FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Registered Organisations Commissioner v Transport Workers’ Union of Australia [2018] FCA 32

ORDERS

REGISTERED ORGANISATIONS COMMISSIONER Applicant | ||

AND: | TRANSPORT WORKERS' UNION OF AUSTRALIA Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT:

1. DECLARES that in contravention of subsection 231(1) of the Fair Work (Registered Organisation ) Act 2009 (Cth) (‘RO Act’), the Respondent failed to keep a copy of the register of members as it stood on each of the following dates:

(a) 31 December 2009 in respect of the New South Wales Branch of the Respondent (the NSW Branch);

(b) 31 December 2010 in respect of the NSW Branch;

(c) 31 December 2011 in respect of the NSW Branch;

(d) 31 December 2012 in respect of the NSW Branch; and

(e) 31 December 2013 in respect of the Western Australia Branch of the Respondent.

2. DECLARES that in contravention of subsection 172(1) of the RO Act (and equivalent provisions of the predecessor legislation), on each of 20,907 occasions, the Respondent failed to remove from its register of members the names and postal addresses of each of 20,907 persons who had not paid their membership dues for a continuous period of 24 month since the amount became payable, within the ensuing 12 months.

3. ORDERS the Respondent to pay a civil penalty of $271,362.36 to the Commonwealth within 21 days hereof.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

PERRAM J:

[1] | |

[4] | |

[5] | |

[16] | |

[24] | |

[28] | |

(b) Failure to purge non-financial members in the NSW Branch | [52] |

[71] | |

[77] | |

[80] | |

[81] | |

[82] | |

(e) The Nature and Extent of any loss suffered by reason of the contravention. | [84] |

(f) Whether the Respondent has been found liable for conduct in breach of the RO Act. | [85] |

[86] | |

[88] | |

[93] | |

[94] | |

[95] | |

(l) Whether the conduct occurred at the level of senior management | [98] |

[99] | |

[100] | |

[105] | |

[113] | |

[113] | |

[114] | |

[115] |

1 The Applicant (‘the Commissioner’) alleges that the Respondent union (‘the TWUA’) has contravened the record keeping provisions of the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Act 2009 (Cth) (‘the RO Act’). It seeks the imposition of civil penalties on the TWUA for these contraventions together with declaratory relief.

2 At the times relevant to this proceeding, the RO Act was administered, not by the Commissioner, but by the General Manager of the Fair Work Commission. Indeed, the proceeding was originally commenced by the General Manager as the applicant. Subsequently, on 11 May 2017, the General Manager ‘transferred’ her rights and obligations to the Commissioner and the Commissioner was then substituted for the General Manager as the Applicant in this proceeding on 6 June 2017. No point was taken by the TWUA about the legal efficacy of these steps which I assume, without in any way deciding, in the Commissioner’s favour. In these reasons, the relevant statutory provisions refer to the General Manager. The Commissioner’s entitlement to pursue the remedies conferred on the General Manager is to be understood in that light.

3 There are four sets of allegations made against the TWUA, two of which are admitted and two of which are denied. For the reasons which follow, I conclude that the TWUA is not liable for the contraventions which it denies. However, it is liable for the contraventions it admits and should pay a pecuniary penalty of $271,362.36 in respect thereof. The Commissioner should also be granted the declaratory relief he seeks. It is useful to begin with the allegations which are denied.

4 The two allegations which are denied both relate to an election which was held in November 2010 for a number of offices in the Queensland Branch of the TWUA. These offices included that of the Queensland Branch Secretary. The first allegation concerns an alleged failure to keep an election roll.

(a) Failure to keep roll of voters as at 17 August 2010

5 A registered organisation such as the TWUA must have a set of Rules (RO Act s 140). The TWUA complied with this obligation and had a set of Rules. Rule 60 of those Rules dealt with Branch elections. By Rule 60(16), the poll for such an election was to open on the second Monday of November 2010 and, by Rule 60(18), was to close some 18 days later. Of particular importance to this case is Rule 60(3a) which provided that ‘[t]he roll of voters is to close at 5 pm on: (a) the third Tuesday of August 2010’. That day was 17 August 2010.

6 The Commissioner contends that the TWUA was obliged to keep a copy of the roll of voters as at that date and that it did not do so (this is not the precise formal allegation made, which I set out later, but it is a useful introductory summary). The provisions said to give rise to this obligation were s 231(2) of the RO Act and reg 148(1) of the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Regulations 2009 (Cth) (‘the RO Regulations’). These provided as follows:

‘231 Certain records to be held for 7 years

(1) An organisation must keep a copy of its register of members as it stood on 31 December in each year. The organisation must keep the copy for the period of 7 years after the 31 December concerned.

Civil penalty: 60 penalty units.

(2) The regulations may provide that an organisation must also keep a copy of the register, or a part of the register, as it stood on a prescribed day. The organisation must keep the copy for the period of 7 years after the prescribed day.

Civil penalty: 60 penalty units.

…

148 Prescribed day for keeping copy of register (s 231(2))

(1) For subsection 231(2) of the Act, the prescribed day for keeping a copy of the register, or a part of the register, is the day provided for in the rules of an organisation, in accordance with subparagraph 143(1)(e)(i) of the Act, as the day on which the roll of voters for a ballot for an election for office is to be closed.

…’.

7 It will be seen that s 231(2) does not refer to the roll of voters. By contrast, reg 148(1) does refer to the roll of voters but only to identify the day in respect of which the record keeping obligation in s 231(2) is to apply. In terms, s 231(2) and reg 148(1) do not expressly say that the TWUA was required to keep the details of the members who were entitled to vote in the election as it stood on the roll closure date. The Commissioner argued, however, that the details of members who were eligible to vote as at the roll closure date were ‘a part of the register’ of members and hence caught by s 231(2).

8 I do not accept this submission. The language used in s 231 makes clear that what is being discussed in s 231(2) is the register of members. What is the register? The RO Act does not directly impose an obligation on a registered organisation to have a register of members but s 141 specifies that a registered organisation must have certain rules and, by s 141(1)(b)(xii), those rules must provide for:

‘141 Rules of organisations

…

(xii) the keeping of a register of the members, arranged, where there are branches of the organisation, according to branches; and

…’

9 In the case of the TWU’s Rules this was done by Rule 15(2):

‘(2) The Branch Secretary of each Branch must keep at the Branch Office a roll of Membership, recording the Membership number, name, address and date of enrolment of each Member enrolled in that Branch.’

10 By Rule 16, there were five Branches of the TWUA: standalone Branches in NSW, Queensland and Western Australia, and hybrid Branches in Victoria/Tasmania and South Australia/Northern Territory. It was therefore obliged to keep a register for each Branch. In this case, the relevant Branch was the Queensland Branch.

11 I do not think that the roll of voters created for a particular election is ‘part of the register’ of members for the purpose of s 231(2) of the RO Act. It is certainly something generated from the register of members but it is not part of that register. It does not fit the description in Rule 15(2) of the TWUA Rules. Further, nothing in the RO Act appears to suggest to the contrary and the idea is supported by practical considerations. In terms of checking the validity of an election, the register of members is more useful than the roll itself as it may show who has not been included in that roll. For example, a financial member who was not included in the roll by oversight will be readily detectable from the register of members. Furthermore, including the roll of voters in the register of members will cause persons to be included in the register twice. I make these observations to show that the interests of democratic process are likely more served by the preservation of the register of members as it was on the day the poll closed than it is by preservation of the roll itself.

12 Mr Jordan of counsel, who appeared for the Commissioner, emphasised the objects of the RO Act set out in s 5 (for example, requiring registered organisations to be conducted on a democratic basis) and submitted that this should colour the construction of the words ‘a part of’ in s 231(2). Accepting as I do the significance of the RO Act’s objects, I do not agree with his proposed construction of s 231(2). Those objects are not furthered by that construction for the reasons I have just given. Further, in my view, the words ‘a part of’ in s 231(2) (and reg 148(1)) refer to the fact that registered organisations frequently have memberships which are separated into different divisions and whose memberships within that divisional structure can be quite distinct.

13 Even assuming that a roll of voters could be ‘a part of’ the register, I do not see how it is established that it must be. For that to be so, there would need to be some requirement for such a roll to be kept within the register of members. But there is no such obligation in the RO Act, the RO Regulations or the TWUA Rules.

14 The Commissioner’s formal allegation about this in the Amended Statement of Claim was as follows:

‘16. The Respondent was required to keep a copy of that part of its register of members that contained the details of the members who were eligible to vote in election E2010/2636 as it stood on the roll closure date for election E2010/2636 for seven years by operation of section 231(2) of the RO Act and Regulation 148(21) of the RO Regulations.’

15 For the reasons I have given, I do not think this allegation is legally sound for there was no obligation on the TWUA to keep such a roll within the register. I therefore reject the Commissioner’s case that a breach of s 231(2) has been established. What is alleged could not constitute a breach of s 231(2). The Commissioner advanced an alternate case in his written submissions that the Queensland Branch had also failed to keep a copy of the register as at 17 August 2010. This submission did not depend on the existence within the register of the roll of eligible voters. As such it could be proved simply by showing that the register had not been kept. However, this written submission did not correspond with the Commissioner’s pleaded case and I do not propose to entertain it. For completeness, an allegation that the register was not produced when requested was pursued, but this involved s 235(2) of the RO Act rather than s 231(2). I deal with that allegation in the next section. If a case had been pleaded that the register had not been kept, or that argument is somehow otherwise available, then I would have found that the register had not been kept as required by s 231(2). There was evidence that a floppy disk had been located in an old safe in a storage room which contained a copy of the register. However, all of this evidence was hearsay and I excluded it. I admitted the same evidence on penalty for reasons explained at [32] below. However, it is not necessary in light of the conclusions I have reached to address the consequences of that state of affairs.

(b) Failure to provide access to the register

16 The second contravention which is denied by the TWUA concerns an allegation that between 29 May 2015 and 12 June 2015 it failed to make available to the General Manager a copy of the register relating to the Queensland Branch as it stood on 17 August 2010 (being the roll closure date, it will be recalled). This is alleged to have involved a contravention of s 235(2) of the RO Act.

17 Section 235(2) provides:

‘235 Commissioner may authorise access to certain records

(1) A person (the authorised person) authorised by the Commissioner may inspect, and make copies of, or take extracts from, the records kept by an organisation under sections 230 and 231 (the records) at such times as the Commissioner specifies.

(2) An organisation must cause its records to be available, at all relevant times, for the purposes of subsection (1) to the authorised person.

Civil penalty: 60 penalty units.

…’

18 The Commissioner relied upon a letter dated 8 May 2015 from a Mr Chris Enright (of the Fair Work Commission) to the National Secretary of the TWUA. At the signing block of the letter Mr Enright described himself as a ‘Delegate of the General Manager’.

19 In the letter, Mr Enright referred to an inquiry into the TWUA which had been ongoing since 5 March 2015 under s 330 of the RO Act. The letter informed the National Secretary that the scope of the inquiry was now to be widened so as to include an investigation into whether the TWUA had been keeping part of its register of members comprised of the roll of voters on the roll closure date for the 7 year periods referred to in s 231(2). It concluded with a section which was as follows:

‘5. Request for information

You are requested to provide the following information by Friday 29 May 2015.

1. A full copy of the part of the register of members that relates to the Queensland Branch as it stood on the day on which the roll of voters closed for the contested election in E2010/2636 under s 231(2) and regulation 148.

2. A list of the names of the persons who were removed from the register of members by the NSW Branch due to being unfinancial for more than 36 months in September 2014 under s 172 set out as follows:

a. the name of the person

b. the date the person became a member of the organisation

c. the date the person became unfinancial for more than 36 months

d. the date the person was removed from the register under s 172.

Should you wish to obtain further information regarding the above please contact Andrew Schultz [email provided] or at [phone number provided].

Yours sincerely,

(signed)

Chris Enright

Delegate of the General Manager’

20 There is no dispute that the register of members as at the roll closure date was not produced to the General Manager at the time it was requested. It is Mr Enright’s request as embodied in this letter that the Commissioner now relies upon to found his allegation of a contravention of s 235(2).

21 The TWUA submitted that no infringement of s 235(2) could be shown. This was because the letter did not purport to require the TWUA to do what it was that s 235(2), in fact, provided for. To read the letter was to see that it did not require the TWUA to make its register available to an ‘authorised person’. In effect, there were three points wrapped up in this submission:

(a) the letter was couched as a request not a requirement;

(b) it did not require the TWUA to cause the register to be available at a specified time. It required a copy of the register to be produced to the Fair Work Commission; and

(c) s 235 required the Commissioner to authorise a person to be the person to whom access was to be granted. No person had been authorised by Mr Enright to be that person. Further, if Mr Enright, as the delegate, was to be that person (which was denied), s 235 did not authorise the delegate to authorise himself to be that person.

22 Propositions (a) and (b) are correct. This was not a case of the General Manager (or the General Manager’s delegate) specifying that the TWUA must make its register available to a nominated authorised person between 8 May 2015 (the date of the letter) and 29 May 2015 (the last date specified in the letter). It was a request by Mr Enright to give him, inter alia, a copy of the register. These are quite different things as the RO Act itself shows. For example, s 236 permits the Commissioner in some circumstances to require the production of a copy of the records of a registered organisation. By contrast, s 235 is about access to, and copying of, records by an authorised person. These are quite different concepts.

23 For those reasons, I do not accept that s 235 was enlivened by Mr Enright’s letter of 8 May 2015. It is not necessary to determine in that circumstance whether Mr Enright could, in his capacity as the General Manager’s delegate, appoint himself as the authorised person under s 235. The result is the same: no contravention of s 235(2) can be established on the basis of Mr Enright’s letter of 8 May 2015.

3. The Admitted Contraventions

24 The TWUA accepted that it had committed two sets of contraventions of the RO Act. The first of these were breaches of s 231(1) which required it to keep for seven years a copy of the register of its members as it stood on 31 December each year. The TWUA admitted that its NSW Branch had not done this for its register as at 31 December 2009, 31 December 2010, 31 December 2011 and 31 December 2012. It also admitted that its WA Branch had failed to do so as at 31 December 2013.

25 The second set of admitted breaches concerned the obligation created by s 172(1) of the RO Act to remove non-financial members from the register of members within 12 months of the date on which they had been non-financial for 24 months. The TWUA admitted that it had failed to do this in relation to its NSW Branch. The number of non-financial members concerned was very large, some 20,949 was the number agreed by the parties in their Amended Statement of Agreed Facts. However, the number of contraventions ultimately pursued by the Commissioner in his written submissions was 20,907 and I propose to act on that number.

26 In respect of both sets of contraventions, the TWUA submitted that it should either be relieved of any penalty under s 315(2) of the RO Act or the penalty should be set at the lower end of the range. As will be seen, I do not accept these submissions.

27 It is useful first to survey the separate factual landscape for each set of contraventions.

(a) Failure to keep register as at 31 December

28 As I have said, the failures in relation to 2009-2012 are those of the NSW Branch whilst the failure in relation to 2013 is that of the WA Branch. By s 305(3) of the RO Act, a contravention of a civil penalty provision by a Branch is taken to be a contravention by the organisation of which the Branch forms part. The obligation on both Branches was imposed by s 231(1) of the RO Act which is set out above at [6]. The power of the Court to impose a civil penalty for contravention of that provision arises from s 306 of the RO Act which provides:

‘306 Pecuniary penalty orders that the Federal Court may make

(1) In respect of conduct in contravention of a civil penalty provision, the Federal Court may make an order imposing on the person or organisation whose conduct contravened the civil penalty provision a pecuniary penalty of not more than:

(a) in the case of a body corporate—5 times the pecuniary penalty specified for the civil penalty provision; or

(b) in any other case—the pecuniary penalty specified for the civil penalty provision.

(2) A penalty payable under this section is a civil debt payable to the Commonwealth. The Commonwealth may enforce the order as if it were an order made in civil proceedings against the person or organisation to recover a debt due by the person or organisation. The debt arising from the order is taken to be a judgment debt.

(3) A person is not liable to more than one pecuniary penalty under this Part in relation to the same conduct.’

29 Also relevant because of the Commissioner’s application for declaratory relief is s 308:

‘308 Other orders

(1) The Federal Court may make such other orders as the Court considers appropriate in all the circumstances of the case.

(2) Without limiting subsection (1), the orders may include injunctions (including interim injunctions), and any other orders, that the Court thinks necessary to stop the conduct or remedy its effects.

(3) Orders may be made under this section whether or not orders are also made under section 306 or 307.’

30 The evidence concerning these contraventions was contained in:

an Amended Statement of Agreed Facts (Exhibit 1);

an affidavit of Timothy Dawson sworn 16 June 2017. Mr Dawson is the Secretary of the WA Branch;

an affidavit of Mr Nicholas Mclntosh sworn 9 June 2017. Mr McIntosh is presently one of the two Assistant Secretaries of the TWU of NSW (as opposed to the NSW Branch of the TWUA);

an affidavit of Wendy Carr sworn 9 June 2017. Ms Carr is the Director of Legal and Operations of the TWUA; and

an affidavit of Mr Christopher Enright sworn 12 May 2017. Mr Enright is the Executive Director of the Registered Organisations Commission.

31 There was another affidavit of Mr Enright of 31 August 2017 but it was not relevant to these particular contraventions.

32 On the topic of penalty, each of the affidavits was admitted in its entirety apart from the last sentence of paragraph 39 of Mr Enright’s affidavit. In that sentence, he sought to annex certain parts of the Royal Commission into Trade Union Governance and Corruption’s (‘Royal Commission’) report. I rejected it because the material contained in the report was, in part, gathered using compulsory powers. It would be unfair to permit such materials to be utilised in a penal proceeding. Otherwise, the parties were in agreement that the present proceeding concerned ‘sentencing’. This mattered because, on that assumption, the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) only applies in a sentencing proceeding if the Court directs that it does (s 4(2)(a)) and I had not done so. There was no suggestion that a proceeding to impose a civil penalty is not a proceeding which relates to ‘sentencing’ within the meaning of s 4(2)(a) and I proceed upon the basis that that assumption is correct. An assessment of the correctness of that assumption might involve a number of matters including s 305(4) of the RO Act:

‘305 Civil penalty provisions

...

(4) The Federal Court must apply the rules of evidence and procedure for civil matters when hearing and determining an application for an order under this Part.

It is not necessary given the parties’ position to pursue this further.

33 Of the witnesses mentioned above, only Mr McIntosh was cross-examined (another witness, Mr Carter, was cross-examined but his evidence was largely only relevant to a matter which I have concluded that the TWUA cannot have contravened as a matter of law). Mr McIntosh was, in my opinion, a reliable witness.

34 The position of the NSW Branch of the TWUA appears to have been this: operating in New South Wales are two legally separate organisations. One is the TWU NSW which is registered as a State union under the provisions of the Industrial Relations Act 1996 (NSW) (‘the State Act’). The other is the NSW Branch of the TWUA, that is to say, the NSW Branch of a federal union registered under the RO Act. The TWUA also has a national office.

35 Mr McIntosh gave evidence that there are a number of operational overlaps between these two NSW entities. These included the fact that one membership fee was paid to enrol as a member of both organisations and that with the exception of three staff members, all staff members perform functions which overlap between the two organisations. He gave other examples too but it is not necessary to set them out.

36 He explained these overlaps, I think, by way of background to evidence he also gave about the primacy of the TWU NSW vis-à-vis the TWUA in relation to industrial matters in New South Wales. He also said that as a matter of historical practice, primacy had tended to have been given in NSW to the TWU NSW’s Rules rather than to those of its federal counterpart.

37 Mr McIntosh had no difficulty explaining that which was within his experience. When it came to the question of what had happened in the NSW Branch with regards to its register, however, Mr McIntosh was not directly involved at the relevant times. The Secretary of the TWU NSW was Mr Sheldon (from 2006 until 2008: T-46-47) and Mr Forno (from 2008 until 2014: T-46). A Mr Olsen was the Secretary of the TWU NSW after Mr Forno. Mr McIntosh also gave evidence that Mr Forno had been the Secretary of the NSW Branch of the TWUA at the same time as he had been the Secretary of the TWU NSW. Mr McIntosh’s cross-examination revealed in addition that Mr Sheldon had been the Secretary of the NSW Branch of the TWUA: T-47. Although Mr McIntosh did not explain this, the documentary evidence establishes that Mr Sheldon was the National Secretary of the TWUA in the years 2009-2015. The National Office of the TWUA had many other senior officers during this period. No attempt was made to identify these people or if they were available to give evidence. None of them gave evidence in this Court. No effort was made to explain who the senior officials of the NSW Branch of the TWUA were during the relevant period, beyond in a glancing way, the role of Mr Forno and to a lesser extent, Mr Sheldon. Mr Sheldon and Mr Olsen were not said to be unavailable. Mr Forno retired in 2014 due to ill health. The nature of his condition was disclosed in Mr McIntosh’s evidence as being Parkinson’s disease. But Mr Forno was not so unwell that Mr McIntosh had been unable to speak to him. Further, the evidence about Mr Forno’s condition only emerged during the cross-examination of Mr McIntosh. No formal evidence about his condition was sought to be elicited by the TWUA. I simply do not know how unwell he is. Mr McIntosh had spoken only to Mr Forno (T-44, T-60) and a Mr Marfatia (but only in 2015) about the matter. The evidence did not disclose in any substantial way who Mr Marfatia was. With respect to the TWUA, the evidence about who was running its NSW Branch at the critical times was surprisingly vague given the magnitude of the civil penalties confronting it. This case is concerned about the consequences which should flow from what are essentially management failures. The absence of any clear evidence about who management actually were or indeed, peering through that curiously self-imposed fog, the failure to call any of them to give evidence, is a striking matter.

38 Be that as it may, Mr McIntosh said that based on his discussions with Mr Forno and Mr Marfatia (and also on some materials put before the Royal Commission), Mr McIntosh believed that what had happened was this:

39 Between 2009 and 2013, the NSW Branch of the TWUA operated a membership system known as ‘Membership Today’. This system was outsourced and each day the system was overwritten by new data. This had the effect that it was not possible to retrieve historical data. In practical terms this meant that although a record was kept of the register on 31 December each year it could only be accessed on that day (or, probably more accurately, until it was next updated). Consequently, as Mr McIntosh explained it, Membership Today did not allow the TWUA to capture point-in-time data. Since it had not kept hard copies of the register on 31 December it had failed to keep the records as required.

40 There was an agreed fact to a similar effect in Exhibit 1 so it seems to me that this explanation should be regarded as uncontroversial. That, of course, explains why an historical record could not be accessed. But it would have been perfectly possible to take a hardcopy of the register on 31 December for each year and to keep it as the record. The question arises: why was that simple step not taken?

41 According to Mr McIntosh, the answer was that the NSW Branch of the TWUA simply did not know that it was required to keep a copy of the register as at 31 December each year. There was no such obligation on the TWU NSW under the State Act and it appears not to have come to the attention of the NSW Branch of the TWUA that it might stand in a different situation. I infer that the primacy of that union’s affairs over those of the NSW Branch of the TWUA goes some of the way to explaining the problem.

42 The problem in the NSW Branch has now been rectified. From September 2013, a new system has been implemented called ‘Members’ Connect’ which keeps a copy of the register as at 31 December automatically. The copy is kept in multiple locations to ensure that it is always available. Since 2 September 2014, there has also been in place a system which is triggered once a member has been non-financial for 32 months with the result that he or she is automatically removed from the membership rolls.

43 That shows that the technical issue of why the register could not be accessed at later times has been solved. But what of the apparent ignorance of the NSW Branch of its record keeping obligations under the RO Act? On that issue the TWUA elicited evidence from Ms Carr, its director of legal and operations, who was not called for cross-examination.

44 She told the Court by way of affidavit that in 2015 the union’s National Office had put in place a system to ensure that Branches were aware of their obligations under the RO Act and in particular the requirement to maintain a register of members. That system consisted of Ms Carr sending an email to each Branch Secretary seeking ‘certain information for the annual return’. This included, apparently, a declaration from each Secretary that they have maintained a register of members in accordance with the RO Act.

45 The actual terms of this email were as follows:

‘Dear Secretaries,

Arising out last weeks NCOM, Secretaries were to provide the following:

1. Membership numbers (all workers on the register of members including unfinancial members) as at 31 December 2013 and 2014;

2. The actual register of members as at 31 December 2014;

3. A signed statement that the register has been maintained in accordance with the Act.

In order for you to provide the statement in point 3, I was to prepare a pro-forma statement for Secretaries so as to satisfy the requirements for National Office to attest to the declaration now required to be signed by National Office as the organisation. To that end I have prepared the statement below which I would appreciate if each of you would fill out and place on your respective letterheads, sign and return to me along with the information to be provided in points 1 and 2. Please note that our return of information is required to be submitted by 31 March however the response to the letter received from the FWC in relation to their investigation is to be provided by 27 March.

I, [Name], being the Secretary of the Transport Workers’ Union [ Branch], declare the following:

1. I am authorised to make this declaration.

2. The register of members for the [ Branch] has, during the immediately preceding calendar year, been kept and maintained as required by s 230(1)(a) and s 230(2) of the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Act 2009 (the Act).

3. The information contained in the records required to be kept in accordance with s 230(1)(b), (c), and (d) of the Act has been provided to the organisation (National Office of the Transport Workers’ Union of Australia) and is a correct record of that information.

Signed:

Dated:’

(errors in original)

46 I accept that this is a systemic way of ensuring that the contraventions do not happen again.

47 Turning then to the position of the WA Branch, the facts seem to be these: the parties were able to agree as a fact that the WA Branch had not kept the register as it was on 31 December 2013 but beyond the admission of the contravention their agreement did not go. It was left to Mr Dawson, the secretary of the WA Branch, to explain the union’s position.

48 Mr Dawson was not cross-examined and there is no reason not to accept his evidence. His evidence was, however, somewhat limited. Having been asked to produce a copy of the register of members as at 31 December 2013, the WA Branch had been ‘unable to locate it’. It had kept a copy of a list of ‘effective members’ but this was not the same thing. Based on discussions with the WA Branch’s Financial Controller and Office Manager he was told that the database in question ‘did not allow us to interrogate it…to produce a copy of the record of registered members as at 31 December 2013’.

49 Mr Dawson was not the Secretary in 2013, the person who was the Secretary was not identified and the person who knew what had actually happened – the Financial Controller – was not identified either. The evidence before the Court is, therefore, from someone who does not know what happened reporting from someone who is not identified. No explanation was proffered as to why the people who do know were not called. Despite that I am able to infer that the breach was not deliberate. No motive for such deliberate behaviour was suggested and the most likely explanation is that what was involved was the software deficiency identified by Mr Dawson. Why the software was deficient and who knew what in the WA Branch have not been revealed in this Court.

50 Mr Dawson was able to say that a new system was implemented in April 2017 called ‘Sugar CRM’ which remains in place. It has the capacity to produce a copy of the register as at 31 December of each year. Mr Dawson also said that both a snapshot and a hardcopy of it are kept. I accept this.

51 Insofar as systems change is concerned, the evidence of Ms Carr above applies to the WA Branch as well.

(b) Failure to purge non-financial members in the NSW Branch

52 Section 172 of the RO Act provides:

172 Non‑financial members to be removed from the register

(1) If:

(a) the rules of an organisation require a member to pay dues in relation to the person’s membership of the organisation; and

(b) the member has not paid the amount; and

(c) a continuous period of 24 months has elapsed since the amount became payable; and

(d) the member’s name has not been removed from the register kept by the organisation under paragraph 230(1)(a);

the organisation must remove the name and postal address of the member from the register within 12 months after the end of the 24 month period.

Civil penalty: 60 penalty units.

(2) In calculating a period for the purposes of paragraph (1)(c), any period in relation to which the member was not required by the rules of the organisation to pay the dues is to be disregarded.

(3) A person whose name is removed from the register under this section ceases to be a member of the organisation on the day his or her name is removed. This subsection has effect in spite of anything in the rules of the organisation.

Note: A non‑financial member’s membership might cease and his or her name be removed from the register earlier than is provided for by this section if the organisation’s own rules provide for this to happen.

53 This was in force from 1 July 2009. Prior to its coming into effect, it was preceded by an identical s 172 in the former Schedule 1 of the Workplace Relations Act 1996 (Cth) which in turn was preceded from 12 May 2003 by an identical s 172(1) of Schedule 1B of the same Act.

54 Contraventions of these Acts between 12 May 2003 and 2 September 2014 are alleged and admitted. It is not disputed that there were 20,907 non-financial members purged by the NSW Branch of the TWUA from its register on 2 September 2014. The precise contraventions were as follows:

Period | Breaches |

12 May 2003 to 27 June 2012 | 18,033 |

29 June 2012 to 27 December 2012 | 513 |

28 December 2012 to 2 September 2014 | 2,361 |

Total | 20,907 |

55 The explanation given by Mr McIntosh was that:

The State Act did not require the removal of non-financial members.

The NSW Branch was unaware of its obligation under s 172 in relation to the TWUA.

The affairs of the TWU NSW and the NSW branch of the TWUA overlapped with the former predominating.

The practice of the TWU NSW was not to remove non-financial members from the register but rather to encourage them to become members again.

All persons who applied to become members of the TWU NSW automatically became members of the NSW Branch of the TWUA.

Membership details were simultaneously entered into the membership lists for both organisations.

A single membership fee was paid for membership of both entities into a single facility.

That facility was operated by the TWU NSW.

The TWU NSW annually remitted a portion of the fees to the NSW Branch of TWUA.

The Australian Labor Party (‘ALP’) is affiliated with the TWU NSW but not the TWUA.

56 There are a number of matters which may be inferred from this. First, the decision (as explained by Mr Forno to Mr McIntosh) to leave non-financial members on the register of the TWU NSW was a deliberate decision. On Mr McIntosh’s evidence of what Mr Forno said, it was made so as to allow the union to follow the course of persuading those whose membership had lapsed to return to the fold. Secondly, whatever was done in relation to membership of the TWU NSW was mirrored by the NSW Branch of the TWUA. This was an aspect of their overlapping functions.

57 It was, I think, faintly suggested by the Commissioner that the reason why the TWUA had left non-financial members on its register was to bolster its membership so as to increase its influence in delegate numbers within the ALP. As Mr McIntosh pointed out, however, the ALP is structured around State unions, not federal ones such as the TWUA. No alternate submission was developed by the Commissioner that the TWU NSW had left its non-financial members on the register to increase its influence within the ALP and that the state of the NSW Branch of the TWUA’s register was the result of its membership being treated in the same way as the State union’s membership. Indeed, Mr McIntosh’s evidence (above) was apparently to the contrary. However, this is a distraction which, even assuming it was raised, need not be resolved. On either view, the action of the State Union (and hence the NSW Branch of the federal union) was deliberate. It does not seem to me to matter much for the purposes of s 172 whether the members were not purged so that they could be tempted back into the fold (as Mr McIntosh told the Court that Mr Forno had told him) or instead to bolster the position of the State union inside the ALP. The point is that the action was deliberate.

58 That is not to say that s 172 was itself breached deliberately. Rather, it is just to say that the action which contravened s 172 was not accidental or merely unfortunate.

59 Mr McIntosh gave evidence that to the best of his knowledge no-one within the NSW Branch of the TWUA was aware of the obligation to purge non-financial members until 2014. There is, however, material which may suggest to the contrary.

60 On 9 October 2009, the Federal Secretary of the National Office, Mr Anthony Sheldon, lodged with the Australian Industrial Registry the following certificate:

‘Workplace Relations Act 1996

Australian Industrial Registry

STATEMENT OF OFFICER OF ORGANISATION IN RELATION TO REGISTER OF MEMBERS

In relation to the requirement that the Transport Workers’ Union of Australia provide information to the Industrial Registry pursuant to section 233(1) of Schedule 1B of the Workplace Relations Act 1996, I declare that:

1. The Transport Workers’ Union of Australia maintained a register of members in accordance with section 230(1) and Section 230(2) of Schedule 1B.

Dated: 9-10-09 | [Signature] Anthony Sheldon Federal Secretary’ |

It will be recalled that Mr Sheldon had been the Secretary of the NSW Branch of the TWUA between 2006-2008.

61 Similar declarations exist for the years ending 31 December 2010, 31 December 2011, 31 December 2012 and 31 December 2013. From these declarations several matters may be inferred. First, the TWUA’s senior management in its National Office during the period 2009-2013 was aware that it had obligations under (successively) Schedule 1B and Schedule 1 of the Workplace Relations Act 1996 (Cth) and the RO Act with respect to its members and these included those in ss 230(1) and (2). They provided:

230 Records to be kept and lodged by organisations

(1) An organisation must keep the following records:

(a) a register of its members, showing the name and postal address of each member and showing whether the member became a member under an agreement entered into under rules made under subsection 151(1);

(b) a list of the offices in the organisation and each branch of the organisation;

(c) a list of the names, postal addresses and occupations of the persons holding the offices;

(d) such other records as are prescribed.

Civil penalty: 60 penalty units.

(2) An organisation must:

(a) enter in the register of its members the name and postal address of each person who becomes a member, within 28 days after the person becomes a member;

(b) remove from that register the name and postal address of each person who ceases to be a member under section 171A, or under the rules of the organisation, within 28 days after the person ceases to be a member; and

(c) enter in that register any change in the particulars shown on the register, within 28 days after the matters necessitating the change become known to the organisation.

Note: An organisation may also be required to make alterations to the register of its members under other provisions of this Act (see, for example, sections 170 and 172).

Civil penalty: 60 penalty units.

62 Secondly, I infer that its senior management in the National Office was aware of this in the period 2003 to 2008. This is because the certificates it lodged were required by law and I assume that the law was complied with in the period 2003 to 2008.

63 One then comes to a difficult question: is it permissible to infer that the senior management of both the National Office of the TWUA and of the NSW Branch of the TWUA were aware of s 172? So far as the National Office is concerned, there is material which supports the drawing of such an inference. It consists of the declarations themselves. Senior management of the National Office knew that there was a law (successively Schedule 1B, Schedule 1 and the RO Act) which imposed rules about the membership register. It knew that the union had to comply with these rules. It certainly knew of s 230. In the absence of evidence to the contrary, I would assume each member of senior management of the National Office was careful and competent. If they knew of s 230 then they knew of s 172 (see the note to s 230(2) which specifically refers to s 172).

64 The position in relation to the NSW Branch of the TWUA is different. There is Mr McIntosh’s evidence to which I have already referred:

‘To the best of my knowledge, no one within the TWUA NSW Branch was aware of the obligation to purge unfinancial members until 2014.’

65 I do not think that Mr McIntosh was lying to me about this. However, there does not appear to me to be any particularly compelling reason why Mr McIntosh, given his background, would know such a thing. Between 2006-2011, Mr McIntosh was employed in an unspecified position within the TWU NSW. In 2011, he was promoted to the Chief Advisor to the then Secretary of the State union, Mr Forno. In 2014, he was elected to the position of South Coast Southern Sub-Branch Secretary for both the TWU NSW and the NSW Branch of the TWUA. He was also elected to the NSW Branch of the TWUA’s Management Committee. It was not until 2016 that he was relocated to Sydney when he resigned his position to become a Campaigns Officer.

66 Much more useful would have been the evidence of Mr Forno and Mr Sheldon. With Mr Forno, one might have explored what he knew of the RO Act and what his relationship was with the National Office, which did know about s 172. None of this is explained. Mr Sheldon is the one who signed the declarations as to the TWUA’s compliance with the RO Act. He could have told the Court that he was, or was not aware, of s 172 at the time he was the Secretary of the NSW Branch of the TWUA.

67 What may be inferred from this? The senior management of the National Office is not the same as the senior management of the NSW Branch of the TWUA. The only overlap which the evidence establishes at the senior level is that constituted by Mr Sheldon. However, he was the Secretary of the NSW Branch of the TWUA between 2006 and 2008 and the National Secretary of the TWUA only after that between the years 2009-2015. Whilst I am satisfied that Mr Sheldon was aware of s 172 in that period, I do not think that I can legitimately infer from that material that he was aware of s 172 (or its equivalents in the Workplace Relations Act 1996 (Cth)) in the earlier period between 2006 and 2008 when he was the Secretary of the NSW Branch of the TWUA.

68 The only evidence about Mr Forno’s state of mind during the period when he was the Secretary of the NSW Branch of the TWUA between 2008 and 2014 is Mr McIntosh’s hearsay evidence that Mr Forno had told him that no-one was aware of the obligation created by s 172. I accept, of course, that Mr Forno did tell Mr McIntosh this. However, I am disinclined to give Mr Forno’s statement much weight given that it has not been tested. That difficulty with Mr Forno’s statement is not alleviated even if one accepts, as I do not, that there may have been sufficient reasons for the TWUA not to have called him to give evidence. Whether that be so or not, the evidence remains untested.

69 There is another integer of relevant evidence. It is Ms Carr’s evidence about the steps she has put in place to ensure compliance with the provisions into the future. It is open to infer from this evidence that some of the State Branches of the TWUA were not complying with the provisions previously. By itself that does not tell one, however, whether these breaches of the provisions occurred because they did not know about them or, instead, because they knew of them but decided to ignore them. Mr Olsen’s position as the Secretary of the NSW Branch of the TWUA relates to the wrong period and does not assist.

70 I do not accept that is open to me to infer that the Secretary of the NSW Branch of the TWUA was aware of s 172 during the period between 2003 and 2013. The evidence only shows that Mr Sheldon became aware of s 172 in 2009, after the time he was the Secretary. The evidence I am prepared to act upon does not show that Mr Forno knew of s 172 either one way or the other. The evidence that Mr Olsen might have given would not matter. The evidence of Ms Carr is consistent with both views. Because I do not know the relationship between the National Office and the NSW Branch of the TWUA, I do not have a sufficient basis to accept that the knowledge of the National Office can be attributed to the NSW Branch. In light of all of that material, I believe I would err in law if I were to infer that either of Mr Sheldon or Mr Forno knew about s 172 during their respective tenures as Secretary. This is not a case of declining to draw an inference which is open; rather, I do not think it is open at all. That being so, although it would have been enlightening to hear what Mr Forno and Mr Sheldon had to say about s 172, the failure of the TWUA to call them does not allow me to fill what is a lacuna in the evidence adduced by the Commissioner. As Dixon CJ observed in Jones v Dunkel [1959] HCA 8; (1959) 101 CLR 298 at 305 ‘[t]he facts proved must form a reasonable basis for a definite conclusion affirmatively drawn of the truth of which the tribunal of fact may reasonably be satisfied.’ I conclude that it is not shown that the NSW Branch of the TWUA was aware of s 172 at the times it contravened that provision although its actions were deliberate in the sense that the Branch intended to leave non-financial members on the register. This is not a case, therefore, where it can be said that the NSW Branch disobeyed s 172 knowing that it was doing so.

4. Approach to Penalties under the RO Act

71 Perhaps unusually for a Commonwealth civil penalty statute, the civil penalty provisions of the RO Act do not offer any guidance on what matters are to be, or may be, taken into account in imposing a civil penalty. However, civil penalty regimes are now common and there is a large body of case law canvassing the different kinds of relevant consideration. Of course, every statute is different and what may be relevant under one may not necessarily make a great deal of sense under another (for example, profit levels and turnover are frequently mentioned as being potentially of importance but they would appear to be of less relevance in the context of registered organisations).

72 Also important are the objects of the RO Act. These include by s 5: encouraging members to participate in the affairs of organisations of which they are members (s 5(3)(b)); encouraging the efficient management of organisations and high standards of accountability to their members (s 5(3)(c)); and providing for the democratic functioning and control of organisations (s 5(3)(d)).

73 Noting those objects, one of the better known catalogues of relevant factors when assessing whether or not to impose a civil penalty was assembled by French J in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Limited [1990] FCA 521; (1991) ATPR 41-076 at [42]. This was in relation to the former s 76 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) but the factors (now referred to as ‘the French Factors’) were confirmed to have continuing vitality under the new s 76E of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (see, e.g., Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd (No 4) [2011] FCA 761; (2011) 282 ALR 246 at 250-251 [11]). In a different context, the civil penalty provisions of the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Act 2006 (Cth) were considered in Chief Executive Officer of Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre v TAB Limited (No 3) [2017] FCA 1296 at [10]. There the Court tailored the French Factors to the specific requirements of that particular record keeping legislation. That case involved a somewhat more severe record keeping regime than that of the RO Act – a civil penalty of $45 million was imposed on the respondent in that case for not complying with its record keeping obligations. Nevertheless, subject to some minor trimming, the factors set out at [10] in that case seem to provide a useful template for the kinds of consideration which deserve, at least, some attention. Some of them were referred to by North J in General Manager of Fair Work Australia v Health Services Union [2014] FCA 970 (‘HSU case’), a case concerning the RO Act and civil penalties.

74 Of course, the absence of a matter from the list does not mean it should not be taken into account. Particular cases may well raise their own individual aspects. But the list is a good place to start:

(a) The Court should address the deterrent nature of a civil penalty. The position of the individual contravenor is to be examined (‘specific deterrence’). Is the registered organisation likely to contravene again? But the position of other registered organisations must be considered too (‘general deterrence’). What must be done in order to ensure that other registered organisations in similar situations will be deterred from contravening?

(b) The penalty must not be seen merely as a cost of doing business. Although this principle is usually most applicable in a commercial context, it is not without application under the RO Act. Some of the record keeping obligations may be onerous and expensive to comply with. The penalty to be imposed should be such that it will be seen that compliance with the RO Act will be a preferable course to receiving a civil penalty.

(c) On the other hand, care must be exercised to ensure that the penalty is not a form of retribution. Another way of putting this is that the penalty should not be oppressive. As the Full Court explained in NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [1996] FCA 1134; (1996) 71 FCR 285 at 293, where a penalty exceeds what the requirements of deterrence demand then it will be, in that sense, oppressive. It does not mean that the Court should not impose civil penalties which are difficult to bear.

(d) The nature and extent of the contravention should be examined and this will include also a consideration of the circumstances in which the contravention occurred.

(e) The nature and extent of any harm caused by the contravention should, if possible, be assessed. In the context of the RO Act, this will naturally invite a consideration of any harm caused to the democratic integrity of the registered organisation arising from the record keeping failure. In an appropriate case, it may extend to a consideration of any loss caused to a particular person or persons. This may include non-pecuniary matters such as the loss of voting rights but may also include dilution of voting rights.

(f) The Court should consider whether the registered organisation has previously been found to have contravened the RO Act.

(g) The extent of the registered organisation’s contrition should be considered. Is it actually sorry?

(h) The Court should assess the maximum civil penalty which could be imposed for the contravention. This is necessary to gauge where the upper limit rests.

(i) The size of the registered organisation should be considered. This is relevant to gauging the extent of the wrongdoing. What may be an understandable oversight in a small organisation may be much more significant in a large one.

(j) The Court should ascertain the financial position of the registered organisation. This is relevant, inter alia, to the issue of specific deterrence and also to oppression.

(k) The deliberateness of the conduct should be considered together with the time over which it extended, including whether the contravention was systematic or covert.

(l) The Court should ask itself whether the contravening conduct arose at the level of senior management or further down the registered organisation’s structure.

(m) The Court should consider the state of the registered organisation’s culture of compliance.

(n) The Court should assess the degree of co-operation exhibited by the registered organisation during the regulator’s inquiries and in the civil penalty proceedings themselves.

(o) Where there are multiple contraventions, the Court should determine whether they are to be seen as a single course of conduct or not.

75 After these matters have been considered, the penalty is to be formulated using the process of ‘instinctive synthesis’ described in Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25; (2005) 228 CLR 357 (‘Markarian’). Lastly, a final check is to be made to ensure that the penalty imposed matches the total wrongdoing involved in the contravention.

76 I deal with each of these in turn.

77 So far as the interests of specific deterrence are concerned, these are, in my opinion, low. So far as the breaches by the NSW Branch of s 172 are concerned, Mr McIntosh gave evidence, which I accept, that a new system was now in place which automatically removes non-financial members after 32 months. In light of Ms Carr’s evidence, I accept that these breaches are unlikely to occur at any other Branch in the future.

78 So far as the contraventions of s 231 are concerned, the TWUA has fixed the problem in NSW and Western Australia. Ms Carr’s evidence satisfied me that these contraventions will not recur.

79 The imperatives of general deterrence will be obvious. Because of the democratic principles underpinning the RO Act (see s 5 above), record keeping under this legislation is a significant matter. The drafting of s 172 of the RO Act gives rise to, in particular, the very real risk of systemic breaches which can, potentially, generate a large liability for civil penalties. It needs to be understood by registered organisations that this is a serious piece of legislation and the apparently mundane obligations it imposes are to be obeyed.

80 There was no evidence as to what the compliance costs involved in the present case were. However, it does not seem likely to me that they were large. This is not a case, therefore, where one needs to be astute to ensure that any civil penalty is pitched adequately to ensure that the registered organisation prefers the penalty to the paperwork.

81 I remind myself that a civil penalty should predominantly serve the two ends of general and specific deterrence and should not be oppressive.

(d) The Nature and Extent of the Contravention

82 In light of what I have said above, the breach of s 172 was widespread and resulted from deliberate conduct. It was done, however, in ignorance of s 172. Some attempt was made by the Commissioner to demonstrate that leaving the non-financial members on the register generated representational difficulties under the Rules. For example, it was said that the ability of a member to requisition a special general meeting was made that much more difficult when the size of the membership was artificially increased by 20,000 or so. Mr McIntosh, on the other hand, described such difficulties as theoretical. Certainly, the Commissioner did not point to any particular instance of an actual problem. I am inclined to regard the breaches as potentially presenting some problems under the Rules although these are unlikely to have been especially grave. Largely, therefore, the effect of the contraventions, at least in the case of the TWUA (as opposed to the State union about which I say nothing) appear to have been neutral.

83 The breaches of s 231 were the result in NSW of oversight. The oversight should not have occurred but it seems no more than an oversight. I do not really know what happened in WA but, as I have already explained, will proceed on the basis that it was an oversight too.

(e) The Nature and Extent of any loss suffered by reason of the contravention.

84 None was suggested.

(f) Whether the Respondent has been found liable for conduct in breach of the RO Act.

85 It has not.

86 I have previously expressed the view that an artificial construct such as a corporation cannot be contrite as this is an emotion which exists exclusively in the human domain: see ACE Insurance Limited v Trifunovski (No 2) [2012] FCA 793 at [113]-[115] (‘Trifunovski’). My view was that it is better to ask simply whether the corporation has changed its behaviour. Generously, Katzmann J accepted the force of those observations in Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Pilbara Iron Company (Services) Pty Ltd (No 4) [2012] FCA 894 (‘Pilbara Iron’) at [34] but nevertheless disagreed that nothing more can be expected of a corporation than that it has changed its behaviour. Her Honour observed at [34]:

‘A corporation may admit its wrongdoing and spare the other parties the costs of prosecuting the case. In a jurisdiction, such as this, where costs can only be awarded in exceptional cases that is a meaningful expression of contrition. The corporation may also offer recompense. It may apologise. The decision-makers themselves could offer apologies. It may introduce precautions to guard against the risk of reoffending.’

I agree with this. My statement in Trifunovski that the only meaningful proxy for contrition in the case of corporate entities was whether there had been behavioural change is too narrowly drawn. The list proposed by Katzmann J is a superior proxy list and I embrace it in favour of my narrower formulation.

87 I accept in this case that the behaviour will not recur. As I detail below, however, I think the TWUA could have been more co-operative than it has been. It is true that it admitted the contraventions as early as it could. My impression is that the TWUA did not regard the contraventions as warranting significant punishment. That attitude was reflected in the application it has made (and which I refuse below) to be relieved from any liability. Into the same category can be put its failure to call Mr Sheldon or Mr Forno or, in the latter’s case, to explain why he was not being called. Also in that category may be put the limited evidence as to what happened in Western Australia. It is surprising in a case which is being put up in the form of admitted contraventions that a statement of agreed facts was not agreed to in relation to all facts (as is common in civil penalty litigation). There is not much saving to the public purse when witnesses still have to be called and cross-examined. As Katzmann J noted in Pilbara Iron, in a costs free jurisdiction such as the present (see RO Act, s 329(1)) this is a material matter. My impression, therefore, is that the TWUA’s contrition is at the lower end of the scale.

88 The prescribed civil penalty for a breach of s 231(1) is presently 60 penalty units. By s 306(1) a penalty up to that amount may be imposed hence it operates as a maximum. For a body corporate this is increased five-fold: s 306(1)(a). The maximum penalty is, therefore 300 penalty units. The prescribed penalty for a breach of s 172(1) is also 60 penalty units; again the maximum penalty will be 300 penalty units. Prior to 29 June 2012, the maximum penalty for a breach of both sections was 20 penalty units yielding a maximum penalty (in the body corporate context) of 100 penalty units per contravention.

89 The value of the penalty unit has inflated over time. Until 28 December 2012, the penalty unit so far as this case is concerned was defined to be $110. On that day, it was increased to $170 at which it remained until 31 July 2015 when it was increased to $180 (see Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) s 4AA; Crimes Legislation Amendment (Serious Drugs, Identity Crime and Other Measures) Act 2012 (Cth) Schedule 3, cl 7; Crimes Legislation Amendment (Penalty Unit) Act 2015 (Cth) Schedule 1, cl 2).

90 A series of decisions in this Court have established that the value of the penalty unit to be applied in formulating a civil penalty is the value at the time of the contravention: Murrihy v Betezy.com.au Pty Ltd (No 2) [2013] FCA 1146; (2013) 221 FCR 118 at 127 [28].

91 In the case of s 231(1), the contraventions occurred on 1 January 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014. It was on each of those days that the TWUA first failed to keep the register. The maximum penalty for each of the first two contraventions, when the RO Act imposed a penalty of not more than 100 units for a body corporate, is therefore $11,000. For the third contravention, when the penalty was a maximum of 300 units and the value of a penalty unit remained $110, the maximum penalty is S33,000. For the last two it will be $51,000 (300 units x $170). The maximum possible penalty for all contraventions is $106,000.

92 In the case of s 172, the situation is complicated by the fact that different numbers of contraventions happened in each year. Further, the maximum corporate penalty was increased from 100 penalty units to 300 units on 29 June 2012. The following table will illustrate the potential maximum penalties involved:

Period | Total | Civil penalty (units) | Penalty unit | Max penalty for single contravention | Total maximum penalty |

12/5/03 to 28/6/12 | 18,033 | 100 | $110 | $11,000 | $198,363,000 |

29/6/12 to 27/12/12 | 513 | 300 | $110 | $33,000 | $16,929,000 |

28/12/12 to 30/7/15 | 2,361 | 300 | $170 | $51,000 | $120,411,000 |

12/5/03 to 30/7/15 | 20,907 | $335,703,000 |

(i) The Size of the Registered Organisations

93 The TWUA is a large and significant national union.

(j) The Financial Position of the Respondent

94 Neither party made a submission about this. The best I can do is take into account what can be gleaned from the 2014 Financial Report. Obviously it is out of date and I will proceed, in that light, with considerable caution. The report suggests that the TWUA made a loss in 2014 of $972,120 which its National Committee of Management attributed to costs associated with the Royal Commission. It recorded net assets of $5,467,934. Given the cessation of the Royal Commission it seems likely that the position of the TWUA has not deteriorated. I treat this as a neutral matter.

(k) The Deliberateness of the Conduct

95 In relation to the NSW Branch of the TWUA, the difficulty with s 231 has been adequately explained. I know what happened and why. The explanation demonstrates that the contravention arose from a systemic failure to acquaint itself with its record keeping obligations under the RO Act.

96 Of course, this is not a case where the records were deliberately not kept. However, in the realm of non-deliberate contraventions, I regard these contraventions as serious. So far as the WA Branch is concerned, I do not really know very much. However, as I have said, I am not prepared to infer that the conduct was deliberate. No motive appears which would provide a sensible reason for thinking the conduct deliberate.

97 The situation is different in relation to s 172. My conclusion is that the names were left on the register deliberately to facilitate members being encouraged to renew but this was done in ignorance of s 172. Given Ms Carr’s evidence it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the National Office should have done more to bring the State Branches up to speed on their obligations under the RO Act, but I do not think that it is open to conclude that the National Office kept the State Branches deliberately in the dark. I prefer the conclusion of human error. Those who understood s 172, the National Office, did not keep the State registers. Those who kept the State registers did not know about s 172 on the evidence before me. The matter fell between two stools. This is not satisfactory but neither is it shown to be deliberate.

(l) Whether the conduct occurred at the level of senior management

98 In relation to the breaches of s 231, Mr McIntosh’s evidence did not identify who was responsible for these systemic failures in NSW which is unhelpful. In effect, however, it seems to me that there were two failures. The first was having a system which could not be historically interrogated. The second, in light of the first, was a failure to create a copy of the register on that date. To be clear about this: even with the defective software, it was still possible to comply with s 231 just by printing the register off on 31 December. Why this was not done was not explained. I was not told who designed the system or who provided the criteria for its operation. I was not told who within the organisation was responsible for the register. However, the material I have referred to above very much suggests that the National Secretary bore some responsibility for it. It was not suggested to me that adequate systems were in place but that somehow junior staff had made some kind of mistake. Rather, I can only conclude that what occurred appears to have been a senior management failure. This analysis applies also to the WA Branch’s failure in relation to s 231 and to the contraventions of s 172 by the NSW Branch.

(m) State of the Culture of Compliance

99 It appears to me that I should conclude that the culture of compliance under the RO Act is now satisfactory in light of Ms Carr’s evidence.

100 I repeat my remarks above in relation to contrition. This matter is to be gauged, in part, by the correspondence between the parties. Contrary to the submissions of the TWUA, I do not regard it as having been completely co-operative prior to the commencement of proceedings or after that time.

101 For example, in its first responsive letter of 8 August 2014 the union denied there was much of a problem and referred to its historical practices: ‘If you have the view that the long-standing approach adopted by the Union is not consistent with the requirements of the RO Act, we would be grateful if you could outline your reasoning and the Union will consider any opinion expressed.’ This was not a co-operative statement.

102 In the section dealing with the accuracy of its reported membership, the union’s position was initially that there was little in the problem: ‘Such error, for the most part, has led to under-reporting of TWU members’ (emphasis in original). This was wrong as is now admitted. Things were a little better in its next letter of 8 September 2014. On the position of the NSW Branch, the National Assistant Secretary said this:

‘The NSW Branch has maintained its membership register in accordance with the Rules of the TWUA of NSW. The membership roll has been maintained in a manner that retained non-financial members albeit maintaining delineation between financial and non-financial members. The requirement of s 172 of the RO Act has never been brought to the attention of the NSW Branch and has been overlooked. The NSW Branch has rectified this omission and removed from the membership register all membership who have been unfinancial for 36 months or more and will continue to do so into the future.’

103 The statement ‘The requirement of s 172 of the RO Act has never been brought to the attention of the NSW Branch…’ strikes me as exhibiting a curious understanding of the union’s obligations under the RO Act. So far as the proceedings are concerned, the TWUA admitted the contraventions in a timely, and indeed voluntary, fashion. But again, although there has been a measure of co-operation, I would not say it can be described as full. Although a statement of agreed facts was eventually put before the Court, it was by no means complete and Mr McIntosh gave evidence to supplement it. The union failed to call several important witnesses on s 172: Mr Forno, Mr Sheldon or someone from Western Australia who had knowledge. The gap that left in the evidence is forensically the Applicant’s problem. But a truly co-operative TWUA would not have left the Applicant with that problem. To do so is not co-operative. That is the TWUA’s right but I am not required to treat the assertion of that right as an act of co-operation.

104 That said, apart from the register of members which the union was unable to produce, it essentially did everything the General Manager, and later the Commissioner, asked of it albeit with a certain, perhaps graceless, tone. It is not, however, to be punished for the tone of its correspondence. In my opinion, its degree of co-operation should be rated as somewhere between the upper levels of poor and the lower levels of average; perhaps, mediocre.

Section 172

105 The Commissioner submitted that I should treat the 20,907 contraventions as a single episode of misconduct but impose the maximum penalty. There is, of course, a question as to which of the three available maximum penalties that would be.

106 The figure of $335,703,000 is the totality of the penalty which could be imposed. The relevant principles in relation to the application of the course of conduct principle are:

(a) the principle applies where there is an interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of two or more offences;

(b) in that circumstance, an offender is not to be multiply punished for what is essentially the same criminality;

(c) it is therefore necessary to identify what the ‘same criminality’ is;

(d) this is a factual inquiry;

(e) identical motive will seldom be sufficient to justify the application of the principle;

(f) the principle guides the sentencing process but does not bind it; and

(g) in particular, a judge is not bound to treat a series of offences arising from a single course of conduct as concurrent offences if the resulting term (or fine) does not reflect the criminality involved.

107 As to each of these, see Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; (2010) 269 ALR 1 at 12-13 [40]-[42] per Middleton and Gordon JJ.

108 One must ask, therefore, whether there is an interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of the 20,907 contraventions of s 172. Plainly, the legal elements are identical. In one sense, the factual elements are identical in that each contravention consists of a failure to remove a non-financial member from the register. But one needs to probe a little deeper. Why was each non-financial member not removed over the 12 year period?

109 It follows from what I have said above that the decision not to remove the non-financial members from the register was done deliberately with a view to being in a better position to persuade them to become financial in the future. But it was done in ignorance of what s 172(1) required. I conclude that this is a case where the legal and factual elements of the 20,907 contraventions are interrelated. The conduct which is to be punished is the conduct of deliberately not removing non-financial members from the register over a 12 year period.

110 I am not bound to treat all 20,907 contraventions of s 172 as a single contravention (although the Commissioner submitted I should). Instead, the Court is but guided by the course of conduct principle. In this case, I do not agree with the Commissioner’s submission. It is true that, often enough, it will be appropriate to punish a single course of conduct as if it were a single contravention. But the underlying and predominant theme is that it is the level of wrongdoing which is ultimately the controlling factor. I take into account that it will often be appropriate to treat course of conduct cases as involving a single contravention. However, this is a case where I propose to depart from the principle. The objective wrongdoing of deliberately not removing non-financial members for 12 years because of a failure to acquaint oneself with one’s legal obligations is, in my opinion, high. It could have been much worse if I had accepted that the NSW Branch of the TWUA was actually aware of s 172. But even so, this is a large systemic failure deriving from an unacceptable ignorance of the TWUA’s legal obligations. Nor, as I note elsewhere, is one dealing here with a small outfit in which such a failing might be explained sympathetically by the size of an office. This is the national union for transport workers in a country the physical size of the United States. The conduct revealed falls far short of what can be expected from such an important union.

Section 231

111 It is appropriate in my view to treat the s 172 and s 231 contraventions separately since they arise from separate failures.

112 It is arguable that the four contraventions of s 231 by the NSW Branch constitute a single course of conduct as they arise from the same failure, viz, a failure to be aware of the statutory obligation. However, to treat all four contraventions as if they were a single contravention would not, in my opinion, capture the full extent of the wrongdoing. I therefore propose to treat them as separate contraventions. The contravention of s 231 by the WA Branch is, however, an unrelated single contravention.

(a) Harm to the members of the TWUA

113 Mr Gibian of counsel, who appeared for the TWUA, and who put the case on its behalf as well as, in my opinion, it could be put, submitted that the inflicting of a penalty on the union would only harm its members. I accept that the imposition of a substantial penalty on the union might well ultimately have some deleterious impact on members either through decreased services or increased fees. However, the punishment of corporate entities with members (such as unions and corporations) always exhibits this quality. I do not think it can really have a substantive impact on punishment. Nevertheless, I do not disregard it.

(b) The Royal Commission and adverse publicity

114 Mr Gibian also emphasised that the TWUA had already been put to a great deal of trouble as a result of these contraventions. It had been exposed to the rigours of Mr Heydon QC’s Royal Commission and its failures had been the subject of much adverse commentary in the media. I accept both of these matters.

6. The Appropriate Penalty and Relief

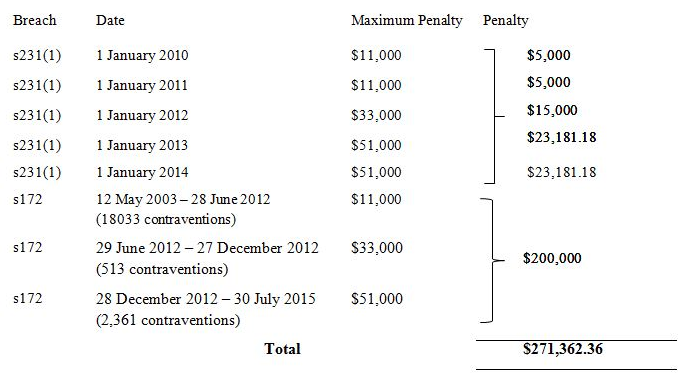

115 I then turn to an instinctive synthesis to formulate the relevant penalties as discussed in Markarian. In my view the appropriate penalties are as follows:

116 I will therefore impose a civil penalty of $271,362.36. I pause to consider, in accordance with the totality principle, whether these penalties fit the overall degree of wrongdoing involved. In my view, they do. I am aware of the penalties imposed by North J in the HSU case. These ranged between $1,237.50 and $22,400. The difference is that North J was not confronted by 20,907 breaches arising from deliberate conduct.

117 The union sought to have the Court exercise the power in s 315(2) of the RO Act to relieve it of liability. There is no need to spend much time on this. At the very least, no such dispensation could be granted unless the Court was of the view that ‘the organisation ought fairly to be excused for the contravention’. I am not remotely of that view.

118 The Commissioner also sought the making of a number of declarations as to the contraventions. These were not opposed by the TWUA although it did query their utility. There will, however, be utility in granting declaratory relief which has the effect of setting out the basis on which liability has been found and the basis for the penalty imposed: Rural Press Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2003] HCA 75; (2003) 216 CLR 53 at 92 [95] per Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v MSY Technology Pty Ltd [2012] FCAFC 56; (2012) 201 FCR 378 at 388 [35]. Accordingly, I will make them as sought.

119 The Commissioner has not sought its costs. It is not necessary to decide, therefore, whether s 329(1) of the RO Act applies to protect the TWUA from a costs order.

120 I make the following orders. The Court: