FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Kemppi v Adani Mining Pty Ltd (No 4) [2018] FCA 1245

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicants’ further amended originating application filed 18 December 2017 is dismissed.

2. The applicants pay the respondents’ costs to be agreed or assessed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REEVES J:

INTRODUCTION

1 Ms Delia Kemppi and her fellow applicants are Wangan and Jagalingou People. They also form a part of a group within the Wangan and Jagalingou People who are opposed to the Carmichael coal mine which Adani Mining Pty Ltd (the first respondent) wishes to develop in Central Queensland.

2 The area of the proposed Carmichael coal mine falls within the claim area of the Wangan and Jagalingou native title determination application (the W & J application). As a consequence, Adani needs to obtain the agreement of the Wangan and Jagalingou People with respect to any native title that may be affected by its development. To that end, in April 2016, Adani, the State of Queensland (the third respondent) and the Wangan and Jagalingou native title claim group (the W & J claim group) entered into an Indigenous Land Use Agreement (the Adani ILUA) under the provisions of Division 3 of Part 2 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the NTA). Subsequently, Adani successfully applied to the Native Title Registrar (the fourth respondent) to enter the Adani ILUA on the Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements (the Register) under Part 8A of the NTA.

3 Ms Kemppi’s main goal in this proceeding was to set aside that registration. The path to that goal comprised two stages. The first stage concerned a certificate that was issued by Queensland South Native Title Services (QSNTS) (the second respondent) in April 2016 under s 203BE(1)(b) of the NTA (the Certificate). That Certificate was subsequently used by Adani to support its application to the Registrar to enter the Adani ILUA on the Register. Accordingly, in the first stage, Ms Kemppi sought, by this proceeding, to have that Certificate declared to be “void and of no effect”. Assuming she is able to obtain that declaration, in the second stage, Ms Kemppi sought a declaration that the Registrar had no jurisdiction to consider Adani’s application and therefore his decision to enter the Adani ILUA on the Register was “void and of no effect”.

4 There were two legs to Ms Kemppi’s attack on the Certificate. In the first leg, she claimed that, in issuing the Certificate, QSNTS acted unreasonably and thereby committed jurisdictional error which, she claimed, justified the declaration of nullity that she sought. In the alternative, in the second leg, she claimed that, in issuing the Certificate, QSNTS failed to take account of a number of relevant considerations which, she claimed, resulted in jurisdictional error which, she claimed, should lead to the same result. Finally, Ms Kemppi made a third challenge to the registration of the ILUA. She claimed that Adani’s application to register the ILUA did not comply with regs 5 and 7(2)(e) of the Native Title (Indigenous Land Use Agreements) Regulations 1999 (Cth) (the Regulations) and, for that reason, the Registrar’s decision to register the ILUA was void and of no effect.

5 Before considering these three grounds of challenges more closely, it is appropriate to provide some further factual context. In the paragraphs that follow, I have relied extensively on the statement of agreed facts adopted by all the parties, except the fourth respondent, who filed a submitting appearance.

FACTUAL CONTEXT

Further details of the W & J application

6 The W & J application was filed on behalf of the W & J claim group by its then authorised applicant (the W & J Applicant) on 27 May 2004. The application covers an area of approximately 30,277 square kilometres on the western edge of Central Queensland and includes the townships of Clermont, Alpha, Rubyvale and Capella. The requisite details of the application were entered on the Register of Native Title Claims (under s 190(1)(a) of the NTA) on 5 July 2004.

7 Ms Kemppi and her fellow applicants (who I will together refer to hereafter as “Ms Kemppi”) comprise five of the 12 members of the presently constituted W & J Applicant. The other seven members are Mr Patrick Malone, Ms Irene White, Ms Priscilla Gyemore, Mr Craig Dallen, Mr Norman Johnson Jnr, Ms Gwendoline Fisher and Mr Les Tilley. One of the consequences of the registration of the W & J application is that Ms Kemppi and the other 11 members of the W & J Applicant also comprise the registered native title claimant for the W & J claim, as that expression is defined in the NTA: see ss 253 and 186(1) of the NTA.

The notices for the authorisation meeting

8 On 16 April 2016, a meeting was held to consider authorising the making of the Adani ILUA under s 251A of the NTA (the authorisation meeting). Prior to that meeting, Adani published notices advertising the meeting in the following newspapers:

(a) The Courier-Mail on 16 March 2016;

(b) The Fraser Coast Chronicle on 18 March 2016;

(c) The Morning Bulletin on 18 March 2016;

(d) The Townsville Bulletin on 18 March 2016;

(e) The South Burnett Times on 22 March 2016;

(f) The Koori Mail on 23 March 2016; and

(g) The Central Queensland News on 23 March 2016.

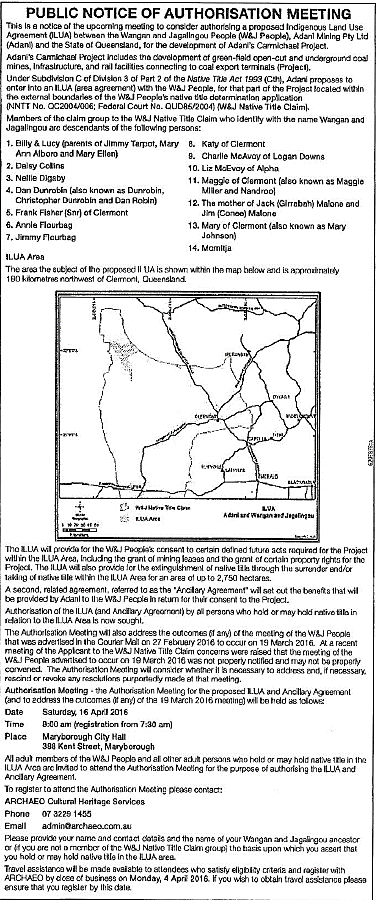

9 An example of those published notices was the following, which was published in the Fraser Coast Chronicle:

10 In addition to publishing the newspaper notices described above, on or about 16 March 2016, Adani sent by express post to each person on a mailing list maintained by QSNTS a document entitled “Public Notice of Authorisation Meeting”, which provided notice of the authorisation meeting in a similar form to that above.

The authorisation meeting

11 The authorisation meeting was held on 16 April 2016. Two forms of record were made of that meeting. One was an extract of the main resolutions passed at the meeting and the other was a detailed record of the meeting entitled “Record of Meeting”. That record was based on notes taken by Ms Wendy Bithell and Mr Chris Athanasiou and their recollection of the events of the meeting.

12 The main resolutions document mentioned above commenced with a preamble and then set out the terms of the main resolutions passed at the meeting. That preamble was as follows:

PREAMBLE

Members of the native title claim group to the Wangan and Jagalingou People Native Title Determination Application (NNTT No. QC2004/006; Federal Court No. QUD85/2004) (W&J Native Title Claim) who identify with the name Wangan and Jagalingou are descendants of the following persons:

1. Billy & Lucy (parents of Jimmy Tarpot, Mary Ann Alboro and Mary Ellen) | 8. Katy of Clermont |

2. Daisy Collins | 9. Charlie McAvoy of Logan Downs |

3. Nellie Digaby | 10. Liz McEvoy of Alpha |

4. Dan Dunrobin (also known as Dunrobin, Christopher Dunrobin and Dan Robin) | 11. Maggie of Clermont (also known as Maggie Miller and Nandroo) |

5. Frank Fisher (Snr) of Clermont | 12. The mother of Jack (Girrabah) Malone and Jim (Conee) Malone |

6. Annie Flourbag | 13. Mary of Clermont (also known as Mary Johnson) |

7. Jimmy Flourbag | 14. Momitja |

(the W&J People).

The W&J People wish to consider the authorisation of a proposed agreement between Adrian Burragubba, Patrick Malone, Irene White, Lyndell Turbane, Priscilla Gyemore, Craig Dallen, Linda Bobongie, Norman Johnson Jnr, Gwendoline Fisher, Les Tilley, Delia Kemppi and Lester Barnard on their own behalf in their capacity as Registered Native Title Claimant for the W&J Native Title Claim and on behalf of the W&J People, Adani Mining Pty Ltd and the State of Queensland, that is intended to be registered as an Indigenous Land Use Agreement (ILUA).

The W&J People also wish to consider the related ancillary agreement to that ILUA (Ancillary Agreement) between Adrian Burragubba, Patrick Malone, Irene White, Lyndell Turbane, Priscilla Gyemore, Craig Dallen, Linda Bobongie, Norman Johnson Jnr, Gwendoline Fisher, Les Tilley, Delia Kemppi and Lester Barnard on their own behalf in their capacity as Registered Native Title Claimant for the W&J Native Title Claim and on behalf of the W&J People and Adani Mining Pty Ltd.

13 The main resolutions recorded in that document included the following:

3. AUTHORISATION OF ILUA AND ANCILLARY AGREEMENT

The persons present and entitled to vote at this meeting comprising the persons who hold or may hold native title to the ILUA Area:

AUTHORISE:

(a) the making of an ILUA between Adrian Burragubba, Patrick Malone, Irene White, Lyndell Turbane, Priscilla Gyemore, Craig Dallen, Linda Bobongie, Norman Johnson Jnr, Gwendoline Fisher, Les Tilley, Delia Kemppi and Lester Barnard on their own behalf in their capacity as Registered Native Title Claimant for the W&J Native Title Claim and on behalf of the W&J People, Adani Mining Pty Ltd and the State of Queensland titled ‘Carmichael Project Indigenous Land Use Agreement’ over the lands and waters described in the ILUA as presented to and discussed at this meeting of 16 April 2016; and

(b) the making of an Ancillary Agreement between Adrian Burragubba, Patrick Malone, Irene White, Lyndell Turbane, Priscilla Gyemore, Craig Dallen, Linda Bobongie, Norman Johnson Jnr, Gwendoline Fisher, Les Tilley, Delia Kemppi and Lester Barnard on their own behalf in their capacity as Registered Native Title Claimant for the Native Title Claim and on behalf of the W&J People and Adani Mining Pty Ltd as presented to and discussed at this meeting of 16 April 2016.

Moved: | Cindy Button |

Seconded: | Leisa Sjaardema |

Votes For: | 293 (green); 1 (red): Total: 294 |

Votes Against: | 1 (green) |

Abstentions: | 3 (green) |

Decision: | Carried |

4. REPRESENTATIVES TO SIGN THE ILUA AND ANCILLARY AGREEMENT ON BEHALF OF THE W&J PEOPLE

The persons present and entitled to vote at this meeting comprising the persons who hold or may hold native title to the ILUA Area:

(a) authorise and direct the persons who comprise the Applicant for the W&J Native Title Claim who are presently:

• Adrian Burragubba;

• Patrick Malone;

• Irene White;

• Lyndell Turbane;

• Priscilla Gyemore;

• Craig Dallen;

• Linda Bobongie;

• Norman Johnson Jnr;

• Gwendoline Fisher;

• Les Tilley;

• Delia Kemppi; and

• Lester Barnard,

on their own behalf in their capacity as Registered Native Title Claimants for the W&J Native Title Claim and on behalf of the W&J People, to sign the proposed ILUA and Ancillary Agreement, to bind themselves and the W&J People to the terms of the ILUA and Ancillary Agreement and to take all steps as are necessary to have the ILUA registered;

(b) where one or more of the persons comprising the Applicant for the W&J Native Title Claim refuse or are unable to sign the proposed ILUA and Ancillary Agreement, the W&J People agree to be bound by, and this Authorisation Meeting evidences the W&J People’s intent to enter into and authorise, the ILUA and Ancillary Agreement; and

(c) agree that the signatories to the proposed ILUA and Ancillary Agreement may make such minor technical or other amendments to the proposed ILUA and Ancillary Agreement as they consider appropriate and necessary to better assist the registration of the ILUA without the need for another Authorisation Meeting of the W&J People.

Moved: | Martin White |

Seconded: | Frank Button |

Votes For: | 291 (green); 1 (red): Total: 292 |

Votes Against: | Nil (green) |

Abstentions: | Nil (green) |

Decision: | Carried |

5. AUTHORISATION FOR ADANI TO MAKE APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION OF THE ILUA ON THE REGISTER OF INDIGENOUS LAND USE AGREEMENTS

The persons present and entitled to vote at this meeting comprising the persons who hold or may hold native title to the ILUA Area:

(a) authorise Adani Mining Pty Ltd to apply to the Native Title Registrar for the proposed ILUA to be registered as an ILUA on the Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements pursuant to section 24CG of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) and to thereafter take all steps as necessary to have the ILUA registered; and

(b) request that Queensland South Native Title Services certify the application for registration of the ILUA in accordance with its statutory function pursuant to section 203BE(1)(b) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth);

(c) confirm that they will do all things reasonably necessary to support the State of Queensland, Adani Mining Pty Ltd and the Native Title Registrar to register the proposed ILUA including, but not limited to not objecting to the registration of the ILUA or the certification of the application to register the ILUA and assisting Adani and the Native Title Registrar to resolve any objections that are made to the registration of the ILUA or the certification of the application to register the ILUA.

Moved: | Rose (Catrine Rosaline) Sjaardema |

Seconded: | Patrick Malone |

Votes For: | 281 (green); 1 (red): Total: 282 |

Votes Against: | Nil (green) |

Abstentions: | Nil (green) |

Decision: | Carried |

14 With respect to resolution 4 above, the agreed facts record the following:

6. Patrick Malone, Irene White, Priscilla Gyemore, Craig Dallen, Norman Johnson Jnr, Gwendoline Fisher and Les Tilley signed [the ILUA] on 16 April 2016

7. [Adani] signed the ILUA on 18 April 2016.

8. The ILUA was signed by the Minister for Natural Resources and Mines on behalf of [State] on 20 April 2016.

9. [Ms Kemppi and her fellow] applicants have not signed the ILUA.

15 The Record of Meeting document mentioned above contained a detailed record of the attendees at the meeting, the information that was provided to those attendees and the details of comments made by the meeting facilitator, Mr Darryl Pearce, and others, during the course of the meeting. With respect to the attendees, the record document recorded that they fell into the following categories:

(a) Wangan & Jagalingou People (green wrist bands);

(b) Persons claiming to hold native title in the ILUA Area, Erica Walker (red wrist band);

(c) Facilitator, Darryl Pearce (yellow wrist band);

(d) Legal adviser to the Facilitator, Chris Athanasiou (yellow wrist band);

(e) Minute Taker, Wendy Bithell (yellow wrist band);

(f) Representatives of Adani Mining (yellow wrist band):

• Ian Sedgman – General Manager, Mine Infrastructure;

• Muthuraj Guruswamy (Raj) – General Manager, Corporate Affairs;

• Llewellyn Lezar – Head of Mining;

• Derek Neilson – Senior Legal Counsel;

• Hamish Manzi – Head of Environment & Sustainability;

• Srinivasa Yarlagadda – Manager, Hydrogeology & Approvals;

• Melinda Bergmann – Manager, Approvals;

• Vinay Panday – Manager, Planning; and

• External legal representatives/consultants: William Oxby and Alice Hoban (Herbert Smith Freehills) and Graham Carter (Environment Land Heritage);

(g) Legal representatives for the Applicant on the W&J Native Title Claim for future act and cultural heritage matters, HWL Ebsworth, Philip Hunter & Lara McQuaid (yellow wrist band);

(h) Representatives of QSNTS assisting with registration and certification (yellow wrist band):

• Jeff Harris – Research Manager;

• Andrew Fahey – Research Officer;

• Nicolas Daza – Research Administration Officer;

• Richard Sporne – Community Relations Officer;

• Ron Fogarty – Community Relations Officer; and

(i) Persons assisting with the conduct of the meeting such as safety personnel (yellow wrist band).

16 As to the information that was provided to the attendees at the meeting, the record document recorded the following:

2. On each chair in the hall there was a white folder titled Wangan & Jagalingou and Adani Carmichael Project ILUA ILUA Authorisation Meeting Materials City Hall, Maryborough Saturday, 16 April 2016 (the “Information Folder”) containing the following documents:

• a yellow document titled Wangan & Jagalingou and Adani Carmichael Project ILUA ILUA Authorisation Meeting City Hall, Maryborough Saturday, 16 April 2016 Agenda, which also stated “Draft Agenda” in the top left hand corner of the cover page (the “Agenda”);

• a blue document titled Wangan & Jagalingou and Adani Carmichael Project ILUA ILUA Authorisation Meeting City Hall, Maryborough Saturday, 16 April 2016 Resolutions, which also stated “Draft Resolutions” in the top left hand corner of the cover page (the “Resolutions”);

• a colour printed booklet titled The Carmichael Project Wangan & Jagalingou and Adani Mining Pty Ltd Indigenous Land Use Agreement Ancillary Agreement Cultural Heritage Management Plans Information Booklet ILUA (the “Information Booklet”); and

• a white document titled Wangan & Jagalingou People Native Title Claim Group (W&J People) Adani’s Carmichael Project Indigenous Land Use Agreement and Ancillary Agreement Authorisation Meeting Maryborough, 16 April 2016 (the “W&J Presentation”).

3. There were two screens at the end of the hall onto which the documents in the Information Folder were projected at the times they were discussed.

4. The meeting opened at 9.00am, following registration which commenced at around 7.00am.

(Emphasis in original)

17 The statements made during the opening session of the meeting were recorded in the record document as follows:

Opening statement by the Applicant.

11. Les Tilley from the W&J People addressed the group and requested a minute’s silence. The minute’s silence was held.

12. Les Tilley thanked the Butchulla People for their welcome. He hoped the W&J People would achieve today what they most desire. Les recognised ancestors, elders and children.

13. Les Tilley thanked Adani for sticking with them for many years and for giving them the opportunity to ensure future generations are taken care of.

14. Less (sic) Tilley said all W&J People were all here for the same thing. He noted families have been torn by negotiations and outside sources and he hoped families can come back together.

15. Regarding voting, Les Tilley said it was the W&J People’s choice. Under Australian law it may be seen as signing away land but under Aboriginal lore it will always be Aboriginal land.

16. Les Tilley said that all W&J People have a say in who represents us and who are our cultural leaders. He stated everyone in the room is a cultural leader.

17. Les Tilley thanked people for coming today.

18. Patrick Malone (W&J People) thanked all for the minute’s silence. He said their family is still in mourning over the loss of their sister Jessie Diver. She was passionate about the claim and they honour her memory today.

19. Darryl Pearce addressed the group and asked that mobile phones be turned off. He said that these meetings are stressful. He also mentioned that when a moment’s silence is taken older people are remembered but the young ones that also are no longer with us should also be remembered.

20. Darryl Pearce said the decision today should be a heart decision. People should be responsible for their decision and know their decision was right and for future generations.

21. Darryl Pearce said questions can be asked throughout the day.

22. Darryl Pearce referred the meeting to the Agenda. The meeting agreed with the Agenda through show of voices.

(Emphasis in original)

18 Following a presentation made by representatives of Adani and a discussion of other topics, the meeting turned to consider the resolutions to authorise the making of the ILUA. The introductory notes concerning that part of the meeting were noted in the record document as follows:

91. 1.20pm. The meeting reconvened. A QSNTS representative advised the Facilitator there were 341 people registered at the close of registration, one of whom (Erika Walker) was not a member of the W&J native title claim group.

92. Darryl Pearce told the meeting that the Register had closed and that 341 people had registered, one of whom was not a member of the W&J native title claim group. He said the impression he was getting was that the people wanted to cut to the chase and make a decision. He asked if that was correct. The majority agreed verbally.

93. Darryl Pearce confirmed who should be in the meeting. The people from the W&J group had a green wristband and family members wore a light blue wristband. Those persons who claim to hold native title in relation to the ILUA area wore a red wristband. Only people with green and red wristbands could vote. He then asked if everyone in the room was comfortable with that. The overwhelming majority verbally agreed.

94. Darryl Pearce referred the meeting to the “blue document” – the Resolutions, which like the other documents in the Information Folder, was projected onto the two screens for the session. He summarised its pre-amble, which is on page 2 of the Resolutions.

(Emphasis in original)

19 The notes in the record document relating to that part of the meeting where a resolution was passed to adopt a decision-making process were as follows:

1. Decision-making Process

95. Darryl Pearce read the first resolution: Decision-Making Process, from page 3 of the Resolutions document:

1. Decision-making process

The persons present and entitled to vote at this meeting comprising the persons who hold or may hold native title to the ILUA Area:

(a) confirm that there is no particular process of decision-making under their traditional laws and customs that must be complied with by them when making decisions about authorising the making of an agreement that is intended to be registered as an ILUA and when dealing with matters arising in relation to matters of that kind; and

(b) confirm that the decision-making process which will be adopted for this meeting is as follows:

(i) the decision to be made will be put in the form of a clearly worded written motion;

(ii) the motion will be read out to the meeting;

(iii) the motion must be moved and seconded by those present before it is decided on;

(iv) a decision in favour of or against the motion will be decided by a majority of a show of hands of those present and entitled to vote on the motion;

(v) if there is any doubt about the result of the show of hands, a ballot may be conducted.

96. Darryl Pearce asked who would like to move the motion. Edna Malone agreed to move the motion.

97. Darryl Pearce asked who would like to second the motion. Theodore Frescon agreed to second the motion.

98. Darryl Pearce asked if anyone would like to comment on the move for the motion. No-one sought to.

99. Darryl Pearce asked if anyone would like to comment against the move for the motion. No-one sought to.

100. Darryl Pearce asked all those who were in favour of the motion to raise their hand with the green armband. Darryl Pearce requested Chris Athanasiou, Philip Hunter and Lara McQuaid to each count the number of persons who had green wrist bands with their arms raised in three allotted sections of the hall which could be delineated by the seating arrangement. This they did. They advised their count which was noted down and tallied by Philip Hunter whilst overseen by Darryl Pearce and Chris Athanasiou.

101. Darryl Pearce then asked all those who oppose the motion as read out to raise their hands. There were none.

102. Darryl Pearce asked all those who wish to abstain from the motion to raise their hands. There were none.

103. Darryl Pearce asked those with the red band who may hold native title to the ILUA Area who are in favour of the motion to raise their arm. Erika Walker, the sole person in this category, raised her hand.

104. Darryl Pearce said there were 284 votes for the motion and none against therefore the motion was passed.

Result:

Moved: | Edna Malone |

Seconded: | Theodore Frescon |

Votes For: | 283 (green); 1 (red): Total: 284 |

Votes Against: | 0 |

Abstentions: | 0 |

Decision: | Motion is carried. |

20 The notes in the record document relating to that part of the meeting where the resolution was passed to authorise the making of the Adani ILUA were as follows:

3. Authorisation of ILUA and Ancillary Agreement

116. Darryl Pearce read out Resolution 3, Authorisation of ILUA and Ancillary Agreement from page 5 of the Resolutions document and apologised for the mispronunciation of any names:

3. Authorisation of ILUA and Ancillary Agreement

The persons present and entitled to vote at this meeting comprising the persons who hold or may hold native title to the ILUA Area:

Authorise

(a) the making of an ILUA between Adrian Burragubba, Patrick Malone, Irene White, Lyndell Turbane, Priscilla Gyemore, Craig Dallen, Linda Bobongie, Norman Johnson Jnr, Gwendoline Fisher, Les Tilley, Delia Kemppi and Lester Barnard on their own behalf in their capacity as Registered Native Title Claimant for the W&J Native Title Claim and on behalf of the W&J People, Adani Mining Pty Ltd and the State of Queensland titled ‘Carmichael Project Indigenous Land Use Agreement’ over the lands and waters described in the ILUA as presented to and discussed at this meeting of 16 April 2016; and

(b) the making of an Ancillary Agreement between Adrian Burragubba, Patrick Malone, Irene White, Lyndell Turbane, Priscilla Gyemore, Craig Dallen, Linda Bobongie, Norman Johnson Jnr, Gwendoline Fisher, Les Tilley, Delia Kemppi and Lester Barnard on their own behalf in their capacity as Registered Native Title Claimant for the W&J Native Title Claim and on behalf of the W&J People, Adani Mining Pty Ltd as presented to and discussed at this meeting of 16 April 2016.

117. Darryl Pearce asked if there was anyone who wished to move the motion.

118. A W&J attendee mentioned not all Applicants are present. Darryl Pearce explained that not all Applicants were required to sign the agreements.

119. Cindy Button moved the motion.

120. Darryl Pearce asked who would like to second the motion. Leisa Sjaardema seconded the motion.

121. Darryl Pearce asked if anyone would like to speak for the motion. No-one sought to.

122. Darryl Pearce asked if anyone would like to speak against the motion. No-one sought to.

123. Darryl Pearce said on the basis that he had asked if anyone wanted to speak on the motion and that no-one had chosen to take the opportunity, that he would take the motion to the floor.

124. Darryl Pearce asked that those persons with a green wrist band who are in support of the motion as read out to raise their hands in the air. Chris Athanasiou, Philip Hunter and Lara McQuaid each counted the number of people who had green wrist bands with their arms raised in their allotted sections of the hall. The counters reported their count, which was noted down and tallied by Philip Hunter.

125. Darryl Pearce then asked that those persons with a green wrist band who are opposed to the motion to raise their hand in the air. Only one hand was raised at the rear of the hall, which was counted by Chris Athanasiou.

126. Darryl Pearce asked that those persons with a green wrist band who wished to abstain from the motion to raise their hand in the air. Chris Athanasiou, Philip Hunter and Lara McQuaid each counted the number of people who had green wrist bands with their arms raised in their allotted sections of the hall. The counters reported their count, which was noted down and tallied by Philip Hunter. Darryl Pearce said that those people who abstained can have their name recorded if they wished. No-one sought to.

127. Darryl Pearce asked those with a red band who may hold native title to the ILUA Area who support the motion to raise their arm. Erika Walker, the sole person in this category, raised her hand.

128. Darryl Pearce said that as there were 294 votes for the motion, 1 against and 3 abstentions it was carried; resolution passed. He congratulated everyone. There was applause from the meeting.

Result:

Moved: | Cynthia Button |

Seconded: | Leisa Sjaardema |

Votes For: | 293 (green); 1 (red): Total: 294 |

Votes Against: | 1 |

Abstentions: | 3 |

Decision: | Motion is carried. |

The Adani ILUA

21 The Adani ILUA was dated 20 April 2016. The parties to it were recorded as:

Adrian Burragubba, Patrick Malone, Irene White, Lyndell Turbane, Priscilla Gyemore, Craig Dallen, Linda Bobongie, Norman Johnson Jnr, Gwendoline Fisher, Les Tilley, Delia Kemppi and Lester Barnard (Representative Parties) on their own behalf in their capacity as Registered Native Title Claimant for the Native Title Claim and on behalf of the W&J People

Adani Mining Pty Ltd ABN 27 145 455 205 (Adani)

State of Queensland (State)

22 In the introductory section of the Adani ILUA, its background was recorded as follows:

A. Adani proposes to develop a project in the ILUA Area, which will include:

(a) the development of greenfield open-cut and underground coal mines, with a yield of up to 60 million tonnes per annum of product coal; and

(b) the construction and operation of a railway line and other appropriate rail facilities connecting those coal mines to one or more ports.

B. The W&J People assert that they hold Native Title Rights and Interests to the ILUA Area, including pursuant to the Native Title Claim. The ILUA Area is located wholly within the external boundary of the Native Title Claim.

C. The Parties have:

(a) entered into this Agreement for the purposes of ensuring the validity of the Agreed Acts, any Surrender or Taking of Native Title and the undertaking of the ILUA Project; and

(b) in that respect, have agreed, on the terms outlined in this Agreement and the Ancillary Agreement, to consent to the Agreed Acts, any Surrender or Taking of Native Title and the undertaking of the ILUA Project.

D. The State is a Party to this Agreement due to the requirement under section 24CD(5) of the NTA in relation to the Surrender. The State is not a party to the Ancillary Agreement.

23 The next section of the Adani ILUA set out the meanings of various expressions used in the body of the document. For present purposes, the following definitions are pertinent:

Agreed Acts means the acts and classes of acts listed in Schedule 2.

…

ILUA Area means the area described at Part 1 of Schedule 1 and shown on the map at Part 2 of Schedule 1.

ILUA Project means the project referred to in paragraph A of the Background and includes (to the extent that Adani, acting reasonably, considers the activities to be necessary or desirable (whether or not exclusively) for, or to support any aspect of the project) the planning, design, development, establishment, construction, extension, operation and maintenance of:

(a) a coal mine or mines within the ILUA Area including exploration and drilling for coal;

(b) removal and stockpiling of overburden;

(c) extraction, processing and production of coal;

(d) conveying and haulage transportation of coal;

(e) loading and marketing of coal;

(f) railway lines and railway infrastructure;

(g) facilities for the extraction, storage, processing and transportation of gas including gas pipelines and other gas infrastructure;

(h) facilities for the extraction, storage, processing and transportation of water including water pipelines, dams, bores and other water infrastructure;

(i) power generation facilities, power transmission facilities and power lines;

(j) access roads, haul roads and bridges;

(k) levees and groin walls;

(l) quarries and borrow pits;

(m) laydown areas and stockpiles;

(n) construction camps, accommodation villages and buildings;

(o) offices, workshops and any other building or structures;

(p) utility and industrial facilities and areas;

(q) airports, airstrips and associated infrastructure;

(r) telecommunication lines, communication cables and towers and other communication facilities;

(s) sewer pipelines and associated infrastructure;

(t) navigational equipment or aids; and

(u) fuel, oil and explosives storage facilities,

as well as a reference to each and every phase and component of the operations referred to above and activities related to, associated with or incidental to the activities referred to above (including the phase of decommissioning and completing any final rehabilitation of those operations and terminating or surrendering the Agreed Acts).

…

Surrender means a surrender to the State of any of the Native Title within the Surrender Area for the purposes of the ILUA Project in accordance with the process set out in clause 9(b).

Surrender Area means an area of not more than 2,750 hectares to be located within the Surrender Zone.

Surrender Zone means the external boundaries formed by the coordinates set out at Part 3 of Schedule 1 and shown on the map at Part 4 of Schedule 1.

(Emphasis in original)

24 The acts and classes of acts listed in Schedule 2, referred to in the definition of “Agreed Acts” above, were as follows:

(a) the Grant of any Approvals (or any other rights and interests) with respect to the ILUA Project, including:

(i) Mining Interests (including the Mining Leases);

(ii) under the Transport Infrastructure Act 1994 (Qld);

(iii) under the Environmental Protection Act 1994 (Qld) and the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (including any environmental authority);

(iv) under the Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004 (Qld) (including any pipeline licences or other petroleum authorities);

(v) the declaration, dedication, use, management or similar act of any part of the ILUA Area for road purposes;

(vi) the de-gazettal or similar act of any roads, reserves or other Crown land;

(vii) tenure under the Land Act 1994 (Qld) and any easements;

(viii) any water licence, dam licence or other Approvals under the Water Act 2000 (Qld);

(ix) any Approvals related to or associated with any infrastructure including power lines, water pipelines, gas pipelines, conveyors, construction camps, buildings, roads, railways and telecommunication lines or other communication facilities; and

(x) under the Sustainable Planning Act 2009 (Qld), Coastal Protection and Management Act 1995 (Qld), Forestry Act 1959 (Qld), State Development and Public Works Organisation Act 1971 (Qld), Vegetation Management Act 1999 (Qld), Electricity Act 1994 (Qld), Fisheries Act 1994 (Qld), Nature Conservation Act 1992 (Qld), Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (Qld), Queensland Heritage Act 1992 (Qld), Building Act 1975 (Qld), Explosives Act 1999 (Qld), Transport Planning and Coordination Act 1994 (Qld), Telecommunications Act 1997 (Cth) and Civil Aviation Act 1988 (Cth);

(b) the undertaking of any acts pursuant to the above Grants or acts considered by Adani, acting reasonably, to be necessary or desirable for, or incidental to, the undertaking of the ILUA Project;

(c) the making, amendment or repeal of legislation (including regulations, by-laws and ordinances) and similar acts necessary or desirable for, or incidental to, the ILUA Project; and

(d) the validation of any of the acts referred to in paragraphs (a) to (c) above that were done invalidly prior to the Conclusive Registration of this Agreement.

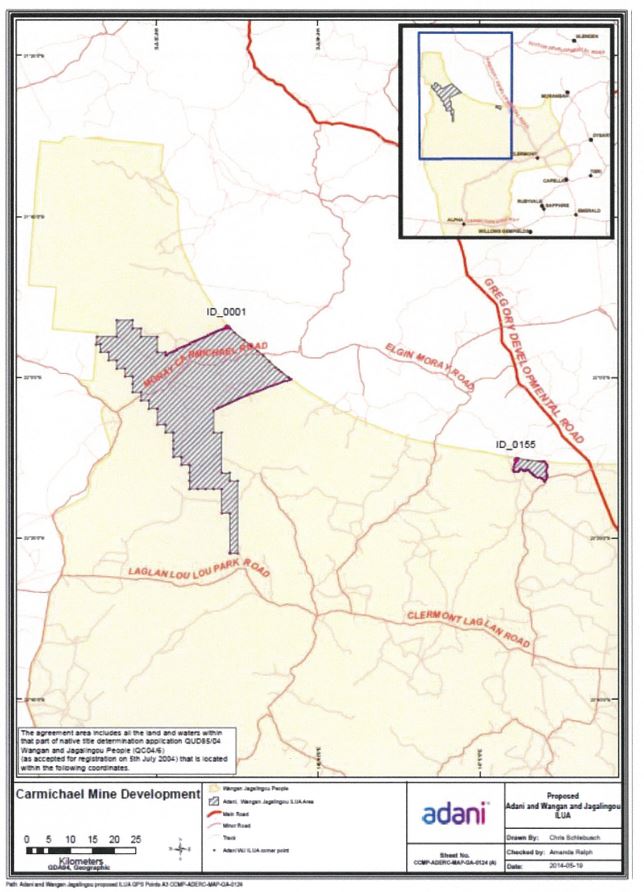

25 The area described at Part 1 of Schedule 1 and the map at Part 2 of Schedule 1, referred to in the definition of “ILUA Area” above, were as follows:

Part 1 - Description of External Boundary (ILUA Area)

The ILUA Area includes all the land and waters within the part of the Native Title Claim that is located within the following co-ordinates:

[A list of co-ordinates was included extending over approximately three pages.]

26 Thereafter, the following was noted:

The above description of the ILUA Area is referenced from the GDA94 datum.

The land and waters comprising the ILUA Area are located wholly within Native Title determination application QUD85/2004 Wangan and Jagalingou People (QC2004/006), as accepted for registration on 5 July 2004.

Part 2 - Map of ILUA Area

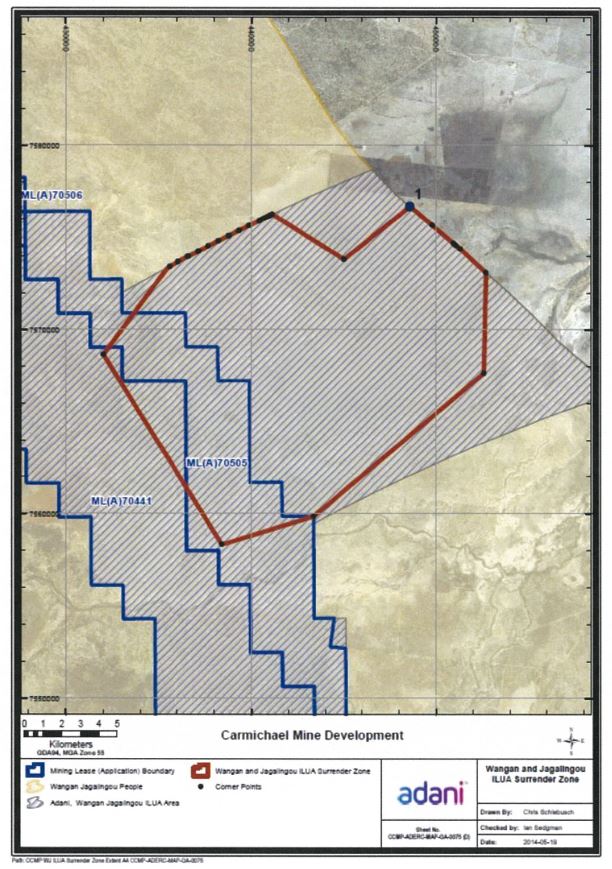

27 Schedule 1 of the Adani ILUA also included two other parts (Parts 3 and 4) that described the details of the Surrender Area and Surrender Zone. They are as follows:

Part 3 - Description of External Boundary (Surrender Zone)

The Surrender Zone includes all the land and waters within the part of the ILUA Area that is located within the following co-ordinates:

[A list of co-ordinates was included extending over approximately one page.]

The above description of the Surrender Zone is referenced from the GDA94 datum.

The land and waters comprising the Surrender Zone are located wholly within Native Title determination application QUD85/2004 Wangan and Jagalingou People (QC2004/006), as accepted for registration on 5 July 2004.

Part 4 - Map of Surrender Zone

28 The operative clauses of the Adani ILUA included the following. First, clause 2 set out the ILUA requirements in the following terms:

2.1 ILUA

The Parties intend that this Agreement be an ILUA (area agreement) under Subdivision C of Division 3 of Part 2 of the NTA and that it be Registered.

2.2 Registration under NTA

(a) The Parties intend that this Agreement be Registered under either section 24CK or section 24CL of the NTA and agree to such Registration of this Agreement.

(b) The Parties also agree that, upon such Registration, to the extent that any Native Title Rights and Interests that exist over the ILUA Area are in any way affected by any of the Agreed Acts and the other matters consented to under clause 9, those Agreed Acts and other matters are valid pursuant to sections 24EB(2) and 24EBA(3) of the NTA and section 15A of the Native Title (Queensland) Act 1993 (Qld).

(c) Each Party undertakes to do all things in its power to ensure that this Agreement is Registered.

2.3 NTA requirements

The Parties intend that this Agreement be an agreement meeting the requirements of sections 24CB to 24CE of the NTA. The Native Title Parties will not raise any objection to the effect that this Agreement does not meet those requirements.

2.4 Application for Registration

(a) Adani is authorised on behalf of the Parties to, and will, make an application to the Registrar under section 24CG of the NTA for this Agreement to be Registered.

(b) The Parties agree that Adani is authorised to undertake all procedural steps required to have this Agreement Registered, including:

(i) the completion of all relevant forms and anything else required to satisfy regulation 7(2)(d) of the Regulations; and

(ii) the making of such technical, typographical or other minor amendments that Adani considers necessary to ensure the Registration of this Agreement and that are approved by the Applicant on behalf of the W&J People and by the State (acting reasonably and promptly).

(c) For the purposes of regulation 7(2)(b) of the Regulations, this clause shall constitute a statement by each Party that it agrees to the application being made.

2.5 Prescribed documents and information

The Parties must do all things necessary to provide the Registrar with a copy of this Agreement and any other prescribed documents or information required under section 24CG(2) of the NTA.

2.6 Statement to the Registrar

(a) The Parties agree that this clause is a statement to the Registrar for the purposes of section 24CG(3)(b) of the NTA.

(b) The Native Title Parties represent and warrant that:

(i) they have made all reasonable efforts (including by consulting the Representative Aboriginal Body) to ensure that all persons who hold or may hold Native Title in relation to land or waters in the ILUA Area have been identified; and

(ii) all of the persons so identified have Authorised the making of the Agreement as required under section 24CG(3)(b) of the NTA.

(c) If the application for Registration of this Agreement is not certified by the Representative Aboriginal Body under section 24CG(3)(a) of the NTA, the Applicant on behalf of the W&J People will assist Adani to provide a statement to the Registrar setting out the grounds on which the Registrar should be satisfied that the statements in this clause are correct as required by section 24CG(3)(b) of the NTA.

2.7 Informing of Representative Aboriginal Body

The Native Title Parties warrant that they have informed the Representative Aboriginal Body of their intention to enter into this Agreement in accordance with section 24CD(7)(a) of the NTA and regulation 7(4) of the Regulations.

2.8 Restriction on details on Register

The Parties agree that, for section 199E of the NTA, this clause is a statement in writing by the Parties that, other than the details required to be entered on the Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements under section 199B(1) of the NTA, they do not wish any details of this Agreement, including any details of the benefits to be provided under this Agreement or the Ancillary Agreement, to be entered on the Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements.

29 Clause 5 identified the area to which the Adani ILUA applied in the following terms:

The area to which this Agreement applies is the ILUA Area.

30 Finally, clause 9 of the Adani ILUA set out, under the heading “Consents”, the details of the manner in which the Agreed Acts would be undertaken that affected native title. That clause was in the following form:

(a) The Parties agree to and consent to:

(i) the Agreed Acts without conditions;

(ii) any Surrender that occurs pursuant to the process set out in clause 9(b);

(iii) any Taking of Native Title; and

(iv) the undertaking of the ILUA Project,

in each case to the extent that it is in accordance with this Agreement and any applicable Law.

(b) With respect to clause 9(a)(ii), the Parties acknowledge and agree that:

(i) pursuant to the process set out in this clause 9(b), Surrenders may occur with respect to one or more areas within the Surrender Area; and

(ii) if:

A. Adani seeks an Approval (with respect to an area within the Surrender Zone) that cannot be Granted unless a Surrender first takes place; and

B. a Surrender over the part of the Surrender Zone that is the subject of the Approval would not result in the total area Surrendered under this Agreement or subject to a Taking of Native Title being greater than the Surrender Area,

then:

C. provided this Agreement has been Registered, a Surrender will occur immediately before the Approval is Granted in relation to any Native Title Rights and Interests that exist within that part of the Surrender Zone that is the subject of the Approval; and

D. Adani must notify the Native Title Parties of the Surrender (such notice to include a copy of a plan of survey identifying the area to which the Surrender relates) and provide the State with a copy of that notification.

(c) The total area the subject of all Surrenders and any Taking of Native Title under clause 9(a)(ii) and 9(a)(iii), must not exceed the Surrender Area and the consents in those clauses 9(a)(ii) and 9(a)(iii) are subject to this limitation.

(d) The Parties agree that any Surrender is intended to extinguish any Native Title that may exist in relation to the relevant part of the Surrender Zone, at the time of the Surrender.

(e) Subject to clause 9(d), to the extent that the Grant or doing of any of the Agreed Acts, or the undertaking of any aspect of the ILUA Project, is a Future Act, the Parties agree that the Non-Extinguishment Principle applies to the doing of such Future Act.

(f) The consents in clause 9(a) are statements for the purpose of section 24EB(1)(b)(i) and 24EBA(1)(a)(i) of the NTA and regulations 7(5)(a) and 7(5)(d) of the Regulations.

(g) Clause 9(d) is a statement for the purpose of section 24EB(1)(d) of the NTA and regulation 7(5)(c) of the Regulations.

(h) For the purposes of section 24EB(1)(c) of the NTA and regulation 7(5)(b) of the Regulations, on and from the date this Agreement is Registered, Subdivision P, Division 3, Part 2 of the NTA is not intended to apply to any Agreed Acts, or to any Surrender or any Taking of Native Title.

(i) For the avoidance of doubt, the Parties agree that, if this Agreement is never Registered or it is Registered and subsequently removed from the Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements, then subject to its termination in accordance with clause 16:

(i) it will remain binding as a contract between the Parties; and

(ii) the Ancillary Agreement will remain binding as a contract between Adani and the Native Title Parties.

The Certificate

31 QSNTS issued the Certificate in its capacity as the Native Title Service Provider holding recognition under s 203FE(1) of the NTA for the Southern and Western Queensland Region. That region includes the claim area of the W & J application.

32 To obtain the Certificate, HWL Ebsworth, the solicitor for the W & J Applicant in relation to future act and cultural heritage matters, wrote to the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of QSNTS, Mr Kevin Smith, on 20 April 2016 requesting that QSNTS certify the application for registration under s 203BE of the NTA. That letter had attached to it the following documents:

(a) the Adani ILUA;

(b) the draft application for registration of the Adani ILUA;

(c) correspondence between HWL Ebsworth and QSNTS dated 19 February 2016 and 11 April 2016;

(d) correspondence between Just Us Lawyers and HWL Ebsworth dated 29 January 2016, 5 February 2016, 7 April 2016 and 13 April 2016;

(e) the published notices (see at [8]–[9] above);

(f) the authorisation meeting correspondence;

(g) the attendance register sheets from the authorisation meeting;

(h) the agenda used at the authorisation meeting and a record of the resolutions and outcomes arising from the authorisation meeting (see at [12]–[13] above);

(i) a draft of a certificate in relation to the application to register the Adani ILUA.

33 In an email dated 22 April 2016, HWL Ebsworth also provided to Mr Smith a copy of the draft minutes of the authorisation meeting (see at [15]–[20] above).

34 Mr Smith signed the Certificate on 26 April 2016. He did so in his capacity as the CEO of QSNTS. The body of the Certificate was in the following form:

This certificate is provided by Queensland South Native Title Services (QSNTS) in respect of an application to register an agreement (the ILUA) between Adrian Burragubba, Patrick Malone, Irene White, Lyndell Turbane, Priscilla Gyemore, Craig Dallen, Linda Bobongie, Norman Johnson Jnr, Gwendoline Fisher, Les Tilley, Delia Kemppi and Lester Barnard on their own behalf in their capacity as Registered Native Title Claimant for the Wangan & Jagalingou People Native Title Determination Application No. QC2004/006 (Federal Court of Australia No. QUD85/2004) (W&J Native Title Claim) and on behalf of the members of the native title claim group to the W&J Native Title Claim (W&J People), the State of Queensland and Adani Mining Pty Ltd ABN 27 145 455 205 (Adani) on the Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements.

The area of land and waters covered by the ILUA (ILUA Area) is wholly within QSNTS’s representative body area. The area covered by the ILUA is within the external boundaries of the W&J Native Title Claim, which was filed in the Federal Court on 27 May 2004. The ILUA Area is not overlapped by any other claimant application.

QSNTS, is the Native Title Service Provider holding recognition under section 203FE of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA) for the Southern and Western Queensland Region.

I, Kevin James Smith, Chief Executive Officer of QSNTS, am authorised by QSNTS to perform its function of certification, and so in accordance with s203BE(5)(a) and (b) with respect to the ILUA, certify that:

(a) all reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that all persons who hold or may hold native title in relation to land or waters in the area covered by the ILUA have been identified; and

(b) all the persons so identified have authorised the making of the Agreement.

REASONS for QSNTS being of that opinion are as follows:

1. All reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that all persons who hold or may hold native title in relation to the land or waters in the area covered by the Agreement have been identified.

(a) QSNTS has undertaken extensive anthropological and genealogical research in relation to the W&J Native Title Claim as well as the region subject to the agreement.

(b) QSNTS maintains a database of details concerning the identification of W&J People and is continuously engaging in a process of checking and updating the database.

(c) The authorisation of the ILUA was the subject of widespread public advertising in seven newspapers:

I. The Courier Mail – 16 March 2016;

II. Fraser Coast Chronicle –18 March 2016;

III. The Morning Bulletin – 18 March 2016;

IV. The Townsville Bulletin – 18 March 2016;

V. South Burnett Times – 22 March 2016;

VI. The Koori Mail – 23 March 2016;

VII. Central Queensland News – 23 March 2016.

(d) Further notification, including a cover letter, a copy of the public notice and an information booklet regarding the ILUA, was sent to the mailing address of all those members of the W&J People on the database maintained by QSNTS.

2. All the persons so identified have authorised the making of the ILUA.

The authorisation process for the making of the ILUA that has taken place can be described as an agreed and adopted decision-making process of the W&J People in authorising the ILUA. It involved:

(a) The legal representative for the W&J Applicant in relation to this agreement consulted with QSNTS on 19 February 2016 and 11 April 2016;

(b) Engagement between the Applicant to the W&J Native Title Claim and Adani at several properly notified and convened meetings of the Applicant, at which on each occasion a quorum of the Applicant were present, and at which decisions were made regarding the proposed authorisation of the ILUA, including approval of the final terms of the ILUA, the ancillary agreement to the ILUA, the meeting rules of conduct and proposed resolutions to be considered at the Authorisation Meeting;

(c) The members of the W&J People, and any other persons who hold or may hold native [title] in the ILUA Area, being called to attend a meeting in Maryborough on Saturday, 16 April 2016 (Authorisation Meeting), which was independently facilitated;

(d) Notification of the Authorisation Meeting having been given by way of widespread public advertising in seven newspapers and by way of individual mail-outs sent to all those persons on the QSNTS database of W&J People;

(e) The Authorisation Meeting was held in Maryborough on Saturday 16 April 2016;

(f) ARCHAEO Cultural Heritage Services, the Applicant’s usual service provider, being retained to assist the W&J People to register their interest in attending the Authorisation Meeting and providing reasonable travel assistance to do so;

(g) QSNTS registering meeting attendees on the day of the Authorisation Meeting, with the assistance of their in-house anthropological team, ensuring that only those adult W&J People or other adult persons who hold or claim to hold native title in the ILUA Area being allowed entry to the Authorisation Meeting, and being entitled to vote on motions;

(h) The registration and attendance of 340 adult members of the W&J People, comprising descendants of 12 of the 14 apical ancestors (who have known descendants) and one adult person who claimed to hold native title in relation to the ILUA Area, at the Authorisation Meeting;

(i) The agenda, the meeting rules of conduct, clearly worded draft resolutions, a summary of the legal advice provided by HWL Ebsworth Lawyers and the information booklet regarding the ILUA being handed out to meeting attendees and displayed at the relevant times on large screens at the Authorisation Meeting;

(j) General discussion of the issues notified to be the subject of Authorisation Meeting at the Authorisation Meeting, including question and answer sessions;

(k) Legal advice on the issues notified to be the subject of Authorisation Meeting being provided by HWL Ebsworth Lawyers;

(l) All resolutions being displayed and read out by the independent facilitator before voting, including meeting attendees being afforded the opportunity to speak for or against the motions;

(m) The W&J People present at the meeting, and where appropriate, the other persons who were present and who hold or claim to hold native tide in the ILUA Area, then endorsing the resolutions, by way of a decision-making process resolved and agreed to at the Authorisation Meeting (by show of hands);

(n) I am satisfied that through the holding of the Authorisation Meeting the W&J People authorised the making of the ILUA in accordance with the decision making process that was agreed to and adopted by the W&J People for that purpose.

The application to register the Adani ILUA

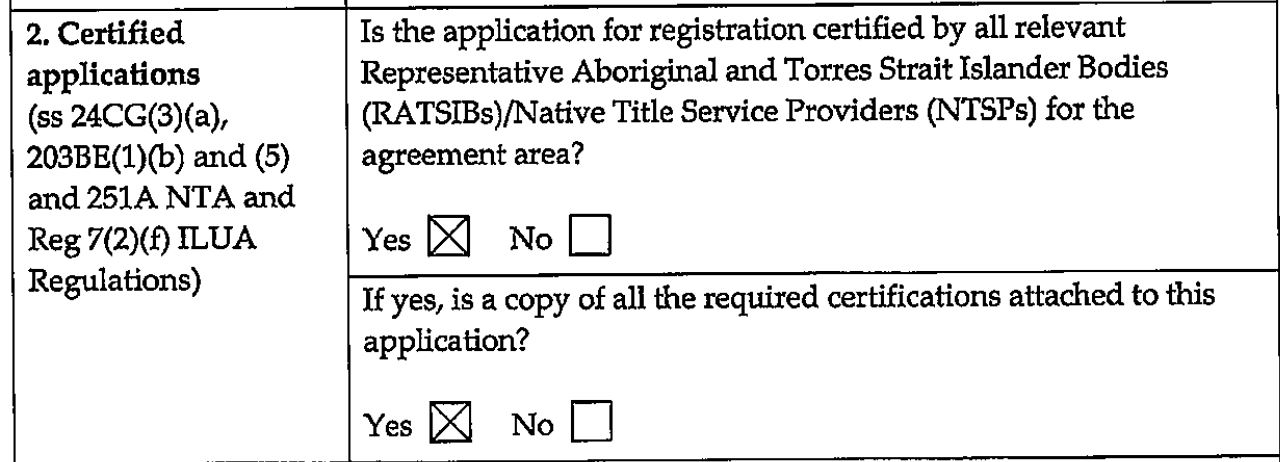

35 By an application dated 27 April 2016, Adani applied to the Registrar for the Adani ILUA to be registered. That Application was in a standard form provided by the National Native Title Tribunal. It followed a question and answer format. For example, after stating the short name of the ILUA, the second section of the application form was as follows:

36 There followed a number of questions and answers dealing with the identification of the parties to the ILUA. Pertinent to the present matter, section 8 of the Application form provided the following parties under the heading “Other native title parties (s 24CD(4)(a) and (b) NTA)”:

…

One person (not previously identified in the answers to questions 5 or 6 above) attended the agreement authorisation meeting claiming to hold native title in relation to the agreement area. Queensland South Native Title Services Ltd, the RATSIB/NTSP for the agreement area, who registered all members of the Wangan & Jagalingou People’s native title claim group and all persons who claim to hold native title in relation to the agreement area who attended the agreement authorisation meeting, formed the view that this person had established a prima facie case that they may hold native title in the agreement area but is not a member of the Wangan & Jagalingou People’s native title claim group.

This person is not a party to the agreement. This person voted in favour of the resolution to authorise the making of the agreement at the agreement authorisation meeting.

(Emphasis omitted)

37 Section 12 of the Application form identified the Adani ILUA in the following terms:

…

A complete description of the agreement area is set out at:

• clause 5 (Area to which this Agreement applies) of the agreement;

• clause 1.1 (Definitions) of the agreement, definition of “ILUA Area”;

• Part 1 of Schedule 1 (Description of External Boundary (ILUA Area)) of the agreement; and

• Part 2 of Schedule 1 (Map of ILUA Area) of the agreement.

No areas within the external boundary of the agreement area are excluded from the agreement area.

…

(Emphasis omitted)

38 Section 13 of the Application form set out a complete description of the Surrender Area as follows:

…

A complete description of the area within which the surrender of native title is intended to extinguish native title rights and interests is set out at:

• clause 1.1 (Definitions) of the agreement, definitions of “Surrender Area” and “Surrender Zone”;

• Part 3 of Schedule 1 (Description of External Boundary (Surrender Zone)) of the agreement; and

• Part 4 of Schedule 1 (Map of Surrender Zone) of the agreement.

…

(Emphasis omitted)

39 Sections 15, 16 and 17 of the Application form identified the provisions of the Adani ILUA which affected native title, as follows:

(a) Consent to future acts (s 24EB(1)(b) of the NTA and reg 7(5)(a) of the Regulations):

• Clause 9 (Consents) of the agreement;

• Schedule 2 (Agreed Acts) of the agreement; and

• clause 1.1 (Definitions) including:

o “Agreed Acts”;

o “Surrender”;

o “Taking of Native Title”; and

o “ILUA Project”.

(Emphasis omitted)

(b) Acts excluded from the right to negotiate (s 24EB(1)(c) of the NTA and reg 7(5)(b) of the Regulations):

• Clause 9(h) of the agreement; and

• clause 1.1 (Definitions) including:

o “Agreed Acts”;

o “Registered”;

o “Surrender”; and

o “Taking of Native Title”.

(Emphasis omitted)

(c) Surrender intended to extinguish native title (s 24EB(l)(d) NTA and Reg 7(5)(c) Regulations):

• Clauses 9(a) and 9(d) of the agreement; and

• clause 1.1 (Definitions) including:

o “Surrender”;

o “Surrender Zone”; and

o “Taking of Native Title”.

(Emphasis omitted)

40 The Application form had attached to it a large number of documents including the Adani ILUA itself and a copy of the Certificate.

The Adani ILUA is registered and this proceeding is commenced

41 On 8 December 2017, having considered Adani’s application, the Registrar entered the pertinent details of the Adani ILUA on the Register.

42 In the meantime, on 24 March 2017, Ms Kemppi filed this proceeding seeking the declarations described earlier.

THE EVIDENCE

Ms Williams’ affidavit

43 Before detailing the evidence that was tendered by the parties at the trial, I will deal with the objections to the tender of the affidavit of Ms A Williams. Ms Williams was a Paralegal Officer employed by QSNTS. She made an affidavit on 16 September 2016 for the purposes of an interlocutory application in the W & J application proceeding QUD 84/2004. It is not in dispute that Ms Williams’ affidavit was read in open court and was relied upon for the purposes of that interlocutory application. During the trial, Ms Kemppi sought to tender Ms Williams’ affidavit. Initially, QSNTS objected to that tender on the ground that the tender would breach the implied undertaking made by each party not to use any document disclosed in a proceeding for any purpose otherwise than in relation to that proceeding, relying upon Esso Australia Resources Ltd v Plowman (1994) 183 CLR 10 at 32 per Mason CJ. In response to this contention, Ms Kemppi relied upon r 20.03(1) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth). That rule provides:

If a document is read or referred to in open court in a way that discloses its contents, any express order or implied undertaking not to use the document except in relation to a particular proceeding no longer applies.

44 In turn, QSNTS pointed to r 20.03(2), which provides: “However, a party, or a person to whom the document belongs, may apply to the Court for an order that the order or undertaking continue to apply to the document” and submitted that, since Ms Williams had not consented to the proposed use of her affidavit and, until such time as she is notified of that proposed use and given an opportunity to apply to the Court for an order continuing the implied undertaking, Ms Kemppi ought not be permitted to tender the affidavit.

45 For the following reasons, I consider Ms Kemppi is entitled to tender Ms Williams’ affidavit. First, in the circumstances described above, r 20.03(1) clearly operates to set aside the implied undertaking. Secondly, I consider the “party” to which r 20.03(2) refers is the party who tendered the document in the proceeding concerned. That is, in this instance, the W & J Applicant. Accordingly, since QSNTS was not a party to that proceeding, that rule does not avail it. Thirdly, since the affidavit was tendered by the W & J Applicant in support of its application in that proceeding, it is debatable whether it is the “person to whom the document belongs”, or whether those words refer to Ms Williams. However, I do not consider it is necessary to determine that issue. That is so because I consider r 20.03(2) is primarily directed to preventing the further disclosure of information that, by its nature, is private or confidential to a party, or the person to whom the document belongs. On its face, Ms Williams’ affidavit does not contain any such information. It sets out the details of various searches she conducted in her capacity as a Paralegal Officer employed by QSNTS. Accordingly, even if it were assumed that she owns the affidavit, taking account of its contents, I do not consider an order under r 20.03(2) would be justified. For these reasons, I will allow the tender of Ms Williams’ affidavit. It will be marked Exhibit A18.

The relevance of the evidence

46 I should say at the outset that I have included the following somewhat lengthy survey of the evidence adduced in this matter in deference to the efforts of the parties and in case this matter goes elsewhere. Its length and detail should not, however, be taken as an indication that I consider all of the evidence to be relevant to an issue I need to decide in this matter. To the contrary, as will emerge later in these reasons, I consider most of this evidence, particularly the evidence adduced by Ms Kemppi, is irrelevant to any such issue.

The evidence Ms Kemppi adduced

47 The evidence Ms Kemppi adduced at the trial essentially fell into three categories. First, there was evidence from a number of Wangan and Jagalingou People who had attended the authorisation meeting on 16 April 2016 and/or an earlier authorisation meeting of the W & J claim group conducted under s 251B of the NTA and held on 21 June 2015. Secondly, there was evidence from a Mr Esposito with respect to an analysis he had undertaken of the attendees at the two meetings mentioned above and another authorisation meeting of the W & J claim group. Thirdly, there was evidence from a number of Wangan and Jagalingou People concerning the criteria for membership of the Wangan and Jagalingou People.

48 In summary, the first category of evidence described above followed two themes. The first was that a large number of people had attended the authorisation meeting on 16 April 2016 that, according to those witnesses, had not attended any earlier W & J claim group meeting or any related meetings. The second theme was that, according to those witnesses, there was no checking of the people who had attended the 16 April 2016 authorisation meeting to determine whether or not they were members of the W & J claim group. The witnesses who attended both meetings included Mr C Dallen, Ms J Broome, Ms C Gyemore and Mr E McEvoy. The witnesses who attended the earlier authorisation meeting on 21 June 2015, but did not attend the authorisation meeting on 16 April 2016, included Ms L Barnard, Ms L Turbane and Mr A Burragubba.

49 The following extracts from the affidavits of these witnesses exemplify the two themes mentioned above:

(a) Mr C Dallen

7. I attended an authorisation meeting held to approve the Adani ILUA on 16 April 2016. I attended with members of my family. Before entering the meeting, we had to sign a registration sheet. The sheets were arranged on desks forming a long barrier at the entrance to the hall in the order of our ancestors who make up the claim group. I registered with my daughters and son. It was straight forward to register. Neither myself nor any member of my family were asked who we were or to show any form of identification. Nor did anybody check any documents or ask us questions about our family history. I recognised that the registration desks were staffed by Queensland Native Title Services (“QSNTS”). The person attending to our registration just accepted we were who we said we were, no questions asked. We were not even asked to declare that we were Wangan and Jagalingou people …

8. There were in my estimation approximately three hundred people in attendance at the meeting. The meeting appeared to be twice the size of any previous meeting of the claim group that I attended.

9. Most of the people I had never seen before at a Wangan and Jagalingou meeting. I saw that they were given arm bands to allow them to vote and participate in the meeting. The most obvious example of this is Marshall Saunders who signed the attendance register (see page 8) under my ancestor, “Dan Dunrobin”. Gunggari country is a long way from our country.

(b) Ms J Broome

4. When I arrived at the meeting, we were made to sign an attendance register under our ancestor. We were not asked to show any I.D . We were not asked to show that we were descendants from Momitja nor whether we identified as Wangan and Jagalingou people. As far as I could see nobody else was asked this either. There were no elders standing near by to vouch that we were Wangan and Jagalingou People. I saw Les Tilly who is the Applicant for the Momitja descent group, he was not standing near the registration desk but in the kitcken (sic) talking to the Adani boys.

7. There were a lot of people I did not know at the meeting. I have been to at least five meetings of the Wangan and Jagalingou claim group. I have a pretty good idea of who is in our mob. However, most of the people at the Adani Meeting I had never seen before at a Wangan and Jagalingou meeting. I met the daughter of “Burra” Bone in the toilets at the Adani Meeting. Burra is prominent in the Cherbourg community. I asked her what she was doing at the meeting and she did not answer me directly.

(c) Ms C Gyemore

8. There were plenty of people at the meeting. It was at least twice as big as any claim group meeting I had previously attended. I have been around a while and I know better than most who should be at our meetings. However, I had no idea who many of the people at the Adani Meeting were. I certainly had never seen them before at any Wangan and Jagalingou meeting.

(d) Mr E McEvoy

6. When I arrived at the meeting, they made me sign an attendance register. Even though I had pre-registered for the meeting the people sitting at the desks at the entry could not find my name on the attendance register, so it took some time for me to sign in. They asked me who my ancestor was and I told them Lizzie McAvoy. They (sic – I) did not observe them to write this down anywhere or ask me for identification and they did not check with anybody that what I told them was correct.

9. The Adani meeting was much larger than any claim group meeting I had previously attended. I thought the meeting of 21 June 2015 was large with an attendance of about 180 people but this meeting was twice as large. I saw several buses pull up full of people from Cherbourg. Many of the people I saw there I had never seen at a Wangan and Jagalingou meeting and had never before claimed to me to be from our country.

50 Ms Barnard, Mr Burragubba, Ms Kemppi and Ms Turbane elected not to attend the authorisation meeting on 16 April 2016. As well as giving evidence about the procedures followed at the earlier W & J claim group and related meetings they had attended, they gave evidence about the criteria for membership of the W & J claim group. For example, in his affidavit Mr Burragubba described a W & J claim group authorisation meeting that he attended on 29 June 2014 as follows:

2. On 29 June 2014 I attended the authorisation meeting, which was facilitated by Queensland South Native Title Services (“QSNTS”). QSNTS formulated the resolutions to be considered at the meeting and they were read out and explained by the Chair prior to being considered by the meeting. The authorisation meeting was held for the purpose of considering who should be eligible to become a member of the claim group for the native title claim. One of the resolutions put to the meeting was whether the people present were sufficiently representative of the claim group to make authoritative decisions about the native title claim. The Chair of the meeting explained that the purpose of the resolution was to enable anybody at the meeting to object to people being present. I did not voice any opposition to the resolution. I knew most of the people in attendance from attending previous meetings and from my association with members of the claim group throughout my life. I was satisfied that they identified as belonging to my traditional country.

3. After this resolution was passed, the meeting went on to consider whether to expand the claim group description by adding to the list of ancestors. I listened to anthropological advice that the apical ancestors to be added were members of the same traditional society as my apical ancestor.

4. From what I had been taught by my mother and father, grandmother and grandfather and other elders connected all the way back, this is fundamental to our traditional law and custom. After the change to the claim group description was approved, people were let into the meeting on the basis that they were descendants from those ancestors. We were again given an opportunity to consider whether those present were part of Wangan and Jagalingou people. I was satisfied that they identified as Wangan and Jagalingou and belong in the claim group. Because of this, I voted for the motion to accept them as also being representative of the Wangan and Jagalingou people.

51 Similarly, Ms Turbane gave evidence in her affidavit about her recollections of attending the same meeting and a subsequent meeting on 21 June 2015 as follows:

5. I attended an authorisation meeting held on 29 June 2014 which was called for the purpose of considering whether to add descent lines to the claim group description of our native title claim. My family was already included in the list of apical ancestors so our recognition as part of our mob was not called into question. However, there was a proposal to add other family groups into the native title claim. This proposal did raise the question of whether there were people in attendance who were now seeking to join our native title claim who had never previously identified with my mother’s country. Queensland South Native Title Services (“QSNTS”) were running the meeting. They put forward a proposition for consideration that the people in attendance were representative of the claim group. The question for my family and I was whether the people at the meeting identified as belonging to my mother’s country. Because I knew most of the people from the new families that were being added I was prepared to accept them as part of our mob.

6. I was appointed as an Applicant for the native title claim at an authorisation meeting held 21 June 2015. The meeting was called to appoint a new applicant with a representative from each descent line. Before we proceeded with the business of the meeting we were again given an opportunity to accept that the people in attendance belonged to our country. I voted for this resolution because I accepted that the people in attendance at the meeting that day identified as belonging to my mother’s country.

52 In cross-examination, some of the witnesses admitted, or it otherwise became apparent, that they were members of other native title claim groups. They included Ms Turbane, Mr Burragubba and Ms Ford.

53 Mr Esposito’s evidence was based on an analysis he conducted of four lists, three of which were admitted into evidence. Those lists were annexed to his affidavit as follows:

(a) Annexure AE1 – the attendance sheets for the authorisation meeting held on 16 April 2016 (this annexure was struck out, although it was still referred to in the body of the affidavit below);

(b) Annexure AE2 – the list of surnames of Wangan and Jagalingou People annexed to the affidavit of Ms Williams;

(c) Annexure AE3 – the attendance sheets for the meeting of the W & J claim group held on 21 June 2015 annexed to the affidavit of Ms Williams; and

(d) Annexure AE4 – the attendance sheets for a meeting of the W & J claim group held on 19 March 2016.

54 With respect to Annexures AE2 and AE4, Mr Esposito said that:

5. I have also been informed by Sharon McAvoy (who was formerly employed by the QSNTS and worked with the data base contained in AE2) QSNTS Data Base that it is composed from all the persons who are recorded as attending a Wangan and Jagalingou claim group meetings occasions prior to the June meeting). As a result I have assumed that the QSNTS Data Base is a relatively accurate record of all the members of the claim group who have attended past authorisation meetings and have been accepted as Wangan and Jagalingou people.

6. I was in attendance at an authorisation meeting of the claim group held on 19 March 2016, and I have obtained from Sharon Ford a copy of the attendance sheets for that meeting …

55 Mr Esposito described the analysis he undertook with respect to the four lists set out above in the following terms:

7. From the information referred to AE1 to AE4, I have composed a table showing all those who are recorded as attending the Adani authorisation meeting (AE1) and comparing with those who are on the QSNTS data base (AE2), those who are recorded as attending the June meeting (AE3) and those who attended the authorisation meeting of 19 March 2016 (AE4) …

56 He outlined the results of that analysis as follows:

8. The table at AE5 shows that 25.36% of those who attended the Adani meeting were also listed on the QSNTS Data Base, 26.53% were listed as also attending the June meeting, and only 1.45% were listed as also attending the authorisation meeting of 19 March 2016.

9. Overall, 208 people or 60.64%, who attended the Adani meeting were not recorded as attending any prior meeting of the Wangan and Jagalingou claim group by virtue of the fact that they were recorded on the QSNTS Data Base or on the attendance sheets of the claim group authorisation meetings of 21 June 2015 or 16 March 2016.

57 In cross-examination, Mr Esposito was asked to read [4], [5] and [10] of Ms Williams’ affidavit (now Exhibit A18: see at [45] above). Those paragraphs stated as follows:

4. On 6 September 2016 I was requested by Tim Wishart, Principal Legal Officer at QSNTS to provide him with a list of the Wangan and Jagalingou claimants and their addresses from the QSNTS database.

5. I was also requested to cross reference the addresses for each of the Wangan and Jagalingou claimants in the QSNST database with the information on the website of the Electoral Commission Queensland (“ECQ”) to produce a table and graph to establish how many Wangan and Jagalingou claimants live in each Local Government Area.

10. Annexed to this Affidavit and marked “AMW-2” is a copy of the report and graph produced by me showing the 278 Wangan and Jagalingou claimants from the QSNTS database and the corresponding Local Government Area in which they reside.

(Emphasis in original)

58 Thereafter the following exchange occurred:

Now, having looked at those paragraphs of Ms Williams’ affidavit, do you agree with me that the document that is at 1415, and which is AE2 to your affidavit, is not itself the QSNTS database. It’s not a copy of it?---Well, to the extent that I suggest I’ve made some adjustments based of some data calculations, yes. But it appears to be the same document.

No. No. But what I’m asking is – do you accept that that document at 1415 is a document that Ms Williams created using the database but it’s not itself the database. It’s not a copy of the database?---Well, yes. It’s from the Queensland South database, yes.

Well, the information is taken from the database?---Yes.

But it’s not a copy of the database?---Apparently. I mean, I assume the database is very large.

And do you agree with me that Ms Williams must have created this list at page 1415 at some time between 6 September 2016, when Mr Wishart asked her to create it, and 16 September 2016, when she prepared her affidavit?---Presumably, yes.

So you agree that that list is created sometime in September 2016?---Well, as far as I can ascertain. I don’t know when she created it.

59 A short time later, in response to a question about the contents of the QSNTS database, Mr Esposito said: “… I don’t know what the Queensland South database actually contains, because it’s a confidential database.”

60 Mr Esposito was then taken to [5] of his affidavit (see at [54] above) and asked a number of questions concerning Annexure AE2:

You refer there to some things that you had been informed by Sharon McEvoy (sic – McAvoy)?---Yes.

And Sharon McEvoy (sic – McAvoy) is also known as Sharon Ford?---Correct.

Do you know when Ms Ford says (sic – ceased) to be employed by QSNTS?---No, not the exact date.

…

Thank you. In paragraph 5, you say that Ms McEvoy (sic – McAvoy) or Ms Ford informed you that the QSNTS database is composed from all the persons who are recorded as attending a Wangan and Jagalingou claim group meeting occasions prior to the June meeting. Do you see that - - -?---Yes.

- - - there? When you refer there to the QSNTS database, do you mean document AE2 in your affidavit?---Correct, yes.

And you agreed with me a moment ago that it seemed that the document that is AE2 was probably created in September 2016?---I can only take your word for that. I really don’t know when it was created.

Right?---It just appears in an affidavit in that time period.

… If you look at the second sentence of paragraph 5, you say:

I’ve assumed that the QSNTS database –

by which is mean AE2 – is that correct?---Well, the first part is a reference to the practice of Queensland South, the database that the (sic – they) keep reflects the attendance at meetings. And then as a result, I’ve assumed that the AE2, the material submitted by Anne Williams from the database is an accurate record.

And if it were the case that it’s not an accurate record, that would undermine the analysis that you’ve conducted later on in your affidavit. Do you agree with that?---Well, no. Not really.

All right?---The analysis, you know, performs a function. It’s a simple comparative analysis of lists, you know, supplemented by working knowledge of those around me in terms of how those - - -

Thank you?--- - - - lists are composed.