FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum Inc v VicForests (No 3) [2018] FCA 652

ORDERS

FRIENDS OF LEADBEATER'S POSSUM INC Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Until the hearing and determination of the proceeding or further order, the respondent, whether by itself, its servants, agents, contractors or howsoever otherwise, is restrained from conducting forestry operations within the meaning of s 40(2) of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) within coupes 312-002-0006, 462-512-0002, 290-525-0002 and 288-505-0001, save for the removal of any harvested timber from the coupe landings.

2. Until the hearing and determination of the proceeding, or further order, the respondent, whether by itself, its servants, agents, contractors or howsoever otherwise, is restrained from:

(a) felling, removing or damaging any trees (whether under-storey, mid-storey or over-storey) or other substantial vegetation within coupe 288-506-0001;

(b) otherwise widening the existing road line within coupe 288-506-0001.

3. The parties are to confer and if possible agree on appropriate orders as to costs of the interlocutory application, including any lump sum figure.

4. In the absence of any agreement as to costs, the parties have leave to file and serve submissions on appropriate costs orders, and any proposed lump sum figure, on or before 4 pm on Friday 25 May 2018.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MORTIMER J:

Introduction and summary

1 On 2 March 2018, I determined a separate question in this proceeding. My reasons for judgment in that matter contain some of the background and detail to this proceeding, and set out my findings on the operation of the exemptions in s 38(1) of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) and s 6(4) of the Regional Forest Agreements Act 2002 (Cth): see Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum Inc v VicForests [2018] FCA 178. I will call those the “separate question reasons”. On 20 April 2018, I published reasons for judgment determining the form of answer to the separate question and a number of other matters relating to the amended statement of claim filed by the applicant: see Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum Inc v VicForests (No 2) [2018] FCA 532. I will call those the “relief reasons”. These reasons should be read with both those earlier sets of reasons.

2 The amended statement of claim raises, as I note in the relief reasons, an entirely new basis for the relief sought against VicForests, one which the applicant contends reflects the Court’s decision on the separate question.

3 I note at the outset that VicForests made no submissions that the framing of the applicant’s contentions on this interlocutory application fell outside the parameters of the Court’s decision on the separate question. To the contrary, its submissions appeared to accept as a premise that the applicant’s contention was available on the basis of the Court’s separate question judgment.

4 On 20 April 2018 when the Court made orders on the separate question, the undertakings by VicForests, to which I refer at [3]-[4] of the separate question reasons, came to an end. Counsel for the applicant informed the Court that logging had commenced in some of the coupes which are the subject of this proceeding, and foreshadowed an application for an interlocutory injunction if no undertakings from VicForests were forthcoming. Counsel for VicForests confirmed that no undertakings would be given. Accordingly, an application for an interlocutory injunction was filed on 23 April 2018. It was returned initially before the duty judge, Steward J, on 24 April 2018. His Honour made interim orders by consent, and the application was adjourned for hearing before me on 2 May 2018.

5 At the hearing of the injunction application, I also listed the matter for trial, commencing on 25 February 2019, for a period of three weeks. That fact is relevant to my decision on the interlocutory application.

6 For the reasons I set out below, injunctions will be granted.

7 Although because of the separate question process, the Court has given substantial consideration to the construction and operation of the exemption in s 38(1) of the EPBC Act and s 6(4) of the RFA Act, the proceeding is otherwise at an early stage. A considerable amount of evidence was adduced on the interlocutory application but none of it has been tested. The parties were content for the Court to proceed on the basis of the evidence they each adduced for the purpose of the interlocutory application, but obviously at trial the situation about some or all of this evidence may be quite different. I have considered it appropriate to confine my consideration of the voluminous evidence produced to that to which the parties directed my attention in submissions, and in particular the evidence which it is necessary to consider in light of the approach I have taken. In other words, I have not formed any views about much of the evidence adduced on the interlocutory application. I have taken the evidence I rely on below on the basis it was adduced: that is, as probative but untested evidence for the limited purpose of the interlocutory application. Whether or not any or all of it ultimately is assessed by the Court as reliable, probative and persuasive, will be a matter for trial and the Court’s consideration after trial.

Interlocutory relief sought

8 The applicant seeks the following substantive relief:

1. Until the hearing and determination of the proceeding, the Respondent, whether by itself, its servants, agents contractors or howsoever otherwise, is restrained from conducting timber harvesting operations within the meaning of s 3 of the Sustainable Forests (Timber) Act 2004 (Vic) within coupes 312-002-0006, 462-512-0002, 290-527-0004, 290-525-0002 and 288-505-0001, save for the removal of any harvested timber from the Coupe landings.

2. Until the hearing and determination of the proceeding, the Respondent, whether by itself, its servants, agents contractors or howsoever otherwise, is restrained from:

(a) felling, removing or damaging any trees (whether under-storey, mid-storey or overstorey) or other substantial vegetation within coupe 288-506-0001;

(b) otherwise widening the existing road line within coupe 288-506-0001.

3. The Respondent pay the Applicant's costs of and incidental to this application.

9 Counsel for the applicant informed the Court that relief was not pressed in relation to coupe 290-527-0004 (known as the Camberwell Junction coupe), because that coupe had already been logged.

10 Counsel for the applicant correctly accepted that, if relief were to be granted, the injunction should be formulated using the language of the EPBC Act, and the term “forestry operations” in particular. As I explain below, this is a matter arising under federal legislation, where the terms of the federal legislation are the controlling provisions: that is the effect of the Court’s determination on the separate question. The nature of the control exerted by the EPBC Act on forestry operations will depend first, on whether the exemption in s 38(1) applies; and only if it does not, on whether there is a contravention of (relevantly) s 18 of the EPBC Act. In the separate question reasons, I referred to the relationship between s 38(1) of the EPBC Act and s 6(4) of the RFA Act and why, in my opinion, s 38(1) was the critical provision. Accordingly, in these reasons I refer mostly to s 38(1).

11 Finally, the application proceeded on the basis that the applicant would give the usual undertaking as to damages, if injunctive relief were granted.

12 There was no submission by VicForests that the injunctive relief was inappropriately directed towards it, despite the fact the evidence reveals it conducts forestry operations through sub-contractors, and also through employees. In other words, it was implicit in VicForests’ submissions (and in its previous undertakings to the Court, as well as its agreement to interim relief), at least for the purposes of this application, that it controlled the conduct of forestry operations in the Central Highlands RFA region, and in that sense was properly identified as a person who was taking an action for the purposes of s 18 of the EPBC Act.

The parties’ evidence and arguments in short summary

13 The applicant relied on several affidavits, with a large number of exhibits:

(a) an affidavit of Stephen Meacher, affirmed on 15 November 2017;

(b) an affidavit of Danya Jacobs, affirmed on 15 November 2017;

(c) a second affidavit of Danya Jacobs, affirmed on 23 April 2018;

(d) a third affidavit of Danya Jacobs, affirmed on 1 May 2018; and

(e) an expert report of Dr van der Ree dated 24 April 2018.

14 In addition, and for a limited purpose, during the hearing the applicant also read an affidavit of Danya Jacobs affirmed on 17 November 2017.

15 Relying on the separate question reasons at [146]-[150], the applicant submits that, in order for forestry operations to be conducted in accordance with the Central Highlands RFA, the forestry operations must comply with the Victorian Code of Practice for Timber Production 2014.

16 VicForests did not make any submissions contrary to this proposition on the interlocutory application.

17 The applicant then submits that cl 2.2.2.2 of the Code requires VicForests to comply with the precautionary principle. Relying on Environment East Gippsland v VicForests [2010] VSC 335; VSC 416; 30 VR 1 at [188] the applicant submits the precautionary principle is engaged or triggered where:

(a) there is a real threat of serious or irreversible damage to the environment; and

(b) the threat is attended by a lack of full scientific certainty.

18 That is the situation, the applicant submits, with the Greater Glider. The evidence is that the Greater Glider is present in the five coupes. There is a threat of serious or irreversible damage to the Greater Glider as a species, and that threat is attended by a lack of full scientific certainty, in part because the Greater Glider is a recently listed threatened species, for which there is no action statement or recovery plan, and about which there are some real gaps in scientific knowledge, as illustrated by the evidence the applicant took the Court to and which I summarise below. The evidence adduced establishes, the applicant contends, the need for new surveys (because of a number of detections of the Greater Glider in the coupes), which VicForests currently does not intend to carry out. The applicant contends the evidence is that VicForests does not intend to adopt any particular or different adaptive measures to accommodate the detections. The applicant submits there are no specific management prescriptions for the Greater Glider in the Central Highlands RFA region. Instead VicForests restates an existing regulatory requirement to retain habitat trees in coupes that are logged, by prioritising the selection of hollow-bearing trees and those most likely to develop hollows in the short term as retained trees. This, it contends, is a generally applicable prescription not specific to the Greater Glider. The only other measure that VicForests may, at its discretion, take is to retain additional habitat trees in a given coupe, but the applicant emphasises that this is at the discretion of whoever the decision is reposed in. The evidence was unclear about who makes that decision, but it appears likely to be an individual who is closely involved with the forestry operation “on the ground”, so to speak.

19 On the balance of convenience, the applicant relies on analogies with the interlocutory decision of Forrest J in Environment East Gippsland v VicForests [2009] VSC 386 at [98]-[106] and submits:

(a) some financial loss may be caused (to third party contractors), but the timber as an asset will be retained and can be logged at a later date;

(b) Other coupes can be logged in the meantime. The relevant Timber Release Plan contains in excess of 2,500 coupes, more than 800 of which are in the Central Highlands Area, only five of which are subject to this application.

(c) Logging of forests causes “irreparable” damage, noting that the evidence is that it takes at least 120 years before hollows begin to form in the dominant eucalypts in montane ash forest.

20 VicForests’ response to the applicant’s arguments is that the Code (including cl 2.2.2.2) provides direction to timber harvesting managers, harvesting entities and operators to “deliver sound environmental performance when planning for and conducting commercial timber harvesting operations”, but in a way which is designed to achieve a number of objectives, of which the protection of listed threatened species is but one. As an example, another objective VicForests identifies for the Code is to permit “an economically viable, internationally competitive, sustainable timber industry”. The Management Standards and Procedures for timber harvesting operations in Victoria’s State forests 2014 in turn provide detailed mandatory operational instructions at the so-called “on the ground” level. This regime was enacted after (and, it would appear, partly in response to) the decision in Environment East Gippsland v VicForests [2010] VSC 335; VSC 416; 30 VR 1 (and the related proceedings, including Forrest J’s interlocutory decision), and therefore VicForests submits there can be no straightforward parallels with what occurred in the Environment East Gippsland proceedings.

21 Relying on observations of Osborn JA in MyEnvironment Inc v VicForests [2012] VSC 91 (appeal dismissed in MyEnvironment v VicForests [2013] VSCA 356; 42 VR 456), VicForests submits that if it has complied with prescriptions designed to reflect a balance between protecting biodiversity values and achieving “other prescribed social and economic considerations”, then it will be difficult to establish that the precautionary principle is engaged at all, let alone conduct is not consistent with it.

22 VicForests contends that is the case in the present situation. In its proposed conduct of the forestry operations in the five coupes, VicForests has complied with the Code and the Management Procedures.

23 It further submits that since it has complied with the Management Procedures (and the applicant does not allege any non-compliance with the Management Procedures), then it is deemed to have complied with the Code, by reason of the operation of cl 1.3.1.1 of the Management Procedures. This submission relies on a particular construction of the Management Procedures and cl 1.3.1.1 in particular. It is disputed by the applicant.

24 VicForests also submits that, if contrary to its submissions, the matter in [23] is not a complete answer, then the proposed forestry operations do not present a serious threat of irreversible damage to the environment such as to engage the precautionary principle. That is because the evidence (a reference to modelling by the Arthur Rylah Institute) shows there is a prediction of over 1.2 million hectares of Victorian state forest and national parks being “highly likely to contain suitable habitat for Greater Gliders, of which approximately 580,000 hectares is excluded from harvesting”. Only 3,000–3,400 hectares of the 1.2 million hectares will be harvested over the next 12 to 18 months, representing 0.2–0.3% of the total potentially suitable Greater Glider habitat. The harvesting area affected by the injunction is approximately 100 hectares and represents less than 0.01% of forest modelled as highly likely to be suitable habitat for the Greater Glider.

25 Alternatively, if the precautionary principle is engaged, VicForests submits what it requires is a response, or conduct, that is proportionate to the level and nature of the threat. In part that is because the principle is qualified so as to require avoidance of serious or irreversible damage to the environment “wherever practicable”. It also involves assessment of the “risk-weighted consequences of optional courses of action”. In this way, and relying on Osborn JA’s analysis in MyEnvironment, VicForests submits that adaptive measures must be directed, or proportionate, to the threat hypothesised. In the present case, a “blanket” injunction is not such a measure.

26 Any adaptive measures which might be properly required by the precautionary principle, VicForests submits, have been taken in the four coupes VicForests contends are in dispute in this interlocutory application. It contends different considerations apply to the Dry Creek Hill roading coupe. VicForests submits:

(a) Farm Spur Gum coupe has an area of general habitat reserve set aside within it as well as pre-1900 Ash trees marked for protection and additional hollow-bearing trees marked for protection;

(b) Backdoor coupe contains an area excluded from harvesting as a visual buffer, a habitat reserve in the north west of the coupe as well as habitat and seed tree retention and stream-side buffers;

(c) Vice Captain coupe contains areas of retained habitat containing larger trees with hollows, as well as Zone 1A Leadbeater’s possum habitat excluded from timber harvesting and a number of isolated pre-1900 Ash trees marked for protection that will be excluded from timber harvesting; and

(d) Dry Spell coupe is presently noted (no coupe plan is in existence yet) to contain habitat reserve areas and Zone 1A Leadbeater’s possum habitat along the ridge line (both of which would be excluded from timber harvesting operations) and a number of isolated pre-1900 Ash trees marked for protection that will be excluded from timber harvesting.

27 VicForests relied on two affidavits:

(a) An affidavit of Andrew McGuire sworn on 1 May 2018; and

(b) An affidavit of William Paul, affirmed on 1 May 2018.

The Victorian forest management regime

28 The Victorian Forest management system, as I found in the separate question reasons (see, for example [219]-[221]), operates as a substitute regime for the assessment and approvals process under the EPBC Act, but an assumption of accrediting that system through the RFA is that it will provide equivalent protection to that available under the EPBC Act itself to the identified matters of national environmental significance. The substitute regime in Victoria has at least four components which I identified at [148] of the separate question reasons, amongst them the Code.

29 As I have noted above, at least for the purpose of the interlocutory application, VicForests did not dispute that non-compliance with the Code, or with the Management Procedures, was capable of depriving a person or entity who conducted an RFA forestry operation of the protection afforded by the exemption in s 38(1) of the EPBC Act.

30 Save for one matter which is important to the determination of whether the applicant has a prima facie case, there was no dispute between the parties about the nature and structure of the relevant aspects of Victoria’s forest management system.

31 Section 46 of the Sustainable Forests (Timber) Act 2004 (Vic) provides:

The following persons must comply with any relevant Code of Practice relating to timber harvesting—

(a) VicForests;

(b) a person who has entered into an agreement with VicForests for the harvesting and sale of timber resources or the harvesting or sale of timber resources;

* * * * *

(d) any other person undertaking timber harvesting operations in a State forest.

32 Although it dealt with an earlier version of the Code, the general statutory framework for the regulation and management of forestry operations is set out by Tate JA in the MyEnvironment appeal proceeding at [33]–[48], and need not be repeated here. The Code is a legislative instrument, made under Pt 5 of the Conservation, Forests and Lands Act 1987 (Vic). The 2007 Code, with which the MyEnvironment and the Environment East Gippsland cases were concerned, contained a different use of the precautionary principle in the context of “mandatory actions” under the Code, and one that was more squarely directed towards the manner in which forestry operations were to be conducted. The reframing of the precautionary principle in the context of “mandatory actions” in the 2014 Code which was more general, and less tied to the actual conduct of forestry operations, appears to have been one of the policy reactions to those two sets of proceedings.

33 Section 1.2.6 of the Code provides that the Management Procedures are an “Incorporated Document” into the Code:

Incorporated Documents

The Management Standards and Procedures for timber harvesting operations in Victoria's State forests (Management Standards and Procedures) are incorporated into this Code to provide detailed mandatory operational instructions, including region specific instructions for timber harvesting operations in Victoria's State forests.

34 Although neither party directly addressed this, it would appear from the fact of such incorporation, that the obligation in s 46 of the Sustainable Forests (Timber) Act 2004 (Vic) to comply with the Code includes an obligation to comply with the Management Procedures.

35 The part of the Code itself on which the parties focussed is the part headed “Conservation of Biodiversity” in Part 2.2.2. The first “operational goal” set out in this part is:

Timber harvesting operations in State forests specifically address biodiversity conservation risks and consider relevant scientific knowledge at all stages of planning and management.

36 That being the “goal”, the next section then addresses how that goal is to be achieved, first through seven “mandatory actions”:

2.2.2.1 Planning and management of timber harvesting operations must comply with relevant biodiversity conservation measures specified within the Management Standards and Procedures.

2.2.2.2 The precautionary principle must be applied to the conservation of biodiversity values. The application of the precautionary principle will be consistent with relevant monitoring and research that has improved the understanding of the effects of forest management on forest ecology and conservation values.

2.2.2.3 The advice of relevant experts and relevant research in conservation biology and flora and fauna management must be considered when planning and conducting timber harvesting operations.

2.2.2.4 During planning identify biodiversity values listed in the Management Standards and Procedures prior to roading, harvesting, tending and regeneration. Address risks to these values through management actions consistent with the Management Standards and Procedures such as appropriate location of coupe infrastructure, buffers, exclusion areas, modified harvest timing, modified silvicultural techniques or retention of specific structural attributes.

2.2.2.5 Protect areas excluded from harvesting from the impacts of timber harvesting operations.

2.2.2.6 Ensure chemical use is appropriate to the circumstances and provides for the maintenance of biodiversity.

2.2.2.7 Rainforest communities must not be harvested.

37 The applicant identifies cl 2.2.2.2 of the Code as the relevant obligation with which it alleges VicForests must comply, in order to gain the protection of the exemption in s 38(1) of the EPBC Act for the conduct of its RFA forestry operations.

38 There are a number of aspects of this “obligation” which will no doubt be fully explored at trial. As I have noted, the framing of the precautionary principle in relation to “mandatory actions” in the 2014 Code is different to that in the 2007 version. I accept, as VicForests submits, that the purposes of the Code, as expressed in s 1.2.2, extend to “providing direction” so that objectives including, but by no means limited to, biodiversity conservation, are pursued.

39 The 2014 Code contains no definition of the term “biodiversity values”, being a key term in the obligation in cl 2.2.2.2, although the Code does contain, in the Glossary, a definition of “biodiversity”:

‘biodiversity’ means the natural diversity of all life: the sum of all our native species of flora and fauna, the genetic variation within them, their habitats, and the ecosystems of which they are an integral part.

40 Page 14 of the 2014 Code sets out a definition of the precautionary principle:

‘Precautionary principle’ means when contemplating decisions that will affect the environment, careful evaluation of management options be undertaken to wherever practical avoid serious or irreversible damage to the environment; and to properly assess the risk-weighted consequences of various options. When dealing with threats of serious or irreversible environmental damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to prevent environmental degradation.

41 The applicant contended, and VicForests appeared to accept, that “serious or irreversible damage to the environment” included conduct which had, or was likely to have, a significant impact on a threatened species listed under the EPBC Act.

42 It is unnecessary to pursue any detailed analysis of the construction and operation of the Code, as only one dispute about its interpretation arose on the interlocutory application. That dispute concerns VicForests’ argument about the “deeming” effect of s 1.3.1.1 of the Management Procedures.

43 The relevant part of the Management Procedures provides:

1.1 Scope

1.1.1.1 The Management Standards and Procedures apply to all commercial timber harvesting operations conducted in Victoria's State forests where the Code applies.

1.2 Role

1.2.1.1 This document provides standards and procedures to instruct managing authorities, harvesting entities and operators in interpreting the requirements of the Code.

1.2.1.2 These Management Standards and Procedures do not take the place of the mandatory actions in the Code.

1.2.1.3 Where there is a conflict between the Code and these Management Standards Procedures, the Code shall prevail.

1.3 Application

1.3.1.1 Notwithstanding clause 1.2.1.3, operations that comply with these Management Standards and Procedures are deemed to comply with the Code.

1.3.1.2 Requests for exemptions or temporary variations to these Management Standards and Procedures will demonstrate to the satisfaction of the Minister or delegate that they are consistent with the Operational Goals and Mandatory Actions of the Code.

44 VicForests contends that 1.3.1.1 prevails, and since the applicant’s argument on the interlocutory application does not involve any allegation that VicForests’ proposed forestry operations in the five coupes are non-compliant with the Management Procedures, VicForests is deemed to have complied with the Code. That, VicForests submits, means its forestry operations have the benefit of the exemption in s 38(1) of the EPBC Act.

45 The applicant contends VicForests’ construction overlooks the role of 1.2.1.2, which it submits is a separate indication, and means that ongoing compliance is required with whatever are identified in the Code as “mandatory actions”. The application of the precautionary principle is one such mandatory action. Thus, the applicant contends, the “deeming effect” of 1.3.1.1 is no easy answer for VicForests.

46 VicForests also correctly submits that although there are set out in Table 13 of Appendix 3 to the Management Procedures a series of “management actions” for certain threatened fauna, there are none for the Greater Glider in relation to the Central Highlands Forest Management Area. Table 13 relates to the obligation in clause 4.2.1.1 of the Management Procedures, which states that those conducting forestry operations must:

Apply management actions for rare and threatened fauna identified within areas affected by timber harvesting operations as outlined in Appendix 3 Table 13 (Rare or threatened fauna prescriptions).

47 A (non-controversial) example from Table 13 is the management action for the Grey Goshawk, in the Central Highlands Forest Management Area (which may or may not be co-extensive with the Central Highlands RFA area; the evidence is not clear on this issue):

Apply a 100 m buffer around nest trees used within the last 5 years. Exclude timber harvesting operations within 250 m of nest trees during breeding season.

48 VicForests is also correct to submit (and the applicant appeared to accept) that there is no explicit requirement in the Code or the Management Procedures, for VicForests to conduct pre-harvest biodiversity surveys before it commences forestry operations in any particular coupe.

The coupes concerned

49 The following evidence is taken from Ms Jacobs’ affidavit of 23 April 2018. In her affidavit, Ms Jacobs assigns different names to these coupes, but I will use the coupe names they have been assigned by VicForests.

50 Coupe 288-505-0001, the Dry Spell coupe. This coupe is identified at para 10.39 of the amended statement of claim. It is located near Snobs Creek. VicForests’ Timber Release Plan, released in around January 2017, describes the forest stand within the Dry Spell coupe as “Ash” and states that 12 hectares nett area is planned for logging by the clearfell method within the coupe.

51 Coupe 290-525-0002, the Vice Captain coupe. This coupe is identified at para 10.38 of the amended statement of claim and is located near the Big River. The Timber Release Plan describes the forest stand within this coupe as “Mixed Species” and states that 20 hectares nett area is planned for logging by the clearfell method within the coupe.

52 Coupe 312-002-0006, the Farm Spur Gum coupe, is identified in para 10.20A of the amended statement of claim. It is located near the Torbreck River. The Timber Release Plan describes the forest stand within this coupe as “Mixed Species” and states that 20 hectares nett area is planned for logging by the seed tree method within the coupe.

53 Coupe 462-512-0002, the Backdoor coupe, which is identified in para 10.35 of the amended statement of claim. It is located in the southern area of the Noojee forest. The Timber Release Plan describes the forest stand within this coupe as “Ash” and states that 36 hectares nett area is planned for logging by the clearfell method.

54 Neither party submitted that for the purpose of assessing their competing arguments on the interlocutory application anything turned on the method of forestry operations to be used – that is, whether clearfell or seed tree retention.

55 The Dry Creek Hill roading coupe (288-506-0001) should be separately considered. That is because on the evidence, like the Camberwell Junction coupe, it has been logged. There was a comparatively large number of Greater Glider detections in this coupe. The applicant seeks to prevent further forestry operations which it contends are planned: namely, the clearing of further areas to construct a “log landing” and the extension of the road.

56 VicForests submitted that the existing road in the Dry Creek Hill coupe will be used as a thoroughfare providing access to timber in coupe 288-506-0002 and for the taking of timber to and from coupe 288-506-0002. It submitted that therefore there is no possible contravening conduct to be restrained, nor is there any serious or irreversible threat to the environment in this coupe.

Evidence about the Greater Glider

Listing

57 The Greater Glider was listed as a threatened species under the EPBC Act on 5 May 2016. On around 15 June 2017 it was listed under s 10 of the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (Vic). In other words, the recognition by federal and state governments of its descent into the realm of a listed threatened species is relatively recent.

58 As part of the listing process under the EPBC Act, on 2 May 2016, the federal Minister approved a Conservation Advice for the Greater Glider under s 266B of the EPBC Act. That Conservation Advice is a document on which the applicant placed some weight in the interlocutory application.

59 At federal level the Greater Glider is listed in the “vulnerable” category, which is defined in s 179(5) of the EPBC Act as:

(5) A native species is eligible to be included in the vulnerable category at a particular time if, at that time:

(a) it is not critically endangered or endangered; and

(b) it is facing a high risk of extinction in the wild in the medium-term future, as determined in accordance with the prescribed criteria.

60 A similar document to the Conservation Advice was produced as part of the listing process under the Victorian FFG Act. In around 11 April 2017, the Victorian “Scientific Advisory Committee” (established under s 8 of the FFG Act) prepared a final recommendation on a nomination for listing the Greater Glider. That recommendation is a document on which the applicant also placed some weight in the interlocutory application.

61 Since the listing which is relevant for this proceeding is the federal listing – that being the one which brings the Greater Glider within the definition of “listed threatened species” for the purposes of s 18 of the EPBC Act – I shall concentrate on the contents of the federal conservation advice.

Characteristics and threats

62 What follows is taken principally from the federal conservation advice exhibited to Ms Jacobs’ affidavit of 15 November 2017.

63 The Greater Glider is the largest gliding possum in Australia, with a head and body length of 35-46 cm and a long furry tail measuring 45-60 cm. It is a nocturnal marsupial, largely restricted to eucalypt forests and woodlands. Populations occur only in eastern Australia, from the Windsor Tableland in north Queensland through to central Victoria. As to its range, the conservation advice states:

The broad extent of occurrence is unlikely to have changed appreciably since European settlement (van der Ree et al., 2004). However, the area of occupancy has decreased substantially mostly due to land clearing. This area is probably continuing to decline due to further clearing, fragmentation impacts, fire and some forestry activities. Kearney et al. (2010) predicted a ‘stark’ and ‘dire’ decline (‘almost complete loss’) for the northern subspecies P. v. minor if there is a 3° C temperature increase.

64 As to its habitat, the conservation advice states:

It is typically found in highest abundance in taller, montane, moist eucalypt forests with relatively old trees and abundant hollows (Andrews et al., 1994; Smith et al., 1994, 1995; Kavanagh 2000; Eyre 2004; van der Ree et al., 2004; Vanderduys et al., 2012). The distribution may be patchy even in suitable habitat (Kavanagh 2000).

65 The conservation advice makes the following points about Greater Glider habitat:

(a) during the day it shelters in tree hollows, with a particular selection for large hollows in large, old trees;

(b) the abundance of Greater Gliders on survey sites was significantly greater on sites with a higher abundance of tree hollows;

(c) home ranges are typically relatively small (1-4 ha);

(d) the Greater Glider was absent from surveyed sites with fewer than six tree hollows per hectare;

(e) it is considered to be particularly sensitive to forest clearance and to intensive logging;

(f) consistently with this, the Greater Glider has a low dispersal ability and Greater Gilders may be sensitive to fragmentation; and

(g) its relatively low reproductive rate may render small isolated populations in small remnants prone to extinction.

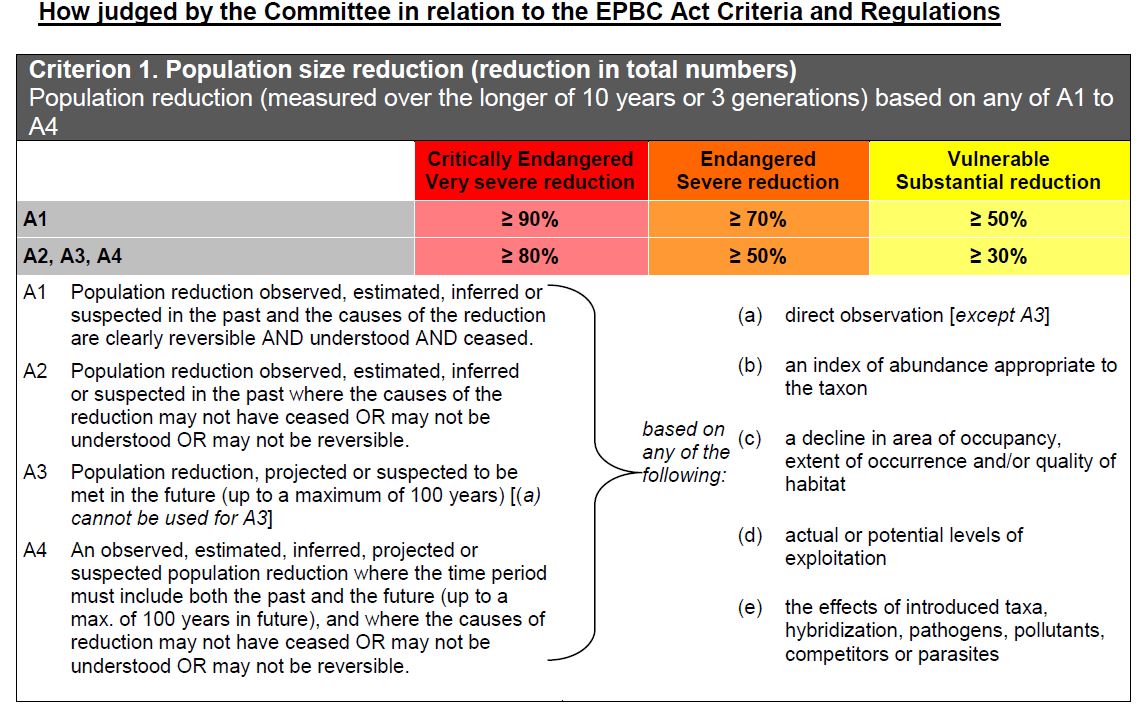

66 The criterion which was found by the Committee to be met, and to justify the listing of the Greater Glider as vulnerable was population reduction over at least ten years or three generations. To be classified as vulnerable, the Committee needed to be satisfied there was a greater than 50% or 30% (depending on the circumstances) reduction in population. To accurately represent the Committee’s findings, it is necessary to reproduce the entire table:

67 The advice states that the Greater Glider was found eligible for listing under the criteria in Criterion 1 A2(b)(c), A3(b)(c) and A4(b)(c).

68 The advice states in summary:

There are no robust estimates of population size or population trends of the greater glider across its total distribution. However, declines in numbers, occupancy rates and extent of habitat have been recorded at many sites, from which a total rate of decline can be inferred.

69 The advice then deals specifically with Victoria, and then with other States where the Greater Glider is found. In relation to Victoria, as well as noting the effects on the Greater Glider population from major bushfires over the last decade or so, the advice states:

Over the period 1997-2010, the greater glider declined by an average of 8.8 percent per year (a rate that if extrapolated over the 22 year period relevant to this assessment is 87 percent) (Lindenmayer et al., 2011). Higher rates of decline were recorded in forests subject to logging than in conservation reserves, and declines were also associated with major bushfires and lower-than average rainfall. More recent surveys undertaken by Lumsden et al., (2013, p.3) stated: ‘A striking result from these surveys was the scarcity of the Greater Glider which was, until recently, common across the Central Highlands’.

70 I note however that later in the document (p 8) the advice refers to researchers’ estimates that there may be greater than 100,000 mature individuals across the country. The Committee’s conclusion about this number was that it meant the population of mature individuals could not be described as “extremely low, very low or low”, and it did not meet some listing criteria on this basis. Rather, it is the overall population decline which is the reason for its listing.

71 The conservation advice summarises the major threats to the Greater Glider in the following way:

Cumulative effects of clearing and logging activities, current burning regimes and the impacts of climate change are a major threat to large hollow-bearing trees on which the species relies.

72 In the table which follows this summary, the predominant threat identified is habitat loss (through clearing, clearfell logging and the destruction of senescent trees due to prescribed burning), and fragmentation. The conservation advice categorises the consequence of the threat (which I understand to mean its effect on the Greater Glider as a species) as “catastrophic”. The table then explains why this threat has effects that can be described in such a way:

The species is absent from cleared areas, and has little dispersal ability to move between fragments through cleared areas; low reproductive output and susceptibility to disturbance ensures low viability in small remnants. Roadside clearing in state forests have destroyed many hollow-bearing trees previously left on the perimeter of logging coupes (Gippsland Environment Group pers. comm., 2015).

73 The reference to the effects of roadside clearing is a matter to which I have given some weight in my conclusions about the roading coupe.

74 Timber production is identified as the third threat (too intense or frequent fires are the second), and is noted to be at the “severe” level. The explanation given in the table is:

Prime habitat coincides largely with areas suitable for logging; the species is highly dependent on forest connectivity and large mature trees. Glider populations could be maintained post-logging if 40% of the original tree basal area is left (Kavanagh 2000); logging in East Gippsland is significantly above this threshold (Smith 2010; Gaborov pers. comm., 2015). There is a progressive decline in numbers of hollow-bearing trees in production forests as logging rotations become shorter and as dead stags collapse (Ross 1999; Ball et al., 1999; Lindenmayer et al., 2011).

75 The last sentence might be seen as casting doubt on the prescription of habitat tree retention, which is a major feature of VicForests’ strategies, and of its arguments on the interlocutory application. No doubt this will become a matter for expert evidence at trial. At this stage however, there is no evidence before the Court about the effectiveness of habitat tree retention practices conducted by VicForests as a conservation measure for the Greater Glider.

76 Hyper-predation by powerful owls (and to a lesser extent sooty owls) is also identified as a specific threat at the “severe” level. The conservation advice states:

Reduction in the stand density of hollow-bearing trees could increase predation threat whilst the species is moving between hollows.

77 The advice turns to the description of conservation measures and management actions. It specifically addresses forestry operations and states:

In production forests some logging prescriptions have been imposed to reduce impacts upon this species, however these are not adequate to ensure its recovery.

In Victoria, logging of areas where greater gliders occur in densities of greater than two per hectare; or greater than 15 per hour of spotlighting, require a 100 ha special protection zone (Vic DNRE1995). However, this threshold is quite high given that density estimates in Victoria range from 0.6 to 2.8 individuals per hectare (Henry 1984; van der Ree et al., 2004), and mature tree densities are declining meaning a lower probability that gliders will occur at higher densities (Gaborov pers. comm., 2015). This management requirement may therefore not adequately protect existing habitat and Greater glider populations.

78 The advice then describes the prescriptions in New South Wales, where the triggers for the habitat tree prescriptions are one Greater Glider per hectare and therefore more readily applied. The advice then makes the following statement about habitat tree retention:

However, such tree-retention measures are typically not species-specific, and do not consider factors which influence the occupancy of hollows and their suitability for different fauna species (Gibbons & Lindenmayer 2002), including intra-specific or inter-specific competition for hollows and changes in predation by owls related to changes in forest structure.

79 The applicant also relied on the recommendation of the Victorian Scientific Advisory Committee, made in relation to the listing of the Greater Glider under the FFG Act. That recommendation drew on some of the same material as the federal Conservation Advice, to which I have referred. It also stated:

Wood production practices are known to substantially deplete Greater Glider populations and gliders usually die if all or most of their home range is intensively logged or cleared (Menkhorst op. cit.).

Detections in the five coupes

80 Ms Jacobs gave evidence (particularly in her 23 April 2018 affidavit) about detections of Greater Glider in the coupes in issue in this proceeding, including the five coupes which are the subject of this interlocutory application. Those detections were made during surveys carried out by Mr Jake McKenzie, whom Ms Jacobs describes as a field naturalist “who regularly conducts fauna surveys in the Central Highlands region forests and has provided me with information and documents about areas of forest that are the subject of these proceedings”.

81 As I have noted, senior counsel for VicForests confirmed that, for the purpose of this interlocutory application, VicForests accepts the evidence of Greater Glider observations by Mr McKenzie as recounted in Ms Jacobs’ evidence.

82 Mr McKenzie’s observations were undertaken between June 2017 and March 2018, at night. He reported his detections (with GPS waypoint locations for each sighting) by email to the Victorian Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning and to VicForests. Mr Paul’s affidavit filed on behalf of VicForests confirms receipt by VicForests of some of these notifications. For some of his reports, he received no response. For others, he was told by the Department the information had been passed to VicForests and he would be advised of the outcome. Whether or not that occurred, is not disclosed by the evidence.

83 Ms Jacobs’ evidence included maps for each of the five coupes, which were produced by Mr Callum Luke, on the basis of Mr McKenzie’s information. There was no challenge by VicForests, at least for the purpose of the interlocutory application, to the reliability of these maps. These maps showed, by way of red dots, the locations of Mr McKenzie’s sightings of Greater Glider. Where more than one animal was sighted, the map had the words “x 2” next to the dot.

84 All of the five coupes have multiple sightings in, or close to the boundary of, the coupe. Ms Jacobs deposes, and VicForests did not contest, that most of the locations of the detections within each coupe lie within what is called the “harvest unit” for each coupe: in other words, within the part of the coupe which will be subject to timber harvesting.

Surveys

85 VicForests’ evidence confirmed there are no mandatory surveys required for Greater Glider in the Central Highlands RFA region. That is because, as Mr Paul explains in his affidavit, there are no specific management prescriptions for the Greater Glider in this region, as opposed (for example) to the East Gippsland region where such prescriptions exist for the Greater Glider.

86 The reason for that discrepancy between East Gippsland and the Central Highlands, given the listing of the Greater Glider in May 2016, is not explained in the evidence. The prescription in East Gippsland appears to have been in place for some time.

87 In his affidavit, Mr Paul explains how VicForests may decide to conduct what are called “targeted species surveys” for a threatened species if, after a “desktop assessment” of the habitat in a particular coupe, the coupe is assessed by VicForests as having an increased likelihood of threatened species being present within the coupe.

88 However, as far as I can see from the evidence, no “targeted species surveys” have been carried out by VicForests in the five coupes in issue on the interlocutory application, despite the notification of detections of Greater Glider to VicForests, and to the Department. Although the evidence shows that the coupe plans for some of the coupes note the detections (see Ms Jacobs’ affidavit of 1 May 2018), as VicForests’ evidence itself on the interlocutory application would tend to suggest, no significant action has been taken by VicForests to alter the nature and extent of its forestry operations in these coupes as a result of noting those detections.

89 Mr Paul did depose that “habitat assessments” were carried out by VicForests staff in each of the coupes. He deposed that VicForests has carried out habitat assessments in four of the five coupes that are the subject of the interlocutory application (excluding the Dry Creek Hill roading coupe) “in the knowledge that Greater Gliders had been observed in, or in areas adjacent to, those coupes”.

90 In his affidavit, Mr Paul goes through the measures which will be taken by contractors in four of the coupes (recalling the roading coupe has already been logged) in terms of habitat retention. His evidence does not go much further in relation to conservation measures for Greater Gliders, in relation to each coupe, than stating that:

…the largest, live, hollow-bearing trees for habitat retention will be retained and additional habitat trees may be retained within 75 meters of the coupe boundary where practicable and safe to do so, in accordance with the Interim Strategy.

91 He also points to the fact that, in some of the coupes, there is modelled Leadbeater’s Possum habitat, which will be excluded from timber harvesting.

92 VicForests also relied on a number of Biodiversity Inspection Maps that had been prepared to show the biodiversity measures implemented in each of the disputed coupes. In some cases, this included indications of where detections of Greater Glider had occurred. However, VicForests’ evidence was that such maps are not, as a general rule, given to the timber harvesting contractors who conduct forestry operations, although information included in the maps may be provided in other maps given to contractors. On VicForests’ evidence, the key requirement on contractors is to comply with the prescriptions and actions contained in the coupe plan.

93 Therefore, there is no evidence to suggest that any additional precautions for Greater Gliders specifically, will be undertaken by the contractors who actually carry out the forestry operations in each coupe.

VicForests’ Interim Strategy

94 Mr Paul deposes that the Interim Strategy was developed by VicForests following the federal listing of the Greater Glider as a threatened species. It was first published on 30 November 2017, after this proceeding was commenced. As its name suggests, it outlines an interim conservation strategy and coupe level prescriptions for the Greater Glider, pending the finalisation of what Mr Paul calls a “landscape based” conservation strategy, and also pending the promulgation of an action statement for the Greater Glider.

95 The strategy sets out three interim measures, one (at 5.1 of the strategy) of which applies only to forest in the Strathbogie Ranges. The other two measures are:

(a) A reference to the importance of living, large hollow-bearing trees as habitat for the Greater Glider, and references to existing prescriptions aimed at preventing the loss of hollow-bearing trees (5.2); and

(b) A measure (5.3) for the discretionary retention (I note the language is VicForests’ “may retain”) of large hollow-bearing trees additional to Code requirements, if first, on a desktop assessment of what is called “Greater Glider High Quality Habitat Class 1 layer” is identified, and then a visual inspection confirms the existence of “High Quality Greater Glider Habitat” within the coupe.

96 There was no dispute that in relation to the five coupes in issue on the interlocutory application, as Mr Paul deposes, a desktop assessment did not identify any “Greater Glider High Quality Habitat Class 1 layer”, so that the possibility of additional habitat tree retention has not been triggered under the interim strategy in relation to these coupes.

97 Of course, as the evidence shows, despite the desktop assessment, there are in fact Greater Gliders present, in not insignificant numbers, in the coupes. These sorts of discrepancies between prediction and reality will no doubt be further explored at trial.

98 VicForests relies on some particular statements in the strategy at pp 2-3:

Little data is in hand with which to define Greater Glider habitat or habitat occupancy. Making the most of the available data, ARI has constructed a model to identify areas within Victoria that are likely to contain suitable glider habitat. The model predicts over 1.2 million hectares of Victorian state forest and national parks are highly likely to contain suitable habitat for Greater Gliders. Approximately 580,000 ha of this predicted area of forest is excluded from timber harvesting (i.e., parks, reserves and other regulatory exclusions):

General Management Zone 640,000 ha

Special Management Zone 66,000 ha

Parks, Reserves and other excluded Forest 580,000 ha

Total suitable habitat 1,286,000 ha

This model does not predict glider occupancy of this forest; it is likely that a significant proportion may not currently support Greater Gliders.

VicForests estimates that 3,000-3,400 ha of the forest that is highly likely to be suitable habitat for the greater glider will be harvested over the next 12-18 months, representing 0.2- 0.3% of the total potentially suitable glider habitat.

99 The strategy gives the estimated completion date of an action statement as “12-18 months” from the date of the strategy. Mr Paul also deposes that no Greater Glider action statement has been released for public consultation. That appears to indicate any such action statement is not likely to be enacted in the short to medium term. Mr Paul’s evidence confirms this, and confirms there is no indication at all that, even if an action statement is enacted, it will have any effect on the Management Procedures VicForests is required to comply with:

At this stage, it is not known when it will be enacted. It is also not known what form it might finally take after it has been released for public consultation, and whether it will lead to any amendment to the Management Procedures, and if so, what form any amendment may take.

Resolution

Applicable principles

100 The parties accepted that pursuant to s 475(5) of the EPBC Act this Court may grant an interim injunction, including an interim injunction which restrains a person from engaging in conduct which is the subject of an application for final injunctive relief. The parties’ submissions also proceeded on the basis, which I accept, that the EPBC Act does not provide any different legal framework for the grant of injunctions, and the general law applies.

101 The parties did not debate the applicable principles, although they also did not refer the Court to any authorities that concerned the grant of injunctive relief in environmental cases (apart from Environment East Gippsland). There is, as I set out below, no shortage of such cases, and in some of them there are matters discussed by way of principle which in my opinion are relevant to the determination of this application.

102 The general statement of principle on the first limb of the test in Australian Broadcasting Corporation v O’Neill [2006] HCA 46; 227 CLR 57 is that an applicant must show a sufficient likelihood of success to justify the grant of an injunction. How the Court determines whether there is a sufficient likelihood depends on the nature of the right being asserted and the practical consequences that are likely to flow if an injunction was granted: O’Neill at [65] (Gummow and Hayne JJ; Gleeson CJ and Crennan J agreeing at [19]). At [65], Gummow and Hayne JJ made it clear that the phrase “sufficient likelihood” does not mean an applicant must show it is more probable than not that it will succeed at trial.

103 The second limb of the test is for the Court to assess where the balance of convenience lies: O’Neill at [65]. In this assessment, the Court will consider whether the injury or damage identified by the applicant for interlocutory relief outweighs, or is outweighed by, the damage or injury the respondent would suffer if injunctive relief is granted: see: Beecham Group Ltd v Bristol Laboratories Pty Ltd [1968] HCA 1; 118 CLR 618 at 622–623; Tegra (NSW) Pty Ltd v Gundagai Shire Council [2007] NSWLEC 806; 160 LGERA 1 at [13]. As Preston J put it in Tegra at [13]:

The greater the hardship to the defendant, the greater the reluctance of the court to grant the injunction. However, if an equal or greater hardship would be caused to the plaintiff by refusing an injunction, that reluctance will be dissipated. (references omitted)

104 Another way of expressing this limb is, as Griffiths J said in Northern Inland Council for the Environment Inc v Minister for the Environment, Heritage and Water [2013] FCA 993 at [8], that the Court must assess the “relative impacts on the parties” of granting the relief sought. I respectfully agree.

105 I note VicForests did not submit that damages would be an adequate remedy here as plainly they would not, since the applicant brings this not in vindication of any private right, but to enforce what it contends are the controlling provisions of the EPBC Act in relation to listed threatened species. Preston J confirmed in Tegra that in environmental cases, this question does not generally arise: see Tegra at [17].

106 It is trite that the two limbs of the test are not entirely independent of one another: see Samsung Electronics Co Limited v Apple Inc [2011] FCAFC 156; 217 FCR 238 at [67]. No linear approach should be taken. Where an applicant presents a strong prima facie case, it may be that the balance of convenience need not be so strong in its favour. The opposite is also true: a weaker prima facie case, but a stronger argument on balance of convenience, may still result in injunctive relief being granted. VicForests directed the Court’s attention to the observations of Beach J in Directed Electronics OE Pty Ltd v OE Solutions Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 142 at [19], and I respectfully agree with those observations.

Prima facie case

107 I consider the applicant has a prima facie case that the forestry operations proposed by VicForests in the five coupes will not be conducted in a way which applies the precautionary principle to the conservation of biodiversity values in the coupes, in circumstances where it is arguable the precautionary principle is engaged and the “biodiversity value” to be conserved is the protection of the Greater Glider as a listed threatened species. However, the applicant’s contentions face a number of challenges, and it is not possible to characterise its contentions on the alleged non-compliance with cl 2.2.2.2 of the Code as strong.

108 I have explained above how I understand the competing contentions on the components of the Victorian forest management regime as it is relevantly set out in the Code and the Management Procedures.

109 At the necessarily more impressionistic level of an interlocutory argument, the structural features of the Victorian regime would appear to favour the contentions of VicForests. I accept the submissions of VicForests that there are aspects of Osborn JA’s reasons in MyEnvironment about the challenges in proving that VicForests is not adhering to the precautionary principle in the conduct of forestry operations. At [271], his Honour said:

If it is accepted that the TRP [Timber Release Plan] relates to coupes which have themselves been produced by a balanced planning exercise which takes account of considerations of ecologically sustainable development and if it is further accepted that the logging will comply with the prescriptions designed to protect LBP [Leadbeater’s Possum] habitat within such coupes, MyEnvironment faces a difficult task in establishing that logging will breach the precautionary principle.

110 The applicant sought to distinguish MyEnvironment. These are matters for trial. At this stage however, I note that this decision is capable of supporting some of the arguments made by VicForests, and I am prepared, at this stage, to accept that may weaken the strength of the applicant’s prima facie case.

111 It may be, especially since the promulgation of the 2014 Code that in relation to certain aspects of biodiversity protection and conservation, that the terms of the Code, and the Management Procedures, have a less coercive effect than might previously have been the case. One of the aspects of this proceeding yet to be explored is what happens if the Commonwealth has accredited a state regime as an adequate and appropriate substitute regime, and then that regime is altered in a way that might be seen to reduce biodiversity protection and conservation, in favour of other objectives of forest management and regulation. I am not making any finding that this is what has occurred in Victoria: rather, I am identifying some of the difficult issues which will have to be debated and resolved at trial.

112 In my opinion, the respective contentions about the interpretation of 1.3.1.1 of the Management Procedures and the “deeming effect” are finely balanced. These will require further development and consideration at trial. Neither party’s interpretation can be said to be obviously correct at this stage. Accordingly this is not a factor which tends one way or the other in my evaluation of the strength of the applicant’s prima facie case.

113 What I consider to raise a prima facie case is the following:

(a) It is arguable that there is a real threat of serious or irreversible damage to the Greater Glider. That threat is apparent from the population decline which has caused it to be listed as a threatened species, and the population decline appears to have been quite dramatic in the Central Highlands region in particular. Of course, the causes for that population decline are several, as identified in the conservation advice. For present purposes, it is not the causes that matter so much as the fact of the decline, and then the further risks posed to the species from timber harvesting in areas where it is known to be present.

(b) It is arguable that the reality of the threat is further confirmed by the characteristics of the Greater Glider to which I have referred at [63]-[79] above.

(c) There is a lack of scientific certainty about the resultant environmental harm or damage to the Greater Glider, and to the habitat it is currently in fact using in the Central Highlands RFA. The conservation advice makes it clear that although something is known about the factors I have set out in [63]-[79] above, there is also uncertainty about where the viable populations of Greater Glider currently are, what their size is and what the medium term effects of forestry operations are on various populations.

(d) One of the matters which presently seems to provide evidence of scientific uncertainty is the fact that VicForests’ own habitat analysis did not model or predict these coupes as having “High Quality Habitat Class 1 layer” Greater Glider habitat, and yet there are what appear to be reasonably significant numbers of gliders living in and using this habitat. That in itself suggests it is arguable there is some scientific uncertainty about the accuracy of the modelling as a predictive tool to be used in planning forestry operations.

114 Accordingly I consider the applicant has a prima facie case that the precautionary principle is engaged in relation to forestry operations in the five coupes which are currently subject to an imminent proposal of forestry operations.

115 There is a prima facie case that VicForests does not propose to carry out the forestry operations in a way which will apply the precautionary principle to the conservation of biodiversity values represented by the Greater Glider. Rather, the evidence on the interlocutory application suggests VicForests has taken no positive steps to supplement its forestry operations with new or different adaptive measures in response to the detections in the coupes. The evidence suggests VicForests is prepared to risk losing not only tangible numbers of individual Greater Gliders to pursue its forestry operations, but further to fragment habitat in fact being used by them (rather than that which might theoretically be available to them). This is in circumstances where, on the present evidence, the available scientific advice indicates that the Greater Glider does not cope well with habitat change, and, although animals may not die from the initial impact, they will usually die shortly afterwards if all or most of their home range is extensively logged or cleared.

116 The matters clearly apply to the four coupes still “intact”, so to speak: namely, the Farm Spur Gum, Backdoor, Vice Captain and Dry Spell coupes. I consider at this stage, the same approach can arguably be taken to the “roading coupe”, Dry Creek Hill RDC, which has been logged. This is a coupe in which the applicant’s evidence showed numerous Greater Glider detections, on what I accept for the purpose of this interlocutory application were, in the opinion of Mr McKenzie, incomplete searches which produced only a proportion of the likely detections if each coupe was thoroughly searched. It is difficult for the Court to know precisely what is left in this coupe by way of habitat for Greater Gliders, and how many might remain in (or be using) this coupe, but a precautionary approach would suggest at this stage that no further disturbance should be permitted.

117 Whether an adaptive management approach (such as modifying timber harvesting restrictions, or imposing additional prescriptions or protections) is a sufficiently precautionary approach, will no doubt be a matter for trial. Whether an “adaptive management approach will achieve its goals of sufficiently reducing uncertainty and adequately managing any remaining risk” where the precautionary principle is engaged is a matter for argument at a later stage in this proceeding, but see: Sustain Our Sounds Incorporated v New Zealand King Salmon Company Ltd [2014] NZSC 40 at [125] and [129]).

118 Questions about whether adaptive management measures go far enough are not relevant to the interlocutory application because VicForests accepted it had not adopted any measures beyond those which were generally applicable under the Code and the Management Procedures such as habitat tree retention. That is, it submitted that it was not required to engage in any adaptive management specific to the needs of the Greater Glider, although I accept Mr Paul’s affidavit was structured to consider each coupe and the detections in each coupe. Nevertheless, what that evidence revealed was that VicForests is not, in fact, proposing that it will inevitably adapt its forestry operations in these four coupes because numbers of Greater Glider have been detected and these coupes can now be identified (on the assumptions operating for the purpose of this interlocutory application) as actual habitat for the Greater Glider. Therefore, the question which also arises in consideration of the precautionary principle about whether the measures proposed to be taken are proportionate to the threat also does not arise because VicForests presently does not propose any additional measures, despite the detections, and the consequent fact that what is at risk is present habitat actually being used by the Greater Glider. Whether or not this becomes an issue at trial depends on the evidence adduced.

119 Of course, as VicForests submits, the Management Procedures impose no specific prescriptions for the Greater Glider that must be applied to forestry operations in the Central Highlands. However, that is the applicant’s point about the operation of the precautionary principle: its function is to engage in circumstances where there are additional or new threats, and to require a cautious approach to be taken to avoid serious or irreversible damage. I see no reason to reject at this stage an argument that the precautionary principle can be engaged on a coupe by coupe basis, especially in relation to a listed threatened species that has been detected as, in fact, present in those coupes.

120 The Interim Strategy does not take VicForests’ arguments any further. It is a rather defensively drafted document. The portion I have extracted at [98] above is one example of such defensiveness. Another is the following passage:

VicForests has considered the need for additional Greater Glider protection measures to be taken on an interim basis while this Action statement is developed. VicForests has no legal obligation to undertake additional protection at this time, but seeks to demonstrate responsible stewardship and fidelity to the precautionary principle. VicForests’ proposed interim measures are outlined below.

121 At this early stage, and given I consider it is arguable the precautionary principle is engaged in relation to the threats to the Greater Glider in the Central Highlands RFA region, then it is arguable that “fidelity” to the precautionary principle would require, at least, further adaptive management measures by VicForests to protect the Greater Glider than are currently in place.

122 I say no more on the prima facie case limb. At this stage, and in relation to these five coupes, I am satisfied the applicant has some likelihood of success in its allegation that the exemption in s 38(1) may not apply, because of VicForests’ alleged non-compliance with the mandatory action in cl 2.2.2.2 of the Code.

123 I do not place any weight one way or the other on the existence of a prescription for the Greater Glider in the East Gippsland FMA, and the absence of one in the applicable prescriptions for the Central Highlands FMA. There is no evidence one way or the other which would enable the Court to make a finding about the explanation for that difference: for example, is it because the populations of Greater Glider in the Central Highlands were until more recently considered to be more robust? It is not possible to say. VicForests is correct to submit that the absence of a specific prescription means that VicForests has no compliance obligations which expressly relate to the Greater Glider in its forestry operations in the Central Highlands RFA region. I do not consider however, that affects (at least not at this early stage of the way the arguments are developed) VicForests’ obligations concerning the precautionary principle. If anything, one might have thought it would suggest, once there are detections, a more precautionary approach. However, I do not decide the interlocutory application on this basis. Rather, I find the differences in prescription between different regions are the kind of matter which will need to be explained and developed at trial.

124 The nature of the allegations made means there are many complex questions of fact and law which must be considered and determined before even a conclusion on the operation of the exemption in s 38(1) can be drawn. Thereafter, the applicant must establish a contravention of s 18 in relation to each action (ie each proposed forestry operation) for each coupe (past and proposed). There is much to consider, on both sides of the equation, before any final view can be reached.

125 VicForests made a number of submissions about the executive or policy choices that had been made by the Victorian Government about the level of protection to be assigned to threatened species in comparison to other objectives concerning forest use and management. Those choices were, it was submitted, reflected in the Code and the Management Procedures in the terms of what they do include, and what they do not. It made submissions to the effect that it was not the Court’s role to interfere in those policy choices.

126 As I indicated during oral argument, those submissions tend to overlook the context of this proceeding. This proceeding is in the federal jurisdiction. It depends on the operation of federal environment legislation. As the Commonwealth submitted, and I found on the separate question, the legislative choice by the federal parliament has been to enact a scheme which has as its objective environment protection and biodiversity conservation of matters of national environmental significance, and to do so by the accreditation of state regimes which have been assessed by the Commonwealth as providing adequate and appropriate substitute protection of those matters of national environmental significance.

127 Listed threatened species are identified by the legislative scheme as a matter of national environmental significance. The Greater Glider is such a species.

128 All persons engaging in actions, as that term is defined in the EPBC Act, which have, or are likely to have, a significant impact on any matter of national environmental significance, will be subject to that federal regime unless a relevant exemption applies. For s 38(1) to apply in relation to the conduct of RFA forestry operations, those forestry operations must be in accordance with the relevant RFA and – as I held – in the case of the Central Highlands RFA, this draws in the state regime controlling the conduct of those forestry operations insofar as they may have an effect on a matter of national environmental significance. For this Court to decide whether the state regime has or has not been observed in the conduct of RFA forestry operations does not involve the Court entering the area of policy choices made by the State. Rather it involves the Court exercising the judicial power that has been committed to it by the EPBC Act.

Balance of convenience

129 As I have set out above, there are some matters which are against the applicant’s arguments, and there are some matters which are finally balanced. It is not possible to say the applicant has a strong prima facie case. This is a matter which will very much depend on how the evidence falls out, including expert evidence. It will also turn to some extent on the legal arguments about the interpretation of the Code.

130 At this stage of the proceeding the Court is entitled to place considerable reliance on the contents of the conservation advice issued for the purpose of the Minister’s decision to list the Greater Glider as a threatened species under the EPBC Act. It appears the Minister accepted the contents of the advice since he decided to list the Greater Glider as recommended. This advice is the foundation of the Minister’s decision under the same legislative scheme which establishes the protection regime in Pt 3, and governs the operation of the exemptions in Pt 4, including s 38(1). I accept that at trial much of what is in the conservation advice may be the subject of competing expert evidence, and that at trial the evidence may well justify a quite different analysis. However, for the purpose of the interlocutory application, the contents of the conservation advice to the federal Minister should be considered reliable, and VicForests did not submit otherwise.

131 The conservation advice emphasises a number of matters, to which I have given weight in my decision, including:

(a) The level of threat to the Greater Glider posed by forestry operations, especially clear felling.

(b) The fact it has a small home range, and an inability to disperse between fragments of habitat through cleared areas.

(c) The research demonstrating mortality rates in the months after logging.

(d) The adverse consequences of habitat fragmentation for the Greater Glider. Fragmentation is, as I understand the conservation advice, another way of describing the removal of connectivity of the forest canopy.

(e) There is no positive evidence before the Court about the effectiveness of habitat tree retention in logged coupes as a conservation measure for the Greater Glider. There is some suggestion in the conservation advice it is not effective. Unless a measure is established to have at least some effectiveness, it is difficult to see how as a matter of simple logic it can be relied on as a protective measure in a biodiversity conservation context.

132 To this should be added the obvious, but important, point that the status of the Greater Glider as a species, as assessed by the federal Minister, is that it faces a high risk of extinction in the wild in the medium-term future.

133 I give little weight to the evidence from Mr Paul that in some of the four coupes there is “modelled Leadbeater’s Possum habitat” that will be excluded from timber harvesting. VicForests appeared to suggest this could give the Court some comfort that such habitat would be of benefit to the Greater Glider. On the evidence highlighted on the interlocutory application, I do not see how that can be the case. The evidence discloses the species have quite different habitat requirements. Further, the Leadbeater’s Possum habitat is only “modelled” and it is unknown on the evidence whether Greater Glider are, in fact, using such habitat in these coupes, or in any other coupes.

134 Both the Code and the Management Standards and Procedures were published in 2014, prior to the listing of the Greater Glider as a threatened species. Mr Paul’s evidence reveals that decision making around how best to protect the Greater Glider is still a work in progress at state level. He could give the Court no certainty in his evidence about any timing around the promulgation of an action statement, nor whether even if promulgated, measures in the action statement would be given effect in the Code or Management Procedures. This makes a precautionary approach all the more important.

135 Protection of threatened species is not a matter for theory. Protection is ultimately a practical matter, to be implemented in real environmental situations. Protection will always need to be implemented “on the ground” in ways which are established, throughout scientific evidence or experience, or a combination of both, to be effective.

136 The evidence on the interlocutory application about the detections of Greater Glider establishes where members of the listed threatened species in fact are. There are numbers – not insignificant and as yet not completely ascertained – of Greater Glider in and around each of the coupes. The fact that some detections are close to or on the boundary of a coupe rather than in the centre of a coupe is not as significant as VicForests submitted, given the Greater Glider home range is 1-4 hectares. A detection locates an animal at a particular point in time, but the animal must hunt and forage, it must move for safety and for other reasons: it is not a statue. Reasonable assumptions must be made about the use of the forest by Greater Glider around the detection sites, generally within their known range of 1-4 hectares.

137 The aim of a listing under the EPBC Act (and under State legislation) is to protect the species, which means protecting sufficient numbers of individual members of the species, and sufficient habitat, to eventually facilitate the recovery of the species. Protection or preservation of habitat is of little assistance if individual members of a species do not use, or are not able to use, that habitat. The habitat is protected to advance and facilitate the protection of the species, not as an end in itself.

138 In my opinion, at this stage of the proceeding, and given the risks for the Greater Glider population in Victoria, and in the Central Highlands in particular, from forestry operations (as revealed in the Conservation Advice), the balance of convenience weighs strongly in favour of preventing further forestry operations in coupes where there is evidence that reasonable numbers of Greater Glider are in fact using that habitat.

139 I consider this the most important aspect, and the one to which I have given the most weight.

140 In Tegra at [34]-[35], Preston J discusses the factor of preserving the status quo and how that may be considered in determining where the balance of convenience lies in a particular case. His Honour describes the status quo as “the state of affairs in the period immediately before the issue of proceedings seeking a permanent injunction”. Preston J continues: