FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

F. Hoffman-La Roche AG v Sandoz Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 874

ORDERS

First Applicant ROCHE PRODUCTS PTY LTD ACN 000 132 865 Second Applicant | ||

AND: | SANDOZ PTY LTD ACN 075 449 553 Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 12 June 2018 |

UPON THE FIRST APPLICANT UNDERTAKING TO THE COURT BY ITS COUNSEL TO:

1. submit to such order (if any) as the Court considers to be just for the payment of compensation, to be assessed by the Court or as it may direct, to any person, whether or not a party, adversely affected by the operation of these orders or any continuation (with or without variation) thereof; and

2. pay the compensation referred to in 1 above to the person or persons there referred to.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Until 11 August 2019, the final determination of these proceedings or further order, the Respondent, whether by itself, its servants, agents or otherwise howsoever, be restrained from infringing the Asserted Patent Claims and each of them, including, without the licence of the First Applicant:

(a) supplying for use;

(b) offering for supply or sale;

(c) supplying;

(d) selling;

rituximab 500mg/mL concentrated injection vial or rituximab 100mg/10mL concentrated injection vial (together, the Sandoz Products).

2. The Respondent forthwith notify the Department of Health (Director of the PBS Price Changes Section, Pricing and Policy Branch of the Technology Assessment and Access Division) and the Minister for Health:

(a) of the granting of the interlocutory injunction set out above, and of its terms; and that

(b) for the purposes of seeking listing of the Sandoz Products on the PBS, the Respondent is no longer able to continue to provide the assurance of supply it has given, until further notice by the Respondent to the Department of Health.

3. If the respondent proposes to give further notice to the Department of Health pursuant to order 2(b) above, the Respondent shall give seven (7) days’ notice in writing to the Applicants of its intention to do so.

4. The costs of, and incidental to, the applicants’ interlocutory application for interim injunctive relief be the Applicants’ costs in the cause.

5. The parties are to confer and supply a draft short minutes of order to the Court within seven (7) days setting out the pre-trial timetable steps to bring the claim for final relief to trial with expedition.

6. Leave be granted to the Applicants to apply to the Court for the extension of Order 1, prior to 11 August 2019, having regard to the circumstances prevailing at that time.

7. These proceedings be listed for a case management hearing at 9:30am on 26 June 2018.

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

1. In this Order, Asserted Patent Claims means the claims of the patents that the First Applicant asserts, on an interlocutory basis, the Respondent threatens to infringe, being:

(a) Claims 18 and 21 of Australian Patent No. 2008207357;

(b) Claim 2 of Australian Patent No. 761844;

(c) Claim 35 of Australian Patent No. 2005211669; and

(d) Claim 3 of Australian Patent No. 2007242919.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[2] | |

[10] | |

[10] | |

[15] | |

[21] | |

[23] | |

[30] | |

[30] | |

[31] | |

[59] | |

[67] | |

[67] | |

[75] | |

[81] | |

[86] | |

[89] | |

[89] | |

[93] | |

[94] | |

[106] | |

[153] | |

[154] | |

[154] | |

[207] | |

[229] |

BURLEY J:

1 In the present interlocutory application the originator of a biologic therapy used for the treatment of various cancers and rheumatoid arthritis seeks urgent orders to restrain a competitor from launching a biosimilar medicine on the basis that the biosimilar will infringe some of the claims of four asserted patents. The respondent contends that the asserted claims are invalid for want of inventive step and that the balance of convenience and justice lies against the grant of the injunction sought. For the reasons set out below I grant an interlocutory injunction, but in a more limited form than that sought by the applicants.

1.1 The parties and the broad issues

2 Rituximab is a biologic therapy prescribed in Australia to treat a number of immunology conditions including lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). The first applicant, F. Hoffman-La Roche AG (FHLR) is a company incorporated in Switzerland. It is the registered proprietor of a number of patents relating to certain methods of use of rituximab in the treatment of a number of specified medical conditions. The second applicant, Roche Products Australia Pty Ltd (Roche Products) is the importer and supplier of products in Australia that are branded MABTHERA and that have rituximab as their active ingredient. Unless otherwise indicated, the applicants are referred to collectively below as Roche.

3 The respondent, Sandoz Pty Ltd (Sandoz), is a wholly owned subsidiary of Novartis Australia Pty Ltd. The ultimate owner of both is Novartis AG which is based in Switzerland. Sandoz has obtained a listing on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) pursuant to the National Health Act 1953 (Cth) (NH Act) for a product called RIXIMYO which is indicated for:

(1) The following forms of Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma (NHL):

(a) Previously untreated Stage III/IV follicular B-cell NHL;

(b) Relapsed or refractory low grade or follicular B-cell NHL;

(c) Diffuse large B-cell NHL (DLBCL) in combination with chemotherapy;

(2) CLL in combination with chemotherapy;

(3) RA in combination with methotrexate; and

(4) Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) in combination with glucocorticoids for the induction of remission.

4 These ARTG listings match those of MABTHERA.

5 Sandoz has applied to have RIXIMYO listed on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). On March 2018, a number of positive recommendations were made for the RIXIMYO products. The evidence suggests that it is likely that, absent an injunction, Sandoz’s products will be listed on 1 August 2018.

6 Roche is concerned that the effect of the PBS listing will be to cause a sequence of irreversible and harmful consequences to it. It now seeks interlocutory orders to restrain Sandoz from infringing the following claims (asserted claims) of the patents listed below (asserted patents):

(1) Australian Patent No. 2008207357 entitled “Combination therapies for B-cell lymphomas comprising administration of anti-CD20 antibody” (NHL Patent). The priority date of the NHL Patent is 11 August 1998 and it is due to expire on 11 August 2019. For the purposes of the interlocutory application, claims 18 and 21 are asserted to be infringed;

(2) Australian Patent No. 761844 entitled “Treatment of hematologic malignancies associated with circulating tumor cells using chimeric anti-CD20 antibody” (CLL Patent). The priority date of the CLL Patent is 9 November 1998 and it is due to expire on 9 November 2019. For the purposes of the interlocutory application, claim 2 is asserted to be infringed;

(3) Australian Patent No. 2005211669 entitled “Treatment of intermediate- and high-grade non-Hodgkins lymphoma with anti-CD20 antibody” (DLBCL Patent). The priority date of the DLBCL Patent is 11 August 1999 and it is due to expire on 2 August 2020. For the purposes of the interlocutory application, claim 35 is asserted to be infringed; and

(4) Australian Patent No. 2007242919 entitled “Therapy of autoimmune disease in a patient with an inadequate response to a TNF-alpha inhibitor” (RA Patent). The priority date of the RA Patent is 9 April 2003 and it is due to expire on 6 April 2024. For the purposes of the interlocutory application, claim 3 is asserted to be infringed.

7 Each of the claims is for a method of treating particular medical conditions using rituximab and I refer to these collectively as the “patented indications”.

8 Roche seeks an order to restrain the infringement of the asserted claims by the supply for use, importation, making, supplying, selling or keeping rituximab 500mg/50mL concentrated injection vial or rituximab 100mg/10mL concentrated injection vial which it defines to be the “Sandoz Products”. It also seeks an order compelling Sandoz to notify the Department of Health and the Minister for Health of the grant of any interlocutory injunction and inform them that it is no longer able to provide the assurance of supply that it has given (in support of the PBS application) until further notice.

9 Sandoz accepts that Roche has a prima facie case of infringement but contends that it has established a strong case that the asserted claims are invalid for lack of inventive step. It contends that the balance of convenience lies against interlocutory orders. Alternatively, it submits that the relief as sought by Roche is too broad and that if any injunction is granted, it should be narrower in scope and restricted to reflect the cascading expiry dates of each patent.

1.2 The pleaded case for interlocutory relief

10 In its points of claim for interlocutory relief (Points of Claim) Roche identifies the allegedly infringing products as being Sandoz’s two RIXIMYO products that have been registered on the ARTG. Roche alleges that Sandoz threatens to do the following in respect of RIXIMYO: supply it for use; import or make it; offer to make it; supply it; sell it; use it; and keep it for any of these purposes. Roche pleads that RIXIMYO is not a staple commercial product, that it contains a chimeric anti-CD20 antibody comprising human constant regions containing rituximab, and that RIXIMYO is a medicament that was and is manufactured for use in treating the patented indications.

11 Roche pleads that by reason of these matters the supply by Sandoz of RIXIMYO will infringe the asserted claims pursuant to ss 117(1) and 117(2)(b) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (Act).

12 Section 117(1) provides that if the use of a product by a person would infringe a patent, the supply of that product by one person to another is an infringement of the patent by the supplier unless the supplier is the patentee or licensee of the patent. Section 117(2)(b) provides that the reference in subsection (1) to the use of a product by a person is a reference to any use of the product, where the product is not a staple commercial product, and the supplier had reason to believe that the person would put it to that use.

13 Roche relies upon Sandoz’s RIXIMYO Product Information sheets (PIs) which provide instructions for use in accordance with the patented indications. Paragraph [18] of Sandoz’s Defence in the substantive proceedings admits that Sandoz has reason to believe that medical practitioners will administer RIXIMYO to patients in Australia in accordance with the instructions given in the RIXIMYO PIs as approved from time to time and in accordance with any instructions that may be given in connection with the supply of RIXIMYO.

14 In its Further Amended Points of Defence and Cross-Claim on Interlocutory Relief (Defence and Cross-Claim), Sandoz states that it will not contest that it has reason to believe that medical practitioners will administer RIXIMYO to patients in Australia in the method of treatment claimed in each of the asserted claims; that its supply of RIXIMYO would amount to exploitation of each of the asserted claims; or that it threatens to authorise medical practitioners to use the method claimed in each of the asserted claims. In short, subject only to its invalidity cross-claim, for the purposes of the interlocutory application Sandoz does not dispute that it proposes to infringe the asserted claims by the supply of RIXIMYO.

15 Sandoz alleges that the invention so far as claimed in each of the asserted claims is not patentable within s 18(1)(b)(ii) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the Act) in that it does not involve an inventive step when compared with the prior art base as it existed before the relevant priority dates. Sandoz pleads that the claims lack an inventive step having regard to the common general knowledge of the person skilled in the art alone. In the alternative, it pleads that the invention so claimed would have been obvious having regard to information contained in documents to which the person skilled in the art may have regard pursuant to s 7(3) of the Act, whether alone or in combination.

16 For the NHL patent, Sandoz relies on the following prior art documents (although it makes no submission in the present application in relation to the relevance of McNeil, in (4) below):

(1) Czuczman et al, “IDEC-C2B8 and CHOP Chemoimmunotherapy of Low-Grade Lymphoma”, Blood, 86 (10 Supp. 1): 55a (1995) (Czuczman);

(2) Maloney et al., “IDEC-C2B8 (Rituximab) Anti-CD20 Monoclonal Antibody Therapy in Patients with Relapsed Low-Grade Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma”, Blood, 90(6): 2188-2195 (1997) (Maloney 1);

(3) Maloney et al, “IDEC-C2B8: Results of a Phase I Multiple-Dose Trial in Patients with Relapsed Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma”, J. Clinical Oncology, 15(10): 3166 – 3247 (1997) (Maloney 2);

(4) McNeil, “Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Trials in Elderly Look Beyond CHOP”, J Nat. Cancer Inst., 90(4):266-7 (1988) (McNeil); and

(5) A combination of two or more of the documents described in paragraphs (1) to (4) above, being documents that the person skilled in the art in the patent area could be reasonably expected to have combined.

17 In its Defence and Cross-Claim, Sandoz also pleads that claim 21 of the NHL patent does not comply with s 40(3) of the Act, however, it did not press that allegation at the interlocutory hearing.

18 For the CLL patent, to which the pre-2001 version of s 7(3) applies, Sandoz relies on the following prior art documents:

(1) Maloney 1;

(2) Maloney 2; and

(3) Maloney 1 in combination with Maloney 2, being documents that are so related that the person skilled in the art would treat them as a single source.

19 For the DLBCL patent, Sandoz relies on the following prior art documents:

(1) McNeil;

(2) Link et al., “Phase II Pilot Study of the Safety and Efficacy of Rituximab in Combination with CHOP Chemotherapy in Patients with Previously Untreated Intermediate- or High-grade NHL”, American Society of Clinical Oncology, Program/Proceedings, 34th Annual Meeting (1998) (Link); and

(3) Coiffier B, “MabThera in Aggressive Lymphoma: An Update on its Efficacy and Toxicity”, Annals of Oncology, 10(Supp. 3): 213 (1999);

(4) A combination of two or more of the documents described in paragraphs (1) to (3) above, being documents that the person skilled in the art in the patent area could be reasonably expected to have combined.

20 In relation to the RA patent, Sandoz relies on the following prior art documents:

(1) Edwards JCW et al., “Efficacy and Safety of Rituximab, a B-Cell Targeted Chimeric Monoclonal Antibody: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis”, Arthritis & Rheumatism, 46(9) S197 (2002) (Edwards 2), whether read alone or in combination with Edwards JCW and Cambridge G, “Sustained improvement in rheumatoid arthritis following a protocol designed to deplete B lymphocytes”, Rheumatology, 40: 205-211 (2001) (Edwards 1);

(2) Patel DD, “B Cell-Ablative Therapy for the Treatment of Autoimmune Diseases”, Arthritis & Rheumatism, 46(8) 1984-5 (2002) (Patel);

(3) De Vita S et al., “Efficacy of Selective B Cell Blockade in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis”, Arthritis & Rheumatism, 46(8) 2029-33 (2002) (de Vita);

(4) Genentech Inc, Press Release entitled “Preliminary Positive Data from Investigational Randomized Phase II Trial Demonstrates Rituxan as a Potential Treatment for Rheumatoid Arthritis” (28 October 2002) (Genentech press release);

(5) Tuscano JM, “Successful Treatment of Infliximab-Refractory Rheumatoid Arthritis with Rituximab”, Arthritis & Rheumatism, 46(12) 3420 (2002) (Tuscano); and

(6) A combination of two or more of the documents described in paragraphs (1) to (5) above, being documents that the person skilled in the art in the patent area could be reasonably expected to have combined.

21 Roche has called the following witnesses: Mr Svend Petersen, who is the General Manager and Managing Director of Roche Products. He has sworn two affidavits, which relate to balance of convenience; Ms Carlene Todd, who is the Director of Market Access and Public Policy of Roche Products. She has affirmed two affidavits, which relate to balance of convenience; Dr John Seymour, who is a haemotologist and the Director of the Integrated Haematology Department at Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre and Royal Melbourne Hospital (RMH). He has affirmed one affidavit, which relates to the validity of the NHL, CLL and DLBCL patents and balance of convenience; Professor Eric Morand, who is a rheumatologist and the Head of the School of Clinical Sciences and Director of Rheumatology at Monash Health. He has affirmed one affidavit, which relates to the validity of the RA Patent and balance of convenience; Mr Kent Garret, who is the Director of Pharmacy at Austin Health, which comprises the Austin Hospital, Heidelberg Repatriation Hospital and Royal Talbot Rehabilitation Centre. He has affirmed one affidavit, which relates to balance of convenience; Mr Brett Rowland, who is a current legal practitioner and Special Counsel of Spruson & Ferguson Lawyers Pty Limited, Roche’s instructing solicitors. He has sworn two affidavits in support of Roche’s application, which relate to balance of convenience; Mr Jude D’Silva, who is the Business Unit Director – Established Products Roche Pharmaceuticals at Roche Products. He has affirmed one affidavit, which relates to balance of convenience.

22 Sandoz has called the following witnesses: Professor Henry Prince AM, who is a haematologist and the Director of the Centre for Blood Cell Therapies at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre and the Director of Molecular Oncology and Cancer Immunology at Epworth Healthcare. He has affirmed one affidavit, which relates to the validity of the NHL, CLL and DLBCL patents and balance of convenience; Professor Russell Buchanan, who is a clinical rheumatologist and Associate Professor of Medicine at the University of Melbourne and the Director of the Rheumatology Unit at Austin Health. He has affirmed one affidavit, which relates to the validity of the RA patent and balance of convenience; Dr David Liew, who is a Consultant Rheumatologist and Clinical Pharmacology Fellow at the Rheumatology Unit at Austin Health. He has affirmed one affidavit, which relates mainly to balance of convenience; Dr Chen Au Peh, who is a Consultant Renal Physician at the Royal Adelaide Hospital. He has affirmed one affidavit, which relates mainly to balance of convenience; Mr Glenn Samwell, who is the Head of BioPharma Australia at Sandoz. He has affirmed one affidavit, which relates to balance of convenience; Mr Matthew Swinn, who is a current legal practitioner and Partner of King & Wood Mallesons, Sandoz’s instructing solicitors. He has sworn one affidavit, which relates to balance of convenience.

2. THE LAW APPLICABLE TO INTERLOCUTORY RELIEF

23 The principles concerning the grant of interim injunctive relief are not controversial. When considering an application for an interlocutory injunction, the Court must address itself to two main inquiries, namely whether the applicant for relief has established a prima facie case in the sense explained in Beecham Group Ltd v Bristol Laboratories Pty Ltd [1968] HCA 1; 118 CLR 618 at 622-623, and whether the balance of convenience and justice favours the grant of an injunction or the refusal of that relief.

24 The requirement of a “prima facie case” does not mean that the applicant for relief must show that it is more probable than not that it will succeed at trial. It is sufficient if the applicant shows a sufficient likelihood of success to justify, in the circumstances, the preservation of the status quo pending trial. How strong that probability needs to be depends upon the nature of the rights that are being asserted and the practical consequences likely to flow from the order that is sought; Australian Broadcasting Corporation v O’Neill [2006] HCA 46; 227 CLR 57 (Gummow and Hayne JJ) at [65].

25 In Samsung Electronics Co Ltd v Apple Inc [2011] FCAFC 146; 217 FCR 238 the Full Court said:

[60] At [19] (p 68) in O’Neill, Gleeson CJ and Crennan J said:

As Doyle CJ said in the last-mentioned case, in all applications for an interlocutory injunction, a court will ask whether the plaintiff has shown that there is a serious question to be tried as to the plaintiff's entitlement to relief, has shown that the plaintiff is likely to suffer injury for which damages will not be an adequate remedy, and has shown that the balance of convenience favours the granting of an injunction. These are the organising principles, to be applied having regard to the nature and circumstances of the case, under which issues of justice and convenience are addressed. We agree with the explanation of these organising principles in the reasons of Gummow and Hayne JJ. (See [65]–[72], and their reiteration that the doctrine of the Court established in Beecham Group Ltd v Bristol Laboratories Pty Ltd (1968) 118 CLR 618 should be followed. See also Firth Industries Ltd v Polyglas Engineering Pty Ltd (1975) 132 CLR 489 at 492 per Stephen J; Winthrop Investments Ltd v Winns Ltd [1975] 2 NSWLR 666 at 708 per Mahoney JA; World Series Cricket Pty Ltd v Parish (1977) 16 ALR 181 at 186 per Bowen CJ.)

[61] The requirement that, in order to obtain an interlocutory injunction, the plaintiff must demonstrate that, if no injunction is granted, he or she will suffer irreparable injury for which damages will not be adequate compensation (the second requirement specified by Mason ACJ in Castlemaine Tooheys at p 153) was not mentioned in Beecham. Nor was it referred to by Gummow and Hayne JJ in O’Neill. Nonetheless, Gleeson CJ and Crennan J included that requirement in their articulation of the relevant “organising principles” (at [19] (p 68) in O’Neill). They also agreed with the explanation of those principles given by Gummow and Hayne JJ at [65]–[72] (pp 81–84) in the same case. One way of reconciling the views of Gleeson CJ and Crennan J with those of Gummow and Hayne JJ on this point is to treat “irreparable harm” as one of the matters which would ordinarily need to be addressed in the Court’s consideration of the balance of convenience and justice rather than as a distinct and antecedent consideration. This has been the approach taken by some judges (eg Ashley J in AB Hassle v Pharmacia (Australia) Pty Ltd (1995) 33 IPR 63 at 76–77; Gordon J in Marley New Zealand Ltd v Icon Plastics Pty Ltd [2007] FCA 851 at [3]; Kenny J in Medrad Inc v Alpine Pty Ltd (2009) 82 IPR 101 at [38] (p 109); and Yates J in Instyle Contract Textiles Pty Ltd v Good Environmental Choice Services Pty Ltd (No 2) [2010] FCA 38 at [55]–[64]).

[62] The assessment of harm to the plaintiff, if there is no injunction, and the assessment of prejudice or harm to the defendant, if an injunction is granted, is at the heart of the basket of discretionary considerations which must be addressed and weighed as part of the Court’s consideration of the balance of convenience and justice. The question of whether damages will be an adequate remedy for the alleged infringement of the plaintiff’s rights will always need to be considered when the Court has an application for interlocutory injunctive relief before it. It may or may not be determinative in any given case. That question involves an assessment by the Court as to whether the plaintiff would, in all material respects, be in as good a position if he were confined to his damages remedy, as he would be in if an injunction were granted (see the discussion of this aspect in Spry, The Principles of Equitable Remedies (8th edn, 2010) at pp 383–389; at pp 397–399; and at pp 457–462).

[63] The interaction between the Court’s assessment of the likely harm to the plaintiff, if no injunction is granted, and its assessment of the adequacy of damages as a remedy, will always be an important factor in the Court’s determination of where the balance of convenience and justice lies. To elevate these matters into a separate and antecedent inquiry as part of a requirement in every case that the plaintiff establish “irreparable injury” is, in our judgment, to adopt too rigid an approach. These matters are best left to be considered as part of the Court’s assessment of the balance of convenience and justice even though they will inevitably fall to be considered in most cases and will almost always be important considerations to be taken into account.

[64] Gleeson CJ also observed in Lenah Game Meats (at [18] (p 219)), that, where there is little or no room for argument about the legal basis of the applicant’s claimed private right, the court will be more easily persuaded at an interlocutory stage that a prima facie case has been established. The court will then move on to consider discretionary considerations, including the balance of convenience and justice. But, as his Honour also observed at [18] (p 219):

The extent to which it is necessary, or appropriate, to examine the legal merits of a plaintiff’s claim for final relief, in determining whether to grant an interlocutory injunction, will depend upon the circumstances of the case. There is no inflexible rule.

[65] The resolution of the question of where the balance of convenience and justice lies requires the Court to exercise a discretion.

[66] In exercising that discretion, the Court is required to assess and compare the prejudice and hardship likely to be suffered by the defendant, third persons and the public generally if an injunction is granted, with that which is likely to be suffered by the plaintiff if no injunction is granted. In determining this question, the Court must make an assessment of the likelihood that the final relief (if granted) will adequately compensate the plaintiff for the continuing breaches which will have occurred between the date of the interlocutory hearing and the date when final relief might be expected to be granted.

[67] As Sundberg J observed in Sigma Pharmaceuticals (Australia) Pty Ltd v Wyeth (2009) 81 IPR 339 at [15] (p 342), when considering whether to grant an interlocutory injunction, the issue of whether the plaintiff has made out a prima facie case and whether the balance of convenience and justice favours the grant of an injunction are related inquiries. The question of whether there is a serious question or a prima facie case should not be considered in isolation from the balance of convenience. The apparent strength of the parties’ substantive cases will often be an important consideration to be weighed in the balance: Tidy Tea Ltd v Unilever Australia Ltd (1995) 32 IPR 405 at [416] per Burchett J; Aktiebolaget Hassle v Biochemie Australia Pty Ltd (2003) 57 IPR 1 at [31] (p 10) per Sackville J; Hexal Australia Pty Ltd v Roche Therapeutics Inc (2005) 66 IPR 325 at [18] (p 329) per Stone J; and Castlemaine Tooheys at 154 per Mason ACJ.

26 The point set out in the passage at [67] is of particular relevance in the present application. Sandoz, whilst accepting that its proposed conduct will prima facie fall within the scope of the claims, contends that it has a sufficiently strong case of invalidity so as to weigh materially in Sandoz’s favour on the question of balance of convenience. That approach has led to the filing of a significant body of evidence going to this subject, with each side relying on the opinions of experienced and highly skilled medical practitioners to support their respective positions.

27 In this context it is apposite to note that a countervailing argument for invalidity must be considered with some care. It is not sufficient to balance the scales by establishing a triable revocation case on the cross-claim. If that is as far as it goes then, assuming (as here) that the applicant for relief has shown a triable issue on infringement, the conclusion would remain that the applicant has a triable question. As Jessup J said in Interpharma Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2008] FCA 1498; 79 IPR 261 (Interpharma):

[17] … as a matter of analysis, unless the case for invalidity is sufficiently strong (at the provisional level) to qualify the conclusion that, overall, the applicant has a serious question, or a probability of success, the court should move to consider the adequacy of damages, the balance of convenience and other discretionary matters. It is the applicant’s title to interlocutory relief which is under consideration, and the bottom-line question, as it were, is whether the applicant has a serious question, or a probability of success, not whether the respondent does in relation to some point of defence raised or foreshadowed.

28 This passage has been adopted as correct by a number of single judges of this Court; Janssen Sciences Ireland UC v Alphapharm Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1399 (Yates J) at [96]; Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp v Apotex Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 928; 97 IPR 414 (Merck) (Jagot J) at [5] and; Organic Marketing Australia Pty Ltd v Woolworths Ltd [2011] FCA 279 at [60] (Katzmann J).

29 Faced with the same issue, Jagot J in Merck observed (at [6]-[7]) that the assessment of the strength of Apotex’s case for invalidity (an inventive step challenge) relied heavily on expert evidence. Were Apotex’s evidence to be the only evidence available, the assessment would have been straightforward. But as might be expected, Merck had also filed expert evidence, addressing the invalidity case. None of this evidence was, or could be, tested by cross-examination. All was prepared by apparently well-qualified experts and, on its face, appeared to be rational and persuasive. Yet the evidence of the experts would lead to different conclusions. Her Honour accordingly asked the parties for assistance in determining whether (and if so, how) she could prefer the evidence of one expert over another on a rational basis when there was no lack of persuasive force apparent from the face of the expert reports and none of the evidence had been tested. She proceeded to consider the evidence of the experts against the metric of whether there was a rational basis upon which the evidence of one could be preferred over another.

30 Before turning to apply the considerations relevant to the grant or refusal of the interlocutory orders sought, it is necessary to set out some background matters which have been addressed in considerable detail in expert and lay evidence. In many instances the experts disagree on matters of fact and opinion. The present hearing is not the place to make findings of fact, or to resolve disputes of opinion and I do not purport to do so here. This section addresses some matters of background that may facilitate a better understanding of the issues in dispute.

31 The immune system normally functions to protect the body from infections. There are various components and many different types of cells that make up the immune system. They include B-cells (or B lymphocytes) and T-cells (or T lymphocytes), which are sub-types of white blood cells.

32 One function of B-cells is to produce antibodies as part of an immune response. Antibodies recognise, target and bind to specific proteins on the surface of foreign bodies (antigens) such as bacteria, viruses and some cancer cells, and cause cell destruction. T-cells are (inter alia) responsible for providing ‘help’ to B-cells and induce the release of chemicals called cytokines (predominantly by macrophages). Cytokines are small proteins that act as signals between different cells upon release. The release of cytokines can induce, exacerbate, or perpetuate inflammation. Tumour necrosis factor (TNFα) and interleukins are examples of cytokines, of which there are at least 30.

33 As stated above, rituximab is a biologic therapy. Broadly, biologic therapies (also referred to as “biological medicines” or “biologics”) are large, complex molecules derived from a biological source, such as bacterium, yeast or blood. They are different to synthetic small molecule medicines in terms of production processes, the complexity of chemical structure, purity and immunogenicity (which is discussed further below). The manufacture of a biologic involves extensive research and development to select the most appropriate cell lines to be modified so that they can be made to reproduce in a manufacturing context.

34 In the case of rituximab, it is a monoclonal antibody. Monoclonal antibodies can be made in a laboratory by injecting mice with antigens from a human cell, which is then harvested, fused with cancerous B-cells (producing a hybridoma), and humanized to avoid triggering an immune response upon administration to human patients.

35 Rituximab binds to the CD20 antigen, which is a protein molecule that can appear on the surface of B-cells. Once bound, rituximab coats the surface of the cell and triggers the body’s immune system to destroy the cell. The CD20 antigen is not present on immature or developing B-cells. As a consequence, rituximab can be used to target mature B-cells, whilst still enabling immature B-cells to develop and replenish the supply of B-cells following treatment. CD20 is also present on almost all types of B-cells, which makes it a good target for treatment of diseases with a pathogenesis involving B-cells.

36 B-cells are thought to play an integral role in the pathogenesis of particular types of leukaemias and lymphomas, and RA. As a consequence, rituximab has been found to be effective in the treatment of these diseases, each of which are discussed further below.

37 Lymphoma is a general term given to cancers that develop in the lymphatic system due to a malignant change to B-cells and T-cells. The lymphatic system is a network of lymph vessels that branch out into the tissues of the body.

38 Lymphoma is not a single disease but a diverse group of diseases. There are several different classification systems used to classify lymphomas, including the World Health Organisation (WHO) Lymphoma Classification System, International Working Formulation and Revised European American Lymphoma Classification. The WHO Lymphoma Classification System recognises 43 different classifications (or sub-types) of lymphoma. Five of these sub-types are classified as Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, characterised by the presence of Hodgkin’s or Reed Sternberg cells. The residual 38 sub-types are classified as NHL.

39 Lymphomas can also be characterised by the speed in which they grow. Low-grade, or indolent, lymphomas grow slowly, cause fewer detectable symptoms and are generally incurable. They typically tend to grow back or relapse within a few years after the first treatment and have a relentless progression of the disease with subsequent episodes of therapy providing a diminishing benefit. Intermediate and high grade, or aggressive, lymphomas grow quickly, cause severe symptoms and (at least today) are generally curable in at least a proportion of patients (although the expert haematologists disagreed as to the proportion that were curable at the priority dates). They do not demonstrate the same course of relapse and remission as low grade lymphomas.

40 The majority of NHL lymphomas are B-cell Lymphomas, accounting for approximately 80% of diagnosed cases in Australia each year. B-cell Lymphomas include DLBCL, Follicular Lymphoma (FL) and Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma (SLL), amongst others. These are discussed further below.

41 DLBCL is the most common aggressive sub-type of NHL and is generally very responsive to treatment and (at least today) curable. It accounts for approximately 30-40% of all NHL. It is characterised by large malignant B-cells that may be observed to be diffuse throughout a biopsy.

42 FL is the most common type of indolent lymphoma. FL makes up about 70-80% of all indolent lymphomas and about 20-30% of all cases of NHL. FL is usually well-controlled with treatment but like most indolent lymphomas is not commonly curable. It is characterised by tumor cells that appear in a circular or clump-like pattern, which replace the normal structure of a lymph node.

43 SLL is a less common type of indolent lymphoma. The structure and infiltrating pattern of SLL cells are different to those of FL cells, and SL cells tend to express antigens that are not commonly seen on B-cells.

44 Bulky disease is a term used to describe the presence of sites where there is a large amount of lymphoma and the patient has large tumours above a certain threshold maximum tumour diameter. Bulky disease can occur with many different types of lymphoma, including FL and DLBCL. However, the adverse prognostic implications of bulky disease are most profound in DLBCL.

45 Leukaemias manifest primarily in the blood. Different types of leukaemias are named after the cells that are affected and how quickly they grow.

46 CLL is a slow growing leukaemia of mature B-cells and the most common type of leukaemia in the Western world. It is the leukaemic counterpart of SLL. CLL and SLL cells are morphologically indistinguishable. When the cells are found predominantly in the circulating blood and bone marrow, the cancer presents as CLL. When lymphoma cells are found predominantly in the lymphatic system, the cancer presents as SLL.

47 At the priority dates, CLL cells were known to have a number of features which overlap with the features of SLL cells. However, according to Dr Seymour (the expert haematologist for Roche), before these dates SLL and CLL were considered distinct diseases, and it is only more recently that there has been an understanding that they are related entities. This appears to be an area of dispute.

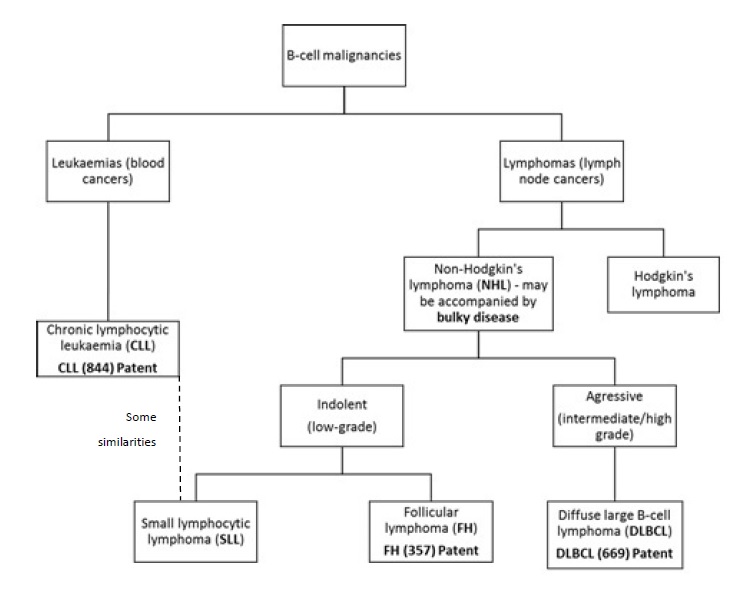

48 The flowchart below demonstrates the relationship between the diseases described above. This chart was provided by Roche during the course of the hearing. It has been slightly modified to accommodate a difference of opinion between the experts as to what grade of lymphoma DLBCL represents.

49 RA is an autoimmune disease in which the immune system inappropriately attacks joint tissue, causing painful chronic inflammation and irreversible destruction of cartilage, tendons and bones. Untreated, RA causes progressive, irreversible and erosive joint damage, which ultimately leads to the destruction of the joint itself. This leads to permanent disability and loss of productivity, and is a recognised cause of premature death.

50 The aetiology of RA remains unknown and it is currently incurable. B-cells play an integral role in the disease pathogenesis of RA, although the exact nature of this role is still unknown today. Whether this was commonly known before the priority dates is a matter of contention between the experts.

51 Classes of drugs used in the treatment of RA include conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (CS-DMARDS) and biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (bDMARDS).

52 CS-DMARDS reduce damage to joints by controlling the inflammatory process in the joints and act by suppressing the body’s immune system. One particular CS-DMARD is methotrexate. Methotrexate is (and was at the priority date) the standard first-line treatment for RA. At the priority date, methotrexate was prescribed as a monotherapy or in combination with other approved treatments. Approximately a third of patients respond very well to monotherapy methotrexate and another third respond well to methotrexate in combination with another CS-DMARD. Combination therapies were generally considered more therapeutically effective than methotrexate alone.

53 bDMARDS are a newer class of medicines for the treatment of RA that target various naturally occurring substances in the immune system involved in generating inflammation. The use of bDMARDs in the treatment of RA was first presented in the late 1990s. They are generally classified as tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFα-inhibitors) and non-TNF inhibitors. It appears that only TNFα-inhibitors were available in Australia before the priority date.

54 As stated above, TNFα is a type of cytokine, which induces, exacerbates or perpetuates inflammation. TNFα-inhibitors block the inflammatory effects of TNFα. Inflixmab, the first TNFα inhibitor, was approved and listed on the ARTG in August 2000 and received PBS listing in November 2003. Etanercept, the second TNFα inhibitor, was approved and listed on the ARTG in March 2003 and received PBS listing in August 2003.

55 A biosimilar medicine is a biologic that has been approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration as similar to another biologic which has already been approved for marketing (the reference biologic). There are particular differences between biosimilars and generic small molecule drugs. For example, in contrast to the active pharmaceutical ingredients in generic small molecule drug products, the active component of biosimilars are much larger more complex molecules that have the potential to vary in many ways from the reference biologic. As a consequence, they are subject to a different set of regulatory considerations.

56 Further, a particular risk for biologics (both reference biologics and biosimilars) is that they can provoke an immune response in patients (referred to as immunogenicity). This can have a variety of consequences for the patient including the need to administer higher or more frequent doses to maintain the therapeutic effect; adverse side effects; or ineffective therapy. It can be difficult to predict which patients will have such a response. Clinicians are also concerned that immunogenicity may be heightened by multiple switches between biologics. There is no dispute that there are well publicised and common concerns amongst hospital directors of pharmacy and clinicians about immunogenicity in relation to biosimilars.

57 Under a Strategic Agreement between the Commonwealth Government and Medicines Australia Limited, a series of changes to the PBS regime will soon be introduced. These changes will enable the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC), which inter alia recommends new medicines for listing on the PBS, to make particular recommendations on a case by case basis when considering a PBS listing of a biosimilar product. These include recommending:

(1) a different prescribing process for biosimilars and reference biologics (such as MABTHERA) through allowing a lower level of authority (meaning the administrative arrangements that apply prior to prescribing certain PBS medicines) to the biosimilar than exists for the reference biologic at the point of introduction of the biosimilar, which may be at commencement of therapy or continuation of therapy (or both); and

(2) for treatment of naïve patients only, the prescribing of the new biosimilar compared with the reference biologic is the preferred choice for these patients, which may be further reinforced in the prescribing software.

58 These are referred to as the “biosimilar uptake drivers”. Roche emphasises that it is currently uncertain how these proposed biosimilar uptake drivers will operate in practice and the extent of their impact. However, it expects them to accelerate the adoption of biosimilars. Sandoz disputes that the drivers will have a material impact on uptake.

59 MABTHERA has been registered on the ARTG since 6 October 1998. It is approved for the indications set out in paragraph 3 above.

60 MABTHERA is a concentrate solution for an intravenous (IV) infusion or subcutaneous injection. Most patients receive an IV infusion either as an inpatient or (most commonly) an outpatient of a hospital or clinic. MABTHERA was first listed on the PBS on 1 February 1999 for the indication of relapsed refractory FL. The scope of the PBS listing has now been expanded to include treatment of out-patients with:

(1) Untreated/relapsed lymphoid cancers in combination with chemotherapy, limited to the number of cycles recommended by the standard guidelines; and

(2) RA where the patient fails a 6 month course of traditional disease-modifying drugs (DMARDS), such as methotrexate, and has poorly controlled disease (being 20 or more affected joints, 4 or more large affected joints and raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C reactive protein (CRP) levels). Once the patient has received an initial approval, the patient needs to achieve a 50% improvement in joint count and 20% improvement in ESR or CRP levels, documented every 6 months, to remain on the PBS subsidised agents.

61 Sales are only subsidised by the Commonwealth under the PBS scheme where the patient is an outpatient. No subsidies are provided for treatment of inpatients.

62 There is no dispute that rituximab generally and MABTHERA in particular is a high cost medication. It may be dispensed under three different PBS reimbursement programs; highly specialised drugs, efficient funding of chemotherapy arrangements, and the general PBS schedule. The evidence of Ms Todd indicates, using an average Australian NHL patient as an example, that for a public hospital, the dispensed price for MABTHERA would be $2,641.56 per treatment. If subsidised under the PBS, the patient would make a co-payment of $39.50 (or $6.40 for a concessional patient) and there is no cost to the hospital. If the treatment is not for the PBS listed indications listed in paragraph 60 above, the full cost of the treatment is borne by either the hospital or the patient unless the patient qualifies for a compassionate program.

63 The evidence indicates that MABTHERA may be prescribed “off-label”, that is, for indications other than those for which it is registered on the ARTG. By comparing the PBS indications against the ARTG registrations and the patented indications one may see that some off-label use is subsidised by the PBS (because it extends to any treatment of an outpatient with any type of untreated or relapsed lymphoid cancer in combination with chemotherapy). In contrast, other types of off-label use will not be subsidised by the PBS (for example, the treatment of inpatients and where MABTHERA is used to treat lymphoid cancers as a monotherapy, rather than in combination with chemotherapy). Moreover, some on-label use is also not subsidised by the PBS. This is particularly the case for treatment of RA, as only a limited subset of RA patients will be entitled to PBS subsidies.

64 As explained in more detail below, the asserted claims extend to off-label and on-label uses and PBS and non-PBS subsidised uses. However, there also remains a proportion of both off-label and on-label uses that do not fall within the scope of the asserted claims.

65 Sales of MABTHERA are made by Roche Products to public and private hospitals, wholesalers and compounding or mixing houses.

66 Supply of pharmacy products to public hospitals in Australia is the subject of competitive tenders. Tender submissions are called for 3 to 6 months before the existing tender expires. They can also be called upon a change in market conditions, including the arrival of a cheaper equivalent product on the market. Ms Matthews gives evidence that, due to the concerns about immunogenicity and switching, there is a strong desire on the part of clinicians and the hospital administration of the RMH to have consistency for patients following a switch from the reference biologic to a biosimilar.

67 According to the “Field of the Invention” the NHL patent relates to the use of anti-CD20 antibodies or fragments thereof in the treatment of B-cell lymphomas, particularly the use of such antibodies and fragments in combined therapeutic regimens.

68 The “Background of the Invention” states that the use of the CD20 antigen as diagnostic and/or therapeutic agents for B-cell lymphoma has previously been reported. It goes on to say:

Previous reported therapies involving anti-CD20 antibodies have involved the administration of a therapeutic anti-CD20 antibody either alone or in conjunction with a second radiolabelled anti-CD20 antibody, or a chemotherapeutic agent.

In fact, the Food and Drug Administration has approved the therapeutic use of one such anti CD20 antibody, Rituxan®, for use in relapsed and previously treated low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). Also the use of Rituxan® in combination with a radiolabelled murine anti-CD20 antibody has been suggested for the treatment of B-cell lymphoma.

However, while anti-CD20 antibodies and, in particular, Rituxan® (US.; in Britain, MabThera®; in general Rituximab), have been reported to be effective for treatment of B-cell lymphomas, such as non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, the treated patients are often subject to disease relapse. Therefore, it would be beneficial if more effective treatment regimens could be developed.

More specifically, it would be advantageous if anti-CD20 antibodies had a beneficial effect in combination with other lymphoma treatments, and if new combined therapeutic regimens could be developed to lessen the likelihood or frequency of relapse.

69 The patent then provides a “Summary of the Invention” followed by a “Detailed Description of the Invention”.

70 The Detailed Description commences by referring to combined therapeutic regimens for the treatment of B-cell lymphomas. Those include a method for treating relapsed B-cell lymphoma, where a patient having prior treatment has relapsed and is administered an effective amount of a chimeric anti-CD20 antibody (including, rituximab). The prior treatments include bone marrow or stem cell transplantation, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. The previous chemotherapy may be selected from a wide group of chemotherapeutic agents and combination regimens, including CHOP, ICE, Mitazantrone, Cytarabine and a number of other listed forms. The Detailed Description also refers to methods for treating a subject having B-cell lymphoma where the subject is refractory for other therapeutic treatments, including those listed above.

71 The NHL patent provides that the combined therapeutic regimens disclosed can be performed whereby said therapies are given simultaneously, that is, the anti-CD20 antibody is administered concurrently or within the same timeframe (i.e., the therapies are going on concurrently, but the agents are not administered precisely at the same time).

72 The relevant claims in the NHL patent are claims (which is dependent on claim 16) and 21:

16. A method for treating low grade or follicular non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in a human patient comprising administering to the patient rituximab in combination with chemotherapy, wherein the chemotherapy is cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) or cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (CVP), and wherein a therapeutically effective amount of rituximab is administered to the patient simultaneously with said chemotherapy.

…

18. The method of claim 16 wherein the chemotherapy is CVP.

…

21. A method for treating low grade B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in a human patient comprising treating the patient with CVP therapy followed by administering to the patient rituximab maintenance therapy provided for 2 years, wherein rituximab is administered at a dose of 375 mg/m2.

73 Claim 18 is accordingly for a method of treating either low grade or follicular NHL involving the simultaneous administration of rituximab with a particular type of chemotherapy, being cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisonc (CVP).

74 Claim 21 is a method for treating only low grade B-cell NHL by treating the patient with CVP therapy followed by administering rituximab “maintenance therapy” for 2 years with rituximab administered at 375mg/m2.

75 The “Field of the Invention” identifies that the CLL patent is directed to the treatment of haematologic malignancies associated with high numbers of circulating tumor cells by the administration of a therapeutically effective amount of chimeric or humanized antibody that binds to the B-cell surface antigen Bp35 (CD20).

76 The “Background of the Invention” then restates, in broadly the same form, much of the detail in the Background quoted above in the NHL patent.

77 The “Brief Description of the Invention” commences by stating that the inventors have “developed a novel treatment for hematologic malignancies characterized by a high number of tumour cells in the blood involving the administration of effective therapeutically effective amount of an anti-CD20 antibody”. A specific object of the invention is to treat B-prolymphocytic leukemia (B-PLL) or CLL comprising administration of a therapeutically effective amount of RITUXAN® (that is, MABTHERA).

78 In the “Detailed Description of the Invention” the patent states:

The invention involves the discovery that hematologic malignancies and, in particular, those characterized by high numbers of tumor cells in the blood may be effectively treated by the administration of a therapeutic-CD20 antibody. These malignancies include, in particular, CLL, B-PLL and transformed non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

This discovery is surprising notwithstanding the reported great success of RITUXAN® for the treatment of relapsed and previously treated low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. In particular, this discovery is surprising given the very high numbers of tumor cells observed in such patients and also given the fact that such malignant cells, e.g., CLL cells, typically do not express the CD20 antigen at the high densities which is characteristic of some B-cell lymphomas, such as relapsed and previously-treated low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Consequently, it could not have been reasonably predicted that CD20 antigen would constitute an appropriate target for therapeutic antibody therapy of such malignancies.

79 Roche asserts the infringement of claim 2 of the CLL patent, which is dependent on claim 1. The two claims provide:

1. A method of treating chronic lymphcytic leukemia (CLL) in a human patient by administering 500-1500 mg/m2 of rituximab to the patient.

2. The method of claim 1, wherein said rituximab is administered in combination with chemotherapy.

80 Accordingly, the claimed invention may be summarised to be a method of treating CLL by administering 500-1500mg/m2 of rituximab to a patient in combination with chemotherapy.

81 The DLBCL patent is entitled “Treatment of intermediate- and high-grade non-Hodgkins lymphoma with anti-CD20 antibody”. The “Field of the Invention” concerns methods of treating DLBCL with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies and fragments thereof.

82 The “Background of the Invention” commences with the following statements:

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is characterised by the malignant growth of B lymphocytes. According to the American Cancer Society, an estimated 54,000 new cases will be diagnosed, 65% of which will be classified as intermediate- or high-grade lymphoma. Patients diagnosed with intermediate-grade lymphyoma have an average survival rate of 2-5 years, and patients diagnosed with high-grade lymphoma survive an average of 6 months to 2 years after diagnosis.

Intermediate- and high-grade lymphomas are much more aggressive at the time of diagnosis than are low-grade lymphomas, where patients may survive an average of 5-7 years with conventional therapies. Intermediate- and high-grade lymphomas are often characterized by large extranodal bulky tumors and a large number of circulating cancer cells, which often infiltrate the bone marrow of the patient.

83 The Background goes on to observe that conventional therapies have included chemotherapy and radiation, possibly accompanied by bone marrow or stem cell transplantation if a donor is available. While patients often respond to conventional therapies, they usually relapse within several months. A relatively new approach has been to treat patients with a monoclonal antibody directed to a protein on the surface of cancerous B-cells.

84 The “Summary of Invention” states that the present invention concerns the use of anti-CD20 antibodies for the treatment of DLBCL. The inventors are said surprisingly to have found that rituximab, already approved for the treatment of low-grade follicular NHL, is effective to treat DLBCL in combination with chemotherapy in patients who have relapsed from or are refractory to chemotherapy.

85 Claim 35 is presently advanced by Roche. It is:

A method for treating a patient with diffuse large cell lymphoma accompanied by bulky disease, comprising administering to the patient a therapeutically effective amount of unlabeled Rituximab and CHOP chemotherapy, wherein the unlabeled Rituximab is administered on Day 1 of each chemotherapy cycle and the CHOP is administered on Day 1 of each chemotherapy cycle.

86 The RA patent is entitled “Therapy of autoimmune disease in a patient with an inadequate response to a TNF-alpha inhibitor”. The “Field of the Invention” states that the invention concerns therapy with antagonists which bind to B-cell surface markers, such as CD20. In particular, the invention concerns the use of such antagonists to treat autoimmune disease in a mammal who experiences an inadequate response to a TNFα-inhibitor.

87 Claim 3 of the RA patent is asserted by Roche. It is dependent on claims 1 and 2. Claims 1 – 3 are as follows:

1. A method of treating rheumatoid arthritis in a human patient who experiences an inadequate response to a TNFα-inhibitor, comprising administering to the patient an antibody that binds to CD20, wherein the antibody is administered as two intravenous does [sic] of 1000mg.

2. The method of claim 1, wherein the antibody comprises rituximab.

3. The method of claim 1 or claim 2, wherein the patient is further treated with concomitant methotrexate (MTX).

88 When read together, having regard to the dependencies, claim 3 is for a method of treating RA in a patient who experiences an inadequate response to a TNFα-inhibitor, comprising administering rituximab in 2 x intravenous doses of 1000mg, wherein the patient is further treated with concomitant methotrexate.

5. CONSIDERATION OF THE QUESTION OF ARGUABLE CASE

89 Sandoz challenges the validity of each of the patents on the basis that they lack an inventive step. As noted in Samsung at [67], the apparent strength of the parties’ substantive cases will often be an important consideration to be weighed in the balance of whether or not to grant interlocutory injunctive relief. Sandoz accepts, for the purposes of the present application, that its proposed conduct will infringe the asserted claims. That concession yields the result that, subject only to the invalidity challenge, Roche has established the strongest of arguable cases. The critical question then becomes; what is the strength of Sandoz’s invalidity challenge?

90 A great deal of expert evidence has been filed by both sides concerning the cross-claim. The expert opinion evidence reflects numerous disagreements including; as to what the person skilled in the art knew at the priority dates; what research work they would undertake; and what expectation of success there would have been in relation to that work. Sandoz does not ask that the Court try to resolve the evidentiary conflicts reflected in the affidavit materials. Indeed it is not appropriate to do so. It is not the function of the Court to conduct a preliminary trial of the action or, in general, to resolve conflict between the parties’ evidence and grant or refuse the application on the basis of such findings; Warner-Lambert Co LLC v Apotex Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 59; 311 ALR 632 (Full Court) (Warner-Lambert) at [72], [91].

91 Nevertheless, Sandoz urges that the Court can conclude that there is a “very serious challenge” to the validity of the patents and that this weighs heavily against the grant of the orders sought. In this connection, Sandoz states that it does not invite the Court to make findings in respect of contested facts and opinions but it nevertheless asks the Court to conclude that it has a strong prima facie case.

92 In response, Roche accepts for present purposes that the case advanced by Sandoz on the cross-claim is arguable, but no more. It submits that the overwhelming strength of its infringement case is not weakened by the existence of a merely arguable cross-claim and that this is a relevant factor in the consideration of the application.

5.2 The Person skilled in the art

93 It appears to be common ground between the parties that the personal skilled in the art for the cancer patents is a haematological malignancy specialist with both clinical and research experience, and the person skilled in the art for the RA patent is a rheumatology specialist with clinical and research experience. There is no dispute that the expert witnesses who have given evidence are suitably qualified.

5.3 The relevant law on inventive step

94 Section 18(1)(b)(ii) of the Act relevantly provides that an invention is a patentable invention for the purposes of a standard patent if the invention, so far as claimed in any claim, when compared to the prior art base as it existed before the priority date, involves an inventive step.

95 Section 7(2) of the Act provides:

For the purposes of this Act, an invention is to be taken to involve an inventive step when compared with the prior art base unless the invention would have been obvious to a person skilled in the relevant art in the light of the common general knowledge as it existed in the patent area before the priority date of the relevant claim, whether that information is considered separately or together with the information mention in s 7(3).

96 Section 7(3) has been amended over the years and care must be taken to ensure that the correct form is used for each patent. The form that is applicable to the challenge to the CLL patent is that which applied immediately before amendments were made in 2001 to the Act, and is as follows:

For the purposes of subsection (2), the kinds of information are:

(a) prior art information made publicly available in a single document or through doing a single act; and

(b) prior art information made publicly available in 2 or more related documents, or through doing 2 or more related acts, if the relationship between the documents or acts is such that a person skilled in the relevant art in the patent area would treat them as a single source of that information;

being information that the skilled person mentioned in subsection (2) could, before the priority date of the relevant claim, be reasonably expected to have ascertained, understood and regarded as relevant to work in the relevant art in the patent area.

97 The form of section 7(3) applicable to the consideration of the validity of the NHL, DLBCL and RA patents is that which immediately followed the 2001 amendments:

The information for the purposes of subsection (2) is:

(a) any single piece of prior art information; or

(b) a combination of any 2 or more pieces of prior art information;

being information that the skilled person mentioned in subsection (2) could, before the priority date of the relevant claim, be reasonably expected to have ascertained, understood, regarded as relevant and, in the case of information mentioned in paragraph (b), combined as mentioned in that paragraph.

98 Plainly enough, the onus to establish lack of inventive step rests upon the party challenging validity; s 7(2).

99 In AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd [2015] HCA 30; 257 CLR 356 (AstraZeneca) French CJ said (footnotes omitted):

[15] Relevant content was given to the term "obvious" by Aickin J in Wellcome Foundation Ltd, posing as the test:

"whether the hypothetical addressee faced with the same problem would have taken as a matter of routine whatever steps might have led from the prior art to the invention, whether they be the steps of the inventor or not."

The idea of steps taken "as a matter of routine" did not, as was pointed out in AB Hässle, include "a course of action which was complex and detailed, as well as laborious, with a good deal of trial and error, with dead ends and the retracing of steps". The question posed in AB Hässle was whether, in relation to a particular patent, putative experiments, leading from the relevant prior art base to the invention as claimed, are part of the inventive step claimed or are "of a routine character" to be tried "as a matter of course". That way of approaching the matter was said to have an affinity with the question posed by Graham J in Olin Mathieson Chemical Corporation v Biorex Laboratories Ltd. The question, stripped of references specific to the case before Graham J, can be framed as follows:

"Would the notional research group at the priority date, in all the circumstances, which include a knowledge of all the relevant prior art and of the facts of the nature and success of [the existing compound], directly be led as a matter of course to try [the claimed inventive step] in the expectation that it might well produce a useful alternative to or better drug than [the existing compound]?"

That question does not import, as a criterion of obviousness, that the inventive step claimed would be perceived by the hypothetical addressee as "worth a try" or "obvious to try". As was said in AB Hässle, the adoption of a criterion of validity expressed in those terms begs the question presented by the statute.

100 See also Kiefel J at [66] and [67].

101 Before a document containing prior art information can be used along with common general knowledge for the purposes of the s 7(2) inquiry, it is necessary that it meet the requirements of s 7(3). For the pre-2001 version of s 7(3) it has been held that prior art information which is publicly available in a document is “ascertained” if it is discovered or found out. “Understood” means having discovered the information, the skilled person would have comprehended it or appreciated its meaning or import. The words “relevant to work in the relevant art”, in the context of the pre-2001 version of s 7(3), are directed to publicly available information not part of the common general knowledge, which the skilled person could be expected to have regarded as solving a particular problem or meeting a long-felt want or need; AstraZeneca per Kiefel J at [68], citing Lockwood Security Products v Doric Pty Ltd [No 2] [2007] HCA 21; 235 CLR 173 (Lockwood No 2) at [132].

102 In AstraZeneca, Keifel J said (footnotes omitted, emphasis original):

[69] Lockwood [No 2] also explains that, in answering the question of obviousness, the information referred to in s 7(3), like that part of the prior art base which is the common general knowledge, is considered for a particular purpose. That purpose is to look forward from the prior art base to see what the skilled person is likely to have done when faced with a problem similar to that which the patentee claims to have solved with the claimed invention. It is this aspect of the s 7(2) enquiry which assumes particular importance on these appeals.

103 The test posits a looking forward from the prior art base, without the benefit of hindsight.

104 In Lockwood No 2, the High Court said:

[51] In Alphapharm, this court reiterated that “obvious” means “very plain”, as stated by the English Court of Appeal in General Tire & Rubber Co v Firestone Tyre and Rubber Co Ltd . The majority in Alphapharm also confirmed that the question of whether an invention is obvious is a question of fact, that is, it is what was once a “jury question”. Broadly speaking, the question is not a question of what is obvious to a court. As well as being a question of fact, the question of determining whether a patent involves an inventive step is also “one of degree and often it is by no means easy”, because ingenuity is relative, depending as it does on relevant states of common general knowledge. This difficulty is further complicated now by the need, in some circumstances, to consider s 7(3) information as well as common general knowledge.

105 The emphasis that the High Court placed on obviousness being a “jury question” is of importance in the present case. Where an inventive step challenge involves competing issues of fact and opinion it will often be difficult for a party to establish any more than that a case is arguable. It is deceptively simple to assert in submissions that a simple invention as reflected in a claim which consists of two integers is obvious. However, in each case the question must be considered against the background of the common general knowledge of the invention as claimed. Where these matters are complicated by conflicting evidence and a priority date that is more than 15 years in the past, it may be undesirable for a Court to find at the interlocutory stage that the inventive step challenge is any more than “arguable”.

5.4 Consideration of the invalidity case

106 I commence my observations by repeating that I do not here make any findings of fact or conclusions in relation to the various arguments articulated. The task at hand is to determine as best one can, whether the cross-claim advanced may, as Sandoz urges, be described as “strongly arguable”, or whether, as Roche urges, it is simply “arguable”; and feed my preliminary view on this subject into the calculus for deciding whether or not to grant the relief sought.

107 Sandoz advances its challenge to the three cancer patents (the NHL patent, the CLL patent and the DLBCL patent) on the basis of the evidence of Professor Prince, who gave a lengthy affidavit in which he responded to a series of questions from the solicitors representing Sandoz. He first provides a background to the haematological conditions that he treats on a regular basis, being “NHL, FL, CLL and DLBCL”. He then identifies the treatments for these conditions that were available at the priority dates and then describes rituximab, how it works, the way it is prescribed and how it is dispensed and administered.

108 Next, Professor Prince considers:

the extent to which, as at the Relevant Dates, I would have considered it to be a matter of routine to investigate the use of rituximab in treating different types of lymphoma and leukaemia if I had been a member of a team seeking to investigate new treatments for lymphoma and leukaemia.

109 In answering this question Professor Prince identifies a significant number of factual matters that he considers haematologists would have known concerning the way that the relevant conditions were treated as at the relevant priority dates.

110 Having regard to those matters, Professor Prince expresses his opinion that the likelihood that he and his Australian colleagues would have wished to investigate the uses for rituximab in treating patients with a wide range of B-cell lymphomas and related leukemia conditions is “very high”. Once rituximab was available, investigations into the various applications for it and the optimal dosing and combined treatment regimens would have occurred, not only as a matter of routine, but in his opinion as an urgent priority in the expectation that it may well produce new treatment options for patients.

111 Professor Prince then turns to answer the question posed by the solicitors (set out at [108] above) in relation to the treatment of each of these conditions. He then considers each piece of prior art in the context of his knowledge at the priority dates and then turns, for the first time, to consider each patent and each relevant claim in the context of his knowledge.

112 Before turning to the more particular matters to which Professor Prince refers, it is necessary to record that his evidence was answered by Dr Seymour, also a haematologist. Dr Seymour takes issue with some of the factual matters to which Professor Prince refers.

113 One of the more important points of difference is that Dr Seymour strongly disagrees that it was clear “at the outset” that rituximab had the potential to be useful in the treatment of a variety of lymphomas and leukaemias. Dr Seymour considers that the efficacy of rituximab across a broad range of lymphomas and leukaemias only appears to be obvious in hindsight. He accepts that at the priority dates there was a theoretical rationale for believing that it may have the potential to be effective in some of the different types of NHL, which may have warranted evaluation. However he, and he believes other physicians, did not expect that rituximab would be effective in multiple different types of B-cell lymphomas and leukaemias. There was no precedent for any such therapeutic agent to have such broad efficacy, and no other agent has achieved such broad efficacy since. Dr Seymour expresses the view that he still finds rituximab’s broad spectrum of activity to be “remarkable”. He states that he could not have predicted it and does not believe that it could have been predicted by other physicians.

114 Roche submits that this point of difference goes to a critical aspect of the inventive step challenge and applies to the whole of the inventive step cross-claim. It submits that the evidence of Professor Prince consistently addresses the wrong legal issue. Specifically, it contends that he does not address whether the inventions as claimed are obvious in the sense required by the modified Cripps Question (quoted by French CJ in AstraZeneca at [15]), but instead gives evidence that (to paraphrase) it would be worthwhile “to undertake further investigation of options for treatment in the expectation that these may well produce new treatment options”. Statements in the evidence that Professor Prince may have, at the priority date, considered it desirable, worthwhile, or interesting to investigate various options for treatment do not, Roche submits, address the legal test and simply indicate that Professor Prince would have engaged in largescale research programs with rituximab.

115 I now turn to the more specific evidence that Professor Prince gives in relation to the NHL patent.

116 Professor Prince observes that rituximab had already been approved by the FDA for the treatment of patients with relapsed or refractory low-grade or follicular B-cell NHL as at the priority dates. He states that it would have been clear to him that it would be “logical and ethical” to further investigate treatment paradigms using rituximab as a first-line treatment in combination with CHOP or CVP. The typical first-line treatment as at the priority date was CHOP or CVP chemotherapy and so the most logical and ethical investigation would have been therapy of a combination of rituximab with one or other of these forms of chemotherapy.

117 Furthermore, Professor Prince states that it was reported in the literature at the priority dates that rituximab showed synergy with chemotherapy treatments, for the patients who could tolerate it, and he would have investigated this synergy by administering combination therapies of rituximab with CHOP and CVP respectively in the expectation that it may well lead to better outcomes than the administration of one or other of these alone. His view was that, for the sake of patient and outpatient-clinic convenience, he would have administered both rituximab and the chemotherapy on the same day at the start of a chemotherapy cycle. These matters concern the contents of claim 18 of the NHL patent.

118 Next, Professor Prince considers that the most straightforward approach would have been to trial rituximab in the dose of 375mg/m2, because this was the FDA approved dose for treatment of patients with relapsed or refractory low grade or follicular B-cell NHL.

119 Furthermore, he observes that at the priority dates it was known that low-grade NHL was considered to be incurable and that it was common for patients to relapse within 18 months to 2 years of first-line treatment. Professor Prince considers that maintenance therapy during this relapse period was considered appropriate both at the relevant dates and now. He draws an analogy with interferon-α, another immunological therapy for cancer, which was being used in combination with chemotherapy as a maintenance therapy for NHL at the relevant date. Professor Prince concludes that he would have been interested in investigating the role of rituximab as a maintenance treatment during the typical relapse period of 18 months to 2 years with the expectation that it may well prolong a patient’s remission period. These matters address the contents of claim 21.

120 After providing this evidence, Professor Prince was provided with the prior art documents, including Czuczman, Maloney 1 and Maloney 2. It is not necessary to describe the prior art in detail. Broadly, they report studies that investigated non-simultaneous administration of rituximab and chemotherapy (in particular CHOP) in low grade or follicular lymphoma. Czuczman reports a synergy with chemotherapeutic agents and non-overlapping toxicities. It is common ground between the experts that the prior art documents did not disclose simultaneous administration of rituximab and the chemotherapy agent together; the use of CVP (as opposed to CHOP); or the use of rituximab in maintenance therapy. The experts disagree about whether it would have been obvious to try a treatment regime with those integers, with the relevant expectation of success.

121 In particular, Dr Seymour:

(1) Disputes any assertion that it was well-established and widely appreciated at the priority dates that rituximab shared synergy with chemotherapy treatments. He notes that the only studies investigating synergy prior to Czuczman were in vitro studies. Nevertheless, he acknowledges that Czuczman was promising and that the combination of rituximab and CHOP had greater effectiveness than expected.

(2) Opines that he would not have expected CVP to have the same “remarkable” effect as CHOP. In his view, CVP combined with rituximab was potentially less effective than CHOP combined with rituximab, because CVP only had one of the putative sensitizing agents alleged in earlier articles to have a sensitizing effect with rituximab, not two.

(3) Would not have chosen to administer rituximab and chemotherapy simultaneously for a number of reasons, including the fact that the earlier articles report an advantage in administering rituximab before chemotherapy so as to exploit the sensitisation phenomenon, and his concern that the immunosuppression caused by simultaneous treatment might impair the efficiency of rituximab.