FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Huon Aquaculture Group Limited v Minister for the Environment [2018] FCA 1011

Table of Corrections | |

9 July 2018 | At [72], the word “not” has been deleted between “would” and “be”. |

9 July 2018 | At [120], the word “and” has been deleted between “both” and “Mr”. |

At [169], “curios” has been replaced with “curious”. | |

9 July 2018 | At [274], “their respective clients” has been changed to “the Fourth and Fifth Respondents”. |

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

2. The Applicants pay the Fourth and Fifth Respondents’ costs as agreed or assessed.

3. The Applicants pay the Third Respondent’s costs up to and including 27 April 2017 as agreed or assessed.

4. The Third Respondent have leave to file and serve an application to vary Order 3, together with submissions limited to 5 pages, no later than 4.00 pm on Friday 3 August 2018.

5. The Applicants have leave to file and serve responsive submissions, limited to 5 pages, no later than 4.00 pm on Friday 31 August 2018.

6. The Third Respondent have leave to file and serve reply submissions, limited to 2 pages, no later than 4.00 pm on Friday 14 September 2018.

7. The Court will determine any application made pursuant to Order 4 on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

Table of contents

KERR J:

1 The Applicants seek a declaration that a decision made by the Commonwealth Minister for the Environment (the Minister) on 3 October 2012 pursuant to s 75 of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (the EPBC Act) that a proposed action was not a controlled action if undertaken in a particular manner, is invalid. The proposed action was, greatly compressed by way of summary, the expansion of finfish farming in Macquarie Harbour.

2 The proposed action had been referred to the Minister by Mr Kim Evans, Secretary of the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (DPIPWE). He did so under cover of a lengthy submission dated 29 May 2012 (Ex A1 pp 2-111).

3 In that referral, Mr Evans had informed the Minister as follows:

Three separate companies have been working jointly on the proposed expansion of salmonid farming activities in Macquarie Harbour … all three of which have existing salmonid framing operations … [i]t is expected that these companies will take up the expanded lease area.

(Ex A1 p 11)

In response to a question in the referral template asking for the identity of the person proposing to take the action, Mr Evans had advised the Minister:

Given that the three individual companies are jointly involved in the proposed expansion and that DPIPWE will be actively managing both implementation of the amended MFDP [Marine Farming Development Plan], along with the adaptive management framework associated with the proposal … it was considered that one EPBC referral would be the most efficient and effective way of progressing the proposal. For this reason DPIPWE is the proponent for the action rather than each of the individual companies. It is the intent that the management approaches and mitigation measures will be applied by companies through leases and licences that the companies will hold.

(Ex A1 p 107)

4 An unusual feature of these proceedings is that the challenge to the validity of the Minister’s decision has been brought by one of the three fish farmers named by Mr Evans in the referral as having worked jointly on the proposed expansion, Huon Aquaculture Group Limited (Huon). Although nominally three companies are seeking relief, the two other Applicants are subsidiaries of the First Applicant Huon.

5 Huon brings these proceedings notwithstanding it later having expanded its own finfish farming operations in Macquarie Harbour in reliance on what it now asserts had been the Minister’s merely purported decision. The Minister is the Third Respondent. The other two fish farmers are the Fourth Respondent, Petuna Aquaculture Pty Ltd (Petuna) and the Fifth Respondent, Tassal Operations Pty Ltd (Tassal).

6 The Third, Fourth and Fifth Respondents each deny that the Minister’s decision was invalid.

7 The Minister does not submit that Huon has no arguable grounds for its application. The Minister however submits (and is joined in his submission by the Fourth and Fifth Respondents) that the Court should reject Huon’s entitlement to relief on established principles applying to discretionary remedies without traversing (but assuming for that purpose) the merits of Huon’s application.

8 The Respondents therefore further plead in their respective defences (although variously differently expressed) that, having regard to Huon’s delay in bringing these proceedings, its prior inconsistent conduct, and that the two other fish farmers, Petuna and Tassal (which had also relied on the validity of the Minister’s decision) would suffer financial and legal detriment if the Court were to make the declaration Huon seeks, Huon is not entitled to declaratory relief.

9 Huon submits that the Court should reject that proposition. It has adduced evidence that the motivation for Huon bringing these proceedings is that its directors believe on reasonable grounds that the expansion of salmonid aquaculture in Macquarie Harbour pursuant to the Minister’s purported decision has resulted in environmental damage in Macquarie Harbour, including but not limited to a significant reduction in dissolved oxygen levels. It submits that the Court is entitled to accept that evidence and conclude that Huon has reasonable grounds for that belief.

10 Huon submits that a declaration that the Minister’s decision was invalid would not have the draconian consequences the Respondents hypothesise of causing it and the two other fish farmers, Petuna and Tassal, to cease operating in Macquarie Harbour. Rather, it would restore the position of the three fish farmers to that which pre-existed the expansion purportedly authorised by the Minister’s decision, with much lesser consequences.

11 Having regard to the terms of the EPBC Act there is, Huon submits, no sound discretionary basis for denying the issue of a declaration. Huon contends that the Court should address the case it advances on the merits. On that basis, Huon submits it can make good its challenge pleaded at [38] of its Third Further Amended Statement of Claim. Huon contends that the Minister’s decision was invalid for reasons of uncertainty and lack of finality, as well as it not being directed to the particular persons undertaking the action, and being dependent on decisions to be made from time by time by a third party, being the Secretary of DPIPWE, the former First Respondent (see at [12]-[15] below).

1.1 The history of these proceedings

12 Before the Court addresses the evidence and the parties’ respective contentions, it is appropriate first to observe that this litigation has had a complex procedural background.

13 Huon initially named the Secretary of DPIPWE as the First Respondent and the Director of the Environment Protection Authority (the EPA) as the Second Respondent in its originating application. Huon did so on the premise that DPIPWE, rather than the individual fish farmers (itself, Petuna and Tassal) was the person taking the action that had been referred to the Minister for his decision.

14 Huon’s pleadings in that regard were later abandoned before the scheduled trial of certain separate questions which the Court had agreed to decide. One of those questions had involved the correct identity of the person taking the action.

15 Once Huon had amended its pleadings, the First and Second Respondents applied to cease to be parties. The Court gave its reasons for granting their applications in Huon Aquaculture Group Limited v Secretary, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (No 2) [2018] FCA 89.

16 In the context of the procedural background to these proceedings it is also appropriate to note that following the Court’s earlier interlocutory decision in Huon Aquaculture Group Limited v Secretary, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment [2017] FCA 1615 (Huon No 1), Huon further amended its pleadings by deleting its earlier contentions that the action as determined by the Minister to not be a controlled action if undertaken in a particular manner has, will have, or is likely to have a significant impact on a declared World Heritage Area and/or a listed threatened species.

17 In the aftermath of those amendments to Huon’s pleadings, there being no objection from any party, the Court determined not to proceed with a trial of the remaining separate questions. Instead, a full hearing was scheduled and a trial was conducted on all issues. The parties did not further amend their pleadings, and the Court did not consider it necessary to order revised pleadings following the First and Second Respondents ceasing to be parties. Huon’s Third Further Amended Statement of Claim and the Respondents’ several defences thereto, in so far as they refer to the First and Second Respondents, are to be comprehended as references to the Secretary of DPIPWE and the Director of the EPA respectively.

18 I now set out the background to the Minister’s decision.

2.1 Description of Macquarie Harbour

19 Macquarie Harbour is on the west coast of Tasmania. Both the Harbour and those parts of it subject to existing Tasmanian regulatory control for aquaculture were described in the referral dated 29 May 2012 made by DPIPWE under its Secretary’s signature in the following terms:

… The harbour lies approximately 175 km to the north west and south west of the major Tasmanian cities of Hobart and Launceston respectively. The nearest township to the marine component is Strahan, approximately 11 km to the north of the closest proposed development on the water.

The area covered by the Macquarie Harbour [Marine Farming Development Plan] is the physical extent of the harbour outside the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area (TWWHA) and includes part of the South West Conservation Area. It consists of all that area bounded by the high water mark between lines drawn from Coal Head and Steadmans Point across the harbour to the south east and the entrance to the harbour to the north west at a line drawn between Braddon Point through Bonnet Island Light to the western shore …

The harbour itself is a large estuary where saline ocean waters mix with freshwaters predominantly from the Gordon and King Rivers and Birchs Inlet. The harbour has a shallow restricted entrance which opens into a long deep basin with depths ranging from 0 – 50 m in the centre of the harbour; an old Gordon River channel follows the southern shoreline before reaching shallow sand banks to the north west of Table Head; and shallow water at the entrance to the Gordon River and a formed delta at the mouth of the Kind River.

The natural harbour is approximately 33 km long and 9 km wide with a total surface area of 276 square km. The water column in the harbour is typically three-layered: fresh, marine, and intermediate, trending to a salt wedge structure near the two rivers. (Ex A1 p 8)

20 No party submits that that was not an accurate description of the harbour.

2.2 Marine farming in Macquarie Harbour was an established use prior to the passage of the EPBC Act in 1999

21 The referral also advised (Ex A1 p 25):

… [F]ish farming in Macquarie Harbour commenced prior to the EPBC in the mid 1980s, and incremental changes since then were determined unlikely to have a significant impact on MNES [matters of national environmental significance].

22 It is not contentious that each of Huon, Petuna and Tassal had individual pre-existing marine leases in Macquarie Harbour and were growing and harvesting fish before the passage of the EPBC Act. Their individual entitlements to continue fish farming in Macquarie Harbour after the passage of the EPBC Act had been “grandfathered” by s 43B of the EPBC Act:

Actions which are lawful continuations of use of land etc.

(1) A person may take an action described in a provision of Part 3 without an approval under Part 9 for the purposes of the provision if the action is a lawful continuation of a use of land, sea or seabed that was occurring immediately before the commencement of this Act.

(2) However, subsection (1) does not apply to an action if:

(a) before the commencement of this Act, the action was authorised by a specific environmental authorisation; and

(b) at the time the action is taken, the specific environmental authorisation continues to be in force.

Note: In that case, section 43A applies instead.

(3) For the purposes of this section, neither of the following is a continuation of a use of land, sea or seabed:

(a) an enlargement, expansion or intensification of use;

(b) either:

(i) any change in the location of where the use of the land, sea or seabed is occurring; or

(ii) any change in the nature of the activities comprising the use;

that results in a substantial increase in the impact of the use on the land, sea or seabed.

23 The actions of Huon, Petuna and Tassal respectively in connection with growing and harvesting salmon in Macquarie Harbour were a lawful continuation of a use of land, sea or seabed that was occurring immediately before the commencement of the EPBC Act. That use was lawful. It was authorised by and was subject to regulation under Tasmanian law. It is thus uncontentious in these proceedings that each of the then operators (Huon, Petuna and Tassal) had been entitled to continue marine farming in Macquarie Harbour beyond the coming into force of the EPBC Act subject to the qualifications imposed by s 43B(3). Those qualifications included that there be no enlargement, expansion or intensification of use.

2.3 The then system of regulation under Tasmanian law

24 The then applicable state legislation which regulated finfish farming was described in the referral by Mr Evans as follows:

2.4 Context, planning framework and state/local government requirements

…

Marine farming in Tasmanian waters is subject [to] the provisions of the Marine Farming Planning Act 1995 (MFPA) and the Living Marine Resources Management Act 1995 (LMRMA). Both Acts sit within the overarching Resource Management and Planning System of Tasmania (RMPS) which is made up of a suite of legislation containing the objectives of the RMPS.

The MFPA provides for the preparation of Marine Farming Development Plans, amendments to plans and reviews of plans. Plans use a zoning concept to identify areas that are suitable for marine farming activities. The plans identify the maximum area that can be allocated for a marine farming lease or leases within marine farming zones, broad categories of species that may be farmed within those lease areas and the operational constraints (called management controls) on those operations.

The objectives of the MFPA are to integrate marine farming activities with other marine users, minimise any adverse impacts, take account of land uses and take account of the community’s right to have an interest in those activities.

The MFPA prescribes statutory processes for the preparation of MFDPs, amendment and review of plans. These provisions include environmental assessments, public consultation and consideration of issues by an independent and expertise based Panel established to make recommendations to the Minister of Primary Industries and Water. The Minister is charged with the responsibility to approve or not approve plans or amendments to plans.

Fourteen MFDPs have been prepared to cover the major areas in Tasmania suited to marine farming activities.

While the MFPA provides for the occupation of State waters for marine farming activities and controls the extent of these activities the LMRMA includes provisions to licence a leaseholder to farm specific species and further impose operational constraints on activities.

The regulation of marine farming activities is therefore achieved through multiple controls:

• Statutory provisions under the MFPA and LMRMA

• Management controls contained within marine farming development plans

• Marine farming licence conditions.

The Macquarie Harbour Marine Farming Development Plan October 2005 provides for the culture of salmonids (Atlantic salmon, rainbow trout and brook trout) in 10 marine farming zones up to a maximum leasable area of 564 hectares. …

The approval of developments and operation of terrestrial components associated with marine farming is regulated primarily through the Land Use and Planning Approvals Act 1993 (LUPAA) and the Environmental Management and Pollution Control Act 1994 (which are both part of the RMPS). Depending on the nature and location of facilities other approvals may be required under State legislation including the following acts: Threatened Species Protection Act 1995, Aboriginal Relics Act 1975 and the Historic Cultural Heritage Act 1995. In addition, activities not covered by leases and licences, occurring within reserved areas should be undertaken in accordance with the State’s Reserve Management Code of Practice. For reserves managed by the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service (PWS) approvals are required under the National Parks and Reserves Management Act 2002 to undertake certain activities. A Reserve Activity Assessment process is used by PWS to ensure any relevant activities are compliant with relevant statutes, policies and plans. In undertaking the assessment the benefits of the proposed activity (social, economic and environmental) are also identified as are any measures taken to maximise benefits to the environment and to minimise impacts upon it.

Activities associated with marine farming that may take place in areas adjacent to that covered by the MFPD may also require regulation under other State legislation, including: Natura Conservation Act 2002: (reservation, wildlife management), Animal Health Act 1995 (introduction or pest species), Weed Management Act 1999 (introduction of weeds), Plant Quarantine Act 1997 (introduction of plant pests) Crown Lands Act 1976 (regulation of activities on Crown Land), Veterinary Chemicals (Control of Use) Act 1995 (safe use of chemicals, including disposal) and Marine and Safety Authority Act 1997 and associated regulations (boat speed and safe handling).

(Ex A1 pp 21-22)

25 While extensively regulated, no party submits that the fish farmers’ prior individual actions had been the subject of a specific environmental authorisation as defined in s 43A of the EPBC Act.

2.4 Passage of the EPBC Act 1999

26 The EPBC Act received Royal Assent on 16 July 1999 and came into force on 16 July 2000. The EPBC Act, among other things, established a scheme that required a person proposing to take an action he or she thinks may be a controlled action (that is one that has, will have, or is likely to have a significant impact on a matter of national environmental significance as defined in Pt 3, Div 1) to refer the proposed action to the Minister (s 68).

27 It is unnecessary for the purposes of these reasons to set out the provisions of Pt 3 of the EPBC Act. It is sufficient to indicate that as relevant to these proceedings Pt 3 includes provisions relating to World Heritage properties, National Heritage places and listed threatened species and communities.

28 Given the nature of fish farming and Macquarie Harbour’s adjacency to the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area, it may be thought self-evident that any action involving the enlargement, expansion or intensification of use of Macquarie Harbour for aquaculture after the commencement of the EPBC Act was an action that had to be referred to the Minister.

2.5 Huon, Petuna and Tassal take the view that the expansion of fish farming in Macquarie Harbour was desirable

29 It is uncontentious that, after the coming into effect of the EPBC Act, the three operators came to share the view that their fish farming operations in Macquarie Harbour could and should be expanded. Despite the concerns Huon has since come to have regarding the pressures increased fish stocking have placed on the general health of Macquarie Harbour, at that time Huon shared the views of Petuna and Tassal that an expansion of fish farming in Macquarie Harbour could be conducted sustainably and was desirable. Huon’s counsel, Mr Galasso SC, in his opening submission accepted that Huon had “participated in the contemplation of the expansion of marine farming in Macquarie Harbour” (transcript p 8 lines 6-7).

30 Under the Tasmanian regulatory system a change of that kind required an amendment to the Macquarie Harbour Marine Farming Development Plan October 2005 (MHMFDP). The operators’ application for such an amendment was required to be accompanied by an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) pursuant to s 23 of the Marine Farming Planning Act 1995 (Tas) (Ex A1 p 22). Accordingly Huon, Petuna and Tassal cooperated in preparing and producing an EIS (Ex A2 pp 85-1176) to accompany draft amendments to the MHMFDP. They also were responsible for the preparation and production of an Addendum to that EIS (Ex A2 pp 1-1176). The introduction to the Executive Summary of the EIS states (Ex A2 p 106):

The Tasmanian salmonid (Atlantic salmon and rainbow trout) industry provides significant economic benefits to the State and has contributed to Tasmania’s reputation as a quality producer of fine foods. Within 20 years of the first commercial harvests, farmed salmonids have become the leading farming activity in Tasmania ahead of dairy, vegetables, poppies, pyrethrum, beef, fine wool, wine and the once iconic apple industry. In the 2010-2011 financial year the industry produced 32,328 T of salmonids with a farm gate value of $379 million. It has become a standout Tasmanian brand icon.

The industry continues to experience strong sales momentum despite the current challenging economic environment. Sales are proving resilient with sales approaching $400 million at wholesale levels. The salmon and trout farming industry currently create over 1,200 direct jobs and $150 million to the Tasmanian Gross State Product.

The purpose of this proposal is to expand existing salmon farming operations in Macquarie Harbour by 362 ha of leasable area, with a view to maximising sustainable production in the harbour. This proposal is in line with the industry’s 2010-2030 strategic plans to double total salmon production in Tasmania by 2030 and to strategically enable ongoing growth in the industry.

A Social Return on Investment (SROI) analysis has been conducted on this proposed expansion. The SROI analysis suggests that the proposed expansion will deliver, during the first five years, an additional $24.2 million in social value in areas identified by the local community.

This means that, on top of the actual capital and operating investment by the proponent and within the constraints of the models used, the combined increases in social return and Gross Regional Product could be expected to provide an additional $88.6 million in benefit to the North West region in the first five years following the start of the proposed expansion phase.

The three companies currently growing salmonids in Macquarie Harbour, Tassal Operations Pty Ltd (Tassal), Huon Aquaculture Group Pty Ltd (Huon) and Petuna Aquaculture Pty Ltd (Petuna), collectively the Proponent, are collaborating in the sustainable development of the harbour and subsequently in the development of this proposal and the accompanying EIS.

2.6 Tasmanian government and DPIPWE agree with Huon, Petuna and Tassal that expanded marine farming in Macquarie Harbour should be facilitated

31 Following receipt of that EIS and its Addendum, the state government amended the MHMFDP in May 2012. The amendment increased the leasable area for fish farming in Macquarie Harbour to facilitate increased production.

32 However, the planned expansion required Commonwealth approval. Section 42B(3) of the EPBC Act expressly excluded (inter alia) the expansion of an action from the exemption provided for an existing use.

33 Section 69 of the EPBC Act provides a mechanism for a state or an agency of a state with administrative responsibilities for matters for which it is responsible to refer a proposed action a party is proposing to take that requires the Minister’s decision as to whether or not it is a controlled action:

State or Territory may refer proposal to Minister

(1) A State, self-governing Territory or agency of a State or self-governing Territory that is aware of a proposal by a person to take an action may refer the proposal to the Minister for a decision whether or not the action is a controlled action, if the State, Territory or agency has administrative responsibilities relating to the action.

(2) This section does not apply in relation to a proposal by a State, self-governing Territory or agency of a State or self-governing Territory to take an action.

Note: Section 68 applies instead.

2.7 Proposal to expand marine farming in Macquarie Harbour referred to the Minister

34 On 29 May 2012, DPIPWE referred the proposed expansion of marine farming activity in Macquarie Harbour to the Minister for determination pursuant to the EPBC Act. The referral, together with 12 appendices, is at pp 2-354 of Ex A1.

35 A “short description” of the proposed action is set out at p 6 of Ex A1:

The proposed action is:

• The expansion of marine farming operations, that will occur consistent with the 2012 amendment to the Macquarie Harbour Marine Farming Development Plan, which will include the following activities:

• The arrangement and securing of sea pens for fish farming;

• The construction of associated water based infrastructure;

• The operation of fish farms including:

• Servicing and maintenance of sea pens and associated water and land based infrastructure;

• Feeding and managing the health, waste, processing and predators of fish in the farms;

• Transportation of fish to and from the farms across water and land.

(Footnote omitted.)

36 The referral provided a more detailed description of the proposed action (Ex A1 pp 11-20):

Background – Expansion of Marine Farming

The approval of the amendment to the MFDP has paved the way for the following to occur:

• change in location of existing marine farming zones and lease areas

• increase in leasable area within zones

• addition of a new zone

• changes to management controls/operations which apply to zones

Changes to Lease Areas and Locations

To progress expansion of salmonid farming activities in Macquarie Harbour the Marine Farming Planning Act 1995 required an amendment to the existing Macquarie Harbour Marine Farming Development Plan October 2005. A full description of the amendment as it was initially proposed can be seen in Appendix 2 with the final amendment provided in Appendix 3. The marine farming review panel (MFRP) recommended further modifications to management controls post public consultation which, whilst not changing the intent of the management controls proposed in Appendix 2, did clarify wording around a number of issues.

The area covered by the Macquarie Harbour Marine Farming Development Plan October 2005 (DPIPWE 2005) is the physical extent of the harbour outside of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area (TWWHA) and consists of all that area bounded by the high water mark between a line drawn from Coal Head and Steadmans Point across the harbour to the south east (being the Western Boundary of the TWWHA) and the entrance to the harbour to the west at a line drawn between Braddon Point through Bonnet Island Light to the western shore. …

The Act provides for the preparation of MFDPs that designate areas of State waters as marine farming zones and the maximum area that may be used for marine farming operations within zones. The Act also provides for provisions for operational constraints on marine farming activities.

The Macquarie Harbour MFDP prescribes 10 marine farming zones within the plan area which provide for the culture of salmonids in 564 hectares of marine farming lease area.

The amendment to the Macquarie Harbour MFDP has resulted in moving some zones to areas better suited to salmonid culture and expanding the maximum leasable area by 362 hectares to 926 hectares – this expansion includes the addition of a farming zone.

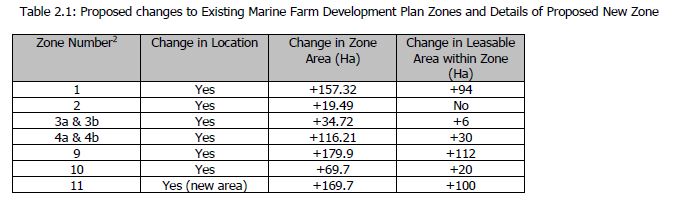

Variations to zone locations and sizes (including maximum leasable areas) has taken effect with the approval of the amendment, however new lease areas and variations to existing leases (including sizes and locations) will need to be approved consistent with the amendment. It is the intention of industry and the Planning Authority that these steps occur within quick succession. The specific changes to each zone are discussed in Appendix 1. … Table 2.1 indicates changes to locations and leasable areas.

Three separate companies have been working jointly on the proposed expansion of salmonid farming activities in Macquarie Harbour. These include Tassal Operations Pty Ltd (Tassal), Huon Aquaculture Group Pty Ltd (Huon) and Petuna Aquaculture Pty Ltd (Petuna), all three of which have existing salmonid farming operations within the MFDP area as it existed prior to the 2012 Amendment. It is expected that these companies will take up the expanded lease area. …

Changes to Management Controls

Section 3 of the Macquarie Harbour Marine Farming Development Plan October 2005 contains management controls to manage and mitigate negative effects that marine farm operations may have within the plan area.

The MFDP as amended has a number of existing management controls that will remain unchanged. Eleven new management controls have been inserted and 5 controls have been amended to cater for the proposed expansion. Appendix 3 illustrates the revised management controls and Appendix 4 provides context around new versus amended controls.

The Proposed Action

The proposed action is:

• the expansion of marine farming operations, that will occur consistent with the 2012 amendment to the Macquarie Harbour Marine Farming Development Plan, including the following activities:

• The arrangement and securing of sea pens for fish farming;

• The construction of associated water based infrastructure;

• The operation of fish farms including:

• Servicing and maintenance of sea pens and associated water and land based infrastructure;

• Feeding and managing the health, waste, processing and predators of fish in the farms;

• Transportation of fish to and from the farms across water and land.

The following components of each aspect of the action are described below, with specific details on activities to occur within each marine farming zone provided in Appendix 1 and Appendix 2:

Salmon Farming Operations Consistent with the MFDP

• Construction and Infrastructure Development

• Mooring and Grid System

• Size and Configuration of Sea Pens

• Other Infrastructure/Construction

• Operation of fish farms

• Servicing and Maintenance of Sea Pens and Associated Infrastructure

• Boat Movements

• Infrastructure Maintenance

• Feeding and Managing Health, Waste, Processing and Predators of fish in the Farms

• Fish size/stocking density

• Fish Health

• Predator Control

• Waste Management

• Environmental Management

• Transportation of fish to and from the farms across water and land

Salmonid Farming Operations Consistent with the MFDP

The expansion of salmon farming operations within Macquarie Harbour, consistent with the 2012 Amendment of the MFDP will include activities associated with the construction of aquatic components of marine farms and ongoing operation of both terrestrial and aquatic components of marine farms. These include:

• The construction, arrangement and securing of sea pens for fish farming;

• The construction of associated land and water based infrastructure;

• The operation of fish farms including:

• Servicing and maintenance of sea pens and associated water and existing land based infrastructure;

• Feeding and managing the health, waste, processing and predators of fish in the farms;

• Transportation of fish to and from the farms across water and land.

Construction and Infrastructure Development

In order to operate, the expansion of fish farms in Macquarie Harbour requires the construction and placement of new and existing infrastructure.

New mooring and grid structures are required to moor existing, and additional sea pens to. The size of these pens varies across leases, as does their configuration and locations. Additional on water structures are also required for servicing expanded farms (e.g. barges).

Mooring and Grid system

Each company will use their own mooring system to attached sea pens/cages to. There are currently approximately 132 cages in Macquarie Harbour across 5 leases. Planned expansion of the industry under the amendment to the MFDP will see an increase in cage numbers to approximately 211. The mooring systems to be used across zones are described in Appendices 1 and 2. Baseline surveys which establish whether there will be any impacts from mooring and grid systems are not part of this action.

Size and configuration of Sea Pens

The location and configuration of pens associated with the amendment of the MFDP for each company are described in Appendices 1 and 2. … There are no change[s] to Zones 7 and 8 as a result of this proposal.

Other Infrastructure/Construction Aspects

Additional land and water based infrastructure will be required in order to operate fish farms associated with the proposed expansion. There is likely to be a need for some improvements to land based facilities over time.

Huon aquaculture immediately require a new centralised feeding system barge, with a view to a centralised feeding system involving dedicated feed barges proposed for each zone into the future. Additional power generators will be associated with new barges.

Two additional feeding boats are also likely to be required in the next 7 years.

Tassal’s feed storage shed is inadequate to cater for current needs and is in a poor state of repair – in addition access to the site is restricted (Appendix 2).

It is estimated that traffic movements will increase from around 90 to a maximum of 228 within 5 years – to manage this impost on Strahan township, and to streamline operations an aquaculture hub away from the Strahan township has been proposed.

Operation of Fish Farms

The operation of fish farms in Macquarie Harbour requires a range of activities within the key areas listed below:

• Servicing and maintenance of sea pens and associated water and land based infrastructure;

• Feeding and managing the health, waste, processing and predators of fish in the farms;

• Transportation of fish to and from the farms across water and land.

Servicing and Maintenance of Sea Pens and Associated Infrastructure

Servicing of on water infrastructure involves the movement by boat of maintenance teams multiple times a day to sea pens to undertake a range of maintenance (and stock husbandry) tasks. Boat movements and maintenance tasks are described in detail below.

Boat Movements

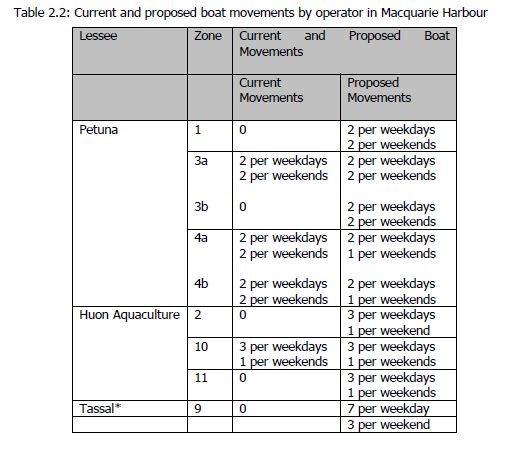

Boat movements associated with marine farming activities in Macquarie Harbor can be placed into two categories; vessel movements from shore based operations to marine based operations and vessel movements within lease areas. Table 2.2 illustrates current and proposed boat movements by type.

Vessel movements from shore based operations to marine based operations consist of staff transfers to lease areas, feed transfer, net and equipment transfer, dive team movements and harvest vessels (Table 2.2). The proposed increase in movements represents an increase from 59 movements to 158 movements per week. Table 2.2 does not include movements undertaken by smaller vessels within lease areas.

Companies in Macquarie Harbour usually moor a number of vessels within the lease areas which are used to service the lease during operational hours. These vessels generally do not leave the lease area but travel between cages and mother barges.

* Tassal uses two existing marine farming leases in Macquarie Harbour which will be serviced by the same vessels on the one trip, therefore the traffic from Strahan to the leases will not change considerably but the distance travelled by the vessels will increase.

It should also be noted that harvesting will not occur all year round and from the same lease each year, for example, Tassal will harvested for 6 months of the year from Zone 9 every second year. The figures above have included harvest vessel movements all year round. Appendix 1 contains detailed descriptions of boat movements by zone.

Infrastructure Maintenance

A variety of maintenance tasks are undertaken either routinely or for a specific purpose. These tasks include:

• Checking of cage nets via scuba diving

• Inspection of bird nets

• Repair of nets

• Vessel maintenance for barges

• Routine generator and other equipment maintenance

• Inspection of moorings (divers and ROV)

Off water infrastructure maintenance, including maintenance on large barges occurs either at land based sites or in specialised workshop environments in Devonport and Burnie. Boat servicing, outboard servicing etc occurs at the slip yard in Strahan. Net maintenance and construction occur at land based net areas.

Specific maintenance activities are described by zone in Appendix 1. There will be no change to activities occurring at Zone 7 and Zone 8.

Feeding and managing the health, waste, processing and predators of fish in the farms

The management of fish farming activities includes the management of:

• fish size and stocking densities;

• fish feeding;

• fish health;

• predator control;

• waste management;

• environmental management.

Fish Size/Stocking Density

It is the intention that two species will be cultivated in the expanded marine farming operations in Macquarie Harbour: rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and atlantic salmon (Salmo salar).

Sites would be stocked with intake fish ranging in size from 80g – 300g depending on species and company. Harvest size would range from over 4kg to 5kg.

Current estimates are that around 3.2 million smolt are used in the harbour per year – this figure is expected to increase to around 6.3 million smolt with the expansion.

The maximum stocking density of fish would increase from 15 kg/m³ to 17 kg/m³ of cage volume.

Species and stocking approaches by zone can be seen in Appendix 1.

Information regarding fish size and number, stocking density (also biomass limits on an area basis i.e. tonnes/ha) and feed volume all have links to the modelling used to determine the sustainable carrying capacity (total biomass and stocking density) of Macquarie Harbour for this development. They are also associated with the adaptive management framework that is proposed. Of these, the potential to prescribe stocking density and biomass limits have been incorporated into management controls.

Fish Feeding

Feeding is currently undertaken via boats using water cannons as well as by centralised feed systems with the operator either using camera feedback systems to control the feeding or, the system responding to appetite ingestion rate of the fish to feed to satiation without waste.

The feed used is commercial extruded feed and dry extruded sinking pellets sourced from both within Tasmania and interstate. There is no change to the types of feed to be used in the expansion from currently farmed area. The volumes of feed will vary depending on market expansion, smolt type, smolt size, transfer date, photoperiod regime, water temperature, fish health, and harvest profile.

Sediment monitoring is carried out during the Annual Video Surveys as required by marine farming licence conditions, as well as during routine internal environmental monitoring programs companies run. Monitoring methods follow those employed to assess seafloor condition as outlined in the Monitoring Protocols of the Fish farm licences.

Details of each company’s approach can be seen in Appendix 1.

Fish Health

Currently, there are no serious disease issues in Macquarie Harbour. Previously, a number of diseases have been identified in Macquarie Harbour; these have included yersiniosis, marine aeromonad disease of salmonoids (MAS) and vibriosis. In 2006, Ichthyophonus caused mortality in rainbow trout. In addition, Aquabirnavirus, Reovirus and a rickettsia-like organism (RLO) have also been detected.

The key component in the preventative disease program for Macquarie Harbour is vaccination against Marine Aeromonad Disease and vibriosis. Since the introduction of the vaccination process, there have been no outbreaks of these diseases. Additionally, there is mandatory health surveillance carried out by Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (DPIPWE) personnel within the framework of the Tasmanian Salmonid Health Surveillance Program (Tas SHSP) which is a joint Industry and Government Program.

Further, the current operators within the plan area have developed a Fish Health Management Plan (FHMP) which will provide a specific detailed strategy for the ongoing management of fish health in Macquarie Harbour (See Appendix 2). The operators have signed off on the strategies outlined in the FHMP which consists of a combination of compliance, best practice and regulation through management controls and marine farming licence conditions. The FHMP addresses detailed, standard operating practices to prevent disease from entering the harbour, to prevent spread and impact of disease in the harbour and to respond to emergency disease situations. The FHMP will be reviewed annually or more frequently if needed.

Under expanded operations there will be an associated increase in the real amount of vaccinations being administered to smolt – currently trout and salmon have one vaccination by injection and one by bath in the hatchery and this will continue.

Chemical Usage

Chemical use in the marine environment will be restricted to fuels and oil based lubricants associated with boats, and disinfectants, cleaning agents and antibiotics. Fuels would constitute by far the majority, by volume, of the total amount of chemicals proposed to be used. Small volumes of disinfectants are used in a variety of manners for hygiene purposes, and cleaning agents are used on harvest infrastructure following harvesting operations. Antibiotics would only be prescribed over short periods to address illness and animal welfare issues. It is not possible to forecast antibiotic use, but it is expected that antibiotic use will remain low, if not absent, due to improved husbandry practices and effective vaccines.

It is proposed that most chemical usage will continue across the expansion area proportional to the increase in biomass being farmed. Based on this, it is predicted that a 263% increase will occur in the chemical use associated with the expansion.

Predator Control

Australian and New Zealand Fur Seals are a potential predator of salmon and trout in marine farms. The main means of controlling seal predation will be via exclusion, by means of heavily weighted sinker ring and tensioned cage nets and above water predator nets. Net barriers may also be required above the handrails to prevent seals from jumping into the cages. There is ongoing investigation and trialling of new exclusion and deterrent technologies. Under the DPIPWE’s seal management protocols, marine farmers can apply to the Department to relocate problem seals.

Birds are also a potential problem. The means of control to be used is prevention of access to the fish or to feed pellets, by means of properly designed and supported bird nets. See Appendix 1 for further zone specific details.

Waste Management

Both solid and liquid wastes are produced by marine farms and are managed by different means. It is expected that there will be a net increase in most waste streams generated commensurate with an increase in stocked cage numbers. Whilst this will not be realised during the first year of the expansion, there will be a gradual staged increase over time until all sites are fully stocked, at which point a 62% increase from current levels of land-based disposal of waste will be realised. Fish mortality wastes are expected to increase by 60% from current levels (see below).

Solid wastes include fish bodies (mortalities), waste from the harvesting process (including body parts and bloodwater), wastes on nets and uneaten feed.

Mortalities are collected and buried at an approved mort lease site or mort pit. Bloodwater and solid waste from the harvest process is contained in harvest bins during the harvest and either delivered to a processing facility at Devonport or, the waste is separated with the solid component going to mort pits, and the liquid component released in to the municipal sewerage scheme through a Trade Waste Agreement with Cradle Mountain Water Authority depending on the marine farming company (Appendix 1).

Current levels of fish mortalities across the industry in Macquarie Harbour are generally around 1.97% (approx 63000 fish) of stocked numbers by live weight. It is expected that this rate would remain comparable following the expansion resulting in approx 124000 dead fish at full production. This would be an increase from current totals of around 60%.

Local government approval is required for fish waste volumes <100 tonnes to mort landfill sites. Currently three mort pits located around Strahan (Table 1.1). At full production levels this approval would be exceeded. It is not anticipated that this approved tonnage of mortality disposal would be exceeded within the first two years of the proposed amendment. Once the Council approval is exceeded the companies would need to gain Tasmanian Environmental Protection Authority approval for an alternative disposal option.

Discussions with a third party who currently render all fish mortalities from the east coast of Tasmanian have commenced to investigate ensilage options available for the collection and disposal of mortalities. The increased number of fish mortalities as a result of the proposed expansion would mean that the ensiling of this waste would be economically viable for the third party to the extent that transport costs would be off set. Initial discussions have revealed that it is likely that the third party would employ a local site Manager to ensure that the ensilage facility was run to the Environment Protection Authority approved standards.

Nets are, in general, simply hung to dry at the net processing sites. The dry bio-solids fall off the nets and are swept up and collected in bags and disposed of to landfill.

Uneaten feed is minimised through the use of underwater-video camera feedback systems and additional tools such as electronic pellet sensors. Any pellets that do fall through the cages are detected in routine video surveys, and the information is used to continuously improve feed management.

Fish faeces fall through the bottom of the fish cages and are deposited on the seabed below the cages. The cage positions are routinely fallowed to allow the biological processes in the sediment to process the organic matter, and for the sediments to recover.

All inputs into the marine environment that arise from the present amendment are to be mitigated through the adaptive management framework. This process drives the harbour Fish Farming Environmental Management Plan (FFEMP) which uses as its basis the modelling and a comprehensive regulatory and industry based monitoring program targeting both water quality and benthic parameters.

Targeted monitoring of benthic and water column parameters will be used to validate the model into the future and results for the validation will support the decision making process for fish farm stocking levels in the harbour.

At present environmental standards for substrate deposition are contained under Marine Farming Licence Conditions, Compliance with Environmental Standards. Recovery and accumulation rates are being addressed through the FFEMP using modelling and the results from the benthic part of the monitoring program and other related research will be used to inform future modelling. For remineralisation the Proponent is collaborating with Institute of Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) and DHI consultants to initiate a research project to elucidate these processes in the harbour.

In terms of mitigation measures that may be implemented through farm operations year class fallowing is considered integral to any sustainable farming to allow regeneration of benthic communities and facilitate good environmental maintenance procedures for the production environment. Fallowing is assessed on a regular basis by the Proponent through the use of ROVs below the pens, both as part of the annual regulatory requirements (licence conditions) for substrate assessment and as an operational tool for assessing feed wastage and substrate impact.

In the future the fallowing period implemented will be based initially on the results of the benthic monitoring (directed through the FFEMP) as production increases. Appropriate management responses will be implemented if unacceptable changes are observed.

Liquid wastes include black and grey water from barges. Black water is either treated with an approved sewage treatment system and discharged after prescribed water quality parameters stipulated in marine farming licence conditions have been met or, it is transported to Strahan and released into the municipal sewage system. Grey water is either discharged within lease areas or released into the municipal sewage system depending on the company (Appendix 1).

Environmental Management

Biogeochemical and hydrological modelling has been used to determine a sustainable maximum carrying capacity of farmed salmonids in Macquarie Harbour of 35 T/ha of total lease area or subleased area held by a leaseholder, based on the planned expansion area.

The modelling that has been undertaken is considered to be contemporary. It is however acknowledged that the modelling, as with any form of predictive assessment, has limitations. To balance any potential limitations of the model a FFEMP will be implemented, which will provide an adaptive monitoring and modelling approach to track the initial predictions of the model over time and refine future modelling. See section 4 for further details. Continuing measurements of information to inform the benthic monitoring program and establishment of water quality baseline environmental data are not part of this action.

Transportation of fish to and from the farms across water and land

Significant increases in on and off water vehicular movements are likely to occur as a result of expansion of farming in Macquarie Harbour.

Boat movements are described in detail in Appendix 1 and represented in Table 2.2. Overall movements will increase from 59 movements to 158 movements per week.

The change in traffic movements one way into Strahan from Hobart and the North West coast by operator are outlined in Appendix 1 – these figures include passenger vehicles and small delivery/service type vehicles.

Existing farming operations are not considered to be part of the current action as fish farming in Macquarie Harbour commenced prior to the EPBCA in the mid 1980s, and incremental changes since then were determined unlikely to have a significant impact on MNES. In addition ongoing measurements associated with the benthic monitoring program and the establishment of water quality baseline environmental information are not included in the action.

(Footnotes omitted, emphasis in original.)

37 The involvement of Huon, Petuna and Tassal in requesting an amendment to the MHMFDP was identified in the referral as follows (Ex A1 p 22):

The three companies currently farming salmonids in the harbour have jointly requested an amendment to the Macquarie Harbour MFDP under section 33 of the MFPA to move and expand existing marine farming zones and leasable area and to create a new zone with leasable area. The requested amendment has resulted in an increase in leasable area of 362 hectares. Specific detains are contained in section 2.1 of this referral.

38 The Court notes that the detailed statement of the proposed action expressly excluded “[c]ontinuing measurements of information to inform the benthic monitoring program and establishment of water quality baseline environmental data” from the action (Ex A1 p 20). The reason for that is not apparent. It may be because DPIPWE had regarded those matters as within its own regulatory responsibilities rather than as a component of the action, but the documentation is silent on that.

39 As the history of this matter reveals, the way the referral had been expressed, as set out above, led the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (the Department) initially to treat the action as having been referred under s 68, that is as an action proposed to be undertaken by DPIPWE itself (see below at [46]-[61]).

2.8 The nature of the referral mechanism

40 Subject to other provisions of the EPBC Act, including those relating to the Minister’s obligations to invite and consider comment and the Minister’s power to request further information (see s 76), none of which are contentious in these proceedings, the Minister is required, within 20 business days, to determine whether or not the proposed action is a controlled action or not: see s 75(5).

41 As was noted in Blue Wedges Inc v Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts [2008] FCA 8; (2008) 165 FCR 211 by Heerey J at [22], the referral mechanism thus operates as a kind of “triage system”.

42 The Minister, in undertaking that function, is required to consider all adverse impacts the referred action has, will have, or is likely to have on the matters of national environmental significance protected by each of the provisions of Pt 3 of the EPBC Act (s 75(2)(a)). He or she is required to exclude from his or her consideration any beneficial impacts the action has, will have, or is likely to have on those matters (s 75(2)(b)).

43 The Minister is thus charged with the task of determining within a relatively short timeframe which one of the following is to apply to a referred proposed action: (a) the proposed action is not a controlled action because it would not have a significant impact on any matter of national environmental significance; (b) that the proposed action is not a controlled action because the Minister believes it will be taken in a particular manner; or (c) it is a controlled action.

44 A controlled action is required to be evaluated pursuant to one or other of the assessment processes prescribed by Pt 8 of the EPBC Act.

45 For completeness, I note that those three options do not exhaust the possible outcomes: within the same short timeframe the Minister may determine that a proposed action is clearly unacceptable (s 74B).

2.9 The Minister seeks further information from DPIPWE

46 I am satisfied that, upon receiving the referral, the Department understandably, but in error, proceeded initially on the basis that DPIPWE itself was proposing to take the action.

47 On 6 June 2012, after receiving the referral, on the Minister’s behalf the Department sought further information regarding the proposed action from DPIPWE (Ex A1 pp 357-358). Nothing in that correspondence suggests the Department at that stage regarded Huon, Petuna and Tassal as being (collectively) the proponent of the action. That the Department sought further information only from DPIPWE entitles the Court to draw the inference that at that time the Department was operating under the apprehension that DPIPWE was the person proposing to the action. Section 75(5) provides that the time in which the Minister is required to make a decision in respect of a referral does not run while further information is sought pursuant to subs 76(1) or (2). Those subsections “stop the clock” only if the information has been sought from “the person proposing to take the action”.

48 On 27 June 2012, DPIPWE provided additional information in response to the Minister’s request (Ex A1 pp 359-367).

49 It is apparent that that further information failed to satisfy the Department that it should advise the Minister that the action would not be a controlled action. On 5 July 2012, Mr Andrew Tankey, Acting Assistant Director of the Environment Assessments Branch emailed Ms Fionna Bourne of DPIPWE regarding “outstanding issues for the Macquarie Harbour referral” (Ex A1 pp 368-369). In his email, Mr Tankey identified that the Department still had concerns regarding issues in relation to the Maugean Skate and the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area.

50 Mr Tankey told DPIPWE that the information it had provided at that stage was inadequate. There was an absence of detail regarding commitments. He exampled that trigger levels for ammonia, nitrate and dissolved oxygen had not been provided. Mr Tankey advised DPIPWE that “Not Controlled Action – Particular Manner” outcomes “are only possible where there are specific, quantified commitments that bind the referring party to undertaking the action in a specific way”.

51 On 5 September 2012 Mr Evans responded on behalf of DPIPWE to Mr Tankey’s request of 5 July 2102 that DPIPWE provide additional information about the proposed action.

52 Mr Evan’s response contained the following statements and undertakings:

The proposed expansion of marine farming activities under the Macquarie Harbour Marine Farming Development Plan as amended will result in the relocation of 59 percent of the existing marine farming lease area that currently occurs in less than 20 metres into the central, deeper water region of the Harbour. This will effectively reduce the lease area in regions where the Maugean Skate have been identified.

In relation to benthic impacts, and their possible impact on MNES – Maugean Skate, as previously outlined, baseline environmental surveys must be undertaken by lease holders prior to the commencement of marine farming operations within any marine farming lease area. Assessment includes the collection of information on the physical, chemical and biological characteristics of sediments, current flow, bathymentry and habitat assessment. The information is used as a benchmark against which marine farming operations are monitored.

In addition to the baseline monitoring assessment, marine farm licence conditions require leaseholders to undertake annual benthic video assessments of lease areas and compliance sites located 35 metres outside lease areas (See Attachment 1 standard monitoring methods and requirements). Compliance monitoring reports are assessed against marine farming licence conditions specific to benthic impacts associated with particulate organic deposition from finfish farming operations.

All marine farming operations in Tasmanian waters have the same licence conditions relating to unacceptable benthic impacts. The licence conditions are based on extensive international and local research, with the local research particularly focusing on the effects of marine farming derived organic enrichment on sediment condition and recovery processes. The following licence conditions relating to unacceptable benthic impact are currently in all marine farming licences for operations in Macquarie Harbour. These conditions will also be included in the licences granted for the operation of the proposed expanded marine farming operations.

There must be no significant visual, physio-chemical or biological impacts at or extending beyond 35 metres from the boundary of the Lease Area. The following impacts may be regarded as significant:

Visual Impacts:

• Presence of fish feed pellets;

• Presence of bacterial mats (e.g. Beggiatoa spp.);

• Presence of gas bubbling arising from sediment, either with or without disturbance of the sediment;

• Presence of numerous opportunistic polychaetes (e.g. Capitella sppp., Dovilleid spp.) on the sediment surface.

In the event that a significant visual impact is detected at any point 35 metres or more from the leave boundary the licence holder may be required to undertake a triggered environmental survey or other remedial activity determined by the Director.

Physio-chemical:

• Redox: A corrected redox value which differs significantly from the reference site(s) or is <O mV at a depth of 3cm within a core sample.

• Sulphide: A corrected sulphide level which differs significantly from the reference site(s) or is >250µM at a depth of 3cm within a core sample.

Biological:

• A 20 times increase in the total abundance of any individual taxonomic family relative to reference sites.

• An increase at any compliance site of greater than 50 times the total Annelid abundance at reference sites.

• A reduction in the number of families by 50 per cent or more relative to reference sites complete absence of fauna.

There must be no significant impacts within the Lease Area. The following impacts may be regarded as significant:

Visual impacts within Lease Area:

• Excessive feed dumping.

• Extensive bacterial mats (e.g. Beggiatoa spp.) on the sediment surface prior to restocking.

• Spontaneous gas bubbling from the sediment.

lf a significant impact (as defined in the licence conditions and outlined above) is detected within or outside the lease areas, during annual compliance monitoring surveys, targeted management responses are required, in addition to possible further investigation and depositional modelling.

Targeted management responses are implemented by way of management controls outlined in the Macquarie Harbour Marine Farming Development Plan as amended, by the Secretary of the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment and involve one or more of the following actions:

• reduction in biomass,

• reduction in nitrogen output, or

• redistribution of biomass.

These management controls ore designed to regulate the stressor, both soluble and particulate, loads. Given that organic enrichment effects are lease specific, direction by the Secretary to reduce input is primarily focused on reducing biomass load, or redistributing biomass load within a specific marine farming lease area, including fallowing a particular pen bay or pen bays.

Where a significant impact, as defined, is observed, and specific management actions are required by the Secretary to be implemented, the leaseholder is required to undertake a follow-up benthic video assessment to m on it or benthic recovery.

The regulation of benthic impact from marine farming operations, as described above, has been in place for all marine farming operations in Tasmanian waters for the last 16 years. During this period it has been demonstrated that organic loading effect s from farming operations can be effectively managed using the environmental management framework outline above. This, together with the information regarding the distribution of Maugean Skate within Macquarie Harbour, including in close proximity to existing marine farm operations, leads the Department to the view that the expansion of marine farming activities in Macquarie Harbour will not have a significant impact on the MNES – Maugean Skate.

Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area and Maugean Skate

Issues associated with water quality have the potential to impact on two MNES – the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area and the Maugean Skate. The Department has worked closely with representatives of the three companies who will be undertaking the marine farming expansion activities to develop an appropriate water quality monitoring program and water quality limits to ensure that the proposed expanded marine farming activities do not have a significant impact on these matters of MNES.

As you are aware, as part of the ongoing development of the model which was used by the State Government to assess the amendment to the Macquarie Harbour Marine Farming Development Plan, the three companies have been collecting monthly water quality data since September 2011. The model will be recalibrated during the first review cycle of the adaptive management framework, using at least 12 months of water quality data within the harbour that reflects the current extent of marine farming activities.

Marine farming licences will contain conditions that require the licence holders to undertake a water quality program to monitor changes in indicator levels relative to prescribed limits within Macquarie Harbour.

The monitoring program will involve continued assessment of the water quality indicators – ammonia, nitrate and dissolved oxygen, at 11 sites throughout the Harbour (refer Map 2 for sample locations) until mid 2013 after which the number of monitoring sites will be reviewed. In addition the marine farming licences will require quarterly reporting and interpretation of the results of the water quality monitoring program.

Water quality limits will be contained within marine farming licences, and will be based on the 80th/20th percentile values of the water quality indicators, based on the predictive biogeochemical and hydrological model outputs. The percentage values of the water quality indicators will be:

• Ammonia - 80th percentile;

• Nitrate - 80th percentile;

• Oxygen - 20th percentile.

As a precautionary measure to ensure that expansion of salmonid production in the harbour does not significantly impact on water quality, interim water quality limits have been established for the above water quality indicators. These interim limits will be in place until the first review of the adaptive management framework is completed in mid 2013, and will be included as mandatory conditions within the marine farming licences.

In mid 2013 the interim water quality limit levels will be reviewed. The approach to water quality limits after the review will be based on the 80th/20th percentile as is the case for the interim levels outlined above. The reviewed figures will be derived from a recalibrated biogeochemical and hydrological model that will be informed, amongst other things, by at least 12 months of water quality data collected from the harbour, and further predictive modelling.

The interim water quality limits and the water quality monitoring requirements contained within marine farming licences will not be updated, and additional finfish biomass above and beyond that indicated in the Secretary’s letter of 27 June 2012 will not be able to be added to the harbour until such time as the review is completed, and the marine farming licence conditions amended to reflect the outcome of the review.

The environmental condition of Macquarie Harbour has undergone a number of assessments, and in each of those assessments it has been determined that the harbour is not pristine, and has had some level of impact from past activities.

For example the Australian Natural Resource Atlas describes Macquarie Harbour as being of modified condition, and under the Conservation Significance of Tasmanian Estuaries project of my Department the harbour is classified as having low conservation significance as a result of being moderately degraded. (See Attachment 2 for further information).

In addition, if the ANZECC Classifications and Recommendations framework is used Macquarie Harbour would be described as a slightly to moderately disturbed ecosystem in which biological diversity may have been adversely affected to a relatively small but measurable degree by human activity.

The ANZECC Guidelines 2000 recommended that guidelines be developed on the basis of biological effects data, where such data is not available, or alternatively use base guidelines on the 80th and/or 20th percentiles of data from reference sites. In particular for slightly to moderately disturbed ecosystems such as Macquarie Harbour it is recommended that:

The trigger values are derived from the 80th and/or 20th percentile values obtained from an appropriate reference system. For stressors that cause problems at high concentrations (eg. nutrients, salinity), that the 80th percentile of the reference distribution as the low-risk trigger value. For stressors that cause problems at low levels (eg. low dissolved oxygen in waterbodies), use the 20th percentile of the reference distribution as a low-risk trigger value.

Biogeochemical and hydrological modelling has been used to consider the effects on water quality arising from the expanded salmonid farming activities. The modelling has predicted that certain parameters will be elevated with increased production. Assessment of the effects of the modelled outputs predicts that at the maximum level of modelled production there will be no significant impact on the environment and ecosystems of Macquarie Harbour, and that the expected effects fall within an ‘acceptable’ level of change.

The predictive biogeochemical and hydrological model output has been adopted for use for establishing the values of the water quality indicators because it is a specific tool that has been developed for Macquarie Harbour, taking account of the existing knowledge as it relates to the hydrodynamics of the harbour, and the existing environmental conditions, rather than applying a generic set of environmental guidelines. The model defines the limits of predicted change within acceptable ecological and toxicological levels as discussed in relevant literature and environmental guidelines. As such, the model will be used as the reference system when setting the water quality limits.

The interim limit levels for each of the water quality indicators are as follows:

Indicator | Limit |

Ammonia (at 2 metres) | 0.033 mg/L |

Ammonia (at 20 metres) | 0.024 mg/L |

Nitrate (at 2 metres) | 0.053 mg/L |

Oxygen (at 2 metres) | 6.82 mg/L |

It is noted that the above limit levels for ammonia are significantly below the level of 0.460 mg/L outlined by Batley and Simpson (2009) as representing a low risk of acute or toxic effects in a slightly to moderately disturbed system. Given that nitrate is significantly less toxic than ammonia the Canadian Water Quality Guidelines: Nitrate Ion, Scientific Criteria Document (2012) recommends a long-term exposure guideline of 45 mg/L for nitrate for the protect ion of temperate marine species. The interim limit levels for nitrate proposed above is significantly less than this. Finally for oxygen, the interim limit level is well above that recommended by the US Environment Protection Authority as a safe/low risk chronic protective value. (See Attachment 3 for further information).

As with benthic impacts, the above interim water quality limit levels will be included as a mandatory condition of all marine farming licences. Specifically, marine farming licences will state that:

The regional annual rolling median value of any of the following indicators where directly attributable to marine farming operations, must not exceed the limits specified in the following table:

Indicators and Limits:

Indicator | Limit |

Ammonia (at 2 metres) | 0.033 mg/L |

Ammonia (at 20 metres) | 0.024 mg/L |

Nitrate (at 2 metres) | 0.053 mg/L |

Oxygen (at 2 metres) | 6.82 mg/L |

Reporting of biomass and nitrogen inputs will also be a requirement of licence conditions, with quarterly reporting required for each marine farming lease area.

The assessment of indicators will be made on pooled results from the regional compliance monitoring stations … If the observed regional annual rolling median value for an indicator exceeds the specific limit prescribed in the marine farming licence condition, a management response will be required. Again, as with benthic impacts the management actions required by the Secretary would involve one or more of the following actions:

• reduction in biomass,

• reduction in nitrogen output, or

• redistribution of biomass.

The final point on water quality as it relates to the MNES - Maugean Skate is to note that the listing statement or the species indicates that it inhabits low-nutrient brackish water, 5-7 metres deep. Recent and historical water quality data from Macquarie Harbour suggests that the water within the harbour is not low in nutrients, for example datasets from the 1980’s (Creswell et al., 1989) and (DPIPWE 2011) and the present indicate that water in Macquarie Harbour for nitrate and ammonia exceed the ANZECC Guidelines recommended low risk trigger values for environmental protection of estuaries. This data provides evidence that would suggest that a low nutrient environment is not a requirement for the Maugean Skate’s survival.

The regulation of water quality parameters for marine farming operations, as described above, will ensure that a reduction in water quality arising from the expansion of marine farming activities in the harbour will be effectively managed using the environmental management framework outlined above. As a result the Department is of the view that the expansion of marine farming activities in Macquarie Harbour will not have a significant impact on water quality within the harbour nor a concomitant significant impact on the MNES – Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area or the Maugean Skate.

I hope the above, together with the attached documents provides sufficient information for you to make an assessment as to whether the proposed marine farming expansion activities within Macquarie Harbour are a controlled action. …

(Ex A1 pp 381-387)

2.10 Department receives legal advice that referral is for an action to be undertaken by Huon, Petuna and Tassal

53 I infer that late in its consideration of the referral the Department received legal advice that, properly understood, the action would in fact be undertaken by Huon, Petuna and Tassal. The substance of that advice is referred to in a document entitled “Supporting advice from the Heritage Branches” reproduced in the departmental brief later submitted to the Minister. It contains the following (Ex A1 p 465):

The referral has been made by the Tasmanian Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (Heritage understands that legal advice has been obtained by EACD as to the proponent … as activities carried out under the MFDP would be undertaken by one of three aquaculture companies expected to operate under the plan: Petuna Aquaculture Pty Ltd, Huon Aquaculture Group Pty Ltd and Tassal Operations Pty Ltd.

Note that, at the request of EACD, this advice assumes an “Action” that is comprised of the operation of one or more of these three companies under the revised MFDP.

54 On 5 September 2012 (coincidentally the same day as Mr Evans had respondent to Mr Tankey’s earlier email seeking specific, quantified commitments binding on the referring party) Mr Tankey sent an email to Ms Bourne containing the following (Ex A2 pp 1179 – 1180):

Following our recent conversation on Monday I wanted to confirm our approach for this referral process that we will need to follow to progress to a statutory decision (once the adequate additional information has been received).

Our advice on evaluation of this referral, is that this referral is most appropriately considered under section 69 of our Act, whereby DPIPWE has referred the action on behalf of the operators. To ensure a legally robust decision we will need to write to the operators and ask them to provide the additional information that you are currently preparing. This formality is necessary to ensure that we meet the relevant procedural fairness requirements for administrative decision-making.

To cover off on this, we will be writing to the operators to confirm they have received the original referral which you have submitted, and also the [department’s] additional information request.

To assist us in this, can you please provide contact details (both post and email) for each of the operators? We would like to send this letter to each company as soon as possible, and we will copy you into these letters.

The subsequent step will be for us [to] have formal sign-off from the operators on the final additional information to be provided to DSEWPAC (for example, to confirm that they can and will undertake any specific commitments in this documentation). To ensure this happens as efficiently as possible, we suggest that DPIPWE coordinates the submission of the additional information through the operators. (For example, you may wish to submit the information to DSEWPAC with a cover letter signed by all parties that binds the operators to the material you have prepared).

55 In order “[t]o cover this off on this” (to use the language of that email), on 7 September 2012, Mr James Tregurtha, the Assistant Secretary of the South-Eastern Australia Environment Assessments, Environment Assessment and Compliance Division of the Department, wrote to each of the operators to inform them that a referral had been made by DPIPWE, which was “being considered in accordance with section 69 of the EPBC Act” (Ex A1 pp 370-375).

56 Mr Tregurtha’s correspondence, sent in identical terms save as to addressees, identified Huon, Petuna and Tassal as proposing to “jointly undertake the action”.

57 Each letter informed its recipient that the Department had received a referral under the EPBC Act from DPIPWE. Each letter attached the Department’s correspondence of 4 June 2102 as had been previously sent to DPIPWE requesting further information. As addressed to Huon, Mr Tregurtha’s letter was as follows:

In considering the referral, we understand that the following persons (‘the operators’) are proposing to jointly undertake the action:

1. Yourself, (Huon Aquaculture Group Pty Ltd ABN; 79 114 456 781)

2. Tassal Operations Pty Ltd; ABN 38 106 324 127; and

3. Petuna Aquaculture Pty Ltd, ABN 62 009 485 581.