FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Kemppi v Adani Mining Pty Ltd (No 3) [2018] FCA 40

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application filed 1 December 2017 be dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REEVES J:

INTRODUCTION

1 Ms Delia Kemppi and her fellow applicants (who I will refer to jointly in these reasons as “Ms Kemppi”) comprise five of the 12 members of the Applicant (the W & J Applicant) that has been authorised by the Wangan and Jagalingou People to pursue, on their behalf, the Wangan and Jagalingou native title determination application (the W & J application). In that capacity, Ms Kemppi has applied for an interlocutory injunction to restrain, until the final determination of this proceeding, Adani Mining Pty Ltd from seeking, and the State of Queensland from granting, approval under cl 9(b) of an Indigenous Land Use Agreement (the ILUA) made and registered under the apposite provisions of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the NTA).

2 The hearing of this injunction application has been expedited because, notwithstanding the fact that the trial of this proceeding is due to commence about six weeks hence, both Adani and the State have indicated they intend to proceed in the manner described above. They are entitled to do that because the ILUA mentioned above was registered on the Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements under Part 8A of the NTA (the Register) on 8 December 2017.

THE FACTUAL CONTEXT

3 This injunction application arises in the following factual context. The W & J application has been on foot for almost 14 years: it was filed in the Court on 27 May 2004. It covers an area of approximately 30,277.6 square kilometres on the western edge of Central Queensland and includes the townships of Clermont, Alpha, Rubyvale and Capella. Significantly, for the purposes of the present application, it also includes the area where Adani proposes to develop a coal mine known as the Carmichael Coal Mine.

4 The W & J application was entered on the Register of Native Title Claims (under s 190(1)(a) of the NTA) on 5 July 2004. One of the consequences of that registration is that Ms Kemppi and the other members of the W & J Applicant, from time to time, also comprise the Registered Native Title Claimant for the claim (the W & J registered claimant) as that expression is defined in the NTA: see ss 253 and 186(1)(d).

5 In April 2016, Adani entered into the ILUA with the W & J registered claimant and the State. That followed a meeting of the Wangan and Jagalingou People held on 16 April 2016 which authorised the making of the ILUA under s 251A of the NTA.

6 Soon thereafter, Adani applied to the Native Title Registrar under s 24CG of the NTA to have the ILUA registered on the Register.

7 For the purposes of that application, Adani sought and obtained from Queensland South Native Title Services (QSNTS) a Certificate under s 203BE of the NTA (the Certificate). QSNTS issued the Certificate in its capacity as the Native Title Service Provider holding recognition under s 203FE of the NTA for the Southern and Western Queensland Region. That region includes the claim area for the W & J application. The Certificate expressed opinions about the matters set out in s 203BE(5)(a) and (b) of the NTA.

8 As is already mentioned above, the Registrar entered the ILUA on the Register on 8 December 2017.

9 In the meantime, on 24 March 2017, Ms Kemppi filed this proceeding seeking, among other things, a declaration that the Certificate is void and of no effect and a declaration that, as a consequence, the Registrar lacked the jurisdiction to register the ILUA on the Register.

10 In June 2017, this proceeding was set down for trial to commence on 12 March 2018.

THE RELEVANT PROVISIONS OF THE ILUA

11 This application seeks the following orders:

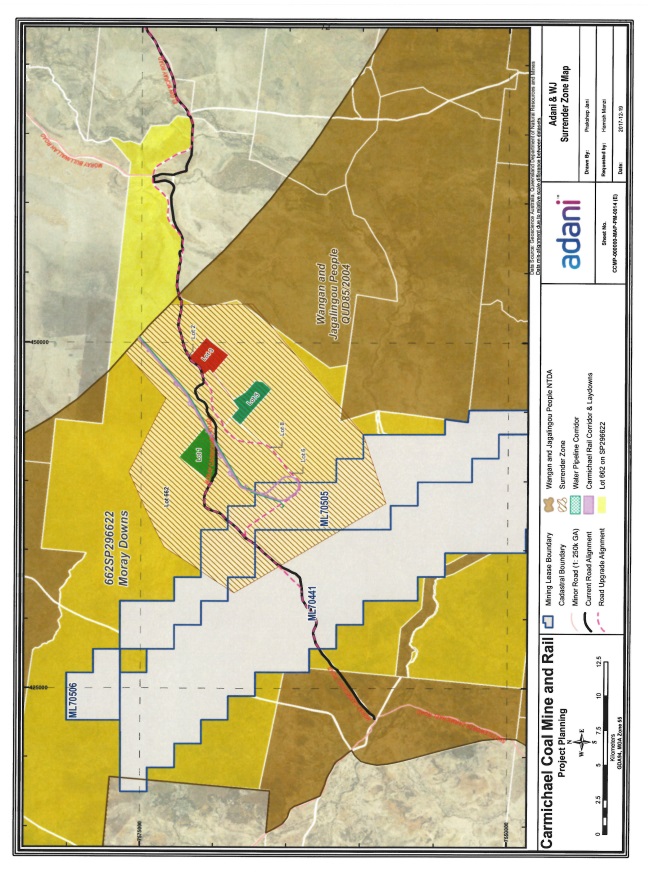

1. An order that, until further order, [Adani] must not seek an “Approval” (as defined in clause 1.1 of the [ILUA] to which clause 9(b) of the [ILUA] applies.

2. An order that, until further order, the [State] must not:

(a) grant an Approval to which clause 9(b) of the [ILUA] applies;

(b) do an act which is the “Taking of Native Title” (as defined in clause 1.1 of the [ILUA]) in reliance upon clause 9(a)(iii) of the [ILUA].

12 As is apparent from these proposed orders, the clause of the ILUA at the heart of this application is cl 9. It provides:

9 Consents

(a) The Parties agree to and consent to:

(i) the Agreed Acts without conditions;

(ii) any Surrender that occurs pursuant to the process set out in clause 9(b);

(iii) any Taking of Native Title; and

(iv) the undertaking of the ILUA Project,

in each case to the extent that it is in accordance with this Agreement and any applicable Law.

(b) With respect to clause 9(a)(ii), the Parties acknowledge and agree that:

(i) pursuant to the process set out in this clause 9(b), Surrenders may occur with respect to one or more areas within the Surrender Area; and

(ii) if:

A. Adani seeks an Approval (with respect to an area within the Surrender Zone) that cannot be Granted unless a Surrender first takes place; and

B. a Surrender over the part of the Surrender Zone that is the subject of the Approval would not result in the total area Surrendered under this Agreement or subject to a Taking of Native Title being greater than the Surrender Area,

then:

C. provided this Agreement has been Registered, a Surrender will occur immediately before the Approval is Granted in relation to any Native Title Rights and Interests that exist within that part of the Surrender Zone that is the subject of the Approval; and

D. Adani must notify the Native Title Parties of the Surrender (such notice to include a copy of a plan of survey identifying the area to which the Surrender relates) and provide the State with a copy of that notification.

(c) The total area the subject of all Surrenders and any Taking of Native Title under clause 9(a) (ii) and 9(a)(iii), must not exceed the Surrender Area and the consents in those clauses 9(a)(ii) and 9(a)(iii) are subject to this limitation.

(d) The Parties agree that any Surrender is intended to extinguish any Native Title that may exist in relation to the relevant part of the Surrender Zone, at the time of the Surrender.

(e) Subject to clause 9(d), to the extent that the Grant or doing of any of the Agreed Acts, or the undertaking of any aspect of the ILUA Project, is a Future Act, the Parties agree that the Non-Extinguishment Principle applies to the doing of such Future Act.

(f) The consents in clause 9(a) are statements for the purpose of section 24EB(1)(b)(i) and 24EBA(1)(a)(i) of the NTA and regulations 7(5)(a) and 7(5)(d) of the Regulations.

(g) Clause 9(d) is a statement for the purpose of section 24EB(1)(d) of the NTA and regulation 7(5)(c) of the Regulations.

(h) For the purposes of section 24EB(1)(c) of the NTA and regulation 7(5)(b) of the Regulations, on and from the date this Agreement is Registered, Subdivision P, Division 3, Part 2 of the NTA is not intended to apply to any Agreed Acts, or to any Surrender or any Taking of Native Title.

(i) For the avoidance of doubt, the Parties agree that, if this Agreement is never Registered or it is Registered and subsequently removed from the Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements, then subject to its termination in accordance with clause 16:

(i) it will remain binding as a contract between the Parties; and

(ii) the Ancillary Agreement will remain binding as a contract between Adani and the Native Title Parties.

13 The expressions used in this clause: “Approval”; “Surrender”; “Surrender Area”; “Surrender Zone”; and “Taking of Native Title”, are defined in cl 1.1 of the ILUA to mean:

Approvals means any authorisation, lease, title, tenure including freehold tenure, licence, permit, approval, certificate, declaration, regulation, consent, direction or notice whether or not from any Government Agency or other competent authority that Adani, acting reasonably, considers is necessary or desirable for, or incidental to, the undertaking of the ILUA Project on any part of the ILUA Area.

Surrender means a surrender to the State of any of the Native Title within the Surrender Area for the purposes of the ILUA Project in accordance with the process set out in clause 9(b).

Surrender Area means an area of not more than 2,750 hectares to be located within the Surrender Zone.

Surrender Zone means the external boundaries formed by the coordinates set out at Part 3 of Schedule 1 and shown on the map at Part 4 of Schedule 1.

Taking of Native Title means a taking of Native Title Rights and Interests within the Surrender Area for the purposes of the ILUA Project pursuant to the State Development and Public Works Organisation Act 1971 (Qld), the Transport Planning and Coordination Act 1994 (Qld), the Transport Infrastructure Act 1994 (Qld), the Acquisition of Land Act 1967 (Qld) or any other legislation which provides for the taking of land or waters or of rights or interests relating to land or waters.

14 The map at Part 4 of Schedule 1 mentioned in the definition of the expression “Surrender Zone” above is similar to the one annexed to Mr Manzi’s affidavit below (see at [18]).

15 Ms Kemppi has contended (correctly in my view) that the statement in cl 9(g), combined with the operation of s 24EB(1)(d) of the NTA, means that whatever native title exists in the area concerned will be extinguished permanently by the approval of a surrender under cl 9(b) above.

THE SURRENDER AREAS CONCERNED

16 Mr Lezar is the Head of Mining at Adani. He has been employed in that role since about August 2015, having commenced with Adani in November 2012. In that capacity, he is responsible for Adani’s mining operations as they concern the Carmichael Coal Mine and Rail Project (Carmichael Project) in the Galilee Basin in Central Queensland. In one of his affidavits filed for the purposes of this application, Mr Lezar outlined the details of the Carmichael Project in the following terms:

(a) the development and operation of the Carmichael Coal Mine, which is a greenfield open-cut and underground thermal coal mine in the northern part of the Galilee Basin, approximately 160 kilometres north-west of the town of Clermont and approximately 350 kilometres north of the town of Emerald;

(b) the development and operation of a 388 kilometre greenfield rail line (Rail) to facilitate export of the coal from the Carmichael Coal Mine through relevant port facilities (Port); and

(c) the associated infrastructure and utilities required by Adani to support the operations of the Carmichael Coal Mine and Rail infrastructure including:

(i) coal handling and processing plants;

(ii) water supply and management infrastructure;

(iii) workers’ accommodation village;

(iv) an airport; and

(v) mine industrial areas.

17 Further, Mr Lezar said that the Carmichael Project required the construction, among others, of the following facilities:

(a) approximately 14 kilometres of track as part of the Rail component of the Project (with an adjacent water pipeline);

(b) a workers’ accommodation village;

(c) an airport;

(d) an industrial area (including a waste facility); and

(e) telecommunications towers.

18 Mr Manzi is the Head of Environment and Sustainability at Adani. Annexed to an affidavit he made for the purposes of this application is the map below, which depicts the locations of the above items within the Carmichael Project area.

19 This map requires some explanation. First, the cross hatched area located in about the centre of the map is the area described in the ILUA as the “Surrender Zone”. There is no evidence as to the size of the Surrender Zone, but the Surrender Area is no more than 2,750 hectares. The six lots appearing as marked within that Zone – numbered 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 and 8 – together comprised the “Surrender Area” described in the ILUA. As such, those lots and the railway corridor described below are to be subjected to the “Surrender” process described in cl 9(b) of the ILUA above. Lots 1, 3 and 5 show the locations of items (b), (c) and (d) above, respectively, and Lots 2, 6 and 8 (faintly marked on the map) show the locations of the three communication towers which together comprise item (e) above.

20 In his affidavit, Mr Manzi said that those six lots are currently designated as unallocated State land. He described in some detail the process Adani had followed since December 2016 to purchase those lots from the State. He said that by 8 December 2017, all the requirements Adani had to meet under its agreement with the State for that purchase had been satisfied.

21 The order sought in 2(a) (see at [11] above) refers to those six lots.

22 The corridor for the railway track and water pipeline (item (a) above) is shown as a continuous line extending from the top right hand border of the hatched area shown on the map above to the loop near the marking “ML70505”.

23 In his affidavit, Mr Manzi described how the land within the rail corridor (inside and outside the Surrender Zone) is situated partly in the Galilee Basin State Development Area and partly in the Abbot Point State Development Area. He said that Adani had submitted a proposal to the State that that land be compulsorily acquired for the purposes of the rail component of the Carmichael Project. He described how the process for compulsory acquisition included “the issuing of a written Notice of Intention to Resume, the objection process, the application process (that application being by the Coordinator General to the Minister) and the resumption process”. Based upon a Tenure Search he had conducted recently, he said that a Notice of Intention to Resume was recorded with respect to that land on 23 March 2017. There is no evidence before me as to when that compulsory acquisition process will be completed.

24 The order sought in 2(b) (see at [11] above) refers to the land affected by this compulsory acquisition process within the Surrender Zone.

THE PRINCIPLES

25 The basic principles applying to the grant of an interlocutory injunction of the present kind are relatively well-established. There are two main inter-related inquiries. Ms Kemppi must make out a prima facie case in the sense that she must show that she has a sufficient likelihood of success at trial to justify the grant of the injunction to preserve the status quo. She must also show that the balance of convenience favours that course: see Australian Broadcasting Corporation v O’Neill (2006) 227 CLR 57, [2006] HCA 46 (O’Neill) at [65]–[72] per Gummow and Hayne JJ (Gleeson CJ and Crennan J agreeing at [19]); Samsung Electronics Company Ltd v Apple Inc (2011) 217 FCR 238, [2011] FCAFC 156 (Samsung) at [57]; and Warner-Lambert Company LLC v Apotex Pty Ltd (2014) 311 ALR 632, [2014] FCAFC 59 at [69]–[70].

26 As the Full Court observed in Samsung, to establish that there is a prima facie case, Ms Kemppi is not necessarily required to demonstrate that her case is, on balance, likely to succeed, but rather the Court has to assess “the strength of the probability of [that] ultimate success”. That will vary from case to case, depending “upon the nature of the rights asserted and the practical consequences likely to flow from the grant of the injunction which is sought” (see Samsung at [57] and [59]). In the circumstances of this case, the strength of Ms Kemppi’s probability of ultimate success is very much a live issue. Accordingly, both counsel paid close attention to it in their submissions.

27 In the second but interrelated inquiry, namely the balance of convenience, the Court has to make an assessment of the harm that may be occasioned to the applicant if no injunction is granted and the harm that may be occasioned to the respondent if an injunction is granted and to weigh those two considerations along with any others of relevance (see O’Neill at [65] and Samsung at [62]). The interrelatedness of the two inquiries requires, as well, that the apparent strength of the parties’ substantive cases be considered in the light of the balance of convenience considerations mentioned above (Samsung at [67]).

28 Ms Kemppi also submitted that there was a third inquiry: whether the plaintiff will suffer irreparable injury for which damages will not be adequate compensation unless an injunction is granted. However, for the reasons given by the Full Court in Samsung at [61] and [63], I do not consider that is correct. Instead, as the Court explained at [63], that is a matter that falls to be addressed as a part of the “assessment of the balance of convenience and justice”.

29 With these principles in mind, I now turn to consider the strength of the probability of Ms Kemppi’s ultimate success in her claims and then consider that in the light of, among any other relevant considerations, the competing prejudices that are likely to be occasioned to her, and to Adani, assuming the injunction is not granted, or granted, respectively.

THE STRENGTH OF THE PROBABILITY OF MS KEMPPI’S ULTIMATE SUCCESS

30 Because of the urgency applying to this application, I do not propose to examine all of the many issues or contentions that were raised in the written and oral submissions of the parties. In particular, I do not consider it is necessary to examine the s 24EB issue in order to deal with this application. That is all the more so where Ms Kemppi’s position on that issue was understandably contradictory.

31 In Ms Kemppi’s further amended statement of claim (FASC), there are four components to her claims: unreasonableness in the issue of the Certificate ([35] of the FASC); a failure to consider relevant considerations when issuing the Certificate ([35A]) of the FASC); a claim that the ILUA did not contain a “complete description” of the Surrender Area as required by regs 5 and 7(2)(e) of the Native Title (Indigenous Land Use Agreements) Regulations 1999 (Cth) ([37]–[42] of the FASC); and a claim that all the members of the W & J Applicant had to sign the ILUA in order for it to be valid and effective ([43]–[46] of the FASC).

32 Given that the trial of this proceeding is due to commence before me in a little under six weeks’ time, it is not appropriate that I should express any concluded, or even detailed, views on the countering submissions of counsel concerning these four claims. As to the first two claims, it will suffice to reiterate the reservations I expressed about the probability of success of those claims, as they are currently pleaded in the FASC, in my earlier decision in this proceeding (Kemppi v Adani Mining Pty Ltd (No 2) [2017] FCA 1086 at [17]–[20], [29]–[31], [35], [39] and [46]–[48]).

33 The third claim is essentially a matter of statutory construction. In my view, the competing constructions advanced by counsel for Ms Kemppi and Adani each have their strengths. That being so, it could not be said that Ms Kemppi’s construction is lacking in strength in the sense of its probability of success. However, even assuming her construction is correct, the more difficult question is whether a failure to comply with the regulation in question caused the application for registration of the ILUA to be invalid such that the Registrar thereafter lacked jurisdiction to consider that application. This involves an aspect of the s 24EB issue mentioned above: if Ms Kemppi is correct that the registration is void ab initio, there is no need for an injunction but, if she is not correct, she will fail on this critical aspect in her substantive proceedings at trial.

34 The fourth claim involves the interpretation of resolutions 3 and 4 that were passed at the meeting on 16 April 2016 which authorised the making of the ILUA. As Adani’s counsel pointed out, the terms of those resolutions as pleaded at [43] of the FASC are not complete. In particular, resolution 4(b), as follows, has been excluded:

where one or more of the persons comprising the Applicant for the W&J Native Title Claim refuse or are unable to sign the proposed ILUA and Ancillary Agreement, the W & J People agree to be bound by, and this Authorisation Meeting evidences the W&J People’s intent to enter into and authorise, the ILUA and Ancillary Agreement; and

35 Since the question posed by this claim is whether the making of the ILUA was conditional on all of the members of the W & J Applicant signing it, this additional part of resolution 4 is clearly significant to the strength of Ms Kemppi’s probability of ultimate success on this claim.

36 Having regard to all these matters, and while retaining the circumspection that is necessary in the peculiar circumstances I have mentioned above, I do not consider Ms Kemppi has, on balance, a strong probability of ultimate success in any of the four claims pleaded in her FASC. This conclusion therefore requires me to approach the interrelated “balance of convenience and justice” inquiry, as it was described in Samsung, with particular caution. I will now turn to consider that question.

THE PREJUDICE MS KEMPPI CLAIMS SHE WILL SUFFER IF THE INJUNCTION IS NOT GRANTED

37 I should preface this section of my reasons by reiterating the observation I have made above that, if the Surrender process provided for in cl 9(b) of the ILUA proceeds, the extinguishment of native title that will thereby occur will be permanent. Furthermore, I accept as a general proposition Ms Kemppi’s contention that damages are not an adequate remedy for the extinguishment of an Aboriginal person’s native title rights and interests. Finally, I reject Adani’s contention that I should take into account as a relevant factor the fact that the Wangan and Jagalingou People have not yet obtained a determination of native title in their favour. I do so because this proceeding focuses on the ILUA which has come into existence as a result of the Wangan and Jagalingou People exercising the rights they have under the NTA partly as a consequence of them filing the W & J application and achieving its registration on the Register of Native Title Claims under Part 7 of the NTA.

38 To pursue her claims in this proceeding, Ms Kemppi relies entirely on her status as a member of the W & J Applicant and the W & J registered claimant. So much is clear from her FASC at [1]–[5] inclusive. In my view, that presents an immediate difficulty for her. That is so because, where there are multiple members of an applicant, or a registered native title claimant, the members have to act jointly and collectively in discharging their role: see Burragubba v State of Queensland [2016] FCA 984 at [282] and Burragubba v State of Queensland (2017) 346 ALR 414; [2017] FCAFC 133 (Burragubba) at [141]–[142] and [147]. It follows that a single member, or even a minority of the membership, of an applicant, or a registered native title claimant, cannot claim to exercise the authority of the applicant, or the registered native title claimant, as Ms Kemppi purports to do in this proceeding. That being so, I do not see how she can validly claim to suffer any prejudice in that capacity if this injunction were not granted.

39 When I asked him about these matters, Ms Kemppi’s counsel responded that, while it was not expressly pleaded in her FASC, it was implicit that Ms Kemppi was also acting in her capacity as a member of the Wangan and Jagalingou People. This followed, he said, from the fact that, as he correctly pointed out, a prerequisite for membership of an applicant is that the person must be a member of the authorising native title claim group: see s 61 of the NTA. He also said that Ms Kemppi did not claim to assert any individual native title rights and interests, but instead she was seeking to assert and protect the communal native title rights and interests of the Wangan and Jagalingou People. Even if these matters were open to be considered in the absence of any pleading of them in the FASC, I consider they face a similar difficulty to that outlined above with respect to Ms Kemppi’s minority position in the W & J Applicant and the W & J registered claimant.

40 The ILUA process in the NTA allows those claiming native title rights and interests under the Act to validate a future act which affects native title, that is an act which has the effect of extinguishing it: see s 24AA(3). In this case, that ILUA process was engaged when the Wangan and Jagalingou People authorised the ILUA as an Area Agreement (see Part 2 Div 3 Subd C) under s 251A of the NTA. As has already been remarked above, once the ILUA was registered on 8 December 2017, since it complied with the conditions set out in s 24EB(1) of the NTA (see at [15] above), it was effective to validly extinguish native title according to its terms. Indeed, that is exactly what Adani and the State are seeking to do by activating the Surrender process in cl 9(b) of the ILUA.

41 But Adani and the State are not the only parties to the ILUA. Integral to the ILUA process under the NTA is the consent to an extinguishment by those who hold, or claim to hold, the native title concerned, in this case the Wangan and Jagalingou People. They are an essential party to the ILUA because only they can consent to the removal of the protection of native title provided for under the NTA (see s 11(a)). This is not an issue about Ms Kemppi’s standing as an applicant in these proceedings as discussed by the Full Court in Burragubba at [171]–[177]. Rather, it goes to the validity of her asserted claim to protect a set of native title rights and interests that are held by a community of Aboriginal people, namely the Wangan and Jagalingou People, of which she is a member. Moreover, it goes to the validity of that assertion in circumstances where the community that claims to hold those native title rights and interests, the Wangan and Jagalingou People, has authorised the making of an ILUA under the provisions of the NTA, which ILUA has the critical effect of consenting to the extinguishment of the very native title rights and interests that Ms Kemppi is now asserting she can protect. Hence, Ms Kemppi is not just seeking, by this application, to prevent Adani and the State from acting under the ILUA, she is also indirectly seeking to challenge the decision of the Wangan and Jagalingou People to consent to the extinguishment of their native title rights and interests by means of the ILUA and therefore allowing the State to make the grants to Adani.

42 In all these circumstances, I do not therefore consider Ms Kemppi can validly assert that she is able to protect the native title rights and interests of the Wangan and Jagalingou People in the way she purports to in this application. If that is so, it necessarily follows that she will suffer no prejudice, in this respect, if this injunction is not granted. Put differently, whatever prejudice she may suffer has already been brought about by the decision of the majority of the Wangan and Jagalingou People to authorise the making of the ILUA and therefore the extinguishment of the native title rights and interests in question.

43 It should also be noted that, even if there are defects in the registration process for the ILUA, as Ms Kemppi claims, and that deprives the ILUA of its capacity to validate an extinguishment of native title in the way described above, that will not remove the fact that a majority of the Wangan and Jagalingou People attending the meeting on 16 April 2016 authorised the making of the ILUA and therefore the consequent extinguishment of their native title. Clause 9(i) of the ILUA expressly recognises this fact.

44 However, this does not provide a complete answer on this question because Ms Kemppi has separately pointed to a number of sites, or features, of significance to her and her people that she claims are located within the Surrender Zone for the ILUA. The relevant details of those sites and features have been set out in the affidavits made by Mr Adrian Burragubba and Ms Elizabeth (Lizzy) McAvoy filed in support of Ms Kemppi’s application. Mr Bradley Maher, Adani’s Indigenous Engagement Manager, filed an affidavit in response to those affidavits and then both Mr Burragubba and Ms McAvoy filed affidavits in response to his affidavit.

45 Mr Burragubba is a Wangan and Jagalingou person. In his first affidavit, he described his family and cultural history and set out how he claimed his traditional country would be affected by the Carmichael Project. He described in some detail the stories relating to his country and its features as they had been recounted to him by his father. With respect to the Surrender Area in the ILUA, he described various waterways and creeks that he said would be affected if the Carmichael Project were to proceed. He also referred to some information that had been provided to him by his sister, Lizzy McAvoy. In particular, he said:

My sister has told me that there are birthing trees for the women of her skin along Obgenbeena, Obungeena and Ogungeena Creeks. She told me she is the custodian for these places and they must be respected and not harmed or she will fail in her duty to our ancestors.

46 In the penultimate paragraph of his affidavit, Mr Burragubba summed up his concerns in the following terms:

The Adani project will prevent me from performing my ceremonies in honour of Mundunjara and my Biguns. It will destroy many of my Tree Biguns and remove the spirits of my ancestors from country. It will prevent me from keeping my song lines alive and this will result in the country in the vicinity of the Adani project becoming culturally and physically barren. It will drive Mundunjara from much of the country. The Surrender Area, will be lost for ever, because I will be unable to perform ceremony in honour of Mundunjara. My people will no longer be able to obtain sustenance from the country and my sister’s birthing sites will be desecrated.

47 Ms McAvoy is also a Wangan and Jagalingou person. In her first affidavit, she referred to paragraph 20 of her brother’s affidavit above and said: “I confirm my skin is Oboroogen and there are places within the surrender area for the Adani ILUA which are birthing places for women of my skin”. She then described how she was chosen as the custodian for those sites and described the details of them as follows:

These birthing places are marked by certain trees. They provide cover and shade at the time of giving birth. The trees themselves are sacred to us. They are my Tree Biguns. They provide protection to mothers and newborns from Gundadi who is the evil spirit who will try to take away children and mothers at the time of giving birth when they are most vulnerable. My Tree Biguns provide protection for mothers and babies of our skin no matter where they are, even if they give birth away from our country. This is because women of my skin are connected to our Tree Biguns and birthing places by virtue of our birth. It is my sacred obligation to protect those places and trees so that women of my skin will be healthy in child bearing and our children will survive. In the old days, our old women had our babies there in those trees. They are our trees and they belong to the women of my skin. They are women’s business.

48 She concluded her affidavit by stating that:

My law forbids me to tell of the exact location of our Birthing places. Only women of my skin are permitted to know and go to these places. However, because I fear that Adani intends to destroy my tree Biguns and despoil our sacred birthing places, I have marked on a map showing the surrender area of the Adani ILUA, the general location of some of those places.

49 In his affidavit in response to the two affidavits referred to above, Mr Maher began by pointing out that cl 13.4 of the ILUA excluded all Aboriginal cultural heritage matters from its operation with the consequence that Adani had a statutory cultural heritage duty of care under the Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Act 2003 (Qld). Mr Maher then described two cultural heritage management plans that have been adopted under that legislation by agreement with the Wangan and Jagalingou People: one in 2011 and the other in 2014. He also described in some detail the procedures, including the consultation and negotiation processes that Adani was required to follow with the Wangan and Jagalingou People for the identification and protection of Aboriginal cultural heritage matters in the Carmichael Project area.

50 Commenting on the seven paragraphs of Mr Burragubba’s affidavit which identified sites or features said to be in the Surrender Zone under the ILUA, Mr Maher claimed that the only features described in those paragraphs that were actually located within that Zone were five creeks: Pear Gully, North Creek, Eight Mile Creek, Obungeena Creek and Ogenbeena Creek. However, he claimed that the infrastructure proposed to be constructed within the Surrender Zone would not impact upon Pear Gully, Obungeena Creek or Ogenbeena Creek. He also claimed that there was no risk of damage to the birthing trees along Obgenbeena Creek. I interpose to note that Mr Burragubba actually referred to the Surrender Area throughout his affidavit rather than the Surrender Zone. However, as will appear below, this distinction has little impact on the outcome of this issue. In response to Ms McAvoy’s first affidavit, where she identified the approximate locations of the birthing trees, Mr Maher said that those locations were located in the Surrender Zone, but were not located in the Surrender Areas.

51 In his affidavit in response to Mr Maher’s affidavit, Mr Burragubba said that he did not “have confidence that the Cultural Heritage Management process will identify and protect our cultural heritage within the surrender area”. He also said that, even if that process were effective, it would not preserve his access to those areas to conduct ceremonies, nor to hunt. While he agreed that most of the features or sites he had identified in his earlier affidavit were not within the Surrender Zone, he claimed they would still be impacted by the activities associated with Adani’s Carmichael Project. With respect to the birthing trees, he said that he had been informed by Ms McAvoy that “the construction of the infrastructure will devastate the sacred women’s birthing places for which she is the custodian”.

52 In her affidavit in response to Mr Maher’s affidavit, Ms McAvoy confirmed what Mr Burragubba had said in his affidavit about the birthing trees and she said they were particularly sacred to her. In particular, she said that “the extinguishment of native title over those areas will lead to the desecration of those sites because mothers would no longer be allowed to access them. As a result, Adani will need to find other areas in which to build its infrastructure.” As to the location of the birthing sites concerned, in an apparent contradiction to the statement in her first affidavit above, she said: “I did not identify the location of the birthing sites referred to in my affidavit of 19 December 2017. This was because my ancestors told me not to do so.” She added:

[T]he location of birthing places are women’s business. We are forbidden to reveal the location of these sites to men. The Adani people are all men and I do not have the permission of my ancestors to reveal our women’s business to those men. A man cannot speak over a woman about these places or about this country.

53 Finally, on this topic, in further response to Mr Maher’s affidavit, she said: “Adani needs to exclude lots 1, 3 and 5 from the surrender area, so that I can still access the birthing sites rather than just exclude the areas from any development footprint.”

54 On this aspect, Adani’s counsel made two broad contentions. First, as to the native title rights and interests asserted by Ms Kemppi, he submitted that, even if she does have a valid interest in protecting the native title rights and interests of the Wangan and Jagalingou People as she claims, the likelihood of any damage being occasioned to those rights and interests is significantly diminished by the tiny fraction of the claim area under the W & J application that falls within that area (0.00082 of a percentage). Secondly, he contended that the matters raised by Mr Burragubba and Ms McAvoy would be fully protected under Adani’s cultural heritage duty of care under the Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Act 2003 (Qld). To the extent that any of the sites or features were located in the construction zone for the Carmichael Project, he submitted, pointing to the affidavit of Mr Maher, that Adani will take practical steps to avoid harm to those sites or features.

55 I accept the evidence of Mr Burragubba and Ms McAvoy about the sites and features located within, and within the vicinity of, the Surrender Zone, albeit that it is not clear from that evidence that any of those sites or features are actually located within the Surrender Area. Further, because they are at least located within the vicinity of the Surrender Zone, I accept that they are likely to be affected by the construction works associated with the Carmichael Project. However, as Adani points out, this application is confined to the prejudicial effect of extinguishing native title within the Surrender Area by means of the surrender process under cl 9(b) of the ILUA. It is not concerned with the construction works in the Carmichael Project site more broadly, or even within the Surrender Zone. Insofar as the sites and features identified by Mr Burragubba and Ms McAvoy are concerned, the question therefore is whether they will be adversely affected if that extinguishment is allowed to proceed. In answering that question, I accept the evidence of Mr Maher about the operation of the cultural heritage management plan applying to the Carmichael Project area and the likelihood that it will ensure the protection of those sites and features under the Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Act 2003 (Qld). I also bear in mind the reservations expressed by Mr Burragubba and Ms McAvoy about that process. In the end result, I think the position is this. If any of the sites and features concerned are within the Surrender Area and if the native title in that particular area is extinguished, that could arguably have some consequences for access to, and control of, those sites and features of the kind mentioned by Mr Burragubba in his affidavits, which consequences are not specifically accommodated under the Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Act 2003 (Qld). That being so, the extinguishment that will occur by the operation of cl 9(b) could be said to cause prejudice to Ms Kemppi and her group, including Mr Burragubba and Ms McAvoy. I will therefore take that prejudice into account in determining whether or not this injunction should be issued.

THE PREJUDICE ADANI CLAIMS IT WILL SUFFER IF THE INJUNCTION IS GRANTED

56 On this aspect of the application, Adani relied upon the affidavits of Mr Lezar described earlier in these reasons. Ms Kemppi relied upon an affidavit made by Mr Murray Meaton. Mr Meaton is a resource economist and has been engaged in the past to offer financial advice to various mining projects in Australia. In this respect, it should also be noted that Mr Lezar’s second affidavit responded to Mr Meaton’s affidavit and annexed the Execution Schedule for the Project, the absence of which Mr Meaton remarked on in his affidavit.

57 In his affidavit, Mr Lezar claimed that any delay caused by the grant of this injunction will create uncertainty for the Carmichael Project. He said it is therefore likely to create “a real risk that a financier will delay its decision on whether to fund the Project” and that a delay in obtaining funding will delay the entire Project. He also claimed that any delays caused by the grant of this injunction will cause reputational risks for Adani with contractors and other third parties. He said that, to date, Adani had spent $1 billion on the mine and more than $400 million on the rail and port components of the Project. As is noted above, Mr Lezar annexed an Execution Schedule for the Project to his second affidavit. Under that Schedule, Adani plans to commence construction of the airport in March 2018, the workers’ accommodation village in mid-February 2018, the waste facility in April 2018 and to commence procurement for the telecommunication towers in February 2018. He claimed that if this injunction were to be granted, each of these items would almost certainly be delayed. He said design work on the accommodation facility began in November 2017 and $1 million has been allocated to that work. However, he said that, while a further $18 million has been approved for the design works on the other facilities mentioned above, no money will be expended on those works and no construction will commence until the position is clear with respect to this injunction.

58 Based on Mr Lezar’s evidence, Adani’s counsel submitted that it had established a risk of prejudice that was real and significant if the injunction were to be granted. He also submitted that any delay was likely to be much longer than the six weeks period until trial because allowances would need to be made for the time taken to deliver a decision and to resolve any appeal that may ensue.

59 In his affidavit, Mr Meaton pointed out that the ILUA only applied to a small area of the total project and to a small section of the railway line, that is it did not apply to the 388 kilometres between the mine and the port facility. On the risk posed to the financing of the Project associated with any delay caused by the grant of an injunction, Mr Meaton said that while financiers “will be keenly interested in the ILUA process, they are also capable of separating out [that] … risk”. He therefore claimed that the grant of this injunction “will have very limited impact on [the financiers’] assessment of project risk”. Mr Meaton also claimed that any delay associated with the grant of an injunction was unlikely itself to delay the whole Project because finance has not yet been secured for the Project, and nor have all other necessary approvals. In this respect, he pointed to public announcements made by Adani to the effect that it would make a public announcement by the end of March 2018 as to whether it had secured the finance necessary to fund the Project. Mr Meaton opined that the reputational risk associated with any delay associated with the grant of an injunction was small in the context of the broader community opposition to the Project. In summation, Mr Meaton said that “there will be risk to the project with delays but these are very small, given the length of project development to date (over six years) and the time still needed before operations commence”.

60 In his submissions on this aspect, Ms Kemppi’s counsel contended that the injunction sought is unlikely to create any substantial delay to the Carmichael Project. Among other things, he submitted that that was so because the period for which the injunction will be in place will be reasonably short, given that the trial is due to commence on 12 March 2018.

61 In assessing the prejudice that Adani is likely to suffer if this injunction is granted, first, I accept that, if it is granted, any delay is likely to extend for some months, rather than just the six weeks between now and the trial commencing on 12 March 2018. I also accept that any delay caused by the grant of an injunction is likely to pose some additional real risks for the Project, especially in obtaining finance for it. While I reject Mr Meaton’s dismissal of those additional risks as “very small”, I agree that their impact has to be viewed in the context of all the many commercial and other risks that already exist for the Project. Furthermore, delays in construction projects are notorious. I do not therefore place much significance in a delay of some months in a construction project which has to date been on foot for approximately six years. In short, while the delay risks for the Project associated with granting this injunction are real, in isolation, I would assess their impact as more than very small, but not the significant risk that Adani seeks to attach.

62 Before turning to consider how this conclusion interacts with my conclusion above about the strength of the probability of Ms Kemppi’s ultimate success in this proceeding, there are two further issues that I need to address. They are Ms Kemppi’s refusal to provide an undertaking as to damages and the impact that granting this injunction may have on third parties.

MS KEMPPI’S REFUSAL TO PROVIDE AN UNDERTAKING AS TO DAMAGES

63 With respect to her refusal to provide the usual undertaking as to damages, Ms Kemppi sought to claim there was an “exceptional circumstance” that justified that refusal, namely that she was seeking to prevent the “permanent extinguishment of [her] asserted native title rights and interests in areas of cultural significance”. She called in aid of this contention the decision of Rares J in Weribone on behalf of the Mandandanji People v State of Queensland [2013] FCA 255 (Weribone).

64 On this aspect, Adani contended that the circumstances advanced by Ms Kemppi were not exceptional. It also contended that Weribone was distinguishable and that Ms Kemppi’s refusal to provide an undertaking as to damages was sufficient, in itself, to dismiss her application.

65 I do not consider the decision in Weribone provides any support for Ms Kemppi’s refusal to provide an undertaking as to damages in this application. I therefore agree with Adani’s counsel that the decision in Weribone is plainly distinguishable. In Weribone, the Court itself took the initiative to make the so-called “injunction” orders (see at [56]–[57] and [90]). Furthermore, it is clear from what Rares J said in his reasons that his Honour issued the orders in the public interest and to protect the processes of the Court (see at [68]–[69] and [80]). The orders his Honour made were therefore more in the nature of preservation of property orders than interlocutory injunction orders sought by a party to the proceeding.

66 It follows that, in Weribone, no party actually applied for an injunction order to prevent another party from exercising his, her or its rights pending trial. More significantly, as a consequence, no party actually sought an undertaking as to damages (see at [89]). Indeed, in the highly unusual circumstances that applied, his Honour noted that there was no obvious person who could have been required to provide such an undertaking if one had been sought (see at [88]). The question whether an undertaking as to damages should have been provided only arose at a later stage of the proceeding when the lawyer for one of the disputing parties raised it (see at [78]). All of the quotations from Weribone set out in Ms Kemppi’s submissions were therefore made in this very unusual context.

67 Importantly, however, for present purposes, his Honour did not say in those observations, as Ms Kemppi’s submissions seem to suggest, that a claim to protect native title rights and interests was an “exceptional circumstance” that warranted an applicant for interlocutory injunction not being required to provide an undertaking as to damages. To the contrary, his Honour summarised the effect of the various authorities to which he referred as follows (at [86]):

that the discretion to grant an interlocutory injunction or similar remedy is ordinarily to be exercised only on condition that an undertaking as to damages is offered. If it is not, the Court will proceed very cautiously, but may still consider that it should grant that relief without requiring an undertaking.

(Emphasis added)

68 For these reasons, I propose to proceed with the same heightened caution in this application. In summary, I do not consider there is any special circumstance that justified Ms Kemppi not offering the usual undertaking as to damages in this matter.

THE IMPACT ON THIRD PARTIES

69 On this issue, Ms Kemppi’s counsel submitted that there was no evidence that any third party would be adversely affected by the grant of the injunction sought by her. In particular, he submitted that was so with respect to the interests of the Wangan and Jagalingou People who voted in favour of the ILUA.

70 Adani responded that there was evidence that any delay to the Carmichael Project would, in turn, delay the provision of benefits to the Wangan and Jagalingou native title claim group. That evidence, it claimed, was contained in the affidavit of Mr Carter, where he annexed a document which set out the financial and other benefits the Wangan and Jagalingou People, and entities associated with them, were to receive under the terms of the ILUA and related agreements. It appears from that document that those financial benefits are linked to the commercial production of coal by Adani at the Project.

71 In Samsung, the Full Court remarked (at [68]–[69]) that, in considering an application for an injunction, it may be necessary to “consider and evaluate the impact that the grant or refusal of [it] will have or is likely to have on third persons and the public generally”. However, the Court went on to note that this consideration “will rarely be decisive”.

72 As it turns out in this case, I have effectively taken account of the impact on the absent third party to the ILUA, namely the Wangan and Jagalingou native title claim group, in my assessment of the prejudice Ms Kemppi is likely to suffer if this injunction is not granted. I do not therefore consider it is a matter that I should also take into account separately.

CONCLUSION

73 Taking account of: my assessment of the lack of strength in the probability of Ms Kemppi’s ultimate success in this proceeding; the competing prejudices I have identified above which, while fundamentally different in character, do not, in my view, tip the balance one way or the other; and, most importantly, Ms Kemppi’s refusal to provide the usual undertaking as to damages in support of her application; I consider the balance of convenience and justice in this application does not favour the grant of an injunction to Ms Kemppi to preserve the status quo.

74 For these reasons, I will order that the interlocutory application filed on 1 December 2017 be dismissed.

I certify that the preceding seventy-four (74) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Reeves. |

QUD 194 of 2017 | |

ADRIAN BURRAGUBBA | |

Fifth Applicant: | LINDA BOBONGIE |

NATIVE TITLE REGISTRAR |