FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pental Limited [2018] FCA 491

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent PENTAL PRODUCTS PTY LTD ACN 103 213 467 Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

PENAL NOTICE

TO: PENTAL LIMITED AND PENTAL PRODUCTS PTY LIMITED

IF YOU (BEING THE PERSON BOUND BY THIS ORDER):

(A) REFUSE OR NEGLECT TO DO ANY ACT WITHIN THE TIME SPECIFIED IN THIS ORDER FOR THE DOING OF THE ACT; OR

(B) DISOBEY THE ORDER BY DOING AN ACT WHICH THE ORDER REQUIRES YOU NOT TO DO,

YOU WILL BE LIABLE TO IMPRISONMENT, SEQUESTRATION OF PROPERTY OR OTHER PUNISHMENT.

ANY OTHER PERSON WHO KNOWS OF THIS ORDER AND DOES ANYTHING WHICH HELPS OR PERMITS YOU TO BREACH THE TERMS OF THIS ORDER MAY BE SIMILARLY PUNISHED.

THE COURT ORDERS BY CONSENT THAT:

Declarations

1. The first and second respondents (together, Pental), during the period between 7 February 2011 and 16 February 2016, represented on the product packaging for the White King Power Clean Flushable Toilet Wipes in a 40-wipe pack and White King Power Clean Flushable Toilet Wipes in a 100-wipe pack (also described as White King Flushable Bathroom Power Wipes) (White King Wipes) and on its websites at www.pental.com.au and www.whiteking.com.au (Websites) that the White King Wipes:

(a) were made from a specially designed material which disintegrated in the sewerage system like toilet paper, when in fact the White King Wipes were not made from a specially designed material which disintegrated in the sewerage system like toilet paper;

(b) had similar characteristics to toilet paper when flushed, when in fact the White King Wipes did not have similar characteristics to toilet paper when flushed; and

(c) would break up or disintegrate in a timeframe and manner similar to toilet paper, when in fact the White King Wipes did not sufficiently break up or disintegrate in a timeframe and manner similar to toilet paper,

(together, Disintegration Representations). By making the Disintegration Representations, Pental, in trade or commerce:

(d) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law, which is Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (ACL);

(e) made false or misleading representations that White King Wipes had a particular quality in contravention of s 29(1)(a) of the ACL;

(f) made false or misleading representations that White King Wipes had particular performance characteristics, uses and/or benefits in contravention of s 29(1)(g) of the ACL; and

(g) engaged in conduct that was liable to mislead the public as to the nature, characteristics and suitability for purpose of the White King Wipes, in contravention of s 33 of the ACL.

2. Pental, during the period between 7 February 2011 and 12 July 2016 (Relevant Period), by representing on the product packaging for White King Wipes and on the Websites, in trade or commerce, that White King Wipes were suitable to be flushed down the toilet and into sewerage systems in Australia, when in fact this was not the case because the White King Wipes did not break up or disintegrate in a timeframe and manner similar to toilet paper in circumstances where sewerage systems in Australia were, including during the Relevant Period, and are primarily designed to carry urine, faeces and toilet paper:

(a) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s 18 of the ACL;

(b) made false or misleading representations that White King Wipes had a particular quality in contravention of s 29(1)(a) of the ACL;

(c) made false or misleading representations that White King Wipes had particular performance characteristics, uses and/or benefits in contravention of s 29(1)(g) of the ACL; and

(d) engaged in conduct that was liable to mislead the public as to the nature, characteristics and suitability for purpose of the White King Wipes, in contravention of s 33 of the ACL.

3. Pental be restrained from representing, in trade or commerce in connexion with the supply of personal or cleaning wipe products, that those products are “flushable” until the earlier of:

(a) 6 years from the date of this Order;

(b) the date on which a code, guideline or standard in relation to the use of the word “flushable” for wipes, which is legally enforceable, comes into force in Australia and the representations made are in accordance with that code, guideline or standard.

4. An order pursuant to s 246 of the ACL that Pental:

(a) establish the Compliance Programme set out in Annexure A to these Orders which is specifically designed to:

(i) ensure an understanding and awareness by all officers, employees or contractors of Pental of the responsibilities and obligations in relation to the conduct set out in Orders 1 and 2 above and any similar related conduct; and

(ii) review and revise the internal operations of its business which led to it engaging in the conduct set out in Orders 1 and 2 above and any similar related conduct;

(b) maintain and administer, at its own expense, the Compliance Programme for a period of three years; and

(c) provide at its own expense, a copy of any documents to be provided to the ACCC pursuant to Annexure A.

Costs

5. The respondents pay the applicant’s costs:

(a) of the liability aspect of the proceedings, being the costs of and incidental to the proceedings up to and including 3 November 2017, to be fixed in the sum of $85,000 and payable within 30 days of the date of this Order; and

(b) of the penalty aspect of the proceedings, being the costs of and incidental to the proceedings on and from 4 November 2017, on a party and party basis.

Pecuniary penalties

6. The first respondent pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a total pecuniary penalty of $550,000 in respect of the contraventions referred to in Orders 1 and 2 above, within 30 days of the date of this order.

7. The second respondent pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a total pecuniary penalty of $150,000 in respect of the contraventions referred to in Orders 1 and 2 above, within 30 days of the date of this order.

Lump sum costs

8. By 24 April 2018, the applicant file and serve an affidavit setting out the lump sum costs amount that it seeks pursuant to Order 5(b) above as well as the costs it has incurred.

9. By 8 May 2018, the respondents file and serve any evidence in response to the evidence served by the applicant pursuant to Order 8 above.

10. The quantum of lump sum costs sought by the applicant pursuant to Order 5(b) above be determined on the papers following receipt of any material filed in accordance with Orders 8 and 9 above.

Time for appeal

11. Pursuant to FCR 36.03(b), the time fixed by which any notice of appeal against these Orders be filed and served be the date 7 days after the publication to the parties of the revised reasons for judgment.

Annexure A

COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMPLIANCE PROGRAMME

The respondents, Pental Limited and Pental Products Pty Ltd (together, Pental) will establish a Competition and Consumer Compliance Programme (Compliance Programme) that complies with each of the following requirements:

Appointments

1. Within 30 days of the date of the Order of the Court, Pental will appoint a director or a senior manager with suitable qualifications or experience in corporate compliance as a Compliance Officer with responsibility for ensuring the Compliance Programme is effectively designed, implemented and maintained (Compliance Officer).

2. Within three months of the date of the Order of the Court, Pental will appoint a suitably qualified, internal or external, compliance professional with expertise in competition and consumer law (Compliance Advisor).

3. Pental will instruct the Compliance Advisor to conduct a competition and consumer law risk assessment within three months of being appointed as the Compliance Advisor (Risk Assessment).

4. Pental will use its best endeavours to ensure that the Risk Assessment covers the following matters, to be recorded in a written report (Risk Assessment Report):

(a) identifies the areas where Pental is at risk of breaching ss 18, 29 and 33 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), comprising Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA);

(b) assesses the likelihood of these risks occurring;

(c) identifies where there may be gaps in Pental’s existing procedures for managing these risks; and

(d) provides recommendations for any action to be taken by Pental having regard to the above assessment.

Compliance Policy

5. Pental will, within 30 days of the date of the Order of the Court, issue a policy statement outlining Pental’s commitment to compliance with the CCA (Compliance Policy).

6. Pental will ensure that the Compliance Policy:

(a) contains a statement of commitment to compliance with the CCA;

(b) contains an outline of how commitment to CCA compliance will be realised within Pental;

(c) contains a requirement for all staff to report any Compliance Programme related issues and CCA compliance concerns to the Compliance Officer;

(d) contains a guarantee that whistleblowers with competition and consumer law compliance concerns will not be prosecuted or disadvantaged in any way and that their reports will be kept confidential and secure; and

(e) contains a clear statement that Pental will take action internally against any persons who are knowingly or recklessly concerned in a contravention of the CCA and will not indemnify them in the event of any court proceedings in respect of that contravention.

Complaints Handling System

7. Pental will ensure that the Compliance Programme includes a competition and consumer law complaints handling system (Complaints Handling System).

8. Pental will use its best endeavours to ensure this system is consistent with AS/ISO 10002:2006 Customer satisfaction - Guidelines for complaints handling in organizations, tailored as required to Pental’s circumstances.

9. Pental will ensure that staff and customers are made aware of the Complaints Handling System.

Whistleblower Protection

10. Pental will ensure that the Compliance Programme includes whistleblower protection mechanisms to protect those coming forward with competition and consumer law complaints.

11. Pental will use its best endeavours to ensure that these mechanisms are consistent with AS 8004:2003 Whistleblower protection programs for entities, tailored as required to Pental’s circumstances.

Staff Training

12. Pental will ensure that the Compliance Programme provides for regular (at least once a year) training for all directors, officers, employees, representatives and agents of Pental, whose duties could result in them being concerned with conduct that may contravene ss 18, 29 and 33 of the ACL.

13. Pental must ensure that the training is conducted by a suitably qualified compliance professional or legal practitioner with expertise in competition and consumer law.

14. Pental will ensure that the Compliance Programme includes a requirement that awareness of competition and consumer compliance issues forms part of the induction of all new directors, officers, employees, representatives and agents, whose duties could result in them being concerned with conduct that may contravene ss 18, 29 and 33 of the ACL.

Reports to Board/Senior Management

15. Pental will ensure that the Compliance Officer reports to the Board and/or senior management every six months on the continuing effectiveness of the Compliance Programme.

Compliance Review

16. Pental will, at its own expense, cause an annual review of the Compliance Programme (Review) to be carried out in accordance with each of the following requirements:

(a) Scope of Review – the Review should be broad and rigorous enough to provide Pental and the ACCC with:

(i) a verification that Pental has in place a Compliance Programme that complies with each of the requirements detailed in paragraphs 1-15 above; and

(ii) the Compliance Reports detailed at paragraph 17 below.

(b) Independent Reviewer – Pental will ensure that each Review is carried out by a suitably qualified, independent compliance professional with expertise in competition and consumer law (Reviewer). The Reviewer will qualify as independent on the basis that he or she:

(i) did not design or implement the Compliance Programme;

(ii) is not a present or past staff member or director of Pental;

(iii) has not acted and does not act for, and does not consult and has not consulted to, Pental in any competition and consumer law related matters, other than performing Reviews under the Order of the Court; and

(iv) has no significant shareholding or other interests in Pental.

(c) Evidence – Pental will use its best endeavours to ensure that each Review is conducted on the basis that the Reviewer has access to all relevant sources of information in Pental’s possession or control, including without limitation:

(i) the ability to make enquiries of any officers, employees, representatives and agents of Pental;

(ii) documents relating to the Risk Assessment, including the Risk Assessment Report;

(iii) documents relating to the Compliance Programme, including documents relevant to the Compliance Policy, Complaints Handling System, Staff Training and induction programme; and

(iv) any reports made by the Compliance Officer to the Board or senior management regarding the Compliance Programme.

(d) Pental will ensure that a Review is completed within one year of the date of the Order of the Court, and that a subsequent Review is completed within each year for three years.

Compliance Reports

17. Pental will use its best endeavours to ensure that within 30 days of the completion of a Review, the Reviewer includes the following findings of the Review in a report provided to Pental (Compliance Report):

(a) whether the Compliance Programme includes all the elements detailed in paragraphs 1-15 above, and if not, what elements need to be included or further developed;

(b) whether the Compliance Programme adequately covers the parties and areas identified in the Risk Assessment, and if not, what needs to be further addressed;

(c) whether the Staff Training and induction is effective and if not, what aspects need to be further developed;

(d) whether the Complaints Handling System is effective and if not, what aspects need to be further developed;

(e) whether Pental is able to provide confidentiality and security to competition and consumer law whistleblowers, and whether staff are aware of the whistleblower protection mechanisms;

(f) whether there are any material deficiencies in the Compliance Programme, or whether there are or have been any instances of material non-compliance with the Compliance Programme (Material Failure), and if so, recommendations for rectifying the Material Failure/s1.

Pental response to Compliance Reports

18. Pental will ensure that the Compliance Officer, within 14 days of receiving the Compliance Report:

(a) provides the Compliance Report to the Board or relevant governing body;

(b) where a Material Failure has been identified by the Reviewer in the Compliance Report, provides a report to the Board or relevant governing body identifying how Pental can implement any recommendations made by the Reviewer in the Compliance Report to rectify the Material Failure.

19. Pental will implement promptly and with due diligence any recommendations made by the Reviewer in the Compliance Report to address a Material Failure.

Reporting Material Failures to the ACCC

20. Where a Material Failure has been identified by the Reviewer in the Compliance Report, Pental will:

(a) provide a copy of that Compliance Report to the ACCC within 14 days of the Board or relevant governing body receiving the Compliance Report; and

(b) inform the ACCC of any steps that have been taken to implement the recommendations made by the Reviewer in the Compliance Report; or

(c) otherwise outline the steps Pental proposes to take to implement the recommendations and will then inform the ACCC once those steps have been implemented.

Provision of Compliance Programme documents to the ACCC

21. Pental will maintain a record of and store all documents relating to and constituting the Compliance Programme for a period not less than five years.

22. If requested by the ACCC during the period of five years following the date of the Order of the Court, Pental will, at its own expense, cause to be produced and provided to the ACCC copies of all documents constituting the Compliance Programme, including:

(a) the Compliance Policy;

(b) the Risk Assessment Report;

(c) an outline of the Complaints Handling System;

(d) Staff Training materials and induction materials;

(e) all Compliance Reports that have been completed at the time of the request;

(f) copies of the reports to the Board and/or senior management referred to in paragraphs 16 to 19.

ACCC Recommendations

23. Pental will implement promptly and with due diligence any recommendations that the ACCC may make that the ACCC deems reasonably necessary to ensure that Pental maintains and continues to implement the Compliance Programme in accordance with the requirements of the Order of the Court.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

(Revised from the transcript)

LEE J:

A Introduction

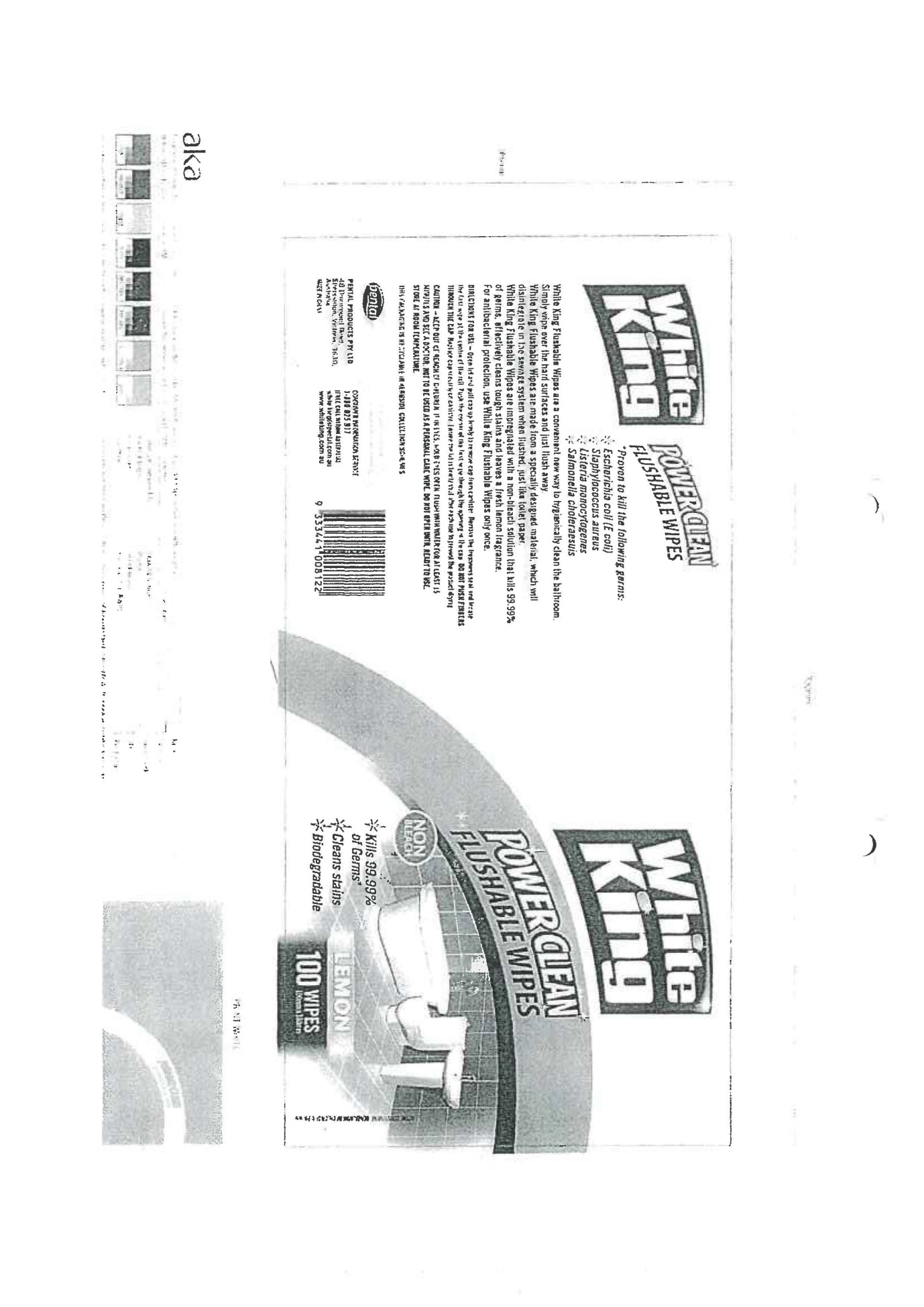

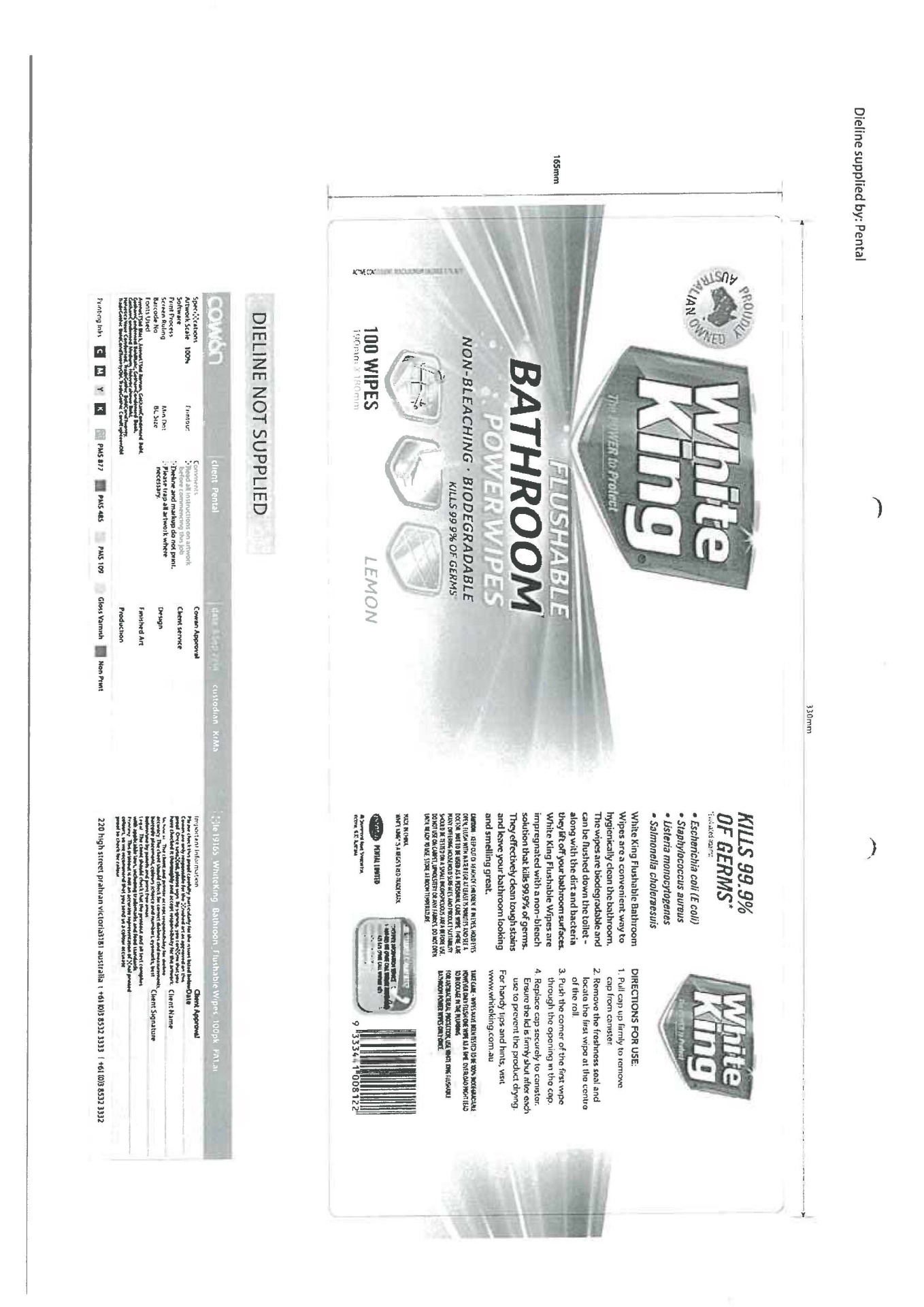

1 This proceeding concerns the following products promoted and supplied by Pental Ltd and Pental Products Pty Ltd (to which I will refer collectively as Pental unless it is necessary to refer to the specific entity):

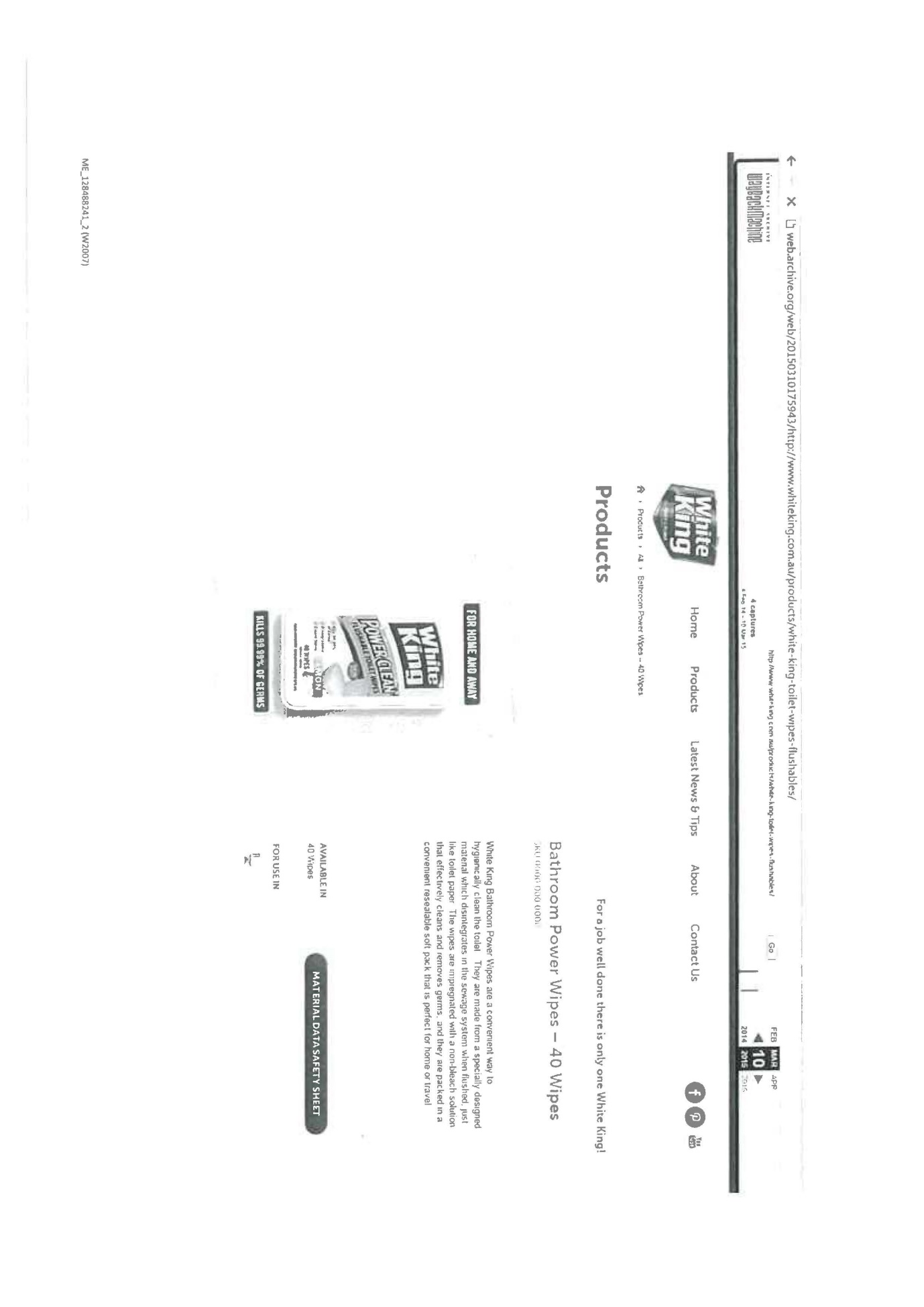

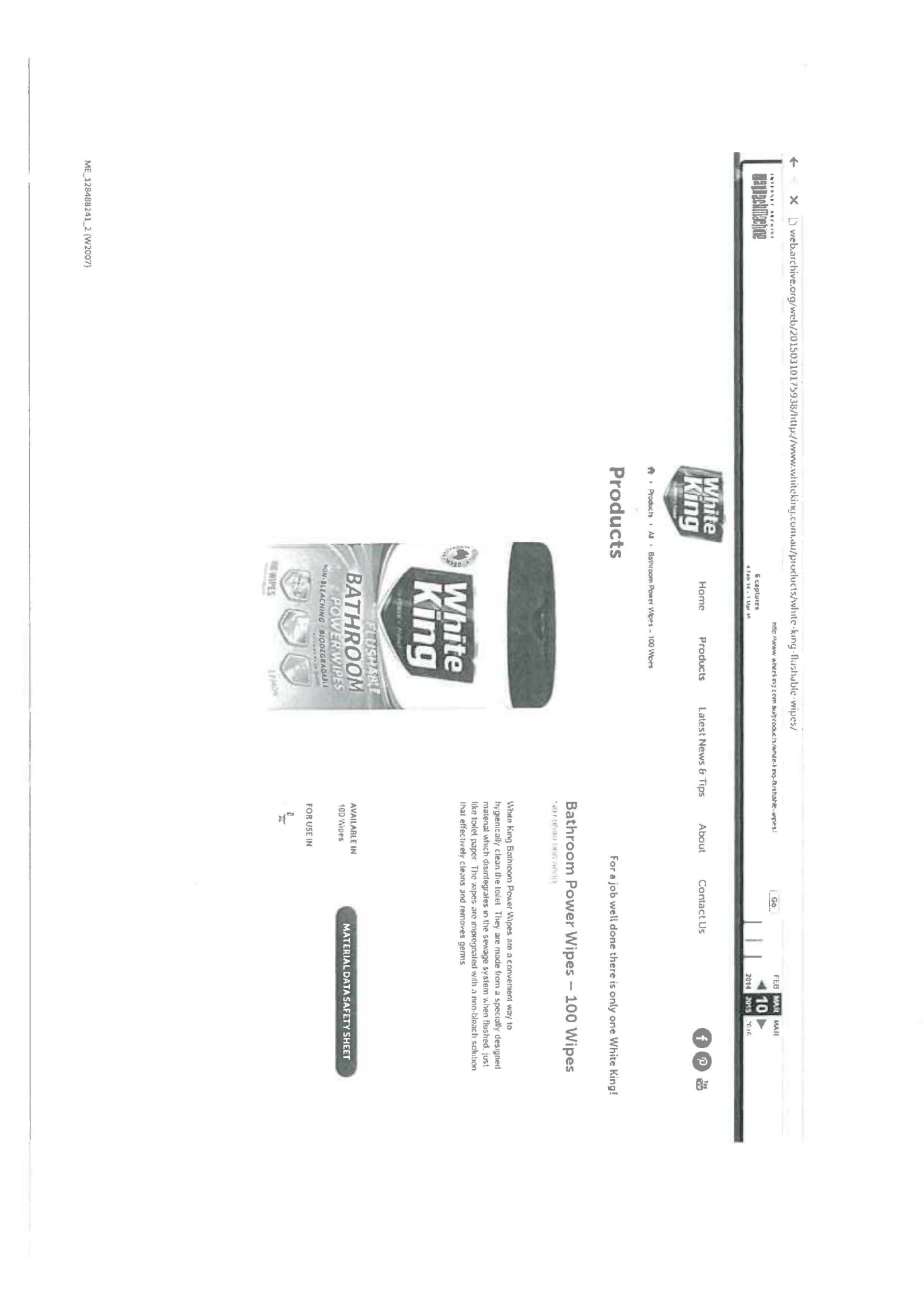

(a) White King Power Clean Flushable Toilet-wipes in a 40-wipes pack (40-wipes pack) (from 7 February 2011 until December 2015); and

(b) White King Power Clean Flushable Toilet-wipes (renamed as the White King Flushable Bathroom Power Wipes from September 2014) in a 100-wipes pack (100-wipes pack) (from 7 February 2011 until 12 July 2016).

From time to time I will refer to these products collectively as the wipes. I also note, for completeness, that the period during which the contraventions took place, being 7 February 2011 to 12 July 2016, will be referred to in these reasons as the Relevant Period.

2 It is agreed between the applicant (ACCC) and Pental that during the Relevant Period, Pental made representations, express and implied (collectively, representations), that the wipes:

(a) were made from a specially designed material which disintegrated in the sewerage system like toilet paper, had similar characteristics to toilet paper when flushed, and would break up or disintegrate in a timeframe and manner similar to toilet paper (Disintegration Representations); and

(b) were suitable to be flushed down the toilet into sewerage systems in Australia, and were therefore “flushable” (Flushability Representations).

3 The representations were made by Pental on both the product packaging of the wipes and on the website domains www.whiteking.com.au and www.pental.com.au (websites).

4 It is also agreed between the parties that the representations were false and misleading and amounted to conduct which contravened ss 18(1), 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g), and 33 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), being Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA). The agreement reached between the parties, as to both the characterisation of the conduct and the fact that it amounted to contravening conduct, is indicative of the cooperative approach that has been taken to the presentation of this hearing, which has allowed me to proceed to judgment expeditiously. Most matters resolved between the parties, including the issue of costs, which was resolved on the morning I delivered these reasons ex tempore.

5 The only outstanding matter which requires determination is the amount of the pecuniary penalty sought by the ACCC. The ACCC seeks pecuniary penalties against both Pental entities in the amount of $1.68 million. The position taken by Pental, perhaps not surprisingly, was radically different: it contended that in all the circumstances the Court should impose total penalties of approximately $240,000 for the admitted contraventions. I pause to note that the submissions made as to penalty have been both appropriate and of assistance in the Court reaching a view as to the appropriate penalty: see Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; (2015) 258 CLR 482.

6 Relevant to the dispute as to penalty, were some contested evidentiary matters which related to the nature and extent of Pental’s conduct and the loss and damage suffered as a result of the conduct (see s 224(2)(a) of the ACL); these matters also potentially touched upon the circumstances in which the conduct took place (see s 224(2)(b)). I will return to these matters below.

B Factual Findings

B.1 Facts Not In Contest

7 Exhibit A in the proceeding is constituted by two documents containing a series of agreed facts; the first document is dated 3 November 2017 and the second, which was tendered during the course of the hearing, was finalised on 9 April 2018. What follows in this section of these reasons is largely drawn from these documents.

8 Pental Ltd is a publicly listed company supplying home care, personal care, and hygiene products, both directly and through its subsidiaries. Pental Products is a wholly-owned subsidiary of the listed entity, and markets and supplies products to retailers in Australia, including major supermarkets and independent grocers.

9 During the Relevant Period, Pental Products supplied the wipes, although at some time during the Relevant Period there was a change made to the packaging of the wipes to make reference to the listed entity. Pental Products acquired the White King brand from the Sara Lee Corporation (Sara Lee) in early 2011. Pursuant to the contract of acquisition from Sara Lee:

(a) Sara Lee warranted that the wipes complied with all applicable laws, statutes, and regulations; and

(b) Sara Lee provided to Pental “biodegradability test results” dated 4 December 2009 from the Guangzhou Industry Microbe Test Centre (Chinese testing), which, it is common ground, indicate that the wipes complied with certain Chinese standards for biodegradability.

10 It will be necessary to return to the Chinese testing later. The wipes were supplied, as noted at [1] above, in two different packages. Although identically constituted, the wipes within the packages were of different sizes. At all times, consistently with the practice adopted by Sara Lee, the wipes were manufactured in China and imported by a third party corporation separate from Pental, being FMCG International Pty Ltd (FMCG). As part of the acquisition of the White King brand, Pental Products inherited the relevant supply arrangements and continued to obtain the wipes from FMCG. As might be expected, during the Relevant Period, Pental Ltd was the owner of the websites, to which I have already made reference. However, it is agreed that both Pental entities were responsible for the content of the websites. At all relevant times, Pental advertised the wipes on the websites by displaying images of the product packaging accompanied by product descriptions.

11 Between February 2011 and June 2011, Pental continued to supply the wipes with Sara Lee’s name and contact details on the packaging, but by the end of this period, Pental changed the packaging to remove Sara Lee’s details and to make reference to the name ‘Pental Products Pty Ltd’. The evidence reveals that the name ‘Pental Products Pty Ltd’ appeared on the 40-wipes pack from 20 June 2011 until the supply of the product ceased in December 2015, and on the 100-wipes pack from 20 June 2011 until September 2014.

12 Importantly, for reasons that will be explained below, in September 2014, Pental undertook what was described, in marketing speak, as a ‘brand refresh’, which included packaging changes to the 100-wipes pack. No cognate change was made to the packaging of the 40-wipes pack at the time of the brand refresh. By way of graphic illustration, appended to these reasons as:

(a) Appendix A, is a copy of the artwork for the packaging of the 100-wipes pack as inherited from Sara Lee in February 2011 and separately as changed with Pental branding and contact details from June 2011;

(b) Appendix B, is a copy of the packaging of the 100-wipes pack following the brand refresh in September 2014;

(c) Appendix C, is a copy of the website advertising as inherited from Sara Lee in February 2011; and

(d) Appendix D, is a copy of the product descriptions on the websites from February 2014 until February 2016.

13 A review of these materials indicates that the result of the brand refresh was to make the following changes to the packaging of the 100-wipes pack:

(a) removal of the “disintegrate…just like toilet paper” statement;

(b) addition of the “biodegradable” and “only flush one wipe at a time” statements;

(c) renaming of the product as “White King Flushable Bathroom Power Wipes”; and

(d) replacement of ‘Pental Products Pty Ltd’ with ‘Pental Ltd’, which, it is agreed, was done to increase consumer awareness of the name of the listed entity.

14 It is also evident that the packaging of the 100-wipes pack, post the brand refresh, was on the product available for purchase from around February 2015 until at least mid-2016.

15 As I previously noted, the packaging of the 40-wipes pack was not altered, and it retained the statement “disintegrate…just like toilet paper”. Senior management of Pental made the decision not to amend the packaging of the 40-wipes pack “because it was contemplating whether to discontinue supply of this product due to poor sales”.

16 It is further agreed that the websites each retained the statements which were said to give rise to the Disintegration Representations on the product packaging until June 2015. At that time, following the decision to cease the importation and supply of the 40-wipes pack, Pental removed the images of the 40-wipes pack and associated product descriptions from the websites. However, stock remained and was supplied to retailers until December 2015, when the product was no longer available for purchase from Pental.

17 In November 2015, Pental commissioned an organisation described as ‘D-Labs’ to conduct comprehensive disintegration testing on the 100-wipes pack, as compared to toilet paper. The results of the testing demonstrated that after half an hour of mechanical agitation in water, on average, less than one per cent of the wipe disintegrated, as compared with 96 per cent for toilet paper. Prior to this time, Pental had not commissioned any external testing at all (including any disintegration testing of the wipes) and the only external testing that Pental had to support the claims made by it was the Chinese testing, which it agreed was not sufficient to demonstrate data relevant to the flushability of the product.

18 In February 2016, after receiving correspondence from the ACCC, Pental removed from the websites reference to the statements which gave rise to the Disintegration Representations. Further, in June 2016, after receiving a notice pursuant to s 155 of the CCA, Pental made the decision to remove the word “flushable” from the packaging of the 100-wipes pack (and the corresponding references to flushability on the websites), and thereafter commenced the supply of the revised product packaging (which changed the name to “White King Bathroom Power Wipes”) from July 2016.

19 At around that time, the ACCC commissioned Sydney Water to conduct water agitated disintegration testing on the wipes, which testing also involved comparison with toilet paper. The results of this testing showed that after six hours of mechanical agitation in water, on average, between 4.4 per cent and 8.8 per cent of the wipe disintegrated, whereas 98.7 per cent of one brand of toilet paper disintegrated, and between 89 and 92 per cent of another brand of toilet paper disintegrated.

20 As I have already indicated, the characterisation of both the Disintegration Representations and the Flushability Representations is agreed.

21 With regard to the Disintegration Representations, it is accepted that their making amounted to false or misleading conduct because:

(a) the wipes were not made from a specially designed material that disintegrated in the sewerage system like toilet paper; and

(b) the wipes did not have similar characteristics to toilet paper when flushed; and

(c) the wipes did not disintegrate in the timeframe and manner similar to toilet paper.

22 As to the Flushability Representations, it is agreed, for the same reasons identified in the preceding paragraph, that these representations were false or misleading, with the further additional contextual circumstance that sewerage systems in Australia were and are primarily designed to carry, as sewage, urine, faeces and toilet paper.

23 During the Relevant Period, the number of packages of wipes sold by Pental was as follows:

Financial Year | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 |

40-wipes pack | 60,336 | 84,096 | 11,700 | 13,752 | 111,600 |

100-wipes pack | 145,236 | 117,438 | 121,956 | 131,616 | 94,656 |

24 A good deal of documentary evidence was placed before the Court as to the gross revenue and gross margin of the wipes (as compared with the overall revenue derived from all operations of Pental). It is unnecessary for me to descend to analysing the detail of that material as it eventually emerged that it was common ground that the gross revenue for the wipes during the Relevant Period amounted to about 0.76 per cent of the total gross revenue for Pental Ltd.

B.2 Additional Evidence

25 A considerable amount of affidavit material was adduced by both parties. I will make reference to the material which has informed my determination of the pecuniary penalty later in these reasons, but I should commence by making reference to the evidence of: (a) Mr Charles McLeish who joined Pental as its general manager in May 2011, reporting to the then chief executive officer, and who then became the chief executive officer of Penal Ltd in January 2014; and (b) Mr Justin Butterfield, who commenced employment with Pental in August 2013 in various sales, administrative and customer services roles and eventually became the Category Marketing Manager. Both witnesses were extensively cross-examined.

26 Mr McLeish presented as a witness who appreciated the seriousness of the conduct that had been admitted by the corporations of which he had stewardship. Subject to one matter to which I will make reference later in these reasons, I accept his evidence that, in particular, it was only in mid-2014 (following him becoming aware of various media reports regarding problems with wet wipes blocking sewerage systems) that he turned his mind in any concentrated way to what, for him, was a relatively minor part of Pental’s overall business. It was as a consequence of him making enquiries at this time that he became aware that Mr Randall Anthonisz, a Technical Manager for the White King branded products who had been ‘inherited’ from Sara Lee, had conducted internal testing of the wipes, which showed that the wipes did not disintegrate when placed in a bucket of water (notwithstanding that, curiously, multiple wipes had been flushed by Mr Anthonisz, as some form of informal ‘testing’, without causing blockages in the plumbing system at Pental’s Port Melbourne office).

27 In evidence which, to my mind, had a ring of truth about it, Mr McLeish explained his lack of focus prior to this time in relation to the wipes as follows (T 38-9):

I’m saying that it represented less than one per cent of my total sales. I had enough priorities in the business at the time to keep 130 people employed at Shepparton, to pay back a $60 million-odd debt to the ANZ bank. I had a lot of other priorities and I apologise for not paying enough attention to wipes.

28 Despite the wipes being perceived by Mr McLeish to be a relatively minor part of the overall Pental business, prior to 2014, Mr McLeish had not been entirely unaware of potential difficulties. On 11 July 2011, he had been copied into an email from a sales manager to Mr Anthonisz, among others. That email conveyed the information that the Australasian Sales Manager, Ms Connie Pisa, had spoken to a customer, who had alleged that they had flushed no more than five wipes down their toilet, but that as a result it had become blocked, causing some damage. In particular, the customer had made an allegation that the Pental “advertising is misleading to say the least. They are not flushable”.

29 Having said this, the email was part of an email chain copied to Mr McLeish, which included comments by Mr Anthonisz that the flushing of five wipes was unlikely to have caused the toilet to block as described by the customer and suggesting that the relevant toilet may have been in poor condition. It appears that during the Relevant Period, approximately five other customer complaints were made to Pental, but it was not suggested to Mr McLeish that he was specifically put on notice of those complaints.

30 I will come back to the conclusions I draw from Mr McLeish’s evidence later in these reasons, but overall I found him to be a reliable witness who was prepared to make concessions where appropriate.

31 I consider that Mr Butterfield, in responding to some customer complaints, engaged in considerable overstatement in representing the rigour of the testing undertaken by Pental to justify its claims, and I consider that this conduct (although not the subject of any pleaded case by the ACCC) amounted to a less than frank exchange with complaining customers. Mr Butterfield also seemed to recognise the seriousness of the conduct engaged in by Pental.

32 Initially, Mr Butterfield attempted to give evidence concerning the revenue derived from the wipes. I give this evidence little weight, given the fact it had not been prepared by him. Importantly, Mr Butterfield gave evidence, which I accept, that following the brand refresh which had removed the Disintegration Representations from the 100-wipes pack, the websites were not updated to remove claims that the wipes could disintegrate like toilet paper until February 2016, due to an administrative oversight. Mr Butterfield was not challenged on this evidence, it is not inherently improbable and it follows that it ought to be accepted: see Precision Plastics Pty Limited v Demir (1975) 132 CLR 362 at 371 per Gibbs J.

33 Leaving aside reliance on admissions, the affidavit evidence relied upon by the ACCC was directed to what the ACCC ultimately submitted was the principal harm caused by the contravening conduct, namely to the operations of municipal wastewater authorities across Australia, including the impacts on the broader sewerage system. While the evidence discloses that there has been some anecdotal impact upon individual consumers due to plumbing blockages, the broader pecuniary harm to which the ACCC points is that of the impact on wastewater networks.

34 The evidence of employees of wastewater authorities in Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria was essentially unchallenged as to the impact of wipes on sewerage systems. I will come back to the question of loss and damage below and the contention of Pental in submitting that the incremental contribution of the contravening conduct to the problems suffered by wastewater authorities was minimal. It suffices, for present purposes, to note that the overall problem caused by products such as, or similar to, wipes being flushed inappropriately, is substantial and Australia-wide.

35 Put simply, sewerage systems are not designed to carry these types of products which do not behave in a way that is consistent with toilet paper. At one level this is a statement of the glaringly obvious, but what may be thought to be more surprising is the documentation of the significant volume of inappropriate product being removed from wastewater networks. The details are, mercifully, unnecessary to recount.

36 What should be noted, however, is the evidence of Mr Colin Hester which demonstrates that the problem imposes additional and unnecessary cost burdens on the Queensland utility as it compounds the costs incurred by that utility in removing blockages from its networks and disposing of debris removed from sewage treatment plants. Mr Hester estimates that annually, the Queensland utility spends around $1.5 million on removing blockages and $400,000 on disposal of debris. Additionally, about $2.5 million is expended on breaks and blockages (noting that the evidence discloses that products such as the wipes in general are a significant contributing factor), and around $600,000 is expended annually in disposing of the debris removed from sewage treatment plants.

37 Mr Glenn Wilson gives evidence about the costs incurred by a particular utility provider in Victoria (Yarra Valley Water) in responding to blockages caused by objects or solids that are not designed to be carried into its sewerage systems, including, but not limited to, products such as the wipes. By way of illustration, in the 2014 financial year, such costs totalled $2.49 million and in the 2015 financial year, the costs totalled approximately $2.32 million.

38 I accept from the ACCC’s evidence that the problem encountered by the wastewater authorities caused by, among other things, the inappropriate disposal of products such as the wipes, is a significant one. The question of Pental’s incremental contribution to this problem will be addressed when I have regard to the mandatory factors contained in s 224 of the ACL.

39 Having set out the agreed facts and those parts of the evidence adduced that warranted particular attention or emphasis during the hearing, I now turn to the principles I need to apply when fixing pecuniary penalties.

C pecuniary penalties

C.1 Statutory Provisions and Relevant Factors

40 Under s 224(1)(a)(ii) of the ACL, a pecuniary penalty may be imposed at the court’s discretion for any act or omission that contravenes ss 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) or 33 of the ACL (of course, the other contravention relied upon by the ACCC, that of the norm referred to in s 18 of the ACL, does not give rise to liability for pecuniary penalties).

41 At times material to the determination of the pecuniary penalties in this proceeding, s 224(3) provided that for a body corporate, the maximum penalty for each contravention of ss 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) and 33 is $1.1 million. Pursuant to s 224(4) of the ACL, if the same conduct constitutes a contravention of two or more provisions, a person is not liable to more than one pecuniary penalty in respect of that conduct.

42 Guidance as to the exercise of the discretion is provided by s 224(2) of the ACL, which provides that in determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, the court must have regard to all the following matters (mandatory s 224 factors):

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; and

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by a court in proceedings under Chapter 4 or Part 5-2 to have engaged in any similar conduct.

43 The mandatory s 224 factors are broad ranging. As Edelman J observed in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v RL Adams Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 1016 at [40]:

There will be very few facts that are not included within the breadth of these matters. For instance, the “circumstances” in which the act takes place includes circumstances which precede the act as well as those which are contemporaneous to it.

44 Additionally, the cases have identified a number of matters which can be taken into account under s 224 of the ACL. In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd (No 4) [2011] FCA 761; (2011) 282 ALR 246 (Singtel Optus (No 4)) at 250-251 [11], Perram J described a number of matters which could be taken into account under a similar provision. It is important to stress that the factors identified by Perram J serve as general guidance and do not establish some sort of prescriptive list. Having said this, the factors do provide a useful checklist of matters which may have applicability depending upon the individual circumstances of the given case. The factors are:

(1) the size of the contravening company;

(2) the deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended;

(3) whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management of the contravener or at some lower level;

(4) whether the contravener has a corporate culture conducive to compliance;

(5) whether the contravener has shown disposition to cooperate;

(6) whether the contravener has engaged in similar conduct in the past;

(7) the financial position of the contravener; and

(8) whether the contravening conduct was systematic, deliberate or covert.

45 To these factors, Edelman J, in RL Adams at [42], added the following:

(1) whether the contravener made a profit from the contraventions;

(2) the extent of the profit made by the contravener; and

(3) whether the contravener engaged in the conduct with the intention to profit from it.

46 I will return to the mandatory s 224 factors below. I will also return to these additional, or, perhaps more accurately, more granularly expressed factors, to the extent that they seem to me to be of significance in determining the pecuniary penalties in this proceeding.

C.2 Fixing Penalties

C.2.1 General Principles

47 There was no substantial dispute between the parties as to the relevant principles to be applied. Given the recent discussion of the applicable principles in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd [2016] FCA 1516; (2016) 118 ACSR 124 at 141-142 [78]-[83] (Wigney J) and by the Full Court (Dowsett, Greenwood and Wigney JJ) in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2017] FCAFC 113; (2017) 271 IR 321 at 341-353 [96]-[149] (ABCC v CFMEU), there is limited utility in me setting out, except by way of brief summary, the applicable principles.

48 It is clear that the principal object of a pecuniary penalty is to attempt to put a price on a contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravener and by others who might be tempted to contravene. In this sense, both specific and general deterrence are important: see ABCC v CFMEU at 341 [98]. Given these objects, a pecuniary penalty ought be fixed with a view to ensuring that the penalty cannot be regarded by either the contravener or by others as simply an acceptable cost of doing business: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; (2013) 250 CLR 640 at 659 [66] (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ).

49 In relation to general deterrence, it is important to send a message that contraventions of the law are unacceptable: see Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Southcorp Limited (No 2) [2003] FCA 1369 (reported as Australian Securities and Investment Commission v Southcorp Ltd (2003) 130 FCR 406) at 418 [32] per Lindgren J. As to fixing the pecuniary penalty, this involves the identification and balancing of all factors relevant to the contravention, including, necessarily, the mandatory s 224 factors, and ultimately making what has been described as a “value judgment” as to what is the appropriate penalty in light of the protective and deterrent purpose of the pecuniary penalty: see ABCC v CFMEU at 342 [100].

50 Put generally, the factors that are relevant when fixing a pecuniary penalty relate to both the objective nature and seriousness of the contravening conduct and the particular circumstances of the contravener. As to objective seriousness of the contravention, matters for consideration include the extent to which the contravention was the result of deliberate, covert or reckless conduct (as opposed to carelessness); whether the contravening conduct was isolated or systematic; the duration of the conduct and, in circumstances where the contravener is a corporation, the seniority of the officers responsible; and the existence of systems within that corporation which are indicative of whether there was a culture of compliance.

51 As the mandatory s 224 factors make clear, it is also relevant to have regard to the loss or damage suffered as a result of the contravening conduct (see s 224(2)(a)). The obverse is also true: it is appropriate to look at the extent of profit, if any, which results from the contravening conduct.

52 This last factor, of course, not only relates to objective seriousness, but also concerns the particular circumstances of the malefactor. I have already made reference to the list of factors to which one has regard in fixing a penalty in relation to a corporate contravener, including its size, financial circumstances and related matters. Of course, in having regard to the particular financial circumstances of a corporation, the size of the corporation does not itself justify a higher penalty than might otherwise be imposed: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 330; (2015) 327 ALR 540 (ACCC v Coles) at 559-560 [89]-[92] per Allsop CJ. But the corporation’s size may be thought, logically, to be highly relevant to the question of the size of the penalty that should operate in order to properly give effect to the need for specific deterrence.

C.2.2 Course of Conduct, Totality and Fixing Penalties for Multiple Contraventions

53 An issue that has vexed courts in pecuniary penalty cases is whether, in cases involving multiple contraventions, it is permissible and appropriate for the court to impose a single pecuniary penalty or to group similar contraventions together and impose single penalties in respect of those groups, particularly where the contraventions were part of a course or courses of conduct: see ABCC v CFMEU at 343 [108].

54 In this proceeding, the ACCC submitted that the so-called ‘course of conduct’ principle means that consideration should be given to whether the contraventions arise out of the same course of conduct, in order to determine whether it is appropriate that a concurrent or single penalty ought be imposed for multiple contraventions. In this regard, the ACCC called in aid a number of cases, including Trade Practices Commission v Bata Shoe Co of Australia Pty Ltd (1980) ATPR 40-162 at 42,277 per Lockhart J; Mornington Inn Pty Ltd v Jordan [2008] FCAFC 70; (2008) 168 FCR 383 at 396 [41], 397 [44] and 398 [45] per Stone and Buchanan JJ; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Telstra Corporation Ltd [2010] FCA 790; (2010) 188 FCR 238 at 277 [231]-[234] per Middleton J; Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20; (2012) 287 ALR 249 at 262-263 [53] (Keane CJ, Finn and Gilmour JJ). The ACCC submitted that the course of conduct principle operates as a check to ensure that penalties imposed for each contravention are not such as to amount to double punishment for what is, in reality, the same conduct.

55 The course of conduct principle has been applied in the civil pecuniary penalty context in a number of cases. This is despite the fact that, as the Full Court observed in ABCC v CFMEU at 345 [115], the principle, which arises from sentencing principles in the criminal law, has been applied where only a pecuniary penalty can be imposed (and that the issue of concurrent or cumulative prison sentences cannot arise). The Full Court also noted that the principle has also been applied in circumstances where a pecuniary penalty is said to be imposed as a matter of deterrence rather than as punishment, despite the fact that the principle is largely based on the need to avoid double punishment. What can be drawn from the cases is that it has been common for judges to impose single penalties for multiple contraventions of civil penalty provisions under a number of statutory regimes, including the ACL and its relevant predecessors. This is despite the fact that there is no express provision in these regimes to authorise, in explicit terms, the application of this approach to the setting of pecuniary penalties.

56 The Full Court in ABCC v CFMEU explained, at 352-353 [148]-[149]:

[148] The important point to emphasise is that, contrary to the Commissioner’s submissions, neither the course of conduct principle nor the totality principle, properly considered and applied, permit, let alone require, the Court to impose a single penalty in respect of multiple contraventions of a pecuniary penalty provision. There is no doubt that, in an appropriate case involving multiple contraventions, the Court should consider whether the multiple contraventions arose from a course or separate courses of conduct. If the contraventions arose out of a course of conduct, the penalties imposed in relation to the contraventions should generally reflect that fact, otherwise there is a risk that the respondent will be doubly punished in respect of the relevant acts or omissions that make up the multiple contraventions. That is not to say that the Court can impose a single penalty in respect of each course of conduct. Likewise, there is no doubt that in an appropriate case involving multiple contraventions, the Court should, after fixing separate penalties for the contraventions, consider whether the aggregate penalty is excessive. If the aggregate is found to be excessive, the penalties should be adjusted so as to avoid that outcome. That is not to say that the Court can fix a single penalty for the multiple contraventions.

[149] In an appropriate case, however, the Court may impose a single penalty for multiple contraventions where that course is agreed or accepted as being appropriate by the parties. It may be appropriate for the Court to impose a single penalty in such circumstances, for example, where the pleadings and facts reveal that the contraventions arose from a course of conduct and the precise number of contraventions cannot be ascertained, or the number of contraventions is so large that the fixing of separate penalties is not feasible, or there are a large number of relatively minor related contraventions that are most sensibly considered compendiously. As revealed generally by the reasoning in Commonwealth v Director, FWBII, there is considerably greater scope for agreement on facts and orders in civil proceedings than there is in criminal sentence proceedings. As with agreed penalties generally, however, the Court is not compelled to accept such a proposal and should only do so if it is considered appropriate in all the circumstances. It is also at the very least doubtful that such an approach can be taken if it is opposed or the proceedings are defended.

(Emphasis added)

57 As to totality, it is well-established that where multiple penalties are imposed upon a particular wrongdoer, the totality principle requires the court to make a ‘final check’ on the penalties to be imposed, considered as a whole. In circumstances where a court believes that the cumulative total of the penalties to be imposed will be too low or too high, the court should alter the final penalties to ensure that they are appropriate in all the circumstances: Trade Practices Commission v TNT Australia Pty Limited (1995) ATPR 41-375 (Burchett J); Clean Energy Regulator v MT Solar Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 205 at [81]-[82] per Foster J; Registrar of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Corporations v Matcham (No 2) [2014] FCA 27; (2014) 97 ACSR 412 at 447 [292]-[294] per Jacobson J.

58 In fixing an appropriate penalty, regard should be had to the maximum penalty. That being said, as Allsop CJ observed in ACCC v Coles at 543 [6]:

The setting of the penalty is a discretionary judgment that does not involve assessing with any precision the “range” within which the conduct falls or by applying incremental deductions from the maximum penalty. Nonetheless, the maximum penalty must be given due regard because it is an expression of the legislature's policy concerning the seriousness of the proscribed conduct. It also permits comparison between the worst possible case and the case the court is being asked to address and thus provides a yardstick.

(Citation omitted)

59 With these principles in mind, I turn to the consideration of the penalty and, as a preliminary matter, the application in the circumstances of this proceeding of the course of conduct principle.

C.3 Consideration of Penalty

C.3.1 Application of the Course of Conduct Principle

60 It is convenient to commence by having regard to the course of conduct principle which, for reasons which will be evident from the above analysis, is not an entirely separate principle from the totality principle which requires penalties to not exceed what is proper for the entire contravening conduct: see MT Solar at [81]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Baxter Healthcare Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 929 at [22] per Mansfield J. In doing so, it is important to emphasise that identifying courses of conduct is merely a discretionary tool or analytical expedient along the way to determining an appropriate penalty and a precise allocation of the number of courses of conduct is not some sort of calculus which results in varying outcomes depending upon the characterisation of the contravening conduct as falling into one or other of the identified courses of conduct. The limitations with the analytical tool are well illustrated in the circumstances of this proceeding. On the one hand, the ACCC invites me to conclude that there were six courses of conduct, being:

(1) The making of the Disintegration Representations on the packaging of the 100-wipes pack.

(2) The making of the Disintegration Representations on the packaging of the 40-wipes pack.

(3) The making of the Disintegration Representations on the websites.

(4) The making of the Flushability Representations on the packaging of the 100-wipes pack.

(5) The making of the Flushability Representations on the packaging of the 40-wipes pack.

(6) The making of the Flushability Representations on the websites.

61 By way of contrast, the primary position of Pental is that the conduct involved a single course of conduct, because the Disintegration Representations and Flushability Representations essentially relate to one subject matter, being the suitability of the wipes for disposal by flushing down the toilet. In this regard, Pental agreed that the wipes do not disintegrate like toilet paper and that it was misleading or deceptive to represent that they were flushable. Hence, it was said that both sets of representations are inextricably linked and overlapping as a matter of substance. In the alternative, Pental submitted that the contravention should be characterised as two courses of conduct, being the making of the two types of representations on the product packaging and also on the websites.

62 In my view, neither of the positions taken by the parties satisfactorily captures the courses of conduct in this case and it is appropriate that I explain why.

63 There is no justification, intellectually or otherwise, in distinguishing between the representations made in relation to the 100-wipes pack and the 40-wipes pack. Although there is some temporal difference (a matter to which I will return), the representations made during the Relevant Period were the same in respect of a common subject matter, that is, the wipes themselves, which were relevantly identical save for their packaging and dimensions.

64 Similarly, I do not accept Pental’s submission that it is appropriate to, in effect, ‘roll up’ the representations conveyed at the point of sale by the packaging and the distinct advertising tool that was used, namely publication of essentially the same representations on the websites. Apart from the fact that the purpose of the respective representations was quite different (one appealing to the market generally, while the other was to individual consumers at the point they made their choice at the grocer), there is a difference in the time during which the Disintegration Representations were made, on both the packaging and the websites.

65 Moreover, at this juncture, it is convenient to make an important, but somewhat different point: the conduct involves two separate entities, albeit the listed entity controlled the subsidiary. Consistently with the decision of the Full Court (Middleton, Beach and Moshinsky JJ) in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cement Australia Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 159, each contravener must be separately responsible for its own course of conduct: see [391]. There were two Pental entities and each engaged in its own course of conduct. It does not seem to me to be consistent with the Full Court’s approach to adopt the submission of Pental that I can, in effect, treat the actions of two separate entities as one course of conduct.

66 It follows from the above that I consider that, to the extent relevant, there are four relevant courses of conduct engaged in by each Pental entity, namely:

(1) The Disintegration Representations made on the packaging of the wipes.

(2) The Disintegration Representations made on the websites.

(3) The Flushability Representations made on the packaging of the wipes.

(4) The Flushability Representations made on the website.

67 I made reference earlier in these reasons to the mandatory s 224 factors and the 11 factors identified in Singtel Optus (No 4) and RL Adams which serve as general guidance. Without diminishing the need to have regard to all relevant factors, including, critically, the mandatory s 224 factors, the parties organised their submissions by reference to various topics which separated them, that call for findings, and which inform the proper evaluation of the contravening conduct. It is to these categories that I now turn.

C.3.2 Nature of the Conduct

68 It is important at the outset to distinguish between the two entities. As noted above, Pental Products supplied the wipes to major supermarkets and independent grocers, but both entities both promoted and supplied the wipes to consumers and engaged in the contravening conduct. Pental Ltd, was, however, the registered owner of the websites, and although both entities were responsible for the content of the websites, Pental Ltd controlled the actions of Pental Products and was the company ultimately responsible for the conduct.

69 In this sense, Pental Ltd had overall responsibility and, as I explain below, the brand refresh and related decisions were made by officers of Pental Ltd, rather than Pental Products. There was no contesting the proposition that Pental Ltd was the directing mind and will of the activities of Pental Products, including the contravening conduct. I will deal separately with the issue of pecuniary loss and damage, but it is important to note that the conduct of Pental involved a detriment to consumers in distorting consumer choice in relation to a key feature of the product it marketed and sold.

70 It is evident from the nature of the representations and how they were conveyed that both types of representations were a key feature of the marketing of the wipes and, in this sense, were presumably regarded as a key distinguishing characteristic between the Pental wipes and similar products which were not marketed as having the characteristics of flushability and disintegration. Pental accepted that the making of the representations was serious. It accepted that the representations misled consumers into a misapprehension that the wipes:

(a) were made from some form of specially designed material that was capable of disintegrating into the sewerage system;

(b) were able to disintegrate in a manner similar to toilet paper;

(c) held similar characteristics to toilet paper; and

(d) were suitable for flushing.

71 As the belated testing commissioned by Pental, and the ACCC’s testing, indicates, these representations were not only wrong, but badly wrong. Moreover, they were wrong in respect of a key feature of the product which was so central as to be included in the name. The ACCC points out that Pental stated that its marketing strategy was to target a “younger demographic, interested in the convenience of a touch-up or on-the-go clean, with its wipes marketed as biodegradable, for use in [the] bathroom/toilet and capable of being disposed of by flushing the product down the toilet”. It follows that consumers were misled about a central characteristic of the wipes.

72 During the course of submissions, I raised with senior counsel for the ACCC, after viewing and handling the contents of Exhibit E (which was a 100-wipes pack), that it seemed to me screamingly obvious to anyone touching one of the wipes, that it was unlikely to break down in a manner consistent with toilet paper. In this regard, I indicated that, to the extent that the Disintegration Representations were made, it would have to be a very foolish or naïve person who would have been misled by the representations. It was pointed out to me that although my comment as to obviousness may be correct (and indeed, part of the cross-examination carried out by Mr White SC was directed to how obviously untenable the Disintegration Representations were), this apparent gulf between what was being said and the reality is not something that would have been evident to a consumer prior to the purchase of the wipes, and hence is not an answer to the distortion of consumer choice occasioned by the Disintegration Representations and the Flushability Representations.

73 Although, as I have noted, Pental agrees the conduct is serious, it submitted that the conduct is at the “lower range” of seriousness. In particular, it points to four matters. The first is that there is no evidence that the conduct put consumers at risk of personal detriment or harm. Secondly, there is evidence to suggest that consumers did not regard the Flushability Representations as a determinative feature. Thirdly, the wipes were sold in modest numbers. Fourthly, the ACCC did not take action against another entity for essentially the same conduct.

74 The second and fourth of these matters can be put to one side on the basis that the evidence does not support these submissions. As to the second matter, namely that sales data in evidence establishes that the removal of the Flushability Representations was not an important feature of the wipes, the sales data proves no such thing. In order to sustain such a submission there would be a need to prove, by admissible evidence, that all other things remained equal and that there was no elasticity, or, more particularly, no diminution in the demand for the product following the removal of the Flushability Representations. Such evidence simply does not exist and, intuitively, it would be odd if the Flushability Representations, which were at the very heart of the marketing of the wipes, would have been insignificant.

75 As to the fourth matter, I rejected the tender of material relating to what might be described as differential regulatory enforcement measures, for the simple reason that I have no idea what passed between the ACCC and the identified competitor. Nor do I have any idea of the regulatory choices made by the ACCC in respect of the use of its own resources and the appropriate regulatory approach to take following a different investigation. The material the subject of the rejected tender was both irrelevant and apt to mislead and, if taken into account, would have resulted in me having regard to incomplete and unverifiable information.

76 There is, however, substance in the third matter in that the wipes were sold in relatively modest numbers. This is demonstrated by the fact that Pental’s market share of the following product categories, which included the wipes, was:

(a) in respect of the product category ‘general household cleaning wipes’ – approximately 2.5 per cent or less; and

(b) in respect of the product category ‘wipes’ (which includes ‘general household cleaning wipes’ and ‘personal hygiene wipes’) – less than one per cent.

77 This does not mean that there were not large numbers of individual wipes sold. However, it does mean that, in a relative sense, the number of wipes sold by Pental could be regarded as modest.

78 As to the first matter identified, namely that there was no evidence that consumers were put at risk of personal detriment or harm, this submission is correct as far as it goes; plainly, this conduct is distinguishable from representations relating to product safety and the like. However, this is not an answer to what I described above as the distortion of consumer choice occasioned by the conduct. It was correct for Pental to accept the characterisation of the conduct as serious. For my part, however, it is easy to envisage far more egregious conduct, and when I come below to considering the issue of recklessness and deliberateness of the conduct, this will become clear.

C.3.3 Duration of the Conduct

79 The conduct occurred over a period which spanned five years. As to duration, there is some difference between the two types of representations in that the Flushability Representations were made throughout the Relevant Period, but the Disintegration Representations were made until 16 February 2016 on the websites, with the representation being removed in a staggered manner (being removed from the 40-wipes pack when the product ceased to be marketed in December 2015, and from the 100-wipes pack and the websites from September 2014).

C.3.4 Pecuniary Loss and Damage

80 The ACCC submitted that the principal harm caused by the conduct was to the operations of municipal wastewater authorities, as is evident from the evidence summarised above. In response, Pental submitted that this assertion was not substantiated on the ACCC’s evidence. It submitted that, at most, the material adduced by the ACCC demonstrated that wipes generally, together with other materials being flushed into sewage in wastewater networks, contributed to operational issues and ongoing maintenance for wastewater authorities. Contrary to the ACCC’s submissions, Pental submitted that the evidence did not establish that Pental’s conduct or the wipes caused harm to the operations of sewerage systems. It was said that, by application of principles relating to causation, the evidence fell well short of the relevant requirement to demonstrate that the contravening conduct caused, in a ‘but for’ sense, loss and damage.

81 In this regard, Pental pointed to the evidence in Exhibit KWS3. That document, adduced in evidence by the ACCC, was entitled “Wipes Disposal Behavioural Change Study – Phase 2: Quantification” prepared in September 2014, being a study commissioned by Sydney Water with the results of an online survey. There was no suggestion by the ACCC that these survey results were not somehow representative of usage and disposal practices at times other than in September 2014, and in the absence of other evidence, I infer that the conduct was likely to be similar during the Relevant Period.

82 What Exhibit KWS3 shows is not only the nature of the material flushed, which would be put under the general category of household wipes and related products (including hand and body cleansing wipes, facial cleansing wipes, disposable nappies, household cleaning wipes, etc.), but also responses to the question: “Why do consumers believe ‘it’s OK to flush?’”

83 In answer to that question, so-called ‘pack claims’ and the perception that a wipe was biodegradable, accounted for a significant proportion of responses as to why it was acceptable to flush.

84 Evidence was adduced by the parties as to customer research that Sydney Water commissioned in three stages. It was not suggested by the ACCC that this customer research was otherwise than reflective of consumer behaviour during the entirety of the Relevant Period, and in the absence of any evidence to the contrary, I would infer that it is reflective of consumer behaviour during that period. The research involved Sydney Water customers aged 15 and over being approached online and asked to take part in a survey. In order to qualify, the individual must have used a product in at least one of five ‘key’ wipe categories in the preceding week, which included household cleaning wipes. There were 602 customer responses online with data that qualified them to take part in the survey, and the results were published in the report referred to at [81] above.

85 What that document reveals is that a wide variety of products are flushed into wastewater networks irrespective of pack claims or a perception by reason of the packaging that the products are biodegradable. At least, that seems to be a conclusion drawn by reference to the material that appears under the headings, “Flushing Behaviour in Perspective” and “Why do consumers believe ‘it’s OK to flush’?” Items such as hand and body cleansing wipes, baby wipes, disposable nappies, facial cleaning wipes, household cleaning wipes and cotton and earbuds were flushed without any apparent reference to claims made on packaging, although claims on packaging were an important reason why a number of people flushed items.

86 The evidence is not entirely clear and it would be a mistake to make too much of the survey, but it does seem to support the notion, consistent with the overall quantity of wipes sold by Pental as compared to the overall market, that the contribution of Pental to the undoubtedly significant damage occasioned to wastewater networks could be accurately described as being minor. However, I do not accept Pental’s submission that no causal relationship whatsoever can be demonstrated between the contravening conduct and the relevant damage.

87 It is plain, given the results of the testing conducted for Pental in November 2015, and the ACCC testing, that it is inevitable that the Pental wipes contributed materially (albeit in a minor way) to the loss and damage suffered. This is a matter which ought to be taken into account when fixing an appropriate penalty.

C.3.5 Deliberateness or Recklessness

88 The ACCC’s submission that Pental’s conduct was deliberate for a not insignificant period was the subject of much focus at the hearing. In considering this submission, it is necessary to have regard to the chronology of events in a little more detail.

89 Upon the acquisition of the White King brand in September 2010, Pental, in effect, ‘inherited’ the representations that were then being made in relation to the wipes. Mr McLeish gave evidence, which I accept, that he did not consider it likely that there was a problem with the wipes in circumstances where a corporation the size of Sara Lee was making the representations and had provided the contractual warranties referred to at [9(a)] above.

90 In truth, what was being relied upon in making the representations, both prior to and after the acquisition of the White King brand, was the Chinese testing. The Chinese testing is, of course, problematical as although it purportedly shows that the wipes became fully biodegraded within 28 days, no comparative testing with toilet paper was undertaken and the testing provided no basis, let alone a reasonable basis, for any representations as to flushability.

91 It is apparent that by reason of the misguided comfort taken by senior executives of Pental from the pre-existing conduct of Sara Lee and the contractual warranties, neither prior to, nor upon, acquisition of the White King brand did Pental take any steps to verify the results independently or ascertain whether, if the Chinese testing was correct, 28 days was an appropriate time for biodegradation. Nor were any steps taken to determine the flushability of the wipes. Indeed, the evidence establishes that Pental did not have a copy of the relevant biodegradability standard in its possession and was not able to know what it actually measured.

92 What then changed?

93 Mr McLeish’s evidence, which I have accepted, was that he was focused on other things. It is perhaps understandable, given his false sense of security occasioned by the Sara Lee warranties, that he was directing his attention to the interests of the Shepparton employees and repayment of the bank facility. This did not mean, however, that all was quiet within Pental on the wipes front: indeed, there were a number of flashing lights. In November 2013, a complaint was received from a customer who experienced a plumbing blockage, who revealed that the plumber who cleared the blockage, had conveyed his opinion that it was the wipes that had caused the blockage. In January 2014, another complaint was received which, importantly, not only referred to another blocked sewerage pipe, but also conveyed the information that the plumber called to fix the problem “also mentioned that he had seen the (sic) similar problems everywhere on a regular basis”. Similarly, in May 2014, another customer referred to the representations and asserted that “the wipes do not break down ‘like toilet paper’”, and made an allegation that the representation on the packaging was “extremely misleading and unrepresentative of the product”.

94 For whatever reason, these customer complaints were, with respect to Mr Butterfield (who had joined Pental in August 2013), not the subject of sufficient action within the corporation. On 15 October 2013, a customer noted as follows:

I am writing this email to let you know how disappointed I am in one of your products. I have recently started using your ‘Power Clean Flushable Wipes’. Our toilet become blocked and overflowed with waste and created a HUGE mess and health hazard. The real estate agent I rent through organised a plumber asap and he discovered that the blockage was caused from wipes that were not breaking down. Because of this I am now left with not only the unimaginable mess but also a $130 bill. Your product is very misleading and obviously is not flushable as it does not break down once flushed, as it says on the packaging.

(Emphasis and errors in original)

95 In response, Mr Butterfield indicated that:

Our flushable wipes are put through extensive testing to ensure they meet biodegradable standards similar to that of toilet paper, so that we can make the claim they are flushable.

96 It is somewhat disturbing that a representation as to ‘extensive testing’ was made in response to a customer complaint, in circumstances where the only basis for the representations was the Chinese testing which, as I have explained, provided no basis for the Flushability Representations. Although no individualised case of misleading or deceptive conduct was relied upon in relation to the responses to the complainants, the responses are indicative of the way in which there was a lack of action and care in dealing with this issue. Indeed, Pental accepted that this lack of care amounted, relevantly, to recklessness.

97 What the evidence discloses is that things changed in mid-2014, when Mr McLeish became aware of media reports regarding problems with wipe-type products blocking sewerage systems. His evidence, which I accept, was that it was at about this time that he became aware of the idiosyncratic testing which had been conducted internally by Mr Anthonisz (who had ceased employment with Pental in January 2014). This testing showed that the wipes did not break up when placed in a bucket of water (although they were able to be flushed down the toilet at Pental’s offices without causing a blockage).

98 At around the same time, on 30 July 2014, another complaint from a customer was received. This customer, happily describing herself as a real “White King girl” who had Pental’s “products proudly on display”, noted that she had an issue with the “power clean flushable wipes” and stated:

yes, they do flush, but they also clog up the pipes of my house’s waste system! They don’t “disintegrate in my sewage system like toilet paper” as you claim on the back of the package and as you can see from my attached photo your product remains whole, with little sign of breakdown of the product.

(Errors in original)

99 Mr James Blackmore, the R&D Technical Manager of Pental Ltd, promptly raised this complaint with Ms Nilmini Rajapakse, the Quality Assurance Manager for Pental Products. He noted, correctly, that this was not the first time this had occurred and asked whether Ms Rajapakse was able to check how many complaints had been received and whether or not the problem identified as a “common occurrence”. The response of Ms Rajapakse was to say:

For long term, we need to think about the words ‘just as toilet paper’; Eventhough we have test reports etc. they don’t do a comparison breakdown speeds; all it says is that it is bio degradable.

(Errors in original)

100 Mr Blackmore responded, noting that:

We are in agreement on everything including the claim “just as toilet paper” I might get a competitors pack and review.

(Errors in original)

101 It is common ground that Mr Blackmore (who replaced Mr Anthonisz as the R&D Technical Manager) was part of the leadership team. Although Mr Blackmore did not give evidence, I infer that it was at this time, which was around the time that Mr McLeish became aware of the media reports, the issue became escalated within Pental.

102 This appears to have been the catalyst for the 100-wipes pack being renamed in September 2014 as the “White King Flushable Bathroom Power Wipes” (as part of the brand refresh) and the accompanied packaging changes to the 100-wipes pack, including removal of the statement that the wipes disintegrated like toilet paper.