FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Voxson Pty Ltd v Telstra Corporation Limited (No 10) [2018] FCA 376

File number: | NSD 2436 of 2013 |

Judge: | PERRAM J |

Date of judgment: | |

Date of publication of reasons: | 21 March 2018 |

Catchwords: | EVIDENCE – Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) r 34.50 – experimental evidence – whether leave to admit experimental evidence should be granted – whether Respondents are prejudiced – where Applicant did not comply with rule EVIDENCE – Intellectual Property Practice Note (IP-1) – process statement – whether Respondents should be ordered to tender process description – where Applicant sought cross-examination of person who verified process description EVIDENCE – hearsay evidence – whether hearsay evidence is admissible – whether historical image of webpage is hearsay evidence – where historical image was obtained using Wayback Machine COMMUNICATIONS LAW – Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 (Cth) – whether evidence is interception of communication passing over a telecommunication system – whether evidence is inadmissible as being unlawful – where data was obtained using proxy servers to communicate with person sending the communication |

Legislation: | Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) ss 69, 147 Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 (Cth) ss 5, 5G, 5H, 6, 7, 63 Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) r 34.50 Intellectual Property Practice Note (IP-1) |

Cases cited: | Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Air New Zealand Limited (No 5) [2012] FCA 1479 Bayer Bioscience N.V. v Deltapine Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2006] FCA 1762; (2006) 71 IPR 40 Beadcrete Pty Ltd v Fei Yu trading as Jewels 4 Pools [2012] FCA 1091 E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 934; (2008) 77 IPR 69 Generic Health Pty Ltd v Bayer Pharma Aktiengesellschaft [2014] FCAFC 73; (2014) 222 FCR 336 IO Group Inc v Prestige Club Australasia Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 1147 Olympic Airways SA v Spiros Alysandratus & Consolidated Travel (Vic) Pty Ltd (unreported, VSC, Harper J, 26 May 1997) Proctor v Kalivis [2009] FCA 1518; (2009) 263 ALR 461 |

Registry: | New South Wales |

Division: | General Division |

National Practice Area: | Intellectual Property |

Sub-area: | Patents and Associated Statutes |

Category: | Catchwords |

Number of paragraphs: | |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | K & L Gates |

Counsel for the First Respondent: | Mr N Murray with Mr R Clark |

Solicitor for the First Respondent: | Spruson & Ferguson Lawyers |

Counsel for the Fifth, Seventh, Eighth and Ninth Respondent: | Mr A Bannon SC with Ms C Cochrane and Ms L McGovern |

Solicitor for the Fifth, Seventh, Eighth and Ninth Respondent: | Allens |

1. Introduction

1 This trial commenced on Tuesday 6 March 2018. During the first four days I made a number of evidentiary and procedural decisions as follows:

(a) the grant of leave on Wednesday 7 March 2018, over objection, to the Applicant, Voxson, to adduce evidence in relation to evidence about experiments notwithstanding that there had been no compliance with the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (‘FCR’) r 34.50;

(b) the refusal of an application by Voxson that the Respondent Vodafone call as a witness Mr Walls;

(c) the refusal of an application by Voxson that Vodafone tender its process description;

(d) a ruling that certain evidence was not illegally obtained;

(e) the rejection of certain pages sought to be adduced in evidence generated by the ‘Wayback Machine’;

(f) the rejection of evidence about the date of publication of a paper entitled ‘Proposal for High Accuracy Positioning System for Land Mobile Communication Systems’ by Mr Ishikawa; and

(g) the rejection of Exhibit STA-10 to the affidavit of Ms Taylor.

2 These are my reasons for those decisions.

2. Experimental Evidence

3 FCR r 34.50 provides:

‘34.50 Experimental proof as evidence

(1) If a party (the proponent) proposes to tender, as evidence in a proceeding, experimental proof of a fact, the proponent must apply for orders in relation to the experimental proof, including orders about any of the following:

(a) the service on other parties of particulars of the experiment and of each fact that the proponent asserts is, will or may be proved by the experiment;

(b) any persons who must be permitted to attend the conduct of the experiment;

(c) the time when, and the place where, the experiment must be conducted;

(d) the means by which the conduct and results of the experiment must be recorded;

(e) the time by which any other party (the opponent) must notify the proponent of any grounds on which the opponent will contend that the experiment does not prove a fact that the proponent asserts is, will or may be proved by the experiment.

(2) Evidence of the conduct and results of the experiment is admissible in the proceeding, only:

(a) if the proponent has complied with subrule (1) and any orders given under that subrule; or

(b) with the leave of the Court.

(3) If an order mentioned in paragraph (1)(e) has been made, and the opponent has not complied with the order in relation to a ground, the opponent may rely on the ground only with the leave of the Court.’

4 Subrule (1) is mandatory; the party proposing to use the experimental evidence ‘must’ make the application contemplated by the rule. An interesting feature of the rule is that the Court is not empowered to refuse to permit the experiment to be conducted. Provision is made by subrule (1)(e) for the opposing party to signal its concerns about the methodology of the experiment but the Court is not asked under subrule (1) to make any determination of issues of that kind. The rule is not, as Heerey J observed in Bayer Bioscience N.V. v Deltapine Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2006] FCA 1762; (2006) 71 IPR 40 at 42 [10], a power to permit or refuse experiments.

5 In this case, Voxson accepted that it did not comply with the rule in relation to evidence of experiments conducted by two of its witnesses. It sought, therefore, leave under subrule (2). The two witnesses are Mr Lopez and Mr Hendriks. They conducted testing of a range of handsets to capture the messaging data flowing between the handsets and a third-party server providing A-GPS local positioning information (known as a SUPL server). Voxson conceded for the purposes of the present application that the tests carried out by its witnesses were experiments for the purposes of FCR r 34.50. No evidence was elicited from Voxson as to why no application prior to trial had been made but Mr Shavin QC for Voxson told me from the bar table, and I of course accept, that the non-compliance had arisen because of oversight.

6 The power to grant leave is not expressed to be confined by any particular matters. However, the following are relevant to its exercise:

(a) whether the persons who conducted the experiment are available for cross-examination: Generic Health Pty Ltd v Bayer Pharma Aktiengesellschaft [2014] FCAFC 73; (2014) 222 FCR 336 (‘Bayer’) at 375 [129];

(b) the extent to which the party conducting the experiment has prevented the other party from viewing the experiment (Bayer at 375 [128]);

(c) the time at which the application for leave is made (Beadcrete Pty Ltd v Fei Yu trading as Jewels 4 Pools [2012] FCA 1091 (‘Beadcrete’) at [7] per Jagot J); and

(d) prejudice to the other party (Beadcrete at [12]). This is related to (b), but there may be other species of prejudice, too.

7 This is not, of course, an exhaustive list of discretionary considerations.

8 So far as the facts are concerned, I am satisfied that the Respondents are not really prejudiced by what has occurred. The evidence of Mr Lopez and Mr Hendriks is that before they conducted their tests (or perhaps as a first step in those tests) they performed a factory reset of each of the handsets which were to be tested. Their intention in doing so was to restore each to its factory settings. Each was of a kind which had been available for sale from shops during the limitation period with software pre-installed by the Respondent.

9 Considerable debate took place on the present application as to whether Voxson could demonstrate that the handsets had actually been purchased during the limitation period and hence that their factory reset conditions were the correct ones. I assume in favour of the Respondents that had Voxson made the application prior to the tests being conducted:

(a) the parties could have ascertained whether the handsets had been purchased during the limitation period; and

(b) the Respondents might have suggested improvements on the test design.

10 Even so, I do not think the Respondents are prejudiced by the receipt into evidence of the test results. The test results are, in fact, just messaging data. Neither Mr Lopez nor Mr Hendriks purports to given any evidence about the meaning of the test results. It is Mr Crowe who seeks to say that the test results may be applied to handsets purchased during the limitation period. The Respondents remain at liberty to submit that Mr Crowe’s evidence should be rejected because of the difficulties in showing that the handsets had been purchased during the limitation period.

11 I do not think, in that circumstance, that the Respondents are truly prejudiced by what has occurred. In saying that I do not disregard the fact that the Respondents have been prevented from participating in the testing process or that because the handsets have been reset it is impossible now to know what their initial condition was. But when Mr Crowe is available for cross-examination and the methodological difficulties of what has occurred are not difficult to articulate, I do not see the Respondents’ position is compromised. And this is so, even with the lateness of the application,

12 It was for those reasons that I permitted the evidence of the testing processes to be given. Subsequent to this determination, Vodafone sought to reopen this issue on the basis of the illegality issue which I deal with below. Since I have concluded that no illegality was involved no occasion arises to reopen this issue.

3. Calling Mr Walls

13 In the course of the steps leading up to the trial I directed Vodafone to put on a process description of how its network operated in relation to A-GPS. It did so by putting on a complex description of its network operations. This statement was prepared by a Mr Walls, then, but no longer, of Vodafone. It did not purport to be Mr Walls’ evidence although he verified that its contents were true and he indicated that he was aware that he might be cross-examined about it. Such process descriptions are nothing new and this Court has certainly given its imprimatur to their use in patent litigation. So much appears from paragraphs 6.14-6.15 of the Intellectual Property Practice Note (IP-1) (‘Practice Note’) issued by the Chief Justice on 25 October 2016. Those paragraphs appear in section 6 which is concerned with patent litigation. They are as follows:

‘6.14 Further, where infringement is in issue, the parties should consider whether the alleged infringing party should provide a product description, or method or process description, in respect of the accused product or the accused method or process, so as to avoid the need for experiments or other scientific or technical investigations and/or to obviate or minimise the scope of any application for discovery.

6.15 Such a description, if appropriate, must be unambiguous in its terms and sufficiently detailed so as to properly address the allegations pleaded by the opposing party or parties. The description must be verified by a person who is personally acquainted with the facts to which the description relates and contain an acknowledgement that it is a true and complete description of the product or the method or process in question. The verification should also contain an acknowledgement by the person involved that he or she may be required to attend Court in order to be cross-examined on the contents of the description. Further, the party providing the description may be required to prove it at trial.’

[emphasis added]

14 Mr Shavin QC, who appeared with Ms Cunliffe of counsel for Voxson, submitted that the last two sentences of para 6.15 indicated, first that Mr Walls could be required for cross-examination and, secondly, that Vodafone could be required to prove the process description by tendering it.

15 I do not accept either that is what those two sentences mean or, if they did, that they would be legally effective to permit the Court to direct a party as to the evidence it was to call.

16 As to the first matter, it is apparent from para 6.14 that process statements are a mechanism for reducing the burden of discovery. Instead of requiring a Respondent to discover a large quantity of documentation from which its processes might deduced by an Applicant, it is easier just to have the Respondent describe the process. And, just as discovery is generally verified by a person with knowledge from the party giving discovery, so too it is sensible to require someone with knowledge to attach their oath to what has been done.

17 Sometimes discovery is found to be deficient. For a long time it was accepted that the affidavit verifying the discovery was both conclusive and unable to be cross-examined upon. However, that is no longer the case. Besanko J reviewed the authorities in Proctor v Kalivis [2009] FCA 1518; (2009) 263 ALR 461 at 468-469 [35]-[41] and it is clear from his Honour’s treatment that the modern position is:

(a) the affidavit of discovery is not conclusive;

(b) the usual remedy for deficient discovery, where it is demonstrated, is the ordering of a further affidavit of discovery; but

(c) in limited circumstances, cross-examination of the verifying deponent may be ordered.

18 It may be that ‘limited circumstances’ will be shown when there is a basis for believing that the approach of the party giving discovery has, in some way, been illegitimate (Olympic Airways SA v Spiros Alysandratus & Consolidated Travel (Vic) Pty Ltd (unreported, VSC, Harper J, 26 May 1997)) or, perhaps, where the only way the deficiencies can be exposed is by cross-examination (IO Group Inc v Prestige Club Australasia Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 1147 at [50] per Flick J).

19 It is tolerably clear, therefore, that when the Practice Note refers to the possibility of the author of the process statement being cross-examined, it is referring to a discovery mechanism. The Practice Note is not discussing a right at trial. It is contemplating the right of the party who has sought the process statement to challenge its adequacy by way of interlocutory application. It is not inevitable that such a challenge must occur before trial although generally, perhaps almost always, it will. Regardless of when it occurs, however, it is a cross-examination to be permitted in the limited circumstances set out above and as part of an effort to secure, by interlocutory means, a further and better process statement. As such, even in those rare cases where this might occur mid-trial, the cross-examination is not directly part of the trial process itself. The cross-examination is directed only to seeking to show the inadequacy of the process statement so that a further statement may be directed to be produced.

20 Furthermore, I do not accept that the last sentence of para 6.15 means that the Court can order Vodafone either to tender its process statement or to prove the process by some other means. I read the sentence as meaning no more than that a party who has provided a process statement is not relieved of the obligation of proving its process by admissible evidence if it seeks to do so; in particular because the process statement is likely largely to be inadmissible hearsay, the party providing it should not expect to be able to tender the statement as proof. This contrasts with the position of the party who has obtained the process statement in whose hands the hearsay it contains takes the form of admissions and is therefore admissible.

21 I do not think, therefore, that the Practice Note provides support for Mr Shavin’s contentions. In any event, a mechanism under which one party could require during a trial that the other party call a witness against their will is such a significant departure from ordinary trial process that it could not be achieved by Practice Note. It is not necessary to pursue this further.

22 It was for those reasons I refused Voxson’s application to require Vodafone to make Mr Walls available for cross-examination and its accompanying application to make Vodafone tender its process statement.

4. The Telecommunications Intercept Issue

23 On the second day of the trial Mr Bannon SC, who appeared with Ms Cochrane and Ms McGovern for Vodafone, drew to the Court’s attention the possibility that the evidence of Mr Lopez and Mr Hendriks might be inadmissible because it had been unlawfully obtained. As noted above, each gave evidence of having extracted message data from communications sent by a SUPL server to a series of handsets they were testing. Section 7(1) of the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 (Cth) prohibits a person from intercepting a communication passing over a telecommunication system and s 63(1) prohibits the giving of evidence of information obtained as a result of an interception in contravention of s 7(1). Vodafone did not formally object to the evidence but merely brought the matter to the Court’s attention.

24 Mr Lopez and Mr Hendriks performed similar tests on the handsets. They were both attempting to obtain the message data sent from a SUPL server to the handsets. I deal first with Mr Lopez. The message data passing between a SUPL server and a handset is encrypted. In order to overcome that problem Mr Lopez configured two proxy servers which he leased from Amazon Web Services. He set them up so that the handset being tested would send a message back to the first of the proxy servers. That server would then send the message to the second proxy server which would then send it to the SUPL server. The SUPL server would then reply to the second proxy server which would pass the message back to the first proxy server. The first proxy server would then log the message in plain text, i.e., in unencrypted form. By these means, Mr Lopez was able to obtain the message data sent by the SUPL server to the handset in unencrypted form. Mr Hendriks performed much the same process except that he combined the functions of both proxy servers into one proxy server.

25 In any event, the gist of what was done in both case remains the same:

the interposition of a proxy server which received the encrypted message data from the SUPL server; and

the taking of a log of that message data in unencrypted form.

26 So far as the SUPL server was concerned it simply replied to a request from an IP address by sending data back to that IP address. The IP address in this case was the IP address provided by the operator of the proxy server which, in Mr Lopez’s case, was Amazon Web Services.

27 I do not think that any breach of s 7(1) can have happened as a result of such an arrangement. The short reason for this is that operator of the SUPL server intended to send the message data to the IP address to which it in fact sent the message data. Consequently, upon the message data’s arrival at the proxy server the communication was complete. After that time, it was not possible to intercept the communication consisting of the message data because it was no longer travelling across a telecommunications system.

28 That short reason may be expressed more technically as follows: s 7(1) prohibits the interception of a ‘communication passing over a telecommunications system’. A communication includes data (s 5) so the message data was a communication to which s 7(1) applied. A communication ‘passes over a telecommunications system’ from the time it is sent by the person sending the communication (here the operator of the SUPL server) to the time it ‘becomes accessible to the intended recipient of the communication’ (s 5F).

29 There are two relevant concepts here: ‘intended recipient’ and ‘accessible’. As to the former, if a communication is addressed to a person who is not an individual then the intended recipient of the communication is that person (s 5G(b)). In this case, the communication was addressed by means of an IP address to the operator of the proxy server. Consequently, the intended recipient was that operator.

30 When did the communication become ‘accessible’ to the operator of the proxy server? The answer is provided by s 5H:

‘5H When a communication is accessible to the intended recipient

(1) For the purposes of this Act, a communication is accessible to its intended recipient if it:

(a) has been received by the telecommunications service provided to the intended recipient; or

(b) is under the control of the intended recipient; or

(c) has been delivered to the telecommunications service provided to the intended recipient.

(2) Subsection (1) does not limit the circumstances in which a communication may be taken to be accessible to its intended recipient for the purposes of this Act.’

31 Satisfaction of any of these subparagraphs causes the communication to be accessible to the intended recipient. In this case, there may be some nice questions about (b) and whether the operator of the proxy server has control of the communications it receives on behalf of the person hiring the server. However, these are of no moment because (a) and (c) are both satisfied. It is inevitable that the proxy server was connected to the internet by means of a carriage service provided by someone. Consequently, when the communication was delivered to that carriage service provider (as it inevitably must have been) subparagraph (a) was satisfied (as must also have been (c)). From that moment the communication was accessible by the intended recipient, the operator of the proxy server. It follows that from that time the communication was no longer passing over a telecommunications system. What Mr Lopez and Mr Hendriks did with the proxy server (or in Mr Lopez’s case the second proxy server) might, I suppose, have been an interception within the meaning of 7(1) (as defined in s 6) (although I have my doubts about that too) but this does not matter. Even assuming it was, s 7(1) only applies to interceptions which occur whilst the communication is passing across a telecommunications system which the communications coming from the SUPL server could not be once they were received by the proxy server.

32 Accordingly, s 63(1) does not prevent the receipt of Mr Lopez and Mr Hendrik’s evidence.

5. The Wayback Machine

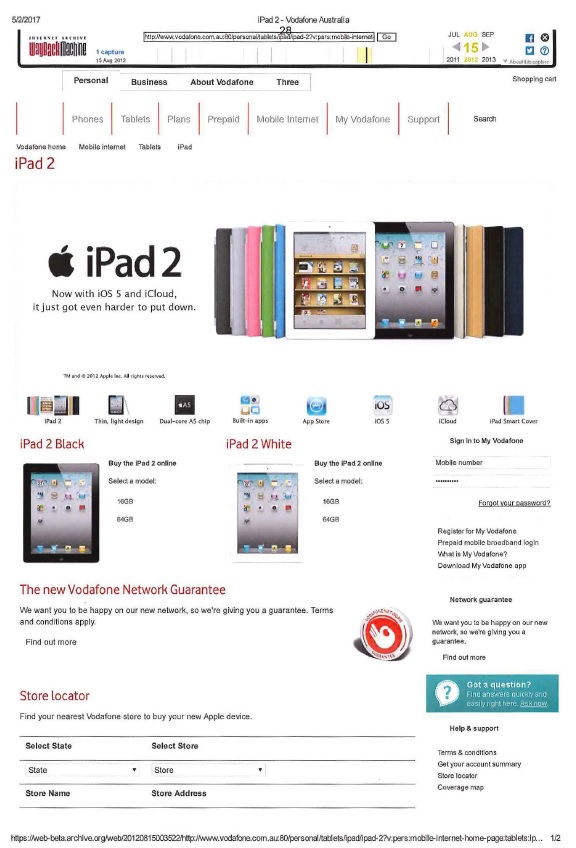

33 Voxson sought to adduce evidence of the historical state of webpages which had been maintained by the Respondents over a range of dates in late 2012. It did so by annexing to Ms Taylor’s affidavit of 9 May 2017 webpages she had printed off using an application known as the Wayback Machine which is provided from a webpage located at archive.org. This was opposed by the Respondents on the basis that the webpages printed off by Ms Taylor were inadmissible hearsay.

34 The pages are certainly hearsay. Each page appears to be some form of copy of the requested webpage over which there is superimposed at the top a statement indicating that the page has been generated by the Wayback Machine for a given date. An example of this is as follows:

35 The operator of the Wayback Machine is therefore making a representation that it copied the webpage into its archive and recorded the date on which it did so and that the webpage which appears in its archive is the webpage which existed on that date. Since Voxson wishes to prove what the state of the Respondents’ websites was on the relevant dates using these pages, it follows that it wishes to adduce the pages generated by the Wayback Machine as evidence that those pages were, in fact, in that form on those dates. This is hearsay. I should also add that Voxson also seeks to prove the truth of the contents of the archived webpages produced by the Wayback Machine. This involves second-hand hearsay: a representation by the operator of the Wayback Machine that the webpages had a particular content on a particular date and a representation by the Respondents by means of the pages in question as to the matters which Voxson seeks to prove. In both cases, however, Voxson must at least establish that the pages generated by the Wayback Machine can be brought within an exception to the hearsay rule. I do not think that they can.

36 I do not accept that the webpages produced by the Wayback Machine are shown, in this case, to be business records within the meaning of s 69 of the Evidence Act 1995. Section 69 provides:

‘69 Exception: business records

(1) This section applies to a document that:

(a) either:

(i) is or forms part of the records belonging to or kept by a person, body or organisation in the course of, or for the purposes of, a business; or

(ii) at any time was or formed part of such a record; and

(b) contains a previous representation made or recorded in the document in the course of, or for the purposes of, the business.

(2) The hearsay rule does not apply to the document(so far as it contains the representation) if the representation was made:

(a) by a person who had or might reasonably be supposed to have had personal knowledge of the asserted fact; or

(b) on the basis of information directly or indirectly supplied by a person who had or might reasonably be supposed to have had personal knowledge of the asserted fact.

(3) Subsection (2) does not apply if the representation:

(a) was prepared or obtained for the purpose of conducting, or for or in contemplation of or in connection with, an Australian or overseas proceeding; or

(b) was made in connection with an investigation relating or leading to a criminal proceeding.

(4) If:

(a) the occurrence of an event of a particular kind is in question; and

(b) in the course of a business, a system has been followed of making and keeping a record of the occurrence of all events of that kind;

the hearsay rule does not apply to evidence that tends to prove that there is no record kept, in accordance with that system, of the occurrence of the event.

(5) For the purposes of this section, a person is taken to have had personal knowledge of a fact if the person’s knowledge of the fact was or might reasonably be supposed to have been based on what the person saw, heard or otherwise perceived (other than a previous representation made by a person about the fact).

Note 1: Sections 48, 49, 50, 146, 147 and subsection 150(1) are relevant to the mode of proof, and authentication, of business records.

Note 2: Section 182 gives this section a wider application in relation to Commonwealth records.’

37 No admissible evidence has been placed before the Court to establish the matter in s 69(1)(a)(i) (that the webpages form part of the records of the business conducted by the operator of the website) or the matter in s 69(2), viz, that the web pages were created by someone who might be expected to have had personal knowledge of the facts which have been recorded (here, the particular state of an internet page on a given date). It is not difficult to imagine such evidence could readily be obtained but that does not fill the void left by the fact that it has not been. An attempt was made to prove some facts about the Wayback Machine from its public information page at archive.org/about. However, that involves relying on that page for the truth of its contents which is a hearsay use of the material (to which objection was taken). It was submitted, in answer to that problem, that the public information page was itself a business record of the Internet Archive. However, no evidence establishes that and, indeed, it appears merely to be a statement for public information. As such there no reason to think it lies outside the general (but not invariable) rule that the contents of public website are not business records of the businesses which maintain them: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Air New Zealand Limited (No 5) [2012] FCA 1479 at [15].

38 Consequently, the other archival pages generated by the Wayback Machine are not shown (in this case) to be business records. A similar conclusion on the facts was reached by Flick J in E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 934; (2008) 77 IPR 69 at 95 [126]. Whether this conclusion will always follow, however, depends on the evidence put before the Court.

39 It was then said that the same pages could be admissible under s 147 which provides:

‘147 Documents produced by processes, machines and other devices in the course of business

(1) This section applies to a document:

(a) that is produced wholly or partly by a device or process; and

(b) that is tendered by a party who asserts that, in producing the document, the device or process has produced a particular outcome.

(2) If:

(a) the document is, or was at the time it was produced, part of the records of, or kept for the purposes of, a business (whether or not the business is still in existence); and

(b) the device or process is or was at that time used for the purposes of the business;

it is presumed (unless evidence sufficient to raise doubt about the presumption is adduced) that, in producing the document on the occasion in question, the device or process produced that outcome.

(3) Subsection (2) does not apply to the contents of a document that was produced:

(a) for the purpose of conducting, or for or in contemplation of or in connection with, an Australian or overseas proceeding; or

(b) in connection with an investigation relating or leading to a criminal proceeding.

Note: Section 182 gives this section a wider application in relation to Commonwealth records and certain Commonwealth documents.’

40 For the presumption in subs (2) to be enlivened it must be shown that it is reasonably open to find that the Wayback Machine is a process or device that, if properly used, produces the outcome of retrieving historic webpages. However, there is no admissible evidence before the Court as to this issue. I do not know what the processes of the Wayback Machine are or the extent to which it does, in fact, produce the outcome that Voxson claims it does. The argument under s 147 therefore fails for proof. Even if that inference had been open, there is much to be said for the submission made by Mr Clark for Telstra that to inspect the pages which had been produced from the Wayback Machine was to see at once that the pages could not be accurate representations of the webpages’ historical appearances. The material attached to Ms Taylor’s affidavit is mostly of a promotional nature emanating from the Respondents. Yet the formatting is quite disordered and many of the photographs are missing. One does not perhaps need a particularly vivid imagination to think that these formatting problems are likely to be the result of some internal issue and may not affect the substance of the recording process. But there is no getting away from the proposition that the archiving process performed by the Wayback Machine plainly has limitations. Without understanding those limitations I would incline to the view, if it had been necessary to form one, that the presumption in subs (2) would be rebutted by the matters to which Mr Clark pointed.

41 In any event, all roads lead to Rome. The evidence of the Wayback Machine pages is inadmissible.

6. The Japanese Archive

42 Vodafone sought to elicit evidence demonstrating that a particular article entitled ‘Proposal of high accuracy positioning system for land mobile communication systems’ written by a Mr Ishikawa was published on 21 April 1992. There is no dispute that there is such an article or that it was written by Mr Ishikawa. There is a dispute, however, about when it was published. The priority date is in 2 December 1992 and Vodafone wishes to show that it was published prior to that date.

43 To do so, one of its solicitors searched an on-line database called J-Global which is maintained by the Japan Science and Technology Agency. He inserted the name of the article and retrieved two records from the archive suggesting that it had been published in two different places on two different dates, 21 May 1992 and on an unspecified day in March 1992. Vodafone wishes to adduce the evidence of the two dates as evidence of the fact that the article was published before 2 December 1992.

44 On its face this is a hearsay use of the representation. The operator of the J-Global database is saying that the article was published at those times and Vodafone is seeking to prove that what the operator said to prove the truth of the representation. It is therefore hearsay. To this Vodafone submits that records are business records.

45 As with the Wayback Machine, I just do not know enough about J-Global to address the issues raised by s 69(1). The issue is not whether the articles in the J-Global archive are business records. It is whether the date information stored in relation to each article is a business record. As I have previously said, usually a business’s publicly available website will not be one of its business records. However, different questions may intrude where the business involved is a business of keeping a particular class of record. But I do not know whether that is what the Japan Science and Technology Agency is or even what J-Global is. I am therefore not satisfied that these are business records. Assuming a similar argument was also mounted under s 147, I reject it for largely the same reasons.

7. Other objections

46 Objection was taken to p 3270 of annexure STA-10 to Ms Taylor’s affidavit. STA-10 consisted of some extracts from a webpage maintained by Vodafone. The webpages dealt with the topic, inter alia, of how to configure a Nokia E72 handset to connect with a SUPL server for A-GPS location.

47 One objection was that Ms Taylor had not downloaded the material herself. Instead it was downloaded by another solicitor in the same office in August or September 2014. This is a hearsay objection in substance. One only knows that the pages were downloaded from the website because the other solicitor told Ms Taylor that information. Ms Taylor’s information is therefore hearsay. I reject this aspect of her evidence. Ms Cunliffe submitted that the underlying records could be seen as business records of the law firm in question but this is not possible as they were created in contemplation of litigation: cf. s 69(3). On the other hand, I would not uphold the relevance objection based on the fact that the website is not from the Australian site. It is far too early to be dogmatic about which websites matter and which do not.

48 Next Telstra took objection to paragraphs 11, 12(a), 12(c) and 12(d) of Ms Taylor’s affidavit and the corresponding annexures. The point in each case is the same and is conveniently resolved by reference to paragraph 11 and STA-6. Ms Taylor accessed the website www.ztemobiles.com.au and obtained the user manual for the Telstra ‘Dave’ T83 mobile telephone. STA-6 was part of the user manual for the handset. STA-6 also contains a printout from the ZTE Mobile site for that phone which refers to GPS services under the Overview and Specification tabs. Mr Clark submitted that there was no evidence as to when the T83 was sold by Telstra hence it could not advance a case under s 117 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) on infringement. That may well be right but I do not propose to exclude the evidence at this stage on that basis. Similar reasoning applies to the other paragraphs and annexures. I also decline to make the s 136 direction sought.

I certify that the preceding forty-eight (48) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Perram. |

NSD 2436 of 2013 | |

VODAFONE PTY LIMITED (ACN 062 954 554) | |

Ninth Respondent: | VODAFONE NETWORK PTY LIMITED (ACN 081 918 461) |