FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Perera v GetSwift Limited [2018] FCA 732

Table of Corrections | |

At paragraph [99], the heading “D.2.1 Stays & Abuse of Process” has been removed. | |

14 June 2018 | At paragraph [255], the word “not” has been inserted between the words “were” and “identified”. |

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent JOEL MACDONALD Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 23 May 2018 | |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. This proceeding be permanently stayed.

2. For the avoidance of doubt, the permanent stay of this proceeding does not prevent the applicant making and moving upon any application as a group member in proceedings NSD 580 of 2018 pursuant to s 33T of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) where he contends that Mr Webb, the applicant in that proceeding, is not able adequately to represent the interests of the group members in that proceeding including, without limitation, in circumstances where Mr Webb has failed to comply with any order relating to security for costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 440 of 2018 | ||

BETWEEN: | SHAUN MCTAGGART First Applicant SAMANTHA MCTAGGART Second Applicant | |

AND: | GETSWIFT LTD First Respondent JOEL MACDONALD Second Respondent BANE HUNTER Third Respondent | |

JUDGE: | LEE J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 23 may 2018 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. This proceeding be permanently stayed.

2. For the avoidance of doubt, the permanent stay of this proceeding does not prevent the applicants making and moving upon any application as group members in proceedings NSD 580 of 2018 pursuant to s 33T of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) where they contend that Mr Webb, the applicant in that proceeding, is not able adequately to represent the interests of the group members in that proceeding including, without limitation, in circumstances where Mr Webb has failed to comply with any order relating to security for costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 580 of 2018 | ||

BETWEEN: | RAFFAELE WEBB Applicant | |

AND: | GETSWIFT LTD First Respondent JOEL MACDONALD Second Respondent | |

JUDGE: | LEE J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 23 MAY 2018 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicant file and serve a statement of claim on or by 4:00 pm on 28 May 2018.

2. The respondents file and serve a defence to the statement of claim on or by 4:00 pm on 6 June 2018.

3. On or by 2:00 pm on 7 June 2018, the applicants serve on the respondent and the solicitor for Mr Perera and the solicitor for the McTaggart applicants a copy of a proposed opt out notice and provide a copy to the Associate to Justice Lee.

4. On or by 2:00 pm on 7 June 2018, the applicants serve on the respondent a copy of a draft common fund order and provide a copy to the Associate to Justice Lee.

5. The matter be listed for a case management hearing at 9:00 am on 8 June 2018, for the purpose, among other things, of making orders in relation to the form and distribution of the opt out notice and that Mr Perera and the McTaggart applicants, International Litigation Partners No 18 Pte Ltd and Vannin Capital Ltd have leave to intervene, if they so wish, at the case management hearing for the purposes of making submissions as to the form of the opt out notice.

6. Leave be granted to the applicants to issue a subpoena to ComputerShare Investor Services Pty Ltd in substantially the same form as comprises Annexure “A” to the interlocutory application filed in NSD 226 of 2018 dated 9 March 2018.

7. Costs of the proceedings to date be reserved.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

LEE J:

[1] | |

[10] | |

[10] | |

B.2 The Procedural Contradiction of Securities Class Actions | [30] |

[38] | |

[38] | |

[44] | |

[63] | |

[65] | |

[69] | |

[72] | |

[74] | |

[76] | |

[83] | |

[83] | |

[95] | |

[105] | |

[105] | |

[109] | |

[109] | |

[125] | |

[145] | |

[166] | |

[168] | |

[168] | |

[172] | |

[173] | |

[174] | |

[176] | |

[177] | |

[185] | |

[199] | |

F.7 Substantive Merits of the Individual Cases of the Applicants | [206] |

[210] | |

[216] | |

[218] | |

[225] | |

[226] | |

[231] | |

[235] | |

[240] | |

[242] | |

[242] | |

[244] | |

[247] | |

[250] | |

[250] | |

[251] | |

[253] | |

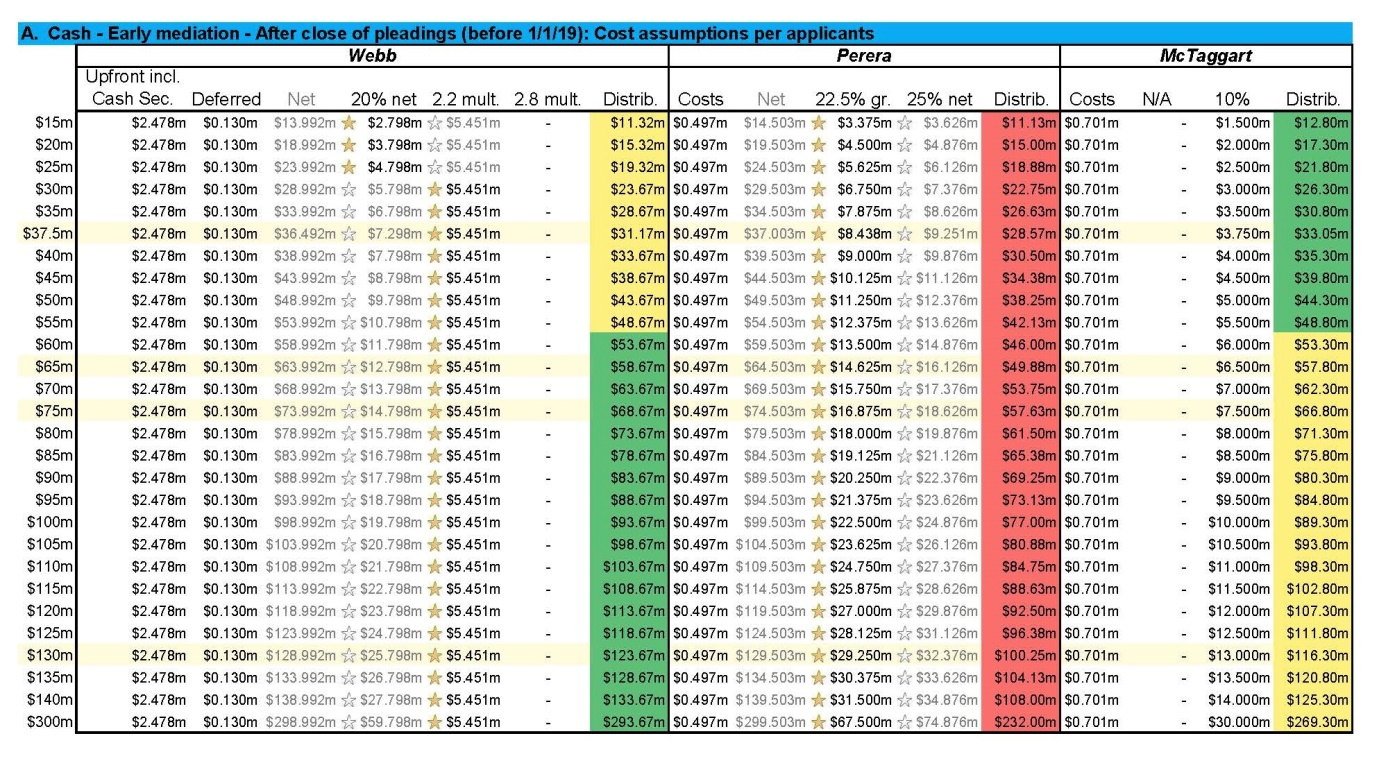

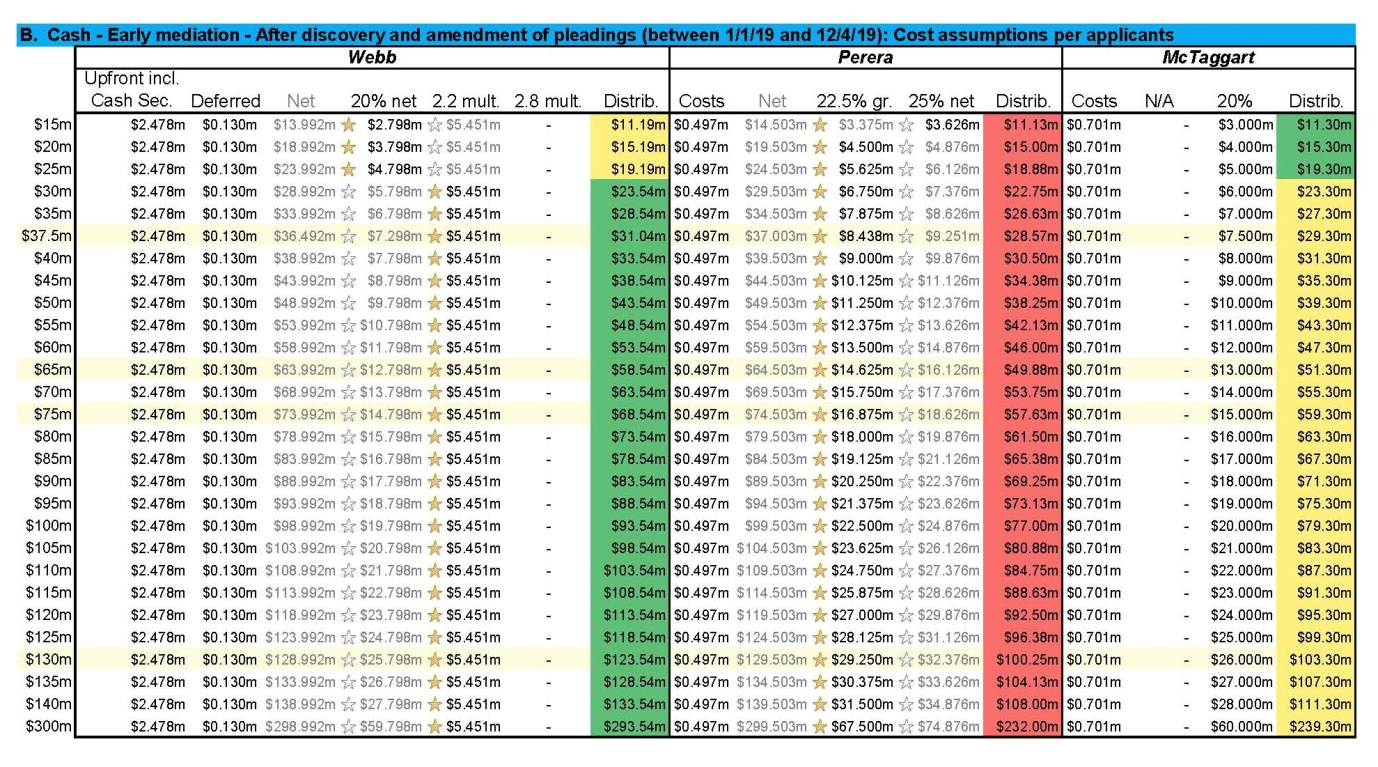

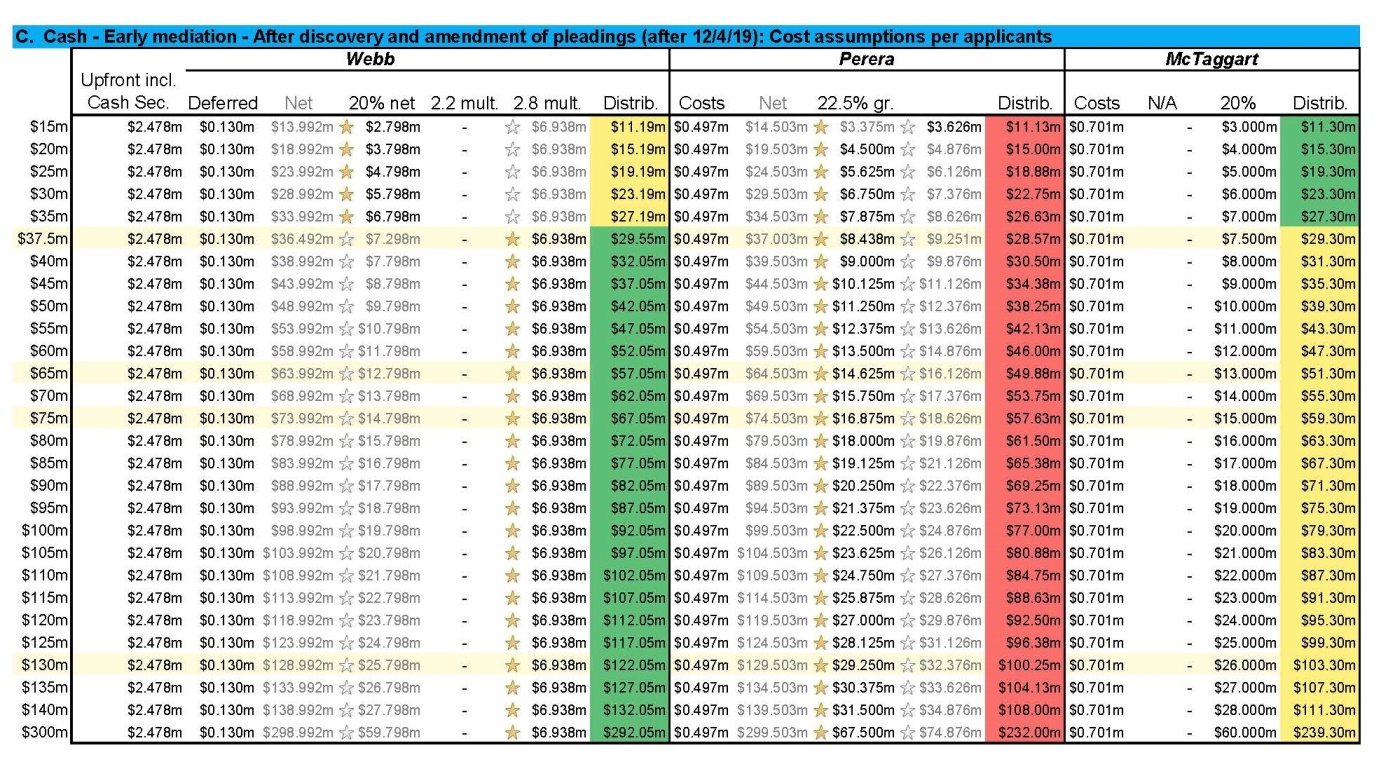

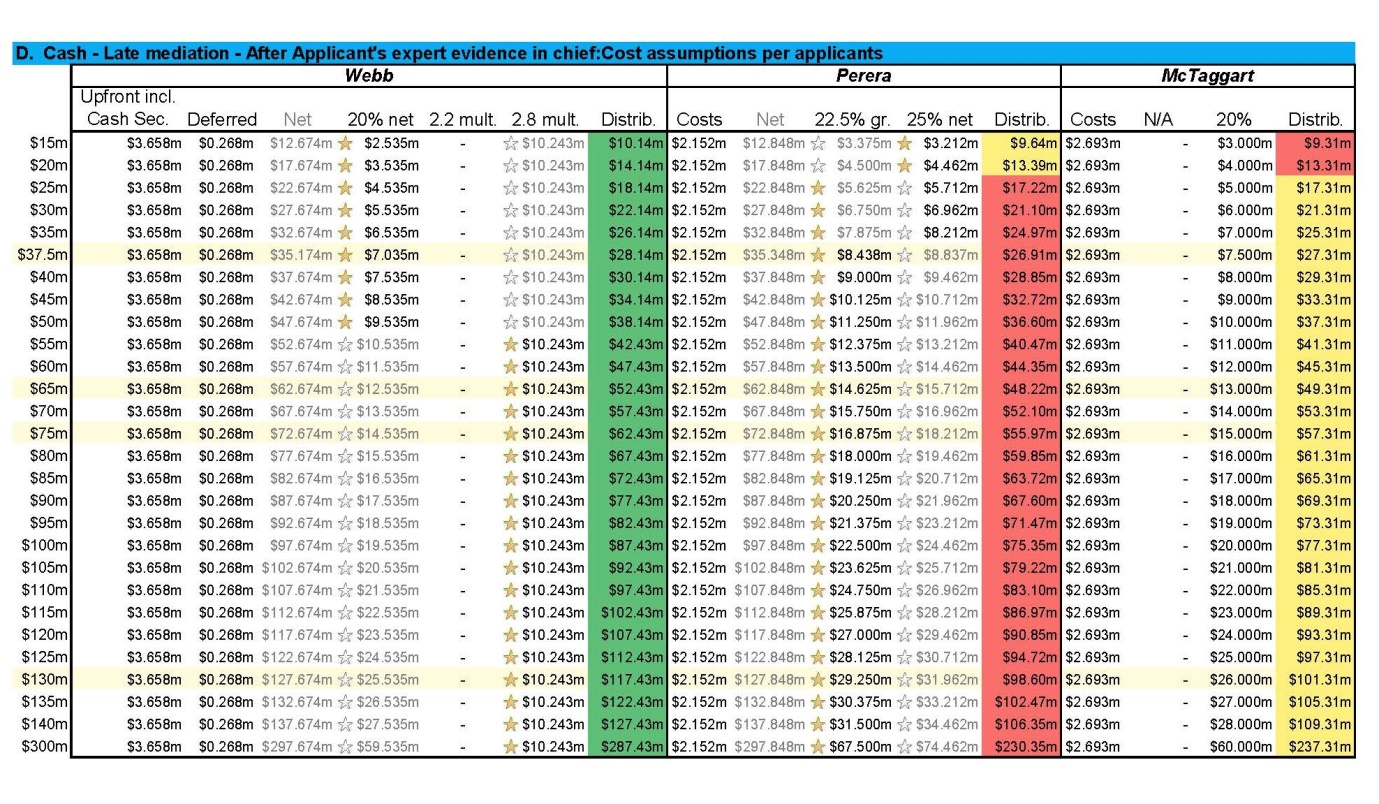

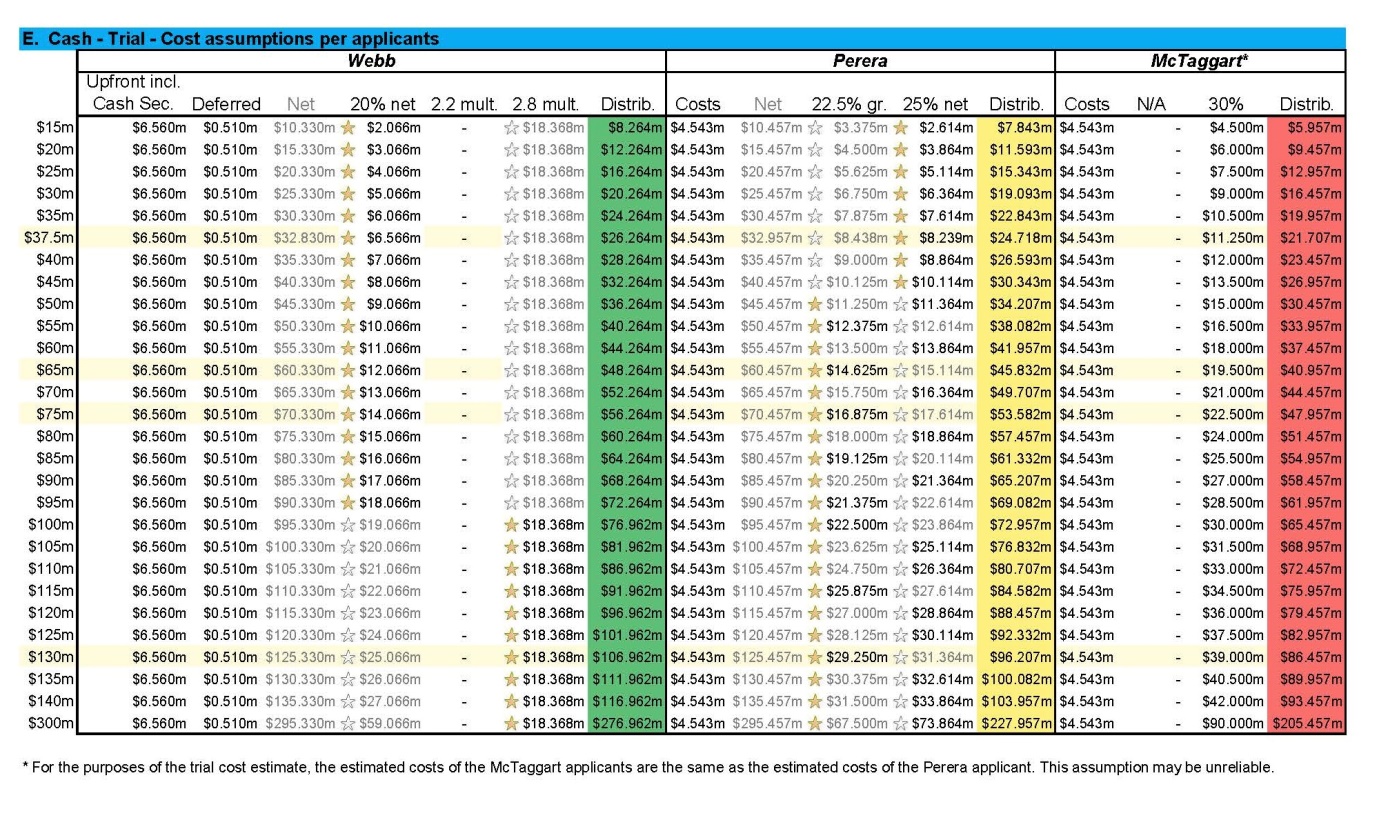

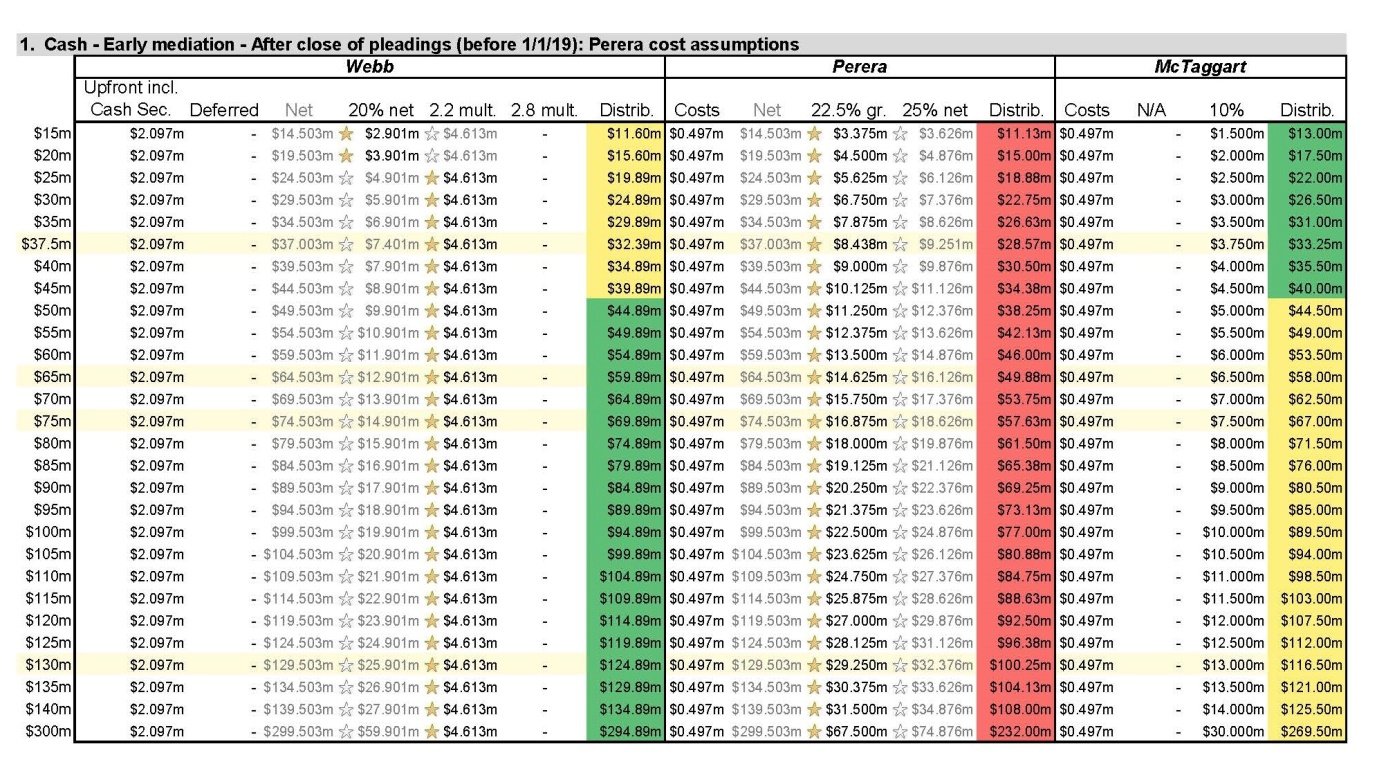

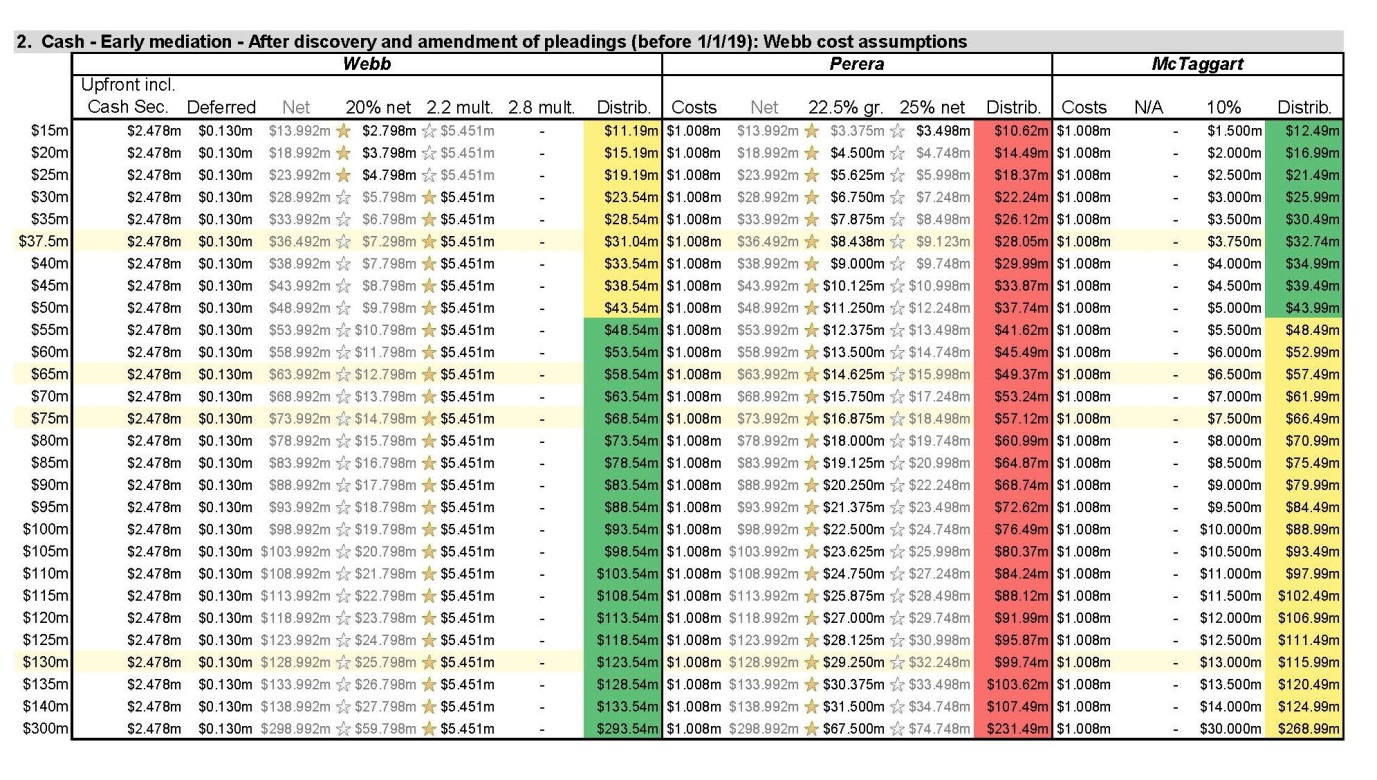

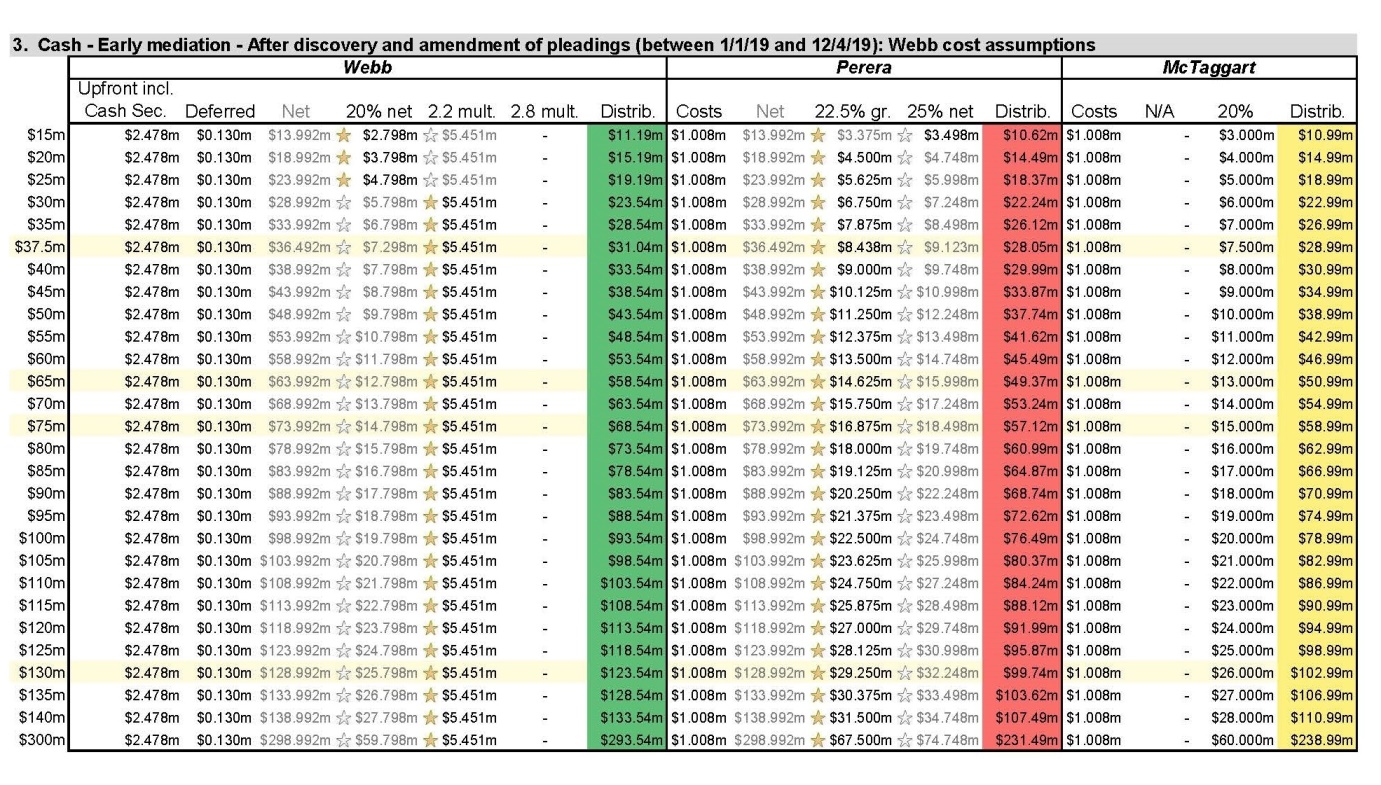

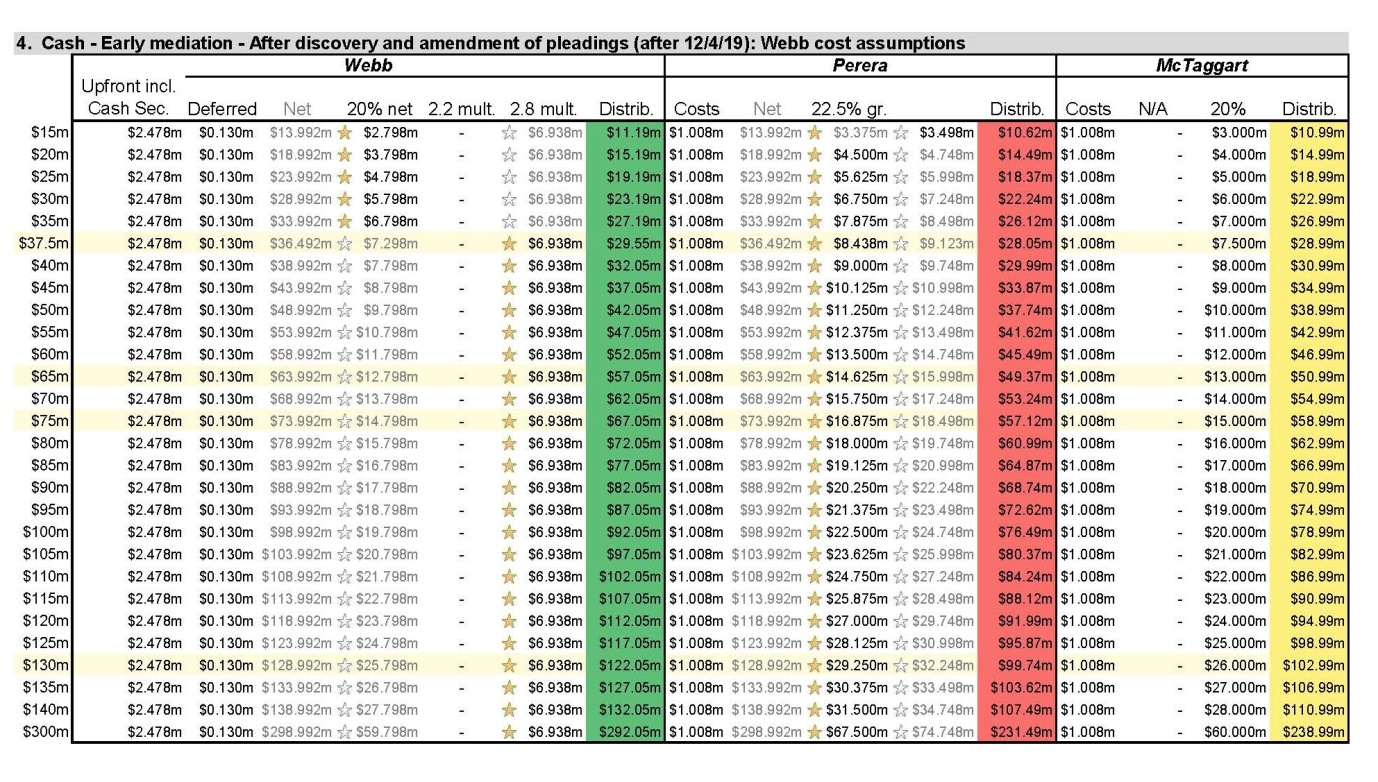

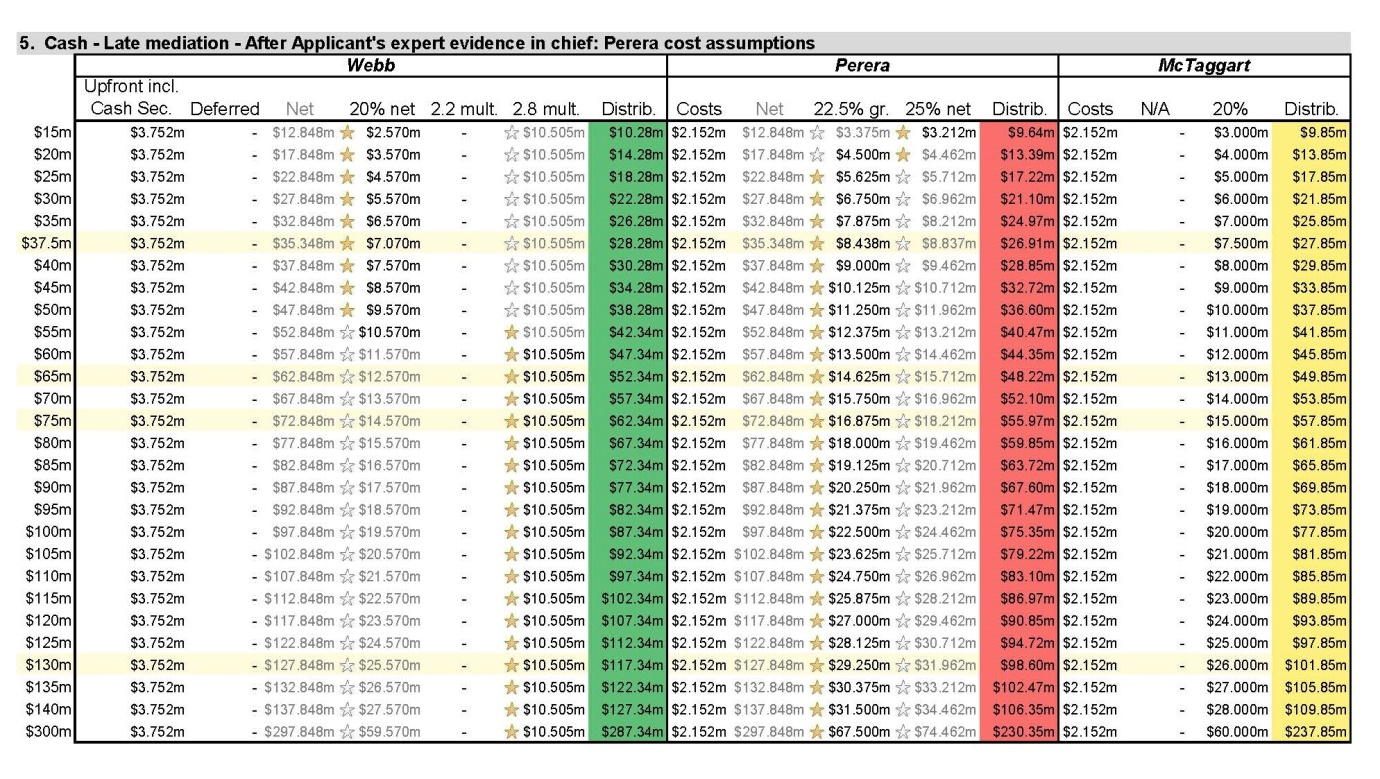

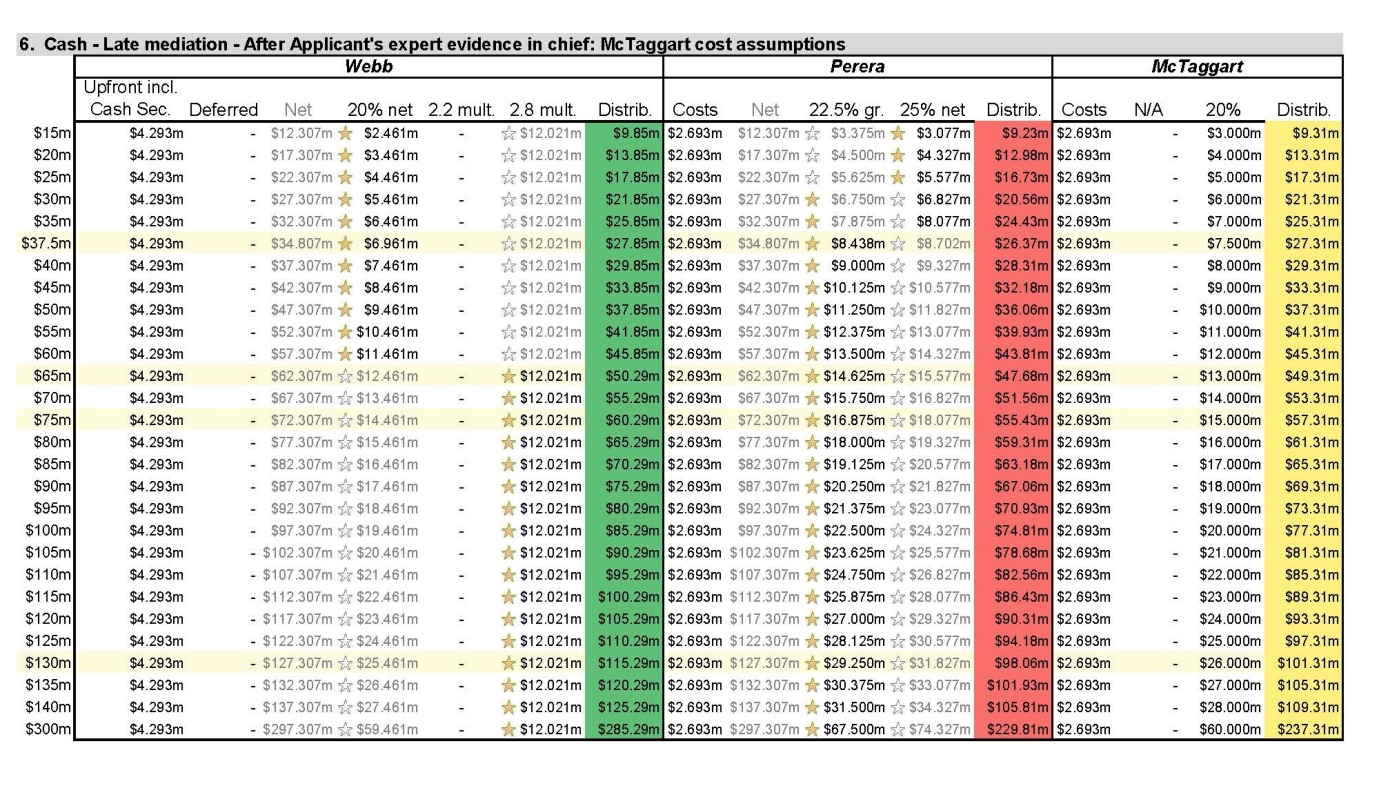

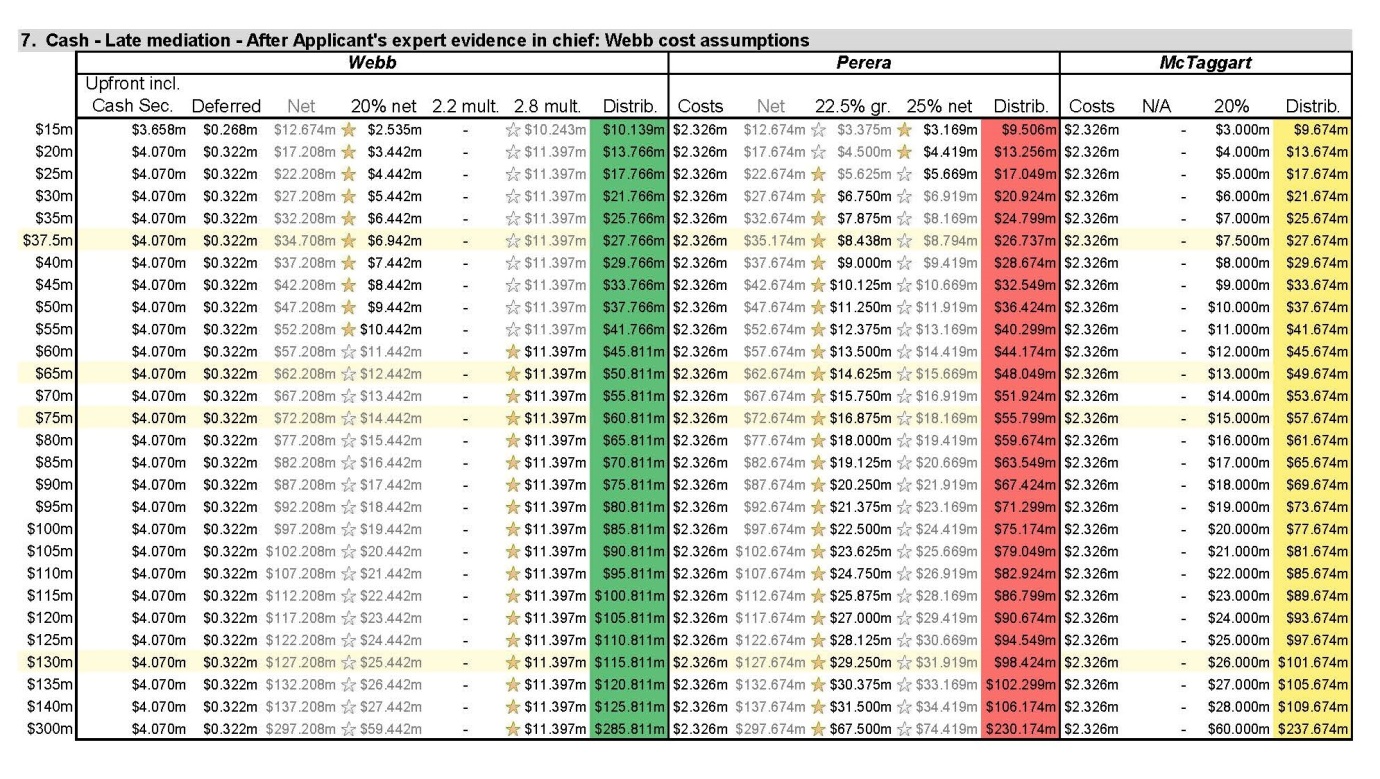

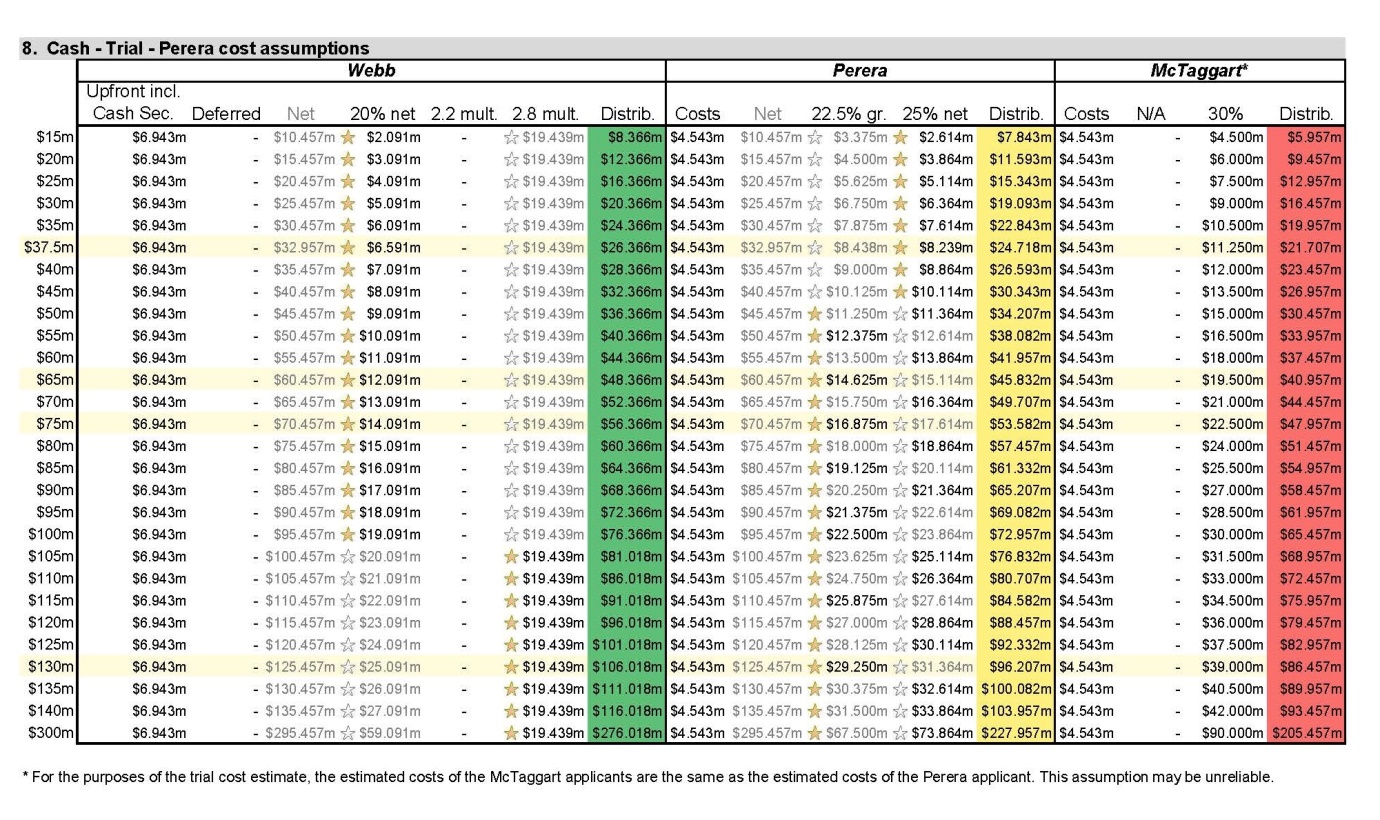

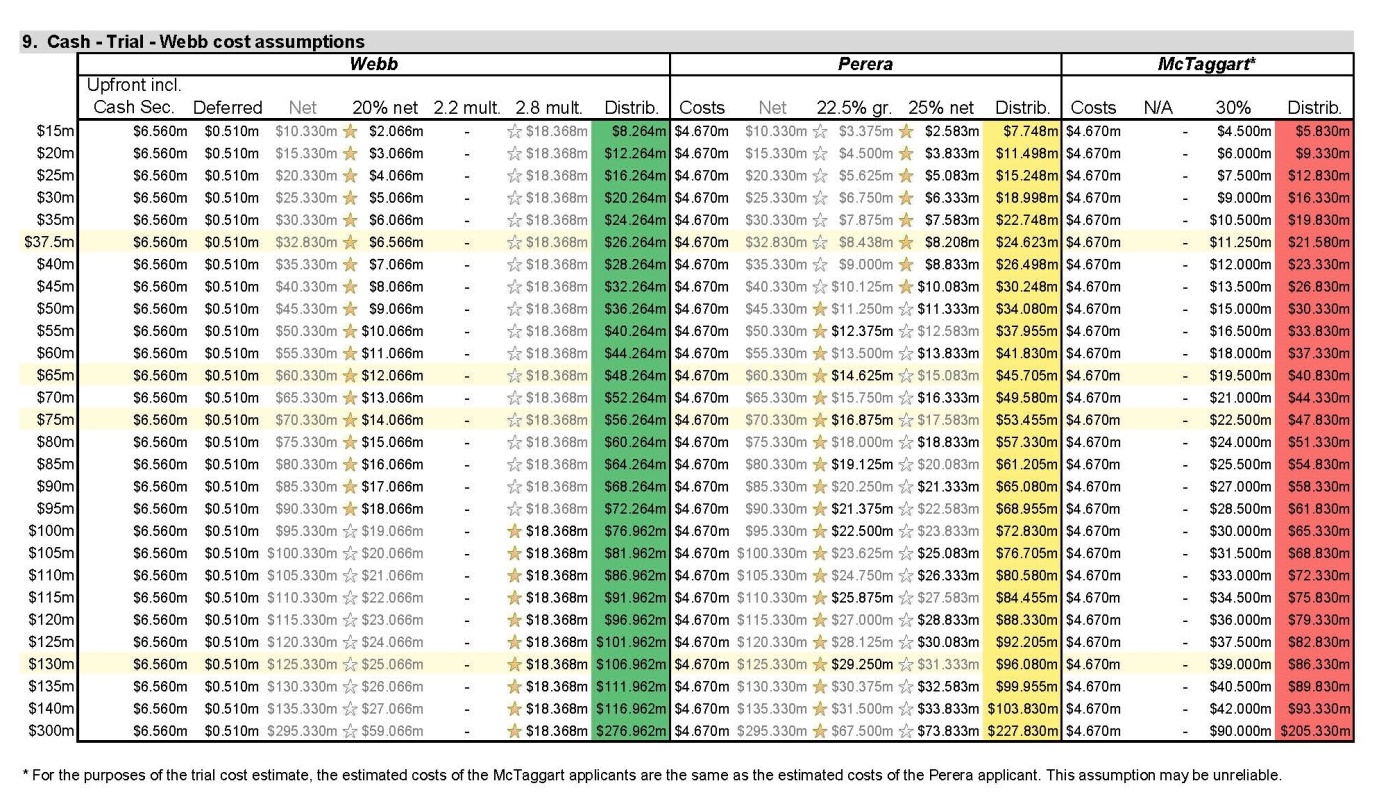

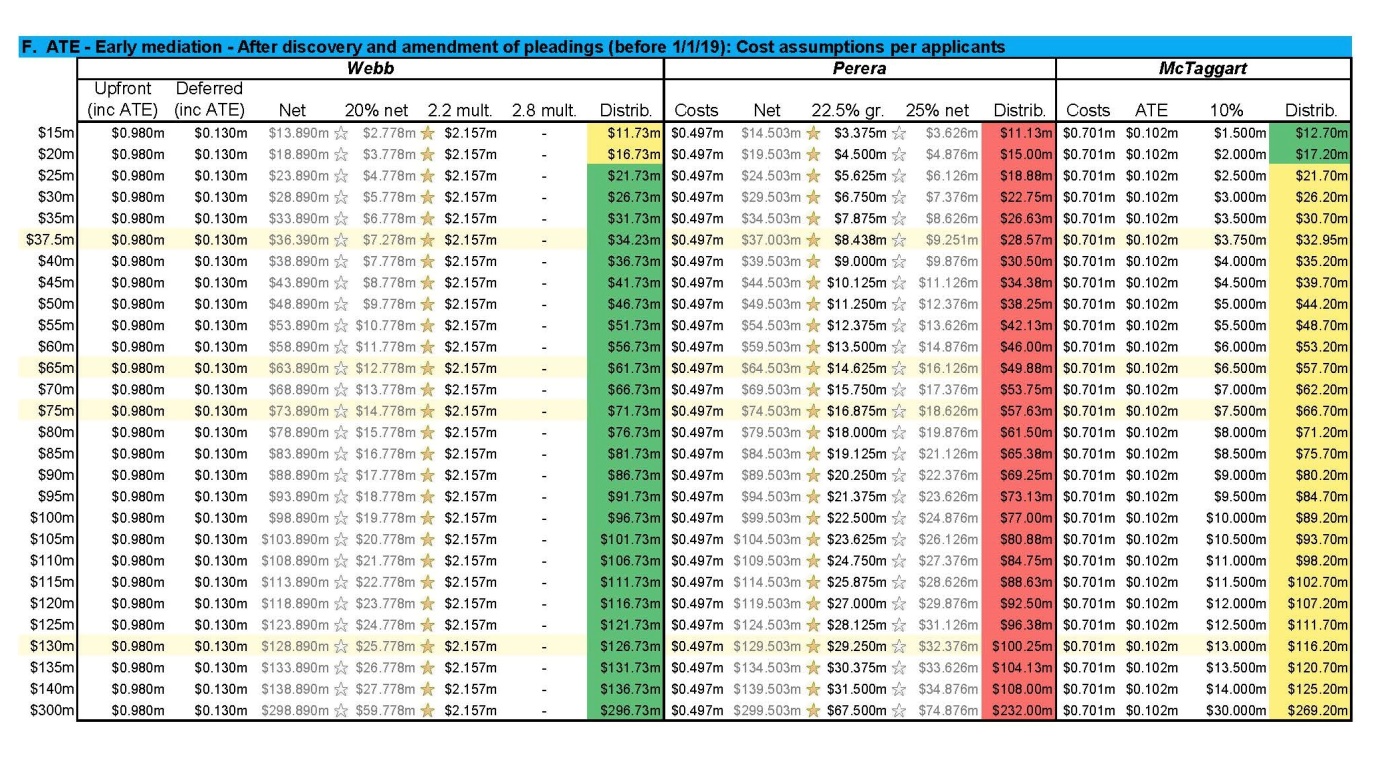

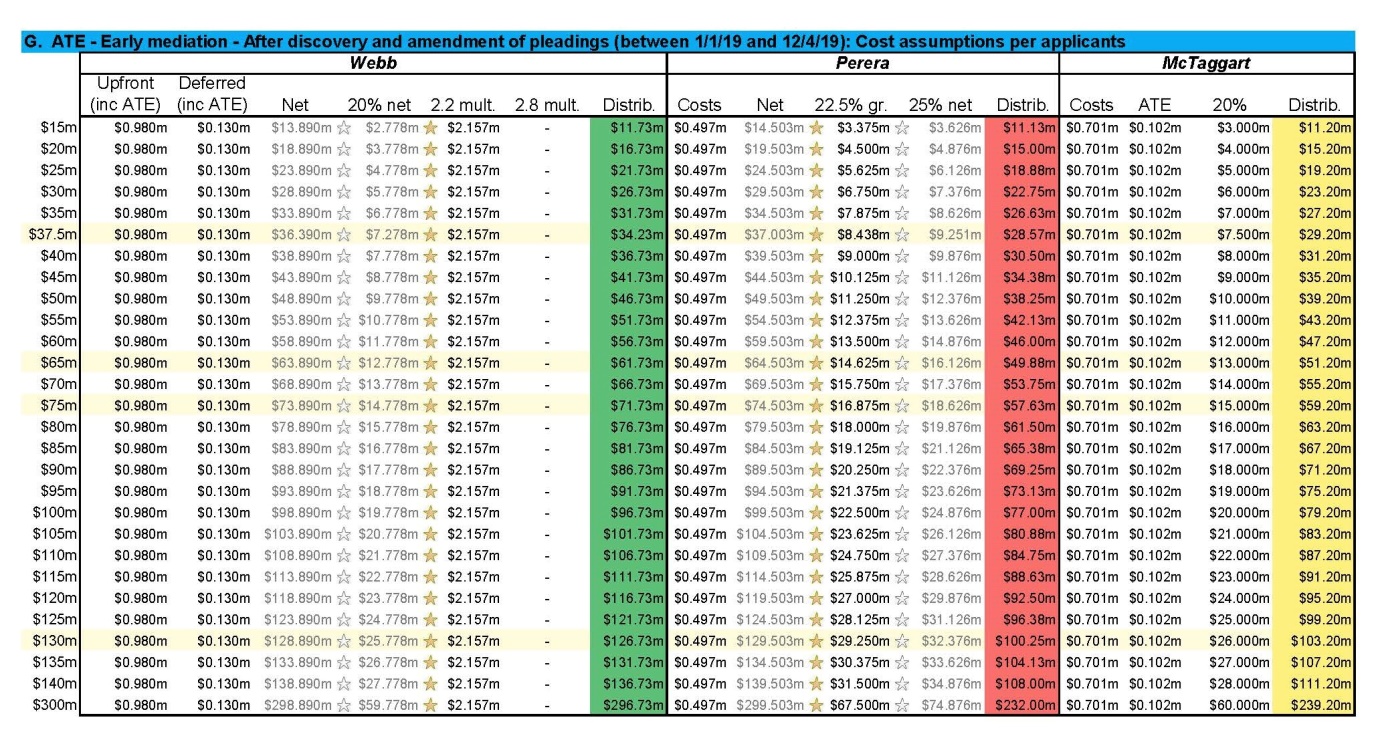

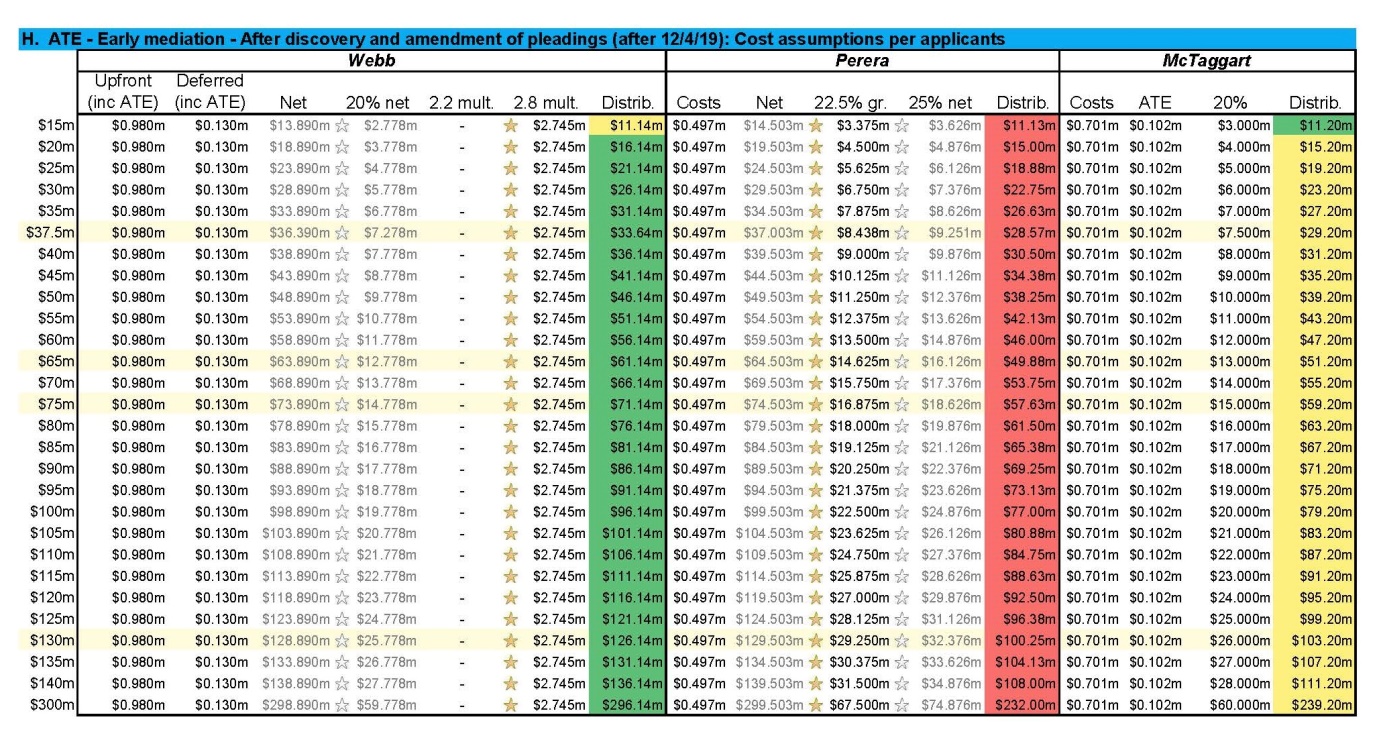

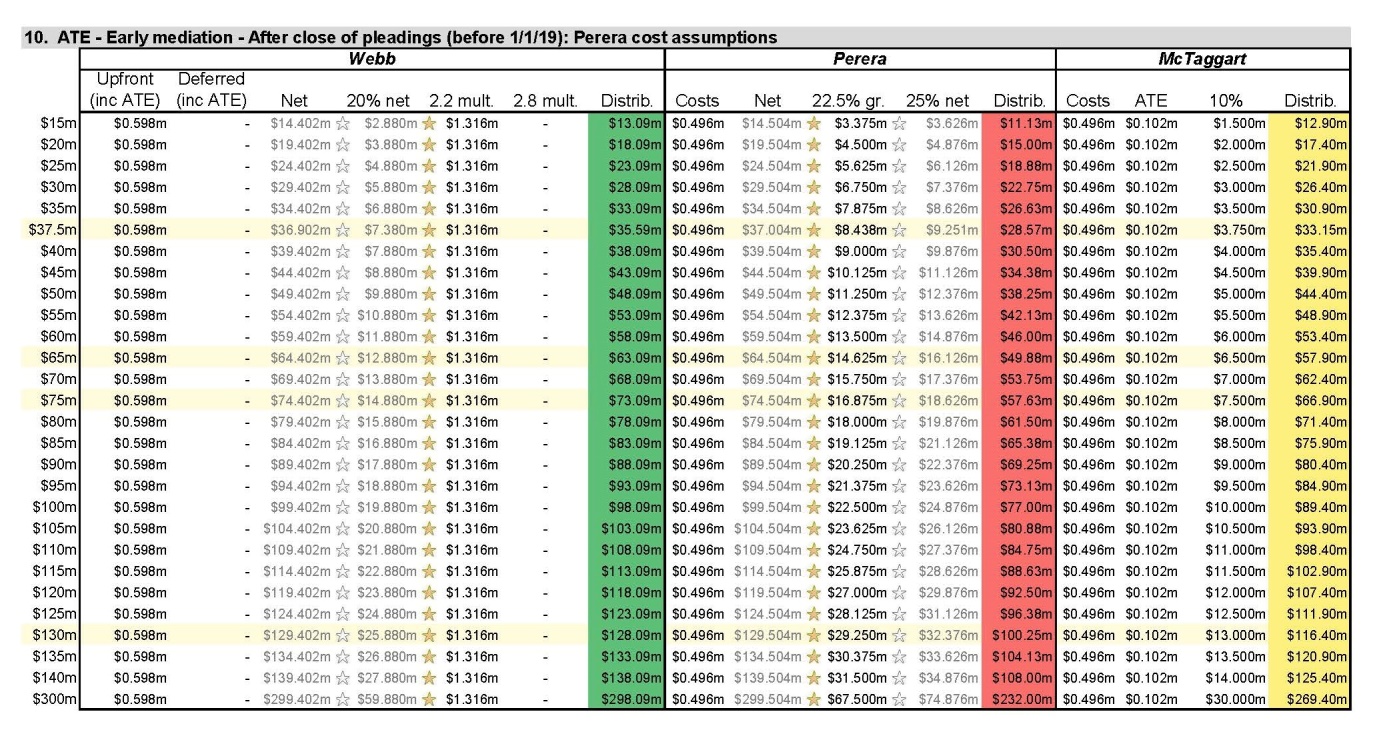

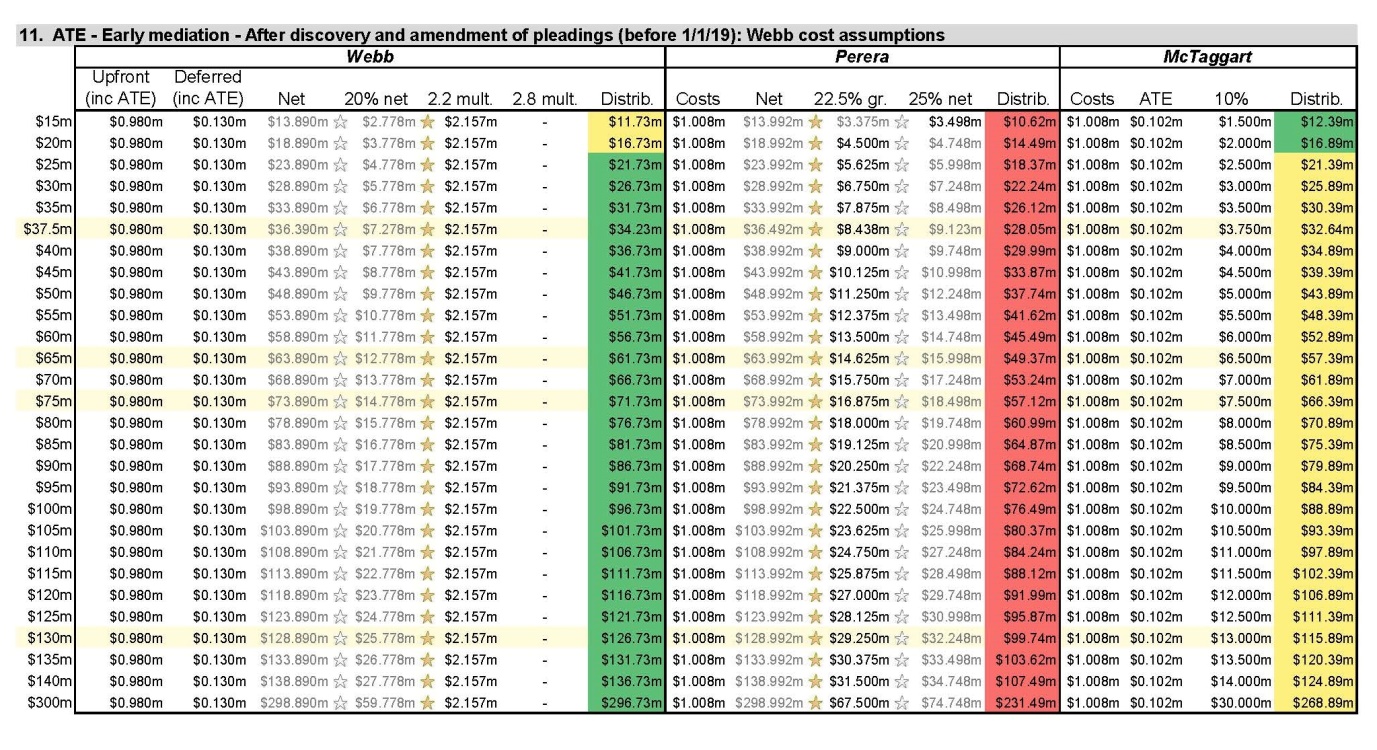

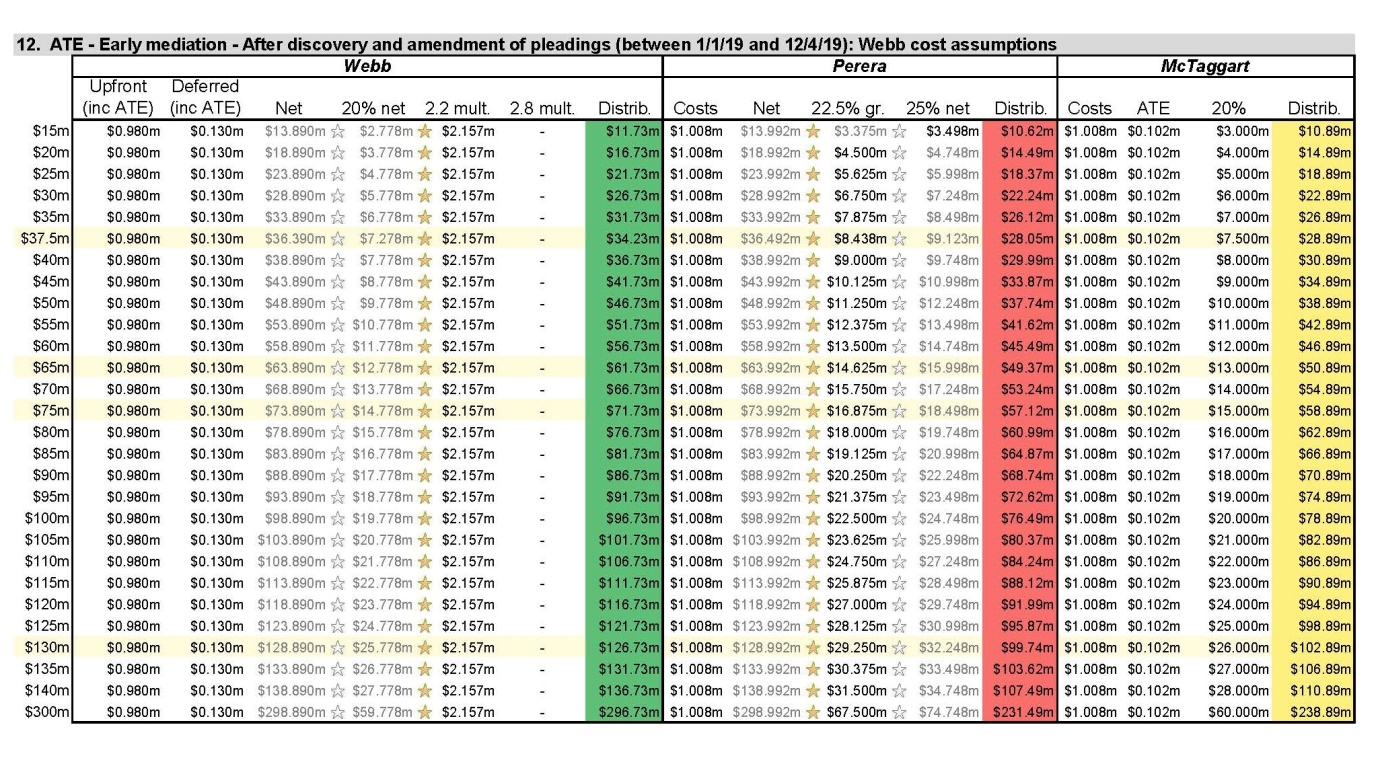

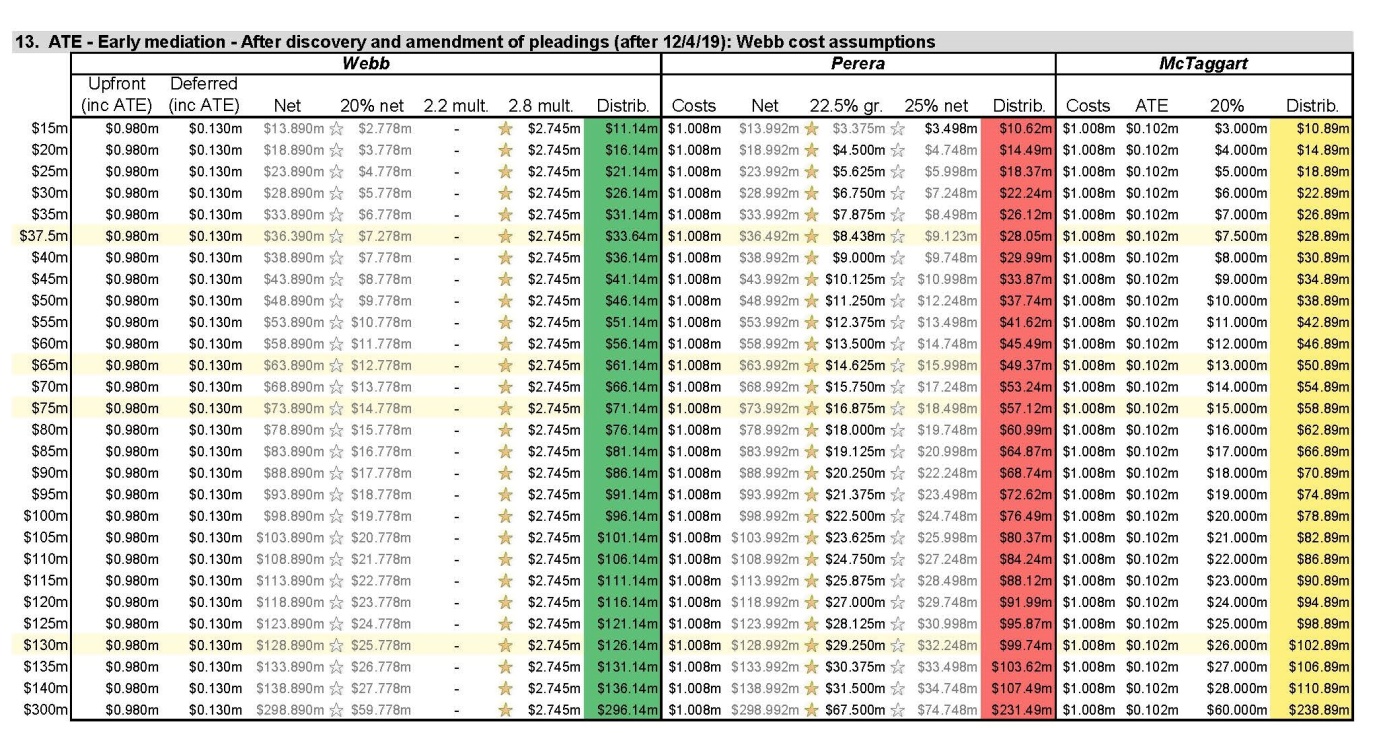

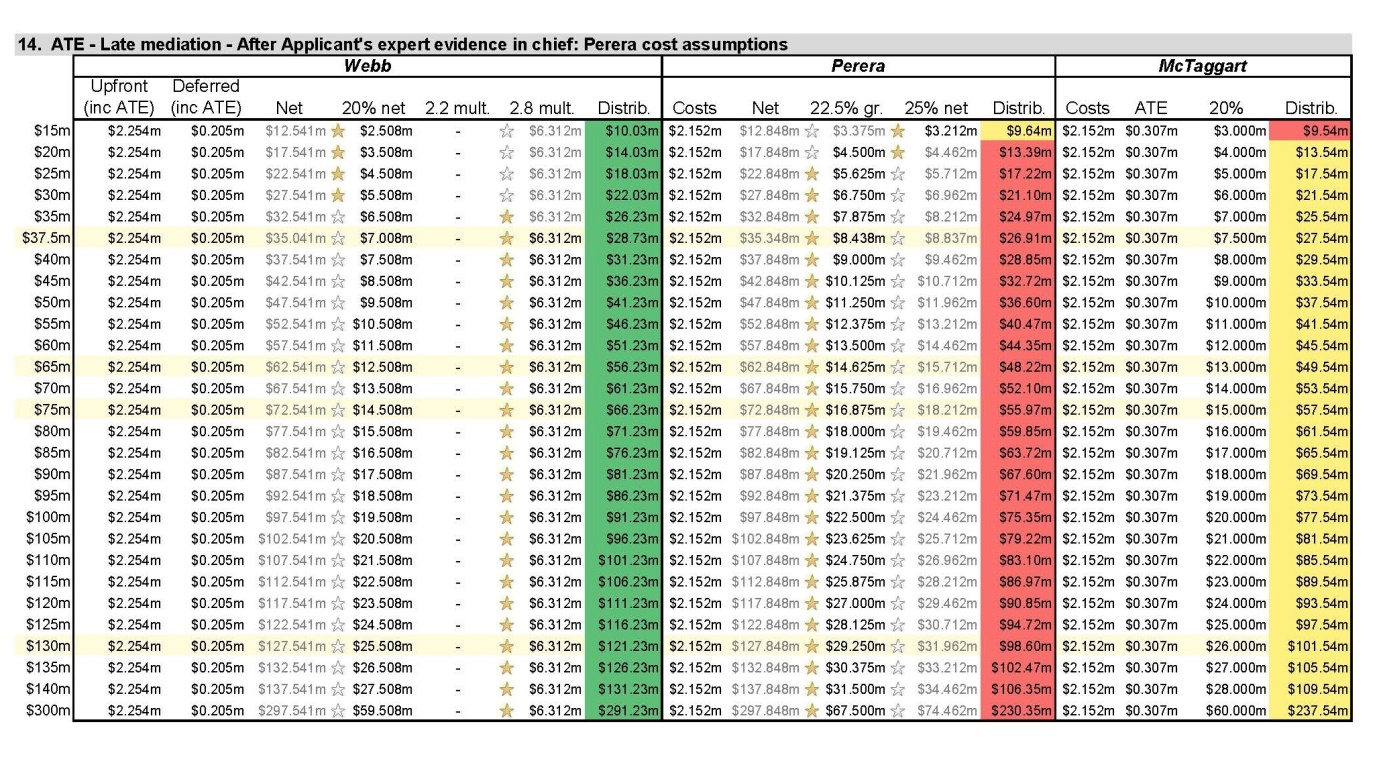

H.2 Miscellaneous Contentions as to Comparative Financial Analysis | [258] |

H.2.1 Mr Perera’s Fundamental Objection to the Process Adopted | [260] |

H.2.2 Mr Perera’s more Specific Objection as to Contingencies | [264] |

H.2.3 The McTaggart Applicants’ Objections as to ATE Costs in the Webb Proceeding | [265] |

H.2.4 The McTaggart Applicants’ Submissions as to Webb “book build” Costs | [276] |

[277] | |

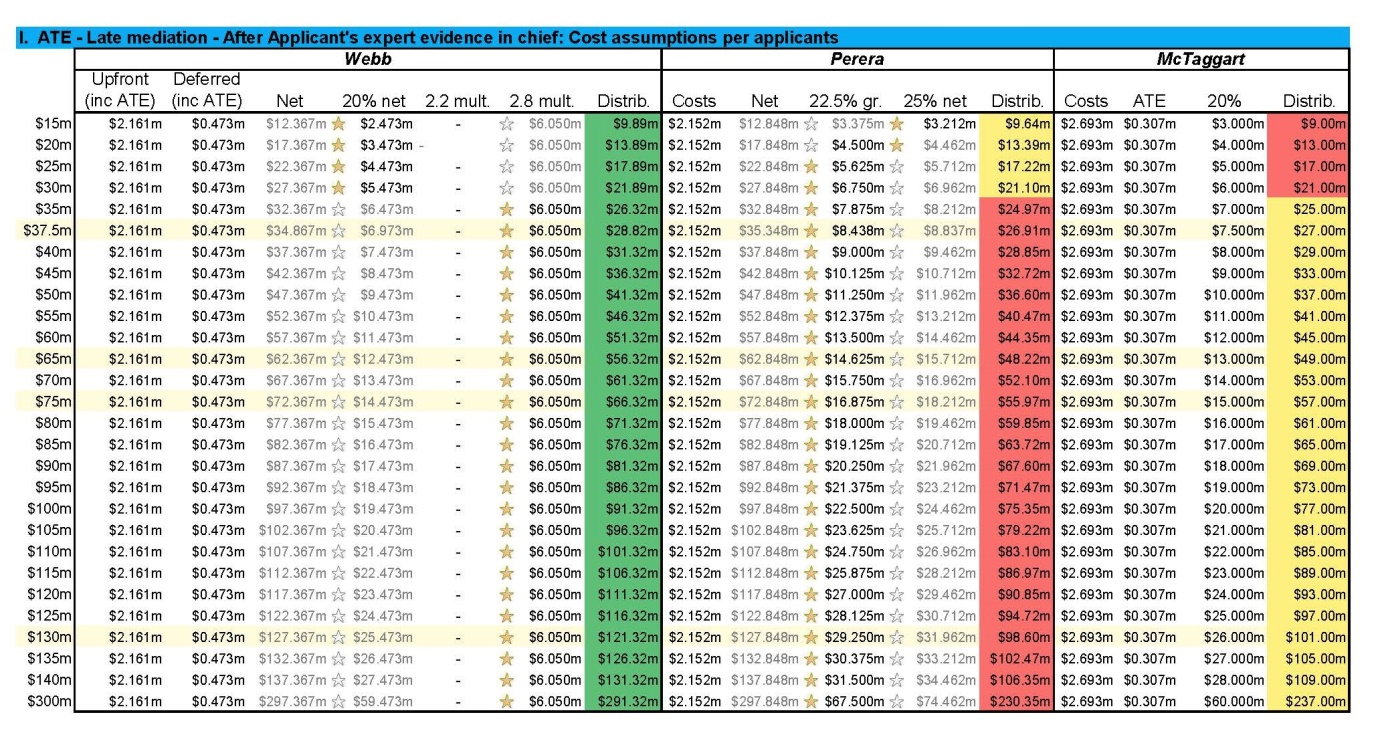

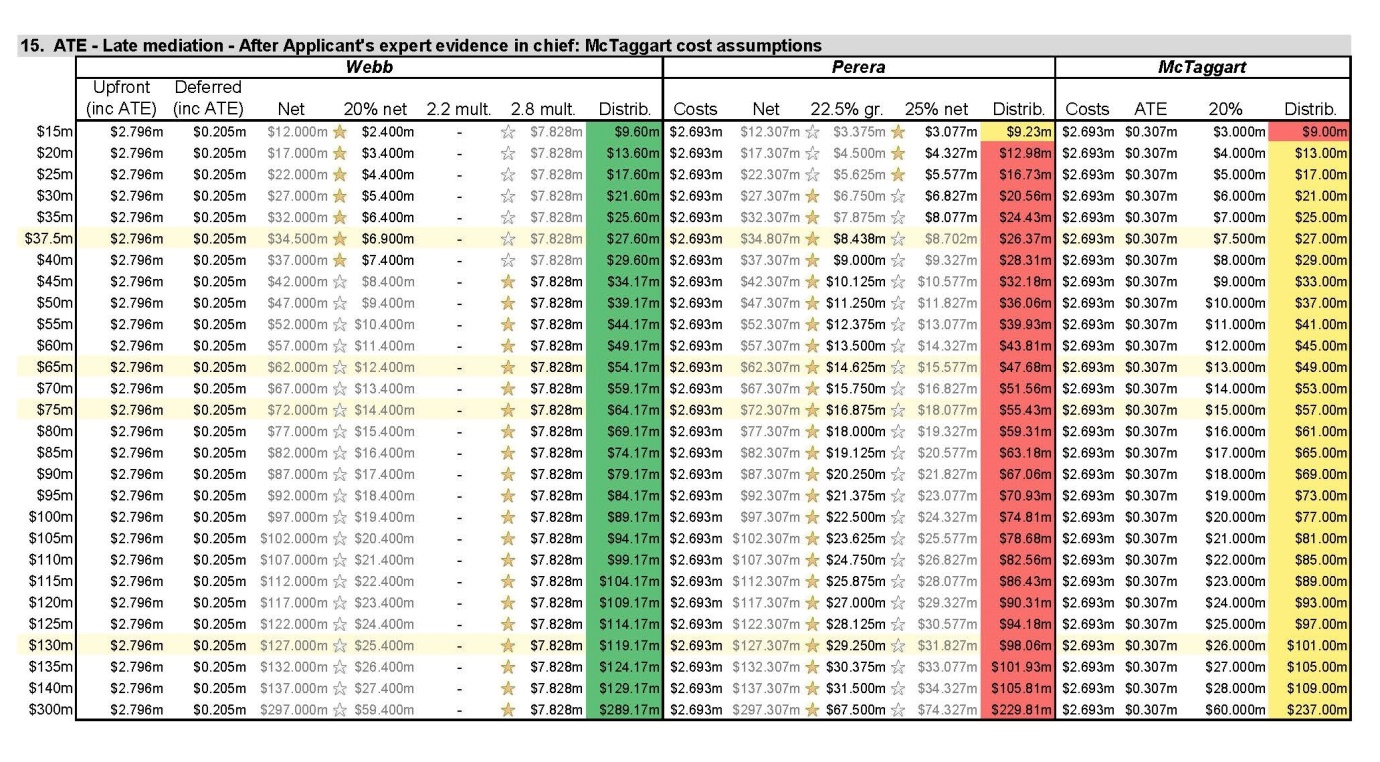

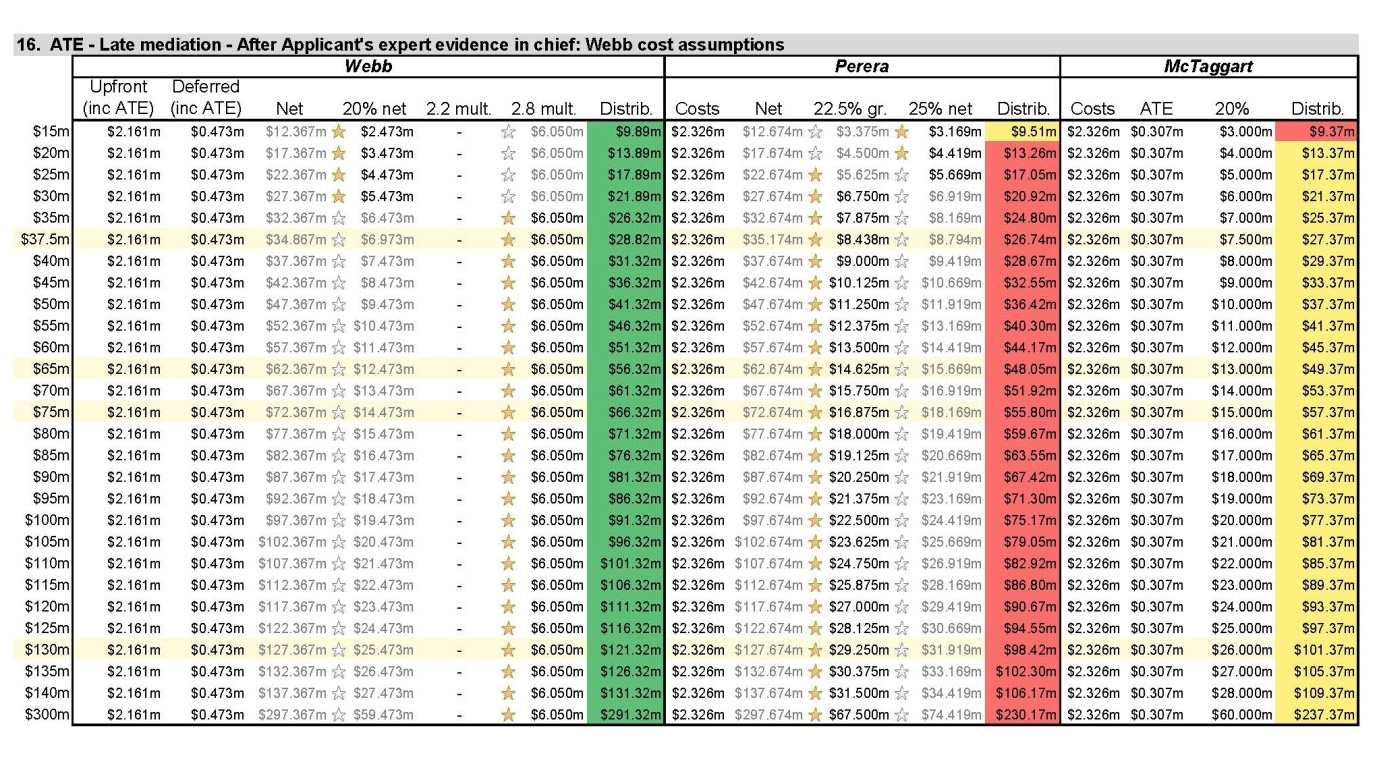

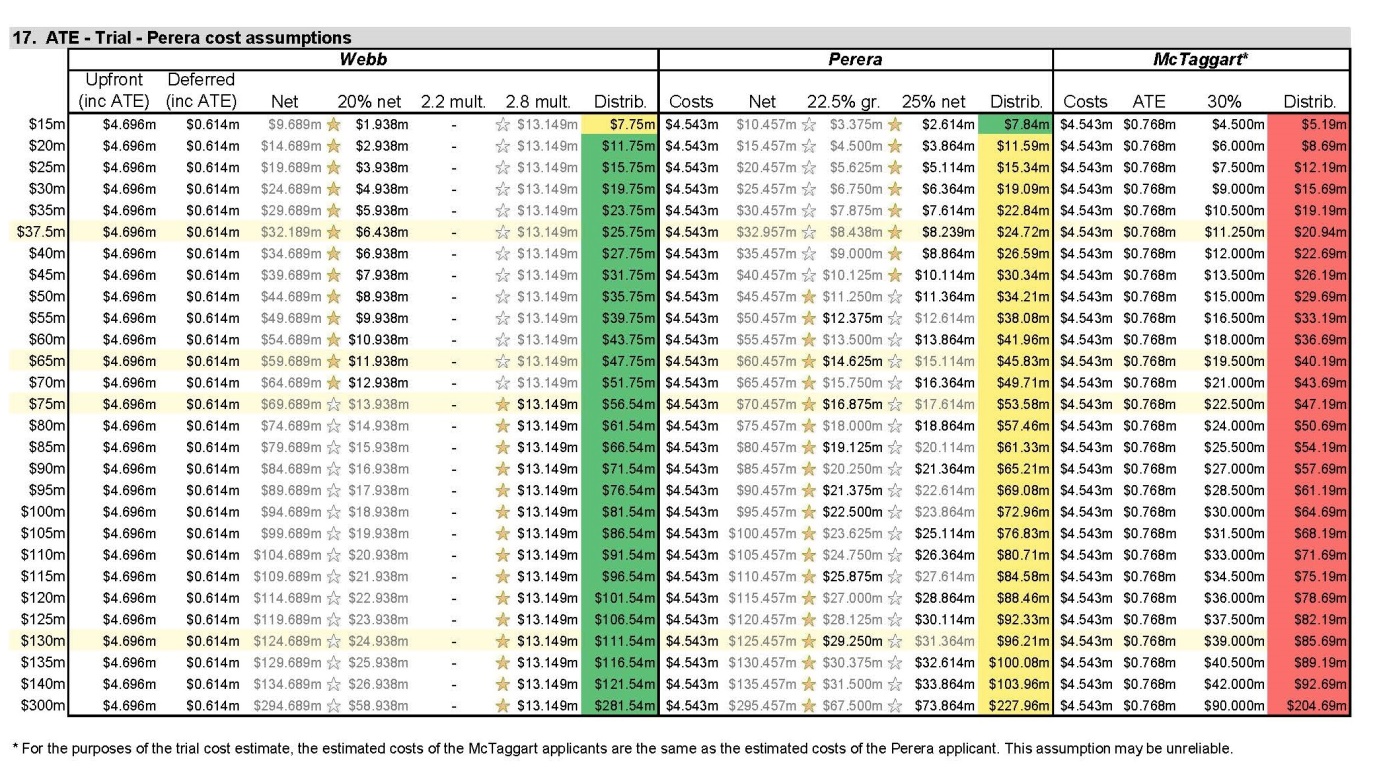

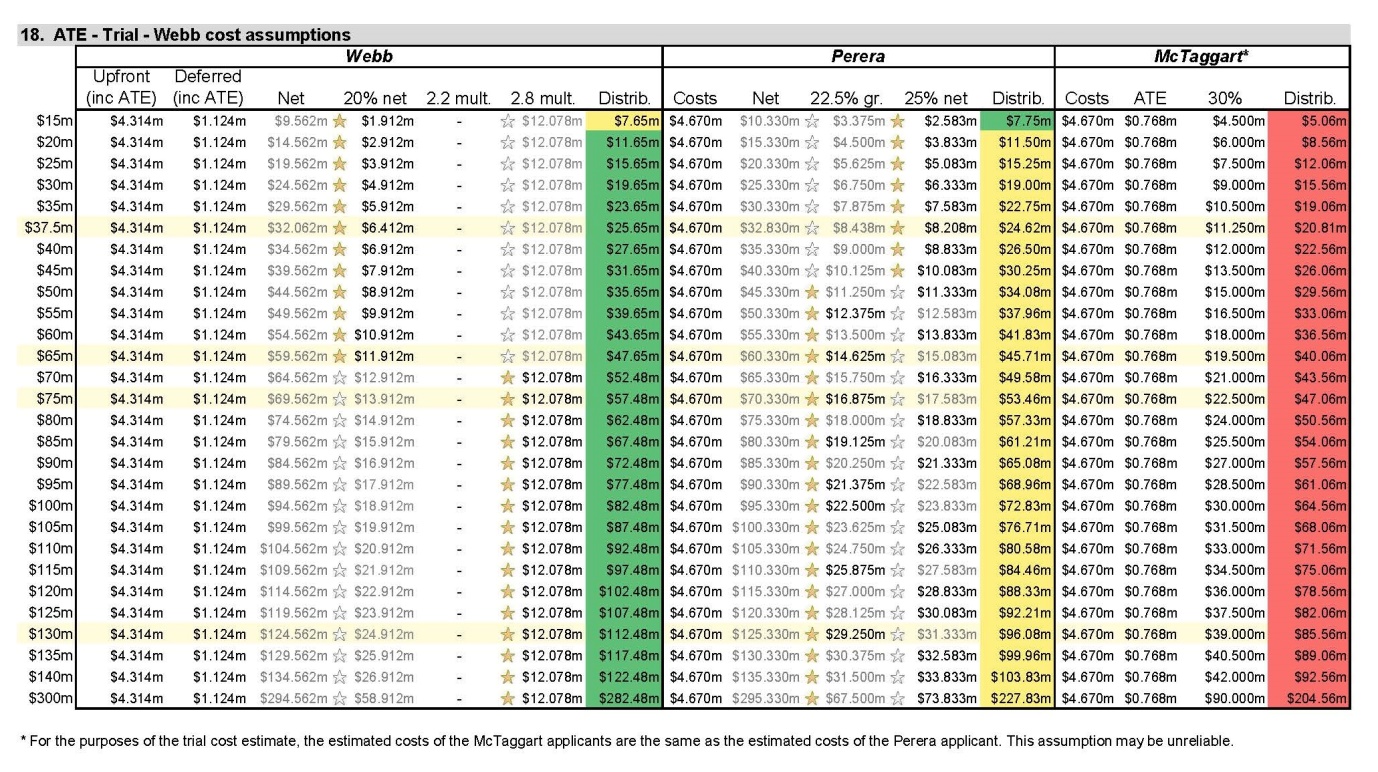

H.2.6 The Evidence in Relation to the Late Mediation and Evidence in Reply | [279] |

[280] | |

[283] | |

[295] | |

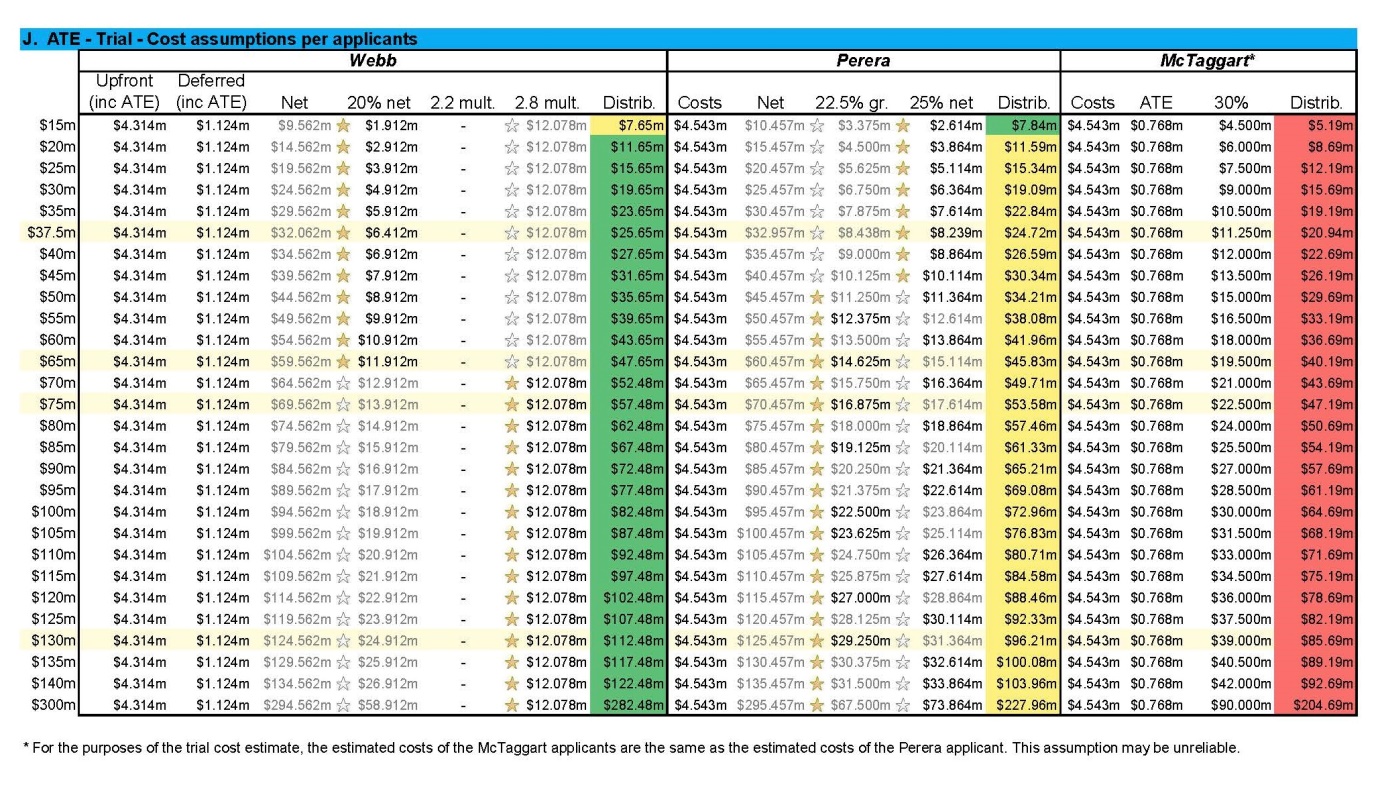

[305] | |

[325] | |

[325] | |

J.2 Conclusions on the Comparative Multifactorial Assessment | [328] |

[331] | |

[331] | |

[350] | |

[350] | |

[351] | |

[356] | |

[362] | |

[371] | |

[377] |

1 The controversy between the first respondent (GetSwift) and persons who acquired an interest in its listed securities presents for consideration a problem of signal importance relating to the conduct in this Court of Part IVA representative proceedings: the Court’s response to the phenomenon of competing securities class actions.

2 In this matter (to use that word in its constitutional sense), three open class actions have been brought at the instigation of three different firms of solicitors, each with the support of different litigation funders: NSD 226 of 2018 (Perera Proceeding), NSD 440 of 2018 (McTaggart Proceeding) and NSD 580 of 2018 (Webb Proceeding).

3 It is beyond the scope of these reasons to conduct an economic analysis of litigation funding and to deal, in any exhaustive way, with how the commercial opportunities presented to funders, and to solicitors with commercial relationships with funders, intersect with the role of the Court as an arm of government and the roles of solicitors as fiduciaries and officers of the Court in the administration of justice – these are very large and complex topics. What requires present attention is how the Court deals with competing commercial enterprises which seek to use the processes of the Court to make money and the role of the Court in ensuring the use of those processes for their proper purpose and informed by considerations including: (a) the statutory mandate (s 37M(3) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (Act)) to facilitate the just resolution of disputed claims according to law and as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible; and (b) the furtherance of the Court’s supervisory and protective role in relation to group members.

4 I will make orders ensuring that only one of the three current open class actions continues. This result, and the ancillary orders facilitating that result, ensures protection of the Court’s processes and gives effect to the considerations to which I have just referred.

5 Regrettably, these reasons are lengthy because of a perceived need to explain the background as to how the issue of multiplicity of competing class actions has arisen, deal with complex and contested issues as to power deal and then, following a comparative analysis, to make a determination as to an appropriate remedial response. At the outset, however, I wish to emphasise three things.

6 First, as I will explain, other occasions of competing class actions have led to different procedural outcomes (and may well do so in the future); this is, after all, a case management decision rooted in the particular circumstances of the cases subject to case management. Here, the issue has emerged very early, the cases proposed to be advanced are substantially the same, and all interested parties are agreed that grasping the nettle now makes sense (although each of the representative applicants, unsurprisingly, differs as to the particular remedial response for which they advocate). This may not be the case in subsequent cases where apparently competing actions may raise different common issues for consideration, or span different time periods, or advance conflicting case theories (that is, bona fide and not as a stratagem to distinguish one case from another). In some cases there may be a sound reason to think the various promotors of the class action may, without undue delay, come to a consensus as to how the issue of competing claims is resolved which is acceptable to the Court. Each instance of competing class actions needs to be managed by reference to the bespoke circumstances before the Court. Having said this, although this case management decision is focussed on the particular circumstances, for reasons I will explain, the issues with which I am confronted reflect themes which now increasingly recur in what has emerged as the usual form of securities class actions.

7 Secondly, the comparative assessment undertaken below is a multifactorial one reflecting the considerations identified by the parties and also the accumulated experience of how analogous multiplicity issues have been handled by courts in Australia, and also how North American courts have dealt with competing class actions, albeit in the different context of certification. It should be stressed that any principled assessment between class actions is not so crude so as to be determined by reference only to the relative size of the funding commission spruiked in promotional material. It is inconsistent with the principled exercise of judicial power, and also unedifying, for the Court to be perceived as akin to a metaphorical auctioneer going around the room adopting the curial equivalent of entreating: “Are we all done? It’s now going to go under the hammer!” The Court’s role is to quell controversies in accordance with Chapter III of the Constitution and, in doing so, ensure its processes are used for the purposes for which they were designed. To the extent a determination is required as to which open class securities class action goes forward, the weight to be given to a particular relevant consideration, including ‘headline’ commission rates of funders, will necessarily vary depending on the particular circumstances.

8 Thirdly, much of what follows has, as its point of departure, the expectation that this dispute will resolve in the same way as all other securities class actions have done to date: by way of a paction sanctioned by the Court. I have not yet seen a defence, let alone evidence. Ratiocinations premised on this settlement assumption are based on nothing more than empirical evidence as to what is likely, and must not be seen as an indication that this matter is one GetSwift should or will necessarily settle; nor that any settlement will involve the payment of substantial compensation to group members. Moreover, as will be seen, this judgment involves reference to modelling done by reference to various damages scenarios. It should be obvious, but is worth emphasising, that these scenarios have been chosen to reflect various hypotheses based on ranges of damages suggested by the applicants’ solicitors (including estimates which have been disavowed as not reflecting the reality of a particularised claim). Modelling needs inputs and, in the absence of any evidence, nothing should be made of the figures chosen which, at least in part, simply reflect past experience of cases of this sort.

9 I will return to the first two of these matters below, but part of working out how to manage and resolve a perceived problem, is appreciating why it exists. With this in mind, it is useful to start with asking the question: how did we get here? Or, put more particularly, how did the phenomenon of competing securities class actions arise?

B.1 The Competing Securities Class Action Emerges

10 The first Australian securities class action which bears all the essential characteristics of the genus was the Aristocrat class action (NSD 362 of 2004 Dorajay Pty Ltd v Aristocrat Leisure Ltd). As an illustration of how things have changed, and how the possibility of civil liability to investors for a breach of continuous disclosure obligations has seeped into the legal consciousness, it is well to remember the circumstances that gave rise to that litigation. A senior executive of Aristocrat had brought an action for wrongful dismissal. In the defence, Aristocrat, a listed company, contended that it was entitled to dismiss the executive for a number of reasons, including the fact that he had been responsible for failing to disclose material information to the market of investors in Aristocrat shares. The notion of a listed entity defending a legal proceeding by impliedly admitting that its investors may have been misled is something which seems from another age, and yet it is less than a generation ago.

11 The post-Aristocrat securities class action not only has a common form, but often has a familiar genesis and development. A significant drop in the value of securities is scrutinised to determine whether it is likely that the relevant drop had been occasioned by the late revelation of material information. Premised on assumptions that: (a) the value of the relevant security reflects the expected discounted value of future cash flows to the security holders; and (b) that the security operates in an efficient market, the information released prior to the price-drop is reviewed to ascertain whether it was likely to have caused the market to alter its expectation of future cash flows (hence causing a repricing of the security to reflect these altered expectations). Analysis takes place as to whether there is a sufficient basis for assuming the existence of contravening conduct during a period anterior to the revelation (this will usually involve close consideration of any relevant disclosures and available analyst reports). Further analysis is undertaken as to the size of the potential loss that may be related to the suspected contravening conduct over an identified period (the duration of which is identified by the preceding analysis).

12 Following this, if all the relevant boxes are ticked, the bugle is sounded. Funding terms are discussed and (at least prior to the advent of common funds orders) there is a concerted effort to sign up institutional and other group members. At some time during this developmental stage, an announcement might be made of a potential class action, garnering media attention which may augment the number of affected shareholders who may wish to participate actively in the proposed class action, but also may precipitate a further decline in the price of the securities.

13 Of course, some actions may have different origins, such as an approach by a ‘whistle-blower’ or revelations through public inquiries, and the time needed for the analysis may vary considerably, but to anyone who has been involved actively in securities class actions since their advent, the pattern described above is familiar.

14 I hasten to add that by identifying a commonplace pattern, I do not suggest that the development of the usual form of securities class actions should be looked upon askance. To the contrary, an informed observer would likely recognise that a consequence of these developments has been a heightened awareness among corporations, through their officers, of their obligations to act in such a way as to avoid continuous disclosure breaches and contravention of the norms prohibiting misleading and deceptive conduct. This is not the place to debate the social utility of securities class actions; this would involve a range of considerations which raise complex and collateral assessments (such as, for example, its impact on the price of D&O and ‘Side C’ liability cover), but despite what some would describe as their ‘commercialisation’ and concerns which may arise concerning a premature announcement of a proposed class action that never proceeds, it can be argued cogently that they have served, and continue to serve, a role in not only providing for significant amounts to be paid to investors for claimed losses occasioned by allegations of corporate malefaction (that would, absent securities class actions, never have been paid), but they also have occasioned a private regulatory discipline on the conduct of listed companies and their dealings with the market of investors in their securities.

15 The securities class action has also been important as the vehicle driving the procedural development of Part IVA of the Act. One of these developments is of direct relevance to the present issue. It can be traced back to Aristocrat, where the primary judge, in an interlocutory hearing, took the view that a closed class (which included a criterion restricting composition of the group to those who had retained the solicitors for the applicant) was inappropriate because closed classes had the effect that “the clear legislative intention [of Part IVA] is subverted”: see Dorajay Pty Ltd v Aristocrat Leisure Ltd [2005] FCA 1483; (2005) 147 FCR 394 at 433 [135] per Stone J. That decision was followed shortly thereafter: see Rod Investments (Vic) Pty Ltd v Clark [2005] VSC 449 (Hansen J)) and Jameson v Professional Investment Services Pty Ltd [2007] NSWSC 1437; (2007) 215 FLR 377 (Young CJ in Eq). The heterodoxy that a class defined by reference to a funding or similar criterion was invalid was, however, eventually exposed in Multiplex Funds Management Ltd v P Dawson Nominees Pty Ltd [2007] FCAFC 200; (2007) 164 FCR 275 (French, Lindgren and Jacobson JJ), in essence because of the text of a critical provision within Part IVA, s 33C, which expressly provided that a proceeding could be commenced by only some of the persons who had claims against a respondent.

16 This was a boon to litigation funders. It meant that a class could be constructed of persons who had signed funding agreements with an individual funder, thus eliminating the difficulty of so-called ‘free riders’, that is, persons who had not signed funding agreements but who would be part of any open class. However, like a ‘Whac-A-Mole’ game, where one mole is whacked by a mallet but another pops up, a further problem then emerged – if closed classes were allowed, how did a respondent obtain certainty against additional claims by settling only a closed class? A further procedural expedient resulted: allowing the ‘opening up’ and then ‘closing down’ of a class – this allowed certainty to be delivered to a respondent in settling what had originally been commenced as closed class proceedings (although this, in turn created its own controversies, which now appear to be largely resolved: see Melbourne City Investments Pty Ltd v Treasury Wine Estates Ltd [2017] FCAFC 98; (2017) 252 FCR 1 at 20-22 [70]-[76] per Jagot, Yates and Murphy JJ).

17 But how should these arrangements, pursuant to which these funded proceedings were brought, be characterised? The superficial answer was simply as a means by which a proceeding governed by Part IVA of the Act could be conducted to the benefit of group members, the funder and the solicitors. A more complex answer was provided by the Full Court in Brookfield Multiplex Ltd v International Litigation Funding Partners Pte Ltd [2009] FCAFC 147; (2009) 180 FCR 11, where the majority (Sundberg and Dowsett JJ) found that the bilateral (or, with the solicitors, trilateral) arrangements pursuant to which these funded class actions were conducted were unregistered managed investment schemes for the purposes of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). A majority of the Full Court held that the class action (or, more particularly, the scheme constituted by the agreements which allowed the class action to be funded and maintained) had the following characteristics: (a) the promises given by the group members and the funder were ‘money’s worth’ contributed for the purposes of the litigation funding arrangement made in return for their acquiring rights to share in any judgment sum, and the benefit of the funder’s promises to meet legal costs; (b) the opportunity to prosecute a claim, with virtually no exposure to any costs or outgoings in the event of failure, was a benefit accruing to group members produced as a result of all parties carrying out their obligations under the scheme and that a successful prosecution of those claims would yield financial benefits to group members, the funder and, indirectly, the solicitors; (c) the pooling of contributions, which was effected by the group members making their individual promises available for the purposes and benefit of the scheme and, ultimately, for the funder’s benefit; (d) the litigation funding arrangement was a common enterprise in that there was a shared purpose of pursuing group members’ claims successfully that would then benefit the group members, the funder and the solicitors.

18 The Full Court’s conclusions remain authoritative as a statement of how at least two of the three arrangements put in place for the prosecution of a class action against the present respondent should be conceptualised. This is notwithstanding the fact that unlike Brookfield Multiplex, all of the class actions with which we are concerned are open class. As will be explained, two of the three class actions involve the now familiar arrangement of funding agreements being signed by a number of group members and hence involve contractual relationships similar, but not identical, to those involved in Brookfield Multiplex. The third involves no funding agreements in the conventional sense (as between group members and the funder) but a single agreement to fund the litigation, relying on the Court making a common fund order. This characterisation point is significant in that this type of litigation, unlike conventional litigation, is one where there exists a shared purpose of each of the participants in the enterprise which transcends the representative applicants’ individual purpose to maintain their claim for statutory compensation. It will be necessary to return to thus unusual aspect of Part IVA funded proceedings below. This characterisation is also useful in illustrating that despite their differences, each proceeding, in effect, represents a common enterprise of a commercial character which uses the Court’s processes to obtain mutual benefits for each of the group members, the funder and the solicitors. The use of the processes of the Court in this way is, of course, entirely licit, but it brings into focus the point I made at the outset: the necessity of the Court, in safeguarding its processes, to control the use of those processes for a commercial enterprise and ensure that any such use is consistent with the role of the Court, the just and efficient resolution of claims, and the Court’s supervisory and protective role towards group members.

19 Returning to the background narrative, in May 2010, a Class Order (Australian Securities and Investments Commission, Class Order, [CO10/333], 5 May 2018) exempted funded proceedings from the definition of managed investment schemes and also exempted funders and lawyers from the requirement to hold an Australian Financial Service Licence or act as an authorised representative of a licensee to provide financial services associated with funded proceedings. According to a discussion paper prepared by the New South Wales Office of the Legal Services Commissioner entitled “The Regulation of Third Party Litigation Finding in Australia” (March 2012), this had been immediately preceded by an announcement, by the then responsible Minister, noting that the Federal Government recognised that class actions are already subject to a regulatory regime consisting of legislation, court rules, and the legal profession rules protecting the interests of clients and, as a consequence, that the government did not consider it necessary to impose further regulatory burdens for litigation funders. The result was a reversion to business as usual, allowing conduct of closed class securities actions, and an environment whereby any regulation was as imposed by legislation governing the conduct of class actions and the Court and, indirectly, by the norms governing the conduct of lawyers.

20 An inevitable consequence of the rise of the closed class representative proceedings was the rise of the competing class action. The reason was simple: if a proceeding could be commenced on behalf of only some of the investors, then this allowed a further, differently funded class action to ‘hoover up’ the balance (or a substantial part) of the unsigned class.

21 If one pauses, one might be forgiven for thinking that these developments and, in particular, the emergence of these common enterprises, would not have been expected by those who were responsible for the report of the Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) tabled in Parliament in December 1988 entitled ‘Grouped Proceedings in the Federal Court’ (ALRC Report) upon which Part IVA of the Act was largely, but not wholly, based. The original design, as noted in the ALRC Report at [92], was identified as follows:

The main objective of [the class action regime]…is to secure a single decision on issues common to all and to reduce the cost of determining all related issues arising from the wrongdoing. To achieve maximum economy in the use of resources and to reduce the cost of proceedings, everyone with related claims should be involved in the proceedings and should be bound by the result.

(Emphasis added)

22 Consistently with this, in describing the general objectives of the Bill which inserted Part IVA in the Act, the then Attorney-General stated that it would:

provide a new representative action procedure in the Federal Court. The new procedure will enhance access to justice, reduce the costs of proceedings and promote efficiency in the use of court resources…The Bill gives the Federal Court an efficient and effective procedure to deal with multiple claims. Such a procedure is needed for two purposes. The first is to provide a real remedy where, although many people are affected and the total amount at issue is significant, each person’s loss is small and not economically viable to recover in individual actions. It will thus give access to the courts to those in the community who have been effectively denied justice because of the high cost of taking action. The second purpose of the Bill is to deal efficiently with the situation where the damages sought by each claimant are large enough to justify individual actions and a large number of person wish to sue the respondent. The new procedure will mean that groups of person, whether they are shareholders or investors, or people pursuing consumer claims, will be able to obtain redress and do so more cheaply and efficiently than would be the case with individual actions.

(Second Reading Speech by Attorney-General, House of Representatives, 14 November 1991, Hansard, at pp 3174-3175)

23 Given the policy objectives of Part IVA of the Act, the emergence of the notion rejected in Brookfield Multiplex, preventing closed classes by reference to a solicitor or funding criterion, is on one level understandable, because it was clearly anticipated that open classes of those affected by mass wrongs would be the norm and not the exception. The leitmotiv of the ALRC Report was the provision of access to justice to those with claims that could not be pursued practically by ordinary, inter partes litigation; it was not an occasion for consideration being given to the rise of litigation funding which, it must be said, has allowed Part IVA to be used very successfully in prosecuting mass claims. So much so that, according to a leading academic expert in Australia’s class action regime, Professor Vince Morabito (An Empirical Study of Australia’s Class Action Regimes, Fifth Report: The First Twenty-Five Years of Class Actions in Australia (Report, Monash University, 20 July 2017) https://ssrn.com/abstract=3005901), since the introduction of Part IVA in 1992, there have been (at least as at July 2017), over 513 class actions commenced in relation to 335 legal disputes. Of course, a significant number of these proceedings are multiple class actions over the same legal dispute, as is evident from these statistics.

24 The prevalence and commercial attractiveness to funders of the securities class action, compared to other types of class actions, is evident from the following statistics also gathered by Professor Morabito (as provided to the ALRC), on substantive claims advanced in funded Part IVA proceedings filed between the introduction of Part IVA in 1992 and 3 March 2018:

Types of claims | Number of class actions |

Claims by shareholders | 61 (52.1%). |

Claims by investors | 25 (21.3%) |

Consumer protection claims | 11 (9.4%) |

Mass tort claims | 4 (3.4%) |

Claims by employees/workers | 4 (3.4%) |

Product liability claims | 4 (3.4%) |

Claims by franchisees, agents &/or distributors | 4 (3.4%) |

Claims by real estate owners | 1 (0.8%) |

Claims by alleged victims of racial discrimination in non-migration proceedings | 1 (0.8%) |

Claims by alleged victims of cartels | 1 (0.8%) |

Misfeasance in public office claim | 1 (0.8%) |

Total | 117 (100%) |

25 This brings us to the final development of which mention ought to be made and which has had the important effect of encouraging the commencement of open class representative proceedings. This was the emergence of the common fund order in Money Max Int Pty Ltd (Trustee) v QBE Insurance Group Limited [2016] FCAFC 148; (2016) 245 FCR 191 (Murphy, Gleeson and Beach JJ). Rather than the economics of a class action being dictated by the size of sign-up, a common fund order allows an open class representative proceeding to be commenced without the necessity to build a book of group members who have bargained away part of the proceeds of their claim. Instead of addressing the ‘free-rider’ problem by making ‘funding equalisation orders’ (to redistribute the additional amounts received ‘in hand’ by unfunded class members pro rata across the class as a whole), the Court indicated its willingness to fashion a solution whereby the funder, who had borne the risks of the litigation, is recompensed from the common fund of proceeds obtained by the group as a whole.

26 Following on from this, in Blairgowrie Trading Ltd v Allco Finance Group Ltd (recs and mgrs appt) (in liq) (No 3) [2017] FCA 330; (2017) 343 ALR 476, Beach J accepted, in the context of that case, that it was reasonable for the funder to receive a funding commission rate of 30% of the net settlement sum having regard to a range of factors, including those identified in Money Max at 209 [80], being:

(a) the proportion of group members who had voluntarily accepted the funding agreement, and how the proposed rate under the common fund order compared to the rate recoverable under the funding agreement;

(b) how the proposed rate compared to other funding commission rates available, and to alternative funding mechanisms;

(c) the risks assumed by the funder;

(d) whether the commission to be received by the litigation funder was proportionate to the amount received by the group members; and

(e) whether group members had an opportunity to opt out of the proceeding, or to notify their objections to the proposed funding commission.

27 Beach J observed that the percentage a funder receives varies from case to case, but most commonly falls within a range of 25% to 40%, and that the proposed common fund order was at the lower end of that range. Had the gross settlement sum been substantially higher, Beach J would have applied a ‘sliding scale’ to the commission rate and accordingly set a lower rate “so that the amount paid to the funder would have remained proportionate to the investment and risk undertaken by the funder” (at 516 [160]).

28 Most recently, in Caason Investments Pty Limited v Cao (No 2) [2018] FCA 527 at [159]-[174], Murphy J returned to the topic in the context of a funder seeking a common fund order at a rate of 30% of the gross recovery, which his Honour was prepared to order for reasons which included: first, a common fund order (which involved the funder not seeking the commission rate or project management fees to which it was contractually entitled) left all group members better off; secondly, it represented a simpler and more transparent mechanism for fairly apportioning funding charges; thirdly, group members were able to opt out if they wished; fourthly, the funder’s rate of return was low; and fifthly, it accorded with the Money Max factors referred to above, including that the rate was within the range of the funding rates available or common in the class action litigation funding market and that it was not a large settlement. Common fund orders are sought in this case. I return below to some criticisms of common fund orders and how the common fund order in this case may address some of these criticisms.

29 The developments I have traced, culminating in the prospects of recovery out of a common fund, have now led to the present competitive market where funders and solicitors are in competition for carriage of class actions which they subjectively perceive as having prospects of success and hence the prospect of delivering a commercial return (a conclusion which could no doubt have been drawn by even a moderately interested observer). According to a recent presentation by the President of the ALRC, the Honourable Justice SC Derrington entitled, ‘Litigation Funding Inquiry’ (Speech delivered at the Increased Regulation of Litigation Funding – A Timely Crackdown or a Regulatory Solution in Search of a Problem? Seminar, Monash University, 9 April 2018), approximately 25 funding entities are currently operating in the Australian market. Additionally, according to information provided to the ALRC, approximately one-quarter of class actions that were proceeding through the Court in 2015 and 2016 were related actions. The only available conclusion is that this competitive market for funding and the emergence of open class securities class actions means that this Court is highly likely to continue to be confronted with the spectre of competing funded securities class actions.

B.2 The Procedural Contradiction of Securities Class Actions

30 One matter left out of this historical survey is a characteristic of this type of litigation, which is both striking and singular. That is, that since the Aristocrat class action, there have been over 60 funded securities class actions commenced but not one of these actions has proceeded to the delivery of judgment following a fully contested hearing (albeit two have settled after an initial trial, but before judgment and at least one has settled during the course of the initial trial).

31 It might be thought that there is something odd about Chapter III judicial power being invoked with great regularity without the controversy, in respect of which jurisdiction is invoked, ever being resolved by final determination of contested common issues between the parties. There are a number of reasons why this might be the case. First, such litigation is expensive. Secondly, it involves risk as at least one issue, commonly described as ‘market based causation’, is yet to receive express acceptance by the High Court (notwithstanding its acceptance by Perram J, in obiter, in Grant-Taylor v Babcock and Brown Ltd (in liq) [2015] FCA 149; (2015) 322 ALR 723 at 765-766 [219]-[220]; in the decision of the Full Court (on a pleading dispute) in Caason Investments Pty Ltd v Cao [2015] FCAFC 94; (2015) 236 FCR 322 at 333 [68] per Gilmour and Foster JJ; the decision of Brereton J in Re HIH Insurance Ltd (in liq) [2016] NSWSC 482; (2016) 335 ALR 320; and the relatively recent observations of two Full Courts as to indirect causation in ABN AMRO Bank NV v Bathurst Regional Council [2014] FCAFC 65; (2014) 224 FCR 1 at 272 [1375]-[1376] per Jacobson, Gilmour and Gordon JJ and Chowder Bay Pty Ltd v Paganin [2018] FCAFC 25 at [61] per Besanko, Markovic and Lee JJ). Thirdly, speaking generally, many cases have involved a real risk for the respondent of proof of contravening conduct, as such costly litigation is likely to be commenced only when the subjective view of those commencing the litigation is that it is likely that contravening conduct will be able to be established; this is because it is only in such circumstances that there is an efficient allocation of the resources of the funder (although, it must be said, these subjective views may well be wrong and a more competitive funding market and the entry of different players may lead to some cases being commenced which would not otherwise have been prosecuted at a more embryonic and ‘risk averse’ stage of the development of securities class actions). Fourthly, connected to the previous point, respondents and insurers have generally been likely to seek to minimise risk by being open to settlement, provided an acceptable sum can be agreed (including in cases of real risk for the respondent where the amount paid cannot be characterised as payment of a ‘nuisance sum’).

32 To this list I would add a further and potentially worrisome reason for cases not proceeding to judgment following an initial trial. By reason of the very nature of the commercial model I have described, a desire exists on behalf of the funders to not only obtain a return, but to obtain that return with celerity. To those acting for applicants, there is a need to be alive to the possibility arising of a conflict between the commercial imperatives and demands of the funder, and the interests of the applicants and group members in maximising the recovery of their claims. To suggest simplistically that there is always an alignment between the funder and group members (because each have an interest in maximising relevant claims) is to fail to appreciate the difference between a commercial enterprise seeking consistent and predictable returns (and management of risk spanning a number of projects), with the position of a group member involved in one action who has a relatively small amount at stake which the group member may be willing to wager on the possibility of a greater return. I recently discussed this issue in Clarke v Sandhurst Trustees Limited (No 2) [2018] FCA 511 at [6]-[7] in the context of a settlement approval in a case where relatively modest damages were sought, and yet costs and funding charges were large compared to the recovery ultimately returned to group members.

33 No doubt this issue could prove a fertile ground for a sophisticated economic and behavioural analysis, but it suffices to note that those acting for applicants have an important role in the administration of justice in ensuring that the interests of group members are not swamped by the interests of funders in obtaining predictable and early returns. This important role is buttressed by the protective and supervisory role that this Court has in approving settlements of such litigation. I stress that, to the extent relevant, the history of settlement approvals suggests that there has been no difficulty and there is no reason whatsoever to doubt the conscientiousness of those commonly acting for applicants, but it might be thought at the very least surprising that this type of litigation never, ever runs to a conclusion. For reasons I have explained, the factors favouring resolution of these types of claims are often powerful, but given that no cases have fully run, one must be alive to the possibility that at least in some cases, the economic interests of funders may have driven or influenced compromise in cases where running the case to judgment may have been better from the perspective of group members. At the very least, the notion of the sliding scale whereby the amount recoverable by a funder increases to reflect the increased risk associated with running a case to a conclusion may serve to operate as an important counterweight in this regard. Further, as I will explain below, the related point is that any funding terms set at the outset of litigation should reflect the reality that these cases never have resulted in a final judgment.

34 The result of all of this is that there is potential procedural contradiction in the way in which securities class actions are conducted and managed. On the one hand, one goes through the solemnity of making orders on the basis that the litigation will be the subject of an initial trial at which contested issues will be determined by the application of judicial power, while on the other hand recognising that this, at least until now, never happens. Vast costs are commonly incurred and often, in the events that happen, are ultimately wasted. In my view, the time has come for the Court to recognise the reality (including in the context of applications such as the present), that securities class actions, at least as presently structured, are overwhelmingly likely to resolve by a bargain, subject to Court approval. To use an imperfect metaphor, managing litigation and incurring legal costs on the basis of an expectation that these cases will run is a bit like a passenger purchasing a railway ticket every day from Eastwood to Central, while knowing it is almost inevitable that they will be getting off the train every day at Strathfield, or, as is unfortunately more commonly the case, at Redfern (for the Victorians in the present matter, one can replace the destinations used in the last sentence with Williamstown Beach to Flinders Street, Footscray and North Melbourne, respectively).

35 In saying this, it must be recognised that the settlements do not happen by accident. A determined, well-resourced respondent will not make a substantial settlement offer unless persuaded that the applicant is prepared, absent settlement, to run the case and is capable of doing so. Settlements also usually reflect a material risk that the applicant will succeed on liability and can establish losses suffered by the class. For a respondent to be persuaded of such a risk usually requires the applicant’s lawyers to undertake substantial work. Similarly, a conscientious applicant will not accept a low settlement offer unless persuaded that there is a significant risk that the case will fail on liability or that the claimed losses will not be established. To be in a position to accept a conditional settlement offer requires work, often very substantial work.

36 Having noted this, the Court is to facilitate the quick and efficient disposition of litigation. In the case of securities class actions which will likely settle, this seems to me to require the Court to take an active role (including by fashioning interlocutory orders as to discovery and evidence) so that if, as anticipated, the case settles, it settles with alacrity or at least as early as practicable, with the minimum of cost for all parties and group members. Moreover, any orders as to common funds ought to reflect the reality of the empirical data as to prevalence of settlement of these cases, bearing in mind that the risk of a funder paying adverse costs of a trial in a securities class action has never once materialised.

37 It is against the background of these historical and contextual matters, that I come to the present issue.

C The Factual & Procedural History of the Matter

38 GetSwift is a technology company founded in 2015, listed in 2016, and which relevantly provides software for businesses to manage what are described as ‘last-mile’ delivery functions. After listing, GetSwift, at various times, made announcements to the ASX about agreements and ‘partnerships’ signed with clients. On 11 December 2017, the company announced a $75 million capital raising, at $4.00 per share. On 19 January 2018, the Australian Financial Review reported that GetSwift had allegedly failed to inform the market that its agreements with some customers had been terminated, and further alleged that it had announced the revenue forecasts tied to an agreement with the Commonwealth Bank of Australia prematurely. Shortly thereafter, on 22 January 2018, GetSwift shares were placed in a trading halt, and two days later were suspended from official quotation, pending the company’s response to questions from the ASX. A number of announcements relevant to the company’s suspension from official quotation (including questions raised by the ASX) were then apparently released up to reinstatement to official quotation on 19 February 2018.

39 The evidence on this application suggests that before entering the trading halt on 22 January 2018, GetSwift’s share price was $2.92, however, following reinstatement, it declined to $0.51 as at the close of trade on 21 February 2018 – a total decline of approximately 82.5%.

40 Ms Banton, a partner of Squire Patton Boggs (SPB), a large international law firm, gives evidence that SPB began investigating possible claims against GetSwift on 19 January 2018 and published a ‘Notice of Investigation’ into a potential class action on 2 February 2018 on the SPB website. Its purpose was to seek to bring the SPB investigations and the potential class action to the attention of shareholders who acquired shares in GetSwift in the period 24 February 2017 to 19 January 2018. A dedicated ‘GetSwift Class Action’ webpage and email address were established so that interested investors could register their interest online and obtain more information. Eventually, 103 shareholders chose to register with the SPB (Perera Funded GMs). The Perera Funded GMs are persons who also entered into funding arrangements with a funding entity, International Litigation Partners No 18 Pte Ltd (ILP18).

41 Mr Pagent, a partner of Corrs Chambers Westgarth (CCW), a large national firm of solicitors, gives evidence that on 20 February 2018, a litigation funder, Vannin Capital Operations Limited (Vannin) announced it was investigating a potential class action against GetSwift and its executive directors and invited shareholders who purchased shares in GetSwift between 24 February 2017 and 19 January 2018 to register their interest in the proposed class action. Apparently, 441 investors registered their interest in participating in the class action via the website www.getswiftclassaction.com.au; and 208 investors signed litigation funding agreements with Vannin (McTaggart Funded GMs).

42 Mr Phi, a solicitor with Phi Finney McDonald (PFM), which he describes as a “specialist class action law firm”, gives evidence that prior to 20 February 2018, preliminary steps were taken by PFM to consider and assess the merits of a potential claim against GetSwift. Preliminary discussions also took place between Mr Phi and representatives of Therium Capital Management Limited (Therium) about funding. Mr Phi gives evidence, which I accept, that he decided against announcing a potential class action until after GetSwift resumed trading as, in his experience, announcing a class action prior to the resumption of trading (or even shortly after an alleged corrective disclosure) may allow a respondent to argue that any share price fall was caused, at least in part, by the threat of a class action. He also deferred because: (a) his view was that it was appropriate to review analyst reports and media commentary to form a view as to the precise cause of a particular share price reaction; and (b) his preference was not to announce a class action until after he was satisfied that appropriate funding could be secured on terms he considered were favourable to group members. Despite this initial preference, following the filing of the Perera Proceeding on 20 February 2018, he caused an announcement of PFM’s investigation to be published on PFM’s website and the potential PFM class action was reported by the media the following day.

43 Mr Phi also deposes to a flurry of activity immediately prior to the filing of the Perera Proceeding. On 19 February 2018, two further potential class actions were publicly announced before close of trading that day. The solicitors announcing those potential claims were Gadens and MC Lawyers & Advisers. I pause to note that nothing further has been heard by any party as to these two, at one time, proposed class actions.

C.2 The Competing Actions Emerge and the Court Orders

44 As noted above, the Perera Proceeding was commenced by SPB on 20 February 2018 against GetSwift and Mr Joel Macdonald, an officer of GetSwift. A report was published by the Australian Financial Review the same day reporting that ‘International Litigation Partners’ was the funder. The originating application was listed for a first case management hearing on 23 March 2018, which was then adjourned to 29 March 2018.

45 An overlapping class action, being the McTaggart Proceeding, was issued by CCW on 26 March 2018 against GetSwift, Mr Macdonald and Mr Bane Hunter, the Executive Chairman of GetSwift. Following communication with my chambers, this proceeding was also listed for a first case management hearing on 29 March 2018.

46 On 29 March 2018, following discussion with the parties and a short adjournment, I indicated that I was disposed to make orders facilitating each of the applicants putting before the Court their proposals for how the issue of the competing class actions should be dealt with. The transcript records that there was no opposition to this course by either of the applicants or GetSwift, and orders were made in the Perera Proceeding and the McTaggart Proceeding for the parties, by 4 pm on 9 April 2018, to exchange and then file any affidavit evidence and submissions directed to:

(a) the manner and form by which security for costs is to be provided in the respective proceedings;

(b) the details, including any proposed percentage subject to further order, of the terms of any common fund order to be sought in the proceedings;

(c) whether, subject to the filing of a defence, any issues in the proceeding are suitable for reference to a referee or whether a Court appointed or joint expert be appointed or retained in relation to any issue;

(d) an estimate by the applicants’ solicitors, on affidavit, of the costs that are likely to be incurred (on the assumption) that issues of contravening conduct and causally related loss are in dispute;

(e) the number of funded group members and the aggregate number of shares held by all funded group members;

(f) what, if anything, is proposed to deal with potential overlap between the Perera Proceeding and the McTaggart Proceeding, such as a consolidation of the two proceedings; a permanent stay of one of the proceedings; an order declassing one of the proceedings under either s 33N(1) or s 33ZF of the Act; an order closing the class in one (but not the other) proceeding; or orders allowing a joint trial of both proceedings with each left constituted as open class proceedings;

(g) in the event a temporary or permanent stay or declassing of a proceeding is proposed, the matters relied upon in support of that contention.

47 I then, again without objection, listed the two proceedings for a further case management hearing on 13 April 2018, with a view to determining any application made by any party relating to the matters the subject of submissions filed pursuant to the orders made on 29 March 2018.

48 In effect, as is evident from these orders, I put in place a process by which each of the then applicants could put their ‘best foot forward’ to come up with a detailed proposal and, if only one proceeding was to go forward, explain why it was that their proceeding should be preferred. To preserve the integrity of the process as to funding proposals, I further noted in the orders that “there should be no discussion between the applicants, the applicants’ lawyers or the funder in this proceeding and the applicant, the applicant’s lawyers or the funder in the Related Proceeding as to the content of the material to be filed and served pursuant to [the orders] until after the exchange provided for by that order”. The parties complied with my orders, albeit slightly late.

49 An unexpected development then arose.

50 Very shortly after the exchange between Mr Perera and the McTaggart applicants, an interlocutory application was filed on behalf of Mr Raffaele Webb seeking orders: that he be granted leave to intervene in both proceedings; for a regime for a notice to group members to be approved; as to distribution of the notice; and for an adjournment of the case management hearing until late May or June 2018.

51 I arranged for the immediate relisting of the matter and a further case management hearing took place on 11 April 2018. At that time, following exchanges between the Bench and the parties, the adjournment of the case management hearing was not pressed and I made orders that Mr Webb have leave nunc pro tunc to intervene in the Perera Proceeding and the McTaggart Proceeding for the limited purpose of appearing at the case management hearing on 11 April 2018, and for the purpose of making any application he wished to make on 13 April 2018. Consistently with the orders earlier made, I ordered Mr Webb to exchange with the other applicants any affidavit evidence, submissions, and any other material related to the same issues which were the subject of the earlier exchange. I again preserved the integrity of the process by not allowing access by Mr Webb or his legal advisers to any material already filed and by noting in the orders that there be no discussions between the applicants. Finally, to prevent any procedural vulgarities that might have arisen as to the status of Mr Webb as an intervener, I indicated that I would grant leave to Mr Webb, on 13 April 2018, to file in Court, and have returnable instanter, an originating application commencing a Part IVA proceeding.

52 It is convenient to interrupt the account of what occurred to deal with a matter that has arisen in written submissions filed after oral submissions on behalf of both Mr Perera and the McTaggart applicants. These applicants submit that Mr Webb obtained some advantage by reason of what occurred.

53 The McTaggart applicants submit that when the Court comes to weigh up the respective advantages and disadvantages of the competing proposals, the Court should take into account “the fact that the Webb applicant enjoyed a process advantage compared with the McTaggart (and Perera) applicants”. This was said to arise because, after setting up what the parties accepted was a “competitive tender” process, Mr Webb’s “late entry put him at a clear advantage” apparently because at the time they submitted their respective proposals, the McTaggart applicants (and Vannin) and Mr Perera (and ILP18) “thought they were in a two-horse race, not a three-horse race, and they bid accordingly. But Webb knew it was a three-horse race, and he was able to bid accordingly”. It is also said that some apparent unfairness was occasioned because whereas Mr Perera and the McTaggart applicants were required to submit their evidence and proposals by 4.30 pm on 9 April 2018, Mr Webb was given until 4.30 pm on 12 April 2018 and this meant that Mr Webb was allowed to incorporate developments between 9 April and 12 April.

54 Mr Perera colourfully submits that allowing persons such Mr Webb (PFM/Therium) to come along “at the heel of the hunt” would “encourage a phenomenon of entrepreneurial lawyers and funders parasitically lying in wait to steal the work product of those who have conscientiously been investigating claims on behalf of real people who have retained them”. The submission continues:

It might be added that what the conduct of Webb/PFM/Therium has led to in this case, is undermining the entire point of the competitive bid process which the Court’s orders put in train. Had it been known at the outset that there were three tenderers, what occurred would likely have been different, just as one does not go to an auction to buy a house expecting to pay the same price if there is only one other registered bidder, as if there are more than one. The market was distorted, and the process will have miscarried to the extent Webb/PFM/Therium’s proposal is considered at all.

55 I reject these submissions for at least seven reasons.

56 First, Mr Webb did not have access to any of the material filed by the other applicants. He (and PFM and Therium) like Mr Perera (and SPB and ILP18) and the McTaggart applicants (and CCW and Vannin), all knew that to the extent the Court was having regard to their respective responses to the topics the subject of the common orders, those responses were to be prepared without contacting or having access to the materials of the other applicants.

57 Secondly, it is notable that the McTaggart applicants’ submissions are silent as to the details of the ‘developments’ which are asserted to have presented Mr Webb with a competitive advantage between the first exchange (between Mr Perera and the McTaggart applicants on 9 April) and the second exchange (between Mr Perera and the McTaggart applicants on the one hand, and Mr Webb on the other, on 12 April). Given Mr Webb did not have access to any of the details of the earlier proposals put forward, no relevant distortion occurred.

58 Thirdly, no complaint whatever was made by the legal representatives of Mr Perera and the McTaggart applicants at the case management hearing on 11 April 2018 as to the orders made on that date binding Mr Webb and the respondents. Ultimately, and more generally, the orders made as to the process to be adopted were not the subject of objection by any party.

59 Fourthly, what was put in place was not some process of bargaining between the Court (in its protective role as to group members) and scheme promotors; the analogy to an auction is, with respect, inapt. Each applicant party was to put its best foot forward. The applicant parties did so, and to the extent I consider relevant, the proposals will be judged on their individual merits. In this regard, the evidence that ILP18 would have approached the process differently in the event a third participant was to be involved (and not just a competition with Vannin) is not to the point. What the orders sought to elicit, among other things, was a considered proposal which best served the twin ends of furthering the overarching purpose and protecting the interests of group members, not the optimal commercial ‘deal’ for the funder pitched at the level to beat (but only just) the commercial ‘deal’ likely proposed by another funder.

60 Fifthly, the notion that Mr Webb has acted in a way which can be accurately described as “parasitically lying in wait to steal the work product” of others is, with respect, not a fair characterisation of what has occurred. Mr Webb did not put up his hand by the time of the first case management hearing and indeed I expressed some criticism of this on 11 April 2018 (when I made it plain that toing and froing between applicant lawyers was not going to defer progress of the substantive proceeding). In defence of Mr Webb, however, Mr Phi provided an explanation of why his attention was directed to attempting to negotiate funding terms (which, on the evidence, only occurred on 4 April 2018) and as to why he deferred the commencement of proceedings. For reasons I will come back to, the evidence revealed that this was time well spent. Moreover, no doubt the orders made by the Court at the first case management hearing were not anticipated by Mr Webb.

61 Sixthly, to the extent relevant, senior counsel for Mr Webb has submitted that the proposal put forward by Mr Webb reflects, at least as to funding rates and budgeted legal costs, those funding terms agreed with Therium and the budget proposed by PFM on 4 April 2018 – well before any orders were made on 11 April 2018.

62 Seventhly, let me assume for a moment that Mr Webb had some unarticulated process advantage. There has been no descent into the detail as to how the supposedly superior and well thought through proposals and submissions made by Mr Perera and the McTaggart applicants would have changed. Each now submits that their respective proposals are superior, if the Court conducts a principled multifactorial analysis. As I noted in the Introduction, to proceed on the basis of an auctioneer procuring further bids would not only be unseemly, but also would undermine what the Court was trying to achieve: each applicant party putting forward considered and optimal funding proposals which, in the view of that applicant party, would best advance the interests of group members.

C.3 The Conduct of the Hearing and Summary of the Proposals

63 When all the proceedings came before the Court for the first time on 13 April 2018, detailed evidence was adduced and submissions were made as to the approach the Court should take to resolve the issue of the competing class actions, the powers of the Court in this regard and the comparative merits of the competing proposals. Indeed, in an attempt to conclude argument, the Court sat late until it became clear that further time was needed to complete submissions. Indeed, as it happened, further argument then spanned three further listings with additional submissions and materials being filed after each listing.

64 By the end of this process, it was possible to summarise the principal contentions of each of the applicants and GetSwift. I will return to the various submissions made by each of the applicant parties of a comparative nature below, but the principal submissions can be broadly summarised as follows.

65 As to power and the applicable legal principles, it was submitted that neither Part IVA, nor any other part of the Act, gives the Court the power to act as regulator with complete discretion and that the structure and words of the statute delimit ‘regulatory activity’ in two ways: first, the foundation of Part IVA is that representative proceedings can be commenced on behalf of “some or all” persons with claims against the same person (s 33C(1)) without their consent, and group members have the statutory right to choose to opt out (s 33J), necessarily carrying with it a consequential choice to vindicate their rights outside a group proceeding commenced on their behalf. Hence, Part IVA expressly contemplates that there may be more than one proceeding against the one respondent; and secondly, as a consequence of the opt out regime, it is not prima facie vexatious, oppressive or an abuse of process for a group member to commence a separate, individual proceeding (or a separate class action), unless the group member has not opted-out of an earlier-commenced class action: see Smith v Australian Executor Trustees Limited [2016] NSWSC 17 at [22] (Ball J); Oliver v Commonwealth Bank of Australia (No 2) [2012] FCA 755; (2012) 205 FCR 540 at 541-542 [3] and 544 [15] (Perram J).

66 It follows, it was submitted, that the mere fact that a second class action is commenced does not provide a sound basis for permanently staying either the second, or the first, action. Put another way, it was said to be a “logical fallacy” that the mere existence of competing class actions is a principled basis for permanently staying one of them. Mr Perera recognised that these submissions as to power were inconsistent with the obiter views expressed by Beach J in McKay Super Solutions Pty Ltd (Trustee) v Bellamy’s Australia Ltd [2017] FCA 947, where his Honour observed that were it not for the fact that a substantial number of group members had committed themselves to litigation funding agreements and retainers in each proceeding before the Court, his Honour would have permanently stayed one of them: [8], [96]-[97]. It was further submitted “it is exceedingly doubtful whether, absent specific legislative warrant, this Court has the power on such grounds to permanently stay a regularly commenced representative proceeding which is not an abuse of process” and that a permanent stay “would be a novel step which would almost certainly be appealed, resulting in significant delay to the effective prosecution of group members’ claims”.

67 As to the appropriate orders to be made, Mr Perera submitted that the Perera Proceeding should proceed as an open class action, and the Court should temporarily stay, or adjourn, the other proceedings until shortly after the date for opt out has passed in the Perera Proceeding and, subject to consideration of the number of persons who opt out, the remedy was then to either close or declass the other proceedings. At least when the McTaggart Proceeding was its only competitor, the contention was that the discrimen for deciding whether to close or declass (under s 33N of the Act) was whether the McTaggart Proceeding had “insufficient registered group members to justify it continuing as a representative proceeding”. This submission, and the further submission that the Webb Proceeding should, in any event, be declassed, necessarily presupposes that the Court has such a power in the present circumstances. This contention is controversial and it will be necessary to return to it below.

68 As to the proposal of Mr Perera as to the conduct of the Perera Proceeding, it had the following components:

(a) Mr Perera is the representative party, having acquired seven parcels of shares in November and December 2017 (each of which were sold at a profit) and he bought his first loss-making shares on 5 January 2018;

(b) Mr Perera represents group members (including Perera Funded GMs who comprise 103 members of the class and who acquired 2,575,804 shares in the relevant period);

(c) the Perera Proceeding is funded by ILP18; this is a special purpose entity and corporations related to ILP18 have monies on trust with SPB;

(d) both funding agreements and retainer agreements (between the Perera Funded GMs and SPB) have been entered into with each of the Perera Funded GMs;

(e) the ILP18 funding agreement provides for a commission ranging between 25% and 40% (discriminating between group members on the basis of the amount of shares held) but it is proposed that a common fund order be made which involves payment of the lesser of 25% of net proceeds or 22.5% of gross proceeds (which sum will be capped to ensure that it is an amount not greater than 25% of net proceeds);

(f) as to a proposal relating to security for costs, Mr Perera indicated that ILP18 was prepared to abide by any order as to security, be it by way of cash deposit, bond or insurance cover;

(g) no suggestion was made that any substantive question could be referred to a referee or be the subject of evidence from a Court appointed expert.

69 As to power, the submission made by the McTaggart applicants is that s 33ZF of the Act includes the power to close a class “although it is doubtful whether it permits a permanent stay of a representative proceeding”. The McTaggart applicants point out that the concept of an abuse of process is not at large nor without meaning and it usually is demonstrated when proceedings are instituted for an improper purpose. It is said to be clear from the authorities that the bar for the order of a permanent stay is relatively high, and courts are reluctant to grant them, noting that a party bringing proceedings is entitled to expect them to proceed in the ordinary way in the absence of some countervailing consideration.

70 The ultimate submission is that the McTaggart Proceeding should remain an open class proceeding and the Perera Proceeding should be closed under s 33ZF(1) of the Act. In relation to the Webb Proceeding, it is submitted that Mr Webb should be notified that the McTaggart Proceeding will be an open class, and the Perera Proceeding will be a closed class. Following this notification, if Mr Webb and Therium wish to continue with the Webb Proceeding, this claim should proceed as a single claim heard together with the other proceedings. Although not stated directly, this also presupposes that the Court should proceed to declass the Webb Proceeding.

71 The proposal of the McTaggart applicants as to the conduct of their proceeding had the following components:

(a) the McTaggart applicants are the representative parties, having bought 151,208 shares starting in September 2017 and, after selling some at a profit, sold all the remaining shares they then held on 19 February 2018, the day trading resumed, which is alleged to have crystallised a loss of $182,223;

(b) the McTaggart applicants represent group members (including the McTaggart Funded GMs, who comprise 208 members of the class who acquired 1,545,374 shares in the relevant period);

(c) the McTaggart Proceeding is funded by Vannin which is wholly owned by a substantial corporation known as Vannin Capital PCC, which meets Vannin’s request for funds to finance its litigation funding operations;

(d) although funding agreements have been entered into between Vannin and each of the McTaggart Funded GMs, no retainer agreements have been entered into between the McTaggart Funded GMs and CCW;

(e) the funding agreement entered into provides that the funding commission would be 10% if proceeds are received before the end of this year, 20% if received before 26 September 2019 and 30% if received thereafter; the McTaggart applicants did not indicate that they were prepared to make an application for a common fund at the time they initially filed materials in support of their proposal, preferring to abide further developments; notwithstanding this, during the course of oral submissions, it was indicated that the McTaggart applicants would be content with a common fund order which provided for essentially the same terms as in the funding agreement: being 10% of gross proceeds before 31 December 2018, 20% of gross proceeds until a date 42 days prior to the initial trial, and 30% of gross proceeds thereafter;

(f) as to security, the McTaggart applicants indicated that a sum of $250,000 is presently held in the trust account of CCW and noted that the funding agreement requires Vannin to obtain ATE (After The Event) insurance of an amount well and truly in excess of an amount likely to be awarded for security; alternatively, during the course of oral submissions, it was indicated that the McTaggart applicants were prepared to provide security by way of cash deposit;

(g) no suggestion was made that any substantive question could be referred to a referee or be the subject of evidence from a Court appointed expert.

72 As to power, Mr Webb did not contend that the Court lacked power to either permanently stay or declass proceedings in the present circumstances. What was clear was that Mr Webb agreed with both other applicants that only one proceeding should proceed as an open class. As to the appropriate orders to be made, Mr Webb contended that orders should be made allowing the Webb Proceeding to proceed on behalf of an open class and variously submitted directions should be made to either stay, declass or adjourn the other proceedings.

73 As to the proposal of Mr Webb as to the conduct of the Webb Proceeding, it had the following components:

(a) Mr Webb was identified as the applicant having purchased shares in GetSwift during the relevant period (there was no further evidence as to his purchases);

(b) there are no funded group members in the Webb Proceeding;

(c) Mr Webb produced a letter from Therium dated 12 April 2018, in which the ‘Investment Committee’ of another Therium entity represented that it had committed a sum for the purposes of Therium funding the costs incurred by PFM and indemnifying Mr Webb in relation to adverse costs;

(d) the only retainer agreement entered into is between Mr Webb and PFM; no funding agreement which provides a ‘deadlock’ provision to resolve issues which may arise in the settlement context between Mr Webb and Therium exists;

(e) the common fund order proposed by Mr Webb would entitle Therium to a funding commission that is the lesser of:

(i) a multiple of the expenses that Therium has paid in the proceedings, being 2.2 times, if the parties enter into a settlement agreement on or before 12 April 2019, or 2.8 times if there is a successful resolution after 12 April 2019; or

(ii) 20% of the net litigation proceeds (that is, the settlement sum less approved professional fees and disbursements);

(f) security for costs was proposed to be by way of an ATE policy together with a deed of indemnity but, during the course of oral submissions, Mr Webb indicated he was prepared to put up cash security should the Court so order (although the latter mode of providing security would involve a greater expense which, it was said, would be incurred by group members);

(g) in relation to issues that may be the subject of references or Court appointed experts, Mr Webb asked the Court to appoint a referee to conduct periodic reviews of the reasonableness of Mr Webb’s legal costs, with only those costs assessed as reasonable being costs included for part-payment of Mr Webb’s legal costs; additionally, Mr Webb accepts that there is scope for the Court to appoint (or for the parties to engage jointly) a forensic economist to assist the Court in respect of matters of loss causation and the quantification of loss and damage.

74 As to power, GetSwift submitted that this Court had an “inherent jurisdiction to stay its proceedings” as either an abuse of process or if the proceedings were unjustifiably oppressive or otherwise brought the administration of justice into disrepute among right-thinking people: see Jeffery & Katauskas Pty Limited v SST Consulting Pty Ltd [2009] HCA 43; (2009) 239 CLR 75 at 93-94 [28] per French CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Crennan JJ. The categories of abuse of process and vexation or oppression are not closed and are insusceptible of precise formulation. In the context of Part IVA proceedings, that means that the Court has power to stay a proceeding if it is likely that one party will be subject to vexation and oppression where “two extant civil actions are brought in circumstances where one will suffice to vindicate the rights at issue”. Additionally, GetSwift submitted that there was no issue as to power in relation to declassing any of the class actions.

75 As to the issue of discretion, apart from the fact that GetSwift submitted that the appropriate form of security ought to be cash paid into Court, and that GetSwift wished to be heard as to the timing and quantification of security, it recognised that ultimately it was a matter for the Court as to which of the three proceedings should go forward.

C.4 Group Definition and Overlap – A Logical Difficulty

76 Having identified aspects of each proposal in general, and prior to examining the approach that has developed in relation to dealing with competing class actions, I mention a matter which was not the subject of submissions, but creates a logical difficulty in ascertaining whether, as assumed by the parties, there exists a perfect overlap of the classes. This is the issue of class definition.

77 All three class definitions contain a similar ‘causally connected loss or damage’ criterion defining group membership, which are specified as follows (emphasis added):

(a) In the amended statement of claim filed in the Perera Proceeding: “Suffered loss or damage by, or which resulted from, the conduct of the Respondents, pleaded in this Statement of Claim”.

(h) In the statement of claim filed in the McTaggart Proceeding: “Suffered loss or damage by reason of the conduct of the Respondents pleaded in this Statement of Claim”.

(i) In the originating application in the Webb Proceeding: “Suffered loss and damage by or resulting from the contravening conduct of the Respondents as described in the accompanying affidavit”.

78 A logical difficulty presents itself. The argument advanced by all parties contained the implicit premise that all classes were identical, but this is not necessarily the case. There are differences in the way the contravening conduct is identified. Although these differences are minor, it is at least logically possible that loss or damage may have been suffered by one group member arising only from one element of the contravening conduct that is advanced in one proceeding, but not in another.

79 This is but an illustration of a broader logical problem, largely ignored, but which is inherent in this sort of subjective, causative element to a group definition. The argument that a subjective criterion causes practical difficulty was rejected by Wilcox J in Nixon v Philip Morris (Australia) Ltd [1999] FCA 1107; (1999) 95 FCR 453 at 486 [126]-[127] and Moore J in King v GIO Australia Holdings Ltd [2000] FCA 617; (2000) 100 FCR 209 at 226 [45]. In particular, Moore J considered that defining group membership by reference to a loss and damage criterion was unobjectionable.

80 With respect, neither of those cases really grapples with the logical difficulty of a ‘causally connected loss or damage’ criterion. Upon commencement of a Part IVA proceeding, it is necessary to identify group members as required by s 33H, being, in accordance with s 33A, “a member of the group of persons on whose behalf a representative proceeding has been commenced”. A large number of provisions within Part IVA have embedded within them the notion that it is possible to identify, with particularity, during various stages of a proceeding, who in fact are the group members, for example: s 33J (the right to opt out); s 33L (where there are less than seven group members); s 33Q (determination of issues where not all issues are common); s 33R (individual issues); s 33S (directions relating to commencement of further proceedings by group members); s 33T (applications by group members as to adequacy of representation); s 33X (notice to be given to group members of certain matters); s 33ZB (the ‘statutory estoppel’ binding group members to orders).