FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation (No 2) [2018] FCA 751

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Plaintiff | ||

AND: | WESTPAC BANKING CORPORATION (ACN 007 457 141) Defendant | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 14 days of the date hereof the plaintiff file and serve proposed minutes of orders and short submissions (limited to 3 pages) to give effect to these reasons and for the further conduct of the matter.

2. Within 14 days of receipt of the plaintiff's proposed minutes and submissions, the defendant file and serve proposed minutes of orders and short submissions (limited to 3 pages) in response.

3. The further hearing of this proceeding be adjourned to a date to be fixed.

4. Costs reserved.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BEACH J:

1 The Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) has brought these pecuniary penalty proceedings against Westpac Banking Corporation (Westpac) concerning its trading over the period 6 April 2010 to 6 June 2012 (the relevant period) in Prime Bank Bills in the Bank Bill Market allegedly to influence the setting of the Bank Bill Swap Reference Rate (BBSW).

2 ASIC's claims are framed:

(a) first, as contraventions of ss 1041A and 1041B of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the Corporations Act) involving market manipulation, market rigging and creating a false or misleading appearance with respect to the relevant market(s);

(b) second, as contraventions of ss 12CA, 12CB and 12CC of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (the ASIC Act), involving unconscionable conduct;

(c) third, as contraventions of s 1041H of the Corporations Act and ss 12DA, 12DB and 12DF of the ASIC Act, involving misleading or deceptive conduct and misrepresentation; and

(d) fourth, as contraventions of s 912A of the Corporations Act, involving various breaches of Westpac's financial services licensee obligations.

3 The BBSW is a key benchmark interest rate in Australian financial markets. The purpose and function of the BBSW is to provide an independent and transparent reference rate for the pricing and revaluation of Australian dollar derivative instruments, securities and commercial loans.

4 Trading in Prime Bank Bills on the Bank Bill Market informed the setting of the BBSW, which setting during the relevant period was dependent upon views submitted to the Australian Financial Markets Association Ltd (AFMA) by AFMA-designated BBSW panellists by 10.05 am on each Sydney business day in respect of the yields of the best bids/offers for Prime Bank Bills in each tenor at or around 10.00 am on that day. Westpac was both a BBSW panellist and an AFMA-designated Prime Bank. Almost all trading in the Bank Bill Market took place in the period between approximately 9.55 am and 10.05 am on each Sydney business day, which I will designate as the BBSW Rate Set Window, albeit that there is a dispute between the parties as to whether trading between 10.01 am and 10.05 am informed the setting of BBSW which strictly ought to have been based on relevant trading as at 10.00 am.

5 Bank accepted bills of exchange (Bank Bills) are instruments by which banks may either borrow or lend funds for a short term. By selling a Bank Bill that a bank has accepted, a bank borrows funds. By buying a Bank Bill, a bank lends funds. Bank Bills entitle the holder to receive the face value of the Bank Bill on maturity. But they are traded at a discount to their face value, with the size of the discount representing the amount of interest (or yield) payable on the Bank Bill. The higher the yield, the lower the price of the Bank Bill and vice versa. Prime Bank Bills are Bank Bills where the acceptor is a Prime Bank. I will explain these and other terms later, although for ease of reference I have annexed a glossary to these reasons.

6 During the relevant period, Westpac was a party to a large number of derivative instruments, lending transactions and deposit products (BBSW Referenced Products) pursuant to which:

(a) an obligation to pay an amount of money was quantified when the BBSW in the relevant tenor was set on a particular day;

(b) the amount, and in the case of interest rate derivatives whether the amount was payable by Westpac to the counterparty or by the counterparty to Westpac, depended upon the rate at which the BBSW in the relevant tenor set on that day; or

(c) more generally, Westpac's or the counterparty's rights or liabilities thereunder were influenced by or derived from BBSW.

7 On each Sydney business day in the relevant period, the books in Westpac's Group Treasury included holdings of BBSW Referenced Products in relation to which:

(a) an obligation to pay an amount of money would be quantified when the relevant BBSW was set on that day; and

(b) that amount, and, in the case of some of the BBSW Referenced Products, whether the amount was payable by Westpac to the counterparty or by the counterparty to Westpac, depended upon or was influenced by the rate at which the relevant BBSW was set on that day,

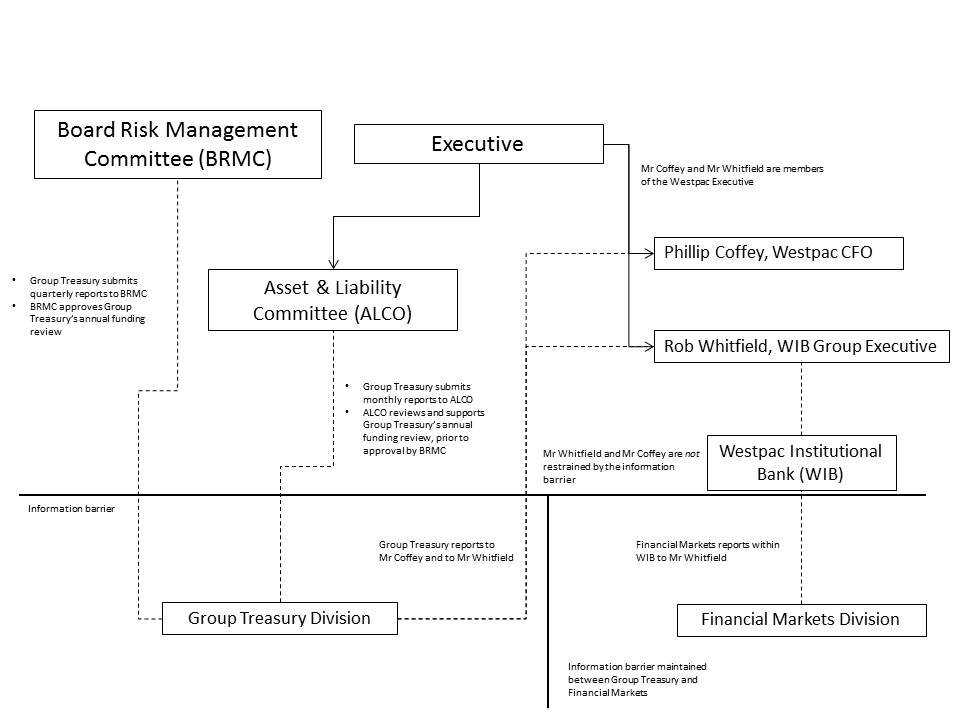

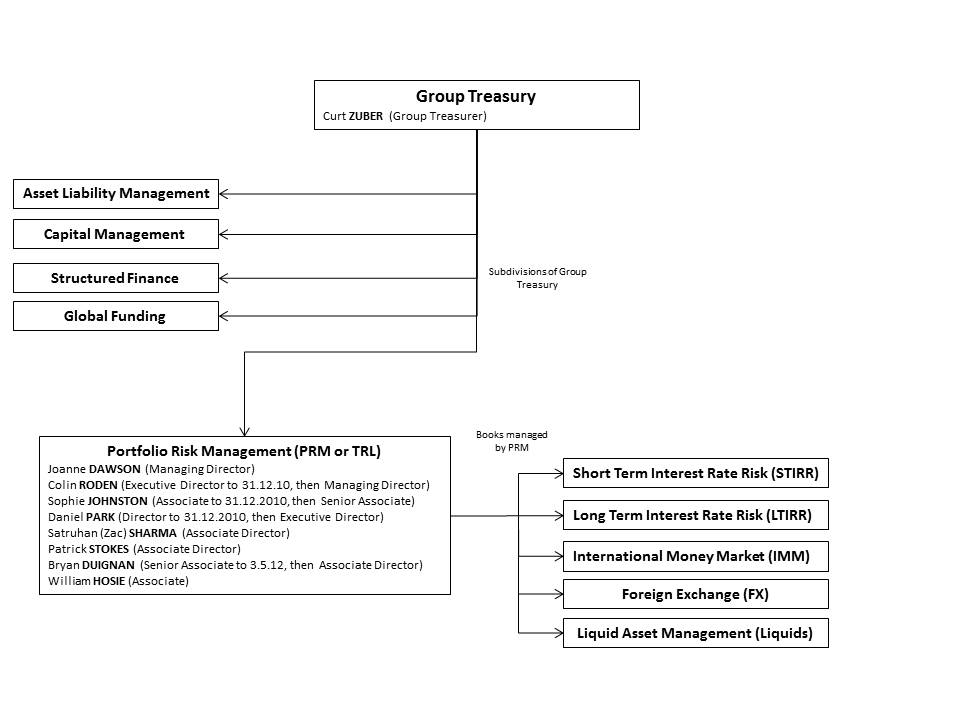

and therefore the profit and loss of those books was affected by movement in the BBSW on that day (BBSW Rate Set Exposure). For the moment it is sufficient to note that although Westpac had a separate division, Financial Markets, which had its own BBSW Rate Set Exposure, when I am referring to BBSW Rate Set Exposure generally speaking I am referring to the Group Treasury BBSW Rate Set Exposure. This is because Westpac's traders in Prime Bank Bills had reference only to the latter exposure. Equally relevantly, the Group Treasury BBSW Rate Set Exposure can be taken as a proxy for Westpac's BBSW Rate Set Exposure in terms of considering the motivational influences on Westpac's traders trading in Prime Bank Bills. In these reasons I have also refrained from using terms such as "net" or "gross" exposure. But it should be appreciated that the Group Treasury BBSW Rate Set Exposure on a particular day is the sum of individual books' exposures, some of which will have a short exposure and some of which will have a long exposure on a particular day, such that in aggregate there will either be a long exposure or a short exposure. Let me elaborate.

8 On each trading day in the Bank Bill Market and prior to the BBSW Rate Set Window, Group Treasury was able to and did ascertain its BBSW Rate Set Exposure, which was either:

(a) a long exposure, meaning that the aggregate of the net earnings of certain books managed by the relevant desks insofar as being referable to the BBSW:

(i) would be increased in the event that the BBSW was set by AFMA at a higher rate on that day; and

(ii) correspondingly, would be decreased in the event that the BBSW was set by AFMA at a lower rate on that day; or

(b) a short exposure, meaning that the aggregate of the net earnings of certain books managed by the relevant desks insofar as being referable to the BBSW:

(i) would be increased in the event that the BBSW was set by AFMA at a lower rate on that day; and

(ii) correspondingly, would be decreased in the event that the BBSW was set by AFMA at a higher rate on that day.

9 On days when Group Treasury including its relevant desks had in sum a long exposure, it was receiving BBSW and so benefited by the BBSW setting higher. Conversely, on days when there was in sum a short exposure, it was paying BBSW and so benefited by the BBSW setting lower.

10 ASIC contends that there existed throughout the relevant period, including on specific contravention dates, a material profit-making opportunity for Westpac to use its trading in Prime Bank Bills in the Bank Bill Market in the BBSW Rate Set Window to advantage its positions and exposures under the BBSW Referenced Products. It is said that Westpac developed and pursued a practice in furtherance of enhancing the earnings generated from its BBSW Rate Set Exposure to the disadvantage of counterparties. In particular, ASIC says that on specific days in the relevant period (the contravention dates) and also from time to time during the relevant period, it was the practice of Westpac to trade Prime Bank Bills including to trade newly issued Negotiable Certificates of Deposit (NCDs), which I will include in the expression "Prime Bank Bills", in the BBSW Rate Set Window:

(a) with the sole or dominant purpose of influencing the level at which the BBSW was set in a way that was favourable to its BBSW Rate Set Exposure; and

(b) which therefore resulted in yields which did not reflect the forces of genuine supply and demand.

11 I will refer to this practice as the Rate Set Trading Practice. It is said that the Rate Set Trading Practice was in existence and implemented generally throughout the relevant period, and specifically on purchase contravention dates and sale contravention dates. Let me elaborate further.

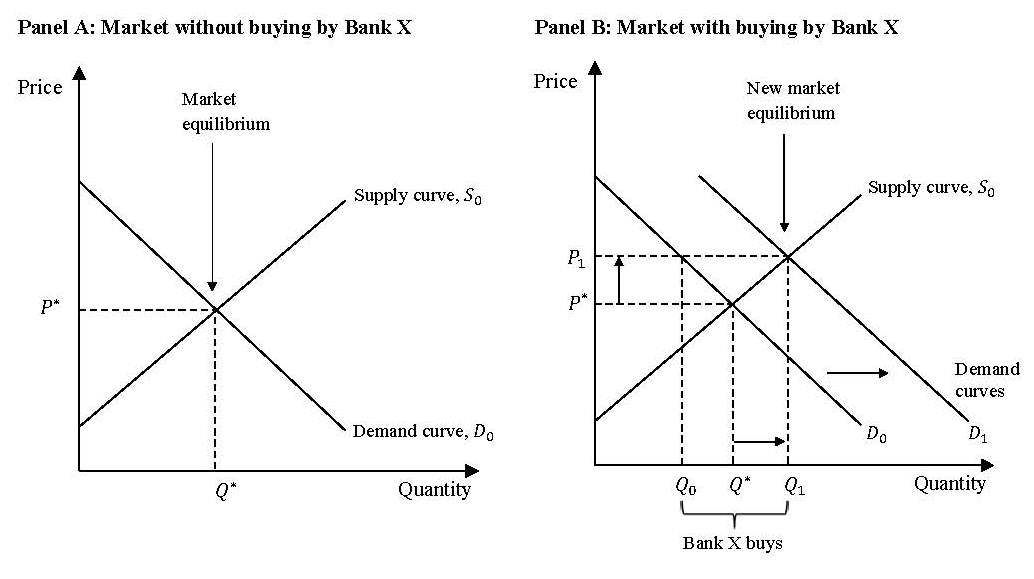

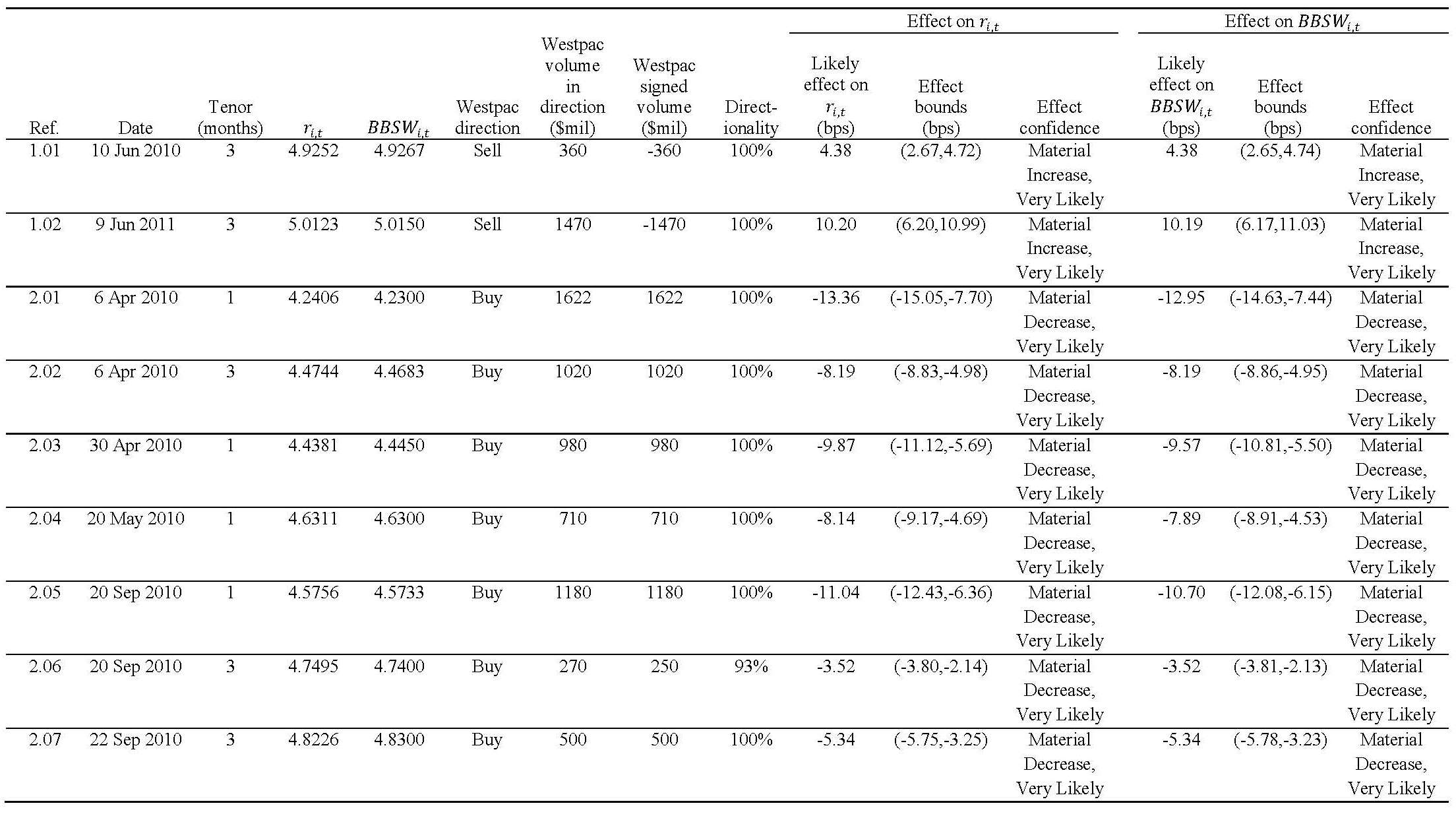

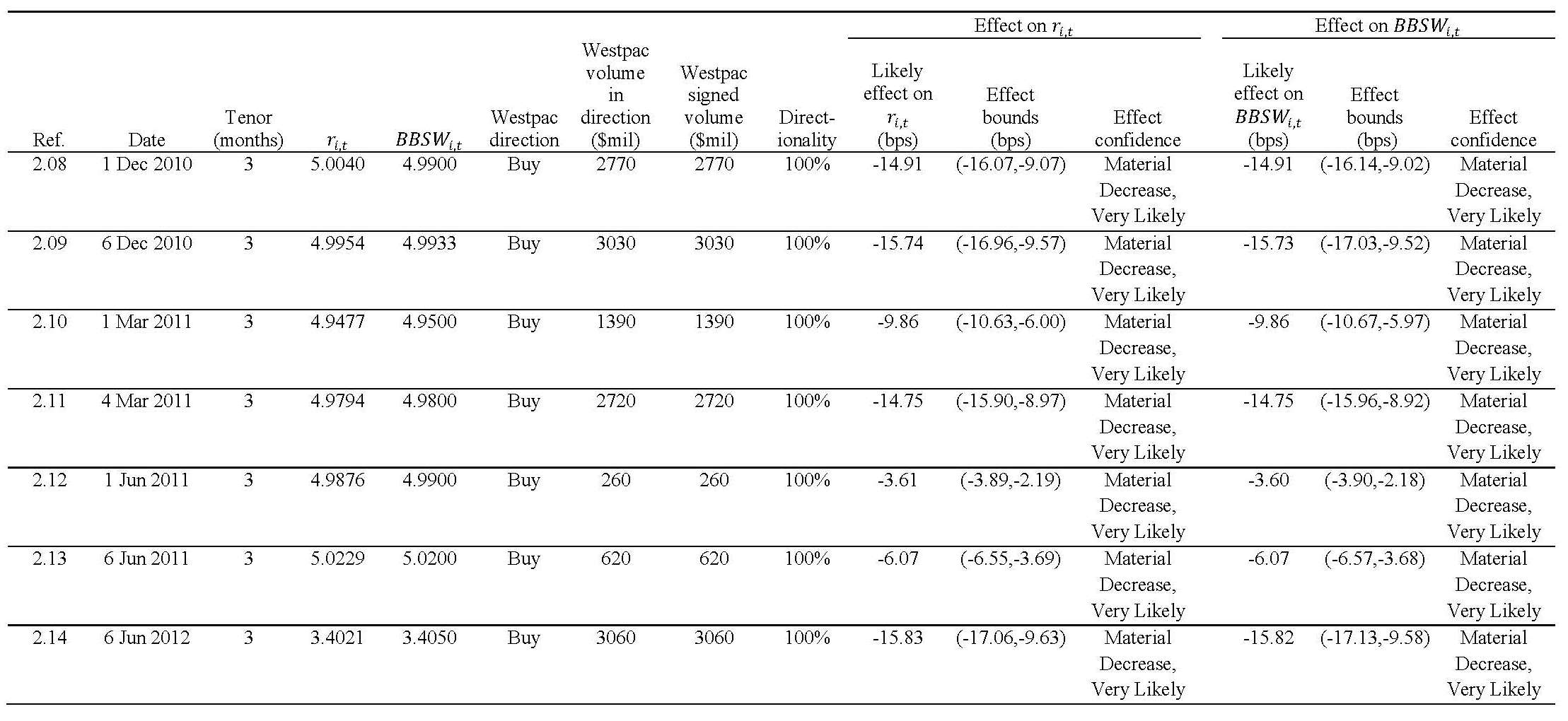

12 It is said that on each of the purchase contravention dates (6 April (2 different Prime Bank Bill tenors), 30 April, 20 May, 20 September (2 different Prime Bank Bill tenors), 22 September, 1 December and 6 December 2010, 1 March, 4 March, 1 June and 6 June 2011, and 6 June 2012), Westpac knew that a substantial short BBSW Rate Set Exposure existed, and purchased Prime Bank Bills in the Bank Bill Market during the BBSW Rate Set Window with the sole or dominant purpose of lowering or maintaining the rate at which the BBSW for the relevant tenor(s) was set by AFMA on that day and thereby sought to increase its earnings by minimising its BBSW referenced payment obligations.

13 It is said that the purchase contraventions:

(a) were undertaken by Westpac for the sole or dominant purpose of lowering or maintaining:

(i) the yield at which Prime Bank Bills were trading at approximately 10.00 am on the relevant day; and

(ii) the level at which the BBSW was set by AFMA on the relevant day;

(b) therefore resulted in yields which did not reflect the forces of genuine supply and demand in the Bank Bill Market on the relevant day; and

(c) had, or were likely to have, the effect of creating an artificial price for trading in three classes of traded BBSW Referenced Products, being relevantly for present purposes limited to bank accepted bill futures contracts (BAB Futures), cross-currency swaps and interest rate swaps.

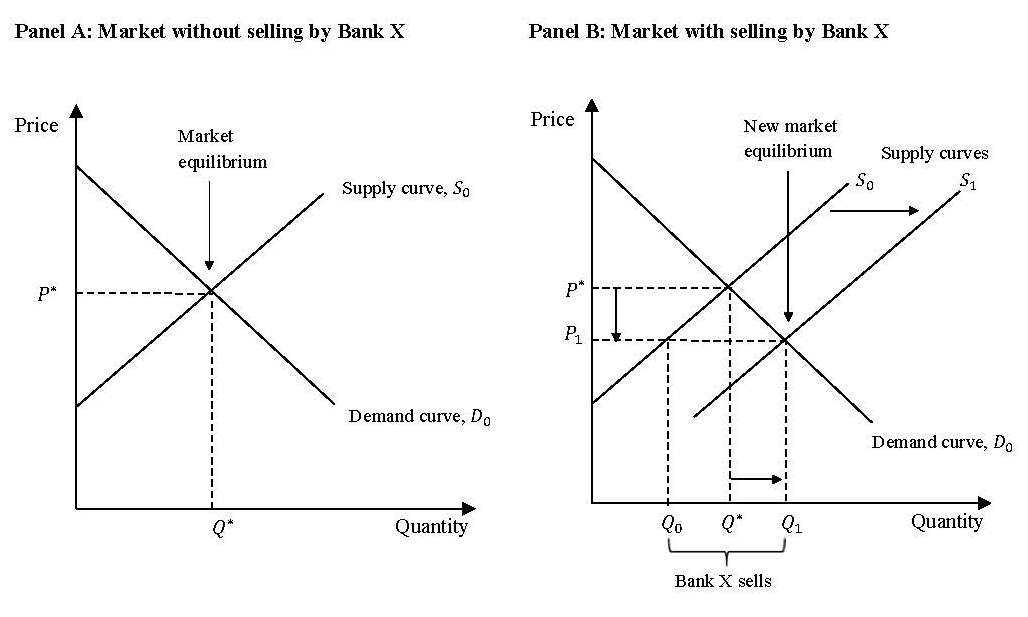

14 Further, it is said that on each of the sale contravention dates (10 June 2010 and 9 June 2011) Westpac knew that a substantial long BBSW Rate Set Exposure existed, and sold Prime Bank Bills in the Bank Bill Market during the BBSW Rate Set Window with the sole or dominant purpose of raising or maintaining the rate at which the BBSW for the relevant tenor(s) was set by AFMA on that day and thereby sought to increase its earnings accordingly.

15 It is said that the sale contraventions:

(a) were undertaken by Westpac for the sole or dominant purpose of raising or maintaining:

(i) the yield at which Prime Bank Bills were trading at approximately 10.00 am on the relevant day; and

(ii) the level at which the BBSW was set by AFMA on the relevant day;

(b) therefore resulted in yields which did not reflect the forces of genuine supply and demand in the Bank Bill Market on the relevant day; and

(c) had, or were likely to have, the effect of creating an artificial price for trading in the three types of traded BBSW Referenced Products referred to above.

16 ASIC contends that such conduct including the implementation of the Rate Set Trading Practice contravened ss 1041A and 1041B of the Corporations Act. It is said that the conduct had, or was likely to have, the effect of creating an artificial price for trading in the said traded BBSW Referenced Products, being BAB Futures, interest rate swaps and cross-currency swaps. It is also contended that such conduct also had, or was likely to have, the effect of creating a false or misleading appearance with respect to the market for, or the price for trading in, those derivative instruments. Because of statutory restrictions, the case concerning ss 1041A and 1041B has been confined to the financial products of BAB Futures, interest rate swaps and cross-currency swaps; the detailed reasons as to why this is so will become apparent much later in my reasons.

17 Further, ASIC contends that the trading on the contravention dates and more broadly the Rate Set Trading Practice, coupled with the non-disclosure of the practice, constituted unconscionable conduct and misleading or deceptive conduct in that such conduct had the actual or likely effect of influencing the calculation of payments required under BBSW Referenced Products to the detriment of counterparties to those instruments or put them at a risk of which they were unaware. I would note that this part of the case involves a broader set of derivative and financial instruments than just BAB Futures, interest rate swaps and cross-currency swaps.

18 It is said that counterparties did not appreciate that Westpac and other participants in the Bank Bill Market could manipulate the BBSW and that they were vulnerable to loss. Further, it is said that the counterparties reposed trust in Westpac to deal fairly with them in respect of the BBSW Referenced Products entered into between them and Westpac. In evidence before me, many of the counterparties deposed to their understanding that the BBSW was a benchmark rate that was not affected by actions, including trading during the BBSW Rate Set Window, intended to cause the BBSW to set at a level other than that which should have obtained under the forces of genuine supply and demand. The counterparties have said that had the true position been disclosed to them, they would have regarded Westpac's conduct in trading directed at influencing the BBSW to its advantage as unfair and contrary to the trust that they had reposed in Westpac.

19 Further, ASIC says that Westpac's failure to disclose its Rate Set Trading Practice to counterparties also gave rise in all the circumstances to a representation to counterparties that BBSW Referenced Products referenced a benchmark rate that was genuine, independent and transparent. It is said that by reason of Westpac engaging in its Rate Set Trading Practice such a representation was false or misleading.

20 Further, ASIC contends that Westpac as the holder of an Australian financial services licence breached statutory obligations as to honesty, fairness, compliance with financial services laws, the taking of steps to manage conflicts of interest and to ensure compliance by its employees with such laws, and also failed to ensure the adequate training and competence of its employees.

21 Now as to these four sets of claims, the present trial has proceeded on the basis of liability only at this stage. The case has been presented by the legal representatives for both ASIC and Westpac with notable efficiency.

22 Now as I have said, ASIC alleges that during the relevant period, including on the contravention dates, Westpac traded with the sole or dominant purpose of influencing where the BBSW set. It is said that I should so find having regard to the contemporaneous communications which directly evidence the existence of that practice, the fact that Westpac had the opportunity to engage in such a practice, the fact that Westpac's traders had a broad discretion and there were no hard limits on Prime Bank Bills trading, the fact that Westpac and its traders had an incentive to engage in such a practice, and the fact that Westpac knew that its trading could affect the BBSW. It is also said that objective trading and exposure data is consistent with the existence of this practice, and that Westpac's alternative explanations for its trading are not credible. Now proof of purpose against a corporation usually resorts to inferential reasoning based upon circumstantial evidence and the exclusion of reasonably open exculpatory explanations. But in the present case ASIC says that there is a significant body of contemporaneous evidence comprised of extensive written communications, including by informal means such as instant chat messaging or email, coupled with voice recordings of an array of internal Westpac communications, from which it is said that I can readily infer that the impugned trading was motivated by the alleged dominant manipulative purpose.

23 Now ASIC bears the onus of proof on each of the elements of the causes of action to the requisite civil standard having regard to the gravity of the matters alleged: s 140(2) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (the Evidence Act) and Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 at 361 and 362. But I would note that ASIC's purpose case does not principally follow the conventional path of demonstrating manipulative purpose from the absence of any rational explanation for the impugned trading. In most cases it has downplayed the objective circumstances of the trading and asked me to principally infer manipulative purpose from the contemporaneous communications. But many of these communications are open to competing interpretations, particularly when understood in context. Now ASIC has sought to construe such communications in ways different from the explanations given by Westpac's witnesses. But in order for ASIC to discharge its onus, I am required to be comfortably satisfied that its interpretation is what was meant and intended by the parties to the communications. Accordingly, where there has been uncertainty as to what was said or what was meant or conveyed after considering the context and all relevant circumstances, I have resolved that uncertainty in Westpac's favour.

24 In summary, I have rejected ASIC's case under ss 1041A and 1041B of the Corporations Act. Although I accept that Westpac through its traders did on four occasions during the relevant period (6 April 2010, 20 May 2010, 1 and 6 December 2010) trade in Prime Bank Bills in the Bank Bill Market with the dominant purpose of influencing the level at which BBSW was set in a way that was favourable to its BBSW Rate Set Exposure, I do not consider that contraventions of ss 1041A and 1041B have been made out. I say that for the following brief reasons. First, the statutory provisions are focused upon effect or likely effect rather than on dominant purpose, although purpose in some circumstances can be used to infer effect or likely effect. Second, to the extent that ASIC has relied upon Director of Public Prosecutions (Cth) v JM (2013) 250 CLR 135 to use dominant purpose in essence and in context as a sufficient condition to establish effect or likely effect, that case is relevantly distinguishable in a number of important respects that I will expand upon later. It dealt with the relatively more straight-forward case of share trading on the Australian Stock Exchange where the product traded, the purpose for trading and the effect of trading were all in the same dimension. But in my case I am dealing with a three-dimensional construct. In the present case, it is important not to elide distinctions that need to be made between three dimensions: (a) the first dimension is the trading of Prime Bank Bills in the Bank Bill Market; (b) the second dimension is the setting of BBSW, which is not of itself a price but rather the trimmed average mid-rate of the observed best bid/best offer for Prime Bank Bills for certain tenors calculated by AFMA; and (c) the third dimension is the pricing of BAB Futures, interest rate swaps and cross-currency swaps in separate financial markets. For the purposes of s 1041A, in the present case the relevant "artificial price" that is to be considered is the price(s) for BAB Futures, interest rate swaps and cross-currency swaps. In simplistic terms, ASIC's case proceeds on the foundation of taking a product in the first dimension and its trading (Prime Bank Bills in the Bank Bill Market) to achieve a purpose in the second dimension (influencing where BBSW set) to produce or likely bring about an artificial price in the third dimension (pricing under BAB Futures, interest rate swaps and cross-currency swaps). For the moment, it is sufficient to say that I am not satisfied that the holding of the relevant dominant purpose on the said four occasions, together with the other evidence, establishes the effect or likely effect of creating or maintaining an artificial price for or under such derivative instruments. And as for s 1041B, I likewise do not consider that establishing such a purpose for trading in Prime Bank Bills establishes a false or misleading appearance with respect to the market(s) in or price for trading of such derivative instruments.

25 Second, I would reject ASIC's more general allegation concerning the existence of the Rate Set Trading Practice during the relevant period. I am not prepared to infer from the isolated instances on the specific four occasions that I have identified or from the totality of the evidence that there was a pattern or system such as to give rise to such a practice. Further, to characterise such isolated examples as in and of themselves constituting such a practice over the relevant period would be to prefer form over substance and to allow the pleader's construct to inappropriately distort the analysis.

26 Third, in my view, on the four occasions that I have identified, Westpac engaged in unconscionable conduct under s 12CC of the ASIC Act (as in force prior to 1 January 2012), that is, under the statutory construct rather than under the unwritten law. But in making this finding I have avoided descending into the "formless void of individual moral opinion" (Paciocco v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd (2015) 236 FCR 199 at [306] per Allsop CJ citing Deane J in Muschinski v Dodds (1985) 160 CLR 583 at 616 who in turn cited Carly v Farrelly [1975] 1 NZLR 356 at 367 per Mahon J). It is sufficient for me to say that applying Allsop CJ's analysis in Paciocco at [259] to [306] and without dwelling in the paradigm of moral obloquy, Westpac's conduct was against commercial conscience as informed by the normative standards and their implicit values enshrined in the text, context and purpose of the ASIC Act specifically and the Corporations Act generally.

27 Fourth, I have also concluded that by reason of inadequate procedures and training, Westpac contravened its financial services licensee obligations under s 912A(1) of the Corporations Act.

28 For convenience, I have divided my analysis into the following sections:

(a) Financial and derivative instruments – [30] to [142];

(b) The Bank Bill Market and BBSW – [143] to [271];

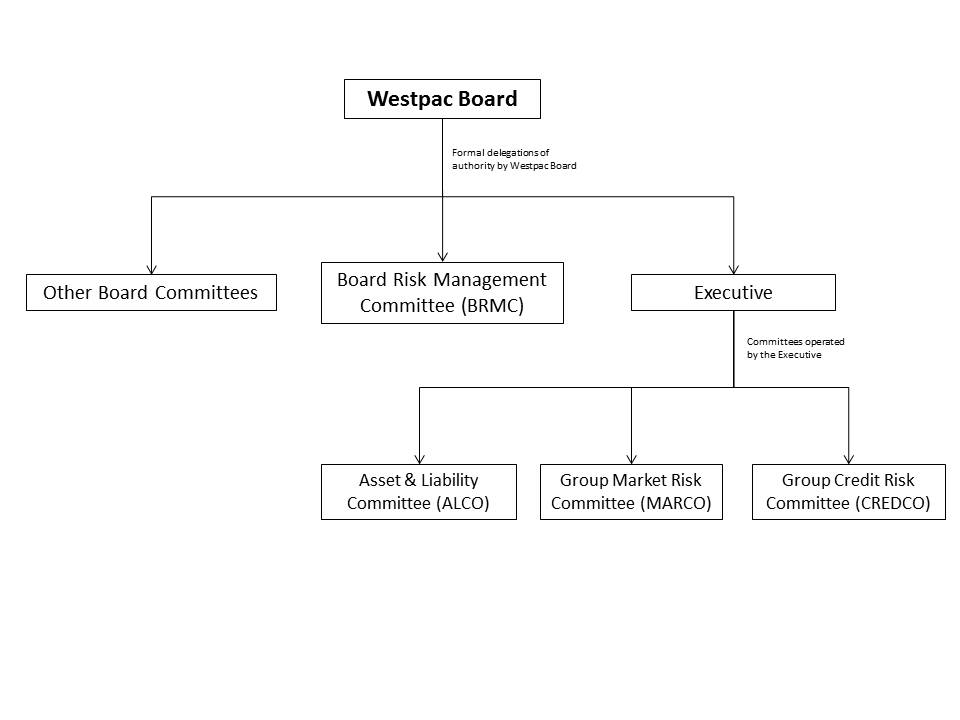

(c) Westpac structure and governance – [272] to [351];

(d) Funding and liquidity activities – [352] to [400];

(e) Management of non-interest rate risks – [401] to [417];

(f) Management of interest rate risks – [418] to [544];

(g) Rationales for trading Prime Bank Bills – [545] to [616];

(h) Dynamics of the Bank Bill Market and trading strategies– [617] to [715];

(i) Opportunity and incentives to manipulate – [716] to [793];

(j) Susceptibility of the Bank Bill Market and BBSW to manipulation – [794] to [856];

(k) Reliability of Westpac's witnesses – [857] to [924];

(l) Contravention dates and alleged practice – [925] to [1677];

(m) Trading and price impacts – [1678] to [1885];

(n) Market manipulation (ss 1041A and 1041B) – [1886] to [2126];

(o) Unconscionable conduct – [2127] to [2253];

(p) Misleading or deceptive conduct – [2254] to [2334];

(q) Financial services licensee obligations – [2335] to [2533];

(r) Conclusions – [2534] to [2539].

29 It has been necessary to deal with these topics in this sequence and with this cumulative development in order to avoid an analysis based only upon superficial snapshots of the key communications and trading behaviour referable to the specific purchase and sale contravention dates. That said, the linear sequence of these reasons cannot fully capture in text the iterative and interactive nature of the analysis which has been necessary to ensure that findings on some aspects are informed by my analysis and findings on other aspects.

FINANCIAL AND DERIVATIVE INSTRUMENTS

30 Let me at this point make some introductory remarks concerning various financial instruments and the use of BBSW as a reference rate. Any capitalised expressions have corresponding definitions set out in this section or in the glossary to these reasons.

(a) Bank Bills

31 A Bank Bill is a bill of exchange, as defined in s 8 of the Bills of Exchange Act 1909 (Cth), which has been accepted by a bank and bears the name of the accepting bank as acceptor, and which obliges the bank to pay the face value of the bill to the holder of the bill on the date that it matures.

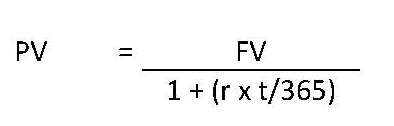

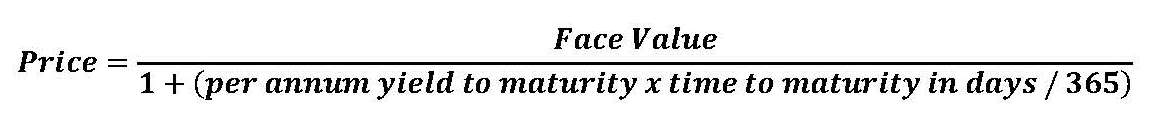

32 Bank Bills trade at a price calculated by discounting the face value of the Bank Bills to reflect an interest rate or yield paid by the Bank Bills. The price (present value) of a Bank Bill can be expressed by the following formula:

Where: | |

PV = | Present value (price) |

FV = | Face value |

r = | Per annum yield to maturity |

t = | Time to maturity in days |

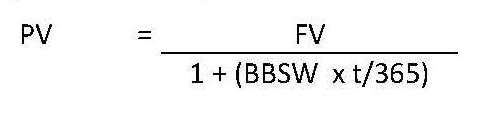

33 Where the yield used to price a Bank Bill is BBSW (in cases say where the Bank Bill is bought or sold outside of the Bank Bill Market and it is separately agreed), the formula for the price (present value) of the Bank Bill is:

34 Further, as I have said, there is a category of Bank Bills known as Prime Bank Bills where the acceptor is a Prime Bank; a Prime Bank is one designated as such by AFMA as I will explain later.

(b) 3 month Bank Accepted Bill Futures (BAB Futures)

35 Under a BAB Futures contract one party agrees to buy a 3 month Prime Bank Bill at an agreed yield (and thus price) on the expiry date of the contract and the other party agrees to sell a 3 month Prime Bank Bill at an agreed yield (and thus price) on the expiry date of the contract. For convenience, in these reasons I will refer to the different tenors of Prime Bank Bills in month(s) rather than days. Likewise, references to the applicable BBSW will be described in month(s). The glossary to my reasons sets out any necessary conversion.

36 BAB Futures contracts are standardised contracts with the following terms:

(a) the contracts relate to the delivery of 3 month Prime Bank Bill(s) with a face value of $1,000,000;

(b) the contracts expire on one of four dates per year being the Thursday before the second Friday in each of March, June, September and December; the expiry date is known as the close out date;

(c) the contracts are "deliverable", meaning that if the BAB Futures contract is held to expiry then one party must actually deliver the 3 month Prime Bank Bill(s) to the other party, who must buy the Prime Bank Bill(s); and

(d) the contracts expire at 12.00 pm noon on the expiry day and the delivery occurs the following day (so delivery occurs on the second Friday in each of March, June, September and December); the delivery date is known as the settlement date.

37 BAB Futures contracts are traded on an exchange, which was known as the Sydney Futures Exchange (SFE) during the relevant period until 31 July 2010 and then from 1 August 2010 known as ASX24. A party can enter into BAB Futures contracts with a term (time left to the expiry date) of up to five years. BAB Futures contracts are quoted in terms of yield per annum (in percentage terms) deducted from 100. So a BAB Futures contract quoted at "96" means that the parties to the BAB Futures contract agree to buy (or sell) a $1,000,000 3 month Prime Bank Bill on the expiry date at a price that represents a yield of 4% (that is, the "price" of the 3 month Prime Bank Bill will be discounted to reflect a yield of 4%).

38 The BAB Futures contract price reflects:

(a) the market's view of what the price of 3 month Prime Bank Bills will be at the date of expiry of the BAB Futures contract; and

(b) the current interest rate that applies to the period until the BAB Futures contract expiry date, which determines the cost of holding the BAB Futures contract.

39 The profit or loss made on a BAB Futures contract can be understood by considering a BAB Futures contract which is held to expiry.

40 On the expiry date the party who has agreed to sell 3 month Prime Bank Bills will need to hold or obtain 3 month Prime Bank Bills in order to deliver these to the other party. If:

(a) the price of Prime Bank Bills falls (and thus the yield on Prime Bank Bills, and the BBSW, increases) to a level which is below the level implied by the BAB Futures contract price at the time it was entered into (meaning that the Prime Bank Bill yield is above the original BAB Futures contract implied yield), then the selling party will be paying less for the 3 month Prime Bank Bills than they will receive selling them (delivering them) pursuant to the BAB Futures contract (making a gain); and

(b) the price of Prime Bank Bills increases (and thus the yield on Prime Bank Bills, and the BBSW, falls) to a level which is above the level implied by the BAB Futures contract price at the time it was entered into (meaning that the Prime Bank Bill yield is below the original BAB Futures contract implied yield), then the selling party will be paying more for the 3 month Prime Bank Bills than they will receive selling them (delivering them) pursuant to the BAB Futures contract (making a loss).

41 On the expiry date, the party who has agreed to buy 3 month Prime Bank Bills will need to take delivery of the 3 month Prime Bank Bills once delivered. If:

(a) the price of Prime Bank Bills falls (and thus the yield on Prime Bank Bills, and the BBSW, increases) to a level which is below the level implied by the BAB Futures contract price at the time it was entered into (meaning that the Prime Bank Bill yield is above the original BAB Futures contract implied yield), then the purchasing party will be paying more for the 3 month Prime Bank Bills than the market price they could sell them at or otherwise buy them at (making a loss); and

(b) the price of Prime Bank Bills increases (and thus the yield on Prime Bank Bills, and the BBSW, falls) to a level which is above the BAB Futures contract price at the time it was entered into (meaning that the Prime Bank Bill yield is below the original BAB Futures contract implied yield), then the purchasing party will be paying less for the 3 month Prime Bank Bills than the market price they could sell them at or otherwise buy them at (making a gain).

42 Only approved Prime Bank Bills were eligible for delivery. Approved Prime Bank Bills had to, of course, be accepted by a Prime Bank, have a face value of $1 million, mature 85 to 95 days from the settlement date and be classified as "early" month paper; I will explain this concept later.

43 In practice, a significant majority of BAB Futures contracts are not held to expiry, instead they are "closed out". A party can "close out" a BAB Futures contract on the ASX24 exchange by entering into an equivalent BAB Futures contract, but taking the opposite leg (e.g. agreeing to buy the 3 month Prime Bank Bills rather than sell, or sell rather than buy). So, for example a BAB Futures contract which is purchased three months out from expiry can be closed out two months from expiry by entering into an opposite position in another BAB Futures contract which is also two months out from expiry.

44 Further, trading in BAB Futures contracts involves maintaining a margin account. On each day that the BAB Futures contract is held, the margin account is adjusted to reflect the change in the BAB Futures contract price (based on where other BAB Futures contracts with the same expiry date are trading). The effect is that the gain or loss from the BAB Futures contract is not all realised on the expiry date, but is instead reflected in daily changes to the margin account over the term of the BAB Futures contract.

45 This daily adjustment is referred to as the Daily Settlement Price. The Daily Settlement Price was during the relevant period determined under the applicable exchange Operating Rules and Procedures as follows:

(a) from 6 April 2010 until about 31 July 2010, pursuant to rule 1.9 "Daily Settlement Price" of the SFE Operating Rules; and

(b) from 1 August 2010 until 6 June 2012, pursuant to item [2500] "Determination of Daily Settlement Price" in the ASX24 Operating Rules Procedures.

46 ASIC says that the Daily Settlement Price on a final trading day (prior to expiry) is referred to as the "Expiry Settlement Price", but no provision in the Operating Rules made that express. I will return to the question of the significance of the Daily Settlement Price later.

47 Now although trading in BAB Futures is conducted anonymously on-market via ASX24, which functions as a clearing house for BAB Futures, trading in the BAB Futures market requires a participant to maintain a margin account (as I have said) with the ASX. As trading in BAB Futures is a leveraged transaction, parties do not pay (or receive) the full value of the contract at the time the transaction is entered into. Instead, both buyers and sellers of BAB Futures pay an initial margin and are also liable for daily variation margin calls:

(a) The initial margin (paid by both the buyer and the seller) covers the maximum probable one-day move in the rate of the futures contract, as assessed by ASX Clear (a wholly owned subsidiary of the ASX). ASX Clear sets the initial margin for BAB Futures contracts with reference to the volatility of the yields for BAB Futures. It does not do so by reference to volatility in BBSW. ASX Clear uses the "SPAN" methodology to calculate margin requirements, which references historical data in relation to movements in the yields of BAB Futures contracts within the period of approximately the preceding three months.

(b) The variation margin is an amount that either is paid, or received, by a party to reflect a movement in the value of its BAB Futures position on a mark-to-market basis. On each day that the BAB Futures contract is held, the margin account is adjusted to reflect that change in the BAB Futures contract rate (based on where other BAB Futures contracts with the same expiry are trading at 4.30 pm on each trading day). In times of high volatility, ASX Clear may also call intra-day margins.

48 The margin posted by a party entering into a BAB Futures contract will be returned when the party "closes out" its position. Now as I have said, a party can "close out" a BAB Futures contract by entering into an BAB Futures contract with the same expiry date but taking the other leg, that is, agreeing to buy a 3 month Prime Bank Bill rather than sell, or sell rather than buy.

49 Further, a party can hold a BAB Futures contract to expiry. If a party is "short" BAB Futures at the close out date, that party is obliged to deliver 3 month Prime Bank Bills on the settlement date to the party who is "long" BAB Futures on expiry. The 3 month Prime Bank Bill must be sold and purchased at the rate agreed when the BAB Futures were initially entered into.

50 Let me say something at this point in terms of the phenomenon of convergence, although I will return to it much later in my reasons. This phenomenon is relevant to the question of whether there is a causal relationship between changes in Prime Bank Bill yields and changes in BAB Futures rates, and if so what. That in turn is relevant to the question of whether the price for trading of BAB Futures was affected by changes in BBSW arising from trading in the Bank Bill Market, which itself is one of the questions that I need to consider under ss 1041A and 1041B for one of the traded BBSW Referenced Products being BAB Futures. For the moment, let me just note the following concerning convergence.

51 Typically, the close out date is the only point in time at which the rate for Prime Bank Bills and the rate for BAB Futures may converge. At any other time, the rate for trading BAB Futures is reflective of the market's view of where 3 month yields or perhaps BBSW will be at the close out date. While each market participant's view of this will be affected by whatever indicia they consider to be important, in general terms the market's view of where interest rates will be at the expiry of BAB Futures is usually informed by participants' expectations of future movements to the cash rate, which, in turn, is affected by a number of other factors including the Reserve Bank of Australia's (RBA) monetary policy stance, global economic events and credit expectations of banks. If the majority of participants trading in the BAB Futures market expect interest rates to decrease, then in the ordinary course the implied yield at which BAB Futures are trading decreases and therefore the rate for BAB Futures increases. Conversely, if participants in the BAB Futures market expect interest rates to increase, then in the ordinary course the implied yield at which BAB Futures are trading increases and therefore the rate for BAB Futures decreases.

52 Now while 3 month yields or perhaps BBSW and the BAB Futures rate should in theory converge on the close out date, there is often a discrepancy between the two due to the market dynamics around the close out date. This discrepancy can be caused by participants in both the BAB Futures market and the Bank Bill Market having a similar view on future movements on interest rates, but with a different result.

53 So, if foreign investors in BAB Futures take the view that the RBA will reduce interest rates as a result of an economic downturn, this will probably cause BAB Futures to trade at a lower implied yield (and a higher rate). However, at the same time, the Prime Banks in the domestic Bank Bill Market may seek to raise funds as a result of economic downturn by issuing Prime Bank Bills, and that issuance may increase the yield at which Prime Bank Bills are trading.

54 In addition, whereas 3 month BBSW is published at 10.15 am, BAB Futures expire at midday. So, a new piece of economic data or financial information may become accessible to the market between the time at which BBSW sets and the time the BAB Futures market closes which affects the rate at which BAB Futures trade and causes the BAB Futures rates to move away from the three month BBSW published at 10.15 am.

55 Further as to the question of convergence, Mr Simon Masnick, an officer in Westpac's Financial Markets division, gave evidence to the following effect:

(a) At any point in time prior to the close out date, the BAB Futures rate should represent the market's consensus view of the likely yield of a Prime Bank Bill at the close out date. Typically, the market has greater certainty as to the likely yield of a Prime Bank Bill as the close out date draws nearer (particularly after the RBA's cash rate announcement in the month of the close out date). However, the close out date is the only point in time at which the rate for 3 month Prime Bank Bills and the rate for BAB Futures are likely to converge, and even this is subject to matters which may cause a mismatch at expiry.

(b) The BAB Futures rate and the rate of the underlying asset (that is, a 3 month Prime Bank Bill) usually start to converge in the days leading up to the close out date. However, this convergence does not mean that, on any particular day, the level at which 3 month BBSW sets at 10.00 am determines (or even influences) the BAB Futures rate for that day. Momentary or daily movements in the level at which 3 month BBSW sets on any given day have little to no impact on the BAB Futures rate on that same day (particularly if the close out date is not within a few days of trading in BAB Futures). Primarily, this is because the market's view of future movements in the cash rate is the factor which most directly informs both the BAB Futures rate and the level at which 3 month BBSW sets on any given day. For example, Mr Masnick regularly observed instances where important economic information such as Consumer Price Index (CPI) figures or employment data was released at around 11.30 am (that is, after 3 month BBSW set on that particular day). When this occurred, the BAB Futures rate would change prior to, and independently of, any change in the level of BBSW, which would not take place until the following day.

(c) In addition, the BAB Futures rate will at any given point in time have additional information built into it which is not yet reflected in, and not relevant to, the rate of Prime Bank Bills (and so the level of BBSW). That is because BBSW is the market's assessment of the correct rate for Prime Bank Bills today, while the BAB Futures rate is the market's assessment of the rate of Prime Bank Bills at a future date (that is, the close out date).

(d) The most significant factors that influence the rate at which BAB Futures trade are the following. First, the market's perception of what the level of BBSW will be at the date of the BAB Futures expiry. Second, the term of the BAB Futures contract. That is, whether a participant is buying the BAB Future which expires in less than three months' time, or the following BAB Future which expires in less than six months' time. Third, market volatility which might affect the credit spread between the cash rate and BBSW. Fourth, whether a party is a buyer or a seller.

(e) Further, Mr Masnick observed that the volume of trading in the BAB Futures market is significantly greater than the amount of trading in the Bank Bill Market. Typically, parties trading in BAB Futures do not intend to take delivery of, or issue (in the case of Prime Banks), Prime Bank Bills into the futures close out. Instead, many parties trade BAB Futures so as to hedge interest rate swaps or speculate on likely cash rate and BBSW outcomes into the future. Accordingly, he observed that the trading behaviour of some market participants in the BAB Futures market often had little or no regard to the level at which BBSW set on a given day. For example, speculative trading in significant volumes commonly had a material effect upon the rate at which BAB Futures traded irrespective of any daily movements in the level of 3 month BBSW.

(f) Mr Masnick had never referred to nor heard of the 3 month AUD Bank Bill 5.00 pm New York closing time yield (the Bloomberg Closing Yield), on which ASIC's expert witness before me, Dr Tiago Duarte-Silva, relied as a key integer for his measurement of the change in Prime Bank Bill yields on any day. Specifically, Dr Duarte-Silva posited that the change in the yield in Prime Bank Bills on each date could be calculated by reference to the difference between the level at which BBSW sets and the Prime Bank Bill yield at the 5.00 pm New York (which equates to 7.00 am to 9.00 am in Australian Eastern time depending on the date). But ASIC has now abandoned any reliance upon the evidence of Dr Duarte-Silva. No doubt this was due to problematic aspects of his statistical methodology which were exposed during one of the three concurrent evidence sessions that I held. But in any event in Mr Masnick's experience, the Bloomberg Closing Yield was not a source of information used by traders to trade in BAB Futures or Prime Bank Bills. I will return to Dr Duarte-Silva's evidence later, notwithstanding ASIC's abandonment of it. It is forensically relevant as far as I am concerned to show what could not be proved.

(c) Interest rate swaps

56 An interest rate swap is an agreement between two parties to exchange streams of single currency cash-flow based on a notional amount for a set period. The most common type of interest rate swap is a "fixed for floating rate swap". Under a "fixed for floating rate swap" there are two legs. One leg of the swap has payment obligations calculated with reference to a floating interest rate (most commonly the BBSW). The swap party taking this leg of the swap has obligations to pay to the other swap party cash-flows equal to the agreed notional amount multiplied by the agreed floating interest rate. The other leg of the swap has payment obligations calculated with reference to an agreed fixed interest rate (known as the "swap rate"). The swap party taking this leg of the swap has obligations to pay to the other party cash-flows equal to the agreed notional amount multiplied by the swap rate.

57 Rather than both parties making payments, the parties exchange cash payments based on the net difference between the two cash-flows (referred to as the "Swap Cash Settlement Amount"). These net interest payments are made at regular intervals (the payment days are referred to as "reset dates"). The intervals (also known as "interest accrual periods") may be set monthly, quarterly, annually, or at another time period agreed between the parties. Typically, the interest accrual period is the same as the relevant tenor of the floating rate. So, for example, an interest rate swap which resets quarterly will use the 3 month BBSW as the floating leg reference rate. Payments only reflect net interest payments. No "principal" payments of the notional amount are made by the parties.

58 As I have said, the "reset date" is the date on which the floating rate is observed, and which typically occurs at the beginning of the interest accrual period. The reset date is usually different from the payment date, which is the date on which the net payment for a particular interest accrual period is made.

59 There is usually a difference between the date that the parties agree to enter into the interest rate swap (the "transaction date") and the date the interest rate swap first resets (the "commencement date"). Often, the commencement date will be the day after the transaction date. This is referred to by traders as being "T + 1". If, for example, the commencement date was three days after the transaction date, this would be referred to as "T + 3". Typically, subsequent reset dates are determined with reference to the commencement date. For instance, if the interest rate swap resets monthly, the second reset date will be the date corresponding to the commencement date in the following month.

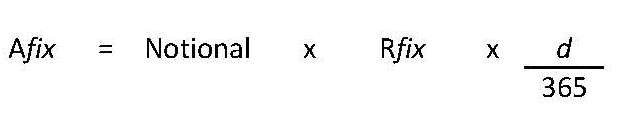

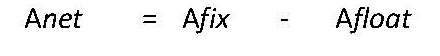

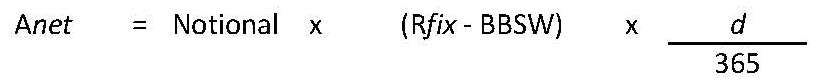

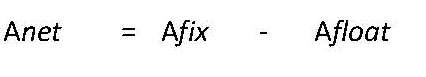

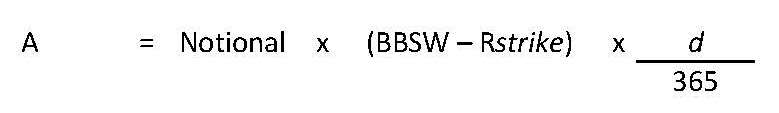

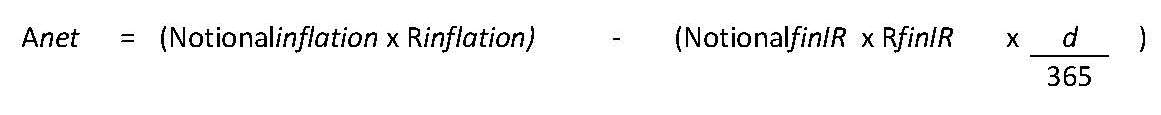

60 The formula for calculating the cash-flow obligations of both swap counterparties to a fixed for floating rate swap on a reset date can be expressed as follows:

Payment obligation of the party paying the fixed interest rate leg of the swap

Where:

| |

Afix = | Amount required to be paid by the party paying the fixed interest rate leg of the swap |

Notional = | Notional amount |

d = | Day count (between reset dates) |

Rfix = | Fixed rate |

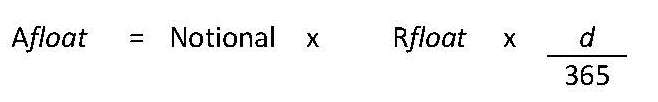

Payment obligation of the party paying the floating interest rate leg of the swap

Where: | |

Afloat = | Amount required to be paid by the party paying the floating interest rate leg of the swap |

Notional = | Notional amount |

d = | Day count (between reset dates) |

Rfloat = | Floating rate |

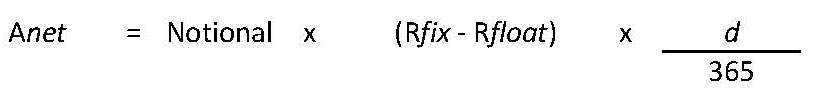

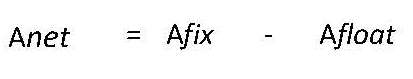

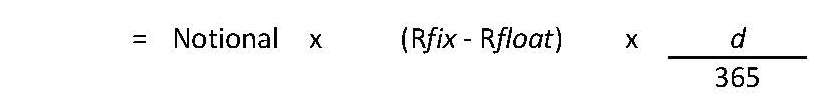

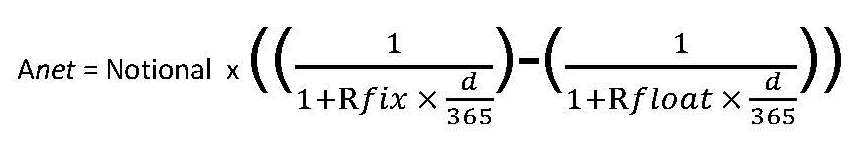

The net cash-flow payment (Swap Cash Settlement Amount)

Which can also be written as follows by expanding the equation:

Where: | |

Anet = | Swap Cash Settlement Amount |

61 The floating rate in an interest rate swap is most commonly the BBSW. In these swaps:

(a) the "Rfloat" input in the equations above is the BBSW;

(b) the payment obligation of the party paying the floating rate is directly referenced to the BBSW; and

(c) the Swap Cash Settlement Amount (Anet) is directly referenced to the BBSW.

62 As to pricing, a matter about which I will say something more later, ASIC contends that the price for trading, within the meaning of s 1041A of the Corporations Act, in an interest rate swap:

(a) consists of the obligations to exchange periodical cash payments undertaken by both parties to the swap at the time of acquiring an interest rate swap; and

(b) is quantified in monetary terms on each reset date using the formula to calculate the Swap Cash Settlement Amount set out above.

63 ASIC contends that where the BBSW is used as the floating rate in an interest rate swap, the BBSW is an input into the formula for calculating the Swap Cash Settlement Amount and therefore the BBSW is an input into the price for trading of the interest rate swap. I would note at this point that Westpac's thesis as to the "price" for trading of an interest rate swap focuses more on the agreement or stipulation of the fixed rate referable to the fixed rate leg.

64 In relation to exposure, for interest rate swaps which used the BBSW as the relevant floating rate, an exposure to the BBSW rate would be realised at each reset date. As set out above, the formulae for calculating the obligations of the swap party paying the floating rate and the Swap Cash Settlement Amount which both parties were obligated to pay directly referenced the BBSW.

65 As for profit or loss, the profit or loss to the parties to an interest rate swap is realised on the reset dates. As set out above, the formula to calculate the Swap Cash Settlement Amount on a fixed for floating swap is:

Which can also be written:

66 Where the floating rate used is the BBSW, this equation becomes:

67 Accordingly, where the floating rate in a fixed for floating interest rate swap is the BBSW, the rate at which the BBSW sets on the reset dates will determine which swap party needs to make a payment and the value of the payment (being the Swap Cash Settlement Amount). If the BBSW increases, the swap party paying the floating leg of the swap will have to pay more (or will receive less) and the party paying the fixed leg of the swap will have to pay less (or will receive more). If the BBSW decreases, the swap party paying the floating leg of the swap will have to pay less (or will receive more) and the party paying the fixed leg of the swap will pay more (or will receive less).

68 There are typically four types of counterparties with which one would enter into an interest rate swap relevant to the present context:

(a) Other banks and financial institutions, including foreign banks, that primarily use interest rate swaps to hedge their exposure to movements in interest rates as a result of their borrowing and lending activities.

(b) Corporate customers, that commonly enter into interest rate swaps as a means of cash flow management in order to convert a floating interest rate exposure (for example, under a finance facility with a bank) to a fixed rate exposure or vice versa.

(c) Institutional customers, such as superannuation funds or life insurance funds, that use interest rate swaps to manage the interest rate exposure of their portfolios of assets and liabilities.

(d) Speculative investors, such as hedge funds, that might use interest rate swaps to take an outright position in relation to the direction of movements in interest rates in order to generate a profit if that position is realised.

69 Let me turn to some other matters concerning the details of an interest rate swap. One aspect that is of particular relevance is the determination of the amount of the fixed rate on the fixed rate leg of the swap, which is relevant to an issue that I will discuss much later concerning the "price" of an interest rate swap.

70 An interest rate swap is a zero net present value contract on the date on which the transaction is entered into, with the fixed rate leg set so that the payment obligations of the party paying the fixed rate (and receiving the floating rate) is equal to the net present value of the floating rate payment obligations of the party paying that rate. For example, assume that a party enters into a one year "fixed for floating" interest rate swap with a notional principal of $1 million where the reference rate for the floating leg of the swap is 3 month BBSW. In this example, the value of the fixed leg of the swap will equal the net present value of the four quarterly payments on the 3 month BBSW on the notional principal of $1 million. Accordingly, while the payment obligations of the party paying the fixed interest rate are known with certainty and the floating rate is to be determined on the four future rate reset dates, the parties expect them (notionally at least) to have the same total net present value for the term of the swap.

71 After the commencement date of the swap, however, the respective payment obligations of the parties to the swap will change as a result of movements in interest rates. While the fixed rate leg does not change over the term of the swap, the parties' respective payment obligations over the term of the swap will fluctuate depending on movements in the level at which the floating reference rate sets on the relevant rate reset dates. Ultimately, movements in the level of the floating reference rate will affect the sum of the parties' payment obligations over the term of the swap. Similarly, throughout the term of the swap, the mark-to-market value of the swap will change to the extent of subsequent movements of expectation of the level of the floating reference rate. The mark-to-market value of the swap is recalculated on a daily basis and a party may choose to crystallise their position (either at a gain or a loss) by selling an interest rate swap at the mark-to-market rate.

72 In practice, the amount of the fixed rate leg of the swap is determined by reference to two components:

(a) the swap yield curve, where the term of the interest rate swap will determine the relevant point on the swap yield curve; and

(b) a margin or "spread", where the margin which is applied essentially reflects the credit risk of a specific counterparty plus other transaction costs.

73 Mr Masnick for Westpac gave evidence to the following effect. Westpac regularly reviews the shape of its swap yield curve so as to ensure its traders have the best tools available to trade interest rate swaps effectively. Westpac's swap yield curve is built using a number of sources of information. During the relevant period, the swap yield curve was built using the following sources of information:

(a) swaps with a term of up to two years are set by reference to the BAB Futures yield;

(b) swaps with a term of longer than two years are set by reference to the Commonwealth government bond futures yield plus a margin (which is referred to as the Exchange For Physical (EFP) margin);

(c) the Overnight Indexed Swap (OIS) rate, which was used to discount future cash-flows on the interest rate swap;

(d) a credit valuation adjustment to account for the credit risk of counterparties; and

(e) Westpac's profit margin (including the cost of capital and other related expenses).

74 In addition to the swap yield curve, Westpac traders during the relevant period would commonly have regard to the following information when trading in interest rate swaps:

(a) their assessment of the likely future movements in interest rates;

(b) the trading in other financial instruments which are set by reference to market views in relation to future movements in the cash rate, such as interest rate futures and BAB Futures;

(c) the current level of trading, and recent market trades, in interest rate swaps;

(d) the particular credit worthiness of the specific counterparty with which Westpac was proposing to enter into the swap, which is determined by Westpac's credit risk team;

(e) whether an exchange margin (or other credit risk mitigant) can be agreed between the parties; and

(f) other factors specific to a particular counterparty (for example, whether the counterparty is a strategic client of Westpac).

75 Because of the variety of information that was taken into account when trading interest rate swaps, during the relevant period there was not, at any point in or period of time, one single rate at which Westpac's traders would enter into an interest rate swap. Each transaction involved considering the full range of factors listed above, which meant that the rate at which interest rate swaps entered into by Westpac at or around the same time would differ as a result of the application of these factors to each transaction.

(d) Cross-currency swaps

76 A cross-currency swap is a variation on an interest rate swap. It is an agreement between two parties to exchange:

(a) a principal amount and associated interest payments denominated in one currency; for

(b) a principal amount and associated interest payments denominated in another currency.

The parties pay their respective interest payments on dates referred to as "reset dates" and typically exchange the principal amount at the swap creation and maturity date (either in the two currencies or in one currency based on an agreed exchange rate). This is, of course, different to an interest rate swap, where no principal amounts are exchanged.

77 There are numerous types of cross-currency swaps. A simple example is a cross-currency swap where the parties agree to swap:

(a) an Australian dollar ("AUD") principal plus interest payments determined by an AUD interest rate (such as BBSW); with

(b) a principal of another currency (currency X) plus interest payments determined by a X currency interest rate (either fixed or floating as agreed between the parties).

78 A common type of cross-currency swap called a "floating for floating" basis swap involves exchanging a floating rate in one currency (say, BBSW) for a floating rate in another currency (say, the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR)).

79 Cross-currency swaps involving AUD commonly use the BBSW as the AUD interest rate.

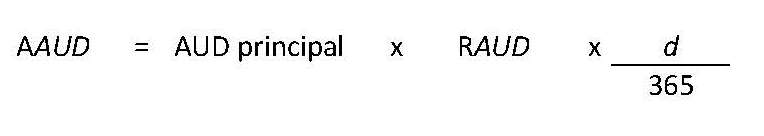

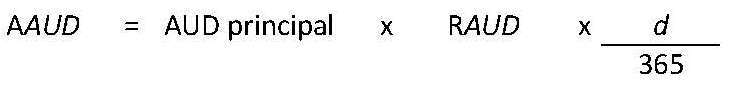

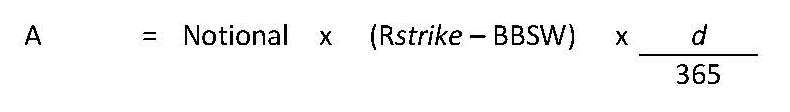

80 The formula for calculating the cash-flow obligations of both swap counterparties on a reset date (other than the creation or maturity date) can be expressed as follows:

Payment obligation of the party paying the AUD leg of the swap

Where: | |

AAUD = | Amount required to be paid by the party paying the AUD leg of the swap |

AUD principal = | AUD principal amount |

RAUD = | Australian interest rate |

d = | Day count (between reset dates) |

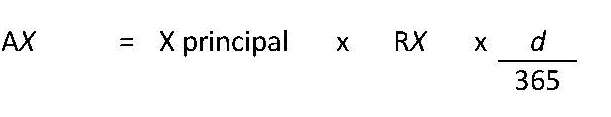

Payment obligation of the party paying the foreign currency leg of the swap

Where: | |

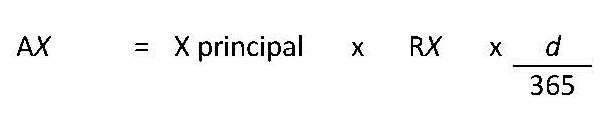

AX = | Amount required to be paid by the party paying the X currency leg of the swap |

X principal = | X currency principal amount (foreign currency amount) |

RX = | X currency interest rate |

d = | Day count (between reset dates) |

81 The rate in a cross-currency swap where one leg uses AUDs is commonly BBSW. In these cross-currency swaps:

(a) the "RAUD" input in the equation above is BBSW;

(b) the payment obligation of the party paying the AUD leg of the swap is directly referenced to BBSW; and

(c) if the payments on the reset dates are netted out (using an exchange rate to convert the non-AUD payment to AUDs) then the net payment amount is directly referenced to BBSW.

82 As for pricing, on which I will say something more later, ASIC contends that the price for trading, within the meaning of s 1041A of the Corporations Act, in a cross-currency swap:

(a) consists of the obligations to exchange periodical cash payments undertaken by both parties to the swap at the time of acquiring a cross-currency swap; and

(b) is quantified in monetary terms on the creation of the cross-currency swap and on each reset date, using (on each reset date) the formula set out above.

83 ASIC contends that where the BBSW is used as the Australian interest rate in a cross-currency swap the BBSW is an input into the formula for calculating the payment amount paid by the party making AUD payments on each reset date and the maturity date and therefore the BBSW is an input into the price for trading of the cross-currency swap. Contrastingly, Westpac says that the price for trading is more aptly focused, in the present context, on the margin added to the AUD floating rate (say, BBSW) where under the cross-currency swap one has a floating interest rate on each side, say on the AUD side, BBSW, and on the USD side, LIBOR. But where there is a fixed rate on one side, then the fixed rate would determine the price for the trade.

84 In relation to exposure, for cross-currency swaps which used the BBSW as the relevant floating rate on the AUD leg, an exposure to the BBSW rate would be realised at each reset date. As set out above, the obligations of the swap party paying the AUD interest rate and the Swap Cash Settlement Amount which both parties are obligated to pay (if netted off) directly referenced the BBSW. The amount used by Westpac to calculate its BBSW Rate Set Exposure arising from a cross-currency swap was the size of the notional amount upon which the swap obligations were based.

85 As to profit or loss, the profit or loss to the parties to a cross-currency swap is realised on the reset dates.

86 As set out above, the formula for calculating the cash-flow obligations of both swap counterparties (to a swap involving the AUD) on a reset date can be expressed as follows:

Payment obligation of the party paying the AUD leg of the swap

Payment obligation of the party paying the foreign currency leg of the swap

87 Where the AUD rate used is the BBSW, the rate at which the BBSW sets on the reset dates will determine the payment obligation of the party paying the AUD leg of the swap. Where the two swap payments are netted out (by applying an agreed exchange rate), which swap party needs to make a payment and the value of the payment (being the Swap Cash Settlement Amount) will also be dependent on where the BBSW sets on the relevant reset date.

88 Similar to interest rate swaps, there is also usually a difference between the date that the parties agree to enter into the cross-currency swap (the "transaction date") and the date the cross-currency swap first resets (the "commencement date"). Often, the commencement date will be the day after the transaction date. This is referred to by traders as being "T + 1". If, for example, the commencement date was three days after the transaction date, this would be referred to as "T + 3". Typically, subsequent reset dates are determined by reference to the commencement date. For instance, if the cross-currency swap resets monthly, the second reset date will be the date corresponding to the commencement date in the following month.

89 In terms of matters relevant to the trading of a cross-currency swap and the margin added to the AUD floating interest rate, where one has a floating interest rate on each side, the following may be noted.

90 Theoretically, the net present value of a cross-currency swap is zero because, on the date on which the transaction is entered into, the present value of interest payment obligations on a principal amount determined by an Australian interest rate equals the present value of interest payment obligations on the same principal amount determined by a foreign interest rate. In practice, a margin is added to the Australian interest rate which is due to supply and demand factors. Accordingly, the Australian interest rate of a cross-currency swap is expressed as a floating rate plus a margin. The margin may, inter-alia, reflect the particular credit risk of the individual counterparty. This credit risk is greater for cross-currency swaps than for interest rate swaps because the former requires the exchange of principal amounts whereas the latter involves only the exchange of the difference in the rates on the notional amount.

91 Cross-currency swaps are generally used in the Australian market by large corporate customers to convert interest rate risk from foreign currency raised in offshore wholesale debt markets (typically in the United States) into an exposure to domestic interest rates. For example, assume a party (such as a large Australian company) issues a USD 1 million bond in the United States with a term of two years and receives an equivalent amount of USDs, the floating interest rate on which is referenced to 3 month LIBOR. A cross-currency swap allows that party to convert a floating exposure to 3 month LIBOR to an exposure to 3 month BBSW. As a cross-currency swap involves the exchange of a principal amount, the large Australian company also receives the AUD equivalent of USD 1 million (calculated by reference to an agreed spot foreign exchange rate) with which it can meet its liabilities payable in AUDs. At the maturity date the parties re-exchange the initial principal at the same agreed exchange rate, with which the party receiving the USD 1 million can pay its liabilities with respect to the bondholders.

92 In Australia, the most common type of cross-currency swap entered into is an AUD/USD basis swap. It is common for Australian corporations to issue foreign currency debt into offshore bond markets which can absorb larger debt issuances at competitive levels. As a result, there is generally greater demand for USD floating reference cross-currency swaps in the Australian market, which affects the prevailing rate for AUD/USD cross-currency swaps. In this context, given the imbalance between payment flows, the basis point margin added to the Australian reference benchmark rate incentivises parties to take the USD floating rate leg of the swap because the basis point margin for entering into the swap is paid by the party paying interest determined by reference to Australian interest rates only.

93 During the relevant period, Westpac traders would have regard to the following information to determine the appropriate rate(s) and any relevant margin at which to enter into a cross-currency swap:

(a) the rate for cross-currency swaps observed on broker screens;

(b) the particular flows within a particular trading book of Westpac; and

(c) Westpac's profit margin including a credit spread to reflect the particular credit risk of the individual counterparty.

(e) Electronic platforms

94 During the relevant period, interest rate swaps and cross-currency swaps were either:

(a) privately negotiated between two counterparties; or

(b) conducted indirectly through facilitation by a broker.

95 During the relevant period, companies offering voice brokerage services such as ICAP Brokers Pty Ltd (ICAP) and Tullett Prebon (Australia) Pty Ltd (Tullett) facilitated cross-currency swap and interest rate swap transactions. That is, they provided the ability for two counterparties to negotiate a swap transaction. They did not provide an active market in which "live" bids and offers were shown on the brokers' screens. Rather, the rates displayed on the screens were only indicative of where a counterparty might be willing to transact. It was only possible to get a confirmed rate at which a party was willing to transact by contacting the counterparty directly or through a broker.

96 There were also various electronic platforms.

97 The electronic platform called BETSY operated by Bloomberg Tradebook Australia Pty Ltd facilitated transactions in interest rate swaps. According to the evidence adduced before me:

(a) BETSY was only available to large financial institutions and, as a result, facilitated interest rate swaps to a very narrow section of the broader market for interest rate swaps. The vast majority of interest rate swaps were negotiated bilaterally, either privately or through voice brokering.

(b) Only 10 trades in interest rate swaps that had a payment referenced to BBSW were facilitated by BETSY during the relevant period (one of which was a "test" trade). By way of comparison, during the relevant period, the annual market turnover for interest rate swaps and cross-currency swaps was around $6 trillion. During the relevant period, Westpac entered into approximately 10,000 swap transactions each year.

(c) BETSY did not allow participants to post "live" bids and offers for interest rate swaps to customers. Rather BETSY allowed participants to propose interest rate swaps with specific terms or make requests for quotes, after which the details of any trade could be negotiated bilaterally between the parties. In this way, BETSY provided a similar service to those companies providing voice brokerage services such as ICAP and Tullett.

(d) BETSY did not compel participants to make bids and offers available to customers at any time. In addition, dealers were permitted to ignore orders from customers made via BETSY.

(e) The execution, settlement and clearance of any transaction facilitated by BETSY was at the sole discretion of the parties to the transaction and was subject to the parties' independent confirmation and documentation processes.

(f) Parties were not contractually obliged to inform Bloomberg of instances where a counterparty did not proceed to settlement despite accepting a transaction via BETSY.

98 Further, the BGC Trader platform (an electronic trading facility operated by BGC Partners (Australia) Pty Ltd and BGC Brokers LP named "BGC Trader") facilitated transactions in various financial products including interest rate swaps and cross-currency swaps. From the evidence adduced before me the following may be noted:

(a) BGC Trader was only available to large financial institutions and, as a result, facilitated interest rate swaps to a very narrow section of the broader market for interest rate swaps and cross-currency swaps. By way of comparison, around $6 trillion was traded in the broader market for interest rate swaps and cross-currency swaps during the relevant period. The vast majority of interest rate swaps and cross-currency swaps were negotiated bilaterally, either privately or through voice brokering.

(b) BGC Trader's "Volume Match auction" did not allow participants to post "live" bids and offers for interest rate swaps for cross-currency swaps and did not compel participants to show bids or offers. The Volume Match auction for interest rate swaps operated once daily for certain floating rate tenors and maturities, and the auction for cross-currency swap transactions occurred less frequently than that.

(c) Given that the bids and offers observed on BGC Trader were anonymous, any trade confirmation provided by BGC Trader was always subject to credit risk checks which was conducted independently by the relevant parties on a bilateral basis (or via their broker).

(d) The execution, settlement and clearance of any transaction facilitated by BGC Trader was at the sole discretion of the parties to the transaction and was subject to the parties' independent confirmation and documentation processes.

(e) Parties were not contractually obliged to inform BGC Trader of instances where a counterparty did not proceed to settlement despite accepting a transaction via BGC Trader.

99 I will say something more about these electronic trading facilities later in my reasons.

(f) Forward rate agreements

100 A forward rate agreement (FRA) is an agreement to lend or borrow money at a specified price (agreed rate) on a future date for a set period. Expressed another way, a FRA involves two parties agreeing to exchange interest payments based on two different agreed rates, at a future date (called the "settlement date"), based on a specified notional amount.

101 FRAs typically reference a set fixed rate, which is agreed between the parties and a floating rate, which is BBSW. Under these FRAs the parties agree to exchange the difference between cash-flows based on the agreed fixed rate and cash-flows based on the BBSW, for a specified period, based on a notional amount.

102 The payment of interest based on a specified notional amount at a particular interest rate and for a particular period can be implemented by:

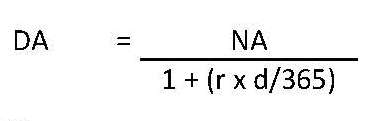

(a) the lender paying to the borrower the specified notional amount, discounted according to the formula:

Where: | |

DA = | The discounted amount |

NA = | The specified notional amount |

r = | Applicable interest rate (expressed as an annual rate) |

d = | Number of days (between reset dates) |

and

(b) the borrower paying to the lender the full specified notional amount.

103 Where such payments of interest are exchanged between two parties based on the same specified notional amount, and in respect of the same period, but at different interest rates, the respective payments of the full specified notional amount (as referred to above) offset each other precisely and can therefore be ignored.

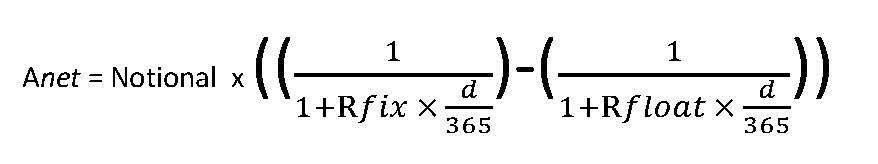

104 On this basis, the formula for calculating cash-flow obligations and the net payment on the settlement date can be expressed as follows:

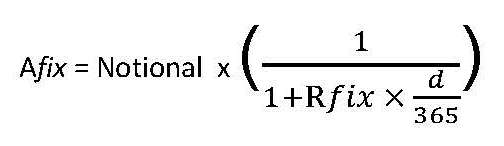

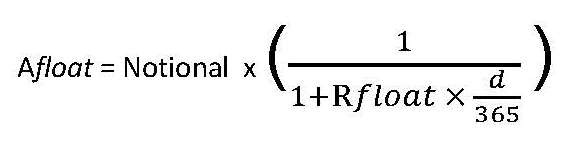

Payment obligation of the party lending at the fixed interest rate (therefore borrowing at the floating rate)

Payment obligation of the party lending at the floating interest rate (therefore borrowing at the fixed rate)

The net cash-flow payment

Which can also be expressed as:

Where: | |

Notional = | Notional amount |

d = | Day count (between reset dates) |

Rfix = | Fixed rate |

Rfloat = | Floating rate |

Afix = | Amount required to be paid by the party lending at the fixed interest rate leg of the FRA |

Afloat = | Amount required to be paid by the party lending at the floating interest rate leg of the FRA |

Anet = | Cash payment required on payment date |

105 The floating rate in a FRA is commonly BBSW. In these FRAs:

(a) the "Rfloat" input in the equations above is BBSW;

(b) the payment obligation of the party lending at the floating rate is directly referenced to BBSW; and

(c) the net payment amount (Anet) due on the settlement date is directly referenced to BBSW.

106 In relation to exposure, for FRAs which used the BBSW as the relevant floating rate, an exposure to the BBSW would be realised on each payment date. As set out above the obligations of the FRA party paying the floating rate and the net payment amount which both parties were obligated to pay, directly referenced the BBSW.

107 In relation to profit or loss, the profit or loss to the parties to a FRA is realised on the settlement date. As set out above, the payment amount due on the settlement date, can be expressed as:

108 Where the BBSW is used as the floating rate in a FRA, the rate at which the BBSW sets on the settlement date will determine which party needs to make a payment and the value of the payment.

(g) Asset swaps

109 An asset swap is a form of interest rate swap in which one of the cash-flow streams relates to an underlying asset. One cash-flow stream of the asset swap is based on a non-asset rate (a financial interest rate), commonly the BBSW. The other stream is calculated based on the yield generated by an underlying asset, for example, a bond held by a party to the swap. In a similar manner to an interest rate swap discussed above, the parties exchange periodic cash payments based on the net difference between the two cash-flows at regular intervals. Usually, only net interest payments are made, and no "principal" payments.

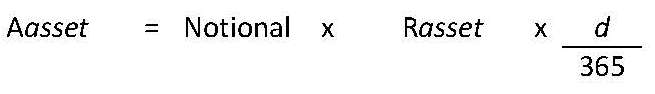

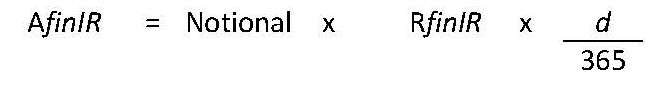

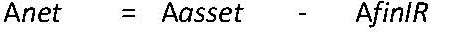

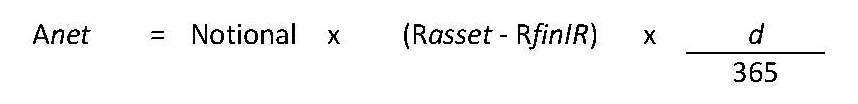

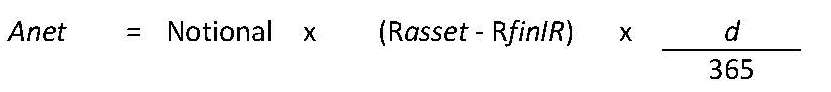

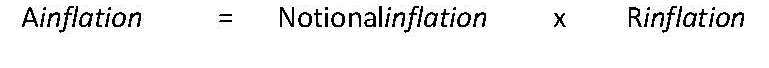

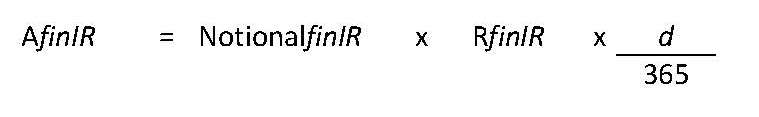

110 The formula for calculating the cash-flow obligations of both swap counterparties on a reset date can be expressed as follows:

Payment obligation of the party paying the asset referenced rate

Where: | |

Aasset = | Amount required to be paid by the party paying the asset referenced interest rate leg of the swap |

Notional = | Notional amount |

d = | Day count (between reset dates) |

Rasset = | Interest rate based on the yield generated by an underlying asset |

Payment obligation of the party paying the financial interest rate

Where: | ||

AfinIR = | Amount required to be paid by the party paying the financial interest rate leg | |

Notional = | Notional amount | |

d = | Day count (between reset dates) | |

RfinIR = | Financial interest rate | |

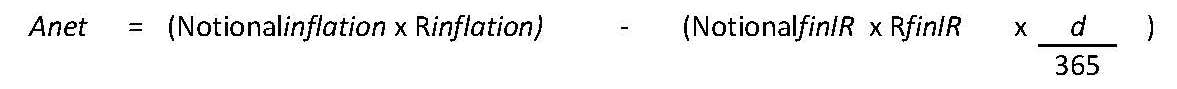

The net cash-flow payment (Swap Cash Settlement Amount)

This can also be written as follows by expanding the equation:

Where: | |

Anet = | Swap Cash Settlement Amount |

111 The non-asset rate in an asset swap is commonly BBSW. In these asset swaps:

(a) the payment obligation of the party paying the financial rate is directly referenced to BBSW;

(b) the "RfinIR" input in the formula above is BBSW; and

(c) the Swap Cash Settlement Amount is directly referenced to BBSW.

112 In relation to exposure, for asset swaps which used the BBSW as the relevant floating rate, an exposure to the BBSW would be realised at each reset (or fixing) date. As set out above, the obligations of the swap party paying the floating rate and the Swap Cash Settlement Amount which both parties are obligated to pay, directly referenced the BBSW.

113 In relation to profit or loss, the profit or loss to the parties to an asset swap is realised on the reset dates. As set out above, calculation of the settlement amount where the financial interest rate is a floating rate can be expressed using the following formula:

114 Accordingly, where the non-asset interest rate used in an asset swap is the BBSW, the rate at which the BBSW sets on the reset dates will determine which swap party needs to make a payment and the value of the payment being the Swap Cash Settlement Amount.

(h) Interest rate options (caps, floors and collars)

Interest rate cap

115 An interest rate cap is an agreement between two parties in which the buyer purchases from the seller one call option, or a series of call options, on future borrowing rates (each individual call option is called a "caplet"). In exchange for payment of a premium, the buyer acquires the right (but not the obligation) to require the seller to compensate it on prescribed reference dates if the agreed floating interest rate is greater than an agreed strike rate (known as the "cap rate"). The floating interest rate used in interest rate caps is typically BBSW. If so:

(a) the parties agree that when the BBSW exceeds the cap rate, the seller will pay to the buyer the difference between interest on the notional amount calculated using the BBSW and interest on the notional amount calculated using the cap rate;

(b) a payment is only required if the BBSW exceeds the cap rate on the prescribed reference date(s); and

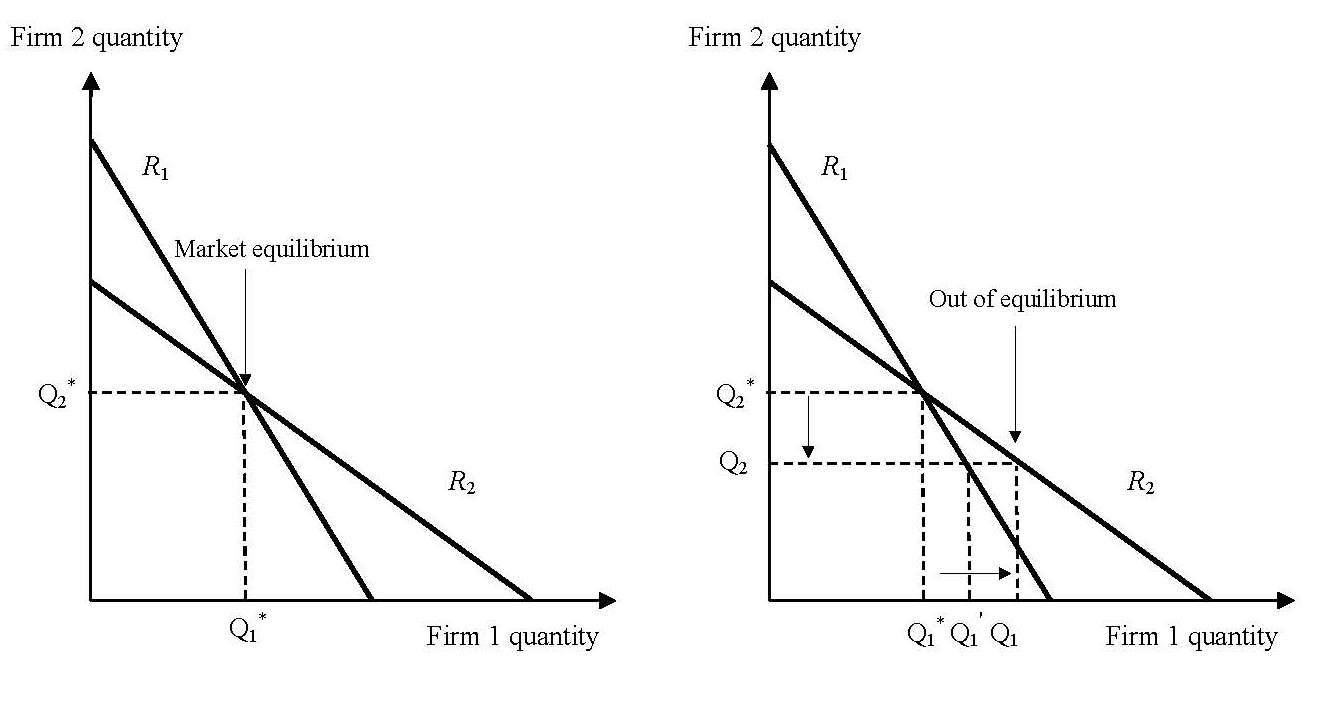

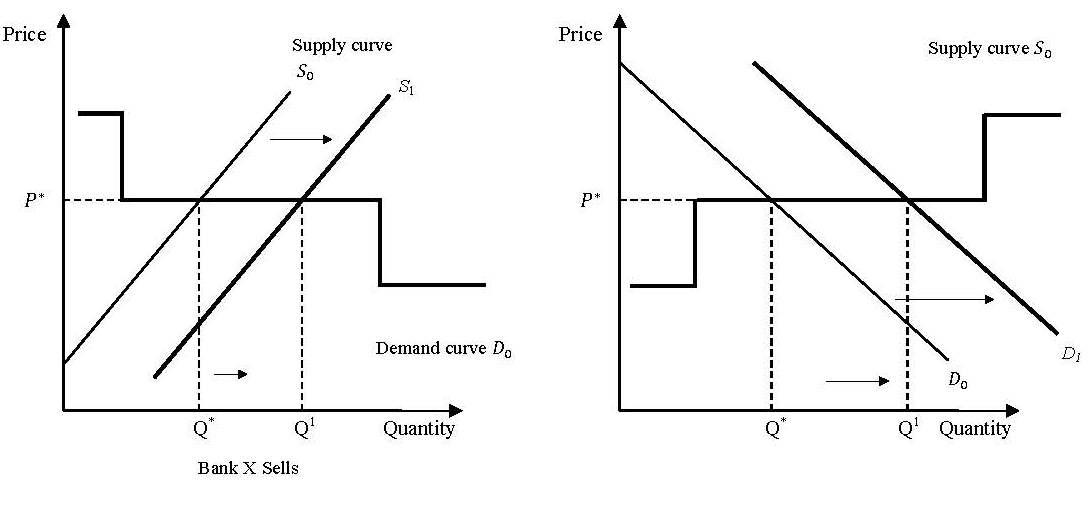

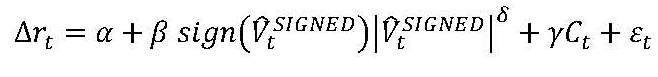

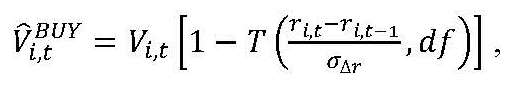

(c) if the BBSW exceeds the cap rate, the payment the seller must make to the buyer is based on the difference between the BBSW and the cap rate, the term of the period ending on the relevant reference date, and the contract's notional amount. Payments can be made "discounted in advance" or "non-discounted in arrears".