FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Seiko Epson Corporation v Calidad Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1403

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer, and by no later than 13 December 2017, provide to my associate joint draft short minutes of order reflecting the findings set out in these reasons, including on the question of costs and tracking any areas of disagreement.

2. On or before 19 December 2017, the parties provide written submissions (of not more than 5 pages) setting out the basis on which they contend their position is to be preferred.

3. The matter be listed for case management at 9.30 am on 20 December 2017.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[1] | |

[3] | |

[11] | |

[24] | |

[24] | |

[46] | |

[62] | |

[62] | |

[63] | |

2.4 Summary of steps taken to modify the original Epson cartridges | [70] |

3 PATENT INFRINGEMENT – THE RELEVANT PRINCIPLES AND APPROACH | [75] |

[75] | |

3.2 A patentee’s rights to control the use of patented goods after sale | [80] |

[118] | |

[127] | |

3.5 The legal relevance of the modifications to the original Epson cartridges | [144] |

[144] | |

[146] | |

[161] | |

[179] | |

[179] | |

[182] | |

[200] | |

5 HOW DO THE ORIGINAL EPSON CARTRIDGES EMBODY THE INVENTION AS CLAIMED? | [209] |

[218] | |

[218] | |

6.2 Analysis of the modifications to the original Epson cartridges | [226] |

[227] | |

[227] | |

[238] | |

[247] | |

[247] | |

[256] | |

[260] | |

[260] | |

[264] | |

[266] | |

[266] | |

[267] | |

[269] | |

[269] | |

[275] | |

[278] | |

[278] | |

[280] | |

[284] | |

[284] | |

[285] | |

[287] | |

[287] | |

[289] | |

[292] | |

[294] | |

[295] | |

[295] | |

[306] | |

[307] | |

[312] | |

[329] | |

[329] | |

[335] | |

[346] | |

[367] | |

[367] | |

[369] | |

[371] | |

8.5 Consideration of the availability to Seiko of a civil remedy | [396] |

[419] | |

[419] | |

[422] | |

[428] | |

[428] | |

[432] | |

[438] | |

[438] | |

[440] | |

[441] | |

[447] |

BURLEY J:

1 In the fiercely competitive world of computer printers and ink refills for those printers, the first applicant, Seiko Epson Corporation (Seiko) is a global player. It is a manufacturing company resident in Japan which sells printer products, including printer cartridges, under or by reference to the trade mark EPSON (Epson trade mark). It sells or authorises the sale of printer cartridges (original Espon cartridges) worldwide. The original Epson cartridges embody the invention claimed in the 2 patents in suit; patent no. 2009233643 (643 patent) and patent no. 2013219239 (239 patent). After their sale, the original Epson cartridges are used, and some are obtained by a third party to the proceedings, Ninestar Image (Malaysia) SDN. BHD (Ninestar). Ninestar then refills them with ink. In doing so, it makes modifications to them and then, relevantly to the present proceedings, sells them to the third respondent, Calidad Distributors Pty Ltd (CDP) which imports them into Australia and sells them.

2 The central dispute in these proceedings concerns the right of a patentee to control or limit what may be done with a patented product after it has been sold. This gives rise to consideration of the intersection of the general rights of property ownership in a chattel once sold, and the monopoly rights conferred on a patentee under the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (Act). When a patentee sells a chattel that embodies an invention claimed in a patent, can the patentee restrain the subsequent use made of it by a purchaser or a successor in title to the purchaser? This case explores that question. The case also raises a question under the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (TM Act) as to whether the registered owner of a trade mark is able to bring civil proceedings for the breach of a criminal offence section under the TM Act. Other causes of action that arise include trade mark infringement, an action for misleading or deceptive conduct pursuant to s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)) (ACL) and breach of contract. Seiko and its exclusive distributor in Australia, Epson Australia Pty Ltd (EAP) (referred to collectively as Seiko), bring these proceedings against CDP and three related companies (collectively, Calidad) for each of these causes of action. They contend that the first respondent, Calidad Pty Ltd (CPL), the second respondent, Calidad Holdings Pty Ltd (CHP) and the fourth respondent, Bushta Trust Reg (Bushta) are liable together with CDP as joint tortfeasors.

1.2 Summary of the issues and conclusions

3 The original Epson cartridges are ink cartridges that are sold by or with the permission of Seiko. Eleven different types of these cartridges are relevant to these proceedings. Each is compatible with 1 or more printers. When the ink in an ink cartridge runs out, it is necessary for the cartridge to be replaced. Seiko has a lively, worldwide business that supplies replacement ink cartridges for its printers. Calidad operates a business that competes with Seiko in the supply of replacement ink cartridges for Seiko’s printers in Australia. The Calidad products are sold under 5 different Calidad product numbers (250, 253, 258, 260H and 260S) (Calidad products). Eleven different original Epson cartridges (T0711, 125, 126, 18, ICLM50, 98, 73N, 133, 138, T200 and T200XL) were modified by Ninestar to produce one or other of the Calidad products. To complicate matters, different modifications were made at different times.

4 In relation to its claim for patent infringement, Seiko contends that Calidad infringes the claims of its patents by importing and selling the Calidad products. Calidad accepts that its products fall within the relevant claims of the patents, but submits that it has a complete answer to the allegation of patent infringement based on the fact that Seiko released the original Epson products on the market and, upon their sale, authorised any purchaser and subsequent owner of the cartridges to treat them as an ordinary chattel. More particularly, Calidad submits that Seiko implicitly authorised Ninestar to refill and modify the original Epson cartridges, after which Ninestar was free to sell them to Calidad who was then free to import them into Australia and sell them. In the United States, upon the first sale of a product that embodies a claimed invention, the patent rights in that product are said to be exhausted, which means that the patentee can no longer exert control over the product; Impression Products, Inc. v Lexmark Intern., Inc. 137 SCt 1523 (2017) (Lexmark). In Australia, a different principle has developed which arises from National Phonograph Co of Australia Ltd v Menck (1911) 12 CLR 15 (Privy Council) (National Phonograph). Applying the principles set out in that case, I have found that Seiko’s infringement claim succeeds for Calidad’s past range of products, but not in respect of its current products. In order to explain how this conclusion has been reached, a fairly detailed exegesis is required of the following topics; the relevant law, the patents in suit, the respective original Epson products and Calidad products and, finally, analysis of the modifications made to create the Calidad products. These matters are addressed in sections 2 – 6.

5 Seiko next contends that the Epson trade mark has been used by Calidad on the integrated circuit chip of 2 sample Calidad products, and as a consequence, Calidad has infringed that trade mark pursuant to s 120(1) of the TM Act. In section 7 below, I conclude that the impugned use was not use of the word Epson in a trade mark sense and that the cause of action is not made out.

6 Seiko thirdly contends that Calidad has acted in breach of statutory duty by dealing with the Calidad products in circumstances where the Epson trade mark has been obscured or removed from them. This, it submits, amounts to a breach of s 148 of the TM Act. That section falls within Part 14 of the TM Act, which deals with criminal offences. As a threshold matter, I have determined in section 8 of these reasons that this section of the TM Act does not confer upon Seiko a separate entitlement to sue for breach of statutory duty. In the event that it were so entitled, I have concluded that upon a proper construction of s 148 Calidad has, in any event, not acted in breach.

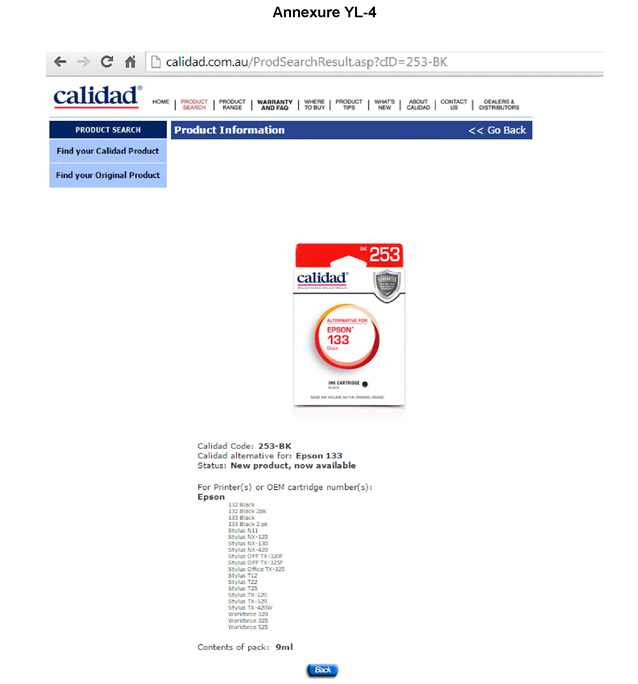

7 Fourthly, Seiko contends that by the use of the word “new” in the phrase “Status: New product, now available” as it appears on a Calidad website, Calidad has engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in breach of ss 18(1), 29(1)(a) and/or 29(1)(c) of the ACL. In section 9 I find that that cause of action is not made out.

8 The fifth cause of action is for breach of a settlement deed entered between 3 of the respondents and Seiko in order to resolve a prior dispute. Calidad admits that CDP acted in breach of a provision of the deed. The only issues requiring resolution are the remedy, if any, in respect of that breach, whether a clause proscribing infringement of the 643 patent has also been breached, and the liability of the other respondents for it. In that regard in section 10 I find that CPL, CHP and CDP have acted in breach of the deed.

9 Finally, in respect of the question of liability of the non-CDP Calidad parties for infringement of the patents, I find in section 11 that each is a joint tortfeasor together with CDP.

10 At this point it is worthwhile to note that in this hotly contested litigation the parties cooperated successfully to limit and refine the issues between them so as to minimise the areas of dispute that require determination. They are to be congratulated. Part of this cooperation resulted in the settlement of a cross claim brought by Calidad. Another led to an agreement between the parties that it was only necessary for the Court to consider one claim of one patent in order to determine the patent infringement issues (being claim 1 of the 643 patent). A further aspect of cooperation was to cut down the number of categories of products that required specific consideration as much as is reasonably possible. That still left some 9 categories of Calidad products requiring consideration, but the task would have been much more cumbersome had the parties not largely agreed on those categories.

11 A number of witnesses were called to give evidence and several of them were cross-examined. No submissions were made to the effect that any witness lacked credibility. In general I found that all of the witnesses endeavoured to assist the Court in their evidence. Except where otherwise indicated below, I have accepted their evidence.

12 Keisuke Nishida is a member of the senior staff of Seiko. He has worked for Seiko since April 1998 in roles including head of development of the printhead of inkjet printers from 1999 to 2003 and the management of Seiko’s intellectual property. He gives evidence about the original Epson cartridges and the equivalent Calidad cartridges, providing photographs of each. In his second affidavit he gives evidence that the memory types of the integrated circuit chips (or memory chips) used in the original Epson cartridges are either Electrically Erasable Programmable Read Only Memory (EEPROM) or Ferroelectric Random Access Memory (FRAM). Mr Nishida was cross-examined with the assistance of a Japanese interpreter.

13 Diane Karam, is the Business Manager for Consumables, Moverio and LabelWorks employed by EAP. She gives evidence about the purchase of samples of the Calidad products in Australia. She was not cross-examined.

14 Yi Lu is a solicitor employed by Allens, the firm representing Seiko in these proceedings. She gives formal evidence about the patents in suit, the Settlement Deed, the website hosted at the domain name calidad.com.au and samples of cartridges and their components relevant to the proceedings. She was not cross-examined.

15 William Greg Hawkins is a recently retired senior engineer who completed a Bachelor of Science in Chemistry with honours from Union College, Schenectady, New York in 1976, a Masters in Science in physical chemistry from Cornell University in 1978 and was awarded a PhD in physical chemistry from Cornell University in 1980. He has held a number of senior research and development positions in various corporations involved, amongst other things, in inkjet technology and his engineering and management experience covers a number of fields relevant to the current dispute, including; device and circuit design, process, circuit and fluidic simulation, packaging, ink development and integration into printheads/maintainability and print driver development. He gives evidence in relation to the process for remanufacturing cartridges, including matters relevant to memory chips, the chip replacement process, the testing of chips, the programming of memory chips, integrating chips with cartridges, refilling ink and other similar and related matters. He also responds to the evidence of Mr Li, Mr Shen and Mr Knight. Dr Hawkins was cross-examined.

16 Fady Anton is a Senior Product Manager employed by EAP. He gives evidence about some sample Calidad products that he purchased in Australia. He was not cross-examined.

17 Vince Di-Mento is the Service Network Manager of EAP. He gives evidence going to the provenance of certain parts of the original Epson cartridges that were put into evidence. He was not cross-examined.

18 Bo Li is a Supervisor Software Engineer within the Research and Development department at Apex Microelectronics Co Ltd (AMC). He received a Bachelor’s Degree in Automation from Hebei University of Engineering in 2011 and since that date has been employed as a software engineer at AMC. In January 2016 he was promoted to his current role. AMC is a manufacturer and supplier of equipment that rewrites the data stored on original equipment manufacturer (OEM) integrated circuit chips that are attached to integrated circuit boards used in OEM printer cartridges. Mr Li gave two affidavits that explain the role of AMC in taking the original Epson cartridges and producing the Calidad cartridges. Mr Li was cross-examined with the assistance of an interpreter.

19 Wei Shen is a production engineer employed by Apex Technology Co Ltd who works at Ninestar in Selangor, Malaysia. He explains the procedure that Ninestar uses to restore used Epson cartridges to working condition for the purpose of their supply to Calidad. He gives evidence that Ninestar is one of the world’s largest manufacturers of generic printer consumables and that it remanufactures used OEM toner and inkjet printer cartridges. Mr Shen has been employed by Ninestar as a production engineer since 2007 and since 2014 he has been in charge of managing the restoration process at Ninestar’s facility in Malaysia. Mr Shen gave two affidavits in the proceedings and was cross-examined with the assistance of an interpreter.

20 David Gordon Gibbons is a director of Recycling Times Media Corporation (China) and has been active in the Australian industry involved in the remanufacturing of used printer cartridges since 1992. He has been a member of the Australasian Cartridge Remanufacturers Association since 1994 and since then has been involved in the provision of educational and consulting services to the global remanufacturing industry. Mr Gibbons was not cross-examined.

21 James Kenyon is a sales manager employed by CDP and the son of the founder of Calidad, Robin Kenyon. He has an Advanced Diploma in Business and Marketing and commenced working at Calidad in about 2004. He gives evidence about the activities of Calidad in relation to the Calidad products. He was cross-examined.

22 Paul Charles Knight is a consultant engineer employed by Marinov Consulting Services. He obtained a Bachelor of Science majoring in Computer Science from the University of New South Wales in 1972 and in 1974 obtained a Bachelor of Engineering (with honours), majoring in electronic design, from the same university. He completed a Master of Engineering Science in 1976. Since 1973 Mr Knight has worked in the field of software engineering. Since 2000 he has worked for Memjet Australia (or its predecessor) which is involved in technologies and components relevant to the computer printing industry and in that year became involved in an ongoing project focusing on the improvement of the speed, efficiency and quality of colour inkjet printing. Mr Knight gives evidence of some background aspects of the technology concerning the component parts of inkjet printers. Much of that evidence was uncontested and forms the basis of the background technology in section 2.1 below. He also gave evidence of his understanding of the disclosure of the patents in suit in the proceedings. He was provided with copies of the affidavit evidence of Mr Li and Mr Shen and gave certain opinions as to the processes involved in converting the original Epson cartridges into the Calidad cartridges. Mr Knight was cross-examined.

23 Philip Kerr is a solicitor employed by Allens. He gave an affidavit proving formal matters relevant to the claim for breach of statutory duty under s 148 of the TM Act. He was not cross-examined.

24 A printed circuit board or integrated circuit board is a non-conductive material (such as plastic or fibre glass) that has electronic components mounted onto it. The electronic components are connected together to form one or more working circuits or assemblies via strips of a conducting material (such as copper), which are printed or etched onto the board (also known as "traces"). A printed circuit board can have multiple layers with traces on both external and internal layers, and internal planes, which are layers of copper internal to the printed circuit board, used to distribute power to the components.

25 The electrical components on a printed circuit board generally include:

(a) traces and (in some cases) internal planes;

(b) pads;

(c) one or more integrated circuits (described further below), which connect to the board via leads; and

(d) discrete electronic components (such as, for example, transistors, capacitors, inductors, light emitting diodes ("LEDs")).

26 Integrated circuits (also known as "chips") are a collection of electronic components arranged on a piece of semi-conductor material (such as silicon). The components are connected in such a way to enable the circuit to control the flow of one or more electrical currents through the circuit in order to achieve some useful function. The components of an integrated circuit are commonly microscopic.

27 The feature that distinguishes an integrated circuit from an electrical circuit more generally is the fact that the circuit is 'integrated', meaning it is a single device containing multiple components rather than an electronic circuit that is built out of discrete components.

28 Piezoelectric devices are devices that are made of certain materials (for instance ceramics or quartz) which mechanically respond when the voltage is applied and removed. They generally require high voltages and both the high voltage requirement and the fact that they respond mechanically when a voltage is applied means that piezoelectric devices are not generally built into integrated circuits.

29 The electrical currents that flow through an integrated circuit and between integrated circuits and/or other discrete components on one or more printed circuit boards often constitute digital information in the form of bits, which are the smallest unit of data, comprising single binary values, either 0 or 1.

30 Integrated circuits (and the boards on which they sit) can be designed to perform a number of different functions. For example, in relation to printers, they can include memory, which stores digital information, and communication devices between the printer and the computer (for example in a Universal Serial Bus (USB), or Ethernet).

31 Short circuiting is a problem for any electrical circuit. Short circuiting occurs when an accidental path is created in an electrical circuit, which results in an electrical current moving down an unintended path. For example, short circuiting may occur if a conductive material (such as metal or liquid) connects two conductors together, resulting in the electrical current flowing from one conductor through the conductive material to the other conductor. Short circuiting can interrupt the electrical signal in the circuits, thereby preventing the circuit from functioning properly. In cases where a high voltage is directed onto a low voltage circuit, this can also cause the components in the low voltage circuit to fuse, thereby rendering it (and consequently the electrical device) unusable. This is because modern integrated circuits, which tend to be powered at quite low voltages, are susceptible to damage from higher than specified voltages.

32 An electronic printer is a device that takes an electronic representation of an image and produces an impression of that image on a medium (such as paper). Printers in the Australian household consumer market generally include inkjet and laser printers. Inkjet printers have a number of very small nozzles through which liquid ink is forced, in the form of small droplets, onto the paper. Laser printers produce an image electrostatically on an intermediate surface. That electrostatic image attracts toner and applies it to the paper, using heat to set the toner onto the paper.

33 Inkjet printers (as well as most other printers) comprise hardware and firmware. Hardware is the physical machinery that exists inside the printer. Firmware is the software or set of instructions programmed onto the hardware. Electronic printers generally also need to be associated with a printer driver, which is a piece of software commonly installed on the computer that is connected to the printer.

34 Inkjet printers can differ substantially depending on the make and model of the printers and there are many different ways of achieving the same result. However, the key aspects that inkjet printers commonly include are:

(a) a power source, which includes a converter that converts the mains electricity (which in Australia is 240 volts) to a lower voltage that is useable by the printer hardware;

(b) a communications interface which provides an electrical or wireless interconnection with a computer (this could be via, for example, USB, Ethernet, Wireless network ("wifi") or Bluetooth technology);

(c) a main processor, which would typically be an integrated circuit on a printed circuit board of the type described above, that handles all the basic system functions that control the printer mechanism and convert the image data into ink ejection control signals.

(d) the main processor will have some memory which may be on the same integrated circuit or an external integrated circuit on the printed circuit board. A memory is an integrated circuit that commonly contains cells that store electrical charge (which represents the binary data that I refer to above) and circuitry to read and write the electrical charge to the cells. The main processor addresses cells to read and write binary data. The pattern of the bits represents the digital data;

(e) one or more ink cartridges (colour inkjet printers commonly utilise four colours, cyan, magenta, yellow and black; the colours will commonly be housed in four separate cartridges, however, others have multi-colour cartridges with separate ink orifices for each colour);

(f) a printhead assembly, which contains the components (including the nozzles referred to above and the heating element or piezoelectric device). The printhead assembly ejects the ink from the ink cartridges onto the page (in some cases the printheads are located in the ink cartridges but in other cases the printheads are located on the printer itself). The printhead assembly, if separate from the ink cartridge, commonly includes a needle designed to pierce the ink cartridge to enable ink to flow, via tubes and sometimes a filter, down to the nozzles, where a heating element or piezoelectric device cause droplets of the ink to be pushed out of the nozzles onto the paper;

(g) a carriage, which holds the ink cartridges and printhead assembly, that is attached to a mechanism to move the carriage (including the ink cartridge and the printhead assembly) along the width of the paper;

(h) a feed paper mechanism, which commonly includes paper input and output trays and one or more rollers and motors that interact to feed the paper through the printer; and

(i) a control panel to allow the user to interact with the operation of the printer.

35 Depending on the sophistication of the inkjet printer, it may also have a number of sensors to detect (for example):

(a) whether the ink cartridges are installed in the printer;

(b) the ink levels in the printer cartridges;

(c) whether the lid of the printer is open or closed;

(d) whether there is paper in the input tray;

(e) whether there is too much paper in the output tray; and

(f) whether there is a paper jam in the printer.

36 There are various types of sensors used in relation to inkjet printers such as optical, mechanical and piezoelectric device sensors.

37 There are many ways in which the information about the remaining ink levels can be stored. However, a common way as at December 2005 (priority date) and today was to store the remaining ink level information on an integrated circuit on the printer cartridge itself. These types of integrated circuits are called EEPROM, and form part of a non-volatile memory family. The data stored in the memory in this family can be retained by the integrated circuit even when it is not powered (another example of a type of memory that falls into this class is a flash drive, also known as a USB memory stick).

38 By storing the information about the ink levels in a memory on the printer cartridge, the information about how much ink is in the printer cartridge is transportable with the cartridge, so the ink information is retained even if the cartridge is removed and replaced or moved to another printer.

39 Having memory on the ink cartridge itself also allows physically identical ink cartridges containing different amounts of ink (for instance small, medium and large volume cartridges) to be sold and used in the same printer. This is because the available ink volume can be determined from information written to the memory on the cartridge.

40 Storing the information concerning the ink levels on an integrated circuit on the printer cartridge requires a communication protocol to be established between the memory on the cartridge and the main processor in the printer. This is because it is the main processor that contains the firmware capable of receiving, processing and re-writing the data onto the memory on the cartridge. The only function of the memory on the cartridge (at least in this context) is to store information and communicate it back to the main processor when prompted. The main processor may also have the ability to re-write the information on the memory. The information on the memory is stored as bits, i.e. as a series of binary numbers (0s and 1s), which is described above.

41 Generally, the communication protocol involves the following:

(a) to read data from the memory on the cartridge, the main processor sends a request to the memory on the cartridge over a data line. The memory responds by sending the requested data back to the main processor over the same data line, which enables the main processor to determine the binary values that are stored on the memory on the cartridge;

(b) for the main processor to write data to the memory on the cartridge, the main processor sends a request which includes the data to be written to the memory on the cartridge over the same data line referred to above. This causes the hardware within the memory to alter the charge pattern written into the memory cells, i.e. the binary values that are stored on the memory on the cartridge.

42 Estimating the amount of ink that remains in the cartridge in the manner described above can involve the main processor tallying the number of (for example) pages printed or ink drops ejected intermittently (for example at the end of the print job or at the end of each page). The main processor then sends a communication to the memory on the cartridge, which re-writes the binary value that is stored in the memory, representing the new estimated ink level.

43 Estimating the amount of ink that remains in the cartridge using a sensor can involve the main processor intermittently interrogating the sensor on the printer cartridge to determine if the ink level is above the threshold.

44 In some cases, once the ink levels reach a particular threshold level, the firmware in the main processor will recognise this and prevent the print job from occurring. The main processor will not allow the print job to occur until an ink cartridge is installed whose memory indicates an adequate level of ink. This means that, even if the used ink cartridge is refilled, if the data stored on the memory on the cartridge still indicates an inadequate ink level, the main processor will recognise the ink cartridge as empty and will prevent the print job from occurring.

45 In addition to storing binary code about the ink levels, the memory on the cartridge may also have fields that relate to other information that is communicated to and interpreted by the main processor in a similar manner to that describe above. This could include, for example, the type of ink, the colour of the ink, the brand of the cartridge, the date of manufacture etc. The memory could also contain a field relating to the serial number of the cartridge, which would enable the main processor to determine when a cartridge has been changed.

2.2 The original Epson products

46 The original Epson cartridges are cartridges sold by or with the permission of Seiko and have the Epson model numbers T0711, 125, 126, 18, ICLM50, 98, 73N, 133, 138, T200 and T200XL. They contain an integrated circuit chip mounted on or connected to a printed circuit board (or integrated circuit board). Different models of the original Epson cartridges have different types of memory chips located on the rear of the integrated circuit boards, and have differing compatibility with Epson printers.

47 Original Epson cartridges are designed so that a printer with which they are compatible is able to read and process the data in the memory chip. The memory chips store information regarding the printer cartridge, such as the volume of ink, the status of the cartridge, its date of manufacture and model number. Each category of information is stored in its own memory address on the memory chip.

48 The functions of the integrated circuit chip on the original Epson cartridges attracted significant attention during the course of argument. Dr Hawkins’ affidavit evidence addressed those functions. His opinions on the subject were largely uncontested, and are summarised in part below.

49 A memory chip is one of the integrated circuit chips in a computer or other piece of electronics whose function is to store information. It is comprised of an array of individual memory cells, each of which stores a single bit of information. It also has peripheral circuitry surrounding the memory cells. The original Epson cartridges use either EEPROM or FRAM memory chips. These represent non-volatile memory, which means that (unlike volatile memory chips) data stored in the memory is retained even if power is removed from the chip.

50 Information is stored on a memory chip as binary data in the form of a series of 1s and 0s. Each such 1 or 0 is known as a “bit”, which is the smallest unit used for data. Each bit is stored on a unique physical location in the memory chip, that is, each memory cell contains one bit. One particular electrical state at a physical location would be interpreted as a 1 and another electrical state at that location would be interpreted as a 0. With EEPROMs, the presence of electrons at a physical location on the memory chip would be at interpreted as a 0, while the absence of electrons at that location would be interpreted as a 1. For FRAMs, data is stored on a capacitor (that is, a stack that has a lower electrode, a layer of piezoelectric material such as PZT (lead zirconate titanate), and an upper electrode) that has a ferroelectric insulator between the capacitor plates. The ferroelectric insulator material contains many charged irons that are present in 1 of 2 locations within the ferroelectric material, and as a consequence, the capacitor is polarised in 1 of 2 directions to represent either a 1 or a 0. The polarisation is retained when no voltage is applied to the capacitor.

51 The memory chips in the Epson cartridges have two different modes, “normal” mode and “test” mode. When in operation in the printer, a printer cartridge’s chip will be in normal mode. The “test mode” is accessed when testing the chips after manufacture and when certain types of data in certain types of Calidad products is re-written.

52 The primary function of a memory chip in an ink cartridge is to keep track of ink in the ink cartridge. It is important for the printer to know how much ink remains in the ink cartridge. There is a high risk that some of the inkjet printhead channels will not be re-primed by the printer’s maintenance station if the ink is depleted to the point that the inkjet channels are emptied. While it is sometimes possible to recover such a de-primed printhead, the recovery takes a lot of ink and is not always successful. If the printhead cannot be recovered, then a new printer or printhead would need to be purchased or print defects would have to be accepted by the user.

53 Inkjet printers can print either a single drop size or a small number of different drop sizes. The printer’s electronics count the drops fired to determine how much ink has been used. The amount of ink used is monitored and then periodically entered by the printer into the memory chip on the ink cartridge. The printer prevents printing from taking place after the printer determines from the memory chip in the ink cartridge that the ink remaining on the cartridge has fallen below a threshold amount.

54 There are several additional benefits attached to tracking the quantity of ink used on the cartridge integrated circuit chip. One is to alert the printer user that the ink cartridge is getting close to empty. Another is to allow information regarding ink quantity to be transferred to any compatible printer in which the cartridge is used. Further, memory chips on ink cartridges often contain information about the original size of the ink supply (for example, whether it is a regular or high-capacity cartridge), the expiration date of the cartridge, and the length of time since the cartridge was first inserted into the printer, which may assist in determining whether the printer has been idle for a long period of time, which would affect reliability.

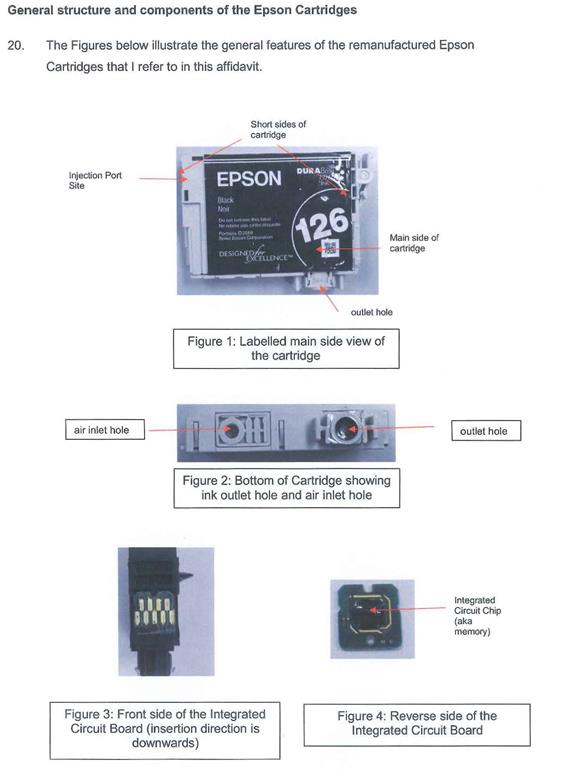

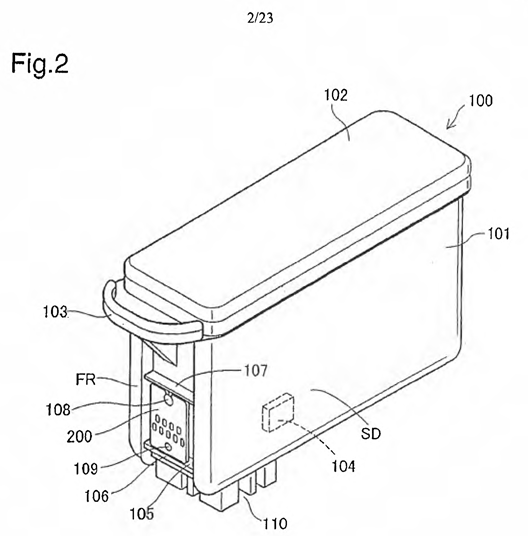

55 The description that follows is taken from the evidence of Mr Shen, who in his first affidavit includes some photographs of an Epson cartridge bearing the number “126” in order to illustrate the processes that Ninestar uses to refill those cartridges with ink. The figures below were included in Mr Shen’s evidence to illustrate the general physical features of an original Epson cartridge which was subsequently the subject of the Ninestar remanufacturing process which led to the Calidad product.

56 The cartridge is rectangular in shape and is roughly 6.5 cm long, 1.1 cm wide and 4.7 cm high. Figure 1 includes the words “Injection Port Site” and an arrow pointing to the left hand side of the cartridge. An injection port is added by Ninestar as part of its refilling the process, but is not present in the original Epson cartridge. In the original Epson cartridge there is an outlet hole towards the right of the base of the cartridge that protrudes about 7 millimetres, as the arrow notes.

57 Figure 2 depicts the base of the cartridge. One can see an air inlet hole on the left and an outlet hole on the right.

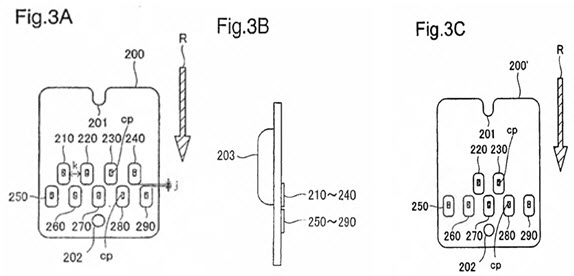

58 The lower portion of the right hand side of the cartridge is depicted in Figure 3. The photograph depicts the facing surface of an integrated circuit board. The circuit board contains two rows of contact points, with 4 in the upper row, and 5 contact points in the lower row. It may be seen that the integrated circuit board is a single unit that has been attached to the cartridge. Figure 4 shows the reverse side of the integrated circuit board after it has been removed from the cartridge. It may be seen that the integrated circuit chip (also known as “memory”) is located on the reverse side of the integrated circuit board.

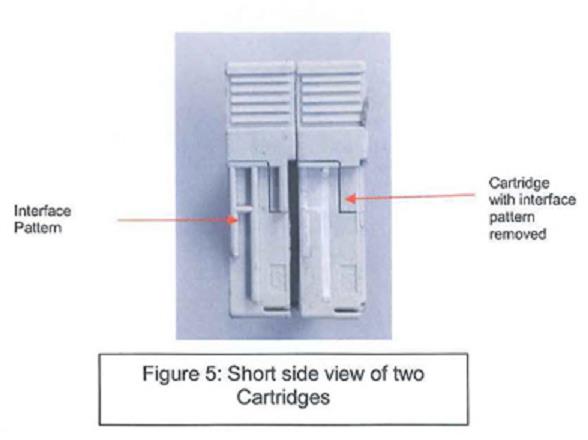

59 Figure 5 (below) depicts an “interface pattern” located on the left hand side (looking at Figure 1) of the cartridge which takes the form of 3 vertical ribs that project downwards on the side and one horizontal rib joining the first 2 of the ribs. The image on the left hand side of Figure 5 shows the pattern as it originally appeared. The image on the right hand side of Figure 5 shows a cartridge after Ninestar has removed this pattern.

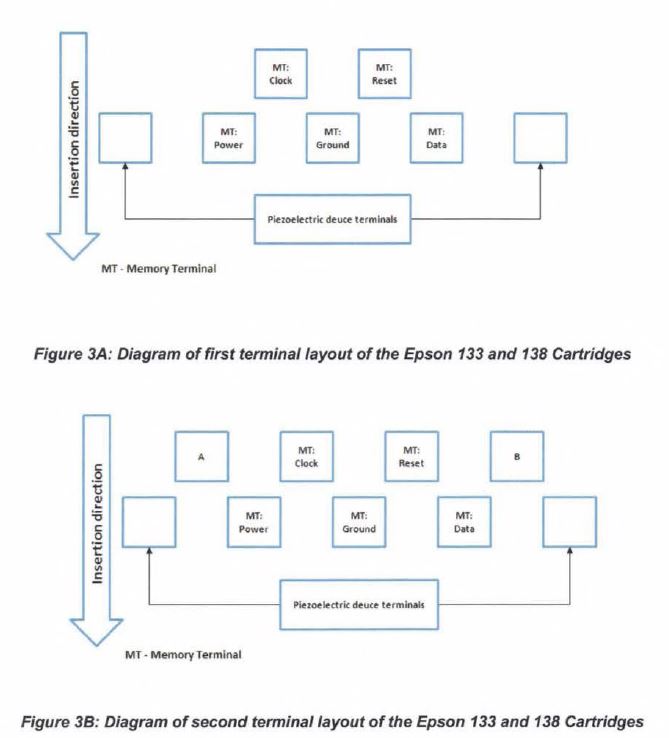

60 All of the memory chips in the original Epson cartridges are connected to the integrated circuit board via terminals. The terminals include; a 3.3 volt power supply, a ground, a reset terminal which enables the printer, via a communications agreement, to return the memory to its idle state, and clock and data terminals, which enable the transfer of the communication signals between the chip in the printer. Many of the cartridges (except the Epson T200 cartridges) also have a piezoelectric sensor which is used to detect the ink level in the cartridge. The piezoelectric sensor requires 2 terminals which are applied with 36 volts to drive the piezoelectric sensor. The arrangement of terminals differs slightly from one Epson cartridge to another, but not in a manner which is material to the issues in dispute. The terminal arrangement for the Epson 133 and 138 cartridges is set out in the evidence of Mr Li as follows:

61 In the case of the Epson T200 cartridge, in lieu of the piezoelectric sensor is a prism at the base of the cartridge to determine when the ink level has dropped below a particular level. Instead of having 2 terminals relating to an ink sensor, the terminals relate to a common resistor with 62K resistance. However, the arrangement of terminals is not materially different to that of the other Epson cartridges.

62 The process of modifying or converting the original Epson cartridges to Calidad products is described in the evidence of Mr Shen and Mr Li, who were cross-examined in some detail, the result of which was to provide a good picture of the work that was performed. The evidence of Dr Hawkins addresses a number of steps that would be necessary in order for the Calidad products to be produced, focusing in particular on the memory chips. His evidence particularly addressed first, the research and development work that would be necessary to convert a used original Epson cartridge into a Calidad product. This involves research and development and resetting or rewriting of the software contained in the memory chips. Secondly, the work that would be necessary in order to reset or rewrite the information contained in the memory chips in order to permit converted original Epson products to operate as Calidad products. Although Dr Hawkins evidence was stated primarily at a theoretical level, Mr Li and Mr Shen, insofar as either had knowledge of the matters to which Dr Hawkins evidence related, frankly and openly confirmed most of the matters that he had surmised. Ultimately, the parties were not in substantial dispute about the steps taken by Ninestar to modify the Epson products. In section 6 below I return to make findings as to the particular steps taken in respect of each original Epson cartridge converted into a Calidad product.

63 Ninestar, and AMC are related companies that are collectively owned by Apex Technology Co Ltd (Apex). Apex recently acquired Lexmark, a global technology company that provides imaging and output solutions.

64 Ninestar is one of the world’s largest manufacturers of generic printer consumables, which include toner and inkjet printer cartridges. It has been operating for over 13 years and supplies products to over 100 countries. Ninestar’s products include Epson printer cartridges that were originally sold by Seiko and which, once used and discarded by the customer, are collected by third parties and restored by Ninestar to working condition. Cartridges of this type are the subject of the present proceeding. In addition to restoring Seiko printer cartridges, Ninestar also restores cartridges originally made by other original equipment manufacturers including HP, Canon, Brother, Lexmark and Dell.

65 AMC is a manufacturer and supplier of equipment that rewrites the data stored on OEM integrated circuit chips that are attached to the integrated circuit boards used in OEM printer cartridges at the time of first sale. The equipment made and supplied by AMC can be used to rewrite the data stored on different OEM chips, including those that are attached to integrated circuit boards on Canon, HP, Samsung and Epson printer cartridges. AMC also manufactures and supplies replacement integrated circuit chips that are compatible with OEM printer cartridges and may be substituted for the OEM chips on integrated circuit boards. These Mr Li refers to as “compatible chips”. Mr Li gives evidence that AMC is one of the largest manufacturers of compatible chips for printer cartridges in the world. He gives evidence that he supervises a team of 5 people who are responsible for all software engineering research and development work related to both compatible chips and the equipment used to rewrite the data stored on OEM chips.

66 There is no dispute that the original Epson cartridges have been sold by or with the permission of Seiko.

67 Ninestar, for a fee, obtains used original Epson cartridges from third party suppliers who have collected them. It is unclear on the evidence whether the third party suppliers acquired the cartridges from the original consumers of the original Epson cartridges or otherwise obtained them, perhaps by collecting them from recycling bins. I find that it is likely that a portion of the original Epson cartridges have been sold or given by the consumers to the third party suppliers, and that otherwise they have come into the hands of the third party suppliers by a variety of means, including, perhaps, collection from recycling facilities.

68 At the time when Ninestar acquires the original Epson cartridges, the information on the memory chip records that the cartridge is “used” such that when it is inserted into a compatible printer, the printer will not work because the information conveyed from the memory chip to the printer is that the cartridge is empty.

69 In order to be refilled and made available for sale the steps set out in detail in the table at [73] below must be taken. Broadly, for a re-filled cartridge to work, it is necessary to reconfigure or rewrite the information on the memory chip so that when it is inserted into a compatible printer, the information in the memory chip does not indicate that the cartridge is used or empty.

2.4 Summary of steps taken to modify the original Epson cartridges

70 The Calidad parties admit that CDP has imported, offered to sell, sold and/or otherwise disposed of and kept for the purpose of doing those acts in Australia the following, which are the Calidad products:

(a) Calidad 250 cartridges;

(b) Calidad 253 cartridges;

(c) Calidad 258 cartridges;

(d) Calidad 260H cartridges (high capacity volume); and

(e) Calidad 260S cartridges (standard capacity volume).

71 Calidad products are supplied to Calidad by Ninestar and promoted in Australia as remanufactured Epson cartridges. They are compatible with certain Epson printers which are sold by or with the permission of Seiko (compatible Epson printers). The parties accept that in broad terms there are 4 steps undertaken by or with the approval of Ninestar in the modification of the original Calidad cartridges to make each Calidad product. However, Calidad contends that two significant aspects of the modification work performed are irrelevant. The first is the preparatory research and development work conducted by or on behalf of Ninestar in order to determine how to make modifications to the contents of the memory chip. The second is the change brought about to the contents of the memory chip. The 4 broad steps are:

(a) the preparation of the cartridge for ink refill (preparation);

(b) the refilling of the printer cartridge with ink not supplied by Seiko or with Seiko’s approval (refilling processes);

(c) the replacement, reprogramming or resetting of the memory chip (memory replacement/reprogramming);

(d) the research and development work in order to make alterations to the contents of the memory chip when it is in either “normal mode” or “test mode”.

72 Some of the steps have changed over time for each model of the Calidad cartridges and there are some variations on the steps which are applied to different models. As a consequence, there are 9 different categories of Calidad product reflecting, in broad terms, the types of work performed leading to a Calidad product.

73 Set out below is a table listing each Calidad product, the original Epson product from which it was derived and, in summary form, the steps taken by Ninestar to produce the Calidad product. To a substantial degree there was no dispute between the parties as to the modifications conducted. The only exception lies in Category 2 step (3), which is addressed further in section 6.4 below. A difference of principle emerges between the parties as to the relevance of the research and development processes. That is not a dispute as to fact, but rather as to the legal significance of those processes.

No. | Type of modification | Calidad model / type |

Current (all cartridges sold after April 2016, excluding the Calidad 260H referred to in Category 1) | ||

Category 1 | (1) Preparation (2) refilling processes + (3) Reset in normal mode; (4) Normal mode R&D processes+ | Calidad 260 Std (originally Epson T200) Formerly, Calidad 260H (originally Epson T200XL) |

Category 2 | (1) Preparation (2) Refilling processes + (3) Reset/reprogram in test mode for ink level, cartridge status (4) Test mode R&D processes + | Some Calidad 253 (originally Epson 133) Some Calidad 258 (originally Epson 138) |

Category 3 | (1) Preparation (2) Refilling processes + (3) Reset/reprogram in test mode for model number, ink colour, ink level, cartridge status and date of manufacture (4) Test mode R&D processes + | Some Calidad 253 (originally cartridges other than Epson 133) Some Calidad 258 (originally cartridges other than Epson 138) |

Category A | Cartridge categories 2 or 3 above, without the gas membrane cut (95% of cases) | 5% of Calidad 253 and Calidad 258 cartridges |

Former (all cartridges sold before April 2016) | ||

Category 4 | (1) Preparation (2) refilling processes + (3) Chip replacement process (4) Compatible chip R&D processes + | Calidad 260H (originally cartridges other than Epson T200XL) |

Category 5 | Same as category 4 cartridges which have also had interface pattern cutting process | Some Calidad 250 |

Category 6 | Same as categories 2 or 3 plus interface pattern cutting process | Some Calidad 253 Some Calidad 258 |

Category 7 | Categories 5 or 6 cartridges plus replace integrated circuit assembly | Some Calidad 250 imported in 2014-2015 Some Calidad 253 imported in 2014-2015 Some Calidad 258 imported in 2014-2015 |

Category B | Cartridge categories 5, 6, or 7 above, without the gas membrane cut (95% of cases) | Some Calidad 250 Some Calidad 253 Some Calidad 258 |

74 It is necessary later to consider in more detail the modifications made by Ninestar, but before doing so I turn to the legal context in which the modifications must be considered.

3. PATENT INFRINGEMENT – THE RELEVANT PRINCIPLES AND APPROACH

75 Seiko places the original Epson cartridges on the open market and sells them. They are then used for the purpose for which they are intended, and subsequently, Ninestar acquires some of the used cartridges. Ninestar then refills them with ink. In the process of doing so, it makes modifications whereupon they become what has been defined in the proceedings as the Calidad products. CDP then acquires those products, imports them into Australia, offers them for sale and sells them.

76 There is no dispute that the original Epson cartridges and the Calidad products possess all of the essential features of claim 1 of the 643 patent. However, Calidad contends that it does not infringe the patents because it is the beneficiary of a licence. It submits that after selling the original Epson products, Seiko’s rights to control the subsequent use of them is, in effect, exhausted. This, it submits, arises from National Phonograph. It submits that a presumption arises from a sale of products that embody an invention that, upon sale, full rights of ownership are vested in the purchaser unless conditions are imposed by the patentee. It submits that in the present case no such conditions have been established and, as a result, Calidad does not infringe. In the alternative, Calidad submits that a patentee’s exclusive rights under s 13(1) of the Act do not include the right to prevent the owner repairing or refurbishing a patented product, or have subsequent dealings in that repaired or refurbished product (including importation). The relevant question under s 13 is whether a “new” product, as distinct from a repaired or refurbished product, has been manufactured and dealt with by the alleged infringer. This will be determined as a matter of fact and degree. In the present case, Calidad submits that the work done by Ninestar does not amount to a “making”. In this respect, Calidad relies on United Kingdom authority, and in particular Schütz (UK) Ltd v Werit (UK) Ltd [2013] UKSC 16; (2013) 100 IPR 583 (Schütz) and United Wire Ltd v Screen Repair Services (Scotland) Ltd [2001] RPC 24 (House of Lords) (United Wire).

77 Seiko’s response is that Calidad infringes the patent because it has, without authorisation, imported and sold the Calidad products, not because it has “made” them. The only defence potentially available to Calidad lies in an implied licence. Two implied licences are potentially available to a defendant who has acquired a patented product. The first arises from a sale sub modo - a sale made in the absence of restrictive conditions within National Phonograph. It submits that such licences extend only to the “use” or “re-sale” of a product and do not extend to remanufacturing of the type done by Ninestar or the subsequent importing of that product by Calidad. Seiko further contends that even if there were potentially an implied licence that extends to a making or importation, the original Epson cartridges contain certain “in-built restrictive conditions” in the form of limitations on the manner in which the memory chip operates which act to limit the licence, and these limitations put Ninestar and Calidad on notice that the work done by Ninestar is not authorised. Seiko also contends that any implied licence does not travel with the goods once they have been discarded by the user and collected by persons who subsequently sold them to Ninestar. In this context, Ninestar is not a purchaser, and cannot benefit from any licence.

78 The second implied licence, Seiko submits, is an implied licence to repair a patented article. That licence does not emerge from Australian authority, but may be understood by reference to the United Kingdom decision in Solar Thomson Engineering Co Ltd v Barton [1977] RPC 537 (Solar Thomson). In Australia, the Schütz and United Wire decisions have no application. Further, Seiko submits that to the extent that the Court decides to follow the line of authority represented by United Wire and Schütz then, in any event, the modifications made to the original Epson products to result in the Calidad products do not involve a “repair”.

79 Before turning to consider factual matters, it is necessary first to consider the principles relevant to the consequence of a patentee selling a product that embodies a claimed invention that is subsequently modified and then imported into Australia and sold.

3.2 A patentee’s rights to control the use of patented goods after sale

80 The exclusive rights of the patentee pursuant to s 13(1) of the Act are, during the term of the patent, to exploit the invention and to authorise another person to do so. The definition of “exploit” in the Dictionary (Schedule 1 to the Act) is:

exploit, in relation to an invention, includes:

(a) where the invention is a product – make, hire, sell or otherwise dispose of the product, offer to make, sell, hire or otherwise dispose of it, use or import it, or keep it for the purpose of doing any of those things; or

(b) where the invention is a method or process – use the method or process or do any act mentioned in paragraph (a) in respect of a product resulting from such use.

81 The exclusive right to “use” a product the subject of a patent means that upon sale or resale of a product the patentee will have continuing control of the use. The purchaser of a chattel such as a garden hose or a fishing rod which is the subject of a patent can never consider himself or herself to be entitled to all of the usual incidents of ownership, because the patentee could impose limitations on his or her “use”. However, there is a level of impracticality about this arrangement. It creates a tension between the notion that the purchaser of a chattel is its owner who can deal with it as he or she wishes, and the notion that a patentee can continue to have control over any use to which the chattel may be put after sale. Historically, 2 competing theories were developed to address this tension, both of which operated to confer on the purchaser of the fishing rod untrammelled rights to use it as its owner.

82 One arises from the notion that upon a first authorised sale of a chattel by or with the approval of a patentee, the patentee exhausts all patent rights in the subject matter of its invention. This is often called the “exhaustion of rights” doctrine. This is the approach that has been adopted for many years in the United States and which was recently confirmed by the United States Supreme Court in Lexmark. The other is that there exists an implied licence to use a chattel in any manner in which the purchaser desires upon purchase, unless the patentee imposes conditions at the time of sale. Both of these theories were considered in the influential decision of National Phonograph. The majority in the High Court (National Phonograph Co of Australia Ltd v Menck (1908) 7 CLR 481) favoured an approach that broadly adopted an exhaustion of rights approach. On appeal to the Privy Council ((1911) 12 CLR 15), this was overturned and an implied licence approach was adopted, in the manner set out below.

83 In National Phonograph the National Phonograph Company (NPC) sold Edison records that were made “in accordance with, and under the protection of, the letters patent” (at 17). That is, the records embodied the invention claimed. NPC’s business model was to sell its records to intermediaries (“jobbers”) under contracts that enabled them in turn to sell them to dealers. The dealers were themselves subject to contracts with NPC which imposed restrictions upon how they could sell the records. It was a term of the dealer contract that if the dealer was removed from the list of authorised dealers, then he could no longer sell, deal in or use, either directly or indirectly, the records. The defendant had his name removed from the list of dealers and yet declared that he was free to dispose of the goods as he wished. He was found not to have acted in breach of any contract, but was nevertheless bound not to make use of the patented products in any way inconsistent with restrictions imposed by the patentee of which he was given notice.

84 The relevant part of the dispute concerned whether the rights conferred upon a patentee pursuant to s 62 of the Patents Act 1903 (Cth), which gave the patentee full power, sole privilege and authority to “make, use, exercise, and vend the invention”, entitled the patentee to constrain Mr Menck (the question of importation did not arise).

85 In the High Court, the majority found that a patentee is not entitled to impose conditions upon the sale or use of patented articles separately from any contract that it might have with a subsequent purchaser. This conclusion arose from a survey of the law of England and the United States as it stood at the time of the decision (that is, 1908), and the conclusion was that neither demonstrated a clear line of authority (7 CLR at 518 per Griffiths CJ). The majority favoured the view that it is an elementary principle of the law of personal property that the owner of chattels has an absolute right to use and dispose of them as he or she thinks fit, and that no restrictions can be imposed upon this right, except by positive law or by contract. The right asserted by NPC depended on whether the words “use” and “vend” in s 62 of the Patents Act 1903 (Cth) imposed such a restriction. Chief Justice Griffiths, as one of the judges in the majority, found that neither term could be construed, on the authorities, in such a way as to warrant a deviation from the elementary principle and broadly found that a patentee exhausts all patent rights upon the first sale of the goods.

86 NPC appealed to the Privy Council ((1911) 12 CLR 15), which overturned the decision of the High Court, Lord Shaw delivering the judgment. The Privy Council found that it was not in question that the elementary principle that an owner may use and dispose of ordinary goods as he or she thinks fit remains correct. It recognised that there exists a tension (referred to as a “difficulty” at page 22) between that principle, and the right of property granted under the Patents Act by way of monopoly “to make, use, exercise, and vend the invention … in such manner as to him seems meet”. The tension was reflected in the two separate and conflicting strands of reasoning between the majority in the High Court (Griffiths CJ, Barton, and O’Connor JJ) and the dissentient judges (who, on this point were Isaacs J and possibly Higgins J). The former found that upon sale of a chattel the subject of a patent, the product “passed out of the limit of the monopoly”. The latter preferred an analysis whereby any conditions imposed by the sale by the patentee simply ran with the goods.

87 The Privy Council rejected both approaches. Lord Shaw said (at 23 to 24, emphasis added):

There is no doubt that, if the doctrine contended for by the appellants and affirmed by the dissentient Judges in the Court below were to be given effect to, namely, that the conditions imposed by the patentee run with the goods, a radical change in the law of personal property would have been made. But if that latter view be an extreme view, and if the restriction upon alienation, use or otherwise of the chattel purchased, be a restriction arising from the fact that the person who has become owner has done so with the knowledge brought home to him of the limitation of his rights of alienation or otherwise, then there seems to be no radical change whatever.… These limitations are merely the respect paid and the effect given to those conditions of transfer of the patented article which the law, laid down by Statute, gave the original patentee power to impose.

88 It is relevant to one of the present arguments that in this passage the Privy Council emphatically rejected that conditions imposed by a patentee “run with the goods”. The Court adopted the language of licence. It said (at 24):

It may be added that where a patented article has been acquired by sale, much, if not all, may be implied as to the consent of the licensee to an undisturbed and unrestricted use thereof. In short, such a sale negatives in the ordinary case the imposition of conditions and the bringing home to the knowledge of the owner of the patented goods that restrictions are laid upon him.

89 It was in this way that the Privy Council was able to reconcile the tension that it had earlier identified. It did so by adjusting “the incidence of ownership of ordinary goods with the incidence of ownership of patented goods in such a manner as to avoid any collision of principle” (at 22). In its conclusion (at 28) it said (emphasis added):

In their Lordships’ opinion, it is thus demonstrated by a clear course of authority, first, that it is open to the licensee [of the patentee], by virtue of his statutory monopoly, to make a sale sub modo, or accompanied by restrictive conditions which would not apply in the case of ordinary chattels; secondly, that the imposition of these conditions in the case of a sale is not presumed, but, on the contrary, a sale having occurred, the presumption is that the full right of ownership was meant to be vested in the purchaser; while thirdly, the owner’s rights in a patented chattel will be limited if there is brought home to him the knowledge of conditions imposed, by the patentee or those representing the patentee, upon him at the time of sale. It will be observed that these propositions do not support the principles relied upon in their absolute sense by any of the Judges of the Court below. On the one hand, the patented goods are not, simply because of their nature as chattels, sold free from restriction. Whether that restriction affects the purchaser is in most cases assumed in the negative from the fact of sale, but depends upon whether it entered the conditions upon which the owner acquired the goods. On the other hand, restrictive conditions do not, in the extreme sense put, run with the goods, because the goods are patented.

90 It is to be noted that in this and other passages, the focus is upon the owner’s rights in a “patented chattel”. That is, the physical embodiment of the invention, as defined by the claims.

91 Contrary to the view of Griffiths CJ in the High Court, their Lordships did not consider that the law so stated was at all novel. They considered that it arose from a clear lineage that could at least be traced to statements of Lord Hatherley LC in Betts v Willmott (1871) LR 6 Ch App 239 (Betts v Willmott). In that case it was held that if the owner of a patent manufactures and sells the patented article in France, the sale carries with it a licence to use the article in England. Lord Hatherley LC said (at 245):

…unless it can be shewn, not that there is some clear injunction to his agents, but that there is some clear communication to the party to whom the article is sold, I apprehend that, inasmuch as he had the right of vending the goods in France or Belgium or England, or in any other quarter of the globe, he transfers with the goods necessarily the license to use them wherever the purchaser pleases. When a man has purchased an article he expects to have control of it, and there must be some clear and explicit agreement to the contrary to justify the vendor in saying that he has not given the purchaser his license to sell the article, or to use it whereever he pleases against himself.

92 It is particularly relevant to the present case that this passage identifies that the implied licence arising upon the sale includes a licence upon the part of a person who has acquired a patented product abroad to import it into the country. Here, Ninestar acquired the original Epson cartridges abroad, modified them and then CDP acquired those products from Ninestar and imported them into Australia for subsequent sale.

93 As to the nature of the right of the patentee to limit subsequent use, the Privy Council endorsed the following reasoning of Farwell J in British Mutoscope and Biograph Co Ltd v Homer (1901) 1 Ch 671 (British Mutoscope) at 673 – 674 (emphasis added):

… it has recently been held in Incandescent Gas Light Co. Ltd. v Brogden that a purchaser who buys with knowledge of the conditions under which his vendor is authorised to use the patented invention is bound by such conditions, and that such conditions are not contractual, but are incident to and a limitation of the grant of the license to use, so that if the conditions are broken there is no grant at all.

94 This passage provides an indication that whilst the patentee may impose restrictions upon a purchaser or subsequent title holder of the patented product, the licence does not arise strictly from contract but rather as an incident of the nature of the patent rights.

95 The Privy Council in National Phonograph moved on to approve the observations of Cozens-Hardy LJ in McGruther v Pitcher (1904) 2 Ch 306 at 312 who remarked that in an action by a patentee claiming an injunction to restrain an infringement of patent it is open to the defendant to plead a licence by the plaintiff. His Lordship said:

That license may be express, or it may be implied from the sale by the patentee of the patented article, but, if the defendant pleads a license, then it is competent for the plaintiff to reply, “The license which I granted is a limited licence, and you, the person who has now got the patented article, were aware it was only a limited licence, and you cannot therefore defend yourself against my claim for an infringement of my patent, because you are going outside the license which to your knowledge I gave with reference to this article”.

96 It is apparent from this passage, as well as from the passage quoted from page 28 of National Phonograph in [89] above that the onus lies upon the patentee to establish that upon sale, conditions limiting the use that may be made of the patented product are notified to the owner, and that in the case of any subsequent owner, they too have notice prior to coming into ownership.

97 On the facts of National Phonograph the defendant was not free to deal with the goods as he wished, because the NPC had given him notice of restrictions that it wished to impose upon any dealings with goods. Despite having acquired the patented records, that notice was sufficient to constrain the defendant. The conclusion of the Privy Council was as follows (at 28-29, emphasis added):

Applying these principles to the present case, the result is this: the respondent, Mr Menck, has been acquitted of every charge of violation of contract which was laid against him by the appellants. He has also succeeded in showing that the claim made by the appellants as patentees was in its nature extreme and unsound in law. But he made this mistake: he assumed that, being guiltless of violation of contract, he was as free as an ordinary member of the public who had acquired possession of articles embodying the appellants’ patent. His misfortune, however, consists in this, that by the very fact that he entered into contractual relations with the appellants, he has become seized with the knowledge of the conditions on which they dispose of their goods, and he is not free to propone the plea that such conditions have not been brought home to him. When he therefore announced his intention to deal in these articles as ordinary articles of commerce, he must be held to have pursued a mistaken course, the course of treating himself as an unrestricted instead of a restricted trader. In this particular case the result may involve some hardship to him, but their Lordships cannot see their way to a departure from the principle that a restriction rests upon a purchaser of goods which are covered by a grant of patent, and which have come into the possession of a purchaser in the full knowledge of the restrictions imposed by the patentee upon their disposal.

98 Accordingly, there is a presumption that a sale sub modo (sale without restriction) confers an unrestricted right of use upon the purchaser or subsequent owner of the patented product, which covers at least the rights to import, use and dispose of the product. To avoid this consequence, a patentee must make a sale subject to limitations which are effective to restrict the importation, use or disposal of the product by the purchaser or successor in title to the purchaser. It must show that notice of any restriction was brought to the knowledge of the purchaser at the time of sale.

99 In T. A. Blanco White’s Patents for Inventions, 4th ed (1974) at 3-219 (Blanco White) the learned authors say (emphasis added):

A sale of a patented article made by a patentee gives to the purchaser, in the absence of notice to the contrary, license under the patent to exercise in relation to that article all the normal rights of an owner, including the right to resell. It follows that in order to establish infringement the patentee must prove that alleged infringing articles were not made by him, either here or abroad [citing Betts v Willmott at 242, 244]. The position is the same where the article has been made in the United Kingdom under license from the patentee, or (it would seem) where in any other way it comes upon the United Kingdom market with his consent;… The implied license extends to repair of the article bought - to the “prolonging of its life” - but not to renewal under pretence of repair; for repair is one of the normal activities of an owner, but sale of one patented article gives the purchaser no license to make himself others.

100 In Interstate Parcel Express Co Pty Ltd v Time-Life International (Netherlands) BV (1977) 138 CLR 534 (Interstate Parcel) the High Court referred to National Phonograph in obiter dicta. In that case, a bookseller imported books from an American wholesaler and sold them in Australia. In response to an allegation of copyright infringement, the bookseller submitted that it took the books free of any restrictions, relying on National Phonograph. Justice Gibbs quoted (at 540) the first sentence of the passage in Blanco White set out above, and also the following passage from 10-104, as summarising the decided case law in relation to implied licences upon sale of patented products:

In the absence of any express term to the contrary, when a patented article is sold by or with the consent of the patentee (or the proprietor of a registered design) the purchaser will take it together with a full license to deal with it as if it were not patented. Further, any person into whose hands it may later come is entitled to assume that such a full license has been given with it; it makes no difference that he may later discover that this was not so, if he was ignorant of it at the time of purchase.

101 After setting out aspects of the reasoning of the Privy Council in National Phonograph, Gibbs J expressed doubt that the conditions that may be imposed by a patentee conformed with normal principles of licences, but nevertheless, noting that the long line of distinguished judges had concluded that it was so, accepted that it was indeed the consent or licence of the patentee to use the article that might be implied from the sale (at 542). Justice Stephen considered that such a licence arises from the “quite special case” of the sale by a patentee of patented goods, which turned upon the unique ability which the law confers upon patentees of imposing restrictions upon what use may, after sale, be made of those goods (at 549). His Honour said (at 549 - 550);

But, to ensure that consequence despite the existence, albeit in the instance unexercised, of this power on the patentee’s part, the law treats the sale without express restriction as involving the grant of a license from the patentee authorising such future use of the goods as the owner for the time being sees fit. The law does this because, without such a license, any use or dealing with the goods would constitute an infringement of the patentee’s monopoly in respect of the use, exercise and vending of the patent. A sale of goods manufactured under patent is thus a transaction of a unique kind because of the special nature of the monopoly accorded to a patentee; the license, whether absolute or qualified, which arises upon such a sale is attributable to the existence and character of that monopoly.

102 It follows from the principles set out in National Phonograph and as subsequently interpreted that, if a restriction of the right to use was not imposed as a condition of the purchaser’s acquisition of the goods, but at another time or by some other means is sought to be imposed by the patentee, it is not effective.

103 This was the view taken by Jacob J (sitting in the United Kingdom Patents Court) in Roussel-Uclaf v Hockley International Ltd [1996] RPC 441 (Roussel). In that case, the patentee, Roussel, made a pharmaceutical product in France and supplied it to a Chinese joint venture company. The defendant, Hockley International, an English company, acquired the product directly or indirectly from the Chinese company. The European law of patent exhaustion did not apply, because there was no relevant sale inside the European economic zone. Hockley International relied upon the National Phonograph principles in asserting that it took the product free of any restrictions. Justice Jacob found that it did, and stated the applicable principle as follows (at 443):

It is the law that where the patentee supplies his product and at the time of the supply informs the person supplied (normally via the contract) that there are limitations as to what may be done with the product supplied then, provided those terms are brought home first to the person originally supplied and, second, to subsequent dealers in the product, no license to carry out or do any act outside the terms of the license runs with the goods. If no limited license is imposed on them at the time of the first supply no amount of notice thereafter either to the original supplyee (if that is the appropriate word) or persons who derive title from him and turn the general license into a limited licence.

104 That reasoning was adopted by Arnold J in HTC Corporation v Nokia Corporation [2013] EWHC 3247; [2014] RPC 19 at [156].

105 Justice Jacob confirmed that Roussel, as the patentee, must establish the relevant restriction (at 443), and accordingly, bore the onus. In relation to the supply by Roussel to the Chinese company, Roussel relied upon a practice of labelling the goods with restrictions as to re-export. However, the Court held that it had not established that the particular products in question bore those labels, or that a restriction was imposed or brought home by any other means (at 443 - 444). Accordingly, no conditions were imposed on that subsequent supply.

106 In relation to supply to Hockley International, Roussel relied upon a letter sent directly by Roussel to Hockley asserting that the products were subject to conditions as to sale and use. Justice Jacob considered that this was not a restriction imposed as a condition of Hockley’s acquisition of the products; the time for imposing such condition having passed with the making of the contract of supply (at 444):

Next I turn to the position of the defendants as subsequent supplyees. Had it been brought home to them that there are such conditions? In a sense it is virtually impossible to do this once it has not been established that it was not brought home to the original purchasers. What is relied upon is indeed the letter which I have just quoted. That says in the previous sentence: “it is not correct that our client’s technical grade material is freely available to the world market without conditions as to its use”. That is a pretty opaque way, if it be intended, to say that there is a positive imposition of a limited permission to use. … The question is not whether the market is grey or any other colour or shade, but whether or not conditions of a limited licence were imposed when the product was first supplied by Roussel. This letter of 24 December 1993 does not convey to the defendants that the product was originally supplied subject to a limited licence.

107 The essence of the licence is that it arises automatically upon the unconditional sale of the patented product. The patentee must act to negative the licence if limitations are to apply.

108 National Phonograph was recently considered and applied by Dowsett J in Austshade Pty Ltd v Boss Shade Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 287; (2016) 118 IPR 93 (Austshade). In that case, at [80], his Honour drew the following conclusions in relation to the application of National Phonograph:

80. The decision in National Phonograph establishes three primary propositions:

• First, the principle applicable to ordinary goods bought and sold is that the owner may use and dispose of those goods as he or she thinks fit. Notwithstanding any agreement which such owner may have made with the person from whom he or she bought the goods (by which he or she is bound contractually), he or she is not bound, in his or her capacity as owner, by any restrictions concerning the use or sale of the goods. Hence it is, “out of the question” to suggest that any such restrictive conditions run with the goods. The rights of an intermediate owner in that “capacity” are to be distinguished from the contractual arrangements which may bind him or her in dealing with the person from whom the goods were acquired. The point is that the intermediate owner may give to his or her purchaser, good title to the goods, notwithstanding any contractual restriction imposed upon the intermediate owner at the time of his or her acquisition of the goods.