigned or novated recap. Indeed, the express terms of the recap permitted the substitution of a vessel, not the discharge of the existing contract and a novation of its terms with different parties.

91 Ordinarily, a shipowner’s obligations under a charterparty are of a personal nature that cannot be performed vicariously. In Fratelli Sorrentino v Buerger [1915] 3 KB 367 at 371-372, Bankes LJ said of a situation in which the owner sold the ship while she was under charter (see too Scrutton at [4-019]; Dimech v Corlett (1858) 12 Moo PC 199 at 223; 14 ER 887 at 896 per Coleridge J for Dr Lushington, the Right Hon Pemberton Leigh and Cresswell J):

Each case must depend upon the language of the charterparty and its own particular circumstances. It can, however, I think, be stated as a general rule that where a charterparty contains obligations which can from their nature only be performed by the party himself who entered into the contract, that party cannot, by parting with the ship or otherwise, do anything which puts it out of his power to fulfil the obligations personally. He has no right to substitute any other person to perform those obligations in his place. It is not, however, every parting with a ship, whether by sale or otherwise, while she is under charter which puts it out of the power of the vendor to perform the obligations (if any) which he has undertaken to perform personally. (emphasis added)

92 Here, the owners of Thorco Challenger agreed with Mount Isa that they could perform the charterparty by substituting a vessel, with Mount Isa’s approval. They did not agree that a new party could be substituted into the charterparty itself. There is a distinction between a substitution of a vessel that the parties to the recap contemplated in their contract were the originally nominated vessel not to undertake the voyage, and a substitution of one of the parties to the recap, for which it made no express provision.

93 Although Anglo-Australian principles of maritime law proceed on the personification theory that attributes a legal personality to a ship in a proceeding in rem, that theory does not make the ship a party to a contract of carriage on it or to a charterparty of it or to a contract for the sale of the vessel itself. MarShip cited no authority involving a clause permitting owners (or a disponent owner) in a charterparty to substitute not only a different vessel but her different owners as parties to that contract as well. As I have noted, the only Admiralty authorities on this point that counsel or my researches have found rejected the proposition that the original owners whose ship was contracted to perform a voyage under a charterparty can novate that contract to other owners (and so remove themselves as contracting parties) when exercising a right to substitute a vessel.

94 A charterer (here Mount Isa) may have a contracted right to approve the substitution of the ship to perform the charter. This can be a ship in the same ownership as, or chartered by, the owners of the originally proposed ship who, after all, need to make the substitution in order to perform their contractual obligations under the charterparty. The right to substitute affords the owners (or disponent owner) of the vessel originally agreed on to undertake the voyage the ability to perform their obligations by a different mode of performance, namely by the substituted vessel.

95 Here, there was no express term in the voyage charter that provided for a novation or assignment of the owner’s rights and liabilities to the owners (or disponent owners) of the substituted vessel. Nor was there any evidence that such a novation or assignment was an ordinary incident of commercial dealings in ship chartering contracts. In essence, MarShip’s argument has a silent premise that the substitution clause included an implied term that, if a vessel were substituted then, her owners (or disponent owner) too would become parties in substitution for the contracting party whose ship was no longer going to perform the charter.

96 For a court to imply a term in a contract, based on the factual circumstances of the parties, Lord Simon of Glaisdale (for himself, Viscount Dilhorne and Lord Keith of Kinkel) in BP Refinery (Westernport) Pty Ltd v Shire of Hastings (1977) 180 CLR 266 at 283 (as applied by French CJ, Bell and Keane JJ in Commonwealth Bank of Australia v Barker (2014) 253 CLR 169 at 185-186 [21] and see too per Kiefel J at 201 [62], 209 [90]) held that:

the following conditions (which may overlap) must be satisfied: (1) it must be reasonable and equitable; (2) it must be necessary to give business efficacy to the contract, so that no term will be implied if the contract is effective without it; (3) it must be so obvious that “it goes without saying”; (4) it must be capable of clear expression; (5) it must not contradict any express term of the contract.

97 Here, the substitution clause works well enough without the need for any implication of a novation when a substitution occurs. There is no commercial need to make the implication to give any business efficacy to the charterparty. Nor is the proposed implication “so obvious that it goes without saying”.

98 The context in which the recap was agreed included Mount Isa’s insistence that “Owners/ Disponent Owner/ commercial manager Thorco” had to confirm or do several things in relation to Thorco Challenger (see [54]-[55] above), including that she was fully suitable for Australian trading. That requirement, of course, would also apply to any substituted vessel – namely each of the owners, any disponent owner and Thorco Denmark had to confirm or ensure that the substitute ship met the five particular requirements. If the owners or disponent owners of Thorco Challenger wanted to substitute another vessel, there is no apparent reason why it would give business efficacy, or it would be obvious, that they would cease to be liable if the substituted ship did not comply with any of those requirements and the owners or disponent owner would assume that liability in substitution. To the contrary, when the owners or disponent owner of Thorco Challenger wished to change the ship to perform the charterparty, there is every reason why they should remain liable to ensure that any substitute also met the five requirements.

99 When Thorco Denmark negotiated the recap on behalf of its unnamed and undisclosed principals, being the owners or disponent owner of Thorco Challenger, Mount Isa required that, in addition to the other terms, the undisclosed principal and Thorco Denmark comply with the five additional requirements.

100 The form of the recap also raised a further issue as to the identity of the parties to the charterparty evidenced in that recap. That arose because on five occasions the recap provided that “Owners/ Disponent Owner/ commercial manager Thorco” promised something, including, for example, confirming that “the vessel is fully suitable for Australia [sic] Trading.”

101 On one view, the form of those five promises could suggest that the undisclosed persons or entities described as ‘Owners’, ‘Disponent Owner’, and ‘commercial manager Thorco’ were all parties who together promised to provide the ship for Mount Isa, and that whatever Thorco entity was the undisclosed principal would also make each promise. Finn, Rares and Besanko JJ discussed such a construction in Carminco Gold & Resources Ltd v Findlay & Co Stockbrokers (Underwriters) Pty Ltd (2007) 243 ALR 472 at 479-482 [22]-[32].

102 In my opinion, the five promises were expressed in such a way that having regard to the terms of the recap as a whole, the collocation of three promisors (Owners/ Disponent Owner/ commercial manager Thorco) became parties to a collateral contract with Mount Isa and made the five promises to it in consideration of which Mount Isa entered into the charterparty with the owners (or disponent owner) of Thorco Challenger on the terms set out in the balance of the recap dated 27 November 2014. In context, this collateral contract operated in much the same way as a guarantee offered by a director or shareholder of a contracting party to the other party. I have formed this opinion because, first, the balance of the terms of the recap had nothing to do with the collocation of the three promisors, except that one of them, being the person that, in fact, had the immediate right to charter Thorco Challenger to Mount Isa, would be a party to both the charterparty and the collateral contract, and secondly, the substitution clause in a practical, commercial sense could only have conferred a right and corresponding obligation on a person who actually had such control of the vessel that they could ensure that, it or a substitute would perform the voyage.

103 For these reasons, I am of opinion that the contract of carriage under which Thor Commander carried the cargo was the bill of lading and not the charterparty constituted in the recap dated 27 November 2014.

4.6 Can Mount Isa sue on the bill of lading?

104 The amended Hague Rules in Sch 1A to COGSA have force of law in Australia in respect of, and apply to, a contract of carriage of goods by sea pursuant to ss 7 and 10(1)(b)(i) and (iii) of that Act, where, as s 10(2)(b)(iii) provides, the contract is relevantly:

contained in or evidenced by a non-negotiable document (other than a bill of lading or similar document of title), being a contract that contains express provision to the effect that the amended Hague Rules are to govern the contract as if the document were a bill of lading.

105 The amended Hague Rules apply to the carriage of the cargo on Thor Commander since cl 2(a) and (b) of the bill of lading so provides. That is because, it is common ground, no enactment that gave effect to the Hague Rules or the Hague-Visby Rules was in force in Peru, the country of shipment.

106 The amended Hague Rules define certain expressions differently to the Sea-Carriage Documents Act. Had there been any relevant difference between the Sea-Carriage Documents Act and the amended Hague Rules, a question may have arisen (but did not arise) under s 109 of the Constitution as to how much, if any, of the former still could operate consistently with the latter.

107 Importantly, Art 3(8) operated to apply the provisions of the amended Hague Rules, and to invalidate any provisions of the bill of lading or the charterparty, so far as its provisions may have been incorporated into the bill as part of the contract of carriage of the cargo, that might otherwise have relieved or lessened the liability of Thor Commander or MarShip, as her owners, for any loss or damage that Mount Isa suffered.

108 Relevantly, Art 10(7) applied the amended Hague Rules only to a negotiable sea-carriage document “issued under a charterparty … and only while the document regulates the relationship between the holder of it and the carrier of the relevant goods”.

109 Here, the bill of lading was not “issued under the charterparty” – i.e. as a receipt to the charterer – but under the obligation of the master to issue CMA, as shipper, with a bill of lading to evidence the contract of carriage of the anodes on MarShip’s vessel. That is because, although the master of Thor Commander acted under the instructions of his owners to sign (or authorise the signing of) the bill of lading in accordance with the charterparty, MarShip was not a party to that charterparty, for the reasons above.

110 It follows that the bill of lading was not issued “under the charterparty” in the circumstances. Indeed, if the expression in Art 10(6) and (7) “under a charterparty” referred to the mere fact that the ship happened to be under charter (including a demise charter), the amended Hague Rules would be likely to have little utility. That would be contrary to the object identified in s 3(1) of COGSA of providing a regime of marine cargo liability that is up-to-date, equitable, efficient, and compatible with that of Australia’s major trading partners and current developments within the United Nations in relation to marine cargo liability arrangements.