FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Stone v Melrose Cranes & Rigging Pty Ltd, in the matter of Cardinal Project Services Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 2) [2018] FCA 530

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to s 588FA(1)(a) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) the defendant pay Cardinal Project Services Pty Ltd (in liq) the sum of $197,068.38 (Sum).

2. The defendant pay interest on the Sum.

3. On or before 3 May 2018 the parties file and serve submissions, not exceeding 3 pages in length, on the questions of calculation of interest on the Sum, including the period for which interest should be paid, and costs of the proceeding and to indicate in those submissions whether those issues can be dealt with on the papers.

4. If an oral hearing is required on the questions of interest and costs referred to in Order 3 then the matter will be listed on a date convenient to the parties and the Court for that purpose.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[5] | |

[15] | |

[15] | |

[23] | |

[30] | |

[34] | |

[46] | |

[52] | |

[54] | |

[57] | |

[64] | |

[65] | |

[65] | |

[74] | |

5. WAS CPS INSOLVENT IN THE PERIOD 15 JUNE 2011 TO 15 DECEMBER 2011? | [140] |

[140] | |

[165] | |

[166] | |

[183] | |

[183] | |

[184] | |

[186] | |

[200] | |

5.3 Have the Liquidators established that CPS was insolvent? | [201] |

[227] | |

[237] | |

[250] | |

[255] | |

[260] | |

[265] | |

[270] | |

[279] | |

[288] |

MARKOVIC J:

1 On 1 February 2012 the plaintiffs, Richard Andrew Stone and Peter William Marsden (Liquidators), were appointed as liquidators of Cardinal Project Services Pty Ltd (in liq) (CPS), having previously been appointed as joint and several administrators pursuant to s 436A of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Act).

2 The Liquidators seek orders under s 588FF of the Act that 18 payments made to the defendant, Melrose Cranes & Rigging Pty Ltd (Melrose Cranes), totalling $308,544.58, are voidable transactions within the meaning of s 588FE(2) of the Act because those transactions were unfair preferences within the meaning of s 588FA of the Act. The payments in issue are:

Date of Payment | Amount ($) |

01.07.11 | 54,021.28 |

29.07.11 | 1,297.10 |

31.08.11 | 20,000.00 |

09.09.11 | 7,500.00 |

16.09.11 | 7,500.00 |

23.09.11 | 10,750.00 |

30.09.11 | 10,750.00 |

07.10.11 | 10,750.00 |

11.10.11 | 88,866.80 |

14.10.11 | 10,750.00 |

21.10.11 | 10,750.00 |

28.10.11 | 10,750.00 |

28.10.11 | 7,000.00 |

31.10.11 | 15,609.40 |

04.11.11 | 10,750.00 |

11.11.11 | 10,750.00 |

18.11.11 | 10,750.00 |

01.12.11 | 10,000.00 |

Total | 308,544.58 |

3 It is not in dispute that CPS made the payments the subject of the Liquidators’ claim to Melrose Cranes and that those payments were transactions within the meaning of s 9 of the Act. However, in summary, Melrose Cranes:

denies that the payments were unfair preferences within the meaning of s 588FA of the Act and relies on s 588FA(3) of the Act, alleging that any payments that have been made are an integral part of the continuing business relationship between Melrose Cranes and CPS and thus those transactions are exempted from the operation of s 588FA(1);

denies that CPS was insolvent at the time that each of the payments were made;

says that the Court should not make an order prejudicing it pursuant to s 588FG(2) of the Act; and

says that in the event that the Liquidators are entitled to an order directing it to pay an amount to them, it seeks a set-off pursuant to s 553C of the Act for the amount that it says CPS was indebted to it as at the relation-back day.

4 This proceeding was heard over a period of seven days. The parties were seemingly unwilling to agree to any matter which might have narrowed the issues. Indeed until the first day of the hearing, when Melrose Cranes sought leave to file its further amended defence, it had denied that the payments in issue had been made. While parties are of course entitled to take issue with allegations made against them, proceedings in this Court should be conducted having regard to ss 37M and 37N of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (Federal Court Act). In my opinion this proceeding taking two years to come to trial; running over seven days; and involving over 4,000 pages of material tendered in evidence was not conducted in that manner, particularly when viewed in light of the amount in issue.

5 Part 5.7B of the Act provides for the recovery of property or compensation for the benefit of creditors of insolvent companies.

6 Section 588E sets out presumptions to be made in a recovery proceeding which includes an application under s 588FF of the Act by a company’s liquidator. Pursuant to s 588E(9), a presumption for which s 588E provides, operates except so far as the contrary is proved for the purposes of the proceeding concerned. Section 588E(3) provides:

If:

(a) the company is being wound up; and

(b) it is proved … that the company was insolvent at a particular time during the 12 months ending on the relation‑back day;

it must be presumed that the company was insolvent throughout the period beginning at that time and ending on that day.

7 The Liquidators seek relief under s 588FF of the Act. Relevantly, s 588FF(1)(a) empowers the Court, where it is satisfied that a transaction of a company is voidable because of s 588FE, to make an order directing, in this case, Melrose Cranes to pay some or all of the money that the company paid under the transaction.

8 Section 588FA of the Act provides:

(1) A transaction is an unfair preference given by a company to a creditor of the company if, and only if:

(a) the company and the creditor are parties to the transaction (even if someone else is also a party); and

(b) the transaction results in the creditor receiving from the company, in respect of an unsecured debt that the company owes to the creditor, more than the creditor would receive from the company in respect of the debt if the transaction were set aside and the creditor were to prove for the debt in a winding up of the company;

even if the transaction is entered into, is given effect to, or is required to be given effect to, because of an order of an Australian court or a direction by an agency.

…

(3) Where:

(a) a transaction is, for commercial purposes, an integral part of a continuing business relationship (for example, a running account) between a company and a creditor of the company (including such a relationship to which other persons are parties); and

(b) in the course of the relationship, the level of the company’s net indebtedness to the creditor is increased and reduced from time to time as the result of a series of transactions forming part of the relationship;

then:

(c) subsection (1) applies in relation to all the transactions forming part of the relationship as if they together constituted a single transaction; and

(d) the transaction referred to in paragraph (a) may only be taken to be an unfair preference given by the company to the creditor if, because of subsection (1) as applying because of paragraph (c) of this subsection, the single transaction referred to in the last‑mentioned paragraph is taken to be such an unfair preference.

9 The term “transaction” is defined in s 9 of the Act to mean a transaction to which the company is a party including, among other things, a payment made by the company. It is not in issue between the parties that each of the payments made by CPS to Melrose Cranes was a transaction for the purposes of s 588FA of the Act.

10 Section 588FC of the Act provides:

A transaction of a company is an insolvent transaction of the company if, and only if, it is an unfair preference given by the company, or an uncommercial transaction of the company, and:

(a) any of the following happens at a time when the company is insolvent:

(i) the transaction is entered into; or

(ii) an act is done, or an omission is made, for the purpose of giving effect to the transaction; or

(b) the company becomes insolvent because of, or because of matters including:

(i) entering into the transaction; or

(ii) a person doing an act, or making an omission, for the purpose of giving effect to the transaction.

11 The term “insolvency” is defined in s 95A of the Act. It provides that a person is solvent if, and only if, the person is able to pay all of their debts as and when they become due and payable. A person who is not solvent is insolvent: s 95A(2) of the Act.

12 Section 588FE concerns voidable transactions. Section 588FE(2) provides that a transaction is voidable if it is an insolvent transaction of the company and it was entered into, or an act was done for the purpose of giving effect to it, during the six months ending on the relation-back day; or after that day but on or before the day when the winding up began.

13 The relation-back day is the day on which the winding up is taken to have begun, which in this case, is the day on which the administrators were appointed to CPS, 15 December 2011: see ss 9 and 513C, and since 1 March 2017, s 91 of the Act.

14 In its further amended defence Melrose Cranes relies on s 588FG(2) of the Act which provides that:

A court is not to make under section 588FF an order materially prejudicing a right or interest of a person if the transaction is not an unfair loan to the company, or an unreasonable director‑related transaction of the company, and it is proved that:

(a) the person became a party to the transaction in good faith; and

(b) at the time when the person became such a party:

(i) the person had no reasonable grounds for suspecting that the company was insolvent at that time or would become insolvent as mentioned in paragraph 588FC(b); and

(ii) a reasonable person in the person’s circumstances would have had no such grounds for so suspecting; and

(c) the person has provided valuable consideration under the transaction or has changed his, her or its position in reliance on the transaction.

3.1 Part of the Cardinal Group

15 CPS was a wholly owned subsidiary of Cardinal Group Pty Ltd (Cardinal). CPS’ directors were Sam Ebeid, Andrew Travers and Michael Burns.

16 Cardinal was also the trustee for the Cardinal Group Unit Trust, the Reefway Asset Trust and the Reefway Environmental Services Trust. In its capacity as trustee for the Cardinal Group Unit Trust, it held all of the shares in Complete Concrete Cutting Pty Ltd (CCC) and Cardinal Logistics Services Pty Ltd (CLS). I will collectively refer to CPS and these entities as the Cardinal Group.

17 Messrs Ebeid, Travers and Burns were also directors of Cardinal, CCC and CLS.

18 Card Services Pty Ltd (Card Services) was a labour hire company which employed all of the staff that worked in the Cardinal Group. The sole shareholder in Card Services was Douglas Bell. On 15 December 2011 the Liquidators were appointed as liquidators of Card Services. Card Services was deregistered on 25 August 2013. Prior to the incorporation of Card Services, Cardinal Group Services Pty Ltd (CGS), a wholly owned subsidiary of Cardinal, provided labour hire services to the Cardinal Group. CGS was deregistered on 7 November 2014.

19 On 1 February 2012 the Liquidators were also appointed as joint and several liquidators to Cardinal, CCC and CLS having previously been appointed as joint and several administrators of those companies.

20 According to the report to creditors dated 23 January 2012, issued pursuant to s 439A of the Act by the Liquidators of Cardinal, CPS, CCC and CLS, (January 439A Report) the Cardinal Group was a large privately owned environmental services business specialising in waste management, recycling, hazardous waste management, site remediation, demolition and industrial and building services. The trading names of the businesses were Reefway Environmental Services, Recycled Resources, Smartskip, Cardinal Project Services and Complete Concrete Cutting.

21 Reefway Environmental Services provided waste management and recycling services to the construction and infrastructure industry; Smartskip provided additional waste management services; Recycled Resources produced road base, aggregates, sand, soil, decorative gravel and timber mulches for the building, construction and landscaping markets by reprocessing waste material; and Complete Concrete Cutting provided concrete coring, wire sawing and concrete bursting services.

22 CPS provided contracting services in the construction, infrastructure and industrial sectors in four divisions: hazmat management; demolition and site reconfiguration; civil works and industrial services contracting. The divisions worked in conjunction with and utilised the services of Reefway Environmental Services, Recycled Resources and Smartskip for waste disposal.

3.2 The Cardinal Group from 2008 to 2010

23 It is instructive to set out the financial position of the Cardinal Group and CPS in the period leading up to the appointment of the administrators.

24 For the year ended 30 June 2008, the period in which the business known as Reefway Waste Management was acquired, the Cardinal Group reported a profit attributable to members of the group of $1,963,940. Its balance sheet recorded total current assets of $10,593,214 and total current liabilities of $11,936,693. There was negative working capital of approximately $1.3m.

25 For the year ended 30 June 2009 the Cardinal Group reported a profit attributable to members of the group of $515,140. Its balance sheet recorded total current assets of $10,119,278 and total current liabilities of $9,253,987. There was a working capital surplus of approximately $800,000.

26 For the year ended 30 June 2010 the Cardinal Group reported a profit attributable to members of the group of $39,901. Its balance sheet recorded total current assets of $13,990,313 and total current liabilities of $12,635,217. There was a working capital surplus of approximately $1.3m.

27 In December 2010 the Cardinal Group sought up to $20m in equity financing. The information memorandum issued for that purpose informed prospective investors that the funds raised would be used to complete the acquisition program, provide working capital and fund other acquisitions. The equity financing was sought at a time when the Cardinal Group was in the process of what it described as “the second stage of its development through the acquisition of Smartskip”. In relation to that acquisition the information memorandum provided:

The acquisition is being fully debt funded by NAB who have completed financial and legal due diligence on both the Group and the target company in November 2010. The financial due diligence was carried out by Price Waterhouse Coopers (PWC) and the legal due diligence by Coors (sic) Chambers Westgarth and Maddocks.

NAB have approved a facility of $27 million to replace existing ANZ debt and revolving lease facility ($16 million), to complete the stage 2 acquisition including costs ($7 million) and to provide a revolving working capital facility ($3 million). NAB have also agreed to provide funding for future acquisitions subject to due diligence and meeting their funding criteria.

The Sale and Purchase agreement has been signed for this acquisition and the anticipated take over date is the 4th of January 2011. An analysis by PWC has identified synergies of $3.1 million of which the Group has included $480,000 in the first year of operations.

28 The information memorandum also included a summary of the four acquisitions referred to therein and their financial impact on the Cardinal Group in a table headed “Acquisition Assumptions”. For the financial year ended 30 July 2011 the amount shown for actual revenue was $62,774,000 and for actual EBITDA $8,197,000.

29 Cardinal Group failed to raise the equity finance it sought.

30 By letter dated 6 December 2010 the NAB agreed to provide finance to Cardinal. Four facilities were to be provided:

an amortising term loan facility in the amount of $7m;

a non-amortising term loan facility in the amount of $9.8m;

a revolving lease facility in the amount of $6m; and

a revolving working capital facility in the amount of $4.2m.

Cardinal’s obligations as borrower were to be guaranteed on a joint and several basis by it and all entities within the group. The term sheet enclosed with the letter from the NAB provided under the heading “Security” that the facilities would be secured by:

(a) First Mortgage over all freehold land and buildings;

(b) First Fixed & Floating charge over all local group entities; and

(c) Interlocking Guarantee and Indemnity between all consolidated entities.

(d) Limited Director's guarantee for $5m based on the proportional shareholding of each shareholder*.

(e) Consents and undertaking for leased properties

*To be released once leverage ratio, for the reporting period, is below 2.50x on an LTM basis.

31 On 23 December 2010 Cardinal, as borrower and each of the companies specified as a guarantor in schedule 1, which included CPS, entered into a loan facilities agreement with the NAB (NAB Facility) pursuant to which $27m was made available to Cardinal. The NAB Facility provided for monies to be advanced as follows:

(1) $7m to be made available to Cardinal for an “Amortising Term Facility” to finance a portion of the purchase consideration of the acquisition of the “Smartskip NSW” business and any acquisition costs;

(2) $9.8m to be made available to Cardinal for a “Bullet Term Facility” to repay and fully discharge the Loan Facilities Agreement with the Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd (ANZ);

(3) cash advances or asset leases to Cardinal upon request by it from time to time with the aggregate not to exceed the “Asset Lease Facility Limit”, to be used to repay and discharge all outstanding commitments under the ANZ Asset Lease Facility or to finance any necessary equipment for the “Core Business” of Cardinal and each guarantor; and

(4) a working capital facility to be made available to the “Obligors” who were Cardinal and each guarantor, by way of cash advances, L/Cs or bank guarantees when requested and a business card facility to finance or support the working capital needs of Cardinal and each guarantor and for their general corporate purpose.

32 Clause 23 of the NAB Facility headed “Guarantee and indemnity” provided, among other things, that each guarantor guaranteed the payment to the NAB of the “Guaranteed Money” as defined and indemnified the NAB against any liability or loss arising and any costs the NAB suffers or incurs in the circumstances set out, including where a guarantor defaults under the guarantee.

33 By deed of charge and mortgage of shares and units dated 23 December 2010 CPS, among others, as beneficial owner charged its “Charged Property” to the NAB to secure the payment of the “Secured Money”. The “Charged Property” was defined to mean “any legal or equitable estate or interest of [CPS] in any present and future undertaking and property other than the Mortgaged Property, including [CPS’s] uncalled capital and called but unpaid capital from time to time and the uncalled premiums and called but unpaid premiums from time to time on its shares”. On 24 December 2010 a form 309 – notification of details of a charge – was lodged with the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) for the charge given by CPS in favour of the NAB.

3.4 Review of the NAB Facility

34 Approximately eight months after entry into the NAB Facility, on 30 August 2011 Laura Beard, a senior relationship manager for the NAB’s strategic business services, sent an email to Mr Travers in which she wrote:

I refer to your recent discussions with John Diamontopoulos and confirm that the Cardinal Group has been referred to our Strategic Business Services area. In conjunction with John (who will continue to manage the banking relationship) I will also be managing your relationship with NAB in particular all credit related decisions will now be approved by myself and the strategy moving forward.

As you are aware the Bank has concerns given the recent decline in profitability, stretched creditor position, ATO arrears and request for increased funding. Accordingly, to assist the Bank in considering how we move forward we will be organising the engagement of an Investigative Accountant’s (‘IA’) review of the Cardinal Group which I understand John has discussed this with you. The investigative accountant will be Chris Hill from PPB and he will be in contact with you shortly.

In this regard, please find attached a letter to yourself regarding the engagement of the IA and a letter to the IA. If you could kindly execute the letter as soon as possible and I will liaise with Chris Hill to contact you directly.

Should you have any queries or concerns regarding this matter please do not hesitate in contacting myself or John.

35 By letter dated 29 August 2011 from Ms Beard to Mr Hill of PPB Advisory (PPB), the NAB confirmed Mr Hill’s appointment to conduct a business review in respect of its facilities with the Cardinal Group and an additional entity, Pike River Pty Ltd as trustee for 25 Pike Street Unit Trust. In its letter the NAB noted that it had identified issues including: cash flow constraints resulting in a request for increased funding; covenant breaches; deferral of amortisation; creditor pressure and ATO arrears; decline in profitability; and set out the scope of the review to be undertaken.

36 On 28 September 2011 James Brown, the financial controller for the Cardinal Group, sent an email to Mr Diamantopoulos in which he said, among other things:

As discussed, an amount has been taken from our account unexpectedly overnight. This is in relation to a court judgement made in December last year against Cardinal Project Services (which has just been brought to my attention). As you are aware, we are carefully managing our cash flow and working towards giving a financial presentation outlining our actuals and budget moving forward, and ask that we get covered for $250,000 until then.

The judgment referred to by Mr Brown had been obtained by Nahas Construction Pty Ltd (Nahas) in the District Court of New South Wales (District Court) and was the subject of a garnishee order issued in the Local Court of New South Wales (Local Court) and served on the NAB (see [64] below).

37 In an email dated 28 September 2011 addressed to Mr Diamantopoulos and later copied to others including Ms Beard, Mr Ebeid said:

Further to James’ email below.

I note that as discussed yesterday, the directors of cardinal loaned $265,000 to Cardinal Projects, to cover the overdrawn overdraft and CLS accounts.

Unfortunately this garnishee has been drawn from the Cardinal Projects account and accordingly that loan is presently unable to be used as intended. The service of this order is in dispute, although I note that this is not relevant to NABs current position.

We will transfer $200,000 from Cardinal Projects to bring the overdraft within its limits, however, wages payments of approximately $150,000 need to be processed from that account today and a further $80,000 will need to be processed tomorrow.

We are expecting some large payment over the coming week … and once received we will use these monies to bring our facilities back into line.

We respectfully request that the NAB allow the wages payments to be processed from the overdraft account with a view to this account being brought back into line in by Wednesday, 4 October 2011.

38 On 11 October 2011 Ms Beard sent a further engagement letter to Mr Hill of PPB in substantially the same terms as the letter dated 29 August 2011. The facility schedule included in the letter had been updated to show the total amount owing to the NAB as $25,767,931, with the amount owing under the facility known as the “multi option facility” (the facility made available to the Obligors which included CPS) being $9,169,931.

39 On 25 October 2011 Mr Ebeid sent an email to Mr Diamantopolous copied to, among others, Ms Beard, requesting the NAB to allow wage payments of approximately $200,000 to be processed from the overdraft account “with a view to this account being brought back into line on or before Friday, 4 November 2011”. Ms Beard responded by email of the same date stating:

NAB confirms payment of wages tomorrow and Thursday, however, no further payments will be honoured until both accounts (Cardinal Projects and Cardinal Logistics) are brought back within limit. In terms of managing cashflow going forward we would expect that you advise the Bank prior to any excess occurring (regardless of the initial excess being caused by principal and interest payments) and detail receipts due in with evidence so the Bank can make an informed position.

(original emphasis)

40 On 23 November 2011 Cardinal Group provided a proposal to the NAB for its consideration. The email from Mr Ebeid under cover of which the proposal was sent provided:

We enclose a proposal for your consideration and look forward to discussing it with the Bank and its advisors tomorrow. You will note the proposal involves a substantial injection of equity from third parties, whilst several profit enhancement and cost cutting initiatives are implemented. This is a relevant point given the capital injection demonstrates the extent of the directors (sic) commitment and their desire to sort through the Bank’s current concerns with the Group.

We are seeking some concessions from the Bank in return for this equity injection but wish to negotiate such terms in a cooperative spirit.

We look forward to working with the Bank to achieve a satisfactory result for all stakeholders and to avoid, what could otherwise be, a significant shortfall to the Bank if the business was wound up and/or receivers appointed.

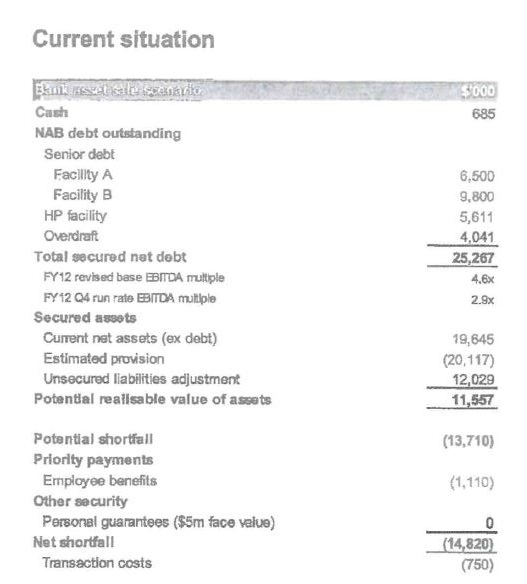

41 Under the heading “Current situation” the proposal analysed what it described as a “Bank asset sale scenario” as follows:

The following assumptions and commentary accompanied that analysis:

- Current net debt balance as at 23 November 2011

- Realisable value analysis detailed on slide 13

- Priority payments ahead of security basket

o employee leave and other entitlements of $1.1m

- Transaction costs represent:

o estimated receivership costs

o legal expenses

o accounting/taxation advice

- Personal guarantees detailed on slide 19

- Excludes director and CBS loans

- Net assets as at 30 September 2011

42 A recapitalisation proposal was then outlined. It foreshadowed a cash injection, directors’ loans for working capital, loans from an entity described as CBS, waiver of directors’ fees and salaries for 12 months and a monthly contribution from CBS making a total new funding commitment of $3.918m. On the other side of the ledger, the proposal was subject to a request for a loan principal reduction of $6.3m or 25% of the debt; the waiving of personal guarantees; and the resetting of covenants.

43 On 8 December 2011 PPB issued its report. It recommended that it was not in the NAB’s interests to lend additional funds to the Cardinal Group and that a fundamental restructure was required, in particular of “the loss making (sic) entities of Reefway, Smartskip and Recycling Resources”. Key findings included that:

the Group’s cash flow forecast indicated a cash requirement of $4.12m in March 2012 over the existing funding facilities and that the directors were proposing to fund $0.9m in the short-term leaving a funding shortfall of $3.2m;

the current debt levels of $26m appeared unsustainable based on EBITDA forecasts of $4.9m for FY12; and

the Group use seven separate management information systems across the different business units resulting in questionable financial information.

44 PPB’s recommended strategy was for a restructure and recapitalisation. It advised that the best result for the NAB in the short-term would be an equity injection sufficient to cover the forecast funding shortfall which, given the directors’ limited capacity to inject capital, would require the involvement of a third party. PPB then said that:

Without an equity injection to cover any funding shortfall, or a credible proposal from the directors, we consider the best available alternative for the Bank to be as follows:

• The Recycling businesses (being Reefway, Smartskip and Recycled Resources) are put into administration with a view to “stopping the bleeding” and then sold to repay a portion of the Bank’s indebtedness. The businesses could be “groomed” for sale during the administration process with a view to maximising value.

• CPS, the profitable subsidiary, continues as a going concern to service the reduced debt levels. The directors’ equity injection of $900k ideally would be utilised to reduce current debt levels, however, this may be required for working capital for the restructured Group.

45 On 19 December 2011, four days after the appointment of the administrators, the NAB appointed Mr Hill and Mr Robinson as receivers and managers to Cardinal, CPS, CCC and CLS and they took control of all of the assets of the companies pursuant to the fixed and floating charges held by the NAB.

46 The January 439A Report discloses that the directors estimated the total liabilities of the Cardinal Group to be $48.4m which comprised amounts owing to the NAB; amounts owing to partly secured and unsecured creditors; and tax liabilities. The directors estimated a net deficiency of liabilities over assets for the Cardinal Group of $36.495m and a net deficiency in CPS of $5.67m in circumstances where the estimated amounts owing by CPS to the NAB and to partly secured creditors were unknown. The administrators expressed the view that they expected the directors’ estimated net deficiency of the Cardinal Group to increase.

47 In that report, as part of their initial investigation into whether the companies in the Cardinal Group were trading while insolvent, the administrators undertook a detailed review of the ageing of trade creditors. They noted the ageing of trade creditors deteriorated from July 2011 until the date of their appointment, with a dramatic increase in deterioration from September 2011 when the Cardinal Group implemented repayment arrangements with a significant number of creditors. The administrators concluded that, given the large number of creditors across the Cardinal Group, both in terms of number and value, it was clear that there was an argument that the directors may have continued to trade while insolvent but advised against pursuing such a claim in light of their opinion that the directors would not have the capacity to meet any judgment.

48 The administrators’ ultimate recommendation was that the companies in the Cardinal Group be wound up. In particular in relation to CPS, the administrators advised:

• We, do not consider it would be in the creditors (sic) best interests for the Administrations to end given CPS is insolvent.

• We, do not consider a DOCA should be accepted as there is no proposal submitted.

• We do consider in the interests of all creditors that CPS be wound up.

(emphasis in original)

49 In their report to creditors dated 30 April 2013 issued by the Liquidators pursuant to s 508 of the Act, the Liquidators noted that they had received total creditor claims by way of proofs of debt for the companies in the Cardinal Group of $20,275,671, of which $7,174,583 were claims made by creditors of CPS. The Liquidators also noted that they had formed the view that the directors may have committed an offence by trading the companies’ businesses whilst they were insolvent.

50 In their report to creditors dated 15 January 2014 the Liquidators noted that they had lodged their preliminary report pursuant to s 533 of the Act with ASIC about the affairs of the Cardinal Group and possible offences committed by its directors; that they had been requested by ASIC to prepare a supplementary report; and that they had lodged a funding request with the ASIC administration fund. They also noted that, at that stage, insufficient funds had been realised to allow a dividend to be paid to unsecured creditors; realisations were insufficient to meet all of the costs of the winding up; and any return was subject to the success of recovery actions.

51 In their report to creditors dated 29 April 2015, the Liquidators noted that the requested funding was approved and that the Liquidators had lodged their supplementary report with ASIC on 17 July 2014. The Liquidators also set out creditor claims. As at that time the Liquidators had received creditor claims by way of proofs of debt from creditors of CPS in the amount of $7,148,143.

52 Mr Stone is one of the Liquidators and gave evidence about the Cardinal Group and CPS.

53 In Mr Stone’s opinion CPS was insolvent at the time that it made the payments to Melrose Cranes the subject of the Liquidators’ claim; or, alternatively, CPS was insolvent at the time when an act was done or an omission was made for the purpose of giving effect to those payments or, alternatively, CPS became insolvent by reason of matters including making those payments.

54 Mr Stone was provided with consolidated management accounts for the Cardinal Group and Card Services prepared up to 31 May 2011. The management accounts were prepared on an individual entity basis up to 15 December 2011. Mr Stone said that, according to the consolidated management accounts, as at 31 May 2011 the Group which he defines as comprising the Cardinal Group (see [16] above) and Card Services (Group) had:

(1) a current ratio of 0.95 indicating that liquidity issues were present at the time;

(2) a debt to equity ratio of 8.29 which showed the Group’s heavy reliance on debt funding to finance its operation;

(3) a positive net asset position of $4.4m. However, intangibles, wholly comprising good will, were carried in the balance sheet at $8m in 2010 and $12m in 2011. In Mr Stone’s opinion, given the trading losses and difficulties that the Group began to experience, the carrying value of good will at those dates should have been much less and he believes that the balance sheets overstated the Group’s net asset position; and

(4) a gross profit percentage for the 11 months to 31 May 2011 of 17.95% indicating a reasonable margin. However, Mr Stone said that this did not flow through to the bottom line and that business expenditure and overheads were significant and resulted in a net loss of $100,000 for the period.

55 Mr Stone noted that from 1 March 2011 the following notable events occurred:

(1) in March 2011 the Group began incurring losses;

(2) the Group had multiple financial reporting systems that had to be manually consolidated resulting in substantial problems in producing timely and accurate financial information about its trading performance, position and the ability to produce forecasts;

(3) Cardinal Group employees were transferred to Card Services. Mr Stone believes that the transfer of employees was possibly part of a strategy to transfer a large amount of liabilities to another entity and present other companies in the Cardinal Group in a more favourable financial position prior to seeking additional funds from external sources;

(4) Cardinal was the primary borrower for the Group which had an overdraft facility with the NAB that had a limit of $4m. The overdraft limit was reached and extended on more than one occasion. In November 2011 a request was made to extend the overdraft for seven days to facilitate salary and wage payments. As at the date of the appointment of the administrators the balance of the overdraft was $4.3m;

(5) the Group was insolvent on a cash flow basis from at least 1 January 2011. Mr Stone’s evidence is that the cash flow statements show a cash flow short fall for the six months up until 31 December 2010 of $496,000 followed by monthly cash flow short falls for each month from January to May 2011;

(6) a consolidated cash flow budget was prepared for the Group for the financial year ended 30 June 2012 predicting net cash inflows of $1.6m. However, the budget indicated that the Group would still require a $2.1m overdraft at the end of the financial year. The forecast overdraft balance as at 31 December 2011 was $3.4m. As at the date of the appointment of the administrators, the actual balance of the overdraft was $4.3m. In Mr Stone’s opinion the cash flow forecast was optimistic and could not be achieved;

(7) from August 2011 the NAB increased its monitoring of the Group’s borrowings and in or around October 2011 requested that PPB prepare an investigative accountant’s report. The Group had requested an additional $4.6m in funding from the NAB prior to PPB’s engagement;

(8) the Group experienced difficulties in obtaining additional finance from external sources. No equity funding was obtained following the issuing of an information memorandum in December 2010;

(9) a director’s proposal to personally provide a cash injection either failed or was abandoned;

(10) the working relationship between the directors deteriorated in the lead up to the Group being placed into administration;

(11) the Group’s financial controller resigned in July 2011;

(12) the Group’s insurance coverage lapsed on 30 November 2011 due to the non-payment of premiums; and

(13) across the Group there were outstanding income tax returns for the financial year ended 30 June 2011 and outstanding GST lodgements from 1 July 2011.

56 A quantity of the Group’s books and records were destroyed on 29 and 30 November 2011 and the Group’s electronic record keeping system was tampered with. According to a tax invoice dated 30 November 2011 from Shredlock, it undertook “secure on site shredding” of 55 x 240 litre bins on 29 November 2011 and 20 x 240 litre bins on 30 November 2011.

57 CPS used MYOB to maintain and prepare management accounts from June 2011. It previously used a different system, CHEOPS, to maintain its accounts. Mr Stone said that CPS continued to use CHEOPS until the date of appointment of the administrators for the project management side of its business.

58 On the date of their appointment as administrators, the Liquidators obtained a backup copy of the MYOB files for each of the companies in the Cardinal Group. They also obtained a hard copy of the records in CHEOPS but did not take an electronic copy of that data as CHEOPS was a bespoke system and the Liquidators did not have the software to support it.

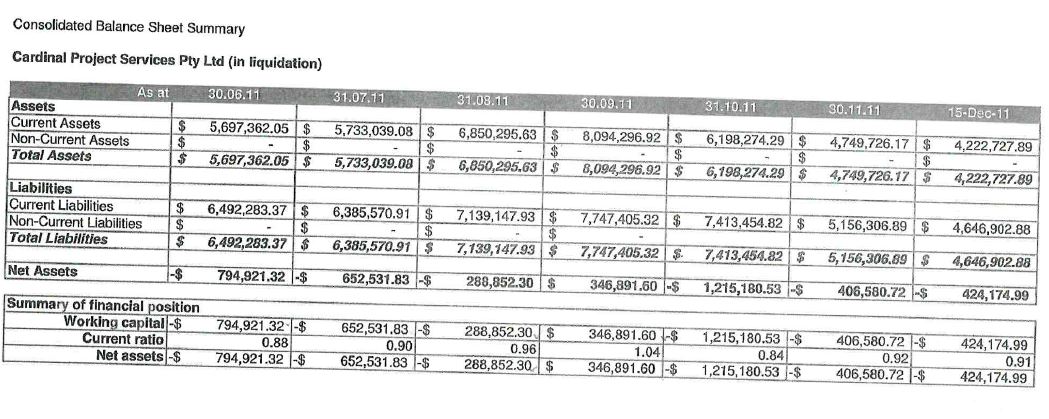

59 Mr Stone undertook an analysis of CPS’ balance sheets to determine the level of working capital assets together with an analysis of monthly liabilities. That analysis disclosed the following:

(1) CPS held virtually no assets and only minimal cash at bank. Its primary asset was receivables. Thus movements in the net asset position and liquidity of CPS were linked directly to movements in receivables;

(2) for each period from June 2011 to the date of appointment of the administrators, CPS had insufficient assets to pay its liabilities with the deficiency fluctuating between $147,279 and $3.752m;

(3) for the majority of the period from June 2011 to the date of appointment of the administrators, CPS (on an adjusted basis) had a current ratio of less than one, indicating a likely inability to meet all short-term debts due and payable during the period;

(4) CPS’s net cash at bank position varied significantly from month to month, ranging from $92,000 to $817,000. CPS’ NAB account went from having a balance of $583,000 in October 2011 to being overdrawn by $50,000 as at the date of appointment of the administrators;

(5) CPS had problems collecting debts as evidenced by the ageing of the debtors’ ledger. At the date of appointment of the administrators, the balance outstanding was over $3.3m with debtors in the 90+ days category of over $1.6m;

(6) the receivables balance reported on the MYOB balance sheet fluctuated between $3.2m and $5.7m during the period from June 2011 to the date of appointment of the administrators;

(7) CPS made loans to several related entities totalling $3.3m at the time of appointment of the administrators. Those loans were not recoverable because they were made to companies that were put into liquidation simultaneously with CPS. The loans appeared in the balance sheet in June 2011 and grew to $3m by the date of appointment of the administrators. In Mr Stone’s opinion, the unrecoverable intercompany and related party receivables meant that CPS’ reported net asset position was significantly overstated although, in cross-examination Mr Stone accepted that, in order to come to a view about the recoverability of an intercompany loan at any particular time, it was necessary to review the solvency situation of the particular company owing money at that time;

(8) creditors were paid outside the usual payment terms which resulted in demands being made for payment. As at the date of the administrators’ appointment $6.8m in trade creditors was outstanding of which a total of $3.5m had been outstanding for 90+ days. Creditors lodged proofs of debt in the amount of $7.1m; and

(9) special payment arrangements were entered into with a number of creditors. Mr Stone was provided with a schedule of payment plans for the Cardinal Group upon his appointment as administrator. The schedule, commencing in September 2011, showed average weekly payments of $361,000 to pay off debts in excess of $1.7m. Mr Stone noted that 38 creditors received payments through these arrangements and that payments made in accordance with these arrangements were not reconcilable to specific invoices.

60 Mr Stone also identified and considered other indicia of insolvency. He noted that:

(1) solicitor’s letters, demands and judgments were issued to CPS including statutory demands, letters of demand and statements of claim. Details of these are set out at [64] below;

(2) CPS had outstanding ATO lodgements namely, its 2011 tax return and business activity statements for the September and December 2011 quarters. CPS’ balance sheet indicated it was indebted to the ATO for approximately $587,000 although, at the time the ATO had not yet formally advised the amount it was owed; and

(3) CPS was placed on a prepayment arrangement with suppliers.

61 Mr Stone was extensively cross-examined about the MYOB accounts for CPS for each month from June to November 2011 and as at 15 December 2011, the date of appointment of the administrators. The following emerged:

(1) the aged payable summaries for each month end and as at 15 December 2011 record the same total payable of $6,786,720.59. The effect is that the identity of the creditors recorded on the aged payable summary for CPS as at 30 June 2011 and for each month end thereafter are in fact the creditors as at 15 December 2011;

(2) the aged receivable summaries for each month end and as at 15 December 2011 record the same total outstanding figure of $3,261,418.64. The effect is that the total debtor amount recorded on the aged receivable summary as at 30 June 2011 and for each month end thereafter is in fact the total debtor amount as at 15 December 2011;

(3) the ageing information in the aged payable and the aged receivable summaries is not accurate and cannot be relied upon in any way to identify the actual age of creditors;

(4) the totals recorded in the aged payable summary and in the aged receivable summary as at 30 June 2011 do not support or correlate with the figures for total trade payables and for total receivables in the balance sheet as at 30 June 2011. The same issue arises as between the totals recorded in the aged payable and the aged receivable summaries and the balance sheets as at July 2011, August 2011, September 2011, October 2011 and November 2011;

(5) the balance sheet as at 30 June 2011 under current liabilities includes negative amounts for some credit cards. Mr Stone agreed that if an amount is owed on a credit card it should be recorded as a positive amount and that it is a “peculiar” balance for a credit card but that he did not investigate;

(6) the total due in the aged payables summary as at 15 December 2011 does not correlate with the amount for total trade payables in the balance sheet as at 15 December 2011;

(7) no investigations were undertaken in relation to the October 2011 trading loss to the extent that it was inconsistent with the pattern of profits in prior months and in November 2011; and

(8) Mr Stone said that, as a matter of accounting, ordinarily the profit shown on a profit and loss statement is reconciled at the foot of a cash flow statement rather than the top. He also agreed that the cash flow statements came from the same database as the profit and loss and balance sheet and that it would follow that if the profit and loss in the balance sheet are wrong then the cash flow statements are going to be wrong.

62 Mr Stone was also cross-examined about the MYOB accounts which were in evidence for the Reefway Asset Trust; Reefway Environmental Services; the Cardinal Group Unit Trust; Smartskip; CLS; and CCC. Mr Stone conceded that there were issues with those accounts. For example, aged payable and aged receivable summaries for all entities, other than the Reefway Asset Trust for which there were no such summaries, suffered from the same issue as identified for those summaries for CPS; the balance sheets for the Reefway Asset Trust for October, November and December 2011 were identical; and in some cases, the totals in the aged payable and aged receivable summaries as at 15 December 2011 did not correlate with the amounts for trade creditors and/or trade debtors in the balance sheet as at 15 December 2011.

63 Ultimately, Mr Stone gave evidence that none of the discrepancies identified affected his opinion as to the solvency of CPS.

64 A number of outstanding accounts, demands and other forms of claims against CPS and attempts by CPS to compromise amounts owing by it were in evidence before me as was a schedule referred to by Mr Stone headed “Cardinal Project Services” which set out a “Summary of demands” (Summary Schedule). Those documents included:

(1) a statement of claim filed on 6 July 2011 in the Local Court by the Water Cart Pty Ltd, trading as North Western Truck Services, claiming $5,500 plus interest and costs for services provided between 3 March 2011 and 27 April 2011;

(2) a demand from Medibank Health Solutions Pty Ltd dated 21 July 2011 for unpaid invoices relating to five employees from March and April 2011;

(3) a final demand from National Commercial Services Pty Ltd dated 25 August 2011 for a debt owing to Sydney Southwest Area Health from 4 December 2010 in the amount of $105;

(4) a statement of account from Future Air dated 1 September 2011 for an invoice for $1,936 dated 28 June 2011 which included a notation that “if payment not received within seven days this account will be handed over to our collection agency”;

(5) an email dated 6 September 2011 from Kim Grylls, credit collections manager of Corporate Transpacific Industries Group Ltd, attaching a final demand and “the default against [CPS] with Veda Advantage” in which Ms Grylls noted that she was preparing the file for legal action. The email attached a letter dated 25 August 2011 to CPS demanding payment of $40,665.88 by 4.00 pm on 1 September 2011, failing which Transpacific noted that it may be forced to register a payment default with Veda Advantage for the balance owing and that further action, including legal proceedings, may be taken forthwith. The enclosed outstanding accounts were for the period 19 May 2011 to 9 June 2011;

(6) the Summary Schedule noted that a notice of demand dated 13 September 2011 had been served by Concrete Recyclers (Group) Pty Ltd (Concrete Recyclers) claiming $36,637.00 for outstanding invoices since May 2011;

(7) a letter dated 26 September 2011 from McIntosh McPhillamy & Co, solicitors for Screenmasters Australia Pty Ltd, which included:

We refer to our previous correspondence of 14 September 2011 wherein we served upon you on behalf of our client a Creditor’s Statutory Demand for Payment of Debt dated 14 September 2011, requiring payment of outstanding debts owing to our client as at that date in the amount of $59,609.79 within twenty-one (21) days after service of the Statutory Demand.

We note that subsequent to service of the Statutory Demand upon you, part payments have been made by you to our client in reduction of the outstanding debt.

Please be advised that our client, in acceptance of both part payments, does not waive its entitlement to require payment of the outstanding debt in full in compliance with the Statutory Demand. Further, we confirm our instructions that in the event the payment of the debt has not been made in full by you in compliance with the Statutory Demand … we are instructed to commence proceedings … seeking an order of the Court that you be placed into liquidation for reason of your deemed insolvency as a consequence of your failure to comply with the Statutory Demand.

(8) a letter dated 28 September 2011 from the NAB notifying CPS that the NAB had been served with a garnishee order obtained in the Local Court in proceeding 2011/71761 by Nahas. The NAB informed CPS that it was “required by law to comply with the Garnishee Order and has debited … the amount of $226,866.25”;

(9) a letter dated 7 October 2011 from Colman Moloney & Co, solicitors for Acrow Formwork & Scaffolding Pty Ltd (Acrow), requiring payment of the sum of $131,346.70 owing to their client for goods or services provided to CPS plus their costs of $150 within seven days. In the event of a failure to pay, those solicitors were instructed to issue recovery proceedings;

(10) a letter dated 14 October 2011 from Elliott May lawyers, issued on behalf of Transpacific Industries Pty Ltd, enclosing a creditor’s statutory demand for payment of debt, demanding payment of $40,665.86 and an affidavit in support;

(11) a statement of claim filed in the District Court in proceeding 11/369314 between Acrow as plaintiff and CPS and Messrs Ebeid, Travers and Burns as defendants claiming an amount of $129,850, being the “balance due for the use and hire of labour and equipment supplied by [Acrow] at the request of [CPS] during and between the months of May 2011 and August 2011” plus interest and costs;

(12) an email exchange between MSB lawyers, solicitors for BU Hazardous Material Removal & Demolition Pty Ltd (in liquidation) (BU Hazardous) and Avondale Lawyers, solicitors for CPS, and terms of settlement in Local Court proceeding 2011/197174 between BU Hazardous as plaintiff and CPS as defendant. The latter provided for full and final settlement of BU Hazardous’ claim by payment of $35,000 in instalments over the period 23 September 2011 to 23 December 2011. In the event of failure to pay, judgment would be entered in favour of BU Hazardous in the amount claimed in the statement of claim filed on 16 June 2011 being $48,863.75. The terms of settlement were filed in the Local Court on 5 October 2011 and the first instalment paid in accordance with those terms on 23 September 2011;

(13) an email dated 22 September 2011 from Mr Ebeid to Renato Cocchietto and Kenneth Johnson at SITA, with the subject line: “SITA payment plan” in which Mr Ebeid said, among other things:

Thank you both for your time yesterday to discuss our account.

We appreciate your understanding and assistance during this difficult time.

As discussed we will make payments of $25,000 on the Friday of every week for the next 10 weeks, with a view to increasing these amounts and having our account brought into line in December/January.

As a sign of good faith, please find attached a remittence (sic) advice for the initial $25,000 payment which was made yesterday.

(14) a letter dated 17 October 2011 from Bibby Financial Services in relation to supplier Zwf NSW Pty Ltd seeking payment of an overdue amount of $66,766.28;

(15) a notice of intention to issue legal proceedings dated 24 October 2011 issued by EC Credit Control Pty Ltd on behalf of Metro Tipper Hire notifying CPS, among other things, that unless settlement of the amount claimed of $45,666.89 was received within seven days of the date of the notice, Metro Tipper Hire may commence legal proceedings without further notice;

(16) an email dated 3 November 2011 from Sarah Ferguson, administration manager of CPS, to Jake Elliott and Mr Ebeid attaching a letter of demand from I-recruit. In her email Ms Ferguson wrote by reference to the letter of demand that “it states they need payment in full of 168k by tomorrow or they go legal. They have called today saying if it isn’t paid by tomorrow, they will go legal but they will also pull all their labour hire off the job sites, can someone please give them a call”;

(17) a letter dated 25 November 2011 from Recoveries National, debt recovery agents acting on behalf of Kennards Hire Pty Ltd (Kennards), demanding immediate payment of the amount of $7,069.70 owing to Kennards for the period 3 August 2011 to 21 September 2011 and noting that, if payment was not received within 48 hours, Kennards would “have no further options but to instruct their solicitors to commence formal proceedings without further notice”;

(18) a letter dated 29 November 2011 from Bowsers Fire Protection Experts seeking payment of invoices totalling $20,641.50 which remained outstanding despite “many requests for payment and assurances given by [CPS] that [they] would be paid”. The letter stated:

We require full payment in the amount of $20,641.50 by the close of business on 1 December 2011. Please ensure this amount is received by that date. Failing receipt of the full amount on or before that date, we will have no option but to immediately suspend all works and to take appropriate steps to recover payment. This will include … referral of the matter to our legal advisers for appropriate action.

Obviously having regard to our 10 year working relationship our preference is not to have to resort to these measures to recover payment. However the current situation, where we have not been paid for work completed as far back as July, and in light of the failure by [CPS] to honour its promises of payment … we currently see no alternative.

(19) a letter dated 30 November 2011 from Galluzzo Lawyers seeking payment on behalf of their client, Concut (NSW) Pty Ltd, of $66,598.60 within seven days for invoices issued in September and October 2011. Failure to pay would result in action being taken pursuant to the Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment Act 1990 (NSW);

(20) a statutory demand for $163,034 issued by North Shore Paving Co Pty Ltd on 5 December 2011 as set out in the Summary Schedule;

(21) a statement of claim filed in District Court proceeding 11/398537 on 9 December 2011 by Boral Ltd as plaintiff against CPS and Messrs Travers, Ebeid and Burns as defendants claiming $138,727.41 plus interest and costs;

(22) a letter dated 12 December 2011 from Caroline Najjar Lawyer enclosing, by way of service, a creditor’s statutory demand for payment of debt and accompanying affidavit on behalf of her client Corporate Ventures (Aust) Pty Ltd;

(23) a letter dated 13 December 2011 from Nexus Collections enclosing a creditor’s statutory demand for payment of a debt that was issued by Lindores Personnel No 2 Pty Ltd claiming payment of $221,687.03 and an affidavit in support; and

(24) a letter dated 15 December 2011 from Oceanic Mercantile Pty Ltd enclosing a creditor’s statutory demand for payment of debt issued by Force Corp Pty Ltd for $30,522.23 for invoices issued in the period 10 July 2011 to 20 November 2011 and an affidavit in support.

4.1 Background to the Melrose Cranes’ business

65 Melrose Cranes is a family business established in 1998 by Gregg Peter Melrose (Mr Melrose), its managing director and Debbie Melrose (Mrs Melrose), the administration manager.

66 Melrose Cranes provides cranes for hire, usually to the construction industry, on a short-term and sometimes on a longer term basis. It operates approximately 110 pieces of heavy plant, of which more than 30 are mobile cranes, and provides mobile crane and transport services throughout the east coast of Australia. In 2011 Melrose Cranes had approximately 99 pieces of heavy plant, 28 of which were mobile cranes.

67 As managing director, Mr Melrose is in charge of the day-to-day operations of Melrose Cranes. It was clear from his evidence that he takes a “hands-on” approach to the business. He knows where each piece of equipment that Melrose Cranes owns is at any time and the jobs the company has on a daily basis. During the course of the day Mr Melrose monitors the company’s operations through conversations and telephone calls with senior staff members and major customers. Mr Melrose said, and I accept, that very little happens within the business without him being aware of it, either as it happens or soon after. I pause here to observe that Mr Melrose struck me as an experienced businessman who had invested a lot of time and energy in building up the Melrose Cranes business, a family owned and run business. But in his eagerness and understandable desire to protect the business, I found some of Mr Melrose’s evidence to be self-serving. While it may not have been Mr Melrose’s intention to be less than frank in his responses, it was difficult to reconcile some of his evidence with the objective facts and to accept some of his evidence in the circumstances described below.

68 As administration manager, Mrs Melrose’s day-to-day tasks included finance, accounts and office administration as well as overseeing staff (of which there were five including Mrs Melrose) and undertaking administrative tasks, including payroll and invoicing.

69 As part of her role, Mrs Melrose followed up payment of tax invoices issued to clients. She described her usual procedure as follows:

(1) she monitored the age of the customers’ accounts. Mrs Melrose said that, while Melrose Cranes’ payment terms were 30 days from the date of invoice, it was usual to be paid by larger clients with multiple invoices each month anywhere between 45 to 60 days from the end of the month and that, in her experience, payment around 45 to 60 days from the end of month was standard in the industry. Mr Melrose gave evidence to similar effect about the time in which payment was usually made, noting that in some cases the arrangements were the subject of agreement and in other cases Melrose Cranes simply permitted it to happen;

(2) she called clients to follow up payment if payment had not been received within 30 to 45 days from the end of the month. This sometimes resulted in a client being called before they would usually make payment in the ordinary course but that procedure assisted Mrs Melrose in identifying if there were any issues that might arise regarding payment. A call would usually involve following up whether all invoices due for payment had been authorised; what the expected payment date would be; and whether it was necessary for authority for payment to come from site, and if so, whether the client or she would follow up the authorisations;

(3) if any issues were identified at that stage, Mrs Melrose corresponded with or talked to the engineer or Melrose Cranes’ project manager responsible for the job;

(4) if an account went beyond a client’s usual payment time, Mrs Melrose called to follow up payment and kept calling a client until a definite payment date was fixed;

(5) if a payment date was fixed, Mrs Melrose followed up that payment on the agreed date. If no date for payment could be arranged or the date nominated by the client went beyond 60 days, or earlier depending on the particular circumstances of the client or the reasons given, or alternatively, if an issue was identified, then Mrs Melrose informed Mr Melrose and the project manager handling the job and asked either of them to ring the client. Mr Melrose or the project manager would then call the client and after that Mr Melrose made a decision on any further action to be taken; and

(6) when payments were received, unless otherwise instructed or it was obvious from the amount of the payment made, the payment was ordinarily allocated to the oldest outstanding invoice.

70 Practically, in following up payment of accounts, at the end of each month Mrs Melrose generated a receivables list from the MYOB system maintained by Melrose Cranes and created a handwritten alphabetical list by client of all amounts due in a document headed “Receivables – Contact List” (Receivables List) with five columns headed respectively: company, phone number, contact, amount and date/remarks. Mrs Melrose reviewed the Melrose Cranes cheque account daily to monitor any incoming payments. She recorded any payment in MYOB, made a note of it on the Receivables List and then contacted debtors in the Receivables List by telephone to follow up payment.

71 Mr Melrose said that he informally monitored payment of large accounts quite closely and that he became involved in following up payment of accounts when Mrs Melrose brought an overdue account to his attention or if he thought that the size of particular invoices deserved his attention. Given Mr Melrose’s hands-on approach to the business, this is not surprising. He noted that some clients had a practice of not paying until followed up and that he tended to get involved with clients who he thought were employing that strategy.

72 According to Mr Melrose the crane business is quite competitive on price and rigid insistence on payment within 30 days would be likely to put off good clients. For that reason he did not pay close attention to whether clients were paying within 30 days. However, if Mr Melrose became aware that a particular client was not adhering to its usual payment times, he looked at what was happening in relation to payment of accounts and, if necessary, contacted the client.

73 Mr Melrose operated a diary in which he recorded matters that related to Melrose Cranes, its staff, jobs being undertaken or the follow up of payment of accounts as well as personal reminders every now and then. A copy of Mr Melrose’s diary for the 2011 calendar year (2011 Diary) was in evidence. It was a day to a page diary and was complete save for the pages for 22 to 29 October 2011 inclusive. Mr Melrose was provided with his original diary and agreed in cross-examination that those pages were missing. He was unable to provide a satisfactory explanation as to why that was so. The following exchange took place:

Q. Where are they?

A. I don’t know.

Q. Do you have any recollection where they could be?

A. No, I don’t.

Q. Who has access to your diary?

A. Only me.

Q. So it’s only you that could have --- ?

A. It’s left on my desk.

Q. --- removed the pages?

A. Generally, I’m the only one that uses it.

Q. Yes. Where is your desk?

A. In my office.

Q. Who has got access to your office?

A. Everybody.

Q. But, to your knowledge, no one touches your diary?

A. To my knowledge, yes.

Q. I mean, for example, when one looks at the handwriting in the diary throughout the calendar year, that’s all your handwriting, isn’t it?

A. Yes. Yes. Yes, it is.

Q. So you’ve got no recollection at all as to why that week is missing?

A. No, I don’t.

74 In early 2008 Mr Melrose was contacted by Glen Felstead, a person with whom he had had previous dealings, who at that time was working for CPS. From that time, Melrose Cranes began a business relationship with CPS.

75 On 25 February 2008 CPS provided a completed credit application to Melrose Cranes. The application included a declaration which had been signed by Mr Travers in which it was declared that CPS understood that the terms of payment to Melrose Cranes were “strictly net thirty (30) days” and that “[t]his means that payment for goods and services is due within 30 days from invoice date”. The terms and conditions included in the application also relevantly provided:

20. Payment will be required thirty (30) days from the date of the invoice unless other arrangements have been quoted/arranged between the Contractor and the Client. In the event of failure of the Client to pay the invoice within the timeframe stipulated or arranged, then the Contractor reserves the right to charge interest on such sum or sums which remain outstanding beyond the time stipulated or arranged at the rate of two percent per month, and recover all costs incurred in the collection of any outstanding monies including debt collections and solicitors expenses and costs.

The credit application included a personal guarantee which had been signed by Messrs Ebeid and Travers.

76 The credit application required trade references to be provided. Two completed trade references were provided to Melrose Cranes: one given by Concrete Recyclers noting that its payment terms were 30 days, that payment was usually received in 45-50 days and that average monthly trading was between $4,000 and $15,000; and a second given by Blacktown Waste Service noting, among other things, that its payment terms were 30 days, that payment was usually received in 45-60 days and that average monthly trading was $55,000-$110,000.

77 Mr Melrose said that from 2008 some of the invoices Melrose Cranes issued to CPS provided for payment 30 days from the invoice date but that the most common arrangement between Melrose Cranes and CPS was for payment to be made by the last day of the following month and that payment up to 45 days after the end of the month in which the invoice was issued was not unusual. Mr Melrose also said that sometimes no specific agreement was made in relation to payment but that, even so, he accepted payment within those times and, on the whole, payments from Cardinal were regular and consistent. However, it was clear from the invoices themselves and from Mr Melrose’s evidence in cross-examination that nearly all, not some, of the invoices issued by Melrose Cranes in the period from June 2010 to December 2011 provided for payment within 30 days from the date of invoice.

78 On 28 September 2010 Melrose Cranes suspended CPS’ credit account. Mr Melrose’s email to Mr Felstead dated that day recorded that Melrose Cranes “have had no satisfaction with advice regarding payment of our July Account” and that after Mr Melrose spoke with Sarah he was told that a “partial payment of $20,218 would be made only with no specific advice regarding the remainder”. Accordingly Mr Melrose notified Mr Felstead that he was not left with any alternative and temporarily suspended CPS’ credit account. As at 22 September 2010, prior to receipt of $20,218, CPS owed Melrose Cranes $206,962.88 with the amount owing as at 30 July 2010 being $116,248.06. In cross-examination Mr Melrose said that he suspended the account because there was a significant amount owing and he was concerned about CPS’ capacity to pay its debts.

79 The Receivables Lists for March 2011, April 2011, May 2011, June 2011 and July 2011 each include CPS. In the Receivables List for:

(1) March 2011 a balance of $88,882.75 is recorded as owing by CPS. Against that Mrs Melrose recorded part payments of $20,000 and $40,000 on 27 May 2011 and 1 June 2011 respectively. Mrs Melrose also recorded that on 1 June she “spoke to and faxed urgent/processing payment March balance with Vicky [Leftakis]” and included a further note: “ring Friday. Tell GM to ring Tom”. Mrs Melrose requested payment and made the latter note as a reminder to ask Mr Melrose to ring CPS to follow up payment because the invoice was not paid on time;

(2) April 2011 a carried forward amount of $13,882.75 is recorded. Mrs Melrose made notations in the date/remarks column including:

GM dealing with Vicky [Leftakis]/Tom.

$6,000 tonight = $6,651.15 Pd EFT 21/6

2 Liverpools Fri night . $7,231.60 due + April $922.90 = Total $8,154.50

$6,587.40 EFT = 24/6

$374.20 – will pay next Friday 1/7

Mrs Melrose accepted that of the amount due at the end of April 2011, $10,034.20 related to an invoice dated 20 March 2011 in relation to which a payment of $9,660 was made on 3 June 2011 leaving a balance of $374.20. She accepted that the payment was late and that the reason why she was keeping Mr Melrose up to date was because CPS had overdue invoices;

(3) May 2011 Mrs Melrose recorded amounts owing from pre-May and May. On 29 July 2011 Mrs Melrose sent a copy of a statement dated 29 July 2011 as a reminder by fax to Ms Leftakis in relation to those amounts with a message that included:

Reminder: Has this been paid today by EFT. See above old March, April & May Invoices marked * Please call me on your return from lunch to confirm you are paying April 52823 & May $2,339.70 today as previously advised And… to advise reason/request for SHORTPAID Invoice 52453. Please call today…

(4) June 2011 the initials “GM” were recorded by Mrs Melrose in the “phone number” column. That was a reference to Mr Melrose who was handling the follow up because there was a large amount outstanding. On 1 June 2011 Mrs Melrose sent a fax to Ms Leftakis at CPS chasing up monies and payment of the outstanding balance for March 2011.

80 In about May 2011 CPS engaged Melrose Cranes for a job in Akuna Street, Canberra (Canberra Job). Mr Melrose was initially contacted by Bobby Jovanovski, who he understood was assisting Mr Felstead with the Canberra Job. Subsequently Mr Melrose contacted Mr Felstead and discussed the requirements of the Canberra Job. After providing a quote, Melrose Cranes entered into a contract dated 18 May 2011 with CPS which provided, among other things, that payment claims were to be made on the 25th day of each month valued up to the 30th day of the month and that payment of the claim as agreed or approved would be made by the 30th day of the next month after the payment claim was submitted, provided the claim was submitted by the due date.

81 On 1 June 2011 Mrs Melrose sent an invoice by facsimile to Ms Leftakis as part of what she said was her usual procedure to follow up payment. The invoice, which showed an outstanding balance for invoices rendered prior to April 2011 of $28,882.75 and a total amount due of $43,634.03, included a handwritten note in the following terms:

For your reference to chase up invoices. Thanks Vicky for your assistance. Please follow up with the relevant Site manager for urgent authorization & payment of the outstanding balance for MARCH. The last 4 Invoices were sent to you on 11/4/11. I will check up with you in a day or so. Thanks…

82 On 21 June 2011 Andrew Gray, one of the principal people working on the Canberra Job as senior project manager and heavy crane manager, and Mr Melrose received an email from Mr Jovanovski in relation to the Canberra Job in which Mr Jovanovski notified them that CPS would potentially need the crane for an additional week’s hire “from 7/7/11–13/7/11 under the same hire agreement of $30,000/week”. Mr Gray responded on behalf of Melrose Cranes noting that they were “happy to do the 1 week extension of time 7/7/11–13/7/11 under the same agreement but need your written Order”. On 23 June 2011 Mr Jovanovski sent an email to Messrs Gray and Melrose confirming “the requirement of the 250t crane for an additional one week hire from 7/7/11–13/7/11 at $30,000/week. The existing contract still stands with the date for practical completion new (sic) extended to 13/7/11”.

83 On 4 July 2011 Julie-Anne Leslie, who managed accounts for Melrose Cranes, sent an email to Ms Leftakis setting out the amounts outstanding “after your payment was applied”. As at that date the total outstanding was $3,636.80.

84 On 16 July 2011, as the work was finalised, the crane left the Canberra Job. Mr Melrose had received no complaints from anyone about the job nor had any of Melrose Cranes’ staff raised any issue about payment of its accounts. Melrose Cranes issued its last invoice for the Canberra Job on 16 July 2011.

85 On 29 July 2011, in accordance with her usual procedure for following up payment, Mrs Melrose sent an invoice by facsimile to Ms Leftakis which showed a total amount due of $221,633.98 of which $1,297.10 was for invoices issued prior to May 2011 and $2,339.70 was for invoices issued in May 2011.

86 Because payments for the Canberra Job were due 30 days from the date of invoice and because of the amounts involved, Mr Melrose, rather than Mrs Melrose, principally undertook the follow up with CPS for payment for that job. A handwritten note made by Mrs Melrose on 5 August recorded:

June 30 days $146.497.18 was due under Bobby’s 30 day contract @ 30/7/11. Will f/up with Bobby. Note GM emailed Bobby!!

87 On 5 August 2011 Mr Melrose sent an email to Mr Jovanovski in relation to the Canberra Job in which he said:

Under the terms of your contract 1924312 you owe me $146,497.18 which was due and payable on 30 July 2011. Your accounts department (Vicki [Leftakis]) has no knowledge of this payment and I can’t afford to wait for her to find out. During the course of the project, which we were appreciative to get, you often drove the contract details back to me with regard to credits etc. We did the job cheap. We did the job well. I’d like to be paid on Monday. Please ring me, not email me, to tell me what time I can pick up a cheque on Monday.

A further $71,500 will be due and payable on 30 August 2011. Please confirm that payment will be ready on that day.

88 Mr Melrose said that, despite his email dated 5 August 2011, he had no concern about payment. He simply wanted to put pressure on CPS to pay as soon as possible. Mr Melrose said that it was not unusual for Melrose Cranes to undertake large contracts; that he liked to monitor payment of significant amounts quite closely; and that, given the amount due was over $100,000, he kept an eye on it as he would with any client that owed that amount. Mr Melrose also said that the style and tone of the email he sent to Mr Jovanovski was not unusual for him but was a way of “getting attention” and was very similar to emails he has sent to any number of other clients in similar circumstances becoming “something like a standard style email”. But this evidence does not sit comfortably with Mr Melrose’s evidence (at [69(1)] above) that the most common arrangement between Melrose Cranes and CPS was for payment to be made by the last day of the month following issue of the invoice and that payment up to 45 days after the end of the month in which the invoice was issued was not unusual. I do not accept Mr Melrose’s evidence that he was not concerned about payment. The evidence set out below reinforces that view.

89 Shortly after sending his email dated 5 August 2011 to Mr Jovanovski, Mr Melrose had a conversation with him to the following effect:

Mr Melrose: Can you find out what’s going on with my money mate? Obviously you haven’t paid, unless there is an issue with us being paid. Is there? There is a fair bit owing and I need to know when payment will be made.

Mr Jovanovski: Yeah I’ll check it out and get back to you.

90 Mr Melrose does not recall the response he subsequently received from Mr Jovanovski but he does recall that, after hearing back from him, he called Mr Felstead with whom he had more of a relationship and from whom he felt he would “get an upfront response”. Mr Melrose had a conversation with Mr Felstead to the following effect:

Mr Melrose: Mate, I have spoken with Bobby and I didn’t get much of an answer out of him. What is happening with payment for Canberra?

Mr Felstead: I’m not quite sure. I know that we were having some issues with Canberra and were working through them. As I understand it, our estimators might have underquoted the job, but don’t quote me on that. I have been given assurances that everything is under control. There are no issues with Melrose Cranes at all...

Mr Melrose Thanks for that Glen. I need to know what is happening so can you get someone to call me back and let me know what they are going to do about it.

Mr Felstead: Sure. No worries.

91 On 9 August 2011, only 9 days after the invoice was due, Mr Melrose sent an email to Mr Felstead in relation to the Canberra Job attaching a letter of the same date. The letter, a copy of which was provided to, among others, John O’Shannassy of O’Shannassy Lawyers and Tom Simonds of Chase Building Group Pty Ltd, included:

Under the terms of the contract between Melrose Cranes & Rigging Pty Limited (MCR) and Cardinal Project Services (CPS) at Clause #18 notice is officially given of a major dispute regarding the non-payment of our outstanding account of $149,855.13 which is predominantly in relation to the Akuna Street Canberra Job. Your contract terms are quite specific and payment should have been made on 30 July 2011. Under your terms a meeting is required to resolve the issue within five (5) days of this notice. Under my terms (also signed) interest is compounding at the rate of 1.2% daily until paid in full.

MCR reserves the right to utilise the Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment Act 1999 to obtain payment if the meeting does not resolve this issue. The Head Contractor in Canberra, Chase, has been informed of the situation. At the same meeting it is imperative that the outstanding amount of $71,500 which is due and payable on the 30 August 2011 also be discussed.

This situation is not of my doing or choice. As a Director I have many responsibilities and putting MCR at risk for $221,355.13 (plus interest) has to be managed. As you know CPS had a budget and MCR had a crane. We assisted each other for mutual benefit. The contract was verbally quoted to me more than once during demolition by Bobby and we complied as required. All I am asking is that CPS does the same.

Unfortunately your credit account is now frozen pending an agreeable outcome.

(underlining in original)

(emphasis added)