FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Air New Zealand Limited (No 15) [2018] FCA 1166

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

Act means the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) as it then was, now the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth).

air freight services means services provided by way of the international transport of goods

by air.

Hong Kong BAR-CSC means the Hong Kong Board of Airline Representatives Cargo Subcommittee.

Hong Kong CAD means the Hong Kong Civil Aviation Department.

Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology means the methodology for applying fuel surcharges on air freight services from Hong Kong that was based on a methodology published by Lufthansa and was approved by the Hong Kong CAD on the application of the Hong Kong BAR-CSC.

Singapore BAR-CSC means the Singapore Board of Airline Representatives Cargo Subcommittee.

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(a)(ii) of the Act by making an arrangement or arriving at an understanding on 23 July 2002 with international airline competitors that were members of the Hong Kong BAR-CSC containing the following provisions:

1.1 that the airlines would replace the existing methodology which they used to calculate the imposition of fuel surcharges on the supply of air freight from Hong Kong to other ports, including to ports in Australia, with the Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology;

1.2 that the airlines would impose fuel surcharges on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong to other ports, including to ports in Australia, in accordance with the Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology.

(the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding)

2. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD0.40/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 1 August 2002 until 12 September 2002.

3. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD0.80/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 13 September 2002 until 20 February 2003.

4. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(a)(ii) of the Act by making an arrangement or arriving at an understanding by February 2003 with international airline competitors that were members of the Hong Kong BAR-CSC containing a provision that the airlines would impose fuel surcharges on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong to other ports, including to ports in Australia, in accordance with the methodology that was approved by the Hong Kong CAD on the application of the Hong Kong BAR-CSC (the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding).

5. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD1.20/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 21 February 2003 until 26 March 2003.

6. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD1.60/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 27 March 2003 until 21 April 2003.

7. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD1.20/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 22 April 2003 until 30 April 2003.

8. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD0.80/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 1 May 2003 until 18 December 2003.

9. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD1.20/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 19 December 2003 until 10 May 2004.

10. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD1.60/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 11 May 2004 until 8 August 2004.

11. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD2.00/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 9 August 2004 until 15 September 2004.

12. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD2.40/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia , in the period from 16 September 2004 until 5 November 2004.

13. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD2.80/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 6 November 2004 until 15 November 2004.

14. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD3.20/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 16 November 2004 until 6 December 2004.

15. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD2.80/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 7 December 2004 until 3 January 2005.

16. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD2.40/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 4 January 2005 until 21 March 2005.

17. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD2.80/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 22 March 2005 until 4 April 2005.

18. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD3.20/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 5 April 2005 until 11 July 2005.

19. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD3.60/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 12 July 2005 until 5 September 2005.

20. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD4.00/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 6 September 2005 until 26 September 2005.

21. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD4.40/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia , in the period from 27 September 2005 until 27 October 2005.

22. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD4.80/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 28 October 2005 until 21 November 2005.

23. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD4.40/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 22 November 2005 until 28 November 2005.

24. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD4.00/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 29 November 2005 until 5 December 2005.

25. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD3.60/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia , in the period from 6 December 2005 until 20 February 2006.

26. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD4.00/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 21 February 2006 to 8 May 2006.

27. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD4.40/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 9 May 2006 until 15 May 2006.

28. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD4.80/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 16 May 2006 until 9 October 2006.

29. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding by imposing a fuel surcharge of HKD4.40/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 10 October 2006 until 17 October 2006.

Hong Kong Insurance Surcharges

30. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(a)(ii) of the Act by making an arrangement or arriving at an understanding on 3 October 2001 with international airline competitors that were members of the Hong Kong BAR-CSC containing a provision that the parties would impose an insurance surcharge of HKD0.50/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong to other ports, including to ports in Australia, with effect from 11 October 2001 (the October 2001 Hong Kong Insurance Surcharge Understanding).

31. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of the October 2001 Hong Kong Insurance Surcharge Understanding by imposing an insurance surcharge of HKD0.50/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 25 October 2001 until 10 January 2003.

32. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(a)(ii) of the Act by making an arrangement or arriving at an understanding on 16 December 2002 with international airline competitors that were members of the Hong Kong BAR-CSC containing a provision that the parties would impose an insurance surcharge of HKD0.25/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong to other ports, including to ports in Australia, with effect from 11 January 2003 (the December 2002 Hong Kong Insurance Surcharge Understanding).

33. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of the December 2002 Hong Kong Insurance Surcharge Understanding by imposing an insurance surcharge of HKD0.25/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 11 January 2003 until 21 January 2004.

Singapore Insurance Surcharge

34. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(a)(ii) of the Act by making an arrangement or arriving at an understanding on 23 January 2003 with international airline competitors that were members of the Singapore BAR-CSC containing a provision that the parties would continue to charge the amount they were currently charging their customers for the insurance and security surcharge on the supply of air freight services from Singapore to other ports, including to ports in Australia, (namely, SGD0.18/kg) (the Singapore ISS Understanding).

35. The Respondent contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act by giving effect to the provisions of the Singapore ISS Understanding by maintaining an insurance and security surcharge of SGD0.18/kg on the supply of air freight services from Singapore, including to ports in Australia, in the period from 23 January 2003 until at least 1 January 2007.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

36. The Respondent pay the Commonwealth of Australia , within 30 days of these orders being made, pecuniary penalties in respect of the contraventions declared in orders 11 to 29, and in respect of the contraventions declared in orders 10 and 35 in so far as that conduct occurred after 17 May 2004, in the following amounts:

36.1 $3.5 million in respect of Air New Zealand’s contravention of s 45(2)(b)(ii) in giving effect to the Singapore ISS Understanding; and

36.2 $11.5 million in respect of Air New Zealand’s contraventions of s 45(2)(b)(ii) in giving effect to the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding.

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

37. The Respondent has undertaken to make a contribution to the Applicant’s costs in the sum of $2 million, to be paid within 30 days of these orders being made.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

GLEESON J:

1 On 27 June 2018, by consent, I made multiple declarations of contraventions of ss 45(2)(a)(ii) and 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (as it then was, now the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)) (“Act”) by the respondent (“Air New Zealand”) and ordered Air New Zealand to pay agreed pecuniary penalties in respect of particular contraventions, in the following amounts:

(1) $3.5 million in respect of Air New Zealand’s contravention of s 45(2)(b)(ii) in giving effect to the “Singapore ISS Understanding”; and

(2) $11.5 million in respect of Air New Zealand’s contraventions of s 45(2)(b)(ii) in giving effect to the “2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding” and the “Hong Kong Imposition Understanding”

(“orders”). The nature of the “Singapore ISS Understanding”, the “2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding” and the “Hong Kong Imposition Understanding” are explained at [14], [9]-[10] and [11] below (respectively).

2 I also noted Air New Zealand’s undertaking to make a contribution to the costs of the applicant (“ACCC”) of the proceeding in the sum of $2 million.

3 These are my reasons for making the orders.

4 The parties filed joint submissions in support of the orders and tendered a statement of agreed facts (“agreed facts”) pursuant to s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). The agreed facts, which are annexed to these reasons, were intended to supplement the findings made by Perram J in the principal judgment at first instance, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Air New Zealand Limited [2014] FCA 1157; (2014) 319 ALR 388 (“principal judgment”).

5 The parties sought declarations in respect of the making or arriving at, and the giving effect to provisions of, each of these understandings and pecuniary penalties in relation to conduct which continued or began within six years of the commencement of the proceeding on 17 May 2010.

6 I accepted the joint submissions, which were signed by senior counsel for the ACCC and senior and junior counsel for Air New Zealand. My reasons below substantially adopt those submissions.

Overview

7 The proceeding concerned Air New Zealand’s contraventions of ss 45(2)(a)(ii) and 45(2)(b)(ii) in making or arriving at, and giving effect to provisions of, a series of arrangements or understandings with international airline competitors concerning the level of fuel surcharges and insurance and security surcharges (“ISS”) to be imposed on the supply of international air freight services from Hong Kong and Singapore to other ports, including to ports in Australia, between 2002 and 2007.

8 In short, these arrangements or understandings comprise:

(1) the “Hong Kong Fuel Surcharge Understandings”, being:

(a) the “2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding” (23 July 2002 to 17 October 2006); and

(b) the “Hong Kong Imposition Understanding” (February 2003 to 17 October 2006);

(2) the “Hong Kong Insurance Surcharge Understandings”, being:

(a) the “October 2001 Hong Kong Insurance Surcharge Understanding” (3 October 2001 to 10 January 2003); and

(b) the “December 2002 Hong Kong Insurance Surcharge Understanding” (16 December 2002 to 21 January 2004); and

(3) the “Singapore ISS Understanding” (23 January 2003 to at least 1 January 2007).

9 The “2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding” was an arrangement or understanding between Air New Zealand and international airline competitors that were members of the “Hong Kong BAR-CSC”. The “Hong Kong BAR-CSC” is the Hong Kong Board of Airline Representatives Cargo Subcommittee: see the principal judgment at [428]-[432]. This arrangement or understanding contained the following provisions:

(1) that the airlines would replace the existing methodology which they used to calculate the imposition of fuel surcharges on the supply of air freight from Hong Kong to other ports, including to ports in Australia, with the “Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology”; and

(2) that the airlines would impose fuel surcharges on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong to other ports, including to ports in Australia, in accordance with the “Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology”.

10 The “Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology” was the methodology for applying fuel surcharges on air freight services from Hong Kong that was based on a methodology published by Lufthansa and was approved by the “Hong Kong CAD” on the application of the Hong Kong BAR-CSC. The “Hong Kong CAD” is the Hong Kong Civil Aviation Department.

11 The “Hong Kong Imposition Understanding” was an arrangement or understanding between the Air New Zealand and international airline competitors that were members of the Hong Kong BAR-CSC. This arrangement or understanding contained a provision that the airlines would impose fuel surcharges on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong to other ports, including to ports in Australia, in accordance with the methodology that was approved by the Hong Kong CAD on the application of the Hong Kong BAR-CSC.

12 The “October 2001 Hong Kong Insurance Surcharge Understanding” was an arrangement or understanding between the Air New Zealand and international airline competitors that were members of the Hong Kong BAR-CSC. This arrangement or understanding contained a provision that the parties would impose an insurance surcharge of HK$0.50/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong to other ports, including to ports in Australia, with effect from 11 October 2001.

13 The “December 2002 Hong Kong Insurance Surcharge Understanding” was an arrangement or understanding between Air New Zealand and international airline competitors that were members of the Hong Kong BAR-CSC. This arrangement or understanding contained a provision that the parties would impose an insurance surcharge of HK$0.25/kg on the supply of air freight services from Hong Kong to other ports, including to ports in Australia, with effect from 11 January 2003.

14 The “Singapore ISS Understanding” was an arrangement or understanding between Air New Zealand and international airline competitors that were members of the “Singapore BAR-CSC”. The “Singapore BAR-CSC” is the Singapore Board of Airline Representatives Cargo Subcommittee: see the principal judgment at [717] to [720]. This arrangement or understanding contained a provision that the parties would continue to charge the amount they were currently charging their customers for the insurance and security surcharge on the supply of air freight services from Singapore to other ports, including to ports in Australia (namely, SGD0.18/kg).

15 Pursuant to s 77(2) of the Act, Air New Zealand’s conduct in making, or arriving at, each of the understandings, and in giving effect to provisions of the Hong Kong Insurance Surcharge Understandings, was out of time for penalty. However, Air New Zealand’s conduct in giving effect to the Singapore ISS Understanding and the Hong Kong Fuel Surcharge Understandings was not out of time for penalty.

Background to proceeding

16 The proceeding arose in the context of long-running litigation brought by the ACCC against 15 international airlines, each alleged to have contravened s 45 of the Act by making or arriving at, and giving effect to, various understandings concerning the level of fuel, insurance and other surcharges to be imposed on the supply of international air freight services.

17 Proceedings were commenced by the ACCC against each of these airlines between 2008 and 2010. Between 2008 and December 2012 (shortly after the commencement of trial in relation to airlines, including Air New Zealand and PT Garuda Indonesia Limited (“Garuda”), which continued to dispute their liability), the ACCC reached agreement as to the resolution of proceedings with 13 of the 15 airlines. Each of those airlines admitted to contravening the Act and were consequently ordered to pay pecuniary penalties of various amounts. While the conduct at issue in the Air New Zealand proceedings overlapped with some of the conduct in the proceedings against some of those other airlines, the proceedings against the other airlines also included conduct by those airlines in respect of routes other than from Hong Kong and Singapore.

18 The question of whether the conduct of Air New Zealand (in Hong Kong and Singapore) and Garuda (in Hong Kong and Indonesia) constituted contraventions of s 45 of the Act was the subject of contested proceedings before this Court between November 2012 and June 2013. At first instance, Perram J concluded that certain conduct of each airline would have contravened s 45 of the Act, but for his Honour’s finding that the conduct did not take place in ‘a market in Australia’ within the meaning of s 4E of the Act. On appeal, in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v PT Garuda Indonesia Ltd [2016] FCAFC 42; (2016) 244 FCR 190 and, in the High Court of Australia, in Air New Zealand Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2017] HCA 21; (2017) 344 ALR 377, it was concluded that there was a market in Australia for the air cargo services for which Air New Zealand and Garuda competed, with the consequence that both airlines had contravened ss 45(2)(a)(ii) and 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act.

Orders by consent

19 In deciding whether to make orders by consent, the Court must first be satisfied that it has the power to make the orders proposed, and that the orders are appropriate: see s 23 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (“Federal Court Act”); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Real Estate Institute of Western Australia Inc [1999] FCA 8; (1999) 161 ALR 79 (“Real Estate Institute”) at [17].

20 For the reasons that follow, the parties submitted, and I accepted, that the orders which I made were within the Court’s power and appropriate in the circumstances.

Declarations

21 The Court has a wide discretionary power to make declarations under s 21(1) of the Federal Court Act: see Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd [1972] HCA 61; (1972) 127 CLR 421 (“Forster”) at 437-438 per Gibbs J; Ainsworth v Criminal Justice Commission [1992] HCA 10; (1992) 175 CLR 564 at 581-582 per Mason CJ, Dawson, Toohey and Gaudron JJ; and Tobacco Institute of Australia Ltd v Australian Federation of Consumer Organisations Inc (No 2) [1993] FCA 105; (1993) 41 FCR 89 at 99.

22 The factual basis for the declarations sought appears at [520]-[591], [596]-[658], [694]-[701] and [1112]-[1127] of the principal judgment. In respect of the further matters the Court must find to reach a conclusion on relief, including declarations, the parties relied on the additional matters set out in the agreed facts.

23 It is open to the Court to grant declaratory relief on the basis of agreed facts and admissions, as distinct from evidence: see, for example, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dataline.Net.Au Pty Ltd [2006] FCA 1427; (2006) 236 ALR 665 at [57]-[59], endorsed on appeal in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dataline.Net.Au Pty Ltd [2007] FCAFC 146; (2007) 161 FCR 513 at [92]; Hadgkiss v Aldin (No 2) [2007] FCA 2069, (2007) 169 IR 76 at [21]-[22]; and Secretary, Department of Health & Ageing v Pagasa Australia Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 1545 at [75]-[76].

24 Further, it has become a common practice of this Court to do so in areas of public interest: see, for example, Ponzio v B & P Caeli Constructions Pty Ltd [2007] FCAFC 65; (2007) 158 FCR 543; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v The Australian Medical Association Western Branch Inc [2001] FCA 1471; (2001) 114 FCR 91, [38];and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v MSY Technology Pty Ltd [2012] FCAFC 56; (2012) 201 FCR 378 (“MSY Technology”).

25 In Forster, at 437-438 (quoting Russian Commercial and Industrial Bank v British Bank for Foreign Trade Ltd [1921] 2 AC 438 at 448 per Dunedin LJ), Gibbs J stated that before making a declaration three requirements should be satisfied:

(1) the question the subject of the declaration must be a real and not hypothetical or theoretical one;

(2) the applicant must have a real interest in raising it; and

(3) there must be a proper contradictor, in the sense of someone with a true interest in opposing the declaration sought.

26 Each requirement is satisfied in the present instance because:

(1) the question of whether Air New Zealand has contravened s 45(2) of the Act on each relevant occasion is a real and not hypothetical one;

(2) the ACCC, as a public regulator under the Act, has a genuine interest in seeking the declaratory relief; and

(3) Air New Zealand, as the respondent the subject of the proposed declarations, has a genuine interest in opposing the making of those declarations, even though it has “[come] to see that interest served by not opposing the relief claimed”: MSY Technology at [16]-[18] (Greenwood, Logan and Yates JJ).

27 Further, as summarised by the Court in MSY Technology at [35], there must be some utility in the granting of declaratory relief, and the declarations sought must be precise as to the way in which the relevant statute was contravened. The form of declarations ordered should not speak merely of the terms used in the legislation, without giving any content to those expressions and without indicating the gist of the findings made: Rural Press Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2003] HCA 75; (2003) 216 CLR 53 (“Rural Press”) at [89]-[90] (Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ).

28 In the present case, there is utility in setting out the basis of Air New Zealand’s liability and, in turn, the basis for the pecuniary penalties imposed: Rural Press at [95] (Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ).

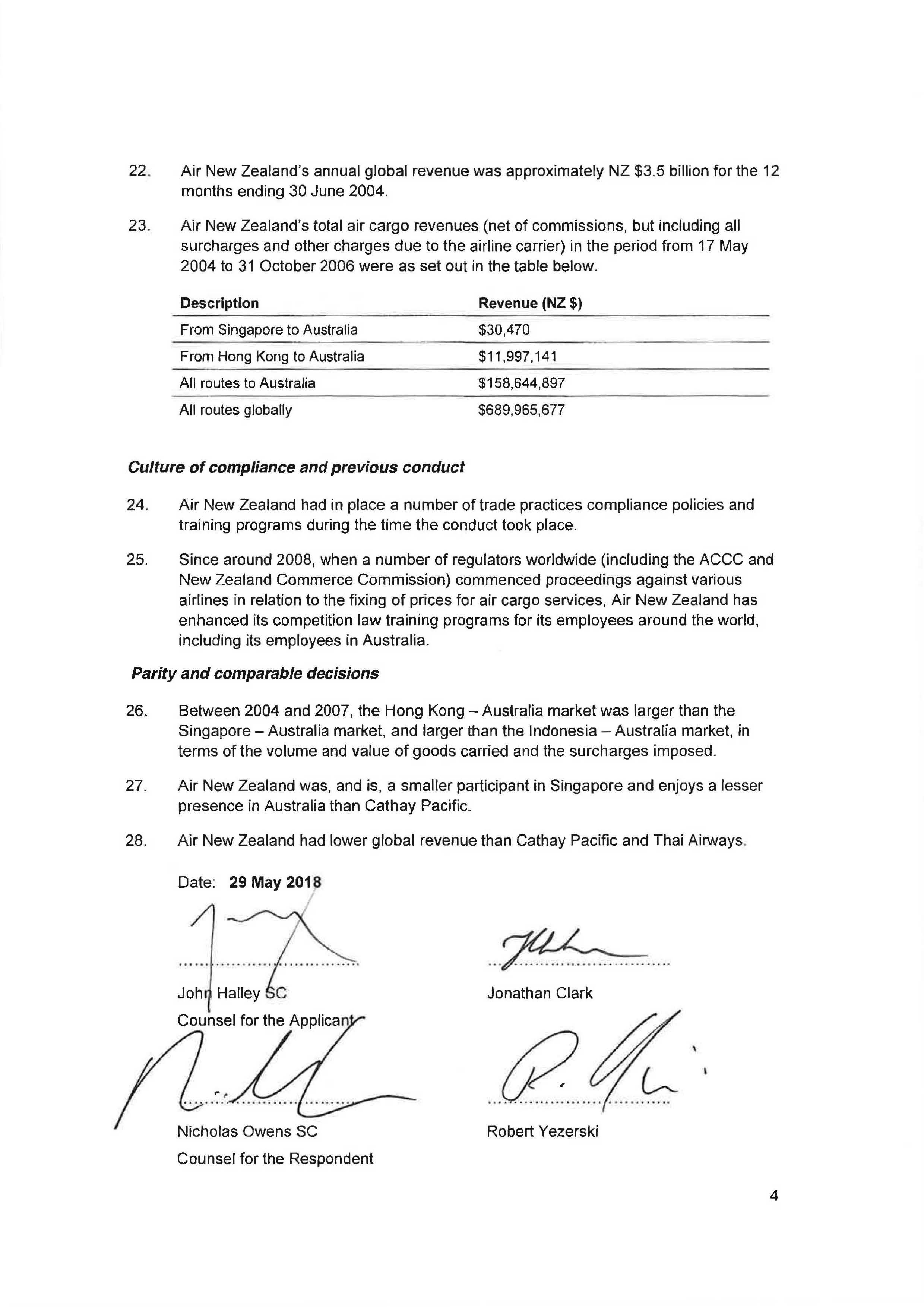

29 The proposed declarations identify the basis upon which Air New Zealand was found to have contravened ss 45(2)(a)(ii) and 45(2)(b)(ii) on each occasion with precision, and in sufficient detail to appreciate the ‘gist’ of Air New Zealand’s contravening conduct.

30 Finally, having regard to the reasoning in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2006] FCA 1730; (2007) ATPR 42-140 at [6], the declarations sought are also appropriate because they serve to:

(1) record the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct;

(2) vindicate the ACCC’s claims that Air New Zealand contravened the Act;

(3) assist the ACCC to carry out the duties conferred upon it by the Act;

(4) inform the public of the harm arising from Air New Zealand’s conduct; and

(5) deter other corporations from contravening the Act.

Pecuniary penalties: General principles and penalty factors

31 Litigation concerning contraventions of Part IV of the Act can be very complex, time consuming and costly, as the course of this proceeding has demonstrated. The ACCC has incurred costs exceeding $11 million since the commencement of the hearing at first instance involving Air New Zealand and Garuda on 6 November 2012, which ran over a period of six months, with 57 sitting days. The trial was followed by a six day appeal and a further appeal to the High Court.

32 Even where the question of liability has been resolved (as in the present instance), significant time and resources will often be required to establish matters relevant to penalty, such as the precise economic impact of the conduct on the relevant market(s), to the requisite standard.

Court’s approach to agreements on penalty

33 The public interest in parties resolving civil penalty matters with regulators such as the ACCC has been reaffirmed by the High Court in Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; (2015) 258 CLR 482 (“Fair Work”), in which the plurality stated (at [46]):

[T]here is an important public policy involved in promoting predictability of outcome in civil penalty proceedings and ... the practice of receiving and, if appropriate, accepting agreed penalty submissions increases the predictability of outcome for regulators and wrongdoers. As was recognised in Allied Mills and authoritatively determined in NW Frozen Foods, such predictability of outcome encourages corporations to acknowledge contraventions, which, in turn, assists in avoiding lengthy and complex litigation and thus tends to free the courts to deal with other matters and to free investigating officers to turn to other areas of investigation that await their attention.

34 In light of this, the Court has historically looked favourably upon negotiated settlements, provided their terms recognise that the ultimate responsibility for the final terms and making of any orders resolving the proceedings lays with the Court: see Fair Work; NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [1996] FCA 1134; (1996) 71 FCR 285 (“NW Frozen Foods”).

35 The key principles concerning whether a Court should accept a penalty that has been agreed between a regulator and respondent in civil penalty proceedings have long been established.

36 In NW Frozen Foods at 298-299, the Full Court described the appropriate approach to agreed penalties as follows:

We agree with the statement made in several of the cases cited that it is not actually useful to investigate whether, unaided by the agreement of the parties, we would have arrived at the very figure they propose. The question is not that: it is simply whether, in the performance of the Court’s duty under section 76, this particular penalty, proposed with the consent of the corporation involved and of the Commission, is one that the Court should determine to be appropriate.

37 With respect to what constitutes an “appropriate” penalty, the Court in NW Frozen Foods further stated at 291:

A proper figure is one within the permissible range in all the circumstances. The Court will not depart from an agreed figure merely because it might otherwise have been disposed to select some other figure, or except in a clear case.

38 The approach in NW Frozen Foods was subsequently endorsed both by a differently constituted Full Court in Minister for Industry, Tourism and Resources v Mobil Oil Australia Pty Ltd [2004] FCAFC 72; (2004) ATPR 41-993 (“Mobil Oil”) and, later, by the High Court in Fair Work.

39 Finally, in Real Estate Institute at [181], French J (as his Honour then was) described the Court’s responsibility in relation to orders sought by consent in the following manner:

The question whether an undertaking is to be accepted or a consent order made is not concluded by a finding that it is within the power of the Court to do so. The power of the Court to make the orders sought is “defined and conferred by public law not by private agreement”: Fisse, “Against Settlement” (1984) 93 Yale Law Journal 1073 . In the exercise of that power the Court is not merely giving effect to the wishes of the parties, it is exercising a public function and must have regard to the public interest in doing so. This principle applies to the resolution of private litigation by consent orders or undertakings. A fortiori it applies to proceedings brought by the Crown or public or statutory authorities to enforce the law in the public interest. The Court has a responsibility to be satisfied that what is proposed is not contrary to the public interest and is at least consistent with it.. . Consideration of the public interest, however, must also weigh the desirability of non-litigious resolution of enforcement proceedings.

40 A recent example of a case collecting and applying the relevant authorities, consistently with the summary above, is Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Virgin Australia Airlines Pty Ltd (No 2) [2017] FCA 204 at [10]-[22] (“Virgin Australia”). This decision concerned the imposition of a pecuniary penalty for breaches of the Australian Consumer Law where liability had already been determined by the Court. The Virgin Australia decision demonstrates that the public policy identified by the High Court in Fair Work is served by the parties reaching agreements as to penalty and other relief, even in circumstances where there has been a trial on questions of liability.

41 The essential question for the Court in the present case, therefore, is not whether, “unaided by the agreement of the parties”, it would have arrived at the same precise figure as that presently proposed by the parties. Rather, the question is whether the Court considers that the penalties proposed are “appropriate” (in the sense of falling within “the permissible range in all the circumstances”), keeping in mind the Court’s obligation to have regard to the public interest, and that the ultimate responsibility for the final terms of any orders made lays with it. In approaching this question, the Court may either first consider the proposed penalty, and then whether it falls within the permissible range; or first consider the appropriate range, and then determine whether the proposed penalty falls within that range: Mobil Oil at [54].

Primacy of deterrence

42 It has long been accepted that the principal object of imposing a pecuniary penalty under s 76 of the Act is deterrence: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; (2013) 250 CLR 640 at [65]; Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20; (2012) 287 ALR 249 (“Singtel Optus”) at [62]; NW Frozen Foods at 292-293.

43 The primacy of deterrence as the central consideration in setting pecuniary penalties has been recently reinforced by the High Court in Fair Work (at [55]), in which the plurality explicitly rejected retribution and rehabilitation as objects of civil pecuniary penalties, and observed that the purpose of a civil penalty “is primarily if not wholly protective in promoting the public interest in compliance”. In so doing, the plurality also approved the following statement by French J (as his Honour then was) in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1990] FCA 762; (1991) ATPR 41-076 at [40] (“CSR”):

Punishment for breaches of the criminal law traditionally involves three elements: deterrence, both general and individual, retribution and rehabilitation. Neither retribution nor rehabilitation, within the sense of the Old and New Testament moralities that imbue much of our criminal law, have any part to play in economic regulation of the kind contemplated by Pt IV [of the Act]... The principal, and I think probably the only, object of the penalties imposed by s 76 is to attempt to put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravenor and by others who might be tempted to contravene the Act.

44 Prior to Fair Work, French J’s approach in CSR had also been approved by the majority of the Full Court in NW Frozen Foods at 292.

45 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Midland Brick Co Pty Ltd [2004] FCA 693; (2004) ATPR 42-008 at [22], Lee J explained the role of deterrence in the enforcement mechanisms available under the Act as follows:

The object of orders made under s 76, or s 80, of the Act is to protect the integrity of markets and to prevent the subversion and distortion thereof by conduct that has the purpose or effect of adversely affecting competition. The Act sets out the norms to be met by corporations engaged in trade or commerce and in the main seeks to obtain adherence to those standards by providing for penalties to be imposed, and injunctions to be granted, that will be sufficient to deter corporations from risking, whether deliberately or negligently, the consequences of contravening the Act.

46 Deterrence has two aspects: specific deterrence in respect of the particular respondent at hand, and general deterrence of others “who may be disposed to engage in prohibited conduct of a similar kind”: Trade Practices Commission v Mobil Oil Australia Ltd [1984] FCA 403; (1984) 4 FCR 296 at [11]. In NW Frozen Foods at 294-295, the majority of the Full Court (Burchett J and Kiefel J (as her Honour then was)) made it clear that:

The Court should not leave room for any impression of weakness in its resolve to impose penalties sufficient to ensure the deterrence, not only of the parties actually before it, but also of others who might be tempted to think that contravention would pay …

47 Similarly, in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v ABB Transmission and Distribution Ltd [2001] FCA 383; (2001) ATPR 41-815 at [13] the Court observed that:

… If general deterrence is the principal object of imposing a penalty, the number of cases that still come before the court, and the seriousness of the conduct that is involved in some of them, suggests that past penalties are not achieving that object. For a penalty to have the desired effect, it must be imposed at a meaningful level. Most antitrust violations are profitable. Accordingly, the penalty must be at a level that a potentially offending corporation will see as eliminating any prospect of gain.

48 The price fixing aspects of the collusive understandings involved in the present instance raise particular and serious concerns in relation to both general and specific deterrence.

49 The importance of achieving general deterrence in price fixing cases was elucidated in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v McMahon Services Pty Ltd [2004] FCA 1425; (2004) ATPR 42-031 at [15], in which the Court observed:

Once it is understood that deterrence, and particularly general deterrence, is the primary principle in the imposition of penalty for price fixing, then at least two conclusions flow from that. First, it means that penalties for collusive price fixing will need to be substantial and significant. This is, of course, reflected in the size of the maximum penalty upon corporations of $10 million. However, it also follows logically from the principle. Collusive price fixing, particularly between tenderers, is difficult to detect. Public enforcement often only occurs with “a tip from an affected party or an insider”. Given these difficulties and the potential for large profits from such practices there is a chance that those in the market place might be prepared to factor the risk of a low penalty into its pricing structure as a ‘business cost’. That would be inimical to the statutory purpose of ensuring that the prices do not occur. The penalty must be sufficiently high that a business, acting rationally and in its own best interest, will not be prepared to treat the risk of such a penalty as a business cost.

50 For similar reasons, specific deterrence is also crucial, as stated in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v J McPhee & Son (Australia) Pty Ltd (No 5) [1998] FCA 310; (1998) ATPR 41-628 at 40,891-40,892:

This form of contravention commonly occurs in secret and between parties who seek a mutual benefit. The risk of detection is often low and the potential gain to the contravenors, and damage to the community, large. Therefore the penalty needs to be correspondingly high.

51 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; (2013) 250 CLR 640, at [65], a majority of the High Court referred with approval to the comments at [62]-[63] in Singtel Optus that a penalty must not be regarded as an “acceptable cost of doing business” and noted that:

General and specific deterrence must play a primary role in assessing the appropriate penalty in cases of calculated contravention of legislation where commercial profit is the driver of the contravening conduct.

52 It is the view of the ACCC, which Air New Zealand accepts, that specific and general deterrence is of paramount importance in the present case. Effective deterrence requires consideration of the benefits anticipated and received by Air New Zealand as a result of giving effect to the contravening provisions of the relevant understandings.

53 There is a need, for the reasons set out above, for a significant penalty to be imposed in respect of cartel arrangements and price fixing, so as to deter both Air New Zealand and other multinational corporate groups carrying on business in Australia from engaging in such conduct in the future.

54 A penalty must not be so high as to be oppressive. What is necessary is to impose a penalty of appropriate deterrent value, in the sense explained by French J at [40] in CSR. As stated in NW Frozen Foods (at 293), “[i]f deterrence is the object, the penalty should not be greater than is necessary to achieve this object; severity beyond that would be oppression”.

Penalty factors

55 Pursuant to s 76 of the Act, the Court may order that a company pay to the Commonwealth such pecuniary penalty as it determines to be appropriate, if the Court is satisfied that the company has contravened a provision (or provisions) of Pt IV of the Act.

56 Section 76(1) requires the Court to have regard to ‘all relevant matters’ in assessing the appropriate level of pecuniary penalty to be imposed in a given case, including the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission, the circumstances in which the act or omission took place, and whether the respondent has previously been found by the Court to have engaged in similar conduct.

57 The factors relevant to the assessment of an appropriate pecuniary penalty were addressed by French J (as his Honour then was) at [42] in CSR. They are:

(1) the nature and extent of the contravening conduct;

(2) the amount of loss or damage caused;

(3) the circumstances in which the conduct took place;

(4) the size of the contravening company;

(5) the degree of power the contravening company has, as evidenced by its market share and ease of entry into the market;

(6) the deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended;

(7) whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level;

(8) whether the contravening company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the Act, as evidenced by education programs and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention; and

(9) whether the contravening company has shown a disposition to cooperate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the Act in relation to the contravention.

58 The above factors, however, do not exhaust potentially relevant considerations or regiment the discretionary sentencing function: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 330; (2015) 327 ALR 540 at [9] per Allsop CJ.

59 Those matters were approved and expanded upon with the following additional considerations in NW Frozen Foods and J McPhee & Son (Aust) Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2000] FCA 365; (2000) 172 ALR 532 (“McPhee”):

(1) whether the respondent had engaged in similar conduct in the past;

(2) the effect on the functioning of the market, and other economic effects, of the conduct;

(3) the financial position of the contravening company; and

(4) whether the conduct was systematic, deliberate or covert.

60 More recently, in the consumer law context, Edelman J also considered the following factors to be relevant:

(1) the extent of contrition;

(2) whether the contravening company made a profit from the contraventions;

(3) the extent of the profit made by the contravening company; and

(4) whether the contravening company engaged in the conduct with an intention to profit from it: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Woolworths Limited [2016] FCA 44 at [126]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v RL Adams Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 1016 at [42].

Maximum penalties and limitation period

61 The High Court considered the role of maximum penalties in the process of criminal sentencing in Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25; (2005) 228 CLR 357 (“Markarian”). A similar approach has been adopted in the assessment of pecuniary penalties under s 76 of the Act: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Liquorland (Australia) Pty Ltd (ACN 007 512 419) [2005] FCA 683; (2005) ATPR 42-070 at [68]. See also Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; (2016) 340 ALR 25 at [154]-[156] in the context of s 224 of the Australian Consumer Law.

62 In Markarian, Gleeson CJ, together with Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ, set out the following principles relevant to the appropriate use of maximum penalties:

(1) the judgment involved in passing sentence in a case is a discretionary judgment, and what is required is that the sentence take into account all relevant considerations in forming the conclusion reached (at [27]);

(2) legislatures do not enact maximum available sentences as mere formalities – careful attention to maximum penalties will almost always be required, first because the legislature has legislated for them; secondly, because they invite comparison between the worst possible case (i.e., “so grave as to warrant the imposition of the maximum prescribed penalty”: The Queen v Kilic [2016] HCA 48; (2016) 259 CLR 256 at [18]) and the case before the court at the time; and thirdly, because in that regard they do provide, taken and balanced with all of the other relevant factors, a sentencing yardstick (at [31]);

(3) that said, it will rarely be appropriate to look first to a maximum penalty and proceed by making a proportional deduction from it (at [31]);

(4) the Court should not adopt a mathematical approach of applying increments or decrements from a predetermined range, or attributing specific numerical or proportionate values to the various relevant factors, as the process of sentencing involves balancing many different and conflicting features (at [37], citing Wong v The Queen [2001] HCA 64; (2001) 207 CLR 584 at [74]-[76] per Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ); and

(5) despite the above, as the law strongly favours transparency, and accessible reasoning is necessary in the interests of all stakeholders, there may be occasions when “some indulgence in an arithmetical process will better serve these ends” – however, this will not be the case where there are numerous and complex considerations which must be weighed (at [39]).

63 In Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry Maritime, Mining and Energy Union [2017] FCAFC 113; (2017) 254 FCR 68 (“CFMEU”), the Full Court considered the permissibility of imposing a single pecuniary penalty for multiple related contraventions of the Building and Construction Industry Improvement Act 2005 (Cth). At [148], the Full Court stated:

There is no doubt that, in an appropriate case involving multiple contraventions, the Court should consider whether the multiple contraventions arose from a course or separate courses of conduct. If the contraventions arose out of a course of conduct, the penalties imposed in relation to the contraventions should generally reflect that fact, otherwise there is a risk that the respondent will be doubly punished in respect of the relevant acts or omissions that make up the multiple contraventions.

64 However, at [145] the Full Court did acknowledge that the Court retains discretion to accept a single penalty for multiple contraventions:

[W]here the parties jointly propose to the Court that, having regard to the particular facts and nature of the contraventions, it would be appropriate to impose a single penalty, or to group the contraventions in terms of separate courses of conduct and impose single penalties in respect of those groups, the Court may accept that proposal and order a single penalty, or single penalties in respect of groups of contraventions.

65 At the time of the contraventions:

(1) section 76(1A) of the Act provided that the maximum penalty payable by a body corporate for each act or omission constituting a contravention of a provision of Pt IV of the Act was $10 million; and

(2) section 77(2) provided that pecuniary penalties may only be sought by the ACCC in respect of conduct which took place within six years of the commencement of proceedings.

66 The ACCC’s proceedings against Air New Zealand were commenced on 17 May 2010. The contraventions which have been found spanned the period from 23 July 2002 until at least 1 January 2007. Accordingly, only contraventions which took place, or continued, on or after 17 May 2004 are within time for penalty. For each of those contraventions, the maximum penalty is $10 million.

Parity principle

67 The parity principle requires that, when penalties are imposed, “there should not be such an inequality as would suggest that the treatment meted out has not been even handed”: NW Frozen Foods at 295. The development of a consistent approach to the fixing of pecuniary penalties necessitates reference to prior decisions: Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2015] FCAFC 59; (2015) 229 FCR 331.

68 The policy rationale for the parity principle was explained by Kirby J in Postiglione v The Queen [1997] HCA 26; (1997) 189 CLR 295 (“Postiglione”). His Honour cited Lowe v The Queen [1984] HCA 46; (1984) 154 CLR 606 (“Lowe”) and stated at 335:

Consistency in punishment is “a reflection of the notion of equal justice”. It is an attribute of “any rational and fair system of criminal justice”. On the other side of the coin, inconsistency in punishment is regarded as “a badge of unfairness” which erodes public confidence in the integrity of the administration of justice. The removal of serious and unjustifiable disparities in the treatment of like cases is a legitimate goal of the administration of criminal justice.

69 Referring to Kirby J’s judgment in Postiglione, Finkelstein J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v ABB Transmission & Distribution Ltd (No 2) [2002] FCA 559; (2002) 190 ALR 169 (“ABB”) made a similar point at [40]:

Consistency in punishment is an attribute of a rational and fair system of justice. Inconsistency would erode the public confidence in the administration of justice: Postiglione v R (1997) 189 CLR 295, 335. The parity principle only applies in a case of offenders whose circumstances are comparable.

70 Where the circumstances are not equal, due discrimination should be made: R v Tiddy (1969) SASR 575 at 577. As Gibbs CJ stated in Lowe at 609:

It is obviously desirable that persons who have been parties to the commission of the same offence should, if other things are equal, receive the same sentence, but other things are not always equal, and such matters as the age, background, previous criminal history and general character of the offender, and the part which he or she played in the commission of the offence, have to be taken into account.

71 Further, as observed in NW Frozen Foods at 295 in the context of the Act:

A hallmark of justice is equality before the law, and, other things being equal, corporations guilty of similar contraventions should incur similar penalties: Trade Practices Commission v Axive Pty Ltd (at 42,795). There should not be such an inequality as to suggest that the treatment meted out has not been even-handed: cf the criminal law case Lowe v The Queen (1984) 154 CLR 606. However, other things are rarely equal where contraventions of the Trade Practices Act are concerned.

“Totality” and “course of conduct” principles

72 In determining the appropriate penalty for a multiplicity of offences, the Court must have regard to the ‘totality principle’: see R v Holder & Johnston [1983] 3 NSWLR 245; Mill v The Queen [1988] HCA 70; (1988) 166 CLR 59 (“Mill”); and Cahyadi v The Queen [2007] NSWCCA 1; (2007) 168 A Crim R 41. This principle provides that the total penalty imposed for related offences ought not to exceed what is proper for the entire contravening conduct involved: Trade Practices Commission v TNT Australia Pty Ltd (1995) ATPR 41-375 at 40,169.

73 The totality principle is designed to ensure that overall an appropriate sentence or penalty is appropriate and that the sum of the penalties imposed for several contraventions does not result in the total of the penalties exceeding what is proper having regard to the totality of the contravening conduct involved: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd [1997] FCA 450; (1997) 75 FCR 238 at 243.

74 In Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; (2010) 269 ALR 1 at [41], Middleton and Gordon JJ emphasised the importance of applying the totality principle to avoid double punishment:

[The totality] principle recognises that where there is an interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of two or more offences for which an offender has been charged, the Court must ensure that the offender is not punished twice for the same conduct.

75 When appropriate penalties have been identified for each contravention, the Court should conduct a ‘final check’ to ensure that the total penalty is not unjust or disproportionate to the circumstances: Mornington Inn Pty Ltd v Jordan [2008] FCAFC 70; (2008) 168 FCR 383 at [42]-[43] (“Mornington Inn”), applying Mill at 62-63.

76 This approach requires the Court, as an initial step, to impose a penalty appropriate for each act of contravention, or, if applicable, course of conduct, and then as a check, at the end of the process, consider whether the aggregate is considered excessive: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cement Australia Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 159 at [629]. If the total of the proposed penalties is considered to be appropriate it is not necessary to impose any further reduction: see Mornington Inn at [90]-[92]; and Cement Australia Pty Ltd at [629].

77 In contrast, the ‘course of conduct’ principle is concerned with circumstances where “whatever the number of technically identifiable offences committed, [the contravener] was truly engaged upon one multi-faceted course of [contravening] conduct”: Attorney-General (SA) v Tichy (1982) 30 SASR 84 at 92-93, cited with approval in Johnson v R [2004] HCA 15; (2004) 205 ALR 346 at [4]-[5]; see also Mornington Inn at [41]-[46].

78 The Full Court further considered the application of both principles in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2017] FCAFC 113; (2017) 254 FCR 68. At [148] and [149], the Court stated:

[148] The important point to emphasise is that, contrary to the Commissioner's submissions, neither the course of conduct principle nor the totality principle, properly considered and applied, permit, let alone require, the Court to impose a single penalty in respect of multiple contraventions of a pecuniary penalty provision. There is no doubt that, in an appropriate case involving multiple contraventions, the Court should consider whether the multiple contraventions arose from a course or separate courses of conduct. If the contraventions arose out of a course of conduct, the penalties imposed in relation to the contraventions should generally reflect that fact, otherwise there is a risk that the respondent will be doubly punished in respect of the relevant acts or omissions that make up the multiple contraventions. That is not to say that the Court can impose a single penalty in respect of each course of conduct. Likewise, there is no doubt that in an appropriate case involving multiple contraventions, the Court should, after fixing separate penalties for the contraventions, consider whether the aggregate penalty is excessive. If the aggregate is found to be excessive, the penalties should be adjusted so as to avoid that outcome. That is not to say that the Court can fix a single penalty for the multiple contraventions.

[149] In an appropriate case, however, the Court may impose a single penalty for multiple contraventions where that course is agreed or accepted as being appropriate by the parties. It may be appropriate for the Court to impose a single penalty in such circumstances, for example, where the pleadings and facts reveal that the contraventions arose from a course of conduct and the precise number of contraventions cannot be ascertained, or the number of contraventions is so large that the fixing of separate penalties is not feasible, or there are a large number of relatively minor related contraventions that are most sensibly considered compendiously. As revealed generally by the reasoning in [Commonwealth of Australia v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; (2015) 326 ALR 476], there is considerably greater scope for agreement on facts and orders in civil proceedings than there is in criminal sentence proceedings. As with agreed penalties generally, however, the Court is not compelled to accept such a proposal and should only do so if it is considered appropriate in all the circumstances.

Pecuniary penalties: application of principles to the conduct in this proceeding

79 As earlier noted, pecuniary penalties were only sought, and may only be ordered, in respect of contraventions by Air New Zealand which took place on or after 17 May 2004. For each of these contraventions, the maximum penalty is $10 million.

80 Air New Zealand’s conduct in giving effect to provisions of the Singapore ISS Understanding constituted a single contravention of s 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act. Accordingly, the maximum available penalty in respect of Air New Zealand’s Singapore conduct is $10 million.

81 The characterisation of Air New Zealand’s conduct in giving effect to provisions of each of the 2002 Hong Kong Lufthansa Methodology Understanding and the Hong Kong Imposition Understanding is more complicated. This is because, while the acts by which Air New Zealand gave effect to each of these understandings were not identical and constitute separate contraventions, its act of imposing a new surcharge level on each occasion simultaneously gave effect to provisions of both understandings.

82 On this basis, I accept that it is appropriate for the Court to have regard to one maximum penalty for each of the 20 fuel surcharge impositions in Hong Kong, yielding a total maximum penalty of $200 million in respect of Air New Zealand’s Hong Kong conduct (rather than $400 million on the basis that each surcharge imposition gave rise to two contraventions).

83 Having so identified the theoretical maximum penalty, the principles relating to course of conduct must be taken into account.

Nature and extent of contravening conduct, and the circumstances in which it took place

84 The conduct constituting the making or arriving at, and the giving effect to provisions of, the Hong Kong Fuel Surcharge Understandings and the Singapore ISS Understanding is set out at [520] to [591], [596] to [658] and [1112] to [1127] of the principal judgment.

Historical background

85 The historical background to the fuel surcharge agreements is set out at [492]-[505] of the principal judgment. A summary of those matters follows.

1996 to 2000: The IATA Fuel Price Index and Resolution 116ss Methodology

86 In 1997, the members of the International Air Transport Association (“IATA”) passed a resolution (“Resolution 116ss”) to the effect that the IATA prepare and publish a fuel price index for its members (“IATA Fuel Price Index”), and provide for the imposition of fuel surcharges in accordance with a methodology linked to the index (“Resolution 116ss Methodology”). IATA was at the time, and remains, the peak airline industry body of which major international airlines are members.

87 The IATA Fuel Price Index measured movements in the price of aviation fuel against a base of the average of prices in five ports in June 1996 (where the base index equals 100). The Resolution 116ss Methodology provided that when the index reached 130 (i.e., 130% of the baseline price) for two consecutive weeks, airlines would impose the local currency equivalent of US$0.10 per kilogram of air freight as a “fuel surcharge”, and also that this surcharge would be removed when the index fell below 110 for two consecutive weeks. The methodology provided details for imposing the surcharge, such as the means of including the surcharge on air waybills and the freight forwarders’ eligibility for commission.

88 The surcharge generated by the index rose and fell with movements in the spot price of fuel, but did not necessarily reflect changes in the actual fuel costs of any of the particular airlines which applied it.

89 In May 1998, IATA advised its members that the fuel surcharge should not be imposed until Resolution 116ss had received regulatory approval, including from the United States Department of Transportation.

90 In December 1999, the IATA Fuel Price Index exceeded 130, being the trigger point for the imposition of a fuel surcharge, had Resolution 116ss been in force.

91 On 28 January 2000, IATA sought regulatory approval and anti-trust immunity for Resolution 116ss from the US Department of Transportation, but this was refused in March 2000. Shortly thereafter, IATA notified its members that Resolution 116ss was not effective, and ceased publishing its fuel price index.

2000 to 2002: The Lufthansa Fuel Price Index and New Lufthansa Methodology

92 Either before, or immediately after, IATA ceased the publication of the IATA Fuel Price Index, Lufthansa commenced publishing its own fuel price index on its website, which effectively replicated the IATA Fuel price Index (“Lufthansa Fuel Price Index”).

93 Lufthansa subsequently added a further level to its index which when increased to 170 for two consecutive weeks set the surcharge at €0.17 per kilogram and when decreased (for two consecutive weeks) to 150 set the surcharge at €0.10 per kilogram.

94 On 29 September 2000, the 170 trigger point was reached. However, throughout 2001, the price of aviation fuel fell and the index dropped. By December 2001/January 2002, the surcharge was itself removed.

95 Being copied from the original IATA Index (and hence Resolution 116ss), the Lufthansa Fuel Price Index was not triggered unless it reached 130. The fact that the index remained below 130 through the second half of 2001 meant that the Lufthansa Index was not triggered and no fuel surcharge was imposed.

96 In January 2002, Lufthansa announced a new fuel surcharge methodology with smaller increments at more frequent intervals (“Lufthansa Methodology”). The Lufthansa Methodology was as follows:

Level | Fuel Surcharge | Imposition – Index | Removal – Index |

1 | €0.05 / kg | 115 | 100 |

2 | €0.10 / kg | 135 | 120 |

3 | €0/15 / kg | 165 | 145 |

4 | €0/20 / kg | 190 | 170 |

97 Similar to Resolution 116ss, the Lufthansa Methodology calculated the fuel surcharges based on the actual per kilogram weight of international air freight and used a two week period for an index threshold to trigger a fuel surcharge increase or decrease. The fuel surcharge was imposed in euros or the equivalent in local currency. Several other airlines announced and charged fuel surcharges based on the Lufthansa Methodology.

Contravening conduct

98 The conduct lasted for around four years in respect of both sets of understandings, and concerned price-fixing on the carriage of all air cargo on two major routes to Australia. However, only around two and a half years of conduct in relation to giving effect to provisions of the Hong Kong Fuel Surcharge Understandings (17 May 2004 to 17 October 2006) and three years of conduct in relation to giving effect to provisions of the Singapore ISS Understanding (17 May 2004 to 1 January 2007) are within time for penalty.

99 The conduct in relation to both understandings could not have been effective unless airlines such as Air New Zealand participated because, as the Court observed (in respect of similar conduct in relation to Indonesia) in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Malaysia Airline System Berhad (No 2) [2012] FCA 767 at [27]:

[T]he conduct required the participation of all major carriers in Indonesia to be successful. Irrespective of the direct financial benefit [to the contravener], its participation in the conduct alone requires a penalty of the order proposed by the parties.

Circumstances in which the conduct took place

100 In the four years from 1 July 2003 to 30 June 2007, the total amount of air cargo estimated to have been carried annually in each of the relevant markets was:

(1) in respect of the Singapore–Australia market, between 93,572 and 116,565 tonnes; and

(2) in respect of the Hong Kong–Australia market, between 116,611 and 151,595 tonnes.

101 The surcharge revenue generated by Air New Zealand to Australia in respect of the Singapore ISS Understanding was insignificant. In the period from 17 May 2004 to 31 October 2006, the total value of insurance surcharges collected by Air New Zealand for the carriage of air cargo from Singapore directly to Australia was NZ$1,829, which was charged against four different air waybills.

102 To place the revenue derived by Air New Zealand in appropriate context, two circumstances should be noted. First, the incentive to participate in the relevant understandings was not limited to particular routes and nor was the requirement to impose surcharges limited to any particular routes. While the actual benefit to Air New Zealand cannot be known (see further below), the total amount of revenue derived by Air New Zealand from the ISS on all routes from Singapore to ports around the world was about NZ$500,000 per annum. In assessing the significance of the circumstance for penalty purposes, it was not contended that Air New Zealand contravened the Act by giving effect to the provisions of the Singapore ISS Understanding to the extent those provisions concerned routes other than to Australia, but simply that it is a relevant circumstance in considering deterrence. Second, pursuant to the Singapore ISS Understanding, a levy on all freight flown to Australia from Singapore was imposed by virtually all carriers. The surcharge was SG$0.18 per kilogram, yielding a total impost by all carriers of between roughly SG$17 million and SG$21 million per year, inclusive of transhipments (which may overinflate total volumes and revenues). Of this, Air New Zealand collected NZ$1,829.114. This is also a relevant circumstance in considering deterrence.

103 Air New Zealand derived a much greater sum of money through the imposition of fuel surcharges pursuant to the Hong Kong Fuel Surcharge Understandings. In the period from 17 May 2004 to 31 October 2006, the total value of fuel surcharges collected by Air New Zealand for air cargo from Hong Kong to Australia was NZ$1,719,973, which was charged against 12,354 air waybills.

104 Once again, to place the revenue derived by Air New Zealand in appropriate context, it should be observed that the figures quoted in the previous paragraph do not reflect the larger revenue generated by Air New Zealand from surcharges on cargo from Hong Kong to ports other than Australia. Again, it was not contended that Air New Zealand contravened the Act by giving effect to the provisions of the Hong Kong Fuel Surcharge Understandings to the extent those provisions concerned routes other than to Australia but rather that it is a relevant circumstance in considering deterrence. Air New Zealand estimates it carried between 0.6% and 1.6% of the annual air cargo from Hong Kong to Australia when transhipments are included. Thus, while the actual benefits of the conduct cannot be known, the total surcharges imposed on cargo from Hong Kong to Australia by all the airlines pursuant to the Hong Kong Fuel Surcharge Understandings would have been between around NZ$100 million and NZ$300 million in total between 17 May 2004 and 31 October 2006 when transhipments are included, of which Air New Zealand collected NZ$1,719,973. This again is relevant to deterrence.

105 Neither the ACCC nor Air New Zealand is aware as to what proportion of the surcharges was ultimately borne by any particular consumer or business in Australia. As a general rule, the ultimate consumer will bear most (if not all) of the transport costs, in the price paid for the cargo. Others in the supply chain, such as wholesalers or retailers, may choose to absorb some part of the cost some part of the time. These others comprise persons both in Australia and overseas.

106 Further, in relation to fuel surcharges, the revenue derived from them does not demonstrate actual loss to shippers or their customers or the size of any benefit to Air New Zealand. Absent the Hong Kong Fuel Surcharge Understandings, some price increases would have occurred to cover the increased costs of fuel, which did increase over the relevant period. It may have also been that some airlines would have been forced to exit certain routes, allowing the remaining air cargo carriers operating on those routes to impose other increases with less constraint. These competitive outcomes cannot be known.

Size, financial position and market power of the contravening company

107 Air New Zealand is a mid-sized supplier of aviation services in Australia. Between 2004 and 2007, Air New Zealand employed around 10,500 fulltime-equivalent employees around the world, and offered scheduled cargo and passenger services to around 23 destinations worldwide, including to Australia (and excluding destinations available through interlining). During this time, Air New Zealand’s cargo operations in each of Hong Kong, Singapore and Australia employed between three to five full time equivalent employees per country.

108 In both the Singapore – Australia and the Hong Kong – Australia markets, Air New Zealand faced other significant competitors which were major international carriers. The ACCC did not contend that Air New Zealand was able to act in those markets without being constrained by competitors.

109 Between 2004 and 2007, Air New Zealand was responsible for the carriage of around 0% to 0.01% of air freight from Singapore to Australia, and around 0.6% to 1.6% of air freight from Hong Kong to Australia (based on weight) when transhipments are included. It was responsible for the carriage of around 5% to 6.2% of the total amount of air freight sent to Australia from all ports worldwide.

110 By comparison, Qantas carried around 24% of air cargo to and from Australia, having the largest market share of any airline involved in the ACCC’s investigation.

111 Air New Zealand’s business comprises the respondent, as well as subsidiaries, joint ventures and associates (together, the “Air New Zealand Group”). The Air New Zealand Group’s annual earnings before interest and tax (“EBIT”) in the period from 1 July 2003 to 30 June 2007, was between NZ $148 million and NZ $283 million. Air New Zealand’s EBIT for the financial year ending 30 June 2017 was NZ $568 million.

112 Air New Zealand’s total air cargo revenues (net of commissions, but including all surcharges and other charges due to the airline carrier) in the period from 17 May 2004 to 31 October 2006 were as set out in the table below:

Description | Revenue |

Singapore to Australia | NZ$30,470 |

Hong Kong to Australia | NZ$11,997,141 |

All routes to Australia | NZ$158,644,897 |

All routes globally | NZ$689,965,677 |

Whether conduct was systematic, deliberate or covert

113 The conduct was deliberate, in the sense that the agreeing and fixing of prices with its competitors was intentionally engaged in by representatives of Air New Zealand. However, there was no finding that the conduct was engaged in with the intent of contravening Australian law (or the law of any other jurisdiction).

114 The giving effect to provisions of both the Hong Kong Fuel Surcharge Understandings and the Singapore ISS Understanding was also systematic, in that it took place within the context of the existence of various mechanisms for coordinating prices in Hong Kong and Singapore. Air New Zealand’s conduct in giving effect to provisions of the Hong Kong Fuel Surcharge Understandings also required it to take active steps to monitor the Lufthansa Price Index, deal with other cartel members to obtain approval from the Hong Kong CAD, notify customers and change its level of fuel surcharges accordingly.

115 In Hong Kong, airlines were required to obtain approval from the Hong Kong CAD for the imposition of fuel or insurance surcharges. The airlines reached an agreement to secure that approval, and to jointly impose those surcharges once they were approved. The Hong Kong CAD encouraged airlines to lodge a joint application for the approval of any fuel index mechanism (such as the one contemplated by the airlines’ agreement) through the Hong Kong BAR-CSC. The airlines, however, were not directed to do so and each could have, subject to some commercial inconvenience, applied its own fuel index mechanism.

116 Once the approval of the Hong Kong CAD was obtained, each airline that chose to impose a surcharge was permitted to charge only that surcharge and no other. The Hong Kong CAD approval did not require the airlines to levy a surcharge. The available fuel surcharges that were approved, and imposed pursuant to the Hong Kong Fuel Surcharge Understandings, were accordingly known to the local regulator. They were also communicated to shippers by the Hong Kong BAR-CSC.

117 The conduct is not in the most serious category of cartel offences in which the cartel participants act in knowing contravention of the law. The amount of the price increase through surcharging was known to the customers and the regulators even though the agreement to impose it was not.

Involvement of senior management